This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Scott Burton, Forester

Author: Edward G. (Edward Gheen) Cheyney

Release Date: June 9, 2018 [eBook #57298]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SCOTT BURTON, FORESTER***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/scottburtonfores00chey |

“Hello, Scotty, have you decided yet which one it will be?” Dick Bradshaw called, eagerly, as he ran up the walk to the old Burton home. He had been away for two weeks, and when he left, the selection of a forest school for Scott had been the all absorbing question.

“Yes,” Scott answered, “it was decided a week ago. You know there never has been any doubt in my mind. I picked out the Western college in the first place, but father and mother did not want me to go so far away from home. I persuaded them last week that it was the best thing to do, and they consented.”

Dick’s face fell. “That means I shall not see you for four years,” he growled.

“Oh no, Dick,” Scott answered quickly, “not over three at the most, and possibly not over two. That was what persuaded father and mother to let me go. You see they may give me enough extra credit for that extra high school work and those three years of summer school we took, to enable me to squeeze through in two years. I have sent in my credits, and shall find out when I get there.”

Dick brightened up a little. The boys had grown up together in the little New England village, the closest of friends, and the idea of a long separation was pretty hard, especially for the one who was to stay at home. They had always had the same tastes in books, studies and pleasures. Both were hard students and both preferred long walks in the woods and fields to the games that most boys play. These traits had kept them somewhat apart from the other boys, and thrown them almost exclusively on each other’s society.

“When do you go?” Dick asked.

“Early tomorrow morning,” Scott answered. “You see it takes two days to get there. I was afraid you would not get back in time for me to see you at all.”

“Tomorrow!” Dick exclaimed indignantly. “Why didn’t you pick out Yale? You could have come home once in a while then, and we could have had a great time together there next year.” Dick was planning on taking some special work in biology at Yale the next season.

Scott was stung by the reproach in Dick’s voice. “You know perfectly well I would have done it if I could. Yale has a graduate school and I could not get in. Why don’t you come out with me?”

“Maybe I shall if you find out that it is any good. Why do you want to go to a place that you do not know anything about?” Dick remonstrated.

“But I do know something about it, Dick. I know that it is in a new country that I have never seen, that it has a good reputation, and that a large part of the work is given in camp. What more do you want?”

“Well,” Dick answered, “that camp part sounds good to me and if the biology is taught in a camp I may be out there with you next year. You find out about that and let me know. I have to be going now. I just came up on the way from the train to find out what you had decided. Mother is waiting for me. See you later.” And he hurried down the walk.

“Come over after supper,” Scott called after him and walked slowly into the house. This thing of leaving Dick when he was taking it so hard was the toughest pull of all. He knew Dick through and through, and he suddenly realized that he did not know anything about any of the people where he was going. His intimate knowledge of boys was limited almost entirely to Dick, and he felt a certain timidity in meeting so many strangers.

As he entered the old home where he had always lived he felt that it was dearer to him than he knew, in spite of the fact that he was so eager to leave it. His father was a doctor there in the little village of Wabern, Mass., a man devoted to his profession, which yielded a large amount of work with a small income. He had always taken it for granted that his only child would follow in his footsteps, and for many years he had tried in every way to interest the boy in his work. He had taken him on many a long drive on the rounds of his work and tried to impress on him the beauties of healing sickness and alleviating pain. It was not till Scott was a strapping big fellow of sixteen that the astonished father realized that his boy had drifted hopelessly away from the medical profession.

He had noted with pride Scott’s collection of plants, bugs, small animals and rocks, and the boy’s love for such things pleased him. It came to him as a shock when he discovered that the boy’s point of view was entirely different from his own. For him the specimens were all related in some way to the medical profession; to Scott they represented only the different phases of nature. It was the make-up of the great “outdoors” which interested him, and he longed to be a part of it. It was the opportunity of such a life that first attracted him toward forestry, and his mind once made up he bent all his energies to preparing for the work. His father and mother concealed their disappointment as best they could and helped him along in this unknown line of work.

At last the time had come when a special course at college was necessary, and the question of which school had to be decided. Scott’s lack of a degree barred him from the graduate schools of the East, and in his heart he was rather glad of it. He knew every plant, animal and rock in that section of the country and was eager for new fields to conquer. The greater proportion of actual woods work was a further incentive. With these things in mind he had studied the catalogs of the different schools by the hour, and had finally decided on Minnesota. His parents had objected at first on account of the distance from home but they had finally yielded to his wish.

And now the question was settled. His application had been accepted, Dick had given a grudging approval, and he was actually packing up to go.

In the hall he met his father, a mild-eyed man of fifty, just returning from his daily round of mercy.

“Well, Scott,” he said cheerfully, “you are leaving the old nest and taking a pretty long flight for the first one. See that you fly straight, boy. Your mother and I have done all that we can to develop your wings, and the rest of it is up to you. Let’s go to dinner.”

Mrs. Burton was waiting for them in the dining-room. She was very tired from the work of preparing Scott for his journey, and blue at the thought of losing him, but she smiled her sweetest smile, and did her best to cheer the boy’s last meal at home. There was nothing unusual about the dinner, but Scott felt a certain close companionship with his father and mother, an equality, that he had never felt before. It gave him a new feeling of confidence and responsibility that no amount of lecturing could have done.

Before they arose from the table the doctor said: “Here’s something for you to remember, Scott. You already know that book knowledge is not everything. You know that a great deal can be learned from nature, but there is one important source of knowledge that you must not neglect. You are going where there will be hundreds of young men, men of all kinds and character. They will be a good sample of the men of the world, and it is important that you should know them. Do not do there as you have done here at home, pick one man for your constant companion and be indifferent to all the others. You must know them all. Study some of them for the good traits that you ought to have, and others for the bad traits that you want to avoid. You can learn something from everyone of them. You must learn from them how to take a man’s measure for yourself and not have to rely on the judgment of others. If you learn to judge men truly your success in other things will be pretty certain.

“Just one thing more. You have insisted on taking up work that is different from the life I had always planned for you. Perhaps you think that I am hurt and resent it. That is not true. I want you to feel that I have every confidence in your judgment and ability to make a success of anything you undertake even when you choose something of which I am entirely ignorant. This new work should prepare you to make some use of wild land, as I understand it, and I am going to make you a proposition.

“That ten thousand-acre tract of cut-over forest in New Hampshire that your grandfather left us should be made to produce something. I am willing to give you this tract for your own on two conditions. The first is that you successfully complete your course and pass your Civil Service examinations as a proof of your training; and second, that you show your ability to pick responsible men for your companions. Of the latter I shall have to be the judge. Fill those two conditions and the land is yours.”

For the life of him Scott could not find anything to say. It was the first time his father had ever spoken to him in that way, as one man to another and it choked him up queerly. He could not even thank his father for the offer. He was relieved when Dick Bradshaw came in and went with him to his room to help finish packing and look over his equipment.

The two boys talked till almost midnight over the possibilities of the western country and the new things that would be found there. The necessity of Scott’s catching an early train finally forced them to separate with many a promise of a very active correspondence.

Scott slept like a top till his mother called him at four o’clock. The train was due at five-fifteen, and everything had to be done in a rush. His mother preferred it so. Almost before he knew it he had eaten a hurried breakfast, had hastened to the station, and was looking out of the car window into the hazy morning with the brave tones of his mother’s voice still ringing in his ears, “Good-bye, Scott. Remember how you have lived and write me what you do. As long as you can do that you are safe.”

All day long he sat with his nose almost glued against the windowpane noting every change in topography and speculating on the geological formation. Occasionally he thought of his father’s injunction and tore himself away from the window long enough to notice the people around him. The country outside was of much greater interest to him, but there kept ringing through his brain continuously, “I will give you that ten thousand-acre tract.” Surely no other boy had ever had such a chance as that. It was as big as many a German national forest.

About noon of the second day he passed through St. Paul, and on to Minneapolis. A thrill passed through Scott as he realized that he was actually west of the Mississippi River.

