The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Story-book of Science, by Jean-Henri Fabre This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Story-book of Science Author: Jean-Henri Fabre Translator: Florence Constable Bicknell Release Date: March 20, 2018 [EBook #56795] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY-BOOK OF SCIENCE *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Six | 3 |

| II | The Fairy Tale and the True Story | 7 |

| III | The Building of the City | 11 |

| IV | The Cows | 16 |

| V | The Sheepfold | 20 |

| VI | The Wily Dervish | 25 |

| VII | The Numerous Family | 30 |

| VIII | The Old Pear-Tree | 37 |

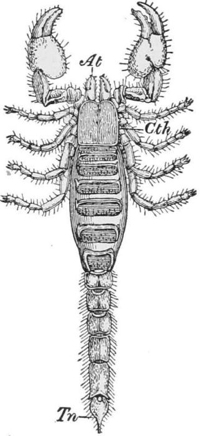

| IX | The Age of Trees | 40 |

| X | The Length of Animal Life | 45 |

| XI | The Kettle | 49 |

| XII | The Metals | 52 |

| XIII | Metal Plating | 55 |

| XIV | Gold and Iron | 59 |

| XV | The Fleece | 64 |

| XVI | Flax and Hemp | 67 |

| XVII | Cotton | 71 |

| XVIII | Paper | 77 |

| XIX | The Book | 80 |

| XX | Printing | 84 |

| XXI | Butterflies | 88 |

| XXII | The Big Eaters | 93 |

| XXIII | Silk | 99 |

| XXIV | The Metamorphosis | 104 |

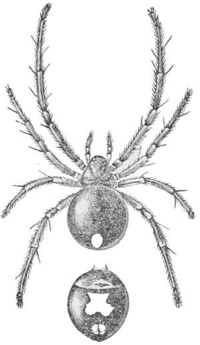

| XXV | Spiders | 108 |

| XXVI | The Epeira’s Bridge | 112 |

| XXVII | The Spider’s Web | 116 |

| XXVIII | The Chase | 120 |

| XXIX | Venomous Insects | 126 |

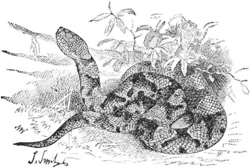

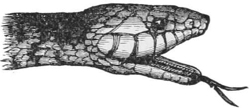

| XXX | Venom | 132 |

| XXXI | The Viper and the Scorpion | 136 |

| XXXII | The Nettle | 140 |

| XXXIII | Processionary Caterpillars | 144 |

| XXXIV | The Storm | 150 |

| XXXV | Electricity | 155 |

| XXXVI | The Experiment with the Cat | 160 |

| XXXVII | The Experiment with Paper | 163 |

| XXXVIII | Franklin and De Romas | 165 |

| XXXIX | Thunder and the Lightning-Rod | 172 |

| XL | Effects of the Thunderbolt | 179 |

| XLI | Clouds | 181 |

| XLII | The Velocity of Sound | 187 |

| XLIII | The Experiment with the Bottle of Cold Water | 192 |

| XLIV | Rain | 197 |

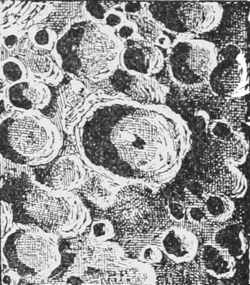

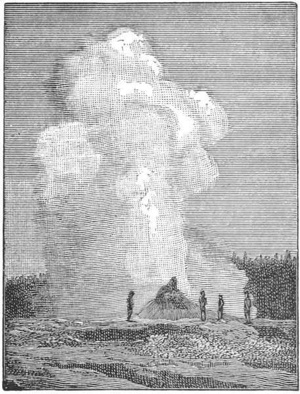

| XLV | Volcanoes | 201 |

| XLVI | Catania | 205 |

| XLVII | The Story of Pliny | 210 |

| XLVIII | The Boiling Pot | 216 |

| XLIX | The Locomotive | 221 |

| L | Emile’s Observation | 227 |

| LI | A Journey to the End of the World | 232 |

| LII | The Earth | 238 |

| LIII | The Atmosphere | 244 |

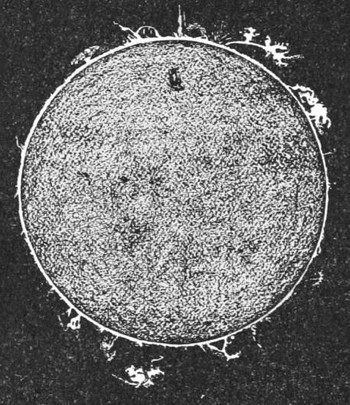

| LIV | The Sun | 250 |

| LV | Day and Night | 257 |

| LVI | The Year and Its Seasons | 264 |

| LVII | Belladonna Berries | 271 |

| LVIII | Poisonous Plants | 275 |

| LIX | The Blossom | 284 |

| LX | Fruit | 290 |

| LXI | Pollen | 295 |

| LXII | The Bumble-Bee | 301 |

| LXIII | Mushrooms | 307 |

| LXIV | In the Woods | 313 |

| LXV | The Orange-Agaric | 317 |

| LXVI | Earthquakes | 322 |

| LXVII | Shall We Kill Them Both? | 329 |

| LXVIII | The Thermometer | 334 |

| LXIX | The Subterranean Furnace | 337 |

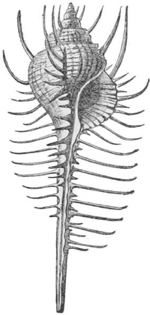

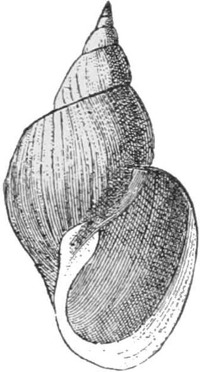

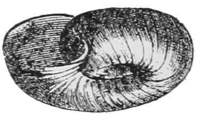

| LXX | Shells | 344 |

| LXXI | The Spiral Snail | 349 |

| LXXII | Mother-of-Pearl and Pearls | 353 |

| LXXIII | The Sea | 358 |

| LXXIV | Waves Salt Seaweeds | 363 |

| LXXV | Running Water | 369 |

| LXXVI | The Swarm | 373 |

| LXXVII | Wax | 378 |

| LXXVIII | The Cells | 382 |

| LXXIX | Honey | 389 |

| LXXX | The Queen Bee | 395 |

Of the increasing success and widening popularity of the elementary science series written chiefly in the seclusion of Sérignan by the gifted French naturalist who was destined to give that obscure hamlet a distinction hardly inferior to the renown enjoyed by Maillane since the days of Mistral, it is unnecessary at this late date to say more than a word in passing. The extraordinary vividness and animation of his style amply justified his early belief in the possibility of making the truths of science more fascinating to young readers, and to all readers, than the fabrications of fiction. As Dr. Legros has said in his biography[1] of Fabre, “He was indeed convinced that even in early childhood it was possible for both boys and girls to learn and to love many subjects which had hitherto never been proposed; and in particular that Natural History which to him was a book in which all the world might read, but that university methods had reduced to a tedious and useless study in which the letter ‘killed the life.’”

1. “Fabre, Poet of Science.” By Dr. C. V. Legros. New York: The Century Co.

The young in heart and the pure in heart of whatever age will find themselves drawn to this incomparable story-teller, this reverent revealer of the awe-inspiring secrets of nature, this “Homer of the insects.” The identity of the “Uncle Paul,” who in this book and others of the series plays the story-teller’s part, is not hard to guess; and the young people who gather about him to listen to his true stories from wood and field, from brook and hilltop, from distant ocean and adjacent millpond, are, without doubt, the author’s own children, in whose companionship he delighted and whose education he conducted with wise solicitude.

In his unselfish eagerness to see the truths of natural science brought within the comprehension and the enjoyment of all, Fabre would have been the first to wish for a wide circulation for his own books in many countries and many languages; and thus, though it is now too late to obtain his authorization of these translations, one cannot regard it as a wrong to his memory to do what may lie in one’s power to spread the knowledge he has so wisely and wittily, with such insight and ingenuity, imparted to those of his own country and tongue.

It remains to add that in the following pages the somewhat stiff dialogue form of the original has given place to the more attractive and flexible narrative style, with as little violence as possible to the author’s text.

ONE evening, at twilight, they were assembled in a group, all six of them. Uncle Paul was reading in a large book. He always reads to rest himself from his labors, finding that after work nothing refreshes so much as communion with a book that teaches us the best that others have done, said, and thought. He has in his room, well arranged on pine shelves, books of all kinds. There are large and small ones, with and without pictures, bound and unbound, and even gilt-edged ones. When he shuts himself up in his room it takes something very serious to divert him from his reading. And so they say that Uncle Paul knows any number of stories. He investigates, he observes for himself. When he walks in his garden he is seen now and then to stop before the hive, around which the bees are humming, or under the elder bush, from which the little flowers fall softly, like flakes of snow; sometimes he stoops to the ground for a better view of a little crawling insect, or a blade of grass just pushing into view. What does he see? What does he observe? Who knows? They say, however, that there comes to his beaming face a holy joy, as if he had just found himself face to face with some secret of the wonders of God. It makes us feel better when we hear stories that he tells at these moments; we feel better, and furthermore we learn a number of things that some day may be very useful to us.

