The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Sea Monarch, by Percy F. Westerman This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Sea Monarch Author: Percy F. Westerman Illustrator: E.S. Hodgson Release Date: September 29, 2018 [EBook #57989] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SEA MONARCH *** Produced by R.G.P.M. van Giesen

| CHAP. | |

| I. | THE MYSTERIOUS CASE OF THE "ZIETAN" |

| II. | INTRODUCES THE "PLAYMATE" AND HER SKIPPER |

| III. | RUN DOWN |

| IV. | A PRISONER ON THE MYSTERIOUS SHIP |

| V. | CAPTAIN BROOKES |

| VI. | THE CONNING-TOWER OF THE "OLIVE BRANCH" |

| VII. | RUMOURS OF WAR |

| VIII. | TREACHERY |

| IX. | AN ACT OF PIRACY |

| X. | CLEARED FOR ACTION |

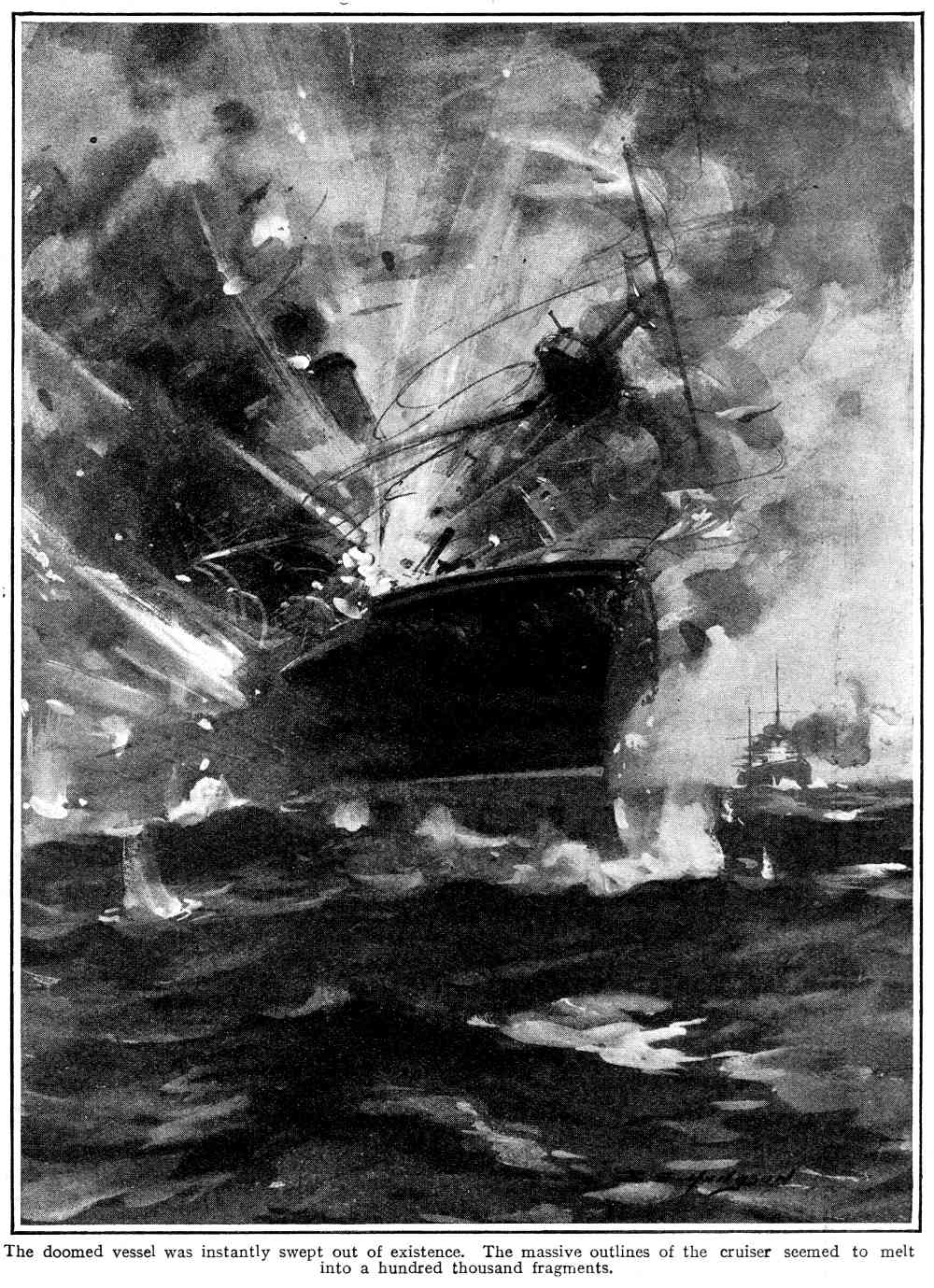

| XI. | WIPED OUT |

| XII. | THROUGH THE MINE FIELD |

| XIII. | TRAPPED |

| XIV. | RUNNING THE GAUNTLET |

| XV. | A ONE-SIDED ENGAGEMENT |

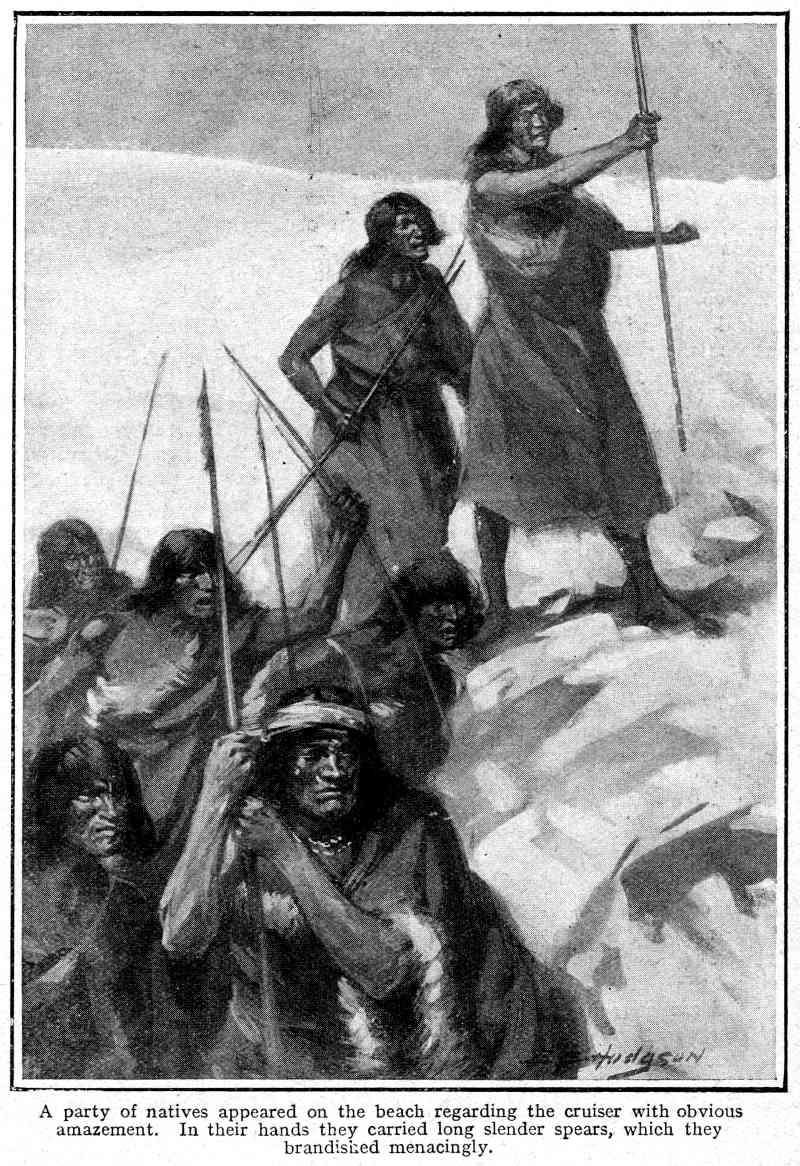

| XVI. | IN THE CLUTCHES OF THE PATAGONIANS |

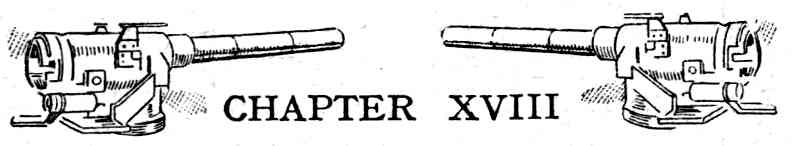

| XVII. | GERALD'S RUSE |

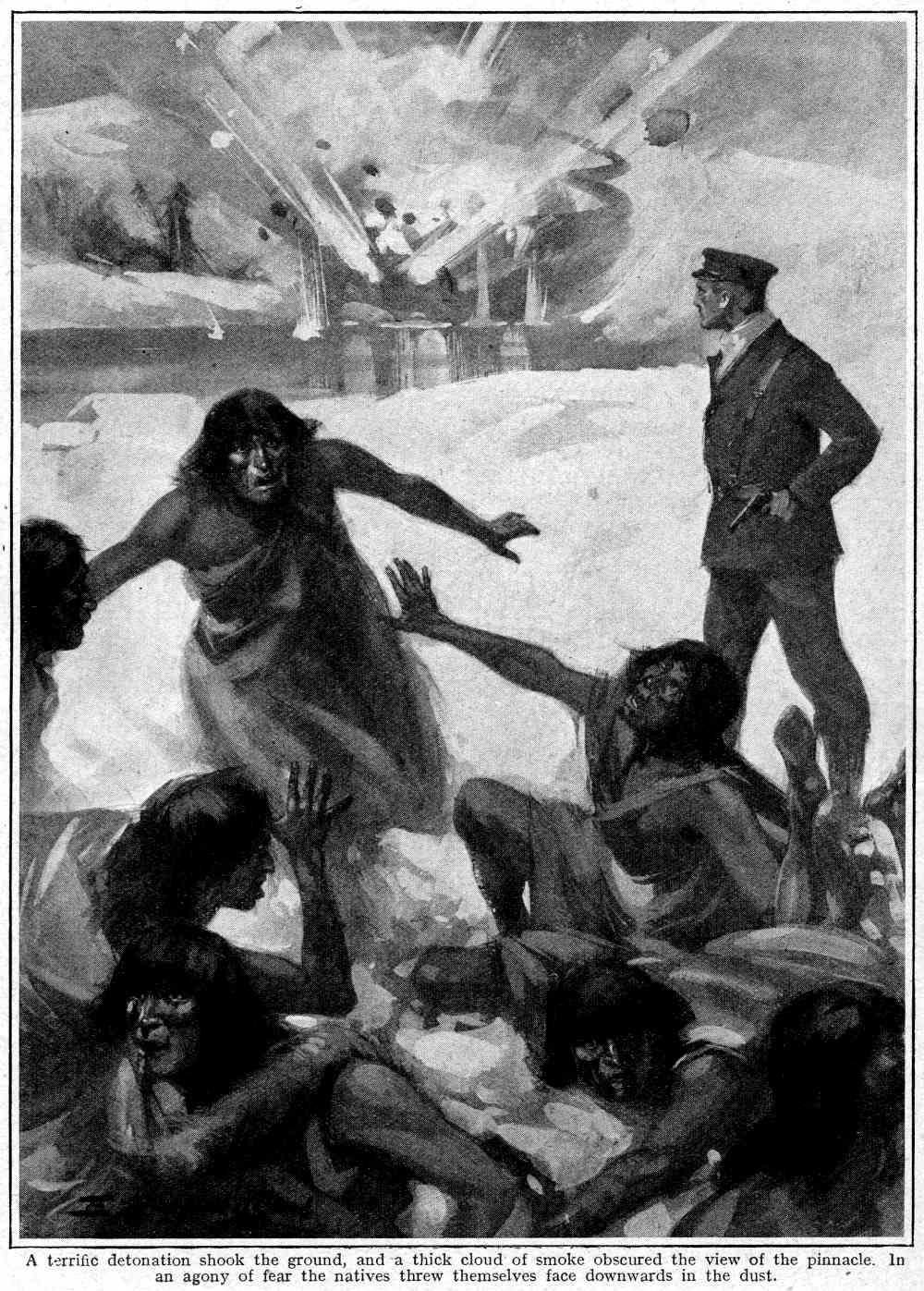

| XVIII. | THE CAPTAIN'S REVENGE |

| XIX. | GERALD'S PROMOTION |

| XX. | THE AIRMAN |

| XXI. | THE MISSING WIRELESS GEAR |

| XXII. | THE TOUCHSTONE OF PERIL |

| XXIII. | THE CRIPPLED SUBMARINE |

| XXIV. | A FRUSTRATED PLOT |

| XXV. | THE EMPIRE'S ORDEAL |

| XXVI. | THE VINDICATION OF THE "OLIVE BRANCH" |

[Illustration: CHAPTER I]

[Illustration: CHAPTER I]

IT was a scorching afternoon in the month of August. The slanting rays of the sun beat powerfully upon the tranquil waters of Portsmouth Harbour, while the white ensigns of the numerous warships fluttered idly in the almost motionless air.

Swinging easily at her moorings to the first of the young flood lay the torpedo-boat destroyer Calder, presenting a very different appearance from its trim state of a few days before. Engine-room defects had occasioned her return to harbour, and as these were of a somewhat serious nature, the opportunity was taken to place the destroyer into dockyard hands for at least two months. The commissioned officers had obtained permission to go on leave, while the Calder, in the charge of a gunner, was to be put into dock the following day.

Ting-ting! Ting-ting! Ting-ting! Ting-ting! Eight bells had hardly sounded ere two men appeared on deck, scrambling agilely through the small hatchway that did duty for the ward-room companion. The first was the tall, lean-featured lieutenant-commander. The other, Sub-Lieutenant Gerald Tregarthen, needs a slightly longer introduction.

He was almost the same height as the commander, or a fraction under 5ft. 11 ins. in his socks, and was broad in proportion. His features, tanned by constant exposure to sun, wind, and spray, were clear-cut, almost boyish in expression, while at times there was a roguish light in his deep blue eyes.

Yet beneath the apparently boyish exterior lurked the spirit of a man. When occasion arose those merry lips would compress themselves into a thin, straight line, the powerful chin would be thrust aggressively forward, and a dangerous glint in his eyes would betoken that resolution, coolness, and daring which are the indispensable characteristics of a successful naval officer.

His service career, in spite of its comparative shortness, had been one continued success, yet success had not been gained without sheer hard work. With a "first" in gunnery, torpedo, and navigation, he found himself at an early age well up on the list for promotion.

