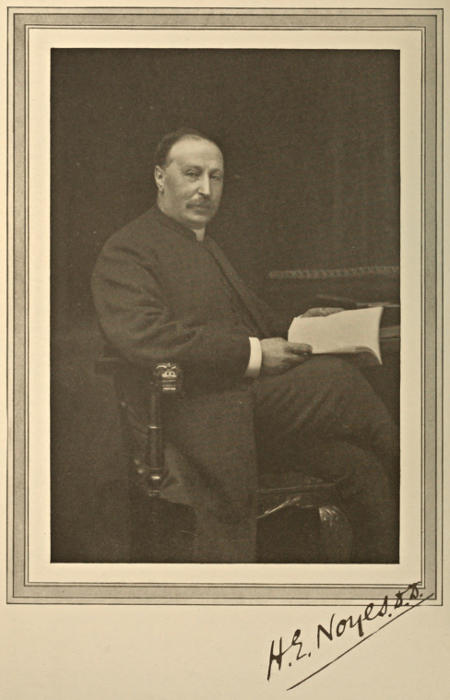

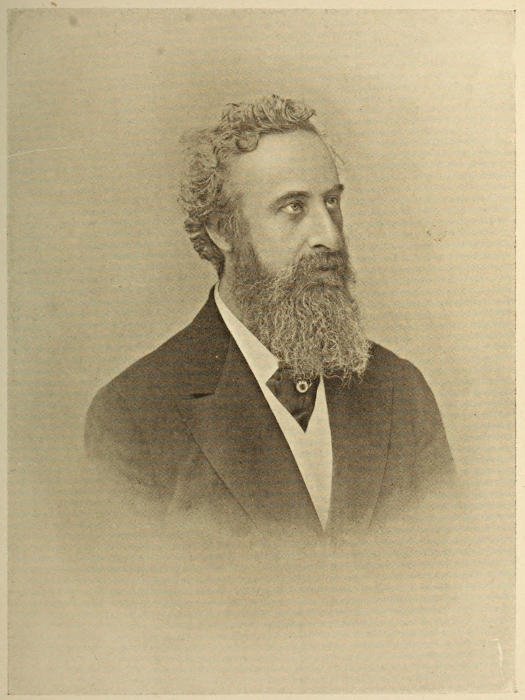

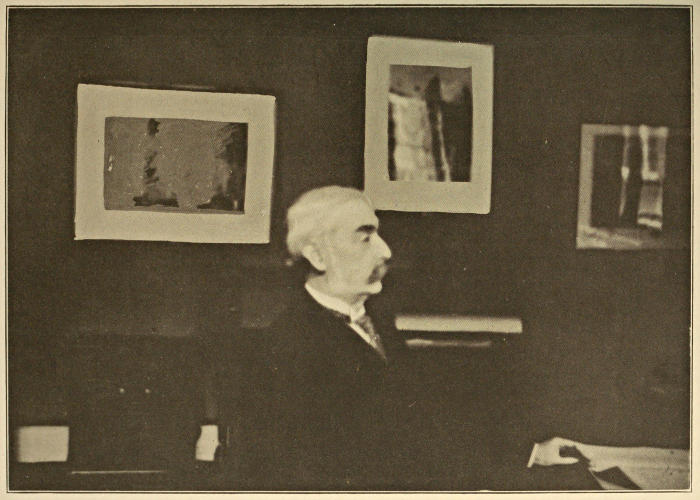

H. E. Noyes, D.D.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Seventeen Years in Paris, by H. E. Noyes

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Seventeen Years in Paris

A Chaplain's Story

Author: H. E. Noyes

Release Date: January 21, 2018 [EBook #56412]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SEVENTEEN YEARS IN PARIS ***

Produced by MFR and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: During his time in Paris, the author didn’t achieve a perfect command of the French language; many French words and place names are incorrectly spelt and/or accented. These errors have been preserved.

H. E. Noyes, D.D.

Seventeen Years

in Paris:

A CHAPLAIN’S STORY.

BY

H. E. NOYES, D.D.

(Late Hon. Chaplain to His Majesty’s Embassy,

and Incumbent of the Embassy Church,

Rue d’Aguesseau, Paris).

BAINES and SCARSBROOK,

PRINTERS AND PUBLISHERS,

75 Fairfax Road, Swiss Cottage, London, N.W.

1910.

DEDICATED TO THE BRITISH AND AMERICAN

COLONIES IN PARIS, WITH WHOM I

SPENT THESE HAPPY YEARS,

1891-1907.

In sending forth this brief account of my long chaplaincy in Paris, I desire to say that I do so at the request of many friends, who were kind enough to express their interest. It is not intended to be an account of life generally in Paris, or a description of the beauties and treasures of the City. There are many books which do this better than I could hope to do, for the life of a chaplain in Paris is a very strenuous one—every day bringing its work, and often much unexpected work, that it was difficult to give much time to sight-seeing. My predecessor, Rev. T. Howard Gill, said to me when I accepted the position, “Do not stay more than seven years—it is enough for any man.” I stayed nearly seventeen. I have not attempted either to give any full account here of the spiritual side of my work—I would only say that I have every reason to thank God that I went, both for the work He enabled me to do and the experience that I have gained. There is an erroneous impression in some minds about Continental work, viz., that it unfits a man for Parochial work at home. I heard this expressed upon my appointment to my present sphere. The fact, however, is very different. The work is so varied, so constant, and often so unexpected, that one gains as much experience in six months in a city like Paris as British Chaplain as one would gain in a much longer time at home.

It may be true that in small chaplaincies in lonely places, with but few English people in residence, men get out of touch with Church life and work in England, but it is not the same in the permanent chaplaincies in thickly populated places.

In Paris we had our organisations much as at home. Daily Services, Sunday Schools, Mothers’ Meetings, Visitors, etc., and although the numbers attending (owing to distance) were not so great as at home, the work was much the same.

I have given several hints which I trust may be useful to parents intending to send their children abroad for education, and also to those who may be purposing to reside in Paris.

As we are going to press the notice appears in the papers of the death of Sir Edmund Monson, formerly Ambassador in Paris. The country loses in him a distinguished and faithful servant, and all who knew him will regret a kind and generous friend.

