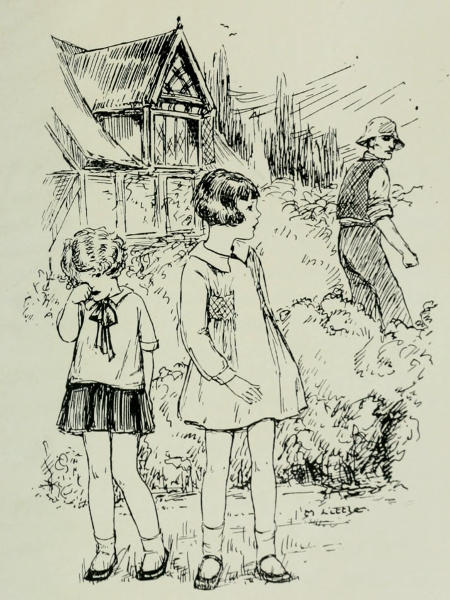

QUITE A LITTLE CROWD GATHERED TO WATCH MICKY.

Project Gutenberg's The Boy from Green Ginger Land, by Emilie Vaughan-Smith This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Boy from Green Ginger Land Author: Emilie Vaughan-Smith Release Date: November 28, 2018 [EBook #58370] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOY FROM GREEN GINGER LAND *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE

BOY FROM GREEN GINGER LAND

QUITE A LITTLE CROWD GATHERED TO WATCH MICKY.

THE BOY FROM GREEN

GINGER LAND

BY

E. VAUGHAN-SMITH

AUTHOR OF ‘CRAGS OF DUTY,’ ETC.

Illustrated

LONDON

WELLS GARDNER, DARTON & CO., LTD.

PATERNOSTER BUILDINGS, E.C.

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

WELLS GARDNER, DARTON AND CO., LTD.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THREE CHILDREN AND A DOG | 1 |

| II. | FIR-TREE COTTAGE | 11 |

| III. | THE FEUDAL CASTLE | 24 |

| IV. | SUNDAY | 40 |

| V. | A VISIT TO MARY | 49 |

| VI. | DIAMOND JUBILEE JONES | 58 |

| VII. | TRIALS OF PHILANTHROPY | 71 |

| VIII. | DIAMOND JUBILEE’S SUPPER | 89 |

| IX. | BAD NEWS | 105 |

| X. | OMNIBUS NUTS | 122 |

| XI. | THE SPARE ROOM BLANKETS | 135 |

| XII. | TROUBLES | 151 |

| XIII. | GONE! | 167 |

| XIV. | GREEN GINGER LAND | 186 |

| XV. | MICKY AT THE FAIR | 201 |

| XVI. | EMMELINE TALKS THINGS OVER | 215 |

| XVII. | DIAMOND JUBILEE IS ADOPTED FOR THE SECOND TIME | 235 |

| ‘QUITE A LITTLE CROWD GATHERED TO WATCH MICKY.’ |

| ‘KITTY GAVE SUCH A BOUND OF DELIGHT THAT SHE NEARLY UPSET HER TEA.’ |

| ‘IT WAS LOCKED AND BOLTED, TOP AND BOTTOM.’ |

| ‘“OH, WHAT SHALL WE DO?” SHE SOBBED.’ |

‘Emmeline, it’s your turn to choose a game to-day. What story shall we do?’

‘No, Micky; it’s your turn,’ put in his twin sister Kitty. ‘Emmeline chose the day before yesterday.’

‘I know it’s my turn really, Kitty, but gentlemen always let ladies choose,’ said eight-year-old Micky with dignity. ‘I’d very much advise “Swiss Family Robinson,” because it seems such a splendid opportunity, now the curtain-rods are down, to use the short ones as sugar-canes; and Mary’s so sorry we’re going away to-morrow that she won’t be cross even if the paint does get a little kicked off the bath when it’s being wrecked.’

‘Micky, I think it’s horrid of you to talk of Mary’s being sorry like that,’ said Emmeline—‘just[2] as if you didn’t care a bit about our having to leave the home of a lifetime, and the only real friend who has been with us since we were babies, to go and live with an aunt who doesn’t care for us!’

‘How do you know Aunt Grace doesn’t care for us? She’s always very jolly when she comes here, and she never forgets birthdays,’ said Micky, who had a sense of justice. ‘She sends such sensible things, too—postal orders, or steam-engines that really work, or real good books of adventure. She never gives you poetry-books.’ This last was a sore point with Micky just then, for his godmother had recently presented him with a gilt-edged volume of ‘The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth,’ for which he had been expected to write a laborious round-hand letter of thanks.

‘Presents are all very well, but they don’t prove that a person loves you,’ said Emmeline; ‘and as to her being jolly when she comes here, she never stays more than a day or two at a time, and always seems in a great hurry to get back to London again. Do you think, if she had really cared anything about us, she would have left us a whole year after darling mother died before offering to come and look after us?’

This was rather out of Micky’s depth, so he prudently changed the subject. ‘Well, let’s get[3] started with the game,’ he said, ‘else we shall have to get tidy for tea before we’ve even been properly wrecked.’

But Emmeline was not to be put off so easily. ‘Micky,’ she demanded solemnly, ‘how can you be so taken up with story-games when we’re as good as living a story ourselves?’

The twins’ eyes sparkled. Anything savouring of romance was as the breath of life to them, and Emmeline was really rather impressive when she talked in that grave way.

‘How do you mean?’ asked Kitty, eagerly.

‘Why, what I have just been saying,’ replied Emmeline. ‘Here are we, three orphans, left to the care of a worldly aunt——’

‘But are you quite sure she’s worldly?’ asked Kitty, looking alarmed. Kitty was not altogether clear what ‘worldly’ meant, but from the way Emmeline pronounced the word it sounded like something very bad.

‘I’m afraid so,’ said Emmeline. ‘I remember once, when mother and I spent a night with her in London, and she and her friend kept talking about a ball they had just been to.’

‘But balls aren’t wrong, are they?’ asked Kitty. Emmeline was twelve, and Kitty regarded as a great authority on all questions of morals.

‘I don’t know that they’re exactly wrong,’[4] acknowledged Emmeline, ‘but they are a great waste of time. When I’m grown up I never mean to go to them, but shall spend all my time working for the poor. Besides, it isn’t only her going to balls that makes me think Aunt Grace worldly, but the way she dresses and—everything. I quite expect that when we know more of her we shall find her just like one of the fine ladies one reads of in books.’

‘Will she be cruel to us, do you suppose?’ asked Kitty with zest. She did not really believe that merry, good-natured Aunt Grace could be cruel, any more than she really, at the bottom of her heart, believed in a romance of Micky’s about a certain blood-thirsty burglar who lived in the spare-room wardrobe, but it made life more exciting to pretend to herself that she did.

‘Of course not. What a silly question, Kitty!’ exclaimed Emmeline impatiently. ‘I dare say she will be too busy with parties and so on to bother herself much about us, but she’ll be quite kind—at least, to us. Punch is the only one I feel at all doubtful about.’ She flung herself down on to the hearthrug, and rested her head against that of a fox-terrier who was lying there half asleep, and who gave a little growl of remonstrance at being disturbed. ‘We hadn’t got him when she was here last, you[5] see, so we can’t tell what she’ll think of him. I shouldn’t a bit wonder if she didn’t let us bring him to Woodsleigh, or even if she does, she’ll keep him chained up all day, poor darling! People who think much about clothes never do like dogs, except just silly little toy things.’

Micky and Kitty broke out together in a chorus of indignation and horror.

‘If they are so horrid as to chain Punch up in the kennel all day I shall jolly well stay out with him and keep him company!’ shouted Micky.

‘Oh, Emmeline, you don’t really think there’s any danger of Aunt Grace not letting darling Punch come?’ said Kitty, almost in tears.

‘Well, I hope not,’ said Emmeline; ‘anyhow I’ve written to her about it, so till we’ve had time to get her answer there’s no use worrying any more.’ There was not, but the very suggestion that Punch might have to be left behind had cast a gloom upon the party—a gloom which did not altogether lift even when the brilliant idea struck Micky that the brooms in the housemaid’s cupboard, if placed upside down and balanced against the wall, would make excellent palm-trees for the Robinsons’ desert island.

On the whole, Emmeline was the happiest of the three just then, for, grieved as she was at leaving Mary and possibly Punch, the prospect[6] of going to live with her aunt was not altogether without its secret charm for her. The good little girl who had such a beautiful influence on her worldly relations played a prominent part in several of her favourite books, and it was that part which Emmeline pictured herself playing with regard to Aunt Grace. She would have been ashamed to express this idea in so many words even to herself, far more to the twins, but it none the less reconciled her a good deal to the new life which lay before them.

