![[Image

of the book's cover is unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Grandeur That Was Rome, by J.C. Stobart This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Grandeur That Was Rome Author: J.C. Stobart Release Date: March 15, 2018 [EBook #56747] [Last updated: May 20, 2018] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GRANDEUR THAT WAS ROME *** Produced by Chuck Greif, Thierry Alberto and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

![[Image

of the book's cover is unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

|

Contents (etext transcriber's note) |

UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME

THE GLORY THAT WAS GREECE

BY J. C. STOBART, M.A.

SOME OPINIONS OF THE PRESS

“Mr. Stobart does a real service when he gives the reading but non-expert public this fine volume, embodying the latest results of research, blending them, too, into as agreeable a narrative as we have met with for a long while.... There is not a dull line in his book. He has plenty of humour, as a writer needs must have who is to deal with men from the human standpoint.... It is beautifully produced, and the plates, both in colour and monochrome, are as numerous and well-chosen as they are striking and instructive.”—The Guardian.

“Mr. Stobart has produced the very book to show the modern barbarian the meaning of Hellenism. He exhibits the latest discoveries from Cnossus and elsewhere, the new-found masterpieces along with the old. He criticises and appraises the newest theories, ranging from the influence of malaria to the origins of drama. He has something for everybody.... The book is nobly illustrated ... no such collection of beautiful things of this kind has yet been placed before the English public.”—THE Saturday Review.

“He really helps to make ancient Greece a living reality; and the illustrations, a conspicuous feature of the book, are good and well selected, the photographic views gaining much from the reproduction on a dull-surfaced paper.”—Times.

“A more beautiful book than this has rarely been printed.... The pictures of Greek scenery, sculpture, vases, etc., are exceptionally good.”—Evening Standard.

“No better guide through the labyrinth of things Hellenic has appeared in our day, and both brush and camera yield of their choicest to make the book an enduring joy.”—Daily Chronicle.

THE GRANDEUR THAT WAS ROME

A Survey of Roman Culture

and Civilisation: by

J. C. Stobart, M.A.

LATE LECTURER IN HISTORY

TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

![[Image unavailable.]](images/colophon.jpg)

LONDON

SIDGWICK & JACKSON LTD.

3 Adam Street, Adelphi

1912

{vi}

All rights reserved

Printed by

BALLANTYNE & COMPANY LTD

AT THE BALLANTYNE PRESS

Tavistock Street Covent Garden

London

{vii}

This book is a continuation of “The Glory that was Greece,” written with the same purpose and from the same point of view.

The point of view is that of humanity and the progress of civilisation. The value of Rome’s contribution to the lasting welfare of mankind is the test of what is to be emphasised or neglected. Hence the instructed reader will find a deliberate attempt to adjust the historical balance which has, I venture to think, been unfairly deflected by excessive deference to literary and scholastic traditions. The Roman histories of the nineteenth century were wont to stop short with the Republic, because “Classical Latin” ceased with Cicero and Ovid. They followed Livy and Tacitus in regarding the Republic as the hey-day of Roman greatness, and the Empire as merely a distressing sequel beginning and ending in tragedy. From the standpoint of civilisation this is an absurdity. The Republic was a mere preface. The Republic until its last century did nothing for the world, except to win battles whereby the road was opened for the subsequent advance of civilisation. Even the stern tenacity of the Roman defence against Hannibal, admirable as it was, can only be called superior to the still more heroic defence of Jerusalem by the Jews, because the former was successful and the latter failed. From the Republican standpoint Rome is immeasurably inferior to Athens. In short, what seemed important and glorious to Livy will not necessarily remain so after the lapse of nearly two thousand years. Rome is so vast a fact, and of consequences so far-reaching, that every generation may claim a share in interpreting{viii} her anew. There is the Rome of the ecclesiastic, of the diplomat, of the politician, of the soldier, of the economist. There is the Rome of the literary scholar, and the Rome of the archæologist.

It is wonderful how this mighty and eternal city varies with her various historians. Diodorus of Sicily, to whom we owe most of her early history, was seeking mainly to flatter the claims of the Romans to a heroic past. Polybius, the trained Greek politician of the second century B.C., was writing Roman history in order to prove to his fellow-Greeks his theory of the basis of political success. Livy was seeking a solace for the miseries of his own day in contemplating the virtues of an idealised past. Tacitus, during an interval of mitigated despotism, strove to exhibit the crimes and follies of autocracy. These were both rhetoricians, trained in the school of Greek democratic oratory. Edward Gibbon, too (I write as one who cannot change trains at Lausanne without emotion), saw the Empire from the standpoint of eighteenth-century liberalism and materialism. Theodor Mommsen made Rome the setting for his Bismarckian Cæsarism, and finally, M. Boissier has enlivened her by peopling her streets with Parisians. It is, in fact, difficult to depict so huge a landscape without taking and revealing an individual point of view. There is always something fresh to see even in the much-thumbed records of Rome.

Although a large part of this book is written directly from the original sources, and none of it without frequent reference to them, it is, in the main, frankly a derivative history intended for readers who are not specialists. Except Pelham’s Outlines, which are almost exclusively political, there is no other book in English, so far as I am aware, which attempts to give a view of the whole course of ancient Roman History within the limits of a single volume, and yet the Empire without the Republic is almost as incomplete as the Republic without the Empire. As for the Empire, although nothing can supersede or attempt to replace The Decline and Fall, yet the schola{ix}r’s outlook on the history of the Empire has been greatly changed since Gibbon’s day by the discovery of Pompeii and the study of inscriptions. Therefore while I fully admit my obligations to Gibbon and Mommsen (as well as to Dill, Pelham, Bury, Haverfield, Greenidge, Warde Fowler, Cruttwell, Sellar, Walters, Rice Holmes, and Mrs. Strong, and to Ferrero, Pais, Boissier, Seeck, Bernheim, Mau, Becker, and Friedlander) this book professes to be something more than a compilation, because it has a point of view of its own.

The pictures are an integral part of my scheme. It is not possible with Rome, as it was with Greece, to let pictures and statues take the place of wars and treaties. Wars and treaties are an essential part of the Grandeur of Rome. They should have a larger place here, were they less well known, and were there less need to redress a balance. But the pictures are chosen so that the reader’s eye may be able to gather its own impression of the Roman genius. When the Roman took pen in hand he was usually more than half a Greek, but sometimes in his handling of bricks and mortar he revealed himself. For this reason—and because I must confess not to be a convinced admirer of “Roman Art”—there is an attempt to make the illustrations convey an impression of grand building, vast, solid, and utilitarian, rather than of finished sculpture by Greek hands. Pictures can produce this impression far more powerfully than words. Standing in the Colosseum or before the solid masonry of the Porta Nigra at Trier, one has seemed to come far closer to the heart of the essential Roman than ever in reading Vergil or Horace. The best Roman portraits are strangely illuminating.

I have to acknowledge with gratitude the permission given me by the Director of the Königlichen Messbildanstalt of the Royal Museum at Berlin to reproduce four of the magnificent photographs of Dr. O. Puchstein’s discoveries at Ba’albek. I am indebted also to Herr Georg Reimer, of Berlin, for allowing me to reproduce four of the complete series of Reliefs from Trajan’s Column published by him in heliogravure under the{x} care of Professor Cichorius. The coloured plate of the interior of the House of Livia is reproduced by permission of the German Archæological Institute from Luckenbach’s Kunst und Geschichte (grosse Ausgabe, erster Teil); and from the same work I have been allowed to reproduce the reconstruction of the Roman Forum in the time of Cæsar. Professor Garstang has kindly supplied a photograph, with permission to reproduce of the bronze head of Augustus discovered by him at Meroe and recently presented to the British Museum. The Cambridge University Press has allowed me to give two pictures from Prof. Ridgeway’s Early Age of Greece; and the photograph of the Alcántara Bridge was kindly supplied by Sr. D. Miguel Utrillo, of Barcelona. The majority of photographs have been supplied by Messrs. W. A. Mansell and Co.; but for many subjects, especially of Roman remains outside Italy, I must acknowledge my indebtedness to a number of amateur photographers, who not only avoid the hackneyed point of view but also achieve a high level of technique. Sir Alexander Binnie has kindly permitted the inclusion of eight photographs and Mr. C. T. Carr of four; while I must also make acknowledgment to Miss Carr, Mr. R. C. Smith, and Miss K. P. Blair.

As before, I am much indebted to Mr. Arnold Gomme for his assistance with the proofs.

