The Project Gutenberg EBook of Blue Jackets, by Edward Greey

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Blue Jackets

The adventures of J. Thompson, A.B. among "the heathen chinee"

Author: Edward Greey

Release Date: November 11, 2018 [EBook #58270]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BLUE JACKETS ***

Produced by deaurider, Martin Pettit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

OR,

THE ADVENTURES OF J. THOMPSON, A. B.

AMONG "THE HEATHEN CHINEE."

A NAUTICAL NOVEL.

BY

EDWARD GREEY.

IN ONE VOLUME.

BOSTON:

J. E. TILTON & CO.

——

1871.

[All Rights Reserved.]

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1870, by

EDWARD GREEY,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Shanley & Lynch, Print, 39 Vesey St., N. Y.

The most cruel and ignominious punishment man can inflict upon his fellow men, is still enforced in the English Naval Service; though many indignantly deny it, and stigmatize this story as "a libel on the British Navy." Unfortunately for "Blue Jackets" this is not so, and the novel is founded on facts, as I have been in the service, and, on many occasions, seen sailors subjected to most painful degradation at the caprice of those, who, because they were officers, seemed to forget that the men possessed feelings in common with them. As facts are the best proofs, I quote the "London Daily News," November 7, 1870, which records that on October 30, 1870, a scene, similar in barbarity to the one described in the fifth chapter, occurred in Plymouth Sound, England, on board the "Vanguard" (Captain E. H. G. Lambert), "within hearing of a large number of women and children, who were waiting permission to go on board the iron-clad."

It may interest readers to know, that the adventures of J. Thompson, A. B., among "The Heathen Chinee," are not entirely fictitious, the descriptions of the peculiar habits of "The Coming Man" being from personal observation during a lengthened sojourn in China.

EDWARD GREEY.

New York, January 1, 1871.

| CHAPTER. | PAGE. | |

| I. | Woolwich Dockyard at Noon.—A Deserter from H. M. S. Stinger | 1 |

| II. | The Boatswain's Tea-Party.—Engagement of J. Thompson, able seaman, and Miss Mary Ann Ross | 10 |

| III. | The Court-Martial on board H. M. S. Victory | 16 |

| IV. | Thompson gets into a Difficulty with the Regular Army.—Amateur Theatricals, and a Surprised Party | 23 |

| V. | The Merciful Sentence is Carried Out | 32 |

| VI. | H. M. S. Stinger leaves for the Cape.—Some of the Letters written upon that important occasion | 37 |

| VII. | In Simon's Bay, Cape of Good Hope.—Extraordinary Delusion on the part of Captain Puffeigh with regard to a lovely German Fraulein | 44 |

| VIII. | The Persecution of Charles Dunstable, ordinary seaman | 50 |

| IX. | At Singapore.—Thompson Visits Mr. Oldcrackle, and is Most Hospitably Entertained.—The Effect of a Lovely Pair of Black Eyes upon a too Susceptible Sailor | 55 |

| X. | Fatal Result of Crushe's Tyranny.—Death of a Good Officer, and Execution of his Assassin | 64 |

| XI. | Hong-Kong.—The Stingers Among the Pirates.—Last Moments of Old Jemmy | 72 |

| XII. | The Stingers March to the Rescue of a Young Lady.—Smoking Out a Pirate's Nest | 81 |

| XIII. | Puffeigh falls in with a Yankee Captain, of whom he Buys some Experience.—Clare's Hallucination | 89 |

| XIV. | Capture of Thompson by "The Heathen Chinee."—Captain Puffeigh and Lieutenant Crushe are Promoted, and leave the Ship | 95 |

| [Pg viii]XV. | Thompson Escapes from Sse-tsein, and Ships on board a Canal Boat.—Captain Mo and his Wife Jow.—Bigamy | 107 |

| XVI. | An Assault at Arms, and the Stories of two inoffensive Sailors | 117 |

| XVII. | A-tae | 126 |

| XVIII. | Captain Woodward and Yaou-chung.—How the Taontai "Played it" upon his Guests | 134 |

| XIX. | "O-mi-tu-fuh!"—A Chinese Girl's Love and Devotion.—Thompson's Appearance as a Star Comedian | 143 |

| XX. | The Battle of Chow-chan Creek.—Marriage of Miss Moore | 152 |

| XXI. | The Stinger Visits Japan.—Mr. Shever's Last Pipe | 161 |

| XXII. | Up the River.—Clare Goes through Fire and Water.—On to Canton | 168 |

| XXIII. | Thompson turns Bill-Sticker.—The Notice to Quit Served on Governor Yeh.—Poetry | 177 |

| XXIV. | What the Stingers did towards Taking Canton | 187 |

| XXV. | Farewell to "The Heathen Chinee."—Hard Times again for the Stingers.—Thompson Re-visits his Old Flame at the Cape | 194 |

| XXVI. | Thompson Falls (Platonically) in Love with a Charming Young Lady "who calls herself Cops" while he is Courted by her Bonne.—Cement for a Broken Heart | 204 |

| XXVII. | The Widow's Wooing and What Came of it.—Thompson is Exposed to a Raking Fire, but comes off with Flying Colours | 214 |

| XXVIII. | Home | 224 |

BLUE JACKETS;

OR, THE ADVENTURES OF

J. THOMPSON, A. B., AMONG "THE HEATHEN CHINEE."

The big bell of Woolwich Dockyard had just commenced its deafening announcement that "dinner time" had arrived, producing at its first boom, a change from activity to rest in every department of that vast establishment.

Burly convicts, resembling in their brown striped suits human zebras, upon hearing the clang, immediately threw down their burdens, and, followed by the severe-looking pensioners who acted as their guards, sauntered carelessly towards the riverside, where they knew boats waited to convey them on board the hulks. As these scowling outcasts drifted along, they here and there passed parties of perspiring sailors still toiling under the direction of some petty officer; noticing which, the convicted ones would grin and nudge each other, glad to find that while they could cease their labour at the first stroke of the bell, there were free men who dared not even think of relaxing their hands until ordered to do so by their superiors; and many of the rogues turned their forbidden quids, and thanked their stars that they were convicted felons, and not men-of-wars's men.

In the smithies, at the first welcome stroke of the bell, hammers, which were then poised in the air, were dropped with a gentle thud upon the fine iron scales with which the floor was covered; the smiths, like all other artisans, having the greatest disinclination to work for the Government one second beyond the time for which they were paid. The engines kept up their din a few moments after all other sounds had ceased, but finding themselves deserted gave it up, and, judging by the way they jerked the vapour from their steam pipes, appeared to be taking a quiet smoke on their own account.

From forge, workshop, factory, mast-pond, saw-mill, store, and building shed—from under huge ships propped up in dry-dock, or towering grandly on their slips,—from lofty tops and dark holds,—out of boat and lighter,—from every nook and corner swarmed mechanics and labourers,—all these uniting in one eager mob, elbowed and jostled their way towards the gate, like boys leaving school.

The dockyard was bounded by a high wall upon the side nearest the town, whilst its river frontage was guarded by sentries, who not only protected the Queen's property, but prevented her jolly tars from taking boat in a manner not allowed upon Her Majesty's service.

The doors of the great gate were thrown wide open, and the crowd poured through as if quite ignoring the presence of a number of detectives, who were posted near it, to prevent deserters from the ships of war from passing out with the workpeople; special precaution being taken at that time, as the country required every sailor she could muster, to man the ships then being fitted out for service against the Russians.

When the rush was at its height a sailor disguised in the sooty garb of a smith emerged from behind a stack of timber, piled near the main entrance, and joining a party of workmen, who evidently recognized him, was forced on with them towards the gate, the man walking as unconcernedly as any ordinary labourer. As they neared the detectives the attention of the latter was suddenly distracted by the noise of a passing circus procession, and for a moment the officials were off their guard.

"Keep your face this way, mate, and look careless at the peelers," whispered one of the party to the deserter, and the man so warned did as he was directed, although he scarcely breathed as he brushed by them, the very buttons on their uniforms seeming to spy him out, and to raise a fear in his breast that he would find a hand rudely laid upon his collar, and hear the words, "You're a prisoner?" However, they did not even look at him, and in another moment he found himself free.

