Project Gutenberg's Harper's Young People, May 30, 1882, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Harper's Young People, May 30, 1882

An Illustrated Weekly

Author: Various

Release Date: September 24, 2018 [EBook #57968]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S YOUNG PEOPLE, MAY 30, 1882 ***

Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| vol. iii.—no. 135. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, May 30, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

"BOW-WOW!"

"BOW-WOW!"

It was Friday afternoon, right in the middle of May, and it seemed as if the wide front door of Prome Centre Academy would never get through letting out just one more squad of boys or girls. It was quite the customary thing for Felix McCue to have to wait a little later than the rest.

Miss Eccles was a faithful teacher, and she had often told Felix what an interest she took in him; but he could have heard it a great deal more thankfully at any other time than just after school, and when he knew the other boys were waiting for him. He knew they were, because he had showed them his slate in the arithmetic class, and they had read on it, in big letters, "Got something to tell you. Big."

He had printed every word of it, and he was glad he had done so now, for if he had not he would have been all alone when he at last got outside of the great door. He did not do that, either, until Miss Eccles had looked him in the face for ten of the longest minutes, and talked to him, with a ruler in one hand and a book in the other.

Felix had listened, and he had said "yessum," very respectfully, every time she mentioned George Washington or Benjamin Franklin, but for all that he was only three seconds in reaching the open air, after she said:

"You may go now, Felix, but I hope you will bring no more bumble-bees into this school-room."

"Yessum," and he was off so quickly that he did not hear Miss Eccles, who was trying hard not to laugh right out, and saying to herself:

"The queer little rogue! To think of his telling me, 'Plaze, mum, thim bees knew just the wans to go for; ye cudn't have picked out betther b'ys to have 'em light on.' And what I'm to do with him puzzles me. He's one of the brightest boys in the whole school."

At that moment Felix was walking away from the academy with a boy of about his own size on either side of him.

"B'ys," he was saying, "did yez know me uncle Mike was boss at the shtone quarry?"

"I did," said Bun Gates, on his left; and Rube Hollenhouser, on the right, inquired, almost anxiously, "Was that the big news you kept us waiting for?"

"Was it that, indade? No; but he was along the green this very noon, while I was hidin' Pete Mather's hat in the big maple-tree, and he towld me if I wanted to see the biggest blast of rock that iver was touched off at wan firing, I'd betther be where I could see the shtone quarry a little before noon to-morrow."

That was big enough news to satisfy anybody. The quarry was only a mile or so down the creek, and not a long distance from the bank. It had not been worked for some years, but Mr. Mike McCue was known to be a contractor for the new railroad, and Felix was his nephew. There was perfect confidence to be put, therefore, in the tidings; but Felix added:

"He bid me not tell everybody, for they don't want a crowd around. I asked him wud it be safe on the wather, and he said, 'Yes, it wud, or in it, or undher it, or on the far side of it.' So that's the way we'd betther go."

It was a trifle doubtful which of the ways suggested by his uncle was the one Felix recommended adopting, but Bun instantly exclaimed:

"We can get old Harms's boat. He'll lend it to me any day. It'll hold half a dozen."

"Kape shtill about it, thin. Mebbe Uncle Mike doesn't want to scare the village. He said they'd all hear it whin it kem."

"Loud as that?" said Rube. "Are they going to blast the whole quarry at once?"

"That's what I asked him, and he said, 'No; ownly the wist half of it.' It's the new powdher they're putting in. None of your common shooting powdher at all. It's a kind that bursts fifty times at wance."

There was a touch of silence after that utterance, for there were strange stories in circulation as to the explosive power of the new invention the railroad men were using. Rube Hollenhouser had heard old Squire Cudworth say that a "hatful of it would blow up the Constitution of the United States"; and if that were true, what would not be the effects of a wagon-load or so touched off all at once upon the stone quarry?

Bun and Rube were no sooner back from driving their cows that night than they both went over to the blacksmith's house, and secured the loan of his boat. Of course they told him what they wanted it for, and he said, instantly:

"Is that so, boys? Tell you what I'll do. I'd like to see that blast. I'll go myself. Plenty of room in the boat."

"What shall we do when we get to the mill-dam?" asked Bun. "The quarry's away below the pond."

"We can get another boat below the dam. If we can't, we can haul mine around it in five minutes."

The boys had been considering this problem at that very moment, but one look at Harms the blacksmith was enough to convince any one of his bodily ability to drag any boat on that creek around anything. He was tremendously large and strong, and curly-headed and good-natured. Everybody liked him, and he had more gray beard and mustache than any other man in Prome Centre.

"It's all fixed, then," said Rube.

"I told Deacon Chittenden about it when I drove his cows in for him, and he said right away that Katy and Bill could go. They won't take up any room."

"Plenty of room. Let 'em come. I'd just like to see how far that new powder can blow a rock. Glad you told me. We'll start in good season to be there."

So far everything had worked to a charm; but while Bun Gates told his mother at the supper table what was going to happen, his brother Jeff spoke right out, "Mother, may I go?"

"Yes," said his mother.

And Aunt Dorcas added at once, "Certainly, and Lois too. But, Almira, you or I, or both of us, had better go along to take care of them."

Bun said something about the size of Harms's boat, but Aunt Dorcas silenced him with: "Don't I know how many she can carry? Besides, I'm bound to see that quarry blown up, just for this once."

So Bun was put down; but when they all got out in front of the gate an hour or so after breakfast next morning, there was Rube Hollenhouser in front of his gate, and Felix McCue and little Biddy McCue were with him, and right across the street were Mrs. Chittenden and Katy Chittenden and Bill, and Bun said to himself, "If we had my speckled pig and Chittenden's brindled cow, and if Harms took his dog, the boat'd be 'most full."

Aunt Dorcas and Mrs. Chittenden began to think the party was growing pretty large, but there was no need of it; for when they reached the creek, near the bridge, there stood old Harms, and the first word he spoke was:

"I kind o' guessed how it'd be. Mornin', ladies. Glad we've got a good load for both boats. You get in with me, and the boys can handle t'other one."

It was just like Harms. In another minute he remarked: "Git in now, and we'll shove off."

Aunt Dorcas was already in the very front seat of that boat, and Mrs. Chittenden was in the middle, trying to balance herself. She made William sit beside her, and they two made the boat look wider, there was so much extra room on that seat.

The other boat, the one Harms had borrowed, was almost half a size larger, and it had a cargo this time; for Lois Gates and Katy Chittenden were on the front seat, and behind them were Felix and Biddy. Rube was on the rowing seat, and Bun and Jeff were in the stern.

It was a grand ride down the creek, but when they came out on the mill-pond, Mrs. Chittenden exclaimed:

"I'd no idea it was so wide. Dear me! If I had dreamed of any such risk as this, I'd never have come."

"Nonsense!" said Aunt Dorcas. "If Mr. Harms's end of the boat keeps above water, all the rest will."

"He's a very heavy man," sighed Mrs. Chittenden.

So he was, and when they reached the drag way, around the mill-dam, and saw him put a roller on the grass and gravel, and drag those boats around, one after the other, on the roller, and put them in the water below, they understood that his weight counted for something.

Three-quarters of a mile further down the creek; and now it grew wide and ran slowly, and seemed to have formed a habit of being generally deeper. The easterly bank sloped away from the water's edge, becoming higher and steeper the further they drifted down. It was Biddy McCue who first shouted:

"Yon's the quarry. See the min on the ridge above? Uncle Mike said there might be less than a hundred of thim."

It looked as if there were at least a score or two, and the bald, perpendicular front of the great limestone ledge was worth looking at for a moment.

"Katy," said Lois, eagerly, "do you see the quarry? That's what they're going to blow away."

"Dear me!" exclaimed Mrs. Chittenden. "Mr. Harms, is there any danger?"

"Not unless there's an awful pile of that new powder behind those rocks. What they want to do is to tumble the upper front of the ledge over, so it'll fall into the quarry and they can get at it. I'd just like to see a rock like that come down, pretty nigh a hundred feet."

"Uncle Mike," said Felix, "told us he'd blown up hapes of stone in his day, but he'd niver fired a blast like this wan."

"Misther Harms, what wud become of us all if the powdher worruked the wrong way?"

