The Project Gutenberg EBook of Thames Valley Villages, Volume 1 (of 2), by Charles G. Harper This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Thames Valley Villages, Volume 1 (of 2) Author: Charles G. Harper Illustrator: W. S. Campbell Release Date: June 23, 2018 [EBook #57365] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THAMES VALLEY VILLAGES, VOL 1 *** Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: Illustrations have been moved so as not to fall in the middle of paragraphs (leaving them as close to the original position in the book as possible). A few minor printing errors were corrected.

Volume II is available as Project Gutenberg ebook #57366.

THAMES VALLEY VILLAGES

WORKS BY CHARLES G. HARPER

The Portsmouth Road, and its Tributaries: To-day and in Days of Old.

The Dover Road: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike.

The Bath Road: History, Fashion, and Frivolity on an Old Highway.

The Exeter Road: The Story of the West of England Highway.

The Great North Road: The Old Mail Road to Scotland. Two Vols.

The Norwich Road: An East Anglian Highway.

The Holyhead Road: The Mail-Coach Road to Dublin. Two Vols.

The Cambridge, Ely, and King’s Lynn Road: The Great Fenland Highway.

The Newmarket, Bury, Thetford, and Cromer Road: Sport and History on an East Anglian Turnpike.

The Oxford, Gloucester, and Milford Haven Road: The Ready Way to South Wales. Two Vols.

The Brighton Road: Speed, Sport, and History on the Classic Highway.

The Hastings Road and the “Happy Springs of Tunbridge.”

Cycle Rides Round London.

A Practical Handbook of Drawing for Modern Methods of Reproduction.

Stage Coach and Mail in Days of Yore. Two Vols.

The Ingoldsby Country: Literary Landmarks of “The Ingoldsby Legends.”

The Hardy Country: Literary Landmarks of the Wessex Novels.

The Dorset Coast.

The South Devon Coast.

The Old Inns of Old England. Two Vols.

Love in the Harbour: a Longshore Comedy.

Rural Nooks Round London (Middlesex and Surrey).

Haunted Houses: Tales of the Supernatural.

The Manchester and Glasgow Road. This way to Gretna Green. Two Vols.

The North Devon Coast.

Half Hours with the Highwaymen. Two Vols.

The Autocar Road Book. Four Vols.

The Tower of London: Fortress, Palace, and Prison.

The Somerset Coast.

The Smugglers: Picturesque Chapters in the Story of an Ancient Craft.

The Cornish Coast. North.

The Cornish Coast. South.

The Kentish Coast. [In the Press.

The Sussex Coast. [In the Press.

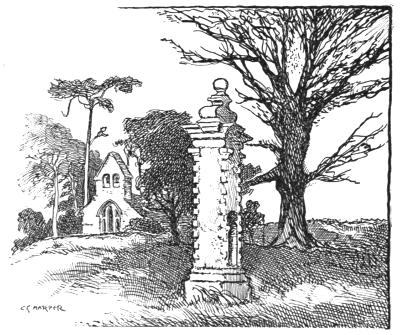

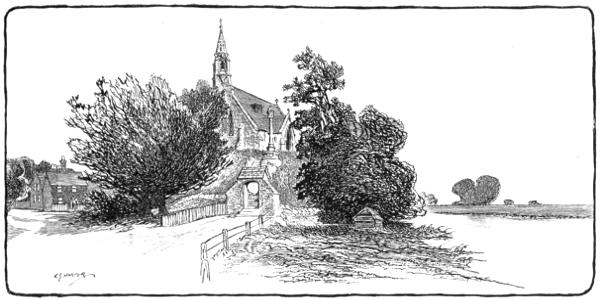

AT ASHTON KEYNES.

THAMES VALLEY

VILLAGES

BY

CHARLES G. HARPER

VOL. I

ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY W. S. CAMPBELL

AND FROM DRAWINGS BY THE AUTHOR

ISIS

London: CHAPMAN & HALL, Ltd.

1910

PRINTED AND BOUND BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Cirencester—Source of the Thames—Kemble—Ashton Keynes—Cricklade—St. Augustine’s Well | 8 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Castle Eaton—Kempsford—By the Thames and Severn Canal to Inglesham Round House—Lechlade—Fairford—Eaton Hastings Weir—Kelmscott—Radcot Bridge | 50 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Great Faringdon—Buckland—Bampton-in-the-Bush—Cote—Shifford | 110 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Harvests of the Thames: Willows, Osiers, Rushes | 128 |

| [viii]CHAPTER V | |

| New Bridge, The Oldest on the Thames—Standlake—Gaunt’s House—Northmoor—Stanton Harcourt—Besselsleigh | 138 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Cumnor, and the Tragedy of Amy Robsart | 161 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Wytham—The Old Road—Binsey and the Oratory of St. Frideswide—the Vanished Village of Seacourt—Godstow and “Fair Rosamond”—Medley—Folly Bridge | 186 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Iffley, and the Way Thither—Nuneham, in Storm and in Sunshine | 200 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Abingdon | 216 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Sutton Courtney—Long Wittenham—Little Wittenham—Clifton Hampden—Day’s Lock and Sinodun | 234 |

| [ix]CHAPTER XI | |

| Dorchester—Benson | 260 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Wallingford—Goring | 272 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Streatley—Basildon—Pangbourne—Mapledurham—Purley | 293 |

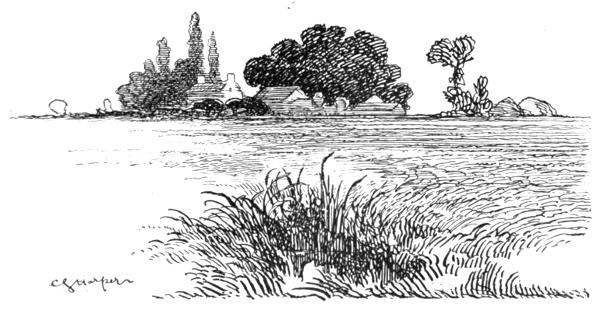

| At Ashton Keynes | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| Cirencester Church: Showing the Great Buttress | 11 |

