The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Dance, by Daniel Gregory Mason This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Dance Author: Daniel Gregory Mason Editor: Ivan Narodny Release Date: March 20, 2019 [EBook #59104] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DANCE *** Produced by Turgut Dincer, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

Cover created by Transcriber from content in the original book, and placed in the Public Domain.

The List of Illustrations was added by Transcriber and placed into the Public Domain.

THE ART OF MUSIC

The Art of Music

A Comprehensive Library of Information

for Music Lovers and Musicians

Editor-in-Chief

DANIEL GREGORY MASON

Columbia University

Associate Editors

EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL

Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin

Managing Editor

CÉSAR SAERCHINGER

Modern Music Society of New York

In Fourteen Volumes

Profusely Illustrated

NEW YORK

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC

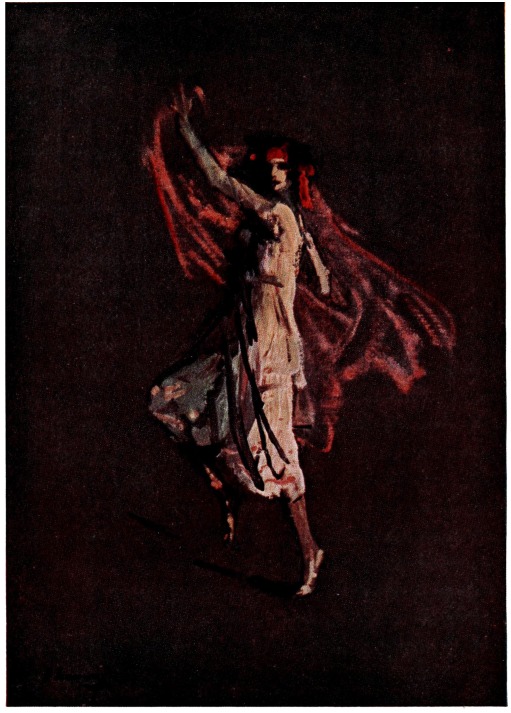

Odalisque in ‘Scheherazade’ (Russian Ballet)

Design by Léon Bakst

THE ART OF MUSIC: VOLUME TEN

Department Editor:

IVAN NARODNY

Introduction by

ANNA PAVLOWA

Ballerina, Imperial Russian Ballet

NEW YORK

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC

Copyright, 1916, by

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc.

[All Rights Reserved]

vii

‘The gods themselves danced, as the stars dance in the sky,’ is a saying of the ancient Mexicans. ‘To dance is to take part in the cosmic control of the world,’ said the ancient Greek philosophers. ‘What do you dance?’ asks the African Bantu of a member of another tribe after his greeting. Livingston said that when an African wild man danced, that was his religion. It is said that the savages do not preach their religion but dance it. According to the Bible, the ancient Hebrews danced before their Ark of the Covenant. St. Basil describes the angels dancing in Heaven. According to Dante, dancing is the real occupation of the inmates of Heaven, Christ acting as the leader of a celestial ballet. ‘Dancing,’ said Lucian, ‘is as old as love.’ Dance had a sacred and mystic meaning to the early Christians upon whom the Bible had made a deep impression: ‘We have piped unto you and ye have not danced.’

The service of the Greek Church—even to-day—is for the most part only a kind of sacred dance, accompanied by chants and singing. The priest, walking and gesturing with an incense-pan up and down before the numerous ikons, kneeling, bowing to the saints, performing queer cabalistic figures with his hands in the air, and following always a certain rhythm, is essentially a dancer. It is said that dancing of a similar kindviii was performed in the English cathedrals until the fourteenth century. In France the priests danced in the choir at the Easter Mass up to the seventh century. In Spain similar religious dancing took deepest root and flourished longest. In the Cathedrals of Seville, Toledo, Valencia and Xeres the dancing survives and is the feature at a few special festivals.

‘The American Indian tribes seem to have had their own religious dances, varied and elaborate, often with a richness of meaning which the patient study of the modern investigators has but slowly revealed,’ writes Havelock Ellis. It is a well-known fact that dancing in ancient Egypt and Greece was an art that was practiced in their temples. ‘A good education,’ wrote Plato, ‘consists in knowing how to sing well and how to dance well.’ According to Plutarch, Helen of Sparta was practicing the Dance of Innocence in the Temple of Artemis when she was surprised and carried away by Theseus. We are told by Greek classics that young maidens performed dances before the altars of various goddesses, consisting of ‘grave steps and graceful, modest attitudes belonging to that order of choric movement called emmeleia.’ The ancient Egyptian Astronomic Dance can be considered the sublimest of all dances; here, by regulated figures, steps, and movements, the order and harmonious motion of the celestial bodies was represented to the music of the flute, lyre and syrinx. Plato alludes to this dance as ‘a divine institution.’

In spite of the high status of dancing in the ancient civilizations, it has not progressed steadily, as have the other arts. It has remained the least systematized and least respected of arts, generally considered as lacking in seriousness of intention, fitness to express grave emotions, and power to touch the heights and depths of the intellect. Being an art that expresses itself first in the human body, the dance has aroused reprobationix in certain pious, puritanical minds of mediæval type, who have considered it a collection of ‘immodest and dissolute movements by which the cupidity of the flesh is aroused.’ It is this particular view that has damned dance with bell, book and candle. The main reason for this has been the hostile attitude of the church to all folk-arts which manifested a more or less conspicuous ethnographic individuality—that is, were stamped as of Pagan and not Christian origin. All folk-dancing, broadly speaking, is a natural form of æsthetic courtship. The male intends to win the female by his beauty, grace and vigor, or vice versa. From the point of view of sexual selection we can understand, on the one hand, the immense ardor with which every sensuous part of the human body has been brought into the play of the dance, and, on the other, the arguments of the pseudo-moralists to classify it with the frivolous and least tolerated arts.

The stamp of frivolity, put upon the dance by the Christian clergy, has retarded its natural development for several centuries. Italy and Germany, having been the cradles of all modern music and stage arts, have given little inspiration to a systematic development of the art of dancing. The seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that have meant so much to the perfection of the opera, vocal and orchestra technique, gave nothing of any significance to choreography. The church that tolerated Bach, Paësiello, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, put an open ban upon everything that had any relation to the dance. The great musical classics of the past centuries have treated dance as an insignificant side issue, thereby putting a label of inferiority upon this loftiest of arts. All the dance music of the great classics sounds naïve and lacking in choreographic images. Yet dance and music are like light and shadow, each depending upon the other. As canvas is to a painter, so is music to a dancer the essentialx element upon which he can draw his picture. The fact that the art of dancing has not evolved into its normal state of equality with the other arts, is wholly due to the lack of musical leadership. Neither the reforms of Noverre nor those of Fokine nor Marius Petipa can be of fundamental value if they lack the phonetic designs which alone a choreographic artist can transform into plastic events. Essentially, and æsthetically speaking, dancing should be the elemental expression alike of symbolic religion and love, as it used to be from the earliest human times.

Dancing and architecture are the two primary and plastic arts: the one in Time, the other in Space; the one expressing the soul directly through the medium of the human body, the other giving only an outline of the soul through the medium of fossilized forms. The origin of these two arts is earlier than man himself. Both require mathematics, the one rhythmically, the other symmetrically. For dancing the mathematical forms are to be found in music, for architecture, in geometry. ‘The significance of dancing, in the wide sense, thus lies in the fact that it is simply an intimate concrete appeal of that general rhythm which marks all the physical and spiritual manifestations of life,’ writes Havelock Ellis. ‘The art of dancing moreover is intimately entwined with all human traditions of war, of labor, of pleasure, of education, while some of the wisest philosophers and ancient civilizations have regarded the dance as the pattern in accordance with which the moral life of man must be woven. To realize therefore what dance means for mankind—the poignancy and the many-sidedness of its appeal—we must survey the whole sweep of human life, both at its highest and at its deepest moments.’

