Plate 1.

Drawn by F.F. Giraud. 1823. Engraved by J. Stewart.

London. Published 1824, by Messrs. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green.

A

SHORT TREATISE

ON THE

SECTION OF THE PROSTATE GLAND,

IN

LITHOTOMY.

F. WARR, Printer,

RED LION PASSAGE, RED LION SQUARE.

A

SHORT TREATISE

ON THE

SECTION OF THE PROSTATE GLAND

IN

LITHOTOMY;

WITH AN EXPLANATION OF A SAFE AND EASY METHOD OF CONDUCTING

THE OPERATION ON THE PRINCIPLES OF

CHESELDEN.

ILLUSTRATED BY ENGRAVINGS.

By C. ASTON KEY,

SURGEON TO GUY’S HOSPITAL, AND TO THE MAGDALEN.

“Occupons-nous maintenant d’un Lithotomiste bien plus célèbre qui mérite la reconnoissance de son siècle et celle des siècles à venir; je veux dire Cheselden.”

Deschamps.

LONDON:

LONGMAN, HURST, REES, ORME, BROWN, AND GREEN, PATERNOSTER ROW:

S. HIGHLEY, 74, FLEET STREET; T. & G. UNDERWOOD, 32, FLEET STREET;

AND E. COX & SON, ST. THOMAS’S STREET, SOUTHWARK.

MDCCCXXIV.

In selecting the Name that graces the head of this page, I am influenced, not only by feelings as a surgeon, to render a slight tribute to unrivalled professional reputation, but also by gratitude for the many acts of friendship I have personally received at his hands.

Educated under his eye, I am proud to acknowledge, that I consider myself indebted to his professional instructions, and to his excellent advice, for whatever information and advancement I possess; and I am sensible, that in no way more satisfactory to him can I repay his kindness, than by unceasing labor in a science which it is his constant study to improve, and by endeavours to attain a respectable character in a profession of which he constitutes the brightest ornament.

C. ASTON KEY.

18, St. Helen’s Place, April, 1824.

To Cheselden Operative Surgery is indebted for one of the most important improvements, that the whole range of the profession can present. The certainty and safety with which a most painful disease can be relieved, stamps the lateral operation of Lithotomy as a bold and highly rewarded effort of genius,—as a present of inestimable value to suffering humanity,—and as a just cause of triumph to our national feelings as surgeons.

It has now undergone the test of nearly a century, and, like all improvements of real value, it has past through its ordeal with increased rather than diminished credit.

Connected with a school that gave birth to the present lateral operation, and deeply impressed with the conviction of its superiority over every other mode of operating in this[vi] disease, I need offer no apology for reviewing what appears to me to be the true principle of the operation.

A review of this kind is perhaps the more required at the present time, when attempts are made by English, as well as Continental surgeons, to revive a mode of operating that presents no advantage under ordinary circumstances,—that was discarded by Cheselden,—and needs an equal test of time and experience to shew its comparative merit. If want of success in the lateral operation has thus led to its abandonment, it becomes a question, how far it may be traced to a neglect of those principles which guided Cheselden. To such as are laying aside lateral Lithotomy; the following observations, by recalling their attention to his principles, may prove useful; to those who still continue to practice it, they may, by throwing a few lights on the subject, be interesting; and to the younger members of the profession, by explaining a new and simple method of performing the operation, they may perhaps be not entirely devoid of instruction.

In the performance of surgical operations, it is the paramount duty of the surgeon, a duty rendered doubly indispensable, both as the feelings of humanity and the improvement of the profession are concerned, not to deviate from the rules which have been found efficient in the hands of experienced and dexterous operators; nor to suggest any important change in the mechanism of an operation that can be at variance with principles established on the firm basis of experience.

After the records recently laid before the public by two able and successful Lithotomists,[1] it may appear superfluous,[2] or even presumptuous in me, to clothe in the formal garb of a publication the observations which the following pages contain. To disarm the severity of the critic, however, and to invite those who shrink, and frequently with reason, at the idea of innovation on established practice, I may premise, that it is not intended to change in any one respect the principles of the lateral operation, but merely to suggest an easier mode of accomplishing the same object. Indeed, I trust I shall be able to shew, that the proposed method will enable the surgeon to adhere more closely to the operation as first proposed and practised by the great Cheselden.

If more satisfactory proof of the superiority of his operation be required than his success from the year 1731 at St. Thomas’s Hospital, where he cut fifty-two patients and lost only two, the extraordinary zeal of all the surgeons of Europe to acquaint themselves with his plan, and the desire evinced by surgeons of the highest fame closely to follow his steps, would alone characterise it as a safe and simple operation. It must however be confessed that his method, as practised by himself, required a greater share of anatomical knowledge than at that time fell to the lot of the[3] generality of persons educated even for the higher branches of the profession; this gave rise to slight changes in the operation, which were thought to be improvements; among these ranks the introduction of the Cutting-Gorget, first used by Sir Cæsar Hawkins, and receiving various modifications under successive operators down to the present day. The employment of the Gorget in the division of the prostate gland, has been stigmatized as substituting mechanism for skill; if that were the only remark that could apply to this instrument, it would be rather an argument in its favor than an objection to its general use, as the success of the operation would depend less on individual dexterity. But the objection to it in my opinion is, that, from the manner in which it is introduced into the bladder, it cannot divide the parts according to Cheselden’s operation. To explain this defect in the Gorget, it is necessary to understand the direction of Cheselden’s incisions.