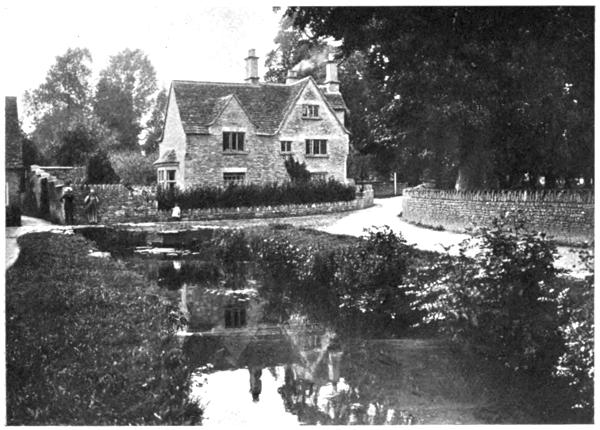

| The Old Mill House, Ashton Keynes | 23 |

| The Infant Thames, Ashton Keynes | 31 |

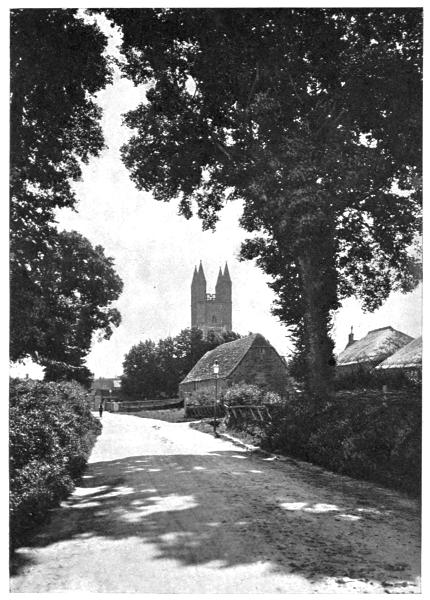

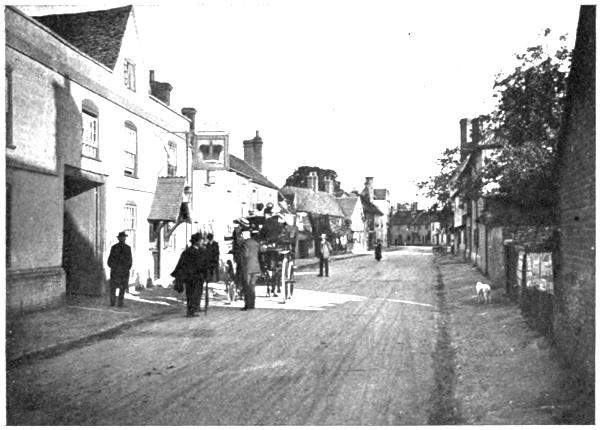

| Approach to Cricklade | 35 |

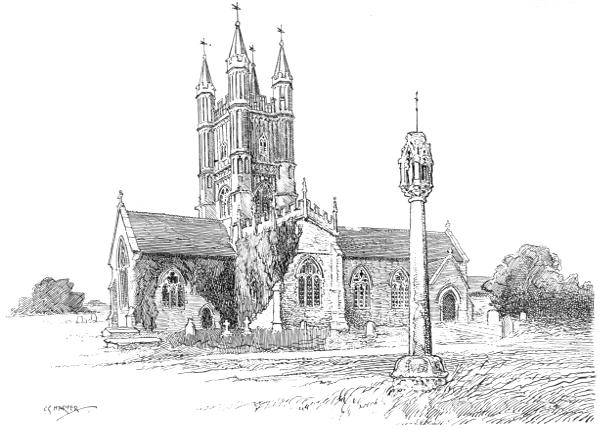

| St. Sampson, Cricklade | 39 |

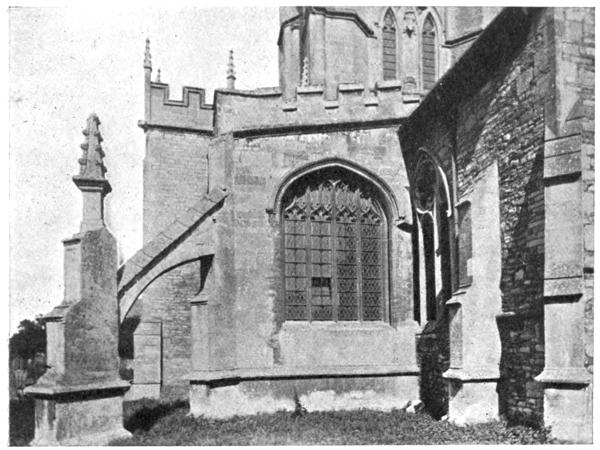

| Strainer-Buttress, St. Sampson’s, Cricklade | 43 |

| “Lertoll Well” | 43 |

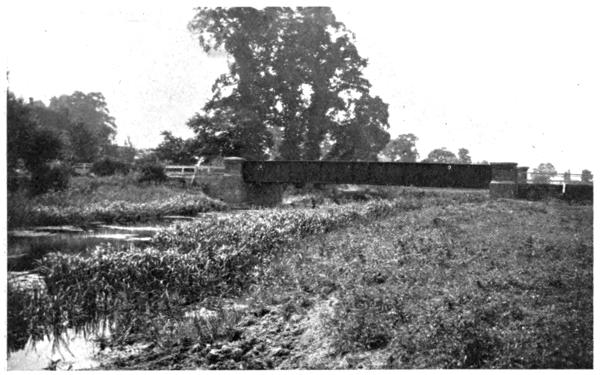

| The Iron Girder Bridge, Castle Eaton | 51 |

| The Old Bridge, Castle Eaton | 51 |

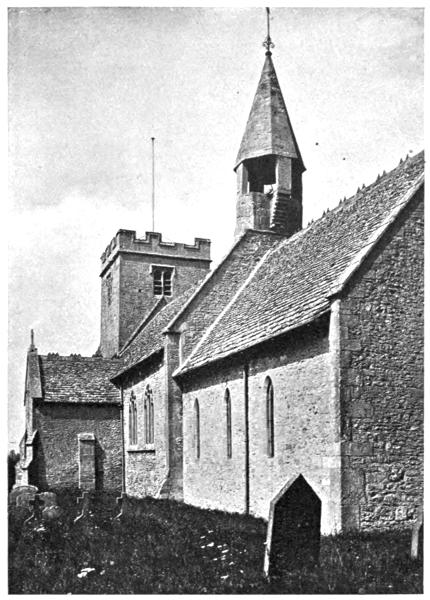

| Castle Eaton Church: Showing Sanctus-Bell Turret | 55 |

| The Thames and Severn Canal, Near Kempsford | 55 |

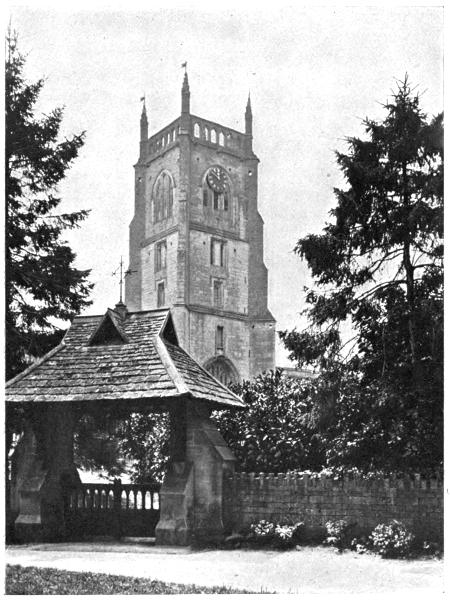

| Kempsford Church | 61 |

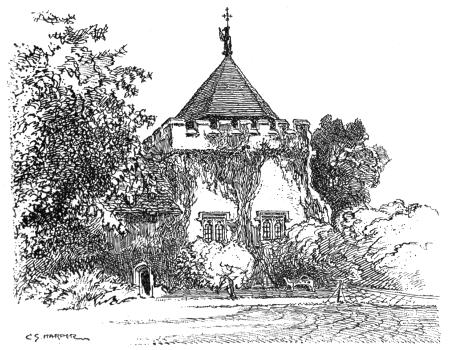

| Inglesham Round House | 67 |

| A Street in Fairford | 71 |

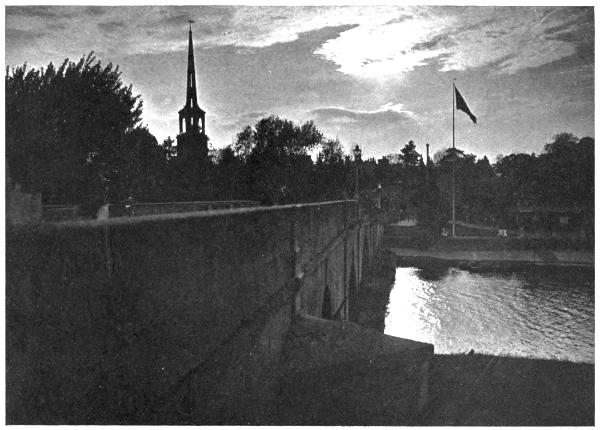

| Lechlade | 75 |

| Fairford, from the River Coln | 79 |

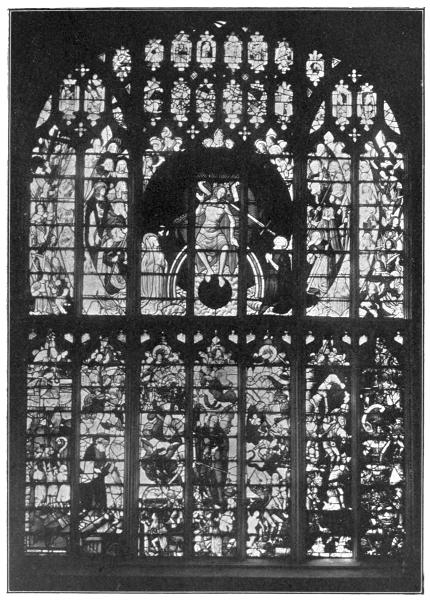

| The Great West Window, Fairford, Displaying the “Doom” | 83 |

| Monument in the Park, Fairford, where the Famous Windows were Buried | 87 |

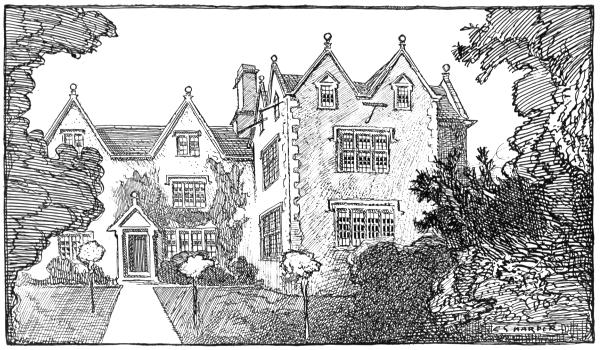

| Kelmscott Manor | 95 |

| [xii]Kelmscott Church | 99 |

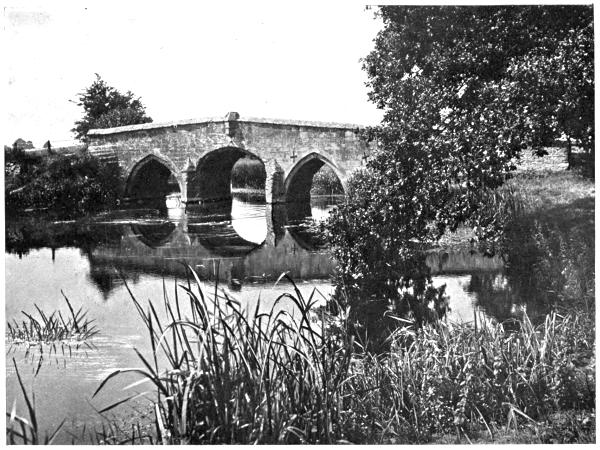

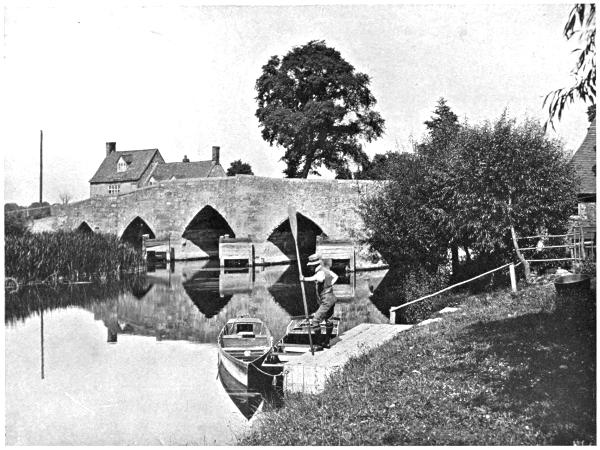

| Radcot Bridge | 103 |

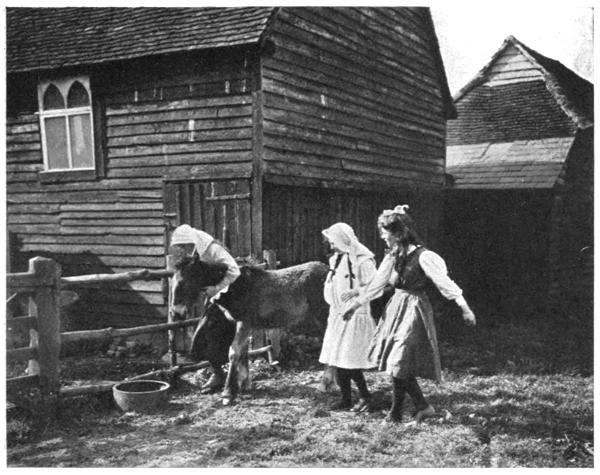

| A Thames-side Farm | 125 |

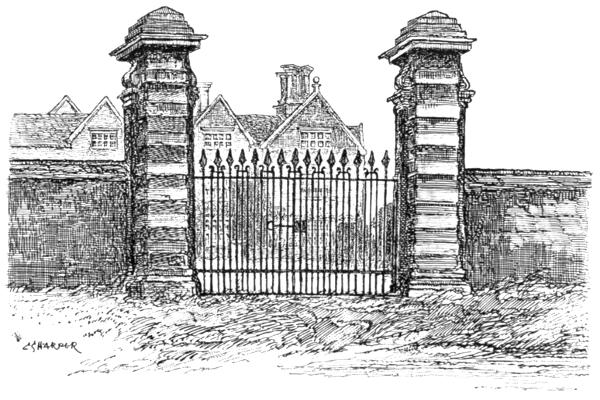

| Gateway, Cote House | 125 |

| A Thames-side Farm | 129 |

| New Bridge: the Oldest Bridge across the Thames | 139 |

| Northmoor: Church and Dovecote | 143 |

| Stanton Harcourt: Manor House and Church | 147 |

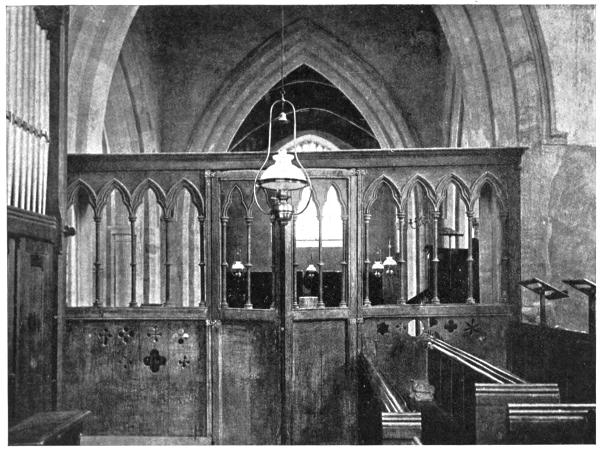

| Early English Screen (Unrestored), Stanton Harcourt | 153 |

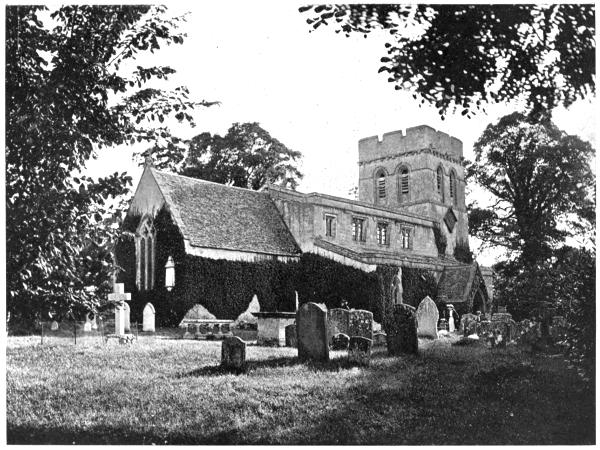

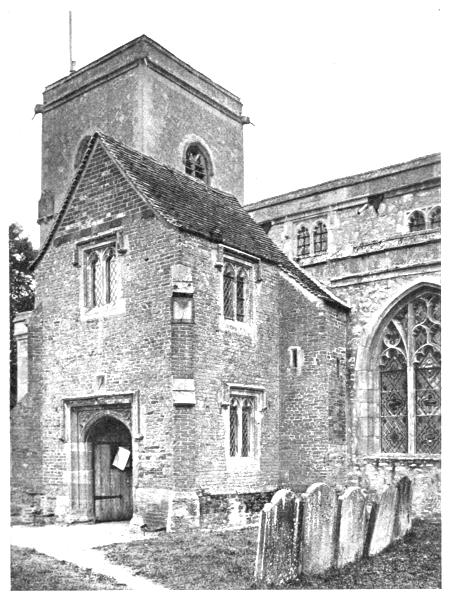

| Cumnor Church | 163 |

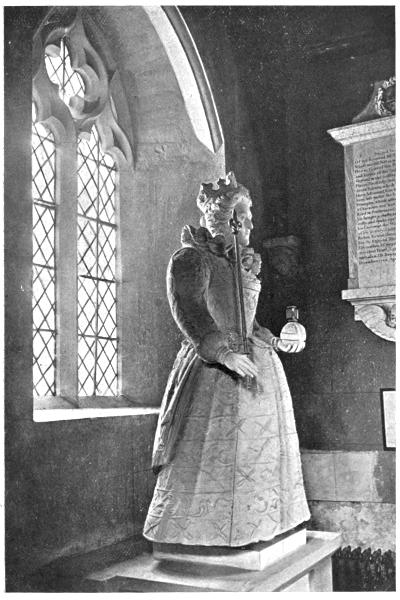

| Statue of Queen Elizabeth, Cumnor Church | 167 |

| Tomb of Anthony Forster, Cumnor | 173 |

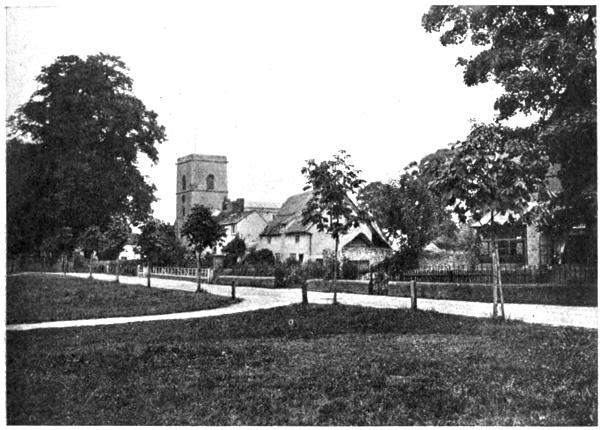

| Eynsham | 187 |

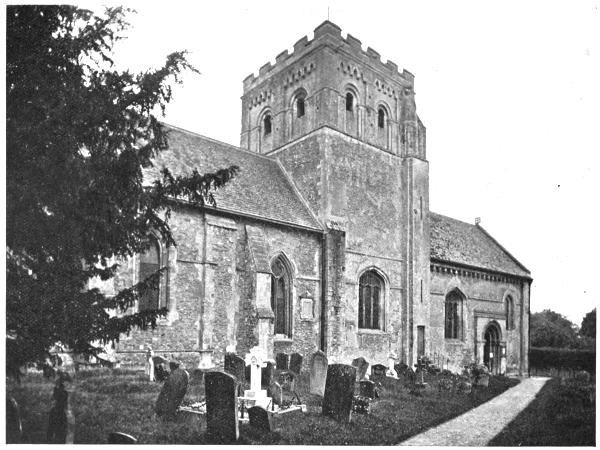

| Iffley Church: North Side | 201 |

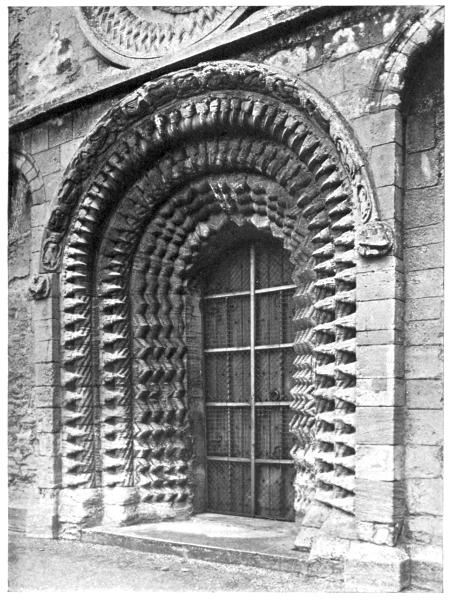

| West Door, Iffley Church | 205 |

| The Bridge, Nuneham Courtney | 209 |

| Carfax Conduit, Nuneham Courtney | 213 |

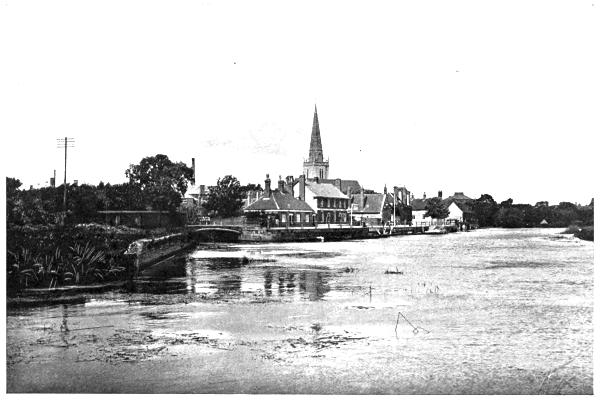

| Abingdon | 217 |

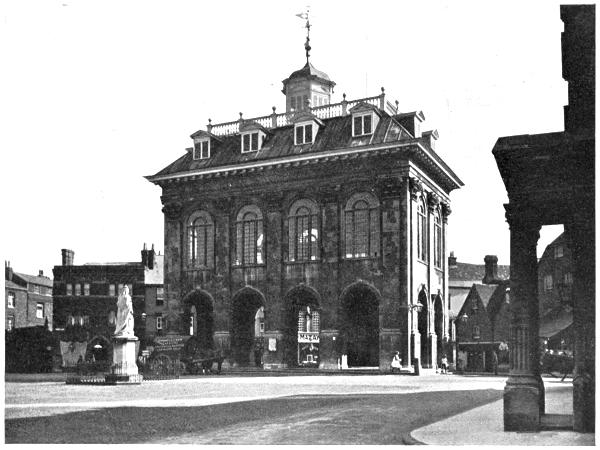

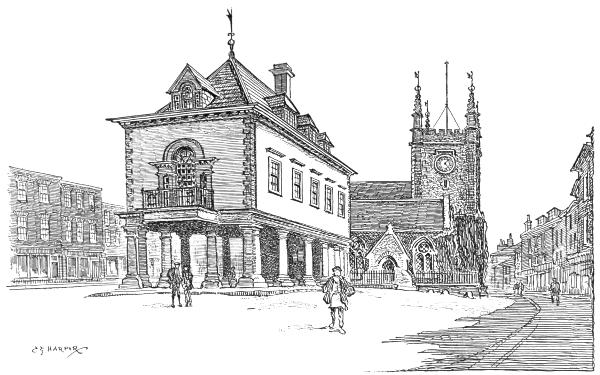

