The Project Gutenberg eBook, Robert Louis Stevenson, by Alexander H. Japp

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Robert Louis Stevenson

a Record, an Estimate, and a Memorial

Author: Alexander H. Japp

Release Date: May 5, 2007 [eBook #590]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII)

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON***

Transcribed from the Charles Scribner’s Sons 1905 edition by David Price, email [email protected]

By ALEXANDER H. JAPP, LL.D., F.R.S.E

author of “thoreau: his life and aims”; “memoir of thomas de quincey”; “de quincey memorials,” etc., etc.

WITH HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED LETTERS FROM R. L. STEVENSON IN FACSIMILIE . . .

second edition

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

153-157 FIFTH AVENUE

1905

Printed in Great Britain.

Dedicated to

C. A. LICHTENBERG, Esq.

and

Mrs LICHTENBERG,

of villa margherita, treviso,

with most grateful regards,

ALEXANDER H. JAPP.

19th December 1904.

A few words may here be allowed me to explain one or two points. First, about the facsimile of last page of Preface to Familiar Studies of Men and Books. Stevenson was in Davos when the greater portion of that work went through the press. He felt so much the disadvantage of being there in the circumstances (both himself and his wife ill) that he begged me to read the proofs of the Preface for him. This illness has record in the letter from him (pp. 28-29). The printers, of course, had directions to send the copy and proofs of the Preface to me. Hence I am able now to give this facsimile.

With regard to the letter at p. 19, of which facsimile is also given, what Stevenson there meant is not the “three last” of that batch, but the three last sent to me before—though that was an error on his part—he only then sent two chapters, making the “eleven chapters now”—sent to me by post.

Another point on which I might have dwelt and illustrated by many instances is this, that though Stevenson was fond of hob-nobbing with all sorts and conditions of men, this desire of wide contact and intercourse has little show in his novels—the ordinary fibre of commonplace human beings not receiving much celebration from him there; another case in which his private bent and sympathies received little illustration in his novels. But the fact lies implicit in much I have written.

I have to thank many authors for permission to quote extracts I have used.

ALEXANDER H. JAPP.

I. INTRODUCTION AND FIRST

IMPRESSIONS

II. TREASURE ISLAND AND SOME

REMINISCENCES

III. THE CHILD FATHER OF THE MAN

IV. HEREDITY ILLUSTRATED

V. TRAVELS

VI. SOME EARLIER LETTERS

VII. THE VAILIMA LETTERS

VIII. WORK OF LATER YEARS

IX. SOME CHARACTERISTICS

X. A SAMOAN MEMORIAL OF R. L.

STEVENSON

XI. MISS STUBBS’ RECORD OF A

PILGRIMAGE

XII. HIS GENIUS AND METHODS

XIII. PREACHER AND MYSTIC FABULIST

XIV. STEVENSON AS DRAMATIST

XV. THEORY OF GOOD AND EVIL

XVI. STEVENSON’S GLOOM

XVII. PROOFS OF GROWTH

XVIII. EARLIER DETERMINATIONS AND RESULTS

XIX. MR EDMUND CLARENCE STEDMAN’S

ESTIMATE

XX. EGOTISTIC ELEMENT AND ITS EFFECTS

XXI. UNITY IN STEVENSON’S STORIES

XXII. PERSONAL CHEERFULNESS AND INVENTED GLOOM

XXIII. EDINBURGH REVIEWERS’ DICTA INAPPLICABLE TO

LATER WORK

XXIV. MR HENLEY’S SPITEFUL PERVERSIONS

XXV. MR CHRISTIE MURRAY’S IMPRESSIONS

XXVI. HERO-VILLAINS

XXVII. MR G. MOORE, MR MARRIOTT WATSON, AND OTHERS

XXVIII. UNEXPECTED COMBINATIONS

XXIX. LOVE OF VAGABONDS

XXX. LORD ROSEBERY’S CASE

XXXI. MR GOSSE AND MS. OF TREASURE ISLAND

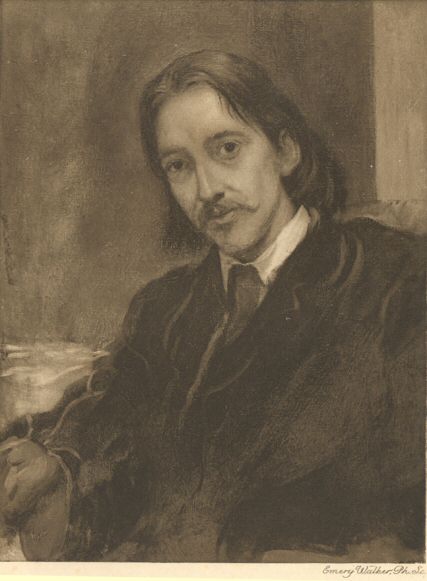

XXXII. STEVENSON PORTRAITS

XXXIII. LAPSES AND ERRORS IN CRITICISM

XXXIV. LETTERS AND POEMS IN TESTIMONY

APPENDIX

My little effort to make Thoreau better known in England had one result that I am pleased to think of. It brought me into personal association with R. L. Stevenson, who had written and published in The Cornhill Magazine an essay on Thoreau, in whom he had for some time taken an interest. He found in Thoreau not only a rare character for originality, courage, and indefatigable independence, but also a master of style, to whom, on this account, as much as any, he was inclined to play the part of the “sedulous ape,” as he had acknowledged doing to many others—a later exercise, perhaps in some ways as fruitful as any that had gone before. A recent poet, having had some seeds of plants sent to him from Northern Scotland to the South, celebrated his setting of them beside those native to the Surrey slope on which he dwelt, with the lines—

“And when the Northern seeds are growing,

Another beauty then bestowing,

We shall be fine, and North to South

Be giving kisses, mouth to mouth.”

So the Thoreau influence on Stevenson was as if a tart American wild-apple had been grafted on an English pippin, and produced a wholly new kind with the flavours of both; and here wild America and England kissed each other mouth to mouth.

The direct result was the essay in The Cornhill, but the indirect results were many and less easily assessed, as Stevenson himself, as we shall see, was ever ready to admit. The essay on Thoreau was written in America, which further, perhaps, bears out my point.

One of the authorities, quoted by Mr Hammerton, in Stevensoniana says of the circumstances in which he found our author, when he was busily engaged on that bit of work:

“I have visited him in a lonely lodging in California, it was previous to his happy marriage, and found him submerged in billows of bed-clothes; about him floated the scattered volumes of a complete set of Thoreau; he was preparing an essay on that worthy, and he looked at the moment like a half-drowned man, yet he was not cast down. His work, an endless task, was better than a straw to him. It was to become his life-preserver and to prolong his years. I feel convinced that without it he must have surrendered long since. I found Stevenson a man of the frailest physique, though most unaccountably tenacious of life; a man whose pen was indefatigable, whose brain was never at rest, who, as far as I am able to judge, looked upon everybody and everything from a supremely intellectual point of view.” [1]

We remember the common belief in Yorkshire and other parts that a man could not die so long as he could stand up—a belief on which poor Branwell Brontë was fain to act and to illustrate, but R. L. Stevenson illustrated it, as this writer shows, in a better, calmer, and healthier way, despite his lack of health.

On some little points of fact, however, Stevenson was wrong; and I wrote to the Editor of The Spectator a letter, titled, I think, “Thoreau’s Pity and Humour,” which he inserted. This brought me a private letter from Stevenson, who expressed the wish to see me, and have some talk with me on that and other matters. To this letter I at once replied, directing to 17 Heriot Row, Edinburgh, saying that, as I was soon to be in that City, it might be possible for me to see him there. In reply to this letter Mr Stevenson wrote:

“The Cottage, Castleton of Braemar,

Sunday, August (? th), 1881.“My dear Sir,—I should long ago have written to thank you for your kind and frank letter; but, in my state of health, papers are apt to get mislaid, and your letter has been vainly hunted for until this (Sunday) morning.

“I must first say a word as to not quoting your book by name. It was the consciousness that we disagreed which led me, I daresay, wrongly, to suppress all references throughout the paper. But you may be certain a proper reference will now be introduced.

“I regret I shall not be able to see you in Edinburgh: one visit to Edinburgh has already cost me too dear in that invaluable particular, health; but if it should be at all possible for you to pass by Braemar, I believe you would find an attentive listener, and I can offer you a bed, a drive, and necessary food.