The deserter was an able seaman named Tom Clare, a sober, excellent sailor, and the devoted husband of a worthy girl to whom he had been but a few weeks united. Tom had not long before arrived home from the China Station in H. M. S. Porpoise, and finding some property bequeathed to him, had applied to the Admiralty for his discharge, but his application was refused; and although he offered to provide one or more substitutes, his petition was returned to him, with orders to proceed at once to the ship to which he had been drafted, under penalty of being arrested as a deserter. Tom found, to his sorrow, there was no alternative. If he stayed, the authorities would at once arrest him, as they were notified of his whereabouts. He knew England had just entered upon a tremendous struggle with Russia; so, hoping it would soon be over, and the demand for seamen decrease, he determined to face his misery, and proceed to Woolwich to join the Stinger, that ship being rapidly fitted out for foreign service.

As it was customary to allow the men leave to go on shore at least twice a week, Clare was accompanied to the port by his wife, his only request being that she should never attempt to visit him on board his ship, to which she reluctantly agreed, but thought it very hard that her husband should make such a stipulation. Leaving her in respectable lodgings, he walked down to the docks, was directed to his ship, and in a few moments found himself before the first lieutenant. This officer, by name Howard Crushe, was a tall cadaverous-looking man, with a face upon which meanness and cruelty were plainly depicted. Clare knew him at once, Crushe having been the second lieutenant of his last ship, and as such having twice endeavoured to get him flogged.

"Come on board to jine, if you please, sir," said the seaman.

"Oh! that's you, Mr. Clare, is it?" sneered this ornament of the navy.

"Yes, sir," replied Tom, putting a cheerful face on it, and endeavouring to appear rather pleased than otherwise to see his old officer.

"Do you remember I promised you four dozen when you sailed with me in the Porpoise, eh? Well, my fine fellow, mind your p's and q's, or you'll find I shall keep my word. I remember! You're the brute who objected to my kicking a whelp of a boy. All right! I'm glad you have been drafted to my ship, as I can make it a little heaven for you."

Clare remembered the circumstance to which Crushe alluded, he having once[Pg 3] interfered to save a poor boy from brutal treatment at the hands of that officer, and now he was in his power he knew he was a marked man.

The lieutenant called for Mr. Shever, the boatswain, and told him to put the sailor in the starboard-watch, at the same time privately informing that warrant officer of his dislike to the man.

"Leave him to me, sir. I knows him. He is a werry good man, but has them high-flown notions," was the reply of the boatswain.

Tom was taken forward and put to work; and when the dinner pipe went, proceeded on board the receiving hulk with the rest of the Stinger's, having fully made up his mind to be civil, and do his duty, in spite of the depressing aspect of the future. "Perhaps he'll not try and flake me, arter all," he thought. "If I does my best and don't answer him sassy, he can't be such a cold-blooded monster as to do what he ses. I suppose he only wanted to frighten me." As the sailor pondered over this, his face showed that although he endeavoured to argue himself into the belief that all would come right, still his mind was filled with alarm at the prospect before him.

The Stinger was, according to the Navy-List, commanded by Captain Puffeigh, a short, fat, vulgar, fussy little man; but in reality Crushe, who had married the captain's niece, had sole control of the ship, Puffeigh merely coming on board once a week, and staying just long enough to throw the first lieutenant's plans into confusion. The crew knew there was a captain belonging to the ship, but probably not two of their number could tell who he was. Crushe was the officer they looked to, and all of them soon found out that he was a Tartar. His first act of despotism towards Clare was to stop his leave to go on shore; and this he did on the day the man joined the ship.

"Please, sir, do let me go ashore to see my wife," pleaded the sailor.

"Let your fancy come off with the other girls," was the lieutenant's brutal rejoinder.

Tom bit his lips, and turned away disgusted and almost mad, knowing it would not do to show what he felt. He thought, "of course the lieutenant imagines all women who have anything to do with sailors are bad; he don't know how good she is. I wish I could have him face to face on shore, I'd cram them ere words down his lean throat, I would."

Tom's leave had been stopped for over a fortnight, and all his appeals met with insults from Crushe, when one morning, the crew having been transferred from the hulk to the Stinger, Captain Puffeigh visited the ship; and after a superficial survey, desired the first lieutenant to muster the men, observing, "I think it's time they should know who I am." The fact was, he began to be a little jealous of his lieutenant's power, and thought it best to show his authority.

After much piping and shouting on the part of Shever and his mates, the men were mustered upon the quarter-deck, and they certainly were "a motley crew." There was the usual proportion of petty-officers, all old men-of-war's men; able seamen, principally volunteers from the merchant service; ordinary seamen, mostly outcasts driven by dire necessity to join the navy; and first and second class boys. The latter were, with a few exceptions, workhouse-bred, and imagined themselves in clover. They served their country by doing all the dirty work of the ship from 4 A.M. until 6 P.M., after which time, until piped to rest, the lads amused themselves by learning to drink and smoke, or by listening to the intellectual conversation and songs of the gentlemanly outcasts before mentioned. Men like Clare felt rather disgusted upon finding themselves ranked with such fellows; although had this collection of human beings been under the guidance of a humane commander and first lieutenant, they might after a time[Pg 4] have been moulded into a good crew. Of course they were a rough lot, as the Queen's service offered, at that time, but few inducements to decent sailors.

Puffeigh walked up and down the line, scanning the faces of the men with anything but a pleasant expression upon his countenance. He picked out the sailors at a glance, and spoke to them, asking the usual question, were they satisfied with their ship? When he came to Clare he stopped for a moment, and observed to Crushe, "What a fine fellow that is!"

"One of the worst characters in the fleet," replied the first lieutenant.

However, the captain questioned him as he had done the others, upon which Tom briefly and respectfully asked the commander for permission to go on shore, like the rest of the men.

"Speak to Lieutenant Crushe about that. I leave those things to him entirely."

Tom was about to reply that he had done so, when the captain cut him short with, "There, my man, discipline must be maintained," and then gave the order to "pipe down."

The dignified Puffeigh strutted aft, and Lieutenant Crushe, calling Clare to him, said, between his teeth, "You sweep! I'll keep my word with you as soon as we get into blue water."

Tom knew full well what that meant: he was to be flogged; so he determined to desert, and get out of the country. His country required his services, but no man could stand such treatment. His mind was made up, and he wrote to his wife as follows:

"H. M. Stinger, Woolwich doc-yard, 12 October, ——

"Dear Polly,

"Come aborde at dinner time on Sunday. Mind you are not laite.

"Your loving husband,

"Tom Clare."

His wife had not seen him since the day he joined the ship, although she had several times been tempted to go on board; but remembering his earnest wish, was obliged to content herself with the letters he sent her; and the poor fellow often went without a meal in order to find time to write her a line. He could not bear to have his fair young wife herded upon the wharf with the degraded creatures who daily swarmed down to the ship, but come she must now, as it was the only chance by which he could escape from his hateful bondage.

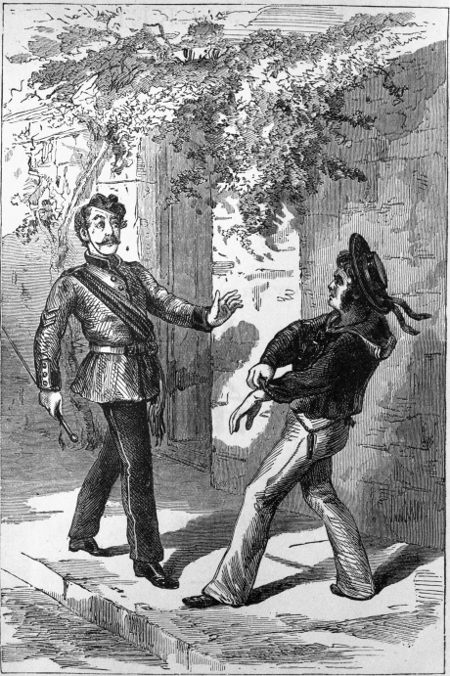

On the appointed day Polly went down, and was one of the first to be passed on board by the ship's-corporal. Tom's lips quivered as he saw her descend the gangway ladder, and soon he was by her side. There was no loud demonstration, but the fervent pressure of their hands showed how happy they were to meet again, even in that place. By a fortunate accident, the boatswain was absent, and his cabin left in charge of a good-natured A. B., by name Jerry Thompson.