| The Town Hall, Abingdon | 223 |

| St. Helen’s, Abingdon | 227 |

| Old Houses, Steventon Causeway | 231 |

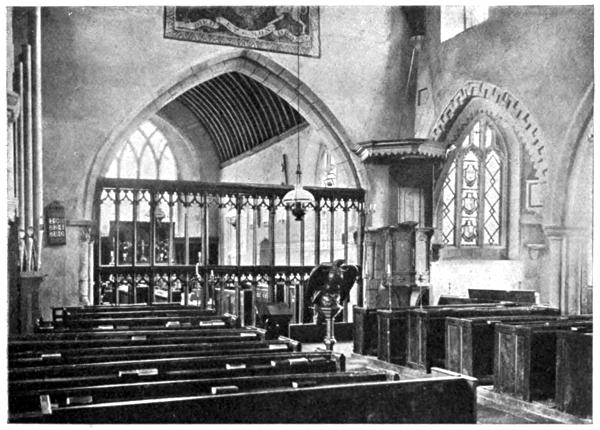

| Sutton Courtney Church | 235 |

| Sutton Courtney | 239 |

| Interior, Sutton Courtney Church | 239 |

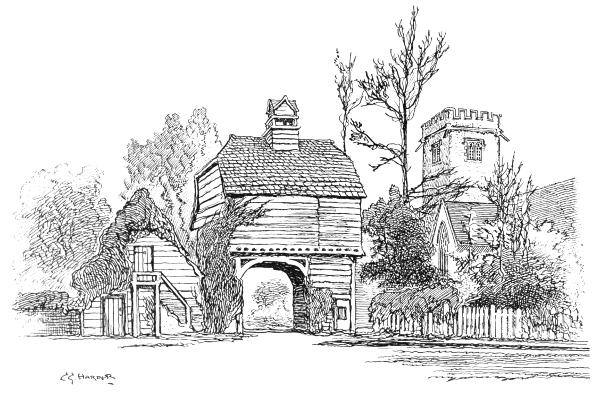

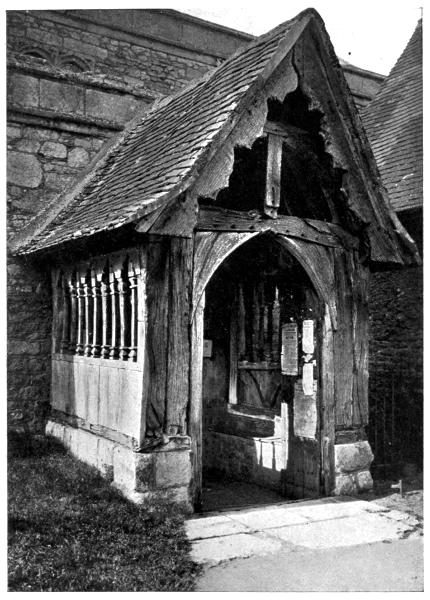

| Ancient Timber Porch, Long Wittenham (Unrestored) | 245 |

| Day’s Lock, and Sinodun Hill | 249 |

| Clifton Hampden | 257 |

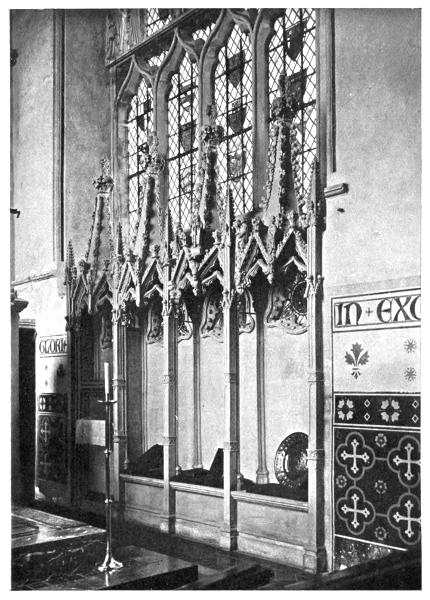

| Sedilia, Dorchester Abbey | 261 |

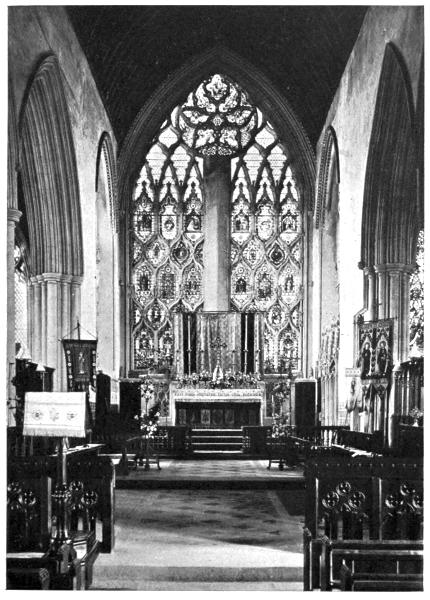

| The East Window, Dorchester Abbey | 265 |

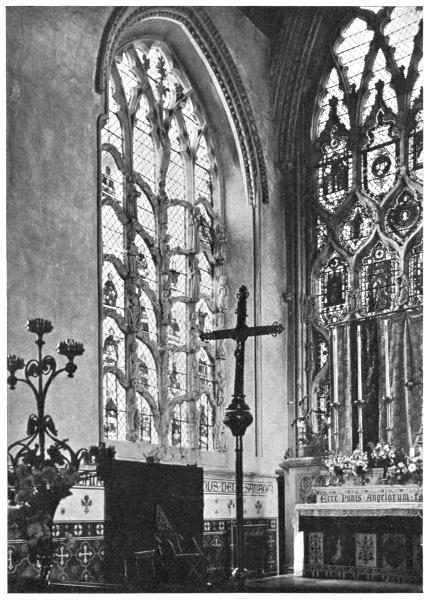

| The Jesse Window (on the left), Dorchester Abbey | 269 |

| Dorchester | 273 |

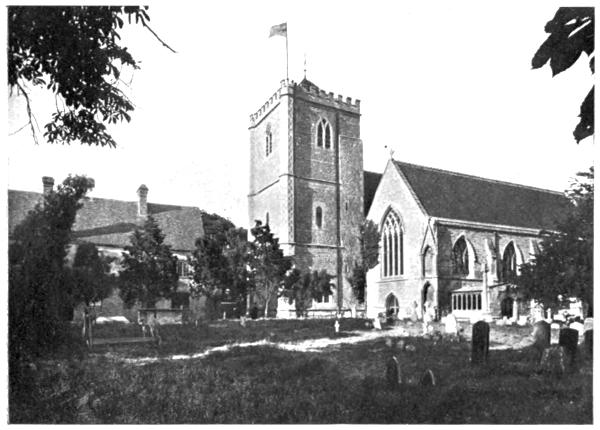

| Dorchester Abbey | 273 |

| [xiii]Wallingford | 277 |

| Wallingford: Town Hall, and Church of St. Mary-the-More | 281 |

| Goring Church | 285 |

| Hour-Glass Stand, South Stoke | 285 |

| Pangbourne Church | 291 |

| Basildon Church | 291 |

| Whitchurch | 297 |

| Mapledurham Mill | 301 |

| Mapledurham House | 305 |

| Near Kemble | 19 |

| At Ewen | 21 |

| At Ashton Keynes | 22 |

| Ashton Keynes Mill | 27 |

| Old Woodwork, Castle Eaton | 58 |

| Norman Porch, Kempsford | 60 |

| Inglesham Church | 65 |

| Ancient Carving, Lechlade Church | 73 |

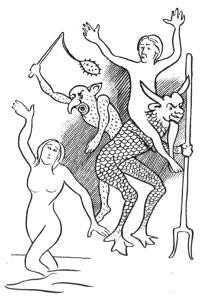

| Fiends | 82, 85 |

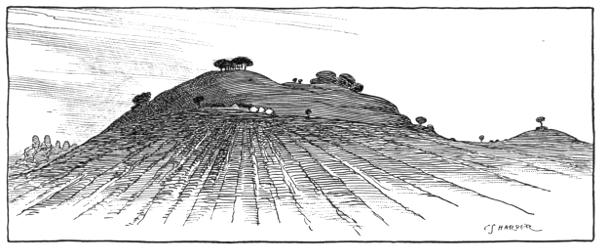

| Faringdon Clump | 101 |

| St. Stephen | 107 |

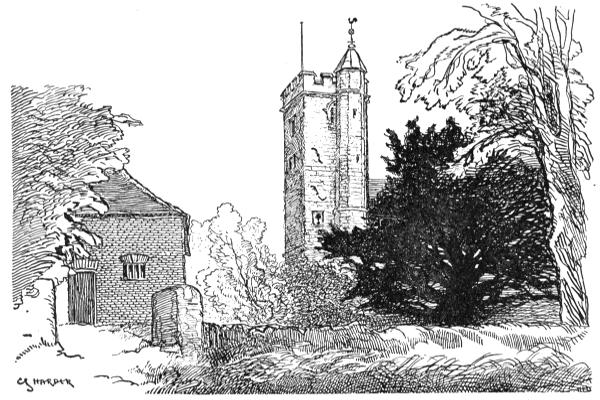

| Clanfield Church | 108 |

| Faringdon Market House | 117 |

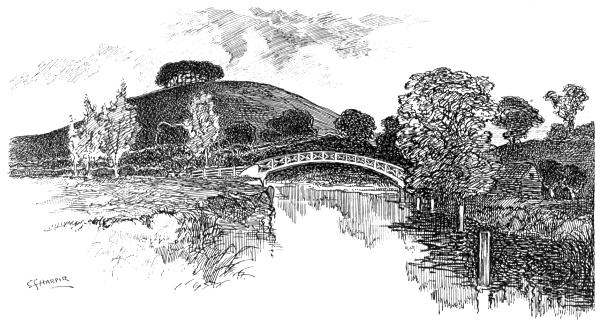

| Wooden Bridge across the Upper Thames | 118 |

| Bampton Church | 123 |

| The Kitchen, Stanton Harcourt | 150 |

| Besselsleigh: Church and Fragment of Manor House | 157 |

| Binsey Church | 192 |

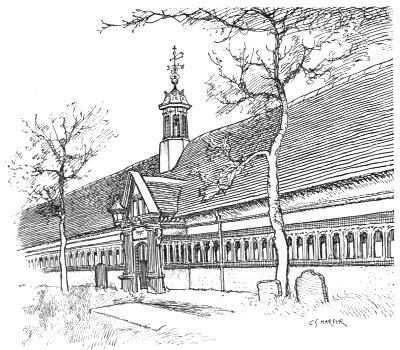

| Christ’s Hospital, Abingdon | 221 |

| St. Nicholas, Abingdon | 225 |

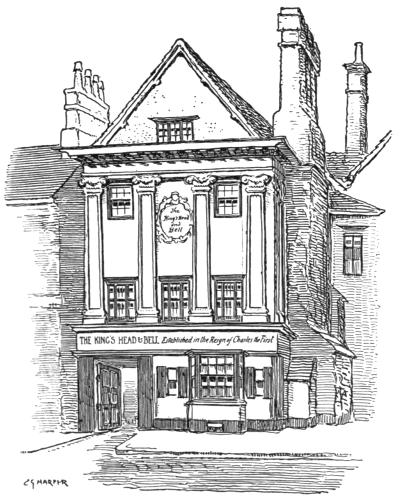

| The “King’s Head and Bell,” Abingdon | 233 |

| Norman Belfry-window, Sutton Courtney | 238 |

| Little Wittenham | 245 |

| Wittenham Clumps | 253 |

The Thames we all know intimately, for the river was discovered by the holiday-maker in the ’seventies of the nineteenth century; but we do not all know the villages of the Thames Valley, and it was partly to satisfy a long-cherished curiosity on this point, and partly to make holiday in some of the little-known nooks yet remaining, that this tour was undertaken.

