Project Gutenberg's Spons' Household Manual, by E. Spon and F. N. Spon

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Spons' Household Manual

A treasury of domestic receipts and a guide for home management

Author: E. Spon

F. N. Spon

Release Date: August 3, 2018 [EBook #57630]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SPONS' HOUSEHOLD MANUAL ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book. There are only 3 in this book.

Quantities are separated from the unit by a space, for example ‘3 ft.’ or ‘12½ lb.’ Some quantities had a linking - such as ‘12½-lb.’ For consistency this - has been removed in the etext.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Numerous minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

A TREASURY OF

DOMESTIC RECEIPTS

And Guide for

HOME MANAGEMENT.

London:

E. & F. N. SPON, 125 STRAND.

New York:

SPON & CHAMBERLAIN, 12 CORTLANDT STREET.

1894

Time was when the foremost aim and ambition of the English housewife was to gain a full knowledge of her own duties and of the duties of her servants. In those days, bread was home-baked, butter home-made, beer home-brewed, gowns home-sewn, to a far greater extent than now.

With the advance of education, there is much reason to fear that the essentially domestic part of the training of our daughters is being more and more neglected. Yet what can be more important for the comfort and welfare of the household than an appreciation of their needs and an ability to furnish them. Accomplishments, all very good in their way, must, to the true housewife, be secondary to all that concerns the health, the feeding, the clothing, the housing of those under her care.

And what a range of knowledge this implies,—from sanitary engineering to patching a garment, from bandaging a wound to keeping the frost out of water pipes. It may safely be said that the mistress of a family is called upon to exercise an amount of skill and learning in her daily routine such as is demanded of few men, and this too without the benefit of any special education or preparation; for where is the school or college which includes among its “subjects” the study of such every-day matters as bad drains, or the gapes in chickens, or the removal of stains from clothes, or the bandaging of wounds, or the management of a kitchen range? Indeed, it is worthy of consideration whether our schools of cookery might not with very great advantage be supplemented by schools of general household instruction.

Till this suggestion is carried out, the housewife can only refer to books and papers for information and advice. The editors of the present volume have been guided by a determination to make it a book of reference such as no housewife can afford to be without. Much of the matter is, of course, not altogether new, but it has been arranged with great care in a[iv] systematic manner, and while the use of obscure scientific terms has been avoided, the teachings of modern science have been made the basis of those sections in which science plays a part.

Much of the information herein contained has appeared before in lectures, pamphlets, and newspapers, foremost among these last being the Queen, Field, Lancet, Scientific American, Pharmaceutical Journal, Gardener’s Chronicle, and the Bazaar; but it has lost nothing by repetition, and has this advantage in being embodied in a substantial volume that it can always be readily found when wanted, while every one knows the fate of leaflets and journals. The sources whence information has been drawn have, it is believed, in every case been acknowledged, and the editors take this opportunity of again proclaiming their indebtedness to the very large number of lecturers and writers whose communications have found a place within these covers.

The Editors.

Hints for selecting a good House, pointing out the essential requirements for a good house as to the Site, Soil, Trees, Aspect, Construction, and General Arrangement; with instructions for Reducing Echoes, Water-proofing Damp Walls, Curing Damp Cellars

Water Supply.—Care of Cisterns; Sources of Supply; Pipes; Pumps; Purification and Filtration of Water

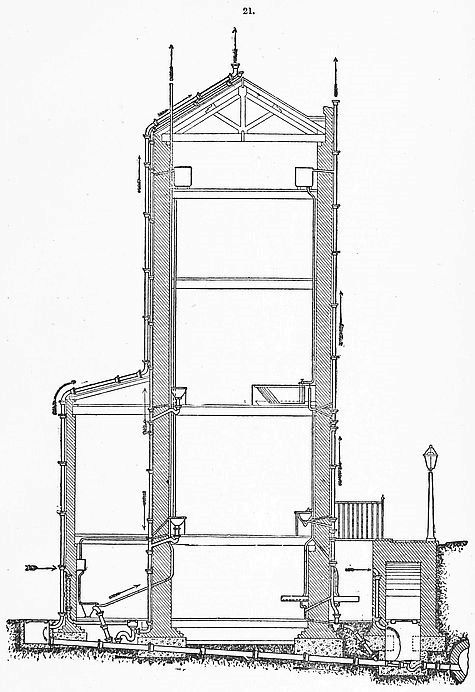

Sanitation.—What should constitute a good Sanitary Arrangement; Examples (with illustrations) of Well- and Ill-drained Houses; How to Test Drains; Ventilating Pipes, &c.

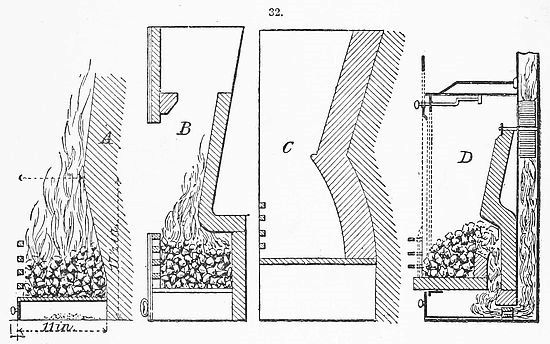

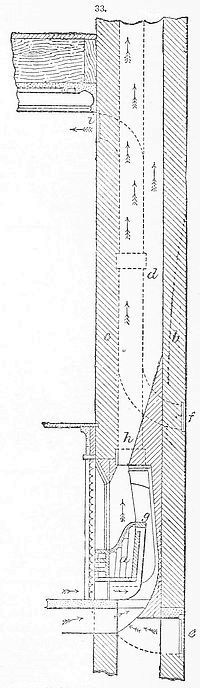

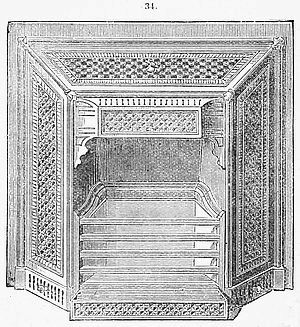

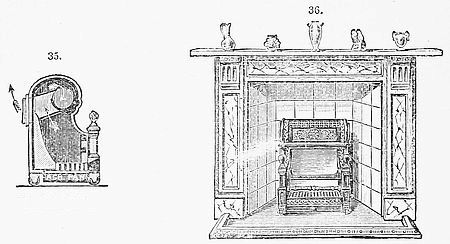

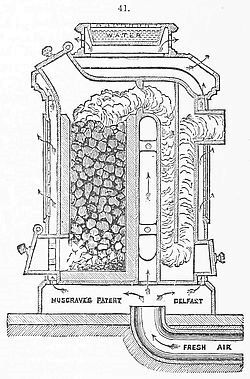

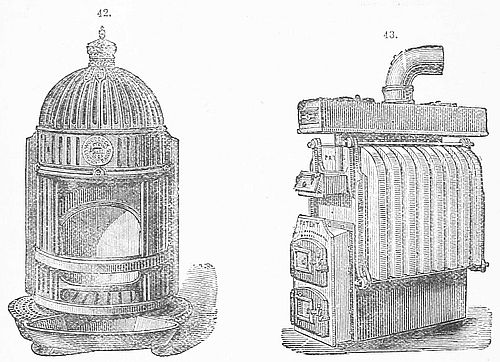

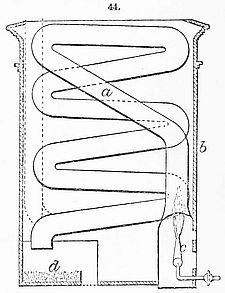

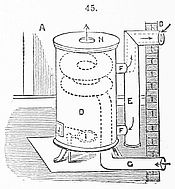

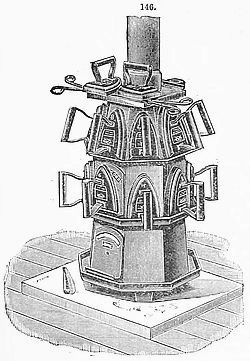

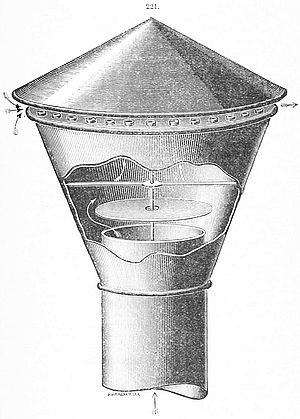

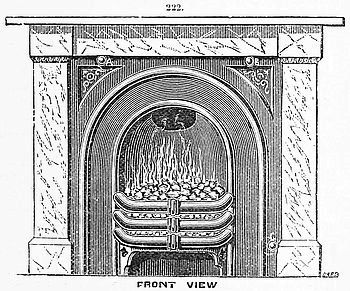

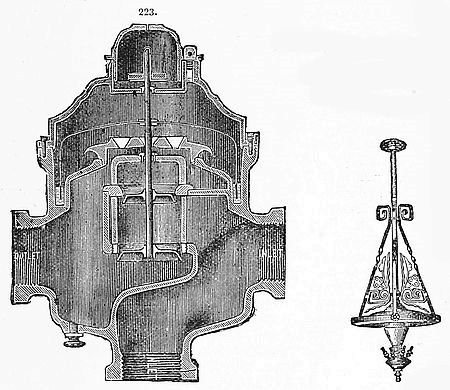

Ventilation and Warming.—Methods of Ventilating without causing cold draughts, by various means; Principles of Warming; Health Questions; Combustion; Open Grates; Open Stoves; Fuel Economisers; Varieties of Grates; Close-Fire Stoves; Hot-air Furnaces; Gas Heating; Oil Stoves; Steam Heating; Chemical Heaters; Management of Flues; and Cure of Smoky Chimneys

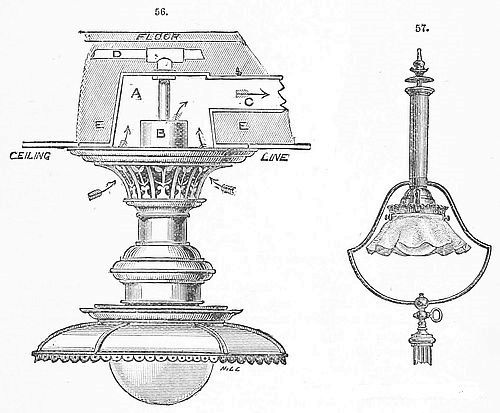

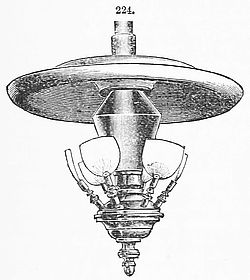

Lighting.—The best methods of Lighting; Candles, Oil Lamps, Gas, Incandescent Gas, Electric Light; How to Test Gas Pipes; Management of Gas

Furniture and Decoration.—Hints on the Selection of Furniture; on the most approved methods of Modern Decoration; on the best methods of arranging Bells and Calls; How to Construct an Electric Bell

Thieves and Fire.—Precautions against Thieves and Fire; Methods of Detection; Domestic Fire Escapes; Fireproofing Clothes, &c.

The Larder.—Keeping Food fresh for a limited time; Storing Food without change, such as Fruits, Vegetables, Eggs, Honey, &c.

Curing Foods for lengthened Preservation, as Smoking, Salting, Canning, Potting, Pickling, Bottling Fruits, &c.; Jams, Jellies, Marmalade, &c.

The Dairy.—The Building and Fitting of Dairies in the most approved modern style; Butter-making; Cheese-making and Curing

The Cellar.—Building and Fitting; Cleaning Casks and Bottles; Corks and Corking; Aërated Drinks; Syrups for Drinks; Beers; Bitters; Cordials and Liqueurs; Wines; Miscellaneous Drinks

The Pantry.—Bread-making; Ovens and Pyrometers; Yeast; German Yeast; Biscuits; Cakes; Fancy Breads; Buns

