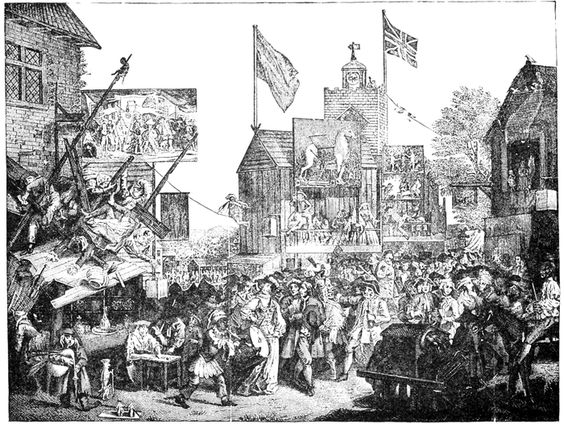

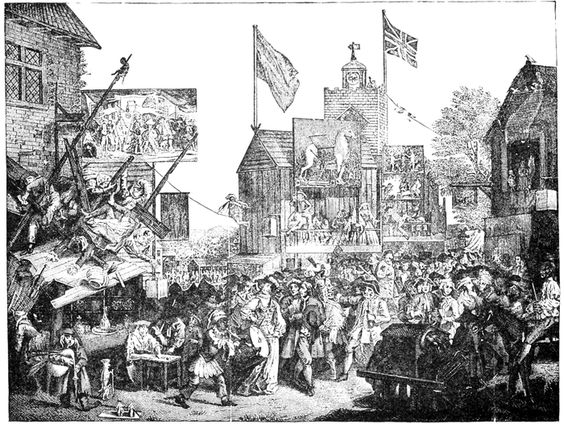

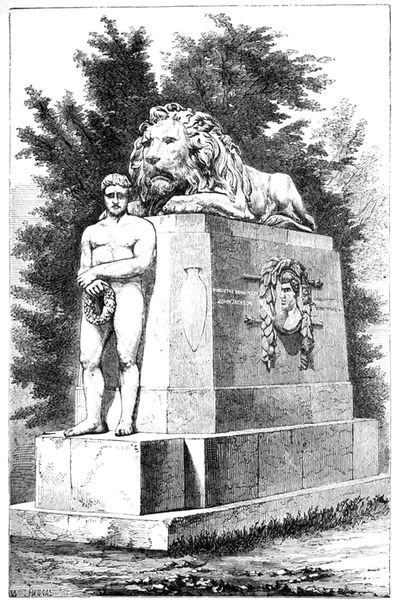

SOUTHWARK FAIR.

Vol. 1. Frontispiece

Project Gutenberg's Pugilistica, Volume 1 (of 3), by Henry Downes Miles

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Pugilistica, Volume 1 (of 3)

The History of British Boxing Containing Lives of the Most

Celebrated Pugilists; Full Reports of Their Battles from

Contemporary Newspapers, With Authentic Portraits, Personal

Anecdotes, and Sketches of the Principal Patrons of the

Prize Ring, Forming a Complete History of the Ring from

Fig and Broughton, 1719-40, to the Last Championship Battle

Between King and Heenan, in December 1863

Author: Henry Downes Miles

Release Date: May 9, 2019 [EBook #59465]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUGILISTICA, VOLUME 1 (OF 3) ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing, deaurider and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

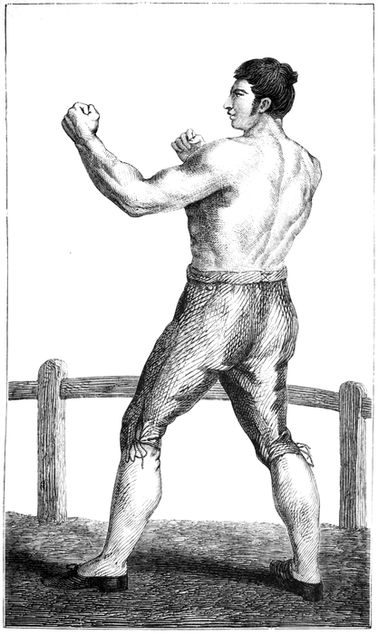

SOUTHWARK FAIR.

Vol. 1. Frontispiece

The history of “the Ring,” its rise and progress, the deeds of the men whose manly courage illustrate its contests in the days of its prosperity and popularity, with the story of its decline and fall, as yet remain unwritten. The author proposes in the pages which follow to supply this blank in the home-records of the English people in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The space covered in these volumes extends over one hundred and forty-four years, from the time when James Fig (the first acknowledged champion) opened his amphitheatre in the Oxford Road, in May, 1719, to the championship battle between John Camel Heenan, the American, and Tom King, the English champion, at Wadhurst, in Kent, on the 10th of December, 1863.

The author trusts he may claim, without laying himself open to a charge of egotism, exceptional qualifications for the task he has undertaken. His acquaintance with the doings of the Ring, and his personal knowledge of the most eminent professors of pugilism, extend over a retrospect of more than forty years. For a considerable portion of that period he was the reporter of its various incidents in Bell’s Life in London, in the Morning Advertiser, and various periodical publications which, during the better days of its career, gave a portion of their space to chronicle its doings. That the misconduct of its members, the degeneracy and dishonesty of its followers led to the deserved extinction of the Ring, he is free to admit: still, as a septuagenarian, he desires to preserve the memory of many brave and honourable deeds which the reader will here find recorded.

A few lines will suffice to elucidate the plan of the work.

Having decided that its most readable form would be that of a series of biographies of the principal boxers, in chronological order, so far as practicable, it was found convenient to group them in “Periods;” as each notable champion will be seen to have visibly impressed his style and characteristics on the period in which he and his imitators, antagonists or, as we may call it, “school” flourished in popular favour and success.

A glance at the “Lives of the Boxers” thus thrown into groups will explain this arrangement:—

Period I.—1719 to 1791.—From the Championship of Fig to the first appearance of Daniel Mendoza.

Period II.—1784 to 1798.—From Daniel Mendoza to the first battle of James Belcher.

Period III.—1798 to 1809.—From the Championship of Belcher to the appearance of Tom Cribb.

Period IV.—1805 to 1820.—From Cribb’s first battle to the Championship of Tom Spring.

⁂ To each period there is an Appendix containing notices and sketches of the minor professors of the ars pugnandi and of the light-weight boxers of the day.

Period V.—1820 to 1824.—From the Championship of Spring to his retirement from the Ring.

Period VI.—1825 to 1835.—From the Championship of Jem Ward to the appearance of Bendigo (William Thompson) of Nottingham.

Period VII.—1835 to 1845.—From the appearance of Bendigo to his last battle with Caunt.

Period VIII.—1845 to 1857.—The interregnum. Bill Perry (the Tipton Slasher), Harry Broome, Tom Paddock, &c.

Period IX.—1856 to 1863.—From the appearance of Tom Sayers to the last Championship battle of King and Heenan, December, 1863.

In “the Introduction” I have dealt with the “Classic” pugilism of Greece and Rome. The darkness of the middle ages is as barren of record of “the art of self-defence” as of other arts. With their revival in Italy we have an amusing coincidence in the “Memoirs of Benvenuto Cellini,” in which a triumvirate of renowned names are associated with the common-place event of “un grande punzone del naso”—a mighty punch on the nose.

“Michael-Angelo (Buonarotti’s) nose was flat from a blow which he received in his youth from Torrigiano,[1] a brother artist and countryman, who gave me the following account of the occurrence: ‘I was,’ said Torrigiano, ‘extremely irritated, and, doubling my fist, gave him such a violent blow on the nose that I felt the cartilages yield as if they had been made of paste, and the mark I then gave him he will carry to the grave.’” Cellini adds: “Torrigiano was a handsome man, of consummate audacity, having rather the air of a bravo than a sculptor: above all, his strange gestures,” [were they boxing attitudes?] “his enormous voice, with a manner of knitting his brows, enough to frighten any man who faced him, gave him a tremendous aspect, and he was continually talking of his great feats among ‘those bears of Englishmen,’ whose country he had lately quitted.”

Who knows—sempre il mal non vien par nocuere—but we have to thank the now-neglected art, whose precepts and practice inculcated the use of Nature’s weapon, that the clenched hand of Torrigiano did not grasp a stiletto? What then would have been the world’s loss? The majestic cupola of St. Peter’s, the wondrous frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, “The Last Judgment,” the “Sleeping Cupid” of Mautua, the “Bacchus” of Rome, and all the mighty works of the greatest painter, sculptor, and architect of the 16th century, had probably been uncreated had not Michael-Angelo’s fellow-student learned among “those bears of Englishmen,” the art of administering a “mighty punch on the nose” in lieu of the then ready stab of a lethal weapon.

The testimony of St. Bernard to the merits of boxing as a substitute for the deadly combats of his time, with an extract from Forsyth’s “Excursion in Italy,” will be found at page xv. of the Introduction to this volume; and these may bring us to the period when the first Stuart ascended the throne of “Merrie Englande.”

In Dr. Noble’s “History of the Cromwell Family,” we find the following interesting notice of the fistic prowess of the statesman-warrior who, in after-times, “made the sovereigns of Europe court the alliance and dread the might of England’s arm.” At p. 94 vol. i., we read:—

“They have a tradition at Huntingdon, that when King Charles I. (then Duke of York), in his journey from Scotland to London, in the year 1604, rested in his way at Hinchenbrooke, the seat of Sir Oliver Cromwell; the knight, to divert the young prince, sent for his nephew Oliver, that he, with his own sons, might play with his Royal Highness. It so chanced that the boys had not long been together before Charles and Oliver disagreed, and came to blows. As the former was a somewhat weakly boy, and the latter strong, it was no wonder the royal visitor was worsted. Oliver, even at this age, so little regarded dignity that he made the royal blood flow copiously from the Prince’s nose. This was looked upon by many as a bad presage for the King when the civil war had commenced.” The probability of this incident has been flippantly questioned. The writer has lighted on the following in the dry pages of “Toone’s Chronology,” under James I. “1603. April 27th. The King, arriving at Hinchenbrooke, was magnificently entertained by Sir Oliver Cromwell, where also the Cambridge Doctors waited upon his Majesty. May 3. The King arrived at Theobalds, in Hertfordshire, the seat of Mr. Secretary Cecil’s. He made 200 Knights on his arrival in London and on his journey thither from Edinburgh.” And in the next page we read: “1604. Jan. 4. Prince Charles came into England (from Scotland) and was created Duke of York. He had forty pounds per annum settled on him that he might more honourably maintain that dignity.” It may be as well to observe that Charles I. and Cromwell were of an age (both born in 1599), and each of them five years old in 1604‒5; so that this juvenile encounter is highly probable, exemplifying that “the child is father of the man.”

