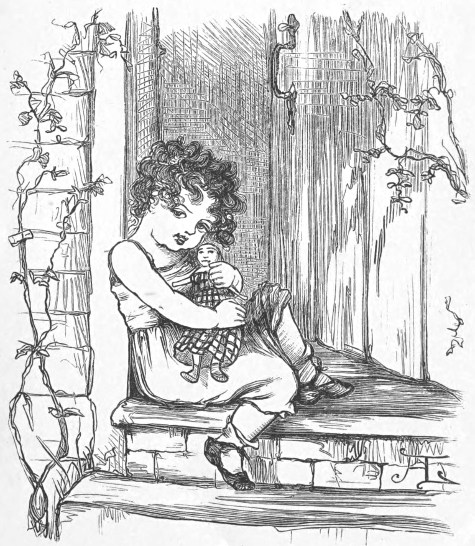

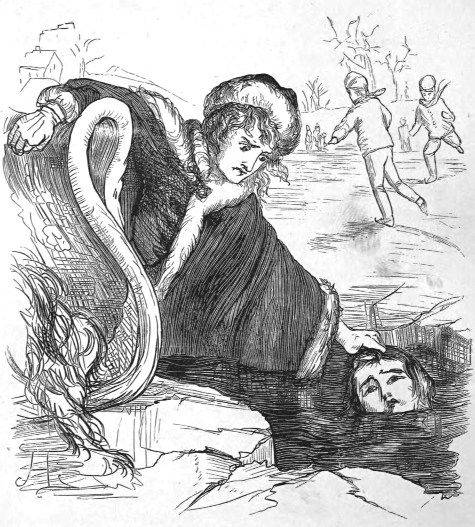

MISSY.—Page 50.

BY

LOUISE CHANDLER MOULTON,

AUTHOR OF "BED-TIME STORIES," AND "SOME WOMEN'S HEARTS."

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY ADDIE LEDYARD.

BOSTON:

ROBERTS BROTHERS.

1875.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874, by

LOUISE CHANDLER MOULTON,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Cambridge:

Press of John Wilson & Son.

[AFTER A TWELVEMONTH.]

| PAGE | |

| Against Wind and Tide | 5 |

| Blue Sky and White Clouds | 20 |

| The Cousin from Boston | 34 |

| Missy | 50 |

| The Head Boy of Eagleheight School | 68 |

| Agatha's Lonely Days | 82 |

| Thin Ice | 100 |

| My Lost Sister: A Confession | 114 |

| What came to Olive Haygarth | 128 |

| Uncle Jack | 143 |

| Nobody's Child | 159 |

| My Little Gentleman | 175 |

| Ruthy's Country | 191 |

| Job Golding's Christmas | 210 |

| My Comforter | 224 |

Jack Ramsdale was a bad boy. He had been a bad boy so long that secretly he was rather tired of it; but he really did not know how to help himself. It was his reputation, and it is a curious thing how naturally we all live up to our reputations; that is to say, we do the things which are expected of us. There is a deal of homely sense in the old proverb, "Give a dog a bad name and hang him." Give a boy a bad name, and he is reasonably sure to deserve one. Not but that Jack Ramsdale had fairly earned his bad name. His mother had died before he was old enough to remember her, so he had never known what a home was. Once, when his father was unusually[Pg 6] good-natured, he had asked him some questions about his mother.

"She was one of God's saints, if ever there was one," the man answered, half reluctantly. "Everybody wondered that she took up with me, but maybe it was because she saw I needed her more than anybody else did. She might have made a different man of me if she'd lived; at least, I've always thought so. I never drank so much when she was alive but what I kept a comfortable home over her head. But when she was gone, it didn't appear to me there was any thing left to live for. I lacked comfort sorely, and I don't say but what I've sought for it in by-paths,—by and forbidden paths, as she used to say."

"I wish I could ha' seen her," said Jack.

"She was a dreadful motherly creetur, and was always hangin' over you. Cold nights I've known her get up half-a-dozen times, often, to see if the clothes was all up over your shoulders; and sometimes I've seen her stand there looking down at you in the biting cold till I thought she'd freeze; but I didn't dare to say any thing, for her lips were[Pg 7] movin', and I knew she was prayin' for you. She was a prayin' woman, your mother was. I used to think her prayers would save both of us."

"I can't make out how she looked," Jack persisted. He was so anxious to hear something about this dead mother who had loved him so. Ever since she died, he had been knocked round from pillar to post, as they say, with his father. Sam Ramsdale was good help, as all the farmers knew, when he was sober; but he was not reliable, and then he had the disadvantage of always being incumbered with the boy, whom he took with him everywhere,—an unkempt, undisciplined little fellow whom no one liked. Now, as his father talked, it seemed to him so strange a thing to think that some one used to stand beside his bed in cold winter nights and pray for him, that he could hardly believe it; and he said again, out of his desolate longing,—

"I wish I could ha' seen how she looked."

"I don't suppose folks would ha' said she was much to look at." His father spoke, in a musing sort of way. "She was a little pale slip of a[Pg 8] woman, with soft yellow hair droopin' about her white face, and eyes as blue as them blue flowers you picked up along the road. But there, I can't talk about her, and I ain't a goin' to, what's more; and don't you ever ask me again!"

From that time Jack never dared to ask any more questions about his mother, but all through his troublesome, turbulent boyhood he remembered the meagre outlines of the story which had been told him. No matter how bad he had been through the day, the nights were few when he failed to think how once a pale slip of a woman, with soft yellow hair around her white face, and eyes blue as the blue gentians, had bent above his slumbers and said prayers for him.

When he was ten years old his father died in the poor-house. Drink had enfeebled his constitution; a sudden cold did the rest. There were a few weeks of terrible suffering, and then the end came. Jack was with him to the last. There was nowhere else for him to be, and the father liked to have him in his sight. One day, just before the end, when they were all alone, the man called the boy to his bedside.

"I can't tell you to follow my example, Jack; that's the shame of it. I've got to hold myself up as a warnin', and not as an example. Just you steer as clear o' my ways as you can; but remember that your mother was a prayin' woman. I s'pose nobody'd believe it, Jack; but since I've been lyin' here I've kinder felt nearer to her than I ever did before since she died. Seems as if I could a'most hear her prayin' for me; and I think, by times, that the God she lived so close to won't say no. It's the 'leventh hour, Jack, the 'leventh hour, I know that as well as anybody; but she used to sing a hymn about while the lamp holds out to burn. When I get there I shall get rid of this awful thirst for drink. It's been an awful thirst; no hunger that I know of can match it; but I shall get rid of that when this old body goes to pieces. And what does a Saviour mean, if it ain't that He'll save us from our sins if we ask Him?"

As he said these last words he seemed sinking into a sort of stupor, but he started out of it to say once more,—

"Never follow my example, Jack, boy. Remember your mother was a prayin' woman."

Those were the last connected words any one ever heard him speak. After that the night came on,—the double night of darkness and of death. Once or twice the woman who acted as nurse, bending over him, heard him mutter, "The 'leventh hour, Jack!" and afterwards she wondered whether it was a presentiment, for it was just at eleven o'clock that he died.

Jack had been sent to bed a little before, and when he got up in the morning, he knew that he was all alone in the world.

After the funeral Deacon Small took him home. He wouldn't be of much use for two or three years to come, the deacon said. Maybe he could drive up the cows, and ride the horse to plough, and scare the crows away from the corn, but he couldn't earn his salt for a number o' years to come. However, somebody must take him, and he guessed he would. It would be a good spell before the "creetur" would come of age, and the last part of the time he might be smart enough to pay off old scores.

But surely Jack Ramsdale must have eaten more salt than ever boy of ten ate before if he did not work enough for it, for it was Jack here, and Jack there, all day long. Jack did everybody's errands; Jack drew Mrs. Small's baby-grandchild in its little covered wagon; Jack scoured the knives; Jack brought the wood; Jack picked berries; Jack weeded flower-beds. From being an idle little chap, in everybody's way, as he had been in his father's time, he was pressed right into hard service, for more hours in the day than any man worked about the place. Now work is good for boys, but all work and no play—worse yet, all work and no love—is not good for any one. Jack grew bitter; and where he dared to be cruel, he was cruel; where he dared to be insolent, he was insolent. Not toward Deacon Small, however, were these qualities displayed. The deacon was a hard master, and the boy feared, and hated, and obeyed him. But as the years went on, five of them, he grew to be generally considered a bad boy. At fifteen he was strong of his age, a man, almost, in size.

