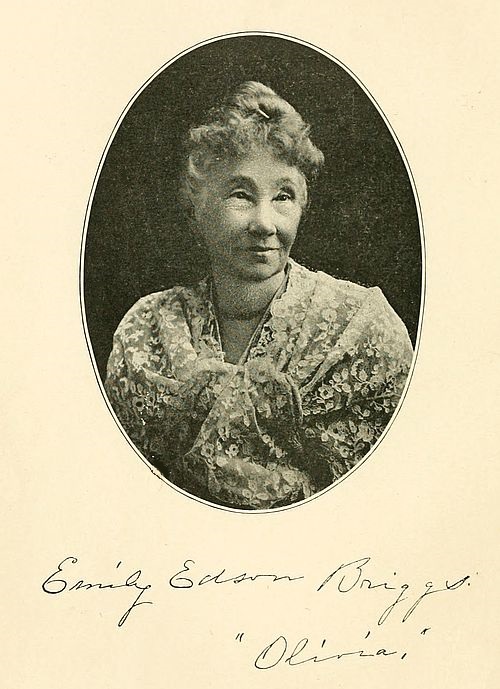

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Olivia Letters, by Emily Edson Briggs

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Olivia Letters

Being Some History of Washington City for Forty Years as

Told by the Letters of a Newspaper Correspondent

Author: Emily Edson Briggs

Release Date: January 3, 2019 [EBook #58604]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE OLIVIA LETTERS ***

Produced by ellinora, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

THE OLIVIA LETTERS

Being Some History of Washington City for Forty Years as Told by the Letters of a Newspaper Correspondent

By

EMILY EDSON BRIGGS

New York and Washington

THE NEALE PUBLISHING COMPANY

1906

Copyright, 1906, by

EMILY EDSON BRIGGS

| A TRIBUTE TO ARCHITECTURE, | 7 |

| A SOLDIER’S BURIAL, | 10 |

| LINCOLN’S BIRTHDAY, | 14 |

| ADVICE POLITICAL, | 18 |

| A PLEA FOR THE NEGRO, | 22 |

| AT DRY TORTUGAS, | 26 |

| STATE ASSOCIATIONS, | 30 |

| BINGHAM AND BUTLER, | 34 |

| A WEST END RECEPTION, | 37 |

| IN THE ARENA OF THE SENATE, | 42 |

| SPEAKER COLFAX, | 45 |

| THE HIGH COURT OF IMPEACHMENT, | 48 |

| MRS. SENATOR WADE, | 52 |

| AT THE PRESIDENT’S LEVEE, | 55 |

| MARY CLEMMER AMES, | 59 |

| AT THE IMPEACHMENT TRIAL, | 62 |

| HON. BENJAMIN F. WADE, | 66 |

| TWO NOTABLE WOMEN, | 69 |

| JUDGE NELSON, | 72 |

| A FAITHFUL SERVANT, | 75 |

| JOHN A. BINGHAM, | 79 |

| ANSON BURLINGAME, | 82 |

| A TALENTED QUARTETTE, | 85 |

| THE DRAGONS OF THE LOBBY, | 91 |

| PRESIDENT GRANT’S INAUGURAL, | 95 |

| PRESIDENT JOHNSON’S FAMILY, | 100 |

| SENATORIAL PEN PICTURES, | 105 |

| SENATOR SPRAGUE, | 112 |

| SEALED SISTERS OF MORMONISM, | 117 |

| AWAITING AUDIENCE AT THE WHITE HOUSE, | 121 |

| JOHN M. BARCLAY, | 126 |

| WOMAN SUFFRAGE, | 130 |

| ELIZABETH CADY STANTON, | 136 |

| ISABELLA BEECHER HOOKER, | 143 |

| GATHERING OF THE STRONG-MINDED, | 148 |

| AT A COMMITTEE HEARING, | 157 |

| HONORING THE PRINCE, | 164 |

| LEVEE AT THE EXECUTIVE MANSION, | 168 |

| OFFICIAL ETIQUETTE, | 173 |

| GENERAL PHIL SHERIDAN, | 181 |

| MIDWINTER SOCIETY, | 188 |

| PROFESSOR MELAH, | 199 |

| SOME SENATORIAL SCENES, | 208 |

| [6] THE ROBESON TEA PARTY, | 214 |

| DELEGATES FROM THE SOUTHLAND, | 218 |

| THE TREASURY TRIO, | 223 |

| VICTORIA C. WOODHULL, | 229 |

| SPREADING THE LIGHT, | 236 |

| AN OPPOSING PETITION, | 242 |

| UPHOLDING THE BANNER, | 247 |

| CHAMPIONS OF THE SUFFRAGE CAUSE, | 252 |

| MRS. GRANT’S TUESDAY AFTERNOONS, | 256 |

| DYING SCENES OF THE FORTY-FIRST CONGRESS, | 262 |

| PRAISE FOR DEPARTING LEGISLATORS, | 267 |

| THE BLACK MAN IN CONGRESS, | 274 |

| BY THE GRACE OF THE QUEEN, | 280 |

| A DISSERTATION ON DRESS, | 288 |

| MEETING OF OCCIDENT AND ORIENT, | 294 |

| THE PUBLIC GREET THE JAPANESE, | 298 |

| SAMUEL F. B. MORSE, | 302 |

| ON THE PROMENADE, | 305 |

| CHARLES SUMNER, | 309 |

| WOMAN’S INFLUENCE FOR GOOD, | 315 |

| THE KING REUNIONS, | 320 |

| CARL SCHURZ, | 325 |

| ON CAPITOL HILL, | 330 |

| GEORGETOWN ARISTOCRACY, | 336 |

| SENATORS EDMUNDS AND CARPENTER, | 343 |

| HOME LIFE OF MRS. GRANT, | 349 |

| THE GREAT REAPER, | 357 |

| CLOSING SCENES IN THE HOUSE, | 364 |

| A MATRIMONIAL REGISTER, | 369 |

| BACHELORS AND WIDOWERS, | 376 |

| THE BOTANIC GARDEN, | 382 |

| WHITE HOUSE RECEPTIONS COMPARED, | 388 |

| VICE-PRESIDENT ARTHUR, | 396 |

| KATE CHASE SPRAGUE, | 403 |

| LACK OF A LEADER, | 412 |

| BEN HILL AND ROSCOE CONKLING, | 419 |

| PRESIDENT GARFIELD’S CABINET DAY, | 424 |

| A NEW YEAR RECEPTION, | 430 |

| AT THE TRIAL OF GUITEAU, | 435 |

| ARCTIC EXPEDITIONS, | 441 |

Honor Paid to the Builders of the Dome of the National Capitol.

Washington, January, 1866.

The time has come when our wealthy citizens need not to go abroad to see the finest specimen of architecture of the kind in the world. Visitors to the shrine of St. Paul and St. Peter return westward and award the palm of superiority to the dome of the nation’s Capitol. Towering 300 feet from the base to the summit, its superb proportions unsurpassed in the world of art, at once attract the attention of all beholders, and, as the king of the landscape, it reigns supreme. But to see it in all its regal beauty it should be aflame of a night, with its innumerable gas jets; then it becomes in every sense of the word, a “mountain of light,” and shares the honors of the evening with the “Pleiades,” “Orion,” and the “Milky Way.”

The Pharaoh who built the mighty pyramid of Egypt simply constructed his own monument, and in the same way the architect of the dome, a citizen of good old Philadelphia, has woven his name into a fragment of the web of Time. Thomas U. Walter—do you know him?—the man who held this mighty tower in his brain, in all its perfection, long, long before it ever saw the light of day. When you and I, dear reader, are not so much as a pinch of dust—when the names of Washington and Lincoln are as remote as the sages who lived before Christ—the great architects of the world will live, whether they sprung from the tawny mud of the Nile, the soil of classic Greece, or the rich vegetable mould of the western hemisphere.

Previous to 1856 a dome had been constructed of brick,[8] stone, and wood, sheathed in copper. Its height was 145 feet from the ground. This was torn away to give place to the present structure, which is composed entirely of iron and glass.

