The Project Gutenberg EBook of Slow Burn, by Henry Still This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Slow Burn Author: Henry Still Release Date: April 24, 2019 [EBook #59345] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SLOW BURN *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The problems of space were multiple enough

without the opinions and treachery of Senator

McKelvie—who really put the "fat into the fire".

All Kevin had to do was get it out....

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, October 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"Tell 'em to look sharp, Bert. This pickup's got to be good." Kevin Morrow gulped the last of his coffee and felt its bitter acid gurgle around his stomach. He stared moodily through the plastic port where the spangled skirt of stars glittered against the black satin of endless night and a familiar curve of the space station swung ponderously around its hub.

Four space-suited tugmen floated languidly outside the rim. Beyond them the gleaming black and white moonship tugged gently at her mooring lines, as though anxious to be off.

Bert Alexander radioed quiet instructions to the tugmen.

"Why the hell couldn't he stay down there and mind his own business?" Kevin growled. "McKelvie's been after our hide ever since we got the appropriation, and now this." He slapped the flimsy radio-gram.

He looked up as the control room hatch opened. Jones came in from the astronomy section.

"Morning, commander," he said. "You guys had breakfast yet? Mess closes in 30 minutes." Kevin shook his head.

"We're not hungry," Bert filled in.

"You think you've got nerves?" Jones chuckled. "I just looked in on Mark. He's sleeping like a baby. You wouldn't think the biggest day of his life is three hours away."

"McKelvie's coming up to kibitz," Morrow said.

"McKelvie!"

"The one and only," Bert said. "Here, read all about it."

He handed over the morning facsimile torn off the machine when the station hurtled over New England at 18,000 miles an hour. The upper half of the sheet bore a picture of the white-maned senator. Clearly etched on his face were the lines of too many half-rigged elections, too many compromises.

Beneath the picture were quotes from his speech the night before.

"As chairman of your congressional watchdog committee," the senator had said, "I'll see that there's no more waste and corruption on this space project. For three years they've been building a rocket—the moon rocket, they call it—out there at the space station.

"I haven't seen that rocket," the senator had continued. "All I've seen is five billion of your tax dollars flying into the vacuum of space. They tell me a man named Mark Kramer is going to fly out in that rocket and circle the moon.

"But he will fail," McKelvie had promised. "If God had intended man to fly to the moon, he would have given us wings to do it. Tomorrow I shall fly out to this space station, even at the risk of my life. I'll report the waste and corruption out there, and I'll report the failure of the moon rocket."

Jones crumpled the paper and aimed at the waste basket.

"Pardon me while I vomit," he said.

"We've been there," Kevin sighed deeply. "I suppose Max Gordon will be happy."

"He'll wear a hole in his tongue on McKelvie's boots," Bert said bitterly.

"Is it that bad?"

"How else would he get a first class spaceman's badge?" Morrow said. "He can't add two and two. But if stool pigeons had wings, he'd fly like a jet. We can't move up here without McKelvie knowing and howling about it.

"Don't worry," Jones said, "If the moon rocket makes it, public opinion will take care of the senator."

"If he doesn't take care of us first," Kevin said darkly. "He'll be aboard in 15 minutes."

Dawn touched the High Sierras as the station whirled in from the Pacific, 500 miles high.

"Bert. Get me a radar fix on White Sands."

Morrow huddled over the small computer, feeding in radar information as it came from his assistant.

"Rocket away!" Blared a radio speaker on the bulkhead. The same message carried to the four space-suited tugmen floating beyond the rim of the wheel, linked with life-lines.

Jones watched interestedly out the port.

"There she is!" he yelled.

Sunlight caught the ascending rocket, held it in a splash of light. The intercept technique was routine now, a matter of timing, but for a moment Kevin succumbed to the frightening optical illusion that the rocket was approaching apex far below the station. Then, slowly, the slender cylinder matched velocity and pulled into the orbit, crept to its destination.

With deceptive ease, the four human tugs attached magnetic shoes and guided the projectile into the space station hub with short, expert blasts of heavy rocket pistols.

"Take over Bert," Morrow directed, "I guess I'm the official greeter." He hurried out of the control room, through a short connecting tube and emerged floating in the central space surrounding the hub where artificial gravity fell to zero. Air pressure was normal to transfer passengers without space suits.