Scott hastened from the train with the rest of the passengers, and pushed his way through the crowded gate into the station. He was burning to see the College he had been dreaming about for so long. He had no idea where it was located but he felt certain that a College which had attracted him from such a great distance must be a matter of pride to all the citizens and very easily found.

He walked to the first street corner and asked a passerby. “Can you tell me the way to the Forest School?”

The stranger stopped abruptly. “The what?”

“The Forest School.”

“To the Forest School,” the man repeated wonderingly. “No, I’m afraid I can’t. I am a stranger here myself. Never heard of it.”

Scott tried another man with a busy up-to-date air. “Pardon me, can you tell me the way to the Forest School?”

The man passed on with an indifferent look and paid no further attention to him.

“Humph,” Scott thought. “City manners seem to be different from ours at home.”

He watched a few people pass by and selected for his next victim an elderly gentleman with a kindly face and a leisurely air.

“Pardon me, sir, can you tell me the way to the Forest School?”

The old gentleman stopped courteously and apologized for not quite catching the question.

Scott repeated it.

The old man shook his head doubtfully. “Never heard of it, my boy. What sort of a place is it?”

Scott was beginning to think that he must have come to the wrong city. However, the old gentleman was exceedingly polite, and the boy tried to explain. “It is a school where they train foresters, sir.”

“Oh,” said the old gentleman in a rather doubtful tone. “Strange I have never heard of it. Let’s ask the policeman.”

They consulted that dignitary, but he had never heard of it and could find no clue in his little yellow book.

Suddenly the old man seemed to have an inspiration. “Isn’t part of the University, is it?” he asked.

“Why, certainly it is,” Scott blurted indignantly. The ignorance of these people was remarkable.

“Oh well, then,” said the old gentleman, “that’s easy. Take that car right there and get off at Fourteenth Street. You can see it from there.”

Scott thanked him and hurried into the car. He felt that his troubles were over at last and he would soon be a duly registered embryo forester. The University loomed up big as he left the car at Fourteenth Street, and the gayly dressed students were wandering everywhere in the idleness of registration day.

Scott tackled an amiable looking fellow and once more inquired the way to the Forest School. The amiable student stopped and grinned at him sympathetically. “Well now, old man, that’s too bad. You are miles off your course.”

Scott’s face fell. “Why, isn’t this the University?” he asked.

“Certainly this is the University,” answered the wise one, “but the Forest School is part of the Agricultural Department, and that is miles away at the end of yonder carline. Take the car back the way you came clear to the end of the carline, and you’ll find the Agricultural College half a mile beyond that.”

“Thank you very much,” said Scott gratefully, “you are the first person I have met in the whole city who seems to really know anything about it.”

“Don’t mention it, old man,” said his new friend with a bow. “You’ll get there in the end all right.”

The ride back to the end of the carline seemed almost endless, but the fact that one of those splendid young fellows had called him “old man,” and the thought that he would soon be one of them cheered him up wonderfully. The car came to the end of the track at last and he walked down the road briskly, eager to be a full-fledged student and swagger like the fellow with the red shoes and the decorated sweater who had talked to him. He could see the buildings on the hill ahead, but was rather surprised to find a high board fence around the grounds; the gate, too, was locked. A man in uniform answered his knock.

“Is this the Agricultural College?” Scott asked by way of an introduction, for he felt sure that it was.

“No, sonny,” the man answered with a broad grin, “this is the County Poor Farm, and you are the fourth man them smart alecks have sent out here today. Now you get back on that car you just left and tell the conductor to put you off at the Agricultural College, and don’t let anybody else steer you.”

Scott thanked him with downcast mien, and trudged dejectedly back to the car. Visions of that gay young sophomore who had called him “old man,” and deceived him so cheerfully floated before him in a red haze. He wondered what his father would think of his judgment. He swore all kinds of vengeance, and it looked for a while as though the whole sophomore class was in danger.

He drew back as the car passed the University for fear the sophomore might be waiting to see him go by. Sure enough there he was on the corner and Scott had a hard time to restrain himself from going out to thrash him then and there. He eyed the conductor suspiciously when he called the Agricultural College to try to detect whether he was in the general conspiracy against all freshmen. He did not feel nearly so sure of the real Agricultural College when he saw it as he had of the County Poor Farm. However, it was the right place at last, and a printed sign pointed the way to the registrar’s office.

Nearly all the students he met on the long winding path leading up to the administration building were carrying suitcases, and most of them gazed nervously about them like strangers in a strange land. Scott threaded his way through the crowds of students grouped idly around the halls and stairway to a place in the long line which was crawling slowly past the registrar’s window. A young man wearing the badge of the Y. M. C. A. approached him and asked if he was looking for a room, but Scott remembered the trip to the county poor farm too vividly to take any more advice from a student, and refused to even discuss the matter with him. The crowd in the line was certainly a mixed one, and from their appearance he concluded that his father was right in saying that they were a good sample of nearly all the different kinds of people in the world. The large proportion of girls worried him a good deal till he found that they were registering for domestic science, an entirely separate course from his own. He had not been accustomed to the idea of coeducation, so popular in the West.

In due time he reached the window and presented his permit.

“Scott Burton,” the registrar read in kindly tones, “of Wabern, Mass. I remember your case. You have a number of advanced credits. Let’s see. Here is the report of your case from the enrollment committee. They have allowed you credit for one semester of mathematics, four of language, four of rhetoric, four of botany, two of geology, two of zoology, and two of chemistry. That leaves you only elementary forestry, dendrology, mechanical drawing and forest engineering to complete the work of the first two years.”

That was a little better than Scott had even dared to hope. He asked eagerly, “Then I can finish in two years?”

“Possibly, you will have to see the Students’ Work Committee tomorrow about that. They may let you take some extra work on probation but you will have to drop it if your marks are not up to grade at the end of the first four weeks. In the meanwhile you will be registered as a freshman. Here is your registration card. See that it is filled in, and your fees paid by five P. M. tomorrow.”

“Thank you,” said Scott. “Can you tell me where I can get some information about a boarding house?”

The registrar gave him one of the printed lists that the student had tried to give him a little while before, and turned to the next student in the line.

With his registration card in his pocket Scott felt more certain of himself again. He was not only a student, he was almost a junior, and if the other students in the halls had happened to notice him they would have seen a very different looking boy from the one who had gone in a half-hour before.

Armed with the list of rooming houses furnished him by the registrar Scott set out in search of a room. His stock of money was limited, and he regretted that his old chum, Dick Bradshaw, was not there to share his room, and incidentally his room rent. For to Scott, who had always lived at home, and never associated very closely with many other boys of his own age, the selection of a roommate was a problem which he considered would require much thought and a thorough knowledge of his intended partner. His New England conservatism kept him from even dreaming of going in with a stranger.

The search proved rather long and tiresome. The upper classmen had picked all the best rooms before they left in the spring the year before, and the assortment now available was not very attractive. Single rooms were hard to find at all and the prices something to inspire awe.

Scott approached a rather attractive little house which stood back in a pleasing yard something like the one at his home. The usual sign, “Rooms to Rent,” was not in sight, but he rang the bell and waited patiently for someone to answer it. Presently the door opened a crack and a silver-haired old lady eyed him curiously. Her face looked kindly enough but the sound of her voice made Scott almost jump.

“What do you want?” she snapped.

“I beg your pardon,” said Scott, “but can you tell me where there are any rooms to rent around here?”

“No.” Like the crack of a pistol.

“They seem to be rather hard to find,” Scott remarked apologetically.

“Yes,” the old lady fired at him as she slammed the door. “I guess the people in this park want to live in their own houses.”

Scott gazed at the closed door in astonishment. “Well,” he thought, “there is one thing sure—I should hate to live in yours.”

He was becoming discouraged, and was turning wearily away from the twelfth house—almost the last one on his list—when he nearly collided with a young fellow who was bounding up the front steps three at a jump.

The landlady took pity on Scott’s weary look, and addressed herself to the newcomer. “Mr. Johnson, do you know of any place where this young man can find a room?”