Uncle Paul is an excellent, God-fearing man, obliging to every one, and “as good as bread.” The village has the greatest esteem for him, so much so that they call him Maître Paul, on account of his learning, which is at the service of all.

To help him in his field work—for I must tell you that Uncle Paul knows how to handle a plow as well as a book, and cultivates his little estate with success—he has Jacques, the old husband of old Ambroisine. Mother Ambroisine has the care of the house, Jacques looks after the animals and fields. They are better than two servants; they are two friends in whom Uncle Paul has every confidence. They saw Paul born and have been in the house a long, long time. How often has Jacques made whistles from the bark of a willow to console little Paul when he was unhappy! How many times Ambroisine, to encourage him to go to school without crying, has put a hard-boiled new-laid egg in his lunch basket! So Paul has a great veneration for his father’s two old servants. His house is their house. You should see, too, how Jacques and Mother Ambroisine love their master! For him, if it were necessary, they would let themselves be quartered.

Uncle Paul has no family, he is alone; yet he is never happier than when with children, children who chatter, who ask this, that, and the other, with the adorable ingenuousness of an awakening mind. He has prevailed upon his brother to let his children spend a part of the year with their uncle. There are three: Emile, Jules, and Claire.

Claire is the oldest. When the first cherries come she will be twelve years old. Little Claire is industrious, obedient, gentle, a little timid, but not in the least vain. She knits stockings, hems handkerchiefs, studies her lessons, without thinking of what dress she shall wear Sunday. When her uncle, or Mother Ambroisine, who is almost a mother to her, tells her to do a certain thing, she does it at once, even with pleasure, happy in being able to render some little service. It is a very good quality.

Jules is two years younger. He is a rather thin little body, lively, all fire and flame. When he is preoccupied about something, he does not sleep. He has an insatiable appetite for knowledge. Everything interests and takes possession of him. An ant drawing a straw, a sparrow chirping on the roof, are sufficient to engross his attention. He then turns to his uncle with his interminable questions: Why is this? Why is that? His uncle has great faith in this curiosity, which, properly guided, may lead to good results. But there is one thing about Jules that his uncle does not like. As we must be honest, we will own that Jules has a little fault which would become a grave one if not guarded against: he has a temper. If he is opposed he cries, gets angry, makes big eyes, and spitefully throws away his cap. But it is like the boiling over of milk soup: a trifle will calm him. Uncle Paul hopes to be able to bring him round by gentle reprimands, for Jules has a good heart.

Emile, the youngest of the three, is a complete madcap; his age permits it. If any one gets a face smeared with berries, a bump on the forehead, or a thorn in the finger, it is sure to be he. As much as Jules and Claire enjoy a new book, he enjoys a visit to his box of playthings. And what has he not in the way of playthings? Now it is a spinning-top that makes a loud hum, then blue and red lead soldiers, a Noah’s Ark with all sorts of animals, a trumpet which his uncle has forbidden him to blow because it makes too much noise, then—But he is the only one that knows what there is in that famous box. Let us say at once, before we forget it, Emile is already asking questions of his uncle. His attention is awakening. He begins to understand that in this world a good top is not everything. If one of these days he should forget his box of playthings for a story, no one would be surprised.

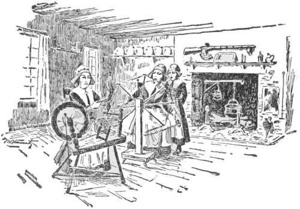

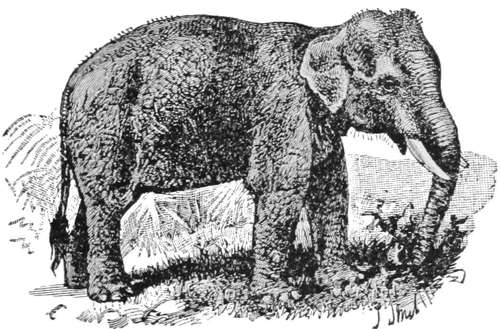

THE six of them were gathered together. Uncle Paul was reading in a big book, Jacques braiding a wicker basket, Mother Ambroisine plying her distaff, Claire marking linen with red thread, Emile and Jules playing with the Noah’s Ark. And when they had lined up the horse after the camel, the dog after the horse, then the sheep, donkey, ox, lion, elephant, bear, gazelle, and a great many others,—when they had them all arranged in a long procession leading to the ark, Emile and Jules, tired of playing, said to Mother Ambroisine: “Tell us a story, Mother Ambroisine—one that will amuse us.”

And with the simplicity of old age Mother Ambroisine spoke as follows, at the same time twirling her spindle:

“Once upon a time a grasshopper went to the fair with an ant. The river was all frozen. Then the grasshopper gave a jump and landed on the other side of the ice, but the ant could not do this; and it said to the grasshopper: ‘Take me on your shoulders; I weigh so little.’ But the grasshopper said: ‘Do as I do; give a spring, and jump.’ The ant gave a spring, but slipped and broke its leg.

“Ice, ice, the strong should be kind; but you are wicked, to have broken the ant’s leg—poor little leg.

“Then the ice said: ‘The sun is stronger than I, and it melts me.’

“Sun, sun, the strong should be kind; but you are wicked, to melt the ice; and you, ice, to have broken the ant’s leg—poor little leg.

“Then the sun said: ‘The clouds are stronger than I; they hide me.’

“Clouds, clouds, the strong should be kind; but you are wicked, to hide the sun; you, sun, to melt the ice; and you, ice, to have broken the ant’s leg—poor little leg.

“Then the clouds said: ‘The wind is stronger than we; it drives us away.’

“Wind, wind, the strong should be kind; but you are wicked, to drive away the clouds; you, clouds, to hide the sun; you, sun, to melt the ice; and you, ice, to have broken the ant’s leg—poor little leg.

“Then the wind said: ‘The walls are stronger than I; they stop me.’

“Walls, walls, the strong should be kind; but you are wicked, to stop the wind; you, wind, to drive away the clouds; you, clouds, to hide the sun; you, sun, to melt the ice; and you, ice, to have broken the ant’s leg—poor little leg.

“Then the walls said: ‘The rat is stronger than we; it bores holes through us.’

“Rat, rat, the strong—”

“But it is all the same thing, over and over again, Mother Ambroisine,” exclaimed Jules impatiently.

“Not quite, my child. After the rat comes the cat that eats the rat, then the broom that strikes the cat, then the fire that burns the broom, then the water that puts out the fire, then the ox that quenches his thirst with the water, then the fly that stings the ox, then the swallow that snaps up the fly, then the snare that catches the swallow, then—”

“And does it go on very long like that?” asked Emile.

“As long as you please,” replied Mother Ambroisine, “for however strong one may be, there are always others stronger still.”

“Really, Mother Ambroisine,” said Emile, “that story tires me.”

“Then listen to this one: Once upon a time there lived a woodchopper and his wife, and they were very poor. They had seven children, the youngest so very, very small that a wooden shoe answered for its bed.”

“I know that story,” again interposed Emile. “The seven children are going to get lost in the woods. Little Hop-o’-my-Thumb marks the way at first with white pebbles, then with bread crumbs. Birds eat the crumbs. The children get lost, Hop-o’-my-Thumb, from the top of a tree, sees a light in the distance. They run to it: rat-tat-tat! It is the dwelling of an ogre!”

“There is no truth in that,” declared Jules, “nor in Puss-in-Boots, nor Cinderella, nor Bluebeard. They are fairy tales, not true stories. For my part, I want stories that are really and truly so.”

At the words, true stories, Uncle Paul raised his head and closed his big book. A fine opportunity offered for turning the conversation to more useful and interesting subjects than Mother Ambroisine’s old tales.

“I approve of your wanting true stories,” said he. “You will find in them at the same time the marvelous, which pleases so much at your age, and also the useful, with which even at your age you must concern yourselves, in preparation for after life. Believe me, a true story is much more interesting than a tale in which ogres smell fresh blood and fairies change pumpkins into carriages and lizards into lackeys. And could it be otherwise? Compared with truth, fiction is but a pitiful trifle; for the former is the work of God, the latter the dream of man. Mother Ambroisine could not interest you with the ant that broke its leg in trying to cross the ice. Shall I be more fortunate? Who wants to hear a true story of real ants?”

White Ant

“I! I!” cried Emile, Jules, and Claire all together.

“THEY are noble workers” began Uncle Paul, “Many a time, when the morning sun begins to warm up, I have taken pleasure in observing the activity that reigns around their little mounds of earth, each with its summit pierced by a hole for exit and entrance.