His schooling had been confined to the short winter terms, and he had always been the terror of every successive schoolmaster.

When he was fifteen, a new teacher came,—a handsome, graceful young man, just out of college. He was slight rather than stout, well-dressed, well-mannered, fit, you would have said, for a lady's drawing-room, rather than the country schoolhouse in winter, with its big boys, tough customers, many of them, and Jack Ramsdale the toughest customer of all. After Mr. Garrison had passed his examination, one of the committee, impressed by what he thought a certain-fine-gentleman air in the young man, warned him of the rough times in store for him, and especially of the rough strength and insubordination of Jack Ramsdale. Ralph Garrison smiled a calm smile, but uttered no boasts.

He had been a week in the school before he had any especial trouble. Jack was taking his measure. The truth was, the boy had a certain amount of taste, and Garrison's gentlemanliness impressed him more than he would have cared to own. It is[Pg 13] possible that he might have gone on, quietly and obediently, but that now his bad name began to weigh him down. The boys who had looked up to him as a leader in evil grew impatient of his quiet submission to rules. "Got your match, Jack?" said one. "Goin' to own beat without giving it a try?" said another. And Jack began to think that the evil laurels he had won, as the bravo and bully of the school, would fall withered from his brow if he didn't make some effort to fasten them.

So one morning, midway between recess and the close of school, he took out an apple and began paring it with a jack-knife and eating it. For a moment Mr. Garrison looked at him; then he remarked, with ominous quietness, in a tone lower and more gentle than usual,—

"Jack, this is not the place or time for eating."

"My place and time to eat are when I am hungry," Jack answered, with cool insolence, cutting off a mouthful, and carrying it deliberately to his mouth.

"You will put up that apple instantly, if you please."

Still the teacher spoke very gently, and turned a little pale. The persuasive words and the slight paleness misled Jack. He thought his victory was to be so easily won, there would not even be any glory in it. He smiled and ate, quite at his ease.

"You will come here whether you please or not," was the next sentence from the teacher's desk. Jack cut off another mouthful and sat still.

Then, he never knew how it was, but suddenly, in the twinkling of an eye, he felt himself pulled from his seat out into the middle of the floor while knife and apple flew from his hand. He kicked, he struggled, he tried to strike; but an iron grasp held his wrists. The strong muscles of the stroke-oar at Harvard did good service. The handsome face was pale, but the lips were set like steel, and the cool eyes never wavered as they fixed and held those of the young bully. Then suddenly he whipped from his pocket a ball of strong fish-line and bound the struggling wrists tightly, and, pushing a chair toward his captive, said, coolly,—

"I want nothing more of you till after school. You can sit or stand, as you please. Now I will hear the first class in arithmetic."

There was a strange hush in the school, and every scholar knew who was master.

When all the rest had gone, the teacher turned to Jack Ramsdale.

"I took you a little by surprise," he said. "Perhaps you are not yet satisfied that I am stronger than you."

"Yes, I'm satisfied," Jack answered. "I ain't so mean but what I'm willing to own beat when it's done fair and square."

Mr. Garrison, meanwhile, was untying his wrists. As he unwound the last coil, he said,—

"The forces of law and order are what rule the world. I think if you fight against them, you'll always be likely to find yourself on the losing side."

A great bitter wave of defiance swelled up in Jack's heart; not against Mr. Garrison as an individual, but against such as he,—handsome, graceful, cultured; against his own hard lot; against a prosperous world; against, it almost seemed, God, Himself.

"What do you know about it?" he said [Pg 16]sullenly. "You never had to fight. It was all on your side. God did it. He made you handsome and strong, and had you go to school and college, and grow up a gentleman. And he made me"—how the face darkened here—"what you see. He took my mother, who did love me and pray for me, away from me when I wasn't more than three years old. He gave me to a father who drank hard and taught me nothing good. And then he took even him from me, and handed me over to Deacon Small; and I tell you, teacher, you don't know what a tough time is till you've summered and wintered with Deacon Small. I've got a bad name, and who wonders? and I feel like living up to it. I hadn't any thing against you, specially; but if I'd given in peaceably to all your rules, the boys would have said I had grown chicken-hearted, and a little name for pluck is all the name I have got."

Mr. Garrison looked at him a few moments, steadily. Then he said,—

"It does seem as if fate had been hard on you. But do you know what I think God has been doing[Pg 17] for you, in giving you all these hard knocks; for things don't happen; God never lets go the reins."

The boy looked the question he did not speak, and Mr. Garrison went on.

"I think He has been making you strong, just as rowing against wind and tide made my wrists strong, until now you could fight all your enemies if you would.

"The thing we are put here for," he continued, "is to do our best; and if we are doing that, in God's sight, there is nothing that can prevail against us; not fate, or foes, or poverty, or any other creature. There is nothing in all the universe that is strong enough to stand against a soul that is bound to go up and not down. You may go home, now."

It was one of Mr. Garrison's merits that he knew when to stop. Jack Ramsdale went home with that last sentence ringing in his ears,—

"There is nothing in all the universe that is strong enough to stand against a soul that is bound to go up and not down."

The words went with him all the rest of the day. They lay down with him at night, and he looked out of his window and fixed his eyes on a bright, far-off star, and thought of them.

What if he should turn all the strength that was in him to going up and not down? If he did right, who could make him afraid? If he served willingly, he need fear no master. It was very late, and the star, obedient to the law which rules the worlds, had marched far on, out of his sight, before he went to sleep. He had made a resolve. In the strength of that resolve he awoke to the new day.

"I will not go down," he said to himself; "I will go up and on!"

He was not all at once transformed from sinner to saint. Such sudden changes do not belong to this slow world. But the purpose and aim of his life was changed. Never again did he lose sight of the shining heights he meant to climb. If the mother in the heavenly home could look down on the world below, she knew that not in vain had she been "a praying woman." To Mr. Garrison the[Pg 19] boy's devotion was something wonderful,—humble, loyal, faithful, and never ceasing. From being the teacher's terror, Jack had become the teacher's friend.

"Say yes, and you'll be such a dear papa."

Papa bent down and kissed his girl, before he asked, half reproachfully,—

"And how if I say 'no'? Shan't I be dear, then?"

Kathie blushed, and then laughed.

"Why, of course you'll be dear, any way; but may be it's partly because you are so good, and hate so to say no to your own little daughter, that I love you so much."

"To my little daughter as tall as her mother? Do you know, small person, that I've often thought it might be better for that same little daughter if I said no to her oftener? I couldn't love you more, but I'm afraid I might love you more wisely. A hundred and twenty-five dollars for a new party dress! Bring your own mature[Pg 21] judgment to bear on it, and tell me if it appears quite sage, even to you."

Kathie thought so hard for a moment that she fairly scowled with earnestness; then she answered,—

"Yes, on the whole, I think it will be eminently judicious. You see, I shall be going out a good deal now, and I can do so many different things with a handsome silk, and if I got a tarleton, or any of those cheap, thin goods, it would be used up at once."

Papa smiled.

"Well, if you are quite sure you're right, I'll bring the check home this noon, and you and mamma can begin your search for this wonderful yellow gown."

"Yellow!" Kathie clapped her hands to her ears. "What did I ever do to make you think I would wear a horrid yellow gown?"

"Oh, was it red you said you wanted?"

"Worse and worse. You talk like a Hottentot. My gown is to be blue, soft, and lustrous, like a summer sky, and I am to look in it,—well, you shall see on Christmas Eve."

Then, with half a dozen good-by kisses, the father of this only child—happy, easy-going, and too indulgent—took himself off down town, and Kathie danced away to the sewing-room to find her mother and inform her of her success.

Kathie Mason, at sixteen, was a girl bright, and sweet, and bonny enough to tempt any parent to a little over-indulgence. She had soft, sunny, yellow hair; and lovely, dark brown eyes; with a look in them that kept saying, "Oh, be good to me!"; a delicate, flower-like face; and a mouth red as Fair Rosamond's, which has long been dust now, but which poets and painters raved about centuries ago. She had a graceful little figure, and a clear, fresh young voice; and she had a heart, too, which was in the right place, though she herself was almost a stranger to it. She loved beauty dearly, whether in books, or nature, or human faces, or blue silk gowns, and it was just as natural to her to be a picture, whatever way she looked or moved, as it was to be Kathie.

