BY

JAMES DWIGHT.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lawn-tennis, by James Dwight This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Lawn-tennis Author: James Dwight Release Date: October 19, 2018 [EBook #58137] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LAWN-TENNIS *** Produced by MWS, Adrian Mastronardi, Chris Jordan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

DEDICATION.

To William Renshaw, Esq., Champion of England, this book is dedicated by his friend and pupil the Author.

PUBLISHED BY

WRIGHT & DITSON, BOSTON, U. S. A.,

AND

“PASTIME” OFFICE, 28 PATERNOSTER ROW,

LONDON, E. C.

COPYRIGHT

1886,

By JAMES DWIGHT.

There is at present no work on Lawn-Tennis written by any of the well-known players or judges of the game, and it is with great diffidence that I offer this book to fill the gap until something better comes.

It is intended for beginners, and for those who have not had the opportunity of seeing the best players and of playing against them.

To the better players it would be presumption for me to offer advice. I should not, indeed, have ventured to write at all had I not had unusual opportunities of studying the game against the best players, and especially against the Champion, Mr. W. Renshaw, and his brother.

| PART I. | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| Preface | vii | |

| I. | How to Learn to Play | 1 |

| II. | The Court and Implements of the Game | 6 |

| III. | The Service | 12 |

| IV. | The First Stroke | 18 |

| V. | The Stroke | 21 |

| VI. | The Volley | 23 |

| VII. | The Half-Volley | 28 |

| VIII. | The Lob | 30 |

| PART II. | ||

| I. | The Game | 32 |

| II. | Match Play | 46 |

| III. | The Double Game | 56 |

| IV. | Ladies’ and Gentlemen’s Doubles | 64 |

| V. | Umpires and Umpiring | 68 |

| VI. | Odds | 71 |

| VII. | Bisque | 73 |

| VIII. | Cases and Decisions | 80 |

| IX. | List of Winners | 88 |

LAWN-TENNIS.

One is often asked the best method of learning to play. I fancy that the best way, could one often adopt it, would be to let a marker, as in a tennis-court, hit the balls gently to the beginner, pointing out to him his mistakes, so that he might not acquire a bad style. If he begins by going on to the lawn and playing a game, his only object will be to get the balls over the net, and he will be almost sure to fall into bad habits of play. This is, however, the most amusing way to learn, and will probably always be the one in general use. If the novice does adopt it, let him at least watch good players whenever he can, not with any idea of trying their severe volleys, &c., but in order to see the position of the feet and of the racket in play. When he has learned to play fairly well, he should still watch good players at every opportunity; but what he then needs to study is the position in the court where they stand; when[2] they go forward and when back, and what balls they volley instead of playing off the ground. He will, in this way, get some idea of the form which he should try to acquire. Mr. E. L. Williams, in a recent article in the Lawn-Tennis Magazine, advises playing against a wall, and I believe in the benefit obtained from this sort of practice. In fact, I have often advised players to try it. Any sort of a wall will do; the wall of a room, if there is nothing better. Hit the ball quietly up against the wall, wait till it has bounded and is just beginning to fall, then hit it as nearly as possible in the same place. Always make a short step forward as you hit, with the left foot in a forehanded stroke, and with the right in a backhanded one. Try to hold the racket properly (see page 10), and do not hit with a stiff arm. The shoulder, elbow, and wrist ought all to be left free, and not held rigid. As soon as you can hit the ball up a few times forehanded, try the same thing backhanded, and when you are reasonably sure of your stroke, take every ball alternately fore and backhanded. This will give you equal practice in both strokes, and will also force you to place the ball each time. Add now a line over which the ball must go; in a room a table or bureau will do very well, and, if possible, mark out a small square in which the ball shall strike. This may sound very childish to a beginner, but I am sure that very valuable practice can be got in this way, and I have spent a great many hours in a room at this occupation. After a time you should volley every ball, first on one side and then on the other. Then half-volley, and after that try all the different combinations: volley forehanded, and half-volley backhanded, &c.[3] Always stick to some definite plan, as in that way you get practice in placing. There is another stroke that can well be learned in this way. Hit the ball up against the wall so that it will strike the ground on your left and go completely by you, then step across and backward with your right foot, swing on the left foot till your back is towards the wall, and try to return the ball by a snap of your wrist. With practice, you will manage to return a ball that has bounded five or six feet beyond you. Try also the same stroke on the forehand side. You can get in this way alone more practice in handling a racket, and in making the eye and hand work together, than you are likely to get in ten times the length of time out of doors. Ask some friend, who really knows, to tell you if you hold your racket in the right way, and to point out to you any faults of style that you may have. It is of the greatest importance not to handicap yourself at the start by acquiring bad form. Good form is simply the making of the stroke in the best way, so as to get the greatest effect with the least exertion. While nothing can be more graceful than good form, no one should make it his chief object to play gracefully; the result will only be to make him look absurd.

When you begin to play games, do not try all the strokes that you see made. Begin by playing quietly in the back of the court. Try simply to get the ball over the net, and to place to one side or the other, and to do this in good form, i.e., to hold the racket properly, and to carry yourself in the right way. As you improve you can increase the speed of your strokes, and can play closer to the side-lines. Remember that a volleying game is harder to play, and you should learn to play well[4] off the ground before trying anything else. Above all things, never half-volley. If you can return the ball in no other way, let it go and lose the stroke. This may sound absurd, but I feel sure that most young players lose more by habitually trying to take half-volleys when there is no need of it, than they gain by any that they may make. It is a stroke that should never be used if it is possible to avoid it. If you make up your mind to let the ball go unless you can play it in some other way, you will thus learn to avoid wanting to half-volley. When you become a really good player, you can add this stroke to your others, and you will not have got into the habit of using it too often. It is a mistake to play long at a time. For real practice three sets a day are quite enough. When practising for matches, you can play the best of five sets three times a week. Almost all players play too much, and by the middle of the season many of them are stale. Always try to play with some one better than yourself, and take enough odds to make him work to win. In the same way give all the odds that you can.

Remember, while playing, certain general principles. Don’t “fix” yourself. Keep the knees a little bent, and your weight thrown forward and on both feet, so that you can start in any direction. If the feet are parallel it is impossible to start quickly. Always keep moving, even if you do not intend to go anywhere. Play quietly and steadily without any flourish, and try to win every stroke. A great many players seem unable to keep steadily at work, and play a careless or slashing stroke every now and then. This is a great mistake, and one often loses a great deal by it. Try to acquire a habit of[5] playing hard all the time. The racket should be carried in both hands, for, if you let it hang down, more time will be needed to get it across your body. Never cut nor twist a ball except in service; it tends to make the ball travel more slowly, and will deceive nobody. The underhand stroke puts a little twist on the ball, but it is an over twist and not a side one. Try to meet the ball fairly, i.e., to bring the racket against it in the line of its flight; or, in other words, don’t hit across the ball.

Watch carefully your own weak points. Any good player ought to be able to show them to you, and you should then try to improve your game where it is weak. If you practise carefully and your only object is to learn, there is no reason why you should not get into the second class. To be among the very best players requires physical advantages, as well as a stout heart and great interest in the game. One is often advised to pretend to put a ball in one place and then to put it in another. I can assure you that it does not pay. Too many strokes are lost by it. Exactly the same thing is true about pretending to go to one side and then coming back again. One is apt to get off one’s balance in making such a feint, and it is quite hard enough to get into position for a ball without having to start the wrong way first.