"What way would that be?" said Mr. Harms.

"The other way. I mean, if instead of blowing out the front of the rock, it lift that all shtanding where it is, and blew out the country to the back of it?"

Before the big blacksmith could answer this question, Aunt Dorcas, who had been looking at her watch, remarked:

"Half-past eleven o'clock. If that thing's going to go off before dinner-time, it's got to go pretty soon."

"Boys," shouted Rube, "see 'em run! There's only one left on the ridge."

"That's me uncle Mike," said Felix, proudly. "He always touches off the big blasts himself, and thin there's no powdher wasted."

"He's running too," said Bun. "He's afraid the new powder might get ahead of him."

"Look now, all of you!" shouted Mr. Harms. "Biggest blast ever heard of around these parts."

They hardly breathed for the next few seconds, but Aunt Dorcas had her watch in her hand, and she was just saying, "Half a minute," when a little puff of smoke and dust shot up at the top of the limestone ridge. It was followed by other little puffs—nobody could tell how many, for they were all smothered in a sudden cloud that arose for many feet. The broad front of stone leaned suddenly out, as if it wished to look down and see what was going on in the old quarry below. Then it lost its balance at the same instant, and toppled swiftly over. A huge, dull, booming report went out from the cloud of smoke and dust on the summit, and that was followed by another great burst of thunderous, crashing sound, as the masses of solid stone came down upon the rocky level below.

It all went by before Aunt Dorcas could look at her watch, and she was just about to do so, when everybody else shouted "Oh!" and there was a loud splattering splash in the water between the two boats. The only "flying rock" sent out by the great blast had narrowly missed doing serious mischief. It had not been a very large one, but only one human being in either of those boats failed to dodge and lean the other way. That Mr. Harms did not dodge or lean accounted for the fact that his boat was only rocked to and fro a little, but for five minutes afterward Aunt Dorcas was compelled to scold those seven children for tipping their boat over, "without any kind of reason for it. The stone never came nigh you."

Still it was a good thing that the water was only two feet deep, and that the weather was nice and warm.

"B'ys," said Felix McCue, the moment he got his feet on the bottom, and stood up, dripping, and holding up Biddy, "did yez iver see a blast like that?"

"Oh, Bun!" screamed Lois, "are there any more stones coming? Was it the blast that upset us?"

"Mother! mother!" sputtered poor Katy Chittenden, "did it blow you over too?"

"Rube," said Bun, "Jeff isn't scared a mite. Are you? I ain't."

"Scared?—no," said Rube. "I wouldn't have missed it for anything, and all we've got's a ducking."

The big blacksmith did a good deal toward restoring a comfortable state of mind all around; but he could not make out that the other boat-load were in a comfortable state of body; and so they set out for home. Long before they got there, however, Katy said to Lois,

"If it wasn't for my new bonnet strings, I wouldn't care," and Lois replied:

"Yes; but think how that rock looked when it let go and tumbled over. It was awful! I'm satisfied."

On February 23, 1685, there was born in Halle, Saxony, to an honest surgeon named Handel, a son, whom he christened George Frederick, and who was destined half a century later to become the first musician in the world.

Little Handel's father abhorred music. As soon as the boy began to show an aptitude for it, his father took him away from school, for fear that some one would teach him his notes. Whether among teachers or scholars I don't know, but the boy found a friend who contrived to procure for him a little dumb spinet, and this he secreted in an attic, and learned not only his notes from it, but how to use his fingers in practicing. Still his father opposed him, and but for a certain visit he paid, his genius might have been long hidden in the dull house at Halle.

The elder Handel was invited to visit his son who was in the service of the great Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels, and young George, knowing music was to be heard, if not easily learned, in that place, determined to go too. So he ran after his father's carriage so far that the parent's stern heart relented, and he was taken in.

GEORGE FREDERICK HANDEL.

GEORGE FREDERICK HANDEL.

In the old castle at Weissenfels he quickly found out which of the inmates were musical, and soon made friends with them. One day, after the chapel service, he jumped on to the organ stool, and played in such an astonishing manner that the Duke, who was still lingering in the chapel, sent up to inquire who was playing. The boy and his indignant father were summoned: but the Duke's evident delight in the child's music softened old Handel's heart. He gave his consent to his son's musical education, and[Pg 484] almost from that moment George Frederick Handel became known as a musician.

I can not tell you anything more of his childhood or youth but that he studied very hard, and that, like every true genius, he was humble while he was learning. We must skip over many years to the time when he went to England; for there he produced his greatest works, and to this day the English reverence him as their own.

George I., King of England, you know, had been Elector of Hanover, and so he as well as his successor felt a strong interest in Handel. The latter went to England in 1710, and there he found that much attention was paid to Italian music. Operas were very fashionable. They were quite a novelty then. Fine ladies and gentlemen filled the opera-house. They crowded the greenrooms behind the scenes, and chatted and talked at the "wings," as if they were in a drawing-room. Fashion governed nearly everything, and so Handel, realizing this, set to work upon an opera. He wrote Rinaldo in fourteen days, and it was produced at Drury Lane with a splendor that created great excitement throughout London. We never hear Rinaldo now, but its airs are beautiful, and one of these, "Lascia ch'io Pianga," lingers in the heart of every one who hears it.

Well, Handel began to teach the Prince of Wales's daughters, to write a great deal of music, and to be very much the fashion, and very famous. So he roused the jealousy of petty people, and, strange as it may seem, opinions differed to such an extent, and such a fuss was made, that society was divided into two factions. One party favored a distinguished musician named Buononcini, and the other Handel. The war raged, and during it a wit and poet named John Byrom wrote the following verse, which has since been famous:

"Some say, as compared to Buononcini,

That Mynheer Handel's but a ninny;

Others aver that he to Handel

Is scarcely fit to hold a candle.

Strange all this difference should be

'Twixt tweedledum and tweedledee."

Handel's genius, however, was not to be suppressed by any such foolish contentions. He worked on as usual, and in 1749 produced the work with which his name is most associated, the oratorio of The Messiah.

I do not think you can go into any part of England without finding people who love The Messiah. It used to seem to me it was the one work every one knew about. And it is well worthy of such general knowledge. In it are airs that must move every Christian heart. It seems to teach so many things—reverence, love, hope, and a glimpse of a heaven that has in it God's many mansions. When I hear it sung it always seems to me that the voices are those of the angels who sang on Bethlehem's plains, "Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good-will toward men."

I want to tell you something about oratorios in general; that is, how they originated, and what they are as musical works. Oratorios, strictly speaking, are dramatic and musical compositions where the parts are sung without scenery or special costume, and they are on sacred subjects.

Dramatic representations of sacred stories are as old as Christianity. In the Middle Ages they were very common. At times of public rejoicing they were given, or during any special season, like Advent or Lent, and so far were they recognized as part of public life that the government or special societies paid their expenses.

These old performances were very roughly put on the stage, but gradually from them grew an idea of a distinctly musical and dramatic sacred work. In Germany, "Passion Music" was written. In Italy, it had long been thought of and given; finally, the oratorio as we have it now was developed by various great composers.

Let us consider the oratorio for a moment as represented by Handel's Messiah. The most famous part perhaps is the "Hallelujah Chorus." Hear this sung by thousands: do you not thrill with joy and praise? As the music swells on, with its bursts of melodious exultation, we feel ourselves lifted away from everything common and base. Then take the sweeter and softer airs: "Behold the Lamb of God," "With His stripes we are healed," and then the great chorus, "For unto us a Child is born," with the rush and sweep of the "Wonderful." Where do we seem to be? With the shepherds watching on that star-lit plain; with Mary at the cradle of her Divine Child; with the Wise Men offering up their gifts of frankincense and myrrh in that illumined stable. The light of God's glory dazzles us as we listen, and we can only echo in our humble hearts, with our heads bowed, that repeated joyous "Wonderful!"

Now do you not think a musician who could make any Christian heart full of such reverence and love ought always to be honored? I like to think of Handel revered as he is now. His life was not happy in many ways. Many things troubled him. He used to sit hours playing on his organ, and I have no doubt trying to reconcile himself to the blindness which fast came upon him. He had many friends, but no family ties of his own. He wrote on unceasingly, and some other time I may tell you more of his work. Just now I have had space only to speak of his greatest oratorio.

