The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Juggler's Oracle, by Herman Boaz

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Juggler's Oracle

or, The Whole Art of Legerdemain Laid Open

Author: Herman Boaz

Release Date: July 12, 2018 [EBook #57487]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE JUGGLER'S ORACLE ***

Produced by Charlie Howard and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by the

Library of Congress)

OR,

THE WHOLE ART

OF

Legerdemain Laid Open:

CONSISTING OF

ALL THE NEWEST AND MOST SURPRISING

TRICKS AND EXPERIMENTS,

WITH

CARDS,

CUPS AND BALLS,

CONVEYANCE OF MONEY AND RINGS,

BOXES,

FIRE,

STRINGS AND KNOTS;

WITH

MANY CURIOUS EXPERIMENTS

By Optical Illusion, Chymical Changes, and

Magical Cards, &c.

THE WHOLE

Illustrated by upwards of Forty Wood Engravings.

BY THE SIEUR H. BOAZ,

THIRTY YEARS PROFESSOR OF THE ART.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR WILLIAM COLE,

10, NEWGATE STREET.

PRINTED BY G. H. DAVIDSON,

IRELAND YARD, DOCTORS’ COMMONS.

iii

| Page. | ||

| Description of the Operator | 1 | |

| TRICKS WITH CARDS. | ||

| 1. | To deliver Four Aces, and to convert them into Knaves | 2 |

| 2. | Method of making the Pass | 3 |

| 3. | The Card of Divination | 4 |

| Another Way | 5 | |

| 4. | The Four Confederate Cards | 5 |

| 5. | The Fifteen Thousand Livres | 5 |

| 6. | The Magic Ring | 7 |

| 7. | The Card in the Mirror | 8 |

| 8. | The Marvellous Vase | 9 |

| 9. | The Nerve Trick | 10 |

| 10. | To make the Constable catch the Knave | 11 |

| 11. | To change a Card into a King or Queen | 11 |

| 12. | To tell a Person what Card he took Notice of | 12 |

| 13. | To tell what Card is at the Bottom, when the Pack is shuffled | 12 |

| 14. | Another Way, not having seen the Cards | 12 |

| 15. | To tell, without Confederacy, what Card one thinks of | 13 |

| 16. | To make a Card jump out of the Pack, and run on the Table | 13 |

| 17. | To tell a Card, and to convey the Same into a Nut or Cherry-Stone | 13 |

| 18. | To let Twenty Gentlemen draw Twenty Cards, and to make one Card every Man’s Card | 13 |

| 19. | To transform the Four Kings into Aces, and afterwards to render them all Blank Cards | 13 |

| 20. | To name all the Cards in the Pack, and yet never see them | 15 |

| 21. | To show any one what Card he takes Notice of | 15 |

| 22. | To tell the Number of Spots on the Bottom Cards, laid down in several Heaps | 16 |

| 23. | To make any two Cards come together which may be named | 17 |

| 24. | Card nailed to the Wall by a Pistol-shot | 17 |

| 25. | To tell what Card one thinks of | 19 |

| 26. | Another Way | 19 |

| 27. | To make a Card jump out of an Egg | 20 |

| 28. | The Little Sportsman | 20 |

| CUPS AND BALLS. | ||

| 29. | To pass the Balls through the Cups | 22 |

| 30. | A still more Extraordinary Mode of Playing at Cups and Balls | 26 |

| CONVEYANCE OF MONEY, &c. | ||

| 31. | To convey Money from one Hand to the other | 28iv |

| 32. | To convert Money into Counters, and the Reverse | 28 |

| 33. | To put a Sixpence into each Hand, and, with Words, bring them together | 29 |

| 34. | To put a Sixpence into a Stranger’s Hand, and another into your own, and to convey both into the Stranger’s Hand with Words | 29 |

| 35. | To show the same Feat otherwise | 29 |

| 36. | To throw a Piece of Money away, and find it again | 30 |

| 37. | To make a Sixpence leap out of a Pot or to run along a Table | 30 |

| 38. | To make a Sixpence sink through a Table, and to vanish out of a Handkerchief | 30 |

| 39. | To know if a Coin be a Head or Woman, and the Party to stand in another Room | 31 |

| 40. | To command Seven Halfpence through the Table | 31 |

| 41. | To command a Sixpence out of a Box | 32 |

| 42. | To blow a Sixpence out of another Man’s Hand | 32 |

| 43. | To make a Ring shift from one Hand to another, and to make it go on whatever Finger is required, while Somebody holds both Arms | 33 |

| 44. | To transfer a Counter into a Silver Groat | 34 |

| 45. | To make a Silver Twopence be plain in the Palm of your Hand, and be passed from thence wherever you like | 35 |

| 46. | To convey a Sixpence out of the Hand of one that holds it fast | 35 |

| 47. | To convey a Shilling from one Hand into another, holding your Hands apart | 36 |

| 48. | To transform any small Thing into any other Form, by folding of Paper | 36 |

| 49. | Another Trick of the same Nature | 36 |

| 50. | A Watch recovered after being beaten to Pieces in a Mortar | 37 |

| TRICKS WITH BOXES, &c. | ||

| 51. | The Egg-Box | 38 |

| 52. | The Penetrative Guinea | 39 |

| 53. | The Chest which opens at Command | 40 |

| 54. | The Melting-Box | 41 |

| 55. | Trick upon the Globe-Box | 42 |

| 56. | Trick with the Funnel | 44 |

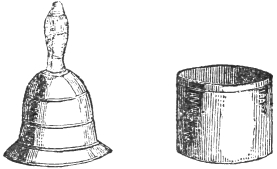

| 57. | The Magical Bell and Bushel | 44 |

| 58. | Out of an Empty Bag to bring upwards of an Hundred Eggs; and, afterwards, a living Fowl | 45 |

| 59. | Bonus Genius; or, Hiccius Doctius | 46 |

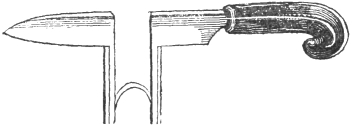

| 60. | To make a Knife leap out of a Pot | 47 |

| 61. | To turn a Box of Bird-seed into a living Bird | 47 |

| EXPERIMENTS WITH FIRE. | ||

| 62. | To produce a Carmine Red Flame | 48 |

| 63. | An Orange-coloured Flame | 48 |

| 64. | To make Balloons with Soap and Water that catch Fire and detonate | 48v |

| 65. | A Brilliant Blue Flame | 49 |

| 66. | An Emerald Green Flame | 49 |

| 67. | Loud Detonations, like the Discharge of Artillery | 49 |

| 68. | A Well of Fire | 50 |

| 69. | To make a Room seem all on Fire | 50 |

| 70. | To walk on a Hot Iron Bar, without Danger of Burning | 50 |

| 71. | To eat Fire, and blow it up in your Mouth with a Pair of Bellows | 50 |

| 72. | To Light a Candle by a Glass of Water | 52 |

| 73. | Fulminating Powder | 52 |

| 74. | To set Fire to a Combustible Body by the Reflection of Two Concave Mirrors | 52 |

| 75. | To give the Faces of the Company the Appearance of Death | 53 |

| 76. | To dispose two Little Figures, so that one shall light a Candle, and the other put it out | 53 |

| 77. | To construct a Lantern which will enable a Person to read by Night, at a great Distance | 53 |

| TRICKS WITH STRINGS, KNOTS, &c. | ||

| 78. | To cut a Lace asunder in the Middle, and to make it Whole again | 54 |

| 79. | To burn a Thread and make it Whole again with the Ashes | 54 |

| 80. | To pull many Yards of Ribbon out of the Mouth | 55 |

| 81. | To cut a Piece of Tape into Four Parts, and make it Whole again with Words | 55 |

| 82. | To unloose a Knot upon a Handkerchief, by Words | 57 |

| 83. | To draw a Cord through the Nose | 58 |

| 84. | To take Three Button-Moulds off a String | 59 |

| OPTICAL ILLUSIONS. | ||

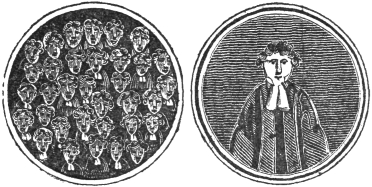

| 85. | The Multiplying Mirror | 60 |

| 86. | The Magic-Lantern | 61 |

| 87. | The Phantascope | 61 |

| 88. | The Enchanted Mirrors | 63 |

| 89. | The Wonderful Phantoms | 64 |

| 90. | The Real Apparition | 65 |

| 91. | To draw a Deformed Figure, which will appear well proportioned from a certain Point of View | 67 |

