GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XL. May, 1852. No. 5.

Contents

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

Drawn by Deshays Engd by Tucker

SUNRISE.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XL. PHILADELPHIA, MAY, 1852. No. 5.

May has ever been the favorite month of the year in poetical description; but the praises so lavishly bestowed upon it took their rise from climates more southern than ours. In such, it really unites all the soft beauties of Spring with the radiance of Summer, and has warmth enough to cheer and invigorate, without overpowering.

May, sweet May, again is come,

May that frees the land from gloom;

Children, children! up and see

All her stores of jollity.

On the laughing hedgerow’s side

She hath spread her treasures wide;

She is in the greenwood shade,

Where the nightingale hath made

Every branch and every tree

Ring with her sweet melody:

Hill and dale are May’s own treasures,

Youths rejoice! in sportive measures

Sing ye! join the chorus gay!

Hail this merry, merry May!

Up, then, children! we will go,

Where the blooming roses grow;

In a joyful company,

We the bursting flowers will see;

Up, your festal dress prepare!

Where gay hearts are meeting, there

May hath pleasures most inviting,

Heart, and sight, and ear, delighting;

Listen to the bird’s sweet song,

Hark! how soft it floats along.

Courtly dames! our pleasures share;

Never saw I May so fair:

Therefore, dancing will we go,

Youths rejoice! the flow’rets blow!

Sing ye! join the chorus gay!

Hail this merry, merry May!

Book of the Months.

We give some further extracts, which poets, at different periods, have sung in praise of the merry month of May:

Happy the age, and harmless were the dayes

(For then true love and amity was found)

When every village did a May-pole raise,

And Whitsun-ales and May-games did abound:

And all the lusty younkers in a rout,

With merry lasses daunced the rod about;

Then friendship to their banquet bid the guests,

And poore men fared the better for their feasts.

Pasquil’s Palinodia, 1634.

From the moist meadow to the withered hill,

Led by the breeze, the vivid verdure runs,

And swells, and deepens, to the cherished eye.

The hawthorn whitens; and the juicy groves

Put forth their buds, unfolding by degrees,

Till the whole leafy forest stands displayed

In full luxuriance.

Thomson.

Each hedge is covered thick with green,

And where the hedger late hath been,

Young tender shoots begin to grow,

From out the mossy stumps below.

But woodmen still on Spring intrude,

And thin the shadow’s solitude,

With sharpened axes felling down,

The oak-trees budding into brown;

Which, as they crash upon the ground,

A crowd of laborers gather round,

These mixing ’mong the shadows dark,

Rip off the crackling, staining bark;

Depriving yearly, when they come,

The green woodpecker of his home;

Who early in the Spring began,

Far from the sight of troubling man,

To bore his round holes in each tree,

In fancy’s sweet security;

Now startled by the woodman’s noise,

He wakes from all his dreamy joys.

Clark.

The sun is up, and ’tis a morn of May

Round old Ravenna’s clear-shown towers and bay—

A morn, the loveliest which the year has seen,

Last of the Spring, yet fresh with all its green;

For a warm eve, and gentle rains at night,

Have left a sparkling welcome for the light;

And there’s a crystal clearness all about;

The leaves are sharp, the distant hills look out,

A balmy briskness comes upon the breeze,

The smoke goes dancing from the cottage trees;

And when you listen you may hear a coil

Of bubbling springs about the grassy soil;

And all the scene, in short—sky, earth and sea,

Breathes like a bright-eyed face that laughs out openly.

Leigh Hunt.

I know where the young May violet grows,

In its lone and lowly nook,

On the mossy bank where the larch tree throws

Its broad dark boughs in solemn repose,

Far over the silent brook.

Bryant.

———

BY HENRY WILLIAM HERBERT, AUTHOR OF “FRANK FORESTER’S FIELD SPORTS,” “FISH AND FISHING,” ETC.

———

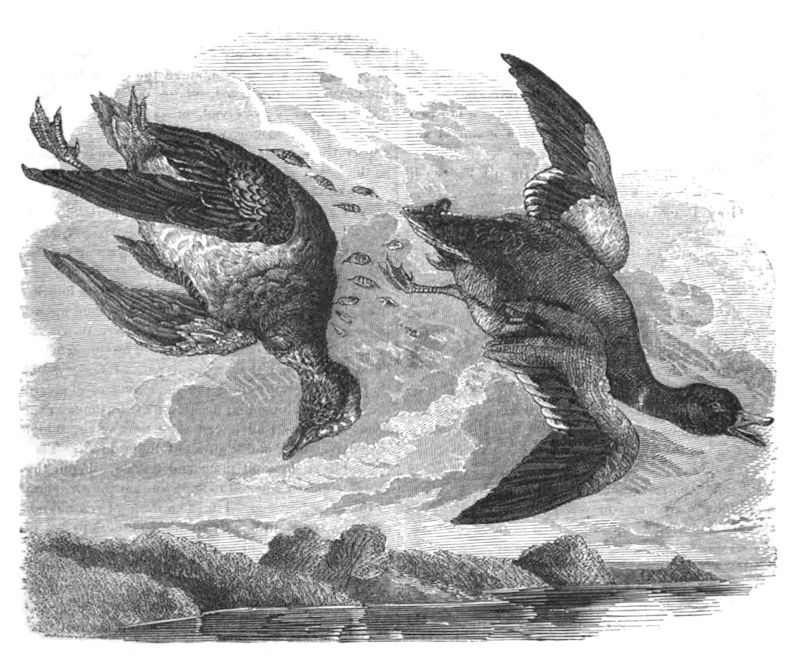

THE MALLARD. Anas Boschas. Green-head, Gray-duck.

THE AMERICAN WIDGEON. Anas Americana. Bald-pate.

Both these beautiful ducks, perhaps, with the exception of the lovely Summer Duck, or Wood Duck, Anas Sponsa, the most beautiful of all the tribe, are along the seaboard of the Northern States somewhat rare of occurrence, being for the most part fresh water species, and when driven by stress of weather, and the freezing over of the inland lakes and rivers which they frequent, repairing to the estuaries and land-locked lagoons of the Southern coasts and rivers, as well as to the tepid pools and warm sources of Florida, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama and Louisiana, in all of which States they swarm during the summer months.

On many of the inland streams and pools of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and the Far West in general, including all the bays, shallows and tributaries of the Great Lakes, as well as all the lovely smaller lakes of New York, especially where the wild-rice, or wild-oat, zizania aquatica, is plentiful, they are found in very great numbers, especially in the spring and summer time, nor are they unfrequently killed on the snipe-grounds of New Jersey, around Chatham, Pine-brook, and the Parcippany meadows on the beautiful Passaic, and on the yet more extensive grounds on the Seneca and Cayuga outlets, in the vicinity of Montezuma Salina, and the salt regions of New York.

In the shallows of the lake and river St. Clair, above Detroit, on the rivière aux Canards, and the marshes of Chatham in Canada East, all along the shores of Lake Erie on the Canadian side, especially about Long Point, and in the Grand River, they literally swarm; while in all the rivers, and shallow rice-lakes on the northern shores of Lake Huron, which are the breeding-places of their countless tribes, they are found, from the breaking up of the ice to the shutting up of the bays and coves in which they feed, in numbers absolutely numberless.

The Mallard is generally believed to be the parent and progenitor of the domestic duck, which, although far superior in beauty of plumage and grace of form and deportment, it very closely resembles; yet when or where it was domesticated, is a question entirely dark and never to be settled. It is certain that the domestic duck was unknown to the Greeks and Romans, so late as to the Christian era, although the paintings in the Egyptian tombs demonstrate beyond a peradventure that it was familiar to that wonderful people from a very remote period; as it is also known to have been among the Chinese, who rear and cultivate them to a very great extent. Indeed, it is I think in the highest degree probable that the Duck, in its domestic state, is an importation into Europe from the East, where, as I believe in every quarter of the globe, the Mallard is a common and indigenous native of the fresh waters.

The Mallard, or wild drake, commonly known in the Eastern States as the Green-head, westward as the Gray Duck, and in Alabama as the English Duck, weighs from thirty-six to forty ounces, and measures twenty-three inches in length, by thirty-five in breadth.

The bill is of a yellowish-green color, not very flat, about an inch broad, and two and a half long from the corners of the mouth to the tip of the nail; the head and upper half of the neck are of a deep, glossy, changeable green, terminated in the middle of the neck by a white collar, with which it is nearly encircled; the lower parts of the neck, breast and shoulders are of a deep, vinous chestnut; the covering scapular feathers are of a kind of silvery-white, those underneath rufous, and both are prettily crossed with small, waved threads of brown. Wing coverts ash, quills brown, and between these intervenes the speculum, or beauty spot, common in the duck tribe, which crosses the wing in a transverse, oblique direction. It is of a rich, glossy purple, with violet or green reflections, and bordered by a double streak of sooty black and pure white. The belly is of a pale gray, delicately crossed and penciled with numberless narrow, waved, dusky lines, which on the sides and long feathers that cover the thighs are more strongly and distinctly marked. The upper and under tail coverts, lower part of the back and rump, are black, the latter glossed with green; the four middle tail feathers are also black, with purple reflections, and, like those of the domestic duck, are stiffly curled upward. The rest are sharp-pointed, and fade off to the exterior edges from brown to dull white. Iris of the eye bright yellow, feet, legs and webs reddish-orange, claws black.