Gerald Tregarthen was in mufti; but his well-cut civilian clothes could not conceal the erect bearing and breezy alertness that characterised the British naval officer. Taking advantage of the Calder's temporary idleness, he had applied and obtained permission for six weeks' leave, and, strange as it may appear, his intention was to spend the best part of that time afloat.

There is a story told of a London 'bus-driver who devoted a rare holiday to playing the role of passenger on his own vehicle. Similar motives doubtless prompt hundreds of bluejackets and marines to hire private skiffs during their leave. One has but to go to Southsea beach, the shores of the Hamoaze, or the mouth of the Medway to see jolly tars and jovial "joeys" rowing in shore-boats as if that form of recreation was the greatest treat imaginable. It is, then, not so much to be wondered at that Gerald Tregarthen elected to spend most of his leave on board the 4-ton cutter Playmate, at that moment lying in Poole Harbour, the yacht being owned by his old school-chum, Jack Stockton.

The appearance of the two officers on deck was immediately followed by the hoarse orders of the quarter-master. The boat's crew manned the falls, and the little craft was brought alongside the destroyer's starboard quarter. Tregarthen's luggage, consisting only of a well-filled portmanteau, was handed over the side, and, having bade his senior officer goodbye, the sub-lieutenant took his place in the stern-sheets. A quarter of an hour later Gerald Tregarthen landed at the King's Stairs, and, followed by a seaman bearing his portmanteau, walked rapidly through the dockyard to the main gate. Here a lynx-eyed driver; spotting a likely fare, ran his taxi close up to the spot where the young sub. was standing.

"Town station for all you're worth," exclaimed Tregarthen, but ere he could enter the taxi a boy rushed up to him.

"Evening paper, sir? All the latest naval appointments."

This is a bait that rarely fails to draw the naval man. Taking the paper Tregarthen boarded the vehicle, and was soon bowling along towards the railway station.

Two unavoidable delays were sufficient to alter Tregarthen's arrangements, for on arriving at the town station he found that he had missed the 4.45 Bournemouth train by a bare two minutes. Little did he imagine that the loss of those two minutes was fated to effect a tremendous change in his career at no distant date.

"Next train 6.2, sir," replied a porter in answer to the sub.'s anxious inquiry.

"Just my luck. Over an hour to wait," soliloquised the disappointed sub., and sitting down and placing his portmanteau by his side, he unfolded the sheets of the newspaper.

The "Naval Appointments" he read with more than ordinary interest, inwardly commenting on the good luck or otherwise of those of the numerous officers he knew personally. Then the "Movements of H.M. Ships" attracted his attention. Lower down in the columns was a paragraph that, though he paid scant heed to it at the time, was to vitally affect him within the next few days:—

The new ironclad Almirante Constant left the Tyne yesterday. A persistent rumour is being circulated in certain quarters that the vessel, which has been built with the utmost secrecy, is not, after all, to become a unit of the Brazilian navy. Our correspondent has made careful and exhaustive inquiries on this point, but the officials concerned maintain a strict reticence. One thing is certain, however—she is not at present armed, the contract for her ordnance being placed, we understand; with an American firm.

"Blest if I can understand why these South American republics want such up-to-date ships," mused the sub. as he turned over the refractory pages. "It's like giving a child a razor to play with. Well, I suppose it means work for the North Country shipyards; but should any European power lay its hands on half a dozen of them I'm afraid our naval supremacy will have but a very small margin. Hallo! What's this?"

A telegram from Wilhelmshaven, dated the 11th inst., states that the Imperial third class cruiser Zietan has arrived here apparently in difficulties, in charge of two tugs. Captain Schloss immediately landed and despatched a lengthy report to the German Admiralty, but, as shore leave is refused, our correspondent is unable to obtain details of the accident from any of the officers or crew. We have reason to believe that a serious disaster has taken place on board.

Later.——From the master of the tug Vulkan we learn that the cruiser Zietan, while two hundred miles west of Heligoland, suddenly encountered a violent and unprecedented magnetic storm. Practically every electric wire on board was fused, the wireless gear was hopelessly broken down, and the compasses rendered absolutely useless. The Zietan was, in fact, instantaneously reduced in fighting value to below that of a cruiser of thirty years ago. It is stated that the ship is still highly charged with electromagnetism, and will have to go into dock for a lengthy period. Captain Schloss was heard to express his doubts that the cruiser would ever be fit for sea-service again.

Gerald Tregarthen read this report with more than ordinary interest. At first he was inclined to scoff at the intelligence. It savoured too much of a fairy story, while it was more than possible that the master of the German tug had been, to use a nautical term, "pumped." Even in his somewhat brief career the sub-lieutenant had experienced several severe electrical storms in the tropics, but the ship's compasses and delicate electrical gear had never been seriously affected. This new danger, should it be repeated, threatened to increase the trials and troubles of the navigator a thousandfold.

"By George!" he exclaimed suddenly. "I must wire to Jack Stockton, or he'll wonder what's happened. But where shall I wire to? It's no use addressing it to the yacht—the post office people will keep the telegram till called for. I have it. I'll wire to Stockton, care of station-master, Poole."

Accordingly Tregarthen strolled over to the post office, discharged his mission, and returned to the dreary platform. At length the long-drawn hour passed, and, taking his seat in a first-class carriage, the sub-lieutenant steeled himself to endure the discomforts of a tedious journey.

At Southampton West his supply of literature was exhausted, so a sixpenny novel and a copy of a London evening paper were purchased. Occupying a prominent position in the newspaper was a further report from Reuter's agent in Wilhelmshaven:—

The mysterious disaster to the cruiser Zietan appears to be far more serious than was at first supposed. The ship is evidently heavily charged with an unknown form of electricity. Her standard compass has been sent to the Imperial Laboratory at Berlin. Meanwhile the huge cruiser Von der Tann, that was lying in the next dock to that occupied by the Zietan, has been affected by the inexplicable current. To avoid further ill-effects, orders have been given to undock the Zietan and move her out in the stream.

The next paragraph was to the effect that all telegraphic reports relating to the Zietan incident had been received via Middlekerke and Dumpton Gap, the submarine cable between Borkum and Lowestoft being interrupted. A telegraph cable ship had left the Thames in order to locate and remedy the fault.

"Seems something in this business after all," remarked Tregarthen; then, as his eye caught the blurred type of the "Stop Press News," he read:—

Zietan incident cable via Lowestoft reports that all traces of phenomenon have vanished. Compasses and electrical gear in normal working order.

The young officer folded up the paper and thrust it under the straps of his portmanteau. The cheap novel remained unread. For the rest of the journey Tregarthen was in a brown study, cudgelling his brains as to what he would do should he ever find himself in command of a vessel under similar circumstances. It was growing dark as the train drew up at Poole. Alighting, Gerald, rapidly passing along the crowded platform, sought his old school-fellow. But no Jack Stockton was to be seen.

[Illustration: CHAPTER II]

[Illustration: CHAPTER II]

I SUPPOSE I must try and find the Playmate," thought Tregarthen. "Perhaps Jack has not received my wire. I hope he hasn't cleared out without waiting for me, though I shouldn't be surprised. It used to be a favourite trick of his not to wait a minute for anyone."

When Tregarthen had reached the quayside he found that the whole length of the spacious wharf was lined with a double row of coasting brigs, schooners, lighters, and the ubiquitous Rochester barges. On the Hamworthy side the feeble glimmer of the quay lights faintly illuminated the white hulls of a few yachts, but the sub-lieutenant knew that they were of too great a tonnage to correspond with his ideas of the Playmate.

Where, then, in all that jumble of floating craft, was Stockton's yacht to be found?

Gerald Tregarthen was at a loss. Beyond a few half intoxicated seamen lurching back to their vessels the quay was deserted. He was on the point of making for the nearest hotel when a voice came apparently from beneath his feet.

"Ferry, sir?"

The young officer looked down. Close to where he stood a flight of stone steps led to the water's edge. It was nearly low tide, and the steps looked particularly uninviting in the dim reflection from the oily water. At the foot of the landing, with barely a couple of inches to spare betwixt the cutwater of a brig and the ponderous rudder of a Thames barge, was a boat, its occupant holding on to a ringbolt in the stonework by means of a short boat-hook.

"Ferry, sir?"

"Do you know of a yacht—a cutter called the Playmate?" asked Tregarthen.

"Can't say as 'ow I does, sir," replied the ferry-man. "But I'll call my mate; maybe he'll know." And placing his hands trumpet-wise to his mouth he shouted: "Buck-up! Buck-up Cartridge, where be ye?"

The echo of the man's powerful voice had barely died away when a hail came from the opposite shore. "Hulloa, there?" immediately followed by the faint splash of oars.

"Old Buck-up'll know if there be any craft o' that name," remarked the ferry-man, and as the new comer's boat rubbed its nose against the quarter of the ferry-boat the query was anxiously repeated.

"Wot, Playmate, owned by a gent o' the name o' Stockton? Why, sure I do. She's lying off the Stakes."

"Can you put me aboard?" asked Tregarthen, a load removed from his mind at the assurance that his chum had not set sail.

"Certainly, sir," replied Cartridge; and, handing his portmanteau to the ferry-man, who in turn passed it on to the second water-man, Tregarthen stepped across the first craft into the second.

With long, easy strokes the boat glided with the still strong ebb past the line of shipping and into the staked channel. Here, being comparatively open, the N.W. wind blew fresh, and the young officer shivered in spite of his experience on the bridge of a destroyer. He missed the thick pilot-coat, and the comforting shelter of the storm-dodgers.

Between long, low banks of reeking mud the boat passed, till at length, a good quarter of a mile from the quay, appeared the dim outlines of half a dozen yachts of all sizes, their anchor-lights gleaming fitfully upon the dew-sodden decks and mainsail covers, and casting broken shafts of light upon the ruffled water.

"There be the Playmate, sir," exclaimed the waterman, resting on his oars and looking over his shoulder. Tregarthen followed the direction of his gaze.

Twenty yards away lay a smart little white cutter. Even in the gloom the sub-lieutenant could distinguish her graceful spoon bow, her short yet becoming quarter, and the businesslike sheer of her sides. Across her boom a canvas awning was lashed over the diminutive cockpit. From the cabin a light flickered upon the awning, and gleamed cheerfully through the fluted glass skylight. To Tregarthen the vision of that light seemed an indescribable comfort. The tedious journey, the disappointment of Stockton's non-appearance, the cheerless welcome of the bleak and desolate harbour—all were forgotten. He had found a haven of rest.

"Playmate, ahoy!"

The waterman jerked one oar into his boat and with the other skilfully checked her way till she gently rubbed sides with the yacht.

"Hallo, there! Is that you, Cartridge?"

"Yes, sir; I've brought a gent off to see you."

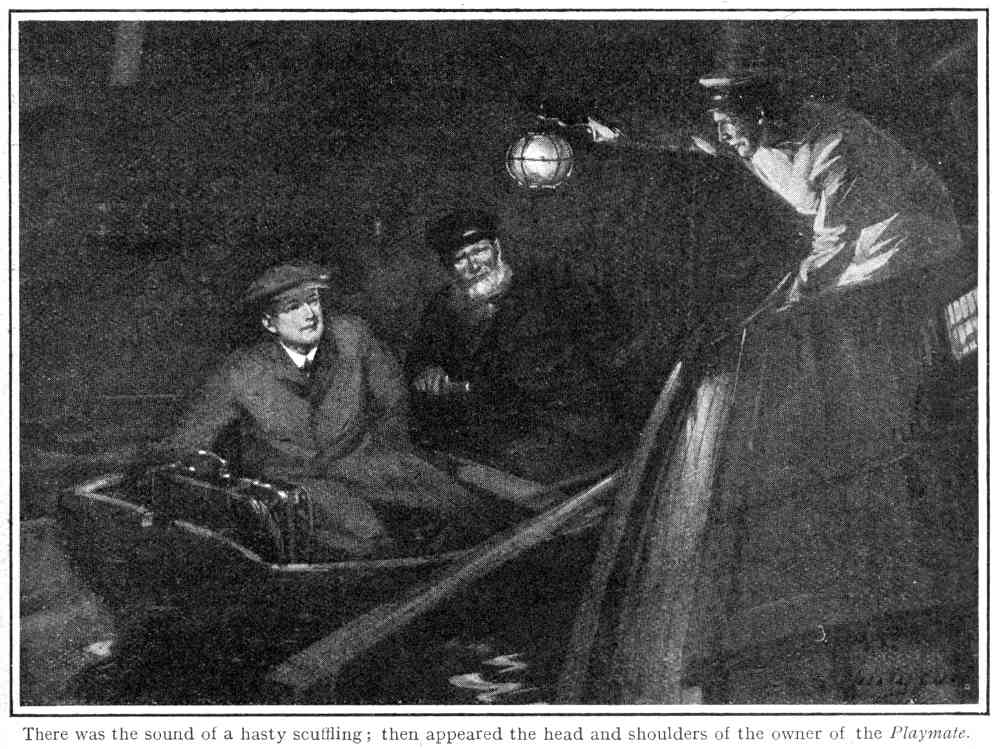

There was the sound of a hasty scuffling, the awning was partially unlaced, and a hand holding a lantern appeared, followed by the head and shoulders of the owner of the cutter Playmate.

The rays of the lamp fell upon the features of the owner. He had a somewhat long, thin face, with a characteristically square jaw, and light eyebrows that formed an almost continuous line across his brows.

"Hallo, you!" he exclaimed, as the identity of his visitor was revealed. "I'd given you up."

"So it appears," replied Tregarthen. "Didn't you get my wire?"

"Wire—what wire? But don't stay there; come aboard. You'd better use the fore-hatch, unlacing this awning is a blessed nuisance."

Stockton's head vanished as its owner retreated into the cabin. Tregarthen, having paid the boatman, seized the main shrouds and swung himself lightly on deck. Then making his way for'ard he removed the partially open hatchway leading to the fo'c'sle.

"Hold on! Hold on a minute!" shouted Jack. "You're putting your foot into the soup!"

Checking his downward progress just in time, Gerald waited till the skipper, and cook combined, removed a saucepan from the top of a roaring Primus stove, pushed the stove out of the way, and gave the word that all was clear.

The next instant Tregarthen found himself in the fo'c'sle.

It was a small, wedge-shaped apartment, barely 4ft. in height and 7ft. wide at its broadest part, tapering away to less than 6ins. for'ard. This limited space was still further curtailed by a number of lockers and cupboards, the stove, a bundle of sails and warps, and the still weed-covered chain cable. Jack Stockton, pipe in mouth, and huddled up on an upturned bucket, was busily engaged in preparing some flat-fish, that he had just caught, for supper.

