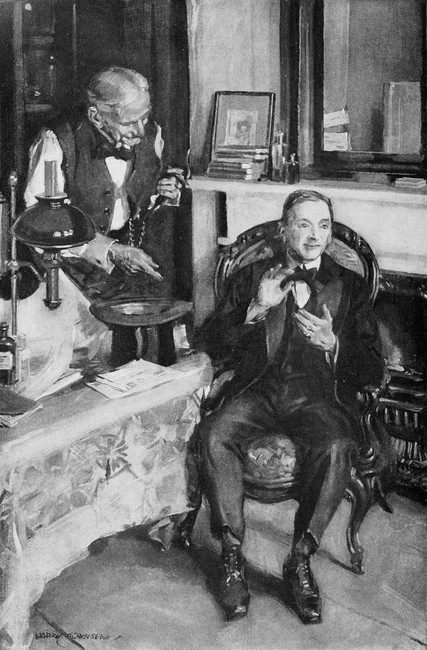

Drawn by N. C. Wyeth. Half-tone plate engraved by H. Davidson

“THE FIVE WHITE-CLAD ANCIENT WOMEN WHO, MORNING AND

EVENING,

CROSSED THE PATIO TO THE CHAPEL”

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine,

July, 1913, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, July, 1913

Vol. LXXXVI. New Series: Vol. LXIV. May to October, 1913

Author: Various

Release Date: March 25, 2018 [EBook #56839]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CENTURY ILLUSTRATED, JULY 1913 ***

Produced by Jane Robins, Reiner Ruf, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

This e-text is based on ‘The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine,’ from July, 1913. The table of contents, based on the index from the May issue, has been added by the transcriber.

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation have been retained, but punctuation and typographical errors have been corrected. Passages in English dialect and in languages other than English have not been altered.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

FICTION NUMBER

| PAGE | ||

| BEELZEBUB CAME TO THE CONVENT, HOW | Ethel Watts Mumford | 323 |

| Picture by N. C. Wyeth. | ||

| MILLET’S RETURN TO HIS OLD HOME. | Truman H. Bartlett | 332 |

| Pictures from pastels by Millet. | ||

| MAN WHO DID NOT GO TO HEAVEN ON TUESDAY, THE | Ellis Parker Butler | 340 |

| BORROWED LOVER, THE | L. Frank Tooker | 348 |

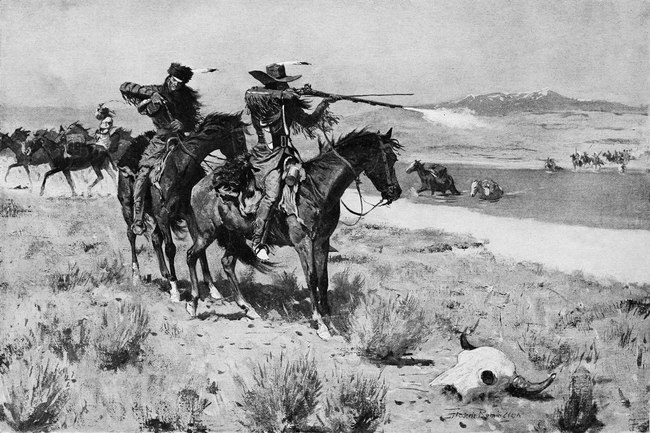

| REMINGTON, FREDERIC, RECOLLECTIONS OF | Augustus Thomas | 354 |

| Pictures by Frederic Remington, and portrait. | ||

| SPINSTER, AMERICAN, THE | Agnes Repplier | 363 |

| COMING SNEEZE, THE | Harry Stillwell Edwards | 368 |

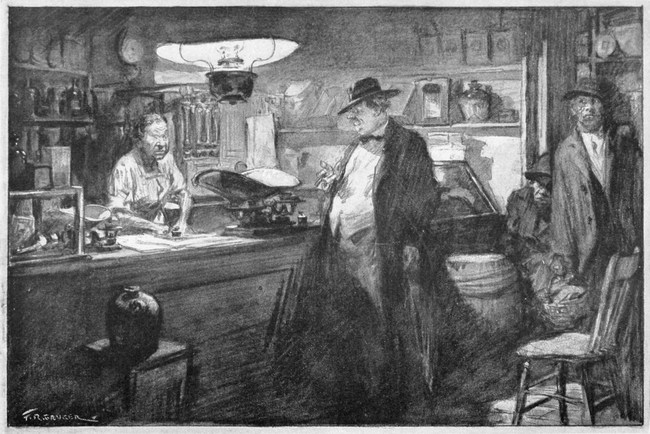

| Picture by F. R. Gruger. | ||

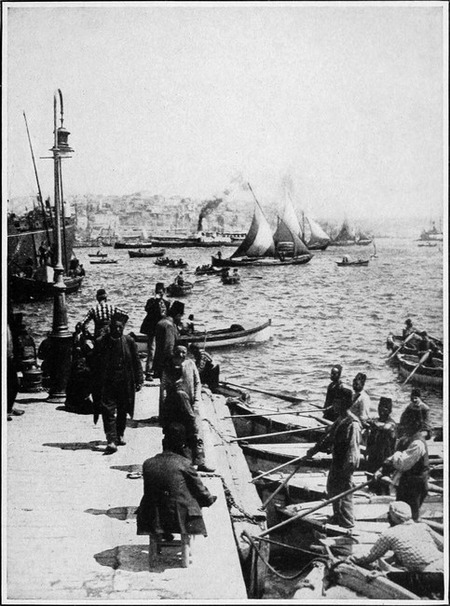

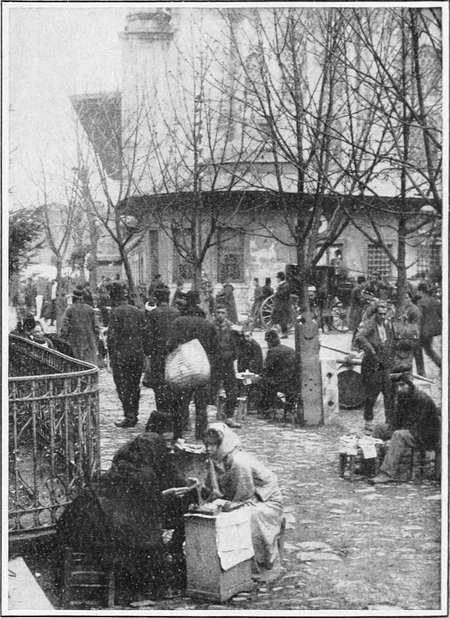

| BALKAN PENINSULA, SKIRTING THE | Robert Hichens | |

| V. In Constantinople. | 374 | |

| Pictures by Jules Guérin and from photographs. | ||

| NOTEWORTHY STORIES OF THE LAST GENERATION. | ||

| The New Minister’s Great Opportunity. | C. H. White | 390 |

| With portrait of the author, and new picture by Harry Townsend. | ||

| CAMILLA’S FIRST AFFAIR. | Gertrude Hall | 400 |

| Pictures by Emil Pollak-Ottendorff. | ||

| T. TEMBAROM. | Frances Hodgson Burnett | |

| Drawings by Charles S. Chapman. | 413 | |

| MANNERING’S MEN. | Marjorie L. C. Pickthall | 427 |

| VERITA’S STRATAGEM. | Anne Warner | 430 |

| ST. ELIZABETH OF HUNGARY. By Francisco Zubarán. Engraved on wood by | Timothy Cole | 437 |