When Polly was descending the main hatchway ladder, Jerry, who knew all about Crushe's behaviour towards Clare, stepped forward, saying, "This way, mum," and, to the delight of the couple, they were shown into Mr. Shever's cabin, and thus enabled to have four hours' uninterrupted chat; the sailor going off, after placing before them his own dinner and allowance of grog. Jerry had a susceptible heart, and would do any thing to serve a woman.

Tom rapidly ran over his reasons for attempting to escape, and you may be sure Polly agreed and sympathized with him in everything.

"What a shame," she exclaimed, "to keep you on board, when even the boys get as much leave as they choose to ask for!"

"Never mind, my dear," he replied. "I'll not ask 'em for leave this day week, if all goes well."

Polly left the ship in good spirits, and was gallantly escorted to the dock-gates by the kind-hearted A. B., who said to her on parting,

"Mum, if ever Tom wants a friend, I'll do my best for him, for the sake of his wife. You see, mum, I'm not a married man myself, but I can feel for them as is."

"God bless you, sir, for your kindness," sobbed Polly.

"Jerry, mum, not sir; we ain't allowed that rate in a man-o'-war."

Polly laughed through her tears, and nodding to the sailor, passed quickly through the turnstile, and was soon out of sight.

Before the week was over she had made all the arrangements for her husband's flight; having smuggled off a complete suit of well-worn smith's clothes, and paid the men from whom she obtained them a sum of money to assist Tom in getting through the gate.

As we have described, Clare played his part well, and passed the detectives without the slightest suspicion on their part that a deserter had escaped before their eyes.

On leaving the men who had assisted him, Clare turned to the left, keeping with the crowd as much as possible. All along the foot of the wall were crouched anxious wives and children, waiting with "father's dinner," in order to save him a long walk. Many of these watchers peered into his face, and some of the little ones would clap their hands and cry, "Here's daddy!"

Tom walked on for a few moments, hardly able to realize he was free, when suddenly Polly, who had followed him from the dock-gate, caught him by the arm.

"For heaven's sake, Polly, don't draw notice on me; walk on ahead, dear, I'll follow you; but don't look behind you, unless you would have me took."

Poor Tom! The loving taunt of that speech was understood by his wife. She have him taken! Why, he knew the poor girl would die for him.

Away she walked, quite in a different direction from that of her old lodgings; up one street and down another, until they were fairly out in the country, she praying all the time that her love might never be retaken, and thanking God her husband was now free. The footfall behind her was delightful music; while he, devouring her with his eyes, and longing once more to clasp her to his heart, thanked heaven in his own rough sailor style.

"Am I dreaming?" he muttered. "No, there she is, the beauty—there she is—thank the good God who guards her always—I am awake—it's real—I ain't asleep."

He imagined that walk the longest he had ever taken.

"Will she never bring to?" he thought.

At last she stopped before a neat cottage, and lifting the latch, darted in. Her husband was not long after her, and she was soon clasped in his arms.

"Polly, dear heart! Wife! look at me!" he almost sobbed as he tenderly pressed her to his heart. "Bear up, my pretty one! I'm here, and all safe, and never going away again."

But the poor girl was too happy to reply, and a flood of tears gave relief to her feelings, ere she was composed enough to talk about his plans of escape. When her agitation had somewhat abated, Polly produced a suit of farmer's clothes; and after Tom had shaved off his whiskers, she cut the curly locks from his head, although it very much grieved her to do so. When the process was complete, she called in her father and mother, who had come up from Kingsdown to assist their girl in her[Pg 6] trouble. Clare had taken a seat by the fire, and his disguise was so complete, that the good old people could not, until he spoke to them, make out who he was.

"That beant you, Tom, be it?"

"Yes, it's me, father."

"Why, you do puzzle me. I don't know you a bit. You looks like the young squire."

Many were the congratulations which passed between them, and when the old fisherman handed Tom a passage ticket for himself and Polly, by which Clare found he could leave Liverpool for New York on the following Wednesday, he caught the old man in his arms and fairly hugged him.

It was settled they should leave the house about six o'clock P.M., and as the police were sure to be on the alert, a cart was procured in which they were to be conveyed to London, it being arranged that a brother of their kind hostess was to act as driver, while Tom and Polly were to lie down in the straw until they arrived in the big city. Once there, they might walk to the railway station. If all went well they would reach Liverpool the next day, where they could remain unmolested, until the ship sailed for America.

"Come, Tom," said the old woman, "you must be hungry, lad. I warrant you, a bit of meat and a drop o' beer won't come amiss," upon which she bustled about; and, with the assistance of Polly, a meal was prepared and placed upon the table.

Tom sat by the window, keenly watching the few stragglers who passed by, when suddenly he started back and turned pale, as a corporal of marines walked up, looked suspiciously at the cottage, and then crossing the road, questioned an old fellow, who was breaking stones.

Clare could not make out what he said, but imagined from the motions of the corporal that he was inquiring who lived in the cottage. Tom called Polly and told her his suspicion,—it was a moment of great anxiety for both of them. At length, however, the corporal turned upon his heel, and retraced his steps down the lane. Their landlady was sent for; and as the good creature knew all about her lodgers' plans, they freely imparted their fears to her, begging she would call the old stone-breaker in-doors, and ascertain what questions the petty officer had put to him, Tom and his wife retreating to the stairs, where they overheard the following conversation:

"I say, master, who was that speaking to ye this minute?"

"Don't know, missis; but I expects he be a perlice."

"What did he say to you, master?"

"'Well,' he says to me, ses he, 'do you know,' he ses, 'who lives over there?' he ses; that's what he ses to me, missis, as near as I can recollect."

"What did you tell him?"

"Why, I says, ses I, 'Look here! what do you want to know for?' I says."

"Well, go on, go on! What else did he ask you?"

"'Well,' ses he, 'have you seen any one go in there this morning,' he ses. 'Yes!' ses I. 'Who?' he ses. 'Well,' ses I, 'I seed Missis Drake,' I ses, 'and her lodger,' I ses, 'and a man,' I ses."

"You old foo—! Excuse me, Master Noyce, but you did not see no man come in but my lodger. There, go away! You allus was a stupid, and I'm sure of it now."

"Come, missis! I don't want no blowin' up. You axed me civil, and I gave you an answer," retorted the old man, turning sulkily away.

"Yes! you ses, and you ses, and you've been and gone and done it, you wooden-headed old post!" whimpered the good-natured woman, after she had closed the door[Pg 7] upon him. "You've done it this time, you donkey!" whereupon she sat down in a chair, and had a good cry.

Tom and his wife came out of their place of concealment, and begged she would not take on so, as it was no fault of hers that the man had given the information; but the kind creature was with difficulty assured "it might all turn out to be nothing." She felt that, after all the poor fellow's trouble, he would be captured and flogged, and their arguments only increased her sympathy for the unfortunate couple. However, the afternoon passed away with no more signs of the corporal, and by six o'clock everything was in readiness. The old folks had embraced their girl, and poor Tom was leading her out, when suddenly a party of marines rushed into the house, and the corporal in charge laid hands on Clare, and told him he was his prisoner.

Polly clung to her husband's arm, not fully realizing the dreadful truth; but soon she saw all, and that Tom was about to be torn from her. Rushing between the corporal and her husband, and endeavouring to force him from the former's grasp, she raved like a mad woman.

"You dare touch him! Take your hands away, you wretch! Do you hear? Leave go!"

Clare was about to speak to her, when the corporal said with a sneer, "Pull that thing away, and gag her if she gives any more of her talk. She need not make such a fuss; she'll soon find another feller."

These words had hardly passed his lips before Tom had the speaker down upon the floor, with both his hands tightly clutching the soldier's windpipe.

"You brute, I'll kill you!" he yelled. And he seemed likely to carry out his threat. However, the marines threw themselves upon the deserter, who, after a desperate struggle, was beaten senseless, handcuffed, and dragged away.

When the old fisherman, his wife's father, saw how brutally they ill-treated Tom, he seized a stick and endeavoured to assist him, but was overpowered and beaten, until he, too, lay like a dead man, the corporal encouraging his men "to pitch into the old scoundrel."

Polly and her mother were happily unconscious of the last part of the outrage, both having fainted when Clare seized upon the soldier. Some neighbours, aroused by the screams of their landlady, came to the assistance of the women, who after a short time were restored to their senses.

When Polly became somewhat composed, she asked for her husband.