Gerald began to cough. What with the heat of the stove, the tobacco smoke, the combined odours of the fish, the soup, and the seaweed, to say nothing of the smoky paraffin lamp, made the confined quarters well-nigh unbearable. It was infinitely worse than the fo'c'sle of a destroyer in a heavy seaway, yet Stockton endured it with equanimity—even with pleasure. It was one of the joys of yachting in the rough.

"Excuse the mess!" he exclaimed. "You see, I didn't expect you after the arrival of the train you agreed upon. But I'll have everything shipshape in a jiffy. Where's your gear?"

"On deck."

"Then bring it below. You may as well get into the cabin, and I'll be with you soon. Mind your head!"

The warning came too late. Tregarthen forgot that the cabin of a 4-ton yacht is a mere dog-kennel compared with the diminutive wardroom of H.M.S. Calder, but luckily his thick cap saved his skull from a nasty blow from a deck beam.

Then with a thud his portmanteau was deposited on the floor of the fo'c'sle, and Stockton's voice was heard: "Here, bear a hand, and get this thing into the cabin."

Gerald hastened to give the requested assistance. This time the small of his arched back came into violent contact with the top of the doorway communicating with the fo'c'sle. Thereupon, acting with more discretion, he slowly dragged his belongings into the cabin, and sat down upon one of the sofa-bunks.

By degrees he recovered his ruffled composure, and took a careful survey of his limited surroundings. A glance in a bevelled mirror revealed the fact that his encounter with the deck-beam had had the effect of crumpling his collar into a series of longitudinal creases.

"It's time I put a sweater on," he thought, and opening his portmanteau he produced one of those thick, serviceable articles, and measuring the distance between his head and the deck-beams—a margin of barely 6ins.—Tregarthen removed his collar and plunged into his sweater. This done his sense of comfort was materially increased.

"Now what do you propose doing?" he asked, as the crew of the Playmate tackled a hearty supper. "Going west?"

"I thought of making a dash across the Channel. Any objection?"

Tregarthen whistled.

"Bit risky, isn't it?"

"I don't think so. This packet is as stiff as a house; the gear's sound, and all the stores are aboard."

"You've a compass, of course?"

"A little beauty."

"Then I'm game. By the bye, have you seen to-day's paper?"

"No; I went ashore, but quite forgot to get one. Why—anything startling?"

"Only this," replied Gerald, producing the newspapers he had purchased on the journey, and pointing to the Zietan paragraph. "What do you think of it?"

"Not much," replied Jack, in a matter-of-fact tone. "At any rate, I don't suppose it will affect us."

"When do you propose to make a start?" Stockton did not immediately reply, but, gaining the cockpit, he unlaced a portion of the awning.

"Now if you like," he replied. "The young flood has set in, though, but with the wind in this quarter we can stem it and pick up the east-going tide outside. Just hand me down that bundle of charts."

Gerald did so, and his chum picked out one of the English Channel.

"We ought to make St. Catherine's before daybreak," continued Jack "And then with a decent slice of luck we can make a slant across and pick up Cape Barfleur before sunset. It's barely fifty miles as the crow flies. So we'll get under way now, and when we are outside the harbour you can turn in. I had a good spell below during the day, so a night's watch won't trouble me."

"All right; I'm game," repeated Tregarthen. Twenty minutes later the Playmate was heeling over to the steady breeze. Her voyage, that was fated to be the forerunner of a wealth of peculiar adventures, had begun.

[Illustration: CHAPTER III]

[Illustration: CHAPTER III]

A FEW years ago a commander-in-chief is reported to have declared that our seamen are the worst boat-sailors in the world, while another naval officer of high rank has written: "I don't think there is any foreign navy that is not better than us in the handling of their boats—ours is a disgrace." Thanks, however, to the forethought of the Admiralty in providing fore and aft rigged cutters for the use of the cadets at Dartmouth this stigma is gradually being removed.

Owing to the opportunities thus provided Gerald Tregarthen was no novice on board a yacht. He had steered the college cutters to victory on several occasions, and, now once having acquired the knack of dealing with the Playmate's peculiarities, he was quite capable of taking charge of the tiller while Jack Stockton attended to the numerous duties so necessary when about to make a long passage.

Gallantly breasting the young flood the Playmate thrashed her way down the well-lighted channel, passed between the sandy dunes that mark the entrance to Poole Harbour, and negotiated the long, buoyed passage under the lee of Studland Heath. Then, the outer bar-buoy being rounded, the yacht was gybing, and her course shaped for the as yet invisible Needles Light.

This done Jack Stockton put on his oilskins, in anticipation of a "dusting," and Gerald Tregarthen turned in for a few hours' rest.

Left to himself the skipper of the Playmate settled down to his night's vigil. Lighting his pipe he took up a position on the lee side of the cockpit, whence, by occasionally raising himself, he could command a view ahead. Then, keeping the lee shrouds in line with a conveniently placed star, he was able to dispense with the inconvenience of having his eyes glued to the compass-card. Jack was an old hand at the pastime of yachting. Scorning the use of a motor as being detrimental to the joys of sailing, he relied upon his weather lore, the judicious use of the barometer, and a thorough knowledge of the tides to make his voyages, and rarely did he fail to make his desired port. He was an ideal yachtsman—calm and resolute in difficulties, patient in adverse circumstances, loth to run unnecessary risks, yet full of courage and reliance.

With the pale grey dawn the Playmate was within the influence of the mighty St. Catherine's Race, where, fair weather or foul, the tide surges over the uneven bed of the sea at a good five knots.

"Pity to wake him," exclaimed Stockton, as he put the helm hard up, jibbed, and headed for the distant French coast. "Still it can't be helped."

With the gybe Gerald Tregarthen's berth on the leeward side was transformed into the windward one, and the heel and pitching of the little craft deposited him bodily on the floor of the cabin.

"Hallo! Where are we?" he asked, sleepily.

"You, my dear fellow, are wedged in between the swing-table and the floor; I am still at the helm, waiting to be relieved; and the Playmate is approximately two miles southwest of St. Catherine's. Have I made clear our relative positions?"

"Quite, old fellow," replied Tregarthen, scrambling out of the partially closed sliding hatchway. "I'll give you a spell."

"Here you are, sou' by west quarter west," said Stockton, indicating the course; and crawling into the fo'c'sle, he was soon hard at work preparing breakfast.

Having satisfied himself as to the course Tregarthen looked astern. It was a magnificent picture. Away on the port hand a huge man-of-war was heading towards Spithead. By her tripod masts and the peculiar arrangement of her funnels and upper works the sub-lieutenant recognised her as the Foudroyant, the latest phase in British naval construction. A mile ahead was a topsail schooner, close-hauled on the starboard tack, her brown and patched canvas gilded by the slanting rays of sunshine, while still further away a few tramps were steaming steadily up Channel, their outlines barely discernible against the morning mist. "How's the glass?" asked Gerald, as his chum regained the cockpit with a deep tray covered with eatables.

"Steady as a rock. Here, wedge this tray in somewhere, and I'll bring out the coffee. We must rough it a bit when we are having meals under way."

In spite of the pitching of the yacht both members of the crew did full justice to the meal. This over, Jack resumed his place at the helm, and Gerald proceeded to his task of "washing up."

The young sub-lieutenant could not help laughing at the ludicrousness of his position. Here was he—an officer of H.M. Navy—cooped up in a most uncomfortable posture in a cramped fo'c'sle, and undertaking a task that he had never before performed. How his brother-officers would roar with amusement could they but see him. Yet he had to confess that the novelty of the whole thing was delightful.

"What about a wash?" he asked, some time later.

"You'll have to whistle for one," replied Jack. "At least, till we reach port. Fresh water's precious at the present time. I'll tell you what—we'll have a bathe over the side."

Gerald looked at the wake of the little craft. The Playmate was bowling along at a bare three knots, and having passed the disturbed waters of the race was now sailing more steadily in the gentle, regular heave of the open Channel.

"How will you manage it—heave-to?"

"No; one at a time. Keep her as she is." Jack quickly divested himself of his clothing, and, grasping the bight of the slackened-off main-sheet, he lowered himself into the sea. There he hung, towed through the waves, with a miniature cascade pouring over his head, till, having had enough, he dexterously regained the yacht.

"Capital!" he exclaimed, shaking the dripping water from his face. "But it's much colder than one would expect for the time of year."

"Deep water always is," replied Gerald, as he prepared to follow his companion's example.

"Are you going to get the dinghy aboard?" he asked, after the ablutionary exercises had been completed. "She's a bit of a drag astern, I fancy."

"No; let her stop. I'm going to turn in now. If it comes on to blow—I don't think it will—give me a shout, and we'll soon whip the dinghy aboard and lash her down securely. In any case turn me out at eight bells."

Gerald thereupon took charge of the helm. The Playmate had already reeled off more than thirty miles of her cross-Channel passage. But though the atmosphere astern was perfectly clear, ahead the horizon was obscured by a haze that blended sea and sky together in an indistinct blurr. The wind, too, was slowly yet gradually dying away, and the yacht was doing little more than two knots.

With the falling of the wind the haze increased in density, so that, two hours after Gerald had taken the helm, the Playmate was fairly in the thick of a dreaded sea-fog.

"Jack, old man, have you a fog-horn aboard?"

Stockton was wide-awake in an instant.

"By George! This is thick," he exclaimed, for already the yacht's bowsprit end was lost to view in the white, curling vapour. "No, I've no fog-horn; I always use a rowlock. Here's one. We'll lash it up to the sliding-hatch."

This done, he struck the suspended rowlock a couple of sharp taps with a mallet.

"There's enough noise to warn any vessel within a cable's length of us," he continued. Gerald grunted. He knew the ways of the sea. A tramp steamer, forging through the fog at a steady eight knots—as they frequently do—would not pay much heed to anything less than a siren.

"All right," he assented; "I'll see to that. You may as well turn in again."

"I've had enough sleep to last me for a time," replied Jack. "I'll keep watch with you. Here, put this on, or you'll get soaked to the skin," he added, producing an oilskin from one of the lockers, and proceeding to don a second one himself.

"What's that?" asked Gerald, after a prolonged interval, as a dull, pulsating sound, quite unlike the noise of a steamer's engines, was borne faintly to their ears.

"Hanged if I know! Here, old chap, get a sweep out, and keep way on her. I'll sound the fog-bell."

Tregarthen did as he was asked, for the yacht was now practically becalmed, while Stockton made a vigorous onslaught upon the improvised fog-bell with his mallet.

Nearer and nearer came the mysterious vibrating sound; then, with appalling suddenness, a shrill, long-drawn blast from a siren sounded as if from overhead.

"By Jove! We'll be run down!" exclaimed Jack, calmly, though he fully realised the danger.

The next instant a hoarse voice shouted: "Ahoy there! Starboard your helm!"

Instinctively Jack thrust the tiller hard over; the yacht, responding slowly to the helm, commenced to describe a wide curve; but in less than ten seconds from the time of the hail a ponderous monster of grey-coloured steel loomed out of the fog, its upper portion lost to view in the mist.

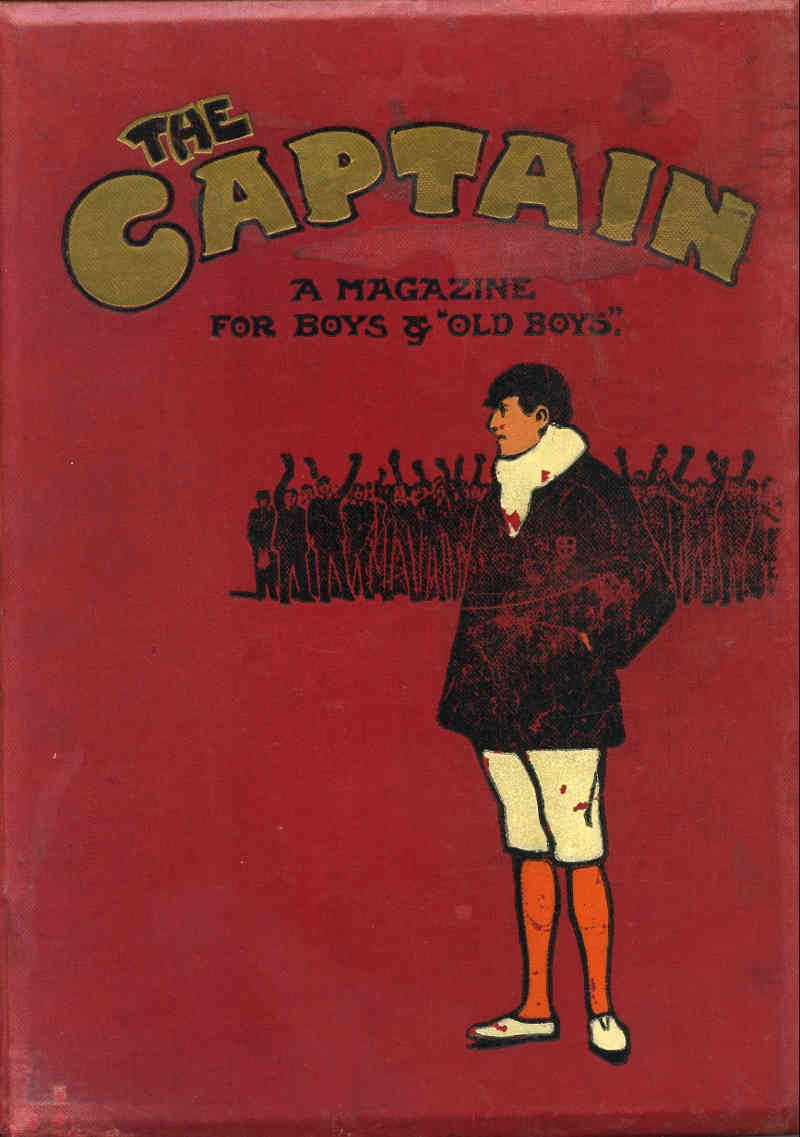

Crash!