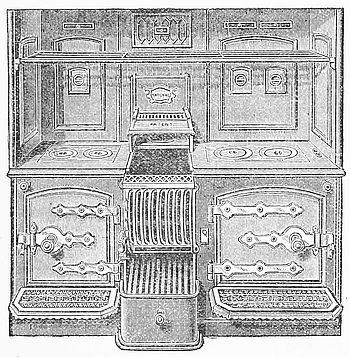

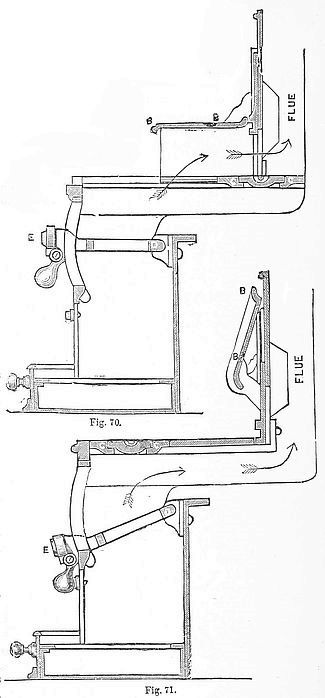

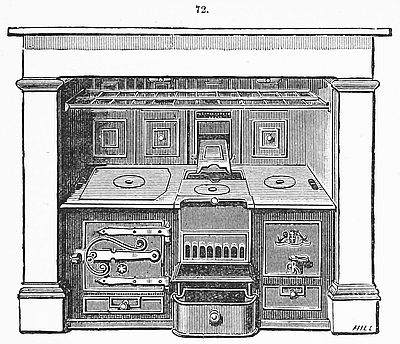

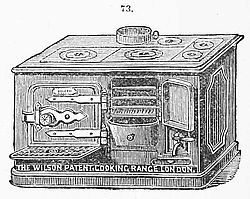

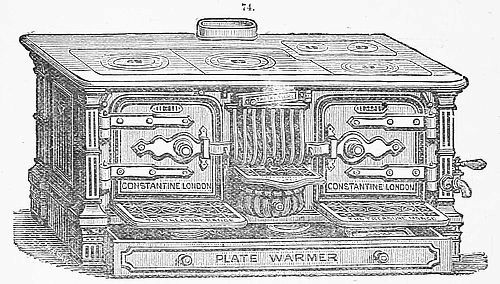

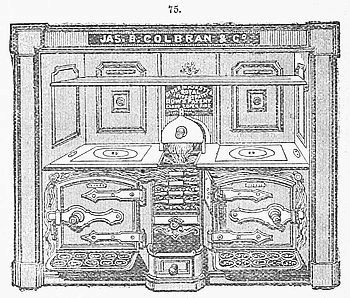

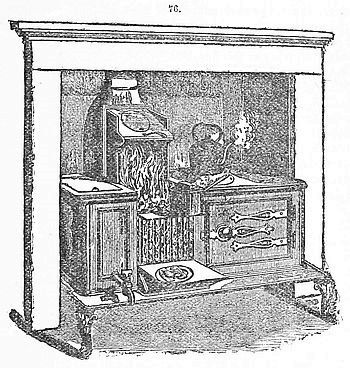

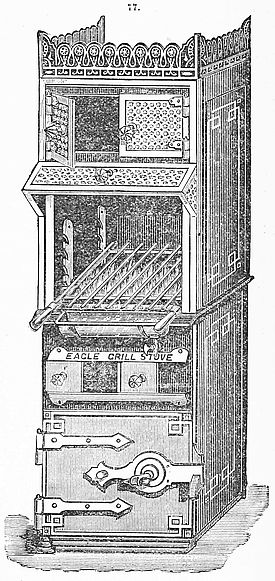

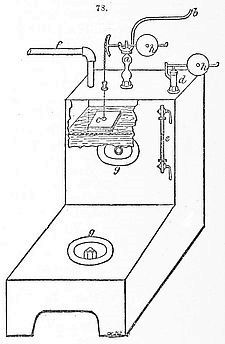

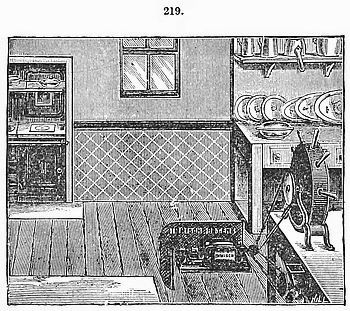

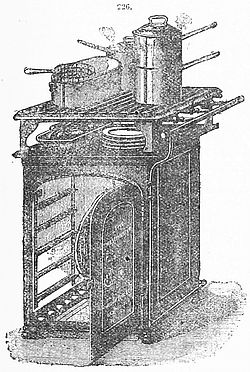

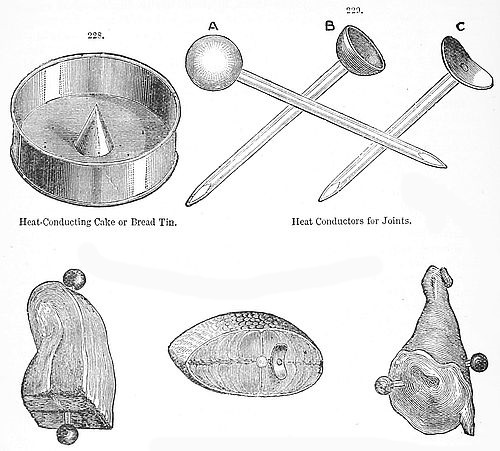

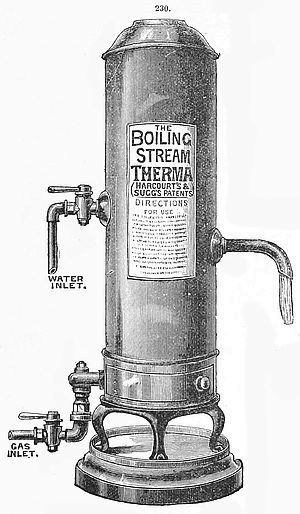

The Kitchen.—On Fitting Kitchens; a description of the best Cooking Ranges, close and open; the Management and Care of Hot Plates, Baking Ovens, Dampers, Flues, and Chimneys; Cooking by Gas; Cooking by Oil; the Arts of Roasting, Grilling, Boiling, Stewing, Braising, Frying

Receipts for Dishes.—Soups, Fish, Meat, Game, Poultry, Vegetables, Salads, Puddings, Pastry, Confectionery, Ices, &c., &c.; Foreign Dishes

The Housewife’s Room.—Testing Air, Water, and Foods; Cleaning and Renovating; Destroying Vermin

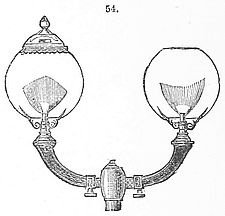

Housekeeping, Marketing

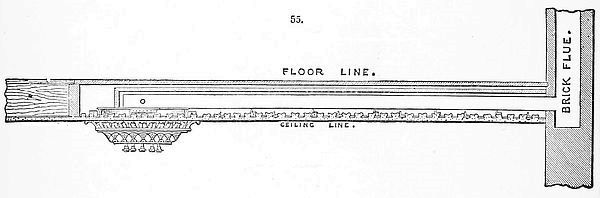

The Dining-Room.—Dietetics; Laying and Waiting at Table; Carving; Dinners, Breakfasts, Luncheons, Teas, Suppers, &c.

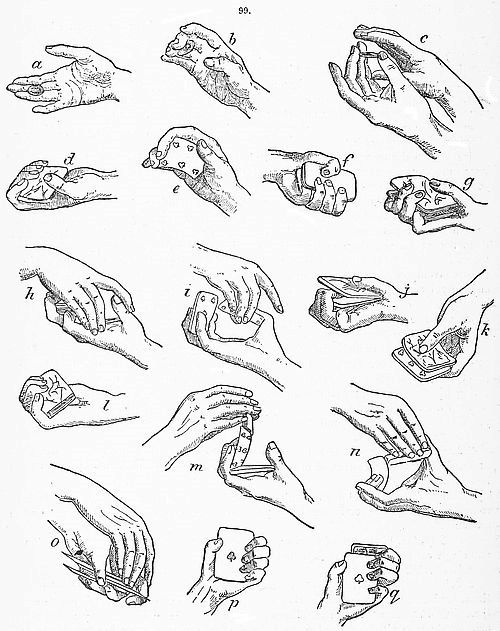

The Drawing-Room.—Etiquette; Dancing; Amateur Theatricals; Tricks and Illusions; Games (indoor)

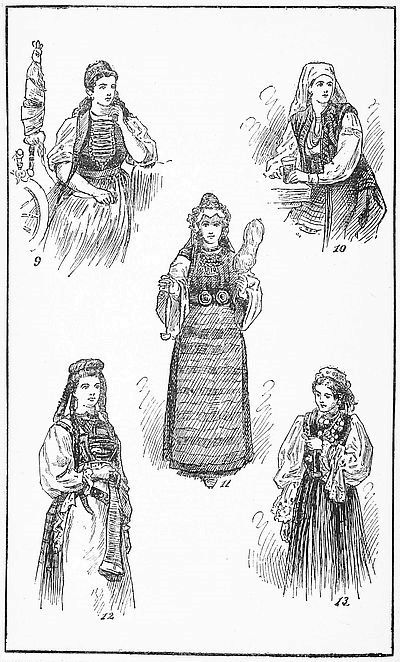

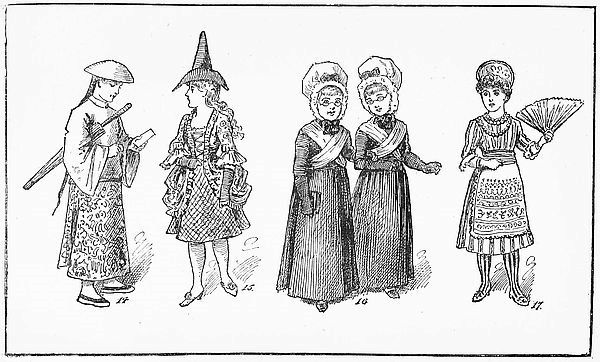

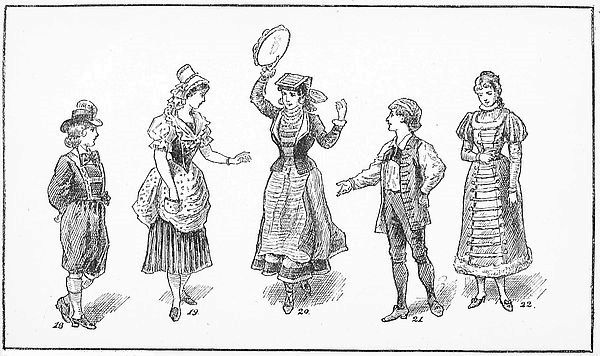

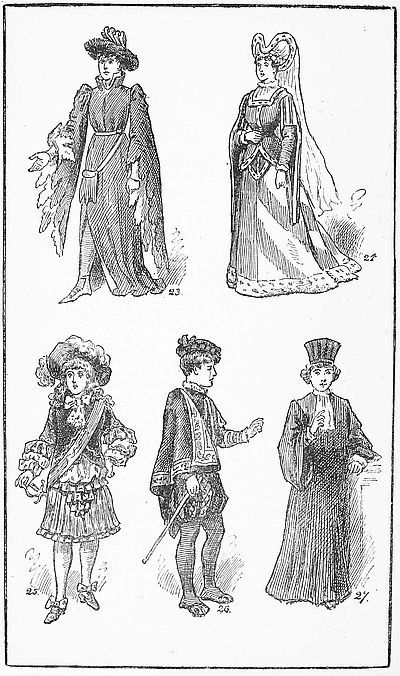

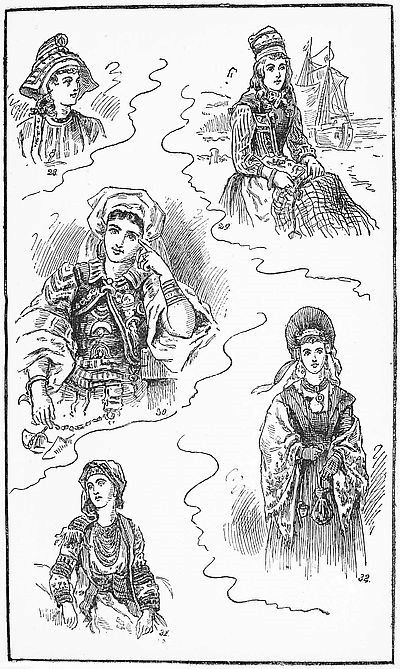

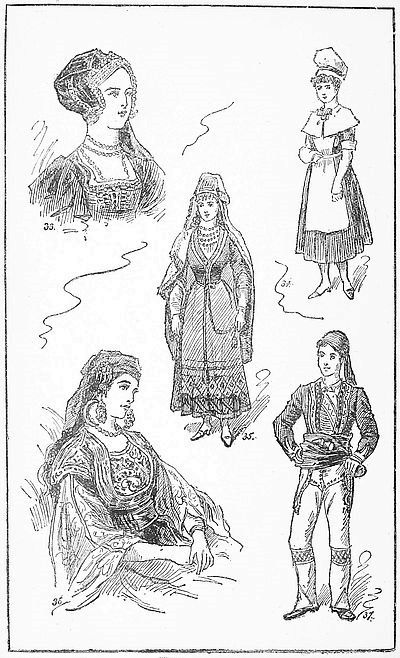

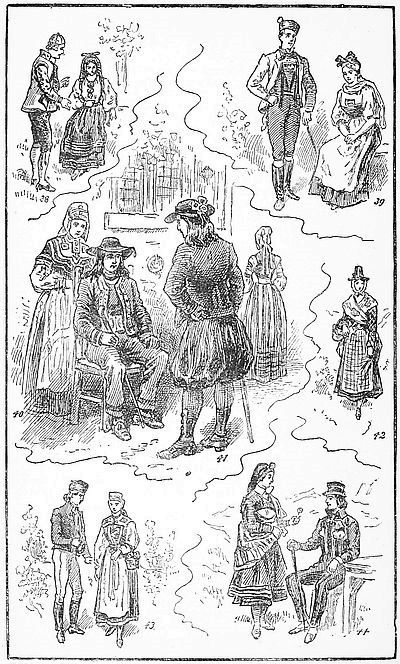

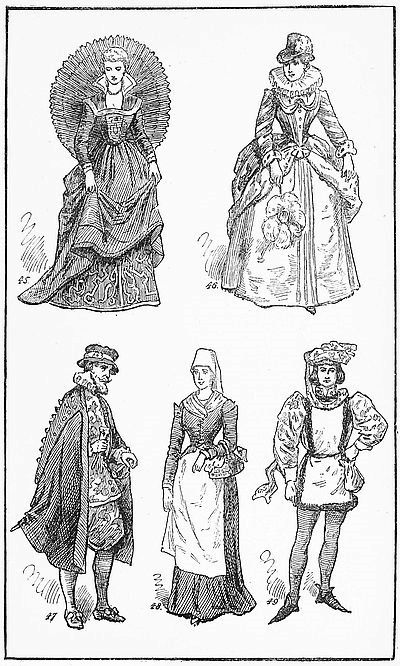

The Bedroom and Dressing-Room.—Sleep; the Toilet; Dress; Buying Clothes; Outfits; Fancy Dress

