The Project Gutenberg EBook of Highland Mary, by Clayton Mackenzie Legge

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Highland Mary

The Romance of a Poet

Author: Clayton Mackenzie Legge

Illustrator: William Kirkpatrick

Release Date: October 8, 2019 [EBook #60455]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HIGHLAND MARY ***

Produced by Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

HIGHLAND MARY

“Highland Mary.”

HIGHLAND

MARY

The Romance of a Poet

A

NOVEL

By

CLAYTON MACKENZIE LEGGE

Illustrated by

WILLIAM KIRKPATRICK

1906

C. M. CLARK PUBLISHING CO.

BOSTON

Copyright, 1906.

THE C. M. CLARK PUBLISHING CO.,

Boston, Mass.

Entered at

Stationer’s Hall, London.

Dramatic and all other

Rights Reserved.

TO

The Rev. Dr. Donald Sage Mackay, D.D.,

Pastor of the Collegiate Church,

New York City.

I RESPECTFULLY DEDICATE THIS BOOK

With apologies to Dame History for having taken liberties with some of her famous characters, I would ask the Reader to remember that this story is fiction and not history.

I have made use of some of the most romantic episodes in the life of Robert Burns, such as his courtship of Mary Campbell and his love affair with Jean Armour, “the Belle of Mauchline,” and many of the historical references and details are authentic.

But my chief purpose in using these incidents was to make “Highland Mary” as picturesque, lovable and interesting a character in Fiction as she has always been in the History of Scotland.

Clayton Mackenzie Legge.

In the “but” or living-room (as it was termed in Scotland) of a little whitewashed thatched cottage near Auld Ayr in the land of the Doon, sat a quiet, sedate trio of persons consisting of two men and a woman. She who sat at the wheel busily engaged in spinning was the mistress of the cot, a matronly, middle-aged woman in peasant’s cap and ’kerchief.

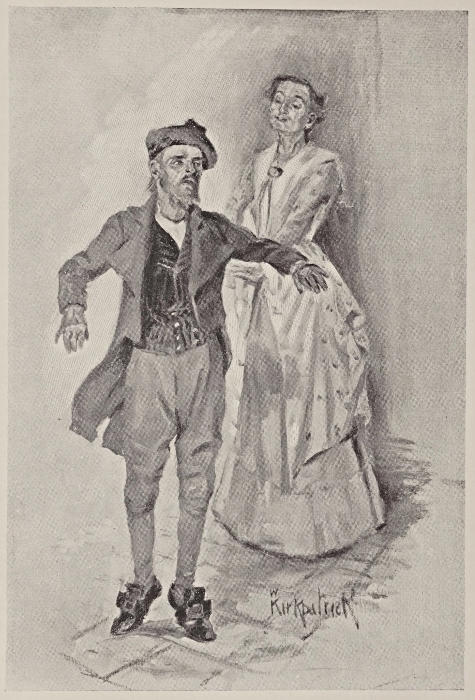

The other two occupants of the room for years had been inseparable companions and cronies, and when not at the village inn could be found sitting by the fireside of one of their neighbors, smoking their pipes in blissful laziness. And all Ayrshire tolerated and even welcomed Tam O’Shanter and his cronie, “Souter Johnny.”

Tam was an Ayrshire farmer, considered fairly well-to-do in the neighborhood, while Souter (shoemaker) Johnny was the village cobbler, who seldom, if ever, worked at his trade nowadays. All the afternoon had they sat by the open fireplace, with its roomy, projecting chimney, watching the peat burn, seldom speaking, smoking their old smelly pipes, and sighing contentedly as the warmth penetrated their old bones.

Mrs. Burns glanced at her uninvited guests occasionally with no approving eye. If they must inflict their presence on her, why couldn’t they talk, say something, tell her some of the news, the gossip of the village? she thought angrily; their everlasting silence had grown very monotonous to the good dame. She wished they would go. It was nearing supper time, and Gilbert would soon be in from the field, and she knew that he did not approve of the two old cronies hanging around monopolizing the fireplace to the exclusion of everyone else, and she did not want any hard words between them and Gilbert. Suddenly with a final whirl she fastened the end of the yarn she was spinning, and getting up from her seat set the wheel back against the whitewashed wall.

Then going to the old deal dresser, she took from one of the drawers a white cloth and spread it smoothly over the table, then from the rack, which hung above it, she took the old blue dishes and quickly set the table for their evening meal. At these preparations for supper the old cronies looked eagerly expectant, for none knew better than they the excellence of the Widow Burns’ cooking, and a look of pleasant anticipation stole over their sober faces as they perceived the platter of scones on the table ready to be placed on the hot slab of stone in the fireplace.

Knocking the ashes from his pipe, Tam rose unsteadily to his feet, and standing with his back[3] to the fire, he admiringly watched the widow as she bustled to and fro from table to dresser. “Ah, Mistress Burns, ye’re a fine housekeeper,” he remarked admiringly. “An’ ye’re a fine cook.”

Mrs. Burns turned on him sharply. “So is your guidwife,” she said shortly, glancing out through the low, deep, square window to where her second son could be seen crossing the field to the house. She hoped he would take the hint and go.

“Aye, Mistress, I ken ye’re recht,” replied Tam, meekly, with a dismal sigh. “But it’s a sorry bet o’ supper I’ll be gang hame to this night, an’ ye ken it’s a long journey, too, Mistress Burns,” he insinuated slyly.

“Sure it’s a lang, weary journey, Tam,” said Souter Johnny, commiseratingly. “But think o’ the warm welcome ye’ll be haein’ when ye meet your guidwife at the door,” and a malicious twinkle gleamed in his kindly but keen old eyes.

“How is your guidwife, Tam O’Shanter?” inquired Mistress Burns, as she placed some scones on the hot hearthstone to bake.

“She’s a maist unco woman, Mistress,” replied Tam sorrowfully. “There’s no livin’ wi’ her o’ late. She’s no a help or comfort to a mon at a’!” he whined. Here Tam got a delicious whiff of the baking scones, and his mouth as well as his eyes watered as he continued pathetically, “If she could only cook like ye, Mistress. Oh, ’twas a sorry day for[4] Tam O’Shanter when he took such a scoldin’ beldame for wife,” and Tam sat down, the picture of abject distress.

Souter regarded his cronie with a grim smile. He had no pity for Tam, nor for any man, in fact, who would not or could not rule his own household. (Souter, by the by, had remained a bachelor.) However, he did his best to console Tam whenever his marital troubles were discussed.

“Never mind, Tam,” he said sympathetically, helping himself to a scone while Mistress Burns’ back was turned. “Ye ken where ye can find all the comfort and consolation ye can hold, if ye hae the tippence.”

Tam wiped away a tear (tears came easily to the old tyke in his constant state of semi-intoxication) and gave a deep, prolonged sigh. “Aye, Souter, an’ I feel mair at home in the Inn than I do with my guidwife,” he answered mournfully. “I dinna mind telling ye, she’s driven me to the Deil himsel’, by her daur looks an’ ways. The only friend I hae left is Old John Barleycorn,” and he wailed in maudlin despair.

“He’s your best enemy, ye mean,” retorted Souter dryly, relighting his pipe, after having demolished, with evident relish, the last of his stolen scone.

“Waesucks, mon,” he continued, assuming the tone of Dominie Daddy Auld, who had tried in vain to convert the two old sinners, much to their amusement and inward elation. “Your guidwife told ye[5] weel. Ye’re a skellum, Tam, a blethering, blustering, drunken blellum,” and the old rogue looked slyly at Mistress Burns to note the effect of his harangue.

“Aye, ye’re right, Souter Johnny,” said the good dame, nodding approval to him, and going up to Tam, who was still sitting groaning by the fireside, she shook him vigorously by the shoulder. “Stop your groaning and grunting, ye old tyke, and listen to me,” she said sharply. “Take your friend’s advice and gi’ old John Barleycorn a wide berth.” Here her voice dropped to a whisper, “or some day ye’ll be catched wi’ warlocks in the mire, Tam O’Shanter.” He stopped his noise and straightened up in his chair.

“Aye, and ghosties and witches will come yelpin’ after ye as ye pass the auld haunted kirk at Alloway,” added Souter sepulchrally, leaning over Tam with fixed eyes and hand outstretched, clutching spasmodically at imaginary objects floating before Tam’s suspicious, angry eyes. Tam, however, was not to be so easily frightened, and brushing Souter aside, he jumped to his feet. “Souter Johnny, dinna ye preach to me, mon,” he roared menacingly. “Ye hae no reght. Let Daddy Auld do that! I dinna fear the witches or ghosties, not I.” He staggered to the window and pointed to an old white horse standing meekly by the roadside.

“Do ye see any auld faithful Maggie standin’ out there?” he cried triumphantly. Not waiting for[6] their answer, he continued proudly, “Nae witches can catch Tam O’Shanter when he’s astride his auld mare’s back, whether he is drunk or sober,” and he glared defiantly at his listeners. At that moment the door from the “ben” opened, and Gilbert Burns entered the room. An angry frown wrinkled his forehead as his gaze fell upon the two old cronies. A hard worker himself, he could not abide laziness or shiftlessness in another. He strode swiftly up to Tam, who had suddenly lost his defiant attitude, but before he could speak the bitter, impatient words which rushed to his lips, his mother, knowing his uncertain temper, shook her head at him remonstratingly. “Ah, lad, I’m fair ye hae come in to rest a while, an’ to hae a bit o’ supper,” she hurriedly said. “Set ye doon. I hae some scones for ye, an’ Mollie has some rabbit stew. Noo gie me your bonnet and coat, laddie,” and taking them from him she hung them on the peg behind the door, while Gilbert with a look of disgust at the two old cronies sat down and proceeded to butter his scones in moody silence. Tam and Souter, however, did not appear in any wise abashed, and perceiving they were not to be invited to eat with Gilbert, they resumed their seats each side of the fireplace and heaved a disconsolate sigh.

