Project Gutenberg's Anatomy of the Cat, by Jacob Reighard and H. S. Jennings

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Anatomy of the Cat

Author: Jacob Reighard

H. S. Jennings

Illustrator: Louise Burridge Jennings

Release Date: December 1, 2018 [EBook #58394]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ANATOMY OF THE CAT ***

Produced by deaurider, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

For some illustrations, larger versions are available by clicking the link in the illustration caption

(Fig. nnn) (not available in all formats).

ANATOMY OF THE CAT

BY

JACOB REIGHARD

Professor of Zoology in the University of Michigan

AND

H. S. JENNINGS

Instructor in Zoology in the University of Michigan

WITH

ONE HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-THREE ORIGINAL FIGURES

DRAWN BY

LOUISE BURRIDGE JENNINGS

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

1901

Copyright, 1901,

BY

HENRY HOLT & CO.

ROBERT DRUMMOND, PRINTER, NEW YORK.

[iii]

PREFACE.

Although the cat has long been in common use for the

practical study of mammalian anatomy, a clear, correct, not

too voluminous account of its structure, such as should be in

the hands of students in the laboratory, has remained a

desideratum. A number of works have been published on the

cat, some of them of much value, yet there is none which

fulfils exactly the conditions mentioned. The books which

have appeared on this subject are the following:

1. Strauss-Durckheim, H. Anatomie descriptive et comparative

du Chat. 2 vols. Paris, 1845.

2. Mivart, St. George. The Cat: an Introduction to the

Study of Back-boned Animals, especially Mammals. New

York, 1881.

3. Wilder, Burt G., and Gage, Simon H. Anatomical

Technology as applied to the Domestic Cat. New York, 1882.

4. Gorham, F. P., and Tower, R. W. A Laboratory

Guide for the Dissection of the Cat. New York, 1895.

5. Jayne, H. Mammalian Anatomy. Vol. I. Philadelphia,

1898.

The first of these works treats only of the muscles and

bones, and is not available for American students. Its excellent

plates (or Williams’s outline reproductions of the same)

should be in every laboratory.

The second book named is written in such general terms

that its descriptions are not readily applicable to the actual

structures found in the dissection of the cat, and experience

has shown that it is not fitted for a laboratory handbook. It

contains, in addition to a general account of the anatomy of

the cat, also a discussion of its embryology, psychology,

palæontology, and classification.

[iv]

The book by Wilder and Gage professedly uses the cat as

a means of illustrating technical methods and a special system

of nomenclature. While of much value in many ways, it does

not undertake to give a complete account of the anatomy of

the animal.

The fourth work is a brief laboratory guide.

The elaborate treatise by Jayne, now in course of publication,

is a monumental work, which will be invaluable for reference,

but is too voluminous to place in the hands of students.

At present only the volume on the bones has been published.

As appears from the above brief characterization, none of

these books gives a complete description of the anatomy of the

cat in moderate volume and without extraneous matter. This

is what the present work aims to do.

In the year 1891-92, Professor Reighard prepared a partial

account of the anatomy of the cat, which has since been in use,

in typewritten form, in University of Michigan classes. It has

been used also at the Universities of Illinois, Nebraska, and

West Virginia, and in Dartmouth College, and has proven so

useful for college work in Mammalian Anatomy that it was

decided to complete it and prepare it for publication. This

has been done by Dr. Jennings.

The figures, which are throughout original, are direct reproductions

of ink drawings, made under the direction of Dr.

Jennings by Mrs. Jennings.

The book is limited to a description of the normal anatomy

of the cat. The direct linear action of each muscle taken alone

has been given in the description of muscles; other matters

belonging to the realm of physiology, as well as all histological

matter, have been excluded. It was felt that the monumental

work of Jayne on the anatomy of the cat, now in course of

publication, forms the best repository for a description of variations

and abnormalities, so that these have been mentioned in

the present volume only when they are so frequent as to be of

much practical importance.

Except where the contrary is stated, the descriptions are

based throughout on our own dissections and observations and

are in no sense a compilation. For this reason we have not[v]

thought it necessary to collect the scattered references to the

anatomy of the cat that may occur in the literature. A

collection of such references may be found in Wilder and

Gage’s Anatomical Technology. In addition to the works

already referred to, we have of course made use of the standard

works on human and veterinary anatomy. Among these

should be mentioned as especially useful the Anatomie des

Hundes by Ellenberger and Baum. Other publications which

have been of service in the preparation of the work are Windle

and Parson’s paper On the Myology of the Terrestrial Carnivora,

in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London

for 1897 and 1898, T. B. Stowell’s papers on the nervous

system of the cat in the Proceedings of the American Philosophical

Society (1881, 1886, 1888) and in the Journal of

Comparative Neurology (vol. I.), and F. Clasen’s Die Muskeln

und Nerven des proximalen Abschnitts der vorderen Extremität

der Katze, in Nova Acta der Ksl. Leop.-Carol. Deutschen

Akademie der Naturforscher, Bd. 64.

Nomenclature.—The question of nomenclature has been

one of difficulty. What is desired is a uniform set of

anatomical names,—a system that shall be generally used by

anatomists. At present the greatest diversity prevails as to

the names to be applied to the different structures of the body.

The only set of terms which at the present time seems to have

any chance of general acceptance is that proposed by the

German Anatomical Society at their meeting in Basel in 1895,

and generally designated by the abbreviation BNA. This

system has therefore been adopted, in its main features, for use

in the present work. It seems impossible at the present time,

however, to impose any one set of terms absolutely upon

anatomists of all nations, and we have felt it necessary to use

for certain familiar structures, in place of the BNA terms,

names that have come to have a fixed place in English

anatomy, and may almost be considered component parts of

the English language. The German anatomists have expressly

recognized the fact that this would be to a greater or less

degree necessary among anatomists of different nations, and

have characterized their list as for the present tentative, and[vi]

capable of farther development. The only purpose of a name

is that it shall furnish a key to a common understanding;

where the BNA name does not furnish such a key to English

readers, and where there is a term in established English usage

that does serve this purpose and seems unlikely to be supplanted,

we have used the latter. But we have endeavored to

make the number of these exceptions as small as possible, and

in such cases we have usually cited at the same time the term

proposed by the German society, followed by the abbreviation

BNA. When, on the other hand, we have adopted a BNA

term for which there is also a commonly used English equivalent,

the latter has likewise usually been cited in parenthesis.

In deciding whether or not to use in a given case the BNA

term many difficult cases arose. Will the common English

name innominate bone (os innominatum) be replaced by the

BNA term os coxæ or coxal bone? We have held this to be

highly improbable, and have therefore used the term innominate

bone, merely citing os coxæ (BNA) as a synonym. In the

same way we have used centrum as a designation of a part of a

vertebra, in place of corpus (BNA); premaxillary bone or premaxilla

in place of os incisivum (BNA); malar bone in place

of os zygomaticum (BNA); trapezoid as a name of one of the

bones of the carpus, in place of os multangulum minus (BNA),

etc. In other cases where it has seemed probable that the

BNA term would come into common use, though now unfamiliar,

this and the more common English expression are

both used or used alternatively; such has been the case, for

example, with the Gasserian ganglion or semilunar ganglion

(BNA). In naming the cerebral sulci and gyri the system in

use for man is not well fitted for bringing out the plan of those

in the brain of the cat, so that it was necessary to reject the

BNA names for these structures.

As to the use of the Latin terms and their equivalents in

English form, we have made a practice of employing in the

text sometimes one, sometimes the other; this has the advantage

of giving variety, and of impressing the interchangeability

of the Latin and English forms on the mind of the student.

Where a given structure is called by two equally well-known[vii]

names, we have used both, holding that the student should

become familiar with each and recognize their identity of

meaning.

In general we have maintained the principle that the

primary purpose of such a work as the present is not to illustrate

or defend any particular system of nomenclature, but to

aid in obtaining a knowledge of the structures themselves.

With this end in view, we have used such terms as would in

our judgment best subserve this purpose, making the BNA

system, as the one most likely to prevail, our basis. In applying

the system we have had to keep in mind a number of

sometimes conflicting principles. In some cases the judgment

of other anatomists will doubtless differ from our own; but this

we feel to be inevitable. The matter of an absolutely uniform

nomenclature is not ripe for settlement at the present time.

Some further explanation is needed in regard to the topographical

terms, or terms of direction, used in the present

work. We have adopted the BNA terms in this matter also.

The terms superior, inferior, anterior, and posterior have been

avoided, as these terms do not convey the same meaning in

the case of the cat as they do in man, owing to the difference

in the posture of the body. In place of these terms are used

dorsal and ventral, cranial and caudal. As terms of direction

these, of course, must have an absolutely fixed meaning, signifying

always the same direction without necessary reference

to any given structure. For example, cranial means not

merely toward the cranium, but refers to the direction which is

indicated by movement along a line from the middle of the

body, toward the cranium; after the head or cranium is

reached, the term still continues in force for structures even

beyond the cranium. Thus the tip of the nose is considered

to be craniad of the cranium itself. Lateral signifies away

from the middle plane; medial toward it. Inner and outer or

internal and external are used only with reference to the structure

of separate organs, not with reference to the median plane

of the body.

In describing the limbs the convexity of the joint (the elbow

or knee) is considered as dorsal, the concavity being therefore[viii]

ventral. Medial refers to that side of the limb which in the

normal position is toward the middle of the body; lateral to

the outer side. Terms of direction which are derived only from

the structure of the limb itself are in some cases more convenient

than the usual ones. In the fore limbs the terms radial

(referring to the side on which the radius lies) and ulnar

(referring to the side on which the ulna lies) are used; in the

hind limbs the terms tibial and fibular are used in a similar

manner. Distal means toward the free end of a limb or other

projecting structure; proximal, toward the attached end.

For all these terms an adverbial form ending in -ad has

been employed. Experience has shown this to be very useful

in practice, and while not expressly recommended by the BNA,

it is not condemned. Terms ending in -al are therefore

adjectives; those ending in -ad are adverbs.

In compounding these terms of direction, the hyphen has

been omitted in accordance with the usage recommended by

the Standard Dictionary. Thus dorsoventral is written in

place of dorso-ventral, etc. The student will perhaps be

assisted in understanding these compounds if he notes that

the first component always ends in -o, so that the letter o practically

serves the purpose of a hyphen in determining how the

word is to be divided.

In one particular the BNA nomenclature is not entirely

consistent. While recommending or at least permitting the

use of the general terms dorsal and ventral in place of the

human posterior and anterior, and cranial and caudal in place

of superior and inferior, it retains the words anterior, posterior,

superior, and inferior as parts of the names of definite organs.

For example, we have the muscle serratus anterior in place

of serratus ventralis; serratus posterior inferior in place of

serratus dorsalis caudalis. This is very unfortunate, from a

comparative standpoint, but we have felt it necessary to retain

the BNA terms in order that the structures of the cat may

receive the same names as the corresponding structures of

man.

In the matter of orthography we have endeavored to follow

the best English anatomical usage, as exemplified in Gra[ix]y’s

Human Anatomy,—therefore writing peroneus in place of

peronæus, pyriformis in place of piriformis, etc.

The book is designed for use in the laboratory, to accompany

the dissection and study of the structures themselves.

Anatomy cannot be learned from a book alone, and no one

should attempt to use the present work without at the same

time carefully dissecting the cat. On the other hand, anatomy

can scarcely be learned without descriptions and figures of the

structures laid bare in dissection, so that this or some similar

work should be in the hands of any one attempting to gain a

knowledge of anatomy through the dissection of the cat.

The figures have all been drawn from actual dissections,

and have been carefully selected with a view to furnishing the

most direct assistance to the dissector. It is hoped that no

figures are lacking that are required for giving the students the

necessary points of departure for an intelligent dissection of any

part of the body. The fore limb is illustrated somewhat more

fully than the hind limb, because it was thought that the fore

limb would usually be dissected first; the hind limb will be

easily dissected, with the aid of the figures given, after the

experience gained in dissecting the fore limb.

As the book is designed to accompany the dissection of the

specimen in the laboratory, it was deemed best to give succinct

specific directions for the dissection of the different systems of

organs, together with suggestions as to methods of preserving

and handling the material. These are included in an appendix.

[x]

[xi]

CONTENTS.

| |

|

|

|

PAGE |

| The Skeleton of the Cat |

1 |

| |

I. The Vertebral Column |

1 |

| |

Thoracic Vertebræ |

1 |

| |

Lumbar Vertebræ |

7 |

| |

Sacral Vertebræ: Sacrum |

8 |

| |

Caudal Vertebræ |

11 |

| |

Cervical Vertebræ |

11 |

| |

Ligaments of the Vertebral Column |

16 |

| |

II. The Ribs |

18 |

| |

III. The Sternum |

20 |

| |

IV. The Skull |

21 |

| |

Occipital Bone |

22 |

| |

Interparietal |

25 |

| |

Sphenoid |

25 |

| |

Presphenoid |

29 |

| |

Temporal |

30 |

| |

Parietal |

36 |

| |

Frontal |

37 |

| |

Maxillary |

39 |

| |

Premaxillary |

41 |

| |

Nasal |

42 |

| |

Ethmoid |

42 |

| |

Vomer |

44 |

| |

Palatine |

45 |

| |

Lachrymal |

46 |

| |

Malar |

47 |

| |

Mandible |

47 |

| |

Hyoid |

49 |

| |

The Skull as a Whole |

49 |

| |

Cavities of the Skull |

57 |

| |

Joints and Ligaments of the Skull |

61 |

| |

V. The Thoracic Extremities |

62 |

| |

Scapula |

62 |

| |

Clavicle |

64 |

| |

Humerus |

64 |

| |

Radius |

67 |

| |

Ulna |

68 |

| |

Carpus |

69 |

| |

Bones[xii] of the Hand |

71 |

| |

Joints and Ligaments of the Thoracic Limbs |

73 |

| |

VI. The Pelvic Extremities |

76 |

| |

Innominate Bones |

76 |

| |

Femur |

79 |

| |

Patella |

80 |

| |

Tibia |

80 |

| |

Fibula |

82 |

| |

Tarsus |

82 |

| |

Bones of the Foot |

85 |

| |

Joints and Ligaments of the Pelvic Limbs |

86 |

| The Muscles |

93 |

| |

I. Muscles of the Skin |

93 |

| |

II. Muscles of the Head |

96 |

| |

A. Superficial Muscles |

96 |

| |

B. Deep Muscles |

107 |

| |

a. Muscles of Mastication |

107 |

| |

b. Muscles of Hyoid Bone |

112 |

| |

III. Muscles of the Body |

115 |

| |

1. Muscles of the Back |

115 |

| |

A. Muscles of the Shoulder |

115 |

| |

B. Muscles of the Vertebral Column |

123 |

| |

a. Muscles of the Lumbar and Thoracic Region |

126 |

| |

b. Dorsal Muscles of the Cervical Region |

131 |

| |

C. Muscles of the Tail |

136 |

| |

2. Muscles on the Ventral Side of the Vertebral Column |

138 |

| |

A. Lumbar and Thoracic Regions |

138 |

| |

B. Muscles on the Ventral Side of the Neck |

139 |

| |

3. Muscles of the Thorax |

144 |

| |

A. Breast Muscles (Connecting the Arm and Thorax) |

144 |

| |

B. Muscles of the Wall of the Thorax |

148 |

| |

4. Abdominal Muscles |

153 |

| |

IV. Muscles of the Thoracic Limbs |

156 |

| |

1. Muscles of the Shoulder |

156 |

| |

A. Lateral Surface |

156 |

| |

B. Medial Surface |

161 |

| |

2. Muscles of the Brachium or Upper Arm |

164 |

| |

3. Muscles of the Antibrachium or Forearm |

172 |

| |

Fascia of the Forearm |

172 |

| |

A. Muscles on the Ulnar and Dorsal Side of the Forearm |

173 |

| |

B. Muscles on the Radial and Ventral Side of the Forearm |

179 |

| |

4. Muscles of the Hand |

184 |

| |

A. Between the Tendons |

184 |

| |

B. Muscles of the Thumb |

184 |

| |

C. Between the Metacarpals |

185 |

| |

D. Special Muscles of the Second Digit |

185 |

| |

E. Special Muscles of the Fifth Digit |

185 |

| |

V. Muscles of the Pelvic Limbs |

186 |

| |

1. Muscles of the Hip |

186 |

| |

A. On the Lateral Surface of the Hip[xiii] |

186 |

| |

Fascia of the Thigh |

186 |

| |

B. On the Medial Surface of the Hip |

192 |

| |

2. Muscles of the Thigh |

194 |

| |

3. Muscles of the Lower Leg |

203 |

| |

A. On the Ventral Side |

203 |

| |

B. On the Dorsal and Lateral Surfaces |

209 |

| |

4. Muscles of the Foot |

212 |

| |

A. Muscles on the Dorsum of the Foot |

212 |

| |

B. Muscles on the Sole of the Foot |

212 |

| |

C. Muscles of the Tarsus |

215 |

| The Viscera |

217 |

| |

I. The Body Cavity |

217 |

| |

II. Alimentary Canal |

221 |

| |

1. Mouth |

221 |

| |

Glands of the Mouth |

223 |

| |

Teeth |

224 |

| |

Tongue |

226 |

| |

Muscles of the Tongue |

228 |

| |

Soft Palate |

229 |

| |

Muscles of the Soft Palate |

230 |

| |

2. Pharynx |

231 |

| |

Muscles of the Pharynx |

232 |

| |

3. Œsophagus |

234 |

| |

4. Stomach |

234 |

| |

5. Small Intestine |

236 |

| |

6. Large Intestine |

237 |

| |

7. Liver, Pancreas, and Spleen |

239 |

| |

III. Respiratory Organs |

243 |

| |

1. Nasal Cavity |

243 |

| |

2. Larynx |

246 |

| |

Cartilages of the Larynx |

247 |

| |

Muscles of the Larynx |

249 |

| |

3. Trachea |

251 |

| |

4. Lungs |

252 |

| |

Thyroid Gland |

254 |

| |

Thymus Gland |

254 |

| |

IV. Urogenital System |

255 |

| |

1. Excretory Organs |

255 |

| |

Kidneys |

255 |

| |

Ureter |

256 |

| |

Bladder |

256 |

| |

(Suprarenal Bodies) |

257 |

| |

2. Genital Organs |

257 |

| |

A. Male |

257 |

| |

B. Female |

263 |

| |

Muscles of the Urogenital Organs, Rectum, and Anus |

268 |

| |

a. Muscles Common to the Male and Female |

268 |

| |

b. Muscles Peculiar to the Male |

271 |

| |

c. Muscles Peculiar to the Female[xiv] |

272 |

| The Circulatory System |

274 |

| |

I. The Heart |

274 |

| |

II. The Arteries |

280 |

| |

1. Pulmonary Artery |

280 |

| |

2. Aorta |

281 |

| |

A. Thoracic Aorta and its Branches |

281 |

| |

Common Carotid Artery |

283 |

| |

Subclavian Artery |

290 |

| |

B. Abdominal Aorta and its Branches |

301 |

| |

External Iliac Artery and its Branches |

309 |

| |

III. The Veins |

315 |

| |

1. Veins of the Heart |

315 |

| |

2. Vena Cava Superior and its Branches |

316 |

| |

Veins of the Brain and Spinal Cord |

324 |

| |

3. Vena Cava Inferior and its Branches |

325 |

| |

Portal Vein |

326 |

| |

IV. Lymphatic System |

330 |

| |

1. Lymphatics of the Head |

331 |

| |

2. Lymphatics of the Neck |

332 |

| |

3. Lymphatics of the Thoracic Limbs |

332 |

| |

4. Lymphatics of the Thorax and Abdomen |

333 |

| |

5. Lymphatics of the Pelvic Limbs |

334 |

| The Nervous System |

335 |

| |

I. The Central Nervous System |

336 |

| |

1. Spinal Cord |

336 |

| |

2. The Brain |

339 |

| |

(1) Myelencephalon |

344 |

| |

(2) Metencephalon |

347 |

| |

(3) Mesencephalon |

351 |

| |

(4) Diencephalon |

352 |

| |

(5) Telencephalon |

357 |

| |

II. The Peripheral Nervous System |

369 |

| |

1. Cranial Nerves |

369 |

| |

I. Olfactory Nerve |

369 |

| |

II. Optic Nerve |

369 |

| |

III. Oculomotor Nerve |

369 |

| |

IV. Trochlear Nerve |

370 |

| |

V. Trigeminal Nerve |

370 |

| |

VI. Abducens |

375 |

| |

VII. Facial Nerve |

375 |

| |

VIII. Auditory Nerve |

377 |

| |

IX. Glossopharyngeal Nerve |

378 |

| |

X. Vagus Nerve |

378 |

| |

XI. Accessory Nerve |

382 |

| |

XII. Hypoglossal Nerve |

383 |

| |

2. Spinal Nerves |

383 |

| |

A. Cervical Nerves |

383 |

| |

The Brachial Plexus |

386 |

| |

B. Thoracic Nerves[xv] |

393 |

| |

C. Lumbar Nerves |

394 |

| |

Lumbar Plexus |

395 |

| |

D. Sacral Nerves and Sacral Plexus |

399 |

| |

E. Nerves of the Tail |

404 |

| |

3. Sympathetic System |

404 |

| Sense Organs and Integument |

409 |

| |

I. The Eye |

409 |

| |

II. The Ear |

415 |

| |

III. Olfactory Organ |

426 |

| |

IV. Organ of Taste |

426 |

| |

V. Integument |

427 |

| Appendix: Practical Directions |

429 |

| Index |

473 |

[xvi]