H. E. NOYES, D.D.

St. Mary’s Vicarage,

Kilburn, N.W.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| ROYAL AND OTHER VISITS | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE BRITISH EMBASSY | 25 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| MEMORABLE SERVICES | 48 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE ENGLISHMAN ABROAD | 66 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| EDUCATION IN FRANCE | 74 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| DIFFICULTIES OF ENGLISH PEOPLE ABROAD | 79 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| BRITISH CHARITIES IN PARIS | 94 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| BRITISH JOURNALISTS IN PARIS | 105 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| VARIA | 112 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| PRESENT CONDITIONS OF RELIGIOUS LIFE ON THE CONTINENT | 122 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND ON THE CONTINENT | 135 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| AMERICANS IN PARIS | 139 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| L’ENVOI | 144 |

| Rev. H. E. Noyes, D.D. | Frontispiece | |

| Rue de Rivoli | To face page | 2 |

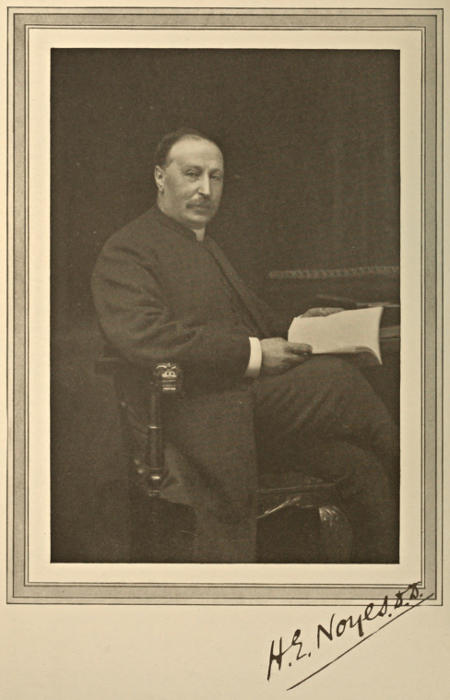

| His Majesty Entering the Church, followed by Sir E. Monson | ” | 6 |

| His Majesty Leaving the Embassy Church | ” | 14 |

| Sir Walter Vaughan-Morgan, Lord Mayor of London, 1905-1906 | ” | 22 |

| Mr. Wright | ” | 23 |

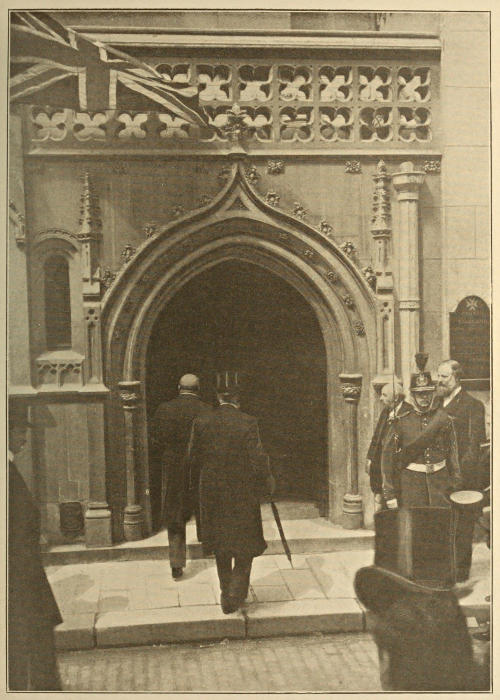

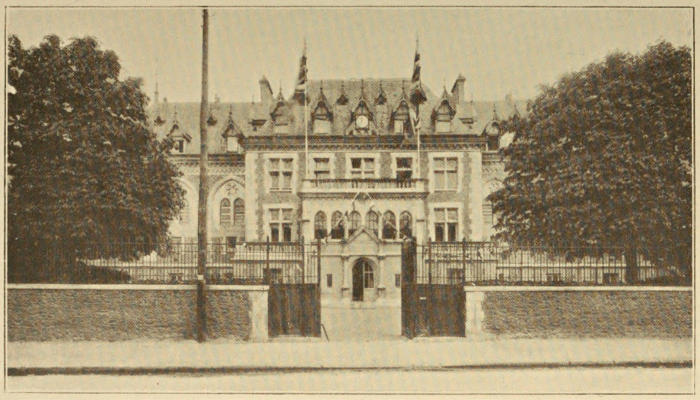

| Entrance to British Embassy | ” | 24 |

| The Earl of Lytton | ” | 26 |

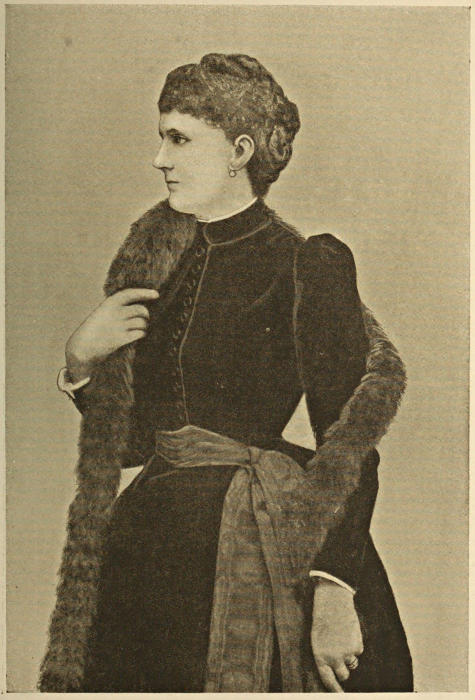

| The Countess of Lytton | ” | 28 |

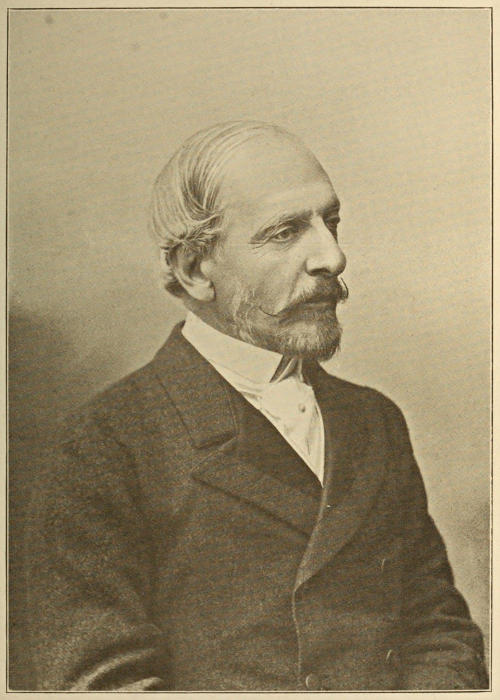

| The Marquis of Dufferin and Ava | ” | 30 |

| The Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava | ” | 32 |

| Trainbearers at the Lady Plunket’s Wedding | ” | 34 |

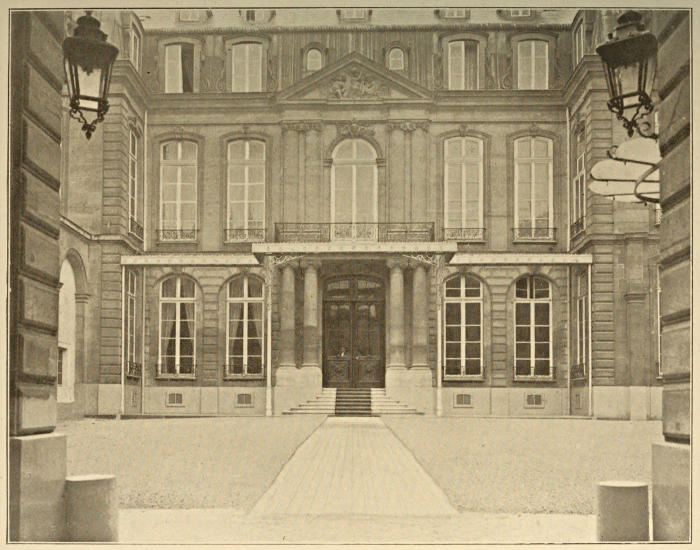

| Court Yard, British Embassy | ” | 42 |

| Sir Henry Austin Lee | ” | 46 |

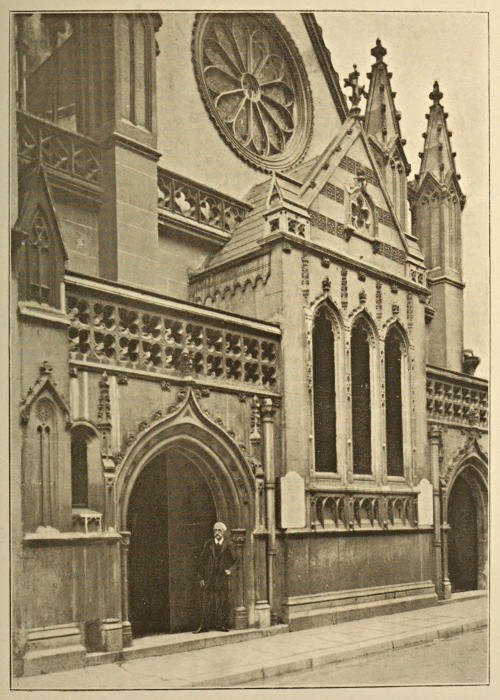

| British Embassy Church, from the Rue d’Aguesseau | ” | 48 |

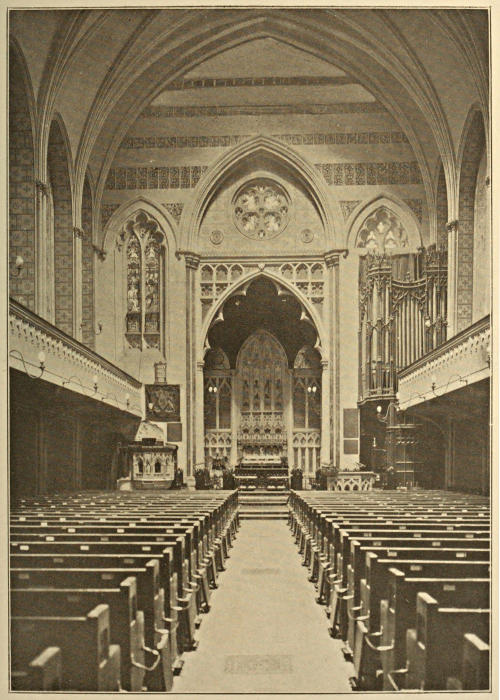

| British Embassy Church (Interior) | ” | 54 |

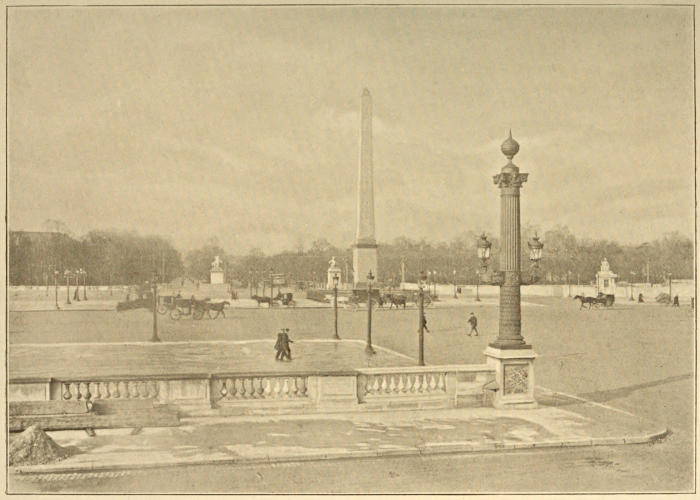

| Place de la Concorde | ” | 66 |

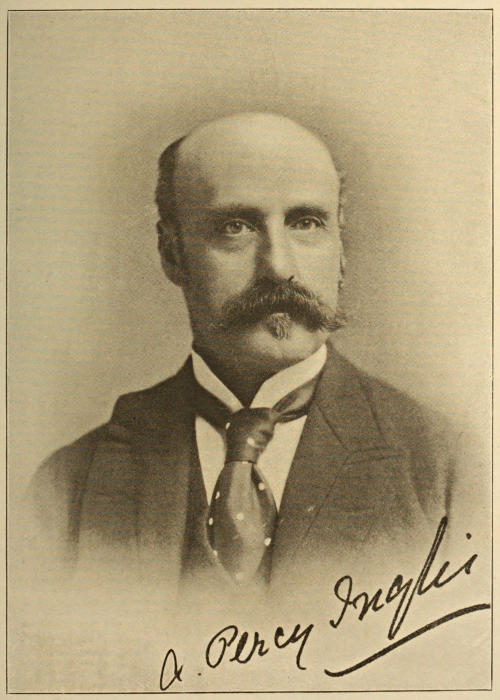

| A. Percy Inglis (British Consul-General) | ” | 84 |

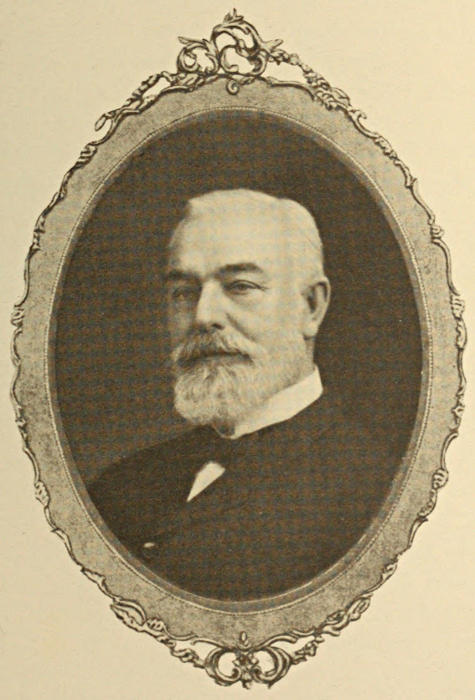

| Sir John Pilter | ” | 94 |

| Hertford British Hospital | ” | 98 |

| The Elysée, from the Faubourg St. Honoré | ” | 112 |

| Place de la Concorde | ” | 118 |

| The Historic Fountain, Place de la Concorde | ” | 118 |

Photos of City by Leblanc, Paris.

BY

H. E. NOYES, D.D.

