The Project Gutenberg EBook of Apparitions and thought-transference: an examination of the evidence for telepath, by Frank Podmore This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Apparitions and thought-transference: an examination of the evidence for telepathy Author: Frank Podmore Release Date: February 3, 2018 [EBook #56489] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK APPARITIONS *** Produced by Charlene Taylor, Bryan Ness, Jane Robins and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE CONTEMPORARY SCIENCE SERIES.

EDITED BY HAVELOCK ELLIS.

AN EXAMINATION OF THE EVIDENCE

FOR TELEPATHY.

BY

FRANK PODMORE, M.A.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS.

LONDON:

WALTER SCOTT, LTD.,

24 WARWICK LANE, PATERNOSTER ROW.

1894.

INTRODUCTORY PAGE

1

Position of the subject—Founding of the Society for Psychical Research—Definition of telepathy—General difficulties of the inquiry—Special sources of error—Fraud—Hyperæsthesia—Muscle-reading—Thought-forms and number-habit.

EXPERIMENTAL TRANSFERENCE OF SIMPLE SENSATIONS IN THE NORMAL STATE 18

Transference of Tastes—Of pain, by Mr. M. Guthrie and others—Of sounds—Of ideas not definitely classed, by Professor Richet, the American Society for Psychical Research, Dr. Ochorowicz—Transference of visual images, by Dr. Blair Thaw, Mr. Guthrie, Professor Oliver Lodge, Herr Max Dessoir, Herr Schmoll, Dr. von Schrenck-Notzing, and others.

EXPERIMENTAL TRANSFERENCE OF SIMPLE SENSATIONS WITH HYPNOTISED PERCIPIENTS 58

Transference of tastes, by Dr. Azam—Of pain, by Edmund Gurney—Of visual images, by Dr. Liébeault, Professor and Mrs. Henry Sidgwick, Dr. Gibotteau, Dr. Blair Thaw.

EXPERIMENTAL PRODUCTION OF MOVEMENTS AND OTHER EFFECTS 82

Inhibition of action by silent willing, by Edmund Gurney, Professor Barrett, and others—Origination of action by silent willing, by Dr. Blair Thaw, M. J. H. P., and others—Planchette-writing, by Rev. P. H. Newnham, Mr. R. H. Buttemer—Table-tilting, by the Author, by Professor Richet—Production of local anæsthesia, by Edmund Gurney, Mrs. H. Sidgwick.

EXPERIMENTAL PRODUCTION OF TELEPATHIC EFFECTS AT A DISTANCE 105

Induction of sleep, by Dr. Gibert and Professor Janet, Professor Richet, Dr. Dufay—Of hysteria and other effects, by Dr. Tolosa-Latour, M. J. H. P.—Transference of ideas of sound, by Miss X., M. J. Ch. Roux—Of visual images, by Miss Campbell, M. Léon Hennique, Mr. Kirk, Dr. Gibotteau.

GENERAL CRITICISM OF THE EVIDENCE FOR SPONTANEOUS THOUGHT-TRANSFERENCE 143

On chance coincidence—Misrepresentation—Errors of observation—Errors of inference—Errors of narration—Errors of memory—"Pseudo-presentiment"—Precautions against error—"Where are the letters?"—The spontaneous cases as a true natural group.

TRANSFERENCE OF IDEAS AND EMOTIONS 161

Transference of pain, Mr. Arthur Severn—Of smell, Miss X.—Of ideas, Miss X., Mrs. Barber—Of visual images, Mr. Haynes, Professor Richet, Dr. Dupré—Of emotion, Mr. F. H. Krebs, Dr. N., Miss Y.—Of motor impulses, Archdeacon Bruce, Professor Venturi.

COINCIDENT DREAMS 185

Discussion of the evidence for telepathy derivable from dreams—Chance-coincidence—Simultaneous dreams, the Misses Bidder—Transference of sensation in dreams, Professor Royce, Mrs. Harrison—Dreams conveying news of death, etc., Mr. J. T., Mr. R. V. Boyle, Captain Campbell, Mr. E. W. Hamilton, Mr. Edward A. Goodall—Clairvoyant dream, Mrs. E. J.

ON HALLUCINATION IN GENERAL 207

Common misconceptions—Hypnotic hallucinations, experiments by MM. Binet and Féré, Mr. Myers—Point de repère—Post-hypnotic hallucinations, Professor Liégeois, Edmund Gurney—Spontaneous hallucinations, Professor Sidgwick's census—Table showing classification of spontaneous hallucinations—Origin of hallucinations, sometimes telepathic—Proof of this, calculation of chance-coincidence, allowance for defects of memory—Conclusion.

INDUCED TELEPATHIC HALLUCINATIONS 226

Possible misconceptions—Accounts of experiments, by Rev. Clarence Godfrey, Herr Wesermann, Mr. H. P. Sparks, and A. H. W. Cleave, Mrs B——, Dr. von Schrenck-Notzing, Dr. Wiltse, Mr. Kirk.

SPONTANEOUS TELEPATHIC HALLUCINATIONS 247

Auditory hallucinations, Miss Clark, Mr. William Tudor—Visual hallucinations—Incompletely developed, Countess Eugenie Kapnist, Miss L. Caldecott, Dr. Carat—Completely developed, Miss Berta Hurly, Mrs. McAlpine, Miss Mabel Gore Booth—Hallucinations affecting two senses, Rev. Matthew Frost, M. A——.

COLLECTIVE HALLUCINATIONS 268

Illusions, epidemic hallucinations, illusions of memory—Explanations of collective hallucination—Auditory hallucinations, Mr. C. H. Cary, Miss Newbold—Visual hallucinations, Mrs. Greiffenberg, Mrs. Milman and Miss Campbell, Mr. and Mrs. C——, Mr. Falkinburg, Dr. W. O. S., Rev. C. H. Jupp—Collective hallucinations with percipients apart, Sister Martha and Madame Houdaille, Sir Lawrence Jones and Mr. Herbert Jones.

SOME LESS COMMON TYPES OF TELEPATHIC HALLUCINATION 297

Reciprocal cases, Rev. C. L. Evans and Miss —— —A misinterpreted message, Miss C. L. Hawkins-Dempster—Heteroplastic hallucination, Mrs. G——, Frances Reddell, Mr. John Husbands, Mr. J—— —"Haunted houses," Mrs. Knott and others, Surgeon-Major W. and others.

ON CLAIRVOYANCE IN TRANCE 326

Definition of clairvoyance—Accounts of phenomena observed with Mrs. Piper, by Professor Lodge, Professor W. James, and others—Accounts of experiments by Mr. A. W. Dobbie, Dr. Wiltse, Mr. W. Boyd, Dr. F——, Dr. Backman.

ON CLAIRVOYANCE IN THE NORMAL STATE 351

Observations of M. Keulemans—Crystal-visions, Miss X., Dr. Backman, Miss A. and Sir Joseph Barnby—Spontaneous clairvoyance, Mrs. Paquet, Mr. F. A. Marks, Mrs. L. Z.—Clairvoyance in dream, Mrs. Freese—Clairvoyant perceptivity in an experiment, Dr. Gibotteau.

THEORIES AND CONCLUSIONS 371

Resumé, the proof apparent—The proof presumptive—The alleged influence of magnets and metals—The alleged marvels of spiritualism—Usage of the word telepathy—On various theories of telepathy—Difficulties of a physical explanation—Value of theory as a guide to investigation—Is telepathy a rudimentary or a vestigial faculty?—Our ignorance stands in the way of a conclusive answer—Imperative need for more facts.

The following pages aim at presenting in brief compass a selection of the evidence upon which the hypothesis of thought-transference, or telepathy, is based. It is now more than twelve years since the Society for Psychical Research was founded, and nearly eight since the publication of Phantasms of the Living. Both in the periodical Proceedings of the Society and in the pages of Edmund Gurney's book,[1] a large mass of evidence has been laid before the public. But the papers included in the Proceedings are interspersed with other matter, some of it too technical for the taste of the general reader; whilst the two volumes of Phantasms of the Living, which have for some time[xii] been out of print, were too costly for the purse of some, and too bulky for the patience of others. The attention which, notwithstanding these drawbacks, that work excited on its first appearance, the friendly reception which it met with in many quarters, and the fact that a considerable edition has been disposed of, encouraged the hope that a book on somewhat similar lines, but on a smaller scale, might be of service to those—and their number has probably increased within the last few years—who take a genuine interest in this inquiry. Accordingly in the autumn of 1892 I obtained permission from the Council of the Society for Psychical Research to make full use, in the compilation of the present work, not merely of the evidence already published by us, but of the not inconsiderable mass of unpublished records in the possession of the Society.

