Project Gutenberg's Captain Lucy in the Home Sector, by Aline Havard This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Captain Lucy in the Home Sector Author: Aline Havard Illustrator: Ralph Pallen Coleman Release Date: June 20, 2018 [EBook #57362] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CAPTAIN LUCY IN THE HOME SECTOR *** Produced by ellinora, David King, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

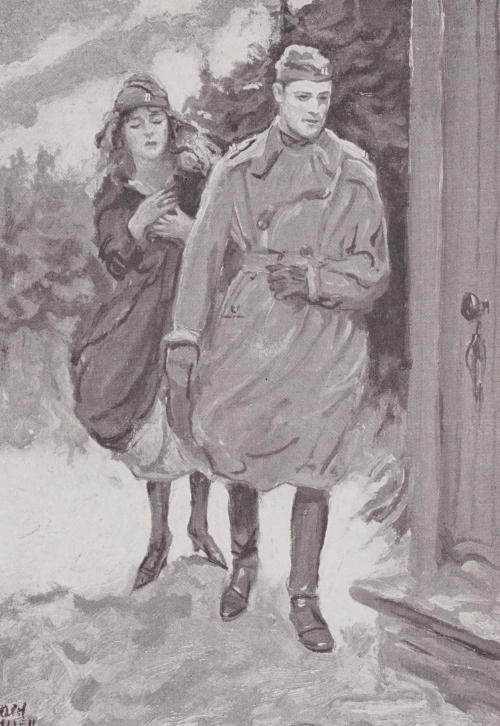

She Gave a Quick, Grateful Sob

If the young people who read this last story of Lucy Gordon’s army life are disappointed that the end of the war does not bring her home to America they cannot possibly be as disappointed as she herself. She hoped that the war had really finished with the armistice but, like lots of us, she found that there was a great deal left to do that she had not counted upon. Peace was slow in coming, and the American army overseas had its hands as full trying to hasten it as all America on this side had, and still has, in trying to get back to peace-time ways.

The tangle of affairs in war-swept Europe is more than Lucy can understand, though she sees a little of that great unrest, and catches a glimpse of its hidden dangers, even in the Home Sector.

She does what she can to help, generously, and, though peace is not come and America is still distant, she and Bob and all the Gordon family find happiness together, and look forward with brave confidence to the glorious future of the dear country to which they will before long be homeward bound.

Aline Havard.

| I. Along the Rhine | 9 |

| II. Franz and His Family | 28 |

| III. Scouting on the Dwina | 48 |

| IV. The Silly Ass | 69 |

| V. From Russia into Germany | 96 |

| VI. The Mystery of the Forest | 117 |

| VII. Alan Takes a Hand | 137 |

| VIII. For Adelheid | 159 |

| IX. Bob and Elizabeth | 182 |

| X. A Letter to Franz | 204 |

| XI. With Larry’s Aid | 226 |

| XII. Unknown To History | 249 |

| XIII. Across the Channel | 272 |

| XIV. A Midsummer Night’s Dream | 289 |

| She Gave a Quick, Grateful Sob | Frontispiece |

| He Waved the Flaming Streamers About His Head | 65 |

| Larry Stood With Lucy by the Door | 127 |

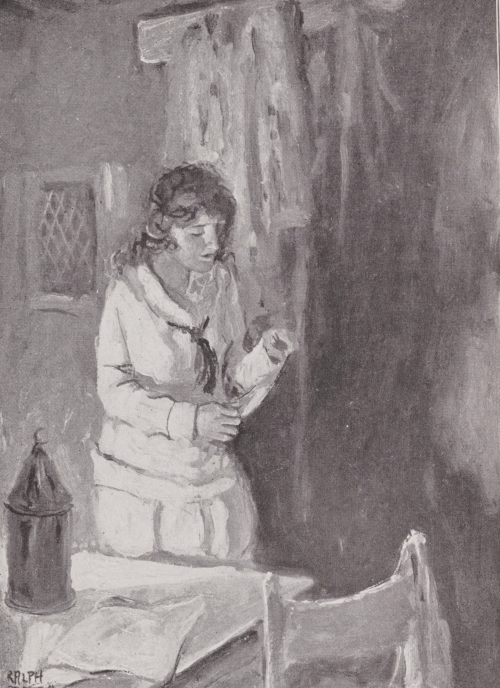

| Lucy Read the Few Lines of German | 217 |

| “Here She Is,” Bob Answered | 304 |

The Home Sector,—that was what Larry Eaton called it, a little irony beneath his irrepressible cheerfulness, when he had been ordered to Coblenz with the American Army of Occupation. He had called it so with his eyes on the Stars and Stripes already floating over the general’s headquarters in the old German city, and after a sidelong glance at Lucy Gordon’s sober face. “It’s the first step on the way home, Lucy,” he said, as the two walked along the grassy banks of the river, the pale December sunlight shining on the water and, at their left, on the low houses at the outskirts of Coblenz. “Don’t look so downhearted, old pal.”

Lucy smiled and shook off her depression. It was hard ever to be gloomy for long in Larry’s company. The young aviator had something invincibly gay and hopeful in his nature, and a philosophic acceptance of things, until they could be bettered, that often quieted Lucy’s rebellious moments. “I’m not downhearted, Larry,” she protested. “At least not very. But I did want to go home,—not after a while, you know, but right away, when the armistice was signed. I know it’s wonderful to be at peace, and to have Father safe and stationed here, but,—I don’t care very much about living in Germany.”

“Don’t you?” asked Larry, laughing. “As Beattie would say, you’re jolly right.”

“And there’s no use thinking we’ll all be together,” Lucy persisted. “Even though Father has his quarters here and Mother will finish her work and come, where will Bob be?”

“Scouting over the Bolshevik lines in the frozen north,” said Larry, a tinge of envy in his voice. “I’d change with him if I could.”

“Would you? Oh, Larry, I should think you’d had enough.”

“So we have, but so long as there’s fighting to be done I’d rather be there than cooling my heels along the Rhine. And our men aren’t having an easy time,—that poor little force at Archangel.”

“Oh, I know there’s lots of work to do!” Lucy exclaimed, suddenly roused from her childish depression, and involuntarily she opened the woolen cape she wore and glanced at her nurse’s aide’s uniform. “I’ll stop growling and try to help.”

“I don’t think you’ll have much trouble doing it,” said Larry, smiling down at her, “judging by what you’ve done so far. Only this time you’ll have an easier job of it,—no prisoners to set free. You can’t imagine a peacefuller spot than that little hospital you’re going to. It’s lost in the forest, and even the village near it looks half asleep and as though it might tumble any minute down the hillside.”

“The peacefuller it is the better I’ll like it,” said Lucy with something of a sigh. “I’ve had enough of war.”

Although General Gordon was stationed with the Fifth Army Headquarters in Coblenz, where already, a month after the armistice, American troops had taken possession of houses in the German city and were preparing for their long stay in the occupied territory, Lucy herself was still on duty elsewhere. With the end of the fighting, need for war workers of all sorts had not grown less. Mrs. Gordon could not yet leave her hospital at Cannes, and Lucy had been urged to keep on as nurse’s aide with an insistence that could not but fill her with honest pride and satisfaction. The army surgeons spoke to her of the increasing need of nurses among the convalescents, and Miss Pearse frankly begged Lucy not to abandon her.

“You can go to Coblenz in the spring, Lucy dear,” the young nurse persuaded, when new plans and changes of base occupied every mind in the joyful week after the armistice. “We have to garrison Coblenz for fifteen years, they say, so your father will probably be there a good while. But perhaps he won’t,” she added, smiling at Lucy’s face, grown disconsolate at her words. “Anyway, while you’re over here I know you’d sooner be helping. There’s almost more to do than ever. The men have been rather let down by the war’s end and all the delays following. They don’t know what to do with themselves, especially the wounded who are slow in getting well. We’ve got to give them a Christmas that will stifle their homesickness a little. And I can’t half work without you, Lucy. I’m so used to having my little aide to call on. You’ll stay, won’t you?”

This was not the sort of persuasion Lucy could resist, when her heart was already in the work that she had learned in such a hard school of suffering and anxiety. She eagerly consented to follow Miss Pearse wherever her father would allow her to go, which ended by being a little convalescent hospital outside the village of Badheim, ten miles west of Coblenz on the banks of the Moselle. Cold breezes from the two rivers swept it, and the air was pure and sweet with the odor of pine. After the shell-torn villages of France, Badheim hospital, as Miss Pearse described it, seemed lovely and inviting to Lucy in its woodland stillness. Yet something, she felt, would keep her from yielding to its peaceful spell: it was a part of Germany. It was unspoiled because France was desolate. She could not forget this long enough to look about her at any German landscape with untroubled eyes.

