This may prove to you that

Television can change your

life more than you think!

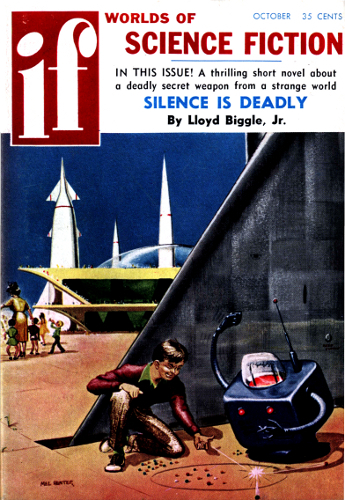

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, October 1957.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The world newspapers had heralded the event for months. "The First Personal Visit from Outer Space" was the most important headline of the decade. Now there were perhaps sixty thousand people crowding behind ropes and guards at the Earth Interspace Airport, waiting patiently for Mr. Kramvit of Planet Six.

Fourth Vice President Vincent J. Carrowick had been selected to be Mr. Kramvit's guide for the length of his visit. He was waiting now, with Secretary Gordon, in the airport's executive office.

Carrowick spoke first, "Well, this is it. I've spoken to Kramvit at least eight times on the Vidcope phone, but I'm as nervous as a contestant right now."

Gordon eyed the screen which was noting the ship's approach. "I don't see why you should be. You know what he's like basically. Their bodies and physical capabilities are the same as ours, and most of the people of Six speak English almost as well as we do, by now."

He looked at Carrowick, "Are their Vidcopes going to stay on Kramvit during his entire visit?"

Carrowick spoke slowly, "Yes. At least they're going to try; on all six of the Planets. Kramvit's going to carry a pin microphone on his person all the time. So they should see and hear us no matter where we are."

"How long do you intend to be out of the country with him?" asked Gordon.

"Well, most of his time will be spent here, visiting all fifty-three states. We'll take one cruise to pay token visits to the heads of all countries first, then back here until he goes home. Hey! He's landing, let's go!"

... After over an hour of welcoming speeches, photographs and newspaper reporters, Marryl Kramvit was alone in the executive office with Vice President Carrowick and Secretary Gordon.

"If we didn't know you were from Six, we would certainly take you for an Earthman," Carrowick was saying, "Why, your clothes, your coloring, everything about you is just the same!"

Kramvit smiled and said, "Well, thank you. Physically, of course, we are the same. The clothes—well, ours are quite a bit different, as you know. I had these made by a superb tailor who copied them from our Vidcope screens.

"Many of our females," Kramvit continued, "have already started to wear some of your ladies' styles, and quite becoming they are."

Carrowick put on his cloak, and said, "Well, let's be on our way. You're to meet our President for lunch, and then we start our tour, if that's all right with you."

"Why, of course, that's why I'm here, and I'm anxious to see your world. Particularly America."

The trip around the world had gone as smoothly as could be expected. Were it not for the multitudes that gathered at each airport in order to catch a glimpse of Kramvit, it would have been just perfect. Kramvit, however, was as cordial to the throngs as he was to the heads of their respective countries. He was a fine good will ambassador. A little flicker of disappointment was usually evident when the people saw for themselves that this man from another world looked and acted just as they did.

All in all, Carrowick was quite pleased, and he and Kramvit were now in the Vincent and Marryl stage, except in public.

"Well, you've been in most of the countries of the Earth," said Carrowick, as they relaxed in the private plane, "and visited forty of our States of America. What do you think, Marryl?"

"I'm pleased, of course," answered Kramvit. "You're aware, I'm sure, Vincent, that Six and the other five planets of the Orb are a bit farther advanced than Earth. But, I don't think it will be very long before you're up to us.

"I've been able to understand almost everything I've seen," he continued, "and I've made notes of what I couldn't understand; one thing, Vincent, you haven't explained to me at all."

"What's that?"

"Well, so far as I can see, there are only two economic classes here on Earth. I've seen what appear to me to be only very wealthy people and very, very poor people. I've also noticed," here Kramvit smiled, "that you have sort of avoided these poor people, and what I assume to be their dwellings. I've seen glimpses of the squalor and terribly poor sections in each of your states so far."

