“My name is Fenn,” he volunteered, bowing over the Guardian’s hand.

Project Gutenberg's Camp Fire Girls in War and Peace, by Isabel Hornibrook This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Camp Fire Girls in War and Peace Author: Isabel Hornibrook Illustrator: John Goss Release Date: March 26, 2018 [EBook #56849] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CAMP FIRE GIRLS IN WAR AND PEACE *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

“My name is Fenn,” he volunteered, bowing over the Guardian’s hand.

| I. | Gas Valley |

| II. | The Minute-Girl |

| III. | The Camp at Twilight |

| IV. | A Wandering Powder-Puff |

| V. | Camouflage |

| VI. | Playing Submarine |

| VII. | Menokijábo |

| VIII. | The Leader |

| IX. | The “Creature Far Above” |

| X. | Aviators Unawares |

| XI. | Knights of the Wing |

| XII. | A Good Line |

| XIII. | The Main Bitt |

| XIV. | The Launching |

| XV. | Seeking the Spark |

| XVI. | Wigwag |

| XVII. | A Radio Freak |

| XVIII. | The Peace Babe |

| XIX. | The Gold Star |

| XX. | Christmas of 1918 |

“My name is Fenn,” he volunteered, bowing over the Guardian’s hand

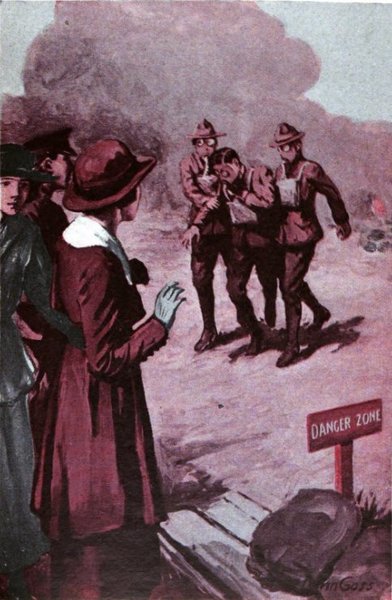

Supported on either side by his comrades

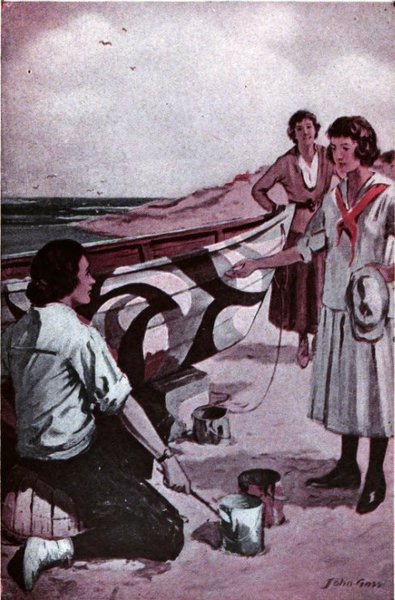

“W’at for you painta her like dat--de leetla boat--eh?”

“I don’t care what anybody says; I’m going to rest a while”

He sprang from under the wildly swaying timber

“I do believe it is the--mysterious--seal-hunter”

“Gas!”

Briefest and biggest of all words thrust by the Great War into the fore-ranks of speech, the word rang aloud upon the summer air.

A kernel of compressed menace, it burst explosively, spread elastically, until the very sky--the peaceful, lamb’s-wool New England sky--seemed darkened by its threat, until the brown buds, withered in their tender youth, and the rags of yellow grasses blighted before by its poisoned breath, trembled and wilted, as it were, anew!

It even withered the morning-glory bloom upon the faces of a quartette of young girls, who stood a few yards to windward of a little red-and-white post labeled “Danger Zone,” on the other side of which the warning was given.

Breathlessly, nervously, they shrank together until their shoulders touched, like fledgling birds struck by the terrors of the first storm that assails them in the nest, seeking for contact and comfort.

“Now the party is beginning--the ball opening, as our boys say over in France, when a gas attack is being launched against them. That smoke-candle off there on the edge of the trench, which is doing more than’s required of it--bursting into flame as well as smoke--that’s the illumination for ‘Fritzie’s’ party! And the rattle--you hear the policeman’s rattle, don’t you, shaking its teeth down in the trenches--that’s the opening stunt of the orchestra. See?”

It was a young lieutenant, a boy-officer of twenty-three, who spoke, with a silver dart in his gray eye matching the gleaming bars upon his shoulders, as he bent towards the tallest of the four girls whose face was paling under her velvet hat, uniquely embroidered by her own hand with certain silken emblems, typifying her name and symbol, together with the rank she held as a Camp Fire Girl.

“Smoke-candle! D’you mean that foot-high metal thing flaring away there behind the sand-bags, one of a dozen or so, stationed along the trench-brim? They don’t look much like ordinary candles, but they certainly can smoke! Such horrid, blinding sulphur smoke, too! Bah!”

She caught her breath a little, that oldest girl, her wide dark eyes watering, as a tiny yellow feather of the sulphur fumes, stealing stealthily to windward, wafted from the wing of the main cloud drifting off to leeward, tickled her throat in teasing fashion.

“Yes, it is blinding thick, isn’t it? We must move farther to windward, away from it.” The lieutenant smiled down at her, thinking the hat with its wide brim, and its delicate, emblematic frontispiece against the rich velvet--representing crossed logs, a tongue of flame rising from them and shading into a pearly pinion purporting to be smoke--was the prettiest headgear he had ever seen.

“Thick! So thick that you could drink it, if--if it wasn’t so horridly pea-soupy and pungent, eh?” laughed another girl, who stood next to the tallest one, their shoulders touching. “It’s as dense as the fog our Captain Andy used to tell us about; the fog out on the fishing banks--Grand Banks--which he declared was so thick at times that the poor fish didn’t know when they were atop of the water; they went on swimming up in the fog. Don’t you remember, Olive?” she asked as she merrily nudged the older, dark-eyed girl who wore the Torch Bearer’s insignia of logs, flame, and smoke--an insignia that stood for a high-beating heart, as ready and eager to do its share in this moment of world conflict, as that typified by the silver bars on the lieutenant’s shoulders and the cross-gun on his khaki collar.

It was he, Lieutenant Iver Davenport, or, to come down to detail, Lieutenant Iver O. P. Davenport, who, thanks to his middle initials and that keen silver of scrutiny between his narrowed eyelids, was christened in his infantry company “O Pips,” the camp nickname for an observation post, he who answered, with brotherly freedom, glancing over the Torch Bearer’s shoulder at the brown-eyed girl beyond her.

“Yes, sis, it’s as thick as the fogged-fish yarn, or as the fabled fog that the half-breed pathfinder who was attached to our Boy Scout troop used to tell of when he’d begin quite modestly that he ‘hadn’t seen fog ver’ tick--non--only one time he see fog so tick dat one mans try for drink eet an’ mos’ choke hisself; and wen dey take out dat fog wat dat mans try for drink, dey take dat for make broomstick--yaas!’ Oh! you couldn’t get ahead of Toiney; he who--was it three summers ago?--pulled one of your Camp Fire Group out of dangerous quicksands, eh?”

“Yes, that will be three years ago next August and we’re going to camp in that same region of white sand-dunes this coming summer, too, under the spell of the Green Com Moon,” returned the boy-officer’s sister, Sara Davenport, named by the Council Fire Sesooā, the Flame.

“Well! we won’t see Toiney again.” The eyes of the taller girl, Olive Deering, watered, but in their dark, liquid depths shone Toiney’s gold star, never to be eclipsed. “He sleeps under the daisies of France. You should have heard him march off to enlist, singing:

“Bravo! Ah, well, he’s gone on the longue chemin now--the long trail--a trail of light it must be,” murmured Lieutenant O Pips half under his breath, his eyes, keen and misty, searching that dense yellow cloud to leeward, billowing down into a ziggagging maze of trenches--the cloud thrown off by the smoking sulphur candles, of which here and there one did more than was required of it, yielded complete combustion and burst into a ragged, rose-red banner of flame, that added weirdness to the daylight scene.

Speaking of Toiney--light-hearted, raggedly romantic half-breed--who had made the supreme sacrifice, presently drew the girls’ thoughts to those living comrades-in-arms of Toiney, the American soldiers now lined up under that baleful yellow cloud, down in the invisible trenches, undergoing the training of being “put through gas,” in order to render them expert in adjusting their gas-masks directly the warning was given--the rattle sprung.

“‘Fritzie’s party,’ as you call it, seems rather halting; they haven’t brought on all the fireworks yet, have they?” suggested a third girl, known by the Council Fire as Munkwon, the Rainbow, in every-day life, as now, Arline Champion, the shell-like tint of her cheeks deepening to a hectic flush from the same expectant emotion which had paled her sisters.

“No, sometimes the chemists of the Gas Defense Department who have charge of these sham attacks, turn loose the smoke-cloud several minutes before they thicken it with the poison waves--gas waves,” the officer answered. “They send it over every old way so that no man down there may be caught napping,” with a brief excited puff of laughter.