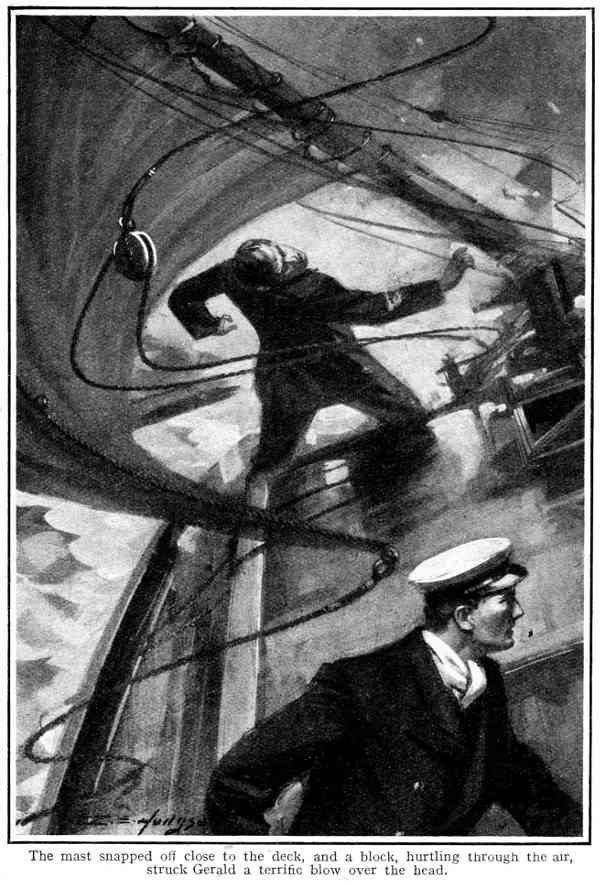

Although doing a bare five knots the sharp steel bow of the huge vessel caught the Playmate fairly on the port side amidships. The stout planks were shorn through as if made of match-board, the mast snapped off close to the deck, and, as the stick with its spread of canvas fell over the side the water poured in a cataract over the lee-coaming, and through the huge rent in the side of the doomed yacht.

[Illustration: CHAPTER IV]

[Illustration: CHAPTER IV]

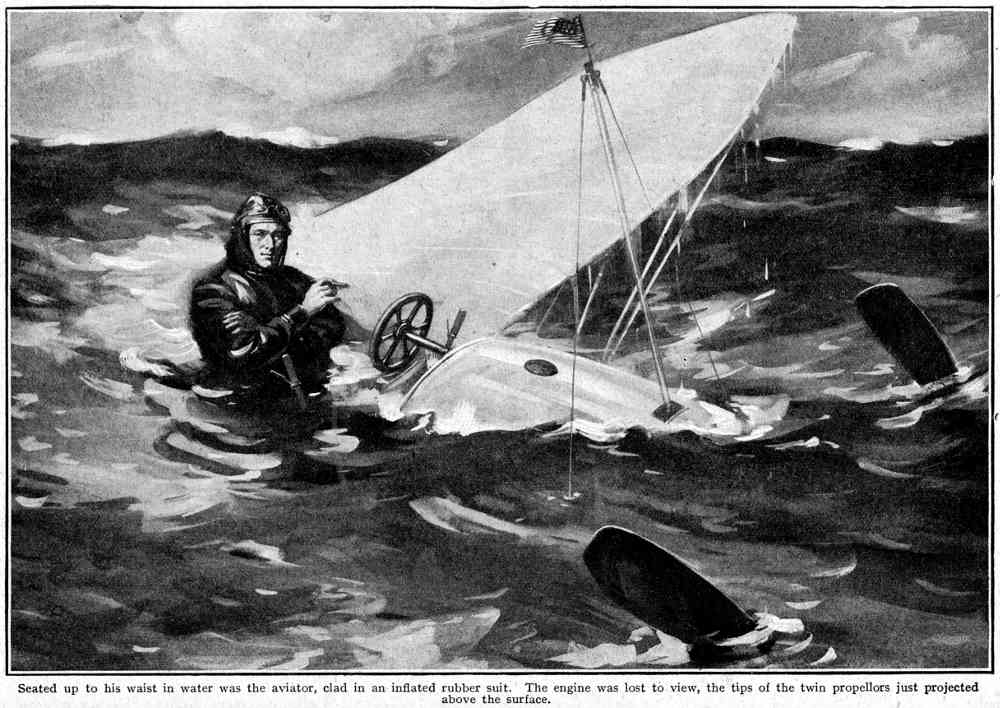

AT the moment of impact Gerald strove to ward off the oncoming vessel with the unwieldy oar, but the blade found no holding-place against the wet, heaving bows of the leviathan of destruction. Then, with the carrying away of the mast, a block hurtling through the air struck him a terrific blow over the head. Thousands of white lights flashed across his vision as he found himself lying in the already flooded cockpit; yet in his state of partial insensibility he was dimly aware that Jack had seized him round the waist.

With a powerful heave Stockton literally threw his friend into the dinghy, which had meanwhile floated alongside the yacht. Then, springing into the little cockleshell, he whipped out his knife, and with a swift sweep severed the painter. Not a moment too soon.

The colliding vessel had already stopped, and was gathering sternway. The withdrawal of the sharp, wedge-shaped bows from the shattered yacht caused the water to pour in with redoubled violence, and in a smother of bubbles and foam the Playmate plunged downwards to her last resting-place.

Jack Stockton seized the oars, which fortunately had been left in the dinghy, and rowed desperately towards the craft that had been the cause of the disaster. Already she was a mere blur in the fog; once lost sight of, the position of the two occupants of the dinghy, adrift in mid-Channel without food or water, would be perilous in the extreme.

Beyond the first hail perfect silence had been maintained on board the huge grey vessel. As Jack gradually gained on her—for the engines had apparently been reversed only for a few revolutions—a rope was flung dexterously over his head. This he made fast to the dinghy's bow-ring, and in absolute silence another coil descended from the lofty fo'c'sle.

Deftly Jack passed a bight round his friend's body just below the arms, and like a sack of flour Gerald was hoisted upwards. This much Tregarthen remembered, though but dimly, and on gaining the deck he lost consciousness.

When the young sub-lieutenant opened his eyes he found himself lying in the uppermost of two bunks in a small yet conveniently arranged cabin.

"Where the dickens am I?" he murmured, drowsily.

He sat up, and at once discovered that the pyjama suit he was wearing was not his own; then he became aware that his head was throbbing painfully, and on raising his hand to the aching place his fingers encountered a strip of plaster.

Then the details of the collision flashed across his mind, and the anxious question rose to his lips: "Where's Jack?"

Steadying himself by grasping the rounded edge of the bunk, Gerald leant sideways. The effort nearly caused him to lose his balance, but the result of his investigations showed that the lower bunk was unoccupied.

For the space of quite five minutes the injured officer lay still, striving to collect his thoughts as to where and when he last saw his late companion.

Above the centre of the top bunk was an open scuttle, through which the salt-laden breeze whistled like a youthful whirlwind. From where he lay Tregarthen could see that the thickness of the vessel's side at this opening was at least 7ins.—a truly enormous size for the plating of any but a powerful war vessel, and even then it was unusual to continue the armoured belt so far above the water-line.

Curiosity prompted the sub-lieutenant to essay another change of position. This time he met with better success, and was able to look through the narrow, circular aperture.

His eyes dilated with astonishment. The fog had completely vanished, and the sun shone brilliantly from an unclouded sky upon the deep blue waters. But the change in the atmospheric conditions was not the cause of the young officer's surprise; it was the apparent motion of the water.

Without the faintest suspicion of a bow-wave—at least as far as Tregarthen could judge—the huge vessel was tearing through the sea at a terrific rate. Taking into consideration the height of the scuttle above the sea-level, Gerald came to the conclusion that the craft was a cruiser of the largest type, yet in spite of her size he estimated her speed at not less than forty-five knots. The Calder, lightly built as she was, could not attain that rate, her greatest pace being a good thirty-eight knots. And with this extraordinary speed there was a total absence of vibration or noise, save the howling of the wind caused by the vessel's own motion, while the faint pulsation of the engines, that had first betrayed her presence in the fog, had entirely ceased.

Then Tregarthen made another discovery. The mysterious vessel was, as far as he could judge by the position of the sun, heading nearly south-west. That meant that, willing or unwilling, he was being spirited away from the shores of Old England at a phenomenal speed—but whither?

Gerald next proceeded to make a systematic investigation of the cabin; but there was nothing to indicate the nationality or nature of the vessel that had effected his rescue. He had an idea that she was a British craft, as the only hail was given in his native tongue; but he had heard the officers of German and Dutch vessels give orders in perfectly good English to pilots and boatmen in home waters.

Besides the double bunks there were a portable wash-hand basin, a bath slung from the ceiling, a small chest of drawers, a couple of cane-seated chairs, and a looking-glass. On one of the chairs were his clothes, in a perfectly dry condition.

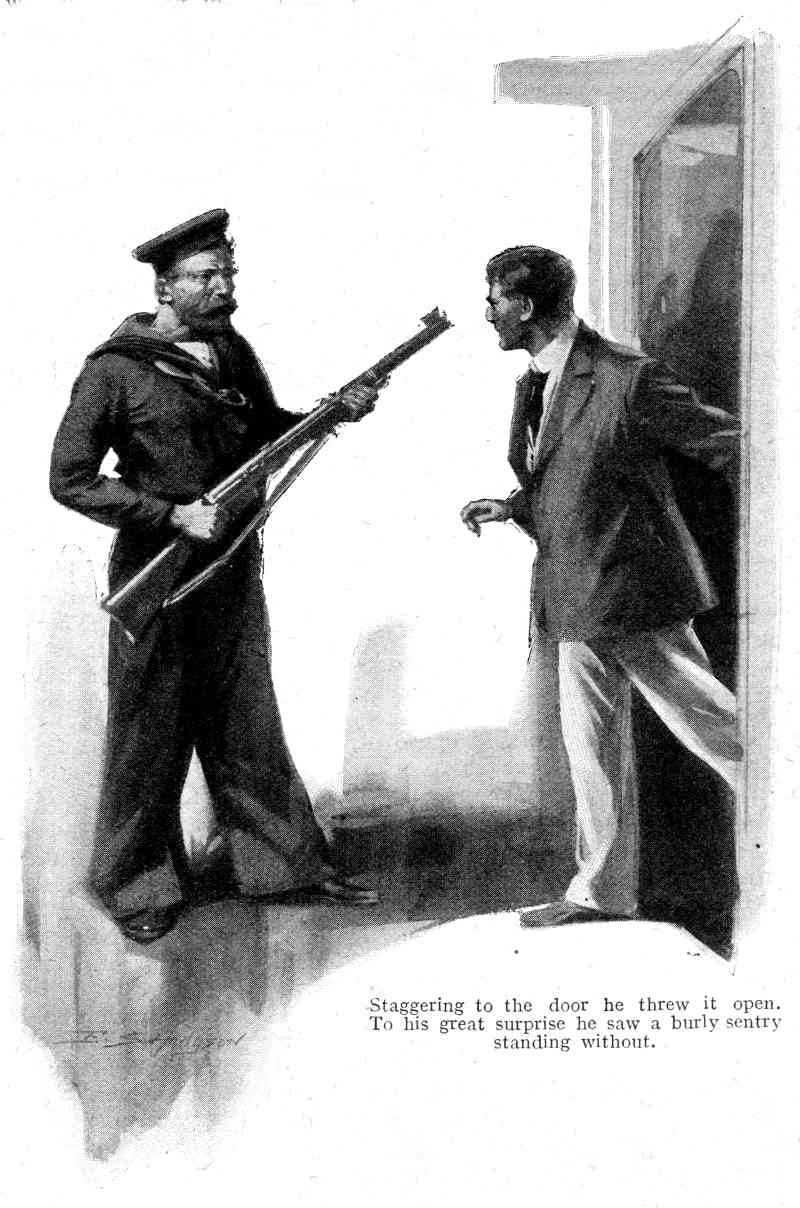

With considerable effort he managed to dress; then, staggering towards the door, he threw it open.

To his great surprise he saw a sentry standing without. He was a tall, burly-looking sailor, dressed in a uniform somewhat resembling that of a British seaman, although the blue jean collar was of a deeper shade, and black tape replaced the white ornamentation worn in the Royal Navy. The man had no name on his cap-ribbon, but a device representing a leaf upon his right arm. A black leather bandolier encircled his waist, a cutlass taking the place of a bayonet. He carried "at the slope" a rifle of a similar pattern to the latest form of Lee-Enfield, except that the stock was terminated 6ins. from the muzzle, which was enclosed at that end by a metal cylinder of about 3ins. in diameter. A portion of this cylinder was flattened, apparently for the purpose of using the sights.

This much Tregarthen took in at a glance, but with a peremptory gesture the man indicated that all egress was debarred. There was nothing to do but to obey the mute instructions. Gerald retreated to the cabin, and immediately he heard the sound of a key being turned in the lock. He was a prisoner.

Gerald—too much astonished to concentrate his thoughts—sat down in complete bewilderment. The tragic events of the ill-fated cruise, the mysterious nature of the vessel that had rescued him, the unsolved problem of his friend's disappearance, and finally the ignominy of being held in captivity, crowded in upon his already aching brain. Then an irresistible desire to smoke came over him. He felt in his pocket for his pipe, till, remembering that he had left it in the cabin of the Playmate, he bethought him of his cigarette-case, fervently hoping that its contents had escaped damage from the sea-water. To his surprise he found the case filled with a different kind to those he was accustomed to. Evidently his captors meant to allow him every comfort.

Without compunction he began to explore the contents of the chest of drawers. With one exception they proved to be empty, and, what was more, evidently new and unused. In the top drawer, however, was a case containing a brush and comb and shaving materials—also in a perfectly new condition.

In the midst of his investigations the door was unlocked, and, with a preliminary knock, a little, alert-looking man attired in a neat and well-fitting uniform entered.

"Good afternoon, Mr. Tregarthen," he exclaimed. "I trust you are feeling better? My name is White, at your service, and I am the senior surgeon on board."

"Thanks, sir, I am feeling nearly fit. But might I ask what ship is this, and why I am kept under lock and key?"

The doctor shook his head deprecatingly.

"I regret I can give you no information on that point. You must, I am afraid, wait till you have seen the captain."

"But my friend—is he safe?"

"He is safe."

"And——"

"No more questions, if you please, Mr. Tregarthen," interrupted the surgeon, firmly, and in a manner that betokened the uselessness of further inquiries. "Meanwhile, before the captain sends for you, some light refreshment will doubtless be beneficial. I am pleased to see that you are little the worse for your misfortunes."

So saying the medico withdrew, and a steward silently entered the cabin, bearing a tray on which an appetising meal was tastefully spread.

This man was even more unsociable than the doctor, and with as few words as possible he left the cabin, the door being again locked.

Left once more to his own reflections Tregarthen acknowledged that the mystery was almost as dark as before. He had made two discoveries. Firstly, Jack Stockton was safe on board, though possibly a prisoner like himself. Secondly, the ship was more than likely manned by a British-speaking crew, but whether British or American Gerald was unable to say.

At length the sun sank beneath the horizon—a red ball of flaming fire in an indigo sky.

Gerald glanced at his watch. It was a half-hunter, and the well-fitting case had not admitted any water during his immersion The hands pointed to a quarter to seven.

