Project Gutenberg's Harper's Round Table, January 19, 1897, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Harper's Round Table, January 19, 1897 Author: Various Release Date: October 11, 2019 [EBook #60470] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S ROUND TABLE, JANUARY 19, 1897 *** Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1897, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, JANUARY 19, 1897. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 899. | two dollars a year. |

Throughout most of the ranch country there are two kinds of deer, the black-tail and the white-tail. The white-tail is the same as the deer of the East; it is a beautiful creature, a marvel of lightness and grace in all its movements, and it loves to dwell in thick timber, so that in the plains country it is almost confined to the heavily wooded river bottoms. The black-tail is somewhat larger, with a different and very peculiar gait, consisting of a succession of stiff-legged bounds, all four feet striking the earth at the same time. Its habits are likewise very different, as it is a bolder animal and much fonder of the open country. Among the Rockies it is found in the deep forests, but it prefers scantily wooded regions, and on the plains it dwells by choice in the rough hills, spending the day in the patches of ash or cedar among the ravines. Fifteen years ago the black-tail was very much more abundant than the white-tail almost everywhere in the West, but owing to the nature of its haunts it is more easily killed out, and now, though both species have decreased in numbers, the white-tail is on the whole the more common.

My ranch-house is situated on a heavily wooded bottom, one of the places of which the white-tail are fond to this[Pg 282] day. On one occasion I killed one from the ranch veranda, and two or three times I have shot them within half a mile of the house. Nevertheless, they are so cunning and stealthy in their ways, and the cover is so dense, that usually, although one may know of their existence right in one's neighborhood, there is more chance of getting game by going off eight or ten miles into the broken country of the black-tail.

One Christmas I was to spend at the ranch, and I made up my mind that I would try to get a good buck for our Christmas dinner; for I had not had much time to hunt that fall, and Christmas was almost upon us before we started to lay in our stock of winter meat. So I arranged with one of the cowboys to make an all-day's hunt through some rugged hills on the other side of the river, where we knew there were black-tail.

We were up soon after three o'clock, when it was yet as dark as at midnight. We had a long day's work before us, and so we ate a substantial breakfast, then put on our fur caps, coats, and mittens, and walked out into the cold night. The air was still, but it was biting weather, and we pulled our caps down over our ears as we walked toward the rough low stable where the two hunting ponies had been put overnight. In a few minutes we were jogging along on our journey.

There was a powder of snow over the ground, and this and the brilliant starlight enabled us to see our way without difficulty. The river was frozen hard, and the hoofs of the horses rang on the ice as they crossed. For a while we followed the wagon road, and then struck off into a cattle trail which led up into a long coulee. After a while this faded out, and we began to work our way along the divide, not without caution, for in broken countries it is hard to take a horse during darkness. Indeed, we found we had left a little too early, for there was hardly a glimmer of dawn when we reached our proposed hunting-grounds. We left the horses in a sheltered nook where there was abundance of grass, and strode off on foot, numb after the ride.

The dawn brightened rapidly, and there was almost light enough to shoot when we reached a spur overlooking a large basin around whose edges there were several wooded coulees. Here we sat down to wait and look. We did not have to wait long, for just as the sun was coming up on our right hand we caught a glimpse of something moving at the mouth of one of the little ravines some hundreds of yards distant. Another glance showed us that it was a deer feeding, while another behind it was walking leisurely in our direction. There was no time to be lost, and sliding back over the crest, we trotted off around a spur until we were in line with the quarry, and then walked rapidly toward them. Our only fear was lest they should move into some position where they would see us; and this fear was justified. While still one hundred yards from the mouth of the coulee in which we had seen the feeding deer, the second one, which all the time had been walking slowly in our direction, came out on a ridge crest to one side of our course. It saw us at once and halted short; it was only a spike buck, but there was no time to lose, for we needed meat, and in another moment it would have gone off, giving the alarm to its companion. So I dropped on one knee, and fired just as it turned. From the jump it gave I was sure it was hit, but it disappeared over the hill, and at the same time the big buck, its companion, dashed out of the coulee in front, across the basin. It was broad-side to me, and not more than one hundred yards distant; but a running deer is difficult to hit, and though I took two shots, both missed, and it disappeared behind another spur. This looked pretty bad, and I felt rather blue as I climbed up to look at the trail of the spike. I was cheered to find blood, and as there was a good deal of snow here and there, it was easy to follow it; nor was it long before we saw the buck moving forward slowly, evidently very sick. We did not disturb him, but watched him until he turned down into a short ravine a quarter of a mile off; he did not come out, and we sat down and waited nearly an hour to give him time to get stiff. When we reached the valley, one went down each side so as to be sure to get him when he jumped up. Our caution was needless, however, for we failed to start him; and on hunting through some of the patches of brush we found him stretched out already dead.

This was satisfactory; but still it was not the big buck, and we started out again after dressing and hanging up the deer. For many hours we saw nothing, and we had swung around within a couple of miles of the horses before we sat down behind a screen of stunted cedars for a last look. After attentively scanning every patch of brush in sight, we were about to go on when the attention of both of us was caught at the same moment by seeing a big buck deliberately get up, turn round, and then lie down again in a grove of small leafless trees lying opposite to us on a hill-side with a southern exposure. He had evidently very nearly finished his day's rest, but was not quite ready to go out feeding; and his restlessness caused him his life. As we now knew just where he was, the work was easy. We marked a place on the hill-top a little above and to one side of him; and while the cowboy remained to watch him, I drew back and walked leisurely round to where I could get a shot. When nearly up to the crest I crawled into view of the patch of brush, rested my elbows on the ground, and gently tapped two stones together. The buck rose nimbly to his feet, and at seventy yards afforded me a standing shot, which I could not fail to turn to good account.

A winter day is short, and twilight had come before we had packed both bucks on the horses; but with our game behind our saddles we did not feel either fatigue, or hunger, or cold, while the horses trotted steadily homeward. The moon was a few days old, and it gave us light until we reached the top of the bluffs by the river and saw across the frozen stream the gleam from the fire-lit windows of the ranch-house.

When the great hurricane swept over Apia Harbor, in Samoa, seven years ago, and wrecked the six American and German war-ships that were gathered there, the world was thrilled with the story of the heroism of the sailors on the United States man-of-war Trenton. Of all the incidents of that memorable disaster, the one which will live longest in the memory of readers is the bravery with which the men of the Trenton faced death. Their vessel had snapped her anchor chains, and was steadily drifting toward the rocks, but the men lined the rigging and gave rousing cheers to the British ship Calliope, which, with all steam on, was headed for the open sea. The Trenton's band was also ordered on deck, and to the strains of "The Star-spangled Banner" the old ship went to her death. As she passed the Vandalia, over which the waves were breaking, the Trenton's men cheered the few survivors in the rigging, and the feeble shout that came in response was the saddest feature of the disaster. When the Trenton's band struck up, amazement fell upon the Americans and other foreigners on shore who were trying to save the lives of those whom the current brought to the beach. Then, when the strains of the national air were recognized, a great shout went up, and men wept to think of heroism that laughed at death.

A similar incident of bravery in the face of death comes from the coast of China, and the crew of the German gun-boat Iltis were the heroes who showed genuine courage when all hope of safety was gone. The Iltis left Che-foo on July 23, passed Wei-hai-wei—made memorable by the defeat and suicide of old Admiral Ting, of the Chinese navy—and rounded the Shan-tung peninsula. As the vessel passed the northern point of the promontory the wind freshened to a gale, and with all sails furled the ship held her way to the south, parallel to the coast. The storm was soon recognized as a typhoon of great violence; the driving sleet and the thick darkness confused the look-out, and the strong currents carried the ship near to the rocky shore. Without warning the vessel struck, and remained[Pg 283] hard and fast on a sunken rock. The engine-room filled rapidly, and all hands were warned to come on deck. There they saw that the prospect was hopeless, as every wave helped to stave in the strong steel plates. Rockets were sent up, but no response came from the shore; no boat could live in the wild seas which washed over the doomed vessel. The commander, Lieutenant-Captain Braun, ordered all the men aft, and gathering them around him, called upon them to give three cheers for the Emperor. These were given with a will, and a moment after the masts went overboard, smashing the officers' bridge, and then the ship parted.

The Captain and the greater part of the crew were on the after-part of the ship, which still remained high out of the water. When it was seen that the wreck would last but a few minutes more, gunner Raehm addressed the crew and begged them to join in singing the Flaggenlied, or flag-song. This stirring song was then sung to the accompaniment of the roaring breakers and the howling storm. Its final verse, in German, is as follows:

Und treibt des wilden Sturms Gewalt

Uns an ein Felsenriff,

Gleichviel in welcherlei Gestalt

Gefahr droht unserm Schiff:

Wir wanken und wir weichen nicht,

Wir thun nach Seemanns Brauch,

Getreu erfüll'n wir uns're Pflicht

Auch bis zum leztzen Hauch,

Und rufen freudig sterbend aus,

Getreu bis in den Tod:

"Der Kaiser und die Flagge hoch!