Mrs. Burns, who had left the room for a moment, now entered bearing a large bowl of the steaming stew, which she set before her son, while directly after her appeared old Mollie Dunn, the half-witted household[7] drudge. The time was when Mollie had been the swiftest mail carrier between Dumfries and Mauchline, but she was now content to have a home with the Burns family, where, if the twinges of rheumatism assailed her, she could rest her bones until relief came. She now stood, a pleased grin on her ugly face, watching Gilbert as he helped himself to a generous portion of the stew which she had proudly prepared for the evening meal.

“Molly,” said her mistress sharply, “dinna ye stand there idle; fetch me some hot water frae the pot.”

Molly got a pan from the rack and hurried to the fireplace, where Tam was relighting his pipe with a blazing ember, for the dozenth time. Molly had no love for Tam, and finding him in her way, she calmly gave a quick pull to his plaidie, and Tam, who was in a crouching position, fell backward, sprawling on the hearth in a decidedly undignified attitude. With the roar of a wounded lion, he scrambled to his feet, with the assistance of Souter, and shaking his fist at the laughing Molly, he sputtered indignantly, “Is the Deil himsel’ in ye, Molly Dunn? Ye’re an impudent hussy, that’s what ye are.” Molly glared at him defiantly for a moment, then calmly proceeded to fill her pan with hot water, while the old man, bursting with indignation, staggered over to the dresser where Mistress Burns was brewing some tea.

“Mistress Burns,” he remonstrated almost tearfully, “ye should teach your servants better manners. Molly Dunn is a——” but he never finished his sentence, for Molly, hurrying back with the hot water, ran into him and, whether by design or accident it was never known, spilled the hot contents of the pan over Tam’s shins, whereupon he gave what resembled a burlesque imitation of a Highland fling to the accompaniment of roars of pain and anger from himself and guffaws of laughter from Souter and Molly. Even Mrs. Burns and Gilbert could not resist a smile at the antics of the old tyke.

“Toots, mon,” said Molly, not at all abashed at the mischief she had done, “ye’re no hurt; ye’ll get mair than that at hame, I’m tellin’ ye,” and she nodded her head sagely.

“Molly, hold your tongue,” said Mistress Burns reprovingly, then she turned to Tam. “I hope ye’re nae burnt bad.” But Tam was very angry, and turning to Souter he cried wrathfully, “I’m gang hame, Souter Johnny. I’ll no stay here to be insulted; I’m gang hame.” And he started for the door.

“Dinna mind Molly; she’s daft like,” replied Souter in a soothing voice. “Come and sit doon,” and he tried to pull him toward the fireplace, but Tam was not to be pacified. His dignity had been outraged.

“Nay, nay, Souter, I thank ye!” he said firmly.[9] “An’ ye, too, Mistress Burns, for your kind invitation to stay langer,” she looked at him quickly, then gave a little sniff, “but I ken when I’m insulted,” and disengaging himself from Souter’s restraining hand, he started for the door once more.

“An’ where will ye be gang at this hour, Tam?” insinuated Souter slyly. “Ye ken your guidwife’s temper.”

“I’m gang over to the Inn,” replied Tam defiantly, with his hand on the open door. “Will ye gang alang wi’ me, Souter? A wee droppie will cheer us both,” he continued persuasively.

Souter looked anxiously at Gilbert’s stern, frowning face, then back to Tam. “I’d like to amazin’ weel, Tam,” he replied in a plaintive tone, “but ye see——”

“Johnny has promised me he’ll keep sober till plantin’ is over,” interrupted Gilbert firmly; “after that he can do as he likes.”

“Ye should both be ashamed o’ yoursel’s drinkin’ that vile whisky,” said Mrs. Burns angrily, and she clacked her lips in disgust. “It is your worst enemy, I’m tellin’ ye.”

“Ye mind, Mistress Burns,” replied Souter, winking his left eye at Tam, “ye mind the Scriptures say, ‘Love your enemies.’ Weel, we’re just tryin’ to obey the Scriptures, eh, Tam?”

“Aye, Souter,” answered Tam with drunken gravity, “I always obey the Scriptures.”

“Here, mon, drink a cup of tea before ye gang awa’,” said Mrs. Burns, and she took him a brimming cup of the delicious beverage, thinking it might assuage his thirst for something stronger. Tam majestically waved it away.

“Nay, I thank ye, Mistress Burns, I’ll no’ deprive ye of it,” he answered with extreme condescension. “Tea doesno’ agree with Tam O’Shanter.” He pushed open the door. “I’m off to the Inn, where the tea is more to my likin’. Guid-day to ye all,” and, slamming the door behind him, he called Maggie to his side, and jumping astride her old back galloped speedily toward the village Inn. The last heard of him that day was his voice lustily singing “The Campbells Are Coming.”

After he left the room Mistress Burns handed Souter the cup of tea she had poured for Tam, and soon the silence was unbroken save by an occasional sigh from the old tyke as he sipped his tea.

Presently Gilbert set down his empty cup, rose and donned his coat. “Here we are drinking tea, afternoon tea, as if we were of the quality,” he observed sarcastically, “instead of being out in the fields plowing the soil; there’s much to be done ere sundown.”

“Weel, this suits me fine,” murmured Souter contentedly, draining his cup. “I ken I was born to be one o’ the quality; work doesno’ agree wi’ me, o’er weel,” and he snuggled closer in his chair.

“Ye’re very much like my fine brother Robert in that respect,” answered Gilbert bitterly, his face growing stern and cold. “But we want no laggards here on Mossgiel. Farmers must work, an’ work hard, if they would live.” He walked to the window and looked out over the untilled ground with hard, angry eyes, and his heart filled with bitterness as he thought of his elder brother. It had always fallen to him to finish the many tasks his dreaming, thoughtless, erratic brother had left unfinished, while the latter sought some sequestered spot where, with pencil and paper in hand, he would idle away his time writing verses. And for a year now Robert had been in Irvine, no doubt enjoying himself to the full, while he, Gilbert, toiled and slaved at home to keep the poor shelter over his dear ones. It was neither right nor just, he thought, with an aching heart.

“Ye ken, Gilbert,” said Souter Johnny, breaking in on his reverie, “Robert wasna’ born to be a farmer. He always cared more, even when a wee laddie, for writin’ poetry and dreamin’ o’ the lasses than toilin’ in the fields, more’s the pity.”

Mrs. Burns turned on him quickly. “Souter Johnny, dinna ye dare say a word against Robert,” she flashed indignantly. “He could turn the best furrough o’ any lad in these parts, ye ken that weel,” and Souter was completely annihilated by the angry flash that gleamed in the mother’s eye, and it was a very humble Souter that hesitatingly held out[12] his cup to her, hoping to change the subject. “Hae ye a wee droppie mair tea there, Mistress Burns?” he meekly asked.

Mrs. Burns was not to be mollified, however. “Aye, but not for ye, ye skellum,” she answered shortly, taking the cup from him and putting it in the dishpan.

“Come along, Souter,” said Gilbert, going to the door. “We hae much to do ere sundown and hae idled too long, noo. Come.”

“Ye’re workin’ me too hard, Gilbert,” groaned Souter despairingly. “My back is nigh broken; bide a wee, mon!”

A sharp whistle from without checked Gilbert as he was about to reply. “The Posty has stopped at the gate,” exclaimed Mistress Burns excitedly, rushing to the window in time to see old Molly receive a letter from that worthy, and then come running back to the house. Hurrying to the door, she snatched it from the old servant’s hands and eagerly held it to the light. Molly peered anxiously over her shoulder.

“It’s frae Robbie,” she exclaimed delightedly. “Keep quiet, noo, till I read it to the end.” As she finished, the tears of gladness rolled down her smooth cheek. “Oh, Gilbert,” she said, a little catch in her voice, “Robert is comin’ back to us. He’ll be here this day. Read it, lad, read for yoursel’.” He took the letter and walked to the fireplace. After a slight[13] pause he read it. As she watched him she noticed with sudden apprehension the look of anger that darkened his face. She had forgotten the misunderstanding which had existed between the brothers since their coming to Mossgiel to live, and suddenly her heart misgave her.

“Gilbert lad,” she hesitatingly said as he finished the letter, “dinna say aught to Robert when he comes hame about his rhyming, will ye, laddie?” She paused and looked anxiously into his sullen face. “He canna bear to be discouraged, ye ken,” and she took the letter from him and put it in her bosom. Gilbert remained silent and moody, a heavy frown wrinkling his brow.

“Perhaps all thoughts of poesy has left him since he has been among strangers,” continued the mother thoughtfully. “Ye ken he has been doin’ right weel in Irvine; and it’s only because the flax dresser’s shop has burned to the ground, and he canna work any more, that he decides to come hame to help us noo. Ye ken that, Gilbert.” She laid her hand in tender pleading on his sunburnt arm.