Anna Pavlowa.

xi

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction by Anna Pavlowa | vii | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | The Psychology of Dancing | 1 |

| Æsthetic basis of the dance; national character expressed in dances; ‘survival value’ of dancing; primitive dance and sexual selection; professionalism in dancing—Music and the dance; religion and the dance; historic analysis of folk-dancing and ballet. | ||

| II. | Dancing in Ancient Egypt | 12 |

| Earliest Egyptian records of dancing; hieroglyphic evidence; the Astral dance; Egyptian court and temple rituals; festival of the Sacred Bull—Music of the Egyptian dances; Egyptian dance technique; points of similarity between Egyptian and modern dancing; Hawasis and Almeiis; the Graveyard Dance; modern imitations. | ||

| III. | Dancing in India | 24 |

| Lack of art sense among the Hindoos; dancing and the Brahmin religion; the Apsarazases, Bayaderes and Devadazis; Hindoo music and the dance; dancing in modern India; Fakir dances; philosophic symbolism of the Indian dance. | ||

| IV. | Dances of the Chinese, the Japanese and the American Indians | 30 |

| Influence of the Chinese moral teachings; general characteristics of Chinese dancing; court and social dances of ancient China; Yu-Vang’s ‘historical ballet’; modern Chinese dancing; dancing Mandarins; modern imitations; the Lantern Festival—Japan: the legend of Amaterasu; emotional variety of the Japanese dance; pantomime and mimicry; general characteristics and classification of Japanese dances—The American Indians: The Dream dance; the Ghost dance; the Snake dance. | ||

| V. | Dances of the Hebrews and Arabs | 43 |

| Biblical allusions; sacred dances; the Salome episode and its modern influence—The Arabs; Moorish florescence in the Middle Ages; characteristics of the Moorish dances; the dance in daily life; the harem, the Dance of Greeting; pictorial quality of the Arab dances.xii | ||

| VI. | Dancing in Ancient Greece | 52 |

| Homeric testimony; importance of the dance in Greek life; Xenophon’s description; Greek religion and the dance; Terpsichore—Dancing of youths, educational value; Greek dance music; Hyporchema and Saltation; Gymnopœdia; the Pyrrhic dance; the Dipoda and the Babasis; the Emmeleia; The Cordax; the Hormos—Greek theatres; comparison of periods; the Eleusinian mysteries; the Dionysian mysteries; the Heteræ; technique. | ||

| VII. | Dancing in the Roman Empire | 72 |

| Æsthetic subservience to Greece; Pylades and Bathyllus; the Bellicrepa saltatio; the Ludiones; the Roman pantomime; the Lupercalia and Floralia; Bacchantic orgies; the Augustinian age; importations from Cadiz; famous dancers. | ||

| VIII. | Dancing in the Middle Ages | 78 |

| The mediæval eclipse; ecclesiastical dancing in Spain; the strolling ballets of Spain and Italy; suppression of dancing by the church; dances of the mediæval nobility; Renaissance court ballets; the English masques; famous masques of the seventeenth century. | ||

| IX. | The Grand Ballet of France | 86 |

| Louis XIV and the ballet; the Pavane and the Courante; reforms under Louis XV; Noverre and the ballet d’action; Auguste Vestris and others; famous ballets of the period—the Revolution and the Consulate; the French technique, the foundation of ‘choreographic grammar’; the ‘five positions’; the ballet steps—Famous danseuses; Sallé, Camargo; Madeleine Guimard; Allard. | ||

| X. | The Folk-Dances of Europe | 104 |

| The rise of nationalism—The Spanish folk-dances: the Fandango; the Jota; the Bolero; the Seguidilla; other Spanish folk-dances; general characteristics; costumes—England: the Morris dance; the Country dance; the Sword dance; the Horn dance—Scotland: Scotch Reel, Hornpipe, etc.—Ireland: the Jig; British social dances—France: Rondo, Bourrée and Farandole—Italy: the Tarantella, etc.—Hungary: the Czardas, Szolo and related dances; the Esthonians—Germany: the Fackeltanz, etc.—Finland; Scandinavia and Holland—The Lithuanians, Poles and Southern Slavs; the Roumanians and Armenians—The Russians: ballad dances; the Kasatchy and Kamarienskaya; conclusion. | ||

| XI. | The Celebrated Social Dances of the Past | 144xiii |

| The Pavane and the Courante; the Allemande and the Sarabande; the Minuet and the Gavotte; the Rigaudon and other dances—The Waltz. | ||

| XII. | The Classic Ballet of the Nineteenth Century | 151 |

| Aims and tendencies of the nineteenth century—Maria Taglioni—Fanny Elssler—Carlotta Grisi and Fanny Cerito; decadence of the classic ballet. | ||

| XIII. | The Ballet in Scandinavia | 161 |

| The Danish ballet and Boumoville’s reform; Lucile Grahn, Augusta Nielsen, etc.—Mrs. Elna Jörgen-Jensen; Adeline Genée; the mission of the Danish ballet. | ||

| XIV. | The Russian Ballet | 170 |

| Nationalism of the Russian ballet; pedagogic principles of the Russian school; French and Russian schools compared—Begutcheff and Ostrowsky; history of the Russian ballet—Didelot and the Imperial ballet school; Petipa and his reforms—Tschaikowsky’s ‘Snow-Maiden’ and other ballets; Pavlowa and other famous ballerinas; Mordkin; Volinin, Kyasht, Lopokova. | ||

| XV. | The Era of Degeneration | 189 |

| Nineteenth-century decadence; sensationalism—Loie Fuller and the Serpentine Dance—Louise Weber, Lottie Collins and others. | ||

| XVI. | The Naturalistic School of Dancing | 195 |

| The ‘return to nature’; Isadora Duncan—Duncan’s influence: Maud Allan; Duncan’s German followers—Modern music and the dance; the Russian naturalists; Glière’s ‘Chrisis’—Pictorial nationalism: Ruth St. Denis—Modern Spanish dancers; ramifications of the naturalistic idea. | ||

| XVII. | The New Russian Ballet | 214 |

| The old ballet arguments pro and con—The new movement: Diaghileff and Fokine; the advent of Diaghileff’s company; the ballets of Diaghileff’s company; ‘Spectre of the Rose,’ ‘Cleopatra,’ Le Pavilion d’Armide, ‘Scheherezade’—Nijinsky and Karsavina—Stravinsky’s ballets: ‘Petrouchka,’ ‘The Fire-Bird,’ etc.; other ballets and arrangements. | ||

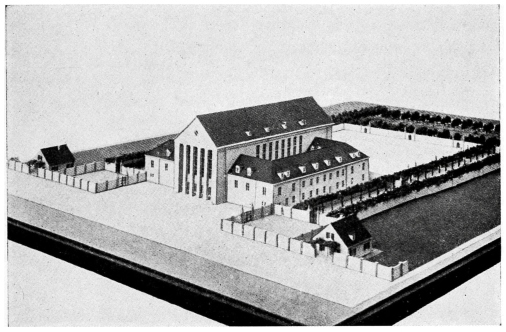

| XVIII. | The Eurhythmics of Jacques-Dalcroze | 234 |

| Jacques-Dalcroze and his creed; essentials of the ‘Eurhythmic’ system—Body-rhythm; the plastic expression of musical ideas; merits and shortcomings of the Dalcroze system—Speculation on the value of Eurhythmics to the dance.xiv | ||

| XIX. | Plastomimic Choreography | 247 |

| The defects of the new Russian and other modern schools; the new ideals; Prince Volkhonsky’s theories—Lada and choreographic symbolism—The question of appropriate music. | ||

| Epilogue: Future Aspects of the Dance | 261 | |

| Odalisque in ‘Scheherazade’ (Russian Ballet) | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

