The Project Gutenberg EBook of Races and Peoples, by Daniel Garrison Brinton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Races and Peoples

Lectures on the Science of Ethnography

Author: Daniel Garrison Brinton

Release Date: June 12, 2018 [EBook #57315]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RACES AND PEOPLES ***

Produced by Julia Miller, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

1

RACES AND PEOPLES

LECTURES

ON THE

SCIENCE OF ETHNOGRAPHY

BY

DANIEL G. BRINTON, A.M., M.D.,

Professor of Ethnology at the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia,

and of American Archæology and Linguistics in the University of Pennsylvania;

President of the American Folk-Lore Society and of the

Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Philadelphia; Member

of the Anthropological Societies of Berlin and Vienna and of

the Ethnographical Societies of Paris and Florence, of

the Royal Society of Antiquaries, Copenhagen, the

Royal Academy of History of Madrid, the

American Philosophical Society, the

American Antiquarian Society,

Etc., Etc., Etc.

PHILADELPHIA

PHILADELPHIA

DAVID McKAY, Publisher

1901

2

Copyright

By D. G. Brinton.

3

TO

HORATIO HALE,

PHILOLOGIST TO THE UNITED STATES EXPLORING

EXPEDITION IN 1838-42,

WHOSE MANY AND VALUABLE

CONTRIBUTIONS TO LINGUISTICS AND ETHNOGRAPHY

PLACE HIM TO-DAY AMONG THE FOREMOST AUTHORITIES

ON THESE SCIENCES,

THIS VOLUME

IS INSCRIBED IN RESPECT AND FRIENDSHIP

BY THE AUTHOR.

4

5

PREFACE.

The lectures which appear in this volume were delivered

at the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia,

in the early months of 1890. They have since been written

out, and references added in the foot-notes to a number

of works and articles, which will enable the student to

pursue his readings on any point in which he may be interested.

My endeavor has been to present the results of

the latest and most accurate researches on the subjects

treated; though no one can be better aware than myself

that in compressing such an extensive science into so

limited a space, I have often necessarily been superficial.

It is some excuse for the publication, if one is needed,

that I am not aware of any other recent work upon this

science written in the English language.

Philadelphia, August, 1890.

6

7

CONTENTS.

| LECTURE I. |

|

PAGE |

| THE PHYSICAL ELEMENTS OF ETHNOGRAPHY |

17 |

| Contents.—Differences and resemblances in individuals and

races the basis of Ethnography. The Bones. Craniology.

Its limited value. Long and short skulls. Height of skull.

Sutures. Inca bone. The orbital index. The nasal index.

The maxillary and facial angles. The cranial capacity. The

teeth. The iliac bones. Length of the arms. The flattened

tibia. The projecting heel. The heart line. The Color.

Its extent; cause; scale of colors. Color of the eyes. The

Hair. Shape in cross section; abundance. The muscular

structure; anomalies in; muscular habits: arrow releases.

Steatopygy, Stature and proportion; the “canon of proportion;”

special senses; the color-sense. Ethnic relations of

the sexes. Beauty; muscular power; brain capacity; viability.

Correlation of physical traits to vital powers. Tolerance

of climate and disease. Causes of the fixation of ethnic

traits. Climate; food supply; natural selection; conscious

selection; the physical ideal; sexual preference; abhorrence

of incest; exogamous marriages. Causes of variation in

types. Changes in environment; migrations; reversion;

albinism and melanism; fecundity and sterility. The mingling

of races; métissage. Physical criteria of racial superiority.

Review of physical elements.

8 |

|

| LECTURE II. |

| THE PSYCHICAL ELEMENTS OF ETHNOGRAPHY |

51 |

| Contents.—The mental differences of races. Ethnic psychology.

Cause of psychical development. |

|

| I. The Associative Elements. 1. The Social Instincts:

sexual impulse; primitive marriage; conception of love;

parental affection; filial and fraternal affection; friendship;

ancestral worship; the gens or clan; the tribe; personal

loyalty; the social organization; systems of consanguinity;

position of woman in the state; ethical standards; modesty.

2. Language: universality of; primeval speech; rise of

linguistic stocks; their number; grammatical structure;

classes of languages; morphologic scheme; relation of

language to thought; significance of language in ethnography.

3. Religion: universality of; early forms; family and tribal

religions; universal or world religions; ethnic study of religions;

comparison of Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism;

material and ideal religions; associative influences of religions.

4. The Arts of Life: architecture; agriculture;

domestication of animals; inventions. |

|

| II. The Dispersive Elements: adaptability of man to surroundings.

1. The Migratory Instincts: love of roaming;

early commerce; lines of traffic and migration. 2. The

Combative Instincts: primitive condition of war; love of

combat; its advantages; heroes; development through

conflict. |

|

| LECTURE III. |

| THE BEGINNINGS AND SUBDIVISIONS OF RACES |

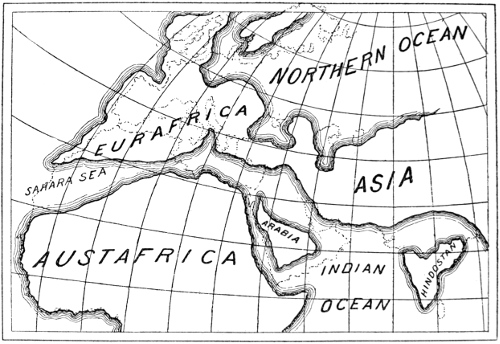

79 |

| Contents.—The origin of Man. Theories of monogenism and

polygenism; of evolution; heterogenesis. Identities point

to one origin. Birthplace of the species. The oldest human

relics. Remains of the highest apes. Question of climate.

Negative arguments. Darwin’s belief that the species originated

9

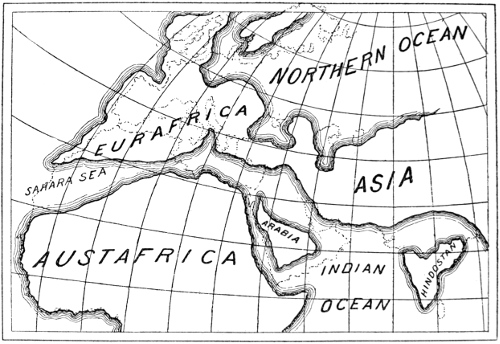

in Africa confirmed; but with modifications. Quarternary

geography of Europe and Africa. Northern Africa

united with Southern Europe. Former shore lines. The

Sahara Sea. The quaternary continents of “Eurafrica”

and “Austafrica.” Relics of man in them. Man in pre-glacial

times. The Glacial Age. Effect on man. His condition

and acquirements. Appearance of primitive man.

His development into races. Approximate data of this.

Localities where it occurred. The “areas of characterization.”

Relations of continents to races. Theory of Linnaeus;

of modern ethnography. The continental areas:

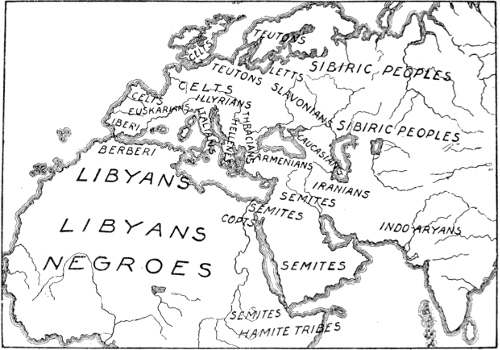

Eurafrica; Austafrica; Asia; America. Classification of

races. Subdivisions of races; branches; stocks; groups;

peoples; tribes; nations. General ethnographic scheme.

Other terms: ethnos and ethnic; culture; civilization.

Stadia of culture. |

|

| LECTURE IV. |

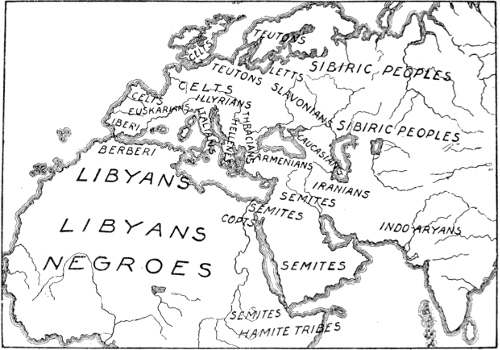

| THE EURAFRICAN RACE; SOUTH MEDITERRANEAN BRANCH |

103 |

| Contents.—The White Race. Synonyms. Properly an African

Race; relative areas; purest specimens. Types of the

White race; Libyo-Teutonic type; Cymric type; Celtic

type; Euskaric type. Variability of traits. Primal home

of the White Race not in Asia, but in Eurafrica. Early

migrations and subdivisions. North Mediterranean and

South Mediterranean branches. |

|

| A.—The South Mediterranean Branch. |

| I. The Hamitic Stock. Relation to Semitic. 1. The Libyan

Group. Location. Peoples included. Physical appearance.

The Libyan blondes; languages. Early history;

European affiliations; relations to Iberian tribes: the names

Iberi and Berberi. Government. Migration. The Etruscans

as Libyans. Later history; present culture. Syrian

Hamites and their influence. 2. The Egyptian Group.

10

Kinship to Libyans. Physical appearance. The stone age

in Egypt. Antiquity of Egyptian culture. Its influence.

Physical traits. 3. The East African Group. Relations to

Egypt. |

|

| II. The Semitic Stock. First entered Arabia from Africa.