It will be seen that the present book has little claim to novelty of design; but it is not merely an abridged edition of the larger work referred to. On the one hand it has a somewhat wider scope, and includes accounts of telepathic clairvoyance and other phenomena which did not enter into the scheme of Mr. Gurney's book. On the other hand, the bulk of the illustrative cases here quoted have been taken from more recent records; and, in particular, certain branches of the experimental work have assumed a quite new importance within the last few years. Thus the experiments conducted by Mrs. Henry Sidgwick at Brighton have strengthened the demonstration of[xiii] thought-transference, and have gone far to solve one or two of the problems connected with the subject; and the evidence for the experimental production of telepathic effects at a distance has been greatly enlarged by the work of MM. Janet and Gibert,[2] Richet, Gibotteau, Schrenck-Notzing, and in this country by Mr. Kirk and others.[3] It may be added that some of the criticisms called forth by Phantasms of the Living, and our own further researches, have led us to modify our estimate of the evidence in some directions, and to strengthen generally the precautions taken against the unconscious warping of testimony.

To say, however, that the following pages owe much to Edmund Gurney is but to acknowledge the obligation which all students of the subject must recognise to his keen and vigorous intellect and his colossal industry. My own debt is a more personal one. To have worked under his guidance, and to have been stimulated by his example, was an invaluable schooling in the qualities demanded by an inquiry of this nature. Of the living, I owe grateful thanks, in the first instance, to Professor and Mrs. Henry Sidgwick, who have read through the whole of the book in typescript, and have given help and counsel throughout. Miss Alice Johnson, Mr. F. W. H. Myers, the late Dr. A. T. Myers, Miss Porter,[xiv] and others have also given me welcome help in various directions. In acknowledging this assistance, however, it is right to add that, though I trust in my estimate of the evidence presented, and in the general tenour of the conclusions suggested, to find myself, with few exceptions, in substantial agreement with my colleagues, yet I have no claim to represent the Society for Psychical Research, nor right to cloak my own shortcomings with the authority of others.

One word more needs to be said. The evidence, of which samples are presented in the following pages, is as yet hardly adequate for the establishment of telepathy as a fact in nature, and leaves much to be desired for the elucidation of the laws under which it operates. Any contributions to the problem, in the shape either of accounts of experiments, or of recent records of telepathic visions and similar experiences, will be gladly received by me on behalf of the Society for Psychical Research, at 19 Buckingham Street, Adelphi, W.C.

FRANK PODMORE.

August 1894.

INTRODUCTORY—SPECIAL GROUNDS OF CAUTION.

It is salutary sometimes to reflect how recent is the growth of our scientific cosmos, and how brief an interval separates it from the chaos which went before. This may be seen even in Sciences which deal with matters of common observation. Amongst material phenomena the facts of Geology are assuredly not least calculated to excite the curiosity or impress the imagination of men. Yet until the middle of the last century no serious attempt was made to solve the physical problems they presented. The origin of the organic remains embedded in the rocks had indeed formed the subject of speculation ever since the days of Aristotle. Theophrastus had suggested that they were formed by the plastic forces of Nature. Mediæval astrologers ascribed their formation to planetary influences. And these hypotheses, with the alternative view of the Church, that fossil bones and shells were relics of the Mosaic Deluge, appear to have satisfied the learned of Europe until the time of Voltaire, who reinforced the rationalistic position, as he conceived it, by the suggestion that the shells, at[2] any rate, had been dropped from the hats of pilgrims returning from the Holy Land. Yet Werner and Hutton were even then preparing to elucidate the causes of stratification and the genesis of the igneous rocks. Cuvier in the next generation was to demonstrate the essential analogies of the fossils found in the Paris basin with living species; Agassiz was to investigate the relation of fossil fishes and to show the true nature of their embedded remains. Nay, even in the middle of the present century, so slow is the growth and spread of organised knowledge, it was possible for a pious Scotchman to ascribe the origin of mountain chains to a cataclysm which, after the fall of Man, had broken up and distorted the once symmetrical surface of the earth;[4] for a Dean of York to essay to bring the Mediæval theory up to date and prove that the whole series of geological strata, with their varied organic remains, were formed by volcanic eruptions acting in concert with the Mosaic Deluge;[5] and for another English divine to warn his readers against any sacrilegious meddling with the arcana of the rocks, because they represented the tentative essays of the Creator at organic forms—a concealed storehouse of celestial misfits![6]

The subject-matter of the present inquiry has passed, or is now passing, through stages closely similar to those above described. "Ghosts" and warning dreams have been matters of popular belief and interest since the earliest ages known to history, and are prevalent amongst even the least advanced races at the present time. The Specularii and Dr. Dee have familiarised us with clairvoyance and crystal vision. Many of the alleged marvels of[3] witchcraft were probably due to the agency of hypnotism, which in later times, under the various names of mesmerism, electrobiology, animal magnetism, has attracted the curiosity of the unlettered, and from time to time the serious interest of the learned. These phenomena indeed were made the subject of scientific inquiry, first in France and later in England, during the first half of the present century; have now again, after a brief period of eclipse, been investigated for the last two decades by competent observers on the Continent, and are at length winning a recognised footing in scientific circles in this country. Yet within the last two or three years we have witnessed the spectacle of more than one medical man, of some repute in this island, laughing to scorn all the researches of Charcot and Bernheim, just as their prototypes a generation or two ago ignored the results of Cuvier and Agassiz, and held it an insult to the Creator to accept the scientific explanation of coprolites.

And as regards the other subjects, to which must be added the alleged marvels of the Spiritualists, there have indeed been one or two isolated series of observations by competent inquirers, but for the most part the learned have held themselves free to ascribe the phenomena without investigation to fraud and hysteria, and the unlearned to "magnetism," "psychic force," or the Devil. For whilst men of science, preoccupied for the most part with other lines of inquiry, have kept themselves aloof, the vacant ground was naturally occupied by the ignorant and credulous, and by those who looked to win a harvest from ignorance and credulity. It is not of course implied that all persons who interested themselves in such matters came under one or other of these categories. There were many sensible men and women amongst them, but they lacked for the most part the special training necessary for such inquiries, or they failed through want of co-operation[4] and support. No serious and organised attempt at investigation was made until, in 1882, the Society for Psychical Research was founded in London, under the presidency of Professor Henry Sidgwick. He and his colleagues were the pioneers in the research, and their example has been widely followed. Two years later an American society under the same title (now a flourishing branch of the English society) was founded in Boston; and there are at the present time societies with similar objects at Berlin, Munich, Stockholm, and elsewhere. Moreover, the Société de Psychologie Physiologique, which was founded in Paris, under the presidency of M. Charcot, in 1885, has devoted much attention to some forms of telepathy.

But the forces of superstition and charlatanry, to which this vast territory has been ceded for so long, have bequeathed an unfortunate legacy to those who would now colonise it in the name of Science; and the preliminary difficulties of the undertaking can perhaps most effectually be met by a frank recognition of that fact. On the one hand, a large number of thinking men have been repelled, and still feel repulsion, from a subject whose record is so unsavoury. On the other hand, the appetite for the marvellous which has been so long unchecked is not easily restrained. The old habits of inaccuracy, of magnifying the proportions of things, of confusing surmises with facts, cannot be eradicated without long and careful discipline. To one writer, indeed, those dangers seemed so serious that he solemnly warned the Society for Psychical Research, at the outset of its career, against the risk of stimulating into disastrous activity inborn tendencies to superstition, by even the semblance of an inquiry into these matters. Without going to such lengths, it may be conceded to the critic that even with those who endeavour to apply scientific methods to the investigation the mental attitude is liable to be warped by the environment, and that here, as elsewhere, evil communications may corrupt.[5] As regards the actual investigators this difficulty is growing less serious, as more men who have received their training in other branches of science are attracted to the inquiry, and as the affinities of the subject to long-recognised departments of knowledge become daily more apparent. In another direction, however, this mental attitude presents still a more or less formidable obstacle. Many of the observations on which students of the subject are compelled to rely are derived from persons who have had no training in such habits of accuracy as are required in scientific research. When accounts of the ornithorhynchus first reached this country naturalists laughed at the traveller's tale of a beast with the tail of a beaver and the bill and webbed feet of a duck. In the same way scientific men for long refused to admit the existence of aerolites, as they now decline to credit the reports of a Sea Serpent of colossal proportions. In all these cases, so long as the alleged facts rest solely on the testimony of men untrained in habits of close observation and accurate reporting, a suspension of judgment seems to be justified. And if these considerations are valid in ordinary cases, a much higher degree of caution may be reasonably demanded of investigators who leave the neutral ground of the physical sciences to enter upon a field in which the emotions and sympathies are most keenly engaged, and in which the incidents narrated may have served to afford support to the dearest hopes and sanction to the deepest convictions of the narrator. So insidious, in such a case, is the work of the imagination, so untrustworthy is the memory, so various are the sources of error in human testimony, that it may be doubted whether we should be justified in attaching weight to the phenomena of telepathic hallucination and clairvoyance, to which a large part of this book is devoted, if the alleged observations were incapable of experimental verification. Certainly in such a case, though the recipient of an experience of this kind[6] might cherish a private conviction of its significance, it would hardly be possible for such a view to win general assent.

