The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Century World's Fair Book for Boys and

Girls, by Tudor Jenks

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Century World's Fair Book for Boys and Girls

Being the Adventures of Harry and Philip with Their Tutor,

Mr. Douglass, at the World's Columbian Exposition

Author: Tudor Jenks

Release Date: June 5, 2019 [EBook #59681]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CENTURY WORLD'S FAIR ***

Produced by ellinora, Robert Tonsing and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

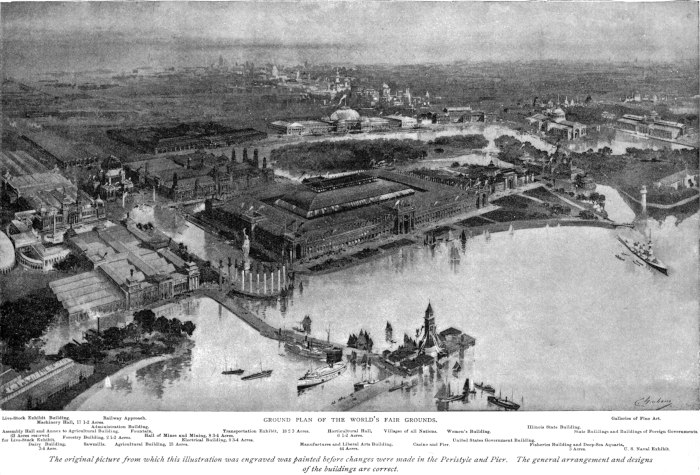

PAGE |

||

|---|---|---|

| Started by Cable — The Journey by Sleeper — Arrival in Chicago — Finding Rooms — The Fair at Last! | 1 |

|

| The Fête Night — Rainbow Fountains — The Search-lights — On the Lake — The Fireworks — Passing a Wreck — Diving in the Grand Basin | 17 |

|

| The Party Separates — Harry Goes to the Battle-ship — The Government Building — The Convent and the Caravels — The Movable Sidewalk | 31 |

|

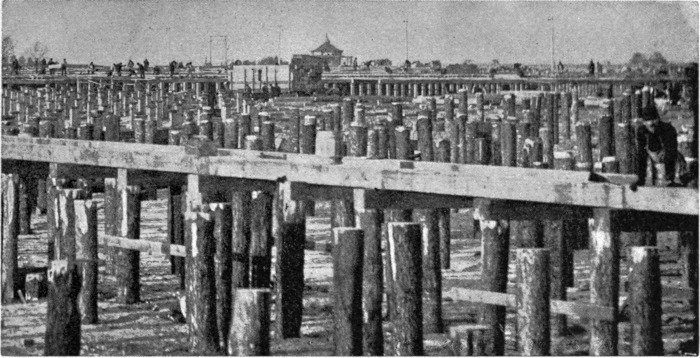

| Harry Returns to the Hotel — Philip Tells of his Blunder — The Anthropological Building — The Log Cabin — The Alaskan Village — The Old Whaling-ship “Progress” — A Sleepy Audience — Plans | 43 |

|

| A Place where Visitors were Scarce — The Rolling-chairs and Guides — Mistaken Kindness — Entering the Plaisance — The Javanese Village — Snap-shots — Cairo Street — The Card-writer — The Soudanese Baby | 55 |

|

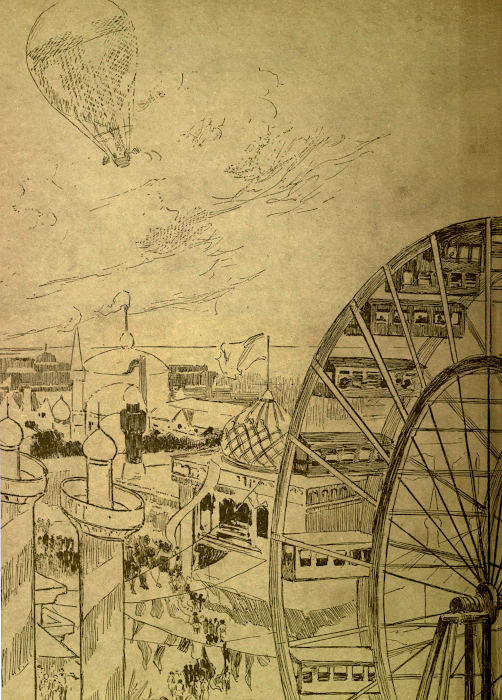

| The Midway Plaisance Visit Continued — Lunch at Old Vienna — The Ferris Wheel — The Ice Railway — The Moorish Palace — The Animal Show | 71 |

|

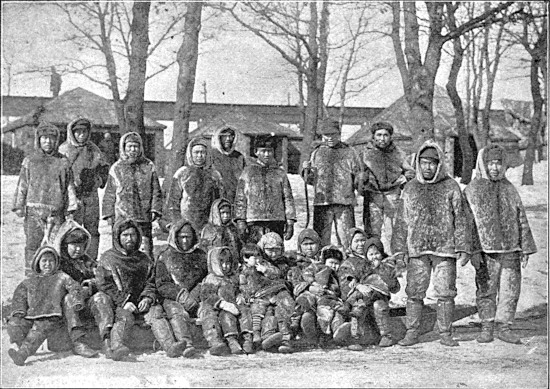

| Harry Gets a Camera — The State and National Buildings — The Eskimo Village — Snap-shots Out of Doors — A Passing Glance at Horticultural Hall — Doing their Best | 85 |

|

| What People Said — The Children’s Building — The Woman’s Building — The Poor Boys’ Expensive Lunch — The Life-saving Drill | 99 |

|

| The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building — A Rainy Day — A Systematic Start — “Irish Day” — Harry Strikes — Some Minor Exhibits — The Few Things They Saw — The Elevator to the Roof | 113 |

|

| vi Philip at the Art Galleries — The Usual Discouragement — Walking Home — The “Santa Maria” under Sail | 127 |

|

| Going after Letters — The Agricultural Building — Machinery Hall — Lunch at the Hotel — Harry’s Proposal — Buffalo Bill’s Great Show | 141 |

|

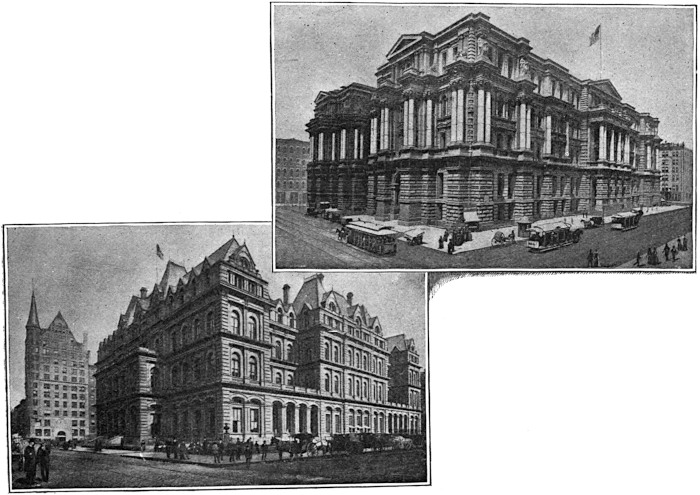

| The Tally-ho — How it Dashed Along — The Parks Along the Lake — Chicago — The Auditorium and Other Sky-dwellers — The Whaleback | 155 |

|

| Philip’s Day — Visits the Photographic Dark-room — The Fisheries Building — The Aquaria — Fishing Methods — The Government Building — The Japanese Tea-house | 171 |

|

| The Convent of La Rábida — Old Books and Charts — Paintings — A Fortunate Glimpse of the “Santa Maria” — Portraits of Columbus — The Cliff-Dwellers — Cheap Souvenirs — World’s Fairs in General | 187 |

|

| The Electricity Building — Small Beginnings — A New Souvenir — The Curious Exhibits — Telephones and Colored Lights — The Telautograph — Telegraphy — Mines and Mining — A Puzzled Guard | 197 |

|

| The “Golden Doorway” — Transportation Building — An Endless Array — Bicycles, Boats, and Bullock-wagons — The Annex — The Railroad Exhibits | 209 |

|

| A Rainy Day — The Plaisance Again — The Glass-works — The German Village — The Irish Village — Farewell to the Phantom City | 221 |

|

| Packing for Home — A Glimpse of Niagara — Philip Tells His Adventure — Foiling a Clever Swindler — A Convincing Exposure | 231 |

|

| Mr. Douglass has a Remarkable Experience | 239 |

“MR. DOUGLASS wants to see you, Master Harry,” said the maid, coming to the door of the boys’ room.

“What’s he found out now, I wonder?” said Harry to Philip, in a low tone. “I don’t remember anything I have done lately.”

“He’s in a hurry, too,” said the girl, closing the door.

Harry ran down to Mr. Douglass’s room on the first floor. The two boys were beginning their preparation for college, and were living in a suburb of New York city with their tutor, Mr. Douglass, a college graduate, and a man of about thirty-five. Harry’s father, Mr. Blake, was abroad on railroad business, and did not expect to return for some months. Philip was Harry’s cousin, but the two boys were very unlike in disposition—as will be seen. Their bringing up may have been responsible for some of the differences in traits and character, for Harry was a city boy, while his cousin was country-bred.