“There are some that come from the bottom of this hole. Others follow them, and still more, on and on. They carry between their teeth a tiny grain of earth, an enormous weight for them. Arrived at the top of the mound, they let their burden fall, and it rolls over the slope, and they immediately descend again into their well. They do not play on the way, or stop with their companions to rest a while. Oh! no: the work is urgent, and they have so much to do! Each one arrives, serious, with its grain of earth, deposits it, and descends in search of another. What are they so busy about?

“They are building a subterranean town, with streets, squares, dormitories, storehouses; they are hollowing out a dwelling-place for themselves and their family. At a depth where rain cannot penetrate they dig the earth and pierce it with galleries, which lengthen into long communicating streets, sub-divided into short ones, crossing one another here and there, sometimes ascending, sometimes descending, and opening into large halls. These immense works are executed grain by grain, drawn by strength of the jaws. If any one could see that black army of miners at work under the ground, he would be filled with astonishment.

“They are there by the thousands, scratching, biting, drawing, pulling, in the deepest darkness. What patience! What efforts! And when the grain of sand has at last given way, how they go off, head held high and proud, carrying it triumphantly above! I have seen ants, whose heads tottered under the tremendous load, exhaust themselves in getting to the top of the mound. In jostling their companions, they seemed to say: See how I work! And nobody could blame them, for the pride of work is a noble pride. Little by little, at the gate of the town, that is to say at the edge of the hole, this little mound of earth is piled up, formed by excavated material from the city that is being built. The larger the mound, the larger the subterranean dwelling, it is plain.

“Hollowing out these galleries in the ground is not all; they must also prevent landslides, fortify weak places, uphold the vaults with pillars, make partitions. These miners are then seconded by carpenters. The first carry the earth out of the ant-hill, the second bring the building materials. What are these materials! They are pieces of timber-work, beams, and small joists, suitable for the edifice. A tiny little bit of straw is a solid beam for a ceiling, the stem of a dry leaf can become a strong column. The carpenters explore the neighboring forests, that is to say the tufts of grass, to choose their pieces.

“Good! see this covering of an oat-grain. It is very thin, dry, and solid. It will make an excellent plank for the partition they are constructing below. But it is heavy, enormously heavy. The ant that has made the discovery draws backward and makes itself rigid on its six feet. No success: the heavy mass does not move. It tries again, all its little body trembling with energy. The oat-husk just moves a tiny bit. The ant recognizes its powerlessness. It goes off. Will it abandon the piece? Oh! no. When one is an ant, one has the perseverance that commands success. Here it is coming back with two helpers. One seizes the oat in front, the others hitch themselves to the side, and behold! it rolls, it advances; it will get there. There are difficult steps, but the ants they meet along the route will give them a shoulder.

“They have succeeded, not without trouble. The oat is at the entrance to the under-ground city. Now things become complicated; the piece gets awry; leaning against the edge of the hole, it cannot enter. Helpers hasten up. Ten, twenty unite their efforts without success. Two or three of them, engineers perhaps, detach themselves from the band, and seek the cause of this insurmountable resistance. The difficulty is soon solved: they must put the piece with the point at the bottom. The oat is drawn back a little, so that one end overhangs the hole. One ant seizes this end while the others lift the end that is on the ground, and the piece, turning a somersault, falls into the well, but is prudently held on to by the carpenters clinging to the sides. You may perhaps think, my children, that the miners mounting with their grain of earth would stop from curiosity before this mechanical prodigy? Not at all, they have not time. They pass with their loads of excavated material, without a glance at the carpenters’ work. In their ardor they are even bold enough to slide under the moving beams, at the risk of being crippled. Let them look out! That is their affair.

“One must eat when one works so hard. Nothing creates an appetite like violent exercise. Milkmaid ants go through the ranks; they have just milked the cows and are now distributing the milk to the workers.”

Here Emile burst out laughing. “But that is not really and truly so?” said he to his uncle. “Milkmaid ants, cows, milk! It is a fairy tale like Mother Ambroisine’s.”

Emile was not the only one to be surprised at the peculiar expressions Uncle Paul had used. Mother Ambroisine no longer turned her spindle, Jacques did not plait his wickers, Jules and Claire stared with wide-open eyes. All thought it a jest.

“No, my dears,” said Uncle Paul. “I am not jesting; no. I have not exchanged the truth for a fairy tale. It is true there are milkmaid ants and cows. But as that demands some explanation, we will put off the continuation of the story until to-morrow.”

Emile drew Jules off into a corner, and said to him in confidence: “Uncle’s true stories are very amusing, much more so than Mother Ambroisine’s tales. To hear the rest about those wonderful cows I would willingly leave my Noah’s Ark.”

THE next day Emile, when only half awake, began to think of the ants’ cows. “We must beg uncle,” said he to Jules, “to tell us the rest of his story this morning.”

No sooner said than done: they went to look for their uncle.

“Aha!” cried he upon hearing their request, “the ants’ cows are interesting you. I will do better than tell you about them, I will show them to you. First of all call Claire.”

Claire came in haste. Their uncle took them under the elder bush in the garden, and this is what they saw:

The bush is white with flowers. Bees, flies, beetles, butterflies, fly from one flower to another with a drowsy murmur. On the trunk of the elder, amongst the ridges of the bark, numbers of ants are crawling, some ascending, some descending. Those ascending are the more eager. They sometimes stop the others on the way and appear to consult them as to what is going on above. Being informed, they begin climbing again with even more ardor, proof that the news is good. Those descending go in a leisurely manner, with short steps. Willingly they halt to rest or to give advice to those who consult them. One can easily guess the cause of the difference in eagerness of those ascending and those descending. The descending ants have their stomachs swollen, heavy, deformed, so full are they; those ascending have their stomachs thin, folded up, crying hunger. You cannot mistake them: the descending ants are coming back from a feast and, well fed, are returning home with the slowness that a heavy paunch demands; the ascending ants are running to the same feast and put into the assault of the bush the eagerness of an empty stomach.

“What do they find on the elder to fill their stomachs?” asked Jules. “Here are some that can hardly drag along. Oh, the gluttons!”

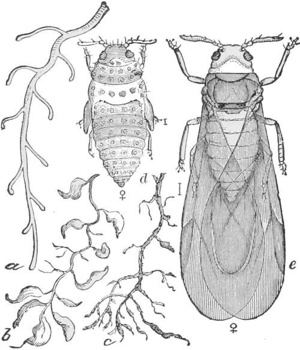

“Gluttons! no,” Uncle Paul corrected him; “for they have a worthy motive for gorging themselves. There is above, on the elder, an immense number of the cows. The descending ants have just milked them, and it is in their paunch that they carry the milk for the common nourishment of the ant-hill colony. Let us look at the cows and the way of milking them. Don’t expect, I warn you, herds like ours. One leaf serves them for pasturage.”

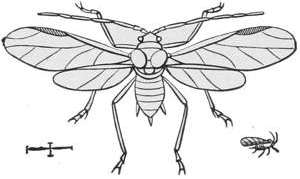

Uncle Paul drew down to the children’s level the top of a branch, and all looked at it attentively. Innumerable black velvety lice, immobile and so close together as to touch one another, cover the under side of the leaves and the still tender wood. With a sucker more delicate than a hair plunged into the bark, they fill themselves peacefully with the sap of the elder without changing their position. At the end of their back, they have two short and hollow hairs, two tubes from which, if you look attentively, you can see a little drop of sugary liquid escape from time to time. These black lice are called plant-lice. They are the ants’ cows. The two tubes are the udders, and the liquor which drips from their extremity is the milk. In the midst of the herd, on the herd, even, when the cattle are too close together, the famished ants come and go from one louse to another, watching for the delicious little drop. The one who sees it runs, drinks, enjoys it, and seems to say on raising its little head: Oh, how good, oh, how good it is! Then it goes on its way looking for another mouthful of milk. But plant-lice are stingy with their milk; they are not always disposed to let it run through their tubes. Then the ant, like a milkmaid ready to milk her cow, lavishes the most endearing caresses on the plant-louse. With its antennæ, that is to say, with its little delicate flexible horns, it gently pats the stomach and tickles the milk-tubes. The ant nearly always succeeds. What cannot gentleness accomplish! The plant-louse lets itself be conquered; a drop appears which is immediately licked up. Oh, how good, how good! As the little paunch is not full, the ant goes to other plant-lice trying the same caresses.

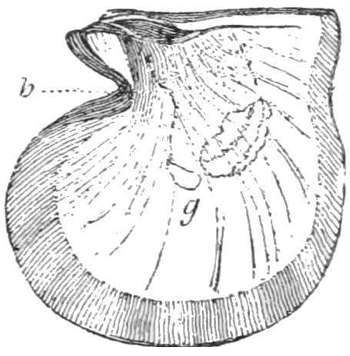

Plant-louse

Uncle Paul let go the branch, which sprang back into its natural position. Milkmaids, cattle, and pasture were at once at the top of the elder bush.

“That is wonderful, Uncle,” cried Claire.