In his first operation he adhered to the plan of Frère Jacques, and Raw; but, from the ill success attending it, he was soon induced to lay it aside. He then practised the operation, which, from the lateral division of the prostate[4] gland, has since been denominated the Lateral Operation. This, his second operation, is thus described by Douglas in his appendix.

“His knife entered first the muscular part of the urethra, which he divided laterally, from the pendulous part of its bulb to the apex, or first point of the prostate gland, and from thence directed his knife upward and backward all the way to the bladder.”

Morand, to whom Cheselden communicated the particulars of his operation, describes it as follows:—

“Je fais d’abord une incision aux tégumens, aussi longue qu’il est possible, en commençant près de l’éndroit où elle finit au grand appareil; je continue de couper de haut en bas entre les muscles accélérateur de l’urine et érecteur de la verge, et à côté de l’intestin rectum. Je tâte ensuite pour trouver la sonde, et je coupe dessus, le long de la glande prostate, continuant jusqu’à la vessie, en assujettissant le rectum en bas pendant tout le temps de l’operation.”[2]

Deschamps gives the following account:—“L’incision des tégumens faite, il continue de couper de haut en bas entre les[5] muscles accélérateur et érecteur de la verge, et à côté de l’intestin rectum; il s’assure ensuite de la situation de la sonde sur la quelle il coupe le long de la glande prostate jusqu’à la vessie, ayant soin d’assujettir le rectum en bas, pendant toute l’operation, avec un ou deux doigts de la main gauche.”[3]

The first of these accounts is certainly not very perspicuous, or, as Deschamps says, “à la verité bien imparfaite.” It is evident, however, that the edge of the knife must have been turned obliquely towards the rectum in the division of the prostate gland; and also that the gland must have been divided, not at its upper part where it is thinnest, but through its thickest and depending part. If the cutting edge were not carried very obliquely downwards, the rectum would have run no risk of being wounded; nor would he have changed his operation in consequence of having twice cut the gut, as he himself confessed to Morand. For though Douglas does not assign the reason for his giving up the operation, but merely says that, “Mr. Cheselden has for very good reasons laid this method aside, and substituted another very different in its room, which he now practices with very great applause,”[6] &c.; yet, with the ingenuousness that always accompanies talent, he confessed having wounded the rectum more than once: “Le chirurgien Anglais, malgré la direction très oblique qu’il donnoit à son incision, avoue l’avoir interessé plus d’une fois.”[4]

Though he abandoned this mode of conducting the incision, he still adhered to the principle which guided him, namely, making a very free incision, by the side of the rectum, and dividing the prostate very low down.

The following descriptions of his third and last operation will impress the mind of every person, that his incision of the prostate could not be horizontal, but must have been inclined towards the rectum, even more than in his second operation.

The operation appears to have been as follows:—An assistant holding a long and curved staff, Cheselden, with a pointed convex edged knife, made his usual large external incision through the muscles of the bulb and crus penis, and part of the levator ani, till he could feel with the fore finger of his left hand the prostate gland, at the same time keeping[7] the rectum down and preventing it being endangered: then pressing his finger behind the prostate, and feeling the groove of the staff, he turned the edge of his knife upward, pierced the cervix vesicæ, till the edge rested in the groove; and completed the division of the prostate and membranous part of the urethra by withdrawing the knife towards himself.

Douglas describes it in the following manner:—“Having cut the fat pretty deep, especially near the intestinum rectum, covered by the sphincter and levator ani, he puts the fore finger of his left hand into the wound, and keeps it there till the internal incision is quite finished; first to direct the point of his knife into the groove of his staff, which he now feels with the end of his finger, and likewise to hold down the intestinum rectum, by the side of which his knife is to pass, and so prevent its being wounded. This inward incision is made with more caution and more leisure than the former.”

“His knife first enters the rostrated or straight part of his catheter, through the side of the bladder, immediately above the prostate, and afterward the point of it continuing to run in the same groove in a direction downwards and forwards, or towards himself, he divides that part of the sphincter[8] of the bladder that lies upon that gland, and then he cuts the outside of one half of it obliquely according to the direction and whole length of the urethra, that runs within it, and finishes his internal incision by dividing the muscular portion of the urethra on the convex part of his staff. When he began to practice this method he cut the very same parts the contrary way, &c.”[5]

Deschamps, noticing the above description of Cheselden’s operation, speaks clearly as to the prostate being cut low down: “Il dirige son bistourie le long de la sonde vers la partie inferieure et laterale de la vessie derriere la glande prostate, et au dessus des vesicules seminales.”[6] With regard to the edge of the knife, Deschamps says that the rectum runs no risk of being wounded in the division of the prostate: “le tranchant de l’instrument etant dirigé en haut et s’eloignant par consequent de l’intestin.”[7]