The female, and young male until after the first moult, is very different in plumage from the adult drake, partaking none of his beauties, with the exception of the spot on the wings. All the other parts are plain brown, marked with black, the centre of every feather being dark and fading to the edges. She makes her nest, lays her eggs—from ten to sixteen in number, of a greenish white—generally in the most sequestered mosses or bogs, far from the haunts of man, and hidden from his sight among reeds and rushes. To her young, helpless, unfledged family, and they are nearly three months before they can fly, she is a fond, attentive and watchful parent, carrying or leading them from one pool to another, as her fears or inclinations direct her, and she is known to use the same wily stratagems, in order to mislead the sportsman and his dog, as those resorted to by the ruffed grouse, the quail and the woodcock, feigning lameness, and fluttering, as if helplessly wounded, along the surface of the water, until she has lured the enemy afar from her skulking and terrified progeny.

The Mallard is rarely or never shot to decoys, or stools as they are termed, since these are but little used except on the coast, where this duck is, as I have previously observed, of rare occurrence, although it is occasionally found in company with the Dusky Duck, anas obscura, better known to gunners as the Black Duck.

“Like the Dusky Duck,” says Mr. Giraud, in his very clever and agreeable manual on the birds of Long Island, “when pursued by the sportsman, it becomes shy and feeds at night, dozing away the day out of gun-shot from the shore.

“Early in the month of July, 1837, while hunting over the meadows for smaller game, I came upon a pair of Mallard Ducks, moving slowly down the celebrated ‘Brick-house creek.’ The thought occurred to me that they were a pair of tame ducks that had become tired of the monotony of domestic life, and determined on pushing their fortunes in the broad bay. As I advanced they took wing, which undeceived me, and I brought them down. They proved to be an adult male and female. From this circumstance I was led to suppose that they had bred in the neighborhood. I made a diligent search, and offered a sufficient bounty to induce others to search with me—but neither nest nor young could be found. Probably when migrating, they were shot at and so badly wounded as to be unable to perform their fatiguing journey, perhaps miles apart, and perchance only found companions in each other a short time before I shot them.”

When the young birds are about three-fourths grown, and not as yet fully fledged or able to fly strongly, at which age they are termed flappers, they afford excellent sport over water-spaniels, when they are abundant in large reed beds along the brink of ponds and rivers. When full grown, moreover, when they frequent parts of the country where the streams are narrow and winding, great sport can be had with them at times, by walking about twenty yards wide of the brink and as many in advance of an attendant, who should follow all the windings of the water and flush the birds, which springing wild of him will so be brought within easy range of the gun.

The Mallard is wonderfully quick-sighted and sharp of hearing, so that it is exceedingly difficult to stalk him from the shore, especially by a person coming down wind upon him, so much so that the acuteness of his senses has given rise to a general idea that he can detect danger to windward by means of his olfactory nerves. This is, however, disproved by the observations of that excellent sportsman and pleasant writer, John Colquhoun of Luss, as recorded in that capital work, “The Moor and the Loch,” who declares decidedly, that although ducks on the feed constantly detect an enemy crawling down upon them from the windward, will constantly, when he is lying in wait, silent and still, and properly concealed, sail down upon him perfectly unsuspicious, even when a strong wind is blowing over him full in their nostrils.

For duck shooting, whether it be practiced in this fashion, by stalking them from the shore while feeding in lakelets or rivers, by following the windings of open and rapid streams in severe weather, or in paddling or pushing on them in gunning-skiffs, as is practiced on the Delaware, a peculiar gun is necessary for the perfection of the sport. To my taste, it should be a double-barrel from 33 to 36 inches in length, at the outside, about 10 gauge, and 10 pounds weight. The strength and weight of the metal should be principally at the breech, which will answer the double purpose of causing it to balance well and of counteracting the call. Such a gun will carry from two to three ounces of No. 4 shot, than which I would never use a larger size for duck, and with that load and an equal measure of very coarse powder—Hawker’s ducking-powder, manufactured by Curtis and Harvey, is the best in the world, and can be procured of Mr. Brough, in Fulton Street, New York—will do its work satisfactorily and cleanly at sixty yards, or with Eley’s green, wire cartridges, which will permit the use of shot one size smaller, at thirty yards farther. The utility of these admirable projectiles can hardly be overrated, next to the copper-cap, of which Starkey’s water-proof, central-fire, is the best form, I regard them as the greatest of modern inventions in the art of gunnery.

Such a gun as I describe can be furnished of first-rate quality by Mr. John Krider of Philadelphia, Mr. John, or Patrick Mullin of New York, or Mr. Henry T. Cooper of the same city, ranging in price, according to finish, from one hundred to one hundred and fifty dollars, of domestic manufacture; and I would strongly recommend sportsmen, requiring such an implement, to apply to one of these excellent and conscientious makers, rather than even to import a London gun, much more than to purchase at a hazard the miserable and dangerous Birmingham trash, manufactured of three-penny skelp or sham drawn-iron, got up in handsome, velvet-lined mahogany cases, and tricked out with varnish and gimcrackery expressly for the American market, such as are offered for sale at every hardware shop in the country.

The selling of such goods ought to be made by law a high misdemeanor, and a fatal accident occurring by their explosion should entail on the head of the sender the penalty of willful murder.

The Mallard is found frequently associating in large plumps with the Pintail, or Sprigtail, another elegant fresh water variety, the Dusky-Duck on fresh waters, the Greenwinged Teal in winter to the southward, and with the Widgeon on the western waters.

On the big and little pieces—two large moist savannas on the Passaic river in New Jersey, formerly famous for their snipe and cock grounds, but now ruined by the ruthless devastations of pot-hunters and poachers—I have shot Mallard, Pintail, and Black Duck, over dead points from setters, out of brakes, in which they were probably preparing to breed, during early snipe-shooting; but nowhere have I ever beheld them in such myriads as in the small rice-lakes on the Severn, the Wye, and the cold water rivers debouching into the northern part of lake Huron, known as the Great Georgian Bay, and on the reed-flats and shallows of Lake St. Clair, in the vicinity of Alganac, and the mouths of the Thames and Chevail Ecarté rivers.

I am satisfied that by using well made decoys, or stools, and two canoes, one concealed among the rice and reeds, and the other paddling to and fro, to put up the teams of wild fowl and keep them constantly on the move, such sport might be had as can be obtained in no other section of this country, perhaps of the world; and that the pleasure would well repay the sportsman for a trip far more difficult and tedious, than the facilities afforded by the Erie Rail-road and the noble steamers on the lakes now render a visit to those glorious sporting-grounds.

The American Widgeon, the bird which is represented as falling headforemost with collapsed wings, shot perfectly dead without a struggle, in the accompanying woodcut, while the Mallard goes off safely, quacking at the top of his voice in strange terror, though nearly allied to the European species, is yet perfectly distinct, and peculiar to this continent.

It is thus accurately described by Mr. Giraud, although but an unfrequent visitor of the Long Island bays and shores:

“Bill short, the color light grayish blue; speculum green, banded with black. Under wing coverts white. Adult male with the coral space, sides of the head, under the eye, upper part of the neck and throat brownish white, spotted with black. A broad band of white, commencing at the base of the upper mandible, passing over the crown.” It is this mark which has procured the bird its general provincial appellation of “Baldpate.” “Behind the eye a broad band of bright green, extending backward on the hind neck about three inches; the feathers on the nape rather long; lower neck and sides of the breast, with a portion of the upper part of the breast reddish brown. Rest of the lower parts white, excepting a patch of black at the base of the tail. Under tail coverts the same color. Flanks brown, barred with dusky; lower part of the hind neck and fore part of the back undulated with brownish and light brownish red, hind part undulated with grayish white; primaries brown; outer webs of the inner secondaries black, margined with white—inner webs grayish brown; secondary coverts white, tipped with black; speculum brilliant green formed by the middle secondaries. Length twenty-one inches, wing ten and a half. Female smaller, plumage duller, without the green markings.”

The Widgeon breeds in the extreme north, beyond the reach of the foot of civilised man, in the boundless mosses and morasses, prodigal of food and shelter, of Labrador, and Boothia Felix, and the fur countries, where it spends the brief but ardent summer in the cares of nidification, and the reproduction of its species.

During the spring and autumn, it is widely distributed throughout the Union, from the fresh lakes of the northwest to the shores of the ocean, but it is most abundant, as well as most delicious where the wild rice, Zizania pannicula effusa, the wild celery, balisneria Americana, and the eel-grass, Zostera marina, grow most luxuriously. On these it fares luxuriously, and becomes exceedingly fat, and most delicate and succulent eating, being almost entirely a vegetable feeder, and as such devoid of any fishy or sedgy flavor.

In the spring and autumn it is not unfrequently shot in considerable numbers, from skiffs, on the mud banks of the Delaware, in company with Blue-winged Teal; and in winter it congregates in vast flocks, together with Scaups, better known as Bluebills, or Broadbills, Redheads, and Canvasbacks, to which last it is a source of constant annoyance, since being a far less expert diver than the Canvasback, it watches that bird until it rises with the highly-prized root, and flies off with the stolen booty in triumph.

The Widgeon, like the Canvasback, can at times be toled, as it is termed, or lured within gunshot of sportsmen, concealed behind artificial screens of reeds, built along the shore, or behind natural coverings, such as brakes of cripple or reed-beds, by the gambols of dogs taught to play and sport backward and forward along the shore, for the purpose of attracting the curious and fascinated wild fowl within easy shooting distance. And strange to say, so powerful is the attraction that the same flock of ducks has been known to be decoyed into gunshot thrice within the space of a single hour, above forty birds being killed at the three discharges. Scaups, or Blackheads, as they are called on the Chesapeake tole, it is said, more readily than any other species, and next to these the Canvasbacks and Redheads; the Baldpates being the most cautious and wary of them all, and rarely suffering themselves to be decoyed, except when in company with the Canvasbacks, along with which they swim shoreward carelessly, though without appearing to notice the dog.

