This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments, Volume II (of 2)

Editor: Sir John Scott Keltie

Release Date: May 18, 2019 [eBook #59469]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS, HIGHLAND CLANS AND HIGHLAND REGIMENTS, VOLUME II (OF 2)***

| Note: |

This volume originally was printed as four separate books

(see transcriber's note below). Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. Book 5, pages 1-192: https://archive.org/details/historyofscottis005kelt Book 6, pages 193-384: https://archive.org/details/historyofscottis006kelt Book 7, pages 385-592: https://archive.org/details/historyofscottis007kelt Book 8, pages 593-818: https://archive.org/details/historyofscottis008kelt |

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

This is Volume II of a two-volume set. The first volume can be found at:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/59468 .

This 1875 edition originally was published in eight separate books as a subscription publication. The Preface, Title pages, Tables of Contents and Lists of Illustrations (the Front Matter) were published in the final eighth book, and referenced books 1-4 as Volume I, and books 5-8 as Volume II. This etext follows the same two-volume structure. The relevant Front Matter has been moved to the front of each volume, and some illustrations have been moved to where the two Lists of Illustrations indicate they should be. No text was added or changed when the books were seamlessly joined to make Volume I and Volume II.

When reading this book on the web, the Index has active links to pages in both volumes. When reading on a handheld device only the internal links within this volume are active.

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each chapter.

Basic fractions are displayed as ½ ⅓ ¼ etc; other fractions are shown in the form a/b, for example 1/12 or 1/16. Regimental designations of the form a/b are unchanged, for example ‘1/4th Native Infantry’.

In Chapter XLV the English translation of Gaelic text is usually positioned side by side with that text, just as it was printed in the original book. If the window size does not allow this, the English translation follows the Gaelic passage. On handheld devices choose a small or medium size font to view these passages, to avoid a possible truncation of the column of text. Several of these passages are quite long.

Many tables in the original book (between pages 562 and 802) had } or { bracketing in some cells. These brackets are not helpful in the etext tables and have been removed to improve readability and save table space.

The two tables on page 755 were very large in width and each has been split into two parts; the left-side ‘Names’ column has been duplicated in the second part.

Many other minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

WITH AN ACCOUNT OF

THE GAELIC LANGUAGE, LITERATURE, AND MUSIC

By the Rev. THOMAS MACLAUCHLAN, LL.D., F.S.A. Scot.

AND AN ESSAY ON HIGHLAND SCENERY

By the late Professor JOHN WILSON

EDITED BY

JOHN S. KELTIE, F.S.A. Scot.

Illustrated

WITH A SERIES OF PORTRAITS, VIEWS, MAPS, ETC., ENGRAVED ON STEEL,

CLAN TARTANS, AND UPWARDS OF TWO HUNDRED WOODCUTS,

INCLUDING ARMORIAL BEARINGS

VOL. II.

A. FULLARTON & CO.

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

1875

| Chapter | Page | |

| Part First continued.—GENERAL HISTORY OF THE HIGHLANDS | 1 | |

| XLII. | Social Condition of the Highlands—Chiefs—Land Distribution—Agriculture—Agricultural Implements—Live Stock—Pasturage—Farm Servants—Harvest Work—Fuel—Food—Social Life in Former Days—Education—Dwellings—Habits—Wages—Roads—Present State of Highlands, | 1 |

| XLIII. | State of Highlands subsequent to 1745—Progress of Innovation—Emigration—Pennant’s account of the country—Dr Johnson—Wretched condition of the Western Islands—Introduction of Large Sheep Farms—Ejection of Small Tenants—The Two Sides of the Highland Question—Large and Small Farms—Depopulation—Kelp—Introduction of Potatoes into the Highlands—Amount of Progress made during latter part of 18th century, | 31 |

| XLIV. | Progress of Highlands during the present century—Depopulation and Emigration—Sutherland clearings—Recent State of Highlands—Means of Improvement—Population of chief Highland Counties—Highland Colonies—Attachment of Highlanders to their Old Home—Conclusion, | 54 |

| XLV. | Gaelic Literature, Language, and Music. By the Rev. Thomas Maclauchlan, LL.D., F.S.A.S., | 66 |

| Part Second.—HISTORY OF THE HIGHLAND CLANS. | ||

| I. | Clanship—Principle of Kin—Mormaordoms—Traditions as to Origin of Clans—Peculiarities and Consequences of Clanship—Customs of Succession—Highland Marriage Customs—Position and Power of Chief—Influence of Clanship on the People—Number and Distribution of Clans, &c., | 116 |

| II. | The Gallgael or Western Clans—Lords of the Isles—The various Island Clans—The Macdonalds or Clan Donald—The Clanranald Macdonalds—The Macdonnells of Glengarry, | 131 |

| III. | The Macdougalls—Macalisters—Siol Gillevray—Macneills—Maclachlans—MacEwens—Siol Eachern—Macdougall Campbells of Craignish—Lamonds, | 139 |

| IV. | Robertsons or Clan Donnachie—Macfarlanes—Argyll Campbells and offshoots—Breadalbane Campbells and offshoots—Macleods, | 169 |

| V. | Clan Chattan—Mackintoshes—Macphersons—Macgillivrays—Shaws— Farquharsons—Macbeans—Macphails—Gows—Macqueens—Cattanachs, | 197 |

| VI. | Camerons—Macleans—Macnaughtons—Mackenricks—Macknights—Macnayers— Macbraynes—Munroes—Macmillans, | 217 |

| VII. | Clan Anrias or Ross—Mackenzies—Mathiesons—Siol Alpine—Macgregors—Grants—Macnabs—Clan Duffie or Macfie—Macquarries—Macaulays, | 235 |

| VIII. | Mackays—Macnicols—Sutherlands—Gunns—Maclaurin or Maclaren—Macraes—Buchanans— Colquhouns—Forbeses—Urquharts, | 265 |

| IX. | Stewarts—Frasers—Menzies—Chisholms—Stewart Murray (Athole)—Drummonds—Grahams— Gordons—Cummings—Ogilvies—Fergusons or Fergussons, | 297 |

| Part Third.—HISTORY OF THE HIGHLAND REGIMENTS. | |

| INTRODUCTION.—Military Character of the Highlands, | 321 |

| 42nd Royal Highland Regiment (Am Freiceadan Dubh, “The Black Watch”), | 324 |

| Appendix.—Ashantee Campaign, | 803 |

| Loudon’s Highlanders, 1745–1748, | 451 |

| Montgomery’s Highlanders, or 77th Regiment, 1757–1763, | 453 |

| Fraser’s Highlanders, or Old 78th and 71st Regiments— | |

| Old 78th, 1757–1763, | 457 |

| Old 71st, 1775–1783, | 465 |

| Keith’s and Campbell’s Highlanders, or Old 87th and 88th Regiments, | 475 |

| 89th Highland Regiment, 1759–1765, | 478 |

| Johnstone’s Highlanders, or 101st Regiment, 1760–1763, | 479 |

| 71st Highland Light Infantry, formerly the 73rd or Lord Macleod’s Highlanders, | 479 |

| Argyle Highlanders, or Old 74th Regiment, 1778–1783, | 519 |

| Macdonald’s Highlanders, or Old 76th Highland Regiment, | 520 |

| Athole Highlanders, or Old 77th Regiment, 1778–1783, | 522 |

| 72nd Regiment, or Duke of Albany’s Own Highlanders, formerly the 78th or Seaforth’s Highlanders, | 524 |

| Aberdeenshire Highland Regiment, or Old 81st, 1777–1783, | 565 |

| Royal Highland Emigrant Regiment, or Old 84th, 1775–1783, | 565 |

| Forty Second Royal Highland Regiment, Second Battalion, now the 73rd Regiment, | 566 |

| 74th Highlanders, | 571 |

| 75th Regiment, | 616 |

| 78th Highlanders or Ross-shire Buffs, | 617 |

| 79th Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, | 697 |

| 91st Princess Louise Argyllshire Highlanders, | 726 |

| 92nd Gordon Highlanders, | 756 |

| 93rd Sutherland Highlanders, | 777 |

| Appendix to the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment (Black Watch), 1873–1875 (Ashantee Campaign), | 803 |

| Fencible Corps, | 807 |

| Index, | 808 |

VOLUME II.

| Subject. | Painted by | Engraved by | Page | |

| Map Showing the Districts of the Highland Clans, | Edited | by Dr Maclauchlan, | J. Bartholomew, | To face title. |

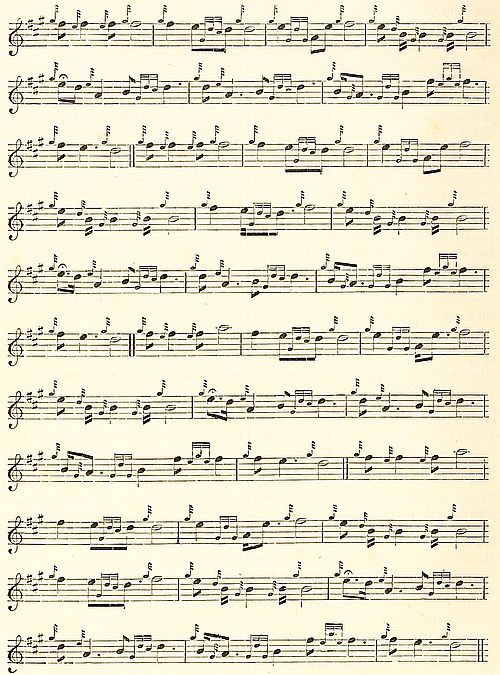

| View of Castle Urquhart, Loch Ness, | J. Fleming, | W. Forrest, | 296 | |

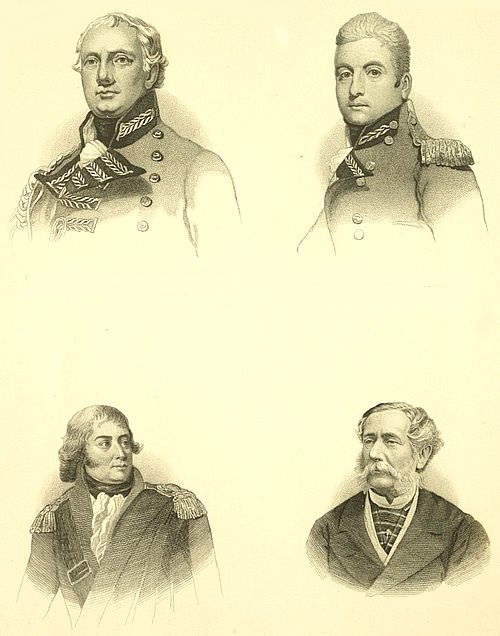

| Colonels of the 42nd Royal Highlanders, | From Original Sources, | H. Crickmore, | 325 | |