J. C. S.

Canterbury, 1912{xi}

| PAGE | ||

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | xii | |

| INTRODUCTION | ||

| The Perspective of Roman History: Latinism: Italy and the Roman | 1 | |

| CHAP | ||

| I. | THE BEGINNINGS OF ROME | |

| The Growing Republic: The Constitution: The Early Roman: Early Religion: Law | 16 | |

| II. | CONQUEST | |

| The Provinces: The Imperial City | 44 | |

| III. | THE LAST CENTURY OF THE REPUBLIC | |

| The Gracchi: Marius: Sulla: Pompeius and Cæsar: Late Republican Civilisation | 82 | |

| IV. | AUGUSTUS | |

| The Senate: The People and the Magistrates: Army and Treasury: The Provinces | 160 | |

| V. | AUGUSTAN ROME | |

| Reformation of Roman Society: Augustan Literature: Art: Architecture | 223 | |

| VI. | THE GROWTH OF THE EMPIRE | |

| The Principate: Imperial Rome: Education and Literature: Art: Law: Philosophy and Religion | 253 | |

| EPILOGUE | 305 | |

| CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY | 317 | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 325 | |

| INDEX | 329 | |

NOTE

The cameo on the front cover of this volume is from a sardonyx head of Germanicus in the Carlisle collection.

PHOTOGRAVURE PLATES

| HEAD OF AUGUSTUS WITH CROWN OF OAK-LEAVES | Frontispiece | |

| Engraved by Emery Walker from a photograph by Bruckmann of the original in the Glyptothek, Munich. An idealised portrait of the emperor in middle life. He wears the corona civica. See p 169 | ||

| “CLYTIE” | 248 | |

| Engraved by Emery Walker from a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the original marble in the British Museum. An idealised portrait-bust of a lady of the imperial family, possibly Antonia, the work of a Greek artist of the Augustan Age. The name “Clytie” has no authority: the frame of petals is purely decorative | ||

| MAP (IN COLOUR) | ||

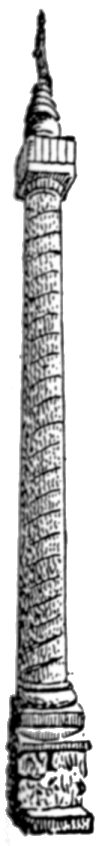

| THE ROMAN EMPIRE AT ITS FULLEST EXTENT | 194 | |

| PLATES | ||

| 1 | GENERAL VIEW OF ROMAN FORUM | 4 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. The view is taken from the Capitol, looking S.E. at the Arch of Titus, on the left of which part of the Colosseum is visible. The background on the right is filled by the Palatine Hill and the substructures of Caligula’s Palace, in front of which the walls of the Temple of Augustus are visible. To the right of the middle are three columns and part of the entablature of the Temple of Castor. In the centre is the Column of Phocas. The foreground is occupied by the Arch of Severus (l.) the Temple of Saturn (r.) and two Corinthian columns of the Temple of Vespasian | ||

| 2 | THE ROMAN CAMPAGNA | 6 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. The ruined arches belonged to the Aqueduct of Claudius. See p. 293 | ||

| 3 | VIEW OF SPOLETO | 8 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. Modern view showing a typical hill-town or arx. Spoletium is chiefly famous in ancient history for its {xiv}gallant repulse of Hannibal in 217 B.C. | ||

| 4 | THE CAPITOLINE WOLF | 18 |

| From a photograph by Anderson of the original bronze in the Palace of the Conservatori, Rome. The wolf herself is ancient, probably of Etruscan workmanship. See p. 18 | ||

| 5 | (Fig 1) ARCHAIC BRONZE “PAN” | 20 |

| Primitive Etruscan work. A horned and bearded god | ||

| (Fig. 2) ARCHAIC BRONZE. “ARTEMIS” | ||

| From photographs by Mansell & Co, of the originals in the British Museum, showing the development of Etruscan bronze-work | ||

| 6 | ETRUSCAN VASE | 22 |

| Drawn from Vase F. 488 in the Etruscan Room, British Museum. A curiously debased design, which like much of Etruscan art suggests unintelligent copying of Greek models | ||

| 7 | ETRUSCAN TOMB IN TERRA-COTTA | 24 |

| From a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the original in the Terra-cotta Room, British Museum. The reader will notice the close resemblance of this work, particularly the relief depicting the battle and the mourners, to Greek relief-work of the sixth century B.C. | ||

| 8 | VIA APPIA: THE APPIAN WAY | 40 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. The remains of Roman tombs may be seen on each side of the road | ||

| 9 | LAKE TRASIMENE | 50 |

| From photographs by C.T. Carr. The scene of the famous battle of 217 B.C., in which Hannibal ambushed the Roman army on the shores of the lake | ||

| 10 | BRONZE STATUE OF AULUS METILIUS [“THE ARRINGATORE”] | 56 |

| From a photograph by Almari of the original bronze statue in the Archæological Museum, Florence. One of the rare examples of early republican portraiture, found near Lake Trasimene, a statue of Aulus Metilius (unknown to history) in the guise of an orator. It is assigned to the end of the third century B.C., and is said to represent the transition between Etruscan and Roman portraiture. I think, however, that it would be true to describe it as a Roman head, probably copied from a death-mask, upon a Greek body. Where is the Etruscan element? | ||

| 11 | PUBLIUS SCIPIO AFRICANUS | 72 |

| From a photograph by Brogi of the original bronze in the Naples Museum. The authenticity of the portrait cannot be guaranteed, but it is a fine example of Republican portraiture | ||

| 12 | (Fig. 1) ETRUSCAN WARRIOR: BRONZE STATUETTE | 88 |

| Possibly imported from Greece | ||

| (Fig. 2) ROMAN LEGIONARY OF THE EMPIRE; BRONZE STATUETTE | ||

| From photographs by Mansell & Co. of the originals in the British Museum. These two bronze statuettes show the essential similarity of Roman and Etruscan (or Greek) armour, which consists mainly of a {xv}cuirass of leather plated with metal | ||

| 13 | SCABBARD OF LEGIONARY SWORD | 98 |

| From photographs of the original in the British Museum. The scabbard is in the scale of 1:4. The sword was only 21 in. long and 2½ in. at the greatest breadth. It was found at Mainz. The scabbard is of wood ornamented with plates of silver-gilt. At the top is a relief showing Tiberius welcoming Germanicus on his victorious return from Germany (A.D. 17) In the centre is a portrait medallion of Tiberius. The relief at the bottom indicates the return of the standards of Varus to a Roman temple. Below is an Amazon armed with the German battle-axe | ||

| 14 | CN. POMPEIUS MAGNUS | 104 |

| From a photograph by Tryde of the original marble in the Jacobsen collection at Copenhagen. There is no sufficient reason to doubt the authenticity of this famous portrait of Pompey the Great. It closely resembles a beautiful gem in the Chatsworth collection | ||

| 15 | BUST OF CICERO | 108 |

| From a photograph by Alinari of the original in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. A fine ancient portrait; but its authenticity cannot be guaranteed | ||

| 16 | TEMPLE OF FORTUNA VIRILIS, ROME | 112 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. Erected in 78 B.C. Notice the Ionic columns used purely as ornament | ||

| 17 | TEMPLE OF VESTA, TIVOLI | 116 |

| From a photograph by Alinari. Commonly known as “The Temple of the Sibyl,” but more properly assigned to Vesta. This is considered to be work of about 80 B.C. The style is Corinthian | ||

| 18 | (Fig. 1) VENUS GENETRIX | 120 |

| From a photograph by Alinari of the statue in the Louvre. Described on p. 156 | ||

| (Fig. 2) THE MEDICI VENUS | ||

| From a photograph by Alinari of the statue in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. This celebrated and once admired statue is now regarded as typical of the degenerate Greek work produced for the Roman market. The technique is still admirable | ||

| 19 | JULIUS CÆSAR | 136 |

| From a photograph by the Graphic Gesellschaft of the original black basalt head in the Berlin Museum. Its antiquity is not above suspicion | ||

| 20 | (Fig. 1) BUST OF JULIUS CÆSAR | 138 |

| From a photograph by Anderson of the original in the Vatican, Rome. A fine portrait, undoubtedly a close copy of an authentic original, as is the equally famous example in the British Museum | ||

| (Fig. 2) BUST OF BRUTUS | ||

| From a photograph by Anderson of the bust in the Capitoline Museum, Rome. The authenticity of this has been doubted, but on insufficient grounds. Evidently a work of about the same period as the “Young {xvi}Augustus” (plate 25) | ||

| 21 | ARRENTINE POTTERY | 140 |

| Plate from “The Art of the Romans” by H. B. Walters, by kind permission of Messrs Methuen & Co. Arretine pottery takes its name from Arretium (Arezzo), the chief centre of this native Italian industry. It is distinguished by the fine crimson clay of which it is made. The designs stamped in relief from moulds are generally imitated from Greek metal-work or Samian ware. The pieces are seldom more than 6 in. in height | ||