The Nursery.—The Room; Clothing; Washing; Exercise; Sleep; Feeding; Teething; Illness; Home Training

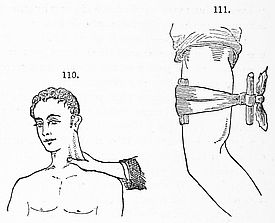

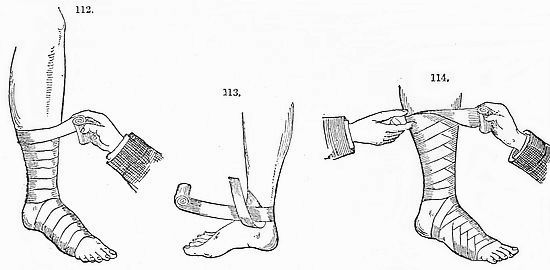

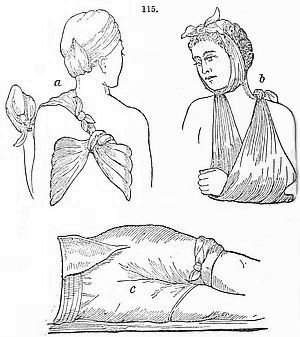

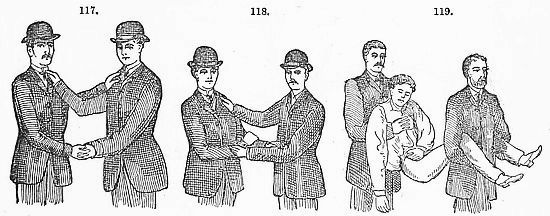

The Sickroom.—The Room; the Nurse; the Bed; Sickroom Accessories; Feeding Patients; Invalid Dishes and Drinks; Administering Physic; Domestic Remedies; Accidents and Emergencies; Bandaging; Burns; Carrying Injured Persons; Wounds; Drowning; Fits; Frostbites; Poisons and Antidotes; Sunstroke; Common Complaints; Disinfection, &c.

The Bathroom.—Bathing in General; Management of Hot-Water System.

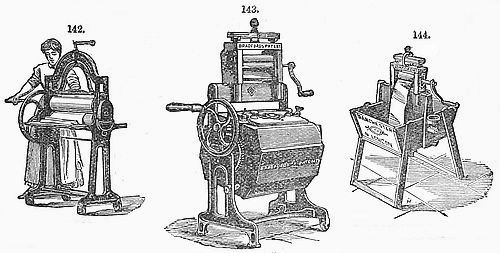

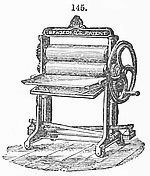

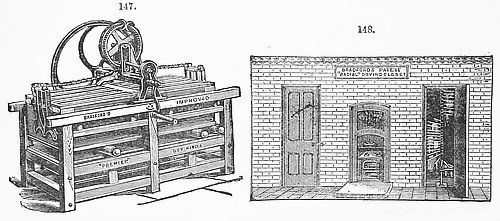

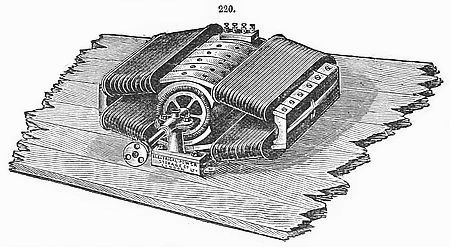

The Laundry.—Small Domestic Washing Machines, and methods of getting up linen; Fitting up and Working a Steam Laundry

The Schoolroom.—The Room and its Fittings; Teaching, &c.

The Playground.—Air and Exercise; Training; Outdoor Games and Sports

The Workroom.—Darning, Patching, and Mending Garments

The Library.—Care of Books

The Farmyard.—Management of the Horse, Cow, Pig, Poultry, Bees, &c.

The Garden.—Calendar of Operations for Lawn, Flower Garden, and Kitchen Garden

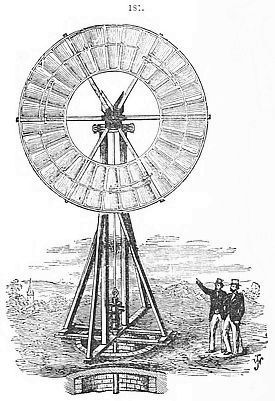

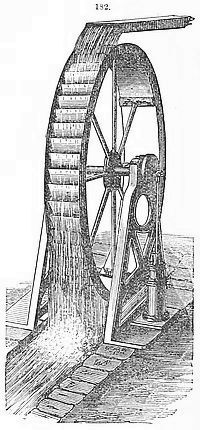

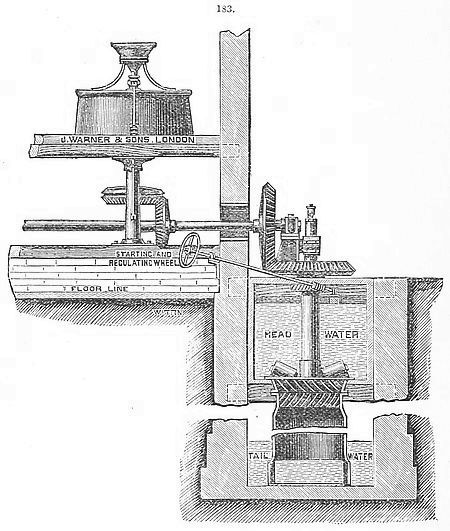

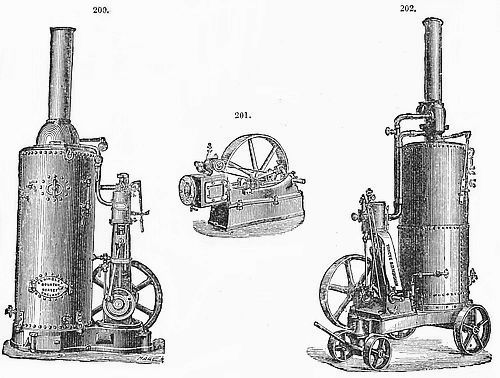

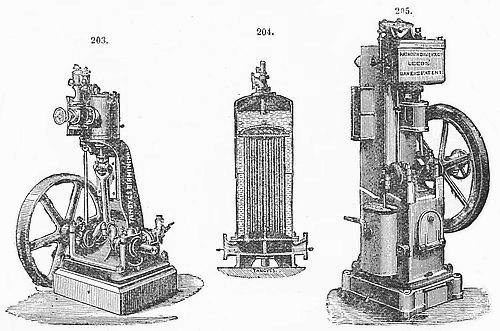

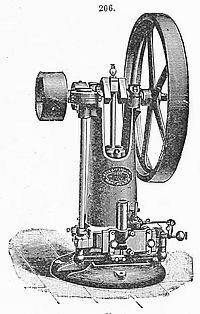

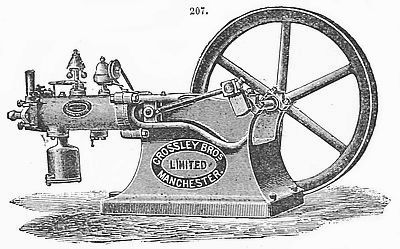

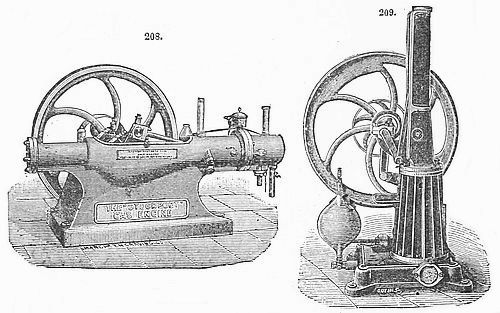

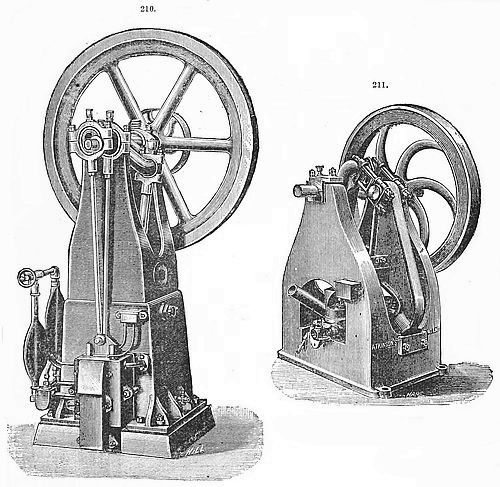

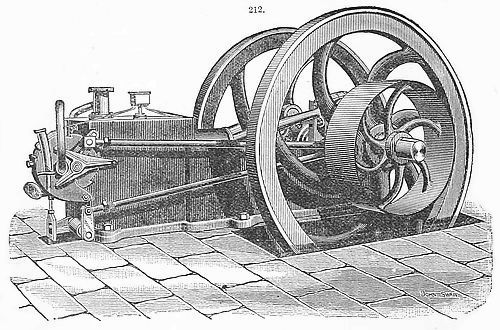

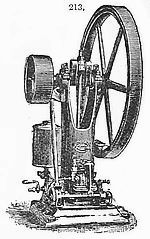

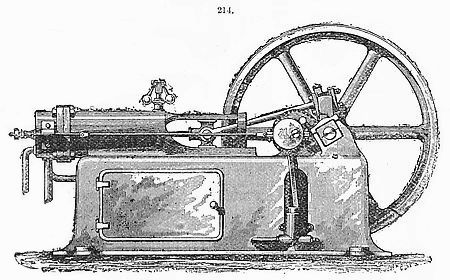

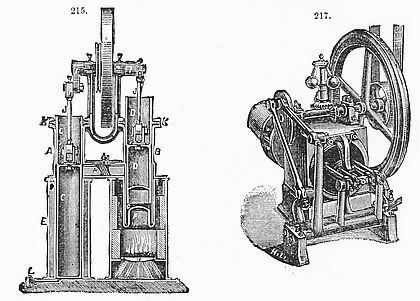

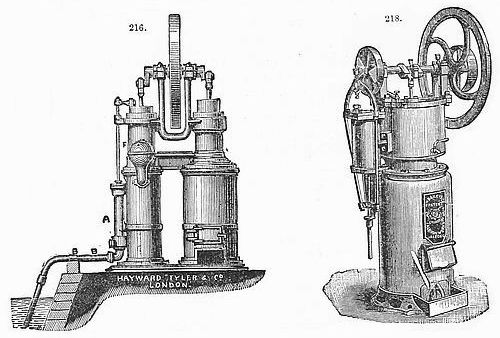

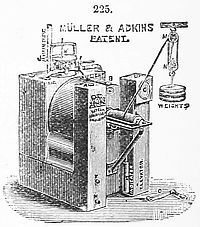

Domestic Motors—A description of the various small Engines useful for domestic purposes, from 1 man to 1 horse power, worked by various methods, such as Electric Engines, Gas Engines, Petroleum Engines, Steam Engines, Condensing Engines, Water Power, Wind Power, and the various methods of working and managing them

Household Law.—The Law relating to Landlords and Tenants, Lodgers, Servants, Parochial Authorities, Juries, Insurance, Nuisance, &c.

SPONS’

HOUSEHOLD MANUAL.

It is both convenient and rational to commence this volume with a chapter on the conditions which should guide a man in the choice of his dwelling. Unfortunately there is scarcely any subject upon which ordinary people display more ignorance, or to which they pay so little regard. In the majority of instances a dwelling is chosen mainly with regard to its cost, accommodation, locality, and appearance. As to its being healthy or otherwise, no evidence is volunteered by the owner, and none is demanded by the intending resident. The consequences of this indifference are a vast amount of preventible sickness and a corresponding loss of money. The following remarks are intended to educate the house-seeker in the necessary subjects, being subdivided under distinct headings for facility of reference.

Site.—Of modern scientists who have studied the great health question, none has more ably treated the essentials of the dwelling than Dr. Simpson in his lecture for the Manchester and Salford Sanitary Association. This Association has done wonders in improving sanitation in the Midlands, and we cannot do better than follow Dr. Simpson’s teaching.

Soil.—He insists, first of all, on the great importance of the soil being dry—either dry before artificial means are used to make it so, or dry from drainage. To this end some elevation above the surrounding land conduces. A hollow below the general level should, as a matter of course, be avoided; for to this hollow the water from all the adjacent higher land will drain, and if the soil be impervious the water will lodge there. It will thus be damp, and, as is well known, it will be a colder situation than neighbouring ones which are a little raised above the general level. Those who live where they can have gardens will find the advantage of the higher situation in its being much less subject to spring and early autumn frosts than the hollow just below. This is due not only to the former being damper, but to the fact that the heat of the ground on still nights passes off into space (is “radiated”) more rapidly than from the higher situation, where there is more movement in the air. The soil should not be retentive of moisture, as clay is when undrained; nor should it be damp and moist from the ground water (concerning which a few words will be said farther on), as is much alluvial soil, i.e. soil which has been at some former time carried down and deposited by rivers or floods. On the whole, sand or gravel, if the site be sufficiently elevated, is probably the best, as it allows all water to get away rapidly. Then come various rocks, as granite, limestone, sandstone, and chalk.