The connecting lock clanked open. The rocket pilot stepped out.

"He got sick," the pilot whispered to Kevin. "I swabbed him off, but he's hoppin' mad."

The senator's mop of white hair appeared in the port. Kevin braced to absorb a tirade, but McKelvie's deep scowl changed to an expression of bliss as he floated weightless into the tiny room.

"Why, this is wonderful!" he sputtered. He waved his arms like a bird and kicked experimentally with a foot.

"Grab him!" Kevin shouted. "He's gone happy with it."

The pilot was too late. McKelvie's body sailed gracefully through the air and his head smacked the bulkhead. His eyes glazed in a frozen expression of carefree happiness.

Kevin swore. "Now he'll accuse us of a plot against his life. Help me get him to sick bay."

The two men guided the weightless form into a tube connecting with the outer ring. As they pushed outward, McKelvie's weight increased until they carried him the last 50 feet into the dispensary compartment.

Max Gordon burst wild-eyed into the room.

"What have you done to the senator?" he shouted. "Why didn't you tell me he was coming up?" Morrow made sure McKelvie was receiving full medical attention before he turned to the junior officer.

"He went space happy and bumped his head," Kevin said curtly, "and there was no more reason to notify you than the rest of the crew." He walked away. Gordon bent solicitously over his unconscious patron.

Kevin found Anderson in the passageway.

"I ordered them to start fueling Moonbeam," Bert said.

"Good. Is Mark awake?"

"Eating breakfast. The psycho's giving him a clinical chat."

"I wish it were over." Morrow brushed back his hair.

"You've really got the jitters, huh chief?"

Morrow turned angrily and then tried to laugh.

"I'd sell my job for a nickel right now, Bert. This will be touch and go, without having the worst enemy of space flight aboard. If this ship fails, it's more than a rocket or the death of a man. It'll set the whole program back 50 years."

"I know," Bert answered, "but he'll make it."

Footsteps sounded in the tube outside the cabin. Mark Kramer walked in.

"Hi, chief," he grinned, "Moonbeam ready to go?"

"The techs are out now and fuel's aboard. How about you? Shouldn't you get some rest?"

"That's all I've had since they shipped me out here." Kramer laughed. "It'll be a snap. After all, I'll never make over two gees and pick up 7000 mph to leave you guys behind. Then I play ring around the rosy, take a look at Luna's off side and come home. Just like that."

"Just like that," Kevin whispered meditatively. The moon rocket, floating there outside the station's rim was ugly, designed never to touch a planet's atmosphere, but it was the most beautiful thing man had ever built, assembled in space from individual fragments boosted laboriously from the Earth's surface.

Another clatter of footsteps approached the hatch. Max Gordon entered and stood at attention as Senator McKelvie made a dignified entrance. The senator wore an adhesive patch on his high forehead. He turned to Kramer.

"Young man," he rumbled, "are you the fool risking your life in that—that thing out there? You must know it'll never reach the moon. I know it'll never—"

Kramer's face paled slightly and he moved swiftly between the two men. Without using force, he backed the senator and Gordon through the hatch and slammed it behind him. Anger was a knot of green snakes in his belly.

"I want to talk to that pilot," McKelvie said belligerently.

"I'm sorry, senator. The best psychiatrists on Earth worked eight months to condition Kramer for this flight. He must not be emotionally disturbed. You can't talk to him."

"You forbid...?" McKelvie exploded, but Morrow intercepted smoothly.

"Gordon. I'm sure the senator would like a tour of the station. Will you escort him?"

McKelvie's face reddened and Max opened his mouth to object.

"Gordon!" Morrow said sharply. Max closed his mouth and guided the grumbling congressman up the tube.

"Twenty minutes to blastoff," Bert reported.

"Right," Kevin acknowledged absently. He studied taped data moving in by radio facsimile from the mammoth electronic computer on Earth.

"Our orbit's true," he said with satisfaction and wiped a sweaty palm on his trousers. "Get the time check, Bert." Beeps from the Naval Observatory synchronized with the space station chronometer.

"Alert Kramer."

"He's leaving the airlock now," Bert said. From the intercom, Morrow listened to periodic reports from crew members as McKelvie and Gordon progressed in their tour.