“He always shirked his work before,” replied Gilbert bitterly, “and nae doot he will again. But he maun work, an’ work hard, if he wants to stay at Mossgiel. Nae more lyin’ around, scribblin’ on every piece of paper he finds, a lot of nonsense, which willna’ put food in his mouth, nor clothe his back.” Mrs. Burns sighed deeply and sank into the[14] low stool beside her spinning wheel, he hands folded for once idly in her lap, and gave herself up to her disquieting thoughts.

“Ye can talk all ye like,” exclaimed Souter, who was ever ready with his advice, “but Robert is too smart a lad to stay here for lang. He was never cut out for a farmer nae mair was I.”

“A farmer,” repeated Mrs. Burns, with a mirthless little laugh. “An’ what is there in a farmer’s life to pay for all the hardships he endures?” she asked bitterly. “The constant grindin’ an’ endless toil crushes all the life out o’ one in the struggle for existence. Remember your father, Gilbert,” and her voice broke at the flood of bitter recollection which crowded her thoughts.

“I have na forgotten him, mither,” replied Gilbert quietly. “Nor am I likely to, for my ain lot in life is nae better.” And pulling his cap down over his eyes, he went back to the window and gazed moodily out over the bare, rocky, profitless farm which must be made to yield them a living. There was silence for a time, broken only by the regular monotonous ticking of the old clock. After a time Mrs. Burns quietly left the room.

“Oh, laddie,” whispered Souter as the door closed behind her, coming up beside Gilbert, “did ye hear the news that Tam O’Shanter brought frae Mauchline?”

“Do you mean about Robert an’ some lassie[15] there?” inquired Gilbert indifferently, after a brief pause.

“Aye!” returned Souter impressively, “but she’s nae common lass, Gilbert. She’s Squire Armour’s daughter Jean, called the Belle of Mauchline.”

“I ken it’s no serious,” replied Gilbert sarcastically, “for ye ken Robert’s heart is like a tinder box, that flares up at the first whisper of passion,” and he turned away from the window and started for the door.

“I canna’ understand,” reflected Souter, “how the lad could forget his sweetheart, Highland Mary, long enough to take up wi any ither lassie. They were mighty fond o’ each ither before he went awa’ a year ago. I can swear to that,” and he smiled reminiscently.

A look of despair swept over Gilbert’s face at the idle words of the garrulous old man. He leaned heavily against the door, for there was a dull, aching pain at his heart of which he was physically conscious. For a few moments he stood there with white drawn face, trying hard to realize the bitter truth, that at last the day had come, as he had feared it must come, when he must step aside for the prodigal brother who would now claim his sweetheart. And she would go to him so gladly, he knew, without a single thought of his loneliness or his sorrow. But she was not to blame. It was only right that she should now be with her sweetheart, that he must say farewell to those[16] blissful walks along the banks of the Doon which for almost a year he had enjoyed with Mary by his side. His stern, tense lips relaxed, and a faint smile softened his rugged features. How happy he had been in his fool’s paradise. But he loved her so dearly that he had been content just to be with her, to listen to the sweetness of her voice as she prattled innocently and lovingly of her absent sweetheart. A snore from Souter, who had fallen asleep in his chair, roused him from the fond reverie into which he had fallen, and brought him back to earth with a start. With a bitter smile he told himself he had no right to complain. If he had allowed himself to fall in love with his brother’s betrothed, he alone was to blame, and he must suffer the consequence. Suddenly a wild thought entered his brain. Suppose—and his heart almost stopped beating at the thought—suppose Robert had grown to love someone else, while away, even better than he did Mary? He had heard rumors of Robert’s many amourous escapades in Mauchline; then perhaps Mary would again turn to him for comfort. His eyes shone with renewed hope and his heart was several degrees lighter as he left the house. Going to the high knoll back of the cottage, he gazed eagerly, longingly, across the moor to where, in the hazy distance, the lofty turrets of Castle Montgomery, the home of the winsome dairymaid, Mary Campbell, reared their heads toward the blue heavens.

At the foot of the hill on which stood Castle Montgomery flowed the River Doon, winding and twisting itself through richly wooded scenery on its way to Ayr Bay. On the hillside of the stream stood the old stone dairy, covered with ivy and shaded by overhanging willows. Within its cool, shady walls the merry lassies sang at their duties, with hearts as light and carefree as the birds that flew about the open door. Their duties over for the day, they had returned to their quarters in the long, low wing of the castle, and silence reigned supreme over the place, save for the trickling of the Doon splashing over the stones as it wended its tuneful way to join the waters of the Ayr.

Suddenly the silence was broken; borne on the evening breeze came the sound of a sweet, high voice singing:

sang the sweet singer, plaintively from the hilltop. Nearer and nearer it approached as the owner followed the winding path down to the river’s bank. Suddenly the drooping willows were parted, and there looked out the fairest face surely that mortal eyes had ever seen.

About sixteen years of age, with ringlets of flaxen hair flowing unconfined to her waist, laughing blue eyes, bewitchingly overarched by dark eyebrows, a rosebud mouth, now parted in song, between two rounded dimpled cheeks, such was the bonnie face of Mary Campbell, known to all around as “Highland Mary.” Removing her plaidie, which hung gracefully from one shoulder, she spread it on the mossy bank, and, casting herself down full length upon it, her head pillowed in her hand, she finished her song, lazily, dreamily, letting it die out, slowly, softly floating into nothingness. Then for a moment she gave herself up to the mere joy of living, watching the leaves as they fell noiselessly into the stream and were carried away, away until they were lost to vision. Gradually her thoughts became more centered. That particular spot was full of sweet memories to her. It was here, she mused dreamily, that she and Robert had parted a year ago. It was here on the banks of the Doon they so often had met and courted and loved, and here it was they had[19] stood hand in hand and plighted their troth, while the murmuring stream seemed to whisper softly, “For eternity, for all eternity.” And here in this sequestered spot, on that second Sunday of May, they had spent the day in taking a last farewell. Would she ever forget it? Oh, the pain of that parting! Her eyes filled with tears at the recollection of her past misery. But she brushed them quickly away with a corner of her scarf. He had promised to send for her when he was getting along well, and she had been waiting day after day for that summons, full of faith in his word. For had he not said as he pressed her to his heart:

A whole year had passed. She had saved all her little earnings, and now her box was nearly filled with the linen which she had spun and woven with her own fair hands, for she did not mean to come dowerless to her husband. In a few months, so he had written in his last letter, he would send for her to come to him, and they would start for the new country, America, where gold could be picked up in the streets (so she had heard it said). They could not help but prosper, and so the child mused on happily. The sudden blast of a horn interrupted her sweet day dreams, and, hastily jumping to her feet,[20] with a little ejaculation of dismay she tossed her plaidie over her back, and, filling her pail from the brook, swung it lightly to her strong young shoulder.

she trilled longingly, as she retraced her steps up the winding path, over the hill, and back to the kitchen, where, after giving the pail into the hand of Bess, the good-natured cook, she leaned against the lintel of the door, her hands shading her wistful eyes, and gazed long and earnestly off to where the sun was sinking behind the horizon in far-off Irvine. So wrapped was she in her thoughts she failed to hear the whistle of Rory Cam, the Posty, and the bustle and confusion which his coming had created within the kitchen. The sharp little shrieks and ejaculations of surprise and delight, however, caused her to turn her head inquiringly. Looking through the open door, she saw Bess in the center of a gaping crowd of servants, reading a letter, the contents of which had evoked the delight of her listeners. “An’ he’ll be here this day,” cried Bess loudly, folding her letter. “Where’s Mary Campbell?” she demanded, looking around the room.

“Here I am, Bess,” said Mary, standing shyly at the door.

“Hae ye heard the news, then, lassie?” asked Bess, grinning broadly.

“Nay; what news?” inquired Mary, wondering why they all looked at her so knowingly.

“I’ve just had word frae my sister in Irvine, an’ she said——” Here Bess paused impressively. “She said that Rob Burns was burnt out o’ his place, an’ that he would be comin’ hame to-day.” Bess, who had good-naturedly wished to surprise Mary, was quite startled to see her turn as white as a lily and stagger back against the door with a little gasp of startled surprise.

“Are ye sure, Bess?” she faltered, her voice shaking with eagerness.

“It’s true as Gospel, lassie; I’ll read ye the letter,” and Bess started to take it out, but with a cry of joy Mary rushed through the door like a startled fawn, and before the astonished maids could catch their breath she had lightly vaulted over the hedge and was flying down the hill and over the moor toward Mossgiel farm with the speed of a swallow, her golden hair floating behind her like a cloud of glorious sunshine. On, on she sped, swift as the wind, and soon Mossgiel loomed up in the near distance. Not stopping for breath, she soon reached the door, and without pausing to knock burst into the room.

Mrs. Burns had put the house in order and, with a clean ’kerchief and cap on, sat patiently at her wheel, waiting for Robert to come home, while Souter quietly sat in the corner winding a ball of yarn from the skein which hung over the back of the chair, and looking decidedly sheepish. When Mary burst in[22] the door so unceremoniously they both jumped expectantly to their feet, thinking surely it was Robert.