As she danced along she was humming a verse of a gay little French chanson, where some lover[Pg 23] said his love was like a rose; and you thought it might have been written about herself, only Kathie had no thorns. As she drew near the sewing-room she stopped, for her mother and the dress-maker were talking busily. Miss Atkinson was a pathetic little woman, with eyes which looked as if the color had been washed out of them by many tears, a thin, frail body, and a voice not complaining, but simply plaintive. Somehow Kathie hated to break in upon the slow pathos of those tones with her blue silk ecstasy, so she stood leaning against the door for a few moments and waited.

"You see," the little woman was saying, "it was a great pull-back, my being sick two months in the summer, and then my brother being so much worse. But it will all come right, somehow. If I can manage to get Alice clothed up so she can go to school, I shall be thankful; for she's a bright child, and it's too bad to have her wasting her time. But then, food and fire must come first, and if people are sick they are sick, and two hands can't do any more than they can."

There was nothing to oppose to this mild fatalism; so Kathie's mother only said, very sympathizingly, that it was hard, and that it seemed as if, with her sister and her sister's child to support, Miss Atkinson had all she could do before, without undertaking any new responsibilities for the ailing brother and his family.

"Oh! but there's no one else to do it if I don't, you see," quoth the little dress-maker, almost cheerfully—as cheerfully, that is, as her voice could be made to speak; but Kathie noticed that a moment after she pressed her hand on her side and drew a sharp, hard breath.

"Does your side pain you, Miss Atkinson?" she asked, kindly.

"Not much more than usual. It's rather bad, most days. I went to work too soon after I was sick, the doctor said. But he didn't tell me how the rest were going to live if I laid by any longer; and, dear me, I'm thankful enough to be able to work at all."

Kathie thought she should be ashamed to have this poor little woman, who had two people [Pg 25]besides herself to provide for, entirely, and no knowing how many more, in part, work on her blue silk superfluity. Clearly that must be made by some other dress-maker; and she could not even speak to her mother about it now; so she just asked for some work, and sat down with it, thinking more seriously than, perhaps, she had ever thought in her gay, butterfly life before.

"How old is your little niece, Alice?" she asked, after a while.

"Ten, and she is as far along in her studies now as a good many girls of twelve. I did mean to have sent her straight through, normal school and all, and let her prepare to be a teacher; but it doesn't look much like it, now William's taken so poorly. I expect I shall have to pretty much clothe his three children besides Alice."

"Can't your sister, little Alice's mother, help you at all?"

"Well, yes, she does help. She does all she's able to, and more; for, you see, she's feeble, too. She keeps house for us, and cooks, and washes and makes our things after I fit them, and keeps[Pg 26] us mended; but there's nothing she can do to bring in any thing. But there, I beg your pardon ten times over, apiece. It's against my principles to go out sewing, and harrow up folks' minds with my troubles; only, you see, I'm a little nervous and unsettled to-day on account of Alice's crying pretty hard this morning because she hadn't any thing to wear to school."

Papa Mason took Kathie aside when he came home to dinner, and with a little fun, and teasing, and pretence of mystery, produced the check. There it was, one hundred and twenty-five dollars, all right, and three weeks between now and Christmas Eve to get her blue silk gown made.

While she ate her roast beef she began to think again. One question kept asking itself over in her mind,—Why should some people have blue silk gowns, and others have no gowns at all? I rather think we have all asked ourselves this same thing, in one form of words or another. Since the great Father made and loves us all, why should one be Queen Victoria and another little Alice staying at home from school for want of a few[Pg 27] yards of woollen and a pair of boots? Political economists have ciphered it all out, beautifully; but Kathie did not know that, and so the vexing question puzzled her. What if it was done just to give us a chance to help each other? she asked herself, at last, and the text of a sermon she heard once came into her mind,—"Bear ye one another's burdens." If all fared just alike there would be no chance for helpfulness, or charity, or self-denial; so may be clothes would be put on people's backs at the expense of better things in their hearts. It must be that God knew best. Oh! if one couldn't think that, the world might as well fall to pieces at once.

"Will you have pudding, dear? I have asked you three times," said Mrs. Mason's voice, with a little extra energy in it; and Kathie looked up out of her dream with a certain vagueness in her eyes, and answered,—

"A hundred and twenty-five," whereat they all laughed.

"I can't give you a hundred and twenty-five puddings; but, if you'll please make a beginning[Pg 28] with this one, no doubt the rest will come before the year is over."

Whereupon Kathie roused herself from her speculations, ate her pudding, and sent her plate for more, with a good, healthy, girlish appetite.

That afternoon she sewed quite diligently, and talked little; but her eyes were bright, and her face all the time eager with some thought.

After tea was over, and Miss Atkinson had gone, and papa had stepped out to see a business friend, Kathie sat down, as was one of her habits, on a low stool beside her mother, and laid her head in her lap. Mrs. Mason knew that all the afternoon's thinking would come out before the child got up again; so she just smoothed the fluffy, yellow hair with her hand and waited.

"Don't you think, mamma, that Miss Atkinson must be a good deal better Christian than the rest of us, she's such a patient burden-bearer? She never seemed to think for one moment that it was hard she should have to work so, or that she couldn't have what she wanted herself. All that troubled her was because she couldn't do what she had planned for Alice."

Then, when Mrs. Mason had made some slight answer, there was silence again for a time; and then Kathie cried impulsively,—

"Mamma, what a perfect good-for-nothing I am. I never carried a burden for any one in my life. I have just been a dead weight on some one else's hands."

"Not a dead weight, by any means," and Mrs. Mason laughed, "and really, papa and I have found it rather a pleasure than otherwise to carry you."

The loving girl kissed the hand that had been stroking her hair, but she was quite too much in earnest to laugh.

"Well, mamma, you know it doesn't say,—'Bear ye one another's burdens, all of you but Kathie, and she needn't.' I think this rule without any exceptions means me, just as much as it does any one; and I shan't feel quite right in my own mind till I begin to follow it. I want to bear part of Alice."

Kathie was talking very fast by this time, and her cheeks were very pink, and her brown eyes very bright.

"You see I've thought it all out, this afternoon. If Miss Atkinson will feed her and house her, I do think I might undertake to clothe her until she is through school and ready to teach; and don't you think I'd feel better when I came to die to have done some little thing for somebody? You see it would come very easy. My dresses, and cloaks, and hats would all make over for her. There wouldn't be much to buy outright, except boots, and stockings, and under clothes, generally."

"And wouldn't you find all that rather a heavy drain on your pocket-money? I don't ask to discourage you, childie; only I want you to consider it all thoroughly, for if you should once undertake this thing and lead Miss Atkinson and Alice to depend on it, there could be no drawing back then."

"Yes, I have thought about it all. Didn't you see me working it out in my head this afternoon, like a sum in arithmetic? I think half the money papa gives me for lunches, and presents, and the other things pocket-money goes for, would be just as good for me as the whole; and I am sure with[Pg 31] half of it I could keep Alice along nicely after I once got her started; and its just about this start I want to speak to you now. Papa gave me a hundred and twenty-five dollars to-day to buy me a blue silk gown for Aunt Jane's Christmas-Eve party. Now fifty dollars will get me a lovely white muslin, and a blue sash, and all the fresh little fixings I should need; and that would leave seventy-five dollars, with which I could buy flannels, and boots, and water-proof, and a good, warm, strong outfit altogether, for Alice to commence with. Now do you think papa would be willing? I don't want to ask him, for he doesn't understand silks and muslins, or what Alice needs; but would you answer for him? Just think, mamma, what burdens poor Miss Atkinson has to bear."

Mrs. Mason started to say,—"It is all for her own relations,"—but stopped, for the command didn't read, "Relations, bear ye one another's burdens." Had she any right to interfere between Kathie and this first work of charity the child had ever been inspired to undertake? Would not this object[Pg 32] of interest outside herself, apart from blue silk gowns, and flounces, and furbelows, do something for her girl that was likely to be left undone otherwise? What a very cold loving-one-another we were most of us doing in this world, after all? So she bent over and kissed the eager, lovely, upturned face that waited for her words, and said fondly,—

"Yes, I will answer for papa, my darling. I approve your plan heartily, but I will not offer help. This shall be all your own good work."