It was on April 6 that The Messiah was given at Covent Garden, and Handel attended the performance. He came home to his house in Brook Street very weary, and there, eight days later, he died, April 14, 1759. His grave is in Westminster Abbey.

Author or "Toby Tyler," "Tim and Tip," etc.

It was so near the time for the circus to begin that Toby was obliged to hurry considerably in order to distribute among his friends the tickets the skeleton had given him, and he advised Abner to remain with Mrs. Treat while he did so, in order to escape the crowd, among which he might get injured.

Then he gave his tickets to those boys who he knew had no money with which to buy any, and so generous was he that when he had finished he had none for himself and Abner.

That he might not be able to witness the performance did not trouble him very greatly, although it would have been a disappointment not to see Ella ride; but he blamed himself very much because he had not saved a ticket for Abner, and he hurried to find Ben that he might arrange matters for him.

The old driver was easily found, and still more easily persuaded to grant the favor which permitted Abner to view the wonderful sights beneath the almost enchanted canvas.

From one menagerie wagon to another Toby led his friend as quickly as possible, until they stood in front of the monkeys' cage, where Mr. Stubbs's supposed brother was perched as high as possible, away from the common herd of monkeys, which chatted familiarly with every one who bribed them.

Toby was in the highest degree excited; it seemed as if his pet that had been killed was again before him, and he crowded his way up to the bars of the cage, dragging Abner with him, until he was where he could have a full view of the noisy prisoners.

Toby called to the monkey as he had been in the habit of calling to Mr. Stubbs, but now the fellow paid no attention to him whatever. There were so many spectators that he could not spend his time upon one unless he were to derive some benefit in return.

Fortunately, so far as his happiness was concerned, Toby had the means of inducing the monkey to visit him, for in his pocket yet remained two of the doughnuts Mrs. Treat had almost forced upon him; and remembering how fond Mr. Stubbs had been of such sweet food, he held a piece out to the supposed brother.

Almost instantly that monkey made up his mind that the freckle-faced boy with the doughnut was the one particular person whom he should be acquainted with, and he came down from his perch at a rapid rate. So long as Toby was willing to feed him with doughnuts he was willing to remain; but when his companions gathered around in such numbers that the supply of food was quickly exhausted, he went back to his lofty perch, much to the boy's regret.

"He looks like Mr. Stubbs, an' he acts like him, an' it must be his brother sure," said Toby to himself as Abner hurried him away to look at the other curiosities. When he was at some distance from the cage he turned and said, "Good-by," as if he were speaking to his old pet.

During the performance that afternoon Abner was in a delightful whirl of wonder and amazement; but Toby's attention was divided between what was going on in the ring and the thought of having Mr. Stubbs's brother all to himself as soon as the performance should be over.

He did, however, watch the boy who sold pea-nuts and lemonade, but this one was much larger than himself, and looked rough enough to endure the hardships of such a life.

Toby was also attentive when Ella was in the ring, and he was envied by all his acquaintances when she smiled as she passed the place where he was sitting.

Abner would have been glad if the performance had been prolonged until midnight; but Toby, still thinking of Mr. Stubbs's brother, was pleased when it ended.

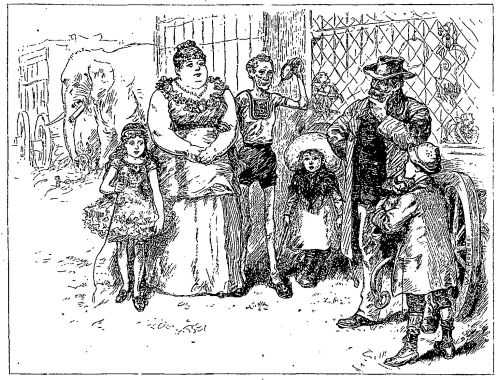

He and Abner waited by the animals' cages until the crowd had again satisfied their curiosity; and as the last visitor was leaving the tent, old Ben came in, followed by Mr. and Mrs. Treat, both in exhibition costume.

Toby was somewhat surprised at seeing them, for he knew their busiest time was just at the close of the circus, and while he was yet wondering at their coming, he saw Ella approaching from the direction of the dressing tent.

He had not much time to spend in speculation, however, for Ben said, as he came up:

"Now, Toby, you shall see Mr. Stubbs's brother, and talk to him just as long as you want to."

The skeleton and his wife and Ella looked at each other and smiled in a queer way as Ben said this; but Toby was too much excited at the idea of having the monkey in his[Pg 486] arms to pay any attention to what was going on around him.

Ben, unlocking the door of the cage, succeeded after considerable trouble in catching the particular inmate he wanted, and handing him to Toby, said:

"Now let's see if he knows you as well as Stubbs did."

Toby took the monkey in his arms with a glad cry of delight, and fondled him as if he really were the pet he had lost.

Whether it was because the animal knew that the boy was petting him, or because he had been treated harshly, and was willing to make friends with the first one who was kind to him, it is difficult to say. It is certain that as soon as he found himself in Toby's arms he nestled down with his face by the boy's neck, remaining there as contentedly as if the two had been friends for years.

"There! don't you see he knows me?" cried the boy, in delight, and then he sat down upon the ground, caressing the animal, and whispering all sorts of loving words in his ear.

"He does seem to act as if he had been introduced to you," said old Ben, with a chuckle. "It would be kinder nice if you could keep him, wouldn't it?"

"'Deed it would," replied Toby, earnestly. "I'd give everything I've got if I could have him, for he does act so much like Mr. Stubbs, it seems as if it must be him."

Then Ella whispered something to the old driver, the skeleton bestowed a very mysterious wink upon him, the fat woman nodded her head until her cheeks shook like two balls of very soft butter, and Abner looked curiously on, wondering what was the matter with Toby's friends.

He soon found out what it was, however, for Ben, after indulging in one of his laughing spasms, asked:

"Whose monkey is that you've got in your arms, Toby?"

"Why, it belongs to the circus, don't it?" And the boy looked up in surprise.

"No, it don't belong to the circus; it belongs to you—that's who owns it."

"Me? Mine? Why, Ben—"

Toby was so completely bewildered as to be unable to say a word, and just as he was beginning to think it some joke, Ben said:

"The skeleton an' his wife, an' Ella an' I, bought that monkey this forenoon, an' we give him to you, so's you'll still be able to have a Mr. Stubbs in the family."

"'OH, BEN!' WAS ALL TOBY COULD SAY."

"'OH, BEN!' WAS ALL TOBY COULD SAY."

"Oh, Ben!" was all Toby could say. With the monkey tightly clasped in his arms, he took the old driver by the hand; but just then the skeleton stepped forward, holding something which glistened.

"Mr. Tyler," he said, in his usual speech-making style, "when our friend Ben told us this morning about your having discovered Mr. Stubbs's brother, we sent out and got this collar for the monkey, and we take the greatest possible pride in presenting it to you; although, if it had been something that my Lilly could have made with her own fair fingers, I should have liked it better."

As he ceased speaking, he handed Toby a very pretty little dog-collar, on the silver plate of which was inscribed:

Toby took the collar, and as he fastened it on the monkey's neck, he said, in a voice that trembled considerably with emotion:

"You've all of you been awful good to me, an' I don't know what to say so's you'll know how much I thank you. It seems as if ever since I started with the circus you've all tried to see how good you could be; an' now you've given me this monkey that I wanted so much. Some time, when I'm a man, I'll show you how much I think of all you've done for me."

The tears of gratitude that were gathering in Toby's eyes prevented him from saying anything more, and then Mrs. Treat and Ella both kissed, him, while Ben said, in a gruff tone:

"Now carry the monkey home, an' get your supper, for you'll want to come down here this evening, an' you won't have time if you don't go now."

Ella, after making Toby promise that he would see her again that night, went with Mr. and Mrs. Treat, while old Ben, as if afraid he might receive more thanks, walked quickly away toward the dressing-rooms, and there was nothing else for Toby and Abner to do but go home.

It surely seemed as if every boy in the village knew that Toby Tyler had remained in the tent after the circus was over, and almost all of them were waiting around the entrance when the two boys came out with the monkey.

