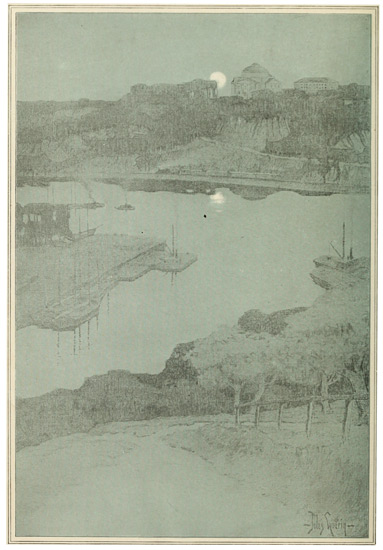

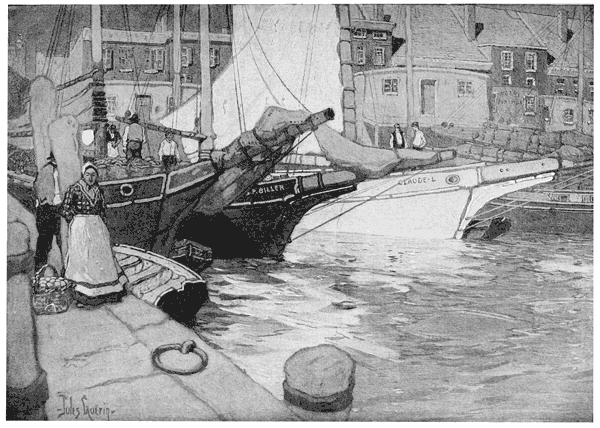

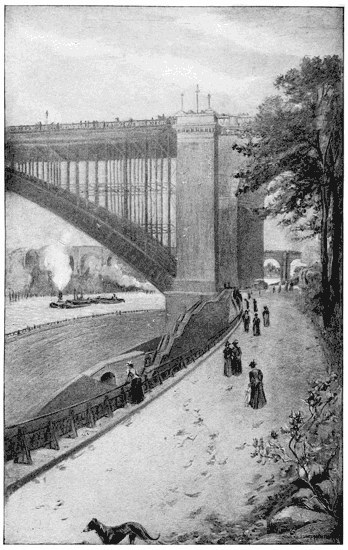

Drawn by Jules Guérin.

See "The Water Front of New York."

On the Harlem River—University Heights from Fort George.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Scribner's Magazine, Volume XXVI, October 1899, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Scribner's Magazine, Volume XXVI, October 1899 Author: Various Release Date: September 28, 2018 [EBook #57984] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SCRIBNER'S MAGAZINE, OCTOBER 1899 *** Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation and spelling in the original document have been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

Drawn by Jules Guérin.

See "The Water Front of New York."

On the Harlem River—University Heights from Fort George.

VOL. XXVI OCTOBER, 1899 NO. 4

Copyright, 1899, by Charles Scribner's Sons. All rights reserved.

Down along the Battery sea-wall is the place to watch the ships go by.

Coastwise schooners, lumber-laden, which can get far up the river under their own sail; big, full-rigged clipper ships that have to be towed from the lower bay, their top masts down in order to scrape under the Brooklyn Bridge; barques, brigs, brigantines—all sorts of sailing craft, with cargoes from all seas, and flying the flags of all nations.

White-painted river steamers that seem all the more flimsy and riverish if they happen to churn out past the dark, compactly built ocean liners, who come so deliberately and arrogantly, up past the Statue of Liberty, to dock after the long, hard job of crossing, the home-comers on the decks already waving handkerchiefs. Plucky little tugs (that whistle on the slightest provocation), pushing queer, bulky floats, which bear with ease whole trains of freight cars, dirty cars looking frightened and out of place, which the choppy seas try to reach up and wash. And still queerer, old sloop scows, with soiled, awkward canvas and no shape to speak of, bound for no one seems to know where and carrying you seldom see what. And always, everywhere, all day and night, whistling and pushing in and out between everybody, the ubiquitous, faithful, narrow-minded old ferry-boats, 387 with their wonderful helmsman in the pilot-house, turning the wheel and looking unexcitable....

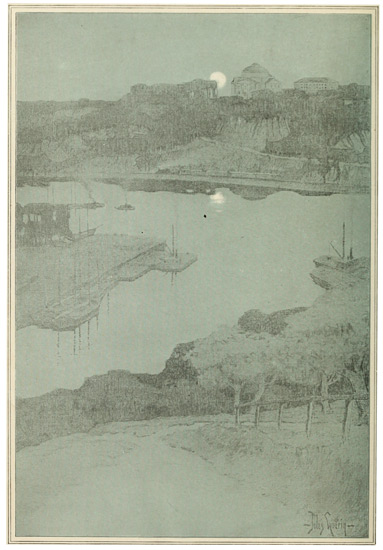

The old town does not change so fast about its edges.—Page 394.

(Along the upper East River front looking north toward Blackwell's Island.)

That is the way it is down around Pier A, where the Tammany Dock Commission meets and the Police Patrol boat lies, and by Castle Garden, where the river craft pass so close you can almost reach out and touch them with your hand.

The "water-front" means something different when you think of Riverside and its greenness, a few miles to the north, with Grant's tomb, white and glaring in the sun, and Columbia Library back on Cathedral Heights.

Here the "lordly" Hudson is not yet obliged to become busy North River, and there is plenty of water between a white-sailed schooner yacht and a dirty tug slowly towing in silence—for there is no utter excuse for whistling—a cargo of brick for a new country house up at Garrisons; while on the shore itself instead of wharves and warehouses and ferry-slips there are yacht and rowing club houses and an occasional bathing pavilion; and above the water edge, in place of the broken ridge of stone buildings with countless windows, there is the real bluff of good green earth with the well-kept drive on top and the sun glinting on harness and handle-bars.

Now, between these two contrasts you will find—you may find, I mean, for most of you prefer to exhaust Europe and the Orient before you begin to look at New York—as many different sorts of interests 388 and kinds of picturesqueness as there are miles, as there are blocks almost.

For instance, down there by the starting-point. If you go up toward the bridge from South Ferry a block or so and pull down your hat-brim far enough to hide the tower of the Produce Exchange, you have a bit of old New Amsterdam, just as it has been for years, so old and so Amsterdamish, with its long, sloping roofs, gable windows, and even wooden-shoe-like canal-boats, that you may easily feel that you are in Holland, if you like. As a matter of fact, it is more like Hamburg, I am told, but either will do if you get an added enjoyment out of things by noting their similarity to something else and appreciate mountains and sunsets more by quoting some other person's sensations about other sunsets and mountains. 389

New New York.

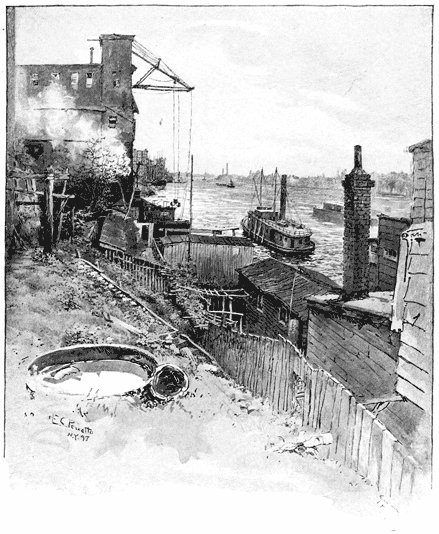

Not a stone's throw further up ... the towering white city of 1900.—Page 391.

(Between South Ferry and the Bridge.)

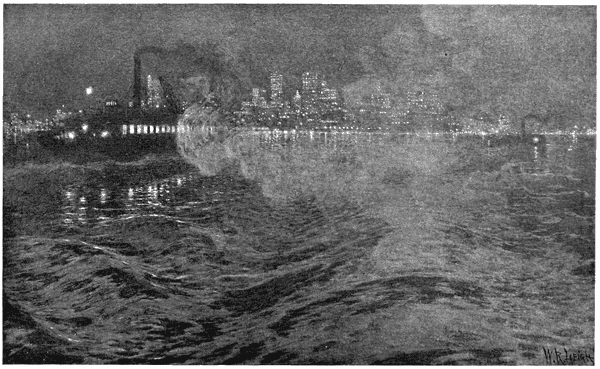

From the point of view of the Jersey commuter ... some uncommon, weird effects.—Page 394.

(Looking back at Manhattan from a North River ferry-boat.)

But if you believe that there is also an inherent, characteristic beauty in the material manifestations of the spirit of our own new, vigorous, fearless republic—and whether you do or not, if you care to look at one of these sudden contrasts referred to—not a stone's throw farther up the water-front there is a notable sight of newest New York. This, too, is good to look at. Behind a foreground of tall masts with their square rigging and mystery (symbols of the world's commerce, if you wish), looms up a wondrous bit of the towering white city of 1900, a cluster of modern high buildings which, notwithstanding the perspective of a dozen blocks, 392 are still high, enormously, alarmingly high—symbols of modern capital, perhaps, and its far-reaching possibilities, or they may remind you, in their massive grouping, of a cluster of mountains, with their bright peaks glistening in the sun far above the dark shadows of the valleys in which the streams of business flow, down to the wharves and so out over the world.