These birds, with their congeners, are also shot from points, as at Carrol’s Island, Abbey Island, Maxwell’s Point, Legoe’s Point, and other places in the same vicinity about the Bush and Gunpowder rivers, while flying over high in air; and so great is the velocity of their flight when going before the wind, and such the allowance that must be made in shooting ahead of them, that the very best of upland marksmen are said to make very sorry work of it, until they become accustomed to the flight of the wild fowl. They are also shot occasionally in vast numbers at holes in the ice which remain open when the rest of the waters are frozen over; and yet again, by means of swivel guns, carrying a pound of shot or over, discharged from the bows of a boat, stealthily paddled into the flocks at dead of night, when sleeping in close columns on the surface of the water. This method is, however, much reprobated by sportsmen, and that very justly, as tending beyond any other method to cause the fowl to desert their feeding-grounds.

In conclusion, we earnestly recommend both these beautiful birds to our sporting readers, both as objects of pleasurable pursuit and subjects of first rate feeds. A visit at this season to Seneca Lake, the Montezuma Meadows, or that region, could not fail to yield rare sport.

———

BY MISS MATTIE GRIFFITH.

———

Deep in my heart there is a sacred urn

I ever guard with holiest care, and keep

From the cold world’s intrusion. It is filled

With dear and lovely treasures, that I prize

Above the gems that sparkle in the vales

Of Orient climes or glitter in the crowns

Of sceptered kings.

The priceless wealth of life

Within that urn is gathered. All the bright

And lovely jewels that the years have dropped

Around me from their pinions, in their swift

And noiseless flight to old Eternity,

Are treasured there. A thousand buds and flowers

That the cool dews of life’s young morning bathed,

That its soft gales fanned with their gentle wings,

And that its genial sunbeams warmed to life

And fairy beauty ’mid the melodies

Of founts and singing birds, lie hoarded there,

Dead, dead, forever dead, but oh, as bright

And beautiful to me as when they beamed

With Nature’s radiant jewelry of dew.

And they have more than mortal sweetness now,

For the dear breath of loved ones, loved and lost,

Is mingling with their holy perfume.

Like

A very miser, day and night I hide

The hoarded riches of my dear heart-urn.

Oft at the midnight’s calm and silent hour,

When not a tone of living nature seems

To rise from all the lone and sleeping earth,

I lift the lid softly and noiselessly,

Lest some dark, wandering spirit of the air

Perchance should catch with his quick ear the sound.

And steal my treasures. With a glistening eye

And leaping pulse, I tell them o’er and o’er,

Musing on each, and hallow it with smiles

And tears and sighs and fervent blessings.

Then,

With soul as proud as if yon broad blue sky

With all its bright and burning stars were mine.

But with a saddened heart, I close the lid,

And once again return to busy life,

To play my part amid its mockeries.

———

BY FREDERIKA BREMER.

———

It was a most glorious afternoon! The air was delightful. The sun shone with the softest splendor upon the green cultivated meadow-land, divided into square fields, each inclosed with its quick-set fence; and within these, small farm-houses and cottages with their gardens and vine-covered walls. It was altogether a cheerful and lovely scene. Westward, in the far distance, raised themselves the mist-covered Welsh mountains. For the rest, the whole adjacent country resembled that which I had hitherto seen in England, softly undulating prairie. There will come a time when the prairies of North America will resemble this country. And the work has already begun there in the square allotments, although on a larger scale than here; the living fences, the well-to-do farm-houses, they already look like birds’-nests on the green billows; for already waves the grass there with its glorious masses of flowers, over immeasurable, untilled fields, and the sunflowers nod and beckon in the breeze as if they said: “Come,—come, ye children of men! The board is spread for many!”

The glorious flower-spread table, which can accommodate two hundred and fifty millions of guests! May it with its beauty one day unite more true happiness than at this time the beautiful landscape of England. For it is universally acknowledged, that the agricultural districts of England are at this time in a much more dubious condition than the manufacturing districts, principally from the fact of the large landed proprietors having, as it were, swallowed up the small ones; and of the landed possession being amassed in but few hands, who thus cannot look after it excepting through paid stewards, and this imperfectly. I heard of ten large landed proprietors in a single family of but few individuals: hence the number of small farmers who do not themselves possess land, and who manage it badly, as well as the congregating of laborers in houses and cottages. The laws also for the possession of land are so involved, and so full of difficulty, that they throw impediments in the way of those who would hold and cultivate it in much smaller lots.

The young barrister, Joseph Kay, has treated this subject explicitly and fully, in his lately published work “On the Social Condition and Education of the People.”

I, however, knew but little of this canker-worm at the vitals of this beautiful portion of England, at the time when I thus saw it, and therefore I enjoyed my journey with undivided pleasure.

In the evening, before sunset, I stood before Shakspeare’s house.

“It matters little being born in a poultry-yard, if one only is hatched from a swan’s egg!” thought I, in the words of Hans Christian Andersen, in his story of “The Ugly Duckling,” when I beheld the little, unsightly, half-timbered house in which Shakspeare was born; and went through the low, small rooms, up the narrow wooden stairs, which were all that was left of the interior. It was empty and poor, except in memory; the excellent little old woman who showed the house, was the only living thing there. I provided myself with some small engravings having reference to Shakspeare’s history, which she had to sell, and after that set forth on a solitary journey of discovery to the banks of the Avon; and before long, was pursuing a solitary footpath which wound by the side of this beautiful little river. To be all at once removed from the thickly populated, noisy manufacturing towns into that most lovely, most idyllic life, was in itself something enchanting. Add to this the infinite deliciousness of the evening; the pleasure of wandering thus freely and alone in this neighborhood, with all its rich memories; the deep calm that lay over all, broken only by the twittering of the birds in the bushes, and the cheerful voices of children at a distance; the beautiful masses of trees, cattle grazing in the meadows; the view of the proud Warwick Castle, and near at hand the little town, the birthplace of Shakspeare, and his grave, and above all, the romantic stream, the bright Avon, which in its calm winding course seemed, like its poet-swan—the great Skald—to have no other object than faithfully to reflect every object which mirrored itself in its depths; castles, towns, churches, cottages, woods, meadows, flowers, men, animals. This evening and this river, and this solitary, beautiful ramble shall I never forget, never! I spent no evening more beautiful whilst in England.

It was not until twilight settled down over the landscape that I left the river-side. When I again entered the little town, I was struck by its antique character as well in the people as in the houses; it seemed to me that the whole physiognomy of the place belonged to the age of Shakspeare. Old men with knee-breeches, old women in old-fashioned caps, who with inquisitive and historical countenances, furrowed by hundreds of wrinkles, now gazed forth from their old projecting door-ways; thus must they have stood, thus must they have gazed when Shakspeare wandered here; and he, the black-garmented, hump-backed old man who looked so kind, so original and so learned, just like an ancient chronicle, and who saluted me, the stranger, as people are not in the habit of doing now-a-days—he must certainly be some old rector magnificus who has returned to earth from the sixteenth century. Whilst I was thus dreaming myself back again into the times of old, a sight met my eyes which transported me five thousand miles across the ocean, to the poetical wilderness of the new world. This was a full-blown magnolia-flower, just like a magnolia grandiflora, and here blossomed on the walls of an elegant little house, the whole of whose front was adorned by the branches and leaves of a magnolia reptans, a species with which I was not yet acquainted. I hailed with joy the beautiful flower which I had not seen since I had wandered in the magnolia groves of Florida, on the banks of the Welaka, (St. John,) and drank the morning dew as solitary as now.

Every thing in that little town was, for the rest, à la Shakspeare. One saw on all sides little statues of Shakspeare, some white, others gilt—half-length figures—and very much resembling idol images. One saw Shakspeare-books, Shakspeare-music, Shakspeare-engravings, Shakspeare articles of all kinds. In one place I even saw Shakspeare-sauce announced; but that did not take my fancy, as I feared it might be too strong for my palate. True, one saw at the same place an announcement of Jenny Lind-drops, and that did take my fancy very much, for as a Swede, I was well pleased to see the beautiful fame of the Swedish singer recognized in Shakspeare’s town, and having a place by the side of his.

Arrived at my inn, close to Shakspeare’s house: I drank tea; was waited upon by an agreeable girl, Lucy, and passed a good night in a chamber which bore the superscription “Richard the Third.” I should have preferred as a bed-room “The Midsummer Night’s Dream,” a room within my chamber, only that it was not so good, and Richard the Third did me no harm.

I wandered again on the banks of the Avon on the following morning, and from a height beheld that cheerful neighborhood beneath the light of the morning sun. After this I visited the church in which were interred Shakspeare and his daughter Susanna. A young bridal couple were just coming out of church after having been married, the bride dressed in white and veiled, so that I could not see her features distinctly.

The epitaph on Shakspeare’s grave, composed by himself, is universally known, with its strong concluding lines—

“Blessed be the man that spares these stones,

And cursed be he that moves my bones.”

Less generally known is the inscription on the tomb of his daughter Susanna, which highly praises her virtues and her uncommon wit, and which seems to regard Shakspeare as happy for having such a daughter. I thought that Susanna Shakspeare ought to have been proud of her father. I have known young girls to be proud of their fathers—the most beautiful pride which I can conceive, because it is full of humble love. And how well it became them!