[xvii]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| FIG. |

PAGE |

| 1. |

Skeleton |

2 |

| 2. |

Fourth Thoracic Vertebra |

3 |

| 3. |

Fourth Thoracic Vertebra |

3 |

| 4. |

Thoracic Vertebræ |

5 |

| 5. |

Lumbar Vertebræ |

7 |

| 6. |

Sacrum |

9 |

| 7. |

Sacrum |

9 |

| 8. |

Caudal Vertebra |

11 |

| 9. |

Caudal Vertebra |

11 |

| 10. |

Cervical Vertebræ |

12 |

| 11. |

Sixth Cervical Vertebra |

13 |

| 12. |

Atlas |

13 |

| 13. |

Axis |

15 |

| 14. |

Ligaments of the Odontoid Process |

18 |

| 15. |

Rib |

19 |

| 16. |

Sternum |

20 |

| 17. |

Occipital Bone |

22 |

| 18. |

Occipital Bone |

22 |

| 19. |

Interparietal |

25 |

| 20. |

Sphenoid |

25 |

| 21. |

Presphenoid |

29 |

| 22. |

Temporal |

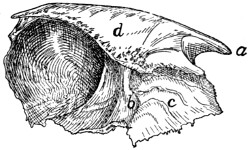

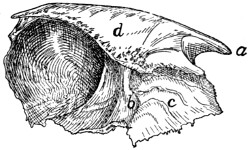

31 |

| 23. |

Temporal |

31 |

| 24. |

Tympanic Bulla |

33 |

| 25. |

Petrous Bone |

34 |

| 26. |

Frontal |

37 |

| 27. |

Maxillary Bone |

39 |

| 28. |

Maxillary Bone |

39 |

| 29. |

Premaxillary |

41 |

| 30. |

Nasal |

42 |

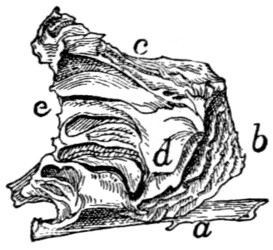

| 31. |

Ethmoid and Vomer |

43 |

| 32. |

Ethmoid and Vomer |

43 |

| 33. |

Palatine |

45 |

| 34. |

Lachrymal |

46 |

| 35. |

Malar |

46 |

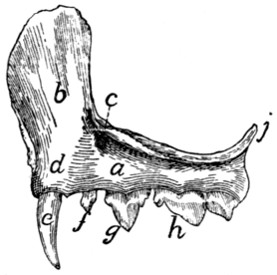

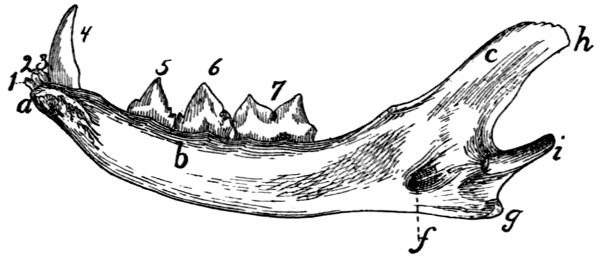

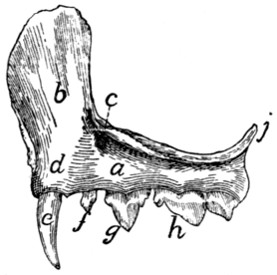

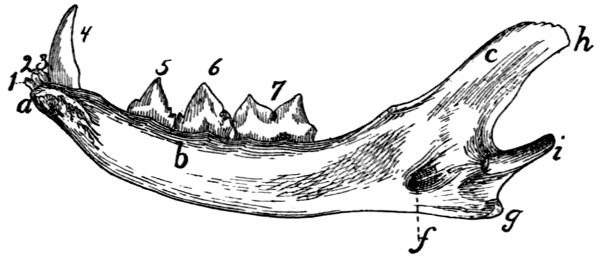

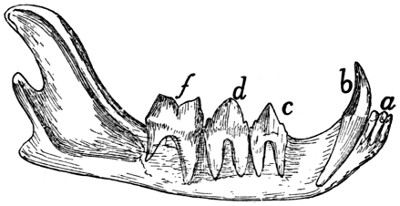

| 36. |

Mandible |

48 |

| 37. |

Mandible |

48 |

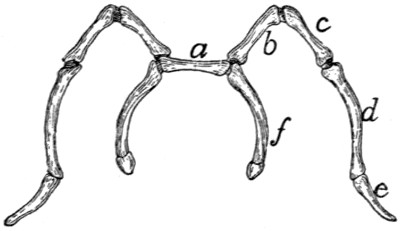

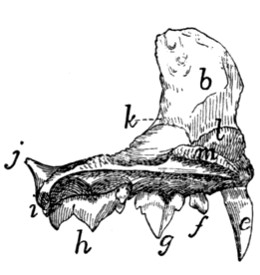

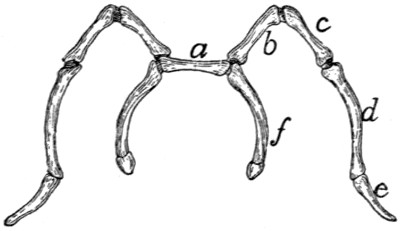

| 38. |

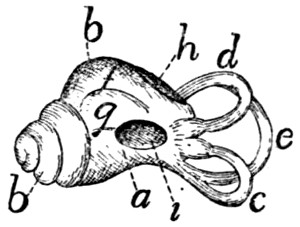

Hyoid |

49 |

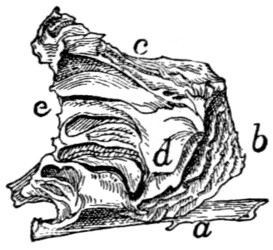

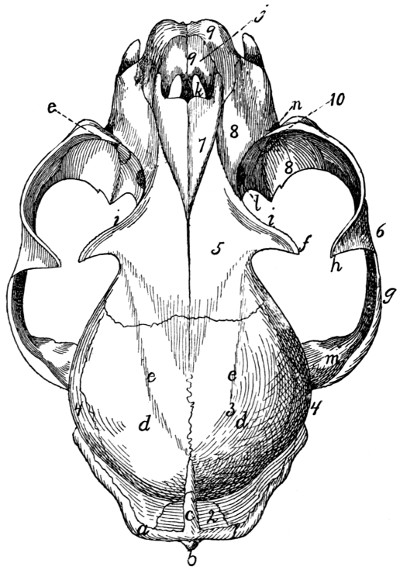

| 39. |

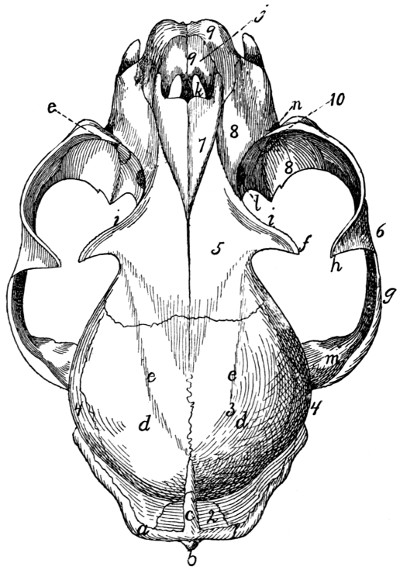

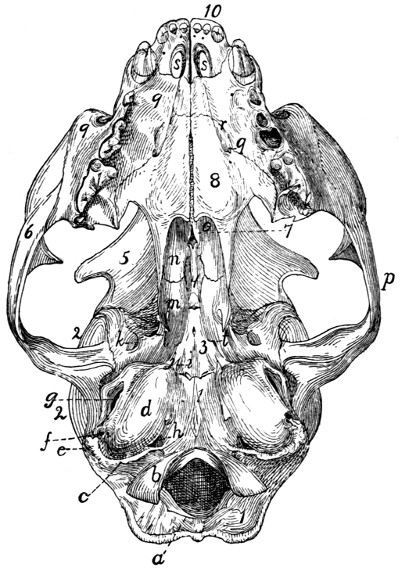

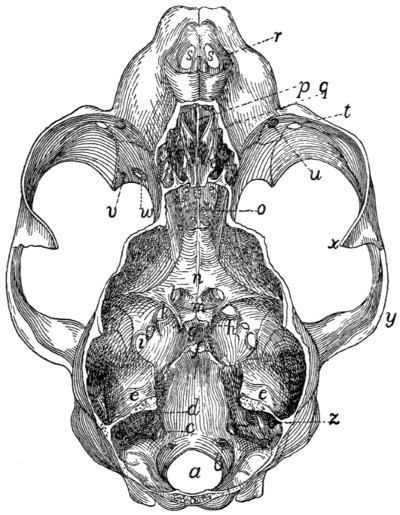

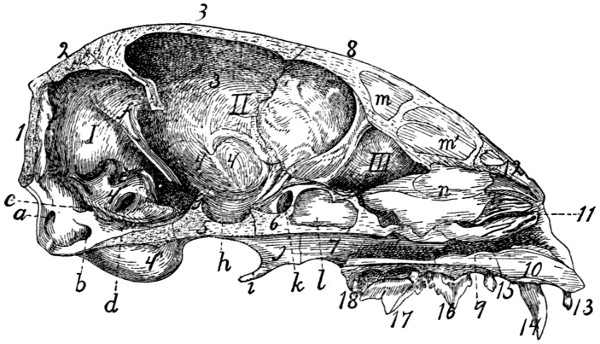

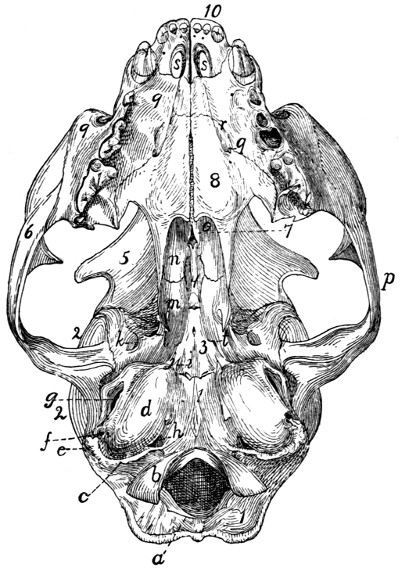

Skull, Dorsal Surface[xviii] |

50 |

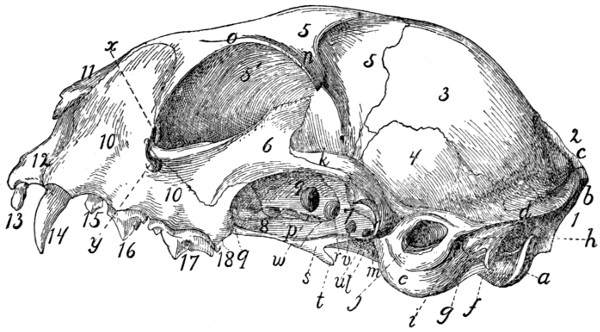

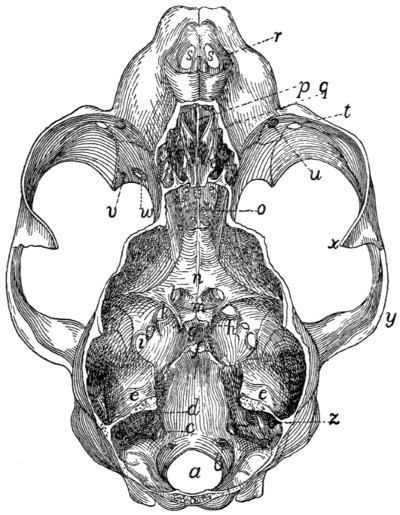

| 40. |

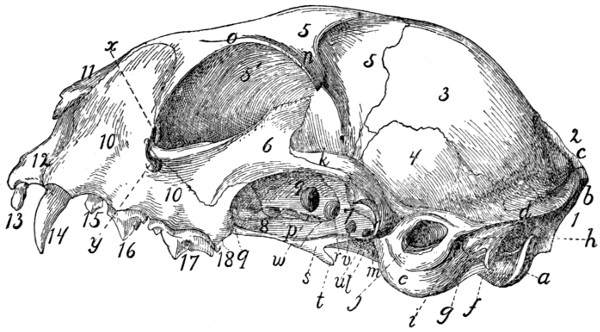

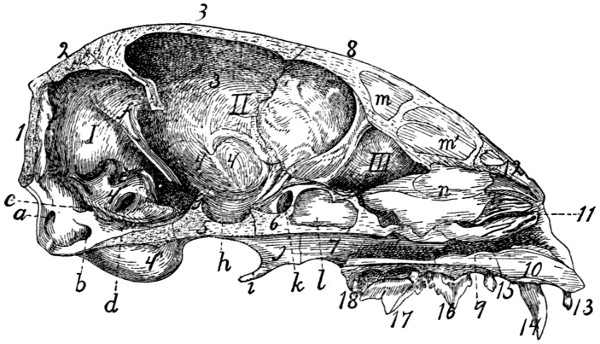

Skull, Side View |

53 |

| 41. |

Skull, Ventral Surface |

55 |

| 42. |

Cavities of Skull |

57 |

| 43. |

Skull, Median Section |

60 |

| 44. |

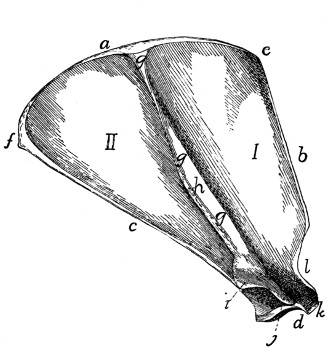

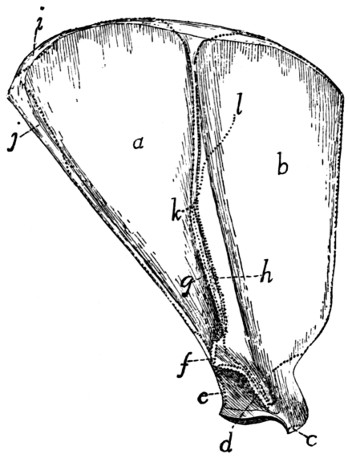

Scapula |

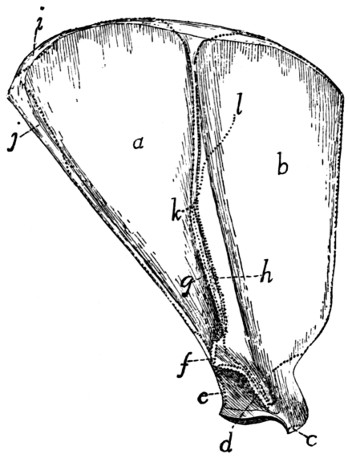

62 |

| 45. |

Scapula |

62 |

| 46. |

Clavicle |

64 |

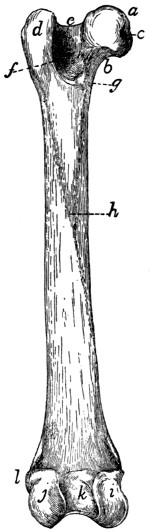

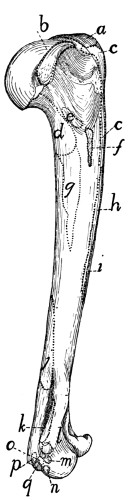

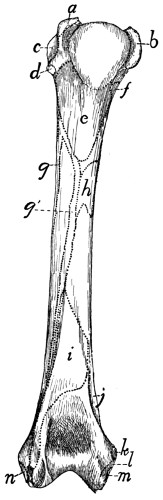

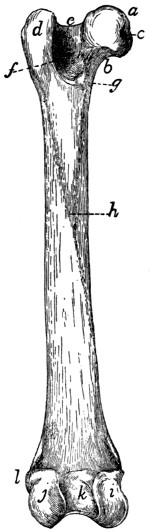

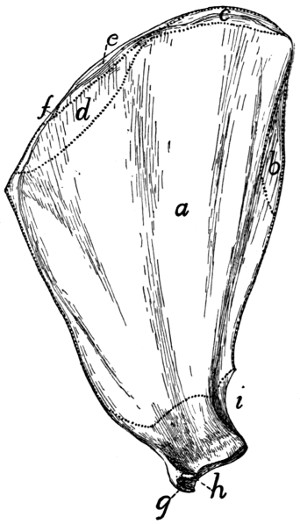

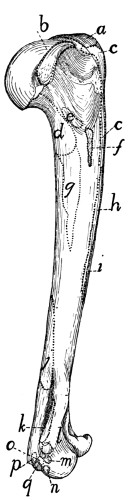

| 47. |

Humerus |

65 |

| 48. |

Humerus |

65 |

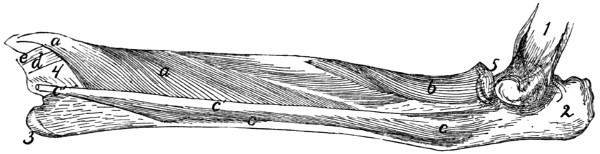

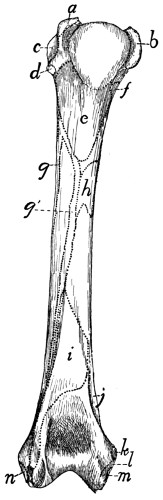

| 49. |

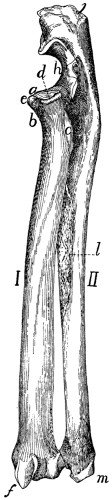

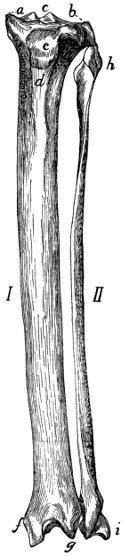

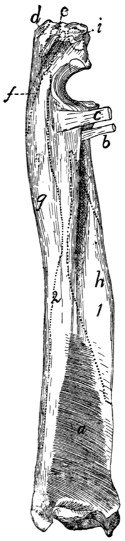

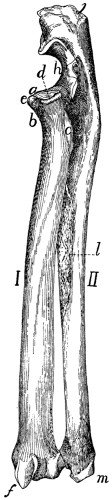

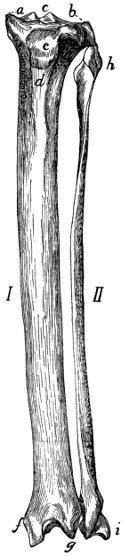

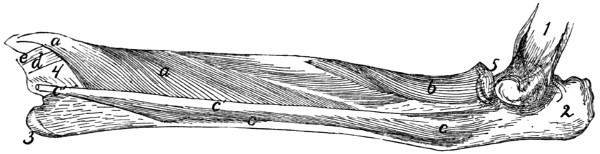

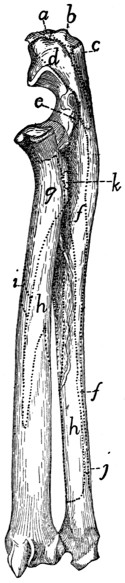

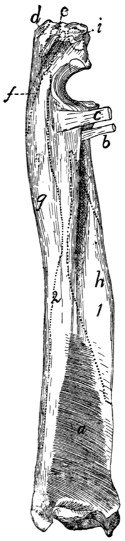