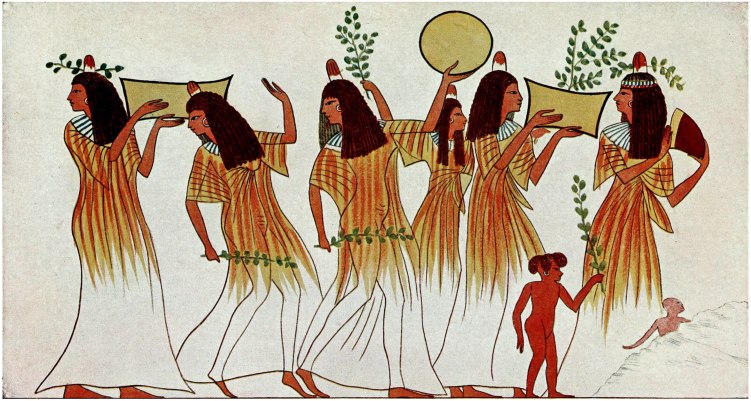

| Egyptian women dancing with cymbals | 21 |

| Greek and Roman Dances as Depicted on Ancient Vases | 68 |

| Danseuses en Scène (The Ballet) | 102 |

| The Ball | 150 |

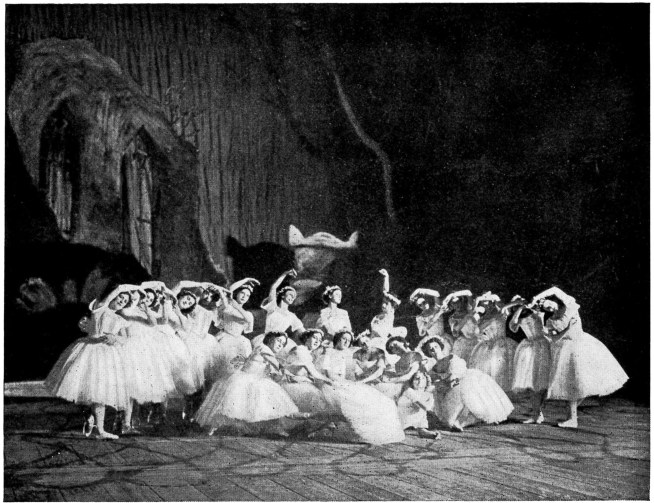

| Sylphides; a Typical Classic Ballet | 156 |

| Pavlowa | 174 |

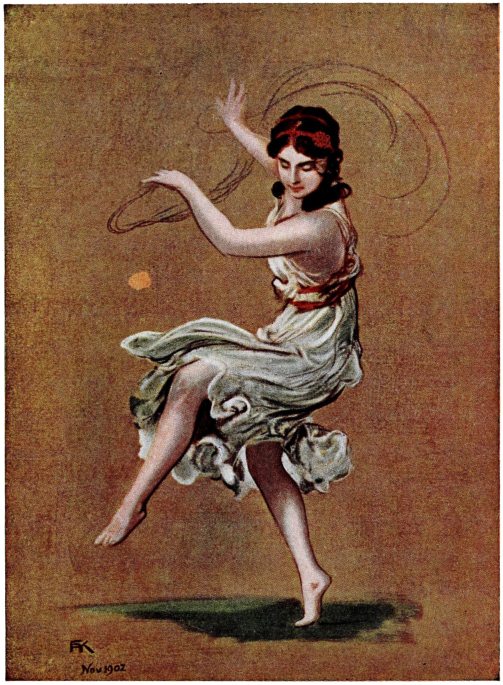

| Duncan | 200 |

| Maud Allan | 211 |

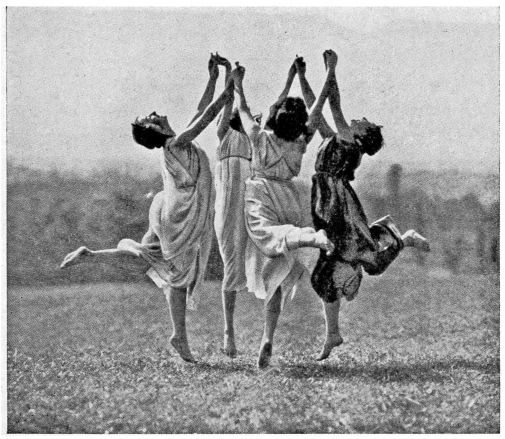

| A Plastic Pantomime (Dalcroze Eurhythmics) | 245 |

1

Æsthetic basis of the dance; national character expressed in dances; ‘survival value’ of dancing; primitive dance and sexual selection; professionalism in dancing—Music and the dance; religion and the dance; historic analysis of folk-dancing and ballet.

Every true art is a direct and immediate act of life. As in music and dancing, so in life, rhythm is the skeleton of tone and movement and also the basis of existence. We breathe rhythmically and our heart beats rhythmically. We walk, laugh and weep rhythmically. Rhythm is the only frame to the moving material of the visuo-audible art. What except rhythm can unite living men in order to convert them from a chaotically moving crowd into a work of art? It was undoubtedly the innate feeling for rhythm that actuated the primitive man to dance. All existing races show a strong tendency to dance, as well in their primitive as in the more or less civilized state. The plastic forms of the human body lend themselves more to an æsthetic expression that contains architecture, sculpture, painting, poetry, drama and music, than anything else in creation. The mimic expressions of the face, the agility of the steps, the grace of gestures and poses are all natural means which a man can employ in his dance. The symmetric lines of the body that are produced after the melodic patterns of the music form the æsthetic basis of the art of dancing. The ability to give a living2 meaning to these lines is what makes a dance beautiful and divine. Although frequently the beauty of a line and movement can be observed in animals and birds, yet there it is an unconscious act, lacking in that individual and subjective feeling that we call inspiration.

The foremost element in every dance is—the step. Step is also, practically speaking, the first movement of life. In consequence of pure physical laws each step requires a new impulse and thus divides it into two periods: motion and repose. The continuance of these two rhythmic periods produces the feeling of symmetry and joy, which in its turn creates the various combined movements that again are divided into various sub-motions and partial measures. The development of steps in a dance is based on two principles: the movement of the feet, and the combined movement of the body and hands for grace or mimicry. Consequently dance is nothing but a chain of bodily movements that are subjected to a certain musical rhythm and follow the emotional expressions of the dancer. According to an innate principle dance, like speech, was practiced by the primitive races as a medium of the most vital expressions. By means of a dance the savages express their joy, sorrow, anger, tenderness and love. Dance has its peculiar psychology, which varies according to racial temperament, climate and other conditions. This is best illustrated in the various styles of the folk-dance. To the vigorous races of Northern Europe in their cold and damp climate dancing became naturally a function of the legs. The Scandinavian and Finnish folk-dances betray more heavy and massive motion, while those of Spain, Hungary and Italy or France give an impression of romantic grace, coquettish agility and fire. The folk-dances of the Cossacks are usually violent and acrobatic, as is their life. Energy or dreaminess, fire or coolness, and a multitude of other racial qualities assert themselves automatically in a3 folk-dance. The list of forces that make and preserve a nation’s dances is incomplete without the addition of the powerful element of national pride, weakness or other peculiarities. On the contrary, in the Far East, in Japan, Java, China, etc., dancing is exclusively a motion of the hands and fingers alone. In ancient Rome dancing was predominantly the rhythmic motion of the body, with vibratory or rotatory movements of breast or flanks. The Stomach Dance of the Arabians betrays the wild passion of a nomadic desert race.

According to Louis Robinson, dancing is an innate instinct that has an indirect bearing upon the existence of the human race. Robinson argues that throughout Nature instincts, like the organs of our bodies, are the product of the strict laws of evolution, and have been built up to meet some need. At some critical time in the past they had a certain survival value—i. e., they were capable of determining in the struggle for existence which individuals or tribes should go under and which should survive. This principle can be taken as one of the axioms which must be our pilots in every attempt to account for the faculties which each of us brings into the world, as distinct from those acquired in the life of the individual.

Practically every savage people has elaborate dances and spends a good deal of time in such exercises. Among adults dancing takes the place of the play of children. When we come to analyze the play of all young creatures from the historical standpoint we find it forms part of an elaborate natural system of physical training. The perpetual motion of the kitten while it is awake is obviously a training for those accomplishments which in later life mean a livelihood. Such astonishing skill and agility as are shown by the cats in securing prey cannot be attained by any ready-made machinery like that of the dragon-fly or the mantis: they must be built up and manufactured. Herein the4 nervous mechanism of the mammalia has prevailed over the limited mechanical perfection of lower things such as reptiles, fish, and insects. Most of them can do some one thing or other supremely well, but the mammalia, with their better nervous system and receptive brains, can excel in many things. We, with our greater gifts of the same sort, are the most versatile and teachable of all; hence we prevail over the rest of creation. The kitten, the puppy, and the young savage, by their continual restless and organized activity, gain great advantage in certain movements necessary in after life, and foster the growth of the particular muscles which later on will be absolutely requisite in the serious business of holding their place in the world. Obviously such instincts would become out of date and inappropriate should the general manner of living undergo a complete change. Hence we find that much of the play of young children in civilized lands has little or no reference to the serious life which comes afterwards. Such instincts, however, were developed during or before the long stretch of time of the Stone Age, when all men played hide and seek, and chased one another, and threw things, and ran, and jumped, and wrestled for exactly the same reason that makes us scan commercial articles, attend markets, and work in our studies or offices. What is observable in any nursery or playground affords a good illustration of the persistence of instincts long after the need which created them has passed away. For some reason the play instinct in most creatures tends to lapse at the time of full bodily maturity. It does not cease entirely, but apparently it no longer suffices as an incentive for the battle of life.

Man in the savage state is naturally lazy and does not like to exert himself when food comes easily. When no urgent need or human authority is pushing him, he prefers to eat to repletion and then to lie in the sun5 or loaf. We even find this primitive habit cropping up in strenuous lands where the stimulus of moral education and competition has been at work for generations.