| CHEMICAL CHANGES. | ||

| 92. | To change the Colour of a Rose | 67 |

| 93. | To turn Water into Wine | 67 |

| 94. | Arbor Dianæ; or, the Silver Tree | 68 |

| 95. | The Lead Tree | 68 |

| 96. | The Tree of Mars | 68 |

| 97. | To form a Metallic Tree, in the Shape of a Fir | 69 |

| 98. | To make a Gold or Silver Tree, to serve as a Chimney Ornament | 69 |

| 99. | Sympathetic or Secret Inks | 70 |

| 100. | Preparation of Green Sympathetic Ink | 70vi |

| 101. | Blue Sympathetic Ink | 70 |

| 102. | Yellow Sympathetic Ink | 71 |

| 103. | Purple Sympathetic Ink | 71 |

| 104. | Rose-coloured Sympathetic Ink | 71 |

| 105. | Application of the Secret Inks | 71 |

| 106. | A Drawing which alternately represents Winter and Summer Scenes | 71 |

| 107. | Demonstration of the various Strata of Earth which cover the Globe | 72 |

| 108. | To freeze Water in the Midst of Summer, without the Application of Ice | 72 |

| MISCELLANEOUS TRICKS AND EXPERIMENTS. | ||

| 109. | To swallow a long Pudding made of Tin | 73 |

| 110. | An artificial Spider | 74 |

| 111. | To pass a Ring through your Cheek | 74 |

| 112. | To cut a Hole in a Cloak, Scarf, or Handkerchief, and by Words to make it Whole again | 75 |

| 113. | The Dancing Egg | 75 |

| 114. | To make three Figures Dance in a Glass | 76 |

| 115. | To shoot a Swallow, and to bring him to Life again | 77 |

| 116. | Singular Trick with a Fowl | 77 |

| 117. | To put a Lock upon a Man’s Mouth | 77 |

| 118. | To thrust a Bodkin into the Forehead, without Hurt | 79 |

| 119. | To thrust a Bodkin through your Tongue | 79 |

| 120. | To appear to cut your Arm off, without any Hurt or Danger | 80 |

| 121. | Tricks with a Cat | 80 |

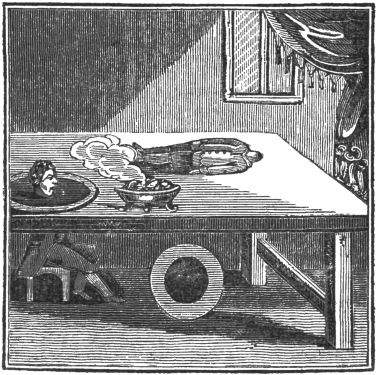

| 122. | To make a Calf’s Head bellow, when served up to Table | 81 |

| 123. | To make a Ball rise above the Water | 81 |

| 124. | Mode of sealing Letters, whereby the Impression cannot be taken | 81 |

| 125. | The Enchanted Egg | 82 |

| 126. | To cut a Man’s Head off, and to put the Head into a Platter, a Yard from the Body | 82 |

| 127. | To cause Beer to be wrung out of the Handle of a Knife | 83 |

| 128. | To cut a Glass by Heat | 84 |

1

Is an art whereby a person seems to work wonderful, incredible, and almost impossible feats. There is no supernatural or infernal agency in the case; for every trick is performed by nimbleness, agility, and effrontery.

The Operator, or Conjurer, should be a person of bold and undaunted resolution, so as to set a good face upon the matter, in case of the occurrence of any mistake whereby a discovery of the nature of the trick in hand may take place by one of the spectators.

He ought to have a great variety of strange terms and high-sounding words at command, so as to grace his actions, amaze the beholders, and draw their attention from the more minute operations.

He ought likewise to use such gestures of body as may help to draw off the attention of the spectators from a strict scrutiny of his actions.

In showing feats and juggling with cards, the principal point consists in the shuffling them nimbly, and always keeping one card either at the bottom or in some known place of the pack, four or five cards from it; hereby you will seem to work wonders, for it will be easy for you to see one card, which, though you be perceived to do it, will not be suspected, if you shuffle them well afterwards; and this caution I must give you, that, in reserving the bottom card, you must always, whilst you shuffle, keep it a little before or a little behind all2 the cards lying underneath it, bestowing it either a little beyond its fellows before, right over the fore-finger, or else behind the rest, so as the little finger of the left hand may meet with it, which is the easier, readier, and better way. In the beginning of your shuffling, shuffle as thick as you can, and, in the end, throw upon the pack the nether card, with so many more, at the least, as you would have preserved for any purpose, a little before or a little behind the rest, provided always that your fore-finger (if the pack lie behind) creep up to meet with the bottom card; and, when you feel it, you may then hold it until you have shuffled over the cards again, still leaving your kept card below. Being perfect herein, you may do almost what you like with cards by this means: what pack soever you use, though it consist of eight, twelve, or twenty cards, you may keep them still together unsevered, next to the card, and yet shuffle them often, to satisfy the admiring beholders. As for example, and for brevity sake, to show divers feats under one:—

Make a pack of these eight cards, viz. four knaves and four aces; and, although the eight cards must be immediately together, yet must each knave and ace be evenly set together, and the same eight cards must lie also in the lowest place of the pack; then shuffle them so always, at the second shuffling; so that, at the end of shuffling the said pack, one ace may lie undermost, or so as you may know where it goeth and lieth always: I say, let your aforesaid pack, with three or four cards more, lie inseparable together, immediately upon and with that ace. Then using some speech or other device, and putting your hands, with the cards, to the edge of the table, to hide the action, let out, privately, a piece of the second card, which is one of the knaves, holding forth the pack in both your hands, and showing to the standers-by the nether card, which is the ace, or kept card, covering also the head or piece of the knave, which is the next card, and, with your fore-finger, draw out the same knave, laying it down on the table; then3 shuffle them again, keeping your pack whole, and so have your two aces lying together at the bottom. And, to reform that disordered card, and also to grace and countenance that action, take off the uppermost card of the bunch, and thrust it into the midst of the cards, and then take away the nethermost card, which is one of your said aces, and bestow it likewise; then you may begin as before, showing another ace, and instead thereof lay down another knave, and so forth, until, instead of four aces, you have laid down four knaves; the spectators, all this while, thinking that four aces lie on the table, are greatly amused, and will wonder at the transformation. You must be well practised in shuffling the pack, lest you overshoot yourself.

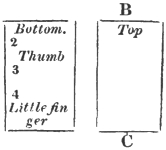

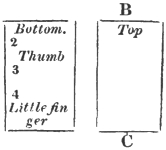

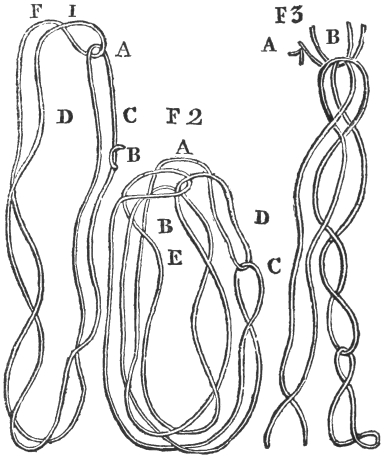

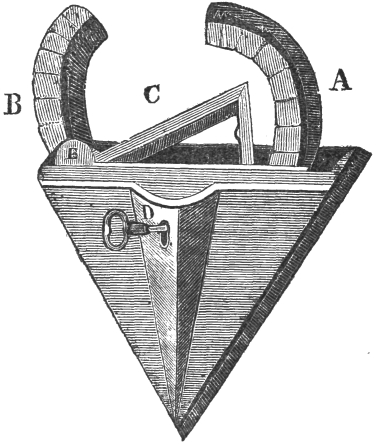

This art consists in bringing a certain number of cards from the bottom of the pack to the top. I shall explain the method of doing it, before proceeding further, as many of the following recreations depend on the dexterous performance of this manœuvre. Hold the pack of cards in your right hand, so that the palm of your hand may be under the cards. Place the thumb of that hand on one side of the pack, the first, second, and third fingers on the other side, and your little finger between those cards that are to be brought to the top, and the rest of the pack. Then place your left hand over the cards, in such a manner that the thumb may be at C, and the fingers at B, according to the following figures:—

4 The hands and the two parts of the cards being thus disposed, you draw off the lower cards, confined by the little finger and the other parts of the right hand, and place them, with an imperceptible motion, on the top of the pack. It is necessary, before you attempt any of the recreations that depend on making the pass, that you can perform it so dexterously that the eye cannot distinguish the motion of your hand; otherwise, instead of deceiving others, you will expose yourself. It is also proper that the cards make no noise, as that will occasion suspicion. This dexterity is not to be attained without some practice. It is sometimes usual to prepare a pack of cards, by inserting one or more that are a small matter longer or wider than the rest; and that preparation will be necessary in some of the following recreations.