"Where is my love? Where is my brave, handsome husband? Gone? Have those wretches taken him? You coward, father, to let them take my Tom! O God! They'll flog him! I can't bear it! Let me go! I shall go mad!"

And the poor girl had fit after fit, until they feared she would die of exhaustion. The heart-broken old people watched her through the night, thinking and almost praying that death would come to her relief.

The prisoner was conveyed on board his ship, and taken aft upon the quarter-deck, where he was reported to the officer of the watch, a mate named Cravan, derisively called by the midshipman "Nosey," and that officer being a creature of the first lieutenant's, took upon himself to reprimand the man.

"So you have caught him, eh?"

"Yes, sir," replied the corporal with a military flourish, "but we had no end of trouble. He were in a low den outside the town, along with a lot of vimen, and ven I arrested him, he werry nigh killed me."

"I were with my wife, sir," pleaded the prisoner.

"Your wife, of course! Any trollop is your wife. It is a very convenient relationship," sneered the bully.

Roused by this coarse speech, and not caring for consequences, Clare raised his manacled hands, and dealt the brutal speaker a blow between the eyes, which stretched him upon the deck. The sailor was about following up the attack, but was prevented by the marines, who after a desperate struggle secured him, and stopped further violence on his part.

"Put him in irons!" yelled Cravan, rising to his feet. "And," added he, as the prisoner was dragged from his presence, "you hound! your woman will bring you to the gratings yet!"

Clare was taken below, heavily ironed, and thrown into the ship's prison. There, bruised in body and sick at heart, he watched away the weary night. He almost regretted he had not killed the mate. No doubt this was wrong and horrible; but we must remember he had been driven nearly mad, and knew full well the punishment for the attack upon Cravan would be death—or a worse fate to a man of feeling—a flogging.

Once during the night he was visited by a midshipman who evidently pitied him. Tom's wrists were raw and bleeding, so the youngster tore up his handkerchief, and bound it round the handcuffs, the sentry who accompanied the officer holding the light, and laughing to himself all the time to think any one could be so "soft." James Ryan—this was the middy's name—was a warm-hearted Irish lad, and would never allow a man to be treated like a dog, if he had power to prevent it. Clare did not say anything when the boy had completed his task of mercy; in fact, it was almost impossible for him to speak, so overcome was he by the kindness. When the door was closed upon him, he heard the sentry say, with a chuckle,

"Didn't seem to thank ye for it much, sir?"

"Perhaps he felt all the more," replied the generous boy. This was true, as Tom thanked him in his heart.

Few who do not know the service can understand the goodness of the middy, who was laughed at for weeks afterwards for his act of mercy. If any one lost his handkerchief, he was directed to Ryan for it, with the remark that "possibly he had given it to some deserter."

Mr. Cravan submitted his bruises to the inspection of a sympathizing assistant-surgeon, and then went to bed, or, as sailors term it, "turned in," determined to be revenged on the man who had so violently attacked him. "He's safe for four dozen, anyhow," he murmured, as he arranged the bandage over his aching eyes, "and it will do the brute good."

The next day he received the condolence of Puffeigh and Crushe; but Lieutenant Ford and the rest of the ward-room officers did not conceal the disgust they felt at his behaviour, and he also found himself cut by many of his mess-mates in the gun-room.

A few evenings after this he went to a ball, and as only one or two of those present knew the facts of the case, he received many sympathizing inquiries. The poor fellow who had so nearly been killed by a brute of a deserter was an object of great attention to many present, and "Nosey" Cravan for once experienced little difficulty in obtaining partners. He was, however, not a little piqued by the reply of the belle of the evening, to his request to honour him with her hand for the next waltz. Bending towards him, and smiling as if she were conveying a complimentary reply, she whispered, "No, sir, I cannot dance with such a hero."

This young lady was a cousin of Lieutenant Ford's, and had heard from her relation that Mr. Cravan had grossly insulted the man who attacked him; therefore, when[Pg 9] elated with his success among the ladies, the mate ventured to solicit her as a partner, she quietly put him down.

"She never can mean to snub me because I spoke rather roughly to the fellow. Well, I suppose Ford has told them his version of the affair. She's a deuced peculiar sort of a girl, and probably thinks the man ought not to be flogged for his infernal conduct, and has romantic ideas that the fellow has feelings like ours," thought Cravan. He, however, wandered into the supper-room, and finding a vacant place, was soon too far gone in champagne to trouble himself what people thought of him, under any circumstances whatever.

The Stinger being nearly ready for sea, the boatswain's wife determined to give a party in honour of the event, and suggested that Mr. Shever should ask a few of his men. Now, this was certainly very contrary to all that warrant officer's ideas of propriety.

"What! ask blue jackets? why, my dear, it is against all precedent," he exclaimed.

"Bother your president," said the good natured woman. "Ask a few of the poor fellows; I warrant you they will behave well; then, knowing me, if ever you are sick, they will look after you."

After many pros and cons the husband as usual, yielded to his wife's persuasion, and agreed to invite Gummings, a quartermaster, Price, a boatswain's mate, and the tender-hearted Jerry Thompson.

Jerry was of middle height, well built and active, with good-looking oval face bronzed by exposure in many climes, dark eyes, and curly chestnut-coloured hair. Frank, generous and good natured to a fault, he was liked by every man and boy in the ship,—while his respectfully cheeky manner was tolerated by his officers, who passed over his freedom of speech and action.

At various times Jerry had determined to give up the sea and settle on shore, but after a few month's trial his roving propensities would get the better of him, and in spite of the lamentations of the children and regrets of his numerous circle of lady friends, he would pack his chest and be off to sea again.

Previous to joining the Stinger he had for some months been employed as a super at the Surrey Theatre; but growing weary of that life, and the country being at war, he joined the navy, as he remarked, "from patriotic motives of a hard-up description." This was his first trial of a man-of-war's life, he being, to all intents and purposes, a merchant-service sailor, which will account for his want of reverence for the authorities and traditions of H. M. Navy.

Mr. Shever was serving out spun yarn one morning, when Jerry came to him for orders. Giving directions as to the business on which the seaman had consulted him, the boatswain, after a short pause, suddenly asked "if he had ever been to a party?"

"Many a one," replied the sailor, "The last one of any importance was with my Lord Buckingham."

"Come, now," growled the boatswain, "I wants no chaff. I knows a lady who intends giving a party, and probably she may ask you."

Jerry at once saw how the land lay, and assured the official that, "in case of his being a favored one, he would be on his best behavior."

"None of your—" (here the boatswain lifted his hand as if in the act of imbibing some intoxicating fluid). "You know I don't allow none of that sort of goings on in my house; and," added he, "the party breaks up when I pipes down; that will be your signal."

Mr. Shever was somewhat doubtful in his own mind whether Jerry was sufficiently sedate for admission to such a select company as his wife had asked; but, as she had set her mind upon it, come he must, or a family difficulty might arise, in which case[Pg 11] Mr. Shever would as usual, come off second best. His idea of "piping down" when he thought his visitors should depart was both novel and nautical.

He merely stated to the other sailors that he wanted them to take a cup of tea at his house on a certain day; they were old and tried men, and he knew they would not be any trouble to him.

Whenever the boatswain had an opportunity he would put a few questions to Jerry, or ask his advice on important points of the coming entertainment. Mr. Shever was of the opinion that "tea and shrimps, with a song afterwards, was the correct sort of thing;" while Jerry suggested "tea and muffins, with a dance to follow,—the whole to wind up with a glass of punch." On this coming to Mrs. Shever's ears, she at once adopted the idea as an entirely original plan of her own, and declared "if Mr. Shever did not order a fiddler and a harpist, she would forthwith pack up, visit her mother, and remain there until the Stinger had sailed."

Jerry looked forward with pleasure to the entertainment, and determined to show the natives a few of his most elaborate steps in the hornpipe line, being sure he would be called upon to amuse the company in that way.

At last the day arrived, and at about six o'clock P.M. Thompson was on his way to the boatswain's house. His companions were dressed in their very best, and looked as unhappy as two baboons who had tried on a suit of clothes for the first time. On the road he endeavoured to instil a little cheerfulness into them, but it proved a total failure.

"We mustn't chew, and we mustn't get tight, and we mustn't smoke," growled Gummings.

"We've got to stay until he pipes down, and then all the publics will be shut," muttered Price.