“If, however, you should not be able to come thus far, I can promise two things. First, I shall religiously revise what I have written, and bring out more clearly the point of view from which I regarded Thoreau. Second, I shall in the preface record your objection.

“The point of view (and I must ask you not to forget that any such short paper is essentially only a section through a man) was this: I desired to look at the man through his books. Thus, for instance, when I mentioned his return to the pencil-making, I did it only in passing (perhaps I was wrong), because it seemed to me not an illustration of his principles, but a brave departure from them. Thousands of such there were I do not doubt; still they might be hardly to my purpose; though, as you say so, I suppose some of them would be.

“Our difference as to ‘pity,’ I suspect, was a logomachy of my making. No pitiful acts, on his part, would surprise me: I know he would be more pitiful in practice than most of the whiners; but the spirit of that practice would still seem to me to be unjustly described by the word pity.

“When I try to be measured, I find myself usually suspected of a sneaking unkindness for my subject, but you may be sure, sir, I would give up most other things to be as good a man as Thoreau. Even my knowledge of him leads me thus far.

“Should you find yourself able to push on so far—it may even lie on your way—believe me your visit will be very welcome. The weather is cruel, but the place is, as I daresay you know, the very wale of Scotland—bar Tummelside.—Yours very sincerely,

Robert Louis Stevenson.”

Some delay took place in my leaving London for Scotland, and hence what seemed a hitch. I wrote mentioning the reason of my delay, and expressing the fear that I might have to forego the prospect of seeing him in Braemar, as his circumstances might have altered in the meantime. In answer came this note, like so many, if not most of his, indeed, without date:—

The Cottage, Castleton of Braemar.

(No date.)“My dear Sir,—I am here as yet a fixture, and beg you to come our way. Would Tuesday or Wednesday suit you by any chance? We shall then, I believe, be empty: a thing favourable to talks. You get here in time for dinner. I stay till near the end of September, unless, as may very well be, the weather drive me forth.—Yours very sincerely, Robert Louis Stevenson.”

I accordingly went to Braemar, where he and his wife and her son were staying with his father and mother.

These were red-letter days in my calendar alike on account of pleasant intercourse with his honoured father and himself. Here is my pen-and-ink portrait of R. L. Stevenson, thrown down at the time:

Mr Stevenson’s is, indeed, a very picturesque and striking figure. Not so tall probably as he seems at first sight from his extreme thinness, but the pose and air could not be otherwise described than as distinguished. Head of fine type, carried well on the shoulders and in walking with the impression of being a little thrown back; long brown hair, falling from under a broadish-brimmed Spanish form of soft felt hat, Rembrandtesque; loose kind of Inverness cape when walking, and invariable velvet jacket inside the house. You would say at first sight, wherever you saw him, that he was a man of intellect, artistic and individual, wholly out of the common. His face is sensitive, full of expression, though it could not be called strictly beautiful. It is longish, especially seen in profile, and features a little irregular; the brow at once high and broad. A hint of vagary, and just a hint in the expression, is qualified by the eyes, which are set rather far apart from each other as seems, and with a most wistful, and at the same time possibly a merry impish expression arising over that, yet frank and clear, piercing, but at the same time steady, and fall on you with a gentle radiance and animation as he speaks. Romance, if with an indescribable soupçon of whimsicality, is marked upon him; sometimes he has the look as of the Ancient Mariner, and could fix you with his glittering e’e, and he would, as he points his sentences with a movement of his thin white forefinger, when this is not monopolised with the almost incessant cigarette. There is a faint suggestion of a hair-brained sentimental trace on his countenance, but controlled, after all, by good Scotch sense and shrewdness. In conversation he is very animated, and likes to ask questions. A favourite and characteristic attitude with him was to put his foot on a chair or stool and rest his elbow on his knee, with his chin on his hand; or to sit, or rather to half sit, half lean, on the corner of a table or desk, one of his legs swinging freely, and when anything that tickled him was said he would laugh in the heartiest manner, even at the risk of bringing on his cough, which at that time was troublesome. Often when he got animated he rose and walked about as he spoke, as if movement aided thought and expression. Though he loved Edinburgh, which was full of associations for him, he had no good word for its east winds, which to him were as death. Yet he passed one winter as a “Silverado squatter,” the story of which he has inimitably told in the volume titled The Silverado Squatters; and he afterwards spent several winters at Davos Platz, where, as he said to me, he not only breathed good air, but learned to know with closest intimacy John Addington Symonds, who “though his books were good, was far finer and more interesting than any of his books.” He needed a good deal of nursery attentions, but his invalidism was never obtrusively brought before one in any sympathy-seeking way by himself; on the contrary, a very manly, self-sustaining spirit was evident; and the amount of work which he managed to turn out even when at his worst was truly surprising.

His wife, an American lady, is highly cultured, and is herself an author. In her speech there is just the slightest suggestion of the American accent, which only made it the more pleasing to my ear. She is heart and soul devoted to her husband, proud of his achievements, and her delight is the consciousness of substantially aiding him in his enterprises.

They then had with them a boy of eleven or twelve, Samuel Lloyd Osbourne, to be much referred to later (a son of Mrs Stevenson by a former marriage), whose delight was to draw the oddest, but perhaps half intentional or unintentional caricatures, funny, in some cases, beyond expression. His room was designated the picture-gallery, and on entering I could scarce refrain from bursting into laughter, even at the general effect, and, noticing this, and that I was putting some restraint on myself out of respect for the host’s feelings, Stevenson said to me with a sly wink and a gentle dig in the ribs, “It’s laugh and be thankful here.” On Lloyd’s account simple engraving materials, types, and a small printing-press had been procured; and it was Stevenson’s delight to make funny poems, stories, and morals for the engravings executed, and all would be duly printed together. Stevenson’s thorough enjoyment of the picture-gallery, and his goodness to Lloyd, becoming himself a very boy for the nonce, were delightful to witness and in degree to share. Wherever they were—at Braemar, in Edinburgh, at Davos Platz, or even at Silverado—the engraving and printing went on. The mention of the picture-gallery suggests that it was out of his interest in the colour-drawing and the picture-gallery that his first published story, Treasure Island, grew, as we shall see.

I have some copies of the rude printing-press productions, inexpressibly quaint, grotesque, a kind of literary horse-play, yet with a certain squint-eyed, sprawling genius in it, and innocent childish Rabelaisian mirth of a sort. At all events I cannot look at the slight memorials of that time, which I still possess, without laughing afresh till my eyes are dewy. Stevenson, as I understood, began Treasure Island more to entertain Lloyd Osbourne than anything else; the chapters being regularly read to the family circle as they were written, and with scarcely a purpose beyond. The lad became Stevenson’s trusted companion and collaborator—clearly with a touch of genius.

I have before me as I write some of these funny momentoes of that time, carefully kept, often looked at. One of them is, “The Black Canyon; or, Wild Adventures in the Far West: a Tale of Instruction and Amusement for the Young, by Samuel L. Osbourne, printed by the author; Davos Platz,” with the most remarkable cuts. It would not do some of the sensationalists anything but good to read it even at this day, since many points in their art are absurdly caricatured. Another is “Moral Emblems; a Collection of Cuts and Verses, by R. L. Stevenson, author of the Blue Scalper, etc., etc. Printers, S. L. Osbourne and Company, Davos Platz.” Here are the lines to a rare piece of grotesque, titled A Peak in Darien—

“Broad-gazing on untrodden lands,

See where adventurous Cortez stands,

While in the heavens above his head,

The eagle seeks its daily bread.

How aptly fact to fact replies,

Heroes and eagles, hills and skies.

Ye, who contemn the fatted slave,

Look on this emblem and be brave.”

Another, The Elephant, has these lines—

“See in the print how, moved by whim,

Trumpeting Jumbo, great and grim,

Adjusts his trunk, like a cravat,

To noose that individual’s hat;

The Sacred Ibis in the distance,

Joys to observe his bold resistance.”

R. L. Stevenson wrote from Davos Platz, in sending me The Black Canyon:

“Sam sends as a present a work of his own. I hope you feel flattered, for this is simply the first time he has ever given one away. I have to buy my own works, I can tell you.”

Later he said, in sending a second:

“I own I have delayed this letter till I could forward the enclosed. Remembering the night at Braemar, when we visited the picture-gallery, I hope it may amuse you: you see we do some publishing hereaway.”

