The Project Gutenberg EBook of Making Tin Can Toys, by Edward Thatcher This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Making Tin Can Toys Author: Edward Thatcher Illustrator: Isabel Thatcher Release Date: April 7, 2018 [EBook #56939] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MAKING TIN CAN TOYS *** Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

MAKING TIN CAN TOYS

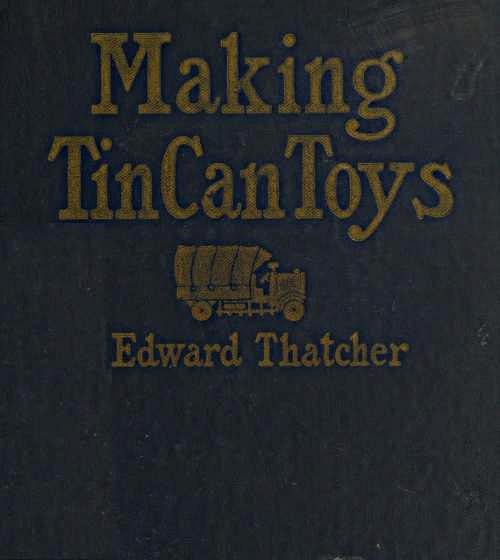

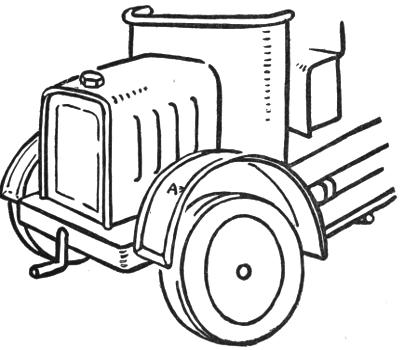

Army truck constructed entirely from used tin cans

MAKING TIN CAN TOYS

BY

EDWARD THATCHER

ORIGINATOR OF TIN CAN TOYS AND INSTRUCTOR OF METAL

WORKING, TEACHERS COLLEGE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

NEW YORK CITY, 1904-1919

DRAWINGS MADE AND THE

AUTHOR’S MODELS PAINTED

By ISABEL THATCHER

PHILADELPHIA AND LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1919, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PRINTED BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

AT THE WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

PHILADELPHIA, U. S. A.

Tin can toys were invented after a fruitless search of the toy shops for a large tin locomotive. I had a long can in my shop at home that I thought could be very easily worked up into a toy locomotive boiler by adding a few fittings, such as a piece of tin rolled up into the form of a smokestack. Part of a small can could be used for a steam dome, or I could use the top part of a certain tooth-powder can, the distributor top of which would look very much like a whistle. A cocoa tin came in very handy for a cab, and a thumb-tack box served for a headlight. The wheels were made of can lids soldered together, and the toy locomotive was made, much to the joy of my very young son, who has had it in constant service for over a year, and it is still good for many trips at the end of a string.

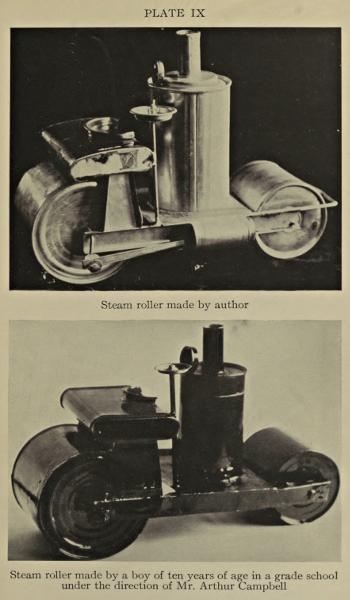

I had always used tin cans for making such articles as water motors, glue pots, melting ladles, mooring buoys for model yachts, etc., but the locomotive was the first toy, made wholly from tin cans, that I had produced, and this suggested other toys. The steam roller was next made.

I found that the cans lend themselves very easily[2] to the making of toys, so much of the work being already done.

The materials used to make these toys are plentiful and inexpensive—cans are everywhere. The tools needed are few and easy to use, and I found that so many different and amusing durable toys could be made from used tin cans, and also that everyone seemed to have such fun making the toys, that I decided to use them for teaching purposes.

Tin can toy making has been thoroughly tried out in a grade school under a very able teacher, who understands making them. Pupils of ten, eleven and twelve years of age have proved that these toys are easy to make, and many schools now have the work well established.

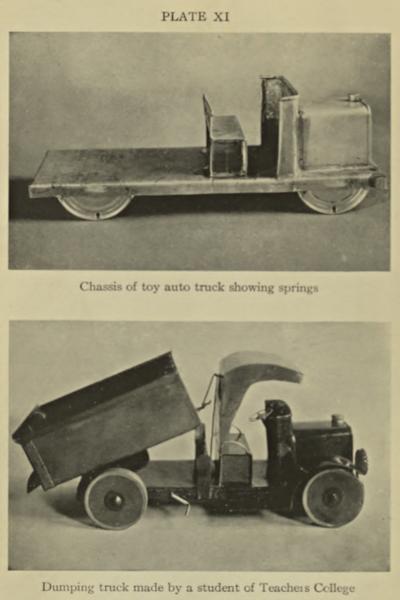

The steam roller, shown in Plate XI, was made by a boy of ten after a model which I made for it. This same boy developed quite a trade of his own by soldering up various pieces of tinware for his mother and the neighbors.

But, better still, working with the tin cans has developed the inventive faculties of my class to a surprising degree. The pupils have thought out and made many models of their own—not only toys but useful things as well. Various members of the class investigated the large trucks, automobiles, hoisting engines, locomotives, boats and such things seen in[3] any water-front community, to see how they were made and how they worked, and why. These pupils then returned to the school shops and made models of their own, many of which showed considerable invention and ingenuity.

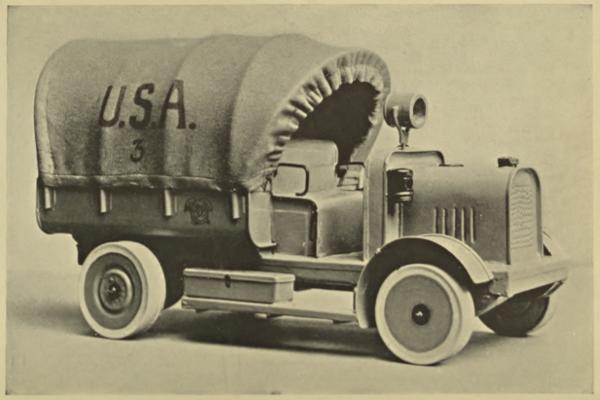

I decided to teach the Occupational Aides in my classes at Columbia University how to make these toys, so that they in turn could teach the wounded soldiers in the hospitals.

It is a great pleasure to know that as this book goes to press many a wounded soldier has been and is still being amused and benefited by making the tin can toys here.

But the making of tin can toys is by no means limited to hospitals and schools. Any one who cares to tinker, to handle tools, to use up waste materials, may find pleasure and profit from assembling tin cans and parts of them. Many useful and attractive things may be made for the home, shop, or camp.

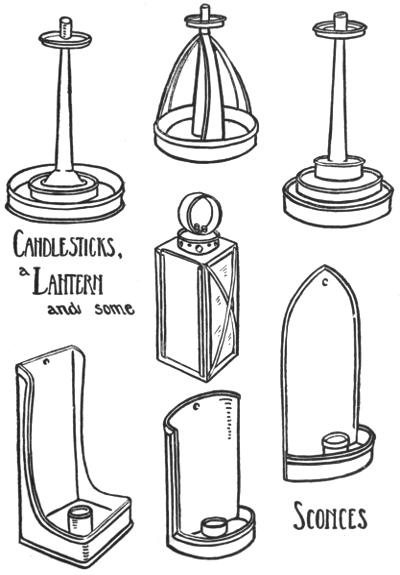

I have found it quite possible to make many decorative things from tin cans, and for some years I have made lanterns, candlesticks, sconces and trays of all kinds. The shape of the cans themselves lends them to decoration when assembled by a person having a sense of design and proportion.

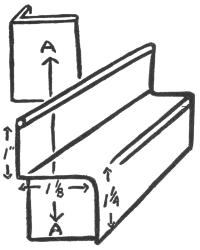

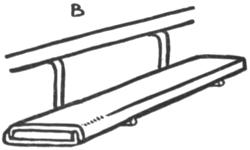

There is nothing weak or flimsy about a well-made tin can toy. A strip of flat tin is very easily[4] bent; if that same strip of tin is bent at right angles through its whole length, like the angle iron encountered in structural iron work, it will be found to be remarkably stiff.

Bend up an angle on each side of a strip of tin, like a channel iron used in buildings; it will sustain a remarkable load.

I have used the common forms employed in structural steel for building up the toys shown in this book with the result that they are surprisingly solid and durable, though made entirely from cans or the tin taken from flattened-out cans and boxes.

No rough or sharp edges are left about these toys. The edges of a piece of tin may be folded over or “hemmed”—or a folded strip of tin may be slipped over an edge that needs strengthening. Thus all danger of cutting the fingers or of thin edges being bent out of shape is done away with.

Although made of tin, there need be nothing “tinny” about a well-made, well-painted tin can toy.

Very few and very simple tools are required for the work and the solder, soldering flux, rivets, wire and paint are very inexpensive items, as so little need be used for each piece produced.

Soldering is by far the most important of the operations involved in tin can toy making. But it is very simple, once it is understood. When the[5] principles that govern the process of soldering are thoroughly mastered there is no difficulty at all about it. Chapters IV and V should be thoroughly read and re-read before trying to solder, and at least two practice pieces well soldered together before going any further.

Since the tin can toys were introduced into my classes at college I have taught more than two hundred pupils how to make them. Many of these pupils had little or no experience with tools and had never expected to have any until the war came along and changed the ideas of many people as to their ability to work with their hands. I have yet to encounter a pupil who could not solder after a very short period of instruction.

Look at the end of a small olive oil can or the end of a tin commonly used to contain cocoa, then think of the shape of the radiator and hood of the modern automobile. The shape of the can and the shape of the hood of the automobile are very much alike. A few holes punched in the end of the can in regular rows transform it into a miniature radiator in appearance, and some slits cut in the side of the can look very much like the vents in the side of a real auto hood. Solder the cap of a tooth-paste or paint tube in place over the radiator, and the hood and radiator are completed.

To have formed up a hood of this sort from a plain sheet of metal would have taken far more skill than the average tinker is likely to possess, but you have it ready made in the can, and this is the whole idea of tin can toy building.

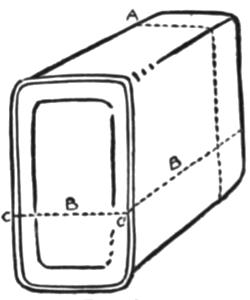

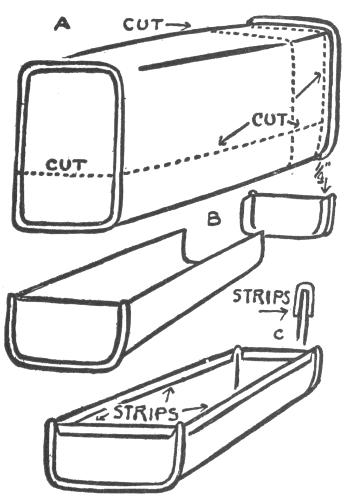

Less than half of a rectangular two-quart can used for a certain cooking oil makes up into a truck body so like the bodies on the real trucks that it would be difficult to find or make one more like them.

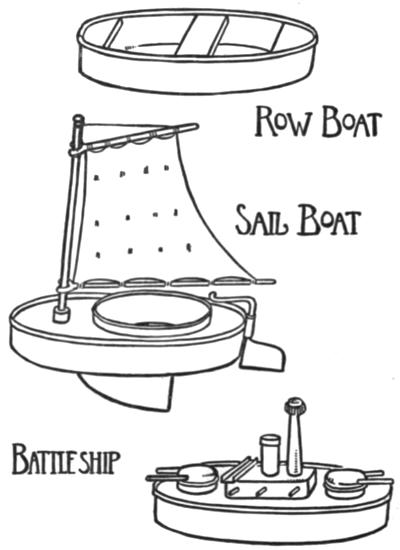

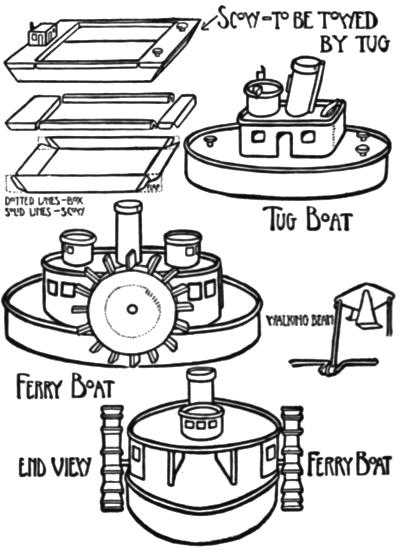

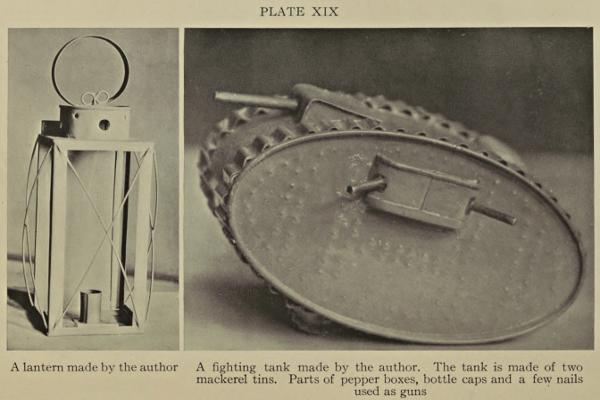

Many different kinds of boats that will really float may be made from mackerel and herring tins which are usually made in the shape of boats. Two mackerel tins soldered together suggest the fighting tank. Only a little work is necessary to transform these cans into real toys.