Again in Malcolm’s “Manners and Customs of London,” vol. i., p. 425, we find the subjoined extract from The Protestant Mercury, of January, 1681, which we take to be the first prize-fight on newspaper record.

“Yesterday a match of boxing was performed before his Grace the Duke of Albemarle, between the Duke’s footman and a butcher. The latter won the prize, as he hath done many before, being accounted, though but a little man, the best at that exercise in England.”

“Here be proofs”: 1, of ducal patronage; 2, of a stake of money; 3, of the custom of public boxing; 4, of the skill of the victor, “he being but a little man;” and all in a five-line paragraph. The names of the Champions are unwritten.

This brings us to the period at which our first volume opens, in which will be found the deeds and incidents of the Pugilists, the Prize-ring, and its patrons, detailed from contemporary and authentic sources, down to the opening of the present century. We cannot, however, close this somewhat gossiping preface without an extract from a pleasant paper which has just fallen under our notice, in which some of the notable men who admired and upheld the now-fallen fortunes of boxing are vividly introduced by one whose reminiscences of bygone men and manners are given in a sketch called “The Last of Limmer’s.” To the younger reader it may be necessary to premise, that from the days when the Prince Regent, Sheridan, and Beau Brummel imbibed their beeswing—when the nineteenth century was in its infancy—down to the year of grace 1860, the name of “Limmer’s Hotel” was “familiar in sporting men’s mouths as household words,” and co-extensive in celebrity with “Tattersall’s” and “Weatherby’s.”

Said “brimmers,” hodie “bumpers,” being a compound of gin, soda-water, ice lemon, and sugar, said to have been invented by John Collins, but recently re-imported as a Yankee novelty. This per parenthesis, and we return to our author.

“In that little tunnelled recess at the bottom of the dark, low-browed coffee-oom, the preliminaries of more prize-fights have been arranged by Sir St. Vincent Cotton, Parson Ambrose, the late Lord Queensberry, Colonel Berkeley, his son, the Marquis Drumlanrig, Sir Edward Kent, the famous Marquis of Waterford, Tom Crommelin, the two Jack Myttons, the late Lord Longford, and the committee of the Fair-play Club, than in the parlour of No. 5, Norfolk Street (the sanctum of Vincent Dowling, Editor of Bell’s Life), in Tom Spring’s parlour, or Jem Burn’s ‘snuggery.’

“Let it not be imagined that any apology is needed, nor will be here vouchsafed in defence of those to whom, whatever may have been their station in life, the prize-ring was formerly dear. The once well-known and well-liked Tom Crommelin, for instance, is the only survivor among those whom we chance to have named, but in his far-distant Australian home he will have no cause to remember with regret that he has often taken part in the promotion of pugilistic encounters.

“During the present century Great Britain has produced no more manly, no honester, or more thoroughly English statesman than the uncle of the present Earl Spencer, better known in political history under the name of Lord Althorp. The late Sir Denis Le Marchant, in his delightful memoir of the nobleman who led the House of Commons when the great Reform Bill was passed, tells us that ‘Lord Althorp made a real study of boxing, taking lessons from the best instructors, whilst practising most assiduously, and, as he boasted, with great success. He had many matches with his school-fellow, Lord Byron, and those who witnessed his exploits with the gloves, and observed his cool, steady eye, his broad chest and muscular limbs, and, above all, felt his hard blows, would have been justified in saying that he was born to be a prize-fighter rather than a Minister of State.’ Long after the retirement of Lord Althorp from office, Mr. Evelyn Denison, who died as Lord Ossington, paid him a visit at Wiseton, ‘The pros and cons of boxing were discussed,’ writes the late Speaker, ‘and Lord Althorp became eloquent. He said that his conviction of the advantages of pugilism was so strong that he had been seriously considering whether it was not a duty that he owed to the public to go and attend every prize-fight which took place, and thus to encourage the noble science to the extent of his power. He gave us an account of prize-fights which he had attended—how he had seen Mendoza knocked down for the first five or six rounds by Humphries, and seeming almost beaten until the Jews got their money on, when, a hint being given, he began in earnest and soon turned the tables. He described the fight between Gully and the Chicken—how he rode down to Brickhill himself, and was loitering about the inn door, when a barouche and four drove up with Lord Byron and a party, and Jackson, the trainer—how they all dined together, and how pleasant it had been. Next day came the fight, and he described the men stripping, the intense excitement, the sparring, then the first round, and the attitudes of the men—it was really worthy of Homer.’

“A pursuit which was enthusiastically supported and believed in by William Windham, Charles James Fox, Lord Althorp, and Lord Byron, stands in little need of modern excuse on behalf of its promoters when Limmer’s was at its apogee. Full many a well-known pugilist, with Michael-Angelo nose and square-cut jaw, has stood, cap in hand, at the door of that historical coffee-room within which Lord Queensberry—then Lord Drumlanrig—and Captain William Peel and the late Lord Strathmore were taking their meals. In one window stands Colonel Ouseley Higgins, Captain Little, and Major Hope Johnstone. A servant of the major’s, with an unmistakable fighting face, enters with a note for his master. It is from Lord Longford and Sir St. Vincent Cotton asking him to allow his valet to be trained by Johnny Walker for a proximate prize fight. The servant, who is no other than William Nelson, the breeder (before his death) of Plebeian, winner of the Middle Park Plate, however, firmly declines the pugilistic honours his aristocratic patrons design for him, so the fight is off. Hard by maybe seen the stately Lord George Bentinck, in conference with his chief-commissioner, Harry Hill,” &c., &c. We here break off the reminiscences of Limmer’s, as the rest of this most readable paper deals solely with the celebrities of the turf.

The last time the writer saw the late Sir Robert Peel, was at Willis’s Rooms, in King Street, on the occasion of an Assault of Arms, given by the Officers of the Household Brigade, whereat the art of self-defence was illustrated by the non-commissioned officers of the Life Guards, Grenadier Guards, and Royal Artillery. Corporal-Majors Limbert and Gray, Sergeants Dean and Venn, Corporal Toohig (Royal Artillery), with Professors Gillemand, Shury, and Arnold, displayed their skill with broadsword, foil, single-stick, and sabre against bayonet. The gloves, too, were put on, and some sharp and manly bouts played by the stalwart Guardsmen. The lamented Minister watched these with approving attention. Then came a glove display in which Alec Keene put on the mittens with Arnold, the “Professor of the Bond Street Gymnasium.” The sparring was admirable, and sir Robert, who was in the midst of an aristocratic group, pressed forward to the woollen boundary-rope. His eyes lighted up with the memories of Harrow school-days and he clapped his hands in hearty applause of each well-delivered left or right and each neat stop or parry. The bout was over, and neither was best man. The writer perceived the deep interest of Sir Robert, and conveyed to the friendly antagonists the desire of several gentlemen for “one round more.” It was complied with, and closed with a pretty rally, in which a clean cross-counter and first and sharpest home from Keene’s left proved the finale amid a round of applause. The practised pugilist was too many for the professor of “mimic warfare.” Next came another clever demonstration of the arts of attack and defence by Johnny Walker and Ned Donnelly. Sir Robert was as hilarious as a schoolboy cricketer when the winning run is got on the second innings. Turning to Mr. C. C. Greville and the Hon. Robert Grimstone, he exclaimed, “There is nothing that interests me like good boxing. It asks more steadiness, self-control, aye, and manly courage than any other combat. You must take as well as give—eye to eye, toe to toe, and arm to arm. Give my thanks to both the men, they are brave and clever fellows, and I hope we shall never want such among our countrymen.” It is gratifying to add that, to our knowledge, these sentiments are the inheritance of the third Sir Robert, whose manly and patriotic speech, at Exeter Hall, on the 17th of February, 1878, rings in our ears as we write these lines.

With such patrons of pugilism as those who faded away in “the last days of Limmer’s,” departed the fair play, the spirit, and the very honesty, often tainted, of the Ring. A few exceptional struggles—due rather to the uncompromising honesty and courage of the men, or the absence of the blacklegs, low gamblers, Hebrews, and flash publicans from the finding of the stakes, or making the market odds—occurred from time to time; but these were mere flickerings of the expiring flame. The Ring was doomed, not less by the misconduct of its professors than by the discord and dishonest doings of its so-called patrons and their ruffianly followers, unchecked by the saving salt of sporting gentlemen and men of honour, courage, and standing in society. Down, deeper down, and ever downward it went, till in its last days it became merely a ticket-selling swindle in the hands of keepers of Haymarket night-houses, and slowly perished in infamy and indigence. Yet, cannot the writer, looking back through a long vista of memorable battles, and with the personal recollection of such men as Cribb (in his latter days), Tom Spring, Jem Ward (still living), Painter, Neale, Jem Burn, John Martin, Frank Redmond, Owen Swift, Alec Keene, with Tom Sayers, his opponent John Heenan, and Tom King, the Ultimus Romanorum (now—1878—taking prizes as a floriculturist at horticultural shows), believe that the art which was practised by such men was without redeeming qualities. He would not seek to revive the “glory of the Ring,” that is past, but he has thought it a worthy task to collect and preserve its memories and its deeds of fortitude, skill, courage, and forbearance, of which these pages will be found to contain memorable, spirit-stirring, and honourable examples.

The curious reader may find some interest in a few paragraphs on the Bibliography of Boxing; for the Ring had a contemporary literature, contributed to by the ablest pens; and to this, in the earlier periods of its history, the author would be an ingrate were he not to acknowledge his indebtedness.

The earliest monograph is a neatly printed small quarto volume, entitled, A Treatise on the Useful Art of Self-Defence. By Captain Godfrey. The copy in the British Museum (bearing date 1740) appears to be a second edition. It has for its title Characters of the Masters. There is also a handsomely bound copy of the work in the Royal Library, presented to the nation by George III. The volume is dedicated to H.R.H. William, Duke of Cumberland. Frequent quotations are made from this book.