Have a pack in which there is a longer card than the rest; open the pack at that part where the long card is, and present the pack to a person in such a manner that he will naturally draw that card. He is then to put it into any part of the pack, and shuffle the cards. You take the pack and offer the same card in like manner to a second or third person; observing, however, that they do not stand near enough to observe the card each other draws. You then draw several cards yourself, among which is the long card; and ask each of the parties if his card be among those cards, and he will naturally say yes, as they have all drawn the same card. You then shuffle all the cards together, and, cutting them at the long card, you hold it before the first person, so that the others may not see it, and tell him that is his card. You then put it again in the pack, and, shuffling them a second time, you cut again at the same card, and hold it in like manner to the second person; and so of the rest.

If the first person should not draw the long card, each of the parties must draw different cards; when, cutting the pack at the long card, you put those they have drawn over it, and, seeming to shuffle the cards indiscriminately, you cut them again at the long card, and show5 one of them his card. You then shuffle and cut again, in the same manner, and show another person his card, and so on; remembering that the card drawn by the last person is the first next the long card; and so of the others.

This recreation may be performed without the long card, in the following manner: let a person draw any card whatever, and replace it in the pack; you then make the pass, and bring that card to the top of the pack, and shuffle them without losing sight of that card. You then offer that card to a second person, that he may draw it, and put it in the middle of the pack. You make the pass, and shuffle the cards a second time, in the same manner, and offer the card to a third person; and so again to a fourth or fifth.

You let a person draw any four cards from the pack, and tell him to think of one of them. When he returns you the four cards, you dexterously place two of them under the pack, and two on the top. Under those at the bottom you place four cards of any sort, and then, taking eight or ten from the bottom cards, you spread them on the table, and ask the person if the card he fixed on be among them. If he say no, you are sure it is one of the two cards on the top. You then pass those two cards to the bottom, and, drawing off the lowest of them, you ask if that is not his card. If he again say no, you take that card up, and bid him draw his card from the bottom of the pack. If the person says his card is among those you first drew from the bottom, you must dexterously take up the four cards that you put under them, and, placing those on the top, let the other two be the bottom cards of the pack, which you are to draw in the manner before described.

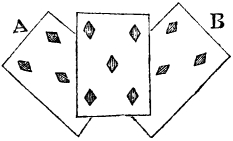

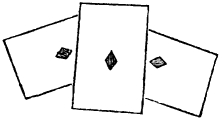

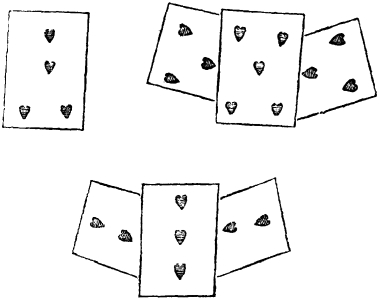

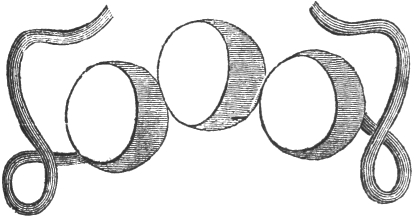

You must be prepared with two cards like the following:—

6

and with a common ace and five of diamonds. The five of diamonds, and the two prepared cards, are to be disposed thus:—

and, holding them in your hand, you say,—“A certain Frenchman left fifteen thousand livres, which are represented by these three cards, to his three sons; the two youngest agreed to leave their 5000, each of them, in the hands of the elder, that he might improve it.” While you are telling this story, you lay the five on the table, and put the ace in its place, and at the same time artfully change the position of the other two cards, that the three cards may appear as in the following figure:—

7

You then resume your discourse. “The eldest brother, instead of improving the money, lost it all by gaming, except three thousand livres, as you here see.” You then lay the ace on the table, and, taking up the five, continue your story. “The eldest, sorry for having lost the money, went to the East Indies with these 3000, and brought back 15,000.” You then show the cards in the same position as at first. To render this deception agreeable, it must be performed with dexterity, and should not be repeated, but the cards immediately put in the pocket; and you should have five common cards in your pocket, ready to show, if any one should desire to see them. Another recreation of this sort may be performed with fives and threes, as follows:—

Make a ring large enough to go on the second or third finger, in which let there be set a large transparent stone, to the bottom of which must be fixed a small piece of black silk, that may be either drawn aside or expanded by turning the stone round. Under the silk is to be the figure of a small card. Then make a person8 draw the same sort of card as that at the bottom of the ring, and tell him to burn it in the candle. Having first shown him the ring, you take part of the burnt card, and, reducing it to powder, you rub the stone with it; and, at the same time, turn it artfully round, so that the small card at bottom may come in view.

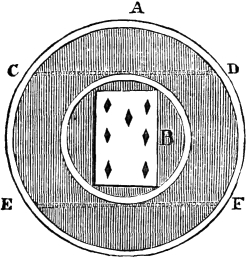

Provide a mirror, either round, like the following figure,

or oval; the frame of which must be at least as wide as a card. The glass in the centre must be made to move in the two grooves, C D and E F; and so much of the silvering must be scraped off as is equal to the size of a common card. Observe that the glass be likewise wider than the width of the card. Then paste over the part where the quicksilver is rubbed off a piece of pasteboard, on which affix a card that exactly fits the space, which must at first be placed behind the frame. This mirror must be placed against a partition, through which are to go two strings, by which an assistant in the adjoining room can easily move the glass in the grooves, and consequently make the card appear or disappear at pleasure.

9 Matters being thus prepared, you contrive to make a person draw the same sort of card with that fixed to the mirror, and place it in the middle of the pack: you then make the pass, and bring it to the bottom: you then direct the person to look for his card in the mirror, when the confederate, behind the partition, is to draw it slowly forward, and it will appear as if placed between the glass and the quicksilver. While the glass is being drawn forward, you slide off the card from the bottom of the pack, and convey it away. The card fixed to the mirror may easily be changed each time the experiment is performed. This recreation may also be made with a print that has a glass before it, and a frame of sufficient width, by making a slit in the frame, through which the card is to pass; but the effect will not be so striking as in the mirror.

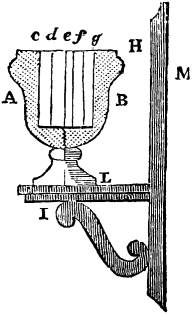

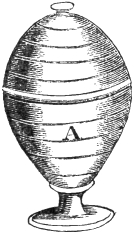

Place a vase of wood or pasteboard, like the following:—

A B, on a bracket L, to the partition M.

Let the inside of this vase be divided into five parts, c, d, e, f, g; and let the divisions c and d be wide enough to admit a pack of cards, and those of e, f, g, one card10 only. Fix a thread of silk at the point H, the end of which, passing down the division d, and over the pulley I, runs along the bracket L, and goes out behind the partition M. Take three cards from a piquet pack, and place one of them in each of the divisions, e, f, g, making the silk thread or line go under each of them. In the division c put the pack of cards, from which you have taken the three cards that are in the other divisions. Then take another pack of cards, at the bottom of which are to be three cards of the same sort with those in the three small divisions, and, making the pass, bring them to the middle of the pack, and let them be drawn by three different persons. Then give them all the cards to shuffle, after which place the pack in the division d, and tell the parties they shall see the three cards they drew come, at their command, separately out of the vase. An assistant behind the partition then drawing the line with a gentle and equal motion, the three cards will gradually rise out of the vase. Then take the cards out of the division c, and show that those three cards are gone from the pack. The vase must be placed so high that the inside cannot be seen by the company. You may perform this recreation also without an assistant, by fixing a weight to the end of the silk line, which is to be placed on a support, and let down at pleasure, by means of a spring in the partition.

Having previously looked at a card, bid the person draw one, taking care to show him that which you know; when he has it, let him put it at the bottom; let him shuffle the cards, then look at them again, and, finding the card, place it at the bottom; then cut them in half; give the party that half which contains his chosen card at the bottom, to hold between his finger and thumb, just at the corner; bid him pinch them as tight as he can; then striking them pretty sharply, they will all fall to the ground, except the bottom one, which is the card he has chosen. This is a very curious trick, and, if cleanly done, is really astonishing. It may be accounted for from the nature of the nerves, which are always more retentive when any thing is attempted to be taken, either by force or surprise.