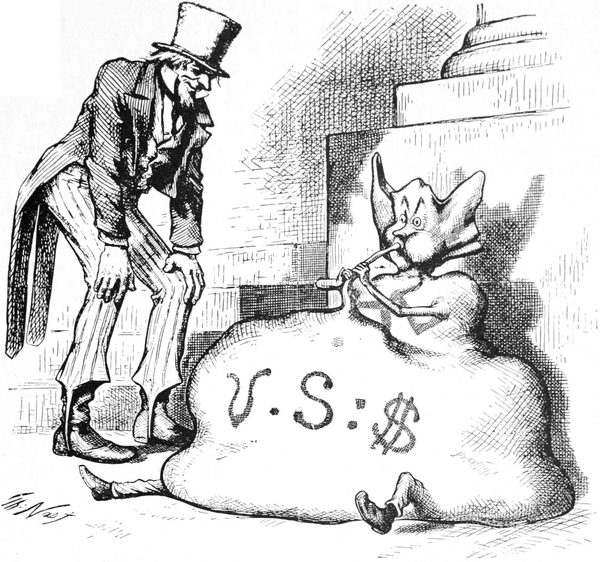

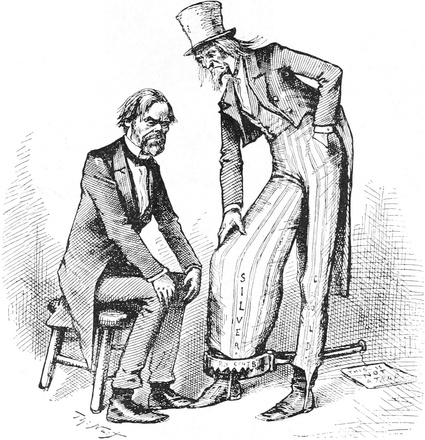

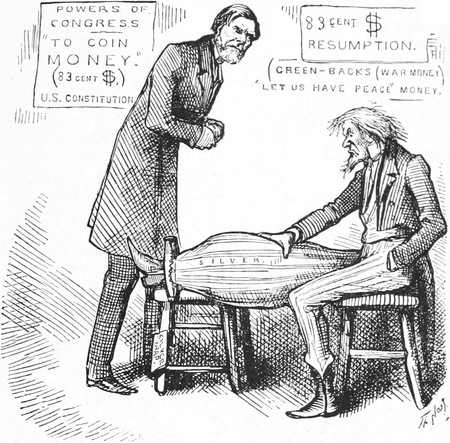

| HARD MONEY, THE RETURN TO | Charles A. Conant | 439 |

| Portraits and cartoons by Thomas Nast. | ||

| MORGAN’S, MR., PERSONALITY | Joseph B. Gilder | 459 |

| Picture from photograph. | ||

| SOCIALISM IN THE COLLEGES. | Editorial | 468 |

| MONEY BEHIND THE GUN, THE | Editorial | 470 |

| ONE WAY TO MAKE THINGS BETTER. | Editorial | 471 |

| “SCHEDULE K,” COMMENTS ON | Editorial | 472 |

| CHRISTMAS, ON ALLOWING THE EDITOR TO SHOP EARLY FOR | Leonard Hatch | 473 |

| BUSINESS IN THE ORIENT. | Harry A. Franck | 475 |

| CARTOONS. | ||

| Foreign Labor. | Oliver Herford | 477 |

| Ninety Degrees in the Shade. | J. R. Shaver | 477 |

VERSE

| MY CONSCIENCE. | James Whitcomb Riley | 331 |

| Decoration by Oliver Herford. | ||

| HOUSE-WITHOUT-ROOF. | Edith M. Thomas | 339 |

| SIERRA MADRE. | Henry Van Dyke | 347 |

| PRAYERS FOR THE LIVING. | Mary W. Plummer | 367 |

| LITTLE PEOPLE, THE | Amelia Josephine Burr | 387 |

| BELLE DAME SANS MERCI, LA | John Keats | 388 |

| Republished with pictures by Stanley M. Arthurs. | ||

| EDEN, BEAUTY IN | Alfred Noyes | 399 |

| GETTYSBURG, HIGH TIDE AT, THE | Will H. Thompson | 410 |

| BLANK PAGE, FOR A | Austin Dobson | 458 |

| MAETERLINCK, MAURICE | Stephen Phillips | 467 |

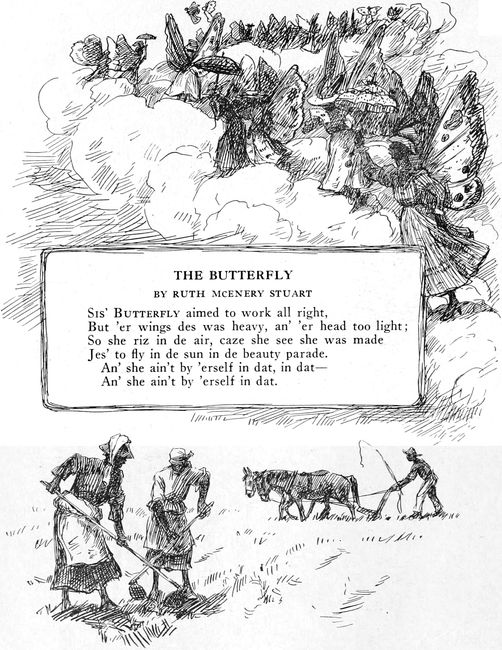

| BROTHER MINGO MILLENYUM’S ORDINATION. | Ruth McEnery Stuart | 475 |

| BALLADE OF PROTEST, A | Carolyn Wells | 476 |

| SAME OLD LURE, THE | Berton Braley | 478 |

| LIMERICKS: | ||

| Text and pictures by Oliver Herford. | ||

| XXX. The Gnat and the Gnu. | 479 | |

| XXXI. The Sole-Hungering Camel. | 480 | |

BY ETHEL WATTS MUMFORD

Author of “The Eyes of the Heart,” “Whitewash,” etc.

WITH A PICTURE BY N. C. WYETH

Copyright 1913, by THE CENTURY CO. All rights reserved.

SISTER EULALIA rose from the bench by the door in answer to Sister Teresa’s call. The broken pavement in the outer patio of the Convent of La Merced echoed the tapping of her stick as she slowly made her way to the arch leading to the interior of the building. Sister Eulalia was blind, but as nearly the whole seventy years of her life had been passed within these same gray walls familiarity supplied the defect of vision. Her daily tasks never had been interrupted since, a full half-century before, a wind-driven cactus-thorn had robbed her of sight. She wore with simple dignity the white woolen garb of the order, with its band of blue ribbon from which depended a silver cross, the snowy coif framing her saintly face with smooth bands that contrasted with the wrinkled surface of her skin. To the eye of an artist, her frail figure in its quaint surroundings of Spanish architecture, dating from the early years of the seventeenth century, would have made an irresistible appeal. But no artist ever sought that remote, almost forgotten city, and for the few Indians and half-breeds who have inherited the fallen glories of Antigua de Guatemala, the moribund convent held no interest. Occasionally one of the older “Indigenes” whose conscience troubled him would leave an offering of food at the twisted iron gate and mumble a request for prayers of intercession; or the dark-eyed half-Spanish children would stare with something of both fascination and fear at the five white-clad ancient women who, morning and evening, crossed the patio to the chapel: Sister Eulalia on the arm of Sister Teresa, Sister Rose de Lima and Sister Catalina, one on each side of the Mother Superior. To these two younger sisters—their years were but sixty-six and sixty-nine—had fallen, by common consent, the care of the Mother Superior, whose age no one knew, so great[Pg 324] it was, and whose infirmities the nuns loyally concealed. By them her wandering sentences were received as divine revelations, and indeed her strange, thin voice, as it repeated Latin texts with level insistence, conveyed a weird, Delphic impression.

The Mother Superior had been a woman of learning, of beauty, and of high birth, but all that had been long ago. Now she was but a pale shade repeating vaguely the words learned in a former life. Her features remained fine and fair, as if preserved in some crystalline substance. Her skin was unlined, for care and sorrow could reach her no more.

Unless she were being conducted to and from the chapel by her devoted handmaidens, or lay at rest in the state bed of the visitors’ room, she sat in the high carved seat at the end of the refectory table, her thin hands folded, her eyes fixed on the symbolic cross on her breast, unconscious of those who came and went about her, or of the echoing aisles and lofty pillared porticos that surrounded her abstracted existence.

As the blind nun crossed the court and entered the refectory, she became conscious of an unusual stir. She divined the presence of each of the sisters, divined them strangely intent and not a little agitated. The voice of Sister Rose de Lima reached her in a whisper of portent.

“The reverend Mother has spoken—in Spanish!”

A pause followed the announcement. There was a slight sound from the white prophetess. Sister Teresa and Sister Catalina, who stood beside her, drew insensibly closer. Their hands were joined, finger-tip to finger-tip, in the prayerful pose of medieval funereal statues; their withered faces were drawn with expectation. At the opposite end of the table stood Sister Rose, leaning forward breathlessly. Sister Eulalia remained at the entrance, rigid, as if turned into stone. The moments lengthened. The sunlight danced in golden motes through the long windows, innocent now of their olden glories of painted glass, and showed the worn carving of memorial stones emblazoned with coats of arms, half erased by the passing of many sandaled feet. The stone walls betrayed by protruding nails the absence of their wood-carvings and panels. The badly repaired rifts in the earthquake-torn walls showed garishly. The white figures, as in a tableau, remained still and unmoving, and the seated form of the Mother Superior appeared as lifeless as the waxen figure of Jesus under its shade of glass on the little altar.

She opened her eyes, if such a slow unclosing of the lids could be so called, revealing two wells of opaque blackness. A quick sigh escaped the lips of the three nuns. Sister Eulalia heard, and slowly knelt, ready to receive the word should such be sent.

The reverend Mother’s colorless lips moved. At first no sound issued from them. Then, with strange forceful vibration, her voice broke the waiting stillness.

“Woe!” she cried. “Woe! ‘The Fiend, as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour!’”

Four withered hands hastily made the sign of the cross.

Heavily as they had lifted, the waxen lids closed over the opaque black eyes. The rigid body relaxed slightly, and the Mother Superior relapsed into her wonted insensibility.

“We are surely to be tempted!” said Sister Eulalia. “Sisters, we must be strong to resist the Fiend.” Sister Teresa nodded. “We are warned,” she added.

Sister Rose crossed herself again.

Very gently Sister Catalina assured herself of the comfort of the reverend Mother, and the four aged nuns turned to their tasks again, but with beating hearts. The Fiend would beset them soon, and in some dreadful guise. Sister Rose breathed a prayer for strength, as she filled the tiny red lamp burning ever before the waxen image. Sister Teresa hurriedly began “Aves,” as she peeled an onion; Sister Catalina’s “paternosters” preceded her into the garden; and Sister Eulalia’s beads slipped hastily through her knotted fingers as she returned to the mechanical perfection of her work at the loom.

“As a roaring lion!”—Sister Eulalia’s blind eyes could conjure more dreadful sights than the faded vision of her less afflicted companions would ever see. Now she brought them before her in endless array of horror. She would know him only by his roar, she thought, and he might creep up close noiselessly. Her ear was[Pg 326] alert to the lightest sound. But the day wore on and no roaring beast came with hellish clamor to affright the gentle recluse.

Drawn by N. C. Wyeth. Half-tone plate engraved by H. Davidson

“THE FIVE WHITE-CLAD ANCIENT WOMEN WHO, MORNING AND

EVENING,

CROSSED THE PATIO TO THE CHAPEL”

Sister Catalina entered the patio from the garden-close, a yellow hill-rose in her hand to pleasure her afflicted companion with its subtle peppery scent; an act not sanctioned by the drastic rules of the convent. But years upon years had rolled by, bringing a gentle sagging of discipline. Occasionally one of the few priests who still clung to the wrecked cathedrals came to hear confessions of puerile and trifling misdemeanors, and a severer penance than a dozen “Aves” was unknown and unmerited. Sister Eulalia inhaled the rose’s fragrance gratefully. Her blunt, weaving-calloused fingers sought and found the soft petals of the flower with loving touch.

It was thus that the Rev. Dr. Joel McBean saw them. He paused, delighted. What a characteristic picture! How well composed; how symbolical of a decaying faith! His kodak was instantly leveled, and with a snap the sisters were immortalized. For Dr. McBean was known far and wide on the west coast for his lectures on the benighted people of other lands. His present visit to Central America combined his vacation with a search for new material for his winter tour.

The click of the camera caused Eulalia, the sightless, to turn sharply. Catalina, who was slightly deaf, seeing her companion’s movement, looked about and stood still in open-mouthed amazement. Then she made the gesture common to all women in all lands, and emitted the sound that accompanies it when the invading hen must be incited to flight.

“Shoo!” she cried. “Shiss—shiss!” and waved her garden apron at the intruder.

Sister Eulalia grasped the hem of Catalina’s flowing sleeve.

“What is it? Oh, what is it?” she gasped.

“A man! A strange man!” came the answer in a frightened whisper.

