The Project Gutenberg EBook of Popular Superstitions, and the Truths

Contained Therein, by Herbert Mayo

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Popular Superstitions, and the Truths Contained Therein

With an Account of Mesmerism

Author: Herbert Mayo

Release Date: October 30, 2018 [EBook #58197]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POPULAR SUPERSTITIONS ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Les Galloway and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. Variations in hyphenation have been standardised but all other spelling and punctuation remains unchanged.

The cover was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

AND

THE TRUTHS CONTAINED THEREIN,

WITH AN

ACCOUNT OF MESMERISM.

BY

HERBERT MAYO, M.D.,

FORMERLY SENIOR SURGEON OF MIDDLESEX HOSPITAL; PROFESSOR OF ANATOMY AND

PHYSIOLOGY IN KING’S COLLEGE; PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE ANATOMY

IN THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS, LONDON.

F.R.S., F.G.S., ETC.

FROM THE THIRD LONDON EDITION.

PHILADELPHIA:

LINDSAY AND BLAKISTON.

1852.

WM. S. YOUNG, PRINTER.

iii

In the following Letters I have endeavoured to exhibit in their true light the singular natural phenomena of which old superstition and modern charlatanism in turn availed themselves—to indicate their laws, and to develop their theory. The subject is so important that I might well have approached it in a severer guise. But, slight as this performance may appear, I profess to have employed upon it the keenest and most patient efforts of reflection of which I am capable. And as to its tone at the commencement, and the prominence given to popular and trivial topics, I candidly avow that, without some such artifice, I doubt whether I should have found a publisher of repute to publish, or a circle of readers to read, my lucubrations.

It was in the winter of 1846 that the original seven Letters were written, of which the present fourteen are the third and expanded reprint. The hour had come foriv successfully assailing certain already shaking prejudices of the reading public. The Selbstschau of Zschokke, and the researches of Von Reichenbach, were in the hands of the literary and philosophic. The seer-gift of the former (see Letter IV.) had established the fact that one mind can enter into direct though one-sided communion with another. The undenied Od-force of the latter (see Letter I.) is evidently the same influence with that, the first crude announcement of which, by Mesmer, had scared the world into disbelief. It had now become possible to explain ghostly warnings, and popular prophecies, the wonders of natural trance, and of animal magnetism, without having recourse to a single unproven principle. I therefore made the attempt; other more efficient labourers have co-operated in the same object; and public opinion is no longer hostile to this class of inquiries.

Bad Weilbach, near Mayence,

1st August, 1851.

v

| LETTER I. The Divining-Rod.—Description of, and mode of using the same—Mr. Fairholm’s statement—M. de Tristan’s statement—Account of Von Reichenbach’s Od-force—The Author’s own observations, | 9 |

| LETTER II. Vampyrism.—Tale exemplifying the superstition—The Vampyr state of the body in the grave—Various instances of death-trance—The risk of premature interment considered—The Vampyr visit, | 30 |

| LETTER III. Unreal Ghosts.—Law of sensorial illusions—Cases of Nicolai, Schwedenborg, Joan of Arc—Fetches—Churchyard ghosts, | 53 |

| LETTER IV. True Ghosts.—The apparitions themselves always sensorial illusions—The truth of their communications accounted for—Zschokke’s seer-gift described, to show the possibility of direct mental communication—Second-sight—The true relation of the mind to the living body, | 70 |

| LETTER V. Trance.—Distinction of esoneural and exoneural mental phenomena—Abnormal relation of the mind and nervous system possible—Insanity—Sleep—Essential nature of trance—Its alliance with spasmodic seizures—General characters of trance—Enumeration of kinds, | 86 vi |

| LETTER VI. Trance-Sleep.—The phenomena of trance divided into those of trance-sleep, and those of trance-waking—Trance-sleep presents three forms; Trance-waking two. The three forms of trance sleep described; viz., death-trance, trance-coma, simple or initiatory trance, | 98 |

| LETTER VII. Half-waking Trance, or Somnambulism.—The same thing with ordinary sleep-walking—Its characteristic feature, the acting of a dream—Cases, and disquisition, | 106 |

| LETTER VIII. Trance-waking.—Instances of its spontaneous occurrence in the form of catalepsy—Analysis of catalepsy—its three elements: double consciousness, or pure waking-trance; the spasmodic seizure; the new mental powers displayed—Cases exemplifying catalepsy—Other cases unattended with spasm, but of spontaneous occurrence, in which new mental powers were manifested—Oracles of antiquity—Animal instinct—Intuition, | 116 |

| LETTER IX. Religious Delusions.—The seizures giving rise to them shown to have been forms of trance brought on by fanatical excitement—The Cevennes—Scenes at the tomb of the Abbé Paris—Revivals in America—The Ecstatica of Caldaro—Three forms of imputed demoniacal possession—Witchcraft; its marvels, and the solution, | 136 |

| LETTER X. Mesmerism.—Use of chloroform—History of Mesmer—The true nature and extent of his discovery—Its applications to medicine and surgery—Various viieffects produced by mesmeric manipulations—Hysteric seizures—St. Veitz’s dance—Nervous paralysis—Catochus—Initiatory trance—The order in which the higher trance-phenomena are afterwards generally drawn out, | 153 |

| LETTER XI. Supplemental.—Abnormal neuro-psychical relation—Cautions necessary in receiving trance communications—Trance-visiting—Mesmerising at a distance, and by the will—Mesmeric diagnosis and treatment of disease—Prevision—Ultra-vital vision, | 175 |

| LETTER XII. The Odometer or Divining-Ring.—How come upon by the author—His first experiments—The phenomena an objective proof of the reality of the Od-force, | 209 |

| LETTER XIII. The Solution.—Examination of the genuineness of the phenomena—Od-motions produced by bodies in their most inert state—Analysis of the forces which originate them—Od-motions connected with electrical, magnetic, chemical, crystalline, and vital influences—Their analysis, | 219 |

| Postscript. —Further analysis of Od-motions—Proof of their genuineness—Explanation of their immediate cause, | 242 |

| LETTER XIV. Hypnotism. Trance-Umbra.—Mr. Braid’s discovery—Trance-faculties manifested in the waking state—Self-induced waking clairvoyance—Conclusion, | 248 |

9

The Divining Rod.—Description of and mode of using the same—Mr. Fairholm’s statement—M. de Tristan’s statement—Account of Von Reichenbach’s Od force—The Author’s own observations.

Dear Archy,—As a resource in the solitary evenings of commencing winter, it occurred to me to look into the long-neglected lore of the marvellous, the mystical, the supernatural. I remembered the deep awe with which I had listened, many a year ago, to tales of seers, ghosts, vampyrs, and all the dark brood of night. And I thought it would be infinitely agreeable to thrill again with mysterious terrors, to start in my chair at the closing of a distant door, to raise my eyes with uneasy apprehension towards the mirror opposite, and to feel my skin creep through the sensible “afflatus” of an invisible presence. I entered, accordingly, upon a very promising course of appalling reading. But, a-lack and well-a-day! a change had come over me since the good old times when fancy, with fear and superstition behind her, would creep on tiptoe to catch a shuddering glimpse of Kobbold, Fay, or incubus. Vain were all my efforts to revive the pleasant horrors of earlier years: it was as if I had10 planned going to a play to enjoy again the full gusto of scenic illusion, and, through absence of mind, was attending a morning rehearsal only; when, instead of what I had anticipated, great-coats, hats, umbrellas, and ordinary men and women, masks, tinsel, trap-doors, pulleys, and a world of intricate machinery, lit by a partial gleam of sunshine, had met my view. The enchantment was no longer there—the spell was broken.

