Project Gutenberg's Galileo Galilei and the Roman Curia, by Karl von Gebler This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Galileo Galilei and the Roman Curia Author: Karl von Gebler Translator: Jane (Mrs. George) Sturge Release Date: September 1, 2019 [EBook #60215] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GALILEO GALILEI *** Produced by ellinora and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

2 vols. Demy 8vo. Cloth, 32s.

THE RENAISSANCE OF ART IN FRANCE. By Mrs. Mark Pattison. With Nineteen Steel Engravings.

2 vols. Demy 8vo. Cloth, 24s.

THE CIVILIZATION OF THE PERIOD OF THE RENAISSANCE IN ITALY. By Jacob Burckhardt. Authorized Translation by S. G. C. Middlemore.

“The whole of the first part of Dr Burckhardt’s work deals with what may be called the Political Preparation for the Renaissance. It is impossible here to do more than express a high opinion of the compact way in which the facts are put before the reader.... The second volume of Dr. Burckhardt’s work is, we think, more full and complete in itself, more rich in original thought, than the first. His account of the causes which prevented the rise of a great Italian drama is very clear and satisfying.”—Saturday Review.

LONDON: C. KEGAN PAUL & CO., 1, PATERNOSTER SQUARE.

GALILEO GALILEI

AND THE ROMAN CURIA.

FROM AUTHENTIC SOURCES.

BY

KARL VON GEBLER.

TRANSLATED, WITH THE SANCTION OF THE AUTHOR, BY

MRS. GEORGE STURGE.

LONDON:

C. KEGAN PAUL & CO., 1, PATERNOSTER SQUARE.

1879.

Madam,—

It is the desire of every author, every prosecutor of research, that the products of his labours, the results of his studies, should be widely circulated. This desire arises, especially in the case of one who has devoted himself to research, not only from a certain egotism which clings to us all, but from the wish that the laborious researches of years, often believed to refute old and generally-received errors, should become the common property of as many as possible.

The author of the present work is no exception to these general rules; and it therefore gives him great pleasure, and fills him with gratitude, that you, Madam, should have taken the trouble to translate the small results of his studies into the language of Newton, and thus have rendered them more accessible to the English nation.

But little more than two years have elapsed since the book first appeared in Germany, but this period has been a most important one for researches into the literature relating to Galileo.

In the year 1869 Professor Domenico Berti obtained permission to inspect and turn to account the Acts of Galileo’s Trial carefully preserved in the Vatican, and in 1876 he published a portion of these important documents, which[vi] essentially tended to complete the very partial publication of them by Henri de L’Epinois, in 1867. In 1877 M. de L’Epinois and the present writer were permitted to resuscitate the famous volume, which again lay buried among the secret papal archives; that is, to inspect it at leisure and to publish the contents in full. It was, however, not only of the greatest importance to become acquainted with the Vatican MS. as a whole, and by an exact publication of it to make it the common property of historical research; it was at least of equal moment to make a most careful examination of the material form and external appearance of the Acts. For the threefold system of paging had led some historians to make the boldest conjectures, and respecting one document in particular,—the famous note of 26th February, 1616,—there was an apparently well-founded suspicion that there had been a later falsification of the papers.

While, on the one hand, the knowledge gained of the entire contents of the Vatican MS., for the purpose of my own publication of it,[1] only confirmed, in many respects, my previous opinions on the memorable trial; on the other hand, a minute and repeated examination of the material evidence afforded by the suspicious document, which, up to that time, had been considered by myself and many other authors to be a forgery of a later date, convinced me, contrary to all expectation, that it indisputably originated in 1616.

This newly acquired experience, and the appearance of many valuable critical writings on the trial of Galileo since the year 1876, rendered therefore a partial revision and correction of the German edition of this work, for the English and an Italian translation, absolutely necessary. All the[vii] needful emendations have accordingly been made, with constant reference to the literature relating to the subject published between the spring of 1876 and the spring of 1878. I have also consulted several older works which had escaped my attention when the book was first written.

May the work then, in its to some extent new form, make its way in the British Isles, and meet with as friendly a reception there as the German edition has met with in Austria and Germany.

To you, Madam, I offer my warm thanks for the care with which you have executed the difficult and laborious task of translation.

Accept, Madam, the assurance of my sincere esteem.

KARL VON GEBLER.[2]

Meran, 1st April, 1878.

The Vatican Manuscript alluded to in the foregoing letter, and constantly referred to in the text, was published by the author in the autumn of 1877, under the title of “Die Acten des Gallileischen Processes, nach der Vaticanischen Handschrift, von Karl von Gebler.” Cotta, Stuttgard. This, with some introductory chapters, was intended to supersede the Appendix to the original work, and to form a second volume, when a new German edition should be called for. It did not, however, appear to me that any purpose would be served by reprinting all the Latin and Italian documents of the Vatican MS. in this country, as students who wish to consult them can easily procure them as published in the original languages in Germany, and I hope for a wider circle of readers than that composed exclusively of students. I therefore proposed to Herr von Gebler to give the History, Description, and Estimate of the Vat. MS., etc., in an Appendix, together with a few of the more important documents; to this, with some suggestions, as for instance, that some of the shorter documents should be given as notes to the text, he fully agreed, with the remark that I must know best what would suit my countrymen. The Appendix, therefore, differs somewhat both from the original Appendix and from the introductory[x] portions of the new volume, for these also were revised for the Translation.

The translations from Latin and Italian documents have been made from the originals by a competent scholar, and all the more important letters and extracts from letters of Galileo have been compared with the Italian. The Table of Contents, headings to and titles of the chapters, and Index, none of which exist in the original, have been added by myself.

JANE STURGE.

Sydenham, November, 1878.

Abridged from the “Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung” of 6th December, 1878.

The author of this work died at Gratz on the 7th of September, 1878. In devoting a few lines to his memory we have not a long and distinguished career to describe, for a brief span of life was all that was granted him, but to the last moment he sought to turn it to the best account.

The present work has enjoyed a wide circulation in Germany, but few of its readers could have known anything of the author but his name. The protracted studies which form the basis of it, the skilful handling of documentary material which seemed to betray the practised historian, must have suggested a man of ripe years, whose life had been passed in study, as the author; no one certainly would have sought him among the young officers of a cavalry regiment, whose tastes generally lie in any direction rather than that of historical research.

Karl von Gebler was the son of Field-marshal Wilhelm von Gebler, and was born at Vienna in 1850. Although early destined for the military career, he laid the foundations of a superior education in the grammar schools. Having passed through the gymnasium, in 1869 he joined the 7th regiment of the line as a private, and before long attained the rank of lieutenant in the 4th regiment of Dragoons. Being[xii] an excellent draftsman and skilled in military surveying, he was often employed on the general’s staff in drawing maps. In addition to his extensive knowledge of military affairs, he had many of the accomplishments befitting his calling; he was an excellent shot and a bold rider. But the duties of a cavalry officer were soon too limited for his active mind and intellectual tastes, and he sought also to win his spurs on the fields of literature. He occupied his leisure in translating the work of a French staff officer, “Success in War,” to which he made some additions. He also published “The True Portrait of a Royal Hero of the 18th Century,” in a newspaper; and finally, “Historic Sayings.”

A night ride, undertaken in the performance of his official duties, from which he returned at daybreak to exercise at the riding school, brought on severe hemorrhage and inflammation of the lungs. The two physicians who attended him gave him up; in a consultation at his bedside, prudently held in Latin, they gave him twenty-four hours to live. One of them having taken leave, the other returned to the patient, who, with quiet humour, greeted him with the classic words, “Morituri te salutant!” The worthy doctor found, to his horror, that the patient had understood all that had passed, and had no easy task to persuade him that his case was not so bad after all. He had, however, in consequence of some local circumstances, already ordered the coffin.

Gebler’s constitution surmounted the danger; by the spring he was able to join his parents at Gratz. But his health had sustained so severe a shock that he was compelled to abandon the military career. His parents removed to Gries, near Botzen, for the sake of a milder climate on his account. Here he revived wonderfully; he seemed to have taken a new lease of life, and devoted himself altogether to literary pursuits. The critical studies before mentioned of the assumed historic sayings of great men, and among them of Galileo’s famous dictum, “E pur si muove,” brought him into closer acquaintance with this hero of science. He accumulated so large a[xiii] material for a biographical sketch of the great Italian, that the limits of an essay seemed too narrow, and he resolved to undertake a more comprehensive work on the subject, which he thought would fill up a gap in German literature. In the autumn of 1875 the work, which had occupied him four years, was completed. It was not a little gratifying to the young author that one of the first publishers in Germany, Cotta, of Stuttgard, undertook the publication on very favourable terms, and brought it out in 1876. It met with great approval, and brought him into association with many eminent literary men in Italy and Germany. Galileo’s own country was foremost in recognition of his services. The academies of Padua and Pisa, and the Accadémia dei Lincei sent him special acknowledgments, and King Victor Emmanuel rewarded him with the order of the Crown of Italy.