Towns often present one specially dangerous, and therefore specially objectionable[2] soil—that where hollows have been filled up with refuse of all kinds. This refuse is made up of all kinds of vegetable, and, more or less, animal matter, often of the most noxious character, together with cinders, old mortar, and no one knows what besides. This becomes a foul fermenting mass, which is often built upon and the houses inhabited before the process of decomposition is completed, and the noxious gases cease to be given off. Many outbreaks of disease have been traced most unmistakably to this criminal act of putting up jerry buildings on pestilential sites. It is easy for any one to understand how this may be when he thinks of the way the house acts on the soil it is built upon, or rather on the moisture and gases contained in the soil. The house is warmed by the fires and by the people living in it, and the heated air has a tendency to rise. The pressure on the gases in the soil is lessened, and they are drawn up into the house, which acts as a suction pump. This could not happen if the foundation were air-tight; but this is rarely the case, and too often indeed “cottage property” is built without any foundation at all. Drs. Parkes and Sanderson recommended that such soil should not be built upon “for at least two years,” but it would be well to give it another year. Attention must also be paid to the “ground water”—the great underground sea of which we find evidences almost anywhere that we seek for them. Sometimes it is found even a foot or two only from the surface, in other places at 15, 20, or 40 ft. This water rises and falls in some places rapidly, rising after heavy rains, and falling in dry weather. If it is always near the surface, the place must be damp and unhealthy; and we should try to find out something about the ground water before fixing on the site of our house. If possible, do not live where it is less than 5 or 6 ft. from the surface.

Trees.—Vegetation assists in rendering the soil healthy. Trees absorb large quantities of moisture from the soil, and sometimes, as in the case of the blue gum-tree of Australia, they seem even to do something more than this. It is said that the common sunflower of our gardens has a considerable influence in this way. Trees should not be crowded close to a house, as they keep off much sun, and so neutralise some of their good effects, but at a reasonable distance they are beneficial.

Aspect.—The aspect of a dwelling will necessarily be made to vary with the climatic conditions of the locality in which it is situated. In northern latitudes, such as Great Britain occupies, we are rarely oppressed by sunshine, and need not seek special protection from it. We should rather be anxious not to be deprived too much of its genial and life-giving rays. On the other hand, we are often visited by bleak and bitter winds, and though a free circulation of air is desirable round a dwelling, there should be some shelter to break the violence of a cold prevailing wind. In the country, where in all probability there is no system of drainage for the district, we should be careful not to place the house so as to receive our neighbour’s drainage, nor that from our own outbuildings. In a town the situation should be as open as can be obtained. The wider the street and the greater the open space at the back the better, and the back-to-back houses should be avoided altogether. (Simpson.)

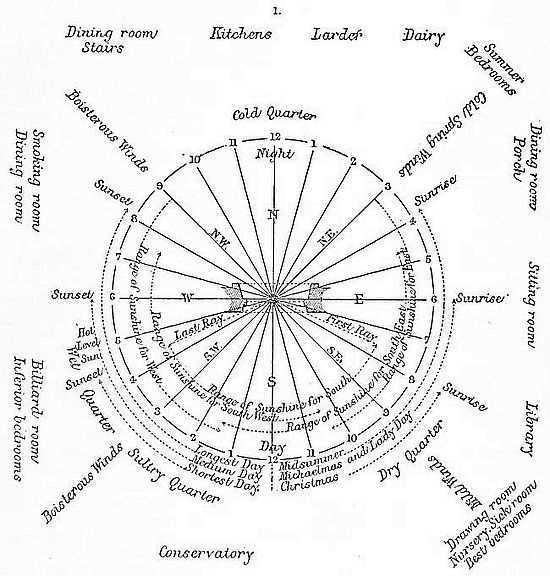

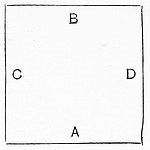

As Eassie remarks, in one of the Health Exhibition Handbooks, aspect and prospect have very much to do with comfort in housebuilding, since a dwelling may be designed so as to fully command the scenery while its plan might be very ill-adapted to the prevalent weather, and the sun’s daily course. A house having a pleasant prospect may be a decidedly unpleasant dwelling if the rooms have been arranged without regard to the points of the compass. This will become quite evident from a careful study of the annexed representation of Prof. Kerr’s “aspect compass” (Fig. 1), which illustrates most clearly the direction and character of the prevailing winds of this country, and the sunny and shady quarters, the imaginary window of the dwelling occupying the centre of the circle.

Obviously, as Eassie points out, the effects of aspect will not be the same on the inside and outside of the room. Looking from a window in the north, the prospect or landscape will be lighted from behind; to the spectator looking from the south, it will[3] never be go lighted; looking from the east, the landscape will be so lighted at sunset; and looking from the west, it will be well lighted throughout the day. The great thing is to reconcile aspect and prospect in the choice of a house; but this can seldom be done, and where it cannot, the question of aspect must be first attended to, as being of importance to the rooms, and the question of prospect made secondary. The north is not suitable for a drawing-room, because the aspect is cold; it is more suitable for a dining-room, as during the winter the prospect is not seen so much. When the room used for morning meals looks to the north, a bay window erected to the east will catch the early sunbeams, and render it pleasant. The northern aspect is too cold as a rule for bedrooms; but it is quite suitable for the servants’ day apartments, and admirably adapted to the larder and dairy. It is especially suited for staircases, as no blinds are requisite, and the passages can be maintained in a cool state.

1. Aspect Compass for Great Britain.

The north-east aspect—next to the north—is best for a dining-room; it is better for the servants’ offices than even the north; and when an end window is wanted for a drawing-room, this forms no unpleasant aspect. Bedrooms which face north-east enjoy the morning sun, and during the summer range are agreeably cool at night. With regard[4] to the east, this is also a good aspect for the dining-room, especially when no distinction is made between the dining-room and the breakfast-room; and with regard to a sitting-room the more eastward tendency it has the better. It is not adapted for a drawing-room, because in the afternoon there is an entire want of sunshine, and on account of the unhealthy east winds. This point of the compass is suitable, however, for a library or business-room, because by the time breakfast is over the sun will fairly have warmed the interior of the room. It is also a good aspect for the porch, and one side of a conservatory should always face the east.

The south-east aspect is most suitable for the best rooms of a house, because it escapes some of the east wind, and part of the scorching heat and beating rain of the south. It is admirably adapted, therefore, for a drawing-room or day-room, is the most pleasant aspect for bedrooms, and is best suited for the nursery or for the rooms of an invalid. The south-west aspect is the least congenial of all, because it is so open to a sultry sun and blustering winds. This aspect should never be chosen for a dining-room; in summer it is unpleasantly hot for bedrooms; and it is not suitable for a porch or entrance, on account of the driving rains which prevail during a portion of the year. The south aspect is not very desirable for the windows of a dining-room, and is unpleasant for a morning-room, unless a verandah has been provided. The larder and dairy should never face the south. The west aspect is not quite agreeable for a dining-room, on account of the excessive heat prevailing in the summer afternoons; neither is it desirable for the drawing-room; and it should never preferably be chosen for bedrooms, although it is very agreeable for a smoking-room. One side of a conservatory should always face to the west. The north-west aspect is very good for a billiard-room, also for a dining-room, if the windows are fitted up with blinds to shade the sun.

Construction. Foundation.—Bearing in mind what Dr. Simpson has said as to the house acting as a suction pump, drawing up moisture and gases, often most noxious, from the soil on which it is built, it is clear that the foundation ought to be air-tight and water-tight; for besides the emanations due to the soil, we must remember that escape from the gas-pipes laid in the street is a very common occurrence, that sewers are apt to leak, and so the soil in the neighbourhood of houses may become saturated with filth. Fatal instances are known where coal gas and other foul vapours have been drawn, as it were, long distances and poisoned the air of a house or houses. The only way of guarding against this is to have the foundations, and some distance outside the foundations, laid in concrete. There should also be a space between the basement wall and the surrounding earth. No one, in Eassie’s opinion, would think of building a dwelling on a patch of ground without first removing the vegetable mould to some depth below the level of the floor; and however good the soil, it is very desirable to cover the site with a layer of concrete to keep out damp and bad exhalations. Rawlinson even advises a bed of charcoal below the concrete. Simpson insists that if a cottage floor has to be laid on the bare ground, there ought at least to be a bed of good concrete below the tiles. Cellars add to the dryness and healthiness of a house if the walls and floors are made impervious to air and water, and are properly ventilated. The walls of the house ought to have a damp-proof course to prevent the moisture rising in them. To show the importance of this, Simpson quotes a well-known fact, but one seldom thought of when we look at the brick walls of our houses. An ordinary well-baked brick, which is 9 in. long, 4½ in. broad, and 2½ in. deep, though apparently solid, is not really so. It contains innumerable minute spaces through which air may pass, and into which water may enter; and when it is soaked in the latter, and all the air is driven out, it will contain nearly 16 oz. (the old pint) of water. If one brick will retain in its pores so large a quantity, it is easy to see that a large wall may hold what most people would at first think an incredible amount. As Dr. de Chaumont says, “A cottage wall only 16 ft. long by 8 ft. high, and only one brick thick, might hold 46 gallons of water!”

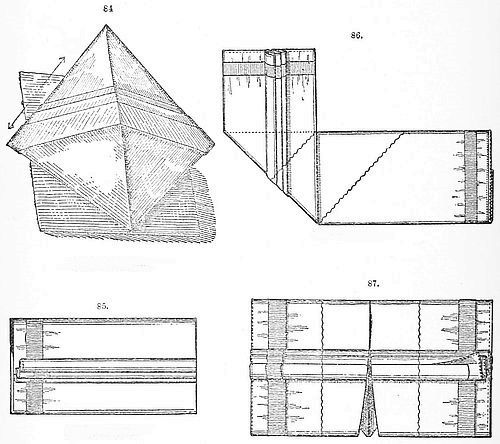

Walls may be made damp not only by water rising in them, but by rain driving[5] against them, and by water running down from the roof in consequence of the stoppage of a rain-water pipe. The latter cause is simple and easily remedied, but the former is far too frequent in cheaply-built houses. It may be prevented by having cavity walls, as they are called—that is, a double wall with a space between. There are several advantages from this. The air space, besides helping to keep the inner wall dry, is a good non-conductor, and so the house is all the warmer. There are other methods which may be used in addition to this, as cementing, plastering, or covering with slates or boards. There is some difference of opinion as to the advantage or disadvantage of the walls of a house being porous, as bricks are when dry; and Prof. de Chaumont seems to think that in our climate the porosity of the walls is not a point we need trouble ourselves about maintaining. Still, in Simpson’s opinion, with the ordinary arrangements of houses as regards supply of air and ventilation, some porosity of the walls is desirable. Without the freest and most perfect ventilation, walls absolutely impervious to air, and therefore to water in a gaseous form, will almost always be more or less damp on the inside.

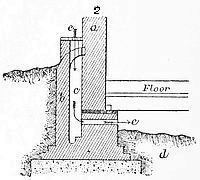

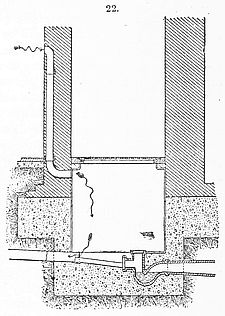

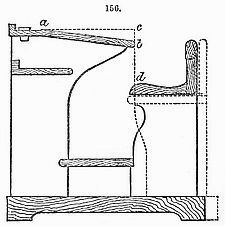

2. Damp Course and Area Wall.

Another source of dampness in dwellings, as pointed out by Eassie, is to be found in the practice of building the house walls close against the earth, without taking the precaution to erect a blind area-wall between the house wall and the earth excavation. Fig. 2 exhibits both these important improvements—the damp-course and the area-wall—applied to the same dwelling: a represents the main wall of the house, and b the area-wall, which is built against the excavated subsoil, leaving the space c between the two walls; the thick black line underneath the floor-joist represents the damp-proof course, which interposes between the subsoil d, with the foundations built upon it, and the main wall of the house. This damp-proof course usually consists of a layer of pitch or asphalte, or slates bedded in cement, or specially glazed tiles, known as Taylor’s or Doulton’s manufactures. By the use of this impervious course, the upward passage of the ground water is effectually arrested. The intervening area c it is also well to drain, but this water should never drain into the soil drain, if avoidable, and certainly not until it has been thoroughly disconnected. There should always, also, be a current of air introduced from the outer air, by way of ventilators put at the top of the blind area c, and an air brick placed above or below the damp-proof course—preferably above—in order that the space between the ground and the joists or stone flooring of the basement may be thoroughly ventilated. This ventilation is shown by the arrows between e and e. Such air currents should always be provided under floors, whether there be a basement or not, and also always between the joists of the upper floors, and in the roof, in order to ward off dry-rot and ensure a constant circulation of air. (Eassie.)

Roof.—The first detail to be decided on is the “pitch” or slope to be given to the roof, and this will depend both on the nature of the covering material and the character of the climate. In the tropics, where rain falls in torrents, a flat pitch helps to counteract the rush of water; in colder regions the pitch must be such as to readily admit of snow sliding off as it accumulates, to prevent injury to the framework by the increased weight. The pitches ordinarily observed, stated in “height of roof in parts of the span,” are as follows:—Lead, 1/40; galvanized iron or zinc, ⅕; slates, ¼; stone, slate, and plain tiles, 2/7; pantiles, 2/9; thatch, felt, and wooden shingles, ⅓ to ½.