At the commencement of the rebellion the labor of completing the dome was progressing rapidly. Strangers visiting Washington will remember what seemed to look like acres of ground strewn with immense piles of iron. Facing the east and west fronts of the Capitol, immense timbers were raised to fearful heights, to which pulleys and ropes were attached that looked strong enough to lift the world. Weather permitting—for workmen had to lie by for either wind or rain—little black objects might be seen crawling in and out, building up a nest after the most approved waspish fashion. A closer inspection showed these to be workmen. Now let Charles Fowler, esq., one of the firm of New York builders, tell his story:

“I never had a comfortable night’s sleep during all the time the work was going on. I lived in perpetual fear of some horrible accident. We could not keep people out of the rotunda. Suppose there had been a weak place in one of the timbers, a flaw in an iron pin, a rotten strand in one of the ropes—and against neither of these things could we entirely guard—there is no knowing how many lives might have been lost.” “What precautions did you take?” “We made everything four times as strong as it was necessary to lift two tons of iron to a given height.” “Were any lives lost?” “I only had three men killed in all the time. We had stopped work for dinner one day, and when the workmen returned they found one of their number dead on the ground. No one saw him fall, but it was plain he had missed his foothold on the scaffold and been precipitated to the ground. His head had come in contact with some projecting beam. That was the end of him. Another lost his life in the same way; but the third, poor fellow! it makes my hair stand on end to think of it—a rope gave way and caught him.” “The lightning hug of an anaconda?” “Yes, yes; that is it. Poor Charlie! he never knew what hurt him. It chopped him up in an instant. You don’t know how quick a big rope can do that thing.”

The dome might have been completed in five years, but the Secretary of the Interior during the dark days of the rebellion stopped the work, at a great pecuniary loss to the contractors. On the average 200 men were employed[9] in building the dome, including those who were working on the castings in the foundry. The largest pieces of iron weighed two tons each.

The chief engineers employed were Gen. M. C. Meigs and Gen. Wm. B. Franklin. These engineers were detailed from the War Department because the building was Government property. Everything pertaining to this work is under the care of the engineer, and for its faithful execution he is responsible. It is the engineer who accepts the plan of the architect and judges of strength and merit. It is the engineer who makes the contracts and disburses the money. The word of the engineer is law. He is the autocrat in his own dominion, from whose fiat there is no appeal.

As we have already said, the dome is composed wholly of iron and glass, whilst the image which crowns it is made of bronze, designed by Crawford, and executed by Clark Mills. The weight of this goddess is about 1,700 pounds. Everything included, the dome weighs 10,000,000 pounds, which if turned into gold by the enchanter’s wand would about pay the national debt.

This brief and imperfect sketch is gathered from glances from the outside. The interior of the dome from the floor to the rotunda requires the pen of a genius to do justice to the so-called works of art found scattered in all directions. It is a long mathematical calculation to find out how many square inches of canvas have been ruined. A plaster caricature of our beloved Lincoln occupies the center of the floor, made by the tender hands of a youth of 17 summers. The fruit of genius, in all stages of the ripening process, its maturity forever arrested, lies gently decaying. It is enough to make the cheek of an American blush, if the spectacle were not so pitiful. A few gems gleam out of the rubbish. Exclusive of art, the dome of the Capitol cost the nation $1,000,000.

Olivia.

Last Scene of all Pathetically Depicted.

Washington, January 31, 1866.

A close observer in Washington is greatly surprised at the easy transition from a state of war to that of peace. An intelligent person might say there is no true peace. We will leave this discussion to the politicians, and say we are no longer awakened in the small hours of the night by the rumbling of the Government ambulances bringing the wounded and dying from the battlefields to the hospitals. We never shall forget that peculiar sound, unlike that produced by any other vehicle. Perhaps it was the zigzag course the driver often took to avoid any little obstruction in the street, which might jar and aggravate the wounded occupant, that made it seem so long in coming. But the movements were always slower than a funeral march.

But sad as this procession seemed, painful almost beyond expression, there was still a sadder sight. It was the same fashioned ambulance, with “U. S. Hearse” marked in large letters on the side of it. Our ears could never distinguish the movements of this from any grocer’s wagon. Sometimes we have been crossing a street, this solitary equipage would dash past, and if we were quick enough to catch a glance at the open end of it, we might see a stained coffin, perhaps two of them, with nothing to distinguish them but their manly proportions. No carriages, no mourners, no comrades, even, with reversed arms, all alone, save detailed soldiers enough to perform the act of burial; even the “chaplain” often absent.

Happening to meet an old soldier whom we knew just[11] as the Government hearse was passing, said he, “I hope you don’t mind that; you see that is only a part of the play. It don’t make much difference how you drop the seed; the Lord will take care of the harvest.” In an instant religion stood stripped of its vaulted roof and broad aisles—Te Deums, new bonnets, gewgaws and pew rent. Anxious for his salvation, we inquired, “Do you ever go to church?” and thus this bronzed soldier answered, “Got too much faith to go very often. They don’t ask a fellow to sit down. Got to stow away somewhere in the back gallery, or near the door, out of everybody’s way. And besides that, I don’t want to go to their heaven. I ain’t got on the right kind of uniform to serve under their General. But hang it, Heaven is big enough for us all—horses and dead rebs into the bargain.”

Only yesterday, as it were, the cloud, the vapor, the storm of war, the wrath of the conflict, bleeding wounds, breaking hearts. To-day the sun shines upon free, proud America, the most powerful nation on the face of the earth—a nation that stands forth pure and undefiled, her late difficulties overcome, or will be just as soon as old Thad Stevens reports the surgical operation a success. Fifteen able doctors are at work, and have been ever since Congress has been in session, and the country can rest assured that everything is going on as well as can be expected.

It is a pleasant place to visit, this Capitol of ours, on a sunshiny afternoon. ’Tis true that when once seated in the House of Representatives there is that feeling which one might be supposed to have if hermetically sealed up in a huge can; but one is disabused of this feeling as soon as the greatness of the surroundings is comprehended. There is no mistaking the Republican side of the House; there is such a placid, self-satisfied look upon the faces of the members, as much as to say, “We have got it all in our own hands.” The Democratic side is greatly in the minority, so far as numbers are concerned;[12] but they are a plucky set of men, mostly with thin lips, which they are in the habit of bringing tight together, reminding one of a certain little instrument made for torture; and woe to the House when an unfortunate Republican falls into the trap, for then follow long, windy discussions of no mortal use to the country and amounting to only so much waste of time and money.

The gallery known as the “Gentlemen’s” is generally filled with masculines who have little or nothing to do; but as they do not impede the wheels of legislation, and are kept out of the way of mischief in the meantime, the country is obliged for their attendance. And now I come to the ladies who grace and honor with their presence the national Capitol. How shall I describe these beautiful human butterflies in glaring hoops and gig-top bonnets, curls and perfumery? If the eyes of the traveler ache to behold in a solid mass the different strata of American society, let him visit the national Capitol when Ben Wade is going to make a speech. Nobody from the White House! These ladies have a good old-fashioned way of staying at home. (Wonder if they dry their clothes in the East Room as good queen Abigail used to do?) Carriages arrive at the east front of the Capitol—solemn carriages; heavy bays—made more for strength than beauty; driver with a narrow band around his hat, a little badge—just enough to show that he does not belong to “them independent Jehus that lurk around Willard’s and the National.” Driver and footman blended in one piece of ebony; driver descends, opens the carriage door, and madame, the proud wife of a Senator, descends, not with agility, for senatorial dignity brings years, rich, ripe, golden maturity, perfection of dress and manners, dark, rich silk, velvet mantle—none of your plebeian coats! The portals of the great Capitol open and Madame le Senator disappears.

Now come the wives of the wealthy members; not the leading ones, for great men seldom take time to get rich.[13] Showy carriage, driver and footman in gloves, an elegant carriage costume, an occasional flash of early autumnal beauty, oftener positively commonplace. And now comes Jehu, who has left his “stand” before Willard’s or the National just long enough to turn an honest penny. Perhaps he is bringing a member’s wife whose carriage costume outshines her neighbor, the owner of the footman in gloves. She wishes it understood that she is not a resident of Washington; here temporarily, just long enough to keep her husband from butting his brains out against reconstruction.