Cheselden, in his last edition of his anatomy, thus describes his incision. “I first make as long an incision as I can, beginning near the place where the old operation ends, and cutting down between the musculus accelerator urinæ and[9] erector penis, and by the side of the intestinum rectum: I then feel for the staff, holding down the gut all the while with one or two fingers of my left hand, and cut upon it in that part of the urethra which lies beyond the corpora cavernosa urethræ, and in the prostate gland, cutting from below upwards to avoid the gut.”[8]

Mr. John Bell’s remarks in his description of this operation are concise:—“He struck his knife into the great hollow under the tuber ischii, entered it into the body of the bladder immediately behind the gland, and drawing the knife towards him, cut the whole substance of the gland, and even a part of the urethra;” or, in other words, “cut the same parts the contrary way,” alluding to this operation as contrasted with the second.[9]

Mr. Sharp, giving instruction on the same subject, says, “The wound must be carried deep between the muscles till the prostate can be felt, when searching for the staff, and fixing it properly, if it has slipped, you must turn the edge of your knife upwards, and cut the whole length of the gland from within outwards.”[10] When speaking of the knife[10] he remarks, “That the back of the knife being blunt is a security against wounding the rectum when we cut the neck of the bladder from below upwards.”

The concurring testimony of those most likely to be acquainted with the true principles of Cheselden’s operation fully establishes the fact, which to me seems an important one, namely: that the prostate gland was divided in a manner very different from the direction in which the Gorget cuts it. Cheselden’s aim evidently was, to divide the prostate in the depending part of the left lobe, with a considerable inclination towards the rectum. The most dexterous operator with the Gorget cannot effect this: the direction which the Gorget takes is the very reverse of this; it is directed to be inclined upwards, by which the upper surface of the gland only is sliced off, and the major part of the gland remains whole.

In the quotations given above, two points are clearly made out:—first, that the edge of the knife was turned upward; and, secondly, that the knife was in this position carried into the neck of the bladder behind the prostate gland.

With the preceding account of what I conceive to be the intent of Cheselden’s operation, I have deemed it right to preface the following observations, in the hope that what I have to offer on the subject will not be construed into a deviation from, but rather a closer approximation to that desirable object than can be attained by the employment of the instruments commonly used.

The form of the staff has always appeared to me, to present the greatest difficulty in executing the operation on the true principles of the Lateral Lithotomy.[11] At the part where it serves the purpose of a director it is curved; a form certainly least adapted to convey a cutting instrument with safety where the eye of the operator cannot follow it; and whether the knife or Gorget be used, difficulties, though of a different kind, present themselves. When the former is propelled along the groove of the curved staff, as in Mr. Martineau’s operation, the edge must be turned, if not directly downward, at least not sufficiently towards the left side of the patient to effect the necessary division of the[12] prostate gland; unless the operator be skilful enough to turn the blade and divide the lobe of the gland, in doing which he is obliged to make two incisions, as Mr. Martineau has observed. “I introduce,” says that gentleman in his valuable paper in the Medico Chirurgical Transactions, “the point of my knife into the groove of my staff as low down as I can, and cut the membranous part of the urethra, continuing my knife through the prostate into the bladder; when, instead of enlarging the wound downwards, and thus endangering the rectum, I turn the blade towards the ischium and make a lateral enlargement of the wound in withdrawing my knife. I thus avoid cutting over and over again, which often does mischief, but can give no advantage over the two incisions, which I generally depend upon, unless in very large subjects, when a little further dissection may be required.”

While quoting this gentleman’s description I take the opportunity of mentioning that I had the pleasure of seeing him operate at Norwich in the Summer of 1818, and from his deservedly high character as a successful Lithotomist, I was induced to pay most minute attention to the several steps of his operation; and I am satisfied from my own observation,[13] as well as from his words, that he conducts his incisions of the several parts precisely on the principles laid down by Cheselden. The depth, extent, and direction of his external incision, and the division of the prostate gland, appear to me to accord in every particular with the operation of the great Lithotomist. What more satisfactory proof can be required of the imprudence of quitting a path chalked out to us by one able surgeon, and trodden with unparalleled success by another; a path sanctioned by that most unerring of all tests, experience; and rendered still more secure by the light which anatomy throws upon it.

In the use of the Gorget, a more unpleasant feeling is experienced by the operator; namely, the danger of the beak slipping from the groove of the curved staff; a danger, not imaginary, but with reason insisted upon ever since Hawkins’s first introduction of the Cutting-Gorget, as well by its strenuous advocates as by its enemies. The operator has to attend to two sensations, the running of the beak along the staff’s groove, and the resistance afforded by the prostate gland; while he is overcoming the latter he becomes unconscious of the former, and at the time he impales the prostate,[14] loses all certainty of the beak being within the groove; this difficulty depends as much on the curve of the staff as on the nature of the Cutting-Gorget, and is one that every candid surgeon must acknowledge frequently to have experienced.