If Toby had staid there until each one of his friends had looked at and handled the monkey as much as he wanted to, he and Abner would have remained until morning, and Mr. Stubbs's brother would have been made very ill-natured.

He waited until his friends had each looked at the monkey, and then he and Abner started home, escorted by nearly all the boys in town.

The partners in the amateur circus scheme were nearly as wild with joy as Toby was, for now their enterprise seemed an assured success, since they had two real ponies and a live monkey to begin with. They seemed to consider it their right to go to Uncle Daniel's with Toby; and when the party reached the corner that marked the centre of the village, they decided that the others of the escort should go no farther—a decision which relieved Toby of an inconvenient number of friends.

As it was, the party was quite large enough to give Aunt Olive some uneasiness lest they should track dirt in upon her clean kitchen floor, and she insisted that both the boys and the monkey should remain in the yard.

Toby had an idea that Mr. Stubbs's brother would be treated as one of the family; and had any one hinted that the monkey would not be allowed to share his bed and eat at the same table with him, he would have resented it strongly.

But Uncle Daniel soon convinced him that the proper place for his pet was in the wood-shed, where he could be chained to keep him out of mischief, and Mr. Stubbs's brother was soon safely secured in as snug a place as a monkey could ask for.

Not until this was done did the partners return to their homes, or the centre of attraction, the tenting grounds, nor did Toby find time to get his supper and go for the cows.

Not once during the afternoon had Toby said anything to Abner of the good fortune that might come to him through old Ben; but when he got back from the pasture and met Uncle Daniel in the barn, he told him what the old driver had said about Abner.

"Are you sure you heard him rightly, Toby, boy?" asked the old gentleman, pushing his glasses up on his forehead, as he always did when he was surprised or perplexed.

"I know he said that; but it seems as if it was too good to be true, don't it?"

"The Lord's ways are not our ways, my boy, and if He sees fit to work some good to the poor cripple, He can do it as well through a circus driver as through one of His elect," said Uncle Daniel, reverentially, and then he set about milking the cows in such an absent-minded way that he worried old Short-horn until she kicked the pail over when it was nearly half full.

There are little green beds in many a row

On our hill-sides fair and our valleys low,

And lying still in their hollows deep,

The gallant soldiers are fast asleep.

Oh, gently we tread when we pass a mound

Which under the flag is holy ground.

And over our country here and there

Those little green beds grow bright and fair

When the May flowers drop in the lap of June,

And sweet in the pastures the wild bees croon.

With banner and bugle and beat of drum,

To honor the brave, then the people come.

They come with the roses red and white,

And the starry lilies as pure as light;

They scatter the blossoms everywhere,

And the perfume thrills on the sighing air

As they wreathe with beauty each lowly mound

That under the flag is holy ground.

O children, glad as the summer skies,

With your dancing dimples and laughing eyes,

Little you dream of the wild work done

Ere the soldiers' rest in these beds was won;

And you only know that here brave ones lie

Sleeping so soundly as years go by.

Nothing they heed of the work or play

Of the busy world in the merry May.

Though life was sweet to the hero band,

They died for love of our native land;

And so we garland each lowly mound

That under the flag is holy ground.

My husband and I were staying at a country house sixteen miles from Champion Bay, quite in the "bush," and miles away from any one. Our host was an influential person, and the owner of one of the largest stock farms on the great continent of Australia.

Everything was arranged for the hunt the day before, Mr. B—— having selected and had brought in from the bush those horses which he thought most suitable. The luncheon was all packed up overnight, and sent to the hunting ground at four o'clock in the morning, accompanied by a barrel of water, a luxury unattainable in the country we were bound for.

When we rose in the morning we saw from our windows some of the gentlemen already starting, and about an hour afterward the carriage which was to convey our party of five to the meet was brought round to the door.

After we had driven about nine miles we came to a hollow, where we found our horses waiting. Mine was a very neat gray, full of spirit, but very good-tempered, while my husband's mount was a pretty bay mare, very fast, which pulled considerably. We set off, each of us armed with boomerangs, or heavy curved sticks from eighteen inches to two feet in length. Our horses were excited, but we had to ride along as quietly as possible, for fear we should start a kangaroo and let it get away too far ahead.

We had not long to wait before a beautiful "flying doe" got up about three-quarters of a mile in front of us, when every one let his horse go as hard as he could, until the pace became tremendous, the horses having to jump all the bushes they came to.

After we had galloped for several miles, the country became rough and thickly grown with black-boys—a species of palm-tree, so called from its black stem. Unfortunately, my husband, in avoiding a collision with a lady, managed to come up against one of them, and it being strong, did not give with the weight of the horse, and knocked him out of the saddle. For a moment I was rather frightened, but as he called to me that he was all right, and told me to go on, I did so. He soon got his horse back, and came after us as quickly as possible.

Of course this little episode rather threw me out of the hunt, and in the distance I saw Miss L—— going a good pace with the kangaroo close ahead of her. She rode very well, and never once left it. After a while I found myself pretty close to it, and by this time our horses were getting a little bit used up. It seemed a long time before the kangaroo was knocked over. As soon as one of us got alongside of it, it doubled, and then the work of getting sufficiently near to upset it had to begin again. The pace they go is almost incredible, especially that of a "flying doe," and before one is accustomed to it their hopping has a peculiar effect. Each spring they give, their tails beat the ground as if worked by machinery. Mr. B—— eventually knocked over the "flying doe" at Miss L——'s request, she being uncertain how it ought to be done. I am glad to say it was not killed, but "ear-marked," and let go.

We gave our horses a little rest, and then started off again. Luckily the day was cloudy, or the heat on the sand plains would have been unbearable. This time again we were most fortunate, and soon saw a very big kangaroo going away ahead of us. After a short time we came to a bit of thick bush which the kangaroo made for. If not excited, one would think twice about going straight into it. However, I saw two bush-riders go at it, so thought I would try too, much to their amusement, and I was rewarded. Just in the middle the kangaroo doubled, and being then quite close to him, I had all the fun to myself, and Bismarck—my horse—entered into it perfectly.

Crash we went through the bush regardless of the possibility of eyes being poked out by boughs, and our faces being scratched all over. In fact, I found the only thing to do was to sit tight, keep my head down, and let the horse go. He followed the kangaroo until we found ourselves in the open again. Then we came alongside of him in a canter, as he was getting tired, so I got Bismarck very close, and knocked him down. I then thought he would give us no more trouble, but much to my surprise, when pulling up the horse, I saw him get up and begin to go off. I was determined he should not get away, so our chase began again. We soon were together, and I made Bismarck keep a little bit ahead of him, waiting for our opportunity to upset him. He was actually hopping along under my feet, and I knocked his head with my foot. He tore my habit by putting one of his paws through it, and scratched one of Bismarck's fore-legs in trying to cross him. This he was not quick enough in doing, and was soon down on the ground. The actual run was, I believe, only two miles. The kangaroo was afterward killed, and his paws cut off for me as a remembrance of my first hunt, but in drying they were spoiled, and I never got them. His tail was taken home to be made into soup, which is most excellent.

After luncheon the gentlemen went off to find another kangaroo if possible. They were all on foot, except my husband and Mr. B——'s nephew. However, they soon found a fine one, and four of them carried it in to us alive. They tied a rope round it, and fastened it to a tree. At first the animal tried hard to get away, but finding it useless, remained very still. We had a few dogs out with us, but they are not required if there are a good many people mounted. Of course, to any one hunting by himself, they would be a necessity. Just before our start homeward it was proposed to let the kangaroo go, and with some difficulty they managed to untie the rope. The kangaroo being at bay, it stood upon its hind-legs, with its back to a tree, and kept striking out with its paws. It really was a piteous sight, standing there with its big brown eyes, and it did not seem to realize it was free, although the dogs barked and people shouted to make it move.

At last it went off, and I longed for it to get away; but before going any distance it stood up again, with the dogs round it, and the poor brave kangaroo was soon dragged by them to the ground. It seemed quite a melancholy ending to our day.

"You see, mamma dear, Charley asked

For just one lock of hair;

I thought I'd cut it off myself,

I knew you would not care.

"Please now, mamma, don't look so grave,

The piece is very small;

And, see—I cut it off just where

It doesn't show at all."

