This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Middle Kingdom, Volume I (of 2)

A Survey of the Geography, Government, Literature, Social Life, Arts, and History of the Chinese Empire and its Inhabitants

Author: S. Wells (Samuel Wells) Williams

Release Date: September 8, 2018 [eBook #57868]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MIDDLE KINGDOM, VOLUME I (OF 2)***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/middlekingdomsu01will |

Images with blue borders are linked to higher-resolution versions of the illustrations. Move the cursor onto the image and click to see the higher-resolution image.

Some characters might not display in this html version (e.g., empty squares.) If so, the reader should consult the original page images noted above.

Large tables have been reformatted to fit smaller screens.

Page headers are formatted as sidenotes.

Upon the triple altar, or Tien Tan (Volume I., p. 76), the central temporary shrine is dedicated to Hwang-Tien Shangtí, or ‘Imperial Heaven’s Ruler above.’ Upon the Emperor’s right, nearest the chief pavilion, are tablets to his ancestors, Tienming, Shunchí, Yungching, and Kiaking; the corresponding opposite house is similarly devoted to Tientsung, Kanghí, Kienlung, and Taukwang. The small buildings behind and below these are the Taming chí Wei, the ‘Altar of the Sun’ or ‘Great Luminary’ (on the right), and the Ye-ming chí Wei, or ‘Altar of the Night Luminary.’ The last structure on the worshipper’s right contains tablets to the Chau-tien Sing, or ‘All Stars;’ to the Urh-shih pat Suhsing, or ‘Twenty-eight Constellations in the Ecliptic;’ to the Peh-tan Sing, or Ursa Major; and to the Muh, Kin, Shui, Fo, and Tu, or Five Elements—‘Wood, Metal, Water, Fire, and Earth.’ Facing this building on the left are shrines to Siueh-sz’, Yü-sz’, Fung-sz’, and Lui-sz’, the superintendents of Snow, Rain, Wind, and Thunder.

論總國中

A SURVEY OF THE GEOGRAPHY, GOVERNMENT, LITERATURE,

SOCIAL LIFE, ARTS, AND HISTORY

OF

THE CHINESE EMPIRE

AND

ITS INHABITANTS

BY

S. WELLS WILLIAMS, LL.D.

PROFESSOR OF THE CHINESE LANGUAGE AND

LITERATURE AT YALE COLLEGE; AUTHOR

OF TONIC AND SYLLABIC

DICTIONARIES OF THE CHINESE LANGUAGE

REVISED EDITION, WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND A NEW MAP OF THE EMPIRE

Volume I.

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1900

Copyright, 1882, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Trow’s

Printing and Bookbinding Company

201-213 East Twelfth Street

NEW YORK

To

GIDEON NYE, Jr.,

OF CANTON, CHINA,

A

TESTIMONIAL OF THE

Respect and Friendship

OF THE AUTHOR.

During the thirty-five years which have elapsed since the first edition of this work was issued, a greater advance has probably been made in the political and intellectual development of China than within any previous century of her history. While neither the social habits nor principles of government have so far altered as to necessitate a complete rewriting of these pages, it will be found, nevertheless, that the present volumes treat of a reformed and in many respects modern nation. Under the new régime the central administration has radically increased its authority among the provincial rulers, and more than ever in former years has managed to maintain control over their pretentions. The Empire has, moreover, established its foreign relations on a well-understood basis by accredited envoys; this will soon affect the mass of the people by the greater facilities of trade, the presence of travellers, diffusion of education, and other agencies which are awaking the people from their lethargy. Already the influences which will gradually transform the face of society are mightily operating.

The changes which have been made in the book comprise such alterations and additions as were necessary to describe the country under its new aspects. In the constant desire to preserve a convenient size, every doubtful or superfluous sentence has been erased, while the new matter incorporated has increased[x] the bulk of the present edition about one-third. The arrangement of chapters is the same. The first four, treating of the geography, combine as many and accurate details of recent explorers or residents as the proportions of this section will permit. The extra-provincial regions are described from the researches of Russian, English, and Indian travellers of the last twenty years. It is a waste, mountainous territory for the most part and can never support a large population. Great pains have been taken by the cartographer, Jacob Wells, to consult the most authentic charts in the construction of the map of the Empire. By collating and reducing to scale the surveys and route charts of reliable travellers throughout the colonies, he has produced in all respects as accurate a map of Central Asia as is at this date possible. The Eighteen Provinces are in the main the same as in my former map.

The chapter on the census remains for the most part without alteration, for until there has been a methodical inspection of the Empire, important questions concerning its population must be held in abeyance. It is worth noticing how generally the estimates in this chapter—or much larger figures—have since its first publication been accepted for the population of China. Foreign students of natural history in China have, by their researches in every department, furnished material for more extensive and precise descriptions under this subject than could possibly have been gathered twoscore years ago. The sixth chapter has, therefore, been almost wholly rewritten, and embraces as complete a summary of this wide field as space would allow or the general reader tolerate. The specialist will, however, speedily recognize the fact that this rapid glance serves rather to indicate how immense and imperfectly explored is this subject than to describe whatever is known.

That portion of the first volume treating of the laws and their administration does not admit of more than a few minor[xi] changes. However good their theory of jurisprudence, the people have many things to bear from the injustice of their rulers, but more from their own vices. The Peking Gazette is now regularly translated in the Shanghai papers, and gives a coup d’œil of the administration of the highest value.

The chapters on the languages and literature are considerably improved. The translations and text-books which the diligence of foreign scholars has recently furnished could be only partially enumerated, though here, as elsewhere in the work, references in the foot-notes are intended to direct the more interested student to the bibliography of the subject, and present him with the materials for an exhaustive study. The native literature is extensive, and all branches have contributed somewhat to form the résumé which is contained in this section, giving a preponderance to the Confucian classics. The four succeeding chapters contain notices of the arts, industries, domestic life, and science of the Chinese—a necessarily rapid survey, since these features of Chinese life are already well understood by foreigners. Nothing, however, that is either original or peculiar has been omitted in the endeavor to portray their social and economic characteristics. The emigration of many thousands of the people of Kwangtung within the last thirty years has made that province a representative among foreign nations of the others; it may be added that its inhabitants are well fitted, by their enterprise, thrift, and maritime habits, to become types of the whole.

The history and chronology are made fuller by the addition of several facts and tables;[1] but the field of research in this direction has as yet scarcely been defined, and few certain dates have been determined prior to the Confucian era.[xii] The entire continent of Asia must be thoroughly investigated in its geography, antiquities, and literature in order to throw light on the eastern portion. The history of China offers an interesting topic for a scholar who would devote his life to its elucidation from the mass of native literature.

The two chapters on the religions, and what has been done within the past half century to promote Christian missions, are somewhat enlarged and brought down to the present time. The study of modern scholars in the examination of Chinese religious beliefs has enabled them to make comparisons with other systems of Asiatics, as well as discuss the native creeds with more certainty.

The chapter on the commerce of China has an importance commensurate with its growing amount. Within the past ten years the opium trade has been attacked in its moral and commercial bearings between China, India, and England. There are grounds for hope that the British Government will free itself from any connection with it, which will be a triumph of justice and Christianity. The remainder of Volume II. describes events in the intercourse of China with the outer world, including a brief account of the Tai-ping Rebellion, which proximately grew out of foreign ideas. No connected or satisfactory narrative of the events which have forced one of the greatest nations of the world into her proper position, so far as I am aware, has as yet been prepared. A succinct recital of one of the most extraordinary developments of modern times should not be without interest to all.

The work of condensing the vast increase of reliable information upon China into these two volumes has been attended with considerable labor. Future writers will, I am convinced, after the manner of Richthofen, Yule, Legge, and others, confine themselves to single or cognate subjects rather than attempt such a comprehensive synopsis as is here presented. The[xiii] number of illustrations in this edition is nearly doubled, the added ones being selected with particular reference to the subject-matter. I have availed myself of whatever sources of information I could command, due acknowledgment of which is made in the foot-notes, and ample references in the Index.

The revision of this book has been the slow though constant occupation of several years. When at last I had completed the revised copy and made arrangements as to its publication, in March, 1882, my health failed, and under a partial paralysis I was rendered incapable of further labor. My son, Frederick Wells Williams, who had already looked over the copy, now assumed entire charge of the publication. I had the more confidence that he would perform the duties of editor, for he had already a general acquaintance with China and the books which are the best authority. The work has been well done, the last three chapters particularly having been improved under his careful revision and especial study of the recent political history of China. The Index is his work, and throughout the book I am indebted to his careful supervision, especially on the chapters treating of geography and literature. By the opening of this year I had so far recovered as to be able to superintend the printing and look over the proofs of the second volume.