It is well to observe the rules carefully in practice, or else they may distract one’s attention in a match. This is especially true of the service. Frequently foot-faulting in a match spoils your service altogether. In practice you should always see that the net is at the right height, and should always use good balls. It is bad practice, and is also very unsatisfactory, to play with bad balls. When the weather is too bad to use good balls it is too bad to play at all.

The court is 78 ft. long. It is 27 ft. wide for the single game, and 36 ft. for the double game. At most club-grounds a measuring-chain is used to mark out the court, but for a private court a chain is seldom at hand. The easiest way to mark out a court without a chain is to use two long measures. Select the place for the net; then measure 36 ft. across; at each end put in a peg, and over each peg slip the ring of a measure. On one measure take 39 ft., and on the other 53 ft. ¾ in.; pull both taut, and the place where the two ends meet will be one corner of the court. Put in a peg at 21 ft. from the net for the end of the service-line. Next transpose the measures and repeat the same process. This will give the other corner of the court, and at 21 ft. will be the other end of the service-line, and one half of your court is ready. Take exactly the same measures on the other side of the net, and the measurement of your court is complete. The side-lines of the single court are made by marking off 4 ft. 6 in. from each end of the base-lines, and running lines parallel to the side-lines of the double court from one base-line to the other. Everything necessary is thus found except the central-line, which runs from the middle of one service-line to the middle of the other.[7] The posts of the net stand 3 ft. outside of the side-lines. If the court is intended for double play only, the inner side-lines need not be carried farther from the net than the service-lines. If a single court only is to be marked out, the diagonal is about 47 ft. 5 in., instead of 53 ft. ¾ in.

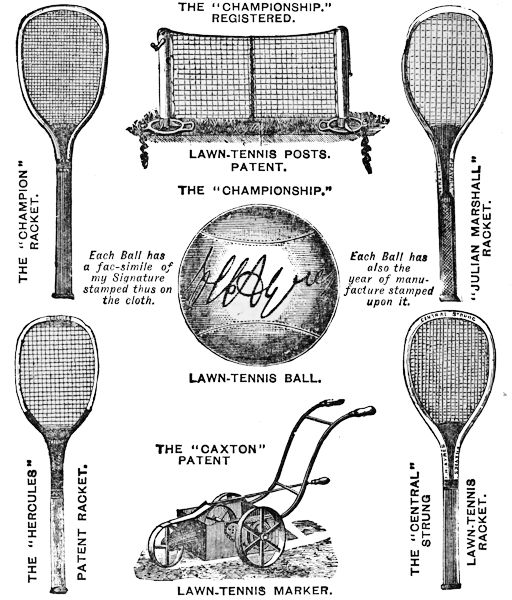

Net.—The net should be bound along the top with heavy white cotton or duck, to the depth of two or three inches. Without this binding it is very difficult to see the top of the net in a bad light. The most important points in a net are that the meshes should be too small to allow a ball to pass through them, and that the twine should not be so large as to obstruct the view of the opposite court.

Shoes.—There is little to say about shoes, although one’s comfort depends a great deal on them. They should be a little too large, with the toes square or round, but never pointed. Those made of buckskin, with leather straps over the toes, are the most comfortable. For the soles no rubber compares with steel points—i.e., small nails about five-eighths of an inch long, driven into the sole of the shoe, and protruding from it about one-quarter to three-eighths of an inch. Points injure the ground less than rubber, as to a great degree they prevent slipping. For gravel or asphalt the best soles are made of very soft red rubber, which lasts a long time and is very easy to the feet.

Balls.—Ayres’s balls are used at every tournament of importance in England, and, while this is the case, it is necessary for tournament players to practise with them, though those of some other manufacturers are quite as good for ordinary play.[8]

Rackets.—The choice of a racket is an important matter, and it is also a difficult one. Young players seem to take pleasure in selecting the most extraordinary rackets in a shop. Let me strongly advise them to avoid all unusual handles, heads, or methods of stringing. All these eccentricities are useless at the best. Nothing is so good as the simplest form of racket, possessing an octagonal handle, and strung in the usual way. Such a racket is used by all the better match-players in England. Opinions differ as to what the exact size of the head should be, but it is certain that there is nothing to be gained by having it square or triangular. Again, the edges of the rim should not be bevelled. It only weakens the frame, while it does not increase the size of the playing face of a racket in the smallest degree. A ball must be hit almost exactly in the centre of the racket to make a stroke at all, for, if hit so near the edge that the bevelled rim can affect it, it cannot possibly go any distance.

As regards the proper weight of a racket, 14½ oz. is heavy enough for any one. I know of only two of the well-known players who use heavier rackets than this. I should advise any one learning to play to get a racket of 14¼ oz., and he can afterwards get one of 14½ oz. should he feel that his first one is too light. There can be no question that a light racket can be more easily brought round than a heavy one, and is more easily controlled in every way. On the other hand, a racket must have wood enough in the frame to make it perfectly unyielding when striking a ball, and must be heavy enough to give an effective stroke. These conditions are fulfilled in a racket of 14¼ to 14½ oz.; a[9] lighter one loses something in power, and a heavier one is unmanageable for most men. One meets from time to time a player with a racket of 15 or 15½ oz., who shows it with pride, and explains that his wrist is so strong that he requires an unusual racket. As a matter of fact, such a player seldom uses his wrist at all, but rather he should be thankful for the advantage that a good wrist gives him, instead of handicapping himself by using an absurdly heavy racket. Almost more important than the weight of the racket is its balance. By balance is meant the way in which a racket hangs in the hand. Many rackets of 14 oz. feel as heavy as others of 14½ oz. There is only one way of judging the balance, and that is by holding the racket by the end of the handle, as if in actual play, and trying how it comes up, and if it feels light or heavy. If it comes up heavily, discard it at once and try another. Should it feel light and easily managed, weigh it yourself, no matter whether the weight is stamped on it or not. It may be that it felt well balanced only because it was too light for use; but should it be found to weigh 14¼—14½ oz., the balance of it must be good. You should look carefully at the workmanship and see that the wood is free from knots and cracks. The grain should run evenly round the whole frame. Look especially at the parts of the hoop, just above the centre-piece, for there it is that a racket usually breaks. See also that the wedge is quite firm. Choose a racket in which the wood is left in the natural state, as varnish, &c., is often used to conceal a flaw.

A racket should be very nearly, if not quite, straight[10] For myself, I prefer one with a very slight bend to one side, but I can give no reason for doing so.

No player should have a racket that he cannot hold absolutely stiff from the very end of the handle. It is essential that a racket should be light enough for him to volley with it at the very end of his reach without any yielding in his wrist. If his wrist is not strong enough to stand this strain with a racket of the usual weight, it is better for him to use a lighter one. Though losing something in the severity of his strokes, he will gain enough in sureness to more than make up for it.

How to hold the Racket—One finds many different ways of holding the racket among good players, and no exact rule has ever been received as correct. Still, nearly all good players observe certain principles in holding a racket. It is of the first importance that you should be able to play a ball either fore- or back-handed without changing your hold on the racket. If the hold is changed, there is always danger of not getting the racket into the right position quickly enough. Such a change must require a certain amount of time and attention, which cannot well be spared in sharp play. The method that I should recommend is as follows:—Lay the racket on a table with the smooth side up. Open the hand with the thumb nearly at right angles to the fingers, and then clasp the handle in such a way as to make its upper right edge (or what would be its right edge if it were cut square) fit into the hollow of the joint between the thumb and forefinger. In closing the fingers on the handle, do not put them directly round it, but with the first joint of each finger slanting up the handle, which will cause the top joints to slant down the[11] other way. The first two fingers should be a little separated from the other fingers, and from each other. The end of the handle should be well within the hand, with the little finger round the leather rim. The thumb should not go round on to the ends of the fingers, but should slope upwards across the upper side of the handle.