When Harry knocked at the door of Mr. Douglass’s study, he knew by the tutor’s tone in inviting him in that the teacher had not called him simply for a trivial reprimand. It was certainly something serious; perhaps news from Harry’s father and mother.

“Sit down, Harry,” said the tutor,—“and don’t be worried,” he added, seeing how solemn the boy looked. “I have had a message by cable from your father; but it’s good news, not bad. Read it.”

He handed Harry the despatch. It read:

Take Hal and Phil to Fair. My expense. Letter to Chicago. See Farwell about money and tickets.

“Rather sudden, isn’t it?” said Mr. Douglass, smiling.

“Yes,” said Harry, “but—immense! Don’t you think so?”

“I’m glad to go,” the tutor said. “It seems to me that a visit to the Fair is worth more than all the studying here you boys could do in twice the time you’ll spend there; and it’s a lucky opportunity for me.”

“Then you’ll go?” said Harry, to whom the news seemed a bit of fairy story come true, with the Atlantic cable for a magic wand.

“Of course,” answered the tutor. “The only thing that surprises me is the quickness of your father’s decision.”

“That’s just like him,” said Harry. “He’s a railroad man, you know, and they always go at high pressure. Why, he’d rather talk by telephone, even when he can’t get anything but a buzz and a squeak on the wire, than send a messenger who’d get there in half the time.”

“But has he said anything about sending you before?”

“No. The fact is, people abroad are slow to know what a whacker this Fair is! They think it’s a mere foreign exposition. Father’s just found out that Uncle Sam has covered himself with glory, and now he wants Phil and me to see the bird from beak to claws—the whole American Eagle.”

“But sha’n’t we have trouble about tickets?” asked Mr. Douglass.

“No,” said Harry. “Father’s a railroad man. That’s what ‘See Farwell’ means. You let me go to see him. He’s the general manager, or some high-cockalorum. He’ll see us through by daylight.”

“Very well,” said Mr. Douglass, “I’m just as glad to go as you are. Philip and I will attend to the packing, and you shall go to New York this afternoon and see Mr. Farwell. Now you can tell Philip about it.”

Harry ran out of the room, slamming the door behind him, but Mr. Douglass only laughed. Perhaps he would have slammed it, too, if he’d been in the boy’s place.

“Well?” said Philip, looking up from the Xenophon he was translating.

“Thanks be to Christopher Columbus!” said Harry, with a jig-step.

“Has he done anything new?” Philip asked, looking over his spectacles.

“I guess not,” said Harry, “but we’re going to the Fair.”

“How can we?” Philip asked.

Harry threw the cable despatch down upon the table, and turned to get his hat. Philip read the telegram, carefully wiped his glasses, rose, put the Xenophon into its place upon his book-shelves, and said:

“Xenophon will have to attend to his own parasangs for a while.”

“You pack up for me, and I’ll see to the railroad-tickets,” said Harry. “I have just about time to catch the train for New York.”

That was a hard and busy day for all three of the party. Perhaps Harry’s share was the easiest, for, by showing his father’s despatch to Mr. Farwell, he had everything made easy for him. Still, even influence might not have secured them places except for the aid of chance. It happened that a prominent man had, at the last moment, to give up a section in the Wagner sleeper, and this was turned over to Harry. So, late in the afternoon the boy came back with what he called “three gilt-edged accordion-pleated tickets.”

Meanwhile Mr. Douglass and Philip had put into three traveling-bags as much as six would hold, and the party went to bed early to get a good rest before the long journey.

4

Next day at nearly half-past four the three travelers walked through the passageway at the Grand Central Depot, had their tickets punched,—and Philip noticed that the man at the gate kept tally on a printed list of the numbers of different tickets presented,—and entered the mahogany and blue-plush Wagner cars.

In a few minutes some one said quietly: “All right,” and the train gently moved out.

“I can remember,” said Mr. Douglass, “when a train started with a shock5 like a Japanese earthquake. Now this seemed to glide out as if saying, ‘Oh, by the way, I think I’ll go to Chicago!’”

Harry laughed. “Yes,” he said, “and how little fuss there is about it. Why, abroad, I remember that they had first a bell, then a yell, then a scream, then the steam!”

As the train passed through the long tunnel just after leaving the station, Mr. Douglass remarked:

“How monotonous those dark arches of brickwork are!”

“Yes,” said Philip, “they should have a set of frescos put in them.”

“But no one could see the pictures,” said Mr. Douglass, “we pass them so fast.”

“That’s true,” said Harry, with a pretended sigh; “but they might have to be instantaneous photographs.”

Philip looked puzzled for a minute and then laughed. After they left the tunnel, they passed through the suburbs of New York, entered a narrow cut that turned westward, and were soon sailing along the Hudson River—or so it seemed. There was no shore visible beside them, except for an occasional tumble-down dock, and beyond lay the river—a soft, gray expanse relieved against the Palisades, and later against more distant purple hills. It was a rest for their eyes to see only an occasional sloop breaking the long stretch of water, and the noise of the train was lessened because there was nothing to echo back the sounds from the river.

Mr. Douglass found his pleasure in the scenery, the widenings of the river, the soft outlines of the hills, the long reflection of the setting sun. But the boys cared more to see the passengers.

“Isn’t it funny,” said Philip, “how Americans take things as a matter of course? I really believe that if the train was a sort of Jules Verne unlimited express for the planet Mars, the people would all look placid and read the evening papers.”

“Of course,” said Harry. “What else can they do? Would you expect me to go forward and say: ‘Dear Mr. Engineer, but do you really think you know what all these brass and steel things are? Don’t you feel scared? Won’t you lie down awhile on the coal, while I run the engine for you?’”

“Nonsense!” said Philip, laughing. “But they might show some interest.”

“They do,” said Harry; “but that’s not what I’m thinking of. I’m thinking I’ll be a civil engineer.”

“Why?” said Philip.

“Just think,” Harry answered, pointing from the car window, “what a6 good time they must have had laying out this road! Why, it was just a camping-out frolic, that’s all it was.”

“Didn’t you hear the waiter say dinner was ready?” said Mr. Douglass.

“No,” said Philip; “but I knew it ought to be, if they care for the feelings of their passengers. Where is the dining-car?”

“At the end of the train,” said Mr. Douglass. “Come, we’ll walk through.”

So, in single file (“like cannibals on the trail of a missionary,” Harry said), they passed from car to car. The cars were connected by vestibules—collapsible 7 passageways, folding like an accordion—and it was not necessary to go outside at all. The train was an unbroken hallway.

“It is much like a long, narrow New York flat,” said Philip. “People who live in flats must feel perfectly at home when they travel in these cars.”

They found the dining-car very pretty and comfortable. Along one side were tables where two could sit, face to face. On the opposite side of the aisle the tables accommodated four. The boys and their tutor took one of the larger tables. The bill of fare was that of a well-appointed hotel or restaurant,—soup, fish, entrées, joint, and dessert,—and it was difficult to realize that they were eating while covering many miles an hour; in fact, the only circumstance that was a reminder of the journeying was a slight rim around the edge of the table to keep the dishes from traveling too.

“It is strange,” said Mr. Douglass, “how people have learned to eat dishes in a certain order, such as you see on a bill of fare. Probably this order of eating is the result of tens of millions of experiments, and therefore the best way.”

8

9

“The best for us,” said Philip; “but how about the Chinese?”

Mr. Douglass had to confess himself the objection well taken.

“I believe the Chinese were created to be the exceptions to all rules,” he said.

The dining-car had an easy, swaying motion that was very pleasant, and altogether the dinner was a most welcome change from the ordinary routine of a railway journey.

As the boys walked back to their own section, Philip noticed a little clock set into the woodwork at one end of the smoking-car. He was surprised to see that it had two hour-hands, one red and one black.

He pointed it out to Mr. Douglass, who told him that the clock indicated both New York and Chicago times—which differ by an hour, one following what is called “Eastern,” the other “Central” time.

By the time they were again settled in their places it was dark outside; and, as Philip poetically said, they seemed to be “boring a hole through a big dark.” One of the colored porters looked curiously at Philip, as if he had overheard this remark without understanding its poetical bearing.

“He thinks you are a Western desperado!” said Harry, with a grin.

“Boys,” said Mr. Douglass, “the porters will soon make up the beds, and I want you to see how ingeniously everything is arranged.”

Here is what the porter did:

He stood straddling on two seats, turned a handle in the top of a panel, and pulled down the upper berth. It moved on hinges, and was supported after the manner of a book-shelf by two chains that ran on spring pulleys.

Then he fastened two strong wire ropes from the upper to the lower berths.

“What’s that for?” asked Harry.

“To prevent passengers from being smashed flat by the shutting up of the berth,” Philip answered, after a moment’s puzzling over the question.

“You can have the upper berth, Philip,” said Harry, impressively. “It’s better ventilated than the lower, they say; but I don’t mind that.”

Meanwhile the porter took from the upper berth two pieces of mahogany, cut to almost fill the space between the tops of the seats and the side roofs of the car. The edges were grooved, and slid along upon and closely fitted the top of the seat and a molding on the roof. These side-pieces were next fastened by a brass bolt pushed up from the end of the seat-back.

Then the bed-clothing (kept by day in the lower seats and behind the upper panel) was spread on the upper berth, and the mattress of the lower berth was made up from the seat-cushions, supported upon short slats set from seat to seat.