1. The Arabian Group. Early divisions and culture. The

Arabs. Physical types; mental temperament; religious

idealisms. 2. The Abyssinian Group. Tribes included.

Period of migration. Condition. 3. The Chaldean Group.

Tribes included. The modern Jew. |

|

| LECTURE V. |

| THE EURAFRICAN RACE; NORTH MEDITERRANEAN BRANCH |

141 |

| Contents.—B.—The North Mediterranean Branch. |

| I. The Euskaric Stock. Basques and their congeners. Physical

type. Language. |

|

| II. The Aryac Stock. Synonyms. Origin of the Aryans.

Supposed Asiatic origin now doubted. The Aryac physical

type. The prot-Aryac language. Culture of proto-Aryans.

The “proto-Aryo-Semitic” tongue. Development of inflections.

Prot-Aryac migrations. Southern and northern

streams. Approximate dates. Scheme of Aryac migrations.

Divisions. 1. The Celtic Peoples. Members and

location. Physical and mental traits. 2. The Italic Peoples.

Ancient and modern members. Physical traits. The

modern Romance nations. Mental traits. 3. The Illyric

Peoples. Members and physical traits. 4. The Hellenic

Peoples. Ancient and modern Greeks. Physical type.

Influence of Greek culture. 5. The Lettic Peoples. Position

and language. 6. The Teutonic Peoples. Ancient

and modern members. Mental character. Recent progress.

7. The Slavonic Peoples. Ancient and modern members.

Physical traits. Recent expansion. Character. Relations

to Asiatic Aryans. 8. The Indo-Eranic Peoples. Arrival

in Asia. Location. Members. Indian Aryans. Appearance.

Mental aptitude.

11 |

|

| III. The Caucasic Stock. Its languages. Various groups

and members. Physical types. Error of supposing the

white race came from the Caucasus. |

|

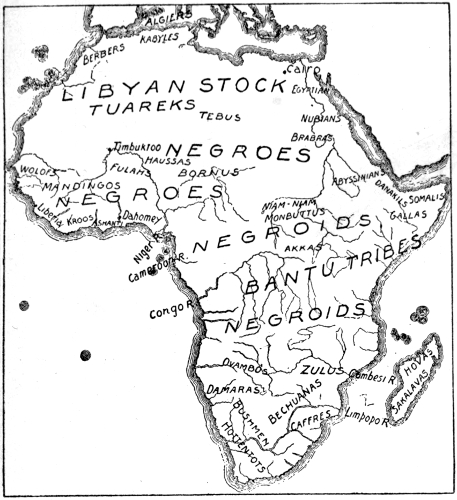

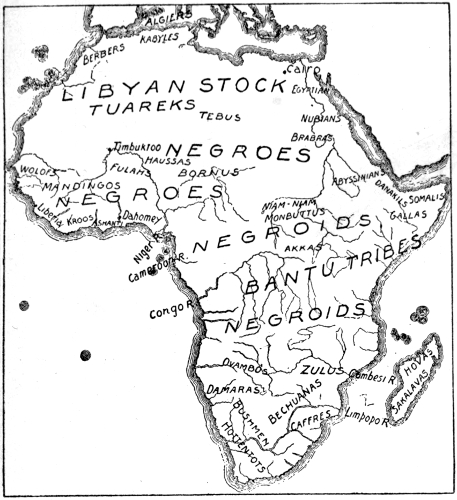

| LECTURE VI. |

| THE AUSTAFRICAN RACE |

173 |

| Contents.—Former geography of Africa. Area of characterization

of the race. Its early extension. Divisions. |

|

| I. The Negrillos. Classical tales of Pygmies. Physical characters.

Habits. Relationship to Bushmen. Description

of Bushmen and Hottentots. |

|

| II. The Negroes. Home of the true negroes. 1. The Nilotic

Group. 2. The Sudanese Group. 3. The Senegambian

Group. 4. The Guinean Group. |

|

| III. The Negroids. Physical traits. Early admixtures.

1. The Nubian Group. 2. The Bantu Group. |

|

| General Observations on the Race. Low intellectual position.

Origin of negroes in the United States. |

|

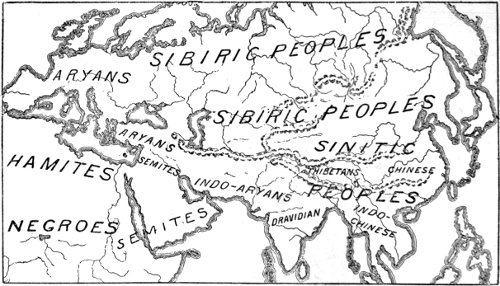

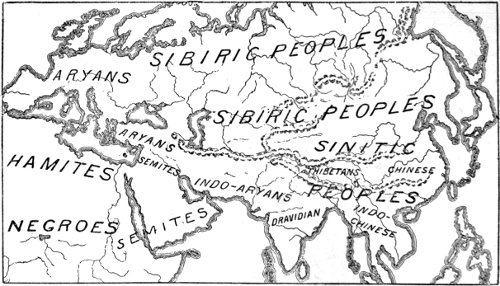

| LECTURE VII. |

| THE ASIAN RACE |

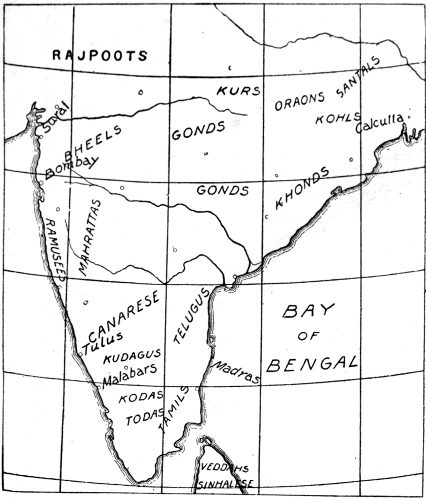

195 |

| Contents.—Physical geography of Asia. Physical traits of

the Race. Its branches. |

|

| I. The Sinitic Branch. Subdivisions. 1. The Chinese.

Origin and early migrations. Psychical elements. Arts.

Religions. Philosophers. Late migrations. 2. The Thibetan

Group. Character. Physical traits. Tribes. 3. The Indo-Chinese

Group. Members. Character and Culture. |

|

| II. The Sibiric Branch. Synonyms. Location. Physical

appearance. 1. The Tungusic Group. Members. Location.

Character. 2. Mongolic Group. Migrations. 3. The

Tataric Group. History. Language. Customs. 4. The

Finnic Group. Origin and migrations. Physical traits.

12

Boundaries of the Sibiric Peoples. The “Turanian”

theories. 5. The Arctic Group. Members. Location.

Physical traits. 6. The Japanese Group. Members. Location.

History. Culture. The Koreans. |

|

| LECTURE VIII. |

| INSULAR AND LITTORAL PEOPLES |

221 |

| Contents.—Variability of islanders and coast peoples. Physical

geography of Oceanica. Ethnographic divisions. |

|

| I. The Negritic Stock. Subdivisions. 1. The Negrito

Group. Members. Former extension. Physical aspect.

Culture. 2. The Papuan Group. Location. Physical

traits. Culture and language. 3. The Melanesian Group.

Physical traits. Habits. Languages. Ethnic affinities

of Papuas and Melanesians. |

|

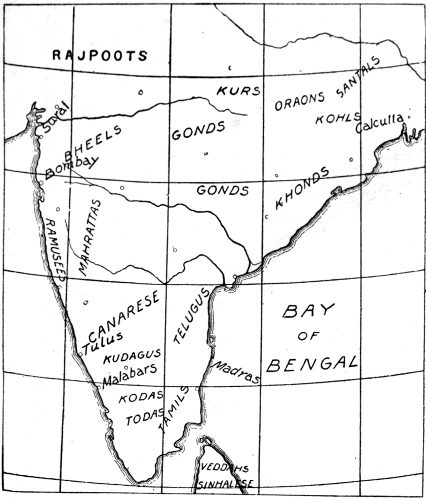

| II. The Malayic Stock. Location. Subdivisions. Affinities

with the Asian Race and original home. 1. The Western or

Malayan Groups. Physical traits. Character. Extension.

Culture. Presence in Hindostan. 2. The Eastern or

Polynesian Group. Physical traits. Migrations. Character

and culture. Easter Island. |

|

| III. The Australic Stock. Affinities between the Australians

and Dravidians. 1. The Australian Group. Tasmanians

and Australians. Physical traits. Culture. 2. The

Dravidian Group. Early extension. Members. Culture.

