Project Gutenberg's The Magic of the Horse-shoe, by Robert Means Lawrence

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Magic of the Horse-shoe

With other folk-lore notes

Author: Robert Means Lawrence

Release Date: June 27, 2018 [EBook #57411]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAGIC OF THE HORSE-SHOE ***

Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

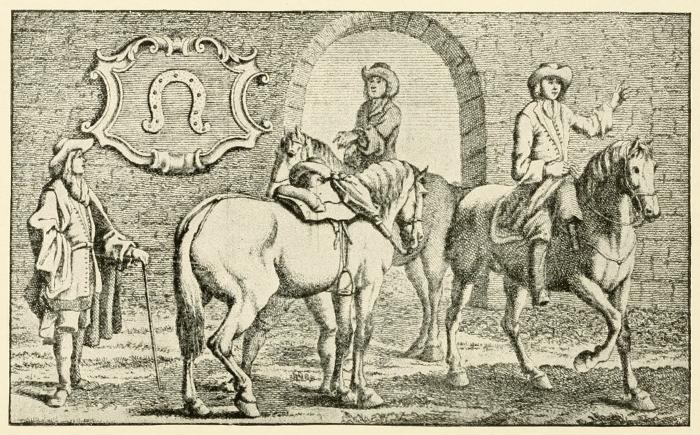

ARMS OF THE TOWN OF OAKHAM, RUTLANDSHIRE, ENGLAND.

[From an Old Engraving.]

THE

MAGIC OF THE HORSE-SHOE

With Other Folk-Lore Notes

BY

ROBERT MEANS LAWRENCE, M. D.

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1898

COPYRIGHT, 1898, BY ROBERT MEANS LAWRENCE.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The study of the origin and history of popular customs and beliefs affords an insight, otherwise unattainable, into the operations of the human mind in early times. Superstitions, however trivial in themselves, relics of paganism though they be, and oftentimes comparable to baneful weeds, are now considered proper subjects for scientific research. While the ignorant savage is a slave to many superstitious fancies which dominate his every action, the educated man strives to be free from such a bondage, yet recognizes as profitable the study of those same beliefs. The heterogeneous character of the material drawn from so many sources has rendered it difficult, if not impossible, to follow any distinctly systematic treatment of the subject. However, the development in recent years of a widespread interest in all branches of folk-lore warrants the hope that any volume devoted to this subject, and representing somewhat diligent research, may[iv] have a certain value, in spite of its imperfections. The expert folk-lorist may find much to criticise; but this book, treating of popular beliefs, is intended for popular reading. It has been the writer’s aim to make the chapter on the Horse-Shoe as exhaustive as possible, as this attractive symbol of superstition does not appear to have received hitherto the attention which it merits. This chapter is the outgrowth of a paper read at the seventh annual meeting of the American Folk-Lore Society, at Philadelphia, December 28, 1895, an abstract of which appeared in the Society’s Journal for December, 1896.

Extended quotations are indicated by smaller type.

R. M. L.

Boston, September 1, 1898.

| PAGE | |

| The Magic of the Horse-shoe | 1 |

| Fortune and Luck | 140 |

| The Folk-Lore of Common Salt | 154 |

| The Omens of Sneezing | 206 |

| Days of Good and Evil Omen | 239 |

| Superstitious Dealings with Animals | 279 |

| The Luck of Odd Numbers | 312 |

| Topical Index | 341 |

The evolution of the modern horse-shoe from the primitive foot-gear for draught animals used in ancient times furnishes an interesting subject for investigation. Xenophon and other historians recommended various processes for hardening and strengthening the hoofs of horses and mules,[1] and from this negative evidence some writers have inferred that the ancients were ignorant of farriery. It seems indeed certain that the practice of protecting the feet of horses was not universal among the Greeks and Romans. Fabretti, an Italian antiquary, examined with care the representations of horses on many ancient columns and marbles, and found but one instance in which the horse appeared[2] to be shod;[2] and in most specimens of ancient art the iron horse-shoe is conspicuous by its absence. But in the mosaic portraying the battle of Issus, which was unearthed at Pompeii in 1831, and which is now in the Naples Museum, is the figure of a horse whose feet appear to be shod with iron shoes similar to those in modern use;[3] and in an ancient Finnish incantation against the plague, quoted in Lenormant’s “Chaldean Magic and Sorcery,” occur these lines:—

O Scourge depart; Plague, take thy flight … I will give thee a horse with which to escape, whose shoes shall not slide on ice, nor whose feet slip on the rocks.

No allusion to the horse-shoe is made by early writers on veterinary topics. But, on the other hand, there is abundant testimony that the ancients did sometimes protect the feet of their beasts of burden. Winckelmann, the Prussian art historian, describes an antique engraved stone representing a man holding up a horse’s foot, while an assistant, kneeling, fastens on a shoe.[4] In the works of the Roman poet Catullus occurs the simile of the iron shoe of a mule sticking in the mire.[5] Contemporary historians relate that the Emperor Nero caused his mules to be shod with silver,[6] while golden[3] shoes adorned the feet of the mules belonging to the notorious Empress Poppæa.[7] Mention of an iron horse-shoe is made by Appian,[8] a writer not indeed remarkable for accuracy; but the phrase “brasen-footed steeds,” which occurs in Homer’s Iliad, is regarded by commentators as a metaphorical expression for strength and endurance. Wrappings of plaited fibre, as hemp or broom, were used by the ancients to protect the feet of horses.[9] But the most common form of foot covering for animals appears to have been a kind of leathern sock or sandal, which was sometimes provided with an iron sole. This covering was fastened around the fetlocks by means of thongs, and could be easily removed.[10]

Iron horse-shoes of peculiar form, which have been exhumed in Great Britain of recent years, have been objects of much interest to archæologists. In 1878 a number of such relics shaped for the hoof and pierced for nails were found at a place called Cæsar’s Camp, near Folkstone, England.[11] In the south of Scotland, also, ancient horse-shoes have been found, consisting of a solid piece of iron made to cover the whole hoof and very heavy. In the year 1653 a piece of iron resembling a horse-shoe, and having nine nail-holes, was[4] found in the grave of Childeric I., king of the Franks, who died A. D. 481. Professor N. S. Shaler believes that the iron horse-shoe was invented in the fourth century, and from the fact that it was first called selene, the moon, from its somewhat crescent-like shape, he concludes that it originated in Greece.[12] But even in the ninth century, in France, horses were shod with iron on special occasions only,[13] and the early Britons, Saxons, and Danes do not appear to have had much knowledge of farriery. The modern art of shoeing horses is thought to have been generally introduced in England by the Normans under William the Conqueror.[14] Henry de Ferrars, who accompanied that monarch, is believed to have received his surname because he was intrusted with the inspection of the farriers; and the coat-of-arms of his descendants still bears six horse-shoes.[15]

On the gate of Oakham Castle, an ancient Norman mansion in Rutlandshire, built by Wakelin de Ferrars, son of the first earl of that name, were formerly to be seen a number of horse-shoes of different patterns.

The estate is famous on account of the tenure of the barons occupying it. Every nobleman who journeyed[5] through its precincts was obliged as an act of homage to forfeit a shoe of the horse whereon he rode, or else to redeem it with a sum of money; and the horse-shoes thus obtained were nailed upon the gate, but are now within on the walls of the castle.

These walls are covered by memorials of royal personages and peers, who have thus paid tribute to the custom of the county.[16]

Queen Elizabeth was thought to have initiated this practice, though this opinion is incorrect. According to tradition she was once journeying on a visit to her lord high treasurer, William Cecil, the well-known Lord Burleigh, at his residence near Stamford. While passing through Oakham her horse is said to have cast a shoe, and in memory of the mishap the queen ordered a large iron shoe to be made and hung up in the castle, and that every nobleman traveling through the town should follow her example.

A similar usage prevails to-day, new shoes being provided of shapes and sizes chosen by the donors.[17]

While John of Gaunt (1339-99), son of Edward III. of England, was riding through the town of Lancaster, his horse cast a shoe, which was kept as a souvenir by the townspeople, and fastened in the middle of the street. And in accordance with a time-honored[6] custom a new shoe is placed in the same spot every seven years by the residents of Horse-Shoe Corner.[18]

The practical value of the horse-shoe is tersely expressed in the old German saying, “A nail preserves a country;” for the nail keeps in place the horse-shoe, the shoe protects the foot of the horse, the horse carries the knight, the knight holds the castle, and the castle defends the country.