The first impediment a surgeon meets with, is the giving the first impetus to the Gorget; by raising his hand, he is aware of the hazard he runs of the blade slipping between the gut and the prostate; by depressing it, he is in danger of thrusting the beak at right angles against the staff, so that the Gorget cannot run along the groove; and not unfrequently in the efforts of the surgeon to propel it onwards, the beak is nearly broken off the Gorget’s blade, and the staff is withdrawn with a bent back. These accidents I have witnessed; and by those who have seen much of Gorget Lithotomy, such occurrences will be recognised as by no means uncommon. Mr. John Bell so happily illustrates the nicety required in the introduction of this instrument, that for the sake of the point the high colouring will be forgiven. “The operator holds the staff steady for a moment, then moving the Gorget with his right hand, feels by the left when the beak runs fairly and smoothly in the groove; then, the[15] two hands acting in concert with each other, the operator balances the staff and Gorget, and, by making the two hands feel each other, prepares them for co-operating in the most critical moment of driving in the Gorget; and when all is prepared for driving home the Gorget into the bladder, the surgeon depresses the handle of the staff, so as to carry the point of it deep into the cavity of the bladder; his staff stands at this moment at right angles with the patient’s body; he rises from his seat, stands over the patient for an instant of time, balancing the staff and Gorget once more, and feeling once more that the beak is fairly in the groove, he runs it home into the bladder.” Mr. Martineau speaks forcibly on the tact necessary to introduce the Gorget along the curve of the staff, and to prevent it slipping:—“To perform this part of the operation with dexterity, I would recommend every young operator to practice the directing of the Gorget in the groove of his staff when he holds them in his hand, and he will perceive how easily the beak may slip out, if the convex part of the staff be not familiar to his observation.”[12]

It should be borne in mind, that Cheselden never used the staff as a director in the manner it is used at the present day. His left hand being employed in holding the gut down, an assistant kept the instrument fixed, while Cheselden divided the parts upon the groove of the staff in withdrawing his knife.

To the Gorget exclusively belongs the merit of first employing the staff in the modern light of a director. Is it surprising that the blind should err in a crooked path?

In addition to the hazard and difficulty with which the introduction of the Gorget is beset, a reflecting surgeon has only to consider its anatomical imperfections (if I may be allowed the expression), to convince himself of the impossibility of performing the operation à la Cheselden. For this purpose he should be aware of the manner in which the Gorget performs its part of the operation. In its introduction the operator is directed to give the beak a slight inclination upwards, to avoid the risk of slipping between the bladder and rectum; a direction so contrary to the anatomical bearing of the parts he has to divide, as necessarily to thrust the staff upwards against the arch of the pubes, and thus[17] to make the several sections too high; giving rise to the following unavoidable evils:—

First. The cutting edge of the Gorget is conducted so high under the narrow angle of the pubic arch, as to incur a great risk of wounding the pudic artery; a frequent consequence of the introduction of the Gorget in adults, being, as is well known to surgeons, a profuse gush of arterial blood; and, what is more material, not unfrequently great difficulty in restraining the hæmorrhage after the operation.

Secondly. In the section of the prostate, the Gorget is carried upward through the large plexus of veins which surround the upper surface of the gland, by which long continued venous hæmorrhage is produced, filling the opening into the bladder with coagula, and preventing the ready exit of urine, both by the wound and penis; thus producing the infiltrations of urine into the cellular membrane, which frequently cause so much irritation after Lithotomy.

Thirdly. The section of the prostate is made in a direction most unfavourable to the extraction of a calculus. Instead of the free incision made through the depending lobe of the gland by Cheselden, the Gorget merely slices off the upper[18] and narrowest part, leaving the body of the gland, which affords so much resistance to a stone, untouched. This slicing of the gland never affords room enough for a large calculus to pass, and, in the violent efforts to extract it, either the bladder is torn laterally, or, what is worse, the prostate is dragged towards the external wound, and its ligamento cellular connexion with the arch and ramus of the pubes destroyed. When the operation is properly performed, that is, when the wound in the prostate is sufficient for the passage of the calculus, the connexion between the prostate and the arch of the pubes remains; and affords an opposing barrier, when the finger is attempted to be thrust upwards by the side of the bladder. The consequences attending the destruction of the attachment of the prostate are worthy of consideration.