Die Flagge schwarz, weiss, roth!"

Freely rendered into English this reads:

And shout the might of wild, wild storms

On to a reef us drive,

And dangers menace—'t matters not

From where—our ship and life,

Our posts we never will desert;

And sailorlike and true

Until the last breath goes from us

We will our duty do.

And, joyful dying then we shout

United true in death—

"The Kaiser and our standard hoch!

The flag black, white, and red!"

The survivors, with tears in their eyes, described the singing of this battle chant, in which the poet described the fate of the Iltis and the doom of her crew. The last verse had just been roared out with a will when the stern of the vessel heeled over, and a moment later the whole after-half of the ship plunged from the rocks, carrying down to death officers and men, except two sailors, who reached the shore. Those on the other half of the wreck remained for thirty-six hours without food, when they were rescued by the Chinese. Only nine men were saved, making eleven in all who reached the shore out of a total of seventy-seven men and officers.

The true and zealous golfer is not to be deterred from his favorite sport by the ordinary accidents of the weather, and indeed it is one of the great merits of golf that it can be played under almost any atmospheric conditions. Baseball, cricket, tennis, croquet, and archery are poor fun on a very windy day, while a wet one makes play impossible. And then these games have each of them a recognized season, and as winter comes on bat, bow, and ball must be laid aside for good. Football and hockey are independent so far as rain and cold are concerned, but the exercise is too violent a one to be continued into the warm days of spring and summer.

Golf, on the other hand, is restricted to no particular season, and it is one of the rules governing medal competitions that competitors may not discontinue play on account of bad weather. Of course on abnormally warm days any sort of physical exertion may become a burden, and in very cold weather stiffened fingers and frozen "lies" do not conduce to good scoring. But there is only one thing that really puts an end to the game, and that is a heavy fall of snow. With a light sprinkling of an inch or two, very good golf may be played by using red balls and having the putting-greens carefully swept, for the snow serves the purpose of a universal tee, and a special ruling may be enacted allowing the player (in the event of the ball being buried) the privilege of lifting or of lightly brushing the snow aside. Among the pines of Lakewood, New Jersey, golf is played all through the winter, for on that sandy soil the snow lies but a short time, owing to the mildness of the climate and the proximity of the ocean. But of course Lakewood is an exceptionally favored spot for these northern latitudes. In and around New York city there is generally enough snow by New-Year's day to stop play, and golf at the big clubs is virtually at an end after the holidays and through the months of January, February, March, and April. Even after the snow has disappeared the frost must be allowed to get entirely out of the ground before play is resumed, or the course, and particularly the putting-greens, may be ruined.

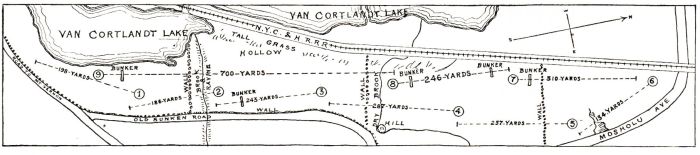

FIG. 1.

FIG. 1.

We must therefore admit that golf may have its "close" season, at least for places that lie north of Mason and Dixon's famous line, but no golfer worthy of the name is content to entirely abandon all attempts at practice. If he can do nothing better, he will at least try "putting" into tumblers laid on their sides on the dining-room floor, or he will find some pretext to steal away to the attic for a few trial swings at a mythical ball. Inventive genius has appreciated this unquenchable craving on the part of the enthusiastic golfer, and several ingenious appliances have been patented and put upon the market, by the use of which he may keep up his practice in putting, approaching, and even driving.

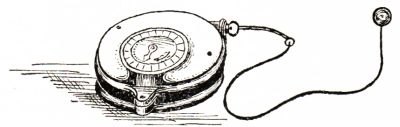

In Fig. 4 is shown an apparatus called Linka. Inside the machine is a powerful spring pulley-wheel, and over this runs a stout cord with an ordinary golf-ball attached at the free end. When the ball is teed and struck away, the propelling force is communicated through the spring to a self-registering dial. So many pounds of pressure indicate so many yards in distance, and the scale is graduated in five-yard divisions from zero up to 225 yards. Fifteen or twenty feet of clear space is ample for the use of the machine.

FIG. 2.

FIG. 2.

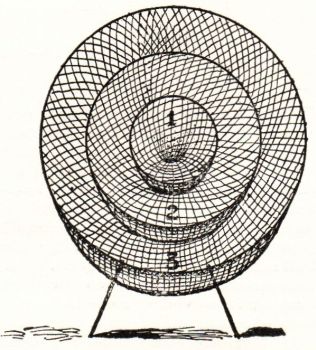

For practice in approaching the putting-green there is the stand shown in Fig. 3. It consists of three concentric hoop-nets, and the accuracy of the shot is determined by the particular hoop into which the ball is played. Of course a free ball is used, and the weak point in the apparatus is that it does not indicate the distance covered (a point which in real play is quite as important as accurate direction). But it may be arbitrarily assumed that a ball in the smallest hoop has been laid within a foot of the hole, while the middle and outer rings may stand for six and fifteen feet respectively.

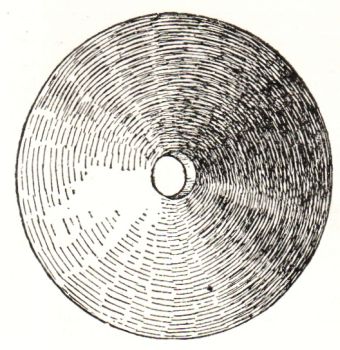

A cheap and effective substitute for the approaching-stand is the simple target depicted in Fig. 2. It may be painted either upon canvas or roughly sketched out in chalk upon the barn door. The canvas should be eight feet square, and provided with guy-ropes and ring-bolts for attaching to the floor and ceiling. If the lower edge of the canvas just touches the floor, the centre of the target and the "bunker-line" will consequently be three feet above it. (The use of the bunker-line will be explained further on.) The diameter of the outer circle should be four feet; of the middle one, two and a half feet; and of the inner ring, one foot. The bull's-eye, which represents the hole proper, should be four inches in diameter. As before, a ball striking in the outer ring is supposed to lie fifteen feet from the hole; one in the middle ring, at six feet; and one in the inner ring, at one foot. A ball that strikes the bull's-eye is assumed to be in the hole. A ball on the line is credited to the inside division.

FIG. 3.

FIG. 3.

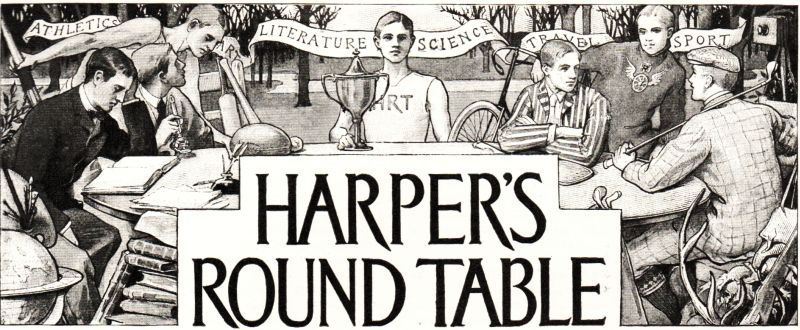

For putting there has been devised the stand shown in[Pg 284] Fig. 1. It is nothing but a circular convex piece of tin with a hole in it. The tin has a diameter of eight and a half inches, and that of the hole is two and a half. The convexity is such that the depth of the hole is three-quarters of an inch. It looks easy, but nevertheless it takes a good deal of skill to "putt" a ball up the slope and safely into the cup. If the direction be not accurate the ball will fall off, and if the force be too great it will run completely over the hole in a very irritating manner.

Now all of these appliances may afford amusing practice, and there is no reason why they should not be so used in combination as to give much of the variety and excitement of a regular round of the links. Granted the use of the attic or that of the barn floor, and we may at once proceed to set up our miniature course of in-door golf. The principal expense will be in the purchase of the driving-machine, which costs several dollars at the shops; but we will assume that a small club has been formed, and that the cost of the several pieces of apparatus is to be equally divided among the playing members. The substitute for the approaching-stand (Fig. 3) may be gotten up very cheaply, and the putting-stand can be bought for fifty cents.

FIG. 4.

FIG. 4.

It is essential that there should be enough of clear space to allow a full swing with the driving-clubs. Fifteen feet will do, but eighteen or twenty will be better. The ball attached to the driving-machine must have a free course in front of it of at least a dozen feet, for otherwise its full force will not be communicated to the spring, and the dial will not register correctly. The machine itself is placed a little to one side, so as not to interfere with the club, and the ball should be teed about a yard in front of it. After the tee shot, when the ball is supposed to be on the ground (as in actual play), we may use an old door-mat as a substitute for turf, and we will call this the "driving-pad."