My experiences in the forty-three years of my life in China were coeval with the changes which gradually culminated in the opening of the country. Among the most important of these may be mentioned the cessation of the East India Company in 1834, the war with England in 1841-42, the removal of the monopoly of the hong merchants, the opening of five ports to trade, the untoward attack on the city of Canton which grew out of the lorcha Arrow, the operations in the vicinity of Peking, the establishment of foreign legations in that city, and finally, in 1873, the peaceful settlement of the kotow, which rendered possible the approach of foreign ministers to the Em[xiv]peror’s presence. Those who trace the hand of God in history will gather from such rapid and great changes in this Empire the foreshadowing of the fulfilment of his purposes; for while these political events were in progress the Bible was circulating, and the preaching and educational labors of missionaries were silently and with little opposition accomplishing their leavening work among the people.

On my arrival at Canton in 1833 I was officially reported, with two other Americans, to the hong merchant Kingqua as fan-kwai, or ‘foreign devils,’ who had come to live under his tutelage. In 1874, as Secretary of the American Embassy at Peking, I accompanied the Hon. B. P. Avery to the presence of the Emperor Tungchí, when the Minister of the United States presented his letters of credence on a footing of perfect equality with the ‘Son of Heaven.’ With two such experiences in a lifetime, and mindful of the immense intellectual and moral development which is needed to bring an independent government from the position of forcing one of them to that of yielding the other, it is not strange that I am assured of a great future for the sons of Han; but the progress of pure Christianity will be the only adequate means to save the conflicting elements involved in such a growth from destroying each other. Whatever is in store for them, it is certain that the country has passed its period of passivity. There is no more for China the repose of indolence and seclusion—when she looked down on the nations in her overweening pride like the stars with which she could have no concern.

In this revision the same object has been kept in view that is stated in the Preface to the first edition—to divest the Chinese people and civilization of that peculiar and indefinable impression of ridicule which has been so generally given them by foreign authors. I have endeavored to show the better traits of their national character, and that they have had up to this[xv] time no opportunity of learning many things with which they are now rapidly becoming acquainted. The time is speedily passing away when the people of the Flowery Land can fairly be classed among uncivilized nations. The stimulus which in this labor of my earlier and later years has been ever present to my mind is the hope that the cause of missions may be promoted. In the success of this cause lies the salvation of China as a people, both in its moral and political aspects. This success bids fair to keep pace with the needs of the people. They will become fitted for taking up the work themselves and joining in the multiform operations of foreign civilizations. Soon railroads, telegraphs, and manufactures will be introduced, and these must be followed by whatsoever may conduce to enlightening the millions of the people of China in every department of religious, political, and domestic life.

The descent of the Holy Spirit is promised in the latter times, and the preparatory work for that descent has been accomplishing in a vastly greater ratio than ever before, and with increased facilities toward its final completion. The promise of that Spirit will fulfil the prophecy of Isaiah, delivered before the era of Confucius, and God’s people will come from the land of Sinim and join in the anthem of praise with every tribe under the sun.

S. W. W.

New Haven, July, 1883.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| General Divisions and Features of the Empire, | 1-48 |

| Unusual interest involved in the study of China, 1; The name China probably a corruption of Tsin, 2; Other Asiatic names for the country, 3; Ancient and modern native designations, 5; Dimensions of the Empire, 6; Its three Grand Divisions: The Eighteen Provinces, Manchuria, and Colonies, 7; China Proper, its names and limits, 8; Four large mountain chains, 10; The Tien shan, ibid.; The Kwănlun, 11; The Hing-an and Himalaya systems, 13; Pumpelly’s “Sinian System” of mountains, 14; The Desert of Gobi and Sha-moh, 15; Its character and various names, 17; Rivers of China: The Yellow River, 18; The Yangtsz’ River, 20; The Chu or Pearl River, 22; Lakes of China, 23; Boundaries of China Proper, 25; Character of its coast, 26; The Great Plain, 27; The Great Wall of China, its course, 29; Its construction and aspect, 30; The Grand Canal, 31; Its history and present condition, 36; Minor canals, 37; Public roads, De Guignes’ description, ibid.; General aspects of a landscape, 40; Physical characteristics of the Chinese, 41; The women, 42; Aborigines: Miaotsz’, Lolos, Li-mus, and others, 43; Manchus and Mongols, 44; Attainments and limits of Chinese civilization, 46. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Geographical Description of the Eastern Provinces, | 49-141 |

| Limited knowledge of foreign countries, 49; Topographies of China numerous and minute, 50; Climate of the Eighteen Provinces, 50; Of Peking and the Great Plain, 51; Of the southern coast towns, 53; Contrast in rain-fall between Chinese and American coasts, 55; Tyfoons, 56; Topographical divisions into Fu, Ting, Chau, and Hien, 58; Position and boundary of Chihlí Province, 60; Table of the Eighteen Provinces, their subdivis[xiv]ions and government, 61; Situation, size, and history of Peking, 62; Its walls and divisions, 64; The prohibited city (Tsz’ Kin Ching) and imperial residence, 67; The imperial city (Hwang Ching) and its public buildings, 70; The so-called “Tartar City,” 72; The Temples of Heaven and of Agriculture, 76; Environs of Peking, 79; Tientsin and the Pei ho, 85; Dolon-nor or Lama-miao, 87; Water-courses and productions of the province, 88; The Province of Shantung, 89; Tai shan, the ‘Great Mount,’ 90; Cities, productions, and people of Shantung, 92; Shansí, its natural features and resources, 94; Taiyuen, the capital, 96; Roads and mountain passes of Shansí, 97; Position and aspect of Honan Province, ibid.; Kaifung, its capital, 99; Kiangsu Province, ibid.; Its fertility and abundant water-ways, 100; Nanking, or Kiangning, the capital, 101; Porcelain Tower of Nanking, 102; Suchau, “the Paris of China,” 103; Chinkiang and Golden Island, 105; Shanghai, 106; The Province of Nganhwui, 109; Nganking, Wuhu, and Hwuichau, 110; Kiangsí Province, 111; Nanchang, its capital, and the River Kan, 112; Porcelain works at Kingteh in Jauchau, 113; Chehkiang Province, its rivers, 114; Hangchau, the capital, 115; Ningpo, 120; Chinhai and the Chusan Archipelago, 123; Chapu, Canfu, and the “Gates of China,” 127; Fuhkien Province, ibid.; The River Min, 128; Fuhchau, 130; Amoy and its environs, 134; Chinchew (Tsiuenchau), the ancient Zayton, 136; Position, inhabitants, and productions of Formosa, 137; The Pescadore Islands, 141. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Geographical Description of the Western Provinces, | 142-184 |

| The Province of Hupeh, 142; The three towns, Wuchang, Hanyang, and Hankow, 143; Scenery on the Yangtsz’ kiang, 145; Hunan Province, its rivers and capital city, 146; Shensí Province, 148; The city of Sí-ngan, 150; Topography and climate of Kansuh Province, 152; Sz’chuen Province and its four streams, 154; Chingtu fu and the Min Valley, 156; The Province of Kwangtung, 158; Position of Canton, or Kwangchau, 160; Its population, walls, general appearance, 161; Its streets and two pagodas, 163; Temple of Longevity and Honam Joss-house, 164; Other shrines and the Examination Hall, 166; The foreign factories, or ‘Thirteen Hongs,’ 167; Sights in the suburbs of Canton, 169; Whampoa and Macao, 170; The colony of Hongkong, 171; Places of interest in Kwangtung, 173; The Island of Hainan, 175; Kwangsí Province, 176; Kweichau[xv] Province, 178; The Miaotsz’, 179; The Province of Yunnan, 180; Its topography and native tribes, 183; Its mineral wealth, 184. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Geographical Description of Manchuria, Mongolia, Ílí, and Tibet, | 185-257 |

| Foreign and Chinese notions of the land of Tartary, 185; Table of the Colonies, their subdivisions and governments, 186; Extent of Manchuria, 187; Its mountain ranges, 188; The Amur and its affluents, the Ingoda, Argun, Usuri, and Songari, 189; Natural resources of Manchuria, 191; The Province of Shingking, ibid.; Its capital, Mukden, and other towns, 192; Climate of Manchuria, 195; The Province of Kirin, 196; The Province of Tsi-tsi-har, 198; Administration of government in Manchuria, 199; Extent of Mongolia, 200; Its climate and divisions, 201; Inner Mongolia, 202; Outer Mongolia, 204; Urga, its capital, ibid.; Civilization and trade of the Mongols, 206; Kiakhta and Maimai chin, 207; The Province of Cobdo, 208; The Province of Koko-nor, or Tsing hai, 209; Its topography and productions, 211; Towns between Great Wall and Ílí, 213; Position and topography of Ílí, 215; Tien-shan Peh Lu, or Northern Circuit, 218; Kuldja, its capital, 219; Tien-shan Nan Lu, or Southern Circuit, 221; The Tarim Basin, ibid.; Cities of the Southern Circuit, 224; Kashgar, town and government, 227; Yarkand, 229; The District of Khoten, 230; Administration of government in Ílí, 231; History and conquest of the country, 233; Tibet, its boundaries and names, 237; Topography of the province, 239; Its climate and productions, 241; The yak and wild animals, ibid.; Divisions: Anterior and Ulterior Tibet, 244; H’lassa, the capital city, 245; Manning’s visit to the Dalai-lama, 246; Shigatsé, capital of Ulterior Tibet, 247; Om mani padmí hum, 249; Manners and customs in Tibet, 251; Language, 252; History, 254; Government, 255. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Population and Statistics, | 258-295 |