Carrowick seemed a bit shocked, but Kramvit continued. "Also, you have addressed almost all of the working people with whom we've been in contact as Poor Mr. Jones and Poor Miss Smith, and so on. While those of the wealthy class, you simply addressed as Mr. or Mrs. Why?"

Carrowick was shocked. "Didn't you know? No, I see you really didn't. I'm terribly sorry, Marryl, we here on Earth take it so much for granted, and I assumed it was the same all over the Orb."

"No, I don't know what you mean," said Kramvit, "on Six and the others, we have our quota of poor people. We also have a middle class, (in which I think I would belong) and some very wealthy people. But the definite dividing line here, I don't understand.

"I know some of your ancient history, but I've noticed complete integration wherever I've been. I've seen absolutely no discrimination as far as color, faith or religion is concerned. I saw no caste system at all, even in India, and inter-marriage, it seems, has become completely acceptable."

"That is so," interrupted Carrowick. "We've had no such prejudice at all as long as I've been alive. It has avoided a lot of trouble. Nobody has been able to think up a reason for a war, since."

"Then why," asked Kramvit, "have I seen these Poors, as you call them, sitting only in the rear of busses? Why have I not seen one of these unfortunate looking people in any of the restaurants in which we've eaten, or for that matter, in most any public place?"

"The reason for them not being in any of the restaurants is simple. They can't afford the prices. Haven't you noticed all the Vidcope, or V.C. centers here?"

"Yes, I have."

"You've seen some of the V.C. shows, haven't you?"

"I didn't pay much attention to them," answered Kramvit. "I'm not much for V.C. Incidentally, we call it T.V., for television, at home. Many of our people have become quite addicted to it in the last few years. I can take it or leave it alone. Usually the latter, I'm afraid."

Carrowick asked, "Aren't all your shows Qua shows?"

"I'm sorry, what is a Qua show?"

"You're jesting, of course," laughed Carrowick. "They were once called Quiz shows. Now, they're Quas, for question and answer, I guess."

"Oh, yes," said Kramvit, "we do have many of those."

"Why, that's all we have here, on commercial V.C." exclaimed Carrowick. "And, there's the obvious answer to your original question!"

"The answer? I'm sorry, I don't see what you mean."

"It's simple," said Carrowick. "The Poors are people who have never been a contestant on a Qua show! The wealthy are those who either have been winners, or whose ancestors were."

It was Kramvit's turn to be shocked. "I don't believe it."

"Oh, yes, it's true," said Carrowick. "Of course, some of the Poors have been contestants, but didn't win."

Kramvit was staring at Carrowick. "You are quite serious, aren't you?"

"Of course," answered Carrowick, "the situation has been so, for perhaps two hundred years—we've come to take it for what it is."

"I'll wager that the Poors don't take it quite as calmly as you do. Don't tell me that they're satisfied with their position."

"I wouldn't say they were satisfied," was the answer, "but they know no other way of life, and don't have much choice in the matter."

Kramvit was finding it difficult to picture the situation. "Well, as I've told you," he said, "we have T.V. on Six, but we've been stressing variety and drama shows. Don't you have any big V.C. stars, like comedians or singers here?"

"No, we don't. I've never seen any variety or drama shows on V.C."

"I'm surprised. You see, we have been using all the air time, or most of it, for entertainment purposes. Commercially, T.V. is just a baby with us. We've been using it much longer than you have, technically, but not commercially. I'd say that we've had sponsored shows for about fourteen years."

"Oh, then it is a comparatively new thing with you," said Carrowick. "We've had commercial Vidcope for over five hundred years."

Kramvit shook his head. "I still can't see why your Poors have to live in such poverty. Don't they get paid on their jobs?"

"Why, sure they do," answered Carrowick, "but their rate of pay is not particularly high. You see, only the Poors do all the menial and service work; aside from high service positions like government work, of course. There are so many Poors and so few jobs for them, that those that work are little better off than those that don't."

"I see," said Kramvit, "and is there no protection for these unemployed? I mean Social Security or unemployment insurance, which I know you did have a long time ago."

"No, there isn't. We had to stop that because if we kept it up we'd have no workers at all," replied Carrowick. "Believe me, Marryl, I don't particularly like the situation. We've tried integration in one or two sections, but only riots resulted. I think that eventually we'll eliminate some of the prejudices, but it can't be pushed or hurried. It'll take many years to do it. I'm sure I won't live to see it gone completely."

