The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hernando Cortes, by Joachim Heinrich Campe

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Hernando Cortes

Life Stories for Young People

Author: Joachim Heinrich Campe

Release Date: June 11, 2019 [EBook #59732]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HERNANDO CORTES ***

Produced by D A Alexander, Stephen Hutcheson, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by the Library of Congress)

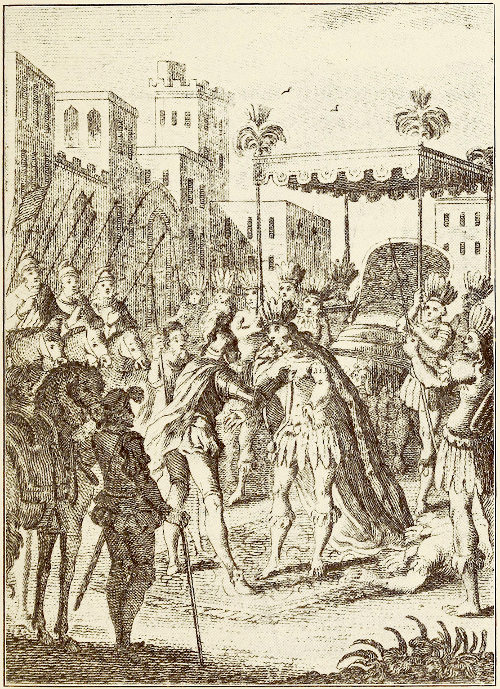

CORTES AND MONTEZUMA

Life Stories for Young People

Translated from the German of

Joachim Heinrich Campe

BY

GEORGE P. UPTON

Translator of “Memories,” “Immensee,” etc.

WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1911

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1911

Published September, 1911

THE · PLIMPTON · PRESS

[W · D · O]

NORWOOD · MASS · U · S · A

The story of the career of Hernando Cortes during his conquest of Mexico is a story of extraordinary courage, undaunted resolution, and hideous cruelty. It is a story of the subjection of a “little people,” overcome and enslaved by a superior nation, which, in its lust for gold and territorial aggrandizement, left no methods of stratagem, cunning, military science, and barbarous cruelty untried to achieve its purpose. Granted that the early Emperors of Mexico were tyrannical in their treatment of the natives and that their religious rites were accompanied by human sacrifices and cannibalism, Mexican cruelty pales before the horrible scenes enacted by so-called civilized Spain in this dreadful Mexican drama. The three principal figures are Hernando Cortes, Montezuma, and Guatemozin—Cortes, the conqueror; Montezuma, the weak-spirited Emperor, victim of his own people’s fury; Guatemozin, the patriot. Cortes was a born adventurer, and in his youth possessed of skill in all military exercises. He was a man of consummate cunning and captivating address, of soaring ambition and marked ability as an administrator and general. Apparently he never knew what it was to fear, and consequently no danger was great enough to appall him. He was so skilled in stratagem that no situation was devious enough to prevent its solution. He had the same greed of gold as all Spaniards of his day had, and no means of obtaining it were considered dishonorable as long as they were successful. But courageous, resolute, and ambitious as Cortes was, he will go down through the ages branded with infamy for his treatment of Montezuma, for the frightful massacres at Cholula and Otumba, for his execution of Guatemozin, last of the Aztec Emperors, for the burning of caciques and chiefs which he ordered, and for the countless atrocities of his men which he permitted. In his old age, like Columbus, he suffered from the neglect of an ungrateful Court, but, while we can sympathize with Columbus in that situation, we can feel no sympathy for Cortes as we recall the black chapters of his career.

G. P. U.

Chicago, July, 1911.

In the year 1511 Diego, Columbus’ son, finding that the gold mines of Hispaniola were nearly exhausted, decided to take possession of the neighboring island of Cuba, or Fernandina, as it was called, in honor of the King of Spain. The force which he sent for the capture of the island was placed under the command of Velasquez,[1] a man described by his contemporaries as possessing extraordinary experience as a soldier, having served seventeen years in European campaigns, also of a renowned family and name, eager for glory and yet ambitious for wealth.

Velasquez speedily subjugated the whole island and at once actively busied himself with the adoption of measures for its welfare. He established many settlements, secured farmers by free grants of land and slaves, devoted special attention to the raising of sugar-cane, such a valuable article of commerce in later times, and, above all, to the development of gold mines, which promised better returns than those of Hispaniola. But the subjugation of Cuba was too small a matter to satisfy his ambition, as he would remain subject to the higher authority of Diego Columbus, from which he wished to free himself. The best means for accomplishing this seemed to him the making of important discoveries which would secure him an independent sovereignty. With this end in view, he turned his attention to the westward, in which direction he had every reason to believe he should find a great mainland region which no European had ever reached.

Chance favored his plans. Hernandez de Cordova, a Spaniard,[2] undertook an expedition from Cuba in 1517, with three vessels, to a neighboring island for the capture of slaves. Storms drove him upon the coast. In reply to his question as to the name of the country the natives said, “Tektetan,” meaning in their language, “I do not understand you.” The Spaniards thought this was the name of the place and distorted it into “Yucatan.” Thus the peninsula of the mainland, which lies opposite Cuba and divides the Caribbean Sea from the Gulf of Mexico, came by its present name. Cordova first landed at the northeastern end of the peninsula, at Cape Catoche, then sailed along the peninsula, stopping at various places, and at last came to the region of the Campeche of to-day, where the sea forms the Bay of Campeche.

The daring Spaniards had many fierce encounters with the natives, whom they found far more civilized and at the same time more warlike than the other islanders. They were clad in garments of a woven woollen material. Their weapons were wooden swords, tipped with flint, spears, bows, arrows, and shields. Their faces were painted in different colors, and their heads adorned with tufts of feathers. They were the first Americans who constructed dwellings of stone and cement.

In their various encounters with these people the Spaniards sometimes came off losers. In one of them two Indian boys having the Christian names of Julian and Melchior fell into their hands. They proved of great advantage, for they served the Spaniards as interpreters in subsequent communications with the Mexicans. One day, when they had landed to fill their casks with fresh water, fifty Indians approached and inquired if they had come from the place where the sun rises. When the Spaniards answered in the affirmative, they were conducted to a temple, constructed of stone, in which they beheld various ugly images of deities sprinkled with fresh blood. Suddenly two men in white mantles, with long, flowing, black hair, stepped forward, holding small earthen braziers, into which they threw a kind of resin. They directed the smoke toward the Spaniards and ordered them upon pain of death to leave the country. Finding it dangerous to remain there, they obeyed and returned to their vessels. At another spot, where they had landed, they were surrounded by so large a multitude of hostile Indians that forty-seven were killed and many wounded in their efforts to get back to their vessels. Among the seventy wounded was Cordova himself. After this disaster they hurried back to Cuba as rapidly as they could, where their leader died after making a report to Velasquez of all that had happened.

Velasquez was delighted at the discoveries made in his name, and decided to continue them. Four vessels were fitted out, and Grijalva,[3] a man of great ability and courage, upon whose uprightness and good judgment Velasquez believed he could depend, was given command of them. He was specially instructed to confine himself to making discoveries without establishing colonies in the new regions. Grijalva left Cuba May 1, 1518, and directed his course toward Yucatan, but the ocean currents drove him southerly, so that he first made land at Cape Catoche. Subsequently he discovered the island of Cozumel, off the Yucatan coast. From there he sailed along the coast to Potonchan, where Hernandez had been so foully dealt with. The Spaniards were eager to land and avenge the disaster, and Grijalva consented. The Indians, full of pride and defiance, and delighted with this fresh opportunity, attacked the Spaniards courageously, but they were driven back. Two hundred paid the penalty with their lives for their rashness, and the rest fled panic-stricken all over the country.