In playing approach shots a free ball is used, and it may be placed on the "driving-pad" and about fifteen feet from the approaching-stand or canvas target. In the middle of the floor should be a mark for the placing of the putting-stand during the process of "holing out." A chalk line should be drawn from this mark fifteen feet long, with cross marks at the one, six, and fifteen foot points. So much for the mechanical apparatus; now for the course itself.

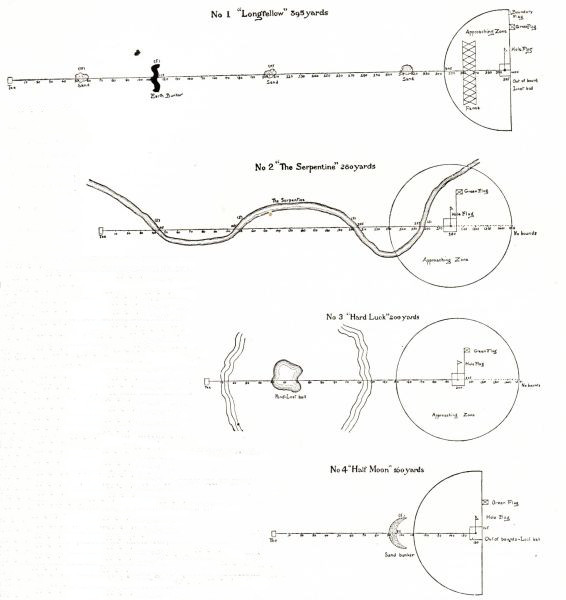

No. 1.—Ball in earth bunker or fence, drop five yards

back and add one stroke. Ball in sand, play off bare floor. No. 2.—Ball

in "Serpentine," drop five yards back and add one stroke. No. 3.—Ball

in pond is lost. Tee again and add two strokes. No. 4.—Ball in sand

bunker, drop five yards back and add one stroke.

No. 1.—Ball in earth bunker or fence, drop five yards

back and add one stroke. Ball in sand, play off bare floor. No. 2.—Ball

in "Serpentine," drop five yards back and add one stroke. No. 3.—Ball

in pond is lost. Tee again and add two strokes. No. 4.—Ball in sand

bunker, drop five yards back and add one stroke.

Suppose that our course is to be a nine-hole one, we must provide ourselves with some sheets of stout wrapping-paper, a three-foot rule, and an assortment of colored pencils. Each imaginary "hole" must now be sketched out upon a separate sheet, after the fashion shown in the plan. The sheet should be three feet long, and a convenient scale of measurement will be a quarter-inch to five yards. Five inches will therefore represent 100 yards; seven and one-half inches, 150 yards; ten inches, 200 yards; and so on. Thirty inches is equivalent to 600 yards, which should be the maximum. The putting-greens should be thirty feet, or ten yards, square. A line should be drawn from tee to centre of the putting-green, and each ten-yard point along it should be marked by a red dot with the number underneath, 10, 20, 30, and so on. A circle fifty yards in diameter is drawn around the hole, and the space enclosed is called the "approaching-zone." Water hazards may be indicated by blue shading, the ordinary earth bunker by red, stone walls by black, and the tees and putting-greens by green. Everything should be drawn accurately to scale, and the artistic appearance of the little map will be improved by introducing hole and line flags in the proper colors. On an eighteen-hole course red flags are used for the nine outgoing holes, and white ones for the incoming ones. Red and white flags are used to indicate the line of play at blind holes, and green flags may mark the boundaries of the course.

Any boy who has a practical knowledge of golf, and who is possessed of reasonable ingenuity, may lay out in this manner a series of holes which, if properly varied, will make the play very interesting. The principal difficulty is the proper arrangement of the hazards, and this will be largely determined by the average driving ability of the club members. Generally speaking, a bunker must never be so situated as to spoil a really good drive. Hazards are intended to punish bad shots and not to injure good ones. Accordingly we may place a hazard ten yards from the tee, or any distance between that and 100 yards. But a bunker 160 yards from the tee would be in just the place to trap a really good drive, while the topped or short one would go unpunished. Side hazards will not be required on our in-door course, as there is no way of determining the "slice" or "pull" of our drives. Each player must be provided with a stick-pin to mark his progress on the map, and these may be distinguished by dipping the heads into different colors of melted sealing-wax. The maps of the holes are tacked up on the wall in regular succession as the play goes on. And now we are ready for the actual match, and we will suppose that we are playing the "Longfellow hole."

M. and N. are the players, and M. has the "honor." This being his tee drive, he is allowed to use a rubber or some other kind of artificial tee, and of course he plays with the ball attached to the driving-machine. The dial shows that he has driven 115 yards, and has therefore carried the earth bunker. He sticks in his pin at the 115-yard point, and N. has his turn. We will suppose that N. tops his ball, and the dial shows that his ball has travelled only 50 yards. He sticks in his pin at that point on the[Pg 285] map. N. being the farthest from the hole, must now play again, and this time he must not use a tee, but must simply place the ball on the "driving-pad." As he is fifty yards from the bunker he will probably use his brassie, and this time he gets in a good shot of 130 yards, which will advance him to the 180-yard point.

The play goes on in this manner until both balls have been played inside the "approaching-zone" or fifty-yard circle. Then the driving-machine is set aside, and the approach shot is made with a free ball, and at the stand (Fig. 3) or target (Fig. 2). As before explained, a ball in the bull's-eye means that the player has holed out, if in the smallest ring he is one foot from the hole, and six and fifteen feet away for the middle and outer rings respectively. A ball that misses the target altogether is held to be "foozled," and must be taken back and played again (counting a stroke each time) until the player has succeeded in hitting the bull's-eye or one of the numbered rings. And particularly note this: if, as in this case, there is a hazard between the player's ball and the green, the ball must not only hit the target, but it must do so above the horizontal mark called on the diagram (Fig. 2) the bunker-line. Failing in this, the player is held to be in the bunker, and must add a penalty stroke to his score, and try again, until he does succeed in hitting the target above the bunker-line. The balls being now within holing-distance they are placed at their respective marks (one foot, six feet, or fifteen feet from the putting-stand), and holed out in the ordinary manner.

The small type under the plans give specific directions for the playing of each hole, and may be varied at discretion. In sand the player must drive off the bare floor instead of from the pad, and for a heavy lie or long grass an old bear-skin (or other long-haired skin) rug may be substituted. The half-circles mean that a ball driven beyond the marked figures is out of bounds and lost.

Finally, in the event of a long shot that exactly covers the distance to the hole, the player may be considered to have holed out in that shot. M. is 110 yards from the green. He drives, and the dial indicates exactly 110 yards. M. is down by a lucky fluke, and does not have to do any approaching or putting.

It is hardly worth while to make any argument against the assertion that all this is not golf. Of course it is not golf, but it is as near to it as we are likely to get within the limits of our four walls. Driving with the machine is good practice for the "long game," even though it cannot help us in correcting that dreaded "slicing" and "pulling." But these last, again, are principally matters of a faulty aim; it is the eye that needs correction. Practice with the approaching-target may teach us the sense of direction with our wrist shots, and we can leave the distance problem for our open-air play. The putting will train both eye and hand. Finally, the game is a practical one, and with a little ingenuity and intelligence in laying out the imaginary course, it may serve very well by way of amusement during the winter afternoons and evenings when the mercury without is hovering around the zero mark and the snow lies deep upon the links.

While Miss Joanna Middleton was imparting the news of her startling discovery to her sisters in the house, Teddy and her aunt Thomasine were walking as swiftly as possible toward the lower end of the garden. Theodora's face betrayed that she was greatly excited, and she held her aunt's hand tightly, and almost dragged her along in her haste to get there.

"My dear Teddy," said Miss Thomasine at length, while she fairly gasped for breath, "I am not accustomed to walking so fast. I—I really must stop for a moment."

"Oh, do excuse me, Aunt Tom! I never thought. You see, I am so used to running."

They stopped, and stood facing each other for a moment.

"What have you under your apron?" asked Miss Thomasine.

Theodora's face grew redder still, and she cast down her eyes. This was unusual, for the child had a frank, fearless habit of fixing her brown eyes upon those of the person to whom she was speaking which was very winning. Her face had a way of showing every emotion which she might be feeling, and her aunt saw at once that something was the matter.

"Are you so troubled about the kitten, Teddy, my dear?" asked Miss Thomasine. "Do you begin to feel sorry that you fought the boy?"