The next morning Miss Atkinson was told of the new plan. Her faded eyes opened twice as widely as usual. She was not sure she heard aright.

"Do you mean to say Miss Kathie, that you undertake, with your mamma's full consent, to clothe Alice until she is through school?"

"That is precisely what I bind myself to do," Kathie answered, gravely copying the solemnity of the little dress-maker.

"Then all I have to say is, bless you, and bless the Lord. You never can tell what good you're doing."

And then the poor little woman began to cry, just for pure joy; and she sobbed till Mamma Mason felt her eyes growing misty, and Kathie ran away out of the room.

Be sure that Miss Atkinson made up Kathie's muslin lovingly. It would not be her fault if it were not prettier than any silk. And truly, when Christmas Eve came and Kathie was dressed for Aunt Jane's party, there could hardly have been a more radiant vision than this white-robed shape with the sunny, soft hair, the gleaming brown eyes, and the wild-rose cheeks, where the color came and went. Her father looked her over with all his heart in his eyes, and a tenderness which quivered in his voice, though he tried to speak jestingly.

"So there wasn't blue sky enough for any thing but your sash, and you had to take white clouds for the rest."

"Just that. Don't you like the clouds?"

He bent and kissed her.

"Yes, I like the clouds; and I think the sunshine struck through them for somebody."

We had been friends ever since I could remember, Nelly and I. We were just about the same age. Our parents were neighbors, in the quiet country town where we both lived. I was an only child; and Nelly was an only daughter, with two strong brothers who idolized her.

We were always together. We went to the same school, and sat on the same bench, and used the same desk. We learned the same lessons. I had almost said we thought the same thoughts. We certainly loved the same pleasures. We used to go together, in early spring, to hunt the dainty may-flowers from under the sheltering dead leaves, and to find the shy little blue-eyed violets. We went hand in hand into the still summer woods, and gathered the delicate maiden-hair, and the soft mosses, and all the summer wealth of bud and[Pg 35] blossom. Gay little birds sang to us. The deep blue sky bent over us, and the happy little brooks murmured and frolicked at our feet.

In autumn we went nutting and apple gathering. In the winter we slid, and coasted, and snowballed. For every season, there was some special pleasure,—and always Nelly and I were together,—always sufficient to each other, for company. We never dreamed that any thing could come between us, or that we could ever learn to live without each other.

We were thirteen when Nelly's cousin from Boston—Lill Simmonds, her name was—came to see her. It was vacation then, and I had not seen Nelly for two days, because it had been raining hard. So I did not know of the expected guest, until one morning Nelly's brother Tom came over, and told me that his Aunt Simmonds, from Boston, was expected that noon, and with her his Cousin Lill.

"She'll be a nice playmate for you and Nelly," he said. "She's only a year older than you two, and she used to have plenty of fun in her. Nelly wants you to come over this afternoon, sure."

That was the beginning of my feeling hard toward Nelly. I was unreasonable, I know, but I thought she might have come to tell me the news, herself. I felt a sort of bitter, shut-out feeling all the forenoon, and after dinner I was half minded not to go over,—to let her have her Boston cousin all to herself.

My mother heard some of my speeches, but she was wise enough not to interfere. When she saw, at last, that curiosity and inclination had gotten the better of pique and jealousy, she basted a fresh ruffle in the neck of my afternoon dress, and tied a pretty blue ribbon in my hair, and I looked as neat and suitable for the occasion as possible.

At least I thought so, until I got to Nelly's. She did not watch for my coming, and run to the gate to meet me, as usual. Of course it was perfectly natural that she should be entertaining her cousin, but I missed the accustomed greeting; and when she heard my voice at the door, and came out of the parlor to speak to me, I know that if my face reflected my heart, it must have worn a most sullen and unamiable expression.

"I'm so glad you've come, Sophie," she said cheerfully. "Lill is in the parlor. I want you to like her. But you can't help it, I know, she's so lovely; such a beauty."

"Perhaps I shan't see with your eyes," I answered, with what I imagined to be most cutting coldness and dignity.

"Oh yes! I guess you will," she laughed. "We have thought alike about most things, all our lives."

I followed her into the parlor, and I saw Lill. If you are a country girl who read, and have ever been suddenly confronted with a city young lady in the height of fashion, to whom you were expected to make yourself agreeable, you can, perhaps, understand what I felt; particularly if by nature you are not only sensitive, but somewhat vain, as I am sorry to confess I was. I had been used to think myself as well-dressed, and as well-looking as any of my young neighbors; I was neither as well-dressed nor as well-looking as Lill Simmonds.

Nelly was right. She was a beauty. She was[Pg 38] a little taller than Nelly or I,—a slender, graceful creature, with a high-bred air. It was years before they had begun to crimp little girls' hair, but I think Lill's must have been crimped. It was a perfect golden cloud about her face and shoulders, and all full of little shining waves and ripples. Then what eyes she had—star bright and deep blue and with lashes so long that when they drooped they cast a shadow on the pale pink of her cheeks. Her features were all delicate and pure; her hands white, with one or two glittering rings upon them; and her clothes! My own gowns had not seemed to me ill-made before; but now I thought Nelly and I both looked as if we had come out of the ark. It was the first of September, and her dress had just been made for fall,—a rich, glossy, blue poplin, with soft lace at throat and wrists, and a pin and some tiny ear jewels of exquisitely cut pink coral.

"Yes," I thought to myself bitterly, "no wonder Nelly was dazzled. She may like to be the contrast, to help Miss Fine-Airs show off; but I object to that character, and I shall keep pretty clear of this house while Miss Lill is in it."

I spoke to her politely enough, I suppose; and she answered me, it might have been either shyly or haughtily: I chose in my then mood to think the latter. Decidedly the afternoon was not a success.

Nelly did her best to make it pleasant; but she and I couldn't go poking about into all sorts of odd places, as we did when we were alone, and we did not know what the Boston cousin would like to do; so we put on our company manners and talked, and for an illustration of utter dulness and dreariness commend me to a "talk" between three girls in their early teens, who have nothing of the social ease which comes of experience and culture, and where two of them have nothing in common with the other, as regards daily pursuits and habits of life. Lill talked a little about Burnham's—it was before Loring's day—but we had read no novelists but Scott and Dickens, and we couldn't discuss with her whether it wasn't too bad that Gerald married Isabel and did not marry Margaret.

We might have brightened a little over the supper, but then Mrs. Simmonds, who had been[Pg 40] sitting upstairs with Nelly's mother, was present,—a stately dame, in rustling silk and gleaming jewels, who overawed me completely. I was glad to go home; but the little root of bitterness I had carried in my heart had grown, until, for the time, it choked out every thing sweet and good.

While the Boston cousin stayed, I saw little of Nelly. I am telling the truth, and I must confess it was my fault. I know now that Nelly was unchanged; but, of course, she was very much occupied. Whenever I saw her she was so full of Lill's praises that I foolishly thought I was nothing to her any more, and Lill was every thing. If I had chosen to verify her words, instead of chafe at them, I, too, might have enjoyed Lill's grace and beauty, and learned from her a great many things worth knowing. But I took my own course, and if the cup I drank was bitter, it was of my own brewing.

At last, one afternoon, Nelly came over by herself to see me. I was most ungracious in my welcome.

"I don't see how you could tear yourself away[Pg 41] from your city company," I said, with that small, hateful sarcasm, which is so often a girl's weapon. "They say self-denial is blest: I hope yours will be."

Perhaps Nelly guessed that my hatefulness had its root in pain; or it may have been that her own heart was too full of something else for her to notice my mood.

"Lill is going to-morrow," she said, gently.

"Indeed!" I answered; "I don't know how the town will support the loss of so much beauty and grace. I suppose I shall see more of you then; but I must not be selfish enough to rejoice in the general misfortune."

Nelly's gentle eyes filled with tears at last.

"Sophie," she said, "how can you be so unkind, you whom I have loved all my life? I am going, too, with Lill, and that is what I came to tell you. Ever since she has been here, Aunt Simmonds has been trying to persuade mother to let me go back for a year's schooling with Lill, but it was not decided until last night. Mother thought, at first, that I must wait to have my winter things made;[Pg 42] but Aunt Simmonds said she could get them better in Boston, and the same woman would make them for me who makes Lill's."

"Indeed! How well dressed you will be!" I said bitterly. "How you will respect yourself!"