10

While the beds were being made, the boys were amused to see some ladies laughing at the man’s method of getting the clothes and pillows into place. A woman seems to coax the bed into shape, but a man bullies it into submission.

“They think it’s funny to see him make a bed,” said Harry, in an undertone; “but if they were to try to throw a stone, or bait a fish-hook, I guess the darky would have a right to smile some too.”

To finish his work, the porter hung a thick pair of curtains on hooks along a horizontal pole, and then affixed a long plush strip to which were fastened large gilt figures four inches high—the number of the section.

“It would be fun to change the numbers around,” remarked Harry, pensively. “Then nobody would know who he was when he got up. But perhaps it would make a boy unpopular if he was caught at it.”

Mr. Douglass admitted that it might.

As the porter made up their own section, Harry pulled out his sketch-book and made a little picture of him.

“It’s hard times on the railroad now,” he remarked, as he finished the sketch. “See how short they have to make the porters’ jackets! But it must save starch!”

The boys had wondered how the people would get to bed, but there seemed no difficulty about it. As for our boys, who had the upper berth, one by one they took off their shoes, coats and vests, etc., and then climbed behind the curtains, where they put their pajamas over their underclothes.

After they were in bed, they talked but little, for they were tired.

“This rocking makes me drowsy,” Philip said; “it’s like a cradle.”

“Yes,” Harry answered, as the car lurched a little—“a cradle rocked by a mother with the St. Vitus’s dance!”

While going to sleep, the boys were puzzled to account for the strange noises made by the train. At times it seemed to have run over a china-shop, and at other times the train rumbled hoarsely, as if it were running over the top of an enormous bass-drum.

Soon the great train was transporting two boys who were fast asleep in Section No. 12; they woke fitfully during the night, but only vaguely remembered where they were, until the cold light of morning was reflected from the top of the car.

11

Dressing was more difficult than going to bed, but by a combination of patience and gymnastics Harry and Philip were soon able to take places in the line that led to the wash-room. Thence, later, they came forth ready for breakfast (for which they had to “line up” again), and another all-day ride.

At breakfast, the next table to them was occupied by a gentleman named Phinney, and his son. Harry knew the son slightly, having once been his schoolmate. Young Phinney was making a second visit to the Fair, and he told Harry that on the former trip the train had run around Niagara Falls in such a way as to give the passengers an opportunity to view them.

13

The train had stopped there for five minutes, and they had climbed down near the rapids to a point where there was an excellent view of “the great cataract”—so young Phinney called it. He gave the boys some pictures showing the falls, and indeed there was a picture of the falls upon the side of the breakfast bill of fare.

During the forenoon the train was passing through Canada—the boys’ impression of that country being a succession of flat fields, ragged woods, sheep, swine, and a few pretty, long-tailed ponies grazing upon browning turf. Philip said that it was like “the Adirondacks spread flat by a giantess’s rolling-pin.”

At Windsor the train, separated into sections, was run upon a ferry-boat (upon which one small room was marked “U. S. Customs”) and carried over to Detroit. Here Mr. Douglass made the boys laugh by suddenly jumping back from the window. He had been startled by a large round brush that was poked against the window from outside to dust it.

From Detroit the train ran through Michigan—mainly through a flat country of rich farming land. Philip, who had never been West, was much surprised at the uninterrupted stretches of level ground. Mr. Douglass asked him what he thought of the region. Philip adjusted his glasses and replied slowly: “Well, it’s fine for the farmers, but it is no place for speaking William Tell’s piece about ‘Ye crags and peaks, I’m with you once again!’”

“You must not forget, though,” said Mr. Douglass, “that it is the rich farming lands that really underlie America’s prosperity. When you see the Fair, you will understand better what a rich nation we are; but without our great wheat-lands we should, like England, be dependent upon commerce for our very existence.”

The boys were much less talkative as the train neared Chicago. They were somewhat tired, and were also thinking of the amount of walking and sight-seeing that was before them.

All at once, at about half-past five, New York time (for the travelers had not yet changed their watches to an hour earlier), Mr. Douglass pointed out of the right-hand forward window. Both boys looked. There, in the distance, rose above the city houses a gilded dome, and from the opposite car-window they saw just afterward a spider-web structure.

“I know it!” Philip sang out; “that’s the Administration Building. But what is the other?”

“The Ferris Wheel,” answered Harry.

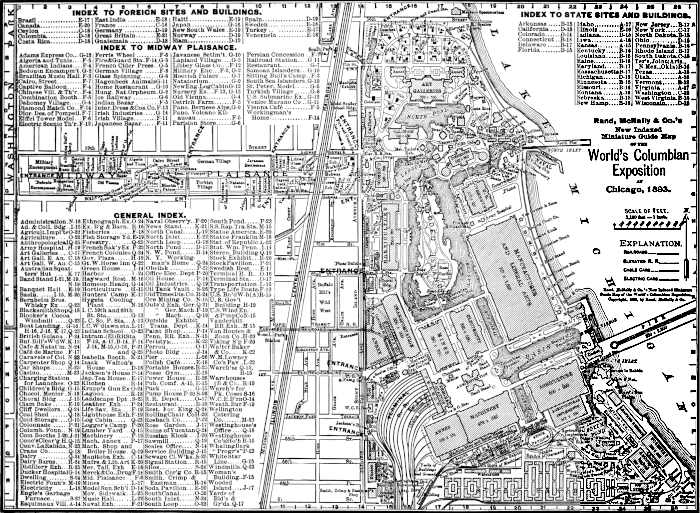

“Yes,” said the tutor, “we are going to leave the car not far from the Plaisance gate.”

“Sixtieth street next!” cried the brakeman.

14

“Come, we get out here. It’s nearest the grounds, and I have been told it is wise to lodge as near as possible.”

When the cars stopped, the party descended upon a platform with “rails to the right of them, rails to the left of them,” and trains and crowds in all directions. Mr. Douglass led the way out into the huddled settlement of apartment-houses, hotels, and lodgings that has sprung into existence around Jackson Park, the Fair Grounds.

Then began their search for rooms. At first it seemed discouraging; neatness outside was not always a sign of what to expect inside. They labored up-stairs and down again several times. At one attractive private house they entered, expecting quiet, homelike rooms. In the tiny parlor they found five cots set “cheek by jowl” as close as they could be jammed. They smiled at this, but found the rest of the rooms as fully utilized. Mr. Douglass made some objection, and was told by the self-possessed landlady that “some very fine gentlemen thought her fifty-cent beds were very elegant.” At another house they were passing, a boy who couldn’t have been over five years old rushed out like a little Indian on the warpath, crying, “Hi! You lookin’ fer rooms?” Amused at the little fellow’s enterprise, our travelers followed him, the boy going forward on his sturdy little legs, and crying, “Hi, there, Mama! Here’s roomers! I got you some roomers!”

But unfortunately the boy proved more attractive than the rooms. After a long walk, but without going far from the Fair Grounds, they took rooms at a very good hotel. The price was high, perhaps, but reasonable considering the advantages and the demand for lodgings. They took two rooms, one with a double bed for the boys, the other a single room for the tutor.

Gladly they dropped the satchels that had made their muscles ache, and after leaving the keys of their rooms with the hotel clerk, they set forth for their first visit to the Fair. In order that guests should not forget to leave their keys, each was inserted at right angles into a nickel-plated strip of metal far too long to go comfortably into the pocket even of an absent-minded German professor.

“One advantage of being in a hotel,” said Mr. Douglass, as they walked toward the entrance of the grounds, “is the fact that on rainy, disagreeable days we can get meals there if we choose. It is not always pleasant to have to hunt breakfast through the rain. But usually we shall dine where we happen to be in the grounds; there are restaurants of all sorts near the exhibits, from a lunch-counter up.”

15

Along the sidewalk that led from their hotel to the entrance were dining-rooms, street-peddlers’ counters, peddlers with trays—all meant as inducements to leave money in the great Western metropolis. One thing the boys found very amusing was an Italian bootblack’s stand surrounded on three sides by a blue mosquito-netting.

“If it had been on all sides,” said Harry, “I could have understood it, because it might be a fly-discourager. But now I think it must be only a way of attracting attention.”

They had arrived, luckily, on a “fête night.” Though tired and hungry, they all agreed that it would never do not to take advantage of so excellent a chance to secure a favorable first impression. So they bought tickets at a little wooden booth, and, entering a turnstile one by one, were at last in the great White City.

“Well,” remarked Harry, as the wicket turned and let him into the grounds, “if any one wishes to take down what I said on entering the grounds, he can write down these thrilling words: ‘Here we are at last!’”

“We won’t try to do more than get a general idea of things to-night,” said Mr. Douglass. “We shall find claims upon our eyesight at every step. But what a crowd!”

The crowd was certainly enormous. At first most of the people seemed to be coming out, but this idea was a mistake. It came from the fact that those going the same way as our party attracted their attention less than those whom they met and had to pass.

They walked between the Pennsylvania Railroad exhibit and the Transportation Building, and entered the Administration Building, which seemed the natural gateway to the Court of Honor and its Basin—always the central point of interest. The paving seemed to be a composition not unlike18 the “staff” that furnished the material for the great buildings, the balustrades, the statues, and the fountains. It was just at dusk, and the light was soft and pleasant to the eyes. Once in the Administration Building, all our sight-seers threw back their heads and gazed up within the dim and distant dome enriched by its beautiful frescos.

