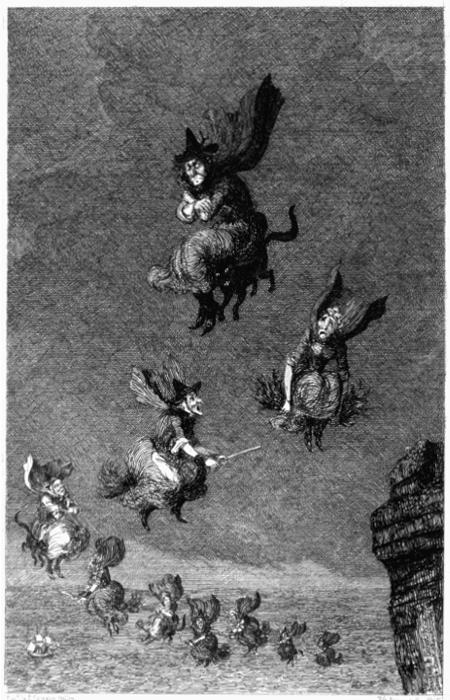

A Flight of Witches.

Project Gutenberg's Popular Romances of the West of England, by Robert Hunt

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Popular Romances of the West of England

or, The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall

Author: Robert Hunt

Release Date: March 8, 2019 [EBook #59033]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POPULAR ROMANCES OF THE WEST ***

Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

A Flight of Witches.

POPULAR ROMANCES

OF THE

WEST OF ENGLAND;

OR,

The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of

Old Cornwall.

COLLECTED AND EDITED BY

ROBERT HUNT, F.R.S.

SECOND SERIES.

LONDON:

JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN, PICCADILLY.

1865.

[Right of Translation is reserved.]

“‘Have you any stories like that, gudewife?’

“‘Ah,’ she said; ‘there were plenty of people that could tell those stories once. I used to hear them telling them over the fire at night; but people is so changed with pride now, that they care for nothing.’”

Campbell.

LONDON: JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN, PICCADILLY.