11

Take a pack of cards, and look out the four knaves; lay one of them privately on the top of the pack, and the other three down upon the table, saying, “Here, you see, are three knaves got together, about no good you may be sure;” then lay down a king beside them, saying, “But here comes the constable and catches them together: ‘Oh, says he, have I caught you? Well, the next time I catch you together, I’ll punish you severely for all your rogueries.’ ‘Oh,’ but say they, ‘you shan’t catch us again together in haste;’ so they conclude to run three several ways. ‘Well, I’ll go here,’ says one (so take one of the knaves, and put him at the top of the pack). ‘And I’ll go here,’ says another (so put him at the bottom). ‘Then I’ll go here,’ says a third (so put him in the middle). ‘Nay,’ says the constable, ‘if you run, I’ll make sure of one; so I’ll follow the first.’” Then take the king and put him at the top, and let any one cut the cards asunder two or three times; then deal, cut the cards one by one, and you shall find three together, and the constable with them.

Note.—This feat would be best done with a pack of cards that has two knaves of that sort which you put in the middle.

To do this, you must have the picture in your sleeve, and, by a swift sleight, return the card, and fetch out the picture with a back bending. The manner of doing this is better learnt by frequent trials than can be taught by many words. But, if you would do this feat, and yet hold your hand straight and unmoved, then you must peel off the spots or figure of a card, as thin as you can, and just fasten it on the picture with something that will make it stick a little; then, having shown the spots or figure of the card, you may draw it off, and roll it up with your thumb into a very narrow compass, holding it undiscovered, between the inside of the thumb and the ball of your fore-finger; and so produce the picture, to the admiration of the beholders.

12

Take any number of cards, as ten, twelve, and then, holding them with their backs towards you, open four or five of the uppermost, and, as you hold them out to view, let any one note a card, and tell you whether it be the first, second, or third from the top; but you must privately know the whole number of those cards you took. Now shut up your cards in your hands, and take the rest of the pack, which place upon them; then knock their ends and sides upon the table; so it will seem impossible to find the noted card, yet it may easily be done, thus: subtract the number of cards you held in your hand from fifty-two, the whole number in the pack, and to the remainder add the number of the noted card; so the same shall be the number of the noted card from the top; therefore take off the cards one by one, smelling to them till you come to the noted card.

When you have seen a card privately, or as though you marked it not, lay the same undermost, and shuffle the cards till your card be again at the bottom. Then show the same to the bystanders, bidding them remember it. Now shuffle the cards, or let any other shuffle them, for you know the card already, and therefore may, at any time, tell them what card they saw, which, nevertheless, must be done with caution or show of difficulty.

If you can see no card, or be suspected to have seen that which you mean to show, then let a bystander shuffle, and afterwards take the cards into your own hands, and, having shown them, and not seen the bottom card, shuffle again, and keep the same cards as before you are taught; and either make shift then to see it when their suspicion is past, which may be done by letting some cards fall, or else lay down all the cards in heaps, remembering where you laid the bottom card; then see how many cards lie in some one heap, and lay the flap where your bottom card is upon that heap, and all the13 other heaps upon the same; and so, if there were five cards in the heap whereon you laid your card, then the same must be the sixth card, which now you must throw out, or look upon with suspicion, and tell them the card they saw.

Lay three cards at a distance, and bid a bystander be true, and not waver, but think on one of the three, and by his eye you shall assuredly perceive which he thinks on; and you shall do the like if you cast down a whole pack of cards with the faces upwards, whereof there will be few, or none plainly perceived, and they also court cards; but as you cast them down suddenly, so must you take them up presently, marking both his eyes and the card whereon he looks.

Take a pack of cards, and let any one draw a card that he likes best, and afterwards take and put it into the pack, but so as you know where to find it at pleasure. Then take a piece of wax, and put it under the thumb-nail of your right hand, and thus fasten a hair to your thumb, and the other end of the hair to the card. Now spread the pack of cards open upon the table, and, making use of any technical words or charms, seem to make it jump on the table.

Take a nut or cherry-stone, and burn a hole through the side of the top of the shell, and also through the kernel, if you will, with a hot bodkin, or bore it with an awl, and with a needle pull out the kernel, so as the same may be as wide as the hole of the shell; then write the name of the card on a piece of fine paper, and roll it up hard. Put it into the nut or cherry-stone, and stop the hole up with a little wax, and rub the same over with14 a little dust, and it will not be perceived; then let some bystander draw a card, saying, “It is no matter what card you draw,” and, if your hands so serve you to use the cards well, you shall proffer him, and he shall receive, the same card that you have rolled the name of up in the nut. Now take another nut and fill it up with ink, and stop the hole up with wax, and then give that nut which is filled with ink to some boy to crack, and, when he finds the ink come out of his mouth, it will cause great laughter. Many other feats of this kind may be done, so as to keep the company in good humour.

Take a pack of cards and let any gentleman draw one; then let him put it into the pack again, but be sure where to find it again at pleasure; then shuffle the cards again, and let another gentleman draw a card; but be sure that you let him draw no other than the same card as the other drew, and so do for ten or twelve, or as many cards as you think fit; when you have so done, let another gentleman draw another card, but not the same, and put that card into the pack where you have kept the other one, and shuffle them till you have brought both the cards together; then showing the last card to the company, the other will be considered a more wonderful achievement.

A clever juggler will take four kings in his hand, and apparently show them to the bystanders, and then, after some words and charms, he will throw them down upon the table, taking one of the kings away, and adding but one other card; then taking them up again, and blowing upon them, he will show you them transformed into blank cards, white on both sides; then throwing them down as before, with their faces downwards, he will take them up again, and, blowing upon them, will show you four aces.

This trick is not inferior to any that is performed with cards, and yet is very pretty.

15 To perform it, you must have cards made for the purpose, half cards we may call them; that is, one half kings and the other half aces; so, laying the aces one over the other, nothing but the king will be seen, and then, turning the kings downwards, the four aces will be seen; but you must have two whole cards, one a king to cover one of the aces, or else it will be perceived, and the other an ace to lay over the kings, when you mean to show the aces; then, when you would make them all blank, lay the cards a little lower, and hide the aces, and they will appear all white. The like you may make of four knaves, putting upon them the four fives; and so of the other cards.

To do this, you must privately drop a little water or beer, about the size of a crown-piece, upon the table before which you sit; then rest your elbows upon the table, so that the cuffs of your sleeves may meet, and your hands stick up to the brims of your hat; in this posture your arms will hide the drop of water from the company; then let any one take the cards and shuffle them, and put them into your hands; also let him set a candle before you, for this trick is best done by candlelight. Then holding the cards in your left hand, above the brim of your hat, close up to your head, so that the light of the candle may shine upon the cards, and holding your head down, so in the drop of water, like a looking-glass, you shall see the shadow of all the cards before you. Now draw the finger of your right hand along upon the card, as if you were feeling it, and then lay it down. Thus you may lay down all the cards in the pack, one by one, naming them before you lay them down, which will seem very strange to the beholders, who will think that you have felt them out.

Let any one take a card out of the pack, and note it; then take part of the pack in your hand, and lay the rest down upon the table, bidding him lay his noted card16 upon them; then, turning your back towards the company, make as though you were looking over the cards in your hand, and put any card at the fore-side; and, whilst your are doing this privately, wait till the cards are laid out in heaps, to find what the bottom cards are. Bid any one take four cards of the same number, viz. four aces, four deuces, four trèys, and any other number not exceeding ten (for he must not take court cards), and lay them out; then take the remaining cards, if any such there be, and divide their number by four, and the quotient shall be the number of spots of the four cards; if twelve cards remain, then on each bottom card are trèys, and, if there be no remaining cards, then the four bottom cards are aces.

Bid any one take the whole pack of cards in his hand, and, having shuffled them, let him take off the upper card, and, having taken notice of it, let him lay it down upon the table, with its face downwards, and upon it let him lay so many cards as will make up the number of spots on the noted card, e. g. twelve. If the card which the person first took notice of was a king, queen, knave, or a single ten, bid him lay down that card with its face downwards, calling it ten; upon that card let him lay another, calling it eleven, and upon that another, calling it twelve; then bid him take off the next uppermost card, saying, “What is it?” Suppose it were a nine, laying it down on another part of the table, and calling it nine, upon it let him lay another, calling it ten; upon it another, calling it eleven; and upon it another, calling it twelve; then let him look on the next uppermost card: and so let him proceed to lay them out in a heap, in all respects as before, till he has laid out the whole pack; but, if there be any cards at the last (I mean if there be not enough to make up the last noted card twelve), bid him give them to you; then, to tell him the number of all the spots contained in all the bottom cards of the heaps, do thus:—from the number of heaps subtract four, and multiply the remainder by fifteen, and to the product add the number of those remaining cards which he gave17 you, if any did remain; but, if there were but four heaps, then those remaining cards alone show the number of spots sought.