"I'm not a bit sorry, Aunt Tom. I'm glad, glad, glad! But you needn't look so disappointed; the sorry feeling may come later. It usually does after I've been naughty, but sometimes not for a good while. For instance, when I've been naughty in the morning I very often don't begin to feel sorry till toward sunset. I suppose I begin to think then of that verse in the Bible about not letting the sun go down on your wrath. So perhaps late in the afternoon I may begin to feel a little bit sorry about Andy Morse, though I don't know. But are you rested yet, Aunt Tom? I do want to get to the funeral, but not unless you are quite ready," she added, politely.

"Suppose you take my other hand," said Miss Thomasine, "and I will hold my sunshade in this one."

For some reason this arrangement did not appear to please Theodora. However, she put both of her hands under her apron, and after a curious sound of the clatter of china, she produced her right hand and gave it to her aunt.

"What have you there, Teddy, my dear? What are you hiding under your apron?" asked the gentle little lady.

"Oh, nothing much, Aunt Tom. At least—that is—yes, there is something, but—well—I would rather not tell you what it is, if you don't mind."

Soon they turned a corner, and reached the spot where the six Hoyt boys were awaiting them.

"We thought you were never coming, Ted! What kept you so long?" shouted Paul, who was the eldest, and therefore master of ceremonies. Catching sight of Miss Thomasine, he stopped abruptly. "Aren't you going to have a funeral?" he asked. "We've got everything ready."

"Oh yes, we're going to have it," responded she; "Aunt Tom came with me to see how we do it. I'm sorry to have kept you waiting, but I really could not get here before; and now I must speak to Arthur a minute. You other boys just entertain Aunt Tom, please. She would like to rest. What a lovely grave, and what sweet flowers! Arthur, come here a minute."

They walked a short distance away, and then disappeared behind some currant-bushes. The other boys appeared to be unequal to the task of entertaining Miss Thomasine, so a profound silence reigned, making plainly audible the murmur of Theodora's voice.

"Hurry up there," said Paul, impatiently. "If you want me to help with this funeral you must come quick. What are you talking about, anyway?"

"Never mind," replied Teddy, running into sight, followed by Arthur. "It's a secret, and you mustn't ask."

Her aunt noticed that both hands were now visible, and that she carried nothing in them; but Miss Thomasine soon forgot that she had felt any curiosity in the matter, and turned her attention to the proceedings of these very remarkable children. She also forgot that she had been deputed by her sisters to stop these proceedings, and became wholly and at once an interested spectator.

"We will start from here and walk once around the garden," said Teddy, "and we will make quite a long procession, for there are so many of us. I wish we had some music. We might pretend that the poor dear kitten was a soldier."

"So we will," cried Clement. "I'll get my drum quicker than a wink."

Before he had finished speaking he was over the garden wall.

"And get my trumpet," shouted Raymond.

Presently Clem returned, and all was now ready. Upon the boys' express wagon reposed a pasteboard box, in which had been placed the kitten, more honored in its death than in its short, unhappy life. Yellow daisies, asters, and golden-rod were heaped upon the cart in magnificent profusion, but the handle was draped in black.

Arthur and Walter acted as horses, and subdued their natural speed to a funereal gait; Clem and Raymond marched before, one beating his drum with measured rat-tat-tat, the other blowing long and melancholy wails upon his Fourth-of-July horn. On either side the cart walked Paul and Charlie, while close behind came Theodora and her aunt Thomasine.

"You will make a perfect chief mourner," whispered Teddy, "for your hat is so black and so is your cape. I shall hold my handkerchief to my eyes, so."

"But, my dear," expostulated Miss Thomasine, "I really cannot. I do not approve. Remember, it is only a kitten."

"Yes, yes, I do remember. That poor dead kitten! Please come, Aunt Tom! Don't spoil it all, and try to look as sad as you can!"

And before Miss Thomasine really knew it, the procession had begun to move and she was in it. Around the garden they walked, and finally returned to their starting-place, where the grave had been already dug. Paul and Charlie attended to this part of the ceremonies, the musicians blew and beat a parting salute upon their instruments, Theodora mopped her dry eyes, and the horses, when all was over, relieved their feelings by running away.

"Wasn't it fun?" exclaimed Teddy. "I never did like anybody so much as you boys, and you do a funeral beautifully. Do you really have to go back now, Aunt Tom? I wish you could stay here and play with us. Charlie is going to let me try his bicycle, and I'd like you to see me."

"Oh, my dear child," cried Miss Thomasine. "It will never do in the world. You must not—indeed you must not! If you knew the feeling that your aunts and I have about bicycles."

"But they are not dangerous, Aunt Tom. Indeed, lots of people ride them."

"It is not the danger so much as the— Well, my dear, you must never do it without asking your other aunts. A lady on a bicycle!"

"But I'm not a lady; I'm only a child. Besides, lots of ladies ride them. I've seen them in Alden over and over again."

"It does not seem to me as if they can be real ladies. But come into the house and ask your aunt Adaline. I cannot take any more responsibility. I feel uncomfortable now about that funeral. I do not know what your other aunts will say."

"Oh dear!" grumbled Theodora; "it is such a bother to have to ask so many people what I can do. If it were just you, Aunt Tom, I shouldn't mind, but five are such a lot, and you all think everything is so dreadful. I am sure mamma would let me ride a wheel." Her aunt made no reply, and they walked toward the house. "There, I suppose I ought not to have said that," added Teddy, penitently, after a moment's pause. "It was disrespectful, I suppose. But oh, Aunt Tom, if you only won't all say I can't ride a wheel, it is all I ask!"

They found the door standing open, and from the sound[Pg 287] of voices it was evident that some one was in the parlor, and immediately the parlor door was opened a crack, and at it appeared Miss Melissa, beckoning mysteriously to her sister.

"Come!" she whispered. "Thomasine, the— My dear sister, be prepared! a cruel blow!"

"What do you mean, Melissa?" cried Miss Thomasine, her nerves quite unstrung by the performance in which she had so recently taken part, and also by her late altercation, if so it could be called, with her niece.

"Come!" repeated Miss Melissa, and her sister went into the drawing-room, almost expecting to find that there had been a death in the family.

Theodora ran up stairs. "They have found it out! they have found it out!" she thought, and flying to her room she closed and bolted the door. Ten minutes later her name was called from without.

"Miss Theodora, are you there?" It was Mary Ann, one of the maids. Teddy did not speak nor move.

"Miss Theodora," said Mary Ann again, tapping at the door and rattling the handle as she spoke. "I think, miss, you had better let me in. Your aunts want to speak to you."

Slowly Teddy rose from the bed, where she had flung herself, and reluctantly opened the door. Her dark hair, which was cut short across her forehead and hung in a wavy mass behind, looked sadly dishevelled, and her face showed unmistakably that she had been crying. "What do they want me for?" she asked.

"A terrible thing has happened, miss," replied Mary Ann, in an awed whisper; "the Middleton bowl is broke—the Middleton bowl as was worth hundreds of dollars, I've heard tell, that folks has been comin' from all over the country to see ever since I've lived here, and that's goin' on fifteen years."

"But why do they want me?" asked Theodora, showing no surprise when told of the calamity, as Mary Ann noted.

"Because, miss, somebody has broke it, and as it ain't one of the ladies themselves, it must have been either you or some of the help. So, miss, if 'twas you and you don't tell it, some of us has got to suffer."

"Mary Ann," said Teddy, stopping short at the stairs, "must I really go down? Can't I run away? Won't you help me to run away, Mary Ann? I'll give you something nice if you will."

"La, miss, don't talk and look so wild! You just tell 'em you did it quite accidental, and they'll forgive you. The Miss Middletons is real ladies, and they won't scold, but they'll take it awful hard if you try to deceive 'em. Just tell 'em you did it."

"I can't possibly do that. Oh, Mary Ann, I wish I were in South America with my father and mother!"

She had reached the parlor door by this time, and there she paused. Presently, summoning all her courage, she pushed it open and entered.

"Poor little miss!" said Mary Ann to herself. "Of course she did it, and I'm real sorry for her."

And then she went off to the kitchen to tell the other frightened servants that there was no doubt as to who was guilty.

The parlor was a very large room, and Venetian-blinds at the seven long windows shut out the light of day as much as possible. Two of them, at one end of the room, had been drawn up this morning, however. As has been said, the parlor was furnished in old-fashioned mahogany. There were eight-legged tables, quaintly shaped shelves and cabinets, Chippendale chairs, and even an ancient piano, made in the style of eighty years ago.

The Misses Middleton were modern in one respect only; their drawing-room was filled with bric-à-brac. There were lacquered-ware tea-poys from Japan and quaint idols from India, while rare old bits of china filled every available space. Near one of the windows stood a Chinese table. It was curiously carved, and the top was inlaid with bits of wood and ivory in the shapes of mysterious Chinese symbols, and upon this table had always rested, in honor and apparent security, the famous Middleton bowl.