Before this work was finished he had removed with his father, having in the meanwhile lost his mother, to Meran, and during the first year of his residence there his health improved so much that he was able to take part in social life, and to enlarge the sphere of his labours and influence. Society in this little town owed much in many ways to the intellectual and amiable young officer. Whenever a good and noble cause required support, his co-operation might be reckoned on. In common with many other lovers of art and antiquity, he took a lively interest in the preservation and restoration of the Maultasch-Burg, which promises to be one of the chief sights of Meran. Unhappily he did not live to see the completion of the work.

With increase of health his zest for work increased also, and he addressed himself to a great historical task. The subject he selected was the Maid of Orleans. The preliminary studies were difficult in a place destitute of all aids to learning. His researches were not confined to the collection of all the printed material; in 1876 he had planned to search out the documentary sources wherever they were to be found, but before this he made close studies in the field of psychology and mental[xiv] pathology. The work of Ruf on the subject, the learned chaplain of a lunatic asylum, attracted his attention, and he entered into communication with the author. Ruf’s great experience and philosophical acquirements were of great service to Gebler in his preliminary studies on Joan of Arc. But the project was not to be carried out. Just as he was about to write the second chapter, an essay of Berti’s at Rome occasioned him to enter on fresh studies on Galileo.

Domenico Berti, who had examined the original Acts of Galileo’s trial, though, as his work shows, very superficially, spoke contemptuously of the German savans, comparing them with blind men judging of colours, as none of them had seen the original Acts in the Vatican. This had special reference to the document of 26th February, 1616, which the German writers on the subject, and Gebler among them, declared to be a forgery. Being a man of the strictest love of truth, this reproach induced him, in spite of his health, which had again failed, in May, 1877, to go to Rome, where he obtained access to the Vatican. For ten weeks, in spite of the oppressive heat, he daily spent fourteen hours in the Papal Archives, studying and copying with diplomatic precision the original Acts of Galileo’s trial. As the result of his labours, he felt constrained to declare the document in question to be genuine. Actuated only by the desire that truth should prevail, in the second part of his work, written at Rome, he without hesitation withdrew the opinion he had previously advocated as an error.

His first work had made a flattering commotion in the literary world, but the additional publication called forth a still more animated discussion of the whole question, which the readers of this journal will not have forgotten. Gebler took part in it himself, and, then suffering from illness, wrote his reply from a sick bed.

His sojourn in Rome had sadly pulled him down. On his return home, in July, 1877, he had lost his voice and was greatly reduced. But in October of the same year he once more roused himself for a journey to Italy. The object of the[xv] previous one was to follow his hero in yellow and faded historic papers, but this time the task he had set himself was to pursue the tracks of Galileo in all the cities and places in any way connected with his memory. The result of these travels was an article in the Deutsche Rundschau, No. 7, 1878, “On the Tracks of Galileo.” In this paper Gebler again dispels some clouds in which Galileo’s previous biographers had enveloped him. We in these less romantic days are quite willing to dispense with the shudder at the stories of the dungeon, etc., and are glad to know that Galileo was permitted to enjoy a degree of comfort during his detention not often granted to those who come into collision with the world.

“On the Tracks of Galileo” was Gebler’s last literary work. His strength of will and mental powers at length succumbed to his incurable malady. The mineral waters of Gleichenberg, which he had been recommended to try, did him more harm than good. He wrote thence to a friend, “I am in a pitiable condition, and have given up all hope of improvement.” Unfortunately he was right. He had overtasked his strength. His zeal for science had hastened his end, and he may well be called one of her victims.

His last days were spent at Gratz, where his boyhood had been passed, and he rests beside his only brother. Both were the pride and joy of their father, now left alone.

In appearance Karl von Gebler was distinguished and attractive looking. No one could escape the charm of the freshness and originality of his mind, in spite of constant ill health. The refined young student, with the manners of a man of the world, was a phenomenon to his fellow-workers in the learned world. We have heard some of them say that they could not understand how Gebler could have acquired the historian’s craft, the technical art of prosecuting research, without having had any special critical schooling.

The writer of these lines will never forget the hours spent with this amiable and, in spite of his success, truly modest young man in his snug study. The walls lined with books,[xvi] or adorned with weapons, betrayed at a glance the character and tastes of the occupant, while a pendulum clock dating from the time of Galileo recalled his work on the first observer of the vibrations of the pendulum to mind. He always liked to wind up the venerable timepiece himself, and took a pleasure in its sonorous tones. When I once more entered the study after his death, the clock had run down, the pendulum had ceased to vibrate, it told the hour no more.

While Italy and France possess an ample literature relating to Galileo, his oft-discussed fate and memorable achievements, very little has been written in Germany on this hero of science; and it would almost seem as if Copernicus and Kepler had cast the founder of mechanical physics into the shade. German literature does not possess one exhaustive work on Galileo. This is a great want, and to supply it would be a magnificent and thankworthy enterprise. It could only, however, be carried out by a comprehensive biography of the famous astronomer, which, together with a complete narrative of his life, should comprise a detailed description and estimate of his writings, inventions, and discoveries. We do not feel ourselves either called upon or competent to undertake so difficult a task. Our desire has been merely to fill up a portion of the gap in German literature by this contribution to the Life of Galileo, with a hope that it may be an incentive to some man of learning, whose studies qualify him for the task, to give our nation a complete description of the life and works of this great pioneer of the ideas of Copernicus.

We have also set ourselves another task; namely, to throw as much light as possible, by means of authentic documents, on the attitude Galileo assumed towards the Roman curia, and the history of the persecutions which resulted from it. To this end, however, it appeared absolutely necessary to give, at any rate in broad outline, a sketch of his aims and achievements as a whole. For his conflict with the ecclesiastical power was but the inevitable consequence of his subversive telescopic discoveries and scientific reforms. It was necessary to make the intimate connection between these causes and their historical results perfectly intelligible.

In the narration of historical events we have relied, as far as possible, upon authentic sources only. Among these are the following:—

1. Galileo’s correspondence, and the correspondence relating to him between third persons. (Albèri’s “Opere di Galileo Galilei.” Vols. ii., iii., vi., vii., viii., ix., x., xv., and Suppl., in all 1,564 letters.)

2. The constant reports of Niccolini, the Tuscan ambassador at Rome, to his Government at Florence, during and after Galileo’s trial. (Thirty-one despatches, from August 15th, 1632, to December 3rd, 1633.)

3. The Acts of the Trial, from the MS. originals in the Vatican.

4. The collection of documents published, in 1870, by Professor Silvestro Gherardi. Thirty-two extracts from the original protocols of the sittings and decrees of the Congregation of the Holy Office.[3]

5. Some important documents published by the Jesuit Father Riccioli, in his “Almagestum novum, Bononiæ, 1651.”[4]

We have also been careful to acquaint ourselves with the[xix] numerous French and Italian Lives of Galileo, from the oldest, that of his contemporary, Gherardini, to the most recent and complete, that of Henri Martin, 1869; when admissible, we have cautiously used them, constantly comparing them with authentic sources. As the part of the story of Galileo of which we have treated is that which has been most frequently discussed in literature, and from the most widely differing points of view, it could not fail to be of great interest to us to collect and examine, as far as it lay in our power, the views, opinions, and criticisms to be found in various treatises on the subject. We offer our warm thanks to all the possessors of private, and custodians of public libraries, who have most liberally and obligingly aided us in our project.

One more remark remains to be made. Party interests and passions have, to a great extent, and with but few exceptions, guided the pens of those who have written on this chapter of Galileo’s life. The one side has lauded him as an admirable martyr of science, and ascribed more cruelty to the Inquisition than it really inflicted on him; the other has thought proper to enter the lists as defender of the Inquisition, and to wash it white at Galileo’s expense. Historical truth contradicts both.

Whatever may be the judgment passed on the present work, to one acknowledgment we think we may, with a good conscience, lay claim: that, standing in the service of truth alone, we have anxiously endeavoured to pursue none other than her sublime interests.

KARL VON GEBLER.