| PAGE | ||

| THE SAINTS. | ||

| 1. | Legends of the Saints, | 3 |

| 2. | The Crowza Stones, | 5 |

| 3. | The Longstone, | 7 |

| 4. | St Sennen and St Just, | 8 |

| 5. | Legends of St Leven— | |

| The Saint and Johana, | 9 | |

| The Saint’s Path, | 10 | |

| The St Leven Stone, | 10 | |

| The Two Breams, | 11 | |

| 10. | St Keyne, | 12 |

| 11. | St Dennis’s Blood, | 15 |

| 12. | St Kea’s Boat, | 16 |

| 13. | St German’s Well, | 17 |

| 14. | How St Piran reached Cornwall, | 19 |

| 15. | St Perran, the Miner’s Saint, | 20 |

| 16. | The Discovery of Tin, | 21 |

| 17. | St Neot, the Pigmy, | 22 |

| 18. | St Neot and the Fox, | 23 |

| 19. | St Neot and the Doe, | 23 |

| 20. | St Neot and the Thieves, | 24 |

| 21. | St Neot and the Fishes, | 25 |

| 22. | Probus and Grace, | 26 |

| 23. | St Nectan’s Kieve and the Lonely Sisters, | 27 |

| 24. | Theodore, King of Cornwall, | 33 |

| HOLY WELLS. | ||

| 25. | Well-Worship, | 35 |

| 26. | The Well of St Constantine, | 38 |

| 27. | The Well of St Ludgvan, | 39 |

| 28. | Gulval Well, | 43 |

| 29. | The Well of St Keyne, | 45 |

| [iv]30. | Maddern or Madron Well, | 47 |

| 31. | The Well at Altar-Nun, | 50 |

| 32. | St Gundred’s Well at Roach Rock, | 53 |

| 33. | St Cuthbert’s or Cubert’s Well, | 54 |

| 34. | Rickety Children, | 55 |

| 35. | Chapell Uny, | 56 |

| 36. | Perran Well, | 56 |

| 37. | Redruth Well, | 56 |

| 38. | Holy Well at Little Conan, | 56 |

| 39. | The Preservation of Holy Wells, | 57 |

| KING ARTHUR. | ||

| 40. | Arthur Legends, | 59 |

| 41. | The Battle of Vellan-druchar, | 62 |

| 42. | Arthur at the Land’s End, | 63 |

| 43. | Traditions of the Danes in Cornwall, | 65 |

| 44. | King Arthur in the Form of a Chough, | 66 |

| 45. | The Cornish Chough, | 68 |

| 46. | Slaughter Bridge, | 68 |

| 47. | Camelford and King Arthur, | 69 |

| 48. | Dameliock Castle, | 71 |

| 49. | Carlian in Kea, | 71 |

| SORCERY AND WITCHCRAFT. | ||

| 50. | The “Cunning Man,” | 73 |

| 51. | Notes on Witchcraft, | 76 |

| 52. | Ill-wishing, | 78 |

| 53. | The “Peller,” | 81 |

| 54. | Bewitched Cattle, | 82 |

| 55. | How to Become a Witch, | 83 |

| 56. | Cornish Sorcerers, | 83 |

| 57. | How Pengerswick Became a Sorcerer, | 84 |

| 58. | The Lord of Pengerswick an Enchanter, | 86 |

| 59. | The Witch of Fraddam and Pengerswick, | 90 |

| 60. | Trewa, the Home of Witches, | 92 |

| 61. | Kenidzhek Witch, | 93 |

| 62. | The Witches of the Logan Stone, | 94 |

| 63. | Madgy Figgy’s Chair, | 96 |

| 64. | Old Madge Figgey and the Pig, | 99 |

| 65. | Madam Noy and Old Joan, | 101 |

| 66. | The Witch of Treva, | 102 |

| 67. | How Mr Lenine Gave Up Courting, | 104 |

| 68. | The Witch and the Toad, | 105 |

| [v]69. | The Sailor Wizard, | 108 |

| THE MINERS. | ||

| 70. | Traditions of Tinners, | 111 |

| 71. | The Tinner of Chyannor, | 115 |

| 72. | Who are the Knockers? | 118 |

| 73. | Miners’ Superstitions, | 122 |

| 74. | Christmas-Eve in the Mines, | 123 |

| 75. | Warnings and “Tokens,” | 124 |

| 76. | The Ghost on Horseback, | 125 |

| 77. | The Black Dogs, | 126 |

| 78. | Pitmen’s Omens and Goblins, | 126 |

| 79. | The Dead Hand, | 128 |

| 80. | Dorcas, the Spirit of Polbreen Mine, | 129 |

| 81. | Hingston Downs, | 131 |

| FISHERMEN AND SAILORS. | ||

| 82. | The Pilot’s Ghost Story, | 133 |

| 83. | The Phantom Ship, | 135 |

| 84. | Jack Harry’s Lights, | 136 |

| 85. | The Pirate-Wrecker and the Death Ship, | 137 |

| 86. | The Spectre Ship of Porthcurno, | 141 |

| 87. | The Lady with the Lantern, | 143 |

| 88. | The Drowned “Hailing their Names,” | 146 |

| 89. | The Voice from the Sea, | 146 |

| 90. | The Smuggler’s Token, | 147 |

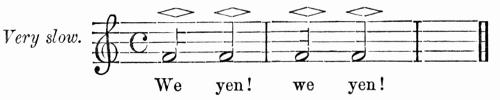

| 91. | The Hooper of Sennen Cove, | 148 |

| 92. | How to Eat Pilchards, | 149 |

| 93. | Pilchards Crying for More, | 149 |

| 94. | The Pressing-Stones, | 149 |

| 95. | Whipping the Hake, | 152 |

| DEATH SUPERSTITIONS. | ||

| 96. | The Death Token of the Vingoes, | 155 |

| 97. | The Death Fetch of William Rufus, | 156 |

| 98. | Sir John Arundell, | 157 |

| 99. | Phantoms of the Dying, | 158 |

| 100. | The White Hare, | 162 |

| 101. | The Hand of a Suicide, | 164 |

| 102. | The North Side of a Church, | 164 |

| 103. | Popular Superstitions, | 165 |

| OLD USAGES. | ||

| 104. | Sanding the Step on New Year’s-Day, | 169 |

| [vi]105. | May-Day, | 170 |

| 106. | Shrove Tuesday at St Ives, | 171 |

| 107. | “The Furry,” Helstone, | 171 |

| 108. | Midsummer Superstitious Customs, | 172 |

| 109. | Crying the Neck, | 173 |

| 110. | Drinking to the Apple-Trees on Twelfth Night Eve, | 175 |

| 111. | Allhallows-Eve at St Ives, | 177 |

| 112. | The Twelfth Cake, | 177 |

| 113. | Oxen Pray on Christmas Eve, | 178 |

| 114. | “St George”—The Christmas Plays, | 179 |

| 115. | Geese-Dancing—Plough Monday, | 182 |

| 116. | Christmas at St Ives, | 183 |

| 117. | Lady Lovell’s Courtship, | 188 |

| 118. | The Game of Hurling, | 193 |

| 119. | Sham Mayors— | |

| The Mayor of Mylor, | 196 | |

| The Mayor of St Germans, | 197 | |

| The Mayor of Halgaver Moor, | 198 | |

| 120. | The Faction Fight at Cury Great Tree, | 198 |

| 121. | Towednack Cuckoo Feast, | 200 |

| 122. | The Duke of Restormel, | 200 |

| POPULAR SUPERSTITIONS. | ||

| 123. | Charming, and Prophetic Power, | 203 |

| 124. | Fortune-Telling, Charms, &c., | 204 |

| 125. | The Zennor Charmers, | 208 |

| 126. | J. H., the Conjurer of St Colomb, | 209 |

| 127. | Cures for Warts, | 210 |

| 128. | A Cure for Paralysis, | 212 |

| 129. | A Cure for Rheumatism, | 212 |

| 130. | Sundry Charms, | 213 |

| 131. | Cure for Colic in Towednack, | 213 |

| 132. | For a Scald or Burn, | 213 |

| 133. | Charms for Inflammatory Diseases, | 213 |

| 134. | Charms for the Prick of a Thorn, | 213 |

| 135. | Charms for Stanching of Blood, | 214 |

| 136. | Charm for a Tetter, | 214 |

| 137. | Charm for the Sting of a Nettle, | 215 |

| 138. | Charm for Toothache, | 215 |

| 139. | Charm for Serpents, | 215 |

| 140. | The Cure of Boils, | 215 |

| 141. | Rickets, or a Crick in the Back, | 215 |

| 142. | The Club-Moss, | 216 |

| [vii]143. | Moon Superstitions, | 217 |

| 144. | Cures for Whooping-Cough, | 218 |

| 145. | Cure of Toothache, | 219 |

| 146. | The Convalescent’s Walk, | 220 |

| 147. | Adders, and the Milpreve, | 220 |

| 148. | Snakes Avoid the Ash-Tree, | 223 |

| 149. | To Charm a Snake, | 223 |

| 150. | The Ash-Tree, | 224 |

| 151. | Rhyme on the Even Ash, | 225 |

| 152. | A Test of Innocency, | 225 |

| 153. | The Bonfire Test, | 226 |

| 154. | Lights Seen by the Converted, | 226 |

| 155. | The Migratory Birds, | 226 |

| 156. | Shooting Stars, | 227 |

| 157. | The Sun Never Shines on the Perjured, | 228 |

| 158. | Characteristics, | 229 |

| 159. | The Mutton Feast, | 232 |

| 160. | The Floating Grindstone, | 232 |

| 161. | Celts—Flint Arrow-heads, &c., | 233 |

| 162. | Horns on the Church Tower, | 233 |

| 163. | Tea-Stalks and Smut, | 234 |

| 164. | An Old Cornish Rhyme, | 234 |

| 165. | To Choose a Wife, | 234 |

| 166. | The Robin and the Wren, | 235 |

| 167. | To Secure Good Luck for a Child, | 235 |

| 168. | Innocency, | 235 |

| 169. | Rain at Bridal or Burial, | 235 |

| 170. | Crowing Hens, &c., | 236 |

| 171. | The New Moon, | 236 |

| 172. | Looking-Glasses, | 236 |

| 173. | The Magpie, | 236 |

| 174. | The Month of May Unlucky, | 237 |

| 175. | On the Births of Children, | 237 |

| 176. | On Washing Linen, | 237 |

| 177. | Itching Ears, | 237 |

| 178. | The Spark on the Candle, | 238 |

| 179. | The Blue Vein, | 238 |

| 180. | The Croaking of the Raven, | 238 |

| 181. | Whistling, | 239 |

| 182. | Meeting on the Stairs, | 239 |

| 183. | Treading on Graves, | 239 |

| 184. | A Loose Garter, | 240 |

| 185. | To Cure the Hiccough, | 240 |

| 186. | The Sleeping Foot, | 240 |

| [viii]187. | The Horse-Shoe, | 240 |

| 188. | The Black Cat’s Tail, | 240 |

| 189. | Unlucky Things, | 241 |

| 190. | The Limp Corpse, | 241 |

| 191. | “By Hook or by Crook,” | 242 |

| 192. | Weather Signs, | 242 |

| 193. | Weather at Liskeard, | 243 |

| 194. | The First Butterfly, | 243 |

| 195. | Peculiar Words and Phrases, | 244 |

| MISCELLANEOUS STORIES. | ||

| 196. | The Bells of Forrabury Church, | 247 |

| 197. | The Tower of Minster Church, | 249 |

| 198. | Temple Moors, | 250 |

| 199. | The Legend of Tamara, | 251 |

| 200. | The Church and the Barn, | 252 |

| 201. | The Penryn Tragedy, | 253 |

| 202. | Goldsithney Fair and the Glove, | 255 |

| 203. | The Harlyn Pie, | 256 |

| 204. | Packs of Wool the Foundation of the Bridge of Wadebridge, | 256 |

| 205. | The Last Wolf in England, | 258 |

| 206. | Churches Built in Performance of Vows, | 258 |

| 207. | Bolait, the Field of Blood, | 259 |

| 208. | Woeful Moor, and Bodrigan’s Leap, | 261 |

| 209. | Pengerswick Castle, | 263 |

| 210. | The Clerks of Cornwall, | 264 |

| 211. | A Fairy Caught, | 265 |

| 212. | The Lizard People, | 267 |

| 213. | Prussia Cove and Smuggler’s Holes, | 267 |

| 214. | Cornish Teeny-tiny, | 268 |

| 215. | The Spaniard at Penryn, | 269 |

| 216. | Boyer, Mayor of Bodmin, | 270 |

| 217. | Thomasine Bonaventure, | 271 |

| 218. | The Last of the Killigrews, | 274 |

| 219. | Saint Gerennius, | 278 |

| 220. | Cornish Dialogue, | 280 |

| APPENDIX. | ||

| A. | St Piran—Perran Zabuloe, | 287 |

| B. | The Discoverer of Tin, | 288 |

| C. | St Neot, | 289 |

| D. | The Sisters of Glen-Neot, | 290 |

| E. | Millington of Pengerswick, | 291 |

| F. | Saracen, | 292 |

ROMANCES AND SUPERSTITIONS

OF

HISTORIC TIMES.

2d Series.

The process through which a man, who has made himself remarkable to his ignorant fellow-men, is passed after death—first, into the hero performing fabulous exploits, and eventually into the giant—is not difficult to understand.

The remembrance of great deeds, and the memory of virtues,—even in modern days, when the exaggerations of votaries are subdued by the influence of education,—ever tends to bring them out in strong contrast with the surrounding objects. The mass of men form the background, as it were, of the picture, and the hero or the saint stands forth in all his brightness of colour in the foreground.

Amidst the uneducated Celtic population who inhabited Old Cornwall, it was the practice, as with the Celts of other countries, to exalt their benefactors with all the adornments of that hyperbole which distinguishes their songs and stories. When the first Christian missionaries dwelt amongst this people, they impressed them with the daring which they exhibited by the persecution which they uncomplainingly endured and the holy lives they led.

Those who were morally so superior to the living men, were represented as physically so to their children, and every generation adorned the relation which it had received with the ornaments derived from their own imaginations, which had been tutored amidst the severer scenes of nature; and consequently the warrior, or the holy man, was transmuted into the giant.

If to this we add the desire which was constantly shewn by the earlier priesthood to persuade the people of their miraculous powers—of the direct interference of Heaven in their behalf—and of the violent conflicts which they were occasionally enduring with the enemy of the human race, there will be no difficulty in marking out the steps by which the ordinary man has become an extraordinary hero. When we hear of the saints to whose memories the parish churches are dedicated, being enabled to hurl rocks of enormous size through the air, to carry them in their pockets, and indeed to use them as playthings, we perceive that the traditions of the legitimate giants, have been transferred to, and mixed up with, the memories of a more recent people.

In addition to legends of the Titanic type, this section will include a few of the true monastic character. The only purpose I have in giving these is to preserve, as examples, some curious superstitions which have not yet entirely lost their hold on the people.