We are all aware that, when we are lazy for any length of time, we get slack and soft. The primitive savage who lives by hunting and is in continual danger of raids from his neighbors, cannot afford to get slack. He must keep himself fit every day of life. How was this to be managed by our prehistoric forefathers when there was no fighting, with the weather soft, and a delicious fish easily to be caught quite near the dwelling? It is pretty safe to say that, owing to the want of condition—if they were not dancing tribes—they did not leave descendants which are among us in the twentieth century.

It seems strange how readily a group of negroes who are apparently exhausted after a long day’s work will join in dance with their fellows, and how, when not very tired, they will in their laziest moments spring up and take vigorous exercise of this kind. Every doctor will tell you that there are plenty of women to-day who have not the strength nor the energy to do any work or to walk a couple of miles, but who will dance from evening till morning without showing any great fatigue. Among such Pagans as the Zulus and Masai, who organize themselves for war almost as well as has ever been done by the most civilized Christians, there is practically no distinction between military exercises and dancing. This is proof enough to show that dancing had a survival value throughout the long stretch of the Stone Age. Dancing taught primitive men to move in compact bodies without confusion, and especially without getting so bunched together that they could not use their weapons.

To-day the true war-dance only persists among us in the form of military marchings, but the other primitive6 dances have left numerous descendants of all kinds and degrees, down to the modern tango. Among these non-military dances the survival value, apart from the healthy exercise which they provided and their general disciplinary effects, worked through the agency of sexual selection.

In the case of the primitive dances the working of sexual selection was beneficial as conducive to racial fitness. The dances in which women took part gave opportunity for appraisement of exactly the kind needed for a sound choice of mates under savage conditions. It afforded the chance, so lacking in our present civilization, of advertising any admirable qualities which might be possessed. It was a test not only of physical grace and perfection, but of activity, taste and temper. It contributed to honest matrimonial dealing—especially when danced in the approved ballroom costumes of savage times.

There have been many discussions as to why clothes were first worn—whether for ornament, warmth, or decency—but one may fairly say without any doubt whatever that, from the first ages until now, dance clothing has been mainly decorative. Here we find an ethical justification of matters connected with dancing dress, which has often provoked severe criticism among puritans. Without a doubt from the earliest times until now the dance has been a chief purifying agent in the marriage market—has played the part, in fact, of those market inspectors appointed to guard against adulteration.

It is a most extraordinary thing, when we come to consider man’s place in Nature, that he ever began to dance. Not that dancing is uncommon in Nature; many birds, especially those of the crane tribe, execute elaborate dances during their season of courtship, and as a mere pastime when they have nothing else to do. Few, if any, of the mammalia appear to indulge in organized7 dances, unless we give such a name to the frisking of young lambs and the prancing evolutions of horses and antelopes. Assuredly, in our direct line of descent nothing of the kind could have existed as far back as our knowledge and imagination will carry us. You cannot very well dance in the trees, which, according to Darwin, were the real nurseries of our species; and when you come down to solid earth your weak prehensile lower members would only make you ridiculous and contemptible if they attempted any performance of the kind.

Mother Nature, however, is a dame of infinite varieties, and seems continually to be trying the most bizarre experiments apparently without the least prompting or justification. The products of these experiments are called ‘sports,’ and there seems no limit to their possibilities. Chimpanzees delight in thumping hollow trees and knocking pieces of wood together, while it is said that the gorilla waddles to war to the sound of the drum, improvising a substitute by beating his hands against his brawny chest.

In the Western world professionalism in dancing has happily not had the blighting effect on the pursuit that it seems to have had on some other forms of pastime. But if we go to the East we find that practically all other forms of dancing have ceased to exist. We see the effect of this tendency most fully developed in China, where the recreative dancing of European society seems to be quite beyond the comprehension of a well-bred Chinese, who naïvely asks the question: ‘Why do you not pay people to dance for you?’

Stage dancing seems to be an interesting instance of the degeneration into pure luxury or something which was at one time a helpful influence to the race. This is a tendency observable in many phases of life when the pressure of evolutionary forces is somewhat relaxed. Most of the luxuries pertain to matters which8 at one time had a survival value, and it cannot be said that they have retired from among the evolutionary forces even to-day; but their effect, if still beneficial to the race, lies in aiding Nature to eliminate the unfit.

From the earliest times on dancing has been dependent upon music of some kind. The question whether music is older than dancing has not been answered satisfactorily by academic anthropologists yet. However, all scholars agree that the appearance of these two arts must have been more or less simultaneous, the one influencing the other. But undoubtedly the first dance music was not instrumental but vocal. The savages to-day dance most of their sexual dances to rhythmic recitation of certain words. Music is in every phase of evolution the only true essence of that which forms the subject of the dance.

To the transformation of more or less primitive folk-dances into those of strictly religious character is due the principal idea of the modern ballet. In the Oriental temples dancing underwent a strange transformation. While dancing was made the basis of dramatic and symbolic ideas, yet this very fact became detrimental to the musical influence upon the choreography. The Egyptians, whom we consider the pioneers in religious dances, originated elaborate temple ballets, which were based more upon a dramatic than a musical theme. Though the tradition speaks of rounds, of symbolic and sidereal motions, and the instruments chiefly employed, as the Egyptian guitar, used both by men and women, the single and double pipe, the harp, lyre, and flute, yet essentially this all resembled a pantomime rather than actual dance.

It is very likely that all the ancient sacred dances originated with the subconscious idea of counteracting9 the sensuous or strictly playful influence of the social dances. The whole pedigree of our Western religions seems to show a remarkable absence of this method of encouraging religious feeling. The reasons why such manifestations were discouraged by Jewish and Christian moralists pertains to physiology rather than theology. As already said, man’s nature is compounded of many diverse elements, and the machinery of emotion at present at work within us dates back to our animal past. Our most refined and exalted feelings spring from the same nervous reservoirs and pass through the very channels which were at one time solely occupied by grosser passions. The Egyptian church that grew directly of the folk-art of the country was a stranger to Greece and Rome, and still more so to our Christian religion. The ethical ideals that actuated the Egyptian priests in introducing dancing at the altar, sprang directly from the soil and meant, in bringing the better part of human nature to the top, to act as a kind of separator. The priests discovered that the higher emotions, with the help of sacred dancing, can be put to excellent service as impulses to improved conduct. The Christian missionaries, coming from the East, found nothing elevating and ennobling in our Western dancing, which did not appeal to them on account of the very differences of the style and racial character. It is due to their opposition that the religious dances have faded out under the Western civilization. The warfare against dancing generally, on the part of the Apostles of Christianity, dates back to the fanatic era of theological and nationalistic differences. In all countries where the religion descends directly from a racial folk-lore, dancing has remained in high esteem at home and in the temples. This we find true in Egypt, Greece, India and China. In the Jewish form of worship there seems to have been no formally recognized dancing, although we have records of several displays of this10 kind, as in the case of King David, when, ‘clothed in a linen ephod, he danced before the Ark of the Lord with all his might.’

In Greece, cradle of the arts, the Muses manifested themselves to man as a dancing choir, led by Terpsichore. The Romans imitated the Greeks in all their arts and imported with the Greek slaves Greek dances. But Rome was too barbaric to appreciate the full value of Greece’s poetic arts. The solemn religious dance instituted by Numa and practiced by the Salian priests soon degenerated into ceremonial march that was abolished when Rome became Christian, through a papal decree in 744. Darkness of night fell on the development of secular and religious dancing, a darkness that endured for centuries. The influence of the Nile in Egypt and Cadiz in Spain, which for centuries had been the two great centres of the ancient dancing and supplied their dancers to the Roman potentates, faded out slowly in the history of European nations. The folk-dances were labelled as low and undignified amusements of Pagan peasants. Dance in every form remained an outcast, despised and condemned until the court circles of Italy and France distorted it to an amusement at domestic gatherings and masquerades. It is said that the modern ballet had its origin in the spectacular masquerades arranged for the marriage of Galeazzo, Visconti, Duke of Milan, in 1489. The impression of this performance spread to the Court of Florence. Catherine de Medici, the Queen of France, brought the Italian court pantomime to Paris, where the French kings and queens grew to admire dancing and took actual part in it. The attempts of Noverre to elevate the art of dancing to what it had been in ancient Egypt and Greece, were successful only externally. Music, the soul of dancing in the modern sense, was lacking, and without this soul the art of plastic form is incomplete. Though the Russian reformers elevated11 dancing from a domestic amusement to a serious and lofty stage art, they did not succeed wholly in giving to it the foundation that it deserves among the other arts. All the past and living goddesses of choreography have not had the freedom, the phonetic means and dramatic threads to thrill their audiences as they would, if man had not distorted and hidden the natural meaning of the dance that inspired his barbaric ancestors.