Emmeline Bolton had always been a child of the type whose virtue specially appeals to nurses. All the grown-up people, indeed, who had ever been brought much into contact with her agreed in considering her a very good girl. In some respects she deserved their favourable opinion, for she was truthful, obedient, and conscientious by nature, but perhaps the fact that she had never been very strong had more to do with her reputation for goodness than she herself or anyone else quite realised.

The child lived in an atmosphere of warm and constant approval which was not altogether wholesome. Such had been the state of affairs two years ago, when all three children had fallen ill of measles. Micky and Kitty had had the disease lightly, but with Emmeline it took a serious form. For two days and nights she had[7] lain delirious, and there came a moment when Mary, believing her to be unconscious, had sobbed out to the trained nurse: ‘I always had a feeling that the dear child was too sweet and good to be long for this world!’

This presentiment proved a groundless one. As Emmeline grew better the words which she had heard in her half-delirious state came back to her, and she dwelt on them constantly. Just at first they frightened her a little, but when she had become quite strong and well again she ceased to be alarmed, and only felt pleasantly elated at being too good to be long for this world. It almost—though not quite—made up for having straight brown hair and a pale peaked face instead of golden curls and glowing cheeks like the twins, who were so pretty that people in the street sometimes turned round to look after them.

If Emmeline’s mother had lived she would probably have perceived that the child was in grave danger of growing into a little Pharisee, and she might have done something to check it, but she had become very ill almost as soon as the children had recovered from the measles, and had died less than a year later. After her death the children had gone on living at the old home at Eastwich, a great East Anglian town, under the joint charge of Mary and Miss Rogers, their daily governess. The arrangement was never intended[8] to be more than a temporary one, for their aunt, Miss Bolton, who was also their guardian, wished them to go and live with her at Woodsleigh, a place some twelve miles distant from Eastwich, as soon as she regained possession of a cottage there, which had been left her by her father, but let for several years past. Mary was to go to her own home to keep house for a brother, so that to-morrow, when her children, as she always called them, went to begin their new life with Aunt Grace, she would have to be left behind at Eastwich.

‘Come, my darlings,’ said Mary, landing so abruptly on the Swiss Family Robinson’s desert island that most of the palm-trees were knocked over, ‘tea’s quite ready, and there’s buttered toast and coffee.’

Buttered toast and coffee were always regarded as special treats, but somehow to-day nobody seemed to have quite as much appetite for them as usual. Mary and Micky kept making jokes, and they all tried to be very merry, but not even the presence of Punch, who was allowed to sit on a chair between the twins in special honour of the occasion, made the festivity much of a success. They could none of them forget it was the last tea with Mary in the old home.

Emmeline stayed up that evening until some time after the twins had gone to bed, and sat[9] on the floor leaning her head against Mary’s knee.

‘Well, my darling,’ said Mary after a while, ‘I hope you’ll all be very happy and good with your Aunt Grace. Of course some of her ways may be a bit different from what you’re used to, but there, I’m sure she’s as well-meaning a young lady as ever breathed, and we know that everything must work out for the best, or it wouldn’t be let happen. Well, I know you’ll always be a good child, dear Miss Emmeline, and help Master Micky and Miss Kitty, bless their dear little hearts!’

Poor Mary! She would have been horrified if she could have guessed that any words or tone of hers could have led Emmeline to set Aunt Grace down as worldly, for Mary was a thoroughly good woman, but all unconsciously a little accent of doubtfulness showed itself in her voice and confirmed Emmeline’s impression.

For several years past the little girl had undressed herself, but for this last time Mary put her to bed just as she had done in the far-off days of Emmeline’s dimmest memories.

Long after Mary had kissed her good-night the child lay awake, thinking how dreary it would be at Woodsleigh to have no old nurse to tuck her up, and passionately resolving that, come what might, she at least would always keep true to the[10] old ways Mary had taught her. She made the resolution purely and simply out of loyalty to Mary, and not with any view to her mission towards Aunt Grace, which for the moment she had quite forgotten.

To-morrow morning came all too soon. A pleasant letter from Aunt Grace arrived at breakfast-time, containing a warm invitation for Punch to take up his abode at Woodsleigh, which was a great relief and pleasure to the rest of the party, but otherwise the day was a trying one. Mary went about with a duster swathed round her head, as she always did during the spring-cleaning, and there was a general feeling of bustle and discomfort. The children wandered restlessly from room to room, trying to help, but usually only succeeded in being in the way, and secretly they rather longed for the cab which was to take them to the station in time for the 11.35 train.

The cab came at last, and less than a quarter of an hour later they found themselves installed with Punch and endless baggage in a second-class railway carriage, while Mary stood on the platform smiling bravely. Another few minutes, and the train was starting with a shriek and a pant. All three children leaned out of the window, waving[12] frantically, till the line curved round a corner and Mary and her fluttering handkerchief were lost to sight. After that it was Punch who saved the situation. All his journeys to the seaside had failed to accustom him to railway travelling, and he now took refuge under the seat, looking so cowed and miserable that nobody could think of anything but how to comfort and reassure him. They were so much occupied with this as to be quite taken by surprise at reaching their destination in what seemed an astonishingly short time.

The only people waiting on Woodsleigh platform were a lad who served both as porter and ticket-collector and Aunt Grace herself—an Aunt Grace who looked wonderfully young and pretty to be aunt and guardian to such a big girl as Emmeline. She was, in fact, very much what her niece Kitty might become a few years hence when transformed from a tomboy into a fashionable, grown-up young lady. She hurried forward to open the carriage door for the children, and greeted the whole party, including Punch, with such frank delight at seeing them that not even Emmeline could help being charmed, and a limpet-like twin was soon clinging to either side of her in a devoted, if rather inconvenient, fashion.

‘We shall have to leave the boxes to be brought up by the milk-cart in the course of the afternoon,’[13] explained Aunt Grace when the luggage had all been taken out of the train. ‘We’re very primitive at Woodsleigh, and the milk-cart’s the only thing we can boast of in the way of a public conveyance. It won’t come till later on in the afternoon, but I can lend brushes and sponges, so I hope you’ll be able to manage all right till then.’

‘We did wash our hands just before coming, and Mary brushed all our hairs,’ Micky was careful to assure her, ‘so you needn’t trouble to lend us things. But thank you all the same,’ he added hastily, for fear of hurting her feelings.

‘Micky, you know Mary always makes us wash our hands and faces after railway journeys!’ said Emmeline—a remark which Micky, who was just then stooping down to undo Punch’s lead, found it convenient not to hear.

‘I hope before long to get a donkey and donkey-cart of our own,’ observed Aunt Grace as they left the station and came out into a village street; ‘then we shan’t have to depend on the milk-cart, and it will be much more convenient altogether.’

‘Oh, Aunt Grace, how lovely!’ exclaimed Kitty, giving a joyous little skip. ‘Donkeys are such dears!’

‘I shall ride ours bare-back,’ announced Micky, ‘and teach him all sorts of tricks.’

‘I’m always so glad to think of a donkey having[14] a good home,’ said Emmeline; ‘people are so cruel to them sometimes. When we stayed at the seaside, it often made us quite sad to see how they were ill-treated.’

‘Yes, I know,’ said Aunt Grace; ‘it is very sad. Two or three years ago I was staying at the seaside with some children, who made a special point of hiring the ones with unkind masters for extra long rides, and never letting them be whipped, so as to give them a rest from being ill-treated.’

‘I wish I knew those nice children,’ said Kitty.

‘And I expect they found the donkeys really went quite as well, didn’t they, Aunt Grace?’ asked Emmeline, who had not yet learned that virtue often has to be its own reward.

‘Well, I’m afraid I can’t say they did,’ owned Aunt Grace with a little twinkle in her eye; ‘at the best of times they went at a slow and stately pace somewhat resembling a funeral procession, and at the worst of times they sat down comfortably in the middle of the road and refused to budge. Still, I don’t doubt that if my friends had had the bringing up of those donkeys from the first, they would have gone all right without being beaten. It was simply that the poor creatures had got so used to it that they didn’t understand anything else.’

‘Aren’t we nearly at your house?’ asked Kitty[15] presently; ‘we seem getting quite outside the village now.’

‘No, we have still about ten minute’s walk before we get to Fir-tree Cottage,’ replied Aunt Grace; ‘it stands right away from other houses, just outside a large wood. It’s very nice in most ways being quite out of the village, for it makes one so much freer to do just as one likes, but it’s rather inconvenient sometimes being so far from the station. It’s really not so very much farther to Chudstone Station—the one you passed next before Woodsleigh; indeed, when I have plenty of time, I sometimes start from there instead of from Woodsleigh, for it makes a delightful walk through the wood.’

‘How jolly to live in a cottage and so near a wood!’ cried Kitty, giving another little skip.