Delightfully suggestive and highly enjoyable, too, were the meetings in the little drawing-room after dinner, when the contrasted traits of father and son came into full play—when R. L. Stevenson would sometimes draw out a new view by bold, half-paradoxical assertion, or compel advance on the point from a new quarter by a searching question couched in the simplest language, or reveal his own latest conviction finally, by a few sentences as nicely rounded off as though they had been written, while he rose and gently moved about, as his habit was, in the course of those more extended remarks. Then a chapter or two of The Sea-Cook would be read, with due pronouncement on the main points by one or other of the family audience.

The reading of the book is one thing. It was quite another thing to hear Stevenson as he stood reading it aloud, with his hand stretched out holding the manuscript, and his body gently swaying as a kind of rhythmical commentary on the story. His fine voice, clear and keen it some of its tones, had a wonderful power of inflection and variation, and when he came to stand in the place of Silver you could almost have imagined you saw the great one-legged John Silver, joyous-eyed, on the rolling sea. Yes, to read it in print was good, but better yet to hear Stevenson read it.

When I left Braemar, I carried with me a considerable portion of the MS. of Treasure Island, with an outline of the rest of the story. It originally bore the odd title of The Sea-Cook, and, as I have told before, I showed it to Mr Henderson, the proprietor of the Young Folks’ Paper, who came to an arrangement with Mr Stevenson, and the story duly appeared in its pages, as well as the two which succeeded it.

Stevenson himself in his article in The Idler for August 1894 (reprinted in My First Book volume and in a late volume of the Edinburgh Edition) has recalled some of the circumstances connected with this visit of mine to Braemar, as it bore on the destination of Treasure Island:

“And now, who should come dropping in, ex machinâ, but Dr Japp, like the disguised prince, who is to bring down the curtain upon peace and happiness in the last act; for he carried in his pocket, not a horn or a talisman, but a publisher, in fact, ready to unearth new writers for my old friend Mr Henderson’s Young Folks. Even the ruthlessness of a united family recoiled before the extreme measure of inflicting on our guest the mutilated members of The Sea-Cook; at the same time, we would by no means stop our readings, and accordingly the tale was begun again at the beginning, and solemnly redelivered for the benefit of Dr Japp. From that moment on, I have thought highly of his critical faculty; for when he left us, he carried away the manuscript in his portmanteau.

“Treasure Island—it was Mr Henderson who deleted the first title, The Sea-Cook—appeared duly in Young Folks, where it figured in the ignoble midst without woodcuts, and attracted not the least attention. I did not care. I liked the tale myself, for much the same reason as my father liked the beginning: it was my kind of picturesque. I was not a little proud of John Silver also; and to this day rather admire that smooth and formidable adventurer. What was infinitely more exhilarating, I had passed a landmark. I had finished a tale and written The End upon my manuscript, as I had not done since The Pentland Rising, when I was a boy of sixteen, not yet at college. In truth, it was so by a lucky set of accidents: had not Dr Japp come on his visit, had not the tale flowed from me with singular ease, it must have been laid aside, like its predecessors, and found a circuitous and unlamented way to the fire. Purists may suggest it would have been better so. I am not of that mind. The tale seems to have given much pleasure, and it brought (or was the means of bringing) fire, food, and wine to a deserving family in which I took an interest. I need scarcely say I mean my own.”

He himself gives a goodly list of the predecessors which had “found a circuitous and unlamented way to the fire”:

“As soon as I was able to write, I became a good friend to the paper-makers. Reams upon reams must have gone to the making of Rathillet, The Pentland Rising, The King’s Pardon (otherwise Park Whitehead), Edward Daven, A Country Dance, and A Vendetta in the West. Rathillet was attempted before fifteen, The Vendetta at twenty-nine, and the succession of defeats lasted unbroken till I was thirty-one.”

Another thing I carried from Braemar with me which I greatly prize—this was a copy of Christianity confirmed by Jewish and Heathen Testimony, by Mr Stevenson’s father, with his autograph signature and many of his own marginal notes. He had thought deeply on many subjects—theological, scientific, and social—and had recorded, I am afraid, but the smaller half of his thoughts and speculations. Several days in the mornings, before R. L. Stevenson was able to face the somewhat “snell” air of the hills, I had long walks with the old gentleman, when we also had long talks on many subjects—the liberalising of the Scottish Church, educational reform, etc.; and, on one occasion, a statement of his reason, because of the subscription, for never having become an elder. That he had in some small measure enjoyed my society, as I certainly had much enjoyed his, was borne out by a letter which I received from the son in reply to one I had written, saying that surely his father had never meant to present me at the last moment on my leaving by coach with that volume, with his name on it, and with pencilled notes here and there, but had merely given it me to read and return. In the circumstances I may perhaps be excused quoting from a letter dated Castleton of Braemar, September 1881, in illustration of what I have said—

“My dear Dr Japp,—My father has gone, but I think I may take it upon me to ask you to keep the book. Of all things you could do to endear yourself to me you have done the best, for, from your letter, you have taken a fancy to my father.

“I do not know how to thank you for your kind trouble in the matter of The Sea-Cook, but I am not unmindful. My health is still poorly, and I have added intercostal rheumatism—a new attraction, which sewed me up nearly double for two days, and still gives me ‘a list to starboard’—let us be ever nautical. . . . I do not think with the start I have, there will be any difficulty in letting Mr Henderson go ahead whenever he likes. I will write my story up to its legitimate conclusion, and then we shall be in a position to judge whether a sequel would be desirable, and I myself would then know better about its practicability from the story-telling point of view.—Yours very sincerely, Robert Louis Stevenson.”

A little later came the following:—

“The Cottage, Castleton of Braemar.

(No date.)“My dear Dr Japp,—Herewith go nine chapters. I have been a little seedy; and the two last that I have written seem to me on a false venue; hence the smallness of the batch. I have now, I hope, in the three last sent, turned the corner, with no great amount of dulness.

“The map, with all its names, notes, soundings, and things, should make, I believe, an admirable advertisement for the story. Eh?

“I hope you got a telegram and letter I forwarded after you to Dinnat.—Believe me, yours very sincerely, Robert Louis Stevenson.”

In the afternoon, if fine and dry, we went walking, and Stevenson would sometimes tell us stories of his short experience at the Scottish Bar, and of his first and only brief. I remember him contrasting that with his experiences as an engineer with Bob Bain, who, as manager, was then superintending the building of a breakwater. Of that time, too, he told the choicest stories, and especially of how, against all orders, he bribed Bob with five shillings to let him go down in the diver’s dress. He gave us a splendid description—finer, I think, than even that in his Memories—of his sensations on the sea-bottom, which seems to have interested him as deeply, and suggested as many strange fancies, as anything which he ever came across on the surface. But the possibility of enterprises of this sort ended—Stevenson lost his interest in engineering.

Stevenson’s father had, indeed, been much exercised in his day by theological questions and difficulties, and though he remained a staunch adherent of the Established Church of Scotland he knew well and practically what is meant by the term “accommodation,” as it is used by theologians in reference to creeds and formulas; for he had over and over again, because of the strict character of the subscription required from elders of the Scottish Church declined, as I have said, to accept the office. In a very express sense you could see that he bore the marks of his past in many ways—a quick, sensitive, in some ways even a fantastic-minded man, yet with a strange solidity and common-sense amid it all, just as though ferns with the veritable fairies’ seed were to grow out of a common stone wall. He looked like a man who had not been without sleepless nights—without troubles, sorrows, and perplexities, and even yet, had not wholly risen above some of them, or the results of them. His voice was “low and sweet”—with just a possibility in it of rising to a shrillish key. A sincere and faithful man, who had walked very demurely through life, though with a touch of sudden, bright, quiet humour and fancy, every now and then crossing the grey of his characteristic pensiveness or melancholy, and drawing effect from it. He was most frank and genial with me, and I greatly honour his memory. [2]

Thomas Stevenson, with a strange, sad smile, told me how much of a disappointment, in the first stage, at all events, Louis (he always called his son Louis at home), had caused him, by failing to follow up his profession at the Scottish Bar. How much he had looked forward, after the engineering was abandoned, to his devoting himself to the work of the Parliament House (as the Hall of the Chief Court is called in Scotland, from the building having been while yet there was a Scottish Parliament the place where it sat), though truly one cannot help feeling how much Stevenson’s very air and figure would have been out of keeping among the bewigged, pushing, sharp-set, hard-featured, and even red-faced and red-nosed (some of them, at any rate) company, who daily walked the Parliament House, and talked and gossiped there, often of other things than law and equity. “Well, yes, perhaps it was all for the best,” he said, with a sigh, on my having interjected the remark that R. L. Stevenson was wielding far more influence than he ever could have done as a Scottish counsel, even though he had risen rapidly in his profession, and become Lord-Advocate or even a judge.