Late Honorary Chaplain to His Majesty’s Embassy.

The Daily Press has naturally recorded the visits of Royalty, Members of Parliament, the Lord Mayor of London, etc., to Paris during the period of which I write, but as in each case there were services in the Embassy Church, there are certain facts from the chaplain’s point of view which will, I hope, be of interest to my readers. A clerical friend once said to me, “Everybody who is anybody has been to your Church in Paris.” It certainly was a fact that during my chaplaincy many distinguished people attended the ordinary Divine Service besides the crowds at special times when Royalty was present. I may mention the late Duke of Devonshire, the Right Hon. W. E. and Mrs. Gladstone—who often came twice on the Sunday when visiting Paris—H.R.H. the late Duke of Cambridge, who was many times present. On one occasion the Duke arrived in Paris from a long journey early on Sunday morning, but he was in the Embassy gallery at the 11 o’clock service. Upon his late visits—and he was in Paris not long before the[2] end—he was unable to face the stairs to the gallery, and sat below with the congregation. In the early days of my chaplaincy, the late Sir Condie Stephen was an attaché at the Embassy, and a most regular attendant at both morning and evening services. The late Archbishop of Canterbury was once at service in my time, and sent me a most kind message. Bishops, Home, Colonial, and American, were occasionally seen, and many clergy. I noticed on two or three occasions Mr. Pierpoint Morgan among the worshippers. On one occasion four English dukes were present at morning service. The late Sir G. Stokes, Sir W. Freemantle, Lord Rathmore, and the other members of the Suez Canal Board were regular in attendance month by month, the former a devout worshipper and a kind, genial friend.

Great interest was naturally excited in the English Colony when we had Royal visitors. Her late Majesty was not in Paris during my Chaplaincy, although she was several times in the South of France, being usually met at some convenient station by the President of the French Republic. Whatever may have been the feeling of the French people towards the English before the “Entente Cordiale,” they always had the highest respect and admiration for our beloved Queen, and I never heard that she met with the least annoyance from “the most polite nation in the world.”

RUE DE RIVOLI.