"Sophie, I don't know you," Nelly burst out, indignantly. "The hardest of all was to leave you, for we've been together all our lives; but you are making it easy. Good-by."

She put her arms round me, even then, and kissed me, and I responded coldly. Oh how could I, when I loved her so? I watched her out of sight, and then I sank down upon the grass, and laid my head upon a little bench where we had often sat together, and sobbed and cried till I could scarcely see. I was half tempted to go over to Nelly's, and ask her to forgive me; but my wicked pride and jealousy wouldn't let me. Lill would be there, I thought, and she wouldn't want me while she had Lill. So I stayed away.

The next morning they all went off. When I heard the car-whistle at the little railroad station a mile and a half away, I began to cry again.[Pg 43] Then, if it had not been too late, I would have gone and implored my friend to forgive me, and not shut me out of her heart. But the day for repentance was over.

The slow months went on. I missed Nelly at school, at home, everywhere. I longed for her with an incurable longing. It was to me almost as if she were dead. People wrote many less letters in those days than they do now, and neither Nelly nor I had learned to express any thing of our real selves on paper. We exchanged three or four letters, but they amounted to little more than the statement that we were well, and the list of our studies. One look into Nelly's eyes would have been worth a thousand such.

There were other pleasant girls in town, but I took none of them into Nelly's vacant place: how could I? Who of them would remember all my past life, as she did,—she who had shared with me so many perfect days of June, so many long, bright summers and melancholy autumns, and winters white with snow? I was, as I have shown you, jealous and hateful and cruel, but never for a moment fickle.

At last Nelly came again. It was a day in the late June, and she found me just where she had left me, under the old horse-chestnut tree in the great old-fashioned garden. I knew it must be almost time for her coming, but I had not asked any one about it. Somehow I couldn't. I very seldom even spoke her name in those days. So she stole upon me unawares, and the first I knew her arms were round me,—her warm, tender lips against my own,—and her sweet, unchanged voice cried,—

"O Sophie, this is good, this is coming home, indeed!"

I cried like a very child. Nell didn't quite understand that; but then she had not had, like me, a hard place in her heart, which needed happy tears to melt it away. I think, in spite of the tears, I was more glad of the meeting even than she. After a little while she said,—

"Come, I want you to go home with me now, and see Lill."

Will you believe that even then the old, bitter jealousy began to gnaw again at my heart?[Pg 45] She had been with Lill almost a year; could she not be content to give me a single hour without her? Perhaps she saw my thought in my face; for she added, in such a sad, pitiful tone, "Poor Lill!"

"Poor Lill," indeed! with her beautiful golden hair, and her eyes like stars, and her lovely gowns, and her city airs, "poor Lill!"

"I should never think of calling Miss Simmonds poor," I said, with the old hardness back in my voice.

"You will when you see her, now," Nelly answered gently. "She had a hard fall on the icy pavement, last winter, and she hurt her hip, and it's been growing worse and worse. She can hardly walk at all, now, and she has suffered awfully. But she has been, oh so patient!"

And how I had dared to envy that girl! I was shocked and silenced. I walked along by Nelly's side very quietly. When we got there she took me up into her room, and there I saw Lill Simmonds. I should hardly have known her. The golden glory of hair floated about her still.[Pg 46] The eyes were star-bright yet, but the cheeks which the long lashes shaded were pink no longer, and they were so thin and hollow that it was pitiful to see them.

She wore a wrapper of some soft blue stuff, and on her lap lay her frail, transparent hands. She started up to meet us with a smile which for a moment gave back some of the old brightness to her face, but which faded almost instantly. I sat down beside the lounging-chair where she was lying, but I could not talk to her. The sight of her wasted loveliness was all too sad. After a little while she said to Nelly,—

"Won't you, you are always so good to me, go and fetch me a glass of the cool water from the spring at the foot of the garden?"

Nelly went instantly, and then Lill turned to me and put her hand on my arm.

"I asked her to go, Sophie," she said, "because I wanted to speak to you. I wanted to say something to you which it would hurt her to hear. I used to be very jealous of you, Sophie. I wanted Nelly to love me best, but she never[Pg 47] did. She had loved you so long that I could see you were always first in her heart. And now I am glad. I shall never be well again, and when I am gone I would not like Nelly to be so unhappy as she would be if she had loved me first and best. She will miss me, and she will be very sorry for me; but she will have you, and you can comfort her. I am ashamed now of that old jealousy. I think it made me not nice to you last summer."

Lill jealous of me! I was dumb with sheer amazement. And I, how much bitterness and injustice I had to confess! But before I could put it into words Nelly had come back, and a look from Lill kept me silent.

That night, when I went away, I put my arms round my darling and kissed her with my whole heart, as I had not done for a year. She never knew how much went into that kiss, of sorrow and shame and self-reproach.

What months those were which followed! I was constantly with Nelly and her cousin. Mrs. Simmonds was there, but Lill spent most of her[Pg 48] day-time hours with us girls; to spare her mother, probably, who was with her every night, and also because she loved us both. Sometimes, on fine days, she would walk a little under the trees; and I have knelt unseen, in a passion of loving humility, and kissed the grass over which she had dragged after her her helpless foot. Growing near to death, she grew in grace. As Nelly said, one day,—

"Her wings are growing. She will fly away with them soon."

And so she did. Through the summer she lingered, suffering much at times, but always patient and gentle and uncomplaining. And when the dead leaves of autumn went fluttering down the wind, she died with the dead summer, and upborne on the wings of some messenger of God her soul went home.

Even her mother hardly dared mourn for her,—her life had been so pure and so peaceful,—her death was so tranquil and so happy. I had ceased, long before, to be jealous of her. No one could love her too much. She was my saint;[Pg 49] and her memory has hallowed many a thought during the long, world-weary years since. I need but to close my eyes to see a pale, patient face, with its glory of golden hair and its eyes bright as stars; and often, on some soft wind, I seem to hear her voice, speaking again the last words I ever heard her speak,—

"Love each other always, my darlings, and remember I loved you both."

We have obeyed her faithfully, Nelly and I. Through the long years since, no coldness or estrangement has ever come between us. My first and last jealousy was buried in Lill's grave; and Nelly and I have proved, to our own satisfaction at least, that a friendship between two girls may be strong as it is sweet, faithful as it is fond,—the inalienable riches of a whole life.

Miss Hurlburt had wandered farther into the woods than was her habit, beguiled by the wonderful loveliness overhead, underfoot, all about her. It was an afternoon in early October, but warm as June. The leaves were of a thousand brilliant hues; for one or two nights of keen frost, a week before, had seemed to set them on fire. There were boughs as scarlet as the burning bush before which Moses wondered and worshipped. There were others of deep orange; and others, still, of variegated leaves, where the green lingered and was mixed with scarlet and brown and yellow, till some of them looked like patterns in a kaleidoscope.

Underfoot was the delicate, fresh woodland moss. Sometimes pine needles made the path[Pg 51] soft; and sometimes, leaves, which had died earlier than their mates, rustled under Miss Hurlburt's tread. Above, high over the flaming tree boughs, was the deep, lustrous, blue sky, with all its heavenly secrets. The air was full of that wonderful, radiant haze of autumn which makes the distance vague with beauty. And the temperature, as I said, was of June; so warm that Miss Hurlburt had taken off her hat, and let the scarlet mantle fall from her shoulders.

She herself, had a painter been there to study the scene, would have been no unworthy wood nymph. Her figure was full, but not too full for grace. Health and strength were in every line of it. Her fine, abundant hair, like that of which Lowell wrote, "outwardly brown, but inwardly golden," was brushed back from her low, broad forehead, and coiled in a great heavy knot, from which a stray curl or two had escaped, at the back of her proud little head.

She had great brown eyes, full of thought and feeling; cheeks, in which the rich, warm color glowed; bright, full, half-parted lips. She [Pg 52]carried herself with grace, regal though unstudied. She never consciously remembered that she was Eleanor Hurlburt,—whose father owned the two great factories in the valley, and all the lands far and near, even these royal woods through which she walked,—but, unconsciously to herself, the fact gave firmness and elasticity to her step, and self-possession to her air.

She very seldom wandered alone so far away from home. The factory hands were a necessary part of the great wealth which surrounded Miss Hurlburt's life with ease and luxury; but some of them might not be altogether pleasant to meet in lonely places,—so she usually was driven out in the elegant Victoria, with the spanking bays which were her father's pride, by the decorous family coachman; or drove herself in her jaunty little pony phaeton, with her own man, all bands and buttons, seated in the rumble behind.