“I have heard,” said the tutor, who felt bound to serve as guide so far as his experience would warrant, “that people are unable to understand the vastness of St. Peter’s dome at Rome. This dome is even higher, and so I feel sure that, large as it seems to us, our ideas of it fall far below the reality. However, we shall see this many times. Let us go on through, and see the Court of Honor.”

Leaving by the east portal, the three came out upon the broad plaza that fronts the basin. By this time the sky was a deep, dark blue, and every outline of the superb group of buildings was sharply relieved.

For a while the three stood silent. There was nothing to say; but each of them felt that the work of men’s hands—of the human imagination—had never come so near to rivaling Nature’s inimitable glories. The full moon stood high above the buildings at their right, but even her serenity could not make the great White City seem petty.

The boys knew no words to express what they felt. They only knew that in their lives they had never been so impressed except when gazing upon a glorious sunset, an awe-inspiring thunderstorm, or the unmeasured expanse of the ocean.

Philip was the first to speak.

“Must it be taken down? Why couldn’t they leave it? It is—unearthly!”

“Boys,” said Mr. Douglass, “I don’t preach to you often, and certainly there is no need of it now. But, at one time or another, each of us has tried to imagine what Heaven could be like. When we see this,” and he looked reverently about him, “and remember that this is man’s work, we can see how incapable we are of rising to a conception of what Heaven might be.”

But their rhapsodies could not last long in such a pushing and thronging time. People brushed against them, talking and laughing; the rolling-chairs zigzagged in and out, finding passageway where none appeared; distant bands were playing, and all about them was the living murmur of humanity. Groups were sitting upon every available space: tired mothers with children, young men chatting, and serious-faced country people plodded silently along amid their gayer neighbors.

21

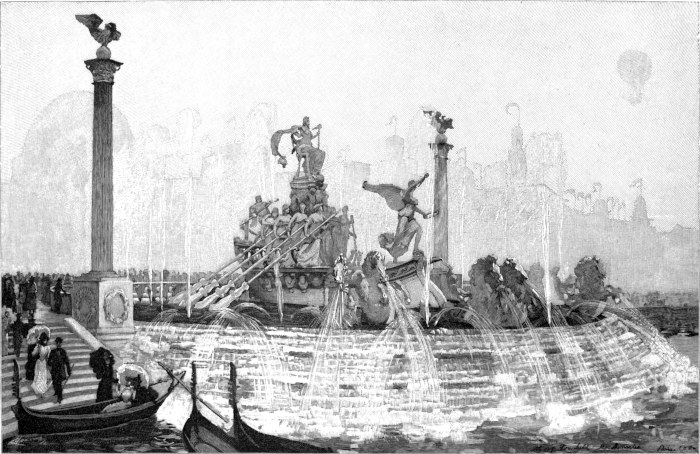

For a time the three wandered almost without purpose; then, reaching the further end of the Basin, they looked back at the superb MacMonnies Fountain—the galley that bore the proudly poised figure of Progress.

Opposite, and facing the fountain, rose the massive but perhaps less expressive statue of the Republic. Though the boys were speechless with admiration, delight, and wonder, they found—as others have done—that fine sights do not satisfy the appetite any better than fine words butter parsnips. So Harry turned to Mr. Douglass, saying, “Mr. Douglass, don’t you hear the dinner-horn? It seems to me that I do.”

“All right,” he answered; “let us go over to the Casino restaurant and have a comfortable dinner; but first suppose we stop a moment for a look into the Electricity Building. I saw by a program posted up near the entrance that it is open to-night.”

As they came nearer, they found the crowd rapidly increasing in density; and when they entered, passing the heroic statue of Franklin, they found themselves entirely at the mercy of the moving throng of people. So thick were the sight-seers packed that the boys could see little except the great Edison Pillar, and that was visible only because it rose so high in air. While they watched the pillar, incrusted with incandescent lights, different22 colored bulbs sprang into glowing life or faded out, showing a kaleidoscope of patterns changing continually.

“We sha’n’t get any dinner if we don’t get out now,” said Philip, who was struggling to keep his eye-glasses from being displaced.

“Come, then,” said Harry; and they turned to stem the tide. For a time they made slight progress; but, luckily, a row of wheeling-chairs came charging slowly but firmly, cutting a path by gentle persistence. Falling in behind these pioneers, they succeeded in escaping to the open air, and then made their way to the Casino. Just before reaching this great restaurant, they saw the convent of La Rábida, which appeared between the Agricultural Building and the Casino.

“See!” said Philip. “There’s the model of the convent. Do you know what it reminds me of? It is like a little gray nun sitting demurely in the corner of a grand ball-room!”

And, indeed, the unpretending little building was a distinct rest to the eye, after the proud proportions of its surroundings. As the statues spoke of the future, the convent reminded one of the past.

Entering the Casino brought them back sharply to the present, with its needs and its inconveniences. The prosaic need for dinner was the first to be thought of, and, enormous as was the restaurant, the crowd that night filled every seat, and left plenty of stragglers to stand watchfully about, eager to fill themselves and any vacant chair.

“Boys,” said the tutor, sadly, “if we stand here an hour, it will be only a piece of luck if we find a place. Where shall we go?”

“I heard a man say that there was a lunch-counter in the southeastern corner of the Manufactures, etc., etc., Building,” said Harry. “This is no time for French bills of fare and finger-bowls. Come, let’s go over there.”

No one cared to argue the question, and, keeping the lake on their right, they crossed to the largest building, and found a primitive lunch-counter on the ground floor. Boys and rough-looking men, perched on high stools, shouted out orders to “girls” from eighteen to fifty years old.

After waiting a few minutes, Mr. Douglass found a seat, which the boys insisted he should take, and a little later they found two together. The man who left the seat Harry crowded into had on a wide-brimmed felt hat, the edges of which had been perforated all around in openwork.

“He’s a cow-boy,” Harry whispered in delighted tones.

Meanwhile Philip was trying to attract the attention of the very stout and independent young girl who waited upon that section of the counter.23 He raised his hand, but she only sneered and remarked, “I see yer!” which brought a roar of laughter from some talkative customers. Soon, however, she condescended to turn an ear in the boys’ direction, and they succeeded in ordering two sandwiches and two cups of coffee. When they had finished, Harry said, “Phil, we’ll forgive the sandwiches for the sake of the coffee!”

After this hasty supper, Mr. Douglass told them that there were two fine displays that evening—the electric fountains and fireworks on the lake-front.

“Let us see both,” said Harry. “There’s a place for launches down by the Basin, and the man was yelling out when I came by: ‘One launch is going to stay awhile in the Basin, and then going out into the lake,’—I think he said at half-past seven.”

Philip looked at his watch. “We’re too late by half an hour,” he said impatiently.

“Why, no, Philip,” said Mr. Douglass. “Our watches show New York time. We have half an hour to spare.”

24

“True,” answered the boy. “You are right. I had forgotten that; and, by the way, now is a good time to reset our watches.”

So they turned the hands back an hour, and felt thankful that another sixty minutes had been added to the evening.

“Now,” said Mr. Douglass, “I have a popular motion to present. It is moved that we cease moving, and sit down for a while.”

“Seconded and carried!” cried Harry; “and, what’s more, I see some chairs”; and he pointed to a row that were strangely vacant, while all around were occupied. The boys walked toward them. Suddenly Harry, who was ahead, came back.

“I don’t care to sit down just now,” he said; and his companions, coming nearer, saw that the chairs were put over a great break in the pavement to warn people away. They turned to walk toward the boat-landing, and just then the electric fountains in the corners of the Basin nearest the Administration Building began to play. Two foamy domes mounted upward, and were magically tinted in fairy hues, changing and interchanging, rising and retiring, twisting, whirling, and falling in violet, sea-green, pink, purple—it was a tiny convention of tamed rainbows. And, meanwhile, from lofty25 towers great electric sunbeams fell upon the dome of the Administration Building, and created a cameo against the sky: upon the MacMonnies Fountain, giving it a transfigured snowy loveliness: upon one beautiful group after another, bringing them to vivid life. The beams were at times full of smoke and spray, that gave a shimmering motion to their light.

“I have been to a circus,” said Harry, “where they had four rings going at once. That was bad; but this—this makes me wish I was a spider, with eyes all over me.”

“The extra legs would not come in badly, either,” said Philip, reflectively.

“Well said!” agreed Mr. Douglass. “Let us get into the little steamer; we can rest there.”

They made their way to the landing, bought tickets, stepped aboard just as the boat moved off, and were soon gliding gently out upon the Basin.

27

After a short delay to let the passengers view the fountains a little longer, the steamer sped under a bridge, through the great arch of the Peristyle, and made out into the open lake.

To their surprise, the boys found a heavy rolling “sea” on; but as soon as the fireworks began, they forgot all else. Rockets, bombs, showers of fire, floating lights—they came so rapidly that there was a continuous gleam of colored light reflected from the waves. Their launch rounded the fireworks station, and then came to a standstill not far from the Naval exhibit, the model man-of-war “Illinois.”