The Gymnasiud, or Boxing Match. A Poem. By the Champion and Bard of Leicester House, the Poet Laureate (Paul Whitehead), 1757. See page 19 of this volume.

In Dodsley’s Collections, 1777, &c., are various poetic pieces by Dr. John Byrom, Bramston (Man of Taste), and others, containing sketches of pugilism and allusions to the “fashionable art” of boxing, “or self-defence.”

During this period, The Gentleman’s Magazine, The Carlton House Magazine, The Flying Post, The Daily News Letter, The World, The Mercury, The Daily Advertiser (Woodfall’s), and other periodical publications, contained reports of the principal battles in the Ring.

Recollections of Pugilism and Sketches of the Ring. By an Amateur. 8vo. London, 1801.

Recollections of an Octogenarian. By J. C. 8vo. London, 1805. (See pp 29, 30.)

Lives of the Boxers. By Jon Bee, author of the “Lexicon Balatronium,” and “The Like o’ That.” 8vo. London, 1811.

Pancratia: a History of Pugilism. 1 vol. 8vo. 1811. By J. B. London: George Smeeton, St. Martin’s Lane.

Training for Pedestrianism and Boxing. 8vo. 1816. By Captain Robert Barclay (Allardyce of Ury).

This pamphlet contains an account of the Captain’s training of Cribb for his fight with Molineaux.

The Fancy: A Selection from the poetical remains of Peter Corcoran, Esq., student of Law (Pseudonymous). London: 1820. Quoted p. 313 of this volume.

Boxiana: Sketches of Antient and Modern Pugilism. Vol. I. 8vo. London: G. Smeeton, 139, St. Martin’s Lane, Charing Cross, July, 1812.

This very scarce volume, which was the production of George Smeeton, a well known sporting printer and engraver, was the basis of the larger work Boxiana, subsequently written and edited by Pierce Egan, and of which five volumes, appeared between 1818 and 1828. The well-written “Introduction,” much disfigured by the illiterate editor, were incorporated, and the handsome copperplate title-page will be found bound into the later work published by Sherwoods, Jones & Co. Pierce Egan was, at one time, a compositor in Smeeton’s office, and continued the work for Sherwoods.

Boxiana. Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism, from the days of the renowned Broughton and Slack to the Championship of Crib. By Pierce Egan. In two volumes. London: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, Paternoster Row, 1818.

This was the first complete book. A third volume followed in 1825. There are two fourth volumes owing to a circumstance which requires explanation. That published by George Virtue, and bearing the name of Pierce Egan, has for its title New Series of Boxiana: the only Original and Complete Lives of the Boxers. By Pierce Egan. London: George Virtue, Ivy Lane, Paternoster Row. Vol. I., 1828. Vol. II., 1829. These are generally bound as Vols. IV. and V., in sets of Boxiana. The other volume, IV., is identical in title, but not in contents, with Pierce Egan’s first volume of the “new series,” omitting those words. It was written by Jon Bee, for Messrs. Sherwoods, who moved an injunction against Pierce Egan for selling his fourth volume to another publisher. Lord Chancellor Eldon merely compelled Pierce Egan to prefix the words “new series” to his book, and the matter ended.

A Lecture on Pugilism: Delivered at the Society for Mutual Improvement, established by Jeremy Bentham, Esq., at No. 52, Great Marlborough Street, Oxford Street, April 14th, 1820. By S[eptimus] M[iles]. 8vo., 24 pp., White, 1820. This curious and elaborate defence of pugilism seems rather to have been a rhetorical exercitation for discussion at a debating society than a defence. It is printed at the end of the third volume of Boxiana.

Boxing; with a Chronology of the Ring, and a Memoir of Owen Swift. By Renton Nicholson. London: Published at 163, Fleet Street. 1837.

Owen Swift’s Handbook of Boxing. 1840. With Steel Portrait by Henning. This was also written by the facetious Renton Nicholson—styled “Chief-Baron Nicholson,” and originator of the once-famous “Judge and Jury” Society.

The Handbook of Boxing and Training for Athletic Sports. By H. D. M[iles]. London: W. M. Clark, Warwick Lane, Paternoster Row, 1838.

Fistiana; or, the Oracle of the Ring. By the Editor of Bell’s Life in London. This pocket volume, containing a Chronology of the Ring, the revised rules, forms of articles, duties of seconds, umpires, and referee, reached its 24th and last edition in 1864, and expired only with the ring itself. Its author, Mr. Vincent George Dowling, the “Nestor of the Ring,” a gentleman and a scholar, also contributed the article “Boxing” to Blaine’s “Cyclopædia of Rural Sports,” Longmans, 1840.

Fights for the Championship. 1 vol., 8vo. By the Editor of Bell’s Life in London. London: published at 170, Strand, 1858.

Championship Sketches, with Portraits. By Alfred Henry Holt. London: Newbold, Strand, 1862.

The Life of Tom Sayers. By Philopugilis. 8vo., with Portrait. London: S. O. Beeton, 248, Strand, 1864. [By the author of the present work.]

Among the authors of the early years of the present century, whose pens illustrated the current events of boxers and boxing, we may note, Tom Moore the poet, who contributed occasional squibs to the columns of the Morning Chronicle, and in 1818 published the humorous versicles, Tom Cribb’s Memorial to Congress, quoted at p. 306 of this volume. Lord Byron. See Moore’s “Life and Letters,” “Memoir of Jackson,” pp. 97, 98.

Christopher North (Professor Wilson) the Editor of Blackwood’s Magazine in the Noctes Ambrosiane, puts into the mouth of the Ettrick Shepherd (James Hogg) an eloquent defence of pugilism, while he takes opportunity, through Sir Morgan O’Doherty, to praise the manliness, fair play, and bravery of contemporary professors of boxing. Several sonnets and other extracts from Blackwood will be found scattered in these volumes.

Dr. Maginn (the Editor of Frazer’s Magazine), also exercised his pen in classic imitations apropos of our brave boxers.

Last, but not least, the gifted author of Pendennis, The Virginians, Esmond, Vanity Fair, Jeames’s Diary, &c., &c., has perpetuated the greatness of our latest champions in a paraphrase, rather than a parody of Macaulay’s “Lays of Ancient Rome,” entitled “Sayerinus and Henanus; a Lay of Ancient London,” which contains lines of power to make the blood of your Englishmen stir in days to come, should the preachers of peace-at-any-price, pump water, parsimonious pusillanimity, puritanic precision and propriety have left our youth any blood to stir. See “Life of Sayers,” in vol. iii. Volumes cannot better express the contempt which this keen observer of human nature and satirist of shams entertained for the mawworms, who “compound for sins they are inclined to by damning those they have no mind to,” than the subjoined brief extract:—

“Fighting, of course, is wrong; but there are occasions when.... I mean that one-handed fight of Sayers is one of the most spirit-stirring little stories; and with every love and respect for Morality, my spirit says to her, ‘Do, for goodness’ sake, my dear madam, keep your true, and pure, and womanly, and gentle remarks for another day. Have the great kindness to stand a leetle aside, and just let us see one or two more rounds between the men. That little man with the one hand powerless on his breast facing yonder giant for hours, and felling him, too, every now and then! It is the little Java and the Constitution over again.’”—W. M. Thackeray.

Or the following “happy thought,” to which Leech furnished an illustrative sketch:—

“Serious Governor.—‘I am surprised, Charles, that you can take any interest in these repulsive details! How many rounds (I believe you term them) do you say these ruffians fought? Um, disgraceful! the Legislature ought to interfere; and it appears that this Benicia Man did not gain the—hem—best of it? I’ll take the paper when you have done with it, Charles.’”—Punch Illustration, April 8, 1860.

1719. James Fig, of Thame, Oxfordshire.

1730‒1733. Pipes and Gretting (with alternate success).

1734. George Taylor.

1740. Jack Broughton, the waterman.

1750. Jack Slack, of Norfolk.

1760. Bill Stevens, the nailer.

1761. George Meggs, of Bristol.

1762. George Millsom, the baker.

1764. Tom Juchau, the paviour.

1765‒9. Bill Darts.

1769. Lyons, the waterman.

1771. Peter Corcoran (doubtful). He beat Bill Darts, who had previously been defeated by Lyons.

1777. Harry Sellers.

1780. Jack Harris (doubtful).

1783‒91. Tom Johnson (Jackling), of York.

1791. Benjamin Brain (Big Ben), of Bristol.

1792. Daniel Mendoza.

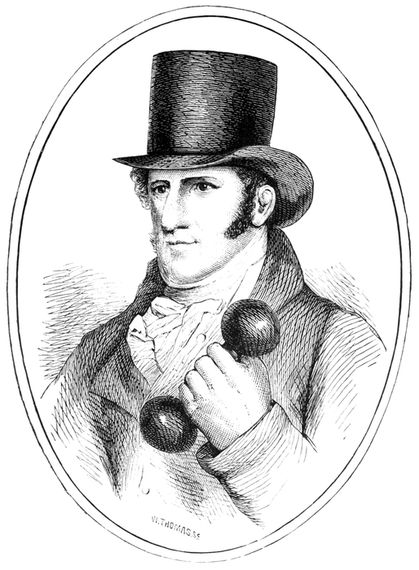

1795. John Jackson. (Retired.)

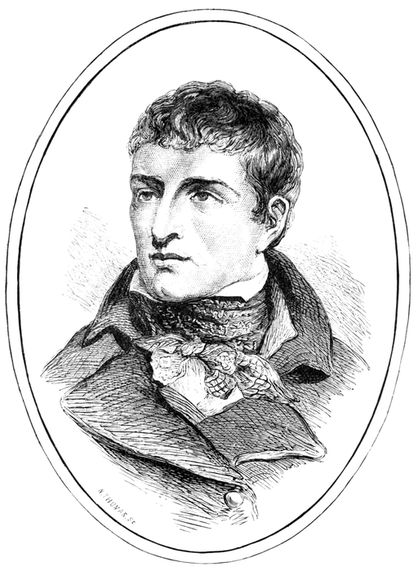

1800‒5. Jem Belcher, of Bristol.