| Interest and difficulties of this subject, 258; Ma Twan-lin’s study of the censuses, 260; Tables of various censuses, 263; These estimates considered in detail, 265; Four of these are reliable, 269; Evidence in their favor, 270; Comparative population-density of Europe and China, 272; Proportion of arable and[xvi] unproductive land, 274; Sources and kinds of food in China, 276; Tendencies toward increase of population, 277; Obstacles to emigration, 278; Government care of the people, 280; Density of population near Canton, ibid.; Mode of taking the census under Kublai khan, 281; Present method, 282; Reasons for admitting the Chinese census, 285; Two objections to its acceptance, 286; Unsatisfactory statistics of revenue in China, 289; Revenue of Kwangtung Province, 290; Estimates of Medhurst, De Guignes, and others, 291; Principal items of expenditure, 292; Pay of military and civil officers, 293; The land tax, 294. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Natural History of China, | 296-379 |

| Foreign scientists and explorers in China, 296; Interesting geological features, 297; Loess formation of Northern China, ibid.; Its wonderful usefulness and fertility, 300; Baron Richthofen’s theory as to its origin, 303; Minerals of China Proper: Coal, 304; Building stones, salts, jade, etc., 307; The precious metals and their production, 310; Animals of the Empire, 313; Monkeys, 314; Various carnivorous animals, 317; Cattle, sheep, deer, etc., 320; Horses, pigs, camels, etc., 323; Smaller animals and rodents, 326; Cetacea in Chinese waters, 329; Birds of prey, 331; Passerinæ, song-birds, pies, etc., 332; Pigeons and grouse, 335; Varieties of pheasants, 336; Peacocks and ducks, 338; An aviary in Canton, 340; Four fabulous animals: The kí-lin, 342; The fung-hwang, or phœnix, 343; The lung, or dragon, and kwei, or tortoise, 344; Alligators and serpents, 345; Ichthyology of China, 347; Gold-fish and methods of rearing them, 348; Shell-fish of the Southern coast, 350; Insects: Silk-worms and beetles, 352; Wax-worm: Native notions of insects, 353; Students of botany in China, 355; Flora of Hongkong, coniferæ, grasses, 356; The bamboo, 358; Varieties of palms, lilies, tubers, etc., 360; Forest and timber growth, 362; Rhubarb, the Chinese ‘date’ and ‘olive,’ 364; Fruit-trees, 366; Flowering and ornamental plants, 367; The Pun tsao, or Chinese herbal, 370; Its medicine and botany, 371; Its zoölogy, 374; Its observations on the horse, 375; State of the natural sciences in China, 377. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Laws of China, and Plan of its Government, | 380-447 |

| Theory of the Chinese Government patriarchal, 380; The principles of surveillance and mutual responsibility, 383; The Penal Code[xvii] of China, 384; Preface by the Emperor Shunchí, 385; Its General, Civil, and Fiscal Divisions, 386; Ritual, Military, and Criminal Laws, 389; The Code compares favorably with other Asiatic Laws, 391; Defects in the Chinese Code, 392; General survey of the Chinese Government, 393; 1, The Emperor, his position and titles, ibid.; Proclamation of Hungwu, first Manchu Emperor, 395; Peculiarities in the names of Emperors, 397; The Kwoh hao, or National, and Miao hao, or Ancestral Names, 398; Style of an Imperial Inaugural Proclamation, 399; Programme of Coronation Ceremonies, 401; Dignity and Sacredness of the Emperor’s Person, 402; Control of the Right of Succession, 403; The Imperial Clan and Titular Nobles, 405; 2, The Court, its internal arrangements, 407; The Imperial Harem, 408; Position of the Empress-dowager, 409; Guard and Escort of the Palace, 410; 3, Classes of society in China, 411; Eight privileged classes, 413; The nine honorary “Buttons,” or Ranks, 414; 4, The central administration, 415; The Nui Koh, or Cabinet, 416; The Kiun-kí Chu, or General Council, 418; The King Pao, or Peking Gazette, 420; The Six Boards (a), of Civil Office—Lí Pu, 421; (b), of Revenue—Hu Pu, 422; (c), of Rites—Lí Pu, 423; (d), of War—Ping Pu, 424; (e), of Punishments—Hing Pu, 426; (f), of Works—Kung Pu, 427; The Colonial Office, 428; The Censorate, 430; Frankness and honesty of certain censors, 431; Courts of Transmission and Judicature, 433; The Hanlin Yuen, or Imperial Academy, 434; Minor courts and colleges of the capital, 435; 5, Provincial Governments, 437; Governors-general (tsungtuh) and Governors (futai), 438; Subordinate provincial authorities, 441; Literary, Revenue, and Salt Departments, 443; Tabular Résumé of Provincial Magistrates, 444; Military and Naval control, 445; Special messengers, or commissioners, 446. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Administration of the Laws, | 448-518 |

| 6, Execution of laws, checks upon ambitious officers, 448; Triennial Catalogue and its uses, 449; Character and position of Chinese officials, 451; The Red Book, or status of office-holders, 452; Types of Chinese high officers: Duke Ho, 452; Career of Commissioner Sung, 454; Public lives of Commissioners Lin and Kíying, 457; Popularity of upright officers, Governor Chu’s valedictory, 462; Official confessions and petitions for punishment, 464; Imperial responsibility for public disasters, 466; A prayer for rain of the Emperor Taukwang, 467; Im[xviii]perial edicts, their publication and phraseology, 469; Contrast between the theory and practice of Chinese legislation, 473; Extortions practised by officials of all ranks, 474; Evils of an ill-paid police, 478; Fear and selfishness of the people, 480; Extent of clan systems among them, 482; Village elders and clan rivalries, 483; Dakoits and thieves throughout the country, 486; Popular associations—character of their manifestoes, 488; Secret societies, The Triad, or Water-Lily Sect, 493; A Memorial upon the Evils of Mal-Administration, 494; Efforts of the authorities against brigandage, 497; Difficulties in collecting the taxes, 498; Character of proceedings in the Law Courts, 500; Establishments of high magistrates, 503; Conduct of a criminal trial, 504; Torture employed to elicit confessions, 507; The five kinds of punishments, 508; Modes of executing criminals, 512; Public prisons, their miserable condition, 514; The influence of public opinion in checking oppression, 517. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Education and Literary Examinations, | 519-577 |

| Stimulus of literary pursuits in China, 520; Foundation of the present system of competition, 521; Precepts controlling early education, 522; Arrangements and curriculum of boys’ schools, 524; Six text-books employed: 1, The ‘Trimetrical Classic,’ 527; 2, The ‘Century of Surnames,’ and 3, ‘Thousand-Character Classic,’ 530; 4, The ‘Odes for Children,’ 533; 5, The Hiao King, or ‘Canons of Filial Duty,’ 536: 6, The Siao Hioh, or ‘Juvenile Instructor,’ 540; High schools and colleges, 542; Proportion of readers throughout China, 544; Private schools and higher education, 545; System of examinations for degrees and public offices, 546; Preliminary trials, 547; Examination for the First Degree, Siu-tsai; 549: For the Second Degree, Kü-jin, 550; Example of a competing essay, 554; Final honors conferred at Peking, 558; A like system applied to the military, 560; Workings and results of the system of examinations, 562; Its abuses and corruption, 566; Social distinction and influence enjoyed by graduates, 570; Female education in China, 572; Authors and school-books employed, 574. | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Structure of the Chinese Language, | 578-625 |

| Influence of the Chinese language upon its literature, 578; Native accounts of the origin of their characters, 580; Growth and[xix] development of the language, 581; Characters arranged into six classes, 583; Development from hieroglyphics, 584; Phonetic and descriptive properties of a character, 587; Arrangement of the characters in lexicons, 589; Classification according to radicals, 591; Mass of characters in the language, 593; Six styles of written characters, 597; Their elementary strokes, 598; Ink, paper, and printing, 599; Manufacture and price of books, 601; Native and foreign movable types, 603; Phonetic character of the Chinese language, 605; Manner of distinguishing words of like sound, 609; The Shing, or tones of the language, 610; Number of sounds or words in Chinese, 611; The local dialects and patois, 612; Court or Mandarin dialect, 613; Other dialects and variations in pronunciation, 614; Grammar of the language, 617; Its defects and omissions, 621; Hints for its study, 623; Pigeon English, 624. | |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Classical Literature of the Chinese, | 626-673 |