Meran, November, 1875.

| PAGE | ||

| PART I. GALILEO’S EARLY YEARS, HIS IMPORTANT DISCOVERIES, AND FIRST CONFLICT WITH THE ROMAN CURIA. |

||

| CHAPTER I. Early Years and First Discoveries. |

||

| Birth at Pisa.—Parentage.—His Father’s Writings on Music.—Galileo destined to be a Cloth Merchant.—Goes to the Convent of Vallombrosa.—Begins to study Medicine.—Goes to the University of Pisa.—Discovery of the Synchronism of the Pendulum.—Stolen Lessons in Mathematics.—His Hydrostatic Scales.—Professorship at Pisa.—Poor Pay.—The Laws of Motion.—John de’ Medici.—Leaves Pisa.—Professorship at Padua.—Writes various Treatises.—The Thermoscope.—Letter to Kepler.—The Copernican System.—“De Revolutionibus orbium Cœlestium” | 3 | |

| CHAPTER II. The Telescope and its Revelations. |

||

| Term of Professorship at Padua renewed.—Astronomy.—A New Star.—The Telescope.—Galileo not the Inventor.—Visit to Venice to exhibit it.—Telescopic Discoveries.—Jupiter’s Moons.—Request of Henry IV.—“Sidereus Nuncius.”—The Storm it raised.—Magini’s attack on Galileo.—The Ring of Saturn.—An Anagram.—Opposition of the Aristotelian School.—Letter to Kepler | 16 | |

| [xxii]CHAPTER III. Removal To Florence. |

||

| Galileo’s Fame and Pupils.—Wishes to be freed from Academic Duties.—Projected Works.—Call to Court of Tuscany.—This change the source of his Misfortunes.—Letter from Sagredo.—Phases of Venus and Mercury.—The Solar Spots.—Visit to Rome.—Triumphant Reception.—Letter from Cardinal del Monte to Cosmo II.—The Inquisition.—Introduction of Theology into the Scientific Controversy.—“Dianoja Astronomica.”—Intrigues at Florence | 27 | |

| CHAPTER IV. Astronomy and Theology. |

||

| Treatise on Floating Bodies.—Controversy with Scheiner about the Solar Spots.—Favourable reception of Galileo’s Work on the subject at Rome.—Discussion with the Grand Duchess Christine.—The Bible brought into the controversy.—Ill-fated Letter to Castelli.—Caccini’s Sermon against Galileo.—Lorini denounces the Letter to the Holy Office.—Archbishop Bonciani’s attempts to get the original Letter.—“Opinion” of the Inquisition on it.—Caccini summoned to give evidence.—Absurd accusations.—Testimony of Ximenes and Attavanti in Galileo’s favour | 42 | |

| CHAPTER V. Hopes and Fears. |

||

| Galileo’s Fears.—Allayed by letters from Rome.—Foscarini’s Work.—Blindness of Galileo’s Friends.—His Apology to the Grand Duchess Christine.—Effect produced by it.—Visit to Rome.—Erroneous opinion that he was cited to appear.—Caccini begs pardon.—Galileo defends the Copernican System at Rome.—His mistake in so doing | 59 | |

| CHAPTER VI. The Inquisition and the Copernican System, and the Assumed Prohibition to Galileo. |

||

| Adverse “Opinion” of the Inquisition on Galileo’s Propositions.—Admonition by Bellarmine, and assumed Absolute Prohibition to treat of the Copernican Doctrines.—Discrepancy between Notes of 25th and 26th February.—Marini’s Documents.—Epinois’s Work on Galileo.—Wohlwill first doubts the Absolute Prohibition.—Doubts confirmed by Gherardi’s Documents.—Decree of 5th March, 1616, on the Copernican System.—Attitude of the Church.—Was the Absolute Prohibition ever issued to Galileo?—Testimony of Bellarmine in his favour.—Conclusions | 76 | |

| [xxiii]CHAPTER VII. Evil Report and Good Report. |

||

| Galileo still lingers at Rome.—Guiccardini tries to effect his Recall.—Erroneous idea that he was trying to get the Decree repealed.—Intrigues against him.—Audience of Pope Paul V.—His friendly assurances.—His Character.—Galileo’s return to Florence | 91 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. The Controversy on Comets. |

||

| Studious Seclusion.—Waiting for the Correction of the Work of Copernicus.—Treatise on Tides.—Sends it to Archduke Leopold of Austria.—The Letter which accompanied it.—The three Comets of 1618.—Galileo’s Opinion of Comets.—Grassi’s Lecture on them.—Guiducci’s Treatise on them, inspired by Galileo.—Grassi’s “Astronomical and Philosophical Scales.”—Galileo’s Reply.—Paul V.—His Death.—Death of Cosmo II.—Gregory XV.—“Il Saggiatore” finished.—Riccardi’s “Opinion” on it.—Death of Gregory XV.—Urban VIII. | 98 | |

| CHAPTER IX. Maffeo Barberini as Urban VIII. |

||

| His Character.—Taste for Letters.—Friendship for Galileo when Cardinal.—Letters to him.—Verses in his honour.—Publication of “Il Saggiatore” with Dedication to the Pope.—Character of the Work.—The Pope’s approval of it.—Inconsistency with the assumed Prohibition | 108 | |

| CHAPTER X. Papal Favour. |

||

| Galileo goes to Rome to congratulate Urban VIII. on his Accession.—Favourable reception.—Scientific discussions with the Pope.—Urban refuses to Revoke the Decree of 5th March.—Nicolo Riccardi.—The Microscope.—Galileo not the Inventor.—Urban’s favours to Galileo on leaving Rome.—Galileo’s reply to Ingoli.—Sanguine hopes.—Grassi’s hypocrisy.—Spinola’s harangue against the Copernican System.—Lothario Sarsi’s reply to “Il Saggiatore.”—Galileo writes his “Dialogues” | 114 | |

| [xxiv]PART II. PUBLICATION OF THE “DIALOGUES ON THE TWO PRINCIPAL SYSTEMS OF THE WORLD,” AND TRIAL AND CONDEMNATION OF GALILEO. |

||

| CHAPTER I. The “Dialogues” on the Two Systems. |

||

| Origin of the “Dialogues.”—Their popular style.—Significance of the name Simplicius.—Hypothetical treatment of the Copernican System.—Attitude of Rome towards Science.—Thomas Campanella.—Urban VIII.’s duplicity.—Galileo takes his MS. to Rome.—Riccardi’s corrections.—He gives the Imprimatur on certain conditions.—Galileo returns to Florence to complete the Work | 127 | |

| CHAPTER II. The Imprimatur for the “Dialogues.” |

||

| Death of Prince Cesi.—Dissolution of the Accadémia dei Lincei.—Galileo advised to print at Florence.—Difficulties and delays.—His impatience.—Authorship of the Introduction.—The Imprimatur granted for Florence.—Absurd accusation from the style of the Type of the Introduction | 138 | |

| CHAPTER III. The “Dialogues” and the Jesuits. |

||

| Publication of the “Dialogues.”—Applause of Galileo’s friends and the learned world.—The hostile party.—The Jesuits as leaders of learning.—Deprived of their monopoly by Galileo.—They become his bitter foes.—Having the Imprimatur for Rome and Florence, Galileo thought himself doubly safe.—The three dolphins.—Scheiner.—Did “Simplicius” personate the Pope?—Conclusive arguments against it.—Effect of the accusation.—Urban’s motives in instituting the Trial | 151 | |

| [xxv]CHAPTER IV. Discovery of the Absolute Prohibition of 1616. |

||

| Symptoms of the coming Storm.—The Special Commission.—Parade of forbearance.—The Grand Duke intercedes for Galileo.—Provisional Prohibition of the “Dialogues.”—Niccolini’s Interview with the Pope and unfavourable reception.—Report of it to Cioli.—Magalotti’s Letters.—Real object of the Special Commission to find a pretext for the Trial.—Its discovery in the assumed Prohibition of 1616.—Report of the Commission, and charges against Galileo | 163 | |

| CHAPTER V. The Summons to Rome. |

||

| Niccolini’s attempt to avert the Trial.—The Pope’s Parable.—The Mandate summoning Galileo to Rome.—His grief and consternation.—His Letter to Cardinal Barberini.—Renewed order to come to Rome.—Niccolini’s fruitless efforts to save him.—Medical Certificate that he was unfit to travel.—Castelli’s hopeful view of the case.—Threat to bring him to Rome as a Prisoner.—The Grand Duke advises him to go.—His powerlessness to protect his servant.—Galileo’s mistake in leaving Venice.—Letter to Elia Diodati | 175 | |

| CHAPTER VI. Galileo’s Arrival at Rome. |

||

| Galileo reaches Rome in February, 1632.—Goes to the Tuscan Embassy.—No notice at first taken of his coming.—Visits of Serristori.—Galileo’s hopefulness.—His Letter to Bocchineri.—Niccolini’s audience of the Pope.—Efforts of the Grand Duke and Niccolini on Galileo’s behalf.—Notice that he must appear before the Holy Office.—His dejection at the news.—Niccolini’s advice not to defend himself | 191 | |