| (1.) John, Earl of Crawford. | (2.) Sir George Murray, G.C.B., G.C.H. | |||

| (3.) Sir John Macdonald, K.C.B. | (4.) Sir Duncan A. Cameron, K.C.B. | |||

| Lord Clyde (Sir Colin Campbell), | H. W. Phillips, | W. Holl, | 409 | |

| Monument in Dunkeld Cathedral to the 42nd Royal Highlanders, | 434 | |||

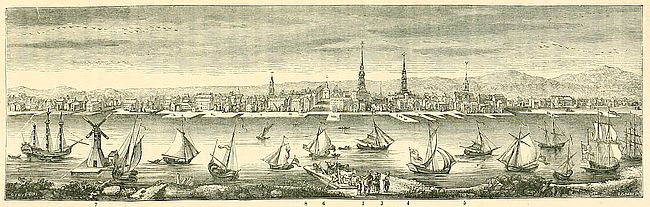

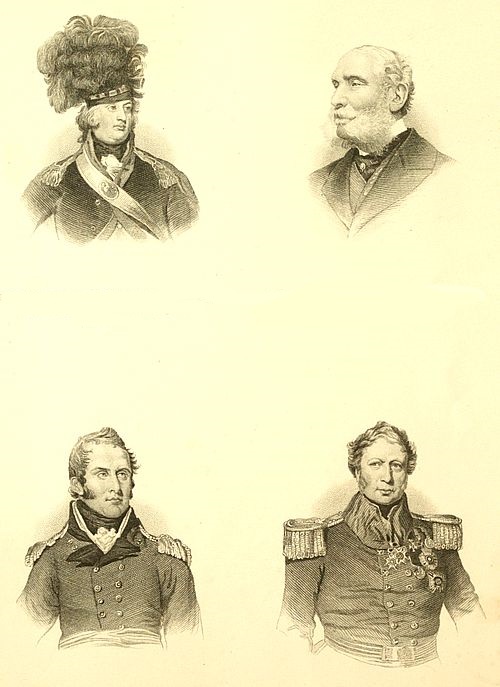

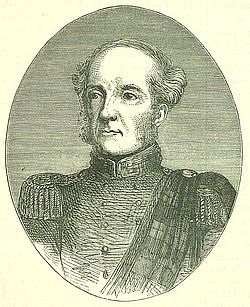

| Colonels of the 71st and 72d Highlanders, | From Original Sources, | H. Crickmore, | 479 | |

| (1.) John, Lord Macleod. | (2.) Sir Thomas Reynell, Bt., K.C.B. | |||

| (3.) Kenneth, Earl of Seaforth. | (4.) Sir Neil Douglas, K.C.B., K.C.H. | |||

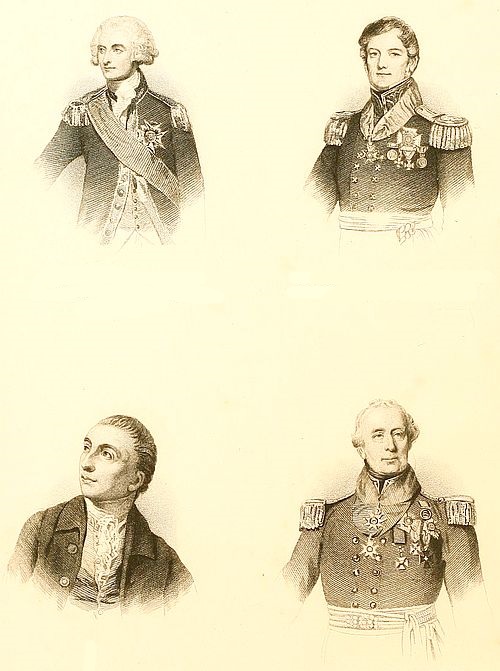

| Colonels of the 78th and 79th Highlanders, | From Original Sources, | H. Crickmore, | 617 | |

| (1.) F. H. Mackenzie, Lord Seaforth. | (2.) Sir Patrick Grant, G.C.B., G.C.M.G. | |||

| (3.) Sir Ronald Craufurd Ferguson, G.C.B. | (4.) Sir James Macdonell, K.C.B., K.C.H. | |||

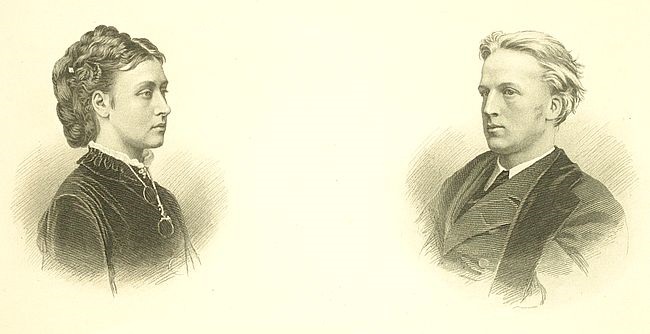

| The Princess Louise, | From Photograph by Hill and Saunders, | W. Holl, | 726 | |

| The Marquis of Lorne, | From Photograph by Elliot and Fry, | W. Holl, | 726 | |

| Colonels of the 91st, 92d, and 93d Highlanders, | From Original Sources | H. Crickmore, | 756 | |

| (1.) General Duncan Campbell of Lochnell. | (2.) George, Marquis of Huntly. | |||

| (3.) Major-General W. Wemyss of Wemyss. | (4.) Sir H. W. Stisted, K.C.B. | |||

| Map—Crimea, with Plan of Sebastopol, | J. Bartholomew, | 777 | ||

| TARTANS. | |||||

| Macdonald, | 136 | Mackintosh, | 201 | Macnab, | 258 |

| Macdougall, | 159 | Farquharson, | 215 | Mackay, | 266 |

| Maclachlan, | 165 | Macnaughton, | 229 | Gunn, | 278 |

| Argyll Campbell, | 175 | Macgregor, | 243 | Forbes, | 290 |

| Breadalbane Campbell, | 186 | Grant, | 250 | Menzies, | 306 |

| WOODCUTS IN THE LETTERPRESS. | ||

| 74. | Old Scotch plough, and Caschroim, or crooked spade, | 9 |

| 75. | Quern, ancient Highland, | 18 |

| 76. | A Cottage in Islay in 1774, | 25 |

| 77. | Music, ancient Scottish, scale, | 106 |

| 78. | Macdonald coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 136 |

| 79. | Clanranald ””” | 153 |

| 80. | Macdonnell of Glengarry ”” | 156 |

| 81. | Macdougall ”” | 159 |

| 82. | Macneill ”” | 162 |

| 83. | Maclachlan ”” | 165 |

| 84. | Lamond ”” | 168 |

| 85. | Robertson ”” | 169 |

| 86. | Macfarlane ”” | 173 |

| 87. | Argyll Campbell ”” | 175 |

| 88. | Breadalbane Campbell ”” | 186 |

| 89. | Macleod ”” | 191 |

| 90. | Mackintosh ”” | 201 |

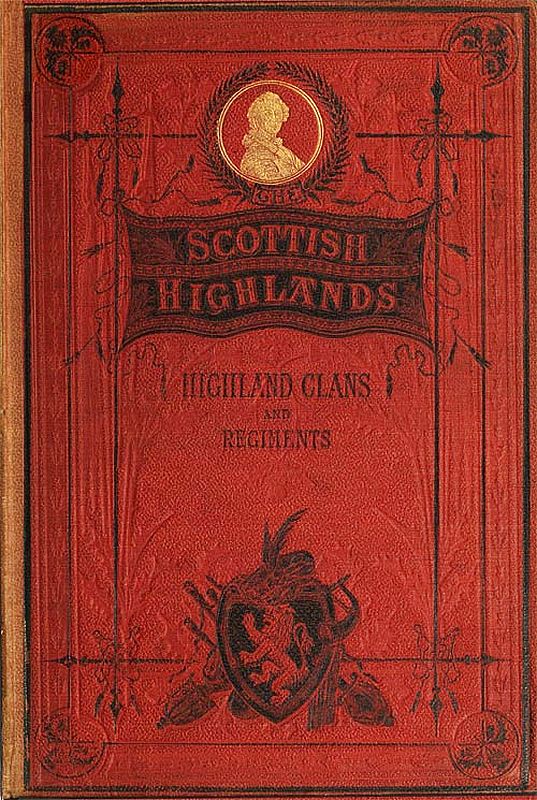

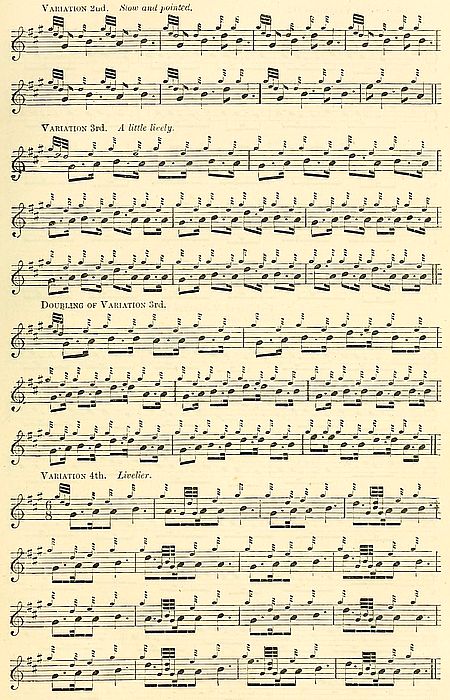

| 91. | “Mackintosh’s Lament,” bagpipe music, | 204 |

| 92. | Dalcross Castle, | 209 |

| 93. | Macpherson coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 210 |

| 94. | James Macpherson, editor of the Ossianic poetry, | 211 |

| 95. | Farquharson coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 215 |

| 96. | Cameron ””” | 217 |

| 97. | Maclean ””” | 223 |

| 98. | Sir Allan Maclean, | 227 |

| 99. | Macnaughton coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 229 |

| 100. | Munro of Foulis ””” | 231 |

| 101. | Ross ””” | 235 |

| 102. | Mackenzie ””” | 238 |

| 103. | Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh, | 240 |

| 104. | Macgregor coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 243 |

| 105. | Rob Roy, | 245 |

| 106. | Grant coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 250 |

| 107. | Castle Grant, | 254 |

| 108. | Mackinnon coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 256 |

| 109. | Macnab ””” | 258 |

| 110.[vi] | The last Laird of Macnab, | 261 |

| 111. | Macquarrie coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 262 |