‘As to living in a cottage, I’m afraid you won’t find it quite your idea of one,’ said Aunt Grace, ‘though it really was one before grandfather built on the front part of the house. The wood’s real enough though, and begins only just outside our back-garden gate, which is very charming of it.’

‘I thought grandfather was a Professor,’ remarked Micky, looking puzzled.

‘Why, so he was,’ said Aunt Grace.

‘But if he built the front part of the house he must have been a stone-mason, like Mary’s brother,’ objected Micky.

‘Aunt Grace didn’t mean that he built it with his own hands, you silly child!’ said Emmeline, laughing.

‘But I don’t wonder Micky thought I did,’ said Aunt Grace kindly; ‘it was very natural.’

Aunt Grace was right in saying that Fir-tree Cottage was not the kind of cottage to which the children were used. It was what they considered quite a large house, standing well back from the road among lawns and shrubberies, and when they walked in at the front door they found themselves, not in the poky little passage that Kitty had been picturing to herself from her remembrances of seaside lodgings, but in a hall as large as the one at their old home, and far more charming, for it was bright with ferns and flowering plants and cosy with cushioned seats and lion-skin rugs. In this hall they were met by a rather austere-looking person whom Aunt Grace called Jane.

‘Jane was my nurse when I was a little girl,’ she said, ‘so we are very old friends, and now she is going to help look after you;’ at which Jane smiled grimly, and Emmeline thought how horrid it would be to have her to look after them instead of kind, gentle Mary.

‘Now, we must certainly take Punch to be introduced to Cook,’ said Aunt Grace; ‘she’s a splendid person for animals.’

This introduction was so successful that Emmeline forgot all disagreeable impressions. Cook was found in her bright airy kitchen with its red-tiled floor and rows of shining dish-covers, and she and Punch seemed quite delighted with one another. ‘That’s a rare nice little dog,’ she kept saying as he smelt round her skirts with marked approval. ‘Have you shown them the kennel, miss?’ she added. ‘I give that a good scrubbing yesterday as soon as ever I heard he was coming, so that will be all nice and fresh for him now. There’s clean straw in too.’

‘We must go and admire it,’ said Aunt Grace, and they went through the scullery and out into the back-yard, in one corner of which was an enormous dog-kennel.

‘The last dog who lived here was a St. Bernard,’ explained Aunt Grace, ‘so Punch will find his quarters very roomy ones.’

‘Aunt Grace, you aren’t going to keep him chained up except when he goes for walks, are you?’ asked Kitty.

‘Why, of course not,’ said Aunt Grace; ‘this is his private bedroom, that’s all, and I no more expect him to stay here all day than I shall expect you to stay in your bedrooms.’

This so greatly relieved the children that they were in a mood to be delighted with everything when Aunt Grace led them upstairs to show[18] them their own bedrooms. She took them first to the room which the two girls were to share, and they both exclaimed at the sight of its dainty white-painted furniture and fresh muslin hangings. In each half of the room was a little white bed, a white wash-hand stand, and a white chest of drawers with a looking-glass standing on the top of it.

‘It’s quite like grand grown-up ladies, both of us having a wash-stand and a dressing-table to ourselves,’ said Kitty, with much satisfaction; ‘there was only one of each in the night-nursery at home.’

‘They are such pretty ones, too,’ said Emmeline. ‘I do love white enamel.’

‘I’m very glad you like them,’ said Aunt Grace, looking pleased; ‘I always think one has so much more heart in keeping one’s room tidy if the furniture’s nice.’

‘Yes, you won’t have to leave your things about here, Kitty,’ remarked Emmeline, in her elder-sisterly way.

Kitty was not listening; she had rushed to the window. ‘I do believe—yes, you really can just see the sea!’ she exclaimed. ‘Oh, Aunt Grace, may we go there every day?’

‘I’m afraid it’s rather too far off to go there every day,’ said Aunt Grace; ‘it’s a good five miles. Still, I hope we shall be able to go there[19] quite often—at all events when we’ve got our donkey-cart.’

There was a door between the girls’ room and the next, which Aunt Grace pointed out to them. ‘My room is the next,’ she said, ‘so you’ll be able to run in for any help you want. Jane will come in and do your hair in the mornings, but of course she won’t always be there for the odds and ends of things that need doing.’

‘I’ve done my own hair for quite a long time,’ Emmeline was careful to inform her.

Aunt Grace did not seem much impressed. ‘That’s a good thing,’ she observed cheerfully.

They went to Micky’s room after that. They had to cross the passage and go down some steps in order to reach it, for it was in the part of the house which had been the original Fir-tree Cottage, where the rooms were all much lower—like cottage rooms in fact. There were but two of them on the upstairs floor, and the other one was to be the schoolroom. Underneath these two rooms were two others, now used as the scullery and larder. Micky’s room was not quite so daintily furnished as his sisters’, but it had a delightful view out on to the lawn and wood beyond, which made it a very pleasant one. What especially gratified Micky, however, was its being alone. ‘You need a man to sleep in this part of[20] the house,’ he remarked; ‘burglars would be sure to choose it to attack, because they’d think there would be fewer people to shoot them, so it’s a jolly good thing it’s me you’ve put here, and not the girls.’

‘Micky always sleeps with his gun at the foot of his bed, just in case,’ said Kitty.

Just at that moment the dinner-bell rang.

‘Well, I must run and get ready,’ said Aunt Grace. ‘Can I lend anybody anything?’

‘Thank you; we should be very grateful for a sponge,’ said Emmeline, ‘and, Aunt Grace, Micky must wash, mustn’t he? Just look at his hands!’

Micky made a face at her, and Aunt Grace said calmly: ‘I expect he will wash: gentlemen usually do. But I feel it’s a question we must leave to himself—at all events till his luggage comes.’

Emmeline flushed crimson. Then a choky feeling came into her throat; her eyes began to sting, and she had to hurry out of the room lest she should burst out crying. It was not only that she was hurt for herself, but her sense of loyalty was grieved. Mary had always made Micky wash his hands before dinner. It would always be like this, she said to herself. The others would leave off all the good ways they had been taught, and whenever Emmeline, the only[21] one who would never forget, tried to remind them, Aunt Grace would snub her.

The chokiness and the stinging gradually passed off, and Emmeline could trust her voice again.

‘Kitty, you really needn’t have gone and told Aunt Grace about our only having one wash-stand and dressing-table at home,’ she snapped, as they were washing their hands.

‘Why ever not?’ asked Kitty, opening her eyes.

‘It makes us seem such babies,’ said Emmeline, crossly; ‘and, though of course you and Micky are babies, it’s rather hard on me.’

Fortunately Kitty was both sweet-tempered and tactful, so she made no answer, and the subject dropped. Emmeline, however, went down to the dining-room in anything but a good temper. Even the sight of Micky with spotlessly clean face and hands failed to soothe her; it was exactly like Micky to go and wash his hands just in order to make her seem in the wrong.

‘I think this clock is a little bit slow,’ said Aunt Grace, after a few minutes of eager chatter on the twins’ part and silence on Emmeline’s, which an onlooker might have described as sulky, but which she herself considered dignified. ‘Would you mind telling me the right time by that lovely little watch of yours, Emmeline?’

Wily Aunt Grace! That little gold watch which had been given her by her mother was the pride and joy of Emmeline’s heart. Nothing so delighted her as to be asked the time. She gave the required information with the utmost graciousness; the dining-room clock was exactly three minutes slow, it seemed, by the right time. Aunt Grace actually left her seat then and there and went to the mantelpiece to move on the minute-hand three spaces, and Emmeline began to wonder whether a person who cared so much about the right time, and showed such a proper amount of faith in her gold watch, could be so very worldly after all!

The children and Aunt Grace were just setting out for an exploring expedition in the wood after dinner when Emmeline suddenly felt Micky, who was walking by her side a little behind the others, press a hot, sticky coin into her hand.

‘Why, what is it?’ she asked, with a wonder which did not grow less when she discovered that it was a penny.

‘It’s to make up for making that face,’ said Micky, who had grown very red. ‘It was beastly rude of me, but for the moment I had quite forgotten about you being a girl.’

KITTY GAVE SUCH A BOUND OF DELIGHT THAT SHE NEARLY UPSET HER TEA.

‘Micky darling,’ said Emmeline, so much touched and ashamed that the tears quite came into her eyes this time, ‘I really can’t take your penny. Besides, it was all my fault for interfering.’

‘It wasn’t,’ said Micky stoutly. ‘And anyhow, please do take it. I shan’t feel a gentleman again till you do. Perhaps,’ he added as an afterthought, ‘you might spend it on some marbles. I’ve lost so many of mine down the mouse-hole and other places that there really aren’t enough now when Kitty wants to play too, and perhaps if you had some of your own you wouldn’t mind lending them us sometimes. But don’t, of course, get them unless you like; it’s only a suggestion.’