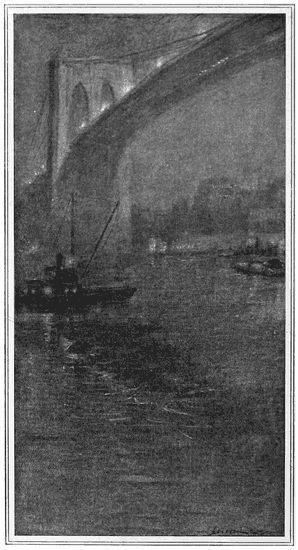

Swooping silently, confidently across from one city to the other.... Page 394.

(East River and Brooklyn Bridge.)

Now, separately they may be impossible, these high buildings of ours—these vulgar, impertinent "sky-scrapers;" but, as a group, and in perspective, they are fine, with a strong, manly beauty all their own. It is the same as with the young nation; we have grown up so fast and so far that some of our traits, when considered alone, may not be pleasing, but they appear in a different light when viewed as a whole and from the right point of view.

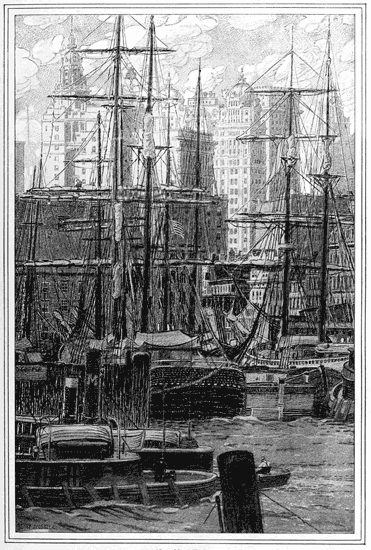

For the little scenes ... quaint and lovable, one goes down along the South Street water-front.—Page 397.

Smacks and oyster-floats near Fulton Market (At the foot of Beekman Street, East River.)

Or, on the other hand, for scenes not representatively commercial, nor residential 394 either in the sense that Riverside is, but more of the sort that the word "picturesque" suggests, to most people: There are all those odd nooks and corners, here and there up one river and down the other, popping out upon you with unexpected vistas full of life and color. Somehow the old town does not change so fast about its edges as back from the water. It seems to take a longer time to slough off the old landmarks.

The comfortable country houses along the shore, half-way up the island, first become uncomfortable city houses; then tenements, warehouses, sometimes hospitals, even police stations, before they are finally hustled out of existence to make room for a foul-smelling gas-house or another big brewery. Many of them are still standing, or tumbling down; pathetic old things they are, with incongruous cupolas and dusty fanlights and, on the river side, an occasional bit of old-fashioned garden, with a bunker which was formerly a terrace, and the dirty remains of a summer-house where children once had a good time—and still do have, different-looking children, who love the nearby water just as much and are drowned in it more numerously. It is not only by way of the recreation piers that these children and their parents enjoy the water. It is a deep-rooted instinct in human nature to walk out to the end of a dock and sit down and gaze; and hundreds of them do so every day in summer, up along here. Now and then, through these vistas you get a good view of beautiful Blackwell's Island and its prison and hospital and poorhouse buildings. Those who see it oftenest do not consider it beautiful. They always speak of it as "The Island."

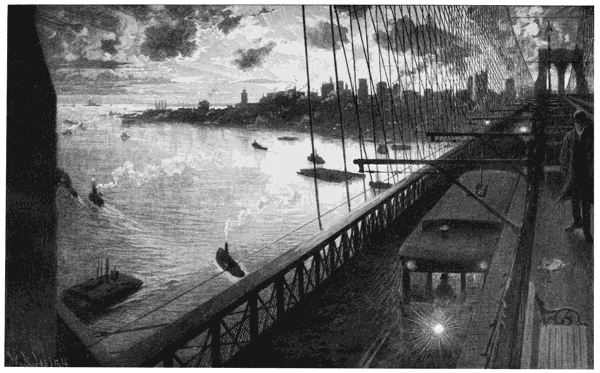

For those who do not care to prowl about for the scattered bits of interest or who prefer what Baedeker would call "a magnificent panorama," there are plenty of good points of vantage from which to see whole sections at once, such as the Statue of Liberty or the tops of high buildings, or, obviously, Brooklyn Bridge, which is so very obvious that many Manhattanese would never make use of this opportunity were it not for an occasional out-of-town visitor on their hands. No one ought to be allowed to live in New York City—he ought to be made to live in Brooklyn—who does not go out there and look back at his town once a year. He could look at it every day and get new effects of light and color. Even in sky-line he could find something new almost every week or two. In a few years there will be a more or less even line—at least a gentle undulation—instead of these raw, jagged breaks that give a disquieting sense of incompletion, or else look as if a great conflagration had eaten out the rest of the buildings.

The sky-line and its constant change can be watched to best advantage from the point of view of the Jersey commuter on the ferry; he also has some wonderful coloring to look at and some uncommon, weird effects, such as that of a late autumn afternoon (when he has missed the 5.16 and has to go out on the 6.26) and it is already quite dark, but the city is still at work and the towering office-buildings are lighted—are brilliant indeed with many perfectly even rows of light dots. The dark plays tricks with the distance, and the water is black and snaky and smells of the night. All sorts of strange flares of light and puffs of shadow come from somewhere, and altogether the commuter, if he were not so accustomed to the scene, ought not to mind being late for dinner. However, the commuter is used to this, too.

That scene is spectacular. There is another from the water that is dramatic. Possibly the pilots on the Fall River steamers become hardened, but to most of us there is an exciting delight in creeping up under that great bridge of ours and dramatically slipping through without having it fall down this time; and then looking rather boastfully back at it, swooping silently, confidently across from one city to the other, as graceful and lean and characteristically American in its line as our cup defenders, and as overwhelmingly powerful and fearless as Niagara Falls. However, much like the Thames embankment is the bit of East Fifty-ninth Street in a yellow fog, and however skilful you may be in making an occasional acre of the Bronx resemble the upper Seine, this big bridge of ours cannot very well remind anyone of anything abroad, because there aren't any others.

Even in sky-line he could find something new almost every week or two.—Page 394.

The end of the day—looking back at Manhattan from the Brooklyn Bridge.

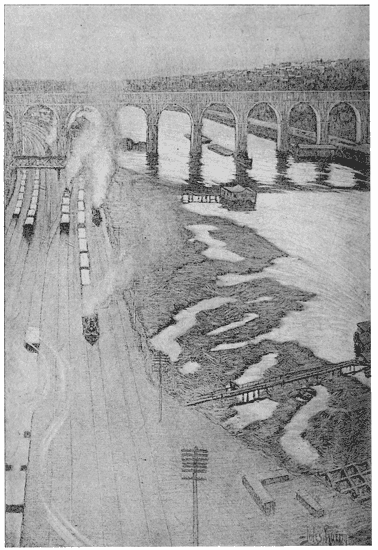

This is the tired city's playground.—Page 399.

Washington Bridge and the Speedway—Harlem River looking south.

For the little scenes that are not inspiring or awful, but simply quaint and lovable, 397 one goes down along the South Street water-front. Fulton Market with its memorable smells and the marketeers and 'longshoremen; and behind it the slip where clean-cut American-model smacks put in, and sway excitedly to the wash from the Brooklyn ferry-boats, which is not noticed by the sturdy New Haven line steamers nearby. On the edge of the street and the water are the oyster-floats, half house and half boat, which look like solid shops, with front doors, from the street side until the seas hitting them they, too, begin to sway awkwardly and startle the unaccustomed passer-by.

It is down around here that you find slouching idly in front of ship-stores, loafing on cables and anchors, the jolly jack tar of modern days. From all parts of the world he comes, any number of him if you can tell him when you see him, for he is seldom tarry and less often jolly, unless drunk on the very poor stuff he gets in the variously evil-looking dives thickly strewn along the water-fronts. Some of these are modern plate-glass saloons, but here and there is a cosy old-time tavern (with a step-down at the entrance instead of a step-up), low ceiling, dark interior, and in the window a thickly painted ship's model with flies on the rigging.

Farther down, near Wall Street ferry, where the smells of the world are gathered, you may see the stevedores unloading liqueurs and spices from tropical ports, and coffees and teas; nearby are the places where certain men make their livings tasting these teas all day long, while the horse-cars jangle by.