But to-day it happened that she was walking. I said "it happened," because we speak in that way before we think; though nothing is farther from my belief than that any thing ever happens[Pg 53] in this world which God has made, and in which He never loses sight of the smallest or poorest thing. At any rate, Miss Hurlburt was walking, and she wandered on, until at last she heard a tender little voice singing a tender little song. It was so fine and clear, it might almost have been the carol of a bird, only birds have not yet learned the English language, and this voice sang:

Such a quaint little song, such a quaint little voice! Miss Hurlburt wondered for a moment who it could possibly be. Then she remembered hearing that, while she was away in the summer, an elderly English woman and a little girl had been allowed to take possession of the cabin in the woods which her father owned.

It was a little house with two rooms, which had[Pg 54] been built, long ago, as a lodge for hunters; but which had for several years stood vacant, being too far from the factories to be a convenient residence for any of the hands.

Miss Hurlburt went on a few steps farther, and saw the singer. It was a pretty picture. A little creature, who looked about five or six years old, sat in the door-way tending a battered doll. She was almost as brown as a gypsy, this small waif, but there was a singular grace about her. Her black hair hung in thick, short curls. She had great, bright, black eyes; lips as red as strawberries; and teeth as white as pearls.

Miss Hurlburt moved on softly, so as not to disturb her; and the waif took up her doll, and talked to it wisely and soberly, after the manner of some mothers.

"Now, Pinky, me love, I have singed you a song. Now you must be good for a whole week of hours, or I shan't sing to you, never no more. I mean any more, Pinky. Be very careful how you speak, always; no good children ever go wrong in their talking."

By this time Miss Hurlburt had almost reached her side.

"Does your child give you much trouble?" she said, in a tone friendly and inviting confidence.

The mite shook her head, with all its black curls.

"Pinky, me love? No; she only gives me trouble when she is bad. She is good most always, unless it rains."

"Is she bad then?" with an air of anxious interest.

"Certain she is: who wouldn't be? She has to stay in the house then; and she doesn't like it. Would you? How can persons be good when they don't have what they want?"

By this time a nice, motherly-looking old English woman had heard the talk, and came forward to the door.

"Missy," she said, "always thinks Pinky is bad when she is bad herself; and Missy is most always cross when it rains."

"What is your name?" Miss Hurlburt asked, bending to smooth the black curls.

"Berenice Ashford," the child answered, in a slow, painstaking manner, as if the words had been taught her with care; "but they don't call me that,—they call me 'Missy.'"

"Is she your grandchild?" was the next question, addressed to the elderly woman, who had set a chair near the door and asked the young lady to sit down.

"No, that she isn't, and I would like much to find out whose child she is. To be sure, I should miss her more than a little, if I had to part with her: but, all the same, I should like to find her kindred. She belongs to gentle-folks, and I can't do for her what ought to be done."

A few more questions drew out the whole story. The woman, Mrs. Smith, had a son in America, who was doing well at his trade of dyeing; and he had sent for her to come out to him. He had sent money enough for her expenses, and she had taken passage in the second cabin of a steamer.

Among her fellow-passengers were Missy and her mother,—the latter a beautiful young lady, Mrs. Smith said, but very pale and sad. She had[Pg 57] complained sometimes of a keen and terrible pain in her heart; but she had made little conversation with any one. When they were five days out, she had been found in the morning dead in her berth, with Missy sound asleep beside her.

There was no possible clew to her history. In her trunk, full of her own clothes and Missy's, was no scrap of handwriting, no address. The one or two books which were there, bore on their fly-leaves only the inscription "E. Forsyth." She had taken passage as Mrs. Forsyth, but the captain knew nothing more about her.

Mrs. Smith had somehow taken possession of Missy. She had played with the child and amused her a good deal, before her mother died; and now the little creature clung to her as her only friend.

There was something over a hundred dollars in the mother's trunk, but as yet Mrs. Smith said she had not used it. When she reached New York, instead of being met by her son, an old neighbor came for her to the steamer, brought her the news of his death, and gave her the money—nearly a thousand dollars in all—which he had been saving[Pg 58] to make the new home they were to have together comfortable.

It was an awful blow, and she clung to Missy, then, for it seemed as if the child was all she had left in the world. The captain said that he would advertise for the little one's friends; but, meantime, he was evidently very glad to be relieved of the responsibility of her.

"How happened you to come here?" Miss Hurlburt asked.

"I had always lived in the country, miss, and I didn't want to stay any longer than I could help in New York; and my son had been meaning to bring me here. It seemed a little comfort, to come where I should have come with him. He had engaged with Mr. Hurlburt—the one who owns the big factories—to come here and see to the dyeing; and Mr. Hurlburt was so good as to give me this little house rent-free, for a while. By and by I want to get something to do. If I could be housekeeper somewhere where I could keep Missy, or head-nurse, or something of that sort, it would suit me,—but there's no hurry."

"Mr. Hurlburt is my father," the young lady said, when she had heard the story through. "We must see what can be done. Missy, should you like to live with me?"

The child considered. Then she addressed her doll, inquiringly.

"Pinky, me love, should you like to live with the lady? I guess she's good. Would you go, if your mother went?" Then she pretended to listen. "'No, I thank you,' Pinky says; 'she couldn't go without Grandma Smith.'"

"Of course Pinky couldn't," Miss Hurlburt said, laughing. "Well, then, I'll come again to see you, and bring Pinky's new gown."

That evening, at dinner, Miss Hurlburt was radiant. She knew her father liked to see her well dressed, and she made a handsome toilet. She coaxed him into his very best humor by all the arts only daughters of widowed fathers are wont to use; and then, when he was seated comfortably before the open fire, which tempered the chill of the October evening, she unfolded her plan and her wishes.

The beginning and the end were that she wanted Missy,—she must have Missy,—and the middle was that she couldn't be so cruel as to take from Mrs. Smith her one comfort, so she wanted Mrs. Smith. She represented herself as fearfully overworked, in keeping the establishment in order. Now how nice it would be if Mrs. Smith could take all the troublesome details of that off her hands; could see that the house was clean, and the washing well done, and the buttons on. She had needed just such a person a long time, but she hadn't known where to find her; and now here she was, really made to order, as it seemed.

Of course she had her way. The world called Jonathan Hurlburt a stern man, but it was not often he could say "no" to his motherless daughter. The very next day Miss Hurlburt went with her proposition to the little cabin in the wood; and, before a week was over, Missy and Grandma Smith were duly installed as members of the Hurlburt household.

As for the business part of the experiment, Mrs. Smith proved worth her weight in gold, as they[Pg 61] say. Before three months were over, Mr. Hurlburt discovered that she saved him five times her wages in money, and added immeasurably to the household comfort,—indeed, he concluded that she was, as Eleanor had said, really made to order.

As for Missy, with her quaint ways, her odd, old-fashioned speeches, and the little songs she sang, she was speedily the delight of the household. She lost no whit of her affection for Grandma Smith, but it was Miss Hurlburt who was her idol.

"Pinky, me love," she used often to say to her faithful doll friend, "did you ever see any miss so nice as our Miss Hurlburt? You had better not say you did, Pinky, me love; because then it would be me very sorrowful duty to whip you for telling lies."

Miss Hurlburt's delight in her little waif was unbounded. She dressed her up, like a child in a story-book. When she drove in her Victoria, Missy always sat beside her, gorgeous in velvet suit and soft ermine furs; and at home Missy was never far away.

Before spring, another strange event took place. I will not say happened, for no chapter of accidents would ever have read so strangely. A young English manufacturer came over to America. Mr. Hurlburt had had, by letter, various dealings with the firm which he represented; and, on hearing of his arrival in New York, wrote, begging a visit of some length from him. The young man, whose object in his American journey was partly business and partly pleasure, saw an opportunity to combine both in this visit, and accepted the invitation.

He amused himself more or less with Missy, as did every one who came to the house; but he had been a member of the household for several days before it occurred to him that she was not Miss Hurlburt's young sister. Under this impression he remarked one night,—

"How curiously slight is the resemblance between yourself and your little sister, Miss Hurlburt!"

"Oh! Missy is not my sister," was the smiling answer. "She is treasure-trove, Mr. Goring."