She disappears, and still the carriages are arriving and we see many heads of bureaus, the Army and the Navy represented, and a sprinkling of upper clerk’s wives. More carriages, and the demi-mondes flutter out, faultless in costume, fair as ruby wine, and much more dangerous. The carriages bring the cream, and the street cars the skim milk. But there is another way of going to the Capitol, which is quite as exclusive as in carriage, and does away with that clumsy vehicle. I am speaking of those who detest the street cars, and yet remember that carriages more properly belong to gouty uncles and invalid aunts. It is to pick one’s way daintily over the pavement. Sniffing the pure air and the fragrance of the dead leaves in the Capitol grounds—good anti-dyspeptic tonic. Try it and speak from experience as we do. The allotted pages filled, au revoir.

Olivia.

Memorial Address of Honorable George Bancroft.

Washington, February 19, 1866.

The 12th day of February has passed into history, wisely chronicled by one of the first historians of the age, and ere this the oration of the Honorable George Bancroft has been discussed in almost every hamlet in the land. It was an able effort, but nevertheless, one longed for a little less history and a little more Lincoln.

All the great and wise men of the nation were gathered together, and there was a man in the gallery busily employed in taking photographs. Hereafter the wise men of the country will bear witness that the Honorable George Bancroft is a better writer than speaker. And here let me record an historical fact. It is the memory of a delicious little nap indulged in by one of the Supreme Court Judges. Whether it was the peculiar tones of the orator, like a dull minister’s voice of a Sunday afternoon, or the sound of the rain pattering on the roof, or the shadows of so many great men falling aslant the judge’s mental horizon which caused this somnolence I am unable to say; but he did sleep for a brief time, bringing great joy to many hearts, for it proved that those awful judges in black gowns are mortal like the rest of us and that dignity is something that can be laid aside like any other covering.

But I proceeded to the foreign ministers, who nobly came forward, like martyrs, to mingle their sympathy with ours. And it was the heroic part of the ceremonies to see how manfully these aristocrats endured the castigation. What business had lords to accept cards of invitation unless they were willing to be told some unpleasant[15] truths? Did they suppose the great historian would dwell on the life and virtues of Abraham Lincoln and leave out the history of this mighty republic? The Marquis De Montholon, the representative of His Majesty Napoleon III, drew his expressive brow into a frown terrific in the extreme, and pulled his kid gloves in a manner which denoted great nervousness. But this may be owing entirely to the mercurial character of the French nation.

Another foreign minister drew the cape of his overcoat up over his head during certain portions of the oration. But it was not owing to any wish of stopping his ears—merely a preventive to cold-catching, as the doors were open and certain draft of air perambulated the hall, taking liberties with these great men just as if they had been nobodies. Her Majesty the Queen of England’s servant, Sir Frederick Bruce, is one of the handsomest men of the age. I never look at such a man without feeling that nature’s laws have been followed and perfected in such veritable lords of creation. Compare a lion to its mate, the songster of the forest with plain birds who prefer domestic duties to gadding about the woods, whistling all sorts of love-sick tunes, and who disputes where the palm of beauty is found? The most exquisite woman that was ever made is no more to be compared to the handsomest man than the humble pea-fowl to his majesty the peacock. Yet the peacock thinks his mate the most exquisite of all created things, and what woman would be so unwise as to upset his opinions? I return to Sir Frederick Bruce, but would as soon attempt to paint the moonbeams as to describe his personal appearance. He is a thoroughbred, just like Bonner’s “Silver Heels” and “Fearless;” skin as translucent as wine; hands and feet as small as a woman’s. Men are like grapes, they need a little frost to sweeten and perfect them; and a man is never handsome until he has been rounded and polished by the hand of Time. And this is confirmed by the additional[16] instances of Chief Justice Chase and Honorable James Watson Webb, both of them on the threshold of the winter of life, yet never before so perfect in manly beauty.

The two men who occupied the most prominent positions before the oratory were His Excellency the President, and the Chief Justice of the United States. I am not going to record their lives; the pen of the historian will do that. I desire merely to say that they were representative Americans, who rose from the humblest position to the topmost round of the ladder of fame. And may it prove a solemn warning to those mothers who are accustomed to apply the slipper to unruly urchins. I beg them to desist, lest they may be breaking the spirit or souring the disposition of some future President or Chief Justice of the United States.

Among the celebrities in the gallery I noticed the widow of Daniel Webster. But as I have given my opinion about the beauty of women, I shall make no departure from it, unless the ends shall justify the means. The wife of the Lieutenant General, Julia Dent Grant, occupied a front seat in the gallery, just as she had a right to do. She wore a pink hat, a red plaided scarf, and black gloves, and a little upstart woman who sat near me had the impudence to say the general’s lady “looked horrid.” She no doubt would have been put out for the above expression but the gallery was so crowded that no officer could be found at the proper time to discharge his duty.

Just before the time arrived for opening this great historical meeting Washington contained two sets of people besides the saints and sinners, and these were the envious and the envied. The envied were the fortunate holders of tickets to the meeting, and the envious were the great outsiders. But when the third hour of that memorable speaking arrived the tables were turned. Members began to twist around as if they were schoolboys, the victims[17] of pins which in some unaccountable way had been put in the cushions of their chairs, points upward. A celebrated New York politician treated himself to a newspaper; tobacco-boxes circulated freely and all sorts of expressions came over the human countenance which are possible when men get into positions where they are obliged to behave themselves and don’t want to. I will add, everything must come to an end, and so did this great occasion.

As I have nearly filled the allotted space, I must only glance at the great ball at the Marquis De Montholon’s and say it was equal, but not superior, to the same kind of parties given by our accomplished countrywoman, Mrs. Senator Sprague. In both cases no expense is spared in the entertainment of guests, and any amount of greenbacks, duty in the shape of costly silks and laces; but I learn that precious stones are more or less abandoned, since the shoddy and petroleum have learned to shine.

The shadows of Lent are upon us, and this fact crowded the President’s last levee to suffocation. It was exceedingly painful to notice the violation of good taste in some of my countrywomen by their appearance before the Executive and the ladies of the mansion in bonnet and wrappings. Unless ladies can conform to the usages of good society they had better remain at home.

Olivia.

President Johnson Gives Evidence of His Occupancy of the Chair of the Executive.

Washington, March 1, 1866.

It is so well known that it is almost needless for me to repeat that politics in Washington are shaken from center to circumference, and the country seems astounded at the bearing of a little innocent speech which emanated from His Excellency the President, from the balcony of the White House. Didn’t Mr. Johnson take measures to prepare the minds of Congress and the people by his veto and still more significant message? Didn’t he send his “Premier” to the great metropolis to assure the people that “the war would cease in ninety days”? If the people are astonished, who is to blame for it? Have they forgotten the fact that they have a Southern President? Andrew Johnson is a man. Andrew Johnson is human. This is proved by his wise and decorous behavior on inauguration day, by his kindness of heart to the down-trodden, and by his willingness to grant pardons to those who humble themselves so much as to ask it. Isn’t his adopted State shivering out in the cold, and his own flesh and blood by marriage denied admittance to Congress—said flesh and blood holding credentials in his hands the genuineness of which cannot for a moment be doubted? But there is one way by which a great deal of trouble can be saved the country and end the war which is surely coming upon the land. It is not a war of cold steel, but the clash of mental weapons, and it is feared that the party which can rally the most humbug is sure to win, just as they used to do in the good old Democratic days when Andrew Johnson sat in the Senate and had political[19] sagacity to see in what direction power lay. Wasn’t he a “Dimmicrat” then? And isn’t he a Democrat to-day? Having no further use for the cloak called Unionism, he throws it aside. Shall we acknowledge that we have been humbugged—acknowledge that we have been dolts, idiots? No; rather let us uphold the President and the Constitution. Let us all turn Democrats—every man, woman and child in the land—and then there will be nothing to fight for. But lest some unscrupulous politicians may fail to profit by good advice, I hasten to call the attention of postmasters and custom-house officers who have lately been flying the star-spangled banner, and advise them to lower it immediately; also to make haste and don a new political garment, made by the first tailor in the land, else they will come to grief, for already the Democrats, those long-neglected sufferers, are on the wing for Washington, to be present at the distribution of the spoils, and those unfortunate Republicans who were so unwise as to vote for Andy Johnson deserve to be ousted, and the vacant places should be filled by those returned rebels, for shouldn’t there be more rejoicing over the one that is found than the ninety and nine who never go astray?