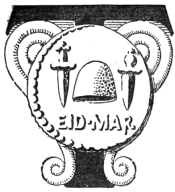

| 22 | COIN PLATE (IN COLLOTYPE) | 142 |

| 1. Coin of Pontus, with head of Mithradates the Great. See pp. 103, 158 | ||

| 2. Silver Tetradrachm, with heads of Antony and Cleopatra. See pp. 122, 155 | ||

| 3. Denarius of Sulla Rev Q. Pompeius Rufus, consul with Sulla in 88 B.C. | ||

| 4. Denarius of Julius Cæsar Rev figure of Victory, with name of L Æmilius Buca, triumvir of the mint | ||

| 5. Coin of Tiberius, with head of Livia and inscription SALVS AVGVSTA | ||

| 23 | AUGUSTUS: THE BLACAS CAMEO | 144 |

| Collotype plate from a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the original in the Gem Room, British Museum. Probably the work of Dioscorides, who had the exclusive right of portraying Augustus | ||

| 24 | AUGUSTUS: THE “PRIMAPORTA” STATUE | 148 |

| From a photograph by Anderson of the statue in the Vatican, Rome. The emperor is depicted as a triumphant general, haranguing his troops. In the centre of the breastplate is a Parthian humbly surrendering the standards to a Roman soldier | ||

| 25 | AUGUSTUS AS A YOUTH | 150 |

| From a photograph by Anderson of the bust in the Vatican, Rome. A distinctly Greek portrait, possibly taken during his early days at Apollonia; an authentic original bust | ||

| 26 | AUGUSTUS: BRONZE HEAD, FROM MEROË | 152 |

| From a photograph supplied by Prof. Garstang of the original bronze, discovered by him in 1910, at Meroe in Egypt, and since presented to the British Museum | ||

| 27 | M. VIPSANIUS AGRIPPA | 154 |

| From a photograph by Alinari of the bust in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. The design of the bust is inconsistent with the belief that this is a contemporary portrait. But it resembles the portraits of the general on the coins | ||

| 28 | (Fig. 1) ROMAN BRIDGE AT RIMINI | 156 |

| This fine marble bridge was begun by Augustus and completed by Tiberius. Ariminum was the northern terminus of the great Flaminian Road | ||

| (Fig. 2) ROMAN AMPHITHEATRE AT VERONA | ||

| From photographs by C. T. Carr. The amphitheatre was erected by {xvii}Diocletian about A.D. 290 and was restored by Napoleon. It would contain about 20,000 spectators. Verona was the capital under Theodoric the Ostrogoth | ||

| 29 | TWO VIEWS OF THE PONT DU GARD | 158 |

| This is part of the great aqueduct which supplied Nismes with water. The bridge has a span of 880 feet across the valley of the Gardon. The lower tiers are built of stone without mortar or cement of any kind. | ||

| 30 | (Fig. 1) INTERIOR OF ROMAN TEMPLE, NISMES | 160 |

| (Fig. 2) LOWER CORRIDOR OF ARENA, NISMES | ||

| The amphitheatre at Nismes is larger than that of Verona. There are sixty arches on the ground and first floors, with larger apertures at the four cardinal points | ||

| 31 | THE ARENA, NISMES | 162 |

| Notice the consoles in the attic story. These are pierced with round holes to contain the poles which once supported an awning for the protection of the spectators from the heat | ||

| 32 | (Fig. 1) TRIUMPHAL ARCH, ST. REMY, ARLES | 164 |

| Arles (Arelate) was one of the chief towns of Gallia Narbonensis, and a colony of Augustus. The upper part of the arch has perished. The sculptures represent chained captives. There is no inscription and the date of the monument is uncertain | ||

| (Fig. 2) MAUSOLEUM OF JULIUS, ST. REMY, ARLES | ||

| This mausoleum was erected by three brothers Julius to the memory of their parents. Thousands of Gauls took the name of Julius in honour of Cæsar and Augustus. The style, which is essentially Græco-Roman, is appropriate to the period of Augustus. The reliefs again represent captives. | ||

| Plates 29-32 are from photographs taken by Sir Alexander Binnie | ||

| 33 | (Fig. 1) ARCH OF MARIUS, ORANGE | 166 |

| From a photograph by Neurdein. Apparently erected to the memory of C. Marius, who defeated the Teutons at Aquæ Sextiæ in 102 B.C. The neighbourhood of Orange (Arausio) was the scene of a great Roman defeat three years earlier. But the style of the monument points to a date at least a century later. The style of the reliefs is dated by the best authorities in the reign of Tiberius. The name of the sculptor, Boudillus, appears to be Gallic | ||

| (Fig. 2) S. LORENZO, MILAN | ||

| From a photograph by Brogi. Remains of a handsome Corinthian colonnade which formerly belonged to the palace of Maximian. In the fourth century A.D., Mediolanum was frequently a place of imperial residence. In this period Milan was larger than Rome | ||

| 34 | BARBARIAN WOMAN, KNOWN AS “THUSNELDA” | 168 |

| From a photograph by Almari. This famous statue, which stands in the Loggia dei Lanzi, at Florence, is popularly called after the wife of Arminius, who died in exile at Ravenna. It is probably a typical Teutonic captive and very possibly occupied a place in the niche of a triumphal arch. Mrs. Strong assigns it to the period of Trajan {xviii} | ||

| 35 | (Fig. 1) ALTAR OF THE LARES OF AUGUSTUS | 172 |

| From a photograph by Alinari of the original in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Augustus introduced Cæsar-worship into Rome by means of these altars to the Lares (household gods) and the Genius of Augustus. This altar dates from A.D. 2. Augustus is in the centre, Livia his wife to the right, and Gaius or Lucius Cæsar to the left. Mrs Strong describes these reliefs as “a series of singular charm” | ||

| (Fig. 2) SACRIFICIAL SCENE, FROM THE ARA PACIS | ||

| From a photograph by Anderson of the original in the Villa Medici, Rome. An earlier example of the favourite sacrificial theme. The artist has sacrificed, as usual, the hinder part of his victim to his desire to introduce as many as possible of the portrait studies. The relief has been much and badly restored | ||

| 36 | THE “TELLUS” GROUP, ARA PACIS | 174 |

| From a photograph by Brogi of the original in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Discussed on pp. 244-245 | ||

| 37 | RELIEF, ARA PACIS | 176 |

| From a photograph by Anderson of the original in the Museo delle Terme, Rome. The scene is a sacrifice. The majestic bearded figure on the right is perhaps emblematical of the senate—one of the finest conceptions of Græco-Roman art and little inferior to the elders on the Parthenon frieze. Above the attendants on the left is a small shrine of the Penates | ||

| 38 | SILVER PLATE FROM BOSCOREALE | 178 |

| 1. A silver mirror-case of exquisite design: the central medallion represents Leda and the swan | ||

| 2. One of the beautiful examples of Augustan art in which natural forms are used with brilliant decorative effect | ||

| From photographs by Giraudon of the originals in the Louvre | ||

| 39 | (Fig. 1) GERMANICUS | 180 |

| Sardonyx cameo from the Carlisle collection. Photograph by Mansell & Co. | ||

| (Fig. 2) GEM OF AUGUSTUS: CAMEO OF VIENNA | ||

| Photograph by Mansell & Co. Sardonyx cameo probably by Dioscorides, A.D. 13 | ||

| Below: German captives and Roman soldiers erecting a trophy | ||

| Above: Augustus and Roma enthroned. Behind them are Earth, Ocean, and (?) the World, who is crowning him with the corona civica. Behind his head is his lucky sign—the constellation of Capricornus. Tiberius escorted by a Victory is stepping out of his triumphal chariot and Germanicus stands between | ||

| 40 | AUGUSTUS AND FAMILY OF CÆSARS: CAMEO | 182 |

| From a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the original in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. The largest and finest sardonyx cameo in existence. It is cut in five layers of the stone so that wonderful effects of tinting are produced, sometimes at the expense of the modelling. Tiberius and his mother Livia occupy the centre. Germanicus and his mother {xix}Antonia stand before him. The figures to the left may be Gaius (Caligula) and the wife of Germanicus. Behind the throne Drusus is looking up to heaven, where the deified Augustus floats, surrounded by allegorical figures. Below are barbarian captives | ||

| 41 | (Figs. 1 and 3) STUCCO RELIEFS | 184 |

| From photographs by Anderson of the originals in the National Museum, Rome. Much of the ornamentation of Roman villas was in stucco or terra-cotta taken from the mould and often tinted. Both the flying Victory and the Bacchic relief showing a drunken Silenus are extremely graceful specimens of the art, both essentially Greek | ||

| (Fig. 2) DECORATIVE ORNAMENT, ARA PACIS | ||

| From a photograph by Anderson of the fragment in the Museo delle Terme, Rome. A fine example of the naturalistic ornament of the Augustan period | ||

| 42 | (Fig. 1) FRAGMENT OF AUGUSTAN ALTAR | 188 |

| From a photograph by Anderson of the original in the Museo delle Terme, Rome. Quoted by Wickhoff as “a triumph of the Augustan illusionist style” a design of plane-leaves, admirable in fidelity to nature. Observe the rich mouldings of the framework | ||

| (Fig. 2) ROMAN RELIEF | ||

| From a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the original in the British Museum. From the tomb of a poet. The Muse stands before him holding a tragic mask | ||

