The Project Gutenberg EBook of Poems of Giosuè Carducci, by

Giosuè Carducci and Frank Sewall

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Poems of Giosuè Carducci

Translated with two introductory essays: I. Giosuè Carducci

and the Hellenic reaction in Italy. II. Carducci and the

classic realism

Author: Giosuè Carducci

Frank Sewall

Release Date: March 9, 2018 [EBook #56711]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POEMS OF GIOSUÈ CARDUCCI ***

Produced by ellinora, Bryan Ness, Barbara Magni and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

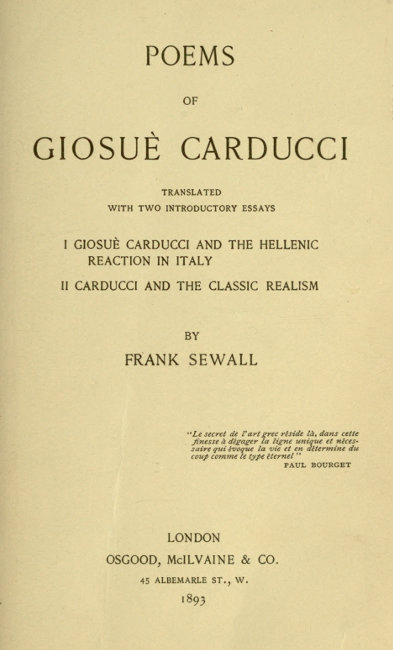

POEMS

OF

GIOSUÈ CARDUCCI

TRANSLATED

WITH TWO INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS

I GIOSUÈ CARDUCCI AND THE HELLENIC

REACTION IN ITALY

II CARDUCCI AND THE CLASSIC REALISM

BY

FRANK SEWALL

“Le secret de l'art grec réside là, dans cette finesse à dégager la ligne unique et nécessaire qui évoque la vie et en détermine du coup comme le type éternel”

PAUL BOURGET

LONDON

OSGOOD, McILVAINE & CO.

45 ALBEMARLE ST., W.

1893

The De Vinne Press, New-York, U. S. A.

[iii]

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | vii | |

| Essays | ||

| i. | Giosuè Carducci and the Hellenic Reaction in Italy | 1 |

| ii. | Carducci and the Classic Realism | 29 |

| Translations | ||

| i. | Roma | 57 |

| ii. | Hymn to Satan | 58 |

| iii. | Homer | 66 |

| iv. | Virgil | 67 |

| v. | Invocation to the Lyre | 68 |

| vi. | Sun and Love | 70 |

| vii. | To Aurora | 71 |

| [iv] | ||

| viii. | Ruit Hora | 76 |

| ix. | The Ox | 77 |

| x. | To Phœbus Apollo | 78 |

| xi. | Hymn to the Redeemer | 81 |

| xii. | Outside the Certosa | 84 |

| xiii. | Dante—Sonnet | 85 |

| xiv. | In a Gothic Church | 86 |

| xv. | Innanzi, innanzi! | 88 |

| xvi. | Sermione | 89 |

| xvii. | To a Horse | 93 |

| xviii. | A Dream in Summer | 94 |

| xix. | On a Saint Peter's Eve | 97 |

| xx. | The Mother | 99 |

| xxi. | “Passa la nave mia, sola, tra il pianto” | 101 |

| xxii. | Carnival. | |

| Voice from the Palace | 102 | |

| Voice from the Hovel | 103 | |

| Voice from the Banquet | 105 | |

| Voice from the Garret | 106 | |

| Voice from Beneath | 107 | |

| xxiii. | Sonnet to Petrarch | 109 |

| xxiv. | Sonnet to Goldoni | 110 |

| xxv. | Sonnet to Alfieri | 111 |

| xxvi. | Sonnet to Monti | 112 |

| [v] | ||

| xxvii. | Sonnet to Niccolini | 113 |

| xxviii. | In Santa Croce | 114 |

| xxix. | Voice of the Priests | 115 |

| xxx. | Voice of God | 116 |

| xxxi. | On my Daughter's Marriage | 117 |

| xxxii. | At the Table of a Friend | 119 |

| xxxiii. | Dante | 120 |

| xxxiv. | On the Sixth Centenary of Dante | 126 |

| xxxv. | Beatrice | 127 |

| xxxvi. | “A questi dí prima io la vidi. Uscia” | 130 |

| xxxvii. | “Non son quell'io che già d'amiche cene” | 131 |

| xxxviii. | The Ancient Tuscan Poetry | 132 |

| xxxix. | Old Figurines | 133 |

| xl. | Madrigal | 134 |

| xli. | Snowed Under | 135 |

[vii]

In endeavouring to introduce Carducci to English readers through the following essays and translations, I would not be understood as being moved to do so alone by my high estimate of the literary merit of his poems, nor by a desire to advocate any peculiar religious or social principles which they may embody. It is rather because these poems seem to me to afford an unusually interesting example of the survival of ancient religious motives beneath the literature of a people old enough to have passed through a succession of religions; and also because they present a form of realistic literary art which, at this time, when realism is being so perverted and abused, is eminently refreshing, and sure to impart a healthy impetus to the literature of any people. For these reasons I have thought that, even under the garb of very inadequate translations, they would constitute a not unwelcome contribution to contemporary literary study.

I am indebted to the courtesy of Harper & Brothers for the privilege of including here, in an amplified form, the essay on Giosuè Carducci and the Hellenic Reaction in Italy, which appeared first in Harper's Magazine for July, 1890.

F. S.

Washington, D. C., June, 1892.

[1]

The passing of a religion is at once the most interesting and the most tragic theme that can engage the historian. Such a record lays bare what lies inmostly at the heart of a people, and has, consciously or unconsciously, shaped their outward life.

The literature of a time reveals, but rarely describes or analyses, the changes that go on in the popular religious beliefs. It is only in a later age, when the religion itself has become desiccated, its creeds and its forms dried and parcelled for better preservation, that this analysis is made of its passing modes, and these again made the subject of literary treatment.

Few among the existing nations that possess a literature have a history which dates back far enough to embrace these great fundamental changes, such as that from paganism to Christianity, and also a literature that is coeval with those changes. The Hebrew race possess indeed their ancient Scriptures, and with them retain their ancient religious ideas. The Russians and Scandinavians deposed their pagan deities to give place to the White Christ within comparatively recent times, but they can hardly be said to have possessed a literature [2] in the pre-Christian period. Our own saga of Beowulf is indeed a religious war-chant uttering the savage emotions of our Teutonic ancestors, but not a work of literary art calmly reflecting the universal life of the people.

It is only to the Latin nations of Europe, sprung from Hellenic stock and having a continuous literary history covering a period of from two to three thousand years, that we may look for the example of a people undergoing these radical religious changes and preserving meanwhile a living record of them in a contemporaneous literature. Such a nation we find in Italy.

So thorough is the reaction exhibited during the last half of the present century in that country against the dogma and the authority of the Church of Rome that we are led to inquire whether, not the church alone, as Mr. Symonds says,[1] but Christianity itself has ever “imposed on the Italian character” to such an extent as to obliterate wholly the underlying Latin or Hellenic elements, or prevent these from springing again into a predominating influence when the foreign yoke is once removed.

To speak of Christianity coming and going as a mere passing episode in the life of a nation, and taking no deep hold on the national character, is somewhat shocking to the religious ideas which prevail among Christians, but not more so than would have been to a Roman of the time of the Cæsars the suggestion that the Roman Empire might itself one day pass away, a transient phase only in the life of a [3] people whose history was to extend in unbroken line over a period of twenty-five hundred years.