"Mr. Morrow?"

"Right."

"This is Adams in Section M. The senator and Gordon have been in the line chamber for 10 minutes."

"Boot 'em out," Kevin said crisply. "Blastoff in 15 minutes."

"That machinery controls the safety lines," Bert said.

Kevin looked up with a puzzled frown, but turned back to watch Kramer creeping along a mooring line to the moon ship. A group of tugmen helped the space-suited figure into the rocket, dogged shut the hatch and cleared back to the station rim.

"Station to Kramer," on the radio, "are you ready?"

"All set," came the steady voice, "give me the word."

"All right. Five minutes." Kevin turned to the intercom. "Release safety lines."

In the weightlessness of space the cables retained their normal rigid line from the rim of the station to the rocket. They had been under no strain. Their shape would not change until they were reeled in.

"Two minutes," Morrow warned. Tension grew as Anderson began the slow second count. The hatch opened. McKelvie and Gordon entered the control room. No one noticed it.

"Five ... four ... three ... two ... one ..."

A gout of white fire jabbed from the stern of the rocket. Slowly the ship moved forward.

Morrow watched tensely, hands gripping a safety rail.

Then his face froze in a mask of disbelief and horror.

"The lines!" he shouted. "The safety lines fouled!"

He fell sprawling as the space station lurched heavily, tipped upward like a giant platter under the inexorable pull of the moon rocket.

Kevin scrambled back to the viewport, the shriek of tortured metal in his ears. Horror-stricken, he saw the taut cables that had failed to release. Then a huge section of nylon, aluminum and rubber ripped out of the station wall, was visible a second in the rocket glare, and vanished.

Escaping air whistled through the crippled structure. Pressure dropped alarmingly before the series of automatic airlocks clattered reassuringly shut.

Kevin's hand was bleeding. He staggered with the frightening new motion of the space station. Gordon and the senator had collapsed against a bulkhead. McKelvie's pale face twisted with fear and amazement. Blood streaked down the pink curve of his forehead.

Individual station reports trickled through the intercom. Miraculously, the bulk of the station had escaped damage.

"Line chamber's gone," Adams reported. "Other bulkheads holding, but something must have jammed the line machines. They ripped right out."

"Get repair crews in to patch leaks," Morrow shouted. He turned frantically to the radio. "Station to Moonbeam. Kramer! Are you all right?"

He waited an agonizing minute, then a scratchy voice came through.

"Kramer, here. What the hell happened? Something gave me a terrific yaw, but the gyro pulled me back on course. Fuel consumption high. Otherwise I'm okay."

"You ripped out part of the station," Kevin yelled. "You're towing extra mass. Release the safety lines if you can."

The faint answer came back, garbled by static.

Another disaster halted a new try to reach him.

With a howling rumble, the massive gyroscope case in the bulkhead split open. The heavy wheel, spinning at 20,000 revolutions per minute, slowly and majestically crawled out of its gimbals; the gyroscope that stabilized the entire structure remained in its plane of revolution, but ripped out of its moorings when the station was forcibly tilted.

Spinning like a giant top, the gyro walked slowly across the deck. McKelvie and Gordon scrambled out of its way.

"It'll go through!" Bert shouted. Kevin leaped to a chest of emergency patches.

The wheel ripped through the magnesium shell like a knife in soft cheese. A gaping rent opened to the raw emptiness of space, but Morrow was there with the patch. Before decompression could explode the four creatures of blood and bone, the patch slapped in place, sealed by the remaining air pressure.

Trembling violently, Kevin staggered to a chair and collapsed. Silence rang in his ears. Anderson gripped the edge of a table to keep from falling. Kevin turned slowly to McKelvie and Gordon.

"Come here," he said tonelessly.

"Now see here, young man—" the senator blustered.

"I said come here!"

The two men obeyed. The commander's voice held a new edge of steel.

"You were the last to leave the line control room," he said. "Did you touch that machinery?"

Gordon's face was the color of paste. His mouth worked like a suffocating fish. McKelvie recovered his bluster.

"I'm a United States senator," he stuttered, "I'll not be threatened...."