Languages. |

|

| LECTURE IX. |

| THE AMERICAN RACE |

247 |

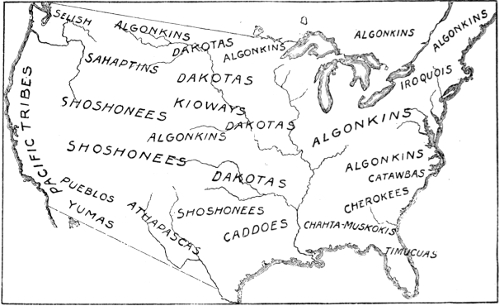

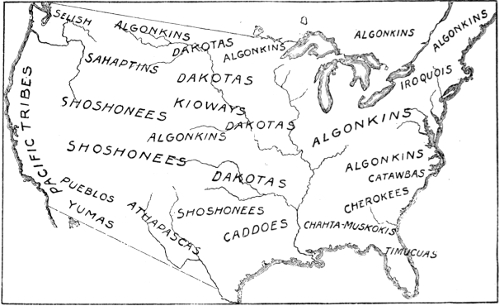

| Contents.—Peopling of America. Divisions. 1. The Arctic

Group. Members. Location. Character. 2. The North

Atlantic Group. Tinneh, Algonkins, Iroquois, Dakotas,

Muskokis, Caddoes, Shoshonees, etc. 3. The North Pacific

Group. Tlinkit, Haidahs, Californians, Pueblos. 4. The

13

Mexican Group. The Aztecs or Nahuas. Other nations.

5. The Inter-Isthmian Group. The Mayas. Their culture.

Other tribes. 6. The South Atlantic Group. The Caribs,

the Arawaks, the Tupis. Other tribes. 7. The South Pacific

Group. The Qquichuas or Peruvians. Their culture.

Other tribes. |

|

| LECTURE X. |

| PROBLEMS AND PREDICTIONS |

277 |

| Contents.—I. Ethnographic Problems. 1. The problem of

acclimation. Various answers. Europeans in the tropics.

Austafricans in cold climates; in warm climates. The

Asian race. Tolerance of the American race. Theories of

acclimation. Conclusion. 2. The problem of amalgamation.

Effect on offspring. Mingling of white and black

races. Infertility. Mingling of colored races. Influence

of early and present social conditions. Is amalgamation

desirable? As applied to white race; to colored races.

3. The problem of civilization. Urgency of the problem.

Influence of civilization on savages. Failure of missionary

efforts. Cause of the failure. Suggestions. |

|

| II. The Destiny of Races. Extinction of races. 1. The

American race. Are the Indians dying out? Conflicting

statements. They are perishing. Diminution of insular

peoples; causes of fatality. The Austafrican race. The

Mongolian race stationary. Wonderful growth of the

Eurafrican race. Influence of the Semitic element. The

future Aryo-Semitic race. |

|

| Relation of ethnography to historical and political science. |

|

| INDEX OF AUTHORS |

301 |

| INDEX OF SUBJECTS |

309 |

14

15

MAPS, SCHEMES AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

16

17

LECTURES ON ETHNOGRAPHY.

LECTURE I.

THE PHYSICAL ELEMENTS OF ETHNOGRAPHY.

Contents.—Differences and resemblances in individuals and races

the basis of Ethnography. The Bones. Craniology. Its limited

value. Long and short skulls. Sutures. Inca bone. The orbital

index. The nasal index. The maxillary and facial angles. The

cranial capacity. The teeth. The iliac bones. Length of the

arms. The flattened tibia. The projecting heel. The heart

line. The Color. Its extent; cause; scale of colors. Color of

the eyes. The Hair. Shape in cross section; abundance. The

muscular structure; anomalies in; muscular habits; arrow releases.

Steatopygy. Stature and proportion; the “canon of proportion;”

special senses; the color sense. Ethnic relations of

the sexes. Correlation of physical traits to vital powers. Causes

of the fixation of ethnic traits. Climate; food supply; natural

selection; conscious selection; the physical ideal; sexual preference;

abhorrence of incest; exogamous marriages. Causes of

variation in types. The mingling of races. Physical criteria of

racial superiority. Review of physical elements.

That no two persons are identical in appearance is

such a truism that we are apt to overlook its significance.

The parent can rarely be recognized from

18

the traits of the child, the brother from those of the

sister, the family from its members.

On the other hand, the individual peculiarities become

lost in those of the race. It is a common statement

that to our eyes all Chinamen look alike, or that

one cannot distinguish an Indian “buck” from a

“squaw.” Yet you recognize very well the one as a

Chinaman, the other as an Indian. The traits of the

race thus overslaugh the variable characters of the

family, the sex or the individual, and maintain themselves

uniform and unalterable in the pure blood of

the stock through all experience.

This fact is the corner-stone of the science of Ethnography,

whose aim is to study the differences, physical

and mental, between men in masses, and ascertain

which of these differences are least variable and hence

of most value in classifying the human species into its

several natural varieties or types.

In daily life and current literature the existence of

such varieties is fully recognized. The European and

African, or White and Black races, are those most

familiar to us; but the American Indian and the Mongolian

are not rare, and are recognized also as distinct

from each other and ourselves. These common terms

for the races are not quite accurate; but they illustrate

a tendency to identify the most prominent types of the

species with the great continental areas, and in this I

shall show that the popular judgment is in accord with

scientific reasoning.

If an ordinary observer were asked what the traits

19

are which fix the racial type in his mind, he would

certainly omit many which are highly esteemed by the

man of science. He would have nothing to say, for

instance, about the internal structures or organs, because

they are not visible; but in approaching the subject

from a scientific direction, we must lay most

stress upon these, as their peculiarities decide the external

traits which strike the eye.

Nor does the casual observer note the mental or

physical differences which exist between the races

whom he recognizes; yet these are not less permanent

and not less important than those which concern

the physical economy only. In both these directions

the student of ethnography as a science must pursue

careful researches.

In the present lecture I shall pass in review the

physical elements held to be most weighty in the discrimination

of racial types; and, first, those relating to

The Bones.—Most important are the measurements

of the skull, that science called craniology, or craniometry.

Ethnologists who are merely anatomists have made

too much of this science. They have applied it to the

exclusion of other elements, and have given it a prominence

which it does not deserve. The shape of the

skull is no distinction of race in the individual; only in

the mass, in the average of large numbers, has it importance.

Even here its value is not racial. Within

the limits of the same people, as among the Slavonians,

for example, the most different skulls are found,

20

and even the pure-blood natives of some small islands

in the Pacific Ocean present widely various forms.1

Experiments on the lower animals prove that the

skull is easily moulded by trifling causes. Darwin

found that he could produce long, or short, or non-symmetrical

skulls in rabbits by training.2 The shape

also bears a relation to stature. As a general rule

short men have short or rounded heads, tall men have

long heads. The longest skulled nation in Europe

are the Norwegians, who are also the tallest; the

roundest are the Auvergnats, who, of all the European

whites, are the shortest.

Nevertheless, employed cautiously, in large averages,

and with a careful regard for all the other ethnic

elements, the measurements of the skull are extremely

useful as accessory data of comparison.

21

Some craniologists have run up these measurements

to more than a hundred; but those worth mentioning

in this connection are but few. There is, first, the

proportion which the length of the head has to its

breadth. This makes the distinction between long,

medium and broad skulls, “dolicho-cephalic,” “meso-cephalic,”

and “brachy-cephalic.” In the medium

skull the transverse bears to the longitudinal diameter

the proportion of about 80:100. The proportion

75:100 would make quite a long skull, and 85:100

quite a broad skull, the extreme variations not exceeding

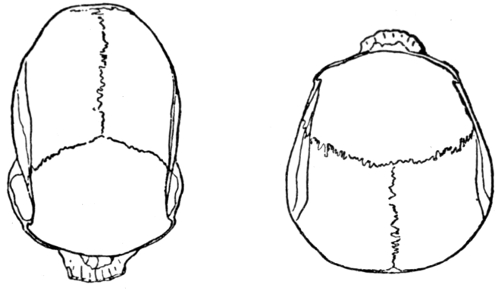

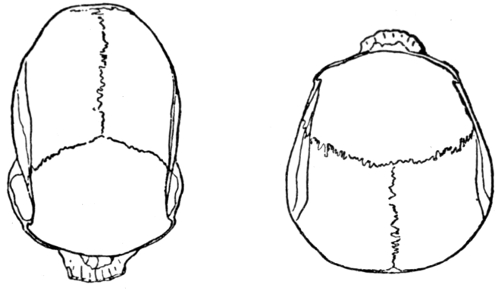

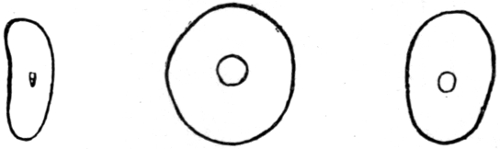

70:100-90:100. (Figs. 1 and 2.)

Figs. 1 and 2.—Long and Short Skulls.

The Asiatic race or typical Mongolians are generally

brachy-cephalic, the Eskimos and African negroes

dolicho-cephalic; while the whites of Europe and

American Indians present great diversity.

The lengthening of the skull may be anteriorly or

posteriorly, and this is probably more significant of

brain power than its width. In the black race the

lengthening is occipital, that is at the rear, indicating

a preponderance of the lower mental powers.

22

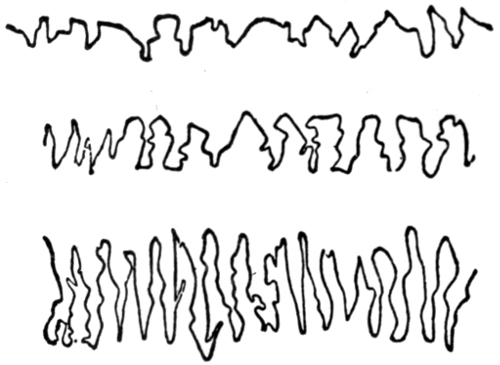

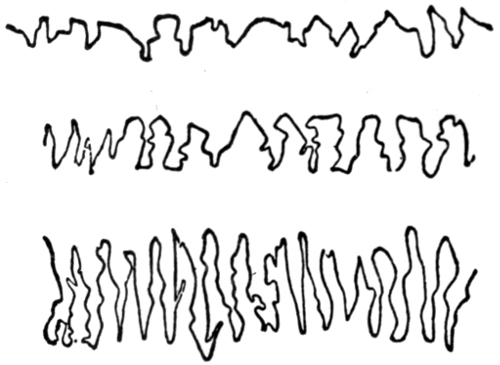

Fig. 3.—Lines of Sutures in the Skull.