Old Slip and other odd-named streets are along here, where once the water came before the city outgrew its clothes, before Water Street, now two or three blocks back, had lost all right to its name. Here the big slanting bowsprits hunch away in over South Street as if trying to be quits with the land for its encroachment, and the plain old brick buildings huddled together across the way have no cornices for fear of their being poked off. Queer old buildings they are, sail lofts with their peculiar roofs, and sailors' lodging-houses, and the shops where the seaman can buy everything he needs from suspenders to anchor cables, so that after a ten-thousand mile cruise he can spend all his several months' pay within two blocks of where he first puts foot on shore and within one night from when he does so. Very often he has not energy enough to go farther or money to buy anything, thanks to the slavery system which conducts the sailors' lodging-houses across the way. There is nothing very picturesque about our modern merchant marine and its ill-used and over-worked sailors; it is only pathetic.

Those are some of the reasons, I think, why East River is more interesting to most of us than North River. Another reason, perhaps, is that East River is not a river at all, but an arm of the ocean which makes Long Island, and true to its nature in spite of man's error it holds the charm of the sea. The North River side of the town in the old days had less to do with the business of those who go down to the sea in ships; was more rural and residential and now its water-front is so jammed with railway ferry-houses and ocean steamship docks that there is little room for anything else.

However, these long, roofed docks of famous Cunarders and American and White Star Liners, and of the French steamers (which have a round roof dock of a sort all their own) are interesting in their way, too, and the names of the foreign ports at the open entrance cause a strange fret to be up and going; especially on certain days of the week when thick smoke begins to pour from the great funnels which stick out so enormously above the top story of the now noisy piers. Cabs and carriages with coachmen almost hidden by trunks and steamer-rugs crowd in through the dock-gates, while, within, the hold baggage-derricks are rattling and there is an excited chatter of good-by talk....

Here is where the town ends, and the country begins.—Page 399.

(High Bridge as seen Looking South from Washington Bridge.)

By the time you get up to Gansevoort Market, with its broad expanse of cobblestones, the steamship lines begin to thin out and the ferries are now sprinkled more sparsely. Where the avenues grow out into their teens, there are coal-yards and lumber-yards. On the warehouses and factories are great twenty-foot letters advertising soap and cereals, all of which are the best.... Farther up is the region of slaughter-houses and smells, gas-houses and their smells.... And so 399 on up to Riverside, and beyond that the unknown wildness of Manhattan's farthest north, and Fort Washington with its breastworks, which it is pleasing to see, are being visited and picnicked upon more often than formerly.

But over on the east edge of the town there is more to look at and more of a variety. All the way from the Bridge and the big white battle-ships squatting in the Navy Yard across the river; up past Kip's Bay with its dapper steam-yachts waiting to take their owners home from business; past Bellevue Hospital and its Morgue, and the antediluvian-looking United States Frigate New Hampshire moored nearby, (now used by the Naval Reserve), past Thirty-fourth Street ferry with its streams of funerals and fishing-parties; Blackwell's Island with its green grass and the young doctors and officials upon it, playing tennis obliviously; Hell Gate with its boiling tide, where so many are drowned every year; East River Park with its bit of green turf (it is too bad there are not more of these parks on our water-fronts); past Ward's Island with its public institutions; Randall's Island with more public institutions—and so up into the Harlem where soon around the bend the occasional tall mast looks very incongruous as seen across a stretch of real estate.

And now you have a totally different feel in the air and a totally different sort of "scenery." It is as different as the use it is put to. Below McComb's Dam Bridge, clear to the Battery, it was nearly all work; up here it is nearly all play.

On the banks of the river, rowing clubs, yacht clubs, bathing pavilions—they bump into each other they are so thick; on the water itself their members and their contents bump into each other on holidays—launches, barges, racing-shells and all sorts of small pleasure craft.

Near the Manhattan end of McComb's Dam Bridge are the famous fields of famous football victories, baseball championships, track games, open-air horse shows; across the bridge go the bicyclers, hordes of them, brazen braided bicyclists who use chewing gum and lean far over, and all the other varieties.

Up the river are college and school ovals and athletic fields; on the ridges upon either side are walks and paths for lovers. For the lonely pedestrian and antiquarians, two old revolutionary forts and some good colonial architecture. Whirly go-rounds and big wheels for children, groves and beer-gardens for picnickers; while down on one bank of the stream upon the broad speedway go the full-blooded trotters with their red-faced masters behind in light-colored driving coats, eyes goggled, arms extended.

On the opposite banks are the two railroads taking people to Ardsley Casino, St. Andrew's Golf Club, and the other country clubs and the pretty links at Van Cortlandt Park, and taking picnickers and family parties to Mosholu Park, and regiments and squadrons to drill and play battle in the inspection grounds nearby, and botanists and naturalists and sportsmen for their fun farther up in the good green country.

No wonder there is a different feeling in the air up along this best known end of the city's water-front. The small, unimportant looking winding river, long distance views, wooded hills, green terraces, and even the great solid masonry of High Bridge, and the asphalt and stone resting-places on Washington Bridge somehow help to make you feel the spirit of freedom and outdoors and relaxation. This is the tired city's playground.

Here is where the town ends, and the country begins.

All men who fain would pass their days

Amid old books and quiet ways,

Quaint thoughts and autumn's mellow haze,

The uses of tranquillity—

The peace you love be with your souls!

Come, fill we up our brown pipe-bowls,

And discourse to the bickering coals

Of kindness and civility.

Sirs, you remember Omar's choice—

Wine, verses, and his lady's voice

Making the wilderness rejoice?

It lacks one more ingredient.

A boon the Persian knew not of

Had made to mellower music move

The lips, to wine, perhaps to love,

A trifle too obedient.

This weed I call the herb o' grace.

My reasons are—as someone says—

Between me and the fireplace.

Ophelia spoke of rue, you know.

There's rue for you, and some for me,

But you must wear it differently.

Quite true, of course. This pipe, I see,

Draws hard. They sometimes do, you know.

Alas, if we in fancy's train

To drowse beside our fires are fain,

Letting the world slip by amain,

Uneager of its verities,

Our neighbors will not let us be

At peace with inutility.

They quote us maxims, two or three,

Or similar asperities

I question not, a man may bear

His still soul walled from noisy care,

And walk serene in places where

An ancient wrath is denizen.

The pilgrim's feet may know no ease,

And yet his heart's delight increase,

For all ways that are trod in peace

Lead upward to God's benison.

Poor ethics, these of mine, I fear;

And yet when our green leaves and sere

Have dropped away, perhaps we'll hear

Some questions answered curiously.

This battered book here on my knees?

Is Herrick, his Hesperides.

Gold apples from the guarded trees

Are stored here not penuriously.

Lyrist of mellow, gurgling phrase,

And quaint thought o' the elder days,

Loved holiness and primrose ways

About in equal quantities.

Wassail and yule-tide, feast and fair,

Blown petticoats, a child's low prayer,

And fine old pagan joy is there.

A wild-rose muse's haunt it is.

Dear herb o' grace, that kindred art

To all who choose the better part,

Grant us the Old World's childlike heart,

Now grown an antique rarity!

With Mayflowers on our swords and shields

We'll learn to babble o' green fields,

Like Falstaff, whom good humor yields

A place still in its charity.

Visions will come at times—I note

One with a cool white delicate throat—

Of names that shine on men remote,

And dreams of high endeavoring.

Care not for these, nor care to roam

Ulysses o'er the beckoning foam.

"Here rest and call content our home,"

Beside our fire's soft wavering.

THE first winter had interrupted all work upon the rock; but Taffy and his men had used the calm days of the following spring and summer to such purpose that before the end of July the foundations began to show above high-water neaps, and in September he was able to report that the building could go forward in any ordinary weather. The workmen were carried to and from the mainland by a wire hawser and cradle, and the rising breastwork of masonry protected them from the beat of the sea. Progress was slow, for each separate stone had to be dovetailed above, below, and on all sides with the blocks adjoining it, besides being cemented; and care to be taken that no salt mingled with the fresh water, or found its way into the joints of the building. Taffy studied the barometer hour by hour, and kept a constant lookout to windward against sudden gales.

On November 16th the men had finished their dinner and sat smoking under the lee of the wall and were expecting the call of the whistle when Taffy, with his pocket-aneroid in his hand, gave the order to snug down and man the cradle for shore. They stared. The morning had been a halcyon one; and the northerly breeze, which had sprung up with the turn of the tide and was freshing, carried no cloud across the sky. Two vessels, a brigantine and a three-masted schooner, were merrily reaching down channel before it, the brigantine leading; at two miles' distance they could see distinctly the white foam running from her bluff bows, and her forward deck from bulwark to bulwark as she heeled to it.

One or two grumbled. Half a day's work meant half a day's pay to them. It was all very well for the Cap'n, who drew his by the week.

"Come, look alive!" Taffy called sharply. He pinned his faith to the barometer, and as he shut it in its case he glanced at the brigantine and saw that her crew were busy with the braces, flattening the forward canvas. "See there, boys. There'll be a gale from the west'ard before night."

For a minute the brigantine seemed to have run into a calm. The schooner, half a mile behind her, came reaching along steadily.