The gentleman in question realized that he was distinctly de trop, but he strongly desired to gather more lecture material from this promising source. Setting down the camera, he took out his well-thumbed volume of “Handy Spanish” and sought for a suitable phrase of explanation and introduction. There were headings about “The Hotel,” “The Laundry,” “The Eating and Procuring of Meals,” “At the Railway Station,” “The Diligence,” “The Physician”; but among the thousand useful phrases, not one seemed to offer itself aptly. At last he found the heading he sought: “Cameras—Films—Developing, etc.” “Have you any cyanide?” did not fit. “Have you a darkroom in this hotel?” seemed ambiguous. “Direct me to the photographer” would not do. Ah! Eureka! “May I take your picture?” He bowed politely, approached the now thoroughly frightened nuns, and with carefully spaced utterance made his request. “May I take your picture?” he repeated, with a graceful sweep of his white hand. “Fotografia—cuadro—”

Sister Rose appeared in the doorway, followed by Teresa. His gesture included them also, and the ancient gateway, the columned portico, and the quaint façade of the little chapel.

“Beautiful!” he cried. “Multo bueno! Hermosa, hermosa—muy hermosa!”

He wanted to take their picture! The nuns were completely at sea. Why should this stranger, this man with queer apparel and strange speech, want their picture? They possessed only one—the portrait of Our Lady of Mercy above the little altar of the chapel—and why should any one want a thing that so obviously it was impossible for them to give? Bewildered, they looked from one to another. Sister Rose, being the youngest and most mentally alert, became aware of the sacerdotal character of their visitor: the gold cross at the end of his chain, the wide-bordered felt hat which he waved so gracefully, the neat black clothes, the breviary that bulged from his pocket; but, more than all, the expression of his smiling face and gentle, near-sighted eyes.

“He is a priest—see you not?” she said excitedly. “His dress, his manner, bespeak it. He comes from some foreign land. Alas! that the reverend Mother cannot speak with him in Latin!”

“It is true,” said Catalina. “Pardon, reverend Father,” she quavered, “I did not know! Our picture—you shall see it.”

She turned toward the chapel, but the visitor waved her back. The group before him was irresistible, just as they were. Catalina instinctively obeyed his gesture, marveling.

“Are—are there any more of you?” he inquired in his halting Spanish.

Now at last they understood. The reverend Father was making the rounds of the clerical houses in order to make his report to the bishop. That had happened once before. Sister Rose launched into explanations.

“No. We are all that are left, except the Mother Superior,” she told him. “We are allowed here on sufferance only, for as, of course, the reverend Father knows, the churches have all been taken by the state, and but for the reverend Mother, who was kinswoman to some one great in the land, we should have been sent forth. Alas! our numbers have dwindled—grave upon grave we have made, each nun for herself, and now all are filled save five. We have not, it is quite true, turned the holy sod of our last sleeping-places as often as is the rule; but we have grown old, and the work is hard—”

It was the lecturer’s turn to be utterly confused and routed; the sudden change of manner, the deference shown to him all at once; above all the avalanche of Spanish was too much for him, but he still retained his amateur photographer’s zeal. With a hand raised to draw their attention, but which the nuns mistook for pastoral blessing, he steadied the camera against his narrow chest, and snapped a second picture. With a polite “Thank you” and a sigh of satisfaction, he wound the reel, heartily regretting the while that the limits of the camera’s focus must necessarily leave out the perfection of the setting—the towering, smoking peak of the Volcan de Fuego on the right, stained red and yellow by its sulphurous outpourings, and the menacing green inactivity of Agua’s deadly summit; all the gloom and glow of those earthquake-seamed walls, and tottering, carved gateways.

“Mil gracias!” He thanked them awkwardly. “I—well—goodness! how does one say it?” He seized upon the “Handy Spanish Phrases” again, and ran his finger down the line of camera sentences. “Please make me six prints.” “This is over-exposed.” “You have fogged the plate.”—“Tut, tut!” he exclaimed impatiently, “how in the world do you say ‘I’ll give you a blue-print’?—blue-print—blue-print—Ah! this will do. ‘An excellent portrait’—presented—for you,” he explained, and supplemented the statement with an elaborate pantomime. The nuns watched his gesticulations with breathless interest. He pointed to each in turn, made a circle around his own face, smiling blandly and nodding appreciation.

The sisters conferred.

“It clears!” said Sister Rose. “He asks us have we broken the rules and looked at ourselves in a looking-glass.” She advanced toward Dr. McBean and spoke for the sisterhood with deep earnestness. “Oh, no, reverend Father, we have not seen our own reflections for fifty years, and more—oh, never! There never has been a mirror on the walls of La Merced. Vanity is not our sin. Thanks be to Our Lady, not even in the convent well have we looked to see our faces reflected. Oh, no!”

Dr. McBean caught a word here and there, and felt that he was being vehemently reassured about something, probably that the nuns would be grateful for his kindness; that the elderly virgins knew nothing whatever of such a thing as a camera, and had no idea of the use to which he put his black box, would have seemed so ridiculous that the possibility of it never occurred to him. With more bows, and renewed and halting thanks, he took his departure.

“To-morrow,” he called. “Mañana—I will bring the blue-prints—mañana. Adios! Gracias!”

The nuns watched his departure in silence, but as the sound of his tripping footsteps died away, they turned to one another excitedly.

“Tell me, you who have eyes—what was he like?” begged Eulalia.

The others turned to her pityingly.

“Thou shalt hear. We had forgotten thine affliction, poor sister. He is thin of the leg and round above. He wears glasses on a small nose. His eyes are blue, and his hands are beautiful and white, like the hands of Father Ignatius—the saints rest his soul! He wore black, with a cassock very short indeed; and a round white collar, and a gold cross hung at his waist. He bore a small black box, that doubtless contained a holy relic, for ofttimes he clasped it to his bosom and cared for it most lovingly.”

“How strange,” mused Eulalia,[Pg 328] “that the reverend Fathers should send one to question us thus unannounced, and one who also speaks so strangely! His words were confusing, and I caught not often the sense, though I listened with all my ears. Had it not been for Sister Rose, I never should have guessed his mission.”

“Had’st thou seen him, thou would’st have known,” said Sister Teresa. “His calling was not to be mistaken; moreover, with the reliquary he blessed us.”

They had great food for speculation. Such excitement had not come into their lives in unnumbered years. The dreadful prophecy of the Mother Superior was forgotten. For the first time in a decade Eulalia was heard to lament her loss of sight. Try as she would, she could not make a satisfactory mental picture from her companions’ descriptions of their visitor. These were vivid and detailed enough, but somehow she could not bring them to take definite shape. Over and over again they discussed the form and face, the manners and raiment of Dr. Joel McBean. Not a gesture they did not speculate upon and imitate, not a sentence of his incoherent Spanish that was not dissected, analyzed, and wondered about. In particular, why did he want their picture, and then leave without it?

But “to-morrow” he had said, to-morrow he would come; then perhaps they would understand.

The sunlight turned copper-red, warning them of the lateness of the hour and putting a sudden end to their excited converse. Suddenly sobered and recalled to its own world, the flustered dove-cote subsided. With stately tread they sought the reverend Mother. She suffered herself to be lifted from her chair, and with eyes downcast took her slow way to the chapel, with the help and guidance of her two faithful attendants.

THE perspiration stood in great beads upon the brow of Joel McBean as he emerged from a black, unventilated closet in the Posada del Rey, a tray of chemicals in his hand. He held the developed films up to the light and nodded with satisfaction. The pictures were excellent, clear and sharp, well composed, excellently suited to the enlargement of the stereopticon. He examined each with minute care, but found none requiring the intensifier. There at last they were fixed forever, the replicas of this strange land of contradictions—pictures that should make his audiences realize how fortunate they were to be able to stay at home in comfort while an intrepid and intelligent explorer braved the trials of arduous travel in order to bring the simulacrum of these other lands to their very doors, together with enlightening and well-turned elucidations of the manners and customs of these benighted dwellers in lands forgotten. Already he felt glowing sentences stirring in his brain, sonorous and uplifting words, at once pitying and broad-minded. “Tolerance”—that was the motto of his discourses; tolerance always, but coupled with the well-directed searchlight of comparison. What a point he would make of these aged, recluse women—their ignorance, their useless lives, their abasement before the Juggernaut of outworn rules! He flattered himself that his presence, momentary as it was, had brought new impetus, and a realization of other and more intelligent peoples, to these remnants of obsolete conditions. “Obsolete conditions”—ah, a good expression!

He slipped the sensitized paper under the films in their wooden cases, and set them for a moment on the rim of his balcony overlooking the cobbled pavement of the unfrequented King’s Highway, upon which the tropic sun beat with white fury. A moment only sufficed, and he withdrew the prints. They proved marvelously good; as portraits they could not have been excelled. He smiled with satisfaction. How pleased these benighted little sisters would be, he thought, for he was a kindly man. He slipped the photographs between the leaves of his “Handy Spanish Phrases,” and, walking along the red-tiled gallery, made his way across the blue-and-white-walled patio, and while parrots shrieked at him and capuchin monkeys chattered, he passed from their cages toward the great, sweating water-jars, and emerged into the glare of the street.

Everywhere the remains of huge triumphal arches met his eye; enormous buildings of state and vast churches, seamed and cracked by the volcano’s upheavals, now flowered with creepers and plumed with growing trees. The silence indicated complete desertion, except where one caught, from time to time, in some shattered palace, a glimpse of an Indian[Pg 329] family at their squalid tasks, or the bray of a burro echoing from some stately ruin.

At last the twisted wrought-iron gate and the flanking spiral columns of the gateway of the convent came in sight. Dr. McBean quickened his steps.

He had been eagerly awaited within those solemn walls. After matins the excited sisters had gossiped and chatted over the events of the previous day, and then proceeded—each quietly, in her own cell, and unknown to her fellows—to make an elaborate toilet. The least faded blue ribbons were put on, a fresh coif was found, spots and stains were removed from worn white garments, while the little silver crosses received an unaccustomed furbishing.

Somewhat shamefaced they met, and laughed like children as each realized the worldliness of the others, till again Sister Eulalia’s complaint turned them to consolatory condolences. A frown of petulance had settled between Sister Eulalia’s brows. To be sure, it was lost in a maze of wrinkles, but it was there. In her old heart was revolt against the sorrow accepted so bravely fifty years before. She did not realize her sin, absorbed as she was in the Great Interest.