Fourthly. To be fully aware of the mischief attending this laceration of the prostatic connexions, a knowledge of the cause of death after Lithotomy is necessary. It is a prevailing opinion, that stone patients die of peritonitis, brought on by the injury done to the bladder during the operation; a mistake which, though not leading to any serious error in the after-treatment, is so far attended with mischief, inasmuch[19] as it misleads the mind of the surgeon from the true source of the fatal event. I will not venture the assertion, that inflammation of the peritoneum is never a sequela of Lithotomy, but that it is an extremely rare occurrence, and still more rarely the cause of death, examinations post mortem have fully convinced me. During the ten years I have been at our hospitals, I have never yet seen an unsuccessful case examined after the operation, in which inflammation of the peritoneum could be regarded as the cause of death; and as invariably I have found that one circumstance was uniformly present, namely, suppurative inflammation of the reticular texture surrounding the bladder. Those who are unaccustomed to morbid examinations may be inclined to be sceptical on this point, and may think that an injury done to the prostate and neck of the bladder, by a cutting instrument, would be productive of more serious evil to the constitution, than a laceration of reticular texture. Some also may probably look on this explanation as a refinement of modern surgery, and one not borne out by facts; the fact, however, is indisputable; and analogy will bear us out in attributing the highest constitutional symptoms to active suppuration of[20] cellular tissue. In injuries of the scalp, if the wound has penetrated the tendon of the occipito frontalis, we expect extensive suppuration, not from the injury to the tendon, quoad tendon, but from the laceration or other injury done to the cellular membrane between the tendon and pericranium. In like manner wounds of fasciæ, whether of the hand, foot, or other parts of the extremities, are dangerous in their consequences, not from the injury done to the tendinous fibres, but from the exquisitely acute inflammatory action set up in the subjacent cellular tissue. This reticular membrane may be regarded as an infinite number of serous cavities, communicating with each other, and presenting an incalculable extent of surface. Inflammation spreading rapidly through these cells will quickly affect a surface much greater than that of the peritoneum, and I have witnessed symptoms as acute, pain as severe, and the peculiar depression attending peritonitis as marked in the reticular inflammation, as in the most acute and fatal case of inflammation of the abdominal cavity. The instances I have met with of the texture surrounding the bladder being affected with suppurative inflammation, and terminating fatally, whether arising from Lithotomy or operations[21] for fistulæ in perinæo, are sufficiently numerous to allow me thus to generalize on the subject, and afford a very useful lesson to those who endeavour to profit by examinations after death. In the inspection of those who die after Lithotomy, it is not sufficient to look into the peritoneal cavity, to open the bladder, or to examine the state of the wound; the peritoneum lining the lower part of the abdominal muscles should be stripped off, and the source of evil will then be laid open. The finger will enter a quantity of brick-dust coloured pus in the cellular substance around the bladder, and if considerable force has been used in the extraction of the stone, will readily find its way towards the wound in the perineum; the barrier between the adipose structure of the perineum and the reticular texture of the pelvis being broken down, the suppurative inflammation spreads rapidly along the latter, and may be traced in some cases, between the peritoneum and abdominal muscles, as high as the umbilicus; in one case I have seen it extend to the diaphragm.

Lastly. Every surgeon who operates with the Gorget is under the apprehension of it slipping between the bladder and rectum: if the beak slips from the groove before it[22] has entered the bladder, it is supposed to have passed between the gut and the prostate. From the bearing of the Gorget during its introduction, I always entertained some doubt as to this being the direction which the Gorget takes under such circumstances. In the only instance in which I have had an opportunity of ascertaining the real course of the Gorget in this accident, I found that the instrument, which was supposed to have passed between the bladder and rectum, had taken a very different course; it had slipped from the groove of the staff, had been propelled under the arch of the pubes, and had entered the reticular texture above, and to the left side of the bladder. I believe this to be the usual course of the Gorget, when it slips out of the staff: to force it between the bladder and rectum, the beak must be thrust downwards, a direction which is never given to the instrument in passing it into the bladder.

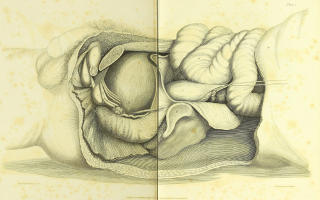

A reference to the plate of the side view of the pelvis, will illustrate the several defective points in the Gorget operation to which I have adverted.

With a view to obviate the evils attending the employment of the Gorget and curved staff, and, at the same time, to adhere closely to the operation of Cheselden, I use a straight director, which I find to answer all the purposes of a common staff, to be entirely free from its objections, and to combine advantages which a curved instrument cannot possess.[13]

I was first led to try an instrument of this form on the dead subject, by the following accidental occurrence. Being called upon to examine a child who had died with stone in its bladder, I was desirous of performing the operation, before making any examination of the body; and having neither staff, Gorget, nor stone-knife with me, I was obliged to operate with a common director, a scalpel, and dressing forceps; and I was forcibly struck with the facility with which the director conducted the knife into the bladder.

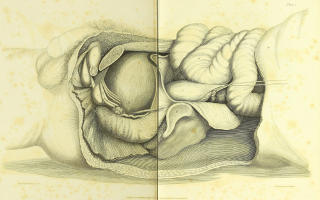

The introduction of this instrument (see plate), is not attended with any difficulty; it enters the bladder of the adult,[24] or infant, with as much facility as one of the accustomed form. When held in the position for the first incision of the operation it might strike a surgeon, in the habit of using a common staff, that the point of the director was not in the bladder, an objection that, if correct, would justly condemn it as a dangerous instrument. To satisfy my own doubt on the subject when first I used it, I cut open the bladder, while an assistant held the director in the position delineated in plate 2; and in every subject on which I tried it, I found the extremity projecting some way into the base of the bladder. In plate 2 will be found a correct view of the bladder, with the instrument passed into it. At first I had the extremity made straight, but thinking that in depressing the handle it might be caught by a projecting fold in the bladder, which would considerably embarrass the operator, I had the point slightly curved upwards, and as the knife is never introduced so far into the bladder as to reach the curve, it will cause no difficulty in its introduction. The groove is made somewhat deeper than in the common staff, to prevent any risk of the knife slipping out. The extremity is not grooved, but rounded[25] like a common sound, to prevent abrasion of the prostate or mucous lining of the bladder. The handle is somewhat larger, to afford a better purchase to the hand of the operator.