Grijalva resumed cruising along the coast. He was astonished everywhere at the sight of villages or towns with houses made of stone and cement, which in passing appeared to the Spaniards finer and better built then they really were. The resemblance between this region and Spain seemed so close to them that they gave it the name of New Spain—a name which it retains to this day. Next they came to the mouth of a river, called by the natives Tabasco, but the Spaniards named it Grijalva, in honor of their leader. The whole region roundabout had such a flourishing appearance and seemed to be populated so densely that Grijalva could not resist the desire to obtain accurate information about it. So he went ashore with his entire armed force. There he encountered a multitude of armed Indians, who with terrible outcries sought to prevent their further advance. But he paid no attention to their menaces, marched up to a bowshot’s distance from them, then halted, drew his men up in battle order, and sent the two Americans, Julian and Melchior, who had been taken by Hernandez, to inform them that he had not come there to injure them, but to do them good, and that he was anxious to make a peaceful agreement with them.

The Indians, who had been gazing in astonishment at the closed ranks, the costumes, and weapons of the Europeans, were still more astonished at this declaration. Some of their leaders ventured to advance. Grijalva cordially welcomed them and told them through the interpreters that he and his followers were subjects of a great King who was the absolute ruler of all the countries where the sun rises. This King had sent him to demand their submission to his authority, and he awaited their answer. Thereupon a low murmuring ensued among the Indians, which was stilled by one of their leaders, who replied courageously in the name of his people that it seemed strange to them that the Spaniards should speak of peace and at the same time demand submission. It seemed strange to them also that they should be offered a new ruler without ascertaining whether they were dissatisfied with their present one. As far as the question of war or peace was concerned he was not authorized to give a decisive answer. He must submit that question to his superiors. With these words he retired, leaving the Spaniards not a little astonished at this sensible reply. After a short time he returned and told Grijalva that his superiors did not fear war with the Spaniards, if it must be, for they had not forgotten what happened at Potonchan. But they considered peace better than war, and, as a token of this, he had brought many necessaries of life for gifts.

Shortly after this, the cacique himself appeared, unarmed and with a small retinue. After friendly greetings on each side he took from a basket golden articles of various kinds set with jewels, and fabrics decorated with beautifully colored feathers, and said to Grijalva that he loved peace and had brought these gifts in confirmation of his words, but, that there might be no opportunity for misunderstanding, he begged him to leave the country as soon as possible. The Spanish leader acknowledged the politeness of the cacique by making gifts in return, and promised to conform to his wishes as soon as he could get under sail.

After cruising some distance along the coast, they reached an island with many stone houses and a temple. In the centre of this temple, which was open on all sides, they saw various hideous idols placed about an altar, elevated a few steps. Near to it were six corpses, which, according to the prevailing horrible custom, seemed to have been offered up as sacrifices on the preceding night. On account of this dreadful spectacle the Spaniards named the place Isla de los Sacrificios (“Island of Sacrifice”). Everywhere they found evidences that the inhuman practice of sacrificing men to their deities prevailed among these people. Coming to anchor at another island, which was called Kulva by the natives, they saw many more corpses of freshly slaughtered men, which caused even the barbarous Spanish soldiers to shudder at such cruelty. Grijalva gave his surname, Juan, to this island, from which eventually came the name, St. Juan de Ulloa, by which it is now known.

Wherever they went gold was found in abundance. This and the sight of many fruitful spots which they passed aroused a general desire among the men to effect a settlement, but Grijalva persisted in carrying out the orders of Velasquez, and everywhere that he landed, took possession of the country in the name of the King. He continued sailing along the coast until he reached Pánuco. At the mouth of a river there he was so furiously assailed by a swarm of Indians that a dreadful massacre became necessary before they could be driven back. After this, while attempting to sail still farther along the coast, adverse currents forced him to return to Cuba. Upon his arrival he met with bitter reproaches from the unreasonable governor, Velasquez, because he had not availed himself of the excellent opportunity to establish a colony in that rich region, although he had been expressly forbidden to do so when he sailed.

Grijalva had sent back one of his principal officers, Pedro de Alvarado, with a rich collection of jewels, and golden vessels and ornaments, secured from the natives by exchanging European knick-knacks for them, and he had told much about the rich country. When Grijalva returned, after an absence of six months, he met with censure because he had carried out the instructions of the governor! The modest, unassuming man bore the undeserved reproaches calmly. To him belongs the honor of being the first European navigator to set foot on Mexican soil and open up intercourse with the Aztecs.

Velasquez, an ambitious but at the same time distrustful and fickle man, decided to continue the great discoveries made in his name, and to secure the rich profits which they promised. With this object in view he fitted out a strong fleet with the utmost expedition. The question then arose, Who should take command of it? Not having the courage to participate personally in an undertaking exposed to so many dangers and hardships, he was forced to look for another leader. The choice was a difficult one, for one man seemed to him too cowardly, another too courageous, this one too dull, another too crafty. He was anxious to find a man who would combine with the necessary judgment and courage absolute devotion to him and slavish obedience to his orders, and who would not only accomplish great deeds but at the same time give him all the advantage of them. Fortunately he found such a man, one admirably fitted for such an undertaking, but he did not understand how to make use of him. That man was Cortes.

Hernando Cortes, of noble family, was born in 1485 at Medellin, a small town in the Spanish province of Estremadura. From his earliest youth he had unusual courage, unwearied patience in overcoming difficulties, a restless, active spirit, and a burning desire to distinguish himself by great deeds. In his childhood he was weakly. In his fourteenth year he was sent to the University of Salamanca, his father, who built great hopes upon his brilliant talents, having destined him for the law. He chose a calling for him which opened up better prospects for an industrious young man than any other, but the son had no sympathy with his father’s purpose. He showed little fondness for books and after his second year of study returned home, to the great disappointment of his parents, and spent his time without following any special avocation. He showed an inclination for a military life, particularly a life full of adventure.

All eyes at that time were directed to the West Indies, and his own eyes were turned to the same region. He decided to enroll himself among those bold spirits who defied all hardships and dangers if only they might enrich their fatherland with new possessions and gain for themselves a glorious name. He was in his twentieth year (1504) when he sailed from Spain and betook himself to San Domingo. On his very first voyage his courage and steadfastness were put to a severe test. He encountered innumerable dangers and trials, but the bold, strong youth, whose physical and mental strength had not been weakened by indolence, effeminacy, and shameless debaucheries, laughed at them. To work was a pleasure to him, to hunger and thirst a trifle, to die, if necessary, an indifferent matter.

The vessel which carried Cortes was one of a large number lying at the Canary Islands, taking on stores for their voyages, as was the practice of all vessels at that time when making the passage to the New World. Its commander was a greedy fellow who was anxious to reach the New World market before the rest so as to get a high price for his goods. He sailed away secretly by night, but a furious storm overtook him, dismasted his vessel, and forced him to go back to the Canary Islands. The other captains generously waited for their faithless companion, but he managed to slip away again by night. He lost his course, however, was exposed to hard storms and adverse winds, and his vessel was so violently tossed about that all on board feared for their lives and were not a little enraged at the author of their troubles. The young Cortes, however, was not disturbed by the danger, and contemplated the future joyfully. At last, after long wandering about, the vessel arrived at its destination. A dove which had gone astray lit upon the mast. As it flew off they followed the direction of its flight and reached Hispaniola, where the other vessels had arrived a long time before and the ship-masters had sold their goods.

Cortes reached San Domingo at a time when Ovando was still governor. His very appearance secured for him a favorable reception. He was prepossessing, pleasing of countenance, and unaffectedly friendly in his contact with every one, but his peculiar qualities of disposition made him still more the favorite. He was open-hearted, indulgent, and magnanimous, but he was also shrewd, far-sighted, and reserved. He spoke maliciously of no one and was good-humored in conversation. He was always ready to confer favors but he could not bear to have them mentioned. These meritorious qualities soon made him a favorite with every one. Immediately upon arrival he went to pay his respects to the governor, but Ovando was absent, attending to affairs in the interior. His secretary, however, received him cordially, and assured him it would not be difficult for him to obtain an abundance of land from Ovando upon which he could settle. Cortes answered: “I have come here to provide myself with gold, not to plough like a field laborer.”