"That there two-master's got a fool for skipper," grumbled a voice. But almost at the moment the wind took her right aback—or would have done so had the crew not been preparing for it. Her stern swung slowly around into view, and within two minutes she was fetching away from them on the port tack, her sails hauled closer and closer as she went. Already the schooner was preparing to follow suit.

"Snug down, boys! We must be out of this in half an hour."

And sure enough, by the time Taffy gained the cliff by the old light-house the sky had darkened and a stiff breeze from the northwest, crossing the tide, was beginning to work up a nasty sea around the rock and top it from time to time over the masonry and the platforms where, half an hour before, his men had been standing. The two vessels had disappeared in the weather; and as Taffy stared in the direction a spit of rain—the first—took him viciously in the face.

He turned his back to it and hurried homeward. As he passed the light-house door old Pezzack called out to him:

"Hi! wait a bit! Would 'ee mind seein' Joey home? I dunna what his mother sent him over here for, not I. He'll get hisself leakin'."

Joey came hobbling out and put his right hand in Taffy's with the fist doubled. 403

"What's that in your hand?"

Joey looked up shyly. "You won't tell?"

"Not if it's a secret."

The child opened his palm and disclosed a bright half-crown piece.

"Where on earth did you get that?"

"The soldier gave it to me."

"The soldier? nonsense! What tale are you making up?"

"Well, he had a red coat, so he must be a soldier. He gave it to me and told me to be a good boy and run off and play."

Taffy came to a halt. "Is he here—up at the cottages?"

"How funnily you say that! No, he's just rode away. I watched him from the light-house windows. He can't be gone far yet."

"Look here, Joey—can you run?"

"Yes, if you hold my hand; only you mustn't go too fast. Oh, you're hurting!"

Taffy took the child in his arms, and with the wind at his back, went up the hill with long stride. "There he is!" cried Joey as they gained the ridge; and he pointed; and Taffy, looking along the ridge, saw a speck of scarlet moving against the lead-colored moors—half a mile away perhaps, or a little more. He sat the child down, for the cottages were close by. "Run home, sonny. I'm going to have a look at the soldier, too."

The first bad squall broke on the headland just as Taffy started to run. It was as if a bag of water had burst right overhead, and within quarter of a minute he was drenched to the skin. So fiercely it went howling inland along the ridge that he half-expected to see the horse urged into a gallop before it. But the rider, now standing high for a moment against the sky-line, went plodding on. For a while horse and rider disappeared over the rise; but Taffy guessed that on hitting the cross-path beyond, they would strike away to the left and descend toward Langona Creek; and he began to slant his course to the left in anticipation. The tide, he knew, would be running in strong; and with this wind behind it he hoped—and caught himself praying—that it would be high enough to cover the wooden footbridge and make the ford impassable; and if so, the horseman would be delayed and forced to head back and fetch a circuit farther up the valley.

By this time the squalls were coming fast on each other's heels and the strength of them flung him forward at each stride. He had lost his hat, and the rain poured down his back and squished in his boots. But all he felt was the hate in his heart. It had gathered there little by little for three years and a half, pent up, fed by his silent thoughts as a reservoir by small mountain-streams; and with so tranquil a surface that at times—poor youth!—he had honestly believed it reflected God's calm, had been proud of his magnanimity, and said "forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us." Now as he ran he prayed to the same God to delay the traitor at the ford.

Dusk was falling when George, yet unaware of pursuit, turned down the sunken lane which ended beside the ford. And by the shore, when the small waves lapped against his mare's fore-feet, he heard Taffy's shout for the first time and turned in his saddle. Even so it was a second or two before he recognized the figure which came plunging down the low cliff on his left, avoiding a fall only by wild clutches at the swaying alder boughs.

"Hello!" he shouted, cheerfully. "Looks nasty, doesn't it?"

Taffy came down the beach, near enough to see that the mare's legs were plastered with mud, and to look up into his enemy's face.

"Get down," he panted.

"Hey?"

"Get down, I tell you. Come off your horse, and put up your fists."

"What the devil is the matter? Hello!... Keep off, I tell you! Are you mad?"

"Come off and fight."

"By God, I'll break your head in if you don't let go.... You idiot!"—as the mare plunged and tore the stirrup-leather from Taffy's grip—"She'll brain you, if you fool round her heels like that!"

"Come off, then."

"Very well." George backed a little, swung himself out of the saddle and faced him on the beach. "Now perhaps you'll explain."

"You've come from the headland?"

"Well?"

"From Lizzie Pezzack's." 404

"Well, and what then?"

"Only this, that so sure as you've a wife at home, if you come to the headland again, I'll kill you; and if you're a man, you'll put up your fists now."

"Oh, that's it? May I ask what you have to do with my wife, or with Lizzie Pezzack?"

"Whose child is Lizzie's?"

"Not yours, is it?"

"You said so once; you told your wife so; liar that you were."

"Very good, my gentleman. You shall have what you want. Woa, mare!" He led her up the beach and sought for a branch to tie his reins to. The mare hung back, terrified by the swishing of the whipped boughs and the roar of the gale overhead; her hoofs, as George dragged her forward, scuffled with the loose-lying stones on the beach. After a minute he desisted and turned on Taffy again.

"Look here; before we have this out there's one thing I'd like to know. When you were at Oxford, was Honoria maintaining you there?"

"If you must know—yes."

"And when—when this happened, she stopped the supplies."

"Yes."

"Well, then, I didn't know it. She never told me."

"She never told me."

"You don't say——"

"I do. I never knew it until too late."

"Well, now, I'm going to fight you. I don't swallow being called a liar. But I tell you this first, that I'm damned sorry. I never guessed that it injured your prospects."

At another time, in another mood, Taffy might have remembered that George was George, and heir to Sir Harry's nature. As it was, the apology threw oil on the flame.

"You cur! Do you think it was that? And you are Honoria's husband!" He advanced with an ugly laugh. "For the last time, put up your fists."

They had been standing within two yards of each other; and even so, shouted at the pitch of their voices to make themselves heard above the gale. As Taffy took a step forward George lifted his whip. His left hand held the bridle on which the reluctant mare was dragging, and the action was merely instinctive, to guard against sudden attack.

But as he did so his face and uplifted arm were suddenly painted clear against the darkness. The mare plunged more wildly than ever. Taffy dropped his hands and swung round. Behind him, behind the black contour of the hill, the whole sky welled up a pale blue light which gathered brightness while he stared.

The very stones on the beach at his feet shone separate and distinct.

"What is it?" George gasped.

"A ship on the rocks! Quick, man! Will the mare reach to Innis?"

"She'll have to." George wheeled her round. She was fagged out with two long gallops after hounds that day, but for the moment sheer terror made her lively enough.

"Ride, then! Call up the coast-guard. By the flare she must be somewhere off the creek here. Ride!"

A clatter of hoofs answered him as the mare pounded up the lane.

Taffy stood for a moment listening. He judged the wreck to be somewhere on the near side of the light-house, between it and the mouth of the creek; that was, if she had already struck. If not, the gale and the set of the tide together would be sweeping her eastward, perhaps right across the mouth of the creek. And if he could discover this, his course would be to run back, intercept the coast-guard and send them around by the upper bridge.

He waited for a second signal to guide him—a flare or a rocket; but none came. The beach lay in the lew of the weather, deep in the hills' hollow and trebly landlocked by the windings of the creek; but above him the sky kept its screaming as though the bare ridges of the headland were being shelled by artillery.

He resolved to keep along the lower slopes and search his way down to the creek's mouth, when he would have sight of any signal shown along the coast for a 405 mile or two to the east and northeast. The night was now as black as a wolf's throat; but he knew every path and fence. So he scrambled up the low cliff and began to run, following the line of stunted oaks and tamarisks which fenced it; and on the ridges—where the blown hail took him in the face—crouching and scuttling like a crab, sideways, moving his legs only from the knees down.

In this way he had covered half a mile and more when his right foot plunged in a rabbit hole and he was pitched headlong into the tamarisks below. Their boughs bent under his weight; but they were tough, and he caught at them and just saved himself from rolling over into the black water. He picked himself up and began to rub his twisted ankle. And at that instant, in a lull between two gusts, his ear caught the sound of splashing—yet a sound so unlike the lapping of the driven tide that he peered over and down between the tamarisk boughs.

"Hullo there!"

"Hullo!" a voice answered. "Is that someone alive? Here, mate—for Christ's sake!"

"Hold on! Whereabouts are you?"

"Down in this here cruel water." The words ended in a shuddering cough.

"Right—hold on a moment!" Taffy's ankle pained him, but the wrench was not serious. The cliff shelved easily. He slid down, clutching at the tamarisk boughs which whipped his face. "Where are you? I can't see."

"Here!" The voice was not a dozen yards away.

"Swimming?"

"No—I've got a water-breaker—can't hold on much longer."

"I believe you can touch bottom there."

"Hey? I can't hear."

"Try to touch bottom. It's firm sand hereabouts."