When Dr. McBean entered the patio he was met by the four nuns, who advanced smiling, with murmured hopes of a happy sleep of the night before and perfect health to-day.

“I kept my promise, you see,” he beamed, handing the prints to Sister Teresa, and speaking in his native tongue. “The pictures are really very good, and I hope you will enjoy having them. Thank you so much—and good-by. I start on my journey again to-day; so I must be off. Good-by, again. Adios—buanos dais!”

The nuns curtsied and bowed. He paused a moment in order to jot in his note-book: “Ignorant peoples invariably gratefully receive and appreciate—all evidences superior civilization”—bowed again and departed.

It was not till any further glimpse of him was denied by the corner wall that they turned to the photographs. They looked in astonishment, which increased to puzzled wonder; then a look of fear crossed Sister Teresa’s face. Sister Eulalia, with tears in her eyeless lids, had disconsolately sought her seat on the weaving-bench. These marvels were not for her. For a moment she hated her companions—they were no longer companions. She was alone in her misery.

From the depths of self-pity she was rushed to sudden astounded attention by sounds of wrath, of venomous speech, of resentment and anger. Sister Eulalia could not believe her ears, and the angry conversation gave her no hint of its cause. It seemed the babblings of sheer madness.

Sister Teresa had been the first to exclaim.

“See!” she cried, “I cannot understand! This is thy portrait to the life, Sister Catalina, and thine, Sister Rose, also this likeness of Sister Eulalia. But where am I? Who is this strange nun?”

Sister Catalina gazed at the picture in deep perturbation. “But I see thee well,” she affirmed. “It is thy very self upon the paper, but it is I who am not there, and this is the strange nun!” She pointed to her own portrait.

Sister Rose intervened. “Foolish! It is thy very self, and Sister Eulalia, and Sister Teresa, yes; but I am not there, and in my place is a stranger!” She pointed to her own semblance. “Who is this?”

Both Sister Teresa and Sister Catalina looked at her scornfully. “It is thyself,” they said in one breath.

Sister Rose colored till she symbolized her name, but it was the red of anger that mantled her cheeks.

“Indeed, it is not!” she answered hotly. “I have not a withered face, a jaw like a knife, and such eyes!”

“I tell thee, that”—Sister Catalina pointed, that there be no further mistake—“that is thou! This is the stranger.”

“Stranger?” laughed Rose; “then we know thee not!”

It was Sister Catalina’s turn to flame with anger. “It is not true!” she cried, stamping her foot with a grotesque parody of infantile rage. “I look like that! I know better! I remember as if it were to-day how I looked in the great mirror in my father’s house!”

“I tell thee naught but the truth,” exclaimed Sister Teresa, now quite beside herself. “Give me the picture!” She snatched at the print. A tussle ensued, punctuated by the sharp sound of a slap as they fought for the apple of discord.

Sister Catalina being the youngest, and,[Pg 330] owing to her daily labors in the garden, the most active of the trio, obtained possession of the photograph, but not till, with a desperate push, she had thrust Sister Teresa so sharply forward that she fell panting against the iron gate. The force of the impact made the rusty iron clang, and Sister Teresa sank to the ground with a faint cry.

Not till then could Sister Eulalia master her fright and nervousness sufficiently to enter the arena. With outstretched hands, forgetful of her crutch, she advanced to the center of the patio. Her first words were sufficiently arresting to bring a sudden cessation of hostilities.

“Oh, my sisters!” she cried, “oh, my sisters—the Fiend! The Fiend!”

Involuntarily three pairs of terror-stricken eyes looked about. The sun-flooded courtyard held no unfamiliar shape; the sky was undarkened by any dreadful wing. No fateful roar broke the morning hush. But Sister Eulalia had sunk to her knees, tears streaming down her cheeks.

“We were warned,” she shrilled, “but we were not proof against him. How should we know him in the guise of a holy man?” The listeners gasped. “Look, oh, my sisters, what has happened. I—even I, whom God had blessed with blindness that I might not see—I complained aloud. Envy and hatred were in my heart that ye saw marvels while I lay in darkness. I am ashamed—I am ashamed!”

She rocked backward and forward, a prey to remorse.

With a cry of sudden terror, Sister Catalina flung the crumpled photograph from her. It fluttered like a blown leaf, was caught by a vagrant breeze and wafted toward Sister Teresa, crouching by the gate. As if the white-hot fires of the dreaded volcano had suddenly poured toward her in searing streams, she screamed aloud, dragged herself to her feet with surprising alacrity, and rushed for protection to her former assailant, throwing her arms about Sister Catalina in a paroxysm of fear.

“Ay, cry aloud your terror, sisters,” continued Sister Eulalia. “What was this thing of mystery the Fiend brought among ye? In the winking of an eye it brought strife and anger. How wise were they who forbade us looking-glasses. For ye forgot your own images till ye knew them no more. Behold, this thing that showed ye yourselves, as in a glass that was not glass, let in the very spirit of the devil. All the years of our happiness together in God were as nothing before the magic of the Evil One, whom we welcomed. Though we were warned, though we knew him the ‘Prince of Disguise’! Pray for pardon—pray quickly, that our souls be not lost forever!”

They knelt in prayer, signing themselves with the cross, surprised, indeed, that their hands did not refuse their mission in punishment for their sin. The noonday sun beat mercilessly upon the veiled heads as they bent in petition. At last Sister Catalina interrupted the droning cadence.

“Sister whom God hath blessed with blindness, I will lead thee to this evil thing. Thine eyes are closed against its wiles. Take it, thou, to the chapel, and there, with a taper lit at the altar, we will burn it, that it may return to the Father of Lies, who sent it.”

Sister Eulalia winced with fear, but realizing her peculiar mission she suffered herself to be led by the trembling nun till her fingers closed on the cursed paper. Painfully, on their knees, as one mounts the holy stairs in penance, they crawled to the chapel and prostrated themselves at the rail. With tears of remorse, the sisters embraced. A taper, one of the precious few in the tin box under the altar-lace, was lighted at the flame of the tiny red lamp. The print as it flared up seemed to show the pictured faces in twisted grimace; then it blackened, withered to ash, and dispersed in gray filaments.

For a moment the penitents remained in silent contemplation, then with one accord they crossed the patio to the refectory. Though the reverend Mother hear them not, yet they must make confession.

As they entered they stopped short, spellbound. The opaque black eyes were open wide, staring at them from the crystalline whiteness of the Mother Superior’s face. To the culprits that gaze was as accusing as any clarion voice of Judgment. They bowed their heads.

The reverend Mother’s lips moved.

“Vanitas vanitatum!” she cried, and again—“Vanitas vanitatum!”

The echoes took up the sound as a bell that will not be silenced—Vanitatum.

BY JAMES WHITCOMB RILEY

WITH LETTERS FROM HIMSELF AND HIS SON

BY TRUMAN H. BARTLETT

REPRODUCTIONS MADE FOR THE CENTURY OF PAINTINGS AND PASTELS BY MILLET IN THE COLLECTION OF THE LATE QUINCY A. SHAW

WHEN Jean François Millet, with his wife and nine children, went to Cherbourg in August, 1870, soon after the breaking out of the Franco-German War, he carried with him some of his own pictures and several belonging to Théodore Rousseau that had been left in his care, which were owned by a Mr. Hartmann, a friend of both artists. Once in that city, there was no certainty that Millet could sell a picture or get means to live upon from any one. To be sure, Barye and his family were already there, but he had a large family to look after, and was helping Armand Sylvestre, the writer, who lived there.

Detrimont, the picture-dealer, had advanced eight hundred francs on a painting he had previously ordered of Millet; but when this money should be gone Millet was sure to be in very embarrassing straits. Sensier’s business relations with Millet had long since ceased, and he had gone with the government to Tours. What was the poor painter to do, and what did he think? Behind him were twenty-one years of incessant labor and harsh experiences, a procession of great works of art sent into the world, out of which he had got a bare living. He was tired and health-broken, and had a large family to care for; he was worried over the dark days of his country, while possessing hardly a dollar and living in a city always indifferent to his genius.

But fortune had not quite forsaken poor Millet. Durand Ruel had managed to get out of Paris and reach London with some pictures. He, too, was in no prosperous condition, and in his anxiety he determined to give an exhibition in that city and take his chances as to the result. Trusting in the merits of the “Norman Peasant,” which he believed would be recognized in London, even in war-time, he wrote to Millet asking for some pictures and promising to send him some money—a small sum at once, if he were in need. Ruel added as a further encouragement that if he had any luck he would continue to order pictures and forward money for them as fast as he could.

The London scheme worked so well that Millet was enabled to stay in Cherbourg and its vicinity for sixteen months; and yet there was trouble in it. Nothing ever seemed to come to him in bright colors that was not shaded or involved in some train of unpleasant circumstance; and what made it still more fateful was the fact that he could not extricate himself by his own efforts. Never was a leaf more powerless before the wind than was Millet in the worldly entanglements that pursued him to his latest breath.

“I will begin a picture for you at once with the greatest ardor,” he wrote to Ruel. When he had finished it, it was taken by his son François to the wharf, where the little steamer lay that was to carry it to Southampton, while the father went to the custom-house to get a permit. The collector of customs, although knowing perfectly well who the artist was, refused to accept his declaration of authorship—all that ever was required—unless the artist would swear to it on the Bible. This extra demand, and the arrogant manner of the collector, was interpreted by Millet as an insult, and he left the official’s presence in anger and despair. He could not forward this or any other picture without the oath, and how was he to live if he did not? To his surprise and joy, he found on going to the wharf where the picture was to leave for Southampton that it had been taken on board the steamer. A seaman who had charge of embarking freight had seen the name of Millet on the box, and had asked young François about it, and whether that was the Millet who came from Greville. Learning that it was, he said,[Pg 333] “Oh, all right! Never mind the permit; bring it aboard, and I will see that no one disturbs it.”