We have all heard of pouring oil on the waters, but most of us have supposed that the phrase meant only the soothing of angry people by gentle words, and that it was what the grammars call a figurative expression.

But sailors and fishermen have often tried the experiment of sprinkling oil upon stormy waves with great success. The oil when dropped upon the billows spreads over their surfaces, forming a fine film, and smoothing a safe path for ships that would otherwise be in danger.

Many curious instances of this are given by the captains of whalers and merchant ships. The master of the Gem, a British brigantine, bound from Wilmington, North Carolina, to Bristol, encountered a hurricane, which blew frightfully for thirty-six hours. The vessel was in the utmost peril, when the captain remembered to have read an article on the use of oil at sea. He at once poured a quantity into a canvas bag, and fastened it to a rope six fathoms long, trailed it to windward of the ship, and the oil leaked out, and made smooth water around the vessel.

In September, 1846, a terrific gale of wind lashed the Atlantic to fury, and a little fishing-boat was seen tearing her way through the white waves to the coast of Sable Island. Watchers on the shore saw two men on board throwing something at intervals into the air.

When the boat arrived on shore, as she did in safety, with all her crew, it was found that the captain had stationed two men near the fore-shrouds, where he had lashed two casks of oil. Each man was armed with a wooden ladle two feet long, with which he dipped up the blubber and oil, and threw it as high as he could into the sea. The wind carried it to leeward, and as it spread far over the water, though the waves rose very high, they did not break. The little Arno rode into Sable Island, leaving a shining path in her wake.

The way in which the oil is used by those who wish to preserve their boats from wreck is very simple.

The King Cenric, for instance, a sailing ship bound from Bombay to Liverpool, with coal, was caught in a heavy gale, which lasted five days. Her officers filled two canvas clothes-bags with oil, and made two or three small holes in each. The bags were then towed along by the ship.

Our own Dr. Franklin, who always used his eyes, tried the experiment of calming rough water by oil in the harbors of Newport and Portsmouth. He had observed the serenity of the waves around the whaling ships, and he said that even a tea-spoonful of oil produced a wonderful effect.

Mr. John Shields, of Perth, Scotland, has been trying the experiment on a grand scale in Peterhead North Harbor. His apparatus carries twelve hundred feet of piping into deep water two hundred yards seaward of the bar. There are three conical valves, fixed seventy-five feet apart, at the sea end of the pipe, and when the pipes are charged with oil, by means of a force-pump in a hut on shore, the oil escapes so rapidly that the wildest waves become gentle ripples.

Mr. Shields has been improving and testing his invention for two years, and expects by means of it to make the dangerous harbor of Peterhead entirely safe, however furious the weather.

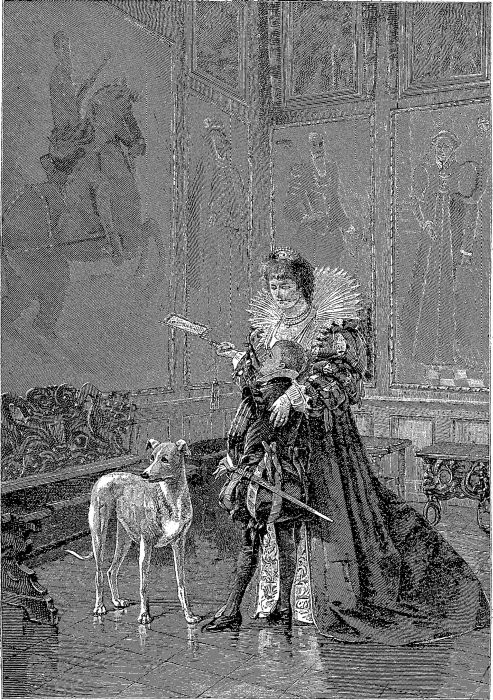

IN THE HALLS OF HIS ANCESTORS.

IN THE HALLS OF HIS ANCESTORS.

Amateur photography is getting to be exceedingly popular. The price of outfits is so low that they are within reach of all, and from what we hear it would seem that a goodly number of the readers of Young People are engaging in it. A few words therefore on the subject from one who has been through the first few months of enthusiasm and disappointment which succeed the purchase of an instrument may be of service to those who have embarked on the ocean of amateur photography.

Of course you will use the dry plates. I say of course, because for the amateur they are cheaper, more convenient, produce better results, and afford a wider latitude of subject than the wet plates. We will suppose, then, that you have provided yourself with a good camera and lens, chemicals, plates, baths, and all that go to make a complete outfit.

Your first trouble will be with your dark room. It must be absolutely dark; the faintest ray of white light will destroy the most perfectly timed picture. Any closet will do, so long as you can have perfect darkness and room to work. The most luxurious dark room I ever saw was ten feet square, provided with hot and cold water, and lighted by two large windows with panes of ruby glass. The gold-colored glass looks the same, but is worthless for photographic purposes. On the other hand, I have worked in a closet two feet deep, by the dim light of a single ruby lamp. But in photography as in everything else the "golden mean" is preferable.

If kept in a perfectly dark box, the dry plates need not be developed for months. Travellers often change plates, and even develop and fix them, at night, in their rooms, by the aid of a ruby lantern. As the changing of plates is an operation which consumes but little time, this may be done with safety, but we would recommend the young photographer to make use of his dark room for the process of developing.

Besides the pans, or baths as they are called, for the chemicals, you must have in the dark room a supply of clear water, and a vessel in which to throw it after it has been used. Dry plates require frequent washing, as we shall see further on. Your dark room must be, then, of moderate size, free from white light, provided with clean water, and free from dust. If it is dusty, you will have minute specks on the picture. The plates must be kept in this room, and must be transferred to and from the plate-holders here.

Next comes the business of mixing the chemicals. There are several different formulas for the development of dry plates, but I have found the ferrous-oxalate developer to be the simplest and best. The most convenient way to prepare the solutions is to take two common glass preserve jars, put in about a quarter of a pound of neutral oxalate of potash in one, and about the same amount of protosulphate of iron in the other; then pour on warm water, and let the crystals dissolve.

It makes no difference how much water you put in; the object is to get a "saturated" solution; that is, a solution in which the water has absorbed all the chemical matter it can take up. After the chemicals have had time to dissolve—say fifteen or twenty minutes—filter the solutions into separate bottles, and cork them tightly, to keep out the dust. Always filter all your solutions before using them; even filter the water if it is not perfectly clear. Cleanliness is a prime necessity in photography, and the amateur can not be too careful.

Now comes the "fixing" solution, which is made by dissolving four ounces of hyposulphite of soda in twenty ounces of water. Filter into a bottle, and cork it until used. Make at the same time a saturated solution of common alum, and use it for washing the plates after taking them out of the developer, and before fixing. Directions are given by many involving the use of cyanide of potassium, tartaric acid, bromide of ammonia, and the like; but it is better for the beginner to use as few chemicals as possible. More pictures are spoiled than saved by inexperienced doctoring.

After your chemicals are all prepared, put a plate in your holder, or wooden box with slides, one or more of which accompany every outfit. Focus your camera on some object; a row of buildings, the side of a house, or a board fence is preferable for this experiment. Take off the cap, and pull the slide about half of the way out. Expose about six seconds, and pull out the slide the rest of the way. Expose this six seconds again, and replace the slide. You now have two exposures, of six and twelve seconds respectively, on the same plate. This is for timing the lens. It is impossible to give any definite rules for the time of an exposure; experience must teach this.

In a gallery where the surroundings are the same and the light varies but little, it is comparatively easy to determine how long a plate should be exposed in the camera. But in out-of-door work the amateur must take into consideration the state of the weather and the atmosphere, the presence or absence of reflecting surfaces, such as a stretch of sand-beach, a sheet of water, or the proximity of a light-colored building, and time the plate accordingly.

After you have taken the test-plate, return to your dark room, and pour into the bath four ounces of neutral oxalate, and mix with it one ounce of iron solution. Take the plate from the holder, wash it in cold water, and drop it into the mixture. The image will begin to appear in from three to five minutes. After it has become clearly defined, wash it again in cold water, and put it in the alum solution for a few minutes. Another washing, and it is ready for the fixing solution, which will keep the picture from turning black, as it would otherwise do, if exposed to the light.