Yet, on second thoughts, the daylight scene was worth contemplating. A new object, of stronger interest, suggested itself. I might examine and learn the mechanism of the illusions which had failed to furnish me the projected entertainment. In the books I had looked into, I discerned a clue to the explanation of many wonderful stories, which I could hitherto only seriously meet by disbelief. I saw that phenomena, which before had appeared isolated, depended upon a common principle, itself allied with a variety of other singular facts and observations, which wanted only to be placed in philosophical juxtaposition to be recognised as belonging to science. So I determined to employ the leisure before me upon an inquiry into the amount of truth in popular superstitions, certain that, if the attempt were not premature, the labour would be well repaid. There must be a real foundation for the belief of ages. There can be no prevalent delusion without a corresponding truth. The visionary promises of alchemy foreshadowed the solid performances of modern chemistry, as the debased worship of the Egyptians implied the existence of a proper object of worship.

Among the immortal productions of the Scottish Shakspeare—you smile, but that phrase contains the true belief, not a popular delusion; for the spirit of the11 poet lives not in the form of his works, but in his creative power and vivid intuitions of nature; and the form even is often nearer than you think:—but this excursiveness will never do; so, to begin again.

Among the novels of Scott—I intended to say—there is not one more wins upon us than the Antiquary. Nowhere has the great author more gently and indulgently, never with happier humour, portrayed the mixed web of strength and infirmity in human character; never, besides, with more facile power evoked pathos and terror, and disported himself amid the sublimity and beauty of nature. Yet, gentle as is his mood, he misses not the opportunity—albeit, in general, he displays an honest leaning towards old superstitions—mercilessly to crush one of the humblest. Do you remember the Priory of St. Ruth, and the summer-party made to visit it, and the preparations for the subsequent rogueries of Dousterswivel in the tale of Martin Waldeck, and the discovery of a spring of water by means of the divining rod?

I am inclined, do you know, to dispute the verdict of the novelist on this occasion, and to take the part of the charlatan against the author of his being; as far, at least, as regards the genuineness of the art the said charlatan then and there affected to practise. There exists, in fact, strong evidence to show that, in competent hands, the divining rod really does what is pretended of it. This evidence I propose to put before you in the present letter. But, as the subject may be entirely new to you, I had best begin by describing what is meant by a divining rod, and in what the imputed jugglery consists.

Then you are to learn that, in mining districts, a superstition prevails among the people that some are born gifted with an occult power of detecting the proximity of12 veins of metal, and of underground currents of water. In Cornwall, they hold that about one in forty possesses this faculty. The mode of exercising it is very simple. They cut a hazel twig, just below where it forks. Having stripped the leaves off, they cut each branch to something more than a foot in length, leaving the stump three inches long. This implement is the divining rod. The hazel is selected for the purpose, because it branches more symmetrically than its neighbours. The hazel-fork is to be held by the branches, one in either hand, the stump or point projecting straight forwards. The arms of the experimenter hang by his sides; but the elbows being bent at a right angle, the fore-arms are advanced horizontally; the hands are held eight to ten inches apart; the knuckles down, and the thumbs outwards. The ends of the branches of the divining fork appear between the roots of the thumbs and fore-fingers.

The operator, thus armed, walks over the ground he intends exploring, in the full expectation that, if he possesses the mystic gift, as soon as he passes over a vein of metal, or an underground spring, the hazel-fork will begin to move spontaneously in his hands, rising or falling as the case may be.

You are possibly amused at my gravely stating, as a fact, an event so unlikely. It is, indeed, natural that you should suppose the whole a juggle, and think the seemingly spontaneous motion of the divining fork to be really communicated to it by the hands of the conjurer—by a sleight, in fact, which he puts in practice when he believes that he is walking over a hidden water-course, or wishes you to believe that there is a vein of metal near. Well, I thought as you do the greater part of my life; and probably the likeliest way of combating your13 skepticism, will be to tell you how my own conversion took place.

In the summer of 1843 I dwelt under the same roof with a Scottish gentleman, well informed, of a serious turn of mind, fully endowed with the national allowance of shrewdness and caution. I saw a good deal of him; and one day, by chance, this subject of the divining rod was mentioned. He told me, that at one time his curiosity having been raised upon the subject, he had taken pains to ascertain what there is in it. With this object in view he had obtained an introduction to Mrs. R., sister of Sir G. R., then living at Southampton, whom he had learned to be one of those in whose hands the divining rod moved. He visited the lady, who was polite enough to show him in what the performance consists, and to answer all his questions, and to assist him in making experiments calculated to test the reality of the phenomenon, and to elucidate its cause.

Mrs. R. told my friend that, being at Cheltenham in 1806, she saw, for the first time, the divining rod used by Mrs. Colonel Beaumont, who possessed the power of imparting motion to it in a very remarkable degree. Mrs. R. tried the experiment herself at that time, but without any success. She was, as it happened, very far from well. Afterwards, in the year 1815, being asked by a friend how the divining rod is held, and how it is to be used, on showing it she was surprised to see that the instrument now moved in her hands.

Since then, whenever she had repeated the experiment, the power had always manifested itself, though with varying degrees of energy.

Mrs. R. then took my friend to a part of the shrubbery where she knew, from former trials, the divining14 rod would move in her hands. It did so, to my friend’s extreme astonishment; and even continued to move, when, availing himself of Mrs. R.’s permission, my friend grasped her hands with sufficient firmness to prevent, as he supposed, any muscular action of her wrists or fingers influencing the result.

On a subsequent day my friend having thought over what he had seen, repeated his visit to the lady. He provided himself, as substitutes for the hazel-fork which he had seen her employ, with portions of copper and iron wire about a foot and a half long, bent something into the form of the letter V. He had made, in fact, divining forks of wire, wanting only the projecting point. He found that these instruments moved quite as freely in Mrs. R.’s hands as the hazel-fork had done. Then he coated the two handles of one of them with sealing-wax, leaving, however, the extreme ends free and uncovered. When Mrs. R. tried the rod so prepared, holding the parts alone which were covered with sealing-wax, and walked on the same piece of ground as in the former experiments, the rod remained perfectly still. As often, however, as—with no greater change than adjusting her hands so as to touch the free ends of the wire with her thumbs—Mrs. R. renewed direct contact with the instrument, it again moved. The motion ceased again as often as the direct contact was interrupted.

This simple narrative, made to me by the late Mr. George Fairholm, carried conviction to my mind of the reality of the phenomenon. I asked my friend why he had not pursued the subject further. He said he had often thought of doing so, and had, he believed, mainly been deterred by meeting with the work of the Compte de Tristan, entitled Recherches sur quelques effluves ter15restres, Paris, 1829, in which facts similar to those which he had himself verified were given, and a number of additional curious experiments detailed.

At Mr. Fairholm’s instance I procured the book, and, at a later period, read it. I may say that it both satisfied and disappointed me. It satisfied me, inasmuch as it fully confirmed all that Mr. Fairholm had stated. It disappointed me, for it threw no additional light upon the phenomena. M. de Tristan had in fact brought too little physical knowledge to the investigation, so that a large proportion of his experiments are puerile. However, his simpler experiments are valuable and suggestive. These I will presently describe. In the mean time, you shall hear the Count’s own narrative of his initiation into the mysteries of the divining rod.

“The history of my researches,” says M. de Tristan,16 “is simply this. Some twenty years ago, a gentleman who, from his position in society, could have no object to gain by deception, showed to me, for my amusement, the movement of the divining rod. He attributed the motion to the influence of a current of water, which appeared to me a probable supposition. But my attention was more engaged with the action produced by the influence, let the latter be what it might. My informant assured me he had met with many others in whom the same effects were manifested. When I returned home, and had opportunities of making trials under favourable circumstances, I found that I myself possessed the same endowment. Since then I have induced many to make the experiment, and I have found a fourth, or certainly a fifth, of the number capable of setting the divining rod in motion at the very first attempt. Since that time, during these twenty years, I have often tried my hand, but for amusement only, and desultorily, and without any idea of making the thing an object of scientific investigation. But at length, in the year 1822, being in the country, and removed from my ordinary pursuits, the subject again came across me, and I determined forthwith to try and ascertain the cause of this phenomena. Accordingly, I commenced a long series of experiments, from fifteen to eighteen hundred in number, which occupied me nearly fifteen months. The results of above twelve hundred were written down at the time of their performance.”