"And," asked Kramvit, "have you been a winner on a Qua show?"

"Oh, no. I'm not one of those nouveau riche; my great grandfather won eight million dollars, tax free, when he was just a boy. That took care of us, and will take care of us from here on in."

"I see," said Kramvit. "Vincent, I want to visit some of these people in their homes. Will you take me?"

Carrowick was shocked again. "I don't think you'll enjoy it, Marryl. Do you really feel it's necessary?"

"Please don't refuse me, Vincent. I do feel it's important. I've understood almost everything I've seen here on Earth. Either because we've been faced with it ourselves on Six, or I've read about it. But this is entirely new to me."

"All right," agreed Carrowick reluctantly. "I'm supposed to show you anything you want to see, but you won't like it."

"Let me be the judge of that."

They had ridden to the end of the upper level moving street in comfortable armchairs. All of Carrowick's arguments couldn't swerve Kramvit from his idea of visiting some Poors. Kramvit was just about through with his explanation of how all the automobiles on Six drove underground, and didn't have to use the lower street level, as they did here; when they came to the end of the moving street.

Now they were both walking through the filthy, garbage laden streets of the Poors' village. The smell wrinkled Carrowick's nose, and he was not displeased to see that Kramvit wasn't quite enjoying it, either.

"Doesn't the sanitation department know about this?" asked Kramvit. "Don't they ever remove this dirt?"

"No," answered Carrowick, "the Poors have to carry it to appointed garbage dumps themselves. They let it pile up until even they can't stand it, then they usually get rid of some of it."

He went on to explain that in all the cities, except in Poor villages, all garbage recepticles led to giant underground incinerators. Here the fires burned continually. But in the hot weather, the heat from these fires was used as power to run an underground air conditioner, so that all the streets were cooled. In the wintertime, of course, these same fires warmed the cities and highways.

As they walked, they were both aware of the many Poors scrounging and searching in the debris. They were also aware of the silence that fell as they neared groups of people. The Poors just stared at them, and talked excitedly when they were out of earshot.

"They're not used to seeing any of us in their villages," remarked Carrowick.

Kramvit smiled, somewhat bitterly, it seemed to Carrowick, "No, I shouldn't think they would be."

As they rounded a corner, Kramvit pointed to a car parked about a hundred feet away. It was almost leaning against a broken down shack, and was so dirty that it was impossible to make out its color.

"How did that get here, Vincent? Surely, nobody here can afford a car."

Carrowick laughed, "No, they can't. That happens to be this year's Sputzmobile, one of our most expensive cars. Although you wouldn't know it from the looks of that one. They are given as consolation prizes to losers on almost all the larger Qua shows."

"I see. Why don't those people sell the cars? It seems to me they could use the money."

"I guess they could," answered Carrowick. "But to whom could they sell it? Very few of us ever buy a second hand car. We all change our cars as soon as the new ones appear. Anyway, most of the losers want to keep them; they consider it a mark of distinction."

He frowned, and continued, "They drive them around the villages whenever they can beg, borrow or steal some regular grade atomic pellets. And, whenever they can maneuver through these streets. Those that own them sort of look down their noses at the other Poors. They consider themselves aristocrats of their village, because they, at least, have been called to appear on a Qua. Actually, they're to be pitied, they're worse off than the others."

"Why is that?" asked Kramvit.

"Well, once they've appeared on a Qua show, and lost, they'll usually never be asked again. That's the worst of it, since they have nothing more to look forward to. Also, I believe that most of the Poors leave whatever jobs they may have, as soon as they get the call. They feel it's beneath their dignity somehow. No Poor that gets on a Qua ever expects to lose. Of course, once they do lose, they can't get their jobs back. Because when they leave it's like creating a vacuum—all the Poors in the vicinity flock to apply for his position."

They were just adjacent to one of the Poors' houses at the moment, and Kramvit asked if he could visit the people that lived there. Carrowick said he could, but he doubted if they'd find anyone home. It was after four o'clock, and the large network Quas had already begun. All the Poors that could navigate would be at the large open air V.C. centers, which were usually located near the garbage dumps.

