THE RED CROSS GIRLS IN

THE BRITISH TRENCHES

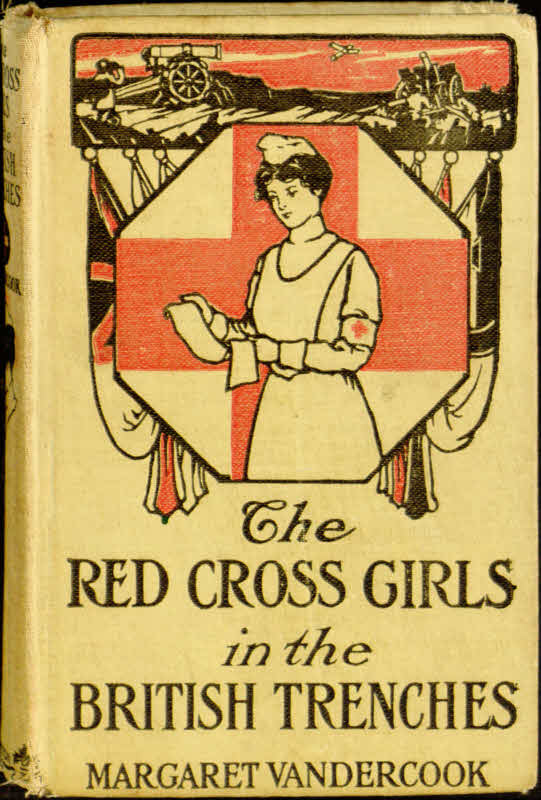

It Did Not Occur to Her That She Was in Equal Peril—(See page 250)

By

MARGARET VANDERCOOK

Author of “The Ranch Girls Series,” “Stories

about Camp Fire Girls Series,” etc.

Illustrated

The John C. Winston Company

Philadelphia

Copyright, 1916, by

The John C. Winston Co.

[5]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Social Failure | 7 |

| II. | Different Kinds of Courage | 26 |

| III. | Farewell | 41 |

| IV. | Making Acquaintances | 58 |

| V. | “Lady Dorian” | 71 |

| VI. | A Trial of Fire | 85 |

| VII. | The Landing | 97 |

| VIII. | A Meeting | 109 |

| IX. | “But Yet a Woman” | 124 |

| X. | Behind the Firing Lines | 138 |

| XI. | Out of a Clear Sky | 150 |

| XII. | First Aid | 161 |

| XIII. | The Summons | 169 |

| XIV. | Colonel Dalton | 179 |

| XV. | Newspaper Letters | 190 |

| XVI. | The Ambulance Corps | 202 |

| XVII. | Dick | 214 |

| XVIII. | A Reappearance | 226 |

| XIX. | The Test | 235 |

| XX. | A Girl’s Deed | 249 |

| XXI. | An Unexpected Situation | 258 |

| XXII. | Recognition | 271 |

[7]

THE RED CROSS GIRLS IN

THE BRITISH TRENCHES

The dance was over and Mildred Thornton climbed disconsolately up the long stairs. From her thin shoulders floated a delicate white scarf and her dress was of white lace and tulle. Yet Mildred had no look of a conquering Princess, nor yet of Cinderella, who must have carried her head proudly even after the ball, remembering the devotion of her Prince.

But for Mildred there was no Prince to remember, nor devotion from anyone. She was in that mood of hopeless depression which comes from having attended a dance at which one has been a hopeless failure.[8] Her head drooped and though her cheeks were hot, her hands were cold.

Downstairs in the library she could hear her brother having his good-night talk with their mother. Of course he did not intend that she should overhear what was being said, and yet distinctly his words floated up to her.

“Well, dearest, I did what I could, I swear it. Do hand me another one of those sandwiches; playing the devoted brother takes it out of me. But poor old Mill is no go! The fellows were nice enough, of course; they danced with her whenever I asked them, but the worst of it was they would not repeat the offense. You know Mill dances something like an animated telegraph pole, and though she is a brick and all that, she hasn’t an ounce of frivolous conversation. Do you know, I actually heard her talking about the war, and no one in our set ever speaks of the war now; we are jolly tired of the subject.”

Whatever her mother’s reply, it was given in so low a tone as to be inaudible. But again Dick’s voice was pitched louder.

[9]

“Oh, all right, I’ll keep up the struggle a while longer, as I promised, but it’s no use. Have you ever thought of what will become of your adored son’s popularity if he has to continue in New York society with a ‘Mill’ stone hung about his neck?”

On the stairs the girl bit her lips, flinging back her head to keep the tears away. For at once there had followed the sound of her brother’s pleased laugh over his own wit, then her mother’s murmured protest.

So plainly could Mildred Thornton see the picture in the library that it was not necessary for her to be present except in the spirit. Indeed, it was in order that she might not intrude upon Dick’s confession that she had insisted upon going at once to her own room as soon as they arrived at home. Nevertheless, no one need tell her that her brother had not the faintest intention of being unkind. He never liked hurting people’s feelings; yet when one is handsome and charming, sometimes it is difficult to understand how those who are neither must feel.

In her own room a moment later, Mildred,[10] touching the electric button, flooded her apartment with a soft yellow light. Then deliberately placing herself before a long mirror the girl began a study of her own appearance. After all, was she so much less good looking than other girls? Was that the reason why Dick had been compelled to report to their mother her extraordinary lack of social success? And if this had been the only occasion, once would not have mattered. But after three months of the same story, with everything done to help her, beautiful clothes, her own limousine, her father’s money and reputation, her mother’s and brother’s efforts—why, no wonder her family was discouraged. But if only her mother had not been so disappointed and so chagrined, Mildred felt she would not have cared a great deal. There were other things in life besides society.

Yet now, without fear or favor, Mildred Thornton undertook to form an impartial judgment of herself.

In the mirror she saw reflected a girl taller than most girls, but even in these days when slenderness is a mark of fashion,[11] certainly one who was too thin. However, there was comfort in the fact that her shoulders were broad and flat and that she carried her head well.

“For one must find consolation in something,” Mildred murmured aloud. Then because she did not consider that the consolations were as numerous as they might have been, she frowned. It was unfortunate, of course, that her hair, though long and heavy, was also straight and flaxen and without the yellow-brown lights that were so attractive. Then assuredly her chin was too square and her mouth too large.

Closer she peered into the mirror. Her nose was not so bad; it could not be called piquant, nor yet pure Greek, but it was a straight, American nose. And at any rate her eyes were fairly attractive; if one wished to be flattering they might even be called handsome. They were almost steel color, large and clear, with blue and gray lights in them. Her eyebrows and lashes were much darker than her hair. If only their expression had not always been so serious!

[12]

Turning her head first on one side and then on the other, attempting to dart ardent, challenging glances at herself, suddenly Mildred made a little grimace. Then throwing back her head she laughed. Instantly the attraction she had been hoping for appeared in her face although the girl herself was not aware of it.

“Mildred Thornton, what an utter goose you are! It is tragic enough to be a stick and a wall flower. But when you attempt behaving like the girls who are belles, you simply look mad.”

Moving aside from the mirror Mildred now let her party gown slip to the floor.

She was standing in the center of a beautiful room whose walls were gray and gold. The rug under her feet was also gray with a deep border of yellow roses. Her bed was of mahogany and there was a mahogany writing desk and table and low chairs of the same material. Through an open door one could glimpse a private sitting room even more charming. Indeed, as there was no possible luxury missing so there could be no doubt that Mildred Thornton[13] was a fortunately wealthy girl, which of course meant that she had nothing to trouble her.

Nevertheless, at this moment Mildred was thinking, “Oh, if only I were thirty instead of nineteen, I wonder if I might be allowed to be happy in my own way.”

Then without remembering to throw a dressing gown across her shoulders, tip-toeing across the floor without any apparent reason, the girl unlocked a secret drawer in her desk. Opening it she drew out a large, unusual looking envelope. She was staring at this while her eyes were slowly filling with tears, when there came a sudden knock at her door.

At the same instant the envelope was thrust back into the drawer, and not until then did Mildred answer or move toward her door.