The early days of the children’s new life were so full of interest and discoveries that even Emmeline did not manage to be nearly as homesick as she fancied she was.

To begin with, they had explored the whole house, a good deal of the wood, and every inch of the garden. They had discovered, moreover, that the said garden was the most delightful of play-places, chiefly because it was splendid for story games. It owed its excellence from this point of view to the fact that it contained a summer-house and a wood-pile, either or both of which could serve if need were as houses for the story people to live in, which, as Kitty remarked, ‘made things seem ever so much realer.’ To be sure, there were times when they had to pretend a good deal about the wood-pile; it just depended how Mr. Brown, the gardener, had arranged it, but it usually did for desert islands, where the dwellings might be supposed to be rather rough and ready,[25] and if the worst came to the worst there was always the summer-house.

For the whole of one glorious red-letter afternoon, indeed, the story people had revelled in the run of yet a third house. Just outside the back-yard was a little shed, always respectfully referred to by Micky and Kitty as ‘Mr. Brown’s study,’ that being the place where he was accustomed to black the boots and clean the knives. On the afternoon in question Mr. Brown had stayed at home for some reason, so that his study was left undefended from the twins, who entered in and took possession. It made an even more desirable abode than the summer-house, for not only was it pervaded by a delicious smell of knife-powder and boot-blacking and mustiness, but also it was much better furnished; there were stools, and shelves, and knives, and boots, and packets of seeds and queer little pots, with nice messy stuff inside them, whereas in the summer-house there was nothing at all except a wooden bench, which was fixed to the wall and ran round three sides of it. So the story people lived there for the whole of that afternoon with great satisfaction to themselves, but, unhappily, not with any satisfaction at all to Jane when she came to fetch them in to tea and found Mr. Brown’s usually neat ‘study’ turned almost inside out, and Micky and Kitty all over boot-blacking. Aunt Grace and Emmeline returned[26] from a garden-party to find not only the twins, but Alice, the little day-girl who had been inveigled into joining the game, in the deepest disgrace, and Jane muttering terrible things about ‘warnings.’ Fortunately the affair passed off without such dire consequences, but from that time forward Mr. Brown’s study was forbidden ground.

It was a great disappointment; but consolation was not long in coming, for it was only a very few days later that they discovered the Feudal Castle.

Aunt Grace had gone to a garden-party, and the three children were spending a blissful afternoon in the wood. Emmeline had curled herself up comfortably with a story-book, but the twins happened to be Red Indians that day, and had gone off on a desperate expedition against the Pale Faces. Before long they came rushing back to Emmeline, and insisted on dragging her off to see ‘something wonderful.’

‘Something wonderful’ proved to be merely an empty cottage, hardly more than a hut, indeed, which, from its broken windows, torn thatch, worm-eaten door, and altogether forlorn appearance, looked as if it had been deserted for several years. Emmeline grasped its capabilities at first sight, and when the twins led her inside and triumphantly displayed a three-legged chair with a broken seat, and part of what had once been a table—when she saw the grate, rusty and cobwebbed[27] with disuse, but a real grate nevertheless, she was quite ready to agree with them that the story people had found their ideal house at last.

‘Isn’t this perfectly lovely?’ said Kitty, dancing about. ‘And, Emmeline, it has two rooms. Come and see the other one.’

The other room contained nothing at all except somebody’s very old boot, and a straw hat with the crown almost out, both of which Kitty pointed out as great finds. Emmeline, however, was left cold by these treasures.

‘They look as if they had belonged to rather dirty people,’ she said. ‘I think we’d better clear them out. Besides,’ she added, as Kitty looked disappointed, ‘this is a Feudal Castle, and they are not the sort of things people in Feudal Castles would wear.’

From that time forward the empty cottage was always known as the Feudal Castle. It was felt to be a most brilliant suggestion of Emmeline’s.

It would have quite spoilt the romance of the Feudal Castle if it had become a place of common resort, so from the very first the Bolton children bound themselves by a solemn pledge of secrecy not to reveal its existence to anyone. It was in an unfrequented part of the wood, where they themselves never happened to have gone before, and it did not strike them that perhaps other people might have done so.

Unfortunately they could not spend as much time in the Feudal Castle as they would have liked, for lessons began again the very day after it was discovered. In themselves lessons were pleasanter than they had ever been before, for Miss Miller, their new governess, who bicycled over each morning from one of the neighbouring villages, was brighter and more interesting than old-fashioned Miss Rogers. To be sure, Emmeline was at first inclined to resent it as a slight to Miss Rogers when she found herself expected to do by short division sums she had ‘always been taught’ to do by long; but she was a sensible girl on the whole, and when once she had thoroughly mastered the new method, and found out how much quicker and neater it was than the old one, she began to take quite a pride in working her sums by it, and altogether became so docile and well-behaved a pupil that Miss Miller soon shared the general opinion that she was a model child.

To Emmeline’s relief, and possibly also a little to her disappointment, she was not required to depart from the ways in which she had been brought up in any more important respects than that question of short division versus long. So far from amusing herself all Sunday, as Emmeline had a vague impression that fashionable people did, Aunt Grace attended more services than Mary herself had done, and was certainly just as[29] particular with regard to the children’s Sunday observances; indeed, in some ways she was even more so, for instead of being content with a bare repetition of the Catechism, she insisted on seeing that they clearly understood its meaning. And whereas Emmeline had formerly learned merely a verse or two of a hymn, Aunt Grace now expected her to learn the Collect and Gospel for the week, which was a far more serious task. Emmeline could not well grumble at it openly, but at the bottom of her heart she was possibly a little irritated with Aunt Grace for behaving so very differently from what she had pictured.

‘There is going to be a Meeting in the village schoolroom to-night,’ said Aunt Grace as she was pouring out tea one fine Saturday evening in September, about a month after the children’s arrival at Woodsleigh. ‘Mr. Faulkner—that’s Mrs. Robinson’s clergyman brother—is going to speak about the work of a Home for poor friendless boys and girls, of which he is the Chaplain. I wonder if you three would like to come.’

‘I should like it very much,’ said Emmeline.

‘Will it be all talking, or will there be a magic lantern?’ asked Micky, cautious before committing himself.

‘Will it keep us up lovely and late?’ cried Kitty.

‘I believe there’s to be a magic lantern, and we shan’t be back till about ten, I suppose,’ said Aunt[30] Grace; whereupon Kitty gave such a bound of delight that she nearly upset her tea, and Micky graciously expressed his opinion that the Meeting wouldn’t be half bad.

‘Work among children is always particularly interesting,’ said Emmeline; ‘their characters are still so plastic that they can be moulded into whatever shape you want.’ She had once heard a visitor make the remark, and had treasured it up for future use.

‘I didn’t know you had had such a wide experience in bringing up young people, Emmeline,’ said Aunt Grace, with a twinkle in her eye; and Emmeline grew rather red.

‘The only condition I make to the twins’ going is that they shall lie down after tea till it is time to start,’ went on Aunt Grace after a moment, ‘else they will be so very tired to-morrow morning.’

The twins looked rather blank at this. ‘Will there be supper when we come home?’ asked Micky.

‘Yes,’ said Aunt Grace, with a smile.

‘Oh well, then, we’ll lie down if you really want us to,’ said Micky, and as it never occurred to Kitty to dispute what he had decided, the matter was regarded as settled.

On their way to the Meeting Aunt Grace told the children a little about the lecturer, whom she[31] had already met in London. For several years he had worked so devotedly in one of the very worst parts of the great city that at last his health had given way, and the doctors had said that for the present, at all events, it would be madness to take any but light country duty. At the time the verdict had almost broken his heart, for he was quite wrapped up in his people, above all in the poor little children of the parish, many of whom were being brought up as pickpockets. It had been a great consolation to him, however, when he was offered the Chaplaincy of this Home, where he knew that his work would still lie among children like those he had left.

‘Some of them, indeed, are the very same,’ added Aunt Grace. ‘For instance, I know of one boy there—that is, I think he is there still, though he must be about the age for leaving by now—whose life Mr. Faulkner once saved. He wasn’t a clergyman then, but a doctor, and this boy was lying at death’s door with diphtheria. He had been horribly neglected by some cruel people with whom he lived, and by the time Mr. Faulkner discovered him the illness had been allowed to get such a hold that the child would probably have been choked by some horrible stuff that was growing in his throat if Mr. Faulkner hadn’t sucked up the poisonous stuff through a tube which he put into the throat. Of course, it was[32] a terribly dangerous thing to do—indeed, he caught the illness through doing it—but it saved the boy’s life. Before that time he had been one of the most abandoned little child-thieves in the parish, but ever since he has been absolutely devoted to Mr. Faulkner, and he is now growing up into a very fine character. I believe he hopes to go out as a Missionary one day, which would be a wonderful end for anyone who began as a little pickpocket.’