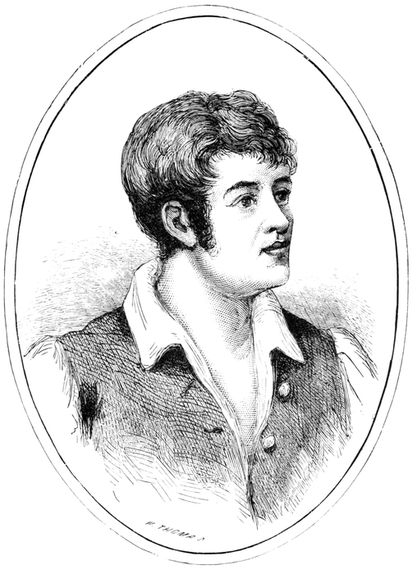

1805. Henry Pearce, the “Game Chicken.”

1808. (Retired). John Gully (afterwards M.P. for Pontefract).

1809. Tom Cribb, received a belt and cup, and retired.

1824. Tom Spring, received four cups, and retired.

1825. Jem Ward, received the belt.

1833. Jem Burke (the Deaf ’un), claimed the title.

1839. Bendigo (Wm. Thompson), of Nottingham, beat Burke, and received the belt from Ward.

1841. Benjamin Caunt, of Hucknall, beat Nick Ward, and received belt (transferable).

1845. Bendigo beat Caunt, and received the belt.

1850. Wm. Perry (Tipton Slasher), claimed belt, Bendigo declining his challenge.

1851. Harry Broome beat Perry, and claimed the title.

1853. Perry again challenged the title, and Broome retired from the ring.

1857. Tom Sayers beat Perry, and received the belt.

1860. Tom Sayers retired after his battle with Heenan, and left belt for competition.

1860. Samuel Hurst (the Staleybridge Infant), beat Paddock, the claimant, and received the belt.

1861. Jem Mace, of Norwich, beat Hurst, and claimed the title.

1863. Tom King beat Mace, and claimed the belt, but retired, and Mace claimed the trophy.

1863. Tom King beat J. C. Heenan for £1,000 a-side at Wadhurst, December 10th.

The origin of boxing has been assumed by some superficial writers as coeval with the earliest contests of man. This view appears to the writer both crude and unphilosophical. It might be argued with equal probability that the foil was antecedent to the sword, the sword to the dagger, or the singlestick to the club with which the first murder was perpetrated. The clumsiest and, so far as rude and blood-thirsty attack could contrive them, the most deadly weapons were the first used; the sudden destruction of life, not the art of defence, being the brutal instinct of the vengeful, cunning, and cowardly savage, or the treacherous manslayer. This, too, would lead us fairly to infer—as the most dangerous forms of the cæstus are the most ancient, and the naked fist in combat appears nowhere to have been used in the gladiatorial combats of Greece or Rome—that to England and her Anglo-Saxon race is due this fairest and least dangerous of all forms of the duel; and to attribute to a recent period the padded boxing-glove (at present the air or pneumatic glove), by means of which the truly noble art of self-defence can be safely and healthfully practised and illustrated.

The most polished people of antiquity included boxing among their sports. With them it was also a discipline, an exercise, and an art. A discipline, inasmuch as it was taught to pupils; an exercise, as followed in the public games; and an art, on account of the previous trainings and studies it presupposed in those who professed and practised it. Plutarch indeed asserts that the “pugilate” was the most ancient of the three gymnic games performed by the athletæ, who were divided into three classes—the Boxers, the Wrestlers, and the Runners. And thus Homer views the subject, and generally follows this order in his descriptions of public celebrations. This, too, is the natural sequence, in what philosopher Square would call “the eternal fitness of things.” First, the man attacks (or defends himself) with the fist; secondly, he closes or wrestles; and should fear, inferior skill, or deficient strength tell him he had better avoid the conflict, he resorts to the third course, and runs.

A word on the derivation of our words, pugilism, pugilist, and boxing, all of which have a common origin. Pugilism comes to us through the Latin pugilatus, the art of fighting with the fist, as also does pugnus, a fight. The Latin again took these words from the Greek πυγμὴ (pugmè), the fist doubled for fighting; whence also they had πύγμάχος (pugmachos), a fist-fighter, and πύγμαχια (pugmachia), a fist-fight. They had also πυγδον (pugdon), a measure of length from the elbow (cubitus) to the end of the vihand with the fingers clenched. Another form of the word, the Greek adverb πυξ (pux), pugno vel pugnis, gives us πυξος (puxos, Lat. buxus), in English, BOX; and it is remarkable that this form of the closed hand is the Greek synonyme for anything in the shape of a closed box or receptacle, and so it has passed to the moderns. The πυξ, box or pyx, is the chest in which the sacramental vessels are contained. Thus mine Ancient Pistol pleads for his red-nosed comrade:—

The French have also imported le boxe into their dictionaries, where the Germans had it already, as buchs, a box. But enough of etymology; wherever we got the word, the thing itself—fair boxing, as we practise it—is of pure English origin. The Greeks, however, cultivated the science in their fashion, confined it by strict rules, and selected experienced masters and professors, who, by public lessons, delivered gratis in Palestræ and Gymnasiæ, instructed youth in the theory and practice of the art. Kings and princes, as we learn from the poets, laid aside their dignity for a few hours, and exchanged the sceptre for the cæstus; indeed, in Greece, boxing, as a liberal art, was cultivated with ardour, and when (once in three years) the whole nation assembled at Corinth to celebrate their Isthmian games, in honour of Neptune, the generous admiration of an applauding people placed the crown on the brow of the successful pugilist, who, on his return home, was hailed as the supporter of his country’s fame. Even Horace places the pugilist before the poet:—

And in another place:—

The sententious Cicero also says:—“It is certainly a glorious thing to do well for the republic, but also to speak well is not contemptible.”

Having alluded to the poets who have celebrated pugilism, we will take a hasty glance at the demigods and heroes by whom boxing has been illustrated. Pollux, the twin brother of Castor—sprung from the intrigue of Jupiter with the beauteous Leda, wife of Tyndarus, King of Sparta, and mother of the fair Helen of Troy—presents us with a lofty pedigree as the tutelary deity of the boxers. The twins fought their way to a seat on Mount Olympus, as also did Hercules himself:—

the sign Gemini in our zodiac representing this pair of “pugs.” As one of viithe unsuccessful competitors with Pollux, we may here mention Amycus. He was a son of Neptune, by Melia, and was king of the Bebryces. When the Argonauts touched at his port, on their voyage to Colchis, he received them with much hospitality. Amycus was renowned for his skill with the cæstus, and he kept up a standing challenge to all strangers for a trial of skill. Pollux accepted his challenge; but we learn from Apollonius that Amycus did not fight fair, and tried by a trick to beat Pollux, whereupon that “out-and-outer” killed him, pour encourager les autres, we presume.[2] There were two other pugilists of the same name among the “school” taken by Æneas into Italy as we shall presently see.

Eryx, also, figures among the heaven-descended pugilists. He was the son of Venus, by Butes, a descendant of Amycus, and very skilful in the use of the cæstus. He, too, kept up a standing challenge to all comers, and so came to grief. For Hercules, who “barred neither weight, country, nor colour,” coming that way, took up the gauntlet, and knocked poor Eryx clean out of time; so they buried him on a hill where he had, like a pious son, built a beautiful temple in honour of his rather too easy mamma. It is but fair, however, in this instance, to state that there is another version of the parentage of Eryx, not quite so lofty, but, to our poor thinking, quite as creditable. It runs thus:—Butes, being on a Mediterranean voyage, touched at the three-cornered island of Sicily (Trinacria), and there, sailor fashion, was hooked by one Lycaste, a beautiful harlot, who was called by the islanders “Venus.” She was the mother of Eryx, and so he was called the son of Venus. (See Virgil, Æneid, b. v., l. 372.) However this may be, the temple of Eryx and the “Erycinian Venus” were most renowned, and Diodorus, the Sicilian, tells us that the Carthaginians revered Venus Erycina as much as the Sicilians themselves, identifying her with the Phœnician Astarte. So much for the genealogy of the fourth boxer.

Antæus here claims a place. We have had a couple from heaven (by Jupiter), and one from the sea (by Neptune), our next shall be from earth and ocean combined. Antæus, though principally renowned as a wrestler, is represented with the cæstus. He was the son of Terra, by Neptune; or, as the stud-book would put it, by Neptune out of Terra. He was certainly dreadfully given to “bounce,” for he threatened to erect a temple to his father with the skulls of his conquered antagonists; but he planned his house before he had procured the materials. The story runs, that whenever he kissed his “mother earth” she renewed his strength, from which we may fairly infer that he was an adept in the art of “getting down,” like many of our modern pugilists. Hercules, however, found out the dodge by which the artful Antæus got “second wind” and renewed strength. He accordingly put on “the squeeze,” and giving him a cross-lift, held him off the ground till he expired, which we take to have been foul play on the part of his Herculean godship.[3] There was another Antæus, a friend of Turnus, killed by Æneas in the Latin wars.

Of the Homeric boxers, Epeus and Euryalus are the most renowned. Epeus was king of the Epei, a people of the Peloponnesus; he was son of Endymion, and brother to Pæon and Æolus. As his papa was the paramour of the goddess of chastity, Diana, the family may be said to have moved in viiihigh society. The story of Endymion and the goddess of the moon has been a favourite with poets. Epeus was a “big one,” and, like others of Homer’s heroes, a bit of a bully.

In the twenty-third book of the Iliad we find the father of poetry places the games at the funeral of Patroclus in this order:—1, The chariot race; 2, the cæstus fight; 3, the wrestling; 4, the foot race. As it is with the second of these only that Epeus and Euryalus are concerned, we shall confine ourselves to the Homeric description.

So far the first report of a prize fight, which came off 1184 years B.C., in the last year of the siege of Troy, anno mundi, 3530.

There was another Epeus, son of Panopæus, who was a skilful carpenter, and made the Greek mare, commonly but erroneously called the Trojan horse,[4] in the womb of which the Argive warriors were introduced to the ruin of beleaguered Troy, as related in the second book of the “Æneid.”

Euryalus will be known by name to newspaper readers of the present day as having given name to the steam frigate in which our sailor Prince Alfred took his earliest voyages to sea: to the scholar he is known as a valiant Greek prince, who went to the Trojan war with eighty ships, at least so says Homer, “Iliad,” b. ii.