To one who lives, or exists, or resides—the reader is invited to choose his own epithet—beside the lower Thames, there must needs at times come a longing to know that upper stream whence these mighty waters originate, to find that fount where “Father Thames” starts forth in hesitating, infantile fashion; to seek that spot where the stream, instead of flowing, merely trickles. To such an one there comes, with every recurrent spring, the longing to penetrate to the Beyond, away past where the towns and villages, the water-works and breweries cluster thickly beside the river-banks; above the town of Reading, the Biscuit Town, and town of sauce and seeds; beyond the fashionable summer scene of Henley[2] Regatta, and past the city of Oxford, to the Upper River and its unconventionalised life.

When spring comes and wakes the meadows with delight, and the osiers and the rushes again feel life stirring in their dank roots, the old schoolboy feeling of curiosity, of mystery, of a desire for exploration, springs anew. You walk down, it may be, to some slipway or draw-dock by Richmond or Teddington, or wander along those shores contemplating the high-water-marks left by the late winter floods, which not even the elaborate locking of the river seems able to prevent; and observing the curious line of refuse of every description brought down by the waters, and now left, high and dry, a matted mass of broken rushes, water weeds, twigs, string and the like, marvel at the wealth of corks that displays itself there. Children have been known to make expedition towards the distant hills, seeking that place where the rainbow touches the ground; for the sly old legend tells us that on the spot where the glorious bow meets the earth there lies buried a crock of gold. An equally speculative quest would be to fare forth and seek the Place whence the Corks Come. There (not for children, but for “grown-ups”) should be, you think, the Land of Heart’s Desire.

There are, I take it, three chief things that the world of men most ardently wishes for. An unregenerate man’s first desires are to wealth, to a woman, and to a drink; or, in the words attributed to Martin Luther:

and the valley of the Thames, from Oxford to Richmond, would seem, by the evidence of these millions of corks of all kinds, to be a place flowing with champagne, light wines, all kinds of mineral waters, and bottled beers.

Corks, rubber rings from broken mineral-water bottles, and big bungs that hint of two-or three-gallon jars, abound; these last telling in no uncertain manner of the magnificent thirsts inspired among anglers who sit in punts all day long, and do nothing but keep an eye on the float, and maintain the glass circulating.

A thirsty person wandering by these bestrewn towing-paths must sigh to think of the exquisite drinks that have gone before, leaving in this multitude of corks the only evidence of their evanescent existence. Shall we not seek it, this land of the foaming champagne, that comes creaming to the brim of the generous glass; shall we not hope to locate those shores, far or near, where the bottled Bass, poured into the ready tumbler, tantalises the parched would-be drinker of it in the all-too-slowly-subsiding mass of froth that lies between him and his expectant palate? Shall we not, at least if we be of “temperance” leanings, quaff the cool and refreshing “stone-bottle” ginger-beer; or, failing that, the skimpy and deleterious “mineral-water” “lemonade” that is chiefly compounded of sugar and carbonic-acid gas, and blows painfully and at high-pressure through the titivated nostrils? Shall we not—— but hold there! Waiter, bring me—what shall it be?—an iced stone-bottle ginger!

That was the brave time, the golden age of the river, when, rather more than a generation ago, the discovery of the Thames as a holiday haunt was first made. The fine rapture of those early tourists, who, deserting the traditional seaside lounge for a cruise down along the placid bosom of the Thames, from Lechlade to Oxford, and from Oxford to Richmond, were (something after the Ancient Mariner sort) the first to burst into these hitherto unknown reaches, can never be recaptured. The bloom has been brushed from off the peach by the rude hands of crowds of later visitors. The waterside inns, once so simple under their heavy beetling eaves of thatch, are now modish, instead of modest; and Swiss and German waiters, clothed in deplorable reach-me-down dress-suits and lamentable English of the Whitechapel-atte-Bowe variety, have replaced the neat-handed—if heavy-footed—Phyllises, who were almost in the likeness of those who waited upon old Izaak Walton, two centuries and a quarter ago.

To-day, along the margin of the Thames below Oxford, some expectant mercenary awaits at every slipway and landing-place the arrival of the frequent row-boat and the plenteous and easily-earned tip; and the lawns of riparian villas on either hand exhibit a monotonous repetition of “No Landing-Place,” “Private,” and “Trespassers Prosecuted” notices; while side-channels are not infrequently marked “Private Backwater.”

All the villages immediately giving upon the stream have suffered an equally marked change, and have become uncharacteristic of their old selves, and converted[5] into the likeness of no other villages in this our England, in these our times. There is, for example, a kind of theatrical prettiness and pettiness about Whitchurch, over against Pangbourne; and instead of looking upon it as a real, living three-hundred-and-sixty-five-days-in-the-year kind of place, you are apt to think of what a pretty “set” it makes; and, doing so, to speak of its bearings in other than the usual geographical terms of east and west, north and south; and to refer to them, indeed, after the fashion of the stage, as “P.” or “O.P.” sides.

But if we find at Whitchurch a meticulous neatness, a compact and small-scale prettiness eminently theatrical, what shall we say of its neighbour, Pangbourne, on the Berkshire bank of the river? That is of the other modern riverain type: an old village spoiled by the expansion that comes of being situated on a beautiful reach of the Thames, and with a railway station in its very midst. Detestable so-styled “villas,” and that kind of shops you find nowhere else than in these Thames-side spots, have wrought Pangbourne into something new and strange; and motor-cars have put the final touch of sacrilege upon it.

Perhaps you would like to know of what type the typical Thames-side village shop may be, nowadays? Nothing easier than to draw its portrait in few words. It is, to begin with, inevitably a “Stores,” and is obviously stocked with the first object of supplying boating-parties and campers with the necessaries of life, as understood by campers and boating-parties. As tinned provisions take a prominent place in those[6] holiday commissariats, it follows that the shop-windows are almost completely furnished with supplies of tinned everything, festering in the sun. For the rest, you have cheap camp-kettles, spirit-stoves, tin enamelled cups and saucers, and the like utensils, hammocks and lounge-chairs.

Thus the modern riverside village is unpleasing to those who like to see places retain their old natural appearance, and dislike the modern fate that has given it a spurious activity in a boating-season of three months, with a deadly-dull off-season of nine other months every year. We may make shift to not actively dislike these sophisticated places in summer, but let us not, if we value our peace of mind, seek to know them in winter; when the sloppy street is empty, even of dogs and cats; when rain patters like small-shot on the roof of the inevitable tin-tabernacle that supplements the over-restored, and spoiled, parish church; and when the roar of the swollen weir fills the air with a thudding reverberance. Pah!

The villas, the “maisonettes,” are empty: the gardens draggle-tailed; the “Nest” is “To Let”; the “Moorings” “To be Sold”; and a general air of “has been” pervades the place, with a desolating feeling that “will again be” is impossible.

But let us put these things behind us, and come to the river itself; to the foaming weir under the lowering sky, where such a head of water comes hurrying down that no summer frequenter of the river can ever see. There is no dead, hopeless season in nature; for although the trees may be bare, and the groves dismantled, the wintry woods have their own beauty,[7] and even in mid-winter give promise of better times.

But along the uppermost Thames, from Thames Head to Lechlade and Oxford, the waterside villages are still very much what they have always been. All through the year they live their own life. Not there do the villas rise redundant, nor the old inns masquerade as hotels, nor chorus-girls inhabit at weekends, in imitative simplicity. A voyage along the thirty-two miles of narrow, winding river from Lechlade to Oxford has no incidents more exciting than the shooting of a weir, or the watching of a moor-hen and her brood.

Below Oxford, we have but to adventure some little way to right or left of the stream, and there, in the byways (for main roads do not often approach the higher reaches of the river), the unaltered villages abound.

CIRENCESTER—SOURCE OF THE THAMES—KEMBLE—ASHTON KEYNES—CRICKLADE—ST. AUGUSTINE’S WELL

The head-spring of the Thames is, in summer, not so easy a place to find. It rises on the borders of Wilts and Gloucestershire, and has been marked down and written about sufficiently often; but the exact spot is quested for with difficulty, and when the traveller has found it, he is, after all, not sure of his find, for the place is supplied, in these latter days, with no recognisable landmark, and even the road-men and the infrequent wayfarers along that ancient way, the Akeman Street, which runs close by, appear uncertain. That it is “over there, somewhere,” is the most exact information the enquirer is likely, at a venture, to obtain.

There are excellent reasons for this distressing incertitude. The winter reason is that Trewsbury Mead, the great flat meadow in which Thames Head is situated, is so water-logged that it is often a morass, and not infrequently a lake. In summer, on the other hand, the spot is so parched, partly on account of the season, but much more by reason of the pumping-works in the immediate neighbourhood, that not only[9] the Thames Head spring is quite dry, but the bed of the infant Thames itself is generally dry for the first two miles of its course.

Thames Head is situated three miles south-west of Cirencester, that beautiful old stone-built town whose name we are traditionally told to pronounce “Ciceter,” just as Shakespeare wrote it. That was the old popular way, before the folks of the surrounding country could read or write, and knew no better; but to-day, when “education” is the birthright of all, though culture be the acquisition of few, they are the rustic-folk—the “lower orders”—who say “Cirencester,” as my lords and gentlemen and ladies were wont to do; while nowadays the upper circles refer to “Ciceter.” It is a curious reversal. If you say, in these times, “Cirencester,” you, in so doing, proclaim yourself, socially, an outsider, fit only to feed out of the same trough as those creatures who pronounce “Marjoribanks,” “Cholmondeley,” or “Wemyss” as spelled. We all know—or ought—that “Marshbanks,” “Chumley,” and “Weems” are your only ways, if you would be socially saved. These are the last resorts of those who have no other distinction to mark them out from the common herd: just a verbal inflection, combined, possibly, with a method of hand-shaking. To what straits we are reduced, in these democratic times, to express our superiority!

There is another way to the pronunciation of “Cirencester,” lately come into favour with provincials of this neighbourhood. It is a method of the simplest: merely the adoption of the clipped[10] way common to the local milestones, which tell the tale of so many miles to “Ciren.”

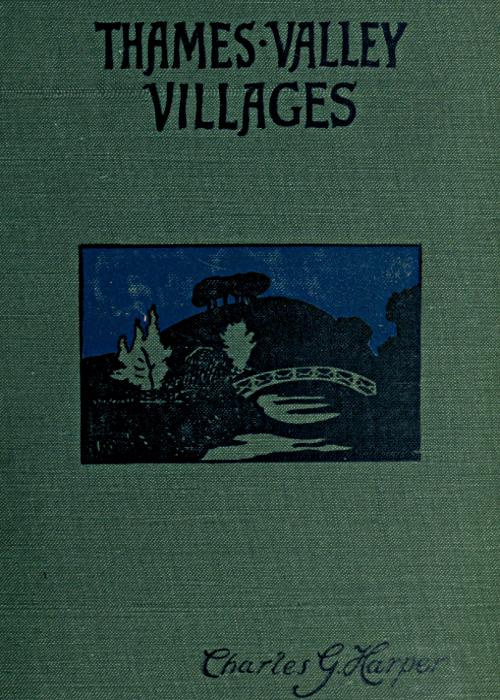

The noblest thing in Cirencester is the beautiful old church, which rises in its midst, beside the remarkably broad High Street, with much of that scale and stateliness we commonly associate with a cathedral. It is one of the noblest works of the Perpendicular period, when architects grew aspiring, but did not always succeed in building artistically as well as big. Here the two aims have been achieved. But a third desideratum, that of building securely, was not originally included, it would appear, for one of the most astonishing things about this structure is the great masonry strut which would be called a “shore” if it were only in timber, and is so clearly for utility, and absolutely unbeautiful and unarchitectural, that to style it a buttress would be to disparage the exquisite adornments that buttresses at their best are capable of being. This great crutch for a noble tower in danger of falling so soon as it was built, nearly five hundred years ago, is, however, justified of its existence, for the lofty belfry yet stands securely. The ingenious way in which the supporting masonry is built diagonally through the west wall of the south aisle, down to the ground, compels admiration for the engineering skill displayed.

CIRENCESTER CHURCH: SHOWING THE GREAT BUTTRESS.

The great three-storeyed porch, by far the largest porch, and certainly the most singular, in England, built in advance of the south aisle, and looking proudly upon the street, would seem to have been built for the convenience of the many priests who served the large number of chantries established from time to time[13] in the church. It is a very late and very beautiful Perpendicular work. Not long after its completion the greasy rascals were sent packing, in the life-giving Reformation that saved the nation. It for long afterwards served as the Town Hall, but was commonly known as “the Vice”—a strange survival and corruption of “parvise.”

The interior of the church discloses a nave-arcade of very lofty and graceful proportions; a work probably as completely satisfactory as anything in this country. And there is very much else to study here. There are monuments, worn and battered, to knights and dames, wine-merchants, wool-merchants, grocers, and other old tradesmen of the town. Among them may be noticed the brass to Reginald Spycer, 1442, with his four wives—Reginald in the middle, and the four ladies beside him, two and two. A late example is that of Philip Marner, 1587, representing him full-length, robed, with staff in one hand and a flower in the other. A dog sits beside him. In the upper left-hand is a pair of shears, indicating that he was a clothier. The rhymed inscription says:—

In a glazed frame is preserved an ancient blue velvet pulpit-cloth, given in 1478 by Ralph Parsons, a priest, whose cope it had been.

The road that runs, white and broad, in a straight[14] undeviating line, from Cirencester to Thames Head, and so on at last, after many miles, to Bath—the “Akemanceaster” that has given the Akeman Street its name—comes in three miles to a stone bridge spanning a canal. This is “Thames Head Bridge,” and the canal is the Thames and Severn Canal, which, beginning at Inglesham, just above Lechlade, ends at Stroud. The length of this water-way is thirty miles. The works were begun in 1783 and completed in 1789.