The following story from Grimm’s “Household Tales” (vol. ii. p. 303) may be appropriate in this place, as illustrating the same idea, besides pointing a moral.

The Nail.

A merchant had done a good business at the fair; he had sold his wares and lined his money-bags with gold and silver. Then he wanted to travel homeward and be in his house before nightfall. So he packed his trunk with the money on his horse and rode away. At noon he rested in a town, and when he wanted to go farther the stable-boy brought out his horse and said: “A nail is wanting, sir, in the shoe of its left hind foot.” “Let it be wanting,” answered the merchant; “the shoe will certainly stay on for the six miles I have still to go; I am in a hurry.” In the afternoon, when he once more alighted and had his horse fed, the stable-boy went to him and said, “Sir, a shoe is missing from your horse’s left hind foot; shall I take him to the blacksmith?” “Let it still be wanting,” answered the man, “the horse can very well[7] hold out for the couple of miles which remain; I am in haste.” He rode forth, but before long the horse began to limp. It had not limped long before it began to stumble, and it had not stumbled long before it fell down and broke its leg. The merchant was forced to leave the horse where it was, and unbuckle the trunk, take it on his back, and go home on foot. And there he did not arrive until quite late at night. “And that unlucky nail,” said he to himself, “has caused all this disaster.” Hasten slowly.

Your wife’s a witch, man; you should nail a horse-shoe on your chamber-door.—Sir Walter Scott, Redgauntlet.

As a practical device for the protection of horses’ feet, the utility of the iron horse-shoe has long been generally recognized; and for centuries, in countries widely separated, it has also been popularly used as a talisman for the preservation of buildings or premises from the wiles of witches and fiends.

To the student of folk-lore, a superstition like this, which has exerted so wide an influence over men’s minds in the past, and which is also universally prevalent in our own times, must have a peculiar interest. What, then, were the reasons for the general adoption of the horse-shoe as a talisman? It is our purpose to consider the various theories seriatim.

Among the Romans there prevailed a custom of driving nails into cottage walls as an antidote against the[8] plague. Both this practice and the later one of nailing up horse-shoes have been thought by some to originate from the rite of the Passover. The blood sprinkled upon the door-posts and lintel at the time of the great Jewish feast formed the chief points of an arch, and it may be that with this in mind people adopted the horse-shoe as an arch-shaped talisman, and it thus became generally emblematic of good luck.

The same thought may underlie the practice of the peasants in the west of Scotland, who train the boughs of the rowan or mountain-ash tree in the form of an arch over a farmyard gate to protect their cattle from evil.

The supernatural qualities of the horse-shoe as a preservative against imaginary demons have been supposed to be due to its bifurcated shape, as any object having two prongs or forks was formerly thought to be effective for this purpose. As with the crescent, the source of this belief is doubtless the appearance of the moon in certain of its phases.

Hence, according to some authorities, is derived the alleged efficacy as amulets of horse-shoes, the horns and tusks of animals, the talons of birds, and the claws of wild beasts, lobsters, and crabs. Hence, too,[9] the significance of the oft-quoted lines from Robert Herrick’s “Hesperides:”—

The horn of the fabulous unicorn, in reality none other than that of the rhinoceros, is much valued as an amulet, and in west Africa, where the horns of wild animals are greatly esteemed as fiend-scarers, a large horn filled with mud and having three small horns attached to its lower end is used as a safeguard to prevent slaves from running away.[19]

In the vicinity of Mirzapur in central Hindostan the Horwas tie on the necks of their children the roots of jungle plants as protective charms; their efficacy being thought to depend on their resemblance to the horns of certain wild beasts.

The Mohammedans of northern India use a complex amulet, composed in part of a tiger’s claw and two claws of the large-horned owl with the tips facing outward,[20] while in southern Europe we find the necks of mules ornamented with two boar’s tusks or with the horns of an antelope.

Amulets fashioned in the shape of horns and crescents are very popular among the Neapolitans.[21][10] Elworthy quotes at some length from the “Mimica degli antichi” of Andrea de Jorio (Napoli, 1832), in illustration of this fact. From this source we learn that the horns of Sicilian oxen and of bullocks are in favor with the nobility and aristocracy as evil-eye protectives, and are frequently seen on their houses and in their gardens; stag’s antlers are the favorites with grocers and chemists, while the lower classes are content with the horns of rams and goats. The Sicilians are wont to tie pieces of red ribbon to the little horns which they wear as charms, and this is supposed vastly to increase their efficiency.

In southern Spain, particularly in Andalusia, the stag’s horn is a very favorite talisman. The native children wear a silver-tipped horn suspended from the neck by a braided cord made from the hair of a black mare’s tail. It is believed that an evil glance directed at the child is received by the horn, which thereupon breaks asunder, and the malevolent influence is thus dissipated.[22]

Among the Arabs the horn amulet is believed to render inert the malign glance of an enemy, and in the oases of the desert the horned heads of cattle are to be seen over the doors of the Arab dwellings as talismans.[23]

In Lesbos the skulls of oxen or other horned creatures are fixed upon trees or sticks to avert the evil eye from the crops and fruits.[24]

In Mongolia the horns of antelopes are prized on account of their alleged magical properties; fortune-tellers and diviners affect to derive a knowledge of futurity by observation of the rings which encircle them. The Mongols set a high value upon whip-handles made from these horns, and aver that their use by horsemen promotes endurance in their steeds.[25]

Inasmuch as the horns of animals serve as weapons both for attack and defense, they were early associated in men’s minds with the idea of power. Thus in ancient times the corners of altars were fashioned in the shape of horns, doubtless in order to symbolize the majesty and power of the Being in whose honor sacrifices were offered.[26]

Apropos of horns as symbols of strength, the peasants of Bannú, a district of the Punjab, believe that God placed the newly created world upon a cow’s horn, the cow on a fish’s back, and the fish on a stone; but what the stone rests upon, they do not venture to surmise. According to their theory, whenever the cow shakes her head, an earthquake naturally results.[27]

The Siamese attribute therapeutic qualities to the horns and tusks of certain animals, and their pharmacopœia contains a somewhat complex prescription used as a febrifuge, whose principal ingredients are the powdered horns of a rhinoceros, bison, and stag, the tusks of an elephant and tiger, and the teeth of a bear and crocodile. These are mixed together with water, and half of the resulting compound is to be swallowed, the remainder to be rubbed upon the body.[28]

The mano cornuta or anti-witch gesture is used very generally in southern and central Italy. Its antiquity is vouched for by its representation in ancient paintings unearthed at Pompeii.[29] It consists in flexing the two middle fingers, while the others are extended in imitation of horns. When the hand in this position is pointed at an obnoxious individual, the malignity of his glance is believed to be rendered inert.[30]

In F. Marion Crawford’s novel, “Pietro Ghisleri,” one of the characters, Laura Arden, was regarded in Roman society as a jettatrice, that is, one having the evil eye. Such a reputation once fastened on a person involves social ostracism. In the presence of the unfortunate individual every hand was hidden to make[13] the talismanic gesture, and at the mere mention of her name all Rome “made horns.” No one ever accosted her without having the fingers flexed in the approved fashion, unless, indeed, they had about them some potent amulet.

It is a curious fact that the possession of the evil eye may be imputed to any one, regardless of character or position. Pope Pius IX. was believed to have this malevolent power, and many devout Christians, while on their knees awaiting his benediction, were accustomed slyly to extend a hand toward him in the above-mentioned position.[31]

In an article on “Asiatic Symbolism” in the “Indian Antiquary” (vol. xv. 1886), Mr. H. G. M. Murray-Aynsley says, in regard to Neapolitan evil-eye amulets, that they were probably introduced in southern Italy by Greek colonists of Asiatic ancestry, who settled at Cumæ and other places in that neighborhood. Whether fashioned in the shape of horns or crescents, they are survivals of an ancient Chaldean symbol. It has been said that nothing, unless perhaps a superstitious belief, is more easily transmissible than a symbol; and the people of antiquity were wont to attribute to every symbol a talismanic value.[32]

The modern Greeks, as well as the Italians, wear[14] little charms representing the hand as making this gesture.[33]

But not alone in the south of Europe exists the belief in the peculiar virtues of two-pronged objects, for in Norway reindeer-horns are placed over the doors of farm-buildings to drive off demons;[34] and the fine antlers which grace the homes of successful hunters in our own country are doubtless often regarded by their owners as of more value than mere trophies of the chase, inasmuch as traditional fancy invests them with such extraordinary virtues.