The philosophical conclusion of our historic analysis of dance leads back to the same axioms that actuated the savage in his practice of agility: the sexual selection and primitive sport, both necessary for evolution and the existence of the race. However, there is neither sexual motive nor instinct for ‘physical culture’ in the ‘Heavenly Alchemy’ of evolution that has created the poetic movements of Taglioni and her successors. The ancient racial propensities have developed into more spiritual ideas. Like the tendency of evolution generally, to universalize an individual and individualize the universe, so in dance the racial characteristics are transformed into cosmic motives. In this stage beauty becomes symbolic and concrete emotions take on a more and more abstract form. The survival value of the greatest art of the dance lies in ennobling the intellect and soul, which has necessarily an indirect bearing upon the physical. Ultimately this means perfection of the whole human organism. It inspires the mind and influences the body.

Civilization has brought humanity to a state where the physical needs depend upon the psychical. We have devised a more complicated form of sexual selection and more complicated means of existence than the primitive dances employed in our animal past. Beauty in the long course of evolution has grown more spiritual, accordingly dancing as an art has become an evolutionary medium of the intellect.

12

Earliest Egyptian records of dancing; hieroglyphic evidence; the Astral dance; Egyptian court and temple rituals; festival of the Sacred Bull—Music of the Egyptian dances; Egyptian dance technique; points of similarity between Egyptian and modern dancing; Hawasis and Almeiis; the Graveyard dance; modern imitations.

Long before the rest of the world had emerged from barbarism Egypt had reached a high state of civilization. But the history of Egyptian civilization was hidden behind a curtain of mysteries, until the key to the hieroglyphs was discovered. Then, the imposing pyramids opened suddenly their sealed lips and the world stood aghast at their revelations. The ruins of Memphis and Thebes became books of interesting reading. The discovered inscriptions and papyri revealed the high state of development that the dance had reached in the ancient Egyptian temples. The first dancing in Egyptian history is recorded by Manetho, the priest of Heliopolis who lived in 5004 B. C.,—which is approximately one thousand years before the creation of the world, according to Biblical chronology. Plato alludes to Egyptian art and dancing performed ten thousand years before his time. Schliemann, the great archeologist, maintained that the history of Egypt was written in various dance-phases, as can be seen from the inscriptions of their ancient sarcophagi and pyramids.

13 Scarce as are the hieroglyphic materials, nevertheless they reveal to us that the Egyptians, during the reign of the Pharaohs, highly admired the art of dancing. Most of the Egyptian documents or inscriptions begin with dancing figures. These figures are to be found in the most ancient records, which proves that dancing must have been known as an art to the Egyptians not for hundreds but for thousands of years. Herodotus, ‘the father of history,’ tells us that the dances performed to Osiris were as elaborate as the music of a hundred instruments and a chorus of three hundred singers. According to Diodorus, Hermes gave to mankind the first laws of eurhythmics. ‘Hermes taught the Egyptians the art of graceful body movements.’ A fragmentary inscription of a sarcophagus in the Museum of Petrograd describes that Maneros, ‘who conquered so many nations, did this not by means of torch and sword but by teaching the divine art of music and dancing.’ The ancient Egyptian legend surrounds Maneros with nine dancing Muses, which the Greeks probably copied from Egypt later. Music and dancing were employed by the Egyptians at home, in social festivals, on the occasion of marriage, birth and death, and in the temples. Their folk-dances were as gay and fiery as the temperament of the race. This is best illustrated in the recently discovered frescoes of peasants dancing, evidently after their daily work in the fields.

Being worshippers of all the celestial bodies, the Egyptians practiced in their temples certain astronomical ballets. It is said that Hermes, the inventor of the lyre, produced from his instrument as many tones as there were stars in the sky. The three strings of his lyre meant Winter, Summer and Spring. This gives an idea to what an extent astronomy and nature figured in all their dancing and music. The Astral Dance was an imitation of the movement of the various constellations.14 In this their imagination knew no limit. The altar, around which most of the astral dances were performed, represented the sun. According to the descriptions of Plutarch, the dancers made with their hands the signs of the zodiac in the air, while dancing rhythmically from the east to the west, in imitation of the movement of various planets. After every circle the dancers stopped for a few moments as if petrified, which was meant to represent the immovability of the earth. By means of combined gestures and mimic expressions, the priests gave intelligible pantomimic stories of the astral system and the harmony of eternal motion. Lucian called this one of the most divine inventions.

It is a pity that all the hieroglyphic records known to us do not give any adequate explanation of the ancient Egyptian Astral Dance. The descriptions left by Greek writers are too general and are frequently incorrect. Various scholars have made efforts to discover the mystic meaning of the dance of the ‘Seven Moving Planets,’ but in vain. How much the idea of an astral dance has impressed the European ballet-masters is proved in that Dauberval and Gardel produced in the eighteenth century ballets of this character. However, in this case the performers were not priests but fantastically dressed ballet dancers who, representing various stars and planets, jumped and turned around the prima ballerina, who represented the sun.

To what an extent the love of pantomime and dancing prevailed in Egypt can be judged from the recently made decipherings by Setche of the inscriptions of the sarcophagus of a prime minister which describes the code of an elaborate court ritual. The inscription tells how a newly-appointed minister should meet his ruler. He should enter the imperial hall, dancing so that from his gestures, poses and miming could be read devotion,15 loyalty, chivalry, grace, tenderness, vigor and energy. Pharaoh, in his turn, would meet the minister with a different sort of dance. The reception would end with the joining of all the court functionaries, musicians and priests in a great procession.

The Egyptian clergy exercised a great influence upon the people. Imitating the court of the Pharaohs, they surrounded the religious rituals with unnecessary secrets. The more mysterious they made the ceremonies the more they impressed the people. In consequence of such an attitude on the part of the clergy, a large majority of religious dances grew so complicated in their symbolic details that they degenerated into nonsense. A large number of the Egyptian sacred dances were based on the cult of Isis and Osiris, the one a feminine, the other a masculine divinity. This gave the fundamental idea of maintaining a large number of the so-called ‘sacred’ courtesans, who took an active part in most of the temple dances. Herodotus tells us that the presence of these ‘sacred’ courtesans in the Egyptian temple ceremonies during the last Dynasties is responsible for the downfall of this ancient civilization.

Most of the Egyptian temple dances were performed by men and women alike. On the other hand, there existed special feminine and strictly masculine ballets. Of the feminine dances, the most known is the dance which was performed during the celebrated sacrificial festival of the sacred bull Apis. After the black bull on whose back grew naturally the figure of a white eagle was found, forty temple maidens were selected to feed it forty days on the shores of the Nile. All this time the maidens had to practice the great ballet that they were to perform thereafter. The Festival of the Sacred Bull was opened with a solemn dance of the priests in the temple of Osiris at Memphis. Then the bull was carried through the city by the maidens16 in a spectacular procession, accompanied by singing and dancing. When the bull was brought before the huge statue of Osiris the real ballet was performed by priests and maidens together. The ballet, which lasted for half a day, was opened with a slow introduction in march form. In this the dancers personified the birth process of divinities, particularly of Osiris. In the second movement, which probably resembled a modern allegro energico, were depicted the youth and romantic adventures of Osiris with the goddess Isis. Priests in fantastic costumes represented Osiris and his warriors, while the maidens played the rôle of Isis and her companions. The last movement of the ballet closed with a festival finale, which meant the victory of Osiris in conquering India. When the sacred bull was drowned in the Nile a violent funeral ballet was performed by the priests. As the recently discovered bas-reliefs illustrate, the dancing priests wore costumes consisting of a yellow tunic and round caps.

While some of the Egyptologues maintain that dancing was performed only on special occasions such as the above, others are of the opinion that every Egyptian temple service contained some kind of dance. However, the hieroglyphic inscriptions of various periods prove that there were hundreds of different temple dances. Of particular interest is the recently discovered ‘Dance of Four Dimensions,’ which was performed in the temple of Isis. In this both priests and priestesses participated. It differed from the other dances in that the dancers carried along their musical instruments.

Since the art of dancing had reached such a high degree of culture in Egypt it is evident that the people must have possessed a highly developed form of music.17 Though musical history denies the fact that harmony was known to the ancient civilization, yet the recent archeologic discoveries and hieroglyphic decipherings speak eloquently of the use of various instruments in a kind of orchestra, and there are frequent allusions to temple choirs of a hundred and more singers. Dr. Schliemann even believes that the Egyptians had their specific musical notation which was still in use by the Arabs when they came to Spain. It is only natural to believe that an art of such a high standard was taught in a school, as the technique that they evidence is the result of long and systematic studies. ‘It is very likely,’ a Russian archeologist writes, ‘that the Egyptian academy of music and dancing was connected with the temple of Ammon.’