St Just, from his home in Penwith, being weary of having little to do, except offering prayers for the tinners and fishermen, went on a visit to the hospitable St Keverne, who had fixed his hermitage in a well-selected spot, not far from the Lizard headland. The holy brothers rejoiced together, and in full feeding and deep drinking they pleasantly passed the time. St Just gloried in the goodly chalice from which he drank the richest of wines, and envied St Keverne the possession of a cup of such rare value. Again and again did he pledge St Keverne; their holy bond of brotherhood was to be for ever; Heaven was to witness the purity of their friendship, and to the world they were to become patterns of ecclesiastical love.

The time came when St Just felt he must return to his flock; and repeating over again his vows, and begging St Keverne to return his visit, he departed—St Keverne sending many a blessing after his good brother.

The Saint of the west, had not left his brother of the south, many hours before the latter missed his cup. Diligent search was made in every corner of his dwelling, but no cup could be found. At length St Keverne could not but feel that he had been robbed of his treasure by his western friend. That one in whom he had placed such confidence—one to whom he had opened his heart, and to whom he had shewn the most unstinting hospitality—should have behaved so treacherously, overcame the serenity of the good man. His rage was excessive. After the first burst was over, and reason reasserted her power, St Keverne felt that his wisest course was to pursue the thief, inflict summary punishment on him, and recover his cup. The thought was followed by a firm resolve, and away St Keverne started in pursuit of[6] St Just. Passing over Crowza Down, some of the boulders of “Ironstone” which are scattered over the surface caught his eye, and presently he whipped a few of these stone pebbles into his pockets, and hastened onward.

When he drew near Tre-men-keverne he spied St Just. St Keverne worked himself up into a boiling rage, and toiled with increased speed up the hill, hallooing to the saintly thief, who pursued his way for some time in the well-assumed quiet of conscious innocence.

Long and loud did St Keverne call on St Just to stop, but the latter was deaf to all calls of the kind—on he went, quickening, however, his pace a little.

At length St Keverne came within a stone’s throw of the dissembling culprit, and calling him a thief—adding thereto some of the most choice epithets from his holy vocabulary—taking a stone from his pocket, he let it fly after St Just.

The stone falling heavily by the side of St Just convinced him that he had to deal with an awkward enemy, and that he had best make all the use he could of his legs. He quietly untied the chalice, which he had fastened to his girdle, and let it fall to the ground. Then, still as if unconscious of his follower, he set off to run as fast as his ponderous body would allow his legs to carry him. St Keverne came up to where his cup glistened in the sunshine. He had recovered his treasure, he should get no good out of the false friend, and he was sadly jaded with his long run. Therefore he took, one by one, the stones from his pockets—he hurled them, fairly aimed, after the retreating culprit, and cursed him as he went.

There the pebbles remain where they fell,—the peculiarity of the stone being in all respects unlike anything around, but being clearly the Crowza stones,—attesting the truth of[7] the legend; and their weights, each one being several hundred pounds, proving the power of the giant saint.

Many have been the attempts made to remove these stones. They are carried away easily enough by day, but they ever return to the spot on which they now repose, at night.

Some say it was St Roach, others refer it to St Austell; but all agree in one thing, that the Longstone was once the staff of some holy man, and that its present state is owing to the malignant persecution of the demon of darkness. It happened after this manner. The good saint who had been engaged in some mission was returning to his cell across St Austell Downs. The night had been fine, the clearness of the sky and the brightness of the stars conduced to religious thoughts, and those of the saint fled heavenwards. The devil was wandering abroad that night, and maliciously he resolved to play a trick upon his enemy. The saint was wrapt in thought. The devil was working his dire spells. The sky became black, the stars disappeared, and suddenly a terrific rush of wind seized the saint, whirled him round and round, and at last blew his hat high into the air. The hat went ricocheting over the moor and the saint after it, the devil enjoying the sport. The long stick which the saint carried impeded his progress in the storm, and he stuck it into the ground. On went the hat, speedily followed the saint over and round the moor, until thoroughly wearied out, he at length gave up the chase. He, now exposed to the beat of the tempest bareheaded, endeavoured to find his way to his cell, and thought to pick up his staff on the way. No staff could be found in the[8] darkness, and his hat was, he thought, gone irrecoverably. At length the saint reached his cell, he quieted his spirit by prayer, and sought the forgetfulness of sleep, safe under the protection of the holy cross, from all the tricks of the devil. The evil one, however, was at work on the wild moor, and by his incantations he changed the hat and the staff into two rocks. Morning came, the saint went abroad seeking for his lost covering and support. He found them both—one a huge circular boulder, and the other a long stone which remains to this day.[1]

The Saint’s, or, as it was often called, the Giant’s Hat was removed in 1798 by a regiment of soldiers who were encamped near it. They felt satisfied that this mysterious stone was the cause of the wet season which rendered their camp unpleasant, and consequently they resolved to remove the evil spell by destroying it.

These saints held rule over adjoining parishes; but, like neighbours, not unfrequently, they quarrelled. We know not the cause which made their angry passions rise; but no doubt the saints were occasionally exposed to the influences of the evil principle, which appears to be one of the ruling powers of the world. It is not often that we have instances of excess of passion in man or woman without some evidence of the evil resulting from it. Every tempest in the physical world leaves its mark on the face of the earth. Every tempest in the moral world, in a similar manner, leaves some scar to tell of its ravages on the soul. A most enduring monument in granite tells us of the rage to[9] which those two holy men were the victims. As we have said, there is no record of the origin of the duel which was fought between St Just and St Sennen; but, in the fury of their rage, they tore each a rock from the granite mass, and hurled it onwards to destroy his brother. They were so well aimed that both saints must have perished had the rocks been allowed to travel as intended. A merciful hand guided them, though in opposite directions, in precisely the same path. The huge rocks came together; so severe was the blow of impact that they became one mass, and fell to the ground, to remain a monument of the impotent rage of two giants.

The walls of what are supposed to be the hut of St Leven are still to be seen at Bodellen. If you walk from Bodellen to St Leven Church, on passing near the stile in Rospletha you will see a three-cornered garden. This belonged to a woman who is only known to us as Johana. Johana’s Garden is still the name of the place. One Sunday morning St Leven was passing over the stile to go as usual to his fishing-place below the church, to catch his dinner. Johana was in the garden picking pot-herbs at the time, and she lectured the holy man for fishing on a Sunday. They came to high words, and St Leven told Johana that there was no more sin in taking his dinner from the sea than she herself committed in taking hers from the garden. The saint called her foolish Johana, and said if another of her name was christened in his well she should be a bigger fool than Johana herself. From that day to this no child called Johana has been christened in St Leven. All parents who[10] desire to give that name to their daughters, dreading St Leven’s curse, take the children to Sennen.

The path along which St Leven was accustomed to walk from Bodellen, by Rospletha, on to St Leven’s Rocks, as they are still called, may be yet seen; the grass grows greener wherever the good priest trod than in any other part of the fields through which the footpath passes.

On the south side of the church, to the east of the porch, is a rock known by the above name. It is broken in two, and the fissure is filled in with ferns and wild flowers, while the grass grows rank around it. On this rock St Leven often sat to rest after the fatigue of fishing; and desiring to leave some enduring memento of himself in connexion with this his rude but favourite seat, he one day gave it a blow with his fist and cracked it through. He prayed over the rock, and uttered the following prophecy:—

This stone must have been venerated for the saint’s sake when the church was built, or it would certainly have been employed for the building. It is more than fifty years since I first made acquaintance, as a child, with the St Leven Stone, and it may be a satisfaction to many to know that the progress of separation is an exceedingly slow one. I cannot detect the slightest difference in the width of the fissure now and then. At the present slow rate of opening, the packhorse and panniers will not be able to pass through the[11] rock for many thousands of years to come. We need not, therefore, place much reliance on those prophecies which give but a limited duration to this planet.[2]

Although in common with many of the churches in the remote districts of Cornwall, “decay’s effacing fingers” have been allowed to do their work in St Leven Church, yet there still remains some of the ornamental work which once adorned it. Much of the carving is irremediably gone; but still the inquirer will find that it once told the story of important events in the life of the good St Leven. Two fishes on the same hook form the device, which appears at one time to have prevailed in this church. These are to commemorate a remarkable incident in St Leven’s life. One lovely evening about sunset, St Leven was on his rocks fishing. There was a heavy pull upon his line, and drawing it in, he found two breams on the same hook. The good saint, anxious to serve both alike, to avoid, indeed, even the appearance of partiality, took both the fishes off the hook, and cast them back into the sea. Again they came to the hook, and again were they returned to their native elements. The line was no sooner cast a third time than the same two fishes hooked themselves once more. St Leven thought there must be some reason unknown to him for this strange occurrence, so he took both the fishes home with him. When the saint reached Bodellen, he found his sister, St Breage,[3] had[12] come to visit him with two children. Then he thought he saw the hand of Providence at work in guiding the fish to his hook.