From the collection of the late Quincy A. Shaw. Half-tone plate engraved by R. C. Collins

THE SPADERS

FROM THE PASTEL BY JEAN FRANÇOIS MILLET

There seemed to be an undying enmity against Millet on the part of the representative authorities of Cherbourg, beginning when they gave him a niggardly allowance to pursue his first studies in Paris, accentuated when they refused to continue it, and brutally intensified when he returned for refuge in 1870. Nor did it cease; for not long after his death some resident artists were discovered counterfeiting Millet’s works and selling them to those who were supposed to have been familiar with what he had done for more than thirty years. The punishment meted out to these rascally imitators was only two months in prison, and even then there were those who regarded the penalty as too severe for the offense.

There were still more troubles to come, for Millet tried to do some sketching out of doors, but the authorities prevented him. Writing to Sensier in September, 1870, he says: “It is utterly impossible for me to make a single mark of the pencil outside of the house. I should be immediately cut down or shot. I have been arrested twice and brought before the military authorities, and was released only after they had inquired about me at the mayor’s office, though they advised me strongly not even to show an indication of holding a pencil.”

The following extracts from other letters to Sensier will illustrate the precious patriotism of these military authorities when their own comfort was in question, as well as let a little light upon their ardent efforts to sustain their struggling country in its darkest days of 1870–71. He says:

“What a chance those miserable Prussians have for devastating the country! I fear that, though touching Paris lightly at present, they will still hold it so that they may continue their work in other places. I fear that they will make believe to attack Paris, and under the shadow of that pretense devastate the country of everything it has that they need. During this time Paris will exhaust its provisions, and,[Pg 334] famine once there, they will do with it as they please. In supporting the Prussians the country will eventually exhaust itself; then will come universal famine. What do they think of all this at Tours? There is one thing I wish to tell you: for a long time they have sent from here to England sheep, pigs, potatoes, and every kind of provisions, but since the war these exports have increased. A good deal of complaint has been made, and for my part I ask myself how they can send these things to strangers abroad—and probably by indirect ways to the enemy—when we have so great a need for them. How can they rob a country now given to misery, as ours is?—for a large part of France is not only devastated but is prevented from planting crops for the coming year.

“Naturally, you know of Gambetta’s circular for preventing the exporting of provisions. That circular did not give details of everything that should not be exported. The authorities here have slyly dodged that and have permitted things to be sent away that were not mentioned in the circular. This has almost made a revolution. The people tried to prevent the embarking of these articles, but the national guard surrounded the dock and the shipment was made. I think these authorities are horrible. They let eggs, butter, and fowls be sent away. The mayor and the prefect should be whipped. If you can only tell Gambetta this! It appears that a great quantity of cannon is in the arsenal here, of which no use is made. They say that the chassepôts that came from England were left out of doors in the rain and mud. The maritime authorities do nothing, and the people cry out against them. It is said that there are eight thousand sailors here who wish to go into action, but not one is permitted to leave.

“Neither will the authorities send the cannon to Lille—those that were ordered to be sent long ago—and Lille begs for them. Eleven hundred cannon here, and not one used or sent away to the places where they are needed! There are also several gunboats which the officers say could be employed on the rivers, but they, too, are idle, although certain officers are doing their best to have something done with them. Why not tell Gambetta all this, so that he could give rigid orders? Durand Ruel has sent me a thousand francs. It was time! Oh, it was time! It will be quickly spent; and so I must work to get more when I need it.”

Before Millet returned to Barbizon he went with his family to look for the last time upon the scenes of his youth, to walk over the fields that his forefathers had tilled for generations, to visit the church where his dead had worshiped, and to sit beside their graves. It was a pilgrimage that deeply touched every chord of his nature as it never had been touched before.

He was conscious that he had lived an unusual life, that he had contributed his share to his country’s glory, and that, too, when rarely released from the awful chain of untoward circumstances. Yet no word of bitter complaint ever escaped his lips, nor did he fully confide his thoughts to any one. He knew that some tidings of him had reached his native hamlet and had given pleasure to its humble dwellers. “He longed,” says his son François, “to see whether he could again feel his youth. I think he did, for he never seemed to be present, not even when he told us children of the wondrous legends of the priory of Greville.”

The following is a part of François’ story of their journey to Gruchy.

“When we all went to Gruchy we stopped on the way at Vauville, and as we came to the little inn we were met by a large and fine-looking old woman who approached us as if we were princes, and after saluting us she said very humbly: ‘Gentlemen, we haven’t much for the table.’ ‘Haven’t you soup?’ asked Father. ‘Oh, yes!’ she replied, ‘but do you care for that?’ ‘Certainly, we like soup,’ was the answer. ‘Very well, then, you shall have some soup.’ ‘Have you any butter?’ ‘Yes, we have butter.’ ‘Very well, we like butter.’ ‘Then, gentlemen, you shall have butter, and you can eat as we do.’ ‘But I am very hungry,’ said one of my brothers. ‘Then,’ said the woman, ‘we will kill a rabbit for the boy.’

“While we were waiting for our food we sat around a fireplace in which was burned a kind of dry brush, thrown into it with a pitchfork. It made a tremendous blaze, giving Father much pleasure, and he said that that was the way they had fire when he was a boy in the old home.

From the collection of the late Quincy A. Shaw. Half-tone plate engraved by C. W. Chadwick

THE SHEPHERD

FROM THE PASTEL BY JEAN FRANÇOIS MILLET

“After we had eaten we went out to make some sketches of the church and priory. Soon after our arrival, a peasant, eighty-seven years old, who had known my grandfather, came to the hotel to find us and to renew his acquaintance with Father. He invited us to come to the priory and take breakfast with his son, who lived there and had charge of the property. We accepted the invitation, and just before it was time to go the old man came with two carts, a large one with[Pg 336] rude board sides for Father, Mother, and the older children, and a small one for the younger ones and the servant. In this way we were trundled off to the priory, where we were very warmly welcomed by the old man’s son.

“The dining-room was very large, with an enormous fireplace, and great iron locks were on the doors. Our breakfast consisted of little beans and butter. While we were eating, a half-crazy uncle of our host sat in the fireplace, watching, as he said, for a headless prior who continually visited the convent, entering it through the chimney. ‘I must not let him come down,’ he said, ‘so I watch him; but he must not know that I see him.’

“The priory is very rich in legends concerning every phase of the life that has been lived in it for many generations. This man had cared for it since it had been used as one of the buildings of a farm; and, in cultivating the ground, had lived so secluded a life, and dwelt so constantly upon the history of the priory, that he had become insane, his head turned in faithfulness to duty.

“The priory is on a hill, while the village of Vauville is below, near the sea, and hidden from the building.

“On entering the church at Vauville we encountered the curé, who appeared very curious and desirous to talk with strangers, as they very seldom come there. While Father was looking at the picture over the altar, he said, ‘It is not bad; it has good color’; whereupon the curé, who had come up hurriedly, remarked, ‘You are looking at the picture, I see. It seems to interest you.’ ‘Yes,’ said Father. ‘Ah, well, I can tell you who painted it—one Mouchel, a child of Cherbourg. I don’t know how much he is known away from us, but he had a pupil who was helped by the city of Cherbourg and has now become known as a man of great talent.’

“The curé was very polite, and he conducted us to the door without dreaming that he had seen the pupil of Mouchel, though Father was that person.

“One day when we were in the café of the inn, a little old man with large blue eyes came to the door and looked at Father, and said in the patois of the locality, which consists more of movements of the head, peculiar accents of words, and of pauses, than of a full language, ‘Ah! do you know? Yes.’ Then Father’s chin moved upward in deep emotion. ‘Ah! I knew you when you were a little toad. We are old now. Ah, changes have come! You know it.’ ‘Come in,’ said Father, still more affected, pointing to a chair and table. Then turning to me, with his head close to my ear, he whispered, ‘It is Peter, our old servant. He took care of my father when he died, as well as all the rest of the family.’ After Father had become somewhat composed, he said to the innkeeper, ‘Give Peter all he wants.’ ‘Oh, I want nothing now, but to see you. To go back into the years. Ah, we are old now!’ This was too much for Father, and, rising to go out, he said quietly to the innkeeper, ‘He is now a drunkard, but give him everything.’

“One night at the little inn, the wind blew a real tempest; it was fearfully dark and the roar of the sea was something terrific, so the proprietor said to his servant, who was putting thorns on the fire to make a great blaze, as if to calm the elements outside, ‘How would you like to go on such a night as this to the priory?’ ‘Oh, I don’t know,’ he replied, ‘there are things you cannot reason about, and happenings you had better keep away from. Perhaps it would be better to stay at home on a night like this. The old boy up there is not a good sleeper. He is out and around nights like this, watching his stacks of grain, for he, as you know, though very learned, is in league with the devil in some way. At any rate, the devil has something to do with him. He always looks at me suspiciously, as if I had stolen his wheat, though he knows well enough that it was the devil that did it. For, even in the daytime, when he counts his sheaves, there are always some lacking, and in the night still more are missing. He can’t even drink his own cider without the devil hiding his pitcher and playing all sorts of tricks with him. No, it’s better to stay indoors when things outside are so uncertain.’

From the collection of the late Quincy A. Shaw. Half-tone plate engraved by H. Davidson

THE LESSON IN KNITTING

FROM THE PAINTING BY JEAN FRANÇOIS MILLET

“The proprietor of the inn had been a cook in Paris, but had returned to his native hamlet to live the rest of his days. He soon began to talk, perhaps to please us, as we said nothing. ‘They are strange men, those of this country,’ he began;[Pg 339] ‘I myself have been in Paris, and I have seen many things; but I could not stay away from here, and so I came back. You see, sir, we people of these parts cannot live away. I don’t know why, but there is no place like our own land. So I came back from Paris to spend the time still left to me. But there was one who did not come back. Nor is this country without its interest. Many years ago a young fellow named Millet lived near here, and he had the strange fancy to be a painter, making pictures on cloth, sir, and, almost incredible as it may seem, he went to Paris. Going to Paris nowadays is nothing, but then it was a very serious matter. They do say that though he had much trouble he had courage also, and has succeeded, so that he is on the road to celebrity and has become a great honor to his country. A man of much talent, of whom we are all very proud.’ Father said nothing, but I saw he was smiling broadly. When we left the inn for good, the proprietor looked at Father very carefully, as if he suspected that he had not entertained an ordinary traveler; and finally, his suspicions evidently growing, he said, ‘I remember the physiognomy of the Millets, who were well known along this coast as fine-looking men.’ We could see that he was ready to ask whether Father was not the young fellow who went to Paris. His curiosity was gratified later.