Even now, walking with Larry along the Rhine, she watched the smooth flow of the river and looked across at the vineyard-clad slopes and at the great old fortress towering opposite Coblenz with coolly critical gaze. All at once she turned to Larry, with sudden recollection that this was her last day of freedom and perhaps her last chance in weeks of talking with Bob’s friend, to ask longingly:

“Larry, can’t you tell me anything more of what Bob is doing at Archangel? He doesn’t write much about his work, and the letters are so slow. I know it’s hard up there. And they don’t get ahead. The Bolsheviki are strong.”

“Our force is hardly of a size to accomplish much. It ought to be enough men or none,” declared Larry, with the troubled, puzzled look that sometimes came over his face, making him look extraordinarily sober and thoughtful by contrast with his usual cool cheerfulness. “But don’t worry too much about Bob,” he added, putting aside the doubts which had made him speak so earnestly. “He’s doing scouting work. He’s far safer than he was on the German front. The cold is the disagreeable part.”

“I know. I’ve knitted him everything I thought he could pile on. He doesn’t say much about it, but I looked up Archangel on the map and, Larry, it’s near the North Pole.”

“Not quite, but I won’t say it’s a pleasant climate. Perhaps they won’t stay there much longer.”

“Well, I thought on Armistice Day that it was over, really over,—the war, I mean. But here it seems to be tailing out in every direction.”

“Yes, it has rather a nasty way of refusing to be finished,” Larry agreed, looking around him as he spoke at the passers-by, for they were now re-entering the town. “To judge by their manner these Boches seem to think it’s quite over and that we’re friends again. Yet some of them, I’m sure, are very far from feeling that way.”

“What do you really think?” asked Lucy curiously. “They smile at us and are eager to sell things. But Larry, how can they feel friendly?”

“I can’t fathom them,” said Larry, not much given to analyzing character at any time. “Most of them seem spiritless enough, but I’ve seen a few bitter looks, all the same, and some eyes that shone with hate at sight of us. I don’t trust one of them.”

“Oh, they’ll have to take it out in hating us,” said Lucy easily. “They can’t do any worse now.”

Lucy had had enough of plotting and conspiracy. She was determined to put German treachery out of her mind and live in confident simplicity once more.

“Fed-up with the war, eh, Lucy?” Captain Beattie had remarked, when Lucy and the young Britisher met by chance in Cantigny soon after the armistice. “Well, you know, I rather am myself. Let’s cross the Channel and leave it all behind.”

And that was what Lucy longed to do, putting the Atlantic in place of the Channel, in spite of trying to persuade herself of the contrary after Miss Pearse’s urging. All through the war she had looked forward to that day, the fighting ended, that would see the Gordon family on board the first ship bound for America. Even adventurous spirits have their homesick moments. Foreign sights and sounds had, while this mood lasted, lost their charm for her. She looked around her now at the old gabled houses of Coblenz, at the Germans passing, who paused to stare with blank curiosity at the Americans, already a familiar part of the city’s inhabitants, and she felt no sympathy with her surroundings.

“I’m going to bury myself in that forest and work so hard at the hospital that I’ll forget I’m in Germany,” she told Larry, as they neared the house commandeered for General Gordon’s quarters. “You might come out and see me once in a while, though, Larry, and tell me how peace is getting on.”

“I’ll be out every year or two and bring you the news,” Larry promised. “Maybe I’ll feel the need of a little rest cure myself. I’m pretty well exhausted.”

Lucy laughed as she met the blue twinkling eyes above his tanned cheeks. An orderly opened the house door as Larry held out his hand in good-bye.

The following day Lucy joined Miss Pearse and half a dozen other Red Cross workers to travel by motor-lorry to Badheim. The road ran along the Moselle, a lovely woodland countryside which went far toward bringing back Lucy’s lost serenity.

“I love the country, don’t you, Miss Pearse?” she said, breathing deep breaths of the piney air. “I should think sick men would get well quickly here.”

“I hope they will,” the young nurse responded. “But I’m sure they’d get well quicker if these woods were in Maine or in Michigan,—anywhere at home.”

Her voice betrayed her and Lucy looked at her friend with a quick thrill of sympathy. Miss Pearse was as homesick as she herself, in spite of her stoic calm. And, meeting the glance of an orderly who sat on a case of supplies in one corner of the lorry, Lucy read the same longing in his eyes even before he exclaimed almost involuntarily, “Or not even woods or rivers, Miss. Just the docks at Hoboken would look good enough to me.”

The little village of Badheim was perched upon a hillside, the road winding at its foot. The lorry turned sharply away from the Moselle to begin a long climb up a heavily wooded slope. The forest now closed in on both sides,—majestic oaks, mixed with pines and hemlocks which sang and murmured as the river breeze swept over them. Rabbits darted across the road and squirrels chattered in the overhanging branches. All at once the hospital appeared, a big frame building in a clearing near the top of the hill, its roof in spreading gables, like a Swiss chalet, and the Stars and Stripes floating over it.

Behind it were half a dozen cottages for the staff. The whole had a weather-beaten look, for it had stood there more than fifty years, and an air of solitude enveloped it, as though it were much further removed from town and village than it really was. Lucy decided in one glance that it needed sunlight and cheerful voices to keep from being a gloomy spot where the murmur of the swaying pines would change to sighs of loneliness.

In fact the convalescent soldiers seated on the verandas or strolling over the grassy clearing and in the borders of the woodland looked sober and purposeless, their idle steps leading vaguely from one spot to the other, without any spur of hopeful energy. Lucy understood at last Miss Pearse’s eloquent persuasions, and seeing how sorely help was needed here, she forgot her own repinings and was herself again.

Miss Pearse and Lucy installed themselves in a room in one of the cottages beside the hospital,—a sort of shed built of heavy unpainted planks, with sloping roof and leaded window-panes. A stove fed with pine-boughs warmed the drafty interior somewhat from the December cold.

While the two newcomers were unpacking and settling themselves in their narrow quarters the hospital’s head nurse came in and talked to them, dropping down on the nearest chair to do so; for she was tired and glad of a moment’s rest.

“You will think there is terrible confusion here, for we are all at loose ends,” she told them. “We haven’t enough nurses nor orderlies, and nothing is in smooth running order. I hope you won’t mind, for a few weeks, not having a regular routine but doing whatever presents itself.”

“That will just suit me,” remarked Lucy, brushing her corn-colored hair before the little mirror. “Send me on all the errands you can think of, Miss Webster.”

The head nurse laughed, looking kindly at Lucy’s pretty face, lighted by the smile that her unaffectedness made very attractive. “I’ll find plenty for you to do, don’t worry,” she said confidently. “When nothing else turns up, go about among the convalescents and talk to them of home.”

“Are there bad cases here? What sort, mostly?” Miss Pearse asked.

“Some are men who have been gassed and their lungs are injured. Those are the discouraged ones who think they can never get well. Then we have a good many with broken limbs slowly mending, and some recovering from pneumonia and trench fever. There are about eighty in all, and most of them getting on splendidly, if they would only forget their homesickness and that they must spend Christmas in Germany.”

“U-um, but it’s not so easy to forget that,” murmured Lucy, understandingly. “And, though of course this hospital has fine air and all that, it’s not a very cheerful place, do you think? With all these German woods shutting it in?”

“German woods are just like any other woods, Lucy,” said Miss Pearse laughing. “Don’t be making trouble. We’re ready now, Miss Webster.”

The hospital wards were nearly empty for a part of the day, during which almost all the patients got up and sat on the verandas, or were wheeled about if they could not walk. Lucy was surprised to see a good number of French soldiers scattered among the Americans, and looking a good deal more cheerful than her own countrymen, as though they knew that their return home could not be much longer postponed.

Miss Webster explained to her: “These Frenchmen were in need of special treatment—we have mineral baths here. Or else they were in American hospitals and were brought along with other convalescents. They will almost all go before Christmas.”

Lucy was put to work in the diet kitchen, which she left at lunch time to carry trays to those of the convalescents whose capricious appetites needed special encouragement. The trays were numbered and so were the chairs in which the invalids reclined, but as Lucy, carrying a tray holding chicken broth and biscuits and numbered forty-five, approached the chair bearing that number, the occupant got up and, walking slowly down the veranda steps, strolled off toward the edge of the clearing.

The man was a French officer, a blond of tall and powerful build, though now his blue uniform hung loosely on his shrunken frame and his slow steps were a trifle uncertain. Lucy put down the tray and ran after him, calling out, “Quarante-cinq! Quarante-cinq!” Then as she neared him and saw the insignia on his uniform she changed her form of address to, “Monsieur le capitaine! Attendez, s’il vous plait?”