"So I can." The splashing and coughing came nearer, came close. Taffy stretched out a hand. A hand, icy-cold, fumbled and gripped it in the darkness.

"Christ! Where's a place to lie down?"

"Here, on this rock." They peered at each other, but could not see. The man's teeth chattered close to Taffy's ear.

"Warm my hands, mate—there's a good chap." He lay on the rock and panted. Taffy took his hands and began to rub them briskly.

"Where's the ship?"

"Where's the ship?" He seemed to turn over the question in his mind, and then stretched himself with a sigh. "How the hell should I know?"

"What's her name?" Taffy had to ask the question twice.

"The Samaritan of Newport, brigantine. Coals she carried. Ha'n't you such a thing as a match? It seems funny to me, talkin' here like this, and me not knowin' you from Adam."

He panted between the words, and when he had finished, lay back and panted again.

"Hurt?" asked Taffy, after a while.

The man sat up and began to feel his limbs, quite as though they belonged to some other body. "No, I reckon not."

"Then we'd best be starting. The tide's rising. My house is just above here."

He led the way along the slippery foreshore until he found what he sought, a foot-track slanting up the cliff. Here he gave the sailor a hand and they mounted together. On the grass slope above they met the gale and were forced to drop on their hands and knees and crawl, Taffy leading and shouting instructions, the sailor answering each with "Ay, ay, mate!" to show that he understood.

But about half way up, these answers ceased, and Taffy, looking round and calling, found himself alone. He groped his way back for twenty yards, and found the man stretched on his face and moaning.

"I can't ... I can't! My poor brother! I can't!"

Taffy knelt beside him on the soaking turf. "Your brother? Had you a brother on board?"

The man bowed his face again upon the turf. Taffy, upright on both knees, heard him sobbing like a child in the roaring darkness.

"Come," he coaxed; and putting out a hand touched his wet hair. "Come—." They crept forward again; but still as he followed, the sailor cried for his drowned brother; up the long slope to the ridge of the headland where, with the light-house and warm cottage windows in view, all speech 406 and hearing were drowned by stinging hail and the blown grit of the causeway.

Humility opened the door to them.

"Taffy! Where have you been?"

"There has been a wreck."

"Yes, yes—the coast-guard is down by the light-house. The men there saw her before she struck. They kept signalling till it fell dark. They had sent off before that."

She drew back, shrinking against the dresser as the lamplight fell on the stranger. Taffy turned and stared, too. The man's face was running with blood; and looking at his own hands he saw that they also were scarlet.

He helped the poor wretch to a chair.

"Bandages—can you manage?" She nodded, and stepped to a cupboard. The sailor began to wail like an infant.

"See—above the temple here: the cut isn't serious." Taffy took down a lantern and lit it. The candle shone red through the smears his fingers left on the horn panes. "I must go and help, if you can manage."

"I can manage," she answered, quietly.

He strode out, and closing the door behind him with an effort, faced the gale again. Down in the lee of the light-house the lamps of the coast-guard carriage gleamed foggily through the rain. The men were there discussing, and George among them. He had just galloped up.

The Chief Officer went off to question the survivor, while the rest began their search. They searched all that night; they burned flares and shouted; their torches dotted the cliffs. After an hour the Chief Officer returned. He could make nothing of the sailor, who had fallen silly from exhaustion or the blow on his head; but he divided his men into three parties, and they began to hunt more systematically. Taffy was told off to help the westernmost gang and search the rocks below the light-house. Once or twice he and his comrades paused in their work, hearing, as they thought, a cry for help. But when they listened, it was only one of the other parties hailing.

The gale began to abate soon after midnight, and before dawn had blown itself out. Day came filtered slowly through the wrack of it to the southeast; and soon they heard a whistle blown, and there on the cliff above them was George Vyell on horseback, in his red coat, with an arm thrown out and pointing eastward. He turned and galloped off in that direction.

They scrambled up and followed. To their astonishment, after following the cliffs for a few hundred yards, he headed inland, down and across the very slope up which Taffy had crawled with the sailor.

They lost sight of his red coat among the ridges. Two or three—Taffy amongst them—ran along the upper ground for a better view.

"Well, this beats all!" panted the foremost.

Below them George came into view again, heading now at full gallop for a group of men gathered by the shore of the creek, a good half-mile from its mouth. And beyond—midway across the sandy bed where the river wound—lay the hull of a vessel, high and dry; her deck, naked of wheel-house and hatches, canted toward them as if to cover from the morning the long wounds ripped by her uprooted masts.

The men beside him shouted and ran on, but Taffy stood still. It was monstrous—a thing inconceivable—that the seas should have lifted a vessel of three hundred tons and carried her half a mile up that shallow creek. Yet there she lay. A horrible thought seized him. Could she have been there last night when he had drawn the sailor ashore? And had he left four or five others to drown close by, in the darkness? No, the tide at that hour had scarcely passed half-flood. He thanked God for that.

Well, there she lay, high and dry, with plenty to attend to her. It was time for him to discover the damage done to the light-house plant and machinery, perhaps to the building itself. In half an hour the workmen would be arriving.

He walked slowly back to the house, and found Humility preparing breakfast.

"Where is he?" Taffy asked, meaning the sailor. "In bed?"

"Didn't you meet him? He went out five minutes ago—I couldn't keep him—to look for his brother, he said."

Taffy drank a cupful of tea, took up a crust, and made for the door.

"Go to bed, dear," his mother pleaded. "You must be worn out." 407

"I must see how the works have stood it."

On the whole, they had stood it well. The gale, indeed, had torn away the wire cable and cage, and thus cut off for the time all access to the outer rock; for while the sea ran at its present height the scramble out along the ridge could not be attempted even at low water. But from the cliff he could see the worst. The waves had washed over the building, tearing off the temporary covers, and churning all within. Planks, scaffolding—everything floatable—had gone, and strewed the rock with match-wood; and—a marvel to see—one of his two heaviest winches had been lifted from inside, hurled clean over the wall, and lay collapsed in the wreckage of its cast-iron frame. But, so far as he could see, the dove-tailed masonry stood intact. A voice hailed him.

"What a night! What a night!"

It was old Pezzack, aloft on the gallery of the light-house in his yellow oilers, already polishing the lantern-panes.

Taffy's workmen came straggling and gathered about him. They discussed the damage together but without addressing Taffy; until a little pock-marked fellow, the wag of the gang, nudged a mate slyly and said aloud:

"By God, Bill, we can build a bit—you and me and the boss!"

All the men laughed; and Taffy laughed, too, blushing. Yes; this had been in his mind. He had measured his work against the sea in its fury, and the sea had not beaten him.

A cry broke in upon their laughter. It came from the base of the cliff to the right—a cry so insistent that they ran toward it in a body.

Far below them, on the edge of a great bowlder which rose from the broken water and seemed to overhang it, stood the rescued sailor. He was pointing.

Taffy was the first to reach him.

"It's my brother! It's my brother Sam!"

Taffy flung himself full length on the rock and peered over. A tangle of ore-weed awash rose and fell about its base; and from under this, as the frothy waves drew back, he saw a man's ankle protruding, and a foot still wearing a shoe.

"It's my brother!" wailed the sailor again. "I can swear to the shoe of en!"

One of the masons lowered himself into the pool, and thrusting an arm beneath the ore-weed, began to grope.

"He's pinned here. The rock's right on top of him."

Taffy examined the rock. It weighed fifteen tons if an ounce; but there were fresh and deep scratches upon it. He pointed these out to the men, who looked and felt them with their hands and stared at the subsiding waves, trying to bring their minds to the measure of the spent gale.

"Here, I must get out of this!" said the man in the pool, as a small wave dashed in and sent its spray over his bowed shoulders.

"You ban't going to leave en," wailed the sailor. "You ban't going to leave my brother Sam."

He was a small, fussy man, with red whiskers; and even his sorrow gave him little dignity. The men were tender with him.

"Nothing to be done till the tide goes back."

"But you won't leave en? Say you won't leave en! He've a wife and three childern. He was a saved man, sir, a very religious man; not like me, sir. He was highly respected in the neighborhood of St. Austell. I shouldn't wonder if the newspapers had a word about en...." The tears were running down his face.

"We must wait for the tide," said Taffy, gently, and tried to lead him away, but he would not go. So they left him to watch and wait while they returned to their work.

Before noon they recovered and fixed the broken wire cable. The iron cradle had disappeared, but to rig up a sling and carry out an endless line was no difficult job, and when this was done Taffy crossed over to the island rock and began to inspect damages. His working gear had suffered heavily, two of his windlasses were disabled, scaffolding, platforms, hods, and loose planks had vanished; a few 408 small tools only remained mixed together in a mash of puddled lime. But the masonry stood unhurt, all except a few feet of the upper course on the seaward side, where the gale, giving the cement no time to set, had shaken the dove-tailed stones in their sockets—a matter easily repaired.