And a little later, when Missy had danced away[Pg 63] in search of Pinky, she told him the whole story. He listened with intense interest.

"And do you know her name?" he asked, at last.

"She says it is Berenice Ashford. You would laugh to hear the slow, painstaking way in which she pronounces it."

Mr. Goring had turned pale as she spoke.

"Excuse me, Miss Hurlburt, but I truly believe your Missy is my niece. My half-brother married against the wishes of his family, and I was the only one of them who ever made the acquaintance of his poor, pretty young wife. Even when he died, last year, the rest would not have any thing to do with her. She had a brother in America, and she wanted to come here, so I took passage for her in the "Asia." She insisted on coming in the second cabin, because it was quieter, she said; but I think it was to save expense, as well. Tom had left her nothing; and, after the rest of the family had rejected her, I could see that it hurt her pride cruelly to let me help her. She should be all right, she said, when she reached her brother. She was[Pg 64] to write me when she got there, but I have never heard a word. I confess that the hope to hear of her was one motive for my coming to this country."

"But she was Mrs. Forsyth," Miss Hurlburt said, in a curiously bewildered state of mind.

"Certainly: Forsyth was my brother's name. Berenice Ashford is the child's Christian name. It was the name of Tom's mother and mine."

"But I wonder you did not know Missy at once."

"Of course to find her here was the very last thing I could have expected. Then I had not seen her for two or three years. I had communicated with my sister-in-law chiefly by letter; and it was my man of business, and not myself, who put her on board the steamer."

"But her brother? Why has he never looked for his sister nor her child?"

Goring smiled.

"You are bent on making me prove my title to Missy, as one does to stolen goods. I think Mrs. Forsyth must have gone on without writing[Pg 65] to him in what steamer she was coming, and he probably did not know my address. Nor do I think he had ever shown any especial interest in his sister. It was only her indomitable pride which made her so determined to go to him, when the family of her husband rejected her. Now, I think, I have proved property, and I'm ready to pay the cost of advertising."

Just then Missy's voice was heard in the hall, addressing a solemn exhortation to "Pinky, me love," on the duty of never being greedy at table. Miss Hurlburt called her in.

"Missy," she said, "what was your papa's name?"

"I never knew; did you ever know, Pinky, me love? Mamma called him Tom."

"And did you ever hear mamma speak of Uncle Richard?" Mr. Goring broke in, eagerly.

"You do remember, Pinky, me love. It is wicked to look as if you didn't. She said we couldn't go to America and find Uncle John, if Uncle Richard had not given us the money. I remember that, but I had 'most forgotten; so if[Pg 66] you forgot, too, I shall not whip you, Pinky, me love."

"I am your Uncle Richard," the Englishman said with entire calmness of manner and gesture, but with tears in his voice and his eyes. Perhaps he expected the child to come at once to his arms; but she stood there, the same composed, self-poised little mite as ever.

"Your great-uncle, Pinky, me love," she announced,—manifesting an unexpectedly clear knowledge of degrees of kinship. "I think maybe we shall like him."

"And you will go with me back to England?" he asked, eagerly; for the little creature's likeness to his dead brother stirred his heart.

"Does she say I must?" Missy asked, shyly, looking at Miss Hurlburt.

"I will never say you must, Missy."

"Then, please, Uncle Richard, I am afraid going in a ship wouldn't agree with Pinky; and we'd rather stay here, unless our Miss Hurlburt will go too."

"Soh, soh!" and Mr. Goring smiled a quizzical smile, "I see I have a heart to storm."

Whose heart he did not say. But he lingered some time in America, coming back at frequent intervals to visit Missy, as he said. The result was that when he returned to England little Missy had become ready to go with him, even at the risk of exposing "Pinky me love," to the perils of the sea; and Miss Hurlburt, thinking she needed something other than masculine oversight, concluded to go with her and take care of her, having first changed her own name to Mrs. Goring. And they all said what a fortunate thing it was that Mrs. Smith was there to keep house.

The boys in Eagleheight school made up their minds before the first fortnight of Max Grenoble's stay among them was over that he had no spirit. The truth was, they didn't exactly understand him. They began when he first came to exercise upon him their usual arts of torture,—the initiation ceremonies for all new boys,—and found him practically a non-resistant. They could not, indeed, be quite sure that they even succeeded in vexing him: he was so imperturbable. At last Hal Somers, goaded to a degree of exasperation by the quiet calmness of the new boy, struck him, with the outcry,—

"There, boys, see how this suits the Quaker."

It was a sound, ringing blow; but Max only laughed a laugh which had a good deal of scorn in it, and said,—

"That's very little to take." Then regarding Hal curiously, "I looked for a tougher blow than that. To see you, Somers, one would think you had a good deal of strength in your arms; but a bad cause is always weak."

Hal would have liked then to "pitch into him" with whatever of strength he had; but I think he was afraid. So he only turned on his heel, muttered something about a fellow not worth fighting with, and walked away. From that time those who did not vote Max Grenoble a coward pronounced him a mystery. He did not look at all as if he were wanting in spirit. He was a great strong Saxon of a fellow, with the head of a young Greek, covered with thick, short golden curls. I wish I could photograph him for you: he was such an embodiment of fresh, vigorous life, with his clear, fearless blue eyes, his short, smiling upper lip, his well-cut features. He was just the fellow to be popular, if only he had not been misunderstood in the first place, and especially if he had not happened to incur Hal Somers's enmity.

Hal had been there two years, and was a [Pg 70]positive force in the school. He had a large capacity in several other directions besides mischief. He had been the best scholar at Eagleheight before Max came to dispute his laurels with him; a favorite, therefore, with the teachers, who always passed over his escapades, which were not few, as lightly as they could. In fact he was a sort of ringleader of the faster boys, and he found time, in spite of his never failing in class, to plan out and head the execution of most of the jollifications which were the terror of the quiet villagers around Eagleheight. He seldom had any of his offences positively brought home and proven, it is true, and the faculty of the institution liked him too well to condemn him on suspicion, or even to try very hard to strengthen suspicion into certainty.

They, the aforesaid faculty, were not at all too ready to give Max Grenoble his due when he first came. He was not, like Hal, of their own training. He had come to them from a rival school, and they were secretly ill pleased to find in him a dangerous competitor with their best scholar. But before six months were over they were[Pg 71] obliged to recognize his claims, and had even come to heartily like him. And, indeed, he was a fellow, as Edmund Sparkler would have said, with no nonsense about him, and likely to make his own way anywhere.

Whenever he had the opportunity to show his skill he was found to excel in all athletic sports; but this was not often, for the boys rather shunned him, and if there were enough for an undertaking without him he was usually left out of it. He had one friend, however,—a poor little weakling of a fellow, named Molyneux Bell, who had been friendless before Max came. Hal Somers and his roystering set had always shoved poor little "Miss Molly," as they called young Bell, to the wall; and it opened paradise to him when great, strong, bright, cheery Max Grenoble took him under his protecting wing. He gave as much as he received too; for Max had a strongly affectionate nature, and would have found himself desolate enough without some one to be fond of. Only "Miss Molly" knew the secret of his friend's non-resistance. One day Max had carried him in his arms[Pg 72] across a stream they came to in one of their walks, and set him gently down on the other side. Molyneux looked up gratefully.

"What great strong arms you have, Max! Why, you carry me as gently as a cradle. I believe you could whip Hal Somers himself, just as easy as nothing. Honest, now, don't you think you could? O, I wish you would! The boys wouldn't dare then to call us 'Miss Molly and her sister.'"

Max laughed heartily.

"I shouldn't be much afraid to try it," he said. "The truth is, I have been awfully tempted to pitch in, sometimes. But last year I made up my mind that the Bible meant what it said when it forbade us to return evil for evil and railing for railing. It comes tough on human nature, though, boy human nature at any rate; but there'd be no merit if there was no struggle, and we're put here to fight with the old man in us, as my father calls it."

"But if you'd tell 'em why you never knock a fellow down when he sauces you."

Max's face crimsoned like a girl's.

"Don't you understand that a fellow couldn't tell such things? at least, I couldn't. I should feel like the Pharisee in the Bible."