The object of the Thames and Severn Canal, which joins the Stroudwater Canal, and reaches the Severn at Framilode, was to provide a commercial water-way between the highest point of the navigable Thames, near Lechlade, and the Bristol Channel. Its course lies along some very high ground just beyond Thames Head, going westward, and in all there are forty-four locks, rising 241 ft. 3 in. There is also a remarkable piece of engineering in the Sapperton Tunnel, through which the canal takes its course. The tunnel is fifteen feet wide, and is driven through Sapperton Hill at a point 250 feet beneath its summit.

It follows that of necessity a canal, so elevated above the surrounding country, must be provided with water by artificial means, and a supply is provided by a pumping-station close at hand to Thames Head Bridge. This raises water to the extent of three million gallons a day: hence the dried-up character of the Thames Head spring, except in winter, and the usual summer phenomenon of the infant Thames being quite innocent of water for a distance of two miles from its source. Of late years the Great Western[15] Railway, which has a station at Kemble, a mile and a half away, has erected a still larger and more powerful pumping-station, for the purpose of supplying water for its own needs at Swindon, fourteen miles distant.

The Akeman Street here divides Wiltshire and Gloucestershire. If we descend from the Thames Head Canal bridge and follow the towing-path in a westerly direction, into Gloucestershire, for half a mile, we come, by scrambling down the canal-bank to the meadow below, to the source of the river, and at the same time to the destruction of a cherished illusion. Picturesque old histories of the Thames have made us familiar with Thames Head, and have shown us dainty vignettes of that spring. One such I have before me as I write these words. It shows a rustic well, overhung by graceful trees, with a little country-girl in homely pinafore dipping a foot in the water as it gushes forth. We need expect no such scene nowadays. The well is buried under fallen masses of the dull, ochre-coloured earth of Trewsbury Mead, and all we see is a rough, dry hollow, overhung by trees which refuse to live up to the grace suggested by the old illustrations. We need not wonder any more why so few people know Thames Head, or why the spot is unmarked. It is merely a memory, and Peacock’s charming verse has long ceased to be applicable:—

But although the pumping-stations so greedily suck up all the available moisture in summer, the spring is said often to burst out in winter, three feet high; and at such times it is only necessary to drive a walking-stick anywhere into the turf of this meadow for a little fount to spring up from the hole thus drilled.

The river thus originated is known alternatively as the “Isis,” and in the writings of old pedantic antiquaries retains that alternative name until Oxford is passed and Dorchester reached; where, according to such authorities, in the confluence of the Isis and the Thame, the “Thame-Isis,” becomes the “Tamesis,” or Thames. To the Oxford boating-man, however, the streams below and above Oxford are respectively the Lower and the Upper River, and “Isis” is reserved for the title of a University magazine, or the name of a boating-club.

“Isis” is, of course, a Latinised form of “Ouse,” which in its turn is a modified form of the Celtic “uisc,” for water, and gives us such other river-names as Usk, Axe, Exe, and Wye; while we find it hidden again in the names of Kirkby Wiske, in Yorkshire, and in that of “whisky,” deriving from “usquebaugh.”

The time when the Upper Thames was first called “Isis” is uncertain. The name is certainly a Latinised form of “Ouse”; but the Romans do not appear to have so styled it. Julius Cæsar, in his Commentaries, speaks only of “Tamesis”; and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, A.D. 905, mentions only the “Thames.” We do not, in fact, read of anything like “Isis” until 1359, when a monk of Chester,[17] Ranulphus Higden, wrote in his Polychronicon a passage which, rendered into English from his Latin original, runs thus: “Tamisa seems to be composed from the names of two rivers, the Ysa, or Usa, and the Thama. The Thama, running by Dorchester, falls into the Ysa; thence the whole river, from its source to the eastern sea, is called Thamisa.” A much later writer, Leland, I think, says, in that rarefied, detached way we expect in old writers, “The common people call it the ‘Thames,’ but scholars call it the ‘Isis.’”

The name of “Thames” is equally Celtic with that of the Latinised “Isis,” nor is it the only Thames in the country, for the river Tamar, dividing Devon and Cornwall; the Teme, in Shropshire and Herefordshire; and the Tame, in Staffordshire, are each closely allied in name.

The generally-accepted source of the Thames at Thames Head has by no means gone undisputed, and a rival exists at Seven Springs, three miles south-east of Cheltenham. This spot is the source of the river Churn, which, falling into the Thames at Cricklade, after a course of sixteen or seventeen miles, takes the stream some ten miles farther up-country than that which issues from Thames Head. Thus we have the singular paradox, that the Churn, this first tributary of the Thames, is considerably longer than the parent stream. This is a problem that would have desolated the logical mind of Euclid, and it has worried geographers and writers of books for uncounted years. No matter how diligently we may seek to track this heresy to its lair—to its original propagation—we shall inevitably be foiled; nor indeed (as in the case[18] of rival religious dogmas) shall we ever be able to definitely settle which of the two is the heresy, and which the true faith. If we rely upon the canon that the source of any river is that point which is situated farthest from its mouth, and then refer to the maps, there can be no doubt whatever that the Churn is the true Thames, and that the Seven Springs source is its head-spring. It is an unavoidable conclusion, like it or like it not; and if we take the trouble to visit Seven Springs, we shall discover that some one has been concerned to mark the spot prominently with the same belief, in the inscription set up there on a wall going down into the pool:—

or, in English,

We can only assume, in the difficulty with which we are thus faced, that the original error, of placing Thames Head at Trewsbury Mead, and naming the stream which issues from Seven Springs the “Churn,” arose in those very remote times, before even the Romans came to Britain, when surveying and map-making were unknown and relative distances were uncertain. That the river Churn bore its present name even at the period when the Romans descended upon Britain is an assured thing, for the Romans named Corinium—the present “Cirencester”—from[19] its situation on the Churn. The existing form of the place-name is of Saxon origin, and is really “Churnchester”—the “castle on the Churn.”

Near Kemble.

Kemble Junction, the railway station that dominates this neighbourhood, marks where the little four-mile branch of the Great Western Railway goes off to Cirencester from the line to Stroud and Gloucester. There is no likely expectation that Cirencester will begin to grow and to lose its old-world character while it remains, as now, at the loose end of this little single-track branch railway; and the hunting-men of this Vale of White Horse district remain quite unconcerned and unafraid of developments. This country, between Cirencester, Cricklade and Lechlade, is a hunting country and an agricultural country, and long centuries ago it lost to Leeds and Bradford, and other like centres, the clothing industry for which this Cotswold district was in mediæval times and after[20] famed. Thus Kemble Junction is by no means a junction of the Swindon or the Clapham Junction type, and is rather a peaceful than a bustling place. The village itself stands on rising ground above this district of springs. Even though it be more remarkable for its stone walls than for anything else, it is a not unpleasing village, for in a neighbourhood such as this, where laminated stone is easily dug out from a few feet below the level of the soil, we expect dry stone walling and stone-built houses; and certainly the hard stony effect is softened by the plentiful trees of the place. The Early English church, with tall spire, 120 feet high, has been so thoroughly “restored,” and swept and garnished, and so plentifully endued with plaster, that architects with a love of antiquity, and all antiquaries, looking upon it, can scarce refrain from tears. Inside the church is a curious monument—

Dedicated to the memory of Beatrice and Edward, the deare wife and son of Mr. Richard Pitt, both interred within these walls, shee the 26th day of Aprill 1650, hee the 29th day of March 1656

| who { | Conflicted | } in ye Church { | militant |

| were buried | materiall | ||

| Do reigne | triumphant. |

She died i’ th’ noone, he in the morne, of Age, yet virtue (though not yeres) fil’d their lives’ page.

We shall probably not be wrong in regarding this as one of the ultra-Puritan families of that Puritan age.

Just below Kemble, on the way to the hamlet of Ewen, the course of the Thames is in summer hardly to be distinguished in the meadows through which it runs. Grass covers it, in common with the meadows themselves; only the grass is of a ranker and coarser kind, and largely admixed with docks. The dry-walling of one of these meadows shows the winter direction of the stream clearly enough, in the row of holes left in building the wall for the water to pass through.

AT EWEN.

Ewen, standing by the roadside, is remarkable only for its rustic cottages, but they are particularly beautiful in their old unstudied way; heavily thatched, and surrounded with old-fashioned gardens. The Thames begins to flow, or to trickle, regularly at Upper Somerford Mill, whose water-wheel, immense in proportion to the little stream, is picturesquely sheltered under wide-spreading trees. The village of Somerford Keynes lies close at hand.

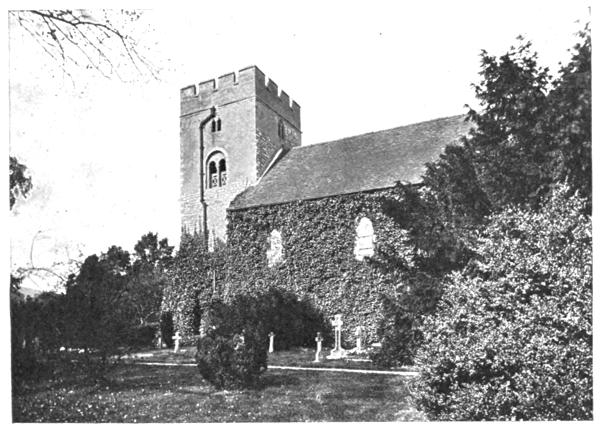

AT ASHTON KEYNES.

The way between this village and Ashton Keynes passes over rough common-land, and enters Ashton Keynes romantically, past the great church, and along a fine avenue of elms beside the manor-house, emerging at what, until a few years ago, was Ashton Keynes Mill. The elm avenue of Ashton Keynes is other than we should expect, if we come to the place primed with a knowledge of what the “Keynes” in the place-name signifies. Those elms should be oaks, for “Keynes” derives from the ancient Norman word for an oak-tree; in later French, “chênaie.” Hence also the name of Horsted Keynes, in Sussex.

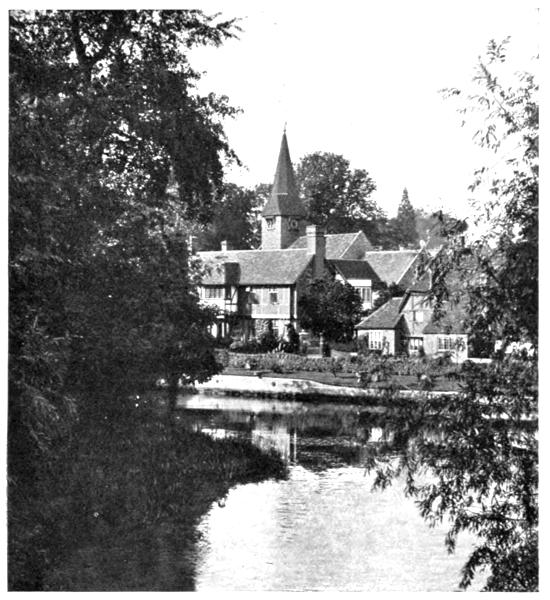

THE OLD MILL HOUSE, ASHTON KEYNES.

Upper Somerford Mill.

All the old mills that once made the Thames additionally picturesque are disappearing. Some go up in flame and smoke, like Iffley Mill, below Oxford, painted and sketched by a thousand artists, and described by a hundred writers of books and descriptive[25] articles, to whose lasting sorrow it was destroyed by fire in 1907. Shiplake Mill met a similar fate a little earlier, and modern milling conditions forbid their ever being rebuilt. Ashton Keynes Mill became disestablished, as a mill, because it could no longer compete with the modern steam-roller flour-mills, that nowadays grind flour much more expeditiously and cheaply than the old water-driven mills. But the old mill-house stands, little altered. It is built substantially, of stone, and has old peaked gables and casemented windows, and so, when its ancient commercial career came at last to an end, its own picturesqueness, and its strikingly beautiful setting, appealed irresistibly to some appreciative person seeking an old English home; with the result that it has been converted into a very charming private residence.

Little need be said about Ashton Keynes church, for it is of very late Gothic, and plentifully uninteresting; but the village itself is a delight. It is the queen of Upper Thames villages, with a picture at every turn. Here the Thames flows quietly down one side of the village street, and at the beginning of that rural, cottage-bordered, tree-shaded highway is the first bridge across the river; an ancient Gothic bridge, with a slipway beside it, where the horses are brought down to wash their legs in summer. Beside the bridge stand the remains of one of the three fifteenth-century wayside crosses which once gave Ashton Keynes a peculiarly sanctified look. The ruins of all three are still here,—smashed originally during the seventeenth-century troubles in which[26] King, Church, Parliament and Puritans contended violently together; and further damaged by the mischievous pranks of many generations of village children.

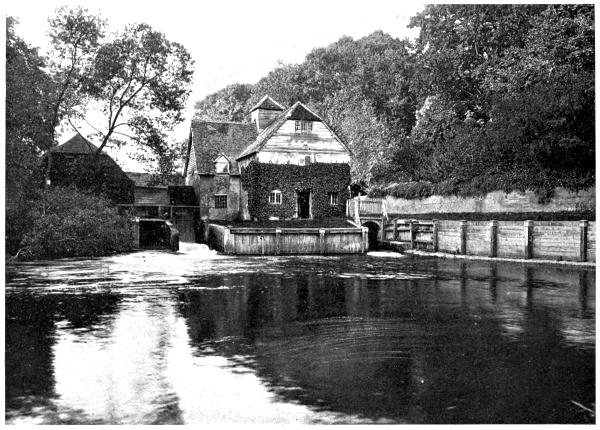

Ashton Keynes Mill.