Here was another mystery. He knew full well that at home the sun set at 7.15 p.m. The ship's course was, as far as he could judge, south-west. How, then, could the apparent discrepancy be accounted for? Perhaps his watch was wrong.

Anxiously Tregarthen waited, listening intently for the ship's bell. Punctually at seven—the second hour of the second dogwatch—came the dim sound of the bell—ting, ting—ting! Two sharp blows followed at a longer interval by another. His watch was right, then, and since the course was not easterly he could only conclude that by a hitherto unattainable speed the mysterious vessel had already gained a latitude corresponding to that of the Bay Of Biscay.

Ere the short twilight deepened into night the cabin was brightly illuminated by the warm glow of a pair of electric lights, one at the middle of each bulkhead.

"Well, there's nothing to amuse myself with, so I might as well turn in," thought Gerald, for the excitement of the day, coupled with the fact that he had had but a short spell of sleep the previous night, was beginning to tell. He was on the point of divesting himself of his clothing when the door was unlocked, and a young man evidently an officer, entered.

"The captain wishes to see you, sir," he announced, bringing his hand to his forehead with professional smartness.

[Illustration: CHAPTER V]

[Illustration: CHAPTER V]

ON ships of all nationalities the captain's wishes are his commands. Tregarthen fully recognised this; so, returning the young officer's salute, he followed his guide from the cabin that had for so many hours been his prison.

It was but a few steps to the captain's cabin, but during his journey Tregarthen made good use of his eyes.

As he left the cabin he looked forward. Here his range of vision was limited by an armoured bulkhead, against which stood an arms-rack, the weapons being similar to that carried by the sentry, each having the peculiar cylindrical arrangement close to the muzzle. On either side of the passage were a number of cabin doors; some were ajar, but heavy curtains prevented him from seeing into the officers' quarters.

Between the bulkhead and the captain's cabin on the half-deck a sentry was pacing to and fro. Smartly he came to the salute; Gerald's companion returned the compliment, then, knocking at the door of the captain's quarters, he waited till a deep voice bade him enter.

"Mr. Gerald Tregarthen, sir," announced the young officer, and with this introduction he withdrew.

Gerald found himself in a spacious, well-lighted cabin, comfortably furnished, yet without any pretence at luxury. Thick carpet covered the floor, the walls were painted in a "flat" olive green colour, relieved here and there by a small square port-hole. Right aft a doorway in the armoured plating gave access to a little gallery or stern-walk. The furniture consisted solely of a large mahogany table, two sofa chairs, a well-filled bookcase, a sideboard, and a smaller table littered with papers and drawings.

But Tregarthen paid scant heed to the contents, of the cabin. His attention was drawn to its only other occupant. He was a man of short stature, yet of a commanding and pompous presence, that is so often found in persons whose bearing alone can atone for their loss of inches. He was of a dark olive complexion, with deep-set eyes, full features, dark brown closely cut hair, and a neatly trimmed moustache and "torpedo" beard, after the style affected by British naval officers. He was dressed in a dark blue "mess" uniform, black braid taking the place of the usual gold lace. This, then, was Captain Brookes, the officer in command of the mysterious cruiser.

For a space of nearly half a minute the captain remained silent, apparently "sizing up" the young British officer who had fallen into his power.

On his part Gerald Tregarthen drew himself up to his full height, and, standing stiffly at attention, looked his captor—since captor he undoubtedly was—squarely in the face, having first given him a salute which the captain punctiliously returned.

"Take a chair, Mr. Tregarthen," began Captain Brookes, waving his hand in the direction of one of the settees.

Gerald would have infinitely preferred to remain standing, but there was a veiled authority in the words, and without a sign of protest he yielded. Something in the man's personality compelled the sub-lieutenant to obey.

"You are, I believe, a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Navy? Lately of His Majesty's destroyer Calder?"

Gerald started. His interrogator seemed to know everything, but, recollecting that Jack Stockton had in all probability been subjected to a cross-examination, he replied: "Yes, sir."

"And, judging by this "—here he tapped an official Navy List that was lying on the table—"you are what might be well described as a promising young officer?"

"Might I ask, sir, why I am detained on board this vessel, and why I am subjected to this inquisition?" asked Tregarthen, ignoring the obvious flattery, yet truth, of the captain's last question.

"To come to the point, sir," replied Captain Brookes, "you came on board because there was no choice in the matter; then, finding you are a man likely to suit my purpose, I decided to retain you."

"To suit your purpose?"

"Precisely. What my intentions are I will hasten to explain in a few words. You are now on board the cruiser Olive Branch, formerly known as the Almirante Constant. The circumstances under which the vessel was acquired from the Brazilian Government I will explain later. The Olive Branch has no nationality; she claims the protection of no state or country. Hers is a particular mission; I, a nonentity, though owning no earthly master, am the controlling authority of a universal enterprise. No doubt men will call me a crank, a maniac, or worse. Most benefactors of mankind are so regarded—until they are dead and gone—but public opinion does not trouble me one iota. To be brief and to the point, my mission is universal peace, and my title is 'The Exterminator of War.'"

The captain paused to allow his words to carry weight. Tregarthen gave no sign of incredulity or otherwise. He looked steadily at the man who had made this astounding statement, wondering whether some symptom of insanity lurked behind the calm exterior of his captor. Captain Brooke's features were lit by an earnestness that denotes sincerity of purpose.

"To continue: The Olive Branch is the last word in naval construction. I do not make this assertion without having carefully weighed the truth of what I say. Warships claiming to be finality in offensive power have been laid down, yet ere they leave the slips plans for still more powerful vessels have already been passed, and so on. Yet even taking the rapid rate of progress into consideration, I can safely say that a hundred years hence—should there be any necessity for them—there will be no vessels equal to the Olive Branch for purposes of offence and defence.

"I am prepared to show that naval warfare, as demonstrated by the Olive Branch, will be so terrible that no nation will dare run the risk of undertaking it. I purpose to police the high seas, and ruthlessly exterminate the fleet of any nation that offers to break the world's peace.

"For years past England has held the proud position of Mistress of the Sea, using her power with firmness and wisdom. But these times are rapidly passing away——"

"Sir, I protest," exclaimed Tregarthen, impetuously.

"Protests are of no avail, unfortunately," replied Captain Brookes, with a suspicion of harshness in his voice. "Review the facts carefully and deliberately, and you will have to admit that what I say is true. Why do other nations, possessing little legitimate interests on the ocean, knowing full well that their seaborne commerce has hitherto been conducted without let or hindrance, suddenly decide to build huge and powerful fleets? To what purpose do they express their intention of rivalling the British fleet? Not from necessity, but from sheer wantonness. Is that not so?"

"Then you, yourself, are an Englishman?"

"I am what I am, a cosmopolitan—a pariah, if you choose to term it so. I prefer to let my identity remain a secret. Now, to put the matter bluntly, are you prepared to throw in your lot with mine for the space of not more than two years?"

"I am not. As a British officer my duties——"

"Then I must take steps to compel you."

"Compel me? You cannot."

"Mr. Tregarthen, before we talk of compulsion—though I admit I was the first to suggest such a step—pray consider the main and side issues of the question. You are bound by a solemn oath to obey your lawful sovereign, King George V. Do you think you could serve him in a better manner than by acquiring the knowledge of what this vessel is, and how she is enabled to possess such irresistible power? The Admiralty would be only too glad of a chance to gain the secret of the Olive Branch. You would to all intents and purposes become a naval attaché, with far greater prospects of gaining invaluable knowledge. Now, this is my offer: Your service for the space of not less than two years; your solemn word that you will obey my orders in all matters, provided you are not called upon to commit a hostile act against your own nation. Means will be afforded you to communicate with the authorities at the Admiralty, in which you can explain the facts under which you were compulsorily detained, and so on. Then, at the end of two years, or before, should my mission be accomplished, you will be permitted to return home, armed with the priceless secrets that are to command universal peace. Is that clear?"

"And the alternative?"

"I do not wish to discuss the alternative beyond saying what I have already stated." Then, seeing that Tregarthen was on the point of giving a direct refusal, Captain Brookes interposed:—

"Now, don't do or say anything foolish. Take time to consider the matter. I'll see you at four bells in the forenoon watch, when I shall expect a definite reply."

GERALD TREGARTHEN, sub-lieutenant of H.M.S. Calder, decides to spend his leave on a small yacht. He accordingly takes train to Poole, where the craft is lying. On the journey he reads in a newspaper a passage relating to the departure from the Tyne of a powerful cruiser, nominally intended for the Brazilian Government, also a series of reports concerning a mysterious accident to the German cruiser Zietan. At Poole he joins his friend and former school-chum.

JACK STOCKTON, owner of the yacht Playmate. The same night they put to sea, intending to cross the Channel. When about thirty miles off the Isle of Wight they encounter a dense sea-fog, and the Playmate is run down by a large vessel. Tregarthen is stunned by some falling gear, but is saved by Stockton, and both are taken on board the ship that has run them down.

When Tregarthen recovers his senses he finds himself alone in a cabin. From observation he comes to the conclusion that the vessel possesses astounding speed and that she is heavily armoured; also that he is a prisoner. At length he is taken into the presence of

CAPTAIN BROOKES, in command of the cruiser Olive Branch. This individual claims that his cruiser is the most powerful vessel afloat, and that it is his mission to exterminate war and secure universal peace, using the super-powerful means at his command to achieve that purpose.

He also informs Tregarthen that, as a British naval officer, he will prove useful to the Olive Branch in her mission, and suggests that the sub-lieutenant should serve on board the cruiser for a period of not more than two years. At the end of that time he will be able to impart the valuable knowledge thus gained to the British Admiralty.

Tregarthen is about to refuse, but Captain Brookes reminds him that in any case he is virtually a prisoner, and adds, "Take time to consider the matter. I'll see you at four bells, when I shall expect a positive reply."