| 112. | Mackay ””” | 266 |

| 113. | Sutherland ””” | 272 |

| 114. | Dunrobin Castle, | 277 |

| 115. | Gunn coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 278 |

| 116. | Maclaurin (or Maclaren) ”” | 279 |

| 117. | Macrae ”” | 280 |

| 118. | Buchanan ”” | 281 |

| 119. | Colquhoun ”” | 284 |

| 120. | Old Rossdhu Castle, | 289 |

| 121. | Forbes coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 290 |

| 122. | Craigievar Castle, | 294 |

| 123. | Urquhart coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 296 |

| 124. | Lorn ””” | 299 |

| 125. | Fraser ””” | 302 |

| 126. | Bishop Fraser’s Seal, | 302 |

| 127. | Sir Alexander Fraser of Philorth, | 303 |

| 128. | Menzies coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 306 |

| 129. | Chisholm ””” | 307 |

| 130. | Erchless Castle (seat of “the Chisholm”), | 308 |

| 131. | Stewart Murray (Athole) coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 309 |

| 132. | Blair Castle, as restored in 1872, | 312 |

| 133. | Drummond coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 313 |

| 134. | Graham ””” | 314 |

| 135. | Gordon ””” | 316 |

| 136. | Gordon Castle, | 318 |

| 137. | Cumming coat of arms, crest, and motto, | 318 |

| 138. | Ogilvy ””” | 319 |

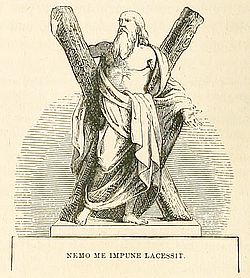

| 139. | Crest and motto of 42nd Royal Highlanders, | 324 |

| 140. | Farquhar Shaw of the “Black Watch” (1743), | 330 |

| 141. | Plan of the Siege of Ticonderoga (1758), | 338 |

| 142. | British Barracks, Philadelphia, in 1764, | 354 |

| 143. | Sir Ralph Abercromby in Egypt, Portrait, | 372 |

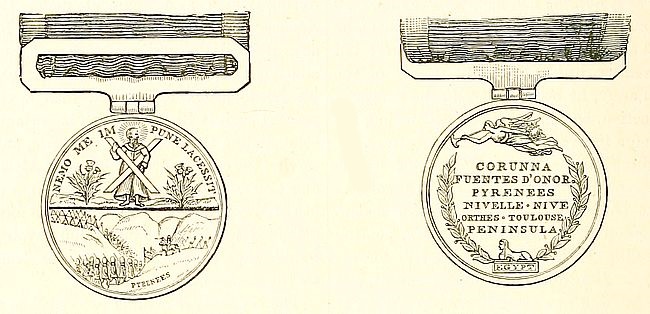

| 144. | } Regimental Medal of the 42nd Royal Highlanders, | |

| 145. | } issued in 1819, | 374 |

| 146. | Medal to the officers of the 42nd Royal Highlanders for services in Egypt, | 374 |

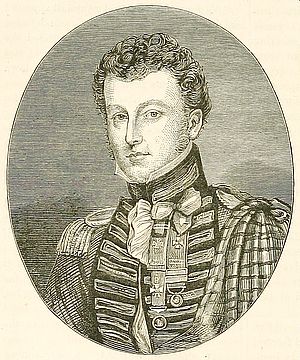

| 147. | Colonel (afterwards Major-General Sir) Robert Henry Dick, | 396 |

| 148. | Vase presented to 42nd Royal Highlanders by the Highland Society of London, | 400 |

| 149. | Col. Johnstone’s (42nd) Cephalonian medal, | 407 |

| 150. | “Highland Pibroch,” bagpipe music, | 446 |

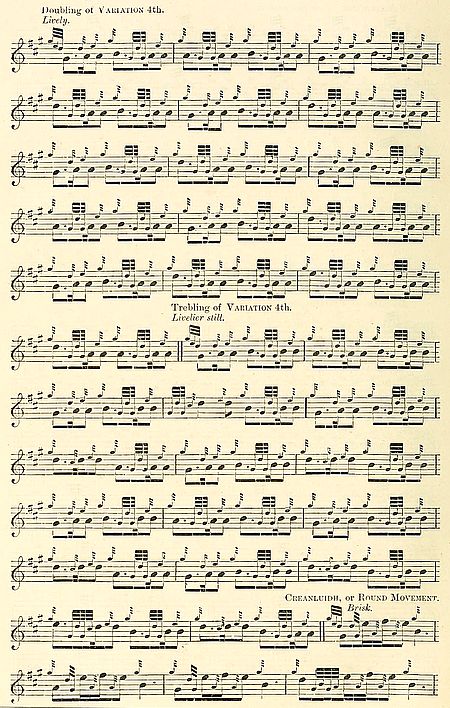

| 151. | View of Philadelphia, U.S., as in 1763, | 455 |

| 152. | Sir David Baird, | 482 |

| 153. | Monument in Glasgow Cathedral to Colonel the Hon. Henry Cadogan (71st), | 498 |

| 154. | Major-General Sir Denis Pack, K.C.B., | 504 |

| 155. | Monument erected by the 71st Highlanders in Glasgow Cathedral, | 517 |

| 156. | Crest of the 72nd, Seaforth Highlanders, | 524 |

| 157. | General James Stuart, | 530 |

| 158. | “Cabar Feidh,” bagpipe music, | 533 |

| 159. | Major-General William Parke, C.B., | 557 |

| 160. | Map of Kaffraria, | 564 |

| 161. | Crest of the 74th Highlanders, | 571 |

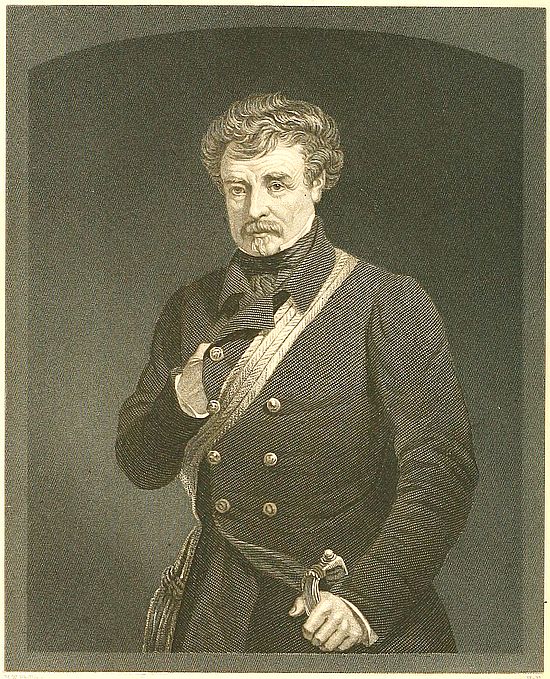

| 162. | Major-General Sir Archibald Campbell, Bart., K.C.B. (74th), | 572 |

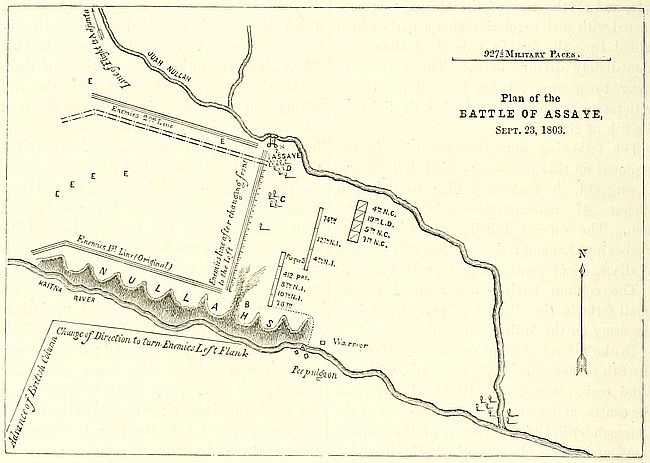

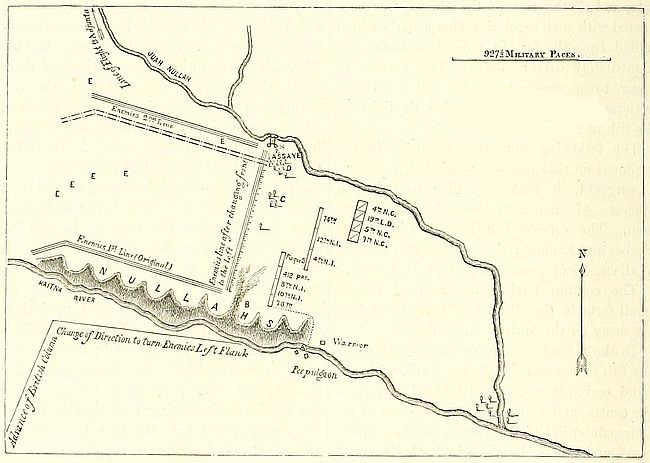

| 163. | Plan of Assaye, 23rd Sept. 1803, | 574 |

| 164. | Lieutenant-Colonel the Hon. Sir Robert Le Poer Trench (74th), | 583 |

| 165. | Medal conferred on the non-commissioned officers and men of the 74th for meritorious conduct during the Peninsular campaign, | 591 |

| 166. | Waterkloof, scene of the death of Lieutenant-Colonel Fordyce (74th), | 598 |

| 167. | Crest of the 78th Highlanders, | 617 |

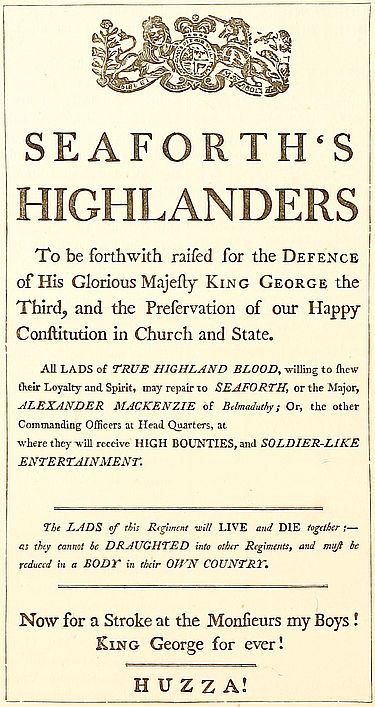

| 168. | Facsimile of a poster issued by Lord Seaforth in Ross and Cromarty in raising the Ross-shire Buffs (78th), | 618 |

| 169. | Plan of the Battle of Assaye, | 631 |

| 170. | Major-General Alexander Mackenzie-Fraser, | 642 |

| 171. | Colonel Patrick Macleod of Geanies (78th), | 650 |

| 172. | Major-General Sir Henry Havelock, K.C.B., | 664 |

| 173. | Suttee Chowra Ghât, scene of the second Cawnpoor Massacre, 15th July 1857, | 668 |

| 174. | Plan of the action near Cawnpoor, 16th July 1857, | 669 |

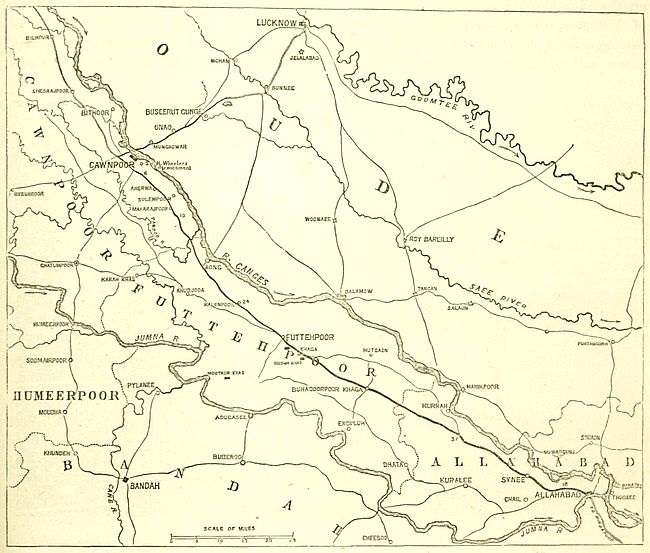

| 175. | Map of the scene of Havelock’s operations in July and August, 1857, | 671 |

| 176. | Mausoleum over the Well of the Massacre at Cawnpoor, | 672 |

| 177. | Plan of the operations for the relief of Lucknow in September and November, 1857, | 677 |