The Frenchman turned around and seeing Lucy pointing with expressive gesture to the veranda where the soup was cooling on the deserted chair he smiled and took off his cap, saying with quick apology, “Pardon, Mademoiselle.” Then changing into good English he continued, “I am sorry to have made you follow me. Thank you very much.”

Lucy walked beside him in silence, stealing glances at his face in puzzled amazement. Where had she seen that face before? It was not really familiar, yet she knew beyond a doubt that she had seen the man and spoken to him and, more than that, at a moment of great fear and anxiety. Almost a shiver caught her now at the dim remembrance. Where had it been?

“You have just arrived here, Mademoiselle?” the officer inquired, turning pleasantly toward her.

All at once Lucy knew. She saw in her mind’s eye the de la Tours’ little house in Château-Plessis, the German soldier entering the dining-room and Michelle’s cry of joy and terror.

“Captain de la Tour!” she exclaimed in vivid recollection, and as the officer looked at her in surprise she went eagerly on, “You don’t remember me? Of course not—how could you? I’m Michelle’s friend, Lucy Gordon. I was in your mother’s house when you came into Château-Plessis as a spy. For a moment I couldn’t remember. Oh, tell me, how is Michelle?”

The Frenchman looked at her closely, his blue eyes shining with pleasure. “I remember you now, Mademoiselle! And that day—will I ever forget it! I am happy to see you, my sister’s very dear friend.” He held out his hand as he spoke—a thin, bony hand from which fever had taken the strength and firmness. “Can you stay a moment? I will give you good news of Michelle.”

“A moment, yes. But don’t let your soup get cold,” said Lucy, handing him the little tray as he sank down on his chair again, breathing hard. “And your mother—is she well, too?”

“Not very well, but nevertheless she thinks more of her absent son than of her own health. I am not able to go home, they say, and Maman fears I shall be lonely at this season, in spite of my kind American friends. She and Michelle are coming to Badheim for the Noël.”

At this Lucy was struck so speechless with delight there was a pause before she could put into words her joyful amazement. “Coming here? Oh, Captain de la Tour, isn’t it good news? I can’t tell you—you can’t guess how glad I am!”

Lucy’s hazel eyes sparkled with the words and her whole face lighted up. Perhaps never until that moment had she realized the place Michelle held in her heart. Now at this lucky chance to review in peace and security the friendship woven among such sad and peril-haunted days she felt a thrill of happiness that raised her spirits almost to their old-time level.

Captain de la Tour watched her with quick sympathy, his pale lips touched for an instant by the brief, radiant smile which could so strikingly change both his and Michelle’s faces from their thoughtful gravity. Lucy longed to ask all about her friend, of whom she had caught so short a glimpse on the eleventh of November, but she had not another moment to spare. “When will they come?” she lingered to ask.

“This week, I think. I am waiting every day to hear,” said Captain de la Tour, his voice filled with eager hope. “I have not seen them since the war ended. I was shot through the lungs the day of the armistice.”

When the luncheon hour was over Miss Pearse said to Lucy, “This is a good chance to do what Miss Webster asked me to find time for. She wants us to go with the orderlies to the spring in the forest and see to the bottling of the water. It won’t take long.”

Lucy was thinking so much about all she would have to tell Michelle that she hardly noticed what Miss Pearse said, but followed her in obedient silence across the clearing behind the hospital and into the woodland. In front of them went two Hospital Corps men drawing hand-carts filled with empty bottles.

There was no snow yet on the ground and, beneath the trees, it was carpeted with moss and pine needles so that footsteps were hushed and the sigh of the branches overhead made so deep and steady a murmur that the forest seemed all at once to have an atmosphere of its own. A great peace pervaded it so that even the soldiers spoke involuntarily in low tones, and glanced about them with a kind of solemnity at the tall trunks of the firs and hemlocks, with here and there an oak spreading its wide, bare branches. The sunlight shone down with a golden gleam into the dim greenness of forest aisles stretching endlessly on every side.

Lucy walked on in enchanted silence. She thought she had never known anything more lovely than this murmurous stillness, the soft carpet beneath her feet, the great evergreen trees closing in around her and the cold, pine-laden air against her face. The mysterious scamper of shy woodland bird and beast delighted her. She would not have guessed that they had gone a hundred yards when, after half a mile’s walk, they came out suddenly into another big clearing, near the center of which stood a little cottage built of unplaned logs, its roof covered with pine boughs and smoke rising from its earthen chimney.

“It looks like a fairy story,” said Lucy softly, remembering Elizabeth’s old forest tales.

The soldiers led the way along the clearing’s edge for a hundred yards and then reëntered the forest. Almost at once the sound of water tumbling over stones broke the stillness and a little spring came into view, a bubbling basin with moss-lined, rocky bottom, and beside it a tiny rustic shed, its door fastened with a rusty padlock.

“That little shed held the bottling machine the Germans used,” Miss Pearse explained to Lucy as the men began to unload their carts, “but it got out of order toward the end of the war, so for a few weeks we shall have to bottle by hand. We are supposed to supervise but it’s quicker work if we help.”

All four knelt down on the mossy earth and began dipping up the spring water with ladles and pouring it through funnels into the big water-bottles. The spring bubbled up unceasingly, so crystal clear that no disturbance of the water could keep the rocky bottom from showing always in trembling outline.

“This is a mineral spring,” said Miss Pearse, setting aside a filled bottle which looked empty in its clearness. “The water is as wonderful as this forest air. Hello, who’s this?”

A little girl five or six years old had crept silently up to the spring and was standing with big blue eyes fixed on the Americans. Her flaxen braids hung over her faded print dress, a ragged red shawl was clutched about her and her feet were thrust into clumsy sabots above which her stockings were slipping down. An uncertain smile that began to dimple her pink cheeks broadened as she met Lucy’s friendly eyes.

“Guten tag,” she murmured shyly.

And “Guten tag,” repeated a man’s voice as the fir branches were brushed aside. A big German, close to middle age, blond and deeply sunburned, ax in hand, stood behind the child, his keen eyes fixed on the workers, a touch of sourness about his lips, though he spoke pleasantly enough.

Lucy looked up at him and the enchantment of the great old forest, of the bubbling spring and the soft-footed little girl vanished in that one glance. She was back again in Germany.

Christmas, 1918, and peace on the Western Front. That was the thought in everyone’s mind at the little Badheim hospital—that for the first time since 1914 the guns were silent on Christmas Day. But Lucy’s happiness was not what she had hoped for, though she seemed as gay as the others as she helped decorate the bare hospital halls with evergreen forest boughs, dark against the bright background of Allied flags. Michelle guessed her secret longing, nevertheless, with the quick sympathy which made the French girl so readily understand the joys and sorrows of those she loved.

“It is not the same for you as for me—this Noël,” she said to Lucy as they worked together to make the long tables cheerful for the homesick soldiers’ eyes, “for you have not your brother back.”

“It isn’t only that I miss him, Michelle,” exclaimed Lucy, glad to put her troubled thoughts into words for Michelle’s friendly ear, “it’s that he’s still in danger. They say he is only scouting over the Bolshevik lines, but you know what that means. The enemy is there—I can’t help worrying.”

“I know you cannot,” agreed Michelle, without offering useless consolation. “It is very hard. I thought Maman and I were of all the most unlucky when Armand was shot on the day of l’armistice, but now he is almost well and we have no more to fear.”

So much and so deeply had Michelle lived and suffered in the past four years that she did not even think to bewail the loss of home and fortune that the war had brought. The Germans were defeated and her mother and Armand spared. That seemed just now the granting of all she had to wish for.

Lucy had found herself more than once watching her friend’s face in the few days since Michelle and her mother arrived at Badheim. On Armistice Day she had realized that Michelle could not respond to the joyful news with any abandon of light-heartedness. The bitter suffering of the long years of war had made the little French girl grow up before her time. Even now, with her blackest cares behind her, with hope and confidence in the future, Michelle’s lovely face was still serious in repose, and her dark blue eyes held a lingering sad watchfulness that did not suit her sixteen years. Only now and then, when the two friends ran into the forest to collect the fir boughs, when Michelle’s black hair was loosened about her neck and her radiant smile chased away all memories from the happy present, did Lucy catch a glimpse of that careless gayety which the war had stolen from her.