From the collection of the late Quincy A. Shaw. Half-tone plate engraved by G. M. Lewis

PEASANT WOMAN AND CHURN

FROM THE DRAWING BY JEAN FRANÇOIS MILLET

“When we visited the graveyard at Greville, where our ancestors were buried, and found their graves, which had no headstones and the wooden crosses of which had long ago gone to dust, we saw that they were covered thickly with weeds nearly as high as our heads. I said nothing, but pointed to them as if asking which member of the family each grave contained; and Father, also pointing, simply said, ‘Father, Mother, Grandmother,’ and so on through the family category. Waiting awhile, much affected, he repeated, as only he could, the words, ‘Oh, the high weeds where sleep the dead!’

“In a few days we went there again and found a man cutting the weeds. Father asked him why he was doing so. ‘To sell them,’ he replied. ‘Sell!’ exclaimed Father. ‘Do you say that you are selling the weeds from the graves?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Does the curé know of it?’ ‘Know of it? Of course he does. He consents to it and thinks it a good thing to do.’ Then, as if speaking to himself, Father said, ‘Ah! the heart has left this place. You are men no more. And the curé—!’

“It was in November, 1870, that Father made the sketch of the superb marine, which he painted in the spring of the next year and sent to Ruel.[1] He made also a great number of sketches and drawings of places near Greville and Vauville, as well as of the priory. Father loved every inch of the earth of his native hamlet. It is a wonderful land.

“We lived in M. Feuardent’s house in Cherbourg, Father doing his work in an ordinary room with no special light facilities. He desired very much to make some pictures of the country and sea around Cherbourg, but the authorities told him that he must not even carry a pencil or a note-book. It was in Cherbourg that he made the drawings of ‘The Milk-maid,’ from sketches taken in Greville.”

[1] Owned by the estate of the late Quincy A. Shaw, of Boston, Massachusetts.

BY EDITH M. THOMAS

BY ELLIS PARKER BUTLER

Author of “Pigs is Pigs,” “Long Sam ‘Takes Out,’” etc.

UNCLE NOAH PRUTT, sitting in the front row of seats, leaned forward and put his hand behind his ear, vainly seeking to hear what his wife was saying to Judge Murphy. From time to time he stood up, trying to hear the better, but each time the lanky policeman pushed him back into his seat.

“Judge, yer Honor,” said the policeman, after the fifth time, “this man here has nawthin’ t’ do with th’ case, an’ he’s disthurbin’ th’ coort. Shall I thrun him out?”

“Let him be, Flaherty, let him be!” said the justice, carelessly, and at the words Uncle Noah arose and came forward to the black walnut bar that separated the raised platform of the justice from the rest of the room.

“Ah pleads not guilty, Judge!” said Uncle Noah, laying one trembling hand on the rail and pushing forward his ear with the other. He was a coal black Negro, with close-kinked white hair that looked like a white wig. His nose was large and flattened against his face, and his eyeballs were streaked with brown veins that gave him a dissipated look. He was the type of Negro that, at fifty, claims eighty years of age, and, so judged, Uncle Noah Prutt might have been anywhere between sixty and one hundred and ten. As he stood at the bar his black face bore a look of the most deeply pained resentment, and his thick lower lip protruded loosely as a sign of woe.

“Sit down!” shouted both the justice of the peace and the policeman, and, with his lip hanging still lower, Uncle Noah backed into his seat. He sat as far forward as he could, and leaned his head still farther forward.

“Who is that man?” asked the justice of no one in particular.

“Him? He’s mah husban’,” said the young colored woman, with a slight up-tilt of her nose. “Yo’ don’ need to pay no ’tention to him at all, Jedge. Ah ain’ ask him to come yere. He ain’ yere in no capacity but audjeence, he ain’.”

“He has no connection with this case?” asked the justice.

“No, sah!” said the young woman, decidedly.

“If he makes any more trouble, Flaherty,” said the justice, “put him out of the court. Now, what is this trouble, Sally?”

The young woman standing against the bar was fit to be classed as a beauty. Well-formed, with a rich yellow skin through which the blood glowed in her cheeks, with masses of black hair and her head carried high, she was superb, even in her cheap print wrapper. Even the fact that her feet were hideous in a pair of broken and run-down shoes of the sort worn by men did not impair her general appearance of an injured brown Venus seeking justice, and when she glanced at the prisoner her bosom heaved with anger and her brown eyes glowed dangerously.

The prisoner sat humped down in a chair in an attitude of the most profound dejection. He was of a darker brown than the woman, and so loose of joint that when he moved he flopped. His feet were so large as to be almost grotesque, and he was so thin that the bones of his shoulders were outlined by his light coat. But as he sat in the prisoner’s seat his face was the most noticeable feature. It was thin and long for a Negro, but with such high and prominent cheek-bones that his eyes seemed hidden in deep caves, and the eyes were like those of a dog that knows he is to be beaten. His wide mouth hung far down at the corners. He was a picture of the utterly crushed, the utterly helpless, the utterly hopeless. He was the shiftless Negro, with the last ray of hope extinguished. He had but one thing to look forward to, and that was the worst. As the justice asked Sally the question the prisoner’s mouth sagged a bit farther at the ends, and his eyes took a still sadder dullness.

“Yo’ ain’ miss it none when yo’ asks whut am dis trouble, Jedge,” said Sally, angrily. “Dis yere ain’ nuttin’ but trouble, an’ I gwine ask yo’ to send dis yere Silas to jail forebber an’ ebber. Yassah! An’ den he ain’ gwine be in jail long enough to suit me. An’ Ah gwine ask yo’ to declare damages ag’inst him, fo’ huhtin’ mah feelin’s, an’ fo’ tryin’ to drown me, an’ fo’ abductin’ me away from dat poor ol’ no-’count Noah whut am mah husban’, an’ fo’ alieamatin’ mah affections, on’y he couldn’t. When Ah whack him awn de head wid dat bed-slat—”

“Now, one minute,” said the justice, raising his hand. “Flaherty, what do you know about this case?”

“Well, yer Honor,” said the policeman, in the confidential tone an officer of the law assumes when he feels that he, and he only, can explain matters, “th’ way ut was was this way: I was walkin’ me beat up there awn Twilf’ Strate this mawrnin’, like I always does, whin I heard a yellin’ an’ a shoutin’. So I run into th’ lot—”

“What lot?” asked Justice Murphy.

“’Twas betwane Olive an’ Beech Strates, yer Honor. This here deff man, Noah Prutt, lives in a shack-like there, facin’ awn th’ strate. Th’ vacant lot is full iv thim hazel-brushes an’ what all I dunno.”

“You said there was a shanty on the lot. How could it be a vacant lot if there was a shanty on it?” asked the justice.

“Now, yer Honor,” said Flaherty, with an ingratiating smile, “there’s moore than wan lot in th’ wurrld, ain’t there? Th’ lot this Noah Prutt lives awn is wan iv thim. And th’ nixt wan is another iv thim. An’ th’ nixt wan t’ that is th’ third iv thim, an’ th’ ould Darky owns all iv thim, and iv th’ three iv thim but wan is vacant, and that’s th’ middle wan. There’s a shanty awn th’ furrst wan, and there’s a shanty awn th’ thurrd wan, an’ as I was sayin’, there’s nawthin’ awn th’ vacant wan excipt brush-like, an’ mebby a few trees, an’ some tin cans, an’ whatnot.”

“Very good!” said his honor. “Go ahead.”

“Well, sor,” said Flaherty, “this Prutt an’ this wife iv his lives in th’ furrst shanty, but th’ other wan is vacant excipt whin ’t is occupied. Th’ ould man rints ut now an’ again, an’ a dang lonely habitation ut is, set ’way back fr’m th’ strate, like ut is. So here I was, comin’ along, whin I hear th’ racket in th’ vacant lot, an’ whin I got there amidst th’ hazel-brush here was this Sally a-hammerin’ this Silas over th’ head wid a bed-slat, an’ him yellin’ bloody-murdther. So I tuck thim up, th’ bot’ iv thim, yer Honor.”

“And that’s all you know of the case?” asked the judge.

“Excipt what she tould me,” said Flaherty.

“And what was that?” asked Judge Murphy.

“Ut was what previnted me from arristin’ her for assault an’ batthery,” said Flaherty, “for if iver a man was assaulted an’ batthered, this same Silas was. She can wield a bed-slat like a warryor.”

“Ah’d ’a’ killed him! Ah’d ’a’ killed him shore!” said Sally.

“She w’u’d!” said Flaherty, briefly. “Thim Naygurs have th’ harrd heads, but wan more whack an’ he’d iv had a crack in th’ cranyum. So I wrested th’ bed-slat from her. Th’ place looked like there’d been a war, yer Honor. Plinty iv thim hazel-brushes she’d mowed down wid th’ bed-slat thryin’ t’ murdther him. An’ whin I heard th’ sthory, I did not blame her.”

“I have been waiting patiently to hear it myself,” said the justice.

“Accordin’ t’ th’ lady,” said Flaherty, “she’s a respictable married woman, yer Honor, bound in th’ clamps iv wedlock to this Noah Prutt, an’ niver stheppin’ t’ wan side iv th’ path iv wifely duty or to th’ other. ’Tis nawthin’ t’ us why a foine-lookin’ gurrl like her sh’u’d marry an’ ould felly like him. Maybe him havin’ two houses atthracted her. I dunno. But, annyway, she’s had t’ wash th’ wolf from th’ doore.”

“Had to do what?” asked the justice.

“Go out doin’ week’s wash t’ kape food in th’ house,” explained Flaherty. “For th’ ould man will not wurrk much. He’s got that used t’ livin’ awn th’ rint iv th’ exthra shanty, ye see. An’ there’s been no rint comin’ in this long whiles, for th’ prisoner at th’ bar has been th’ tinint iv th’ shanty, an’ he ped no rint at all.”

“Why not?” asked the justice.

“Well, sor,” said Flaherty, rubbing the hair at the back of his neck and grinning,[Pg 342] “th’ lady here says he’s been that busy coortin’ her he’s had no time t’ wurrk. ’Twas nawthin’ fr’m wan ind iv th’ week till th’ other but, ‘Will ye elope wid me, darlint?’ an’, ‘Come now, l’ave th’ ould man an’ be me own turtle-dove!’”