Long cylindrical cans suggest boilers for toy locomotives, hoisting and traction engines, steam rollers and the like.

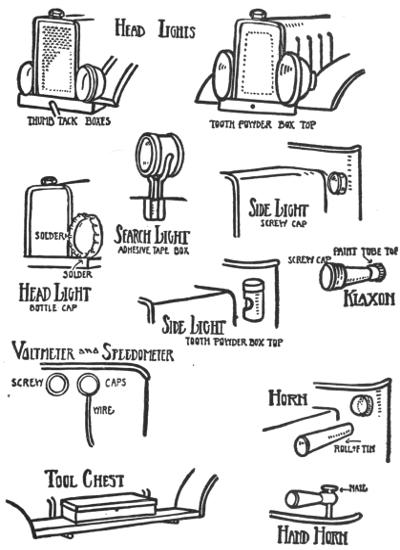

Wheels for rolling stock may be made from cans or the can lids. Small adhesive tape boxes make excellent headlights or searchlights and also pilot houses for tiny tug boats. Bottle caps, thumb-tack boxes, and the small screw tops of olive or cooking oil cans suggest head, side and tail lights for toy automobiles, and many other things.

Aside from the pleasure derived from the actual making of tin can toys, perhaps the greatest[7] satisfaction lies in the fact that you are using material usually thrown away—making something out of nothing.

And so this book is offered to tinkers by a tinker with the hope that they may get some of the pleasure out of it that he has had in writing it.

Edward Thatcher.

Woodstock, Ulster County, New York.

September, 1919.

RECONSTRUCTION AIDE, DIRECTOR OF THE RED CROSS WORK SHOP FOR PATIENTS AT NEUROLOGICAL BASE HOSPITAL 117, LA FAUCHE, HAUTE MARNE, FRANCE

“The hospital was new and its needs were many. We began work the day after our arrival and by the time our small equipment was unpacked (Mrs. Myers refers here to her own personal equipment of tools which was necessarily a small one as it was brought from America. The hospital shops were not equipped with tools until after the Aides had established the work and decided on the necessary tools needed), requests were coming in from all quarters of the hospital for us to make everything from tables and dishes to doughnut cutters. There was such a lack of material that the problem of making them could have been solved by nothing less than ingenuity of the American soldier and the ever present tin can pile.

“Some old French hospital beds found on the salvage heap were quickly converted into work benches. It was then that the tin can ceased to be a thing to be burned and buried and came into its own.

“Our first need was a charcoal furnace to heat[10] our soldering coppers. This was made from two large square tins with an interlining of brick. A bit of an old grate completed this perfectly good furnace which served us well for many months.

“The wants of the kitchen were next considered. For washing dishes we made three huge wooden tubs 2 by 2½ by 6 feet. The lining and drain pipes for these were made from several large tin cans. As the size of the hospital increased there was a constant demand for such things as biscuit pans, doughnut cutters, funnels, potato graters, vegetable strainers, soap dishes and other small necessities.

“For the officers’ wards, barracks, and recreation hut, we made tin candlesticks, flower holders, ash trays, electric light shades, tea trays, desk sets, and filing boxes. All of which were not only useful but quite ornamental, as they were attractively painted and decorated by the patients. The soldiers took great interest in the making of mechanical toys, especially war-like ones, such as tanks, aeroplanes, cannon and army trucks.

“The reflectors for the foot lights of the stage in the Red Cross Recreation Hut were made of tin cans. The end-men in the minstrel show were quite gay in tin can hats—what could have been more simple—a tin brim with an inverted butter can for a crown, gaudily painted and beribboned!

PLATE I

Courtesy Pictorial Review

Wounded soldiers at work

“The princess in the Christmas play was in need of shining armor. Half circles of tin overlapping[11] each other not only served the purpose but were glitteringly gorgeous. The Three Kings in the play were badly in need of crowns; three oatmeal tins were beautifully fashioned into kingly headdresses for them.

“The Christmas tree was brilliant with hundreds of stars, diamonds, and crescents, and candle holders, which was the final contribution of our much sought and never failing friend, the tin can pile, as the hospital was evacuated soon afterwards.

“I have had entire charge of the work and have taught the other Aides the tin can work, as it was a most necessary thing for them to know. Many of these Aides were sent to other hospital workshops and introduced the work there.”

Mrs. Clyde M. Myers, R.A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | 5 | |

| Extract from a Letter Written from France by Mrs. Clyde M. Myers, R.A. | 13 | |

| I. | Tin Cans | 19 |

| VARIOUS KINDS OF CANS AND BOXES—PREPARING CANS FOR THE WORK—CUTTING IN AND OPENING OUT CANS AND BOXES | ||

| II. | Tools and Appliances | 28 |

| TOOL LISTS AND COSTS—LAYING OUT AND MARKING OFF WORK—SHOP APPLIANCES | ||

| III. | Making a Biscuit Cutter from a Small Can | 44 |

| CUTTING THE CAN TO SIZE FOR BISCUIT CUTTER—PUNCHING A HOLE IN TIN—FORMING THE HANDLE—FOLDING—MAKING A SUGAR SCOOP BY THE SAME METHOD | ||

| IV. | Soldering | 54 |

| SOFT SOLDER—SHEET TIN—THE PROCESS OF SOLDERING—HEATING APPARATUS—ELECTRICAL SOLDERING COPPERS—THE COMMON SOLDERING COPPER—FLUXES—TINNING THE COPPER—HEATING | ||

| V. | Soldering (Continued) | 71 |

| PREPARING A JOINT FOR SOLDERING—CLEANING AND SCRAPING—SOLDERING A PRACTICE PIECE—SOLDERING THE HANDLE TO THE BISCUIT CUTTER—A SECOND PRACTICE PIECE—ANOTHER METHOD OF APPLYING SOLDER | ||

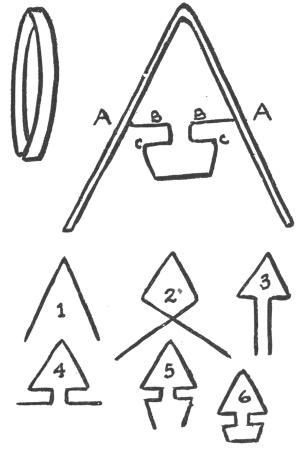

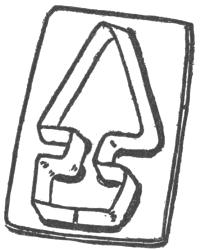

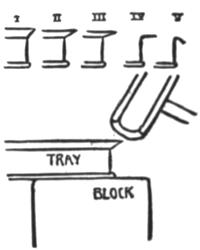

| VI. | Cooky Cutters | 79 |

| THE PINE TREE DESIGN—CUTTING NARROW STRIPS OF TIN—BENDING TO SHAPE OVER DESIGN—SOLDERING COOKY CUTTERS—THE HANDLE | ||

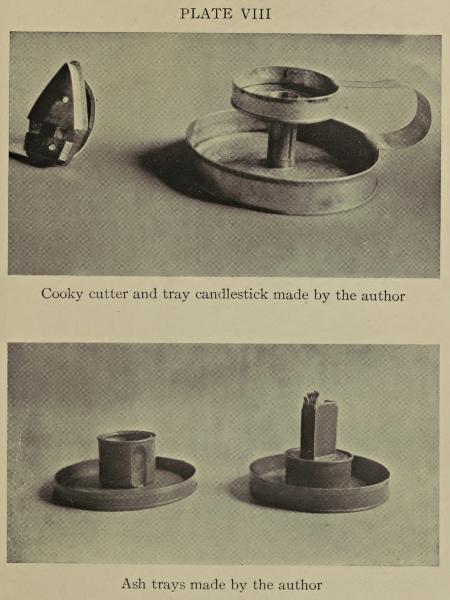

| VII. | Trays | 86 |

| TURNING OVER EDGES ON ROUND TRAYS—USING THE FORMING MALLET—MAKING AN ASH TRAY AND MATCH BOX HOLDER[14] | ||

| VIII. | A Tray Candlestick | 94 |

| THE CANDLE SOCKET—CUTTING A HOLE IN THE DRIP CUP—MAKING THE HANDLE | ||

| IX. | Riveting | 100 |

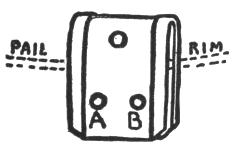

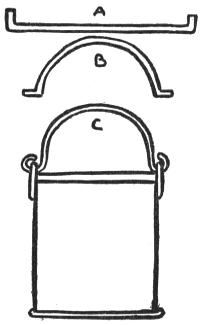

| MAKING A PAIL FROM A TIN CAN—CUTTING AWAY THE SURPLUS TIN AT THE RIM—FORMING THE LUGS FOR THE HANDLE—RIVETING THE LUGS IN POSITION—FORMING A WIRE HANDLE | ||

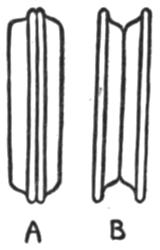

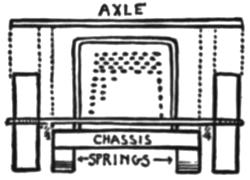

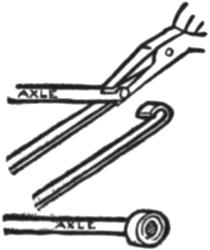

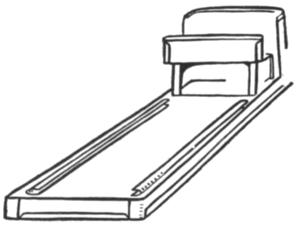

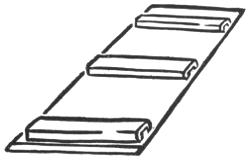

| X. | Making a Toy Auto Truck | 107 |

| FOUR WAYS OF MAKING WHEELS OF TIN CANS: MAKING A WHEEL FROM A CAN WITH SOLDERED ENDS—MAKING WHEELS FROM ROLLED RIM CANS—TWO TYPES OF WHEELS MADE FROM CAN LIDS | ||

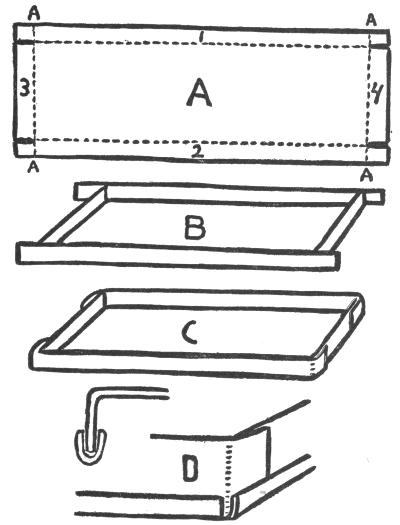

| XI. | Making a Toy Auto Truck (Continued) | 118 |

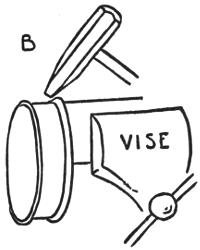

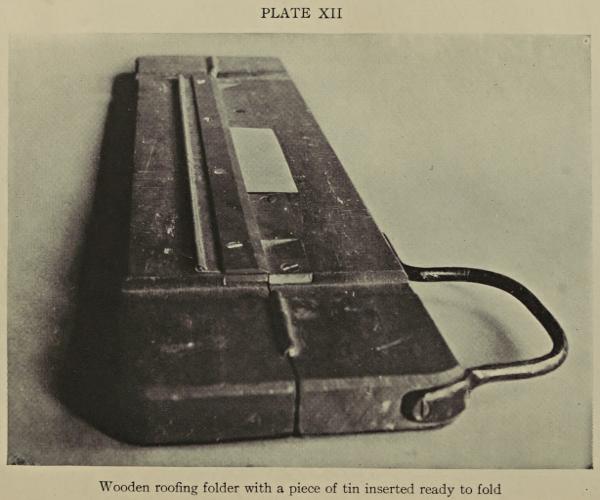

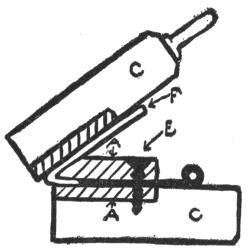

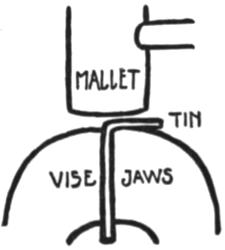

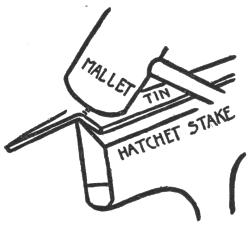

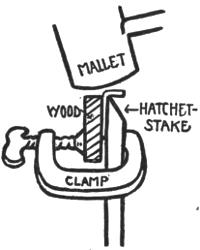

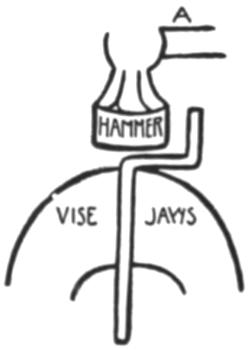

| FORMING THE CHASSIS—USING THE WOODEN ROOFING FOLDER—FOLDING—USING THE VISE FOR SHORT FOLDING—USING THE HATCHET STAKE FOR FOLDING | ||