“And I suppose this sham ‘party’ is just as dangerous for the men in the trenches here, being trained to meet gas, as the real one over there?” Arline persisted.

“Sure! With them, too, it’s the Quick or the Dead, as we say in the army!... If any one is slow about getting into his mask--otherwise his chlorine-fooler----”

It was at that moment that the whole round earth began, as it seemed, to “fool” and make believe that an earthquake heavingly rocked it. Up from the trenches came a loud, rolling report that echoed like thunder through the yellow cloud. Tearing its veil asunder, a broad sheet of flame leaped towards the sky. The ground shook under the girls’ feet. Wildly they clutched each other upon the sere skirts of Gas Valley, as this portion of the great military training-camp, where soldiers were initiated into the horrors of poison gas, was nicknamed.

“Ha! Now the fun’s really on! That turns loose the bitter tear-gas--worse than a corner on onions for making one weep!” blithely exclaimed the officer. “Don’t be nervous! It’s only the explosion of six sticks of dynamite down in the middle of the trenches, which bursts the shells on the surface, each containing a little paraffin cup--rice-paper cup--holding a small quantity of oil, and under that the lachrymatory liquid--the oniony ‘tear-stuff’ that would wring tears from a stone image. There go the chlorine-cylinders, gasping, too!”

He pointed--that young officer, charged like a live bomb himself, the heated tension of the scene and the excitement of having visitors reacting upon a naturally fiery disposition--pointed across the twenty-five yards of blighted vegetation which separated his group from the trenches, at two tall iron cylinders near which stood a couple of masked sentries, looming like brown goblins amid the yellow fringes of the smoke-cloud.

“What! Can they get as near to the horrid, deadly chlorine as all that?” breathlessly gasped the youngest girl, Ko-ko-ko, Little Owl--amid scenes like this, remote from the Council Fire, Lilia Kemp.

“Yes, if their masks are perfect, and properly adjusted. Those are two of the young chemists from the Gas Defense, who are putting over the ‘show,’ and----”

“Oh, goody! I know now why we’re urged to save and collect peach-stones next summer--ever so many other kinds of pits, too--to make carbon for soldiers’ masks! ‘Save the peach-stones; waste not one!’ A few may save a soldier’s life! When I’m drying them in the oven--incidentally burning my fingers, as I’m sure to do, I’ll feel really like--like----”

“Like the real girl behind the lines,” put in Lieutenant O Pips, his eyebrows lifting, in turn interrupting Little Owl as she had blinkingly interrupted him. “See, now, the ‘ball’ is on in good shape! There go the big firecrackers simulating shells, so that the men’s nerves may be prepared for bursting shrapnel; and the electric bombs exploding everywhere, in and out along the surface of the trenches, loosing more tear-gas!--Oh! this--this is spectacular now. But you should just see it at night. Then it’s Inferno, sure enough!”

“It--it’s that, in daylight, when one thinks of the men down there!” Olive Deering bit her lip, gazing steadfastly in the direction of the veiled trenches, above which the yellow smoke-screen was torn by the popping of monster firecrackers, pricked by the laughter of roseate flashes, so bright, so elfin, that who could dream their fairy splendor was but the glitter of a key to unlock tears?

“The men undergoing initiation in the trench-bays? Oh, bless you! they’re all right, unless--unless it should be a case of:

“But there won’t be any ‘blighter’ to-day--there couldn’t be!” He bent, that very tall young officer, nearer to Olive’s ear, the nineteen-year-old girlish ear under the Torch Bearer’s hat. “Nobody knows how I have been looking forward to this day, Olive, this spring day, when you girls would visit me in camp before I went over! I’m sorry that your father, Colonel Deering, and your aunt chose to pay a visit to Headquarters, Brigade Headquarters, instead--instead of coming on here to inspect the fireworks in Gas Valley.”

“Fireworks never to be forgotten!” murmured Olive, coloring a little as the luck of this longed-for holiday coined itself into a silver bar in the eager eyes bent upon her, matching the luck of those other silver shoulder-bars for which the young Plattsburg graduate had “plugged” so hard.

“Father has an old friend who is Captain of Headquarters Troop, but we’ll find him again later,” she said, suddenly rather breathless from the moving conviction that when the youth--for he was little more--beside her faced the poisoned horror-waves of the real Gas Valley “over there,” when he crouched, sleepless, in a cold and muddy trench-bay or led his men over the top, she, for him, would be beyond all others--even more than the brown-eyed sister to whom his glance roved now--the girl behind the lines, beyond the ocean, typifying America the Beautiful, standing for all he would die, smiling, to defend.

It may be that the prospect unrolled itself vaguely before the young soldier’s mind, for, as he straightened himself again, training his keen gaze once more upon the smoke-cloud, thickened with poison-waves, he was humming unconsciously, involuntarily, lines of a crude camp-song:

“Stifling stand-to! Well, I guess the men down there in the trenches are having that now, ‘gooing’ up their masks--their chlorine-foolers--in that popping, heated cloud,” gasped his sister, racy little Sesooā, turning from a certain “kit-inspection” which she was holding upon the toilet and general get-up of another visitor to Camp Evens, not attached to her girlish party.

“Um-m! Isn’t that muff of hers pretty, the--the ‘spiffiest’ thing!” appraised Sara in silent soliloquy, the springy elasticity in herself causing her to rebound more readily than did her companions from the shock of seeing a gas attack launched; at her core there was a gay flame--a buoyant “pep”--which refused to succumb even to Inferno, with its yellow acres of sulphur smoke, its deadly waves of chlorine gas, its tormenting “tear stuff.”

“Humph! Rather late for a muff, though, seeing it’s April. We’ve discarded ours,” reflected further the self-constituted inspector of “kit,” otherwise clothing and equipment, upon the skirts of the military training-camp, as she shot a firefly glance towards the sky, more like July than April--flecked with lamb-like fleeces nestling in an arch of blue. “But then one may be forgiven for holding on to a thing like that! Adds the last touch of style to her costume! I wonder how many birds gave up their lives to make that muff: all dove-gray breast-feathers--tiny feathers--and the fashionable turban which goes with it.

“Her tailored suit is perfect, too; almost puts Olive’s new jersey one in the shade,” was the next random comment after a few seconds of absorption in the noise and novelty of the near-by attack, the monster fire-crackers, snapping, bursting, momentarily flowering in the yellow field of smoke. “And her gray cloth blouse with that soft, swathing collar around the throat, high under her ears!... Some officer’s wife most likely! Wonder what age she might be--thirty--thirty-two? For all her style she isn’t quite thoroughbred-looking like Olive--our Blue Heron,” shooting a sidelong glance at the pale, emotional face under the velvet hat adorned with the delicately embroidered logs and flame. “And she’s not in the same class at all for beauty; judging by the profile, that young woman could dispense with a little of her cheek-bone and chin. But--but what a wonderfully smooth pink skin; looks as if it had just been massaged--was massaged every day! Her skirt’s a trifle long; I suppose her feet aren’t pretty; that would be in keeping with her shoulders, for they’re rather broad--looks as if she played basket-ball and hockey. Athletic type, I guess. Her hair’s much the color of mine, but those silver threads in the mat over the ears--they--they add distinction; almost wish I were turning gray! What!”

The critic caught her breath, for the lone visitor, perhaps feeling the scrutiny, turned and boldly looked at her--looked through her, felt the Camp Fire Girl--with a glance as cool as an Arctic snow-blink. Bluish eyes--this stranger had, the gray-blue of salt ice, that.... Were they trying to infuse a little warmth into the ice-blink? Sesooā’s confused thoughts--rather abashed--never knew. For she hastily turned from this kit-inspection in which she had been furtively indulging, to seek refuge in the smoke-cloud.

And it was at that very moment that she heard a strange, hoarse exclamation from her soldier brother. At that very moment, too, she, together with her Camp Fire Sisters, felt as if the ground, now steady, rocked once more violently, sickeningly, under their feet.

What was happening upon the near edge of that dense sulphur-cloud, to leeward?

Its yellow muzzle was lifting.

Silently, stealthily, it was opening its poisoned mouth--and giving forth!

Up the brown sod-steps, from the yellow-veiled trenches, out over the lumpy, skirting sand-bags, out into the withered vegetation of Gas Valley, stumbled three figures! Masked figures they were, goggle-eyed, grotesque, with white beaks of tubing which, curving downward from those brown face-masks, pecked in the satchels upon their own breasts!

Forth from the cloud they came, goblin figures, with horrid green spots upon their khaki blouses where the deadly chlorine had preyed on their metal buttons.

And before the petrified girlish gaze one--the middle one--rocked and pitched, like a corroded ship at sea, pitching to windward!

“Oh, somebody is injured--poisoned--g-gassed!”