‘Mr. Faulkner must be a saint,’ said Emmeline.

‘So he is,’ agreed Aunt Grace heartily; ‘but I don’t know,’ she added, with a whimsical little smile, ‘whether he’ll any more fit your idea of a saint than Fir-tree Cottage did that of a cottage.’

Aunt Grace was right. Emmeline could not help feeling a little shock of surprise when, soon after they had taken their seats in the schoolroom, a curly-haired little man, with a round, merry face, came and stood before the great white lantern-sheet, and she realised that this must be the Lecturer.

‘Why, that man’s a little boy!’ remarked Kitty, in a stage whisper.

And, indeed, there was something very boyish in his appearance. Not that they had much time to study it, for in another moment the lights were lowered, a hymn appeared on the lantern-sheet,[33] and after it had been sung through lustily the lecture began.

The first picture shown represented a room in London—such a filthy, miserable room as the children could never even have imagined. On a ragged mattress in one corner lay a little boy, so thin that he was more like a skeleton than a child. He had been almost dying, it appeared, when he had been discovered by the Society to which the Home belonged, and rescued from death, or worse, for the room had been kept by a wicked man who was bringing up this child and a number of others to a life of crime.

The next picture was far less harrowing to the feelings of the audience, for it showed the same boy fat, and clean and comfortable after a few years spent in the beautiful Home among the Surrey hills, where Mr. Faulkner was now Chaplain. He had since joined the Royal Navy, said the clergyman, and was now learning to serve his King and country as a brave man should, instead of making a livelihood by robbery.

‘Perhaps he’ll be one of my men some day,’ whispered Micky, who had every intention of ending his life as an Admiral.

Picture followed picture, showing tragic scenes of child life in darkest London, varied from time to time by groups of prosperous children whom the Society had adopted. On the whole it was[34] much like other lectures of its kind, but the Bolton children, who had been at nothing of the sort before, listened and gazed entranced, and felt very regretful when it was over, and a final hymn and a collection brought the proceedings to a close.

Mrs. Robinson, the Vicar’s wife, hurried forward to speak to Aunt Grace as soon as the lights were turned up and people were beginning to disperse.

‘You’ll come to supper with us to-morrow, won’t you?’ she said; ‘I know my brother is much looking forward to meeting you again.’

A pretty rosy colour came into Aunt Grace’s cheeks. ‘Thank you; I shall be delighted to come,’ she said, and she looked as though she meant it.

The Lecturer himself came up to them the next moment, and greeted Aunt Grace as a friend.

‘You’ll let me see you home?’ he asked, eagerly; ‘that lane is so long and dark—I know it of old.’

‘Thank you; but, you see, I have a very sufficient bodyguard in two nieces and a nephew,’ said Aunt Grace, laughing, ‘and I hear Mrs. Robinson just inviting the churchwarden and his wife to go home with her for the express purpose of meeting you, so I’m afraid it wouldn’t do to take you away from them.’

‘Well, I shall come to-morrow, then,’ said Mr. Faulkner. ‘I want to be introduced to your bodyguard’; and he gave the children a mischievous look that made him appear more like a schoolboy than ever.

‘I do love people who have twinkly smiles,’ remarked Kitty to Micky, on the way home after the meeting in the village schoolroom.

Micky’s great blue eyes had a rapt, far-away expression.

‘I wonder if it’s worth while,’ he said thoughtfully.

‘If what’s worth while?’ asked Kitty.

‘To be so horrid and clean as those children were in the Homes, even if you do get plenty to eat.’

‘But, Micky, we are clean—sometimes,’ said Kitty. It was just as well she qualified the statement.

‘Yes, but we are used to it,’ said Micky; ‘things aren’t half as bad when you are used to them.’

‘What part of the lecture did you like best?’ asked Kitty of Emmeline, who was walking along in dreamy silence.

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ said Emmeline. She spoke without thinking, for she did know perfectly well. Mr. Faulkner had spoken of a little twelve-year-old girl named Kathleen, whose[36] pocket-money had been the very first subscription towards the building of the particular Home where he was Chaplain. The heart of this child had become so full of noble pity for her poor little brothers and sisters of the slums that she spent most of her playtime working among them and for them, and came to have such a wonderful influence on them, that they looked upon her more as an angel than an ordinary human girl. The story had fired Emmeline’s imagination, and she was dreaming over it still.

‘Didn’t you enjoy the meeting, Aunt Grace?’ asked Kitty, taking her aunt’s hand.

‘Yes, dear. Why do you ask?’

‘Because you seem so grave, somehow—like when we’ve been naughty.

‘I was thinking, I suppose,’ said Aunt Grace, laughing, and for the rest of the walk she chatted merrily about all kinds of things.

‘It’s easy to see she doesn’t care much about the poor children,’ thought Emmeline, feeling well satisfied with herself; ‘if she did, she wouldn’t make so many jokes.’

All the way home, and while they were having supper afterwards, Emmeline went on thinking of the little girl who had spent her pocket-money and her playtime on the poor.

‘Do you know,’ she said abruptly, in the middle of her basin of soup, ‘I think it would[37] be very nice if we had a collecting-box for that Home. I’ve got a shilling in my money-box upstairs which I’ll put in for a start. I did mean to have saved up to buy “Queechy,” but I’ll gladly give that up for the sake of the poor little children. Kitty and Micky, if you were unselfish you’d give up your money too.’

The twins looked blank, and instead of being touched at Emmeline’s self-sacrifice Aunt Grace said rather sharply, ‘Really, Emmeline, it is not your business to settle what the twins ought to give. Start a box if you like, but I can’t have you forcing the others to contribute to it.’

Emmeline tried to reflect that this was only what she might have expected; people’s worldly relations always did persecute them when they wanted to do anything specially beautiful or unselfish; but she could not help looking hurt, and Kitty, who never could bear anyone to be snubbed, broke in:

‘Oh, but she didn’t mean to force us, Aunt Grace. It was only a suggestion. You shall have my sixpence, Emmeline—at least, threepence of it will be from me and the other threepence from Micky. Then it won’t matter his saving his own money for a new gun. You see, it’s really necessary he should have one that’s not broken when he sleeps in such a lonely part of the house.’

‘Of course,’ agreed Aunt Grace, smiling, as she twisted one of Kitty’s long curls between her fingers. ‘Should you like to ask Mr. Faulkner for a collecting-box when he calls to-morrow, Emmeline?’ she added, in an unusually kind voice for a persecuting relation.

‘No; my extra money-box will do quite well,’ said Emmeline shortly.

The extra money-box had been given her by Micky on her last birthday. Having dropped a carefully treasured sixpence down that same mouse-hole which had been fatal to so many of his marbles, Micky had been at his wits’ end what to give Emmeline till the happy thought had struck him of presenting her with his own money-box, then standing empty and useless. Emmeline had thanked him for it graciously at the time, but Micky had always had an uneasy feeling that it was rather a mean makeshift of a present, so he was delighted to find it turning out at last to be really of some use.

‘I think that’s a splendid plan,’ he said; ‘you’ll be able to open it whenever you want to count how much money you’ve got, which you can’t do with the ordinary stupid sort of missionary-box.’

‘There’s a good deal in that,’ said Aunt Grace. ‘See, here’s a bright new shilling as a contribution to the extra money-box’s first meal. And now I think it’s time all you young people went to bed.’

For some time after she had got into bed that evening Emmeline lay awake dreaming day-dreams of that twelve-year-old girl who had been so wonderfully good to the poor. Strangely enough, however, the child of her visions was no longer a stranger, but Emmeline herself—Emmeline, who had mysteriously become ennobled, and who was known to everyone as ‘the saintly Lady Emmeline.’

There was a letter waiting on Emmeline’s plate when she came down to breakfast next morning. Letters were rare and joyful events to the Bolton children, and Emmeline thought it very annoying of the servants to troop in for prayers before she had had time to glance at the contents of this one.

Sunday prayers, however, never took long, and Emmeline was soon free to fly back to her letter. To her great delight it proved to be from Mary.

Mary began by saying how very much she was missing them all, and how often she thought of them and wondered how they were getting on. Then followed the really exciting part of the letter:

‘Do you think your Auntie would let you three come over and spend the day with me next Saturday? Eastwich Fair will be going on, and it would be nice for you to go and see it, especially as you were disappointed last year on account of the scarlet fever being in the town. Tell Master Micky he shall have shrimps for tea if he can[41] come, and give him and Miss Kitty each a kiss from me.’

Emmeline looked up from her letter with sparkling eyes. ‘Oh, Aunt Grace,’ she cried, ‘this is a letter from Mary, asking us three to go and spend the day with her next Saturday! The Fair will be going on—that’s why she is asking us just now. We may go, mayn’t we?’

‘Three cheers for Mary!’ cried Kitty, jumping up and down, as her custom was when excited.