"I'm not threatening you," Kevin said, "but if you fouled that machinery to assure your prediction about the rocket, I'll see that you hang. Do you realize that gyroscope was the only control we had over the motion of this space station? Whatever it does now is the result of the moon rocket's pull. We may not live to see that rocket again."

As though verifying Morrow's words, the lights dimmed momentarily and returned to normal brilliance. A frightened voice came from the squawkbox.

"Hey, chief! This is power control. We've lost the sun!"

Anderson looked out the port, studied the slowly wheeling stars.

"Mother of God," he breathed. "We're flopping ... like a flapjack over a stove."

And the power mirrors were on only one face of the space station, mirrors that collected the sun's radiation and converted it to power. Now they were collecting nothing but the twinkling of the stars.

The vital light would return as the station continued its new, awkward rotation, but would the intermittent exposure be sufficient to sustain power?

"Shut down everything but emergency equipment," Morrow directed. "When we get back on the sun, soak every bit of juice you can into those batteries." He turned to Gordon and McKelvie. "Won't it be interesting if we freeze to death, or suffocate when the air machines stop?"

Worry replaced anger as he turned abruptly away from them.

"We've got a lot of work to do, Bert," he said crisply. "See if you can get White Sands."

"It's over the horizon, I'll try South Africa." Anderson worked with the voice radio but static obliterated reception. "Here comes a Morse transmission," he said at last. Morrow read slowly as tape fed out of the translator:

"Radar shows moon rocket in proper trajectory. Where are you?"

The first impulse was to dash to the viewport and peer out. But that would be no help in determining position.

"Radar, Bert," he whispered. Anderson verniered in the scope, measuring true distance to Earth's surface. He read the figure, swore violently, and readjusted the instrument.

"It can't be," he muttered at last. "This says we're 865 miles out."

"365 miles outside our orbit?" Morrow said calmly. "I was afraid of that. That tug from the Moonbeam not only cart-wheeled us, it yanked us out." He snatched a sheet of graph paper out of a desk drawer and penciled a point.

"Give me a reading every 10 seconds."

Points began to connect in a curve.

And the curve was something new.

"Get Jones from astronomy," Kevin said at last. "He can help us plot and maybe predict."

When the astronomer arrived minutes later, the space station was 1700 miles above the Earth, still shearing into space on an ascending curve.

"Get a quick look at this, Jones," Kevin spoke rapidly. "See if you can tell where it will be two hours from now."

The astronomer studied the curve intently as it continued to grow under Kevin's pencil.

"It may be an outward spiral," he said haltingly, "or it could be a ... parabola."

"No!" Bert protested. "That would throw us into space. We couldn't—"

"We couldn't get back," Kevin finished grimly. "There'd better be an alternative."

"It could be an ellipse," Jones said.

"It must be an ellipse," Bert said eagerly. "The Moonbeam couldn't have given us 7000 mph velocity."

Abruptly the lights went out.

The radar scope faded from green to black. Morrow swore a string of violent oaths, realizing in the same instant that anger was useless when the power mirrors lost the sun.

He bellowed into the intercom, but the speaker was dead. Already Bert was racing down the tube to the power compartment. Minutes later, the intercom dial flickered red. Morrow yelled again.

"You've got to keep power to this radar set for the next half-hour. Everything else can stop, even the air machines, but we've got to find out where we're going."

The space station turned again. Power resumed and Kevin picked up the plot.

"We're 6000 miles out!" he breathed.

"But it's flattening," Jones cried. "The curve's flattening!" Bert loped back into the control room. Jones snatched the pencil from his superior.

"Here," he said quickly, "I can see it now. Here's the curve. It's an ellipse all right."

"It'll carry us out 9600 miles," Bert gasped. "No one's ever been out that far."

"All right," Morrow said. "That crisis is past. The next question is where are we when we come back on nadir. Bert, tell the crew what's going on. Jones, you can help me. We've got to pick up White Sands and get a fuel rocket up here to push."

"Good Lord, look at that!" Jones breathed. He stared out the port. The Earth, a dazzling huge globe filling most of the heavens, swam slowly past the plastic window. It was the first time they had been able to see more than a convex segment of oceans and continents. Kevin looked, soberly, and turned to the radio.

The power did not fail in the next crazy rotation of the station.

"There's the West Coast." Kevin pointed. "In a few minutes I can get White Sands, I hope."