Mr. Shever walked slowly home, keeping the party always at a respectable distance from him. What would people say if they knew he had invited such strange guests? You see even H. M. boatswains are afraid of Mrs. Grundy.

Mrs. Shever had stationed a small girl at the front door to let in visitors, so that when Jerry touched the bell the door was promptly opened and they were shown into the parlour. Here, enthroned upon the sofa-bedstead, sat the good lady, waiting to receive her company. By her side was seated her sister, a plump jolly girl, about eighteen years of age, who, when she saw the sailors, giggled and bashfully hid her face behind a turkey-feather fan.

The three men walked into the room, and stood looking at the ladies like shy children.

In a few moments Mrs. Shever recovered her composure, which had been slightly disturbed by the sudden entrance of the sailors, although all three of them were well known to her, and addressing Jerry, said, "Good-evening, Thompson, I'm proud to see you; and you too, Price and Gummings." Jerry, not at all abashed after the ice was broken, advanced towards the ladies, and politely inquired after their health. The two sailors looked around with a bewildered air, pulled their forelocks, mumbled, "Service to ye missis," and then retired to a bench behind the door, from which place they did not emerge until tea commenced.

Thompson was soon quite at home; and as one corner of the sofa was vacant, he requested permission to take it. His amusing stories quickly won the young girl's attention, and a formal introduction took place, Mrs. Shever giving him what he termed a handle to his name, by saying, "Miss Mary Ann Ross, permit me to introjuce you to Mr. Thompson." When she rose to bow, the artful fellow seized the opportunity, and[Pg 12] sat down between the ladies; and as they did not ask him to move, he made the most of his position.

Soon after this Mr. Shever arrived, and seeing Thompson ensconced so snugly, tried to catch his eye, to show him that he did not quite approve of his freedom. But it was of no use. Jerry was oblivious of winks and nods, or returned them as witty and artful exchanges to the bewildered boatswain. At last, upon the arrival of Mrs. Shever's mother and father and two of her cousins with their respective young men in waiting. Mr. Shever requested Jerry to "move off that 'ere sofa, and let the girls sit down," upon which his wife told the aforesaid girls to "sit on chairs by the fire, as Mr. Thompson was getting on nicely," and forthwith ordered her husband to go into the kitchen, and help the girl to toast the muffins, adding, "she thought they could spare him well enough."

This flattering sentiment was fully indorsed by Jerry, who declared "he often saw too much of the boatswain," a remark which was received as a real joke by all present excepting the two sailors, who were fast asleep when it was made. They woke up, however, in time to join in the laugh that followed, after which they again sweetly slumbered.

Mr. Shever stood in the passage between the parlour and kitchen until the laughter died away, and, we are sorry to state, said anything but his prayers. "Bless his impudence to sit on the sofa between 'Melia and Mary Ann, and to wink at me like that there, and he only a common sailor. For two pins I'd pipe down now."

Another peal of laughter followed just then, as Jerry had finished relating a joke, the fun of which was torture to the boatswain. The latter seized his call, and putting it to his lips, blew the shrill signal, known on board ship as "pipe down."

"What's that?" exclaimed Mrs. Shever.

"Do you keep a canary?" innocently inquired Thompson. Upon which the boatswain gave another blast of the pipe, and this time it was much louder.

Mrs. Shever rang the bell, and when the servant appeared told her "to inform Mr. Shever if he wanted to amuse himself in that way he'd better wait until he got on board his ship," and added, "I suppose he don't want me to come out to him."

As he did not repeat the noise, it may be presumed he felt as if his wife was just as well where she was; so holding his peace, he turned his attention to toasting the muffins, and winking at the servant girl, which combination of amusement and labour at last made him recover his temper, and by the time he had finished he became quite cheerful again.

"If you please mem, tea's aready in the back bedroom," said the servant.

Mrs. Shever darted a look of displeasure at the girl, but without otherwise noticing the faux pas, invited her visitors to the room above, which was indeed usually devoted to the purpose described by the maid.

The boatswain had what he called "rigged the tea table" after the fashion common on board ship, when the sailors make an effort to entertain some distinguished visitor. In the centre was a huge earthenware jug, filled with choice flowers; and the decorations on this article being of a gorgeous and somewhat eccentric nature, we will briefly describe them. On one side was depicted H. M. S. Bluefire, which with brown sails, red masts and rigging, and blue hull, was bounding over a yellow and black sea, in company with some purple and brown boats. On the reverse side was a representation of the Sailor's Farewell, showing how a gallant tar in a blue suit, scarlet face, and goggle eyes, takes leave of a young woman dressed in a yellow gown, cut very low to show off her pea-green complexion. The said jug was a relic of Mrs. Shever's girlish days; and being a present to her from a sweetheart, who was lost in an Arctic expedition,[Pg 13] was looked upon as an ornament of great value, and as such only brought out on state occasions, like the present.

The table presented a somewhat crowded appearance, as the boatswain had piled up the eatables until there was not room to set another tea-cup. As they had only eleven chairs, he rigged a seat by the window, and when the visitors entered the room, he endeavored to allot this to Jerry.

"Well, mum," said the unabashed sailor, "you have done the thing hansom; ellow me—" upon which he handed the delighted woman to her place at the head of the table. He next installed Mary Ann; and taking a seat between them, cheerfully observed that, "the company had better fall to."

The silent sailors being somewhat modest, were still standing in the passage, and there were two vacant places at the table. The boatswain was about availing himself of one of these, when his wife exclaimed, "Mr. Shever, where's your manners? the visitors are not all accommodated."

Shever brought in the two sailors, who seated themselves upon the extreme edge of their chairs, and looked around at the festive party like infants suddenly led into a confectioner's and left to their own resources.

The unfortunate boatswain had no alternative but to take the seat by the window, from which he was presently drawn to hand round the muffins; this occupation calling forth from Jerry the witty remark that, "Mr. Shever seemed quite in his element," the point of which was utterly lost upon that worthy.

Thompson related some of his most amusing yarns, which were received with roars of laughter by all present, with the exception of the host and the two seamen. The latter, finding themselves behind a heap of bread and butter, were busily employed in reducing the level of the same, varying their banquet with a few pinches of shrimps, which they swallowed whole, utterly oblivious of heads or tails, washing down any little obstacle with tea, which they imbibed from pint mugs, Mrs. Shever knowing it was useless to tickle their palates with ordinary quantities.

"Oh, you funny man!" screamed Mary Ann; "I never heard the likes of you before."

Jerry received this as a direct avowal of admiration on the part of the young lady, and redoubled his exertions to amuse her.

The boatswain was boiling over with rage; and as he dared not object before his wife, was obliged to nurse his wrath, his only relief being to go outside the room, and "pipe down" softly in the passage, or to wink at the servant whenever he could do so with safety.

The ladies pressed Thompson to eat, saying "he had not done justice to the fare." This brought forth an avowal from him, "that to his idea their company was more delightful than the choicest viands." Upon this sentence being explained to Mrs. Shever's mother, who was a deaf old lady, the latter signified her appreciation by hammering on the table with a fork, and crying "braywo," which being looked upon as a genteel proceeding and part of the ceremony by the silent sailors, was immediately adopted by them, and a round of hearty applause followed. The boatswain, seizing this opportunity, placed his call to his lips and "piped belay," a feat which he accomplished without being detected by his wife; although the seamen understood it, and ceased their knocking at once.

The company descended to the parlour, which they cleared for dancing; after this the seamen took up their old positions behind the door, where, like two well-gorged boaconstrictors, they curled themselves up and went to sleep.

As a sort of opening exercise, one of the young men in waiting volunteered a song,[Pg 14] which was chiefly on "wiolets." This he bellowed out in a high tone, turning up his eyes to the ceiling all the while, until, in rendering the more powerful notes, he strongly resembled a blind man.

Jerry listened very attentively, until the last verse was sung, when, attracting Mary Ann's eye, he turned up his optics exactly as the singer was doing. This was too much for her, and she laughed outright; the rest of the company following suit, until the fellow began to think he was singing a comic song instead of a floral howl, and catching the infection himself, laughed louder than any of the party.

The boatswain now introduced the fiddler, who, apologizing for the absence of the harpist, who, he stated, was suffering from a headache, fell to tuning his violin.