Sesooā heard Olive’s cry, which pitched like the advancing figure, and forgot completely the informal “kit-inspection” to which she had been subjecting the buxom young woman of the skin and shoulders, who carried a feather muff under the April sky.

“Yes! Some one has got it--was muddle-headed--did not get his mask on quickly enough. Or else something was wrong with his ‘chlorine-fooler.’”

Now it was her brother’s voice, that of the boy-officer, and she realized--hot-hearted little sister--what it would mean to him that, on this day of all days, it should be that:

Poor Blighter! Supported on either side by his comrades, who dragged him along by the arms, he, the stumbling middle man, wildly clutched his khaki breast, as if holding it together--as if keeping it from bursting!

“Lay him on his side, men--feet higher than his head! Remove his mask, and give him air!”

Again it was the young lieutenant who spoke, and, glancing up at him, the girls saw that the silver luck of this long-anticipated day was tarnished in his eyes, as if the villainous chlorine had preyed upon that, too.

Concern was in those eyes, strong concern. Behind it lurked bitter chagrin, only needing a spark to the fire and tow of a hasty temper to ignite it to leaping anger--with a headlong haste to fix the responsibility for the most untimely accident.

But, through it all, he was aware of another responsibility--that of his four girl-guests.

“Stand off!” he ordered them, almost violently. “Get farther to windward. Some of the gas is clinging to his clothing!” This while the two uninjured soldiers were removing the victim’s mask and their own, tossing his aside upon the grass, together with the respirator-satchel to which it was attached (the type of satchel which would by and by hold the purifying carbon made from Camp Fire Girls’ peach-stones and pits), so that the gas, which had somehow penetrated the mask, might leak out.

Supported on either side by his comrades.

“Keep off! Get away--off--to windward! Don’t you--don’t you get it--the whiff of chlorine from his uniform--r-rich smell----”

Her brother was almost beside himself by this time--Sara knew--in his concern over the whole untimely mishap, and his anxiety for his visitors’ safety.

Obediently--loyally--she moved in the direction from which the fresh breeze blew, herself, dragging two of her companions with her.

But one girl, sneezing, choking, with the flame of the Torch Bearer’s emblem upon her hat, striking downward, lighting her cheeks with a counter-fire--one dared to disobey.

“Gas clinging to his clothing! What--do--I care?” she gasped, feeling her own smooth lungs scorched, her sweet breath seared, not only by the unlaid ghost of chlorine gliding by her, but also by a reflection of the torture going on in that poisoned breast upon the grass, where the victim’s blue, pinched nostrils fought desperately for the wavering breath of life.

Blue Heron, Torch Bearer, looked down at him and, on the instant, she went over the top, as brave men do, in the first wave of knowledge--the seasoned wave of training.

“I--I know what to do for him,” she panted on the wings of a gassed sneeze. “I’ve taken an elementary Red Cross course--have talked with nurses who’ve been across. Some--some idea of going over as a nurse’s aid, if father would let me!... Aromatic spirits of ammonia--that would help! Carry it always when I’m off with dad, because--because of his--faint----”

Even as the unfinished sentence tickled her throat like a tainted feather, she was kneeling beside the gassed soldier, plucking wisps from a tiny fleece of cotton-wool in her pin-seal bag, moistening them from a little phial, holding them, one by one, to the laboring nostrils, or chaffing the victim’s right hand, stiffening like a poisoned claw, between her own girlish palms--trying to rub the life back into it.

Her younger Camp Fire Sisters watched her from the position which they had been ordered to take up, a few yards to windward, where the young April breeze, keeping guard over them like a skipping brother, warded off the ghost of gas.

They clasped their hands tensely as they saw her forced to a position behind the sufferer’s head, to windward of his tainted clothing, by the pale, strained officer who forebore to interfere further because the vanishing gas-ghost was too weak for danger--as they beheld her kneeling there, dauntlessly ministering, quailing not before the staggering horrors of the gas sickness--the spewed blood upon the ground.

“Olive! Olive! Look at her! Isn’t she wonderful--wonderful! And she--she was ‘reared in cotton-wool’ herself, as the saying is!” Tears sprang to Sesooā’s eyes. “Nothing but ease and luxury!... ‘Elementary Course!’ Oh, she never jumped to this by fifteen lessons--and talking with nurses!” The voice was the low moaning of a Flame. “Never! She came to it by the long trail, the Camp Fire trail--hiking, climbing, sleeping out on mountain-tops, or by the seashore, having our little accidents, until--until we just forgot that we were we!”

“You forgot that you were you!” echoed the guardian breeze.

“Not one of us--one of us--was a flower-pot plant!”

“True! You weren’t!” corroborated Brother Gust.

“But Iver--Iver! Oh, this is terribly hard for him!” was the Flame’s next moaning outburst. “Besides his sympathy for the poor soldier, he’s feeling bitterly now that there--there goes his reputation for a smart and seasoned company! He--he’s all ready to be splitting mad with somebody. And he has a temper, my brother Iver. Mine’s like it only I don’t--can’t--explode with quite so much force.”

Lieutenant Iver was exploding now, with all the luck of the holiday tarnished in his eyes, his nostrils smoking like a sulphur-candle in his eagerness to nail the blighter who was responsible for the ghastly accident that had, incidentally, withered the flowers of this day of days for him.

“How--how did it happen?” he asked tensely, addressing one of the infantrymen who had dragged the gassed victim up out of the trenches, a tall sergeant--a young sergeant--to whom it had fallen to inspect the gas-masks, to make sure that they were in perfect order, before the men entered the smoky trench-bays.

“Was he muddle-headed--slow about getting his mask on--when the alarm was given--the rattle sprung?”

“No, it didn’t ‘rattle’ him a bit,” the sergeant answered, meeting the question with level eyes. “He had his mask on quicker than I had, sir--properly adjusted, too--was jollying us through it----”

“Then--then the fault must have been yours. Something was wrong with the mask itself! As Gas N. C. O. for to-day, you were detailed to inspect all respirator-masks before the men entered the trenches. I’ll report you for neglect of duty. You’ll be put in the guardhouse for disobedience.... I don’t know how you came by your stripes!”

The lightning-flash of the officer’s eye withered the drab chevron upon the sergeant’s arm.

“Oh, mercy! that Gas N. C. O. (non-commissioned officer) is in for it now. He--he’ll get a ‘skinning.’ Iver’s temper is up. He’s going to ‘bawl him out,’ or, as they say in camp, give him a fearful rating.”

The hands of Iver’s brown-eyed sister clasped and unclasped feverishly as she spoke, hanging on tiptoe upon the skirts of the main group around the convulsed victim.

Her ears were deliriously strained to catch the next words of that figurative “bawling out” in which scorching satire would take the place of shrill sound. They were low, but fiery enough to sear even her, at a distance.

But before the sergeant had been thoroughly “skinned” an interruption occurred. An older man who happened to be passing, hurriedly--anxiously--joined the group.

He wore two silver bars upon each level shoulder.

“Look! Look! He’s Captain Darling--captain of my brother’s company,” panted Sara to her companions.

Captain Darling did a strange thing--a thing which brought the girls’ hearts skipping into their throats--almost with an hysterical impulse to titter--like the light spray on the deep, deep wave when it bursts overwhelmingly.

He strode over to where the sufferer’s gas-mask lay upon the yellow grass--the chlorine-fooler which had failed to fool--put his hand into the breast-satchel attached to it, pulled out and held up--a few burnt matches.

“Ha! I thought so. This--this exonerates the sergeant. No doubt he did make a thorough inspection! Contrary to orders, the man carried matches in his satchel with his mask. The heat down there, on the threshold of the smoke-cloud, ignited them after he entered the trench--they’re warm still. They injured the mask--burned a tiny hole in the face-piece; see!”

The captain held up the goggle-eyed mask, with its brown face-piece, its white celluloid nose-clip and flutter-valve, through which a soldier’s breath and saliva escaped together. Surely enough, there was a tiny, blackened hole, no bigger than a pin’s head, piercing the rubber of that khaki-colored face-piece!

“Oh! Oh! In spite of all this, I’m glad we came to-day. I hardly realized before how much a man’s life in this terrible war depends upon his gas-mask--upon the disinfectants in his satchel through which he breathes! ‘A few peach-stones may save a soldier’s life!’ Didn’t seem possible! But ’twill make the work we girls are asked to do in war-time seem so--so--different!”

The outburst--low and tearful--came from Arline, a rain-streak, not a rainbow, now!

But Sara Davenport was beyond speech. A fiery hand clasped the back of her neck as she glanced from her officer-brother, fiercely biting his lip while he contemplated the charred match-ends, to the “skinned” sergeant--completely vindicated.