The scene of the Count’s operations was in the valley of the Loire, five leagues from Vendôme, in the park of the Chateau de Ranac. The surface of ground which gave the desired results was from seventy to eighty feet in breadth. But there was another spot equally efficient at the Count’s ordinary residence at Emerillon, near Clery, four leagues south of Orleans, ten leagues south of the Loire, at the commencement of the plains of Solonge. The surface ran from north to south, and had the same breadth with the other. These “exciting tracts” form, in general, bands or zones of undetermined, and often very great length. Their breadth is very variable; some are only three or four feet across, while others are one hundred paces. These tracts are sometimes sinuous; in other instances they ramify. To the most susceptible they are broader than to those who are less so.

M. de Tristan thus describes what happens when a competent person, armed with a hazel-fork, walks over the exciting districts:—

When two or three steps have been made upon the exciting tract of ground, the fork, which at starting is held horizontally, with the point forwards, begins gently to17 ascend; it gradually attains a vertical position; sometimes it passes beyond that, and lowering itself, with its point to the chest of the operator, it becomes again horizontal. If the motion continues, the rod descending becomes vertical, with the point downwards. Finally, the rod may again ascend and resume its first position. When the action is very lively, the rod immediately commences a second revolution; and so it goes on, as long as the operator continues to walk over the exciting surface of ground.

A few of those in whose hands the divining fork moves exhibit a remarkable peculiarity. The instrument, instead of commencing its motion by ascending, descends; the point then becomes directed vertically downwards; afterwards it reascends, and completes a revolution in a course the opposite of the usual one; and as often and as long as its motion is excited, it pursues this abnormal course.

Of the numerous experiments made by M. de Tristan, the following are among the simplest and the best:—

He covered both handles of a divining rod with a thick silk stuff. The result of using the instrument so prepared was the same which Mr. Fairholm obtained by coating the handles with sealing-wax. The motion of the divining rod was extinguished.

He covered both handles with one layer of a thin silk. He then found that the motion of the divining rod took place, but it was less lively and vigorous than ordinary.

By covering one handle of the divining rod, and that the right, with a layer of thin silk, a very singular and instructive result was obtained. The motion of the instrument was now reversed. It commenced by descending.

18

After covering the point of the divining rod with a thick layer of silk stuff, the motion was sensibly more brisk than it had been before.

When the Count held in his hands a straight rod of the same substance conjointly with the ordinary divining rod, no movement of the latter whatsoever ensued.

Finally, the Count discovered that he could cause the divining rod to move when he walked over a non-exciting surface—as, for instance, in his own chamber—by various processes. Of these the most interesting consisted in touching the point of the instrument with either pole of a magnetic needle. The instrument shortly began to move, ascending or descending, according as the northward or southward pole of the needle had been applied to it.

It is unnecessary to add that these, and all M. de Tristan’s experiments, were repeated by him many times. The results of those which I have narrated were constant.

Let me now attempt to realize something out of the preceding statements.

1. It is shown, by the testimony adduced, that whereas in the hands of most persons the divining rod remains motionless, in the hands of some it moves promptly and briskly when the requisite conditions are observed.

2. It is no less certain that the motion of the divining rod has appeared, to various intelligent and honest persons, who have succeeded in producing it, to be entirely spontaneous; or that the said persons were not conscious of having excited or promoted the motion by the slightest help of their own.

3. It appears that in the ordinary use of the divining rod by competent persons, its motion only manifests itself in certain localities.

19

4. It being assumed that the operator does not, however unconsciously, by the muscular action of his hands and wrists produce the motion of the divining rod, the likeliest way of accounting for the phenomenon is to suppose that the divining rod may become the conductor of some fluid or force, emanating from or disturbed in the body by a terrestrial agency.

But here a difficulty arises: How can it happen that the hypothetical force makes so long and round-about a course? Why, communicated to the body through the legs, does not the supposed fluid complete a circuit at once in the lower part of the trunk?

Such, at all events, would be the course an electric current so circumstanced would take.

The difficulty raised admits of being removed by aid derived from a novel and unexpected source. I allude to the discovery, by Von Reichenbach, of a new force or principle in the physical world, which, whether or not it is identical with that which gives motion to the divining rod, exhibits, at all events, the very property which the hypothetical principle should possess to explain the phenomena which we have been considering.

No attempts have indeed been made to identify the two as one; and my conjecture that they may prove so, should it even appear plausible, is so vague, that I should have contented myself with referring to Von Reichenbach’s new principle as to an established truth, and have introduced no account of it into this Letter, had I not a second motive for insuring your cognisance of the curious facts which the Viennese philosopher has brought to light. It is less with the view of furnishing a leg to the theory of the divining rod, than in order to provide the means of elucidating more interesting problems, that I20 now proceed briefly to sketch the leading experiments made by Von Reichenbach, and their results.

Objections have been taken against these experiments, on the ground that their effects are purely subjective; that the results must be received on the testimony of the party employed; and that the best parties for the purpose are persons whose natural sensibility is exalted by disorder of the nerves; a class of persons always suspected of exaggeration, and even, and in part with justice, of a tendency to trickery and deception. But this was well known to Von Reichenbach, who appears to have taken every precaution necessary to secure his observations against error. And when I add, that many of the results which he obtained upon the most sensitive and the highly nervous, were likewise manifested in persons of established character and in good health, and that the fidelity of the author and of his researches is authenticated by the publication of the latter in Woehler and Liebig’s Chemical Annals, (Supplement to volume 53, Heidelberg, 1845,) I think you will not withhold from them complete reliance.

In general, persons in health and of a strong constitution are insensible to the influence of Von Reichenbach’s new force. But all persons, the tone of whose health has been lowered by their mode of life—men of sedentary habits, clerks, and the like, and women who employ their whole time in needlework, whose pale complexions show the relaxed and therefore irritable state of their frames—all such, or nearly all—evince more or less susceptibility to the influence I am about to describe.

Von Reichenbach found that persons of the latter class, when slow passes are made with the poles of a strong magnet moved parallel to the surface—down the back,21 for instance, or down the limbs, and only distant enough just not to touch the clothes—feel sensations rather unpleasant than otherwise, as of a light draft of air blown upon them in the path of the magnet.

In the progress of his researches, Von Reichenbach found that the more sensitive among his subjects could detect the presence of his new agent by another sense. In the dark they saw dim flames of light issuing and waving from the poles of the magnet. The experiments suggested by this discovery afford the most satisfactory proofs of the reality of the phenomena. They were the following:—A horse-shoe magnet having been adjusted upon a table, with the poles directed upwards, the sensitive subject saw, at the distance of ten feet, the appearance of flames issuing from it. The armature of the magnet—a bar of soft iron—was then applied. Upon this the flames disappeared. They reappeared, she said, as often as the armature was removed from the magnet.

A similar experiment was made with a yet more sensitive subject. This person saw, in the first instance, flames as the first had done; but when the armature of the magnet was applied, the flames did not disappear: she saw flames still: only they were fainter, and their disposition was different. They seemed now to issue from every part of the surface of the magnet equally.

It is hardly necessary to add, that these experiments were made in a well-darkened room, and that none of the bystanders could discern what the sensitive subjects saw.

Then the following experiment was made:—A powerful lens was so placed as that it should concentrate the light of the flames (if real light they were) upon a point of the wall of the room. The patient at once saw the22 light upon the wall at the right place; and when the inclination of the lens was shifted, so as to throw the focus in succession on different points, the sensitive observer never failed in pointing out the right spot.

To his new force, which Von Reichenbach had now found to emanate likewise from the poles of crystals and the wires of the voltaic pile, he gave the arbitrary but convenient name of Od, or the Od force.

His next step was to ascertain the existence of a difference among the sensations produced by Od. Sometimes the current of air was described as warm, sometimes as cool. He found this difference to depend upon the following cause: Whenever the northward pole of a magnet, or one definite pole of a large crystal, or the negative wire of a voltaic battery, is employed in the experiment, the sensation produced is that of a draft of cool air. On the contrary, the southward pole of the magnet, the opposite pole of the crystal, the positive voltaic wire, excite the sensation of a draft of warm air.