| XII. | Making a Toy Auto Truck (Continued) | 127 |

| MAKING THE HOOD AND RADIATOR—CUTTING THE VENTS—SOLDERING ON THE FILLER CAP | ||

| XIII. | Making a Toy Auto Truck (Continued) | 135 |

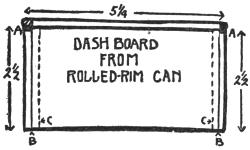

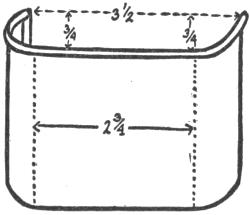

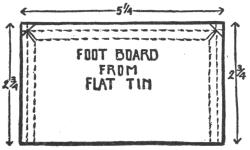

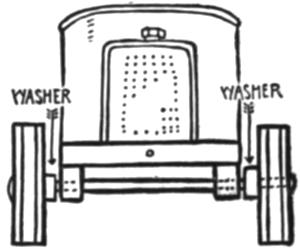

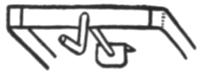

| THE DASH-BOARD—THE SEAT—ASSEMBLING THE TRUCK—SPRINGS—SOLDERING THE WHEELS ON THE AXLES—STRIP WASHERS | ||

| XIV. | Making a Toy Auto Truck (Continued) | 146 |

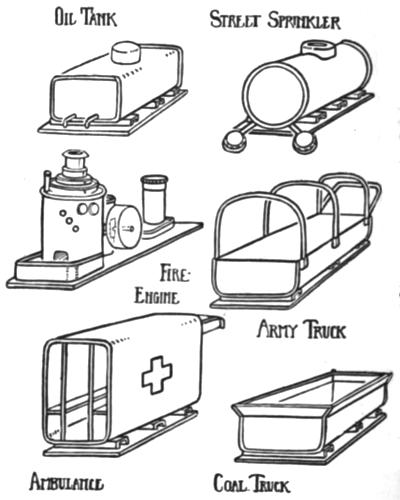

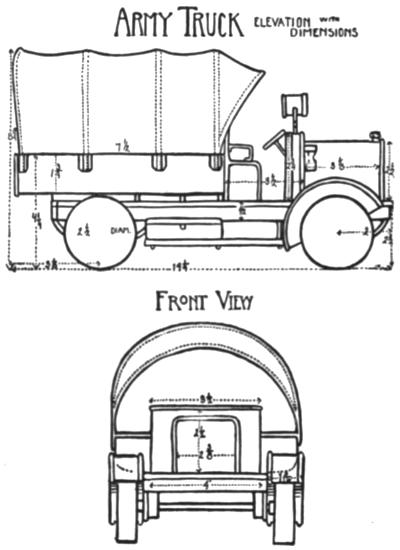

| TRUCK BODIES—DIFFERENT TYPES OF BODIES TO BE FITTED TO THE SAME CHASSIS—THE TANK TRUCK—THE STREET SPRINKLER—THE COAL OR SAND TRUCK—THE ARMY TRUCK—THE AMBULANCE—THE FIRE ENGINE | ||

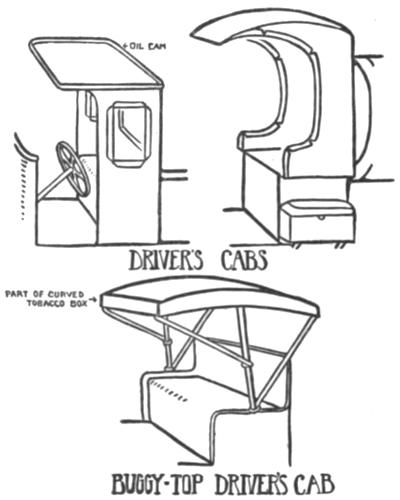

| XV. | Making a Toy Auto Truck (Continued) | 157 |

| THE STARTING CRANK—THE STEERING WHEEL AND COLUMN—MUD GUARDS AND RUNNING BOARDS—LIGHTS, TOOL BOXES, HORNS, ETC.,—DRIVERS’ CABS | ||

| XVI. | Boats | 166 |

| THE ROWBOAT—THE SAILBOAT—THE SCOW—THE TUGBOAT—THE BATTLESHIP—THE FERRY-BOAT[15] | ||

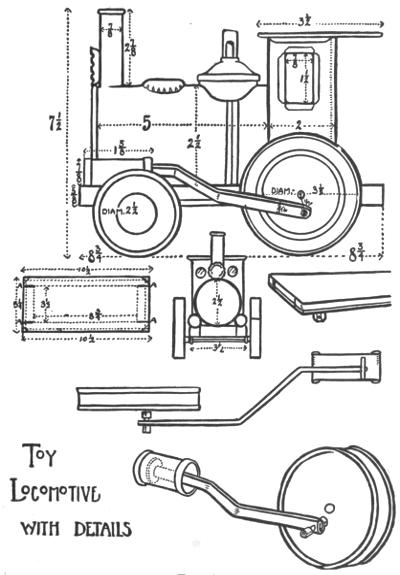

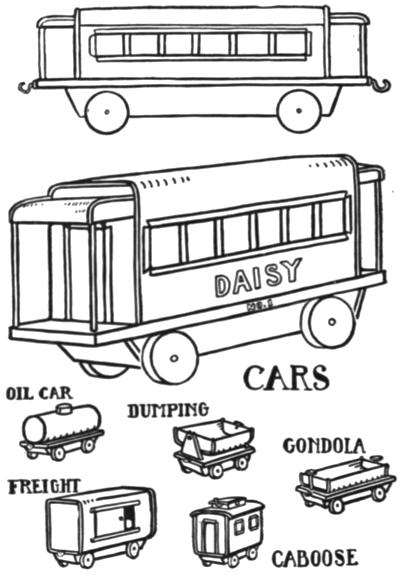

| XVII. | A Toy Locomotive | 174 |

| THE FRAME—BOILER—CAB—WHEELS—CYLINDERS AND CONNECTING RODS—THE SMOKESTACK, STEAM DOME AND WHISTLE, SAND BOX AND HEADLIGHT—CARS—A PASSENGER CAR AND SOME OTHERS | ||

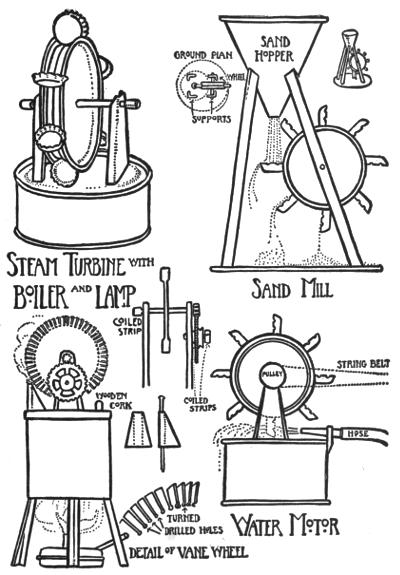

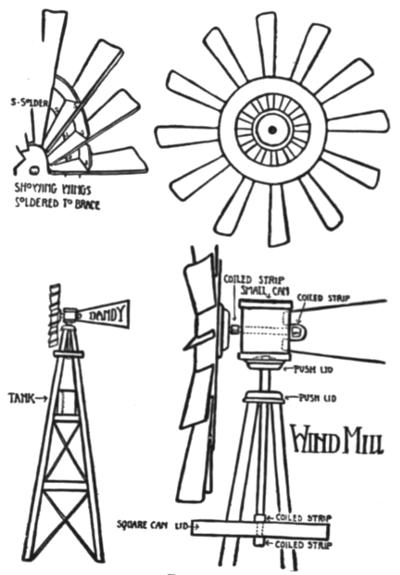

| XVIII. | Simple mechanical Toys | 182 |

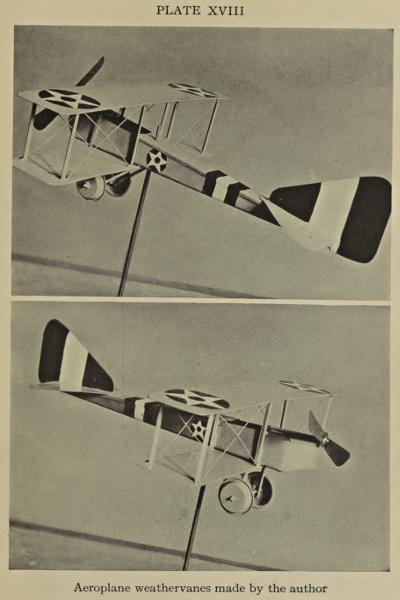

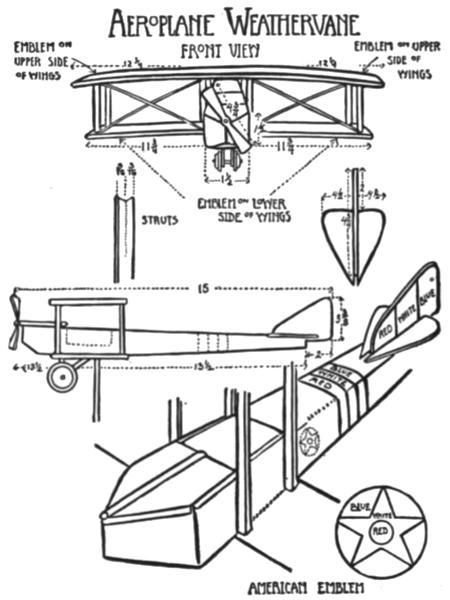

| WATER WHEELS AND SANDMILLS—A SIMPLE STEAM TURBINE AND BOILER—A WINDMILL AND TOWER—AEROPLANE WEATHERVANE | ||

| XIX. | Candlesticks | 192 |

| WALL SCONCES AND A LANTERN | ||

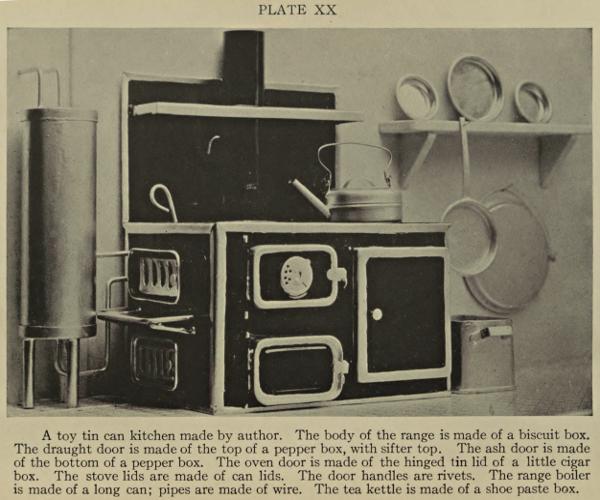

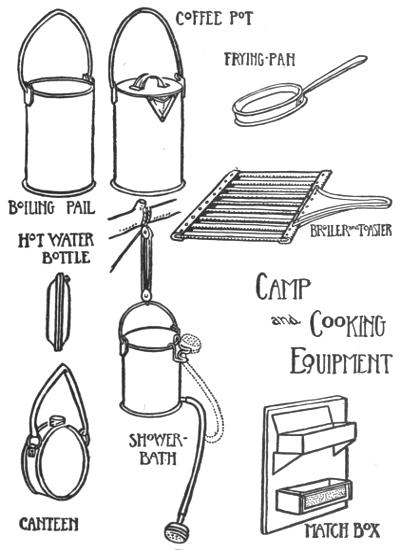

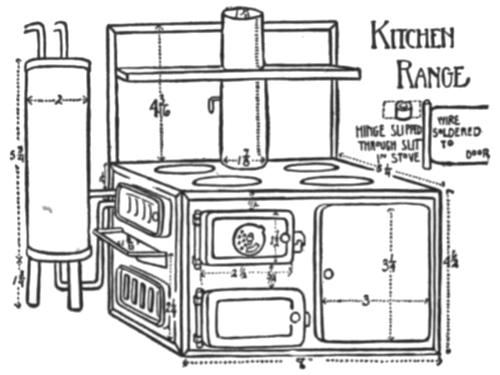

| XX. | Camp and Kitchen Equipment | 195 |

| A COFFEE POT—BOILING PAILS—FRYING PAN—TOASTER—A CAMP SHOWER BATH—CANTEEN OR HOT WATER BOTTLE—A MATCH BOX | ||

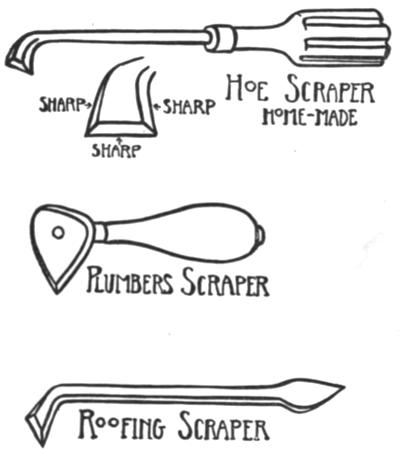

| XXI. | Preparing the Toys for Painting | 200 |

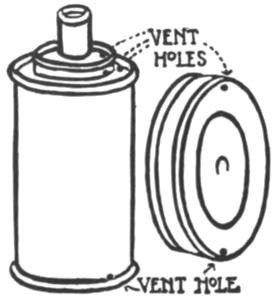

| REMOVING SURPLUS SOLDER WITH SCRAPERS—MAKING A HOE SCRAPER—PLUMBERS’ AND ROOFERS’ SCRAPERS—SCRAPING AND FILING—BOILING THE TOYS IN A LYE BATH—VENT HOLES | ||

| XXII. | Notes on Painting the Toys | 206 |

| PAGE | ||

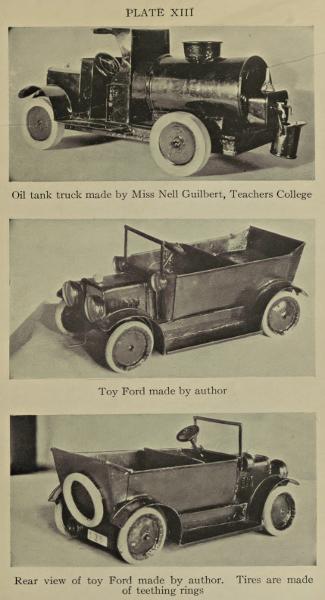

| Army Truck Constructed Entirely from Used Tin Cans | Frontispiece | |

| I. | Wounded Soldiers at Work | 10 |

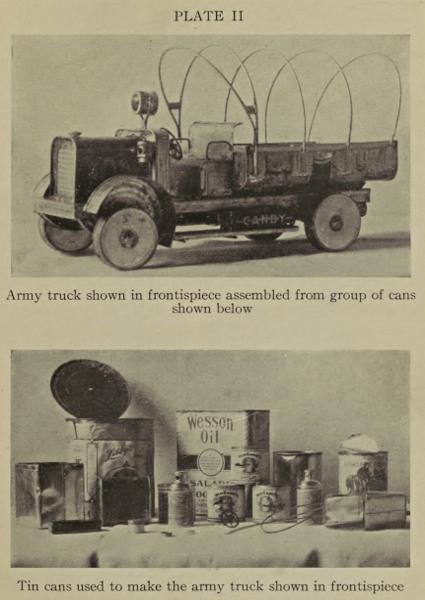

| II. | Army Truck and Tin Cans Used to Make It | 22 |

| III. | The Raw Material from Which Many of the Toys Shown in This Book Were Made | 23 |