Note.—You ought not to see the bottom cards of the heaps, nor should you see them laid out, or know the number of cards in each heap; it suffices if you know the number of heaps and the number of the remaining cards, if any such there be: and therefore you may perform this feat as well standing in another room as if you were present.—You must have a whole pack.

When any one has named what two cards he would have come together, take the cards and say, “Let us see if they are here or not, and, if they are, I’ll put them as far asunder as I can;” then, having found the two cards proposed, dispose them in the pack, and cause them to come together.

This trick would seem much more strange, if, when you have brought the proposed cards together, by laying them in heaps, you lay the heap wherein the proposed cards are at the bottom of the pack, and then shuffle the cards; cut them asunder somewhere in the middle; thus the proposed cards will be found together in the middle of the pack, which will seem very strange.

A card is desired to be drawn, and the person who chooses, is requested to tear off a corner, and to keep it, that he may know the card; the card so torn is then burnt to cinders, and a pistol discharged with gunpowder, with which the ashes of the card are mixed. Instead of a ball, a nail is put into the barrel, which is marked by some of the company; the pack of cards is then thrown up in the air, the pistol is fired, and the card appears nailed against the wall. The bit of the corner which was torn off is then compared with it, and is found exactly to fit; and the nail which fastens it to the wall is recognised by the persons who marked it.

18 Explanation.—When the performer sees that a corner of the chosen card has been torn off, he retires, and makes a similar tear on a like card. Returning, he asks for the chosen card, and passing it to the bottom of the pack, he substitutes expertly in its place the card which he has prepared, which he burns instead of the first. When the pistol is loaded, he takes it in his hand, under the pretence of showing how to direct it, &c. He avails himself of this opportunity to open a hole in the barrel, near the touchhole, through which the nail falls by its own weight into his hand: having shut this passage, he requests one of the company to put more powder and wadding into the pistol; whilst that is doing, he carries the nail and card to his confederate, who quickly nails the card to a piece of square wood, which stops a space left open in the partition, but which is not perceived, as it is covered with a piece of tapestry, similar to the rest of the room; and by which means, when the nailed card is put on, it is not perceived; the piece of tapestry which covers it is nicely fastened on the one end by two pins, and on the other a thread is fastened, one end of which the confederate holds in his hand. As soon as the report of the pistol is heard, the confederate draws his thread, by which means the piece of tapestry falls behind a glass; the card appears the same that was marked, and with the nail that was put in the pistol. It is not astonishing that the trick, being so difficult by its complexity to be guessed at, should have received such universal applause.

N. B. After the pistol has been charged with powder, a tin tube may be slipped upon the charge, into which the nail being rammed along with the wadding, by inclining it a little, in presenting it to one of the spectators to fire, the tube and contents will fall into the performer’s hand, to convey to his confederate. If any one suspects that the nail has been stolen out of the pistol, you persist in the contrary, and beg the company at the next exhibition to be farther convinced; you then are to show a pistol, which you take to pieces, to show that all is fair, without any preparation; you charge it with a nail, which is marked by some person in confederacy with you, or you show it to many people, on purpose to avoid19 its being marked. In this case the card is nailed with another nail; but, to persuade the company that it is the same, you boldly assert that the nail was marked by several persons, and you request the spectators to view it, and be convinced.

Take twenty-one cards, and begin to lay them down three in a row, with their faces upwards; then begin again at the left hand, and lay one card upon the first, and so on the right hand, and then begin at the left hand again, and so go on to the right; do this till you have laid out the twenty-one cards in three heaps, but, as you are laying them out, bid any one think of a card, and, when you have laid them all out, ask him which heap his card is in; then lay that heap in the middle, between the other two. Now lay them all out again into three heaps, as before, and, as you lay them out, bid him take notice where his noted card goes, and put that heap in the middle, as before. Then, taking the cards with their backs towards you, take off the uppermost card, and, smelling to it, reckon it one; then take off another, and, smelling to it, reckon it two; this do till you come to the eleventh card, for that will always be the noted card after the third time of laying them out, though you should lay in this manner ever so often. You must never lay out the cards less than three times, but as often above as you please. This trick may be done by any odd number of cards that may be divided by three.

When one has noted a card, take it and put it at the bottom of the pack; then shuffle the cards till it comes again to the bottom; then see what is the noted card, which you may do without being taken notice of; when you have thus shuffled the cards, turn them with their faces towards you, and knock their ends upon the table, as though you would knock them level; and, whilst you are so doing, take notice of the bottom card, which you may do without suspicion, especially having shuffled them before; then, when you know the card, shuffle them again, and give them to any of the company, and20 let them shuffle them, for you know the card already, and may easily find it at any time.

To do this wonderful feat you must have two sticks, made both of one size, so that no person can know one from another; one of these sticks must be made so as to conceal a card in the middle, thus: you must have one of your sticks turned hollow quite through, and then an artificial spring to throw the card into the egg at pleasure. The operation is thus:—Take and peel any card in the pack, which you please, and roll it up. Now put it into the false stick, and there let it lie until you have occasion to make use of it. Now take a pack of cards, and let any body draw one; but be sure to let it be the same sort of card which you have in the hollow stick. The person who has chosen it is now to put it into the pack again, and, while you are shuffling them, let it fall into your lap. Then, calling for some eggs, desire the person who drew the card, or any other person in the company, to choose any one of the eggs. When they have done so, ask the person if there be any thing in it? He will answer that there is not. Now take the egg in your left hand, and the hollow stick in your right, and then break the egg with the stick.

Having let the spring go, the card will appear in the egg, to the great amazement of the beholders. Now be sure to conceal the hollow stick, and produce the solid one, which place upon the table for the examination of those who are curious.

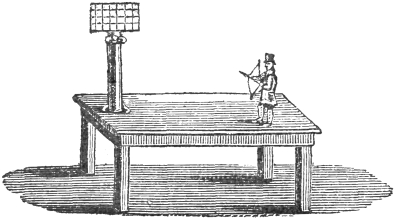

This is a little pasteboard figure which holds a bow, with an arrow, which it shoots at the instant required, and hits a paper placed opposite, on the top of a pedestal:

21

This paper is divided into several squares, which are numbered, and the arrow flies and always hits the number chosen by one of the company. The action of the spring which impels it is restrained by a little pin, which the confederate lets go at pleasure, by moving the levers hid in the table; when you push this pin, the arrow flies with rapidity to the paper, like the operation of a lock of a musket, when you pull the trigger. In placing the automaton on the table, you may place it in such a manner that the arrow be directed towards one of the circles numbered on the paper. To cause that number to be chosen against which the arrow is pointed, you must present to the spectator cards numbered, and dexterously make him choose the number required, which depends on peculiar address, that is scarcely possible to be described by words; it may in general be said to come under the following heads:—First, to put at the bottom one of the cards to be chosen; secondly, to keep it always in the same place, although you mix, or pretend to mix, the cards; thirdly, to pass the card to the middle, when you present the pack; fourthly, to pass many cards before the hands of the spectator, to persuade him that he may choose indifferently; fifthly, to pass these same cards with such rapidity, that he cannot take any but the card intended; sixthly, to slip complaisantly into his hand the card you wish to be taken, at the very moment when, the better to deceive him, you beg of him graciously to take which card he chooses.

22

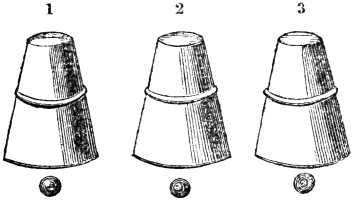

You must place yourself at the farther end of the table, and provide three cups made of tin; you must likewise have your black magical stick, to show your wonders withal. You are also to provide four small cork balls, to play with; but do not let any more than three of them be seen upon the table.

N. B.—Always conceal one ball in the right hand, between the middle finger and the ring finger; and be sure you make yourself perfect to hold it there, for by this means all the tricks of the cups are done.

Now say something to the following effect:—

Then take your balls privately between your fingers, fling one of them upon the table, and say thus—

So then you have three balls on the table to play with, and one left between the fingers of your right hand.

23 The Position of the Cups is thus—

Lay your three balls upon the table; then say, “Ladies and Gentlemen, you see here are three balls, and here are three cups; that is, a cup for each ball, and a ball for each cup.” Then taking the ball which you have in your right hand (which you are always to keep private) and clapping it under the first cup; and, taking up one of the three balls with your right hand, seem to put it into your left hand, but retain it still in your right, shutting your left hand in due time; then say, “Presto, begone.”

Then taking the second cup up, say, “Ladies and Gentlemen, you see there is nothing under my cup;” so clap the ball under that you have in your right hand, and then take the second ball up with your right hand, and seem to put it into your left, but retain it in your right, shutting your left hand in due time, as before, saying, “Vado, begone.”