It is evident that the Egyptians knew practically every choreographic rule and possessed a technique which our most celebrated dancers have not yet reached. Their mimic expressions are superb, as are their eurhythmic gestures and poses. Since the temple in Egypt united under its supreme patronage all the arts, it is only natural that dancing and music knew no other forms of expression, except the home. However, the court of Pharaohs played a big rôle in stimulating a secular style of dance, which the Greeks later performed in a modified form on their stage. Various inscriptions and sarcophagus bas-reliefs depict a corps of several hundred dancers that was maintained by the ruler. The Queen Cleopatra was so fond of dancing that she herself gave performances in a specially constructed hall, dimly lighted and richly decorated. Here she danced nude to her guests behind numerous gauze curtains, using constantly the effects of fused light produced by different colored lanterns. She had a well trained and beautiful voice and played masterfully on various instruments. Also, in connection with her dances, Cleopatra used heavy redolescent perfumes by18 means of which she put her audience into a ‘passionate trance.’

That the Egyptian dancers knew pirouettes, fouetté pirouettes, arabesques, pas de cheval, and other modern ballet tricks 5,000 years ago is proven by the dancing figures that can be seen at the sarcophagi at Beni Hassan. These figures illustrating ballet corps are usual. A common style of Egyptian dancing was the peculiar reverse movement of the two dancers which reached a rhythmic perfection, particularly in dances where many participated, that is absolutely unknown to our choreographic artists. Some dances show great architectural beauty in their pyramidic combinations. The use of the hands at the same time with the use of the legs is evidently more in keeping with a certain style and harmony of line, than that employed by our ballet or classic dancers.

There is in the Egyptian gallery of the British Museum a wall painting taken from a tomb at Thebes. The painting is supposed to have been executed during the eighteenth or nineteenth dynasty, and in it are depicted two dancing girls facing in opposite directions. There is plenty of action and agility depicted in these figures. In one the hands are raised high above the head; in the other they are lowered. One female not dancing is represented playing a double pipe, and others are clapping their hands. The accompanists are dressed, but the dancers wear only a gauze tunic.

All Egyptian professional dancers are represented either nude or very slightly dressed and the performances were given by the people of highest respectability. All Egyptologues are of the opinion that the outline of the transparent robe worn by these dancing girls may, in certain instances, have become effaced; but others say that it is certain they danced naked, as their successors, the Almeiis, do. The view of Sir Gardner Wilkinson that the Egyptians forbade the higher classes19 to learn dancing as an amusement or profession, because they dreaded the excitement resulting from such an occupation, the excess of which ruffled and discomposed the mind, contradicts the opinions of other scholars on the same subject. We read in the Bible that after the Israelites had safely accomplished the passage across the Red Sea, Miriam, the sister of Moses and Aaron, herself a prophetess, took a tambourine in her hand, and danced with other women to celebrate the overthrow of their late task-masters. There are other instances in the Bible which tend to show that among the Jews, who were reared on Egyptian civilization, it was customary for people of the most exalted rank to dance. There is a reproduction of Amenophis II. from one of the oldest tombs of Thebes that goes to show that Egyptians of all classes were highly proficient in the art of dancing. Four upper class women are represented as playing and dancing at the same time, but their instruments are for the most part obliterated. A fifth figure is resting on one knee, with her hands crossed before her breast. The posing of the heads in these figures is masterful. In another painting from Beni Hassan, executed about three thousand five hundred years ago, a dancer is represented in the act of performing a pirouette in the extended fourth position. The arms are fully outstretched, and the general attitude of the figure is precisely what it might be in executing a similar movement at the present day. It is also noticeable that the angle formed by the upper part of the foot and fore part of the leg is obtuse, which is quite in accordance with modern choreographic rules, while the natural inclination of an inexperienced and untrained dancer when holding the limb in such a position would be to bend the foot towards the shin, or at least to keep it in its normal position at right angles.

From many paintings and sculptures that have been20 discovered, we may gather that the primary rules by which the movements of the dancers are governed have not altered since the time of the Pharaohs. The first thing the Egyptian dancers were taught was evidently to turn their toes outward and downward, and special attention was paid to the positions of their arms, which were gracefully extended and raised high, with the hands almost joining above the head. In the small tablet of Baken Amen representing the adoration of Osiris, now in the British Museum, all arm positions of the dancing figures are excellent. In one of the sculptures from Thebes a figure is unmistakably performing an entrechât. Other figures go to show that the Egyptians employed frequently jetés, coupés, cabrioles, toe and finger tricks. There are reproductions representing dance figures for two performers, executing apparently a kind of minuet. Between the dancers in each figure are inscriptions which refer to the name of the dance. Thus, for instance, one was called mek na snut, or making a pirouette. This appears to have been a movement in which the dancers turned each other under the arms, as in the pas d’Allemande.

Besides the temple dances, Egypt had travelling ballet companies, giving their performances in the open air gardens of towns and villages. The nomadic Hawasis whose profession to-day is chiefly dancing, are undoubtedly barbarized descendants of the Hawasis that entertained the Pharaohs with their passionate and fiery social dances. Most of the Hawasi dances were of a sensuous nature, performed exclusively by girls, either naked or in light gauze dresses. The themes of all these dances were often so distinctly feminine, depicting the romantic nature of a woman so graphically, that they were performed only as a part of wedding ceremonies. In regard to this style of dance Sir Gardner Wilkinson expresses the conviction ‘that there is reason to believe that dances representing a continuous21 action or argument of a story were in use privately and were executed by ladies attached to the harem or household.’

Egyptian women dancing with cymbals

From an ancient fresco (in the original colors)

Another secular class of Egyptian dances was that performed by Almeiis. While the style and subject of the Hawasi dances tended to express the sexual passions, the Almeiis had learned to be ‘classic’ and scholarly. The Almeiis of to-day maintain that they descend directly from the dancing Pharaohs. The romantic element in the Almeii dances remains within the limits of a strict code of propriety. For that reason the dancing Almeiis, like the clergy, enjoyed an immunity from the common law. The Almeiis of to-day enjoy the same ancient reputation throughout the East and are invited by the Mohammedan chiefs to teach dancing to their harems. They can be seen dancing in the Arabian desert and in Tunis, Algiers, Tripoli and Morocco. But their present-day dances lack the subtleties and technique that their ancestors possessed five thousand years ago. Their celebrated Sword and Stomach Dances have degenerated into deplorable vaudeville shows. Petipa, the celebrated Russian ballet master, has succeeded in composing a brilliant ballet on the theme of Almeii dances, called ‘The Daughter of the Pharaoh.’ However, excellent as the Russian ballet dancers are, they have never performed it to the satisfaction of its author.

One of the weird ancient Egyptian dances that has survived and is practiced by several Oriental races, particularly in Arabia, Persia and Sahara, is the Graveyard Dance. It is known that the Almeiis used to perform this dance at midnight on the graveyards of rich Egyptians, frequently around the pyramids. Though semi-religious, it did not belong to the classified sacred dances performed under the supervision of the clergy. Prof. Elisseieff thinks that this dance probably originated in lower Egypt and belonged there to a recognized22 temple ceremony, but the priests in upper Egypt failed to recognize it, so the Almeiis monopolized it with great advantage.

The Graveyard Dance performed in the East to-day is wild, weird and ghastly. It is performed by women, dressed in long robes, which cover even their heads. It is danced on moonlight nights by professional Almeiis. These are hired by the relatives or descendants of the rich dead to accompany the wandering soul until it reaches that sphere which belongs to it. There is much strange symbolism and morbid beauty in the Graveyard Dance. Just as weird as the dance is the music, produced from pipes and drums, often accompanied by hooting or sobbing voices. It begins in a slow measure, the dancers marching like spectral shadows in a circle around the musicians. Gradually the music grows quicker, as does the dance. It ends in a wild fury after which the dancers drop unconscious to the ground.

The dances of the living Almeiis and Hawasis and their imitators give little idea of the high art of dancing that was practiced thousands of years ago in ancient Egypt. The modern axis and stomach dances that are practiced by the daughters of the various tribes of the desert are crude acrobatic feats and vulgar degenerations of the graceful and highly developed art that has vanished with the whole ancient civilization of Egypt. In 1900 there appeared in Paris a supposed-to-be descendant of the celebrated ancient Almeiis, La belle, unique et incomparable Fatma, giving performances of ‘Egyptian Wedding Scenes’ and a ‘Dance of Glasses,’ which created a sensation among the decadent artists and writers. However, her success was more due to her beautiful body and its vivid gestures in suggesting certain erotic emotions, than to any real art. On the other hand, Isadora Duncan, Mme. Villiani and Desmond have attempted to arouse interest in the Egyptian23 dances by giving performances that they have claimed to be the genuine classic art of the Nile. According to them, all that a modern dancer needs in becoming Egyptian is to dress as the Egyptians did and produce poses, if possible, with the fewest possible garments, that are to be seen in the ancient fresco paintings, sculptures and hieroglyphs. Then again, the Russian ballet, touring in Europe, announced in its repertoire an Egyptian ballet Cleopatra, which was to be a revelation of unseen beauties of the lost ancient civilization. However, all efforts of the modern imagination are unable to lift the veil of the ages.