The young man turned abruptly and ran his eye frankly over Scott. “What’s your course?” he asked.

“Forestry,” Scott answered, wondering what that had to do with it.

“Sure I do,” said Johnson. “Come on in with me. That’s my course and I am looking for a bunkie. Come on up and leave your suitcase and then you can see about your trunk.”

Scott gazed with astonishment at this new species of being who would take on a second’s notice a roommate whose very name he did not know. But that confident and carefree young gentleman was already leading the way up the stairs without a doubt as to the issue. Scott looked at the landlady to see what effect such a sudden proposition had made on her. He expected to find her wide-eyed and agape with astonishment; instead of that she had closed the front door and was disappearing down the hall. He would certainly have backed out if he had known how, but both the landlady and the stranger seemed to be so certain the deal was closed, that Scott, dazed by the swift passage of events and seeing no possible way out, followed helplessly up the stairs.

“Maybe,” he thought, “it’s one of those dens you read about in the newspaper where young fellows are roped in in this way and robbed. If it is they will need more than that red-headed guy to do it. Dick could lick the shoes off of him and Dick never could box. They would not get very much if they succeeded,” he grinned, “the railroads already have most of it.”

When he entered the room indicated he found his new acquaintance already seated in a revolving chair near the table, reading a large poster. Without raising his eyes from the paper Johnson said, “You may have the two lower drawers of the bureau, I already have my stuff in the others, and the right hand side of the closet. Better go back to the registrar’s office and tell them where to bring your trunk; they charge you storage awful quick at the depot.” And he continued to read the poster.

Scott tried to look the room over carelessly as he thought anyone would who was used to renting a new one every week or so. He found that he was still holding his suitcase in his hand. He looked at his roommate to see if he had noticed it, but that indifferent young man was still absorbed in the poster and oblivious to his surroundings. Scott set the suitcase quietly in the corner and took another careless look around the room.

“Well, I guess this will do,” he remarked flippantly. “I’ll go see about the trunk.”

As he was going out the door Johnson called after him, “Hustle back and I’ll take you to our hash house. They are nearly all foresters there and a couple of them are seniors, too.”

Scott hurried to the registrar’s office, left word about the trunk and started back to his newly acquired room and roommate, both of which he had obtained almost before he knew it and was not yet quite certain whether he wanted them or not. However, it was a great relief to feel that he had some place to go, and he rather thought that he liked it. As he was going down the steps a husky, sunburned fellow with a swinging gait and the free air of the woods joined him.

“Getting straightened out?” he asked pleasantly.

“Yes,” Scott answered, with a readiness that surprised himself. “I got a room, a roommate and a boarding house, all this afternoon.” He was beginning to feel a little proud of it.

“You are lucky,” the other said. “Where are you from?”

“Massachusetts,” said Scott, a little proudly. He felt that it was rather a distinction to live so far away. He expected to see some show of astonishment from this stranger, but instead the answer astonished him.

“I expect we are nearly the Eastern and Western limits of the School,” he said quietly. “I am from Honolulu. Not much timber left in Massachusetts, is there?”

Ordinarily Scott would have been very diffident with a stranger who accosted him in this way, especially after such an experience as he had had that morning, but there was a personal magnetism about this tall, dark, gentlemanly fellow that made him open his rather lonesome heart.

“No,” he answered, “nothing much but second growth. How did you know that I was a forester?”

“Nothing very mysterious about that. Your green registration card is sticking out of your pocket. Well, here is where I leave you. So long.”

Scott found his new home and walked in with an independent air of ownership that sent a thrill through him. Johnson was waiting impatiently for him. As soon as Scott appeared in the door Johnson grabbed his hat and started out. “Hurry up, man. You’re late. These hash houses aren’t home. If you are late you get a short ration.”

Scott took a hasty scrub at his car-stained face and hands, and they hurried away to the boarding house. Most of the men were already seated when they arrived. Scott waited for an introduction to the landlady to inquire whether he could stay there, but Johnson jerked out the chair next to his, looked at him curiously, and ordered him to sit down.

“Don’t you have to see the landlady here?” Scott asked.

“Don’t worry,” Johnson laughed. “She’s probably spotting you now through a crack in the door, and you’ll see her pretty regularly every Saturday night at pay time.”

“Humph,” thought Scott, “I’d like to see anyone get into a boarding-house around home without giving his whole pedigree and paying a week’s board in advance.” He added aloud to Johnson, “I should think a good many fellows would skip their board.”

“No,” said Johnson, “there are not many fellows here who try it and most of them get caught.”

When the rush of passing dishes was over Scott had a chance to look around the table. He was surprised to see what a husky, sunburned, independent looking crowd it was. Two of them, especially, seemed to be almost an Indian red, and directed the conversation with peculiar abandon. He was agreeably surprised to see that one of them was the Hawaiian who had walked down the street with him a few minutes before. He caught Scott’s eye and smiled pleasantly.

Johnson caught the salutation and looked at Scott with an air of surprise and added respect. “I did not know that you knew him,” he said in an undertone, but his remarks were cut short by a peremptory command from another sunburned face at the end of the table.

“Johnson, you haven’t the manners of a goat. Why don’t you introduce your friend?”

“Oh,” said Johnson, somewhat abashed. “Fellows, this is my roommate.”

“That’s a fine introduction for him. What’s his name, pinhead?”

Johnson looked wonderingly at Scott for a minute, grinned at the surrounding company, and burst out laughing. “Blamed if I know his name yet, I just got him this afternoon, and we have not had the time to explain the short sad histories of our young lives to each other yet.” Then to Scott, “You’ll have to introduce yourself, I guess.”

“Scott Burton, forester,” he announced with quiet dignity, and the sunburned senior acknowledged the introduction for the crowd.

After dinner he talked for a little while with the Hawaiian and a few of the other men and went back to the room with Johnson.

“How did you get to know Ormand?” Johnson asked.

“Who’s he?”

“Why that fellow you spoke to at the table. Didn’t you know him?” Johnson asked in surprise.

“He walked down the street with me when I was coming from the registrar’s office,” said Scott. “Who is he?”

“Gee,” said Johnson. “He is president of the senior class and manager of last summer’s corporation.”

“What do you mean by last summer’s corporation?”

“Why, when the juniors go up to the woods for the summer they form a corporation and elect one of the class to manage the business for the bunch. He bosses the whole crowd. He’s the biggest man in the College and that other fellow who called me down about the introduction is Morgan, the next biggest. Funny I did not know your name, wasn’t it?”

“Well,” Scott said, “I should not have known yours if I had not heard other people talking to you. What class are you?”

“Who, me?” said Johnson. “Why, I am a freshman like you.”

“Then how is it that you know all these people so well?” Scott asked.

“Oh, I went to prep school here, and knew them all last year. I have credit in a couple of courses,” Johnson added proudly, “and I have field experience to burn. I do not have to take any German this year or mathematics either.”

“Neither do I,” said Scott. “Our high school is ahead of the ones here, and I have taken so much work in the summer that I got credit for nearly all the work of the first two years.”

“Then you’re a junior?” asked Johnson in a more respectful tone. Respect for the upper classes was about the only weakness that Johnson allowed himself in that direction.

“I suppose so,” said Scott; “they told me at the registrar’s office that I was practically a junior, but would be classed as a freshman till I had completed my elementary forestry, dendrology and forest engineering.”

“Been around the country much?”

“No,” said Scott, “that’s one reason why I came out here to College. I’ve seen every rock in the country around home, but I have never been away from there.”

“Then you have never seen a real forest,” exclaimed Johnson.

“Only the woodlots on the farms.”

“What sort of work did you do in the summer there?”

“Went to summer school and loafed.” Scott, like most of the boys in the East, had always considered the holidays sacred to recreation, and had thought himself particularly virtuous for devoting six weeks of it to summer school each year. “Do you work in vacation time?” he asked.

“You bet,” said Johnson. “I’ve worked every summer since I can remember, and every winter, too, for that matter. I’ve paid all my expenses at school for the past ten years.”