The walls were lined with rare old paintings, and portraits from the hands of Sully, Stuart, and even of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Gainsborough, looked down upon the five descendants of the ancient race of Middleton this September morning when they sat, drawn up in battle array, to receive their niece.

Slowly she walked into the room, and with downcast eyes and burning face she stood before her aunts. They were seated in a semicircle, their backs turned toward the windows, where the shades had been raised; therefore the light streamed full in the face of Theodora.

"What have you to say for yourself, Theodora?" asked Miss Middleton, in an impressive voice.

There was no reply. Miss Thomasine looked unhappy, and covered her face with her handkerchief, and Miss Melissa again made use of her salts. Miss Dorcas began to knit nervously, but Miss Joanna stared straight at Theodora through her gold-rimmed spectacles.

"Have you nothing to say, Theodora?" asked Miss Middleton, after a pause.

"No, Aunt Adaline."

"You have not told her why she has been called, sister!" exclaimed Miss Thomasine. "Perhaps she knows nothing about it."

"Is that probable after what you told us?" asked Miss Middleton, austerely. "However, I will humor you. Theodora, you have seen the Middleton bowl?"

Involuntarily Teddy's eyes turned toward the now empty Chinese table, and then were dropped again.

"Yes, it stood there," continued Miss Middleton, "and at ten o'clock this morning it was still there, for I saw it myself. At a quarter past eleven, when your aunt Joanna came down to dust the parlor, the Middleton bowl was gone! Not a trace of it left but this small piece of china to show that it had ever been there."

Theodora glanced up again, and saw a triangular bit of china, an inch or two long, which her aunt held in her hand and then laid upon the table.

"You know the value of that bowl. You have been told that your great-grandfather brought it home, and that there is said to be but one like it in the world. Now that other is the only one. The Middleton bowl is no more."

She paused, and her sisters, more than one of them, sobbed audibly. Miss Middleton, Miss Joanna, and Theodora herself alone were dry-eyed.

"Have you anything to say for yourself?" asked Miss Middleton, for the third time.

And again Theodora replied, "No, Aunt Adaline."

Miss Middleton's foot moved impatiently. "You must say something, Theodora. In plain words, did you break the bowl?" There was no answer. "Very well. You would have saved yourself in our esteem if you had confessed at once that you broke it, and that it was an accident, as I suppose it was. We should have forgiven you, great as the loss is. Now you are attempting to hide it. I am only thankful that you are not actually denying the fact, but I suppose you realize that it would be useless. The evidence is too strong against you."

"What do you mean, Aunt Adaline?"

"Your aunt Thomasine will explain."

"Oh, sister!" murmured Miss Thomasine. "I almost wish I had not told you; but you took me so by surprise that the words came right out before I knew it. Poor little Teddy! I am sure she did not mean to break it."

"I beg you will not call her by that ridiculous boy's name, Thomasine!" interrupted Miss Joanna. "And you are doing your best to encourage her to keep silence. I think you and sister Adaline are entirely too lenient. If I had my way, I should soon force her to confess."

Teddy, who had almost cried while her aunt Thomasine was speaking, now raised her head and gazed defiantly at Miss Joanna. "I did not break the bowl," she said, in a loud, clear voice.

"Oh, Theodora!" exclaimed the five aunts, in a chorus of dismay.

"I did not break the bowl," she repeated.

"But, my dear, the pieces which you carried under your apron to the garden?" murmured Miss Thomasine, greatly aghast at the turn which affairs were taking.

"How do you know I did?" asked Theodora, her face, which had become pale, again growing red.

"I—I thought I heard them clatter, but I may have been mistaken."

"The only thing to do," said Miss Joanna, "is to go to the garden ourselves, and find what is left of the bowl. You said, Thomasine, that she appeared to have placed the pieces among the currant-bushes. Then we shall discover whether or not you were mistaken. You are painfully weak and indefinite, and I am glad that I, for one, always know what I am talking about. Do you not agree with me, Adaline, that it would be well for us to go?"

Miss Middleton acquiesced, and the five sisters made themselves ready for their walk. They were arrayed in garden hats and black silk mantillas, and each one carried a sunshade. Even in the midst of her misery Theodora wondered at their dressing so exactly alike, and why they all wore gloves that were too large for them.

SLOWLY THEY WALKED, TWO BY TWO, ALONG THE PATH.

SLOWLY THEY WALKED, TWO BY TWO, ALONG THE PATH.

Slowly they walked, two by two, along the path which led to the garden, the maids watching them from the kitchen windows, and John, the hired man, pausing in his work among the sweet-pease to stare after them in astonishment. He also had heard of the calamity which had befallen the household, but he did not know the connection between that and the foot of the garden, and he never before had seen his mistresses walk there at high noon (as it was according to the old dial), though he had lived with them, and hoed their potatoes for twenty years.

Two by two they went, Theodora and her aunt Thomasine in front, the other aunts behind, down the very path over which had passed that delightful funeral procession so short a time before.

"I wish I were that kitten!" thought Teddy, miserably. "I would rather be stoned than this! I suppose there is no way out of it. I've got to show them where I hid the pieces. If I only hadn't left that little bit which I never saw at all, they would have thought the bowl was stolen. They never would have dreamed of my breaking it. How foolish I was!"

One of the Hoyt boys, looking over the wall, saw the approach of the Middleton ladies, and summoning all his brothers who were available, they leaned upon the wall and watched the proceedings with intense interest. Arthur alone, when he saw them coming, dropped the rake which he had been using and fled toward the barn.

"She's only a girl, after all," he said to himself, indignantly. "She can't keep it dark. I told her they'd never guess it if she only held her tongue, and now she has given it away!"

Then his curiosity as to what would happen next overcame his apparent desire for flight, and he returned to his brothers on the garden wall, from the top of which could be had a fine view of the Misses Middletons' currant-bushes. When he arrived at this point of vantage he found that the ladies had reached the object of their walk, and that they stood in a row upon the path.

"Now," said Miss Joanna, with sarcasm—"now we shall see whether Thomasine was mistaken or not!"

She closed her sunshade with a vicious snap, and proceeded to poke with it under the bushes. Theodora watched her for a moment in silence.

"You needn't do that, Aunt Joanna," she said; and walking to a little distance, she stooped and thrust her hand into the mass of green weeds and dead leaves which had accumulated there. Almost immediately she drew forth two pieces of broken china. "Here they are," she said.

Miss Middleton took one piece and Miss Joanna the other. Without a word they turned toward home. Miss Melissa and Miss Dorcas followed, and then Miss Thomasine, holding Theodora by the hand, fell into line behind. They walked away as slowly as they had come.

I could well write a book describing the two months of my life that I spent as an English prisoner of war; but as this is to be a record of my adventures alone, I fear me I would take up too much time if I should allow this fact to leave my mind.

We were awakened early in the morning, and orders were given us to get our baggage ready, as we were going to be transferred from the frigate to one of the prison-ships. The order to get our "baggage" must have been a bit of sarcasm, as there was none of us who possessed a spare shirt to his back.

Our breakfast was doled out to us on the upper deck, and we hastened down the gangway. Such a multitude of bumboats and small craft I had never seen as surrounded the vessel. There was a great hubbub on all sides, and our departure, being such a small number, created little comment. A launch was waiting for us, and one by one we jumped into her stern-sheets.

I almost forgot I was a prisoner in looking about me, for it all was new. I saw more ships gathered together than I had ever seen in the whole course of my life. Some were twice as large as the 74 Plantagenet that I had seen from the deck of the Minetta.

We rowed under the stern of a great vessel pierced on one side for sixty guns.

"This is the sort of a craft," said Sutton, pointing, "that Nelson and their Admirals won battles with. She could swing the Young Eagle at her side; eh, youngster?"

And well she could, I think, for it struck me that she was more of a floating fort than a sailing craft. Sheer-hulks and vessels outfitting crowded the inner harbor, and the constant hammering, tapping, and picking of an army of calkers filled the air.

When we reached the gangway on the port side we climbed up to the tall gallery. I had to smile. We might have been royal personages making a visit, for such ceremony I have never seen equalled. We passed between two files of marines and were inspected by three different groups of officers. They asked questions, and for some time seemed to be quite confident that Sutton was an Englishman. In this belief they were somewhat shaken when they saw his tattoo decorations, however.

At last our names were taken, and we passed below into the foul-smelling air of the 'tween-decks. Five or six hundred men were confined on board this ship, and as the guards had a generous portion set apart for themselves, the prisoners were much crowded. But we were not going to be kept here long; and although the time seemed to go slowly and was certainly most tedious, only a week elapsed before we were informed that we were going to be taken to a large prison near the town of Bristol.

On the twelfth day we were landed on the dock in Plymouth, and the dry ground felt odd to our feet, I can tell you. As luck had it, Sutton, Craig, and myself were in the first draft. It took us several days to travel from Plymouth to Bristol, being closely guarded by a squadron of cavalry and a battalion of infantry on the route.