And would all this trouble have come upon the land if the men had stayed at home managing business and the women had done the legislating? Was a woman ever known to take a frozen viper to her bosom? This great triumph was left for man to accomplish. After the sad experience of masculine politicians, I trust they will be content to remain quietly at home and let wiser and weaker heads take the affairs of the nation into their hands, and our word for it Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens, the cause of this anguish, will have to hide their diminished heads. Sumner and Stevens are both unmarried men; they have been bachelors ever since they were born, and this headstrong course which they have taken, bringing anguish and woe into every city and hamlet in[20] the land, is owing to the want of the softening and refining influence of woman. The President didn’t mention this fact from the balcony of the White House, but he no doubt would have done so if Messrs. Clampit and Aiken (counsel for the conspirators) had called his attention to it.

If some of my readers take exception to the political caste of the beginning of this letter, I will say that nothing else is thought of in Washington, much less talked about, and it is surprising to see the ladies conning newspapers that are devoted exclusively to politics. Never, since the opening guns upon Sumter, has so much feeling been expressed.

The solemnities of Lent are upon us, but, as the heads of the church wisely say that no fast need be indulged in if it endangers the health and life of the penitent—and fasting always does so—the fair Episcopalians of Washington, those of my acquaintance, take the season of Lent to repair their constitutions which have been so sadly used in the whirl of gayety and the frivolity of fashionable life. I am glad the gay season is over. How comfortable to pack away ermine, and banish moire antiques to trunks seldom or never used, there to repose until another season, in company with odors of “night blooming cereus” or some such delicate perfume. But the best use which can be made of dresses which have done duty for one winter is to send them off by express to country cousins. But one must be careful what kind of country cousins one has, for any little generous act of this kind might upset one’s cream for a whole summer. It is a solemn fact that ladies have such sharp eyes that they can detect an old dress made new instantly, and any woman who has the audacity, for the sake of a little well-meant but foolish economy, to humbug her friends of the community in this way deserves the fate which is sure to be meted out to her—that of a little downward slide on the social scale. This applies to the extreme fashionables.

But there is another picture of Washington life. There are some women who come to Washington who bring with their presence the very atmosphere of the State which has the honor of sending their husbands here. They bring the old-fashioned country ways of living and thinking. They refuse to lower the necks of their dresses and are perfectly willing somebody should eclipse them. They even sit with old-fashioned knitting work in the evening, whilst their husbands are writing letters to their constituents, for all members do not keep a private secretary. And I have always noticed that men who wear stockings of their wives’ knitting are the ones who stand firmest when the shock of battle comes.

Spring is upon us. The winter has departed so gently that we almost forgot that he has been our guest for the last three months. And young Spring, with his balmy breezes, is here, for he brings none of his boisterous, blowy gambols with which he regales our kinfolk in more northern latitudes. The season has come suggestive of new-laid eggs and frisky calves gamboling in the pastures, all unmindful of the cruel knife. Oh, for a quiet week in the neighborhood of the Quaker City.

“Man made the town, but God made the country.”

Olivia.

The Pitiable Condition of the Colored Race Deplored.

Washington, March 9, 1866.

National affairs are becoming a little more settled in Washington; at least it is hoped that the iron cloud has a silver lining. Mr. Johnson has assured a well-known politician that he shall make his fight entirely within the lines of the Union party; also that he has no office to bestow on “Copperheads.” This is the last manifesto that has been issued from the White House to my personal knowledge. It is true that politicians declare that they will not believe any more of his assurances, because he is sure to contradict himself next day. But isn’t it a historical fact that all great rulers have always been fond of changes? Didn’t good Queen Bess have a new dress for every day in the year? One day Mr. Johnson assumes a political garb that brings great joy to the rebels, alias “Copperheads.” The next day he dons a suit particularly soothing to the ruffled feelings of the Unionists. To-day he chooses to lay aside the Presidential garb, which, by the way, is as heavy and irksome as a coat of mail, and assumes the garb of a humble citizen, and indulges in a few personal insinuations; and shouldn’t we be thankful that the citizen isn’t lost sight of in the mighty ruler? Isn’t this a proof of the soundness of American institutions? From the North, East, and West, from Tennessee, come scathing denunciations from the men who placed him in power, aided and assisted by one Booth; but he bears it with the dignity becoming his high position.

I have not heard of any dismissals from office on account[23] of differing with him in opinion, but some have been dismissed for expressing them.

Among the number I notice Mrs. Jane Swisshelm, a woman not entirely unknown to fame. She has held an office in the War Department ever since the Indian atrocities in her late home in Minnesota; but her out-spoken sentiments in the paper which she is editing here sealed her fate, and the Secretary of War caused a letter-envelope to be laid upon her desk as potent in its designs as any other of the many warlike and immortal plans which have issued from time to time from his fertile brain, to his credit and honor, and the world’s benefit. And how fortunate for the country that we have a Tycoon who has the undaunted courage to resist the blighting influence of the so-called gentler sex, and is not above reaching forth his hand, thereby making woman feel that he is not to be trifled with. Mrs. Swisshelm’s paper, The Reconstructionist, still survives, upheld by its unflinching editress, and if it fails to throw light upon reconstruction, it is because the President is blind and will not see, for her dismissal from office proves that she has not hid her light under a bushel. But it is rumored in political circles that she has been relieved from office in order to go into the Cabinet, as there are Cabinet changes hinted at, more or less, every day.

The beautiful spring weather in Washington is totally marred by the clouds of dust that sweep the length and breadth of our grand avenues. I can compare it to nothing but those moving pillars of sand which bury travelers in the bosom of the great Sahara. ’Tis true one can escape with life, but new bonnets and dresses are nearly if not quite ruined, and the sacrifice is about the same thing; for in the latter case we realize the loss, whilst in the former our friends are the only sufferers.

But the clouds of dust do not prevent our sooty neighbors from spading the gardens, and just now they are engaged in turning up the soil with their blades in that[24] gentle, easy manner which none but a negro knows how to practice. Washington is a Southern city in every sense of the word. It may have been partially redeemed by Yankee thrift during the war, but it is now fast sinking back to its original condition as it was in the days of the “old regime.” Slavery is dead, it is true, but the black man is not a citizen. He is the humblest laborer in the vineyard. But hard as their lot appears, it is far preferable to hopeless slavery; and though thousands of lives of the present generation may be sacrificed upon the altar of freedom, a new future awaits them; and if their Moses has changed his mind, or concluded that he has other work to do, they must bide their time, and raise up a leader of their own race and color, for the Lord has ordained that every people shall work out their own salvation. This is not a political view of the subject, only a feeble woman’s, who can do nothing for the freedman but utter shriek after shriek for him, which has proved just as efficient as anything that has been done in various quarters. Congress has done all it could do; the President has promised to be their “Moses,” and the negro persists in suffering. Who is to blame for it? Do they not bring their sufferings upon their own heads? What business have they to be born? Isn’t it a crime of the darkest dye? I leave this painful subject for wiser heads to explain, but should anything new transpire in regard to it, I shall make haste to inform my readers at the earliest moment.

Since the grand speech from the White House one is astonished at the sudden development of a spirit which was supposed to have collapsed with the rebellion. Great flaunting pictures of General Lee appear at conspicuous places to attract the attention of passers-by. He has taken Washington at last. One prominent bookstore balances his picture by that of General Grant; but a certain other bookstore betrays its ideas very ridiculously by a set of pictures—General Washington being in the[25] center, Jeff Davis on one side and Jesus Christ on the other! Had the shopkeeper displayed the picture of our lamented Lincoln side by side with the assassin Booth my astonishment would have been no greater. Does the community think treason a crime when such things are allowed in our midst? We hear of no more balls, levees or receptions.

It seems as if the early days of the revolution were upon us again, as if we must prepare ourselves for events which possibly might become calamities in the end. New gypsy bonnets are displayed by milliners, but we have not seen a face peeping out from one, either handsome or ugly. And isn’t this a symptom of the earnestness of the times, just as straws show which way the wind blows? I did not mean to write a political letter; but there are times when we are caught in a storm, our eyes blinded with lightning, our ears filled with thunder; rain pouring, and no umbrella; mud deep, and no overshoes. When the storm subsides may we greet our readers under pleasanter auspices.

Olivia.

Seeking Pardon for Those Imprisoned on That Island.

Washington, February 16, 1867.