There was, indeed, a very pathetic kind of harking back on the might-have-beens when I talked with him on this subject. He had reconciled himself in a way to the inevitable, and, like a sensible man, was now inclined to make the most and the best of it. The marriage, which, on the report of it, had been but a new disappointment to him, had, as if by magic, been transformed into a blessing in his mind and his wife’s by personal contact with Fanny Van der Griff Stevenson, which no one who ever met her could wonder at; but, nevertheless, his dream of seeing his only son walking in the pathways of the Stevensons, and adorning a profession in Edinburgh, and so winning new and welcome laurels for the family and the name, was still present with him constantly, and by contrast, he was depressed with contemplation of the real state of the case, when, as I have said, I pointed out to him, as more than once I did, what an influence his son was wielding now, not only over those near to him, but throughout the world, compared with what could have come to him as a lighthouse engineer, however successful, or it may be as a briefless advocate or barrister, walking, hardly in glory and in joy, the Hall of the Edinburgh Parliament House. And when I pictured the yet greater influence that was sure to come to him, he only shook his head with that smile which tells of hopes long-cherished and lost at last, and of resignation gained, as though at stern duty’s call and an honest desire for the good of those near and dear to him. It moved me more than I can say, and always in the midst of it he adroitly, and somewhat abruptly, changed the subject. Such penalties do parents often pay for the honour of giving geniuses to the world. Here, again, it may be true, “the individual withers but the world is more and more.”

The impression of a kind of tragic fatality was but added to when Stevenson would speak of his father in such terms of love and admiration as quite moved one, of his desire to please him, of his highest respect and gratitude to him, and pride in having such a father. It was most characteristic that when, in his travels in America, he met a gentleman who expressed plainly his keen disappointment on learning that he had but been introduced to the son and not to the father—to the as yet but budding author—and not to the builder of the great lighthouse beacons that constantly saved mariners from shipwreck round many stormy coasts, he should record the incident, as his readers will remember, with such a strange mixture of a pride and filial gratitude, and half humorous humiliation. Such is the penalty a son of genius often pays in heart-throbs for the inability to do aught else but follow his destiny—follow his star, even though as Dante says:—

“Se tu segui tua stella

Non puoi fallire a glorioso porto.” [3]

What added a keen thrill as of quivering flesh exposed, was that Thomas Stevenson on one side was exactly the man to appreciate such attainments and work in another, and I often wondered how far the sense of Edinburgh propriety and worldly estimates did weigh with him here.

Mr Stevenson mentioned to me a peculiar fact which has since been noted by his son, that, notwithstanding the kind of work he had so successfully engaged in, he was no mathematician, and had to submit his calculations to another to be worked out in definite mathematical formulæ. Thomas Stevenson gave one the impression of a remarkably sweet, great personality, grave, anxious, almost morbidly forecasting, yet full of childlike hope and ready affection, but, perhaps, so earnestly taken up with some points as to exaggerate their importance and be too self-conscious and easily offended in respect to them. But there was no affectation in him. He was simple-minded, sincere to the core; most kindly, homely, hospitable, much intent on brotherly offices. He had the Scottish perfervidum too—he could tolerate nothing mean or creeping; and his eye would lighten and glance in a striking manner when such was spoken of. I have since heard that his charities were very extensive, and dispensed in the most hidden and secret ways. He acted here on the Scripture direction, “Let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth.” He was much exercised when I saw him about some defects, as he held, in the methods of Scotch education (for he was a true lover of youth, and cared more for character being formed than for heads being merely crammed). Sagacious, with fine forecast, with a high ideal, and yet up to a certain point a most tolerant temper, he was a fine specimen of the Scottish gentleman. His son tells that, as he was engaged in work calculated to benefit the world and to save life, he would not for long take out a patent for his inventions, and thus lost immense sums. I can well believe that: it seems quite in keeping with my impressions of the man. There was nothing stolid or selfishly absorbed in him. He bore the marks of deep, true, honest feeling, true benevolence, and open-handed generosity, and despite the son’s great pen-craft, and inventive power, would have forgiven my saying that sometimes I have had a doubt whether the father was not, after all, the greater man of the two, though certainly not, like the hero of In Memoriam, moulded “in colossal calm.”

In theological matters, in which Thomas Stevenson had been much and deeply exercised, he held very strong views, leading decisively to ultra-Calvinism; but, as I myself could well sympathise with such views, if I did not hold them, knowing well the strange ways in which they had gone to form grand, if sometimes sternly forbidding characters, there were no cross-purposes as there might have been with some on that subject. And always I felt I had an original character and a most interesting one to study.

This is another very characteristic letter to me from Davos Platz:

“Chalet Buol, Davos, Grisons,

Switzerland. (No date.)“My dear Dr Japp,—You must think me a forgetful rogue, as indeed I am; for I have but now told my publisher to send you a copy of the Familiar Studies. However, I own I have delayed this letter till I could send you the enclosed. Remembering the night at Braemar, when we visited the picture-gallery, I hoped they might amuse you.

“You see we do some publishing hereaway.

“With kind regards, believe me, always yours faithfully,

Robert Louis Stevenson.”

“I shall hope to see you in town in May.”

The enclosed was the second series of Moral Emblems, by R. L. Stevenson, printed by Samuel Osbourne. My answer to this letter brought the following:

“Chalet-Buol, Davos,

April 1st, 1882.“My dear Dr Japp,—A good day to date this letter, which is, in fact, a confession of incapacity. During my wife’s wretched illness—or I should say the worst of it, for she is not yet rightly well—I somewhat lost my head, and entirely lost a great quire of corrected proofs. This is one of the results: I hope there are none more serious. I was never so sick of any volume as I was of that; I was continually receiving fresh proofs with fresh infinitesimal difficulties. I was ill; I did really fear, for my wife was worse than ill. Well, ’tis out now; and though I have already observed several carelessnesses myself, and now here is another of your finding—of which indeed, I ought to be ashamed—it will only justify the sweeping humility of the preface.

“Symonds was actually dining with us when your letter came, and I communicated your remarks, which pleased him. He is a far better and more interesting thing than his books.

“The elephant was my wife’s, so she is proportionately elate you should have picked it out for praise from a collection, let us add, so replete with the highest qualities of art.

“My wicked carcass, as John Knox calls it, holds together wonderfully. In addition to many other things, and a volume of travel, I find I have written since December ninety Cornhill pp. of Magazine work—essays and stories—40,000 words; and I am none the worse—I am better. I begin to hope I may, if not outlive this wolverine upon my shoulders, at least carry him bravely like Symonds or Alexander Pope. I begin to take a pride in that hope.

“I shall be much interested to see your criticisms: you might perhaps send them on to me. I believe you know that I am not dangerous—one folly I have not—I am not touchy under criticism.

“Sam and my wife both beg to be remembered, and Sam also sends as a present a work of his own.—Yours very sincerely,

Robert Louis Stevenson.”

As indicating the estimate of many of the good Edinburgh people of Stevenson and the Stevensons that still held sway up to so late a date as 1893, I will here extract two characteristic passages from the letters of the friend and correspondent of these days just referred to, and to whom I had sent a copy of the Atalanta Magazine, with an article of mine on Stevenson.

“If you can excuse the garrulity of age, I can tell you one or two things about Louis Stevenson, his father and even his grandfather, which you may work up some other day, as you have so deftly embedded in the Atalanta article that small remark on his acting. Your paper is pleasant and modest: most of R. L. Stevenson’s admirers are inclined to lay it on far too thick. That he is a genius we all admit; but his genius, if fine, is limited. For example, he cannot paint (or at least he never has painted) a woman. No more could Fettes Douglas, skilful artist though he was in his own special line, and I shall tell you a remark of Russel’s thereon some day. [4] There are women in his books, but there is none of the beauty and subtlety of womanhood in them.