In the work just referred to Mr. Symonds also briefly hints at another idea of profound significance,—namely, whether there is not an underlying basis of primitive race character still extant in the various sections of the Italian people to which may be attributed the variety in the development of art and literature which these exhibit. In his Studii Letterari (Bologna, 1880), Carducci has made this idea a fundamental one in his definition of the three elements of Italian literature. These are, he says, the church, chivalry, and the national character. The first or ecclesiastical element is superimposed by the Roman hierarchy, but is not and never was native to the Italian people. It has existed in two forms. The first is Oriental, mystic, and violently opposed to nature and to human instincts and appetites, and hence is designated the ascetic type of Christianity. The other is politic and accommodating, looking to a peaceful meeting-ground between the desires of the body and the demands of the soul, and so between the pagan and the Christian forms of worship. Its aim is to bring into serviceable subjection to the church those elements of human nature or of natural character which could not be crushed out altogether. This element is represented by the church or the ecclesiastical polity. It becomes distinctly Roman, following the eclectic traditions of the ancient empire, which gave the gods of all the conquered provinces a niche in the Pantheon. It transformed the sensual paganism of the Latin races and the natural paganism of the Germanic into a religion which, if not Christianity, could be made to serve the Christian church.

In the same way that the church brought in the Christian element, both in its ascetic and its Roman or semi-pagan form, so did feudalism and the German Empire bring in that of chivalry. This, again, was no native development of the [4] Italian character. It came with the French and German invaders; it played no part in the actions of the Italians on their own soil. “There never was in Italy,” says Carducci, “a true chivalry, and therefore there never was a chivalrous poetry.” With the departure of a central imperial power the chivalrous tendency disappeared. There remained the third element, that of nationality, the race instinct, resting on the old Roman, and even older Latin, Italic, Etruscan, Hellenic attachments in the heart of the people. Witness during all the Middle Ages, even when the power of the church and the influence of the empire were strongest, the reverence everywhere shown by the Italian people for classical names and traditions. Arnold of Brescia, Nicola di Rienzi, spoke to a sentiment deeper and stronger in the hearts of their hearers than any that either pope or emperor could inspire. The story is told of a schoolmaster of the eleventh century, Vilgardo of Ravenna, who saw visions of Virgil, Horace, and Juvenal, and rejoiced in their commendation of his efforts to preserve the ancient literature of the people. The national principle also exists in two forms, the Roman and the Italian—the aulic or learned, and the popular. Besides the traditions of the great days of the republic and of the Cæsars, besides the inheritance of the Greek and Latin classics, there are also the native instincts of the people themselves, which, especially in religion and in art, must play an important part. Arnold of Brescia cried out, “Neither pope nor emperor!” It was then the people, as the third estate, made their voices heard—“Ci sono anch'io!” (Here am I too!).

After the elapse of three hundred years from the downfall of the free Italian municipalities and the enslavement of the peninsula under Austrio-Spanish rule, we have witnessed again the achievement by Italians of national independence and national unity. The effect of this political change on the free manifestations of the Italian character would seem to [5] offer another corroboration of Carducci's assertion that “Italy is born and dies with the setting and the rising of the stars of the pope and the emperor.” (Studii Letterari, p. 44.) Not only with the withdrawal of the Austrian and French interference has the pope's temporal power come to an end, but in a large measure the religious emancipation of Italy from the foreign influences of Christianity in every way has been accomplished. The expulsion of the Jesuits and the secularisation of the schools and of the monastic properties were the means of a more real emancipation of opinion, of belief, and of native impulse, which, free from restraint either ecclesiastical or political, could now resume its ancient habit, lift from the overgrowth of centuries the ancient shrines of popular worship, and invoke again the ancient gods.

The pope remains, indeed, and the Church of Rome fills a large space in the surface life of the people of Italy; and so far as in its gorgeous processions and spectacles, its joyous festivals and picturesque rites, and especially in its sacrificial and vicarious theory of worship, the church has assimilated to itself the most important feature of the ancient pagan religion, it may still be regarded as a thing of the people. But the real underlying antagonism between the ancient national instinct, both religious and civil, and that habit of Christianity which has been imposed upon it, finds its true expression in the strong lines of a sonnet of Carducci's, published in 1871, in the collection entitled Decennali. Even through the burdensome guise of a metrical translation, something of the splendid fire of the original can hardly fail to make itself felt. [I]

The movement for the revival of Italian literature may be said to have begun with Alfieri, at the close of the last and the beginning of the present century. It was contemporary with the breaking up of the political institutions of the past in Europe, the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, the [6] brief existence of the Italian Republic, the revival for a short joyous moment of the hope of a restored Italian independence. Again a thrill of patriotic ardour stirs the measures of the languid Italian verse. Alfieri writes odes on America Liberata, celebrating as the heroes of the new age of liberty Franklin, Lafayette, and Washington. Still more significant of the new life imparted to literature at this time is the sober dignity and strength of Alfieri's sonnets, and the manly passion that speaks in his dramas and marks him as the founder of Italian tragedy.

But the promise of those days was illusory. With the downfall of Napoleon and the return of the Austrian rule, the hope of the Italian nationality again died out. Alfieri was succeeded by Vincenzo Monti and his fellow-classicists, who sought to console a people deprived of future hope with the contemplation of the remote past. This school restored rather than revived the ancient classics. They gave Italians admirable translations of Homer and Virgil, and turned their own poetic writing into the classical form. But they failed to make these dead forms live. These remained in all their beauty like speechless marble exhumed and set up in the light and stared at. If they spoke at all, as they did in the verses of Ugo Foscolo and Leopardi, it was not to utter the joyous emotions, the godlike freedom and delight of living which belonged to the world's youthful time; it was rather to give voice to an all-pervading despair and brooding melancholy, born, it is true, of repeated disappointments and of a very real sense of the vanity of life and the emptiness of great aspirations, whether of the individual or of society. This melancholy, itself repugnant to the primitive Italian nature, opened the way for the still more foreign influence of the romanticists, which tended to the study and love of nature from the subjective or emotional side, and to a more or less morbid dwelling upon the passions and the interior [7] life. With a religion whose life-sap of a genuine faith had been drained away for ages, and a patriotism enervated and poisoned by subserviency to foreign rule and fawning for foreign favour, naught seemed to remain for Italian writers who wished to do something else than moan, but to compose dictionaries and cyclopædias, to prepare editions of the thirteenth-century classics, with elaborate critical annotations, and so to keep the people mindful of the fact that there was once an Italian literature, even if they were to despair of having another. The decay of religious faith made the external forms of papal Christianity seem all the more a cruel mockery to the minds that began now to turn their gaze inward, and to feel what Taine so truly describes as the Puritan melancholy, the subjective sadness which belongs peculiarly to the Teutonic race. The whole literature of the romantic school, whether in Italy or throughout Europe, betrayed a certain morbidness of feeling which, says Carducci, belongs to all periods of transition, and appears alike in Torquato Tasso, under the Catholic reaction of the sixteenth century, and in Châteaubriand, Byron, and Leopardi, in the monarchical restoration of the nineteenth. The despair which furnishes a perpetual undertone to the writing of this school is that which is born of the effort to keep a semblance of life in dead forms of the past, while yet the really living motives of the present have found neither the courage nor the fitting forms for their expression.