| CHAPTER VII. The Trial before the Inquisition. |

||

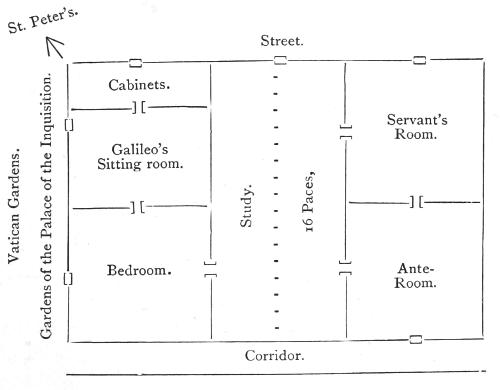

| The first hearing.—Galileo’s submissive attitude.—The events of February, 1616.—Galileo denies knowledge of a special Prohibition.—Produces Bellarmine’s certificate.—Either the Prohibition was not issued, or Galileo’s ignorance was feigned.—His conduct since 1616 agrees with its non-issue.—The Inquisitor assumes that it was issued.—“Opinions” of Oregius, Inchofer and Pasqualigus.—Galileo has Apartments in the Palace of the Holy Office assigned to[xxvi] him.—Falls ill.—Letter to Geri Bocchineri.—Change of tone at second hearing hitherto an enigma.—Now explained by letter from Firenzuola to Cardinal Fr. Barberini.—Galileo’s Confession.—His Weakness and Subserviency | 201 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. The Trial Continued. |

||

| Galileo allowed to return to the Embassy.—His hopefulness.—Third hearing.—Hands in his Defence.—Agreement of it with previous events.—Confident hopes of his friends.—Niccolini’s fears.—Decision to examine Galileo under threat of Torture.—Niccolini’s audience of the Pope.—Informed that the Trial was over, that Galileo would soon be Sentenced, and would be Imprisoned.—Final Examination.—Sent back to “locum suum.”—No evidence that he suffered Torture, or was placed in a prison cell | 217 | |

| CHAPTER IX. The Sentence and Recantation. |

||

| The Sentence in full.—Analysis of it.—The Copernican System had not been pronounced heretical by “Infallible” authority.—The special Prohibition assumed as fact.—The Sentence illegal according to the Canon Law.—The Holy Office exceeded its powers in calling upon Galileo to recant.—The Sentence not unanimous.—This escaped notice for two hundred and thirty-one Years.—The Recantation.—Futile attempts to show that Galileo had really altered his opinion.—After the Sentence, Imprisonment exchanged for Banishment to Trinita de’ Monti.—Petition for leave to go to Florence.—Allowed to go to Siena | 230 | |

| CHAPTER X. Current Myths. |

||

| Popular Story of Galileo’s Fate.—His Eyes put out.—“E pur si Muove.”—The Hair Shirt.—Imprisonment.—Galileo only detained twenty-two Days at the Holy Office.—Torture.—Refuted in 18th Century.—Torture based on the words “examen rigorosum.”—This shown to be untenable.—Assertion that the Acts have been falsified refuted.—False Imputation on Niccolini.—Conclusive Evidence against Torture.—Galileo not truly a “Martyr of Science” | 249 | |

| [xxvii]PART III. GALILEO’S LAST YEARS. |

||

| CHAPTER I. Galileo at Siena and Arcetri. |

||

| Arrival at Siena.—Request to the Grand Duke of Tuscany to ask for his release.—Postponed on the advice of Niccolini.—Endeavours at Rome to stifle the Copernican System.—Sentence and Recantation sent to all the Inquisitors of Italy.—Letter to the Inquisitor of Venice.—Mandate against the publication of any new Work of Galileo’s, or new Edition.—Curious Arguments in favour of the old System.—Niccolini asks for Galileo’s release.—Refusal, but permission given to go to Arcetri.—Anonymous accusations.—Death of his Daughter.—Request for permission to go to Florence.—Harsh refusal and threat.—Letter to Diodati.—Again at work.—Intervention of the Count de Noailles on Galileo’s behalf.—Prediction that he will be compared to Socrates.—Letter to Peiresc.—Publication of Galileo’s Works in Holland.—Continued efforts of Noailles.—Urban’s fair speeches | 267 | |

| CHAPTER II. Failing Health and Loss of Sight. |

||

| Galileo’s Labours at Arcetri.—Completion of the “Dialoghi delle nuove Scienze.”—Sends it to the Elzevirs at Leyden.—Method of taking Longitudes at Sea.—Declined by Spain and offered to Holland.—Discovery of the Libration and Titubation of the Moon.—Visit from Milton.—Becomes blind.—Letter to Diodati.—On a hint from Castelli, petitions for his Liberty.—The Inquisitor to visit him and report to Rome.—Permitted to live at Florence under restrictions.—The States-General appoint a Delegate to see him on the Longitude question.—The Inquisitor sends word of it to Rome.—Galileo not to receive a Heretic.—Presents from the States-General refused from fear of Rome.—Letter to Diodati.—Galileo supposed to be near his end.—Request that Castelli might come to him.—Permitted under restrictions.—The new “Dialoghi” appear at Leyden, 1638.—They founded Mechanical Physics.—Attract much notice.—Improvement of health.—In 1639 goes to Arcetri again, probably not voluntarily | 284 | |

| [xxviii]CHAPTER III. Last Years and Death. |

||

| Refusal of some Favour asked by Galileo.—His pious Resignation.—Continues his scientific Researches.—His pupil Viviani.—Failure of attempt to renew Negotiations about Longitudes.—Reply to Liceti and Correspondence with him.—Last discussion of the Copernican System in reply to Rinuccini.—Sketch of its contents.—Pendulum Clocks.—Priority of the discovery belongs to Galileo.—Visit from Castelli.—Torricelli joins Viviani.—Scientific discourse on his Deathbed.—Death, 8th Jan., 1642.—Proposal to deny him Christian Burial.—Monument objected to by Urban VIII.—Ferdinand II. fears to offend him.—Buried quietly.—No Inscription till thirty-two years later.—First Public Monument erected by Viviani in 1693.—Viviani directs his heirs to erect one in Santa Croce.—Erected in 1738.—Rome unable to put down Copernican System.—In 1757 Benedict XIV. permits the clause in Decree forbidding books which teach the new System to be expunged.—In 1820 permission given to treat of it as true.—Galileo’s work and others not expunged from the Index till 1835 | 299 | |

| APPENDIX. | ||

| I. | History of the Vatican Manuscript | 319 |

| II. | Description of the Vatican Manuscript | 330 |

| III. | Estimate of the Vatican Manuscript | 334 |

| IV. | Gherardi’s Collection of Documents | 341 |

| V. | Decree of 5th March, 1616 | 345 |

| VI. | Remarks on the Sentence and Recantation | 347 |

Albèri (Eugenio): “Le opere di Galileo Galilei.” Prima edizione completa condotta sugli autentici manoscritti Palatini. Firenze, 1842-1856.

*“Sul Processo di Galileo. Due Lettere in risposta al giornale S’opinione.” Firenze, 1864.

Anonym: “Der heilige Stuhl gegen Galileo Galilei und das astronomische System des Copernicus.” Historisch-politische Blätter für das katholische Deutschland; herausgegeben von G. Phillips und G. Görres. Siebenter Band. München, 1841.

“Galileo Galilei. Sein Leben und seine Bedeutung für die Entwickelung der Naturwissenschaft.” Die Fortschritte der Naturwissenschaft in biographischen Bildern. Drittes Heft. Berlin, 1856.

“Galileo Galilei.” Die Grenzboten. XXIV. Jahrgang. I. Semester. Nr. 24. 1865.

*Arduini (Carlo): “La Primogenita di Galileo Galilei rivelata dalle sue lettere.” Florence, 1864.

Barbier (Antoine Alexandre): “Examen critique et complément des dictionnaires historiques les plus répandus.” Paris, 1820. Article Galilée.

*Berti (Prof. Domenico): “La venuta di Galileo Galilei a Padova. Studii. Atti del Reale Istituto Veneto di scienze, lettere ed arti, dal Novembre 1870 all’ ottobre 1871.” Tomo decimosesto, seria terza, dispensa quinta, ottava, nono e decima. Venezia, 1870, 1871.

*“Copernico e le vicende del Sistema Copernicano in Italia nella seconda metà del secolo XVI. e nella prima del secolo XVII.” Roma, 1876.

“Il Processo originale di Galileo Galilei, pubblicato per la prima volta.” Roma, 1876.

“La Critica moderna e il Processo contro Galileo Galilei.” (Nuova Antologia, Gennajo, 1877 Firenze.)

Bouix (L’Abbé): “La condamnation de Galilée. Lapsus des écrivains, qui l’opposent à la doctrine de l’infaillibilité du Pape.”—Revue des Sciences ecclésiastiques. Arras-Paris, février et mars, 1866.

Cantor (Professor Dr. Moritz): “Galileo Galilei.” Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik. 9. Jahrgang. 3. Heft. Leipzig, 1864.