‘For she’s a jolly good fellow!’ chimed in Micky, in what Aunt Grace called his sea-captain’s voice.

‘Have you been used to going to this Fair other years?’ asked Aunt Grace, who was looking rather troubled as she poured out the tea.

‘No, because till Grandmamma Moorby died we always used to go and stay with her for August and September, and last year there was the scarlet fever; but we may go this year, mayn’t we, Aunt Grace?’ repeated Emmeline a little impatiently.

‘I must think about it, Emmeline,’ said Aunt Grace quietly. ‘Kitty, will you pass Emmeline her tea—for one thing, Saturday isn’t a whole holiday, you know.’

‘Oh, but we can work on Wednesday afternoon,’ said Emmeline; ‘one whole holiday comes to the same thing as two half ones.’

‘Not quite,’ said Aunt Grace; ‘your afternoon work is never so much as what you do in the morning. But we’ll see whether it can be arranged.’

‘“We’ll see” always means “yes” in the end,’ said Kitty.

‘No, Kitty,’ said Aunt Grace, rather distressed, ‘I don’t at all promise. I should like you to have the pleasure, but I don’t yet know whether it will be possible.’

‘Oh, Aunt Grace!’ cried Kitty, pouting a little, ‘you can’t not let us go to the Fair. There are such darling baby elephants!’

‘Yes,’ added Micky, ‘and there are boats which go up and down, and up and down, and round and round, till you get as lovely and seasick as if you were on the real sea!’ Micky spoke without any thought of sarcasm.

‘Dear me! I should be very sorry to stand in the way of Micky’s having the pleasure of being seasick!’ said Aunt Grace, with one of her funny little smiles. ‘I’ll see what can be done, children. But don’t say any more about it just now.’

The twins were a good-humoured little couple, and quite aware that Aunt Grace was always glad to give them pleasure when she could, so they left off teasing to go to the Fair and devoted their attention to their boiled eggs. Eggs were a special Sunday treat. Emmeline, however, ate[43] even her egg in glum silence. Perhaps it was scarcely consistent for a young lady who judged her aunt so severely for worldliness to set her heart on attending a fair, but the best of us are inconsistent sometimes. Besides, it was not only the possible loss of the pleasure itself which she resented; there was Mary’s disappointment to be thought of—dear Mary, who had been like a mother to them all while Aunt Grace was enjoying herself in London. Altogether Emmeline felt that she did well to be angry, and went on nursing her grievance all the morning.

The day was a wet one. In the morning it drizzled, though not enough to keep the party from church, but at lunch-time the rain began to descend in such torrents that the usual Sunday walk was clearly out of the question.

‘I’ve got some letters I must write,’ said Aunt Grace as they rose from the table, ‘but I shall have finished them before very long, and then I shall be very pleased to go on with “The Pilgrim’s Progress.”’

She went to the drawing-room, where Emmeline followed her, with the intention of writing an aggrieved letter to Mary, while Micky and Kitty repaired to the schoolroom on some business of their own.

Somehow Emmeline’s grievance did not seem quite so impressive when she came to write it[44] down, or perhaps it was that her pen still travelled too slowly for her thoughts. In any case she grew bored presently, and wandered upstairs to the schoolroom to see what the twins were doing. Judging from the eager sound of their voices as she drew near the schoolroom door, it seemed to be something interesting.

She found them sitting on the floor, playing with their bricks.

‘Well, I never!’ she exclaimed with a very good imitation of Jane’s voice of righteous wrath. ‘To think of playing with bricks on Sunday! You know Mary never let us.’ Emmeline spoke in a quite sincere belief that it was her duty as an elder sister to keep the twins in the way that they should go, but perhaps her elder-sisterly mission was all the easier to-day because she was in a bad humour with the world in general.

The twins only giggled in an exasperating way. ‘Mary isn’t here now,’ sang out Micky.

‘And I’m sure Aunt Grace wouldn’t mind,’ added Kitty defiantly.

The hard lump which Emmeline knew so well at such times rose suddenly in her throat. So even the twins were going over to the enemy! ‘Well, of all the horrid, forgetting children!’ she exclaimed hotly, while the tears rushed to her eyes, and again the twins laughed in a provoking way.

‘Why, what’s happening here?’ asked Aunt Grace’s voice as she opened the schoolroom door.

‘It is a Sunday game—really and truly it is,’ declared Kitty.

‘It isn’t,’ said Emmeline. ‘They would never have thought of playing with bricks on Sunday at home.’

‘It is quite a Sunday game,’ repeated Kitty. ‘We are starting a Home for brick widows and orphans. The long bricks are the widows and the little ones the orphans. It was last night that made us think of it.’

‘Yes,’ said Micky, ‘to-morrow we shall play that the brick-box is a thieves’ den, and the little bricks will be clever little boy-thieves, and the big ones grown-up burglars. That will be much more exciting, only Kitty thought the Home was best for Sunday.’

‘I agree with Kitty,’ said Mr. Faulkner, who had come into the schoolroom behind Aunt Grace without the children noticing him in the heat of the argument. Emmeline looked rather abashed now that she was aware of his presence, but the twins were dauntless as ever.

‘Well, suppose you put the widows and orphans back into the Home now,’ Aunt Grace suggested, ‘and then, if you come down into the drawing-room, Mr. Faulkner will tell some interesting[46] stories about the real orphans. Won’t you, Mr. Faulkner?’

‘I’ll tell stories certainly,’ he replied; ‘whether they’ll be interesting is another matter.’

‘Oh yes, they will,’ said Kitty. ‘We were ever so interested last night, weren’t we, Micky?’

‘That was partly because of the lantern,’ said Micky frankly, as he flung unfortunate brick orphans violently back into the brick-box Home; ‘but the stories were decent, too,’ he added kindly.

A few minutes later the whole party were seated in the drawing-room. The children listened with rapt attention as Mr. Faulkner told stories, some so funny that his audience went into fits of uproarious laughter, and some so pathetic that Aunt Grace’s eyes filled with tears. Even Emmeline was charmed out of her crossness, and became like a different being.

‘Do tell us some more about that wonderful little Kathleen who was so very good to the poor—the child you spoke about last night,’ she pleaded, as Mr. Faulkner paused for a moment.

‘No,’ said Aunt Grace, almost sharply for her; ‘that was the only part of last night’s lecture I didn’t enjoy. I think that little girl was in a false position altogether.’

Mr. Faulkner looked decidedly taken aback. ‘But surely you approve of children trying to help their less happy brothers and sisters?’ he said.

‘Certainly,’ said Aunt Grace, ‘but the help should be of a suitable kind. That child was encouraged to patronise people who were in many ways better and wiser than herself, and certainly far more experienced. I am sure such patronage does harm, not only to those on whom it is bestowed, but to the child who gives it. I expect your little girl soon became self-conscious and self-conceited, however pure her motives may have been to start with.’

‘I can’t say as to that, for I never knew the child,’ said Mr. Faulkner, ‘but as to the effect of her influence, I am sure from many things I have heard that it was nothing but good.’

‘Mr. Faulkner, can you turn coach-wheels?’ broke in Micky anxiously. He felt much inclined to develop a hero-worship for Mr. Faulkner, but could not quite make up his mind to do so till he was satisfied on this important point.

‘Rather!’ said Mr. Faulkner. ‘I’d show you now if it wasn’t Sunday, but I’ll tell you what—if Miss Bolton will let me, I’ll come again to-morrow afternoon, and you and I will have a coach-wheel exhibition. By the way, I suppose you can turn them yourself?’

‘Oh yes, Micky could go in for a coach-wheel championship,’ said Aunt Grace proudly.

‘And can you ride bare-back?’ pursued Micky.

‘I have done so on occasion,’ said Mr. Faulkner, laughing. ‘Can you?’

‘Well, I haven’t yet,’ Micky owned, ‘but I mean to when our donkey comes. We’re going to buy a donkey, you know, as soon as Aunt Grace gets her next quarter’s money.’

So the merry talk went on, while all the time Emmeline sat by in silent indignation. To think of Aunt Grace daring to disapprove of the wonderful child who was Emmeline’s ideal! But Aunt Grace wanted everybody to be as frivolous and worldly as herself!

‘I have been asking the Robinsons about the Fair,’ said Aunt Grace, on Monday morning, ‘and I think it will be all right for you to go under Mary’s charge. But I don’t want it to be on a Saturday. I wonder if she would be able to have you to-day week instead.’

‘It might put out her plans to change the day,’ objected Emmeline, more from a perverse desire to find fault than because she seriously thought so. ‘Why shouldn’t we go on a Saturday?’

‘Because I don’t choose for you to go on a school-holiday, when the place will be crowded with children,’ said Aunt Grace. ‘There’s no saying what you mightn’t catch. If Mary can’t have you on the Monday I’m afraid you must give up the idea of going to the Fair, but I think it would be worth while to write and ask her.’