24

Then taking the third cup up, saying, “Ladies and Gentlemen, you see there is nothing under my last cup,” clap the ball under your right hand, and, taking the third ball up with your right hand, seem to put it into your left hand, but retain it in your right hand; so, shutting your left hand in due time, as before, saying, “Presto, make haste”: so you have your three balls come under your three cups, as thus, and so lay your three cups down upon the table.

Then with your right hand take up the first cup, and clap the ball under that you have in your right hand; saying, “Ladies and Gentlemen, this being the first ball, I’ll put it in my pocket;” but that you must still keep in your right hand to play withal.

So take up the second cup with your right hand, and clap that ball under which you have concealed, and then take up the second ball with your right hand, and say, “This likewise I take and put into my pocket.”

25 Likewise take up the third cup, and, clapping the cup down again, convey the ball that you have in your right hand under the cup; then take the third ball, and say, “Ladies and Gentlemen, this being the last ball, I take this and put it in my pocket.” Likewise then say to the company, “Ladies and Gentlemen, by a little of my fine powder of experience I’ll command these balls under the cups again,” as thus:—

So lay them all along the table, to the admiration of the beholders.

Then take up the first cup, and, clapping the ball under that you have in your right hand, and taking the first ball up with the right hand, seem to put the same into your left hand, but retain it still in your right hand; then say, “Vado, quick, begone when I bid you, and run under the cup.”

Then taking that cup up again, and flinging it under that you have in your right hand, you must take up the second ball, and seem to put it into your left hand, but retain it in your right, saying, “Ladies and Gentlemen, see how the ball runs on the table.”—So, seeming to fling it away, it will appear thus:—

26 Now, taking the same cup up again, clap the ball under as before; and, taking the third ball in your right hand, seem to put it under your left, but still retain it in your right hand; then with your left hand seem to fling it in the cup, and it will appear thus:—

All the balls being under one cup.

If you can perform these feats with the cups and balls dexterously, you may change the balls into apples, pears, plums, or living birds, as your fancy leads you.

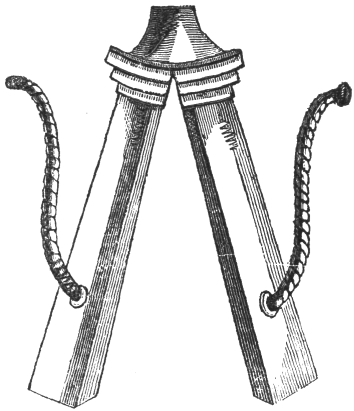

You must provide six cups made of the same size and metal (persons with hands, as seen above, require only three), but keep three of them concealed in the juggling-bag until they are required.

The trick performed by the three first cups is as follows:—Take out of the bag your three cups, and place them on a table. You must have balls of cork provided, and concealed, but one ball must be on the table. Then say, “Ladies and Gentlemen,” turning up your three cups (though at the same time you must have a ball concealed), “you see there is nothing under my cups; I take and put this cup here; I put the second there; and the third there.” The ball you have hid must be clapped under one of the cups at the time you were placing them.

You must have a tin bottom in the inside of one of your cups, and holes punched in it like a grater. Then say, “Ladies and Gentlemen,” (taking the ball off the table, and placing it on the cup the ball is under), “observe, I cover this ball with this cup,” clapping the third cup on the other two; then say, “Presto, I command the ball from under the middle cup to the bottom.”27 Then taking off the first and second cups, the ball, they think, is gone to the bottom; whereas the ball that is laid on the top of the undermost sticks fast to the grater that covers it, and, when the cup is turned up, it is the ball that was conveyed first that appears.

Next place, take the ball that is on the table, and say, “Ladies and Gentlemen, there is but one ball left,” clapping the cup with the tin bottom, where the ball is concealed, over that ball on the table, so as that ball that was sticking to the tin falls down, and makes two; then clapping the cup down, convey another ball you have secured, and say, “Vene tome;” then say, “Ladies and Gentlemen, there are three balls and three cups;” first having secured two balls (having some strange gestures of body and speech to take off the eyes of the spectators), at the same time taking up one of the cups, but putting it down on one of the balls, with the two balls secured; then clap the second cup on the second ball, and the third cup on the third ball.

Now say, “I’ve covered the three balls.” Then turn up one cup, and say, “There is the first ball;” then turn up the other, saying, “There is the second ball.” Then take up either of the balls, and lay it on the top of the third cup, and cover it with the cup that has the tin bottom, clapping the third cup in the place of the other two; say, “Ladies and Gentlemen, there is one ball at the bottom, one in the middle, and the third and last ball I strike through the board, saying, ‘Presto, be gone.’”

Now, you must understand, the third ball you drop, the second sticks to the tin grater, and three balls appear under the lowermost cup; then place your three balls on the table, and your cups opposite the balls; then say, “I cover this ball with this cup, and I cover this third ball with this one cup.” Then turning up one cup, take up the ball, and say, “Presto, I command you under the second cup;” but at the same time you must retain the ball, for the ball that was sticking to the tin is dropped, and makes two; then clapping the cup down, with the ball that you have retained, turn up the cup, and say, “I’ll strike this ball to the other two;” and drop that ball, being three before.

Next place the balls and cups as they were before;28 then clap the first cup on the first ball, and the second on the second; then take up the cup with the grater, which generally is in the middle, saying, “I’ll put this cup in my bag;” and take up this ball, saying, “I’ll put this ball in my bag;” and take up the next ball, saying, “I’ll put this ball in my bag too,” clapping under the cup at the same time the ball you have retained. At last, say, “I shall have too many balls,” or something to that purpose; seem in a fury, and toss your cups away; then put them into your juggling-bag, that, when you show the other three, the company may think they were the first cups.

The conveyance of money is not much inferior to the tricks with Cups and Balls, but much easier to perform. The principal place to hold the coin is the palm of the hand; and the best piece to play with is a sixpence. But, by practice, all coins will be alike, unless they are very small, and then they must be kept between the fingers, almost at the fingers’ ends; whereas the ball is to be kept below, near the palm. The coin ought never to be too large, as that will considerably impede the clever conveyance of it.

Hold open your right hand and lay therein a sixpence, and on the top of it place the top of your left middle finger, which press hard upon it, at the same time using hard words. Then suddenly draw away your right hand from the left, seeming to have left the coin there, and shut your hand cleverly, as if it still were there. That this may appear to have been truly done, take a knife, and seem to knock against it, so as to make a great sound. This is a pretty trick, and, if well managed, both the eye and ear are deceived at the same time.

Another way to deceive the lookers-on is to do as before, with a sixpence, and, keeping a counter in the29 palm of your left hand, secretly, seem to put the sixpence therein, which being retained still in the right hand, when the left hand is opened, the sixpence will seem to be turned into a counter.

He that hath once attained to the faculty of retaining one piece of money in his right hand may show a hundred pleasant deceits by that means, and may manage two or three as well as one. Thus, you may seem to put one piece into your left hand, and, retaining it still in your right, you may, together therewith, take up another like piece, and so, with words, seem to bring both pieces together. A great variety of tricks may be shown in juggling with money.

You take two sixpences evenly set together, and put the same, instead of one sixpence, into a stranger’s hand, and then, making as though you put one sixpence into your own hand, with words, you make it seem that you convey the sixpence in your own into the stranger’s hand; for, when you open your said left hand, there shall be nothing seen, and he, opening his hand, shall find two sixpences, which he thought was but one.

To keep a sixpence between your fingers serves especially for this and such like purposes: hold your hand, and cause one to lay a sixpence upon the palm thereof, then shake the same up almost to your finger’s end, and putting your thumb upon it, you may easily, with a little practice, convey the edge betwixt the middle and fore-finger whilst you proffer to put it into your other hand (provided always that the edge appears not through the fingers, on the back side); take up another sixpence, which you may cause another stander-by to lay down, and put them both together, either closely, instead of one into a stranger’s hand, or keep them still30 in your own hand, and, after some words spoken, open your hands, and, there being nothing in one hand, and both pieces in the other, the beholders will wonder how they came together.

You may, with the middle or ring finger of the right hand, convey a sixpence into the palm, with the same hand, and, seeming to cast it away, keep it still, which, with confederacy, will seem strange: to wit, when you find it again, where another has placed the like piece. But these things cannot be done without practice; therefore. I will proceed to show how things may be brought to pass with less difficulty, and yet as strange as the rest, which, being unknown, are much commended; but, being known, are derided, and nothing at all regarded.

A juggler takes a sixpence and throws it into a pot, or lays it on the middle of a table, and, with enchanted words, causes the same to leap out of a pot, or run towards him or from him along the table, which seems miraculous till you know how it is done, which is thus: Take a long black hair of a woman’s head, fasten it to the rim of a sixpence, by means of a little hole driven through the same with a Spanish needle. In like sort you may use a knife or any small thing; but if you would have it go from you, you must have a confederate, by which means all juggling is graced and amended.