Thompson was uncertain whether to ask the hostess or Mary Ann to dance with him. He was about to speak to Mrs. Shever, when she said good-humouredly, "Now, Mr. Thompson, don't neglect Mary Ann!" upon which he led the blushing girl out, and in a few moments they were "hard at it," this being the only term we can apply to their exertions, Mrs. Shever dancing with her husband, who was about as active as a half-trained elephant.

Jerry was in great favour. His frank manner and amusing stories delighted every one; he danced with all the ladies in succession, and quite won the heart of the oldest one by asking her twice, although there was little danger of her accepting him the second time, as he had completely exhausted her for the evening during the first; nevertheless, the old lady was charmed with him, and declared he was "quite a gentleman."

His best efforts were, however, reserved for his performance with Mary Ann and his hostess, with whom he was, as the boatswain remarked, "as much at home as if the house belonged to him." He amused them during the intervals of the dances with choice songs of a pathetic kind; and, as he possessed a good voice and style, the women were several times melted to tears.

About ten o'clock the hostess produced a steaming bowl of punch, upon which the silent sailors immediately woke up, and received a liberal allowance of the liquid. Carefully holding their mugs, as if anxious that none of the nectar should escape they retreated to their corner, and two sponges could not have absorbed the fluid more expeditiously or quietly than they did. After a time they emerged from their concealment, and finding no one was looking, helped each other to another dose of the delicious beverage, then sank back into their former retirement, this manœuvre being repeated several times during the evening.

Under the influence of Mrs. Shever's brewing the party had become quite noisy, and Thompson had danced his last hornpipe before they found the time had arrived to separate. The boatswain decided to walk a short distance with the seamen; and Price and Gummings after many declarations that "Misshis Sheaver was a dutchessh, and Missir Sheaver wast a perfetchs shentleman, and they never had enjoyshed themselves so much afore," were with the assistance of Jerry, at last fairly got out of the house.

When at some distance from his residence the boatswain suddenly stopped, and drawing forth his pipe, blew the well-known "pipe down;" then assuming his naval authority, he ordered the sailors to go their ways. Upon turning to speak to Jerry, with whom he wished to have an explanation, he found that individual had vanished; thinking it might be from fear of his anger, he did not trouble himself, knowing he could talk to him at a future time, when the sailor would be a little more respectful. Mr. Shever then walked about with his hat off, until his mind was thoroughly composed, when he retired to the bosom of his family.

Jerry had quietly returned to bid Mary Ann good-bye, and entering the house,[Pg 15] found the two ladies busily engaged in putting their hair in paper, preparatory to retiring up-stairs.

"Law, Jerry, how you did frighten me," exclaimed Mary Ann.

As the effects of love at first sight were somewhat increased by the punch he had imbibed, Thompson was not at all hurt at being called Jerry, but he advanced towards the blushing maiden, and saying she looked like an angel, proceeded to kiss her in a vigorous manner.

"For shame!" said the delighted girl. "Have done now, Jerry, or I'll scream."

"You rogue, you," observed Mrs. Shever. "Why you'd kiss me if I didn't stop you. I wish Shever would come in."

The active sailor proceeded at once to demonstrate his admiration of the latter speaker, evidently having little fear of the boatswain's returning just then, and a loud smack on the face, administered "more in sorrow than in anger" announced the completion of the outrage.

"There never was such a shocking man," giggled the matron.

"Don't you try it on again!" cried Mary Ann, in a most provoking manner.

Despite her pleading, Jerry renewed his attention, and as they parted, boldly declared that "he'd have her if she'd have him."

Mary Ann saw him out of the house, and as he kissed her for the last time, quietly murmured, "Jerry, dear, I'll marry you whenever you are ready."

Happy pair! they had now a bright future to anticipate: both could dream of it. It was a pleasant and inexpensive luxury, and about as likely to be realized as such visions usually are. However, "they've done it now," as the boatswain observed, when his wife informed him of the fact of Mary Ann's engagement. "That's what comes of introducing people of low manners into society. There'll be a 'mess-alliance,' and all the parties will be sorry for it when it's too late." Mr. Shever was evidently of opinion that Jerry was far beneath Mary Ann's notice, and possibly forgot that when he married her sister he was only what he now termed a common sailor; while his wife, seeing in Thompson, a good-hearted, merry fellow, woman-like, favoured his suit.

The day after Clare's arrest the Stinger was hauled out of dock, and towed down to Greenhythe, in order to hoist in her powder and heavy stores. After a few days' delay she proceeded to the German Ocean, where she cruised about, while her commander endeavoured to work the ship's company into something like man-of-war shape.

Tom was all this time kept a close prisoner below, as he would have to be tried by court-martial. The ship being on the Home Station, and immediately under the Admiralty, it would hardly do to decide his case in the usual style afloat, viz. by a court, the judge and jury of which are one person, the captain of the ship. Commander Puffeigh was annoyed at the trouble and delay that must ensue before Clare could be punished, and observed to Crushe, "What a pity it is we have not been sent off to a foreign station at once; we could then have settled that scoundrel's business in ten minutes, without the fuss and worry of a court-martial."

One morning, when the crew were at breakfast, Clare was paraded on the quarter-deck, and Captain Puffeigh heard the preliminary evidence against him, which was duly taken down by the ship's clerk, and on that statement a court-martial was applied for, and granted on the ship's return to England. When Tom came on deck he looked careworn and pale; but seeing Mr. Cravan, his face flushed. This was noticed by the captain, who observed to the first lieutenant that "the fellow was case-hardened," an opinion which Crushe at once confirmed.

Mr. Cravan gave his evidence, which was duly recorded by the clerk, and then Crushe charged Clare with having used mutinous language to him before his arrest. Everything that could be brought against the man was stated in the report, which, on being completed, was read over to the prisoner, who was then asked if he had anything to say.

Tom looked at the commander with astonishment, and replied.

"Captain, one half of that 'ere writing aint true, and the other is exaggerated out of all shape."

Upon hearing this bold statement, the gallant Puffeigh at once cried, "Silence! you mutinous fellow; that's enough. I hope you will get your deserts on our return to England. If I had my will, I'd hang all such as you!"

Clare was then taken below again, and put in irons.

The Stinger continued her cruise, until her commander had what he termed "toned his crew down." In this artistic occupation he found a valuable ally in Crushe, who gave full vent to his cowardly nature, and proved himself a bully of the first water. Suffice it to say, by the time the ship reached Portsmouth the first lieutenant was detested by nearly all the officers, and thoroughly feared and hated by the whole of the crew.

On her arrival in port, the ship was at once docked, and Clare sent on board the flag-ship Victory, where he was very fairly treated, as her commander did not understand that the man should be considered a felon until he was tried and convicted.

Polly came off to the ship, and was allowed to spend a few moments with him, in the presence of the master-at-arms. Tom saw, with sorrow, that his situation and[Pg 17] their separation were telling fearfully on his wife's health; he tried to cheer her up, and even joked about his prospects, but without avail, and it was with difficulty she could repress her feelings.

His wife used every argument she could think of to induce him to accept a lawyer's services for his defence, but he would not consent to it, saying, "I'll stand up and tell 'em what I did, and own what was wrong. If so be they turn agin my true defence, they wont believe the lies of a long-shore lawyer."

Like many other sailors, the unfortunate fellow had a dread of the legal profession; and trusting to the mercy of the court, and the facts of the case coming out on his trial, determined to defend himself.

Clare's friends also urged him to alter his determination, but in vain; and with great reluctance they gave up their pleading, and were compelled to abandon him to his own resources.

There was great excitement on the Common Hard at Portsmouth, on the morning when the signal gun from the Victory announced the holding of a court-martial on Clare's case. Crowds of what are termed "the lower orders" were assembled all along the portion of the Hard off which the flag-ship was moored, their object being to witness the embarkation of the officers of the court, who were to be conveyed on board in boats specially detailed for the duty. Every one was in full dress, and the handsome blue and gold uniforms of the officers contrasted strongly with the squalid appearance of the crowd who swarmed around them.

As each member of the court left his carriage at the end of the wharf, he found, to his disgust, that he had to walk between a line of these "lower orders," who, unabashed by his grand air and dazzling uniform, passed remarks upon any one who happened to be unpopular, in a manner more free than pleasant. Not having any fear of the lash, they gave their thoughts free vent.

"There goes lanky Jack, who flogged a boat's crew because his wife ran away with a sojer officer," screamed a woman in the crowd, as Captain Curt, a well-known advocate for the lash, walked down and entered the boat.