In many respects the present revival of Italian literature is a reawakening of the same spirit that constituted the Renaissance of the fourteenth and fifteen centuries, and disappeared under the subsequent influences of the Catholic reaction. Three hundred years of papal supremacy and foreign civic rule have, however, tempered the national spirit, weakened the manhood of the people, and developed a habit of childlike subserviency and effeminate dependence. While restraining [8] the sensuous tendency of pagan religion and pagan art within the channels of the church ritual, Rome has not meanwhile rendered the Italian people more, but, if anything, less spiritual and less susceptible of spiritual teaching than they were in the days of Dante or even of Savonarola. The new Italian renaissance, if we may so name the movement witnessed by the present century for the re-establishment of national unity and the building up of a new Italian literature, lacks the youthful zeal, the fiery ardour which characterised the age of the Medici. The glow is rather that of an Indian summer than that of May. The purpose, the zeal, whatever shall be its final aim, will be the result of reflection and not of youthful impulse. The creature to be awakened and stirred to new life is more than a mere animal; it is a man, whose thinking powers are to be addressed, as well as his sensuous instincts and amatory passion. Such a revival is slow to be set in motion. When once fairly begun, provided it have any really vital principle at bottom, it has much greater promise of permanence than any in the past history of the Italian people. A true renascence of a nation will imply a reform or renewal of not one phase alone of the nation's life, but of all; not only a new political life and a new poetry, but a new art, a new science, and, above all, a new religious faith. The steps to this renewal are necessarily at the beginning oftener of the nature of negation of the old than of assertion of the new. The destroyer and the clearer-away of the débris go before the builder. It will not be strange, therefore, if the present aspect of the new national life of Italy should offer us a number of conspicuous negations rather than any positive new conceptions; that the people's favorite scientist, Mantegazza,—the ultra-materialist,—should be the nation's chosen spokesman to utter in the face of the Vatican its denial of the supernatural; and that Carducci, the nation's foremost and favourite poet, should sing the return of [9] the ancient worship of nature, of beauty, and of sensuous love, and seek to drown the solemn notes of the Christian ritual in a universal jubilant hymn to Bacchus. These are the contradictions exhibited in all great transitions. They will not mislead if the destroyer be not confounded with the builder who is to follow, and the temporary ebullition of pent-up passion be not mistaken for the after-thought of a reflecting, sobered mind. No one has recognized this more truly than Carducci:

Or destruggiam. Dei secoli

Lo strato è sul pensiero:

O pochi e forti, all'opera,

Chè nei profundi è il vero.

Now we destroy. Of the ages

The highway is built upon thinking.

O few and strong, to the work!

For truth 's at the bottom.

It was in the year 1859, when once more the cry for Italian independence and Italian unity was raised, that the newly awakened nation found its laureate poet in the youthful writer of a battle hymn entitled “Alla Croce Bianca di Savoia”—The White Cross of Savoy. Set to music, it became very popular with the army of the revolutionists, and the title is said to have led to the adoption of the present national emblem for the Italian flag. As a poem it is not remarkable, unless it be for the very conventional commingling of devout, loyal, and valorous expressions, like the following, in the closing stanza:

Dio ti salvi, o cara insegna,

Nostro amore e nostra gioja,

Bianca Croce di Savoja,

Dio ti salvi, e salvi il Re!

But six years later, in 1865, there appeared at Pistoja a poem over the signature Enotrio Romano, and dated the “year [10] MMDCXVIII from the Foundation of Rome,” which revealed in a far more significant manner in what sense its author, Giosuè Carducci, then in his thirtieth year, was to become truly the nation's poet, in giving utterance again to those deeply hidden and long-hushed ideas and emotions which belonged anciently to the people, and which no exotic influence had been able entirely to quench. This poem was called a “Hymn to Satan.” The shock it gave to the popular sense of propriety is evident not only from the violence and indignation with which it was handled in the clerical and the conservative journals, one of which called it an “intellectual orgy,” but from the number of explanations, more or less apologetic, which the poet and his friends found it necessary to publish. One of these, which appeared over the signature Enotriofilo in the Italian Athenæum of January, 1886, has been approvingly quoted by Carducci in his notes to the Decennali. We may therefore regard it as embodying ideas which are, at least, not contrary to what the author of the poem intended. From this commentary it appears that we are to look here “not for the poetry of the saints but of the sinners,—of those sinners, that is, who do not steal away into the deserts to hide their own virtues, so that others shall not enjoy them, who are not ashamed of human delights and human comforts, and who refuse none of the paths that lead to these. Not laudes or spiritual hymns, but a material hymn is what we shall here find. “Enotrio sings,” says his admiring apologist, “and I forget all the curses which the catechism dispenses to the world, the flesh, and the devil. Asceticism here finds no defender and no victim. Man no longer goes fancying among the vague aspirations of the mystics. He respects laws, and wills well, but to him the sensual delights of love and the cup are not sinful, and in these, to him, innocent pleasures Satan dwells. It was to the joys of earth that the rites of the Aryans looked; the [11] same joys were by the Semitic religion either mocked or quenched. But the people did not forget them. As a secretly treasured national inheritance, despite both Christian church and Gothic empire, this ancient worship of nature and of the joys of the earth remains with the people. It is this spirit of nature and of natural sensuous delights, and lastly of natural science, that the poet here addresses as Satan. As Satan it appears in nature's secret powers of healing and magic, in the arts of the sorcerer and of the alchemist. The anchorites, who, drunk with paradise, deprived themselves of the joys of earth, gradually began to listen to these songs from beyond the gratings of their cells—songs of brave deeds, of fair women, and of the triumph of arms. It is Satan who sings, but as they listen they become men again, enamoured of civil glory. New theories arise, new masters, new ideals of life. Genius awakes, and the cowl of the Dominican falls to earth. Now, liberty itself becomes the tempter. It is the development of human activity, of labour and struggle, that causes the increase of both bread and laughter, riches and honour, and the author of all this new activity is Satan; not Satan bowing his head before hypocritical worshippers, but standing glorious in the sight of those who acknowledge him. This hymn is the result of two streams of inspiration, which soon are united in one, and continue to flow in a peaceful current: the goods of life and genius rebelling against slavery.”

With this explanation of its inner meaning we may now refer the reader to the hymn itself. [II]

This poem, while excelled by many others in beauty or in interest, has nowhere, even in the poet's later verses, a rival in daring and novelty of conception, and none serves so well to typify the prominent traits of Carducci as a national poet. We see here the fetters of classic, romantic, and religious tradition thrown off, and the old national, which is in substance [12] a pagan, soul pouring forth in all freedom the sentiments of its nature. It is no longer here the question of either Guelph or Ghibelline; Christianity, whether of the subjective Northern type, brought in by the emperors, or of the extinct formalities of Rome, is bidden to give way to the old Aryan love of nature and the worship of outward beauty and sensuous pleasure. The reaction here witnessed is essentially Hellenic in its delight in objective beauty, its bold assertion of the rightful claims of nature's instincts, its abhorrence of mysticism and of all that religion of introspection and of conscience which the poet includes under the term “Semitic.” It will exchange dim cathedrals for the sky filled with joyous sunshine; it will go to nature's processes and laws for its oracles, rather than to the droning priests. While the worship of matter and its known laws, in the form of a kind of apotheosis of science, with which the poem opens and closes, may seem at first glance rather a modern than an ancient idea, it is nevertheless in substance the same conception as that which anciently took form in the myth of Prometheus, in the various Epicurean philosophies, and in the poem of Lucretius. Where, however, Carducci differs from his contemporaries and from the classicists so called is in the utter frankness of his renunciation of Christianity, and the bold bringing to the front of the old underlying Hellenic instincts of the people. That which others wrote about he feels intensely, and sings aloud as the very life of himself and of his nation. That which the foreigner has tried for centuries to crush out, it is the mission of the nation's true poet and prophet to restore.

The sentiments underlying Carducci's writings we find to be chiefly three: a fervent and joyous veneration of the great poets of Greece and Rome; an intense love of nature, amounting to a kind of worship of sunshine and of bodily beauty and sensuous delights; and finally an abhorrence of [13] the supernatural and spiritual elements of religion. Intermingled with the utterances of these sentiments will be found patriotic effusions mostly in the usual vein of aspirants after republican reforms, which, while of a national interest, are not peculiar to the author, and do not serve particularly to illustrate the Hellenistic motive of his writing. The same may be said of his extensive critical labours in prose, his university lectures, his scholarly annotations of the early Italian poets. How far Carducci conforms to the traditional character of the Italian poets—always with the majestic exception of the exiled Dante—in that the soft winds of court favour are a powerful source of their inspiration on national themes, may be judged from the fact that while at the beginning of his public career he was a violent republican, now that he is known to stand high in the esteem and favour of Queen Margherita his democratic utterances have become very greatly moderated, and his praises of the Queen and of the bounties and blessings of her reign are most glowing and fulsome. Without a formal coronation, Carducci occupies the position of poet-laureate of Italy. A little over fifty years of age, an active student and a hard-working professor at the University of Bologna, where his popularity with his students in the lecture-room is equal to that which his public writings have won throughout the land, called from time to time to sojourn in the country with the court, or to lecture before the Queen and her ladies at Rome, withal a man of great simplicity, even to roughness of manners, and of a cordial, genial nature—such is the writer whom the Italians with one voice call their greatest poet, and whom not a few are fain to consider the foremost living poet of Europe.[2]

[14]

It would be interesting to trace the development of the Hellenic spirit in the successive productions of Carducci's muse, to note his emancipation from the lingering influences of romanticism, and his casting off the fetters of conventional metre in the Odi Barbare. But as all this has been done for us far better in an autobiographical sketch, which the author gives us in the preface of the Poesie (1871), we will here only glance briefly at some of the more characteristic points thus presented.