Before coming to the special subject of this chapter, I should like to say a few words about the English Church in the Rue d’Aguesseau, which has always been known as, and is “ipso facto,” the Embassy Church. In former days the English services were held in the ballroom at the Embassy[3] itself, and there was a resident chaplain. I have heard that there was sometimes rather a “rush” after a Saturday night’s ball to get the room ready for divine service on Sunday. This “Chapel” was also at that time somewhat of a Gretna Green, where at twenty-four hours’ notice young couples who had difficulties at home could be united according to English law by a resident chaplain. My friend, Dr. Morgan, of the American Church, kindly sent me a volume of sermons he had picked up on a bookstall, bearing the title “Sermons preached at the Chapel of the British Embassy, and at the Protestant Church of the Oratoire in Paris, by the late Rev. E. Forster, M.A., Chaplain to the British Embassy.” This was in the days when Lord Stuart de Rothesay was Ambassador to the court of France, and the volume bears the date 1828. I believe Lord Stuart de Rothesay was twice Ambassador in Paris—an unusual circumstance. Services are no longer held in the Embassy. The English Colony in Paris having largely increased, it became necessary to provide a suitable building as a church, and at the period when the late Lord Cowley was Ambassador, and largely through his instrumentality, the present Church was purchased, and has from that time to the present been the Embassy Church, where all services of a public and diplomatic character have since been held. Here is a French description of the building, which, while not exactly ecclesiastical, is yet loved and valued by the English Colony.

“L’Èglise Anglicane est située à moins de 100 mètres de la porte de l’Ambassade. C’est un petit monument de style Gothique, aux fenètres ogivales, aux frùes[4] colonnes fleuronnées. A l’intérieur, la chapelle est meublée de deux rangées de bancs, placées face à l’autel. Devant celui-ci se trouve l’aigle de bois doré dont les ailes éployées portent les Livres Saints; à gauche les orgues: à droite, la chaire: une simple tribune de pierre, de forme hexagonale légèrement surélevée. Un balcon court sur les deux côtes de la chapelle, dont le fond est occupé par une tribune.”

The church is in a much better condition than formerly. The congregation during my chaplaincy put a new roof upon it, and decorated it throughout, and constructed a handsome Mortuary Chapel underneath—a sad necessity for the English and American colonies in Paris. I conducted some remarkable services during my time in Paris, which I describe in another chapter—scenes which will not soon be forgotten by those who witnessed them. I was glad to leave behind some £7,000 which had been subscribed towards a Church House, a much-needed establishment, as there is no room for Church purposes or residence for the chaplain. My successor, the Right Rev. Bishop Ormsby, will, I hope, reap the benefit of this effort.