In country districts the roofs of cottages and outbuildings are frequently covered with thatch. This consists of layers of straw—wheaten lasts twice as long as oaten—about 15 in. in thickness, tied down to laths with withes of straw or with string.[6] Thatch is an excellent non-conductor of heat, and consequently buildings thus roofed are both cooler in summer and warmer in winter than others, and no better roof covering for a dairy can be found. Thatch is, however, highly combustible, and as it harbours vermin and is soon damaged, it is not really an economical material, though the first cost is small. A load of straw will do 1½ “squares” of roofing, or 150 superficial feet. First class thatching is an art not readily acquired. While really good thatching will stand for 20 years, average work will not endure 10.

A convenient roofing material when wood is cheap and abundant consists of a kind of “wooden slates,” split pieces of wood measuring about 9 in. long, 5 in. wide, and 1 in. thick at one end but tapering to a sharp edge at the other. Shingles, or wooden slates, are made from hard wood, either of oak, larch, or cedar, or any material that will split easily. Their dimensions are usually 6 in. wide by 12 or 18 in. long, and about ¼ in. thick.

Roofing felt is a substance composed largely of hair saturated with an asphalte composition, and should be chosen more for closeness of texture than excessive thickness. It is sold in rolls 2 ft. 8 in. wide and 25 yd. long, thus containing 200 ft. super in a roll. Before the felt is laid on the boards (¾ in. close boarding), a coating composed of 5 lb. ground whiting and 1 gal. coal tar, boiled to expel the water, is applied, while still slightly warm, on the boards themselves; the felt is then laid on, taking care to stretch it smooth and tight, and the outside edge is nailed closely with ⅞ in. zinc or tinned tacks. The most common application to a felt roof is simple coal tar brushed on hot and sprinkled with sharp sand. It is not well adapted to dwellings.

Dachpappe is a kind of asphalte pasteboard much employed in Denmark; it is laid on close boarding at a very low pitch, and forms a light, durable covering, having the non-conducting properties of thatch. It is sold in rolls 2 ft. 9 in. wide and 25 ft. long, having a superficial content of 7½ sq. yd., at the rate of 1d. per sq. ft. When laid, it requires dressing with an asphalte composition called “Erichsen’s mastic,” sold at 9s. 9d. per cwt., 1 cwt. of the varnish sufficing to cover a surface of 65 sq. yd.

Willesden paper is another extremely light, durable, and waterproof roofing material, which differs essentially from the 2 preceding substances in needing to be fixed to rafters or scantling, and requiring no boarding on the roof. It is a kind of cardboard treated with cuprammonium solution, and has become a recognized commercial article. It is made in rolls of continuous length, 54 in. wide, consequently, when fixing the full width of the card (to avoid cutting to waste), the rafters should be spaced out 2 ft. 1 in. apart from centre to centre, so that the edge of one sheet of card laid vertically from eaves to ridge will overlap the edge of the adjoining sheet 4 in. on every alternate rafter.

By far the most important and generally used roofing material in this country is slate. Its splitting or fissile property makes it eminently useful as a roofing material, as, notwithstanding the fact that it is one of the hardest and densest of rocks, it can be obtained in such thin sheets that the weight of a superficial foot is very small indeed, and consequently, when used for covering roofs, a heavy supporting framework is not required. Slate absorbs a scarcely perceptible quantity of water, and it is very hard and close-grained and smooth on the surface; it can be laid safely at as low a pitch as 22½°. In consequence of this, the general introduction of slate as a roofing material has had a prejudicial effect upon the architectural character of buildings. The bold, high-pitched, lichen-covered roofs of the middle ages—which, with their warm tints, form so picturesque a feature of many an old-fashioned English country town—have given place to the flat, dull, slated roofs. The best roofing slate is obtained from North Wales, chiefly in the neighbourhood of Llanberis. Non-absorption of water is, of course, the most valuable characteristic; an easy test of this can be applied by carefully weighing one or two specimens when dry, and then steeping them in water for a few hours and weighing them again, when the difference in weight will of course represent[7] the quantity of water absorbed. The light-blue coloured slates are generally superior to the blue-black varieties. (J. Slater.)

Some architects bed the roofing slates in hydraulic cement, instead of having them nailed on dry in the usual way, which leaves them subject to be rattled by the wind, and to be broken by any accidental pressure. The cement soon sets and hardens, so that the roof becomes like a solid wall. The extra cost is 10 or 15 per cent., and it is good economy, considering only its permanency, and the saving in repairs; but, besides this, it affords great safety against fire, for slate laid in the usual way will not protect the wood underneath from the heat of a fire at a short distance.

Tiles are much used in some districts, and are often made of a pleasant tint; but a great objection to all tiles is their porosity, which causes them to absorb much water, rotting the woodwork and adding to their own already considerable weight.

Metallic roofing embraces sheet copper, sheet zinc, sheet lead, “galvanised” iron, and thin plates of “rustless” (Bower-Barff) iron. These materials are only used on flat or nearly flat spaces.

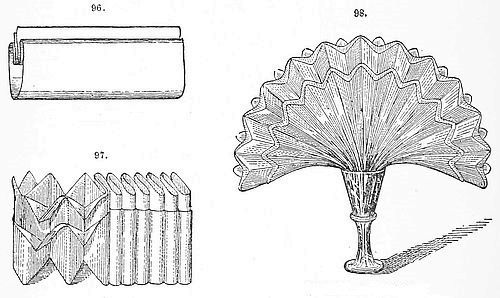

Floors.—Tiles or flags are most frequently used for the floors of kitchens, sculleries, and lobbies. They serve this purpose very well, as they are easily washed and not likely to be injured, but the joints should be made impervious to moisture. In some parts of the country, concrete is used; this answers very well for the same purpose, but it is not good for bedrooms, as it is so cold to the feet. Wood makes the most comfortable floor for sitting or bed rooms, and the best is hard wood capable of bearing a polish. From its convenience and cheapness, common deal is used very generally, and too often in a damp and unsound state, so that the boards shrink and wide gaps are left between. This allows all the foul air from any space—as a cellar or a cavity between the floor and the soil—to ascend into the room. The boards ought to be as close together as possible, and any spaces left between them should be packed tightly with oakum. If this is done, the floors may be stained and varnished, when they can be swept and rubbed clean, and do not require such frequent washing as the ordinary unvarnished floors. This is an important gain, for there is no doubt that emanations rising with the damp from newly-washed floors are often most injurious. If a varnished floor is washed, it dries almost at once. Spaces must be left under the floors, on the ground level, if they are of wood, or they will soon decay; and they ought to be well ventilated. Ceilings, leaving a space between them and the boards of the room above, have come into use, most likely to deaden sound. They often fail of this, while affording fine playgrounds to mice, and even rats. Well-laid boards, of sufficient thickness, and plugged with oakum, would, as regards health, be preferable. (Dr. Simpson.)

General Arrangement.—The chief points to be insisted on in a dwelling are enumerated by Simpson as follows:—Every room should obtain light and air from the outside, and there should be free communication from front to back, so that a current of air may pass through the house. What are called back-to-back houses are very objectionable, and to be carefully avoided. If there is a closet attached to the house, it should, as a matter of course, be ventilated by a window opening both above and below, and, if possible, should be built in a projecting wing or tower, and have double doors, with space between them for a window on each side, so as to have cross ventilation. When there is no closet in the house, it should be completely detached from it, and all piggeries, middens, &c., should be as far removed as possible. Speaking even of large houses, Eassie remarks that they are often very faultily planned in respect to the position in that portion of the interior which is usually appropriated to sinks and water-closets. In the basement, for instance, closets are often placed almost in the middle of the house, and the same mistake is committed on the floors above, a worse error by far; because then the closet would be placed on the landing of the stair opposite the best ground-floor, and chamber-floor rooms—the only ventilation from the closet-rooms being into the staircase, and consequently into the house.

Precaution against Snakes entering Dwellings.—There is no regular system adopted to prevent snakes entering dwelling-houses in Ceylon, as it is of rare occurrence to find any but rat snakes in European dwellings, and these are not venomous; but it is usual to clear away a portion of space about each bungalow and put on sharp gravel, and also to have coir matting laid down upon the verandahs, as snakes dislike crossing over rough surfaces such as gravel and coir. Trees should be at such a distance from the house (or bungalow) as to prevent the possibility of snakes dropping from the branches on to the roof.

Reducing Echoes and Reverberations.—The report of a committee of a Würtemberg association of architects upon the deadening of ceilings, walls, &c., to sound, gave rise to considerable debate, after which the following conclusions were reached. The propagation of sound through the ceiling may be most effectually prevented by insulating the floor from the beams by means of some porous light substance, as a layer of felt, a filling of sand, or of stone coal dust, the latter being particularly effective. It is difficult to prevent the propagation of sound through thin partitions, but double unconnected walls filled in with some porous material have been found to answer the purpose best. Covering the walls and doors with hangings, as of jute, is also quite serviceable.

To those who carry on any operations requiring much hammering or pounding, a simple means of deadening the noise of their work is a great relief. Several methods have been suggested, but the best are probably these:

1. Rubber cushions under the legs of the work-bench. Chambers’s Journal describes a factory where the hammering of fifty coppersmiths was scarcely audible in the room below, their benches having under each leg a rubber cushion.

2. Kegs of sand or sawdust applied in the same way. A few inches of sand or sawdust is first poured into each keg; on this is laid a board or block upon which the leg rests, and round the leg and block is poured fine dry sand or sawdust. Not only all noise, but all vibration and shock, is prevented; and an ordinary anvil, so mounted, may be used in a dwelling-house without annoying the inhabitants. To amateurs, whose workshops are almost always located in dwelling-houses, this device affords a cheap and simple relief from a very great annoyance.

Echoes are broken up by stretching wires across the room at about 4-5 ft. above the heads of the audience. Often there is strong echo from the windows, which is lessened by the use of curtains, but with some sacrifice of light. Very thin semi-transparent blinds would check echo a good deal, but architects should not have large windows in the same plane; large unbroken surfaces of any kind are very apt to reflect echoes, yet we constantly see rooms intended for public meetings so built as to be spoiled by the confusing echoes.

Waterproofing Walls.—In many badly constructed houses with thin walls there is a tendency for damp to make its way into the interior. Several remedies for this inconvenience have been published at various times. The following procedure is described by a German paper as a reliable means of drying damp walls. The wall, or that part of it which is damp, is freed from its plaster until the bricks or stones are laid bare, next further cleaned off with a stiff broom, and then covered with the mass prepared as below, and dry river-sand thrown on as a covering. Heat 1 cwt. of tar to boiling-point in a pot, best in the open air; keep boiling gently, and mix gradually 3½ lb. of lard with it. After some more stirring, 8 lb. of fine brickdust are successively put into the liquid, and moved about until thoroughly disintegrated, which has been effected when, on dipping in and withdrawing a stick, no lumps adhere to it. The fire under the pot is then reduced, merely keeping the mass hot, which in that state is applied to the wall. This part of the work, as well as the throwing on of the river-sand against the tarred surface, must be done with the trowel quickly and with sufficient force. It must be continued until the whole wall is covered both with the tar mixture and the sand.[9] The tar must not be allowed to get cold, nor must the smallest possible spot be left uncovered, as otherwise damp would show itself again in such places, and where no sand has been thrown the following coat of plaster would not stick. When the tar covering has become cold and hard, the usual or gypsum coating may be applied. It is asserted that, if this covering has been properly dried, even in underground rooms, not a sign of dampness will be perceived. About 300 sq. ft. may be covered with the quantities above stated.

An excellent asphalte or mortar for waterproofing damp walls or other surfaces is the following patented composition:—Coal tar is the basis, to which clay, asphalte, rosin, litharge, and sand are added. It is applied cold, and is extremely tenacious and weather-resisting. The area to be covered is first dried and cleaned, then primed with hot roofing varnish—chiefly tar. The mortar is then laid on cold with trowels, leaving a coat ⅜ in. thick. A large area is then coated with varnish and sprinkled over with rough sand. To frost or rain this mortar is impervious. The cost is 5d. per sq. ft., and for large quantities 4d. In the case of stone walls the following ingredients, melted and mixed together, and applied hot to the surface of stone, will prevent all damp from entering, and vegetable substance from growing upon it. 1½ lb. rosin, 1 lb. Russian tallow, 1 qt. linseed-oil. This simple remedy has been proved upon a piece of very porous stone made into the form of a basin; two coats of this liquid, on being applied, caused it to hold water as well as any earthenware vessel.

For brickwork, the Builder gives the following remedy:—¾ lb. of mottled soap to 1 gal. of water. This composition to be laid over the brickwork steadily and carefully with a large flat brush, so as not to form a froth or lather on the surface. The wash to remain 24 hours to become dry. Mix ½ lb. of alum with 4 gal. of water; leave it to stand for 24 hours, and then apply it in the same manner over the coating of soap. Let this be done in dry weather.

Another authority says, coat with venetian red and coal tar, used hot. This makes a rich brown colour. It can be thinned with boiled oil.

A Devonshire man recommends “slap-dashing,” as is often done in Devon. The walls are, outside, first coated with hair-plaster by the mason, and then he takes clean gravel, such as is found at the mouth of many Devonshire rivers, and throws—or, as it is called locally, “scats” it—with a wooden trowel, with considerable force, so as to bed itself into the soft plaster. You can limewash or colour to your liking, and your walls will not get damp through.