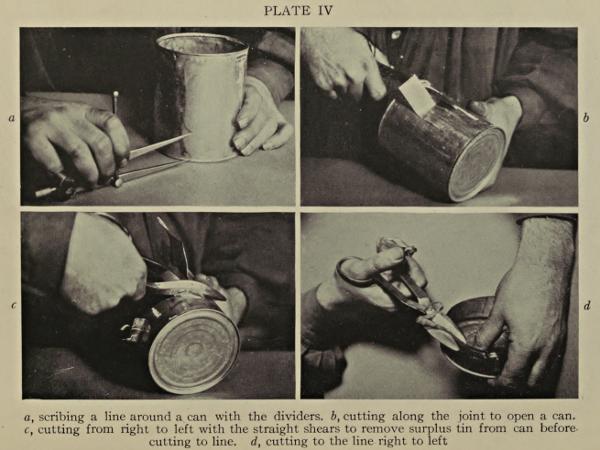

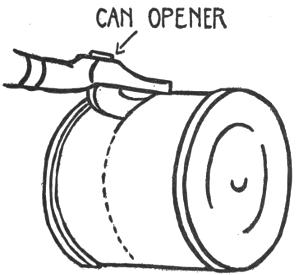

| IV. | Scribing a Line Around a Can with the Dividers. Cutting Along the Joint to Open a Can. Cutting from Right to Left with the Straight Shears. Cutting to the Line, Right to Left | 22 |

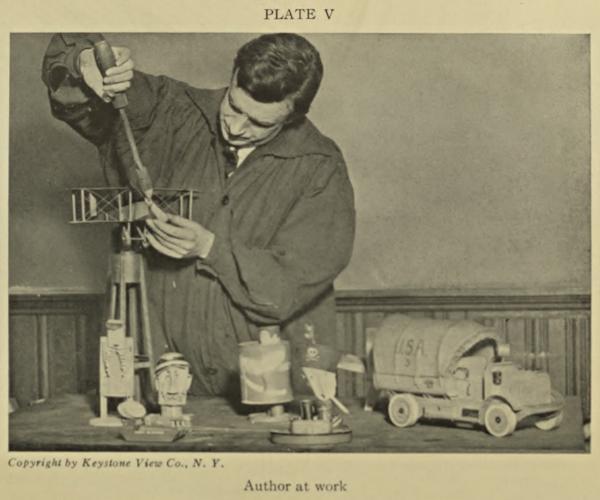

| V. | Author at Work | 23 |

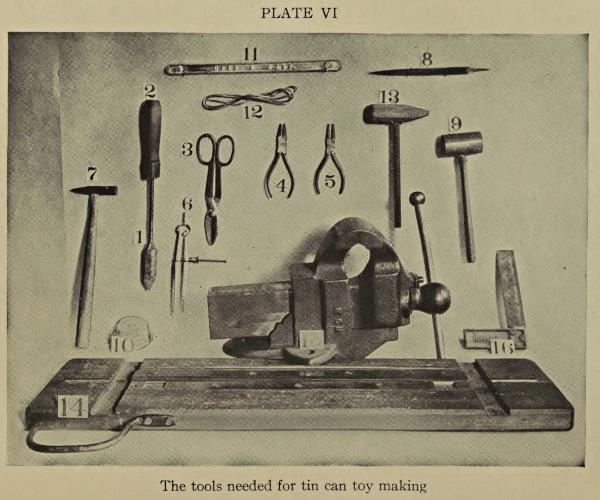

| VI. | The Tools Needed for Tin Can Toy Making | 32 |

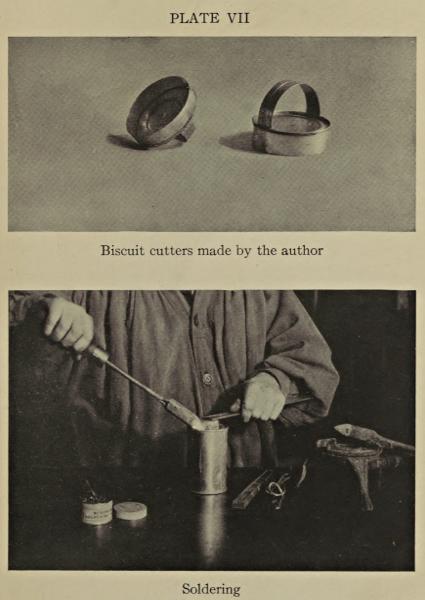

| VII. | Biscuit Cutters. Soldering | 44 |

| VIII. | Cooky Cutter, Tray Candlestick and Ash Trays Made by the Author | 84 |

| IX. | Steam Rollers | 116 |

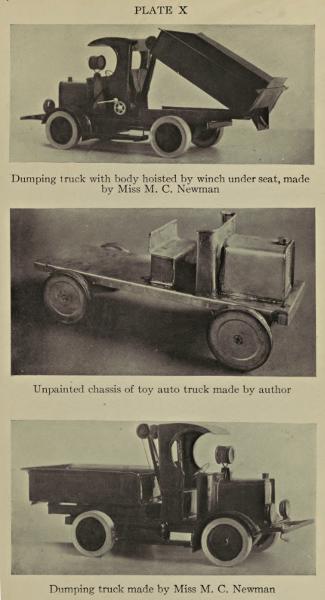

| X. | Dumping Truck and Chassis of Toy Auto Truck. | 120 |

| XI. | Chassis of Toy Auto Truck and Dumping Truck. | 121 |

| XII. | Wooden Roofing Folder | 120 |

| XIII. | Oil Tank Truck and Toy Ford | 152 |

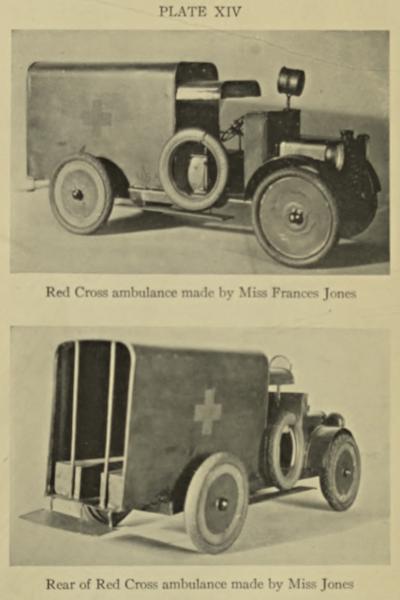

| XIV. | Red Cross Ambulance | 153 |

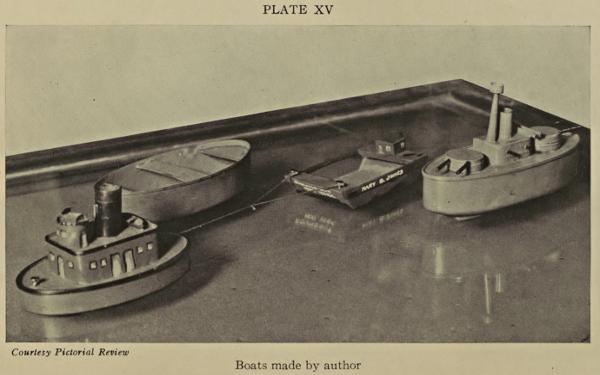

| XV. | Boats | 170 |

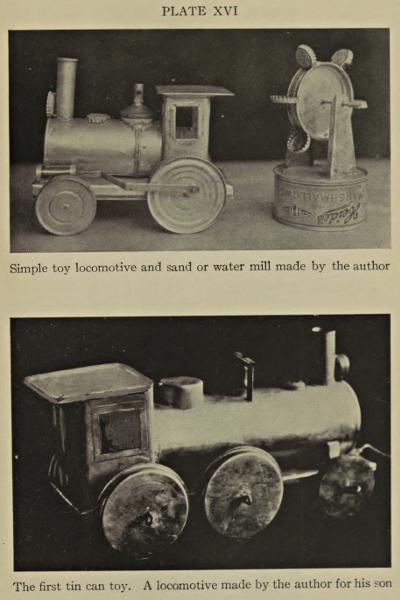

| XVI. | A Simple Toy Locomotive, a Sand or Water Mill and the First Tin Can Toy | 174 |

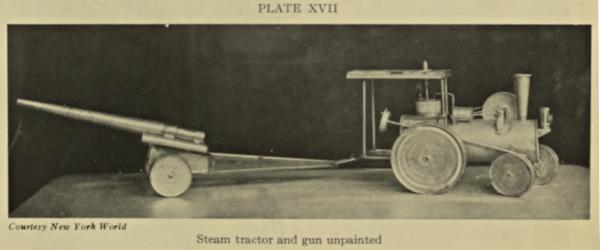

| XVII. | Steam Tractor and Gun | 175 |

| XVIII. | Aeroplane Weathervanes | 188 |

| XIX. | Lantern and Fighting Tank | 192 |

| XX. | A Toy Tin Can Kitchen | 196 |

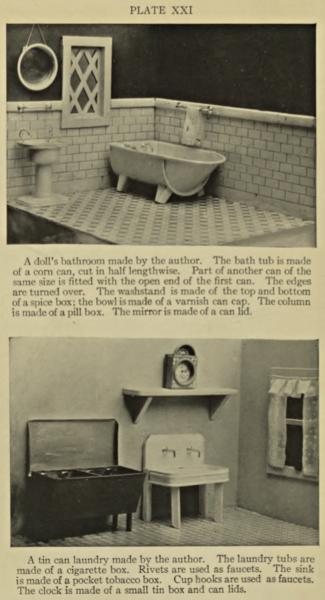

| XXI. | A Doll’s Bathroom and a Tin Can Laundry | 197 |

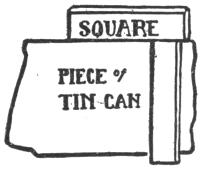

VARIOUS KINDS OF CANS AND BOXES—PREPARING CANS FOR THE WORK—CUTTING IN AND OPENING OUT CANS AND BOXES

There are many shapes and sizes of tin cans and boxes as every one knows; round, square, elliptical, tall, short, or flat. A surprising number of attractive shapes and sizes may be collected in a short time in any community. Housewives are only too glad to find some one to use them.

Cans that are well rinsed with hot water as soon as the contents are removed are not at all objectionable to work with; but cans that have not been rinsed out, or that have been thrown out and exposed to the weather are very unpleasant objects, and besides, a rusty can is very difficult to solder. It is a simple matter to rinse or scald out a can as soon as the contents are removed.

Tomato, corn, pea and condensed milk cans are the most plentiful. Coffee, tea, cocoa, jam, mackerel and sardine cans, olive and cooking oil cans, baking powder and spice cans are all useful for making the[20] things described in this book and for many more besides. Biscuit boxes, tobacco boxes, cold cream, ointment, and the small adhesive tape boxes all contain possibilities. The screw tops of olive oil and cooking oil cans, and bottle caps should be collected for this work. Jelly glass lids, in fact, all shallow tin lids are useful. Syrup and molasses cans with separate lids, that push into place are worth saving, especially the lids. Certain containers of dry material are now largely made of pasteboard with tin tops, lids and bottoms. The tin parts of these containers are often of an attractive shape. The large round gallon cans used by hotels and restaurants are particularly useful, and a sizable piece of tin may be obtained from the sides of the can and the bottoms may be used for large candlestick saucers and many other things. Large square tin boxes used to contain 100 pounds of cocoa may be obtained from some restaurants. These are made of heavy tin and five large sheets may be cut from the bottom and sides. Considerably over $1 would have to be paid for the same amount of tin.

Preparing Cans for the Work.—Cans that have contained paint, stove-blacking, heavy oils or greases, or cans that have been standing about with part of the contents exposed to the air may be thoroughly cleaned of all foreign matter by the hot lye bath. This bath is made up by adding two heaping tablespoonfuls of lye or washing soda to the gallon[21] of boiling water. Cans boiled up in this solution for a few minutes will be cleaned of all paint, paper labels, etc. Keep the hands out of the solution and do not allow any of it to come in contact with the clothes. Lift the work out of it with a wire hook and rinse off the lye with hot water; stand the cans bottom up so that they will drain out without any water remaining in them. The lye solution may be used for a number of times and then may be poured down the sink, as lye is an excellent thing for drain pipes. Do not leave a lye bath in the shop without covering it tightly when not in use, as the fumes from it are sure to rust every tool in the place.

Coffee, tea, cocoa, talcum and other cans that have contained dry material need not be put in the lye bath until ready to paint, unless the labels are too much in the way for soldering. Small boxes such as contain tobacco are almost covered with a sort of varnished paint. This may be scraped away where the box is to be soldered, but if much soldering is to be done the whole box should be boiled up in the lye bath until all the paint is removed. Sometimes the lye softens the paint but does not entirely remove it. More lye may be added to the bath and the work left in it awhile longer, or the work may be removed from the bath and the softened paint scrubbed away with a scrubbing brush and plenty of clean water. After being used several times, the bath will become too muddy and weak for further[22] use and then a fresh one should be made, as the lye is inexpensive.