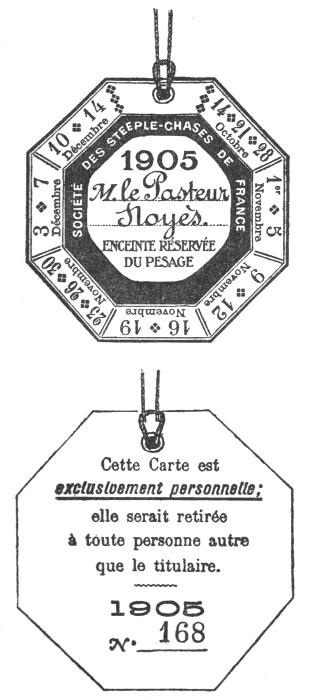

His Gracious Majesty King Edward VII. was several times in Paris during the earlier years of my chaplaincy, as Prince of Wales, but his first visit to the French Republic as King and Emperor was in May, 1903. The visit was official and unique. Those of us who had lived in Paris during the Boer war—when, to say the least, the English were not popular, and had so frequently heard “Vivent les Boers” as we passed along the streets, and even had newspapers flaunted before us which recorded reverses to our arms—were very anxious that the[5] visit should pass off quietly. The English colony was much concerned, and so were the French police. I was advised by the latter to admit to the Church only by ticket, and to take the names and addresses of each applicant for them who might be unknown to me. The following was the text of the ticket I issued: “English Church, Rue d’Aguesseau. Divine Service 11 a.m. It is requested that all seat-holders will be in their places at 10 o’clock. After 10.30 all unoccupied seats will be filled.” The tickets were all numbered and signed with a special stamp marked “Basileus.” The issuing of these tickets gave us considerable work, as we only had 1,000, and some 1,500 to 2,000 people applied for them—many by letter. Nearly the whole of two days was occupied in the distribution.

The “Entente Cordiale” is now happily a “fait accompli”; but at the time of His Majesty’s first official visit there was no thought of it in the public mind, though we know now it was the gracious intention of our peace-loving King that it should come about. I give an excerpt from the “Patrie,” signed by M. L. Millevoye, which at this time gave us some concern, for the “Patrie,” while not a high-class paper, is one that is largely read by the man in the street:

“Parisiens! Le Roi des Anglais n’est pas votre hôte: ce n’est pas vous qui l’avez invité. Cet étranger, cet ennemi vous impose sa visite.… Parisiens, ce roi vous saluera, vous ne le saluerez pas.

“Mais des cris bien français, esclusivement français, peuvent sortir, sans provocations, de vos poitrines. Crier ‘Vive Marchand!’ c’est condamner Fachoda, c’est marquer la flètrissure d’une des plus hyprocrites[6] d’une des plus odieuses brutalités diplomatiques que la France aie subies, Crier Vivent les Boers.… Crier Vive la Russie.… Votre silence même, s’il est général, absolu, aura sa grandeur. Devant vos fronts couverts, devant vos regards implacables, ce roi comprendra qu’on l’atrompé en lui parlant de votre soumission, &c., &c., &c.”

It seemed, however, as if the very presence of His Majesty in Paris at once dissipated any cloud that might have appeared in the sky. The French are remarkable for their readiness to swing round to an opposite opinion when they find reason for so doing. This was very striking in the Dreyfus affair, and, more recently, in the case of M. E. Zola, who, after having been condemned to imprisonment and a heavy fine for his defence of Dreyfus, received the “post mortem” honour of being removed from the cemetery of Montmatre to the Panthéon, that resting place of the illustrious French dead.

HIS MAJESTY ENTERING THE CHURCH, FOLLOWED BY SIR E. MONSON.

The visit of His Majesty to Paris extended from May 1st to 4th, and almost every hour was occupied with the usual official visits, lunches, dinners, and receptions. The English colony looked forward especially to the Sunday when they expected to see and worship with the King in their own Church. There was some anxiety as to whether His Majesty would sit in the Embassy gallery, or in the body of the Church, as in the former case he would hardly be seen by the congregation. I reported to our Ambassador, Sir E. Monson, the great desire that the King would sit with the congregation, and late on Saturday evening I received a message that he had kindly consented to do so. This gracious act gave[7] much pleasure to the colony. There were many young people who had never seen their King before, and I fear his presence was rather distracting to their worship on this occasion.

The police were considerably scared when it was announced that His Majesty would not drive to the Church, but intended to walk. Although only a few yards it was felt to be more or less a danger; but every precaution being taken, all passed off safely. As the congregation was assembling, I was sent for to the door to interview a distinguished-looking man who desired to enter the Church, but had no ticket. I found, however, upon careful enquiry, that he was a detective from Scotland Yard, and required to examine the place where the King was to sit.

This quiet Sunday service, with the King-Emperor attending as an ordinary worshipper, very much impressed the French people. I will quote what was said by the “Figaro” and the “Daily Telegraph” at the time; the former giving the general French feeling much more accurately than the “Patrie,” although even the latter paper soon changed its tone.

The “Figaro” thus describes the service:—

“Les Parisiens sceptiques et volontiers gouailleurs, ont été fortement impressionnés par la très simple cérémonie d’hier matin, la plus grande peut-être de ces trois jours de fête. De la rue Royale à l’avenue de Marigny dix mille curieux descendent tout endimanchés des faubourgs, se massent aux abords de l’Ambassade d’Angleterre, pour voir comment le roi de la Grande-Bretagne et d’Irlande et des possessions britanniques d’outre-mer, défenseur de la foi, empereur des Indes va faire-visite à Dieu. C’est à pied que[8] S. M. Edouard VII., en tenue de ville, se rend à l’Eglise. Et quand il le voit passer ainsi, tout ce peuple saisi d’émotion, chapeau bas, s’incline, dans un silence solennel. La petite Eglise gothique de la rue d’Aguesseau regorge de monde. On a lancé neuf cent trente invitations. La nef, les galeries, les bas-cotés, les tribunes, tout est bondé.

“Les deux premières travées de banquettes sont réservées; et devant elles, à gauche du chœur un fauteuil recouvert de velours rouge, avec un prie-dieu sans appui, et un pupitre sur lequel sont deposés une Bible, et un livre de psaumes, marque la place du Roi.… Le Pasteur et ses assistants ont la soutane et le surplis garni de bandes de satin noir et rouge. Les enfants de chœur assis près de la chaire, ont seulement la soutane noir et le surplis. Sur un signe du secrétaire qui guettait à la porte l’arrivée du Roi, tout le clergé, le Rev. Dr. Noyes en tête, se porte au-devant de sa Majesté et l’attend sur le seuil. Edouard VII. et le Pasteur se saluent en même temps. Le Clergé remonte vers le chœur, précédent le Souverain, que suivent les membres de l’Ambassade d’Angleterre et tous les attachés militaires. Et des que S. M. Edouard VII. a pris place devant son fauteuil—et ouvert son livre de psaumes, l’office divin commence. Les fidéles, dont un instant très court de curiosité n’a pu troubler le recueillement, entument en anglais le Te Deum. Puis les hymnes, les versets de la Bible, les psaumes se succèdent chantés par toute l’assistance. Les fidèles s’agenouillent, et le Roi s’agenouille comme eux; et sa voix se mêle avec leurs voix. Il n’y a plus un souverain et des sujets, ‘Il n’y a qu’une famille dont tous les membres s’addressent, ensemble au Père, ‘Notre Père qui êtes aux cieux.’ C’est la prière que[9] nous ne savons plus. Enfin les chants ayant cessé le Rev. Dr. Noyes se lêve et prononce le sermon dominical. Pendant un quart d’heure environ, il développe la thèse de la Divinite du Christ, et l’office termine, selon l’usage, par un dernier cantique, sans qu’aucune allusion, ainsi qu’il en avait exprimé lùi-même le désir, aie été faite à la presence du Roi.”