This feat is the stranger if it be done by night, a candle being placed between the spectators and the juggler, for by that means their eyes are hindered from discerning the deceit.

A juggler will sometimes borrow a sixpence and mark it before you, and seem to put the same in the middle of a white handkerchief, and wind it so as you may the better see and feel it; then he will take the handkerchief31 and bid you feel whether the sixpence be there or no; and he will also require you to put the same under a candlestick, or some such like thing; then he will send for a basin of water, and, holding the same under the table, right against the candlestick, he will use certain words of enchantment, and, in short, you shall hear the sixpence fall into the basin. This done, let one take off the candlestick, and the juggler take the handkerchief by a tassel and shake it; but the money is gone, which seems as strange a feat as any whatsoever, but, being known, the miracle is turned to a jest; for it is nothing else but to sew a sixpence into a corner of the handkerchief, finely covered with a piece of linen a little bigger than your sixpence, which corner you must convey, instead of the sixpence given you, into the middle of your handkerchief, leaving the other in your hand or lap, which afterwards you seem to pull through the table, letting it fall into the basin.

This is done by confederacy: he that lays it down, says, “What is it?” and that is a sign it is a head; or he says, “What is it now?” and that is a sign it is a woman: cross and pile in silver is done the same way. By confederacy, divers strange things are done: thus, you may throw a piece of money into a pond, and bid a boy go to such a secret place where you have hid it, and he will bring it, and make them believe it is the same that you threw into the pond, and no other.

So let a confederate take a shilling and put it under a candlestick on a table a good distance from you; then you must say, “Gentlemen, you see this shilling;” then take your hand and knock it under the table, and convey it into your pocket; then say, “The shilling is gone; but look under such a candlestick and you will find it.”

To do this, you must employ a tinman to make holes, with room enough for a die to go in and out, and let him clap a good halfpenny upon them all, and so make them fast, that nobody can tell them from true ones.32 Then get a cap to cover your halfpence, also a cap and a die for the company to fling, to amuse them; when you are thus provided, the manner of performing is thus:—Desire any body in the company to lend you seven halfpence, telling them that they will soon be returned; then say, “Gentlemen, this is made just fit for your money;” then clapping your cap on, desire somebody in the company to fling that die, and, in so doing, take off the cap, and convey your false money into it, so that the company may not see you put it in; then with your cap cover the die, while with your right hand you take up the true money, and put it into the left under the table, saying, “Vado, begone; I command the die to be gone, and the money to come in the place;” so take up the cap, and the die is gone, and the money is come. Having covered the money again with the cap, taking the true money with your right hand, and knocking under the table, also making a jingling, as though the money was coming through the table, fling them on the table, and say, “There is the money,” and, with your right hand, take off the cap, saying, “And there is the die;” so convey the false money into your lap, and there is the cap likewise.

You must get a box turned with two lids (one must be a false one), and there put the counter, so that it may rattle; and you must have a small peg or button to your box, to hinder the counter from jingling, and at the bottom of the box you must have half a notch made, just fit for a sixpence to come out. So, to perform this feat, you must desire any body to lend you a sixpence, and to mark it with whatever mark he may please; then let him put it into the box himself; afterwards put the cover on, and, by shaking the box, the sixpence will come into your hand, when you may dispose of it as you please.

Blow on a sixpence, and immediately clap it into one of the spectator’s hands, telling him to hold it fast; then ask him if he is sure he has it. He, to be certain, will open his hand and look. Then say to him, “Nay, but33 if you let my breath go off, I cannot do it.” Then take it out of his hand again, blow on it, and, staring him in the face, clap a piece of horn in his hand, and retain the sixpence, shutting his hand yourself. Bid him hold his hand down, and slip the sixpence into one of his cuffs; then say, “I command the money you hold in your hand to vanish; Vade, now see.” When they have looked, they will think it is changed by virtue of your stone. Then take the horn again, and say, “Vade;” and then say, “You have your money again.” He then will begin to marvel, and say, “I have not.” Then say to him again, “You have; and I am sure you have got it: is it not in your hand? If it be not there, turn down one of your sleeves, for it is in one, I am sure;” where he, finding it, will not a little wonder.

Desire some person in company to lend you a gold ring, recommending him at the same time to make a mark on it, that he may know it again. Have a gold ring of your own, which you are to fasten by a small piece of catgut string to a watch-barrel, which must be sewn to the left sleeve of your coat. Take in your right hand the ring that will be given you: then, taking with dexterity, near the entrance of your sleeve, the other ring fastened to the watch-barrel, draw it to the fingers’ ends of your left hand, taking care nobody perceives it. During this operation, hide between the fingers of your right hand the ring that has been lent to you, and fasten it dexterously on a little hook, sewed on purpose on your waistcoat, near your hips, and hid by your coat.

You will, after that, show your ring, which you hold in your left hand; then ask the company on which finger of the other hand they wish it to pass. During this interval, and as soon as the answer has been given, put the before-mentioned finger on the little hook, in order to slip on it the ring; at that moment let go the other ring, by opening your fingers. The spring which is in the watch-barrel, not being confined longer, will contract and make the ring slip under the34 sleeve without any body perceiving it, not even those who hold your arms: as, their only attention being to prevent your hands from communicating, they will let you make the necessary motions. These must be very quick, and always accompanied by stamping of the foot.

After this operation, show the assembly that the ring is come on the other hand; make them remark that it is the same that had been lent to you, or that the mark is right. Much dexterity must be made use of to succeed in this entertaining trick, that the deception may not be suspected.

Take a groat, or a smaller piece of money, and grind it very thin on one side; then take two counters, and grind them, the one on one side, and the other on the other side; glue the smooth side of the groat to the smooth side of the counter, joining them as close together as possible, especially at the edges, which may be so filed that they shall seem to be but one piece; to wit, one side a counter and the other side a groat. Then take a little green wax, for that is softest, and therefore best, and lay it on the smooth side of the counter, as it does not much discolour the groat; and so will that counter, with the groat, cleave together as though they were glued, and, being filed even with the groat and the other counter, it will seem so perfectly like an entire counter, that, though a stranger handle it, he cannot betray it; then, having a little touched your fore-finger, and the thumb of your right hand, with soft wax, take therewith this counterfeit counter, and lay it openly upon the palm of your left hand, wringing the same hard, so as you may leave the glued counter with the groat apparently in the palm of your left hand, and the smooth side of the waxed counter will stick fast upon your thumb, by reason of the wax wherewith it is smeared: and so you may hide it at your pleasure (always be sure to lay the waxed side downward, and the glued side upward); then close your hand, and, in or after closing thereof, turn the piece, and so, instead of a counter, which they suppose to be in your hand, you shall seem to have a groat, to the35 astonishment of the beholders, if it be well handled. The juggler must not leave any of his tricks wanting for hard and break-jaw words.

Put a little red wax, not too much, upon the nail of your longest finger; then let a stranger put a two-penny piece into the palm of your hand, and shut your fist suddenly, and convey the two-penny piece upon the wax, which, with use, you may so accomplish, as no man shall perceive it; then, and in the meantime, use words of course, and suddenly open your hand; hold the tips of your fingers rather lower than the palm of your hand, and the beholders will wonder where it is gone; then shut your hand suddenly again, and lay a wager whether it be there or no, and you may either leave it there or take it away at pleasure. This, if it be well handled, hath more admiration than any other feat of the hand.—Note: This may be best done by putting the wax upon the two-penny piece, but then you must put it into your hand yourself.

Stick a little wax upon your thumb, and take a bystander by the fingers, showing him the sixpence, and telling him you will put the same into his hand; then wring it down hard with your waxed thumb, and, using many words, look him in the face, and, as soon as you perceive him look in your face, or on your hand, suddenly take away your thumb, and close his hand, and it will seem to him that the sixpence remains. If you wring a sixpence upon one’s forehead, it will seem to stick when it is taken away, especially if it be wet; then cause him to hold his hand still, and, with speed, put out into another man’s hand, or into your own, two sixpences instead of one, and use words of course, whereby you shall make the spectators believe, when they open their hands, that, by enchantment, you have brought both together.

36

It is necessary to mingle some merry pranks among your grave miracles, as, in this case of money, to take a shilling in each hand, and, holding your arms abroad, to lay a wager that you will bring them both into one hand without bringing them any nearer together; the wager being laid, hold your arms abroad, like a rod, and, turning about with your body, lay the shilling out of one of your hands, upon the table, and, turning to the other hand, so you shall win your wager.