“Wonderful, my dear child. The elder is not the only bush that nourishes milk herds for the ants. Plant-lice can be found on many other forms of vegetation. Those on the rosebush and cabbage are green; on the elder, bean, poppy, nettle, willow, poplar, black; on the oak and thistle, bronze color; on the oleander and nut, yellow. All have the two tubes from which oozes the sugary liquor; all vie with one another in feasting the ants.”

Claire and her uncle went in-doors. Emile and Jules, enraptured by what they had just seen, began to look for lice on other plants. In less than an hour they had found four different kinds, all receiving visits of no disinterested sort from the ants.

IN the evening Uncle Paul resumed the story of the ants. At that hour Jacques was in the habit of going the round of the stables to see if the oxen were eating their fodder and if the well-fed lambs were sleeping peacefully beside their mothers. Under the pretense of giving the finishing touches to his wicker basket, Jacques stayed where he was. The real reason was that the ants’ cows were on his mind. Uncle Paul related in detail what they had seen in the morning on the elder: how the plant-lice let the sugary drops ooze from their tubes, how the ants drank this delicious liquid and knew how, if necessary, to obtain it by caresses.

“What you are telling us, Master,” said Jacques, “puts warmth into my old veins. I see once more how God takes care of His creatures, He who gives the plant-louse to the ant as He gives the cow to man.”

“Yes, my good Jacques,” returned Uncle Paul, “these things are done to increase our faith in Providence, whose all-seeing eye nothing can escape. To a thoughtful person, the beetle that drinks from the depths of a flower, the tuft of moss that receives the rain-drop on the burning tile, bear witness to the divine goodness.

“To return to my story. If our cows wandered at will in the country, if we were obliged to take troublesome journeys to go and milk them in distant pastures, uncertain whether we should find them or not, it would be hard work for us, and very often impossible. How do we manage then? We keep them close at hand, in inclosures and in stables. This also is sometimes done by the ants with the plant-lice. To avoid tiresome journeys, sometimes useless, they put their herds in a park. Not all have this admirable foresight, however. Besides, if they had, it would be impossible to construct a park large enough for such innumerable cattle and their pasturage. How, for example, could they inclose in walls the willow that we saw this morning with its population of black lice? It is necessary to have conditions that are not beyond the forces available. Given a tuft of grass whose base is covered with a few plant-lice, the park is practicable.

“Ants that have found a little herd plan how to build a sheepfold, a summer châlet, where the plant-lice can be inclosed, sheltered from the too bright rays of the sun. They too will stay at the châlet for some time, so as to have the cows within reach and to milk them at leisure. To this end, they begin by removing a little of the earth at the base of the tuft so as to uncover the upper part of the root. This exposed part forms a sort of natural frame on which the building can rest. Now grains of damp earth are piled up one by one and shaped into a large vault, which rests on the frame of the roots and surrounds the stem above the point occupied by the plant-lice. Openings are made for the service of the sheepfold. The châlet is finished. Its inmates enjoy cool and quiet, with an assured supply of provisions. What more is needed for happiness? The cows are there, very peaceful, at their rack, that is to say, fixed by their suckers to the bark. Without leaving home the ants can drink to satiety that sweet milk from the tubes.

“Let us say, then, that the sheepfold made of clay is a building of not much importance, raised with little expense and hastily. One could overturn it by blowing hard. Why lavish such pains on so temporary a shelter? Does the shepherd in the high mountains take more care of his hut of pine branches, which must serve him for one or two months?

“It is said that ants are not satisfied with inclosing small herds of plant-lice found at the base of a tuft of grass, but that they also bring into the sheepfold plant-lice encountered at a distance. They thus make a herd for themselves when they do not find one already made. This mark of great foresight would not surprise me; but I dare not certify it, never having had the chance to prove it myself. What I have seen with my own eyes is the sheepfold of the plant-lice. If Jules looks carefully he will find some this summer, when the days are warmest, at the base of various potted plants.”

“You may be sure, Uncle,” said Jules, “I shall look for them. I want to see those strange ants’ châlets. You have not yet told us why ants gorge themselves so, when they have the good luck to find a herd of plant-lice. You said those descending the elder with their big stomachs were going to distribute the food in the ant-hill.”

“A foraging ant does not fail to regale itself on its own account if the occasion offers; and it is only fair. Before working for others must one not take care of one’s own strength? But as soon as it has fed itself, it thinks of the other hungry ones. Among men, my child, it does not always happen so. There are people who, well fed themselves, think everybody else has dined. They are called egoists. God forbid your ever bearing that sorry name, of which the ant, paltry little creature, would be ashamed! As soon as it is satisfied, then, the ant remembers the hungry ones, and consequently fills the only vessel it has for carrying liquid food home; that is to say, its paunch.

“Now see it returning, with its swollen stomach. Oh! how it has stuffed so that others may eat! Miners, carpenters, and all the workers occupied in building the city await it so as to resume their work heartily, for pressing occupations do not permit them to go and seek the plant-lice themselves. It meets a carpenter, who for an instant drops his straw. The two ants meet mouth to mouth, as if to kiss. The milk-carrying ant disgorges a tiny little bit of the contents of its paunch, and the other one drinks the drop with avidity. Delicious! Oh! now how courageously it will work! The carpenter goes back to his straw again, the milk-carrier continues his delivery route. Another hungry one is met. Another kiss, another drop disgorged and passed from mouth to mouth. And so on with all the ants that present themselves, until the paunch is emptied. The milk-ant then departs to fill up its can again.

“Now, you can imagine that, to feed by the beakful a crowd of workers who cannot go themselves for victuals, one milk-ant is not enough; there must be a host of them. And then, under the ground, in the warm dormitories, there is another population of hungry ones. They are the young ants, the family, the hope of the city. I must tell you that ants, as well as other insects, hatch from an egg, like birds.”

“One day,” interposed Emile, “I lifted up a stone and saw a lot of little white grains that the ants hastened to carry away under the ground.”

“Those white grains were eggs,” said Uncle Paul, “which the ants had brought up from the bottom of their dwelling to expose them under the stone to the heat of the sun and facilitate their hatching. They hurried to descend again, when the stone was raised, so as to put them in a safe place, sheltered from danger.

“On coming out from the egg, the ant has not the form that you know. It is a little white worm, without feet, and quite powerless, not even able to move. There are in an ant-hill thousands of those little worms. Without stop or rest, the ants go from one to another, distributing a beakful, so that they begin to grow and change in one day into ants. I leave you to think how much they must work and how many plant-lice must be milked, merely to nurse the little ones that fill the dormitories.”

“THERE are ant-hills everywhere, large or small,” observed Jules. “Even in the garden I could have counted a dozen. From some the ants are so numerous they blacken the road when they come out. It must take a great many plant-lice to nourish all that little colony.”

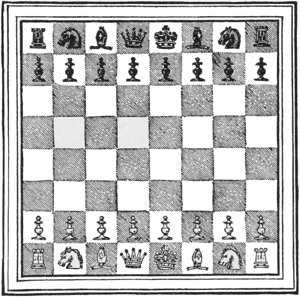

Chess-board with pieces in position

“Numerous though they be,” his uncle assured him, “they will never lack cows, as plant-lice are still more numerous. There are so many that they often seriously menace our harvests. The miserable louse declares war against us. To understand it, listen to this story:

“There was once a king of India who was much bored. To entertain him, a dervish invented the game of chess. You do not know this game. Well, on a board something like a checkerboard two adversaries range, in battle array, one white, the other black, pieces of different values: pawns, knights, bishops, castles, queen and king. The action begins. The pawns, simple foot-soldiers, are destined as always to receive the first of the glory on the battlefield. The king looks on at their extermination, guarded by his grandeur far from the fray. Now the cavalry charge, slashing with their swords right and left; even the bishops fight with hot-headed enthusiasm, and the ambulating castles go here and there, protecting the flanks of the army. Victory is decided. Of the blacks, the queen is a prisoner; the king has lost his castles; one knight and one bishop do wonderful deeds to procure his flight. They succumb. The king is checkmated. The game is lost.

“This clever game, image of war, pleased the bored king very much, and he asked the dervish what reward he desired for his invention.

“‘Light of the faithful,’ answered the inventor, ‘a poor dervish is easily satisfied. You shall give me one grain of wheat for the first square of the chessboard, two for the second, four for the third, eight for the fourth, and you will double thus the number of grains, to the last square, which is the sixty-fourth. I shall be satisfied with that. My blue pigeons will have enough grain for some days.’

“‘This man is a fool,’ said the king to himself; ‘he might have had great riches and he asks me for a few handfuls of wheat.’ Then, turning to his minister:—‘Count out ten purses of a thousand sequins for this man, and have a sack of wheat given him. He will have a hundred times the amount of grain he asks of me.’

“‘Commander of the faithful,’ answered the dervish, ‘keep the purses of sequins, useless to my blue pigeons, and give me the wheat as I wish.’

“‘Very well. Instead of one sack, you shall have a hundred.’

“‘It is not enough, Sun of Justice.’

“‘You shall have a thousand.’