Let it remain in the fixing solution until the white film has disappeared. Then wash it in water, and you have your negative. Now examine this carefully, and see whether the six-second or the twelve-second exposure is the best. After a few experiments you will be able to judge pretty accurately how long to expose a plate.

It would be impossible to enumerate the mistakes which a young photographer will make. The only way is to profit by them, and not make the same one a second time. Many boys who get a photographic outfit are disgusted with it, after one or two trials, because they can not make as good a picture as a professional photographer. The principal causes of failure can, however, be enumerated as follows:

1. Imperfectly darkened operating-room, which will make the picture dim or "foggy."

2. Dust in the dark room, unfiltered chemicals or washing water, which will make pinholes in the negative.

3. Over or under exposure, which will either make the negative too black or too thin to print successfully. This last, however, is excusable in the young beginner.

Finally, boys are apt to be careless. A crack in the door of the operating-room, a bottle left uncorked to collect the dust, dirt or dust on the hands, a little more of this solution or a little less of that, they think would make no difference. Photography requires accuracy and cleanliness, and no one can hope to take a satisfactory picture unless he will cultivate these qualities.

If any boy or girl—and girls, as a general rule, make better amateur photographers than boys—thinks to learn amateur photography for "fun," I should say to him or her, emphatically, Don't. But to any one who has a sincere love for the beautiful in nature, and who is willing to work to obtain lasting mementos of the scenes which are dear to him, a photographic outfit may become a source of never-ending pleasure.

One day several years ago a Georgia boy went fishing. He started for a creek that ran not far from his home; but as he knew there were few fish in it except small cat-fish, he probably did not expect to return with a very well-filled basket. Most boys, however, know how to get a good deal of pleasure out of a day's fishing, even if the fish are small and bite slowly.

Taking his lines and hooks, this Georgia boy went to the creek, and there sat down to dig for bait with his pocket-knife. In digging, he turned up a curious and pretty pebble which attracted his attention. Wiping the earth from it, he found it to be semi-transparent, and about the color of the flame of a wood fire. As he turned it around, it reflected the light in a peculiar way which interested the boy, and so, instead of throwing the pebble away, he put it into his pocket.

As he had never seen a stone of the kind, he showed it to a good many persons as a curiosity in a small way, and after a while he came to value it about as a boy values a marble of the kind called real agate.

On one occasion he showed his pretty stone to a visitor from Cincinnati, who seemed even more interested in it than others had been. This gentleman examined the pebble again and again, and finally asked permission to take it to Cincinnati with him to show to some one there. Not long afterward the gentleman returned, and told the lad that his "pretty stone" was worth a good many thousands of dollars. It was, in fact, what is called a fire opal, a very precious stone, specimens of which are so very scarce and costly that jewellers can not afford to make use of them. The few that have been found since Humboldt carried specimens to Europe have been eagerly bought at enormous prices for the great museums.

When the parents of the Georgia boy learned the nature and value of his discovery they had the stone sent to Europe, and sold to advantage. The sum received for it was quite a little fortune.

I have never heard how many fish the boy caught, but I am very sure that he can not complain of his luck on that day.

Since that time a good many opals have been found in the region in which the boy dug for bait, and among them one or two small fire opals, but none equal in value to his. Some efforts have been made to search the region thoroughly, and to work it as an opal mine. There is a great difference in opals, but when they are really beautiful their value is very large. For an opal in the museum at Venice $250,000 was offered without success. Marc Antony is said to have sent a Roman Senator into exile because he would not sell him an opal ring for which he had paid nearly a million of dollars.

This was the name Walter Radlow's father had requested should be given the gray donkey which he presented to his son on the latter's thirteenth birthday.

"You see, I was at my wits' end what to buy," he afterward explained; "for a dozen birthdays, to say nothing of as many Christmases, had about exhausted my genius for discovering something new, and I was beginning to think I'd have to start all over again with a rattle, when the idea of a donkey and cart popped into my head."

So Popsey was the donkey, and the donkey was Walter's, and—such a donkey! Not one of your meek, spiritless animals, "warranted gentle with ladies and children," that you must beat to make go, and simply cease beating to stop.

Ah, no; Popsey, though not wild or vicious, was full of life, which was just what Walter delighted in; and as Mrs. Radlow had satisfied herself that the beast was really too small to do any serious damage, she ceased to worry about his "playfulness."

But it was not long before Popsey became so attached to his young master that it was thought perfectly safe to allow two-year-old Amy the privilege of a ride now and then, from which she returned in a very mixed state of mind as to whether she wanted to tell papa about Popsey, or Popsey about papa.

One Saturday, about three months after Popsey's advent, Walter's cousins came over from Wallingville to make him a visit. They were the children of Mr. Radlow's only brother, and Helen was fourteen, May twelve, and Jack ten.

They arrived about nine in the morning, to find Walter just recovering from an attack of rheumatism, and suffering from such a raging toothache that he could scarcely bear to speak.

"But don't mind me," he said, as they all gathered about him to condole and bemoan. "When you come from town to the country for the first time in years, and for such a short stay, too, you mustn't stick in the house just because a chap can't go round with you to— Oh!" and poor Walter suddenly dashed his head down against the hop pillow on the lounge, while the girls sympathetically exclaimed, "Too bad!" and Jack looked as if he was afraid it might be "catching."

But in a moment or two Walter bobbed up again to say, "There's the croquet set and archery, tennis and—Popsey."

"Oh yes; that's the donkey, you know," eagerly interrupted Jack. "And, oh, Walter, did you say we might drive him?"

"Of course. I guess Helen can manage the fellow. And, by-the-way, you might take the cart and drive over to the Hillwins'. Fred's got a prime book about middies I've wanted to read ever since Christmas, and if you'll borrow it for me, I think it'll make me forget this—" And the boy expressively ended his sentence by another plunge into the depths of his hop pillow.

When the plan was first mentioned to her, Mrs. Radlow was inclined to doubt Helen's ability to deal with Popsey's peculiarities. Though docile enough with Walter, he might prove troublesome to a stranger.

"But, Aunt Jennie, don't you remember how I drove when we were all up in the mountains one summer? And, besides, you know you wrote to mamma that Popsey was so small that you never worried about the children being out with him."

As this last argument of Helen's could not very well be answered, the coachman was ordered to harness up.

When the cart was brought to the door, and the three visitors prepared to crowd themselves into it, a great outcry was made by Amy, who shouted, "Me too! me too!" so often and so shrilly that, for the sake of securing quiet in the house for Walter, Mrs. Radlow at last consented to let her go.

"I'll hold her on my lap just as tight," pleaded May, "and Jack can stand up behind."

And so it was arranged, and Amy's face, which had been all drawn down for a good cry, wrinkled up into a laugh instead.

Then Popsey was petted and patted, endearingly addressed as "Good donkey," and called upon times innumerable to "whoa" when he had not thought of stirring, after which preliminaries the girls got in, Amy was handed over to them, and Jack climbed up behind.

"Drive around to the front lawn, so Walter can see you," said Mrs. Radlow, when all was ready for a start, whereupon Helen chirped to her steed, and guided him over the grass opposite the second-story window, at which appeared a black head and white pillow, one of which was nodded gayly, and the other waved on high, the two to be[Pg 492] suddenly clapped together again in a fashion, that caused Helen to give Popsey a touch of the whip, and speed off after the "prime book about middies."

"'ISN'T HE JUST TOO CUNNING!'"

"'ISN'T HE JUST TOO CUNNING!'"

"Oh, isn't he just too cunning!" exclaimed May, as the little donkey trotted along, with his big load, as steadily as a family horse.

Amy crowed with delight; Helen made a great show of flourishing her whip (taking good care, however, to keep it out of range of Popsey's long ears), while Jack pranced about behind in genuine boyish joy. The road was easy enough to follow, and inside of three-quarters of an hour Helen drew up before the Hillwins' gate. Their house was the only one within sight, and just beyond it two or three roads crossed one another in quite a confusing manner.