For good work, it is necessary that the cans be thoroughly clean.

Cutting Into and Opening Out Cans and Boxes.—There is one very easy way to cut into and open out a can or box. To make wheels, small trays and other things, a good part of the sides of the can must be cut away leaving a small portion of the sides attached to the bottom. The part that is cut away may be flattened out and used to make various things. As most of the cans used are cut down to various dimensions in this manner, either to use the bottom with part of the sides, or to obtain flat sheets of tin, it will be well to consider the easiest way of doing it.

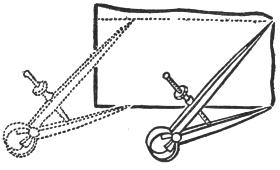

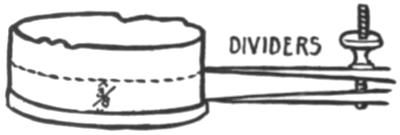

First, determine how much of the bottom portion of the can is to be left intact. Then using a pair of dividers opened to this dimension, make a line parallel with the base of the can and completely around it. To do this, hold the can down to the bench with the left hand so that it may be turned against the divider points as shown in Plate IV, a. Hold the dividers firmly down to the bench and against the can so that the uppermost point is held at exactly the same height from the bench during the turning or marking, while turning the can against the point to mark it.

PLATE II

Army truck shown in frontispiece assembled from group of cans shown below

Tin cans used to make the army truck shown in frontispiece

PLATE III

Courtesy Pictorial Review

The raw material from which many of the toys shown in this book were made

PLATE IV

a, scribing a line around a can with the dividers. b, cutting along the joint to open a can. c, cutting from right to left with the straight shears to remove surplus tin from can before cutting to line. d, cutting to the line right to left

PLATE V

Copyright by Keystone View Co., N. Y.

Author at work

Then using a pair of straight metal shears, cut down each side of the seam or joint in the side of the can to within one-half inch of the horizontal line you have marked with the dividers (see Plate IV, b).

Bend out the narrow strip containing the seam and cut it off with the shears. This will give you an open slot in the side of the can in which the shears may be easily introduced to cut horizontally around it.

Do not try to cut directly on the line marked around the can with the dividers but begin cutting about half an inch above this line and cut completely around the can until you have cut off the whole top part of it. After you have cut away the larger portion of the metal, the narrow strip remaining above the line may be easily cut away as it curls up out of the way as it is cut by the shears.

The can should be held in the left hand with the open end or top toward you (see Plate IV, c). Be sure you hold the can in this manner. With the tin snips held in the right hand, start cutting toward the left hand always when cutting around a can or box. Bend the tin out of the way as you cut. You will find that it is impossible to cut in a straight line or to make a continuous unbroken cut while cutting away a large portion of the can. But, after the larger piece is out of the way, the narrow strip remaining above the line may be easily cut away if you cut toward your left hand and hold the open[24] end of the can toward you. It is impossible to cut a straight line around a cylindrical form with a pair of straight shears unless the shears cut from right to left and that part of the metal which is cut away is nearest the operator.

The beginner will perhaps find it easier to handle the cans if a pair of old thin kid gloves are worn.

If one can afford it, the pair of double cutting shears such as are listed in the supplementary tools on page 31 are excellent things to have for opening and cutting around cans. These shears have three blades, and one blade cutting between two fixed blades cuts away a narrow strip of tin as the shears are worked along in such a manner that a straight line may be followed around a can at the first cutting. The point of the single blade may be punched into the side of a can and the cut started around the can at any point. If many cans are to be cut down, these double cutting shears will save much time and trouble. However, the straight shears will answer well enough, if the above directions are carefully followed.

Be sure to try not to cut to the line the first time you cut around a can. Cut away the larger part first and then cut to the line when there is only a narrow strip to cut away. Do not mind if the first piece cut away looks very rough and jagged. It may be a little difficult at first, but patience and practice will[25] soon make it quite easy to cut open a can in this manner, using a pair of ordinary straight shears.

Cut away the top of the can or the rolled edge adhering to that part of the can which is cut away; trim away all jagged edges; place flat on the bench or anvil and flatten out the tin with light blows of a wooden mallet. Lay this tin aside until needed.

I find it convenient to cut away the top or rolled edge of large round cans before cutting around them near the bottom, as then it is easy to bend the comparatively large sheet of tin out of the way of the shears as I cut around the can at the bottom. A large pair of shears is very convenient for opening large cans, but small ones will do if intelligently used.

When cutting metal with a pair of shears, always remember that the shears cut more powerfully near the joint or bolt, particularly when cutting through a folded seam or soldered joint. Keep the shears well oiled and have them sharpened by a competent mechanic when they become dull.

When cutting narrow strips of tin, be careful not to get the tin jammed between the shear blades so that the blades are forced apart sideways. Keep the bolt tightened so that the blades fit closely together.

One might suppose that cut or burned fingers would be plentiful in a large class of tin toy makers, but such has not proved to be the case. There have[26] been surprisingly few accidents of this sort and none of them at all serious.

One soon learns how to handle tin so as to avoid rough or sharp edges and that a soldering copper is provided with an ample handle so that it may be safely and easily handled when hot.

Some of the students found that old kid gloves with parts of the fingers cut off afforded protection to hands that were not used to shop work.

A bottle of iodine was kept handy and such slight cuts that were encountered were immediately washed with cold water and iodine applied to the cut which was then lightly bandaged. This treatment proved most effective and no ill effects resulted.

A mixture of pure linseed oil and lime water may be obtained at any druggists and this is a very effective remedy for burns. The solution should be well shaken up and applied directly to the burn which should then be bandaged with bandages wet with the mixture.

Common brown laundry soap worked up into a thick lather is an excellent remedy for slight burns.

Care and patience used in handling the tin and the tools will leave very little use for the above remedies in the shop.

The various problems presented in this book of tin can toys should be worked out in the order in which they are presented as each one bears a definite[27] relation to the others. Be sure to work out the simpler problems first—even if you have had considerable experience in other forms of metal working. A number of processes particularly adapted to working tin are used in making tin can toys.

While these processes are very simple, they are somewhat unlike those involved in copper working and jewelry making, though more closely allied to the commercial metal work of to-day.

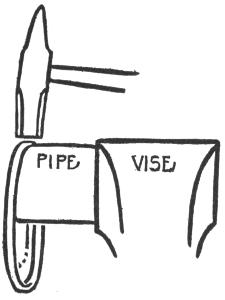

TOOL LISTS AND COSTS—LAYING OUT AND MARKING OFF THE WORK—SHOP APPLIANCES

In this chapter the names and approximate costs of the tools and appliances are given and also suggestions as to fitting up the shop for working with the cans. Various methods are suggested for laying out the work with the ruler, square and dividers.

It must be remembered that tool prices are not fixed and that the prices quoted in the following lists are the market prices of to-day, July 29, 1918. At present, tools are much higher in price than usual owing to conditions brought about by the war. Tool prices vary with market conditions.

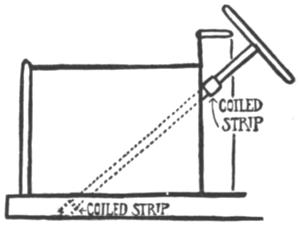

The tools listed may be bought at any good hardware store or ordered from the catalogues of any of the large mail order houses (except the Wooden Roofing Folder and the Forming Mallet). While the folder is not absolutely necessary for folding up angles in the tin, it is much better to have one to make the numerous angles employed in tin work than to attempt folding by hand, and particularly when long angles are to be made for lanterns, towers,[29] automobile chassis and the like. In fact, it is in almost constant use.

The wooden roofing folder is not carried in stock by hardware and mail order houses, but it may be ordered from a dealer in tin-smiths’ or sheet metal workers’ tools. Any good tinner or plumber will tell you where to order one.

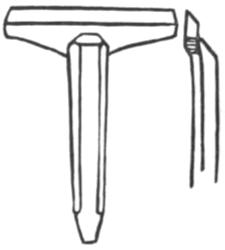

The forming mallet is easily made from a block of maple or a piece of broom handle as described under Shop Appliances.

It is taken for granted that such simple tools as rulers and pencils are at hand.

| 1 soldering copper, weight 1 lb. (1 lb. actual weight of copper end) | $ .75 |

| 1 wooden handle for copper | .10 |

| 1 pair tinners’ shears, 8 or 10 inch | .85 |

| 1 pair flat-nose pliers, 4 inch | .45 |

| 1 pair round-nose pliers, 4 inch | .45 |

| 1 pair dividers, 6 inch | 1.25 |

| 1 small riveting or tack hammer | .40 |

| 1 half round file, smooth milled cut, 8 to 10 inch | .20 |

| 1 wooden mallet, 3 inch face | .25 |

| 1 box of soldering paste | .25 |

| 1 bar of soft solder | 1.25 |

| 2 lbs. soft solder wire | 1.20 |

| 1 wooden forming mallet (home made) | |

| 1 wooden roofing folder (optional) | 4.50 |

| (Roofing folder may be obtained only from dealer in tinners’ tools.) | |

| 1 vise (3 inch jaws) | $3.50 to 5.00 |

| 1 try square, 6 inch | .65 |

Materials Needed Aside from the Cans.—Galvanized wire, 10 or 15 feet each of the following diameters: ⅟₁₆, ⅛, ³⁄₁₆, ¼ (if impossible to obtain all these diameters, get ⅛ inch or larger). Wire nails, about ½ lb. each of the following sizes: 2d, 3d, 4d, 6d, 8d, 10d, 20d (d is the abbreviation for penny). Tinned rivets, several dozen of the smallest size (a box containing one gross is about as cheap as six dozen). Can of lye or 2 pounds of washing soda. For heating the soldering copper, a heater of some kind, such as a blue flame kerosene stove, gas furnace or common one-burner gas stove, charcoal furnace, or gasoline plumbers’ torch with attachments for holding copper. A large can or pail, or an old wash boiler for holding the hot lye solution.

Supplementary Tool List.—The tools named in this list will be found very convenient for making the more advanced models, particularly the hand drill and the twist drills which are used with the hand drill. The supplementary tools are by no means necessary for making the tin can toys, but if one can afford to get them, they will be found extremely convenient. However, almost any of the models may be made with the tools listed on page 29, if one is sufficiently skillful in the use of them. The more work one does with tools the fewer tools one needs if the tools are intelligently used.

The tools in both lists should be purchased, if possible, as they are all tools commonly used in metal working shops. Purchase the tools listed on page 29[31] first and go as far as possible with them, and then purchase as many of the supplementary tools as possible when you need them.

Except when noted otherwise, these tools may be purchased at any good hardware store.

| 1 hand drill, capacity ⅟₃₂ to ³⁄₁₆ inch drills | $1.75 |

| 4 twist drills, ⅟₁₆, ⅛, ³⁄₁₆, ¼ inch diameters | $ .10 to .20 |

| 1 pair large tinners’ shears, 12 or 16 inch | 1.50 |

| 1 pair curved tinners’ shears, 8 inch | 1.25 |

| 1 pair double cutting shears, 8 inch (optional) | 1.85 |

| 1 pair side cutting pliers, 5 inch | .75 |

| 1 pair spring dividers, 6 inch | .75 |

| 1 pair outside calipers, 6 inch | .75 |

| (Spring dividers and outside calipers may sometimes be obtained at the 5-and-10 Cent Stores.) | |

| 1 small soldering copper, weight about 4 ounces | .35 |

| 1 half-round file, 8 inches (fine cut) | .25 |

| 1 round file, 8 inches long, ¼ inch diameter | .20 |

| 1 small cold chisel, ¼ inch in width at cutting edge | .15 |

| 1 large cold chisel, ¾ inch at cutting edge | .25 |

| (An old wood cutting chisel is just as good for cutting tin.) | |

| 3 nail sets, ⅟₁₆, ⅛, ³⁄₁₆ inch in diameter at point, each | .10 |

| (These nail sets may also be used as punches or ground to chisel points. Small chisels and nail sets may be obtained at the 5-and-10 Cent Stores.) | |

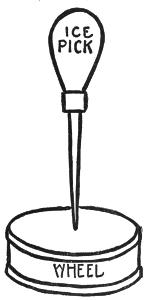

| 1 carpenters’ scratch awl | .25 |

| (An ice pick of the same type will do as well.) | |

| 6 small clamps of different sizes | .10 to .25 |

| (These clamps may usually be found at the 5-and-10 Cent Stores.) | |

| 1 hatchet stake, 9-inch blade | 1.75 |

| (Obtained only from tinners’ and sheet metal workers’ supply houses. A small substitute may be made from a 10-cent hatchet. Purchase the hatchet stake if you can afford it.) | |

| 1 bench drill | $7.50 |

| (The bench drill is by no means necessary for any of the models described in this book, but it is a very convenient tool to have in the shop. With this tool, a hole may always be bored at right angles to the work. The hand drill will answer every purpose if one cannot afford this tool.) |

Laying Out and Marking Off the Work.—Before attempting to begin actual work with the cans, it may be well to consider various ways of measuring to certain dimensions and transferring these measurements to the surface of the tin, and laying out and marking off the work for cutting, folding, etc.

The tools needed for this work are few and simple. A ruler, a marking awl, a small try square, and a pair of spring dividers are all one needs for this part of the work. The ruler may be of wood or metal and should be at least 12 inches in length with the inch divisions marked on it. A plain straight rule of hard wood such as is used in the grade schools will do very well.

PLATE VI

The tools needed for tin can toy making

The marking awl may be purchased at any good tool house or hardware store or an ice pick will do very well if sharpened to a good point so that a line may be easily scratched in the surface of the tin with the point. A large stiff needle may be forced in a pen handle to make an excellent marking awl or a common steel knitting needle may be used if the[33] point is sufficiently sharp. Metal workers always scratch their dimension lines in the surface of the metal as pencil lines are easily rubbed away by the hands when working with the metal.