Radius and Ulna |

68 |

| 50. |

Radius and Ulna |

68 |

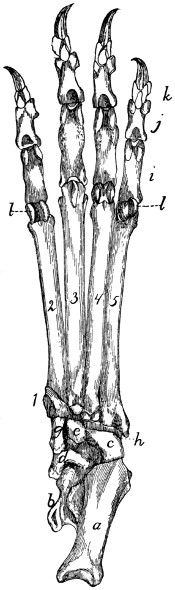

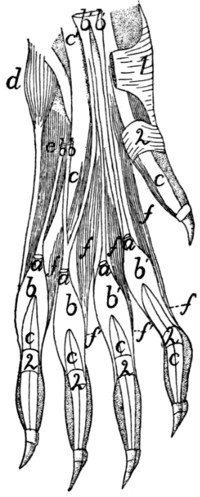

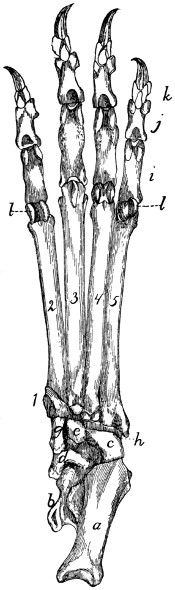

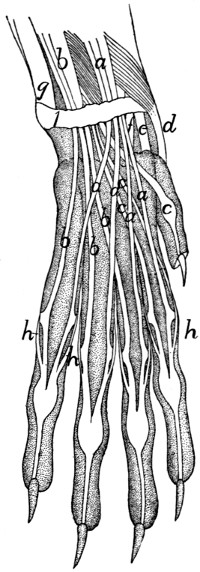

| 51. |

Bones of the Hand |

70 |

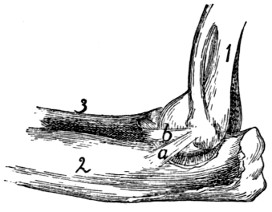

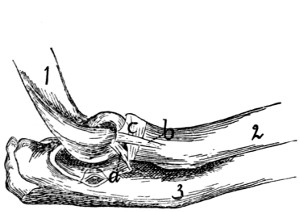

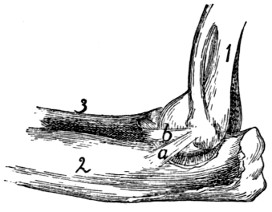

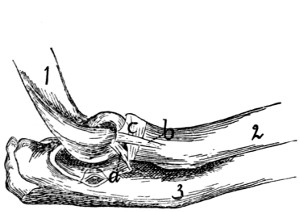

| 52. |

Ligaments of the Elbow |

74 |

| 53. |

Ligaments of the Elbow |

74 |

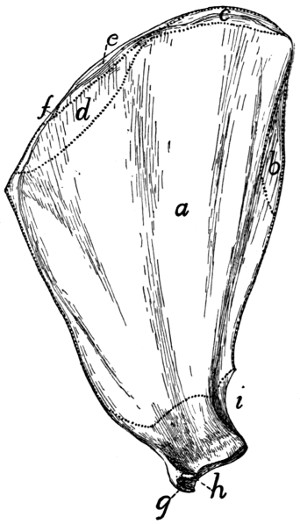

| 54. |

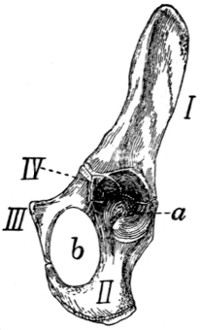

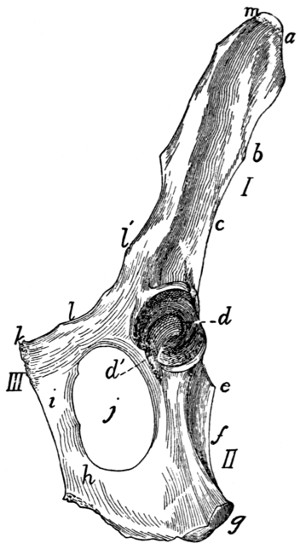

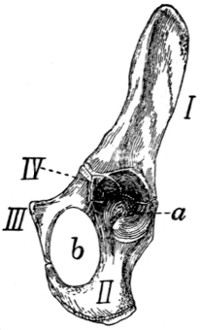

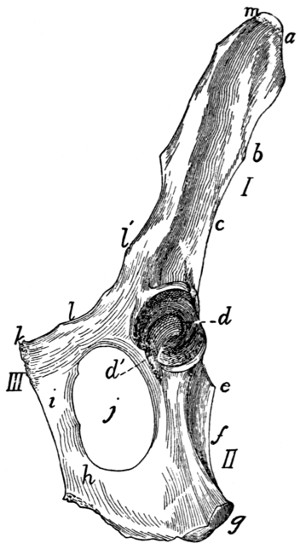

Innominate Bone of Kitten |

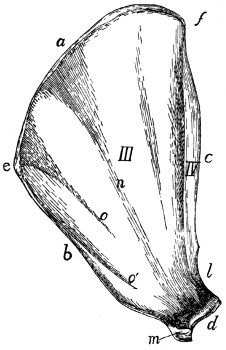

76 |

| 55. |

Innominate Bone |

77 |

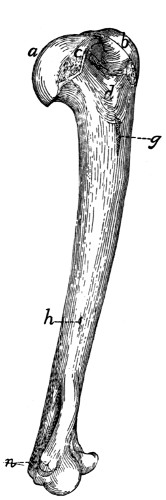

| 56. |

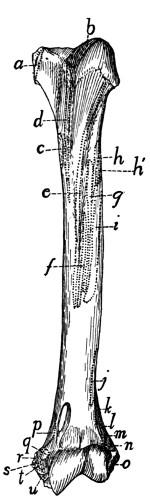

Femur |

79 |

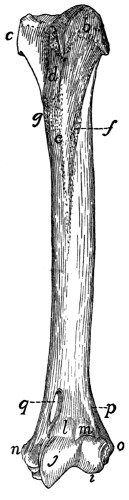

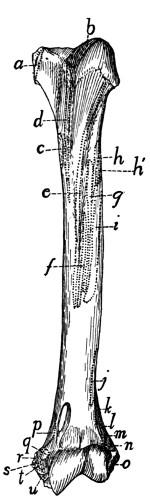

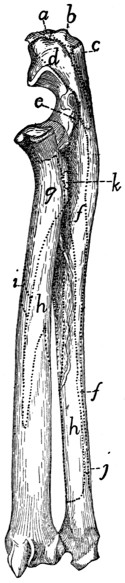

| 57. |

Tibia and Fibula |

81 |

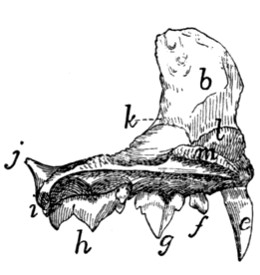

| 58. |

Bones of the Foot |

83 |

| 59. |

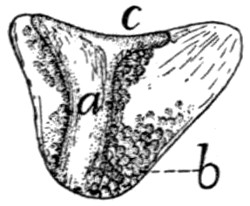

Calcaneus |

83 |

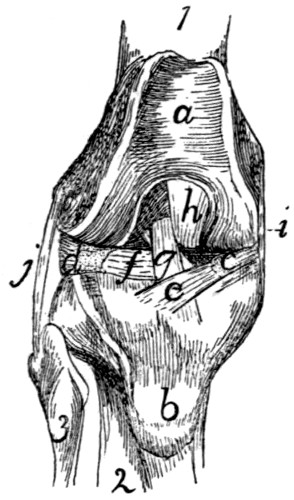

| 60. |

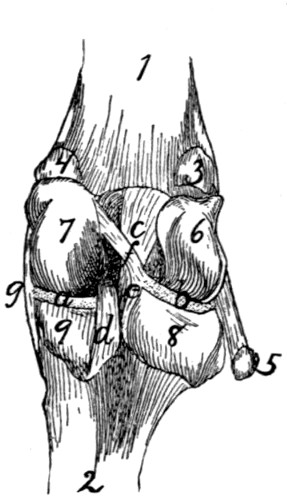

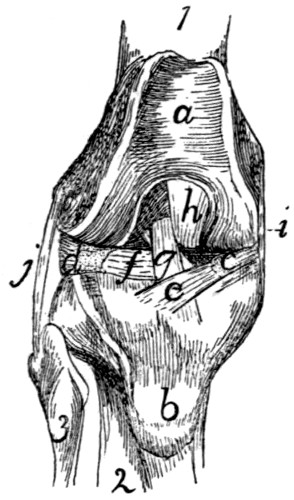

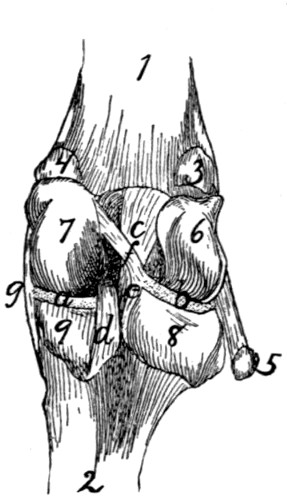

Knee-joint |

89 |

| 61. |

Knee-joint |

89 |

| 62. |

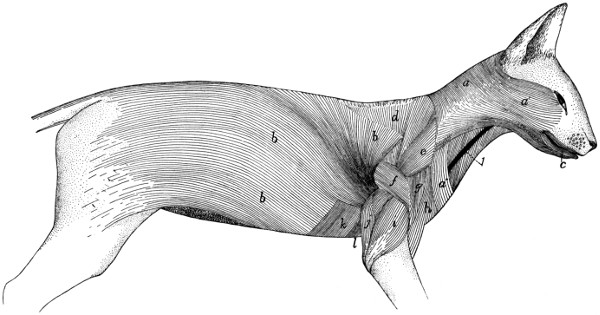

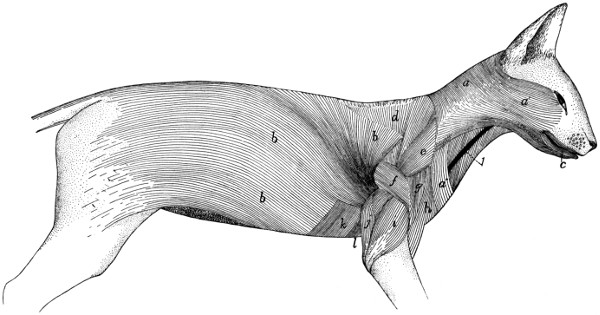

Muscles of the Skin |

94 |

| 63. |

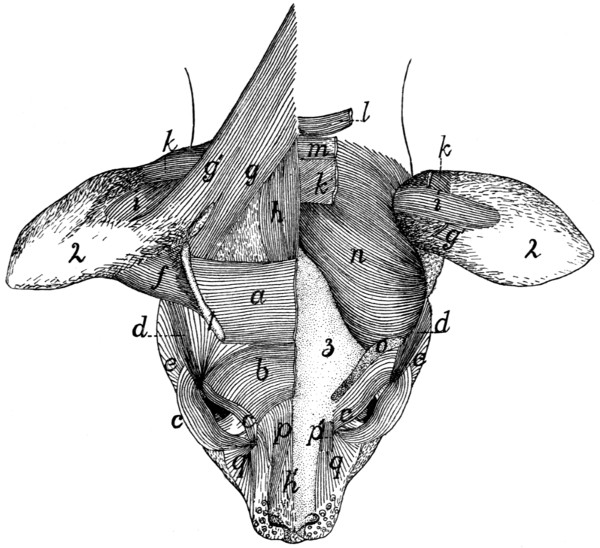

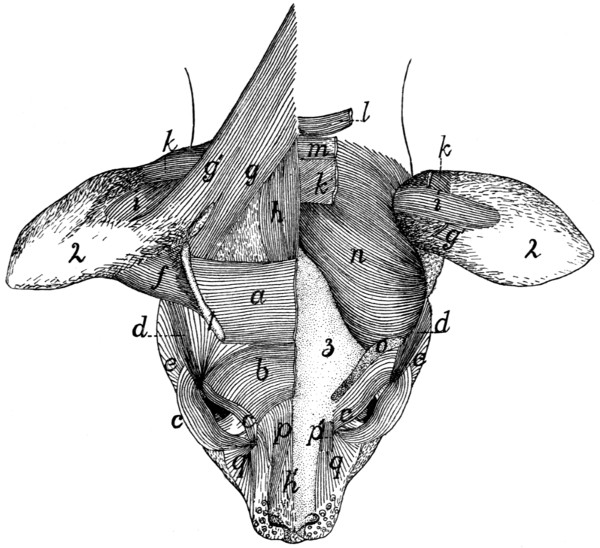

Muscles on Dorsal Side of Head |

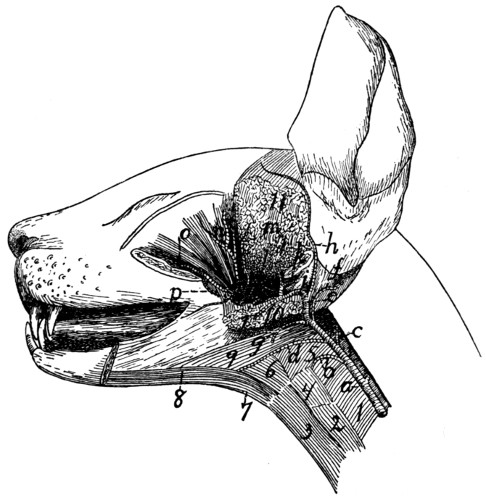

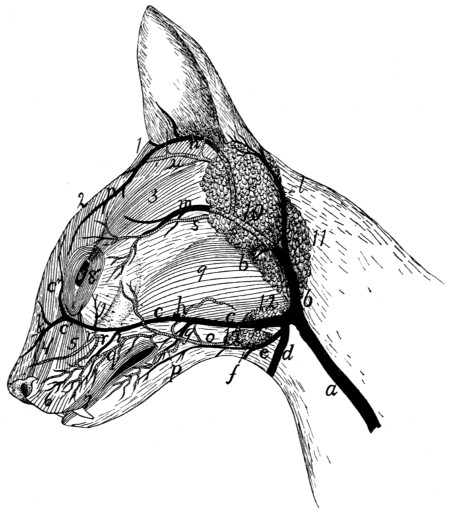

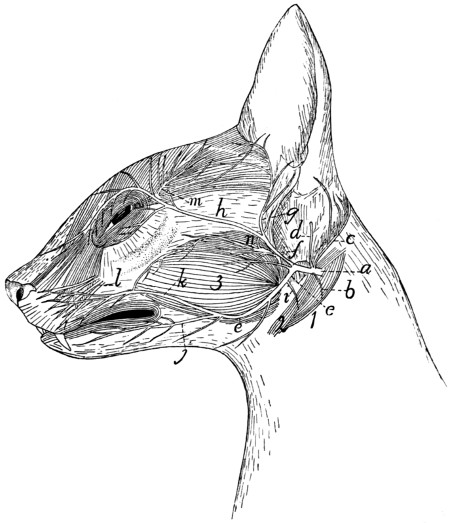

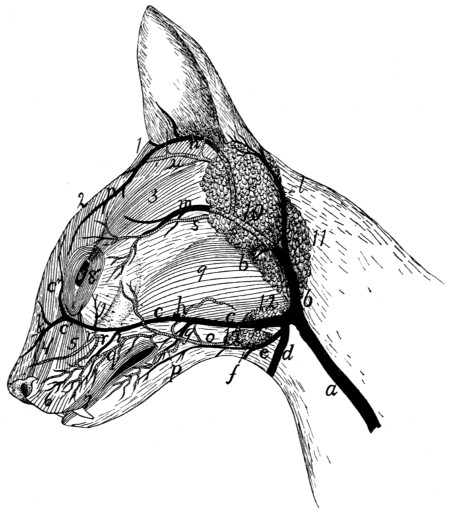

97 |

| 64. |

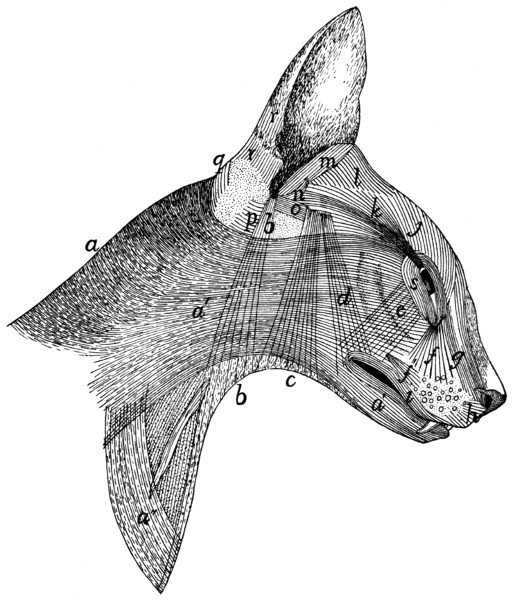

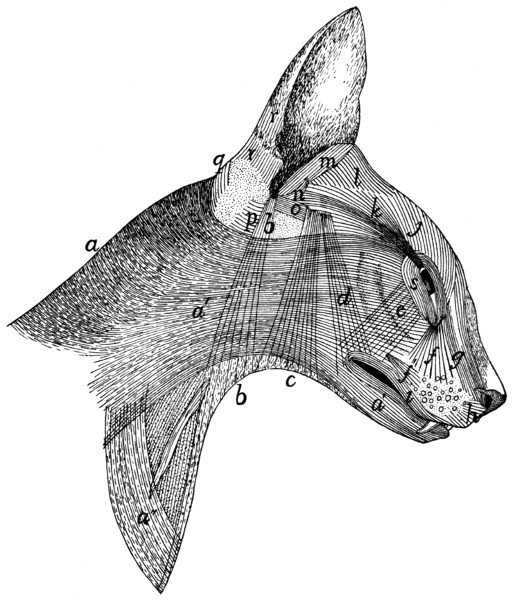

Muscles of Face |

102 |

| 65. |

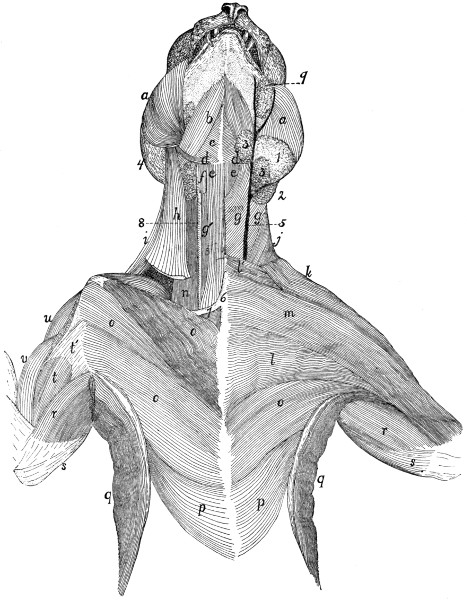

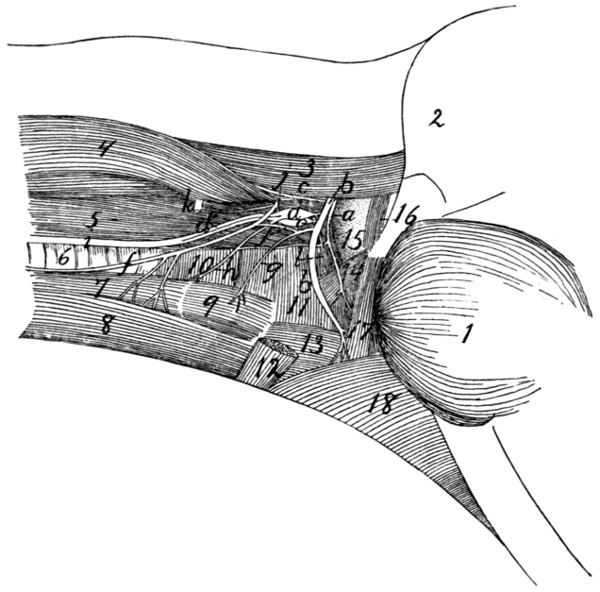

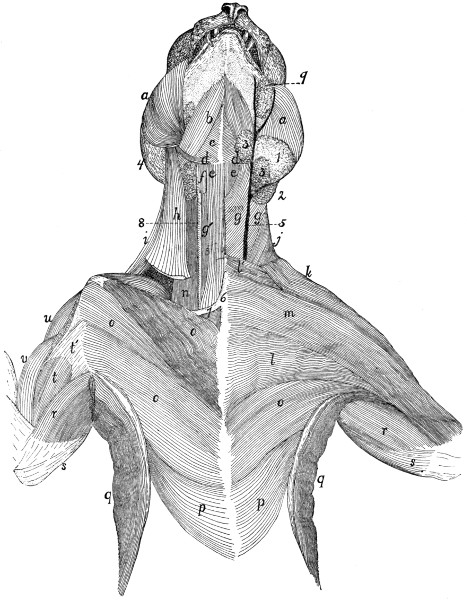

Ventral Muscles of Thorax, Neck, and Head |

109 |

| 66. |

Pterygoid and Palatal Muscles |

112 |

| 67. |

Muscles of Tongue, Hyoid, and Pharynx |

114 |

| 68. |

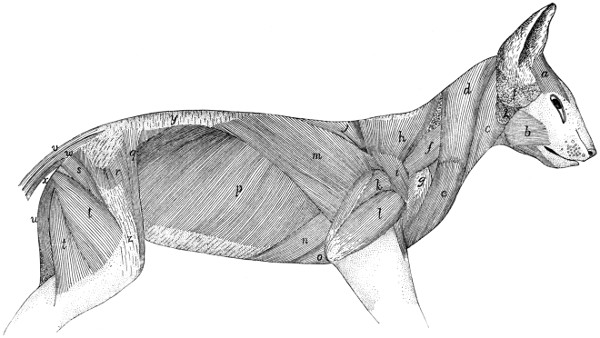

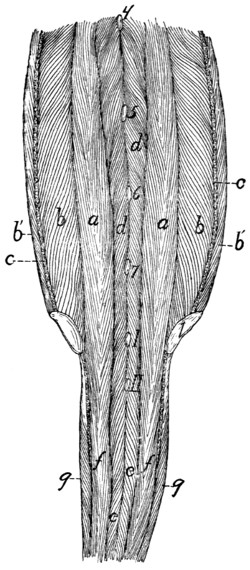

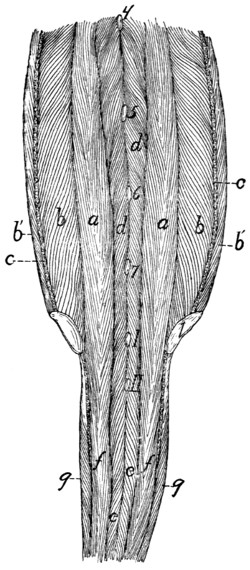

First Layer of Body Muscles |

117 |

| 69. |

Deep Muscles of the Vertebræ and Ribs |

125 |

| 70. |

Dorsal Muscles of Lumbar and Caudal Regions |

127 |

| 71. |

Deep Muscles of Neck |

135 |

| 72. |

Muscles on the Ventral Surface of the Cervical Vertebræ |

143 |

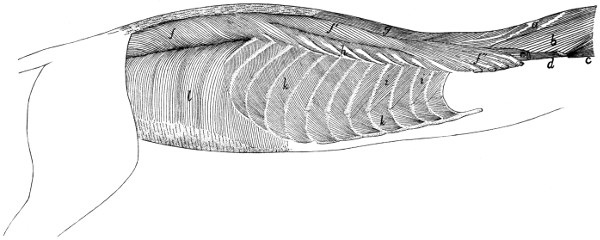

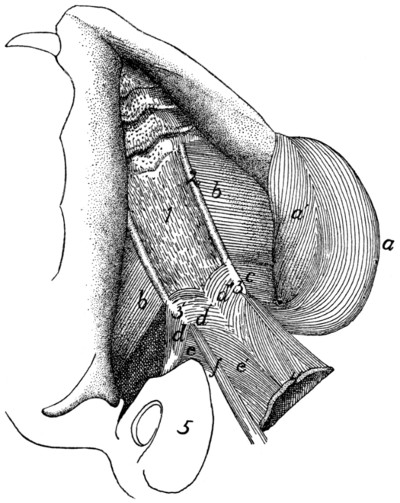

| 73. |

Second Layer of Body Muscles |

149 |

| 74. |

Diaphragm |

152 |

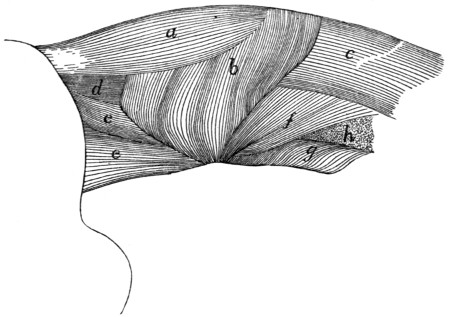

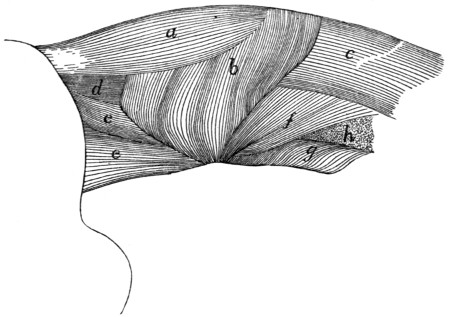

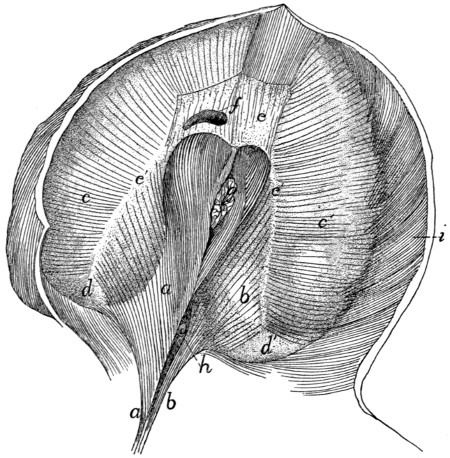

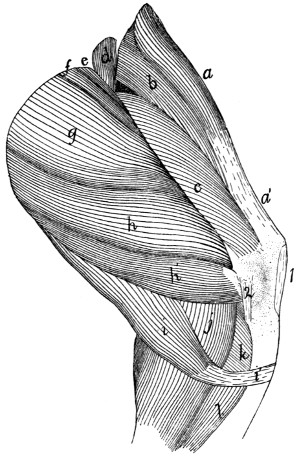

| 75. |

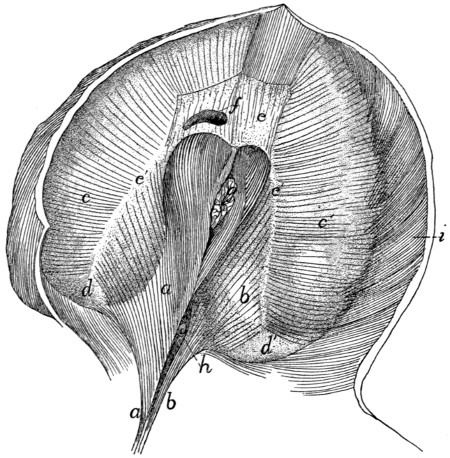

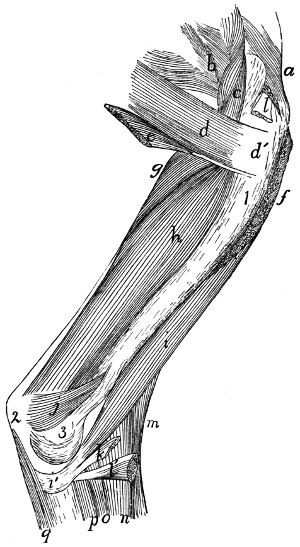

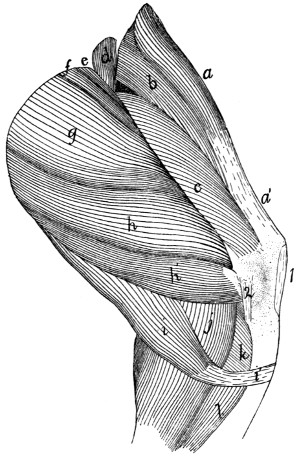

Lateral Muscles of Arm |

158 |

| 76. |

Origin of Lateral Muscles on Scapula |

160 |

| 77. |