“Why, Mary lass, is it ye?” said Mrs. Burns in surprise. “Whatever brings ye over the day? not but we are glad to have ye,” she added hospitably.

“Where is he, Mistress Burns, where’s Robbie?” she panted excitedly, her heart in her voice.

“He isna’ here yet, lassie,” replied Mrs. Burns, with a sigh. “But sit ye doon. Take off your plaidie and wait for him. There’s a girlie,” and she pushed the unresisting girl into a chair.

“Ye’re sure he isna’ here, Mistress Burns?” asked Mary wistfully, looking around the room with eager, searching eyes.

“Aye, lassie,” she replied, smiling; “if he were he wouldna’ be hidin’ from ye, dearie, and after a year of absence, too. But I ken he will be here soon noo.” And she went to the window and looked anxiously out across the moor.

“It seems so lang since he left Mossgiel, doesna’ it, Mistress Burns?” said Mary with a deep sigh of disappointment.

“An’ weel ye might say that,” replied Mrs. Burns. “For who doesna’ miss my laddie,” and she tossed her head proudly. “There isna’ another like Robbie in all Ayrshire. A bright, honest, upright, pure-minded lad, whom any mither might be proud of. I hope he’ll return to us the same laddie he was when[23] he went awa’.” The anxious look returned to her comely face.

An odd little smile appeared about the corners of Souter’s mouth as he resumed his work.

“Weel, noo, Mistress Burns,” he asked dryly, “do ye expect a healthy lad to be out in this sinful world an’ not learn a few things he didna ken before? ’Tis only human nature,” continued the old rogue, “an’ ye can learn a deal in a year, mind that, an’ that reminds me o’ a good joke. Sandy MacPherson——”

“Souter Johnny, ye keep your stories to yoursel’,” interrupted Mrs. Burns with a frown. Souter’s stories were not always discreet.

“Irvine and Mauchline are very gay towns,” continued Souter reminiscently. “They say some of the prettiest gurls of Scotlan’ live there, an’ I hear they all love Robbie Burns, too,” he added slyly, looking at Mary out of the corner of his eye.

“They couldna help it,” replied Mary sweetly.

“An’ ye’re nae jealous, Mary?” he inquired in a surprised tone, turning to look into the flushed, shy face beside him.

“Jealous of Robert?” echoed Mary, opening her innocent eyes to their widest. “Nay! for I ken he loves me better than any other lassie in the world.” And she added naïvely, “He has told me so ofttimes.”

“Ye needna fear, Mary,” replied Mrs. Burns,[24] resuming her place at the wheel. “I’ll hae no ither lass but ye for my daughter, depend on’t.”

“Thank ye, Mistress Burns,” said Mary brightly. “I ken I’m only a simple country lass, but I mean to learn all I can, so that when he becomes a great man he’ll no be ashamed of me, for I ken he will be great some day,” she continued, her eyes flashing, the color coming and going in her cheek as she predicted the future of the lad she loved. “He’s a born poet, Mistress Burns, and some day ye’ll be proud of your lad, for genius such as Rabbie’s canna always be hid.” Mrs. Burns gazed at the young girl in wonder.

“Oh, if someone would only encourage him,” continued Mary earnestly, “for I’m fair sure his heart is set on rhyming.”

“I ne’er heard of a body ever makin’ money writin’ verses,” interposed Souter, rubbing his chin reflectively with the ball of soft yarn.

“Ah, me,” sighed Mrs. Burns, her hands idle for a moment, “I fear the lad does but waste his time in such scribbling. Who is to hear it? Only his friends, who are partial to him, of course, but who, alas, are as puir as we are, and canna assist him in bringin’ them before the public. The fire burns out for lack of fuel,” she continued slowly, watching the flickering sparks die one by one in the fireplace. “So will his love of writin’ when he sees how hopeless it all is.” She paused and sighed deeply. “He maun[25] do mair than write verses to keep a wife and family from want,” she continued earnestly, and she looked sadly at Mary’s downcast face. “And, Mary, ye too will hae to work, harder than ye hae ever known, even as I have; so hard, dearie, that the heart grows sick and weary and faint in the struggle to keep the walf awa’.”

“I am no afraid of hard work,” answered Mary bravely, swallowing the sympathetic tears which rose to her eyes. “If poverty is to be his portion I shall na shrink from sharin’ it wi’ him,” and her eyes shone with love and devotion.

Mrs. Burns rose and put her arms lovingly about her. “God bless ye, dearie,” she said softly, smoothing the tangled curls away from the broad low brow with tender, caressing fingers.

“Listen!” cried Mary, as the wail of the bagpipes was heard in the distance. “’Tis old blind Donald,” and running to the window she threw back the sash with a cry of delight. “Oh, how I love the music of the pipes!” she murmured passionately, and her sweet voice vibrated with feeling, for she thought of her home so far away in the Highlands and the dear ones she had not seen for so long.

“Isna he the merry one this day,” chuckled Souter, keeping time with his feet and hands, not heeding the yarn, which had slipped from the chair, and which was fast becoming entangled about his feet.

“It’s fair inspirin’!” cried Mary, clapping her hands ecstatically. “Doesna it take ye back to the Highlands, Souter?” she asked happily.

“Aye, lassie,” replied Souter. “But it’s there among the hills and glens that the music of the pipes is most entrancin’,” he added loyally, for he was a true Highlander. The strains of the “Cock of the North” grew louder and louder as old Donald drew near the farm, and Mary, who could no longer restrain her joyous impulse, with a little excited laugh, her face flushing rosily, ran to the center of the room, where, one hand on her hip, her head tossed back, she began to dance. Her motion was harmony itself as she gracefully swayed to and fro, darting here and there like some elfin sprite, her bare feet twinkling like will-o’-the-wisps, so quickly did they dart in and out from beneath her short plaid skirt. With words of praise they both encouraged her to do her best.

Louder and louder the old piper blew, quicker and quicker the feet of the dancer sped, till, with a gasp of exhaustion, Mary sank panting into the big armchair, feeling very warm and very tired, but very happy.

“Ye dance bonnie, dearie, bonnie,” exclaimed Mrs. Burns delightedly, pouring her a cup of tea, which Mary drank gratefully.

“Oh, dearie me,” Mary said apologetically, putting down her empty cup, “whatever came o’er me? I’m a gaucie wild thing this day, for true, but I[27] canna held dancin’ when I hear the pipes,” and she smiled bashfully into the kind face bent over her.

“Music affects me likewise,” replied Souter, trying to untangle the yarn from around his feet, but only succeeding in making a bad matter worse. “Music always goes to my feet like whusky, only whusky touches me here first,” and he tapped his head humorously with his forefinger.

“Souter Johnny, ye skellum!” cried Mrs. Burns, noticing for the first time the mischief he had wrought. “Ye’re not worth your salt, ye ne’er-do-weel. Ye’ve spoiled my yarn,” and she glared at the crestfallen Souter with fire in her usually calm eye.

“It was an accident, Mistress Burns,” stammered Souter, awkwardly shifting his weight from one foot to the other in his efforts to free himself from the persistent embrace of the clinging yarn.

With no gentle hand Mrs. Burns shoved him into a chair and proceeded to extricate his feet from the tangled web which held him prisoner. Soon she freed the offending members and rose to her feet. “Noo gang awa’,” she sputtered. “Ye’ve vexed me sair. Gang out and help Gilbert. I canna bide ye round.” Souter took his Tam O’Shanter, which hung over the fireplace, and ambled to the door.

“Very weel,” he said meekly, “I’ll go. Souter Johnny can take a hint as weel as the next mon,” and he closed the door gently behind him and slowly wended his way across the field to where Gilbert was sitting, dreamily looking across the moor.

“Why doesna he come, Mistress Burns?” said Mary pathetically. They had come down to the field where Gilbert was now at work the better to watch for their loved one’s approach. “Twilight is comin’ on an’ ’tis a lang walk to Castle Montgomery at night. I canna wait much langer noo.”

“Never ye mind, lassie; ye shall stay the night with me,” replied Mrs. Burns soothingly, “if Robert doesna come.”

“I’ll take ye back, Mary,” said Gilbert eagerly, going up to her. Perhaps Robert was not coming after all, he thought with wildly beating heart.

“Thank ye, Gilbert, but I’ll wait a wee bit longer,” answered Mary hopefully; “perhaps he’ll be here soon,” and she dejectedly dug her bare toes into the damp earth.

“Well, lassie, I canna waste any mair time,” said Mrs. Burns energetically. “Ye can stay here with Gilbert, while I return to my spinning. Come, Souter, there’s some firewood to be split,” and she quickly walked to the house, followed more slowly by the reluctant Souter.

Gilbert, with his soul in his eyes, feasted on the pathetic loveliness of the sweet face beside him, gazing wistfully toward Mauchline, and his aching heart[29] yearned to clasp her to his breast, to tell her of his love, to plead for her pity, her love, herself, for he felt he would rather die than give her up to another. He drew closer to her.

“What is the matter, Gilbert?” asked Mary anxiously, noting his pale face. “Are ye in pain?”

“Aye, Mary, in pain,” he answered passionately. “Such pain I’ll hope ye’ll never know.” He bowed his head.

“I’m so sorry, lad,” she replied innocently. “I wish I could help ye,” and she looked compassionately at the suffering man.

He raised his head suddenly and looked into her eyes.