“‘Not enough, Terror of the unfaithful. The squares of my chessboard would not have their proper amount.’

“In the meantime the courtiers whispered among themselves, astonished at the singular pretensions of the dervish, who, in the contents of a thousand sacks, would not find his grain of wheat doubled sixty-four times. Out of patience, the king convoked the learned men to hold a meeting and calculate the grains of wheat demanded. The dervish smiled maliciously in his beard, and modestly moved aside while awaiting the end of the calculation.

“And behold, under the pen of the calculators, the figure grew larger and larger. The work finished, the head one rose.

“‘Sublime Commander,’ said he, ‘arithmetic has decided. To satisfy the dervish’s demand, there is not enough wheat in your granaries. There is not enough in the town, in the kingdom, or in the whole world. For the quantity of grain demanded, the whole earth, sea and continents together, would be covered with a continuous bed to the depth of a finger.’

“The king angrily bit his mustache and, unable to count out to him his grains of wheat, named the inventor of chess prime vizier. That is what the wily dervish wanted.”

“Like the king, I should have fallen into the dervish’s snare,” said Jules. “I should have thought that doubling a grain sixty-four times would only give a few handfuls of wheat.”

“Henceforth,” returned Uncle Paul, “you will know that a number, even very small, when multiplied a number of times by the same figure, is like a snow-ball which grows in rolling, and soon becomes an enormous ball which all our efforts cannot move.”

“Your dervish was very crafty,” remarked Emile. “He modestly contented himself with one grain of wheat for his blue pigeons, on condition that they doubled the number on each square. Apparently, he asked next to nothing; in reality, he asked more than the king possessed. What is a dervish, Uncle?”

“In the religions of the East they call by that name those who renounce the world to give themselves up to prayer and contemplation.”

“You say the king made him prime vizier. Is that a high office?”

“Prime vizier means prime minister. The dervish then became the greatest dignitary of the State, after the king.”

“I am no longer surprised that he refused the ten purses of a thousand sequins. He was waiting for something better. The ten purses, however, would make a good sum?”

“A sequin is a gold piece worth about twelve francs. At that rate, the king offered the dervish a sum of one hundred and twenty thousand francs, besides the sacks of wheat.”

“And the dervish preferred the grain sixty-four times doubled.”

“In comparison what was offered him was nothing.”

“And the plant-lice?” asked Jules.

“The story of the dervish is bringing us to that directly,” his uncle assured him.

“A PLANT-LOUSE, we will suppose,” resumed Uncle Paul, “has just established itself on the tender shoot of a rosebush. It is alone, all alone. A few days after, young plant-lice surround it: they are its sons. How many are there? Ten, twenty, a hundred? Let us say ten. Is that enough to assure the preservation of the species? Don’t laugh at my question. I know well that if the plant-lice were missing from the rosebushes, the order of things would not be sensibly changed.”

“The ants would be the most to be pitied,” said Emile.

“The round earth would continue to turn just the same, even when the last plant-louse was dying on its leaf; but it is not, in truth, an idle question to ask if ten plant-lice suffice to preserve the race; for science has no higher object than the quest of providential means for maintaining everything in a just measure of prosperity.

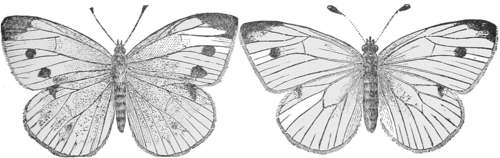

“Well, ten plant-lice coming from one would be far too many if we did not have to take account of destructive agencies. One replacing one, the population remains the same; ten replacing one, in a short time the number increases beyond all possible limits. Think of the dervish’s grain of wheat doubled sixty-four times, so that it becomes a bed of wheat of a finger’s depth over the whole earth. What would it be if it had been multiplied ten times instead of doubled! In like manner, after a few years, the descendants of a first plant-louse, continually multiplied tenfold, would be in straitened circumstances in this world. But there is the great reaper, death, which puts an invincible obstacle to overcrowding, counterbalances life in its overgrowing fecundity, and, in partnership with it, keeps all things in a perpetual youth. On a rosebush apparently most peaceful there is death every minute. But the small, the humble, and weak, are the habitual pasture, the daily bread, of the large eaters. To how many dangers is not the plant-louse exposed, so tiny, so weak, and without any means of defense! No sooner does a little bird, hardly out of the shell, discover with its piercing eyes a spot haunted by the plant-lice, than, merely as an appetizer, it will swallow hundreds. And if a worm, far more rapacious, a horrible worm expressly created and put into the world to eat you alive, joins in, ah! my poor plant-lice, may God, the good God of little creatures, protect you; for your race is indeed in peril.

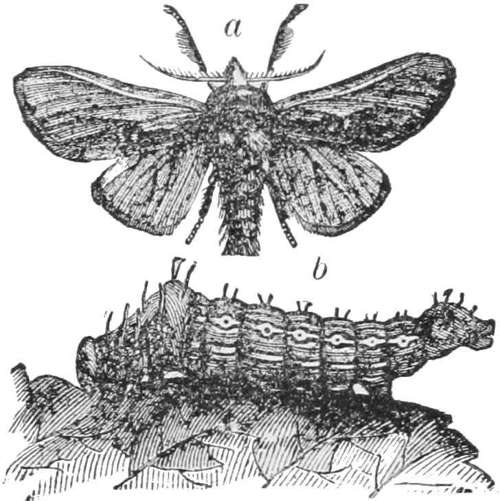

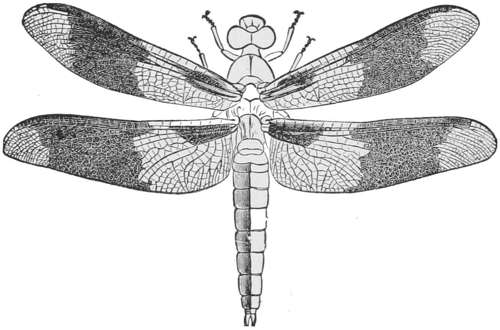

“This devourer is of a delicate green with a white stripe on its back. It is tapering in front, swollen at the back. When it doubles itself up it takes the shape of a tear-drop. They call it the ants’ lion because of the ravages it makes in the stupid herd. It establishes itself among them. With its pointed mouth, it seizes one, the biggest, the plumpest; it sucks it and throws away the skin, which is too hard for it. Its pointed head is lowered again, a second plant-louse seized, raised from the leaf, and sucked. Then another and another, a twentieth, a hundredth. The foolish herd, whose ranks are thinning, do not even seem to perceive what is going on. The trapped plant-louse kicks between the lion’s fangs; the others, as if nothing were happening, continue to feed peacefully. It would take a good deal more than that to spoil their appetite! They eat while they are waiting to be eaten. The lion has had enough. He squats amidst the herd to digest at his ease. But digestion is soon over and already the greedy worm has its eye on those that he will soon crunch. After two weeks of continual feasting, after having browsed as it were on whole herds of plant-lice, the worm turns into an elegant little dragon-fly with eyes as bright as gold, and known as the hemerobius.

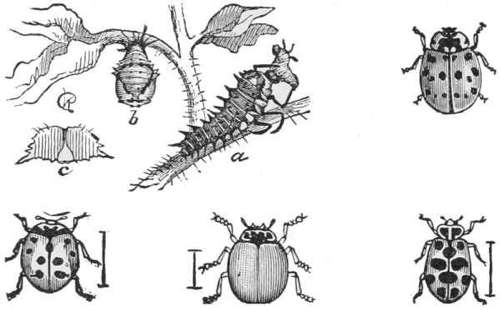

Ladybug

(a) larva (b) pupa (c) first joint of larva

“Is that all? Oh, no. Here is the lady-bug, the good God’s bug. It is round and red, with black spots. It is very pleasing; it has an innocent air. Who would take it also to be a devourer, filling its stomach with plant-lice? Look at it closely on the rosebush, and you will see it at its ferocious feasting. It is very pretty and innocent-looking; but it is a glutton, there is no denying the fact, so fond is it of plant-lice.

“Is that all? Oh, no. Those poor plant-lice are manna, the regular diet of all sorts of ravagers. Young birds eat them, the hemerobius eats them, lady-birds eat them, gluttons of all kinds eat them; and still there are always plant-lice. Ah! that is where, in the fight between fecundity which repairs and the rough battle of life which destroys, the weak excel by opposing legions and legions to the chances of annihilation. In vain the devourers come from all sides and pounce upon their prey; the devoured survive by sacrificing a million to preserve one. The weaker they are, the more fruitful they are.

“The herring, cod, and sardine are given over as pasturage for the devourers of the sea, earth, and sky. When they undertake long voyages to graze in favorable spots, their extermination is imminent. The hungry ones of the sea surround the school of fish; the famished ones of the sky hover over their route; those of the earth await them on the shore. Man hastens to lend a strong hand to the killing and to take his share of the sea food. He equips fleets, goes to the fish with naval armies in which all nations are represented; he dries in the sun, salts, smokes, packs. But there is no perceptible diminution in the supply; for him the weak are infinite in number. One cod lays nine million eggs! Where are the devourers that will see the end of such a family?”