“Recensionen über die 1870 erschienenen Schriften Wohlwill’s und Gherardi’s über den Galilei’schen Process.” Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik. 16. Jahrgang. 1. Heft. 1871.

Caspar (Dr. R.): “Galileo Galilei. Zusammenstellung der Forschungen und Entdeckungen Galilei’s auf dem Gebiete der Naturwissenschaft, als Beitrag zur Geschichte der neueren Physik.” Stuttgart, 1854.

Chasles (Prof. Philarète): “Galileo Galilei, sa vie, son procès et ses contemporains d’après les documents originaux.” Paris, 1862.

*Combes (Louis): “Galilée et L’Inquisition Romaine.” Paris, 1876.

Delambre (Jean Baptiste Joseph): “Histoire de l’astronomie ancienne.” Paris, 1821.

Eckert (Professor Dr.): “Galileo Galilei, dessen Leben und Verdienste um die Wissenschaften.” Als Einladung zur Promotionsfeier des Pädagogiums. Basel, 1858.

Epinois (Henri de L’): “Galilée, son procès, sa condamnation d’après des documents inédits.” Extrait de la Revue des questions historiques. Paris, 1867.

*“Les Pièces du Procès de Galilée, précédées d’un avant-propos.” Rome, Paris, 1877 v. Palmé société Générale de Librairie Catholique.

*“La Question de Galilée, les faits et leurs conséquences.” Paris Palmé, 1878.

Figuier (Louis): “Galilée.” Vies des savants illustres du dix-septième siècle. Paris, 1869.

Friedlein (Rector): “Zum Inquisitionsprocess des Galileo Galilei.” Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik. 17. Jahrgang. 3. Heft. 1872.

Gherardi (Prof. Silvestro): “Il Processo Galileo riveduto sopra documenti di nuova fonte.” Rivista Europea. Anno 1. Vol. III. Firenze, 1870.[6]

“Sulla Dissertazione del dott. Emilio Wohlwill. Il processo di Galileo Galilei.” Estratto della Rivista Europea. Firenze, 1872.

*Gilbert (Prof. Ph.): “Le Procès de Galilée d’après les Documents contemporains.” Extrait de la Revue Catholique tomes I., II. Louvains, 1869.

Govi (Gilberto): “Intorno a certi manuscritti apocrifi di Galileo.” Torino, 1869. Estr. dagli Atti della Accadémia delle Scienze di Torino Vol. V. Adunanza del 21 Nov. 1869.

“Intorno a tre lettere di Galileo Galilei tratte dall’ archivio dei Gonzaga.” Bollettino di bibliografia e di storia delle scienze matematiche e fisiche pubblicato da B. Boncompagni. Tomo III. Roma, 1870.

Govi (Gilberto): “Il S. Offizio, Copernico e Galileo a proposito di un opuscolo postumo del P. Olivieri sullo stesso argomento.” Torino, 1872.

*Grisar (Prof. H. S. J.): “Der Galilei’sche Process auf der neuesten Actenpublicationen historisch und juristisch geprüft.” Zeitschrift für Kath. Theol. II. Jahrgang, pp. 65-128. Innsbruck.

Jagemann: “Geschichte des Lebens und der Schriften des Galileo Galilei.” Neue Auflage. Leipzig, 1787.

Libri: “Galileo Galilei, sein Leben und seine Werke.” Aus dem Französischen mit Anmerkungen von F. W. Carové. Siegen und Wiesbaden, 1842.

Marini (Mgr. Marino): “Galileo e l’inquisizione.” Memorie storico-critiche. Roma, 1850.

Martin (Henri Th.): “Galilée, les droits de la science et la méthode des sciences physiques.” Paris, 1868.

Nelli (Gio. Batista Clemente de): “Vita e commercio letterario di Galileo Galilei.” Losanna (Firenze), 1793.

Olivieri (P. Maurizio-Benedetto Ex. generale dei domenicani e Commissario della S. Rom. ed Univer. Inquisizione): “Di Copernico e di Galileo scritto postumo ora per la prima volta messo in luce sull’ autografo per cura d’un religioso dello stesso istituto.” Bologna, 1872.

Parchappe (Dr. Max): “Galilée, sa vie, ses découvertes et ses travaux.” Paris, 1866.

*Pieralisi (Sante, Sacerdote e Bibliotecario della Barberiniana): “Urbano VIII. e Galileo Galilei: Memorie Storiche.” Roma, 1875. Tipografia poliglotta della L. P. di Propaganda Fide.

*“Correzioni al libro Urbano VIII. Galileo Galilei proposte dall’ autore Sante Pieralisi con osservazione sopra il processo originale di Galileo Galilei pubblicato da Domenico Berti.” Settembre, 1876.

Reitlinger (Prof. Edmund): “Galileo Galilei.” Freie Blicke. Populärwissenschaftliche Aufsätze. Berlin, 1875.

Reumont (Alfred von): “Galilei und Rom.” Beiträge zur italienischen Geschichte. 1 Bd. Berlin, 1853.

Reusch (Professor Dr. F. H.): “Der Galilei’sche Procesz.” Ein Vortrag. Historische Zeitschrift; herausgegeben von Prof. Heinrich von Sybel. 17. Jahrgang. 1875. 3. Heft.

Rezzi (M. Domenica): “Sulla invenzione del microscopio, giuntavi una notizia delle Considerazioni al Tasso attribuite a Galileo Galilei.” Roma, 1852.

*Riccardi (Prof. Cav. Pietro): “Di alcune recenti memorie sul processo e sulla condanna del Galilei. Nota e Documenti aggiunti alla bibliografia Galileiana.” Modena, 1873.

Riccioli (P. Jo. Bapt.): “Almagestum novum.” Bonioniae, 1651.

Rosini (M. Giovanni): “Per l’inaugurazione solenne della statua di Galileo.” Orazione. Pisa, 1839 (2 Oct).

Rossi (Prof. Giuseppe): “Del Metodo Galileiano.” Bologna, 1877.

*Scartazzini (Dr. T. A.): “Der Process des Galileo Galilei.” Unsere Zeit. Jahrgang 13. Heft 7 and 18.

*“Il processo di Galileo Galilei e la moderna critica tedesca.” Revista Europea, Vol. IV. Part V., Vol. V. Parts I and II., 1 and 16 Jan. 1878.

*Schneemann (P. S. J.): “Galileo Galilei und der Römische Stuhl.” Stimmen aus Maria Laach. Kath. Blättern. Nos. 2, 3, 4, Feb. Mar. April, 1878.

Snell (Dr. Carl): “Ueber Galilei als Begründer der mechanischen Physik und über die Methode derselben.” Jena, 1864.

Targioni Tozzetti: “Notizie degli aggrandimenti delle scienze fisiche in Toscana.” Firenze, 1780. (Contains in Vol. ii.: “Vita di Galileo scritta da Nic. Gherardini.”)

Venturi (Cav. Giambattista): “Memorie e lettere inedite finora o disperse di Galileo Galilei.” Modena, 1818-1821.

Viviani: “Raconto istorico della vita di Galileo Galilei.” (Enthalten im XV. Bande der Opere di Galileo Galilei. Prima edizione completa. Firenze, 1856.)

Vosen (Dr. Christian Hermann): “Galileo Galilei und die Römische Berurtheilung des Copernicanischen Systems.” Broschürenverein Nr. 5. Frankfurt am M. 1865.

Wohlwill (Dr. Emil): “Der Inquisitionsprocess des Galileo Galilei. Eine Prüfung seiner rechtlichen Grundlage nach den Acten der Römischen Inquisition.” Berlin, 1870.

*“Ist Galilei gefoltert worden? Eine kritische Studie.” Leipzig, 1877.

“Zum Inquisitionsprocesz des Galileo Galilei.” Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik. 17. Jahrgang. 2. Heft. 1872.

*Wolynski (Dott. Arturio): “Lettere inedite a Galileo Galilei.” Firenze, 1872.

*“Relazione di Galileo Galilei colla Polonia esposte secondo i documenti per la maggior parte non pubblicati.” Firenze, 1873.

“La Diplomazia Toscana e Galileo Galilei.” Firenze, 1874.

Birth at Pisa.—Parentage.—His Father’s Writings on Music.—Galileo destined to be a Cloth Merchant.—Goes to the Convent of Vallombrosa.—Begins to study Medicine.—Goes to the University of Pisa.—Discovery of the Isochronism of the Pendulum.—Stolen Lessons in Mathematics.—His Hydrostatic Scales.—Professorship at Pisa.—Poor Pay.—The Laws of Motion.—John de’ Medici.—Leaves Pisa.—Professorship at Padua.—Writes various Treatises.—The Thermoscope.—Letter to Kepler.—The Copernican System.—“De Revolutionibus Orbium Cœlestium.”