So the new force appeared to be a polar force, and Von Reichenbach called the first series of the above described manifestations Od-negative effects, the second Od-positive effects.

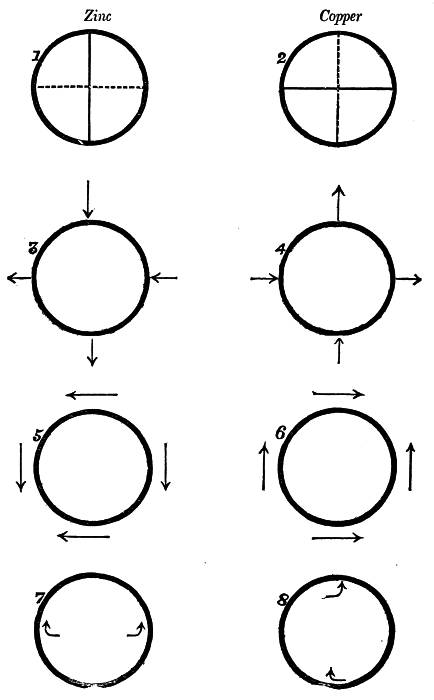

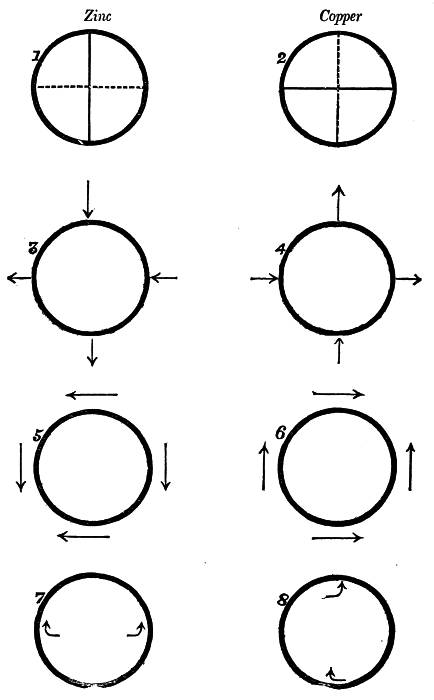

From among his numerous experiments towards establishing the polarity of Od, I select the following:—One of the most sensitive of his subjects held, at his desire, a piece of copper wire, by the middle with the right hand—by one end with the left. Then Von Reichenbach touched the free end of the wire with one pole of a large crystal, in order to charge it with Od. The patient immediately felt a sensation in the right hand, which disappeared as quickly, to be felt by the left hand instead, at the further end of the piece of wire. She then was23 bidden to take hold of the wire with both her hands at the middle, and then to slide them away from each other to the opposite ends: she observed, on doing so, that sensations were produced which were strong and decided when her hands held the two ends of the wire, and diminished in intensity in proportion as the hands were nearer its middle.

Von Reichenbach next came upon the observation that the human hand gives out the Od force; and that the right hand displays the characters of negative Od, the left those of positive Od. The more sensitive subjects recognised, in the dark, the appearance of dim flames proceeding from the tips of his fingers; and all felt the corresponding sensations of drafts of cool or of warm air. Subsequently the whole body was found to share the properties of the hands; the entire right side to manifest negative Od, the entire left side positive Od.

So, in reference to this new force, the human body exhibits a transverse polarity; the condition is thus realized which is required to belong to the hypothetical force through which the divining rod might be supposed to move. If any terrestrial influence were capable of disturbing the Od force in the body, however it might affect its intensity, a current or circuit could only be established through the arms and hands; unless, indeed, some extraordinary means were taken, such as employing an artificial conductor, arched half round the body, to connect the two sides.

The sensations which attend the establishment of a current of Od and interferences with it, in sensitive subjects, are exemplified in the following observations:—

A bar magnet was laid on the palm of the left hand of one of the most sensitive subjects, with its southward pole24 resting on the end of her middle finger, the northward pole on the fore-arm above the wrist. It thus corresponded with the natural polar arrangement of the Od force in the patient’s hand and arm. Accordingly, no sensation was excited. But when the position of the magnet was reversed, and the northward pole lay on the end of the middle finger of the left hand, an uneasy sense of an inward conflict arose in the hand and wrist, which disappeared when the magnet was removed or its original direction restored. On laying the magnet reversed on the fore-arm, the sense of an inward struggle returned, which was heightened on joining the hands and establishing a circuit.

When the patient completed the circuit in another way—namely, by holding a bar magnet by the ends, if the latter were disposed normally, (that is, if the northward pole was held in the left hand, the southward pole in the right,) a lively consciousness of some inward action ensued. A normal circulation of Od was in progress. When the direction of the magnet was reversed, the phenomenon mentioned in the last paragraph recurred. The patient experienced a high degree of uneasiness, a feeling as of an inward struggle extending itself to the chest, with a sense of whirling round, and confusion in the head. These symptoms disappeared immediately upon her letting go the magnet.

Similar results ensued when Von Reichenbach substituted himself for the magnet. When he took Miss Maix’s hands in his normally—that is to say, her left in his right, her right in his left—she felt a circulation moving up the right arm through the chest down the left arm, attended with a sense of giddiness. When he changed hands, the disagreeableness of the sensation was suddenly25 heightened, the sense of inward conflict arose, attended with a sort of undulation up and down the arms, and through the chest, which quickly became intolerable.

A singular but consistent difference in the result ensued when Von Reichenbach repeated the last two experiments upon Herr Schuh. Herr Schuh was a strong man, thirty years of age, in full health, but highly impressible by Od. When Von Reichenbach took his two hands in his own normally, Herr Schuh felt the normal establishment of the Od current in his arms and chest. In a few seconds headache and vertigo ensued, and the experiment was too disagreeable to be prolonged. But when Von Reichenbach took his hands abnormally, no sensible effect ensued. Being equally strong with Von Reichenbach, Herr Schuh’s frame repelled the counter-current, which the latter arrangement tended to throw into him. In the first or normal arrangement, the Od current had met with no resistance, but had simply gone its natural course. The distress occurred from its being felt through Herr Schuh’s accidental sensitiveness to Od; of the freaks of which in their systems people in general are unconscious.

I have concluded my case in favour of the pretensions of the divining rod. It seems to me, at all events, strong enough to justify any one who has leisure, in cutting a hazel-fork, and walking about with it in suitable places, holding it in the manner described. I doubt, however, whether I should recommend a friend to make the experiment. If, by good luck, the divining rod should refuse to move in his hands, he might accuse himself of credulity, and feel silly, and hope nobody had seen him, for the rest of the day. If, unfortunately, the first trial should succeed, and he should be led to pursue the inquiry, the consequences would be more serious: his pro26bable fate would be to fall at once several degrees in the estimation of his friends, and to pass with the world, all the rest of his life, for a crotchety person of weak intellects.

As for the divining rod itself, if my argument prove sound, it will be a credit to the family of superstitions; for without any reduction, or clipping, or trimming, it may at once assume the rank of a new truth. But, alas! the trials which await it in that character!—what an ordeal is before it! A new truth has to encounter three normal stages of opposition. In the first, it is denounced as an imposture; in the second—that is, when it is beginning to force itself into notice—it is cursorily examined, and plausibly explained away; in the third, or cui bono stage, it is decried as useless, and hostile to religion. And when it is fully admitted, it passes only under a protest that it has been perfectly known for ages—a proceeding intended to make the new truth ashamed of itself, and wish it had never been born.

I congratulate the sea-serpent on having arrived at the second stage of belief. Since Professor Owen (no disrespect to his genuine ability and eminent knowledge) has explained it into a sea-elephant, its chance of being itself is much improved; and as it will skip the third stage—for who will venture to question the good of a sea-serpent?—it is liable now any morning “to wake and find itself famous,” and to be received even at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where its remains may commemoratively be ticketed the Ex-Great-Seal.

Postscript, (1850.)—It may save trouble to some future experimenter to narrate my own exploits with the divining rod.