Medial Muscles of Arm |

162 |

| 78. |

Origin of Medial Muscles on Scapula |

163 |

| 79. |

Deep Medial Muscles of Arm |

167 |

| 80. |

Deep Lateral Muscles of Arm |

169 |

| 81. |

Areas of Origin of Muscles on Ventral Surface of Humerus |

171 |

| 82. |

Areas of Origin of Muscles on Medial Side of Humerus |

171 |

| 83. |

Areas of Origin of Muscles on Dorsal Surface of Left Humerus |

171 |

| 84. |

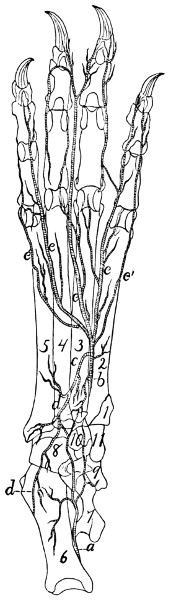

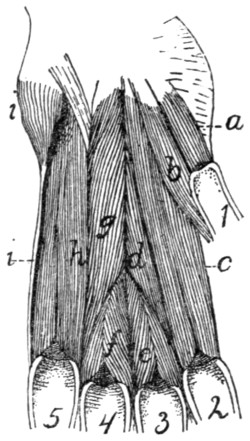

Tendons on Back of Hand |

175 |

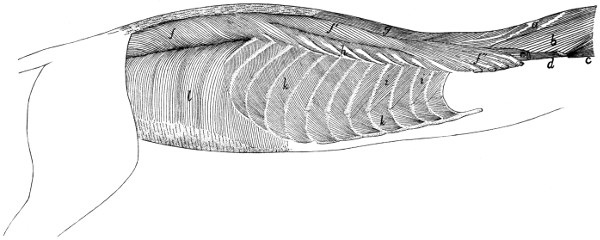

| 85. |

Deep Muscles of Forearm |

177 |

| 86. |

Insertions of Muscles on Radius and Ulna |

178 |

| 87. |

Insertions of Muscles on Radius and Ulna |

182 |

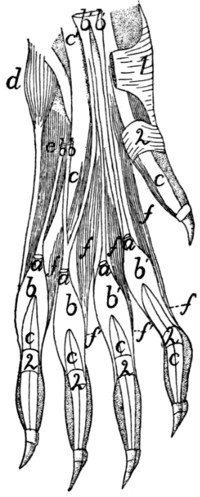

| 88. |

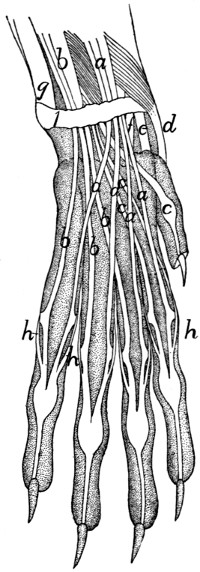

Mm. Lumbricales, etc.[xix] |

183 |

| 89. |

Deep Muscles of Palm of Hand |

184 |

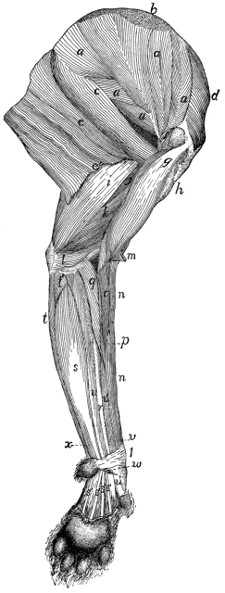

| 90. |

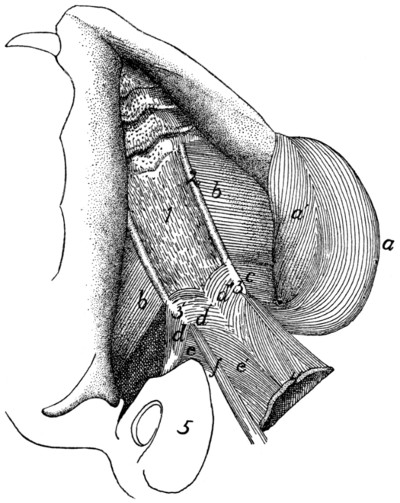

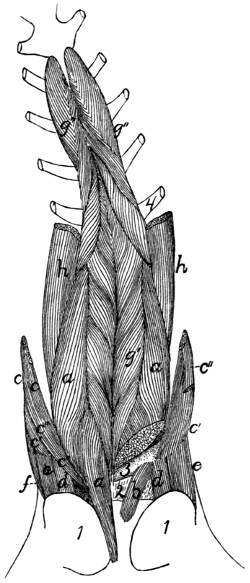

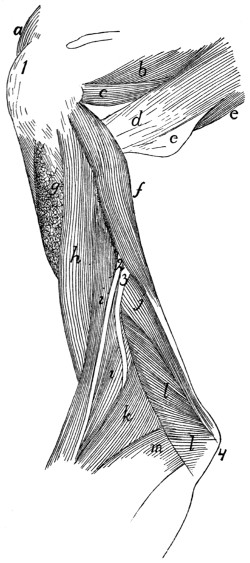

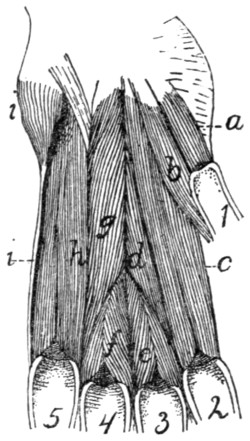

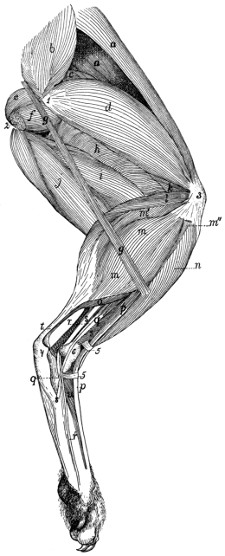

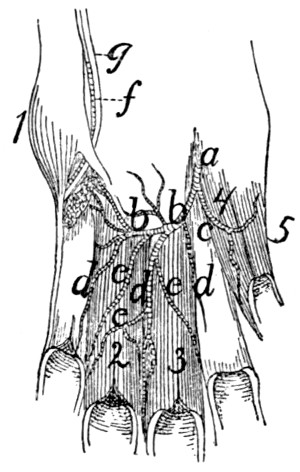

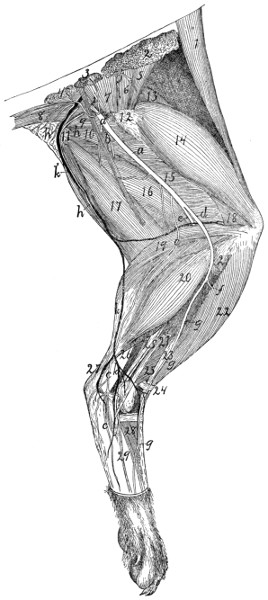

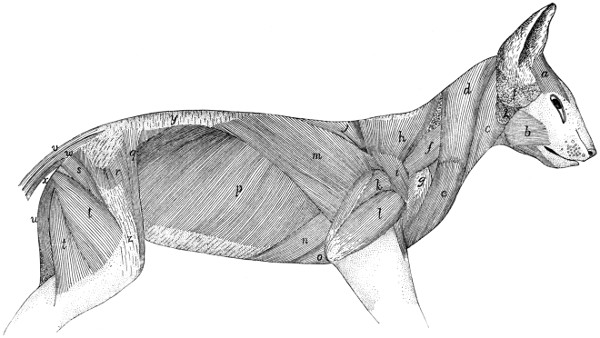

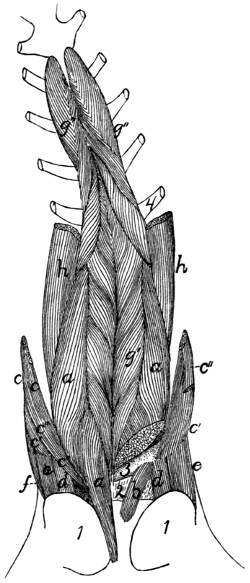

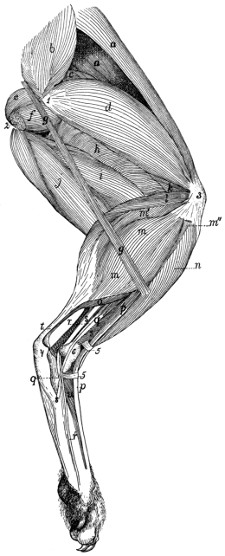

Lateral Muscles of the Leg |

192 |

| 91. |

Medial Muscles of the Leg |

197 |

| 92. |

Deep Medial Muscles of Thigh |

200 |

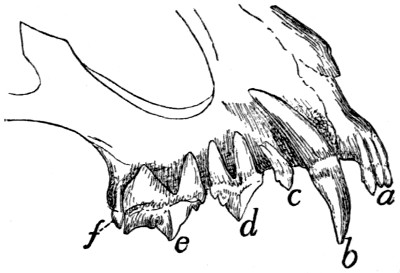

| 93. |

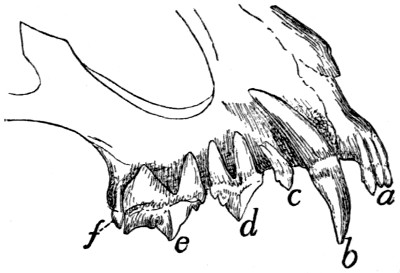

Teeth of the Upper Jaw |

225 |

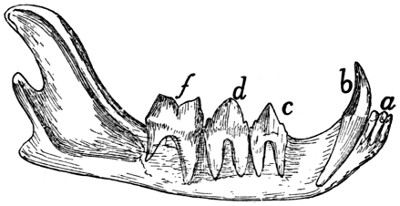

| 94. |

Teeth of the Lower Jaw |

226 |

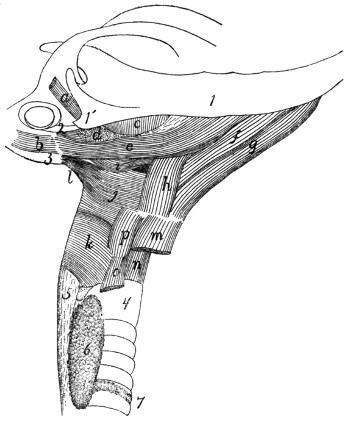

| 95. |

Tongue, Epiglottis, etc. |

227 |

| 96. |

Muscles of Tongue, Hyoid, and Pharynx |

229 |

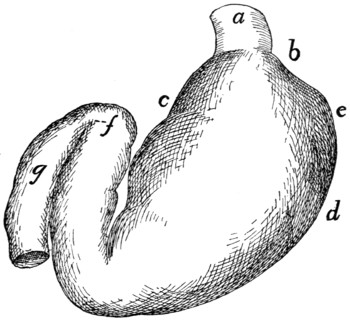

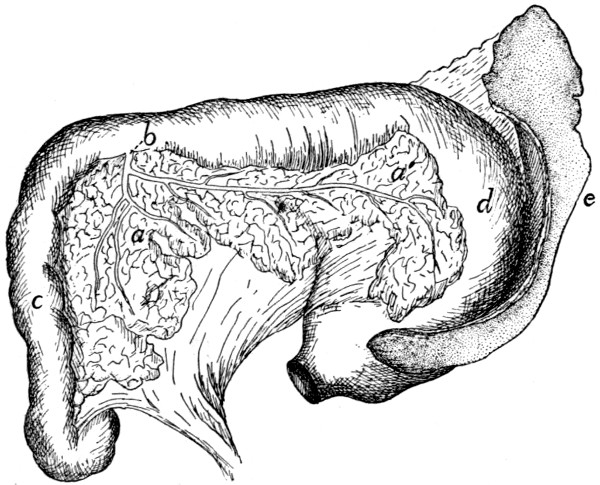

| 97. |

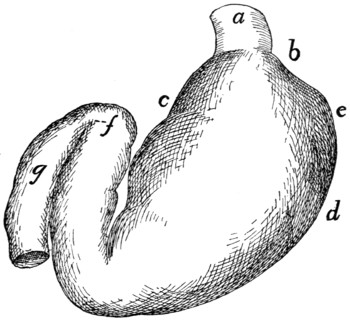

Stomach |

235 |

| 98. |

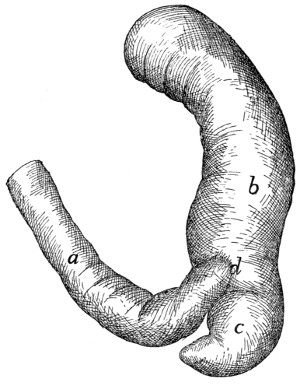

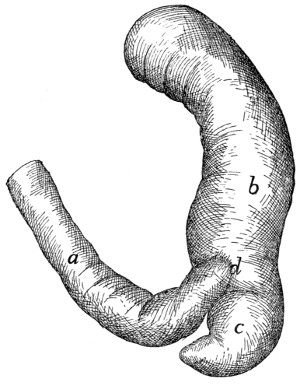

Colon and Cæcum |

238 |

| 99. |

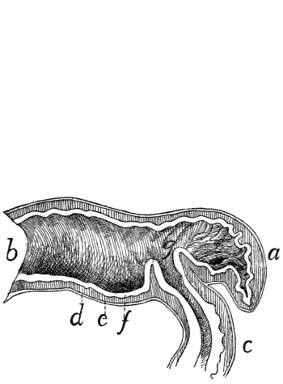

Ileocolic Valve |

238 |

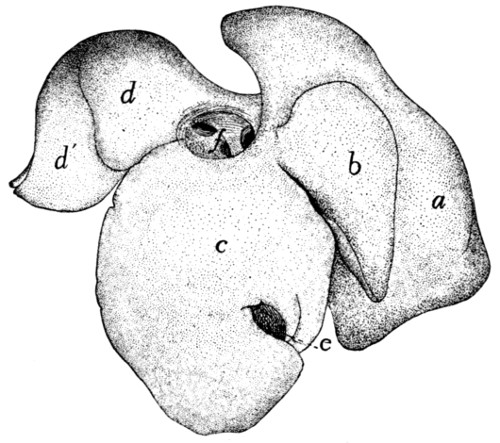

| 100. |

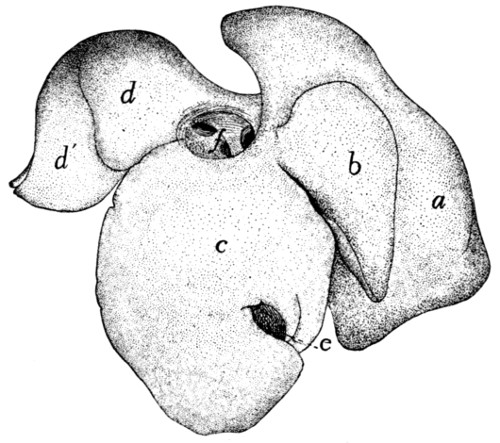

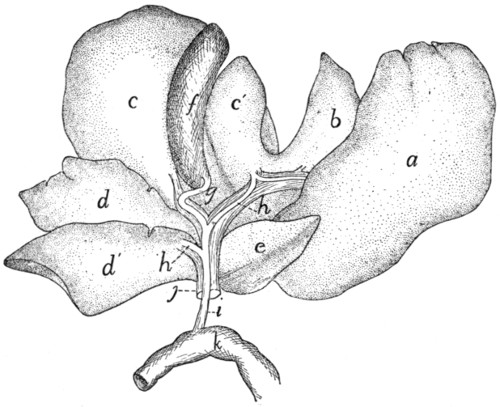

Liver |

240 |

| 101. |

Liver |

240 |

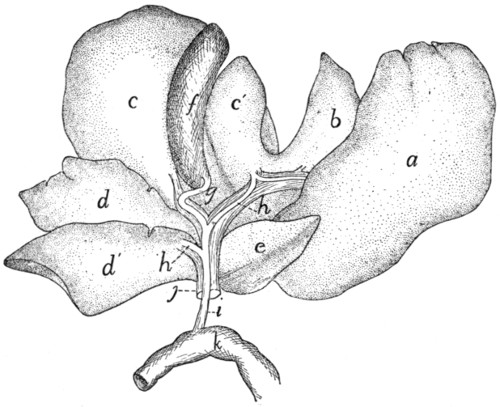

| 102. |

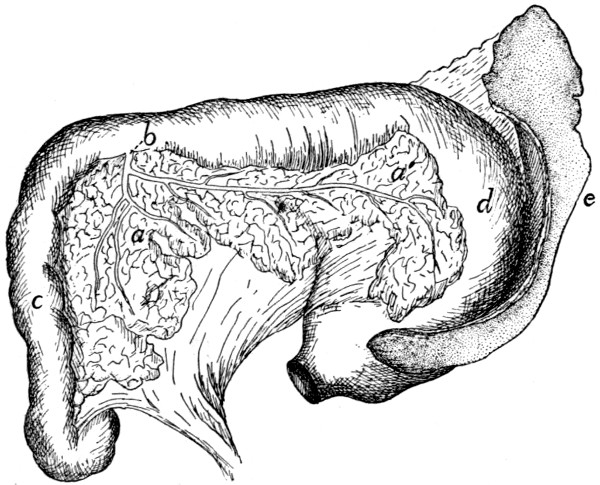

Pancreas and Spleen |

242 |

| 103. |

Cartilages of Nose |

244 |

| 104. |

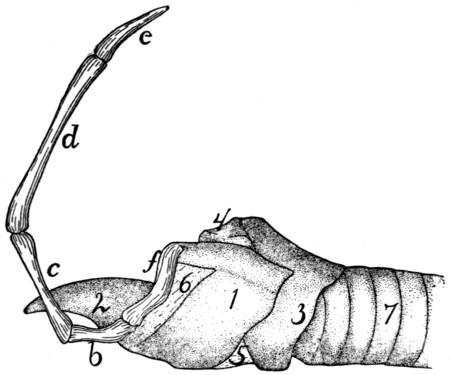

Cartilages of Larynx |

247 |

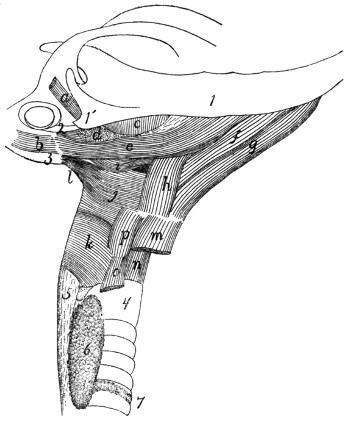

| 105. |

Muscles of Larynx |

250 |

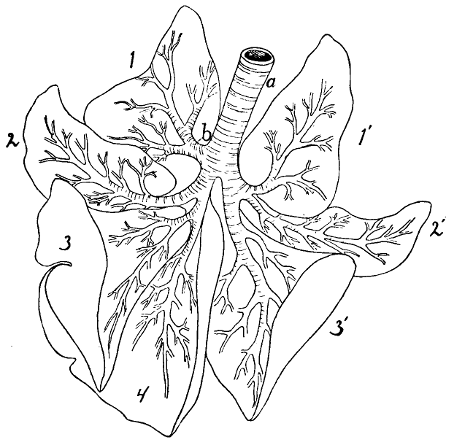

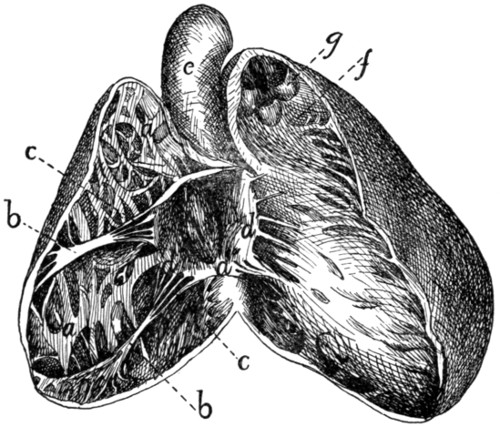

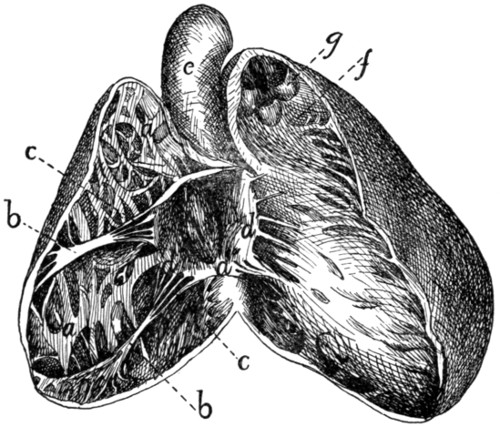

| 106. |

Bronchi |

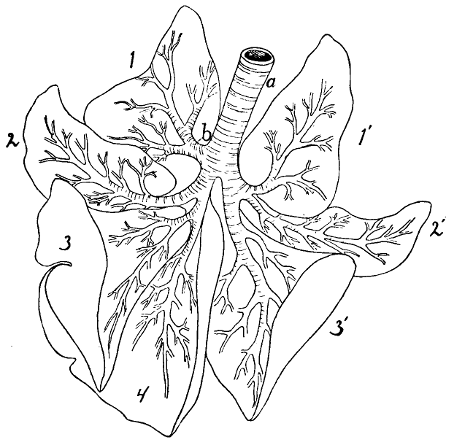

253 |

| 107. |

Thymus Gland |

254 |

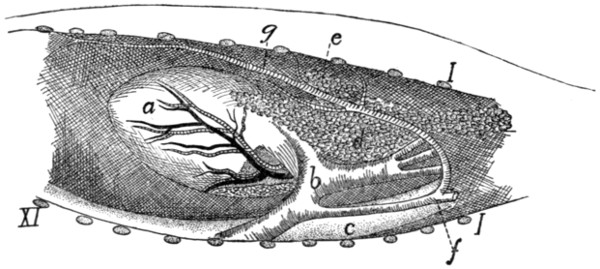

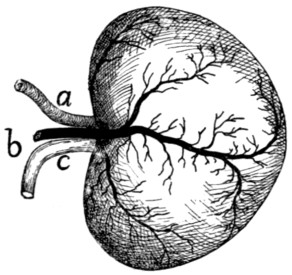

| 108. |

Kidney |

255 |

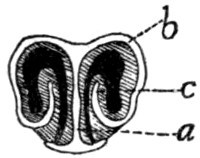

| 109. |

Section of Kidney |

255 |

| 110. |

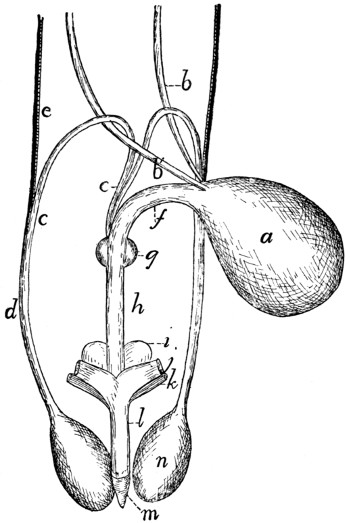

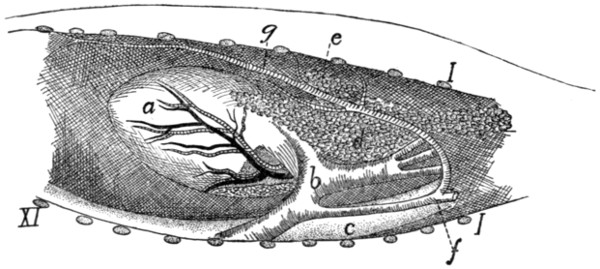

Testis |

260 |

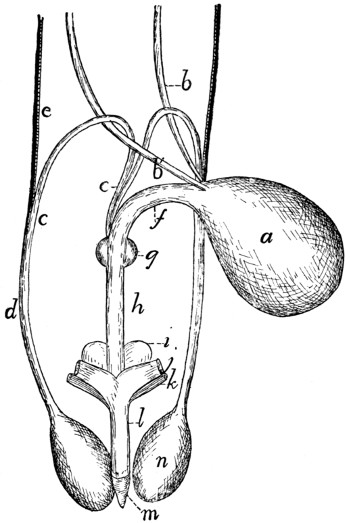

| 111. |

Male Genital Organs |