"It's lucky we haven't any further to go, Helen," remarked May, as she noted the latter fact, "for we'd surely become mixed, and— But I declare, if Amy isn't fast asleep in my arms! Poor dear, the ride's been too long for her, I guess. You go in, Helen, and I'll sit perfectly still so as not to wake her. Don't be long, though."

Jack was already out and standing at Popsey's head, but no sooner had her elder sister vanished from sight under the long grape arbor that led to the house, than May suddenly discovered that she was terribly thirsty.

"Oh, Jack," she cried, "I must go in and get a drink; but I don't want to wake baby, and make her cross, perhaps; so I'll just put her down here in the bottom of the cart on the seat cushion. I'll be back in a minute or two; but mind, keep a tight hold on the donkey, and if Amy wakes up, talk to her till I come."

Jack answered "All right," May jumped down to hurry off after Helen, and then there was no sound to break the country stillness but the autumn wind, as it whirled the dead leaves to the ground, and the rumble of a train as it rushed along the track down by the river.

As it happened, Fred Hillwin was not at home, or he most certainly would have come out to inspect Popsey and keep Jack company. As for Fanny, she was so overjoyed at the unexpected call from her old school friends, that for about five minutes she could do nothing but give expression to her delight. Then the book Walter wanted had to be hunted up, all of which together consumed a good deal of time, the delay seeming especially prolonged to Jack, who soon grew tired of gazing at the top of baby's cap between Popsey's ears, and longed for some more exciting occupation. The donkey stood as if glued to the spot, and Amy slept on as peacefully as if in her little crib at home.

Suddenly the noon-day quiet was broken in upon by the blast of a horn, accompanied by the quick trot of horses' feet.

"A circus, perhaps!" exclaimed Jack; but, alas! whatever it was, nothing could be seen from where he stood, for the sound came from the turnpike just beyond the cross-roads before mentioned.

"Oh, how I would like to see what it is!" sighed the boy. Then he quickly measured with his eye the distance he would have to run, saw that Popsey seemed perfectly stationary, and with a sudden impulse dashed off to the corner, arriving just in time to behold a four-in-hand coach rush by like the wind.

It had scarcely passed him, however, when it stopped with an abruptness that threatened to pitch the passengers on ahead of it.

"What can be the matter?" thought Jack, and with all a boy's curiosity he ran on down the road to find out.

It seemed that one of the "leaders" had stumbled and fallen, and consequently been stepped on by the "wheelers," which resulted in such an entanglement of horses and harness as Jack had never seen before.

With wide-open eyes he looked on at the efforts of the gentlemen to straighten things out, and was about to ask if he could help them, when suddenly, with a cry of "Oh, Popsey—and the baby!" he tore back to the Hillwins' gate, and found the donkey-cart—gone.

With a terrible fear in his heart, the thoughtless boy gave one despairing look around him, and then started off on a run, in the direction in which Popsey had been headed, after a black speck just visible in the distance.

Two minutes later Helen and May came hurrying down the long walk through the garden, provoked with themselves at having staid so long.

"I do hope Amy hasn't waked up," said May; "but I told Jack in case she should— Why, where are they?"

"Perhaps Jack's driven down the road a little," suggested Helen.

But a hurried glance in both directions soon convinced the girls that the donkey-cart was nowhere near, and they were both beginning to feel a dread of they knew not what, when all at once May exclaimed, "Oh, Helen, look! here comes Jack now, and without Popsey!"

In great excitement the sisters ran to meet him, and imagine their horror when, with a voice all broken with sobs, he cried: "Oh! oh! it was only a—a peddler's wagon, and I ran nearly a mile to catch it, and—and now I don't know where to look, because Popsey's run off with the baby!"

Terrified beyond description at the thought of the danger that threatened their aunt's pet, who had been so reluctantly committed to their charge, the girls commanded Jack to tell them instantly just how it had all happened,[Pg 493] which he did with teeth-chattering from fright, and repeated assertions that he had believed Popsey was asleep.

"But didn't I tell you not to stir?—and oh, Helen, it's partly my fault too, for if I hadn't been so foolish as to leave Amy, she—" Here May broke down completely, and leaving her and Jack in tears together, Helen flew back to the house, and soon returned with Mrs. Hillwin, Fanny, the maid, and the cook. Then she pointed out the three roads it was possible the donkey had taken, and burst out crying herself.

"An' shure, miss, don't give way so," said the cook, cheeringly, "but jist take yer stand at the cross-roads beyant, an' ask ivery person that comes along—an' precious few do it be in this wild region, bad luck to it!—ef they're afther seein' a donkey runnin' off wid a baby."

This sensible suggestion was at once acted upon, and while the rest all hurried off in the direction of a turnip-field, which the maid declared Popsey must have sniffed, Helen stood at the junction of the three roads until a pleasant-faced old gentleman in a buggy approached her.

"Oh, sir," she cried, rushing up dangerously close to the wheels, "did you meet a runaway donkey-cart?"

"No, not I," was the answer; and the gentleman repressed a smile, but suddenly grew quite grave as he drew rein and asked if the donkey's name was Popsey.

"Oh, yes, yes," exclaimed Helen. "And have you seen him?"

"No, but I am going to see his owner now, and if you will get in, I will take you along with me. I am the family doctor, and am quite well acquainted with Popsey."

Hardly knowing what she did, but feeling that any sort of motion or action was better than waiting in suspense, Helen accepted the invitation, and began at once to pour forth her tale of grief to the kindly old physician, upon hearing which he whipped up his horse, saying that he was sure no harm had come to Amy.

Then Helen suddenly recollected how she had deserted her post, and was filled with a foreboding lest some one should pass the cross-roads who might know something about the donkey-cart, and there would be no one there to question him.

"Here comes Mr. Radlow's coachman now," exclaimed the doctor, when they had nearly reached their destination, "and driving at a furious rate. I warrant it's turned out just as I expected;" and with the words he signaled to the man to stop.

"Yes, yes, exactly as I imagined," said the physician, when the coachman had hurriedly and excitedly explained that Popsey had come trotting back to the stable with the lines about his heels, and baby Amy crowing joyously in the bottom of the cart, and that in consequence Mrs. Radlow was in a great state of fright concerning the fate of the cousins.

"Well, I'll soon relieve her fears on that score; and do you, Dennis, drive on toward the cross-roads with your carriage as fast as ever you can, and bring the other two children back."

As for Helen, she had not yet recovered from her joyful surprise.

"To think," she exclaimed, "that that donkey should have turned deliberately around and walked off home, nearly four miles, without upsetting anything, while we were looking for him in every other direction! There certainly never was such a dear little animal. But that doesn't excuse Jack's thoughtlessness, and I'm going to give Aunt Jennie leave to punish him very severely."

However, when the case was laid before the doctor, he declared that as the fault lay really with so many persons, and that as the three cousins had suffered sufficiently already from anxiety and suspense, the blame should be changed to praise, and that given to Popsey, who had displayed a disposition to execute the errand upon which he had been sent as speedily as possible.

WHAT HAPPENED WHEN DINAH WENT OUT AND LEFT TOPSY ALL

ALONE.

WHAT HAPPENED WHEN DINAH WENT OUT AND LEFT TOPSY ALL

ALONE.

Good-morning, little bird;

I wish you'd sing for me;

You look as if 'twere fun to live

Out-doors so wild and free.

I've brought Matilda Jane

Because she needs the air;

She is a very pretty child,

With lovely curling hair.

How many little birds

Are flying round to-day!

Now surely you will stay with me

When I've come here to play?

Oh, you have children three,

And they, perhaps, have stirred;

Well, if they need you, hurry home.

Good-morning, little bird.

New York City.

I thought I would write to you about my little bird Billie. He is a canary of the German breed, and is rather long and slim, but he sings very sweetly. I think he is the smartest and most intelligent bird I ever saw outside of a show. I taught him myself to stand on my finger whenever I put my hand in his cage; and he knows when I speak to him, for when I call to him, he will turn his head toward me, as if to say, "What?" I used to make him seesaw on a little stick with his little companion John, who was blind nearly all his life, which was very short; and then I would make him hold a little gun, and balance himself on a ball which I would keep in motion. He would stand on a little cart, and hold the reins with one claw, while I drew him around the room, with John, held in a market-basket, sitting on behind. He seldom tries to fly away, and I have frequently taken him out-doors in my hands, without fear of his escaping. Sometimes, for a change, I used to let him swing like a paroquet in one of my bangles. This I do not think he liked much, for his tail was so long it was hard for him to keep his balance. But the most difficult thing that I taught him to do was to lie on his back and pretend he was asleep. I would lay him down gently, and after kicking his feet, and trying to grasp my fingers, he would lie perfectly still until I touched him, when he would jump up; and then I would have him kiss me, which he can do nicely, moving his bill all the time. I should like to tell you about John, who died, we think, on account of his eyes, which, after we had had him a little time, became covered with white mists, which we think were cataracts.