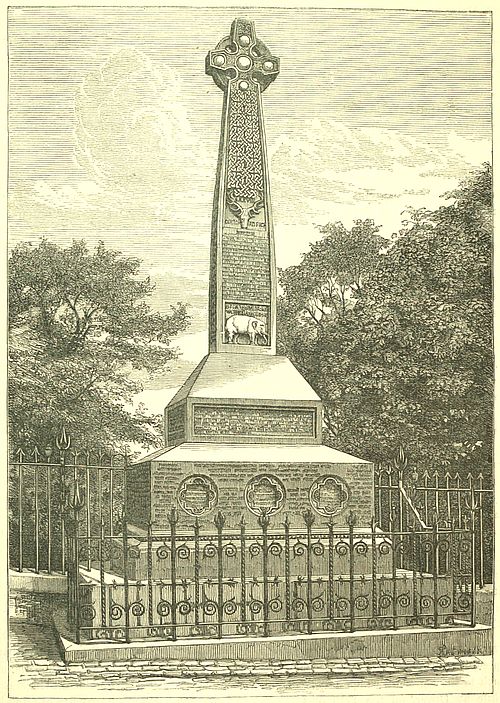

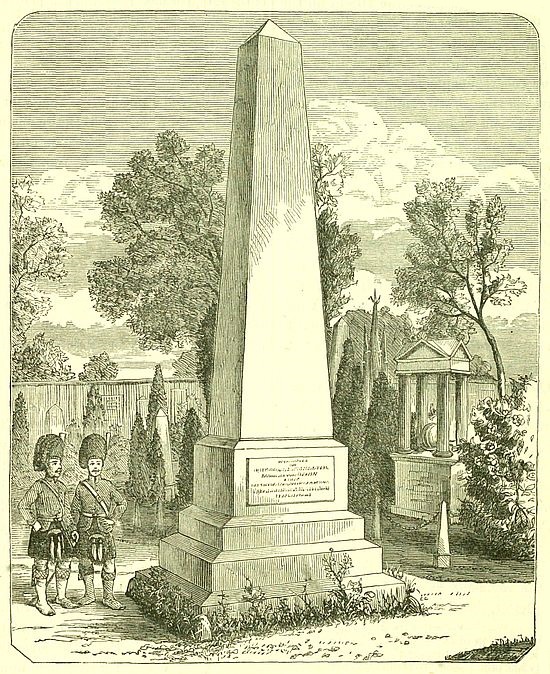

| 178. | Monument to the memory of the 78th Highlanders, erected on Castle Esplanade, Edinburgh, | 689 |

| 179. | Centre Piece of Plate presented by the counties of Ross and Cromarty to the 78th, Ross-shire Buffs, | 691 |

| 180. | Crest of the 79th Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, | 697 |

| 181. | Major-General Sir John Douglas, K.C.B., | 711 |

| 182. | Richard James Mackenzie, M.D., F.R.C.S., | 715 |

| 183. | Lieutenant-Colonel W. C. Hodgson (79th), | 719 |

| 184. | Monument erected in 1857 in the Dean Cemetery, Edinburgh, in memory of the 79th who fell in action during the campaign of 1854–55, | 722 |

| 185. | Crest of the 91st Princess Louise Argyllshire Highlanders, | 726 |

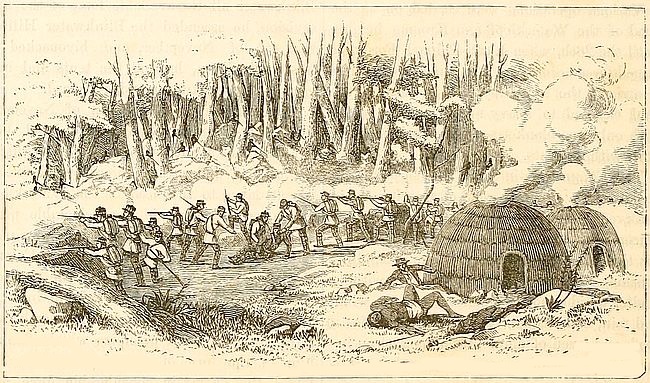

| 186. | The 91st crossing the Tyumie or Chumie River, | 737 |

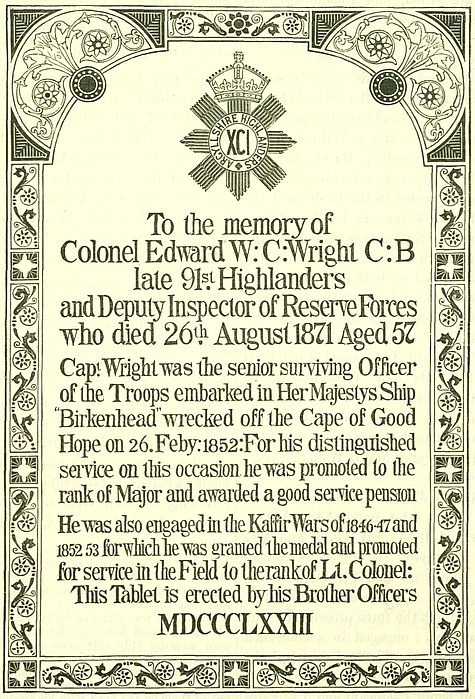

| 187. | Brass Tablet erected in 1873 in Chelsea Hospital to the memory of Colonel Edward W. C. Wright, C.B. (91st), | 742 |

| 188. | Lieutenant-Colonel Bertie Gordon (91st), | 744 |

| 189. | Major-General John F. G. Campbell (91st), | 746 |

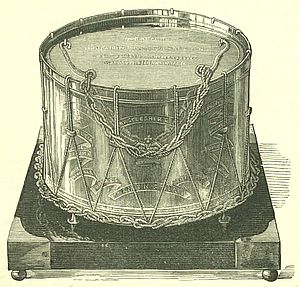

| 190. | Biscuit-Box presented by the men of the 91st Princess Louise Argyllshire Highlanders to the Princess Louise on the occasion of her marriage, | 752 |

| 191. | Crest of the 92nd Gordon Highlanders, | 756 |

| 192. | General Sir John Moore, | 758 |

| 193. | Coat of Arms of Col. John Cameron (92nd), | 762 |

| 194. | Colonel John Cameron (92nd), | 764 |

| 195. | Sir John Macdonald, K.C.B., of Dalchosnie, | 768 |

| 196. | Major-General Archibald Inglis Lockhart, C.B. (92nd), | 770 |

| 197. | Badge of the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders, | 777 |

| 198. | Sir Duncan M’Gregor, K.C.B., | 782 |

| 199. | The Hon. Adrian Hope (93rd), | 788 |

| 200. | The Secunder Bagh, | 791 |

| 201. | Lieutenant-Colonel Wm. M’Bean, V.C. (93rd), | 800 |

| 202. | Centre Piece of Plate, belonging to the Officers’ Mess of the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders, | 801 |

| 203. | Map of Ashantee Country and Gold Coast, | 803 |

| 204. | Sir Garnet J. Wolseley, K.C.M.G., C.B., | 804 |

| 205. | Sir John C. M’Leod, K.C.B. (42nd), | 805 |

Social condition of the Highlands—Black Mail—Watch Money—The Law—Power of the Chiefs—Land Distribution—Tacksmen—Tenants—Rents—Thirlage—Wretched State of Agriculture—Agricultural Implements—The Caschroim—The Reestle—Methods of Transportation—Drawbacks to Cultivation—Management of Crops—Farm Work—Live Stock—Garrons—Sheep—Black Cattle—Arable Land—Pasturage—Farm Servants—The Bailte Geamhre—Davoch-lands—Milk—Cattle Drovers—Harvest Work—The Quern—Fuel—Food—Social Life in Former Days—Education—Dwellings—Habits—Gartmore Papers—Wages—Roads—Present State of Highlands.

As we have already (see ch. xviii.) given a somewhat minute description of the clan-system, it is unnecessary to enter again in detail upon that subject here. We have, perhaps, in the chapter referred to, given the most brilliant side of the picture, still the reader may gather, from what is said there, some notion of what had to be done, what immense barriers had to be overcome, ere the Highlander could be modernised. Any further details on this point will be learned from the Introduction to the History of the Clans.

As might have been expected, for some time after the allaying of the rebellion, and the passing of the various measures already referred to, the Highlands, especially those parts which bordered on the Lowlands, were to a certain extent infested by what were known as cattle-lifters—Anglicé, cattle-stealers. Those who took part in such expeditions were generally “broken” men, or men who belonged to no particular clan, owned no chief, and who were regarded generally as outlaws. In a paper said to have been written in 1747, a very gloomy and lamentable picture of the state of the country in this respect is given, although we suspect it refers rather to the period preceding the rebellion than to that succeeding it. However, we shall quote what the writer says on the matter in question, in order to give the reader an idea of the nature and extent of this system of pillage or “requisition:”—

“Although the poverty of the people principally produces these practices so ruinous to society, yet the nature of the country, which is thinnely inhabitate, by reason of the extensive moors and mountains, and which is so well fitted for conceallments by the many glens, dens, and cavitys in it, does not a little contribute. In such a country cattle are privately transported from one place to another, and securely hid, and in such a country it is not easy to get informations, nor to apprehend the criminalls. People lye so open to their resentment, either for giving intelligence, or prosecuting them, that they decline either, rather than risk their cattle being stoln, or their houses burnt. And then, in the pursuit of a rogue, though he was almost in hands, the grounds are so hilly and unequall, and so much covered with wood or brush, and so full of dens and hollows, that the sight of him is almost as soon lost as he is discovered.