In fact, however, the clue to the interpretation of the more striking phenomena, in the case of which, since they occur for the most part spontaneously, direct experiment or even methodical and continuous observation are rarely possible, is furnished by actual experiment on a smaller scale and with mental affections of a less unusual kind. The thesis which these pages are designed to illustrate and support is briefly: that communication is possible between mind and mind otherwise than through the known channels of the senses. Proof of the existence of such communication, provisionally called Thought Transference or Telepathy (from tele = at a distance, and pathos = feeling), will be found in a considerable mass of experiments conducted during the last twelve years by various observers in different European countries and in America. Before proceeding, in the course of the next four chapters, to examine this part of the evidence in detail, it will be well to consider its various defects and sources of error—defects common in some degree to all experiments of which living beings are the subject, and sources of error for the most part peculiar to this and kindred inquiries. The word experiment in this connection usually, and rightly, suggests the most perfect form of experiment, that in which all the conditions are known, and in which the results can be predicted both quantitatively and qualitatively. If, for instance, we add a certain quantity of nitric acid under given conditions to a certain quantity of benzine, we know that there will result a certain quantity of a third substance which is unlike either of its constituents in taste, smell, and physical properties. Or if we burn a given quantity of coal in a particular engine, we can predict, within narrow limits of error, the total amount of energy which will be evolved. That we cannot in the second instance predict with[7] absolute accuracy the amount of energy produced is simply due to the difficulty of measuring with precision all the factors in the case. But when we leave the problems of chemistry and physics and approach the problems of biology, the difficulties increase a hundredfold. Here not only are we unable to measure the various factors, we cannot even name them. No skill or forethought would have enabled an observer, from however patient a study of parentage and environment, to have predicted the appearance, say, of Emanuel Swedenborg or Michael Faraday. Of the seven children of John Lamb and his wife it might have seemed easier to conjecture that the majority would not survive childhood, and that one would become insane, than that another should take his place amongst those whose writings the world would not willingly let die. And even where, as in most biological researches, the results drawn from observation can be to some extent checked and controlled by direct experiment, generations may elapse before the balance of probabilities on one side or the other becomes so great as to lead to unanimity amongst the inquirers. One of the most interesting, and certainly not the least important, of the questions now occupying biologists, is that of the transmission to the offspring of characters acquired in the lifetime of the individual. Observations have been accumulated on the subject since before the days of Lamarck; and these observations, interpreted and confirmed by experiment, have been adduced and are still held by many as evidence that such transmission occurs. On the other hand, Weismann and his followers contend that no such inference can legitimately be drawn from the observations and experiments quoted, and that the occurrence of such transmission is irreconcilable with what is known of the growth and development of the germ. And for all that has been said and written the opinion of competent biologists is still divided upon the question.

But in many biological problems the conditions are much simpler, and the questions at issue can more readily be brought to the test of experiment. Yet even so various unknown factors are included, and the results obtained are correspondingly difficult of interpretation. No question affects us more nearly than the part played by the several kinds of food in repairing the daily waste of the human body. Statistics and analyses have been collected of workhouse, prison, and military dietaries; innumerable experiments have been conducted on fasting men and hypertrophied dogs and rabbits; and yet the precise function of nitrogenous substances in nutrition is still undetermined. Again, the import of the experiments made during the last few decades by Goltz, Hitzig, Ferrier, Horsley, and others on the functions of various areas of the brain substance, and the exact nature and degree of localisation which those experiments imply, are still matter of debate amongst the physiologists concerned.

To take yet another instance, and one which has a more intimate bearing upon the experiments to be discussed. Some years ago Dr. Charlton Bastian claimed to have proved experimentally the fact of abiogenesis, or the generation of living organisms from non-living matter. He had placed various organic infusions in glass tubes, which were heated to the boiling point and then hermetically sealed. When the tubes were, after a certain interval, unsealed, the contained liquid was found in some cases to be swarming with bacteria. Believing that these micro-organisms and their germs were invariably destroyed by the heat of boiling water, Dr. Bastian saw no other conclusion than that the bacteria were formed directly from the infusion. His conclusions were not accepted by the scientific world. But they were rejected, not because the fact of abiogenesis was regarded as in itself improbable, nor yet because Dr. Bastian was unable to indicate by what steps or processes the[9] transformation of an infusion of hay into living organisms of definite and relatively complex structure could be conceived to take place, but because Pasteur, Tyndall, and others showed that the germs of some of these micro-organisms are capable of sustaining for some minutes the heat of boiling water; and further, that when elaborate precautions were taken, by filtering and otherwise purifying the air, tubes containing similar infusions would remain sterile for an indefinite period.

The conclusion that under certain conditions thought-transference may occur rests upon reasoning similar to that by which Dr. Bastian sought to establish a theory of abiogenesis. Neither the organs by which nor the medium through which the communication is made can be indicated; nor can we even, with a few trifling exceptions, point to the conditions which favour such communication. But ignorance on these points, though a defect, is not a defect which in the present state of experimental psychology can be held seriously to weaken the evidence, much less to invalidate the conclusion. That conclusion rests on the elimination of all other possible causes for the effect produced. But at this point the analogy between the two researches fails. Dr. Bastian's conjecture was based on a short series of experiments conducted by a single experimenter under one uniform set of conditions. At the first breath of criticism the whole fabric collapsed. The experiments here recorded represent the work of many observers in many countries, carried on with different subjects under a great variety of conditions. The results have been before the world for about twelve years, and during that period have been subjected to much adverse and some instructive criticism. But no alternative explanation which has yet been suggested has attained even a momentary plausibility.

Whether the elimination of all other possible causes[10] is indeed complete, or whether, as in Dr. Bastian's case, there may yet lurk in these experiments some hitherto unsuspected source of error, the reader will have the opportunity of judging for himself. To assist him in forming a judgment some of the main disturbing causes will be briefly indicated.

(1) Fraud.—In nearly all the experiments referred to in this book the agent was himself concerned in the inquiry as a matter of scientific interest. But it necessarily happens on occasion that neither agent nor percipient are by education and position absolutely removed from suspicion of trickery in a matter where trickery might to imperfectly educated persons appear almost venial. If any such cases have been admitted, it is because the precautions taken appear to us to have been adequate. At the same time, the investigators of the Society for Psychical Research have come across some instances of fraud in cases where they had grounds for assuming good faith, and it may be useful, therefore, to illustrate some of the less obvious methods of acquiring intelligence fraudulently. The conditions of the experiment should of course, as far as possible, preclude, even where there is no ground for suspecting fraud, communication between the percipient and the agent, or any one else knowing the idea which it is sought to transfer.

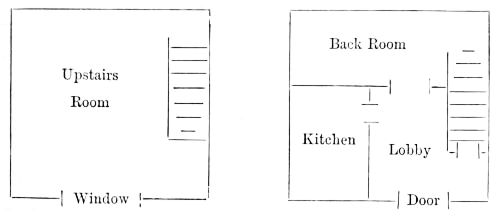

In the autumn of 1888 some experiments were conducted with a person named D., whose antecedents afforded, it was thought, justification for the belief that the claims which he put forward were genuine. D. acted as agent, the percipient being a subject of his own, a young woman called Miss N., who was apparently in a light hypnotic sleep during the experiment. It was soon discovered that the results were obtained by means of a code formed from a combination of Miss N.'s breathing with slight noises—a cough or the creak of a boot—made by D. himself. I have seen a somewhat similar code employed in Prince's Hall, Piccadilly, where the conjurer stood in the middle of[11] the hall with a coin or other object in his hand, a description of which he communicated to his confederate on the platform by means of a series of breathings, deep enough visibly to move his dress-coat up and down on the surface of his white collar, punctuated by slight movements of head or hand. The novel feature in the first case, however, was that the percipient herself furnished the groundwork of the code, the punctuation alone being given by the conjurer. A still more elaborate form of collusion is described at length by Bonjean.[7] In this case the subject, a young woman named Lully, appears to have read the words to be conveyed after the fashion of a deaf mute, by the motion of the lips of the showman. Lully was apparently in a hypnotic trance, with the eyes fast closed. Another form of fraud, since it does not require the aid of a confederate, is perhaps worthy of note. Some years ago a young Australian came to this country with a reputation for "genuine thought-reading," based on the successful mystification of some members of a certain Colonial Legislature. The writer had a few experiments with this person, in which several small objects—a knife, a glass bottle, etc.—placed in the full light of a shaded lamp, were correctly named. The object was in each case placed behind the back of the "Thought-reader," who looked intently at the writer's eyes, which were in turn fixed upon the brightly illuminated object. Experiments made under more usual conditions, not dictated by the "Thought-reader," completely failed; and there can be little doubt that the initial successes were due to the "Thought-reader" seeing the image of the object reflected in the agent's cornea.

(2) Hyperæsthesia.—But, after all, it is rarely necessary to take special precautions against fraud, for there are dangers to be guarded against of a more subtle kind. There are various, and as yet imperfectly[12] known methods of communication by which indications may be unconsciously given and as unconsciously received. Thus, to take the last instance, it is pretty certain that cornea-reading does not always imply fraud, and that hints may be gained in all good faith from any reflecting surface in the neighbourhood of the experimenter; or the movements of lips, larynx, and even hands and limbs may betray the secret to eye or ear. We know little of the limits of our sensory powers even in normal life; and we do know that in certain subconscious states—automatic, hypnotic, somnambulic—these limits may be greatly exceeded, and that indications so subtle as frequently to escape the vigilance of trained observers may be seized and interpreted by the hypnotic or automatic subject. It is clear, therefore, that results which it is possible to attribute to deliberate fraud stand almost necessarily self-condemned. For if the precautions taken by the investigators left such an explanation open, much more were those precautions insufficient to guard against the subtler modes of communication referred to. It is not the friend whom we know whose eyes must be closed and his ears muffled, but the "Mr. Hyde," whose lurking presence in each of us we are only now beginning to suspect.