Soon some of the women passengers began to object to the rolling. One Boston woman said: “This is rough; I don’t like this at all”; but her bespectacled daughter remarked, as a great bomb of rosy light scattered in a rain of fire, “Well, I think it’s the smoothest thing I ever saw!” which bit of slang from the prim little Puritan was a great delight to the boys. And as the search-light suddenly sent its beams into a lady’s face, she nodded cordially, and said, as if meeting a friend, “How do you do?” Then, turning to her own party, added, “They’ve just found me.”

There were many little incidents that amused Harry exceedingly. One small boy, while boarding the boat, ingeniously contrived to knock his hat overboard; it was at once recovered,—a straw hat has no chance racing a steamboat,—but, like Mr. McGinty, was exceedingly moist. So the pilot went down a dark hatchway and fished out an official cap. The boy put it on. The effect was stunning,—there was room for another boy inside,—and Harry made a sketch of it.

But these trifles were only a relief from the grandeur of the display. Philip said it was the Grandest Grand Transformation Scene imaginable. After a “set piece” had been shown, there was a bombardment of “Fort McHenry,” as they called it—a ship and fort outlined in living fire:

and all the rest of a mimic war. Then, as the fort blew up, the Stars and Stripes flamed forth—“Old Glory”—in lines of light; and, far out upon the lake as they were, the rapturous cheering of the crowds came plainly to their ears.

28

“Benedict Arnold would never have made that awful break of his if he could have been here to-night,” said Harry, reflectively; then, as Philip began to speak, he said, “Yes, I know he couldn’t have been. Thanks.”

Another thing that added wonderfully to the effect of the fireworks was a calliope whistle on some yacht or tug. While the people cheered, the musical director of that steam-tug whistle performed on it with a master hand. It shrieked, it cheered, it yelled, it laughed—whatever song without words could be sung by a steam-whistle was performed with variations. And, queer enough, the effect was exceedingly pleasing. It somehow seemed in accord with the whole spirit of the fête. A bold, generous Western extravagance pervaded the whole affair.

On their way back, they suddenly saw before them a long black hulk. It proved, as they passed it, to be a large yacht lying upon her side, with the masts and yards extending out far over the dark waves.

“How did that happen?” Mr. Douglass asked the pilot, pointing to the wreck.

“It was a collision, sir,” replied the pilot; but he gave no particulars.

As the man seemed busy in guiding the swift little steamer, the tutor29 recalled the old adage about “not talking to the man at the wheel,” and asked no further questions.

But the sights of that marvelous American Thousand and One Nights combined were not yet over. As they entered the Basin, their steamer halted to enable them to witness a diving exhibition. On a floating tower stood a man in tights, so lighted up by an electric ray as to be clearly visible from every point around. Raising his hands above his head, he fell thirty-five feet or more into the water. Just as he reached the surface, his hands came swiftly together, and he sank like a plummet. In an instant he was up again, kicking a mass of gleaming spray into the air. Several more “followed their leader.”

It was a thrilling sight, and, on that cold night, chilled the spectators to the marrow.

As they walked along the edge of the Basin after leaving their launch, the boys greatly admired the statues of animals and men set up near the balustrade. There was a bull, several great bears, a farmer and a draft-horse, a bison (who seemed timid and dwarfed by his surroundings), and30 others, nearly all modeled with a massive effect that gave them wonderful dignity.

And still the crowd surged to and fro, but now with a decided tendency toward the outlets; the lights flashed and gleamed; the bands played, while the great moon sailed overhead as if it was all a fête to Diana.

Tired as they were when they reached the hotel, the boys could not refrain from talking over some of the principal things they had seen. They did not say much about the buildings, for they knew they should see them again; but they talked of the people, the fireworks, and such queer comments as they had overheard.

“I expected,” said Philip, “that we should see a great many foreigners—Turks, Swedes, Germans, all sorts. But I didn’t. I saw two or three fellows with fezzes on, but that was about all.”

“I noticed that, too,” Harry responded. “And I didn’t hear much but English spoken. It seems to me that Uncle Sam has done most of this thing himself, and that it’s mainly his own boys that are taking it in.”

“But it’s early days yet,” said Philip, with a prodigious yawn, “to make—aw!—comparisons.”

“That looks more like late hours than early days,” Harry suggested. “Let’s turn in.”

In a few minutes their clothes were on two chairs, and their heads were sunk into adjacent pillows.

Sunday proved a welcome relief after the long journey of Saturday, followed by the fête night at the Fair; and they were glad to begin the busy week that was to follow with one restful day apart from bustle and confusion.

At breakfast Monday morning, one of the dishes Mr. Douglass ordered was steak; and, as he sawed through it, he remarked:

“This is tough!”

“But I thought you didn’t approve of slang?” Harry inquired, with an air of grave interest.

“I wasn’t thinking so much of how I said it as of the fact,” Mr. Douglass replied. “But the proverb says that ‘shoemakers’ children are always the worst shod,’ and so we ought to expect poor beef in Chicago, the great beef-market of the continent; but I don’t like to waste my strength on mere beef while there is so much before us. What are your plans?”

“If you don’t mind,” said Harry, after a moment’s pause, “I’m going to ask you to let me ‘paddle my own canoe.’ It is hard for three to keep together in a crowd.”

“That’s true,” Philip agreed; “and especially when one is near-sighted. I think I tried to follow seven different wrong men yesterday.”

“Yes,” added Harry; “‘Follow my leader’ is a difficult game to play when we are all leaders and followers at the same time.”

“All right,” the tutor said. “To-day, then, we will separate. I may not go to the Fair at all, for I have several letters on my mind. Remember, we came away on very short notice. What will you do, Philip?”

“Oh, I think I shall spend a long while in the Art Galleries. It’s a good place to go to by one’s self, for two people seldom agree about pictures—especially boys.”

32

So, after breakfast, Harry, with a proud feeling of being his own master, set forth by himself. He had a very clear idea of what he wished to do first. He meant to go to the model of a United States man-of-war—the “Illinois.” He had read much about the White Squadron, and felt that he would never have so good an opportunity to understand just how a man-of-war was worked.

He had bought a guide-book to the Fair, and found that the route of the launches would bring him quite near enough to the vessel. But in spite of his singleness of purpose, his thoughts were distracted as soon as he came near the entrance.

He noticed first the clicking of the turnstiles. They revolved so continually, as people passed in, that Harry was reminded of the sound of a watchman’s rattle. Next, he caught sight of a white-robed and turbaned Turk standing in line at the “Workmen’s Gate,” as placidly as if he were in his native Constantinople. Harry’s turn to enter at the “Pay Gate” soon came, and he made his way toward the Court of Honor. As he passed the great Liberty Bell, which was chiming musically, he read upon it the words:

A new commandment I give unto you, that ye love one another.

He could not help remembering what followed the ringing of the original Liberty Bell, and he hoped that this, its namesake, would bring peace rather than war—a sober reflection that he recalled later in the day.

33

To the tune of “Hold the fort, for I am coming,” played by a peal of musical bells,—very fittingly, he thought,—Harry began the quick journey that ended when the little launch came to a landing called “The Clambake.” When the man called out those words, Harry did not budge; but when the man added, “Here’s where yer get off,” he rose and abandoned the craft.

On the way there, Harry learned that the ducks in the Lagoon were useful as well as pretty. The pilot said that two or three ducks would do more toward keeping a pond wholesome than six or eight hard-working men.

He was too early to get upon the “Illinois,” and therefore turned back to see the Viking ship. It was not far away; and just in front of it were three armor-plates in which were the imprints left by the great conical shot used in testing them.

Harry had read all about the old Northmen’s vessel, and ordinarily could have spent hours in studying her mast, her one crossyard, her awning, the shields along her side—but this was a land of wonders. He looked at the boat only long enough to take a mental snap-shot that he34 could develop at leisure, and then walked on toward the United States Government Building, passing on his way a company of marines at drill.

But again he was diverted. He turned into the Weather Bureau, and was glad he had done so, because of the wonderful series of photographs he found on the walls. Lightning flashes in streaks and sheets, clouds in storm and wind, moonlight and snow effects, were there, but in impossible numbers. He sighed, wished that he had more leisure, and left. This time he succeeded in getting to the rifled cannon in front of the Government Building, but stopped only long enough to take a sight over one of them.

He tried to go regularly around the exhibits, but surrendered almost at once. The Patent Office models discouraged him; but the Geological Department!—the great transparent pictures in the windows convinced him that35 he couldn’t (as he once heard a man say) “poss the impossible and scrute the inscrutable.”

But he did notice some things.

He sketched the skull of the Dinoceras mirabile (and copied the name, too), because he was sure that it was the very ugliest thing in the world. He walked around a section of the big tree from California. He really studied a few life-like and life-size groups showing Indians at work, and wished sincerely that he were Methuselah, and that the Fair would last all his days. It was a petrified Wild West show. He said they were splendid, to a gray-bearded Westerner, who replied emphatically:

“They are so—and I have been used to the scoundrels all my life!”

Harry sketched a queer Indian “priest-clown’s” head. At first he felt a little afraid to bring out his book and pencil; but he found out that every one had more to do than watch a boy drawing, and before the day was over he drew whatever he chose, entirely forgetting the crowd.