Upon his return Ovando induced the young man to give up his ambitious designs, for a short time at least, and convinced him that he would certainly become richer if he settled down as a planter than if he trusted himself to chance. Cortes therefore secured land and an allotment of Indians in the settlement of Azua. The monotony of his life was often relieved by the part he took as an adventurer in warlike expeditions, especially in the company of Velasquez, when the latter as Ovando’s representative was forced to suppress uprisings of the natives. In this way he became better known to Ovando, who was exceedingly anxious to retain his services. But as his young, courageous spirit was eager for more important undertakings, he applied for and received permission to accompany Velasquez on his expedition to Cuba in 1511. At last he had an opportunity to display his courage and activity. He quickly rose. In a short time the important position of Alcalde of St. Iago was assigned to him. A quarrel with Velasquez soon after occurred, which might easily have been fatal to the incautious Cortes, had not the friendship of the two been so strong. Cortes, who was not a hero of virtue, fell in love with a young lady of high rank, named Catalina Xuarez, and had promised to marry her, but put off the fulfilment of his promise so long that he incurred the angry reproaches of the governor. These reproaches naturally led to a coolness between Cortes and his patron, and Cortes decided that he would lay his grievances before Velasquez’ superior in Hispaniola. Other dissatisfied ones joined him and they planned to send a messenger. Cortes was selected, for no other would have ventured to cross secretly in an open boat the distance of eighteen miles to the neighboring island. But the conspiracy was discovered, Cortes was arrested, chained, and placed in close confinement. It is said that Velasquez would have hanged him but for the intercession of friends. Meantime the bold Cortes did not long remain in prison. He shoved back one of the fastenings of his chains, freed his limbs, broke the window, and escaped to a church near by. According to the customs of the time a fugitive could not be seized in a sacred place. Velasquez kept guards upon the lookout, and once, when Cortes incautiously ventured out just a little too far, he was caught, and bound, and conveyed to a vessel which was to sail to Hispaniola the next morning. But fortune favored him. He released himself in the night, jumped from the vessel’s side into a boat, thence into the sea, and swam ashore. Exhausted, he sought the same asylum again and declared he would marry Catalina Xuarez, if the governor would pardon him. Velasquez assented, Cortes married Catalina, a reconciliation between himself and Velasquez was effected, and a closer friendship than ever was the result.

When Alvarado returned with glowing accounts of the new discoveries on the mainland, and Grijalva also extolled the great rich western empire, Cortes was the one chosen as the commander of the fleet. The position was accepted by him, and all who were to take part in the expedition were delighted that such an able, courageous, and highly qualified man was to be their leader. Cortes was also delighted at the opportunity of displaying his ability, contributed all that he had in providing an ample store of campaign necessaries, and aided those of his companions who were too poor to obtain what they needed.

Before the equipment in the harbor of St. Iago was completed Cortes stole away, for he had heard that Velasquez designed to take the supreme command from him, fearing that he might carry off all the glory as well as the profits of the enterprise. His entire force numbered three hundred men, and a hundred more joined him from another part of Cuba, members of distinguished families, eager for the glory and boundless treasures which the expedition promised. The day on which Cortes sailed was the eighteenth of November, 1518. The first destination of the fleet was Trinidad, and the next Havana, where several persons and further stocks of supplies were to be taken aboard.

Velasquez for a long time seemed to be satisfied with the choice of Cortes as leader of the expedition, though many a jealous tale-bearer sought to prejudice him against him. But hardly did he see Cortes sail away before he took a different view of the prospect. He thought to himself, What if he should abuse the authority entrusted to him, refuse to be obedient, and make himself absolute ruler in the country he was to conquer in Velasquez’ name? The little clique of Cortes’ enemies ever at his side observed what was troubling him and redoubled their efforts to kindle his jealousy into flame, and at last succeeded. A messenger was instantly sent to the Alcalde at Trinidad, ordering him to remove Cortes from his position as soon as he arrived there. The Alcalde was prepared to carry out his instructions, but Cortes, who was not conscious of any offence, did not believe that he was bound to resign. He assured the Alcalde that Velasquez’ change of mind was due to a misunderstanding and requested him to delay the execution of his instructions until he could send a letter to the governor and receive a reply. The Alcalde, who was not in a position to carry out his instructions by force, gave his consent. Cortes wrote the governor, weighed anchor at once, and sailed for Havana. At the latter place he had to wait some time, partly for his reinforcements and partly to secure one thing or another indispensable to such an important expedition.

At last all was ready. The fleet numbered eleven vessels. The largest, of one hundred tons, not larger than one of our two-masted merchant vessels, was the Admiral’s flag-ship. The three next largest were of seventy-eight tons’ burthen, and the rest small open barges. Cortes’ force had now been increased to six hundred and seventeen, of whom a hundred or so were sailors and artisans, the rest soldiers. Only thirteen of these were armed with muskets and thirty-two with cross-bows. The others carried swords and spears, for the use of fire-arms at that time was very limited. Sixteen horses, ten small cannon or field-pieces, and four falconets or culverins, which are a kind of long, slender cannon, no longer in use, constituted the most important part of the outfit. With this comparatively weak equipment, Cortes sailed for an unknown country to make war against the powerful ruler of Mexico, whose prosperous empire, together with the neighboring provinces, was greater than all the countries over which the King of Spain ruled at that time.

In the meantime Velasquez was furious at the news that Cortes, in spite of his prohibition, had sailed away. He charged his representatives whom he had sent to cancel the appointment with treachery. His rage knew no bounds, and he made vigorous preparations to prevent Cortes from escaping a second time from Havana. He sent one of his most trusty subordinates with express instructions to seize Cortes and send him chained and stoutly guarded to St. Iago.

Fortunately Cortes was informed of the danger impending over him in sufficient time to make himself secure. He quickly summoned his force, of whose good-will he was convinced, explained the danger which threatened them, and asked for their opinion. They unanimously declared he should pay no attention to the fickle governor and that he should not surrender his legal rights nor deliver himself into the power of such an unjust and suspicious judge. They implored him, in view of the importance of the expedition, not to give up his leadership, assured him of their perfect confidence in him, and expressed themselves ready, in the face of all obstacles and dangers, to follow him even to death. Cortes was easily affected and ready to agree to anything which would aid him in carrying out his purpose. After thanking the soldiers for their consent he at once ordered anchors weighed, and sailed from Havana, February 10, 1519.

Cortes decided to take the same course which Grijalva had followed before him, and so made the island of Cozumel his next destination. There he had an opportunity to rescue a Spaniard who had been left upon the coast by a shipwreck, and since that time had been a servant among the Indians. This poor fellow, named Aguilar, during the eight years of his abode there, had lost every European vestige and taken on the appearance, color, speech, and habits of the natives so completely that it was difficult to recognize he had ever been a Spaniard. Like the natives, he went naked, the color of his skin was dark brown, and his hair, after the custom of the country, was wound about his head in coils. He carried an oar on his shoulder, a bow in his hand, and a quiver on his back. His entire possessions were contained in a knit bag and consisted of his provisions and an old prayer-book in which he read industriously. He had so far forgotten his mother-tongue that it was difficult to understand him.

According to his statement he was wrecked in the vicinity with nineteen others. Seven of his comrades were overcome by hunger and exhaustion. The rest fell into the hands of the cacique of that country, a monster who sacrificed five of them to his deities and placed the others in a kind of cage, intending to fatten and then eat them. They had the good fortune, however, to escape. Helpless and despairing, they wandered about the forests, subsisting upon roots and herbs, until at last they met some Indians who took them to a kindly cacique, an enemy of the other. He received them humanely but each day imposed hard tasks upon them. The most of them died in a short time, only two of them, Aguilar and Guerro, surviving. They soon had an opportunity to render the cacique important service in his wars, for which he was very grateful. Guerro married an Indian woman of distinction, was made commander, and gradually became so Americanized that when the Spaniards arrived he did not care to change his conditions. He would not see them, perhaps for shame, for Aguilar said he had pierced his nose and painted various parts of his body as the natives did.