Scott gazed at him in open wonder. “What do you do?” he asked.

“What haven’t I done would be easier. I’ve been ‘bull cook’ on a railroad construction crew in Montana, and driven teams on a slusher in Arizona; I’ve picked apples in Washington, and been a ‘river pig’ on the drive here in northern Minnesota; I’ve carried a rod on a survey party in Colorado, and pushed straw in the harvest fields of North Dakota; I’ve tended furnaces, carried papers, and weighed mail, billed express and smashed baggage during Christmas vacation. Some of ’em were tough and some of ’em were cinches, but they have all netted me a good bunch of experience.”

During the careless listing of his roommate’s experiences Scott had slowly settled back in his chair with a feeling of wondering admiration for Johnson and an overwhelming sense of his own helplessness. He eyed Johnson’s thin freckled face, and ran his glance over his slight, wiry frame, and wondered what he himself, with all his strength, would do if he had to tackle such problems. It had never occurred to him that anyone but a born laboring man could do such things. The feeling of contempt which he had at first for Johnson’s roughness gave way to a kind of new admiration for his ability and self reliance.

“Do you play football?” Johnson asked suddenly.

“No, I never cared anything about it.”

“Baseball?”

“Only a little.”

“Basketball?” Johnson persisted.

“No.”

“Well, where in thunder did you get that build if you have never worked and don’t do any athletic stunts?” Johnson was searching for something to account for Scott’s five feet ten and one hundred and seventy-five pounds, his heavy shoulders and muscular neck. He had the Westerner’s contempt for the tenderfoot of the East. He was not at all surprised that he could not do anything, but was puzzled at his fine physique.

“Oh,” said Scott, “I got that wrestling, boxing and walking around the country. There was an ex-prizefighter who worked for father and he used to give me lessons in the barn every evening.”

Johnson pricked up his ears. “A boxer,” he thought. “Maybe the man was not so helpless after all.”

“You’ll have to box Morgan,” he said aloud, “and if you can do him, you’ll have to fight for the College on rush day. Will you do it?”

“I’ll certainly try,” said Scott, and the East rose a thousand per cent in Johnson’s estimation.

The two boys talked on till nearly midnight and finally went to sleep with entirely new ideas of each other. Unconsciously the prejudices of generations had been broken down and their views broadened across half a continent.

Scott was gradually settling down in his new surroundings, getting accustomed to his new associates, who had struck him as being so totally different from the men he was used to, and becoming familiar with the routine of the class work.

He found himself at a great disadvantage in competition with the other members of the class. He had been taught by good teachers, but their point of view had been different from that of the foresters who had taught the men with whom he was now thrown. These fellows had been looking forward to a definite end for several years and all their training had been with the ultimate object in view. They had a different view of the subjects from the one he had obtained from the academic men who had taught him. He found that they had a grip of the subjects and could apply them in a way that he could not. Moreover, he had a great deal of extra work to make up and he had been allowed to take it only on condition that if he was not up to the scratch at the end of the first six weeks he would have to drop it all.

Not many men could have carried such a burden, and the chairman of the Students’ Work Committee had told him that he was foolish to attempt it. Most men would have either fallen short or have overworked themselves; but Scott did neither. He had always believed in system in his work. He allotted so much time to his studies and allowed nothing to interfere with them; he made it a point not to study for an hour in the evening after supper, and never looked at a book from Saturday noon to Monday morning. He knew that he was able to accomplish more in the long run in this way. As most of the student sports were scheduled for Saturday afternoon he was able to take in most of them and did not become stale.

He had just closed his book one Saturday morning preparatory to going to lunch when Johnson bounced into the room in high feather.

“Come on, Scotty, let’s go to the football game this afternoon. It’s only Lawrence, and won’t be much of a game, but it will give us a chance to get a line on the team.”

Scott agreed readily, the more readily because he had never seen a big football game. They ate lunch hastily, for it was already a little late and the game was scheduled a little earlier than usual. The car was crowded with people going to the field and when they got off the car they found the streets full of people flocking in the same direction.

Johnson led the way into two good seats where they did not belong and succeeded in holding them against all comers. The stands were full, for though it was not considered one of the big games, it was the first game of the season, and the students all turned out to see their team in action. It was the basis for sizing up the chances for the team in the struggle for the Western supremacy. The stands were a brilliant mass of color and the cheer leaders were performing all kinds of contortions to wring the greatest volume of noise from the crowd.

As they took their seats the door of the Armory opened and a squad of players trotted briskly onto the field. There was a restless movement of the crowd on the big stand and a few scattering cheers from the smaller stand opposite, but no organized yells.

“Is that one of the teams?” Scott asked anxiously.

“Yes,” Johnson answered, leaning eagerly forward to size each man up as he took his place.

“Why don’t they cheer them?” Scott asked in surprise.

“That’s the other team,” Johnson answered carelessly.

“I should think that would be all the more reason for cheering them,” Scott said.

Johnson turned a wondering look upon him, but was prevented from answering by a deafening yell from the whole stand in which they both joined heartily. Their own team had appeared.

“How’s that for yelling?” Johnson asked proudly.

“Rather discouraging for the other fellows,” Scott answered.

“Well, that’s what you want to do, isn’t it? Look there, they are lining up already.”

The referee had called the captains together, decided the choice of goal, and the two teams were taking their places.

“Their ball,” Johnson commented, intent on the field.

The referee blew his whistle and there was a moment of intense silence as the blue line charged forward and the ball sailed far out on the kick-off. It was a splendid kick, clear to the corner of the field and high. It dropped neatly into a pair of maroon arms and the crowd cheered wildly.

“Wasn’t that a dandy kick!” Scott exclaimed.

“Now watch them run it back,” Johnson exulted.

But they did not run it back so fast. One of the swift blue ends was on the man and downed him in his tracks.

“That man’s some fast,” Scott said.

“Yes,” Johnson said, “too fast. They ought to look out for him. They’ll carry it back fast enough now; that line can’t hold them.”

The ball was snapped, and an attempt made at an end run, but the same man who had followed the kick downed the man for a loss. An attempt at center fared no better and the fullback dropped back for a kick. The ball went out of bounds almost in the center of the field.

Then the real surprise came. The Lawrence team formed quickly, and by a series of lightning plays swept down toward the Minnesota goal. Nothing seemed able to stop them. The stand was as silent as the tomb.

“Why don’t they yell?” Scott asked. “Now is the time the team needs it.”

“Who could cheer such an exhibition as that?” Johnson asked in disgust.

Suddenly the stand went wild. A Lawrence runner, rounding the end, far out beyond the other team slipped in a puddle and fell. The ball rolled toward the goal line and a Minnesota player fell on it on the five-yard line.

“That was hard luck,” Scott remarked when the cheering had subsided.

“Hard luck!” Johnson exclaimed. “Who do you want to win this game?”

“Minnesota, of course,” Scott retorted indignantly, “but to win on a thing like that does not do them any credit.”

“Kept ’em from scoring, anyway,” Johnson answered doggedly.

The ball was kicked into safety once more and the Lawrence team started on another rush for the goal. Again they seemed irresistible, and only a fumble on the ten-yard line saved a score. What had started as a practice game had developed into a real struggle for victory with Minnesota continually on the defensive.

At the end of the first quarter neither team had scored. Again and again in the next period, the fast Lawrence team carried the ball through their heavier opponents only to lose it near the goal line by some slip of their own. Not once were they held on downs. But fate seemed to be against them, for the whistle blew at the end of the second quarter with the first down on the Minnesota two-yard line.

No sooner had the teams left the field for the ten minutes’ rest between halves than the big University band formed in front of the grandstand and marched around the field playing lively airs to try to put some heart into the crowd. It did not succeed very well; the crowd seemed utterly beaten and without hope.

“Is Lawrence a big college?” Scott asked when the music ceased.

“No,” Johnson groaned in disgust.

“They seem to have a mighty good team,” Scott continued.

“You mean we have a mighty rotten one,” Johnson retorted. “They ought to bury Lawrence, and if they can’t they ought to be ashamed of themselves.”