‘Very well,’ said Emmeline, in a voice which sounded more sulky than pleased.

‘Oh dear, shall I ever understand Emmeline? sighed Aunt Grace to herself, when her niece had gone off to the schoolroom. ‘Micky and Kitty are dear little things, but I always seem somehow to rub Emmeline the wrong way. I thought she would have been so pleased about this Fair.’

So at the bottom of her heart Emmeline was, but a kind of cross-grained loyalty made her resent Aunt Grace’s having thought it needful to consult the Robinsons as to whether a treat proposed by Mary was suitable. It was that feeling which had been at the bottom of her ungracious manner.

Emmeline’s objection that Mary might be inconvenienced by the change of dates proved a groundless one. A warm letter arrived in the course of a day or two to say that she would be only too much delighted to see the children on Monday, if that suited best; and so without further ado it was arranged.

Three eager heads were craned out of the carriage window, when on the following Monday morning the Woodsleigh train slowly steamed into Eastwich Station. Everyone wanted to be the first to catch sight of Mary. ‘There she is!’ screamed Micky, and ‘I see her!’ shrieked Kitty, as they fixed on two different ladies, neither of whom proved on closer view to resemble Mary in the least.

‘But wherever can Mary be?’ cried Kitty, when she was convinced of her mistake.

‘I thought she would have been sure to come and meet us,’ said Mick, in an injured voice.

‘We’ll wait here a few minutes, just in case something has hindered her,’ said Emmeline, ‘and then if she doesn’t come we’ll make our own way to the house.’

The few minutes passed, and still there was no sign of Mary, so they presently left the station and set out by themselves for her house. Emmeline was in the best of good humours, and made herself quite charming to her little brother and sister. She liked nothing so well as to find herself in a position of authority.

The walk was not long. In a very few minutes they were bursting open Mary’s front door, and rushing down the little passage to the kitchen, with joyous cries of ‘Mary, we’re here!’ ‘Mary, we’ve come!’

Mary was seated in an arm-chair by the fire. ‘Take care, dearie,’ she explained, as Micky was charging at her recklessly. ‘I’ve sprained my ankle rather badly, and though it doesn’t hurt so much now, it wouldn’t do to knock it. I do feel that vexed with myself for having done such a stupid thing to-day of all days. Well, my darlings, this is nice to see you again! Why,[52] Master Micky, I do believe you’ve grown even in these few weeks since I saw you.’

‘I must have grown too, then,’ chimed in Kitty: ‘our two heads come to just exactly the same place on the schoolroom door.’ Kitty was quite willing that Micky should be acknowledged her superior in every other way, but that he should have the palm for tallness was rather too much even for her twin-sisterly devotion.

‘So you have, my darling,’ said Mary, while Emmeline anxiously asked after the sprain.

‘Oh, it won’t be anything much,’ said Mary, ‘but I’m afraid I shan’t be able to use my foot for the next few days, and what bothers me is how you’re to go to the Fair without me. Of course, it’s as quiet as it can be just now—it’s only on Saturday afternoons and in the evenings it gets a bit rough—so I don’t see myself how you could possibly come to harm under Miss Emmeline’s charge, but maybe Miss Bolton wouldn’t think it quite the thing. If only I knew anyone whom I could ask to go with you, but I don’t—not at such short notice,’ and Mary’s pleasant face looked thoroughly worried.

‘I’m sure Aunt Grace wouldn’t mind our going with Emmeline,’ said Kitty.

‘No, she’s much too jolly,’ agreed Micky.

Emmeline could not feel so sure. An uncomfortable remembrance came to her that Aunt[53] Grace had specially said they might go under Mary’s charge. Did that mean that they might go by themselves now that Mary was unable to escort them?

‘Well, what do you think, Miss Emmeline dear?’ asked Mary, anxiously.

‘Oh, Emmeline,’ pleaded Kitty, as Emmeline still hesitated, ‘of course she wouldn’t mind! Why you’re twelve years old—almost grown up.’

That decided Emmeline. She could not bear to lose prestige in the eyes of the little sister who thought her almost grown up. ‘I’m sure Aunt Grace couldn’t mind,’ she said boldly; ‘she knows I’m quite to be trusted to look after the others.’

‘That you are, my darling,’ agreed Mary, rather too easily reassured—as a nurse it had been her one weakness that she never could endure to disappoint the children—‘and Micky and Kitty will be as good as gold, I’m sure’; whereupon the twins assumed the expressions of a pair of youthful saints.

‘May Micky and I look at the picture Bible?’ suggested Kitty meekly. Whenever the twins visited that house—they had often done so in the days when Mary was still their nurse—one of two amusements was the recognised order of the day. Either they played—not the real game, but one of their own invention—with a set of[54] elaborate Indian chessmen brought home by a sailor brother of Mary’s; or else they looked at the pictures of a fascinating old French Bible which had somehow come into the possession of Mary’s grandfather.

‘And now, dearie, tell me all about how you’ve been getting on,’ said Mary, as soon as there was quiet in the room, owing to the twins having become blissfully absorbed in the picture of the plague of frogs in the old French Bible. It always sent delicious thrills through them to discover frogs hopping lightheartedly out of Pharaoh’s very modern looking soup tureen, or creeping out from between his bedclothes.

‘Aunt Grace is kind in her own way,’ acknowledged Emmeline—she was always candid about people’s merits even when she disapproved of them—‘but living with her isn’t like living with you, Mary.’

‘Well, dear, it’s not to be expected it should be, seeing that she’s a young lady, and me only an old nurse,’ said Mary simply; ‘but I’m sure whatever changes there are will work out right in the end, for I know she is fond of you.’

‘Yes, she’s fond of us—that is, she is fond of the twins,’ said Emmeline, ‘but she doesn’t care about the sort of things mother cared about, and you care about. What she really cares for is dressing prettily and going to parties, and so on.’

‘I don’t think, dear, we can judge what’s in other people’s hearts,’ said Mary, slowly. She felt somewhat at a loss how to answer Emmeline, for she was too good and loyal to encourage the child in criticising her aunt, but she herself had been brought up to regard most amusements as dangerous, if not actually sinful, and there was no doubt that Aunt Grace was very gay and merry.

‘But I’m not judging what’s in her heart, but what she says,’ persisted Emmeline. ‘I’ll just tell you what she said the other day’; and she related the conversation with Mr. Faulkner about the little Kathleen who had been like an angel to the poor. ‘You don’t think it’s true that children only do harm when they try to do work of that sort?’ she ended.

‘No, indeed,’ said Mary; ‘I think a guileless child can often do more than anyone else to touch a sinner’s heart.’ Mary spoke with earnest conviction. It was true that she had never actually come across such a young person as the guileless child of whom she spoke, but she none the less firmly believed in the type.

‘Mary, isn’t it nearly time for dinner?’ broke in Micky at this point. The twins had just reached the last meal of the Israelites before they left Egypt, and the picture had put it into Micky’s head to be hungry.

‘And, Mary, may we set the table?’ chimed in Kitty.

They were in the midst of setting the table when Mary’s brother George came in from work. He was a burly, good-natured, red-faced person, chiefly remarkable for pockets which bulged out with apples and sweets, and for certain time-honoured jokes which the children always greeted with the cordiality due to such old friends.

‘George always pretends he’s going to put us in his pockets,’ Micky had remarked to Kitty on one occasion; ‘it’s getting a bit stale.’

‘Yes, but we must laugh,’ said Kitty: ‘he’d be so disappointed if we didn’t,’ and accordingly the twins always laughed uproariously as soon as George so much as mentioned his pockets.

They sat down to table after full justice had been done to these pleasantries, and the meal that followed might have been one grand joke from beginning to end to judge from the continual laughter that went on. Mary had remembered everybody’s favourite dishes; there was liver and bacon to please the twins, pancakes for Emmeline, though Shrove Tuesday was about half a year distant, and baked potatoes for them all. When at last everybody had eaten as much of these good things as they could manage, and George had gone back to work, it was high time to start for the Fair.

‘I wonder what time I had better have tea ready for you,’ said Mary, as they were putting on their hats. ‘Did Miss Bolton say you were to go back by any particular train?’

‘She said either the 5.5 or the 5.25,’ replied Emmeline; ‘it doesn’t really matter which, for she isn’t going to meet us at the station. She’s going to a croquet-party at the Vicarage this afternoon, so it would not be convenient, and you see she always trusts me to look after the others.’ Perhaps Emmeline would not have dragged this in if her conscience had been quite at ease about the afternoon’s expedition.

‘Well, then, I’ll expect you back to tea about a quarter past four,’ said Mary. ‘Miss Emmeline will be able to keep count of time with that dear little watch of hers. And now, my darlings, it’s high time you were off, or you’ll have to come back almost as soon as you get there.’