There are many ways in which the service can be delivered, but there is only one in general use. This is the common overhand service delivered from above the right shoulder, with or without twist on the ball.

To serve it, throw the ball up above the head as nearly as possible to the height at which it is to be struck, and strike it as it pauses before falling. Be careful to throw the ball well back and about on a line with the ear. If it is thrown forward the service will probably go into the net. In serving, the arm should be extended to almost its full length, so as to get the greatest possible reach, and the shoulder should be left free and not held stiff. When serving for speed only, the face of the racket should be brought fairly against the ball with no twist whatever, and the head of the racket should be made to come over on the top of the ball by a sharp bend of the wrist. When trying to put twist on the service, the racket should not meet the ball fairly, but should pass round on the outside of it; this will give a twist from right to left.

A very uncommon and difficult service can be given by throwing up the ball a little to the left of one’s head,[13] and carrying the racket round on the left hand side of the ball, which will give a twist from left to right. It is possible to put a heavy spin on the ball in this way, and the service is effective, because it is very uncommon.

The next most important service is the underhand twist service delivered either fore- or back-handed. To begin with the former, the player should stand with the feet near together and his weight on the right foot. The racket should be held nearly vertical and just to the side of the right leg. The ball is dropped outside, and a little in front of, the racket, which is brought forward against the ball, and thus, by a quick inside turn of the wrist imparts a strong twist to it. In striking, the weight is thrown forward on to the left foot, and a short step forward with that foot is made to give pace to the service. The service should not be delivered with a jerk, but by a quiet easy swing; the only really quick motion being the turn of the racket round the ball which gives the twist.

The backhanded underhand service is precisely similar, but is made on the left side with the right foot forward. The ball is struck with the rough side of the racket, and of course breaks from left to right.

There is only one other service that need be mentioned. The arm is at right angles to the body, with the elbow slightly bent, and with the head of the racket a little higher than the wrist. The ball should be struck at the height of the shoulder, and the racket, after striking the ball behind and a little on top, should open and pass forward beneath it so as to impart pure cut to the ball. The ball does not rise as much as with most services, and is often returned into the net when[14] the service is first tried. It is, however, useful only as a change service, or to increase the chance of the ball’s shooting, on a wet ground.

It should be distinctly understood that, in giving any service, the weight of the body must be thrown forward at the time of striking; otherwise no great speed can be obtained.

As the rule now requires the front foot to be on the base-line when the ball is served, it is better to put the toe on the line before serving. The weight of the body is held a little back, and is then thrown forward as the ball is struck. It is not so easy to serve fast in this way as it is by taking a step forward, but, on the other hand, one seldom or never serves a foot fault.

Players too often forget the importance of placing the service. It is very hard to make a good first stroke off a well-placed service, even if it be a slow one. It is also important to conceal the direction of the service as long as possible, so that one’s opponent may not know in which corner of the court to expect it.

Having described the different kinds of service, we have next to consider which of them should be used. The best working service is probably the simple overhand service delivered without twist. It should be placed down the central-line or across to the outer corner of the court, and should be served as fast as possible. Should the first service be a fault, it is the custom to serve again in the same way, but at such a pace that there will be no danger of a second fault. We are often told that a good player should cultivate a second service which should be difficult to return, and at the same time should never be a fault. I can only say that this[15] is easier said than done, as no one has yet succeeded in carrying it out. Again we are told that if a player cannot serve a good second service, he would do better not to try a very hard service the first time, but to serve a medium-paced service which would be at once reasonably sure of going into court, and yet be difficult to place on returning. I must dissent entirely from this advice. I believe that in the single game and with good players the service is a distinct disadvantage. The first service is oftener a fault than not, and the second service can be placed almost as the striker-out pleases. Why not then serve a medium service the first time? Because no service, not even the very slow second service, can be placed so sharply and accurately as a moderately fast one. It is not fast enough to place the striker-out at a disadvantage, and yet it comes back more quickly in the return than a slower one would do, and therefore leaves the server less time to get into position for the first return. Another difference, often overlooked, is, that a player must “fix” himself to a certain extent to deliver a service of even medium speed. He cannot, therefore, get into position as quickly after a fairly fast service as after a slow one, and yet he will be given less time to do so. Of course, he “fixes” himself for the first very fast service, but, in this case, he expects to gain a distinct advantage should his service be good. Off such a service it is very difficult to make a good first stroke, and the server will probably have a chance to come forward and finish the rest with a volley.

My own feeling is that the server must start at a disadvantage unless he can deliver a severe first service. In any other case he must be content to stay back,[16] even outside his court, while his opponent is forward, and his object for the time must be rather to save the rest[1] than to win it.

[1] Or “rally” as it is sometimes improperly termed.

For a second service the forehanded underhand twist is useful, especially when served into the left court. It is not in itself difficult to return, but it keeps low, and will often twist a little more or a little less than the striker-out expects, thus preventing him from making a severe first stroke.

It sometimes pays to place such a service as near as possible to the outer corner of the court, and to follow it up almost to the net. One would think that there would be no difficulty in passing the server as he comes forward, but it requires a very accurate first stroke to do so. If the stroke is not well-placed, there will be a chance for a sharp volley which should win the rest. It needs great quickness to make such a volley, and no one should take such a risk unless he can volley really well. In trying such a coup as this, he must take into account what his chance of winning the rest will be if he gives an easy second service and stays back. If he finds that he has been losing twice out of three times on his second service, it is well worth while to try going up, especially as it is very annoying to his adversary if it comes off.

Many players have an idea that at 40-0 or at 40-15 it pays to serve the second service at full speed, on the ground that at such a score the risk is justifiable. This surely is a mistake. If the server keeps to the game by which he has gained such an advantage he will probably win one stroke in the next two or three. But if he sees fit to take such liberties as to serve twice at full speed[17] he will probably find the score level before he knows it, and his opponent playing with increasing confidence.

I should strongly advise a player to learn thoroughly the reverse overhand service, not only that it is unusual and effective, but because one looks to the left to serve it. You can in this way serve overhand, no matter where the sun may be. With the sun on the right the common overhand service is nearly useless, because the danger of looking at the sun is so great. You may get the service over all right and then be quite unable to see the return.

By first stroke is meant the return of the service. I may safely say that more depends on this stroke than on any other. If the first stroke is good, the striker-out should have a decided advantage; if bad, he is almost at the server’s mercy. What the first stroke should be depends on the service and on the skill of the opponent. Off a very fast service it is difficult to make a good first stroke, because the slightest mistake will be enough to send the ball into the net or out of court. If, however, the first stroke is made exactly right, it is more crushing in proportion to the speed of the service. The server has had to fix himself to give a very fast service, and no time is left him to recover for the return. The difficulty of a very severe return of a very fast service is so great that it must be looked on as fortunate, even among good players. It is always very hard to foresee in just what place the service will pitch, and, therefore, the striker-out cannot prepare himself for any particular stroke. He must be ready to return the ball; that is the first point. For the rest, he must return it as severely as he safely can, and into that part of the court where it will most readily[19] go. By this I do not mean that the service should be returned purposely into the middle of the court, but every fast ball is more naturally returned in one direction than in another, and all I advise is that a very fast service should be returned into whatever part of the court it is easiest to put it. If the first service comes off and is very fast, it will almost always give the advantage, and the striker-out must be content to yield the position and to play for safety.