Though posterity can catch more accurate fragments in the degenerated dances of Almeiis, Hawasis and the few folk-dances of Young Egypt than in the artificial imitations of various choreographic modernists, as a whole we know but a microscopic part of the vanished age of the Pharaohs. The few scarce records that we possess of the Egyptian dancing speak eloquently of an art far superior to anything which our boasted civilization has yet reached.

24

Lack of art sense among the Hindoos; dancing and the Brahmin religion; the Apsarazases, Bayaderes and Devadazis; Hindoo music and the dance; dancing in modern Indian; Fakir dances; philosophic symbolism of the Indian dance.

The civilization of ancient India was, with the exception of China, the only rival to that of Egypt. But it is remarkable that the Indian mind took a totally different direction from the Egyptian. The tendency towards spiritual expansion that manifested itself in Egypt and Greece became in India a tendency towards concentration. The Indian mind lacked the gift of observation and mathematical proportions, so essential in art, that was possessed by the subjects of the Pharaohs. For this reason we find a magnificent Indian philosophy and mystic science, but an undeveloped feeling for æsthetic values. With the exception of weird and bizarre architecture, that manifested itself most powerfully in the pagodas and temples, the Indian sculpture, painting, music and dancing are too primitive for our taste, as they probably were for that of the ancient Egyptians and Greeks.

In all the Indian constructive arts, in their temple decorations and frescoes, we find very few dancing figures, still fewer graceful reproductions of the human body. Their gods and goddesses look to us like monsters. The Indian Venera, to be seen in the Pagoda of Bangilore, looks like a caricature, as compared with the Greek Aphrodite. The Indian goddess of dancing, Ramble,25 who, according to the legend, was a courtesan of Indra, and gave birth to two daughters, Nandra (Luxury) and Bringa (Pleasure), lacks all the loftiness and charm which surrounded the dancing goddesses of Egypt and Greece. There is neither life nor grace in any of the Indian temple art. Even the smile of Indian gods is stupid and inexpressive. The lack of humor and joy mirrors itself best in the art of the Bayaderes, the celebrated dancers of India. Their gestures and movements are void of that exultant gaiety and optimism that predominates in dances of other nations. An air of gloom and pessimism emanates from all the Indian art.

There is no doubt that the peculiarities of Indian music have been obstacles to the development of the national dance. Although it is full of color and feeling, yet the division of their scale into so many more tone units than ours makes it extremely difficult for a dancer to catch the delicate nuances and lines and reproduce them in movement. A few dancing designs here and there give the impression that this art has not changed during the four thousand years of the nation’s existence. Since the whole Indian civilization is the same to-day that it was thousands of years ago, we are pretty safe in our assumption that the dances of the Bayaderes exhibited at Calcutta or Benares now were pretty nearly the same during the life of Buddha. The modern dances, like the old ones, show similarity in the fact that the Indian dancers stand nearly at one spot and hardly move their feet, while mimicking, and moving their body, arms, hands and fingers. The individual peculiarity of all Indian dances lies in the impressionistic poses of their hands and the body.

India deserves to be called the Land of a Thousand Religions. Religion to an Indian represents everything. Like wisdom and life, dance is of divine origin. From time immemorial dancing has been a part of26 Indian temple ceremonies. The Brahmin religion is interwoven with beautiful legends and myths, according to which dancing was the first blessing that Brahma gave to mankind. One of the legends tells us that the divine Tshamuda danced to music while standing on an egg and holding a huge turtle on her back. In such a position she is to-day giving performances to Brahma in the Nirvana. Such a magic Paradise, with plenty of dancing and music, lasting from early morning till late in evening, is promised after death to all faithful souls.

A widespread Indian legend is that which describes the magic dancing of the Apsarazases, or divine nymphs, with which the Indian imagination has populated every hill and brook. The only occupation of the Apsarazases is singing and aerial dancing. For this purpose these sacred nymphs are supplied with feathery wings which enable them to fly freely in the air. Dancers who reach the very climax of their art get magic wings like every Apsarazas and vanish alive from the earth. This legend laid the foundation of the Indian sacred dances, which were taught by the priests to young maidens kept specially for that purpose near the temples. While the European tourist calls all Indian dancers Bayaderes, regardless whether they give their performances on the streets or in the temples, an Indian calls the temple dancers Devadazis, or the ‘slaves of God.’ The common street or social dancer is called Nautch Girl. The Indian Devadazis are raised and educated much as are the Christian nuns. After being graduated from a dancing school, the girls are taken by the priests to the temples in which they give daily performances to the pilgrims and live as sacred courtesans with the clergy.

The main function of the Devadazis consists in giving performances, either singly or in groups, to the priests and the pilgrims. Some of their dances take27 place in front of the pagodas, others inside. The dancers always wear a long garment, covering their body and legs, leaving only the hands and arms bare. Rich people can hire these temple dancers to give performances in their homes, otherwise they never appear outside the temple atmosphere. To an Indian dancer the most important parts of her body are her breasts and fingers. Though she appears in dance barefoot, frequently with rings in her toes, she pays comparatively little attention to her feet. Many of the modern Bayaderes wear an elaborate costume of yellow with wide pantalettes and richly embroidered wraps around the shoulders, leaving arms and breasts bare.

The music accompanying the dances of the Indian Bayaderes is produced by an orchestra consisting of wood wind instruments similar to our flute and oboe, a few string instruments, two different drums and a few tambourines. The leader of the orchestra gives a sign by striking certain brass plates and the Bayaderes, lifting their veils, advance in front of the musicians and begin the dance. The dance, consisting usually only of mimic expressions of two dancers, has a strange melody and a stranger rhythm. Neither the music nor the dance can be compared with anything known in our Western art. Now and then the feet beat measure, otherwise there is little display of leg agility. The face, particularly the eyes, of the Indian dancers are very expressive. But the alphabet of the dance mimicry is so large that it requires a special study in order to understand and appreciate the fine movements of an artist.

All the Indian social ceremonies, such as marriage, birth and burial, are celebrated with dancing and music. This is particularly true of the social ceremonies of the rich. The standing of the dancers is high in India, so that even in the palace of the Rajah dancers are treated like the guests. In certain parts of India28 the Bayaderes have the right to live as guests at any house without paying. Prince Uchtomsky, who made a special study of Indian life and art, writes that in cities visited by the European tourists one rarely gets a glimpse of the real Bayaderes. According to him there are many Indian Bayadere dancers that surpass in their suggestive power our most passionate ballets. Every line of their miniature impressionism in dance has an exotic beauty which implies more than it expresses.

The Indian dancers are usually women, though Pierre Loti writes that he witnessed several dances performed by men. These dances, as described by him, tally closely with those which the writer saw frequently performed by various Mongolian tribes in South-Eastern Russia. But we are inclined to think that these, being wild in their character, could not be classified as dances of Indian origin.

To a certain class of Indian dancing belong the well-known fakir dances, performed by begging pilgrims at public gatherings. These represent the surviving fanaticism of an ancient sect. Their strange performances are to be seen everywhere in Northern India. Absolutely naked and with dishevelled hair, they moan, shriek and groan, jumping wildly up and down and shaking their hands convulsively. When the fanatical execution has reached its climax the fakirs stab themselves with knives or hot irons until they fall into a trance. It is a kind of Oriental ‘Death Dance.’ To an outsider it is unexplainable how they can endure such self-torture for any length of time. In most cases the knives that the fakirs use are so constructed that they do not go deep into the body but scratch only the skin and produce slight wounds. Though their bloody performances make a deep and shocking impression upon the onlookers, yet dances of this kind cannot be classified as an art.