“They are doing the best they can,” Scott said, “and they ought to be supported. They can’t help it if the other fellows are better.”

“That won’t stop them from getting licked,” Johnson growled.

“What difference does it make if they do get licked?” Scott argued. “You ought to give the other people credit—” he began, when there was a half hearted cheer and the teams trotted out on the field again.

“Now let’s see if the ‘old man’ has put a bug in their ear.” Johnson said, leaning forward with renewed hope.

The game started out pretty much as before, but not so fast. The ball was creeping steadily down into Minnesota territory when a poor pass carried it over the head of the Lawrence fullback, he fumbled in trying to recover it, and a Minnesota man got it. The crowd cheered the poor pass wildly.

Scott looked around in astonishment. “What are they yelling for now?” he asked.

“Didn’t you see that pass?” Johnson asked excitedly.

“Don’t see anything to cheer in that, it was just a poor pass such as you could see on any corner lot.”

“Meant ten yards and the ball to us,” Johnson answered shortly. He had made his own way in the world and had usually found the other fellow’s loss to be his gain.

That seemed to be the turning point in the game. The light Lawrence team had expended its strength in the early part of the game. Their substitutes, as in most small colleges, were poor, and the overwhelming weight of the maroon team began to tell. Following up their advantage they carried the ball steadily down the field, crushing the lighter team before them. The crowd went wild with enthusiasm. The yelling was almost a continuous roar.

But the little Lawrence team was game. On their five-yard line they took a brace and would not yield an inch. The big machine which had carried the ball surely, for almost the entire length of the field, lost it on downs, and saw it kicked far over their heads out to the center of the field. The crowd was still in an instant and there was even a slight tendency to hiss, but the better element instantly suppressed it.

The third quarter ended and still there was no score.

The teams changed sides amidst a deathlike silence. The next instant all was wild excitement again. The captain of the Minnesota team had broken away with a clean forward pass, and was speeding away down the field with no one between him and a touchdown but the little Lawrence quarter.

Scott yelled with the loudest of them. “Wasn’t that a corker?” he screamed in Johnson’s ear.

The yelling ended, as suddenly as it had begun, in a groan. The little quarterback agily kept in front of the big runner, followed his every feint, and brought him to the ground with a crash.

“Blame it,” Scott exclaimed. “Wasn’t that a beautiful tackle?”

“Beautiful tackle?” Johnson raged. “I wish he had broken his neck.” This last remark must not be taken to represent the attitude of the majority of the crowd, but it fairly represented Johnson’s attitude in everything but his own actions.

The setback, however, was only temporary. The big team gathered itself together, and carried the ball over for a touchdown. Goal was kicked just three minutes before time was called, and the game ended with a score of seven to nothing in favor of Minnesota.

The big crowd jostled slowly out of the gate and it seemed to Scott that for people who had been so wildly desirous of winning, they were very silent about it when it was accomplished.

“That’s what I call a good game,” Scott said.

“That’s what I call a rotten game,” Johnson retorted. “They ought to have beaten Lawrence thirty to nothing, instead of that they barely succeeded in making seven, and were nearly scored against three or four times.”

“What has that got to do with it?” Scott argued. “It would have been just as good a game if we had not won it at all. The good playing is what you want to see, no matter who does it.”

“Do you mean to say that you would enjoy seeing a good play if the other people made it and it counted against you?”

“Certainly,” Scott answered stoutly. “I enjoyed seeing that quarterback make that tackle though it knocked us out of a touchdown. It would not have been nearly so pretty if he had missed it.”

“That’s one of your Eastern ideas of sport,” Johnson jeered contemptuously. “You can watch the pretty plays the other people make; they look better to me when our own team makes them.”

“If that game had been at home,” Scott continued, “every good play those Lawrence people made would have been cheered the same as our own.”

“Do you call that being loyal to your team?” Johnson asked.

“Certainly. It’s simply giving the other fellow credit for what he does. There is no team loyalty in pretending the fellows they beat are no good, and still less in saying that the team that defeated them was no good.”

That seemed to put the question up to Johnson in a new light. He pondered over it for a minute and then looked up cheerfully.

“I’ll tell you what it is, Scotty. We play to win and let the other fellow look after his credit, but there’s some sense in that last. Can you really see the beauty of the play that goes against you?”

“Certainly.”

“Well,” Johnson laughed, “wait till I see you praising some fellow’s skill in blacking your eye in some boxing bout. Then I’ll believe you. Come on, let’s walk home. We’ll have plenty of time before supper.”

There was a little talk at the supper table of the football game, most of the men taking the same view as Johnson, that it was a pretty poor exhibition because Lawrence had not been completely overwhelmed, but most of the time was taken up with a discussion of the coming campfire. The upper classmen hinted mysteriously of the sacred rites that had been prepared for the new members.

“Ormand,” Morgan hissed in a stage whisper which could be plainly heard by every one at the table, “did you feed the goat tonight?”

“No,” Ormand answered in the same tone, “he’ll be more savage if he is hungry, and besides, he’ll get plenty of green stuff to eat tonight.

“Johnson,” he continued, “if you and Scotty had taken my advice and paddled each other every night for half an hour for the past two weeks you would be better prepared.”

Scott could not help feeling nervous, but it did not seem to worry Johnson.

“You don’t know that we have not been doing it,” he answered flippantly. “It won’t be the first goat I have ridden, and I don’t believe he can out-butt the old ram I tried to herd in Wyoming one summer.”

“You’ll have a good chance for comparison, anyway,” said Ormand rising. “Come on, Morgan, let’s go prepare the torture chamber at the clubhouse.”

The new men at the table responded with varying degrees of bravado according to their natures, but a very apparent feeling of nervous excitement pervaded everyone except Johnson. Nothing could perturb his cheerful good humor.

“Cheer up, Tubby,” he cried to a stout freshman who sat opposite him. “They may sting you a little but there is no chance of their striking a bone. And look at little Steve over there with a face a mile long. Don’t you know they dasent touch you for fear of breaking your glasses?”

In two minutes he had broken the spell and had them all at ease. The self-reliance he had gained through his life of hard knocks was infectious. He enjoyed the influence that it gave him over the others, and he lorded it over them on all occasions, but always in a way that pleased them.

“Now,” he said with a patronizing air, “all of you kids go home, put on two pairs of trousers apiece, and be at the clubhouse at seven o’clock sharp. Come on, Scotty, let’s go read up a little on the nocturnal habits of that sportive goat.”

Scott recognized the subtle influence which Johnson exercised over his classmates and admired his power. He even smiled at the readiness with which he himself left his dessert half eaten to obey his orders.

The football game had made them late for supper and all those who wished to join the forestry club had to be at the clubhouse at seven sharp. They had little time to spare. Scott was at a loss how to dress to do the proper honor to the rites at the clubhouse and yet be ready for the campfire. Johnson suffered from no such perplexity.

“Believe me, Scotty, you can wear your dress suit if you want to, but the ‘sacred rites’ at the clubhouse can, in my humble opinion, be observed a good deal more appropriately in sweater and overalls.”

Scott finally decided to accept Johnson’s better judgment, relied on that gentleman’s knowledge of his surroundings, and donned his sweater. Johnson was already equipped. He cast a longing glance at a sofa cushion on the couch. “Sorry I haven’t room for you, old fellow, if I had I’d sure take you along. Five minutes of seven, Scotty, just time to make it.”

They hurried to the clubhouse in silence. The front door stood open and a carefully shielded light cast a dim glow on a notice pinned to the door jamb. They read the notice eagerly.