The advantage of a straight over a curved line as a conductor to a cutting instrument, is too obvious to require any comment; but its chief superiority consists in allowing the surgeon to turn the groove in any direction he may wish. Before carrying the knife into the prostate, the groove, which has been held downwards for the first incision, may be turned in any oblique line towards the patient’s left side that the operator may think preferable for the division of the prostate. Nor does it preclude the use of the Gorget: this instrument may be propelled along the straight groove with more safety than in the curved staff. To those who have been used to the Gorget it may be difficult to lay it aside; and its employment is certainly less objectionable with the straight director than with the common staff. When the Gorget is employed, the corresponding motion of the left hand is not required to carry it into the bladder; the director should be held perfectly quiet while the Gorget is[26] propelled along its groove. The danger of passing it out of the groove of the director is diminished, if not entirely removed, from which circumstance alone the surgeon gains much additional confidence, and, consequently, the patient much benefit.

The knife resembles in form a common scalpel, but is longer in the blade, and is slightly convex in the back near the point, to enable it to run with more facility in the groove of the director. The scalpel blade has this advantage over the common beaked lithotome, that the external incision can be made with the same instrument as the section of the prostate gland, thus rendering a change of instrument unnecessary. There is less danger also of any membrane getting between the groove and the knife, as the point of the cutting edge, being buried in the groove, will divide whatever lies before it, which is not done by a beaked instrument. The opening made in the prostate, and also in the perineal muscles, can, in some measure, be regulated by the angle which the knife makes with the director as it enters the bladder. In the majority of cases it will merely be necessary to pass the knife along the director, and, having cut the[27] prostate, to withdraw it without carrying it out of the groove; varying the angle according to the age of the patient, the width of the pelvis, and size of the stone. As the direction in which the prostate should be divided (in order to adhere to Cheselden’s operation), is obliquely downwards and outwards, the increasing the angle at which the knife enters the bladder will incur no risk of wounding the pudic artery. When the stone is unusually large, it will be necessary to dilate the prostate in withdrawing the knife.

This want of power to regulate the size of the incision is an objection to which the Gorget is acknowledged to be open. Whether the stone be large or small, the same opening, and that a small one, must serve in either case; and, if the stone be large, the operator cannot avoid employing violence in its extraction.

As not more dexterity is required to introduce this knife upon the director than every surgeon, however unused to Lithotomy, possesses, it is almost needless to caution against the employment of undue force in the section of the prostate. The knife may be conducted with deliberate care into the bladder, the resistance afforded by the prostate will be[28] readily felt, and the hand of the operator should be checked as soon as he feels the prostate has given way. It will be evident that the most important part of the operation is thus divested of that blind force, which renders it hazardous in the hands of the most dexterous, as well as of the most unskilful Lithotomist.

I had, for a considerable time past, been in the habit of operating on the dead subject with the instruments I have described; but until very lately I had no opportunity of trying them on the living subject. To Sir Astley Cooper’s kindness I am indebted for the opportunity, who allowed me to operate on a boy, that had been sent from the country into Guy’s Hospital for the purpose of submitting to the operation.

The mode of conducting the operation is as follows:—

An assistant holding the director, with the handle somewhat inclined towards the operator,[14] the external incision of the usual extent is made with the knife, until the groove is opened, and the point of the knife rests fairly in the director, which can be readily ascertained by the sensation communicated; the point being kept steadily against the groove, the operator with his left hand takes the handle of the[29] director, and lowers it till he brings the handle to the elevation described in plate 3, keeping his right hand fixed; then with an easy, simultaneous movement of both hands, the groove of the director and the edge of the knife are to be turned obliquely towards the patient’s left side; the knife having the proper bearing is now ready for the section of the prostate; at this time the operator should look to the exact line the director takes, in order to carry the knife safely and slowly along the groove; which may now be done without any risk of the point slipping out. The knife may then be either withdrawn along the director, or the parts further dilated, according to the circumstances I have adverted to. Having delivered his knife to the assistant, the operator takes the staff in his right hand, and passing the fore finger of his left along the director through the opening in the prostate, withdraws the director, and exchanging it for the forceps, passes the latter upon his finger into the cavity of the bladder.

In extracting the calculus, should the aperture in the prostate prove too small, and a great degree of violence be required to make it pass through the opening, it is advisable[30] always to dilate with the knife, rather than expose the patient to the inevitable danger consequent upon laceration.