There are many little bridges spanning the Thames at Ashton Keynes, for the stream washes the old stone garden-walls of a long line of cottages, and the entrance to each cottage necessitates a bridge of stone, of brick, or of timber. Stonecrop, candytuft, wallflowers, arabis, snapdragon, and many other semi-wild plants grow in the crevices of these old walls, and drape them all the summer with an unimaginable mantle of beauty; and where the cottages end, and the highway becomes a straight flat road, making for Cricklade, a modern country residence has been built, with the walls of it going down in the same way into the water, and the wild flowers encouraged in the like fashion to inhabit there. A contemplative person might pass a pleasant time at Ashton Keynes, where there is a homely inn, but none of those unamusing “amusements” which serve to render places of holiday resort unendurable. For those not very numerous persons who are satisfied with their own company Ashton Keynes affords decided attractions. No one ever goes there, for it is on the road to Nowhere in Particular, and not even the motor-car is a very familiar sight. Thus the ruminative stranger will have his privacy respected; unless indeed he happens to be either an artist or a photographer, when he is certain to be surrounded by a dense crowd of children, who seem to become instinctively aware of an open sketch-book or a camera at hand, and surround the owners[29] of them in most embarrassing fashion. The artist is the more fortunate of the two, for it is only an easily-satisfied curiosity to see what he is doing which attracts these unwelcome attentions; while the unfortunate photographer is pestered with requests to be “took,” and worried to extremity of despair by hordes of fleeting children obscuring his camera’s field of vision, or posing grotesquely and in most damaging fashion in his choicest foregrounds.

Below Ashton Keynes the Thames is joined by the little Swillbrook, and crossed at the confluence by the small, three-arched masonry Oaklade Bridge. A mile or so below this is Water Hay Bridge, a typical “county” bridge, whose frame of iron girders and railings, painted white, ill assorts with the luxuriance of swaying reeds and thickly-clustered alders that here enshrouds the stream.

We read in old accounts of the Thames that it was navigable for barges as far as this point, and “Water Hay” may possibly be a corruption of Water Hythe, indicating a wharf. It is in this connection to be noted that the Cricklade and Ashton Keynes road crosses here, and that however unlikely it may now seem that the stream could ever have been navigable to this spot for such heavy craft as barges, it must always be borne in mind that, in the many general causes that have led to the shrinkage of rivers throughout the country, and here in especial in the pumping away of the head-spring of the Thames, the stream cannot now closely compare with its old self of a hundred and fifty years ago. We may therefore very well believe those old writers who speak of the Thames[30] being navigable to this point, and imagine, readily enough, a rude wharf where goods were landed, and left for Ashton Keynes and surrounding villages, in days when even the few roads of the present time either did not exist at all, or were so bad that haulage along them was almost impossible, by reason either of the mud, or of the water that very often flooded them.

Between this and the little town of Cricklade the stream winds continually, but the road goes straight over Water Hay Bridge and makes direct for the townlet, three miles distant. The navigation of these first few miles of the Thames was long ago considered to be so irretrievably a thing of the past, that it was permitted the constructors of the North Wilts Canal, in crossing the stream, one mile above Cricklade, to build a brick bridge or aqueduct so low-pitched across it that the crown of the arch scarcely appears above water, and effectually stops any attempt to get even a canoe through.

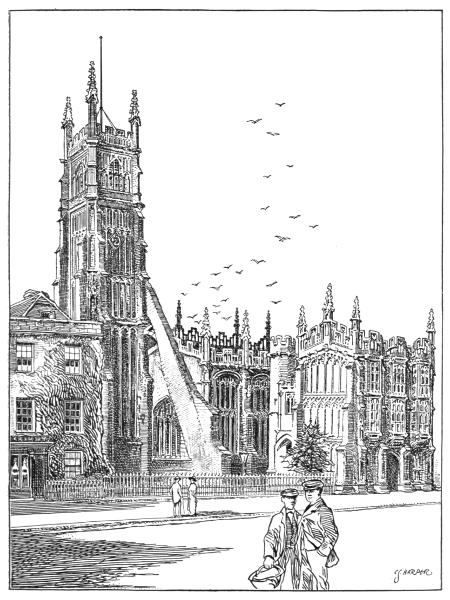

THE INFANT THAMES, ASHTON KEYNES.

The approach to Cricklade from the west by road is a noble introduction to the town. It is a small town, of entirely agricultural character, yet it has been a place of importance in its day; and although that day has long passed, its two churches of St. Sampson and St. Mary prove it to have been once considerable. Cricklade, indeed, standing on the Ermine Way, the Roman road that led from Spinae to Corinium—or in modern terms, from Speen by Newbury to Cirencester—could not have been other than important. The invading Danes, making their way up the Thames Valley in A.D. 905, and again in 1016,[33] found it worth while plundering, and it has from very early times been a market-town. It prospered in a quiet way until the opening of the Thames and Severn Canal, in 1789, for it was, after the ancient wharf at Water Hay had been abandoned, at the head of the Thames navigation; but when the canal came past, outside the northern end of the town, the water-borne traffic halted here no more, and Cricklade was, in a minor-tragical way, ruined. Nor have railways served ever to redress the injustice. The Great Western comes no nearer than the small wayside station of Purton, four miles distant, and although the Midland and South-Western Junction Railway comes to Cricklade, and has a station here, the railway management—judging from the fact of its providing only one train a day each way, at inconvenient hours—would much rather you did not use it, you know, if you don’t mind. And the Cricklade people do not use it, and go the four miles to Purton, instead. We have, therefore, not the slightest prospect of Cricklade ever growing. It is quite in keeping with the rural look of the one long broad street of Cricklade, bordered by houses that are, for the most part, of cottage-like appearance, that it has for centuries been known as the “Peasant Borough”: the technical territorial “township” including no fewer than fifty-one surrounding parishes. That it should have been, until the passing of an early Reform Act, also a Parliamentary borough, returning members to Parliament, does not of itself seem remarkable, knowing as we do that places like Gatton and Old Sarum, with no inhabitants at all, shared the same privilege. Cricklade, however, lost its[34] representation through long-continued and shameless bribery.

Here, in the long silent streets of Cricklade, the stranger is noted curiously in summer, the local season being in winter; for this is now a hunting-centre of the divided Vale of White Horse country, and the hounds are kennelled here.

Cricklade, we are told, is properly “cerriglád”: an ancient British expression signifying a “stony ford”; but is it not, even more properly, “Cerrig-let,” i.e. the stony place where the river Churn has its outlet to the Thames? We have several places in England in which “cerrig” is hidden under various corruptions: notably Crick, in Northamptonshire, and numerous places named Creech, in widely-sundered districts; while in Wales we find Cerrig-y-Druidion in the north, and Crickhowell in the south. In Scotland the word is commonly rendered “Craig.”

APPROACH TO CRICKLADE.

But old writers who flourished before the science of place-names had come into existence generally guessed at the meaning of the names of those places of which they wrote; and extremely bad guesses they almost always made. Their way with “Cricklade” is a shocking example of a “reach-me-down” ready-made meaning, supplying a barbarous misfit. Cricklade, if you please, is, according to these seekers after truth who are content to pick up the first obvious lie that rests in their path, or to seize the first absurdity that suggests itself, is “Greeklade,” the site of a forgotten Greek university established here even before the coming of the Romans. Forgotten! yes: that university is easily forgotten which had never[37] any existence; but this derivation served its day, and was generally accepted. Thus we find the poet Drayton content to write in his Polyolbion:

But Drayton erred only where others had erred for some seven or eight hundred years; for indeed the absurd legend derives from the name of “Greek-islade,” given to the town in the time of Alfred the Great.

St. Sampson’s, the chief church of Cricklade, stands by the road as you enter from the direction of Ashton Keynes; its tall, curiously-panelled tower framed beautifully in the view by a noble group of hedgerow elms. This odd dedication puzzles most people, and in truth St. Sampson, or “Samson,” without the “p,” is a remote and obscure personage who flourished in the sixth century, and is thought to have died A.D. 560. He appears to have been a Breton who fled his country, and in after-years returned to Brittany and became Bishop of Dôl. Two other churches are dedicated to him: South Hill, by Launceston, and Golant, near Lostwithiel, in Cornwall; while the island of Samson, in the Scilly Isles, owes its name to this source. Milton Abbey, in Dorsetshire, was formerly quadruply dedicated to SS. Mary, Michael, Samson, and Bradwalladr; while there still exists a St. Sampson’s church in the City of York. But that owes its name to another fellow—an early Archbishop of York; so early, indeed, that he is not generally included among the primates. He, strangely enough,[38] appears to have been contemporary with, and a friend of, the other Sampson.

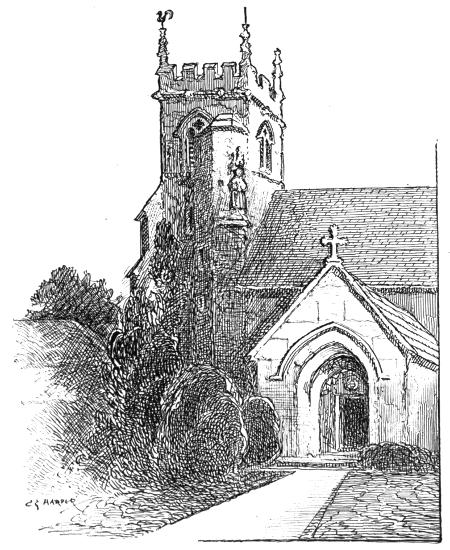

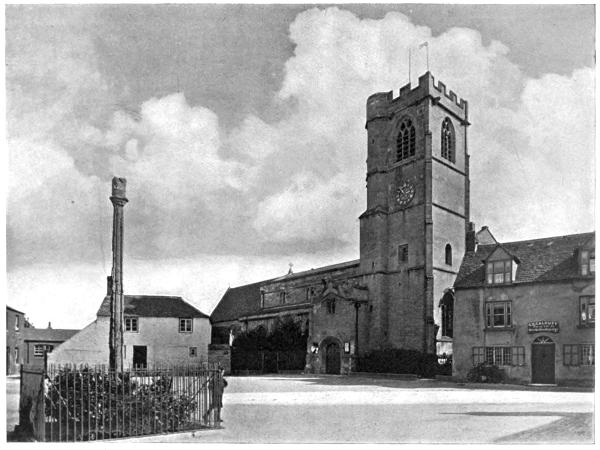

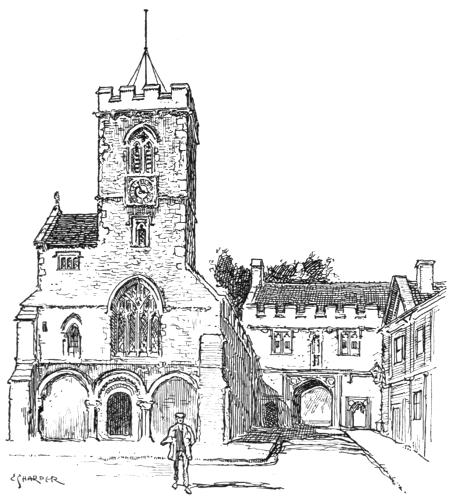

ST. SAMPSON, CRICKLADE.

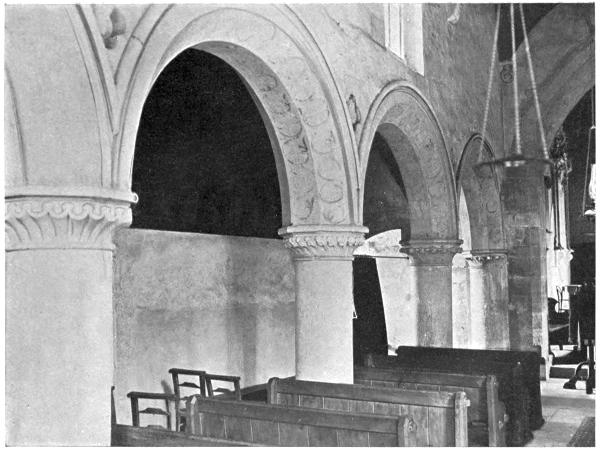

This church of St. Sampson at Cricklade does the saint especial honour, for it is a much more than usually fine cruciform building, greatly superior to the usual parish type. It presents, in general, an exterior view of Perpendicular character, even though, on closer examination, the architectural expert may discover very considerable Early English and Decorated portions. The central tower is its great feature, for you not only see it from afar, but on a closer view it is found to be so strikingly individual that even those persons unusually well-versed in these things are puzzled to find anywhere its fellow. The detailed illustration of it in this book will render unnecessary any lengthy description; and will at the same time reveal the noble quality of its sturdy pinnacles and the exquisitely effective character of the deep panelling that covers the upper stage and mounts into the angle-turrets. It is a finely massive, robust design, to which the elegant light pierced parapet adds a contrasting note of airy grace. In the detailed view of this tower an empty niche will be seen, which probably once held a statue of the eponymous saint of this church. On the side of the tower not shown a keen eye may observe a pair of scissors sculptured at a considerable height from the ground: an indication, doubtless, that the tower, rebuilt in its present form, owed its existence to the benefaction of one of those wealthy clothiers who in the fifteenth century attained in the Cotswold and surrounding districts to their highest degree of prosperity, and gave liberally of their wealth to the[41] rebuilding of churches, the founding of almshouses, and other good deeds, and have left numerous records of their existence in the fine monumental brasses of Wiltshire and Gloucestershire, ensigned with their merchants’-marks or the emblems of their trade—the wool-pack and the shears, in place of the heraldic achievements of nobler persons.

The interior of this charming church is even more noble than the impressive exterior bids us expect. It is at once massive, and well-lighted, and graceful: the climax of its beauty found beneath the central tower, where the piers and arches and finely-ribbed vaulting go soaring up to form a handsome lantern, set about with many shields, sculptured with the arms of Edward the Confessor, of the diocese of Salisbury, and of the Dudleys, Earls of Warwick. Prominent here among these cognizances we shall find the intertwined sickles of the extinct, but once wealthy and powerful, Hungerford family, whose ancient badge is found plentifully all over Wiltshire, and frequently in Somerset. It is a Sir Walter Hungerford of the mid-fifteenth century who is here the subject of allusion in this shield, for he gave the presentation of the living of St. Sampson’s, together with the manor of Abington Court, to the Dean and Chapter of Salisbury, for the express purpose of maintaining the Hungerford Chantry in Salisbury Cathedral, and to assist in keeping in repair the Cathedral campanile.