In spite of Lucy’s troubled thoughts of Bob she found unlimited pleasure and consolation in Michelle’s company. Together the two worked as they had worked in the old days at Château-Plessis, to brighten the wounded men’s gloom. Only now they were among friends, with no sharp-eyed German surgeons on the watch. This thought somehow made Lucy almost resigned to being in Germany.

“We have to be here, instead of at home, but at any rate we can do what we please. It’s we who give the orders now,” she said to Michelle the morning of Christmas Day. A German farmer from beyond Badheim village was unloading supplies from his cart beside the hospital steps, and some of the convalescents with awakening interest were gathered around.

“Yes, the German trees can’t take us prisoner,” said Michelle with whimsical gravity, looking up at the great sighing pines closing in around them. “They are lovely—these forest trees. It was not the Germans, but God who planted them.”

Lucy felt again a touch of the enchantment that had caught her the first day she had entered the forest stillness. But at thought of the cottage in the clearing—now familiar ground—the face of the German woodcutter came before her once more to spoil the beauty. And yet there was nothing about the man, silent or quietly civil with the hospital workers, to make so definite an impression on her mind. She spoke her thoughts aloud.

“I can never see that Franz without remembering all the hatefulness of every German I’ve known in the past two years. While he’s about I can’t forget I am in Germany.”

“He does not forget it either,” was Michelle’s reply.

“Oh, I don’t think he bears us any grudge, Miss. He’s pleasant enough when we walk to the spring or the clearing,” remarked a young convalescent soldier sitting on the steps. “He’s old and soured by a hard life. Poor, too, to judge by the rags the kids wear.”

Michelle looked up at the soldier’s face, a boyish one, with pale cheeks rounding out with returning health and frank, merry gray eyes.

“Franz has not forgiven,” she said again. “Don’t you see he has not?”

The young soldier did not much care one way or the other. “Maybe you’re right,” he agreed peaceably. “We’re going to have some dinner,” he added, following with his eyes the packages being carried toward the kitchen. “Gee, it’s great to be hungry again.”

Christmas dinner was more of a success than anyone had hoped for. The convalescents could not help responding to such kind efforts, and in doing so they forgot their homesickness and began to appreciate their real good-fortune. Then, returning strength gave a good share of them hearty appetites, which found a reasonable number of German or American good things for their satisfaction. And the bright flags, the soft green of the fir branches, and the red berries which Lucy and Michelle had searched for in the forest, made the dining-room and tables gay and almost homelike to the young Americans gathered there. Some were still in wheeled chairs, with hollow cheeks and no interest in the food before them, but even these cheered up a little as talk and laughter grew louder, as songs of home were sung and toasts offered with cheers or laughter.

Larry Eaton was there, at Lucy’s invitation, and he, Madame de la Tour, Armand, Michelle and Lucy sat together at one end of a table. Larry was in wonderful spirits, or else he tried with all his kind heart to make Lucy forget Bob’s absence. Madame de la Tour, in the midst of the noisy, crowded roomful, said little. Her eyes were upon her son as he smiled and talked and tried to coax his feeble appetite for her pleasure.

All at once it seemed to Lucy that the Christmas gayety had more of the pathetic than the merry about it, and that the toasts drunk were bantering and would-be light-hearted ones, because reminders of home brought some of those weak, white-faced convalescents close to tears.

After it was all over and the men scattered, some wheeled away to rest after too much excitement, Lucy, Michelle, Armand and Larry walked into the forest, where the sinking sun had begun to send its slanting beams.

“I’d like to come here to get well,” remarked Larry, sniffing the piney air. As he spoke a cold wind, rising with the approach of sunset, swept through the trees and made the girls draw their capes closer. Larry added thoughtfully, “I mean I’d like it here now—the war over and all. It’s not a place to come to as a German prisoner. Rather spooky, if you were inclined to be down on your luck.”

“Do you find it that way too, Larry?” cried Lucy, delighted to hear her own thoughts put into words. “I’ve felt that so often about this forest in the two weeks I’ve been here. Have you ever read silly books where, when the hero feels desperate about anything, a thunder-storm comes up to give him a background? Well, this forest never changes, yet however I feel, it makes me feel more so.”

“Say it once more, please,” said Larry grinning, while Armand turned amused eyes on Lucy’s serious face.

“I can’t say it properly,” she protested, flushing a little. “I mean that the forest makes me feel everything more deeply. If I’m happy when I come into it, it looks beautiful and I am twice as happy, but if I come here anxious, not having had a word from Bob in days, it’s gloomy and unfriendly, so that I don’t stay any longer than I must.”

“I understand very well,” said Michelle in her pretty, quiet voice. “It is that here, beneath the trees, one can think very clearly, and when the thoughts are sad ones——”

“You’d rather they were interrupted,” put in Larry, pulling off bits of pine-bark to throw at two squirrels chattering on a limb overhead. “Seems to me we’re getting dismal for Christmas Day. Whose idea was this, anyway, to make a call on the Boches?”

“Michelle’s and mine,” said Lucy. “We promised Franz’ children some fruit and candy. Poor things, they have hardly anything. Franz is awfully poor, or else he is a perfect pig.”

“The children—they look cold, Captain Eaton,” added Michelle. “Do you know if all the peasants around Coblenz are very poor?”

“Some are. Of course many suffered in the war, though nothing in comparison to the French. But there’s a real scarcity of food and clothing here now.”

“They have plenty of wood to burn,” said Lucy. “But when the children run out-of-doors they shiver in those rags they wear.”

“The maman looks sad and hopeless. She seems not at all to care,” remarked Michelle wonderingly.

“The father is your special friend, isn’t he, Lucy?” asked Larry, his eyes twinkling.

“Yes, he’s my favorite,” she agreed, refusing to be teased. “He makes me think of the good old days last year in Château-Plessis.”

“Truly, he is not a joli type,” said Armand. “There is something hard about his eyes and smile.”

“Does he act sulky with the hospital staff?” asked Larry.

“Oh, no,” said Lucy. “He supplies us with wood. Probably he can’t help looking the way he does. He’s just German.”

“This must be the son and heir,” said Larry.

A little boy, just able to run alone, with a yellow thatch of hair above his eager face, and arms outstretched to help his stumbling feet, burst through the trees and made for Lucy, panting, “Guten abend, Fräulein! Fröhliche Weihnacht!”

“Merry Christmas yourself, mein Herr,” Larry responded, stooping to pick up the little German as he tripped and fell over a root in his excitement. “Better look where you’re going.”

“Hurt yourself, Freidrich?” asked Lucy in German, while Michelle brushed pine-needles from the child’s hair.

“Nein,” he answered, still panting, and, rising on tiptoe, tried to peep into the basket that Larry carried, not quite daring to approach the young officer, though burning curiosity was fast overcoming his fear.

The next moment two more children came running from the clearing, the little girl whom Lucy had first seen at the spring, and a boy about a year older than Freidrich. All three wore torn cotton clothing over which ragged coats or shawls were held together by their cold, bare fingers. Their flaxen heads were uncovered and their stockings slipped down over wooden shoes.

“Ça m’étonne,” said Michelle, shaking her head. “The German peasants are very careful with their children, as I remember them.”

“Perhaps they can’t get clothes,” suggested Larry. “Wool is terribly high now in Germany. They are rather nice-looking kids.”

“Yes, a little above the peasant class,” remarked Armand, patting the shoulder of the four-year-old boy, Freidrich’s brother, who walked beside the French officer, casting eager, curious glances up at him. “What is your name, little one?” he asked in German.

The child hung his head in silence, but the little girl, her bright eyes turned for a moment from the basket, the center of all their hopes, answered promptly:

“His name is Wilhelm, Herr Officer, and my name is Adelheid. And our father’s name is Franz Kraft. I am seven years old.”

She ended with a smile and a bobbing curtsey. Larry said, in a peculiar German something like Bob’s, “Thank you, my little maiden.” He was about to ask her if the cottage which now appeared in sight was her home, but his German failing him, he asked it instead of Lucy in English, remarking, “He must do quite a business—this Franz. He has enough wood cut already to last the hospital all winter.”

The woodcutter had heaped his fagots in neat piles over about one-half of the clearing, which covered perhaps two acres.

“He has men come to help him cut,” Lucy explained. “They cart the wood away to towns and villages near here. He’s quite a well-known character, to judge by the visitors he has. If he’s popular, I don’t care for German taste.”

“Now, Fräulein? Can we see now?” begged Adelheid, dancing up and down in her impatience.

“Yes, right now,” consented Lucy, sitting down on a pine stump in front of the cottage and taking the basket from Larry.

As she uncovered it a gasp of delight rose from three little throats, and Lucy felt Freidrich’s and Wilhelm’s panting breaths against her face, as they bent toward her in irresistible excitement.