“O dear! Iver will feel now that he’s made a fool of himself, that he’s the blighter, for--for going on the storm-path and fiercely scolding that sergeant before he knew that he was to blame,” thought the fiery little sister. “Just--like--me! How often I feel that way after bursting like a hot pepper!... Iver says himself that he has a ‘whiz-bang’ temper, but it’s too bad that he should be caught discharging ‘whiz-bangs’ before Olive. He worships Olive. I guess when he goes over--as he will, oh-h! so soon--when he’s lonely or homesick, lying out in some horrid shell-hole, or rooted in trench-mud until he feels himself sprouting, he’ll be thinking of her, probably as she is now, kneeling by a gassed soldier--true Minute-Girl--no more the Olive Deering that she was when I first knew her, two years ago, than--than.... Oh, for pity’s sake! There--there’s that ‘Old Perfect’ with the muff and skin and shoulders again. I wonder if she heard him pitching into the sergeant, too. Couldn’t! She was too far off. But she’s smiling at those miserable match-ends. What--what an iceberg! If we had her in camp this summer, we wouldn’t need any underground refrigerator.... Ugh! I’d like--to--bite--her!” From which it may be inferred that the little sister was right in her self-arraignment; that there was more than one temper of the whiz-bang order, a flame at this moment upon the sear skirts of Gas Valley.

But there was no flame under the snow-light smile which shed a peculiar whiteness over the face of the detached visitor to camp. Perhaps she was conscious of its frigidity herself, for, curiously enough, she plucked at the corner of her mouth with her right hand, momentarily withdrawn from the feather muff.

The gray-gloved fingers of that hand--forefinger in evidence--described an airy semicircle, a vaguely twirling motion at her smooth, smooth, lip-corner, with the thumb as pivot! But abruptly the whole hand spread itself out to the sunshine, in bland elegance, as “Old Perfect” caught the girlish glance darted, sidelong, towards her, and then dropped to her side.

Really, it was a glance as preoccupied as the gesture itself, for two-thirds of Sara Davenport’s mind was at the moment a storm-zone, swept by concern for her brother and anxiety for the gassed victim who was himself to blame for his misery--and that clouded the other third.

Any point that the movement might have had was blunted against the broad thrill of an arrival from the base hospital of a stretcher for him, seeing that he must not be tucked away in an ambulance as yet, his only hope of recovery being fresh air and the gas-allaying power of Brother Gust.

But, although the troubled eye of the conscious self may be dim and clouded, there is in each of us, young or old, another self forever on the alert--even when he seems to be dreaming. Men name him the Subconscious.

A shy fellow and retiring, he is, nevertheless, an expert photographer, forever snap-shotting things which concern us, although he has a trick of hiding away the films--sometimes for long--until some shock compels him to produce them.

Perhaps he took such a snap-shot now of the elegant young woman whose smile was a snow-blink--like an Arctic reflection--upon the skirts of the yellow sulphur-cloud.

Perhaps, some day, he might, under unusual spur, produce the negative--the indelible negative for a vivid picture of this whole harrowing scene, when, on the brown outskirts of camp:

“Well! we’re not sitting alone, so that’s more sentimental than suitable.” Sara Davenport broke off short in the low song which she had started, looking away over the yellow cantonments of broad Camp Evens, turned to fine gold by the sun’s last flaming ray.

“And I’m sure it’s been anything but a perfect day! What about the poor blighter, and his matches?” struck in her officer-brother, who, seated edgeways upon the railing of the lofty balcony surrounding the camp Hostess House, half-faced the four girls who had been his guests at the illuminated “smoke party” in Gas Valley.

At a little distance, absorbed in the sunset effects upon the burnished rows of elevated barracks brooding like gilded dove-cots, were Olive’s father, Colonel Deering, and a much-loved spinster-cousin, who, during the morning, had been calling upon an old friend, an officer attached to Headquarters Troop.

“The Blighter! Oh! he’s not outmatched yet,” laughed Olive. “Didn’t--didn’t the last word from the base hospital proclaim that he was getting better?”

“Anyhow, we could forgive him,” murmured Arline half under her breath, in quivering rainbowed speech, “because here we’ve been, for the past year or two, trying to live up to the hardy Minute-Girl program, hiking so many hours a week, sleeping out, though at first we ‘caved’ before a cow-bell,”--a double rainbow, this, shedding a reflection of laughter--“and now--now this morning proves that one of our number, at least, could be truly an Emergency Girl!”

She cast a moved look at Olive.

“Ah, yes!” Sesooā shot an amused glance through her half-closed lashes--pretty eyelashes they were, which began by being dark and, shading to amber, now stole gold tips from the sunset--a peculiarity rather typical of Sara herself, and of her speech at the moment, which showed that she was determined that any allusion to the morning should be tipped off with lightness. “Ah, yes! battling with gas is one thing, but--for Olive--battling with grass and grubs in a war-garden may be quite another! Wait till it comes to fighting weeds an’ witch-grass. How much--how much of the dauntless Emergency Girl will be on deck then, I wonder, in our oasis by the seashore?”

“Oh! she’ll be there--a hundred per cent of her!” protested the Torch Bearer, her courage rising to a treble trill.

“Humph! Your voice sounds as if you had just eaten a canary-bird, my dear--and it was only squab that we had for dinner!” merrily mocked the Flame. “But will--will the note be as sweet when, on some broiling hot morning in July or August, the bugle sounds Fatigue on the edge of those white sand-dunes, where we’re going to camp? And it’s ‘Fall in for work in the field!’ amid the potato-rows on the one semi-green hill that would grow a ‘tater’ within a mile of us! A case of ‘Joan of Arc, they are calling you! Lead your comrades to the field!’ ... Oh! you should have seen Olive in silver-scaled armor, as the Maid of France, with her holy lance uplifted, in some tableaux that we gave for the benefit of the Red Cross. She did make a hit!”

Sara’s eyelashes twinkled in the direction of her brother. He shifted his edgy position a little on the railing. His color rose slightly as he glanced towards the modern Joan, a girl like a white orchid, whose dark eyes and hair, with the capacity for spiritual fervor in her face, offered rare material for such an impersonation. But he did not answer.

Perhaps, when he did go over, this keen-eyed young officer of the fiery mettle, nicknamed in camp O Pips, or Observation Post, from the unerring alertness in him which made him come down hard upon a blunder--he whose temper exploded like a whiz-bang--the picture on which he would dwell oftenest, of the oldest girl in this group, would, he felt, outshine every other.

It would show her kneeling by a gassed soldier, with the flame and smoke of the Torch Bearer’s emblem upon her hat seeming especially designed to fight that other hateful yellow smoke and flame rolling away from her to leeward--the one the type of ideality that would finally win out over the baleful reality of the other, and leave none but the flame of brotherhood, with its sacred smoke of service, burning in the soul of man.

It was the ideal for which the soldier himself was going over to fight--going “shod with the preparation of the Gospel of Peace”--though humanly rough-shod!

He pulled himself together.

“And so you’re going to sport a war-garden on this jumping-off spot that you’re bound for next summer, to camp out during July and August on the edge of those white sand-dunes. I thought nothing could flourish there but sand-snails an’ seals, with--with, perhaps, this summer, an occasional submarine thrown in,” he laughingly remarked. “Aren’t you afraid that if you’re out on the water at all, a sub may come to the surface and fire a tin fish at you?”

“Oh! catch her wasting a torpedo on us when she’d have nothing to hit but my little blunt-nosed dory that you gave me, Iver; or Little Owl’s Indian canoe, which she mends with rosin when it sucks in water like a thirsty cow!” Sara, the lieutenant’s sister, burst into a laugh, looking sidewise at Ko-ko-ko--the Camp Fire Owlet--otherwise Lilia Kemp.

“Well, if it does leak a little, it’s a ‘slick bit of birch-bark,’ for all that, as Captain Andy says.” Lilia chuckled. “You’re all just envious of my genuine Indian canoe, brought by my father from Oldtown, Maine, and built by an Indian named Nodolinât--canoe-maker. I’m thinking of changing my Camp Fire name to Dolina, which has something to do with a canoe, either making or mending it, see?”

“Marring it, you mean! It’s a funny-looking craft when you have the bottom all plastered over with sticky rosin,” challenged Sara. “Oh, besides dory and birch-shell, I suppose we’ll have our old reliable, the broad, flat-bottomed camp skiff, which Captain Andy calls a ‘tender old wagon,’” laughingly.

“Captain Andy! Are you going to have that old king-pin with you again, shouldering the safety of a dozen girls or more? I don’t envy him.” The soldier smiled.

“Now, you do! You know you do! We can’t have him all the time. War got him back into active service. He’s been ‘skippering’ a coaster carrying lumber from some part of Maine round to the Essex shipyards,” said Arline. “Wasn’t that it, Olive? You had a letter from him.”

“Yes, but lately he had to give it up because of his lameness, and is doing his ‘bit’ in other directions,” replied Blue Heron, her dark eyes gazing off into the last rays of the sunset. “You know those country shipbuilding yards aren’t so very far from where we’re going to camp on the white Ipswich beach. By the bye,”--laughter trickling through her speech like sunlit water through a sieve--“by the bye, do you all know who’s going to work in those shipyards, this coming summer, if they draft him for labor? Why, my cousin, Atty Middleton Atwell!”