Different things attracted different people. He heard one farmer-looking man say: “My stars, Ma! Look-a here!” and expected to see a marvel. He found only some stuffed chickens. Probably the farmer had never seen fowls stuffed unroasted.

But when he came to the War Department collection he gave up skipping. He had to see that. Just at the entrance was a splendid bust of General Sheridan, the face wearing the expression the general must have had when he said at Winchester, “Turn around, boys! We’re going36 back!” Against the windows were more fine transparencies, and the whole floor-space was filled with everything having to do with war and soldiers. Small arms, from a brass blunderbuss to the latest breech-loader—yes, and to the earliest, for there was one Chinese breech-loader of the 14th century.

“Instead of trying to get up new things,” said Harry, half aloud, “we ought to go to China and study ancient history.”

Harry had a feeling of discouragement in spite of his interest. He had always entertained a vague idea that some day he might give his mind to it and make a big invention—a phonograph or a flying railway, or some little thing like that; but now, when he saw how everything seemed to have been done, and done better than he could have dreamed of—well, he said to himself, “This Fair has spoiled one great inventor, for I would not dare to think there was anything new!”

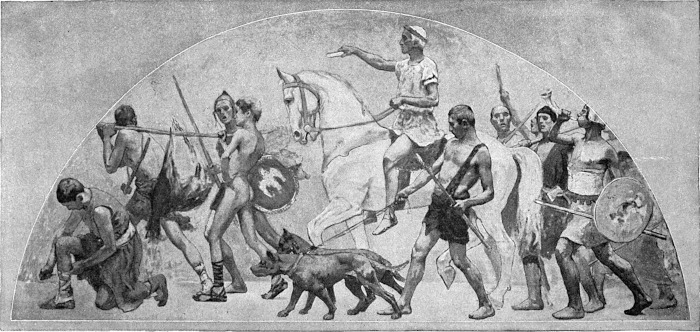

But then he caught sight of a picture called the “March of Time,”—representing a great procession of soldiers, of generals and veterans,—which restored his good spirits, for right in front, “leading the whole crowd,” was a row of rollicking small boys. He was grateful to the artist.

One stand of arms showed muskets—relics of the Civil War—injured by bullets. Into one of them a Confederate bullet had entered to stop a forthcoming37 shot, and, meeting, they had burst open the barrel. Another had been split into ribbons at the muzzle. There were also relics of the Custer massacre, and a gun recaptured from an Indian after he had tastefully ornamented it with brass-headed nails.

The less bloody side of battle was recalled by General Thomas’s “office wagon,” the side of which formed a desk when lowered, and revealed some very neat pigeonholes for papers, pens, and red tape. Uniforms and equipment, models of pontoons, artillery, a model of undermining, one by one each claimed the hasty glance that was all any visitor had to spare. A longer look was claimed by an oil painting showing Lieutenant Lockwood’s observation of the “Farthest North.”

Then Harry returned to the Rotunda, and executed a rapid circular movement, hasty, but full of reverence, toward the cases of Revolutionary and Colonial relics—portraits on ivory, letters, flags, snuff-boxes—an endless array of antiquities. Harry was glad to see one miniature, excellently painted, by Major André; for up to that day he had not thought much of the unfortunate major’s drawing, having seen only the well-known “sketch of himself” in pen and ink. Washington’s diary was another thing the boy found very interesting: as he said, it was “neat as wax and right as a trivet.” Harry wondered whether it wouldn’t be fun to keep a diary. This reminded him of the flight of time, and, looking at his watch, he set his face once more toward the “Illinois,” for it was after half-past ten.

Many were going that way—and, indeed, in every other. Two small boys who, in sailor suits, strode along the pier like two pygmy admirals, gave him another subject for his sketch-book; but they were but atoms in a long procession, for there was no cessation in the coming and going of visitors all the time he was on the vessel.

He went at once below decks, and came plump up against an ice-machine—“to keep the men cool while in action,” he heard a young fellow say. Around the bulkheads were draped flags of all nations, and here and there were hung mess-lockers,—shelves behind wire gratings,—hammocks, neatly varnished kegs for stores, and everything Jack afloat could desire. Upon the lower deck also were glass cases protecting exquisite models of the new cruisers and battle-ships.

“Now, if they’ll give me just one of those as my share,” said Harry, “I’ll go home contented. Anyway, I think I will go to Annapolis and become an officer in the navy.”

38

As if to answer this thought, he came next to the room where the work of the cadets was shown. The splicing, the foot-ball statistics, the fencing foils and masks, were welcomed; but the tables full of text-books and the neat drawings on the walls spoke so plainly of hard study and long hours of work that Harry’s determination was somewhat shaken. And, indeed, before he had left the Government Building, a soldier of the regular army, guarding some exhibits, had said to him, “The time for war is over.” The man seemed to speak seriously, and then it was that Harry recalled the new Liberty Bell and its inscription. War was not all uniforms and parading.

The captain’s room and office were most attractive, except that a set of the “Encyclopædia Britannica” seemed out of its element—a British book with a Latin name hardly rhymed with a United States man-of-war.

A courteous officer on the “Illinois” told Harry that people’s questions were at times hard to answer. “One man,” he said, “looked long at the Howell torpedo, read the labels, and with keen interest wanted to know whether it wasn’t a flying machine!”

Harry thought that he might have been told that it was a machine to39 make other machines fly; but he didn’t interrupt the officer, who gave him a clear explanation of a life-buoy hanging in the cabin.

While ascending to the upper deck, he heard a woman say, “Oh, is there another story?” and wished Rudyard Kipling had been there to tell her that it was quite another story. But he made his way to the conning-tower, paying heed to the admonition of a mischievous boy who said, “Push, but don’t shove.”

The conning-tower was hardly big enough to lose one’s temper in, but gave the commanding officer full view of his surroundings through tiny slits cut through the solid steel. Electric buttons were convenient to push when he wished the guns, rifles, torpedoes, and other assistants to do the rest.

Leaving the vessel, Harry was again launched back to the other end of the grounds, landing at the Agricultural Building. He passed through this great show-house with his eyes well restrained, but did notice some birds flying about under the lofty roof. He wondered if they had come to study the best methods of securing a living at the farmers’ expense, and hoped rather that they wished to know what harmful insects it was best for them to destroy.

After eating lunch at a table in the open air near by, Harry boarded Columbus’s “Santa Maria.” Coming directly from a modern cruiser, the quaint little cockle-shell was a pathetic witness to the great discoverer’s hardships. Harry went into the forecastle, looked at the queer old galley, the swivel-gun, the anchors, and wished that he had been aboard the original on that first westward trip. The modern vessels were scientific, correct, and fine, of course; but somehow Harry would rather have sailed the ocean blue in the days when the galley-fires flared fitfully on these pictured sails.

He skipped the “Pinta” and “Niña,” sketching from the shore a sailor on the latter who was “guarding” the little vessel, only reflecting that those on the biggest vessel were better off than their fellows in these two, and went over to the Convent de la Rábida. Harry thought everybody knew about that building; but he met a group of three men, one of whom asked in all earnestness, “That hain’t the Fisheries Buildin’, is it?” Then the boy remembered how amused the great Napoleon was when they brought to his court a man who had never heard of him, of the Empire, or of the Revolution! Harry40 wondered whether there might not be in the Fair Grounds a few who hardly recalled having heard of a man named Columbus.

Inside the convent were old charts, pictures, and manuscripts, to which Harry gave but a passing glance. But the open court inside at once gave him a sense of antiquity, and the tropical plants recalled thoughts of distant lands, until he caught sight of a tired man worrying a piece of mince-pie for lunch. He started to go out, and only paused before an old globe whereon the lands were full of odd pictures.

“Geography must have been like a book of fairy-stories then,” he thought as he left the convent door and came face to face with to-day.

Oh, but he was tired! His legs ached, his back was lame, and he felt like the deacon’s “one-hoss shay”—as if he might give out “all at once and nothing first.” Seeing in the distance the movable sidewalk, it occurred to him that it was a good place for resting.

41

The convent had been a little depressing. Others felt the same effect, for he heard one woman say, “I’m glad I’m not a monk”—and then, after a reflective pause—“nor a nun.”

As he approached the traveling platform that ran on wheels far out along a pier, this cry met him:

“This way for the movable sidewalk! An all-day ride for five cents—the cheapest thing on the grounds!”

It was irresistible. Harry stepped on the slower platform, then to the quicker one, and dropped into a seat. It proved an excellent change. Out he glided upon the long pier, rested and cooled by the breeze and by the sight of the placid waters, now an opaline green in the afternoon light. Harry thought less of the scene than of his muscles.

“If I wanted to make money at this Fair,” he said, “I would put on sale a patent back-rest and double-back-action support; and after the Fair it could be sold to farmers for weeding.”

Harry made the round trip, and got off nearly where he started. He did not wish to go back to the hotel, but he could not really enjoy anything more, though so long as he could walk he wanted to see, see, see. Nor was it all seeing; a blind man would have enjoyed that day, so many funny remarks were made, so much music was in the air. Bands played, wheels whirled, people chatted, laughed, and exclaimed.

Everybody seemed happy, perhaps because with all the sight-seeing there went plenty of enjoyable exercise in the clear, bracing September air.

As for Harry, he returned to the hotel healthily weary, but not exhausted.