| 43 | ALTAR OF AMEMPTUS | 190 |

| From a photograph by Giraudon of the original in the Louvre. The inscription shows that this altar was dedicated to the spirits of Amemptus, a freedman of the Empress Livia. It belongs therefore to about A.D. 25. | ||

| From the types of ornament employed one may conjecture that Amemptus was a Greek actor and musician. The decorative effect is very charming and the detail most beautifully worked out | ||

| 44 | (Fig. 1) THE TEMPLE OF SATURN, FORUM, ROME | 192 |

| Eight Ionic unfluted columns with part of the entablature. The columns stand upon a lofty base. The Temple of Saturn, which contained the treasury of the senate, was rebuilt in 42 B.C. | ||

| (Fig. 2) THE TEMPLE OF MATER MATUTA, ROME | ||

| From photographs by R.C. Smith. The most complete example of the round temple still existing, the Temple of Vesta in the Forum having disappeared. This is probably a temple of “Mother Dawn.” The five Corinthian columns of Pentelic marble were probably imported from Greece. Most authorities assign it to the Augustan restoration, but others place it among the earliest Republican works. The tiled roof is of course modern, and somewhat spoils its effect. This little temple stood in the Forum Boarium (cattle market) | ||

| 45 | PORCH AND INTERIOR OF THE PANTHEON, ROME | 196 |

| From photographs by Anderson and Brogi. See p. 251 | ||

| 46 | MAISON CARREE, NISMES | 198 |

| From a photograph kindly supplied by Sir Alexander Binnie. Perhaps the finest, certainly the most complete example of Græco-Roman {xx}architecture. The style is Corinthian, but characteristic Roman developments are the high podium or base, and the fact that the surrounding peristyle is “engaged” or attached to the wall except in front (pseudo-peripteral). This temple was dedicated to M. Aurelius and L. Verus. It was surrounded by an open space and then a Corinthian colonnade. Nismes, once the centre of a flourishing trade in cheese, is especially rich in Roman remains | ||

| 47 | THEATRE OF MARCELLUS, ROME | 200 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. The theatre, built by Augustus in B.C. in memory of his ill-fated nephew, was constructed in three tiers, Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. The upper story has disappeared, and the elevation of the ground floor has been spoilt by the rise in the level of the ground | ||

| 48 | INNER COURT, FARNESE PALACE, ROME | 202 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. The splendid cortile of the Farnese Palace, designed by Michael Angelo, is copied from the Theatre of Marcellus, exhibiting the same succession of orders. The juxtaposition of these two plates should assist the reader’s imagination to re-create the original splendours of Roman architecture from the existing ruins | ||

| 49 | (Fig. 1) COLONNADE OF OCTAVIA | 204 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. Erected by Augustus in honour of his beloved sister, who was married first to M. Marcellus then to M. Antony. She was the mother of Marcellus, great-grandmother of Nero and Caligula. She died in 11 B.C. The colonnade was probably built some years before her death. It enclosed the temples of Jupiter Stator and Juno, it also contained a public library and a senate-house which was destroyed by fire in the reign of Titus | ||

| (Fig. 2) ROMAN BAS-RELIEF | ||

| From a photograph by Almari of the original in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. A sacrifice, probably a work of the time of Domitian. The heads, most of them portraits, are of admirable execution, but the overcrowded design is unpleasing. The architectural background is typical of the Flavian period. This slab was used by Raphael in his cartoon of Paul and Barnabas at Lystra | ||

| 50 | COIN PLATE (IN COLLOTYPE): ROMAN EMPERORS | 206 |

1. Nero |

5. Marcus Aurelius | |

| From originals in the British Museum | ||

| 51 | HADRIAN’S WALL: NEAR HOUSESTEADS (BORCOVICIUM), NORTHUMBERLAND | 210 |

| From a photograph by Gibson & Son. See pp. 261-262 | ||

| 52 | PORTA NIGRA, TRIER, GERMANY | 214 |

| From a photograph by Frith. An example of military architecture, truly Roman in character. Probably dates from the time of Gallienus (A.D. 260){xxi} | ||

| 53 | RELIEF FROM TRAJAN’S COLUMN—I | 216 |

| On the left, the emperor surrounded by his staff is haranguing his troops. Observe how the ranks of the army are portrayed in file. On the right, fortifications are being constructed (Cichorius, plate xi) | ||

| 54 | RELIEF FROM TRAJAN’S COLUMN—II | 218 |

| On the left, horses are being transported across the Danube, Trajan is seen steering his galley, sheltered by a canopy. On the right he is landing at the gates of a Roman town on the river banks. The temples are visible within the walls (Cichorius, plate xxvi) | ||

| 55 | RELIEF FROM TRAJAN’S COLUMN—III | 220 |

| A cavalry battle, in which the Romans are charging the mail-clad Sarmatians. The reader will notice the resemblance between the latter and the Norman knights of the Bayeux tapestry (Cichorius, plate xxviii) | ||

| 56 | RELIEF FROM TRAJAN’S COLUMN—IV | 222 |

| On the left the Romans, in testudo formation, are attacking a Dacian fortress. In the centre Trajan is receiving the heads of the defeated enemy (Cichorius, plate li) | ||

| Four collotype plates, reproduced by special permission from Prof. Cichorius’s “Die Reliefs der Traianssaule” (Berlin, Georg Reimer, 1896) Photographs by Donald Macbeth | ||

| 57 | (Fig 1) RELIEF, FROM A SARCOPHAGUS | 224 |

| From a photograph by Alinari of the original in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. An example of “continuous narration” in relief-work. The sarcophagus is ornamented with typical scenes in the life of a Roman gentleman—the chase, the greeting by his slaves, sacrifice, marriage. The design is described as “subtly interwoven” or “fatiguing and confused” according to the taste of the onlooker | ||

| (Fig. 2) ROMAN AND DACIAN | ||

| From a photograph by Graudon of the original relief in the Louvre. The source of this slab is unknown; it evidently belongs to the beginning of the second century A.D., and refers to the Dacian Wars of Trajan, or possibly of Domitian. The contrast between the proud calm Roman and the wild barbarian is very fine, and recalls similar contrasts in Greek sculpture. In the background a Dacian hut and an oak-tree are seen | ||

| 58 | RELIEF FROM THE ARCH OF TITUS | 226 |

| From a photograph by Brogi. Shows the emblems captured in Jerusalem (A.D. 70) being carried in triumph at Rome. We can distinguish the seven-branched candlestick, the table for the show-bread and the Sacred Trumpets. The tablets were inscribed with the names of captured cities | ||

| 59 | RUINS OF PALMYRA (VIEW OF GREAT ARCH FROM THE EAST) | 230 |

| From a photograph by Donald Macbeth of plate xxvi in Robert Wood’s “Ruins of Palmyra,” 1753. The city of Palmyra, traditionally founded by Solomon, at a meeting-point of the Syrian caravan routes, first rose into prominence in the time of Gallienus, when Odenathus, its{xxii} Saracen prince, was acknowledged by the emperor as “Augustus,” i.e. a colleague in the imperial power. After his assassination his widow Zenobia succeeded to his power and ruled magnificently as Queen of the East until she was defeated and made captive by Aurelian. The architectural remains are Corinthian in style, embellished with meaningless oriental ornament | ||

| 60 | BA’ALBEK: THE TEMPLE OF ZEUS | 232 |

| Heliopolis or Ba’albek was the centre of a fertile region of Cœle-Syria on the slopes of Anti-Lebanon. It was always a centre of Baal or Sun worship, it was a city of priests and its oracle attracted great renown in the second century A.D. when it was consulted by Trajan. Antoninus Pius built the great Temple of Zeus (Jupiter), one of the wonders of the world. The worship was rather that of Baal than of Zeus, and oriental in character. It included the cult of conical stones such as that brought to Rome by Elagabalus. The architecture is of the most sumptuous Corinthian style, with some oriental modifications | ||

| 61 | BA’ALBEK: THE TEMPLE OF BACCHUS, INTERIOR | 234 |

| Here we observe the oriental round arch forming the lowest course. The material of the buildings is white granite with decorations of rough local marble | ||

| 62 | BA’ALBEK: THE TEMPLE OF BACCHUS, EAST PORTICO | 236 |

| Observe the rather effective juxtaposition of fluted and unfluted columns | ||

| 63 | BA’ALBEK: THE CIRCULAR TEMPLE, FROM BACK | 238 |

| This small circular temple is of a style without parallel in antiquity. The nature of the cult is unknown | ||

| The last four plates are reproduced by special permission of the Director of the Royal Museum, Berlin, from photographs supplied by the Königlichen Messbildanstalt. They are plates xvii, xxi, xxii, and xxx respectively, in Puchstein and Von Lupke’s “Ba’albek,” published for the German Government by G. Reimer, Berlin | ||