After alluding to the bitterness and violence for which the Tuscans are famous in their abuse, he informs us that from the first he was charged with an idolatry of antiquity and of form, and with an aristocracy of style. The theatre critics offered to teach him grammar, and the schoolmasters said he was aping the Greeks. One distinguished critic said that his verse revealed “the author's absolute want of all poetic faculty.” The first published series of poems was in reality a protest against the religious and intellectual bitterness which prevailed in the decade preceding 1860, “against the nothingness and vanity under whose burden the country was languishing; against the weak coquetries of liberalism which spoiled then as it still spoils our art and our thoughts, ever unsatisfactory to the spirit which will not do things by halves, and which refuses to pay tribute to cowardice.” Naturally, even in literary matters inclined to take the opposite side, Carducci felt himself in the majority like a fish out of water. In the revolutionary years 1858 and 1859 he wrote poems on the [15] Plébiscite and Unity, counselling the king to throw his crown into the Po, enter Rome as its armed tribune, and there order a national vote. “These,” says the poet, “were my worst things, and fortunately were kept unpublished, and so I escaped becoming the poet-laureate of public opinion. In a republic it would have been otherwise. I would have composed the battle pieces with the usual grand words—the ranks in order, arms outstretched in command, brilliant uniforms, and finely curled moustaches. To escape all temptation of this sort I resorted to the cold bath of philosophy, the death-shrouds of learning—lenzuolo funerario dell'erudizione. It was pleasant amid all that grand talk of the new life to hide myself in among the cowled shadows of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. I journeyed along the Dead Sea of the Middle Ages, studied the movements of revolution in history and in letters; then gradually dawned upon me a fact which at once surprised and comforted me. I found that my own repugnance to the literary and philosophical reaction of 1815 was really in harmony with the experience of many illustrious thinkers and authors. My own sins of paganism had already been committed, and in manifold splendid guises, by many of the noblest minds and geniuses of Europe. This paganism, this cult of form, was naught else but the love of that noble nature from which the solitary Semitic estrangements had alienated hitherto the spirit of man in such bitter opposition. My at first feebly defined sentiment of opposition thus became confirmed conceit, reason, affirmation; the hymn to Phœbus Apollo became the hymn to Satan. Oh, beautiful years from 1861 to 1865, passed in peaceful solitude and quiet study, in the midst of a home where the venerated mother, instead of fostering superstition, taught us to read Alfieri! But as I read the codices of the fourteenth century the ideas of the Renaissance began to appear to me in the gilded initial letters like the eyes of nymphs in [16] the midst of flowers, and between the lines of the spiritual laude I detected the Satanic strophe. Meanwhile the image of Dante looked down reproachfully upon me; but I might have answered: ‘Father and master, why didst thou bring learning from the cloister into the piazza, from the Latin to the vulgar tongue? Why wast thou willing that the hot breath of thine anger should sweep the heights of papal and imperial power? Thou first, O great public accuser of the Middle Ages, gavest the signal for the rebound of thought: that the alarm was sounded from the bells of a Gothic campanile mattered but little!’ So my mind matured in understanding and sentiment to the Levia Gravia, and thence more rapidly, in questions of social interest, to the Decennali. There are those who complain that I am not what I was twenty-four years ago:—good people, for whom to live and develop is only to feed, like the calf qui largis invenescit herbis. In the Juvenilia I was the armour-bearer of the classics. In the Levia Gravia I held my armed watch. In the Decennali, after a few uncertain preliminary strokes of the lance, I venture abroad prepared for every risk and danger. I have read that the poet must give pleasure either to all or to the few; to cater to many is a bad sign. Poetry to-day is useless from not having learned that it has nothing to do with the exigencies of the moment. The lyre of the soul should respond to the echoes of the past, the breathings of the future, the solemn rumours of ages and generations gone by. If, on the contrary, it allows itself to be swayed by the breeze of society's fans or the waving of soldiers' cockades and professors' togas, then woe to the poet! Let the poet express himself and his artistic and moral convictions with the utmost possible candour, sincerity, and courage; as for the rest, it is not his concern. And so it happens that I dare to put forth a book of verses in these days, when one group of our literati [17] are declaring that Italy has never had a language, and another are saying that for some time past we have had no literature; that the fathers do not count for much, and that we are really only in the beginnings. There let them remain; or, as the wind changes, shift from one foreign servitude to another!”

In my selection of poems for translation, regard has been had not so much to the chronological order of their production as to their fitness for illustrating the three important characteristics of Carducci as a national poet which were enumerated above.

The first of these was his strong predilection for the classics, as evinced not only by his veneration for the Greek and Latin poets, but by his frequent attempts at the restoration of the ancient metres in his own verse. Of his fervent admiration for Homer and Virgil let the two sonnets III and IV testify, both taken from the fourth book of the Levia Gravia. Already in the Juvenilia, during his “classical knighthood,” he had produced a poem of some length on Homer, and in the volume which contains the one I have given there are no less than three sonnets addressed to the venerated master, entitled in succession, “Homer,” “Homer Again,” and “Still Homer.” I have chosen the second in order. [III]

In the tribute to Virgil [IV] the beauty of form is only equalled by the tenderness of feeling. It shows to what extent the classic sentiment truly lived again in the writer's soul, and was not a thing of mere intellectual contemplation. In reading it we are bathed in the very air of Campania; we catch a distant glimpse of the sea glistening under the summer moon, and hear the wind sighing through the dark cypresses.

Here it will be proper to notice the efforts made by Carducci not only to restore as to their native soil the long-disused metres of the classic poets, but to break loose from all formal restrictions in giving utterance to the poetic impulse. [18] This intense longing for greater freedom of verse he expresses in the following lines from the Odi Barbare:

I hate the accustomed verse.

Lazily it falls in with the taste of the crowd,

And pulseless in its feeble embraces

Lies down and sleeps.

For me that vigilant strophe

Which leaps with the plaudits and rhythmic stamp of the chorus,

Like a bird caught in its flight, which

Turns and gives battle.

In the preface of the same volume (1877) he pleads in behalf of his new metres that “it may be pardoned in him that he has endeavoured to adapt to new sentiments new metres instead of conforming to the old ones, and that he has thus done for Italian letters what Klopstock did for the Germans, and what Catullus and Horace did in bringing into Latin use the forms of the Eolian lyric.”

In the Nuove Rime (1887) are three Hellenic Odes, under the titles “Primavere Elleniche,” written in three of the ancient metres, the beauty of which would be lost by translation into any language less melodious and sympathetic than the Italian. We give a few lines from each:

I. EOLIA

Lina, brumaio turbido inclina,

Nell'aër gelido monta la sera;

E a me nell'anima fiorisce, O Lina,

La primavera.

II. DORICA

Muorono gli altri dii: di Grecia i numi

Non stanno occaso: ei dormon ne' materni

Tronchi e ne' fiori, sopra i monti, i fiumi,

I mari eterni.

[19]

A Cristo in faccia irrigidi nei marmi

Il puro fior di lor bellezze ignude:

Nei carme, O Lina, spira sol nei carme

Lor gioventude.

III. ALESSANDRINA

Lungi, soavi, profondi; Eolia

Cetra non rese più dolci gemiti

Mai nei sì molli spirti

Di Lesbo un dì tra i mirti.