The same memorable day is marked by the setting of one of the most brilliant stars in the firmament of art and the rising of another in the sphere of science, which was to enlighten the world with beams of equal splendour. On the 18th February, 1564, Michael Angelo Buonarotti closed his eyes at Rome, and Galileo Galilei first saw the light at Pisa.

He was the son of the Florentine nobleman, Vincenzo Galilei, and of Julia, one of the ancient family of the Ammanati of Pescia, and was born in wedlock, as the documents of the church clearly attest.[7] His earliest years were spent at Pisa, but his parents soon returned to Florence, which was their settled home. Here he received his early education. His father had distinguished himself by his writings on the theory[4] of music, particularly the mathematical part of it.[8] They were not merely above mediocrity, but aimed at innovation, and if they did not achieve reform, it was to be attributed to the conservative spirit then reigning in Italy, which asserted itself in every department of life, and especially in the spheres of art and science.

Galileo’s father had no property. His income was but scanty, and the fates had endowed him with a numerous family instead of with fortune.[9] Under these untoward circumstances he at first destined the little Galileo, as is related by Gherardini, his earliest biographer, to a career by no means distinguished, though advantageous in a material point of view, and one that conferred much of their wealth on the Florentines, so that it was held in high esteem—he was to be a cloth dealer. But the young noble first received the education befitting his station, that is, a very mediocre teacher instructed him in the Humanities.[10] Fortunately for the clever young scholar, he was handed over to the pious brethren of the convent of Vallombrosa for further education. Here he at once made rapid progress. He acquired great facility in the classics. His thorough study of the masterpieces of antiquity was of the greatest advantage to him. He doubtless thereby laid the foundation of the admirable style to which he afterwards, in some measure, owed his brilliant successes.

Galileo had a great variety of talent. Besides ardent pursuit of the solid branches of learning, he had considerable skill in drawing and music, in which he afterwards attained so much perfection that his judgment was highly esteemed, even[5] by great artists.[11] He played the lute himself with the skill of a master. He also highly appreciated poetry. His later essays on Dante, Orlando Furioso, and Gerusalemme Liberata, as well as the fragment of a play, bear witness to his lively interest in belles lettres. But from his earliest youth he showed the greatest preference for mechanics. He made little machines with an ingenuity and skill which evinced a really unusual talent for such things.[12]

With these abilities his father must soon have arrived at the conclusion that his son was born for something better than for distributing wool among the people, and resolved to devote him to science; only it was necessary that the branch of it to which he turned his attention should offer a prospect of profit. Medicine was decided on as the most likely to be lucrative, although it may not seem the one most suited to his abilities.

On 5th November, 1581, Galileo, then just seventeen, entered the University of Pisa.[13] Even here the young medical student’s independent ideas and aims made way for themselves. At that time any original ideas and philosophical views not derived from the dogmas of Aristotle were unheard of. All the theories of natural science and philosophy had hitherto been referred to theology. It had been held to be the Alpha and Omega of all human knowledge. But now the period was far advanced in which it was felt to be necessary to cast off the narrow garments fashioned by religion, though at first the will to do so exceeded the power. A stir and ferment agitated men’s minds. A period of storm and stress had begun for the study of nature and the philosophical speculation so closely connected with it. Men did not as yet possess energy and ability for direct advance, so they turned with real fanaticism to ancient learning, which, being[6] independent, and not based on religious notions, afforded them satisfaction. Under these circumstances recurrence to the past was real progress.

Unconditional surrender to the ideas of others, entire adoption of opinions, some of which were not too well verified, might suit mediocrity, but it could not suffice for the powerful mind of Galileo, who was striving to find out the truth for himself. The genius of the young student rebelled fiercely against rigid adherence to an antiquated standpoint. To the horror of the followers of Aristotle, who were quite taken aback at such unheard-of audacity, he resolutely attacked in public disputations many oracular dicta of their great master hitherto unquestioned, and this even then made him many enemies, and acquired for him the epithet of “the Wrangler.”[14]

Two circumstances occur during Galileo’s student years, which, in their main features, are not without historical foundation, although in detail they bear an anecdotal impress. One, which is characteristic of Galileo’s observant eye, shows us the student of nineteen devoutly praying in the Cathedral at Pisa; but he seems to have soon wearied of this occupation, for he dreamily fixed his eye on the Maestro Possenti’s beautiful lamp, hanging from an arch, which, in order to light it more readily, had been moved out of its vertical position and then left to itself. The oscillations were at first considerable, became gradually less and less, but notwithstanding the varying distances, they were all performed in the same time, as the young medical student discovered to a nicety by feeling his pulse. The isochronism of the vibrations of the pendulum was discovered![15]

The other story refers to Galileo’s first mathematical studies. Gherardini relates that he was scarcely acquainted with the elements of mathematics up to his twentieth year, which, by the by, seems almost incredible. But while he was[7] diligently studying medicine at Pisa, the court of Tuscany came there for some months. Among the suite was Ostilio Ricci, governor of the pages, a distinguished mathematician and an old friend of the Galilei family; Galileo, therefore, often visited him. One morning when he was there, Ricci was teaching the pages. Galileo stood shyly at the door of the schoolroom, listening attentively to the lesson; his interest grew greater and greater; he followed the demonstration of the mathematical propositions with bated breath. Strongly attracted by the science almost unknown to him before, as well as by Ricci’s method of instruction, he often returned, but always unobserved, and, Euclid in hand, drank deeply, from his uncomfortable concealment, of the streams of fresh knowledge. Mathematics also occupied the greater part of his time in the solitude of his study. But all this did not satisfy his thirst for knowledge. He longed to be himself taught by Ricci. At last he took courage, and, hesitatingly confessing his sins of curiosity to the astonished tutor, he besought him to unveil to him the further mysteries of mathematics, to which Ricci at once consented.

When Galileo’s father learnt that his son was devoting himself to Euclid at the expense of Hippocrates and Galen, he did his utmost to divert him from this new, and as it seemed to him, unprofitable study. The science of mathematics was not then held in much esteem, as it led to nothing practical. Its use, as applied to the laws of nature, had scarcely begun to be recognised. But the world-wide mission for which Galileo’s genius destined him had been too imperiously marked out by fate for him to be held back by the mere will of any man. Old Vincenzo had to learn the unconquerable power of genius in young Galileo, and to submit to it. The son pursued the studies marked out for him by nature more zealously than ever, and at length obtained leave from his father to bid adieu to medicine and to devote himself exclusively to mathematics and physics.[16]

The unexpected successes won by the young philosopher in a very short time in the realm of science, soon showed that his course had now been turned into the proper channel. Galileo’s father, who, almost crushed with the burden of his family, could with difficulty bear the expense of his son’s residence at the University, turned in his perplexity to the beneficence of the reigning Grand Duke, Ferdinand de’ Medici, with the request that, in consideration of the distinguished talents and scientific attainments of Galileo, he would grant him one of the forty free places founded for poor students at the University. But even then there were many who were envious of Galileo in consequence of his unusual abilities and his rejection of the traditional authority of Aristotle. They succeeded in inducing the Grand Duke to refuse poor Vincenzo’s petition, in consequence of which the young student had to leave the University, after four years’ residence, without taking the doctor’s degree.[17]

In spite of these disappointments, Galileo was not deterred, on his return home, from continuing his independent researches into natural phenomena. The most important invention of those times, to which he was led by the works of Archimedes, too little regarded during the Middle Ages, was his hydrostatic scales, about the construction and use of which he wrote a treatise, called “La Bilancetta.” This, though afterwards circulated in manuscript copies among his followers and pupils, was not printed until after his death, in 1655.

Galileo now began to be everywhere spoken of in Italy. The discovery of the movement of the pendulum as a measurement of time, the importance of which was increasingly recognised, combined with his novel and intellectual treatment of physics, by which the phenomena of nature were submitted, as far as possible, to direct proof instead of to the a priori reasoning of the Aristotelians, excited much attention in all scientific circles. Distinguished men of learning, like[9] Clavius at Rome, with whom he had become acquainted on his first visit there in 1587,[18] Michael Coignet at Antwerp, Riccoboni, the Marquis Guidubaldo del Monte, etc., entered into correspondence with him.[19] Intercourse with the latter, a distinguished mathematician, who took the warmest interest in Galileo’s fate, became of the utmost importance to him. It was not merely that to his encouragement he owed the origin of his excellent treatise on the doctrine of centres of gravity, which materially contributed to establish his fame, and even gained for him from Del Monte the name of an “Archimedes of his time,” but he first helped him to secure a settled and honourable position in life. By his opportune recommendation in 1589, the professorship of mathematics at the University of Pisa, just become vacant, was conferred on Galileo, with an income of sixty scudi.[20] It is indicative of the standing of the sciences in those days that, while the professor of medicine had a salary of two thousand scudi, the professor of mathematics had not quite thirty kreuzers[21] a day. Even for the sixteenth century it was very poor pay. Moreover, in accordance with the usage at the Italian Universities, he was only installed for three years; but in Galileo’s needy circumstances, even this little help was very desirable, and his office enabled him to earn a considerable additional income by giving private lessons.