Even saints are blind when they attempt to fathom the ways of the Unseen. The fish were, of course, cooked for supper; and the saint having asked a blessing upon their savoury meal, all sat down to partake of it. The children had walked far, and they were ravenously hungry. They ate their suppers with rapidity, and, not taking time to pick out the bones of the fish, they were both choked. The apparent blessing was thus transformed into a curse, and the bream has from that day forward ever gone by the name, amongst fishermen, of “choke children.”

There are many disputes as to the fish concerned in this legend. Some of the fishermen of St Leven parish have insisted upon their being “chad,” (the shad, clupeida alosa;) while others, with the strong evidence afforded by the bony structure of the fish, will have it to have been the bream, (cyprinus brama.) My young readers warned by the name, should be equally careful in eating either of those fish.

Braghan, or Brechan, was a king in Wales, and the builder of the town of Brecknock. This worthy old king and saint was the happy father of twenty-six children,[13] or, as some say, twenty-four. Of these, fourteen or fifteen were sainted for their holiness, and their portraits are preserved within a fold of the kingly robe of the saint, their father, in the window at St Neot’s Church, bearing the inscription, “Sante Brechane, cum omnibus sanctis, ora pro nobis,” and known as the young women’s window.

Of the holy children settled in Cornwall, we learn that the following gave their names to Cornish churches:—

| 1. | John, | giving name to the Church of | St Ive. |

| 2. | Endellient, | ” ” | Endellion. |

| 3. | Menfre, | ” ” | St Minver. |

| 4. | Tethe, | ” ” | St Teath. |

| 5. | Mabena, | ” ” | St Mabyn. |

| 6. | Merewenna, | ” ” | Marham. |

| 7. | Wenna, | ” ” | St Wenn. |

| 8. | Keyne, | ” ” | St Keyne. |

| 9. | Yse, | ” ” | St Issey. |

| 10. | Morwenna, | ” ” | Morwinstow. |

| 11. | Cleder, | ” ” | St Clether. |

| 12. | Keri, | ” ” | Egloskerry. |

| 13. | Helie, | ” ” | Egloshayle. |

| 14. | Adwent, | ” ” | Advent. |

| 15. | Lanent, | ” ” | Lelant.[4] |

Of this remarkable family St Keyne stands out as the brightest star. Lovely beyond measure, she wandered over the country safe, even in lawless times, from insult, by “the strength of her purity.”

We find this virtuous woman performing miracles wherever she went. The district now known by the name of Keynsham, in Somersetshire, was in those days infested with serpents. St Keyne, rivaling St Hilda of the Northern Isle, changed them all into coils of stone, and there they are in the quarries at the present time to attest the truth of the legend. Geologists, with more learning than poetry, term[14] them Ammonites, deriving their name from the horn of Jupiter Ammon, as if the Egyptian Jupiter was likely to have charmed serpents in England. We are satisfied to leave the question for the consideration of our readers. After a life spent in the conversion of sinners, the building of churches, and the performance of miracles, this good woman retired into Cornwall, and in one of its most picturesque valleys, she sought and found that quiet which was conducive to a happy termination of a well-spent life. She desired, above all things, “peace on earth;” and she hoped to benefit the world, by giving to woman a chance of being equal to her lord and master. A beautiful well of water was near the home of the saint, and she planted, with her blessing, four trees around it—the withy, the oak, the elm, and the ash. When the hour of her death was drawing near, St Keyne caused herself to be borne on a litter to the shade which she had formed, and soothed by the influence of the murmur of the flowing fountain, she blessed the waters, and gave them their wondrous power, thus quaintly described by Carew:—“Next, I will relate to you, another of the Cornish natural wonders—viz., St Keyne’s Well; but lest you make wonder, first at the sainte, before you notice the well, you must understand that this was not Kayne the Manqueller, but one of a gentler spirit and milder sex—to wit, a woman. He who caused the spring to be pictured, added this rhyme for an explanation:—

The patron saint of the parish church of St Dennis was born in the city of Athens, in the reign of Tiberius. His name and fame have full record in the “History of the Saints of the Church of Rome.” How his name was connected with this remote parish is not clearly made out. We learn, however, that the good man was beheaded at Montmartre, and that he walked after his execution, with his head under his arm, to the place in Paris which still bears his name. At the very time when the decapitation took place in Paris, blood fell on the stones of this churchyard in Cornwall. Previously to the breaking out of the plague in London, the stains of the blood of St Dennis were again seen; and during our wars with the Dutch, the defeat of the English fleet was foretold by the rain of gore in this remote and sequestered place. Hals, the Cornish historian, with much gravity, informs us that he had seen some of the stones with blood upon them. Whenever this phenomenon occurs again we may expect some sad calamity to be near.

Some years since a Cornish gentleman was cruelly murdered, and his body thrown into a brook. I have been very lately shewn stones taken from this brook with bright red spots of some vegetable growth on them. It is said that[16] ever since the murder the stones in this brook are spotted with gore, whereas they never were so previously to this dreadful deed.

St Kea, a young Irish saint, stood on the southern shores of Ireland and saw the Christian missionaries departing to carry the blessed Word to the heathens of Western England. He watched their barks fade beneath the horizon, and he felt that he was left to a solitude which was not fitted to one in the full energy of young life, and burning with zeal.

The saint knelt on a boulder of granite lying on the shore, and he prayed with fervour that Heaven would order it so that he might diffuse his religious fervour amongst the barbarians of Cornwall. He prayed on for some time, not observing the rising of the tide. When he had poured out his full soul, he awoke to the fact, not only that the waves were washing around the stone on which he knelt, but that the stone was actually floating on the water. Impressed with the miracle, St Kea sprang to his feet, and looking towards the setting sun, with his cross uplifted, he exclaimed, “To Thee, and only to Thee, my God, do I trust my soul!”

Onward floated the granite, rendered buoyant by supernatural power. Floated hither and thither by the tides, it swam on; blown sometimes in one direction, and sometimes in another, by the varying winds, days and nights were spent upon the waters. The faith of St Kea failed not; three times a day he knelt in prayer to God. At all other times he stood gazing on the heavens. At length the faith of the saint being fairly tried, the moorstone boat floated steadily up the river, and landed at St Kea, which place he soon[17] Christianised, and there stands to this day this monument of St Kea’s sincere belief.

The good St German was, it would appear, sent into Cornwall in the reign of the Emperor Valentinian, mainly to suppress the Pelagian heresy. The inhabitants of the shores of the Tamar had long been schooled into the belief in original sin, and they would not endure its denial from the lips of a stranger. In this they were supported by the monks, who had already a firm footing in the land, and who taught the people implicit obedience to their religious instructors, faith in election, and that all human efforts were unavailing, unless supported by priestly aid. St German was a man with vast powers of endurance. He preached his doctrines of freewill, and of the value of good works, notwithstanding the outcry raised against him. His miracles were of the most remarkable character, and sufficiently impressive to convince a large body of the Cornish people that he was an inspired priest. St German raised a beautiful church, and built a monastic house for the relief of poor people. Yet notwithstanding the example of the pure life of the saint, and his unceasing study to do good, a large section of the priests and the people never ceased to persecute him. To all human endurance there is a limit, and even that of the saint weakened eventually, before the never-ceasing annoyances by which he was hemmed in.

One Sabbath morning the priest attended as usual to his Christian duties, when he was interrupted by a brawl amongst the outrageous people, who had come in from all parts of the country with a determination to drive him from the place of his adoption. The holy man prayed for his persecutors, and he entreated them to calm their angry passions and listen[18] to his healing words. But no words could convey any healing balm to their stormy hearts. At length his brethren, fearing that his life was in danger, begged him to fly, and eventually he left the church by a small door near the altar, while some of the monks endeavoured to tranquillise the people. St German went, a sad man, to the cliffs at the Rame head, and there alone he wept in agony at the failure of his labours. So intense was the soul-suffering of this holy man, that the rocks felt the power of spirit-struggling, and wept with him. The eyes of man, a spiritual creation, dry after the outburst of sorrow, but when the gross forms of matter are compelled to sympathise with spiritual sorrow, they remain for ever under the influence; and from that day the tears of the cliffs have continued to fall, and the Well of St German attests to this day of the saint’s agony. The saint was not allowed to remain in concealment long. The crowd of opposing priests and the peasantry were on his track. Hundreds were on the hill, and arming themselves with stones, they descended with shouts, determined to destroy him. St German prayed to God for deliverance, and immediately a rush, as of thunder, was heard upon the hills—a chariot surrounded by flames, and flashing light in all directions, was seen rapidly approaching. The crowd paused, fell back, and the flaming car passed on to where St German knelt. There were two bright angels in the chariot; they lifted the persecuted saint from the ground, and placing him between them, ascended into the air.