“Atwood Atwell, of Atwood and Atwell, city bankers! What! What! That young sprig from Nobility Hill? I beg your pardon!” The soldier, slipping off his perch, smiled apologetically at Olive, whose girlhood had blossomed in the same luxuriant soil of ancestral wealth. “Why! that kid is worth a million or two in his own right. And his great-grandfather--plus a couple more ‘greats’--signed the Declaration, eh?”

“Is--isn’t that the very reason why he should do his part where it’s most needed, as he’s too young to go across?” The oldest girl’s eyes twinkled challengingly. “Take my other cousin, Clayton Forrest; he’s not twenty-one yet! War was no sooner declared than off he went, hotfoot, and enlisted in the local infantry company being raised in his little town--about fifty young men from his father’s big loom-works signing up with him. And Clay--up to this, Clay was never a ‘grind,’” laughingly, “any more than--than Atwood was!”

“Good enough! And you have two more cousins in the navy, haven’t you?”

“Yes, indeed, she has! Why, it was with one of them, Admiral Haven Warde’s son, that Olive went down in a submarine; actually--actually submerged! Think of it!” put in the Rainbow--Arline--again, rosy now with vicarious excitement, as if the wonderful experience for one of their number touched her with an after-glow. “That--that’s what it means to be daughter of a steel king who’s connected with government shipbuilding yards! Ensign Warde is Junior Aide to the Commandant of the Miles River Navy Yard.”

“And--and it was off there that you--dove! Jove! that was an experience. What did it feel like?” The soldier’s eyes flashed curiously.

“Awfully still an’ tense while we were going down--just about half a minute, you know--with the big engines all stopped and only the electric motors going! And the swish of the water against the sub’s side! I closed my eyes and felt like a shell-fish. But when I opened them again on the bottom, oh! it was a fairy palace down there, under the sea--such bright electric lights glittering on wheels and pipes and I don’t know what not; a--a regular miracle-world of machinery,” in awed girlish tones.

“I suppose so, every inch--about--crammed full of mechanical power, except the forward quarters, where the officers slept!” suggested the lieutenant.

“Yes, and made toast and tea on a little electric contrivance attached to the shining switchboard that controlled the dynamos,” supplemented the favored one who had dived to sea-nymph’s regions in a steel shell, internally so radiant, so charged with magical power that it might make Neptune himself feel outclassed. “I--I was a fish again when we came to the surface once more, broke water, and climbed up into the conning-tower, to look through the periscope’s eye! It seemed such a strange dream-world that I saw outside, not one bit familiar; either very clear and shining and remote, or with waves and boats--and trees along the shore--looming unnaturally large and frowning, according as the telescope was adjusted. Oh-h! I’m sure I was a nice little flounder or haddock then,” merrily, “taking a peep at the upper world.”

“You came near ‘floundering’ out--being shot out, rather--through the mouth of the conning-tower into the gray pulpit, or superstructure, where you might have preached a sermon to the fishes on power, if you hadn’t been killed; that was through--gracious!--through one tiny misstep on an automatic lever, like a sleeping tiger. The Junior Aide, who could control the beast, saved you just in time, eh?” prompted Sara, but abruptly swallowed her chaff as she caught her soldier-brother’s eye.

She knew he was envying that Junior Aide, the young naval ensign, with the gold cord drooping from his left shoulder, thinking that no girl as attractive as Olive--as game in an emergency, too--should have quite so many heroic cousins.

What chance, in her memory, could an ordinary peppery lieutenant in an infantry company have against them--a lieutenant who had let his rash temper betray him into prematurely “skinning” a sergeant?

“I guess I was the blighter myself to-day--or as much of a ‘blight’ as that poor ‘doughboy’ with the matches--for letting temper, headlong anger, gas me. That little flame of a sister of mine, Sara, and I, we have the same sort of ‘pull-the-pin-and-see-me-explode’ temper,” he murmured heavily later, this thought rankling, in the ear of the oldest girl, who had looked into dreamland through the rounded eye of a periscope, when her companions had withdrawn to another corner of the lofty balcony for a better view of the sunset.

“Oh! don’t talk of ‘blights!’” she gasped laughingly. “I’m afraid that ‘bothering bugs’ and plant mildew won’t be in it with me for--for a ‘hoodoo’ when it comes to our working steadily three hours a day, weather permitting, in that green oasis of a war-garden amid the sandy desert of the white dunes, when we’re camping out, the coming summer! And yet I--I was the first to volunteer when the president of the Clevedon County Farm Bureau addressed all the Camp Fires of our city a week ago, and called for recruits for just that very thing. If I don’t stick to my pledge the other girls won’t. And we know America has got to be the ‘world’s pantry.’ But, O dear! give me knitting, sewing, painting war-posters, posing, anything else, from morning till night, except weeding an’ hoeing when the sun’s hot and--and one’s back feels as crooked as--as one of those old French streets that the boys write home about!”

Blue Heron straightened her long, girlish spine with humorous apprehension. She was a tall girl, the white parting on the right side of her dark little head being on a level with the soldier’s cheek-bone, if they were both standing.

“Oh! you’ll carry on.” He smiled at her. “It’s a good line; hold it!”

“As you will when you repel an attack, or--or go over the top!... When d’you suppose you’ll be--starting--across?”

“No knowing! At any minute, perhaps! But--but, if you should be around here a week from to-day, you may see me, still on this side, undergoing gas initiation--getting my medicine down in the trenches at the hands of the Gas Defense Division, Chemical Warfare Service. Certainly those young chemists have a witch’s imagination in the horrors they put over on us!” The soldier laughed.

“And they hold their classes every Thursday. I expect to be in the neighborhood, anyway, because father will. And Sara, you know, is staying with me. The other girls go back to the city to-morrow, to be in time for a ceremonial meeting of our Camp Fire Group, at which we’re going to have a novel initiation of our own--initiate, as a novice, that is, a foreign-born Camp Fire Sister, whom we’ve adopted for nine months, little Flamina Miola, born in Italy! I’m teaching her one or two patriotic poems--along with our special ritual--and you should hear her begin on:

“Good!”

“I chose her name for her, too: Nébis, A Green Leaf. Isn’t that pretty? She’s going to camp out with us this summer.”

“Green Leaf for Little Italy! It is poetic. I hope you’ll make it a laurel leaf. Well! I guess that sometimes, over there, when a fellow misses some of the things that--that make life hum, you know; when I’m ‘gooing’ up my gas-mask or, maybe, drawing pictures with my ‘toothpick’ (bayonet) in the mud, I’ll think of you Camp Fire Girls. You certainly have a corner on the poetic--fringes, beads, ceremonies--and it only seems to hearten you to meet what’s rough--ugly.”

“That’s our outdoor life,” half whispered Olive. “We get so many new sensations, come so near to--to the heart of things that we----Why! sometimes I,”--she caught her breath in a little low gush of confidence--“I feel as if it were only the fag-end of me that was shut up in--in the five feet eight or nine of flesh and blood--bloomers and blouse--called Olive.” The low girlish voice soared softly upon the last word as to a height from which the girlish soul looked out upon a great Adventure.

“You mean that you get a real glimpse into unseen things--spiritual things!” The soldier’s voice was low too--low and thrilled. “Well, since we are wading into the deep things, I may say to as much of Olive as is left in the fetching jersey suit beside me now, that ours is a rough game, but somehow, as it were, I have come nearer--nearer to God since I volunteered.... I wish it could help me to get the better of a--whiz-bang temper.”

The Torch Bearer’s eyes were wet. So were the soldier’s. The last word had been said. All she could do was to put out a tremulous little hand and touch his understandingly. He wanted very much to stoop and kiss it. But he didn’t. For he remembered that, though he wore his Plattsburg shoulder-bars, yet they were hardly more than Boy and Girl. And up to the threshold of this unifying war-time their lives had not run in parallel channels, as did that of the Junior Aide, who was an admiral’s son, for instance.

So he only covered the girlish hand warmly with his own--held it nested for a moment as that of a comrade with whom one has shared the secret trail, the rainbow trail, that leads into the unseen.

And he hid another, and very special, picture away in his soldier’s heart to brighten those moments when, riding endless miles on a troop train, “hitting the hay” at midnight or vegetating in mud until he felt himself sprouting, he might miss those things which make life hum.

“That’s Iver! Oh! no distance, nor trench, could prevent my recognizing him.”

The cry of rapt identification came from Iver Davenport’s seventeen-year-old sister, Sara.

“Yes, one can single out his shoulders at a glance--an inch higher than those of any other man in his company--Lieutenant O. Pips!”

It was Colonel Deering who amusedly spoke, president of the Board of Directors of the Craig Steel Works, retired colonel of a national guard regiment, and father of two very attractive daughters, Olive and Sybil, Camp Fire Girls, of whom only one was present here, on the sear skirts of Gas Valley, the outskirts of the great military training-camp, where the army chemists of the Gas Defense Division were again holding their so-called “classes” initiating soldiers into an experience with poison gas.