“R. L. Stevenson I knew well as a lad and often met him and talked with him. He acted in private theatricals got up by the late Professor Fleeming Jenkin. But he had then, as always, a pretty guid conceit o’ himsel’—which his clique have done nothing to check. His father and his grandfather (I have danced with his mother before her marriage) I knew better; but ‘the family theologian,’ as some of R. L. Stevenson’s friends dabbed his father, was a very touchy theologian, and denounced any one who in the least differed from his extreme Calvinistic views. I came under his lash most unwittingly in this way myself. But for this twist, he was a good fellow—kind and hospitable—and a really able man in his profession. His father-in-law, R. L. Stevenson’s maternal grandfather, was the Rev. Dr Balfour, minister of Colinton—one of the finest-looking old men I ever saw—tall, upright, and ruddy at eighty. But he was marvellously feeble as a preacher, and often said things that were deliciously, unconsciously, unintentionally laughable, if not witty. We were near Colinton for some years; and Mr Russell (of the Scotsman), who once attended the Parish Church with us, was greatly tickled by Balfour discoursing on the story of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife, remarking that Mrs P---’s conduct was ‘highly improper’!”

The estimate of R. L. Stevenson was not and could not be final in this case, for Weir of Hermiston and Catriona were yet unwritten, not to speak of others, but the passages reflect a certain side of Edinburgh opinion, illustrating the old Scripture doctrine that a prophet has honour everywhere but in his own country. And the passages themselves bear evidence that I violate no confidence then, for they were given to me to be worked into any after-effort I might make on Stevenson. My friend was a good and an acute critic who had done some acceptable literary work in his day.

R. L. Stevenson was born on 13th November 1850, the very year of the death of his grandfather, Robert Stevenson, whom he has so finely celebrated. As a mere child he gave token of his character. As soon as he could read, he was keen for books, and, before very long, had read all the story-books he could lay hands on; and, when the stock ran out, he would go and look in at all the shop windows within reach, and try to piece out the stories from the bits exposed in open pages and the woodcuts.

He had a nurse of very remarkable character—evidently a paragon—who deeply influenced him and did much to form his young mind—Alison Cunningham, who, in his juvenile lingo, became “Cumy,” and who not only was never forgotten, but to the end was treated as his “second mother.” In his dedication of his Child’s Garden of Verses to her, he says:

“My second mother, my first wife,

The angel of my infant life.”

Her copy of Kidnapped was inscribed to her by the hand of Stevenson, thus:

“To Cumy, from her boy, the author.

Skerryvore, 18th July 1888.”

Skerryvore was the name of Stevenson’s Bournemouth home, so named after one of the Stevenson lighthouses. His first volume, An Inland Voyage has this pretty dedication, inscribed in a neat, small hand:

“My dear Cumy,—If you had not taken so much trouble with me all the years of my childhood, this little book would never have been written. Many a long night you sat up with me when I was ill. I wish I could hope, by way of return, to amuse a single evening for you with my little book. But whatever you think of it, I know you will think kindly of

The Author.”

“Cumy” was perhaps the most influential teacher Stevenson had. What she and his mother taught took effect and abode with him, which was hardly the case with any other of his teachers.

“In contrast to Goethe,” says Mr Baildon, “Stevenson was but little affected by his relations to women, and, when this point is fully gone into, it will probably be found that his mother and nurse in childhood, and his wife and step-daughter in later life, are about the only women who seriously influenced either his character or his art.” (p. 32).

When Mr Kelman is celebrating Stevenson for the consistency and continuity of his undogmatic religion, he is almost throughout celebrating “Cumy” and her influence, though unconsciously. Here, again, we have an apt and yet more striking illustration, after that of the good Lord Shaftesbury and many others, of the deep and lasting effect a good and earnest woman, of whom the world may never hear, may have had upon a youngster of whom all the world shall hear. When Mr Kelman says that “the religious element in Stevenson was not a thing of late growth, but an integral part and vital interest of his life,” he but points us back to the earlier religious influences to which he had been effectually subject. “His faith was not for himself alone, and the phases of Christianity which it has asserted are peculiarly suited to the spiritual needs of many in the present time.”

We should not lay so much weight as Mr Kelman does on the mere number of times “the Divine name” is found in Stevenson’s writings, but there is something in such confessions as the following to his father, when he was, amid hardship and illness, in Paris in 1878:

“Still I believe in myself and my fellow-men and the God who made us all. . . . I am lonely and sick and out of heart. Well, I still hope; I still believe; I still see the good in the inch, and cling to it. It is not much, perhaps, but it is always something.”

Yes, “Cumy” was a very effective teacher, whose influence and teaching long remained. His other teachers, however famous and highly gifted, did not attain to such success with him. And because of this non-success they blamed him, as is usual. He was fond of playing truant—declared, indeed, that he was about as methodic a truant as ever could have existed. He much loved to go on long wanderings by himself on the Pentland Hills and read about the Covenanters, and while yet a youth of sixteen he wrote The Pentland Rising—a pamphlet in size and a piece of fine work—which was duly published, is now scarce, and fetches a high price. He had made himself thoroughly familiar with all the odd old corners of Edinburgh—John Knox’s haunts and so on, all which he has turned to account in essays, descriptions and in stories—especially in Catriona. When a mere youth at school, as he tells us himself, he had little or no desire to carry off prizes and do just as other boys did; he was always wishing to observe, and to see, and try things for himself—was, in fact, in the eyes of schoolmasters and tutors something of an idler, with splendid gifts which he would not rightly apply. He was applying them rightly, though not in their way. It is not only in his Apology for Idlers that this confession is made, but elsewhere, as in his essay on A College Magazine, where he says, “I was always busy on my own private end, which was to learn to write. I kept always two books in my pocket, one to read and one to write in!”

When he went to College it was still the same—he tells us in the funniest way how he managed to wheedle a certificate for Greek out of Professor Blackie, though the Professor owned “his face was not familiar to him”! He fared very differently when, afterwards his father, eager that he should follow his profession, got him to enter the civil engineering class under Professor Fleeming Jenkin. He still stuck to his old courses—wandering about, and, in sheltered corners, writing in the open air, and was not present in class more than a dozen times. When the session was ended he went up to try for a certificate from Fleeming Jenkin. “No, no, Mr Stevenson,” said the Professor; “I might give it in a doubtful case, but yours is not doubtful: you have not kept my classes.” And the most characteristic thing—honourable to both men—is to come; for this was the beginning of a friendship which grew and strengthened and is finally celebrated in the younger man’s sketch of the elder. He learned from Professor Fleeming Jenkin, perhaps unconsciously, more of the humaniores, than consciously he did of engineering. A friend of mine, who knew well both the Stevenson family and the Balfours, to which R. L. Stevenson’s mother belonged, recalls, as we have seen, his acting in the private theatricals that were got up by the Professor, and adds, “He was then a very handsome fellow, and looked splendidly as Sir Charles Pomander, and essayed, not wholly without success, Sir Peter Teazle,” which one can well believe, no less than that he acted such parts splendidly as well as looked them.

Longman’s Magazine, immediately after his death, published the following poem, which took a very pathetic touch from the circumstances of its appearance—the more that, while it imaginatively and finely commemorated these days of truant wanderings, it showed the ruling passion for home and the old haunts, strongly and vividly, even not unnigh to death:

“The tropics vanish, and meseems that I,

From Halkerside, from topmost Allermuir,

Or steep Caerketton, dreaming gaze again.

Far set in fields and woods, the town I see

Spring gallant from the shallows of her smoke,

Cragg’d, spired, and turreted, her virgin fort

Beflagg’d. About, on seaward drooping hills,

New folds of city glitter. Last, the Forth

Wheels ample waters set with sacred isles,

And populous Fife smokes with a score of towns,

There, on the sunny frontage of a hill,

Hard by the house of kings, repose the dead,

My dead, the ready and the strong of word.

Their works, the salt-encrusted, still survive;

The sea bombards their founded towers; the night

Thrills pierced with their strong lamps. The artificers,

One after one, here in this grated cell,

Where the rain erases and the rust consumes,

Fell upon lasting silence. Continents

And continental oceans intervene;

A sea uncharted, on a lampless isle,

Environs and confines their wandering child

In vain. The voice of generations dead

Summons me, sitting distant, to arise,

My numerous footsteps nimbly to retrace,

And all mutation over, stretch me down

In that denoted city of the dead.”