The second of these examples demands translation as exhibiting perhaps more forcibly than any others we could select the boldness with which Carducci asserts the survival of the Hellenic spirit in the love of nature as well as in art and literature, despite the contrary influences of ascetic Christianity:

The other gods may die, but those of Greece

No setting know; they sleep in ancient woods,

In flowers, upon the mountains, and the streams,

And eternal seas.

In face of Christ,[3] in marble hard and firm,

The pure flower of their naked beauty glows;

In songs, O Lina, and alone in songs,

Breathes their endless youth.

The reader is also here referred to the “Invocation.” [V]

From this glance at the classic form which is so distinct a feature in Carducci's poems, we proceed to examine the feeling and conceptions which constitute their substance, and which will be found to be no less Hellenic than the metres which clothe them. Nothing could stand in stronger contrast with the melancholy of the romantic school of poets, or with the subjective thoughtfulness and austere introspection [20] of the Christian, than the unfettered outbursts of song in praise of the joy of living, of the delights of love and bodily pleasure, and of the sensuous worship of beautiful form, which we find in the poems “Sun and Love” [VI] and the hymn “To Aurora.” [VII]

The latter has in it the freshness and splendour of morning mists rising among the mountains and catching the rosy kisses of the sun. Equally beautiful but full of the tranquillity of evening is the Ruit Hora from the Odi Barbare of 1877. [VIII]

No one will fail to be struck with the beauty of the figure in the last stanza of this poem, nor with the picturesque force of the “green and silent solitudes” of the first, a near approach to the celebrated and boldly original conception of a silenzio verde, a “green silence,” which forms one of the many rare and beautiful gems of the sonnet “To the Ox.” [IX]

As an example of a purely Homeresque power of description and colouring, and at the same time of an intense sympathy with nature and exquisite responsiveness to every thrill of its life, this sonnet stands at the summit of all that Carducci has written, if indeed it has its rival anywhere in the poetry of our century. The desire to produce in English a suggestion at least of the broad and restful tone given by the metre and rhythm of the original has induced me to attempt a metrical and rhymed translation, even at the inevitable cost of a strict fidelity to the author's every word, and in such a poem to lose a word is to lose much. Nothing but the original can present the sweet, ever-fresh, and sense-reviving picture painted in this truly marvellous sonnet. The unusual and almost grotesque epithet of the opening phrase will be pardoned in view of the singular harmony and fitness of the original.

We know not where else to look for such vivid examples [21] as Carducci affords us of a purely objective and sensuous sympathy with nature, as distinguished from the romantic, reflective mood which nature awakens in the more sentimental school of poets. We feel that this strong and brilliant objectivity is something purely Greek and pagan, as contrasted with the analysis of emotions and thoughts which occupies so large a place in Christian writing. No one is better aware of the existence of this contrast than Carducci himself. For the dear love of nature—that boon of youth before the shadows of anxious care began to darken the mind, or the queryings of philosophy, the conflicts of doubt, and the stings of conscience to torment it—for this happy revelling of mere animal life in the world where the sun shines, the soul of the poet never ceases to yearn and cry out. The consciousness of the opposite, of a world of thought, of care, and of conscience ever frowning in sheer stern contrast from the strongholds of the present life and the opinions of men—this is what introduces a kind of tragic motive into many of these poems, and adds greatly to their moral, that is, their human interest. For the poetry of mere animal life, if such were poetry, however blissful the life it describes, would still not be interesting.

Something of this pathos appears in the poem “To Phœbus Apollo,” [X] where the struggle of the ancient with the present sentiments of the human soul is depicted. It will interest the reader to know that at the time this poem was written (it appeared in Book II. of the Juvenilia) the author had not broken so entirely with the conventional thought of his time and people but that he could consent to write a lauda spirituale [XI] for a procession of the Corpus Domini, and a hymn for the Feast of the Blessed Diana Guintini, protectress of Santa Maria a Monti in the lower Valdarno. When called by the Unità Cattolica to account for this sudden transformation of the hymn-writer into the odist of Phœbus [22] Apollo, Carducci replied by reminding his clerical critics that even in his nineteenth year he was given to writing parodies of sacred hymns, and he further offers by way of very doubtful apology the explanation that, being invited by certain priests who knew of his rhyming ability to compose verses for their feasts, the thought came into his head, “being in those days deeply interested in Horace and the thirteenth-century writers, to show that faith does not affect the form of poetry, and that therefore without any faith at all one might reproduce entirely the forms of the blessed laudists of the thirteenth century. I undertook the task as if it were a wager.”

In the lines of the poem To Phœbus Apollo there is traceable a romantic melancholy, the faint remnant of the impression left by those writers through whom, says Carducci, “I mounted to the ancients, and dwelt with Dante and Petrarch,” viz., Alfieri, Parini, Monti, Foscolo, and Leopardi. He has not yet broken entirely with subjective reflection and its gloom, and entrusted himself to the life which the senses realize at the present moment as the whole of human well-being. This sentiment becomes more strongly pronounced in the later poems, where not even a regret for the past is allowed to enter to distract the worship of the present, radiant with its divine splendour and bounty. The one thought that can cast a shadow is the thought of death; but this is not at all to be identified with Christian seriousness in reflecting on the world to come. The poet's fear of death is not that of a judgment, or a punishment for sins here committed, and hence it is not associated with any idea of the responsibility of the present hour, or of the amending of life and character in the present conduct. The only fear of death here depicted is a horror of the absence of life, and hence of the absence of the delights of life. It is the fear of a vast dreary vacuum, of cold, of darkness, of nothingness. The moral effect of such a fear is [23] only that of enhancing the value of the sensual joys of the present life, the use of the body for the utmost of pleasure that can be got by means of it. This more than pagan materialism finds its bold expression in the lines from the Nuove Odi Barbare entitled “Outside the Certosa.” [XII]

In studying the religious or theological tendency of Carducci's muse, it is necessary to bear in mind constantly the inherent national blindness of the Hellenic and, in equal if not greater degree, the Latin mind to what we may call a spiritual conception of life, its duties, and its destiny. But in addition to this blindness towards the spiritual elements or substance of Christianity there is felt in every renascent Hellenic instinct a violent and unrelenting hostility towards that ascetic form and practice which, although in no true sense Christian, the greater religious orders and the general discipline of the Roman Church have succeeded in compelling Christianity to wear. The mortification of nature, the condemnation of all worldly and corporeal delights, not in their abuse, but in their essential and orderly use, the dishonouring of the body in regarding its beauty as only an incentive to sin, and in making a virtue of ugliness, squalor, and physical weakness—these things have the offensiveness of deadly sins to the sensuous consciousness of minds of the Hellenic type. To spiritual Christianity Carducci is not adverse because it is spiritual—as such it is still comparatively an unknown element to Italian minds—but because it is foreign to the national instinct; because it came in with the emperors, and so it is indissolubly associated with foreign rule and oppression. It is the Gothic or Teutonic infusion in the Italian people that has kept alive whatever there is of spiritual life in the Christianity that has been imposed on them by the Roman Church. The other elements of Romanism are only a sensuous cult of beautiful and imposing forms in ritual, music, and architecture on the one hand; [24] and on the other a stern, uncompromising asceticism, which in spirit is the direct contradiction of the former. While the principle of asceticism was maintained in theory, the sincerity of its votaries gradually came to be believed in by no one; the only phase of the church that seized hold of the sympathies and affections of the people was the pagan element in its worship and its festivals; and seeing these, the popes were wise enough to foster this spirit and cater in the most liberal measure to its indulgence, as the surest means of maintaining their hold on the popular devotion. In the ever-widening antagonism between the spirit and the flesh, between the subjective conception of Christianity on the one hand, as represented by the Teutonic race and the empire, and the sensuous and objective on the other, as represented by the Italic race and the pope, may we not discern the reason why the Italian people, in the lowest depths of their sensual corruption, were largely and powerfully Guelph in their sympathies, and why the exiled and lonely writer of the Divina Commedia was a Ghibelline? It is at least in the antagonism of principles as essentially native versus foreign that we must find the explanation of the cooling of Carducci's ardour towards the revered master of his early muse, even while the old spell of the latter is still felt to be as irresistible as ever. This double attitude of reverence and aversion we have already seen neatly portrayed in the reference Carducci makes in the autobiographical notes given above to Dante as the great “accuser of the Middle Ages who first sounded the signal for the reaction of modern thought,” with the added remark that the signal being sounded from a “Gothic campanile” detracted but little from the grandeur of its import. The same contrast of sentiment finds more distinct expression in the sonnet on Dante in Book IV. of the Levia Gravia. [XIII]