In France a piece of stag-horn is thought to be a preservative against witchcraft and disease, while in Portugal ox-horns fastened on poles are placed in melon-patches to protect the fruit from withering glances.

Among the Ossetes, a tribe of the Caucasus, the women arrange their hair in the shape of a chamois-horn, curving forwards over the brow, thus forming a talismanic coiffure; and when a Moslem takes his child on a journey he paints a crescent between its eyes, or tattooes the same device on its body. The modern Greek, too, adopts the precaution of attaching a crab’s claw to the child’s head.[35] In northern Africa the horns of animals are very generally used as amulets,[15] the prevailing idea being everywhere the same, namely, that pronged objects repel demons and evil glances.

Horns are used in eastern countries as ornaments to head-dresses, and serve, moreover, as symbols of rank. They are often made of precious metals, sometimes of wood. The tantura, worn by the Druses of Mount Lebanon in Syria, has this shape.[36]

In the Bulgarian villages of Macedonia and Thrace the so-called wise woman, who combines the professions of witch and midwife, is an important character. Immediately upon the birth of a child this personage places a reaping-hook in a corner of the room to keep away unfriendly spirits; the efficacy of the talisman being doubtless due partly to its shape, which bears considerable resemblance to a horse-shoe.

And in Albania, a sickle, with which straw has just been cut, is placed for a few seconds on the stomach of a newly born child to prevent the demons who cause colic from exercising their functions.[37]

The mystic virtue of the forked shape is not, however, restricted to its faculty of averting the glance of an evil eye or other malign influences, for the Divining Rod is believed to derive from this same peculiarity of form its magical power of detecting the presence of water or metals when wielded by an experienced hand.

It is worthy of note that the symbol of an open hand with extended fingers was a favorite talisman in former ages, and was to be seen, for example, at the entrances of dwellings in ancient Carthage. It is also found on Lybian and Phœnician tombs, as well as on Celtic monuments in French Brittany.[38] Dr. H. C. Trumbull quotes evidence from various writers showing that this symbol is in common use at the present time in several Eastern lands. In the region of ancient Babylonia the figure of a red outstretched hand is still displayed on houses and animals; and in Jerusalem the same token is frequently placed above the door or on the lintel on account of its reputed virtues in averting evil glances. The Spanish Jews of Jerusalem draw the figure of a hand in red upon the doors of their houses; and they also place upon their children’s heads silver hand-shaped charms, which they believe to be specially obnoxious to unfriendly individuals desirous of bringing evil either upon the children themselves, or upon other members of the household.

In different parts of Palestine the open-hand symbol appears alike on the houses of Christians, Jews, and Moslems, usually painted in blue on or above the door.[39][17] Claude Reignier Conder, R. E., in “Heth and Moab,” remarks on the antiquity of this pagan emblem, which appears on Roman standards and on the sceptre of Siva in India. He is of the opinion that the figure of the red hand, whether sculptured on Irish crosses, displayed in Indian temples, or on Mexican buildings, is always an example of the same original idea,—that of a protective symbol.

A white hand-print is commonly seen upon the doors and shutters of Jewish and Moslem houses in Beyrout and other Syrian towns; and even the Christian residents of these towns sometimes mark windows and flour-boxes with this emblem, after dipping the hand in whitewash, in order to “avert chilling February winds from old people and to bring luck to the bin.”[40]

In Germany a rude amulet having the form of an open hand is fashioned out of the stems of coarse plants, and is deemed an ample safeguard against divers misfortunes and sorceries. It is called “the hand of Saint John,” or “the hand of Fortune.”

The Jewish matrons of Algeria fasten little golden hands to their children’s caps, or to their glass-bead necklaces, and they themselves carry about similar luck tokens.

In northwestern Scotland whoever enters a house where butter is being made is expected to lay his hand[18] upon the churn, thereby signifying that he has no evil designs against the butter-maker, and dissipating any possible effects of an evil eye.[41]

As a charm against malevolent influences, the Arabs

of Algeria make use of rude drawings representing an

open hand, placed either above the entrances of their

habitations or within doors,—a symbolical translation

of the well-known Arabic imprecation, “Five fingers in

thine eye!” Oftentimes the same meaning is conveyed

by five lines, one shorter than the others to indicate

the thumb, thus ![]() .[42]

.[42]

The alleged predominant influence of the moon’s wax and wane over the growth and welfare of vegetation was formerly generally recognized. Thus in an almanac of the year 1661 it is stated that:—

If any corn, seed, or plant be either set or sown within six hours either before or after the full Moon in Summer, or before the new Moon in Winter, having joined with the cosmical rising of Arcturus and Orion, the Hædi and the Siculi, it is subject to blasting and canker.[43]

Timber was always cut during the wane of the moon, and so firmly rooted was this superstition that[19] directions were given accordingly in the Forest Code of France.

An early English almanac advised farmers to kill hogs when the moon was growing, as thus “the bacon would prove the better in boiling.”

Even at the present time a host of credulities regarding the moon is prevalent among the ignorant classes of different lands. Thus, for example, the negroes in the vicinity of Washington, D. C., believe that potatoes should be planted before the new moon in order to thrive, and among the negroes and Indians of the State of Missouri, the proper time for weaning a baby or calf is determined by the lunar phases.

Moon-worship was one of the most ancient forms of idolatry, and still exists among some Eastern nations. A relic of the practice is seen in some parts of Great Britain in the custom of bowing to the new moon.

Astrologers regarded the moon as exerting a powerful influence over the health and fortunes of human beings, according to her aspect and position at the time of their birth. Thus in a “Manual of Astrology” by Raphael (London, 1828), she is described as a “cold, moist, watery, phlegmatic planet, and partaking of good or evil as she is aspected by good or evil stars.”[44]

The growing horned moon was thought to exert a mysterious beneficent influence not only over many[20] of the operations of agriculture, but over the affairs of every-day life as well. Hence doubtless arose the belief in the value of crescent-shaped and cornute objects as amulets and charms; of these the horse-shoe is the one most commonly available, and therefore the one most generally used.

In astrology the moon has indeed always been considered the most influential of the heavenly bodies by reason of her rapid motion and nearness to the earth; and the astrologers of old, whether in forecasting future events or in giving advice as to proper times and seasons for the transaction of business affairs, first ascertained whether or not the moon were well aspected. This was also a cardinal point with the shrewd magicians of later centuries. And should any one require proof of the existence of a modern belief in lunar influences, let him consult Zadkiel’s Almanac for the year 1898. Therein he will find it stated that when the sun is in benefic aspect with the moon, it is a suitable day for asking favors, seeking employment, and traveling for health.

Venus in benefic aspect with the moon is favorable for courting, marrying, visiting friends, engaging maid-servants, and seeking amusement.

Mars, for consulting surgeons and dealing with engineers and soldiers.

Jupiter, for opening offices and places of business, and for beginning new enterprises.

Saturn, for having to do with farmers, miners, and elderly people, for buying real estate and for planting and sowing.

For, says the oracle of the almanac, astrologers have found by experience that if the above instructions are followed, human affairs proceed smoothly.

In his work entitled “The Evil-Eye” (London, 1895), Mr. Frederick Thomas Elworthy calls attention to the fact that the half-moon was often placed on the heads of certain of the most powerful Egyptian deities, and therefore when worn became a symbol of their worship. Indeed, the crescent is common in the religious symbolism not only of ancient Egypt, but also of Assyria and India. The Hebrew maidens in the time of the prophet Isaiah wore crescent-shaped ornaments on their heads.[45]

The crescent is the well-known symbol of the Turkish religion. According to tradition, Philip of Macedon (B. C. 382-336), the father of Alexander the Great, attempted to undermine the walls of Byzantium during a siege of the city, but the attempt was revealed to the inhabitants by the light of a crescent moon. Whereupon they erected a statue to Diana, and adopted the crescent as their symbol.