For the rest, it was not as a fanatical worshiper of Shakspeare that I wandered through the scene of his birth and his grave. I owe much to this great dramatist; he has done much for me, but—not in the highest degree. I know of nobler grouping, loftier characters and scenes, in especial a greater drama of life than any which he has represented, and particularly a higher degree of harmony than he has given; and as I wandered on the banks of the Avon, I seemed to perceive the approach of a new Shakspeare, the new poet of the age, to the boards of the world’s stage; the poet who shall comprehend within the range of his vision all parts of the earth, all races of men, all regions of nature—the palms of the tropics, the crystal palaces of the polar circle—and present them all in a new drama, in the large expression and the illuminating light of a vast human intelligence.

Shakspeare, great as he is, is to me, nevertheless, only a Titanic greatness, an intellectual giant-nature, who stands amid inexplicable dissonance. He drowns Ophelia, and puts out the eyes of the noble Kent, and leaves them and us to our darkness. That which I long for, that which I hope for, is a poet who will rise above dissonances, a harmonious nature who will regard the drama of the world with the eye of Deity; in a word, a Shakspeare who will resemble a—Beethoven.

On my way from Stratford to Leamington I stopped at Warwick Castle, one of the few old castles of the middle ages in England which still remain well-preserved, and which are still inhabited by the old hereditary families. The old Earl of Warwick resides now quite alone in his splendid castle, his wife having been dead about six months. Two days in the week he allows his castle to be thrown open for a few hours for the gratification of the curiosity of strangers. It is in truth a magnificent castle, with its fortress-tower and its lofty gray stone walls, surrounded by a beautiful park, and gloriously situated on the banks of the Avon—magnificent, and romantically beautiful at the same time.

In the rooms prevailed princely splendor, and there were a number of good pictures, those of Vandyke in particular. I remarked several portraits of Charles the First, with his cold, gloomy features; several also of the lovely but weak Henrietta Maria; one of Cromwell, a strong countenance, but without nobility; one of Alba, with an expression harder than flint-stone—a petrified nature; and one of Shakspeare, as Shakspeare might have appeared, with an eye full of intense thought, a broad forehead, a countenance elaborated and tempered in the fires of strong emotion; not in the least resembling that fat, jolly, aldermanic head usually represented as Shakspeare’s.

The rooms contained many works of art, and from the windows what glorious views! In truth, thought I, it is pardonable if the proprietor of such a castle, inherited from brave forefathers, and living in the midst of scenes rich in great memories, with which the history of his family is connected—it is pardonable if such a man is proud.

“There he goes!—the Earl!” said the man who was showing me through the rooms; and, looking through a window into the castle-court, I saw a tall, very thin figure, with white hair, and dressed in black, walking slowly, with head bent forward, across the grass-plot in the middle of the court. That was the possessor of this proud mansion, the old Earl of Warwick!

———

BY THOMAS MILNER, M. A.

———

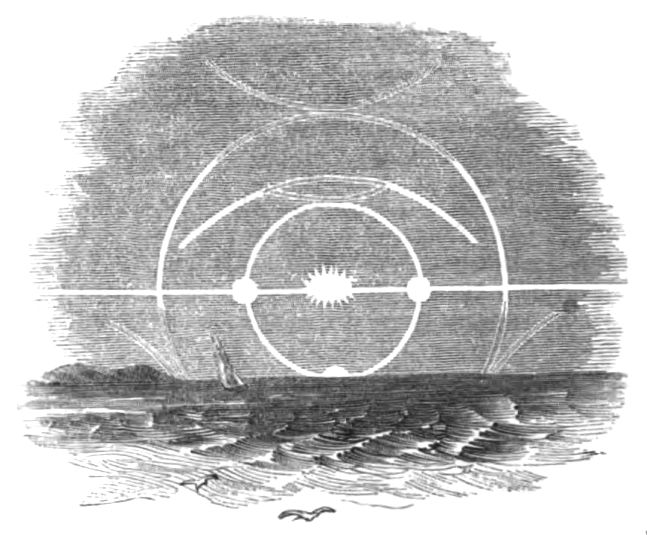

Parhelia.

Parhelia. Mock suns, in the vicinity of the real orb, are due to the same cause as haloes, which appear in connection with them. Luminous circles, or segments, crossing one another, produce conspicuous masses of light by their united intensities, and the points of intersection appear studded with the solar image. This is a meteorological rarity in our latitude, but a very frequent spectacle in the arctic climes. In Iceland, during the severe winter of 1615, it is related that the sun, when seen, was always accompanied by two, four, five, and even nine of these illusions. Captain Parry describes a remarkably gorgeous appearance, during his winter sojourn at Melville Island, which continued from noon until six o’clock in the evening. It consisted of one complete halo, 45° in diameter, with segments of several others, displaying in parts the colors of the rainbow. Besides these, there was another perfect ring of a pale white color, which went right round the sky, parallel with the horizon, and at a distance from it equal to the sun’s altitude; and a horizontal band of white light appeared passing through the sun. Where the band and the inner halo cut each other, there were two parhelia, and another close to the horizon, directly under the sun, which formed the most brilliant part of the spectacle, being exactly like the sun, slightly obscured by a thin cloud at his rising or setting. A drawing of this parhelion is given by Captain Parry, who remarks upon having always observed such phenomena attended with a little snow falling, or rather small spicula or fine crystals of ice. The angular forms of the crystals determine the rays of light in different directions, and originate the consequent visual variety. We have various observations of parhelia seen in different parts of Europe, which in a less enlightened age excited consternation, and were regarded as portentous. Matthew Paris relates in his history:—“A wonderful sight was seen in England, A. D. 1233, April 8, in the fifth year of the reign of Henry III., and lasted from sunrise till noon. At the same time on the 8th of April, about one o’clock, in the borders of Herefordshire and Worcestershire, besides the true sun, there appeared in the sky four mock suns of a red color; also a certain large circle of the color of crystal, about two feet broad, which encompassed all England as it were. There went out semicircles from the side of it, at whose intersection the four mock suns were situated, the true sun being in the east, and the air very clear. And because this monstrous prodigy cannot be described by words, I have represented it by a scheme, which shows immediately how the heavens were circled. The appearance was painted in this manner by many people, for the wonderful novelty of it.”

Paraselenæ. Mock moons, depending upon the causes which produce the solar image, or several examples of it, as frequently adorn the arctic sky. On the 1st of December, 1819, in the evening, while Parry’s expedition was in Winter Harbor, four paraselenæ were observed, each at the distance of 21½° from the true moon. One was close to the horizon, the other perpendicular above it, and the other two in a line parallel to the horizon. Their shape was like that of a comet, the tail being from the moon, the side of each toward the real orb being of a light orange color. During the existence of these paraselenæ, a halo appeared in a concentric circle round the moon, passing through each image. On the evening of March 30, 1820, about ten o’clock, the attention of Dr. Trail, at Liverpool, was directed by a friend to an unusual appearance in the sky, which proved to be a beautiful display of paraselenæ. The moon was then 35° above the southern horizon. The atmosphere was nearly calm, but rather cloudy, and obscured by a slight haze. A wide halo, faintly exhibiting the prismatic colors, was described round the moon as a centre, and had a small portion of its circumference cut off by the horizon. The circular band was intersected by two small segments of a larger circle, which if completed would have passed through the moon, and parallel to the horizon. These segments were of a paler color than the first mentioned circle. At the points of intersection appeared two pretty well defined luminous discs, equaling the moon in size, but less brilliant. The western paraselenæ had a tail or coma, which was directed from the moon, and the eastern also, but less clearly-defined.

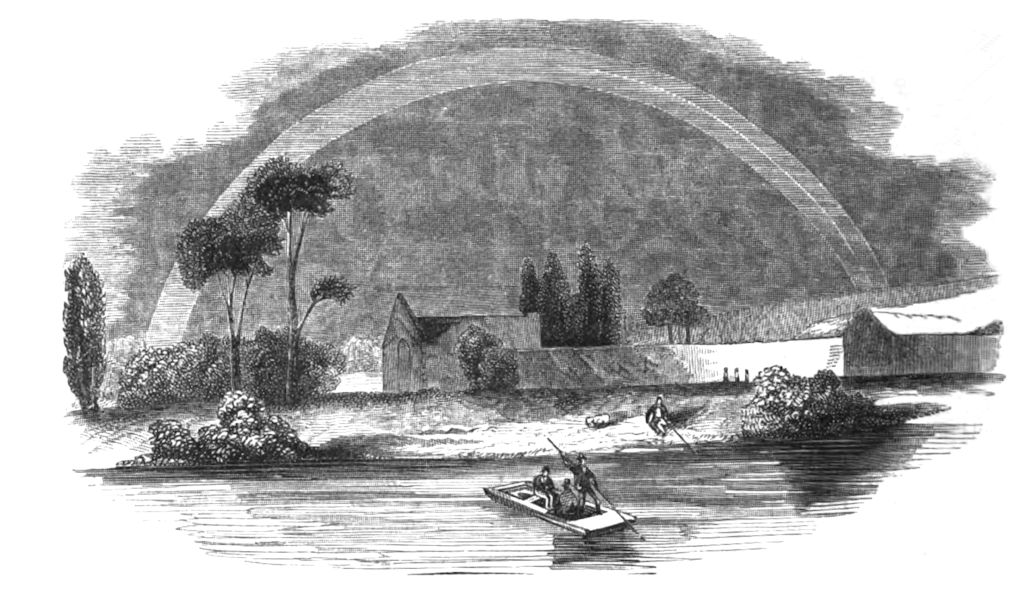

The Rainbow. The most glorious vision depending upon the decomposition, refraction, and reflection of light, by the vapor of the atmosphere reduced to fluid drops, is the well-known arch projected during a shower of rain upon a cloud opposite to the sun, displaying all the tints of the solar spectrum. The first marked approximation to the true theory of the rainbow occurs in a volume entitled De Radiis Visus et Lucis, written by Antonius de Dominis, Archbishop of Spalatro, published in the year 1611 at Venice. Descartes pursued the subject, and correctly explained some of the phenomena; but upon Newton’s discovery of the different degrees of refrangibility in the different colored rays which compose the sunbeam, a pencil of white or compounded light, the cause of the colored bands in the rainbow, of the order of their position, and of the breadth they occupy, was at once apparent. The bow is common to all countries, and is the sign of the covenant of promise to all people, that there shall no more be such a wide-spread deluge as that which the sacred narrative records.