In the spring of 1847, being then at Weilbach in Nas27sau, a region teeming with underground sources of water, I requested the son of the proprietor of the bathing establishment—a tall, thin, pale, white-haired youth, by name Edward Seebold—to walk in my presence up and down a promising spot of ground, holding a divining fork of hazel, with the accessories recommended by M. de Tristan to beginners—that is to say, he held in his right hand three pieces of silver, besides one handle of the rod, while the handle which he held in his left hand was covered with a thin silk.

The lad had not made five steps when the point of the divining fork began to ascend. He laughed with astonishment at the event, which was totally unexpected by him; and he said that he experienced a tickling or thrilling sensation in his hands. He continued to walk up and down before me. The fork had soon described a complete circle; then it described another; and so it continued to do as long as he walked thus, and as often as, after stopping, he resumed his walk. The experiment was repeated by him in my presence, with like success, several times during the ensuing month. Then the lad fell into ill health, and I rarely saw him. However, one day I sent for him, and begged him to do me the favour of making another trial with the divining fork. He did so, but the instrument moved slowly and sluggishly; and when, having completed a semicircle, it pointed backwards towards the pit of his stomach, it stopped, and would go no farther. At the same time the lad said he felt an uneasy sensation, which quickly increased to pain, at the pit of the stomach, and he became alarmed, when I bade him quit hold of one handle of the divining rod, and the pain ceased. Ten minutes afterwards I induced him to make another trial; the results were the same. A few days later, when the lad seemed still more out of28 health, I induced him to repeat the experiment. Now, however, the divining fork would not move at all.

I entertain little doubt that the above performances of Edward Seebold were genuine. I thought the same of the performances of three English gentlemen, and of a German, in whose hands, however, the divining rod never moved through an entire circle. In the hands of one of them its motion was retrograde, or abnormal: that is to say, it began by descending.

But I met with other cases, which were less satisfactory, though not uninstructive. I should observe that, in the hands of several who tried to use it in my presence, the divining fork would not move an inch. But there were two younger brothers of Edward Seebold, and a bath-maid, and my own man, in whose hands the rod played new pranks. When these parties walked forwards the instrument ascended, or moved normally; but when, by my desire, they walked backwards, the instrument immediately went the other way. I should observe that, in the hands of Edward Seebold, the instrument moved in the same direction whether he walked forwards or backwards; and I have mentioned that at first it described in his hands a complete circle. But with the four parties I have just been speaking of, the motion of the fork was always limited in extent. When it moved normally at starting, it stopped after describing an arc of about 225°; in the same way, when it moved abnormally at starting, it would stop after describing an arc of about 135°; that is to say, there was one spot the same for the two cases, beyond which it could not get. Then I found that, in the hands of my man, the divining rod would move even when he was standing still, although with a less lively action; still it stopped as before, nearly at the same point. Sometimes it ascended, sometimes29 descended. Then I tried some experiments, touching the point with a magnetic needle. I found, in the course of them, that when my man knew which way I expected the fork to move, it invariably answered my expectations; but when I had the man blindfolded, the results were uncertain and contradictory. The end of all this was, that I became certain that several of those in whose hands the divining rod moves, set it in motion and direct its motion by the pressure of their fingers, and by carrying their hands nearer to, or farther apart. In walking forwards, the hands are unconsciously borne towards each other; in walking backwards, the reverse is the case.

Therefore, I recommend no one to prosecute these experiments unless he can execute them himself, and unless the divining rod describes a complete circle in his hands; and even then he should be on his guard against self-deception.

Postscript II.—I am now (May, 1851) again residing at the bathing establishment of Weilbach, near Mayence; and it was with some interest and curiosity that the other day I requested Mr. Edward Seebold, now a well-grown young man, in full health, to try his hand again with the divining-rod. He readily assented to my request; and he this time knew exactly what result I expected. But the experiment entirely failed. The point of the divining rod rose, as he walked, not more than two or three inches; but this it does with every one who presses the two handles towards each other during the experiment. Afterwards the implement remained perfectly stationary. I think I am not at liberty to withhold this result from the reader, whom it may lead to question, though it cannot induce myself to doubt, the genuineness of the former performances of Mr.30 E. S.

Vampyrism.—Tale exemplifying the superstition—The Vampyr state of the body in the grave—Various instances of death-trance—The risk of premature interment considered—The Vampyr visit.

In acknowledging my former letter, you express an eager desire to learn, as you phrase it, “all about Vampyrs, if there ever were such things.” I will not delay satisfying your curiosity, although by so doing I interrupt the logical order of my communications. It is, perhaps, all the better. The proper place of this subject falls in the midst of a philosophical disquisition; and it would have been a pity not to present it to you in its pristine colouring. But how came your late tutor, Mr. H., to leave you in ignorance upon a point on which, in my time, schoolboys much your juniors entertained decided opinions?

Were there ever such things as Vampyrs? Tantamne rem tam negligenter! I turn to the learned pages of Horst for a luminous and precise definition of the destructive and mysterious beings whose existence you have ventured to consider problematical.

“A Vampyr is a dead body which continues to live in the grave; which it leaves, however, by night, for the purpose of sucking the blood of the living, whereby it is nourished and preserved in good condition, instead of being decomposed like other dead bodies.”

Upon my word, you really deserve, since Mr. George Combe has clearly shown, in his admirable work on the Constitution of Man, and its adaptation to the surrounding world, that ignorance is a statutable crime before nature,31 and punished by the laws of Providence—you deserve, I say, unless you contrive to make Mr. H. your substitute, which I think would be just, yourself to be the subject of the nocturnal visit of a Vampyr. Your skepticism will abate pretty considerably when you see him stealthily entering your room, yet are powerless under the fascination of his fixed and leaden eye—when you are conscious, as you lie motionless with terror, of his nearer and nearer approach—when you feel his face, fresh with the smell of the grave, bent over your throat, while his keen teeth make a fine incision in your jugular, preparatory to his commencing his plain but nutritive repast.

You would look a little paler the next morning, but that would be all for the moment; for Fischer informs us that the bite of a Vampyr leaves in general no mark upon the person. But he fearfully adds, “it (the bite) is nevertheless speedily fatal,” unless the bitten person protect himself by eating some of the earth from the grave of the Vampyr, and smearing himself with his blood. Unfortunately, indeed, these measures are seldom, if ever, of more than temporary use. Fischer adds, “if through these precautions the life of the victim be prolonged for a period, sooner or later he ends with becoming a Vampyr himself; that is to say, he dies and is buried, but continues to lead a Vampyr life in the grave, nourishing himself by infecting others, and promiscuously propagating Vampyrism.”

This is no romancer’s dream. It is a succinct account of a superstition which to this day services in the east of Europe, where little more than a century ago it was frightfully prevalent. At that period Vampyrism spread like a pestilence through Servia and Wallachia, causing numerous deaths, and disturbing all the land with fear of32 the mysterious visitation, against which no one felt himself secure.

Here is something like a good, solid, practical popular delusion. Do I believe it? To be sure I do. The facts are matter of history: the people died like rotted sheep; and the cause and method of their dying was, in their belief, what has just been stated. You suppose, then, they died frightened out of their lives, as men have died whose pardon has been proclaimed when their necks were already on the block, of the belief that they were going to die? Well, if that were all, the subject would still be worth examining. But there is more in it than that, as the following o’er true tale will convince you, the essential points of which are authenticated by documentary evidence.