| 64 | (Fig. 1) TIMGAD: THE CAPITOL | 240 |

| Timgad (Thamugadi) was founded by Trajan as a Roman colony in A.D. 100. It is on the edge of the Sahara in the ancient province of Numidia. It has recently been explored by the French. The photograph shows the Capitol raised on an artificial terrace. Two of the Corinthian columns have been re-erected | ||

| (Fig. 2) TIMGAD: THE DECUMANUS MAXIMUS AND TRAJAN’S ARCH | ||

| A view of the main street, spanned by a triumphal arch in honour of Trajan. The ruts of the carriage-wheels are still visible as at Pompeii. | ||

| From photographs by Miss K. P. Blair | ||

| 65 | POMPEII: THERMOPOLION, STREET OF ABUNDANCE | 242 |

| From a photograph by d’Agostino. The new street revealed by the most recent excavations of Prof. Spinazzola. The photograph shows us a “hot-wine shop” with the bar and the wine-jars | ||

| 66 | POMPEII: MURAL PAINTING, STREET OF ABUNDANCE | 244 |

| From a photograph by Abeniacar. Another of the most recent finds, a fresco of the Twelve Gods{xxiii} | ||

| 67 | (Fig. 1) THE EMPEROR DECIUS | 246 |

| From a photograph by Anderson of the bust in the Capitoline Museum, Rome. A splendid example of the realistic portraiture in the third century A.D. | ||

| (Fig. 2) MARCUS AURELIUS | ||

| From a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the bust in the British Museum. All the portraits of the virtuous philosopher agree in producing this aspect of tonsorial prettiness which belies the character of a manly and vigorous prince | ||

| 68 | (Fig. 1) THE EMPEROR CARACALLA | 250 |

| From a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the bust in the British Museum | ||

| (Fig. 2) THE EMPEROR COMMODUS | ||

| From a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the bust in the British Museum | ||

| 69 | RELIEFS FROM BASE OF THE ANTONINE COLUMN | 252 |

| From photographs by Anderson of the originals in the Vatican, Rome | ||

| (Fig. 1) WARRIORS | ||

| Represents a military review. The infantrymen with their standards are grouped in the centre, while the emperor leads a procession of the cavalry with their vexilla, who march past with what Mrs Strong describes as a “fine and pleasing movement.” Discussed on p. 292 | ||

| (Fig. 2) APOTHEOSIS OF ANTONINUS AND FAUSTINA | ||

| Antoninus and his less virtuous consort are being borne up to heaven on the back of Fame or the Genius. The youth reclining below bears the obelisk of Augustus to indicate that he personifies the Campus Martius. The figure on the right is Rome. The composition of the scene displays a ludicrous want of imagination | ||

| 70 | TWO VIEWS OF THE AQUEDUCT OF CLAUDIUS | 254 |

| From photographs by Anderson. See p. 293 | ||

| 71 | (Fig. 1) THE ARCH OF TITUS, ROME | 258 |

| See p. 293 | ||

| (Fig. 2) THE ARCH OF CONSTANTINE, ROME | ||

| The Arch of Constantine is adorned with borrowed reliefs, mainly from the Forum of Trajan. It is the best preserved of the Roman arches. From photographs by R. C. Smith | ||

| 72 | THE COLOSSEUM, ROME | 260 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. Described on p. 293. In the foreground is the ruined apse of the Temple of Venus and Rome, built by Hadrian | ||

| 73 | THE COLUMN OF TRAJAN | 262 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. The great Forum of Trajan was constructed by the Greek architect Apollodorus between A.D. 111 and 114. The base of the column formed a tomb destined to contain the conqueror’s ashes. At the top was his statue, now replaced by an image of St. Peter. The story of the Dacian war is told on the spiral relief about 1 metre broad. See plates 53-56{xxiv} | ||

| 74 | DETAIL OF THE ANTONINE COLUMN | 264 |

| From photographs by Anderson. The Antonine Column was constructed on the model of the Column of Trajan, seventy-five years later, and thus affords an insight into the progress of relief sculpture at Rome. The later work shows more attempt at individual expression, not always successful, and the scenes are less crowded. They depict episodes from the German and Sarmatian wars of A.D. 171-175, (a) represents the decapitation of the rebels and (b) the capture of a German village: the huts are being burned while M. Aurelius serenely superintends an execution | ||

| 75 | ANTINOUS | 266 |

| (Fig. 1) from a photograph by Giraudon of the Mondragore bust in the Louvre | ||

| (Fig. 2) from a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the bust in the British Museum | ||

| The significance of the artistic cult of Antinous in the age of Hadrian is discussed on p. 293. It is probably only the diffidence of our native archæologists which has allowed the colossal Mondragore bust its supremacy. The British Museum portrait represents him younger and in the guise of a youthful Dionysius, the expression far more human, and the treatment of the hair far less elaborate and effeminate | ||

| 76 | ANTINOUS: FROM THE BAS-RELIEF IN THE VILLA ALBANI, ROME | 268 |

| From a photograph by Anderson | ||

| 77 | RELIEFS OF MARCUS AURELIUS | 270 |

| (Fig. 1). Marcus Aurelius accompanied by Bassæus Rufus, prætorian prefect, is riding through a wood and receiving the submission of two barbarian chiefs. In my judgment this scene, and especially the figure of the foot soldier at the emperor’s side, is the chef-d’œuvre of Roman historical relief-work | ||

| (Fig. 2). Marcus and Bassæus are sacrificing in front of the temple of the Capitoline Jove. These panels probably belonged to a triumphal arch erected in honour of the German and Sarmatian wars of A.D. 171-175. From photographs by Anderson of the originals in the Conservatori Palace, Rome | ||

| 78 | TWO VIEWS OF THE ARCH OF TRAJAN, BENEVENTUM | 274 |

| From photographs by Alinari. This splendid monument at Beneventum on the Appian Way was erected in A.D. 114 in expectation of the emperor’s triumphant return from the East, where, however, he died. It is constructed of Greek marble and once carried a quadriga in bronze. The reliefs on the inside (Fig. 1) depict the triumph of Trajan after his Parthian campaign. Those on the outside (Fig. 2) represent the Dacian campaigns | ||

| 79 | ALTAR DISCOVERED AT OSTIA | 276 |

| From a photograph by Anderson of the original in the National Museum, Rome. A fine example of decorative art. The motive of the garlanded skull is a favourite one. This altar was, as the inscription shows, a work of Hadrian’s time{xxv} | ||

| 80 | TOMB OF THE HATERII | 278 |

| From a photograph by Alinari of the fragments in the Lateran Museum, Rome. Monument to a physician, and his family of about a.d. 100. The scheme is ugly and barbaric, but it includes some very fine decorative work. The facades of five Roman buildings are shown—the Temple of Isis, the Colosseum, two triumphal arches, and the Temple of Jupiter Stator. The temples are open and the images visible | ||

| 81 | BRIDGE OF ALCANTARA, SPAIN | 282 |

| From a photograph by Lacoste, kindly supplied by Sr. D. Miguel Utrillo. This superb bridge over the Tagus is 650 feet long. The design exhibits a rare combination of grace with strength | ||

| 82 | TOMB OF HADRIAN, ROME | 284 |

| From a photograph by Anderson. The Castel S. Angelo, restored as a fortress by Pope Alexander VI. (Borgia), consists mainly of the Mausoleum of Hadrian; the bridge leading to it was also constructed for the emperor’s funeral. The circular tower was formerly ornamented with columns between which were statues. The famous Barberini Faun was one of them. There was a pyramidal gilt roof, and a colossal quadriga at the top. The whole building was formerly faced with white Parian marble. Besides Hadrian, all the Antonines, and Septimius Severus and Caracalla were buried here. The castle has had a stirring history in mediæval times also. The building is modelled upon the Mausoleum of Caria | ||

| 83 | TWO VIEWS OF HADRIAN’S VILLA, TIVOLI | 286 |

| From photographs by R. C. Smith. See p. 296 | ||

| 84 | TWO MOSAICS (COLOUR-PLATE) | 288 |

| (Fig. 1) SACRIFICIAL RITES, PROBABLY AT A TOMB | ||

| (Fig. 2) PREPARING FOR A SACRIFICE | ||

| From the originals in the British Museum, after photographs by Donald Macbeth | ||

| 85 | MURAL PAINTING: FLUTE-PLAYER (COLOUR-PLATE) | 290 |

| From the original in the British Museum, said to have been found in a columbarium on the Appian Way | ||

| 86 | POMPEII: TWO VIEWS OF THE RUINS | 292 |

| From photographs by R. C. Smith. The upper picture shows how the buried city has been dug out of the ashes from Vesuvius which form the subsoil of the surrounding country. The lower picture is a general view, showing Corinthian columns which formed a colonnade round the open impluvium | ||

| 87 | POMPEII: HOUSE OF THE VETTII CUPID FRESCOES | 294 |

| From photographs by Brogi. The upper picture shows the Cupids engaged as goldsmiths; the lower shows them as charioteers, Apollo and Artemis below. Two examples of the elegant mythological style of the Greek decline, but extremely effective for the purpose. This art is held to have originated in Alexandria | ||