A visit from her mother tonight was really one of the last things in the world she desired. It was wicked to have so little sympathy with one’s own mother and the fault was of course hers. But tonight she was really too tired and depressed[14] to explain why she had made no more effort to be agreeable. Her mother would insist that she had only herself to blame for her evening’s failure. It was hard, of course, that so beautiful a woman could not have had a handsome daughter as well as a handsome son.

But instead of her mother, there in the hall stood a tall, thin man, whose light hair had turned gray. He had a strong, powerful face, deeply lined, one that both men and women turned to look at the second time.

“I heard you come upstairs alone, Mill dear,” Judge Thornton said, smiling like a shamefaced schoolboy. “Don’t tell your mother or Dick, will you, for we had better break it to them by degrees? But I sent a check today for two thousand dollars to the Red Cross Fund to be used in this war relief business, my dear. I had to do it, it was on my conscience. I know your mother and brother won’t like it; they have been scolding for a new motor car and I’ve said I couldn’t afford one. Really four persons ought to be able to[15] get on with two automobiles, when a good many thousands are going without bread. We’ll stand together, won’t we, even if my little girl has to give up one of her debutante parties?”

Already Mildred’s arms were about her father’s neck so that he found it difficult to talk, for that and other reasons.

“I am so glad, so glad,” she kept whispering. “You know how tiresome Dick and mother feel I am because I don’t think we ought to keep on playing and dancing and frivoling, when this horrible war is going on and people are being wounded and killed every minute. If you only guessed how I wanted to use the little knowledge and strength I have to help.”

But the Judge now shook his head decisively and moved away.

“Nonsense, child, you are too young; such an idea is not to be thought of. We ought never to have let you attend those hospital classes, or at least I should not have allowed it. Goodness knows, your mother fought the idea bitterly enough![16] But remember, you promised her that you would give the same time to society that you have given to your nursing, and that is three years. You can’t go back on your word, and besides I won’t have you thinking so much about these horrors; you’ll be making yourself ill. War isn’t a girl’s business.” Certainly Judge Thornton was trying to be severe, but just beyond the door he turned back.

“I sent the check in your name, Mill dear, so you can feel you are doing a little something to help,” he added affectionately. “Good night.”

Afterwards, although tired (and it was quite two o’clock when she was finally in bed), Mildred Thornton found it almost impossible to sleep. At first she kept seeing a vision of herself as she appeared at the dance earlier in the evening. How stiff and solemn and out of place she had seemed, and how impossible it had been to make conversation with the young men her brother had brought forward and introduced to her! In the first place, they had not seemed like men at all, but like the fashionably[17] dressed pictures in the magazine advertisements or the faultless figures adorning the windows in men’s furnishing stores.

Besides, they had only wished to talk of the latest steps in the new dances or the last musical comedy. And what a strange expression that young fellow’s face had worn, when she had asked him if he had ever thought of going over to help in the war! No wonder Dick had been so ashamed of her.

Then, having fallen asleep, Mildred began dreaming. Her father had been right, she must have been thinking more than she should about the war. Because in her dream she kept seeing regiment after regiment of soldiers marching across broad, green fields, with bands playing, flags flying and their faces shining in the sun. Finally they disappeared in a cloud of black smoke, and when this took place she had awakened unexpectedly.

Sitting up in bed with her long flaxen braids hanging over either shoulder, Mildred wondered what had aroused her at this strange hour? Then she remembered[18] that it was the loud, clear ringing of their front door bell. Moreover, she had since become conscious of other noises in the house. Her brother had rushed out of his room and was calling to the man servant who had turned on the lights down in the front hall.

“I say, Brown, be careful about opening that front door, will you? Wait half a moment until I get hold of my pistol and I’ll join you. I don’t like this business of our being aroused at a time like this. It must be just before daylight and New York is full of burglars and cutthroats.”

Dick then retired into his room and the next sound Mildred heard was his voice expostulating with his mother.

“Oh, go on back to bed, dearest, and for heaven’s sake keep father out of this. Certainly there is no danger; besides, if there were I am not such a mollycoddle that I’m going to have Brown bear the brunt. Somebody’s got to open the door or that bell will never stop ringing.”

Then Dick’s feet in his bedroom slippers could be heard running down the uncarpeted[19] stairs. A moment later Mildred got into her wrapper and stood with her arm about her mother’s waist, shivering and staring down into the hall.

If anything should happen to Dick it would be too tragic! Her mother adored him.

The butler was now unfastening the storm doors, while directly behind him Dick waited with his pistol at a convenient level.

Then both men stepped backward with astonished exclamations, allowing a queer, small figure to enter the hall without a word of protest. The next moment Mildred was straining her ears to hear one of the most bewitching voices she had ever imagined. Later an equally bewitching figure unfolded itself from a heavy coat.

“It’s sorry I am to have disturbed you at such an hour,” the girl began. “But how was I to know that the train from Chicago would arrive at three o’clock in the morning instead of three in the afternoon? I was hoping some one would be at the station to meet me, though of course I didn’t expect it, so I just took a cab and found the way here myself.”

[20]

Then the newcomer smiled with a kind of embarrassed wistfulness.

For the first time beholding Dick’s pistol, which was now hanging in a dangerously limp fashion in his hand, she started.

“Oh,” she exclaimed, “I suppose you think that in Nebraska we go about with pistols in our hands instead of pocket handkerchiefs; but, really, we don’t welcome guests with them.”

Having dropped her coat on the floor, the girl under the light looked so tiny that she seemed like a child. She had short, curly dark hair which her tight-fitting traveling cap had pressed close against her face. Her eyes were big and blue, and perhaps because she was pale from fatigue her lips were extremely red.

Indeed, Dick Thornton decided, and never afterwards changed his opinion, that she was one of the best looking girls he had ever seen in his life. But who could she be, where had she come from, and what was she doing in their house at such an extraordinary hour?

Clearing his throat, Dick made a tremendous[21] effort to appear impressive. Yet he was frightfully conscious of his own absurdity. He knew that his hair must be standing on end, that his dressing gown had been donned in a hurry and that he had on slippers with a space between his feet and dressing gown devoid of covering. Moreover, what was he to do with his absurd pistol?

“I am afraid you have made a mistake,” Dick began lamely. “If you are a stranger in New York and have just arrived to visit friends, perhaps we can tell you where to find them. Or, or, if you—” Dick did not feel that it was exactly his place to invite a strange young woman to spend the rest of the night at their home; yet as her cab had gone one could hardly turn her out into the street. Why did not his mother or Mildred come on down and help him out. Usually he knew the right thing to say and do, but this situation was too much for him. Besides, the girl looked as if she might be going to cry.

But she was a plucky little thing, because instead of crying she tried to laugh.

[22]

“I have made a mistake, of course,” she faltered. “I was looking for Judge Richard Thornton’s home on Seventy-fourth Street, the number was 28 I thought. Has the cabman brought me to the wrong place?”

Slowly Mrs. Thornton was now approaching them with Mildred hovering in the background. But Dick did not altogether like the expression of his mother’s face. It showed little welcome for the present intruder. Now what could he say to make her happier before any one else had a chance to speak.

“Why, that is my father’s name and our address all right, and I expect we are delighted to see you. I wonder if you would mind telling us your name and where you have come from? You see, we were not exactly looking for a visitor, but we are just as glad to see you.”

The girl had turned at once toward Mrs. Thornton and it was astonishing how much dignity she possessed in spite of her childish appearance.

“I regret this situation more than I[23] can express. I am sure I owe you an explanation, although I do not know exactly what it can be,” she began. “My name is Barbara Meade. Several weeks ago my father wrote to his old school friend, Judge Richard Thornton, saying that I was to be in New York for a short time on my way to England. He asked if it would be convenient to have me stay with you. He received an answer saying that it would be perfectly convenient and that I might come any day. Then before I left, father telegraphed.” Barbara’s lips were now trembling, although she still kept back the tears. “If you will call a cab for me, please, I shall be grateful to you. I would have gone to a hotel tonight, only I did not know whether a hotel would receive me at this hour.”

“My dear child, you will do no such thing. There has been some mistake, of course, since I have never heard of your visit. But certainly we are not going to turn you out in the night,” Mrs. Thornton interrupted kindly.