These centers were sometimes miles away from many of the Poors, but that's where they were, no matter what the weather, from four in the afternoon to eleven at night, when the Quas finished and the news flashes began.

These centers consisted of a large empty lot, many of which got the overflow from the adjacent garbage dumps, with two scopes seemingly suspended about six feet off the ground in the middle. They were rectangular; about five feet long, and four feet wide. Only a little over an inch thick, the pictures appeared on both sides of each scope. They were at right angles to each other, so that the picture could be seen from any part of the lot.

Carrowick knocked on the old wooden door. There was no answer, and they were about to turn away, when the door opened creakily to display an elderly man. He was clean, except for the dirty rags that were tied around his throat.

Carrowick explained who they were, and the elderly gentleman invited them in.

"Come in, come in. I'm honored by your visit," he said in a hoarse voice. "Well, now I'm almost glad that I have this bad throat, otherwise I would be at the center, and I'd have missed your visit. By the way, my name is Poor Mr. Alex Smith."

The shack consisted of two rooms, one of which was obviously a bedroom. Obviously, because there were a number of flattish mounds of rags, straw and excelsior on the floor, which could serve no other purpose than for sleeping. It was completely devoid of any furniture. The room they were in was the combination living-room, dining room and kitchen. A few old chairs, some crates and a wobbly card table on a bare floor just about filled the room.

Carrowick and Kramvit introduced themselves, and Kramvit started to ask Poor Mr. Smith questions. These were all answered eagerly, and Kramvit was almost convinced that the Poors didn't mind their situation too much; they were all quite used to it.

Poor Mr. Smith asked some questions of Kramvit too, and was answered good naturedly. He showed particular interest in the pin microphone Kramvit wore, and seemed awed when he was told that he was probably being seen and heard by people on Six at this very moment.

While Carrowick showed signs of impatience over the length of the visit, Kramvit asked Smith, "Tell me, my friend, wouldn't you like to see some entertainment on V.C.? Comedians or singers, or dancers, perhaps?"

Poor Mr. Smith laughed, "Why no. Comedians and singers? Who wants to see them when we can watch some lucky souls winning anywhere from one to sixty-four million dollars, or more. I remember about forty years ago, Mr. Krackel, our largest food pill manufacturer at that time, tried something like that."

"Oh, did he?"

"Yes. He had the biggest two hour Qua show on the scopes. His daughter liked to sing, and she talked him into devoting the first fifteen minutes to singing. Well," Smith laughed, "that was the last time he tried that. I read that the ratings for the show that evening went down to zero. The studio was swamped with angry letters. Everyone wanted to know why fifteen minutes of a good Qua show was wasted with such nonsense."

Kramvit smiled and said, "Yes, I can understand that. Tell me, Poor Mr. Smith, what would you do if you won on a Qua?"

"I'd try to help my people, of course. Perhaps like Legislator Brown. He's an ex-Poor, you know, but he worked himself up the hard way. Won a Qua, then studied and studied, and finally made the Legislature. He's the one that passed the law to give us our V.C. centers. He's a great man."

"That's a worthy ambition," said Kramvit.

"Do you people on Six have Qua shows, too?" asked Poor Mr. Smith.

"Yes. But not as many as you do."

"And do you have Poors like me on your planet?"

Kramvit said that they didn't, and went on to explain a little of the situation of Six and the other five planets.

Poor Mr. Smith was amazed. He couldn't believe that there was any place that didn't have Poors.

"Well, don't let it happen, then," he said. "Don't do it. Don't let those Qua shows take over." His voice seemed to be getting stronger, or was it just louder, now.

He leaned closer to Kramvit, his head only a foot away from the pin microphone, and almost shouted, "Do you hear me? Don't let it happen to you." He was near to sobbing now. "Be smart, stay happy—stop those Quas. They'll only...."

Carrowick practically pulled Kramvit out the door, and started to hurry away.

"Well," said Kramvit, "you told me that they didn't mind their situation too much; Poor Mr. Smith almost had me believing the same thing, but he sure didn't convince me."

"He's just a sick, old man," was Carrowick's answer.