“But say, what mean those colored streaks in heaven

Distended, as the brow of God appeased?

Or serve they, as a flowery verge to bind

The fluid skirts of that same watery cloud,

Lest it again dissolve, and shower the earth?

To whom the Archangel: Dexterously thou aim’st;

So willingly doth God remit his ire—

That he relents, not to blot out mankind;

And makes a covenant never to destroy

The earth again by flood; nor let the sea

Surpass its bounds; nor rain to drown the world,

With man therein, or beast; but when he brings

O’er the earth a cloud, will therein set

His triple-colored bow, whereon to look,

And call to mind his covenant.”

It is happily remarked by Mr. Prout, in his Bridgewater Treatise, that no pledge could have been more felicitous or satisfactory; for, in order that the rainbow may appear, the clouds must be partial, and hence its existence is absolutely incompatible with universal deluge from above. So long, therefore, as “He doth set his bow in the clouds,” so long have we full assurance that these clouds must continue to shower down good, and not evil, to the earth.

Rainbow.

When rain is falling, and the sun is on the horizon, the bow appears a complete semicircle, if the rain-cloud is sufficiently extensive to display it. Its extent diminishes as the solar altitude increases, because the colored arch is a portion of a circle whose centre is a point in the sky directly opposite to the sun. Above the height of 45° the primary bow is invisible, and hence, in our climate, the rainbow is not seen in summer about the middle of the day. In peculiar positions a complete circle may be beheld, as when the shower is on a mountain, and the spectator in a valley; or when viewed from the top of a lofty pinnacle, nearly the whole circumference may sometimes be embraced. Ulloa and Bouguer describe circular rainbows, frequently seen on the mountains, which rise above the table-land of Quito. When rain is abundant, there is a secondary bow distinctly seen, produced by a double reflection. This is exterior to the primary one, and the intervening space has been observed to be occupied by an arch of colored light. The secondary bow differs from the other, in exhibiting the same series of colors in an inverted order. Thus the red is the uppermost color in the interior bow, and the violet in the exterior. A tertiary bow may exist, but it is so exceedingly faint from the repeated reflections, as to be scarcely ever perceptible. The same lovely spectacle may be seen when the solar splendor falls upon the spray of the cataract and the waves, the shower of an artificial fountain, and the dew upon the grass. There is hardly any other object of nature more pleasing to the eye, or soothing to the mind, than the rainbow, when distinctly developed—a familiar sight in all regions, but most common in mountainous districts, where the showers are most frequent. Poetry has celebrated its beauty, and to convey an adequate representation of its soft and variegated tints, is the highest achievement of the painter’s art. While the Hebrews called it the Bow of God, on account of its association with a divine promise, and the Greeks the Daughter of Wonder, the rude inhabitants of the North gave expression to a fancy which its peculiar aspect might well create, styling it the Bridge of the Gods, a passage connecting heaven and earth.

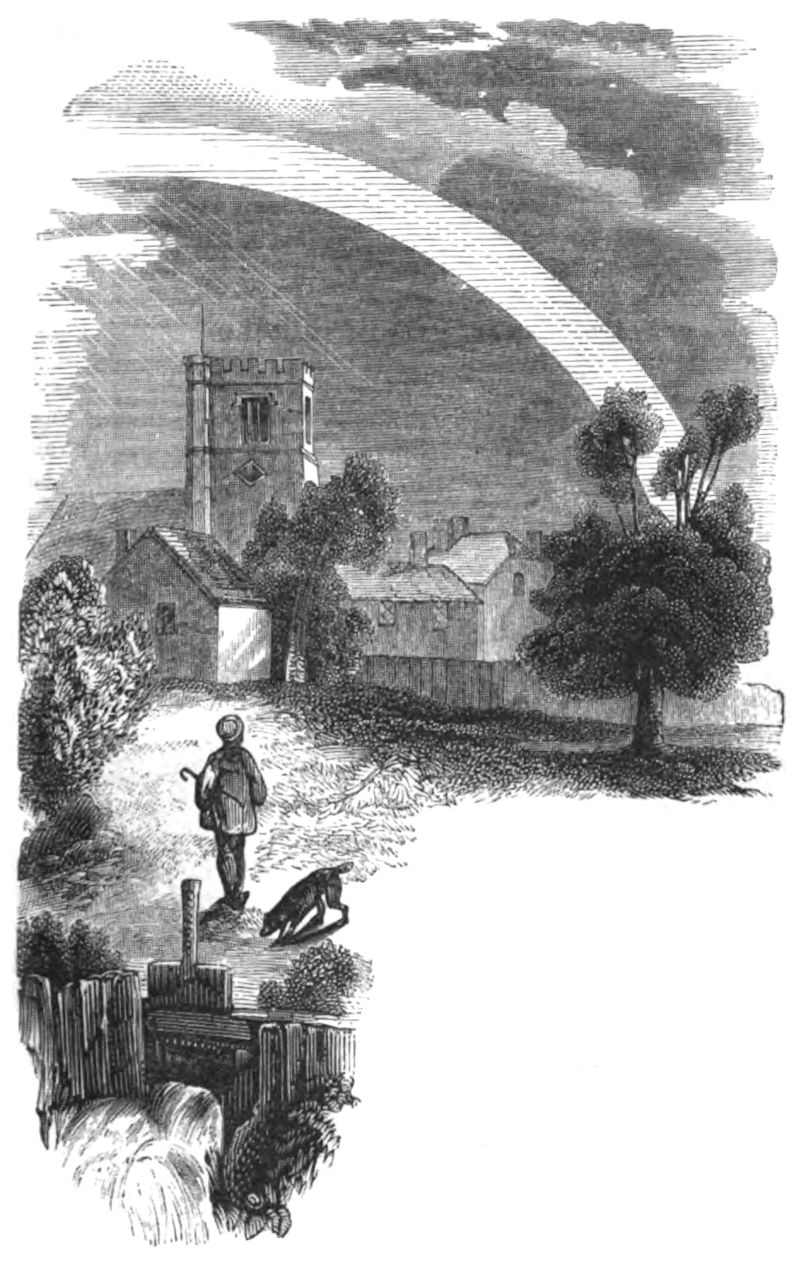

Lunar Rainbow.

The principles which account for the formation of the rainbow explain the appearance of beautiful irridescent arches which have occasionally been observed during the prevalence of mist and sunshine. Mr. Cochin describes a spectacle of this kind, noticed from an eminence that overlooked some low meadow-grounds, in a direction opposite to that of the sun, which was shining very brightly, a thick mist resting upon the landscape in front. At about the distance of half a mile from each other, and incurvated, like the lower extremities of the common rainbow, two places of peculiar brightness were seen in the mist. They seemed to rest on the ground, were continued as high as the fog extended, the breadth being nearly half as much more as that of the rainbow. In the middle between these two places, and on the same horizontal line, there was a colored appearance, whose base subtended an angle of about 12°, and whose interior parts were thus variegated. The centre was dark, as if made by the shadow of some object resembling in size and shape an ordinary sheaf of corn. Next this centre there was a curved space of a yellow flame color. To this succeeded another curved space of nearly the same dark cast as the centre, very evenly bounded on each side, and tinged with a faint blue green. The exterior exhibited a rainbow circlet, only its tints were less vivid, their boundaries were not so well defined, and the whole, instead of forming part of a perfect circle, appeared like the end of a concentric ellipsis, whose transverse axis was perpendicular to the horizon. The mist lay thick upon the surface of the meadows; the observer was standing near its margin, and gradually the scene became fainter, and faded away, as he entered into it. A similar fog-bow was seen by Captain Parry during his attempt to reach the North Pole by means of boats and sledges, with five arches formed within the main one, and all beautifully colored.

The iris lunaris, or lunar rainbow, is a much rarer object than the solar one. It frequently consists of a uniformly white arch, but it has often been seen tinted, the colors differing only in intensity from those caused by the direct solar illuminations. Aristotle states that he was the first observer of this interesting spectacle, and that he only saw two in the course of fifty years; but it must have been repeatedly witnessed, without a record having been made of the fact. Thoresby relates an account received from a friend, of an observation of the bow fixed by the moon in the clouds, while traveling in the Peak of Derbyshire. She had then passed the full about twenty-four hours. The evening had been rainy, but the clouds had dispersed, and the moon was shining very clearly. This lunar iris was more remarkable than that observed by Dr. Plot, of which there is an account in his History of Oxford, that being only of a white color, but this had all the hues of the solar rainbow, beautiful and distinct, but fainter. Mr. Bucke remarks upon having had the good fortune to witness several, two of which were perhaps as fine as were ever witnessed in any country. The first formed an arch over the vale of Usk. The moon hung over the Blorenge; a dark cloud was suspended over Myarth; the river murmured over beds of stones, and a bow, illumined by the moon, stretched from one side of the vale to another. The second was seen from the castle overlooking the Bay of Carmarthen, forming a regular semicircle over the river Towy. It was in a moment of vicissitude; and the fancy of the observer willingly reverted to the various soothing associations under which sacred authority unfolds the emblem and sign of a merciful covenant vouchsafed by a beneficent Creator.