| 88 | POMPEII: FRESCO OF THE SACRIFICE OF IPHIGENIA | 296 |

| Collotype plate from a photograph by Brogi. Probably a copy of one{xxvi} of the great pictures of the old Greek masters, Timanthes, about 400 B.C. If so it is the most important example of early painting in existence. The psychological motive of the composition is a study of grief. Calchas the prophet is grieved with foreknowledge, Ajax and Odysseus are sorrowfully obeying commands which they do not understand. Iphigenia herself shows the fortitude of a martyr, but Agamemnon’s grief, since he was her father, is too great for a Greek to exhibit. Hence his face is hidden. Above appears the deer which Artemis allowed to be substituted for the maiden | ||

| 89 | HOUSE OF LIVIA: INTERIOR DECORATION (COLOUR-PLATE) | 300 |

| Reproduced by permission of the German Institute of Archæology, from Luckenbach’s “Kunst und Geschichte” (grosse Ausgabe, Teil I, Tafel IV), by arrangement with R. Oldenbourg, Munich | ||

| 90 | THE ALDOBRANDINI MARRIAGE, VATICAN, ROME | 302 |

| From a photograph by Brogi of the fresco now in the Vatican. In the centre is the veiled bride, Venus is encouraging her, Charis is compounding sweet essences to add to her beauty, Hymen waits on the bride’s left seated on the threshold stone, outside is a group of three maidens, a musician, a crowned bridesmaid, and a tire-woman. At the other side the bride’s family is seen. This is without question the most charming example of ancient painting | ||

| 91 | BRONZE SACRIFICIAL TRIPOD | 304 |

| From a photograph by Brogi of the original, discovered at Pompeii, now in the National Museum, Naples. An example of Hellenic metal-work of the Augustan age | ||

| 92 | MITHRAS AND BULL | 308 |

| From a photograph by Mansell & Co. of the statue in the British Museum. Represents the Mithraic sacrament of Taurobolium in which the worshippers received new life by bathing in the blood of a bull. Mithras wears a Phrygian cap, for the Mithraic religion, though it arose in Persia, only began to form artistic expression when it passed through the art region of Asia Minor. This motive constantly recurs in the monuments of the second and third century all over Europe | ||

| 93 | MAUSOLEUM OF PLACIDIA, RAVENNA | 312 |

| From a photograph by Alinari. This little church which contains the tombs of the Emperor Honorius, her brother, and of Constantius III., her husband, as well as a sarcophagus of the Empress in marble, formerly adorned with plaques of silver, is eloquent of the shrunken glory of the Western Empire in the fifth century. It was founded about A.D. 440. It is built in the form of a Latin cross, and is only 49 ft. long, 41 ft. broad. The interior contains beautiful mosaics. Ravenna contains many other relics of this period when it was the seat of the Roman government | ||

| 94 | THE BARBERINI IVORY | 314 |

| From a photograph by Giraudon of the original in the Louvre. In the centre Constantine is represented on horseback with spear reversed in token of victory. Round him are Victory, a suppliant barbarian, and Earth with her fruits. To the left is a Roman soldier bearing a{xxvii} statuette of Victory. Below the nations of the East bring their tribute. Above two Victories, in process of transition, into angels, support a medallion of Christ, still of the beardless type associated with Apollo and Sol Invictus. The emblems of sun, moon, and stars show that Christian Art is not yet severed from paganism | ||

| 95 | (Fig. 1) THE PALACE OF DIOCLETIAN, SPALATO | 316 |

| From a photograph by Miss Carr. Diocletian planned this great palace, which is more like a city or fortress, at Spalato (Salonæ) on the Dalmatian coast, for his place of retirement. Its external walls measured 700 ft. by 580 ft. It was fortified on three sides and entered by three gates. The arcading in which the oriental arch springs from the Roman column is the most interesting architectural feature of the extensive ruins now existing | ||

| (Fig. 2) RELIEF FROM THE ARCH OF CONSTANTINE; THE BATTLE OF THE MILVIAN BRIDGE | ||

| From a photograph by Anderson. Shows the really degenerate art of the fourth century A.D. In this battle (A.D. 312) Constantine defeated his rival Maxentius, who was drowned with numbers of his men in the Tiber. The relief shows the drowning | ||

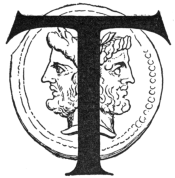

| ROMAN As: BRONZE (FULL-SIZE) WEIGHT 290 g. | 18 |

| The style of the design points to about 350 B.C., and we have no real evidence of a coinage any earlier. The design is not primitive though it is clumsily cast. The head of Janus is often found on Greek coins and so is the galley prow. The weight of the As sank from 12 to 1 oz. in the course of republican history | |

| ETRUSCAN FRESCO: HEAD OF HERCULES | 21 |

| An example of Etruscan painting which does not differ from Greek. This is probably a head of Hercules, whose name is found on Etruscan inscriptions | |

| PREHISTORIC ETRUSCAN POTTERY | 22 |

| From Ridgeway’s “Early Age of Greece.” Black ware decorated with incised ornament: hippocamps or sea-horses on one: found at Falern in Tuscany. Pottery of this type is found on prehistoric sites all over the Mediterranean | |

| THE ROMAN TOGA | 23 |

| The woollen toga was the official dress of the Roman citizen. It was generally worn over a tunic, though antiquarians, like Cato, wore the toga alone. It was worn in the natural colour of the wool, but candidates for office wore it specially whitened, and magistrates had a purple border | |

| MAP OF ITALY, SHOWING GROUND OVER 1000 FEET HIGH | 69 |

| {xxviii} | |

| PLAN OF INFANTRY MANIPLES | 97 |

| GALLIC POTTERY | 114, 115 |

| It is clearly only a provincial development of the Arretine ware which is itself imitated from the Samian ware of Greece | |

| COIN, SHOWING SURRENDER OF THE PARTHIAN STANDARDS | 199 |

| COIN. PORTRAIT OF P. QUINTILIUS VARUS | 217 |

| ROMAN LIMES | 264 |

| A reconstruction of the great frontier lines which encircled the Empire to the North along the Rhine and Danube. This is the style of the limes of Upper Germany | |

| THE ROMAN FORUM IN THE EARLY EMPIRE | 281 |

| HADRIAN’S TOMB, RESTORED | 295 |

| See p. 294 |

THENS and Rome stand side by side as the parents of Western

civilisation. The parental metaphor is almost irresistible. Rome is so

obviously masculine and robust, Greece endowed with so much loveliness

and charm. Rome subjugates by physical conquest and government. Greece

yields so easily to the Roman might and then in revenge so easily

dominates Rome itself, with all that Rome has conquered, by the mere

attractiveness of superior humanity. Nevertheless this metaphor of

masculine and feminine contains a serious fallacy. Greece, too, had had

days of military vigour. It was by superior courage and skill in

fighting that Athens and Sparta had beaten back the Persian invasions of

the fifth century before Christ, and thus saved Europe for

occidentalism. Again it was by military prowess that Alexander the Great

carried Greek civilisation to the borders of India, Hellenising Asia

Minor, Syria, Persia, Egypt, Phœnicia and even Palestine. This he did

just at the moment when Rome was{2} winning her dominion over Latium.

Instead, then, of looking at Greece and Rome as two coeval forces

working side by side we must regard them as predecessor and successor.

Rome is scarcely revealed as a world-power until she meets Greek

civilisation in Campania near the beginning of the third century before

Christ. The physical decline of Greece is scarcely apparent until her

phalanx returns beaten in battle by the Roman maniples at Beneventum.

Moreover, in addition to this chronological division of spheres there is

also a geographical division. Greece takes the East, Rome the West, and

though by the time that Rome went forth to govern her Western provinces

she was already pretty thoroughly permeated with Greek civilisation, yet

the West remained throughout mediæval history far more Latin than Greek.

When Constantine divided the empire he was only expressing in outward

form a natural division of culture.

THENS and Rome stand side by side as the parents of Western

civilisation. The parental metaphor is almost irresistible. Rome is so

obviously masculine and robust, Greece endowed with so much loveliness

and charm. Rome subjugates by physical conquest and government. Greece

yields so easily to the Roman might and then in revenge so easily

dominates Rome itself, with all that Rome has conquered, by the mere

attractiveness of superior humanity. Nevertheless this metaphor of

masculine and feminine contains a serious fallacy. Greece, too, had had

days of military vigour. It was by superior courage and skill in

fighting that Athens and Sparta had beaten back the Persian invasions of

the fifth century before Christ, and thus saved Europe for

occidentalism. Again it was by military prowess that Alexander the Great

carried Greek civilisation to the borders of India, Hellenising Asia

Minor, Syria, Persia, Egypt, Phœnicia and even Palestine. This he did

just at the moment when Rome was{2} winning her dominion over Latium.

Instead, then, of looking at Greece and Rome as two coeval forces

working side by side we must regard them as predecessor and successor.