I have given the above in full as it is an interesting French view of an English church service.

“The Daily Telegraph” recorded this event of the day as follows:

“At the morning service in the English Church, Rue d’Aguesseau, the King was attended by his suite, and accompanied by Sir E. Monson and the staff of the Embassy. This sacred edifice is a building of great interest to English residents in Paris. The Rev. H. E. Noyes, D.D., has been Chaplain to the Embassy since 1891, and during that incumbency has known three eminent representatives of the Empire, Lord Lytton, the Marquis of Dufferin, and Sir Edmund Monson. Our compatriots in the French capital do not forget their Church. It is surely a matter of pleasure to know that at the last Easter celebrations there were no fewer than 930 communicants. To-day the Church was all too small. Though admission was necessarily by ticket, a crowd besieged the doors more than an hour before the beginning of the service. Notre Dame or the Madeleine would have been insufficient for the congregation anxious to be present. Indeed, one feels regret for the hundreds who failed to obtain a coveted ticket of admission. Practically small room was left after seats had been found for the regular congregation, among whom I was pleased to note a large[10] number of English young ladies attending Parisian schools. Many a year hence it will be a pleasant memory for those young persons who participated in this historic service. ‘What a noble national possession is England’s “sublime liturgy,”’ to quote George Borrow’s description of it.

“Who has not felt its impress in a foreign land? I have heard it west of the Rocky Mountains, under the Stars and Stripes, beneath the Southern Cross, in the capital of China, on the Indian, the Atlantic, and the Pacific Oceans, and in war time in South Africa, and the effect is everywhere the same—a finer patriotic glow than almost anything else can call up. It appeals to one as part of the heritage of the English people, like their old Parish Church, or their very language itself. In the Rue d’Aguesseau the prayers for the King and the Royal Family of Great Britain were followed, as they always are here, by petitions for the Presidents of the United States and of the French Republic. The ‘Te Deum’ was finely rendered, as were the hymns ‘Children of the Heavenly King’ and ‘The King of Love my shepherd is.’ Dr. Noyes founded a short, eloquent discourse upon Matthew xiii. 54, 55.”

As the King left the Church the congregation sang the National Anthem with a fervour and emotion, which was natural upon such an occasion.

After lunching at the Foreign Office with that eminent statesman, M. Delcasse, His Majesty returned to the Embassy. Here a most interesting ceremony was held. The King had promised to plant a red chestnut tree in the Embassy garden, and the children of the British schools, to the number of fifty, and the inmates of the Victoria Home (an institution[11] for aged British women who have lived in France for thirty years) were invited to be present. It was a memorable occasion. The King handled the spade as one accustomed to it, and the tree thus planted has flourished remarkably well ever since. It bears a plate stating the date, etc., and will, no doubt, be an object of interest in the beautiful garden of the Embassy for many years to come. The King has a wonderful memory for old friends. I heard him on this occasion asking kindly after the Hon. Alan Herbert, M.D., whom he had known in Paris many years ago. Another interesting incident took place on this afternoon. Among those invited to the Embassy garden was an old soldier, George Colman, nearly ninety years of age, who had been dispatch writer to Lord Raglan in the Crimean War. He was presented to the King, who had a long chat with him, and asked him “Where are your medals?” Colman replied, “Your Majesty, they were stolen from me at the time of the Paris Commune.” “Well,” said the King, “we must see to that.” Colman was not forgotten, and not long after the medals were received at the Embassy. He brought them to shew to me in great delight.

In the evening a large official dinner was given at the British Embassy, which was attended by the President and Madame Loubet, members of the French Government, and many other distinguished guests. Three French artists had the honour of being invited, MM. Carolus-Duran, Detaille, and Bonnat. The City was brilliantly illuminated, and presented all the characteristics of a National fête.

His Majesty left Paris for Cherbourg the next[12] morning, President Loubet accompanying him to the Gare des Invalids. There was a thankful sigh of relief from the many loyal hearts in Paris that all had passed off so well, and that our beloved Monarch was safe. It had been an anxious time, for the happy change to more friendly relations between the two countries had then only just commenced.

The next visit of His Majesty was in May, 1905, just two years after his first official visit. There had been a change at the Embassy. Much to the regret of all who knew him, Sir Edmund Monson had retired, having reached the age limit, and had been succeeded by Sir Francis Bertie, the present Ambassador. There was, moreover, a great change in the attitude of the people, and the “Entente Cordiale” was on the lips of all. The King’s previous visit, and the return visit of M. Loubet to London, resulted in the settling of several outstanding disputes which had long been an anxiety to diplomatists. There was much less ceremonial upon this visit, and the King, instead of going to the Embassy, took his old suite of rooms at the Hotel Bristol in the Place Vendome, where he had often stayed as Prince of Wales. His Majesty came to Paris via Marseilles, where he had a very hearty reception, and arriving at the Gare de Lyon was met by Sir Francis Bertie and the staff of the Embassy, and that all-important functionary, the Prefect of the Police. A good number of people gathered in the Place Vendome in the hope of seeing the King, but the weather was showery, and he drove in a closed carriage, and they were disappointed. The Hotel Bristol in the Place Vendome—formerly a monastery—is managed by an Englishman, Mr. Morlock, who is well known to many crowned heads.[13] The Tsar of Russia stayed there before his accession to the throne; the late King and Queen of Portugal, and many others. Mr. Morlock is a most genial host, and although he has been so long in France is proud of his nationality, and always ready to join in any movement for the good of the British colony. I had been informed that His Majesty would attend Divine Service on the Sunday morning, and took the precaution to admit only by ticket, to prevent over-crowding. It was well I did so, for a great crowd assembled outside the Church, and would have prevented the regular worshippers from entering. Owing to this arrangement the Church was filled before the hour of service, and there was no confusion. It was Eastertide, and the hymns “Jesus lives! no longer now—Can thy terrors, death, appal us” and “Hosanna to the living Lord” were sung with great fervour. I had requested the congregation to remain in their seats during the singing of the National Anthem at the close of the service—the intention being that His Majesty and the staff of the Embassy would then leave and thus prevent crowding at the door. However, the King stayed until the end, and, I was told, joined heartily in the anthem. We always omitted the second verse having the words “Confound their politics,” as being guests in a foreign land.