The height of the skull is another measurement

which is much respected by craniologists; but they

are far from agreed as to the points from which the

lines shall be drawn, so that it is difficult to compare

their results.3 The “sutures,” or lines of union between

the several bones of the skull, present indications

of great value. In the lower races they are

much simpler than in the higher, and they become

obliterated earlier in life; the bones of the skull thus

uniting into a compact mass and preventing further

expansion of the cavity occupied by the brain.4 (Fig.

3.) Occasionally small separated bones are found in

these sutures, more frequently in some races than in

23

others. One of these, toward the back of the head,

occurs so constantly in certain American tribes that it

has been named the “Inca bone.”5

In many savage tribes there are artificial deformations

of the skull, which render it useless as a means

of comparison. The “Flathead Indians” are an example,

and many Peruvian skulls are thus pressed out

of shape. It is singular that this violence to such an

important organ does not seem to be attended with

any injurious result on the intellectual powers.

The orbit of the eyes is another feature which varies

in races. The proportion of the short to the long

diameter furnishes what is known as the “orbital index.”

The Mongolians present nearest a circular

orbit, the proportion being sometimes 93:100; while

the lowest range has been found in skulls from ancient

French cemeteries, presenting an index of 61:100.

The latter are technically called “microsemes;” the

former “megasemes,” while the mean are “mesosemes.”6

In a similar manner the aperture of the nostrils

varies and constitutes quite an important element of

comparison known as the “nasal index.” Where this

aperture is narrow, the nose is thin and prominent;

24

when broad, the nose is large and flat. The former

are “leptorhinian,” the latter “platyrhinian,” while

the medium size is “mesorhinian.” This division coincides

closely with that of the chief races. Almost

all the white race are leptorhinian, the negroes platyrhinian,

the true Asiatics mesorhinian. The Eskimos

have the narrowest nasal aperture, the Bushmen the

widest.

The projection of the maxillaries, or upper and

lower jaws, beyond the line of the face, is a highly

significant trait. When well marked it forms the

“prognathic,” when slight the “orthognathic” type.

It is much more observable in the black than in the

white race, and is more pronounced in the old than in

the young. It is considered to correspond to a

stronger development of the merely animal instincts.

The relation of the lower to the upper part of the

head is measured mainly by two angles, the one the

“maxillary,” the other the “facial” angle. The

former is the angle subtended by lines drawn from the

most projecting portion of the maxillaries to the most

prominent points of the forehead above and the chin

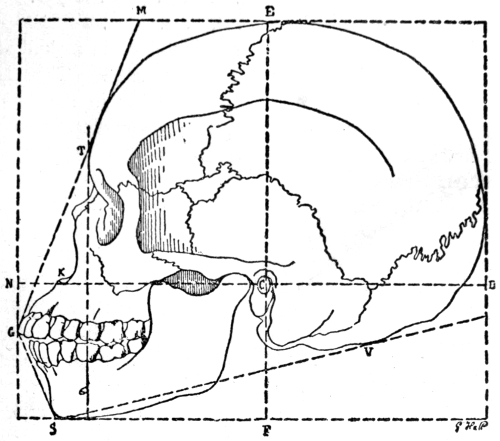

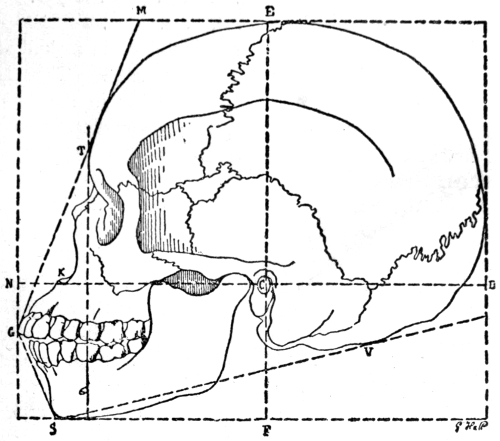

below. (The angle M G S in the accompanying diagram,

Fig. 4.) This supplies data for two important

elements, the prognathism and the prominence of the

chin. The latter is an essential feature of man.

None of the lower animals possesses a true chin, while

man is never without one. The more acute the maxillary

angle, the less of chin is there, and the more

prognathic the subject. The averages run as follows:

25

| The European white |

160°. |

| The African negro |

140°. |

| The Orang-outang |

110°. |

Fig. 4.—Lines and angles of skull measurement.

The facial angle is that subtended by the same line,

from the most prominent point of the upper jaw to

the most prominent part of the forehead, and a second

line drawn horizontally through the center of the aperture

of the ear. (The lines M G, D N.) It expresses

the relative prominence of the forehead and

capacity of the anterior portion of the brain. The

26

more acute this angle, the lower is the brain capacity.

The following are its averages:

| The European white |

80°. |

| The African negro |

70°. to 75°. |

| The Orang-outang |

40°. |

The amount of brain matter contained in a skull is

called its “cerebral or cranial capacity.” This is

proved by investigation to average less in the dark

than in the light races, and in the same race less in the

female than in the male sex. Estimated in cubic centimetres

the extremes are about 1250 cub. cent. in the

Australians and Bushmen to 1600 cub. cent. in well-developed

Europeans. We cannot regard this measurement

as a constant exponent of intellectual power,

as many men with small brains have possessed fine

intellects; but as a general feature it certainly is indicative

of brain weight, and therefore of relative intelligence.

The average human brain weighs 48 ounces,

while that of a large gorilla is not over 20 ounces.

The teeth offer several points of difference in races.

In the negro they are unusually white and strong, and

in nearly all the black people (Australians, Soudanese,

Melanesians, etc.), the “wisdom teeth” are generally

furnished with three separate fangs, and are sound,

while among whites they have only two fangs, and

decay early. The most ancient jaws exhumed in

Europe present the former character. The prominence

of the canine teeth is a peculiarity of some

tribes, while in others the canines are not conical, but

resemble the incisors.

27

The size of the teeth has also been asserted to be

an index of race, and an effort has been made to classify

peoples into small-toothed (microdonts), medium-toothed

(mesodonts), and large-toothed (megadonts).7

But this scheme includes in the first mentioned

class the Polynesians with the Europeans, and

in the second the African negro with the Chinese,

which looks as if the plan has little value.

The milk-teeth have a much closer resemblance to

those of the apes than the second dentition, and some

naturalists have thought that the forms of the second

teeth point often to reversion and are characteristic

of races, but this has not been proved.

The teeth and the period of dentition have been

studied in man with the view to show that certain

races more than others retain the dental forms of the

lower animals, but the latest investigations go rather

to overthrow than to support these theories.8

Turning to the other bones of the skeleton, I shall

note a few peculiarities said to be ethnic. The skeleton

of a negro usually presents iliac bones more vertical

than those of a white man, and the basin is narrower.

This peculiarity is measured by what is called

28

the “pelvic index,” by which is meant the ratio of the

transverse to the longitudinal diameter. The average

ratio is about 90 or 95 to 100.

Another trait of a lower osteology is the unusual

length of the arms. This is found to depend upon the

relative elongation of the fore-arm and its principal

bones, the radius and ulna. From comparisons which

have been instituted between the negro and the white,

it appears that the proportionate length of their arms

is as 78 to 72. The long arms are characteristic of

the higher apes and the unripe fetus, and belong,

therefore, to a lower phase of development than that

reached by the white race.

There is also a peculiarity among many lower peoples

in the shape of the shin-bone or tibia. Usually

when cut in cross-section, the ends present a triangular

surface; but in certain tribes, and in some ancient

remains from the caves, the cross-section is elliptical,

showing that the tibia has been flattened (platycnemic).

This was long regarded as a sign of ethnic inferiority,

but of late years the opinion of anatomists has undergone

a change, and they attribute it to the special use

of some of the muscles of the leg.

The heel-bone, the os calcis or calcaneum, is currently

believed to be longer and project further backward

in the negro than in the white man. There is

no doubt of the projection of the heel, and it is typical

of the true negro race, but it does not seem to be

owing to the size of the bone, as an examination of a

series of calcanca in both races proves. The lengthening

29

is apparent only, and is due to the smallness of

the calf and the slenderness of the main tendon, the

“tendon of Achilles,” immediately above the heel.9

With the pithecoid forms of the bones is often associated

another simian mark. The line in the hand

known to chiromancy as the “heart” line, in all races

but the negro ceases at the base of the middle finger,

but in his race, as in the ape, it often extends quite

across the palm.

The bones offer the most enduring, but not the most

obvious distinctions of races. The latter are unquestionably

those presented by

The Color.—This it is which first strikes the eye,

and from which the most familiar names of the types

have been drawn. The black and white, the yellow,

the red and the brown races, are terms far older than

the science of ethnography, and have always been

employed in its terminology.