The reticence of General Grant covers the future with a haze of obscurity. Different Cabinet combinations appear before the public vision, like so many dissolving views of a midsummer night’s dream. The President-elect appears at a dinner party and escorts one of the gentlemen home, and the latter fortunate individual is decided to be an embryo Cabinet minister, and the lobby cries, “Hail to thee, thane of Cawdor!”

It is very quiet in Washington, but it is the sultry calm which precedes the storm. All are waiting for the secret which is locked in General Grant’s mind as securely as the genie was fastened in the copper box under the seal of the great Solomon. In the meantime President Johnson is busy providing for his friends, as well as other unfortunates, who are not clamoring at the door of the Executive chamber in vain. Day after day, for months, a few fearfully bereaved women have haunted the White House. Among the number might have been found the wife of Sanford Conover, alias Charles A. Dunham, who perjured himself on the trial of John Surratt, and since his sentence has been serving out his term in State’s prison. Day after day this pale-faced, indefatigable woman has been haunting Mr. Johnson; haunting every man whom she supposed could have any influence in her behalf. At last her unwearying efforts have been crowned with success. Judge Advocate Holt and Honorable A. C. Riddle (one of the counsel on the trial) have said that Conover “without solicitation gave valuable information to the Government, which was used to assist the prosecution, and that he is entitled to the[27] clemency of the Executive on the principle that requires from the Government recognition of such service, and that he has already served two years of his term.”

Another smitten woman’s feet have pressed the costly Wiltons of the Executive Mansion as sorrowfully as Hagar’s did the parched sward of the wilderness. It is the wife of Dr. Mudd, the man who was tried with the other conspirators, and is now serving out his life term at the desolate “Dry Tortugas.” During the last dreadful yellow fever epidemic, our officers on the island testify to the almost superhuman efforts of Dr. Mudd in behalf of the prisoners and soldiers. He seemed to have a charmed life among the dead and dying. There was no duty so loathsome that he shrank from it, and when he could do no more for the sufferers in life he helped to cover their remains with the salted sands. Armed with this testimony of the officers, for months Mrs. Mudd has attended Andrew Johnson like a shadow.

One day last summer a personal friend of the President’s was admitted to the Executive presence. As he took the lady’s hand, he smilingly remarked: “I am sorry that I kept you waiting.”

She replied, “There is another lady who has been waiting longer than I have.”

“Do you know her?” asked the President.

“I never saw her before,” said the lady.

The President called a messenger, saying, “See who is in the ante-room waiting.”

A smile crept over the messenger’s face as he answered, “It’s only Mrs. Mudd.”

“Only Mrs. Mudd,” echoed the President, while a spasm of pain chased over his countenance. “That woman here again, after all I have said?” At the same time the President put both hands to his face.

“Why do you allow yourself to be so annoyed?” said the friend, using the license which belongs to a woman’s friendship.

“The President of the United States ought not be annoyed[28] at anything; besides, I have no right to put any one out of this house who comes to see me on business and behaves with propriety. Don’t let us talk about that; let us think of something else.”

Of all forsaken places on this planet, there is none that will compare in terror to the Dry Tortugas. By the side of it St. Helena is a kind of terrestrial paradise. Neither friendly rock, shrub, tree nor blade of grass is to be seen on its surface. It is a small, burning Sahara, planted in the bosom of the desolate sea, without a single oasis to relieve its savage face. The garrison and prisoners have to depend on cisterns for their supply of water, and out of the thirty-seven carpenters who, in the beginning of the rebellion, went there with the corps of engineers to look after repairs, only four returned alive, and two of these have been confirmed invalids ever since. When one of the carpenters was questioned to explain the great mortality, he said it was owing, at this particular time, to the miserable quarters prepared for the workmen, and to the bad water that was dealt out to them, of which, bad as it was, they could not get enough to supply their pressing wants. The island swarms with insects that bite and sting; and if the soldiers on duty there were not frequently relieved and sent to the mainland, mutiny and its attendant horrors would be sure to follow. When a criminal deserves to expiate ten thousand deaths in one, it is only necessary to send him to the Dry Tortugas.

For several months people have been at work here upon certain nominations which have been sent to the Senate. Mrs. Anna S. Stephens has not been only at work on the life of Andrew Johnson, which she has foretold will end with the one immortal triumph (his escape from his impeachment foes), but she also succeeded in getting her son nominated as consul to Manchester, England. While the venerable mother has labored at the White House, the would-be consul’s wife, in charming silks and costly gems, has sought introductions to leading men who might have some influence with the stony Senate,[29] if they only chose to exercise it. It has become well known in Washington that whenever a man feels ambition swelling in his bosom the best remedy is to send some interesting feminine diplomat to court, and if she does not succeed he will then know it was because the case was hopeless from the beginning. In the good old days of Queen Bess, diplomacy was almost altogether in the hands of the woman; then that was certainly one of the most remarkable eras in the world’s history.

James Parton, the distinguished magazine writer, has been here for several days. He has been seen on the floor of the House, and also in close consultation with many leading members of Congress, as well as doorkeepers, messengers, pages, and all others who are supposed to be wise and serious when talked to in regard to a certain very delicate subject. It is said that Mr. Parton is preparing an article upon the Washington lobby. It is said he is going to hold up the monster in the broad light of day—this creeping, crawling thing, which, in more respects than one, bears a strong resemblance to Victor Hugo’s devil fish; for while it is strong enough to strangle the most powerful man, if once fairly drawn under the surface in its awful embrace, yet if you attempt to pluck it to pieces, piecemeal, you are rewarded with only so much loathsome quivering jelly.

This nation will never realize the debt of gratitude it owes the men who are standing as sentinels at the doors of the Treasury. The Committee on Claims are besieged by an army more terrible in its invincibility than ever stormed the earthworks of fort or doomed city. It is true, the arms used by the enemy are of a kind as old as creation, whilst the flash of an eye answers to the old flintlock or modern percussion cap. As yet these noble men have defended every inch of ground, and many of these fair Southern braves have withdrawn their claims for the present, waiting for another set of sentinels who will replace those on duty now. But more of this anon.

Olivia.

Iowans Assemble at the Residence of Senator Harlan.

Washington, February 25, 1867.

Looking at society in Washington from a certain point of view, is like gazing upon the shifting scenes of a brilliant panorama. But one of the most delightful and home-like pictures consists of the different persons temporarily sojourning here, and who have always retained the right of citizenship in their respective States, joining together under the name of an “association” for the interchange of friendly sentiments as well as for the cultivation of fraternal love. It is the business of the president of these meetings to keep a list of the names and residence of all who belong to the association, and strangers coming to Washington can by this means find without trouble their acquaintances and friends. These Western associations are particularly flourishing this winter. One week we are told that the Indiana Association has had a pleasant gathering, and the Honorable Schuyler Colfax and John Defrees, the Public Printer, the sun and moon of the little planetary system, have risen and set together, and the united social element clapped its hands with joy.

Again we read that Iowa, God bless her, with her solid Republican delegation, and her war record as unblemished as a maiden’s first blush, has gathered her citizens together in Union League Hall, as a hen gathered her chickens under her wing. It is at these social meetings that the old home-fires are kindled anew in the hearts of the Iowa wanderers; and when the most profitless carpet-bagger arrives he is treated nearly as well as the prodigal son. Sometimes it happens that the more prominent[31] members “entertain” the association, or in other words, “Iowa” is the invited guest. Only last night Iowa, as represented by the Senate and House of Representatives, the Departments, as well as the strangers stopping here through the inaugural ceremonies, were invited to the elegant mansion of Senator Harlan, where all were welcomed alike by the Senator and his accomplished wife. Here in the spacious parlors met the different members of the outgoing with those of the incoming delegation of that State; and here let it be recorded that neither Congressmen whose term of office expires on the 4th of March, could get himself decapitated by his constituents, but was obliged at the last moment to commit political hari-kari.

Standing a little apart from each other were the two bright particular stars of the evening—Mrs. Harlan, the agreeable hostess, and Mrs. Grimes, the wife of the able Senator of historic fame, two representative women on the world’s stage to-day, and both alike respected for their intrinsic worth, aside from the senatorial laurels which they share. One could hardly realize, when contemplating Mrs. Harlan, a brilliant, sparkling brunette, whose feet have just touched the autumn threshold of age, in her faultless evening costume of garnet silk, point lace and pearls—“Wandering,” say you? Yes, yes; one could hardly realize that this was the same Mrs. Harlan who had remained all night in her ambulance on the bloody field of Shiloh, with the shrieks of the wounded and dying sounding in her ears; and yet, out of just such material are many more American women made.