“It is not easy to determine the number of persons employed in this way; but it may be safely affirmed that the horses, cows, sheep, and goats yearly stoln in that country are in value equall to £5,000; that the expences lost in the fruitless endeavours to recover them will not be less than £2,000; that the extraordinary expences of keeping herds and servants to look more narrowly after cattle on account of[2] stealling, otherways not necessary, is £10,000. There is paid in blackmail or watch-money, openly and privately, £5,000; and there is a yearly loss by understocking the grounds, by reason of theifts, of at least £15,000; which is, altogether, a loss to landlords and farmers in the Highlands of £37,000 sterling a year. But, besides, if we consider that at least one-half of these stollen effects quite perish, by reason that a part of them is buried under ground, the rest is rather devoured than eat, and so what would serve ten men in the ordinary way of living, swallowed up by two or three to put it soon out of the way, and that some part of it is destroyed in concealed parts when a discovery is suspected, we must allow that there is £2,500 as the value of the half of the stollen cattle, and £15,000 for the article of understock quite lost of the stock of the kingdom.

“These last mischiefs occasions another, which is still worse, although intended as a remedy for them—that is, the engaging companys of men, and keeping them in pay to prevent these thiefts and depredations. As the government neglect the country, and don’t protect the subjects in the possession of their property, they have been forced into this method for their own security, though at a charge little less than the land-tax. The person chosen to command this watch, as it is called, is commonly one deeply concerned in the theifts himself, or at least that hath been in correspondence with the thieves, and frequently who hath occasioned thiefts, in order to make this watch, by which he gains considerably, necessary. The people employed travell through the country armed, night and day, under pretence of enquiring after stollen cattle, and by this means know the situation and circumstances of the whole country. And as the people thus employed are the very rogues that do these mischiefs, so one-half of them are continued in their former bussiness of stealling that the busieness of the other half may be necessary in recovering.”[1]

This is probably a somewhat exaggerated account of the extent to which this species of robbery was carried on, especially after the suppression of the rebellion; if written by one of the Gartmore family, it can scarcely be regarded as a disinterested account, seeing that the Gartmore estate lies just on the southern skirt of the Highland parish of Aberfoyle, formerly notorious as a haunt of the Macgregors, affording every facility for lifters getting rapidly out of reach with their “ill-gotten gear.” Still, no doubt, curbed and dispirited as the Highlanders were after the treatment they got from Cumberland, from old habit, and the assumed necessity of living, they would attempt to resume their ancient practices in this and other respects. But if they were carried on to any extent immediately after the rebellion, when the Gartmore paper is said to have been written, it could not have been for long; the law had at last reached the Highlands, and this practice ere long became rarer than highway robbery in England, gradually dwindling down until it was carried on here and there by one or two “desperate outlawed” men. Long before the end of the century it seems to have been entirely given up. “There is not an instance of any country having made so sudden a change in its morals as that of the Highlands; security and civilization now possess every part; yet 30 years have not elapsed since the whole was a den of thieves of the most extraordinary kind.”[2]

As we have said above, after the suppression of the rebellion of 1745–6, there are no stirring narratives of outward strife or inward broil to be narrated in connection with the Highlands. Indeed, the history of the Highlands from this time onwards belongs strictly to the history of Scotland, or rather of Britain. Still, before concluding this division of the work, it may be well to give a brief sketch of the progress of the Highlands from the time of the suppression of the jurisdictions down to the present day. Not that after their disarmament the Highlanders ceased to take part in the world’s strife; but the important part they have taken during the last century or more in settling the destinies of nations, falls to be narrated in another section of this work. What we shall concern ourselves with at present is the consequences of the abolition of the heritable jurisdictions (and with them the importance and power of the chiefs), on the[3] internal state of the Highlands; we shall endeavour to show the alteration which took place in the social condition of the people, their mode of life, their relation to the chiefs (now only landlords), their mode of farming, their religion, education, and other points.

From the nature of clanship—of the relationship between chief and people, as well as from the state of the law and the state of the Highlands generally—it will be perceived that, previous to the measure which followed Culloden, it was the interest of every chief to surround himself with as many followers as he could muster; his importance and power of injury and defence were reckoned by government and his neighbours not according to his yearly income, but according to the number of men he could bring into the field to fight his own or his country’s battles. It is told of a chief that, when asked as to the rent of his estate, he replied that he could raise 500 men. Previous to ’45, money was of so little use in the Highlands, the chiefs were so jealous of each other and so ready to take advantage of each other’s weakness, the law was so utterly powerless to repress crime and redress wrong, and life and property were so insecure, that almost the only security which a chief could have was the possession of a small army of followers, who would protect himself and his property; and the chief safety and means of livelihood that lay in the power of the ordinary clansman was to place himself under the protection and among the followers of some powerful chief. “Before that period (1745) the authority of law was too feeble to afford protection.[3] The obstructions to the execution of any legal warrant were such that it was only for objects of great public concern that an extraordinary effort was sometimes made to overcome them. In any ordinary case of private injury, an individual could have little expectation of redress unless he could avenge his own cause; and the only hope of safety from any attack was in meeting force by force. In this state of things, every person above the common rank depended for his safety and his consequence on the number and attachment of his servants and dependants; without people ready to defend him, he could not expect to sleep in safety, to preserve his house from pillage or his family from murder; he must have submitted to the insolence of every neighbouring robber, unless he had maintained a numerous train of followers to go with him into the field, and to fight his battles. To this essential object every inferior consideration was sacrificed; and the principal advantage of landed property consisted in the means it afforded to the proprietor of multiplying his dependants.”[4]

Of course, the chief had to maintain his followers in some way, had to find some means by which he would be able to attach them to himself, keep them near him, and command their services when he required them. There can be no doubt, however chimerical it may appear at the present day, that the attachment and reverence of the Highlander to his chief were quite independent of any benefits the latter might be able to confer. The evidence is indubitable that the clan regarded the chief as the father of his people, and themselves as his children; he, they believed, was bound to protect and maintain them, while they were bound to regard his will as law, and to lay down their lives at his command. Of these statements there can be[4] no doubt. “This power of the chiefs is not supported by interest, as they are landlords, but as lineally descended from the old patriarchs or fathers of the families, for they hold the same authority when they have lost their estates, as may appear from several, and particularly one who commands in his clan, though, at the same time, they maintain him, having nothing left of his own.”[5] Still it was assuredly the interest, and was universally regarded as the duty of the chief, to strengthen that attachment and his own authority and influence, by bestowing upon his followers what material benefits he could command, and thus show himself to be, not a thankless tyrant, but a kind and grateful leader, and an affectionate father of his people. Theoretically, in the eye of the law, the tenure and distribution of land in the Highlands was on the same footing as in the rest of the kingdom; the chiefs, like the lowland barons, were supposed to hold their lands from the monarch, the nominal proprietor of all landed property, and these again in the same way distributed portions of this territory among their followers, who thus bore the same relation to the chief as the latter did to his superior, the king. In the eye of the law, we say, this was the case, and so those of the chiefs who were engaged in the rebellion of 1715–45 were subjected to forfeiture in the same way as any lowland rebel. But, practically, the great body of the Highlanders knew nothing of such a tenure, and even if it had been possible to make them understand it, they would probably have repudiated it with contempt. The great principle which seems to have ruled all the relations that subsisted between the chief and his clan, including the mode of distributing and holding land, was, previous to 1746, that of the family. The land was regarded not so much as belonging absolutely to the chief, but as the property of the clan of which the chief was head and representative. Not only was the clan bound to render obedience and reverence to their head, to whom each member supposed himself related, and whose name was the common name of all his people; he also was regarded as bound to maintain and protect his people, and distribute among them a fair share of the lands which he held as their representative. “The chief, even against the laws, is bound to protect his followers, as they are sometimes called, be they never so criminal. He is their leader in clan quarrels, must free the necessitous from their arrears of rent, and maintain such who, by accidents, are fallen into decay. If, by increase of the tribe, any small farms are wanting, for the support of such addition he splits others into lesser portions, because all must be somehow provided for; and as the meanest among them pretend to be his relatives by consanguinity, they insist upon the privilege of taking him by the hand wherever they meet him.”[6] Thus it was considered the duty, as it was in those turbulent times undoubtedly the interest, of the chief to see to it that every one of those who looked upon him as their chief was provided for; while, on the other hand, it was the interest of the people, as they no doubt felt it to be their duty, to do all in their power to gain the favour of their chiefs, whose will was law, who could make or unmake them, on whom their very existence was dependent. Latterly, at least, this utter dependence of the people on their chiefs, their being compelled for very life’s sake to do his bidding, appears to have been regarded by the former as a great hardship; for, as we have already said, it is well known that in both of the rebellions of last century, many of the poor clansmen pled in justification of their conduct, that they were compelled, sorely against their inclination, to join the rebel army. This only proves how strong must have been the power of the chiefs, and how completely at their mercy the people felt themselves to be.

To understand adequately the social life of the Highlanders previous to 1746, the distribution of the land among, the nature of their tenures, their mode of farming, and similar matters, the facts above stated must be borne in mind. Indeed, not only did the above influences affect these matters previous to the suppression of the last rebellion, but also for long after, if, indeed, they are not in active operation in some remote corners of the Highlands[5] even at the present day; moreover, they afford a key to much of the confusion, misunderstanding, and misery that followed upon the abolition of the heritable jurisdictions.

Next in importance and dignity to the chief or laird were the cadets of his family, the gentlemen of the clan, who in reference to the mode in which they held the land allotted to them, were denominated tacksmen. To these tacksmen were let farms, of a larger or smaller size according to their importance, and often at a rent merely nominal; indeed, they in general seem to have considered that they had as much right to the land as the chief himself, and when, after 1746, many of them were deprived of their farms, they, and the Highlanders generally, regarded it as a piece of gross and unfeeling injustice. As sons were born to the chief, they also had to be provided for, which seems to have been done either by cutting down the possessions of those tacksmen further removed from the family of the laird, appropriating those which became vacant by the death of the tenant or otherwise, and by the chief himself cutting off a portion of the land immediately in his possession. In this way the descendants of tacksmen might ultimately become part of the commonalty of the clan. Next to the tacksmen were tenants, who held their farms either directly from the laird, or as was more generally the case, from the tacksmen. The tenants again frequently let out part of their holdings to sub-tenants or cottars, who paid their rent by devoting most of their time to the cultivation of the tenant’s farm, and the tending of his cattle. The following extract from the Gartmore paper written in 1747, and published in the appendix to Burt’s Letters, gives a good idea of the manner generally followed in distributing the land among the various branches of the clan:—

“The property of these Highlands belongs to a great many different persons, who are more or less considerable in proportion to the extent of their estates, and to the command of men that live upon them, or follow them on account of their clanship, out of the estates of others. These lands are set by the landlord during pleasure, or a short tack, to people whom they call good-men, and who are of a superior station to the commonality. These are generally the sons, brothers, cousins, or nearest relations of the landlord. The younger sons of famillys are not bred to any business or employments, but are sent to the French or Spanish armies, or marry as soon as they are of age. Those are left to their own good fortune and conduct abroad, and these are preferred to some advantageous farm at home. This, by the means of a small portion, and the liberality of their relations, they are able to stock, and which they, their children, and grandchildren, possess at an easy rent, till a nearer descendant be again preferred to it. As the propinquity removes, they become less considered, till at last they degenerate to be of the common people; unless some accidental acquisition of wealth supports them above their station. As this hath been an ancient custom, most of the farmers and cottars are of the name and clan of the proprietor; and, if they are not really so, the proprietor either obliges them to assume it, or they are glaid to do so, to procure his protection and favour.