It was a bright afternoon when we arrived on the outskirts of the city, where we halted but a few minutes, and I learned that we were yet several miles from Stapleton, where the prisons were situated. Despite our fatigue, we[Pg 290] were hastened along a broad, dusty road that led to the north.

At six o'clock we skirted the edge of a vast domain that I found, by asking, was the private estate of the Duke of Devonshire, and before we knew it we were halted in front of a long row of stone buildings, behind the barred gratings of which appeared hundreds of pallid faces. As we passed over the drawbridge spanning the deep moat, we entered the court-yard, and found ourselves with the brown sombre prison-houses on either hand.

The chatter of French sounded all about us, for the majority of the prisoners were Frenchmen taken in the wars against Napoleon. The Americans were domiciled in a building apart from the Frenchmen, and did not appear to enjoy the garrulous, half-contented spirit of the others.

Thus began two months of prison life that I shall dismiss with a few words, although, as I hinted, I could write a volume about it.

A huge prison, in which are confined some five or six thousand men (our numbers were swelled every day by new drafts of American prisoners and Frenchmen) is much like a city. We had theatrical companies, markets, and exchanges, and men quarrelled and gambled, and plied their trades or callings to some advantage. Time passed quickly, although one day was much like another. We were well guarded and fairly well fed, although clothing and foot-gear were at a premium.

My size and strength had apparently increased since I had left Belair. I stood six feet in height before I was nineteen years of age, and I afterwards added two inches more to this. In the sports, especially in foot-races and wrestling, I found myself a leader. Of course no one could live in such a community as this, even for a short time, without picking up a great deal of useful knowledge, besides imbibing much also that would serve no one in good stead except perhaps as a warning.

My knowledge of the French tongue enabled me to converse with the Frenchmen, and I whiled away many an hour by talking with them and reading a romance so smirched by constant handling as to be almost undecipherable. A small volume of Shakespeare, belonging to an ex-schoolmaster, who kindly loaned it to me, I pored over by the hour.

One day there came a little excitement in our life, and a great hallooing and huzzahing resounded through the prison. It was a reception tendered to a division of the crew of the luckless Chesapeake that was transferred from the hulks to join us. We got up an entertainment in their honor that evening.

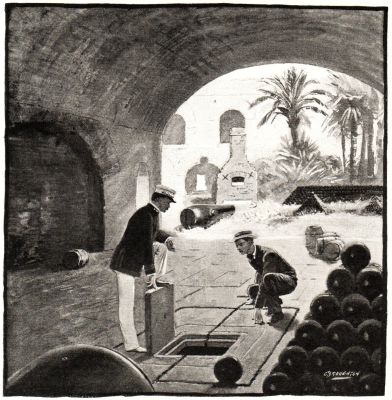

Now to come to the evening of the 16th of September, 1813, that I can set down in this chronicle in large important letters; for on this date, by a combination of fortunate circumstances, I ceased to be a prisoner. It happened thus:

The officers attached to the military force stationed at the prison lived together in a small building at the southwest corner of the rectangle formed by the high walls. Through the building which they occupied a passage ran to a small postern-gate. On several occasions I had been over there bearing messages from the prison-keeper (I was one of the monitor officers in charge of the order of my section of the west wing). But of course I had never progressed further than the small antechamber that opened into the guard-room, where I would wait to secure an audience with the commandant or one of his subordinates.

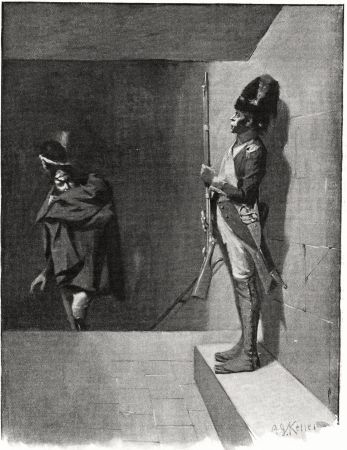

Now on this day I was bound to see a strange condition of affairs—the orderly who generally stood at the door was missing from his post. It was past dusk, and as I pushed in I noticed that the entrance to the guard-room, usually filled with soldiers, was shut. I thought of giving a hail, but then perceiving also that the entrance into the main building was gaping wide, impelled by a sudden impulse I stepped across the threshold into the hallway. I could hear voices coming from somewhere; but a room to the right appeared to be empty; a candle was burning on top of a tall dressing-case, and there across the foot of a narrow cot lay spread the uniform of a Lieutenant; and a great bear-skin shako, with a tall plume, topped one of the bedposts.

Now I think to do what I did then took more courage than anything I have ever attempted. I gave a leap sideways into the room, and closed the door behind me. Actually panting from excitement, I tore off the rags which served me for clothing, and shaking from head to foot I donned the uniform. Luckily the clothes were made for a large man, and they fitted me to perfection. I glanced at myself in the glass as I put the towering head-gear on as a finishing-touch. I was a strange-looking object. My hair, which was long, was done sailor fashion down my back in a queue, but the locks straggled down my cheeks; and, young as I was, my appearance would have been improved by the use of a razor. But I gathered my hair on the top of my head, where it was kept by the weight of the shako, and then I stepped to the door. The voices had ceased, but I plainly perceived that some one was coming down the corridor, which was flagged with stone; the jingling of spurs echoed along the walls. Hastily I closed the door, and extinguished the light with a pinch of my fingers. It was good for me that I had done this, for whoever it was gave the door a push and thrust in his head. How he ever missed seeing me (for I could have struck him with my knee) I cannot see to this day. It was one of the general officers, and attired for duty evidently, as he carried a long sabre hitched under his arm.

"Humph! Not here," he said. "A pretty piece of business."

Then away he clanked, and I heard the slamming of a door to another apartment. I knew that probably he came from the outside, and that the way to freedom, or at least to the open air, must be in the direction from which he was walking. I stepped out into the passageway and tiptoed down it. Then thinking that cautious steps might attract notice, I changed my gait to a military stride, and swaggered along with chest out and shoulders back. My doing this was fortunate, for I went by the open entrance of a small apartment, and a young man in undress uniform sat reading a book with the aid of a small lamp. He glanced out at me, but made no comment. I had affected to yawn, and half covered my face with my hand.

Now I came to the end of the corridor, and here were three doors; the one on the left shut, the centre one partly ajar, and the one on the right closed with large bolts. Looking through the door that was open, I could perceive a man's leg stretched out on a chair as if he were resting, so I turned to the one on the left. I was about to draw the latch when from within I heard the sound of voices in conversation.

"Good for you! Now another throw," some one said. Then came the rattle of a dice-box.

There was nothing for it but to try the farther door, the one that was bolted, and to do this I had to run the risk of attracting the man's attention in the middle room. I stepped by, and giving a quick glance over my shoulder, I saw that he was asleep, with his mouth wide open and his arms folded across his chest. With trembling fingers I drew the bolt of the heavy, iron-studded door, and swung it open.

Here was another passageway much like the first, with rooms on either side and a staircase in a recess at the farther end. Good fortune still favored me. I tramped down it, and found that to go out I had evidently to ascend the steps. When I reached the foot and had placed my hand on the iron guard-rail, I almost gave a gasp of sheer fright. There standing on a little platform at the top was a grenadier, with his musket leaning against him. He had caught sight of me, however, at this same instant; the hall was dimly lighted with a flickering taper, and I was in full view.

THE MAN DREW HIMSELF ERECT, AND HIS MUSKET SNAPPED TO A PRESENT.

THE MAN DREW HIMSELF ERECT, AND HIS MUSKET SNAPPED TO A PRESENT.

But to my surprise the man said nothing, but drew himself erect and his musket snapped to a present. Drawing the heavy cloak that I had thrown about my shoulders up to my nose, I hurried up the steps and returned the soldier's salute in proper manner, but with shaking fingers, as I passed him.

Here I was in the open air, and from the entrance a narrow causeway or bridge led to the top of the wall. But[Pg 291] all danger was not over, for at the farther end stood two more red-coated gentry. One had called the attention of the other to my approach, and there they were, drawn up like two statues at attention. I should have to go between them. But the light was very dim, and only boldness could serve my purpose. So I gazed directly at them, and with a great bound of my heart in my throat, I saw that I was going to be successful. They presented arms as I brushed by.

A small flight of stairs led down the wall on the outside, and here the ditch was spanned by a foot-bridge, and on the bank stood another sentry. I had wondered why I had not been asked for a password of some sort, and now I feared that this last man would prove my downfall, and that surely I would be stopped and asked some question. I hesitated as I stood there half-way down the steps, and at this instant I noticed the sentry across the bridge bring his musket to a half-charge with a ring of his accoutrements. In the dusk I could see four or five figures approaching, and then I heard the sentry call them to halt.