Self-poised and dignified as a marble statue stood Mrs. Grimes, noticeable only for the simplicity of her dress. Yet it was easy to perceive that it was the hand of an artist that had swept back the golden brown hair from the perfect forehead and dainty ears. Quiet in her deportment, she seemed a modest violet in a gay parterre of flowers. A woman of intellectual attainments, she has[32] few equals and no superiors here. This present winter she has mingled much more in general society than usual, and her graceful presence helps to scatter “the late unpleasantness” as the sun drives away the malarial mists of the night.

Among the most prominent Iowans present might have been seen the Hon. William B. Allison, member of Congress from Dubuque, whom Lucien Gilbert Calhoun, of the New York Tribune “dubbed” the handsomest man in Congress. Who would dare to be so audacious as to oppose the light current of small talk that ebbs and flows with an occasional tidal wave through the columns of that solemn newspaper? If the Tribune says he is handsome, an Adonis he shall be; but as space will not allow of a full description, it is only necessary to say that he has large brown eyes, that usually look out in their pleased surprise like Maud Muller’s; but the other day they opened wide with astonishment when they read in a popular newspaper that the same William B. had been accused of receiving more than $100,000 for favoring a certain railroad project. But the hoax was soon unearthed, and Mr. Allison found his reputation once more as clean as new kid gloves.

And now we come to a man in whom the nation may have a pride, Geo. G. M. Dodge, of war memory, one of General Sherman’s efficient aids in his march across the Southern country to the sea; serving honorably in Congress to the satisfaction of his constituents. He has resigned the position that he may devote himself wholly to his profession, as chief engineer of the Pacific Railroad. Young, handsome, daring and aggressive, he is Young America personified. He is the man of the day, as Daniel Boone was the man of the era in which he lived; and his whole soul was embodied in words when he said, “I can’t breathe in Washington.”

We touch the honest, ungloved hand of the host of the evening, Senator Harlan, one of the superb pillars of[33] the Republican party; one who has stood upon principles as firmly as though his feet were planted upon the rock of ages; but once he became Secretary of the Interior, and an angel from Heaven could not go into that sink of pollution and come out with clean, unstained wings. If Senator Harlan lives in a respectable mansion in Washington it is because the interest of the unpaid mortgage upon it is less than the rent would be if owned by a landlord; and let it be remembered that Senator Harlan is the only man in the Iowa delegation who has a whole roof to shelter his head; that his house is the only place where citizens of Iowa can gather together and feel at home. It was the noble idea of hospitality to the State that made the Senator pitch his tent outside the horrors of a Washington boarding-house or a crowded hotel, and not to “shine,” as the envious and malicious would have it. A thrust at Senator Harlan is a stab at every man, woman and child who knows him best, and if it was for the good of this nation that the New York Tribune should be broiled like St. Lawrence on a gridiron, it would only be necessary to make it a Secretary of the Interior, with the Indian Bureau in full blast, as it is to-day, and in less than a single administration there would be nothing left of it but a crumpled hat, an old white coat, and a mass of blackened bones. As honest Western people, let us take care of our honest Western statesmen. Let us have a care for the reputation of the men whom we have trusted in war and in peace, and who have never yet proved recreant to the trust.

Dear Republican: Let us dedicate this letter to our sister State, Iowa, most honest, virtuous, best beloved niece of Uncle Sam. A greeting to the Hawkeyes. May their shadows never grow less, and may her thousands of domestic fires that now dot every hill, slope and valley be never extinguished until the sun and the stars shall pole together and creation be swallowed up in everlasting night.

Olivia.

Characteristics of These Congressional Giants In Debate.

Washington, March 27, 1867.

Scarcely has the day dawned upon the Fortieth Congress before it is our unpleasant task to chronicle its decline. As we say about the month that gave it birth, “it came in like a lion and goes out like a lamb.” At the beginning of the session mutterings of impeachment growled and thundered in the political horizon, but for some unaccountable but wise reason it has all subsided, and the passing away is peculiarly quiet and lamb-like. It almost reminds one of a young maiden dying because of the loss of a recreant lover. The Judiciary Committee are expected to sit all summer on the impeachment eggs; but no woman is so unwise as to count the chickens before they are hatched. It is said that Congress has tied the hands of the President so that he is perfectly incapable of doing any more mischief, and the members go home, and leave Washington desolate. Washington is a live city. It has two states of existence, sleeping and waking. When Congress is in session it is wide awake; when Congress adjourns it goes to sleep, and then woe to the unfortunate letter-writer, for her occupation is gone—everything is gone—the great men, the fashionable women; the great dining-room in the principal hotels are all closed, small eating houses disappear; even stores of respectable size draw in their principal show windows, which proves to the world that they were only “branches” thrown out from the original bodies, which can be found either in Philadelphia or New York, and that the branches never were expected to take root in Washington. Only[35] the clerks in office, the real honey bees in the great national hive, work, and work incessantly, and keep Washington from degenerating into an enchanted city, such as we read about in the Arabian tales.

At the moment of writing Congress is expected immediately to adjourn. The members are in their seats, with the exception of the Honorable, Ben Butler, who at this instant has the floor. He is talking about “confiscated property,” and an observer can see that he has taken the cubic measure of the subject. He is interrupted every few moments, but his equilibrium is not in the least disturbed. As his photographs are scattered broadcast over the land, a pen-and-ink portrait is unnecessary. But we will say that he is a disturbing element wherever he “turns up,” or wherever he goes. It seems to be his fate to be all the time cruising about the “waters of hate.” No man in this broad land is so fearfully hated as Benjamin F. Butler. We do not allude to the South, for that is a unit; but to other surroundings and associations. Some men are born to absorb the love of the whole human race, like the ill-fated Andre; others have the mystic power of touching the baser passions, and Honorable Benjamin F. Butler is master of this last terrible art. But it may be possible that he bears the same relation to the human family that a chestnut burr does to the vegetable world, and if we could only open the burr we might forget our bloody fingers and find ample reward for our pains.

These last days of a closing session have been marked by a war of words waged between the Honorable John A. Bingham and General Butler. Now these little hand-to-hand fights are the very spice of politics when they happen between the opposite ranks. But when Republican measures lance with Republican, when the war is of a fratricidal character, and brother gluts his hand in his brother’s blood, then it becomes the nation to take these unruly members tenderly by the hand and to mourn after the most approved fashion. It cannot be said that Honorable[36] James A. Bingham has the manners of a Chesterfield, but we shall widely differ from letter-writers who call him “Mephistopheles.” There is nothing satanic about him. He is only a very able man, terribly in earnest. When he puts his hand to the wheel he never looks back. Whatever he undertakes must be carried out to the bitter end. If he has seemed conservative, it was only that he might not make haste too fast. He has been the useful brakeman in Congress this winter; never in the way when the locomotive was all right and the track was clear. Those wicked side-thrusts from General Butler in regard to Mrs. Surratt have wounded him, and he chafes like a caged tiger; but he can comfort himself with the idea that there is one the less of the so-called gentler sex to perpetrate mischief, and that a few more might be dealt with in the same summary, gentle manner, if the wants of the community or the ends of justice seemed to demand it.

John Morrissey is in his seat, and, to all appearances, he is on the royal road to one kind of success. Everybody feels kindly towards him because he is so unpretending, and he has the magic touch which makes friends. Quiet, gentlemanly, and unassuming, his voice is never heard except when it is called for or when it is proper for his reputation that he should speak. If he would only slough off the old chrysalis life—yea, cut himself adrift from those gambling houses in New York, he might prove to the world that there is scarcely any error of a man’s life can not be retrieved. We trust that John Morrissey will remember that Congress is a fiery furnace; that it separates the dross from the pure metal; and that, in this wonderful alembic, men’s minds and manners are tested with all the nicety of chemical analysis. Also, that the cream comes to the top and the skim milk goes to the bottom and will continue to do so unless a majority of the members can prevail on old Mother Nature to add a new amendment to her “constitution.”

Olivia.

The Modes and Methods of a Typical Society Function.