“Are ye goin’ to marry Robert this summer, when he returns?” he asked abruptly, his voice husky with emotion.

“Aye, if he wishes it,” answered Mary simply, wondering why he looked so strangely white.

“He has been gone a year, ye ken,” continued Gilbert hoarsely. “Suppose he has changed and no langer loves ye?” She looked at him with big, frightened eyes. She had never thought of that possibility before. What if he did no longer love her? she thought fearfully. She looked about her helplessly. She felt bewildered, dazed; slowly she sank down on the rocky earth, her trembling limbs refusing to support her. Her fair head drooped pathetically, like a lily bent and bruised by the storm.

“If Robert doesna want me any more,” she murmured after a pause, a pathetic little catch in her voice, “if he loves someone else better than he does his Highland Mary, then I—I——”

“Ye’ll soon forget him, Mary,” interrupted Gilbert eagerly, his heart throbbing with hope. She raised her eyes from which all the light had flown and looked at him sadly, reproachfully.

“Nay, lad, I wouldna care to live any longer,” she said quietly. “My heart would just break,” and she smiled a pitiful little smile which smote him like a knife thrust. He caught her two hands in his passionately and pressed them to his heart with a cry of pain.

“Dinna mind what I said, lass,” he cried, conscience stricken; “dinna look like that. I dinna mean to grieve ye, Mary, I love ye too well.” And almost before he realized it he had recklessly, passionately, incoherently told her of his love for her, his jealousy of his brother, his grief and pain at losing her. Mary gazed at him in wonder, scarcely understanding his wild words, his excited manner.

“I’m fair pleased that ye love me, Gilbert,” she answered him in her innocence. “Ye ken I love ye too, for ye’ve been so kind and good to me ever since Robert has been awa’,” and she pressed his hand affectionately. With a groan of despair he released her and turned away without another word. Suddenly she understood, and a great wave of sympathy[31] welled up in her heart. “Oh, Gilbert,” she cried sorrowfully, a world of compassion in her voice. “I understand ye noo, laddie, an’ I’m so sorry, so sorry.” He bit his lips till the blood came. Finally he spoke in a tone of quiet bitterness.

“I’ve been living in a fool’s paradise this past year,” he said, “but ’tis all ended noo. Why, ever since he went awa’ I have wished, hoped, and even prayed that Rob would never return to Mossgiel, that ye might forget him and his accursed poetry, and in time would become my wife.” He threw out his hands with a despairing gesture as he finished.

“Oh, Gilbert,” she faltered, with tears in her eyes, “I never dreamed ye thought of me in that way. Had I only known, I——” she broke off abruptly and looked away toward the cottage.

“Ye see what a villain I have been,” he continued with a bitter smile. “But ye have nothin’ to blame yoursel’ for, Mary. I had no right to think of ye ither than as Robert’s betrothed wife.”

“I’m so sorry, lad,” repeated Mary compassionately. Then her downcast face brightened. “Let us both forget what has passed this day, and be the same good friends as ever, wi’na we, Gilbert?” And she held out her hand to him with her old winning smile.

“God bless ye, lassie,” he replied brokenly. Quietly they stood there for a few minutes, then with a sudden start they realized that deep twilight had fallen[32] upon them. Silently, stealthily it had descended, like a quickly drawn curtain. Slowly they wended their way back to the cottage. When they reached the door Mary suddenly turned and peered into the deepening twilight.

“Listen!” she said breathlessly. “Dinna ye hear a voice, Gilbert?” He listened for a minute. Faintly there came on the still air the distant murmur of many voices.

“’Tis only the lads on their way to the village,” he replied quietly. With a little shiver, Mary drew her plaidie closely about her, for the air had grown cool.

“I think I’ll hae to be goin’ noo,” she said dejectedly. “He willna be here this night.”

“Very well,” answered Gilbert. “I’ll saddle the mare and take ye back. Bide here a wee,” and he left her. She could hardly restrain the disappointed tears, which rose to her eyes.

Why didn’t Robert come? What could keep him so late? She so longed to see her laddie once more. She idly wondered why the lads, whose voices she now heard quite plainly, were coming toward Mossgiel. There was no inn hereabouts. By the light of the rising moon she saw them on the moor, ever drawing nearer and nearer, but they had no interest for her. Nothing interested her now. She leaned back against the wall of the cottage and patiently awaited Gilbert’s return.

“He’s comin’! he’s comin’!” suddenly exclaimed the voice of Mrs. Burns from within the cottage. “My lad is comin’! Out of my way, ye skellum!” and out she ran, her face aglow with love and excitement, followed by Souter, who was shouting gleefully, “He’s comin’! he’s comin’! Robbie’s comin’!” and off he sped in her footsteps, to meet the returned wanderer.

“It’s Robbie! it’s Robbie!” cried Mary joyously, her nerves a-quiver, as she heard the vociferous outburst of welcome from the lads, who were bringing him in triumph to his very door.

“Welcome hame, laddie!” shouted the crowd, as they came across the field, singing, laughing and joking like schoolboys on a frolic.

“Oh, I canna’, I darena’ meet him before them a’,” she exclaimed aloud, blushing rosily, frightened at the thought of meeting him before the good-natured country folk.

She would wait till they all went away, and, turning, she ran into the house like a timid child. Quickly she hid behind the old fireplace, listening shyly, as she heard them approach the open door.

“Thank ye, lads, for your kind welcome,” said Robert as he reached the threshold, one arm around his mother. “I didna’ ken I had left so many friends in Mossgiel,” and he looked around gratefully at the rugged faces that were grinning broadly into his.

“Come doon to the Inn and hae a wee nippie for[34] auld lang syne,” sang out Sandy MacPherson, with an inviting wave of the hand.

“Nay, an’ he’ll not gang a step, Sandy MacPherson,” cried Mrs. Burns indignantly, clinging closely to her son.

“Nay, I thank ye, Sandy,” laughingly replied Robert. “Ye must excuse me to-night. I’ll see ye all later, and we’ll have a lang chat o’er auld times.”

“Come awa’ noo, Robert,” said Mrs. Burns lovingly, “an’ I’ll get ye a bite and a sup,” and she drew him into the house.

“Good-night, lads; I’ll see ye to-morrow,” he called back to them cheerily.

“Good-night,” they answered in a chorus, and with “three cheers for Robbie Burns” that made the welkin ring, they departed into the night, merrily singing “Should auld acquaintance be forgot?” a song Robert himself had written before leaving Mossgiel.

“Ah, Souter Johnny, how are ye, mon?” cried Robert heartily, as his eyes rested on the beaming face of the old man. “Faith, an’ I thought I’d find ye here as of old. ’Tis almost a fixture ye are.”

“Ah, weel,” replied Souter nonchalantly, as he shook Robert’s outstretched hand, “ye ken the Scripture says, ‘an’ the poor ye have always wi’ ye.’” Robert laughed merrily at the old man’s sally.

“Thank goodness, they’ve gone at last,” said Mrs. Burns with a sigh of relief, as she entered the room. “Why, laddie, ye had half the ne’er-do-weels of Mossgiel a-following ye. They are only a lot of leeches and idle brawlers, that’s a’,” and her dark eyes flashed her disapproval.

“I’m sure they have kind hearts, mither, for a’ that,” replied Robert reproachfully.

“Ye’re so popular wi’ them a’, Robbie,” cried Souter proudly.

“Aye, when he has a shillin’ to spend on them,” added Mrs. Burns dryly. “But sit doon, laddie; ye maun be tired wi’ your lang walk,” and she gently pushed him into a chair beside the table.

“I am a wee bittie tired,” sighed Robert gratefully as he leaned back in the chair.

“I’ll soon hae something to eat before ye,” replied his mother briskly.

“I’m nae hungry, mother,” answered Robert. “Indeed, I couldna’ eat a thing,” he remonstrated as she piled the food before him.

“’Tis in love ye are,” insinuated Souter with a knowing look. “I ken the symptoms weel; ye canna’ eat.”

“Ye’re wrong there,” replied Robert with a bright smile. “Love but increases my appetite.”

“Aye, for love,” added Souter sotto voce.

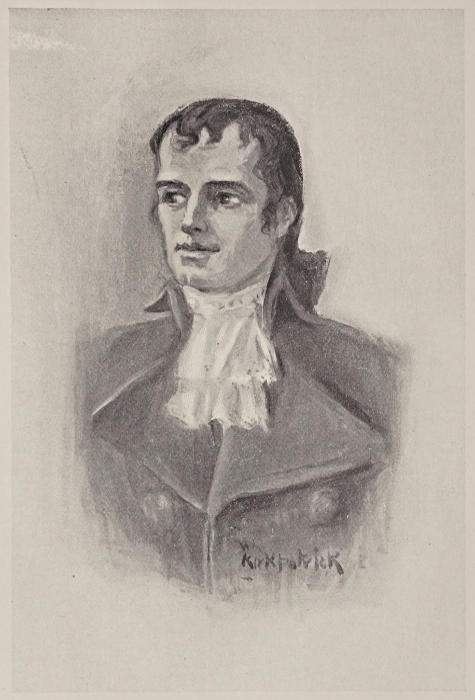

“Ah, mother dear, how guid it seems to be at hame again, under the old familiar roof-tree,” said Robert a little later, as he leaned back contentedly in his chair and gazed about the room with eager, alert glances. As he sits there with his arms folded let us take a look at our hero. Of more than medium height, his form suggested agility as well as strength. His high forehead, shaded with black curling hair tied at the neck, indicated extensive capacity. His eyes were large, dark, and full of fire and intelligence. His face was well formed and uncommonly interesting and expressive, although at the first glance his features had a certain air of coarseness, mingled with an expression of calm thoughtfulness, approaching melancholy. He was dressed carelessly in a blue homespun long coat, belted at the waist, over a buff-colored vest; short blue pantaloons, tucked into long gray home-knit stockings, which came up above his[37] knee, and broad low brogans, made by Souter’s hands. He wore a handsome plaid of small white and black checks over one shoulder, the ends being brought together under the opposite arm and tied loosely behind.