Cortes embraced the poor Aguilar and covered his nakedness with his own cloak. As Aguilar had learned the language of the country during his long stay there, Cortes was rejoiced at his discovery, for he naturally hoped he would be of great service to him in future communications with the Indians. From Cozumel he directed his course to Tabasco, and to that part of it where the river Grijalva empties into the sea. He expected to meet a friendly reception, as Grijalva had, but he was disappointed. At sight of his vessels the natives assumed a hostile aspect and seemed determined to prevent him from landing. He sent Aguilar to them to make an agreement, but it was useless. They would not listen to him, and he had to return without accomplishing his object. The event was as unpleasant to Cortes as it was unexpected. He had not planned to begin his conquest in that place. His object was to reach as soon as possible the region nearest the country of the great Mexican Empire, and begin his operations there. Now he found himself in the unpleasant situation of being forced either to submit to the threats of the natives or to inaugurate hostilities in an outlying province, which, even if they ended successfully, must cost at least time, and lives, of which he had few to spare. If he turned back, the Indians would certainly take it as a mark of cowardice and become more troublesome than ever. After considering this view of the situation, it seemed to him a conclusive reason for attacking them. As the approach of night prevented him from doing so at once, the assault was deferred until the next day, and the intervening night was devoted to the necessary preparations.

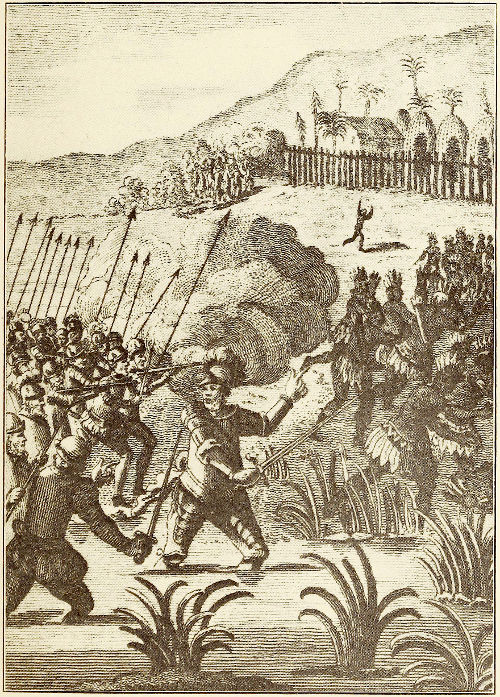

THE ENGAGEMENT BETWEEN THE SPANIARDS AND THE PEOPLE OF TABASCO

At daybreak all were summoned for action. Cortes arranged his fleet in a half circle and in this order, which was necessary on account of the shores, he began sailing up the stream. But before opening the attack, he sent Aguilar to inform the natives that it rested with them to say whether he should come as an enemy or a friend. Aguilar performed his duty, but instead of listening quietly to him the Indians gave the signal for attack and rowed out in their canoes to meet the fleet. They came together and the Indians began the assault with a dreadful storm of arrows and stones which caused great discomfort to the Spaniards, who were still remaining passive. At this Cortes gave the signal for defence. A single shot from the great cannon was decisive. The Indians, astonished at the unexpected thunder which roared about them, and terrified at the sight of its destructive consequences, jumped from their canoes into the water and endeavored with all their might to escape by swimming. The Spanish vessels drew up to the banks, and Cortes landed with his whole force undisturbed. The battle, however, was far from being ended. The Indians, who had left their canoes, fled into the brush, where a still greater number of their warriors were collected. They rushed forward while Cortes was engaged in placing his men in battle order, and attacked him with arrows, spears, and stones, uttering appalling battle cries. Cortes, however, was not disturbed but continued the arrangement of his ranks until the whole corps was in close battle order. Then they charged furiously against the Indians, advanced with wonderful coolness through deep morasses and dense thickets upon the countless swarms of the enemy, and death and terror beat a way for them. The sight of an army with European weapons was as new as it was fearful to the Indians. They could not face it and incontinently took to flight.

The enemy fled to their fortified city of Tabasco. The fortifications consisted only of a row of stakes driven into the ground, after the style of our palisades, and surrounding the city in circular form. Both ends overlapped, and between them a single narrow road led into the city with many windings. Great as the peril seemed to be, Cortes unhesitatingly advanced along this narrow passage, but upon entering the city found the streets blocked up with stakes and the people ready to oppose him. The Indians were forced back again and yet the battle was not ended. They gathered anew in the market place of the city, again offered stubborn resistance, and again were overcome. Thereupon they fled to the woods. Tabasco was captured, and the battle was over. Cortes did not pursue the Indians but took possession of the city for the Spanish crown. He made three incisions with his sword in a large tree and announced that he occupied the city in the name and in favor of the Catholic sovereign, and that he would maintain and defend it with sword and shield against all who should gainsay it. The same declaration was made by his soldiers, and the proceedings were written down and formally attested. The plunder taken by the Spaniards did not come up to their expectations, for the Indians carried off the greater part of articles of value, leaving only some provisions which came in good stead for the tired and hungry Spaniards.

At night Cortes quartered his force—in three divisions—in temples at different places and stationed watchmen to guard against a night attack. He made the rounds at different times to see that they were performing their duty. At daybreak he searched the woods near by, but not an Indian was to be seen or heard, which made him a little suspicious. He sent spies to the adjacent region, who brought him the disquieting news that a multitude of Indians, forty thousand at least, were collected, whom they had watched at some distance, while they were getting ready for an attack. Such news as that might well alarm one in Cortes’ situation! He was confronted with a force a hundred times as large as his own, compelled to fight for their fatherland, their temples, and their lives. He realized the danger, but, master of himself and his emotions, he maintained as calm and composed a mien as if the report were a mere joke. His example inspired his men with like fearlessness, and they stood ready to follow him wherever he should lead.

Cortes drew up his little army in battle array at the foot of a hill. It protected his men in the rear, and at the same time he could use his cannon in the freest and most effective manner. He posted himself with his cavalry in an adjoining thicket, whence at the right time he could charge the enemy unexpectedly. In this order they quietly awaited the onset of the Indians. The ever memorable day upon which the battle was fought was the twenty-fifth of March, 1519, Annunciation Day.

The Indians appeared, most of them armed with bows and arrows. The bowstrings were made of the sinews of some animal or stag’s hair, and the arrows were tipped with sharp bones. In addition to these they carried spears which could be thrown from a distance or used as a hand-weapon. One of their most terrible weapons was a great battle sword, made of very hard wood, the edge of which was formed of exceedingly sharp stones, joined together, and which was so heavy that it had to be wielded with both hands, like an axe. Some of them had clubs, others slings with which they could hurl stones of great size with unusual force and accuracy. The leaders alone protected themselves with quilted woollen coverings, and wooden or tortoise shell shields. The rest went naked, but to give them a frightful appearance they painted their faces and bodies in different colors, and to increase their stature they wore headdresses of tall feathers. Their battle music was in keeping with their looks. They used reed pipes and large sea-shells as wind instruments, and drums made of hollowed tree trunks. The art of fighting in close ranks was entirely unknown to them. They observed a certain order, however, by dividing the whole force into little squads, each with its own leader. They had this in common with the European plan of battle, that they did not engage all their warriors at the same time in a fight, but kept a part in reserve to come to the help of those in front when it should be necessary. Their opening assault was always made with frightful outcries and with great vigor, but if the enemy withstood the first attack and succeeded in throwing the advance into disorder, a panic would strike them and a general retreat ensue.

Such was the enemy the little army of Spaniards now saw advancing upon them in countless numbers. Silent and solid as a wall they awaited the attack. When they had come within bowshot, the battle opened with terrible yells and a shower of arrows which darkened the air. The Spaniards replied with a cannon and musketry fire, which covered the ground with heaps of the closely crowded enemy. The Indians, however, were undaunted. They filled up the void, threw sand in the air to conceal their losses in a cloud of dust, and after another flight of arrows came to a hand to hand struggle. The Spaniards did their best to overcome superiority of numbers, but the impetuosity and the multitude of the enemy were so great that they could not long withstand them. Their ranks were already broken through in several places, and a general massacre seemed imminent when suddenly Cortes appeared with his cavalry and charged into the midst of the enemy. It was a new and dreadful sight to the poor Indians, who had never before beheld horsemen. They thought they were huge monsters, half man and half beast, and were so overcome with fear that their weapons dropped from their hands. The Spaniards improved the opportunity to get into order again, the cannon fire was renewed, and, attacked upon every side, the panic-stricken Indians incontinently fled.