| The Imperial Catalogue as an index to Chinese literature, 626; The Five Classics: I. The Yih King, or ‘Book of Changes,’ 627; II. The Shu King, or ‘Book of Records,’ 633; III. The Shí King, or ‘Book of Odes,’ 636; IV. The Lí Kí, or ‘Book of Rites,’ and other Rituals, 643; V. The Chun Tsiu, or ‘Spring and Autumn Record,’ 647; The Four Books: 1, The ‘Great Learning,’ 652; 2, The ‘Just Medium,’ 653; 3, The Lun Yu, or ‘Analects’ of Confucius, 656; Life of Confucius, 658; Character of the Confucian System of Ethics, 663; 4, The Works of Mencius, 666; His Life, and personal character of his Teachings, 667; Dictionary of the Emperor Kanghí, 672. | |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Polite Literature of the Chinese, | 674-723 |

| Character of Chinese Ornamental Literature, 674; Works on Chinese History, 675; Historical Novels, 677; The ‘Antiquarian Researches’ of Ma Twan-lin, 681; Philosophical Works: Chu Hí on the Primum Mobile, 683; Military, Legal, and Agricultural Writings, 686; The Shing Yu, or ‘Sacred Commands’ of Kanghí, 687; Works on Art, Science, and Encyclopædias, 692; Character and Examples of Chinese Fiction, 693; Poetry: The Story of Lí Tai-peh, 696; Modern Songs and Extempore Verses, 704; Dramatic Literature, burlettas, 714; ‘The Mender of Cracked Chinaware’—a Farce, 715; Deficiencies and limits of Chinese literature, 719; Collection of Chinese Proverbs, 720. | |

| [xx]CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Architecture, Dress, and Diet of the Chinese, | 724-781 |

| Notions entertained by foreigners upon Chinese customs, 724; Architecture of the Chinese, 726; Building materials and private houses, 728; Their public and ornamental structures, 730; Arrangement of country houses and gardens, 731; Chinese cities: shops and streets, 736; Temples, club-houses, and taverns, 739; Street scenes in Canton and Peking, 740; Pagodas, their origin and construction, 744; Modes of travelling, 747; Various kinds of boats, 749; Living on the water in China, 750; Chop-boats and junks, 752; Bridges, ornamental and practical, 754; Honorary Portals, or Pai-lau, 757; Construction of forts and batteries, 758; Permanence of fashion in Chinese dress, 759; Arrangement of hair, the Queue, 761; Imperial and official costumes, 763; Dress of Chinese women, 764; Compressed feet: origin and results of the fashion, 766; Toilet practices of men and women, 770; Food of the Chinese, mostly vegetable, 772; Kinds and preparation of their meats, 776; Method of hatching and rearing ducks’ eggs, 778; Enormous consumption of fish, 779; The art of cooking in China, 781. | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Social Life among the Chinese, | 782-836 |

| Features and professions in Chinese society, 782; Social relations between the sexes, 784; Customs of betrothment and marriage, 785; Laws regulating marriages, 792; General condition of females in China, 794; Personal names of the Chinese, 797; Familiar and ceremonial intercourse: The Kotow, 800; Forms and etiquette of visiting, 802; A Chinese banquet, 807; Temperance of the Chinese, 808; Festivals; Absence of a Sabbath in China, 809; Customs and ceremonies attending New-Year’s Day, 811; The dragon-boat festival and feast of lanterns, 816; Brilliance and popularity of processions in China, 819; Play-houses and theatrical shows, 820; Amusements and sports: Gambling, chess, 825; Contrarieties in Chinese and Western usage, 831; Strength and weakness of Chinese character, 833; Their mendacity and deceit, 834. | |

| PAGE | |

| Worship of the Emperor at the Temple of Heaven, | Frontispiece |

| Title-page, representing an honorary portal, or PAI-LAU. (The two characters, Shing chí, upon the top, indicate that the structure has been erected by imperial command. In the panel upon the lintel the four characters, Chung Kwoh Tsung-lun, ‘A General Account of the Middle Kingdom,’ express in Chinese the title of this work. On the right the inscription reads, Jin ché ngai jin yu tsin kih so, ‘He who is benevolent loves those near, and then those who are remote;’ the other side contains an expression attributed to Confucius, ‘Sí fang chí jin yu shing ché yé,’ ‘The people of the West have their sages.’)—Compare p. 757. | |

| A Road-Cut in the Loess, | 38 |

| An-ting Gate, Wall of Peking, | to face 63 |

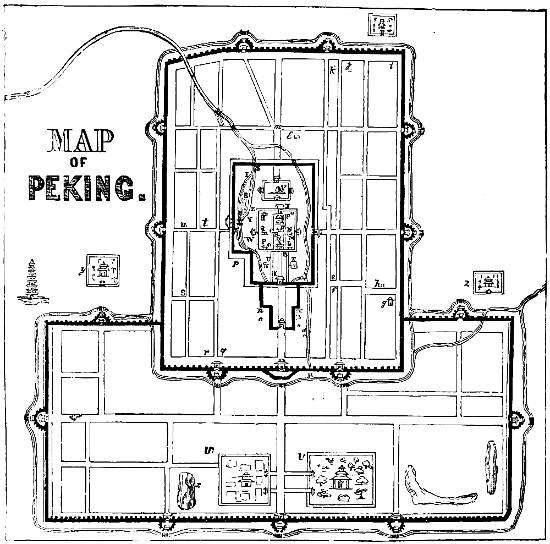

| Plan of Peking, | 66 |

| Portal of Confucian Temple, Peking, | 74 |

| Monument, or Tope, of a Lama, Hwang sz’, Peking, | to face 79 |

| View over the Loess-clefts in Shansí, | 97 |

| Temple of the Goddess Ma Tsu-pu, Ningpo, | to face 123 |

| Lukan Gorge, Yangtsz’ River. (From Blakiston.), | to face 146 |

| View of a Street in Canton, | to face 168 |

| Miaotsz’ Types, | 179 |

| Domesticated Yak, | 242 |

| Façade of Dwellings in Loess Cliffs, Ling-shí hien, | 301 |

| Coal Gorge on the Yangtsz’. (From Blakiston.), | to face 306 |

| FÍ-FÍ AND HAI-TUH. (From a Chinese cut.), | 316 |

| The Chinese Pig, | 324 |

| Mode of Carrying Pigs, | 325 |

| The KÍ-LIN, or Unicorn, | 342 |

| The FUNG-HWANG, or Phœnix, | 343 |

| [xxii]Different Styles of Official Caps, | 414 |

| Mode of Carrying High Officers in Sedan, | 503 |

| Prisoner Condemned to the Cangue in Court, | to face 504 |

| Mode of Exposure in the Cangue, | 509 |

| Publicly Whipping a Thief through the Streets, | 511 |

| Interior of KUNG YUEN, or ‘Examination Hall,’ Peking, | to face 551 |

| Chinese Hieroglyphics and their Modern Equivalents, | 584 |

| Six Styles of Chinese Characters, | 596 |

| Worship of Confucius and his Disciples, | 665 |

| Diagram of Chinese Roof Construction, | 726 |

| The PIH-YUNG KUNG, or ‘Classic Hall,’ Peking, | to face 730 |

| Wheelbarrow used for Travelling, | 747 |

| Bridge in Wan-shao Shan Gardens, near Peking, | 754 |

| Bridge, showing the Mode of Mortising the Arch, | 756 |

| Barber’s Establishment, | 760 |

| Tricks Played with the Queue, | 762 |

| Procession of Ladies to an Ancestral Temple, | to face 765 |

| Appearance of the Bones of a Foot when Compressed, | 767 |

| Feet of Chinese Ladies, | 768 |

| Shape of a Lady’s Shoe, | 769 |

| Boys Gambling with Crickets, | 826 |

| Chinese Chess-board, | 827 |

In this the values of the vowels are as follows:

The consonants are sounded generally as they are in the English alphabet. Ch as in church; hw as in when; j soft, as s in pleasure; kw as in awkward; ng, as an initial, as in singing, leaving off the first two letters; sz’ and tsz’ are to be sounded full with one breathing, but none of the English vowels are heard in it; the sound stops at the z; Dr. Morrison wrote these sounds tsze and sze, while Sir Thomas Wade, whose system bids fair to become the most widely employed, turns them into ssŭ and tzŭ. The hs of the latter, made by omitting the first vowel of hissing, is written simply as h by the author. Urh, or ’rh, is pronounced as the three last letters of purr.