But nowhere is the contrast between the Christian sense of awe in the presence of the invisible and supernatural and the [25] Hellenic worship of immediate beauty and sensuous pleasure displayed in such bold and majestic imagery as in the poem entitled “In a Gothic Church.” [XIV] Here, in the most abrupt and irreverent but entirely frank transition from the impression of the dim and lofty cathedral nave to the passion kindled by the step of the approaching loved one, and in the epithets of strong aversion applied to the holiest of all objects of Christian reverence, the very shock given to Christian feeling and the suddenness of the awful descent from heavenly to satyric vision tell, with the prophetic veracity and power of true poetry, what a vast chasm still unbridged exists between the ancient inherent Hellenism of the Italian people and that foreign influence, named indifferently by Carducci Semitic or Gothic, which for eighteen centuries has been imposed without itself imposing on them.

The true poet of the people lays bare the people's heart. If Carducci be, indeed, the national poet of Italy we have in this poem not only the heart but the religious sense—we had almost said the conscience—of the Italian people revealed to view. Nor is this all Bacchantic; the infusion of the Teutonic blood in the old Etruscan and Italic stock has brought the dim shadows of the cathedral and its awful, ever-present image of the penalty of sin to interrupt the free play of Italian sunshine. But just as on the canvas of the religious painters of the Renaissance angels as amorous Cupids hover about between Madonna and saints, and as in the ordinary music of an Italian church the organist plays tripping dance melodies or languishing serenades between the intoned prayers of the priests or the canto firmo psalms of the choir, so here we behold the sacred aisles of the cathedral suddenly invaded by the dancing satyr, who, escaping from his native woods, has wandered innocently enough into this his ancient but strangely disguised shrine.

The stanzas that follow describe Dante's vision of the [26] “Tuscan Virgin” rising transfigured amid the hymns of angels. The poet, on the contrary, sees neither angels nor demons, but is conscious only of feeling

the cold twilight

To be tedious to the soul,

and then exclaims:

Farewell, Semitic God: the mistress Death

May still continue in thy solemn rites,

O far-off king of spirits, whose dim shrines

Shut out the sun.

Crucified Martyr! Man thou crucifiest;

The very air thou darkenest with thy gloom.

Outside, the heavens shine, the fields are laughing,

And flash with love.

The eyes of Lidia—O Lidia, I would see thee

Among the chorus of white shining virgins

That dance around the altar of Apollo

In the rosy twilight,

Gleaming as Parian marble among the laurels,

Flinging the sweet anemones from thy hand,

Joy from thy eyes, and from thy lips the song

Of a Bacchante!

Odi Barbare.

Notwithstanding the bold assertion of the Hellenic spirit in this and in the greater part of his poems, that, nevertheless, Carducci has not been able to restore his fair god of light and beauty, the Phœbus Apollo, to the undisputed sway he held in the ancient mind is evident from the shadows of doubt, of fear, and anxious questioning which still darken here and there the poet's lines, as in the sonnet Innanzi, Innanzi! [XV] It is here that the stern element of tragedy, the real tragedy of humanity, makes itself felt in this rhapsodist of joy and of love. It comes to tell us that to the [27] Italian as he is to-day life has ceased to be a carnival, and that other sounds than that of the Bacchante's hymn have gained an entrance, with all their grating discord, to his ear: and to silence this intruder will the praises of Lidia and of Apollo suffice, be they sung on a lyre never so harmonious and sweet? In this sonnet is depicted in wonderful imagery the ancient and awful struggle which the sensuous present life sustains with the question of an eternity lying beyond.

While our interest in Carducci is largely owing to the character he bears as the poet of the Italian people, it would be quite erroneous to consider him a popular poet. For popularity, whether with the court, the school, or the masses, he never aimed, as is evident from his satisfaction at narrowly escaping being made a political poet-laureate. Instead of writing down to the level of popular apprehension and taste, he rather places himself hopelessly aloof from the contact of the masses by his style of writing, which, simple and pure as it seems to the cultured reader, is nevertheless branded by the average Italian as learned and obscure, and not suited to the ordinary intelligence. As an innovator both in the form and in the content of his verse, he has still a tedious warfare to wage with a people so conservative as the Italians of old habits and old tastes, confirmed as these have been by the combined influence of centuries of political and ecclesiastical bondage. But Carducci's writing, springing nevertheless from a strong instinct, looks only to the people for a final recognition, even though that has to be obtained through the medium of the learned classes at first. How far he has succeeded in getting this vantage-ground of a general recognition and acquiescence on the part of the learned, the following testimony from Enrico Panzacchi, himself a critic and a poet of high reputation, may help us to conclude:

“I believe that I do not exaggerate the importance of Carducci when I affirm that to him and to his perseverance and [28] steadfast courageous work we owe in great part the poetic revival in Italy.

“I have great faith, I confess, in the initiative power of men of strong genius and will, and, to tell the truth, while it is the fashion of the day to explain always the individual by the age he lived in, I think it is often necessary to invert the rule, and explain the age by the individual.”

He goes on to show that, indifferent alike to conventional laws and public opinion, Carducci always persisted in the constant endeavour to far l'arte, to “do his art.” He defied the critics, and tried to be himself.

Mr. Symonds says of the Renaissance that “it was a return in all sincerity and faith to the glory and gladness of nature, whether in the world without or in the soul of man.” Carducci reflects the spirit of the Renaissance in so far as by setting free the national instincts he has made way for the Hellenic reaction in favour of the “glory and the gladness of the world without.” He has shown, moreover, how foreign to these instincts is Christianity, considered apart from the Roman Church, whether in its ascetic or in its spiritual aspects. But it cannot be said of him, whatever may have been true of the poets of the Renaissance, that he has reawakened or rediscovered “the glory and gladness of nature in the soul of man,” and without this the gladness of the world without is but a film of sunshine hiding the darkness of the abyss. Indeed, if the soul and not the senses be addressed, we question whether beneath all the Dionysian splendours and jollity of Carducci's verses there be not discernible a gloom more real than that of Leopardi. Even for Italy the day is past when Hellenism can fill the place of Christianity; the soul craves a substance for which mere beauty of form, whether in intellect, art, or nature, is a poor and hollow substitute; and to revive not the poetry alone, but the humanity of the nation, a force is needed greater and higher than that to be got by the restoration of either dead Pan or Apollo.

[29]

Sojourning one autumn in a quiet pension at Lugano, I came in contact with a fellow-boarder, who, notwithstanding he bore the title of a Sicilian count of very high-sounding name, proved on acquaintance to be a man of serious literary taste and not above accepting pecuniary compensation for the products of his pen.

He was engaged at that time in translating into the Italian a well-known English classic, and was in the habit of appealing to me occasionally for my judgment as to the accuracy of his interpretation of an English word or phrase.

This led to pleasant interviews on the literary art in general.

It was one day when the conversation turned on the extreme materialism of certain scientific writers of the day, and especially on Mantegazza of Florence, whose grossness in treating of the human passions has called forth expressions of disgust from Italians, as well as others, that my Sicilian friend quietly remarked, “We Italians can never allow the holy Trine to be destroyed—the True, the Good, the Beautiful. It is not enough that a writer tell the facts as they are; nor that his purpose be a useful one; there must be the [30] element of beauty also in his work, or the Italians will not accept it; and the ugly, the monstrous, and deformed the Italians will not endure.”