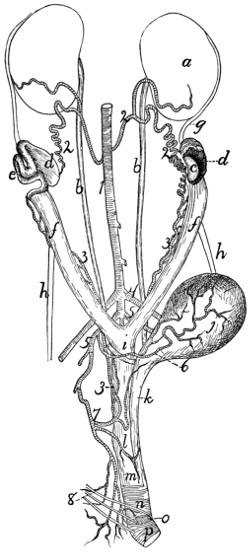

262 |

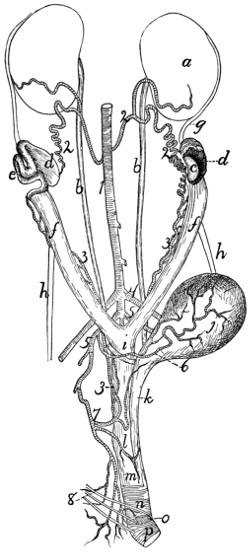

| 112. |

Female Urogenital Organs |

265 |

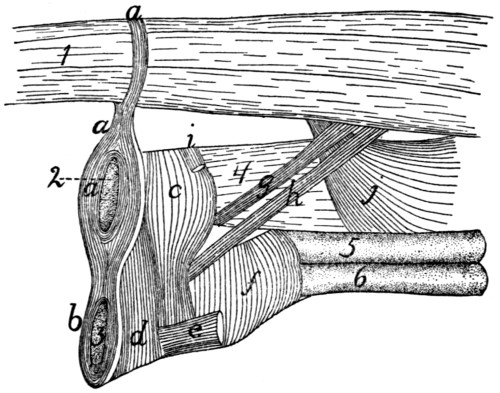

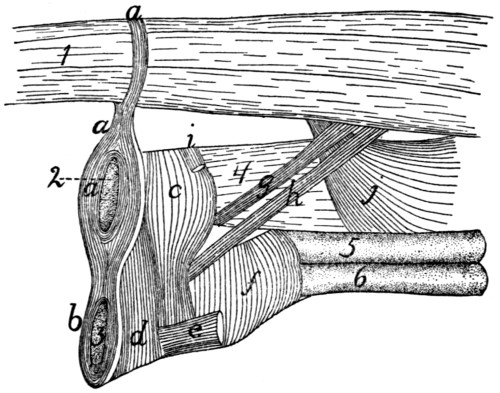

| 113. |

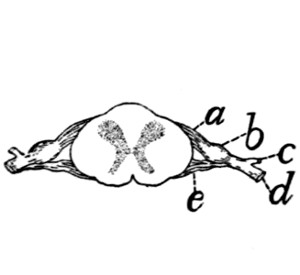

Muscles of Urogenital Organs and Anus in Male |

270 |

| 114. |

Muscles of Urogenital Organs of Female |

272 |

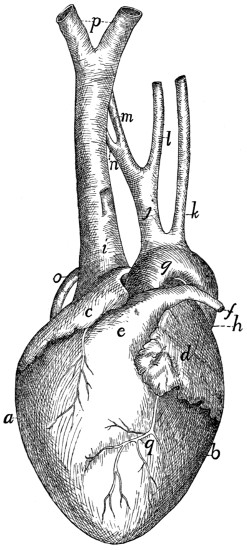

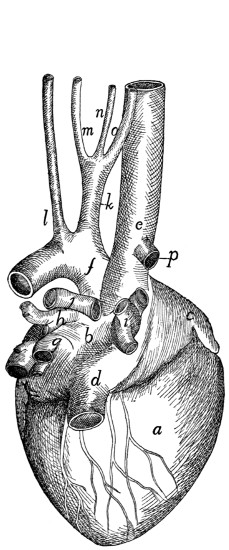

| 115. |

Heart |

276 |

| 116. |

Heart |

276 |

| 117. |

Inside of Heart |

278 |

| 118. |

Vessels of Thorax |

282 |

| 119. |

Common Carotid and Internal Jugular |

284 |

| 120. |

Branches of External Carotid |

288 |

| 121. |

Arteries of Brain |

291 |

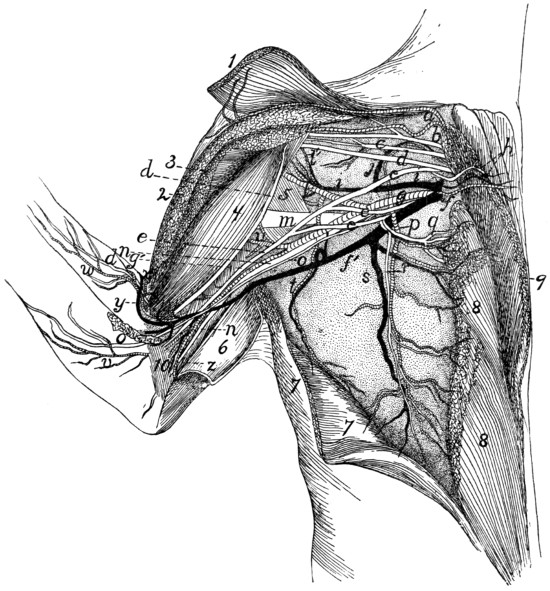

| 122. |

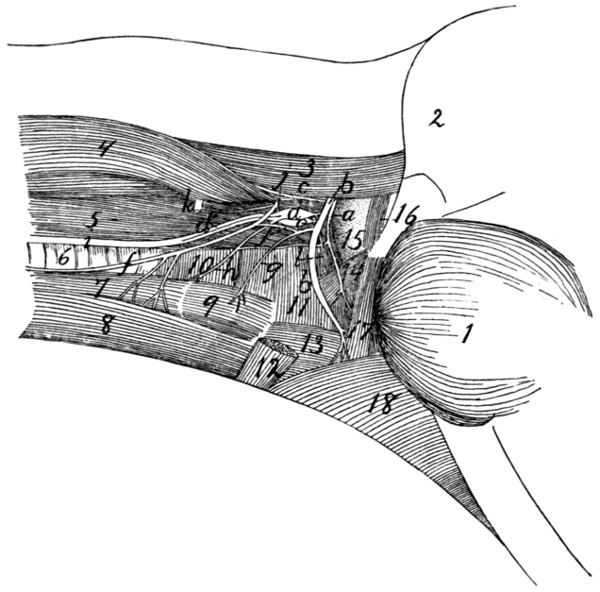

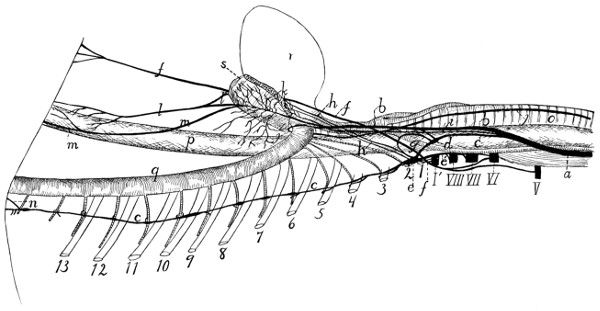

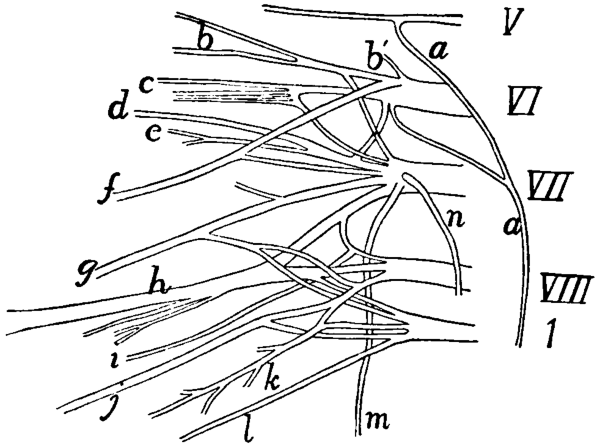

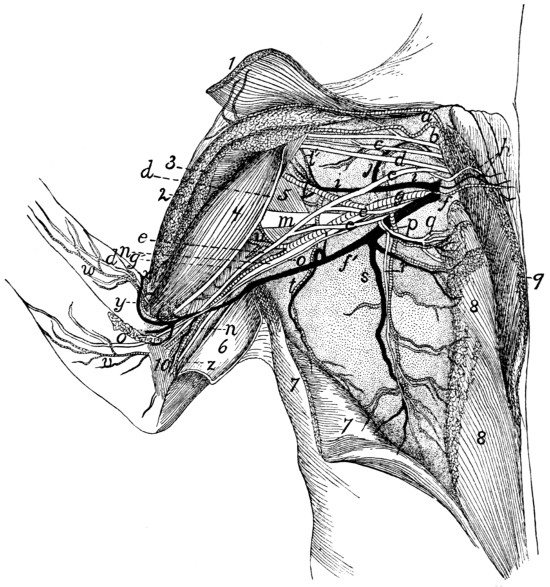

Vessels and Nerves of the Axilla |

295 |

| 123. |

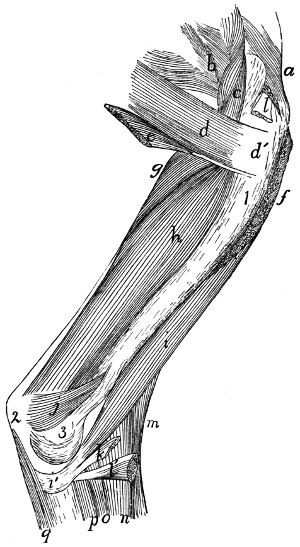

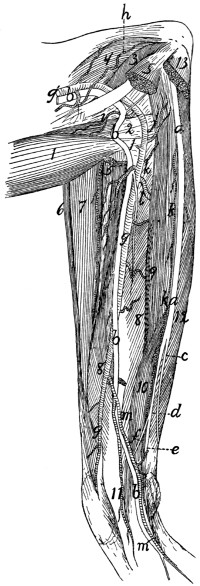

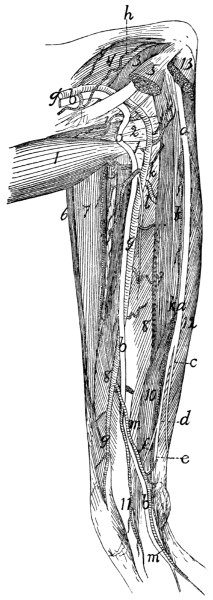

Vessels and Nerves of the Arm |

299 |

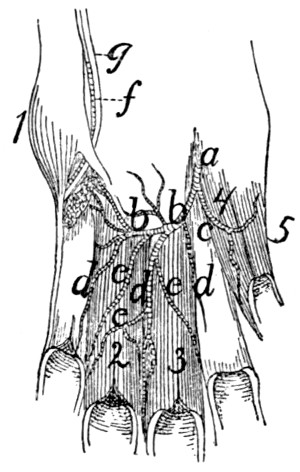

| 124. |

Palmar Arch |

301 |

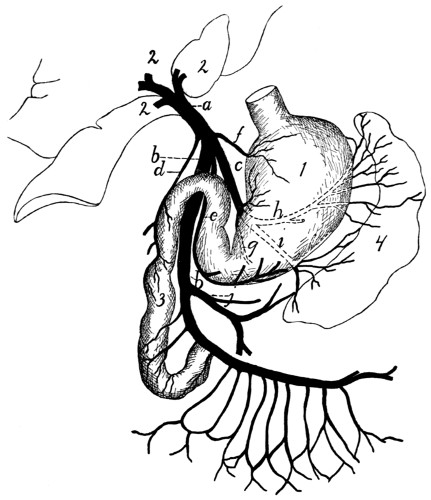

| 125. |

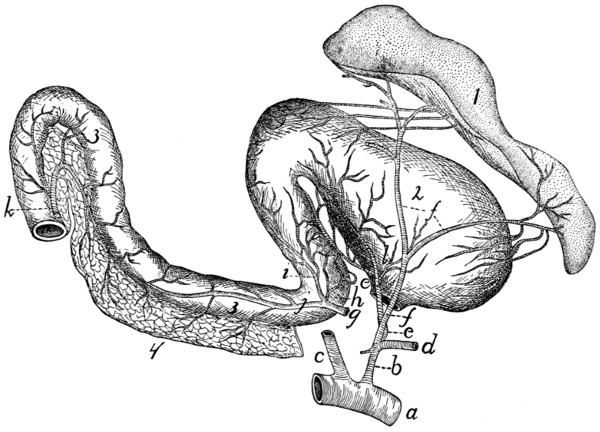

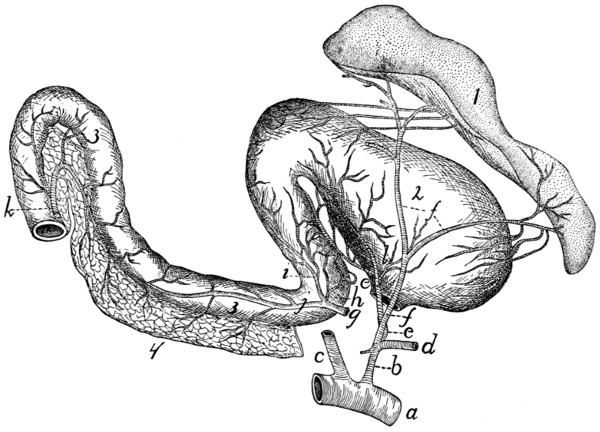

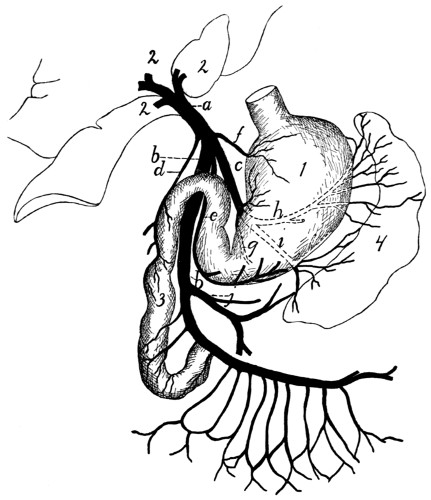

Cœliac Artery |

302 |

| 126. |

Abdominal Blood-vessels |

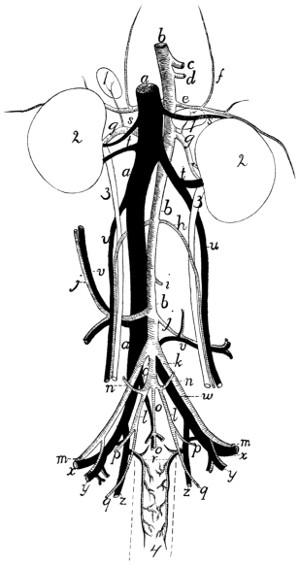

305 |

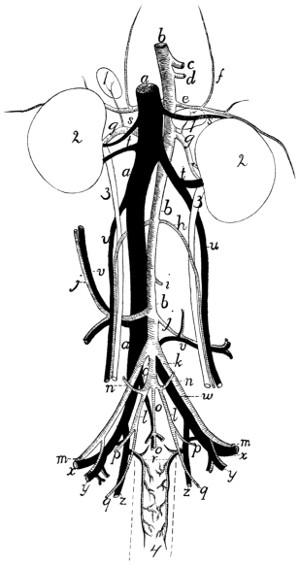

| 127. |

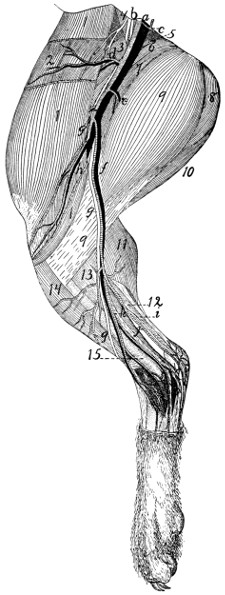

Medial Vessels and Nerves of the Leg |

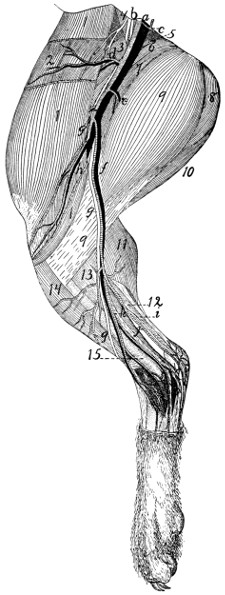

310 |

| 128. |

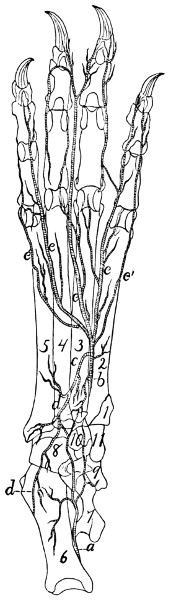

Deep Arteries of Foot |

314 |

| 129. |

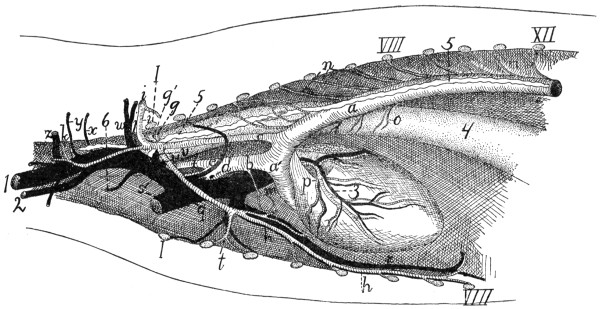

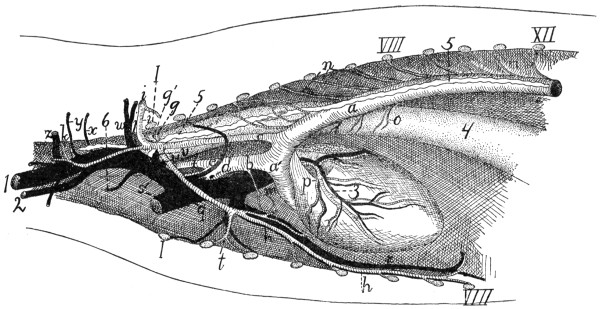

Thoracic Blood-vessels |

317 |

| 130. |

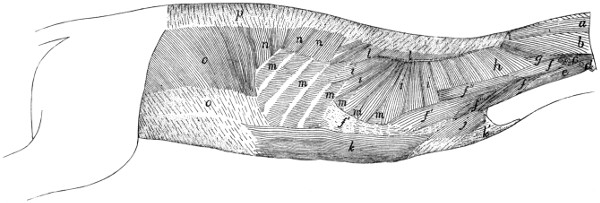

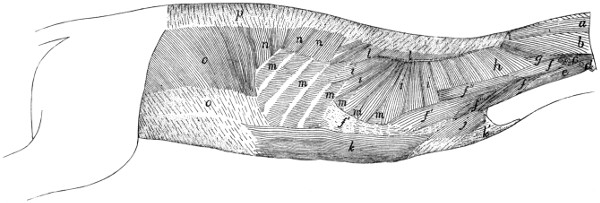

Superficial Vessels and Nerves of the Forearm |

319 |

| 131. |

Blood-vessels of the Face |

322 |

| 132. |

Portal Vein |

327 |

| 133. |

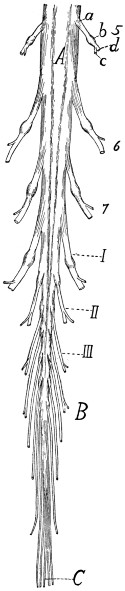

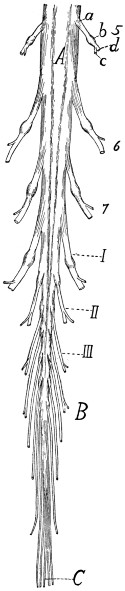

Spinal Cord, cranial portion |

336 |

| 134. |

Section of Spinal Cord |

337 |

| 135. |

Origin of Spinal Nerves |

337 |

| 136. |

Cauda Equina, etc. |

338 |

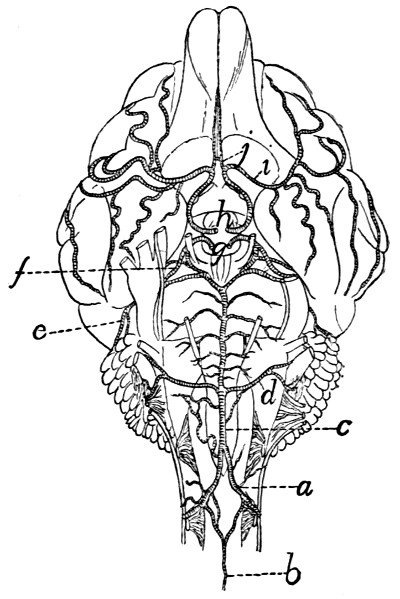

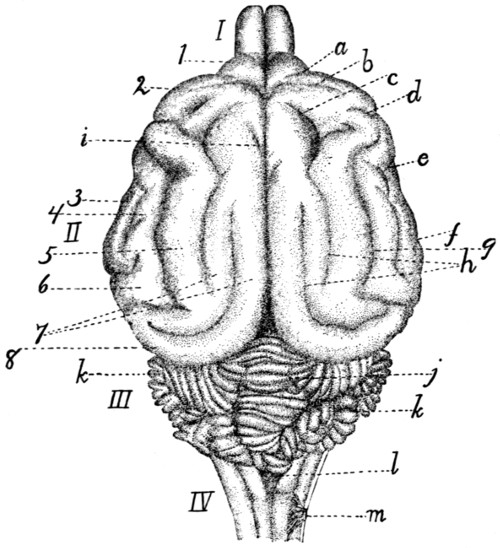

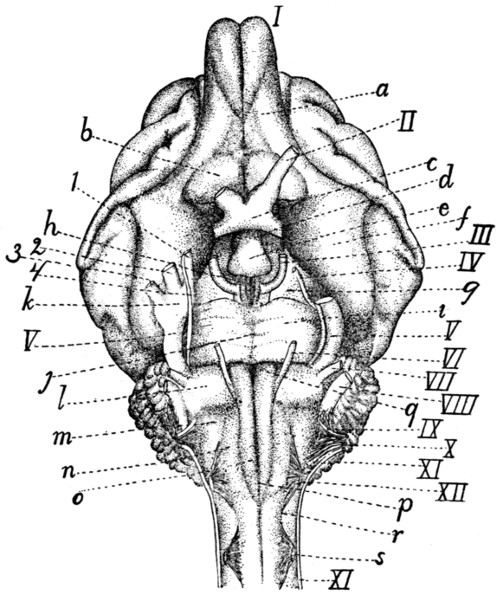

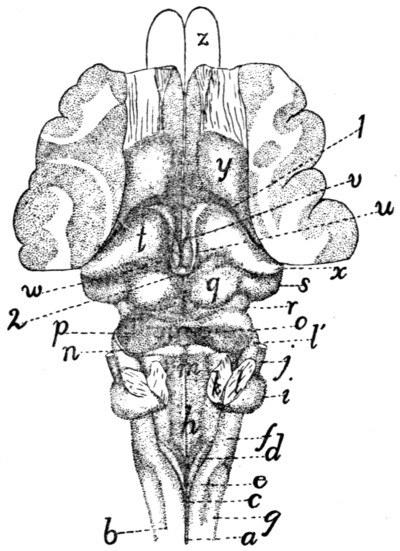

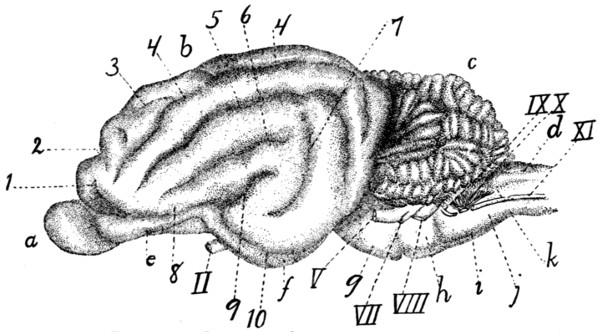

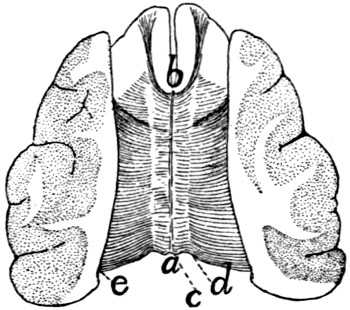

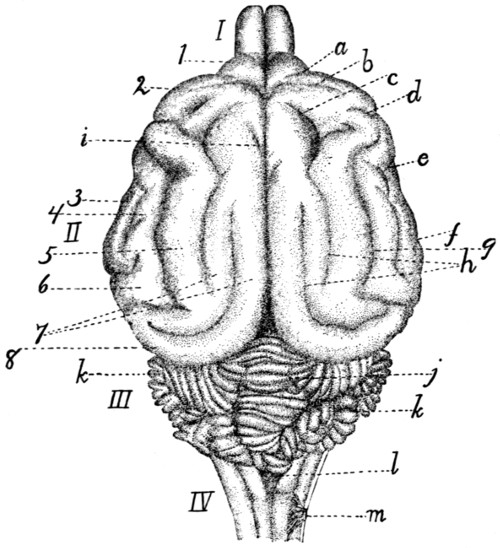

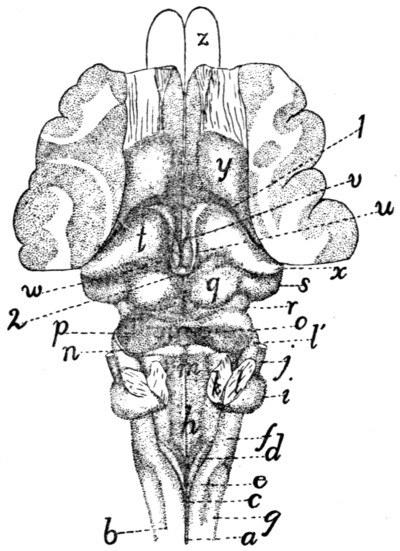

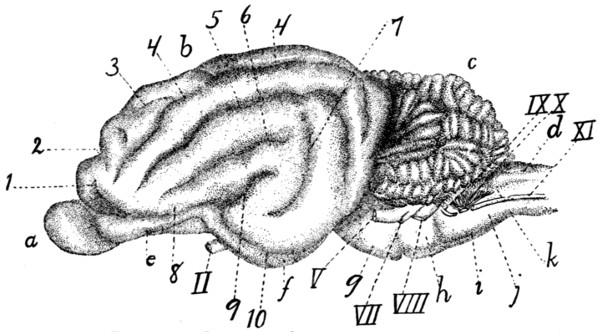

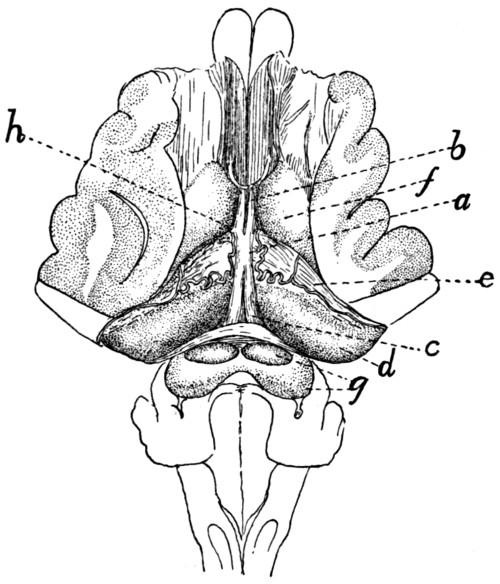

| 137. |

Brain, Dorsal View[xx] |

340 |

| 138. |

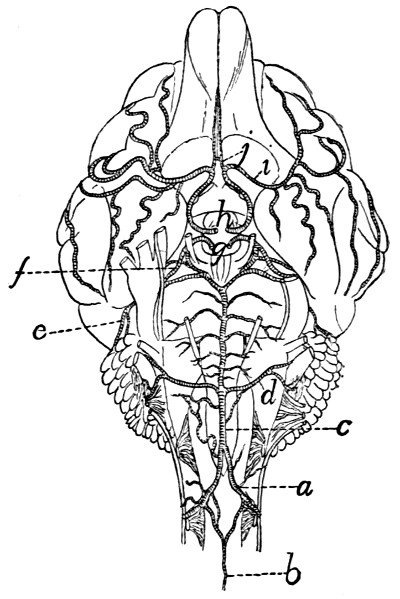

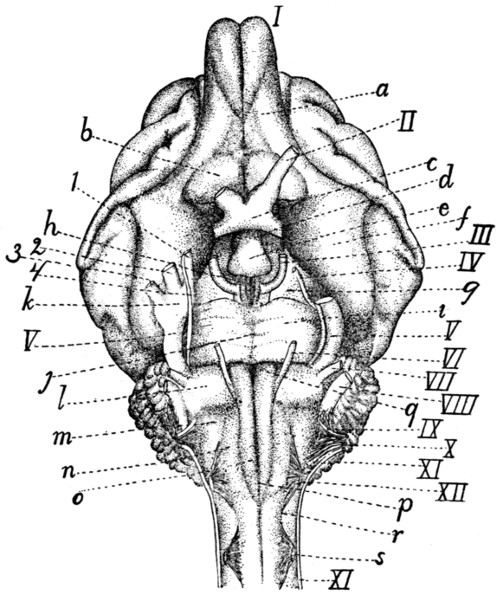

Brain, Ventral View |

342 |

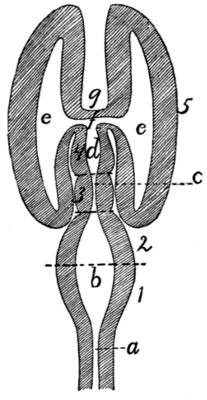

| 139. |

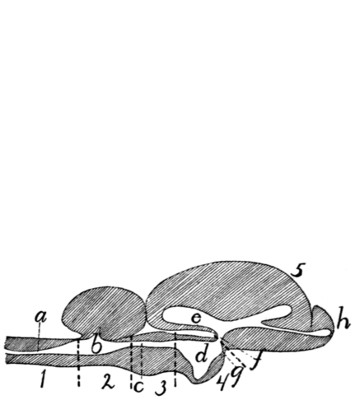

Diagram of Brain |

343 |

| 140. |

Diagram of Brain |

343 |

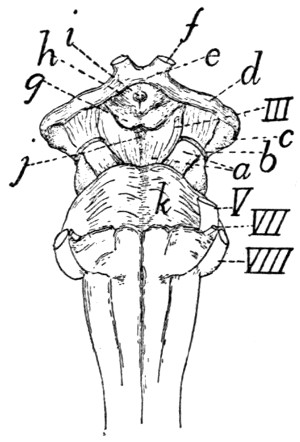

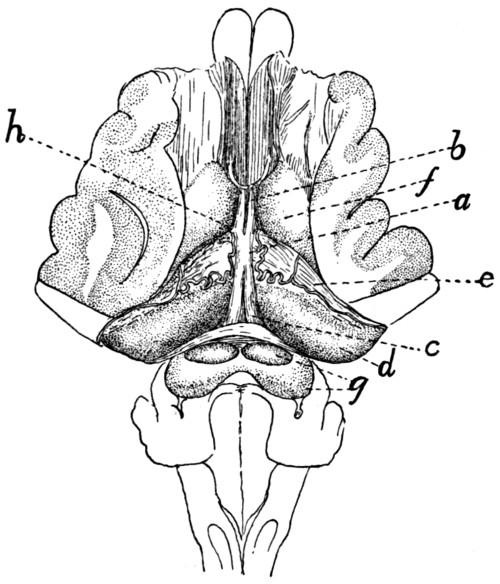

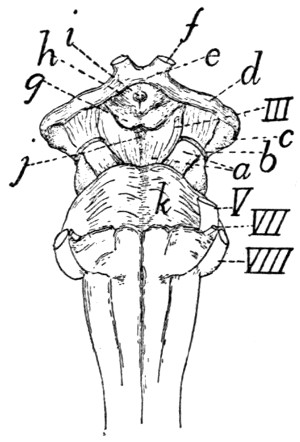

| 141. |