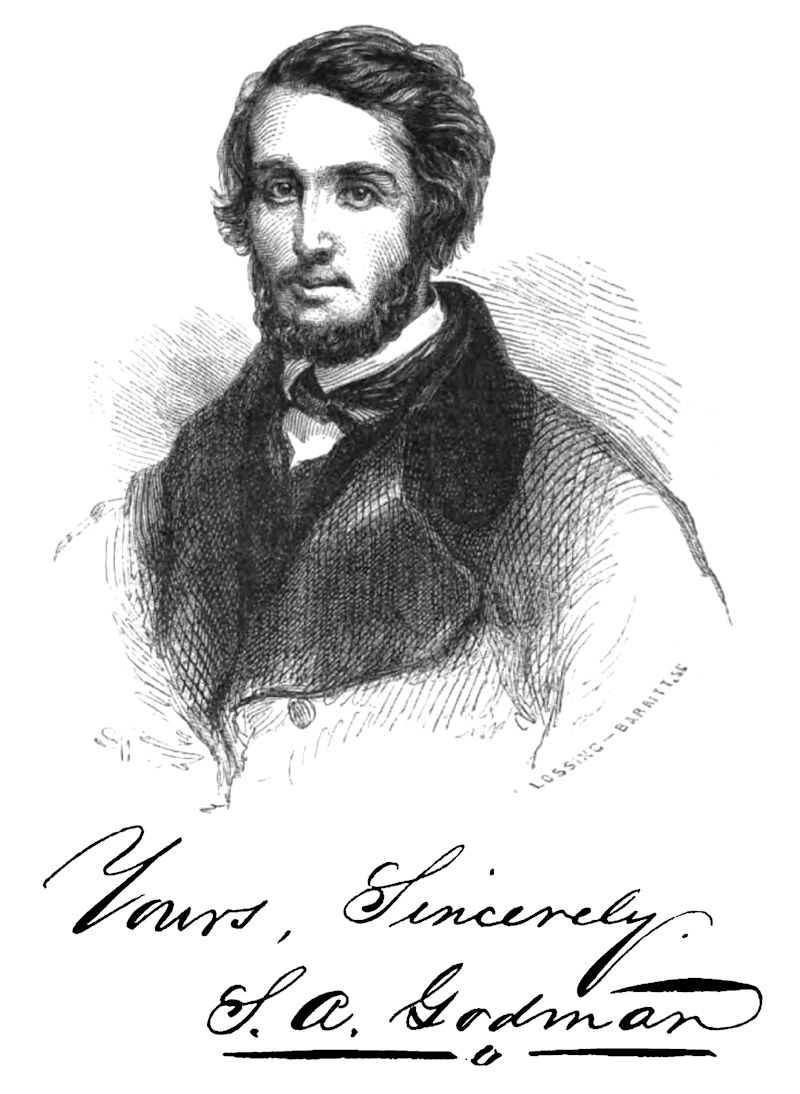

STEWART ADAIR GODMAN.

———

BY CHARLTON H. WELLS, M. D.

———

Emphatically is this, the nineteenth century, the age of intellectuality. Never before has mind exercised such direct, positive and appreciable influence as it now does; for never before, in the history of the world, has there existed such an amount of mental cultivation, of general education, of desire for moral improvement, as is now manifested throughout the entire extent of the civilized globe. Spiritual trains, as it were, are ready laid in every direction; and those minds endowed by the Creator with the fire of genius, that electrical energy which will find vent, enkindle those trains, and at once produce excitement, commotion, action, in the myriad magazines of thought to which they lead.

The days of brute force are amongst the things that were; engulfed by the irresistible, ever-advancing ocean of time, they are only remembered among the legends of the barbarous Past. Intellect rules the world—words are recognized as things—men are venerated in proportion to the amount of mind, soul and spirit they possess: in the ratio of the manifestation of their diviner essence—and not for those qualities, merely physical or adventitious, which make them of kin to the brutes that perish.

Nothing, therefore, is more eagerly sought after by the public, than biographical sketches and portraits of those favored children of nature who are recognized as the possessors of this inestimable inheritance—mind; this priceless treasure—genius. Consequently, we feel assured, that the following brief sketch of one of the most powerful and popular writers of the day, of one, who, descended from a line of talented and patriotic ancestors, has inherited their distinguishing characteristics—stern integrity of purpose, indomitable energy, untiring industry and brilliant genius in an eminent degree—and who, though yet in the first flush of manhood, has already achieved a name and earned a reputation, of which even the aged might be proud—will be gladly perused by the readers of Graham.

Captain Samuel Godman, the paternal grandfather of Stewart A. Godman, was born and educated in Virginia; he was the son of a planter who was by marriage the uncle of Thomas Jefferson. He married, soon after he had attained his majority, and removed to the city of Baltimore, Maryland, where he engaged extensively in the shipping and tobacco business; at that time the heaviest and most lucrative traffic of the place. Here he remained several years, and having accumulated quite a handsome fortune, he removed to the city of Annapolis, where he resided until his death, in 1795. At the breaking out of the Revolutionary struggle, Captain Godman, promptly and with characteristic energy espoused the cause of liberty, and with the assistance of his two brothers, at once raised a company of which he was unanimously elected captain, and tendered their services to his suffering country. This company was gladly accepted, and formed a part of the well-known regiment of the “Maryland Line,” which upheld the honor of the struggling colonies and covered itself with so much glory throughout our ever memorable contest for Independence. During the whole war was Captain Godman true to his responsibility, sharing in every battle in which his regiment took part, and making a liberal use of his private means in supplying the necessities of his command. At the memorable battle of the Cowpens, in Spartanburg district, South Carolina, he was severely wounded, by a musket ball, in the leg, which disabled him for awhile; but he soon, even before the wound had healed, resumed his post at the head of his company, and continued with them until peace was declared, the end had been accomplished and his beloved land was free.

John D. Godman, M. D., the father of Stewart, was born at Annapolis in 1796. Before he was two years of age he had the misfortune to lose both of his parents, and was subsequently defrauded by his father’s executor of his inheritance; thus was he thrown, at an early age, entirely upon his own resources. He also, while yet a boy, served his country: being on board the flotilla during the bombardment of Fort McHenry by the British, in the war of 1812. At the close of the war he commenced the study of medicine. As a student, he was diligent, energetic and persevering, and as an evidence of his proficiency and distinguished attainments, he was called to the chair of Anatomy in the University of Maryland (vacated by an accident to the Professor.) and for several weeks before he graduated, filled this situation with so much propriety as to gain universal applause. After his graduation, he entered upon the active duties of his profession with the same energy and diligence which had distinguished him while a pupil. He filled the chair of Anatomy in the Medical College of Ohio, and subsequently, in 1826, was called to the same chair in Rutger’s Medical College in the city of New York. In these situations he acquired a popularity almost unparalleled. But his professional duties, together with his other scientific pursuits, proved too arduous, in that climate, for a constitution already subdued by labor and broken by disease, and he was compelled to seek a more genial clime. From this time his disease steadily progressed, so as to leave no hope for his final recovery, but he still continued to labor in the field of Science and Literature almost to the last week of his life. He died in the thirty-fourth year of his age. The following merited tribute to the memory of Dr. Godman, we take from an address delivered on that occasion before the Medical Faculty and Students of Columbian College.

“There has recently appeared among us a man so remarkable for the character of his mind, and the qualities of his heart—one whose life, though short, was attended with such brilliant displays of genius, with such distinguished success in the study of our profession and the kindred sciences, that to pass him by without tracing the history of his career, and placing before you the prominent traits of his character, as exhibited in the important events of his life, would alike be on act of injustice to the memory of eminent worth, and deprive you of one of the noblest examples of the age.” To specify the numerous and admired productions of Dr. Godman would occupy too much of our limited space, but they have been before the public for a considerable time, and have been received with high approbation, and several have been republished in foreign countries.

The mother of S. A. Godman was the second daughter of Rembrant Peale, Esq., the celebrated artist—who, still living, is the oldest and the best painter of whom America can boast—his splendid allegorical painting of “The Court of Death,” and his admirable likeness of Washington, painted from an original portrait taken by him of the Father of his Country, which hangs over the Vice-President’s seat in the United States’ Senate Chamber—are familiar to thousands of your readers. Mrs. Godman is a remarkable woman—possessing all the amiable traits that most adorn the gentler sex, combined with an amount of energy and decision of mind seldom to be met with—both developed and improved by a thorough course of education in a celebrated seminary abroad.

Dr. Godman left three children, then too young to appreciate the full extent of their loss—one, a daughter, now married to Dr. W. W. Goldsmith, of Kentucky, is a most gifted and lovely lady; the others were boys, the elder of whom is the subject of the present sketch—the other, Harry R. Godman, M. D., is already known to the reading public, and by the purity and depth of feeling, expressed with so much ease and beauty in his writings, is winning for himself, surely and deservedly, a reputation as one of the best of the younger poets of our country.

Stewart A. Godman was born in Cincinnati, Sept. 8th, 1822, a few weeks before his father resigned his professorship in the Medical College of Ohio; and at the early age of six weeks he commenced his wanderings—being carried by his parents to the city of Baltimore.