Very different is the case with the second service. The server is no longer trying for an advantage, and the striker-out can choose the way in which he will begin the attack. The server will now probably be far back in the court—about the middle of the base-line or a little behind it—and the chances are that he will succeed in returning the first stroke, no matter where it may be placed. It would, therefore, require an unusually severe stroke to finish the rest at once, and it is running too great a risk to attempt such a stroke. The ball should be played sharply down the side-line or across the court to the farther side-line, so as to put the server on the defensive at the start. Of this I shall speak more fully in treating of the “game”; at present I shall only try to explain what strokes there are to use.

1.—The most common and, perhaps, the safest stroke is to play the ball down the side-line into the corner, especially when the service has been into the right court, as this brings the return into the backhand corner, and few players are as good back- as fore-handed.

2.—One can also return diagonally across the court to the far corner. This stroke should be played very[20] hard, for if made slowly there is a chance for an easy return. Moreover, if time is given him, the server may come forward and meet the ball in the middle of the court and kill it by a sharp volley. For this reason it is better not to play this stroke if the server is coming up, but to play either Nos. 1 or 3.

3.—There is another stroke, and the most difficult of all. It is to play the ball slowly across the court to the farther side-line. The ball should strike the ground as near to the net as possible, so that a player who is coming forward cannot reach it before it has bounded and passed on across the side-line. If made correctly, there is no answer to the stroke, except a half-volley. It is an essential part of the stroke that it should be played very slowly, or else the ball must go out of court.

4.—Sometimes, but very seldom, one has to lob the first stroke; for instance, when the first service has been very severe, and the server has followed it up close, one may be unable to make a good stroke to one side of the court, and, if so, it is best to lob.

Again, the server will at times follow up his second service, and, if he gets very close, the safest stroke will be a lob over his head into the back of the court.

By stroke, I mean the motion with which a ball is returned off the ground. Of course, all balls cannot be played in the same way; that must depend on how they come, and on the hardness of the ground. As a rule, however, a player can choose in which of two ways he will play the ball. He can take the ball at the top of its bound, in which case the head of the racket is held a little higher than the hand, and the racket itself is nearly horizontal. The stroke is made with the forearm and wrist, and the arm is straightened as the ball is struck.

The other method is to let the ball fall till within a foot or so of the ground, and then, so to speak, to lift it over the net. The racket is held upright, with the head a little back and the hand forward. The ball is taken beside, and a little in front of, the right foot, and a short step forward is made with the left. In striking, the racket is raised, not from the shoulder, but from the elbow, and the wrist is bent backward. The direction of the ball is given by turning the wrist at the moment of striking, and for this reason it is very difficult for[22] one’s opponent to foresee where the ball will be put. I should explain that the stroke is not meant to be a “slam,” but a quiet, regular stroke, whose strength lies less in its speed than in its accuracy, and in the difficulty of foreseeing its direction.

Of the two strokes I much prefer the second one. It gives one’s opponent more time to place himself, but, on the other hand, one gains both in accuracy and severity of stroke, and can also change the direction of the ball at the last moment.

On a very hard ground the horizontal stroke is the more common, because the ball rises so high that one would have to go very far back in the court to play it with a vertical racket, and in doing so would lose his position. On a slow ground, the chance for the second stroke occurs all the time.

To become an adept at the game, the player must be able to volley well; he must know how the stroke is made, and he must be able to make it, no matter where the ball may come—high or low, right or left, straight or dropping. One common principle applies to all volleys, namely, that the ball must not be allowed to hit the racket, but the racket must hit the ball, and a distinct stroke should be made. A step should always be taken with the opposite foot, i.e., with the left foot in a forehanded stroke, and with the right in a backhanded one.

As an example, take the ordinary forehand volley at about the height of the shoulder (a very common stroke). The elbow should be away from the body and not down by the side, the wrist a little bent upwards, and the head of the racket above the hand. In striking, the weight is thrown forward on to the left foot, which is brought out with a good step in front of the right foot and a little across it. There is no preliminary swing of the racket backward. The head of the racket should be brought forward on to the ball with a sharp bend of the wrist, and the arm should be straightened to nearly its full length.[24] The racket should not be checked suddenly after striking the ball, but should swing well forward, and then by an easy motion the head will come up into the left hand, where the centre-piece should always be carried between the strokes. The elbow, shoulder, and wrist should all be left free, and not held stiff while the stroke is made.

The backhand volley is made in much the same way. The elbow should be raised and away from the body; the head of the racket should be just over the left shoulder, and the stroke should be made by stepping forward with the right foot, straightening the forearm, and bringing the head of the racket sharply forward by bending the wrist. It is this turn of the wrist at the last moment of the stroke that gives sharpness and character to all volleys.

It is much easier to volley a ball at the height of the shoulder back than forehanded, and it is worth while to remember this fact when trying to pass a volleyer from the back of the court.

These two volleys are used with the ball from four to six feet from the ground, both in coming forward from the back of the court, and, more often, when already in position, and your opponent tries to pass you. Both strokes are easy in themselves if the ball comes within reach and if you can foresee on which side it is coming. The real difficulty lies in getting into position for the stroke, and not in the stroke itself.

A more difficult ball to volley is one that is only a foot or so off the ground. Such a ball is best volleyed forehanded, with a vertical racket. The hand comes out directly in front of the body, and the stroke is made[25] almost entirely by the wrist. There should be little or no swing of the racket beforehand.

A ball a little higher, that is, between waist and knee, cannot well be volleyed in the same way. One must step to one side or the other to get room to return it, and it is easier to play it backhanded. One should step forward and bend well down to meet the ball and volley it with the head of the racket a little above the hand.

A great deal of time is saved by these low volleys, and one is sometimes caught while coming forward or going back in a position when nothing else can be done. It is a stroke that a player should learn to make as well as possible, but it is not one that he should use except to gain an advantage by saving time, or when he can do nothing else.

We now come to a wholly different class of volleys, namely, those of a dropping ball, as when a weak return is made off a fast service, or more often when one player is lobbing to drive his opponent back. In this class comes the “Smash,” which is simply a volley made very hard, with all the joints of the arm free, so that as soon as the stroke is started all control of the racket is lost. In a simple volley the joints are not held stiff, but one retains control of the racket throughout the stroke; in a smash one lets the racket go apparently at random. It is not a stroke to play except when very close to the net, and even then a more careful volley will usually be sufficient, and far safer.

It is of this volley that I wish to speak, as the occasion for it comes constantly. It must be made hard, it must be placed, and its direction must not be shown till the last moment. Take the most common case: you are[26] just in front of the service-line, your opponent lobs from the back of the court and the ball does not go very far beyond the service-line. How are you to make the stroke? Of course the ball may come in front or on either side, but it travels so slowly that you can usually take it as you please, and it is best to do so forehanded. You should stand with your feet slightly apart, and in striking should take a short step forward, and a little across with your left foot. The racket is held close to the body with the left hand round the centre-piece till the ball comes within reach. Then lift the racket quietly and strike without any swing backward; but the racket should follow the ball after the stroke, and not be checked suddenly. The whole stroke, from the time when the racket is lifted, should be made without any pause. One often sees a player waiting for the ball with his racket lifted; the effect is ridiculous, and, what is of more importance, it is usually easy to tell where he means to put the ball. The ball should be taken at about the same height as in service, but decidedly more in front, because it is nearer the net. The wrist should be bent forward at the end of the stroke to bring the head of the racket down on top of the ball.