At first sight it would seem hard to trace any illustration of the doctrine of heredity in the case of this master of romance. George Eliot’s dictum that we are, each one of us, but an omnibus carrying down the traits of our ancestors, does not appear at all to hold here. This fanciful realist, this näive-wistful humorist, this dreamy mystical casuist, crossed by the innocent bohemian, this serious and genial essayist, in whom the deep thought was hidden by the gracious play of wit and phantasy, came, on the father’s side, of a stock of what the world regarded as a quiet, ingenious, demure, practical, home-keeping people. In his rich colour, originality, and graceful air, it is almost as though the bloom of japonica came on a rich old orchard apple-tree, all out of season too. Those who go hard on heredity would say, perhaps, that he was the result of some strange back-stroke. But, on closer examination, we need not go so far. His grandfather, Robert Stevenson, the great lighthouse-builder, the man who reared the iron-bound pillar on the destructive Bell Rock, and set life-saving lights there, was very intent on his professional work, yet he had his ideal, and romantic, and adventurous side. In the delightful sketch which his famous grandson gave of him, does he not tell of the joy Robert Stevenson had on the annual voyage in the Lighthouse Yacht—how it was looked forward to, yearned for, and how, when he had Walter Scott on board, his fund of story and reminiscence all through the tour never failed—how Scott drew upon it in The Pirate and the notes to The Pirate, and with what pride Robert Stevenson preserved the lines Scott wrote in the lighthouse album at the Bell Rock on that occasion:

“PHAROS LOQUITUR

“Far in the bosom of the deep

O’er these wild shelves my watch I keep,

A ruddy gem of changeful light

Bound on the dusky brow of night.

The seaman bids my lustre hail,

And scorns to strike his timorous sail.”

And how in 1850 the old man, drawing nigh unto death, was with the utmost difficulty dissuaded from going the voyage once more, and was found furtively in his room packing his portmanteau in spite of the protests of all his family, and would have gone but for the utter weakness of death.

His father was also a splendid engineer; was full of invention and devoted to his profession, but he, too, was not without his romances, and even vagaries. He loved a story, was a fine teller of stories, used to sit at night and spin the most wondrous yarns, a man of much reserve, yet also of much power in discourse, with an aptness and felicity in the use of phrases—so much so, as his son tells, that on his deathbed, when his power of speech was passing from him, and he couldn’t articulate the right word, he was silent rather than use the wrong one. I shall never forget how in these early morning walks at Braemar, finding me sympathetic, he unbent with the air of a man who had unexpectedly found something he had sought, and was fairly confidential.

On the mother’s side our author came of ministers. His maternal grandfather, the Rev. Dr Balfour of Colinton, was a man of handsome presence, tall, venerable-looking, and not without a mingled authority and humour of his own—no very great preacher, I have heard, but would sometimes bring a smile to the faces of his hearers by very naïve and original ways of putting things. R. L. Stevenson quaintly tells a story of how his grandfather when he had physic to take, and was indulged in a sweet afterwards, yet would not allow the child to have a sweet because he had not had the physic. A veritable Calvinist in daily action—from him, no doubt, our subject drew much of his interest in certain directions—John Knox, Scottish history, the ’15 and the ’45, and no doubt much that justifies the line “something of shorter-catechist,” as applied by Henley to Stevenson among very contrasted traits indeed.

But strange truly are the interblendings of race, and the way in which traits of ancestors reappear, modifying and transforming each other. The gardener knows what can be done by grafts and buddings; but more wonderful far than anything there, are the mysterious blendings and outbursts of what is old and forgotten, along with what is wholly new and strange, and all going to produce often what we call sometimes eccentricity, and sometimes originality and genius.

Mr J. F. George, in Scottish Notes and Queries, wrote as follows on Stevenson’s inheritances and indebtedness to certain of his ancestors:

“About 1650, James Balfour, one of the Principal Clerks of the Court of Session, married Bridget, daughter of Chalmers of Balbaithan, Keithhall, and that estate was for some time in the name of Balfour. His son, James Balfour of Balbaithan, Merchant and Magistrate of Edinburgh, paid poll-tax in 1696, but by 1699 the land had been sold. This was probably due to the fact that Balfour was one of the Governors of the Darien Company. His grandson, James Balfour of Pilrig (1705-1795), sometime Professor of Moral Philosophy in Edinburgh University, whose portrait is sketched in Catriona, also made a Garioch [Aberdeenshire district] marriage, his wife being Cecilia, fifth daughter of Sir John Elphinstone, second baronet of Logie (Elphinstone) and Sheriff of Aberdeen, by Mary, daughter of Sir Gilbert Elliot, first baronet of Minto.

“Referring to the Minto descent, Stevenson claims to have ‘shaken a spear in the Debatable Land and shouted the slogan of the Elliots.’ He evidently knew little or nothing of his relations on the Elphinstone side. The Logie Elphinstones were a cadet branch of Glack, an estate acquired by Nicholas Elphinstone in 1499. William Elphinstone, a younger son of James of Glack, and Elizabeth Wood of Bonnyton, married Margaret Forbes, and was father of Sir James Elphinstone, Bart., of Logie, so created in 1701. . . .

“Stevenson would have been delighted to acknowledge his relationship, remote though it was, to ‘the Wolf of Badenoch,’ who burned Elgin Cathedral without the Earl of Kildare’s excuse that he thought the Bishop was in it; and to the Wolf’s son, the Victor of Harlaw [and] to his nephew ‘John O’Coull,’ Constable of France. . . . Also among Tusitala’s kin may be noted, in addition to the later Gordons of Gight, the Tiger Earl of Crawford, familiarly known as ‘Earl Beardie,’ the ‘Wicked Master’ of the same line, who was fatally stabbed by a Dundee cobbler ‘for taking a stoup of drink from him’; Lady Jean Lindsay, who ran away with ‘a common jockey with the horn,’ and latterly became a beggar; David Lindsay, the last Laird of Edzell [a lichtsome Lindsay fallen on evil days], who ended his days as hostler at a Kirkwall inn, and ‘Mussel Mou’ed Charlie,’ the Jacobite ballad-singer.

“Stevenson always believed that he had a strong spiritual affinity to Robert Fergusson. It is more than probable that there was a distant maternal affinity as well. Margaret Forbes, the mother of Sir James Elphinstone, the purchaser of Logie, has not been identified, but it is probable she was of the branch of the Tolquhon Forbeses who previously owned Logie. Fergusson’s mother, Elizabeth Forbes, was the daughter of a Kildrummy tacksman, who by constant tradition is stated to have been of the house of Tolquhon. It would certainly be interesting if this suggested connection could be proved.” [5]

“From his Highland ancestors,” says the Quarterly Review, “Louis drew the strain of Celtic melancholy with all its perils and possibilities, and its kinship, to the mood of day-dreaming, which has flung over so many of his pages now the vivid light wherein figures imagined grew as real as flesh and blood, and yet, again, the ghostly, strange, lonesome, and stinging mist under whose spell we see the world bewitched, and every object quickens with a throb of infectious terror.”

Here, as in many other cases, we see how the traits of ancestry reappear and transform other strains, strangely the more remote often being the strongest and most persistent and wonderful.

“It is through his father, strange as it may seem,” says Mr Baildon, “that Stevenson gets the Celtic elements so marked in his person, character, and genius; for his father’s pedigree runs back to the Highland clan Macgregor, the kin of Rob Roy. Stevenson thus drew in Celtic strains from both sides—from the Balfours and the Stevensons alike—and in his strange, dreamy, beautiful, and often far-removed fancies we have the finest and most effective witness of it.”

Mr William Archer, in his own characteristic way, has brought the inheritances from the two sides of the house into more direct contact and contrast in an article he wrote in The Daily Chronicle on the appearance of the Letters to Family and Friends.