In the case, on which the operation was first performed, the instruments in every respect answered my expectations. Not the slightest impediment was experienced in getting quickly into the bladder. The stone, which was large for a child of between four and five years old, is here delineated to shew the free incision which the mere passing of the knife along the director, and withdrawing it without dilating, will make. The stone was readily extracted, and the boy recovered without the intervention of a bad symptom.

The operation was performed in the presence of Mr. Travers, Mr. Green, and Mr. Tyrrell, Surgeons to St. Thomas’s Hospital.

FINIS.

I have deemed it right to defer this publication to the present period, in order to have the sanction of further experience as to the success and facility of this mode of operating, and also to demonstrate to the Gentlemen at present attending our Hospitals its ready application in practice. Its advantages have been fully confirmed in respect to the quickness, facility, and event of the operation.

Plate 1.

Drawn by F.F. Giraud. 1823. Engraved by J. Stewart.

London. Published 1824, by Messrs. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green.

In the usual manner of dissecting a side view of the pelvic viscera, an unnatural bearing is given to several important parts, by the following circumstances:—To assist the dissector a curved sound is previously introduced into the urethra, the consequence of which is, that the canal necessarily assumes whatever form the instrument may have. Views so taken are therefore incorrect, and give an erroneous idea of the natural course of the canal. The bladder and rectum are also excessively distended, the former being inflated to its utmost, and the latter filled with baked horse-hair. When the bladder is thus distended it rises out of the pelvis; and if in the dissection, the abdominal muscles have been turned aside, and the cellular connexions of the bladder much disturbed, its rise is so considerable as to elevate the prostate gland, and thus give a more horizontal bearing to the prostatic and membranous portions of the urethra. The distending the rectum also adds to the erroneous impression, by elevating the bladder, and thus bringing the base of the bladder, prostate gland and membranous urethra into a nearly horizontal line.

Such a view is calculated to give a correct anatomical idea of the course of the canal under retention of urine, and shews the propriety of using a catheter with the curve recommended by Sir Astley Cooper. The relative situation, however, of these parts is widely different when regarded in a lithotomic point of view.

In a person prepared for the operation the rectum is emptied by purgative medicine and an enema; and the bladder, which in a stone patient seldom contains more than eight ounces of urine, occupies the hollow of the flaccid or contracted rectum. Care has been taken not to distort these parts by the introduction of an instrument into the urethra, nor by more distention than was sufficient to preserve a general outline. To Mr. Giraud, dresser to Sir Astley Cooper, I am indebted for the drawings; the object of this plate being to represent the true bearing of the parts concerned in Lithotomy, they were drawn of the natural size, by measurement, from a young man, twenty-nine years of age, who died after six days illness; and the dissection being completed within twelve hours after his decease, the rigidity of death still remaining retained the parts in situ.

a. Section of the left os pubis.

b. Articular surface of the sacrum.

c. Section of the left crus penis.

d. Bulb of the penis.

e. Membranous portion of the urethra.

f. Prostate gland; its posterior edge concealed by veins.

g. Base of the bladder sinking considerably below the level of the prostate.

The relative bearing of the parts marked e, f, g, may be noticed, in reference to the introduction of the instrument, as delineated in Plate II.

When the pelvis is bent upon the lumbar vertebræ, and the shoulders of the patient raised, as in the posture for Lithotomy, these parts will have a rather more perpendicular bearing than even is in this view represented.

h. The veins returning the blood from the vena magna ipsius penis injected with wax, entering the pelvis under the pubic arch, through the triangular ligament, in which the vein begins to form a plexus, and concealing the posterior edge of the prostate. In the Celsian operation, this part of the neck of the bladder was cut laterally without dividing the prostate, whence may be inferred the cause of its fatality. In the Gorget operation, if the wound in the prostate is too small for the calculus to pass, this part of the bladder is torn.

i. Triangular ligament, section of. This ligament connects the membranous part of the urethra and prostate gland with the arch of the pubes, protects the dorsal nerve, artery, and veins, in their course to the dorsum penis, and serves the purpose of a barrier between the perineum and the reticular texture surrounding the bladder; it sends a process on each side of the prostate gland, to cover the vesiculæ seminales. The escape of urine after Lithotomy can only be productive of mischief, by infiltrating the cells of the scrotum, or by making its way upwards by the side of the bladder behind this ligament, when the prostate has been torn from its connexions.

k. Rectus abdominis, section of.

l. Peritoneum reflected over the fundus and back part of the bladder, and continued over the rectum.

m. Rectum partly distended by the introduction of a portion of inflated ileum.

n. Accelerator urinæ reflected from the bulb, and discovering the granular lobes of Cowpers’ gland between the bulb and membranous urethra.

o. Muscle of the membranous part of the urethra reflected; not forming a loop around the canal, but (as I have noticed in many subjects), descending from the pubes, and attached to the dense ligamento cellular structure which bounds the edge of the accelerator urinæ; it is continuous with the levator ani.

p. Compressor prostatæ and levator ani partly reflected.

q. Section of pyriformis.

r. Vas deferens.

s. Vesiculæ seminalis, partly concealed by the veins returning the blood from the prostate not in this subject injected.

t. Ureter.

u. Small intestines turned over the abdominal muscles on the right side, the latter having been left attached to the sternum and ribs.

w. Lower part of the thorax.

x. Lumbar mass of muscles.

y. Anus.