Ordinarily she was supposed to be a[24] cold woman. Now her manner was so charming that her son and daughter desired to embrace her at the same moment. But there was no time for further discussion or demonstration, because at this instant a new figure joined the little group. Actually Judge Thornton looked more like a criminal than one of the most famous criminal lawyers in New York state.

Nevertheless, immediately he put his arm about Barbara Meade’s shoulders.

“My dear little girl, you need never forgive me; I shall not forgive myself nor expect any one else to do so. Certainly I received that letter from your father. Daniel Meade is one of my dearest friends besides being one of the finest men in the United States. Moreover, I wrote him that we should be most happy to have his daughter stay with us as long as she liked, but the fact of the matter is—” several times the tall man cleared his throat. “Well, my family will tell you that I am the most absent-minded man on earth. I simply forgot to mention the matter to my wife or any one else. So now[25] you have to stay on with us forever until you learn to forgive me.”

Then Dick found himself envying his father as he patted their visitor’s shoulder while continuing to beg her forgiveness.

But the next moment his mother and sister had led their little guest away upstairs. Then when she was safely out of sight Dick again became conscious of his own costume—or lack of it.

[26]

Moving along Riverside Drive with sufficient slowness to grasp details had given the little western visitor an opportunity to enjoy the great sweep of the Hudson River and the beauty of the New Jersey palisades.

On the front seat of the motor car Barbara sat with Dick Thornton, who had offered to take the chauffeur’s place for the afternoon. Back of them were Mrs. Thornton and Mildred. It was a cold April day and there were not many other cars along the Drive. Finally Mrs. Thornton, leaning over, touched her son on the shoulder.

“I think it might be wiser, Dick, to go back home now. Barbara has seen the view of the river and the wind has become so disagreeable. Suppose we turn off into Broadway,” she suggested.

Acquiescing, a few moments later Dick[27] swung his car up a steep incline. He was going at a moderate pace, and yet just before reaching Broadway he sounded his horn, not once, but half a dozen times. The crossing appeared free from danger. Then when they had arrived at about the middle of the street, suddenly (and it seemed as if the car must have leaped out of space) a yellow automobile came racing down Broadway at incredible speed.

It chanced that Barbara observed the car first, although immediately after she heard queer muffled cries coming from Mildred and her mother. She herself felt no inclination to scream. For one thing, there did not seem to be time. Nevertheless, impulse drew her eyes toward Dick Thornton to see how he was affected.

Of course he must have become aware of their danger when the rest of them had. He must know that all their lives were in deadly peril. Yet there was nothing in the expression of his face to suggest it, nor had his head moved the fraction of an inch. Strange to see him half smiling, his color vivid, his dark eyes unafraid, almost[28] as if he had no realization of what must inevitably happen.

Closing her own eyes, Barbara felt her body stiffen; the first shock would be over in a second, and afterwards——

Nevertheless no horrible crash followed, but instead the girl felt that she must be flying along through the air instead of being driven along the earth. For they had made a single gigantic leap forward. Then Barbara became aware that Mildred was speaking in a voice that shook with nervousness in spite of her effort at self-control.

“You have saved all our lives, Dick. How ever did you manage to get out of that predicament?” Afterwards she endeavored to quiet her mother, who was becoming hysterical now that they were entirely safe.

So they were safe! It scarcely seemed credible. Yet when Barbara Meade looked up the racing car was still speeding on its desperate way down Broadway, followed by two policemen on motorcycles, while their own automobile was moving quietly[29] on. The girl had a moment of feeling limp and ill. Then she discovered that Dick Thornton was talking to her and that she must answer him.

He was still smiling and his brown eyes were untroubled, but now that the danger had passed every bit of the color had left his face. Yet undoubtedly he was good looking.

Barbara had to check an inclination to laugh. This was a tiresome trait of hers, to see the amusing side of things at the time when they should not appear amusing. Now, for instance, it was ridiculous to find herself admiring Dick Thornton’s nose at the instant he had saved her life.

His face was almost perfectly modeled, his forehead broad and high with dark hair waving back from it like the pictures of young Greek boys. His brown eyes were deeply set beneath level brows, his olive skin and his mouth as attractive as a girl’s.

Yes, her new acquaintance was handsome, Barbara concluded gravely, and yet his face lacked strength. Personally she[30] preferred the bronzed and rugged type of young men to whom she was accustomed in the west.

But what was it that her companion had been saying?

“I do trust, Miss Meade, that you are not ill from fright. Mildred, will you please lend us mother’s smelling salts for a little while, or had we best stop by a drug store?”

Shaking her head Barbara smiled. She was wearing the same little close-fitting brown velvet hat of the night of her arrival. But today her short curls had fluttered out from under it and her eyes were wide open and bluer than ever with the wonderful vision of the first great city she had ever seen.

“Oh, dear me, no, there is nothing in the world the matter with me,” Barbara expostulated. “Why if I can’t go through a little bit of excitement like that, how do you suppose I am going to manage to be a Red Cross nurse in Europe in war times?”

“You a war nurse?” Dick Thornton’s voice expressed surprise, amusement, and[31] disbelief. He turned his head sideways to glance at his companion. “Forgive me,” he said, “but you look a good deal more like a bisque doll. I believe they do have dolls dressed as Red Cross nurses, set up in the windows of the toy shops. Shall I try to get a place in a window for you?”

Barbara was blushing furiously, although she intended not to allow herself to grow angry. Certainly she must not continue so sensitive about her youthful appearance. There would be many more trials of this same kind ahead of her.

“I am sorry you think I look like a doll,” she returned with an effort at carelessness; “it is rather absurd in a grown-up woman to show so little character. My hair is short because I had typhoid fever a year ago. You know, I’m really over eighteen; I got through school pretty early and as I have always known what I wanted to do, I took some special courses in nursing at school, so I was able to graduate two years afterwards.”

“Oh, I see,” Dick murmured, appearing[32] thoughtful. “Eighteen is older than any doll I ever heard of unless she happened to be a doll that had been put away in an old cedar chest years ago. Then she usually had the paint licked off, the saw-dust coming out and her hair uncurled.” Again Dick glanced around, grave as the proverbial judge. “You know, it does not look to me as if any of those alarming things had yet happened to you, else I might try to turn doctor myself.”

Good-naturedly Barbara laughed. If her new acquaintance insisted upon taking her as a joke, at least she had enough sporting blood not to grow angry, or at least if she were angry not to reveal it.

“Well, what are you going to be, Mr. Thornton?” Barbara queried, shrugging her shoulders the slightest bit. “As long as you need not develop into a physician on my account, are you to be a lawyer like your father?”

Dick suppressed a groan. To look at her would you ever have imagined that this little prairie flower of a girl would develop into a serious-minded young woman[33] demanding to hear about “your career”? Any such idea must be nipped in the bud at once.

“Oh, no, I am certainly not going to study law, and if you don’t mind my mentioning it, I get pretty bored with that suggestion. Everybody I meet thinks because my father is one of the biggest lawyers in the country that I must become his shadow. It is all right being known as my ‘father’s son’ up to a certain point, but I’m not anxious to have comparisons made between us as lawyers.”

Barbara felt uncomfortable. She had not intended opening a subject that seemed to be such an unfortunate one. So she only murmured, “I beg your pardon.”

And though Dick laughed and answered, “Don’t mention it,” there was little more conversation between them for the rest of the drive home.

But once at home in the big, sunny library, stretched out in an arm chair, smoking while the girls were drinking tea, the young man became more amiable.

He had changed his outdoor clothes for a[34] velvet smoking jacket and his shoes for a pair of luxurious pumps.

“I say, Mildred, old girl, would you mind ringing the bell and having Brown bring me some matches?” he asked. Finding his own gone, he had simply turned his head and smiled upon his sister. It happened that the bell was within only a few feet of him and she had to cross the room to accomplish his desire.

Although Mildred was tired from a strenuous half hour devoted to comforting her mother since their return from the ride, without protesting or even appearing surprised, she did as she was asked.

But Barbara Meade felt her own cheeks flushing. One need not stay in the Thornton household for four entire days, as she had, before becoming aware that it was the son of the family to whom every knee must bow. His mother, sister, the servants appeared to adore him. It was true that Judge Thornton attempted to show a little more consideration for his daughter, but he was so seldom at home and when there his attention was usually upon some problem of his own.