Washington, January 15, 1868.

A gradual change is coming over the face of events in Washington. The old monarchy’s dying. Andrew Johnson is passing away. If it were summer, grass would be growing between the stones of the pavement that leads to the stately porch of the Executive Mansion, but the motion of the political and social wheel of life is not in the least retarded. In many respects it would seem as if time were taking us backward in its flight and that we were living over again the last luxurious days of Louis XV. If Madame Pompadour is not here in the flesh, she has bequeathed to this brilliant Republican court her unique taste in the shape of paint-pots, rouge, patches, pointed heels, and frilled petticoats; the dress made with an immense train at the back, but so short in front that it discloses a wealth of airy, fantastic, white muslin; the square-necked waist, so becoming to a queenly neck; the open sleeve so bewitching for a lovely arm. This is the “style” which the fair belles of the capital have adopted. Our letters are meant to embody both political and social themes; but, if the truth must be told, the business of the people of the United States is suffering for want of being transacted. Our great men are too busy with the tangled skein of the next administration. Although half the present session has slipped away, scarcely anything has been accomplished. The real hard work is represented by the lobby, which is as ceaselessly and noiselessly at work as the coral builders in the depths of the sea.

General Butler is trying to enlighten the nation upon the knotty subject of finance. He seems to have taken the dilemma by the horns. It is not decided which will get the best of it, but the people can rest assured that General[38] Butler will make a good fight. Like Andrew Johnson, he has only to point to his past record. It will be remembered that the gallant General paid his respects to the step-father of his country on New Year’s day. An eye witness of this historical event pronounced the “scene” extremely “touching” and one long to be remembered by the fortunate beholders. A sensational writer is engaged upon a new drama founded upon this theme. It will soon be brought out upon the boards at the National Theater under the high-sounding title of “Burying the Hatchet.” The writer of the drama is at a loss whether to call this production comedy or tragedy. It would be extremely comic, only the closing scene ends with Andy’s plumping the hatchet into the grave from sheer exhaustion, and the moment afterward he glides away into obscurity like a graceful Ophidian, or Hamlet’s ghost. The wily warrior is left master of the situation; not at all shut up like a fly in a bottle, but still able to be of use not only to his constituents but to the masses of his admiring countrymen.

But why talk politics when the social strata is so much more interesting? It is the social star which is in the ascendent to-day. The new Cabinet is discussed in shy little nods and whispers, between sips of champagne and creamy ices, in magnificent drawing rooms at the fashionable West End. Aye, why not give our dear Chicago friends a description of the most brilliant party of the season, which took place at the handsome residence of a merchant prince and member of Congress, the Honorable D. McCarthy, of Syracuse, N. Y. As the guests were brought together by card invitations, it follows that only the cream of Washington society was represented. To be sure there was a crowd; but then, it is not so very uncomfortable to be pressed to death by the awful enginery of a foreign minister, a major-general and a Vice-President elect, or to find yourself buried alive by drifts of snowy muslin or costly silk or satin, and your own little feet inextricably lost by being entangled in somebody’s[39] train, and yourself sustained in the trying position by being held true to the perpendicular by the close proximity of your next neighbor. This can be borne by the most sensitive, owing to the delicate nature of the martyrdom.

Between the hours of 9 and 10, and many hours afterwards, carriage after carriage rolled up to the stately mansion, lately occupied by our present minister to England. Two savage policemen guarded the gate, and the coming guests slipped through their fingers as easily as if they had been attaches of the whisky ring. Once out of the carriage you found yourself standing upon the dainty new matting, from which your feet never departed until they pressed the Persian carpet of the inner hall. All wrapped and hooded and veiled, you ascended the broad staircase to find at the first landing an American citizen, of bronze complexion and crispy hair, who led you to the ladies’ dressing-room. Handmaidens of the African type instantly seized you and divested you of your outward shell or covering. A dainty French lady’s maid stood ready to give the last finish to your toilet or to coax into place any stubborn, mulish curl, and to repair, if it was necessary, any little damage or flaw to your otherwise faultless complexion. When you were “all right,” you found your attendant cavalier awaiting you at the door to conduct you, as well as himself, to the presence of the sun and moon of the evening, around whom all this growing planetary system revolved. A cryer at the door calls out the name of the cavalier and lady, in a stentorian voice. You shudder. This is the first plunge into fashionable life; but you come to the surface and find that you are face to face with the duke and duchess, in the republican sense of the word. Your hand is first taken by Mr. McCarthy, who is a tall and elegant person, whom you also know to be one of the “solid men” in Congress, as he certainly is without. You next touch the finger tips of “my lady,” a noble matron in purple velvet, old point lace, and flashing diamonds. At her right hand stand her two pretty daughters, with real roses in their cheeks, and[40] real complexions, delicate enough to have been stolen from milky pearls. No jewels but their bright eyes. No color in their faultless white muslin dress, except little flecks of green that underlie the rich Valenciennes. You leave them, and smuggle yourself in the enclosures of a deep, old-fashioned window. The curtain half hides you while you gaze upon a shifting, glittering panorama, more gorgeous than a midsummer night’s dream. The air is laden with the perfume of rare exotics and the fragrance of the countless handkerchiefs of cob-web lace. Just beyond you at the right stands the servant of Her Majesty, Victoria of England. There is nothing to denote his rank or position in his plain citizen’s dress. A modest order, worn on his left breast, tells you that he is the successor of Sir Frederick Bruce; but in personal appearance Sir Edward Thornton bears no resemblance to his illustrious predecessor. He seems to be enjoying an animated conversation with a lady of rank belonging to his own legation. Monsieur the French Minister, exquisite, dandified, polished as a steel rapier, is talking to the host of the evening. Count Raasloff, the Danish minister, is exchanging compliments with Major-General Hunter. Though all the grand entertainments in Washington are graced by many of the diplomats resident here, they seem to get through the evening as if it were a part of their official duty. They cling together like any other colony surrounded by “outside barbarians.” The marble face of a petite French countess never relaxed a line from its icy frigidity until she found herself stranded in the dressing room up stairs, safely in the hands of the foreign waiting-maid. Then such chattering—the artificial singing birds in the supper room were entirely eclipsed. But let us leave at once these cold, haughty dames, who have nothing to boast of but the so-called blue blood in their veins. The world would never know they existed, unless some pen-artist sketched their portraits. We have had no dazzling foreign star in society here since the departure of Lady Napier. Oh! spirit of a fairy godmother,[41] guide our pen while we touch our own American belles, the fairest sisterhood under the sun. “Who is the belle of the ball room to-night?” every one asks. You must not be told her name, reader, but you shall know everything else. Just imagine Madame Pompadour in the palmiest days of her regal beauty, stepping out of the old worm-eaten frame, imbued with life and clad in one of those white brocaded silks upon which has been flung the most exquisite flowers by the hand of the weaver. Hair puffed and frizzled and curled until the lady herself could not tell where the real leaves off and the false begins. The front breadth of dress is not more than half a yard in depth, but the long-pointed train at the back could not be measured by the eye; a yard-stick must be brought into requisition. There is a dainty little patch on her left cheek, and another still less charming on her temple. A necklace of rare old-fashioned mosaic is clasped around her throat, and a member of Congress from Iowa, who is said to be a judge, pronounces her to be the most beautiful woman in Washington. Oh! that newspaper letters did not have to come to an end. Room for one of Chicago’s fair brides, the only beloved daughter of Senator Harlan, Mr. Robert Lincoln’s accomplished wife. She looked every inch the lily in this sisterhood of flowers. She wore heavy, corded white silk, with any quantity of illusion and pearls.

So far hath the story been told without a word about the feast. The land, the sky and the ocean were rifled, and made to pay tribute to the occasion. Artificial singing birds twittered in the flowers that adorned the tables, while a rainbow of light encircled the same. This beautiful effect was accomplished by the gas-fitter’s art, and this exquisite device came very near bringing Chicago to grief, for the Honorable N. B. Judd found himself at the end of the magic bow, but instead of finding the bag of gold he just escaped a good “scorching.”

Again we touched the hand of the lady hostess, and then all was over.

Olivia.

Messrs. Nye and Doolittle Cross Blades in Ideas and Arguments.

Washington, January 26, 1868.