Perhaps no application is cheaper or more efficacious than the following. Soft paraffin wax is dissolved in benzoline spirit in the proportion of about one part of the former to four or five parts of the latter by weight. Into a tin or metallic keg, place 1 gal. of benzoline spirit, then mix 1½ lb. or 2 lb. wax, and when well hot pour into the spirit. Apply the solution to the walls whilst warm with a whitewash brush. To prevent the solution from chilling, it is best to place the tin in a pail of warm water, but on no account should the spirit be brought into the house, or near to a light, or a serious accident might occur. The waterproofed part will be scarcely distinguishable from the rest of the wall; but if water is thrown against it, it will run off like it does off a duck’s back. Whilst it is being applied the smell is very disagreeable, but it all goes off in a few hours. On a north wall it will retain its effect for many years, but when exposed much to the sun, it may want renewing occasionally. Hard paraffin wax is not so good for the purpose, as the solution requires to be kept much hotter.

Curing a Damp Cellar.—A correspondent inquired of the editor of the American Architect what remedy he would suggest for curing a damp cellar. The difficulty to be overcome, presents the questioner, in a new house is the wet cellar. Conditions present, concrete not strong enough to resist the hydraulic pressure through a clay soil. No footings under wall (which are of brick.) No cement on outside of wall. The water evidently, however, forces its way through the concrete bottom.

(a) Will reconcreting (using Portland cement) resist the pressure of water and keep it out?

(b) If not, will a layer of pure bitumen damp-course between the old and new concrete do the work?

(c) Will it do any good to carefully cement the walls on the inside with rich Portland cement, say 3 ft. high, to exclude damp caused by capillary attraction through the brick wall?

In reply to the above queries the editor gave the following hints, which are equally applicable to builders of new houses as to those occupying old houses with damp cellars:

It is doubtful whether even Portland cement concrete would keep back water under sufficient pressure to force it through concrete made of the ordinary cement. The best material would be rock asphalte, either Seyssel, Neufebatel, Val de Travers, Yorwohle, or Limmer, any of which, melted, either with or without the addition of gravel, according to the character of the asphalte, and spread hot to a depth of ¾ in. over the floor, will make it perfectly water-tight. The asphalte coating should be carried without any break 18 or 20 in. up on the walls and piers, to prevent water from getting over the edge; and if the hydrostatic pressure of the water should be sufficient to force the asphalte up, it must be weighted with a pavement of brick or concrete. This is not likely to be necessary, however, unless the cellar is actually below the line of standing water around it.

This, although an excellent method of curing the trouble, the asphalte cutting off ground air from the house, as well as water, will be expensive, the cost of the asphalte coating being from 20 to 22 cents (10-11d.) a sq. ft.; and perhaps it may not be necessary to go to so much trouble. It is very unusual to find water making its way through ordinary good concrete, unless high tides or inundations surround the whole cellar with water. If the source of the water seems to be simply the soakage of rain into the loose material filled in about the outside of the new wall, we should advise attacking this point first, and sodding or concreting with coal-tar concrete, a space 3 or 4 ft. wide around the building. This, if the grade is first made to slope sharply away from the house, will throw the rain which drips from the eaves, or runs down the walls, out upon the firm ground, and in the course of two or three seasons the filling will generally have compacted itself to a consistency as hard as or harder than the surrounding soil, so that the tendency of water to accumulate just outside the walls will disappear; while the concrete, as it hardens with age, will present more and more resistance to percolation from below.

For keeping the dampness absorbed by the walls from affecting the air of the house, a Portland cement coating may be perhaps the best means now available. It would have been much better, when the walls were first built, to brush the outside of them with melted coal tar; but that is probably impracticable now. If the earth stands against the walls, however, the cement coating should cover the whole inside of the wall. The situation of the building may perhaps admit of draining away the water which accumulates about it, by means of stone drains or lines of drain tile, laid up to the cellar walls, at a point below the basement floor, and carried to a convenient outfall. This would be the most desirable of all methods for drying the cellar, and should be first tried.

Construction for Earthquake Countries.—The conditions will vary somewhat according to the nature of the climate.

R. H. Brunton, who was for many years resident lighthouse engineer in Japan, follows the principles enunciated by Mallet and Prof. Palmieri, giving the buildings weight and great inertia, coupled with a good bond between their various parts. Prof. Palmieri states that, although solidity and strength in a building do not afford perfect protection, still, so long as fracture does not occur, overthrow is impossible. Dyer states[11] that in his opinion, for dwelling-houses in Japan, the modifications of external design required, as compared with those in Britain, arise not so much on account of the earthquakes as from the heats of summer, the colds of winter, and the typhoons of autumn. Iron roofs are good from a merely structural point of view; but in summer it would be impossible to live in the houses provided with them. If a non-conducting material of the same strength and durability as iron could be found, it might be used. “If the houses are so designed as to be comfortable as regards temperature, and the construction made in good brick, or equally strong stone and mortar, so that the walls are of nearly a uniform strength; if no unnecessary top weights are used, and if the various parts do not vibrate with different periods, they will withstand all ordinary earthquakes, and other precautions will be unnecessary, as these generally produce results more serious than those due to the earthquakes.”

The city of Arequipa, Peru, is particularly liable to earthquakes, owing to its proximity to the great volcano, the Misti, 19,000 ft. in height above sea-level, the city being 7000 ft. above sea-level. The general construction of the houses is peculiar. A light coloured volcanic stone is largely used; this, when quarried, is easily shaped, and it hardens gradually. The roofs are for the most part strong arches, a very good mortar being used. In the earthquake of 1868, it was not so much those arches which failed as the walls, and the spandrels between the arches at front and rear. In some parts of the city, arches extending in one direction stood, while those at right angles to these were thrown down. Since 1868, a good many corrugated iron roofs have been introduced; but they are not suitable to the climate, and are not durable.

Earnshaw, from an experience of 25 years in Manila, where the earthquakes are sometimes very severe, comes to the conclusion to build as strongly as possible, and chiefly in wood, tied and bolted together as in a ship, stone and brickwork only being used in the lower story and in the foundations, and especial attention ought to be paid to the quality of the lime and mortar used in construction. Many materials have been used as roofing, such as the heavy tiles made in the country and others imported there. When, in 1880, fully 60 per cent. of the buildings in Manila had been ruined, an order was issued by the municipal authorities to use corrugated iron or zinc sheeting for that purpose. A diversity of opinion existed as to which was the best and most suitable, for not only had earthquakes to be guarded against, but intense heat and disastrous typhoons. With reference to the latter, in 1881, sheets of iron were flying about in the air like paper. He thinks, therefore, that a light, strong tile roofing is preferable to any other.

Prof. C. Clericetti, of Milan, and W. H. Thelwall relate that after the earthquake in the island of Ischia in 1883, which was of a most destructive character, and caused an enormous amount of damage in the island, 2000 persons having lost their lives, and many more being injured, a commission was appointed by the Italian Government to obtain information, and to frame rules for the rebuilding of the structures. It was ascertained that, speaking generally, buildings founded on hard, solid lava had withstood the shock successfully, whilst those founded upon looser or lighter materials, such as tufa or clay, had suffered very much, and therefore in regard to the re-erection of buildings it was pointed out that the first thing to do was to select eligible sites, and to build, wherever possible, upon lava; and, where that was not possible, to dig down to comparatively solid ground, and then fill in a heavy platform of masonry or concrete, 3 ft. or 4 ft. thick, extending over the whole area of the building, and projecting 3 ft. or 4 ft. beyond. The building of any kind of vaulting above ground was forbidden. Light arches were only to be allowed over window’s and openings of that kind. The heavy flat roofs formerly used to a large extent were condemned. The commission recommended that buildings should be chiefly constructed with an iron or wooden framework, carefully put together, joined by diagonal ties, horizontally and vertically, with spaces between the framework filled in with masonry of a light character. The[12] joists and the roof trusses were to be firmly connected together. In plan, buildings should be square, and where the direction of the last shock could be traced, one diagonal should be placed in this direction. Not more than two stories above ground were to be allowed, and there might be one under ground, but it must be of very moderate height. In no case was the height from the lowest point of the ground to the top of the walls to exceed 31 ft. Openings for doors and windows were to be vertically over each other, the jambs being not less than 5 ft. from the corner of the building. No openings for flues were allowed in the thickness of the walls, and no projections from the face of a building, except light balconies of wood or iron. If solidly built structures, and particularly if there was only one story above ground, the roofs might be covered with tiles; but these must be light, and fastened with nails or hooks, so as not to be displaced even by violent shocks.

Water Supply and Purification.—The supply of water to both town and country houses has been dealt with at length by Eassie and Rogers Field in essays written for the Health Exhibition Handbooks, and the following information is mainly condensed and adapted from their papers.

The conditions of supply in the two cases differ in being from a general and public source in the one and from a special and private source in the other. In each case, the consumer has to control the purity and application of the supply after its delivery into the dwelling; and in the second case he is further responsible for the character and quantity of the supply before delivery. The second case, therefore, in a great measure covers the first, and demands extended treatment.

Amount required.—The first consideration is the quantity of water required. The supply to towns from waterworks is usually expressed in “gallons per head of population per diem,” and varies exceedingly, much of the variation being due to waste. This is especially the case in towns where the supply is intermittent. In several towns having a constant supply, steps have been taken systematically to measure the water supplied to different streets and districts, and it has been found that, without restricting the supply in any way, the consumption of water has been immensely reduced, simply by sending inspectors to make a house-to-house visitation and search out and repair leaky pipes and defective taps and ball-cocks. It is by no means an unusual thing for the consumption to be reduced one-half by inspections of this kind, showing that at least one-half of the water which was previously supplied to the houses was simply wasted through leaky fittings.

Many people are inclined to think that waste of this kind is not a bad thing, as it must help to keep the drains flushed. Field points out that this is quite a mistake. A small dribble of water from a leaky pipe or a leaky tap, though it will waste a great deal of water in the course of 24 hours, is perfectly useless for flushing the drains. What is wanted for this is the sudden discharge of a large quantity of water. The dribble of water from leaky pipes and taps does no good in any way, but simply wastes what might be usefully employed, and in many cases causes a supply to run short which would otherwise be ample for all legitimate uses. Another point that it is difficult to realise is the large quantity of water which will run to waste through what is apparently a very small leak. The quantity leaking looks so small in comparison with the quantity running when a tap is open, that one is inclined to think it perfectly insignificant, forgetting that the leakage goes on continuously night and day, whereas the tap is only open for a few minutes. In country houses, where it is often difficult to obtain a sufficient supply of water, it is particularly important to bear in mind the serious influence that leaky pipes and taps have on the consumption, and never to allow such leakage to go on for any length of time.

While useless waste should be prevented, it is most important that the legitimate use of water should be encouraged in every way. As Dr. Richardson has well pointed out, absolute cleanliness, properly understood, is the beginning and the end of sanitary design,[13] and thorough cleanliness, of course, can never be obtained without an ample water supply. Not only should there be sufficient water for baths, lavatories, and washing of all kinds, but there should be a liberal allowance for flushing water-closets and all other sanitary appliances. Taking these sanitary considerations into account, as well as giving due weight to the observations which have been made by engineers and others on the quantity of water actually used in houses under different circumstances, it may be assumed that, if waste is efficiently prevented, a supply of 20-25 gallons per head per diem is sufficient in ordinary cases for houses with baths and water-closets. If horses are kept, a separate allowance should be made for them, and for stable purposes (a useful approximate rule being to reckon a horse as a man); and if water is used for watering gardens or ornamental purposes, this must also be reckoned separately. If earth-closets are adopted instead of water-closets, less water will be required, and 15-20 gallons per head per diem will be sufficient. In cottages with earth or other dry closets, the quantity of water required will be still less: 10 gallons per head will be an ample supply, and even 5-6 gallons may do in cases where it is absolutely necessary to limit the quantity used.

Sources of Supply.—Water for country houses is, in the vast majority of cases, derived from springs or wells. Rain-water collected from roofs is very frequently used as an auxiliary, and occasionally as the main supply. There are instances in which the supply is taken from streams or rivers, and even some in which water running off the surface of the ground is collected in “impounding reservoirs” (a mode often adopted for the water supply of towns); but these cases are exceptional, and attention will here be confined to springs, wells, and roof-water.

The real source of all fresh water supply is rain. Springs and wells form no exception to this rule, though in their case the connection with the rainfall is not so clear at first sight as it is in the case of streams and open watercourses, because the passages by which the rain reaches springs or wells are not visible, and heavy rainfalls often have no apparent effect on their yield. In various parts of the country occur curious intermittent springs (locally called “bournes”), which burst out in some years and not in others, and the connection between which and the rainfall is still more obscure. Rain-water, before it issues from the ground as springs, accumulates in the porous strata beneath, and forms, as it were, large underground reservoirs; it is from these reservoirs that wells, sunk into the porous strata, derive their supply.

The amount of rain varies enormously in different parts of the world, some districts being either absolutely rainless, or having only a very few inches of rain in the year, whereas others have some hundreds of inches in the year. Even in England itself there is considerable variation. The average rainfall for the whole country is about 30 inches a year, but the amount in different parts of the country varies from about 20 inches to nearly 200 inches a year. The eastern side of England, as Field remarks, has much less rain than the western side, and, roughly speaking, if a line be drawn from Portsmouth to Newcastle-on-Tyne, it will divide the country into a dry portion and a wet portion. The portion of the country on the east of this imaginary line will (with the exception of the south coast, which is wetter) have only 25 inches of rain or less, and the portion on the west of the line will have from 30 to 50 inches, with much larger amount in the Cumberland and Welsh mountains, and at Dartmoor.