Any lob that comes near the middle of the court should be played forehanded, but when a ball is much to the left of the central-line it is better to play it backhanded, as it puts one too much out of position to get on the other side of the ball. The stroke is played in the same way as the forehanded one, except that the step is made with the right foot and should be in front of the left, but not across it.

The easiest place to put the ball is into the backhand[27] corner or across to the farther side-line. Without taking his eyes off the ball, the player can usually tell about where his opponent is, and can place the stroke accordingly. In all such volleys he should make up his mind just where he means to put the ball before he takes the step forward, and he should not change it even if he sees that his intention is discovered.

No rule can be given for placing the volley, but in any case the stroke should be severe enough to prevent the next lob from being as good as the last. If you do not gain a distinct advantage by the volley you are pretty sure to be worse off next time. It is worth while to take a good deal of risk in such a stroke, for the moment that you begin to play a lob faintheartedly, you will be passed or driven back in a stroke or two. One’s object should be to kill the ball, if that be possible; if not, to place it so as to get an easier stroke next time. If you can do neither one nor the other, you had better not volley the ball at all, but go back and play a defensive game from the base-line. If you cannot attack you must be ready to defend yourself, and the place to do that is not in the middle of the court.

The half-volley is the prettiest stroke in lawn tennis; it often saves valuable time, and it helps one out of many difficulties. There is only one remark more to be made about it, and that is, never play it if you can possibly avoid it. Unless played exactly right, it will give an easy return, and will allow your opponent to gain the advantage in position if he did not have it before. If he did, it will probably give him a chance to “kill.”

The worst part of the stroke is that it is a very fascinating one, and it is, therefore, played a great deal too often, especially by young players.

The stroke consists in taking the ball just as it begins to rise after striking the ground. It is simply a question of timing the ball. The player cannot watch the ball as he strikes it, and he must trust to his knowledge of the place where the ball will come. It is best made with the racket as nearly vertical as possible, with a short step forward and with a “lift,” or upward motion of the hand and forearm, at the end of the stroke.

To return balls that have already passed, one should step across with the opposite foot, and, stooping very[29] low, should half-volley with a snap of the wrist. In such a case the racket is nearly horizontal. The great point is to time the ball so as to get it exactly in the middle of the racket.

My advice would be never to use a half-volley if the ball could be returned in any other way, and, if compelled to use it, to put pace on the ball and play it as a fast stroke, and not as a slow one.

A lob is a ball tossed in the air so that it shall fall far back in the court, and shall be out of reach of a player standing as far forward as the service-line.

The object is, of course, to make a stroke that cannot be volleyed, except from the back of the court, where the volley is seldom severe.

There are two kinds of lob—one with a low curve, tossed just high enough to be out of reach, and the other tossed very high in the air and meant to fall almost vertically.

The first kind is used only when one’s opponent is very far forward; in fact, almost up to the net. The ball, being hit low, travels with some speed, and therefore gives little time for a player to get back for it.

The other and more common kind of lob is used when one is at a disadvantage, and is near the base-line or quite out of court. The stroke is meant to gain time for one thing, and, if possible, to drive a volleyer back. The higher the ball goes the more perpendicularly it will fall, and the harder it will be to volley.

It is much easier to lob forehanded, and the ball[31] should be taken well in front of one, and to the right if possible. Always lob toward the windward corner of the court, but if there is little or no wind one should choose the backhand corner.

Remember that a lob must go back nearly to the base-line or it will give an easy stroke.

In the preceding pages I have tried to give some idea of the different strokes and of the manner in which they are made. My object now is to take the game as a whole, and to show in what cases the different strokes should be used.

Before this can be done, we must speak of the different styles of game that one meets. I do not refer to garden-party lawn-tennis, but to the styles of the best match-players only.

Seven or eight years ago no one thought of volleying a ball that could be easily played off the ground. The game consisted of carefully placed strokes of medium pace, and the result was long, tedious rests of twenty, forty, and even eighty returns. The first change in this game was caused by the present champion, Mr. W. Renshaw, who conceived the idea of going forward almost to the net and volleying everything that he could reach. This game, though brilliant, was not wholly successful. The volleyer came too close to the net and gave too easy a chance for the ball to go over his[33] head, and probably, too, the volley was not then of sufficient strength. The net was at that time four feet high at the posts, and the angle at which a ball could be volleyed was more restricted than now.

A year later Mr. Renshaw had changed his game in an important point; he no longer came close up, but volleyed from the service-line, or a little in front of it. Complete success attended him, and his style of game soon came to be received as the right one, and to be generally played.

At that time the hitting from the back of the court was slow according to modern ideas, and it was possible to follow up and volley almost every ball without much danger of being passed. The introduction of volleying brought about a change in the back-play. There was clearly no use in careful placing if the volleyer was given time to get in front of the ball. It thus became necessary to hit hard from the back of the court as well as to place the return, and for the cases where this could not be done, lobbing was brought into fashion.

The improvement in the back-play in its turn affected the volleying game. With good placing and hard hitting it was no longer possible to volley as many balls as before, and, as a rule, the volleyer tried to make a severe stroke, which should put his opponent at a disadvantage before coming forward to volley.

It is in this state that we find the game now. It seems a waste of time to discuss the old question of “Volleying v. Back-play.” With the two games pure and simple, and with no mixture of the two, I feel sure that bad back-play will beat bad volleying, and that good volleying will win against good back-play.[34]

One does not, however, see good players confine themselves wholly to either game. As I said just now, one cannot volley every ball, and one needs to be able to make a severe stroke off the ground to get into position to volley. This one can do only by skill in back-play. Every well-known player of the present day believes that both back-play and volleying are necessary for a successful game, and the question now is not which to use, but how to mix the two.

I believe that the superiority of the champion lies mainly in the completeness of his game, in his ability to play any kind of game that may be required. Mr. Lawford no longer plays wholly from the back of the court, but volleys a great deal, and very effectively too. The only player who sticks completely to a back-game is Mr. Chipp, and he has told me that he wishes that he could volley. On the other hand, perhaps the most bigoted volleyer in the world is myself, and I wish most sincerely that I knew how to take a ball off the ground.

It is not possible to lay down fixed rules for volleying certain balls and letting others bound; were it so, all players would play the same kind of game, and the difference between them would be only in speed and accuracy. Every player must judge for himself if he can volley any particular ball more effectively than he can play it off the ground.

Position is nearly everything in the present game, and a player’s first object should be to get into his place; once there, the chances are all in his favour. I do not mean that the player nearest to the net has necessarily the best of it, that must depend on the last stroke and[35] on the place where his opponent is. If he comes up after making a good stroke that has driven his opponent back to the base-line, he has a great advantage, but if his last stroke has been slow and has struck inside the service-line, he is almost certain to be passed, if his opponent does not make a mistake. I cannot dwell enough on the fact that there is no use in volleying unless a distinct advantage can be gained by it, or, at the worst, that the back player must not have an easier return than he had the time before. The moment that a volleyer fails to make a severe or at least a well-placed stroke, he is at a disadvantage, and would be better off in the back of the court than where he is. It is seldom that the two positions can balance, so to speak, and if a volleyer is not distinctly up, he is pretty sure to go down. Of course I do not mean that every ball that is to be volleyed should be smashed; far from it, but I do say that a volley should always be played hard on to the base-line or across the court to the side-line. If neither can be done, it is wrong to volley the ball at all.