We may here note that Tydides (the family name of Diomed, as the son of Tydeus) was Euryalus’s second in the mill with Epeus, wherein we have just seen him so soundly thrashed by the big and bounceable Epeus. As Virgil generally invents a “continuation” or counterpart of the Homeric heroes for his “Æneid,” we find Euryalus made the hero of an episode, and celebrated for his immortal friendship with Nisus: with him he had a partnership in fighting, and they died together in a night encounter with the troops of the Rutulians, whose camp they had plundered, but were overtaken and slain. (Virg. Æneid, ix., 176.) We will now therefore shift the scene from Greece, and come to Sicily and Italy, and the early boxing matches there.

Æneas’ companions were a “school” of boxers, and met with the like in Italy, among whom Entellus, Eryx, and Antæus (already mentioned), Dares, Cloanthus, Gyges, Gyas, etc., may be numbered.

Entellus, the intimate of Eryx, and who conquered Dares at the funeral games of Anchises (father of Æneas) in Sicily, deserves first mention. He was even then an “old ’un,” but, unlike most who have “trusted a battle to a waning age,” comes off gloriously in the encounter; which, as we shall presently see, under Dares, gives an occasion for the second ring report of xantiquity, as well as a minute description of the cæstus itself. The lines from the fifth book of the “Æneid” need no preface. After the rowing match (with galleys), in which Cloanthus (see post) is the victor, Æneas thus addresses his assembled companions:—

Acestes then reproaches Entellus for allowing the prize to be carried off uncontested. Entellus pleads “staleness” and “want of condition,” but accepts the challenge.

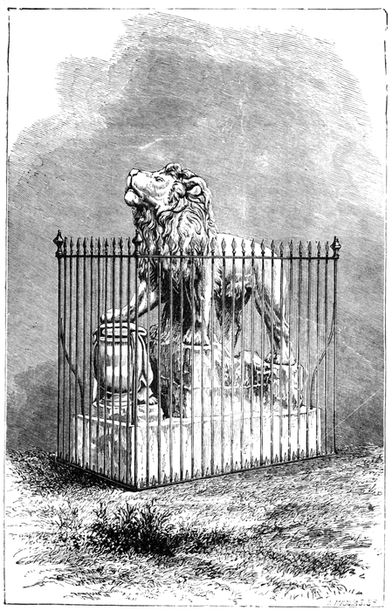

xiEntellus then throws down the gauntlets of Eryx (engraved under Cæstus, pp. xiii., xiv.), but Dares, declining the ponderous weapons, old Entellus offers to accommodate him, by permission of the umpires, with a round or two with a lighter pair.

At this point of the combat—when, after what ought to have closed xiiround 1, by the fall of old Entellus, the latter jumps up and renews the fight, driving Dares in confusion before him—we find that the referee and stakeholder had a judicial discretionary power to stop the fight, the more necessary on account of the deadly gloves in use. Some such power, in cases of closing and attempts at garotting (such as occurred at Farnham and at Wadhurst in 1860 and 1863, and numerous minor battles), should be vested in the referee; but then where is the man who in modern times would be efficiently supported or obeyed in this judicial exercise of authority?

The reader will doubtless be forcibly struck with the close imitation of Homer by the later epic poet. The length of this account—given, as are those in the ensuing pages, under the name of the winner—will render superfluous a lengthy notice of the vanquished—

Dares, another of the companions of Æneas, who also, like St. Patrick, was “a jontleman, and came of dacent people.” Indeed, we see that he claimed to be descended from King Amycus. Your ancient pugilists seem to have been as anxious about “blood” as a modern horse-breeder. Dares was afterwards slain by Turnus in Italy. See Virg. Æneid, v. 369, xii. 363.

Cloanthus, too, fought some good battles; and from him the noble Roman family of the Cluentii boasted their descent. In “Æneid,” v. 122, he wins the rowing match.

Of Gyges’ match we merely learn that Turnus also slew him; and of Gyas, that he greatly distinguished himself by his prowess in the funeral games of Anchises in Sicily. As to the “pious” Æneas himself, another son of Venus, by Anchises, he was a fighting man all his days. First, in the Trojan war, where he engaged in combat with Diomed and with Achilles himself, and afterwards, on his various voyagings in Sicily, Africa, and Italy, where he fought for a wife and a kingdom, and won both by killing his rival Turnus, marrying Lavinia, and succeeding his father-in-law, Latinus. Despite his “piety” in carrying off his old father Anchises from the flames of Troy, and giving him such a grand funeral, Æneas seems to have been a filibustering sort of vagrant; and after getting rid of poor Turnus, not without suspicions of foul play, he was drowned in crossing a river in Etruria, which territory he had invaded on a marauding expedition. We cannot say much against him on the score of “cruelty and desertion” in the matter of Queen Dido, seeing that chronology proves that the Carthaginian Queen was not born until about three hundred years after the fall of Troy, and therefore the whole story is the pure fabrication of the Roman poets, Virgil and Ovid. xiiiThis, however, is by the way, so we will proceed to give a short account of the implements used in ancient boxing.

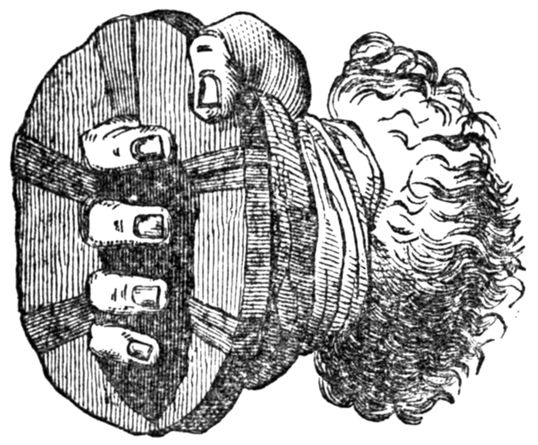

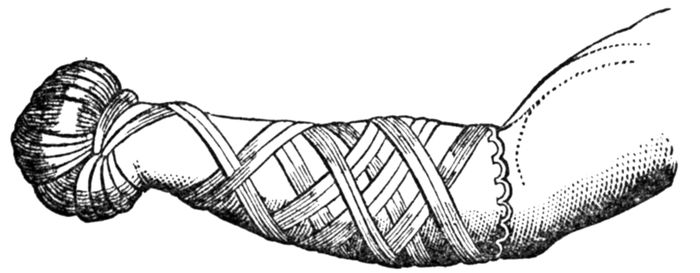

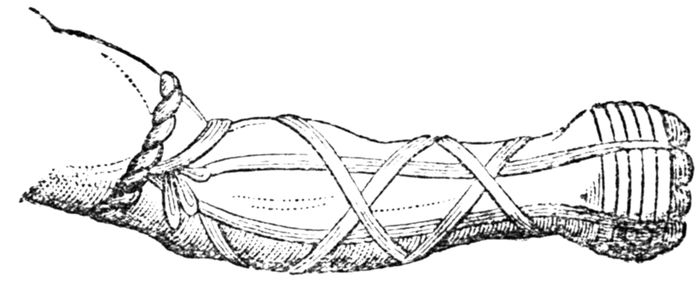

These were the Cæstus, a formidable gauntlet composed of thongs of raw hide, with the woollen glove covering the hand with its vellus or fringe; and the Amphotides, a kind of helmet or defensive armour for the head. Four principal forms of the cæstus are known by extant representations. The first is the most tremendous, and was found in bronze at Herculaneum. The original hand is somewhat above the natural size, and appears to have been part of the statue of some armed gladiator. It is formed of several thicknesses of raw hide strongly fastened together, and cut into a circular form. These have holes to admit the four fingers, the thumb being closed on the outer edge to secure the hold, while the whole is bound by thongs round the wrist and forearm, with its inner side on the palm of the hand and its outer edge projecting in front of the knuckles. Our Yankee friends have a small imitation in their modern “knuckle-dusters.” A glove of thick worsted was worn beneath the gauntlet, ending in a fringe or bunch of wool, called vellus. Lactantius says: “Pentedactylos laneos sub cæstibus habent.” The figure given in the Abbé St. Non’s, “Voyage Pittoresque de Naples et de Sicile,” is here copied.

Fig. 1.—Cæstus.

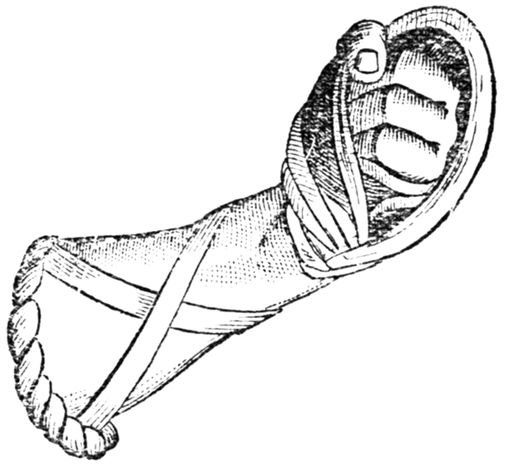

The second form of cæstus, though less deadly at first aspect, is capable of administering the most fatal blows. This sort is represented in a bronze group, engraved in the first volume of the “Bronzi del Museo Kircheriano,” which represents the battle between Amycus and Pollux, already noticed.

Fig. 2.

This (or the fourth form of glove) would also seem to have been that offered by Entellus to Dares in the fifth book of the Æneid, though the “knobs of brass,” “blunt points of iron,” “plummets of lead,” and other xivsuperfluities of barbarity, are not visible. Virgil’s description of the cæstus being the best, we here quote it:—

In Smith’s “Antiquities of Greece and Rome,” and in Lenu’s “Costumes des Peuples de l’Antiquité,” are other patterns. The subjoined is from the last named work.

Fig. 3.

The last form (No. 4) we shall give is also from a bas-relief found at Herculaneum. It is certainly of a less destructive form, the knuckles and back of the hand being covered by the leather, held in its place by a thumbhole, and further secured by two crossed straps to the vellus, which ends half way up the forearm. A similar engraving forms the tail-piece to the fifty-first page of the second volume of the Abbé St. Non’s “Voyage Pittoresque,” already quoted.

Fig. 4.