‘It’s a horrid shame you can’t come too, Mary,’ said Micky; and his sisters declared that it wouldn’t be half so much fun without her.

‘Yes, I don’t know when I’ve been so disappointed about anything,’ said Mary, with unfeigned regret; ‘but you’ll have to tell me all about it when you come back to tea. I shall be looking forward to that all the afternoon.’

Perhaps just because she had been looking forward to the treat so eagerly for days past, Emmeline’s feeling, when she actually found herself at the Fair, was one of disappointment. There, to be sure, were the gaily decorated booths, there were the merry-go-rounds of all kinds and degrees, varying from the ring of wooden horses worked by hand, to the alarming-looking motors which raced round and round at break-neck speed; there were the side-shows, with their air of entrancing mystery to be revealed on payment of one penny; there, in fact, was everything she had been led to expect, but somehow the whole did not make the glittering, fairy-like effect she had been picturing to herself. Besides, even at this hour of the afternoon, there were a good many rough-looking people about, and Emmeline did not like rough people.

But if Emmeline was disappointed, Micky and Kitty were not. All the merry-go-rounds were playing different tunes; all the people who had[59] anything to sell or to show were proclaiming its merits at the tops of their voices; the public was enjoying itself in a very loud fashion; in fact, everybody was doing everything in the noisiest manner possible, and the discord of sounds produced was deafening and delightful to the twins.

‘Isn’t it lovely?’ said Kitty to Micky, as she skipped about; but Micky did not hear, for he was engaged in a scornful colloquy with the owner of the hand-worked wooden horses.

‘Think I’m going to ride on one of those things?’ he was demanding indignantly. ‘Do you take me for a kid?’

‘Emmeline,’ clamoured Kitty, ‘when may we go and see the darling elephants?’

‘You girls can do what you like,’ said Micky grandly, ‘but I’m off for a motor-drive.’

Aunt Grace had provided each twin with a shilling, and Emmeline with a florin to spend at the Fair, so that there was plenty of money for such luxuries as motor-drives.

The motor-drive, or rather several motor-drives, and the call on the darling elephants were gone through in due course, and then Micky fell under the spell of the cocoanut-shy.

‘Do come on, Micky!’ entreated Emmeline, after he had made many unsuccessful shots; ‘I believe they’re fixed[60]——’

The rest of her sentence was lost in indignant astonishment; someone had flicked one of the little feather brooms known as ‘fair-ticklers’ full in her face!

‘Come along, Micky,’ she exclaimed, with angry impatience; ‘I’m sick of this horrid place. Why, what are you doing?’

For Micky had suddenly flung down the ball which he was about to shy at the cocoanuts, and was rushing after a wretched little street arab of about his own size.

‘Give it up! You little cad!’ he shouted, as he caught hold of the boy’s ragged jacket. ‘Give it up this minute!’

‘I ain’t got nothing,’ whined the boy, trying vainly to wriggle out of Micky’s grasp.

‘Yes, you have. I saw you take it,’ and to Emmeline’s intense surprise, Micky suddenly wrenched her own purse out of the street arab’s dirty hand. Her thoughts had been so much taken up by the fair-tickler that she had not even felt it go.

‘I’d give you a jolly good thrashing if you weren’t such a muff!’ exclaimed Micky.

Emmeline collected her astonished wits with an effort.

‘Well, you are a naughty little boy,’ she remarked severely; ‘it would just serve you right if we gave you up to the police.’

The ragged little urchin began to howl. If he had really been much afraid he would probably have run away, but this did not strike Emmeline, and her heart softened towards him, especially when he sobbed: ‘I ain’t had nothing to eat since yesterday morning.’

Kitty, who was looking on with wide-open pitying eyes, gave Emmeline’s hand a sudden squeeze.

‘May I give him the money I’ve got left?’ she whispered.

‘Not till we know more about him,’ said Emmeline. ‘Is your father out of work?’ she added to the boy, with some vague idea that it was the correct thing to ask questions of that kind before giving alms.

‘I ain’t got no father nor mother neither,’ he replied, still in his professional whine.

‘Who looks after you, then?’ asked Emmeline, more gently.

‘Old Sally Grimes,’ was the answer, ‘but she ain’t give me nothing to eat since yesterday morning, and she beat me something awful!’

‘Come along with me,’ said Emmeline. A sudden idea had taken possession of her.

‘What for?’ asked the boy half suspiciously.

‘I’m going to give you something to eat,’ said Emmeline.

The boy’s eyes glistened. It had been a[62] picturesque exaggeration to say that he had had nothing to eat since yesterday morning, but he was really very hungry.

‘Thank you kindly, lady,’ he said, and Emmeline flushed with gratification. ‘Lady’ sounded so much grander than ‘Missy.’

‘What are you going to give him to eat?’ asked Micky, with interest. ‘There’s a man selling ice-cream over there.’

Almsgiving was impossible to Micky just then, for he had spent all his money (his last two cocoanut shies had been paid for by Kitty), but he was quite willing to help with advice.

‘And there’s a girl selling delicious toffee, only she calls it candy,’ said Kitty. ‘Why does she call it candy, Emmeline?’

‘I shouldn’t think of giving a starving boy ice-cream, or toffee either,’ said Emmeline. ‘We’ll go where there’s something more sensible to eat than what you can buy at this Fair. Come along, children.’

On the whole, the twins were not unwilling to leave the Fair. It was rather sad to go so soon, but less so now that twopence of Kitty’s represented all their remaining fortune than it would have been half an hour before, and when even that solitary twopence had been spent on the mysterious toffee that called itself ‘candy,’ their willingness to forsake the Fair became eagerness[63] to see what new thing was about to happen. It was as good as a story-game come true to wander through the streets of Eastwich with this delightfully ragged dirty boy.

‘Where are we going, Emmeline? What are we going to do?’ they cried.

‘You’ll see,’ said Emmeline.

As a matter of fact, she did not quite know herself.

They came out of the Fair into a region of squalid little shops; squalid, at least, they appeared to Emmeline, but her protégé saw them from a different point of view.

‘Please, lady, the fried fish and ’taters in there is all right,’ he hinted wistfully, as they passed an overwhelming smell.

Emmeline hesitated. She had vaguely intended taking him to some superior Tea-Rooms in the High Street, where she herself had sometimes gone for a treat, but now she came to think of it, perhaps the fried-fish shop would be more fitting in this case.

‘I think we’ll go in here, then,’ she decided, to her guest’s obvious satisfaction.

A shopman with a much stained apron gazed at the party in some astonishment as they entered, but he seemed to think Emmeline a trustworthy person, for he made no demur when she ordered a plate of fried fish and potatoes.

‘What’s your name, little boy?’ asked Emmeline, when the shopman had disappeared into the back regions, and they were seated waiting at a grimy table covered with American leather in imitation of marble.

‘Diamond Jub’lee Jones,’ replied the boy glibly.

‘What an extraordinary name!’ exclaimed Emmeline, and the twins began to giggle.

‘I were born on Diamond Jub’lee day,’ he explained, with evident pride.

‘Well, Diamond Jubilee, I’m sure with such a splendid birthday you ought to be a very good, honest boy,’ said Emmeline, by way of improving the occasion. ‘What would Queen Victoria have said if anyone had told her that a boy born on her Diamond Jubilee would ever take to picking people’s pockets? Why, she would have been awfully upset.’

Diamond Jubilee looked round the shop furtively, as though to assure himself that there was nobody within hearing. ‘That ain’t to please meself I picks pockets,’ he mumbled; ‘that’s Mother Grimes. She beats us something awful if we don’t bring nothing home.’

‘You don’t mean to say she is bringing you up as a thief!’ exclaimed Emmeline, in a horrified voice.

What Diamond Jubilee might have answered will never be known, for just at that moment the[65] shopman came back with the fried fish and potatoes, and private conversation was stopped for the time being. Diamond Jubilee threw himself on the food like a ravenous animal, while Micky and Kitty looked on with a fascinated stare. From their point of view, his table manners were quite as well worth watching as those of the elephants they had just been visiting.

Emmeline’s point of view was a more fastidious one, and at any other time she might have been disgusted, but to-day it was with a certain tolerance that she saw Diamond Jubilee put his knife into his mouth. His last words had shed a halo of romance round his unkempt head. It was to children like him that Kathleen had been a good angel.

With that last thought, a plan flashed into Emmeline’s brain—a plan so strange and startling that it almost took her breath away for the moment, and so glorious that it made her want to jump and dance about the shop, only that would have been out of keeping with the dignity of the wonderful plan.

‘Diamond Jubilee, if you have quite done, will you come outside? I’ve something important to tell you.’ Emmeline’s heart was thumping so that she could hardly get the words out.