There is a case recorded by M. Bergson,[8] in which a hypnotised boy is said to have been able to state correctly the number of the page in a book held by the observer, by reading the corneal image of the figures. The actual figures were three millimetres high, and their corneal image is calculated by M. Bergson to have been O.1 mm., or about 1/250 of an inch in height! In some other experiments conducted by M. Bergson with the same subject the acuteness of vision is said to have exceeded even this limit. In another case, recorded by Dr. Sauvaire,[9] a hypnotised[13] subject was able to recognise the King of Clubs, face downwards, in two different packs of cards. In the first of these cases the results, which could not have been attained by the senses under normal conditions, must apparently be attributed to hyperæsthesia. Instances, especially of auditory hyperæsthesia, are of course quite familiar to those who have studied the phenomena of hypnotism. In Dr. Sauvaire's case, however, the power of distinguishing the cards by touch may have been the result of practice. Mrs. Verrall records (Proceedings Soc. Psych. Research, vol. viii. p. 480) that she acquired such a power by means of "a longish series of experiments"; and Mr. Hudson, in Idle Days in Patagonia, tells of a gambler who by careful training had developed the same faculty in a very high degree.

It seems probable in the cases described by M. Bergson and Dr. Sauvaire, and possible also in the case of Mr. D.'s subject, that there was no intentional deception, and that the hypnotised person was not himself aware of the means by which his knowledge was attained.[10] The same remark probably applies to the following case, in which, though the conditions of vision were certainly unusual, it seems not clear whether the degree of success attained should be attributed to abnormal sensibility of the eyes, or to the facility acquired by long practice. In a series of experiments at which the writer assisted, in 1884, an illiterate youth named Dick was hypnotised, a penny was placed over each eye, and the eyes and surrounding features were elaborately bandaged with strips of sticking-plaster; a handkerchief being bound over all. Under these conditions Dick named correctly objects held in front of him, even at a considerable distance, a little above the level of his eyes. Normal vision appeared to be impossible. Mr. R. Hodgson, however,[14] repeated the experiment upon himself, and found after several trials that he also could see objects, though fitfully and imperfectly, under the same conditions, the channel of vision being a small chink in the sticking-plaster on the line where it was fastened to the brow.

(3) Muscle-reading.—From this last case we may pass to the illustrations of "thought-reading" given by professional conjurers and others, where it seems clear that the skill exhibited in the interpretation of unconscious movements and gestures is due rather to long practice and careful observation than to any abnormal extension of faculty. It hardly needs saying that experiments in which contact is permitted between the agent and percipient can rarely be regarded as having evidential value. It has been demonstrated again and again that with the fullest intention of keeping the secret to themselves, most "agents" in such circumstances are practically certain to betray it to the professional thought-reader by unconscious movements of some kind. Indeed, it is difficult to place any limit to the degree of susceptibility to slight muscular impressions which may be attained. A careful experimenter has assured the writer that when acting as percipient in some experiments with diagrams the slight movements of the agent's hand resting upon her head gave her in one case a clue to the figure thought of. And Mr. Stuart Cumberland has exhibited feats still more marvellous before kings and commoners. Nor is it necessary, as already said, for successful muscle-reading that there should be actual contact in all cases. The eye or the ear can sometimes follow movements of the lips or other parts of the body. But though we can look for little evidence from experiments conducted with contact, or under conditions which allow of interpretation by gesture, etc., and their repetition in this connection can rarely be expected to serve any useful purpose, it seems worth pointing out that, if[15] telepathy is a fact, we should expect to find it operating not merely where, from the conditions of the experiment, it must be presumed to be the sole source of communication, but also as an auxiliary to other more familiar modes of expression. It seems not improbable, therefore, that some of the more startling successes of the professional "thought-reader" and some of the results obtained in the "willing game" may be due to this cause.

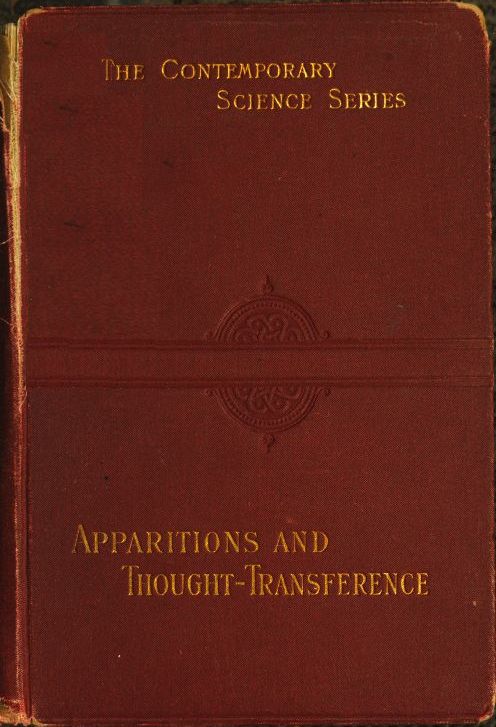

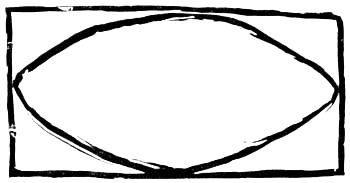

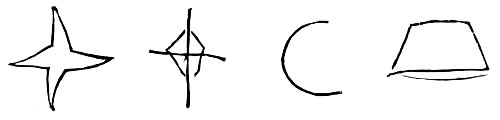

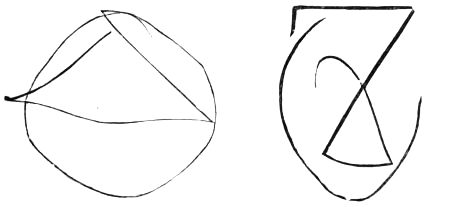

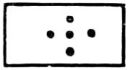

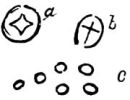

(4) Thought-forms.—There remains one other source of error to be guarded against. An image—whether of an object, diagram, or name—which is chosen by the agent may be correctly described by the percipient simply because their minds are set to move in the same direction. It must be remembered that, however unexpected and spontaneous they may appear, ideas do not come by chance, but have their origin mostly in the previous experience of the thinker. Persons living constantly in the same physical and intellectual environment are apt to present a close similarity in their ideas. It would not even be prima facie evidence of thought-transference, for instance, if husband and wife, asked to think of a town or of an acquaintance, should select the same name. And investigation has shown that our thoughts move in grooves which are determined for us by causes more deep-seated and more general than the accident of particular circumstances. Thus it is found that individuals will show a preference for certain figures or certain numbers over others; and that the preference for some geometrical figures tends to be tolerably constant. The American Society for Psychical Research[11] made some interesting observations on this point in 1888. Blank cards were issued to a large number of persons, with the request that the recipients would draw on the card "ten diagrams." 501 cards were returned, and the diagrams inscribed on them were carefully tabulated. It was[16] found that of the 501 persons no less than 209 drew circles, 174 squares, 160 equilateral triangles and crosses, while three only drew wheels, two candlesticks, and one each a corkscrew, a ball, and a knife. It was found that the simpler geometrical figures[12] occurred not only most frequently but as a general rule early in each series of ten. It follows, therefore, that in an experiment the success of the percipient in reproducing a circle, a square, or a triangle raises a much fainter presumption of thought-transference than if the object reproduced had been a corkscrew or a pine-apple. But so much was perhaps obvious even without a detailed investigation. From a similar analysis of the guesses made, it can be shown that some percipients have decided preferences amongst the simple numerals. And in the same way it seems probable that others have a preference for particular cards. An important illustration of the working of the "number-habit" has been brought forward by Professor E. C. Pickering of the Harvard College Observatory, U.S.A.[13] A revision of part of the Argelander Star-Chart had been undertaken by several observatories, of which the Harvard Observatory was one. For the purposes of the revision the assistant had the Argelander chart before him, whilst the observer, who was in ignorance of the magnitude assigned in the chart, made an independent estimate of the magnitude of each star. If no thought-transference or other disturbing cause affected the result, the amount of deviation of the later observations from the earlier in each tenth of a degree of magnitude would be represented by a smooth curve. As a matter of fact, it was found that the number of cases[17] of complete agreement were much greater, with some observers more than 50 per cent. greater, than they should have been on an estimate of the probabilities. At first sight this excess of the actual over the theoretical numbers suggested the action of thought-transference between the assistant and the observer. But Professor Pickering shows, on a further analysis of the figures, that almost the whole of the excess was due to the preference of both the earlier and the later observers for 5 and 10 over all other fractions of a degree.