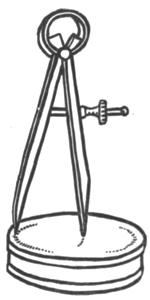

The try square should be about six inches long at the blade or measuring side, and should be entirely constructed of metal and the measuring blade should be marked off in inches and fractions thereof. Good try squares may frequently be purchased in the 5 and 10 cent stores and these are quite accurate enough for the purpose. The spring dividers should be about 6 inches in length. These dividers are held open by the strong spring in the top and are opened and closed by a nut acting on the screw thread. Do not purchase the heavy dividers or compass commonly used by carpenters as these are not as capable of the small adjustments as are the spring dividers. The spring dividers may sometimes be found at the 5 and 10 cent stores and may always be found at good hardware stores and tool houses.

All the tools used for laying out and marking off the work are plainly shown (Plate VI).

Laying Out Work.—It should be borne in mind that a little time spent in carefully measuring, laying out and marking off the work will make a great difference in the finished appearance of that work, so that these simple operations should not be slighted.

The steel square should always be used in laying out rectangular work: lines that are supposed to be[34] at right angles or “square.” Work that is not carefully laid out or square will not fit together neatly if it fits at all.

One of the first things that one has to do in the tin can work is to trim up a piece of tin that is taken from the side of a can and flattened out.

Suppose that such a piece of tin has been cut from a can and flattened out, the edges of such a piece of tin are rather jagged and the whole piece should be trimmed off square before trying to use the tin for various purposes.

First place the ruler as near to the upper edge of the tin as possible and so as not to include any of the jagged cuts. Hold the ruler down firmly and draw the point of the marking awl along the edge of the ruler until a straight line is scratched along the edge of the tin. The surplus tin above this line should be cut away with the metal shears by cutting along from right to left so that the narrow and jagged strip of tin is curled up out of the way by the shears as it is cut. When the surplus tin is cut away you should have a straight clean edge at which to begin the marking operations.

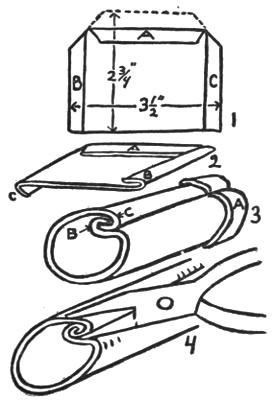

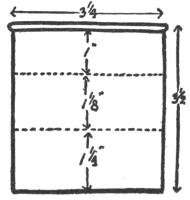

Using the Try Square.—Next, the two ends of the piece of tin should be squared off using the try square for squaring up the ends as follows: Place the heavy solid part of the square firmly against the freshly cut straight edge of the tin, near one end in such a manner that the blade of the square with the[35] inch divisions marked on it lays squarely across the tin, and as near as possible to the end of the piece but not including any of the jagged cuts. The position of the square is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

When the square is in position, mark a line across the tin with the scratch awl held closely to the blade. Cut away the extra tin and you have two sides of your piece of tin squared. Proceed in the same manner to trim off the other end. The remaining or long side of the piece may be squared up either by using the ruler or the spring dividers. The strip of tin that you have squared up on three sides will probably be narrower at one end than at the other. Measure the width of the narrow end with the ruler and then measure off this same distance at the opposite end and mark it with the scratch awl. Use the ruler to connect the two measuring points and scratch a line in the tin by drawing the scratch awl along the edge of the ruler. Cut away the surplus tin and your piece of tin should be squared.

The spring dividers may be opened so that the points rest exactly on each corner of the narrowest end of the strips of tin. Then the dividers are moved to the opposite end of the strip and the lower end or point of the dividers moved back and forth slightly until a slight scratch is made in the surface of the tin to indicate the measuring point. The position of the dividers is shown in Fig. 2. The ruler is used to connect the two measuring points and a line scratched between them.

Small strips of tin may be marked off entirely by the dividers by setting the dividers to the required dimension, placing the dividers so that one point rests against one edge of the strip to be marked off and then drawing the dividers along in such a manner that the point of the dividers that rests on the tin will scratch a line parallel to the edge. The edge of the tin that the point of the dividers rests against must, of course, be cut straight before beginning the marking operations. The strip thus marked off may be cut away and another one marked off in the same manner until the required number of strips is cut.

Suppose that four strips are to be cut, each strip to measure one by ten inches. Square up a piece of tin to measure four by ten inches. Open the dividers so that the points are exactly one inch apart. Rest one point of the dividers against one edge of the tin as shown in Fig. 2 and draw it along the entire length of the tin so as to scratch a line parallel to[37] the edge. Cut off this strip, taking care to make a straight cut and then mark off another strip and cut it off, and so on until all four strips are cut. This method of using the dividers for marking is more accurate and much easier than that of using a ruler to measure off each strip, and certainly more rapid.

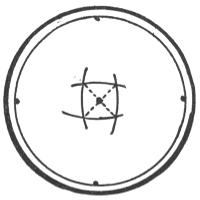

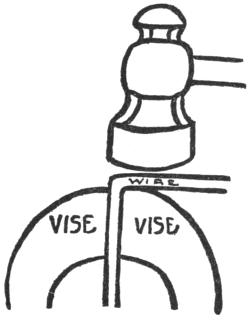

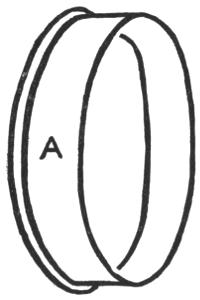

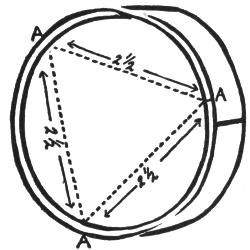

Finding Wheel Centers with the Dividers.—When making wheels of tin cans, some easy method must be used to find the center of the wheel in order to punch or bore a hole for the axle so that the axle may be placed as near the center of the wheel as possible, and so that the wheel will run true once it is placed on the axle.

The dividers may be used for this operation which is very simple. The can is first made up into wheel form as described in Chapter X, page 108. When the wheel is soldered together lay it flat on the bench. Open the dividers so that one point rests against the rim of the wheel or against the rolled edge of the can forming the rim of the wheel. If the wheel is made of a can that has a cap soldered on each end and this cap forms the end of the can (such as the small cans that are used for evaporated milk), then the one leg of the dividers may be rested in the slight line or depression just inside the rim that is invariably found in this can. Open the dividers so that the other point rests as near the center as you can guess it. When the dividers are set to dimension and are in position on the wheel[38] as shown in Fig. 3, then move the point of the dividers that is near the center of the wheel slightly back and forth so that it describes a slight arc and scratches it in the surface of the can and the other point of the divider is held at the point near the rim of the wheel during this operation. Then move the dividers directly across the wheel still set at the same dimension, placing one point against the rim or in the depressed line and describing a slight arc in the tin as before. Set the dividers at right angles to the first two marking points having the dividers still opened to the same dimension as at first and describe another arc. Set the dividers directly across from this point and describe another arc. The wheel should then resemble Fig. 4, the four arcs forming sort of a pillow shape as shown. Draw lines diametrically across connecting each corner of the pillow as shown and where these lines cross is the center of the wheel.

Fig. 3.

If one is so fortunate as to possess a tool called a surface gauge, it will be found very handy for[39] marking or scribing lines parallel to the base of cans. This tool consists of a base of metal in which is fixed an upright post also of metal. An adjustable scriber or needle is fixed to this post so that it may be lowered or raised and set in position as desired. The point is adjusted to the required height and placed against the side of the can or surface to be marked, the operation being conducted on a flat level surface. The can is simply turned against the fixed scriber point until it is entirely marked around. The advantage of the surface gauge over the dividers for this operation is that the scriber point is held rigidly at a fixed dimension above the base of the can while the dividers must be held firmly in place by the hand. However, the dividers will do very well for this operation after a little practice.

Fig. 4.

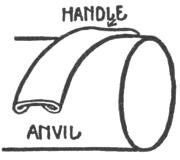

Homemade Substitutes for Expensive Tools.—The tool of first importance in any metal working shop is a good vise. There is no substitute for this tool and a good one that measures three or three and a half inches across the jaws should be purchased[40] from a reliable tool dealer. The next tool of importance is some form of anvil or anvils for flattening or rounding the tin. A small bench anvil may be purchased from the tool dealer. These are much like a blacksmith’s anvil with a flat face and a conical horn and are made of iron and steel. The large mail order houses offer various small anvils of cast iron for farm use and these are excellent for the tin shop.

Excellent substitutes for these anvils are easily made from old flat irons and pieces of gas or water pipe. Short lengths of iron and steel bars may be picked up about any junk pile, and these are very useful to form the tin over.

The Flat Iron Anvil.—An old flat iron, the kind with the handle attached, may be found about almost any household. The handle should be broken off as close to the top of the iron as possible. Use a hammer and cold chisel for this and cut the handle ends deeply all around where they join the iron. When they are deeply nicked, several sharp blows from a large hammer should break the handle away.

File away all roughness until the iron will set level with the smooth or ironing face uppermost. Then you have an excellent flat hard surface for straightening out tin or wire.

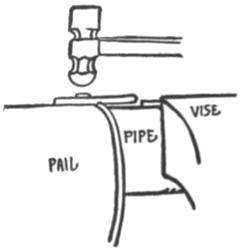

Pipe and Bar Anvils.—Short lengths of iron pipe, round and square iron and steel bars of various diameters may be held in the vise jaws and used to[41] form the work over. Large wire nails may also be used for this purpose.

The smaller sizes, such as ¼, ⅜, or ½ inch in diameter, should be solid iron or steel bars 8 or 10 inches in length, as small pipe crushes and bends rather easily in the vise. Larger sizes, such as ¾, ½, 1 or 2 inches in diameter, are better made of pipe as they are lighter and easier to handle and also easier to obtain.

Get all the sizes suggested if possible and as many short pieces of square or flat bars as you find convenient to store away about the shop. They will come in very usefully for bending or forming operations. The method of holding them in the vise is plainly shown on page 89, Fig. 26.

If you have plenty of bench room and are handy with tools, several of the most used sizes of pipe and bars may be clamped or bolted directly to the bench with wooden or metal holding strips. The larger sizes, such as ¾, 1, 1½, 2 and 3 inches in diameter, will be found very convenient if fastened to the bench in this manner.

The Bench.—The shop bench should be about 31 inches in height. The top of the bench should be about 2½ by 6 feet or larger if possible, and may easily be built by any one familiar with tools. The top should be made of maple about 1½ inches thick. If one cannot afford this bench a common kitchen table makes an excellent substitute. A good strong[42] table of this sort may be purchased at any house-furnishing store. These tables are furnished with a large drawer in which small tools may be kept.

If much of the tin work is done, it will prove advantageous to have some light wooden shelves or racks built about the walls of the shop to store the various sized cans where they may be easily seen and reached.

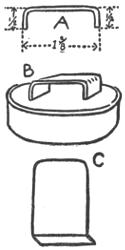

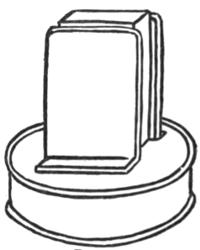

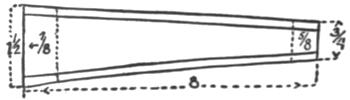

Fig. 5.

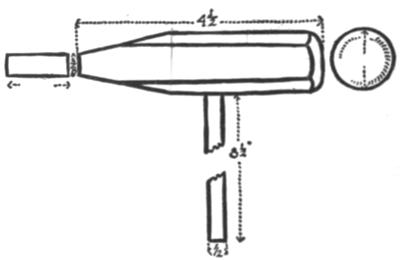

The Forming Mallet.—The special forming mallet designed by the author will have to be made. It was designed especially for work with the tin cans. It is very simple and easily made of maple by any carpenter. One end is a slightly rounded dome shape and the other is in the form of a blunt wedge. The dimensions and general shape of the mallet are[43] shown in Fig. 5. The handle may be made of a piece of ½-inch dowel rod. A substitute for this mallet may be made of a piece of broom handle the end of which is already rounded to about the proper curve. Measure off 4½ inches from the rounded end of the broom handle and saw it off. Bore a ½-inch hole through the center of the piece to fit the piece of dowel rod used for the handle. Whittle down the end to a blunt wedge shape leaving it about ⅜ inch thick at the end. The rounded end may be left as it is.

A piece of ½-inch maple dowel may be picked up in any carpenter shop. This should be 8½ inches long. It should be driven into the hole drilled for it in the mallet, taking care not to split the mallet in so doing. If the broom handle is rather small in diameter it would probably be better to use a piece of ⁷⁄₁₆-or ⅜-inch dowel for the handle. A small nail or brad may be driven through the mallet and handle to secure it in place.

CUTTING THE CAN TO SIZE FOR BISCUIT CUTTER—PUNCHING A HOLE IN TIN—FORMING THE HANDLE—FOLDING—MAKING A SUGAR SCOOP BY THE SAME METHOD

A biscuit cutter is about the simplest thing that may be made from a tin can. It is an excellent thing to begin with as it is so simple and involves three very essential operations in the tin can work: cutting the can to size, forming the handle, and lastly, soldering (see Plate VII, a).

Select a good bright, clean can about 2½ inches in diameter; a baking powder can or a small soup can will do.

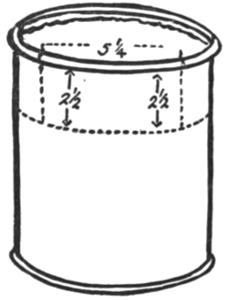

Tin cans are usually made up in two ways. One method is to solder on flanged ends, such as condensed or evaporated milk cans, and the other method is to roll the edges of the can together at each end, using no solder. When looked at closely, the two different types of can are easily told apart. A rolled rim can should be used for the biscuit cutter as it is stronger than the can with the soldered ends.