“Pauvres petits,” murmured Michelle, touching Adelheid’s thin little shoulder.

There was nothing in the basket but fruit and Red Cross candy, with some bits of tinsel saved from the tree that had ornamented the ward where the men lay who were too sick to attend the Christmas dinner. But as Lucy distributed the basket’s contents the children’s cheeks flushed pink and their eyes shone as they stammered, “Danke, gnädige Fräulein, danke.”

A step sounded on the threshold and Adelheid held up her full hands to cry joyfully, “Look, Papachen, look!”

Franz’ big, lean frame filled the doorway, his face heated from woodland labors. With a soiled red handkerchief he began, at sight of his visitors, to brush bark and dirt from his shabby clothing. His expression was somewhat grim as he glanced at the foreigners; but at the children’s insistence, after one quick, frowning contraction of his heavy brows, his sour lips curved in something like a smile. He stroked Adelheid’s head, having made the visitors before his threshold an awkward bow, and, to their astonishment, addressed them in French—German French, remarkable in sound and accent:

“Ponjour, Messieurs et Mestemoiselles. Merci peaucoup. Foulez-fous entrer tans ma bauvre maison?”

Michelle was the first to decipher this utterance. She smiled faintly and shook her head. “We came only to see the children,” she explained, also in French.

Franz’ keen eyes had left her face to scrutinize the two officers who stood behind her, though as soon as their glance met his he shifted his gaze to the children and summoned his difficult smile once more.

“Let’s go,” said Lucy, looking up from where she sat holding Freidrich, and trying to persuade him not to cram all his candy into his mouth at once.

Footsteps sounded again inside the cottage and a woman appeared behind Franz, and, peering out over his shoulder, nodded to Lucy with a smile as cheerless as her husband’s, but tired and spiritless rather than sullen. She was young, but sad and anxious looking. Her light brown hair was twisted up anyhow on her head, and the sleeves of her faded calico were rolled above her elbows.

“Thank you, kind Fräulein,” she said, amiably enough. “The little ones are grateful. Good-day to your young friend, and to each Herr Officer.”

With this greeting she shuffled back into the cottage, without a word to her husband, who was staring at the ground now, forgetting his attempts at civility.

“Good-afternoon,” said Lucy, getting up, still holding little Freidrich’s hand. The others nodded to the German as they turned back toward the forest, the children tagging at their heels.

“We will walk a little way with you, shall we?” asked Adelheid, dancing ahead. She had stuck the bits of tinsel that fell to her share into her flaxen braids, and looked, as she flitted about among the great tree-trunks, like a child come to life out of a German fairy tale.

“Have you lived here always, Adelheid?” asked Larry, smiling at her.

Adelheid’s bright eyes fixed his as for a second she puzzled over his bad German; then, understanding, she said quickly, “Oh, no, Herr Officer. But we have lived here a good while. Let me think. Well, I can’t remember, but we came here when there was fighting. Papachen left off being a soldier to bring us here. He said it was better so—then he need not fight any more. But our mother was not pleased.”

“Need not fight any more because he became a woodcutter?” asked Larry doubtfully.

“I don’t know, mein Herr. That was what he said. He was sad and the mother was sad. We were poor, because we had no longer the farm.”

“You used to have a farm?”

“Yes—a fine one, with pigs and a field. But the fighting came, and they took all that place.”

“Who took it?” Larry persisted.

Adelheid glanced shyly at Armand’s face, then, almost whispering, explained to Larry, “It was the French. They said it all belonged to them. They let us stay where we were, but soon there was a battle and everyone had to run away.”

“What was the place called?” asked Michelle with sudden understanding.

“It was the Reichsland, Fräulein,” said Adelheid, proud of her attentive audience. “They sometimes talked French there.”

“Alsace-Lorraine!” exclaimed Armand.

“That’s where he learned French,” said Larry. “I thought it was strange in a German peasant.”

“He is not a peasant,” insisted Armand. “He is just what the child says—a farmer. When the fighting in Alsace-Lorraine commenced his land was ruined, and he was too much leagued with the Germans to face the French occupation.”

“But I wonder why the Boches let him leave the army,” Larry pondered. “Was your father wounded, Adelheid?” he asked.

“No, mein Herr, I don’t remember it.”

“Adelheid!” Through the forest stillness Franz’ voice sounded harshly. “Komm hier schnell, Adelheid!”

“Ja, ja!” responded the little girl, shouting. With a skip, she seized her brothers by the hand, and, turning for a smiling farewell and a “come soon again,” ran back toward the clearing, the little boys stumbling along at her side.

“Perhaps Papachen suspected that we were hearing the family history,” surmised Larry, watching the children disappear among the firs. “If he has any secrets to hide he had better keep Adelheid locked up.”

“Isn’t she a cunning little girl?” said Lucy. “I wish they weren’t Germans. I don’t know what is the matter with their mother. I suppose she’s poor and worried.”

“Probably she’s thinking of the farm they lost,” said Larry. Then, putting Franz and his family out of his mind as they began mounting the slope which showed the approach of the hospital clearing, “Can’t you get a holiday and come to Coblenz, Lucy? I’m lonely without you or Bob. I’m losing my morale.”

All three of the others laughed at his gloomy voice, and Larry remarked with smouldering resentment, “It’s always that way when I get the blues. I’m laughed at. I’m considered a light-hearted soldier, and if I’m anything else I get no sympathy.”

“Yes you do, Larry—plenty from me,” Lucy protested. “But, you see, I count on you a lot myself, so I have to laugh at the idea of your getting low in your mind, or I’d feel twice as lost as I do alone.”

“Is that plain to you, Captain Eaton?” asked Armand, amused, and Larry, smiling in spite of himself, said more cheerfully:

“That’s a real Lucy explanation. Well, I’ll have to carry on in the Home Sector and play up to my part.”

“Other people have had to,” said Lucy, glancing at Michelle. She could not yet look into her friend’s face without remembering with a warm thrill of admiration the almost hopeless days of captivity when Michelle’s splendid courage and cheerfulness had spurred her to equal fortitude. “I’m afraid I don’t quite stand on my own legs when trouble comes,” she added, with some irrelevance for those who could not follow her thoughts. “I always need someone to keep me going.”

“I don’t know. You’ve stood up pretty well, I think,” said Larry, more eager in her defense than in his own. “For instance, the time you——”

“Escaped from Château-Plessis,” broke in Michelle, with equal enthusiasm. “There was not anyone to push you to the lines of the Alliés, or to shut the Germans’ eyes.”

“And how about the night you flew with me into Germany?” persisted Larry. “I didn’t encourage you then, that’s sure.”

“I don’t mean all that,” Lucy interposed, flushing warmly at having provoked this unexpected praise. “Anyone can be brave once in a while. With me it’s more desperation than courage. If ever you hear that I’ve done anything you think took nerve, you may know I did it because something else frightened me still more.”

“You can’t take your motives to pieces that way,” objected Larry, never good at argument. “You were brave, and that’s all there was to it.”

“But the sort of bravery that I admire,” Lucy continued earnestly, “is the sort that lasts. I was more hopeless after five weeks at Château-Plessis than Michelle after four years. I couldn’t have endured what she did.”

“Oh, perhaps I saw fear and sorrow so often in those years I came to know well their faces and did not mind them,” said Michelle, trying to speak lightly. “My courage was not very great—a prisoner has the same.” She slipped her hand through Lucy’s arm as she spoke. “Do not think I did not sometimes borrow strength from you, mon amie.”

“Both kinds of courage are needed,” said Armand, thoughtfully. “It took both to win the war.”

“You ought to know,” said Lucy to herself, smiling as she looked up at the Frenchman’s thin face, above his wasted frame. She thought of the times he had risked inglorious death as a spy in his country’s service.

“We have a visitor,” said Michelle, as they left the forest and began to ascend the clearing behind the hospital.

She pointed to a gray army motor-car standing in the road. At the same moment Larry exclaimed, “It’s General Gordon’s car. Your father has come, Lucy.”

“Yes, he promised to, as soon as the Christmas celebrations were over in Coblenz.” Lucy quickened her pace and in a minute saw her father coming down the veranda steps to meet her.

“Merry Christmas, Father! I’m so glad to see you!” she cried, hugging him. “You don’t look very gay,” she added, searching his face with her clear eyes. “Father, are you homesick, too?”

“I’m all right, little daughter,” replied General Gordon, smiling, though his face did not relax into its usual calm confidence.

“Come and see Michelle and her brother?” Lucy urged. Her eyes held a sudden anxiety which she tried to put from her as she made the introductions and listened to her father’s pleasant talk with her friends.