Rome is scarcely revealed as a world-power until she meets Greek

civilisation in Campania near the beginning of the third century before

Christ. The physical decline of Greece is scarcely apparent until her

phalanx returns beaten in battle by the Roman maniples at Beneventum.

Moreover, in addition to this chronological division of spheres there is

also a geographical division. Greece takes the East, Rome the West, and

though by the time that Rome went forth to govern her Western provinces

she was already pretty thoroughly permeated with Greek civilisation, yet

the West remained throughout mediæval history far more Latin than Greek.

When Constantine divided the empire he was only expressing in outward

form a natural division of culture.

The resemblances between Rome and Greece even from the first are very clearly marked. In many respects they are visibly of the same family, and, though we no longer speak as confidently of “Aryan” and “Indo-European” as did the ethnologists and philologists of the nineteenth century, yet there remains an obvious kinship of language, customs, and even dress. Many of the most obvious similarities, such as those of religion, are now seen to be the result of later borrowing, but there remains a distinct cousinship, whether derived from the conquest of both peninsulas by kindred tribes of northern invaders, as Ridgeway holds, or from the existence of an aboriginal Mediterranean face, as Sergi believes—or from both.

But with all these resemblances, one of the most interesting features of ancient history lies in the psychological contrast between Greece and Rome, or rather between Athens and Rome. Athens is rich in ideas, full of the spirit of inquiry, and hence fertile in invention, fond of novelty, worshipping brilliance of mind and body. Rome is stolid and conservative, devoted to tradition and law. Gravity and{3} the sense of duty are her supreme virtues. Here we have the two types that succeed and conquer, set side by side for comparison. To which is the victory in the end?

To the Englishman of to-day Rome is in some ways far more familiar than Greece. Apart from obvious resemblances in history and in character, Rome touches our own domestic history, and any man who has marked the stability of old Roman foundations or the straightness of old Roman roads has already grasped a fundamental truth about her. He is surely not far wrong in the general sense of irresistible power, of blind energy and rigid law, which he associates with the name of Rome. Thus, there is not as there was in the case of Greece any radical misconception of the Roman character to be combated.

But there is, it appears, a widely prevalent false perspective in the common view of Roman history. The modern reader, especially if he be an Englishman, is a very stern moralist in his judgment of other nations and ages. In addition to this he is a citizen of an empire now extremely self-conscious and somewhat bewildered at its own magnitude. He cannot help drawing analogies from Roman history and seeking in it “morals” for his own guidance. The Roman empire bears such an obvious and unique resemblance to the British that the fate of the former must be of enormous interest to the latter. For this reason alone we are apt to regard the fall of Rome as the cardinal point of Roman history. To this must be added the influence of Gibbon’s great work. By Gibbon we are led to contemplate above all things (with Silas Wegg) her Decline and Fall. Thus Rome has become for many people simply a colossal failure and a horrible warning. We behold her first as a Republic tottering to her inevitable ruin, and then as an Empire decaying from the start and continuing to fester for some five hundred years. This is one of the cases which prove that History is made not so much by heroes or natural forces as by historians. It is an accident of historiography{4} that the Republic was not described by any great native historian until its close, when amid the horrors of civil war men set themselves to idealise the heroes of extreme antiquity and thus left a gloomy picture of unmitigated deterioration. As there was no great historian in sympathy with the imperial regime, the reputation of the early Empire was left mainly in the hands of Tacitus and Suetonius, the former of whom riddled it with epigrams while the latter befouled it with scandal. Nearly all Roman writers had a rhetorical training and a satirical bent: all Romans were praisers of the past. Thus it is that Roman virtue has receded into an age which modern criticism declares to be mythological. It is a further accident that the genius of Rome’s greatest modern historian was also strongly satirical. It was a natural affinity of temper which led Gibbon to continue the story of Tacitus and to dip his pen into the same bitter fluid.

Thus Rome has found few impartial historians and hardly any sympathetic ones. But is it possible to be sympathetic? While every true scholar feels a thrill at the name of Greece, scarcely any one loves Ancient Rome. At the first mention of her name the average man’s thoughts fly to the Colosseum and the Christian martyr “facing the lion’s gory mane” to the music of Nero’s fiddle. His second thought is to formulate his explanation of her decline and fall. The explanations are as various as political complexions. “Luxury,” says the moralist, “Heathendom,” says the Christian, “Christianity,” replies Gibbon. The Protectionist can easily show that it was due to the Importation of free corn, while the Free Trader draws attention to the enormous burdens which Roman trade had to bear. “Militarism,” explains the peace-lover; “neglect of personal service,” replies the conscriptionist. The Liberal and the Conservative can both draw valuable conclusions from Roman history in support of their respective attitudes of mind. “If it had not been for demagogues like Marius and the Gracchi,” says the Conservative, “Rome might have continued to exhibit the courage and patriotism{5} which she displayed under senatorial guidance in the war against Hannibal, instead of rushing to her doom by way of sedition and disorder.” With equal justice the Liberal points to the stupid bigotry with which that corrupt oligarchy, the senate, delayed necessary reforms. That, he says, was the cause of the downfall of Rome. That was the writing on the wall.

Whether it is or is not possible to love Ancient Rome, I would suggest that this attitude of treating her merely as a subject for autopsies and a source of gloomy vaticinations for the benefit of the British Empire is a preposterous affront to history. The mere notion of an empire continuing to decline and fall for five centuries is ridiculous. It is to regard as a failure the greatest civilising force in all the history of Europe, the most stable form of government, the strongest military and political system that has ever existed.

It is just at this point that our own generation can add something of great importance to the study of Roman history. Whatever may be said for its faith, hope is the great discovery of our age. By the help of that blessed word “Evolution” we have learnt not to put our Golden Ages in the past but in the future. In many instances we have discovered that what our fathers called decay was really progress. May it not be so with Rome?

The destiny or function of Rome in world-history was nothing more or less than the making of Europe. The modern family of European nations are her sons and daughters, and some of her daughters have grown up and married foreign husbands and given birth to offspring. For this great purpose it was necessary that the city itself should pass through the phases of growth, maturity and decay. In political terms, it was part of the Roman destiny to translate the civilisation of the city-state into that of the nation or territorial state. Having evolved the Province it was necessary that the City should expire. Conquest on a colossal scale was part of the programme, absolute centralised{6} dominion was another part. For this purpose the change from republic to autocracy was necessary.

Greece, as we have seen elsewhere, by her system of small states enclosed and protected by city walls, had been able, long before the world at large was nearly ripe for it, to develop a civilised culture with habits of thought and speech which are now called European or Occidental. It was in a highly concentrated social life and under artificial conditions that Athens had laid the foundation of all our arts, sciences and philosophies. It was, however, as we saw, impossible for the civic democracy to expand naturally. She could hold a little empire for a few years by means of precarious sea-power. She could throw off a few daughter cities made in her own likeness. But for missionary work on a large scale the city-state was not adapted. Something much larger than a city and much more single-minded than a democracy was necessary for that purpose. The genius of Alexander the Great, an autocrat and a semi-barbarian, enabled him to do much towards propagating Hellenism in the eastern part of the Mediterranean littoral. But his early death prevented the fulfilment of his task and the half of him that was Greek made him consider the planting of new Greek cities the only means for fulfilling it.

Here then was the part which Rome had to play. She had to do for the West what Alexander had attempted for the East. In some respects her task was harder, for her work lay among warlike barbarians, but easier in that she had not to face the corrupting influence of a rival and more ancient civilisation.

Rome too began as a city-state and it was while she was still in that condition that Greek civilisation came to her and took her by storm. It was the new wine that burst the old bottle when Rome attempted to transform herself into a Greek democracy, and failing became a monarchy once more. It was not, therefore, a case of “decline and fall” when Rome ceased to be a republic. No liberal need heave a sigh for the departed republic. It was an oligarchy that had for a century{7} deserved to be replaced by something better, and the change was even an upward step in liberty for all but a few hundreds of Roman nobles. If we can but turn our minds away from the gossip of the court and the spite of the discontented aristocracy to a just survey of that majestic and enduring system of provincial government, we shall be able to discern progress where historians would have us lament decay.

It was progress again when Rome gradually ceased to be a city-state with a surrounding territory and became successively the capital of an empire and then one of half a dozen great centres of government. Finally it was progress, as we ought by now to be able to see, when the artificial ramparts on the Rhine and Danube broke down and the new nations came into their inheritance. By that time Rome had accomplished her work and the phase of the city-state was over.

Some such convictions as these are, I think, inevitable to any one who views European history as a whole in the light of any theory of historical evolution. Rome has long been the playground of satirists and pessimists. Unfortunately at this date it is difficult if not impossible to shake their verdict and to read Roman history in the new light. To do so you cannot follow the authorities, for they were all on the side of deterioration. The idea of progress was unknown to the ancient world, and above all others the Romans believed that their Golden Age was behind them. It becomes necessary therefore to extract truth from unwilling witnesses, always a precarious and suspicious undertaking. All the Roman men of letters believed with Horace:

Unless we are prepared to accept the rank of progenies vitiosissima we are compelled to discount this whole tendency of thought and read our authorities between the lines. They were all rhetoricians, all bent on praising the past at the expense of the present and the future; none of them were over-scrupulous in dealing with evidence. If all the historians had perished and only the inscriptions remained we should have a very different picture of the Roman empire, a picture much brighter and, I think, much more faithful to truth.