Smashing I hold in great disrespect. As a rule, it is a most unsafe stroke, and, when it can be played without risk, a hard volley will generally be just as good. It is a great satisfaction, both to the gallery and to the player himself, to see a ball smashed through an umbrella or a parasol, but it is an amusement that should be strictly confined to exhibition matches.

Do not volley a very low ball if you can possibly help it. For instance, one is coming forward, and meets a slow return that has passed just over the net and is dropping fast. Such a ball must be volleyed upwards to cross the net, and it will therefore be impossible to[36] make a severe return, and the stroke itself is a difficult one. Let such a ball bound, unless time is of unusual value. Off the ground you will probably be able to make a stroke that will give you a greater advantage than if you had volleyed the ball instead of waiting.

A difficult but useful stroke is the volleying a ball near the ground in the back part of the court. The player is going back, or, more often, coming forward, and meets the ball about half-way between the base-line and service-line. If he can volley it fairly well he can follow up his stroke, and gain the advantage in position which he must have yielded in going back to take the ball off the ground. One saves a great deal of time and of exertion by such a volley, but it is a stroke that cannot be recommended to any except a good volleyer.

One of the hardest balls to volley well is a lob. It is easy enough to return it over the net, but, as I have been trying to explain, there is little use in returning a ball slowly into the middle of the court. I do not believe that it is right to smash a fairly good lob, but I think that it should be volleyed carefully, but still hard, far back in the court, and, if possible, into a corner. There is a long time to think as a lob drops, and many players lose heart and decide to play for safety instead of trying to kill the ball. As a matter of fact, it is safer to hit fairly hard, and the moment that a player begins to hit gently, for fear of putting the ball out of court, he descends to a lower level as a player and diminishes his own chance of success.

Speaking of returning lobs brings me to the question of lobbing, as distinguished from low play. There is undoubtedly a prejudice against lobbing, and a feeling[37] that the low hitting makes the finer game. With this I have nothing to do. I am simply looking for the best game that one can play to win.

I believe firmly in low hard hitting down the lines or across the court when one’s opponent is not quite in position, as, for instance, when he is just coming up, or has had a hard ball to play and has not yet recovered himself. If there is a good chance to pass him, try to do so by all means. If you cannot pass him but can make a stroke that cannot be volleyed hard, in fact, can only be stopped, try it, and the next stroke you can probably pass him.

When, however, one is in the extreme back part of the court, especially in the middle, the chance of passing a good volleyer seems to me to be small. If one is in a corner of the court, one has two strokes to choose from, one down the side-line and the other across the court. If the volleyer does not foresee which stroke will be played, it is unlikely that he can do more than save the ball. But, as just said, if he is in the middle of the base-line, the angle at which the forward player can be passed is very small, and the chances are that the ball will be killed. In such a case I believe that it is good play to lob. It is worth remembering this fact, that it is harder for your opponent to pass you from the middle of the base-line than from the corners of the court. With a strong back-player against you, if you do not get a chance to make a severe stroke into the corner, and have got to return the ball slowly, you will be safer if you return it to the middle of the base-line.

A great objection to lobbing is, that much depends on the weather, and, if there is a strong wind, it will[38] be at a great disadvantage. Of course the wind will affect low hitting as well, but not to the same degree. When lobbing in a wind, always lob to the windward corner, as, after all, the main point with a lob is to put it anywhere in the back part of the court.

If you see that your opponent hesitates to hit a lob hard, be ready to go in the moment the chance comes. It usually is easy to tell if a player intends to stop a lob instead of hitting it, and it is well worth while to take some risk in running up to volley his return. He will probably be too far forward in the court to return your volley well, even if he gets it at all.

If your opponent clearly does not play lobs well, lob whenever there is the slightest doubt of passing him, especially if the sun is in his eyes. If on the other hand he hits your lobs back hard into the corners, it is better not to resort to them unless you can do nothing else.

After saying so much in favour of lobbing, I must add that, though I use the stroke a great deal myself, I believe that a player should play low, if any chance is given him to do so.

If you do play low, don’t play directly down the middle of the court if your opponent is standing there. It is much better to take a greater risk and play for the side-lines. Remember that it is usually easier to pass a volleyer on his forehand side. Remember, also, that the easiest ball to volley is one hit low and hard, because it comes in nearly a straight line. For this reason, especially when a volleyer is coming forward, the most difficult stroke that you can give him to volley is one hit slowly enough to drop low before he can reach it.[39] If you can make him half-volley there will probably be a chance to come in yourself.

It seems to me a mistake to hit as hard as one can in trying to pass a volleyer. One succeeds more often by accurate placing, and by concealing the direction of the stroke till the last moment, than by its actual speed. Of course, a fast stroke will give one’s opponent less time to reach it, but the risk of the ball going into the net or out of court is increased out of proportion to the gain. It is surprising to see how easily a slow stroke will pass a volleyer if he does not know on which side it is coming. Combined speed and placing are perfection, but the placing should be cultivated first, and the speed increased as one improves.

Let us now start as if beginning a game, and we will take the routine points as they arise.

To serve: Stand nearly near the middle of the base-line, a yard, or at the most two yards, from the centre. In this position there is a larger angle, inside of which the service can be placed, than if you stood at one end of the base-line, and, moreover, you are in better position to meet the first stroke.

If your first service is a fast one and is good, follow it up if you can, and volley the return. But remember that your volley must be severe enough to put your opponent at a decided disadvantage, or he will probably pass you with the next stroke.

If your first service is a fault, serve again more slowly. You cannot put much speed into your second service, but you can place it. Try to serve well back to the[40] service-line, and place it so that your opponent will have to play it backhanded, or step to one side before returning it. I do not mean that this placing will produce any great results, but it will tend to diminish the severity of the first stroke. As soon as you have served, get back just outside of the court, or, if the ground is low, stand on the base-line and a very little to the left of the middle. The first stroke is more often put into your backhand corner than anywhere else; few players are quite as strong backhanded, and can, therefore, afford less time in reaching the ball.

One word as to position. It is impossible to start quickly if your feet are parallel. Stand with the heels about a foot apart, the toes a little turned out, and every joint slightly bent. The racket should be close to the body, with the left hand round the centre-piece.

You are now on the defensive, and your opponent will, no doubt, have come forward in front of the service-line. In this position, unless the first stroke has been a weak one, you can hardly hope to win the rest off your first return; it is rather a time to play for safety. If you can do so with a fair chance of success, try a fast stroke down the side-line. If your opponent fails to volley it well, you may hope to pass him next time. I cannot advise trying to cross him on the first return; he has had time to place himself, and if he is not deceived about your stroke, he ought to kill it. If you see no good chance to play down the lines, the best thing to do is to lob. Lob as high as you safely can, so that the ball shall drop almost vertically. Stay back outside of the base-line and wait for your opponent to volley your lob. If he hits it hard, probably you can do little[41] else than lob again. If he simply stops it, you may be able to go in and pass him; if not, lob again and go up and volley his return. This is a winning stroke if your opponent is afraid to let out at a lob.

Where you cannot do this there is nothing to do except to lob until you can get a chance to make a low stroke, off which you can get forward.