When the Byzantine empire was overthrown by Mohammed II., in 1453, the Turks regarded the[22] crescent, which was everywhere to be seen, as of favorable import. They therefore made it their own emblem, and it has since continued to be a distinctively Mohammedan token.

In the Mussulman mind the new moon is intimately associated with devotional acts. Its appearance is eagerly watched for and

The moment the eye lights on the slight thread of silver in the western twilight, it remains fixed there, whilst prayers of thanksgiving and praise are offered, the hands being held up by the face, the palms upward and open, and afterwards passed three times over the visage, the gaze still remaining immovable.[46]

Golden crescents of various sizes were among the most primitive forms of money. Ancient coins frequently bore the likenesses of popular deities or their symbols, and of the latter the crescent appears to have been the one most commonly employed.[47] It was the usual mint-mark of the coins of Thespia in the early part of the fourth century B. C.;[48] is seen on the coins of the reigns of Augustus, Nero, and other Roman emperors; and on the silver pieces of the time of Hadrian is found the Luna crescens with seven stars.[49]

A crescent adorned the head of the goddess Diana[23] in her character of Hecate, or ruler of the infernal regions.

Hecate was supposed to preside over enchantments, and was also the special guardian and protectress of houses and doors.[50] The Greeks not only wore amulets in the shape of the half moon, but placed them on the walls of their houses as talismans;[51] and the Romans used phalĕræ, metallic disks and crescents, to decorate the foreheads and breasts of their horses.

Such ornaments are to be seen on the caparisons of the horses on Trajan’s Column and on other ancient monuments, in the collection of Roman antiquities in the British Museum, and in mediæval paintings and tapestries.[52]

In the portrayals of combats between the Romans and Dacians on the Arch of Constantine, the trappings of the horses of both armies are decorated with these emblems,[53] as are also the bridle reins of a horse shown in a French manuscript of the fifteenth century representing “gentlefolk meeting on horseback.”[54]

Charms of similar shape, made of wolves’ teeth and[24] boars’ tusks, have been found in tumuli in different parts of Great Britain.

A sepulchral stone, which is preserved among other Gallo-Roman relics within the château of Chinon, France, bears the effigy of a man standing upright and clad in a large tunic with wide sleeves. Above the figure is a crescent-shaped talisman, a symbol frequently found in monuments of that period.[55]

But the use of these symbols, although so ancient, is by no means obsolete; the brass crescent, an avowed charm against the evil eye, is very commonly attached to the elaborately decorated harnesses of Neapolitan draught-horses, and is used in the East to embellish the trappings of elephants. It is also still employed in like manner in various parts of Europe and in the England of to-day. In Germany small half-moon-shaped amulets similar to the ancient μηνίσχοι or lunulæ are still used against the evil eye.

In Sweden and Frisia, bridal ornaments for the head and neck often represent the moon’s disk in its first quarter; and it is customary to call out after a newly married pair, “Increase, O Moon.”[56]

Elworthy remarks that the horse-shoe, wherever used as an amulet, is the handy conventional representative of the crescent, and that the Buddhist crescent[25] emblem is a horse-shoe with the curve pointed like a Gothic arch.

The English fern called moonwort (Botrychium lunaria) is thought to owe its reputed magical powers to the crescent form of the segments of its frond. Some writers regard it as identical with the martagon, an herb formerly much used by sorcerers; and also with the Italian sferracavallo.

According to the famous astrologer and herbalist, Nicholas Culpepper, moonwort possessed certain occult virtues, and was endowed with extraordinary attributes, chief among them being its power of undoing locks and of unshoeing horses. The same writer remarked that, while some people of intelligence regarded these notions with scorn, the popular name for moonwort among the countryfolk was “unshoe-the-horse.”[57]

Du Bartas, in his “Divine Weekes,” says in reference to this plant:—

Horses that, feeding on the grassy hills, tread upon moonwort with their hollow heels, though lately shod, at night go barefoot home, their maister musing where their shoes become. O moonwort! tell me where thou hid’st the smith, hammer and pinchers, thou unshodd’st them with.

The horse-shoe has sometimes been identified with the cross, and has been supposed to derive its amuletic power from a fancied resemblance to the sacred Christian[26] symbol. But inasmuch as it is difficult to find any marked similarity in form between the crescent and the cross, this theory does not appear to warrant serious consideration.

Some writers have maintained that the luck associated with the horse-shoe is due chiefly to the metal, irrespective of its shape, as iron and steel are traditional charms against malevolent spirits and goblins. In their view, a horse-shoe is simply a piece of iron of graceful shape and convenient form, commonly pierced with seven nail-holes (a mystic number), and therefore an altogether suitable talisman to be affixed to the door of dwelling or stable in conformity with a venerable custom sanctioned by centuries of usage. Of the antiquity of the belief in the supernatural properties of iron there can be no doubt.

Among the ancient Gauls this metal was thought to be consecrated to the Evil Principle, and, according to a fragment of the writings of the Egyptian historian Manetho (about 275 B. C.), iron was called in Egypt the bone of Typhon, or Devil’s bone, for Typhon in the Egyptian mythology was the personification of evil.[58]

Pliny, in his “Natural History,” states that iron[27] coffin-nails affixed to the lintel of the door render the inmates of the dwelling secure from the visitations of nocturnal prowling spirits.

According to the same author, iron has valuable attributes as a preservative against harmful witchcrafts and sorceries, and may thus be used with advantage both by adults and children. For this purpose it was only necessary to trace a circle about one’s self with a piece of the metal, or thrice to swing a sword around one’s body. Moreover, gentle proddings with a sword wherewith a man has been wounded were reputed to alleviate divers aches and pains, and even iron-rust had its own healing powers:—

If a horse be shod with shoes made from a sword wherewith a man has been slain, he will be most swift and fleet, and never, though never so hard rode, tire.[59]

The time-honored belief in the magical power of iron and steel is shown in many traditions of the North.

A young herdswoman was once tending cattle in a forest of Vermaland in Sweden; and the weather being cold and wet, she carried along her tinder-box with flint and steel, as is customary in that country. Presently along came a giantess carrying a casket, which she asked the girl to keep while she went away to invite some friends to attend her daughter’s marriage.[28] Quite thoughtlessly the girl laid her fire-steel on the casket, and when the giantess returned for the property she could not touch it, for steel is repellant to trolls, both great and small. So the herdswoman carried home the treasure-box, which was found to contain a golden crown and other valuables.[60]

The heathen Northmen believed in the existence of a race of dwarfish artisans, who were skilled in the working of metals, and who fashioned implements of warfare in their subterranean workshops. These dwarfs were also thought to inhabit isolated rocks; and according to a popular notion, if a man chanced to encounter one of them, and quickly threw a piece of steel between him and his habitation, he could thereby prevent the dwarf from returning home, and could exact of him whatever he desired.[61]

Among French Canadians, fireflies are viewed with superstitious eyes as luminous imps of evil, and iron and steel are the most potent safeguards against them; a knife or needle stuck into the nearest fence is thought to amply protect the belated wayfarer against these insects, for they will either do themselves injury upon the former, or will become so exhausted in endeavoring to pass through the needle’s eye as to render them temporarily harmless.[62] Such waifs and strays of popular[29] credulity may seem most trivial, yet they serve to illustrate the ancient and widely diffused belief in the traditional qualities ascribed to certain metals.

One widely prevalent theory ascribed to iron a meteoric origin, but the different nations of antiquity were wont to attribute its discovery or invention to some favorite deity or mythological personage; Osiris was thus honored by the Egyptians, Vulcan by the Romans, and Wodan or Odin by the Teutons.

In early times the employment of iron in the arts was much restricted by reason of its dull exterior and brittleness. There existed, moreover, among the Romans a certain religious prejudice against the metal, whose use in many ceremonies was wholly proscribed. This prejudice appears to have been due to the fact that iron weapons were held jointly responsible with those who wielded them for the shedding of human blood; inasmuch as swords, knives, battle-axes, lance and spear points, and other implements of war were made of iron.[63]

Those mythical demons of Oriental lands known as the Jinn are believed to be exorcised by the mere name of iron;[64] and Arabs when overtaken by a simoom in the desert endeavor to charm away these spirits of evil by crying, “Iron, iron!”[65]

The Jinn being legendary creatures of the Stone Age, the comparatively modern metal is supposed to be obnoxious to them. In Scandinavia and in northern countries generally, iron is a historic charm against the wiles of sorcerers.