In the spring of 1727, there returned from the Levant to the village of Meduegna, near Belgrade, one Arnod Paole, who, in a few years of military service and varied adventure, had amassed enough to purchase a cottage and an acre or two of land in his native place, where he gave out that he meant to pass the remainder of his days. He kept his word. Arnod had yet scarcely reached the prime of manhood; and though he must have encountered the rough as well as the smooth of life, and have mingled with many a wild and reckless companion, yet his naturally good disposition and honest principles had preserved him unscathed in the scenes he had passed through. At all events, such were the thoughts expressed by his neighbours as they discussed his return and settlement among them in the Stube of the village Hof. Nor did the frank and open countenance of Arnod, his obliging habits and steady conduct, argue their judgment incorrect. Nevertheless, there was something occasionally33 noticeable in his ways—a look and tone that betrayed inward disquiet. Often would he refuse to join his friends, or on some sudden plea abruptly quit their society. And he still more unaccountably, and as it seemed systematically, avoided meeting his pretty neighbour Nina, whose father occupied the next tenement to his own. At the age of seventeen, Nina was as charming a picture of youth, cheerfulness, innocence, and confidence, as you could have seen in all the world. You could not look into her limpid eyes, which steadily returned your gaze, without seeing to the bottom of the pure and transparent spring of her thoughts. Why, then, did Arnod shrink from meeting her? He was young; had a little property; had health and industry; and he had told his friends he had formed no ties in other lands. Why, then, did he avoid the fascination of the pretty Nina, who seemed a being made to chase from any brow the clouds of gathering care? But he did so; yet less and less resolutely, for he felt the charm of her presence. Who could have done otherwise? And how could he long resist—he didn’t—the impulse of his fondness for the innocent girl who often sought to cheer his fits of depression?

And they were to be united—were betrothed; yet still an anxious gloom would fitfully overcast his countenance, even in the sunshine of those hours.

“What is it, dear Arnod, that makes you sad? It cannot be on my account, I know, for you were sad before you ever noticed me; and that, I think,” (and you should have seen the deepening rose upon her cheeks,) “surely first made me notice you.”

“Nina,” he answered,34 “I have done, I fear, a great wrong in trying to gain your affections. Nina, I have a fixed impression that I shall not live; yet, knowing this, I have selfishly made my existence necessary to your happiness.”

“How strangely you talk, dear Arnod! Who in the village is stronger and healthier than you? You feared no danger when you were a soldier. What danger do you fear as a villager of Meduegna?”

“It haunts me, Nina.”

“But, Arnod, you were sad before you thought of me. Did you then fear to die?”

“Ah, Nina, it is something worse than death.” And his vigorous frame shook with agony.

“Arnod, I conjure you, tell me.”

“It was in Cossova this fate befell me. Here you have hitherto escaped the terrible scourge. But there they died, and the dead visited the living. I experienced the first frightful visitation, and I fled; but not till I had sought his grave, and exacted the dread expiation from the Vampyr.”

Nina’s blood ran cold. She stood horror-stricken. But her young heart soon mastered her first despair. With a touching voice she spoke—

“Fear not, dear Arnod; fear not now. I will be your shield, or I will die with you!”

And she encircled his neck with her gentle arms, and returning hope shone, Iris-like, amid her falling tears. Afterwards they found a reasonable ground for banishing or allaying their apprehension in the length of time which had elapsed since Arnod left Cossova, during which no fearful visitant had again approached him; and they fondly trusted that gave them security.

35

It is a strange world. The ills we fear are commonly not those which overwhelm us. The blows that reach us are for the most part unforeseen. One day, about a week after this conversation, Arnod missed his footing when on the top of a loaded hay-wagon, and fell from it to the ground. He was picked up insensible, and carried home, where, after lingering a short time, he died. His interment, as usual, followed immediately. His fate was sad and premature. But what pencil could paint Nina’s grief!

Twenty or thirty days after his decease, says the perfectly authenticated report of these transactions, several of the neighbourhood complained that they were haunted by the deceased Arnod; and, what was more to the purpose, four of them died. The evil, looked at skeptically, was bad enough, but aggravated by the suggestions of superstition, it spread a panic through the whole district. To allay the popular terror, and if possible to get at the root of the evil, a determination was come to publicly to disinter the body of Arnod, with the view of ascertaining whether he really was a Vampyr, and, in that event, of treating him conformably. The day fixed for this proceeding was the fortieth after his burial.

It was on a gray morning in early August that the commission visited the quiet cemetery of Meduegna, which, surrounded with a wall of unhewn stone, lies sheltered by the mountain that, rising in undulating green slopes, irregularly planted with fruit trees, ends in an abrupt craggy ridge, feathered with underwood. The graves were, for the most part, neatly kept, with borders of box, or something like it, and flowers between; and at the head of most a small wooden cross, painted black, bear36ing the name of the tenant. Here and there a stone had been raised. One of considerable height, a single narrow slab, ornamented with grotesque Gothic carvings, dominated over the rest. Near this lay the grave of Arnod Paole, towards which the party moved. The work of throwing out the earth was begun by the gray, crooked old sexton, who lived in the Leichenhaus, beyond the great crucifix. He seemed unconcerned enough; no Vampyr would think of extracting a supper out of him. Nearest the grave stood two military surgeons, or feldscherers, from Belgrade, and a drummer-boy, who held their case of instruments. The boy looked on with keen interest; and when the coffin was exposed and rather roughly drawn out of the grave, his pale face and bright intent eye showed how the scene moved him. The sexton lifted the lid of the coffin: the body had become inclined to one side. Then turning it straight, “Ha! ha!” said he, pointing to fresh blood upon the lips—“Ha! ha! What! Your mouth not wiped since last night’s work?” The spectators shuddered; the drummer-boy sank forward, fainting, and upset the instrument-case, scattering its contents; the senior surgeon, infected with the horror of the scene, repressed a hasty exclamation, and simply crossed himself. They threw water on the drummer-boy, and he recovered, but would not leave the spot. Then they inspected the body of Arnod. It looked as if it had not been dead a day. On handling it, the scarf-skin came off, but below were new skin and new nails! How could they have come there but from its foul feeding! The case was clear enough; there lay before them the thing they dreaded—the Vampyr. So, without more ado, they simply drove a stake through poor Arno37d’s chest, whereupon a quantity of blood gushed forth, and the corpse uttered an audible groan. “Murder! oh, murder!” shrieked the drummer-boy, as he rushed wildly, with convulsed gestures, from the cemetery.

The drummer-boy was not far from the mark. But, quitting the romancing vein, which had led me to try and restore the original colours of the picture, let me confine myself, in describing the rest of the scene and what followed, to the words of my authority.

The body of Arnod was then burnt to ashes, which were returned to the grave. The authorities further staked and burnt the bodies of the four others which were supposed to have been infected by Arnod. No mention is made of the state in which they were found. The adoption of these decisive measures failed, however, entirely to extinguish the evil, which continued still to hang about the village. About five years afterwards it had again become very rife, and many died through it; whereupon the authorities determined to make another and a complete clearance of the Vampyrs in the cemetery, and with that object they had all the graves, to which present suspicion attached, opened, and their contents officially anatomized, of which procedure the following is the medical report, here and there abridged only:—

1. A woman of the name of Stana, twenty years of age, who had died three months before of a three days’ illness following her confinement. She had before her death avowed that she had anointed herself with the blood of a Vampyr, to liberate herself from his persecution. Nevertheless, she, as well as her infant, whose body through careless interment had been half eaten by the38 dogs, had died. Her body was entirely free from decomposition. On opening it, the chest was found full of recently effused blood, and the bowels had exactly the appearances of sound health. The skin and nails of her hands and feet were loose and came off, but underneath lay new skin and nails.

2. A woman of the name of Miliza, who had died at the end of a three months’ illness. The body had been buried ninety and odd days. In the chest was liquid blood. The viscera were as in the former instance. The body was declared by a heyduk, who recognised it, to be in better condition, and fatter, than it had been in the woman’s legitimate lifetime.

3. The body of a child eight years old, that had likewise been buried ninety days: it was in the Vampyr condition.

4. The son of a heyduk named Milloc, sixteen years old. The body had lain in the grave nine weeks. He had died after three days’ indisposition, and was in the condition of a Vampyr.

5. Joachim, likewise son of a heyduk, seventeen years old. He had died after three days’ illness; had been buried eight weeks and some days; was found in the Vampyr state.

6. A woman of the name of Rusha, who had died of an illness of ten days’ duration, and had been six weeks buried, in whom likewise fresh blood was found in the chest.

(The reader will understand, that to see blood in the chest, it is first necessary to cut the chest open.)

7. The body of a girl of ten years of age, who had died two months before. It was likewise in the Vampyr state, perfectly undecomposed, with blood in the chest.