The practical deduction from this investigation is that in any experiment care should be taken to exclude, as regards the agent at any rate, the operation of any diagram or number-habit.[14] If an object is thought of, it should if possible be chosen by lot, and should not be an object actually present in the room. If a card, it should be drawn from the pack at random; if a number, from a receptacle containing a definite series of numbers; if a diagram, it is preferable that it should be taken at random from a set of previously-prepared drawings. It will be seen that in the majority of the cases quoted in the four succeeding chapters these precautions have been observed.

EXPERIMENTAL TRANSFERENCE OF SIMPLE SENSATIONS IN THE NORMAL STATE.

It is somewhat remarkable that the facts of thought-transference should only have attracted serious attention within the last two decades. With waking percipients, indeed, such phenomena do not seem to occur unsought with sufficient frequency, or—if we leave on one side for the moment telepathic hallucinations—on a sufficiently striking scale to afford evidence of any transmission of thought or sensation otherwise than through the familiar channels. But the hypnotic state appears to offer peculiar facilities for such transmission, and hypnotism, under the name of mesmerism, has now been closely studied by numerous observers for upwards of a century. The earlier French observers,[15] indeed, occasionally recorded instances of what appears to have been thought-transference between the mesmerist and his subject. But these facts were observed by the way, in the search for phenomena of another kind; and no attempt appears to have been made to follow up the clue by means of direct experiment. Even the English observers of 1840 and onwards, though familiar with what they termed "community of sensation" between the operator and his subject,[19] appear never to have realised its possible significance. Dr. Elliotson, for instance, describes in the Zoist (vol. v. pp. 242-245) some experiments in which a lady, mesmerised by himself, was able to indicate correctly the taste of salt, cinnamon, sugar, ginger, water, and pepper, as Dr. Elliotson placed successively these various substances in his mouth. But he seems to have recorded the results chiefly from curiosity, and to have regarded them as of little scientific interest compared with the stiffening of a limb, or the painless performance of an operation under mesmeric anæsthesia. Dr. Esdaile (Practical Mesmerism, p. 125), Mr. C. H. Townshend (Facts in Mesmerism, pp. 68, 72, 76, etc., etc.), Professor Gregory (Animal Magnetism, p. 231), and other writers of that time, record similar observations. But the subject seems to have been crowded out, on the one hand, with the more cautious observers, by the growing importance of hypnotism as an anæsthetic and a curative agency, on the other by the greater marvels of "clairvoyance" and "spirit" communications.

It was Professor Barrett, of the Royal College of Science, Dublin, who, in a paper read before the British Association at Glasgow in 1876, first isolated the phenomenon from its somewhat dubious surroundings, and drew public attention to its importance. Up to that time "community of sensation" or thought-transference seems to have been known only as a rare and fitful accompaniment of the hypnotic trance. But in the course of the correspondence arising out of his paper Professor Barrett learnt of several instances where similar phenomena had been observed in the waking state. The Willing game was just then coming into fashion, and cases had been observed in which the thing willed had been performed without contact between the performer and the person willing, and apparently without the possibility of any normal means of communication between them. Later, in the years 1881-82, a long series of experiments, in[20] which Professor Sidgwick, the late Professor Balfour Stewart, the late Edmund Gurney, Mr. F. W. H. Myers and others joined with Professor Barrett, seemed to establish the possibility of a new mode of communication. And these earlier results have been confirmed by further experiments continued down to the present time by many observers both in this country and abroad. In the present chapter some account will be given of experiments in the transference of simple ideas and sensations performed with percipients in the ordinary waking state. The next chapter will deal with similar results obtained with hypnotised persons. In Chapters IV. and V. results of a more complicated or unusual character will be described and discussed.

Transference of Tastes.

The particular form of telepathy which first attracted attention to the whole subject, the transmission to the percipient of impressions of taste and pain experienced by the agent, appears to have been observed in the normal state very rarely. One such case may be here quoted. In the years 1883-85 Mr. Malcolm Guthrie, J.P., of Liverpool, the then head of a large drapery business in that city, conducted a long series of experiments with two of his employees, Miss E. and Miss R. In September 1883 Mr. Guthrie, Mr. Edmund Gurney, and Mr. Myers, indicated respectively by the initials M. G., E. G., and M., had a series of trials with these percipients in the transference of tastes. The percipients, who were fully awake, were blindfolded; the packets or bottles containing the substances experimented upon were placed beyond the range of possible vision; and in the case of strongly smelling substances, either at a distance or outside the room; and other precautions were taken by the agents, by keeping the mouth closed and turning the head away, etc., in order that the per[21]cipients should not become aware by the sense of smell of the nature of the substance experimented with. Strict silence was of course observed. It may be conceded that when all possible precautions are taken, experiments with sapid substances must be inconclusive when the agent is in the same room with the percipient; since nearly all such substances have an odour, however faint. In view, however, of the extreme sensibility already demonstrated (see below, pp. 23, etc.) of these particular percipients to transferred impressions of other kinds, it seems probable that the results in this case also were actually due to telepathy. The alternative explanation is to attribute to persons in the normal waking state a degree of hyperæsthesia for which we have no exact parallel even in the records of hypnotism. For to persons of normal susceptibility the odour of a small quantity, e.g. of salt or alum, in the mouth of another person at a distance of two or three feet would certainly be quite inappreciable.

No. 1.—By MR. GUTHRIE AND OTHERS.

| September 3, 1883. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXPT. | TASTER. | PERCIPIENT. | SUBSTANCE. | ANSWERS GIVEN. |

| 1 | M. | E. | Vinegar. | "A sharp and nasty taste." |

| 2 | M. | E. | Mustard. | "Mustard." |

| 3 | M. | R. | Do. | "Ammonia." |

| 4 | M. | E. | Sugar. | "I still taste the hot taste of the mustard." |

| September 4. | ||||

| 5 | E. G. & M. | E. | Worcestershire sauce | "Worcestershire sauce." |

| 6 | M. G. | R. | Do. | "Vinegar." |

| 7 | E. G. & M. | E. | Port wine | "Between eau de Cologne and beer." |

| 8 | M. G. | R. | Do. | "Raspberry vinegar." |

| 9 | E. G. & M. | E. | Bitter aloes | "Horrible and bitter." |

| 10 | M. G. | R. | Alum | "A taste of ink—of iron—of vinegar. I feel it on my lips—it is as if I had been eating alum." |

| 11 | M. G. | E. | Alum | (E. perceived that M. G. was as not tasting bitter aloes, E. G. and M. supposed, but something different. No distinct perception on account of the persistence of the bitter taste.)[22] |

| EXPT. | TASTER. | PERCIPIENT. | SUBSTANCE. | ANSWERS GIVEN. |

| 12 | E. G. & M. | E. | Nutmeg | "Peppermint—no—what you put in puddings—nutmeg." |

| 13 | M. G. | R. | Do. | "Nutmeg." |

| 14 | E. G. & M. | R. | Sugar | Nothing perceived. |

| 15 | M. G. | R. | Do. | Nothing perceived. (Sugar should be tried at an earlier stage in the series, as, after the aloes, we could scarcely taste it ourselves.) |

| 16 | E. G. & M. | E. | Cayenne pepper | "Mustard." |

| 17 | M. G. | R. | Do. | "Cayenne pepper." (After the cayenne we were unable to taste anything further that evening.) |

| Throughout the next series of experiments the substances were kept outside the room in which the percipients were seated. | ||||

| September 5. | ||||

| 18 | E. G. & M. | E. | Carbonate of Soda | Nothing perceived. |

| 19 | M. G. | R. | Caraway seeds | "It feels like meal—like a seed loaf—caraway seeds." (The substance of the seeds seems to be perceived before their taste.) |

| 20 | E. G. & M. | E. | Cloves | "Cloves." |

| 21 | E. G. & M. | E. | Citric acid | Nothing felt. |

| 22 | M. G. | R. | Do. | "Salt." |

| 23 | E. G. & M. | E. | Liquorice | "Cloves." |

| 24 | M. G. | R. | Cloves | "Cinnamon." |

| 25 | E. G. & M. | E. | Acid jujube | "Pear drop." |

| 26 | M. G. | R. | Do. | "Something hard, which is giving way—acid jujube." |

| 27 | E. G. & M. | E. | Candied ginger | "Something sweet and hot." |

| 28 | M. G. | R. | Do. | "Almond toffy." (M. G. took this ginger in the dark, and was some time before he realised that it was ginger.) |

| 29 | E. G. & M. | E. | Home-made Noyau. | "Salt." |

| 30 | M. G. | R. | Do. | "Port wine." (This was by far the most strongly smelling of the substances tried; the scent of kernels being hard to conceal. Yet it was named by E. as salt.) |

| 31 | E. G. & M. | E. | Bitter aloes | "Bitter." |

| 32 | M. G. | R. | Do. | Nothing felt. |

(Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, vol. ii. pp. 3, 4.)