“Curse your persecutors,” said the angels. The saint cursed them; and from that time all holiness left the church he had built. The saint was borne to other lands, and lived to effect great good. On the rocks the burnt tracks of the chariot wheels were long to be seen, and the Well of Tears still flows.

Good men are frequently persecuted by those whom they have benefited the most. The righteous Piran had, by virtue of his sanctity, been enabled to feed ten Irish kings and their armies for ten days together with three cows. He brought to life by his prayers the dogs which had been killed while hunting the elk and the boar, and even restored to existence many of the warriors who had fallen on the battlefield. Notwithstanding this, and his incomparable goodness, some of these kings condemned him to be cast off a precipice into the sea, with a millstone around his neck.

On a boisterous day, a crowd of the lawless Irish assembled on the brow of a beetling cliff, with Piran in chains. By great labour they had rolled a huge millstone to the top of the hill, and Piran was chained to it. At a signal from one of the kings, the stone and the saint were rolled to the edge of, and suddenly over, the cliff into the Atlantic. The winds were blowing tempestuously, the heavens were dark with clouds, and the waves white with crested foam. No sooner was Piran and the millstone launched into space, than the sun shone out brightly, casting the full lustre of its beams on the holy man, who sat tranquilly on the descending stone. The winds died away, and the waves became smooth as a mirror. The moment the millstone touched the water, hundreds were converted to Christianity who saw this miracle. St Piran floated on safely to Cornwall; he landed on the 5th of March on the sands which bear his name. He lived amongst the Cornish men until he attained the age of 206 years.[6]

St Piran, or St Perran, has sometimes gained the credit of discovering tin in Cornwall; yet Usher places the date of his birth about the year 352; and the merchants of Tyre are said to have traded with Cornwall for tin as early as the days of King Solomon.

There are three places in Cornwall to which the name of Perran is given:—

Perran-Aworthall—i.e., Perran on the noted River.

Perran-Uthno—i.e., Perran the Little.

Perran-Zabuloe—i.e., Perran in the Sands.

This sufficiently proves that the saint, or some one bearing that name, was eminently popular amongst the people; and in St Perran we have an example—of which several instances are given—of the manner in which a very ancient event is shifted forward, as it were, for the purpose of investing some popular hero with additional reasons for securing the devotion of the people, and of drawing them to his shrine.[7]

Picrous, or Piecras, is another name which has been floated by tradition, down the stream of time, in connexion with the discovery of tin; and in the eastern portion of Cornwall, Picrous-day, the second Thursday before Christmas-day, is kept as the tinners’ holiday.

The popular story of the discovery of tin is, however, given, with all its anachronisms.

St Piran, or St Perran, leading his lonely life on the plains which now bear his name, devoted himself to the study of the objects which presented themselves to his notice. The good saint decorated the altar in his church with the choicest flowers, and his cell was adorned with the crystals which he could collect from the neighbouring rocks. In his wanderings on the sea-shore, St Perran could not but observe the numerous mineral veins running through the slate rocks forming the beautiful cliffs on this coast. Examples of every kind he collected; and on one occasion, when preparing his humble meal, a heavy black stone was employed to form a part of the fireplace. The fire was more intense than usual, and a stream of beautiful white metal flowed out of the fire. Great was the joy of the saint; he perceived that God, in His goodness, had discovered to him something which would be useful to man. St Perran communicated his discovery to St Chiwidden. They examined the shores together, and Chiwidden, who was learned in the learning of the East, soon devised a process for producing this metal in large quantities. The two saints called the Cornish men together. They told them of their treasures, and they taught them how to dig the ore from the earth, and how, by the agency of fire, to obtain the metal. Great was the joy in Cornwall, and many days of feasting followed the announcement. Mead and metheglin, with other drinks, flowed in abundance; and vile rumour says the saints and their people were rendered equally unstable thereby. “Drunk as a Perraner,” has certainly passed into a proverb from that day.

The riot of joy at length came to an end, and steadily, seriously, the tribes of Perran and St Agnes set to work. They soon accumulated a vast quantity of this precious metal; and when they carried it to the southern coasts, the merchants from Gaul eagerly purchased it of them. The noise of the discovery, even in those days, rapidly extended itself; and even the cities of Tyre learned that a metal precious to them, was to be obtained in a country far to the west. The Phœnician navigators were not long in finding out the Tin Islands; and great was the alarm amidst the Cornish Britons lest the source of their treasure should be discovered. Then it was they intrenched the whole of St Agnes beacon; then it was they built the numerous hill castles, which have puzzled the antiquarian; then it was that they constructed the Rounds,—amongst which the Perran Round remains as a remarkable example,—all of them to protect their tin ground. So resolved were the whole of the population of the district to preserve the tin workings, that they prevented any foreigner from landing on the mainland, and they established tin markets on the islands on the coast. On these islands were hoisted the standard of Cornwall, a white cross on a black ground, which was the device of St Perran and St Chiwidden, symbolising the black tin ore and the white metal.[8]

Whence came the saint, or hermit, who has given his name to two churches in England, is not known.

Tradition, however, informs us that he was remarkably small in stature, though exquisitely formed. He could not, according to all accounts, have been more than fifteen inches[23] high. Yet, though so diminutive a man, he possessed a soul which was giant-like in the power of his faith. The Church of St Neot, which has been built on the ancient site of the hermit’s cell, is situated in a secluded valley, watered by a branch of the river Fowey. The surrounding country is, even now, but very partially cultivated, and it must have been, a few centuries since, a desert waste; but the valley is, and no doubt ever has been, beautifully wooded. Not far from the church is the holy well, in which the pious anchorite would stand immersed to his neck, whilst he repeated the whole Book of Psalms. Great was the reward for such an exercise of devotion and faith. Out of numerous miracles we select only a few, which have some especial character about them.

One day the holy hermit was standing in his bath chanting the Psalms, when he heard the sound of huntsmen approaching. Whether the saint feared ridicule or ill-treatment, we know not; but certainly he left some psalms unsung that day, and hastily gathering up his clothes, he fled to his cell.

In his haste the goodman lost his shoe, and a hungry fox having escaped the hunters, came to the spring to drink. Having quenched the fever of thirst, and being hungry, he spied the saint’s shoe, and presently ate it. The hermit despatched his servant to look for his shoe; and, lo, he found the fox cast into a deep sleep, and the thongs of the shoe hanging out of his vile mouth. Of course the shoe was pulled out of his stomach, and restored to the saint.

Again, on another day, when the hermit was in his fountain, a lovely doe, flying from the huntsmen, fell down[24] on the edge of the well, imploring, with tearful eyes and anxious pantings, the aid of St Neot. The dogs followed in full chase, ready to pounce on the trembling doe, and eager to tear her in pieces. They saw the saint, and one look from his holy eyes sent them flying back into the woods, more speedily, if possible, than they rushed out of it.

The huntsman too came on, ready to discharge his arrow into the heart of the doe; but, impressed with the sight he saw, he fell on his knees, cast away his quiver, and became from that day a follower of the saint’s, giving him his horn to hang, as a memorial, in the church, where it was long to be seen. The huntsman became eventually one of the monks of the neighbouring house of St Petroch.

When St Neot was abbot, some thieves came by night and stole the oxen belonging to the farm of the monastery. The weather was most uncertain,—the seed-time was passing away,—and a fine morning rendered it imperative that the ploughs should be quickly employed. There were no oxen. Great was the difficulty, and earnest were the abbot’s prayers. In answer to them, the wild stags came in from the forests, and tamely offered their necks to the yoke. When unyoked in the evening, they resorted to their favourite pastures, but voluntarily returned each morning to their work. The report of this event reached the ears of the thieves. They became penitent, and restored the oxen to the monastery. Not only so, but they consecrated their days to devotional exercises. The oxen being restored, the stags were dismissed; but they bore for ever a white ring, like a yoke, about their necks, and they held a charmed life, safe from the shafts of the hunters.