A Strong Friend of

"Harper's Young People".

It would be interesting to hear of your method in teaching your pet so many pretty tricks. I suppose you were very gentle and patient, and that you taught him one thing perfectly before letting him begin upon another.

Washington, D. C.

I, like Virginie C. B., am practicing a few of the gymnastics mentioned in No. 118. We have a bar across one of our doorways a foot from the top, which I catch hold of and swing by. I can not draw my chin up to it yet, but can come very near it. After the Postmistress has assured us she has seen Jimmy Brown, his stories are much more interesting to me, for they must be the experiences of a real boy. We always laugh at them, they are so funny.

My sister has been all over the establishment of Harper & Brothers, and saw them printing Young People. I should like to see that, and hope to some time. I think it was Augusta C. who did not like cats. She would not change her mind if she saw our cat, for that lazy animal is awake all night and asleep all day. We have had no less than six cats during the past year. "The Talking Leaves" excited us very much, and I think it was splendid. Toby Tyler is a very nice little boy, I think, and when I first glanced at the picture of the circus coming in, I thought they were taking him away again.

We have some flowers in our back yard, and we like them very much. The seeds are just coming up, and I take great interest in watching them. We have some very pretty pansies, roses, and bridal-wreaths. They are blooming now. I brought some wild flowers from the woods, and my sister brought some violets; they are growing very nicely. We have but one geranium, and its blooms are shrivelled. I do not know what to do to it.

I like to write stories very much, and I love dearly to draw pictures. Last Tuesday was very warm, and you would have thought it was summer if you had suddenly been transported to Washington.

Emily N.

Perhaps your geranium needs rest. Try the plan of pinching off every bud for the next few weeks. The soil may need enriching, or you may have watered it too freely.

Brooklyn, New York.

I have written to Harper's Young People three times, and none of my letters have been printed; but I believe in perseverance, so I am going to try again. I have never read any paper I liked half as well as Harper's Young People. Papa gets it for me, and I read it to my little brother. One night I was reading "Tim and Tip" to him, and I happened to look up, and he was crying. He didn't want me to think he was crying, so he said, "It's only the water that comes out of my eyes." I like Jimmy Brown's stories very much. I think all of the stories in the paper are very interesting. Jimmy Brown and Georgie Hackett seem to possess about the same qualities. My favorite study in school is history.

Emma.

I do not know Georgie Hackett, but poor Jimmy is certainly an interesting boy, though I would not care to have him living at my house, unless he could behave better than he now does. Perseverance is an excellent quality. You could not have a better motto than

"If at first you don't succeed,

Try, try again."

Sanborn, Dakota Territory.

I am a little English girl eight years old, and hope to see this letter printed, to please dear papa, as he does not know I am going to write. I have taken Harper's Young People two years (ever since we left England), and have never written before. I have an Indian pony, on which I ride about; her name is Frances. My brother Jack has one called Charlie. I have a little sister Mabel; she is six, and so fat that mamma calls her Pumpkin. She calls me her fairy lily. I have seen Jumbo in England, and am glad he has come to America. Papa says some time I may see him again. I am very fond of reading. I have lots of books, and my grandma sends me Little Folks every month. I have been learning music for a year, and am getting on nicely. We find lovely flowers about here, and I gather mamma lovely bunches for the table every day. Good-by.

Katie S.

Junction, Idaho.

I am a little boy seven years old. I take Harper's Young People, and I like it very much. I think "Toby Tyler" and "Mr. Stubbs's Brother" are the best of all. Blue Ribbon has a little kitten; she is teaching it to walk. I have a horse; his name is Old Indian. The reason I call him Old Indian is because we bought him of the Indians. I have some nice rides on him. We live on a ranch, and have lots of little calves and little chickens. I do not go to school, but study my lessons at home. I send one dollar for Young People's Cot.

Oliver T. C.

Your contribution has been sent to the lady who receives and takes care of the money for Young People's Cot. Is Blue Ribbon the little kitten's mother? I hope Old Indian is a gentle pony. From his name I should think he might be quite fiery.

Mabel and Ethel can't write for themselves, and they do not know that I am writing to the Post-office Box to tell other little girls about them. What here follows is not a made-up story; it is set down almost word for word as it was spoken. The girls were in their little beds, talking about different things, and papa was sitting at the table reading a book by the light of the lamp. Thunder was heard in the distance, and Ethel remarked that the rain was coming. This led Mabel to ask the question which forms the title of this letter, "Papa, what makes the rain come?"

While thinking about the best way to make her understand the wonderful and beautiful natural process—how the sun draws up vapors from land and sea, and stores the treasures of rain in the clouds, returning them in showers of blessings upon the earth—Ethel broke in with her views, thus relieving me of a difficulty. So I kept quiet as a mouse, and listened while pretending to read. Ethel, half raising herself in bed, thus explained:

"Why, Mabel, I will tell you what makes the rain come. You see, God is up there above the clouds, and He has wings, and flies from place to place, all over. Then, you know, He has a pump, with a big deep well, with lots, oh! lots of water in it, and on the pump there is a rubber tube, with a sprinkler fastened to it. And then He pumps, and pumps, and pumps, and the angels they pump, and the water comes, and spurtles, and spurtles, and spurtles, and spurtles, and spurtles, and spurtles; and that's what makes the rain come."

These were the child's thoughts and expressions on the beautiful phenomena of the rain. The explanation seemed sufficient and satisfactory, as both little thinkers forthwith resigned themselves into the loving arms of "tired nature's sweet restorer," and were carried far away into the happy land of dreams.

F. J. T.

Farmington, Minnesota.

Churchville, Maryland.

As the day is rainy, we have been looking over Harper's Young People, and seeing so many nice letters in Our Post-office Box. I thought, by way of variety, I would send one from Harford County. I have two sisters. One is a teacher, and she is going to read some pieces out of your paper to the children in her school.

We have a colt named Pinafore. The other day I turned another horse, with a halter on, into the same field with him. Pin caught the halter in his mouth, and led him about as he had seen us do. I have a Scotch terrier dog named Jack. I hitch him to a little wagon, and he is better trained than the speckled pig in No. 132.

I think your paper is just splendid, but like to read "Mr. Stubbs's Brother" the best of all. I went to see Jumbo in Baltimore.

Frank B.

Oh, he's so sweet,

The darling thing!

On his small feet

We kisses fling.

He plays, he crows,

Can laugh and sing,

And thinks he knows

'Most everything.

He goes to bed

So sweet at night;

You'll hear his tread

Soon as 'tis light.

He plays, you know.

The whole day through,

And he can blow

His trumpet new.

All places round,

No sweeter toy

Than this is found—

Our baby boy.

Daisy M. (aged 9.)

Davenport, Iowa.

Bayfield, Wisconsin.

I am thirteen years old, and have a little adopted sister, whose name is Elsie, and whom I love just as much as if she were my own sister. She is seven years old. I wish the readers of Young People could see my canary-bird. His name is Jim. I often let him out of his cage, and sometimes he comes hopping up to me, and then he will chirp until I give him a piece of apple or orange.

I am very fond of reading. I have just finished a book called Zigzag Journeys in Europe, and I enjoyed it very much. Our house is a square from Lake Superior. We can stand at any window and look right out on the lake. Bayfield is a great summer resort for invalids and pleasure-seekers. Very nearly all the large steamboats come here. From Bayfield we can also see five of the Apostle Islands.

Susie P.

Would it not be nice if we could have all the cunning and beautiful pets our little friends write about arranged together in a great exhibition? As this is impossible, we must try to see each of them from the pretty pen pictures their little owners send.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.