All these, except No. 12, are heard in the court dialect, which has now become the most common mode of writing the names of places and persons in China. Though foreign authors have employed different letters, they have all intended to write the same sound; thus chan, shan, and xan, are only different ways of writing 閂; and tsse, tsze, tsz’, 𝔷h, tzŭ, and tzu, of 字. Such is not the case, however, with such names as Macao, Hongkong, Amoy, Whampoa, and others along the coast, which are sounded according to the local patois, and not the court pronunciation—Ma-ngau, Hiangkiang, Hiamun, Hwangpu, etc. Many of the discrepancies seen in the works of travellers and writers are owing to the fact that each is prone to follow his own fancy in transliterating foreign names; uniformity is almost unattainable in this matter. Even, too, in what is called the court dialect there is a great diversity among educated Chinese, owing to the traditional way all learn the sounds of the characters. In this work, and on the map, the sounds are written uniformly according to the pronunciation given in Morrison’s Dictionary, but not according to his orthography. Almost every writer upon the Chinese language seems disposed to propose[xxv] a new system, and the result is a great confusion in writing the same name; for example, eull, olr, ul, ulh, lh, urh, ’rh, í, e, lur, nge, ngí, je, jí, are different ways of writing the sounds given to a single character. Amid these discrepancies, both among the Chinese themselves and those who endeavor to catch their pronunciation, it is almost impossible to settle upon one mode of writing the names of places. That which seems to offer the easiest pronunciation has been adopted in this work. It may, perhaps, be regarded as an unimportant matter, so long as the place is known, but to one living abroad, and unacquainted with the language, the discrepancy is a source of great confusion. He is unable to decide, for instance, whether Tung-ngan, Tungon hien, Tang-oune, and Tungao, refer to the same place or not.

In writing Chinese proper names, authors differ greatly as to the style of placing them; thus, Fuhchaufu, Fuh-chau-fu, Fuh Chau Fu, Fuh-Chau fu, etc., are all seen. Analogy affords little guide here, for New York, Philadelphia, and Cambridge are severally unlike in the principle of writing them: the first, being really formed of an adjective and a noun, is not in this case united to the latter, as it is in Newport, Newtown, etc.; the second is like the generality of Chinese towns, and while it is now written as one word, it would be written as two if the name were translated—as ‘Brotherly Love;’ but the third, Cambridge, despite its derivation, is never written in two words, and many Chinese names are like this in origin. Thus applying these rules, properly enough, to Chinese places, they have been written here as single words, Suchau, Peking, Hongkong; a hyphen has been inserted in some places only to avoid mispronunciation, as Hiau-í, Sí-ngan, etc. It is hardly supposed that this system will alter such names as are commonly written otherwise, nor, indeed, that it will be adhered to with absolute consistency in the following pages; but the principle of the arrangement is perhaps the simplest possible. The additions fu, chau, ting, and hien, being classifying terms, should form a separate word. In conclusion, it may be stated that this system could only be carried out approximately as regards the proper names in the colonies and outside of the Empire.

THE

MIDDLE KINGDOM.

The possessions of the ruling dynasty of China,—that portion of the Asiatic continent which is usually called by geographers the Chinese Empire,—form one of the most extensive dominions ever swayed by a single power in any age, or any part of the world. Comprising within its limits every variety of soil and climate, and watered by large rivers, which serve not only to irrigate and drain it, but, by means of their size and the course of their tributaries, affording unusual facilities for intercommunication, it produces within its own borders everything necessary for the comfort, support, and delight of its occupants, who have depended very slightly upon the assistance of other climes and nations for satisfying their own wants. Its civilization has been developed under its own institutions; its government has been modelled without knowledge or reference to that of any other kingdom; its literature has borrowed nothing from the genius or research of the scholars of other lands; its language is unique in its symbols, its structure, and its antiquity; its inhabitants are remarkable for their industry, peacefulness, numbers, and peculiar habits. The examination of such a people, and so extensive a country, can hardly fail of being both instructive and entertaining, and if rightly pursued, lead to a stronger conviction of the need of the[2] precepts and sanctions of the Bible to the highest development of every nation in its personal, social, and political relations in this world, as well as to individual happiness in another. It is to be hoped, too, that at this date in the world’s history, there are many more than formerly, who desire to learn the condition and wants of others, not entirely for their own amusement and congratulation at their superior knowledge and advantages, but also to promote the well-being of their fellow-men, and impart liberally of the gifts they themselves enjoy. Those who desire to do this, will find that few families of mankind are more worthy of their greatest efforts than those comprised within the limits of the Chinese Empire; while none stand in more need of the purifying, ennobling, and invigorating principles of our holy religion to develop and enforce their own theories of social improvement.

The origin of the name China has not yet been fully settled. The people themselves have now no such name for their country, nor is there good evidence that they ever did apply it to the whole land. The occurrence in the Laws of Manu and in the Mahâbhârata of the name China, applied to a land or people with whom the Hindus had intercourse in the twelfth century B.C., and who were probably the Chinese, throws the origin far back into the remotest times, where probability must take the place of evidence. The most credible account ascribes its origin to the family of Tsin, whose chief first obtained complete sway, about B.C. 250, over all the other feudal principalities in the land, and whose exploits rendered him famous in India, Persia, and other Asiatic states. His sept had, however, long been renowned in Chinese history, and previous to this conquest had made itself widely known, not only in China, but in other countries. The kingdom lay in the northwestern parts of the empire, near the Yellow River, and according to Visdelou, who has examined the subject, the family was illustrious by its nobility and power. “Its founder was Tayé, son of the emperor Chuen-hü. It existed in great splendor for more than a thousand years, and was only inferior to the royal dignity. Feitsz’, a prince of this family, had the superintendence of the stud of the emperor Hiao, B.C. 909, and as a mark of favor his[3] majesty conferred on him the sovereignty of the city of Tsinchau in mesne tenure, with the title of sub-tributary king. One hundred and twenty-two years afterwards, B.C. 770, Siangkwan, petit roi of Tsinchau (having by his bravery revenged the insults offered to the emperor Ping by the Tartars, who slew his father Yu), was created king in full tenure, and without limitation or exception. The same monarch, abandoning Sí-ngan (then called Hao-king, the capital of his empire) to transport his seat to Lohyang, Siangkwan was able to make himself master of the large province of Shensí, which had composed the proper kingdom of the emperor. The king of Tsin thus became very powerful, but though his fortune changed, he did not alter his title, retaining always that of the city of Tsinchau, which had been the foundation of his elevation. The kingdom of Tsin soon became celebrated, and being the place of the first arrival by land of people from western countries, it seems probable that those who saw no more of China than the realm of Tsin, extended this name to all the rest, and called the whole empire Tsin or Chin.”[2]

This extract refers to periods long before the dethronement of the house of Chau by princes of Tsin; the position of this latter principality, contiguous to the desert, and holding the passes leading from the valley of the Tarim across the desert eastward to China, renders the supposition of the learned Jesuit highly probable. The possession of the old imperial capital would strengthen this idea in the minds of the traders resorting to China from the West; and when the same family did obtain paramount sway over the whole empire, and its head render himself celebrated by his conquests, and by building the Great Wall, the name Tsin was still more widely diffused, and regarded as the name of the country. The Malays and Arabians, whose vessels were early found between Aden and Canton, knew it as China, and probably introduced the name into Europe before 1500. The Hindus contracted it into Ma-chin, from Maha-china, i.e., ‘Great China;’ and the first of[4] these was sometimes confounded with Manji, a term used for the tribes in Yunnan. Thus it appears that these and other nations of Asia have known the country or its people by no other terms than Jin, Chin, Sin, Sinæ, or Tzinistæ. The Persian name Cathay, and its Russian form of Kitai, is of modern origin; it is altered from Ki-tah, the race which ruled northern China in the tenth century, and is quite unknown to the people it designates. The Latin word Seres is derived from the Chinese word sz’ (silk), and doubtless first came into use to denote the people during the Han dynasty.

The Chinese have many names to designate themselves and the land they inhabit. One of the most ancient is Tien Hia, meaning ‘Beneath the Sky,’ and denoting the World; another, almost as ancient, is Sz’ Hai, i.e., ‘[all within] the Four Seas,’ while a third is Chung Kwoh, or ‘Middle Kingdom.’ This dates from the establishment of the Chau dynasty, about B.C. 1150, when the imperial family so called its own special state in Honan because it was surrounded by all the others. The name was retained as the empire grew, and thus has strengthened the popular belief that it is really situated in the centre of the earth; Chung Kwoh jin, or ‘men of the Middle Kingdom,’ denotes the Chinese. All these names indicate the vanity and ignorance of the people respecting their geographical position and their rank among the nations; they have not been alone in this foible, for the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans all had terms for their possessions which intimated their own ideas of their superiority; while, too, the area of none of those monarchies, in their widest extent, equalled that of China Proper. The family of Tsin also established the custom, since continued, of calling the country by the name of the dynasty then reigning; but, while the brief duration of that house of forty-four years was not long enough to give it much currency among the people, succeeding dynasties, by their talents and prowess, imparted their own as permanent appellations to the people and country. The terms Han-jin and Han-tsz’ (i.e., men of Han or sons of Han) are now in use by the people to denote themselves: the last also means a “brave man.” Tang-jin, or ‘Men of Tang,’ is quite as frequently heard in the[5] southern provinces, where the phrase Tang Shan, or ‘Hills of Tang,’ denotes the whole country. The Buddhists of India called the land Chin-tan, or the ‘Dawn,’ and this appellation has been used in Chinese writings of that sect.