“Some of these tacksmen or good-men possess these farms themselves; but in that case they keep in them a great number of cottars, to each of whom they give a house, grass for a cow or two, and as much ground as will sow about a boll of oats, in places which their own plough cannot labour, by reason of brush or rock, and which they are obliged in many places to delve with spades. This is the only visible subject which these poor people possess for supporting themselves and their famillys, and the only wages of their whole labour and service.

“Others of them lett out parts of their farms to many of these cottars or subtennants; and as they are generally poor, and not allways in a capacity to stock these small tenements, the tacksmen frequently enter them on the ground laboured and sown, and sometimes too stocks it with cattle; all which he is obliged to redeliver in the same condition at his removal, which is at the goodman’s pleasure, as he is usually himself tennent at pleasure, and for which during his possession he pays an extravagantly high rent to the tacksman.

“By this practice, farms, which one family and four horses are sufficient to labour, will[6] have from four to sixteen famillys living upon them.”[7]

“In the case of very great families, or when the domains of a chief became very extensive, it was usual for the head of the clan occasionally to grant large territories to the younger branches of his family in return for a trifling quit-rent. These persons were called chieftains, to whom the lower classes looked up as their immediate leader. These chieftains were in later times called tacksmen; but at all periods they were considered nearly in the same light as proprietors, and acted on the same principles. They were the officers who, under the chief, commanded in the military expeditions of the clans. This was their employment; and neither their own dispositions, nor the situation of the country, inclined them to engage in the drudgery of agriculture any farther than to supply the necessaries of life for their own families. A part of their land was usually sufficient for this purpose, and the remainder was let off in small portions to cottagers, who differed but little from the small occupiers who held their lands immediately from the chief; excepting that, in lieu of rent, they were bound to a certain amount of labour for the advantage of their immediate superior. The more of these people any gentleman could collect around his habitation, with the greater facility could he carry on the work of his own farm; the greater, too, was his personal safety. Besides this, the tacksmen, holding their lands from the chief at a mere quit-rent, were naturally solicitous to merit his favour by the number of their immediate dependants whom they could bring to join his standard.”[8]

Thus it will be seen that in those times every one was, to a more or less extent, a cultivator or renter of land. As to rent, there was very little of actual money paid either by the tacksmen or by those beneath them in position and importance. The return expected by the laird or chief from the tacksmen for the farms he allowed them to hold, was that they should be ready when required to produce as many fighting men as possible, and give him a certain share of the produce of the land they held from him. It was thus the interest of the tacksman to parcel out their land into as small lots as possible, for the more it was subdivided, the greater would be the number of men he could have at his command. This liability on the part of the subtenants to be called upon at any time to do service for the laird, no doubt counted for part of the rent of the pendicles allotted to them. These pendicles were often very small, and evidently of themselves totally insufficient to afford the means of subsistence even to the smallest family. Besides this liability to do service for the chief, a very small sum of money was taken as part of the rent, the remainder being paid in kind, and in assisting the tacksmen to farm whatever land he may have retained in his own hands. In the same way the cottars, who were subtenants to the tacksmen’s tenants, had to devote most of their time to the service of those from whom they immediately held their lands. Thus it will be seen that, although nominally the various tenants held their land from their immediate superiors at a merely nominal rent, in reality what was actually given in return for the use of the land would, in the end, probably turn out to be far more than its value. From the laird to the cottar there was an incessant series of exactions and services, grievous to be borne, and fatal to every kind of improvement.

Besides the rent and services due by each class to its immediate superiors, there were numerous other exactions and services, to which all had to submit for the benefit of their chief. The most grievous perhaps of these was thirlage or multure, a due exacted from each tenant for the use of the mill of the district to convert their grain into meal. All the tenants of each district or parish were thirled or bound to take their grain to a particular mill to be ground, the miller being allowed to appropriate a certain proportion as payment for the use of the mill, and as a tax payable to the laird or chief. In this way a tenant was often deprived of a considerable quantity of his grain, varying from one-sixteenth to one-eighth, and even more. In the same way many parishes were thirled to a particular smith. By these and similar exactions and contributions did the proprietors[7] and chief men of the clan manage to support themselves off the produce of their land, keep a numerous band of retainers around them, have plenty for their own use, and for all who had any claim to their hospitality. This seems especially to have been the case when the Highlanders were in their palmiest days of independence, when they were but little molested from without, and when their chief occupations were clan-feuds and cattle raids. But latterly, and long before the abolition of heritable jurisdictions, this state of matters had for the most part departed, and although the chiefs still valued themselves by the number of men they could produce, they kept themselves much more to themselves, and showed less consideration for the inferior members of the clan, whose condition, even at its best, must appear to have been very wretched. “Of old, the chieftain was not so much considered the master as the father of his numerous clan. Every degree of these followers loved him with an enthusiasm, which made them cheerfully undergo any fatigue or danger. Upon the other hand, it was his interest, his pride, and his chief glory, to requite such animated friendship to the utmost of his power. The rent paid him was chiefly consumed in feasts given at the habitations of his tenants. What he was to spend, and the time of his residence at each village, was known and provided for accordingly. The men who provided these entertainments partook of them; they all lived friends together; and the departure of the chief and his retinue never fails to occasion regret. In more polished times, the cattle and corn consumed at these feasts of hospitality, were ordered up to the landlord’s habitation. What was friendship at the first became very oppressive in modern times. Till very lately in this neighbourhood, Campbell of Auchinbreck had a right to carry off the best cow he could find upon several properties at each Martinmas by way of mart. The Island of Islay paid 500 such cows yearly, and so did Kintyre to the Macdonalds.”[9] Still, there can be no doubt, that previous to 1746 it was the interest of the laird and chief tacksmen to keep the body of the people as contented as possible, and do all in their power to attach them to their interest. Money was of but little use in the Highlands then; there was scarcely anything in which it could be spent; and so long as his tenants furnished him with the means of maintaining a substantial and extensive hospitality, the laird was not likely in general to complain. “The poverty of the tenants rendered it customary for the chief, or laird, to free some of them every year, from all arrears of rent; this was supposed, upon an average, to be about one year in five of the whole estate.”[10]

In the same letter from which the last sentence is quoted, Captain Burt gives an extract from a Highland rent-roll, of date probably about 1730; we shall reproduce it here, as it will give the reader a better notion as to how those matters were managed in these old times, than any description can. “You will, it is likely,” the letter begins, “think it strange that many of the Highland tenants are to maintain a family upon a farm of twelve merks Scots per annum, which is thirteen shillings and fourpence sterling, with perhaps a cow or two, or a very few sheep or goats; but often the rent is less, and the cattle are wanting.

“In some rentals you may see seven or eight columns of various species of rent, or more, viz., money, barley, oatmeal, sheep, lambs, butter, cheese, capons, &c.; but every tenant does not pay all these kinds, though many of them the greatest part. What follows is a specimen taken out of a Highland rent-roll, and I do assure you it is genuine, and not the least by many:—

| Scots Money. | English. | Butter. | Oatmeal. | Muttons. | ||||||||||

| Stones.Lb.Oz. | Bolls.B.P.Lip. | |||||||||||||

| Donald mac Oil vic ille Challum | £3 | 10 | 4 | £0 | 5 | 10⅛ | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ⅛ and 1/16 |

| Murdoch mac ille Christ | 5 | 17 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 9⅛ | 0 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ¼ and 1/16 |

| Duncan mac ille Phadrick | 7 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 12 | 3½ | 0 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0½ | ¼ and ⅛ |

I shall here give you a computation of the first article, besides which there are seven more of the same farm and rent, as you may perceive by the fraction of a sheep in the last column:—

| The money | £0 | 5 | 10⅛ | Sterling. |

| The butter, three pounds two ounces, at 4d. per lb | 0 | 1 | 1½ | |

| Oatmeal, 2 bushels, 1 peck, 3 lippys and ¼, at 6d. per peck | 0 | 4 | 9¼ | and ½ |

| Sheep, one-eighth and one-sixteenth, at 2s | 0 | 0 | 4½ | |

| —————— | ||||

| The yearly rent of the farm is | £0 | 12 | 1½ | and 1/12.” |

It is plain that in the majority of cases the farms must have been of very small extent, almost equal to those of Goldsmith’s Golden Age, “when every rood maintained its man.” “In the head of the parish of Buchanan in Stirlingshire, as well as in several other places, there are to be found 150 families living upon grounds which do not pay above £90 sterling of yearly rent, that is, each family at a medium rents lands at twelve shillings of yearly rent.”[11] This certainly seems to indicate a very wretched state of matters, and would almost lead one to expect to hear that a famine occurred every year. But it must be remembered that for the reasons above given, along with others, farms were let at a very small rent, far below the real value, and generally merely nominal; that besides money, rent at that time was all but universally paid in kind, and in services to the laird or other superior; and that many of the people, especially on the border lands, had other means of existence, as for example, cattle-lifting. Nevertheless, making all these allowances, the condition of the great mass of the Highlanders must have been extremely wretched, although they themselves might not have felt it to be so, they had been so long accustomed to it.

In such a state of matters, with the land so much subdivided, with no leases, and with tenures so uncertain, with so many oppressive exactions, with no incitements to industry or improvement, but with every encouragement to idleness and inglorious self-contentment, it is not to be supposed that agriculture or any other industry would make any great progress. For centuries previous to 1745, and indeed for long after it, agriculture appears to have remained at a stand-still. The implements in use were rude and inefficient, the time devoted to the necessary farming operations, generally a few weeks in spring and autumn, was totally insufficient to produce results of any importance, and consequently the crops raised, seldom anything else but oats and barley, were scanty, wretched in quality, and seldom sufficient to support the cultivator’s family for the half of the year. In general, in the Highlands, as the reader will already have seen, each farm was let to a number of tenants, who, as a rule, cultivated the arable ground on the system of run-rig, i.e., the ground was divided into ridges which were so distributed among the tenants that no one tenant possessed two contiguous ridges. Moreover, no tenant could have the same ridge for two years running, the ridges having a new cultivator every year. Such a system of allocating arable land, it is very evident, must have been attended with the worst results so far as good farming is concerned. The only recommendation that it is possible to urge in its favour is that, there being no inclosures, it would be the interest of the tenants to join together in protecting the land they thus held in common against the ravages of the cattle which were allowed to roam about the hills, and the depredations of hostile clans. As we have just said, there were no inclosures in the Highlands previous to 1745, nor were there for very many years after that. While the crops were standing in the ground, and liable to be destroyed by the cattle, the latter were kept, for a few weeks in summer and autumn, upon the hills; but after the crops were gathered in, they were allowed to roam unheeded through the whole of a district or parish, thus affording facilities for the cattle-raids that formed so important an item in the means of obtaining a livelihood among the ancient Highlanders.