Dorsal View of Midbrain and ’Tween-brain |

350 |

| 142. |

Ventral View of Midbrain and ’Tween-brain |

352 |

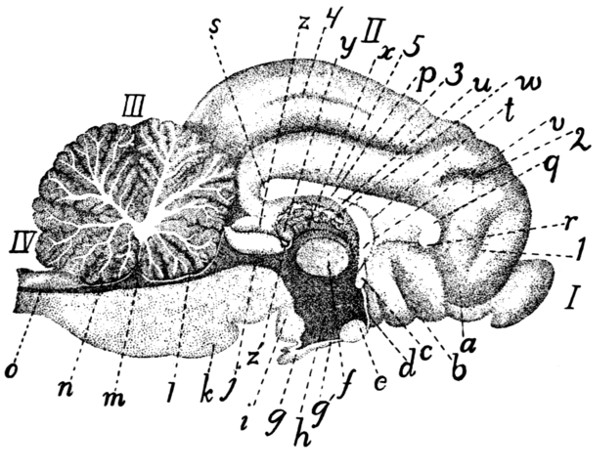

| 143. |

Longitudinal Section of Brain |

356 |

| 144. |

Lateral View of Brain |

358 |

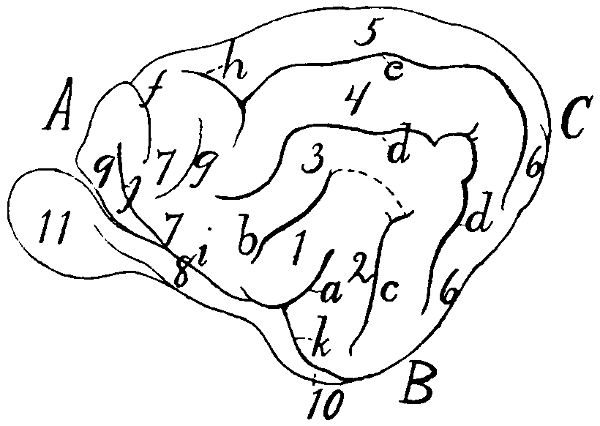

| 145. |

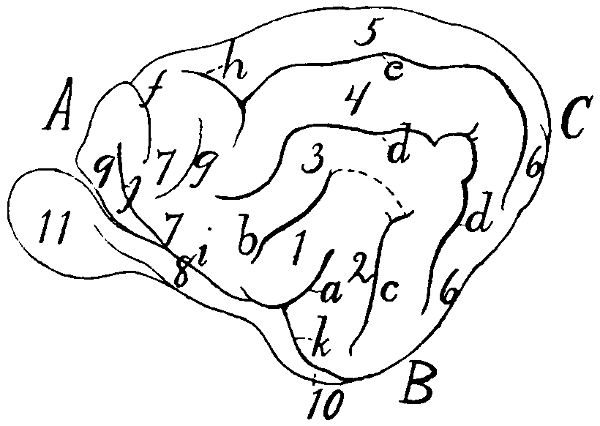

Diagram of Sulci and Gyri |

359 |

| 146. |

Diagram of Sulci and Gyri |

361 |

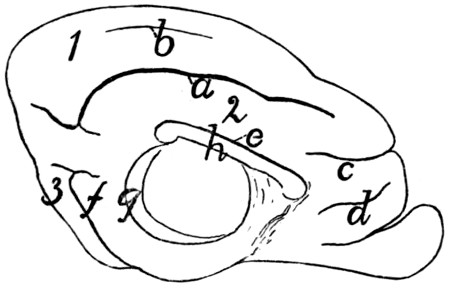

| 147. |

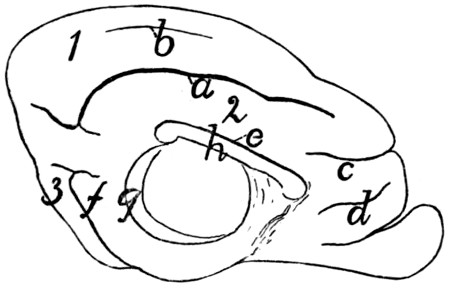

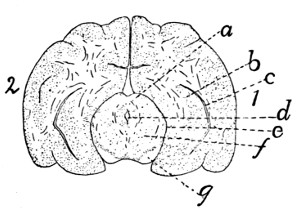

Corpus Callosum |

363 |

| 148. |

Fornix, Hippocampus, and Corpus Striatum |

364 |

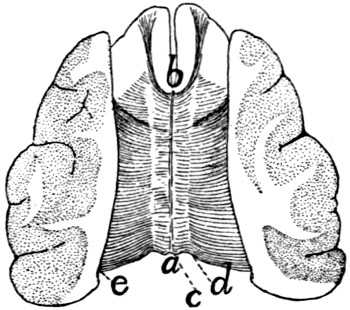

| 149. |

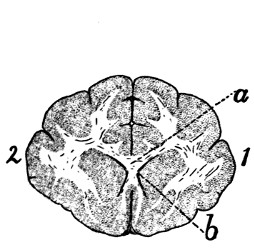

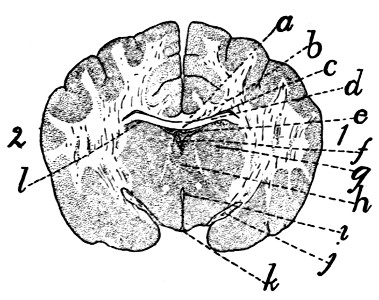

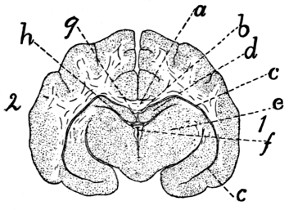

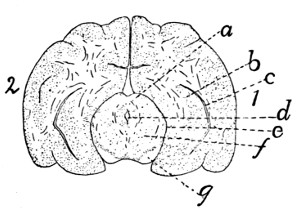

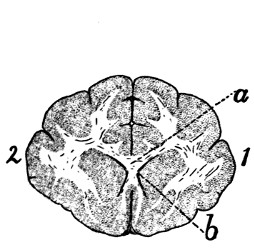

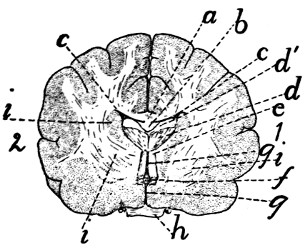

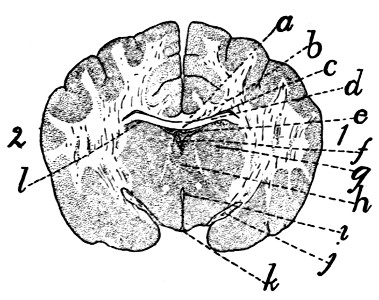

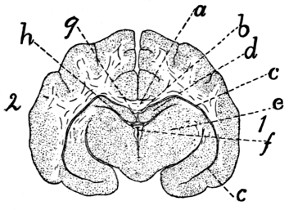

Transverse Section of Brain |

366 |

| 150. |

Transverse Section of Brain |

366 |

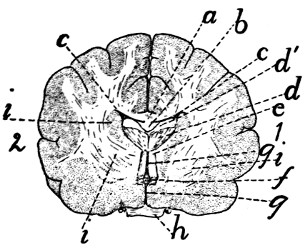

| 151. |

Transverse Section of Brain |

366 |

| 152. |

Transverse Section of Brain |

367 |

| 153. |

Transverse Section of Brain |

367 |

| 154. |

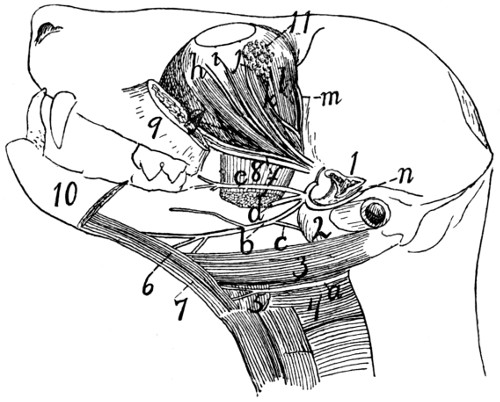

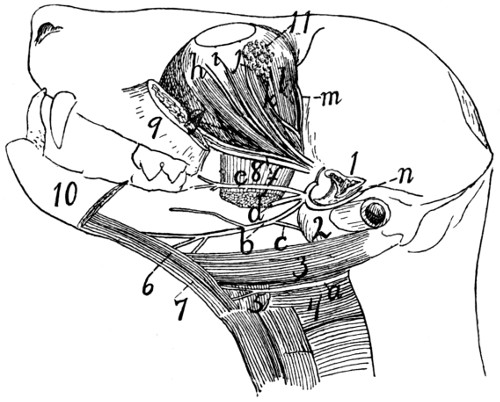

Cranial Nerves |

374 |

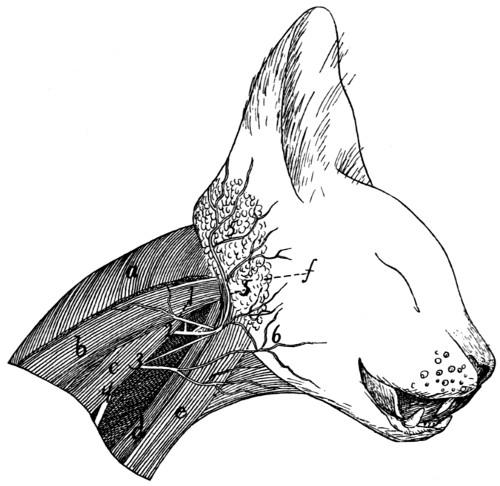

| 155. |

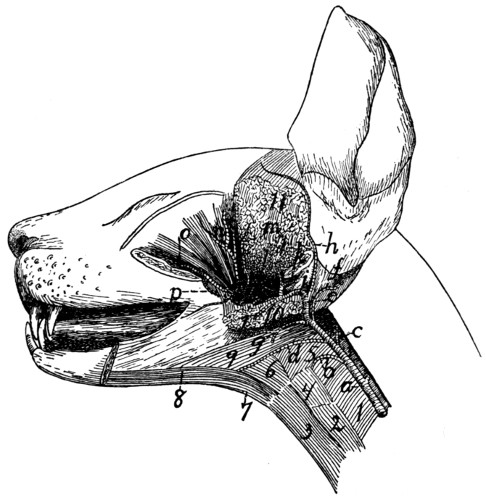

Nerves of Face |

376 |

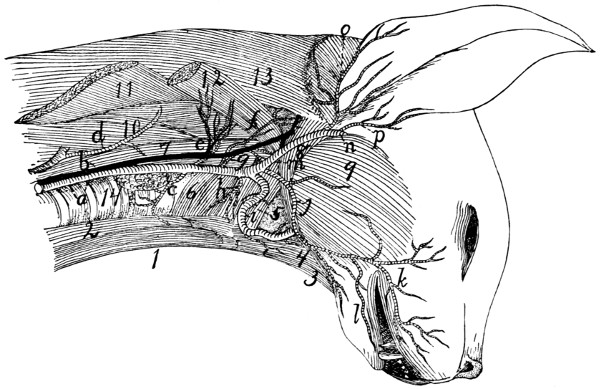

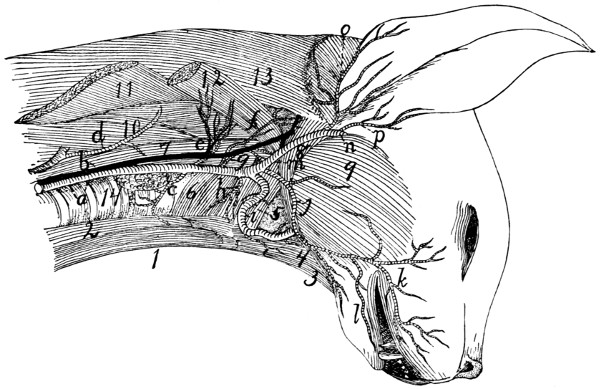

| 156. |

Cranial Nerves in the Neck |

379 |

| 157. |

Sympathetic and Vagus in the Thorax |

381 |

| 158. |

Nerves of the Neck |

384 |

| 159. |

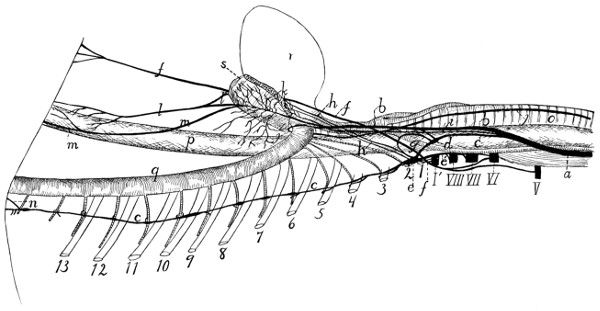

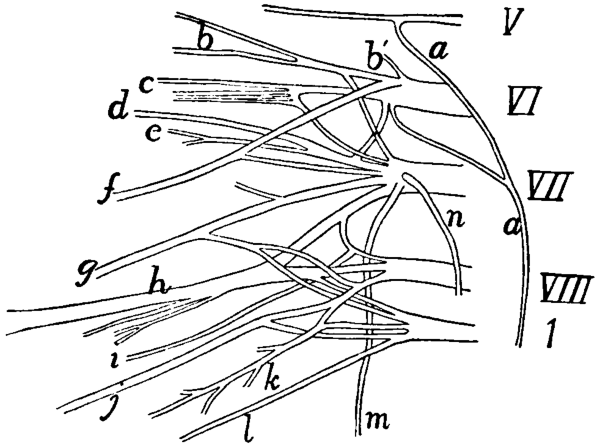

Brachial Plexus |

387 |

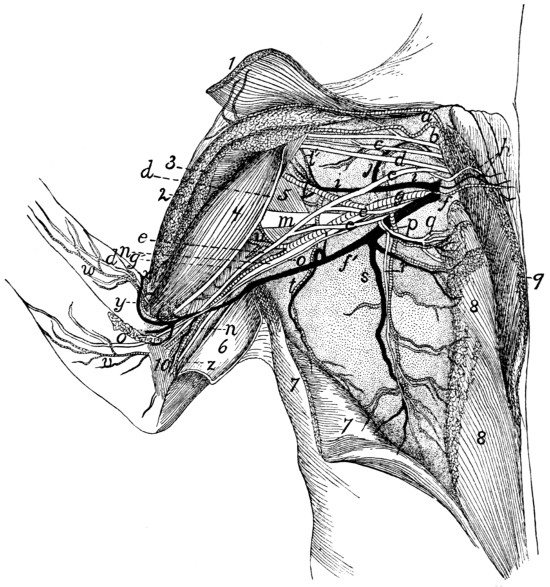

| 160. |

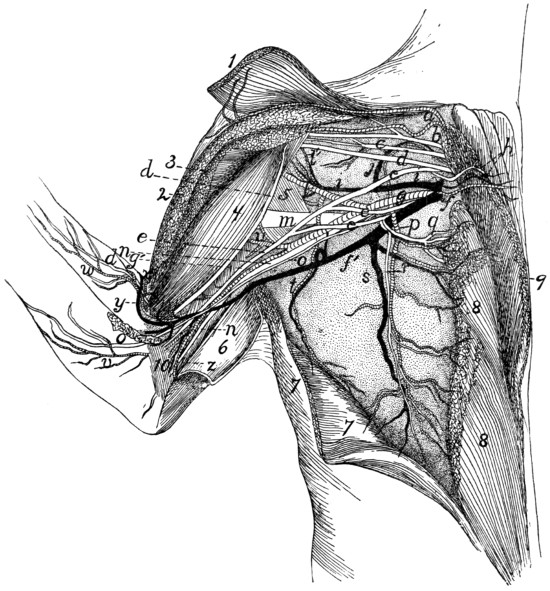

Nerves and Vessels of Axilla |

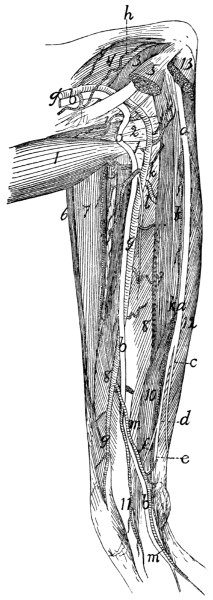

389 |

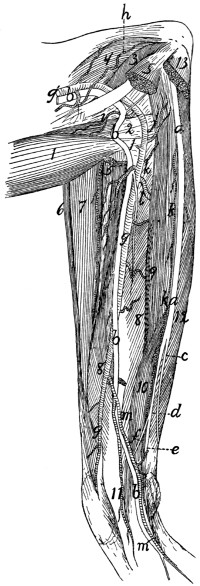

| 161. |

Nerves and Vessels of Forearm |

391 |

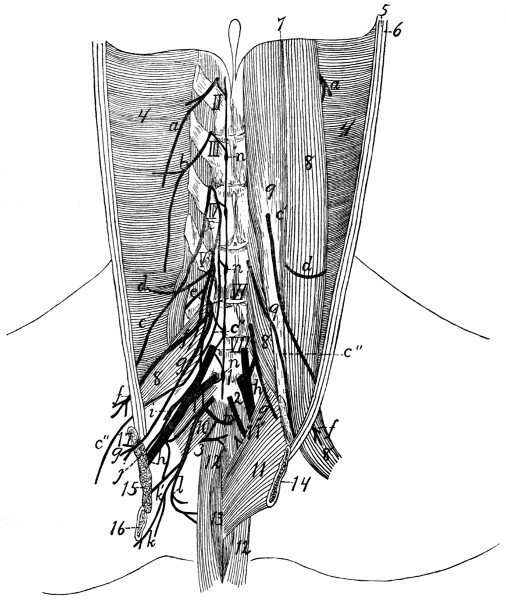

| 162. |

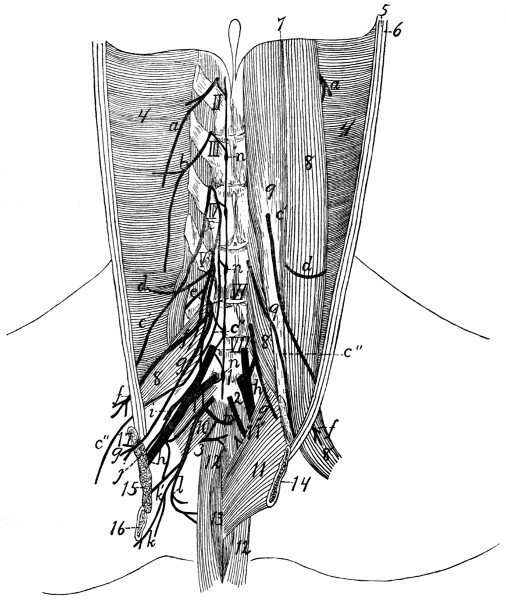

Lumbar and Sacral Nerves |

398 |

| 163. |

Great Sciatic Nerve |

401 |

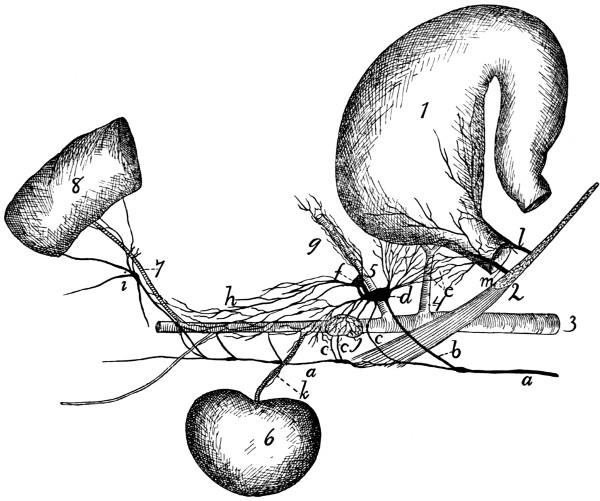

| 164. |

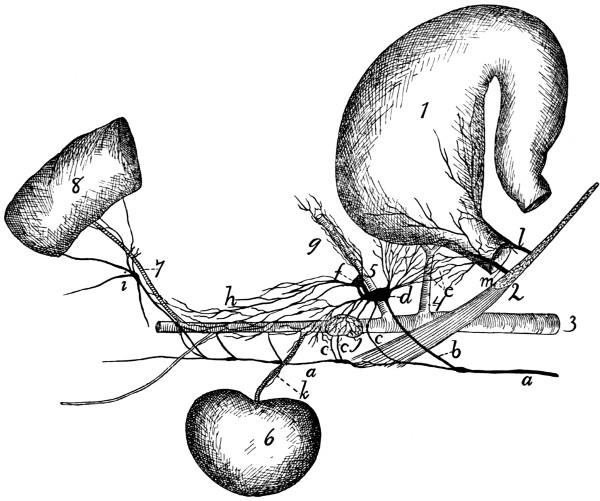

Sympathetic and Vagus in Abdomen |

407 |

| 165. |

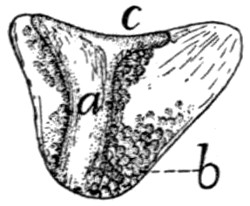

Nictitating Membrane |

410 |

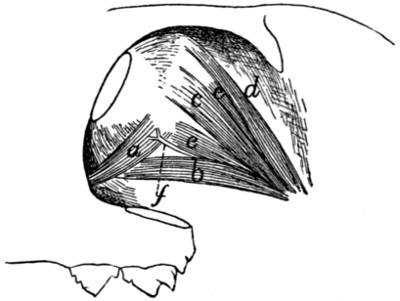

| 166. |

Muscles of Eyeball |

411 |

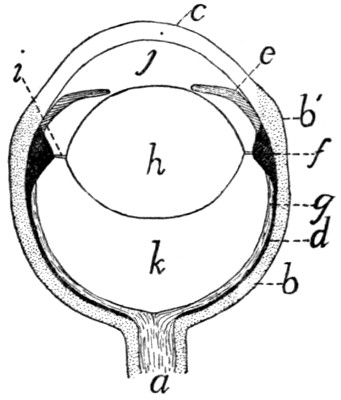

| 167. |

Diagram of Eye |

413 |

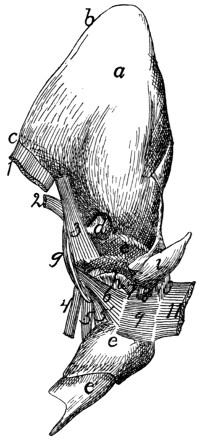

| 168. |

Cartilage of External Ear |

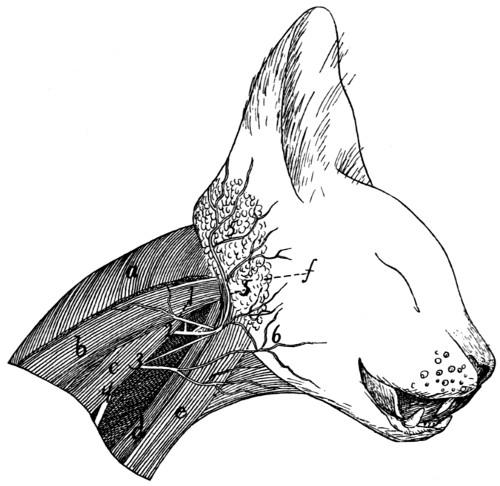

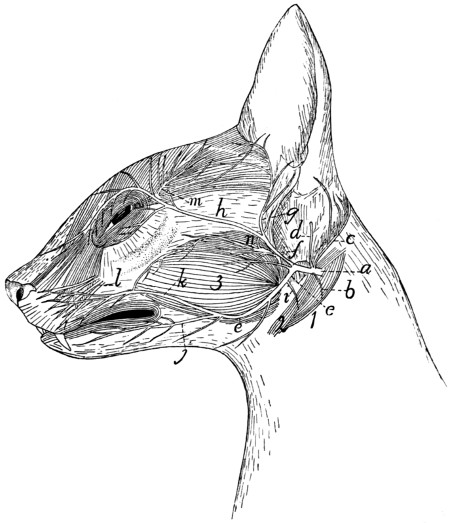

417 |

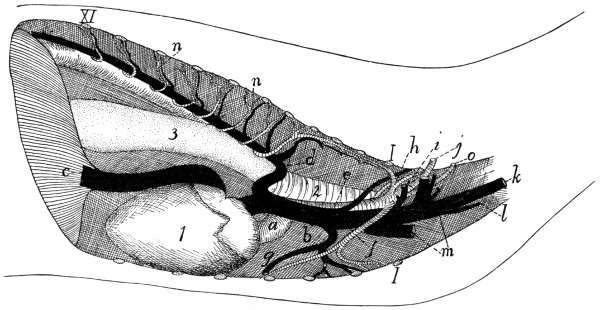

| 169. |

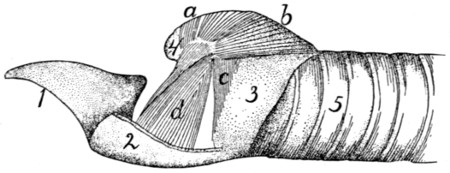

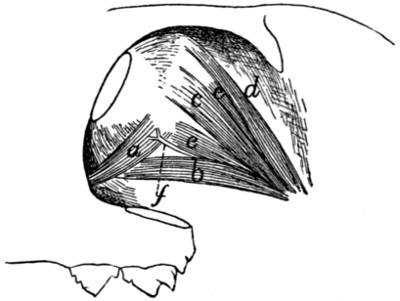

Muscles of External Ear |

419 |

| 170. |

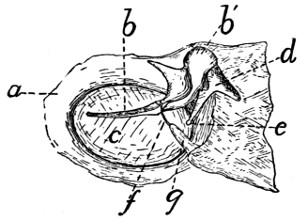

Tympanic Membrane |

422 |

| 171. |

Malleus and Incus |

423 |

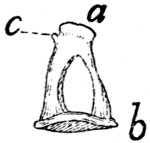

| 172. |

Stapes |

424 |

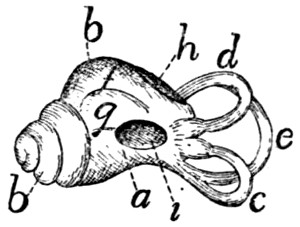

| 173. |

Membranous Labyrinth |

425 |

[1]

ANATOMY OF THE CAT.