On one occasion, when the saint was at his devotions, an angel appeared unto him, and shewing him three fishes in the well, he said, “These are for thee; take one each day for thy daily food, and the number shall never grow less: the choice of one of three fishes shall be thine all the days of thy life.” Long time passed by, and daily a fish was taken from the well, and three awaited his coming every morning. At length the saint, who shared in human suffering notwithstanding his piety, fell ill; and being confined to his bed, St Neot sent his servant Barius to fetch him a fish for his dinner. Barius being desirous of pleasing, if possible, the sick man’s taste, went to the well and caught two fishes. One of these he broiled, and the other he boiled. Nicely cooked, Barius took them on a dish to his master’s bedside, who started up alarmed for the consequences of the act of his servant, in disobedience to the injunctions of the angel. So good a man could not allow wrath to get the mastery of him; so he sat up in his bed, and, instead of eating, he prayed with great earnestness over the cooked fish. At last the spirit of holiness exerted its full power. St Neot commanded Barius to return at once and cast the fish into the well. Barius went and did as his master had told him to do; and, lo, the moment the fishes fell into the water they recovered life, and swam away with the third fish, as if nothing had happened to them.

All these things and more are recorded in the windows of St Neot’s Church.[9]

Every one is acquainted with the beautiful tower of Probus Church. If they are not, they should lose no time in visiting it. Various are the stories in connexion with those two saints, who are curiously connected with the church, and one of the fairs held in the church-town. A safe tradition tells us that St Probus built the church, and failing in the means of adding a tower to his building, he petitioned St Grace to aid him. Grace was a wealthy lady, and she resolved at her own cost to build a tower, the like of which should not be seen in the “West Countrie.” Regardless of the expense, sculptured stone was worked by the most skilful masons, and the whole put together in the happiest of proportions. When the tower was finished, St Probus opened his church with every becoming solemnity, and took to himself all the praise which was lavished on the tower, although he had built only a plain church. When, however, the praise of Probus was at the highest, a voice was heard slowly and distinctly exclaiming,

and thus for ever have Probus and Grace been united as patron saints of this church.

Mr Davies Gilbert remarks, however, in his “Parochial History:” “Few gentlemen’s houses in the west of Cornwall were without the honour of receiving Prince Charles during his residence in the county about the middle part of the civil wars; and he is said to have remained for a time longer than usual with Mr Williams, who, after the Restoration, waited on the king with congratulations from the parish; and, on being complimented by him with the question whether he could do anything for his friends, answered[27] that the parish would esteem themselves highly honoured and distinguished by the grant of a fair, which was accordingly done for the 17th September. This fair coming the last in succession after three others, has acquired for itself a curious appellation, derived from the two patron saints, and from the peculiar pronunciation in that neighbourhood of the word last, somewhat like laest,—

and from this distinction it is usually called Probus and Grace Fair.” We are obliged, therefore, to lean on the original tradition for the true meaning of this couplet.

Far up the deep and rocky vale of Trevillet, in the parish of Tintagel,[10] stands on a pile of rocks the little chapel of the good St Nectan. No holy man ever selected a more secluded, or a more lovely spot in which to pass a religious life. From the chapel rock you look over the deep valley full of trees. You see here and there the lovely trout-stream, running rapidly towards the sea; and, opening in the distance, there rolls the mighty ocean itself. Although this oratory is shut in amongst the woods, so as to be invisible to any one approaching it by land, until they are close upon it, it is plainly seen by the fishermen or by the sailor far off at sea; and in olden time the prayers of St Nectan were sought by all whose business was in the “deep waters.”

The river runs steadily along within a short distance of St Nectan’s Chapel, and then it suddenly leaps over the rock—a beautiful fall of water—into St Nectan’s Kieve. This deep rock-basin, brimming with the clearest water, overflows, and another waterfall carries the river to the lower level of the valley. Standing here within a circular wall of rocks, you see how the falling fluid has worked back the softer slate-rock until it has reached the harder masses, which are beautifully polished by the same agent. Mosses, ferns, and grasses decorate the fall, fringing every rock with a native drapery of the most exquisite beauty. Here is one of the wildest, one of the most untrained, and, at the same time, one of the most beautiful spots in Cornwall, full of poetry, and coloured by legend. Yet here comes prosaic man, and by one stroke of his everyday genius, he adds, indeed, a colour to the violet. You walk along the valley, through paths trodden out of the undergrowth, deviously wandering up hill, or down hill, as rock or tree has interposed. Many a spot of quiet beauty solicits you to loiter, and loitering, you feel that there are places from which the winds appear to gather poetry. You break the spell, or the ear, catching the murmur of the waters, dispels the illusions which have been created by the eye, and you wander forward anxious to reach the holy “Kieve,”—to visit the saint’s hermitage. Here, say you, is the place to hold “commune with Nature’s works, and view her charms unrolled,” when, lo, a well-made door painted lead colour, with a real substantial lock, bars your way, and Fancy, with everything that is holy, flies away before the terrible words which inform you that trespassers will be punished, and that the key can be obtained at ——. Well was it that Mr Wilkie Collins gave “up the attempt to discover Nighton’s Kieve;”[11] for had he, when he had found[29] it, discovered this evidence of man’s greedy soul, it would have convinced him that the “evil genius of fairy mythology,” who so cautiously hid “the nymph of the waterfall,” was no other than the farmer, who, as he told me, “owns the fee,” and one who is resolved also, to pocket the fee, before any pilgrim can see the oratory and the waterfall of St Nectan. Of course this would have turned the placid current of the thoughts of “the Rambler beyond Railways,” which now flow so pleasantly, into a troubled stream of biliary bitterness.

St Nectan placed in the little bell-tower of his secluded chapel a silver bell, the notes of which were so clear and penetrating that they could be heard far off at sea. When the notes came through the air, and fell on the ears of the seamen, they knew that St Nectan was about to pray for them, and they prostrated themselves before Heaven for a few minutes, and thus endeavoured to win the blessing.

St Nectan was on the bed of death. There was strife in the land. A severe struggle was going on between the Churchmen, and endeavours were being made to introduce a new faith.

The sunset of life gave to the saint the spirit of prophecy, and he told his weeping followers that the light of their religion would grow dim in the land; but that a spark would for ever live amidst the ashes, and that in due time it would kindle into a flame, and burn more brightly than ever. His silver bell, he said, should never ring for others than the true believer. He would enclose it in the rock of the Kieve; but when again the true faith revived, it should be recovered, and rung, to cheer once more the land.

One lovely summer evening, while the sun was slowly sinking towards the golden sea, St Nectan desired his attendants to carry him to the bank which overhung the “Kieve,” and requested them to take the bell from the tower and bring it to him.

There he lay for some time in silent prayer, waiting as if for a sign, then slowly raising himself from the bed on which he had been placed, he grasped the silver bell. He rang it sharply and clearly three times, and then he dropped it into the transparent waters of the Kieve. He watched it disappear, and then he closed his eyes in death. On receiving the bell the waters were troubled, but they soon became clear as before, and the bell was nowhere to be seen. St Nectan died, and two strange ladies from a foreign land came and took possession of his oratory, and all that belonged unto the holy man. They placed—acting, as it was believed, on the wishes of the saint himself—his body, all the sacramental plate, and other sacred treasures, in a large oak chest. They turned the waters of the fall aside, and dug a grave in the river bed, below the Kieve, in which they placed this precious chest. The waters were then returned to their natural course, and they murmur ever above the grave of him who loved them. The silver bell was concealed in the Kieve, and the saint with all that belonged to his holy office rested beneath the river bed. The oratory was dismantled, and the two ladies, women evidently of high birth, chose it for their dwelling. Their seclusion was perfect. “Both appeared to be about the same age, and both were inflexibly taciturn. One was never seen without the other. If they ever left the house, they only left it to walk in the more unfrequented parts of the wood; they kept no servant; they never had a visitor; no living soul but themselves ever crossed the door of their cottage.”[12] The berries of the wood, a few roots which they cultivated, with snails gathered from the rocks[31] and walls, and fish caught in the stream, served them for food. Curiosity was excited, the mystery which hung around this solitary pair became deepened by the obstinate silence which they observed in everything relating to themselves. The result of all this was an anxious endeavour, on the part of the superstitious and ignorant peasantry, to learn their secret. All was now conjecture, and the imagination commonly enough filled in a wild picture: devils or angels, as the case might be, were seen ministering to the solitary ones. Prying eyes were upon them, but the spies could glean no knowledge. Week, month, year passed by, and ungratified curiosity was dying through want of food, when it was discovered that one of the ladies had died. The peasantry went in a body to the chapel; no one forbade their entering it now. There sat a silent mourner leaning over the placid face of her dead sister. Hers was, indeed, a silent sorrow—no tear was in her eye, no sigh hove her chest, but the face told all that a remediless woe had fallen on her heart. The dead body was eventually removed, the living sister making no sign, and they left her in her solitude alone. Days passed on; no one heard of, no one probably inquired after, the lonely one. At last a wandering child, curious as children are, clambered to the window of the cell and looked in. There sat the lady; her handkerchief was on the floor, and one hand hung strangely, as if endeavouring to pick it up, but powerless to do so. The child told its story—the people again flocked to the chapel, and they found one sister had followed the other. The people buried the last beside the first, and they left no mark to tell us where,[32] unless the large flat stone which lies in the valley, a short distance from the foot of the fall, and beneath which, I was told, “some great person was buried,” may be the covering of their tomb. No traces of the history of these solitary women have ever been discovered.