The Chinese sometimes wear outside of their clothing a piece of an old iron plough-point as a charm;[66] and they have also a custom of driving long iron nails in certain kinds of trees to exorcise some particularly dangerous female demons which haunt them.[67] The ancient Irish were wont to hang crooked horse-shoe nails about the necks of their children as charms;[68] and in Teutonic folk-lore we find the venerable superstition that a horse-shoe nail found by chance and driven into the fireplace will effect the restoration of stolen property to the owner. In Ireland, at the present time, iron is held to be a sacred and luck-bringing metal which thieves hesitate to steal.[69]

A Celtic legend says that the name Iron-land or Ireland originated as follows: The Emerald Isle was formerly altogether submerged, except during a brief period every seventh year, and at such times repeated attempts were made by foreigners to land on its soil,[31] but without success, as the advancing waves always swallowed up the bold invaders. Finally a heavenly revelation declared that the island could only be rescued from the sea by throwing a piece of iron upon it during its brief appearance above the waters. Profiting by the information thus vouchsafed, a daring adventurer cast his sword upon the land at the time indicated, thereby dissolving the spell, and Ireland has ever since remained above the water. On account of this tradition the finding of iron is always accounted lucky by the Irish; and when the treasure-trove has the form of a horse-shoe, it is nailed up over the house door. Thus iron is believed to have reclaimed Ireland from the sea, and the talismanic symbol of its reclamation is the iron horse-shoe.[70]

Once upon a time—so runs a tradition of the Ukraine, the border region between Russia and Poland—some men found a piece of iron. After having in vain attempted to eat it, they tried to soften it by boiling it in water; then they roasted it, and afterwards beat it with stones. While thus engaged, the Devil, who had been watching them, inquired, “What are you making there?” and the men replied, “A hammer with which to beat the Devil.” Thereupon Satan asked where they had obtained the requisite sand; and[32] from that time men understood that sand was essential for the use of iron-workers; and thus began the manufacture of iron implements.[71]

Among the Scotch fishermen also iron is invested with magical attributes. Thus if, when plying their vocation, one of their number chance to indulge in profanity, the others at once call out, “Cauld airn!” and each grasps a handy piece of the metal as a counter influence to the misfortune which would else pursue them throughout the day.[72] Even nowadays in England, in default of a horse-shoe, the iron plates of the heavy shoes worn by farm laborers are occasionally to be seen fastened at the doors of their cottages.[73]

When in former times a belief in the existence of mischievous elves was current in the Highland districts of Scotland, iron and steel were in high repute as popular safeguards against the visits of these fairy-folk; for they were sometimes bold enough to carry off young mothers, whom they compelled to act as wet-nurses for their own offspring. One evening many years ago a farmer named Ewen Macdonald, of Duldreggan, left his wife and young infant indoors while he went out on an errand; and tradition has it that while crossing a brook, thereafter called in the Gaelic tongue “the[33] streamlet of the knife,” he heard a strange rushing sound accompanied with a sigh, and realized at once that fairies were carrying off his wife. Instantly throwing a knife into the air in the name of the Trinity, the fairies’ power was annulled, and his wife dropped down before him.[74]

In Scandinavian and Scottish folk-lore, there is a marked affinity between iron and flint. The elf-bolt or flint arrowhead was formerly in great repute as a charm against divers evil influences, whether carried around as an amulet, used as a magical purifier of drinking-water for cattle, or to avert fairy spite. It seems possible that iron and steel in superseding flint, which was so useful a material in the rude arts of primitive peoples, inherited its ancient magical qualities.

In the Hebrides a popular charm against the wiles of sorcerers consisted in placing pieces of flint and untempered steel in the milk of cows alleged to have been bewitched. The milk was then boiled, and this process was thought to foil the machinations of the witch or enchantress.[75] The fairies of the Scottish lowlands were supposed to use arrows tipped with white flint, wherewith they shot the cattle of persons obnoxious to them, the wounds thus inflicted being invisible except to certain personages gifted with supernatural sight.[76]

According to a Cornish belief, iron is potent to control the water-fiends, and when thrown overboard enables mariners to land on a rocky coast with safety even in a rough sea.[77] A similar superstition exists in the Orkney Islands with reference to a certain rock on the coast of Westray. It is thought that when any one with a piece of iron about him steps upon this rock, the sea at once becomes turbulent and does not subside until the magical substance is thrown into the water.[78]

The inhabitants of the rocky island of Timor, in the Indian Archipelago, carry about them scraps of iron to preserve themselves from all kinds of mishaps, even as the London cockney cherishes with care his lucky penny, crooked sixpence, or perforated shilling; while in Hindostan iron nails are frequently driven in over a door, or into the legs of a bedstead, as protectives. It was a mediæval wedding custom in France to place on the bride’s finger a ring made from a horse-shoe nail,[79] a superstitious bid, as it were, for happy auspices.

In Sicily, iron amulets are popularly used against the evil eye; indeed iron in any form, especially the horse-shoe, is thought to be effective, and in fact talismanic properties are ascribed to all metals. When, therefore,[35] a Sicilian feels that he is being “overlooked,” he instantly touches the first available metallic object, such as his watch-chain, keys, or coins.[80] In ancient Babylon and Assyria it was believed that invisible demons might enter the body during the acts of eating and drinking and thus originate disease, and the doctrine of demoniacal possession as the cause of illness is still widely prevalent in uncivilized communities at the present day. Wherever, therefore, such notions exist, talismans are naturally employed to render inert the machinations of these little demons; and of all these safeguards, iron and steel are perhaps the most potent. Quite commonly in Germany, among the lower classes, such articles as knives, hatchets, and cutting instruments generally, as well as fire-irons, harrows, keys, and needles, are considered protectives against disease if placed near or about the sick person.[81]

In Morocco it is customary to place a dagger under the patient’s pillow,[82] and in Greece a black-handled knife is similarly used to keep away the nightmare.

In Germany iron implements laid crosswise are considered to be powerful anti-witch safeguards for infants; and in Switzerland two knives, or a knife and fork, are placed in the cradle under the pillow. In Bohemia a[36] knife on which a cross is marked, and in Bavaria a pair of opened scissors, are similarly used. In Westphalia an axe and a broom are laid crosswise on the threshold, the child’s nurse being expected to step over these articles on entering the room.[83]

The therapeutic value of iron and its use as a medicament do not properly belong to our subject; and, indeed, neither the iron horse-shoe nor its counterfeit symbol have usually been much employed in folk-medicine. Professor Sepp, in his work on the religion of the early Germans, mentions, however, a popular cure for whooping-cough, which consisted in having the patient eat off of a wooden platter branded with the figure of a horse-shoe.

In France, also, a favorite panacea for children’s diseases consists in laying on the child an accidentally found horse-shoe, with the nails remaining in it; and in Mecklenburg gastric affections are thought to be successfully treated by drinking beer which has been poured upon a red-hot horse-shoe.[84]

Pliny ascribed healing power to a cast-off horse-shoe found on the road. The finder was recommended carefully to preserve such a horse-shoe; and should he at any future time be afflicted with the hiccoughs, the mere recollection of the exact spot where the shoe had[37] been placed would serve as a remedy for that sometimes obstinate affection.[85]

In Bavaria a popular alleged cure for hernia in children is as follows: From a horse-shoe wherein all the nails remain, and which has been cast by a horse, a nail is taken; and when next a new moon comes on a Friday, one must go into a field or orchard before sunrise and drive the nail by three blows into an oak-tree or pear-tree, according to the sex of the child, and thrice invoke the name of Christ; after which one must kneel on the ground in front of the tree and repeat a Paternoster. This is an example of a kind of therapeutic measure not uncommon among peasants in different parts of Germany, a blending of the use of a superstitious charm with religious exercises.[86]

An ingenious theory ascribes the origin of the belief in the magical properties of iron to the early employment of the actual cautery, and to the use of the lancet in surgery.[87] In either case the healing effects of the metal, whether hot or in the form of a knife, have been attributed by superstitious minds to magical properties in the instruments, whereby the demons who caused the disease were put to flight. In northern India the natives believe that evil spirits are so simple-minded as[38] to run against the sharp edge of a knife and thus do themselves injury; and they also make use of iron rings as demon-scarers, such talismans having the double efficacy of the iron and of the sacred circle.[88]

In Bombay, when a child is born, the natives place an iron bar along the threshold of the room of confinement as a guard against the entrance of demons.[89] This practice is derived from the Hindoo superstition that evil spirits keep aloof from iron; and even to-day pieces of horse-shoes are to be seen nailed to the bottom sills of the doors of native houses.[90] In east Bothnia, when the cows leave their winter quarters for the first time, an iron bar is laid before the threshold of the door through which the animals must pass, and the farmers believe that, if this precaution were omitted, the cows would prove troublesome throughout the summer.[91] So, too, in the region of Saalfield, in central Germany, it is customary to place axes, saws, and other iron and steel implements outside the stable door to keep the cattle from bewitchment.