A thin cord was tied to the door knob and led away up the dark stair. They laid their hands gingerly on the string and started carefully up stairs with nerves on edge. At the first turn on the landing a bright electric light flashed in their eyes for an instant and left them totally blinded in the utter darkness. They groped their way along apprehensively holding to that winding string. There was not a sound to be heard except the noise they themselves made as they stumbled through the rooms littered with all the obstructions that ingenious minds could devise. After what seemed like almost interminable scrambling they mounted another flight of stairs. More winding through obstructed passageways, and down another flight of stairs, then another and another. Scott was beginning to have visions of old medieval dungeons when his wrist bumped into something cold that snapped with a metallic click, and he found himself brought to a stop by a handcuff. It was too dark to distinguish anything, but he could hear the hard breathing of many nervous people. It seemed to him that he had stood there for an eternity with nothing to break the silence save occasionally a cautious step on the stairs which always stopped with the same metallic click.

Suddenly there was a shuffling of many feet and the handcuff led him slowly forward. Much to his surprise he passed through a door directly onto the ground outside—he had thought that he must be at least one story below the level of the street—and found himself in the middle of a long string of men all walking in single file. They were all handcuffed to one long rope. This chain gang was guarded by a line of scouts on either side, and led on by six husky fellows who dragged the front end of the rope.

Slowly the procession marched up the middle of the street, across the campus, through the auditorium where a popular lecture was in progress, and out into the open fields. After a half-mile of winding march in the darkness they entered a black forest. A little farther and the line stopped.

“Prepare to meet your fate,” came from a deep voice immediately in front of them.

More than one man in the crowd trembled so that the links of his handcuffs clinked audibly. Scott, now that the time had really come, felt perfectly calm.

After a few seconds’ pause a long screen of burlap dropped from in front of them and they saw the upper classmen of the club standing in a semi-circle around a small campfire.

Ormand, the president of the club, stepped forward a few paces. “Gentlemen, let me introduce you to the new members of our club. And for you, new members, may your enthusiasm for the club and the College never be less than your surprise at the present moment. Release them.”

The guards quickly unlocked the handcuffs, and the astonished “victims” looked uneasily about them, not knowing what to expect. But the upper classmen came forward to welcome them, and they found themselves really accepted on an equal footing with the rest. Their stunned expression brought forth shouts of laughter.

Johnson was the first to recover. “Well, fellows,” he admitted with a grin, “as I was telling you, I have ridden several goats before and some of them were pretty rough riding, but none of them ever shook me up like this.”

The tension was broken, and the reaction turned the crowd of half stunned men into an hilarious bunch of boys. They danced around the campfire in dizzying circles, and the fantastic shadows flashed weirdly through the surrounding forest. At last they settled down in a contented circle, and the entertainment committee rolled out a barrel of apples, a barrel of cider, a bushel of peanuts and a set of boxing gloves.

They were all hailed with a shout of welcome, but some of the new members looked rather anxiously at the padded gloves. Sam Hepburn, the chairman of the entertainment committee, explained the program.

“Pile in, fellows,” he cried, “and help yourselves. Don’t be bashful. I reckon you all know how to eat, if you don’t, watch Pudge Manning. But we must have some entertainment while we eat. Since we have no orchestra to dispense sweet music, we shall try another form of amusement not unknown to the ancient Gormans. I have here in this hat the names of all the old members. Each new man must draw a slip. In addition to the name each slip has a number on it. Each man must box for two minutes with the man he draws, and the bouts will be pulled off according to the numbers on the slips. I’ll pass around the hat. Each man must draw one and only one.”

The hat was passed quickly around the circle and the drawers examined the slips eagerly to see what sort of opponents they had drawn. There were sighs of relief from some and groans of despair from others.

“Now, fellows,” called Hepburn, “the first bout will start at once. Let the man who has number one come forward and call out his opponent. The ring will be this circle and the bunch the referee. Step lively now.”

A slight youth with a very scared expression stepped timidly forward and called in a very faint voice for Pudge Manning, the biggest man in the junior class. There was a great shout of laughter at the ill-matched pair. Hepburn put the gloves on Manning and Johnson, who had appointed himself the second for all the new members, equipped the frightened little freshman, and tried to brace him up with good advice.

“Kick his shins, son; you can’t reach his face. You have the advantage of him already, you can’t miss him and he will have to be a pretty good shot to land on you. Now go for him.”

Johnson’s advice was in itself as good as a circus. It was hard to tell which was the most ridiculous figure; the huge Manning sheepishly trying to keep from hurting his little adversary, or the trembling little freshman fighting wildly with the fury of desperation. The crowd howled their delight, and when time was called gleefully awarded the decision to the freshman.

Bout followed fast upon bout and the interest never flagged, for the combinations were such that they furnished a plentiful variety. Some were so unevenly matched as to be altogether ridiculous, others were evenly enough matched but so ignorant of the game that the slugging match was wildly exciting, in still other cases science showed its superiority to brute force, but really scientific sparring on both sides was rarely seen.

Johnson drove the crowd almost into hysterics by an exhibition of wildcat fighting against a man almost twice his size. With the agility of a cat he bounded around his big opponent, doing very little damage himself, but continuously maddening the big fellow with ceaseless taunts, and successfully wriggling out of reach of all punishment.

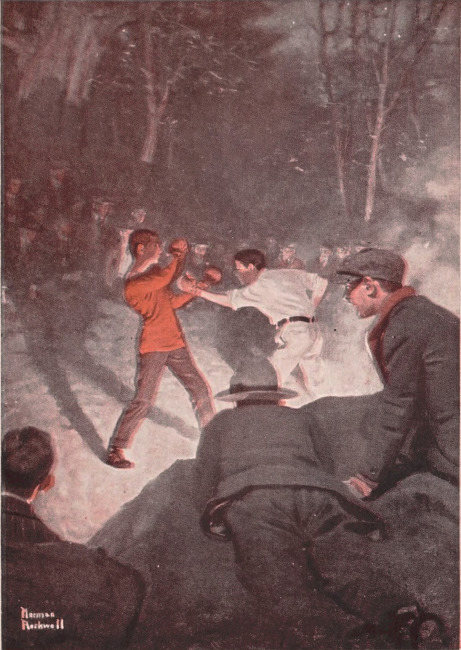

Scott looked on doubled up with laughter. He had not seen any very good boxing, but viewed as a farce it certainly was a howling success. He was well pleased that he had drawn Morgan, the best boxer in the College, for he had not had any practice in a long time, and was eager to measure himself against one of these Westerners who were inclined to look upon the East with some contempt.

Finally his turn came and he called cheerfully for Morgan as he walked over to Johnson to be gloved and given his facetious instructions.

Johnson was more serious with him than with most of the others. “You’re up against the real thing now, Scotty. He can box like a fiend, and has the strength of a moose. Keep your chin in,” he cautioned in a low voice as Scott walked into the ring, “and remember your sporting views,” he chuckled.

The match differed from any that had gone before. Both men were expert with the gloves, and they were fairly matched physically. Morgan was a trifle taller, giving him the advantage in the reach, Scott was a little heavier in the shoulders. They shook hands, stepped back quickly and the fight was on. Morgan had his reputation to sustain, Scott had his to make. The crowd rose in a body to give better vent to its excitement. The two circled rapidly, passing, parrying, sidestepping, dodging; now almost in each other’s arms, now at arm’s length, and occasionally a lightning pass, followed by a sharp spat told of a good blow gone home. Scott found Morgan his equal in out-fighting, but his training with the old prizefighter gave him much the best of the mix-ups.

Suddenly something happened. Scott invited a full swing from Morgan, attempted to side-step, slipped on the damp sod, and received the full blow on the point of his chin. The stars danced merrily before his eyes and he sat down with a thud. He was up almost instantly. “Good shot, old man,” he cried to Morgan, and was boxing again with as much vigor as before.

“By George, he does believe it,” Johnson yelled. No one else knew what he was talking about, but Scott smiled.

When time was called the match was declared a draw. Morgan shook Scott enthusiastically by the hand. “Scotty, you are a winner and it will be up to you to fight in the big fall meet. Why, you are not winded at all.”

“No,” Scott answered quietly, “the old prizefighter who taught me always insisted on each lesson going to ten rounds, and I am used to it.”

“Oh, ho! learned from a professional, did you? That accounts for your not being phased by that blow on the chin, and your strong in-fighting. I should not stand any show with you in a real fight. I’m winded now.”