Many changes have befallen since then: the Church has been reformed, and chantries are no longer possible; but the ancient, beautiful, and interesting detached campanile of Salisbury Cathedral was in[42] existence until nearly the close of the eighteenth century, when it was wantonly destroyed by Wyatt in the course of the disastrous “restorations” in which the Dean and Chapter, charged particularly to maintain the campanile, placidly betrayed their trust, and calmly saw it levelled with the ground. To-day the presentation belongs to the Dean and Chapter of Bristol.

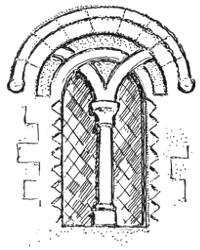

A curious feature of the exterior of St. Sampson’s is the flying angle-buttress to the south-east, supporting a Perpendicular south-east chapel built very clumsily on to the already-existing Decorated chancel. The illustration clearly shows the awkward way in which the addition abuts upon the older building, partly blocking up a very fine window. The addition was obviously not built with good foundations, as the necessity for further adding the flying buttress, and the subsidence still evident in the distinctly out-of-plumb lines of the chapel, still show. The date of the buttress is still visible, carved on the stonework: “Anno Domini 1569.”

The tall canopied cross now standing in the churchyard was originally in the street, but was removed hither to preserve it from the injury it was there likely to suffer; and in its stead we find an object of a very different character, and warranted to withstand the ill-usage of many generations of mischievous children: nothing less than a Russian, or other, gun. The school-buildings immediately in the rear of the cross are the successors of those founded and endowed in 1652 by one Robert Jenner, goldsmith, of London.

STRAINER-BUTTRESS, ST. SAMPSON’S, CRICKLADE.

“LERTOLL WELL”

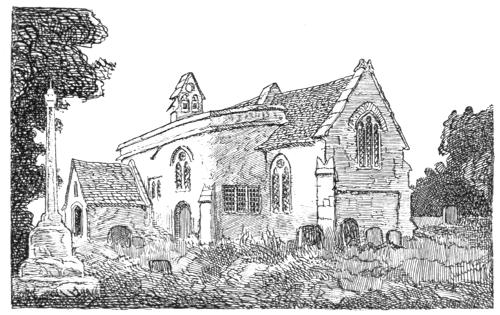

Another similar cross is to be seen in the little[45] churchyard of the curious old church of St. Mary at the other, the northern, extremity of the town, and immediately looking on to the street. St. Mary’s is altogether different in appearance from the noble, upstanding church of St. Sampson, but none the less interesting on that account. It is a huddled-together old building, with a squat tower, or remains of a tower, and altogether on a miniature scale. Queer little dormer windows start out of its broadly-sloping roofs, and they and the south porch are things of delight in the picturesque way. The interior is an affair of very slender Late Perpendicular nave piers and arcade, contrasting with a stern, sturdy Norman chancel-arch.

Proceeding still northward beyond this point, the Thames is seen, here reinforced by its confluence with the river Churn; and if we care further to proceed a few yards, the Thames and Severn Canal will be found.

A strange belief exists among the people of Cricklade, to the effect that any native of the town possesses, as his or her birthright, the privilege of selling anything without a licence in the streets, not only of Cricklade, but of any other town in England and Wales. This belief, although unsupported by any evidence, has been handed down from time immemorial. It would be curious if any native-born inhabitant of Cricklade were to test this by selling any articles in (say) the streets of London, without first providing himself with a hawker’s licence, so that this traditionary right could be proved still effective, or otherwise. The privilege is said to have been conferred by some unspecified king, in acknowledgment[46] of Cricklade having given shelter to his Queen “when in distress.”

In this connection we may profitably turn to the old farm-house, once a manor-house, in Cricklade, by the banks of the Thames, called “Abington Court,” once the property, as we have already seen, of the Dean and Chapter of Salisbury. This is said to have been formerly a Royal hunting-box, and tradition further tells us that Charles the Second was the last monarch to use it. History does not tell us of any Queen in distress at Cricklade, nor of any Queen ever here; but kings have ever been accustomed to maintain many queens (so, without offence, in these pure pages, to call them) from the time of Solomon and David, throughout the ages, and until modern times. It is a kingly privilege, not often allowed to lapse; and it is quite within the bounds of possibility that there was at some time one of these uncertificated consorts at Abington Court, and that here she gave birth to a child, and that this particular (or shall we say, this not very particular?) king thereupon celebrated the occasion by conferring the curious privilege already discussed.

There is something in this ancient house which seems to support the theory: a substantial something in the shape of a large and elaborately-carved old oaken four-poster bedstead, fine enough to have been used by such distinguished personages. No one knows how it came here, but here it remains, and goes with the property. Tenants may come and go, but the bedstead, left by the last royal occupant, stays.

An exceptionally interesting spot exists at a distance[47] of a mile-and-a-half to the north of Cricklade town, in the neighbourhood of Latton and Down Ampney. You will not easily discover this interesting spot, because no map marks it, no guide-book tells of it, and only very few among the older generation of the rural agricultural labourers cherish any recollection of it. The younger folk know nothing whatever of this historic landmark, which is so insignificant and elusive a thing that one might readily be in the same field with it, and yet not see it. It is the pure and never-failing spring of St. Augustine’s Well, once famed in all the country round about; either by that name, or by the alternative title of the “Lertoll Well,” or stream. This pure and cooling fount was long credited with medicinal virtues, less because of any properties in the water itself than because it was blessed by Saint Augustine. For it was to these parts that Augustine came, somewhere about thirteen hundred and twenty years ago, for his conference with the dignitaries of the native British Church. Augustine, accredited by the Pope, Gregory the Great, to England, on a mission to reconvert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity, in addition sought to reconcile the early British Church, which had continued to survive in Wales, with the Church of Rome; and to that end he arranged a conference on or near this spot, beyond the then boundary of Saxon England, in the territory of the British clan known as the Hwiccas. Had Augustine been a different manner of man, the proposals he had to offer for a fusion of the Churches would probably have been entertained; but although long since canonised, he was really very[48] little of a saint, and by no means the eager missioner he is generally represented. He came to England, in the first instance, only because he was sent, very much against his inclination, by his spiritual head, whom he dared not disobey; and his haughty, intolerant temper brought these ideas of unity to naught. At the place of meeting was an oak-tree, for many centuries afterwards known as “St. Augustine’s Oak,” but long since utterly decayed and vanished away. It is said to have been felled about 1825, and the site of it is supposed to be a small group of farm-buildings, rebuilt in modern times, known as the “Oak Barn.” The British clergy had heard unfavourably of Augustine’s domineering spirit, and went with suspicion to meet him. They had agreed, however, when they proceeded to this oak, which must have been a notable landmark, that if he received them standing, they would listen favourably to his proposals; but if he sat when they presented themselves, thus receiving them as inferiors, they would refuse to discuss the question of unity.

Augustine received them sitting, and the conference broke up. He is said to have performed miracles here, at this meeting, and to have touched the eyes of the blind with the water of the Lertoll stream, so that their sight was restored; but none of these prodigies availed with those slighted native clergy.

It is remarkable, however, that an obscure tradition lingers among the peasantry of the neighbourhood to this day, to the effect that the water of this stream is “good for the eyes.” You will not find this tradition in books; it is just a belief handed down[49] from father to son in the course of some forty generations.

The spring is situated in a meadow to the north of the Cricklade and Maisey Hampton road, and bubbles up and runs unheeded away, in these material, sceptical times; but those days are not far removed when the peasantry of Gloucestershire and Wiltshire resorted to it, for cure of their ailments, and filled bottles with the treasured water, for home use.

CASTLE EATON—KEMPSFORD—BY THE THAMES AND SEVERN CANAL TO INGLESHAM ROUND HOUSE—LECHLADE—FAIRFORD—EATON HASTINGS WEIR—KELMSCOTT—RADCOT BRIDGE.

A mile or so below Cricklade, the river Ray flows into the Thames, from the direction of Swindon. Opposite, on the left bank, stands Eisey Chapel, on its little knoll amid the meadows. It is the place of worship of the hamlet of Eisey, a little collection of cottages removed out of sight from the river; and is just a small rustic Perpendicular building, with a bell-cote. Water Eaton, which is not on the water, and Castle Eaton, which does not possess a castle, come next, both deriving the name from ea = “water”; the first named of the two therefore given its name twice over. The “water” of Water Eaton refers perhaps to the old manor-house, rather than the church, the manor-house being in sight of the stream. The prefix to the name must have been added in Saxon times, when the Romanised British were driven out and the descriptive nature of the name “Eaton” forgotten. Although not spelled in the same way as Eton by Windsor, the two mean precisely the same, and have fellows in very many other “Eatons” throughout England.

THE IRON GIRDER BRIDGE, CASTLE EATON.

THE OLD BRIDGE, CASTLE EATON.

Water Eaton manor-house, of heavy Georgian architecture and dull red brick, with characteristically prim rows of heavily-sashed windows, is unimaginative but decorous.

Although Castle Eaton has now no castle, and not even the discoverable site of one, here was formerly situated a stronghold of the Zouches. It is a very quiet village, of a purely agricultural type, and generally littered with straw and fragments of hay. Here the Thames was until quite recent years crossed by a most delightful old bridge, that looked like the ruins of some very ancient structure whose arches had been broken down and the remaining piers crossed by a makeshift affair of white-painted timber. “Makeshift” is perhaps hardly the word to be properly used here, for it seems to indicate a temporary contrivance; and this bridge, if not designed in keeping with the huge, sturdy, shapeless stone and rubble piers, was at any rate sufficiently substantial to have existed for many generations, and to have lasted for many yet to come. Alas that we should have to write of all this in the past tense! But it is so. Twenty years ago, when the present writer paid his first visit to Castle Eaton, the old bridge was all that has just been described—and more; for no pen may write, nor tongue tell, of the beauty of that old, time-worn yet not decrepit, bridge, that carried across the Thames a road of no great traffic, and would have continued still safely to carry it for an indefinite period. It was one of the expected delights of revisiting the Upper Thames, to renew acquaintance with this bridge, sketched years before; and it was[54] with a bitter but unavailing regret and a futile anger that, coming to the well-remembered spot, it was seen to have been wantonly demolished, and its place taken by a hideous, low-pitched iron girder bridge, worthy only of a railway company; and so little likely to be permanent that it is observed to be already breaking into rusty scales and scabs beneath its hideous red paint. The ancient elms that once formed a gracious background to the old bridge stand as of old beside the river bank; but the old bridge itself lies, a heap of stones that the destroyers were too lazy to remove, close by, on the spot on which they were first flung. No description, it has been said, can hope to convey the beauty of Castle Eaton Bridge, for the old stone piers were hung with wild growths, and spangled and stained with mosses and lichens. A sketch of one end of it may serve; but it once formed the subject of a painting by Ernest Waterlow, and in that medium at least, its hoary charm has been preserved. Let a photograph of its existing successor be here the all-too-shameful evidence of the wicked ways of the Thames Conservancy with this once delightful spot in particular, and with such spots in general. We cannot frame to use language too strong for a crime so heinous against the picturesque.

CASTLE EATON CHURCH: SHOWING SANCTUS-BELL TURRET.

THE THAMES AND SEVERN CANAL, NEAR KEMPSFORD.

Let us recapitulate the facts, and draw the indictment more exactly against that sinning body. We shall thus ventilate a righteous indignation, and help to create a healthy public feeling against all such damnable doings, by whomsoever done. We are, of necessity, in this country of change and of an increasing population, faced with a continuous defacement[57] of places ancient, beautiful and historic; and it behoves us to use our utmost efforts to preserve what we have left. What, then, shall we say of such absolutely unnecessary outrages as this? Shall we not revile the whole body responsible, from the Board and the Secretary down to the chief engineer and the staff of underlings who did the deed? The Thames Conservancy, in fact, has been a most diligent destroyer of the beauty of the river; slaving early and late and overtime in that devil’s work, but remaining supremely idle where the encroachments of private persons, or the uglifications by waterworks companies, and modern mill-and factory-builders are concerned. It is the Thames Conservancy that has repaired the banks of the river and has reinforced the walls of its weirs and lock-cuts, with hideous bags and barrels of concrete, that retain their bag-and-barrel shape for all time, and so render miles of riverside sordid in the extreme. We simply cannot afford these ways with the river.

The church of Castle Eaton is in a modest way a remarkable building. It is a moderate-sized Early English structure, chiefly notable for retaining its original stone sanctus-bell turret on the roof. The interior discloses nave and chancel only, with a shallow elementary north aisle, built out from the original building, and supported upon two wooden pillars on stone bases. This extension—a half-hearted addition—was itself made several centuries ago, apparently for the purpose of affording additional seating accommodation at some period when the population had increased. But it has greatly shrunken since[58] then; and in these times when the towns have superior attractions for all wage-earners, it still continues to shrink.

OLD WOODWORK, CASTLE EATON.

A very curious old oak post, some seven feet high, and carved with a spiral pattern, stands at the end of one of the pews, and seems to mark what must have been the old manorial pew; bearing as it does on its ornamental head a shield of arms, dated 1704, probably that of some bygone local family. The whole affair looks remarkably like a part of some old four-poster bedstead, but it may be one of the supports of a former western gallery. A half-length fresco figure of the Virgin—the church being dedicated to St. Mary—is to be seen on one of the walls, and a very large, and apparently fine, brass of a knight was once in the church. But this has been at some time destroyed, and the stone indent itself is now to be found, flung out of the building and used as a paving-stone, outside the west door.