Shortly before three a shout recalled them to the mainland. The tide was drawing toward low water, and three of the men set to work at once to open a channel and drain off the pool about the base of the big rock. While this was doing, half a dozen splashed in with iron bars and pickaxes; the rest rigged two stout ropes with tackles, and hauled. The stone did not budge. For more than an hour they prized and levered and strained. And all the while the sailor ran to and fro, snatching up now a pick and now a crowbar, now lending a hand to haul and again breaking off to lament aloud.

The tide turned, the winter dark came down, and at half-past four Taffy gave the word to desist. They had to hold back the sailor, or he would have jumped in and drowned beside his brother.

Taffy slept little that night, though he needed sleep. The salving of this body had become almost a personal dispute between the sea and him. The gale had shattered two of his windlasses; but two remained, and by one o'clock next day he had both slung over to the mainland and fixed beside the rock. The news spreading inland fetched two or three score onlookers before ebb of tide—miners for the most part, whose help could be counted on. The men of the coast-guard had left the wreck, to bear a hand if needed. George had come, too. And, happening to glance upward while he directed his men, Taffy saw a carriage with two horses drawn up on the grassy edge of the cliff, a groom at the horses' heads and in the carriage a figure seated, silhouetted there high against the clear blue heaven. Well he recognized, even at that distance, the poise of her head, though for two whole years he had never set eyes on her, nor wished to.

He knew that her eyes were on him now. He felt like a general on the eve of an engagement. By the almanac the tide would not turn until 4.35. At four, perhaps, they could begin; but even at four the winter twilight would be on them, and he had taken care to provide torches and distribute them among the crowd. His own men were making the most of the daylight left, drilling holes for dear life in the upper surface of the bowlder fixing the Lewis-wedges and rings. They looked to him for every order, and he gave it in a clear, ringing voice which he knew must carry to the cliff-top. He did not look at George.

He felt sure in his own mind that the wedges and rings would hold; but to make doubly sure he gave orders to loop an extra chain under the jutting base of the bowlder. The mason who fixed it, standing waist-high in water as the tide ebbed, called for a rope and hitched it round the ankle of the dead man. The dead man's brother jumped down beside him and grasped the slack of it.

At a signal from Taffy the crowd began to light their torches. He looked at his watch, at the tide, and gave the word to man the windlasses. Then with a glance toward the cliff he started the working-chant—"Ayee-ho! Ayee-ho!" The two gangs—twenty men to each windlass—took it up with one voice, and to the deep intoned chant the chains tautened, shuddered for a moment, and began to lift.

"Ayee-ho!"

Silently, irresistibly, the chain drew the rock from its bed. To Taffy it seemed an endless time, to the crowd but a few moments, before the brute mass swung clear. A few thrust their torches down toward the pit where the sailor knelt. Taffy did not look, but gave the word to pass down the coffin which had been brought in readiness. A clergyman—his father's successor, but a stranger to him—climbed down after it; and he stood in the quiet crowd watching the light-house above and the lamps which the groom had lit in Honoria's carriage, and listening to the bated voices of the few at their dreadful task below.

It was five o'clock and past before the word came up to lower the tackle and draw the coffin up. The Vicar clambered out to wait it, and when it came, borrowed a lantern and headed the bearers. The crowd fell in behind.

"I am the resurrection and the life...." 409

They began to shuffle forward and up the difficult track; but presently came to a halt with one accord, the Vicar ceasing in the middle of a sentence.

Out of the night, over the hidden sea, came the sound of man's voices lifted, thrilling the darkness thrice: the sound of three British cheers.

Whose were the voices? They never knew. A few had noticed as twilight fell a brig in the offing, standing inshore as she tacked down channel. She, no doubt, as they worked in their circle of torchlight, had sailed in close before going about, her crew gathered forward, her master perhaps watching through his night-glass; had guessed the act, saluted it, and passed on her way unknown to her own destiny.

They strained their eyes. A man beside Taffy declared he could see something—the faint glow of a binnacle lamp as she stood away. Taffy could see nothing. The voice ahead began to speak again. The Vicar, pausing now and again to make sure of his path, was reading from a page which he held close to his lantern.

"Thine eyes shall see the King in his beauty; they shall behold the land that is very far off.

"Thou shalt not see a fierce people, a people of deeper speech than thou canst perceive; of a stammering tongue that thou canst not understand.

"But there the glorious Lord will be unto us a place of broad rivers and streams; wherein shall go no galley with oars, neither shall gallant ship pass thereby.

"For the Lord is our judge, the Lord is our lawgiver, the Lord is our king; he will save us.

"Thy tacklings are loosed; they could not well strengthen their mast, they could not spread the sail; there is the prey of a great spoil divided; the lame take the prey."

Here the Vicar turned back a page and his voice rang higher:

"Behold, a king shall reign in righteousness, and princes shall rule in judgment.

"And a man shall be as an hiding place from the wind, and a covert from the tempest; as rivers of water in a dry place, as the shadow of a great rock in a weary land.

"And the eyes of them that see shall not be dim, and the ears of them that hear shall hearken."

Now Taffy walked behind, thinking his own thoughts; for the cheers of those invisible sailors had done more than thrill his heart. A finger, as it were, had come out of the night and touched his brain, unsealing the wells and letting in light upon things undreamt of. Through the bright confusion of this sudden vision the Vicar's sentences sounded and fell on his ears unheeded. And yet while they faded that happened which froze and bit each separate word into his memory, to lose distinctness only when death should interfere, stop the active brain and wipe the slate.

For while the procession halted and broke up its formation for a moment on the brow of the cliff, a woman came running into the torchlight.

"Is my Joey there? Where's he to, anybody? Hev anyone seen my Joey?"

It was Lizzie Pezzack, panting and bareheaded, with a scared face.

"He's lame—you'd know en. Have'ee got en there? He's wandered off!"

"Hush up, woman," said a bearer. "Don't keep such a pore."

"The cheeld's right enough somewheres," said another. "'Tis a man's body we've got. Stand out of the way, for shame!"

But Lizzie, who, as a rule, shrank away from men and kept herself hidden, pressed nearer, turning her tragical face upon each in turn. Her eyes met George's; but she appealed to him as to the others.

"He's wandered off. Oh, say you've seen en, somebody!"

Catching sight of Taffy she ran and gripped him by the arm.

"You'll help! It's my Joey. Help me find en!"

He turned half about; and almost before he knew what he sought, his eyes met George's. George stepped quietly to his side.

"Let me get my mare," said George, and walked away toward the light-house railing where he had tethered her.

"We'll find the child. Our work's done here. Mr. Saul!" Taffy turned to the Chief Officer—"Spare us a man or two and some flares."

"I'll come myself," said the Chief Officer. "Go you back, my dear, and we'll fetch home your cheeld as right as ninepence. 410 Hi, Rawlings, take a couple of men and scatter along the cliffs there to the right. Lame, you say? He can't have gone far."

Taffy, with the Chief Officer and a couple of volunteers, moved off to the left, and in less than a minute George caught them up, on horseback.

"I say," he asked, walking his mare close alongside of Taffy, "you don't think this serious, eh?"

"I don't know. Joey wasn't in the crowd, or I should have noticed him. He's daring beyond his strength." He pulled a whistle from his pocket, blew it twice and listened. This had been his signal when firing a charge; he had often blown it to warn the child to creep away into shelter.

There was no answer.

"Mr. Vyell had best trot along the upper slope," the Chief Officer suggested, "while we search down by the creek."

"Wait a moment," Taffy answered. "Let's try the wreck first."

"But the tide's running. He'd never go there."

"He's a queer child. I know him better than you."

They ran downhill toward the creek, calling as they went, but getting no answer.

"But the wreck!" exclaimed the Chief Officer. "It's out of reason!"

"Hi! What was that?"

"Oh, my good Lord," groaned one of the volunteers, "it's the crake, master! It's Langona crake, calling the drowned!"

"Hush, you fool! Listen—I thought as much! Light a flare, Mr. Saul—he's out there calling!"

The first match sputtered and went out. They drew close around the Chief Officer while he struck the second, to keep off the wind, and in those few moments the child's wail reached them distinctly across the darkness.

The flame leapt up and shone, and they drew back a pace, shading their eyes from it and peering into the steel-blue landscape which sprang on them out of the night. They had halted a few yards only from the cliff, and the flare cast the shadow of its breast-high fence of tamarisks forward and almost half-way across the creek; and there on the sands, a little beyond the edge of this shadow, stood the child.

They could even see his white face. He stood on an island of sand, around which the tide swirled in silence, cutting him off from shore, cutting him off from the wreck behind. He did not cry any more, but stood with his crutch planted by the edge of the widening stream, and looked toward them.

And Taffy looked at George.

"I know," said George, and gathered up his reins. "Stand aside, please."

As they drew aside, not understanding, he called to his mare. One living creature, at any rate, could still trust all to George Vyell. She hurtled past them and rose at the tamarisk hedge blindly. Silence followed—a long silence; then a thud on the beach below and a scuffle of stones; silence again, and then the cracking of twigs as Taffy plunged after, through the tamarisks, and slithered down the cliff.