Armand was looking tired and in a moment Michelle led him away to rest. General Gordon, Lucy and Larry walked over to the cottage and sat down in one corner of the bare little parlor.

Almost at once Lucy put the question trembling on her lips. “Father, there’s something wrong! Please tell me?”

“I’m sorry—on Christmas Day,” began General Gordon reluctantly. Then at Lucy’s frightened eyes he added quickly, “It’s not so very bad, Lucy. They say he’s all right. Greyson telegraphed me to-day from Archangel. Bob had a fall in his plane and has broken his leg. Greyson assures me there is no danger. He will send word again to-morrow.”

Lucy’s cheeks flamed with the desperate effort to keep back her tears. Her heart was pounding in her throat and she dared not try to speak. But in spite of herself the tears overflowed her eyes and glistened on her lashes when she heard Larry’s troubled voice beside her and felt her father catch her hand in his warm, firm clasp. She gave a quick, grateful sob.

“You know how we feel, Larry,” she said, looking up at him as she winked away her tears.

“Twenty below zero,” said Bob, as he brushed the icicles from the thermometer outside the door of his shack, “and it’s the twenty-third of December. How low does it fall, I wonder, Denby?”

“Don’t know, sir,” answered the corporal gloomily. “I never look at the temperature—I can feel it all right. But Pavlo, here, told me this wasn’t very cold for them.”

Bob closed the door and turned to look at the Russian peasant who was on his knees beside the stove, stoking it with small pieces of wood.

“He seems to keep warm enough, yet he hasn’t as thick clothes on as we,” he remarked, studying Pavlo’s hunched-up figure, in sheepskin jacket and round fur cap.

“No, sir, but he stays on level ground,” said Denby. “I don’t believe there’s anything would keep out the wind up there.” He jerked his head toward the sky, picked up fur helmet, gloves and goggles and handed them to his captain.

“I shan’t want you to go up with me to-day, Denby,” Bob told him. “I’ll take a single-seater and scout along the river.”

Bob wore a heavy fur flying-suit, leather lined. His helmet covered all of head and face not protected by his goggles. Over his boots would be drawn a second pair, made of skins sewn together with the fur left on. Yet he faced the Arctic winter day reluctantly. Bob had always hated extreme cold, even in his boyhood days at home, and two years of the mild French climate had completely spoiled him for ice and blizzards. And the Archangel winter came near to being what up to now he had only known of in books of Polar exploration, read before a blazing fire:—a wilderness of snow and ice, and a thermometer that dropped steadily lower every day, until the freezing misty air penetrated through any number of layers of clothing to the very bone.

It was not only this, however, which made Bob linger at the doorway of his shack instead of starting off to his afternoon’s work with his usual alacrity. He felt no enthusiasm for the present campaign. It seemed to him a miserable mistake, a gloomy anticlimax to the war’s glorious ending. Russia ought not to be an enemy, but an ally. The spectre of Bolshevism, stalking so boldly abroad upon these frozen plains, rose up to cloud the joy he had known for a few weeks after the great victory.

More than this, he knew at heart with the soldier’s clear-seeing mind, that the American and British lives to be pitifully lost on the snow-fields of Archangel could not stem the tide of Bolshevism, which, if it were to be fought at all, needed a mighty effort to crush its maddened onslaught. Bob’s thoughts of all this were vague and undefined as he pulled on his gloves and left the shack with Denby beside him. But they were persistent enough to take the edge off his energy, and to change the ardent eagerness of past months to a dogged, but low-spirited, determination to do his duty.

From a big flying-shed a hundred yards away an aviator was coming toward him, running stiffly over the snow to start the blood in his cramped limbs. A second flying-shed stood near the first, with a small barrack and half a dozen shacks beside it. A snowy road wound past them across the plain to the town of Archangel two miles away. The noon sky was cloudy and threatening, hiding the winter sun from the cold earth. A single plane droned overhead, flying northeast.

“Beastly weather, Gordon, I’ll say. Got a good fire in the shack?” called out the aviator who now approached him, clapping his numbed hands together.

“Yes—I wish I could take it with me,” responded Bob. “What news, Turner? Anything I should know?”

“I got one sketch of their new trench line, but it’s not very satisfactory. Continue scouting along the river, will you? That’s Morton you see up there. He’s going north. By the way, the Bolshies are getting some planes rigged up—pretty good ones. Look out for them. I almost ran into one in these everlasting clouds. So long.”

He ran on toward the shack, while Bob and Denby continued to the flying-shed, where the mechanics, at sight of Denby in overcoat instead of flying clothes, began to roll out a little Nieuport monoplane on to the smooth-packed snow.

“Going up alone, sir?” concluded one of the soldiers, saluting Bob as he put the question.

“Yes,” he nodded, beginning to look over the airplane before him with the intentness of the man who knows that he must trust his life to those frail wings. Denby followed Bob’s eyes, and neither officer nor corporal seemed overpleased with their inspection, though Bob said only:

“No news of the Nieuports we expected this week, Rogers? Did you make inquiries at the port yesterday?”

“Yes, sir—they’ve received nothing there. But I’ve gone well over this one. It flew well, you said, sir, the last time you were up.”

“Oh, yes. Nothing to complain of. Let’s have the boots, Denby.”

The corporal slipped the fur leg-coverings over Bob’s feet, and, when the aviator was seated in the little plane, fastened the straps across his body. Then, unwilling that the others should take his place, he ran to twirl the propeller. The Nieuport ran along the snow and rose into the dull, cold air.

Bob pointed upward, making for a level above the first low-lying belt of clouds. The motor was running smoothly. Bob told himself that he was growing cranky, and that he must cease regretting the Spy-Hawk and make the best of things. But telling himself so did not do much good. He wanted the airplane of his choice to fly in, as a good horseman wants his own racer, tried and proved on many a turf. On the Western Front Bob had had his pick of French and American planes—the famous ace was welcome to all or any. But here at this outpost of the Russian wilderness the supply of airplanes so far was meagre. He had to fly in whatever he could get hold of; and often, against his grain, was obliged to scout in battle-planes, or risk flights under heavy fire in light scouting craft.

Now he was above some of the shifting clouds, and, flying slowly, he looked down upon the river Dwina, its broad stream choked with blocks of ice, between which the deep blue water gleamed. In spite of the clouds and mist a glorious panorama lay spread below him as, hovering for a moment before commencing his eastward flight, he made a careful survey with his glasses in every direction.

He was almost over the river, facing northeast. On his left lay the town of Archangel, its roofs snow-buried. West of it was the ice-bound Gulf of Archangel, and, beyond that, the wide frozen expanse of the White Sea. In front of him stretched the endless plains that fronted the Arctic Ocean. On his right, far up the river, he caught a glimpse of the town of Kholmogory.

There was something inexpressibly dreary and abandoned about the scene. The very names were barbaric and meaningless on his lips. “Petrograd seems almost near home,” he thought, “now that I’m six hundred miles north of it.”

He turned east and began following the course of the Dwina to where, around a little village nestling by its banks, he could see American troops in squads and companies moving here and there, and motor-trucks painfully nosing their way along a snow-blocked road. A trench-line was faintly visible, east and west of the river. Not a shot disturbed the silence, in which the roar of his airplane’s motor was the only sound.

Bob flew on eastward, approaching the Bolshevik lines. The enemy was strongly entrenched, with artillery behind him, but at the first snow-falls the fighting had grown intermittent. Bursts of firing and short, hard-fought engagements alternated with days of inactivity on both sides. As he flew over the trenches now anti-aircraft guns were trained on him and shots came near enough to make him rise another hundred feet.

For the second time in two days Bob remarked with surprise the presence of a growing purpose and organization among his adversaries. The Bolsheviki seemed to be abandoning their somewhat hit-or-miss methods for a better ordered scheme. Ordered by whom? Bob had heard rumors of Russian officers of the old army forced into Bolshevism to train Trotsky’s Red troops.

He flew on behind the trenches, risking a lower level in his desire to see the new lines of communication, unsurveyed up to now by the tiny handful of American and British aviators around Archangel. For a few moments he dodged back and forth in quick tacks to throw the gunners off their aim. Then, leaning out over the cockpit, with his glasses he studied the narrow lines showing dark against the snow-fields. In five minutes the deadly fire of the anti-aircraft guns forced him to rise again above the clouds. He rapidly sketched in on his field map what he had seen, ready to try another descent.