Centuries have passed away, and still the legends of the buried bell and treasure are preserved. Some long time since a party of men resolved to blast the “Kieve,” and examine it for the silver bell. They were miners, and their engineering knowledge, though rude, was sufficient to enable them to divert the course of the river above the falls, and thus to leave the “Kieve” dry for them to work on when they had emptied it, which was an easy task. The “borer” now rung upon the rock, holes were pierced, and, being charged, they were blasted. The result was, however, anything but satisfactory, for the rock remained intact. Still they persevered, until at length a voice was heard amidst the ring of the iron tools in the holes of the rock. Every hand was stayed, every face was aghast, as they heard distinctly the ring of the silver bell, followed by a clear solemn voice proclaiming, “The child is not yet born who shall recover this treasure.”

The work was stopped, and the river restored to its old channel, over which it will run undisturbed until the day of which St Nectan prophesied shall arrive.

When, in the autumn of 1863, I visited this lovely spot, my guide, the proprietor, informed me that very recently a gentleman residing, I believe, in London, dreamed that an angel stood on a little bank of pebbles, forming a petty island, at the foot of a waterfall, and, pointing to a certain spot, told him to search there and he would find gold and a mummy. This gentleman told his dream to a friend, who at once declared the place indicated to be St Nectan’s waterfall. Upon this, the dreamer visited the West, and, upon being led by the owner of the property to the fall, he at once recognised the spot on which the angel stood.

A plan was then and there arranged by which a search might be again[33] commenced, it being thought that, as an angel had indicated the spot, the time for the recovery of the treasure had arrived.

Let us hope that the search may be deferred, lest the natural beauties of the spot should be destroyed by the meddling of men, who can threaten trespassers,—fearing to lose a sixpence,—and who have already endeavoured to improve on nature, by cutting down some of the rock and planting rhododendrons.

The Rev. R. S. Hawker, of Morwenstow, has published in his “Echoes of Old Cornwall” a poem on this tradition, which, as it is but little known, and as it has the true poetic ring, I transcribe to adorn the pages of my Appendix.[13]

Riviere, near Hayle, now called Rovier, was the palace of Theodore, the king, to whom Cornwall appears to have been indebted for many of its saints. This Christian king, when the pagan people sought to destroy the first missionaries, gave the saints shelter in his palace. St Breca, St Iva, St Burianna, and many others, are said to have made Riviere their residence. It is not a little curious to find traditions existing, as it were, in a state of suspension between opinions. I have heard it said that there was a church at Rovier—that there was once a great palace there; and again, that Castle Cayle was one vast fortified place, and Rovier another. Mr Davies Gilbert quotes Whitaker on this point:—

“Mr Whitaker, who captivates every reader by the brilliancy of his style, and astonishes by the extent of his multifarious reading, draws, however, without reserve, on his fertile imagination, for whatever facts may be requisite to construct the fabric of a theory. He has made Riviere the palace and residence of Theodore, a sovereign prince of Cornwall, and conducts St Breca, St Iva, with several companions, not only into Hayle and to this palace, after their voyage from Ireland, but fixes the time of their arrival so exactly, as to make it take place in the night. In recent times the name of Riviere, which had been lost in the common pronunciation, Rovier, has revived in a very excellent house built by Mr Edwards on the farm, which he completed in 1791.”[14]

A spring of water has always something about it which gives rise to holy feelings. From the dark earth there wells up a pellucid fluid, which in its apparent tranquil joyousness gives gladness to all around. The velvet mosses, the sword-like grasses, and the feathery ferns, grow with more of that light and vigorous nature which indicates a fulness of life, within the charmed influence of a spring of water, than they do elsewhere.

The purity of the fluid impresses itself, through the eye, upon the mind, and its power of removing all impurity is felt to the soul. “Wash and be clean,” is the murmuring call of the waters, as they overflow their rocky basins, or grassy vases, and deeply sunk in depravity must that man be who could put to unholy uses one of nature’s fountains. The inner life of a well of waters, bursting from its grave in the earth, may be religiously said to form a type of the soul purified by death, rising into a glorified existence and the[36] fulness of light. The tranquil beauty of the rising waters, whispering the softest music, like the healthful breathing of a sleeping infant, sends a feeling of happiness through the soul of the thoughtful observer, and the inner man is purified by its influence, as the outer man is cleansed by ablution.

Water cannot be regarded as having an inanimate existence. Its all-pervading character and its active nature, flowing on for ever, resting never, removes it from the torpid elements, and places it, like the air, amongst those higher creations which belong to the vital powers of the earth. The spring of water rises from the cold dark earth, it runs, a silver cord glistening in the sunshine, down the mountainside. The rill (prettily called by Drayton “a rillet”) gathers rejoicingly other waters unto itself, and it grows into a brooklet in its course. At length, flowing onward and increasing in size, the brook state of being is fairly won; and then, by the gathering together of some more dewdrops, the full dignity of a stream is acquired. Onwards the waters flow, still gleaning from every side, and wooing new runlets to its bosom, eager as it were to assume the state which, in America, would be called a “run” of water. Stream gathers on stream, and run on run; the union of waters becomes a river; rolling in its maturity, swelling in its pride, it seeks the ocean, and there is absorbed in the eternity of waters. Has ever poet yet penned a line which in any way conveys to the mind a sense of the grandeur, the immensity of the sea? I do not remember a verse which does not prove the incapacity of the human mind to embrace in its vastness the gathering together of the waters in the mighty sea. Man’s mind is tempered, and his pride subdued, as he stands on the sea-side and looks on the undulating expanse to which, to him, there is no end. A material eternity of[37] rain-drops gathered into a mass which is from Omnipotence and is omnipotent. The influences of heaven falling on the sheeted waters, they rise at their bidding and float in air, making the skies more beautiful or more sublime, according to the spirit of the hour. Whether the clouds float over the earth, illumined by sun-rays, like the cars of loving angels; or rush wildly onward, as if bearing demons of vengeance, they are subdued by the mountains, and fall reluctantly as mists around the rocks, condense solemnly as dews upon the sleeping flowers, sink to earth resignedly as tranquil rains, or splash in tempestuous anger on its surface. The draught, in whatever form it comes, is drunk with avidity, and, circulating through the subterranean recesses of the globe, it does its work of re-creation, and eventually reappears a bubbling spring, again to run its round of wonder-working tasks.

Those minds which saw a God in light, and worshipped a Creator in the sun, felt the power of the universal solvent, and saw in the diffusive nature of that fluid which is everywhere, something more than a type of the regenerating Spirit, which all, in their holier hours, feel necessary to clear off the earthiness of life. Man has ever sought to discover the spiritual in the material, and, from the imperfections of human reason, he has too frequently reposed on the material, and given to it the attributes which are purely spiritual. Through all ages the fountains of the hills and valleys have claimed the reverence of men; and waters presenting themselves, under aspects of beauty, or of terror, have been regarded with religious feelings of hope or of awe.

As it was of old, so is it to-day. It was but yesterday that I stood near the font of Royston Church, and heard the minister read with emphasis, “None can enter into the kingdom of God except he be regenerate and born anew of water.” Surely the simple faith of the peasant mother who,[38] on a spring morning, takes her weakly infant to some holy well, and three times dipping it in its clear waters, uttering an earnest prayer at each immersion, is but another form of the prescribed faith of the educated churchman.

Surely the practice of consulting the waters of a sacred spring, by young men and maidens, is but a traditional faith derived from the early creeds of Greece—a continuance of the Hydromancy which sought in the Castalian fountain the divination of the future.

In the parish of St Merran, or Meryn, near Padstow, are the remains of the Church of St Constantine, and the holy well of that saint. It had been an unusually hot and dry summer, and all the crops were perishing through want of water. The people inhabiting the parish had grown irreligious, and many of them sadly profane. The drought was a curse upon them for their wickedness. Their church was falling into ruin, their well was foul, and the arches over it were decayed and broken. In their distress, the wicked people who had reviled the Word of God, went to their priest for aid.