Jones had taken over the radar plot. At last his pencil reached a peak and the curve started down. The station had reached the limit of its wild plunge into space.

"Good," Kevin muttered. "See if you can extrapolate that curve and get us an approximation where we'll cut in over the other side." The astronomer figured rapidly and abstractedly.

"May I remind you young man," McKelvie's voice boomed, "you have a United States senator aboard. If anything happens—"

"If anything happens, it happens to all of us," Kevin answered coldly. "When you're ready to tell me what did happen, I'm ready to listen."

Silence.

"White Sands, this is Station I. Come in please."

Kevin tried to keep his voice calm, but the lives of 90 men rode on it, on his ability to project his words through the crazy hash of static lacing this part of space from the multitude of radio stars. A power rocket with extra fuel was the only instrument that could return the space station to its normal orbit.

That rocket must come from White Sands.

White Sands did not answer.

He tried again, turned as an exclamation of dismay burst from the astronomer. Morrow bent to look at the plotting board.

Jones had sketched a circle of the Earth, placing it in the heart of the ellipse the space station was drawing around it.

From 9600 miles out, the line curved down and down, and down....

But it did not meet the point where the station had departed from its orbit 500 miles above Earth's surface.

The line came down and around to kiss the Earth—almost.

"I hope it's wrong," Jones said huskily. "If I'm right, we'll come in 87 miles above the surface."

"It can't!" Morrow shouted in frustration. "We'll hit stratosphere. It'll burn us—just long enough so we'll feel the agony before we die."

Jones rechecked his figures and shook his head. The line was still the same. Each 10 seconds it was supported by a new radar range. The astronomer's lightning fingers worked out a new problem.

"We have about 75 minutes to do something about it," he said. "We'll be over the Atlantic or England when it happens."

"Station I, this is...."

The beautiful, wonderful voice burst loud and clear from the radio and then vanished in a blurb of static.

"Oh God!" Kevin breathed. It was a prayer.

"We hear you," he shouted, procedure gone with the desperate need to communicate with home. "Come in White Sands. Please come in!"

Faintly now the voice blurred in and out, lost altogether for vital moments:

"... your plot. Altiac computer ... your orbit ... rocket on standby ... as you pass."

"Yes!" Kevin shouted, gripping the short wave set with white fingers, trying to project his words into the microphone, across the dwindling thousands of miles of space. "Yes. Send the rocket!"

"Can they do it?" Jones asked. "The rocket, I mean."

"I don't know," Kevin said. "They're all pre-set, mass produced now, and fuel is adjusted to come into the old orbit. They can be rigged, I think, if there's enough time."

The coast of California loomed below them now, a brown fringe holding back the dazzling flood of the Pacific. They were 3000 miles above the Earth, dropping sharply on the down leg of the ellipse.

At their present speed, the station appeared to be plunging directly at the Earth. The globe was frighteningly larger each time it wobbled across the viewport.

"Shall I call away the tugmen?" Bert asked tensely.

"I can't ask them to do it," Kevin said. "With this crazy orbit, it's too dangerous. I'm going out."

He slipped into his space gear.

"I'm going with you," Bert said. Kevin smiled his gratitude.

In the airlock the men armed themselves with three heavy rocket pistols each. Morrow ordered other tugmen into suits for standby.

"I wish I could do this alone, Bert," he said soberly. "But I'm glad you're coming along. If we miss, there won't be a second chance."

They knew approximately when they would pass over the rocket launching base, but this time it would be different. The space station would pass at 750 miles altitude and with a new velocity. No one could be sure the feeder rocket would make it. Unless maximum fuel had been adjusted carefully, it might orbit out of reach below them. Rescue fuel would take the place of a pilot.

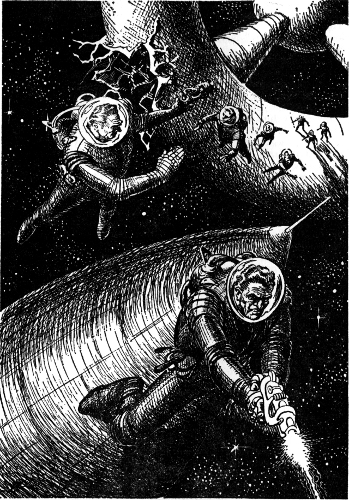

Anderson and Morrow floated clear of the huge wheel, turning lazily in the deceptive luxury of zero gravity. The familiar sensation of exhilaration threatened to wipe out the urgency they must bring to bear on their lone chance for survival. They could see the jagged hole where the Moonbeam had yanked out a section of the structure.