Harry’s route to his hotel lay through the usual throng of men whose one object in life was to make people buy “a splendid meat supper for twenty-five cents!” His legs felt like stilts, and he walked only because he had become so used to it that he could not stop.

As it was still an hour or two before their usual dinner-time, Harry went up to his room, intending to lie down for a while. When he asked at the counter for the key, the clerk told him that his friend “with the eye-glasses” was already in their room.

Harry found Philip lying on the bed, tired but looking contented.

“Why, you’re home early,” said Harry, in surprise. “I thought you were going to spend the whole day in the Art Gallery.”

“So I was,” said Philip, rising to make room for the later arrival. “I started for there. Where have you been?”

“Oh, to the Government Building, the man-of-war, the convent, the caravels—and a lot more,” said Harry, as he flung himself upon the bed, first having made himself comfortable by removing his jacket and shoes.

“Did you like it?”

“Like it? Of course I liked it, old slowcoach! But it’s too much like being invited to two Thanksgiving dinners—enough is better than two feasts.”

“What did you see?” asked Philip.

“See here, Phil,” said Harry, smiling mischievously; “do you think I am unable to take a view through a millstone with a hole in it? You needn’t think you can put me off by asking questions. What I want to44 know is why you didn’t get to the Art Building. It’s not small, you know; you could hardly have passed it without noticing it. Come, out with it, young fellow.”

“To tell the truth,” said Phil reluctantly, but laughing good-naturedly, “I started out all right, for I looked up the way in the guide-book. I found that the cheapest and quickest plan was to take the railway on the grounds—the Intra—something; yes, the Intramural, which means ‘within the wall.’”

“So it does,” answered Harry. “Great thing to know Latin. But fire away. I can see there is more in this Fair than a whole brigade of boys can see. Let’s hear what you did.”

“I took the railway, climbing a lot of steps, and we started. They had signs to tell one where to go, but I couldn’t read them very well, and so I went whizzing along without altogether understanding where I was. The stations they called out meant nothing to me, and I had an idea it took a good while to get across the grounds; and—to make it short—I was looking at the view, first one side, toward the hotels, and then the other, toward the Fair Buildings, and I didn’t wake up to my position till the conductor said, ‘Going round again, young man?’ So I got off, for there I45 was at the same station I got on at. You see, the conductor had noticed me because I sat near where he stood.”

“That’s a good one on you!”

“I know it. But I didn’t like to start over again, so I came down the steps and walked over across the Court of Honor, along by the Agricultural Building, till I came to the caravels and the convent. I saw those, but so did you. I went next to the Krupp gun exhibit by the lake. That gun was enormous! I believe all the gunners could get inside when it rained. They had a printed label on it, and at first I read it: ‘Please set off the gun’; but I knew that wasn’t likely, so I went nearer, and found it said ‘keep’ instead of ‘set.’ Oh, by the way, just before I went in there, I stopped in the doorway and saw some men diving from a tremendous height, out in the lake,—a much higher tower than the one they dived from on the fête night. I also saw in the Krupp building a pretty little model of the house the great gunmaker lived in when he began.”

“What was it like?” asked Harry.

“Oh, just a little square thatched house; but you could see the tiny furniture through the windows. I didn’t stay long there, for they were sprinkling the floor, and it was sloppy.

“Next I went into the Leather Exhibit Building; but there were mostly shoes and things there, and I didn’t see very much I cared about, except some buckskin suits labeled ‘indestructible.’ I would have liked one of those, except that it was trimmed with silver lace.”

46

“A little gaudy for you,” said Harry.

“Yes, but they were fine. So, seeing signs telling people to go up into the gallery where shoes were being made, I went up. I heard machines making a racket, but all I saw was the backs of the other people who got there first.”

“I know,” said Harry; “I made a sketch of one of those very exhibits.”

“Now, where did I go next? Let me see the map—it’s there by you.”

Harry passed over the little plan of the grounds, and Philip examined it a moment. Then he went on:

“I see now. I meant to go into the Forestry Building, but on the way I caught sight of some things in the Anthro—”

“—Thropo-pop-o-ological,” interrupted Harry. “It’s a nice word to say when you’re in a hurry.”

“Yes,” Philip replied, “that was it; so I went in there. And I tell you, you mustn’t miss that. It’s fine. It has everything in it.”

“So they all have,” said Harry, hopelessly.

“But there are gymnasium things, and African weapons, all sorts of savage huts and costumes, Greek statues, and views, and bits of work from the prisons and reformatories, showing how boys are drilled and trained to work at trades. But, as usual, I didn’t think I could see everything, and so I looked at only a few special cases. One that I remember well showed all sorts of games and puzzles—chess, cards, checkers, halma, pachisi, Indian sticks for throwing like dice, the fifteen puzzle, ring puzzles, wire puzzles, all sorts. The chessmen were splendid. There was one Chinese set there, where the pieces stood on pedestals showing three balls carved one inside the other; and the pieces themselves were little mandarins and things, with faces, and beards, and all. There were enough games in the cases for a boy to learn a new one every day as long as he lived.”

“Well?” asked Harry, as Philip paused.

“You don’t want me to tell it all, do you?” Philip asked.

“If you will,” said Harry. “My ears are the only things about me that are not tired; and I am resting the rest of me.”

“All right,” said Philip; “I’m willing. I am so full of it, I could talk a week. But I remember now there was one place I went before the Anthropo Building, and that was to a real log cabin, with all the regular old-fashioned things in it; but never mind, I won’t go back to that, for I’ve a lot more to tell, and one thing I know you’ll like to hear about specially.

47

“The next queer thing was the Cliff-dwellers’ mound, a big structure, made to look like red rock,—sandstone, maybe,—in which these old Indians in the Southwest used to live. I didn’t go into it, although a lot of signs said I ought to; but I saw how the little caves were hollowed out and made into huts, with doors and windows. While I was looking up at it—and it is a high cliff, I tell you!—I saw some nuns all in black climbing over it, and that was a strange sight enough. Out in front were some gray little donkeys,—‘burros,’ used by the exploring party that found the caves. Then I went on to an old-time distillery, outside of which was a real ‘moonshiner’s’ still that had been captured by the revenue officers.

“Then I came to some Alaskan houses. They were made of great rough slabs, with circular doors cut through the trunks of trees in front. There were little models of them in the Anthropo place, too. In front of them stood those carved totem-poles that we used to see in the physical geography book. I saw by the labels on the models that those poles were meant to tell the history of the man in the house behind each one, and that the more rings there were on the carved man’s high hat, the more of a fellow the owner was. There seemed to be lots about whales on them. I suppose capturing a whale was to them like being elected to Congress—maybe harder.

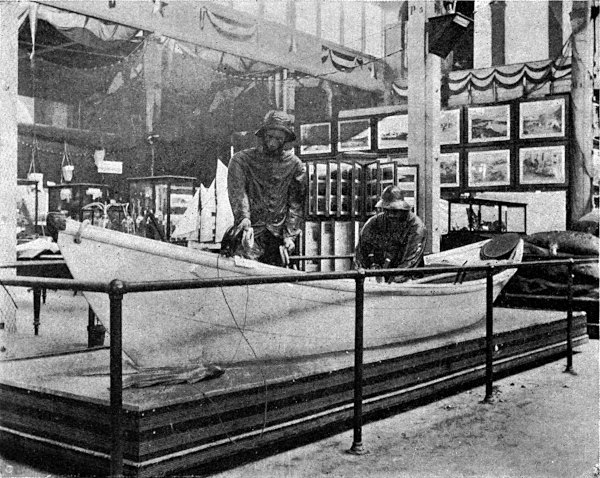

“But, speaking of whales, the next thing I saw was the one I want to tell you specially about. Near the shore there, in what they call the South Pond, was an old-fashioned vessel. I walked over toward it, and read the signs. They said it was a whaling-vessel, a regular old New Bedford whaler. You know about those?”

“I guess I do,” said Harry. “I remember reading ‘Peter, the Whaler,’ and a lot more books like it.”

“Well, at first I wasn’t going in, for they charged a quarter, and there didn’t seem to be many going on board. I was afraid it was not good for anything, but at last I made up my mind to risk twenty-five cents on it. I bought my ticket and climbed the gang-plank. There were just two other men on board besides the sailor in charge.”

“‘Two other men’ is good,” remarked Harry.

“You know what I mean. When we got up on deck, the sailor came forward to speak his little piece. He said if we wanted to know how they caught whales he’d tell us. Then he went on with the whole thing, from ‘Thar she blows!’ down to the cutting up and trying-out of blubber.

48

“I had often read about it, but I tell you, Harry, it was different to see him hold up the harpoon and the lance, the gun for firing a big harpoon and all. And then we saw the vats for boiling the oil. And he said that out of the whale’s head they could dip up whole barrels of clear oil; but the whalebone was the thing they were after nowadays. He said they sometimes got thousands of dollars’ worth out of the mouth of one whale.

“After he finished telling about whaling, he invited us below, to see a collection of marine curiosities they had on board. It was a regular old-style ship, with the beams coming close down to your head. All around were cases of curious things—real sailors’ oddities: carved teeth and shells, swords from sword-fish, idols, weapons, tools—whatever a sailor could collect. One thing I remember was a harpoon-head that had been bent and twisted around itself by a whale till it looked like a scrawl in a copy-book. Then we went forward to the forecastle, to see the queer little bunks where the men sleep.