“Ah tol’ him Ah gwine murder him ef he gwine keep up dat-a-way of proceedin’!” cried Sally, shrilly. “Ah tol’ him! Ah say, ‘Go on away, you wuthless deadbeat Nigger! Wha’ don’ you pay yo’ rent like a man, befo’ yo’ come talkin’ ’bout supportin’ a lady?’ Dass whut Ah tol’ him, Jedge. An’ whut he say? He say, ‘Sally gal! Ah gwine nab yo’ an’ hab yo’. Ah gwine steal yo’ an’ lock yo’ up, an’ nail yo’ up, an’ keep yo’!’ Dass whut he say. An’ he done hit!”

“Stole you, and locked you up?” asked the judge.

“Yassah!” cried Sally, glaring at the trembling Silas. “He lock me up, an’ he nail me up, an’ he try to drown me, ef Ah ain’ say whut he want me to say. Dat low-down, hypocritical Nigger! Yassah! Ah tole him, ‘Silas, ef yo’ don’ go way an’ leave me alone Ah gwine tek mah hands an’ Ah gwine yank all de wool right offen yo’ haid!’ Dass whut Ah say, Jedge. An’ Ah say, ‘Ef yo’ don’ shet up Ah gwine tear yo’ eyes out!’ An’ Ah means it. Talkin’ up to me like dat! An’ den whut he do?”

She held out her hand toward the dejected Silas and shook her finger at him.

“Den whut he do? He see Ah ain’ to be coax’ dat-a-way, ’cause he a no-’count Nigger, an’ he let on he purtind he get religion an’ wuk on mah feelin’s. Yassah! ’Cause he know Ah’s religious mahsilf an’ he cogitate how he come lak a snake in de grass an’ cotch me whin Ah ain’ thinkin’ no meanness of him. So long come dish yere prophet-man, whut call hisself Obediah, whut get all de Niggers wuk up an’ a-shoutin’ over yonder on de ol’ camp groun’s. Ah am’ tek no stock in dat Obediah prophet-man, Jedge, ’cause Ah a good Baptis’, lak mah husban’ yonder; but plinty of de black folks dey run to him, an’ dey hear him perorate an’ carry on, an’ dey get sot in dere minds dat dey gwine to hebben las’ Tuesday night whin de sun set. Yassah, dass whut dey think, ’cause de prophet-man he pretch dat-a-way. An’ dis yere Silas he let on he gwine to hebben along wid de rest of de folks.”

She let her lip curl scornfully.

“Him a-gwine to hebben!” she scoffed. “But Ah ain’ but half believe he got religion lak he say. Ah say, ‘Luk out, Sally! Ef he gwine to hebben nex’ Tuesday let him go; an’ if he ain’ gwine, let him alone.’ But yo’ look at him, Jedge! Jes look at him! He ain’ look so dangeroos, is he? An’ whin he come to me an’ say, ‘Sally, Ah done got quit of de ol’ Nick whut was in me, an’ Ah gwine be lak dat no mo’,’ Ah jes got to believe him. Yassah! He dat pernicious meek an’ lowly an’ sorrumful-like dat Ah ain’ suspict no divilment at all. ‘Ah feel troubled in mah conscience,’ he say, ‘’cause Ah been tryin’ to lead yo’ on de wrong paff, an’ Ah can’t go to hebben nex’ Tuesday les’ yo’ forgib me,’ he say, an’ he look so downheart’ an’ seem lak he so set on gwine to hebben wid de rest ob de folks, dat Ah say, ‘All right, Silas, Ah don’ hold no hard feelin’s. Ef yo’ don’ bodder me no more, Ah forgib yo’ whut is pas’ an’ done for, but ef yo’ gwine to hebben yo’ better clean up yo’ house an’ put hit in order, lak de Book say, before yo’ start, ’cause ef yo’ don’ yo’ gwine get sint back, shore!’ So he let on lak dat how he think, too. He purtind to thank me kinely fo’ dat recommindation, an’ he ask’ c’u’d Ah lind him a scrub pail an’ a mop an’ a broom, twell he clean up he house. An’ I so done.

“Dass all right! He scrub, an’ he wash, an’ he clean, an’ he move all he furniture out in de lot, an’ he clean, an’ he wash, an’ he scrub! He ain’ wuk lak dat fo’ months, Jedge. So den Ah think shore he got religion, lak he let on. So, come Monday, Ah got a job down to Mis’ Gilbert’s scrubbin’ her house, an’ Ah jes got to hab dat pail an’ dat mop an’ dat broom. So Ah tell Noah whut job Ah got, an’ Ah say, ‘Noah, Ah gwine down to Mis’ Gilbert’s house, fo’ to help clean house, an’ ef she want me, Ah gwine stay right dah twell de house all clean’ up.’ Cause dat a long perambulation down to Mis’ Gilbert’s house, Jedge, an’ ef she ask me to stay a couple o’ days, Ah gwine save mah breakfas’ an’ mah suppah whilst Ah stay down yonder. So Ah go outen de house an’ Ah walk down de street twell Ah come to de gate whut lead up to Silas’ house, an’ Ah walk up de paff, an’ Ah knock on de do’. Nobody say nuffin’! Ah knock ag’in. Nobody say nuffin’! Ah open de do’ gintly, an’ Ah peek in. Ai[Pg 343]n’ nobody in de shack at all. So Ah steps in, fo’ to get mah pail an’ mah mop an’ mah broom.

“Dab dey set, right by de do’, an’ excipt fo’ dem, dey ain’ nuffin’ in de shack at all but de straw outen Silas he’s bed, an’ dat all scatter aroun’ lak to dry an’ air out. Excipt dey one bed-slat whut Ah calculate Silas he keep handy fo’ to whack at de rats, which am mighty pestiferous about dat shack. So whin Ah seen he done clean up yeverything as neat as a pin, my heart soften unto him. Ah jes gwine feel sorry fo’ him, de leas’ little bit. So Ah gwine look in de cupboard to see ef he got plenty to eat—an’ he ain’ got nuffin’ in de cupboard but a box of matches, an’ dat all! So Ah feel right smart sorry I been scold him lak I do, an’ Ah gwine pick up mah pail an’ mah mop an’ mah broom whin—bang!—de do’ go shut an’ Ah all in de dark.”

“Some one shut the door?” asked the justice.

“He shet de do’!” shouted Sally, shrilly, pointing her finger at the trembling Silas. “He shet de do’, an’ he lock de do’, an’ he start to nail de do’, lak he say he would! Yassah! Ah bang mahsilf ag’inst de do’ an’ Ah yell an’ shout, an’ de do’ don’t budge, ’cause hit locked. An’ all de while—bam! bam! bam!—he nailin’ de do’ from de outside. Ah poun’ wif mah fists an’ Ah peck up mah pail an’ slam at de do’ twell de pail all bus’ to pieces, an’ Ah bang mah mop to pieces, but—bam! bam! bam!—he go on nailin’.”

She paused for breath, and Silas opened his mouth, as if to speak, but closed it again.

“Yassah!” she shrilled, glaring at Silas, “he nail up de do’ so Ah can’t budge hit, an’ whin Ah try de windows, dey nailed up too.”

“There’s two iv thim doors,” explained Flaherty, “an’ both iv thim open outward. He’d nailed sthrips acrost thim. Th’ two windys has wooden shutters, and he’d nailed thim fast.”

“What!” exclaimed Justice Murphy. “He nailed the woman in?”

“He did, sor!”

“But—but this is outrageous!” exclaimed the justice.

All three glared at the dejected Silas, and did not see Noah Prutt as he arose from his chair.

“Make him pay, Jedge! Make him pay!” cried Noah, eagerly.

“Sit ye down!” cried Flaherty, in a voice of thunder, and Noah subsided. On the edge of his chair he nodded like a toy mandarin. He understood that things were going badly for Silas, and that was enough to please him. Sally turned to him and shouted in his ear.

“Shet up an’ stay shet!” she cried. “This is none of yo’ business, Noah. Ah gwine manage this mahsilf!”

The old man smiled and nodded his willingness. As she turned away he touched her on the arm.

“Thutty dollahs,” he said, and nodded and smiled again.

“Thutty nuffin’s!” she muttered. “Ah guess yo’ Honor will know whut Ah ought to get from dat Silas, an’ whut he ought to get from yo’. ’Cause Ah suffer a heap o’ distress of min’ an’ body whilst Ah been shet up in dat shanty dem three days.”

“Three days!” exclaimed the justice.

“Yassah! Ah been nail up in dat shanty three days an’ three nights,” said Sally, “an’ all dat time Ah been pestered an’ annoyed. Ah been sploshed on mah feet an’ Ah been hungry an’ col’, an’ Ah been insulted. Dat Silas he jus’ hong roun’ dat shanty to make me mizzable, but Ah ain’ give in one bit. No, sah! Ah’d a-died fus’. Fus’ off Ah bang on de do’ an’ Ah bang on de windows, an’ Ah keep wahm, an’ whin Ah get col’ Ah pile some straw in de fireplace an’ Ah get dem matches an’ Ah mek me a straw fire. An’ prisintly Ah hear Silas scramble-scramble on de roof. ‘Whut he up to now?’ Ah say; ‘He gwine try climb down de chimbly? Ef he do Ah whack him wid de bed-slat twell he mighty sorry he try dat.’ But he ain’ try hit. No, sah! Splosh! come a pail of wahtah down de chimbly, an’ out go mah fire, an’ mah feet suttinly get sopped. An’ Silas he say, down de chimbly, lak he voice all clog up wif laughin’, ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit! Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ an’ splosh! yere come anudder pail of wahtah.”

“Why, this is no case for me,” said the justice. “This man should be bound over to the Grand Jury!”

“Ah don’ care whut yo’ bind him to, so as yo’ bind him good an’ strong,” said Sally, vindictively.[Pg 344] “Yevery time Ah try to get wahm by makin’ a fire, down come dat pail of wahtah an’ splosh mah feet, twell Ah think he try to drown me. ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ he shout’. Hit right col’ in dat shanty, Jedge. Hit pernicious col’. Dat wahtah freeze on de flo’, an’ hit freeze on mah shoes, an’ Ah get hungrier an’ hungrier, an’ Ah shout an’ Ah rage, an’ all he say is, ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit! Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ Ah bet he ain’! Whin de time come he gwine somewheres ilse!”