As a rule, the only crops attempted to be raised were oats and barley, and sometimes a little flax; green crops were almost totally unknown or despised, till many years after 1745; even potatoes do not seem to have been at all common till after 1750, although latterly they became the staple food of the[9] Highlanders. Rotation of crops, or indeed any approach to scientific agriculture, was totally unknown. The ground was divided into infield and outfield. The infield was constantly cropped, either with oats or bear; one ridge being oats, the other bear alternately. There was no other crop except a ridge of flax where the ground was thought proper for it. The outfield was ploughed three years for oats, and then pastured for six years with horses, black cattle, and sheep. In order to dung it, folds of sod were made for the cattle, and what were called flakes or rails of wood, removable at pleasure, for folding the sheep. A farmer who rented 60, 80, or 100 acres, was sometimes under the necessity of buying meal for his family in the summer season.[12]

Their agricultural implements, it may easily be surmised, were as rude as their system of farming. The chief of these were the old Scotch plough and the caschroim or crooked spade, which latter, though primitive enough, seems to have been not badly suited to the turning over of the land in many parts of the Highlands. The length of the Highland plough was about four feet and a half, and had only one stilt or handle, by which the ploughman directed it. A slight mould-board was fastened to it with two leather straps, and the sock and coulter were bound together at the point with a ring of iron. To this plough there were yoked abreast four, six, and even more horses or cattle, or both mixed, in traces made of thongs of leather. To manage this unwieldy machine it required three or four men. The ploughman walked by the side of the plough, holding the stilt with one hand; the driver walked backwards in front of the horses or cattle, having the reins fixed on a cross stick, which he appears to have held in his hands.[13] Behind the ploughman came one and sometimes two men, whose business it was to lay down with a spade the turf that[10] was torn off. In the Hebrides and some other places of the Highlands, a curious instrument called a Reestle or Restle, was used in conjunction with this plough. Its coulter was shaped somewhat like a sickle, the instrument itself being otherwise like the plough just described. It was drawn by one horse, which was led by a man, another man holding and directing it by the stilt. It was drawn before the plough in order to remove obstructions, such as roots, tough grass, &c., which would have been apt to obstruct the progress of a weak plough like the above. In this way, it will be seen, five or six men, and an equal number if not more horses or cattle, were occupied in this single agricultural operation, performed now much more effectively by one man and two horses.[14]

The Caschroim, i.e., the crooked foot or spade, was an instrument peculiarly suited to the cultivation of certain parts of the Highlands, totally inaccessible to a plough, on account of the broken and rocky nature of the ground. Moreover, the land turned over with the caschroim was considerably more productive than that to which the above plough had been used. It consists of a strong piece of wood, about six feet long, bent near the lower end, and having a thick flat wooden head, shod at the extremity with a sharp piece of iron. A piece of wood projected about eight inches from the right side of the blade, and on this the foot was placed to force the instrument diagonally into the ground. “With this instrument a Highlander will open up more ground in a day, and render it fit for the sowing of grain, than could be done by two or three men with any other spades that are commonly used. He will dig as much ground in a day as will sow more than a peck of oats. If he works assiduously from about Christmas to near the end of April, he will prepare land sufficient to sow five bolls. After this he will dig as much land in a day as will sow two pecks of bere; and in the course of the season will cultivate as much land with his spade as is sufficient to supply a family of seven or eight persons, the year round, with meal and potatoes.... It appears, in general, that a field laboured with the caschroim affords usually one-third more crop than if laboured with the plough. Poor land will afford near one-half more. But then it must be noticed that this tillage with the plough is very imperfect, and the soil scarcely half laboured.”[15] No doubt this mode of cultivation was suitable enough in a country overstocked with population, as the Highlands were in the early part of last century, and where time and labour were of very little value. There were plenty of men to spare for such work, and there was little else to do but provide themselves with food. Still it is calculated that this spade labour was three times more expensive than that of the above clumsy plough. The caschroim was frequently used where there would have been no difficulty in working a plough, the reason apparently being that the horses and cattle were in such a wretched condition that the early farming operations in spring completely exhausted them, and therefore much of the ploughing left undone by them had to be performed with the crooked spade.

As to harrows, where they were used at all, they appear to have been of about as little use as a hand-rake. Some of them, which resembled hay-rakes, were managed by the hand; others, drawn by horses, were light and feeble, with wooden teeth, which might scratch the surface and cover the seed, but could have no effect in breaking the soil.[16] In some parts of the Highlands it was the custom to fasten the harrow to the horse’s tail, and when it became too short, it was lengthened with twisted sticks.

To quote further from Dr Walker’s work, which describes matters as they existed about 1760, and the statements in which will apply with still greater force to the earlier half of the century:—“The want of proper carriages in the Highlands is one of the great obstacles to the progress of agriculture, and of every improvement. Having no carts, their corn, straw, manures, fuel, stone, timber, sea-weed, and kelp, the articles necessary in the fisheries, and every other bulky commodity, must be transported from one place to another on horseback or on sledges. This must triple or quadruple the expense of their carriage. It must prevent particularly the use of the natural manures with which the country abounds, as, without[11] cheap carriage, they cannot be rendered profitable. The roads in most places are so bad as to render the use of wheel-carriages impossible; but they are not brought into use even where the natural roads would admit them.”[17]

As we have said already, farming operations in the Highlands lasted only for a few weeks in spring and autumn. Ploughing in general did not commence till March, and was concluded in May; there was no autumn or winter ploughing; the ground was left untouched and unoccupied but by some cattle from harvest to spring-time. It was only after the introduction of potatoes that the Highlanders felt themselves compelled to begin operations about January. As to the modus operandi of the Highland farmer in the olden time, we quote the following from the old Statistical Account of the parish of Dunkeld and Dowally, which may be taken as a very fair representative of all the other Highland parishes; indeed, as being on the border of the lowlands, it may be regarded as having been, with regard to agriculture and other matters, in a more advanced state than the generality of the more remote parishes:—“The farmer, whatever the state of the weather was, obstinately adhered to the immemorial practice of beginning to plough on Old Candlemas Day, and to sow on the 20th of March. Summer fallow, turnip crops, and sown grass were unknown; so were compost dunghills and the purchasing of lime. Clumps of brushwood and heaps of stones everywhere interrupted and deformed the fields. The customary rotation of their general crops was—1. Barley; 2. Oats; 3. Oats; 4. Barley; and each year they had a part of the farm employed in raising flax. The operations respecting these took place in the following succession. They began on the day already mentioned to rib the ground, on which they intended to sow barley, that is, to draw a wide furrow, so as merely to make the land, as they termed it, red. In that state this ground remained till the fields assigned to oats were ploughed and sown. This was in general accomplished by the end of April. The farmer next proceeded to prepare for his flax crop, and to sow it, which occupied him till the middle of May, when he began to harrow, and dung, and sow the ribbed barley land. This last was sometimes not finished till the month of June.”[18] As to draining, fallowing, methodical manuring and nourishing the soil, or any of the modern operations for making the best of the arable land of the country, of these the Highlander never even dreamed; and long after[19] they had become common in the low country, it was with the utmost difficulty that his rooted aversion to innovations could be overcome. They literally seem to have taken no thought for the morrow, and the tradition and usage of ages had given them an almost insuperable aversion to manual labour of any kind. This prejudice against work was not the result of inherent laziness, for the Highlander, both in ancient and modern times, has clearly shown that his capacity for work and willingness to exert himself are as strong and active as those of the most industrious lowlander or Englishman. The humblest Highlander believed himself a gentleman, having blood as rich and old as his chief, and he shared in the belief, far from being obsolete even at the present day, that for a gentleman to soil his hands with labour is as degrading as slavery.[20] This belief was undoubtedly one[12] of the strongest principles of action which guided the ancient Highlanders, and accounts, we think, to a great extent for his apparent laziness, and for the slovenly and laggard way in which farming operations were conducted.

There were, however, no doubt other reasons for the wretched state of agriculture in the Highlands previous to, and for long after, 1745. The Highlanders had much to struggle against, and much calculated to dishearten them, in the nature of the soil and climate, on which, to a great extent, the success of agricultural operations is dependent. In many parts of the Highlands, especially in the west, rain falls for the greater part of the year, thus frequently preventing the completion of the necessary processes, as well as destroying the crops when put into the ground. As to the soil, no unprejudiced man who is competent to judge will for one moment deny that a great part of it is totally unsuited to agriculture, but fitted only for the pasturage of sheep, cattle, and deer. In the Old Statistical Account of Scotland, this assertion is being constantly repeated by the various Highland ministers who report upon the state of their parishes. In the case of many Highland districts, one could conceive of nothing more hopeless and discouraging than the attempt to force from them a crop of grain. That there are spots in the Highlands as susceptible of high culture as some of the best in the lowlands cannot be denied; but these bear but a small proportion to the great quantity of ground that is fitted only to yield a sustenance to cattle and sheep. Now all reports seem to justify the conclusion that, previous to, and for long after 1745, the Highlands were enormously overstocked with inhabitants, considering the utter want of manufactures and the few other outlets there were for labour. Thus, we think, the Highlander would be apt to feel that any extraordinary exertion was absolutely useless, as there was not the smallest chance of his ever being able to improve his position, or to make himself, by means of agriculture, better than his neighbour. All he seems to have sought for was to raise as much grain as would keep himself and family in bread during the miserable winter months, and meet the demands of the laird.