Again the Senate chamber recalls the early days of the rebellion, or rather the last stormy winter before its culmination. The galleries are densely crowded; the voice of eloquence is heard ringing in clarion notes through the hall; but in place of the handsome, sneering face of Breckinridge as presiding officer, rare old Ben Wade rises, like a sun of promise, to light up the troubled waters, and to help warn the ship of the Republic off the rocky shore. Scarcely a drop in the river of time since haughty Wigfall arose, and, with right hand clenched defiantly in the face of the Republican side, his flaming eye resting upon Charles Sumner, declared that he owed no allegiance to the Government of the United States. It was the forked flames licking the marble column, for Senator Sumner sat calm and immovable as the figure of Fate. Gone, too, is Davis, the man of destiny; and Toombs, the swaggering braggart, with silver-voiced Benjamin, the only human being endowed with the same melodious, flute-like tongue that bewitched our dear first mother. And yet there is treason enough left to act as leaven in case Senator Doolittle and the President succeed in introducing it into the loaf of reconstruction.

To-day two of the most warlike as well as two of the most powerful men in the Senate have been engaged in real battle; but instead of muscle against muscle, the air has been filled with javelins of arguments and ideas. Let the pen be content with describing the two combatants—Senator[43] Doolittle, of Wisconsin, and Senator Nye, of Nevada.

The battle, like Massachusetts, speaks for itself. Senator Doolittle, the President’s spirit of darkness, bears the same relation to the human race that a bull-dog does to the canine species. His arguments are tough and sharp as a row of glittering teeth, and would do the same horrible execution if the President and small party of barking Democracy at his heels were strong enough to tell him “to go in and win.” Rather above the medium height, built for strength, like a Dutch clipper, with close cropped hair and broad, projecting lower jaw, it must have been an accident that made him let go of the Republican platform, or he must have been choked off by a power entirely beyond his control. But now that he is fast hold of a different faith; no resolution of a Wisconsin senate, no bitter protest of an indignant, injured constituency, can shake him one hair’s breadth. And to this powerful makeup a pair of glistening steel-gray eyes, a presence easier felt than described, and you have plenty of material out of which to construct a triple-headed Cerebus strong enough to guard the gates of—even the Executive mansion.

His antagonist, Senator Nye, of Nevada, has the finest head in the American Senate. Mother Nature must have expended her strength and means in the handsome head and broad shoulders. It must have been originally meant that he should stand six feet and an inch or two in his stocking feet, yet by some of those accidents which never can be guarded against, he is scarcely of the average height. His face presents one of those rare spectacles, those strange combinations, in which intellect and beauty are striving for supremacy.

Eyes of that indescribable hazel that light up with passion or emotion, like an evening dress under the gaslight. Nose chiseled with the precision of the sculptor’s skillful steel, and a mouth in which dwells character, passion, and[44] all the graces, neatly fringed by a decent beard, as every respectable man’s should be. Hands small and bloodless, the usual accompaniment of the powerful brain of an active thinker. Last, but not least, there is enough electricity about him to send a first-class message around the world, with plenty left for all home purposes.

The Senate chamber is a painful place for the eye to rest this winter. Its furniture, carpets, and many other etceteras are suggestive of molten heat. There is a flaming red carpet on the floor, and every chair and sofa blushes like a carnation rose. Red and yellow stare the unfortunate Senator in the face whichever way he turns. Even what little sunlight manages to sneak into this celebrated chamber steals in clothed in those two prismatic, nightmare colors. When the galleries are packed, as they were to-day, there is scarcely more air than in an exhausted receiver, and it is astonishing that so many delicate women can remain so many hours subjected to such an atmosphere. And now that the galleries are sprinkled with dark fruit, thick as a briery hedge in blackberry time; this, taken into consideration, with many other wise reasons, may help to account for the large Democratic gain in the late election returns.

Never within memory, not even during the extravagance of the late war, have so many costly costumes adorned the persons of our American women as the present winter in Washington. And the Capitol, with its oriental luxuriance, seems a fitting place for the grand display. A handsome blonde, enveloped in royal purple velvet, without being relieved by so much as a shadow of any other color or material, brings the words of the Psalmist to all thoughtful minds: “They toil not, neither do they spin (or write), yet Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.”

Olivia.

His Affection for His Mother—Other Characteristics.

Washington, March 2, 1868.

The season of Lent has folded its soft, brooding wings over the weary devotees of fashion in Washington. Luxuriant wrappers, weak tea, and soft-boiled eggs have succeeded the Eugenie trains, chicken salad, and all those delicious fluids that are supposed to brace the human form divine. The penitential season of Lent is just as fashionable, in its way, as the brilliant season which preceded it. There is nothing left for the “Jenkinses” but “to fold their tents like the Arabs, and as silently steal away.”

But as hardy native flowers defy the chilly frost, so Speaker Colfax’s hospitable doors swing upon their noiseless hinges once a week, and the famous house known as the “Sickles mansion” becomes a bee-hive, swarming, overflowing with honeyed humanity; and let it be recorded that no man in Washington is socially so popular, so much beloved, as Schuyler Colfax. General Grant, the man who dwells behind a mask, is worshiped by the multitudes, who rush to his mansion as Hindoos to a Buddhist temple; but Schuyler Colfax possesses the magic quality of knowing how to leave the Speaker’s desk, and, gracefully descending to the floor, place himself amongst the masses of the American people, no longer above them, but with them, one of them—a king of hearts in his own right; a knave also, because he steals first and commands afterwards.

It is needless to say that all adjectives descriptive of fashionable life at the capital have long since been worn thread-bare. Why didn’t Jenkins tell the truth and say,[46] instead of “warm cordiality, elegant courtesy,” pump-handle indifference and metallic smile? Why did he not tell the dear, good people at home the truth, and nothing but the truth, and say that madame the duchess practices smiles or grimaces before the glass, and serves the same up to her dear friends at her evening receptions? Why should not a smile fit as well as her corsets or kid gloves? Too much smile without dimples to cover up the defect destroys the harmonious relation of the features. Not only that, but it invites every fashionable woman’s horror. It paves the way to wrinkles, the death-blows of every belle.

“Look at my face,” says Madame B——, of Baltimore, the widow of royalty, the handsomest woman of three-score years and ten in America, addressing one who shall be nameless. “You are not half my age, and yet you have more wrinkles than I; shall I tell you why?” “To be sure, Madame B——.” “I never laugh; I never cry; I make repose my study.” Now, let it be added that this aged belle of a long-since-departed generation on every night encases her taper fingers in metallic thimbles, and has done so for the last forty years; consequently her hand retains much of its original symmetry, and the decay of her charms is as sweet and as faultless as the falling leaves of a rose.

Speaker Colfax’s receptions, in one sense of the word, are unlike all others. No prominent man in Washington receives his thousands of admirers and says to them, after an introduction, “This is my mother!” She stands by his side, with no one to separate them, bearing a strong personal resemblance to him, whilst she is only seventeen years the older. At what a tender age her love commenced for this boy Schuyler—nobody else’s boy, though he were President! She has put on the chameleon silk, and the cap with blue ribbons, to receive the multitudes that flock in masses to do homage to her son. Pride half slumbers in her bosom, but love is vigilant and wide awake. There is no metallic impression on her countenance;[47] a genuine, heartfelt welcome is extended to all who pay their respects to her idol. So the people come and go, and wonder why Speaker Colfax’s receptions are unlike others. Only a very few stars of the first magnitude in the fashionable world shone at the Speaker’s mansion last night. The Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from Iowa was there, with his elegant, lavender-robed wife—a woman who skims over the treacherous waters of society in Washington as gracefully and safely as a swan upon its native element. David Dudley Field, of New York, was there—a tall, stalwart man, after the oak pattern; and the fine faced woman, with gold enough upon her person to suggest a return to specie payment, was said to be a new wife. Mark Twain, the delicate humorist, was present; quite a lion, as he deserves to be. Mark is a bachelor, faultless in taste, whose snowy vest is suggestive of endless quarrels with Washington washerwomen; but the heroism of Mark is settled for all time, for such purity and smoothness were never seen before. His lavender gloves might have been stolen from some Turkish harem, so delicate were they in size; but more likely—anything else were more likely than that. In form and feature he bears some resemblance to the immortal Nasby; but whilst Petroleum is brunette to the core, Twain is a golden, amber-hued, melting blonde.