[35]

More than once Barbara had felt sorry for Mildred. Of course, her position looked like an enviable one as the only daughter of a wealthy and distinguished man, with a beautiful mother and a charming brother. Nevertheless, however little one liked to criticize their hostess even in one’s own mind, Barbara could not but see that Mildred Thornton’s life with her mother was a difficult one.

In the first place, Mrs. Thornton was a fashionable society woman. In spite of what might seem to most people riches, she was constantly talking about how extremely poor they were and how she hoped that Dick and Mildred would make matches that would bring money into the family. She had the same dark eyes and olive coloring that her son had inherited, and as her hair was a beautiful silver-white, it made her face appear younger. She seemed to treat her daughter Mildred’s plainness as a personal insult to herself and behaved as though Mildred could have no feeling in the matter. Several times the visitor had heard her refer to her daughter’s lack of beauty before strangers.

[36]

But that Dick Thornton should dare treat his sister with the same lack of consideration was insufferable! Barbara had a short, straight little nose with the delicate nostrils that belong to most sensitive persons. Now she could not help their arching with disdain, although she hoped no one would notice her.

Yet Dick was perfectly aware of her indignation and amused by it. He was accustomed to having girls angry with him; it was one of the ways in which they showed their interest.

“I wonder if I would like to know what Miss Barbara Meade is at this moment thinking of me?” he demanded lazily, smiling from under his half-closed brown eyes and blowing a wreath of soft gray smoke into a halo about his own head.

The girl’s blue eyes had the trick of darkening suddenly. It was in this way she betrayed her emotions before she could speak.

“I was thinking,” she answered in a clear, cold little voice, “that I have always been sorry before I never had a brother. But now I am not so sure.”

[37]

An abominably rude speech! The girl could not decide whether or not she regretted having made it. Certainly there was an uncomfortable silence in the big room until Mildred broke it.

She had been gazing thoughtfully into the fire, which the April day made agreeable, and talking very little. Now she shook her head in protest.

“Oh, brothers aren’t altogether bad,” she smiled.

Barbara stammered.

“No, of course not; I didn’t mean that. You must both forgive me. You see, I have only a married sister who is years older than I am, and my father. I suppose I have gotten too used to saying whatever pops into my head. Perhaps the men in the west are more polite to girls than eastern men. I don’t know exactly why, but they are bigger, stronger men; they live outdoors and because their lives are sometimes rough they try to have their manners gentle. Oh, goodness, I have said something else impolite, haven’t I?” Barbara ended in such consternation that her host and hostess both laughed.

[38]

“Oh, don’t mind me; please go right ahead if it relieves your feelings,” Dick remarked so humorously that Barbara felt it might be difficult to dislike him intensely, however you might disapprove of him.

“Only,” he added, “don’t start shooting verbal fireworks at the poor wounded soldiers whom you are going to attempt to nurse. If a fellow is down and out they might prove fatal. I say, Mill, did you ever hear anything more absurd? Miss Meade has an idea that she is going over to nurse the British Tommies. She looks more like she needed a nurse herself—with a perambulator.”

“Yes, I know, Barbara has talked it all over with me,” Mildred replied. “We went together to the Red Cross headquarters today to see about arrangements, when she could cross and what luggage she should take with her. Four American girls are to go in a party and after they arrive in England they will be sent where they are most needed. You see, Barbara’s mother was an Irish woman, so she feels she is partly British; and then her father[39] was a West Point man. She meant to make her living as a nurse anyhow, so why shouldn’t she be allowed to help in the war? I understand exactly how Barbara feels.”

Still gazing into the fire, Mildred’s face had grown paler and more determined. “You see, I am going with her. I offered my own services and was accepted this morning. We sail in ten days,” she concluded.

“You, Mildred? What utter tommy-rot!” Dick exclaimed inelegantly. “The mater is apt to lock you up in your room on a bread-and-water diet for ten days for even suggesting such a thing.” Then he ceased talking abruptly and pretended to be stifling a yawn. For, glancing up, he had discovered that his mother was unexpectedly standing in the doorway. She was dressed for dinner and looked very beautiful in a lavender satin gown, but the expression on her face was not cheering.

Evidently she had overheard Mildred’s confession and his sister was in for at least a bad quarter of an hour. Personally Dick hoped his own words had[40] not betrayed her. For although he was a fairly useless, good-for-nothing character, he wasn’t a cad, and for some reason or other he particularly did not wish their visitor to consider him one.

[41]

In the same sitting room and in the same chair, half an hour later, sat Barbara Meade, but in a changed mood. She was alone.

More ridiculously childish than ever she looked, with her small face white and tears forcing their way into her eyes and down her cheeks.

Yet from the music room adjoining the library came such exquisite strains of a world-old and world-lovely melody sung in a charming tenor voice, that the girl was compelled to listen.

Straight through the song went on to the end. But when it was finally finished there was a moment’s silence. Then Dick Thornton appeared, standing between the portieres dividing the two rooms.

[42]

“Say, I am awfully sorry there was such a confounded row,” he began. “But there is no use taking the matter so seriously, it is poor Mill’s funeral, not yours. You seem to be the kind of independent young female who goes ahead and does whatever reckless thing she likes without asking anybody’s advice. But I do wish you would give the scheme up too. Mildred will never be allowed to go with you. I don’t approve of it any more than mother does. Just you stay on in New York and I’ll show you the time of your life.”

Dick looked so friendly and agreeable, enough to have softened almost any heart. But Barbara was still thinking of the past half hour.

“Thank you,” she returned coldly. “I haven’t the faintest idea of giving up my purpose, even to ‘have the time of my life.’ And I do think you were hateful not to have stood by your sister. Besides, you might at least have said that you did not believe I had tried to influence Mildred, when your mother accused me. She was extremely unkind.”

[43]

Entering the library Dick now took a chair not far from their visitor’s, so that he could plainly observe the expressions on her face.

“Of course, I didn’t stand up for Mill; I wouldn’t let her go into all that sorrow and danger, even if mother consented,” he protested. “Your coming here and all the talk you two girls have had about the poor, brave, wounded soldiers and such stuff, of course has influenced Mill. It has even influenced me—a little. But the fact is the war in Europe isn’t our job.”

“No, perhaps not,” the girl answered slowly, perhaps that she might add the greater effect; “but would you mind telling me just what is your job? You have already told me so many things that were not. Is it doing one-steps and fox trots and singing fairly well? I presume I don’t understand New York society, for out west our young men, no matter how rich their fathers happen to be, try to amount to something themselves; they do some kind of work.”

Under his nonchalant manner Dick had[44] become angry. But no one knew better than he the value of appearing cool in a disagreement with a girl. So he only shrugged his shoulders in a dandified fashion.

“I wonder why you think I am not at present engaged in a frantic search for a job on which to expend my magnificent energy?” Here Dick purposely yawned, extending his long legs into a more reposeful position. “The fact is, I believe I must have been waiting for an uncommonly frank young person from the west to give me the benefit of her advice. What would you suggest as a career for me? Remember, I saved your life this afternoon, so you may devote it to the unfortunate. Now what would you think of my turning chauffeur? I’m not a bad one; you ask our man. Who knows, perhaps driving an automobile is my real gift!”

Of course, her companion’s good humor again put her in the wrong, although Barbara knew that she was wrong in any case. For what possible right had she, after having known Dick Thornton less[45] than a week, to undertake to tell him what he should or should not do? It was curious what a fighting instinct he had immediately aroused in her! She felt that she would almost like to hit him in order to make him wake up and realize that there was something in life besides being handsome and good-natured and smiling lazily upon the world.

However, Barbara now clasped her hands together, church fashion, inclining her curly head.

“Beg pardon again. After all, what should a Prince Charming be except a Prince Charming?” she murmured. “You are a kind of liberal education. I’ve lived such a work-a-day life, I can’t understand why it seems so dreadful to you and your family to do the work one loves in the place where it seems to be most needed. We nurses will be under orders from people older and wiser than we are. If we come close to suffering—well, one can’t live very long without doing that. But I don’t want to bore you; you will be rid of me for life in a little while, and I’ll leave now if your[46] mother and father feel my plans are affecting Mildred.”