The small amount of arable land was no doubt also the reason of the incessant cropping which prevails, and which ultimately left the land in a state of complete exhaustion. “To this sort of management, bad as it is, the inhabitants are in some degree constrained, from the small proportion of arable land upon their farms. From necessity they are forced to raise what little grain they can, though at a great expense of labour, the produce being so inconsiderable. A crop of oats on outfield ground, without manure, they find more beneficial than the pasture. But if they must manure for a crop of oats, they reckon the crop of natural grass rather more profitable. But the scarcity of bread corn—or rather, indeed, the want of bread—obliges them to pursue the less profitable practice. Oats and bear being necessary for their subsistence, they must prefer them to every other produce. The land at present in tillage, and fit to produce them, is very limited, and inadequate to the consumption of the inhabitants. They are, therefore, obliged to make it yield as much of these grains as possible, by scourging crops.”[21]

Another great discouragement to good farming was the multitude and grievous nature of the services demanded from the tenant by the landlord as part payment of rent. So multifarious were these, and so much of the farmer’s time did they occupy, that frequently his own farming affairs got little or none of his personal attention, but had to be entrusted to his wife and family, or to the cottars whom he housed on his farm, and who, for an acre or so of ground and liberty to pasture an ox or two and a few sheep, performed to the farmer services similar to those rendered by the latter to his laird. Often a farmer had only one day in[13] the week to himself, so undefined and so unlimited in extent were these services. Even in some parishes, so late as 1790, the tenant for his laird (or master, as he was often called) had to plough, harrow, and manure his land in spring; cut corn, cut, winnow, lead, and stack his hay in summer, as well as thatch office-houses with his own (the tenant’s) turf and straw; in harvest assist to cut down the master’s crop whenever called upon, to the latter’s neglect of his own, and help to store it in the cornyard; in winter frequently a tenant had to thrash his master’s crop, winter his cattle, and find ropes for the ploughs and for binding the cattle. Moreover, a tenant had to take his master’s grain from him, see that it was properly put through all the processes necessary to convert it into meal, and return it ready for use; place his time and his horses at the laird’s disposal, to buy in fuel for the latter, run a message whenever summoned to do so; in short, the condition of a tenant in the Highlands during the early part of last century, and even down to the end of it in some places, was little better than a slave.[22]

Not that, previous to 1745, this state of matters was universally felt to be a grievance by tenants and farmers in the Highlands, although it had to a large extent been abolished both in England and the lowlands of Scotland. On the contrary, the people themselves appear to have accepted this as the natural and inevitable state of things, the only system consistent with the spirit of clanship with the supremacy of the chiefs. That this was not, however, universally the case, may be seen from the fact that, so early as 1729, Brigadier Macintosh of Borlum (famous in the affair of 1715) published a book, or rather essay, on Ways and Means for Enclosing, Fallowing, Planting, &c., Scotland, which he prefaced by a strongly-worded exhortation to the gentlemen of Scotland to abolish this degrading and suicidal system, which was as much against their own interests as it was oppressive to the tenants. Still, after 1745, there seems to be no doubt that, as a rule, the ordinary Highlander acquiesced contentedly in the established state of things, and generally, so far as his immediate wants were concerned, suffered little or nothing from the system. It was only after the abolition of the jurisdictions that the grievous oppressive hardship, injustice, and obstructiveness of the system became evident. Previous to that, it was, of course, the laird’s or chief’s interest to keep his tenants attached to him and contented, and to see that they did not want; not only so, but previous to that epoch, what was deficient in the supply of food produced by any parish or district, was generally amply compensated for by the levies of cattle and other gear made by the clans upon each other when hostile, or upon their lawful prey, the Lowlanders. But even with all this, it would seem that, not unfrequently, the Highlanders, either universally or in certain districts, were reduced to sore straits, and even sometimes devastated by famine. Their crops and other supplies were so exactly squared to their wants, that, whenever the least failure took place in the expected quantity, scarcity or cruel famine was the result. According to Dr Walker, the inhabitants of some of the Western Isles look for a failure once in every four years. Maston, in his Description of the Western Islands, complained that many died from famine arising from years of scarcity, and about 1742, many over all the Highlands appear to have shared the same fate from the same cause.[23] So that, even under the old system, when the clansmen were faithful and obedient, and the chief was kind and liberal, and many cattle and other productions were imported free of all cost, the majority of the people lived from hand to mouth, and frequently suffered from scarcity and want. Infinitely more so was this the case when it ceased to be the interest of the laird to keep around him numerous tenants.

All these things being taken into consideration, it is not to be wondered at that agriculture in the Highlands was for so long in such a wretched condition.

They set much store, however, by their small black cattle and diminutive sheep, and appear in many districts to have put more dependence upon them for furnishing the means of existence, than upon what the soil could yield.

The live-stock of a Highland farm consisted mainly of horses, sheep, and cattle, all of them[14] of a peculiarly small breed, and capable of yielding but little profit. The number of horses generally kept by a farmer was out of all proportion to the size of his farm and the number of other cattle belonging to him. The proportion of horses to cattle often ranged from one in eight to one in four. For example, Dr Webster mentions a farm in Kintail, upon which there were forty milk cows, which with the young stock made one hundred and twenty head of cattle, about two hundred and fifty goats and ewes, young and old, and ten horses. The reason that so great a proportion of horses was kept, was evidently the great number that were necessary for the operation of ploughing, and the fact that in the greater part of the Highlands carts were unknown, and fuel, grain, manure, and many other things generally carried in machines, had to be conveyed on the backs of the horses, which were of a very small breed, although of wonderful strength considering their rough treatment and scanty fare. They were frequently plump, active, and endurable, though they had neither size nor strength for laborious cultivation. They were generally from nine to twelve hands high, short-necked, chubby-headed, and thick and flat at the withers.[24] “They are so small that a middle-sized man must keep his legs almost in lines parallel to their sides when carried over the stony ways; and it is almost incredible to those who have not seen it how nimbly they skip with a heavy rider among the rocks and large moor-stones, turning zig-zag to such places as are passable.”[25] Walker believes that scarcely any horses could go through so much labour and fatigue upon so little sustenance.[26] They were generally called garrons, and seem in many respects to have resembled the modern Shetland pony. These horses for the greater part of the year were allowed to run wild among the hills, each having a mark indicating its owner; during the severest part of winter they were sometimes brought down and fed as well as their owners could afford. They seem frequently to have been bred for exportation.

Sheep, latterly so intimately associated with the Highlands, bore but a very small proportion to the number of black cattle. Indeed, before sheep-farming began to take place upon so large a scale, and to receive encouragement from the proprietors, the latter were generally in the habit of restricting their tenants to a limited number of sheep, seldom more than one sheep for one cow. This restriction appears to have arisen from the real or supposed interest of the landlord, who looked for the money part of his rent solely from the produce of sale of the tenants’ cattle. Sheep were thus considered not as an article of profit, but merely as part of the means by which the farmer’s family was clothed and fed, and therefore the landlord was anxious that the number should not be more than was absolutely necessary. In a very few years after 1745, a complete revolution took place in this respect.

The old native sheep of the Highlands, now rare, though common in some parts of Shetland, is thus described by Dr Walker. “It is the smallest animal of its kind. It is of a thin lank shape, and has short straight horns. The face and legs are white, the tail extremely short, and the wool of various colours; for, beside black and white, it is sometimes of a bluish grey colour, at other times brown, and sometimes of a deep russet, and frequently an individual is blotched with two or three of these different colours. In some of the low islands, where the pasture answers, the wool of this small sheep is of the finest kind, and the same with that of Shetland. In the mountainous islands, the animal is found of the smallest size, with coarser wool, and with this[15] very remarkable character, that it has often four, and sometimes even six horns.

“Such is the original breed of sheep over all the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. It varies much indeed in its properties, according to the climate and pasture of different districts; but, in general, it is so diminutive in size, and of so bad a form, that it is requisite it should be given up, wherever sheep-farming is to be followed to any considerable extent. From this there is only one exception: in some places the wool is of such a superior quality, and so valuable, that the breed perhaps may, on that account, be with advantage retained.”

The small, shaggy black cattle, so well known even at the present day in connection with the Highlands, was the principal live-stock cultivated previous to the alterations which followed 1745. This breed appears to have been excellent in its kind, and the best adapted for the country, and was quite capable of being brought to admirable perfection by proper care, feeding, and management. But little care, however, was bestowed on the rearing of these animals, and in general they were allowed to forage for themselves as best they could. As we have said already, the Highland farmer of those days regarded his cattle as the only money-producing article with which his farm was stocked, all the other products being necessary for the subsistence of himself and his family. It was mainly the cattle that paid the rent. It was therefore very natural that the farmer should endeavour to have as large a stock of this commodity as possible, the result being that, blind to his own real interests, he generally to a large extent overstocked his farm. According to Dr Walker,[27] over all the farms in the north, there was kept above one-third more of cattle than what under the then prevailing system of management could be properly supported. The consequence of course was, that the cattle were generally in a half-fed and lean condition, and, during winter especially, they died in great numbers.

As a rule, the arable land in the Highlands bore, and still bears, but a very small proportion to that devoted to pasture. The arable land is as a rule by the sea-shore, on the side of a river or lake, or in a valley; while the rest of the farm, devoted to pasturage, stretches often for many miles away among the hills. The old mode of valuing or dividing lands in Scotland was into shilling, sixpenny, and threepenny lands of Scotch money. Latterly the English denomination of money was used, and these divisions were termed penny,[28] halfpenny, and farthing lands. A tacksman generally rented a large number of these penny lands, and either farmed them himself, or, as was very often done, sublet them to a number of tenants, none of whom as a rule held more than a penny land, and many, having less than a farthing land, paying from a few shillings to a few pounds of rent. Where a number of tenants thus rented land from a tacksman or proprietor, they generally laboured the arable land in common, and each received a portion of the produce proportioned to his share in the general holding. The pasturage, which formed by far the largest part of the farm, they had in common for the use of their cattle, each tenant being allowed to pasture a certain number of cattle and sheep, soumed or proportioned[29] to the quantity of land he held. “The tenant of a penny land often keeps four or five cows, with what are called their followers, six or eight horses, and some sheep. The followers are the calf, a one-year-old, a two-year-old, and a three-year-old, making in all with the cow five head of black cattle. By frequent deaths among them, the number is seldom complete, yet this penny land has or may have upon it about twenty or twenty-five head of black cattle, besides horses and sheep.” The halfpenny and farthing lands seem to have been allowed a larger proportion of live stock than the penny lands, considering their size.[30] It was seldom, however, that a tenant confined himself strictly to the number for which he was soumed, the desire to have as much as possible of the most profitable commodity frequently inducing to overstock, and thus defeat his main purpose.

During summer and autumn, the cattle and other live stock were confined to the hills to prevent them doing injury to the crops, for[16] the lands were totally unprotected by enclosures. After the ground was cleared of the crops, the animals were allowed to roam promiscuously over the whole farm, if not over the farms of a whole district, having little or nothing to eat in the winter and spring but what they could pick up in the fields. It seems to have been a common but very absurd notion in the Highlands that the housing of cattle tended to enfeeble them; thus many cattle died of cold and starvation every winter, those who survived were mere skeletons, and, moreover, the farmer lost all their dung which could have been turned to good use as manure. Many of the cows, from poverty and disease, brought a calf only once in two years, and it was often a month or six weeks before the cow could give sufficient milk to nourish her offspring. Thus many of the Highland cattle were starved to death in their calf’s skin.