An unintelligible buzz of voice murmured in the radios. Unconsciously Kevin tried to squeeze the earphones against his ears, but his heavily-gloved hands met only the rigid globe of his helmet.

"You get it, Bert?"

"No."

"This is Jones," a new voice loud and clear. "Earth says 15 seconds to blastoff."

"Rocket away!"

Like a tiny, clear bell the words emerged from static. Bert and Kevin gyrated their bodies so they could stare directly at the passing panorama of Earth below. They had seen it hundreds of times, but now 250 more miles of altitude gave the illusion they were studying a familiar landmark through the small end of a telescope.

"There it is!" Bert shouted.

A pinpoint of flame, that was it, with no apparent motion as it rose almost vertically toward them.

Then a black dot in an infinitesimal circle of flame—the rocket silhouetted against its own fire ... as big as a dime ... as big as a dollar....

... as big as a basketball, the circle of flame soared up toward them.

"It's still firing!" Kevin yelled. "It'll overshoot us."

As he spoke, the fire died, but the tiny bar of the rocket, black against the luminous surface of Earth, crawled rapidly up into their sector of starlit blackness. Then it was above Earth's horizon, nearly to the space station's orbit, crawling slowly along, almost to them—a beautiful long cylinder of metal, symbol of home and a civilization sending power to help them to safety.

Hope flashed through Kevin's mind that he was wrong, that the giant computer and the careful hands of technicians had matched the ship to their orbit after all.

But he was right. It passed them, angling slowly upward not 50 yards away.

Instantly the two men rode the rocket blast of their pistols to the nose of the huge projectile. But it carried velocity imparted by rockets that had fired a fraction of a minute too long.

Clinging to the metal with magnetic shoes, Morrow and Anderson pressed the triggers of the pistols, held them down, trying to push the cylinder down and back.

Bert's heavy breathing rasped in the radio as he unconsciously used the futile force of his muscles in the agonizing effort to move the ship.

Their pistols gave out almost simultaneously. Both reached for another. Thin streams of propulsive gas altered the course of the rocket, slightly, but the space station was smaller now, angling imperceptibly away and down as the rocket pressed outward into a new, higher orbit.

The rocket pistols were not enough.

"Get the hell back here!" Jones' voice blared in their ears. "You can't do it. You're 20 miles away now and angling up. Don't be dead heroes!" The last words were high and frantic.

"We've got to!" Morrow answered. "There's no other way."

"We can't do the impossible, chief," Bert gasped.

A group of tiny figures broke away from the rim of the space station. The tugmen were coming to help.

Then Kevin grasped the hideous truth. There were not enough rocket pistols to bring the men to the full ship and return with any reserve to guide the projectile.

"Get back!" he shouted. "Save the pistols. We're coming in."

Behind them their only chance for life continued serenely upward into a new orbit. There, 900 miles above the earth, it would revolve forever with more fuel in its tanks than it needed.

Fuel that would have saved the lives of 90 desperate men.

By leaving it, Morrow and Anderson had bought perhaps 30 more minutes of life before the space station became a huge meteor riding its fiery path to death in the the upper reaches of the atmosphere.

Both suffered the guilt of enormous betrayal. The fact that they could have done no more did not erase it.

Frantically, Kevin flipped over in his mind the possible tools that still could be brought to bear to lift the space station above its flaming destruction. But his tools were the stone axe of a primitive man trying to hack his way out of a forest fire.

Eager hands pulled them back into the station. For a moment there were the reassuring sounds as their helmets were unscrewed. Then the familiar smells and shape of the structure that had been home for so long. Now that haven was about to destroy itself.

Then Morrow remembered the Earth rocket that had brought Senator McKelvie to the great white sausage in space.

That rocket still contained a small quantity of fuel.

If fired at the precise moment, that fuel, anchored with the rocket in the hub socket, might be enough to lift the entire station.