The Scandinavian peasants, when they venture upon the water, are wont to protect themselves against the power of the Neck, or river-spirit, by placing a knife in the bottom of the boat, or by fixing an iron nail in[39] a reed. The following is the translation of a charm used in Norway for this purpose:—

Neck, Neck, nail in water, the Virgin Mary casteth steel in water. Do you sink, I flit.

In Finland there is an evil fairy known as the Alp Nightmare. Its name in the vernacular is Painajainen, which means in English “Presser.” This unpleasant being makes people scream, and causes young children to squint; and the popular safeguard is steel, or a broom placed beneath the pillow.[92]

Friedrich remarks that the Moslems look upon iron as a divine gift, and that the Finlanders have their tutelary gods of this metal.

Among the Jews there prevails a popular belief that one should never make use of a knife or other steel instrument for the purpose of more readily following with the eye the pages of the Bible, the Talmud, or other sacred book. Iron should never be permitted to touch any book treating of religion, for the two are incompatible by nature, the one destroying human life and the other prolonging it.[93] The Highlanders of Scotland have a time-honored custom of taking an oath upon cold iron or steel. The dirk, which was formerly an indispensable adjunct to the Highland costume, is a[40] favorite and handy object for the purpose. The faith in the magical power of steel and iron against evil-disposed fairies and ghosts was universal, and this form of oath was more solemn and binding than any other.[94]

Among the Bavarian peasants nails and needles have a reputation the reverse of that of the horse-shoe. A horse-shoe nail stuck into the front door of a house will give the owner a serious illness. A needle, when given to a friend, is sure to prick to death existing friendship, even as such friendship is severed by the gift of a knife or pair of scissors. Such an untoward result may be averted, however, if the recipient smile pleasantly when the gift is made. A curious superstition about iron locks prevails in Styria and Tyrol. If you procure from a locksmith a brand-new lock and carry it to church at the time of a wedding ceremony, and if, while the benediction is being said, you fasten the lock by a turn of the key, then the young couple’s love and happiness is destroyed. Mutual aversion will supplant affection until you open the lock again.[95]

Vulcan, the Roman god of fire, the Hephæstus of Grecian mythology, was also the patron of blacksmiths[41] and workers in metals. He was the great artisan of the universe, and at his workshop in Olympus he fashioned armor for the warriors of the heroic age. On earth volcanoes were his forges, and his favorite residence was the island of Lemnos in the Ægean Sea. Beneath Ætna, with the aid of those famed artisans, the Cyclops, he forged the thunderbolts of Jove; and there also, according to tradition, were made the trident of Neptune, Pluto’s helmet, and the shield of Hercules. Hephæstus was thus a controller and master of fire.

The Cyclops were believed by the ancients to have invented the art of forging; and the discovery of the peculiar qualities of iron was attributed to certain mythical beings called the Dactyls, who dwelt in Phrygia, and who were thought to have acquired this knowledge from observation of the fusion of metals at the fabulous burning of Mount Ida. The Dactyls had the reputation of being wizards, whose very names possessed a mysterious protective power when pronounced by persons exposed to sudden dangers.

Certain semi-fabulous tribes of central Asia, workers in metals, kept secret the mysteries of their craft, and were wont to indulge in wild orgies and festivities, which served to inspire with awe the uninitiated. At such times they danced until frenzied with excitement, to the accompaniment of cymbals and tambourines and the clashing of weapons. The people of neighboring tribes[42] feared to approach them, believing that they were possessed of a magical power which enabled them to transform one metal into another and to forge thunderbolts. They were reputed to be masters of fire and of the elements, and their forges, like Vulcan’s, were volcanoes.[96]

These barbarous peoples were sometimes confounded with the Dactyls, Corybantes, Cabiri, and Curetes, traditional metallurgists endowed with supernatural skill, and therefore popularly reckoned as magicians, or even as divinities. For a long period they were supposed to be vested with the exclusive knowledge of metal-working, a knowledge shrouded in mystery.

In the “Kalevalla,” or ancient epic poem of Finland, the blacksmith Ilmarinen is represented as the pioneer and most skilled of artisans, who fashioned both the implements of warfare and domestic utensils. This hero

In the Teutonic mythology, blacksmiths were magical craftsmen; and even in the Middle Ages they were looked upon as superior to other artisans, owing to their faculty of seemingly toying with fire, rendering the dangerous element subservient to their will, and by its aid manipulating iron with ease and dexterity. In Germany their workshops were known as “Wieland’s houses,” in remembrance of the most cunning of smiths in the mythical lore of the North.

As in early ages the origin of metal-working was imputed to divine beings, it was natural that in popular tradition blacksmiths acquired their wondrous technical skill through the assistance of such beings, and hence were exalted above the plane of ordinary mortals because they had received supernatural instruction.…

The following mediæval legend serves to show that memories of the old pagan traditions lingered in the minds of the Scandinavians until long after the establishment among them of Christianity. One evening in the year 1208, a horseman rode up to the house of a blacksmith named Thord Vettir, who lived in southern Norway at Nesjar, near the town of Laurvig on the Skager-Rack, and asked for lodging overnight and shoeing for his horse. The smith assented, and early the next morning began the work, chatting meanwhile with his guest. “Where were you last night?” he inquired of the latter. “In Medaldal,” was the reply.[44] “And where were you the night before?” asked the smith. “In Jardal,” answered the stranger. “You must be a tremendous liar,” said the smith, with great frankness. Then he applied himself to his task in earnest, and forged the biggest horse-shoes which he had ever seen, but which were found to fit the horse’s feet perfectly. In the course of further conversation the traveler remarked that he had long dwelt in the north of Norway and was on his way to Sweden. When he was ready to continue journeying and had mounted his steed, the smith inquired his name. “Have you ever heard of Odin?” was the rejoinder. “I have heard his name,” said the smith. “Then you may see him now,” remarked the horseman, “and, if you do not believe what I have told you, look how I leap my horse over the fence.” Thereupon he spurred the animal and rode straight at the court-yard fence, which was seven ells high. The gallant steed cleared the fence with ease, and neither he nor his rider were seen again by the worthy blacksmith.[98]

The dignity and importance of the blacksmith’s art in early mediæval times in England is illustrated by the following tale from Paul Sébillot’s “Légendes et Curiosités des Métiers,” art. “Forgerons:”—

King Alfred the Great, who reigned in the latter part of the ninth century, on one occasion assembled[45] together seven of his principal mechanics and craftsmen, and announced that he would appoint as their chief that one who could longest dispense with the assistance of the others; and he also invited them all to a banquet, on condition that each should bring with him a specimen of his handiwork and the tools wherewith it was made. At the appointed time they all appeared: the blacksmith brought his hammer and a horse-shoe; the tailor his scissors and a newly made garment; the baker his long-handled wooden bread-shovel and a loaf of bread; the shoemaker his awl and a pair of new shoes; the carpenter his saw and a squared plank; the butcher his chopping-knife and a large piece of meat; and the mason his trowel and a corner-stone. After careful deliberation the company decided that the tailor’s work was the best, and he was accordingly chosen to be chief of the artisans.