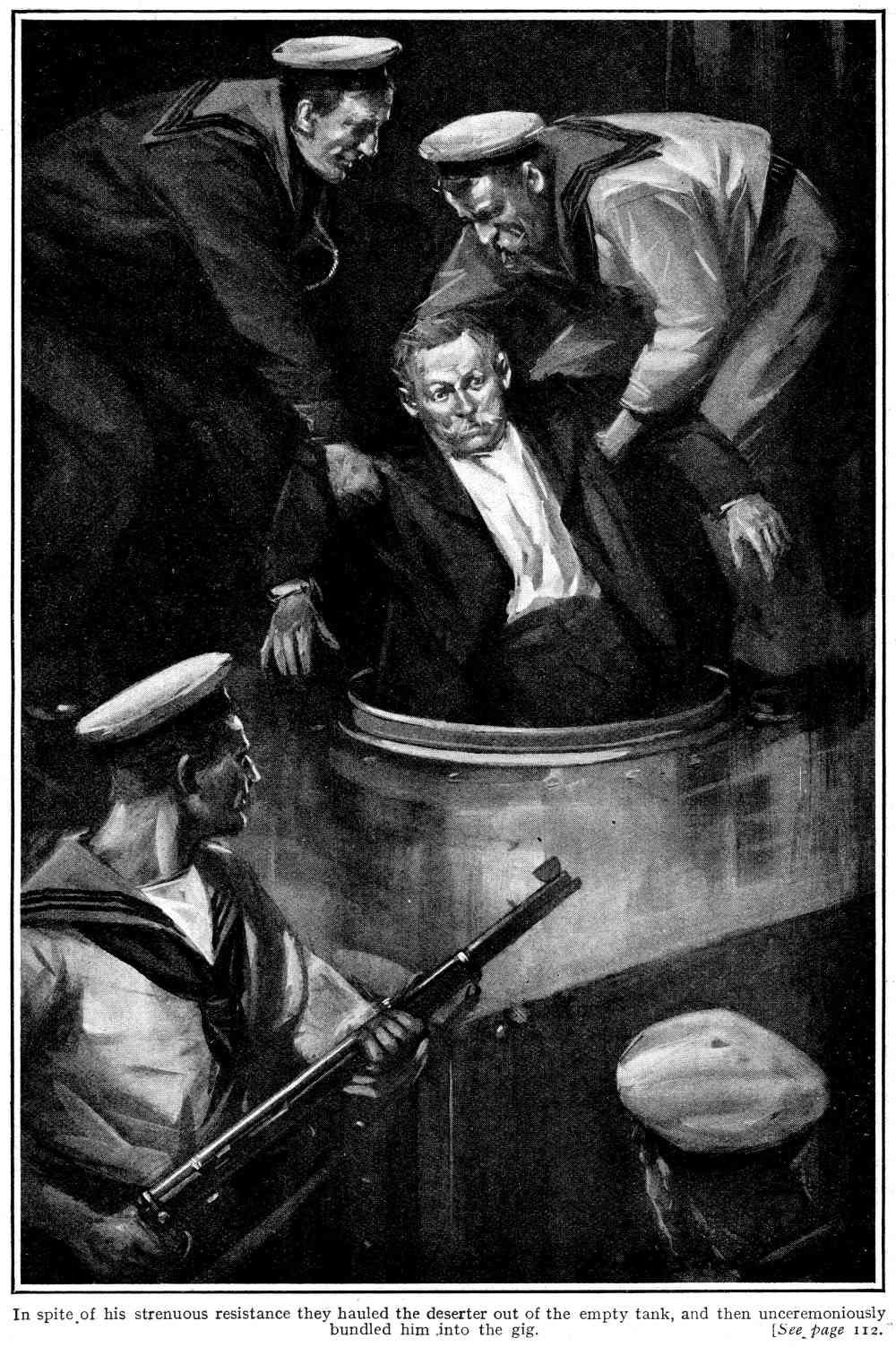

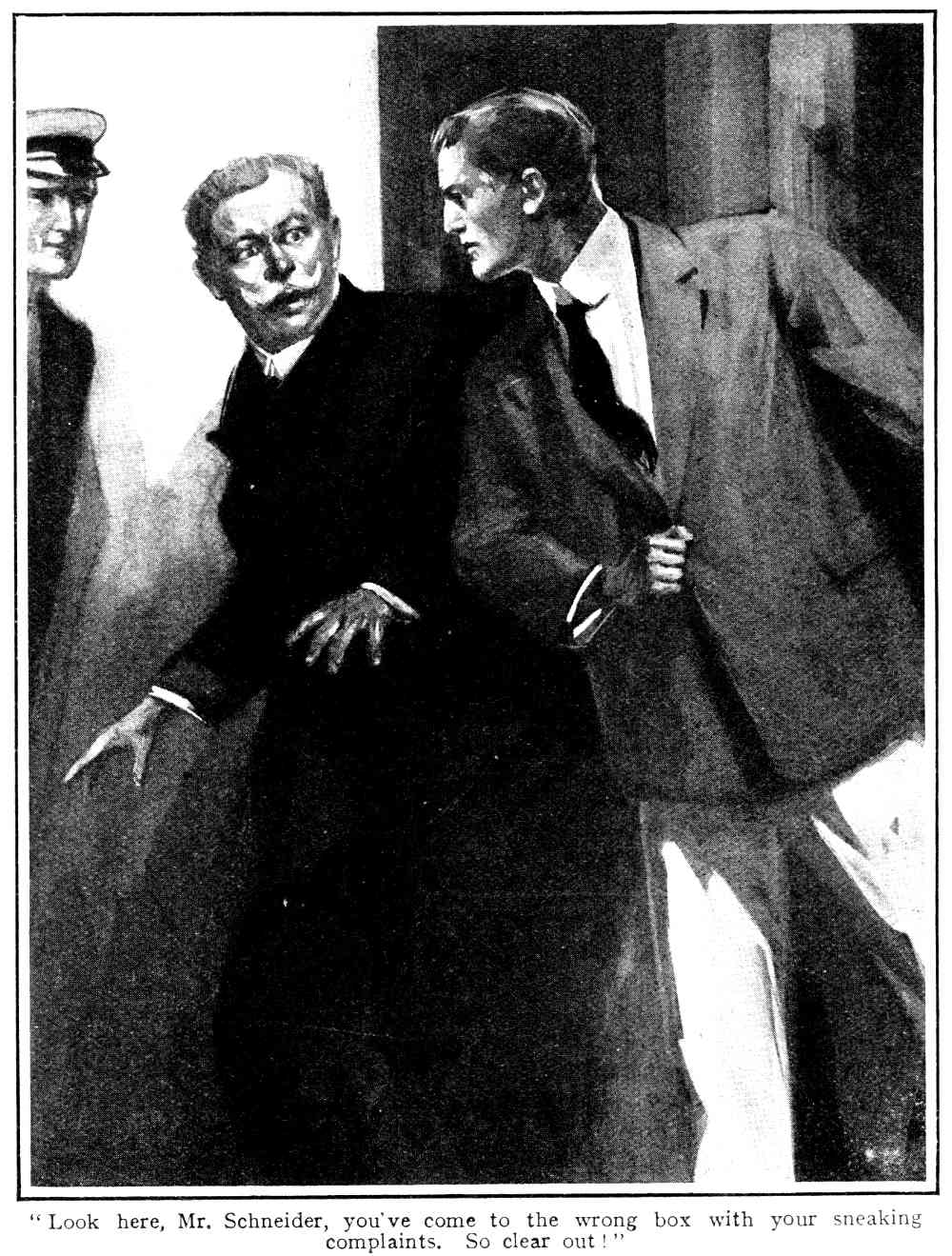

[Illustration: CHAPTER VI]

[Illustration: CHAPTER VI]

PUNCTUALLY at ten o'clock on the following morning Gerald Tregarthen was ushered into the captain's cabin. "Well, sir, what decision have you arrived at?" demanded Captain Brookes.

"No decision at all, sir," replied Tregarthen, firmly. "I want first of all to know what you propose to do with my companion."

"With Mr. Stockton? I suppose I ought, as the pirate you regard me, to hold him as a hostage for your good behaviour. But rest assured, I'll have him shipped aboard the first homeward-bound vessel we sight."

"Before I give you a reply I should like to have a few minutes' conversation with him," said Gerald.

"Your request seems reasonable. You may have fifteen minutes' interview."

While speaking, Captain Brookes had touched the push of an electric bell, and a seaman, evidently a petty officer, was immediately in attendance.

"Take this gentleman to his quarters and desire Mr. Black to bring Mr. Stockton to him."

"Very good, sir," replied the seaman, and holding back the heavy curtains that hung over the door he allowed Tregarthen to precede him.

In less than five minutes Jack Stockton had joined his chum.

"Hulloa, Jack! How have they treated you?"

"Can't complain," was the laconic reply. "They told me you were all right in spite of a crack on the skull. Beyond that I didn't worry much, though I've been thinking about my poor old yacht."

"Yes, it's rough luck," replied Tregarthen. "But she's insured, isn't she?"

"Yes. But what does that matter? I shall never have the same craft again; and, Gerald, she was part and parcel of my existence."

"You'll have another one soon."

"Will I? How do you know?"

"Because they are going to ship you aboard the first vessel we meet."

"Ship me? How about you?"

"Ah! There's the difficulty. You will be sent home, but, worse luck, they are going to keep me here, whether I like it or not."

"Is that a fact? What is this vessel—a pirate?"

"Goodness only knows. But to put the matter in a nutshell, I have to give my decision whether I'll become one of them or not."

"And if you don't?"

"I've been promised something mighty unpleasant."

Thereupon Gerald related the details of the conversation of the previous evening, and the captain's peremptory demand for a definite reply.

"What do you propose to reply?" asked Jack.

"That's what I want to consult you about. You see there's my position to consider. If I do not turn up within thirty-three days from now I shall be branded as a deserter, unless My Lords take gentler measures and mark me down as missing. If I could serve a useful purpose to my country by accepting the man's proposals I'd do it like a shot, subject to certain guarantees."

"Then why not? In any case you are booked. But I say, old fellow, when you are treating for terms, couldn't you stipulate that I am to be retained as well?"

"You?"

"Yes. I admit, Gerald, I don't possess the same qualifications as you do, but at the same time I'm not a duffer afloat. If this vessel is such a wonderful packet, I'd be only too delighted to stay."

"All right," replied Gerald. "My mind's made up. But the quarter of an hour is up, too, so I must be off."

"Well, sir," asked Captain Brookes, "have you come to any conclusion?"

"I am willing, subject to certain conditions, sir," replied Gerald, firmly.

"And those are——"

"That I am to be treated with the respect due to a British naval officer; that I am not called upon to perform any duties prejudicial to my country——"

"That I have already suggested."

"That I may be allowed to dispatch a communication to the Admiralty stating the circumstances under which I am detained here; and, lastly, that my friend Jack Stockton may be allowed to remain here with me, that being his own desire."

"I agree to your requests," replied Captain Brookes, though Tregarthen noted that he used the word "requests" instead of his expression "conditions."

"Very good, sir."

"You quite understand that my orders are to be implicitly obeyed?"

"So long as I am not called upon to commit any act detrimental to my country."

"That has already been decided."

"Too much stress cannot be laid upon that condition, sir."

"Are you prepared to wear the uniform of officers serving on board the Olive Branch?"

"No, sir. The only uniform I am entitled to wear is that of the British Navy. As that is, of course, impossible in these circumstances, I must wear mufti."

"Very well, then," replied the captain. "Now we will make a tour of the ship and you will be able to form some opinion of her capabilities."

So saying, Captain Brookes led the way to the half-deck, whence by the after ladder he gained the quarter-deck. Unlike ships of the British Dreadnought type, the quarter-deck was situated in the after end of the ship, but Gerald noticed that the officers who were walking up and down kept religiously to the port side, leaving the starboard side to the use of the captain. This caused him to wonder how the similarity between the customs of the Royal Navy and those of the mysterious ship was to be accounted for.

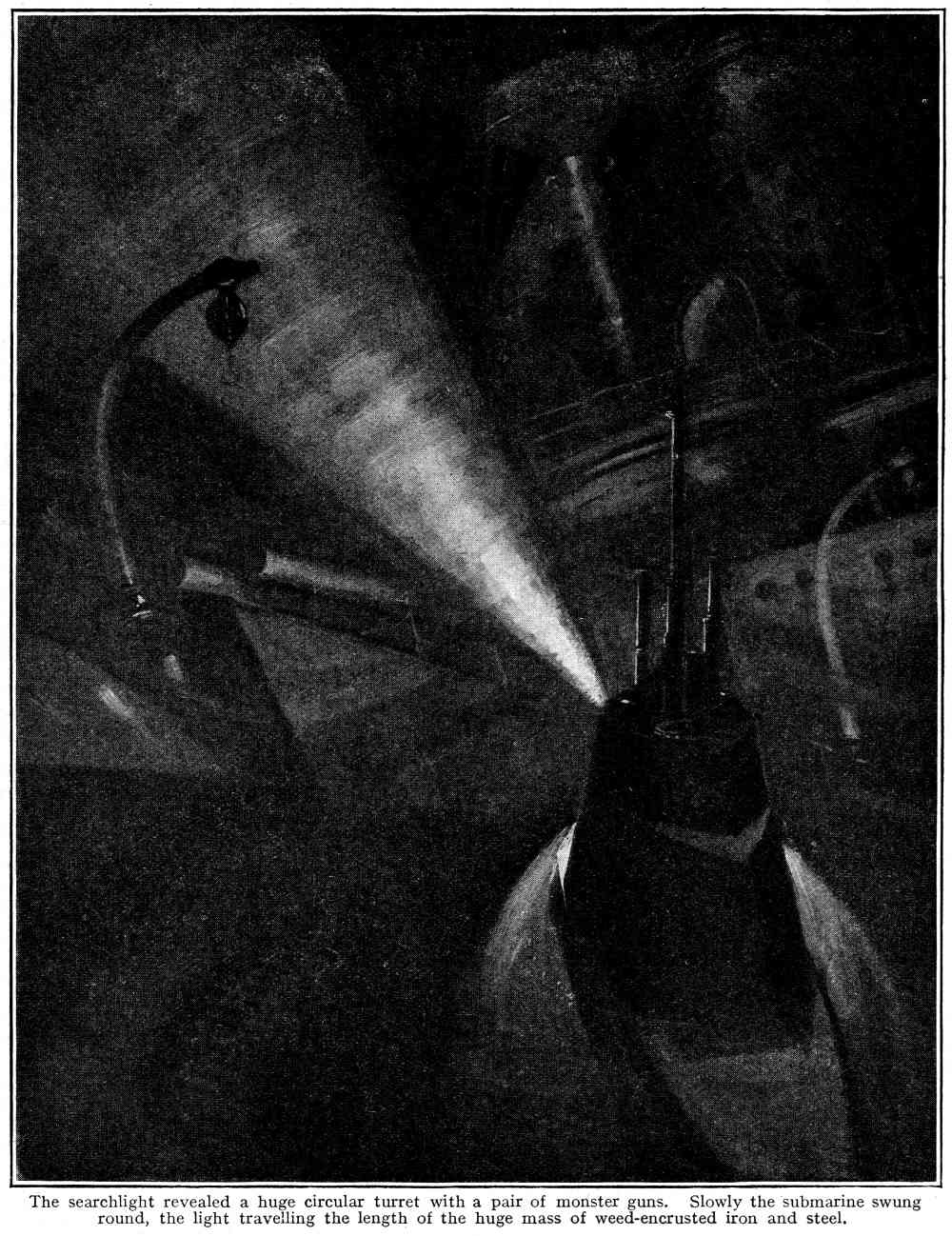

Touching his cap to the quarter-deck Gerald found himself upon a vessel apparently of not less than 10,000 tons displacement, or a little more than half of a modern Dreadnought. She was, as far as he could judge, about 300ft. in length, and 60ft. in breadth. She was flush decked; a low slender funnel, a motor cutter and launch, a massive conning-tower, a pair of turrets, and the necessary hatchways and companions alone occupying the centre line. Placed en echelon were two more turrets, but in none of these were guns mounted, although each turret had two embrasures.

At frequent intervals along the deck were plates of thin steel inclined at an angle of 45degs.

"These are wind screens," observed Captain Brookes. "They are an absolute necessity, I can assure you."

"Don't hesitate to put any questions you may feel inclined to ask," he continued. "It will be to your interests as well as mine for you to do so. I noticed you were looking at the turrets. These are as yet without their armament, although I hope within a day or two to have the guns in position."

"Then at present you are without means of offence?"

"You will hardly care to make that assertion when you have completed your first inspection of the Olive Branch. But what speed do you think we are doing?"

Tregarthen looked over the side. There was a long, gentle swell setting in from the west, but so great was the ship's rate of speed that she appeared to be travelling over a succession of short, steep seas, yet without the faintest suspicion of a roll or a lurch.

"Forty-five," he hazarded.

"Add twenty to it and you will be nearer the mark. Mr. Gimlette," he added, addressing the officer of the watch, "will you please let me have the present reading of the log?"

The officer ran aft to where the patent log indicator on the taffrail was merrily ringing at less than every fifteen seconds.

"Sixty-seven point five knots, sir."

The reply was given smartly, but in a manner that suggested this speed was an ordinary occurrence. Tregarthen could only gasp in astonishment. It meant the Olive Branch was doing an equivalent to a fraction under seventy-five land miles an hour. Were it not for the wind screens it would be almost a matter of impossibility to face the hurricane that whistled overhead.

"You may have noticed the almost total absence of a bow wave," continued the captain. "This is owing to the vessel's remarkable flare—for which the designers must take the credit. By means of an ingenious contrivance the displaced water is led close alongside, yet the 'skin friction' of the hull is not increased. The effect of this diversion is to give the propellers a better grip. As a matter of fact, the 'slip' of the propellers amounts to less than 5 per cent. Now we will make our way for'ard to the conning-tower."

"But what is the motive power?" asked Gerald.

"Petrol, paraffin, or, in fact, any inflammable oil capable of passing through the vaporisers. The motors, which can be attended to by a staff of ten engineers only, actuate five propellers. Thus we are not under the obligation of having to carry stokers. As a matter of fact, the personnel of the Olive Branch, thanks to mechanical appliances of the most modern type, amounts to 105 officers and men."