Plate 2.

Drawn by F.F. Giraud. 1823. Engraved by J. Stewart.

London. Published 1824, by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green.

Represents the director held in the situation for the first incision of the operation. The left side of the bladder having been removed, the extremity of the instrument is seen projecting some way into the base of the viscus, which now sinks lower into the hollow of the rectum, the latter being entirely empty. It will be observed how the slight curve of the staff adapts it to the concavity of the bladder, and prevents it being entangled by a fold during the depression of the handle, preparatory to the section of the prostate. The parts being viewed obliquely from behind, the prostate, urethra, &c. are but imperfectly seen.

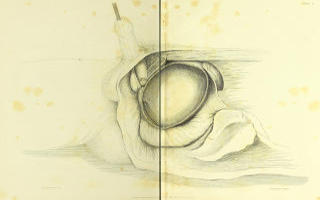

Plate 3.

Drawn by F.F. Giraud. 1823. Engraved by J. Stewart.

London. Published 1824, by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green.

In this plate the section of the prostate gland is shewn; the parts being viewed obliquely from before. The left hand of the operator holding the staff is depressed to conduct the knife into the cavity of the bladder. If attempt be made to depress the handle lower, the operator will feel his hand checked by the ligament of the arch. The knife is seen piercing the prostate in the direction which most nearly accords with Cheselden’s section. This inclination of the knife will enable the operator to make a very free incision, with great facility, without incurring any risk of wounding the pudic artery, the rectum, or the veins surrounding the neck of the bladder; unless a very large incision be required by the size of the calculus, in which case some of the veins must necessarily be divided.

In contrasting this view with Plate I, it will be observed that the prostate is carried somewhat upward from the rectum; this effect is produced by the depression of the handle and the consequent elevation of the extremity of the director. The danger of wounding the rectum is thus still farther diminished.

One great advantage of conducting the operation on this principle arises from the operator not being under the necessity of withdrawing the knife from the groove of the staff, after he has once entered it, during the subsequent steps of the operation. The extent of the incision in the prostate and neck of the bladder may be regulated by the angle which the knife makes in its introduction with the staff. Supposing that an opening be required extending through the prostate from d to b, (which for the majority of calculi, even above the ordinary size, will be quite sufficient, as the neck of the bladder will dilate considerably), the point of the knife must be carried on as far as a in the groove of the staff. For it will be evident that if the same angle be maintained in the act of carrying on the knife, the line c b a will be the position of the knife when the point has reached a. The edge of the knife, although brought apparently so near to the rectum, will not injure it, from its oblique inclination to the patient’s left side.

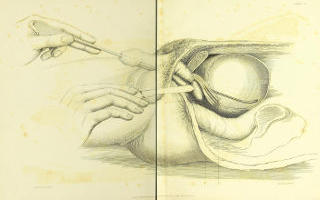

Gives a view of the director used in the operation on a child under five years of age, slightly curved towards the extremity, the more readily to adapt itself to the concavity of the bladder when held in the position in Plate II.

The knife with a scalpel blade, but longer than a common scalpel, and slightly convex on the back near the point, that it may run smoothly along the groove of the staff. When used with a staff of this form the whole of the cutting part of the operation may be easily performed with it.

The size of the calculus which was extracted in the first operation with these instruments is here delineated, in order to shew the extent of the opening in the cervix vesicæ and prostate gland, which in so young a child may be made with safety, according to the method explained in Plate III. The comparative size of the incision that can be made in the adult may be inferred.

[1] I allude to Mr. Martineau’s and Mr. Barlow’s papers on Lithotomy.

[2] Deschamps—page 102.

[3] Deschamps—page 104.

[4] Deschamps—page 109.

[5] Douglas’s Appendix—page 12.

[6] Deschamps—page 106.

[7] Page 107.

[8] Cheselden’s Anatomy—page 330.

[9] Bell’s Surgery—page 173.

[10] Sharp’s Surgery.

[11] The late Mr. Dease was so impressed with the hazard of passing a cutting instrument along the curve of the staff, that he used to withdraw the staff, after he had opened the urethra, and passing a director through the opening into the bladder, dilated the cervix vesicæ, by introducing the Gorget in the usual manner.

[12] Mr. Martineau’s Gorget is merely used as a director to convey the forceps into the bladder; its edges are blunt, and therefore it does not aid in the division of the prostate, which has been already divided by the knife, as a reference to his operation will shew. He had the kindness to send me a model of his Gorget, for which, and his politeness in his communication to me on the subject, I take this opportunity of expressing my thanks.

[13] I should not omit to mention that I did not adopt this alteration in the instruments, without having first operated at the hospital, both with the Cutting-Gorget, and also with the beaked knife, in conjunction with the common staff. I was not led to lay them aside by the issue of the cases, as they were successful; but the difficulty and hazard attending their introduction, together with the general unsuccessful issue of Gorget operations, compared with Cheselden’s method, induced me to use a more simple form of instruments.