The blacksmith was vexed at the choice, and vowed he would work no more, so long as the tailor was chief; he therefore closed his shop and took his departure.

But his absence was speedily felt; the king’s horse lost a shoe, the six comrades one after another broke their tools, and, although the tailor continued to ply his trade longer than the others, he too was soon obliged to cease from work. Thereupon the king and his tradesmen decided to try their hands at blacksmithing, but met with ill success; for the king’s horse trod on[46] his royal master, the tailor burnt his fingers, and the others met with various mishaps. At length they began to quarrel among themselves, even coming to blows, and in the mêlée the anvil was overturned with a crash. Just at this point Saint Clement appeared on the scene arm in arm with the blacksmith. The king saluted the newcomers respectfully, and addressed them as follows: “I have made a bad mistake, my friends, in allowing myself to be beguiled by the tailor’s fine cloth and his skillful handiwork; in common fairness the blacksmith, without whose aid the other workmen can accomplish nothing, should be proclaimed chief artisan.” All the tradesmen except the tailor then begged the worthy smith to make new tools for them, which he forthwith proceeded to do, even including a brand-new pair of scissors for the tailor.

Then the king reorganized the society of artisans and proclaimed as chief the blacksmith, whom all greeted with wishes for good health and happiness.

After this the king called on each one for a song, and the new chief in his turn sang one entitled “The Merry Blacksmith,” which is even nowadays sometimes heard at the festivities of tradesmen’s guilds in England.

Saint Clement, who figures in the above tale, was the patron saint of farriers. He was a Roman bishop, who died A. D. 100. In ecclesiastical tradition he was reckoned among the martyrs, having been bound to an anchor[47] and thrown into the sea on November 23 of that year. His name-day was still observed in recent times by English blacksmiths, who regarded him as the originator of the art of practical farriery, and held an annual festival in his honor.

The blacksmiths’ apprentices of the Woolwich dockyard were wont to form a procession on the evening of Saint Clement’s Day, one of their number personating “Old Clem,” with masked face, oakum wig, and long white beard.

During the festivities this worthy delivered a speech, in part as follows:—

I am the real Saint Clement, the first founder of brass, iron, and steel from the ore. I have been to Mount Ætna, where the god Vulcan first built his forge, and forged the armor and thunderbolts for the god Jupiter.[99]

Saint Eloy, or Saint Eligius, is sometimes represented as the guardian of farriers and blacksmiths. He flourished in the seventh century, and in his youth served as apprentice to a goldsmith at Limoges, where he became very proficient in the art of working the precious metals. His festival occurs on December 1.

According to a well-known legend, Saint Eloy was once shoeing a demoniac horse, which refused to stand still; he therefore cut off the animal’s leg and put on[48] the shoe. Then, making the sign of the cross, he replaced the leg, the horse experiencing no ill effects from the operation.

This saint is mentioned in Barnaby Googe’s “Popish Kingdome,” as follows:—

In certain countries blacksmiths and farriers have always been credited with supernatural faculties, and it seems, therefore, reasonable thus to explain the origin of some portion of the alleged mystic virtues of their handiwork, the iron horse-shoe, although indeed this view does not appear to have been advanced hitherto.

Among ourselves, and in some of the principal European countries, blacksmiths are highly respectable members of society, although they do not usually deal in occult science. But in portions of the Russian empire, as in the province of Mingrelia, the Caucasus, and neighboring regions, blacksmiths do enjoy a certain reputation as magicians. Solemn oaths are taken upon the anvil instead of upon the Bible. In Abyssinia and in the Congo country all iron-workers have the reputation of sorcerers, and among the Tibbous of central Africa they are treated with great deference. When an inhabitant of the Orkney Islands wishes to obtain an amulet, he applies either to a farrier, or to his son or grandson;[49] and the Roumanian gypsies are mostly blacksmiths, their wives obtaining a livelihood by mendicancy, the practice of divination, and the interpretation of dreams; while both men and women are thought to have the faculty of summoning to their aid powerful spirits of the air.[100]

In Morocco, at the present day, there still exists a community of dwarfish artisans, workers in metals, magicians, and adepts in the healing art, who make little books which are used as portable amulets; and the Haratin, who inhabit the Drah valley, deem it sinful even to mention by name these dwarfs, whom they consider entitled to extraordinary respect.

Each member of this mysterious tribe of pigmy smiths is said to wear a haik, or outer garment, having upon the back a representation of an eye, a symbol suggestive of the Cyclops of old.[101]

There was, indeed, as we have seen, a common opinion throughout a great part of Europe that the earliest smiths were supernatural beings; for it was reasoned that the marvelous process of melting and fashioning iron could not have been conceived by man, but must have originated through magical agencies.

In Germany blacksmith’s forges were often situated on highways remote from settlements, and were the[50] resort of travelers and teamsters, who stopped either to have a horse shod, or to obtain veterinary advice. Quite naturally these smithies, like the modern crossroads variety stores, became little centres of sociability and gossip, and even of conviviality. Moreover, questionable characters sometimes frequented these places, and hence their reputation was not always savory. But the blacksmith himself, by virtue of his calling, was looked upon with respect, even after his craft had ceased to inspire the vulgar with mysterious awe.[102]

In south Germany and the Tyrol, when a blacksmith rests from his work on a Saturday evening, he strikes with his hammer three blows upon the anvil, thereby chaining up the Devil for the ensuing week. And so likewise, while hammering a horse-shoe into shape, he strikes the anvil instead of the shoe every fourth or fifth blow, and thus makes doubly secure the chain wherewith Satan is bound.[103]

Blacksmiths are usually clever enough to recognize the Devil, even when disguised as a gentleman.

Once upon a time the Evil One appeared at the door of a smith in the village of Gossensass, on the Brenner road, Tyrol, and wished to have his two horses shod. When the work was done, he inquired how much he should pay; but the shrewd smith refused to take any[51] money, and only stipulated that his customer should never enter the shop again, which the Devil promised and went away.[104]

The magicians of Hindostan, when treating cases of alleged demoniacal possession, after the performance of other mystic rites, are wont to sprinkle the patient with water from a blacksmith’s shop, the water having been endowed with additional virtue by the repeated immersion of iron.[105]

In northeast Scotland a cure for rickets consists in having the child bathed by a blacksmith in the water-trough of the smithy. Then he is laid on the anvil and iron implements are passed over him, the use of each being asked, and the ceremony is followed by a second bath. To insure the efficacy of this process, three blacksmiths of the same name must take part in it.[106]

In Henderson’s “Folk-Lore of the Northern Countries of England,” p. 187, mention is made of a remarkable method of treatment intended for the development of sickly, puny children who are thought to be under the influence of an evil spell which retards their growth,—a notable instance of survival of the old belief in the[52] blacksmith’s magical powers. Very early in the morning the little patient is brought to the shop of a smith of the seventh generation, if such can be found, and laid quite naked on the anvil. The blacksmith raises his hammer thrice as if to strike a glowing horse-shoe, each time letting it gently fall on the child’s body,—a simple ceremony, but vastly promotive of the child’s physical welfare, in the minds of its rustic parents.

The farriers of the Arabs inhabiting the oases of the great Sahara desert are exempt from taxes and enjoy numerous privileges. Of these the most important and striking, as showing the honor accorded to the men of this craft, is the following:—

When, on the battlefield, a mounted farrier is hard pressed by enemies, he runs the risk of being killed so long as he remains upon his horse with weapons in his hand. But if he alights, kneels down, and with the corners of his hooded cloak or burnous imitates the movements of a pair of bellows, thus revealing his profession, his life is spared.[107]

The Baralongs of South Africa regard the art of smelting and forging as sacred, and, when the metal begins to flow, none are permitted to approach the furnaces except those who are initiated in the mysteries of the craft.[108]

In Finland, also, blacksmiths are held in profound respect, and the greatest luxuries are none too good for them. They are presented with brandy to keep them in good humor; and a Finnish proverb says, “Fine bread always for the smith, and dainty morsels for the hammerer.”[109]

Among certain tribes of the west coast of equatorial Africa the blacksmith officiates also as priest or medicine-man, and is a chief personage in the community, which often embraces several adjacent villages. Indeed, there appears to be a quite general belief in different portions of Africa that metal-workers as a class are superior beings,—of higher origin than their fellow-tribesmen. When a savage people, without a knowledge of farriery, acquired by conquest a new territory, and found therein blacksmiths plying their vocation, they naturally regarded these artisans with wonder, not unmixed with fear.[110]

Moreover, the early association, in mythology and tradition, of metal-working and sorcery, appears to explain in a measure, as already suggested, the reason for the magical properties popularly ascribed to horse-shoes and to iron articles generally.