At the end of the school year there was to be a competitive examination. The credits for conduct and for recitations were to be taken into account, and the boy who stood highest on the books, and passed the best examination also, was to be the head boy of the school for the next year. From the first the field was abandoned to two competitors,—Hal Somers and Max Grenoble. All Hal's emulation was aroused. He would succeed. He even forsook his old ways, and for weeks together engaged in nothing that was contraband. He had really fine abilities. He learned some things more readily than Max himself, and he felt that all his prestige depended on his securing this leadership. Max took the matter more coolly, but still he worked with all diligence. And so, till within ten days of the examination, they were neck and neck.

Just then there came a dark night,—a warm, tempting June night,—when the moon was old,[Pg 74] and only the stars shone, like very far-away lamps indeed, through the dusk. A friend of Hal Somers was night monitor, and doubtless the temptation afforded by such apparent security was too much for mischief-loving Hal. It chanced that Max Grenoble had received permission from one of the tutors to go to the neighboring village of an errand, and this fact was known only to his own room-mate, Molyneux Bell. About half-past nine he was returning, and for greater speed crossed a lot belonging to the president of the institution, which saved him an extra quarter of a mile of road. Half way across the lot he met Hal Somers with three other boys behind him, face to face. Hal carried a small lantern, and a great pair of shears such as are used to shear sheep. The light from the lantern struck upon the shears with a glitter which led Max to notice them. In the hands of one of Hal's followers he saw the long, silvery tail of a white horse, and another carried a bunch of hair of a similar hue, evidently the mane of the same animal.

"Hal Somers!"

He spoke in his first moment of surprise, without consideration; but there came no answer. The lantern was blown out in a moment, and the boys made the best of their way toward Eagleheight. As Max walked on more slowly he heard a pitiful neigh, and following the sound, he found President King's pet horse, utterly denuded of mane and tail. It was a joke carried a little too far even for Hal Somers's effrontery, he thought to himself. If there was any thing outside of his school that President King loved and prided himself on more than another, it was Snowflake. He gave her something of the fond care a family man bestows upon his children. Every afternoon she was the companion of his solitude, to whom he talked, with a sort of grave humor of his own, as he took his constitutional upon her back. He would not be likely to have much toleration for the young rascals who had shorn her of all her glory. Max went on, reported himself to Professor Vane, from whom he had obtained his leave of absence, and went to bed without hinting what he had seen, even to his room-mate.

The next morning when the school went to chapel, there was a sense of thunder in the air. President King had seen his favorite, as those who were guilty did not need to be told, after one look at his lowering face. He conducted the devotions with more than his usual solemnity, and then detained the school a little longer.

He uttered a few withering sentences, setting forth what had been done, and commenting satirically upon the invention, the gentlemanliness, the good sense of young men whose brains could originate nothing more brilliant or entertaining than the disfigurement of an unlucky quadruped, and an annoyance and insult to a teacher who had at least this claim upon their respect, that their parents had put them under his charge. Then he gave them the opportunity to confess their folly, assuring them that confession was good for the soul, and adding that he should take it as a favor if any one who knew any thing of the affair, whether personally concerned in it or not, would give him all the information in his power. It was not the practice at Eagleheight to ask any [Pg 77]individual boy whether or not he had been guilty. It was one of President King's notions that to ask such a question of any one who had not manliness enough to confess his fault voluntarily was only leading him into temptation, offering safety as a premium for lying.

As the fellows filed out of chapel, Hal Somers said to his chum,—

"It's all up with me about the leadership. Of course Grenoble will tell, especially now the Prex makes a merit of it."

"Fool if he wouldn't," was the reply, "after the way we fellows have all treated him, too."

All day Hal was in hourly expectation of being sent for to an interview solemn and awful in the president's room. But the hours went on and no summons came. About four o'clock he saw Max Grenoble go into the dreaded chamber of audience. Now, he thought, all would come out. Of course Max had gone to tell all he knew. Would he be suspended, or expelled, he wondered, or would the Prex be satisfied with giving him black marks enough to put the leadership altogether beyond his[Pg 78] reach? Then a plan came to him. The president's room was on the lower floor, and over one of its windows grew a grape vine large enough to conceal him from observation. He would go there and listen. That it was a very mean thing to do he knew as well as any body, but temptation was too strong for him, and giving one look to make sure that he was not observed he hid himself away under the open window. The first words he heard were in the voice of the president:

"As soon as Vane told me you were out last evening, it occurred to me that you would know who was at the bottom of the affair, and it seems you do."

"Yes, sir," firmly and quietly.

"Then there can be no possible doubt that it is your duty to tell."

"It cannot be my duty, sir, to be a sneak. This secret came into my hands by accident. If I had been monitor for the evening, it would, of course, be my duty to make it known. Not having been in any such capacity, I think were I to turn telltale I should be no gentleman."

"It's a new order of things when fifty must come to fifteen to be told what it is to be a gentleman," the president said, hotly. "Perhaps you don't know, sir, that if you persist in your resolution you lose all hope of the leadership? You will be considered an accessory in the crime, and you will lose as many credit marks as would be taken from the ringleader were he detected."

"I can afford to lose those better than my own self-respect," Max said, stoutly, and then added, "I think you would have done the same, President King, when you were at my age."

Hal waited to hear no more, but edged cautiously from his place of concealment. He thought he was not above profiting by Max's generosity. He tried to think Max was a fool, but there was an inner voice in his heart which whispered that there was something sublime in such folly, and, try as he might, this inner voice would not altogether be silenced.

The days went on swiftly. Max kept his scholarship up to the highest standard, but the twenty credit marks taken from his list put all hope of his attaining the leadership out of the question.

It was the very night before the examination when President King answered a tap on his door with his well known, resonant "Come in." His visitor was Hal Somers.

The next morning, after prayers, the president said, very quietly,—

"Young gentlemen, before the examination commences I have to detain you long enough to perform a simple act of justice. I acquit Max Grenoble of all complicity in the misdemeanor committed on the night of the 14th of June; the entire burden of the same having been assumed by Henry Somers, in behalf of himself, William Graves, George Saunders, and John Morse. And as this confession was voluntary, I shall visit upon the offenders no severer penalty than the loss of all their credit marks for the last quarter."

Poor little Molyneux Bell forgot time and place, and threw his handkerchief into the air with one glad shout:—

"I knew Max would come out right at last; I knew he would."

So Max went back the next year to Eagleheight,[Pg 81] as the head boy; and under his leadership a new state of affairs was brought about. He led them not only in class, and in athletic exercises, but in all true manliness. They had found out at length that he had plenty of "pluck and grit," even though he might not emulate Sayers or Heenan. One of his warmest friends was Hal Somers, in whose character enough nobility was latent to recognize at last the sterling worth even of his rival.

They had buried Agatha's mother,—put her away under a sheltering tree, beloved of bird and breeze, which waved its boughs between her and the bending, changeful summer sky. Agatha thought no other spot in the world could be so pleasant or so dear; and she longed, from the depths of her little, ten-years-old heart, to stay there with bird, and breeze, and tree, and the buried mother, who must hear her voice, she thought, even though she could never reply to it again in all the years.

Her father, pale with sorrow himself, had never come near enough to his child to be her comforter now. He talked little to any one of either his joys or his sorrows. Agatha loved him, partly because she had always been taught to love and have faith in him; and, partly, too, because she knew well,[Pg 83] with that childish and intuitive perception which discovers every thing, how dear he was to her mother; but she did not feel near to him, and she could not possibly have told him how she longed to stay there beside that grave. She made no protest when he took her hand to lead her away, though it seemed to her that she left her heart behind her, and that the lump in her breast was a cold stone to which warmth would never come back any more.

She went home, and some one took off her little black hat, and put on an apron over her mourning gown, and then she was left in peace to sit at the window, and look out toward the spot where they had laid her mother, and wonder what was to become of her. They called her to supper, but she was not hungry,—she thought she never should be again,—and there was no mother to beguile her with dainty morsels. When they found she did not want to come they let her alone, and still she sat there and wondered.

At last the twilight fell, and in the dusk her father came to her. He loved her very dearly;[Pg 84] and especially now, that her mother was gone, and only she was left to him, he felt for her an unspeakable tenderness; literally unspeakable, for he did not know how to utter one word of it to his child. He longed to comfort her,—to tell her how dear she was to him,—but he could not. He sat down beside her, and looked at her little pale face, outlined against the western window, with such a depth of pity that it seemed to make his voice quieter and colder than ever when he spoke, because it required such an effort to speak at all.