The Amphotides, a helmet or head-guard, to secure the temporal bones and arteries, encompassed the ears with thongs and ligatures, which were xvbuckled either under the chin or behind the head. They bore some resemblance to the head guards used in modern broadsword and stick play, but seem to have fitted close. They were made of hides of bulls, studded with knobs of iron, and thickly quilted inside to dull the concussion of the blows. Though it may be doubted whether the amphotides were introduced until a later period of the pugilistic era, yet as their representation would prevent the faces or heads of the combatants being seen, sculptors and fresco painters would leave them out unhesitatingly, as they do head-dresses, belts, reins, horses’ harness, etc., regardless of reality, and seeking only what they deemed high art in their representations.

The search after traces of boxing among the barbarism of the Middle Ages, with their iron cruelty and deadly warfare—not unredeemed, however, by rude codes of honour, knightly courtesy, and chivalrous gallantry, in defence of the weak and in honour of the fair—would not be worth the while. The higher orders jousted and tilted with lance, mace, and sword, the lower fought with sand-bags and the quarter-staff.

Wrestling, as an art, seems to have only survived among Gothic or Scandinavian peoples. A “punch on the head,” advocated by Mr. Grantley Berkeley as a poacher’s punishment, is, however, spoken of by Ariosto as the result of his romantic hero’s wrath, who gives the offender “un gran punzone sulla testa,” by way of caution. That there were “men before their time,” who saw the best remedy for the fatal abuse of deadly weapons in popular brawls, we have the testimony of no less an authority than St. Bernard. That holy and peace-loving father of the Church, as we are told by Forsyth, and numerous other writers, established boxing as a safety-valve for the pugnacious propensities of the people. He tells us: “The strongest bond of union among the Italians is only a coincidence of hatred. Never were the Tuscans so unanimous as in hating the other States of Italy. The Senesi agreed best in hating all the other Tuscans; the citizens of Siena in hating the rest of the Senesi; and in the city itself the same amiable passion was subdivided among the different wards.

“This last ramification of hatred had formerly exposed the town to very fatal conflicts, till at length, in the year 1200, St. Bernardine instituted Boxing as a more innocent vent to their hot blood, and laid the bruisers under certain laws, which are sacredly observed to this day. As they improved in prowess and skill, the pugilists came forward on every point of national honour: they were sung by poets and recorded in inscriptions. The elegant Savini ranks boxing among the holiday pleasures of Siena.”[5]

These desultory jottings must suffice to bring the history of boxing among the ancients down to the period of its gradual extinction as an art and its public and authorised practice. A few sentences from the pen of the late V. G. Dowling, Esq.[6] will appropriately close this introductory chapter.

“Both among the Greeks and Romans the practice of pugilism, although differing in its main features from our modern and less dangerous combats, was considered essential in the education of their youth, from its manifest utility in ‘strengthening the body, dissipating all fear, and infusing a manly courage into the system.’ The power of punishment, rather than the ‘art of self-defence,’ however, seems to have been the main object of the ancients; xviand he who dealt the heaviest blow, without regard to protecting his own person, stood foremost in the list of heroes. Not so in modern times; for while the quantum of punishment in the end must decide the question of victory or defeat, yet the true British boxer gains most applause by the degree of science which he displays in defending his own person, while with quickness and precision he returns the intended compliments of his antagonist, and like a skilful chess-player, takes advantage of every opening which chance presents, thereby illustrating the value of coolness and self-possession at the moment when danger is most imminent. The annals of our country from the invasion of the Romans downwards sufficiently demonstrates that the native Briton trusted more to the strength of his arm, the muscular vigour of his frame, and the fearless attributes of his mind in the hour of danger, than to any artificial expedients; and that, whether in attack or defence, the combination of those qualities rendered him at all times formidable in the eyes of his assailants, however skilled in the science or practice of warfare. If illustrations were required to establish this proposition, they are to be found in every page of our history, from the days of Alfred to the battle of Waterloo; and if it be asked how it is that Englishmen stand thus pre-eminent in the eyes of the world, it may be answered that it is to be ascribed to the encouragement given to those manly games (boxing more especially) which are characteristic of their country, and which, while they invigorate the system, sustain and induce that moral courage which experience has shown us to be the result as much of education as of constitution, perhaps more of the former than of the latter. The truth of this conclusion was so strongly impressed on the feelings of our forefathers, even in the most barbarous ages, that we find all their pastimes were tinctured with a desire to acquire superiority in their athletic recreations, thus in peace inculcating those principles which in war became their safest reliance.” Esto perpetua!

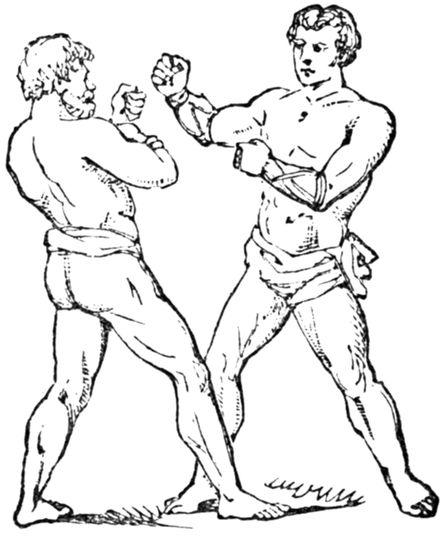

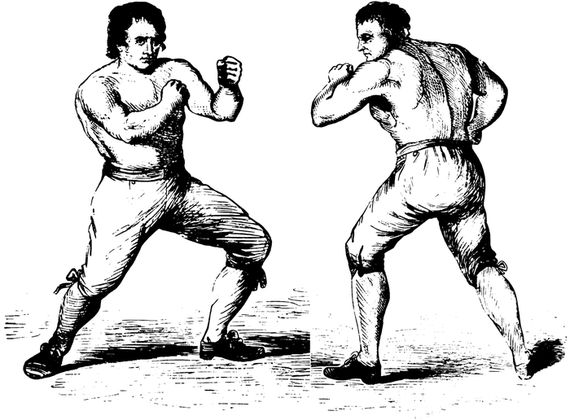

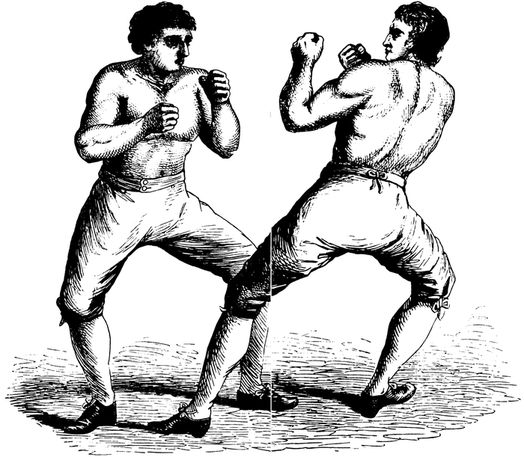

Boxers with the Cæstus.

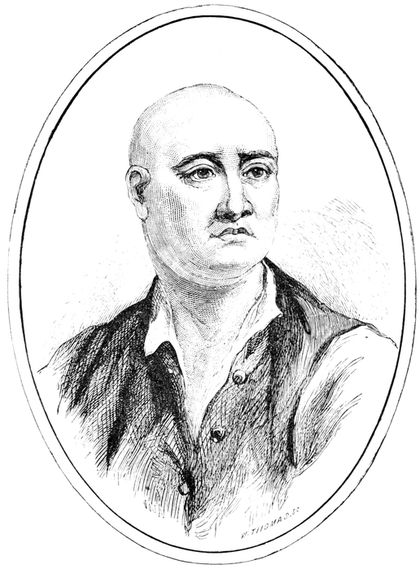

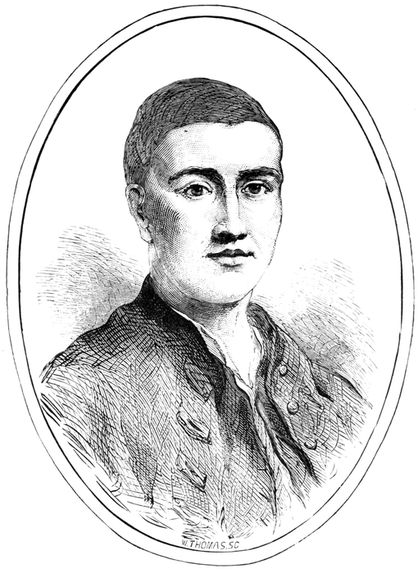

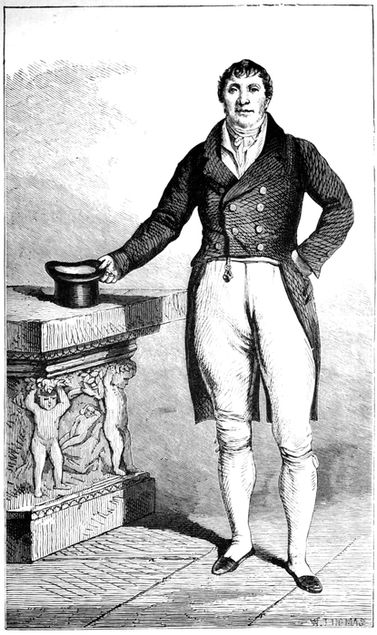

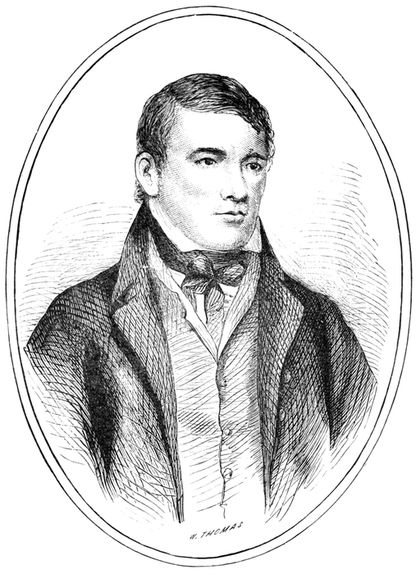

JAMES FIG (Champion).

From Sir James Thornhill’s Portrait, 1732.