Don’t be too anxious to go forward, but if there is any chance to do so, take it at once. Remember that in lobbing you are on the defensive, and that you want to reverse the positions the moment you can.

To return the service, stand completely out of court if the ground is fast; if slow, stand on the base-line. It is much better to be too far back than not far enough. It is easy to come forward, and in coming forward you naturally throw your weight into the stroke. When going back it is very difficult to strike properly, because you have to stop suddenly and throw your weight forward. You are seldom steady on your feet when going back, and in any case your weight is not on the ball.

Do not go too far to one side to receive the service, for you may have to step in either direction. One can actually reach farther backhanded than forehanded, but few players can make the backhand stroke as well.

If the first service into the right-hand court is good, the best working return is probably the one down the side-line into the backhand corner. Follow the stroke up at once, and take your place a yard or two in front of the service-line.

Your opponent may try to cross you; he may play down the side-line or he may lob. The hardest stroke for you to return will be the one down your right side-line,[42] but most players find it a difficult return to make, and prefer to play across the court. If you see that the ball is coming across, step forward two or three paces and volley it hard backhanded down into the forehand corner. If it comes down your side-line, do not come farther up for it, but volley it back down the same side-line, unless you are sure that you can play it across-court before your opponent can reach it. All cross-court strokes, unless very well made, are dangerous, as they allow one’s opponent to come forward, and if he reaches them he will have the best of the position.

Should your adversary lob, walk slowly back with the ball and volley it quietly, but hard, into the back of the court. Other things being equal, the backhand corner is the best place into which to return a lob. If your opponent lingers at all in the left-hand side of his court, volley directly across to the forehand end of the service-line.

Don’t be afraid to hit a lob. There is really no half-way; if you don’t make a good stroke off it, your opponent will probably pass you.

In making these suggestions as to the strokes to play in special cases, I am going as far as I see my way to do in pure theory. For the rest, I can only call attention to a few general principles.

Don’t stand still anywhere in the court. Keep in motion all the time, for it is far easier to start quickly if you do not “fix” yourself. The best example is a marker in a tennis or racket court; he seldom is running, and yet he is almost always where the ball comes. A part of this is no doubt due to his judgment, but a great deal comes from never standing quite still.[43]

Don’t slam at a ball. It is very common to see players “slog” at a fault or at a ball that has struck out of court. It is a great mistake and puts you off your stroke. A very common fault, if one is running for a hard ball that can only just be reached, is to hit at it as hard as one can. The chances are immensely against such a stroke going over the net, while if the racket were simply held in the way the ball would go back.

Don’t give up a rest till it is lost. Try to get the ball back even if it seems to be useless. There is always a chance that it may be missed.

Don’t be deceived by a ball coming over the net, or striking inside the court when you do not expect it. Take it for granted that every ball must be returned.

Never drop a ball short. It is a very tempting stroke, and at times very effective, but one loses a great many strokes in trying it. In almost every case the ball could be killed as well by a hard stroke, and the danger of putting it into the net would be much less. It is very difficult to hit a ball so slowly that it will just go over the net, and if it goes a little too far one’s opponent comes forward to meet it, and can, as a rule, place it wherever he pleases. I play the stroke at times, myself, and each time vow that I will never try it again.

A necessary part of a good player is decision, and the power of making up his mind quickly. Nowhere is this so necessary as in following up the service. If you mean to go up, don’t hesitate for an instant, take the chances and go, and don’t stop half-way. Don’t go up a little way and then wait to see what will happen; you will not be far enough forward to volley, nor far enough back to play off the ground. It puts you in a part of[44] the court where you should never be, namely, somewhere between the base-line and the service-line. The exact position of this forbidden place depends on the speed of the ground. It is at such a distance from the net that the ball comes to you just above the ground, so that you are forced to make a difficult volley or a half-volley. You are not in position for volleying and would be better off farther back.

It is very hard to say exactly where one should stand to volley. The typical place seems to me to be a yard or so in front of the service-line, and, if anything, nearer still. The closer the player is to the net, the less ground he has to cover. Imagine a player standing on the base-line, and imagine a line drawn from him to each end of the opposite service-line. These two lines represent the two most widely-divergent strokes that he can make. If now you stand on the service-line you have to cover 27 ft.; on the base-line 35 ft.; half-way from the service-line to the net, 22 ft.; and at the net only 17 ft. In reality, the amount of space you will have to cover is less, as you cannot make a fast stroke without its going beyond the service-line. Thus the nearer a player is to the net the less space he leaves his opponent to place the ball in, but, on the other hand, the quicker he himself must be to judge and reach the ball. It is a great gain if you can volley the ball while it is still above the level of the net, as it can then be volleyed downward. If you allow the ball to drop much, you have got to volley upwards to get it over the net, and there can be little severity in your stroke, which moreover itself is a more difficult one to make. Again, the sooner you meet the ball, the less time you give your opponent to[45] recover from his last stroke and to prepare himself for the return. For myself, I am always ready to take a good deal of risk in order to stand near enough to make a severe volley. If one’s opponent lobs much it is unsafe to go in close, as one may have to run back for the ball.

In a word, it seems to me that each player must judge for himself in what place he can return his adversary’s strokes to the greatest advantage, and this place will not be the same against different players. You can usually tell if your opponent means to lob, and I believe that it is right to go in closer whenever one is sure that he will not lob, and then fall back again to be ready for any stroke next time.

There is one more point to which I want to call attention. Suppose that you have made a weak volley into the middle of the court and are at the time well forward. Your opponent can probably put the ball about where he pleases. What should you do? Get back by all means if you can, for that is better than staying up with the chances against you. If you can’t do that, stay and fight it out, but remember that there is no use in standing still in the middle. Your opponent can put it either side of you. Wait till he has made up his mind, and then go to one side or the other. Even if you have no idea to which side you ought to go, it is still an even chance that you will choose the right one. In such a case it is the only chance that you have, and if your opponent sees you going the right way he may miss his stroke in trying to change its direction.

Match play is always a very different matter from simple practice. The excitement and anxiety affect nearly all players; some more, some less. The majority, I fancy, play worse in a match, while a few players need the interest of a match to make them play their best.

Then the question of endurance comes in, which in practice is of very little importance, as you can stop playing when you feel tired. A match, moreover, is in itself more exhausting, as you can seldom afford to drop your game to rest yourself, and the anxiety tells greatly on your wind. A player who often plays six or seven hard sets in practice may feel utterly out of breath in the first set of a match, mainly from excitement. The more he plays the less he will notice the difference between practice and matches.

A great difference, too, lies in the fact that a player, being anxious, is afraid to play his game, and tries only to get the ball back. This is a very great mistake, but it is much easier to tell him to play as he usually does than for him to do it. Almost the first advice that[47] I should give to any one who was going into his first match, “Try to play just as you would in practice.” If he cannot win by playing his usual game, he will, as a rule, play worse instead of better by changing it. It may prove, of course, that you cannot win with your usual style of play. In such a case, try something else by all means, but don’t do so until your own game has been fairly tried.

If you are winning, be still more careful to hold to the same game. One often sees a player at forty-love serve fast twice or try a slashing stroke or two. It was not by such play that he reached forty-love. If he keeps to his game he ought to win one stroke in the next three, but who knows what may happen if he tries experiments?

The same thing is done at four games-love, at five games to one or two, or at any such score, and the player who is ahead is often justly rewarded by losing the set.