Upon this occasion His Majesty sat in the Embassy gallery with Sir Francis Bertie and the staff. An amusing incident happened as the King left the Church. A loud crash was heard and caused some excitement. It came from a photographer who had perched himself upon a high ladder with a large camera, hoping for a snapshot. He fell owing to the[14] breaking of the ladder just as the King came out of the porch. He was very disappointed at losing the photograph.

Upon the return to the hotel the King received Admiral Fournier, who had presided over the enquiry relating to the North Sea firing incident, and conferred upon him the insignia of a Knight Grand Cross of the Victorian Order.

The reception of His Majesty on the part of the people was in marked contrast to that of his former visit. There were very few cries in the streets on that occasion, but now one often heard “Vive le Roi” and “Vive l’Angleterre” shouted with a hearty good will. The “Entente Cordiale” was an established fact.

HIS MAJESTY LEAVING THE EMBASSY CHURCH.

The third visit of the King during my chaplaincy took place in March, 1906, when he travelled as the Duke of Lancaster, arriving in Paris from Cherbourg on the Saturday evening. The Royal train was brought round to the Gare des Invalides, where the King was met by Sir Francis Bertie and the staff of the Embassy, M. Mollard representing the President of the Republic, and M. Lepine, Prefect of Police. As His Majesty ascended the stairs a flashlight photograph of the scene was taken by an unauthorised person—much to the annoyance of all present, as the explosion caused a temporary alarm. Next morning the King attended the Embassy Church, and sat in the Royal gallery with Sir Francis and Lady Feodorowna Bertie. Little change was made in the service, except that I preached a short sermon in order to keep within the limited time. My text was “But the Word of God is not bound,” and the collection was for the British and Foreign Bible[15] Society. H.R.H. Princess Henry of Battenberg and the Princess Ena (now Queen of Spain) joined the King at the Embassy for lunch. His Majesty drove to and from the church in a closed carriage, and although there was a great crowd, his desire to be “incognito” was respected. It was upon this occasion that His Majesty handed to M. Fallières the missing leaves from the second volume of “The History of the antiquities of the Jews” for the Bibliothéque Nationale. M. Loubet, former President of the Republic, was one of the many who called upon the King, and it was characteristic of the kind feeling of His Majesty that he returned the call at the private apartment of M. Loubet—an act that was much appreciated by the people generally. I often heard French people speak of it. Upon this visit the Embassy in the Faubourg St. Honore was turned into a Royal Palace, the King and his suite staying there. I was told of the following incident which indicates the change of feeling on the part of the French. After dinner at a fashionable restaurant (while the King was in Paris) the band was called upon to play the English National Anthem by a party of Frenchmen. Then some Englishmen present called for the Marseillaise, which was received with the same honours and enthusiasm.

By a curious chance there was a party of Germans present, and these stood up and uncovered while both the National Anthems were being played. Beyond the various social functions there was no other special incident, and the short visit passed off very satisfactorily in every way.

I have told of the enthusiasm evoked by the first official visit of His Majesty to Paris, and the two[16] subsequent visits, but when it was reported early in 1907 that the King was coming, accompanied by the Queen, enthusiasm knew little bounds. Many of the English Colony had never seen the Queen, and were on tiptoe of expectation. Their Majesties arrived in Paris from London on Saturday evening, February 2nd, at the Gare du Nord, where they received an enthusiastic—though non-official—welcome, for they were travelling as the Duke and Duchess of Lancaster. The photographic fiend was again in evidence, and Her Majesty gave a perceptible start as the magnesium light flashed, although she must be accustomed to this annoyance. I was told that the crowd outside the station was enormous, and the cries “Vive le Roi—Vive la Reine” were very hearty, both there and along the route to the British Embassy, which was to be the temporary home of their Majesties. Notwithstanding the fatigues of the journey the King and Queen paid a visit to the Nouveau Cirque in the evening, much to the delight of those present.

It appeared to me that the Parisians were the more pleased at the “incognito,” as it was as if their Majesties came as friends, and not merely as Royal visitors. The visit was thus less formal yet more cordial; everyone felt that it was not political, but just friendly, and Paris was delighted. The British sovereigns were going to spend a week of pleasure, visiting and entertaining their friends, shopping and motoring. The Rue de la Paix is always attractive, but it seemed to surpass itself on this occasion.

I was naturally very busy preparing for the Sunday service. Tickets were quite necessary, and[17] the demand for them very great. We issued 1,000—our utmost limit—and then came the pain of refusing the hundreds who also desired to attend. I crave pardon for giving the report of the service, written by my friend Mr. Ozane, the well-known and valued correspondent of the “Daily Telegraph.”

He wrote: “I have never seen a larger crowd in and near the church in the Rue d’Aguesseau than that which assembled there this morning. Admission to the sacred edifice was by cards, of which a liberal distribution was made, but any number of persons who must have known that the chance of finding a place was hopeless, had put in an appearance nevertheless. The English colony had mustered in full force, and there was a big gathering of French friends as well. The footpaths close to the Embassy and along the street leading to the Church were crammed with well-dressed people—the fair sex being strongly represented; and there they stood in the brilliant sunshine, but bitterly cold wind, waiting for their Majesties to pass. The King and Queen drove to and from the Church in one of the Ambassador’s carriages, and with Sir Francis Bertie and members of their suite were conducted to the Embassy Gallery. By the time they entered the Church was thronged to repletion, all the arrangements made for the accommodation of the congregation being, however, excellent. The prayers were read by the curate, Rev. W. Harrison, the lessons being read and the sermon preached by the Rev. H. E. Noyes, D.D., who is chaplain to the Embassy. Doctor Noyes is well known as a very eloquent preacher, and taking for his text the 14th verse of the 8th chapter of St. Luke, part of the Gospel for the day, delivered[18] an excellent discourse on the parable of the sower. The choir, under the direction of Mr. Percy Vincent, did itself full justice, and the congregation joined heartily in the service, as it invariably does at this Church, which has only one defect, viz., that it is not large enough to accommodate all the worshippers who would attend it, especially at a season when so many English visitors are passing through Paris. When the service was over it was scarcely possible to make one’s way along the street, so dense was the crowd.”