Satisfied with this display of his superior power, Cortes at once ordered that the fugitives should be spared and only a few of them captured in order to make a peaceful arrangement with the whole nation. Eight hundred Indians lay dead upon the field, and only two Spaniards, but seventy of the latter were wounded. All the Indians who were not too severely wounded had fled. The field was made the site of a city, which, in honor of the day and the event, was called Santa Maria de la Vittoria, and afterward became the capital of the country.

On the following day some of the captives were brought before Cortes. Their faces wore an expression of anxiety and fear for they had no doubt that they would be sentenced to death, but how great was their joy and astonishment when he received them with the greatest kindness, and Aguilar, the interpreter, announced their freedom. Their delight was still further enhanced when Cortes displayed his generosity by making them gifts of trifles, which he knew would secure their good-will. Overcome with joy, they hastened to tell their people how handsomely they had been treated. The result was that the Spaniards won over all those hearts which had been filled with rage and vengeance. To manifest their confidence and good intentions, various Indians shortly came, bringing all kinds of subsistence for which they were generously recompensed. The cacique himself sent messengers with gifts and begged for peace. It was granted, and when, soon afterward, he came in person, assurances of peace on each side were confirmed by presents. Among other expressions of good-will the cacique brought twenty young women who knew how to bake Indian corn bread, and made a present of them to Cortes. One of them, who had been christened Marina, was the daughter of a cacique and had been kidnapped when a child and sold to the cacique of Tabasco. She was not only unusually beautiful but intelligent, and in a short time learned the Spanish language and was of great service to Cortes afterward in his dealings with the Mexicans.

While the cacique and his leaders were with Cortes they chanced to hear the Spanish horses neigh. Thereupon the terrified Indians anxiously inquired what was the matter with these frightful beings, meaning the horses. They were told that they were angry because the cacique and his people had not been punished more severely for their audacity in attacking the Christians. The instant they heard this they hurried off and brought various kinds of game to appease them. They meekly implored forgiveness and promised they would faithfully submit to the Christians in the future.

Their confidence was soon displayed. Spanish knick-knacks were exchanged for the raw products of the country, such as food of all kinds, woollen goods, and golden ornaments. When the natives were asked where the precious metal came from, they pointed westward and replied, “Kulhua,” “Mexico.” It was at once decided to leave the country and proceed to the land of gold. Before they left, Cortes displayed his solicitude for their conversion. He called their attention to the great doctrines of Christianity, and sought to persuade them to abandon heathenish practices. As the Indians offered but little objection, the conversion ceremony began on Palm Sunday. The whole army, with a priest at its head, moved in solemn procession through the blooming fields, surrounded by thousands of Indians, to the principal temple, in which the image of the heathen divinity had been removed from the altar and displaced by the image of Christ. The priest conducted the mass, the soldiers sang, the natives listened in deep silence and were moved to tears. Their hearts were filled with reverence for the divinity of those beings who seemed to control the thunder and lightning with their hands.

After the ceremony was concluded the soldiers bade farewell to their Indian friends, and a few hours afterward the little fleet was on its way to the gold coast of Mexico.

Cortes, satisfied with the fortunate outcome of a struggle which might have had most disastrous consequences, and full of hope for similar good fortune in his future undertakings, left Tabasco. A favoring east wind filled the swelling sails, and the course was westward. On this voyage Cortes visited all those places where Grijalva had been before him. At last he reached the island of San Juan de Ulloa, which Grijalva had visited, and came to anchor between the island and mainland. They had not been there long before they saw two large and long canoes approaching them from shore. The Indians in them seemed to be of some importance and were apparently apprehensive of danger, but Cortes received them on board in a friendly manner. They began to speak, and Cortes awaited an explanation of their visit, but they spoke a language which Aguilar, his interpreter, did not understand. They talked in Mexican, but he had learned only Yucatanish—an entirely different tongue.

In the meantime Cortes to his great delight observed that the slave Marina of Tabasco was conversing with some of the Indians and found that this person, who had been born in a Mexican province and been kidnapped, and taken to Yucatan, could speak the language of both countries with equal facility. Marina spoke with them in her own dialect, communicating what they said to Aguilar in Yucatanish, who in turn spoke to Cortes in Spanish. By this fortunate occurrence Cortes learned that Pilpatoe, the governor of that country, and Teutile, the great Emperor Montezuma’s general, had sent these Indians to ascertain his object in coming and to offer him assistance in continuing his journey, should he need it. Their appearance showed them to be a very different people from those wild tribes of the West Indies before encountered. Cortes recognized the difference immediately and replied in a cordial way that he had come with the friendly purpose of bringing tidings to their ruler which would prove of great importance. He dismissed them with gifts and, without waiting for a reply, began sending his people, horses, cannon, and war material to land. The hospitable natives submitted, hastened to lend helping hands to their future oppressors, and set up straw huts for them. Unfortunates! If some friendly spirit could have revealed the future to them and shown them how dearly they would have to pay for this friendly service, how they would have recoiled from these wolves in sheep’s clothing! How they would have put forth all their strength and joyfully spent the last drop of blood to drive these dangerous strangers from their shores!

On the following day Pilpatoe and Teutile appeared in person with a numerous retinue of armed Mexicans. Their appearance was imposing as befitted the majesty of their great sovereign. Cortes also displayed as much pomp as his circumstances permitted, to impress them with his own importance and that of the sovereign he represented. He ordered his troops to march at his side with military precision and in respectful silence, and received the Mexican officers with a display of dignity which deeply impressed them. Upon being asked who had commissioned him, he haughtily replied with intentional brevity that he came in the name of Charles of Austria, the great and powerful monarch of the East, who had entrusted him with a message to the Emperor Montezuma that could only be delivered in person. He desired therefore that he should be conducted to him.

Ferdinand, the Catholic, who ruled over Spain in the time of Columbus, had no sons, but left a daughter, named Joanna, who married Philip, an Austrian prince. A son was born to them, named Charles, and it is he who is mentioned above. When Ferdinand died, Charles, whose father was no longer living, became heir to his crown. He was also sovereign of the Netherlands, which had come into his possession a year previously. Later he was chosen German Emperor and thus became one of the most powerful monarchs in Europe. As four princes by the name of Charles had occupied the throne before him, he was designated Charles the Fifth.

The Mexicans were much embarrassed by the resolute declaration of Cortes. They knew that his determination to have a personal interview with their Emperor would be extremely disagreeable to the latter. Montezuma had been greatly disturbed at the first appearance of Europeans on the Mexican coast. There was an old saying in his country that a mighty people dwelt toward the east, who sooner or later would attack and overthrow the Mexican Empire. How this saying originated it is not easy to say, but it is certain that the superstitious Mexicans, and Montezuma himself, were terrified by the old prophecy as soon as the Europeans appeared. This was also the reason why Montezuma’s ambassadors were so disturbed when Cortes demanded the interview. Meanwhile, before making a reply to his demand, they sought to win his favor with gifts, among them ten bales of fine woollens, exquisite feather cloaks, whose beautiful and delicate colors rivalled the finest paintings, and a willow basket filled with gold ornaments. Cortes expressed his gratitude for the gifts, which emboldened them to tell him such an interview would be impossible. To their intense astonishment Cortes, with a sinister and angry expression of face, interrupted them by declaring that he could not return to the great monarch, whose representative he was, without carrying out his object. That was more than they had expected and all they could do was to request Cortes to have patience until they could acquaint Montezuma with his purpose and receive his reply. Cortes assented to this and sent gifts to the Emperor. These consisted of a richly carved and colored arm-chair, a head covering having a gold medallion with the image of St. George and the dragon on it, a quantity of necklaces and bracelets and ornaments of cut glass, which, in that country where they had no glass, was regarded by the Mexicans as a precious stone.