"Lord help Tom Clare if there's many more like him in the court," said another lady.

Some commanders were more popular, particularly with the Irish women, who formed no small part of the crowd; and gratuitous advice, such as, "Be aisy wid the poor boy, captain, aroon," or, "Say a good word for poor Tom, for the love of the mother of yez," were freely offered on all sides.

The spectators up to this time were, excepting in their observations, tolerably quiet. But when Commander Puffeigh, Lieutenant Crushe, Mr. Cravan, Mr. Shever, and the other witnesses, came down to the wharf, a loud yell of hatred broke from the people, and several stones were thrown at the officers. Unfortunately on their arrival at the end of the pier, they found no boat to receive them, and for ten minutes had to bear the insults of the mob.

Puffeigh was resplendent in a brand new uniform, which fitted him like a tight pair of boots; in fact, he was so well tailored, that he could scarcely breathe.

"Isn't that a picture for a tax-payer?" cried a voice.

"I say, don't Puffeigh look like old Stiff the beadle this morning?"

"That long beast of a lieutenant is the cove wot drove Tom to desert," roared a costermonger. Upon which a policeman who was near tried to arrest him, but he was hustled away from his grasp, and the man escaped.

At this moment a stone, thrown by some one at the back of the crowd, struck Crushe on the cheek. Turning round, his face livid with rage, he found himself confronted[Pg 18] by an amazon, who coolly putting her arms akimbo, sneeringly asked him "if he would like to strike a woman?"

Shever, who knew the lady, thinking to curry favour, turned to her and said sharply, "I'm surprised at you, Mrs. Holloway."

"Keep your breath for lying at the court-martial, and dry up, or I'll serve you as your wife does," retorted the dame.

Mr. Shever looked at her fiercely for a moment; then, probably thinking she might slap his face if he gazed too intently on her, turned away, and embarked with the officers in a boat, which had at that moment opportunely arrived from the Victory.

The mob yelled and screamed like demons, and several stray stones and oyster-shells went flying after the boat. The captain, imagining these favours were from Clare's friends, expressed his opinion that "he trusted all present would endeavour to get Tom what he deserved;" a gentle hint, which was not lost upon Shever and the sailors who were going on board as witnesses. On arrival alongside the flag-ship, Captain Puffeigh was received with naval honours, ending with a doleful wail on the boatswain's pipe. Fortified by this, and feeling once more safe, he reported himself to the officer of the court. The proceedings immediately commenced, Puffeigh's clerk first identifying Clare as belonging to the Stinger, his name being upon the ship's books. It was noticed by the spectators that the prisoner wore two war medals, and the Royal Humane Society's medal.

Then followed the examination of the witnesses for the prosecution, all of whom had been already primed as to their evidence by Captain Puffeigh, who as is usual, acted the part of prosecutor.

The court was composed of naval officers of rank, and undoubtedly was a fair tribunal, if we could shut our eyes to the fact that many of them had been brought up in a school which denied a blue jacket the common rights possessed by the most wretched outcast on shore. The president was an old and feeble officer, who thought the whole affair a bore, and he remarked to another veteran,

"Ah! formerly every commander tried his own men, unless in very extraordinary cases, and we got on well enough. Now every fellow who requires the lash must be tried by a court-martial if the ship is in a port or near a flag-ship. The service is going to the deuce."

Lieutenant Crushe was the first witness called; and his deposition which was taken down in writing by the Judge advocate, was in substance as follows, Captain Puffeigh being allowed to put a most unwarrantable amount of leading questions.

Having deposed that he was first lieutenant of the Stinger, and identified the prisoner as an able seaman, belonging to her, the following questions were asked by the prosecutor:

"You know the prisoner?"

"Yes."

"About what length of time?"

"About four years. He served with me in my last ship."

"Has his character been good, or bad?"

"Unquestionably bad. But he is a good seaman, and knows his duty."

"You had to find fault with him soon after he was drafted to the ship? State to the court what then occurred."

"I was obliged to stop his leave for insolence, the very day he joined the Stinger; and though I spoke kindly to him, he continued this line of conduct, barely doing the work he was appointed to, and that in a sullen, disrespectful manner."

"He deserted from the Stinger, did he not?"

"He did."

"Knowing his character, you were obliged to send a strong force to bring him on board, were you not?"

"Yes. I sent an armed party of marines, as I was aware that, being a desperate man, he would offer resistance."

"Where was he found secreted by the non-commissioned officer?"

Here the president assumed a grave air and informed Puffeigh that he could not put the last question, as Lieutenant Crushe could not testify to hearsay. The examination then proceeded.

"You had other reasons for sending an armed party to secure the prisoner? Please state them."

"Yes. I was aware that he consorted with people of the worst character."

"Some of them had visited him on board the Stinger, I believe. State if that be so."

"Yes, a young woman, whose conduct while on board led me to suppose that she had come for no good. She came down with some of the worst characters in Woolwich. He was afterwards arrested in her company."

When Crushe stated that the man was arrested in the company of bad people, Clare bit his lips, and tried to address the court, when he was informed that "he would have an opportunity of asking questions at a later period, but at present he must remain silent."

Upon receiving this rebuke his face flushed with shame, seeing which, the members of the court, who took it for a sign of passion and rebellion, looked at each other, as much as to say, "See what a ruffian the prisoner is."

The corporal was the next witness. With a military salute that concise individual stated his name and rank, and was thus examined by Puffeigh.

"You received orders to arrest the prisoner, and take a strongly-armed party with you?"

"I did" (with a salute).

"State to the court what occurred on that occasion."

(Saluting) "Well, sir, you see, being a corporal of the Rile Marine division at Woolwich, I knowed that where the prisoner wor a hiding wor a werry bad place, so I went prepared."

"The prisoner showed a determined resistance, I understand? In fact nearly killed you."

(Saluting) "That he did, sir, and the other willings with him."

"There were women in the house?"

(Saluting) "Yes, sir, a regler bad lot—speshilly one on them—his gal, who used awful langevage. I were expostulatin' with her about it in a werry perlite manner, ven the prisoner sudden seized me by the stock, my back being turned to him, and would have killed me but for my men."

(President) "How many men had you?"

(Saluting) "Twenty."

"All armed?"

(Saluting) "Yes, sir."

(Puffeigh) "Do you know any reason for the prisoner's attack upon you?"

"None in the verld, sir."

Here Tom Clare's face flushed again, but remembering the hint he had shortly before received, he held his peace.

The next witness called was Cravan, who, after the usual preliminary question, thus testified—

"You were the officer of the watch when the prisoner was brought on board as a deserter?"

"Yes, and being kindly disposed towards the man, I expressed my regret at seeing him in such a position."

"What then occurred?"

"He struck me a violent blow with his clenched hands, injuring me severely."

(President) "And this without any provocation on your part?"

"Yes. I had spoken to him in the mildest manner."

"Can you in any way account for this conduct; was the man drunk?"

"No, sir; I believe it was premeditated."

Here Tom could restrain his feelings no longer, but exclaimed,

"It ain't true, gentlemen; he's swearing away my life."

Having been with difficulty quieted, he was asked if he had any questions to put, but Clare declined to cross-examine witnesses, whom he had heard boldly perjuring themselves, and who were encouraged, and evidently instructed what to say, by Captain Puffeigh.

Price and Gummings were next called, their testimony going to show that Clare had told them "he'd run away as soon as he could get a chance;" that his language was mutinous; and that he had declared his intention "of dropping a marlin spike on Lieutenant Crushe's head when he got a chance." Price swearing he had said that "it would be a first rate end for the brute," meaning the first lieutenant. "He said it would be considered justifiable homicide, or words to that effect;" and that when the witness asked him "if he wished to be hanged," the prisoner had laughed and said, "he would be let off." Both witnesses hypocritically tried to put in some words of condolence for their "unfortinit shipmate," but were silenced by the court.

Mr. Shever, the boatswain, was then examined by Captain Puffeigh. After the warrant-officer had corroborated the other evidence, the examination proceeded as follows:

"Have you any idea what led the prisoner to desert?"

"No, sir; but I thought, from the first day he jined the Stinger, that he would desert whenever he got the chance."

"What led you to suppose so?"

"Well, sir, you see he belongs to a low lot, and wor always that mutinous and discontented. He is one of them as is always speakin' about rights. I could make no good on him, although he's a fust-rate sailor."