The rainfall of the wettest year is about double that of the driest year. This gives a very useful rule for roughly ascertaining the extreme rainfalls, which are really more useful for the purpose of water supply than the rainfall for an average year. The fall in the driest year may be assumed to be one-third less than the average, and for the wettest one-third more. Thus, with an average rainfall of 30 inches, the fall of the driest year would be 20 inches, and that of the wettest year 40 inches.

A portion only of the total rain which falls is available for water supply, as there is always more or less loss. In the case of rain falling on roofs, the loss is comparatively[14] small, but in the case of rain falling on the surface of the earth the loss is considerable. The latter is disposed of in three different ways: part of it runs directly into open watercourses and streams, part is taken up by vegetation or lost by evaporation, and part percolates through the surface ground and accumulates in the water-bearing strata which feed the springs and wells.

From observations made on the amount of percolation in different cases, it has been found that the amount of percolation does not depend so much on the amount of rain as on the conditions under which it falls. By far the greater portion of the percolation takes place in winter and comparatively little in summer, the reason being that in winter the ground is wet, evaporation is small, and vegetation is inactive, so that a large proportion of the rain sinks into the ground; whereas in summer the reverse is the case, so that most of the rain is taken up before it can percolate. So great is the difference between summer and winter as regards percolation, that one may generally leave the summer rainfall altogether out of consideration, and assume that, in this country, it depends on the amount of rain which falls during the six months from October to March, whether the underground store of water will be fully replenished or not.

The height of the accumulated underground water is indicated by the level at which water stands in wells: and it is found that this height varies considerably, the variations usually following a regular course: the water is generally lowest in October and November, it then rises till it reaches its highest point in February or March, and after this it falls slowly till the following autumn.

A condition to be studied in selecting a spring as a source of water supply is its “seasonal” variation. As Field points out, a spring which will give an ample quantity of water in the winter may give an insufficient quantity in the autumn, so that the measurement of a spring in winter should never be depended on for determining whether it will do as a source of water supply. The only safe way is to wait till the autumn yield has been ascertained; even then an allowance must be made for the previous winter, if it has been a very wet one, the yield of the spring becoming abnormally high.

Wells may be either shallow or deep. The latter are always preferable, but sometimes the former must be relied on. The great and serious danger in connection with shallow wells is their liability to pollution from cesspools and drains, whose liquid contents (fully as poisonous as the solid) filter through the surrounding soil and go to swell the volume of water in the well, especially if, as nearly always happens, the cesspool is much shallower than the well.

In country villages, frequently the cesspools and wells are so intermixed that the entire bed of water is polluted, and hence all the wells are unsafe. But in isolated houses, if the well and cesspool are some distance apart, pollution of the well will depend chiefly on the direction of the movement of the underground water. If this movement is from the cesspool towards the well, the polluted water will flow towards the well; if the movement is in the contrary direction, the polluted water will flow away from the well. Hence Field’s caution, that before sinking a shallow well where sources of contamination are in the neighbourhood, the direction of the flow of the underground water must first be carefully ascertained, bearing in mind that it is not safe to assume that this flow is in the direction of the fall of the land, though it very frequently is so: if there is the slightest doubt, levels must be taken of the underground water in different places, and the source of contamination be accurately localised. Contamination from surface soakage can frequently be prevented by raising the top of the well above the adjoining ground, and paving the surface round the well with a slope so that the rain-water runs away from it. Norton Tube wells, which consist of an iron tube driven into the ground and surmounted by a pump, are useful for excluding surface pollution. If the pollution is sufficient to contaminate the subsoil and reach the underground water, no precautions that can be taken in constructing the well will keep the pollution out.

Generally, deep wells are safer from contamination than shallow wells, but may still, under certain circumstances, be polluted.

On the question whether a well which has been-polluted by a cesspool will become fit for use after the cesspool has been removed, no rule can be laid down. If the removal of the sources of pollution has been thorough, the well will frequently recover its purity; but under other circumstances the well may remain impure. As to the least distance between wells and cesspools compatible with safety, while the Local Government Board of London is content with 20-30 yards, Dr. Frankland insists on at least 200 yards. It would be more rational to forbid cesspools of all kinds; at the same time, possible leakages from drains, through injury or otherwise, must not be omitted from the estimate of risk of pollution. Again, the effect of increased demand upon the contents of the well at once extends the danger, because as the water in the well is lowered so is the area from which the well draws its supply increased, the ratio varying from 20 to 100 times the depression. Where a whole day’s supply is pumped at once into an elevated tank, the maximum figure will be reached.

Those who intend sinking wells are advised first to read a little book by Ernest Spon, on the ‘Present Practice of Sinking and Boring Wells,’ 2nd edition, 1885.

Rain-water collected from roofs forms a valuable auxiliary supply too often disregarded. In towns it is rarely pure enough for domestic use, but in country districts it is generally wholesome.

A country resident thus describes the manner in which he utilises rain-water, falling upon an ordinary tin roof, covered with some sort of metallic paint, said to contain no lead, and flowing into a large cemented brick cistern, whence it is pumped into the kitchen. The cistern differs from the usual construction in this manner: across the bottom, about 3 ft. nearer one side than the other, is excavated a trough or ditch about 2 ft. wide and 2 ft. deep; along the centre of this depression is built a brick wall from the bottom up to the top of the cistern, and having a few openings left through it at the very bottom. The whole cistern, bottom, sides, and canal included, is cemented as usual, excepting the division wall. Upon each side of the wall, at its base, 6-12 in. of charcoal is laid, and covered with well-washed stones to a further height of 6 in., merely to keep the charcoal from floating. The rain-water running from the roof into the larger division of the cistern, passes through the stone covering, the charcoal, the wall, the charcoal upon the other side, lastly, the stones, and is now ready for the pump placed in this smaller part. It is much better that the water at first pass into the larger division, as the filtration will be slower, and the cistern not so likely to overflow under a very heavy rainfall. He has used this cistern for many years, and was troubled only once, when some toads made their entrance at the top, which was just at the surface of the ground, soon making their presence known by a decided change in the flavour of the water.

If the house chances to be in a dusty situation, several plans will suggest themselves whereby a few gallons at the first of each rain may be prevented from entering the cistern. Should the house be small, and therefore the supply of water from its roof be limited, do not lessen the size of the cistern, but rather increase it, for with one of less capacity some of the supply must occasionally be allowed to go to waste during a wet time, and you will suffer in a drought, whereas a cistern that never overflows is the more to be relied upon in a long season without rain.

Rainfall varies exceedingly in different places, and even in the same situation it is impossible to foretell the amount to be expected during any short period of time, but the most careful observations show that about 4 ft. in depth descends at New York and vicinity every year, or nearly 1 in. a week. If this amount were to be furnished uniformly every week, the size of a cistern need only be sufficient to contain one week’s supply, but we often have periods of 4 weeks without receiving the average of one, and we must build accordingly.

The weekly average of 1 in. equals 1 cub. ft. upon every 12 ft. of surface, or[16] 3630 cub. ft. upon an acre, weighing about 113 tons. Upon a roof 40 ft. by 40 ft., 1600 sq. ft., it would be 133 cub. ft., 1037 gal., or about 26 barrels of 40 gal. each. A cistern 8 ft. across and 10 ft. deep would contain 502 cub. ft.; and one of 10 ft. across and 10 ft. deep, 785 cub. ft., or 6120 gal.—about the average fall upon a roof of the above size for 6 weeks; while the smaller cistern would hold 3900 gal., or a little less than 4 weeks’ rainfall. The weekly supply of 1037 gal. is equal to 148 gal. per day, or nearly 15 gal. to each individual of a family of 10. This is certainly enough, and more than enough, if used as it should be; but where water is plentiful it is wasted, and in our capricious climate, whether we depend upon wells or cisterns, it is wise to waste no water at all, at least during the warm summer months, and lay by not for a wet but a dry day. For this country, Field estimates 2-3 gallons of tank capacity for every square foot of roof area.

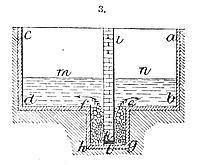

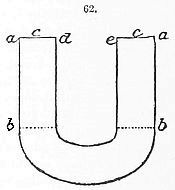

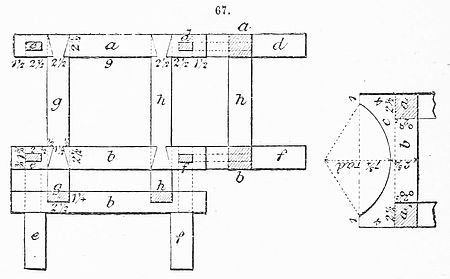

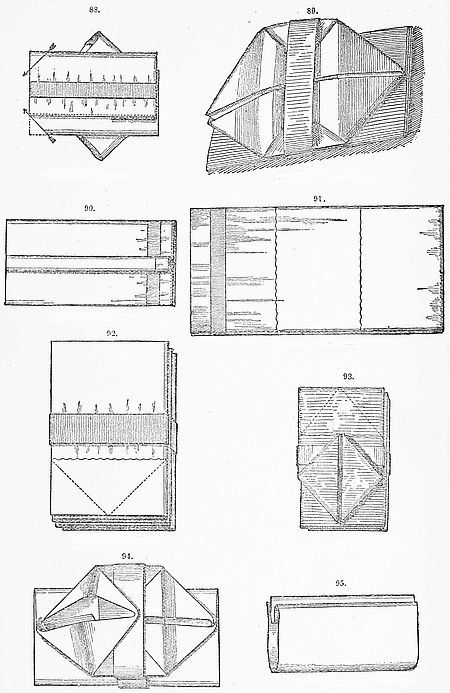

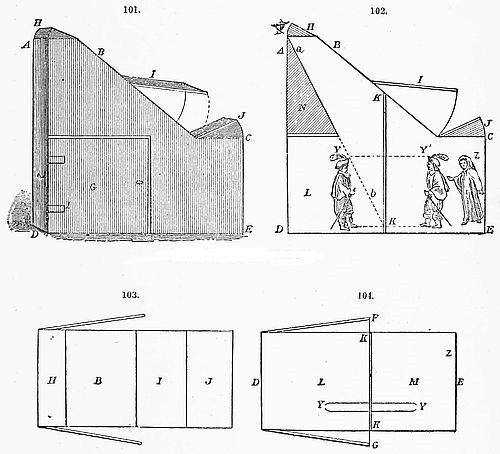

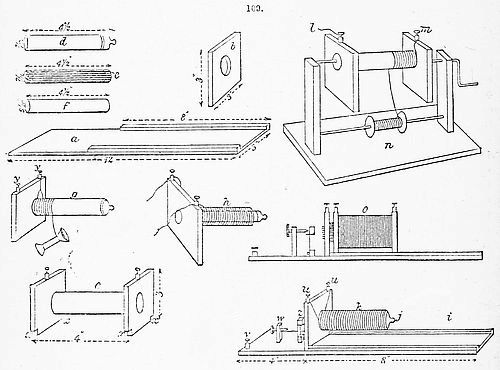

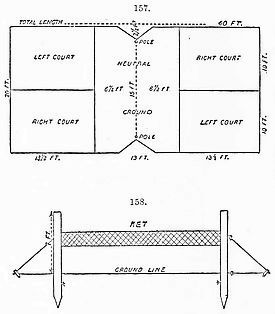

3. Rain-water Tank.

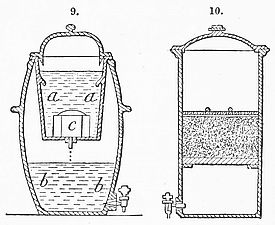

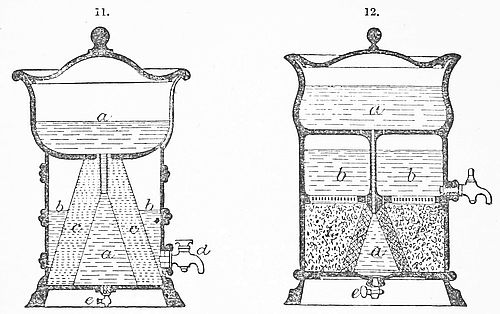

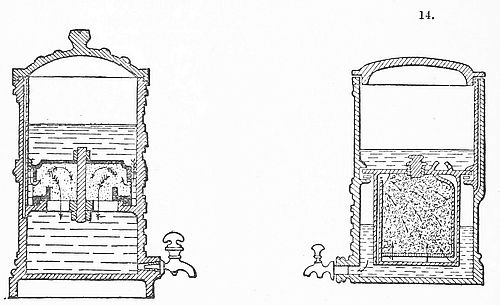

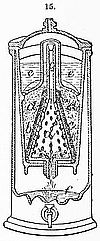

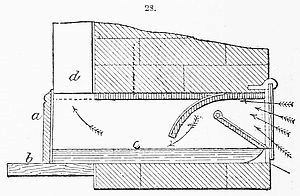

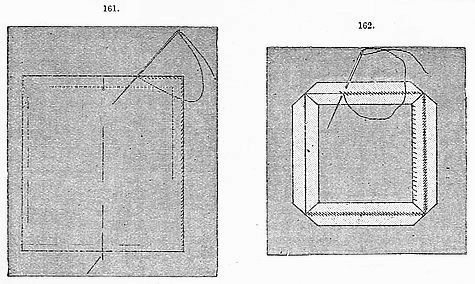

In Fig. 3 a b c d show the excavation that must be made for the cistern, and supposing the diagram to exhibit, as it does, a section of the cistern, the receptacle for the water will be, when finished, taking the relative proportions of the different parts into consideration, just about 9 ft. wide and 4½ ft. deep. Of course, the excavation must be made greater in breadth and depth than the dimensions given, to allow for the surrounding walls and the bottom. The walls may be of brick, cemented within, and backed with concrete or puddled clay without, or of monolithic concrete; but the bottom, in any case, should be made of concrete. The trench e f g h running across the bottom of the cistern is 2 ft. broad and 2 ft. deep. In the middle of this opening is built up a 9 in. brick wall, or a party-wall of concrete, i k. Along the bottom of the wall openings l are left at intervals. The party-wall divides the entire space into the larger outer cistern m, and the smaller inner cistern n. Supposing the breadth from e to f to be 2 ft., and the wall 9 in., spaces of 7½ in. will be left on each side of the wall. These are filled to ¾ the height, or for 18 in., with lumps of charcoal, smooth pebbles, 1-3 in. in diameter, being laid along the top of the charcoal till the trench is filled up. The cistern is so constructed that the water from the roof enters m; it passes downwards through the stones and charcoal, as shown by the arrow at f, goes through the opening and forces its way upwards in the direction of the arrow at e into the cistern n, in which it rises to the level of the water in m, to be drawn thence for use by a small pump.