All the fellows crowded around Scott to congratulate him and forgave him his inability to play football in their admiration of a man who could stand up to Morgan.

“Well, fellows,” Ormand shouted, “that bout was too good to be spoiled by anything else. It’s half past eleven. Let’s put out this fire and march home.”

The fire was soon extinguished, and the crowd filed out of the woods singing familiar songs and yelling fiendishly at every sleeping house they passed. Slowly it melted away as the fellows came to their various rooming houses. When Scott and Johnson turned into their house they heard the singing of the remnant of the band dying away in the distance.

“Scotty,” Johnson said with admiration written in every feature, “you are the new White Hope of the College. When you took that wallop on the jaw and praised the man who did it, I believed what you said this afternoon. Now watch me be your kind of a sport.”

The next three weeks were full of pleasure for Scott Burton, for they brought him hours of his favorite exercise. Ormand, who had considerable influence with the student powers at the University, had made it his business the morning after the campfire celebration to arrange for Scott to represent the freshman class in the heavyweight class in the boxing match held each year to settle the supremacy between the under classes. It was an honor which the foresters had long coveted, and was granted to them only after Ormand had exhausted all his persuasive powers in his effort to show them how totally inadequate all the other candidates were, and how sure his candidate was to win. In his own mind he was not at all certain of the outcome, for the sophomores had a young giant who had won the event without an effort the year before, and held the supremacy in the whole University ever since.

Scott trained like a prizefighter, leaving no stone unturned to put himself in the pink of condition. He changed his recreation hour from the hour after supper to the hour before, and that hour was invariably spent in the boxing room of the gymnasium. Every day he boxed fast and furious bouts with Morgan, Manning, Edwards, Ormand and any of the other big fellows who cared to try it. He could wear them all out one after the other, and he worked incessantly to increase his endurance, for all agreed that it was his best chance to push the fight at a furious pace from bell to bell. For there were other men who were as good boxers as he, but none of them, they figured, with half his endurance or his ability to stand punishment. He was fast on his feet, could close in on any of them at will, and once at close range none of them could compare with him for a moment.

Johnson fussed over him like a mother. He was at the boxing room as regularly as Scott himself, and never left till he could give his charge a good rubdown, and escort him to supper, where he watched his diet with an eagle eye, and ordered away every dessert that Scott really cared for. He domineered to such an extent that Scott more than once threatened to thrash him instead of the sophomore, but Johnson always had his way and tightened up his orders after every encounter.

“Johnson,” he said one day, as he watched a luscious piece of pumpkin pie going back to the kitchen by Johnson’s orders, “when that scrap is over I am going to eat your dessert and mine, too, for a month.”

“You may have my dessert for all the rest of the winter if you win,” Johnson responded earnestly.

“There it goes again,” Scott complained. “What difference does that make? I may put up the very best fight I ever made in my life and get everlastingly licked. Then you would want to do me out of my right to eat your pie simply because the other fellow was too much for me. But if he happens to be a poor scrapper and I win easily you would cheerfully let me eat your desserts for six months. That’s queer logic.”

“Some more of your Eastern sporting views,” Johnson jeered.

“Well you ought to give a fellow credit for what he does, oughtn’t you? If he puts up a perfectly good scrap, give him credit for that. If the other fellow puts up a better one give him credit for that. I am going to eat your dessert anyway, so there is no use in arguing about it.”

They went to their rooms and straight to work. Johnson had wanted Scott to stop his studies for a while, but on that one point Scott balked and insisted on keeping up all his work, for he felt that his ability to handle it at all depended on his keeping it up-to-date. He was working hard on a problem when Johnson announced that it was ten o’clock and time for all prizefighters to be in bed. He emphasized his orders by blowing out the student’s lamp. Scott fired a book at him, which Johnson dodged cheerfully and proceeded to go to bed.

“That’s something else I am going to do,” Scott cried with some spirit. “After the twenty-fourth of October I am going to sit up as late as I blame please.”

“Um-huh,” Johnson answered, unperturbed. “After the twenty-fourth you may sit up all night if you want to, but—after the twenty-fourth. You need not talk too bigity; you may not be able to sit up at all after the twenty-fourth.”

And so it went from day to day. Scott working as never before, and Johnson rigidly enforcing his rules, jollying his way through all the threatened mutinies. In one short week Scott had jumped from an unknown student to the idol of the College. He realized that if he could win that match his position among his fellow students would be established. This idea spurred him on to untiring efforts. Even the girls began to look after him when he passed, and that embarrassed him, for he had always been shy about girls.

At last the all-important day arrived. The morning classes had been dismissed for the occasion. The students assembled on the campus by the hundreds, boys and girls together, crowded around the little open space reserved for the events. For the upper classmen it was a festive celebration to be thoroughly enjoyed. For the under classmen it was a serious contest, and through the good-natured yelling and cheering there ran an undercurrent of antagonism, which broke out in petty scraps and bickerings all through the crowd. The upper classmen were kept busy exercising their police functions to confine the competition to the organized contests.

Finally the crowd settled down with the classes concentrated, each on one of the four sides of the opening. The field marshal announced the cane rush between the sophs and the freshmen as the first event, and called for the representatives of the two classes. The chosen men, forty husky fellows from each class, stepped forward and lined up on opposite sides. All were dressed in the oldest clothes they could find, and looked more like a band of strikers than students seriously inclined toward higher education. The officials brought forward the cane and placed it in the hands of five select men from each class, carefully placing the hands so that neither class had an unfair advantage. The remaining champions were then lined up carefully at equal distances on either side of the cane. When all was arranged there was an instant of intense suspense as the referee took a review of the situation before raising the whistle to his lips.

At the first shrill blast the contestants rushed tumultuously forward on the little writhing knot of men around the cane. Sophomores tugged at freshmen to tear them away from the coveted cane, and freshmen struggled desperately with tenacious sophomores. In an instant they were all merged into one seething mass of humanity. It was practically impossible for those on the outside of the crowd to reach the cane, but they fought as wildly as those in the center. The pressure in the center became so great that one man was squeezed out of the mass like a grape from its skin, and rose head and shoulders above the crowd in spite of his best efforts to stay on the ground. Men on the outskirts vaulted to the heads of the crowd with a running start to crawl over the tightly packed heads and shoulders to the center only to be caught by the feet and dragged violently back to the ground. Frequently tempers were ruffled beyond control, and the consequent slugging matches had to be stopped by the officials. Pieces of wearing apparel littered the ground. Sweater sleeves and pieces of shirts rose high above the crowd. The grim silence of the contestants contrasted strangely with the wild cheering of the spectators. It was impossible to tell where the advantage lay, but that detracted nothing from the enthusiasm. Scott watched the struggle, the first of the kind he had ever seen, with intense interest, and forgot for the time that he would so soon be the central figure of just such another spasm of excitement and frantic cheering. The contestants still fought on with dogged perseverance, but their efforts were becoming weaker, and they were glad to stop at the referee’s whistle.

The upper classmen formed a circle around the ragged crowd, and the judges began their search for the cane. Those on the outskirts were summarily pushed outside the circle till the group was reached who actually had hold of the cane. The hands on the cane were counted, thirteen for the sophomores and ten for the freshmen. The announcement was received with frantic shouting by the sophomore supporters and the heroes were welcomed back to the side lines with wild demonstrations.

But there was not much time for such celebrations. The program was a long one and the officials’ call for the lightweight wrestlers centered the interest of the crowd on a new event. One by one the events passed by and the interest began to flag—for it was a sophomore day and the freshmen seemed wholly outclassed. Decision after decision went to the sophomores, and at the call for each new event the cheers from the freshmen ranks grew weaker. They were becoming overwhelmed by the defeat.

As the freshman middleweight stepped into the ring for the second round of his drubbing, Johnson, who had been pleading with each man in turn to do something for the honor of his class, turned to Scott almost with tears in his eyes. “Now, Scotty,” he said, “you’ll be the next, and you’ve got to win. This bunch of loafers has lost everything for us, and a forester must save the honor of the class. There, that wax figure got knocked down again. That finishes him. Now come on. You’re the last hope between us and a shut out. Show ’em what a forester’s made of. You’ve simply got to win.”