"The prisoner gave you a great deal of trouble, did he not, Mr. Shever?"

"Yes, sir; and when he left I missed a palm and needle, which some woman has since brought aboard, and left in my cabin."

The president here again interfered, as the examination had been allowed to stray from the charges upon which Clare was being tried.

Puffeigh then said there were some questions he would like to submit to the president and court, which, though they did not bear on the charges upon which the prisoner was being tried, certainly would have some effect upon the sentence of the Honorable Court, should they find the prisoner guilty.

The court was then cleared, and after some time, it being again opened, the president informed Captain Puffeigh that the questions could be put.

"Are you aware, Mr. Shever, who the mob were who insulted myself and my officers coming aboard?"

"Yes, sir; they wos friends of the prisoner's. (Sensation in the court.) I believe one on 'em wos his mother." (Great sensation.)

"State to the court the treatment we received."

"They throwed stones at us and dirt, and cut the first lieutenant's face with a large flint. (Immense sensation in the court.) They also mobbed us down, and abused us shameful."

Mr. Shever then went on to state that he had often heard the prisoner say "that he would be cautious what he did." This the worthy boatswain construed into a threat against the first lieutenant. "He considered Clare a dangerous man. Never had seen him drunk, but believed he drank considerable when he had a chance."

We must observe, with regret, that the foregoing evidence of the boatswain was entirely fictitious in its most important portions; in fact, Mr. Shever did on that occasion commit what is commonly called perjury, and the evidence of the seamen was very much of the same unblushing kind. The boatswain knew that if the lieutenant could trust him, and depend upon him to say anything that would carry out his plans, he could do pretty much as he liked with the men, who would not dare to complain of his treatment. His first officer was his model; and being somewhat of a cur, he did not mind swearing to any falsehood that would injure Tom, provided he could curry favour with his superiors.

The prisoner was then asked if he had any questions to put to the witnesses, upon which he replied,

"No, your honour. I've heard 'em say too much already."

This answer was looked upon by the court as evidence of the man's mutinous and dangerous disposition, it being, of course, entirely misconstrued.

Clare was then called upon for his defence. Usually when a sailor is tried this is prepared for him in writing by his counsel, and handed to the Judge advocate, who reads it to the court; but Clare availed himself of the privilege of reading his own defence, and standing up with his earnest face fixed upon the president, he spoke as follows, having committed what he had written to memory:

"Your honors and gentlemen, I bows to you respectfully and begs to be allowed to say a few words in defence of this 'ere crime. I was drove to desert, regler drove, your honors. I jined my ship, intendin' to serve out my time, and if needs be, fight agin the Roosians, and give my life for my country. But that was not to be. Lieutenant Crushe drove me to desert; 'twas him wot hounded me on, and him wot caused me to be here this day a prisoner. Your honors, I could stand it no longer. I have a wife—a good gal—not a common gal—I love her, and I wanted to see her. Yet, gentlemen, knowin' that, and probable that if we went on a furrin station I might never see my wife again, Liutenant Crushe deliberate stopped my leave, and hounded me on to desert. Says he to me one day, "I'll give you a flakin', as soon as I gets you into blue water," or words to that effect, and then I took it into my mind to escape, and not afore that time. I throws myself on the mercy of the court, with regard to striking Mr. Cravan. Your honours, I love my wife. You, surely, who are married love your wives, although I suppose you may think a sailor can't love as you does. I love my poor girl, and they have called her vile names, and said she used bad language. Gentlemen, that's false! Prisoner as I am, and at your mercy, I say that is a lie; she never uttered a bad word in her life. Allow I am bad—a mutineer—a deserter. I won't defend myself agin all that; but I can't hear them lies, and not say a word. If I am wrong, I begs your honors' pardon, but let my wife be cleared from such falsehoods. I struck Mister Cravan because he spoke of my wife as I would not, and could not bear to hear her spoken of. I was mad, possibly; but I am sorry, and pleads guilty, gentlemen, and throws myself upon the mercy of the court, who I beg will look[Pg 22] over my discharge papers from eleven of Her Majesty's ships, in all of which my character stands 'very good.'"

Clare warmed in his defence when he spoke about his wife, until he no longer looked the prisoner. He uttered every word with a peculiarly expressive manner, which would have moved the hearts of most men. But the officers who composed the court heard only in his speech the words of mutiny and sedition. As to his love for the woman he called his wife, that was to them a subject of the most sublime indifference. During his defence, eloquent in its naïve pathos, few of them really appeared to be listening to him. One dozed as if half asleep, and another read a letter, while others again wrote their opinions on certain passages of his speech, and pushed the scraps of paper across to their opposite neighbours.

When Clare ceased speaking, he bowed respectfully to the court; then having signed his defence, handed the paper to the Judge-advocate, after which the court was cleared for deliberation.

The members having consulted for a few moments, now resumed their cocked hats, which up to that time had reposed upon the table before them, and thus decorated, in grim silence, awaited the arrival of the prisoner, who was shortly afterwards brought in.

The Judge-advocate then read the finding of the court, which declared him guilty on both charges,—first of "desertion," and secondly of "striking his superior officer," and the sentence of death was passed upon him for the latter offence. But in consideration of his former services and the very good certificates of character produced by him, the court mercifully commuted the sentence of death, and awarded the punishment of flogging. He would be taken on board H.M.S. Stinger and kept in irons until the day Commander Puffeigh fixed upon as being most convenient for the execution of his sentence, which was, "that he should receive upon his bare back fifty lashes with the cat-o'-nine-tails."

The prisoner, who seemed quite overcome by the sentence, was then taken away and sent on board his ship, to be closely guarded and heavily ironed until the sentence was carried out. As he left the Victory many of her crew who had been his shipmates cast pitying looks upon him but not one of them dared openly to express his opinion.

Clare saw his wife for one moment, as he was entering the dock-yard on his way to the ship, and upon being allowed to speak, told her "to bear up, as his punishment would soon be over, and it was lighter than he expected," &c., &c. In fact, he said all he could to cheer her. Polly, who had thrown her arms around his neck, was then torn from him by the police, who would not allow her to enter the dock gate with the prisoner; and when Tom saw her for the last time, she was being carried away by her grief-stricken father, in whose arms she had fainted.

Lieutenant Crushe gave the crew to understand that in future only those men who pleased him would be allowed leave to go on shore, consequently the "liberty list" of H.M.S. Stinger was a short one.

As the time drew near for leaving the dock, the number of favored ones grew less every day, few being bold enough to go aft and face the lieutenant for the purpose of asking leave of absence. However, Thompson who was not afraid of Crushe, determined to try what he could do; and one evening he, with two other seamen, walked aft, stood between two guns on the port side of the quarter-deck, and waited patiently until that gallant officer condescended to notice them. After keeping the men for some time in a pleasant state of expectation, Crushe suddenly seemed aware of their presence, and with a ghastly twist of his visage, which he intended for a grin, asked the sailors "if they wanted four dozen a-piece? if not, they had better go forward."

"Please, sir," pleaded one of the men, "may I go on shore?"

"What for?" demanded the bully.

"My little gal is sick," said the sailor.

"Come, my fine fellow, that won't do. Go forward, and tell that to the marines."

The man addressed slunk away like a beaten hound. It was true his child was ill, but he was obnoxious to Crushe, so he contented himself with vowing vengeance, and on going forward procured some rank poison in the shape of gin, which he forthwith imbibed, and went to sleep. His little girl died during the night. The poor mother wondered why father did not come home; and it was a bitter grief to her, upon visiting the ship the next morning, to find her husband under punishment for being intoxicated the night before.

"Tell him I'm ashamed of him! and little Carrie so bad!" said the indignant woman to the ship's corporal, who had informed her of her husband's disgrace. "Tell him the dear little angel cried for him till she got too weak, and wanted so to see him before she died; and," added the poor creature, in a low, dreamy voice, "he drunk when he ought to have been with her!"

Bursting into tears, the desolate mother was led away by a sympathizing spectator, to ponder over what she thought her husband's brutality.

When the news was given him by the callous ship's corporal, that "his kid was dead," the man, who was not perfectly sober, smiled and said, "Thank God! she is now better off;" then, crouching down, with his hands tightly pressed to his forehead, wept bitterly.

But we must return to the sailors whom we left standing before the lieutenant on the quarter-deck.