Why it is that these different hues should indelibly

mark whole races, is not entirely explained. The

pigment or coloring matter of the skin is deposited

from the capillaries on the surface of the dermis or

true skin, and beneath the epidermis or scarf skin.10 I

have seen a negro so badly scalded that the latter was

detached in large fragments, and with it came most of

his color, leaving the spot a dirty light brown.

30

The coloration of the negro, however, extends much

beyond the skin. It is found in a less degree on all

his mucous membrane, in his muscles, and even in

the pia mater and the grey substance of his brain.

The effort has been made to measure the colors of

different peoples by a color scale. One such was devised

by Broca, presenting over thirty shades, and

another by Dr. Radde, in Germany; but on long

journeys, or as furnished by different manufacturers,

these scales undergo changes in the shades, so that

they have not proved of the value anticipated.

As to the physiological cause of color, you know that

the direct action of the sun on the skin is to stimulate

the capillary action, and lead to an increased

deposit of pigment, which we call “tan.” This

pigment is largely carbon, a chemical element, principally

excreted by the lungs in the form of carbonic

oxide. When from any cause, such as a peculiar diet,

or a congenital disproportion of lungs to liver, the

carbonic oxide is less rapidly thrown off by the former

organs, there will be an increased tendency to pigmentary

deposit on the skin. This is visibly the fact

in the African blacks, whose livers are larger in proportion

to their lungs than in any other race.11

31

While all the truly black tribes dwell in or near the

tropics, all the arctic dwellers are dark, as the Lapps,

Samoyeds and Eskimos; therefore, it is not climate

alone which has to do with the change. The Americans

differ little in color among themselves from what

part soever of the continent they come, and the Mongolians,

though many have lived time immemorial in

the cold and temperate zone, are never really white

when of unmixed descent.

A practical scale for the colors of the skin is the

following:

| Dark. |

{1. Black. |

| {2. Dark brown, reddish undertone. |

| {3. Dark brown, yellowish undertone. |

| |

| Medium. |

{1. Reddish. |

| {2. Yellowish (olive). |

| |

| White. |

{1. White, brown undertone (grayish). |

| {2. White, yellow undertone. |

| {3. White, rosy undertone. |

The color of the eyes should next have attention.

Their hue is very characteristic of races and of families.

Light eyes with dark skins are rare exceptions.

Other things equal, they are lighter in men than in

women. Extensive statistics have been collected in

Europe to ascertain the prevalence of certain colors,

and instructive results have been obtained.12 The division

usually adopted is into dark and light eyes.

32

| Dark eyes. |

{1. Black. |

| {2. Brown. |

| |

| Light eyes. |

{1. Light brown (hazel). |

| {2. Gray. |

| {3. Blue. |

The eye must be examined at some little distance

so as to catch the total effect.

Next in the order of prominence is

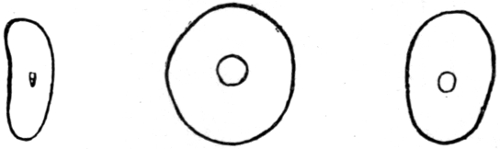

The Hair.—Indeed, Haeckel and others have based

upon its character the main divisions of mankind.

That of some races is straight, of others more or less

curled. This difference depends upon the shape of the

hairs in cross-section. The more closely they assimilate

true cylinders, the straighter they hang; while the

flatter they are, the more they approach the appearance

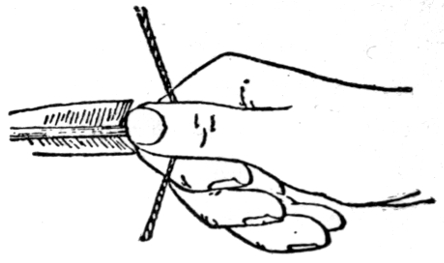

of wool. (Fig. 5.) The variation of the two diameters

(transverse and longitudinal) is from 25:100 to 90:100.

The straightest is found among the Malayans and

Mongolians; the wooliest among the Hottentots, Papuas

and African negroes. The white race is intermediate,

with curly or wavy hair. It is noteworthy

that all woolly-haired peoples have also long, narrow

heads and protruding jaws.

Fig. 5.—Cross Sections of Hairs.

The amount of hair on the face and body is also a

33

point of some moment. As a rule, the American and

Mongolian peoples have little, the Europeans and

Australians abundance. Crossing of races seems to

strengthen its growth, and the Ainos of the Japanese

Archipelago, a mixed people, are probably the hairiest

of the species. The strongest growth on the head is

seen among the Cafusos of Brazil, a hybrid of the Indian

and negro.

The Muscular Structure.—The development of the

muscular structure offers notable differences in the

various races. The blacks, both in Africa and elsewhere,

have the gastrocnemii or calf muscles of the

leg very slightly developed; while in both them and

the Mongolians the facial muscles have their fibres

more closely interwoven than the whites, thus preventing

an equal mobility of facial expression.

The anomalies of the muscular structure seem about

as frequent in one race as in another. The most of

them are regressive, imitating the muscles of the apes,

monkeys, and lower mammals. Indeed, a learned

anatomist has said that the abnormal anatomy of the

muscles supplies all the gaps which separate man

from the higher apes, as all the simian characteristics

reappear from time to time in his structure.13

Certain motions or positions, such as I may call

“muscular habits,” are characteristic of extensive

groups of tribes. The method of resting is one such.

The Japanese squats on his hams, the Australian

stands on one leg, supporting himself by a spear or

34

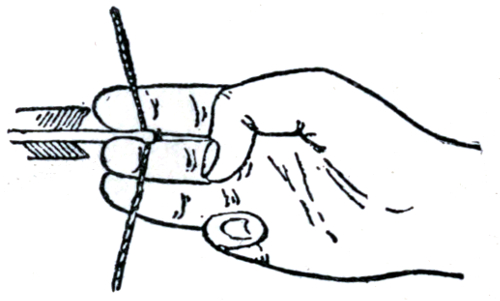

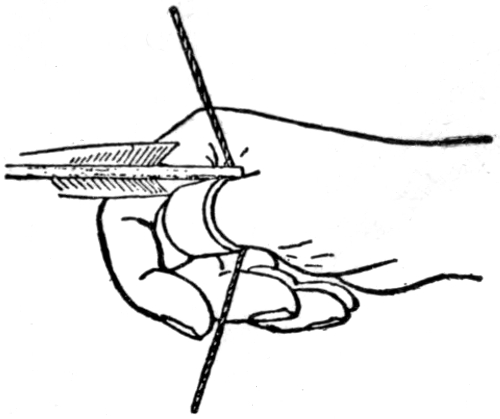

pole, and so on. The methods of arrow-release have

been profitably studied by Professor E. S. Morse.

He finds them so characteristic that he classifies them

ethnographically, with reference to savagery and civilization,

and locality. The three most important are the

primary, the Mediterranean, and the Mongolian releases.

The first is that of many savage tribes, the

second was practiced principally by the white race, the

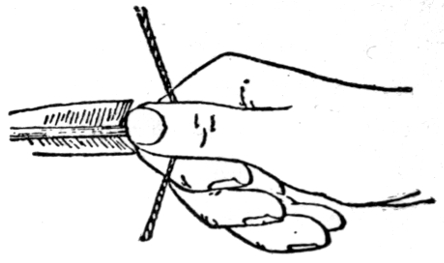

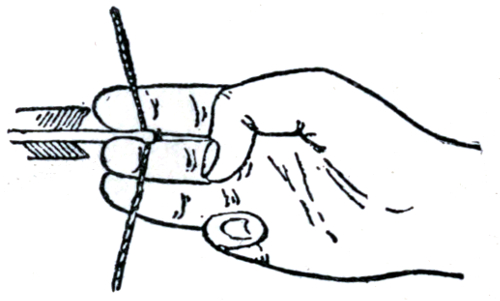

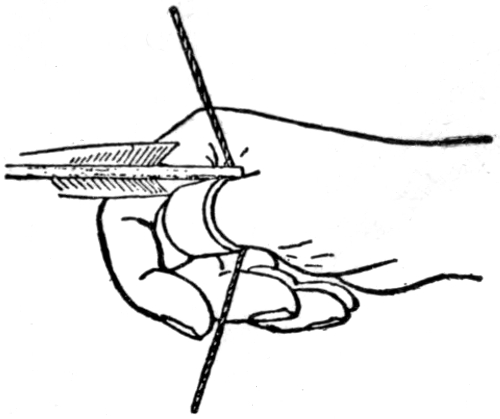

last by the Mongolians and their neighbors. (Figs. 6,

7, 8.) The last two are the most effective, and thus

gave superiority in combat.

Fig. 6.—Primary Arrow-Release.

Fig. 7.—Mediterranean Arrow-Release.

35

Allied to muscular variation are the peculiar deposits

of fatty tissue in certain portions of the system.

The Hottentots are remarkable for the prominence

of the gluteal region, imparting to their figure a

singular projection posteriorly. It is called “steatopygy,”

and appears to have been, in part at least, a

cultivated deformity, regarded among them as a

beauty. The thick lips of the negro, and the long and

pendent breasts of the Australian women, are other examples

of ethnic hypertrophies.

Fig. 8.—Mongolian Arrow-Release.