PLATE VII

Biscuit cutters made by the author

Soldering

Cutting the Can to Size for Biscuit Cutter.—The biscuit cutter should be about ¾ inch deep at the[45] cutting edge. Set the dividers to this dimension and proceed to scribe a line around the can parallel to the base and ¾ inch above the rolled rim of the bottom. This simple scribing operation is described in Chapter I, page 22.

The method of cutting into the can and around the scribed line is very simple and is also described in Chapter I.

Fig. 6.

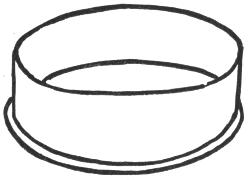

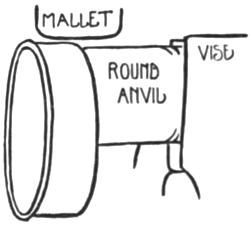

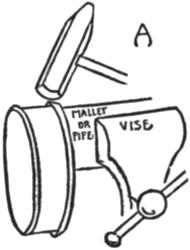

When you have cut the can down to the required dimension, it should appear as shown in Fig. 6. The biscuit cutter may be slightly out of shape after the cutting operation, but this may be easily remedied by placing the biscuit cutter on a small round anvil held in the vise and by tapping it gently with a flat wooden mallet, turning the cutter slowly around on the anvil during the hammering as shown in Fig. 7. Be sure to turn the biscuit cutter slowly around and around the anvil as it is hammered with the mallet. It will soon become round if hammered gently.

Next take a small flat file, one with very fine teeth, usually called a smooth milled file, and with this smooth down any roughness left by the metal shears at the edge of the biscuit cutter. The method[46] of using the file is shown in Fig. 8. It should be held lightly against the work when filing. (Never try to file a piece of tin with a large or roughly toothed file as the coarse teeth will catch on the tin and tear or bend it out of shape.)

Fig. 7.

Fig. 8.

Do not try to file the edge of the cutter to a knife fine edge; simply file away the metal raised by the shears when cutting. If it is cleanly cut and filed to the original thickness of the tin, it will cut biscuit dough very well, as the tin is thin.

Punching a Hole in Tin.—A hole should be punched in the top of the biscuit cutter to admit air, as the biscuit dough is apt to stick in the cutter by the vacuum formed unless an air vent is provided. A small hole about ⅛ inch in diameter will do, but a series of such holes may be punched in if desired.

A punch may be filed up from a wire nail or a regular punch or nail set may be used.

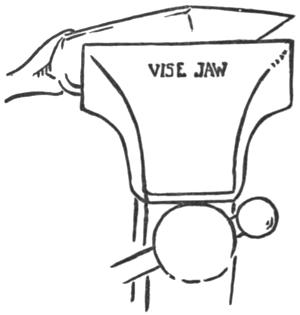

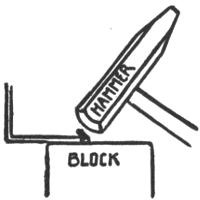

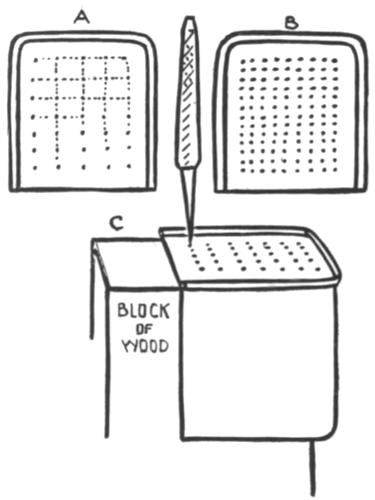

The biscuit cutter is placed over the end of a block of wood held in a vise as shown in Fig. 9, in such a manner that the top of the cutter rests directly on the wood. The punch is placed in the center of the cutter, care being taken to see that the wooden block supports the tin directly under the punch, and then the punch is struck lightly with the hammer until it cuts through the tin.

It may be well to try the punch on a scrap of tin to test it. A clean round hole should result. The punch cuts out a tiny disk of tin and drives it into the wood. The end grain of a wooden block should always be used for punching on.

If a nail is used for a punch, the original point should be filed away. Nail points are usually made in the form of a square pyramid and if these points are driven into a piece of tin a jagged hole will result; such a hole may be used for making a grater for the kitchen, but all other holes should be round and smooth.

To file up a nail for a punch proceed as follows: Place the nail vertically in the vise jaws so that the point projects slightly above the jaws. File the point entirely away until you are filing the entire diameter of the nail and squarely across it.

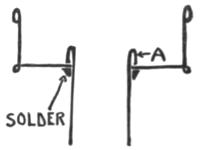

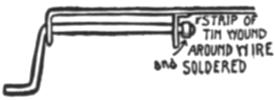

Then reduce the diameter of the nail at the end you have been filing by filing smoothly around it as[48] shown at A, Fig. 10. See that the edge B is clean and sharp and the nail punch is ready for use. The nail used for a punch should always be somewhat larger in diameter than the punching point, as this will provide for a stronger punch and one not so likely to bend. Regular punches are usually made much thicker in the body than at the point, as may be easily seen by looking at one. If desired, punches may easily be made from nails to cut round, square, or triangular holes.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 10.

It is much better to purchase a regular punch or[49] punches for punching round holes, as these may be purchased for 10 or 15 cents at almost any hardware or 5-and-10 cent store. Several different sizes will prove useful, ⅟₁₆, ⅛, ³⁄₁₆ inches in diameter being the most used sizes. As these punches are made of hardened steel they hold their edges for a long time, but nails are made of a fairly soft steel and when used as punches have to be frequently filed sharp.

Forming the Handle.—After the hole is punched in the top of the biscuit cutter, a suitable handle is the next thing to be made. This handle may be made from the piece of tin cut away when cutting down the can for the biscuit cutter. Cut away any rough or jagged edges and then place this piece of tin on the bench or a flat anvil surface and flatten it out with light mallet strokes. Heavy strokes with a mallet will dent the tin.

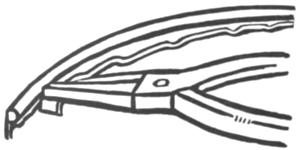

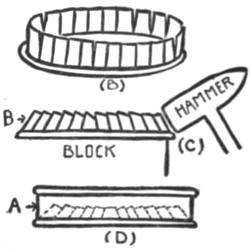

Trim away all rough edges including the rolled edge at the top and square up the piece of tin as described on page 34, Chapter II. Mark off a strip of tin 1¼ inches in width and 4 inches long. Cut this strip out and be sure that it is square at the ends. Open the dividers and set the divider points ¼ inch apart and scribe a line ¼ inch inside each of the long sides of the strip. The edges of the strip of tin thus marked off must be turned or folded in so that the edges of the handle will be strengthened and will not cut the hand. These edges may be folded over with a mallet or by the use of a folding[50] machine. The mallet should be used for this first folding operation; the folding machine and its use will be described further along in the book, page 120, Chapter XI.

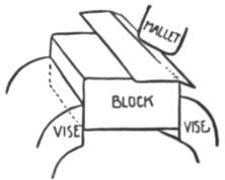

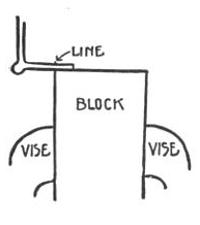

To fold the edges over with the mallet, proceed as follows: Secure a block of hard wood, maple preferred, the block to be about 3 inches square and 6 inches in length. See to it that the block is cut cleanly and squarely across so that the edges at the end are sharp and at right angles. A maple block of this sort may usually be picked up at any lumber yard or carpenter shop, or a maple log may be secured from the wood pile and trimmed up square. One end of the block may be used to punch on.

Fig. 11a.

Fig. 11b.

The block is held in the vise as illustrated in Fig. 11 and the tin to be folded is held on the block in such a manner that the line marking the fold is over the edge of the block. Use either a light wooden mallet or the special forming mallet, and[51] with light blows proceed to bend down at the edge and up to the line as illustrated in Fig. 11, a. Begin at one end and work along the line to the other end of the strip of tin. Do not try to turn the tin down at a right angle at once or in one place and then proceed to turn it down at another, but rather hammer lightly along the whole length at the marking line, turning the tin down at a slight angle from the line to the edge and then going back and starting to hammer where you began, turning the tin down at a greater angle and so on until you have turned the edge at right angles as shown in Fig. 11, b. Always bend tin over very gently and evenly, never forcing it violently into place.

Fig. 12.

Fig. 13.

Fig. 14.

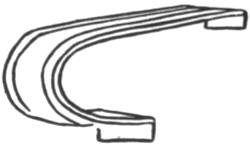

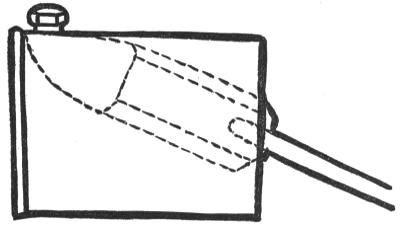

Reverse the strip of tin on the block so that the part just folded stands vertically at the edge of the block as shown in Fig. 12. Hammer the edge of the tin gently over so that it folds back on itself as shown by the dotted line in Fig. 12.

Do not hammer the tin down hard at the folded[52] edge so that it becomes thin and sharp though doubled. It should be rounded over so as to give a rounded edge. A rounded fold is much stronger than a sharp thin one. When one edge is completely folded over, fold down the other in the same manner, so that both edges of the handle for the biscuit cutter appear as in Fig. 13.

Fig. 15.

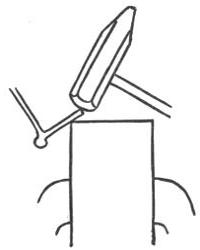

When you have successfully turned or folded over the edges to your satisfaction, then proceed to give the whole handle a semi-circular form.

Place a large round wooden mallet or a piece of 1½ or 2-inch pipe in the vise to use as a form over which to round the handle. The folded part should be inside or next the mallet or pipe form shown in Fig. 14. Press the tin down to the form with the[53] palm of the hand so as to round it into shape; it may be completely formed into shape by this method or the rounded end of the special forming mallet may be used to hammer it into shape if the tin should kink during the bending. The mallet blows should be directed toward the center of the strip so as not to thin the edges too much.

Round the handle over until the ends rest inside the rolled rim of the can or biscuit cutter and you are ready to solder the handle in place.

As the soldering is the most important part of the tin work the next two chapters are devoted to it.

The Sugar Scoop.—A useful sugar or flour scoop may be easily made from a small or large can in exactly the same manner as the biscuit cutter, except that the can is cut off slanting instead of square, Fig. 15. The edges of the scoop should not be turned or folded but should be left as cut so as to form a sharp cutting edge that will easily enter sugar or flour. The handle is shaped in exactly the same manner as that of the biscuit cutter.

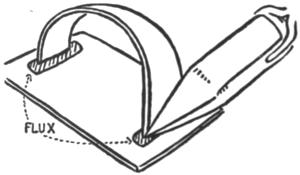

SOFT SOLDER—SHEET TIN—THE PROCESS OF SOLDERING—HEATING APPARATUS—ELECTRICAL SOLDERING COPPERS—THE COMMON SOLDERING COPPER—FLUXES—TINNING THE COPPER—HEATING

Soft Solder.—When two or more pieces of metal are joined together with a metallic cement, they are said to be soldered.

Sheet tin, of which cans are constructed, is always soldered with soft solder, a mixture of lead and tin, usually 50 per cent. lead and 50 per cent. tin.

This solder is usually supplied in wire or bar form at any hardware or electrical supply house.

Copper, brass, bronze, iron, silver, gold, and practically any metal except aluminum may be soldered with soft solder.

Sheet Tin.—Sheet tin, so-called, really consists of a thin sheet of iron coated on both sides with tin. This coating of tin serves several purposes. It enables the solder to adhere easily; it prevents the iron from rusting; and when the sheet tin is made up into can form, the tin coating protects the contents of the can from chemical action on the iron.

The Process of Soldering.—Soft solder is applied to the metal to be soldered in a molten state and this operation requires considerable heat. When heat is applied to metal it usually oxidizes that metal; that is, dirties it.

Solder will not adhere to oxidized metal. The metal must be protected with a coating called a flux while being soldered. Soldering paste, soldering fluid or “killed acid,” resin, paraffin, heavy oils, and vaseline all serve as fluxes, some better than others. The soldering paste is by far the best, as will be shown later.

Soft solder is applied to the tin, on the point of a hot soldering copper, often wrongly called a “soldering iron.” A soldering copper consists of a pointed bar of copper suitably fixed to an iron shank which is firmly set in a wooden handle. The point of the copper must be well coated with solder or “tinned,” so that when it is heated it will pick up the solder and convey it to the joint to be soldered.

The hot copper, charged with solder, is passed slowly along the joint and as the tin to be soldered receives enough heat from the copper, the solder leaves the copper and adheres to the tin, firmly uniting it.

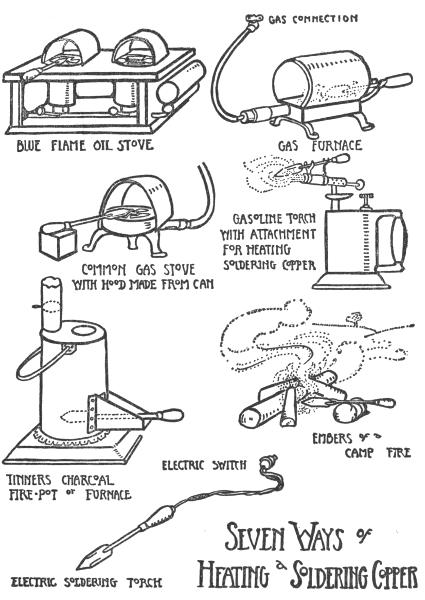

Heating Apparatus.—Some form of heating apparatus is necessary to heat and maintain the soldering copper at the melting or flowing point of the solder. The copper may be heated in a gas furnace[56] especially made for soldering coppers, or over an ordinary gas stove burner or a common blue flame oil stove, or a charcoal fire, a wood fire burned down to embers, or a plumbers’ gasoline torch, but never in a coal fire. Coal contains too much sulphur which oxidizes the copper and renders it useless for soldering purposes.