“These letters show,” he says, “that Stevenson’s was not one of those sunflower temperaments which turn by instinct, not effort, towards the light, and are, as Mr Francis Thompson puts it, ‘heartless and happy, lackeying their god.’ The strains of his heredity were very curiously, but very clearly, mingled. It may surprise some readers to find him speaking of ‘the family evil, despondency,’ but he spoke with knowledge. He inherited from his father not only a stern Scottish intentness on the moral aspect of life (‘I would rise from the dead to preach’), but a marked disposition to melancholy and hypochondria. From his mother, on the other hand, he derived, along with his physical frailty, a resolute and cheery stoicism. These two elements in his nature fought many a hard fight, and the besieging forces from without—ill-health, poverty, and at one time family dissensions—were by no means without allies in the inner citadel of his soul. His spirit was courageous in the truest sense of the word: by effort and conviction, not by temperamental insensibility to fear. It is clear that there was a period in his life (and that before the worst of his bodily ills came upon him) when he was often within measurable distance of Carlylean gloom. He was twenty-four when he wrote thus, from Swanston, to Mrs Sitwell:

“‘It is warmer a bit; but my body is most decrepit, and I can just manage to be cheery and tread down hypochondria under foot by work. I lead such a funny life, utterly without interest or pleasure outside of my work: nothing, indeed, but work all day long, except a short walk alone on the cold hills, and meals, and a couple of pipes with my father in the evening. It is surprising how it suits me, and how happy I keep.’

“This is the serenity which arises, not from the absence of fuliginous elements in the character, but from a potent smoke-consuming faculty, and an inflexible will to use it. Nine years later he thus admonishes his backsliding parent:

“‘My dear Mother,—I give my father up. I give him a parable: that the Waverley novels are better reading for every day than the tragic Life. And he takes it back-side foremost, and shakes his head, and is gloomier than ever. Tell him that I give him up. I don’t want no such a parent. This is not the man for my money. I do not call that by the name of religion which fills a man with bile. I write him a whole letter, bidding him beware of extremes, and telling him that his gloom is gallows-worthy; and I get back an answer—. Perish the thought of it.

“‘Here am I on the threshold of another year, when, according to all human foresight, I should long ago have been resolved into my elements: here am I, who you were persuaded was born to disgrace you—and, I will do you the justice to add, on no such insufficient grounds—no very burning discredit when all is done; here am I married, and the marriage recognised to be a blessing of the first order. A1 at Lloyd’s. There is he, at his not first youth, able to take more exercise than I at thirty-three, and gaining a stone’s weight, a thing of which I am incapable. There are you; has the man no gratitude? . . .

“‘Even the Shorter Catechism, not the merriest epitome of religion, and a work exactly as pious although not quite so true as the multiplication table—even that dry-as-dust epitome begins with a heroic note. What is man’s chief end? Let him study that; and ask himself if to refuse to enjoy God’s kindest gifts is in the spirit indicated.’

“As may be judged from this half-playful, half-serious remonstrance, Stevenson’s relation to his parents was eminently human and beautiful. The family dissensions above alluded to belonged only to a short but painful period, when the father could not reconcile himself to the discovery that the son had ceased to accept the formulas of Scottish Calvinism. In the eyes of the older man such heterodoxy was for the moment indistinguishable from atheism; but he soon arrived at a better understanding of his son’s position. Nothing appears more unmistakably in these letters than the ingrained theism of Stevenson’s way of thought. The poet, the romancer within him, revolted from the conception of formless force. A personal deity was a necessary character in the drama, as he conceived it. And his morality, though (or inasmuch as) it dwelt more on positive kindness than on negative lawlessness, was, as he often insisted, very much akin to the morality of the New Testament.”

Anyway it is clear that much in the interminglings of blood we can trace, may go to account for not a little in Stevenson. His peculiar interest in the enormities of old-time feuds, the excesses, the jealousies, the queer psychological puzzles, the desire to work on the outlying and morbid, and even the unallowed and unhallowed, for purposes of romance—the delight in dealing with revelations of primitive feeling and the out-bursts of the mere natural man always strangely checked and diverted by the uprise of other tendencies to the dreamy, impalpable, vague, weird and horrible. There was the undoubted Celtic element in him underlying what seemed foreign to it, the disregard of conventionality in one phase, and the falling under it in another—the reaction and the retreat from what had attracted and interested him, and then the return upon it, as with added zest because of the retreat. The confessed Hedonist, enjoying life and boasting of it just a little, and yet the Puritan in him, as it were, all the time eyeing himself as from some loophole of retreat, and then commenting on his own behaviour as a Hedonist and Bohemian. This clearly was not what most struck Beerbohm Tree, during the time he was in close contact with Stevenson, while arranging the production of Beau Austin at the Haymarket Theatre, for he sees, or confesses to seeing, only one side, and that the most assertive, and in a sense, unreal one:

“Stevenson,” says Mr Tree, “always seemed to me an epicure in life. He was always intent on extracting the last drop of honey from every flower that came in his way. He was absorbed in the business of the moment, however trivial. As a companion, he was delightfully witty; as a personality, as much a creature of romance as his own creations.”

This is simple, and it looks sincere; but it does not touch ’tother side, or hint at, not to say, solve the problem of Stevenson’s personality. Had he been the mere Hedonist he could never have done the work he did. Mr Beerbohm Tree certainly did not there see far or all round.

Miss Simpson says:

“Mr Henley recalls him to Edinburgh folk as he was and as the true Stevenson would have wished to be known—a queer, inexplicable creature, his Celtic blood showing like a vein of unknown metal in the stolid, steady rock of his sure-founded Stevensonian pedigree. His cousin and model, ‘Bob’ Stevenson, the art critic, showed that this foreign element came from the men who lit our guiding lights for seamen, not from the gentle-blooded Balfours.

“Mr Henley is right in saying that the gifted boy had not much humour. When the joke was against himself he was very thin-skinned and had a want of balance. This made him feel his honest father’s sensible remarks like the sting of a whip.”

Miss Simpson then proceeds to say:

“The R. L. Stevenson of old Edinburgh days was a conceited, egotistical youth, but a true and honest one: a youth full of fire and sentiment, protesting he was misunderstood, though he was not. Posing as ‘Velvet Coat’ among the slums, he did no good to himself. He had not the Dickens aptitude for depicting the ways of life of his adopted friends. When with refined judgment he wanted a figure for a novel, he went back to the Bar he scorned in his callow days and then drew in Weir of Hermiston.”

His interest in engineering soon went—his mind full of stories and fancies and human nature. As he had told his mother: he did not care about finding what was “the strain on a bridge,” he wanted to know something of human beings.

No doubt, much to the disappointment and grief of his father, who wished him as an only son to carry on the traditions of the family, though he had written two engineering essays of utmost promise, the engineering was given up, and he consented to study law. He had already contributed to College Magazines, and had had even a short spell of editing one; of one of these he has given a racy account. Very soon after his call to the Bar articles and essays from his pen began to appear in Macmillan’s, and later, more regularly in the Cornhill. Careful readers soon began to note here the presence of a new force. He had gone on the Inland Voyage and an account of it was in hand; and had done that tour in the Cevennes which he has described under the title Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes, with Modestine, sometimes doubting which was the donkey, but on that tour a chill caught either developed a germ of lung disease already present, or produced it; and the results unfortunately remained.

He never practised at the Bar, though he tells facetiously of his one brief. He had chosen his own vocation, which was literature, and the years which followed were, despite the delicacy which showed itself, very busy years. He produced volume on volume. He had written many stories which had never seen the light, but, as he says, passed through the ordeal of the fire by more or less circuitous ways.

By this time some trouble and cause for anxiety had arisen about the lungs, and trials of various places had been made. Ordered South suggests the Mediterranean, sunny Italy, the Riviera. Then a sea-trip to America was recommended and undertaken. Unfortunately, he got worse there, his original cause of trouble was complicated with others, and the medical treatment given was stupid, and exaggerated some of the symptoms instead of removing them, All along—up, at all events, to the time of his settlement in Samoa—Stevenson was more or less of an invalid.

Indeed, were I ever to write an essay on the art of wisely “laying-to,” as the sailors say, I would point it by a reference to R. L. Stevenson. For there is a wise way of “laying-to” that does not imply inaction, but discreet, well-directed effort, against contrary winds and rough seas, that is, amid obstacles and drawbacks, and even ill-health, where passive and active may balance and give effect to each other. Stevenson was by native instinct and temperament a rover—a lover of adventure, of strange by-ways, errant tracts (as seen in his Inland Voyage and Travels with a Donkey through the Cevennes—seen yet more, perhaps, in a certain account of a voyage to America as a steerage passenger), lofty mountain-tops, with stronger air, and strange and novel surroundings. He would fain, like Ulysses, be at home in foreign lands, making acquaintance with outlying races, with

“Cities of men,

And manners, climates, councils, governments:

Myself not least, but honoured of them all,

Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy.”