“Oh! I’m so glad that we’ll have a chance to see him again--Iver--before he goes over. I didn’t let him know that we were coming to-day; ’twill be quite a surprise when he stalks up out of the trenches--and unmasks.” Again the eager exclamation burst from Sara, a kindling flame of excitement, as standing on the edge of the camp trenches, behind the skirting sand-bags, she craned her young neck over, to gaze along a narrow earth-cut, six feet deep, to a curving trench-bay in which her brother was stationed with a few other officers--all still without their masks--to undergo an initiation on his own account.

“He said, last week, that if we happened to be visiting camp to-day, we might see him getting his medicine at the hands of the young chemists of the Gas Defense Division, who have a witch’s imagination when it comes to horrors.” Olive smiled. “I don’t suppose that this is his first initiation, though, by any manner of means.”

“No, they keep ‘putting them through gas’--or some substitute for poison gas--right along here, so that they may be able to get their masks adjusted inside of six seconds,” remarked her father. “I believe it isn’t really going to be gas and sulphur smoke to-day--simply powder-puffs.”

“Powder-puffs! Pelt--pelt them with powder-puffs!” Sesooā nipped off a comic little shriek.

“Oh! not of the vanity-box order.” Colonel Deering’s smooth-shaven lip twitched. “These puffs are just tiny brown-paper sacks, containing, each, a tablespoonful of black powder with three or four inches of red-capped fuse sticking up out of it. They explode when they strike in the trenches, near a man’s feet, throwing up, each, its own little spitting, venomous spurt of flame, so that if he should be slow about getting into his mask his eyesight might suffer.”

“O dear! To-day I hope it won’t be a case of:

murmured Olive, shuddering with a recollection of last week’s smoky Inferno, with its shaking roar of dynamite, its bright flash of bursting “tear-shells,” its popping of monster fire-crackers in the yellow cloud--and of what that cloud gave forth.

“Oh, no, it won’t! This seems quite tame compared with the real ‘Fritzie’s show’ last week!” Sara’s voice was an echo of her soldier-brother’s. “But who wants to see another smoky spectacle? Not me! To-day, by craning our necks over and looking along the traverse, we can see things--see the boys scrambling into their masks in a blessed hurry! Oh! here come the chemists now, with their bundles of powder-puffs. Funny-looking things those puffs are--like pert snails with their long red necks thrust up, peering around them.”

She laughed, that little Camp Fire Flame, of the shading hair and eyelashes, as the members of the Gas Defense Division, four young privates and a corporal, took up their stations at intervals along the edge of the trenches, near.

Suddenly a gong gave out its loud-tongued signal.

“There! that gives the warning this time,” proclaimed the colonel, almost as eager in his interest as the two girls. “Six seconds and over go the puffs! See the officers and men are all at Gas Alert! See their hands go diving into their breast-satchels, snatching out their masks--adjusting them!”

“Iver had his on the soonest of any,” gloated Iver’s sister. “He--he’s just as quick’s a flash about everything--from temper to task!” the last words half under her breath, in a low chuckle of intense excitement, as she leaned forth over the pale, lumpy sand-bags, on which soldiers rested their weapons in rifle-practice, gazing along the narrow brown traverse beneath.

Over floated breezily the red-necked puffs--a few into one rounded trench-bay, a few into another.

Pop, pop, pop! went their snappy explosions, within a foot or two of an officer’s feet--the men not being stationed very close together--throwing up the prettiest little spitting foam of rose-red flame, lively to look upon against the brown earth of the trench-bay.

But what! All in one petrified instant the pale sand-bag became an ice-bag under the girls’ feet--to which their trembling, curdling soles froze!

Two low, pinched cries of startled fright rang out over that brown trench traverse.

Even Colonel Deering gave way to a hectic exclamation and hung, horrified, over the trench-brim! For--was it only a wild freak of the April gust, intent on the sham-battle, too, or a young chemist’s blundering aim?--one of those pelting powder-puffs drifted astray.

Wildly--wildly astray!

It lit not on the ground at an officer’s feet, but close and warm against his khaki breast--as if it would fire his heart--between his braided blouse and the respirator-satchel upon that heaving breast.

With his bare left hand he grasped it--nestling like a red-necked snail--to toss it to earth. But in the very act it exploded and wrapped those bare wrists of his in golden bracelets of flame;--a fierce, fledgling flamelet, just hatched out, which, winging upward, pecked greedily at the mask over his face, trying to peck through to his eyes! A stinging, searing flame that twined itself brilliantly about his stretched neck, his ears, the sides of his face, the roots of his hair--wherever it could find a sentient inch that the mask did not cover--with the pitting, piercing burn that only black powder can inflict.

“Oh-h--Iver!” Sara Davenport felt as if the earth were seamed with one great brown trench, all flame-lined, swallowing her.

But before her piteous exclamation died away, her brother--that young lieutenant--had plucked the fiery scorpion from his breast, shaken himself free of the hissing, spitting powder, was stamping fiercely up the beaten sod-steps of the trench, removing his mask with fingers that shook--some of them--like charred twigs, in a withering tempest of pain.

“Thank God! I was into my mask pretty quickly. Otherwise--otherwise I’d have been blinded for life!”

He shuddered, that Boy-Officer, who had prematurely “bawled out” a sergeant, as the words broke from him, seeming to make their way out through a great smoking hole upon his breast, where the tight khaki blouse was burned away.

“Iver! Oh--Iver!” From a distance his young sister started towards him.

Blistered within by pain and rising anger--as without by powder--he did not see her. Nor yet the other visitors back of her--one of them the girl with whom he had exchanged twilight confidences a week before!

His eye, a lurid lightning-flash above the bitten, twisted lips, had instantly singled out the face of a young chemist--a penitent private--nearer, as the latter, in an agony of apology, started towards him.

“I--I didn’t mean it, sir,” stammered the youth, feeble in his confusion. “It--’twas an accident----”

For just one-half minute Lieutenant Davenport’s tall figure loomed, rigid, in the sunlight, that powder-hole smoking upon his breast.

His breath smoked, too--the smoke of his agonizing burns.

The lightning of his eye withered the blunderer before him.

Then, suddenly, with masterful grip, the soldier seized the red-eyed powder-puff of temper exploding within him, tossed it deep into the trenches of his soul, and set his foot upon it.

“What! Are you the young rascal who potted me?”

Above his bitten, pain-wrung lips, above the storm of blue powder blisters puffing out around his wrists, his neck, the edges of his face, the explosive lightnings of the eye melted--wavered--towards the mellow sunlight of a smile--a humorous smile.

“Well! take a better aim next time. Pshaw! it might not have been your fault at all--boy.... A puff--a puff may have caught the puff--and landed it on me!”

Moved by a sudden impulse, the lieutenant held out the fingers of his less injured right hand to the blanching private--who touched but did not grasp them!

Silence almost confounded reigned among the three guests, now drawn near!

A voice--a voice broke it, that of Colonel Deering:

he chanted in a low, exultant sing-song. “That Boy--that officer--will go over the top smiling, master of himself, gassed by no blinding smoke-cloud of anger or hate! And his father was always telling me that he had a brute of a temper.”

“So he has! Had! Mine’s like it--somewhat! Oh-h, quite often my flame’s a powder-puff!” Sara Davenport was quivering from neck to heel now, with the purest, proudest flame that can crown a young heart, that of a seventeen-year-old girl’s pride in her hero-brother.

“But, oh! there’ll be no excuse for its--ever--being a spitfire in future; if Iver could--master.... Hif-f! He must be suffering--ter-ri-bly!”

The other, older, dark-eyed girl was silent. But perhaps, at that moment, as she drew her breath sharply through closed teeth, even the romance of looking through a periscope’s eye, with a Junior Aide, having a fascinating gold epaulet cord drooping from his left shoulder, paled beside the romance of that victor’s eye, humorously smiling, triumphant alike over pain and passion.

“A camouflaged dory! Well, if that isn’t a joke! If that isn’t original!”

The cry came, in laughing accents, from three or four Camp Fire Girls lounging upon a milk-white beach, absorbed in the occupation of another of their number, whose wet paint-brush dripped sky-beams upon the sands--blue sky-beams that winked dazzlingly in the August sun, as if filched from heaven’s own arch above.

“Original! About as original as Sara herself! Nobody else would think of it! A humble little dory that doesn’t go more than a mile from shore, and couldn’t come in on a sea-chase of any kind!

“How--how do you know what she’ll come in on?” The artist swung her azure-dripping brush, contemplating her dory’s dazzling side, as she lazily replied to her companions’ further comments. “How do I know what I’ll come in on myself? Queer times these--war-times! I shouldn’t be surprised, some fine morning, to find myself scouring cloud-land as a sky-skimmer, or--or----Now! where did I see that face before?