“’Tis a fine hame-comin’ ye’ve had, laddie,” cried old Souter proudly. “Faith, it’s just like they give the heir of grand estates. We should hae had a big bonfire burnin’ outside our—ahem—palace gates,” and he waved his hand grandiloquently.

“Dinna’ ye make fun of our poor clay biggin’, Souter Johnny,” cried Mrs. Burns rebukingly. “Be it ever so poor, ’tis our hame.”

“Aye, ’tis our hame, mother,” repeated Robert lovingly. “An’ e’en tho’ I have been roaming in other parts, still this humble cottage is the dearest spot on earth to me. I love it all, every stick and stone, each blade of grass, every familiar object that greeted my eager gaze as I crossed the moor to this haven of rest, my hame. And my love for it this moment is the strongest feeling within me.”

His roving eyes tenderly sought out one by one the familiar bits of furniture around the room, and lingered for a moment lovingly on the old fireplace. It was there he had first seen Mary Campbell. She had come to the cottage on an errand, and as she stood leaning against the mantel, the sunlight gleaming through the window upon her golden hair, he had entered the room. It was plainly love at first[38] sight, and so he had told her that same day, as he walked back to Castle Montgomery with the winsome dairymaid. The course of their love had flowed smoothly and uneventfully; he loved her with all the depth of his passionate emotional nature, and yet his love was more spiritual than physical. She was an endless source of inspiration, as many a little song and ode which had appeared in the Tarbolton weekly from time to time could testify. How long the year had been away from her, he mused dreamily. To-morrow, bright and early, he would hurry over to Castle Montgomery and surprise her at her duties.

“Gazed straight into the startled eyes of Robert.”

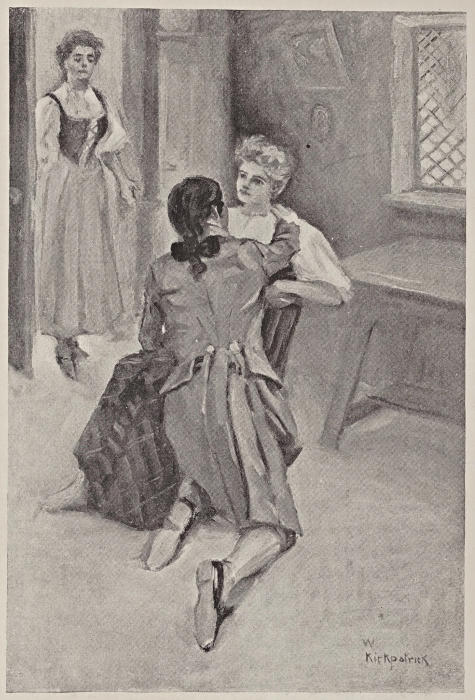

Mary, from her hiding place, had watched all that happened since Robert had come into the room. She had not expected to remain so long hidden, she thought wistfully. She had hoped that Mrs. Burns would miss her, and that she, or Robert, or someone would look for her, but they had not even thought of her, and her lips trembled piteously at their neglect. And so she had stayed on, peeping out at them, whenever their backs were turned, feeling very lonely, and very miserable, in spite of the pride that thrilled her, as she watched her lover sitting there so handsome in the full strength of his young manhood. Perhaps they didn’t want her here to-night. Perhaps it was true, as Gilbert said, “that Robert didn’t love her any more.” The tears could no longer be restrained. If she could only slip out[39] unobserved she would go home. She wasn’t afraid, she thought miserably. She wondered what they were doing now, they were so quiet? Peering shyly around the mantel, she gazed straight into the startled eyes of Robert, who with a surprised ejaculation started back in amazement.

“Why, Mary Campbell!” cried his mother remorsefully, as she caught sight of Mary’s face, “I declare I clear forgot ye, lass.” With a glad cry Robert sprang toward her and grasped her two hands in his own, his eyes shining with love and happiness.

“Mary, lass, were ye hidin’ awa’ from me?” he asked in tender reproach. She dropped her head bashfully without a word. “’Tis o’er sweet in ye, dear, to come over to welcome me hame,” he continued radiantly. “Come an’ let me look at ye,” and he drew her gently to where the candle light could fall on her shy, flushed face. “Oh, ’tis bonnie ye’re looking, lassie,” he cried proudly. He raised her drooping head, so that his hungry eyes could feast on her beauty. She stood speechless, like a frightened child, not daring to raise her eyes to his. “Haven’t ye a word of welcome for me, sweetheart?” he whispered tenderly, drawing her to him caressingly.

“I’m—I’m very glad to hae ye back again,” she faltered softly, her sweet voice scarcely audible.

“Go an’ kiss him, Mary; dinna’ mind us,” cried Souter impatiently. “I can see ye’re both asking[40] for it wi’ your eyes,” he insinuated. And he drew near them expectantly.

“Hauld your whist, ye old tyke,” flashed Mrs. Burns indignantly. “Robbie Burns doesna’ need ye to tell him how to act wi’ the lassies.”

“I’ll not dispute ye there,” replied Souter dryly, winking his eye at Robert knowingly.

Robert laughed merrily as he answered, “Ye ken we’re both o’er bashful before ye a’.”

“Ah, ye’re a fine pair of lovers, ye are,” retorted Souter disgustedly, turning away.

“So the neighbors say, Souter,” responded Robert gayly, giving Mary a loving little squeeze.

And surely there never was a handsomer couple, thought Mistress Burns proudly, as they stood there together. One so dark, so big and strong, the other so fair, so fragile and winsome. And so thought Gilbert Burns jealously, as he came quietly into the room. Robert went to him quickly, a smile lighting up his dark face, his hand outstretched in greeting.

“I’m o’er glad to see ye again, Gilbert,” he cried impulsively, shaking his brother’s limp hand.

“So ye’ve come back again,” said Gilbert, coldly.

“Aye, like a bad penny,” laughingly responded Robert. “Noo that I am burned out of my situation, I’ve come hame to help ye in the labors of the farm,” and he pressed his brother’s hand warmly.

“I fear your thoughts willna’ lang be on farming,”[41] observed Gilbert sarcastically, going to the fireplace and deliberately turning his back to Robert.

“I’ll struggle hard to keep them there, brother,” replied Robert simply. His brother’s coldness had chilled his extraordinarily sensitive nature. He walked slowly back to his seat.

“I ken ye’d rather be writin’ love verses than farmin’, eh, Robert?” chimed in Souter thoughtlessly.

“’Tis only a waste of time writin’ poetry, my lad,” sighed Mrs. Burns, shaking her head disapprovingly.

“I canna’ help writin’, mother,” answered the lad firmly, a trifle defiantly. “For the love of poesy was born in me, and that love was fostered at your ain knee ever since my childhood days.”

She sighed regretfully. “I didna’ ken what seed I was sowing then, laddie,” she answered thoughtfully.

“Dinna’ be discouraged,” cried Mary eagerly, going to him. “I’ve faith in ye, laddie, and in your poetry, too.” She put her hand on his shoulder lovingly, as he sat beside the table, looking gloomy and dejected. “Some day,” she continued, a thrill of pride in her voice, “ye’ll wake to find your name on everybody’s lips. You’ll be rich and famous, mayhap. Who kens, ye may even become the Bard o’ Scotland,” she concluded in an awestruck tone.

“Nay, Mary, I do not hope for that,” replied[42] Robert, his dark countenance relaxing into a smile of tenderness at her wild prophecy, although in his own heart he felt conscious of superior talents.

“Waesucks,” chuckled Souter reminiscently. “Do you mind, Robbie, how, a year ago, ye riled up the community, an’ the kirk especially, over your verses called ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’? Aye, lad, it was an able keen satire, and auld Squire Armour recognized the truth of it, for he threatened to hae ye arrested for blaspheming the kirk and the auld licht religion. He’ll ne’er forgive ye for that,” and he shook his head with conviction.

“He’s an auld Calvinistic hypocrite,” replied Robert carelessly, “and he deserved to be satirized alang wi’ the rest of the Elders. Let us hope the verses may do them and the kirk some good. They are sadly in need of reform.” Then with a gay laugh he told them a funny anecdote concerning one of the Elders, and for over an hour they listened to the rich tones of his voice as he entertained them with jest and song and story, passing quickly from one to the other, as the various emotions succeeded each other in his mind, assuming with equal ease the expression of the broadest mirth, the deepest melancholy or the most sublime emotion. They sat around him spellbound. Never had they seen him in such a changeable mood as to-night.

“And noo, laddie, tell us about your life in Irvine and Mauchline,” said Mrs. Burns.