“You will do no such thing.” Dick’s voice was curt and less polite than usual, but it was certainly decisive and so ended the discussion.

A few minutes later, apparently in a happier frame of mind, Barbara Meade was about to go upstairs when at the door she turned toward her companion.

“Please don’t think I fail to understand, Mr. Thornton, your not wishing Mildred to go through the discomforts and even the dangers of nursing the wounded soldiers. I suppose every nice brother naturally wishes to protect and look after his sister. I told you I had never had a brother, but you must not think for that reason I cannot appreciate what you must feel.”

Then with a quick movement characteristic of her smallness and grace, Barbara was gone.

Nevertheless Dick remained in the library alone until almost dinner time.

Barbara was right in believing that he[47] hated the thought of his sister Mildred’s being away from the care and affection of her own family. Mildred might not be so handsome as he wished her and wasn’t much of a talker, still there was no doubt that she was a trump in lots of ways. Besides, after all, she was one’s own and only sister. Yet Dick was honest with himself. It was not Mildred alone whom he desired to protect from hardships. Absurd, of course, when the girl was almost a stranger to him, yet Barbara Meade appeared more unfitted for the task that she insisted upon undertaking than his sister. In the first place, Barbara was younger, and certainly a hundred times prettier. Then in spite of her ridiculous temper she was so tiny and looked so like a child that one could only laugh at her. Moreover—oh, well, the worst of it was, Dick felt convinced that she was just the kind of a girl he could have a delightful time with, if he had a proper chance. She had confessed to loving to dance in spite of her sarcasm. So she should have at least a few dances with him before fate swept her out of his way forever.

[48]

Ten days later, as early as nine o’clock in the morning, Mrs. Thornton’s limousine was to be seen threading its way in and out among the trucks and wagons along lower Broadway on its way to the American Line steamship pier, No. 62.

Inside the car were seated Mrs. Thornton and Mildred, Judge Thornton, Dick and Barbara Meade. Behind them a taxicab piled with luggage was following. The “Philadelphia” was sailing at eleven o’clock that morning and included among her passenger list four American Red Cross nurses on their way to a mission of relief and love.

In the Thornton automobile not alone was Barbara Meade arrayed for an ocean crossing, but Mildred Thornton also appeared to be wearing a traveling outfit. More extraordinary, the greater part of the luggage on the taxicab behind them bore the initials “M. F. T.” Besides, Mildred was sitting close to her father with her cheek pressed against his shoulder and holding tight to his hand, while the Judge looked entirely and completely miserable.

[49]

Should anything happen to Mildred, he, who loved her best, would be responsible. For he had finally yielded to her persuasions, upholding her in her desire, against the repeated objections of his wife and son. Just why he had come round to Mildred’s wish, for the life of him the Judge could not now decide. What was happening to this world anyhow when girls, even a gentle, sweet-tempered one like Mildred, insisted on “making something of their own lives,” “doing something useful,” “following their own consciences and not some one’s else?” Really the Judge could not at present recall with what arguments and pleadings his daughter had finally influenced him. But he did wonder why at present he should feel so utterly dejected at the thought of Mildred’s leaving, when her mother appeared positively triumphant.

Yet the fact is that within the last few days Mrs. Thornton had entirely changed her original point of view. She had discovered that instead of Mildred’s engaging in an enterprise both unwomanly and unbecoming, actually she was doing the most[50] fashionable thing of the hour. Never before had Mildred received so much notice and praise. Positively her mother glowed remembering what their friends had been saying of Mildred’s nobility of character. How fine it was that she had a nature that could not be satisfied with nothing save social frivolities!

Letters of introduction to a number of the best people in England had been pouring in upon them. One from Mrs. Whitehall to her sister, the Countess of Sussex, was particularly worth while. Mrs. Thornton had never before known that she dared include the writer among her friends. Moreover, Mildred had lately been receiving unexpected attentions from the young men who had never before paid her the slightest notice. Half a dozen of them within the past few days had called to say good-by and express their admiration of her pluck. Two or three had declared themselves openly envious of her. For if there were great things going on in the world, no matter how tragic and dreadful, one would feel tremendously worth while[51] to be right on the spot and able to judge for oneself.

Then Dick had reported that Mildred had been more than a halfway belle at a dance that he had insisted upon his sister and their visitor attending before they shut themselves off from all amusements. Such a lot of fellows wanted to talk to Mill about her plans that they seemed not to care that she could not dance any better.

Although there were only between fifty and sixty passengers booked for sailing on the “Philadelphia’s” list, the big dock was crowded with freight of every kind.

On an adjoining dock there was a tremendous stamping of horses. Not far off one of the Atlantic Transport boats was being rapidly transformed into a gigantic stable. Its broad passenger decks were being divided into hundreds of box stalls. Into the hold immensely heavy boxes were being hoisted with derricks and cranes. The whole atmosphere of the New York Harbor front appeared to have changed. Where once there used to be people about to sail for Europe now there appeared to[52] be things taking their place. No longer were pleasure-loving Americans crossing the ocean, but the product of their lands and their hands.

However, Mildred and Barbara gave only a cursory attention to these impersonal matters, and Mildred’s family very little more. They were deeply interested in a meeting which was soon to take place.

Their little party was to consist of four American nurses sent out to assist the British Red Cross wherever their services were most needed.

So far Mildred and Barbara had not even seen the other two girls. However, Judge and Mrs. Thornton had been assured that one was an older woman, who had already had some years’ experience in nursing and could also act as chaperon. About the fourth girl nothing of any kind had been told them.

Therefore, within five minutes after their arrival at the wharf, Miss Moore, one of the Red Cross workers in the New York headquarters from whom the girls had received instructions, joined them. With[53] her was a girl, or a young woman (for she might be any age between twenty or thirty) for whom Mildred and Barbara both conceived an immediate prejudice. They were not willing to call the sensation dislike, because travelers upon a humanitarian crusade must dislike no one, and especially not one of their fellow laborers.

Eugenia Peabody was the stranger’s name. She had come from a small town in Massachusetts. Her clothes were severely plain, a rusty brown walking suit that must have seen long service, as well as a shabby brown coat. Then she had on an absurd hat that looked like a man’s, and her hair was parted in the middle and drawn back on either side. She had handsome dark eyes, so that one could not call her exactly ugly. Only she seemed terribly cold and superior and unsympathetic.

But the fourth girl, Miss Moore explained, by some accident had failed to arrive in time for the steamer. She was to have come from Charleston, South Carolina, having made her application and sent her credentials from there. It was foolish of[54] her to have waited until the last hour before arriving in New York. Now her train had been delayed, and as her passage had been engaged, the money would simply have to be wasted. Had the Red Cross Society known beforehand, another nurse could have taken her place.

The next hour and a half was one of painful confusion. Surely so few passengers never before had so many friends to see them off. Farewells these days meant more than partings under ordinary circumstances. No matter what pretense might be made to the contrary, in every mind, deep in every heart was the possibility that a passenger steamer might strike a floating mine.

Of course, Barbara had been forced to say her hardest farewells before leaving her home in Nebraska. Nevertheless, she could not now help sharing Mildred’s emotions and those of her family. Besides, the Thorntons had been so kind to her in the past two weeks. Mrs. Thornton had apologized for blaming her for Mildred’s decision, but after all it was easy to understand[55] her feeling in the matter. Judge Thornton was one of the biggest-hearted, dearest men in the world. Then there was Dick! Of course, he was a good-for-nothing fellow who would never amount to much except to be a spoiled darling all his days! Yet certainly he was attractive and had been wonderfully sweet-tempered and courteous to her.

Even this morning he had never allowed her to feel lonely for an instant. Always he saw that she was among the groups of their friends who were showering attentions upon Mildred—books and flowers and sweets, besides various extraordinary things which she was recommended to use in her work.

Dick’s farewell present Barbara thought a little curious. It was an extremely costly electric lamp mounted in silver to carry about in her pocket.

“It is to help you see your way, if you should ever get lost or have to go out at night while you are doing that plagued nursing,” he whispered just as the final whistles blew and the friends of the passengers were being put ashore.