“Nine million eggs!” exclaimed Emile. “Is that a great many?”

“Just to count them, one by one, would take nearly a year of ten working hours each day.”

“Whoever counted them had lots of patience,” was Emile’s comment.

“They are not counted,” replied Uncle Paul; “they are weighed, which is quickly done; and from the weight the number is deduced.

“Like the cod in the sea, the plant-lice are exposed on their rosebushes and alders to numerous chances of destruction. I have told you that they are the daily bread of a multitude of eaters. So, to increase their legions, they have rapid means that are not found in other insects. Instead of laying eggs, very slow in developing, they bring forth living plant-lice, which all, absolutely all, in two weeks have obtained their growth and begin to produce another generation. This is repeated all through the season, that is to say at least half the year, so that the number of generations succeeding one another during this period cannot be less than a dozen. Let us say that one plant-louse produces ten, which is certainly below the actual number. Each of these ten plant-lice borne by the first one bears ten more, making one hundred in all; each of these hundred bears ten, in all one thousand; each of the thousand bears ten, in all ten thousand; and so on, multiplying always by ten, eleven times. Here is the same calculation as the dervish’s grain of wheat, which grew with such astonishing rapidity when they multiplied it by two. For the family of the plant-lice the increase is much more rapid, as the multiplication is made by ten. It is true that the calculation stops at the twelfth instead of going on to the sixty-fourth. No matter, the result would stupefy you; it is equal to a hundred thousand millions. To count a cod’s eggs, one by one, would take nearly a year; to count the descendants of one plant-louse for six months would take ten thousand years! Where are the devourers that would see the end of the miserable louse? Guess how much space these plant-lice would cover, as closely packed as they are on the elder branch.”

“Perhaps as large a place as our garden,” suggested Claire.

“More than that; the garden is a hundred meters long and the same in width. Well, the family of that one plant-louse would cover a surface ten times larger; that is to say, ten hectares. What do you say to that? Is it not necessary that the young birds, little lady-bugs, and the dragon-fly with the golden eyes should work hard in the extermination of the louse, which if unhindered would in a few years overrun the world?

“In spite of the hungry ones which devour them, the plant-lice seriously alarm mankind. Winged plant-lice have been seen flying in clouds thick enough to obscure the daylight. Their black legions went from one canton to another, alighted on the fruit trees, and ravaged them. Ah! when God wishes to try us, the elements are not always unchained. He sends against us in our pride the paltriest of creatures. The invisible mower, the feeble plant-louse, comes, and man is filled with fear; for the good things of the earth are in great peril.

“Man, so powerful, can do nothing against these little creatures, invincible in their multitude.”

Uncle Paul finished the story of the ants and their cows. Several times since, Emile, Jules, and Claire have talked of the prodigious families of the plant-louse and the cod, but rather lost themselves in the millions and thousand millions. Their uncle was right: his stories interested them much more than Mother Ambroisine’s tales.

UNCLE PAUL had just cut down a pear-tree in the garden. The tree was old, its trunk ravaged by worms, and for several years it had not borne any fruit. It was to be replaced by another. The children found their Uncle Paul seated on the trunk of the pear-tree. He was looking attentively at something. “One, two, three, four, five,” said he, tapping with his finger upon the cross-section of the felled tree. What was he counting?

“Come quick,” he called, “come; the pear-tree is waiting to tell you its story. It seems to have some curious things to tell you.”

The children burst out laughing.

“And what does the old pear-tree wish to tell us?” asked Jules.

“Look here, at the cut which I was careful to make very clean with the ax. Don’t you see some rings in the wood, rings which begin around the marrow and keep getting larger and larger until they reach the bark?”

“I see them,” Jules replied; “they are rings fitted one inside another.”

“It looks a little like the circles that come just after throwing a stone into the water,” remarked Claire.

“I see them too by looking closely,” chimed in Emile.

“I must tell you,” continued Uncle Paul, “that those circles are called annual layers. Why annual, if you please? Because one is formed every year; one only, understand, neither more nor less. The learned who spend their lives studying plants, and who are called botanists, tell us that no doubt is possible on that point. From the moment the little tree springs from the seed to the time when the old tree dies, every year there is formed a ring, a layer of wood. This understood, let us count the layers of our pear-tree.”

Uncle Paul took a pin to guide his counting; Emile, Jules, and Claire looked on attentively. One, two, three, four, five—They counted thus up to forty-five, from the marrow to the bark.

“The trunk has forty-five layers of wood,” announced Uncle Paul. “Who can tell me what that signifies? How old is the pear-tree?”

“That is not very hard,” answered Jules, “after what you have just told us. As it makes one ring every year, and we have counted forty-five, the pear-tree must be forty-five years old.”

“Eh! Eh! what did I tell you?” cried Uncle Paul, in triumph. “Has not the pear-tree talked? It has begun its history by telling us its age. Truly, the tree is forty-five years old.”

“What a singular thing!” Jules exclaimed. “You can know the age of a tree as if you saw its birth. You count the layers of wood; so many layers, so many years. One must be with you, Uncle, to learn those things. And the other trees, oak, beech, chestnut, do they do the same?”

“Absolutely the same. In our country every tree counts one year for each layer. Count its layers and you have its age.”

“Oh! how sorry I am I did not know that the other day,” put in Emile, “when they cut down the big beech which was in the way on the edge of the road. Oh, my! What a fine tree! It covered a whole field with its branches. It must have been very old.”

“Not very,” said Uncle Paul. “I counted its layers; it had one hundred and seventy.”

“One hundred and seventy, Uncle Paul! Honest and truly?”

“Honest and truly, my little friend, one hundred and seventy.”

“Then the beech was a hundred and seventy years old,” said Jules. “Is it possible? A tree to grow so old! And no doubt it would have lived many years longer if the road-mender had not had it cut down to widen the road.”

“For us, a hundred and seventy years would certainly be a great age,” assented his uncle; “no one lives so long. For a tree it is very little. Let us sit down in the shade. I have more to tell you about the age of trees.”

“THEY used to tell of a chestnut of Sancerre whose trunk was more than four meters round. According to the most moderate estimate its age must have been three or four hundred years. Don’t cry out at the age of this chestnut. My story is just beginning, and you may be sure that, as a narrator who stimulates the curiosity of his audience, I reserve the oldest for the end.

“Much larger chestnuts are known; for example, that of Neuve-Celle, on the borders of the Lake of Geneva, and that of Esaü, in the neighborhood of Montélimar. The first is thirteen meters round at the base of the trunk. From the year 1408 it sheltered a hermitage; the story has been testified to. Since then four centuries and a half have passed, adding to its age, and lightning has struck it at different times. No matter, it is still vigorous and full of leaves. The second is a majestic ruin. Its high branches are despoiled; its trunk, eleven meters round, is plowed with deep crevices, the wrinkles of old age. To tell the age of these two giants is hardly possible. Perhaps it might be reckoned at a thousand years, and still the two old trees bear fruit; they will not die.”

“A thousand years! If Uncle had not said it, I should not believe it.” This from Jules.

“Sh! You must listen to the end without saying anything,” cautioned his uncle.

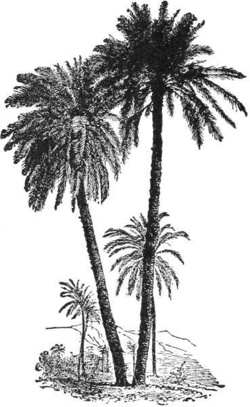

“The largest tree in the world is a chestnut on the slopes of Etna, in Sicily. Look at the map: you will see down there, at the extreme end of Italy, opposite the toe of that beautiful country which has the shape of a boot, a large island with three corners. That is Sicily. On that island is a celebrated mountain which throws up burning matter—a volcano, in short. It is called Etna. To come back to our chestnut, I must tell you that they call it ‘the chestnut of a hundred horses,’ because Jane, Queen of Aragon, visiting the volcano one day and, overtaken by a storm, took refuge under it with her escort of a hundred horsemen. Under its forest of leaves both riders and horses found shelter. To surround the giant, thirty people extending their arms and joining hands would not be enough. The trunk is more than fifty meters round. Judged by its size, it is less a tree-trunk than a fortress, a tower. An opening large enough to permit two carriages to pass abreast goes through the base of the chestnut and gives access into the cavity of the trunk, which is fitted up for the use of those who go to gather chestnuts; for the old colossus still has young sap and seldom fails to bear fruit. It is impossible to estimate the age of this giant by its size, for one suspects that a trunk as large as that comes from several chestnuts, originally distinct, but so near together that they have become welded into one.

“Neustadt, in Württemberg, has a linden whose branches, overburdened by years, are held up by a hundred pillars of masonry. The branches cover all together a space 130 meters in circumference. In 1229 this tree was already old, for writers of that time call it ‘the big linden.’ Its probable age to-day is seven or eight hundred years.