I could not make out the words that followed, but it was all merely perfunctory business I recognized, as the approaching figures were officers. Now fear often gives a man a judgment and cleverness that support him in sore straits. There was but one chance, and I took it. I turned about, retraced my steps, passed the two sentries, who saluted me once more, then again the third man at the head of the stairway, and I was back in the corridor.

When I had turned the angle of the passage, I entered one of the rooms, and crouched down behind a curtain, holding my big hat in my lap. My teeth chattered so that I feared the noise would be audible, and I had been just in time, as, laughing and talking, the officers were approaching.

As I sat crouched in a corner I perceived that they had some huge joke among them. They were walking slowly, and I heard distinctly what passed.

"The idea of Tillinghast forgetting the countersign strikes me as being grand," exclaimed some one, with a guffaw at the end of the sentence.

"Ha! ha! ha!" laughed another. "I told you it was the author of Robinson Crusoe, Tilly."

"Why, confound it all! I always thought that he himself wrote the book," roared a deep bass.

I recognized the speaker as the junior in command of the prison. It was his clothes, by-the-way, that I had on my back at the moment.

"I think the Governor chose it for a play on words," said another. "A poor pun even for him."

"Why we should require a password at all is more than I can see," said Tillinghast. "Come down to my quarters, Carntyne. We have time for a game of whist."

They passed on. I waited a few minutes, putting two and two together, and suddenly it came to me. I had the password at the tip of my tongue! Hastily arising, I stepped outside of the room. It was but a few yards to the bottom of the stairs, and I heard the sentry humming a snatch of a tune, and keeping time to it with the stamping of his feet in a sort of a jig. I was afraid that if I approached him the way that I had done before, he might look closer, so I made believe that I was carrying on the fag end of a conversation with some one, and answered an imaginary question with a laugh (a trifle forced, I must admit).

"No, thanks," I said; "you gentlemen are too much for me. I must hasten. Eh?" (A pause.) "I shall be back by nine o'clock, but I must hurry." Then I charged up the steps as if the devil was after me. The grenadier had hardly time to salute me; and I rushed past the other two at the end of the causeway at the same pace. They made some remark after I had gone by, but I did not catch it. More leisurely I descended the steps on the outside of the wall, and crossed the little foot-bridge to where the last sentry stood. His musket barred my path, but it was a respectful attitude.

"The word, sir?" he said, slurring the usual challenge.

"Defoe," I answered. He hesitated. "Daniel Defoe," I repeated, restraining with difficulty a mad impulse to close with him and pitch him headlong into the ditch.

The response to this was a backward step on the sentry's part, and a stiff attitude of present arms. I replied with somewhat of a flourish, and hastened down the path. It led across a sort of common, bordered by twinkling lights shining from some vine-covered houses, and in the stillness I heard the sound of a fiddle played somewhere, and from another direction the voice of an infant crying at top lung. What was I to do? I had a good fund of general information, perhaps, owing to my reading, and I had made up by this time the hiatus caused by my being out of the world those two years at Belair; but I knew little or nothing of the geography of England, and to save my soul I could not have imagined which would be the best direction to take.

My one idea was to put as much space between me and the prison-yard as I could, so I walked away from it with that end in view alone. It grew very dark, and I kept to the common until I plunged through a thorny hedge and made the road. It seemed to lead straight to the northward, which was as good for me as any other point of the compass, so I hastened along as fast as my legs could carry me.

The big military hat wobbled unsteadily on my head, and I thought how difficult it would be to make any sort of a fight with such an encumbrance to quick motions. But I reasoned I would attract a great deal of attention if I should discard it, so I slung it over my back by the plume, ready to clap it on if necessary, and went forward at a dog-trot.

The villages in this part of the country were so close together that I seemed hardly to leave one before I saw the lights of another. I was evidently on the highway, however, and, strange to say, I met but a few country people walking. They looked at me rather curiously, but did not speak. Thus I had traversed some twelve miles or more before midnight, and as there was a town of some size in the distance, judging by the lights and the sounds of two separate sets of chimes striking the hour, I determined to find some place where I could rest and think over the situation.

At first glance I might pass for one of his Majesty's officers, perhaps, but I could not stand an investigation without discovery. Yet I did not despair, for I was young, and youth builds to suit its fancy. But leg-weariness began to tell on me, and crawling in behind a hedge, I rolled myself in a cloak, and must have fallen to dreaming on the instant, for I began to go over the events of the last two days, and from them my mind strayed back into the past; and among other things, of course, thoughts of Mary Tanner came into my head and drove out all else.

It seemed to me that again I was in a little garden under the shadow of a rose-bush. I could recall Mary's arch smile and the sideway glance of her eye. The imaginary conversation we held continued at great length, and then the scene changed to the sea, and I was the Captain of a ship, sailing, with a fair wind, to some country whose name I could not place, but I knew that there Mary was waiting for me.

All at once I awoke and found myself with one hand in the breast of my brilliant red coat, grasping a little leather bag that was strung around my neck with a thong, containing all that I knew of that I could claim in the way of earthly possessions. These consisted of one of the De Brienne buttons, a single gold piece with the head of King Louis on it, and a package of dried rose leaves twisted into a small bit of paper.

It was gray dawn; cocks were crowing, and the bleating of sheep sounded from near by. With wonderful swiftness the light spread, and soon I could see my surroundings. The road was but a stone's-throw away, and I pushed through the hedge and found myself standing there not knowing which way to turn; in fact, I feared it would make little matter which choice I made—north, east, south, or west. I saw nothing but ultimate recapture before me. "No matter what happens, I shall have a yarn to spin," I said, grimly, to myself, as I stretched my stiffened legs and rubbed my cold hands together to start my chilled blood going.

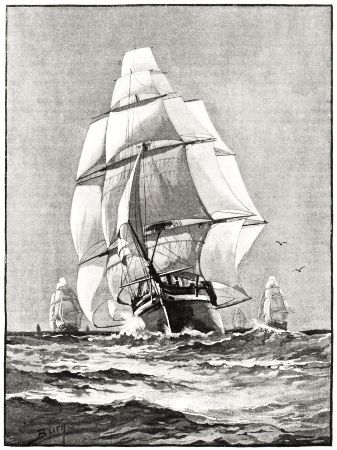

During the great wars of Napoleon the mercantile shipping of the world was much deranged, but at the peace of 1815 it began to revive. New York organized splendid lines of packets, ranging from 500 to 1000 tons, and these had the most of the passenger trade with Europe, principally with Liverpool, London, and Havre. Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut built many smaller vessels, which traded with all parts of the world, and which at the same time carried on an extensive coasting and fishing business, and were manned almost exclusively by American seamen.

As trade increased, ships were built faster than trained seamen could be found to man them. This brought seamen from Europe, and in a few years our shipping, excepting the officers, was manned by foreigners. Many ship-builders of New England were also farmers, who made both occupations pay. Although the size of our ships has been increased, and their models have been improved, there has been no improvement in their materials or in the style of their construction. As a rule, they were built of the best seasoned white oak, copper-fastened, coppered, and through treenailed, and they lasted longer than the best built ships of thirty years ago. They were certainly far more seaworthy than the best wooden ships of to-day. These, then, were the vessels which in so short a time became the subject of remark all over the world. The term clipper was first applied to schooners built at Baltimore (Maryland), designed to trade with South America, Africa, the Mediterranean, and the West Indies. They ranged in size from two hundred tons down to pilot-boats of fifty tons, were sharp at the ends and sharp on the bottoms or floors, and had raking masts. In time they became notorious as slave-traders and pirates, and during the last war with Great Britain were successful privateers. They were first upon the world of waters for speed and weatherly qualities. The "long low black schooner" so often mentioned in exciting sea-stories as a pirate was a clipper.

The late Captain R. B. Forbes, his father, mother, and two brothers, embarked on board the Orders in Council at Bordeaux (France), in 1813, bound for the United States. She was one of a numerous fleet of Baltimore and New York clippers, armed with six nine-pounders, and had a crew of about twenty all told. Shortly after leaving port she was chased by three British cutters, sloop-rigged, and outsailed them, but the wind died away. The boats of the three cutters towed the Wellington, the nearest, within range, and a fight ensued, which lasted over an hour, when a breeze sprang up, and the Orders in Council soon showed her clipperly speed. A parting shot cut the cutter's peak-halyards away, and before they could be replaced the American had escaped. War was then in progress between the United States and Great Britain. During the war of 1812-14 American clipper-privateers captured over one thousand British merchantmen.

The same year, Sir Walter Scott, the author of Waverley, while returning in a cutter along the west coast of Scotland from a cruise among the Shetland and Orkney islands, was chased by an American privateer, and barely escaped capture. The result of this cruise was the production of The Pirate, one of the best of his many delightful books.

THE GREAT RACE ROUND CAPE HORN.