“How did you get out, finally?” asked the justice.

“Ah keep maulin’ at de do’ wif dat bed-slat all de whiles,” said Sally. “Dat a mahty fine piece of bed-slat, dat is. An’ prisintly, whin Ah about to drap wid hunger an’ col’ an’ die where Ah drap, Ah beat a hol’ in de do’. ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ he ’low, an’ whack at de bed-slat wif a club, but Ah right smart mad, an’ Ah pry an’ Ah wuk, an’ prisintly Ah pry off one board. An’ when he see Ah gwine win out he scoot. Yassah! He scoot. Ah ’low he run away ’cause he afraid, but dass not hit. No, suh! He gwine fotch an ax, fo’ to nail up dat do’ ag’in. So prisintly Ah wuk dat do’ open an’ Ah step out, an’ whut Ah see? Ah see dat Silas a-standin’ yere in de paff, wid he ax in he hand an’ he mouf wide open, lak Ah been a ghos’. ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit, her?’ Ah say; ‘Well, if yo’ ain’ gone yit, yo’ gwine mighty soon!’ an’ I wint fo’ him wif de bed-slat, an’ he yell lak blazes whilst Ah gwine murder him. An’ dat how-come de pleeceman heah him an’ save he life.”

The justice folded his hands, his fingers working nervously, as if they longed to take hold of the throat of the dispirited prisoner.

“In all my experience,” he said, “this is the most outrageous case I have ever met! I am only sorry I am not the proper official to try this case. I hope this man gets the full penalty of the law. I can’t express—”

He shook his head.

“Whatever possessed you?” he asked the shrinking Silas.

“His Honor is speakin’ t’ ye!” cried Flaherty, poking Silas with his baton. “Spake up whin he addrisses ye! Why did ye do ut?”

“Ah—” began Silas, in a thin, scared voice.

“Sthand up whin ye addriss th’ coort!” said Flaherty, and Silas stood.

As he stood there was nothing about him that suggested the fiery lover. His drooping shoulders and general air of long-permanent shiftlessness almost gave the lie to the idea that he could have taken the trouble to carry a pail of water to a roof. He looked as if to walk at a shambling gait was about the extreme of any exertion of which he was possible.

“Ah didn’ do hit,” he said weakly, and sat down again.

“Now! now!” said Justice Murphy, sharply. “None of that!”

“Sthand up whin his Honor addrisses ye!” said Flaherty.

“Ah don’ know nuffin’ about hit, Jedge,” said Silas, in a squeaky voice as he half lifted himself out of the chair. “Ah’ll tell yo’ all whut Ah know. Ah wint away from mah shanty Monday, ’cause Ah got to yearn a dollar fo’ to buy a white robe fo’ to go to hebben in Tuesday, an’ Ah chop a cord ob wood an’ yearn mah dollar an’ buy mah white robe. An’ dat night all de prophet’s folks spind de night on de hilltop, a-waitin’ fo’ de dawn ob de great day, an’ a-prayin’ an’ a-singin’ an’ a-fastin’. An’ Tuesday Ah spint awn de hilltop like dat, a-prayin’ an’ a-singin’ an’ a-fastin’ twell de sun sh’u’d set. An’ whin de sun set nuffin’ happen. No, sah. Nobody go nowheres, an’ dey ain’ no prophet no mo’, fo’ he wint away wid whut he done collicted up endurin’ de revival. So whin dat come about Ah quite pertickler hungry, an’ Ah go fo’th t’ yearn some money fo’ to get mah food an’ to pay whut Ah owe Noah, ’cause he been pesterin’ me about he rint. So Ah get some wood to chop, an’ I chop hit. An’ bime-by, whin Ah chop all dat wood, Ah guess Ah’ll go home, an’ Ah go home. An’ whin Ah retch mah shanty, Ah see de do’ bruk, an’ somebody a-yammerin’ on hit, an’ whilst Ah look, out sprong dis Sally Prutt an’ whack me on de haid wid a bed-slat, an’ holler, ‘Ain’ gone to hebben yit! Ain’ gone to hebben yit!’ lak she done gwine crazy, an’ ebbery time she whack she holler, an’ ebbery time she holler she whack. So I gwine get away from dere quick, an’ whin Ah run, she run, an’ she shore gwine murder me, ef dish yere pleeceman am’ come an’ stop her.”

“Just so!” said Justice Murphy, sar[Pg 345]castically. “And you were not near the shanty at all? And you did not nail this woman in it? And you did not pour water down the chimney?”

“No, sah,” said Silas, in a frightened voice.

“Oh, you brack liah!” said Sally, angrily.

“And I suppose you never said, ‘Ain’t gone to heaven yet!’ did you?” said the judge. “You never heard those words, did you?”

Silas looked from side to side, and his lower lip trembled. His back took a more disconsolate droop. There are no words in the English language to describe how utterly downcast and hopeless and woe-saturated he looked. Milton came near it when he said something about “Below the lowest depths still lower depths—” In woe Silas was in depths a couple of stories lower than that.

“Well?” said the justice, sharply.

“Answer his Honor whin he addrisses ye!” shouted Flaherty, and Silas moistened his lips and gulped.

“No, sah! Ah—Ah ain’ hear them wuds perzackly, nevah befo’. Ah ain’ heah, ‘Ain’ gone to hebben.’ Ah jes heah ‘Ain’ gwine to hebben.’”

“Oh, you did hear that, did you?” said the justice. “Who said that?”

Silas stared at his boot. He blinked a couple of times, and then spoke.

“Ol’ Noah, he say thim wuds,” he said. The judge turned to the old Negro on the chair in the front row, and pointed at him.

“That Noah?” he asked. “Is that the man?”

“Yassah,” said Silas, sadly. “Dass de man. He say hit.”

Old Noah, seeing that the conversation was veering his way, arose and came forward, his hand behind his ear and expectation in his face.

“Thutty dollahs, Jedge!” he said eagerly. “Dass de right amount. Thutty dollahs.”

“You go set down!” yelled his wife in his ear, but the old man shook his head.

“Ain’ he gwine pay hit?” he asked resentfully. “Ain’ de jedge gwine mek him pay hit? Whaffo’ Ah nail up de shack ef he ain’ gwine pay hit?”

“Whut yo’ palaver about? Nail up de shack! You ain’ nail up no shack. Dat no-’count Silas he nail up de shack,” shouted Sally.

The old man nodded his head and grinned.

“Yas, dasso! Dasso! Ah nail up de shack, Jedge,” he chuckled. “Ah nail him in. Yassah, Ah done jes so.”

“Him?” shouted the justice, “you mean her?”

“Yassah, Ah nail him in,” said Noah.

“You did?” shouted the justice.

“Ah—Ah beg pawdon, Jedge,” said the old man. “Ah cawn’t heah as—as well as Ah used to heah. Ah cawn’t hear whisperin’ tones no moah. Ah—Ah got to beg yo’ to speak jes a leetle mite louder.”

“WHY DID YOU NAIL HIM IN THE SHACK?” shouted Justice Murphy at the top of his voice.

“Why, ’cause he won’ pay me de rint,” said Noah, as if it was a thing every one should have known. “Ain’ Sally been jes tol’ yo’? Ah surmise she done confabulate about that all de whiles she talkin’. Yo’ mus’ scuse her, Jedge. Whin de womens staht talkin’, nobuddy know whut dey talk about. Dey jes talk fo’ de exumcise. Mah secon’ wife, which am de las’ but one befo’ Ah tuck Sally—”

“Look here!” shouted Justice Murphy. “Why did you nail him in the shack?”

“Zack?” said the old man, doubtfully.[Pg 346] “No, sah, he name Silas. Dass him yondah. I arsk him fo’ de rint, an’ I beg him fo’ de rint, an’ I argyfy about dat rint twell Ah jes wohn out, an’ Ah don’ git no rint at all. So bime-by erlong come dish yere prophet whut you heah about, maybe. Ah ain’ tek no stock in dat prophet-man at all! No, sah! Ah ’s a good Baptis’ an’ Ah don’ truckle to none o’ dem come-easy, go-easy, folks like dat. Ah stay ’way from him, an’ Ah tell Sally she stay way likewise. But dis yere Silas he get de prophet-man’s religion bad. Yassah. He ’low he gwine to hebben las’ Tuesday whin all de res’ ob de gang go. Ah reckon he ain’ gwine go, ’cause Ah feel dey ain’ none ob dem gwine go, but Ah can’t be shore. Mos’ anything li’ble to happen whin times so bad like dey is. So Ah projeck up to Silas an’ Ah say to him, ‘Ef yo’ gwine to hebben nex’ Tuesday, yo’ bettah pay me de rint befo’ yo’ go.’ Dass whut Ah say, Jedge. An’—an’—an’ dass reason-able. ’Cause ef he gwine to hebben Tuesday, Ah ain’ gwine hab no chance to collict dat rint come Winsday. No, sah.”

“Then what?” shouted the justice.

“Nuffin’!” said Noah. “Nuffin’ at all. He say, ‘Scuse me, Noah, but Ah so full ob preparations fo’ de great evint Ah ain’ got time to yearn no money to pay de rint.’ An’ Ah say, ‘Silas, Ah want mah rint!’ So, bime-by, whin Monday mawrnin’ come erlong, Sally she gwine away to do a job o’ work, an’ Ah meyander ober to Silas’ shack, an’ Ah got mah hatchit an’ mah nails, whut Ah gwine mind de fince. An’ whin Ah come to de shack All hear de squawk ob a board in de flo’ an’ Ah know Silas he in de shack, an’ Ah slam de do’ an’ Ah nail up de do’ an’ he carrye on scandalous, but he can’t git yout. An’ Ah don’ care whut he say, ’cause Ah can’t heah ef he cuss or ef he palaver.

“’Cause Ah ain’ gwine hab no tinint go to hebben like dat whin he owe me rint twell he pay de rint. So Ah reckon Ah leave him dere twell de gwine is all gone, an’ Ah ain’ worried erbout Silas gwine alone by hisse’f. He ain’ got de get-up to do nuffin’ alone by hisse’f. So Ah leab him dah twell he natchully bus’ out.”

“You tried to starve him,” shouted the justice. “You threw water down the chimney.”