“There is no help for thee, unless thou cleansest the holy well.”

They laughed him to scorn.

The drought continued, and they suffered want.

To the priest they went again.

“Cleanse the well,” was his command, “and see the power of the blessing of the first Christian emperor.” That cleansing a dirty well should bring them rain they did not believe. The drought continued, the rivers were dry, the people suffered thirst.

“Cleanse the well—wash, and drink,” said the priest, when they again went to him.

Hunger and thirst made the people obedient. They went to the task. Mosses and weeds were removed, and the filth cleansed. To the surprise of all, beautifully clear water welled forth. They drank the water and prayed, and then washed themselves, and were refreshed. As they bathed their bodies, parched with heat, in the cool stream which flowed from the well, the heavens clouded over, and presently rain fell, turning all hearts to the true faith.

St Ludgvan, an Irish missionary, had finished his work. On the hill-top, looking over the most beautiful of bays, the church stood with all its blessings. Yet the saint, knowing human nature, determined on associating with it some object of a miraculous character, which should draw people from all parts of the world to Ludgvan. The saint prayed over the dry earth, which was beneath him, as he knelt on the church stile. His prayer was for water, and presently a most beautiful crystal stream welled up from below. The holy man prayed on, and then, to try the virtues of the water, he washed his eyes. They were rendered at once more powerful, so penetrating, indeed, as to enable him to see microscopic objects. The saint prayed again, and then he drank of the water. He discovered that his powers of utterance were greatly improved, his tongue formed words with scarcely any effort of his will. The saint now prayed, that all children baptized in the waters of this well might be protected against the hangman and his hempen cord; and an angel from heaven came down into the water, and promised the saint that his prayers should be granted. Not[40] long after this, a good farmer and his wife brought their babe to the saint, that it might derive all the blessings belonging to this holy well. The priest stood at the baptismal font, the parents, with their friends around. The saint proceeded with the baptismal ceremonial, and at length the time arrived when he took the tender babe into his holy arms. He signed the sign of the cross over the child, and when he sprinkled water on the face of the infant its face glowed with a divine intelligence. The priest then proceeded with the prayer; but, to the astonishment of all, whenever he used the name of Jesus, the child, who had received the miraculous power of speech, from the water, pronounced distinctly the name of the devil, much to the consternation of all present. The saint knew that an evil spirit had taken possession of the child, and he endeavoured to cast him out; but the devil proved stronger than the saint for some time. St Ludgvan was not to be beaten; he knew that the spirit was a restless soul, which had been exorcised from Treassow, and he exerted all his energies in prayer. At length the spirit became obedient, and left the child. He was now commanded by the saint to take his flight to the Red Sea. He rose, before the terrified spectators, into a gigantic size, he then spat into the well; he laid hold of the pinnacles of the tower, and shook the church until they thought it would fall. The saint was alone unmoved. He prayed on, until, like a flash of lightning, the demon vanished, shaking down a pinnacle in his flight. The demon, by spitting in the water destroyed the spells of the water upon the eyes[15] and the tongue too; but it fortunately retains its virtue of preventing any child baptized in it from being hanged with a cord of hemp. Upon a cord of silk it is stated to have no power.

This well had nearly lost its reputation once—a Ludgvan woman was hanged, under the circumstances told in the following narrative:—

A small farmer, living in one of the most western districts of the county, died some years back of what was supposed at that time to be “English cholera.” A few weeks after his decease his wife married again. This circumstance excited some attention in the neighbourhood. It was remembered that the woman had lived on very bad terms with her late husband, that she had on many occasions exhibited strong symptoms of possessing a very vindictive temper, and that during the farmer’s lifetime she had openly manifested rather more than a Platonic preference for the man whom she subsequently married. Suspicion was generally excited; people began to doubt whether the first husband had died fairly. At length the proper order was applied for, and his body was disinterred. On examination, enough arsenic to have poisoned three men was found in the stomach. The wife was accused of murdering her husband, was tried, convicted on the clearest evidence, and hanged. Very shortly after she had suffered capital punishment horrible stories of a ghost were widely circulated. Certain people declared that they had seen a ghastly resemblance of the murderess, robed in her winding-sheet, with the black mark of the rope round her swollen neck, standing on stormy nights upon her husband’s grave, and digging there with a spade, in hideous imitation of the actions of the men who had disinterred the corpse for medical examination. This was fearful enough; nobody dared go near the place after nightfall. But soon another circumstance was talked of in connexion with the poisoner, which affected the tranquillity of people’s minds in the village where she had lived, and where it was believed she had been born, more seriously than even the ghost story itself. The well of[42] St Ludgvan, celebrated among the peasantry of the district for its one remarkable property, that every child baptized in its water (with which the church was duly supplied on christening occasions) was secure from ever being hanged.

No one doubted that all the babies fortunate enough to be born and baptized in the parish, though they might live to the age of Methuselah, and might during that period commit all the capital crimes recorded in the “Newgate Calendar,” were still destined to keep quite clear of the summary jurisdiction of Jack Ketch. No one doubted this until the story of the apparition of the murderess began to be spread abroad, then awful misgivings arose in the popular mind.

A woman who had been born close by the magical well, and who had therefore in all probability been baptized in its water, like her neighbours of the parish, had nevertheless been publicly and unquestionably hanged. However, probability is not always the truth. Every parishioner determined that the baptismal register of the poisoner should be sought for, and that it should be thus officially ascertained whether she had been christened with the well water or not. After much trouble, the important document was discovered—not where it was at first looked after, but in a neighbouring parish. A mistake had been made about the woman’s birthplace; she had not been baptized in St Ludgvan church, and had therefore not been protected by the marvellous virtue of the local water. Unutterable was the joy and triumph of this discovery. The wonderful character of the parish well was wonderfully vindicated; its celebrity immediately spread wider than ever. The peasantry of the neighbouring districts began to send for the renowned water before christenings; and many of them actually continue, to this day, to[43] bring it corked up in bottles to their churches, and to beg particularly that it may be used whenever they present their children to be baptized.[16]

A young woman, with a child in her arms, stands by the side of Gulval Well, in Fosses Moor. There is an expression of extreme anxiety in her interesting face, which exhibits a considerable amount of intelligence. She appears to doubt, and yet be disposed to believe in, the virtues of this remarkable well. She pauses, looks at her babe, and sighs. She is longing to know something of the absent, but she fears the well may indicate the extreme of human sorrow. While she is hesitating, an old woman advances towards her, upon whom the weight of eighty years was pressing, but not over heavily; and she at once asked the young mother if she wished to ask the well after the health of her husband.

“Yes, Aunt Alcie,” she replied; “I am so anxious. I have not heard of John for six long months. I could not sleep last night, so I rose with the light, and came here, determined to ask the well; but I am afraid. O Aunt Alcie, suppose the well should not speak, I should die on the spot!”

“Nonsense, cheeld,” said the old woman; “thy man is well enough; and the well will boil, if thee’lt ask it in a proper spirit.”

“But, Aunt Alcie, if it sends up puddled water, or if it remains quiet, what would become of me?”

“Never be foreboding, cheeld; troubles come quick without running to meet ’em. Take my word for it, the fayther[44] of thy little un will soon be home again. Ask the well! ask the well!”

“Has it told any death or sickness lately?” asked the young mother.

“On St Peter’s eve Mary Curnew questioned the water about poor Willy.”

“And the water never moved?”

“The well was quiet; and verily I guess it was about that time he died.”

“Any sickness, Aunt Alcie?”

“Jenny Kelinach was told, by a burst of mud, how ill her old mother was; but do not be feard, all is well with Johnny Thomas.”

Still the woman hesitated; desire, fear, hope, doubt, superstition, and intelligence struggled within her heart and brain.

The old creature, who was a sort of guardian to the well, used all her rude eloquence to persuade Jane Thomas to put her question, and at length she consented. Obeying the old woman’s directions, she knelt on the mat of bright green grass which grew around, and leaning over the well so as to see her face in the water, she repeated after her instructor,

Some minutes passed in perfect silence, and anxiety was rapidly turning cheeks and lips pale, when the colour rapidly returned. There was a gush of clear water from below, bubble rapidly followed bubble, sparkling brightly in the morning sunshine. Full of joy, the young mother rose from her knees, kissed her child, and exclaimed, “I am happy now!”[17]

St Keyne came to this well about five hundred years before the Norman Conquest, and imparted a strange virtue to its waters—namely, that whichever of a newly-married couple should first drink thereof, was to enjoy the sweetness of domestic sovereignty ever after.