White Oak

“There was in France, at the beginning of this century, an older tree than the veteran of Neustadt. In 1804 could be seen at the castle of Chaillé, in the Deux-Sèvres, a linden 15 meters round. It had six main branches propped with numerous pillars. If it still exists it cannot be less than eleven centuries old.

“The cemetery of Allouville, in Normandy, is shaded by one of the oldest oaks in France. The dust of the dead, into which it has thrust its roots, seems to have given it an exceptional vigor. Its trunk measures ten meters in circumference at the base. A hermit’s chamber surmounted by a little steeple rises in the midst of its enormous branches. The base of the trunk, partly hollow, is fitted up as a chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Peace. The greatest personages have esteemed it an honor to go and pray in this rustic sanctuary and meditate a moment under the shade of the old tree which has seen so many graves open and shut. According to its size, they consider this oak to be about nine hundred years old. The acorn that produced it must, then, have germinated about the year 1000. To-day the old oak carries its monstrous branches without effort. Glorified by men and ravaged by lightning, it peacefully follows the course of ages, perhaps having before it a future equal to its past.

“Much older oaks are known. In 1824 a wood-cutter of Ardennes felled a gigantic oak in whose trunk were found sacrificial vases and antique coins. The old oak had had fifteen or sixteen centuries of existence.

“After the Allouville oak I will tell you of some more companions of the dead; for it is above all in these fields of repose, where the sanctity of the place protects them against the injuries of man, that the trees attain such an advanced age. Two yews in the cemetery of Haie-de-Routot, department of Eure, merit attention above all. In 1832 they shaded with their foliage the whole of the field of the dead and a part of the church, without having experienced serious damage, when an extremely violent windstorm threw a part of their branches to the ground. In spite of this mutilation these two yews are still majestic old trees. Their trunks, entirely hollow, measure each of them nine meters in circumference. Their age is estimated at fourteen hundred years.

“That, however, is not more than half the age that some other trees of the same kind have attained. A yew in a Scotch cemetery measured twenty-nine meters around. Its probable age was two thousand five hundred years. Another yew, also in a cemetery in the same country, was, in 1660, so prodigious that the whole country was talking about it. They reckoned its age then at two thousand eight hundred and twenty-four years. If it is still standing, this patriarch of European trees bears the weight of more than thirty centuries.

“Enough for the present. Now it is your turn to talk.”

“I like better to be silent, Uncle Paul,” said Jules. “You have upset my mind with your trees that will not die.”

“I am thinking of the old yew in the Scotch cemetery. Did you say three thousand years?” asked Claire.

“Three thousand years, my dear child; and we might go still further back, if I were to tell you of certain trees in foreign countries. Some are known to be almost as old as the world.”

JULES and Claire could not get over the astonishment caused by their uncle’s story of the old trees to which centuries are less than years are to us. Emile, with his usual restlessness, led the conversation to another subject:

“And animals, Uncle,” asked he, “how long do they live?”

“Domestic animals,” was the reply, “seldom attain the age that nature allows them. We grudge them their nourishment, overtire them, and do not give them proper shelter. And then, we take from them their milk, fleece, hide, flesh, in fact everything. How can you ever grow old when the butcher is waiting for you at the stable door with his knife? Useless to speak of these poor victims of our need: to give us long life, they do not live out their time. Supposing that an animal is well treated, that it suffers neither hunger nor cold, that it lives in peace without excessive fatigue, without fear of knacker or butcher; under these good conditions, how many years will it live?

“Let us begin with the ox. Here is a robust one, I hope. What chest and shoulders! And then that big square forehead, with its vigorous horns around which the strap of the yoke goes; those eyes shining with the serene majesty of strength. If old age is the portion of the strong, the ox ought to live for centuries.”

“I should think so too,” assented Jules.

“Quite wrong, my dear children; the ox, so big, strong, massive, is old, very old, at twenty or thirty years. What to us would be verdant youth is for it decrepit old age.

“Let us pass on to the horse. You see I do not take my examples from among the weak; I choose the most vigorous. Well, the horse, as well as its modest companion, the ass, scarcely reaches more than thirty or thirty-five years.”

“How mistaken I was!” Jules exclaimed. “I thought the horse and ox strong enough to live at least a century. They are so big, they take up so much room!”

“I do not know, my little friend, whether you can understand me, but I want to inform you that to take up a great deal of room in this world is not the way to live in peace and to enjoy a long life. There are people who take up a lot of space, not in the body—they are no bigger than we—but in their pretensions and their ambitious manœuvers. Do they live in peace, are they preparing for themselves a venerable old age? It is very doubtful. Let us remain small; that is to say, let us content ourselves with the little that God has given us; let us beware of the temptations of envy, the foolish counsels of pride; let us be full of activity, of work, and not of ambition. That is the only way we are permitted to hope for length of days.

“Let us return without delay to our animals. Our other domestic animals live a still shorter time. A dog, at twenty or twenty-five years, can no longer drag himself along; a pig is a tottering veteran at twenty; at fifteen at the most, a cat no longer chases mice, it says good-by to the joys of the roof and retires to some corner of a granary to die in peace; the goat and sheep, at ten or fifteen, touch extreme old age, the rabbit is at the end of its skein at eight or ten; and the miserable rat, if it lives four years, is looked upon among its own kind as a prodigy of longevity.

“Would you like me to tell you about birds? Very well. The pigeon may live from six to ten years; the guinea fowl, hen, and turkey, twelve. A goose lives longer; it is true that in its quality of goose it does not worry. The goose attains twenty-five years, and even a good deal more.

“But here is something better. The goldfinch, sparrow, birds free from care, always singing, always frisking, happy as possible with a ray of sunlight in the foliage and a grain of hemp-seed, live as long as the gluttonous goose, and longer than the stupid turkey. These very happy little birds live from twenty to twenty-five years, the age of an ox. As I told you, taking up a lot of room in this world is not the way to prepare oneself for a long life.

“As to man, if he leads a regular life, he often lives to eighty or ninety. Sometimes he reaches a hundred or even more. But should he attain only the ordinary age, the average age, as they say, that is about forty, then he is to be considered a privileged creature as to length of life; the foregoing facts show it. And besides, for man, my dear children, length of life is not measured exactly according to the number of years. He lives most who works most. When God calls us to Him, let us take with us the sincere esteem of others and the consciousness of having done our duty to the end; and, whatever our age, we shall have lived long enough.”

NOW, that day, Mother Ambroisine was very tired. She had taken down from their shelves kettles, saucepans, lamps, candlesticks, casseroles, pans, and lids. After having rubbed them with fine sand and ashes, then washed them well, she had put the utensils in the sun to dry them thoroughly. They all shone like a mirror. The kettles particularly were superb with their rosy reflections; one might have said that tongues of fire were shining inside them. The candlesticks were a dazzling yellow. Emile and Jules were lost in admiration.

“I should like to know what they make kettles of, they shine so,” remarked Emile. “They are very ugly outside, all black, daubed with soot; but inside, how beautiful they are!”

“You must ask Uncle,” replied his brother.

“Yes,” assented Emile.

No sooner said than done: they went in search of their uncle. He did not have to be entreated; he was happy whenever there was an opportunity to teach them something.

“Kettles are made of copper,” he began.

“And copper?” asked Jules.

“Copper is not made. In certain countries, it is found already made, mixed with stone. It is one of the substances that it is not in the power of man to make. We use these substances as God has deposited them in the bosom of the earth for purposes of human industry; but all our knowledge and all our skill could not produce them.

“In the bosom of mountains where copper is found, they hollow out galleries which go down deep into the earth. There workmen called miners, with lamps to light them, attack the rock with great blows of the pick, while others carry the detached blocks outside. These blocks of stone in which copper is found are called ore. In furnaces made for the purpose they heat the ore to a very high temperature. The heat of our stove, when it is red-hot, is nothing in comparison. The copper melts, runs, and is separated from the rest. Then, with hammers of enormous weight, set in motion by a wheel turned by water, they strike the mass of copper which, little by little, becomes thin and is hollowed into a large basin.

“The coppersmith continues the work. He takes the shapeless basin and, with little strokes of the hammer, fashions it on the anvil to give it a regular shape.”

“That is why coppersmiths tap all day with their hammers,” commented Jules. “I had often wondered, when passing their shops, why they made so much noise, always tapping, without any stop. They were thinning the copper; shaping it into saucepans and kettles.”

Here Emile asked: “When a kettle is old, has holes in it and can’t be used, what do they do with it? I heard Mother Ambroisine speak of selling a worn-out kettle.”

“It is melted, and another new kettle made out of the copper,” replied Uncle Paul.

“Then the copper does not wear away?”

“It wears away too much, my friend: some of it is lost when they rub it with sand to make it shine; some is lost, too, by the continual action of the fire; but what is left is still good.”

“Mother Ambroisine also spoke of recasting a lamp which had lost a foot. What are lamps made of?”

“They are of tin, another substance that we find ready-made in the bosom of the earth, without the power of producing it ourselves.”