THE SKELETON OF THE CAT.

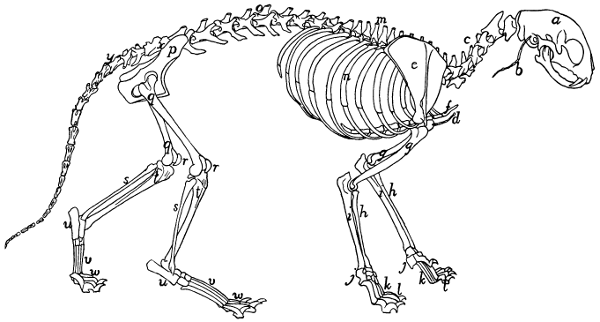

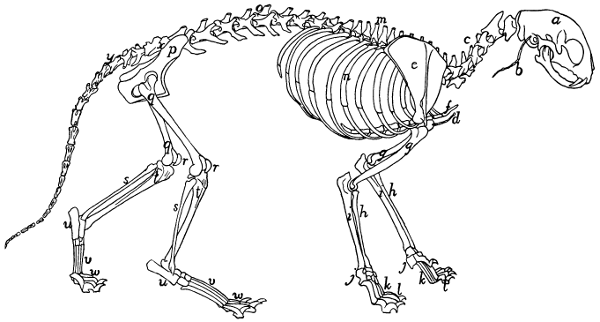

The skeleton of the cat consists of 230 to 247 bones exclusive

of the sesamoid bones (44) and the chevron bones (8).

These are divided as follows: head 35-40, vertebral column

52-53, ribs 26, sternum 1-8, pelvis 2-8, upper extremities 62,

lower extremities 54-56. The number of bones varies with

the age of the individual, being fewer in the old than in the

young animal, owing to the fact that in an old animal some

bones that were originally separate have united.

I. THE VERTEBRAL COLUMN. COLUMNA VERTEBRALIS.

The vertebral column, spinal column, or back-bone, consists

of a varying number of separate bones, the vertebræ. At its

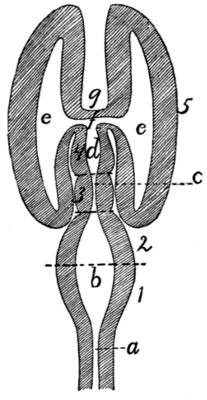

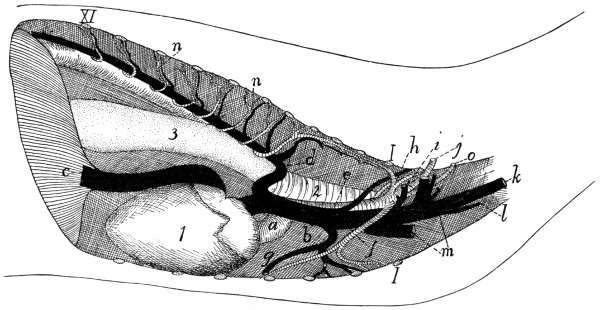

cranial end are seven vertebræ (cervical, Fig. 1, c) which are

without ribs and support the head; caudad of these are thirteen

rib-bearing vertebræ (thoracic, Fig. 1, m); caudad of these are

seven that are again without ribs (lumbar, Fig. 1, o); these

are followed by three vertebræ (sacral, Fig. 1, x) which are

united into a single bone, the sacrum, which supports the

pelvic arch. Following the sacral vertebræ are twenty-two

or twenty-three small ribless vertebræ which support the tail

(caudal, Fig. 1, y).

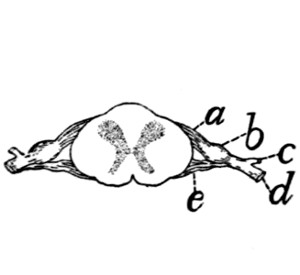

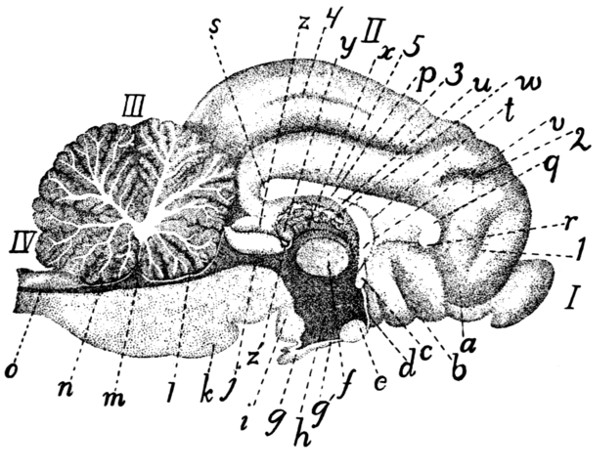

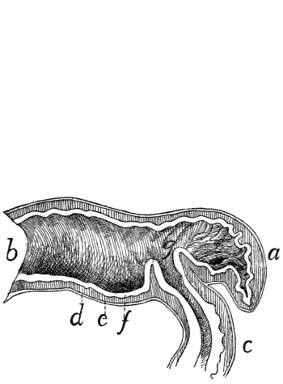

Fig. 1.—Skeleton of Cat.

a, skull; b, hyoid; c, cervical vertebræ; d, clavicle; e,

scapula; f, sternum; g, humerus; h, radius; i, ulna; j, carpus; k, metacarpus;

l, phalanges; m, thoracic vertebræ; n, ribs; o, lumbar vertebræ; p, innominate

bones; q, femur; r, patella; s, fibula; t, tibia; u, tarsus; v,

metatarsus; w, phalanges; x, sacrum; y, caudal vertebræ.

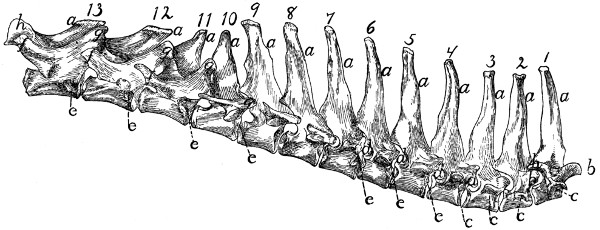

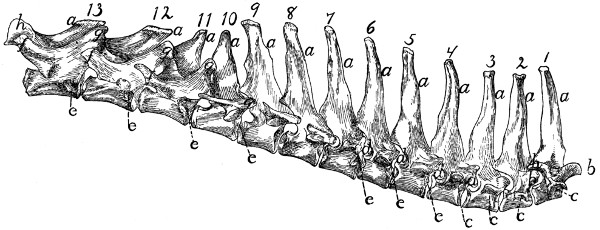

Thoracic Vertebræ. Vertebræ thoracales

(Fig. 4).—The

thoracic vertebræ are most typical, and the fourth one of these

may therefore be first described (Figs. 2 and 3). It forms an

oval ring which has numerous processes and surrounds an

opening which is the vertebral foramen (a). The ventral one-third[2]

[3]

of this ring is much thickened and forms the centrum or

body (corpus) (b) of the vertebra. The centrum is a semicylinder,

the plane face of which bounds the vertebral canal,

while the curved surface is concave longitudinally and is

directed ventrad. The dorsal plane surface of the centrum is

marked by a median longitudinal ridge on either side of which

is an opening (nutrient foramen) for a blood-vessel. The

ends are nearly plane, the caudal being slightly concave; they

are harder and smoother than the other surfaces. They may

be easily separated in a young specimen as thin plates of bone

known as epiphyses.

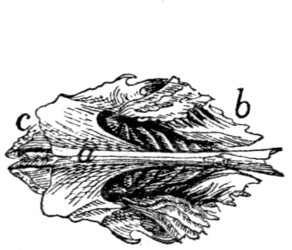

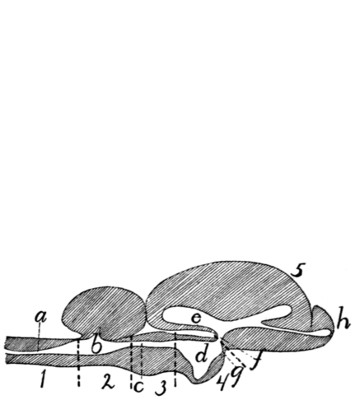

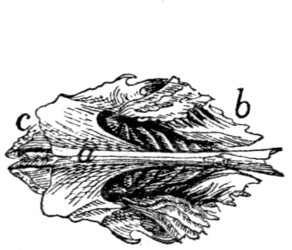

Fig. 2.—Fourth Thoracic Vertebra,

Cranial End.

Fig. 3.—Fourth Thoracic Vertebra,

Side View.

a, vertebral foramen; b, centrum; c,

caudal, and d, cranial, costal demifacets;

e, radix or pedicle; f, lamina; g, transverse process; h, cranial articular facet; i,

caudal articular facet; j, caudal articular process; k, spinous process.

At the caudal end of the centrum, at its dorsolateral angle,

is a smooth area on each side continuous with the surface of the

epiphysis and bounded dorsolaterally by a sharp ridge of bone

(c). It is a costal demifacet. In corresponding positions at

the cranial end of the centrum are two demifacets not limited

by bony ridges (d). When the centra of two contiguous

thoracic vertebræ are placed together in the natural position the

cranial costal demifacets of one together with the caudal demifacets

of the other form two costal facets (Fig. 4, e), one on

each side, and each receives the head of a rib.

The dorsal two-thirds of the vertebral ring forms the vertebral

arch which is continued dorsally into the long, bluntly

pointed spinous process (Figs. 2 and 3, k) for attachment of

muscles.

[4]

The vertebral arch (each half of which is sometimes called

a neurapophysis) rises on each side from the cranial two-thirds

of the dorsolateral angle of the centrum, as a thickened portion,

the radix or pedicle (Figs. 2 and 3, e), which forms the

ventral half of the lateral boundary of the vertebral canal.

From the dorsal end of each radix a flat plate of bone, the

lamina (f), extends caudomediad to join its fellow of the

opposite side and form the vertebral arch. Owing to the fact

that the radix rises from only the cranial two-thirds of the

centrum there is left in the caudal border of the vertebral arch

a notch bounded by the radix, the lamina, and the centrum.

There is also a slight excavation of the cranial border of the

radix. When the vertebræ are articulated in the natural position,

these notches form the intervertebral foramina (Fig. 4,

d), for the exit of the spinal nerves.

At the junction of radix and lamina the arch is produced

craniolaterad into a short process, the transverse process (g),

knobbed at the end. On the ventral face of its free end the

transverse process bears a smooth facet, the transverse costal

facet or tubercular facet (Fig. 4, c), for articulation with the

tubercle of a rib.

On the dorsal face of each lamina at its cranial border is a

smooth oval area, the cranial articular facet (superior articular

facet of human anatomy) (Figs. 2 and 3, h). Its long axis is

oblique and it looks dorsolaterad. The slight projections of

the cranial edge of the laminæ on which the facets are situated

are the inconspicuous cranial articular processes (prezygapophyses).

On the ventral surface of each lamina at the caudal border,

near the middle line is a similar area, the caudal articular

facet (inferior articular facet of human anatomy) (i); these

occupy the ventral surfaces of two projections which form the

caudal (inferior) articular processes (postzygapophyses) (j).

These are separated by a median notch. When the vertebræ

are in their natural position the caudal articular facets lie dorsad

of the cranial facets and fit against them. They thus strengthen

the joint between contiguous vertebræ, while permitting slight

rotary motion.

[5]

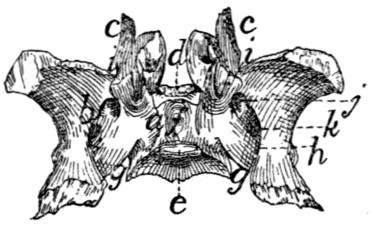

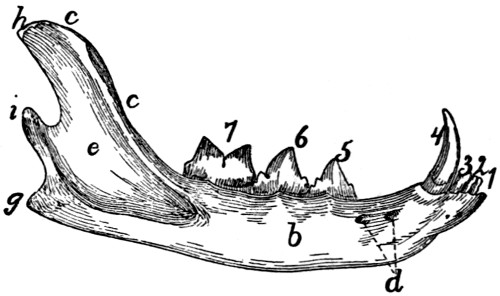

Fig. 4.—Thoracic Vertebræ,

Side View.

a, spinous processes; b, cranial articular processes;

c, transverse costal facets; d, intervertebral

foramina; e, costal facets; f, accessory processes; g, mammillary processes;

h, caudal articular processes.

Differential Characters of the Thoracic Vertebræ (Fig. 4).—Following

the thoracic vertebræ caudad there is to be seen

a gradual increase in the size of the centra brought about by

an increase in their craniocaudal and transverse measurements.

The dorsoventral measurements remain nearly the same.

The costal facets (Fig. 4, e) shift caudad so that on the

eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth thoracic vertebræ each lies

entirely on the cranial end of its centrum, while the caudal end[6]

of the centrum immediately preceding is not marked by any

part of it. In the eleventh thoracic vertebra each costal facet

is usually still confluent with the smooth cranial end of the

centrum. In the twelfth vertebra the facets are separated by

smooth ridges from the cranial end of the vertebra, while in

the thirteenth vertebra they are separated by rough ridges.

The spinous processes (a) of the first four are of about the

same length. They then decrease in length to the twelfth,

while the twelfth and thirteenth are slightly longer than the

eleventh. The first ten slope more or less caudad, while the

spinous process of the tenth (anticlinal) vertebra is vertical

and those of the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth point craniad.

Each of the transverse processes of the seventh thoracic

vertebra shows a tendency to divide into three tubercles; one

of these is directed craniad, the mammillary process (or metapophysis),

one caudad, the accessory process (or anapophysis),

while the third (transverse process proper) looks ventrad and

bears the transverse costal facet. This division becomes

more prominent in the succeeding vertebræ, being most

marked in the ninth and tenth. In the eleventh, twelfth, and

thirteenth vertebræ the mammillary (g) and accessory (f)

processes are very pronounced, while the transverse costal

facet and that part of the transverse process which bears it have

disappeared. The ribs of the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth

vertebræ are thus attached to their respective centra by their

heads alone.

The cranial articular processes (b) are prominent on the

first two thoracic vertebræ; back of these they are very small

as far as the eleventh, so that the articular facets seem to be

borne merely upon the dorsal surface of the cranial edge of the

laminæ. In the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth the cranial

articular processes are large, bearing the articular facets on

their medial surfaces, while the mammillary processes appear

as tubercles on the lateral surfaces of the articular processes.

The caudal articular processes (h) are prominent in the first

thoracic, then smaller until the tenth is reached; in the tenth,

eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth they are large and their facets

are borne laterally, so as to face the corresponding cranial[7]

facets. Thus from the tenth to the thirteenth thoracic vertebra

rotary motion is very limited, owing to the interlocking of the

articular processes.

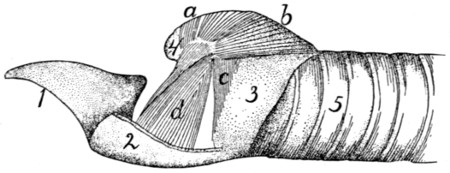

The Lumbar Vertebræ. Vertebræ lumbales

(Fig. 5).—The

last thoracic vertebræ form the transition to the typical

lumbar vertebræ. These are larger than the thoracic vertebræ.

The centra are of the form of the centra of the thoracic vertebræ,

and increase in length to the sixth, but the seventh is about

the length of the first. They increase in breadth to the last.

Fig. 5.—Lumbar Vertebræ.

a, cranial articular processes; b,

mammillary processes; c, caudal articular processes; d, accessory

processes; e, transverse processes; f, spinous processes.

[8]

The cranial articular processes (Fig. 5, a) are prominent

and directed craniodorsad; they have the facets on their

medial surfaces, while their dorsolateral surfaces bear the

mammillary processes (b) as prominent tubercles. The caudal

articular processes (c) are likewise large; their facets look

laterad. When the vertebræ are articulated they are received

between the medially directed cranial processes.

The accessory processes (d) are well developed on the

first vertebra, diminish in size to the fifth or sixth, and are

absent on the seventh and sometimes on the sixth.

The transverse processes (more properly pseudo-transverse

processes) (e) arise from the lateral surface of the centra; are

flat and are directed ventrocraniolaterad. The first is small,

and they increase in length and breadth from the first to the

sixth, those of the last being slightly smaller than in the sixth.

The free ends of the last four are curved craniad.

The spinous processes (f) are flat and directed craniodorsad.

They increase in length to the fifth and then decrease.

The first five are knobbed at the end. In a dorsal view the

spinous process and cranial articular processes of each vertebra

are seen to interlock with the caudal articular processes and

accessory processes of the preceding vertebra in such a way as

to prevent rotary motion, and this arrangement may be traced

craniad as far as the eleventh thoracic vertebra.

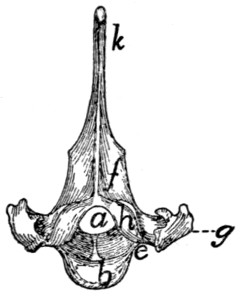

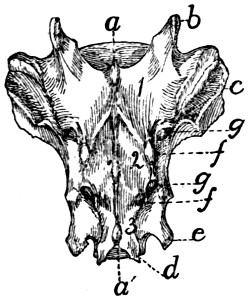

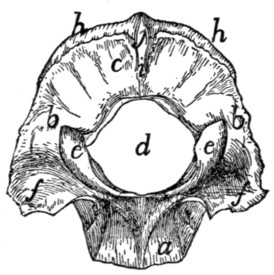

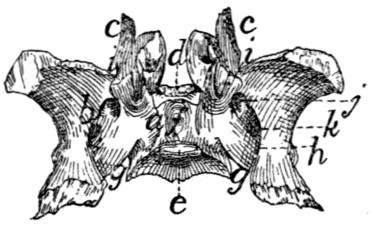

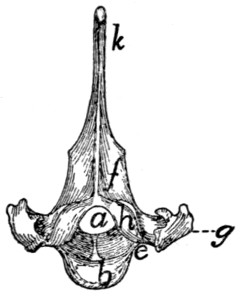

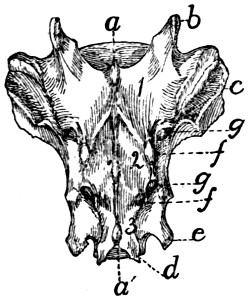

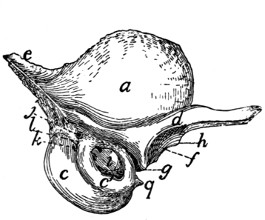

Sacral Vertebræ. Vertebræ sacrales

(Figs. 6 and 7).—The

three sacral vertebræ are united in the adult into a single

bone, the os sacrum, or sacrum. In a kitten the three vertebræ

are separate, while in an animal almost mature the first

two are united and the third is still separate. The sacrum lies

between the last lumbar and the first caudal vertebræ and

articulates laterally with the two innominate bones. It is

pyramidal, with the base of the pyramid directed craniad, and

is perforated by a depressed longitudinal canal, the sacral

canal, which is a continuation of the vertebral canal, and by

four large foramina dorsally and four ventrally. It may be

described as having a cranial end or base and a caudal end or

apex, a dorsal, a ventral, and two lateral surfaces.

The base is slightly oblique and presents a smooth transversely[9]

oval articular facet (the cranial end of the centrum of

the first sacral vertebra), for articulation with the centrum of

the last lumbar vertebra. Dorsad of this is the sacral canal,

more depressed than the vertebral arch craniad of it. It supports

a spinous process (Fig. 6, a) which is directed dorsad.

At the junction of its lamina and radix is seen the prominent

cranial articular process (b) with sometimes slight indications

of a mammillary process on its lateral surface. Laterad of the

articular facet is seen the cranial face of the expanded “pseudo-transverse

process” (c) of the first sacral vertebra. The

ventral border of the base is concave ventrad, forming an arc

of about 120 degrees. The apex shows the caudal end of the

last sacral centrum. Dorsad of this are the vertebral arch with

a very short spinous process (a′), and the caudal articular

processes (d). Laterad of the centrum appears the laterally

directed thin transverse process (e).

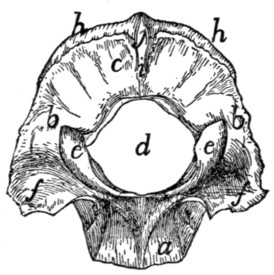

Fig. 6.—Sacrum, Dorsal Surface.

Fig. 7.—Sacrum, Ventral Surface.

Fig. 6.—1, 2, 3, the three sacral

vertebræ. a, a′, spinous processes; b, cranial

articular process of first sacral vertebra; c, expanded transverse process of first

sacral vertebra; d, caudal articular processes of third sacral vertebra; e, transverse

processes of third sacral vertebra; f, tubercles formed by fused articular processes

of the vertebræ; g, dorsal (or posterior) sacral foramina.

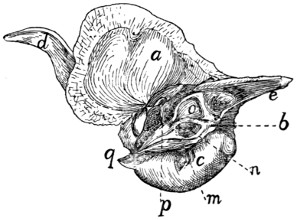

Fig. 7.—1, 2, 3, the three sacral

vertebræ. a, the transverse ridges formed by

the union of the centra; b, cranial articular processes of first vertebra; c, transverse

process of first vertebra; d, caudal articular processes of third vertebra; e, transverse

processes of third sacral vertebra; f, f′, ventral (or anterior) sacral foramina;

g, notch which helps to form third ventral sacral foramen.

The ventral or pelvic surface (Fig. 7) is smooth, concave

craniad, convex caudad, and crossed by two transverse ridges

(a) along which are seen the ossified remains of the intervertebral

fibro-cartilages. At the ends of the first ridge is a pair of

nearly circular ventral (or anterior) sacral foramina (f) for[10]

the passage of sacral nerves. At the end of the second ridge

is a pair of ventral sacral foramina (f′), smaller than the first

pair and continued laterocaudad into shallow grooves for the

ventral rami of the sacral nerves. That portion of the bone

lying laterad of a line joining the medial borders of these two

pairs of foramina is known as the lateral mass of the sacrum

and is composed of the fused transverse processes of the sacral

vertebræ. At the caudal margin of the ventral surface there

is a notch between the lateral mass and the centrum (g).

When the caudal vertebræ are articulated, this notch helps to

form a foramen for the third sacral nerve.

The dorsal surface (Fig. 6) is narrower at its cranial end

than is the ventral surface. Its cranial border bears laterally

a pair of cranial articular processes (b) with their medially

directed facets and between them it is concave, so that a large

dorsal opening is left into the vertebral canal between the last

lumbar vertebra and the sacrum. Caudad of the articular

processes are two pairs of tubercles (f). These are the fused

cranial and caudal articular processes of the sacral vertebræ.

Caudad of them are the caudal articular processes of the last

sacral vertebra (d). Craniolaterad of the middle and cranial

tubercles are dorsal (posterior) sacral foramina (g) for the

transmission of the dorsal rami of the sacral nerves. Three

spinous processes (a) appear between these rows of tubercles.

They decrease in height caudad. That part of the surface included

between the spinous process and the tubercles is made

up of the fused laminæ of the sacral vertebræ. That part

between the tubercles and a line joining the lateral margins of

the dorsal (posterior) sacral foramina is formed by the fused

radices of the sacral vertebræ.

The lateral surface may be divided into two parts. Craniad

is a large rough triangular area with equal sides and with one

of its angles directed ventrocraniad. It is the lateral face of

the pseudo-transverse process of the first sacral vertebra (Fig.

6, c). A smooth curved surface (the auricular facet) along its

ventral edge articulates with the ilium, while the dorsal portion

is rough for attachment of ligaments. Caudad is the

narrow longitudinal triangular area of the lateral faces of[11]

the fused transverse processes of the second and third sacral

vertebræ.

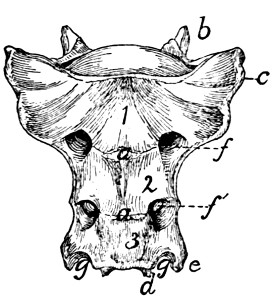

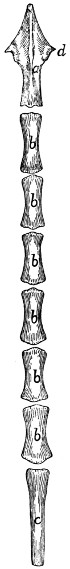

Caudal Vertebræ. Vertebræ caudales

(Fig. 1, y, and

Figs. 8 and 9).—The caudal vertebræ (21-23 in number)

decrease gradually in size to the last one. Caudad they

become longer and more slender

and lose the character of vertebræ.