[56]

As Dick ran down the gang-plank, both Mildred and Barbara were watching him with their eyes full of tears. Suddenly he had to step aside in order not to run over a girl hurrying up the plank from the shore. She was dressed in deep mourning; her hair was of the purest gold and her eyes brown. She had two boys with her, each one of them carrying an extraordinary looking old-fashioned carpet bag of a pattern of fifty years ago.

“I regret it if I have kept you waiting,” she said in a soft, drawling voice to one of the stewards who happened to be nearest the gang-plank. “I’ve come all the way from Charleston, South Carolina, and my train was four hours late.”

The tears driven away by curiosity, Mildred and Barbara now stared at each other. Was this the fourth girl who was to accompany them as a Red Cross nurse? She looked less like a nurse than any one of them. Why, she was as fragile as possible herself, and evidently had never been away from home before in her life. Now she was under the impression that the steamer[57] had been kept waiting for her. Certainly she was apologizing to the steward for delaying them.

Yet a glance at their older companion and both girls felt a warm companionship for the newcomer. For if Miss Peabody had been discouraged on being introduced to them, it was nothing to the disfavor she now allowed herself to show at the appearance of the fourth member of their little Red Cross band.

A little later, with deep blasts from her whistle, the “Philadelphia” began to move out. Amid much waving of handkerchiefs, both on deck and on shore, the voyage had begun.

[58]

“In my opinion no one of you girls will remain in Europe three months, at least not as a nurse. You are going over because of an emotion or an enthusiasm—same thing! You are too young and have not had sufficient experience for the regular Red Cross nursing. Besides, you haven’t the faintest idea of what may lie ahead of you,” Eugenia Peabody announced.

It was a sunshiny day, although not a calm one, yet the “Philadelphia” was making straight ahead. She was a narrow boat that pitched rather than rolled. Nevertheless, a poor sailor could scarcely be expected to enjoy the plunging she was now engaging in. It was as if one were riding a horse who rose first on his forefeet and then on his hind feet, tossing his rider relentlessly back and forth.

[59]

So, although the four Red Cross girls were seated on the upper deck in their steamer chairs and at no great distance apart, no forcible protest followed the oldest one’s statement.

However, from under the shelter of her close-fitting squirrel-fur cap Barbara’s blue eyes looked belligerent. She was wearing a coat of the same kind. The next moment she protested:

“Of course, we have not had the experience required for salaried nurses, and of course we are a great deal younger than you” (as Barbara was not enamored of Eugenia she made this remark with intentional emphasis). “But I don’t consider it fair for you to decide for that reason we are going to be useless. The Red Cross was willing that we should help in some way, even though we can’t be enrolled nurses until we have had two years’ hospital work. Mildred and I have both graduated, and Nona Davis has had one year’s work. Besides, soldiers, often when they are quite young boys, go forth to battle and do wonderful things. Who knows what we may[60] accomplish? Sometimes success comes just from pluck and the ability to hold on. Right this minute you can’t guess, Miss Peabody, which one of us is brave and which one may be a coward; there is no telling till the test comes.”

Then after her long tirade Barbara again subsided into the depth of her chair. What a spitfire she was! Really, she must learn to control her temper, for if the four of them were to work together, they must be friends. Dick Thornton had been right. Perhaps the wounded soldiers might have a hard time with a crosspatch for a nurse. But this Miss Peabody was so painfully superior, so “Bostonese”! Even if she had come only from a small Massachusetts town, it had been situated close to the sacred city, and Eugenia had been educated there. Small wonder that she had little use for a girl from far-off Nebraska!

Nevertheless, Eugenia’s cheeks had crimsoned at Barbara’s speech and her expression ruffled, although her hair remained as smooth as if the wind had not been blowing at the rate of sixty miles an hour.

[61]

“That is one way of looking at things,” she retorted. “I suppose almost anybody willing to make sacrifices can be useful at the front these days,” she conceded. “But, really, I do not consider that I am so very much older than the rest of you, even if I am acting as your chaperon. I have always looked older than I am. I was only twenty-five my last birthday and one can’t be an enrolled Red Cross nurse any younger than that—at least, not in America.”

“Oh, I beg pardon,” Barbara replied. At the same time she was thinking that twenty-five was considerably older than eighteen and nineteen, and that before seven years had passed she expected a good many interesting things to have happened to her.

But a soft drawl interrupted Barbara’s train of thought. Issuing from the depth of a steamer blanket it had a kind of smothered sound.

“I am older than the rest of you think. I am twenty-one,” the voice announced. “I only seem younger because I am stupid[62] and have never been away from home before. My father was quite old when I was born, so I have nearly always taken care of him. He was a general in the Confederate army. I’ve heard nothing but war-talk my whole life and the great things the southern women sacrificed for the soldiers. My mother I don’t know a great deal about.”

For a moment Nona seemed to be hesitating. “My father died a year ago. There was nobody to care a great deal what became of me except some old friends. So when this war broke out, I felt I must help if only the least little bit. I sold everything I had for my expenses, except my father’s old army pistol and the ragged half of a Confederate flag; these I brought along with me. But please forgive my talking so much about myself. It seemed to me if we were to be together that we ought to know a little about one another. I haven’t told you everything. My father’s family, even though we were poor——”

Nona paused, and Barbara smiled. Even Eugenia melted slightly, while Mildred[63] took hold of the hand that lay outside the steamer blanket.

“Don’t trouble to tell us anything you would rather not, Miss Davis,” she returned. “We have only to see and talk to you to have faith in you. Of course, we don’t have to tell family secrets; that would be expecting rather too much.”

With a sigh suggesting relief Nona Davis glanced away from her companions toward the water. The girl was like a white and yellow lily, with her pale skin, pure gold hair and brown eyes with golden centers. In her life she had never had an intimate girl friend. Now with all her heart she was hoping that her new acquaintances might learn to care for her. And yet if they knew what had kept her shut away from other girls, perhaps they too might feel the old prejudice!

But suddenly happier and stronger than since their sailing, Nona straightened up. Then she arranged her small black felt hat more becomingly.

“I don’t want to talk all the time, only really I am stronger than I look. As I[64] know French pretty well, perhaps I may at least be useful in that way.”

The girl’s expression suddenly altered. A reserve that was almost haughtiness swept over it. For she had been the first to notice a fellow passenger walking up and down the deck in front of them. She had now stopped at a place where she could overhear what they were saying. The girls had agreed not to discuss their plans on shipboard. It seemed wisest not to let their fellow passengers know that they were going abroad to help with Red Cross nursing. For in consequence there might be a great deal of talk, questions would be asked, unnecessary advice given. Besides, the girls did not yet know what duties were to be assigned them. They were ordered to go to a British Red Cross, deliver their credentials and await results.

So everything that might have betrayed their mission had been carefully packed away in their trunks and bags. Moreover, in the hold of the steamer there were great wooden packing cases of gauze bandaging, medicines and antiseptics which Judge[65] Thornton had given Mildred and Barbara as his farewell offering. These were to be presented to the hospital where the girls would be stationed.

Now, although Nona Davis had become aware of the curiosity of the traveler who had taken up a position near them, Eugenia Peabody had not. So before the younger girl could warn her she exclaimed:

“Hope you won’t think I meant to be disagreeable. Of course, you may turn out better nurses than I; perhaps experience isn’t everything.”

There was no doubt this time that Eugenia intended being agreeable, yet her manner was still curt. She seemed one of the unfortunate persons without charm, who manage to antagonize just when they wish to be agreeable.

At this moment the stranger made no further effort at keeping in the background. Instead she walked directly toward the four girls.

“I chanced to overhear you saying something about Red Cross nursing,” she began. “Can it be that you are going over to help[66] care for the poor soldiers? How splendid of you! I do hope you don’t mind my being interested?”

Of course the girls did mind. However, there was nothing to do under the circumstances. Barbara alone made a faint effort at denial. Eugenia simply looked annoyed because she had been the one who had betrayed them. Mildred showed surprise. But Nona Davis answered in a well-bred voice that seemed to put undesirable persons at a tremendous distance away:

“As long as you did overhear what we were saying, would you mind our not discussing the question with you. We have an idea that we prefer keeping our plans a secret among ourselves.”

Yet neither Nona’s words nor her manner had the desired effect. The stranger sat down on the edge of a chair that happened to be near.