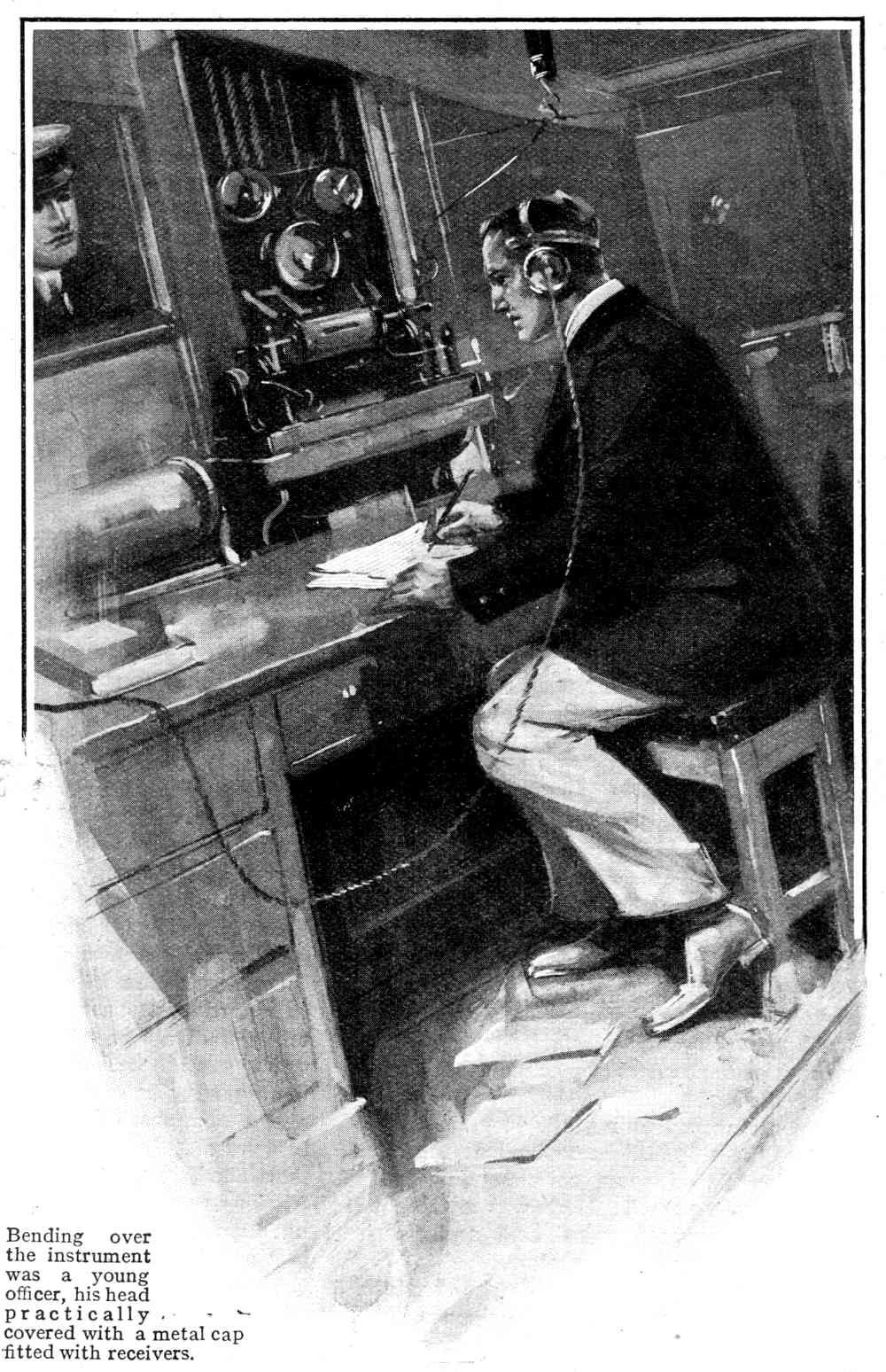

The conning-tower consisted of a circular armoured structure 25ft. in diameter, and barely 5ft. above the upper deck. Around the walls were electrical indicators and a maze of pipes painted in distinctive colours similar to those on board a British man-of-war. But the apparatus that riveted Gerald's attention was a board composed of copper and zinc squares resembling a draught board, with a pair of pointers at two adjacent corners. This device travelled on steel lines that formed an almost complete circle, a gap being left in the direction of the after end of the ship.

"Now, Mr. Tregarthen, what do you suppose this arrangement is for?"

"It appears to me to be a sort of position-finding instrument."

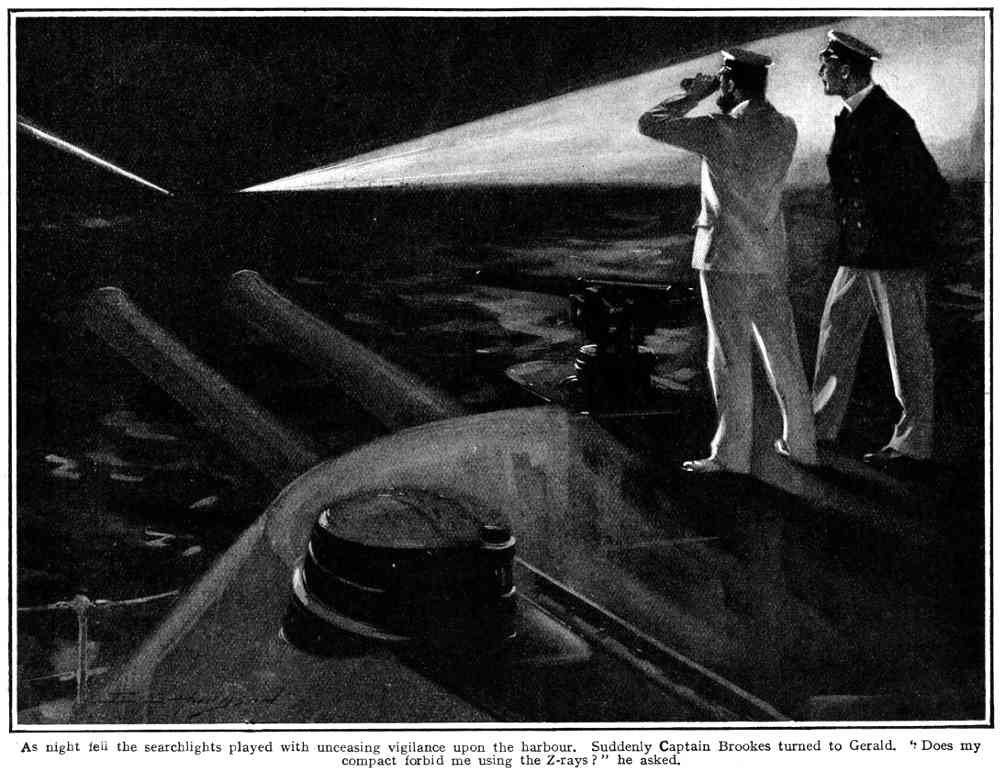

"It is more than that. But first I must request you to maintain a strict secrecy regarding what you see in the conning-tower, at least until I withdraw this restriction. Beyond that you are at perfect liberty to discuss with your companion any details concerning the ship," replied Captain Brookes. "Before you left Poole Harbour did you see a report in the papers concerning the German cruiser Zietan?"

Like a flash the truth swept across Tregarthen's mind. The ex-Brazilian vessel, Almirante Constant, the mysterious agency that had temporarily incapacitated the Zietan, and the ship on which he stood were one and the same. So astonishing was the revelation that even he—an iron-nerved naval officer—gasped with amazement. The captain, who was watching the effect of his question, kept silent, awaiting Gerald's reply.

"I did," he assented after a prolonged interval. "But how did you do it? And how were you aware?"

"One question at a time, please. I am on the point of showing you a somewhat ingenious device; what it has already done I will inform you of in due course. This chequered board is divided, as you see, into eighty-one squares, each division representing one square mile. Thus a 'field,' meaning nine miles in either direction, is at my command. Now, supposing a hostile ship is sighted. Her position is determined by the ordinary range-finding instruments. By placing these two pointers on the square representing the ship's position—the pointers, as you will observe, being capable of alteration of length—I release a wireless current, which I prefer to term the Z-ray—upon the enemy's ship. Instantly the whole of her electrical gear is completely disorganised, and, knowing as you do the vital importance of electricity on board a modern man-of-war, you can realise what it means."

"Then you have already committed a hostile action against the ship of a friendly nation?"

"I suppose I have. It is necessary to experiment, and having good cause to try my device upon a German ship, I proceeded to do so. I am fully aware of the results it occasioned while I kept the Zietan under the influence of the Z-rays."

"However did you manage to know that?" asked Tregarthen. "Have you put into any port since leaving the Tyne?"

"I have neither put into port nor have I entered into communication with any vessel excepting your yacht, so obtaining information by those means is entirely out of the question. How I did find out the results of my experiment I will inform you shortly. But to return to this device. You will doubtless have observed that there are two pairs of pointers? Those with a black disc are merely deterrents. Any vessel that persists in forcing an action after receiving the stern warning given by these pointers has only herself to blame for the consequences; for the moment the pointers with the red disc are superimposed upon the others the fate of the Olive Branch's antagonist is sealed."

"How?" asked Gerald, with ever-growing interest.

"The conjunction of the red-disced pointers release a super charge of electricity—which I term the ZZ-rays—and her magazines are instantly exploded."

"In that case why do you require guns on board? I understood you to say that you expected to have her armament in position in the course of a few days."

"Chiefly as a matter of precaution. The slightest defect in a terminal, switch, or wire might throw the whole of the electrical apparatus out of gear. But there is another danger I have to guard against—the danger of annihilation from the sky. This device you see here has taken me fifteen years of unremitting toil and thought to perfect, and perfected it is as far as my original plans were concerned. But within recent years the advent of the airship and aeroplane has tended to revolutionise warfare. In order to negative the possible ill results of the ZZ-rays to the vessel that releases them the indicator board is arranged so that the minimum range is nine miles. Thus I can put a vessel out of action at any distance between nine and eighteen miles. The Z-rays, having a comparatively low electro-motive force, can be brought into play at a distance of two miles, without danger to the Olive Branch's delicate mechanism. It consequently follows that to use the rays within the distance of 1,000ft.—the effective range of an airship—the consequences would be disastrous to us. I therefore have to rely on other means. Now I think I have explained the contents of the conning-tower pretty fully, so we will resume our tour."

"But what are these for?" asked Tregarthen, pointing to a triple row of metal studs fixed to a mahogany board on the side of the conning-tower.

"To control the gun fire. When the ordnance is installed I'll explain their use. But we will now ascend to the flying bridge."

With the wind howling over this exposed position like a veritable tornado Gerald was glad to gain the shelter of a diminutive chart-house. Here was the electrical steering apparatus, but, to his unbounded astonishment, Tregarthen found that the place was untenanted, the only other occupants of the bridge being a lieutenant and a seaman, both of whom, glass in hand, were scanning the horizon.

"Don't you keep a hand at the helm?" he asked.

Captain Brookes shook his head. "Not on long ocean voyages," he replied. "The ship steers herself. Like plenty of other problems, it's simple when you know how. The Olive Branch's steering apparatus is on the same principle as that of a Whitehead torpedo. The course is set by means of a pointer on the compass-card. The slightest deviation causes a small valve to be opened which actuates the rudder. Of course in confined waters or on going into action we use the steering-gear in the conning-tower."

"I can scarcely grasp the meaning of these wonders," remarked Tregarthen.

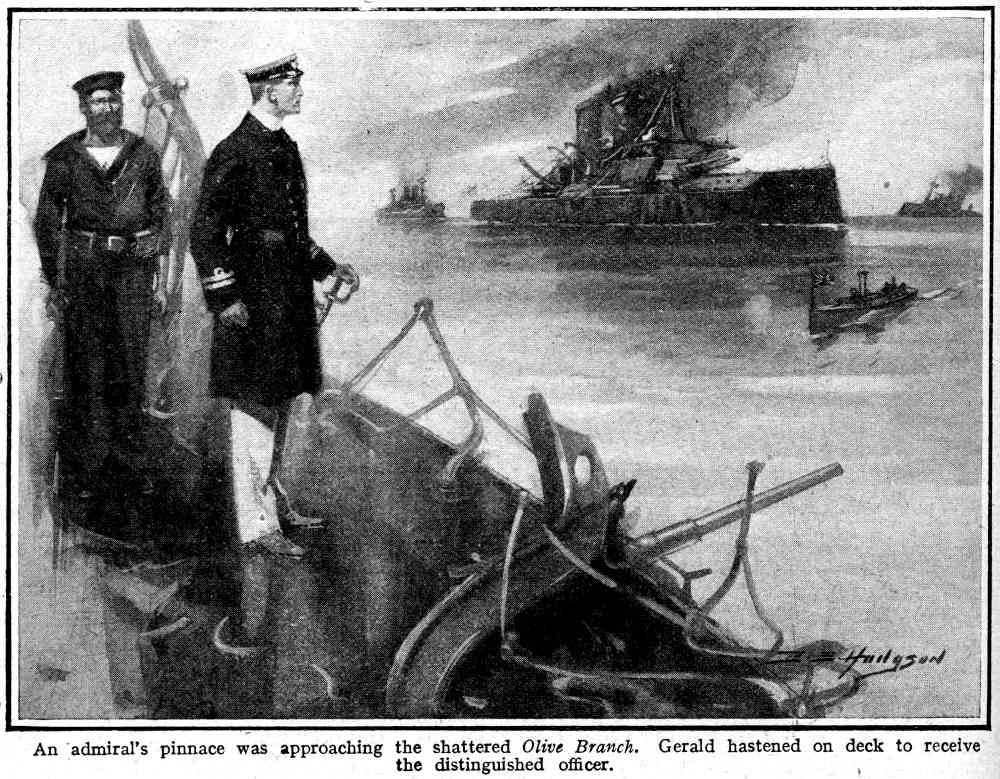

[Illustration: CHAPTER VII]

[Illustration: CHAPTER VII]

"ONE moment, sir," said Gerald as he accompanied the captain across the fo'c'sle, where a party of men were undergoing musketry exercise. "What is the meaning of that cylinder close to the muzzles of the rifles?"

"It's a silencer—the Lucas silencer, to be exact. I took a fancy to the device and acquired the patent. Mr. Ball, bring me one of those rifles, please."

The gunner brought one of the rifles for inspection. As Gerald had already noted it differed little from the Lee-Enfield type.

"The magazine takes a clip of ten rounds of .202 ammunition," announced Captain Brookes, as he pulled out the "cut-off" and thrust a cartridge into the chamber. "Now, listen."

Bringing the rifle to his shoulder the captain pressed the trigger. Beyond the slight recoil and a faint hiss there was nothing to indicate that the weapon had been discharged, until the still-smoking cartridge-case was ejected.

"I am applying this principle to all our ordnance, from the 6in. down to the revolver. It means a great moral advantage to be in a position to launch a hail of charged shells with a complete absence of sound," continued the captain, as he handed back the weapon. "Now we will——"

"Sail-ho!" came a hail from the bridge.

"Where away?" demanded the captain, in stentorian tones.

"Dead ahead, sir."

"That's the Puma, I'll be bound. Mr. Tregarthen, we must postpone the remainder of our inspection for awhile. In the meantime you'll find Mr. Stockton in your cabin. You may inform him that he has the run of the ship, with the exception, of course, of the conning-tower."

So saying, Captain Brookes hurried off to the bridge, the speed of the Olive Branch was reduced to less than twenty knots, and preparations were begun for opening communications with the Puma, which was already within five miles when Tregarthen went below to rejoin his companion.

"It's settled, Jack; you are to stay aboard the Olive Branch," he exclaimed.