Stature and Proportion.—Differences in stature are

tribal, but not racial. The smallest peoples known,

the Negrillos, the Aetas, the Lapps, belong to different

races, as do the tallest, the Patagonians, the Polynesians,

the Anglo-Americans. The researches of Paolo

Riccardi and others prove that stature is correlated

with nutrition; the better the food, other things being

36

equal, the taller the men.14 It is also markedly

hereditary; the stature of children will average that of

their parents.

What is called the “canon of proportions” of the

human body varies with the race and the nation.

There is indeed an ideal, an artistic canon, which the

sculptor or the painter seeks to body forth in his

productions; and this seems in close conformity with

an extensive average of the proportions of the highest

peoples; but it is never found in individuals, and it is

essentially unlike in man and woman, in youth and

age, in the blonde and brunette.15 Nor is the ideal of

the artist also that which is consonant with the greatest

muscular development or highest powers of endurance.

Special Senses.—It cannot be said that the different

races display positive discrepancies in the special

senses. Their development appears to depend on

cultivation, and all races respond equally to equal

training. There is, to be sure, a higher musical sense

in the native African than in the native American, but

quite as much difference is seen between European

nations.

Much has been written of the color-sense as a trait

of nations. It has been said that some tribes, some

races, appreciate hues more keenly than others; that

within historic times marked gains in this respect are

37

noticeable. I think these statements are incorrect.

The savage of any race distinguishes precisely the difference

of hues when it is to his material interest so to

do; but concerns himself not at all about colors which

have no effect on his life. He is well acquainted with

the colors of the animals he hunts, and has a word for

every shade of hue. This proves that his color-sense

is as acute as that of civilized people, and merely lacks

specific training.

Ethnic Relations of the Sexes.—There are some

curious facts in reference to the relative position of the

sexes in different peoples. As a rule the expression

of sex in form and feature is less in the lower than in

the higher races. Travelers frequently refer to the

difficulty of distinguishing the men from the women

among the American Indians or the Chinese. Investigate

the fact, and you will find that it is not that the

women are less feminine in appearance, but the men

less masculine. In other words, the expression of sex

in such peoples is less in man than in woman. This

seems to be true also of the highest ideals of manhood

in artistic conception. The Greek Apollo, the

traditional Christ, present a feminine type of the male.

This was carried to its excess in the Greek Hermaphrodite.

The reason for this approximation to the female in

art-ideals is probably the zoological fact that the law

of beauty in the human species is the reverse of that

in all the other higher mammals, the female sex with

us being the handsomer. This also becomes more

38

evident in the comparison of the best developed

peoples.

On the other hand, the muscular force of the sexes

presents the greatest contrast in nations of the highest

culture. The average European woman of twenty-five

or thirty has one-third less muscular power than the

average European man. But among the Afghans, the

Patagonians, the Druses and other tribes, the women

are as tall and as strong as the men; and in Siam, Ashanti,

Ancient Gaul, and elsewhere, not only the field-laborers

but the soldiers were principally women,

selected because of their greater physical force and

courage.

As the value of mere brute force in a social organization

lessens in comparison to mental powers, the

condition of woman improves, and her faculties find

appropriate play. Her brain capacity, though absolutely

less, is relatively more than man’s. That is, the

difference of the whole average weight of woman and

man is greater in proportion than the difference of their

brain weights.

It is believed, also, that the viability or prospect of

life in woman is greater in higher than in lower peoples;

and generally greater than in men. European

statistics show that 106 boys are born to 100 girls:

but at twelve years of age the sexes are equal, the

boys suffering a greater mortality. At eighty years

of age, there are nearly three women living to one

man, indicating a superior longevity.

Correlation of Physical Traits to Vital Powers.—The

39

physical traits are correlated to the physiological

functions in such a manner as profoundly to influence

the destiny of nations. They enable or disable

man with reference to the climatic and other

conditions of his surroundings. For instance, certain

races can support given temperature better than

others. The intense heat and humidity of Central

Africa or Southern India are destructive to the pure

whites, while the climate north of the fortieth parallel

soon exterminates the blacks. The food on which

the Australian thrives destroys the digestive powers

of the European. Exemption and liability to diseases

differ noticeably in races. The white race is more

liable to yellow fever, malarial diseases, syphilis, scarlet

fever and sunstroke; the colored races to measles,

tuberculosis, leprosy, elephantiasis, and pneumonia.

Indeed, from the physical point of view, the pure

white is weaker than the dark races, worse prepared

for the combat of life, with inferior viability. This

has been shown by the careful researches of statisticians.16

But in the white this is more than compensated

by the development of the nervous system and the

intellectual power. He can bear greater mental strain

than any other race, and the activity of his mind supplies

him with means to overcome the inferiority of

his body, and thus places him at the head of the whole

species.

40

The tolerance of disease is an obscure but momentous

element in the comparison of races. It is

almost a proverb among the Spanish-American physicians

that “when an Indian falls sick, he dies.” The

greater longevity of the European peoples is due to

their ability to support disease long and frequently,

without succumbing to it. On the other hand, surgical

injuries, wounds and cuts, appear to heal more rapidly

among savage peoples.17 It is clear that in civilized

conditions this is less important than tolerance.

The Causes of the Fixation of Ethnic Traits.—These

causes are mainly related to climate and the

food-supply. The former embraces the questions of

temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure (altitude),

malarial or zymotic poisons, and the like. All

these bear directly upon the relative activity of the

great physiological organs, the lungs, heart, liver, skin

and kidneys, and to their action we must undoubtedly

turn for the origin of the traits I have named. On the

food-supply, liquid and solid, whether mainly animal,

fish or vegetable, whether abundant or scanty, whether

rich in phosphates and nitrogenous constituents or the

reverse, depend the condition of the digestive organs,

the nutrition of the individual, and the development

of numerous physical idiosyncrasies. Nutrition controls

41

the direction of organic development, and it is

essentially on arrested or imperfect, in contrast to

completed development, that the differences of races

depend.

These are the physiological and generally unavoidable

influences which went to the fixation of racial

types. They are those which placed early man under

the dominion of natural, unconscious evolution, like

all the lower animals. To them may be added natural

selection from accidental variations becoming permanent

when proving of value in the struggle for existence,

as shown in the black hue of equatorial tribes,

special muscular development, etc.

But I do not look on these as the main agents in the

fixation of special traits. No doubt such agencies primarily

evolved them, but their cultivation and perpetuation

were distinctly owing to conscious selection in

early man. Our species is largely outside the general

laws of organic evolution, and that by virtue of the

self-consciousness which is the privilege of it alone

among organized beings.

This conscious selection was applied in two most

potent directions, the one to maintaining the physical

ideal, the other toward sexual preference.

As soon as the purely physical influences mentioned

had impressed a tendency toward a certain type on the

early community, this was recognized, cultivated and

deepened by man’s conscious endeavors. Every race,

when free from external influence, assigns to its highest

ideal of manly or womanly beauty its special racial

42

traits, and seeks to develop these to the utmost. African

travelers tell us that the negroes of the Soudan

look with loathing on the white skin of the European;

and in ancient Mexico when children were born of a

very light color, as occasionally happened, they were

put to death. On the other hand the earliest records

of the white race exalt especially the element of whiteness.

The writer of the Song of Solomon celebrates

his bride as “fairest among women,” with a neck

“like a tower of ivory;”18 and one of the oldest of

Irish hero-tales, the Wooing of Emer, chants the

praises of “Tara, the whitest of maidens.”19 Though

both Greeks and Egyptians were of the dark type of

the Mediterranean peoples, their noblest gods, Apollo

and Osiris, were represented “fair in hue, and with

light or golden hair.”20

The persistent admiration of an ideal leads to its

constant cultivation by careful preservation and sexual

selection. Thus the peoples who have little hair on

the face and body, as most Chinese and American Indians,

usually do not like any, and carefully extirpate

it. The negroes prefer a flat nose, and a child which

develops one of a pointed type has it artificially flattened.

In Melanesia if a child is born of a lighter hue

than is approved by the village, it is assiduously held

over the smoke of a fire in order to blacken it. The

43

custom of destroying infants markedly aberrant from

the national type is nigh universal in primitive life.

Such usages served to fix and perpetuate the racial

traits.

A yet more powerful factor was sexual preference.

This worked in a variety of ways. If is well known to

stock breeders that the closer animals are bred in-and-in,

that is, the nearer the relationship of father and

mother, the more prominently the traits of the parents

appear in their children and become fixed in the breed.

It is evident that in the earliest epoch of the human

family, the closest inter-breeding must have prevailed

without restriction, as it does in every species of the

lower animals. By its influences the racial traits were

rapidly strengthened and indelibly impressed. This,

however, was long before the dawn of history, for it is

a most remarkable fact that never in historic times has

a tribe been known that allowed incestuous relations,

unless as in ancient Egypt and Persia, for a sacrificial

or ceremonial purpose. The lowest Australians, the

degraded Utes, look with horror on the union of

brother and sister. The general principle of marriage

in savage races is that of “exogamy,” marriage outside

the clan or family, the latter being counted in the

female line only. This strange but universal abhorrence

has been explained by Darwin as primarily the

result of sexual indifference arising between members

of the same household, and the high zest of novelty in

that appetite. Whatever the cause, the consequences

will easily be seen. The racial traits once fixed in the

44

period before this abhorrence arose would remain

largely stationary afterwards, and by exogamous marriages

would be rendered uniform over a wide area.