The light died down as his feet touched the flat slippery stones; died down, and was renewed again and showed up horse and rider, scarce twenty yards ahead, laboring forward, the mare sinking fetlock deep at every plunge.

At his fourth stride Taffy's feet, too, began to sink; but at every stride he gained something. The riding may be superb, but thirteen stone is thirteen stone. Taffy weighed less than eleven.

He caught up with George on the very edge of the water. "Make her swim it!" he panted; "her feet mustn't touch here." George grunted. A moment later all three were in the water, the tide swirling them sideways, sweeping Taffy against the mare. His right hand touched her flank at every stroke.

The tide swept them upward—upward for fifteen yards at least; though the channel measured less than eight feet. The child, who had been standing opposite the point where they took the water, hobbled wildly along shore. The light on the cliff behind sank and rose again.

"The crutch," Taffy gasped. The child obeyed, laying it flat on the brink and pushing it toward them. Taffy gripped it with his left hand, and with his right found the mare's bridle. George was bending forward.

"No—not that way! You can't go back! The wreck, man!—it's firmer——"

But George reached out his hand and 411 dragged the child toward him and onto his saddle-bow. "Mine," he said, quietly, and twitched the rein. The brave mare snorted, jerked the bridle from Taffy's hand, and headed back for the shore she had left.

Rider, horse, and child seemed to fall away from him into the night. He scrambled out, and snatching the crutch, ran along the brink, staring at their black shadows. By and by the shadows came to a standstill. He heard the mare panting, the creaking of saddle-leather came across the nine or ten feet of dark water.

"It's no go," said George's voice; then to the mare, "Sally, my dear, it's no go." A moment later he asked more sharply,

"How far can you reach?"

Taffy stepped in until the waves ran by his knees. The sand held his feet, but beyond this he could not stand against the current. He reached forward, holding the crutch at arm's length.

"Can you catch hold?"

"All right." Both knew that swimming would be useless now; they were too near the upper apex of the sand-bank.

"The child first. Here, Joey, my son, reach out and catch hold for your life!"

Taffy felt the child's grip on the crutch-head, and drawing it steadily toward him, hauled the poor child through. The light from the cliff sank and rose on his scared face.

"Got him?"

"Yes." The sand was closing around Taffy's legs, but he managed to shift his footing a little.

"Quick, then; the bank's breaking up."

George was sinking, knee-deep and deeper. But his outstretched fingers managed to reach and hook themselves around the crutch-head.

"Steady, now ... must work you loose first. Get hold of the shaft if you can; the head isn't firm. Work your legs ... that's it."

George wrenched his left foot loose and planted it against the mare's flank. Hitherto the brute had trusted her master. The thrust of his heel drove home her sentence, and with scream after scream—the sand holding her past hope—she plunged and fought for her life. Still as she screamed, George, silent and panting, thrust against her, thrust savagely against the quivering body, once his pride for beauty and fleetness.

"Pull!" he gasped, freeing his other foot with a wrench which left its heavy riding-boot deep in the sucking mud; and catching a new grip on the crutch-head, flung himself forward.

Taffy felt the sudden weight and pulled—and while he pulled felt in a moment no grip, no weight at all. Between two hateful screams a face slid by him, out of reach, silent, with parted lips; and as it slipped away he fell back staggering, grasping the useless, headless crutch.

The mare went on screaming. He turned his back on her, and catching Joey by the hand, dragged him away across the melting island. At the sixth step the child, hauled off his crippled foot, swung blundering across his legs. He paused, lifted him in his arms, and plunged forward again.

The flares on the cliff were growing in number. They cast long shadows before him. On the far side of the island the tide flowed swift and steady—a stream about fourteen yards wide—cutting him from the sand-bank on which, not fifty yards above, lay the wreck. He whispered to Joey, and plunged into it straight, turning as the water swept him off his legs, and giving his back to it, his hands slipped under the child's armpits, his feet thrusting against the tide in slow rhythmical strokes.

The child after the first gasp lay still, his head obediently thrown back on Taffy's breast. The mare had ceased to scream. The water rippled in the ears as each leg-thrust drove them little by little across the current.

If George had but listened! It was so easy, after all. The sand-bank still slid past them, but less rapidly. They were close to it now and had only to lie still and be drifted against the leaning stanchions of the wreck. Taffy flung an arm about one and checked his way quietly, as a man brings a boat alongside a quay. He hoisted Joey first upon the stanchion, then up the tilted deck to the gap of the main hatchway. Within this, with their feet on the steps and their chests leaning on the side panel of the companion, they rested and took breath.

"Cold, sonny?" 412

The child burst into tears.

Taffy dragged off his own coat and wrapped him in it. The small body crept close, sobbing against his side.

Across, on the shore, voices were calling, blue eyes moving. A pair of yellow lights came toward these, travelling swiftly upon the hill-side. Taffy guessed what they were.

The yellow lights moved more slowly. They joined the blue ones, and halted. Taffy listened. But the voices were still now; he heard nothing but the hiss of the black water across which those two lamps sought and questioned him like eyes.

"God help her!"

He bowed his face on his arms. A little while, and the sands would be covered, the boats would put off; a little while.... Crouching from those eyes he prayed God to lengthen it.

She was sitting there rigid, cold as a statue, when the rescuers brought them ashore and helped them up the slope. A small crowd surrounded the carriage. In the rays of their moving lanterns her face altered nothing, to all their furtive glances of sympathy opposing the same white mask. Someone said, "There's only two, then!" Another with a nudge and a nod at the carriage, told him to hold his peace. She heard. Her lips hardened.

Lizzie Pezzack had rushed down to the shore to meet the boat. She was bringing her child along with a fond wild babble of tender names and sobs and cries of thankfulness. In pauses, choked and overcome, she caught him to her, felt his limbs, pressed his wet face against her neck and bosom. Taffy, supported by strong arms and hurried in her wake, had a hideous sense of being paraded in her triumph. The men around him who had raised a faint cheer, sank their voices as they neared the carriage; but the woman went forward, jubilant and ruthless, flaunting her joy as it were a flag blown in her eyes and blindfolding them to the grief she insulted.

"Stay!"

It was Honoria's voice, cold, incisive, not to be disobeyed. He had prayed in vain. The procession halted; Lizzie checked her babble and stood staring, with an arm about Joey's neck.

"Let me see the child."

Lizzie stared, broke into a silly triumphant laugh, and thrust the child forward against the carriage-step. The poor waif, drenched, dazed, tottering without his crutch, caught at the plated handle for support. Honoria gazed down on him with eyes which took slow and pitiless account of the deformed little body, the shrunken, puny limbs.

"Thank you. So—this—is what my husband died for. Drive on, please."

Her eyes, as she lifted them to give the order, rested for a moment on Taffy—with how much scorn he cared not, could he have leapt and intercepted Lizzie's retort.

"And why not? A son's a son—curse you!—though he was your man!"

It seemed she did not hear; or hearing, did not understand. Her eyes hardened; their fire on Taffy and he, lapped in their scorn, thanked God she had not understood.

"Drive on, please."

The coachman lowered his whip. The horses moved forward at a slow walk; the carriage rolled silently away into the darkness. She had not understood. Taffy glanced at the faces about him.

"Ah, poor lady!" said someone. But no one had understood.

They found George's body next morning on the sands a little below the footbridge. He lay there in the morning sunshine as though asleep, with an arm flung above his head and on his face the easy smile for which men and women had liked him throughout his careless life.

The inquest was held next day, in the library at Carwithiel. Sir Harry insisted on being present and sat beside the coroner. During Taffy's examination his lips were pursed up as though whistling a silent tune. Once or twice he nodded his head.

Taffy gave his evidence discreetly. The child had been lost; had been found in a perilous position. He and deceased had gone together to the rescue. On reaching 413 the child, deceased—against advice—had attempted to return across the sands and had fallen into difficulties. In these his first thought had been for the child, whom he had passed to witness to drag out of danger. When it came to deceased's turn, the crutch, on which all depended, had parted in two and he had been swept away by the tide.

At the conclusion of the story Sir Harry took snuff and nodded twice. Taffy wondered how much he knew. The jury, under the coroner's direction, brought in a verdict of "death by misadventure," and added a word or two in praise of the dead man's gallantry. The coroner complimented Taffy warmly and promised to refer the case to the Royal Humane Society for public recognition. The jury nodded and one or two said, "Hear, hear!" Taffy hoped fervently he would do nothing of the sort.

The funeral took place on the fourth day, at nine o'clock in the morning. Such—in the days I write of—was the custom of the country. Friends who lived at a distance rose and shaved by candle-light, and daybreak found them horsed and well on way toward the house of mourning, their errand announced by the long black streamers tied about their hats. Their sad business over and done with, these guests returned to the house, where, until noon, a mighty breakfast lasted and all were welcome. Their black habiliments' and lowered voices alone marked the difference between it and a hunting-breakfast.