"Yes, I know, thanks to you. They've told me that I'm to share your cabin."

"How did you know that?" asked Gerald. "Captain Brookes agreed to my proposal, and ever since then he has not been out of my sight."

"I don't know; I'm here, and there's an end of it as far as I am concerned," replied Jack, philosophically.

"Well, let's go on deck. We've sighted some vessel or the other."

"What's the game—piracy?" asked Stockton, suspiciously.

"I don't think so. But we're easing down, so look sharp."

Together the two chums gained the quarterdeck, the sentry on the half deck coming to the salute as Tregarthen passed. Here, again, Gerald was puzzled, for the man evidently was aware that the young lieutenant was no longer under arrest but had nominally become an officer of the ship.

The Olive Branch and the Puma lay side by side at about a cable's length apart. There was a total absence of wind, and the sea was as smooth as glass, while overhead the sun beat fiercely down upon the mirror-like surface of the ocean.

On the Olive Branch the bo'sun's mate had piped "Clear lower deck," and already the somewhat meagre crew had mustered on the upper deck, where warps and hawsers were being laid out with the evident intention of making fast to the other vessel.

The Puma was a tramp steamer of about 6,000 tons, with two stumpy masts, a black funnel, and towering wall sides that had been but partially painted, for a considerable portion of her hull still showed the priming coat of red lead. From an ensign staff over her taffrail the stars and stripes hung motionless in the sultry air. The Olive Branch flew no colours.

"I don't think it's piracy this time," remarked Jack. "The men are not armed."

"They seem a well set up lot," said Gerald. "I wonder where they were picked up. Short service naval men and Royal Naval Reserve seamen in all probability."

Tregarthen knew a sailor when he saw one, and his observations were correct. The men had for the most part discarded their No. I suits of blue serge, and were dressed in serviceable white canvas. With the utmost alertness and intelligence they executed their orders, which were given with a noticeable lack of bawling and shouting.

Smartly the Olive Branch was manoeuvred alongside the Puma, large fenders protecting the two vessels from the slight rolling as the latter's derricks were set to work.

In less than two hours eight 6in. guns, each weighing nearly seven tons, were transferred from the hold of the tramp to the deck of the cruiser, besides several smaller quick-firers and a quantity of cases and empty shells. Why the projectiles were shipped apart from their cartridges Tregarthen could not understand, though he resolved to make inquiries at the earliest opportunity.

The work of transhipping the ordnance having been completed, the skipper, a typical New Englander, came aboard the Olive Branch, armed with a sheaf of documents. For half an hour he remained below in the company of Captain Brookes, and on returning to his own ship the hawsers were cast off.

Meanwhile Tregarthen noticed that the cruiser's ensign had been hoisted—a device similar to that worn on the seamen's sleeves, evidently representing an olive branch in green on a white field.

As the two vessels parted company, the cruiser making off at a decorous seventeen knots, there was a mutual dipping of ensigns, and a quarter of an hour later the Puma was hull down to the nor-west.

For the rest of that day all hands were kept busy in mounting the principal armament. The work proceeded with marvellous rapidity, testifying to the splendid mechanical appliances at their command.

Hitherto unnoticed by the sub-lieutenant a powerful crane was cunningly concealed in the wake of each turret, so that when not in use one of the faces of the apparatus lay flush with the deck. By actuating a lever an enormous mass of metal rose to a vertical position, the arm commanding a radius of 20ft., while in the place of a hook was a powerful electromagnet. The top of the hood of each turret was composed of plates of 4in. steel, each section being temporarily held by metal bolts. Round swung the crane, the current was switched on, and plate after plate was whipped off till the turret was ready to receive its pair of guns. These were then easily lowered upon the mountings that were waiting to receive them, and the roof of the turret was next replaced, men setting to work with electric welding machines to permanently seal the armoured slabs.

The work was still in progress when dinner in the ward-room was announced, and before this function Gerald and Jack were introduced to the other officers of the ship by Captain Brookes.

There were fifteen occupants of the wardroom, all told. Some of the officers Gerald had met before, namely, White, the surgeon, and Christopher Weeks, the young lieutenant who had escorted him to the captain's quarters. Taken together the officers of the Olive Branch gave Tregarthen the impression that they were a genial, happy-go-lucky class. They spoke freely on general topics, but studiously avoided "shop," nor did they go into details concerning their past careers.

There was one exception, however.

The scientist, Taylor, who had charge of the laboratory and shell-filling room, was ever ready to let his tongue wag unrestrainedly in spite of the invariable snubbing he received from his messmates.

After dinner Gerald and Jack went on deck. Here strong arc lamps enabled the crew to continue their labours, for Captain Brookes was evidently in a hurry to get the work completed; he was here, there, and everywhere, testing circuits, examining the riveted plates, calling attention to this and that defect, and, in fact, an example of unflagging energy.

"What is this extraordinary hurry for, Mr. Sinclair?" asked Tregarthen of the navigating lieutenant, who had just been relieved on the bridge.

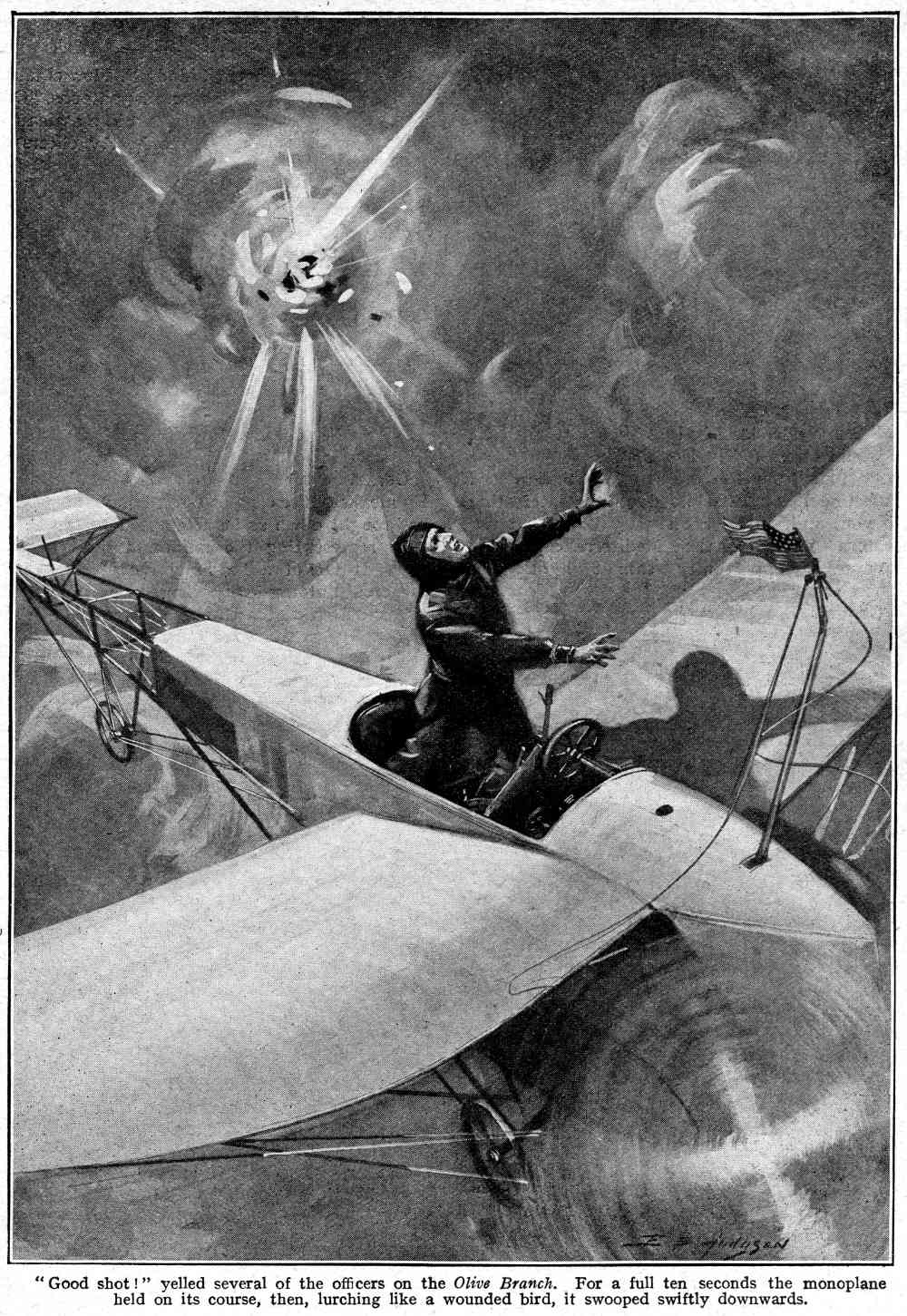

"Don't you know? Hasn't the captain told you the news? We've our first real business in hand. A wireless was received this afternoon that war is to be declared between two South American Republics within a few days. This is where we step in."

"How do they manage the wireless business, I should like to know," remarked Stockton, as the two friends gained the seclusion of their cabin.

"Really, I'm not surprised at anything in this ship," replied Gerald. "How is it going to end? The Olive Branch cannot keep the sea indefinitely. She must take in stores, have her hull coated in dry dock, and undergo a periodical refit. It all costs money, and where does the money come from? Who is this Captain Brookes? A millionaire—a fanatic—or what?"

"I suppose—— Hallo, who's there? Come in." A timid knock at the door had interrupted Jack Stockton's sentence.

A fresh-complexioned round-faced little man edged cautiously into the cabin, and carefully closed the door behind him. It was Taylor, the scientist.

"Well, Mr. Taylor, what can we do for you?" demanded Gerald.

"Hush, sir, not so loud, I pray of you," replied the little man, anxiously, his closely cut greyish hair bristling in his excitement. "My name is Schneider, not Taylor.

"I am a professor of languages and sciences. You came from Poole, is it not? Zen perhaps you are acquainted with Colonel Mortebeque? I was at one time tutor to his son——"

"Look here, Mr. Schneider," broke in Tregarthen, impatiently. "I don't know Colonel What's-his-name, nor do I want to hear your personal history. Come to the point—what do you want with us?"

"Alas!" groaned the professor with a shudder and a curious grimace. "I have been trapped; brought on ze voyage under false representations. It was to be scientist zat I was brought, but ze Captain Brookes he would me make fill ze shells in ze laboratories. I like it not. He is pirate."

"Who says he is a pirate?" asked Gerald sternly.

"Me, I will not say it. But zen, he is a—a what you call it. Ah! I know—a wizard. You two are also in peril. Will you ask ze captain to let you go on land at ze first port we touch, and take me wit you? Zen we run away and be safe."

"Look here, Mr. Schneider, you've come to the wrong box. If you've any complaint, why not lay it before the captain himself? If as you say the captain is a wizard he might be listening now to what you are saying. You understand? Well, then, clear out."

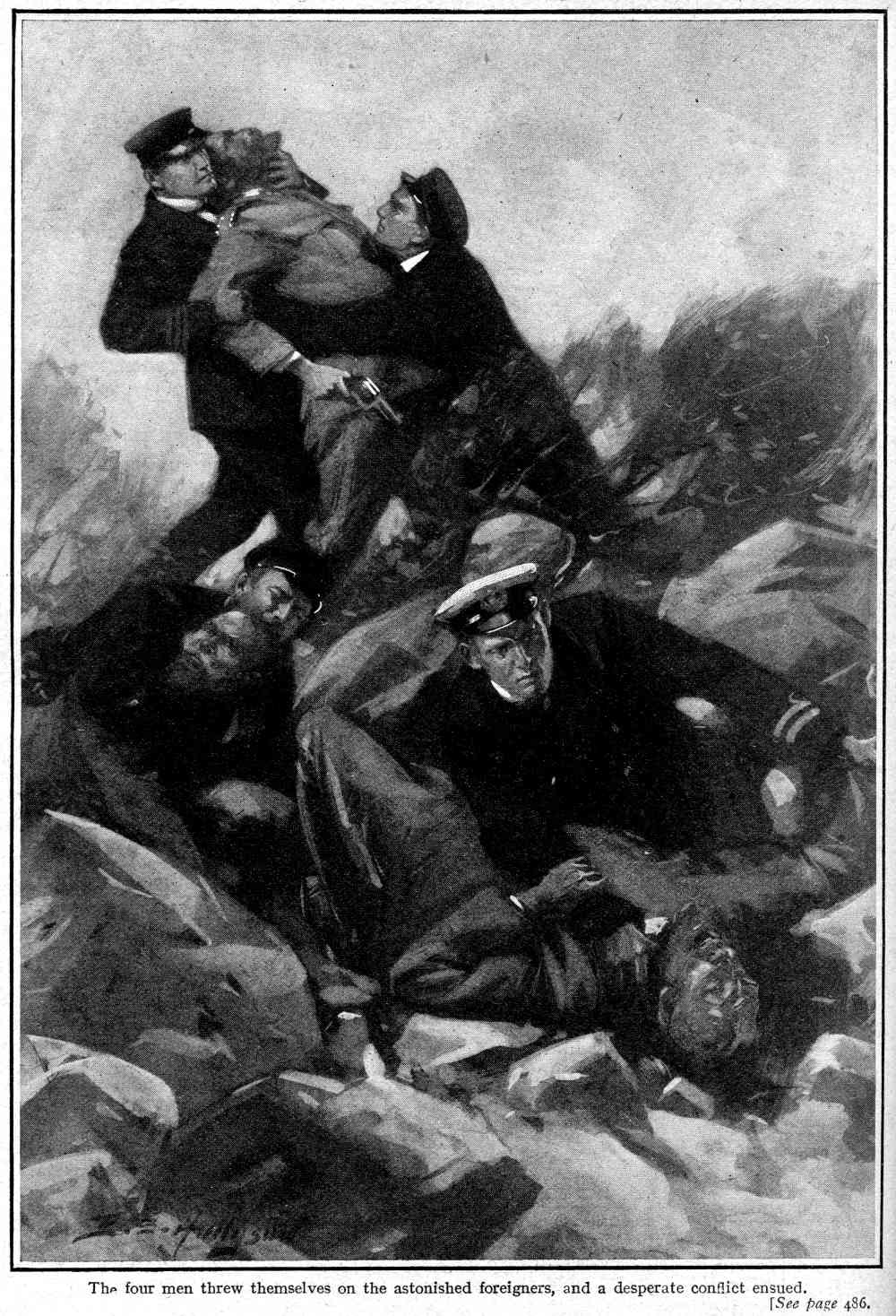

"A bright specimen of a sneaking waster," remarked Jack, as the cabin door closed on the retreating figure of the professor. "I wonder if there's any truth in his tale, eh?"