This form of conscious selection has properly been

rated as one of the prime factors in the problem of

race differentiation.21 The apparently miscellaneous

and violent union of the sexes in savage tribes is in

fact governed by the most stringent traditional laws,

and their confused cohabitations are so only to the

mind of the European observer, not to the tribal conscience.22

Causes of Variation in Types.—The physical type

once fixed by the influences just mentioned remains

very stable; yet may fall under the influence of conditions

which will greatly modify it.

Changes in climatic surroundings and of the food

supply exert a visible effect. These generally come

about by migration, though geologic action has occasionally

completely altered the climate of a given locality,

as at the glacial epoch, which change would

have the same effect as migration.

How far migration may alter race-types after many

generations is not yet defined. The Spanish-American

of pure white blood, whose ancestors have lived

45

for three centuries in tropical America, the citizen of

the United States who traces his genealogy to the

passengers in the Mayflower or the Welcome, have

departed extremely little from the standard of the Andalusian

or the Englishman of to-day, though the

contrary is often asserted by those who have not personally

studied the variants in the countries compared.

Conditions of climate and food materially impress the

individual, but not the race. The Greeks of Nubia

are as dark as Nubians, but let their children return to

Greece and the Nubian hue is lost. This is a general

truth and holds good of all the slight impressions made

upon pure races by unaccustomed environments.

Another cause of variation is the recurrence to

remote ancestral traits, or the appearance of what

seem merely accidental variations, which may be perpetuated.

It is not very unusual in pure African

negroes and Chinese to observe instances of reddish

hair and gray or brown eyes.

Those peculiar congenital conditions known as albinism

and melanism may be frequent and are unquestionably

transmissible by descent.23

The Mingling of Races.—But the mightiest cause

in the change of types is intermarriage between races,

what the French call métissage. This has taken place

from distantly remote epochs, especially along the lines

where two races come into contact. In such regions

46

we always find numerous mixed breeds, leading to a

shading of one race into another by imperceptible

degrees.

The widespread custom of exogamous marriage

fostered the blending of types, and it was greatly

increased in early days by the institution of human

slavery, the habit of selling captives taken in war, the

purchase of wives and concubines, and the rule in

early conquest that the men of the conquered were

killed or sent off, and the women retained as the spoils

of the victors. In all ages man has been migratory,

and very remote relics of his arts show that war and

commerce led to extensive intermixture of races long

before history took up the thread of his wanderings.

It is noticeable, however, that these prolonged interminglings

have not produced another race. The

nearest approach to it is in the Australians, but these

do not refute my statement as we shall see later.

Many ethnologists have indeed classed the mixed types

as separate races, running the number of the sub-species

of the genus homo up to thirty or forty. But

this was hasty generalization.

I would impress upon you this fact, that since the

intermingling of two races does not produce a third

race, it is not likely that any of the existing races arose

from a fusion of two others. The result of observation

shows that after two or three generations the tendency

in mixed breeds is to recur to one or the other

of the original stocks, not to establish a different

variety.

47

Were it not for such constant crossings, we have

reason to believe that the race types would resist all

environment and retain their traits under all known

conditions. It is only where the element of métissage

prominently enters that we are unable to assign individuals

to one or another race.

Such being the case, it is a fair comparison to set

one race over against another and deduce the

Physical Criteria of Racial Superiority.—We are accustomed

familiarly to speak of “higher” and “lower”

races, and we are justified in this even from merely

physical considerations. These indeed bear intimate

relations to mental capacity, and where the body presents

many points of arrested or retarded development,

we may be sure that the mind will also.

There are two explanations of the presence of the

inferior physical traits in certain races of men; the

one, that of the evolutionists, that they are reversions

or perpetuations of the ape-like (simian, pithecoid)

features of the lower animal which was man’s immediate

ancestor; the other, that of the special creationists,

that they are instances of surviving fetal peculiarities,

or else deficiency or excess of development from unknown

causes.

The following are the principal traits of the kind:

Simplicity and early union of cranial sutures.

Presence of the frontal process of the temporal

bone.

Wide nasal aperture, with synostosis of the nasal

bones.

48

Prominence of the jaws.

Recession of the chin.

Early appearance, size and permanence of the “wisdom”

teeth.

Unusual length of the humerus.

Perforation of the humerus.

Continuation of the “heart” line across the hand.

Obliquity (narrowness) of the pelvis.

Deficiency of the calf of the leg.

Flattening of the tibia.

Elongation of the heel (os calcis).

When all or many of these traits are present, the

individual approaches physically the type of the anthropoid

apes, and a race presenting many of them is

properly called a “lower” race. On the other hand,

where they are not present, the race is “higher,” as it

maintains in their integrity the special traits of the

genus Man, and is true to the type of the species.

The adult who retains the more numerous fetal, infantile

or simian traits, is unquestionably inferior to

him whose development has progressed beyond them,

nearer to the ideal form of the species, as revealed by

a study of the symmetry of the parts of the body, and

their relation to the erect stature.

Measured by these criteria, the European or white

race stands at the head of the list, the African or negro

at its foot.

The investigations of anthropologists extend much

beyond the outlines I have now presented you. All

parts of the body have been minutely scanned, measured

49

and weighed, in order to erect a science of the

comparative anatomy of the races. Much of value has

been discovered; but nothing absolutely characteristic,

nothing which enables us to divide more sharply

one race from another than the facts I have given you.

It is a question, indeed, whether not too much, but

too exclusive attention has not been devoted by many

anthropologists to the purely physical aspects of their

science. They have multiplied useless anatomical

refinements and a pedantic nomenclature. The more

valuable general distinctions and their technical terms

I present to you in the following table:—

Scheme of Principal Physical Elements.

| Skull |

Dolichocephalic, long skulls. |

| Mesocephalic, medium skulls. |

| Brachycephalic, broad skulls. |

| |

| Nose |

Leptorhine, narrow noses. |

| Mesorhine, medium noses. |

| Platyrhine, flat or broad noses. |

| |

| Eyes |

Megaseme, round eyes. |

| Mesoseme, medium eyes. |

| Microseme, narrow eyes. |

| |

| Jaws |

Orthognathic, straight or vertical jaws. |

| Mesognathic, medium jaws. |

| Prognathic, projecting jaws. |

| |

| Face |

Chamæprosopic, low or broad face. |

| Mesoprosopic, medium face. |

| Leptoprosopic, narrow or high face. |

| |

| Pelvis |

Platypellic, broad pelvis. |

| Mesopellic, medium pelvis. |

| Leptopellic, narrow pelvis.

50 |

| |

| Color |

Leucochroic, white skin. |

| Xanthochroic, yellow skin. |

| Erythrochroic, reddish skin. |

| Melanochroic, black or dark skin. |

| |

| Hair |

Euthycomic, straight hair. |

| Euplocomic, wavy hair. |

| Eriocomic, wooly hair. |

| Lophocomic, bushy hair. |

51

LECTURE II.

THE PSYCHICAL ELEMENTS OF ETHNOGRAPHY.

Contents.—The mental differences of races. Ethnic psychology.

Cause of psychical development.

I. The Associative Elements. 1. The Social Instincts; sexual

impulse; primitive marriage; conception of love; parental affection;

filial and fraternal affection; friendship; ancestral worship;

the gens or clan; the tribe; personal loyalty; the social organization;

systems of consanguinity; position of woman in the state;

ethical standards; modesty. 2. Language; universality of;

primeval speech; rise of linguistic stocks; their number; grammatical

structure; classes of languages; morphologic scheme;

relation of language to thought; significance of language in ethnography.

3. Religion: universality of; early forms; family and

tribal religions; universal or world religions; ethnic study of religions;

comparison of Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism; material

and ideal religions; associative influences of religions. 4.

The Arts of Life: architecture; agriculture; domestication of

animals; inventions.

II. The Dispersive Elements: adaptability of man to surroundings.

1. The Migratory Instincts; love of roaming; early commerce;

lines of traffic and migration. 2. The Combative Instincts:

primitive condition of war; love of combat; its advantages;

heroes; development through conflict.

The mental differences of races and nations are real

and profound. Some of them are just as valuable

for ethnic classification as any of the physical elements

I referred to in the last lecture, although purely physical

anthropologists are loath to admit this. No one

can deny, however, that it is the psychical endowment

52

of a tribe or a people which decides fatally its luck in

the fight of the world. Those, therefore, who would

master the highest significance of ethnography in its

function as the key to history, will devote to this

branch of it their most earnest attention.

The study of the general mental peculiarities of a

people is called “ethnic psychology.” As a science, it

may be treated by various methods, applicable to the

different aims of research. For our present purpose,

which is to study the growth, migrations and comminglings

of races and peoples, the most suggestive

method will be to classify their mental distinctions

under the two main headings of Associative and Dispersive

Elements. The predominance of one or the

other of these is ever eminently formative in the character

and history of a people, and both must be constantly

considered with reference to their bearings on

the progress of a nation toward civilization.

The psychical development of men and nations finds

its chief explanation, less in the natural surroundings,

the climate, soil, and water-currents, as is taught by

some philosophers, than in their relations and connections

with each other, their friendships, federations

and enmities, their intercourse in commerce, love and

war. Around these must center the chief studies of

ethnographic science, for they contain and present the

means for reaching its highest, almost its only aim—the

comprehension of the social and intellectual progress

of the species.