“That is all right, my dear, if you prefer I shall not mention it. Only there is no reason why I should not know. I am a much older woman than any of you, and I too am going abroad because of this[67] horrible war, though not to do the beautiful work you expect to do.”

At this moment the newcomer smiled in a kind yet anxious fashion, so that three of the girls were propitiated. After all, she was a middle-aged woman of about fifty, quietly and inexpensively dressed, and she had a timid, confidential manner. Somehow one felt unaccountably sorry for her.

“I am traveling with my son,” she explained. “You may have noticed the young man in dark glasses. My son is a newspaper correspondent and is now going to try to get into the British lines. He was ill when the war broke out or we should have crossed over sooner. There may be difficulties about our arrangements. After his illness I was not willing that he should go into danger unless I was near him. Then his eyes still trouble him so greatly that I sometimes help with his work.”

She leaned over and whispered more confidentially than ever:

“I am Mrs. John Curtis, my son is Brooks Curtis, you may be familiar with[68] his name. I only wanted to say that if at any time I can be useful, either on shipboard or if we should run across each other in Europe, please don’t hesitate to call upon me. I had a daughter of my own once and had she lived I have no doubt she would now be following your example.”

Actually the older woman’s eyes were filling with tears, and although the girls felt embarrassed by her confidences they were touched and grateful, all except Nona Davis, who seemed in a singularly difficult humor.

“You are awfully kind, Mrs. Curtis, I am sure,” Mildred was murmuring, when Nona asked unexpectedly:

“Mrs. Curtis, if your son has trouble with his eyes, I wonder why I have so often seen him with his glasses off gazing out to sea through a pair of immense telescope glasses? I should think the strain would be bad for him.”

Half a moment the older woman hesitated, then leaning over toward the little group, she whispered:

[69]

“You must not be frightened by anything I tell you. Sailing under the American flag we of course ought to feel perfectly safe, but you girls must know the possibilities we face these days. I think perhaps because I am with him my son may be a little too anxious. However, I shall certainly tell him he is not to take off his glasses again during the voyage. You are right; it may do him harm.”

A few moments later Mrs. Curtis strolled away. But by this time Nona Davis was sitting bolt upright with more color in her face than she had shown since the hour of her arrival.

“I do hope we may not have to see a great deal of Mrs. Curtis,” she volunteered.

“Why not?” Mildred asked. “I thought her very nice. I feel that my mother would like us to be friends with an older woman; she might be able to give us good advice. Please tell us why you object to her?”

The other girl shook her head.

“I am sure I don’t know. I don’t suppose I have any real reason. You see, I don’t often have reasons for things; at[70] least, not the kind I know how to explain to other people. But my old colored mammy used to say I was a ‘second sighter.’”

[71]

Very carefully the young man in the dark glasses must have considered which one of the four American girls traveling together he might expect to find most worth while. Then he chose Mildred Thornton.

And this was odd, for to a casual observer Mildred was the least good looking and the least gay of the four. Even Eugenia, in spite of her severe manner, had a certain handsomeness and under softening influences might improve both in appearance and disposition.

Nevertheless, it was with Mildred that Nona Davis, coming out of her stateroom half an hour before dinner, discovered the young man talking.

It happened that Nona and Mildred shared the same stateroom while the two other girls were just across the narrow[72] passageway. As the decks were apt to be freer from other passengers at this hour preceding dinner, they had arranged for a quiet walk. But now, although seeing her plainly enough, Nona soon realized that Mildred had no idea of keeping her engagement. She was far too deeply engrossed in her new companion. It was annoying, this eternal feminine habit of choosing any kind of masculine society in preference to the most agreeable feminine! However, Nona made no sign or protest. She merely betook herself to the opposite side of the boat and started a solitary stroll.

There was no one to interfere and she was virtually alone, as this happened to be the windy, disagreeable portion of the deck. Of their meeting with Mrs. Curtis the day before no one had spoken since, but now Nona could not help recalling her own impression. She was sorry for her sudden prejudice and more so for her open expression of it.

“I must try and not distrust people,” she thought remorsefully. “Suspicion made my father’s life bitter and shut me away[73] from other girls. So, should circumstances compel us to meet this Mrs. Curtis and her son (and one never knows when chance may throw strangers together), why I shall never, never say a word against them.”

Nona was looking out toward a curious purple and smoke-colored sunset at the edge of the western sky as she made this resolution. Perhaps because the vision before her had somehow suggested the smoke of battle and the strange, dreadful world toward which they were voyaging. Eugenia was right. No one of them could dream of what lay ahead.

For a moment she had paused and was standing with one hand resting on the ship’s railing when to her surprise Mildred Thornton’s voice sounded close beside her.

“Nona, I want to introduce Mr. Curtis,” she began. “We have been trying to find you. Oh, I confess I did see you a few moments ago, only I pretended I had not. Mr. Curtis was telling me something so interesting I did not wish to interrupt him for fear he might not repeat it.”

[74]

Mildred’s eyes had darkened with excitement and she was speaking in a hushed voice, although no one appeared to be near.

Nona Davis extended her hand to the young man. “My name is Davis,” she began. “Miss Thornton forgot to mention it, for although we have known each other but a few days we are already using our first names.”

Then she struggled with a sense of distaste. The hand that received hers was large and bony and curiously limp and unresponsive. Afterwards Nona studied the young fellow’s face. It was difficult to get a vital impression of him when his eyes were so hidden from view, but of one thing she became assured—he was not particularly young.

He was tall and had a fringe of light brown hair around a circular space where the hair was plainly growing thinner. His face was smooth, his mouth irregular and he had a large inquiring nose. Indeed, Nona decided that the young man suggested a human question mark, although[75] his eyes—and eyes can ask more questions than the tongue—were partly concealed.

“Mr. Curtis has been a war correspondent before,” Mildred went on, showing an enthusiasm that was unusual with her. “He has just returned from the war in Mexico and has been telling me of the horrors down there.”

“But I thought,” Nona Davis replied and then hesitated. What she was thinking was, that Mrs. Curtis had mentioned her son’s long illness. This may have followed his return; he was not particularly healthy looking. Not knowing exactly how to conclude her sentence, she was glad to have Mildred whisper:

“Mr. Curtis says he has secret information that our ship is carrying supplies for the Allies. Oh, of course we are on an American passenger boat and it sounds incredible, but then nothing is past belief these days.”

Nevertheless, the other girl shook her head doubtingly. She was a little annoyed at the expression of entire faith with which Mildred gazed upon their latest acquaintance.[76] She wondered if Mildred were the type of girl who believed anything because a man told her it was true. Odd that she did not feel that way herself, when all her life she had been taught to depend wholly upon masculine judgment. But there were odd stirrings of revolt in the little southern girl of which she was not yet aware. She appeared flowerlike and gentle in her old-fashioned black costume. One would have thought she had no independence of body or mind, but like a flower could be swayed by any wind.

“Oh, I don’t expect we are carrying anything except hospital supplies of the same kind your father is sending, Mildred,” she answered. Then turning apologetically toward the young newspaper man: “I beg your pardon, I didn’t mean to doubt your word, only your information.”

However, Brooks Curtis was not paying any attention to her. Instead he was gazing reproachfully at Mildred and at the same time attempting to smile.

“Is that the way you keep a secret, Miss Thornton?” he demanded. “Of course,[77] your friend is right. I have no absolute information. Who has in these war times? I only wanted you to realize that in case trouble arises you are to count on my mother and me.”

He appeared to make the last remark idly and without emphasis, notwithstanding Mildred flushed uneasily.

“You don’t mean that there may be an explosion on shipboard or a danger of that kind,” she expostulated. “It sounds absurd, I know, but I am nervous about the water. I have crossed several times before, but always with my father and brother.”

While she was speaking Nona Davis had slipped her arm reassuringly inside her new friend’s. “Nonsense,” she said quietly. “Mr. Curtis is trying to tease us.” Then deliberately she drew Mildred away and commenced their postponed walk. It was just as well, because at this instant Mrs. Curtis had come on deck to join her son.