Robert had finished his last story, and sat in meditative silence, watching the smoldering peat in the fireplace.

He hesitated for a moment. “There is little to tell, mother,” he answered, not looking up, “and that little is na worth tellin’.”

“I ken ye’ve come back no richer in pocket than when ye left,” remarked Gilbert questioningly. As his brother made no answer, he continued with sarcastic irony, “But perhaps there wasna’ enough work for ye there.” He watched his brother’s face narrowly.

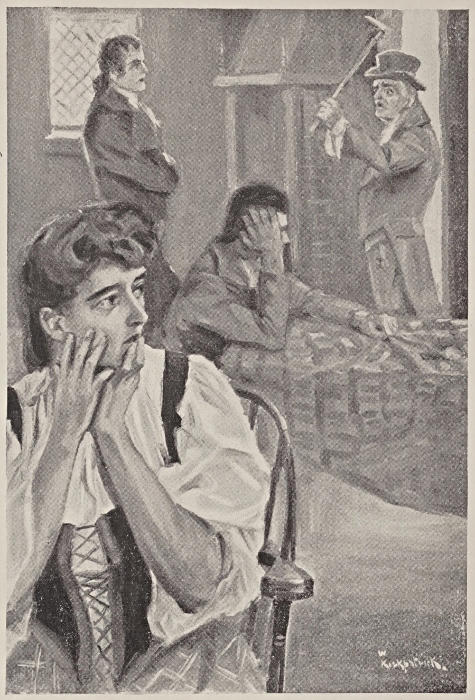

“There was work enough for a’,” replied Robert in a low tone, an agony of remorse in his voice. “An’ I tried to fulfill faithfully the uncongenial tasks set before me, but I would sink into dreams, forgetting my surroundings, my duties, and would set me doon to put on paper the thoughts and fancies which came rushing through my brain, raging like so many devils, till they found vent in rhyme; then the conning o’er my verses like a spell soothed all into quiet again.” A far away rapt expression came over his countenance as he finished, and his dark glowing eyes gazed dreamily into space, as if communing with the Muses. Mrs. Burns and Mary both watched him with moist, adoring eyes, hardly breathing lest they should disturb his reverie. Gilbert stirred in his chair restlessly.

“Ye will never prosper unless ye give up this day[44] dreaming,” he exclaimed impatiently, rising from his chair and pacing the floor.

Robert looked up, the fire fading from his eyes, his face growing dark and forbidding. “I ken that weel, Gilbert,” he answered bitterly. “An’ I despair of ever makin’ anything of mysel’ in this world, not e’en a poor farmer. I am not formed for the bustle of the busy nor the flutter of the gay. I’m but an idle rhymster, a ne’er-do-weel.” He walked quickly to the window and stood dejectedly looking out into the night.

“Nay, ye’re a genius, lad,” declared old Souter emphatically, patting him affectionately on the shoulder. “I havena’ watched your erratic ways for nothin’, an’ I say ye’re a genius. It’s a sad thing to be a genius, Robert, an’ I sympathize wi’ ye,” and the old hypocrite shook his head dolefully as he took his seat at the fireplace.

“I’m a failure, I ken that weel. I’m a failure,” muttered Robert despairingly, his heart heavy and sad.

“Nay, laddie, ye mustna’ talk like that,’tis not right,” cried Mary, bravely keeping back the sympathetic tears from her eyes and forcing a little smile to her lips. “Ye are only twenty-five,” she continued earnestly. “An’ all your life is stretchin’ out before ye. Why, ye mustna ever think o’ failure. Ye must think only of bright, happy things, and ye’ll see how everythin’ will come out all right.[45] Noo mind that. So cheer thee, laddie, or ye’ll make us all sad on this your hame-comin’. Come, noo, look pleasant,” and she gave his arm a loving little shake. As his stern face melted into a sad smile, she laughed happily. “That’s right, laddie.” With a little encouraging nod she left him, and running to Mrs. Burns, she gave her a hug and a kiss, until the old lady’s grim features relaxed. Then like a bird she flitted to the other side of the room.

“Souter Johnny,” she saucily cried, “how dare ye look so mournful like. Hae ye a fit o’ the gloom, man?”

“Not a bit o’ it,” retorted Souter energetically, jumping lightly to his feet. “Will I stand on my head for ye, Mary, eh?”

Mary laughed merrily as Mrs. Burns replied in scathing tones, “Your brains are in your boots, noo, Souter Johnny.”

“Weel, wherever they are,” responded Souter with a quizzical smile, “they dinna’ trouble me o’er much. Weel, I think I’ll be turnin’ in noo,” he continued, stretching himself lazily. “Good-night to ye all,” and taking a candle from the dresser, he slowly left the room.

“Come, lads,’tis bedtime,” admonished Mrs. Burns, glancing at the old high clock that stood in the corner. “Mary, ye shall sleep with me, and, Robert, ye know where to find your bed. It hasna’ been slept in since ye left. Dinna’ forget your[46] candle, Gilbert,” she called out as he started for the door. He silently took it from her hand. “Dinna’ forget your promise,” she whispered anxiously to him as he left the room in gloomy silence.

The look on his face frightened her. There was bitterness and despair in the quick glance he gave the happy lovers, who were standing in the shadow of the deep window. “The lad looked fair heart-broken,” she mused sorrowfully. For a moment she looked after him, a puzzled frown on her brow. Then suddenly the truth dawned on her. How blind she had been, why hadn’t she thought of that before? The lad was in love. In love with Mary Campbell, that was the cause of his bitterness toward his brother. “Both in love with the same lass,” she murmured apprehensively, and visions of petty meannesses, bitter discords, between the two brothers, jealous quarrels, resulting in bloody strife, perhaps; and she shuddered at the mental picture her uneasy mind had conjured up. The sooner Robert and Mary were married the sooner peace would be restored, she thought resolutely. They could start out for themselves, go to Auld Ayr or to Dumfries. They couldn’t be much worse off there than here. And determined to set her mind easy before she retired, she walked briskly toward the couple, who now sat hand in hand, oblivious to earthly surroundings, the soft moonlight streaming full upon their happy upturned faces. She watched them a moment in silence,[47] loath to break in upon their sweet communion. Presently she spoke.

“Robert,” she called softly, “ye’d better gang to your bed noo, lad.”

With a start he came back to earth, and jumping up boyishly, replied with a happy laugh, “I forgot, mother, that I was keeping ye and Mary from your rest.” He glanced toward the recessed bed in the wall where his mother was wont to sleep. “Good-night, mither, good-night, Mary,” he said lovingly. Then taking his candle, he started for the door, but turned as his mother called his name and looked at her questioningly.

“Laddie, dinna’ think I’m meddling in your affairs,” she said hesitatingly, “but I’m fair curious to know when ye an’ Mary will be wed.”

Robert looked inquiringly at Mary, who blushed and dropped her head. “Before harvest begins, mither,” he answered hopefully, “if Mary will be ready and willing. Will that suit ye, lassie?” And he looked tenderly at the drooping head, covered with its wealth of soft, glittering curls.

“I hae all my linen spun and woven,” she faltered, after a nervous silence, not daring to look at him. “Ye ken the lassies often came a rockin’ and so helped me get it done.” She raised her head and looked in his glowing face. “’Tis a very small dowry I’ll be bringin’ ye, laddie,” she added in pathetic earnestness.

He gave a little contented laugh. “Ye’re bringin’[48] me yoursel’, dearie,” he murmured tenderly. “What mair could any lad want. I ken I do not deserve such a bonnie sweet sonsie lassie for my wife.” He looked away thoughtfully for a moment. Then he continued with glowing eyes, “But ye mind the verse o’ the song I gave ye before I went awa’?” he said lovingly, taking her hand in his. His voice trembled with feeling as he fervently recited the lines:

She smiled confidingly up into his radiant face, then laid her little head against his breast like a tired child. “Always remember, sweetheart,” he continued softly, as if in answer to that look, “that Robbie Burns’ love for his Highland Mary will remain forever the tenderest, truest passion of his unworthy life.”

Life at Mossgiel passed uneventfully and monotonously. Robert had settled down with every appearance of contentment to the homely duties of the farmer, and Gilbert could find no fault with the amount of labor done. Morning till night he plowed and harrowed the rocky soil, without a word of complaint, although the work was very hard and laborious. Planting had now begun and his tasks were materially lightened. He had ample leisure to indulge in his favorite pastime; and that he failed to take advantage of his opportunities for rhyming was a mystery to Gilbert, and a source of endless regret to Mary. But his mother could tell of the many nights she had seen the candle light gleaming far into the night; and her heart was sore troubled when in the morning she would see the evidence of his midnight toil, scraps of closely written paper scattered in wild disorder over his small table, but she held her peace. The lad loved to do it, she mused tenderly, and so long as he was not shirking his work, why disturb his tranquillity?

A few weeks after the return of our hero Mary and Mrs. Burns were seated in the living-room, Mrs. Burns as usual busy at her wheel, while Mary[50] sat sewing at the window, where she could look out across the fields and see her sweetheart, who, with a white sheet containing his seed corn slung across his shoulder, was scattering the grain in the earth. She sang dreamily as she sewed, her sweet face beaming with love and happiness. No presentiment warned her of the approaching tragedy that was soon to cast its blighting shadow over that happy household—a tragedy that was inevitable. The guilty one had sown to the flesh, he must reap corruption. The seed had been sown carelessly, recklessly, and now the harvest time had come, and such a harvest! The pity of it was that the grim reaper must with his devouring sickle ruthlessly cut down such a tender, sweet, and innocent flower as she who sat there so happy and so blissfully unconscious of her impending doom.