I thought herein he proved his lineage from a stock older than even his family title—that old race of the land where Theocritus sang as if for beauty alone, and whose Ætna cherishes still her deep-down fires uncooled and untamed by modern as by ancient contrivances of man.

It is this presence of the love of the beautiful that everywhere accompanies the Greek race and their descendants, and imparts what we may call the Hellenic instinct of form. And in this sense of form born of the love of beauty lies the secret of the immortal art of the Greeks, whether as presented in sculpture, architecture, painting, or letters.

The survival of a certain Hellenic religious feeling in the Italian people after centuries of a superimposed Christianity has already been treated of in the previous essay. I desire here to speak of Carducci as affording an example—perhaps one among many, but I know none better—of the restoration of the Greek love of form to modern letters, and so as illustrating what we may designate as the classic realism.

No term has been more abused of late years than this word—realism. Become the watchword of schools of “realists” in every branch of art and literature, it has been reduced at last to a service as empty of meaning as was ever the vaguest idealism empty of reality.

The tendency of the age has been unquestionably one of ultimation; everything presses into the plane of outermost effect. We have seemed to be no more satisfied with the contemplation of intangible ideals: we rest content only with what hand can touch and eye rest upon. The “power in ultimates” is the display of force characteristic of this age of the world. The forces physical and mental have been [31] always there: it has taken a time like the present, an age of inventive frenzy filled with a yearning for the doing and trying of things long dreamt of, to give vent to these hidden forces.

This tendency to ultimation, the seeking expression of inmost emotions and conceptions in material embodiments, has characterized of late years every form of mental activity.

Religion exemplifies it in the impatience the people exhibit at fine analyses of doctrines and laborious attempts at creed-patching, at the same time that they are ready to engage in schemes of benevolence and social reform unparalleled in the history of the past. They would fain substitute a religion of doing for a religion of believing; and so impatient are they of the restrictions of dogma that they resent inquiry into the quality or inward motive of the doing, or even into its moral effect in the long run, so only some “good work” be done and done quickly.

We see the same tendency in music and the drama wonderfully illustrated in the whole conception and effort of the Wagnerian school. Expression is everything. The question is not—Is the thing in itself noble, but is the expression of it complete, unhindered by previous conventionalities? Is nothing kept back, or left to the imagination, but everything, rather, brought out into the actuality of sound, of color, of living performers, and material accessories?

The Ibsen drama, the Tourguenief and Tolstoi school of novelists, not to speak of Zola and his followers in France, writers like Capuana and Verga in Italy, and, although in a quite different vein, Howells among novelists and Whitman among poets in America, have aimed chiefly to give a faithful account of life as it is seen. Some have come dangerously near the assertion that by some mysterious law the bold doing ennobles even a commonplace motive, and that a regard for truth is enough whether there be any beauty behind it or not.

[32]

The power realised in full and free expression is one of the most exquisite delights known to man. We of a northern race who, according to the saying of our French neighbor, “take our pleasures sadly,” do so because of a hereditary conviction of the sanctity of the unexpressed. We have therefore been slowest in arriving at these efforts towards realism, or the untrammelled giving forth of the inward self into outward embodiment. That pure externalism of the southern or Greek nature which sought its highest satisfaction in a visible embodiment of the divine in art, and which distinguishes still the Roman from the Saxon religious nature, has been regarded as verging on the sinful. It is not strange that a tendency so long suppressed when once set free should rush even into lawless extremes, and that an age or school of writers tasting the delights of this liberty for the first time should be loth to resign it and be ready rather to sacrifice all to its further extension. It is quite in accordance with this theory that puritan America should have given birth to Walt Whitman, who, with all his lawlessness, is in many respects the most of a Greek that modern literature can show.

To what extremes this delight has sought indulgence is shown not more plainly in Zola and his school above mentioned than in the whole contemporary school of French pictorial art. We see here how form, as expression, indulged in for its own sake, apart from a due consideration of the substance within the form, becomes itself monstrous and vicious. This is the essentially immoral element in art—the licentious worship of form, or of external shape, regardless of an internal soul or motive.

When the realist says: “With the motive of nature, of society, of man, I have nothing to do; it is enough if I portray faithfully his conduct,” he thereby advertises the fact that he is not an artist, but a kind of moral photographer. He falls short of being an artist in just the degree in which [33] he sees the details of form apart from their soul or spiritual essence; and as this spiritual element is that wherein the unity of the world as idea exists, therefore, failing to apprehend this, he fails to lay hold of the universal aspects which alone can assign true relation and true meaning to any of the details treated of. It is the apprehension of the universal element underlying the particulars that constitutes the peculiar gift of the artist. It is indeed true that nature, or humanity, is its own interpreter and its own preacher; and the most faithful servant of either will be he who most exactly presents his subject as he finds it. But the subject is never found by the true artist detached from its community-life, or severed from the endless woof of combinations, of causes and effects, of law and recompense, which go to make up any present moment of its existence; these constitute its “story.” So far as these inner conditions are recognized and felt in giving the ultimate expression, so far alone is the portrayal a real one in the true sense.

Undoubtedly the inmost motive that can give form to the literature of any age or race is the religious one, by which I mean the recognition of a life within and above nature, not our own, but to which we entertain a personal relation. This is in the truest sense that “soul” which “is form, and doth the body make,” and its presence or absence is what sufficiently distinguishes the true from a false realism.

An age without a religion can produce only a soulless, and so an unreal, art. What it calls art may abound in shape, but will possess no form in the true sense of the word. For form is the combination of particulars with a view to a single purpose, for which every particular exists and to which it is subordinate; it is therefore never a many, but always a one out of many. This inward controlling motive that constitutes out of many the one, is the living substance within every true or real form. That which does not possess this motive [34] of unity is not form, but shape, or an artificial cast made to resemble the living thing, but having no life within it. Art is thus the form that grows from within, while shape is but the impression mechanically imposed on passive and lifeless material from without. The modern French school of realists in art are the fittest examples of this substitution of shape for form, and so of pseudo-realism. They have given us corpses, whether physical or moral, and called them human beings. They have preferred the charnel-house, the dissecting-room, or the field of carnage, as the subjects in which to display most effectively their realism. The more revolting the subject, the more hideously exact the representation, the more credit was claimed for the artist. In literature the case was parallel. Nothing so vile but it was to be admired for its faithfulness in representation. The inner motive, the moral purpose of the writing or the painting, was not only not there, but the producer scorned the judgment that would look for it. Never was religion, or the sentiment of reverence for the spiritual as the world's idea, so manifestly wanting as in these recent French materialists. The abjuring of the romantic and the ideal has gone so far as to extinguish the human element, and so we find in these schools skilfully painted bodies and an almost matchless power of expression; but, after all, how little is expressed!

Compare a Greek statue of Phidias's time with the latest production of a Parisian studio. Both are alike of hard, colourless, senseless marble; but can we not see in one the breathing of a god, while in the other we, at the most, study with a critical vision the outlines of a human animal?

Reality is not reached by the negative process of taking away conventional guises and concealments; and yet modern artists and writers have alike thought to get at truth in this way. But the nude is not the more real for being nude. The reality of an object depends on what is within it, and [35] not on anything that men put on or take away from it. How many writers of late years have been deluding themselves with the idea that if one can only succeed in avoiding everything like a moral purpose, or even interesting situations, and reveal what they call the bare facts of experience, one may thereby attain to the real? As if ever art existed except in the discovering of unity, the interpretation of purpose, and in the suggesting of that which is interesting to the human heart!