The present dynasty calls the empire Ta Tsing Kwoh, or ‘Great Pure Kingdom;’ but the people themselves have refused the corresponding term of Tsing-jin, or ‘Men of Tsing.’ The empire is also sometimes termed Tsing Chau, i.e., ‘[land of the] Pure Dynasty,’ by metonymy for the family that rules it. The term now frequently heard in western countries—the Celestial Empire—is derived from Tien Chau, i.e., ‘Heavenly Dynasty,’ meaning the kingdom which the dynasty appointed by heaven rules over; but the term Celestials, for the people of that kingdom, is entirely of foreign manufacture, and their language could with difficulty be made to express such a patronymic. The phrase Lí Min, or ‘Black-haired Race,’ is a common appellation; the expressions Hwa Yen, the ‘Flowery Language,’ and Chung Hwa Kwoh, the ‘Middle Flowery Kingdom,’ are also frequently used for the written language of the country, because the Chinese consider themselves to be among the most polished and civilized of all nations—which is the sense of hwa in these phrases. The phrase Nui Tí, or ‘Inner Land,’ is often employed to distinguish it from countries beyond their borders, regarded as the desolate and barbarous regions of the earth. Hwa Hia (the Glorious Hia) is an ancient term for China, the Hia dynasty being the first of the series; Tung Tu, or “Land of the East,” is a name used in Mohammedan writings alone.

The present ruling dynasty has extended the limits of the empire far beyond what they were under the Ming princes, and nearly to their extent in the reign of Kublai, A.D. 1290. In 1840, its borders were well defined, reaching from Sagalien I. on the north-east, in lat. 48° 10′ N. and long. 144° 50′ E., to Hainan I. in the China Sea, on the south, in lat. 18° 10′ N., and westward to the Belur-tag, in long. 74° E., inclosing a continuous area, estimated, after the most careful valuation by McCulloch, at 5,300,000 square miles. The longest line which could be drawn in this vast region, from the south-western part[6] of Ílí, bordering on Kokand, north-easterly to the sea of Okhotsk, is 3,350 miles; its greatest breadth is 2,100 miles, from the Outer Hing-an or Stanovoi Mountains to the peninsula of Luichau in Kwangtung:—the first measuring 71 degrees of longitude, and the last over 34 of latitude.

Since that year the process of disintegration has been going on, and the cession of Hongkong to the British has been followed by greater partitions to Russia, which have altogether reduced it more than half a million of square miles on the north-east and west. Its limits on the western frontiers are still somewhat undefined. The greatest breadth is from Albazin on the Amur, nearly south to Hainan, 2,150 miles; and the longest line which can be drawn in it runs from Sartokh in Tibet, north-east to the junction of the Usuri River with the Amur.

The form of the empire approaches a rectangle. It is bounded on the east and south-east by various arms and portions of the Pacific Ocean, beginning at the frontier of Corea, and called on European maps the gulfs of Liautung and Pechele, the Yellow Sea, channel of Formosa, China Sea, and Gulf of Tonquin. Cochinchina and Burmah border on the provinces of Kwangtung, Kwangsí, and Yunnan, in the south-west; but most of the region near that frontier is inhabited by half-independent tribes of Laos, Kakyens, Singphos, and others. The southern ranges of the Himalaya separate Assam, Butan, Sikkim, Nípal and states in India from Tibet, whose western border is bounded by the nominally dependent country of Ladak, or if that be excluded, by the Kara-korum Mountains. The kingdoms or states of Cashmere, Badakshan, Kokand, and the Kirghís steppe, lie upon the western frontiers of Little Tibet, Ladak, and Ílí, as far north as the Russian border; the high range of the Belur-tag or Tsung-ling separates the former countries from the Chinese territory in this quarter. Russia is conterminous with China from the Kirghís steppe along the Altai chain and Kenteh range to the junction of the Argun and the Amur, from whence the latter river and its tributary, the Usuri, form the dividing line to the border of Corea, a total stretch of 5,300 miles. The circuit of the whole empire[7] is 14,000 miles, or considerably over half the circumference of the globe. These measurements, it must be remembered, are of the roughest character. The coast line from the mouth of the river Yaluh in Corea to that of the Annam in Cochinchina is not far from 4,400 miles. This immense country comprises about one-third of the continent, and nearly one-tenth of the habitable part of the globe; and, next to Russia, is the largest empire which has existed on the earth.

It will, perhaps, contribute to a better comprehension of the area of the Chinese Empire to compare it with some other countries. Russia is nearly 6,500 miles in its greatest length, about 1,500 in its average breadth, and measures 8,369,144[3] square miles, or one-seventh of the land on the globe. The United States of America extends about 3,000 miles from Monterey on the Pacific in a north-easterly direction to Maine, and about 1,700 from Lake of the Woods to Florida. The area of this territory is now estimated at 2,936,166 square miles, with a coast line of 5,120 miles. The area of the British Empire is not far from 7,647,000 square miles, but the boundaries of some of the colonies in Hindostan and South Africa are not definitely laid down; the superficies of the two colonies of Australia and New Zealand is nearly equal to that of all the other possessions of the British crown.

The Chinese themselves divide the empire into three principal parts, rather by the different form of government in each, than by any geographical arrangement.

I. The Eighteen Provinces, including, with trivial additions, the country conquered by the Manchus in 1664.

II. Manchuria, or the native country of the Manchus, lying north of the Gulf of Liautung as far as the Amur and west of the Usuri River.

III. Colonial Possessions, including Mongolia, Ílí (comprising Sungaria and Eastern Turkestan), Koko-nor, and Tibet.

The first of these divisions alone is that to which other nations have given the name of China, and is the only part which is entirely settled by the Chinese. It lies on the eastern[8] slope of the high table-land of Central Asia, in the south-eastern angle of the continent; and for beauty of scenery, fertility of soil, salubrity of climate, magnificent and navigable rivers, and variety and abundance of its productions, will compare with any portion of the globe. The native name for this portion, as distinguished from the rest, is Shih-pah Săng or the ‘Eighteen Provinces,’ but the people themselves usually mean this part alone by the term Chung Kwoh. The area of the Eighteen Provinces is estimated by McCulloch at 1,348,870 square miles, but if the full area of the provinces of Kansuh and Chihlí be included, this figure is not large enough; the usual computation is 1,297,999 square miles; Malte Brun reckons it at 1,482,091 square miles; but the entire dimensions of the Eighteen Provinces, as the Chinese define them, cannot be much under 2,000,000 square miles, the excess lying in the extension of the two provinces mentioned above. This part, consequently, is rather more than two-fifths of the area of the whole empire.

The old limits are, however, more natural, and being better known may still be retained. They give nearly a square form to the provinces, the length from north to south being 1,474 miles, and the breadth 1,355 miles; but the diagonal line from the north-east corner to Yunnan is 1,669 miles, and that from Amoy to the north-western part of Kansuh is 1,557 miles. China Proper, therefore, measures about seven times the size of France, and fifteen times that of the United Kingdom; it is nearly half as large as all Europe, which is 3,650,000 square miles. Its area is, however, nearer that of all the States of the American Union lying east of the Mississippi River, with Texas, Arkansas, Missouri and Iowa added; these all cover 1,355,309 square miles. The position of the two countries facing the western borders of great oceans is another point of likeness, which involves considerable similarity in climate; there is moreover a further resemblance between the size of the provinces in China and those of the newer States.

Before proceeding to define the three great basins into which China may be divided, it will give a better idea of the whole subject to speak of the mountain ranges which lie within and near or along the limits of the country. The latter in them[9]selves form almost an entire wall inclosing and defining the old empire; the principal exceptions being the western boundaries of Yunnan, the border between Ílí and the Kirghís steppe, and the trans-Amur region.