Upon this occasion also several painters attached to the Mexican retinue made drawings upon white cotton of the most remarkable European objects they observed. Learning that these drawings were to be sent to the Emperor, Cortes decided to offer the artists still more interesting subjects that would be likely to make a deep impression upon Montezuma. He drew up his entire force in battle array and displayed before the astonished Mexicans a realistic picture of a battle conducted in the European manner. The spectators were so overcome with astonishment and awe that some of them fled, others in a dazed condition threw themselves upon the earth, while the rest fancied that what they saw and heard was a game for their diversion. The artists now had an opportunity to use their pencils in depicting the fearful and destructive effect of European warfare. They worked with trembling hands, and when their pictures were finished, they were sent with the other gifts by swift runners to the Emperor. In that country they had swift runners on all the principal roads leading from the most distant provinces to the capital, ready at any moment to convey intelligence of all that was transpiring at any place.

In a few days the Emperor’s reply was received. As was expected, the interview was declined, but to mitigate the disagreeableness of the refusal, Montezuma accompanied it with gifts which were truly regal. Pilpatoe and Teutile had the unpleasant duty of presenting both. They wisely produced the gifts first, to prepare Cortes, if possible, for a favorable reception of the reply.

The gifts were brought in by a hundred Indians and spread out on mats at Cortes’ feet. The Spaniards greedily gazed at these proofs of the richness of the empire. There were samples of cotton which resembled silk in its gloss and fineness, pictures of animals, trees, and other natural products skilfully wrought out in vari-colored feathers, and gorgeous necklaces, bracelets, rings, and other ornaments of gold. But as the sun eclipses all the other luminaries in the heavens, so were these objects eclipsed by two large circular disks, one of which was of solid gold, the other, of silver. The one represented the sun, the other the moon. As if for the purpose of still further exciting the cupidity of the Spaniards, several caskets filled with precious stones, pearls, and grains of gold from the streams and mines were presented.

Cortes accepted these splendid gifts with expressions of the utmost respect for the giver, and thereupon the ambassadors proceeded to the disagreeable part of their commission. They declared on behalf of their sovereign that he could not permit foreign soldiers to approach the capital or remain longer within the limits of the Mexican Empire. They were requested to retire immediately. Fair and reasonable as the request was, Cortes assumed the mien of one who had been insulted, and asserted even more haughtily than before that he utterly refused to accept the reply, for his own honor and that of his sovereign would be offended should he return without having had the interview. The eyes of the Mexicans, who were accustomed to abject submission to their ruler, were fixed in astonishment upon a man who dared to resist anything which their absolute lord had ordered. Such audacity was so terrible to them that it was some time before they could recover from the shock. At last they regained composure and begged of this bold European a second delay in order to report his unexpected persistency at the capital. Cortes again consented, but upon the condition that he should not have to wait too long for a reply. Firm and decided as he appeared to be in these negotiations, he was not altogether sure that he was on secure ground. Everything convinced him that he had to deal with a powerful and well managed government. It seemed the most hazardous thing in the world to oppose such a power with a handful of Spanish adventurers.

Nevertheless he held to the bold purpose of venturing the undertaking, cost what it might. Two motives actuated him. Religious zeal was the first. He was convinced he would be doing Heaven a great service if he could convert these heathen to Christianity. The second was based on his own doubtful circumstances, for, after what had occurred between himself and Velasquez, the governor, upon leaving Cuba, he could not hope to escape unpunished when he returned. As his life was in danger in any event, he might better risk it in the accomplishment of an unheard of adventure than expose himself to the danger of losing it at the hands of the hangman upon his return. Unfortunately there were several in his army who were growing very anxious, and these were men who were more closely attached to Velasquez than to him. They had used their utmost efforts to disaffect the others and to excite a general uprising so as to force their leader to return to Cuba. But the prospect of securing vast and exhaustless treasures was so strong that nothing else could make a deep impression upon them. Besides, they believed there was good reason now to expect a favorable answer from Mexico.

The reply came at last, but it was not what they had anticipated. Far from being alarmed by the stubbornness of the Spanish general, Montezuma had come to the manly conclusion to abide by his decision that the Europeans must retire. Teutile brought the disagreeable message, as well as more handsome gifts. Cortes thought best this time to assume a less insolent attitude and mildly replied that the Christians esteemed it their duty to instruct their ignorant neighbors in the doctrines of that religion which pointed all men to the only road to happiness! It was for this reason his greater monarch had sent him to show Montezuma and his subjects the error of their ways, which they could no longer look upon without pity. Therefore he could not leave without insisting that this interview should take place. Teutile had hardly the patience to wait for the close of Cortes’ statement. He rose from his seat angrily at last and indignantly declared that as the Emperor’s gracious offers were of no avail, the instructions of his master would be carried out in a more forcible manner. With these words he hastily rushed out, followed by his entire retinue and all the Mexicans who were in the vicinity. In a short time the whole region was abandoned by the natives.

This was more than Cortes had expected. He was surprised and his danger now was greatly increased. With great anxiety he contemplated the results which must follow from this occurrence. The most direful evil threatening them was the utter lack of subsistence, which the hospitable natives had so generously furnished them hitherto. The discontented ones in the army renewed their efforts to force Cortes to return to Cuba. They ventured now openly to inveigh against him, to accuse him of foolhardiness, and to urge their comrades not to suffer him to lead them farther in the way to destruction. Cortes, who was as courageous as he was far-sighted, with the aid of his confidants secretly investigated the sentiments of his army, and when he was informed that the insurgents were not making any deep impression, he summoned the foremost of the instigators, among whom a certain Ordaz was conspicuous, met them in a friendly manner, and inquired the meaning of their conduct. They did not conceal their purpose, but urged even vehemently that they should embark and sail back to Cuba.

Cortes quietly listened to them. Then he replied that so far as he was concerned, in view of the danger to which they were exposed, he did not see how, as their leader, he could oppose their wishes. Therefore he would give his consent. He thereupon caused it to be proclaimed through the camp that all must be ready to embark for the return voyage to Cuba. He clearly foresaw what an uproar this would cause and his anticipations were promptly realized. The Spaniards, who, since their landing, had dreamed of nothing but exhaustless treasures, stood as if thunderstruck when they learned that they had based their assurance upon such slender hopes, and that, without having earned the slightest reward for their previous hardships, they were to return home poorer than when they started away. These reflections were intolerable, and an angry murmur of discontent at the fickleness of their leader spread through the camp.

Cortes was rejoiced at this, for he clearly saw it would aid him in his plans. He contrived with the aid of his confidants to increase the indignation of the soldiers still more. They complained all the more loudly that absolute cowardice was keeping them from the road to glory and wealth. The result was increased excitement and a general demand that their leader should appear before them. That was just what Cortes desired. He came at once with a look of extreme surprise on his face. They unanimously accused him of lack of courage in doubting the successful outcome of an undertaking for the spread of the true religion and for the great glory and advantage of the fatherland. They declared furthermore that for their part they were firmly determined to pursue the glorious course upon which they had entered, and to choose another leader if he faint-heartedly deserted them. Their defiant words were music to his ears, and it was some time before he recovered from his surprise. At last he began to express his astonishment at what he had heard. He assured them that he had never dreamed of giving up hopes which were as great as they were well founded. But, as it had been stated to him that his entire army had become discouraged and wished to go back, he had unwillingly decided to comply with its wishes. At this point his excited soldiers with united voices declared he had been deceived. A few cowards had charged the whole army with cowardice. They were ready to risk their blood and life to carry out his great purpose. He might lead them where he pleased. They were ready to follow him even to the death.

All was as Cortes wished. With an expression of joy and satisfaction he extolled the glorious steadfastness of his soldiers and promised to carry out the desires which they had so unanimously expressed. He would therefore, he added, end his stay in the region where they were and march into the heart of the country with the larger part of the army. A universal and enthusiastic cheer greeted his decision. Now came the last act of the comedy. He was and still remained their leader, but his entire authority depended solely upon their good-will. The absolute authority of the soldiers that had made him their commander, under changed circumstances could take the command away from him. He sought to remove this possibility in the following crafty way. He named a court of justice for the new colony whose membership he knew was favorable to him. Hardly was this done, and hardly had the magistrates assembled, before Cortes appeared in their midst, his staff of commander in hand. After permission had been granted he thus addressed them:

“I regard you, gentlemen, from this time forward as the representatives of our great sovereign. Your decisions will always have the sanctity of law. You unquestionably recognize the necessity that our army must have a leader whose authority does not depend upon the caprice of the soldiers. Now I find myself in this position. Since the governor has revoked my appointment, both my authority and my position, indeed, are doubtful. I consider myself bound, therefore, to resign my command, which rests upon such a doubtful basis, into your hands and to request you, after due consideration, to designate some one in the name of the King who seems to you most worthy of being the commander. For my part, I am ready as a common soldier, pike in hand, to furnish an example to my comrades of obedience to the one selected as leader.”