We have collected in our Introductory Chapter the few scattered notices of pugilism as practised and understood by the earlier Celtic nations. Despite, however, the proclivity of antiquaries, historians, and scholars to find a Roman or Greek origin for every manner, custom, and tradition—as if we had none originally of our own,—we may safely say that Boxing, in the noble manly forbearing and humane practice of the art, is the indigenous offspring of British hardihood, steady courage, and love of gymnic exercise and feats of bodily strength and skill, not unaccompanied with that amount of risk and severe exertion which lend a zest to sports unappreciated and unknown to more effeminate, more cruel, and more cowardly peoples. Let not this be taken as the hasty expression of insular prejudice. The writer, after deeply considering, and often witnessing, the personal contests of men in his own country and abroad, and dispassionately weighing the manner, accessories, and consequences of such contests, feels it a duty he owes to a half-informed and prejudiced society to express the result of his experience and his reflection, without fear, favour, or affection:—fear of the onslaughts of spiritual and moral quacks; favour for those who have degraded or debased a useful and laudable national exercise and sport; or affection, more than is due to an art which he would fain rescue from the obloquy and condemnation to which blind hostility and canting 2prejudice have consigned it. He would fain uphold that pugilistic combat which a fair field, no favour, and surrender at all times at the will of either party, distinguishes from every mode of conflict yet devised or practised for the settlement of those “offences” which the highest authority has told us “needs must come.” At a period within the earlier memories of the writer, a school of babblers flooded the press with theories of the perfectibility of man, the ultimate establishment of universal freedom, and the sublimation of the human faculties by general education and popular science; and a period was confidently predicted by these theorising shallowpates, when war would be an “impossibility” as against the “interests” of men and nations. We have lived to see the most sanguinary and ferocious contest in history among the people whom these sciolists set up as the bright example to the “less educated” nations of the Old World. We may, therefore, safely despise the “new light” philosophy, and revert to the eternal truth already cited—“needs must be that offences will come;” and this necessity being inevitable, the next logical step is to consider how these “offences” may be best dealt with and atoned.

So long as man is liable to the imperfections of his nature he will need the art of defending himself from attack and injury, and of redressing wrong or insult that may be offered him. All experience has taught us that the passions of pride and emulation (honourable like every human attribute within limits), and resentment for injury, are the springs of some of our noblest actions. It is to the stifling and too severe repression of the active energies of a resolute and independent spirit that the soul of man as an individual, and of a nation as a whole, sinks into the vengeful cowardice and cruel pusillanimity of the abject yet ferocious slave. As, then, a greater or less portion of evil must be attached to the best system of popular moral or civil restraint, the wisest policy is that which legislates for man as we find him, and not as the perfect or perfectible (?) creature which theorists and bigots pretend that he ought to be.

At the risk of repetition we will return to our argument. Individuals, as well as states, must have their disputes, their quarrels, and then—their battles. This is, there is no denying, the sad but natural—the regrettable but inevitable, condition and tenure on which human life—nay, all animal existence—is held. There must, then, be some mode through which the passions, when aroused, from whatever cause,—

may be assuaged, subdued, or extinguished; when the necessity for an appeal to the ultima ratio of conflict is unavoidable. And surely, in this extremity 3the fists—the symbol of personal courage, of prompt readiness for defence and attack—are the most harmless, the ever-present, and the least fatal weapons. We will leave, gentle or simple reader, the pistol to your higher-born countrymen of the “upper ten thousand,” if it so please them; the fatal fleuret to the fire-eating Gaul (whether soldier, litterateur, or “pekin”); the back-handed stiletto to the stabbing Italian; the sharp, triangular rapier or the dagger to the saturnine Spaniard; the slaughterous schlager to the beer-bemused burschen[7] of dreamy Vaterland; the gash-inflicting 4knife to the Dutch boor or seaman’s snicker-snee; the death-dealing “bowie,” “Kansas toothpick,” and murderous “six-shooter” to the catawampous citizen of the “univarsal Yankee nation;” the waved kreese, to the muck-running Malay; each tawny savage to his sharp tomahawk, his poisoned arrow, or his barbed assagai; and then we would ask the scribblers of the anti-pugilistic press which of these they are prepared to champion against the fist of the British boxer,—a weapon of defence which, as exemplified in the practice laid down in the latest code of Ring Law, is the perfection of the practice of cool courage, self-reticent combat, restraint, skill, and endurance that can illustrate and adorn the character of an unsophisticated and true-hearted Englishman in the supreme moment of conquest or of defeat.

It has frequently been urged by magistrates, and even ermined judges[8] of quasi-liberal sentiments, that pugilism, as a national practice, and an occasional or fortuitous occurrence, may be winked at by the authorities, or 5tacitly allowed, and prohibited or punished at discretion, as the occasion may seem to require: but that gymnastic schools where boxing is regularly taught, and pitched battles, are social nuisances which the law should rigorously suppress. Granting the possibility of this utter repression, which we deny, it may well be questioned whether we have not tried to suppress a lesser evil to evolve a greater.[9]

To boxing-schools and regulated combats we owe that noble system of fistic ethics, of fair play, which distinguishes and elevates our common people, and which stern, impartial, unprejudiced and logical minds must hail and foster as one of the proud attributes of our national character. We do not in the least undervalue peaceful pursuits, which constitute and uphold the blessings of peaceful life; yet a nation with no idea or principle beyond commerce would be unworthy, nay, would be impotent for national existence, much more for national power and progress. Subjection, conquest, and hence serfdom and poverty, must be its fate in presence of strong, rapacious, and encroaching neighbours. “The people that possesses steel,” said the ancient assailant of the Lydian Crœsus, “needs not long want for gold.” A 6portion, then, of a nation must be set apart, whose vocation it will be to secure and to defend the lives, liberties, and properties of the whole. Hence the honourable calling of the soldier and the sailor; and hence, to fit the people for these, and to prevent the too general indulgence of effeminacy, dread of enterprise, and the contagious spread of an enervating and fanatical peace-at-any-price quietism, it is wise and politic to encourage the manly and athletic sports and contests which invigorate the frame, brace the nerves, inspire contempt of personal suffering, and enable man to defend his rights as well as to enjoy them. Englishmen have learned, and we sincerely hope will continue to learn and to practise, fair boxing, as they have learned other arts of defence,—the use of the rifle among others, in which (as their sires of old did with the yeoman’s bow) they have already excelled Swiss, American, and Australian mountaineers and woodmen: men from countries celebrated for their practice of long shots, and constant handling of the weapon. Let them, therefore, see that the fair use of the fist is not sneered down by the craven or the canter. Were every pugilistic school shut up, the practice of boxing discouraged, and the fiat of our modern intolerant saints carried out, the manly spirit of fair play in our combats would disappear, and the people of this country lose one of their fairest characteristics. A retrospect of the last ten years will answer whether these are times to incur such risk; while at home, how-much-soever we may have had of the fist, we have indeed had too much of the loaded bludgeon, the mis-named “life-preserver,” the garotte, the knife, and the revolver.

Pugilistic exhibitions are falsely said to harden the heart, to induce ferocity of character, and that they are generally attended by the dregs of society. The last aspersion, for reasons that lie on the surface, has the most truth in it. The principle only, indeed the utility and necessity of the practice of boxing, is all we here propose to vindicate. Pugilism includes nothing essentially vicious; nothing, in itself, prompting to excess or debauchery. On the contrary, it asks temperance, exercise, and self-denial. If we are to argue and decide from the abuse of a custom or institution, where are we to stop? Men are not to be cured, even of errors, by the mere arbitrary force of laws, or by a cherished pursuit being vilified and contemned, mostly by those who are ignorant or averse to it. Teach men to respect themselves—this is the first step to make them respect others. Let this rule be applied to the Ring; let it be viewed as a popular institution; it may then, and we have warrant from experience, and in the history contained in these pages, become worthy of support and patronage. A series of biographies, which include the names of Cribb, Jackson, Gully, Shaw, Spring, Sayers, etc. (within the memory of 7men yet living) may be pointed to without a blush; while individual traits of heroism, generosity, forbearance, and humanity, will be found scattered as bright redeeming points through the lives of many of the “rough diamonds” preserved in the “setting” of our pages. We doubt not, were the character of the Ring raised, that successors of as good repute as these worthies would yet be found and arise among the brotherhood of the fist. Should this “consummation devoutly to be wished” ever be realised, our gymnasia, a public necessity, might then be licensed,—a security for their visitors, and adding respectability to their proprietors; for every government possesses the power of making expedient regulations, in the interest of society, even where it may not have the right to absolutely suppress or interdict. If free trade, and unrestricted leave to carry on profession or calling are such fundamental principles with our state economists, why not free boxing? and why not leave the morale of pugilism, as well as the morality of its professors, to find its level in the neglect or the patronage, the esteem or the contempt, of the people at large? Boxing and boxing schools, as free Britons, we must have. Let us, then, consider, how they can be best made to serve the cause of regulated pugilism. On the whole, there is no reason to doubt the practicability, as well as the desirability, of public boxing-schools as a branch of a system of national gymnastics. It is absurd as well as scandalous to assert that they must, ex necessitate, be the resort of profligates and thieves. As to the last named scourges of society, long observation and experience[10] have convinced us that we have our metropolitan and even rural nurseries for them; our “sin and crime gardens” for their special propagation, rearing, and multiplication; and we can conscientiously say, from an equally long observation, that among those thieves’ nurseries and “sin-gardens” the much-vilified Prize Ring has no special claim to be counted.

These remarks have extended to an extreme length, and we will here break off, premising that many opportunities will present themselves in the course of our history to illustrate and enforce the arguments and principles here laid down. Waiving, then, all question as to its origin, the ars pugilistica may be accepted as interwoven for many generations in the manners and habits of the English people; that it has become one of our “popular prejudices,” if you so please to term it; and that we will not abandon it to be suppressed by force or sneered down by cant or sophistry. It has long since, in this favoured country, been purged of its cruelty and barbarism, and restrained within well-considered bounds. No lacerating or stunning additions, such 8as we see pictured in our sketches of the ancient athletes, have been allowed to Nature’s weapon—the clenched fist. On the contrary, for the practice of the neophyte and the demonstration of the art by the professor, soft wool-padded gloves cover the knuckles and backs of the hands of the sparrers. Finally, foul blows, butting with the head, and deliberate falls, have been particularised and forbidden, and an unimpeachable system of fair play established, to be found in the “New Rules of the Ring.” We have nationally imbibed these principles, and hence among our lower orders the feeling of “fair play” is more remarkably prevalent than among any other people of Europe or the New World. Hence personal safety—the exceptions, though occasionally alarming, prove the rule[11]—is more general in England than in any other country. Here alone the fallen combatant is protected; and here the detestable practices of gouging, biting, kicking in vital parts, practised by Americans, Hiberno-Americans, and other foreigners, are heartily denounced and scouted; and to what do we owe these characteristics? We repeat it, to the Principles and Practice of Pugilism.