Road, river, and canal now all make for the village of Kempsford, which does not derive its name from some ancient, prehistoric Kemp, but from “Chenemeresford,” said to signify “the ford on the great boundary”; that is to say, the river. And Kempsford is situated in Gloucestershire, here divided from[59] Wiltshire by the Thames, which forms the natural frontier of many counties along its course, from Thames Head to the sea.

We shall find the best way from Castle Eaton to Kempsford, little more than a mile distant, to be across the meadows and to the towing-path of the Canal, here and onward to its beginning at Inglesham, a very beautiful stretch of water-way; overhung, as it is, by noble trees in places, and rich in rushes and water-lilies. When the Gloucestershire and other County Councils, together with the local Rural District Councils, procured an Act of Parliament for taking over this neglected waterway, great hopes were entertained of reviving an undertaking which had never been remarkable for its financial success, and it was fondly hoped thereby to break the “monopoly” held by the railway. A trust was formed in 1895 by those public bodies interested, and it was agreed to guarantee £600 annually for thirty years for repairing and working the canal. The Great Western Railway was thus rid of an incubus, and the ratepayers of these various districts find themselves saddled with an utterly unremunerative expenditure that no commercial firm would have had the folly to assume. For not only were the repairs of Sapperton Tunnel exceedingly costly, and the general overhauling of the canal expensive, but no traffic worth the mention has been induced to come this way. Those squanderers of public money were heedless of the facts of modern business, and forgot to consider that in these latter days time is more than ever the[60] essence of the contract in worldly affairs. Less able than ever, therefore, are canals to compete with railways. So once more, after a fugitive period of activity, we see the Thames and Severn Canal returning to its old neglected condition.

NORMAN PORCH, KEMPSFORD.

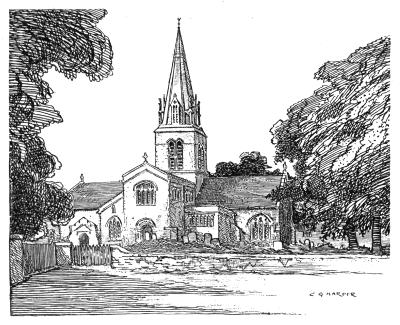

KEMPSFORD CHURCH.

Kempsford church-tower is prominent across the meadows, and we find it to be a notable and interesting church, and the village a place of aristocratic appearance, where humble cottages are few and the manor-house imposing. This is as it should be in a place with its history: the manor having once belonged to Edward the Confessor, who gave it to Harold. William the Conqueror conferred it upon one of his[63] knights, and in the course of the centuries the property came to Henry, Duke of Lancaster, whose son-in-law, John o’ Gaunt, Shakespeare’s “time-honoured Lancaster,” once resided here, greatly favouring this one of his many manors, of which the number scattered all over England was so great that it would have been distressingly hard work for him to visit them each and all in the course of a year.

The only son of Henry, first Duke of Lancaster, was drowned here, and his sorrowing father is said never again to have resided at Kempsford. On the north door of the church is nailed a horseshoe, in allusion, it is said, to one cast by his horse on his departure, and immediately nailed up here by the inhabitants. It is, indeed, often said to be the original shoe, but that is an absurdity. A curious other horseshoe legend and observance is to be noted at the town of Lancaster, John o’ Gaunt’s ancient palatine seat. There, where the two principal thoroughfares of the town cross, is “Horseshoe Corner,” so named from the horseshoe let into the roadway, and renewed in every seven years; in memory, says tradition, of a shoe cast there by his horse.

Kempsford church consists of a long and lofty aisleless nave, with tall central tower. The nave is Norman, with Norman doorways and Perpendicular windows, and very beautiful, gorgeous, and impressive.

The ancient manor-house, frequently styled “the Palace,” came at last into the possession of the Hanger family, Earls of Coleraine, one of whom wantonly destroyed it.

The Thames and the Thames and Severn Canal, running almost side by side at Kempsford, now abruptly part company again, and meet only three-and-a-half miles farther on, at Inglesham. The canal is the more easily followed, since the windings of the Thames in those miles add certainly another mile and a half to the distance, and are to be followed only with extreme difficulty by canoe, or afoot through many fields. Hannington Bridge, crossing it nearly a mile and a half below Kempsford, is the first bridge of any importance, and is a solid, stolid modern masonry building, eminently practical and unimaginative, serving to carry the road from Highworth to Fairford across. The remains of an old weir on the way give pause to the exploring canoeist at most seasons; and a small tributary, the river Cole, hailing from Berkshire, is seen on approaching Inglesham.

There are no churches in these surroundings more interesting than the humble little building at Inglesham, one mile from Lechlade, in an almost solitary situation. It is quite a rustic church, chiefly in that best period of gothic architecture, Early English, and it is so far removed from restoration, or even adequate care, that it is almost falling to pieces. Damp and neglect have wrought much havoc here, and the zealous concern of the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings, by preventing any large scheme of repair, seems not unlikely to result, at no distant date, in the entire dissolution of the structure.

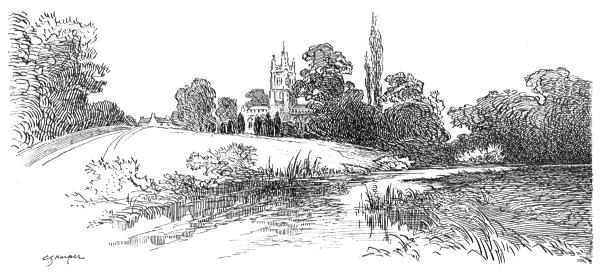

The meeting of the canal and river at Inglesham Hound House is marked picturesquely by the grey round tower of the Hound House itself, and by a row[65] of tall poplars. The Round House is nothing but a glorified lock-keeper’s house, situated beside this, the first lock, where the canal sets forth on its way toward Stroud and the Severn. A mile farther downstream lies the town of Lechlade, across the lovely level meadows, with the tall spire of its church glinting whitely in the sun. It is an exquisite view, and so alluring that you are in haste to make acquaintance with Lechlade itself, that promises so romantically. But let us not hurry. Rather that distant view than Lechlade at close quarters; for although it is in very truth an inoffensive town, it is also sufficiently true to remark that it is dulness incarnate, and that this mile-long glimpse will be found the better part.

INGLESHAM CHURCH.

At Inglesham Round House there are plentiful facilities wherewith to refresh the body and to employ[66] the uncultivated mind; for the lock-keeper’s domain includes a number of apologetic sheds and shanties devised for the benefit of picnic-parties; and anything eatable or drinkable likely to be called for by parties on picnic, or boating, or merely padding the hoof, is obtainable, together with the mechanical music of melodeons or other such appliances that will serve you with pennyworths of minstrelsy, as more or less appropriate sauce. Here also is a greatly-patronised camping-ground, generally plentifully occupied with tents in favourable summers. The river Coln here also flows into the Thames from Fairford.

It is a pretty spot, with its hunchbacked lock-bridge, and the not unhandsome modern foot-and tow-bridge that spans the Thames, helping to compose a picture. It is the Ultima Thule of the Oxford man’s “Upper River”; the farthest point to which it is generally navigable for small boats.

Passing Inglesham Round House, and proceeding over the foot-bridge to the right bank of the Thames, toward Lechlade, we enter Berkshire; crossing over the stone single-span Lechlade bridge into the town and into Gloucestershire.

The town of Lechlade takes its name from the little river Leach which rises at Northleach, fourteen miles in a north-westerly direction, and gives its name to Northleach, East Leach Turville, and East Leach Martin. Although Lechlade—i.e. “Leach-let,” the outlet of the Leach—thus obtains its name, that little river flows into the Thames at a considerable distance away, two and a half miles below the town, at Kelmscott.

INGLESHAM ROUND HOUSE.

The disastrous persons who derived “Cricklade” from “Greeklade,” and invented a university of Greek professors there, made “Lechlade” a rival seat of learning, where Latin was taught, and gave its original name as “Latinlade.” Fuller tells us how this imaginary university—in which he seems to have believed—ended by migrating to Oxford. He is quite poetic about it. “The muses,” he says, “swam down the shores of the river Isis, to be twenty miles nearer to the rising sun.”

Other, and equally weariful, persons made Lechlade, “Leeches-lake,” the home of the College of Physicians (“leeches”) relegated to this obscure town—which, of course, it never was.

It is now hardly conceivable that once upon a time there was a considerable traffic in cheese upon the upper Thames, between Cricklade, Lechlade, Oxford, and London; but such was the case. This was formerly a great cheese-producing district, as it might well be now; and, as roads were bad everywhere and railways were not yet, the only method was to load the cheeses on barges, and so float down-stream.

Lechlade is very well on week-days, in the quiet way of all such decayed townlets, but on Sundays it is not to be recommended. Dulness stalks its streets almost visibly, and the only sounds are the argumentative tones of the preacher in the Wesleyan chapel (a building with black doors and gilded mouldings, after the fashion of a jeweller’s shop) at one end of the street, whose raucous voice can be distinctly heard at the other: not unlike that of a man quarrelling outside a public-house.

But the fates preserve us from a Sunday at Lechlade! It is fully sufficient to skim through the place at such a time, and make for some other that does not so completely figure the empty life. A village is not dull, because it has no pretensions to being a town—and country life is never dull. But at Lechlade the position is so desperate on Sunday that, for sheer emptiness of other incident, a large proportion of the population flock the half-mile that stretches between the town and the railway-station, and hang, deeply interested, upon the bridge, to witness the Sunday evening train depart. It is a curious spectacle, and one that carries the mind of a reminiscent reader back to stories of marooned castaways on desert isles, gazing hopelessly upon the departing ship that has left them to solitude and despair. That must needs be a place of an extreme Sabbath emptiness where the grown-up inhabitants are impelled, by way of enlivening the weary evening, to walk half a mile to witness what seems an incident so commonplace to the inhabitants of places whose pulses beat more robustly.

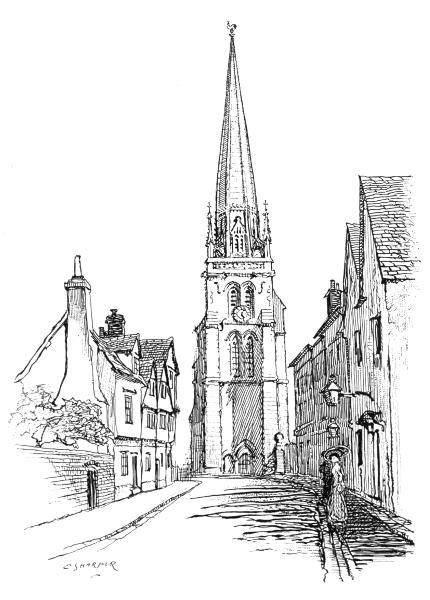

A STREET IN FAIRFORD.

The “pratie pyramis of stone,” as Leland styles the spire of Lechlade church, is almost the only architectural feature of the townlet, if we except a few mildly-pretty stone-built houses of Tudor gables and mullioned windows; among which may be included the “Swan” inn. None of these are included in the accompanying view of the church, which, although graceful without, and promising interest within, has been miserably treated, and swept clear of anything of note. A few curious carvings are to be noted on[73] the lower stage of the tower exterior, including a singular bearded and capped profile head and a hand grasping a scimitar. Although well done, they look like the idle sport of some irresponsible person or persons, and do not appear to have any particular meaning or local application.

ANCIENT CARVING, LECHLADE CHURCH.

The architecture of the building is of no great interest to archæologists, being of somewhat late Perpendicular date, but a charming example of tabernacle-work may be noted on one of the piers of the nave-arcade, adjacent to the font. On the gable of the nave, at the east end, is a figure of St. Lawrence, to whom the church is dedicated. He holds a gridiron, the symbol of his martyrdom, in one hand, and the book in the other.

Fairford is the centre of attraction in this district. It lies away north-west, four miles distant, at the end of the little railway from Lechlade, on the river Coln. The Gloucestershire Coln has its name spelled without a final “e” (for what reason no man knoweth), and gives a title of distinction to a group of villages—Coln St. Denis, Coln Rogers, and Coln St. Aldwin’s—that are famed for their beauty. But Fairford has superior[74] claims to notice, chiefly for the celebrated stained-glass windows of its church.

“Fair-ford” may or may not derive its name from its picturesque situation, but the beauty of the ancient ford of the Coln, now and for long past crossed by a bridge, might well warrant an assumption that the name arose from an æsthetic appreciation of the scenery. Exactly what it is like to-day may be seen by the view shown here, with its noble church placed finely above the meadows.

Fairford is a village that was once a town, prosperous in the far-off days when the wool-growers and the cloth-workers of the Cotswolds made fortunes in their trades and founded families that came in time to a dignified haven in the peerage; and at last declined and died out, or have rejuvenated themselves with American marriages and the dollars incidental thereto. This old process of founding families by way of successful trading we may still see at work, in our own times, under our own intimate observation, encouraged by the institutions of primogeniture and a House of Lords, two most powerful incentives to success.

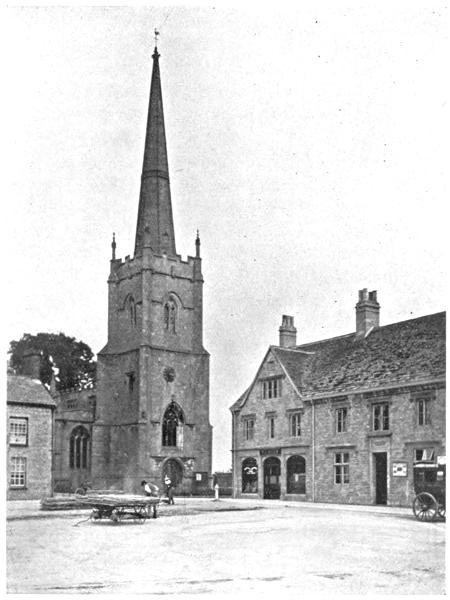

LECHLADE.