39

8. The body of the wife of one Hadnuck, buried seven weeks before; and that of her infant, eight weeks old, buried only twenty-one days. They were both in a state of decomposition, though buried in the same ground, and closely adjoining the others.

9. A servant, by name Rhade, twenty-three years of age; he had died after an illness of three months’ duration, and the body had been buried five weeks. It was in a state of decomposition.

10. The body of the heyduk Stanco, sixty years of age, who had died six weeks previously. There was much blood and other fluid in the chest and abdomen, and the body was in the Vampyr condition.

11. Millac, a heyduk, twenty-five years old. The body had been in the earth six weeks. It was perfectly in the Vampyr condition.

12. Stanjoika, the wife of a heyduk, twenty years old; had died after an illness of three days, and had been buried eighteen. The countenance was florid. There was blood in the chest and in the heart. The viscera were perfectly sound; the skin remarkably fresh.

The document which gives the above particulars is signed by three regimental surgeons, and formally countersigned by a lieutenant-colonel and sub-lieutenant. It bears the date of “June 7, 1732, Meduegna near Belgrade.” No doubt can be entertained of its authenticity, or of its general fidelity; the less that it does not stand alone, but is supported by a mass of evidence to the same effect. It appears to establish, beyond question, that where the fear of Vampyrism prevails, and there occur several deaths, in the popular belief connected with it, the bodies, when disinterred weeks after burial, present40 the appearance of corpses from which life has only recently departed.

What inference shall we draw from this fact?—that Vampyrism is true in the popular sense?—and that these fresh-looking and well-conditioned corpses had some mysterious source of preternatural nourishment? That would be to adopt, not to solve the superstition. Let us content ourselves with a notion not so monstrous, but still startling enough: that the bodies, which were found in the so-called Vampyr state, instead of being in a new or mystical condition, were simply alive in the common way, or had been so for some time subsequent to their interment; that, in short, they were the bodies of persons who had been buried alive, and whose life, where it yet lingered, was finally extinguished through the ignorance and barbarity of those who disinterred them. In the following sketch of a similar scene to that above described, the correctness of this inference comes out with terrific force.

Erasmus Francisci, in his remarks upon the description of the Dukedom of Krain by Valvasor, speaks of a man of the name of Grando, in the district of Kring, who died, was buried, and became a Vampyr, and as such was exhumed for the purpose of having a stake thrust through him.

“When they opened his grave, after he had been long buried, his face was found with a colour, and his features made natural sorts of movements, as if the dead man smiled. He even opened his mouth as if he would inhale fresh air. They held the crucifix before him, and called in a loud voice, ‘See, this is Jesus Christ who redeemed your soul from hell, and died for you.’ After the sound41 had acted on his organs of hearing, and he had connected perhaps some ideas with it, tears began to flow from the dead man’s eyes. Finally, when after a short prayer for his poor soul, they proceeded to hack off his head, the corpse uttered a screech, and turned and rolled just as if it had been alive—and the grave was full of blood.”

We have thus succeeded in interpreting one of the unknown terms in the Vampyr theorem. The suspicious character, who had some dark way of nourishing himself in the grave, turns out to be an unfortunate gentleman (or lady) whom his friends had buried under a mistake while he was still alive, and who, if they afterwards mercifully let him alone, died sooner or later either naturally or of the premature interment—in either case, it is to be hoped, with no interval of restored consciousness. The state which thus passed for death and led to such fatal consequences, apart from superstition, deserves our serious consideration; for, although of very rare, it is of continual occurrence, and society is not sufficiently on its guard against a contingency so dreadful when overlooked. When the nurse or the doctor has announced that all is over—that the valued friend or relative has breathed his last—no doubt crosses any one’s mind of the reality of the sad event. Disease is now so well understood—every step in its march laid down and foreseen—the approach of danger accurately estimated—the liability of the patient, according to his powers of resisting it, to succumb earlier or to hold out longer—all is theoretically so clear that a wholesome suspicion of error in the verdict of the attendants seldom suggests itself. The evil I am considering ought not, however, to be attributed to redundance of knowledge: it arises from its partial lack—from a too42 general neglect of one very important section in pathological science. The laity, if not the doctors too, constantly lose sight of the fact, that there exists an alternative to the fatal event of ordinary disease; that a patient is liable at any period of illness to deviate, or, as it were, to slide off, from the customary line of disease into another and a deceptive route—instead of death, to encounter apparent death.

The Germans express this condition of the living body by the term “scheintod,” which signifies exactly apparent death; and it is perhaps a better term than our English equivalent, “suspended animation.” But both these expressions are generic terms, and a specific term is still wanted to denote the present class of instances. To meet this exigency, I propose, for reasons which will afterwards appear, to employ the term “death-trance” to designate the cases we are investigating.

Death-trance is, then, one of the forms of suspended animation: there are several others. After incomplete poisoning, after suffocation in either of its various ways, after exposure to cold in infants newly born, a state is occasionally met with, of which (however each may still differ from the rest) the common feature is an apparent suspension of the vital actions. But all of these so-cited instances agree in another important respect, which second inter-agreement separates them as a class from death-trance. They represent, each and all, a period of conflict between the effects of certain deleterious impressions and the vital principle, the latter struggling against the weight and force of the former. Such is not the case in death-trance.

Death-trance is a positive status—a period of repose43 —the duration of which is sometimes definite and predetermined, though unknown. Thus the patient, the term of the death-trance having expired, occasionally suddenly wakes, entirely and at once restored. Oftener, however, the machinery which has been stopped seems to require to be jogged—then it goes on again.

The basis of death-trance is suspension of the action of the heart, and of the breathing, and of voluntary motion; generally likewise feeling and intelligence, and the vegetative changes in the body, are suspended. With these phenomena is joined loss of external warmth; so that the usual evidence of life is gone. But there have occurred varieties of this condition, in which occasional slight manifestations of one or other of the vital actions have been observed.

Death-trance may occur as a primary affection, suddenly or gradually. The diseases the course of which it is liable, as it were, to bifurcate, or to graft itself upon, are first and principally all disorders of the nervous system. But in any form of disease, when the body is brought to a certain degree of debility, death-trance may supervene. Age and sex have to do with its occurrence; which is more frequent in the young than in the old, in women than in men—differences evidently connected with greater irritability of the nervous system. Accordingly, women in labour are among the most liable to death-trance, and it is from such a case that I will give a first instance of the affection as portrayed by a medical witness. (Journal des Savans, 1749.)

M. Rigaudeaux, surgeon to the military hospital, and licensed accoucher at Douai, was sent for on the 8th of September, 1745, to attend the wife of Francis Dumont,44 residing two leagues from the town. He was late in getting there; it was half-past eight, A. M.—too late, it seemed; the patient was declared to have died at six o’clock, after eighteen hours of ineffectual labour-pains. M. Rigaudeaux inspected the body; there was no pulse or breath; the mouth was full of froth, the abdomen tumid. He brought away the infant, which he committed to the care of the nurses, who, after trying to reanimate it for three hours, gave up the attempt, and prepared to lay it out, when it opened its mouth. They then gave it wine, and it was speedily recovered. M. Rigaudeaux, who returned to the house as this occurred, inspected again the body of the mother. (It had been already nailed down in a coffin.) He examined it with the utmost care; but he came to the conclusion that it was certainly dead. Nevertheless, as the joints of the limbs were still flexible, although seven hours had elapsed since its apparent death, he left the strictest injunctions to watch the body carefully, to apply stimulants to the nostrils from time to time, to slap the palms of the hands, and the like. At half-past three o’clock symptoms of returning animation showed themselves, and the patient recovered.

The period during which every ordinary sign of life may be absent, without the prevention of their return, is unknown, but in well-authenticated cases it has much exceeded the period observed in the above instance. Here is an example borrowed from the Journal des Savans, 1741.

There was a Colonel Russell, whose wife, to whom he was affectionately attached, died, or appeared to do so. But he would not allow the body to be buried; and45 threatened to shoot any one who should interfere to remove it for that purpose. His conduct was guided by reason as well as by affection and instinct. He said he would not part from the body till its decomposition had begun. Eight days had passed, during which the body of his wife gave no sign of life: when, as he sat bedewing her hand with his tears, the church-bell tolled, and, to his unspeakable amazement, his wife sat up and said—“That is the last bell; we shall be too late.” She recovered.