“Not on this beach, anyway. He’s the first man I’ve noticed around here. Goody! I welcome the sight of him.”

It was Arline Champion, Sara Davenport’s oldest friend, and closest chum, who spoke, digging in the sands with the toe of her tan boot, as she darted a demure glance along a rainbow bridge of sunbeams in pursuit of a prepossessing pedestrian who had passed at the moment upon the extreme edge of the beach where the white sands gleamed through sunlit tide-ripples, like milk in a golden vase.

“Well! wherever I’ve seen him, I’ve seen him. And, what’s more, he has run across me before, too! I felt the thrill (now, which of the colors shall I daub her with next, sky-blue, white, or dark slate?) the thrill that shot from one to the other of us when he passed. ’Twas more than the mere shock of surprise--admiration--of me and my three paint-pots.”

The impressionist artist, Sara, laughed--she who was reproducing, or trying to, with many a glance at the horizon, the dazzling light and shade of this August day in great bold smears upon her small boat’s side--the magical, baffling tints of sky-blue sea, dark, shadowy wave-hollows, white noonday light--to reproduce them as she saw them.

“Why, he was almost on the point of twirling his little mustache, when he first shot a sidelong glance at me--and such a start as he gave!”--the paintress went on. “He caught himself up just in time. If one’s to judge by his dress--sportsman’s suit--he’s not of the class to be rude, exactly.”

“Pshaw! What man living mightn’t be betrayed into twirling his mustache over a camouflaged dory: a little boat all smeared--like a Merry Andrew--with sky-blue, white, and splashing dark spots? Perfect clown! He couldn’t be mortal and not be amused. I wonder he didn’t smile outright as he passed.”

It was an older girl who spoke, a girl whose clear white skin was now slightly tanned, whose dark eyes held a golden spark in their depths, lit by the thrill of her response to the blue-and-white beauty of the August day about her--a response even more elastic than that of her companions.

“Smile! Pshaw! I’d have liked it better if he had smiled. I’d have liked it better if he had--even--spoken! Now--now you needn’t get off ‘tut, tut!’ Olive, in your character of Assistant Guardian; I’ll say it for you.” Sara’s dancing flame was saucy as she rinsed her camouflaging brush in the tide, then dipped it into a dazzling pot of white paint standing beside the blue. “What I mean is that if he had spoken, or--or merely smiled a little, I might”--musingly smearing on the paint--“might have remembered, all of a sudden, where I’ve seen him before.... Now--’twill haunt----”

“Whe-ew! Fancy Sally Davenport, shadow-haunted, ghost-haunted!” Olive burst into a low laugh.

“Oh-h! We know that no ghost fazes you, not even the ghost of chlorine gas. You don’t knuckle under to it!”

The kneeling artist slapped her brush suddenly against her dory’s side, drew it vehemently across the bow in a great white, dazzling smear, then turned impulsively and gazed along the still more dazzling beach upon which the stranger had passed, her gold-tipped eyelashes twinkling, her brown eyebrows drawn together hard, as if thought were dipping a paint-brush into some camouflaging pot of memory and trying to produce a picture--trying with all its might.

But the only result was a vague smear. Sesooā, to give her her Camp Fire name, turned again to her boat-painting, with a baffled sigh--and to her occasional studious glances at the horizon.

“I think I’ll take the camp skiff and row over to the Bar,” she remarked presently. “I might get a few new impressions of how sea and sky and wavy horizon look from there--a broader view of the ocean.”

“You’ll have a hollow impression if you go before dinner,” Olive Deering laughed. “What on earth put this whim into your brain, Sara, of painting your little dory up as a harlequin--a freak?”

“Freak! Harlequin! Well, maybe so. But I’m only putting her into the motley uniform of the high seas, at present, because--because Iver gave her to me. I wouldn’t let anybody else--another soul--touch a paint-brush to her, though.”

There was a low, jealous catch in the girlish voice--almost a sob--which swept the light puzzle of the passing stranger entirely out of mind. For it was August now, not April--early April--and Lieutenant Iver Davenport had had his real baptism of fire, over the top in the bleak No Man’s Land of France--liquid fire and bursting shrapnel, to which a wandering powder-puff was but a waspish prelude.

He had had his “bleeding stand-to--stifling stand-to”--facing the worst horrors in the shape of poison gas that the enemy could put over, had been wounded and citied for gallantry; and his blue-pointed service-star was enshrined forever against the red background of his sister’s heart. She would have given a good deal to know whether another girl did homage in her heart of hearts to that star, too--the tall girl, Olive Deering, Torch-Bearer, whose dark eyes could kindle with the golden spark of a Joan of Arc fire.

Sesooā shot a little measuring flame of inquiry, in the shape of a glance, up at her now and again, as she went on with her blue-and-white daubing, dressing her little boat in the party-colored uniform of the seas, with many a wavy figure and crude hieroglyphic thrown in, to make the disguising dazzle more complete.

“Ah! Madonna! Scusa me! But--but w’at for you painta her like dat--de leetla boat--eh?”

It was a new voice, suddenly drawn near, a voice with a sunny sparkle--a liquid softness--in it which hinted at its having first flowered into speech under skies as radiantly azure, as fleecily flecked, as the dory’s side.

“Why, hullo, Flamina!... Hullo! Little Nébis, our Green Leaf, is that you?” Sara, lowering her paint-brush, which dripped silver tribute now upon the sands, looked up into the new eyes, brown as the velvety barnacles clinging to some sea-rocks near, shyly daring, merrily challenging, through their black upcurling lashes.

Flamina, little foreign-born Camp Fire Sister, only two years in America--adopted some months before by the Morning-Glory Group, who, working for patriotic honors along lines of Americanization, were teaching her the Camp Fire ritual, with the meaning of her Indian name and symbol--Flamina dimpled shyly, like the ebbing tide.

“Ah, bella! Bella! But w’y you make her looka like dat--so fine--so fine?” she cried again, lost in primitive admiration of the boat’s elemental dazzle.

“So fine! Glad I’ve found one appreciative spirit, anyway! I’m painting her in big blue smears and wavy lines as they paint the great ships--American ships--going from here across the ocean now, little Green Leaf Sister, so that they may melt into the colors of the sea and sky and no horrid submarine--you know what a submarine is--coming to the surface may fire a tin fish at them--sink them. See?”

W’at for you painta her like dat--de leetla boat--eh?

“Ha! Tin--feesh?” Flamina, wrinkling her childish brows--she was barely fourteen--looked out at the broad bay, as if she expected to see the brilliant gleam of a metallic fin swimming around there.

“Pshaw! That’s a nickname the sailors have for a torpedo, childie; you know what that is--a big dark bomb that’s fired from a submarine, which skims along just under the surface of the water like a fish, leaving a white streak behind it--swish-h, like that!” Sara drew her level white brush through a sea of sunbeams, to illustrate. “When it strikes a fine ship, then it bursts--blows the ship up. D’you understand?”

“Si--yes! Catcha wise!... I catcha wise!” murmured Flamina, entranced, her curly lashes twinkling above the night-like flash beneath them. “But, bah! your greata Uncle Sam, he not goin’ to let badda submarine stay in sea much longa--eugh?”

“No! No, you bet he isn’t!” The artist slapped the slang with her brush-tip vehemently against the boat’s side. “But he’s your ‘greata Uncle Sam,’ too, now, little Green Leaf. You run over and see the dress--the pretty ceremonial dress with leather fringes--that those two girls are finishing off for you to wear at our next Council Fire meeting here on the white sands. They’re embroidering it with a green leaf, too--your symbol.”

Excitedly Flamina ran off, singing with airy gaiety, a merry dialect song of her childhood, of girlish love for the green country:

“Did you ever hear such gladness as there is in that soaring ‘Ah’? She’s just as full of song as a skylark, isn’t she?” commented Olive, who still lingered near the boat-painter. “In ceremonial dress she’ll be a fairy! I can hardly get over the fact that it’s Sybil--Sybil who’s embroidering it for her with a green leaf, who has shown her how to weave her headband, too; Sybil who, a little while ago, hated to be tied down even to fancy-work for half an hour!”

“Um-m!” Sara cast a musing, half-whimsical glance over her shoulder at a point, about a dozen yards distant, where two girls sat, engaged in fine needlework, upon the sands, with a loose garment of golden-brown khaki between them.

One, the elder, was garnishing it artistically with soft leathern fringes, weaving into them the smiling rainbows of her own thought--she being Arline, the Camp Fire Rainbow--which craved a very happy future for this little foreign-born Camp Fire Sister, adopted temporarily by the Morning-Glory Group.

The other, whose needle was threaded with sunbeams and the green of spring, bent her golden head over her embroidery with equal assiduity and sisterhood of interest; a sight which sent Sesooā’s thoughts leaping back to a city playground, crowded with foreign-born children, the cradle of her contact with these two girls from the wealthier avenues of life--Olive and Sybil--whom she, with the racy flame in her for the moment a spitting powder-puff, had scathingly pronounced “all fluff and stuff!”