“As I was coming away I bought a little book telling all about the old ship; and it is interesting, I tell you. I haven’t read it all yet, but one adventure of that ship the sailor told us about.

49

“She was out with a big fleet, more than thirty, and she was one of the six that got out from an ice-pack. Then a boat came along after, and reported the rest of the ships as wrecked. The ‘Progress’—that’s the one I’m telling about—and the other saved vessels threw all their valuable cargo over and took in the poor fellows from the ice. That was what I call square. You can read all about it later. Wouldn’t you like to?”

There was no answer. Philip turned to look at Harry more closely, and found that the tired boy had fallen fast asleep.

“It’s all right for him to go to sleep,” said Philip to himself, “but I wish he’d say so when he does it; then I’d know when to stop.”

Harry awoke in time for dinner. Mr. Douglass had mailed a number of letters, and he and the boys went to the table together. They found that their walks had given them the best of appetites, and they enjoyed seeing the people at the various tables around them. Mr. Douglass spoke of the excellent appearance made by the crowds, and of their good-humor.

“I was in the Fair Grounds for a short time this afternoon,” he said, “and I found myself noticing the people quite as much as the curious things around me. If one ran against another, there was never any ill-humor or crossness. Usually both apologized politely. And yet in many places the crowds were enormous. Again and again I would look ahead of me, and think that I couldn’t get through the throng.”

51

“I noticed that, too,” said Philip; “but the spaces are big and the people keep moving, so somehow one always finds a place to pass.”

“I tell you what I liked,” said Harry; “and that was the little drinking-fountains, where you drop a penny and get a glass of spring water. I found them very welcome.”

“And the popcorn!” said Philip. “I don’t like it much, but I saw it everywhere. Why, you could smell it in the air sometimes; and every now and then you would hear a crackle-crackle, snap-snap, and there would be a popper full of dancing corn over hot coals.”

“Yes, I saw them,” said Mr. Douglass. “I found it very interesting to talk to the people. Now and then, when I wished to rest awhile, I would sit down on a bench; and pretty soon a man would come up and drop into a seat beside me. Then, in a minute, one of us would say: ‘It’s a fine day,’ or something of the kind, and, without difficulty, a little talk would begin. One man I met told me he was from Massachusetts, and cultivated tobacco. We had a very pleasant conversation, and gave each other advice about what to see. I think this Fair will do a great deal to bring people together.”

“It has already,” said Harry, solemnly. “I have seen a number come together even to-day. Where did you go this afternoon, Mr. Douglass?”

“I went to the Art Gallery part of the time,” the tutor replied. “But I found it, like the other buildings, too overwhelming—whole rooms full of masterpieces of painting and sculpture; something demanding at least a glance wherever one looked. I found I could not stay long. Walking about and looking upward and downward, and from side to side, is more than any one can endure very long. Besides, the pictures are so good that they make one both think and feel keenly, and that is tiring, too. So after about two hours I surrendered, and came out. I walked along the lake shore during part of my way back, purposely avoiding any sights of especial interest.”

“What shall we do to-morrow?” asked Philip.

“Whatever you please,” answered the tutor. “Perhaps you might do some photographing, Philip.”

“I’d like to, but I hardly know where to begin.”

“Suppose,” said Harry, “that we all three go to the Midway Plaisance? It’s a splendid place to get pictures.”

“But I hear,” said Philip, “that you can’t do very much photographing there. You can get a permit for the Fair Grounds, but the Plaisance52 exhibits are outside of the Fair’s control, and you have to secure special permissions there.”

“We might try it,” said Mr. Douglass. “You have brought your big kodak, haven’t you?”

“Yes, with a new roll of forty-eight films in it,” said Philip. “But I shall have to take outdoor scenes, for there’s little chance to give time-exposures.”

“Well, suppose that we hire chairs to-morrow—the rolling-chairs, you know. One can hire either double chairs or single ones; and then we three will be wheeled out to the Midway Plaisance. There we will let the chairs go, and see what we can do. How do you like it, Harry?”

“Oh, it suits me,” said Harry. “To tell the truth, I should like to go there soon, for there are so many really foreign scenes in the streets and villages that it may be I can get some good little sketches. At all events, I’d like to go to the Wild Animal show, and see it all. I met a boy to-day, while I was at lunch, who said that it beat any circus he ever saw.”

“There are a number of absurd cheap shows on the Midway,” said Mr. Douglass, “at least, so the guide-books say; but we can go to the best of53 them, and let the others alone. I find that the people (as I have told you) are more interesting to me than are most of the exhibits, and the Plaisance is always crowded.”

The party had finished dinner, and they went up to their rooms; Philip got out his camera, and looked it over, to be sure all was in working order. Harry laid out his sketch-book and an extra pencil. Mr. Douglass, as he usually did, read over his guide-books, and made up his accounts. But all three went early to bed.

The dauntless three reached the gates next morning at about nine o’clock, and found an even larger crowd than usual. They had to form in line at some distance from the ticket-office, and advanced toward it as slowly as people come out of church. But, as before, good humor was the rule, and, excepting for a few of the weak-minded men who always fight their way through a crowd, there was every effort made to accommodate one another.

Philip heard a woman say, “Why, we are all here to have a good time, and to let other people have the same.” It was worst just in passing the wickets, but once through, the trouble was at an end.

“How shall we go toward the Plaisance?” Mr. Douglass asked. He felt that the expedition was undertaken for the boys’ pleasure, and wished them to have their own way about it.

“Why don’t you take the Intramural, as I did yesterday?” Philip asked. “It will give you and Harry a new view of the grounds, and it’s a very short ride to the other end.”

56

“All right,” said Harry; “but we must keep our wits about us. I knew a boy once who was carried back to where he started from.”

For this little dig, Philip gently knocked Harry’s hat over his eyes. Harry left the hat untouched until Philip put it back in place. “I don’t care how I wear my hat,” said Harry, “so long as it is in the very latest style.”

As they got on the cars, Mr. Douglass noticed that the gates along the sides were all opened and shut at once by the conductor, and at some stations there were large signs saying, “Don’t climb over the gates. They will be opened.”

When they were just westward of the Horticultural Building, Harry remarked, “There is no need of getting into the large crowds,—there is plenty of room over there, and only one man has found it worth while to occupy the space.”

Philip looked where Harry pointed, and saw a workman climbing up a dizzy little stairway half-way to the top of the great glass dome.

“If he should fall through, he’d break a lot of glass,” said Philip, reflectively.

They left the railway near the mammoth Building of Manufactures, and walked to its northern entrance. Here Mr. Douglass secured their chairs, the young men who pushed them having the time of starting noted upon cards that they kept neatly inside their caps. Wheeling into line, they rode comfortably along through the parting crowd, Philip carrying his kodak upon his knees, ready for business. He had secured a little card, tied to a57 string, that permitted him to take pictures “with a four-by-five camera only” for that one day. He had paid two dollars for this privilege, and felt bound to use up his roll of forty-eight exposures.

At first the boys found their chairs a little uncomfortable; but the guides raised the foot-rests until their short legs could reach them, and after that they found the vehicles as comfortable as an arm-chair in a library. It was a bright, clear day—“Just the day for taking snap-shots,” Philip said enthusiastically; and everything was plainly outlined by sharp contrasts of light and shade.

As usual, Mr. Douglass began to talk to his guide, and learned that the young man was a college student who was rolling a chair at the Exposition partly for the money he made and partly for the sake of seeing the Fair and the people from all parts of the world. As Mr. Douglass had worked his own way through college, he was able to give his guide some practical advice, which was gratefully received.

Passing along in front of the Illinois State Building—always conspicuous for its dome—they passed around the Women’s Building, and came to the entrance of the mile of curious structures that made up the58 Midway Plaisance. But before they had come so far, the boys, too, were talking to their guides, who proved to be other college men.

A thing one of them told the boys amused them. The guide said that people, intending to be considerate, would lean far forward when the chair was pushed up a slope. “And that,” he said, “brings all their weight on the little guiding-wheels in front, where there are no springs. Then the wheels turn hard, and we have to ask them to sit back. So, you see, the kindest people sometimes give the most trouble.”

In spite of this warning, when they were ascending the first bridge—one that led across an opening from the Lagoon—both boys leaned forward, as one does in “helping” a horse up hill. But when the guides laughed, the two boys quickly sank back again.

Passing under the elevated railway, they joined the ranks of visitors to the Midway. As they intended to come back another time, they glanced only at the exteriors of most of the buildings, pausing first when they came to the Javanese village. While they rode through the crowd the boys were amused to see the odd glances of those who met them. The luxury of being pushed in a chair was, by many of the newer visitors, considered59 fitting only for sick people, and their eyes plainly said that two strong, healthy boys should walk. The boys knew this, for they had had the same feeling toward riders during their own first day; the second day’s walking, however, entirely changed their views, and they understood that it was a wise economy to save bodily tire when eyes and brain were so busy.

“You can ride right into the Javanese village,” one of the guides told them; so they bought their tickets and were pushed into the grounds.

Surrounded by a bamboo fence with a lofty gateway was a collection of steep-roofed, grass-thatched, one-story huts. Each had a little veranda in front, and as it was sunny, many of the short, dark-skinned little people sat outdoors at work.