The icy air penetrating his lungs made him gasp a little. The air seemed to have substance, body, as though he were in the grip of a block of ice. It got past the ear-tabs of his helmet and made his ears tingle. His feet were numb through leather and fur. In the dull cheerlessness of his mood a profound depression began to steal over him, but at the same time half-unconsciously he fought against it, and some forgotten lines came into his mind with all the vividness of words learned in childhood. He found himself silently repeating them:

He went on saying over the fine solemn words as he swung the Nieuport down again through the fog:

He was hardly at the last line when a Fokker biplane broke through the clouds in front of him.

The enemy plane had not risen in pursuit of the American. Its guns were not trained on the Nieuport. In that fleeting glimpse Bob saw that the Fokker’s gunner, glasses raised, was observing his own lines below, while the pilot manœuvred the plane over rifts in the cloudy floor. But at sight of the Nieuport the gunner flashed his weapons into range, though no shots followed, for at once the drifting clouds hid the two antagonists from each other.

All his slumbering energies aroused, Bob leaned forward with keenest intentness, trying to see through the treacherous misty curtain. He glanced at his machine-guns, made sure that his motor was running smooth, and rose a little higher, hoping to get above the Fokker and avoid surprise.

He thought swiftly as he prepared for attack, still puzzled by the enemy plane’s appearance. It was a German machine—no doubt about that. He supposed the Bolsheviki had bought or stolen it. Vague suspicions, already aroused during the past few days, stirred him once more, but again he rejected them.

“I think he’s a German because inwardly I’m longing to bring down another German plane,” he told himself.

He tried to picture the faces and figures of the men in the Fokker, as they had flashed close beside him, but they were like himself unrecognizable in fur and helmet. Five minutes passed before the Fokker again appeared, this time greeting the Nieuport with a broadside that sent bullets whizzing past Bob’s ears to cut into the fog behind him.

Bob rose again, filled with ardor, and determined, more than ever in the presence of this menacing intruder, to accomplish what he had come out for and get the rest of his sketch of the new Bolshevik lines. He climbed at high speed, darted about until he saw the Fokker cruising through the clouds below, then plunged down above it and delivered a hail of bullets on its broad spreading wings.

As he dodged and rose again he watched the enemy sway and nose-dive into a cloud-bank. He noticed that the wings were bare of emblems. The German crosses—if they had been there—were gone. The Fokker recovered and rose again, the fabric of its upper planes slashed by the Nieuport’s bullets.

Bob was uncertain what tactics to follow. So far he could not be sure whether his adversary was sly or stupid. The Fokker’s pilot seemed to have little initiative, yet he manœuvred the heavy plane skillfully. It dipped and climbed almost at the little Nieuport’s speed. Unless the pilot were a clumsy Bolshevik amateur Bob could never hope to disable the Fokker from his own light craft. The best he could hope was to scare him off or lose him in the clouds.

Suddenly all doubt of the enemy’s skill vanished, for the Fokker headed straight for the Nieuport and, firing repeatedly with well-aimed volleys, circled about the little monoplane, which turned tail and retreated up into the sky, where the heavy Fokker could but slowly follow.

At 9,000 feet Bob paused, for the enemy had stopped rising 1,000 feet below him and seemed to be awaiting developments. Bob was too high for convenient observation and the drifting clouds annoyingly obscured his vision. He peered down at the Bolshevik lines, nevertheless, keeping one eye on his enemy, who was all but in range and waiting inexorably. After ten minutes’ more sketching, by frequent change of position and some clever guesswork, he had got most of the information he wanted. Now he began to cast uneasy glances toward the Fokker which flew back and forth on the watch, just above the clouds.

Bob had never been good at a waiting game, and this cat-like proceeding got on his nerves. He began to feel trapped, and in consequence defiant. He reloaded both guns, speeded up his motor, and without warning dropped like a plummet over the cruising Fokker and emptied both guns over cockpit and rudder.

This done, however, he was obliged to fly still lower before he could attempt a climbing turn. The Fokker, though bullet-riddled and one plane sagging, followed him down, spraying the little Nieuport with a deadly fire. Bob realized now his own rashness in not fleeing at once before an enemy who so outmatched him. The truth was he had not been able to convince himself that any Bolshevik flyer could outmatch him, even in a battle plane twice the Nieuport’s size.

He hid in the clouds, looking with anxious misgiving at his torn wings and suddenly aware that his rudder did not obey him with exactness. Once more the Fokker passed him, slowly this time, for to Bob’s tremendous relief, he saw that the enemy plane was badly crippled and had lost some of its speed. In the same breadth of time he saw at last the pilot’s face. Hidden by helmet and goggles, he recognized the shape of that big chin, the turn of the head, the stoop of the broad shoulders. He had seen that man a thousand times over the battle-fields of France,—Rittermann, one of the last of Germany’s veteran flyers.

Bob turned the Nieuport westward, put on what speed he could and ran away at eighty miles an hour. He steered for his own station, east of Archangel, following the river which wound below him, the water gleaming darkly through the ice in the approaching twilight. But the Nieuport’s rudder did not obey his touch. The monoplane veered northward, slackened speed. Bob looked back, his mind whirling a little, then drew a long hard breath. The Fokker had lost him. He was within the American lines again, but north of the Dwina, above a rough, ice-covered plain cut into hummocks and ridges, broken just beneath him by the bare branches of a wood.

He wanted badly to land but saw no possible landing-place in sight, and the familiar home field was far away. He turned with difficulty and began flying back toward the American trenches, seeking the village by the river where the companies of infantry were billeted. But in the past half hour the early Arctic night had begun to fall. By his wrist-watch it was quarter to three, and he knew that by three o’clock it would be almost dark. The cold was so intense it numbed his power to think, and his rudder, struck by the Fokker’s bullets, responded more feebly every moment.

He flew on eastward, crossed the river below the clouds, and began searching the banks for the village, looking for its lights, for now a glimmering dusk spread over the desolate landscape. In another five minutes the lights shone out,—a dozen tiny twinkling points about two miles ahead of him. He pushed on, hoping against hope to cover that short space, but a few moments more convinced him of the worst. His heart sank like lead as his desperate eyes watched the gleaming white snow-fields below him.

“The first time in all these years,” he thought miserably. “My Spy-Hawk would have held on——”

The Nieuport’s wings sagged lower. Its rudder no longer obeyed Bob’s frenzied pressure. For the first time since that day in 1917 when he and Benton had come down in German territory to be taken prisoners, Bob—an ace and the hero of many victories—was forced to land at night on unknown ground in an airplane that shook and quivered under him as it flew crookedly downward, the Fokker’s bullets too much for its imperfect frame.

A forced landing in the dark—a moment before Bob had thought that bad enough. But now, as the Nieuport quickened the plunge which he was helpless to arrest, he realized that truth with a thrill of terror. The motor missed, choked, stopped running. In the silence that succeeded the propeller’s roar the wind whistled past the wings as the plane fell. Bob looked down at the white-shining earth below, his heart leaping in his throat, his head whirling as the blood rushed to his temples. The snow rose with a dizzy swiftness to meet him. The plane struck, nose down, with a shock that hurled him through the air. He fell onto the hard surface, one leg doubled under him, from which such darts of agony shot through him that with a groan he lost consciousness.

When he came slowly to himself, forced back to life by the stabbing pain in his right leg, Bob opened his eyes on darkness, felt the icy night wind sweep past him and sharp, cold particles pressing against his outspread hands. He rolled over on his back, not without a groan at the renewed torment of his leg, and stared up at the sky, where, between the flying clouds, scattered stars shone with cold brilliance. He felt hard lumps like stones sticking into his back, but he could think clearly enough now to know that the lumps were hardened snow, and that the deadly chill penetrating him through fur and leather garments would but too soon be followed by numbness and yielding to a sleep from which he would never wake.

Painfully raising his head he could see the faint lights of the village, not a mile away. Could he freeze to death within sight of help,—within a few miles of his own flying-field? A desperate determination roused him to fight against the agony of his broken leg and do what lay in his power to save his life. Life was, all at once, inexpressibly dear to him. Spent with pain and cold as he was, the blood flowed warm in his veins and resolution conquered his weakness. But already cold had so far overpowered his brain that his mind was at moments clouded, and it was then that the coward part of him bade him lie down and forget the horrible pain that every movement cost him, and sink into oblivion.

The airplane was not a dozen feet away. He could see its dark blot against the snow, and the outline of its broken wings. If he could climb upon its frame, he thought, away from the snow that was freezing him, he might summon force enough to keep alive till daylight. Daylight on the White Sea! It was not more than six o’clock in the evening now, and dawn would not break before eight o’clock of the following day. He knew that Turner and Denby would soon be out searching for him, but by what lucky chance would they stumble upon him? They had more than fifty miles to cover—a wide expanse, even with airplane search-lights.