The referee had called for the heavyweights, and Johnson, Scott’s faithful second, was tying on his hero’s gloves. Scott felt a little nervous, but knew that he would be all right as soon as the first blow was struck.

Johnson fussed around his roommate like a nervous mother. “Now, Scotty, everything is ready. He’s a regular moose, but remember the game. Go at him like a tornado from the very start and he can’t stand the pace.”

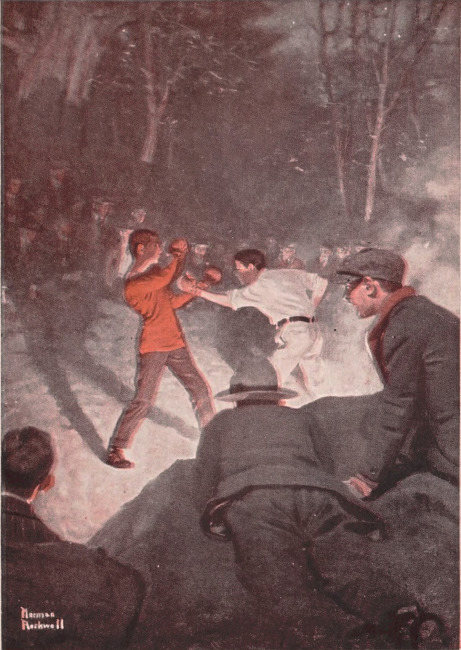

With these final instructions Scott walked out to meet his opponent. The man opposed to him was indeed a giant; he had never boxed with such a big man, and he saw the last gleam of hope dying in the freshman ranks. That would have taken the courage out of many men, but it only made Scott the more determined to save his class’s honor, and bring everlasting fame to the foresters.

The big fellow shook hands condescendingly with a rather patronizing air, which maddened Scott. In stepping back from the handshake the big fellow took a leisurely and rather contemptuous slap at his opponent’s head, but that was the last chance he had to show his superiority. Scott dodged like a flash and landed a straight punch in the big fellow’s stomach. The ease with which he had lorded it over the whole University for a year had made him careless, but he was a good boxer and he knew that he could not afford to play with this new man. Scott left him no time to think it out. He pushed the attack with a fury that brought the spectators to their feet, and wrung from the freshmen the first real cheer they had had the heart to give since the cane rush was decided. Scott rushed his opponent again and again, each time breaking away with a vicious hook to the short ribs that worked havoc with the big fellow’s wind—none too good at the first. It was not, however, a one-sided fight by any means. The sophomore’s superior reach and weight gave him a great advantage, especially in the out-fighting, and he was not slow in grasping the opportunities. Scott’s rushing tactics forced him to make some good openings and it was only his ability to stand punishment that saved him several times.

During the first round he was rushing in on his opponent when he received a straight punch in the right eye that landed him flat on his back. The hopes of the freshman class fell with him, but Scott was up again like a rubber ball amidst a perfect tempest of cheers, was inside the big sophomore’s guard almost before that gentleman realized what had happened, beat a veritable tattoo on his short ribs and was away clear without being touched. He was fighting as strongly and furiously as ever, while his opponent was laboring heavily.

But Scott still had to be very careful to avoid those vicious swings. Twice he received blows on the chin which sent his head back with a snap, and which would have knocked out a less hardened man. He saw that his man was weakening and gave him no peace. He had rushed him to the ropes and was fighting at close range in the hope of getting a chance at his jaw when the whistle ended the first round.

Johnson received him with open arms, and wrapped the bathrobe carefully about him. “You’ve got him going, Scotty, if you can keep up another round like that you’ll get him easy. Can you do it?”

“Yes,” Scott answered, “ten of ’em, if he doesn’t knock my head off in the meantime. He certainly landed some dandy blows on me.”

“Why don’t you play for his jaw more? You’re just hammering away at his ribs all the time; you can’t hurt him there,” Johnson remonstrated.

Scott laughed, “You don’t realize how tall he is. I can’t reach his face unless I’m in close and then I am afraid to reach up so high; it would give him too big an opening. Those rib blows count in the long run, but I do not believe myself that they will be any good in a two-round fight. I’ll have to risk it this time, I guess.”

Johnson was delighted to see that his hero was not winded in the least, and he watched the heavings of the bathrobe opposite with huge satisfaction. The freshmen were hopeful once more, and answered the taunts of the sophomores with some spirit.

At the sound of the whistle Scott shot to his feet like a jack-in-the-box and met his opponent three-fourths of the way across the ring. He tried some sparring at long range, but found that he was still outclassed, even though the sophomore was plainly showing his fatigue. Several stiff blows about the face showed him that it was not yet safe. Once more he ducked, charged, and pounded the big fellow’s wind. He received a blow on the jaw when he thought he was clear out of reach, but he realized that the old vim was no longer back of it.

Scott decided that the time had come to take the one chance he had of a clean decision. He rushed his man furiously, and tried for an opening to the face, but was driven out again without getting it. He noticed that the sophomore’s breath was coming in labored gasps and rushed him again. With a terrific hook to the stomach he lowered the big fellow’s head and landed heavily on his jaw, but the man was indeed a very moose and withstood the blow though it dazed him a little. Relying on this Scott took his chance. He offered a beautiful opening which his opponent took eagerly, throwing all his waning strength into one mighty full-arm swing for Scott’s unprotected chin.

Few in the audience realized what a risk Scott had really taken in trying to side-step a man like that, but he himself realized it to the full and planned it with the greatest care. He side-stepped with the agility of a cat, felt the glove just brush his cheek, and threw all the weight of his splendid shoulders into a hook to the jaw. The blow went true, and the big man wilted in his tracks. Scott caught him in his arms and was letting him gently to the ground, when he wriggled loose, staggered to his feet and struck at Scott blindly but savagely. Before he could fully recover, however, the whistle blew.

Scott stood patiently in the ring waiting for the decision, but not so the crowd. Yelling wildly the freshmen descended with a rush on the one champion the day had brought forth for them, heaved him on their shoulders, half clothed as he was, and swept across the campus through the crowd of spectators. He remonstrated and fought as hard as he had in the ring, but to no purpose. They carried him clear across the campus and out into the street. Scott would have given anything for even his undershirt. He had objected to stripping to the waist even there in the ring, but now that the match was over to be exhibited in this way to all those girls was intolerable. At last it ended. A hundred and eighty-five pounds is not a light weight to carry even if it is a hero and Scott managed at last to fight his way to the ground. He was wondering how he would ever get back to his clothes, even if they had not been carried off by the crowd, when the faithful Johnson pushed his way forward with them.

“Now get out of the way,” Johnson commanded the throng of admirers, “and let me take him home for a little rest.”

“Scott,” he continued as he hustled him to the car, “now you can go home and sit up all night for the rest of the winter. Yes, and hanged if you can’t eat my desserts for the next six years.”

“Humph,” Scott grunted good-naturedly, “and all just because I won.”

As the boys sat in their room that evening in their pajamas talking over the events of the day Scott was impressed more than ever with Johnson’s strange philosophies, apparently gathered from almost unlimited experience. Johnson was in a very good humor over the results of the boxing match and Scott thought it a good opportunity to get him to tell his story.

“Johnson,” he asked curiously, “where haven’t you been? You don’t look very old but there does not seem to be any place that you have not worked in all the United States.”

“Well,” Johnson answered, “I have never been to the South or East, but there are not many sections of the West that I have not seen.”

“How did you do it?” Scott urged. “You said that I could sit up all night, you know, and I could listen very contentedly to an account of all your wanderings. They must be interesting for I suppose you beat your way everywhere. Come on, let’s have the whole story,” and he settled himself down to listen.

Johnson, who loved to have an audience for his adventures, was in his glory. He had had adventures galore and they lost nothing in his telling of them.