Commencing at the north-eastern corner of the basin of the Amur above its mouth, near lat. 56° N., are the first summits of the Altai range, which during its long course of 2,000 miles takes several names; this range forms the northern limit of the table-land of Central Asia. At its eastern part, the range is called Stanovoi by the Russians, and Wai Hing-an by the Chinese; the first name is applied as far west as the confluence of the Songari with the Amur, beyond which, north-west as far as lake Baikal, the Russians call it the Daourian Mountains. The distance from the lake to the ocean is about 600 miles, and all within Russian limits. Beyond lake Baikal, westward, the chain is called the Altai, i.e., Golden Mountains, and sometimes Kin shan, having a similar meaning. Near the head-waters of the river Selenga this range separates into two nearly parallel systems running east and west. The southern one, which lies mostly in Mongolia, is called the Tangnu, and rises to a much higher elevation than the northern spur. The Tangnu Mountains continue under that name on the Chinese maps in a south-westerly direction, but this chain properly joins the Tien shan, or Celestial Mountains, in the province of Cobdo, and continues until it again unites with the Altai further west, near the junction of the Kirghís steppe with China and Russia. The length of the whole chain is not far from 2,500 miles, and except near the Tshulyshman River, does not, so far as is known, rise to the snow line, save in detached peaks. The average elevation is supposed to be in the neighborhood of 7,000 feet; most of it lies between latitudes 47° and 52° N., largely covered with forests and susceptible of cultivation.

The next chain is the Belur-tag, Tartash ling, in Chinese Tsung ling, Onion Mountains, or better, Blue Mountains, so called from their distant hue.[4] This range lies in the south-west of Son[10]garia, separating that territory from Badakshan; it commences about lat. 50° N., nearly at right angles with the Tien shan, and extends south, rising to a great height, though little is known of it. It may be considered as the connecting link between the Tien shan and the Kwănlun; or rather, both this and the latter may be considered as proceeding from a mountain knot, detached from the Hindu-kush, in the south-western part of Turkestan called Pushtikhur, the Belur-tag coming from its northern side, while the Kwănlun issues from its eastern side, and extends across the middle of the table-land to Koko-nor, there diverging into two branches. This mountain knot lies between latitudes 36° and 37° N., and longitudes 70° and 74° E. The Himalaya range proceeds from it south-easterly, along the southern frontier of Tibet, till it breaks up near the head-waters of the Yangtsz’, Salween, and other rivers between Tibet, Burmah, and Yunnan, thus nearly completing the inland frontier of the empire. A small spur from the Yun ling, in the west of Yunnan, in the country of the Singphos and borders of Assam, may also be regarded as forming part of the boundary line. The Chang-peh shan lies between the head-waters of the Yaluh and Toumen rivers, along the Corean frontier, forming a spur of the lower range of the Sihota or Sih-hih-teh Mountains, east of the Usuri.

Within the confines of the empire are four large chains, some of the peaks in their course rising to stupendous elevations, but the ridges generally falling below the snow line. The first is the Tien shan or Celestial Mountains, called Tengkiri by the Mongols, and sometimes erroneously Alak Mountains. This chain begins at the northern extremity of the Belur-tag in lat. 40° N., or more properly comes in from the west, and extends from west to east between longitudes 76° and 90° E., and generally along the 22° of north latitude, dividing Ílí into the Northern and Southern Circuits. Its western portion is called Muz-tag; the Muz-daban, about long. 79° E., between Kuldja and Aksu, is where the road from north to south runs across, leading over a high glacier above the snow line. East of this occurs a mass of peaks among the highest in Central Asia, called Bogdo-ula; and at the eastern end, near Ur[11]umtsi, as it declines to the desert, are traces of volcanic action seen in solfataras and spaces covered with ashes, but no active volcanoes are now known. The doubtful volcano of Pí shan, between the glacier and the Bogdo-ula, is the only one reported in continental China. The Tien shan end abruptly at their eastern point, where the ridge meets the desert, not far from the meridian of Barkul in Kansuh, though Humboldt considers the hills in Mongolia a continuation of the range eastward, as far as the Nui Hing-an. The space between the Altai and Tien shan is very much broken up by mountainous spurs, which may be considered as connecting links of them both, though no regular chain exists. The western prolongation of the Tien shan, under the name of the Muz-tag, extends from the high pass only as far as the junction of the Belur-tag, beyond which, and out of the Chinese Empire, it continues nearly west, south of the river Sihon toward Kodjend, under the names of Ak-tag and Asferah-tag; this part is covered with perpetual snow.

Nearly parallel with the Tien shan in part of its course is the Nan shan, Kwănlun or Koulkun range of mountains, also called Tien Chu or ‘Celestial Pillar’ by Chinese geographers. The Kwănlun starts from the Pushtikhur knot in lat. 36° N., and runs along easterly in nearly that parallel through the whole breadth of the table-land, dividing Tibet from the desert of Gobi in part of its course. About the middle of its extent, not far from long. 90° E., it divides into several ranges, which decline to the south-east through Koko-nor and Sz’chuen, under the names of the Bayan-kara, the Burkhan-buddha, the Shuga and the Tangla Mountains,—each more or less parallel in their general south-east course till they merge with the Yun ling (i.e., Cloudy Mountains), about lat. 33° N. Another group bends northerly, beyond the sources of the Yellow River, and under the names of Altyn-tag, Nan shan, Ín shan, and Ala shan, passes through Kansuh and Shensí to join the Nui Hing-an, not far from the great bend of the Yellow River. Some portion of the country between the extremities of these two ranges is less elevated, but no plains occur, though the parts north of Kansuh, where the Great Wall runs, are[12] rugged and unfertile. The large tract between the basins of the Tarim River and that of the Yaru-tsangbu, including the Kwănlun range, is mostly occupied by the desert of Gobi, and is now one of the least known parts of the globe. The mineral treasures of the Kwănlun are probably great, judging from the many precious stones ascribed to it; this desolate region is the favorite arena for the monsters, fairies, genii, and other beings of Chinese legendary lore, and is the Olympus where the Buddhist and Taoist divinities hold their mystic sway, strange voices are heard, and marvels accomplished.[5]

From near the head-waters of the Yellow River, the four ridges run south-easterly, and converge hard by the confines of Burmah and Yunnan, within an area about one hundred miles in breadth. The Yun ling range constitutes the western frontier of Sz’chuen, and going south-east into Yunnan, thence turns eastward, under the names of Nan ling, Mei ling, Wu-í shan, and other local terms, passing through Kweichau, Hunan, and dividing Kwangtung and Fuhkien from Kiangsí and Chehkiang, bends north-east till it reaches the sea opposite Chusan. One or two spurs branch off north from this range through Hunan and Kiangsí, as far as the Yangtsz’, but they are all of moderate elevation, covered with forests, and susceptible of cultivation. The descent from the Siueh ling or Bayan-kara Mountains, and the western part of the Yun ling, to the Pacific, is very gradual. The Chinese give a list of fifty peaks lying in the provinces which are covered with snow for the whole or part of the year, and describe glaciers on several of them.

Another less extensive ridge branches off nearly due east from the Bayan-kara Mountains in Koko-nor, and forms a moderately high range of mountains between the Yellow River and Yangtsz’ kiang as far as long. 112° E., on the western borders of Nganhwui; this range is called Ko-tsing shan, and Peh ling (i.e., Northern Mountains), on European maps. These two chains, viz., the Yun ling—with its continuation of the Mei ling—and the Peh ling, with their numerous offsets, render the whole of the western part of China very uneven.

On the east of Mongolia, and commencing near the bend of the Yellow River, or rather forming a continuation of the range in Shansí, is the Nui Hing-an ling or Sialkoi, called also Soyorti range, which runs north-east on the west side of the basin of the Amur, till it reaches the Wai Hing-an, in lat. 56° N. The sides of the ridge toward the desert are nearly naked, but the eastern acclivities are well wooded and fertile. On the confines of Corea a spur strikes off westward through Shingking, called Kolmin-shanguin alin by the Manchus, and Chang-peh shan (i.e., Long White Mountains) by the Chinese. Between the Sialkoi and Sihota are two smaller ridges defining the basin of the Nonni River on the east and west. Little is known of the elevation of these chains except that they are low in comparison with the great western ranges, and under the snow line.

The fourth system of mountains is the Himalaya, which bounds Tibet on the south, while the Kwănlun and Burkhan Buddha range defines it on the north. A small range runs through it from west to east, connected with the Himalaya by a high table-land, which surrounds the lakes Manasa-rowa and Ravan-hrad, and near or in which are the sources of the Indus, Ganges, and Yaru-tsangbu. This range is called Gang-dis-ri and Zang, and also Kailasa in Dr. Buchanan’s map, and its eastern end is separated from the Yun ling by the narrow valley of the Yangtsz’, which here flows from north to south. The country north of the Gang-dis-ri is divided into two portions by a spur which extends in a north-west direction as far as the Kwănlun,[6] called the Kara-korum Mountains. On the western side of this range lies Ladak, drained by one of the largest branches of the Indus, and although included in the imperial domains on Chinese maps, has long been separated from imperial cognizance. The Kara-korum Mountains may therefore be taken as composing part of the boundary of the empire; Chinese geographers regard them as forming a continuation of the Tsung ling.