And indeed this morning Squire Willyams, who had taken over the hounds after Squire Moyle's death, had given secret orders to his huntsman; and the pack was waiting at Three-barrow Turnpike, a couple of miles inland from Carwithiel. At half-past ten the mourners drained their glasses, shook the crumbs off their riding-breeches, and took leave; and after halting outside Carwithiel gates to unpin and pocket their hatbands, headed for the meet with one accord.

A few minutes before noon Squire Willyams, seated on his gray by the edge of Three-barrow Brake and listening to every sound within the covert, happened to glance an eye across the valley, and let out a low whistle.

"Well!" said one of a near group of horsemen catching sight of the rider pricking toward them down the farther slope, "I knew en for an unbeliever; but this beats all."

"And his awnly son not three hours under the mould! Brought up in France as a youngster he was, and this I s'pose is what comes of reading Voltaire. My lord for manners and no more heart than a wormed nut—that's Sir Harry and always was."

Squire Willyams slewed himself round in his saddle. He spoke quietly at fifteen yards' distance, but each word reached the group of horsemen as clear as a bell.

"Rablin," he said, "as a damned fool oblige me during the next few minutes by keeping your mouth shut."

With this he resumed his old attitude and his business of watching the covert side; removing his eyes for a moment to nod as Sir Harry rode up and passed on to join the group behind him.

He had scarcely done so when deep in the undergrowth of blackthorn a hound challenged.

"Spendigo for a fiver!—and well found, by the tune of it. See that patch of gray wall, Rablin—there in a line beyond the Master's elbow? I lay you an even guinea that's where my gentleman comes over, and inside of sixty seconds."

But honest reprobation mottled the face of Mr. Rablin, squireen; and as an honest man he must speak out. Let it go to his credit, because as a rule he was a snob and inclined to cringe.

"I did not expect"—he cleared his throat—"to see you out to-day, Sir Harry."

Sir Harry winced, and turned on them all a gray, woeful face.

"That's it," he said. "I can't bide home. I can't bide home."

Honoria bided home with her child and mourned for the dead. As a clever woman—far cleverer than her husband—she had seen his faults while he lived; yet had liked him enough to forgive without difficulty. But now these faults faded, and by degrees memory reared an altar to him as a man little short of divine. At the worst he had been amiable. A kinder husband never lived. She reproached 414 herself bitterly with the half-heartedness of her response to his love; to his love while it dwelt beside her, unvarying in cheerful kindness. For (it was the truth alas! and a worm that gnawed continually) passionate love she had never rendered him. She had been content; but how poor a thing was contentment! She had never divined his worth, had never given her worship. And all the while he had been a hero, and in the end had died as a hero. Ah, for one chance to redeem the wrong! for one moment to bow herself at his feet and acknowledge her blindness! Her prayer was ancient as widowhood, and Heaven, folding away the irreparable time, returned its first and last and only solace—a dream for the groping arms; waking and darkness, and an empty pillow for her tears.

From the first her child had been dear to her; dearer (so her memory accused her now) than his father; more demonstratively beloved, at any rate. But in those miserable months she grew to love him with a double strength. He bore George's name, and was (as Sir Harry proclaimed) a very miniature of George; repeated his shapeliness of limb, his firm shoulders, his long lean thighs—the thighs of a born horseman; learned to walk, and lo! within a week walked with his father's gait; had smiles for the whole of his small world, and for his mother a memory in each.

And yet—this was the strange part of it, a mystery she could not explain, because she dared not even acknowledge it—though she loved him for being like his father, she regarded the likeness with a growing dread; nay, caught herself correcting him stealthily when he developed some trivial trait which she, and she alone, recognized as part of his father's legacy. It was what in the old days she would have called "contradictious;" but there it was, and she could not help it; the nearer George in her memory approached to faultlessness, the more obstinately her instinct fought against her child's imitation of him; and yet, because the child was obstinately George's, she loved him with a double love.

There came a day when he told her a childish falsehood. She did not whip him, but stood him in front of her and began to reason with him and explain the wickedness of an untruth. By and by she broke off in the midst of a sentence, appalled by the shrillness of her own voice. From argument she had passed to furious scolding. And the little fellow quailed before her, his contrition beaten down under the storm of words that whistled about his ears without meaning, his small faculties disabled before this spectacle of wrath. Her fingers were closing and unclosing. They wanted a riding-switch; they wanted to grip this small body they had served and fondled, and to cut out what? The lie? Honoria hated a lie. But while she paused and shook, a light flashed, and her eyes were open, and saw—that it was not the lie.

She turned and ran, ran upstairs to her own room, flung herself on her knees beside the bed, dragged a locket from her bosom and fell to kissing George's portrait, passionately crying it for pardon. She was wicked, base; while he lived she had misprized him; and this was her abiding punishment, that even repentance could purge her heart of dishonoring thoughts, that her love for him now could never be stainless though washed with daily tears. "'He that is unjust let him be unjust still'—Must that be true, Father of all mercies? I misjudged him, and it is too late for atonement. But I repent and am afflicted. Though the dead know nothing—though it can never reach or avail him—give me back the power to be just!"

Late that afternoon Honoria passed an hour piously in turning over the dead man's wardrobe, shaking out and brushing the treasured garments and folding them, against moth and dust, in fresh tissue-paper. It was a morbid task, perhaps, but it kept George's image constantly before her, and this was what her remorseful mood demanded. Her nerves were unstrung and her limbs languid after the recent tempest. By and by she locked the doors of the wardrobe, and passing into her own bedroom, flung herself on a couch with a bundle of papers—old bills, soiled and folded memoranda, sporting paragraphs cut from the newspapers—scraps found in his pockets months ago and religiously tied by her with a silken ribbon. They were mementoes of a sort, 415 and George had written few letters while wooing—not half a dozen, first and last.

Two or three receipted bills lay together in the middle of the packet—one a saddler's, a second a nurseryman's for pot-plants (kept for the sake of its queer spelling), a third the reckoning for a hotel luncheon. She was running over them carelessly when the date at the head of this last one caught her eye. "August 3d"—it fixed her attention because it happened to be the day before her birthday.

August 3d—such and such a year—the August before his death; and the hotel a well-known one in Plymouth—the hotel, in fact, at which he had usually put up.... Without a prompting of suspicion she turned back and ran her eye over the bill. A steak, a pint of claret, vegetables, cheese, and attendance—never was a more innocent bill.

Suddenly her attention stiffened on the date. George was in Plymouth the day before her birthday. But no; as it happened, George had been in Truro on that day. She remembered, because he had brought her a diamond pendant, having written beforehand to the Truro jeweller to get a dozen down from London to choose from. Yes, she remembered it clearly, and how he had described his day in Truro. And the next morning—her birthday morning—he had produced the pendant, wrapped in silver paper. "He had thrown away the case; it was ugly, and he would get her another...."

But the bill? She had stayed once or twice at this hotel with George, and recognized the handwriting. The book-keeper, in compliment perhaps to a customer of standing, had written "George Vyell, Esq.," in full on the bill-head; a formality omitted as a rule in luncheon-reckonings. And if this scrap of paper told the truth—why then George had lied!

But why? Ah, if he had done this thing, nothing else mattered; neither the how nor the why! If George had lied.... And the pendant, had that been bought in Plymouth and not (as he had asserted) in Truro? He had thrown away the case. Jewellers print their names inside such cases. The pendant was a handsome one. Perhaps his check-book would tell.

She arose; stepped half-way to the door; but came back and flung herself again upon the couch. No; she could not ... this was the second time to-day ... she could not face the torture again.

Yet ... if George had lied!

She sat up; sat up with both hands pressed to her ears, to shut out a sudden voice clamoring through them—

"And why not? A son's a son—curse you—though he was your man!"

(To be concluded in November.)

There is a race from eld descent,

Of heaven by earth in joyous mood,

Before the world grew wise and bent

In sad, decadent attitude.

To these each waking is a birth

That makes them heir to all the earth,

Singing, for pure abandoned mirth,

Non nonny non, hey nonny no.

Perchance ye meet them in the mart,

In fashion's toil or folly's throe,

And yet their souls are far apart

Where primrose winds from uplands blow.

At heart on oaten pipes they play

Thro' meadows green and gold with May,

Affined to bird and brook and brae.

Sing nonny non, hey nonny no.

Their gage they win in fame's despite,

While lyric alms to life they fling;

Children of laughter, sons of light,

With equal heart to starve or sing.

Counting no human creature vile,

They find the good old world worth while;

Care cannot rob them of a smile.

Sing nonny non, hey nonny no.

For creed, the up-reach of a spire,

An arching elm-tree's leafy spread,

A song that lifts the spirit higher

To star or sunshine overhead.

Misfortune they but deem God's jest

To prove His children at their best,

Who, dauntless, rise to His attest.

Sing nonny non, hey nonny no.