With these words he kissed his staff of command, handed it reverently to the Chief Justice, placed his letter of resignation on the table, and left. The judges thereupon played out the farce. For appearances’ sake they accepted the resignation, pretended the proper consideration, at last made a new choice, and Cortes was unanimously elected commander. Thereupon the army was summoned, and the choice was announced and enthusiastically welcomed.

Cortes was now the authorized commander at the head of six hundred greedy wolves, before whom the countless hordes of naked Mexicans were as so many defenceless sheep. The High Court appointed by Cortes gave to the settlement, which was established before his departure, the name of Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz, “the rich city of the true Cross.”[4] The budding settlement was called “rich” because it was there they had a chance to judge of the wealth of the Mexican Empire by the gifts which had been sent, and because they expected that the treasures of that rich people, unfortunately for them, would soon be flowing in there. The addition, “true Cross,” was made because they landed there on the anniversary of the Crucifixion. This remarkable appellation of the first European colony in Mexico indicates the two leading passions which animated the Spanish adventurers, namely, avarice and religious enthusiasm. They were animated alike by the longings to fill their purses with gold and Heaven with souls. It was a mixture of the earthly and heavenly, cruelty and apparent humanity, shameless cupidity and pretended piety.

The discontented Velasquez faction in Cortes’ camp soon discovered that they had been deceived and began to murmur afresh. Cortes at once seized those who were the most intemperate in speech and placed them on board the vessels in chains. Those who had been misled into sympathy with the mutineers were sent, under a reliable leader and in the company of several of the loyal ones, into the neighboring region to procure subsistence. After they had returned with abundant supplies, and hunger was appeased, a reconciliation was soon effected. Every one of them acknowledged his authority, and they soon became his most trusty and devoted followers. Their destiny and his were now joined, for they had mutually taken the decisive step and must follow him wherever he led. When peace was fully restored, the Spaniards made all their preparations for departure, and a fortunate event cleared the way of all obstacles. They encountered five Indians, messengers from a cacique, whose possessions were not far distant, who asked to be conducted to the Spanish commander. Their request was granted, and Cortes, with the aid of his interpreter, learned the agreeable news that the cacique of Zempoala had heard of the great deeds accomplished by the Spaniards at Tabasco and was anxious to make a friendly treaty with them. After much questioning Cortes discovered that Montezuma, of whom the cacique of Zempoala was a vassal, was a proud, overbearing, and cruel master, both hated and feared by all his subjects, who were only waiting for an opportunity to free themselves from his yoke.

Cortes was careful to conceal his satisfaction over this intelligence. He knew how easy it is to overthrow the mightiest empire as soon as dissatisfaction and misunderstandings arise between the ruler and his people, and he now had not the slightest doubt of the success of his undertaking, which but for this fortunate event might have proved foolhardy in the extreme. The Indians were dismissed with friendly assurances for themselves and their master, and with the promise that Cortes would shortly pay them a visit. To fulfil his promise and at the same time to investigate a spot which they recommended as a convenient place for a colony, he departed with his whole army after giving orders to his fleet to coast along in that vicinity. At the close of the first day’s march they reached an Indian village which was completely deserted. They found empty houses and temples with images of deities, remnants of human beings who had been sacrificed, and some books, the first which had been discovered in America. They were made of parchment or hide which was smeared over with gum and arranged in leaves. In place of letters they contained pictures of all kinds and symbols connected with the abhorrent Mexican religion.[5] On the following day Cortes continued his march. They came to broad luxurious plains and wooded regions rich with the vegetation of the tropics. The branches of the stately trees were hung with dark red, gracefully curving vines and other parasitic plants of brilliant color. The undergrowth of prickly aloes, interlaced with wild roses and honeysuckles, in several places made almost impenetrable thickets. In the midst of this profusion of fragrant blossoms, countless birds and swarms of butterflies fluttered about, while exquisite singing birds filled the air with their melody. Although the invaders were not very susceptible to the beauties of nature, they could not help expressions of delight, and, as they traversed this earthly paradise, it reminded them of the beautiful regions in their own fatherland.

Cortes was greatly surprised to find the whole country deserted, although it was the territory of the cacique of Zempoala. It looked suspicious to him. But toward evening twelve Indians, carrying provisions, who had been sent by the cacique, met them. They besought the Spanish leader in the name of their master to go to his residence, which was only a sun’s (one day) distance from there. He would find everything there that he and his men needed. Upon being asked why the cacique himself had not come to meet him in person, they replied that he was prevented by physical infirmity. Cortes sent six of the Indians back with thanks, retaining the rest to act as guides. On the following day the cacique’s city came in sight, lying in a fruitful, smiling region, and very handsome in appearance. Some of the soldiers in the advance rushed back, excitedly shouting that the walls of the city were made of solid silver. To their great regret they found they were mistaken, for the walls were only covered with a cement so white and glistening in the sunshine that it easily deceived those who dreamed day and night of nothing but gold and silver. Upon entering the city they found all the streets and public squares filled with curious natives who were unarmed and conducted themselves more quietly than might have been expected of such a multitude of uncivilized beings.

As they approached the house of the cacique, his Indian highness himself appeared. His figure revealed the nature of the infirmity which had prevented him from going out to meet his guests. He was so monstrously fat that he could scarcely walk, his servants having to support and move him along. His shapeless bulk and clumsy manner were so ludicrous that Cortes had some difficulty in restraining his men from loud laughter and in preserving his own seriousness. The attire of the cacique was gorgeous. He was dressed in a cloak profusely set with precious stones, and his ears and lips were perforated and richly adorned. His address of welcome did not in the least correspond with his laughable appearance. It was very clever, and well put together, and closed with the request that Cortes would condescend to be his guest and abide with him, so that they might have an opportunity to talk together at leisure. The rest of the day was spent in partaking of refreshment and enjoying the fruits which grew there in great profusion.

In his interview with the cacique Cortes designedly impressed him with the idea that he had been sent there by the great eastern monarch for the purpose of putting an end to tyranny in that part of the world. This encouraged the cacique to make bitter complaint of the haughtiness and injustice of Montezuma, whom he did not hesitate to characterize as a cruel tyrant, whose yoke was intolerable not only to himself but to others of his vassals. His indignation was so great, as he spoke of it, that tears sprang from his eyes. Cortes endeavored to quiet him and assured him of his protection. He also informed him that the power of the tyrant did not disturb him in the least, for he knew that his own power, which was supported by Heaven, was irresistible. After taking a cordial leave of the hospitable Indian, Cortes set out upon his march to Chiahuitzlan, the place selected for a settlement. Their way led over fruitful plains and through pleasant woodlands, and after a moderate day’s journey they saw the city upon a rocky eminence. The people had fled. As they reached the market-place fifteen Indians emerged from a temple, greeted the strangers, and assured them that their governor and all his people would come back without delay if their safety were guaranteed. Cortes solemnly assured them no one should be hurt and in a short time the cacique and his people overcame their fears and returned. Cortes was pleased to discover that the cacique of Zempoala was there also. Scarcely had the interview begun when bitter complaints were made of Montezuma’s persecutions. Cortes, who heard these complaints now for the second time, consoled them and renewed his promises of protection.