Take a sheet of paper, and fold or double the same, so as one side be a little longer than the other; then put a counter between the two sides of the leaves of the paper, up to the middle of the top of the fold; hold the same so as it be not perceived, and lay a sixpence on the outside thereof, right against the counter, and fold it down to the end of the longer side. When you have unfolded it again, the sixpence will be where the counter was, so that some will suppose you have transformed the money into a counter; and with this many tricks may be done.

Take two papers, three inches square each, divided into two folds, of three equal parts on either side, so as each folded paper remains one inch square; then glue the back side of the two together, as they are folded, and not as they are opened, and so shall both papers seem to be but one, and, which side soever you open, it shall appear to be the same, if you have handsomely done the bottom, as you may well do with your middle finger, so that, if you have a sixpence in one hand, and a counter in the other, you show but one, and you may, by turning the paper, seem to change it; this is best performed by putting it under a candlestick or a hat, and, with words, seem to do the feat, which is by no means an inferior one.

37

A watch is borrowed from one of the company, and, being put into a mortar, another person is shortly after requested to beat it to pieces with a pestle. It is then shown to the company, entirely bruised; in a few minutes the watch is restored entire to its owner, who acknowledges it to be his property. It is easy to devise that, to effect this, the mortar must be placed near a concerted trap, and that it must be covered with a napkin, to afford an opportunity to the confederate to substitute another watch, unperceived by the company. In order to succeed in the illusion of this trick, you must take care to provide yourself with a second watch, somewhat resembling the first in the size, case, &c. which will not be very difficult, as you may either be furnished with a watch by a person with whom the matter is preconcerted, or by addressing yourself to some one whose watch you have before observed, and procured yourself one like it. After having placed all the pieces in the mortar, you must cover them a second time with a napkin, and whilst you amuse the company with some trick or story, you afford time to your confederate to take the bruised pieces away, and replace the first watch in the mortar.

38

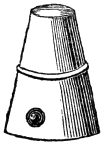

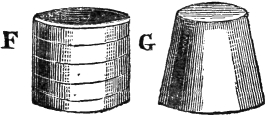

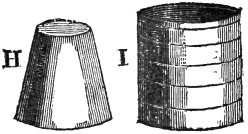

This is the Egg-box, put together like two beehives—one on the top of another. The following is the under-shell,

covered over artificially with the white thin skin of a real egg. The upper shell is of the same shape, but

larger, and is merely the lid of the box. The following

39

is the lower part of the box. Put B, which is the outward shell, upon C, and both upon D, which arrangement puts all in readiness for the performance of the trick. Now call for an egg, and bid all the bystanders look at it, to see that it is a real egg. Then take off the upper part, B C, with your fore-finger and thumb, and placing the egg in the box, say, “Ladies and Gentlemen, you see it fairly in the box;” and, uncovering it again, say, “You shall see me fairly take it out;” putting it into your pocket in their sight. Now open your box again, and say, “There’s nothing;” close your hand about the middle of the box, and, taking B by the bottom, say, “There is the egg again;” which appears to the spectators to be the same that you put in your pocket; then clapping that on again, and taking the lid of C between your fore-finger and thumb, say, “It is gone again.”

Provide a round tin box, of the size of a large snuff-box, and likewise eight other boxes, which will go easily into each other, and let the least of them be of a size to hold a guinea. Each of these boxes should shut with a hinge, and to the least of them there must be a small lock, that is fastened with a spring, but cannot be opened without a key; and observe, that all these boxes must shut so freely, that they may be all closed at once. Place these boxes in each other, with their tops open, in the drawer of the table on which you make your experiments; or, if you please, in your pocket, in such a manner that they cannot be displaced. Then ask a person to lend you a new guinea, and desire him to mark it,40 that it may not be changed. You take this piece in one hand, and in the other you have another of the same appearance, and, putting your hand in the drawer, you slip the piece that is marked into the least box, and, shutting them all at once, you take them out. Then showing the piece you have in your hand, and which the company suppose to be the same that was marked, you pretend to make it pass through the box, and dexterously convey it away. You then present the box, for the spectators do not yet know there are more than one, to any person in company, who, when he opens it, finds another, and another, till he comes to the last, but that he cannot open without the key, which you then give him; and, retiring to a distant part of the room, you tell him to take out the guinea himself, and see if it be that he marked.

This trick may be made more surprising by putting the key into the snuff-box of one of the company; which you may do by asking for a pinch of snuff: the key, being very small, will lie concealed among the snuff. When the person who opens the box asks for the key, tell him that one of his friends has it in his snuff-box, which will cause much amazement and merriment. This part of the trick may be done with a confederate.

There is a little figure of Mahomet within the chest, in the body of which is a spring, made of brass wire, twisted in a spiral form. By this means the little figure, though higher than the chest, can, by the accommodation of the spring, be contained within when it is shut, as the spring in the body closes and shortens. The chest is placed on levers concealed in the table, which communicate their motions by the assistance of the confederate to the bolt and lock. As soon as the staple is disengaged, the spring in the body of the figure, finding no resistance but the weight of the lid, forces it open.

41

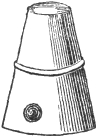

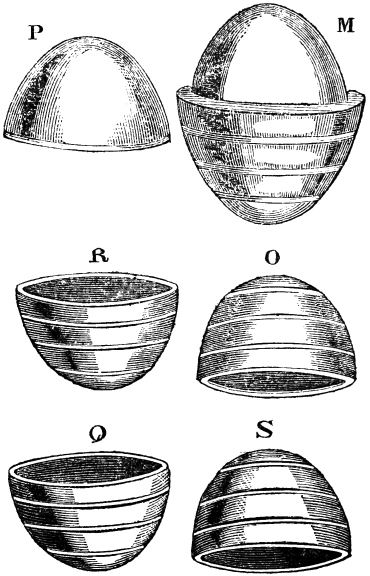

The melting-box is made in the fashion of a screw, so that the lips may hang without discovery.

F is the outer part of the box; G, the first inside part;

H, the second inside part; and I, the round case, made of leather, with a button on the top, and wide enough to slip on and off, half in the bottom of the box, into which put a small quantity of quicksilver, killed or amalgamated, which may be done with the shavings of pewter. In the second part, which is H, let there be six single pence: put these in the first or outermost part, then put G to H, and the box is perfect.

When you go to show this trick, desire any in the company to lend you a sixpence, saying, “you will return it safe”; requesting, withal, that none will meddle with any thing they see, unless you desire them, lest they prejudice you and themselves. Then take the cap off your box, and bid any one see it and feel it, that there be no mistrust; so likewise take the box entire, holding your fore-finger on the bottom, and your thumb on the upper part, turning it upside-down, and say,—“You see here is nothing:” then putting in the sixpence, put the cap over the box again; as the box stands covered upon the table, put your hand under the table, using some cant words; then take off the cap with your fore-finger and thumb, so as you pinch the innermost42 box with it and set it gently on the table; then put the dead quicksilver out of the lower part, into your hand, turning the box with the bottom upwards, and stirring it about with your fore-finger; then say, “Here you see it melted, now I will put it in again, and turn it into single pence;” suddenly take the cap as you took it off, and return it again; bid them blow on it; then take off the cap as you did before, only pinching the uppermost lid in it, and setting it upon the table; hold the box at the top and bottom, with your fore-finger and thumb; then put the six single pence, after they are viewed, and seen to be so, in again, and return the cap as before, saying, “Blow on it if you would have it in the same form you gave it me;” then taking the cap by the bottom, holding the box as before, put out the sixpence, and return the box into your pocket. This is a very good sleight, if well performed.

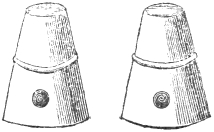

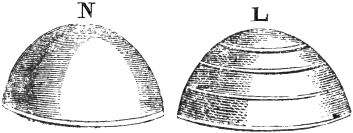

This is a trick not inferior to the best that is shown with boxes: it is a box made of four pieces, and a ball, so big as is imagined to be contained therein; the ball serves in the same way as the egg does in the egg-box, only to deceive the hand and eye of the spectators: this ball, made of wood or ivory, is thrown out of the box upon the table, for every one to see that it is substantial; then, putting the ball into the box, and letting the standers-by blow on the box, taking off the upper shell with your fore-finger and thumb, there appears another, and of another colour,—as red, blue, yellow, or any variety of colours upon each ball that is so imagined to be, which, indeed, is no more than the shell of wood, ingeniously turned and fitted for the box, as you may see in the following figures:—

43

L is the outer shell of the globe, taken off the figures M N, an inner shell; O, the cover of the same; P, the other inner shell; Q, the cover of the same; R, the third shell; S, that which covers it. These globes may be made of more or less variety, according to the wish of the operator.

44