The emptiness of this kind of realism, which is as naked of soul within as of garments without, is proved by the reaction that is already setting in in France, where materialism has made its boldest claims in the domain of art. Not only in art is there a strong movement for restoring the lost elements of romance and piety, leading to a religious severity almost like that of the pre-Raphaelites, but in literature there is a similar protest against the degradation of the real to the plane of mere soulless matter. M. Paul Bourget, who has been through all phases of French expression and knows its extremes, gives voice to this reaction in the following passage from his “Sensations d'Italie”:

“Sans doute, les grands peintres ont vu d'abord et avant tout l'être vivant; mais dans cet être, ils ont dégagé la race et ils ne pouvaient pas la sentir, cette race, sans démêler l'obscur idéal qui s'agite en elle, qui végète dans les créatures inférieures, ignoré d'elles-mêmes et cependant consubstantiel à leur sang. La langueur et la robustesse à la fois de ce pays de montagnes dont le pied baigne dans la fièvre, le mysticisme des compatriotes de Saint François d'Assise et leur sauvagerie, la mélancolie songeuse prise devant l'immobile sommeil des lacs, tous ces traits élaborés par le travail séculaire de l'hérédité, le Pérugin les a dégagés plus nettement qu'un autre, mais it n'a eu qu'à les dégager. Sa divination instinctive les a reconnus, sans peut-être qu'il s'en rendît compte, dans des [36] coupes de joues, des nuances de prunelles, des airs de tête. C'est là, dans cette interprétation à la fois soumise et géniale, que réside la véritable copie de la nature où tout est âme, même et surtout la forme,—âme qui se cherche, qui se méconnaît parfois, qui s'avilit, mais une âme tout de même et qui ne se révèle qu'à l'âme.”[4]

A Frenchman of to-day become an admirer of Perugino!

A tendency to realism, unlike that of French art in subject, but not unlike in method, is that which is exhibited in England in the recent religious novelists of the class headed by the authoress of “Robert Elsmere.” Here, again, the effort has been to get at the real by stripping off conventional religious admissions, pretensions, and errors, and depicting a moral basis of conduct which can exist independently of creed and church. The result has been disappointing, because a creed incapable of perversion or corruption becomes as lifeless and as powerless a factor in human character-building as is the multiplication table; and without a miraculous incarnation of Deity as its basis and its imperative authority, the whole system of Christian ethics, when thus reduced to a scientific conclusion or to an invention of man's individual [37] moral sense, loses not only its power to influence morally, but even to interest other minds. The “real” basis of religion thus arrived at is found to be no religion at all, but only the private opinion of this authoress as to what is good and right, with every divine and therefore every universal and obligatory element in it left out.

I have spoken indiscriminately, above, of the realists in our modern literature as all subject to the temptation to rest satisfied with photographic imitations of nature rather than with a reality created from their apprehension of its ideal form. The end sought for is faithfulness in expression, and the danger is that of making subordinate to this the substance of what is expressed. But among these writers there are all degrees of approach to the genuine realism which undoubtedly, like the art of the Greeks, is a thing that can never die, and which, even if for a long interval set aside, is sure to return again to its rightful place as the only true form of expression.

Among the various aspirants to the title of realist, we have no more interesting examples than in our own Howells and Whitman, both being avowed prophets of this school of writing. In Whitman we see a generous nature run away with by the passion of expression. His words are heaped like sand-dunes. There is a sound of roaring waves, but the landscape is, too often, on the whole, shapeless and wearisome. One feels that there is meaning in the poet's mind, but the expression is excessive, and so without form. The delight of ultimation has become a frenzy of word-piling or word-inventing. The disappointment is like that experienced on seeing a piece of sculpture which reveals a bold and vigorous design with magnificent anatomy and muscular strength, but which has a weak line in the face. It just falls short of being art.

[38]

With Howells the charm of his realism lies in the subtlety of his concealment of it. The deep moral purpose which, like a strong, irresistible current, underlies his recent and more serious writing, is all the more potent because it is not “pointed”; and the reader is allowed to indulge, as if with the author himself, in the little delusion that this is only the ordinary superficial aspect of an every-day world which is being described, and that things do thus merely happen as they happen, without design or reason. So perfect is the form and so true to nature that, with the author, we keep up, too, the little deception, that it is with the form itself that we are pleased, and that this constitutes the realism of which the author is so ardent an advocate. Meanwhile we learn, when the story is ended, that this realism was all informed with a soul of moral and divine purpose, and that this is all that is real in it as in anything else.

To distinguish from the pseudo-realism of matter the genuine realism that is soul-informed, I do not know a better name for the latter than the Classic Realism. I mean by this something as far remote as possible from the classic formalism of the age of Pope and Dryden, as remote indeed as form is from formalism. For in that period it was neither truth to nature nor truth to the imagination that was aimed at in expression, but rather a cold and rigid conformity to the rules of correct writing as found in the recognized standards. “Classic” hence got to mean merely according to the standards. But by a Classic Realism we will certainly understand that effort to obtain a form of expression which recognizes both the internal and the external reality of things, and is able to combine both in one ultimation like the soul and body that make the one man.

The subjectivity of the Saxon mind and a large inheritance of both the classic formalism and the romanticism of former [39] periods of English literature have prevented our English writers from attaining that spontaneous realism which was native to the Hellenic mind; and yet they have the gift to recognise and interpret it when found. This did Tennyson when he chose for translation the following lines closing the Eighth Book of the “Iliad”:

As when in heaven the stars about the moon

Look beautiful, when all the winds are laid,

And every height comes out, and jutting peak,

And valley, and the immeasurable heavens

Break open to their highest; and all the stars

Shine, and the shepherd gladdens in his heart:

So, many a fire between the ships and stream

Of Xanthus blazed before the towers of Troy,

A thousand on the plain: and close by each

Sat fifty in the blaze of burning fire;

And, champing golden grain, the horses stood,

Hard by their chariots, waiting for the dawn.

The same vision into the charmed world of the classic realism had Keats when he wrote his sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman's Homer,” and put a whole age of ecstatic delight into these matchless lines:

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-browed Homer ruled as his demesne:

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when, with eagle eyes,

He stared at the Pacific—and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

Listen to Theocritus describing in most realistic language the Joys of Peace. Notice how he does not so much as mention [40] any emotion, but awakens it by his faithful description of the objective world:

And oh! that they might till rich fields, and that unnumbered sheep and fat might bleat cheerily through the plains, and that oxen, coming in herds to the stalls, should urge on the traveller by twilight. And oh! that the fallow lands might be broken up for sowing, when the cicada, sitting on his tree, watches the shepherd in the open day and chirps on the topmost spray; that spiders may draw their fine webs over martial arms, and not even the name of the battle-cry be heard. [Idyl XVI.]

Keats has felt the same appeal of nature to human sympathy in all the humblest forms of life, and has expressed it in his sonnet on the “Grasshopper and the Cricket”:

The poetry of earth is never dead.

When all the birds are faint with the hot sun,

And hide in cooling trees, a voice will run

From hedge to hedge about the new-mown mead:

That is the grasshopper's—he takes the lead

In summer luxury—he has never done

With his delights, for, when tired out with fun,

He rests at ease beneath some pleasant weed.

The poetry of earth is ceasing never:

On a lone winter evening, when the frost

Has wrought a silence, from the stove there shrills

The cricket's song, in warmth increasing ever,

And seems to one in drowsiness half lost,

The grasshopper's among some grassy hills.

This is realism, but a truly classic realism; it is earth, but the “poetry of earth.”

Probably Whitman has here and there approached as nearly as any English writer to this pure realism, and, when he has not allowed his delight in words to outrun his inward conception, he has given us pictures possessing much of the vivid objectivity of the Greek realists. Compare with [41] the above passage from Theocritus the Farm Picture drawn by Whitman in these two lines:

Through the ample open door of the peaceful country barn

A sun-lit pasture field, with cattle and horses feeding.

Or this:

Lo, 'tis autumn.

Lo, where the trees, deeper green, yellower and redder,

Cool and sweeten Ohio's villages, with leaves fluttering in the moderate wind,

Where apples ripe in the orchards hang and grapes on the trellis'd vines,

(Smell you the smell of the grapes on the vines?

Smell you the buckwheat where the bees were lately buzzing?)

Above all, lo, the sky so calm, so transparent after the rain, and with wondrous clouds,

Below, too, all calm, all vital and beautiful, and the farm prospers well.