He shouted instructions and men raced to obey. Kevin, himself, raced into the nearest tube. There was no sound, but ahead of him the hatch was open to the discharge chamber. He leaped into the zero gravity room.

McKelvie was crawling through the connecting port into the feeder rocket. Kevin sprawled headlong into Gordon. The recoil threw them apart, but Gordon recovered balance first.

He had a gun.

"Get back," he snarled. "We're going down." He laughed sharply, near hysteria. "We're going down to tell the world how you fried—through error and mismanagement."

"You messed up those lines," Kevin said. It didn't matter now. He only hoped to hold Gordon long enough for diversionary help to come out of the tube.

"Yes," Gordon leered. "We fixed the lines. The senator wasn't sure we should, but I helped him over his squeamishness, and now we'll crack the whip when we get back home."

"You won't make it," Kevin said. "We're still more than 600 miles high. The glide pattern in that rocket is built to take you down from 500 miles."

McKelvie's head appeared in the hatch. He was desperately afraid.

"You said you could fly this thing, Gordon. Can you?"

Max nodded his head rapidly, like a schoolboy asked to recite a lesson he has not studied.

Kevin was against the bulkhead. Now he pushed himself slowly forward.

"Stay back or I'll shoot?" Gordon screamed. Instead, he leaped backward through the hatch.

Hampered by his original slow motion, Kevin could not move faster until he reached another solid surface.

The hatch slammed shut before his grasping fingers touched it.

A wrenching tug jostled the space station structure. The rocket was gone, and with it the power that might have saved all of them.

Morrow ran again. He had not stopped running since the beginning of this nightmare.

He tumbled over Bert and Jones in the tube. They scrambled after him back to the control room. The three men watched through the port.

"If he doesn't hit the atmosphere too quick, too hard ..." Kevin whispered. His fists were clenched. He felt no malice at this moment. He did not wish them death. There was no sound in the radio. The plummeting projectile was a tiny black dot, vanishing below and behind them.

When the end came, it was a mote of orange red, then a dazzling smear of white fire as the rocket ripped into the atmosphere at nearly 20,000 miles an hour.

"They're dead!" Jones voice choked with disbelief. Kevin nodded, but it was a flashing thing that lost meaning for him in the same instant. He knew that unless a miracle happened, ninety men in his command would meet the same fate.

Like a perpetual motion machine, his brain kept reaching for something that could save his space station, his own people, the iron-nerved spacemen who knew they were near death but kept their vital posts, waiting for him to find a way.

Stories do not end unhappily—that thought kept cluttering his brain—a muddy optimism blanking out vital things that might be done.

"What's the altitude Jones?"

"520 now. Leveling a bit."

"Enough?" It was a stupid question and Kevin knew it. Jones shook his head.

"We might be lucky," he said. "We'll hit it about 97 miles up. The top isn't a smooth surface, it billows and dips. But," he added, almost a whisper, "we'll penetrate to about 80 miles before...."

"How much time?" Kevin asked sharply. A tiny chain of hope linked feebly.

"About 22 minutes."

"Bert, order all hands into space suits—emergency!"

While the order was being carried out, Kevin summoned the tugmen.

"How many loaded pistols do we have?"

"Six," the chief answered.

"All right. Get this quick. Anchor yourselves inside the hub. Aim those pistols at the Earth and fire until they're exhausted."

The chief stared incredulously.

"I know it's crazy," Kevin snapped. "It's not enough, but if it alters our orbit 50 feet, it'll help." The tugmen ran out. Bert, Kevin and Jones scrambled into space suits. Morrow called for reports.

"All hands," he intoned steadily, "open all ports. Repeat. Open all ports. Do not question. Follow directions closely."

Ten seconds later, a whoosh of escaping air signaled obedience.

"Now!" Kevin shouted, "grab every loose object within reach. Throw it at the Earth. Desks, books, tools, anything. Throw them down with every ounce of strength you've got!"

It was insane. Everything was insane. It couldn't possibly be enough.... But space around the hurtling station blossomed with every conceivable flying object that man has ever taken with him to a lonely outpost. A pair of shoes went tumbling into darkness, and behind it the plastic framed photograph of someone's wife and children.

Jones knew his superior had not gone berserk. He bent anxiously over the radar scope.