If he could not move about as he would, he would invent, make fancy serve him instead of experience. We thus owe something to the staying and restraining forces in him, and a wise “laying-to”—for his works, which are, in large part, finely-healthy, objective, and in almost everything unlike the work of an invalid, yet, in some degree, were but the devices to beguile the burdens of an invalid’s days. Instead of remaining in our climate, it might be, to lie listless and helpless half the day, with no companion but his own thoughts and fancies (not always so pleasant either, if, like Frankenstein’s monster, or, better still like the imp in the bottle in the Arabian Nights, you cannot, once for all liberate them, and set them adrift on their own charges to visit other people), he made a home in the sweeter air and more steady climate of the South Pacific, where, under the Southern Cross, he could safely and beneficially be as active as he would be involuntarily idle at home, or work only under pressure of hampering conditions. That was surely an illustration of the true “laying-to” with an unaffectedly brave, bright resolution in it.

Carlyle was wont to say that, next to a faithful portrait, familiar letters were the best medium to reveal a man. The letters must have been written with no idea of being used for this end, however—free, artless, the unstudied self-revealings of mind and heart. Now, these letters of R. L. Stevenson, written to his friends in England, have a vast value in this way—they reveal the man—reveal him in his strength and his weakness—his ready gift in pleasing and adapting himself to those with whom he corresponded, and his great power at once of adapting himself to his circumstances and of humorously rising superior to them. When he was ill and almost penniless in San Francisco, he could give Mr Colvin this account of his daily routine:

“Any time between eight and half-past nine in the morning a slender gentleman in an ulster, with a volume buttoned into the breast of it, maybe observed leaving No. 608 Bush and descending Powell with an active step. The gentleman is R. L. Stevenson; the volume relates to Benjamin Franklin, on whom he meditates one of his charming essays. He descends Powell, crosses Market, and descends in Sixth on a branch of the original Pine Street Coffee-House, no less. . . . He seats himself at a table covered with waxcloth, and a pampered menial of High-Dutch extraction, and, indeed, as yet only partially extracted, lays before him a cup of coffee, a roll, and a pat of butter, all, to quote the deity, very good. A while ago, and R. L. Stevenson used to find the supply of butter insufficient; but he has now learned the art to exactitude, and butter and roll expire at the same moment. For this rejection he pays ten cents, or fivepence sterling (£0 0s. 5d.).

“Half an hour later, the inhabitants of Bush Street observed the same slender gentleman armed, like George Washington, with his little hatchet, splitting kindling, and breaking coal for his fire. He does this quasi-publicly upon the window-sill; but this is not to be attributed to any love of notoriety, though he is indeed vain of his prowess with the hatchet (which he persists in calling an axe), and daily surprised at the perpetuation of his fingers. The reason is this: That the sill is a strong supporting beam, and that blows of the same emphasis in other parts of his room might knock the entire shanty into hell. Thenceforth, for from three hours, he is engaged darkly with an ink-bottle. Yet he is not blacking his boots, for the only pair that he possesses are innocent of lustre, and wear the natural hue of the material turned up with caked and venerable slush. The youngest child of his landlady remarks several times a day, as this strange occupant enters or quits the house, ‘Dere’s de author.’ Can it be that this bright-haired innocent has found the true clue to the mystery? The being in question is, at least, poor enough to belong to that honourable craft.”

Here are a few letters belonging to the winter of 1887-88, nearly all written from Saranac Lake, in the Adirondacks, celebrated by Emerson, and now a most popular holiday resort in the United States, and were originally published in Scribner’s Magazine. . . “It should be said that, after his long spell of weakness at Bournemouth, Stevenson had gone West in search of health among the bleak hill summits—‘on the Canadian border of New York State, very unsettled and primitive and cold.’ He had made the voyage in an ocean tramp, the Ludgate Hill, the sort of craft which any person not a born child of the sea would shun in horror. Stevenson, however, had ‘the finest time conceivable on board the “strange floating menagerie.”’” Thus he describes it in a letter to Mr Henry James:

“Stallions and monkeys and matches made our cargo; and the vast continent of these incongruities rolled the while like a haystack; and the stallions stood hypnotised by the motion, looking through the port at our dinner-table, and winked when the crockery was broken; and the little monkeys stared at each other in their cages, and were thrown overboard like little bluish babies; and the big monkey, Jacko, scoured about the ship and rested willingly in my arms, to the ruin of my clothing; and the man of the stallions made a bower of the black tarpaulin, and sat therein at the feet of a raddled divinity, like a picture on a box of chocolates; and the other passengers, when they were not sick, looked on and laughed. Take all this picture, and make it roll till the bell shall sound unexpected notes and the fittings shall break loose in our stateroom, and you have the voyage of the Ludgate Hill. She arrived in the port of New York without beer, porter, soda-water, curaçoa, fresh meat, or fresh water; and yet we lived, and we regret her.”

He discovered this that there is no joy in the Universe comparable to life on a villainous ocean tramp, rolling through a horrible sea in company with a cargo of cattle.

“I have got one good thing of my sea voyage; it is proved the sea agrees heartily with me, and my mother likes it; so if I get any better, or no worse, my mother will likely hire a yacht for a month or so in the summer. Good Lord! what fun! Wealth is only useful for two things: a yacht and a string quartette. For these two I will sell my soul. Except for these I hold that £700 a year is as much as anybody can possibly want; and I have had more, so I know, for the extra coins were of no use, excepting for illness, which damns everything. I was so happy on board that ship, I could not have believed it possible; we had the beastliest weather, and many discomforts; but the mere fact of its being a tramp ship gave us many comforts. We could cut about with the men and officers, stay in the wheel-house, discuss all manner of things, and really be a little at sea. And truly there is nothing else. I had literally forgotten what happiness was, and the full mind—full of external and physical things, not full of cares and labours, and rot about a fellow’s behaviour. My heart literally sang; I truly care for nothing so much as for that.

“To go ashore for your letters and hang about the pier among the holiday yachtsmen—that’s fame, that’s glory—and nobody can take it away.”

At Saranac Lake the Stevensons lived in a “wind-beleaguered hill-top hat-box of a house,” which suited the invalid, but, on the other hand, invalided his wife. Soon after getting there he plunged into The Master of Ballantrae.

“No thought have I now apart from it, and I have got along up to page ninety-two of the draught with great interest. It is to me a most seizing tale: there are some fantastic elements, the most is a dead genuine human problem—human tragedy, I should say rather. It will be about as long, I imagine, as Kidnapped. . . . I have done most of the big work, the quarrel, duel between the brothers, and the announcement of the death to Clementina and my Lord—Clementina, Henry, and Mackellar (nicknamed Squaretoes) are really very fine fellows; the Master is all I know of the devil; I have known hints of him, in the world, but always cowards: he is as bold as a lion, but with the same deadly, causeless duplicity I have watched with so much surprise in my two cowards. ’Tis true, I saw a hint of the same nature in another man who was not a coward; but he had other things to attend to; the Master has nothing else but his devilry.”

His wife grows seriously ill, and Stevenson has to turn to household work.

“Lloyd and I get breakfast; I have now, 10.15, just got the dishes washed and the kitchen all clean, and sit down to give you as much news as I have spirit for, after such an engagement. Glass is a thing that really breaks my spirit; and I do not like to fail, and with glass I cannot reach the work of my high calling—the artist’s.”

In the midst of such domestic tasks and entanglements he writes The Master, and very characteristically gets dissatisfied with the last parts, “which shame, perhaps degrade, the beginning.”

Of Mr Kipling this is his judgment—in the year 1890:

“Kipling is by far the most promising young man who has appeared since—ahem—I appeared. He amazes me by his precocity and various endowments. But he alarms me by his copiousness and haste. He should shield his fire with both hands, ‘and draw up all his strength and sweetness in one ball.’ (‘Draw all his strength and all his sweetness up into one ball’? I cannot remember Marvell’s words.) So the critics have been saying to me; but I was never capable of—and surely never guilty of—such a debauch of production. At this rate his works will soon fill the habitable globe, and surely he was armed for better conflicts than these succinct sketches and flying leaves of verse? I look on, I admire, I rejoice for myself; but in a kind of ambition we all have for our tongue and literature I am wounded. If I had this man’s fertility and courage, it seems to me I could heave a pyramid.

“Well, we begin to be the old fogies now, and it was high time something rose to take our places. Certainly Kipling has the gifts; the fairy godmothers were all tipsy at his christening. What will he do with them?”