The horse-shoe is a product of the artisan’s skill by the aid of fire.

This element has in all ages been considered the great purifier, and a powerful foe to evil spirits.[111]

The Chaldeans venerated fire and esteemed it a deity, and among primitive nations everywhere it has ever been held sacred. The Persians had fire-temples, called Pyræa, devoted solely to the preservation of the holy fire.[112]

In the “Rig-Veda,” the principal sacred book of the Hindus, the crackling of burning fagots was listened to as the voice of the gods, and the same superstition prevails still among the natives of Borneo.[113]

In a fragment of the writings of Menander Protector, a Greek historian of the sixth century, it is related that when an embassy sent by the Emperor Justin reached Sogdiana, the ancient Bokhara, it was met by a party of Turks, who proceeded to exorcise their baggage by beating drums and ringing bells over it. They then ran around the baggage, bearing aloft flaming leaves, meantime, by their gestures and movements, seeking to repel evil spirits; after which some of the party themselves[55] passed through fire as a means of purification.[114]

Fire is especially potent against nocturnal demons, and also against the evil spirits which cause disease in cattle. Hence the utility of the ancient “need-fires,” produced by the friction of two pieces of wood, which were thought to be an antidote against the murrain and epizoötics generally,—a custom until recently in vogue in the Scottish Highlands, and formerly practiced in many other regions.

The midsummer fires kindled on Saint John’s Eve, in accordance with an ancient British custom, were regarded as purifiers of the air. Moreover, the whole area of ground illuminated by these fires was reckoned to be freed from sorcery for a year, and, by leaping through the flames, both men and cattle were insured safety against demons for a like period.[115]

In Ireland it was customary for people to run through the streets on Saint John’s Eve carrying long poles, upon which were tied flaming bundles of straw, in order to purify the air, for at that time all kinds of mischievous imps, hobgoblins, and devils were abroad, intent on working injury to human beings.[116]

Midsummer fires were still lighted in Ireland in the[56] latter half of the nineteenth century, a survival of pagan fire-worship. In many countries people gathered about the bonfires, while children leaped through the flames, and live coals were carried into the cornfields as an antidote to blight.[117]

Sometimes the remaining ashes were scattered over the neighboring fields, in order to protect the crops from ravaging vermin or insects; and in Sweden the smoke of need-fires was reputed to stimulate the growth of fruit-trees, and to impart luck to fishing-nets hung up in it.[118]

When a child is born, the Hindus light fires to frighten demons; and for the same reason lamps are swung to and fro at weddings, and fire is carried before the dead body at a funeral.[119]

Devout Brahmins keep a fire constantly burning in their houses and worship it daily, expecting thereby to secure for themselves good fortune. The origin of the respect accorded to fire among these people has been attributed to its potency in alleviating or curing certain diseases,[120] as, for example, when applied in the actual cautery, or by means of the moxa; for, wherever a belief exists in demoniacal possession as the cause of[57] bodily disorders, the cure of the latter is evidence that the malignant spirits have been put to flight.

The fire-worshiping Parsees also keep a fire continuously in the lying-in room; and when a child is ailing from any cause, they fasten to its left arm a magical charm of written words prepared by a priest, exorcising the evil spirits in the name of their chief deity, Ormuzd, and “binding them by the power and beauty of fire.”[121]

On the birth of a child among the Khoikhoi of south Africa a household fire is kindled, which is maintained until the healing of the child’s navel; and when a member of the tribe goes a-hunting, his wife is careful to keep a fire burning indoors; for, if it were allowed to go out, the husband would have no luck.[122]

The conception of a mediæval smith as a master and controller of fire was embodied in a group of figures modeled by the Austrian sculptor, Karl Bitter, and placed at the southern entrance of the Administration Building at the World’s Fair, Chicago, in 1893. This group, which was called “Fire Controlled,” consisted of a female figure, whose uplifted right hand carried a torch, while at her feet stood a brawny smith resting a sledge hammer upon the prostrate form of a fire demon.

Above this group stood a single figure, by the same artist, representing a blacksmith standing at his anvil, with hammer resting against it, and in his belt hung a pair of pincers. In his left hand was a horse-shoe, which he was examining.[123]

The theory has been advanced that in ancient idolatrous times the horse-shoe in its primitive form was a symbol in serpent-worship, and that its superstitious use as a charm may have thus originated. This seems plausible enough, inasmuch as there is a resemblance between the horse-shoe and the arched body of the snake, when the latter is so convoluted that its head and tail correspond to the horse-shoe prongs.

Both snakes and horse-shoes were anciently engraved on stones and medals, presumably as amuletic symbols;[124] and in front of a church in Crendi, a town in the southern part of the island of Malta, there is to be seen a statue having at its feet a protective symbol in the shape of a half moon encircled by a snake.

The serpent played an important rôle in Asiatic and ancient Egyptian symbolism. This has been thought to be due partly to a belief that the sun’s path through[59] the heavens formed a serpentine curve, and partly because lightning, or the fertilizing fire, sometimes flashes upon the earth in a snake-like zigzag.[125] The serpent was endowed with the attributes of divinity on account of its graceful and easy movements, the brightness of its eyes, the function of discarding its skin (a process which was regarded as emblematic of a renewal of its youth), and its instantaneous spring upon its prey.[126] The worship of serpents is of great antiquity, the earliest authentic accounts of the custom being found in Chaldean and Chinese astronomical works. It was nearly universal among the most ancient nations of the world, and this universality has been ascribed to the traditionary remembrance of the serpent in Eden,[127] and has given rise to the opinion of some writers that snake-worship may have been the primitive religion of the human race.[128]

On the walls of houses in Pompeii are to be seen the figures of snakes, which are believed to have been intended as preservative symbols;[129] and we learn from Mr. C. G. Leland’s “Etruscan Roman Remains” that the peasants of the mountainous regions in northern Italy, known as the Romagna Toscana, have a custom of[60] painting on the walls of their houses the figures of serpents with the heads and tails pointing upward. These are intended both as amulets to keep away witches, and as luck-bringers, and are therefore exact counterparts of the horse-shoe and the crescent as magical emblems. The more interlaced the snake’s coils, the more effective the amulet; the idea being that a witch is obliged to trace out and follow with her eye the interweaving convolutions, and that in attempting to do this she becomes bewildered, and is temporarily rendered incapable of doing harm.

In ancient Roman works of art the serpent is sometimes portrayed as a protective symbol. In some bronze figures of Fortune unearthed at Herculaneum, serpents are represented either as encircling the arm of the goddess, or as entwined about her cornucopia, thus typifying, as it were, the idea of the intimate association of the snake with good luck.

The Phœnicians rendered homage to serpents, and history shows that the Lithuanians, Sarmatians, or inhabitants of ancient Poland, and other nations of central Europe, treated these reptiles with superstitious respect. In Russia, also, domestic snakes were formerly carefully nurtured, for they were thought to bring good fortune to the members of a household.[130]

The worship of serpents is still practiced in Persia,[61] Tibet, Ceylon, and other Eastern lands. In western Africa, also, the serpent is a chief deity, and is appealed to by the natives in seasons of drought and pestilence.[131] A talisman having the form of a snake, and known as la sirena, is in use among the lower classes at Naples.

In the folk-lore of the south Slavonian nations the serpent is regarded as a protective genius, not only of the people, but of domestic animals and houses as well. Every human being has a snake as tutelary divinity, with which his growth and well-being are closely connected, and the killing of one of these sacred creatures was formerly deemed a grave offense. To meet with a snake has long been accounted fortunate in some countries. The south Slav peasant believes that whoever encounters one of these creatures, on first going into the woods in the spring, will be prosperous throughout the year. But on the other hand he regards it as an evil omen if he happens to catch a glimpse of his own tutelary serpent. Fortunately, however, a man never knows which particular ophidian is his special guardian.[132]