A little farther along and Nona pressed her delicate cheek against her taller companion’s sleeve. “For heaven’s sake don’t let Miss Peabody know you are afraid of[78] an accident at sea when you are going into the midst of a world tragedy,” she whispered. “Eugenia believes we are hopeless enough as it is. But whenever you are frightened, Mildred—and of course we must all be now and then—won’t you confide in me?” Nona’s tones and the expression of her golden brown eyes were wistful and appealing.

“You see, it is queer, but I don’t fear what other people do. I have certain foolish terrors of my own that I may tell you of some day. For one thing, I am afraid of ghosts. I don’t exactly believe in them, but I was brought up by an old colored mammy who instilled many of her superstitions into me.”

Their conversation ended at this because Barbara and Eugenia Peabody were now walking toward them, both looking distinctly unamiable. It was unfortunate that the two girls should be rooming together. They were most uncongenial, and so far spent few hours in each other’s society without an altercation of some kind.

Nona smiled at their approach. “And[79] east is east and west is west, and never the twain shall meet,” she quoted mischievously. Then she became sober again because she too had a wholesome awe of the eldest member of their party, and Eugenia’s eyes held fire.

Some powerful current of electricity must have been at work in that portion of the universe through which the “Philadelphia” was ploughing her way that evening.

For as soon as they entered the ship’s dining room the four girls became aware of a tense atmosphere which had never been there before. They chanced to be a few moments late, so that the other voyagers were already seated.

Mildred Thornton, by special courtesy, was on the Captain’s right hand and Barbara Meade on his left (this attention was a tribute to Judge Thornton’s position in New York); Nona was next Mildred and Eugenia next Barbara.

Then on Nona Davis’ other side sat a beautiful woman of perhaps thirty in whom the four girls were deeply interested. But not because she had been in the least[80] friendly with them, or with any one else aboard ship, not even with Captain Miller, who was a splendid big Irishman, one of the most popular officers in the service, and to whom the Red Cross girls were already deeply attached.

Four days had passed since the “Philadelphia” sailed and the voyage was now more than half over. But except that she appeared on the passenger list as “Lady Dorian,” no one knew anything of the young woman’s identity. Her name was English, and yet she did not look English and spoke, when conversation was forced upon her, with a slightly foreign accent, which might be Russian, or possibly German. However, she never talked to anyone and only came to the table at dinner time, rarely appearing upon deck and never without her maid.

But tonight as the girls took their places at the dinner table it was evident that Lady Dorian had been speaking and that her conversation had been upon a subject which Captain Miller had requested no one mention during the course of the voyage—the war!

[81]

Every one of the sixteen persons at the Captain’s table looked flushed and excited, Mrs. Curtis at the farther end was in tears, and an English banker, Sir George Paxton, who had lately been in Washington on public business, appeared in danger of apoplexy.

“What is the trouble, Captain?” Barbara whispered, as soon as she had half a chance. She was a special favorite of Captain Miller’s and they had claimed cousinship at once on account of their Irish ancestry.

“Bombs!” the Captain murmured, “not real ones; worse kind, conversational bombs. That Curtis fellow started the question of whether the United States had the right to furnish ammunition to the Allies. Then Lady Dorian began some kind of peace talk, to which the Englishman objected. Can’t tell you exactly what it was all about, as I had to try to quiet things down. They may start to blowing up my ship next; this war talk makes sane people turn suddenly crazy.”

A movement made Barbara glance across[82] the table. Although dinner was only beginning, Lady Dorian had risen and was leaving.

No wonder the girls admired her appearance. Barbara swallowed a little sigh of envy. Never, no never, could she hope to go trailing down a long room with all eyes turned upon her, looking so beautiful and cold and distinguished. This was one of the many trials of being small and darting about so quickly and having short hair and big blue eyes like a baby’s. One’s hair could grow, but, alas, not one’s self, after a certain age!

Lady Dorian was probably about five feet seven, which is presumably the ideal height for a woman, since it is the height of the Venus de Milo. She had gray eyes with black brows and lashes and dark hair that was turning gray. This was perfectly arranged, parted at the side and in a low coil. Tonight she had on a gown of black satin and chiffon. Though she wore no jewels there was no other woman present with such an air of wealth and distinction.

The instant she had disappeared, however,[83] Mrs. Curtis turned to her son, speaking in a voice sufficiently loud to be heard by every one at the Captain’s table.

“I don’t believe for a moment that woman’s name is ‘Lady Dorian.’ She is most certainly not an English woman. Even if she is married to an Englishman she is undoubtedly pro-German in her sentiments. I shouldn’t be surprised if she is—well, most anything.”

Brooks Curtis flushed, vainly attempting to silence his mother. Evidently she was one of the irrepressible people who would not be silenced. The Red Cross girls need not have been flattered or annoyed by her attentions. She appeared one of the light-minded women who go about talking to everybody, apparently confiding their own secrets and desiring other confidences in exchange. She seemed to be harmless though trying.

But the Captain’s great voice boomed down the length of the table.

“No personalities, please. Who is going to tell me the best story before I go back on duty? Perhaps Miss Davis will tell us some negro stories!”

[84]

Nona blushed uncomfortably. She was shy at being suddenly made the center of observation, yet she appreciated the Captain’s intention.

Nevertheless, and in spite of her best efforts, the disagreeable atmosphere in the dining room remained. Mrs. Curtis was not alone in her suspicion of the vanished woman. There was not another person at the table who did not in a greater or less degree share it. Lady Dorian was strangely reserved about her history in these troublous war times. Then she had been trying to keep her point of view concealed. However, to the Red Cross girls, or at least to the three younger ones, she was a romantic, fascinating figure. One could easily conceive of her in a tragic role. Secretly both Barbara and Nona decided to try to know her better if this were possible without intrusion.

An hour after dinner and the Red Cross girls were in bed. There was nothing to do to amuse oneself, as the lights must be extinguished by half-past eight o’clock. The Captain meant to take no risks of over-zealous German cruisers or submarines.

[85]

At dawn Barbara awakened perfectly refreshed. She felt that she had been asleep for an indefinite length of time, and although she made a slight effort, further sleep was impossible. How long before the hour for her bath, and how stuffy their little stateroom had become!

Barbara occupied the upper berth. Swinging herself a little over the side she saw that Eugenia was breathing deeply. Asleep Barbara conceded that Eugenia might almost be called handsome. Her features were well cut, her dark hair smooth and abundant, and her expression peaceful. However, even with consciousness somewhere on the other side of things Eugenia still looked like an old maid. Barbara wondered if she had ever had an admirer in her life. Although wishing to give Eugenia the benefit of the doubt, she[86] scarcely thought so. It would have made her less difficult surely!

Twice Barbara turned over and burrowed her curly brown head in her pillow. She dared not even move very strenuously for fear of waking her companion and arousing her ire. Of course, it was irritating to be awakened at daylight, but then how was she to endure the stupidity and stuffiness of their room without some entertainment? If only she could read or study her French, but there was not yet sufficient daylight, and turning on the electric light was too perilous.

Staring up at the ceiling only a few feet above her head where the life belts protruded above the white planking, Barbara had a sudden vision of what the dawn must be like at this hour upon the sea. How she longed for the rose and silver spectacle. Had she not been wishing to see the sunrise every morning since coming aboard ship? And here at last was her opportunity. Should Eugenia be disagreeable enough to awaken she must simply face the music.

[87]

Noiselessly Barbara’s bare toes were extended over the side of the berth and then she reached the floor with almost no perceptible sound. She was so tiny and light she could do things more quietly than other people. A few moments later she had on her shoes and stockings, her underclothing and her heavy coat, with the little squirrel cap over her hair. It would be cold up on deck. But one need not be particularly careful of one’s costume, since there would probably be no one about except a weary officer changing his watch. It was too early for the sailors to have begun washing the decks, else she must have heard the noise before this. Their stateroom was below the promenade deck.

As Barbara closed the outside door of their room she heard Eugenia stirring. But she slipped away without her conscience being in the least troublesome. If Eugenia was at last aroused, she would not be there to be reproached. The thought rather added zest to her enterprise. Besides, it was wrong for a trained nurse to be a sleepy-head; one ought to be awake and ready at[88] all times for emergencies. Had Barbara needed spurs to her own ideals of helpfulness in her nursing, she had found them in Eugenia’s and in Dick Thornton’s openly expressed doubts of her. Whatever came, she must make good or perish.