During the time of his professorship at Pisa he made his grand researches into the laws of gravitation, now known under the name of “Galileo’s Laws,” and wrote as the result of them his great treatise “De Motu Gravium.” It then had but a limited circulation in copies, and did not appear in print until two hundred years after his death, in Albèri’s “Opere complete di Galileo Galilei.” Aristotle,[10] nearly two thousand years before, had raised the statement to the rank of a proposition, that the rate at which a body falls depends on its weight. Up to Galileo’s time this doctrine had been generally accepted as true, on the mere word of the old hero of science, although individual physicists, like Varchi in 1544, and Benedetti in 1563, had disputed it, maintaining that bodies of similar density and different weight fall from the same height in an equal space of time. They sought to prove the correctness of this statement by the most acute reasoning, but the idea of experiment did not occur to any one. Galileo, well aware that the touchstone of experiment would discover the vulnerable spot in Aristotelian infallibility, climbed the leaning tower of Pisa, in order thence to prove by experiment, to the discomfiture of the Peripatetic school, the truth of the axiom that the velocity with which a body falls does not depend on its weight but on its density.[22]

It might have been thought that his opponents would strike sail after this decisive argument. Aristotle, the master, would certainly have yielded to it—but his disciples had attained no such humility. They followed the bold experiments of the young professor with eyes askance and miserable sophistries, and, being unable to meet him with his own weapons of scientific research, they eagerly sought an opportunity of showing the impious and dangerous innovator the door of the aula.

An unforeseen circumstance came all at once to their aid in these designs. An illegitimate son of the half-brother of the reigning Grand Duke,—the relationship was somewhat farfetched, but none the less ominous for Galileo—John de’ Medici, took an innocent pleasure in inventing machines, and considered himself a very skilful artificer. This ingenious semi-prince had constructed a monster machine for cleaning the harbour of Leghorn, and proposed that it should be brought into use. But Galileo, who had been commissioned to examine the marvel, declared it to be useless, and, unfortunately,[11] experiment fully confirmed the verdict. Ominous head-shakings were seen among the suite of the deeply mortified inventor. They entered into alliance with the Peripatetic philosophers against their common enemy. There were cabals at court. Galileo, perceiving that his position at Pisa was untenable, voluntarily resigned his professorship before the three years had expired, and migrated for the second time home to Florence.[23]

His situation was now worse than before, for about this time, 2nd July, 1591, his father died after a short illness, leaving his family in very narrow circumstances. In this distress the Marquis del Monte again appeared as a friend in need. Thanks to his warm recommendation to the Senate of the Republic of Venice, in the autumn of 1592 the professorship of mathematics at the University of Padua, which had become vacant, was bestowed on Galileo for six years.[24] On 7th December, 1592, he entered on his office with a brilliant opening address, which won the greatest admiration, not only for its profound scientific knowledge, but for its entrancing eloquence.[25] His lectures soon acquired further fame, and the number of his admirers and the audience who eagerly listened to his, in many respects, novel demonstrations, daily increased.

During his residence at Padua, Galileo displayed an extraordinary and versatile activity. He constructed various machines for the service of the republic, and wrote a number of excellent treatises, intended chiefly for his pupils.[26] Among the larger works may be mentioned his writings on the laws of motion, on fortification, gnomonics (the making of sun-dials), mechanics, and on the celestial globe, which attained a wide circulation even in copies, and were some of them printed[12] long afterwards—the one on fortification not until the present century;[27] others, including the one on gnomonics, are unfortunately lost. On the wide field of inventions two may be specially mentioned, one of which was not fully developed until much later. The first was his proportional circle, which, though it had no special importance as illustrative of any principle, had a wide circulation from its various practical uses. Ten years later, in 1606, Galileo published an excellent didactic work on this subject, dedicated to Cosmo de’ Medici, and in 1607 a polemical one against Balthasar Capra, of Milan, who, in a treatise published in 1607, which was nothing but a plagiarism of Galileo’s work disfigured by blunders, gave himself out as the inventor of the instrument. Galileo’s reply, in which he first exhibited the polemical dexterity afterwards so much dreaded, excited great attention even in lay circles from its masterly satire.[28] The other invention was a contrivance by which heat could be more exactly indicated. Over zealous biographers have therefore hastened to claim for their hero the invention of the thermometer, which, however, is not correct, as the instrument, which was not intended to measure the temperature, could not be logically called a thermometer, but a thermoscope, heat indicator. Undoubtedly it prepared the way by which improvers of the thermoscope arrived at the thermometer.[29]

Before proceeding further with Galileo’s researches and discoveries, so far as they fall within our province, it seems important to acquaint ourselves with his views about the Copernican system. From a letter of his to Mazzoni, of 30th May, 1597,[30] it is clear that he considered the opinions of Pythagoras and Copernicus on the position and motion of the earth to be far more correct than those of Aristotle and Ptolemy. In another letter of 4th August of the same year[13] to Kepler, he thanks him for his work, which he had sent him, on the Mysteries of the Universe,[31] and writes as follows about the Copernican system:—

“I count myself happy, in the search after truth, to have so great an ally as yourself, and one who is so great a friend of the truth itself. It is really pitiful that there are so few who seek truth, and who do not pursue a perverse method of philosophising. But this is not the place to mourn over the miseries of our times, but to congratulate you on your splendid discoveries in confirmation of truth. I shall read your book to the end, sure of finding much that is excellent in it. I shall do so with the more pleasure, because I have been for many years an adherent of the Copernican system, and it explains to me the causes of many of the appearances of nature which are quite unintelligible on the commonly accepted hypothesis. I have collected many arguments for the purpose of refuting the latter; but I do not venture to bring them to the light of publicity, for fear of sharing the fate of our master, Copernicus, who, although he has earned immortal fame with some, yet with very many (so great is the number of fools) has become an object of ridicule and scorn. I should certainly venture to publish my speculations if there were more people like you. But this not being the case, I refrain from such an undertaking.”[32]

In an answer from Grätz, of 13th October of the same year, Kepler urgently begs him to publish his researches into the Copernican system, advising him to bring them out in Germany if he does not receive permission to do so in Italy.[33] In spite of this pressing request of his eminent friend, however, Galileo was not to be induced to bring his convictions to the light yet, a hesitation which may not appear very commendable. But if we consider the existing state of science, which condemned the Copernican system as an unheard of and fantastic hypothesis, and the religious incubus which weighed down all knowledge of nature irrespective of religious belief, and if, besides all this, we remember the entire revolution in the sphere both of religion and science involved in the reception of the Copernican system, we shall be more ready to admit that Galileo had good reason to be cautious. The Copernican[14] cause could not be served by mere partisanship, but only by independent fresh researches to prove its correctness, indeed its irrefragability. Nothing but the fulfilment of these conditions formed a justification, either in a scientific or moral point of view, for taking part in overturning the previous views of the universe.

Before the powerful mind of Copernicus ventured to question it, our earth was held to be the centre of the universe, and about it all the rest of the heavenly bodies revolved. There was but one “world,” and that was our earth; the whole firmament, infinity, was the fitting frame to the picture, upon which man, as the most perfect being, held a position which was truly sublime. It was an elevating thought that you were on the centre, the only fixed point amidst countless revolving orbs! The narrations in the Bible, and the character of the Christian religion as a whole, fitted this conception exceedingly well; or, more properly speaking, were made to fit it. The creation of man, his fall, the flood, and our second venerable ancestor, Noah, with his ark in which the continuation of races was provided for, the foundation of the Christian religion, the work of redemption;—all this could only lay claim to universal importance so long as the earth was the centre of the universe, the only world. Then all at once a learned man makes the annihilating assertion that our world was not the centre of the universe, but revolved itself, was but an insignificant part of the vast, immeasurable system of worlds. What had become of the favoured status of the earth? And this indefinite number of bodies, equally favoured by nature, were they also the abodes of men? The bare possibility of a number of inhabited worlds could but imperil the first principles of Christian philosophy.