Various modifications of this form of tank-filter will suggest themselves to readers possessing any mechanical genius. The great point is to prevent contamination from the soil by using good material and making sound work. Further, the overflow pipe of the tank must not communicate with any drain or sewer.

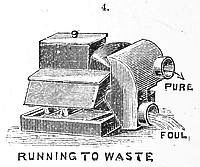

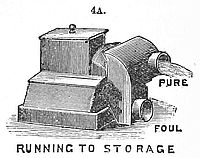

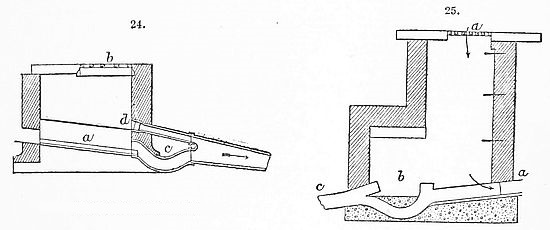

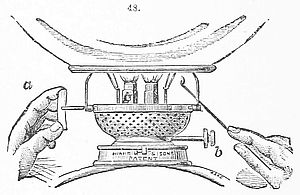

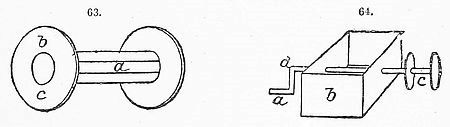

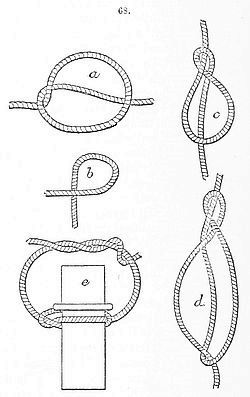

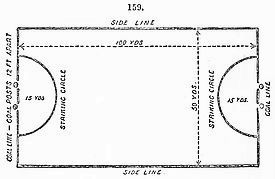

4. Rain-water Separator.

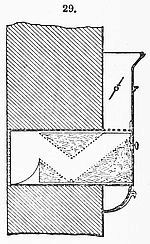

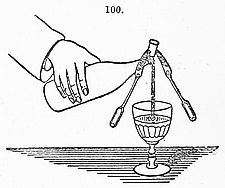

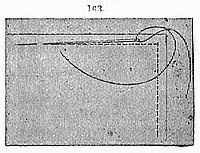

Recently several inventors have introduced apparatus for separating rain-water from impurities. One of these, bearing the name of Roberts, is illustrated in Fig. 4. Its principle of action is to reject the first portion of the rain which falls (as it is this[17] which chiefly washes the dirt off the roof), and only to collect the latter portion of the rain. The water from the roof first runs on to a strainer, that intercepts rubbish; it then passes through one of two channels in the upper part of the canter, balanced upon a pivot. At the commencement of a shower, the canter is raised in the position shown in Fig. 4, “running to waste,” and the bulk of the water passes through a channel which directs it into the lower or wastewater outlet. Meanwhile, a very small proportion of the water is accumulating in the lower part of the canter, very slowly in light rain but more rapidly in heavy rain, so that it is filled up by the time the roof has become clean. Then the weight of water causes it to fall down as shown in Fig. 4A “running to storage,” so that the clean water may run through the upper storage outlet pipe. This very useful little apparatus is made and sold by C. G. Roberts, Collards, Haslemere, Surrey.

4A. Rain-water Separator.

Perhaps this affords as good an opportunity as any of drawing attention to the highly artistic rain-water heads that have lately been introduced by Thomas Elsley, of 32 Great Portland Street, W. These are made to suit every style of architecture and every variety of roof and guttering, and practically without limit as to size. Their quality is beyond praise.

It is essential to bear in mind that rain-water is liable to exert considerable solvent action on lead, consequently pipes and cisterns of this metal must be avoided. The pipes may be of iron, or of specially lead-encased block-tin, and the cisterns of “galvanised” iron or slate.

As Eassie has pointed out, there is much to be considered in the arrangement of rain-water pipes from a sanitary point of view, where a separator and storage tank are not in use, because the foul air delivered from them is sucked into the rooms near the roof, on which the sun’s heat pours. A fire lighted in a room develops the same danger when the rain-water pipe terminates near the windows of the room. Another danger accruing from rain-water pipes which connect directly with the drain is due to the fact that the joints of the iron rain-water pipes are seldom air-tight, and foul air is therefore often driven or sucked into the rooms when the windows are open. It is easy to imagine how dangerous this must be in houses which have been fitted up with iron (or even lead) rain-water pipes running down the interior walls, and having their terminations close to a dormer window, skylight, or staircase ventilator on the roof, with the foot of the rain-water pipe taken direct into a drain leading to a town sewer. But the risk is greatly increased when the rain-water pipes are connected with a closed cesspool, to which the rain-water pipe is acting as a ventilator.

When rain-water pipes deliver into the drain directly, they are often made to act as soil pipes from the closets, in which case the evil is intensified. The soil from the closets is apt to adhere to the interior of the pipe, generally on the side opposite to that traversed by the rain-water, and the poisonous smell escapes at any bad joints and always at the roof orifice.

When the rain-water pipe is of cast iron, other sources of danger are present if the pipe is used also for conveying soil from a closet. Unless the rim of the soil pipe from the closet is joined to the rain-water pipe by a proper cast-iron socketed joint, the connection must be made by means of a piece of lead pipe which receives the soil pipe, and the joint between the lead soil pipe and the upper and lower parts of the cast-iron pipe cannot be properly soldered. Here sometimes grievous calamity follows cases where the combined pipe is ventilating the drain and sewer; the pipe joints are frequently open, and when the windows are unclosed for ventilation the foul air is whisked into the[18] house. Eassie insists that it is cheaper to owner and dweller alike to have a separate soil-pipe erected at first.

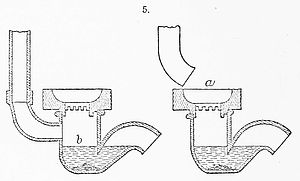

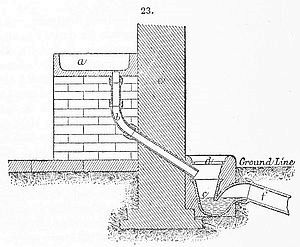

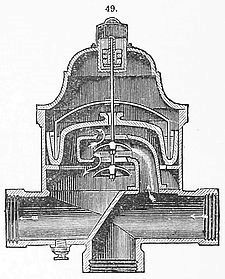

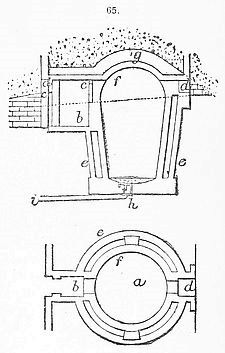

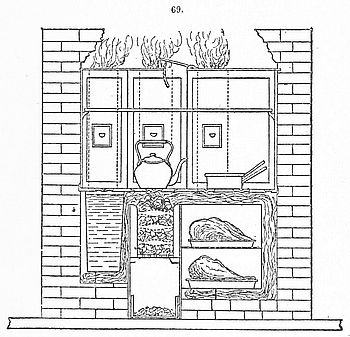

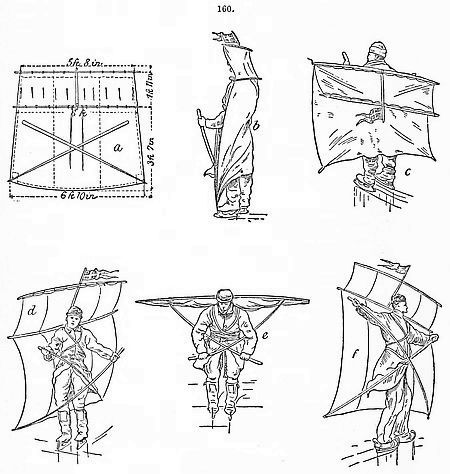

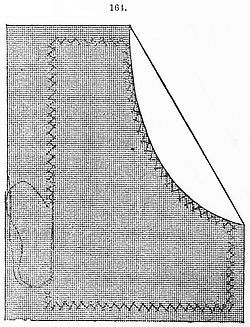

5. Outlet of Rain-water Pipes.

All rain-water pipes should deliver into the open air, and have no connection with the drains, except when they are disconnected. They should discharge their contents over a gully grating as at a, Fig. 5, or underneath the grating as at b, the ends of the pipes in both cases being in the open air. Every householder should insist upon this being carried out. But occasionally the rain-water pipes descend inside the house and there is no open yard where a disconnecting gully can be fixed. In such a case a separate drain should be laid to the nearest area or yard, and separation ensured. In laying down new drains in a house, where the rain-water pipes must descend in the interior, it will be better to provide a separate or twin drain to the nearest open-air space.

Provision must be made at the roof for keeping foreign matters out of the rain-water pipes. Leaves, soot, and dirt will accumulate round the pipe orifices, and very often will cause the gutter to be flooded during a storm. The usual way to avert this is to fix over the opening of the pipe in the bottom of the gutter a galvanised open wire half-globe, or a raised cap of thick lead pierced with tolerably large holes. The cost for this is trifling, but the value is great. Whenever rain-water pipes must run down the inside wall of a house, lead should be adopted. Sometimes rain-water pipes are taken down in the interior, when a very little initial study could have brought them to the exterior face of a wall—where alone they should be taken, whenever it is possible to do so.

On attic roofs, and where only one side of the house can be used for the attachment of rain-water pipes, the water from one side is brought across the roof by means of a “box” gutter of wood, lined at the bottom and sides with lead or zinc, and covered with a board. This often emits a very foul smell, owing to the accumulation of decaying matter. When such guttering cannot be avoided, it should occasionally—say once a week—be carefully cleaned out. The same matters will sometimes silt up and stop the gullies, shown at the foot of the rain-water pipes (Fig. 5), hence it is equally necessary to see that these traps are cleaned out, say monthly.

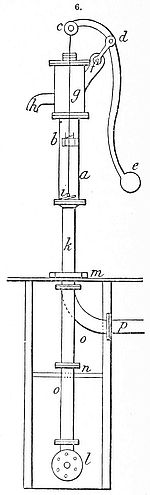

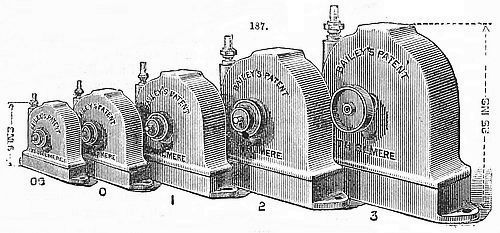

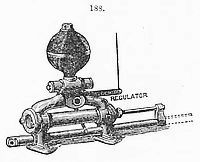

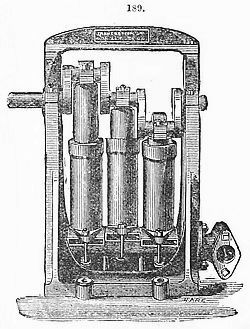

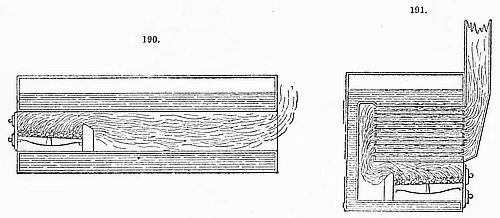

Rain-water pipes are often made the waste pipes of lavatories, baths, sinks, and slop-pails. When properly disconnected at the foot, in the open air, and when the top of the rain-water pipe does not terminate under a window of an inhabited room, this does not much matter; but when the court-yard is limited in area, and there is a window belonging to a living or sleeping room just overhead, where the rain from the roof delivers itself into the upright pipe, an offence will arise from the decomposing fats of soap, which form a slimy mess adhering to the interior of the pipe, that no amount of rainfall will dislodge.