They become finally reduced

to mere centra,—slender

rods of bone knobbed or enlarged

at their two ends (Fig. 8). The

last one is more pointed than the

others and bears at its caudal end

a small separate conical piece,

the rudiment of an additional

vertebra.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 8.—Caudal Vertebra, from near

the caudal end of the tail.

Fig. 9.—Fourth Caudal Vertebra,

ventral view. a, transverse processes;

b, cranial articular processes; c, hæmal

processes; d, chevron bone.

The parts of a typical vertebra—vertebral arch, transverse

processes, cranial and caudal articular processes—may be

recognized in the vertebræ as far back as the eighth or ninth.

The transverse processes (Fig. 9, a) are directed caudad and

decrease rapidly in length. They are very small on the ninth

vertebra, but may be recognized for a considerable distance

back of this. The spinous process disappears at about the

fourth caudal vertebra, and the vertebral canal becomes

gradually smaller caudad, until on the eighth or ninth vertebra

it becomes merely a groove open dorsad.

Caudad of the third vertebra for a considerable distance,

each centrum bears on each lateral face at its cranial end a

short anterior transverse process, and on its ventral face at its

cranial end a pair of rounded tubercles, hæmal processes (c),

which articulate with a small pyramidal chevron bone (d) so

as to enclose a canal. These structures disappear caudad.

Cervical Vertebræ. Vertebræ cervicales

(Fig. 10).—The

cervical vertebræ number seven. The first two of these are so

peculiar as to require a separate description, so that the last five

may be first considered.

Passing craniad from the fourth thoracic vertebra to the

third cervical there is a gradual transition. The centra of the[12]

cervical vertebræ are broader and thinner than those of the

thoracic vertebræ, while the vertebral arches and vertebral

canal are larger (Fig. 11). The caudal end of each centrum

is concave and looks dorsocaudad when the centrum is held

with its long axis horizontal. The cranial end of the centrum

is convex and looks ventrocraniad when the centrum is horizontal.

These peculiarities are more marked in the third

vertebra than in the seventh. The spinous processes grow

rapidly shorter as we pass craniad; the fifth, sixth, and seventh

are directed dorsocraniad, the third and fourth dorsad.

Fig.

10.—Cervical Vertebræ, Side View.

a, spinous processes; b, cranial articular processes; c, caudal articular facet; d,

intervertebral foramina; e, transverse process proper; f, processus costarius; g,

wing of the atlas; h, dorsal arch of the atlas; i, atlantal foramen.

The caudal articular processes are situated at the junction

of the radices and laminæ; their facets (Fig. 10, c) look

ventrocaudolaterad. The cranial articular processes also

become more prominent than is the rule in the thoracic vertebræ;

they are borne at the junction of radix and lamina and

have their facets (Fig. 11, b) directed dorsomediad. The

cranial and caudal articular processes of each side are joined

by a prominent ridge which is most pronounced in the third,

fourth, and fifth vertebræ.

The characteristic feature of the cervical vertebræ is their

transverse process, so called. In each of them it arises by

two roots, one from the centrum and one from the arch.[13]

These two roots, which are broad and thin, converge and unite

so as to enclose a canal or foramen, the foramen transversarium

(Fig. 11, g), for the vertebral artery. Laterad of the

foramen the two parts of the process are, in the third cervical,

almost completely united, the dorsal part being, however, distinguishable

as a tubercle at the caudolateral angle of the thin

plate formed by the process as a whole. This dorsal component

is the transverse process proper (Figs. 10 and 11, e),

while the ventral portion represents a rib, and is hence known

as the processus costarius (f). The expanded plate formed

by the union of these two processes is directed nearly ventrad

and somewhat craniad in the third, fourth, and fifth vertebræ.

The two components of the process gradually separate as we

pass caudad; in the fourth and fifth vertebræ the part which

represents the transverse process proper forms a very prominent

tubercle at the caudolateral angle of the plate formed by the

processus costarius. In the sixth (Fig. 11) the two parts are

almost completely separated; the dorsal part forms (e) a slender

knobbed process, while the processus costarius is divided into

two portions (f and f′) by a broad lateral notch. In the

seventh the ventral part (processus costarius) is usually quite

lacking, though sometimes represented by a slender spicule of

bone. In the former case the foramen transversarium is of

course likewise lacking.

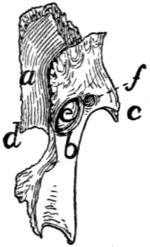

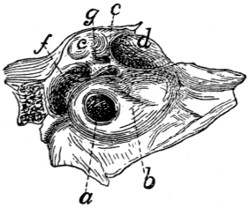

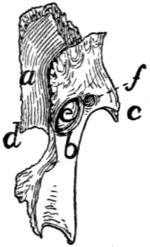

Fig. 11.—Sixth Cervical Vertebra,

Cranial End.

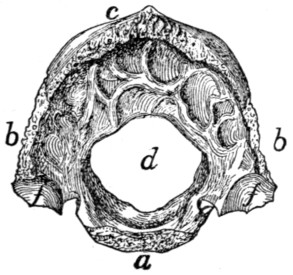

Fig. 12.—Atlas, Ventral View.

Fig. 11.—a, spinous process; b,

cranial articular facet; c, lamina; d, radix or

pedicle; e, transverse process proper; f, f′, processus costarius; g, foramen transversarium;

h, centrum; i, vertebral canal.

Fig. 12.—a, ventral arch; b, tuberculum

anterius; c, lateral masses; d, transverse

processes; e, cranial articular facets; f, groove connecting the foramen transversarium

with the atlantal foramen; g, atlantal foramen; h, caudal articular

facets.

[14]

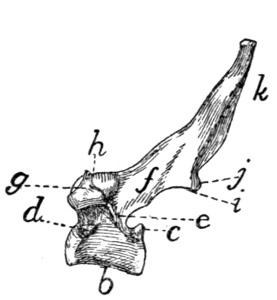

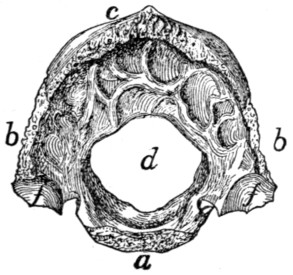

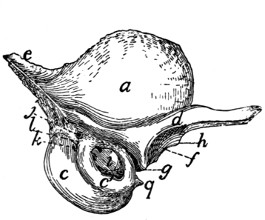

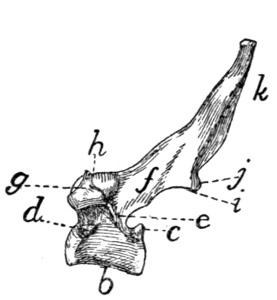

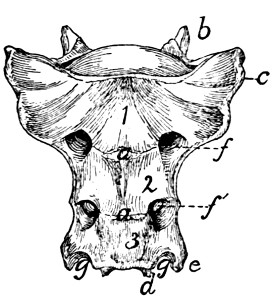

The Atlas (Fig. 10, 1;

Fig. 12).—The first cervical vertebra

or atlas has somewhat the form of a seal ring. The

centrum is absent; it has united with the second vertebra to

form the odontoid process or dens. Its place is taken in the

atlas by a narrow flat arch of bone, narrower at the ends than

in the middle, the ventral arch (Fig. 12, a) of the atlas. This

connects the lateral, thicker portions of the ring ventrally and

bears on its caudal margin a blunt tubercle (tuberculum

anterius, Fig. 12, b). Laterally the ring is thickened, forming

thus the lateral masses (c) which are continued into the broad

thin transverse processes (Fig. 10, g; Fig. 12, d). Each

lateral mass bears at its cranial end on its medial surface a

concave, pear-shaped facet, cranial (or superior) articular facet,

(Fig. 12, e) for articulation with the condyles of the skull.

These facets look craniomediad. Dorsad of each is a foramen,

the atlantal foramen (Fig. 10, i; Fig. 12, g), which pierces

the dorsal arch at its junction with the lateral mass. Caudal

to the facet, on the medial face of each lateral mass, within the

vertebral canal, is a tubercle. To the two tubercles are

attached the transverse ligament (Fig. 14, b) which holds in

place the odontoid process (dens) of the axis.

That part of the lateral mass which bears the articular facet

projects craniad of the dorsal arch and is separated by a deep

triangular notch from the transverse process. Along the

bottom of this notch runs a groove (Fig. 12, f), convex

craniad, which connects the cranial end of the foramen transversarium

and the atlantal foramen. The vertebral artery

passes along it. The foramen transversarium is circular. It

is bounded laterally by the lateral masses, and dorsally by the

dorsal arch.

The dorsal arch (Fig. 10, h) is two to three times as broad

as the ventral, has a thick convex cranial border with a median

notch, and a thin concave caudal border.

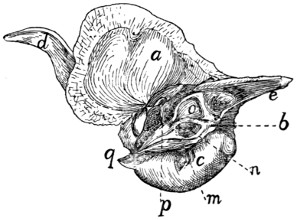

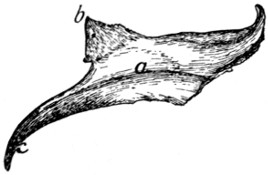

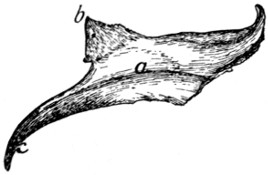

Fig. 13.—Axis or Epistropheus,

Side View.

a, odontoid process or

dens; b, cranial articular

facets; c, spinous process;

d, caudal articular facet;

e, transverse process; f,

foramen transversarium.

The caudal articular facets (Fig. 12, h) are borne by the

caudal ends of the lateral masses. They are slightly concave,

triangular, and look caudomediad, so that their dorsal borders

form with the caudal border of the dorsal arch nearly a semicircle.

The transverse processes are flat and directed laterad.[15]

The attached margin of each is about two-thirds the length of

the thinner free margin. The somewhat thicker caudal end

of the transverse process projects further caudad than any other

part of the vertebra and is separated by a slight notch from the

caudal articular facet. From the bottom of this notch the

foramen transversarium extends craniad and opens at the

middle of the ventral face of the transverse process.

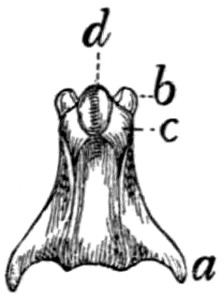

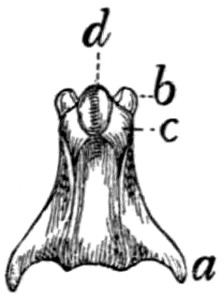

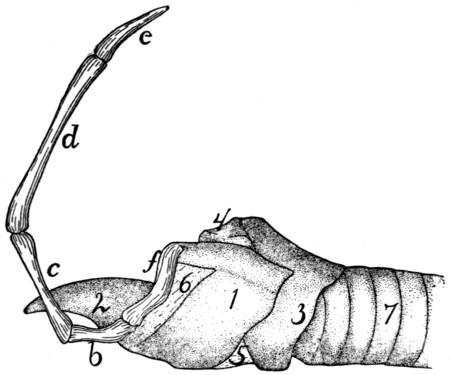

Epistropheus or Axis (Fig. 10, 2;

Fig. 13).—The second

cervical vertebra (epistropheus or axis) is not so wide as the

atlas but is much longer. Craniad the centrum is continued

into a slender conical, toothlike projection,

the dens or odontoid process (Fig.

13, a) which represents the centrum of the

atlas. The dens is smooth below for

articulation with the ventral arch of the

atlas. It is rougher above. Laterad of

the dens the centrum bears a pair of large

cranial articular facets (b) which look

craniolaterad. These have each the form

of a right-angled triangle with rounded

angles, one side of the triangle being

nearly horizontal. Each is separated from

the articular face of the dens by a roughened groove. The

spinous process (c) runs the length of the vertebral arch. It

extends craniad of the vertebral arch nearly as far as the dens,

as a flat rounded projection. Caudad of the vertebral arch it

projects for a short distance as a stout triangular spine. The

caudal articular facets (d) are borne on thickenings of the

caudolateral portions of the arch; they face almost directly

ventrad. The transverse process (e) is slender and triangular

and directed nearly caudad. Its apex reaches no farther than

the caudal or articular face of the centrum. Its base is traversed

by the foramen transversarium (f).

Differential Characters of the Cervical Vertebræ.—It is

possible to identify each of the cervical vertebræ:

The first by the absence of the centrum.

The second by the dens or odontoid process.

The third by the small spinous process and slightly marked[16]

tubercle of the transverse process, and by a median tubercle on

the cranial border of the vertebral arch.

The fourth by the spinous process directed dorsad, and the

short thick tubercle of the transverse process not trifid.

The fifth by the spinous process directed craniad, and the

more slender spine-like tubercle of the transverse process not

trifid.

The sixth by the trifid transverse process.

The seventh by the long spinous process and the slender

simple transverse process, and by the usual absence of the

foramen transversarium.

LIGAMENTS OF THE VERTEBRAL COLUMN.

Fibro-cartilagines intervertebrales.—The separate vertebræ

(except the atlas and axis) are united by the disk-shaped

intervertebral fibro-cartilages, which are situated between the

centra of the vertebræ. Each consists of a central pulpy portion

and a fibrous outer portion, covered by strong intercrossing

tendinous fibers which unite with the periosteum of the

vertebræ.

Ligamentum longitudinale anterius.—On the ventral

face of the centra of the vertebræ, from the atlas to the

sacrum, lies a longitudinal ligament, the anterior longitudinal

ligament. It is very small, almost rudimentary, in the cervical

region: large and strong in the thoracic and lumbar regions.

Ligamentum longitudinale posterius (Fig. 14, a).—A

corresponding ligament (posterior longitudinal ligament) lies

on the dorsal surface of the centra (therefore within the vertebral

canal). It is enlarged between each pair of vertebræ and

closely united to the intervertebral fibro-cartilages.

Ligamentum supraspinale.—Between the tips of the

spinous processes of the thoracic and lumbar vertebræ extend

ligamentous fibers. They are not united to form a distinct

band, and can hardly be distinguished from the numerous

tendinous fibers of the supraspinous muscles. Together they

represent the supraspinous ligament. From the tip of the

spinous process of the first thoracic vertebra to the caudal end

of the spine of the axis extends a slender strand representing[17]

the ligamentum nuchæ or cervical supraspinous ligament.

It is imbedded in the superficial muscles of this region, some

of which take origin from it.

Ligamentous fibers are also present between the spinous

processes of the vertebræ (ligamenta interspinalia): between

the transverse processes (ligamenta intertransversaria), and

between the vertebral arches (ligamenta flava).

Capsulæ articulares.—The joints between the articular

processes are furnished with articular capsules attached about

the edges of the articular surfaces. These are larger and looser

in the cervical region.

Atlanto-occipital Articulation.—The joint between the

atlas and the occipital condyles has a single articular capsule,

which is attached about the borders of the articular surfaces of

the two bones. This capsule is of course widest laterally,

forming indeed two partially separated sacs, which are, however,

continuous by a narrow portion across the ventral middle

line. This capsule communicates with that which covers the

articular surface of the dens, and through this with the capsule

between the atlas and axis. That portion of the capsule which

covers the space between the ventral arch of the atlas and the

occipital bone represents the anterior atlanto-occipital membrane;

it is strengthened by a slender median ligamentous

strand. The posterior atlanto-occipital membrane covers in

the same way the space between the dorsal arch of the atlas and

the dorsal edge of the foramen magnum. In it a number of

different sets of fibers, with regard to direction and to degree

of development, may be distinguished; these have sometimes

been considered separate ligaments.

The lateral ligaments of the atlas begin at the lateral

angle of the cranial margin of the atlas, at about the junction

of its dorsal and ventral arches, and pass cranioventrad to the

jugular processes.

Articulation between the Axis and Atlas.—The articular

capsule is large and loose, being attached to dorsal and ventral

borders of the atlas, about the articular surfaces of the axis,

and to the cranial projection of the spine of the atlas. It also

passes craniad along the ventral side of the dens and communicates[18]

here with the capsule of the atlanto-occipital articulation.

In the dorsal part of the capsule a short

strong ligamentous strand is developed,

connecting the caudal border of the dorsal

arch of the atlas with the tip of the

cranial projection of the spinous process

of the axis.

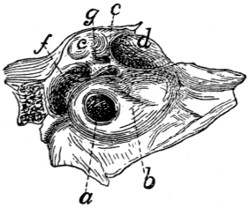

Fig. 14.—Ligaments of

the Odontoid Process

or Dens.

First three cervical vertebræ

and base of the skull,

with dorsal surface removed.

a, ligamentum

longitudinale posterius; b,

transverse ligament of the

atlas; c, ligamenta alaria;

d, odontoid process; e, occipital

condyles; 1, 2, 3,

the first three cervical vertebræ;

4, basal portion of

the occipital bone.

The dens or odontoid process is

held in place by the transverse ligament

(Fig. 14, b) of the atlas, which

passes across the process as it lies within

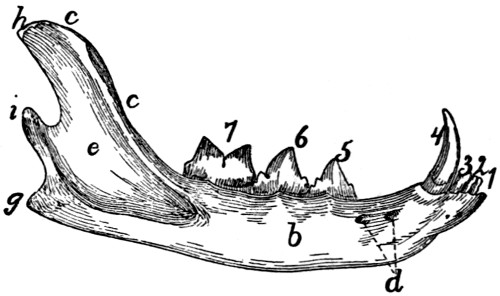

the vertebral canal of the atlas. The

transverse ligament is attached at its

two ends to the medial surface of the

sides of the atlas at about the region

where the dorsal and ventral arches of

the atlas unite.

From the cranial end of the odontoid

process the two ligamenta alaria (Fig.

14, c) diverge craniolaterad to the rough

ventromedial angle of the condyles of

the occipital bone.

II. RIBS. COSTÆ (Figs. 1 and 15.)

The cat has thirteen pairs of ribs. One of the fifth pair

(Fig. 15) may be taken as typical. It is a curved flattened rod

of bone attached at its dorsal end to the vertebral column,

and at its ventral end to a cartilage (costal cartilage, Fig.

15, f) which serves to unite it to the sternum.

The most convex portion of the bone is known as the

angle (e). Each rib presents a convex lateral and a concave

medial surface, a cranial and a caudal border. The

borders are broad dorsad and narrow ventrad, while the surfaces

are narrow dorsad and broad ventrad. The rib has thus

the appearance of having been twisted.

The rib ends dorsad in a globular head or capitulum (a),

by which it articulates with the costal demifacets of two contiguous

thoracic vertebræ. Between the capitulum and angle[19]

on the lateral surface is an elevated area, the tubercle, marked

by the smooth tubercular facet (c) for articulation with the

transverse process of a vertebra.

The constricted portion between the

head and tubercle is known as the

neck (collum) (d). The angle is

marked by a projecting process (e)

(angular process) on its lateral border,

for attachment of a ligament.

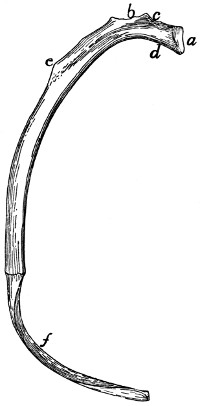

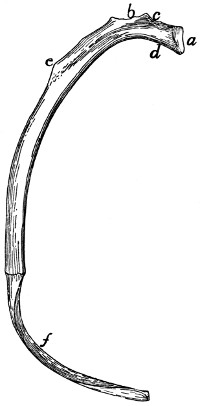

Fig. 15.—Fifth Rib of Left

Side, Cranial View.

a, head; b, tubercle; c, tubercular

facet; d, neck; e, angle,

with angular process; f, cartilage.

The ribs increase in length to

the ninth (the ninth and tenth are

of the same length) and then decrease

to the last. They decrease

in breadth behind the fifth. The

first is nearly in a dorsoventral

plane, while the others have their

dorsal ends inclined slightly craniad.

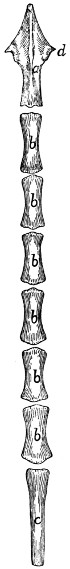

Fig. 16.—Sternum,

Ventral

View.

a, manubrium;

b, the separate

pieces forming

the body; c, bony

part of the xiphoid

process

(the expanded

cartilaginous portion

not being

shown); d, facet

for attachment of

first rib.

The tubercles become less prominent

as we pass caudad and are absent

on the last two or three ribs, which

do not articulate with the transverse

process.

The first nine ribs (true ribs or

costæ veræ) are attached separately

to the sternum by their costal cartilages.

The last four (false ribs or costæ spuriæ) are not

attached separately to the sternum. The costal cartilages of

the tenth, eleventh, and twelfth are united to one another at

their sternal ends. They may be united also to the ninth

costal cartilage or to the sternum by a common cartilage of

insertion, or they may be quite free from the sternum. The

thirteenth costal cartilages are free (floating ribs).

Ligaments of the Ribs.—The articular surfaces between

the head of the rib and the centra, and between the tubercle

and the transverse process of the vertebra, have each an

articular capsule. There are also a number of small ligamentous

bands from the tuberosity and the neck of the rib to

the transverse process of the vertebra.

[20]

III. STERNUM. (Fig. 16.)

The sternum consists of three portions, a

cranial piece or manubrium (a), a caudal piece

or xiphoid process (c), and a middle portion or

body (corpus), which is divided into a number

of segments (b).

To the sternum are united the ventral ends

of the first nine ribs. It thus forms the median

ventral boundary of the thorax. Since the

thorax decreases in dorsoventral measurement

craniad, the long axis of the sternum is inclined

from its caudal end dorsocraniad, and if continued

would strike the vertebral column in the

region of the first cervical vertebra.

The manubrium (a) makes up about one-fifth

the whole length of the sternum and projects

craniad of the first rib. It has the form of a

dagger and presents a dorsal surface and two

lateral surfaces, the latter uniting ventrad to

form a sharp angle. In the middle of the lateral

surface near the dorsal margin is an oval articular

surface (d) borne on a triangular projection.

It looks caudodorsad and is for the first costal

cartilage.

The caudal end articulates with the body by

a synchondrosis and presents a slightly marked

oval facet on each side for the second costal

cartilage.

The body consists of six cylindrical pieces (b)

enlarged at their ends and movably united by

synchondroses. They increase in breadth from

the first, and decrease slightly in length and

thickness. At the caudal end of each near its

ventral border there is a pair of facets looking

caudolaterad. They are for the costal cartilages.

The xiphoid process (c) is a broad thin plate

of cartilage at its caudal end; bony and cylindrical[21]

at its cranial end. It is attached by its base to the

last segment of the body by a considerable cartilaginous interval,

while the opposite end is free and directed caudoventrad.

The cartilage of the ninth rib is attached to the lateral

face of the cartilage between the xiphoid and the body, and

just caudad of this the common cartilage of insertion of the

tenth, eleventh, and twelfth costal cartilages is attached, if

present.

IV. THE SKULL.

The bones of the head consist of the skull proper together

with a number of separate bones forming part of the visceral

skeleton; these are the lower jaw, the hyoid, and the ear-bones.

The skull proper is considered as divided into cranial and

facial portions. The former includes all the bones which take

part in bounding the cranial cavity or cavity of the brain; the

latter includes the bones which support the face.

The cranial portion of the skull includes all that part

enclosing the large cavity which contains the brain. For convenience

this portion may be considered as made up of three

segments, each of which forms a ring surrounding a part of the

cranial cavity. The first or caudal segment or ring consists of

the occipital bone (with the interparietal) surrounding the

foramen magnum. The second segment consists of the

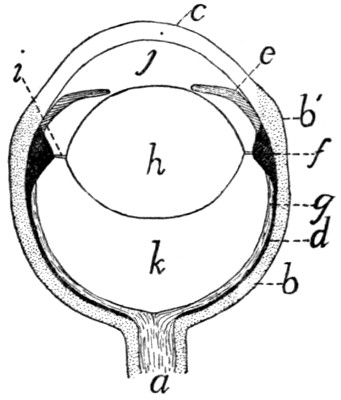

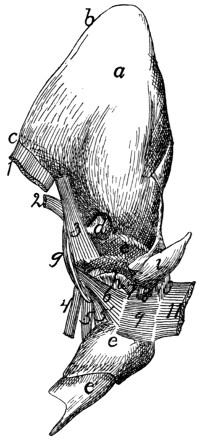

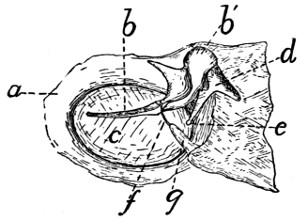

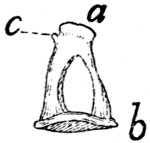

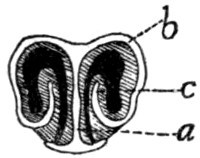

sphenoid ventrad, the parietals laterad and dorsad. Between