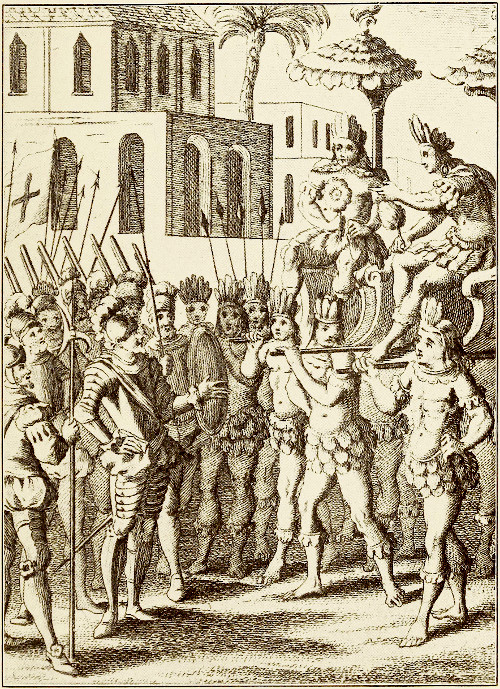

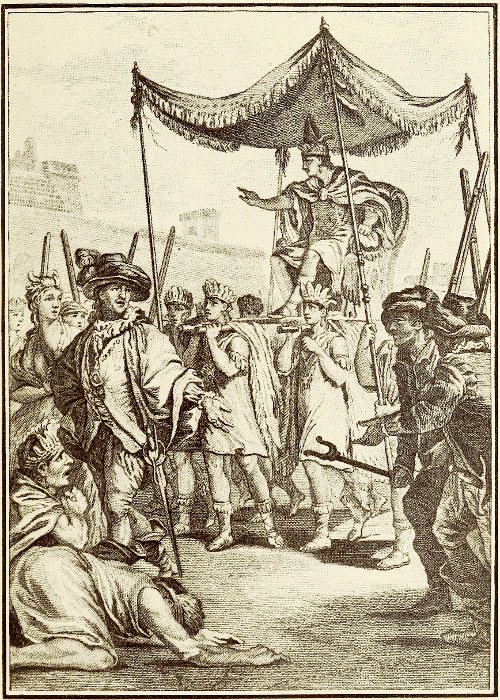

MEXICAN CACIQUES BEFORE CORTES

In the meantime some of the Indians approached the two caciques and whispered something in their ears which greatly astonished them. They sprang up affrighted, and left the spot trembling. Uncertain what might be the cause of their fear, they were followed, and the reason was soon discovered. Six splendidly clad representatives of Montezuma accompanied by a considerable number of slaves, holding feather umbrellas over their heads, passed the Spanish quarters with glances of contempt at Cortes and his officers. Their haughtiness so enraged the soldiers that they were restrained with difficulty from violently assaulting the Mexicans. Marina, who had been sent to gather information, returned with the news that they had bitterly reproached the two caciques for their treachery in receiving strangers, who were the declared enemies of their sovereign. As a penalty for their disloyalty, besides the customary tribute, twenty Indians should be delivered over to them as a sacrifice to the offended deities. Cortes was enraged but wisely refrained from giving expression to his wrath. He assured the caciques they need have no fear of harm and instructed them to bring Montezuma’s messengers before him in chains to give an account of themselves. The caciques, who had been used to absolute obedience to their master, hesitated, but Cortes, leaving them no time for reflection, repeated his orders so emphatically that they dared not offer objection. The messengers were arrested, the Spaniards, for appearances’ sake, taking no part in it. Having gone thus far, the caciques would have gone still further and done to the fettered messengers what Montezuma proposed to do to the Indians, but Cortes objected to such inhumanity and ordered that the prisoners should be guarded by his own men.

Cortes desired, if possible, to conceal the appearance of open hostility to the powerful Montezuma. He cunningly planned to put him under obligations to himself by making him believe he had not the least connection with what had occurred. With this purpose in view he summoned two of the prisoners at night, announced to them that they were free, and instructed them to inform their master that he would strive to secure the liberty of the others, and with this dismissed them. The Indians were told the next day that the prisoners had escaped. Shortly after this, the other prisoners were permitted to join their companions. This tricky dealing had the effect which Cortes expected. In the meantime other caciques were found in the neighboring mountainous region who shared the same hatred toward their Emperor and were equally desirous of escaping his tyrannical rule. All these heads of Indian tribes, bearing the general name of Totonacs, entered into agreements with Cortes, disavowed the authority of Montezuma, and declared themselves vassals of the King of Spain.

Steps were now taken for the founding of a city at the new settlement. The name of Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz was retained for the city, but the name to-day has been abbreviated to Vera Cruz. Every one in the Spanish army assisted in laying the walls and constructing the buildings of the new city. No one refused, and Cortes set an example for all by assisting personally. The work went on with incredible swiftness and in a short time the enclosed place was sufficiently secure against Indian assaults. Meanwhile Montezuma’s messengers had returned and performed the favorable offices expected by Cortes. Their report considerably mitigated the anger of the monarch, who in his first heat of passion had ordered the mustering of a mighty army to extirpate these strangers and their Indian auxiliaries by fire and sword. Now, however, he was greatly concerned and decided to employ kind measures to induce these dreaded strangers, if possible, to go away peacefully. To this end he sent messengers with gifts of great value, two young princes, relatives of the Emperor, being the bearers. They reached the Spanish camp just at the time of the completion of the fortifications. They discharged their duty, presented the costly gifts, thanked Cortes for the assistance he had rendered in releasing the prisoners, and concluded with the request that he would be pleased to leave the territory of their sovereign.

Cortes showed them the greatest honor and made the following reply: He was sorry that the Emperor had been caused trouble by the imprisonment of his messengers, and yet it must be acknowledged that they had brought it upon themselves by an inhuman demand, which he hoped had been made without the Emperor’s knowledge. In any event he must declare that the Christian religion did not recognize the cruel practice of human sacrifice and that he felt himself bound to prevent it wherever and however he could. As for the wrong which had been done the Emperor, that had been compensated for by the release of the prisoners, and, as he was under obligations to the allies he had accepted, he flattered himself that the Emperor would overlook the hasty act of the caciques of Zempoala and Chiahuitzlan, and pardon them. He was obliged to take these vassals of the Emperor under his protection for they had striven to make amends for Teutile’s incivility by giving him a hospitable reception. As to his departure from the country, he had already had the honor to assure their master that a mission of the utmost consequence bound him not to return to his fatherland until he had had a personal interview. A European soldier never feared to perform any duty imposed upon him by his superiors. The messengers, amazed at the cool and stately manner in which Cortes delivered his reply, returned, filled with admiration at his courageous firmness and with secret contempt for their own sovereign, to whom they reported all they had seen and heard.

The new Spanish city was now in a satisfactory state of defence, and Cortes devoted himself in earnest to the completion of other necessary affairs. Fortune seemed decidedly in his favor, but his excessive religious zeal came near ruining everything. Word was brought to him that human sacrifices were to take place in one of the temples of his allies. Enraged at their cruel superstition and that such an enormity should be attempted under his very eyes, he rushed to the temple with some of his soldiers and threatened destruction by fire and sword if they did not instantly release the intended victims. His zeal did not stop with this. He demanded that the priests should pull down their idols, and renounce their false religion forever, although they did not yet know of a better one. The priests prostrated themselves at his feet, moaning and lamenting, and the caciques present trembled. As they refused to pull down their idols, he ordered his soldiers to do it by force. The priests rushed to arms and in a few moments Cortes and his little band were surrounded by a crowd big enough to appall the heart of the stoutest. But Cortes remained unmoved and announced to the assembled multitude that the first arrow fired by them would cost them the lives of their caciques and the destruction of them all. The soldiers advanced to carry out his orders. In an instant the idols were hurled down; the sacred vessels and the altar followed them. They were all destroyed, and the temple was cleaned. The human blood which adhered to the walls was washed off, and the image of the Virgin was set in the place of the idols. The astonished Indians expected that fire would descend from heaven any instant and revenge this indignity to their divinities. But not a spark was seen, and the temple-stormers continued their work audaciously and triumphantly before their very eyes. This weakened their faith and caused them to reflect, with the result that they gradually came to believe that the Spaniards were divinities themselves and mightier than their own gods. They did not long stop to consider, but, gathering up the remnants of their idols, contemptuously threw them into the fire. The temple was consecrated as a Christian church and upon the same day was dedicated with Roman Catholic ceremonies, which the Indians greatly wondered at though they did not understand them.