It was not a matter of jettisoning weight. Every action has an equal reaction, and the force each man gave to a thrown object was as effective in its diminuitive way as the exhaust from a rocket.

"Read it!" Morrow shouted. "Read it!"

"265 miles," Jones cried. "I need more readings to tell if it helped."

There was no sound in the radio circuit, save that of 90 men breathing, waiting to hear 90 death sentences. Jones' heavily-gloved hands moved the pencil clumsily over the graph paper. He drew a tangent to a new curve.

"It helped," he said tonelessly, "We'll go in at 100 miles, penetrate to 90...."

"Not enough," Kevin said. "Close all ports. Repeat. Close all ports!"

An unheard sigh breathed through the mammoth, complex doughnut as automatic machinery gave new breath to airless spaces.

It might never be needed again to sustain human life.

But the presence of air delivered one final hope to Morrow's frantic brain.

"Two three oh miles," Jones said.

"Air control," Kevin barked into the mike, "how much pressure can you get in 15 minutes?"

"Air control, aye," came the answer, and a pause while the chief calculated. "About 50 pounds with everything on the line."

"Get it on! And hang on to your hats," Kevin yelled.

The station dropped another 30 miles, slanting in sharply toward the planet's envelope of gas that could sustain life—or take it away. Morrow turned to Anderson.

"Bert. There are four tubes leading into the hub. Get men and open the outer airlocks. Then standby the four inner locks. When I give the signal, open those locks, fast. You may have to pull to help the machinery—you'll be fighting three times normal air pressure."

Bert ran out. Nothing now but to wait. Five minutes passed. Ten.

"We're at 135 miles," Jones said. Far below the Earth wheeled by, its apparent motion exaggerated as the space station swooped lower.

"120 miles."

Kevin's throat was parched, his lips dry. Increasing air pressure squeezed the space suits tighter around his flesh. A horror of claustrophobia gripped him and he knew every man was suffering the same torture.

"110 miles."

"Almost there," Bert breathed, unaware that his words were audible.

Then a new force gripped them, at first the touch of a caressing finger tip dragging back, ever so slightly. Kevin staggered as inertia tugged him forward.

"We're in the air!" he shouted. "Bert. Standby the airlocks!"

"Airlocks ready!"

The finger was a hand, now, a huge hand of tenuous gases, pressing, pressing, but the station still ripped through its death medium at a staggering 20,000 miles an hour.

Jones pointed. Morrow's eyes followed his indicating finger to the thermocouple dial.

The dial said 100° F. While he watched it moved to 105, quickly to 110°.

Five seconds more. A blinding pain of tension stabbed Kevin behind the eyes. But through the flashing colors of agony, he counted, slowly, deliberately....

"Now!" he shouted. "Open airlocks, Bert. NOW!"

Air rushed out through the converging spokes of the great wheel, poured out under tremendous pressure, into the open cup of the space station hub, and there the force of three atmospheres spurted into space through the mammoth improvised rocket nozzle.

Kevin felt the motion. Every man of the crew felt the surge as the intricate mass of metal and nylon leaped upward.

That was all.

Morrow watched the temperature gauge. It climbed to 135°, to 140° ... 145 ... 150....

"The temperature is at 150 degrees," he announced huskily over the radio circuit. "If it goes higher, there's nothing we can do."

The needle quivered at 151, moved to 152, and held....

Two minutes, three....

The needle stepped back, one degree.

"We're moving out," Kevin whispered. "We're moving out!"

The cheer, then, was a ringing, deafening roar in the earphones. Jones thumped Kevin madly on the back and leaped in a grotesque dance of joy.

Morrow leaned back in the control chair, pressed tired fingers to his temples. He could not remember when he had slept.

The first rocket from White Sands had brought power to adjust the orbit. This one was on the mark.

The next three brought the Senate investigating committee.

But that didn't matter, really. Kevin was happy, and he was waiting.

The control room door banged open. Mark Kramer's grin was like a flash of warm sunlight.

"Hi, commander," he said, "wait'll you see the marvelous pictures I got."

Outside the Moonbeam rode gently at anchor, tethered with new safety lines.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Slow Burn, by Henry Still

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SLOW BURN ***

***** This file should be named 59345-h.htm or 59345-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/9/3/4/59345/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.