The system of the great Copernicus, however, thanks to the anonymous preface to his famous work, “De Revolutionibus Orbium Cœlestium,” had not, up to this time, assumed to be a correct theory, but only a hypothesis, which need not be considered even probable, as it was only intended to facilitate[15] astronomical calculations. We know now that this was a gigantic mistake, that the immortal astronomer had aimed at rectifying the Ptolemaic confusion, and was fully convinced of the correctness of his system; we know that this unprincipled Introduction is by no means to be attributed to Copernicus, but to Andreas Osiander, who took part in publishing this book, which formed so great an epoch in science, and whose anxious soul thereby desired to appease the anticipated wrath of the theologians and philosophers. And we know further that the founder of our present system of the universe, although he handled the first finished copy of his imperishable work when he was dying, was unable to look into it, being already struck by paralysis, and thus never knew of Osiander’s weak-minded Introduction, which had prudently not been submitted to him.[34]

A few days after receiving a copy of the great work of his genius, Copernicus died, on 24th May, 1543; and his system, for which he had been labouring and striving all his life, was, in consequence of Osiander’s sacrilegious act, reduced to a simple hypothesis intended to simplify astronomical calculations! As such it did not in the least endanger the faith of the Church. Even Pope Paul III., to whom Copernicus had dedicated his work, received it “with pleasure.” In 1566 a second edition appeared at Basle, and still it did not excite any opposition from the Church. It was not till 1616, when it had met with wide acceptance among the learned, when its correctness had been confirmed by fresh facts, and it had begun to be looked upon as true, that the Roman curia felt moved to condemn the work of Copernicus until it had been corrected (donec corrigantur).

Having thus rapidly glanced at the opposition between the Copernican system and the Ptolemaic, which forms the prelude to Galileo’s subsequent relations with Rome, we are at liberty to fulfil the task we have set ourselves, namely, to portray “Galileo and the Roman Curia.”

Term of Professorship at Padua renewed.—Astronomy.—A New Star.—The Telescope.—Galileo not the Inventor.—Visit to Venice to exhibit it.—Telescopic Discoveries.—Jupiter’s Moons.—Request of Henry IV.—“Sidereus Nuncius.”—The Storm it raised.—Magini’s attack on Galileo.—The Ring of Saturn.—An Anagram.—Opposition of the Aristotelian School.—Letter to Kepler.

The first six years of Galileo’s professorship at Padua had passed away, but the senate were eager to retain so bright a light for their University, and prolonged the appointment of the professor, whose renown was now great, for another six years, with a considerable increase of salary.[35]

As we have seen, he had for a long time renounced the prevailing views about the universe; but up to this time he had discussed only physical mathematical questions with the Peripatetic school, the subject of astronomy had not been mooted. But the sudden appearance of a new star in the constellation of Serpentarius, in October, 1604, which, after exhibiting various colours for a year and a half, as suddenly disappeared, induced him openly to attack one of the Aristotelian doctrines hitherto held most sacred, that of the unchangeableness of the heavens. Galileo demonstrated, in three lectures to a numerous audience, that this star was neither a mere meteor, nor yet a heavenly body which had before existed but had only now been observed, but a body which had recently appeared and had again vanished.[36] The subject,[17] though not immediately connected with the Copernican question, was an important step taken on the dangerous and rarely trodden path of knowledge of nature, uninfluenced by dogmatism or petrified professorial wisdom. This inviolability of the vault of heaven was also conditioned by the prevailing views of the universe. What wonder then that most of the professors who had grown grey in the Aristotelian doctrine (Cremonio for instance, Coressio, Lodovico delle Colombo, and Balthasar Capra) were incensed at these opinions of Galileo, so opposed to all their scientific prepossessions, and vehemently controverted them.

The spark, however, which was to set fire to the abundant inflammable material, and to turn the scientific and religious world, in which doubt had before been glimmering, into a veritable volcano, the spark which kindled Galileo’s genius and made him for a long time the centre of that period of storm and stress, was the discovery of the telescope.

We will not claim for Galileo, as many of his biographers have erroneously done, priority in the construction of the telescope. We rely far more on Galileo’s own statements than on those of his eulogists, who aim at effect. Galileo relates with perfect simplicity at the beginning of the “Sidereus Nuncius,” published at Venice in 1610, that he had heard about ten months ago that an instrument had been made by a Dutchman, by means of which distant objects were brought nearer and could be seen very plainly. The confirmation of the report by one of his former pupils, a French nobleman, Jean Badovere of Paris, had induced him to reflect upon the means by which such an effect could be produced. By the laws of refraction he soon attained his end. With two glasses fixed at the ends of a leaden tube, both having one side flat and the other side of the one being concave and of the other convex, his primitive telescope, which made objects appear three times nearer and nine times larger, was constructed. But now, having “spared neither expense nor labour,” he had got so far as to construct an instrument which magnified an object[18] nearly a thousand times, and brought it more than thirty times nearer.[37] Although, therefore, it is clear from this that the first idea of the telescope does not belong to Galileo, it is equally clear that he found out how to construct it from his own reflection and experiments. Undoubtedly also the merit of having made great improvements in it belongs to him, which is shown by the fact that at that time, and long afterwards, his telescopes were the most sought after, and that he received numerous orders for them from learned men, princes and governments in distant lands, Holland, the birthplace of the telescope, not excepted.[38] But the idea which first gave to the instrument its scientific importance, the application of it to astronomical observations, belongs not to the original inventor but to the genius of Galileo. This alone would have made his name immortal.[39]

A few days after he had constructed his instrument, imperfect as it doubtless was, he hastened with it to Venice, having received an invitation, to exhibit it to the doge and senate, for he at once recognised its importance, if not to the full extent. We will now let Galileo speak for himself in a letter which he wrote from Venice to his brother-in-law, Benedetto Landucci:—

“You must know then that about two months ago a report was spread here that in Flanders a spy-glass had been presented to Prince Maurice, so ingeniously constructed that it made the most distant objects appear quite near, so that a man could be seen quite plainly at a distance of two miglia. This result seemed to me so extraordinary that it set me thinking;[19] and as it appeared to me that it depended upon the theory of perspective, I reflected on the manner of constructing it, in which I was at length so entirely successful that I made a spy-glass which far surpasses the report of the Flanders one. As the news had reached Venice that I had made such an instrument, six days ago I was summoned before their highnesses the signoria, and exhibited it to them, to the astonishment of the whole senate. Many noblemen and senators, although of a great age, mounted the steps of the highest church towers at Venice, in order to see sails and shipping that were so far off that it was two hours before they were seen steering full sail into the harbour without my spy-glass, for the effect of my instrument is such that it makes an object fifty miglia off appear as large and near as if it were only five.”[40]

Galileo further relates in the same letter that he had presented one of his instruments to the senate, in return for which his professorship at Padua had been conferred on him for life, with an increase of salary to one thousand florins.[41]

On his return to Padua he became eagerly engrossed in telescopic observation of the heavens. The astonishing and sublime discoveries which were disclosed to him must in any case have possessed the deepest interest for the philosopher who was continually seeking to solve nature’s problems, and were all the more so, since they contributed materially to confirm the Copernican theory.

His observations were first directed to the moon, and he discovered that its surface was mountainous, which showed at all events that the earth’s satellite was something like the earth itself, and therefore by no means restored it to the aristocratic position in the universe from which it had been displaced by Copernicus. The milky way, as seen through the telescope, revealed an immense number of small stars. In Orion, instead of the seven heavenly bodies already known, five hundred new stars were seen; the number of the Pleiades, which had been fixed at seven, rose to thirty-six; the planets showed themselves as disks, while the fixed stars appeared as before, as mere bright specks in the firmament.

But the indefatigable observer’s far most important discovery,[20] in its bearing on the Copernican theory, was that of the moons of Jupiter, in January 1610. As they exhibited motions precisely similar to those which Copernicus had assumed for the whole solar system, they strongly fortified his theory. It was placed beyond all doubt that our planet was not the centre of all the heavenly bodies, since Jupiter’s moons revolved round him. The latter was brought, so to speak, by the discovery of his attendants, into relations with the earth which, considering the prevailing views, were humiliating enough, and the more so since Jupiter had four satellites while the earth had only one. There remained, however, the consoling assurance that he and they revolved round our abode!

In honour of the reigning house of his native country, and as an acknowledgment of favours received from it (for since the accession of Cosmo II.[42] Galileo had been in high favour), he called Jupiter’s moons “Medicean stars.” The urgent solicitude of the French court to gain, by Galileo’s aid, a permanent place on the chart of the heavens, is very amusing. Thus, on 20th April, 1610, he received a pressing request, “in case he discovered any other fine star, to call it after the great star of France, Henry IV., then reigning, the most brilliant in the whole universe, and to give it his proper name of Henry rather than that of the family name of Bourbon.” Galileo communicated this flattering request, as he seems to have considered it, with much satisfaction to the secretary of the Tuscan court, Vincenzo Giugni, in a letter from Padua, on 25th June, 1610,[43] as an evidence of the great importance attached to his telescopic discoveries. He added that he did not expect to find any more planets, as he had already made many very close observations.

Galileo published by degrees all the discoveries he had made at Padua, of which we have only noticed the most important, in the work before mentioned, the “Sidereus Nuncius”; it was dedicated to the Grand Duke, Cosmo II., and the first edition appeared at Venice, in March, 1610.