It appears to be a provision of nature, and it is doubtless a wise one, that, no matter what may be the surrounding circumstances, every man destined to produce an impression upon his fellows, and to leave his “footprints on the sands of time,” must, in his earlier years, encounter a series of changes and difficulties, preparing him, as it were perforce, for the position he is to occupy. The inborn, inherent energy that is in them, produces a restlessness and a desire for something, they know not what, that keeps them ever shifting from purpose and pursuit, until at last they find the field and make the opening in which they are fitted to shine. This want of stability, as it seems, and dislike to plod along contentedly in whatever road circumstances have placed them, subjects them oftentimes to the charge of fickleness, and it is only when they have found their natural sphere—and true genius ever will force a path to its legitimate position—is it admitted by lookers-on that it was the resistless cravings of the governing, controlling spirit eagerly seeking its own, that actuated them—instead of fickleness.

This fate was not escaped by young Godman, for, although still comparatively a young man, he has experienced vicissitudes, changes and trials—mental, physical and pecuniary—greater than most persons have to encounter who live to the allotted age of three score years and ten. Naturally of an energetic and bold disposition, averse to restraint, and deprived at the early age of eight years, by death, of his father—a loss in any case so great, but in his, with such a parent, how irreparable—his life has been checkered by the changing phases that ever accompany the life-struggle of each man who strives to attain an eminent position by paths novel and self-suggested. Blessed in an unusual degree with friends, able, willing, indeed anxious, to assist him, he would have had only to follow either of the many openings and advantages that were freely tendered, to have attained certain wealth and station at an early age. The natural independence of his character, however, combined with his strong innate feeling of self-reliance, caused him to undervalue and neglect the many easy roads to success, that by the influence of his father’s numerous friends and admirers were offered—and to prefer the more hazardous and difficult plan of carving out his own road, of being the architect of his own fortune.

His primary education was most thorough; for quick, keen, inquiring and industrious, and having the very best instructors, he made rapid progress in every branch. At a very early age, when the brilliancy of his mind and the promise he gave of doing credit to his preceptors were already apparent, anxious to mingle in the real bustle and business of life, he determined to leave school. At this time he was at the Baltimore College, then under the charge of that finished scholar and accomplished gentleman, John Prentiss, Esq., and despite the persuasions of his friends and teachers he persisted in his determination. Removing then from Baltimore to Philadelphia, he entered the large establishment of that well-known merchant, David S. Brown, Esq., where he remained for three years, and earned a reputation for business tact and ability such as is seldom awarded a youth of his years. Not finding in the details of commerce that mental satisfaction he sought, and unheeding altogether the unusually advantageous prospects before him, much against the advice of Mr. Brown, he resolved to try the profession of medicine. Returning to Baltimore, to which place he was invited by Dr. R. S. Stewart (after whom he was named) then one of the largest practitioners in the Monumental City, but now retired with an ample fortune—he attended one course of lectures at the University of Maryland. Here he stood first among his classmates—but disgusted with the details of hospital practice, at the end of the first winter he found that medicine was not the path he wished to pursue.

His uncle, Thomas Jefferson Godman, residing in Madison, Indiana, was anxious to have young Godman study law, and at his earnest solicitation he went to Madison, and entered as a student the office of the Hon. Jesse D. Bright, now United States Senator. Law, however, was not more congenial to his spirit than medicine; and after three months hard study, he threw aside Blackstone, Chitty, and their compeers, and applied for admittance into the United States Navy, as a midshipman. Although, at the time of his application, which was made directly to the President, there was a very large number of applicants on record for warrants, young Godman received his at once—“in consideration,” as was written in the letter containing the warrant, “of the distinguished services of his grandfather during the Revolution,” and for which neither pension nor remuneration had ever been asked. Only about eighteen months did Godman remain in the navy; at first the glitter, pomp, and excitement of the service pleased, but he soon found that it was no place to rise—for time, not merit, graduated promotion—so quitting the navy, he entered the merchant service, and after making a couple of short voyages, he returned home. His friends, fearful that he would never settle down to regular business, opposed his again going to sea, and persuaded him to re-enter the mercantile business. He then determined to go to Charleston, where, through the influence of a distinguished friend of his father, Dr. E. Geddings, he at once obtained a situation in one of the largest stores in the city. He remained there some eight months, when his independent spirit having been wounded, in consequence of some misunderstanding with his employer, about a leave of absence during the holydays, he relinquished his situation, and again went to sea, as mate of a merchantman. A wanderer, did he thus continue, until almost twenty-one, when an accident, seemingly the most trivial, changed the entire course of his life.

He had just returned to Charleston from a voyage, and had fully determined, having made all his arrangements, to go to China and settle among the inhabitants of the Celestial Empire, when the suggestion of a casual acquaintance caused him to reflect seriously upon the manner in which he was squandering his life and talents; and he at once determined to go into the country for a couple of years, and in the quiet of rural life, to settle his mind, and chalk out a course for the future. Acting upon this resolution, he went to Abbeville District, South Carolina, where, as money was not his object, further than as a means of subsistence for the present, he took a situation in a country store. Whilst here, he became acquainted with and attached to Miss A. R. Gillam, to whom, before he was twenty-two, he was united in marriage. This event necessarily brought about a change in his plans, and induced him to remain in the up-country of South Carolina. His wife died about two years after their union. In 1848 he married Miss M. E. Watts, of Laurens District. A short time previous to this marriage, Godman bought the Laurensville Herald—a small country paper, having only three hundred and fifty subscribers. To this he devoted all his energies, and after having made for it an enviable reputation, he sold it at the expiration of a little more than two years with a subscription list of nearly two thousand. Seeing the necessity that existed for a Southern Literary Newspaper of high standing, he last fall determined to establish such a journal; and the great success and universal popularity of the paper which he is now publishing, “The Illustrated Family Friend,” clearly attests the tact, talent, energy and business qualifications of its editor.

Inheriting the brilliant parts of his father, from his temperament necessarily a hard student and deep thinker, with all the advantages that an extensive and thorough knowledge of the world, which a keen, inquiring, analytical mind must acquire, from close communion with mankind under almost every phase of life—the unexampled success and universal popularity that has been obtained by Godman, as a writer, are not astonishing, though they are remarkable. Philosophic imagination, vividness of conception, energy, and a conscientious endeavor to make all that he does tend to some practical and useful purpose, are his distinguishing mental traits. Although he writes rapidly, his style is easy, graceful, natural, whilst at the same time, it is always bold, vigorous, original, and worthy of all commendation for its elevated moral tone. Should his life be spared, we are certain that he will win for himself a reputation second to no author of whom America can boast; for already, since the demise of the lamented Cooper, he has attained the enviable distinction of being one of the best, if not the best writer of Nautical Romances now living.

Socially, Stewart A. Godman enjoys an unusual degree of personal popularity, and is respected and esteemed by all who know him; in his deportment he is affable and polite to all; in conversation fluent, though unstudied. With a mind stocked with a vast fund of anecdote, and a vivid imagination to point the varied scenes through which he has passed, he is always listened to with interest, while at the same time he imparts knowledge to his friends, who esteem it a privilege to cluster around him in his moments of leisure.

———

BY A NEW CONTRIBUTOR.

———

Through the broad rolling prairie I’ll merrily ride,

Though father may frown, and though mother may chide;

To the green leafy island, the largest of three,

That sleep in the midst of that silent green sea—

For there my dear Fanny, my gentle young Fanny,

My own darling Fanny is waiting for me.

Ho! Selim—push on! The green isle’s still afar,

And morning’s pale light dims the morning’s large star;

Before the sun rises she’ll watch there for me,

Her eyes like twin planets that gaze on the sea.

My young, black-eyed Fanny, my winsome, sweet Fanny,

My own darling Fanny, that waiteth for me.

Come, Selim! come, sluggard! speed swifter than this,

There are ripe, rosy lips that I’m dying to kiss;

And a dear little bosom will bound with delight,

When the star on thy forehead first glitters in sight.

My glad little Fanny! my arch, merry Fanny,

My graceful, fair Fanny, no star is so bright.

Then her soft, snowy arms round me fondly will twine,

And her warm, dewy lips will be pressed close to mine;

And her full, rosy bosom with rapture will beat,

When again, and no more to be parted, we meet.

My lovely young Fanny, my own darling Fanny,

My dear, modest Fanny, no flower is so sweet.

So father may grumble, and mother may cry,

And sister may scold—I know very well why;

’Tis that beauty and virtue are all Fanny’s store,

That while we are rich, she, alas! is quite poor.

My winsome young Fanny, my true, faithful Fanny,

My own darling Fanny, I’ll love you the more.

Ho! Selim! fleet Selim! bound fast o’er the plain,

The morning advances, the stars swiftly wane;

I see in the distance the green leafy isle,

Between us and it stretches many a mile,

Where my fond, faithful Fanny, my own darling Fanny,

Shall welcome us both with a tear and a smile.

———

BY THOMPSON WESTCOTT.

———

Fops differ from scare-crows in this particular—the latter guard the young blades of green things by the appearance of their apparel alone; but dandies are themselves young blades and green things, and are not stationary effigies, but moving frights. They are not stuffed figures which stand still, but empty semblances which perigrinate. They are defective verbs, which “do” and “suffer,” it is true, but are only used in certain moods and tenses: to wit, the indicative mood, and imperfect tense—indicating that such things are, and are not worth much. This etymological fact establishes that dandies do something, and having settled into that conviction, it becomes necessary to inquire with great gravity, what do they do?