THE GREAT RACE ROUND CAPE HORN.

Among the many great results of the discovery of gold in California in 1849, none were more interesting than the clippers which were built in a few years to perform the carrying trade to the new El Dorado. Rapidly as the population increased, it hardly kept pace with the means to furnish supplies, notwithstanding the distance and the tempestuous nature of the sea they had to be carried over. Month after month ships surpassing in beauty and strength all that the world had before produced were built and equipped by private enterprise, to form the means of communication with the new land of promise. The most eminent ship-builders and enterprising merchants vied with one another to lead in the great race round Cape Horn. The common rules which had for years circumscribed mechanical[Pg 293] skill to a certain class of models were abandoned, and the ship-owner contracted only for speed and strength. Ships varying in size from 1000 to 3000 tons were soon built and sent to sea, and their wonderful performances, instead of satisfying, increased the demand to excel. The ship Flying Cloud, of 1700 tons, commanded by Captain Creesy, made the passage from New York to San Francisco in 89 days and 4 hours. Such results would have satisfied most men that they had at last produced a model that would defy competition, but such was not the conclusion of Mr. Donald McKay, who built her and several other successful clippers. He consulted their captains about wherein they had failed to come up to his designs. Like a proof-reader, he only desired to detect their errors. The floor, or bottom, of the Flying Cloud represented the letter V. The next ship he designed was made to represent the letter U. This gave her more capacity and increased stability.

He built the Sovereign of the Seas, of 2400 tons, on his own account. Although she did not make as short a passage from New York to San Francisco as the Flying Cloud, yet she beat the swiftest of the entire fleet, which sailed about the same time, 7 days. In 24 consecutive hours she ran 430 geographical miles, 56 more than the greatest run of the Flying Cloud, and in 10 consecutive days she ran, by observation, 3144 miles. In eleven months her gross earnings amounted to $200,000.

The following were the passages made from New York to San Francisco by the clippers:

| Tons. | Passage. | |

| Flying Cloud | 1700 | 89 days. |

| Flying-Fish | 1600 | 92 days. |

| Sovereign of the Seas | 2400 | 103 days. |

| Bald Eagle | 1600 | 107 days. |

| Empress of the Sea | 2250 | 118 days. |

| Staghound | 1550 | 112 days. |

The following sailed from Boston to San Francisco:

| Tons. | Passage. | |

| Westward Ho | 1700 | 107 days. |

| Staffordshire | 1950 | 101 days. |

Mr. McKay built the Great Republic, of 4550 tons, with four decks; but she was partly burned in New York in 1853, and when repaired the fourth deck was taken off. She sailed several voyages between New York and San Francisco, and was never beaten. During the Crimean war she was hired as a transport by the French government, and with a leading whole-sail breeze not a steamer, far less a sailing-vessel, could keep alongside of her.

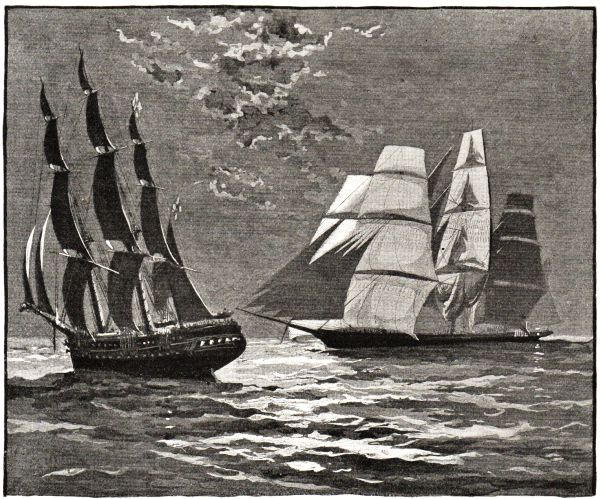

SHOWING DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE LINES OF THE OLD SHIPS AND

THE NEW CLIPPERS.

SHOWING DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE LINES OF THE OLD SHIPS AND

THE NEW CLIPPERS.

The last great ship designed and built by Mr. McKay was the Glory of the Seas, of 2009 tons. She was a combination of the clipper and the New York packet-ship, designed to carry a large cargo, to sail fast, and to work like a pilot-boat. She was 240 feet 2 inches long, had 44 feet extreme breadth of beam, and was 28 feet deep, with three decks. Captain Tom Chatfield, who commanded her several voyages, speaks of her as the grandest vessel he ever knew. She is still afloat, and hails from San Francisco. At one time she was owned by J. Henry Sears & Co., well known as eminent merchants of Boston.

Captain Waterman, in command of the clipper-ship Sea Witch, made some of the quickest passages on record between New York and China. His last command afloat was in the ship Challenge, which he took from New York to San Francisco. Captain Philip Dumaresq, of Boston, who last sailed in the ship Florence in the China trade with New York, ranked high during his whole service[Pg 294] afloat. At sea he never took his clothes off to turn in at night, that he might always be on hand to spring on deck. The quickest passage on record from Shanghai (China) to New York was made in the ship Swordfish by Captain Crocker. Though becalmed a week on the equator, he made the run in 84 days, and beat the overland mail from India a week. It was stated in a San Francisco paper that the Young America made the passage from New York in less time than the Flying Cloud, but it was not confirmed. One hundred days was considered quick time for an outward passage. The ship Northern Light made the passage from San Francisco to Boston in 76 days. She was in ballast, and had fair winds all the way.

To show the rapidity with which clippers were built, the ship John Bertram, of 1080 tons, was launched six weeks from the time her keel was laid, and in two weeks more was on her way from Boston for San Francisco with 1500 tons of cargo on board. When she was launched, her builder, Mr. Robert E. Jackson, fell overboard; her owner, Captain William T. Glidden, plunged after him, without even taking off his coat, and saved him. Old sailors predicted that she would be unlucky, yet she kept afloat thirty years afterward, and cleared her original cost a dozen times.

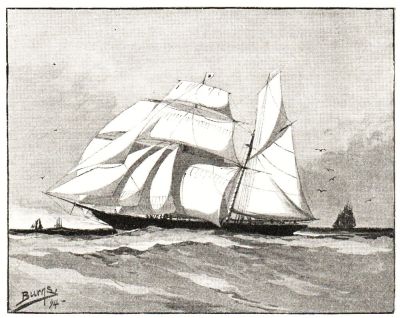

A CLIPPER-BRIGANTINE.

A CLIPPER-BRIGANTINE.

In 1855 there were 268 ships of an average of 1200 tons each under our flag, and most of them were clippers. In addition to these there were many barks, brigs, and schooners remarkable for beauty of model and famous for speed. From 1849 to the breaking out of the civil war we had the cream of the carrying trade of the world. After that our shipping declined rapidly; many of our famous clippers were sold to avoid capture. Steam navigation has superseded sails in the China and Mediterranean trade, and to-day there are not a dozen clipper-ships left under our flag.

When gold was discovered in Australia, the British purchased many of our fine clippers, which were very successful in their passages. The emigrants from British ports soon preferred them to their own vessels, on account of their spacious between-decks and high rate of speed. We also shared largely in the trade, and for several years kept regular lines of swift ships, laden with American goods, which found a ready market in Melbourne. After the adaptation of iron to ship-building, the British copied our clipper lines for most of their new sailing-vessels, and now compete successfully with us in carrying heavy cargoes. Iron ships have the preference in carrying grain from San Francisco to Europe.

In 1813 a vessel from China received a pilot off Cape Cod in a fog, and kept close inshore to avoid two British frigates which were in the bay. When off Plymouth the fog lifted and revealed the frigates about two miles distant, which instantly made all sail in chase. It was only half-flood, and the pilot was afraid that there was not water enough to run in; but he took the chances and succeeded, though both vessels opened fire upon him. Fortunately there was a company of militia on hand with a field-piece, which protected the ship against the boats that were despatched to cut her out. All the men of the place turned out and soon landed her cargo, composed of teas and silks, and then stripped the ship to her lower masts, apprehensive that the boats might make a night attack on her. But they did not.

William Gray, a rich ship-owner, had a clipper-bark which had been knocking about in the West Indies in search of freight. A vessel laden with sugar put into St. Thomas in distress, and sold her cargo, which the American purchased as a venture. She ran the blockade, and Mr. Gray was the first to board her. "Captain," he said, nervously, "I see you're very deep; what have you got in?" "Sugar," was the brief reply, "purchased on the ship's account." He felt that he had made no mistake, especially as Mr. Gray threw his hat in the air before he responded. Picking up his hat, Mr. Gray faced the Captain with a pleasant smile, and said, "It's just our luck, Captain; you have not only saved your ship, but this day there are not fifty boxes of sugar in all Boston, and prices are sky-high."

Early in the century Salem had some swift vessels engaged in the East India and China trade, but these have mostly disappeared.