Further experiments in this direction are much to be desired. But apart from the difficulty above referred to, experiments of the kind are liable to be[23] tedious and inconclusive because of the inability of most persons to discriminate accurately between one taste and another, when the guidance of all other senses is lacking. To conduct such experiments to a successful issue, it would probably be necessary that the percipients should have some preliminary training to enable them to distinguish by taste alone between various salts and pharmaceutical preparations.

Transference of Pains.

Experiments in the transference of pains are not attended with the same difficulties, nor open to the same evidential objections; and some interesting trials of this kind with one of the same percipients, Miss R., met with a fair amount of success. The experiments were carried on at intervals, interspersed with experiments of other kinds, by Mr. Guthrie at Liverpool during nine months in 1884 and 1885. The percipient on each occasion was blindfolded and seated with her back towards the rest of the party, who each pinched or otherwise injured themselves in the same part of the body at the same time. The agents in these experiments—the whole series of which is here recorded—were three or more of the following:—Mr. Guthrie, Professor Herdman, Dr. Hicks, Dr. Hyla Greves, Mr. R. C. Johnson, F.R.A.S., Mr. Birchall, Miss Redmond, and on one occasion another lady. The results are given in the following table:—

No. 2.—By MR. GUTHRIE AND OTHERS.

1.—Back of left hand pricked. Rightly localised.

2.—Lobe of left ear pricked. Rightly localised.

3.—Left wrist pricked. "Is it in the left hand?" pointing to the back near the little finger.

4.—Third finger of left hand tightly bound round with wire. A lower joint of that finger was guessed.

5.—Left wrist scratched with pins. "Is it in the left wrist, like being scratched?"

6.—Left ankle pricked. Rightly localised.

7.—Spot behind left ear pricked. No result.

8.—Right knee pricked. Rightly localised.

9.—Right shoulder pricked. Rightly localised.

10.—Hands burned over gas. "Like a pulling pain ... then tingling, like cold and hot alternately," localised by gesture only.

11.—End of tongue bitten. "Is it the lip or the tongue?"

12.—Palm of left hand pricked. "Is it a tingling pain in the left hand here?" placing her finger on the palm of the left hand.

13.—Back of neck pricked. "Is it a pricking of the neck?"

14.—Front of left arm above elbow pricked. Rightly localised.

15.—Spot just above left ankle pricked. Rightly localised.

16.—Spot just above right wrist pricked. "I am not quite sure, but I feel a pain in the right arm, from the thumb upwards to above the wrist."

17.—Inside of left ankle pricked. Outside of left ankle guessed.

18.—Spot beneath right collar-bone pricked. The exactly corresponding spot on the left side guessed.

19.—Back hair pulled. No result.

20.—Inside of right wrist pricked. Right foot guessed.

(Proc. S.P.R., vol. iii. pp. 424-452.)

Transference of Sounds.

It is noteworthy that there is little experimental evidence for the transmission of an auditory impression. Occasionally, in trials with names and cards the nature of the mistakes made has seemed to indicate audition, as when, e.g., three is given for Queen or ace for eight. But obviously a long series of experiments and a long series of mistakes would be necessary to afford material for any conclusion. Sometimes a percipient has stated that he heard the name of the thing thought of; as, for instance, in a case recorded in Chapter V., where the percipient "heard" the word gloves before "seeing" a vision of them. But such cases appear to be rare. Experiments with a view to test the transmission of actual sounds could of course only be carried out under special conditions, of which one would be the separation of the agent from the percipient by a considerable[25] intervening space—and this condition is, of itself, found to interfere with success. Some evidence, indeed, of a quasi-experimental character for the transference of musical sounds at a distance will be given in a later chapter (Chapter V., No. 33). Experiments with imagined sounds appear to have been rarely tried, or at least, successful results have rarely been recorded.[16] Occasionally indeed experimenters have put on record that in thinking of an object they have mentally repeated the name of the object as well as pictured the object itself, and there are a few cases where the general idea of the object thought of appears to have reached the percipient before the outlines of the form, which may possibly be explained as due to the reception of an auditory before a visual impression.[17]

This lack of evidence for auditory transmission is no doubt largely due to a desire on the part of experimenters in the first instance to make the proof of actual thought-transference as complete as possible. Experiments with sounds would impose a greater strain upon the agents, since in most cases they must be imagined sounds. Moreover, in such experiments it would be at once more difficult to estimate with precision degrees of success, and to preserve a permanent record of the result; and finally, the subject thought of would be more easily communicated either fraudulently, by a code, or by unconscious indications on the part of the agent. In this connection it is possibly significant that whilst in morbid conditions auditory hallucinations are much commoner than visual, the proportion appears to be reversed with[26] telepathic hallucinations. It seems probable that the apparent infrequency of auditory transmission may be in part due to the fact that in the modern world the sense of vision is for educated persons the habitual channel for precise or important information. To the Greek in the time of Socrates no doubt the ear was the main avenue for all knowledge; it was the ear that received not merely the current talk of the market-place and the gymnasium, but the oratory of the law-court, the literature of the stage, and the philosophy of the Schools. But for modern civilised societies the newspaper and the libraries have placed the eye in a position of unquestioned pre-eminence. It seems likely therefore, apart from all defects in such evidence, that the agent would find a greater difficulty, as a rule, in calling up a vivid representation of a sound than of a vision; and that the percipient would experience a corresponding difference in the reception and discrimination of the two classes of impressions.

Transference of Ideas not definitely classed.

Experiments by PROFESSOR RICHET and others.

In the following cases, where the exact nature of the impression received was not apparently consciously classified by the percipient, it may be presumed to have been either of a visual or an auditory nature. M. Charles Richet (Revue Philosophique, Dec. 1884, "La suggestion mentale et le calcul des probabilités") conducted a series of experiments in guessing the suits of cards drawn at random from a pack. 2927 trials were made: ten persons besides M. Richet himself—who acted sometimes as agent and sometimes as percipient—taking part in the experiments. In the 2927 trials the suit was correctly named 789 times, the most probable number of correct guesses being 732. A similar series of trials was conducted,[27] on Edmund Gurney's initiative, by some members of the S.P.R. and others. There were 17 series, containing 17,653 trials, and 4760 successes; the theoretically probable number, on the assumption that the results were due to chance, being 4413. The probability for some cause other than chance deduced from this result is .999,999,98, which represents perhaps a higher degree of probability than the inhabitants of this hemisphere are justified in attaching to the belief that the ensuing night will be followed by another day.[18] In a similar series of experiments carried out under the direction of the American S.P.R. the proportion of successes was little higher than the theoretically probable number.[19] But in the absence of details as to the conditions under which the experiments were made, no unfavourable inference can fairly be drawn from these results. At any rate some very remarkable results were obtained later, in a series of trials made on the lines laid down by the committee of the American Society. The agent in this case was Mrs. J. F. Brown, the percipient Nellie Gallagher, "a domestic lately come from the county of Northumberland, in New Brunswick." The experiments appear to have been carried out with great care, and the results are recorded and analysed at length (Proc. Am. S.P.R., pp. 322-349). 3000 trials were made in guessing the numbers from 0 to 9 or from 1 to 10 inclusive. The order of the digits in each set of 100 trials was determined by drawing lots. The agent sat at one side of a table, the percipient at the other side. At first the percipient sat facing the[28] agent, but after about 1000 trials had been made her back was turned to the table—and this position was continued to the end. The paper containing the numbers to be guessed was placed in the agent's lap, out of sight of the percipient. There was no mirror in the room. In the result the digits were correctly named 584 times, or nearly twice the probable number, 300. The proportion of the successes steadily increased, from 175 in the first batch of 1000 trials, to 190 in the second, and 219 in the third batch.

No. 3.—By DR. OCHOROWICZ.

In the following set of experiments, made by Dr. Ochorowicz, ex-Professor of Psychology and Natural Philosophy at the University of Lemberg, described in his book La Suggestion mentale (pp. 69, 75, 76), there are not sufficient indications in most cases to enable a judgment to be formed as to the special form of sense-impression made on the percipient's mind. The percipient was a Madame D., 70 years of age. She had been shown to be amenable to hypnotism, but during these experiments she was in a normal condition. She is described as being of strong constitution and in good health; intelligent above the average, well read, and accustomed to literary work. The first experiments with Madame D. are not quoted here, not having been conducted, as Dr. Ochorowicz explains, under strict conditions. The objects thought of had been selected by the agent, instead of being taken haphazard, and the choice had frequently been directly suggested by his surroundings. It seemed possible, therefore, to explain the results as due to an unconscious association of ideas common to agent and percipient. Dr. Ochorowicz, however, has shown by his careful analysis of the experiments recorded in the earlier chapters of his book that he is fully aware of the risk of error from this and other causes, and in the[29] series of the 2nd May and the following days he tells us that adequate precautions were taken.