Well! the early loss of a mother, the spoiling of a bereaved father had, perhaps, rendered their youthful ideals rather fluffy in a downy nest of self.

Three years of Camp Fire life at the most impressionable period, of feelings quickened by a romantic ritual, of heart knit to other girl-heart by the entwining flame of the outdoor Council Fire--of coming, as Olive had said, very near to the Father Heart in which lay their unity--this, and more, had brought one to kneeling, undaunted, by a gassed soldier, the other to embroidering an elm leaf--symbolic American elm--upon the dress of a little immigrant of not two years’ standing.

“Your brother Iver said that it ought to be a laurel leaf for Little Italy,” remarked Olive now, with just the slightest reminiscent quiver of the lip and deepening of color, as she seated herself upon the sands at a safe distance from the camouflaging artist, with her three flashing paint-pots, and drew forth a half-knit stocking from a home-woven bag that was like Joseph’s coat of many colors.

“Laurel leaf! It ought to be that for all our allies!” panted Sesooā, halting in her choice between blue and dark slate-color for her next broad harlequin smear.

“Of course!... The brave Belgians! The women of England! The French--oh! aren’t they wonderful! I had a letter from my cousin, Clayton Forrest, this morning. I wanted to tell you about it. He says the little French women are such--such out-an’-out bricks! He never saw anything like their spirit!” Olive’s dark eyes glowed as she turned the “silver” heel of her stocking for the Red Cross.

“Humph!” grunted Sesooā and daubed passionately, in a blue mood, the discounting energy of her exclamation not being at all leveled at the heroines of sunny France, but at Olive’s male cousins, about whom she quite agreed with her brother Iver, that they were altogether too many and too spectacular for such an attractive girl.

She even pooh-poohed the patriotism of the eighteen-year-old lad, worth a million or two in his own right, who was swinging a mallet now in the country shipbuilding yards not far from here.

“Well! Well, Clay was marching through a deserted French village with his company--they were just straggling along in loose order--when he saw something coming towards him that looked like a great round wicker basket--with the bright handle of a copper saucepan and a turkey-red pillow sticking out over the brim--plodding along of itself on two little clattering wooden shoes.

“As it came nearer, he made out a little gray head in a blue foulard--or handkerchief--nodding above it.... O dear! there I’ve dropped two stitches in my heel.”

Olive drew breath, to pick them up.

“It--it was a refugee, not an animated basket; a little old Frenchwoman returning to her home--or what had been her home,” she went on, winking bright drops from her eyes. “And Clay--Clay, who before the War was never a ‘grind,’ must have asked permission to carry the basket for her, and got it, although one could only read between the lines in his letter, for he spoke of finding the ruin which had been her home, and of setting down all her household belongings with a jerk that made the bright saucepans rattle like chattering teeth when--when he saw that there were only four blackened walls standing, over which the Germans had set up a tin roof, with a horrid, winking old tin door.

“They had stabled horses there.

“Clay says he was just afraid to look at the thin, withered little face under the blue foulard.... But he heard a cluck and a stamp. There she was, the little old peasant-woman, tearing down the ugly sign which the enemy had set up, stamping on it with her wooden shoes, and muttering away to herself, so--so pluckily: ‘Tchu! Tchu! Tchu! C’a ne fait rien! C’est la guerre!’ And then she began singing aloud in a voice like a Victory siren:

Sara, pealing the translated echo, that seemed to come ringing across the ocean, sniffed now to her dory’s side, instinctively exchanging her blue-dripping brush, and its corresponding mood, for a dazzling white one, with which she painted in broad smears radiant dreams of Peace--restoration--reconstruction!

“And our boys have gone over to fight, so that ‘they may never have it again!’” murmured Olive in a voice that must have been like the old Frenchwoman’s, between a sob and a song. “They’ll pay our debt to France, and carry on! Carry on, until the cry of some poor, pale little children, who crept up out of cellars in another village they entered, comes true.”

“What--was their--cry?” Sara sniffed as wetly as the outgoing tide; she had forgotten that Corporal Clayton Forrest was one of the superfluous cousins, whose feet, turning aside from paths of luxury, had enlisted in the plodding infantry with fifty companions from his father’s big loom-works.

She had seen him leading a cotillion or escorting fair maidens--debonair cavalier-in-chief of his little New England town.

She pictured him laden with the pots and kettles, the turkey-red pillows, all the household belongings of a little old peasant woman, compressed into a great wicker basket--with the handle of a copper saucepan sticking out over the rim, like the tail of a sitting bird; and she sniffed again because knighthood had not ceased to flower.

“Oh! what was their cry? The children’s cry!” Olive moistly caught her breath. “Ah!... Why! they simply burst open, like poor little pinched buds that had been kept in a cellar--the enemy had held that village four years--when they saw the American soldiers! Clay says they caught at their hands and kissed them--danced wildly round them, crying: ‘Fini, la Guerre! C’fini--c’fini--la--Guerre!’”

“But it isn’t--isn’t ‘Fini, la Guerre!’ yet. And we’ve got to carry on, too; not--not at camouflaging nonsense like this,”--Sara painted a dazzling hieroglyphic, a riddle of the future, upon her boat’s side--“but at real, steady war work, that’s no joke, in that big garden of ours, a young farm, I call it, over there on the hill--Squawk Hill--was there ever such a name!--called after a relative of yours, Olive, the noisy night-heron.... And just between you an’ me”--painting furiously--“I’m getting awf’ly--awf’ly tired of weeding, spraying, hoeing, raking right along, day in and day out, for an hour an’ a half in the morning--hour an’ a half at night!”

“Evening, you mean! Three whole hours--nothing to speak of! But they do string out, when you’re ‘carrying on’!” Blue Heron--Olive--straightened her long, graceful young back; this morning’s stunt of carrying on upon the hill of discordant name had made it feel almost as crooked as an ancient village street, tiled and twisted, in the France which they had been discussing.

“Ah, well, if we show any signs of weakening--we older girls--it’s all up with our pledges as a Group to help feed our boys and the hungry women and children on the other side of the water, for the younger girls don’t take much interest in war-gardening; they’d rather spend all their time, especially at low tide, over there on the long sand-bar, pow-wowing with the seals and birds. And I don’t blame them!” Sara waved a pensive brush towards a distant snow-white, humpy line, just rising like wavy limbs of sea-nymphs from green breakers, the merriest mob of breakers that combed and foamed and shrank as the tide ebbed. “Everything--everything is so wild an’ happy-go-lucky all around us--that----”

“That it makes one feel irresponsible,” sighed Olive; “puts the war a long way off, except--except when one turns the silver heel of a stocking--bah! another stitch down--or gets a letter from over there.”

“Oh! I know how you hate grubbing in the muck, raising vegetables. You were never cut out for a farmerette; that’s your Southern ancestry, on your mother’s side, I suppose--proud planters who left all that sort of thing to slaves!” Sara’s eyebrows went up. “And I must confess”--with a comical shrug--“that there are times when I see very little fun in planting potatoes--and all sorts of other things--with--with about forty-eleven million horrid little bugs just sitting on the fence, as old farmers say, and watching you do it, waiting to pounce on the young shoots directly they come above ground--and not one of them will light on a thistle!... But, bah! C’est la Guerre. And conservation would be nowhere--a lame duck--without cultivation! Besides the hours aren’t--very--long.”

“Yes! if it wasn’t day in and day out, for months at a stretch,” murmured the older girl, arching delicate, dark eyebrows somewhat ruefully over her stocking. “Well, our beets and carrots--all the other vegetable things, too--are coming along. We’ll have quite a cargo soon for Captain Andy to take over in his boat to some of the summer colonies and dispose of. Think of giving a big bunch of profits to the Red Cross!”

“And of having all the little infant carrots that are thinned out--to give others a chance to grow--for our own eating, meantime!” Sara laughed. “Terra-cotta babies, so tender an’ pink! Makes one feel like an ogre to devour them before they ever get a chance to mature.”

“Survival of the fittest, Sally!” Olive sprang lightly to her feet. “I don’t feel as if I could survive another minute without something to eat! Thank goodness! There goes the dear bugle, sounding mess-call--dinner--as if we were military maids. Nothing militant about us, is there, except--except our skirmishes with the big seals, to drive them off the bar. ’Twill be low tide in another hour or so. How about rowing over there?”

“Good!” Sesooā looked out towards that long milk-white, level line, a mile in length, the Ipswich Bar, rising steadily inch by inch from the billowy green of the receding tide. Colonies of birds were settling upon it and brown amphibious forms wallowing up out of the water. “Humph!” she gasped suddenly. “Maybe that sportsman--that man who passed a while ago, whose face I have seen somewhere before, is a seal-hunter, down here shooting seals, those spotted hair-seals. He had a gun over his shoulder. Bah! it just makes me cross to see a pair of eyes that I recognize as I recognized his at once, and not--not be able to place them in any head that I remember.”