He took his lip between his teeth as he turned over again on his face and began crawling toward the Nieuport. He panted as he dragged himself along, for he could do no more than bend his left leg and catch at the snow with his gloved hands. The uneven snow-crust striking his right leg and jarring the broken bones hurt so atrociously that after two yards he stopped dead and, laying his face on the snow, in pain and despair almost lost consciousness once more. But something in him still resisted—something dogged and heroic that had made him the flyer he was—that had led him to Sergeant Cameron’s prison. He raised his head and crawled on again, reached the Nieuport and, finding one of its wings lying almost flat along the ground, managed to drag himself upon it and lay there gasping and dizzy.

The wing was almost on the snow and its torn fabric not much protection from the icy surface. Still there was a difference, and the fact of having accomplished his purpose made Bob more able to keep up the struggle. After a moment he tried to shout, but one hoarse, shaky cry told him the uselessness of wasting his little force. The whistling night wind snatched his feeble voice away before it had travelled over the smallest part of the great spaces around him. He looked up at the airplane’s wings and thought with sudden inspiration that he might set them afire as a signal. He was actually feeling inside his furs for his matches before it occurred to his dazed mind that the gasoline would ignite with the plane and that, helpless as he was, he would never get away in time.

At this quenched hope he was horribly cast down. Despair threatened again to overwhelm him. Nevertheless he went on dully scheming. After a few minutes of aimlessly wandering thoughts another idea came to him, and this time his heart gave a faint leap, almost of hope. He braced himself to endure the agony of movement, squirmed around until he could reach into the airplane’s cockpit and, after a painful search, closed his fingers on a pair of pliers.

He slipped off the sagging wing on to the snow again, lay there a moment breathing hard, for every effort made his strained heart race and hammer, then began cutting the wire of the wing and ripping away the fabric. Presently he held some wide strips of silk and a long piece of wire. He fastened the silk in streamers at the end of the wire and, taking the wire between his teeth, crawled away from the plane. A dozen yards distant human nature could endure no more and he lay back on the snow, feeling nothing but the throbs of agony that darted from his broken leg into every part of his body.

Yet in a minute he sat up, planted the wire in the snow and, drawing out his matches, managed, after several trials in the gusty wind, to set the silk on fire. He caught hold of the wire now, and, heedless of pain, lifted himself as much as he could and waved the flaming streamers about his head until the blaze shrank down to sparks and went out, leaving him with false flashes of light before his eyes in the darkness.

He Waved the Flaming Streamers About His Head

Bob did not know just what happened after that. He lay down again and tried to steel himself once more to endure the pain, to stay awake, and to go on hoping. But the effort to keep repeating these resolves was too terrific. He felt that he was attempting problems utterly beyond his power, and every now and then he would rouse himself with a start and realize that he had been very near dreaming.

The stars shone more thickly now overhead. He tried to count them, lost track, began again. He could hardly remember where he was. He was not nearly so cold as before—he was almost comfortable. He seemed to have no feeling at all in his body, except for his leg which still throbbed dully. All at once, through the numbing of his senses, he was dimly aware of a sound in the snow near him, a kind of crackling, steadily repeated. Some lingering sense of reality made him suddenly realize that the sound was of footsteps approaching him, or at least passing near. As he roused all his remaining energy in a desperate attempt to cry out the footsteps ceased, and from beside the demolished plane a voice shouted:

“Ah, there! Speak if you can! Where are you?”

Bob made some sort of sound—he did not quite know what. But it was enough to bring the footsteps close beside him. A figure loomed above him in the darkness, an electric torch flashed over his prostrate form, and, as the man knelt by Bob’s side, the light showed the uniform of a British tommy, a muffler-wrapped throat and a lean red face, with breath puffing white into the freezing air.

“Came down, eh? It was you what waved the signal?” he inquired, his keen eyes wandering over Bob. “'Ow much are you hurt? Can you walk, me 'elpin’ you?”

“No, I can’t walk. You’ll have to fetch help,” said Bob, still struggling to cling to reality. One-half of him was gloriously happy at this deliverance, but the other half wanted to forget and go to sleep and could hardly tell the soldier what to do. “Go to Nikolsk, that village where you see the lights,” he continued. “Americans are billeted there. Ask them to send a detail of Hospital Corps men with an ambulance. Make sure of where I am. Have you a compass?”

“But can you stick it? I’ll be gone an hour,” said the tommy doubtfully. Bob’s voice was scarcely more than a whisper, and there was a pause between his words when his thoughts failed him.

“I’ll stick it. Make it as quick as you can,” he answered.

The Britisher still lingered. Bob heard him murmur something which sounded like, “Well, looks like it’s got to be done.” The next moment Bob heard a garment of some sort flung down and spread out on the snow beside him, and felt himself lifted cautiously by the shoulders and dragged, before he could protest at the handling, on to something like a blanket. “Carry on now. I’ll keep my feet movin’,” said the tommy, and with the words he ran off into the darkness.

Bob felt with his hands of the fabric spread under him, touched a cloth sleeve and knew that he was lying on the soldier’s overcoat. A faint thrill at this generous act touched his dulled senses. But he no longer felt the cold and did not care whether he lay on snow or blankets. He had a feeling now that all was settled. At moments he even thought that he had got back to his station and was in bed. At any rate he knew that he had not to think or plan any more. He fell asleep.

The hours Bob next lived through were a sort of waking dream. He had moments when he knew well enough that he was being lifted by careful hands into an ambulance which then began to glide on sledge runners over the frozen plain. He felt blankets wrapped about him and, with the first returning warmth, his leg began to stab him again with throbs of anguish. But these half-lucid minutes were followed by long intervals of dreaming that took him hundreds of miles away from the snowy plains, to days that came back to him vaguely now as part of another life.

At last, after a very long time—days or weeks, he could not tell which—he opened his eyes and looked around him with fairly untroubled brain. He was in a room in a Russian house, for a porcelain stove occupied a good part of it. Outside the low window he saw the everlasting snow, some trees, their bare branches swaying in the keen wind, and, in a moment, a soldier walking rapidly toward shelter.

Inside the room, at the foot of his cot, was a small hospital table, with gauze, bandages and bottles upon it. The walls were newly white-washed, two other cots lay beyond his, and a faint smell of chloroform lingered on the air. He turned his heavy head and saw an officer seated beside him.

“Well, Bob, how is it?” inquired the surgeon, taking the patient’s hand in his.

Bob stared at him, moved his tongue with an uneasy feeling that he could not speak, then murmured, still with painful effort, “You, Greyson? They brought me here—all right—then. What day is it?”

“It’s Christmas Day. We brought you here night before last. You’re in Nikolsk village, in our little hospital. Don’t you remember what happened to you day before yesterday?”

“Yes,” Bob answered slowly. The whole tragic scene reappeared before his mind in bits which he struggled to piece together. But all at once the dull ache in his leg brought it vividly back. He started from his pillows, a sudden dread darkening his eyes. “Greyson,” he stammered, “my leg! You won’t—you haven’t——”

“We haven’t and we won’t,” said the surgeon, smiling as he pressed Bob’s shoulders back against the pillows. “Your leg is going to be all right. You’re a tough specimen, Bob—I’ll say that. Most people wouldn’t have come out of it so well.”

“You’re telling me the truth?” Bob persisted, his muscles tense and quivering.

“On my word of honor. The fracture is set and shows every sign of healing. You have no fever.”

Bob lay silent, spent with peaceful gratitude. He began again reviewing his accident, and when he reached the moment when the British tommy bent over him he roused himself to ask:

“That British soldier who brought you word—do you know who he is? I want to thank him. He gave me his coat, too. Is he all right?”

“Yes. He came here yesterday to ask for you. I tried to thank him myself, but as soon as I began he cut me short by saying, 'Never mind that, sir. It ain’t a medal of honor I’m lookin’ for. What I want is for you to promise not to say nothing to my captain about that there night. I was out as you might say without leave, when I happened to see that air chap’s signal blazing.’”

Bob smiled faintly. “I’ll stand his guardhouse sentence for him, if he gets one,” he said unsteadily. “Another few minutes and I couldn’t have held out.” He shivered at thought of those hours of misery, drawing the blankets closer around him. “You sent word to my squadron, of course, Greyson—and to Father?”

“Yes, to both. Turner came over yesterday. He salvaged your airplane and took your maps and sketches back to Headquarters. He said the colonel received them with enthusiasm.”

Under the glow of this satisfaction Bob forgot his regrets, the loss of his plane and his own helplessness. With vague thoughts of past Christmases flitting through his mind he sank into what was this time profound and restful sleep.