| An Object. | |

|---|---|

| 36. A bust of M. N. | Portrait ... of a man ... a bust. |

| 37. A fan. | Something round. |

| 38. A key. | Something made of lead ... of bronze ... it is iron. |

| 39. A hand holding a ring. | Something shining, a diamond ... a ring. |

| A Taste. | |

| 40. Acid. | Sweet. |

| A Diagram. | |

| 41. A square. | Something irregular. |

| 42. A circle. | A triangle ... a circle. |

| A Letter. | |

| 43. M. | M. |

| 44. D. | D. |

| 45. J. | J. |

| 46. B. | A, X, R, B. |

| 47. O. | W, A; no, it is an O. |

| 48. Jan. | J ... (go on!) Jan. |

Third Series, May 6th, 1885.—Twenty-five experiments were made, of which, unfortunately, I have kept no record, except of the three following, which impressed me most. (The subject had her back to us, held the pencil and wrote whatever came into her head. We touched her back lightly, keeping our eyes fixed on the letters we had written.)

| 49. Brabant. | Bra ... (I made a mental effort to help the subject, without speaking.) Brabant. |

| 50. Paris. | P ... aris. |

| 51. Telephone. | T ... elephone. |

Fourth Series, May 8th.—Same conditions.

| 52. Z. | L, P, K, J. |

| 53. B. | B. |

| 54. T. | S, T, F. |

| 55. N. | M, N. |

| 56. P. | R, Z, A. |

| 57. Y. | V, Y. |

| 58. E. | E. |

| 59. Gustave. | F, J, Gabriel. |

| 60. Duch. | E, O. |

| 61. Ba. | B, A. |

| 62. No. | F, K, O. |

| A Number. | |

|---|---|

| 63. 44. | 6, 8, 12. |

| 64. 2. | 7, 5, 9. |

(I told my assistant to imagine the look of the number when written, and not its sound.)

| 65. 3. | 8, 3. |

| 66. 7. | 7. |

| 67. 8. | 8; no, 0, 6, 9. |

Then followed thirteen trials with fantastic figures, details of which Dr. Ochorowicz does not record. He tells us, however, that only five of the representations presented even a general resemblance to the originals.

It is to be observed that in this series of experiments contact was not completely excluded in all the trials. But if Dr. Ochorowicz's memory may be relied upon for the statement that the agent looked at the original letters and diagrams, and not at the percipient's attempts at reproducing them, the hypothesis of involuntary muscular guidance must be severely strained to account for the results. At any rate, in the three remaining trials in this series it seems clear that muscle-reading is inadequate as an explanation.

| A person thought of. | |

| Subject. | Answer. |

| 68. The percipient. | M. O——; no, it's myself. |

| 69. M. D——. | M. D——. |

| An Image. | |

| 70. We pictured to ourselves a crescent moon. M. P—— on a background of clouds, I in a clear dark blue sky. |

I see passing clouds ... a light ... (in a satisfied tone)—it is the moon. |

Transference of Visual Images.

NO. 4.—By DR. BLAIR THAW.

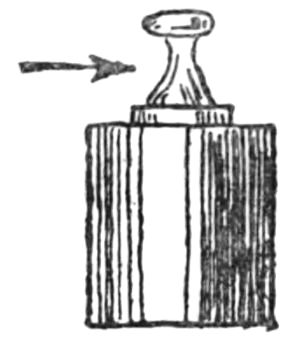

The experiments which follow were made by Dr. Blair Thaw, M.D., of New York. The series quoted, which took place on the 28th of April 1892, comprises all the trials in which Dr. Thaw was himself the percipient. Dr. Thaw had his eyes blindfolded and his ears muffled, and the agent, Mrs. Thaw, and Mr. M. H. Wyatt, who was present but took no part in the agency, kept silent, except when it was necessary to state whether an object, card, number, or colour was to be guessed. The objects were in all cases actually looked at by the agent, the "colour" being a coloured disc, and the numbers being printed on separate cards.[20]

1st Object. SILK PINCUSHION, in form of Orange-Red Apple, quite round.—Percipient: A Disc. When asked what colour, said, Red or Orange. When asked what object, named Pincushion.

2nd Object. A SHORT LEAD PENCIL, nearly covered by the nickel cover. Never seen by percipient. Percipient: Something white or light. A card. I thought of Mr. Wyatt's silver pencil.

3rd Object. A DARK VIOLET in Mr. Wyatt's button-hole, but not known to be in the house by percipient. Percipient: Something dark. Not very big. Longish. Narrow. Soft. It can't be a cigarette because it is dark brown. A dirty colour. Asked about smell, said: Not strong, but what you might call pungent; a clean smell.

Percipient had not noticed smell before, though sitting by Mr. Wyatt some time, but when afterwards told of the violet knew that this was the odour noticed in experiment.

Asked to spell name, percipient said: Phrygian, Phrigid, or first letter V if not Ph.

4th Object. WATCH, dull silver with filigree. Percipient: Yellow or dirty ivory. Not very big. Like carving on it. Watch is opened by agent, and percipient is asked what was done. Percipient says: You opened it. It is shaped like a [32]butterfly. Percipient held finger and thumb of each hand making figure much like that of opened watch. Percipient asked to spell it, said: I get r-i-n-g with a W at first.

PLAYING CARDS.

KING SPADES.—Spades. Spot in middle and spots outside. 7 Spades. 9 Spades.

4 Clubs.—4 Clubs.

5 Spades.—5 Diamonds.

NUMBERS OUT OF NINE DIGITS.

4.—Percipient said: It stands up straight. 4.

6.—Percipient said: Those two are too much alike, only a little gap in one of them. It is either 5 or 6.

3.—3.

1.—Percipient said: Cover up that upper part if it is the 1. It is either 7 or 1.

2.—9, 8.

[From acting so much as agent in previous trials, I knew the shapes of these numbers printed on cardboard, and as agent found the 5 and 6 too much alike. After looking hard at one of them I can hardly tell the difference, and always cover the upper projection of the I because it is so much like a 7.

The numbers were printed on separate pieces of cardboard, and there were about a hundred in the box, being made for some game.]

COLOURS, CHOSEN AT RANDOM.

| Chosen. | 1st Guess. | 2nd Guess. |

|---|---|---|

| BRIGHT RED | Bright Red | |

| LIGHT GREEN | Light Green | |

| YELLOW | Dark Blue | Yellow |

| BRIGHT YELLOW | Bright Yellow | |

| DARK RED | Blue | Dark Red |

| DARK BLUE | Orange | Dark Blue |

| ORANGE | Green | Heliotrope |

The percipient himself told the agents to change character of object after each actual failure, thus getting new sensations.

Percipient was told to go into next room and get something.

1st Object. SILVER INKSTAND chosen.—Percipient says, I think of something, but it is too bright and easy. It is the silver inkstand.

Percipient told to get something in next room.

2nd Object. A GLASS CANDLESTICK.—Percipient went to right corner of the room and to the cabinet with the object on it, but could not distinguish which object.

Percipient had handkerchief off to be able to walk, but was not followed by agents, and did not see them. Agents found percipient standing with hands over candlestick undecided.

From the percipient's descriptions it would seem that the impression here was of a visual nature, though Dr. Thaw himself says, "I cannot describe my sensation as a visualisation of any kind. It seemed rather to be by some wholly subjective process that I knew what the agents were looking at." It is not always, however, an easy task to analyse one's own sensations; and, on the whole, it seems more probable that there was visualisation, but of a very faint and ideal kind.

No. 5.—By MR. MALCOLM GUTHRIE.

Reference has already been made to the long series of experiments carried on during the years 1883-85 by Mr. Malcolm Guthrie of Liverpool. During a great part of the series he was assisted by Mr. James Birchall, Hon. Sec. of the Liverpool Literary and Philosophical Society. Professor Oliver Lodge, Edmund Gurney, Professor Herdman, and others co-operated from time to time. Throughout there were two percipients only, Miss R. and Miss E. The experiments were conducted and the results recorded with great care and thoroughness; and the whole series, in its length, its variety, and its completeness, forms perhaps the most important single contribution to the records of experimental thought-transference in the normal state.[21] Summing up, in July 1885, the results attained, Mr. Guthrie writes:—

"We have now a record of 713 experiments, and I recently set myself the task of classifying them into the 4 classes of successful, partially successful, misdescriptions, and failures. I endeavoured[34] to work it out in what I thought a reasonable way, but I experienced much difficulty in assigning to its proper column each experiment we made. This, however, is a task which each student of the subject will be able to undertake for himself according to his own judgment. I do not submit my summary as a basis for calculation of probability. A few successful experiments of a certain kind carry greater weight with them than a large number of another kind; for some experiments are practically beyond the region of guesses....

"The following is a summary of the work done, classified to the best of my judgment:—

FIRST SERIES.

| Experiments and Conditions. | Total. | Nothing perceived. |

Complete. | Partial. | Misdes- criptions. |

| Visual—Letters, figures, and cards— Contact |

26 | 2 | 17 | 4 | 3 |

| Visual—Letters, figures, and cards— Non-contact |

16 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 5 |

| Visual—Objects, colours, etc.—Contact | 19 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| Do. do. Non-contact | 38 | 4 | 28 | 6 | 0 |

| Imagined visual—Non-contact | 18 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 3 |

| Imagined numbers and names—Contact and Non-contact |

39 | 11 | 12 | 6 | 10 |

| Pains—Contact | 52 | 10 | 30 | 9 | 3 |

| Tastes and smells—Contact | 94 | 19 | 42 | 20 | 13 |

| 302 | 57 | 153 | 53 | 39 | |

| Diagrams—Contact | 37 | 7 | 18 | 6 | 6 |

| Do. Non-contact | 118 | 6 | 66 | 23 | 23 |

| 457 | 70 | 237 | 82 | 68 |

"There were also 40 diagrams for experimental evenings with strangers, in series of sixes and sevens, all misdrawn, and not fairly to be reckoned in the above.