53

I. The Associative Elements.

The sense of fellowship, the gregarious instinct, was

inherited by our first fathers from their anthropoid

ancestors. The “river drift” men, who dwelt on the

banks of the Thames and the Somme before the glacial

epoch, were gathered into small communities, as

their remains testify. The most savage tribes, Fuegians

and Australians, roam about in detached bands.

They are not under the control of a chief, but are led

to such union by much the same motives as prompt

buffaloes to gather in a herd.

These fundamental mental elements which impel to

association are:

1. The Social Instincts.

Strongest of them all is the sexual impulse. The

foundation of every community is the bond of the

man and woman, and the nature of this bond is the

surest test of a community’s position in the scale of

culture. It is not likely that miscellaneous cohabitation,

or that slightly modified form of it called “communal

marriage,” ever existed. No instance of it has

been known to history.24 In the most brutal tribes the

man asserts his right of ownership in the woman.

The rare custom of “polyandry,” where a woman has

several husbands at once, gives her no general license.

It is equally true that the tender sentiments of love

54

appear to be less known to the lowest savages than

they are to beasts and birds. The process of mating

is by brute force, marriage is by robbery, and the

women are in a wretched slavery. Mutual affection

has no existence. Such is the state of affairs among

the Australians, the western Eskimos, the Athapascas,

the Mosquitos, and many other tribes.25

But it is gratifying to find that we have to mount

but a step higher in the scale to find the germs of a

nobler understanding of the sex relation. In many

tribes of but moderate culture, their languages supply

us with evidence that the sentiment of love was awake

among them, and this is corroborated by the incidents

we learn of their domestic life. This I have shown

in considerable detail by an analysis of the words for

love and affection in the languages of the Algonkins,

Nahuas, Mayas, Qquichuas, Tupis and Guaranis, all

prominent tribes of the American Indians.26

Some of the songs and stories of this race seem to

reveal even a capability for romantic love, such as

would do credit to a modern novel. This is the more

astonishing, as in the African and Mongolian races

this ethereal sentiment is practically absent, the idealism

of passion being something foreign to those varieties

of man.

55

The sequel of the sexual impulse is the formation

of the family through the development of parental

affection. This instinct is as strong in many of the

lower animals as in human beings. In primitive conditions

it is largely confined to the female parent, the

father paying but slight attention to the welfare of

his offspring. To this, rather than to a doubt of paternity,

should we attribute the very common habit in

such communities, of reckoning ancestry in the female

line only.

Akin to this is filial and fraternal affection, leading

to a preservation of the family bond through generations,

and in spite of local separation. It is surprising

how strong is this sentiment even in conditions of low

culture. The Polynesians preserved their genealogies

through twenty generations; the Haidah Indians of

Vancouver’s Island boast of fifteen or eighteen.

The sentiment of friendship has been supposed by

some to be an acquisition of higher culture. Nothing

is more erroneous. Dr. Carl Lumholtz tells me he has

seen touching examples of it among Australian cannibals,

and the records of travelers are full of instances

of devoted affection in members of savage tribes, both

toward each other and toward persons of other races.

There are established rites in early social conditions,

by which a stranger is received into the bond of fellowship

and the sanctity of friendship.27 This is often

by a transfer of the blood of the one to the body of the

56

other, or a symbolic ceremony to that effect, the meaning

being that the stranger is thus admitted to the

rights of kinship in the gens or clan. Springing from

this clannish affection is the custom of ancestral worship,

which adds a link to the bond of the family. It

is so widely spread that Herbert Spencer has endeavored

to derive from it all other forms of religion.

But this is a hasty generalization. The religious sentiment

had many other primitive forms of expression.

Through these various personal affections we reach

the development of the family into the gens, the clan

or totem, all of whose members, whether by consanguinity

or adoption, are held to represent one interest.

The union of several gentes under one control constitutes

the tribe, which is the first step toward what is

properly a state. The tribe passes beyond the ties of

affinity by embracing in certain common interests persons

who are not recognized as allied in blood. Yet

it is curious to note that the tribal sentiments are

among the very strongest mankind ever exhibits, surpassing

those of family affection. Brutus felt no hesitation

in sacrificing his son for the common weal.

Classical antiquity is full of admonitions and examples

to the same effect. So powerful is the devotion of the

Polynesians that they have been known when a canoe

was capsized where sharks abounded, to form a ring

around their chief, and sacrifice themselves one by one

to the ravenous fish, that he might escape.

This sentiment of personal loyalty has been in history

57

the main strength of many a government, and has

in it something chivalric and noble, which challenges

our admiration; yet it is quite opposed to the principles

of republicanism and the equal rights of individuals,

and we must condemn it as belonging to a lower

stage of evolution than that to which we have arrived.

The result of these gregarious instincts is the formation

of the social organization, the bond under which

first the primitive horde and later the members of the

developed commonwealth consented to live. From

first to last, wherever found, communities of men are

bound together by ties of consanguinity and affection

rather than mere self-interest. Those writers who

pretend that society once existed without the idea of

kinship, with promiscuity in the sexual relation, and

without some recognized controlling power, have

failed to produce such an example from actual life.

These ties led to the systems of “consanguinity and

affinity” which recur with singular sameness at a certain

stage of culture the world over. They give rise to

what is called the totemic or gentile phase of society,

in which its members are organized into “gentes” or

clans, “phratries” or associations of clans, and the

tribe, which embraces several such phratries. This

theory affected the disposition of property, which belonged

to the clan and not to the individual, and the

form of government, which was usually by a council

appointed from the various clans. The recognition of

the wide prevalence of these ideas in the ancient world

has led to profound modifications of our views respecting

58

its institutions, and a better understanding of

many of the events of history.28

In social organizations one of the criteria of excellence

is the position of woman. Upon this depends the

life of the family and the development of morality.

Those nations which have gained the most enduring

conquests in power and culture have conceded to woman

a prominent place in social life. In ancient Egypt,

in Etruria, in republican Rome, women owned property,

and enjoyed equal rights under the law. Where

woman is enslaved, as among the Australian tribes,

progress is scarcely possible; where she is imprisoned,

as in Mohammedan countries, progress may be rapid

for a time, but is not permanent. Unusual mental

ability in a man is generally inherited from his mother,

and a nation which studies to prevent women from acquiring

an education and from taking an active part in

affairs, is preparing the way to engender citizens of

inferior minds.

Among other ethnic traits, the appreciation of the

ethical standard differs notably. Long ago the observant

Montaigne commented on the conflicting

views of morals in nations, and remarked rather cynically

that what was good on one side of a river was

deemed wicked on the other. This is especially noticeable

in the sense of justice, the rights of property,

59

and the regard for truth. No Asiatic nation respects

truth telling, or can be made to see that it is abstractly

desirable when it conflicts with their immediate interests.

The rights of property are generally construed

entirely differently to ourselves among nations

in the lower grades of culture, because the idea of independent

personal ownership does not exist among

them. What they have belongs to the clan or the

horde, and they merely have the use of it.

The basis of ethics in all undeveloped conditions is

not general but special; it relates to the tribe and the

family, and is in direct conflict with the philosopher

Kant’s famous “categorical imperative,” which makes

the basis the welfare of the whole species. Hence, in

primitive culture and survivals there is a dual system

of morals, the one of kindness, love, help and peace,

applicable to the members of our own clan, tribe or

community; the other of robbery, hatred, enmity and

murder, to be practiced against all the rest of the

world; and the latter is regarded as quite as much a

sacred duty as the former.29 Ethics, therefore, while

a powerfully associative element in the one direction,

becomes dispersive or segregating in others, unless

the sense of duty is taught as a universal and not as a

class or national conception.

The sentiment of modesty is developed by man in

society, and he alone among animals possesses it.

Whatever has been said to the contrary, it is never

60

absent. Frequently, indeed, its manifestation is not

according to our usages, and is thus overlooked.

Women with us expose their faces, which a Moorish

lady would think most indelicate. The Bedawin women

consider it immodest to have the back of the head

uncovered; the Siamese think nothing of displaying

nude limbs, but on no account would show the uncovered

sole of the foot. In certain African courts, the

men wear long robes while the women appear nude.

The necessary functions of the body are everywhere

veiled by retirement, and in the most savage tribes, a

regard for decency is constantly noted.

The second chief associative principle is

2. Language.

Unlike the elements of affection which I have been

tracing, language is not a legacy from a brute ancestor.

It is the peculiar property of the genus Man, and no

tribe has ever been known without a developed grammatical

articulate speech, with abundance of expressions

for all its ideas. The stories of savages so rude

that they were forced to eke out their words with

gestures, and could not make themselves intelligible

in the dark, are fables. The languages of the most

barbarous communities are always ample in forms,

and often surprisingly flexible, rich and sonorous.

We must indeed suppose a time when the speech of

primeval man had a feeble, imperfect beginning.

“The origin of language” has been a favorite theme

for philologists to speculate about, with sparse fruit

61

for their readers. We can, indeed, picture to ourselves

something like what it must have been in its

very early stages, by studying a number of very simple

languages, and noting what parts of the grammar and

dictionary they dispense with. Following this plan, I

once undertook to show what might have been the

language of man far back in palæolithic times. It

probably had no “parts of speech,” such as nouns,