Although, doubtless, brave boxers in every shire of “merrie England” sported their Adam’s livery on the greensward, and stood up toe to toe for “love and a bellyful,” yet the name of James Fig, a native of Thame, in Oxfordshire, is, thanks to the pen of Captain Godfrey and the pencil of the great Hogarth, the first public champion “of the Ring” of whom we have authentic record. Doubtless—

but their deeds and glories, for want of a chronicler, have lapsed into oblivion (carent quia vates sacro), and—

FIG’S CARD.

DISTRIBUTED TO HIS PATRONS, AND AT HIS BOOTHS AT SOUTHWARK FAIR AND ELSEWHERE.

9To Captain Godfrey’s spirited and scarce quarto, entitled “A Treatise on the Useful Science of Defence,” we are indebted for the preservation of the names and descriptions of the persons and styles of the athletes who were his contemporaries. It would seem that though Fig has been acknowledged as the Father of the Ring, he was as much, if not more, distinguished as a cudgel and back-sword player then as a pugilist. Captain Godfrey thus speaks of Fig:—“I have purchased my knowledge with many a broken head, and bruises in every part of me. I chose mostly to go to Fig[12] and exercise with him; partly, as I knew him to be the ablest master, and partly, as he was of a rugged temper, and would spare no man, high or low, who took up a stick against him. I bore his rough treatment with determined patience, and followed him so long, that Fig, at last, finding he could not have the beating of me at so cheap a rate as usual, did not show such fondness for my company. This is well known by gentlemen of distinguished rank, who used to be pleased in setting us together.”

The reputation of Fig having induced him to open an academy (A.D. 1719), known as “Fig’s Amphitheatre,” in Tottenham Court Road, the place became shortly a great attraction, and was crowded with spectators. It was here that Captain Godfrey (the Barclay of his time) displayed his skill and elegance in manly sports with the most determined competitors, the sports being witnessed by royal and noble personages, who supported the science as tending to endue the people with hardihood and intrepidity. About 1720 Fig resided in Oxford Road, now Oxford-street, and at the period of the curious fac-simile, here for the first time engraved, we find him still in the same neighbourhood.

The science of pugilism, as we now understand it, was certainly in its infancy; the system of “give and take” was adopted, and he who could hit the hardest, or submit to punishment with the best grace, seems to have been in highest favour with the amateurs. Yet Fig’s placards profess to teach “defence scientifically,” and his fame for “stops and parries” was so great, that we find him mentioned in the Tatler, Guardian, and Craftsman, the foremost miscellanies of the time.[13] Fig, like modern managers, added to the attractions of his amphitheatre by “stars;” among these were Ned Sutton, the Pipemaker of Gravesend, Timothy Buck, Thomas Stokes, and others, of whom only the names remain. Bill Flanders, or Flinders, “a noted 10scholar of Fig’s,” fought at the amphitheatre, in 1723, with one Chris. Clarkson, known as “the Old Soldier.” The battle is highly spoken of for determined courage in the “diurnals” of the period.

Smithfield, Moorfields, St. George’s Fields, Southwark, and Hyde Park,[14] during this period also had “booths” and “rings” for the display of boxing and stick play. In Hogarth’s celebrated picture of “Southwark Fair” our hero prominently figures, in a caricatured exaggeration, challenging any of the crowd to enter the lists with him for “money, love, or a bellyful.” This picture we have also chosen as an interesting illustration of the great English painter,—a record of manners in a rude period. As one of the bills relating to this fair (which was suppressed in 1763) is extant, we subjoin it:

Besides this nobly patronised amphitheatre of Fig, there were several booths and rings strongly supported. That in Smithfield, we have it upon good authority, was presided over by one “Mr. Andrew Johnson,” asserted to be an uncle of the great lexicographer,[15] There was also that in Moorfields, 11called at times “the booth,” at others “the ring.” The “ring” was kept by an eccentric character known as “Old Vinegar,” the “booth” by Rimmington, whose sobriquet was “Long Charles.” This, it appears, had a curious emblazonment,—a skull and cross-bones on a black ground, inscribed “Death or Victory.” During the high tide of Fig’s prosperity (1733) occurred the battle between Bob Whitaker and the Venetian Gondolier, narrated under the head of “Whitaker.”

Let it not be thought that Fig, among his many antagonists, was without a rival. Sutton, the Gravesend Pipemaker, already mentioned, publicly dared the mighty Fig to the combat, and met him with alternate success, till a third trial “proved the fact” of Fig’s superiority. These contests, though given in all the “Chronologies” and “Histories” of the Ring, were neither more nor less than cudgel-matches, as will be seen by the subjoined contemporary verses by Dr. John Byrom. They are printed in “Dodsley’s Collection,” vol. vi., p. 312, under the title of—

Stanzas iv. to viii. describe the back-sword play, in which both men broke their weapons, and Fig has blood drawn by his own broken blade, whereon he appeals and another bout is granted. Fig then wounds Sutton in the 12arm and the sword play is over. Stanzas ix. and x. wind up the match (with cudgels), as follows:—

At length the time arrived when “the valiant Fig’s” “cunning o’ the fence” no longer availed him. On December 8th, 1734,[16] grim death gave him his final knock down, as appears from a notice in the Gentleman’s Magazine for the month of January, 1735.

“In Fig,” says his pupil and admirer Captain Godfrey (in his “Characters of the Masters,” p. 40, ed. 1747), “strength, resolution, and unparalleled judgment, conspired to form a matchless master. There was a majesty shone in his countenance, and blazed in all his actions, beyond all I ever saw. His right leg bold and firm, and his left, which could hardly ever be disturbed, gave him the surprising advantage already proved, and struck his adversary with despair and panic.”

Two only of Whitaker’s battles have survived the tooth of old Tempus edax rerum: his victory over the Venetian Gondolier and his defeat by Ned Peartree.

In the year 1733 a gigantic Venetian came to this country in the suite of one of our travelling nobility, whose name not being recorded we may set down this part of the story as apocryphal; in fact, as a managerial trick to attract aristocratic patronage. Be that as it may, this immense fellow, who was known by the name of “The Gondolier,” was celebrated for feats of strength: his fame ran before him, and his length of arm and jaw-breaking power of fist were loudly trumpeted. Indeed, a challenge having been issued by the backers of the Venetian, Fig was applied to to find a man to meet this Goliath. The sequel shall be told in Captain Godfrey’s own words:—

“Bob Whitaker was the man pitched upon to fight the big Venetian. I was at Slaughter’s Coffee-house when the match was made by a gentleman of 13advanced station: he sent for Fig to procure a proper man for him. He told him to take care of his man, because it was for a large sum; and the Venetian was of wonderful strength, and famous for breaking the jawbone in boxing. Fig replied, in his rough manner, ‘I do not know, master, but he may break one of his countrymen’s jawbones with his fist; but I’ll bring him a man, and he shall not be able to break his jawbone with a sledge hammer.’

“The battle was fought at Fig’s amphitheatre, before a splendid company, the politest house of that kind I ever saw. While the Gondolier was stripping my heart yearned for my countryman. His arm took up all observation; it was surprisingly large, long, and muscular. He pitched himself forward with his right leg, and his arm full extended; and, as Whitaker approached, caught him a blow at the side of the head which knocked him quite off the stage, which was remarkable for its height. Whitaker’s misfortune in his fall was the grandeur of the company, on which account they suffered no common people in, that usually sat on the ground, and lined the stage all round. It was thus all clear, and Whitaker had nothing to stop him but the bottom. There was a general foreign huzza on the side of the Venetian, as proclaiming our countryman’s downfall; but Whitaker took no more time than was required to get up again, when, finding his fault in standing out to the length of the other’s arm, he, with a little stoop, dashed boldly in beyond the heavy mallet, and with one English peg in the stomach,” by which the captain in another place explains he means what is called “the mark,”—“quite a new thing to foreigners, brought him on his breech. The blow carried too much of the English rudeness with it for him to bear, and finding himself so unmannerly used, he scorned to have any more doings with such a slovenly fist.” We could not resist transcribing this graphic, terse, and natural account of a prize-fight; the rarity of Captain Godfrey’s book, and the bald, diluted, silly amplification of it in “Boxiana,” pp. 22‒25, vol. i., being the moving reasons thereto.

“So fine a house,” says Captain Godfrey, alluding to the company which assembled to see Whitaker fight the Gondolier, “was too engaging to Fig not to court another. He therefore stepped up, and told the gentlemen that they might think he had picked out the best man in London on this occasion; but to convince them to the contrary, he said, that if they would come on that day se’nnight, he would bring a man who should beat this Whitaker in ten minutes by fair hitting. This brought near as great and fine a company as the week before. The ‘man’ was Nathaniel Peartree, who, knowing the other’s bottom, and his deadly way of flinging, took a most judicious manner to beat him. Let his character come in here.—He was an admirable boxer, 14and I do not know one he was not a match for, before he lost his finger. He was famous, like Pipes, for fighting at the face, but was stronger in his blows. He knew Whitaker’s hardiness, and, being doubtful of beating him, cunningly determined to fight at his eyes. His judgment carried his arm so well, that, in about six minutes, both Whitaker’s eyes were shut; when, groping about a while for his man, and finding him not, he wisely gave out (modernicè, gave in), with these odd words—‘Damme, I’m not beat; but what signifies my fighting when I can’t see my man?’”

The columns of the Flying Post and Daily News Letter have many advertisements of “battles royal,” but none of sufficient merit to deserve a place in this history.

Two other pugilists only of the school of Fig claim our notice, and these are Pipes and Gretting. “Pipes was the neatest boxer I remember. He put in his blows about the face (which he fought at most) with surprising time and judgment. He maintained his battles for many years with extraordinary skill, against men of far superior strength. Pipes was but weakly made: his appearance bespoke activity, but his hand, arm, and body were small; though by that acquired spring of his arm he hit prodigious blows; and at last, when he was beat out of his championship, it was more owing to his debauchery than the merit of those who beat him.”