Another player will be tempted in the opposite way. He gets a good lead, and, to make sure of the set, begins to play a very cautious game. The moment he does so he is playing a weaker game. His real game gave him his lead, but that does not show that he can hold his advantage unless he plays as well as he has been playing.

I saw one of the great matches last year lost in just this way—by a desire to make too sure. In conclusion I can only say that each one should play the game that he can play best, and let him have the courage to stick to it, whether he is ahead or behind.

My object in speaking of match play is less to suggest[48] any special game than to point out certain advantages that are constantly thrown away.

First, as to the toss. A coin is better than a racket. More rackets, I feel sure, come up rough than smooth. If you win the toss, go into both sides of the court, and observe carefully how the light comes, the wind, the background, the ground itself, and the amount of room round it. Do not forget that the sun will move a good way during five sets, and it may be possible to get the best side twice in succession.

When playing the best of five sets, take the best court, unless there is some special reason against it. If the worst court will be much worse than it is in half-an-hour, it pays to take it first. One may win the first set in it before it gets too bad, and should then have a certainty of the second and fourth sets. If the first set should be lost, the second and fourth sets should bring the score level, and no harm would have been done.

If a player takes the best court first he is sure of having it twice in a match, and he stands more chance of winning three sets to love. If the court decides the set, he will have the lead all through till the fifth set, and even then will have it for the first game.

In matches that are the best of three sets you have to take each court once, and, if there is a difference in the light, I believe that it pays to take the worse court first. You do not feel the light nearly as much then as you do after changing from the better side, and your opponent does not appreciate the advantage that he has. If the light is so bad that you lose the first set, you ought to be as sure as ever of winning the second. The only exception is in playing against a young or[49] fainthearted player, who will be so much encouraged by winning the first set that he will be harder to beat the second. It is a safe choice against any old match-player, as he will understand the case perfectly.

With a wind blowing up and down the court, it pays best to play the first set with the wind. One gets into one’s stroke better in this way, and, on changing sides, it is easier to hit harder than to keep a constant check on one’s self to avoid hitting out of court.

In knocking up before a match, always take the court with the sun in your eyes, so that, if you lose the toss, you will be accustomed to the sun, and will not have to change from good light to bad. If you win the toss, you will feel the advantage of the light all the more.

It is now very common to change sides every game of the whole match. Should you wish to do so, do not forget to appeal before tossing, or else it can be done in the odd set only.

If you fancy yourself to be a stronger player than your opponent, it is better to change sides every game of the match, or else he may win two sets with the help of the better side, and then everything will depend on the odd set.

If you change sides every game, and are really better than he, you should be able to win every set, or, at least, three sets out of four.

If your opponent is better than yourself, on no account change sides if you can help it. Try to win two sets in the good court, and trust to luck for the odd one. There is always far more chance that the worse player will win any particular set than that he will win two in three or three in five if the conditions are equal.[50]

In one word, if you are the better player, do all that you can to exclude luck from the game, because, if there is no luck for either side, you will probably win. If luck is to come in, no one can say who will get the best of it.

The next point to consider is the service. With duffers the service is an advantage, because the striker-out misses so many balls, or, at least, returns them weakly. With good players, I believe the service to be a decided disadvantage. On a good ground almost every service can be returned. The first service, if fast, seldom comes off; if of moderate speed, it can be returned with ease. A second service should leave the striker-out free to do what he chooses with it.

I should, therefore, always give my opponent the service if I could, unless sides were to be changed every game. In this case the service will always come from one end, and if you lose the toss you can choose from which end.

Against the sun and wind most services will be weak; therefore, if you serve better than your opponent, put the service with the sun and wind. If he serves better than you, you can diminish his advantage by putting the server in the worst court.

If you can serve the reverse overhand service, always put the server against the wind and sun. This service will twist more against the wind or going up hill, and the ordinary service will suffer. Moreover, in serving it, one looks to the left, and can often keep the sun out of one’s eyes when one’s opponent will have to face it.

Should there be a slope in the court, a fast service down hill will be unusually severe. If you are playing[51] a weaker man, put the service up hill; if a stronger serve down hill.

The present rule of changing sides at the end of every game works rather absurdly in one way, as it is a disadvantage to win the toss. It is seldom that a player has not a decided preference for serving from one end rather than from the other, and his opponent will probably prefer the opposite. It is a small advantage to have the better court for the first game, compared with the arrangement of the service. If the winner of the toss chooses the court, his opponent can make him serve or serve himself, as he prefers to have the service come from one end or the other. If the winner chooses to serve he can be put in either court that his opponent sees fit. If you are unlucky enough to win the toss, take the service, if you want the service to come from the worst court, and your opponent may prefer to let it be so rather than to give you the best court. If you want the service to come from the best court, make him serve so that he shall have to choose the worst side to prevent it.

A good instance of the value of the toss happened to me last season. In a double match I lost the toss; my opponents, after consulting, came to me, and offered me the choice on the ground that it made no difference to them. I naturally answered that they had won the toss, and could choose what they liked, but that they must choose something.

The whole matter is complicated by the question of endurance. A five-set match will last two hours, and if the players are evenly matched, condition will make a great difference. What, then, is the best thing for the[52] player who is physically the weaker to do to diminish his opponent’s advantage?

If there is some difference between the sides, but it is still quite possible to win on either, I should advise the weaker player to change sides every game, else he may exhaust himself in trying to win on the worse side. Besides, he is more likely to win three sets-love. Instead of this, when the difference is distinct, but not very great, he may take the worst court and try to win the first set in it while he is still fresh, and then play for the second and fourth sets on the good side. If he is rather a better player than his opponent, he will stand a good chance to win the first set, and he should then have a great advantage, if he only takes care of himself. If he is rather the worse player as well as the weaker, he had better play for two sets on the better side and for the fifth, for he probably cannot win on the worst side, and will injure his chance for the last set if he tries to.

If the difference between the sides is very great and the players about equal, I think that the weaker man should not change sides every game if he can help it. Here, too, his best chance is to win two sets easily and hope for the fifth. If he changes sides, the games may be won alternately by the help of the court, and the sets may be very long.

Of course, the interest of the more enduring player is exactly the opposite. He should prolong the match as much as possible, and when on the worse side should play up all that he can, so as to tire his adversary, even if he cannot win.

A great deal of judgment is requisite to decide when to let a set go. One’s adversary is seldom as easy[53] to beat after he has won a set as he was before, and I think that “chucking” a set is a luxury that should be indulged in very seldom, and only when playing up would spoil one’s chance in the other sets.

A player should never play slackly because he fancies the set won. Every game that he loses encourages his opponent, and also makes it harder for himself to get back to his old game. There is no score at which a set is safe till it is won.

On the other hand, never give up a match till it is lost. I have seen the score two sets to love and five games to two, and the player who was ahead lost the match. It is always worth while to try for one more game. Try to learn to play up the whole time, unless it is absolutely necessary to ease off to save your wind.

I wish to call particular attention to the fact that it is a great mistake to attempt to return the service till you are sure that you are ready. Your opponent will often serve as soon as your face is turned towards him, and there is a strong temptation to return the ball. In such a case you are not really ready. You should take time enough to get to your place, and get your feet under you and your eyes fixed on your opponent. If he serves too soon, let the ball go by untouched, and do the same thing on the second service, and on every other service for which you are not perfectly ready.

When you go in to volley, and you see the ball coming to you, make up your mind in time where you mean to put it. I have often lost a stroke by being too slow in deciding, and having to think where the ball should go at the time that I ought to have been playing it.[54]