There are cases on record of persons, who could spontaneously fall into death-trance. Monti, in a letter to Haller, adverts to several; and mentions, in particular, a peasant upon whom, when he assumed this state, the flies would settle; breathing, the pulse, and all ordinary signs of life disappeared. A priest of the name of Cælius Rhodaginus had the same faculty. But the most celebrated instance is that of Colonel Townshend, mentioned in the surgical works of Gooch, by whom and by Dr. Cheyne and Dr. Baynard, and by Mr. Shrine, an apothecary, the performance of Colonel Townshend was seen and attested. They had long attended him, for he was an habitual invalid, and he had often invited them to witness the phenomenon of his dying and coming to life again; but they had hitherto refused, from fear of the consequences to himself: at last they assented. Accordingly, in their presence, Colonel Townshend laid himself down on his back, and Dr. Cheyne undertook to observe his pulse; Dr. Baynard laid his hand on his heart, and Mr. Shrine had a looking-glass to hold to his mouth. After a few seconds, pulse, breathing, and the action of the heart, were no longer to be observed. Each of the46 witnesses satisfied himself of the entire cessation of these phenomena. When the death-trance had lasted half-an-hour, the doctors began to fear that their patient had pushed the experiment too far, and was dead in earnest; and they were preparing to leave the house, when a slight movement of the body attracted their attention. They renewed their routine of observation; when the pulse and sensible motion of the heart gradually returned, and breathing, and consciousness. The tale ends abruptly. Colonel Townshend, on recovering, sent for his attorney, made his will, and died, for good and all, six hours afterwards.

Although many have recovered from death-trance, and there seems to be in each case a definite period to its duration, yet its event is not always so fortunate. The patient sometimes really dies during its continuance, either unavoidably, or in consequence of adequate measures not being taken to stimulate him to waken, or to support life. The following very good instance rests on the authority of Dr. Schmidt, a physician of the hospital of Paderborn, where it occurred, (Rheinisch-Westphälischer Anzeiger, 1835, No. 57 and 58.)

A young man of the name of Caspar Kreite, from Berne, died in the hospital of Paderborn, but his body could not be interred for three weeks, for the following reasons. During the first twenty-four hours after drawing its last breath, the corpse opened its eyes, and the pulse could be felt, for a few minutes, beating feebly and irregularly. On the third and fourth day, points of the skin, which had been burned to test the reality of his death, suppurated. On the fifth day the corpse changed the position of one hand: on the ninth day a vesicular47 eruption appeared on the back. For nine days there was a vertical fold of the skin of the forehead—a sort of frown—and the features had not the character of death. The lips remained red till the eighteenth day; and the joints preserved their flexibility from first to last. He lay in this state in a warm room for nineteen days, without any farther alteration than a sensible wasting in flesh. Till after the nineteenth day no discoloration of the body, or odour of putrefaction, was observed. He had been cured of ague, and laboured under a slight chest affection; but there had been no adequate cause for his death. It is evident that this person was much more alive than many are in the death-trance; and one half suspects that stimulants and nourishment, properly introduced, might have entirely reanimated him.

I might exemplify death-trance by many a well authenticated romantic story.—A noise heard in a vault; the people, instead of breaking open the door, go for the keys, and for authority to act, and return too late; the unfortunate person is found dead, having previously gnawn her hand and arm in agony.—A lady is buried with a jewel of value on her finger; thieves open the vault to possess themselves of the treasure; the ring cannot be drawn from the finger, and the thieves proceed to cut the finger off; the lady, wakening from her trance, scares the thieves away, and recovers.—A young married lady dies and is buried; a former admirer, to whom her parents had refused her hand, bribes the sexton to let him see once more the form he loved. The body opportunely comes to life at this moment, and flies from Paris with its first lover to England, where they are married. Venturing to return to France, the lady is recognised,48 and is reclaimed by her previous husband through a suit at law; her counsel demurs, on the ground of the desertion and burial; but the law not admitting this plea, she flies again to England with her preserver, to avoid the judgment of the parliament of Paris, in the acts of which the case stands recorded. There are one or two other cases that I dare not cite, the particulars of which transcend the wildest flights of imagination.

It may be thought that these are all tales of the olden time; and that the very case I have given from the hospital at Paderborn shows that now medical men are sufficiently circumspect, and the public really on its guard to prevent a living person being interred as one dead. And I grant that in England, among all but the poorest class, the danger is practically inconsiderable of being buried alive. But that it still exists for every class, and that for the poor the danger is great and serious, I am afraid there is too much reason for believing. It is stated in Froriep’s Notizen, 1829, No. 522, that, agreeably to a then recent ordinance in New York, coffins presented for burial were kept above ground eight days, open at the head, and so arranged, that the least movement of the body would ring a bell, through strings attached to the hands and feet. It will hardly be credited, that out of twelve hundred whose interment had been thus postponed, six returned to life—one in every two hundred! The arrangement thus beneficently adopted at New York is, however, imperfect, as it makes time the criterion for interment. The time is not known during which a body in death-trance may remain alive. Nothing but one positive condition of the body, which I will presently mention, authenticates death. It is frightful to think49 how, in the south of Europe, within twenty-four hours after the last breath bodies are shovelled into pits among heaped corpses; and to imagine what fearful agonies of despair must sometimes be encountered by unhappy beings, who wake amid the unutterable horrors of such a grave. But it is enough to look at home, and to make no delay in providing there for the careful watching of the bodies of the poor, till life has certainly departed. Many do not dream how barbarous and backward the vaunted nineteenth century will appear to posterity!

But there is another danger to which society is obnoxious through not making sufficient account of the contingency of death-trance, that appears to me more urgent and menacing than even the risk of being buried alive.

The danger I advert to is not this; but this is something—

The Cardinal Espinosa, prime minister under Philip the Second of Spain, died, as it was supposed, after a short illness. His rank entitled him to be embalmed. Accordingly, the body was opened for that purpose. The lungs and heart had just been brought into view, when the latter was seen to beat. The cardinal awakening at the fatal moment, had still strength enough left to seize with his hand the knife of the anatomist!

But it is this—

On the 23d of September, 1763, the Abbé Prevost, the French novelist and compiler of travels, was seized with a fit in the forest of Chantilly. The body was found, and conveyed to the residence of the nearest clergyman. It was supposed that death had taken place through apoplexy. But the local authorities, desiring to be satis50fied of the fact, ordered the body to be examined. During the process, the poor abbé uttered a cry of agony.—It was too late.

It is to be observed that cases of sudden and unexplained death are, on the one hand, the cases most likely to furnish a large percentage of death-trance; and, on the other, are just those in which the anxiety of friends or the over-zealousness of a coroner is liable to lead to premature anatomization. Nor does it even follow that, because the body happily did not wake while being dissected, the spark of life was therefore extinct. This view, however, is too painful to be followed out in reference to the past. But it imperatively suggests the necessity of forbidding necroscopic examinations, before there is perfect evidence that life has departed—that is, of extending to this practice the rule which ought to be made absolute in reference to interment.

Thus comes out the practical importance of the question, how is it to be known that the body is no longer alive?

The entire absence of the ordinary signs of life is insufficient to prove the absence of life. The body may be externally cold; the pulse not be felt; breathing may have ceased; no bodily motion may occur; the limbs may be stiff (through spasm); the sphincter muscles relaxed; no blood may flow from an opened vein; the eyes may have become glassy; there may be partial mortification to offend the sense with the smell of death; and yet the body may be alive.

The only security we at present know of, that life has left the body, is the supervention of chemical decomposition, shown in commencing change of colour of the integu51ments of the abdomen and throat to blue and green, and an attendant cadaverous fetor.

To return from this important digression to the former subject of the Vampyr superstition. The second element which we have yet to explain is the Vampyr visit and its consequence—the lapse of the party visited into death-trance. There are two ways of dealing with this knot; one is to cut it, the other to untie it.