“COPPER and tin are called metals,” continued Uncle Paul. “They are heavy, shining substances, which bear the blows of the hammer without breaking. They flatten, but do not break. There are still other substances which possess the considerable weight of copper and tin, as well as their brilliancy and resistance to blows. All these substances are called metals.”

“Then lead, which is so heavy, is a metal too?” asked Emile.

“Iron also, silver and gold?” queried his brother.

“Yes, these substances and still others are metals. All have a peculiar brilliancy called metallic luster, but the color varies. Copper is red; gold, yellow; silver, iron, lead, tin, white, with a very slightly different shade one from another.”

“The candlesticks Mother Ambroisine is drying in the sun,” said Emile, “are a magnificent yellow and so shiny they dazzle. Are they gold?”

“No, my dear child; your uncle does not possess such riches. They are brass. To vary the colors and other properties of the metals, instead of always using them separately, they often mix two or three together, or even more. They melt them together, and the whole constitutes a sort of new metal, different from those which enter into its composition. Thus, in melting together copper and a kind of white metal called zinc, the same as the garden watering-pots are made of, they obtain brass, which has not the red of copper, nor the white of zinc, but the yellow of gold. The material of the candlesticks is, then, made of copper and zinc together; in a word, it is brass, and not gold, in spite of its luster and yellow color. Gold is yellow and glitters; but all that is yellow and glitters is not gold. At the last village fair they sold magnificent rings whose brilliancy deceived you. In gold, they would have cost a fine sum. The merchant sold them for a sou. They were brass.”

“How can they tell gold from brass, since the color and luster are almost the same?” asked Jules.

“By the weight, chiefly. Gold is much heavier than brass; it is indeed the heaviest metal in frequent use. After it comes lead, then silver, copper, iron, tin, and finally zinc, the lightest of all.”

“You told us that to melt copper,” put in Emile, “they needed a fire so intense, that the heat of a red-hot stove would be nothing in comparison. All metals do not resist like that, for I remember very well in what a sorry way the first leaden soldiers you gave me came to their end. Last winter, I had lined them up on the luke-warm stove. Just when I was not watching, the troop tottered, sank down, and ran in little streams of melted lead. I had only time to save half a dozen grenadiers, and their feet were missing.”

“And when Mother Ambroisine thoughtlessly put the lamp on the stove,” added Jules, “oh! it was soon done for: a finger’s breadth of tin had disappeared.”

“Tin and lead melt very easily,” explained Uncle Paul. “The heat of our hearth is enough to make them run. Zinc also melts without much trouble; but silver, then copper, then gold, and finally iron, need fires of an intensity unknown in our houses. Iron, above all, has excessive resistance, very valuable to us.

“Shovels, tongs, grates, stoves, are iron. These various objects, always in contact with the fire, do not melt, however; do not even soften. To soften iron, so as to shape it easily on the anvil by blows from the hammer, the smith needs all the heat of his forge. In vain would he blow and put on coal; he would never succeed in melting it. Iron, however, can be melted, but you must use the most intense heat that human skill can produce.”

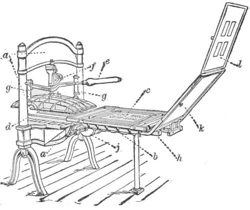

IN the morning some wandering coppersmiths were passing. Mother Ambroisine had sold them the old kettle. Besides the sale, they were to make over the lamp whose foot had melted on the stove, and replate two saucepans. So the smiths lighted a fire in the open air, set up their bellows on the ground, and in a large round iron spoon melted the old lamp, adding a little tin to replace what had been lost. The melted metal was run into a mold, from which it came out in the shape of a lamp. This lamp, still pretty large, was fixed on a lathe which a little boy set in motion; and while it turned, the master touched it with the edge of a steel tool. The tin thus planed off fell in thin shavings, rolled up like curl-papers. The lamp was visibly becoming perfect; it took the proper polish and shape.

Afterward they busied themselves plating the copper saucepans. They cleaned them thoroughly inside with sand, put them on the fire, and, when they were very hot, went over the whole of their surface with a tow pad and a little melted tin. Wherever the pad rubbed, the tin stuck to the copper. In a few moments the inside of the saucepan, red before, was now shiny white.

Emile and Jules, while eating their little lunch of apples and bread, looked on at this curious work without saying a word. They promised themselves to ask their uncle the reason for whitening the inside of the copper saucepans with tin. In the evening, accordingly, they spoke of the tinning and plating.

“Highly cleaned and polished iron is very brilliant,” explained their uncle. “The blade of a new knife, Claire’s scissors, carefully kept in their case, are examples. But, if exposed to damp air, iron tarnishes quickly and covers itself with an earthy and red crust called—”

“Rust,” interposed Claire.

“Yes, it is called rust.”

“The big nails that hold the iron wires where the bell-flowers climb up the garden wall are covered with that red crust,” remarked Jules; and Emile added:

“The old knife I found in the ground is covered with it too.”

“Those large nails and the old knife are encrusted with rust because they have remained for a long time exposed to the air and dampness. Damp air corrodes iron; it becomes incorporated with the metal and makes it unrecognizable. When rusty, iron no longer has the properties that make it so useful to us; it is a kind of red or yellow earth, in which, without looking attentively, it would be impossible to suspect a metal.”

“I can well believe it,” said Jules. “For my part, I should never have taken rust for iron with which air and moisture had become incorporated.”

“Many other metals rust like iron; that is to say, they are converted into earthy matter by contact with damp air. The color of rust varies according to the metal. Iron rust is yellow or red, that of copper is green, lead and zinc white.”

“Then the green rust of old pennies is copper rust,” said Jules.

“The white matter that covers the nozzle of the pump must be lead rust?” queried Claire.

“Exactly. The prime difficulty with rust is that it makes metals ugly: they lose their brilliance and polish; but it works still greater injury. There are harmless rusts which might get mixed with our food without danger: such is iron rust. On the contrary, copper and lead rusts are deadly poisons. If, by mischance, these rusts should get into our food, we might die, or at least we should experience cruel suffering. We will speak only of copper, for lead, on account of its quick melting, cannot go on the fire and is not used for kitchen utensils. Copper rust, I say, is a mortal poison; and yet they prepare food in copper vessels. Ask Mother Ambroisine.”

“Very true,” said she, “but I always have my eye on my saucepans: I keep them very clean and from time to time have them replated.”

“I don’t understand,” put in Jules, “how the work that the tinsmith did this morning could prevent the copper rust being a poison.”

“The smith’s work will not make the copper rust cease to be a poison,” replied Uncle Paul, “but it will prevent the rust’s forming. Of the common metals tin rusts the least. Exposed to the air a long time, it scarcely tarnishes. And then the rust, which forms in small quantities, is innocuous, like iron rust. To prevent copper from covering itself with poisonous green spots, to preserve it from rust, it must be kept from contact with damp air and also with certain alimentary substances such as vinegar, oil, grease—substances that provoke the rapid formation of rust. For this reason the copper saucepan is coated over with tin inside. Under the thin bed of tin which covers it, the copper cannot rust, because it is no longer in contact with the air. The tin remains; but this metal changes with difficulty, and, besides, its rust, if it forms any, is harmless. So they plate copper, that is to say they cover it with a thin bed of tin, to prevent its rusting, and thus to prevent the formation of the dangerous poison that might, some day or other, be mixed with our food.

“They also tin iron, not to prevent the formation of poison, for the rust of this metal is harmless, but simply to preserve it from changing and covering itself with ugly red spots. This tinned iron is called tin-plate. Lids, coffee-pots, dripping-pans, graters, lanterns, and innumerable other things, are of tin-plate; that is to say, thin sheets of iron covered on both sides with a coating of tin.”

“SOME metals never rust; such a one is gold. Ancient gold pieces found in the earth after centuries are as bright as the day they were coined. No dross, no rust covers their effigy and inscription. Time, fire, humidity, air, cannot harm this admirable metal. Therefore gold, on account of its unchangeable luster and its rarity, is preëminently the material for ornaments and coins.

“Furthermore, gold is the first metal that man became acquainted with, long before iron, lead, tin, and the others. The reason why man’s attention was called to gold, long centuries before iron, is not hard to understand. Gold never rusts; iron rusts with such grievous facility that in a short time, if we are not careful, it is converted into a red earth. I have just told you that gold objects, however old they may be, have come to us intact, even after having been in the dampest ground. As for objects of iron, not one has reached us that was not in an unrecognizable state. Corroded with rust, they have become a shapeless earthy crust. Now I will ask Jules if the iron ore that is extracted from the bowels of the earth can be real, pure iron, such as we use.”

“It seems to me not, Uncle; for if iron at any given moment is pure, it must rust with time and change to earthy matter, as does the blade of a knife buried in the ground.”

“My brother seems to reason correctly; I agree with him,” said Claire.

“And gold?” Uncle Paul asked her.

“It is different with gold,” she replied. “As that metal never rusts, is not changed by time, air, and dampness, it must be pure.”