It will not require an overwhelming quantum of credulity to lead the reader to a belief that nothing of much importance has ever been done by an exquisite. He neither adds to the character or the utility of society. He aids not in commerce or manufactures—except, perhaps, as a buyer of coats and kid gloves—being, as to those things, a consumer, whether profitably so or not to the artist in cloth and professor of gloving, a narrow inspection of their ledgers will only answer satisfactorily. He is not what political economists call a producer, unless the labor he bestows upon cultivating his moustache, may entitle him to a place among the “sons of toil.” He adds nothing to the general wealth; although he extravagantly expends the money which he borrowed from a rich friend, or that which his kind grandfather, the tavern-keeper, bequeathed him when he left off selling common brandy, and went to “a world of pure spirits.” Except to “point a moral, or adorn a tale,” the fop is therefore not useful. He is, like vice,

——A monster of such hideous mien,

That to be hated needs but to be seen;

but we trust that the further remarks of the poet, in regard to familiarity of face, will not apply to the dandy, though many of that tribe who saunter along Chestnut street have faces extremely familiar. If a herd of bucks were interrogated as to their own opinions of their positions in society, it is probable that they would assign themselves to the ornamental department. But on that subject a very lively debate might be held, and if it were at length decided that they were decorations to the “solidarity of the peoples,” their relative situation would be like gold leaf on gingerbread; extremely gaudy, to be sure, but very unwholesome to swallow. They are ugly ornaments, like odd figures upon Indian temples, serving no purpose but to mislead the veneration of those who ignorantly worship at the shrine. They are like copper rings in Choctaw noses, ungraceful extras upon the face of nature, and of no intrinsic value. There can only be one point of view in which a buck may be looked at in a useful light, and that is as an object to be laughed at.

In a late number of Graham we devoted some space to an elucidation of the question, “How are dandies made?” and having said sufficient upon that topic, we pass to a notice of their doings. A prompt and significant period might be put to these lucubrations, by the averment that dandies do “an infinite deal of nothing,” but that would not be literally true, for although their actions are of no public importance, still those who write their biographies will be compelled to admit that they do something. Ease is but a word which signifies a comparative release from labor; idleness is but the definition of a state of unprofitable action. Those who have nothing to do cannot exist without doing something; and he who has much time on his hands is compelled to employ it in some pursuit to escape from the horror of positive ennui. Therefore, even dandies, those cob-webs of society, catch flies when the unwary insects come into the meshes of their webs, and at times put themselves to great inconvenience and fatigue, whilst enjoying the felicity of their otium cum dignitate.

But how does the exquisite spend his hours? It may be safely asserted that midnight very often passes before he seeks his bed, after the fatigues of the day and night—and that the sun has mounted high in the meridian before he awakes from slumbers which are not refreshing.

Then, as he endeavors to costume himself in the fifth story room of some fashionable boarding-house, he finds himself environed with difficulties. On a winter morning he will get out of his bed shivering, and find all his toilet arrangements deranged by frost. His water will probably be frozen in his pitcher, and scarcely disposed to yield to the endearing demonstration of his gold-headed cane. His landlady may wait upon him to assure him that his stockings and drawers, which were washed on the previous night, are frozen stiff, and that she has not had time to properly dry and iron them.

This will be sad news, indeed; for although your true dandy riots in coats and variety of apparel which the world can see, he is generally rather short in those articles which every one is presumed to have, but which are not visible to the public eye. Perhaps the freezing of the indispensables which the landlady brings him may put him to serious inconvenience. If so, it must be borne. That will not be the least of his troubles. The necessity of being particular about his whiskers, is by no means the greatest of the cares which annoy him. Hours are daily spent in the study of neck-cloths, the experimental philosophy of dress-coats, the spindleizing of thin legs, and the tightening of pantaloons. Those are home employments to which it is only necessary to allude. The real business of the day commences when the fop, about twelve o’clock, emerges for a walk on the south side of Chestnut street. Here he is noted for those particularities of dress which are his own glory, and “the badge of all his tribe.” Perhaps he meets one of his associates, and arm-in-arm they mince their way along, talking of Miss So-and-so’s party, or the “insufferable stupidity” of some who have not as many coats as themselves; simpering and twaddling, thus their movements may be varied by manœuvres which are indescribably odd. The unmeaning faces which have for some time been expressive of nothing but inanity, will suddenly become o’erspread with an appearance of semi-consciousness, as some dashing belle approaches. By a movement simultaneous and sudden, both exquisites will make a jerking bend of the body from the hips upward—their right hands will be raised to their hats; by the time the lady has passed them, and proceeded six feet in the opposite direction, their beavers will be lifted from their noddles at least twelve inches, held extended a moment, and by the time the belle is twenty feet off, returned to the craniums on which they rested, and the delighted couple pass onward, supposing they have made genteel bows. None but those who have seen a first-rate fop publicly salute a lady of his acquaintance, can have an idea of the ludicrous character of his movements, and the comical nature of the entire manœuvre.

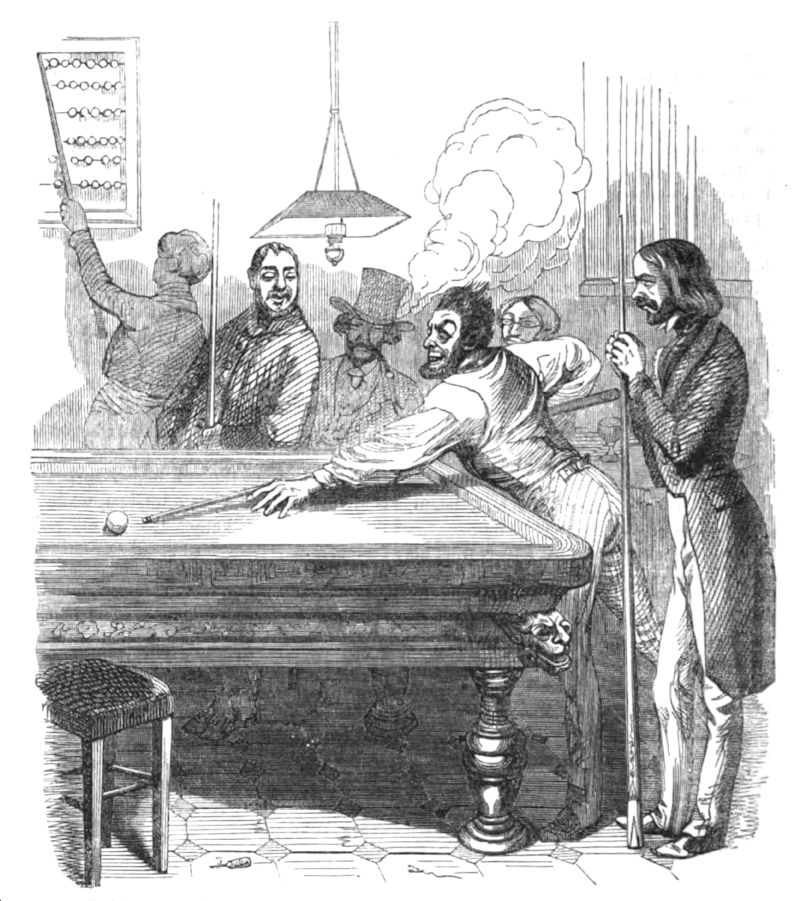

But the twain at length, tire of their promenade and adjourn to some fashionable drinking saloon for a “whiskey skin,” or a “brandy plain.” Still they must have amusement, and they accordingly determine to try their skill at billiards—a gentlemanly game, which will not fatigue their weak muscles or agitate their delicate nerves. The mysteries of this diversion, like the oddities of backgammon, are well calculated to puzzle the uninformed mind. It would, perhaps, be irreverent to compare it to marbles, that fascination of youth, yet it resembles it much, though sooth to say, it is not as readily understood by the unlearned.

Judging from appearances, billiards is a game in which the endeavor of the player is to cause certain ivory balls to hit other balls “back-handed licks.” With a thin rod of wood, the player is constantly going through strange gymnastics. Sometimes he endeavors to strike one spheroid against another. At other times he propels his ivory plaything in such a manner, that it does nothing but fly from side to side of a table enclosed by a padded rim, without producing any visible effect whatever. Occasionally the great object seems to be to push a ball against which mischief is evidently meditated, into a bag, or pocket, some of which are ambushed in the corners, and others in the center of the rim of the table. Then, again, the player does not seem to care a half-penny for this triumph, though within his power, but rather seeks to make one ball strike another, which flies off at a tangent, hits another, and then in backing out from the concussion, touches one of the balls already struck. Whilst all this is going on—an attendant is constantly meddling with a frame of rods above the table, on which are strung white and black wooden beads. Occasionally all the beads are moved one way, then some of them are shifted to the place from which they were removed. The spectator in vain endeavors to ascertain the nature of the game. All that he can tell about it is, that the players bend over the table with scientific calculation, and throw themselves into many strange attitudes whilst considering how much force is necessary to make one ball strike another, or to cause a series of shocks among all which are upon the table. When it is all over, and the cues are returned to the rack, Blessed Ignorance leaves the billiard-saloon, satisfied that somebody has won the game; but why, or how, it is impossible for him to determine, inasmuch as the whole business seems to be a very grave and solemn mystery.

In these ceremonies fops delight, and it is pleasant to hear them boast of their triumphs, in tones which should characterize important achievements.

The afternoon promenade in Chestnut street, upon fine afternoons—when belledom is abroad—is one of the principal occupations of the dandy. There he is preëminent for the instability of his legs, the absurdity of his over-coat, the glossiness of his hat, (the dandy pure et simple, does not affect the Kossuth slouch,) the surprising appearance of his shirt-collar, his cravat-tie comme il faut; his kid gloves—which just now are of a bright green color; his light cane, the head of which is an ivory facsimile in little of an opera-dancer’s leg—and his very noticeable beard and moustache. Glorying in his appearance, conceiting himself to be admired by the numerous beautiful women he passes, he is supremely happy, and condescendingly deigns to stare at the most handsome of those whom he meets, with undisguised impudence.