Suddenly, with an exclamation of astonishment, she jumped excitedly to her feet. “Mistress Burns,” she cried breathlessly, “here are grand lookin’ strangers comin’ up the path. City folk, too, I ken. Look.”

Hastily the good dame ran to the window. “Sure as death, Mary; they’re comin’ here,” she cried in amazement. “Oh, lack a day, an’ I’m na dressed to receive the gentry.” A look of comical dismay clouded her anxious face as she hurriedly adjusted her cap and smoothed out her apron. “Is my cap on straight, Mary?” she nervously inquired. Mary[51] nodded her head reassuringly. “Oh, dear, whatever can they want?” Steps sounded without. “Ye open the door, Mary,” she whispered sibilantly as the peremptory knock sounded loudly through the room. Timidly Mary approached the door. “Hist, wait,” called Mrs. Burns in sudden alarm. “My ’kerchief isna’ pinned.” Hastily she pinned the loose end in place, then folding her hands, she said firmly, “Noo let them enter.” Mary slowly opened the door, which, swinging inward, concealed her from the three strangers, who entered with ill-concealed impatience on the part of the two ladies who were being laughingly chided by their handsome escort. With a wondering look of admiration at the richly dressed visitors, Mary quietly stole out and softly shut the door behind her.

With a murmur of disgust the younger of the two ladies, who was about nineteen, walked to the fireplace, and raising her quilted blue petticoat, which showed beneath the pale pink overdress with its Watteau plait, she daintily held her foot to the blaze. A disfiguring frown marred the dark beauty of her face as her bold black eyes gazed about her impatiently.

“It’s a monstrous shame,” she flashed angrily, “to have an accident happen within a few miles of home. Will it delay us long, think you?” she inquired anxiously, addressing her companion.

“It depends on the skill of the driver to repair[52] the injury,” replied the other lady indifferently. She appeared the elder of the two by some few years, and was evidently a lady of rank and fashion. She looked distinctly regal and commanding in her large Gainsborough hat tilted on one side of her elaborately dressed court wig. A look of amused curiosity came over her patrician face as she calmly surveyed the interior of the cottage. She inclined her head graciously to Mrs. Burns, who with a deep courtesy stood waiting their pleasure.

“We have just met with an accident, guidwife,” laughingly said the gentleman, who stood in the doorway brushing the dust from his long black cloak. He was a scholarly looking man of middle age, dressed in the height of taste and fashion. “While crossing the old bridge yonder,” he continued, smiling courteously at Mrs. Burns, “our coach had the misfortune to cast a wheel, spilling us all willy-nilly, on the ground, and we must crave your hospitality, guidwife.”

“Ye are a’ welcome,” quickly answered Mrs. Burns with another courtesy. “Sit doon, please,” and she placed a chair for the lady, who languidly seated herself thereon with a low murmur of thanks.

“Allow me to introduce myself,” continued the gentleman, coming into the room, his cloak over his arm. “I am Lord Glencairn of Edinburgh. This is Lady Glencairn, and yonder lady is Mistress Jean Armour of Mauchline.”

The young lady in question, who was still standing by the fireplace, flashed him a look of decided annoyance. She seemed greatly perturbed at the enforced delay of the journey. She started violently as she heard Mrs. Burns say, “And I am Mrs. Burns, your lordship.” Then she hurried to the old lady’s side, a startled look in her flashing eyes.

“Mistress Burns of Mossgiel Farm?” she inquired in a trembling voice.

“Yes, my lady,” replied Mrs. Burns. The young lady’s face went white as she walked nervously back to the fireplace.

“My dear Jean, whatever is the matter?” asked Lady Glencairn lazily, as she noticed Jean’s perturbation. “Is there anything in the name of Burns to frighten you?”

“No, your ladyship,” replied Jean falteringly, turning her face away so that her large Gainsborough hat completely shielded her quivering features. “I—I am still a trifle nervous from the upset, that is all.” She seemed strangely agitated.

“Was it not unlucky?” replied Lady Glencairn in her rich vibrating contralto. “’Twill be a most wearisome wait, I fear, but we simply must endure it with the best possible grace,” and she unfastened her long cloak of black velvet and threw it off her shoulders, revealing her matchless form in its tightly fitting gown of amber satin, with all its alluring lines and sinuous curves, to the utmost advantage.

“It willna’ be long noo, your ladyship,” replied Mrs. Burns, smiling complacently. She had quietly left the room while the two were talking, and seeing Souter hovering anxiously around, trying to summon up courage to enter, she had commanded him to go to the fields and tell the lads of the accident, which he had reluctantly done.

“My lads will soon fix it for ye,” she continued proudly. “Robert is a very handy lad, ye ken. He is my eldest son, who has just returned from Mauchline,” she explained loquaciously in answer to Lord Glencairn’s questioning look.

Jean nervously clutched at the neck of her gown, her face alternately flushing and paling. “Your son is here now?” she asked eagerly, turning to Mrs. Burns.

“Aye, he’s out yonder in the fields,” she answered simply.

“Oh, then you know the young man?” interrogated Lady Glencairn, glancing sharply at Jean.

“Yes, I know him,” she answered with averted gaze. “We met occasionally in Mauchline at dancing school, where we fell acquainted.”

Lady Glencairn looked at her with half-closed eyes for a moment, then she smilingly said, “And I’ll wager your love for coquetting prompted you to make a conquest of the innocent rustic, eh, Jean?”

Jean tossed her head angrily and walked to the window.

“Lady Glencairn, you are pleased to jest,” she retorted haughtily.

“There, there, Jean, you’re over prudish. I vow ’twould be no crime,” her ladyship calmly returned. “I’ll wager this young farmer was a gay Lothario while in Mauchline,” she continued mockingly.

“Oh, no, your ladyship,” interrupted Mrs. Burns simply. “He was a flax dresser.”

“Truly a more respectable occupation, madame,” gravely responded Lord Glencairn with a suspicious twinkle in his eye.

“Thank ye, my lord,” answered Mrs. Burns with a deep courtesy. “My lad is a good lad, if I do say so, and he has returned to us as pure minded as when he went awa’ a year ago.”

Lady Glencairn raised her delicately arched eyebrows in amused surprise. Turning to Jean, she murmured drily, “And away from home a year, too! He must be a model of virtue, truly.”

Jean gazed at her with startled eyes. “Can she suspect aught?” she asked herself fearfully.

“Could I be getting ye a cup of milk?” asked Mrs. Burns hospitably. “’Tis a’ I have to offer, but ’tis cool and refreshing.”

“Fresh milk,” repeated Lady Glencairn, rising with delight. “I vow it would be most welcome, guidwife.”

“Indeed it would,” responded her husband. And Mrs. Burns with a gratified smile hurried from the room.

“My dear, don’t look so tragic,” drawled Lady Glencairn carelessly, as she noticed Jean’s pale face and frightened eyes. “We’ll soon be in Mauchline. Although why you are in such a monstrous hurry to reach that lonesome village after your delightful sojourn in the capital, is more than I can conjecture,” and her keen eyes noted with wonder the flush mount quickly to the girl’s cheek.

“It is two months since I left my home, your ladyship,” faltered Jean hesitatingly. “It’s only natural I should be anxious to see my dear parents again.” She dropped her eyes quickly before her ladyship’s penetrating gaze.

“Dear parents, indeed,” sniffed Lady Glencairn to herself suspiciously as she followed their hostess to the door of the “ben.”

With a nervous little laugh Jean rose quickly from her chair by the window and walked toward the door through which they had entered. “The accident has quite upset me, Lady Glencairn,” she said constrainedly. “Would you mind if I stroll about the fields until my nerves are settled?” she asked with a forced laugh.

“No, child, go by all means,” replied her ladyship indolently. “The air will do you good, no doubt.”

“I warn you not to wander too far from the house,” interposed Lord Glencairn with a kindly smile. “We will not be detained much longer.”[57] With a smile of thanks she hastily left the room just as Mrs. Burns entered from the “ben” bearing a large blue pitcher filled with foaming milk, which she placed on the table before her smiling visitors.

Jean breathed a sigh of relief as she closed the door behind her. She felt in another moment she would have screamed aloud in her nervousness. That fate should have brought her to the very home of the man she had thought still in Mauchline, and to see whom she had hurriedly left Edinburgh, filled her with wonder and dread. “I must see him before we leave,” she said nervously, clasping and unclasping her hands. But where should she find him? She walked quickly down the path and gazed across the fields, where in the distance she could see several men at work, repairing the disabled coach. Anxiously she strained her eyes to see if the one she sought was among them, but he was not there. Quickly she retraced her steps. “I must find him. I must speak with him this day,” she said determinedly. As she neared the cottage she turned aside and walked toward the high stone fence which enclosed the house and yard. Swiftly mounting the old stile, she looked about her. Suddenly she gave a sharp little exclamation, and her heart bounded violently, for there before her, coming across the field, was the man she sought, his hands clasped behind him, his head bent low in the deepest meditation. With a sigh of relief she sank down on the step and calmly awaited his approach.