Hellenism we know and understand; every true classical scholar is a Hellenist by conviction. But what is Latinism and who are our Latinists? The altar fires are extinct and the votaries are scattered. Except for a small volume of the choicest Latin poetry of the Augustan age, what that is Latin gives us pleasure to-day? Greek studies seem to attract all that is most brilliant and genial in the world of scholarship: Latin is mainly relegated to the dry-as-dusts. Who reads Lucan out of school hours? Who would search Egypt for Cicero’s lost work “De Gloria”? Who would recognise a quotation from Statius?

It has not always been so. Once they quoted Lucan and Seneca across the floor of the House of Commons. The eighteenth century was far more in sympathy with Ancient Rome than we are. In those days it would not have seemed absurd to argue the superiority of Vergil over Homer. Down to that day Latin had remained the alternative language for educated people, the medium of international communication, even for diplomacy, until French gradually took its place. Only if you specifically sought to reach the vulgar did you write in English. Though Dr. Johnson could write a very pretty letter in French, he used habitually to converse with Frenchmen in Latin; not that it made him more intelligible, for, in fact, no foreigner could understand the English pro{9}nunciation of Latin; but that he did not wish to appear at a disadvantage with a mere Frenchman by adopting a foreign jargon. As for public inscriptions, though half the literary men in London signed a round-robin entreating the great autocrat to write Oliver Goldsmith’s epitaph in English, Johnson “refused to disgrace the walls of Westminster Abbey with an English inscription.”

What is the cause of the eclipse which Latin studies are still suffering? One cause, perhaps, is to be found in the misuse of the language by the pedagogues and philologists of the past in the school and the examination-room. But another cause is the recent discovery of the true Greek civilisation, whereby scholars have come to realise that Latin culture is in the main only secondary and derivative. At the present moment we are passing through a stage of revolt against classicism, convention, and artificiality. We know that Greek culture, truly discerned, is neither “classic” nor conventional nor artificial, but Latinism is still apparently subject to all these terms. The Latinity of Cicero, Vergil, Ovid, Horace, Lucan, and the greater part of the giants, in fact all the Latin of our schools is—what Greek is not—really and truly classical. They were not writing as they spoke and thought. They had studied the laws of expression in the school of rhetoric, and on pain of being esteemed barbarous they wrote under those laws. Style was their aim. Their very language was subject to arbitrary laws of syntax and grammar. The English schoolboy who approaches Cicero by way of the primer’s rules and examples is entering into Latin literature by much the same road as the Romans themselves. The Romans were grammarians by instinct and orators by education. Thus Latin is fitted by nature for schoolroom use, and for all who would learn and study words, which after all are thoughts, Latin is the supremely best training-ground. The language marches by rule. Rules govern the inflexions and the concords of the words. The periods are built up logically and beautifully in obedience to{10} law. Latin, of all languages, least permits translation. You have only to translate Cicero to despise him.

In the world of letters, as in that of politics, there are the virtues of order and the virtues of liberty. Our own eighteenth century was logical in mind because it had to clothe its thoughts in a language of precision. But even Pope and Addison are rude barbarians compared with Vergil and Cicero. De gustibus non est disputandum—let some prefer the plain roast and others the made dish. Latin may be an acquired taste, but no sort of excellence is mortal. Latin will come into its own again along with Dryden and Congreve, along with patches and periwigs. Meanwhile it must be a very dull soul who is unmoved by the grandeur of Roman history, the triumphant march of the citizen legions, the dogged patriotism which resisted Hannibal to the death, and the pageantry and splendour of the Empire. One must be blind not to admire the massive strength of her ruined monuments, arches, bridges, roads, and aqueducts. And one must be deaf indeed not to enjoy the surges of Ciceronian oratory or the rolling music of the Vergilian hexameter. Greece may claim all the charm of the spring-time of civilisation, but Rome in all her works has a majesty which must command, if not love, wonder and respect. Mommsen justly remarks that “it is only a pitiful narrow-mindedness that will object to the Athenian that he did not know how to mould his State like the Fabii and Valerii, or to the Roman that he did not learn to carve like Phidias and to write like Aristophanes.”

Under the flowing toga of Latinism the natural Roman is concealed from our view. It is possible that the progress of research and excavation may to some extent rediscover him and distinguish him, as it has already done for his Hellenic brother, from the polished courtiers of the Augustan age who have hitherto passed as typical products of Rome.

It is astonishing how little we really know of Rome and the Romans after all that has been said and written about{11} them. The ordinary natural Roman is a complete stranger to us. It is certain that he did not live in luxury like Mæcenas, but how did he live and what sort of man was he? We can discern that his language was not in the least like that of Cicero. It appears that he neither dreaded nor disliked emperors like Nero, as did Tacitus and Juvenal. As for his religion, much has already been done, and more still remains to be done, to show that he did not really worship the Hellenised Olympians who pass in literature for his gods. Recent scholarship has done something to reveal to us the presence of a real national art in Rome, or at any rate of an artistic development on Italian soil which made visible steps of its own out of Hellenic leading-strings. Thus there is some hope that the real Roman will not always elude us. But for the present in the whole domain of art, religion, thought, and literature, Greek influence has almost obliterated the native strain. For the present, therefore, we must be content to regard Roman civilisation as mainly derivative, and our principal object will be to see how Rome fulfilled her task as the missionary of Greek thought. This object, together with the unsatisfactory nature of the records, must excuse the haste with which I have passed over the earlier stages of Roman republican history. It is obvious that the first three centuries of our era will be the important part of Roman history from this point of view. Also, if the progress of civilisation be our main study, nothing in Roman history before the beginning of the second century B.C. can come directly under our attention. When the Romans first came into contact with the Greeks they were still barbarians, with no literature, no art, and very little industry or commerce. The earlier periods will only be introductory.

The pleasant land of Italy needs no description here. Our illustrations[2] will recall its sunny hill-sides, its deep{12} shadows, its vineyards and olive-yards. But there are one or two features of its geography which have a bearing upon the history of Rome.

To begin with, the geographical unity of the Italian peninsula is more apparent than real. The curving formation of the Apennines really divides Italy into four parts—(1) the northern region, mainly consisting of the Po valley, a fertile plain which throughout the Republican period was scarcely considered as part of Italy at all, and was, in fact, inhabited by barbarian Gauls; (2) the long eastern strip of Adriatic coast, an exposed waterless and harbourless region, with a scanty population, which hardly comes into ancient history; (3) the southern region of Italy proper, hot, fertile, and rich in natural harbours, so that it very early attracted the notice of the Greek mariners, and was planted with luxurious and populous cities long before Rome came into prominence; and (4) the central plain facing westward, in which the river Tiber and the city of Rome occupy a central position. Etruria and Latium together fill the greater part of it. Its width is only about eighty miles, so that there is no room for any considerable rivers to develop, and, in fact, there are only four rivers of any importance in a coast-line of more than 300 miles. We may call the whole of this region a plain in distinction from the Apennine highlands; but it is, of course, plentifully scattered with hills high enough to provide an impregnable citadel, and to this day crowned with huddled villages.

Rome herself on her Seven Hills began her career by securing dominion over the Latin plain which surrounded her on all sides but the north. The Roman Campagna,[3] which is now desolate and fever-stricken, was once all populous farmland. The river Tiber, though its silting mouth and tideless waters now render it useless for navigation, was in the flourishing days of Ancient Rome navigable for small vessels and Ostia was a good artificial harbour at its mouth. Thus{13} it is history rather than geography which has made Rome into an unproductive capital. We may conclude that geography has placed Rome in a favourable position for securing the control of the Mediterranean and especially of the western part of it.

It is worth while also to notice the neighbours by whom she was surrounded when she first struggled forward into the light. Just across the Tiber to the north of her were the Etruscans of whom we shall see more in the next chapter. Their pirate ships scoured the sea while their merchants did business with the Greeks of Sicily, Magna Græcia and Massilia. It was perhaps her position at the tête du pont that led to Rome’s early prominence in war. Across the water on the coast of Africa was the dreaded city of Carthage, which had for centuries been striving to establish itself on the island of Sicily. All these were seafaring, commercial peoples, but it was not by sea that Rome met them. Behind Rome, among the valleys and on the spurs of the Apennines, were a whole series of sturdy highland clans who like all highlanders noticed the superior fatness of the valley sheep. It was against these Umbrians, Marsians, Pelignians, Sabines, and Samnites that the cities of the plain were constantly at feud, and it was mainly her struggles with these that kept the Roman swords bright in early days.