This hasty sketch of the mountain chains in and around China needs to be further illustrated by Pumpelly’s outlines of their general course and elevation in what he suitably terms the Sinian System, applied “to that extensive northeast-southwest system of upheaval which is traceable through nearly all Eastern Asia, and to which this portion of the continent owes its most salient features.” He has developed this system in the Researches in China, Mongolia and Japan, issued by the Smithsonian Institution in 1866. The mountains of China correspond in many respects to the Appalachian system in America, and its revolution probably terminated soon after the deposition of the Chinese coal measures. Mr. Pumpelly describes the principal anticlinal axes of elevation in China Proper, beginning with the Barrier Range, extending through the northern part of Chihlí and Shansí, where it trends W.S.W., prolonging across the Yellow River at Pao-teh, and hence S.W. through Shansí and Kansuh, coinciding with the watershed between the bend of that river, which traverses it through an immense gorge.

The next axis east begins at the Tushih Gate, and goes S.W. to the Nankau Pass, both of them in the Great Wall, and thence across Shansí to the elbow of the Yellow River, and onward to Western Sz’chuen, forming the watershed within the bend of the Yangtsz’. In the regions between these two axes are found coal deposits. A central axis succeeds this in Shansí, crossing the Yangtsz’ near Íchang, and passing on S.W. through Kweichau to the Nan ling; going N.E., it runs through Honan and subsides as it gets over the Yellow River, till in Shantung and the Regent’s Sword it rises higher and higher as it stretches on to the Chang-peh shan in Manchuria, and the ridge between the Songari and Usuri rivers. Between the last two ranges lie the great coal, iron, and salt deposits in the provinces, and each side of the central axis huge troughs and basins occur, such as the valley of the Yangtsz’ in Yunnan, the Great Plain in Nganhwui and Chihlí, the Gulf of Pechele, and the basins of the Liao and Songari rivers.

The coast axis of elevation is indicated by ranges of granitic mountains between Kiangsí and Kiangsu on the north, and Chehkiang and Fuhkien on the south, extending S.W. through[15] Kwangtung into the Yun ling, and N.E. into the Chusan Archipelago, thence across to Corea and the Sihota Mountains east of the Usuri River. An outlying granitic range, reaching from Hongkong north-easterly to Wănchau, and S.W. to Hainan Island, marks a fifth axis of elevation.

Crossing these anticlinal axes are three ranges, coming into China Proper from the west in such a manner as to prove highly beneficial to its structure. The northern is apparently a continuation of the Bayan-kara Mountains in a S.E. direction into Kansuh, and south of the river Wei into Honan, under the name of the Hiung shan or ‘Bear Mountains.’ The centre is an offset from this, going across the north of Hupeh. The southern appears to be a prolongation of the Himalaya into Yunnan and Kwangsí, making the watershed between the Yangtsz’ and Pearl river basins.

Between the Tien shan and the Kwănlun range on the south-west, and reaching to the Sialkoi on the north-east, in an oblique direction, lies the great desert of Gobi or Sha-moh, both words signifying a waterless plain, or sandy floats.[7] The entire length of this waste is more than 1,800 miles, but if its limits are extended to the Belur-tag and the Sialkoi, at its western and eastern extremity, it will reach 2,200 miles; the average breadth is between 350 and 400 miles, subject, however, to great variations. The area within the mountain ranges which define it is over a million square miles, and few of the streams occurring in it find their way to the ocean. The whole of this tract is not a barren desert, though no part of it can lay claim to more than comparative fertility; and the great altitude of most portions seems to be as much the cause of its sterility as the nature of the soil. Some portions have relapsed into a waste because of the destruction of the inhabitants.

The western portion of Gobi, lying east of the Tsung ling and north of the Kwănlun, between long. 76° and 94° E., and in lat. 36° and 41° N., is about 1,000 miles in length, and between 300 and 400 wide. Along the southern side of the[16] Tien shan extends a strip of arable land from 50 to 80 miles in width, producing grain, pasturage, cotton, and other things, and in which lie nearly all the Mohammedan cities and forts of the Nan Lu. The Tarim and its branches flow eastward into Lob-nor, through the best part of this tract, from 76° to 89° E.; and along the banks of the Khoten River a road runs from Yarkand to that city, and thence to H’lassa. Here the desert is comparatively narrow. This part is called Han hai, or ‘Mirage Sea,’ by the Chinese, and is sometimes known as the desert of Lob-nor. The remainder of this region is an almost unmitigated waste, and north of Koko-nor assumes its most terrific appearance, being covered with dazzling stones, and rendered insufferably hot by the reflection of the sun’s rays from these and numerous movable mountains of sand. Nor in winter is the climate milder or more endurable. “The icy winds of Siberia, the almost constantly unclouded sky, the bare saline soil, and its great altitude above the sea, combine to make the Gobi, or desert of Mongolia, one of the coldest countries in the whole of Asia.”[8]

The sandhills—kuzupchi, as the Mongols call them—appear north of the Ala shan and along the Yellow River, and when the wind sets them in motion they gradually travel before it, and form a great danger to travellers who try to cross them. One Chinese author says, “There is neither water, herb, man, nor smoke;—if there is no smoke, there is absolutely nothing.” The limits of the actual desert are not easily defined, for near the base of the mountain ranges, streams and vegetation are usually found.

Near the meridian of Hami, long. 94° E., the desert is narrowed to about 150 miles. The road from Kiayü kwan to Hami runs across this narrow part, and travellers find water at various places in their route. It divides Gobi into two parts—the desert of Lob-nor and the Great Gobi—the former being about 4,500 feet elevation, and the latter or eastern not higher than 4,000 feet. The borders of Kansuh now extend across this tract to the foot of the Tien shan.

The eastern part, or Great Gobi, stretches from the eastern declivity of the Tien shan, in long. 94° to 120° E., and about lat. 40° N., as far as the Inner Hing-an. Its width between the Altai and the Ín shan range varies from 500 to 700 miles. Through the middle of this tract extends the depressed valley properly called Sha-moh, from 150 to 200 miles across, and whose lowest depression is from 2,600 to 2,000 feet above the sea. Sand almost covers the surface of this valley, generally level, but sometimes rising into low hills. The road from Urga to Kalgan, crossing this tract, is watered during certain seasons of the year, and clothed with grass. It is 660 miles, and forty-seven posts are placed along the route. The crow, lark, and sand-grouse are abundant on this road, the first being a real pest, from its pilfering habits. Such vegetation as occurs is scanty and stunted, affording indifferent pasture, and the water in the small streams and lakes is brackish and unpotable. North and south of the Sha-moh the surface is gravelly and sometimes rocky, the vegetation more vigorous, and in many places affords good pasturages for the herds of the Kalkas tribes. In those portions bordering on or included in Chihlí province, among the Tsakhars, agricultural labors are repaid, and millet, oats, and barley are produced, though not to a great extent. Trees are met with on the water-courses, but not to form forests. This region is called tsau-ti, or Grassland, and maintains large herds of sheep and cattle. It extends more or less northward towards Siberia. The Etsina is the largest inland stream in this division of Gobi, but on its north-eastern borders are some large tributaries of the Amur. On the south of the Sialkoi range the desert-lands reach nearly to the Chang-peh shan, about five degrees beyond those mountains. The general features of this portion of the earth’s surface are less forbidding than Sahara, but more so than the steppes of Siberia or the pampas of Buenos Ayres. The whole of Gobi is regarded by Pumpelly as having formed a portion of a great ocean, which, in comparatively recent geological times, extended south to the Caspian and Black Seas, and between the Ural and Inner Hing an Mountains, and was drained off by an upheaval whose traces and effects can be detected in many parts. “It appears to me,”[18] he adds, “that the ancient physical geography of this region, and the effects of its elevation, present one of the most important fields of exploration.” It will no doubt soon be more fully explored. Baron Richthofen describes Central Asia as properly a shallow trough, 1,800 miles long and about 400 miles wide, whose bottom is about 1,800 feet above the ocean; its ancient shore-line extended between the Kwănlun and Tien shan ranges on the west, from 5,000 to 10,000 feet high, and gradually falling to 3,600 feet in its eastern shore. This is the Han-hai; eastward is Sha-moh, and outside of both these wildernesses are the peripheral regions, where the waters flow to the ocean, carrying their silt, the erosions from the mountains. Inside of the shore-line nothing reaches the oceans, and these results of degradation are washed or blown into the valleys, and the country is buried in its own dust.[9]

The rivers of China are her glory, and no country can compare with her for natural facilities of inland navigation. The people themselves consider that portion of geography relating to their rivers as the most interesting, and give it the greatest attention. The four largest rivers in the empire are the Yellow River, the Yangtsz’, the Amur, and the Tarim; the Yaru-tsangbu also runs more than a thousand miles within its borders.