Kramvit had insisted on visiting another Poor village the next day. Earlier, this time, so that they'd find most of the people home. After five or six visits, Kramvit was persuaded to leave by Carrowick, who reminded him that he was to appear on Earth's largest Qua show himself that very evening. Kramvit didn't want to appear, but Carrowick convinced him that all preparations had been made. This was Earth's way of honoring him, and he simply mustn't and couldn't refuse. Also, his own people would be watching for him on the show. Kramvit had to agree to do it.

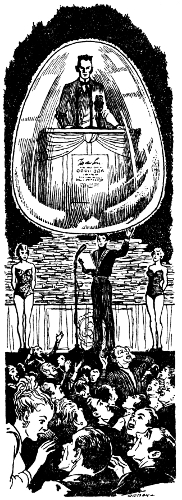

When they had arrived at the studio, Kramvit was amazed at the hustle and bustle that went on around them. The usual investigations, interviews and testing that contestants went through were eliminated for Kramvit, since he was an honored guest.

Air time approached rapidly, and Kramvit couldn't help feeling a bit apprehensive. He wasn't used to appearing before multitudes of this size, and it all made him feel uncomfortable. Carrowick assured him that there was nothing to fear; this was simply a good will appearance. The questions he would have to answer would all be in the science category, and he should have no trouble with them.

Finally, Kramvit found himself standing in the wings of the vast stage. The previous contestant was just answering his last ten part question. He answered all the parts correctly, and left the stage to loud applause. Now the Master of Ceremonies asked who was to be the next guest. A booming voice whose body was nowhere to be seen, went through a flowery introduction of Marryl Kramvit. Two beautiful young ladies, dressed in almost nothing, appeared on each side of him. As the voice finished the introduction, the girls all but dragged him into camera range.

Kramvit jumped with fright as eight young men, each over six feet tall, heralded his entrance with long, loud trumpets. He shook hands with the Master of Ceremonies, chatted for a while, and finally was told to get ready for his questions.

The first group of queries pertained to his particular field, and he answered them correctly and easily. It took about ten minutes to arrive at the $10,000 question. Kramvit knew that if and when he reached a million dollars, he would be asked to come back in a week, which of course he couldn't do, to tell if he would go for two million or keep the one he had. He made a mental note to ask Carrowick as to the fate of those who stopped at one or two million. He wondered if they were looked down upon too.

Right now, the M.C. was telling him that he would have to enter the sound proof booth for the $10,000 question. The booth appeared from nowhere, and he was escorted into it by the two lovely, almost nude, young ladies, who didn't seem to hear the trumpet blasts from the eight young men.

When the door of the booth clicked shut, the booth moved out and over the studio audience, and finally came to a stop in mid-air. There were no wires or cables to be seen attached to the booth, but this didn't bother Kramvit, since he knew the principles involved. He did feel quite ridiculous, hanging suspended, with hundreds of faces upturned to watch him.

It seemed to him that they must be awfully uncomfortable with their necks craned like that. But he knew that the producers of the show were only interested in the effect on the home viewers.

Kramvit lost count of the questions he answered, but he was now being told that he was going for $500,000. A half million dollars! That was the largest amount of money given away on the biggest quiz show on Six; here it was just the beginning.

The question consisted of sixteen parts, and he answered them without interruption until the fourteenth part. After he gave his answer to this one, the M.C. asked him to repeat it. He did, hesitantly, and saw the M.C. look nervously towards the control booth.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Kramvit, that's not the correct answer."

Kramvit felt himself being lowered towards the stage. He was helped out of the booth by the young ladies, and escorted to the M.C. No trumpets, now. The audience was silent as the M.C. thanked Kramvit, and told him how honored he was to be the first to welcome the first visitor from another planet on V.C. He also told him how sorry he was that Kramvit had lost.

Kramvit walked off stage while the audience applauded.

... "The funny thing is, I really knew the answer," Kramvit was saying to Carrowick, with a sheepish grin. "I was just so nervous. I'm not accustomed to this at all."

"Well," said Carrowick, "it's nothing to worry about. As I said, it was just a good will appearance."

They were leaving the studio, when a young man in uniform approached Kramvit.

"Excuse me, sir, a Phonogram for you."

Kramvit looked at the envelope and saw that it was from the High Council of Six. He turned the envelope over and read the name.

It was addressed to, "Poor Mr. Marryl Kramvit"!