457 experiments under proper conditions.

70 nothing perceived.

——

387

319 wholly or partially correct; 68 misdescriptions = 18 per cent."

In the second series there were 123 trials; in 15 cases no impression was received, and in 35 cases, or 32 per cent of the remainder, an incorrect description was given. In the third series, of 133 trials there were 24 in which no impression was received and 40 failures: proportion of failures = 37 per cent. Mr. Guthrie attributes this gradual decline in the proportion of successes to the difficulty experienced by both agents and percipients in maintaining the original lively interest in the proceedings.

No. 6.—By PROFESSOR LODGE, F.R.S.

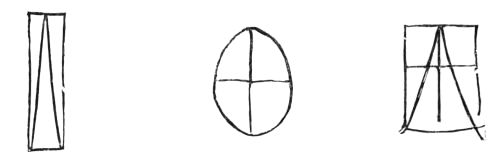

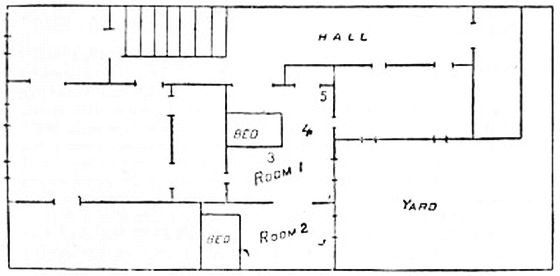

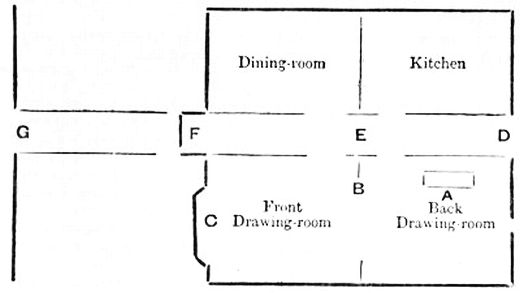

Subjoined is a detailed description of experiments made on two evenings in 1884, recorded by Professor Lodge,[22] which leaves no room for doubt that the impressions received in this instance by the percipient were of a visual nature. The agent on the first evening was Mr. James Birchall, who held the hand of the percipient, Miss R. The only other person present was Professor Lodge. The object was placed sometimes on a wooden screen between the percipient and the agent, at other times behind the percipient, whose eyes were bandaged. The bandage, it should be observed, was a sufficient precaution against cornea-reading; but for other purposes no reliance was placed upon it. It is believed that the precautions taken were in all cases adequate to conceal the object from the percipient if her eyes had been uncovered. In the account quoted any remarks made by the agent or Professor Lodge are entered between brackets.

Object—a blue square of silk.—(Now, it's going to be a colour; ready.) "Is it green?" (No.) "It's something between green and blue.... Peacock." (What shape?) She drew a rhombus.

[N.B.—It is not intended to imply that this was a success by[36] any means, and it is to be understood that it was only to make a start on the first experiment that so much help was given as is involved in saying "it's a colour." When they are simply told "an object," or, what is much the same, when nothing is said at all, the field for guessing is practically infinite. When no remark at starting is recorded none was made, except such an one as "Now we are ready," by myself.]

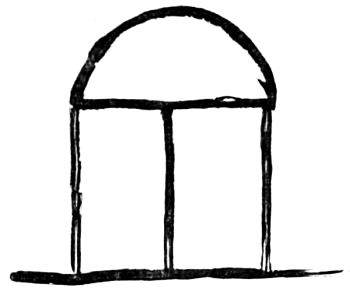

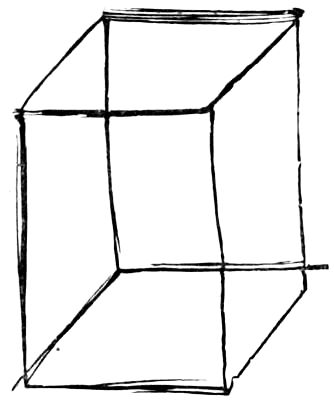

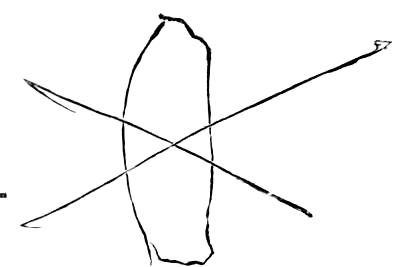

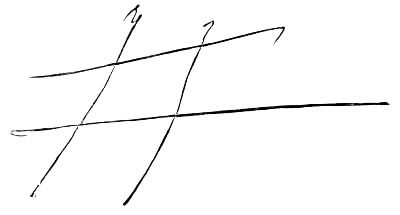

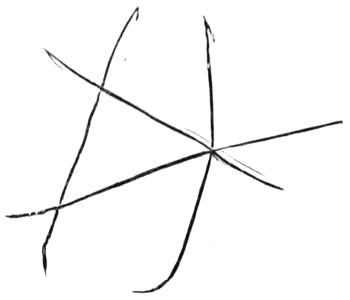

Next object—a key on a black ground.—(It's an object.) In a few seconds she said, "It's bright.... It looks like a key." Told to draw it, she drew it just inverted.

Next object—three gold studs in morocco case.—"Is it yellow?... Something gold.... Something round.... A locket or a watch perhaps." (Do you see more than one round?) "Yes, there seem to be more than one.... Are there three rounds?... Three rings?" (What do they seem to be set in?) "Something bright like beads." [Evidently not understanding or attending to the question.] Told to unblindfold herself and draw, she drew the three rounds in a row quite correctly, and then sketched round them absently the outline of the case, which seemed therefore to have been apparent to her though she had not consciously attended to it. It was an interesting and striking experiment.

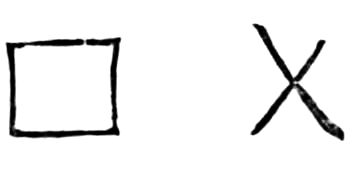

Next object—a pair of scissors standing partly often with their points down.—"Is it a bright object?... Something long-ways [indicating verticality].... A pair of scissors standing up.... A little bit open." Time, about a minute altogether. She then drew her impression, and it was correct in every particular. The object in this experiment was on a settee behind her, but its position had to be pointed out to her when, after the experiment, she wanted to see it.

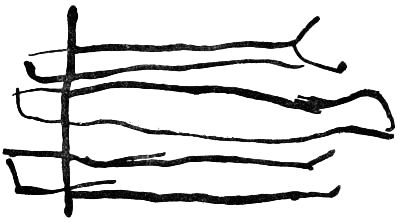

ORIGINAL.

Next object—a drawing of a right-angled triangle on its side.—(It's a drawing.) She drew an isosceles triangle on its side.

Next—a circle with a cord across it.—She drew two detached ovals, one with a cutting line across it.

REPRODUCTION.

Next—a drawing of a Union Jack pattern.—As usual in drawing experiments, Miss R. remained silent for perhaps a minute; then she said, "Now I am ready." I hid the object; she took off the handkerchief, and proceeded to draw on paper placed ready in front of her. She this time drew all the lines of the figure except the horizontal middle one. She was obviously much tempted to draw this, and, indeed, began it two or three times faintly, but ultimately said, "No, I'm not sure," and stopped.

[N.B.—The actual drawings made in all the experiments are preserved intact by Mr. Guthrie.]

[END OF SITTING.]

Experiments with MISS R.—Continued.

I will now describe an experiment indicating that one agent may be better than another.

Object—the Three of Hearts.—Miss E. and Mr. Birchall both present as agents, but Mr. Birchall holding percipient's hands at first. "Is it a black cross ... a white ground with a black cross on it?" Mr. Birchall now let Miss E. hold hands instead of himself, and Miss R. very soon said, "Is it a card?" (Right.) "Are there three spots on it?... Don't know what they are.... I don't think I can get the colour.... They are one above the other, but they seem three round spots.... I think they're red, but am not clear."

Next object—a playing card with a blue anchor painted on it slantwise instead of pips.—No contact at all this time, but another lady, Miss R——d, who had entered the room, assisted Mr. B. and Miss E. as agents. "Is it an anchor? ... a little on the slant." (Do you see any colour?) "Colour is black.... It's a nicely drawn anchor." When asked to draw she sketched part of it, but had evidently half forgotten it, and not knowing the use of the cross arm, she could only indicate that there was something more there but she couldn't remember what. Her drawing had the right slant exactly.

Another object—two pairs of coarse lines crossing; drawn in red chalk, and set up at some distance from agents. No contact. "I only see lines crossing." She saw no colour. She afterwards drew them quite correctly, but very small.

ORIGINALS.

REPRODUCTION.