29 The best dancers that India has ever produced are those who resembled brooding philosophers and prophetic priestesses rather than pleasing artists. The Indian conception of beauty lies in the spiritual and intellectual and but little in the physical and æsthetic forms. The main purpose of the great Indian ballerinas is to inspire their audiences to thought and meditation upon the great powers of nature and the mystic purposes of human life. Their art is exotic and introspective and lacks absolutely the element of purely beautiful inspiration, produced by the great Western dancers. Those of our Western students of art who make us believe that they can perform genuine Indian dances are grossly mistaken, simply because the real Indian dance is not an art and amusement, but the preaching of a certain philosophy. Our materialistic logic is unable to catch the subtle philosophic symbolism that appeals to an Indian mind. We are brought up to enjoy the positive and not the negative plane of life. For us beauty is joy, for the Hindus it is sorrow. An Indian dancer who can move her audience to tears with her dancing will fail to make the least impression upon our audiences.

30

Influence of the Chinese moral teachings; general characteristics of Chinese dancing; court and social dances of ancient China; Yu-Vang’s ‘historical ballet’; modern Chinese dancing; dancing Mandarins; modern imitations; the Lantern Festival—Japan: the legend of Amaterasu; emotional variety of the Japanese dance; pantomime and mimicry; general characteristics and classification of Japanese dances—The American Indians: The Dream dance; the Ghost dance; the Snake dance.

In China the art of dancing was in full bloom for centuries before the Christian era. The great Chinese historians tell us that music and dancing were developed and stood in high esteem in China from the dynasty of Huang-Ta till the rule of They, which is a period of not less than 2450 years. Europe with its civilization did not yet exist when choreography was publicly taught in China. Like every other form of Chinese evolution, dancing thus fell into a state of spiritual torpidity. Forbearance, the foremost virtue of the Chinese race, that was preached by their ancient moralists, like Kon-Fu-Tse and others, stifled in the long run all the passionate emotions of the people and exerted a most detrimental influence upon the arts. Under such conditions the Chinese view of life grew materialistic and dry, the very opposite of the Indian. This peculiarity did not fail to make itself felt in Chinese dancing. The gradual killing of passionate emotions killed also the tendency to imagination in31 the race. The fantasy that populated the air and water, the mountains and forests of other nations with myths, legends, gods and goddesses, was transformed in China into the most realistic reasonings and mechanical dexterity. The industrial spirit of the great nation killed all romantic and poetic aspirations in art, religion and literature. The music of China is as syncopated and monotonous as her views of life. The only poetry that the Chinese possess is that which was written 4000 years ago.

You, which means in Chinese language ‘dance,’ lacks the principal forms of agility of our choreography. Pirouettes, jetés, cabrioles and pas’s are unknown terms to a Chinese ballerina. Their dancing, consisting of slow gestures of the arms, the shaking of head, bowing to the ceiling, and other similar manipulations, makes at the first glance an impression that suggests to our imagination the officiating of Greek priests. The power of a dancer lies in the atmosphere that she creates and the peculiar imitating poses of the body. Chinese dance music is correspondingly slow of rhythm and reminds us in many ways of our ultra-modern orchestral music. However, we read in the works of the Chinese classics that their art of dancing was much higher about two and three thousand years ago.

The ancient Chinese philosophers recommended dancing to strengthen the human body and mind. They emphasized the mimic expressions which all races of the world should learn as an unspoken and universal language. It is written that the great ruler Li-Kaong-Ti took dancing and music lessons from the great teacher of music, Teu-Kung, so that he was able to give entertainments in these arts to his family and guests. He founded a dancing academy at the court and invited learned Mandarins to take charge of the institution. Gradually dancing was introduced in all the colleges and public schools. All Chinese educated classes had32 to be good dancers at that time. The rulers used to dance to the public at great annual festivals to express their gratitude or dissatisfaction. The receptions of various Viceroys at the national capital were opened with dancing performed by the great functionaries and statesmen of the empire. People judged the characteristics of their newly appointed officials and judges from the individual peculiarities of their dance. The Chinese court kept regularly 64 sworn dancers, who were obliged to give historic ‘ballets’ to the rulers. The orchestra was composed of flutes, a drum, one or several tambourines with bells, and a queer instrument in the shape of the figure ‘2.’ About a thousand years before Christ an imperial decree was issued for the purpose of limiting the number of dancers that one or another of the statesmen could employ.

Eight different dances were performed at the Chinese court and eight dancers participated in each dance. The first dance was Ivi-Men—Moving Clouds; this was given in honor of the celestial spirits. The second dance was the Ta-knen—Great Circle; this was performed when the Emperor brought sacrifice at a round votive altar. The third dance was Ta-gien—General Motion; this was performed during the sacrificial festival at the square altar. The fourth dance was Ta-mao—Dance of Harmony; this was the most graceful dance and was dedicated to the Four Elements. The fifth dance was Gia—Beneficial Dance; this dance was dedicated to the spirits of the mountains and rivers, and was slow and majestic. The sixth dance was Ta-gu—Dance of Gratitude; this was dedicated to women. The seventh dance was Ta-u—Great War Dance; this was dedicated to the spirit of Man. The eighth dance was U-gientze—Dance of Waves; this was dedicated to the ancestors and was of elaborate form, containing nine different movements and nine different rhythms. These were all long ‘ballets’ and lasted for several hours each.33 But besides these there were six smaller dances. One of these was called the Dance of the Mystic Bird; another the Dance of Oxtail; another the Dance of the Flag; another the Dance of Feathers; another the Sword Dance; and the last the Dance of Humanity. This was performed only by the Mandarins.

The Chinese historians write that Confucius did not like the Sword Dance, but highly praised the others. Confucius describes the Emperor Yu-Vang, who lived 1100 years before Christ, as the author of many new dances and composer of music to accompany them. One of his dances was a great historical ballet, which must have resembled the Roman pantomimes. This ballet has been performed in a distorted form in the nineteenth century and is mentioned by several Russian writers who lived or travelled in China. Judging from the Chinese writers, the historical ballet must have been a spectacular performance in the style of the Oberammergau Passion Play. It opened with the creation of the world and sea and ended with the latest phase of national history. Some of the dancers represented fish, animals and birds; others, monsters, spirits, rulers and social classes. The music of this ballet was of peculiar symphonic form, very melodious and dramatic. Only fragmentary records of the ancient notation had been preserved in the imperial palace at Pekin, but during recent political disturbances even these vanished and the world has thus been deprived of one of the most valuable of musical documents.

In China the social and religious dancers were one and the same. The touring dancing companies to be seen to-day in China give a faint idea of the ancient choreography. Japanese dancing has made a deep impression upon the Chinese dancers, so that there is a marked element of mixture in the performances that one sees in the present Chinese towns. The Chinese dancers from olden times on have been men and34 women. It seems as if men predominated before, while now the feminine element is in majority. The Chinese dancing costumes are bizarre and picturesque. There are no barefoot dancers among them and their bodies are heavily covered with garments. Nude dancers are unknown in China.

An odd class of Chinese dancers are the dancing Mandarins. In Su-Chu-Fu there exists still an old school that was founded 2500 years ago for the purpose of teaching dancing to the Mandarins. They presumably learned with the idea of using the art in religious rituals. The style of their dancing differs slightly from that of the professional class. Dancing Mandarins can be seen now in China, but their cabalistic gestures and queer mimic expressions are unintelligible to the Western mind. There are no folk or national dances in China and the people do not dance in the same sense as we in our social dances. The idea of a social dance is a torture to an average Chinaman. He enjoys seeing dancing, but never takes part in it. The rich Chinese frequently hire professional dancers and let them give performances at their houses. The Chinese wedding dances are never performed by the bride, groom, or their guests, but by hired professional dancers or dancing Mandarins. The historians tell us that this was not so in remote antiquity. There was a time when the Chinese people danced, though their dances were mostly slow and pantomimic. The Russian ballet dancers, who have toured in China, have told that their performances filled the Chinese audiences with horror and disgust, as our Western acrobatic technique makes them afraid of possible neck-breaking accidents.

The attempts of Europeans to create Chinese ballets for our Western stage have been in so far miserable failures. ‘Kia-King’ by Titus, ‘Chinese Wedding’ by Calzevaro, and ‘Lily’ by San-Leon give no true impression35 of Chinese choreography of any age. Nor are their music or their scenarios similar to any genuine Chinese ballets of the above-named titles.

In our story of Chinese dancing it is worth while to mention the celebrated ‘Lantern Festival’ that is performed every New Year night. It is very likely that the Chinese had once long ago a lantern dance, which has degenerated now into a simple marching procession, in which the people participate in the same sense as the Italians do in their carnival. Confucius writes of it as of a festival in honor of the sun, the source of the light and life. This festival is celebrated three nights continually. Everything considered, we come to the conclusion that the art of dancing of the land of Mandarins has been of little influence and significance to our choreography. The reason for this lies partly in the racial morale, partly in a national psychology that breathes peace and externalism.