The Blue Flame Oil Stove.—For heating the coppers in my country shop, I use a blue flame oil stove, one of the less expensive sort, with the asbestos ring wick and the short removable chimneys. The stove has two burners and will heat from four to six coppers at once. The flames may be regulated nicely so as to give just the required amount of heat and this stove consumes very little kerosene, and, therefore, costs little to operate. In Fig. 16, it will be noticed that there is a curved hood over each stove hole. These hoods may be easily made from part of a large can or of a piece of tin or sheet iron bent into shape. These hoods conserve the heat and throw it about the coppers. I also place a piece of heavy wire netting over the grating of the stove holes to support the coppers and to permit their being laid to one side, out of the intense heat, when not immediately needed.

The blue flame oil stove forms the most satisfactory arrangement for heating coppers that I have ever used in the country. These stoves are easily taken care of and are understood by almost everyone.[57] The directions should be nailed up alongside the stove and carefully followed, particularly as to cleaning the burners once or twice each season.

Fig. 16.

The Gasoline Torch.—The plumbers’ gasoline torch is often used by experienced metal workers for heating coppers. In inexperienced hands, this torch is rather a dangerous affair. Only one copper may be heated at a time and it is difficult not to overheat the copper in the fierce roaring flame. The cost of the torch and the cost of operating it are both greater than the blue flame kerosene stove. However, in experienced hands, it is safe enough and very useful about the shop. In using such a torch the directions should be most carefully followed; all joints, filler openings, etc., must be airtight when operating or a disastrous fire or explosion may result. The tiny jet opening in the burner must be kept clean.

The Gas Furnace.—In my winter shop in the city where gas is available, I use the gas furnace shown in Fig. 16. This is a most satisfactory and widely used heater for soldering coppers, as it gives an intense blue flame that may be easily regulated.

When using a heater of this sort, one must be sure that it is lighted correctly or a smoky yellow flame will result. To produce a blue flame, air must be mixed with the gas; just as it is in a bunsen burner or an ordinary gas stove, for that matter. Gas is admitted to the furnace through a small nozzle at the end of the mixing flue near the rubber hose connection. Air is admitted in the slot under the gas nozzle; a movable slide encircles the mixing[59] flue over the slot to control the amount of air admitted. This slide must be tightly closed over the air vent when the gas is first turned on.

To light the heater, close the air inlet tightly, turn the gas on full and apply a lighted match to the burner. A yellow flame will result. Now open the air vent slowly, by pushing the slide forward a little way. The flame will change from yellow to blue and purple as air is admitted. When the flame is blue, it is giving out the most heat and is in the best condition to heat the copper.

If the flame fires back and lights the gas at the brass nozzle over the air inlet, the gas should be turned off until the flame disappears. The air inlet is then closed, and the gas turned on and lighted, and then the air inlet is slowly opened until the flame turns blue. When the furnace is in use, it should be looked at occasionally to see that the flame has not fired back to the nozzle. Once satisfactorily lighted, the heater may be turned up or down as needed. If the flame is turned down very low the air inlet may have to be closed a bit to prevent the flame from firing back. The copper is placed on the rest provided for it over the flame. After the copper is heated to the flowing point of solder, the flame may be turned down or the copper placed to one side of the flame, so that it does not get too hot.

Charcoal and Wood Fires.—When using a charcoal or a wood fire, the copper should be placed at[60] the bottom among the embers. Small charcoal furnaces used for heating soldering coppers may be bought from the dealer in plumbers’ supplies. Charcoal should not be burned in a closed room as the fumes are deadly unless allowed plenty of constantly changing air. These furnaces may be connected with a chimney or burned in a room with windows opened, without danger.

A soldering copper may be heated in the glowing embers of a camp fire or in the embers in a fireplace.

Electrical Soldering Coppers.—The electrically heated copper is ideal for soldering as the heating coil is enclosed within the copper itself, the wire running out through the handle and connecting with an ordinary electric light socket. The heat is maintained at a proper degree for melting the solder; hence it is an ideal equipment for those who can afford it and where electric current is available. The doctors of certain hospitals have recommended electrical coppers for the use of patients in making tin can toys.

An electric soldering copper costs about $7.50 at the present time.

The Common Soldering Copper.—A suitable soldering copper or “iron” may be purchased at any good tool dealer’s or hardware store; it should weigh about one pound for work with the tin cans.

Almost everyone has purchased a small soldering outfit at one time or another and tried to solder[61] the family wash-boiler or some leaky tinware; usually without success. Such outfits are invariably too small for large work or for the tin can toys.

It must be well remembered that the heat flows from the copper into the work, and that the copper has to heat up the work to the melting point of the solder; hence a large copper weighing several pounds is used to solder wash-boilers, tin roofs, etc., and a small copper weighing a few ounces is used for soldering jewelry, etc.

A large copper in expert hands may be used to solder very small work but a small copper may never be used to solder large work together, because the copper not only has to keep the solder melted to the flowing point, but also has to heat the work itself at the joint to the flowing point of the solder before the solder will leave the copper and adhere to the work.

In actual practice, it has been found that a copper weighing one pound is best. After one gets more adept with the copper, it will be found advantageous to have several coppers of different weights. A half pound and also a four ounce copper will be found very convenient for extremely small work. But, do not begin to solder with a copper weighing less than one pound.

Soldering coppers are usually sold in pairs at the large tool dealers, and coppers listed at two pounds really weigh one pound each; when sending[62] in a written order be sure that you specify that the copper is to weigh one pound singly.

A wooden handle especially made for soldering coppers should be purchased at the same time as the copper; these wooden handles are made large to protect the hand from the heat of the iron shank. The handle is usually furnished with a hole of the proper size drilled in it to permit the pointed end of the shank to be driven in the handle easily with a wooden mallet. If the hole is too small, it should be drilled out so that it is nearly as large as the diameter of the shank. The wooden handle must not be split when driven on with the mallet.

Fluxes.—Before tinning the point of the copper, some flux must be obtained, either a soldering paste or soldering fluid “killed acid.”

An excellent soldering paste called “Nokorode” is by far the best flux obtainable. It is inexpensive, a little goes a long way, and it will not rust or corrode the work as is the case with killed acid and some soldering pastes. It may be easily cleaned from the work after soldering and it makes soldering much easier and simpler for the beginner. Nokorode soldering paste may be obtained at any good electrical supply house or hardware store. If they do not stock it, they will get it for you. There is nothing else just as good on the market, but if for any reason you cannot obtain this particular brand, be[63] sure that any soldering paste you buy is plainly labelled that it will not corrode the work.

Soldering fluid or killed acid is made of muriatic acid in which is dissolved all the pure zinc that it will hold in solution. This fluid is much used by tinners and is certainly an excellent soldering flux, but not nearly as good as the soldering paste for our purposes. However, it is very useful in the shop to dip the tinned point of the hot copper into it to remove the oxide or dirt formed after the copper has been in use for some time. The solder will stick to the point much better after the copper has been cleaned in this manner.

Directions for making the killed acid and the use of other soldering fluxes will be found on page 68.

Tinning the Copper.—Having procured the soldering copper and handle, some flux and soft solder, and having fixed up some sort of heating apparatus, the next step toward soldering is to coat the point of the copper with solder: this is called tinning the copper.

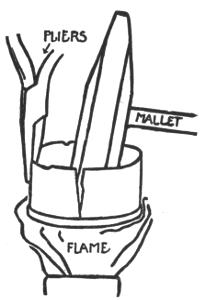

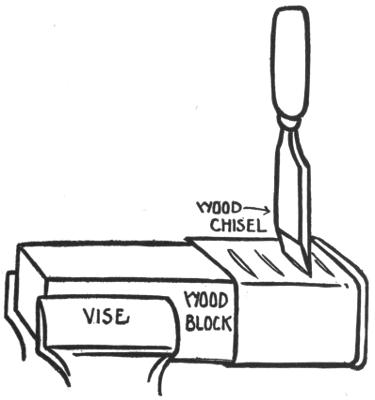

Fix the copper firmly in a vise if one is at hand, as illustrated in Fig. 17. Then file each of the four faces of the point of the copper bright and clean with a flat file. It is better to use an old file for this purpose—one with rather coarse teeth. It will be observed that the copper is placed slantwise in the vise so as to bring one face of the square[64] pyramid parallel with the vise jaws; this position permits filing in a natural horizontal position.

Each face of the point should be rounded slightly toward the point.

Fig. 17.

If a vise is not available, the copper may be held against the edge of the bench with one hand and the point filed clean and bright with the file held in the other, or a coarse sheet of emery cloth may be placed[65] flat on the table and each face of the point rubbed bright on it. A file is by far the best for this purpose, however, and if it is chalked before using, the copper filed away will not clog it.

When the copper is clean and bright at the point each face should be thoroughly covered with a thin film of soldering paste or dipped into the soldering acid.

The copper should then be placed in the fire and heated to the melting point of the solder.

Heating.—While the copper is heating get ready a piece of tin about 2 by 4 inches—any clean flat scrap or part of a can will do. Spread a little soldering paste into the center of the tin and lay it on the bench near the heating apparatus. A few drops of killed acid may be placed on the tin instead of the paste, if the acid is to be used.

After a few minutes heating the copper should be removed from the fire and the end of a strip of solder touched to the point. If the solder melts quickly and easily against the point the copper is ready to tin; if it melts very slowly, “slushy”, the copper should be returned to the fire and heated a bit more. The copper should never be heated red hot under any circumstances; this must be borne in mind. If the copper is heated to a red heat, the soldering paste will be burned off and its action destroyed, for a red hot copper will not pick up[66] solder, nor may it be tinned again until the copper is cool and refiled bright and clean, recoated with flux and reheated. If the copper is heated red hot after the point is tinned, the tinning is burned from the point and solder will not stick to it until it has been cooled, refiled and retinned.

This is the most important point to remember about soldering and is the cause of many failures. Remember that soldering is impossible without a flux to keep the metal clean when it is hot; too much heat will burn soldering paste or killed acid away; the tinning and the solder adhering to the point will be burned or oxidized and rendered brittle and useless.

A heat that will melt the solder almost instantly and cause it to flow with a brilliant glistening color should be maintained at all times when the copper is employed for soldering. This is never a red heat.

When the copper is first heated to be tinned, it should be removed from the fire when it melts the solder easily, and several large drops of solder should then be melted from the bar or strip of solder onto the piece of tin placed by the fire and on which some soldering paste or acid has been spread. Rub each face of the point of the copper into the solder on the tin until each face is thoroughly covered with a bright coating of solder. Hold each face flatly down against the solder on the tin during the rubbing process. The copper may[67] have to be heated once or twice by the beginner, as it may get too cool to melt the solder easily. As soon as the solder begins to work stiffly, “slushy,” and looks gray instead of glistening, it is time to reheat the copper.

An old piece of soft cotton cloth, such as a stocking, on which is sprinkled a little powdered sal-ammoniac is an excellent thing to keep handy when soldering or tinning. The tin coating of the point of the copper should be rubbed on this cloth where the sal-ammoniac is sprinkled, when the copper is hot. This will be found to keep the copper in excellent condition. The sal-ammoniac removes the oxide from the tinning and brightens it up generally about the point.

The tinning will last much longer on the copper if it is dipped occasionally into the soldering paste or acid while hot. This is particularly true if the copper has been a bit overheated.

When the tinning shows signs of wearing off and the copper does not pick up solder readily, it must be retinned, filed, fluxed, heated, and rubbed on the solder which has been put on the tin first used for this purpose. This piece of tin should be kept about the bench, as the copper will have to be retinned frequently. Always remember that the copper will not carry solder to the work unless it is well tinned.

If an electrical soldering copper is used it is usually furnished already tinned at the point, so that it[68] is ready for use as soon as it is connected to a suitable electric socket and the current turned on. The heating coil inside the copper will soon heat it up to the melting point of the solder. After heating, it may be treated as a common copper, wiped occasionally on the cotton cloth and retinned when the tinning is worn away. An electrical copper should never be placed in a vise for filing, but should be held against the bench and filed carefully. A vise is apt to crush the hollow copper and injure the heating coil inside. These coppers should never be placed in a fire or heated in any way except by the electric current.

Electrical coppers do not need as much attention as an ordinary copper for the even heat supplied by the current keeps the copper heated to the flowing point of the solder and is incapable of heating beyond this temperature.

Soldering fluid may be very simply made as follows: Pure zinc is dissolved in muriatic acid until the acid will not dissolve any more of the zinc. The solution thus obtained is then allowed to stand for a time and is then strained through a cloth and poured into a bottle which is kept tightly corked when not in use.

First purchase about six ounces of muriatic acid[69] from a druggist. Take care not to spill any of this acid on the hands or clothes. Next get some pure sheet zinc. The sheet zinc employed for stove mats as it is sold in the plumbers’ shops is not suitable for making soldering fluid, as this form of zinc is alloyed with other metals. Pure zinc may be very easily obtained from old dry batteries which may be found anywhere.

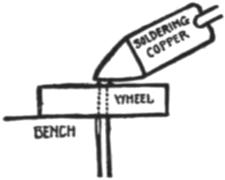

Remove the paper covering from the battery and crack it open with a hammer—remove the carbon from the center of the battery and dump out all the powdered material. Soak the zinc covering of the battery in warm water to remove any paper or material adhering to the zinc and then cut the zinc into pieces about ¼ inch square.