In the afternoon the King paid a visit to President Fallières at the Elysée, which was returned later, Madame Fallières accompanying the President to make the acquaintance of the Queen. In the evening their Majesties dined with their old friends Mr. and Mrs. Standish.

The following is an extract, giving the French impression of the Church service:

“L’Eglise était comble, bien qu’on n’y eût èté admís que sur la présentation de cartes imprimées, spécialement. L’Entrée des souverains y fut saluée par de nouveaux vivats. Ils prirent place dans la tribune de l’ambassade, a gauche de la nef. Puis le service commença. C’était l’office ordinaire du dimanche et la seule modification qu’on y apporta fut l’exécution du ‘God save the King’—joué par les orgues à la fin de la cérémonie, tandis que tous les assistants chantaient en chœur. Le Reverend H. E. Noyes officie. Edouard VII. suit avec une attention soutenue l’office, ainsi d’ailleurs que la reine Alexandra.”

All through the week the liveliest interest was taken in the movements of the King and Queen, and there were some amusing incidents. There was great[19] curiosity to see the King’s automobile, the people apparently having forgotten that he had purchased it in Paris on a previous visit. What they expected to see I don’t know—perhaps some vehicle modelled after the old Royal stage coaches? But the reality was a fine Mercédés car, much the same in outward appearance as others in Paris, but with luxurious interior fittings. It was the rule in France at this time (as since) to have a conspicuous number painted on each car, and this mark the Royal Mercédés had not. It was consequently very soon stopped by a policeman in the Champs Elysées, and a crowd gathered. When, however, it was found to have a Royal owner, it was allowed to pass on. But this was not the end of the matter. Next day it was stopped by a more “exigeant” police officer, who, having failed to get satisfactory answers from the English chauffeur, obliged him to go to the police station. The crowd was highly amused as the news soon spread “C’est l’automobile du Roi,” although the stern police officer continued to ignore it. I believe there was another difficulty the following day. However, so soon as His Majesty heard of his chauffeur’s adventures, he ordered a number to be at once painted on the car, to conform with the French law.

Her Majesty the Queen received many begging and other letters during her short stay, and I was struck by the careful enquiries she caused to be made about each case. I was glad to be able to give, through one of the attachés, information as to several of the applicants who were well known to me.

The consideration of the Parisians for the “incognito” of their Majesties was very marked.[20] It was reported that both the King and Queen expressed their satisfaction at this, and that the former said “Nothing could be nicer or more discreet. The Parisians are the most courteous people in the world.” The same attitude was maintained all through the visit, enabling their Majesties to go about in freedom and comfort, as they constantly did, to the great delight of both nationalities in the gay city.

After the “Entente Cordiale” became an accomplished fact, we had several visits of public bodies to Paris, and I always endeavoured to arrange a special service for them as part of the programme of the visit. In November, 1903, we had a British Parliamentary visit. I had corresponded with the secretary beforehand, and arranged for a special service at 4 p.m. on the Sunday afternoon (29th). We had no room for them at the ordinary morning service. I also consulted Sir E. and Lady Monson, who kindly arranged their reception for 5 o’clock, so that the Members of Parliament, their wives, and daughters could go across to the Embassy at the close of the service. About 300 attended, and, I had reason to know, fully appreciated the arrangement that had been made for them. I preached upon the Great Charter of our Religious Liberty from the text “Render unto Cæsar the things that are Cæsar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” The National Anthem was very heartily sung at the close. Sir E. and Lady Monson received the guests with their usual kindness, and all the magnificent rooms at the Embassy were thrown open to them. All the members of the British party were present, together with French Senators and Deputies, and the leading members of the British Colony in Paris.

This same year we had a visit from the present Bishop of London. I believe his first visit as Bishop. I had written to him to say that I had a number of candidates for confirmation (about 50), but that our own Bishop Wilkinson, coadjutor for London, could not come, and could he ask some other Bishop who might be in London to take the office for us. He wrote: “My dear Noyes, I will come myself.” The British Colony will not soon forget his visit. After the Confirmation, at which he gave a most helpful address, although curiously enough founded upon a misquotation, we had a reception at my house, which was attended by the leading members of the Colony, and those confirmed, with their parents and friends. The Bishop (as always) won the hearts of all by his kindness and geniality. I acted as His Lordship’s chaplain while he was in Paris, and he kindly fell in with all the arrangements I had made, which were numerous.

In February, 1906, we had a visit from the London County Council, most of whom attended the ordinary service in the Embassy Church on February 4th. On Monday (5th), there was a grand reception at the Hotel de Ville. This magnificent structure, erected on the site of the old historic building, is well worth a visit. The decorations and pictures are among the most beautiful in Paris, and when it is lit up and specially decorated with flags, etc., as it was on this occasion, presents a striking scene. The same week the “Minister of the Interior,” an office corresponding to that of our Home Secretary, gave a grand reception in his superb mansion in the Place Beauveau. All the London County Council were invited, together with the leading members of the[22] British Colony. The reception was followed by a concert, in which some of the best known artists in Paris took part. The programme was itself a thing of beauty, bearing in the front a striking picture drawn for the occasion by Lévy, of a sailor looking back over a tempestuous sea at a lighthouse on a pier.

SIR WALTER VAUGHAN-MORGAN, LORD MAYOR OF LONDON 1905-1906.

MR. WRIGHT.

This was a year of visits. In October, the Right Hon. Sir Walter Vaughan-Morgan, Lord Mayor of London, accompanied by many of the City Fathers, came officially to Paris. There was considerable excitement among the citizens of Paris about this visit, for among other things it was rumoured that the Lord Mayor would bring his state carriage, and also Mr. Wright, his well-known coachman, whose fame had preceded him. An enormous crowd gathered to welcome the party, many leaving off work early in order to see them pass, and the streets from Gare du Nord to the Rue Scribe were literally packed with people. The cheers were frequent and loud, and one often heard, “Vivent les Anglais,” and the less common “Vive le lor Maire.” Had this cry ever been heard before in Paris? Mr. Wright, the coachman, had reached Paris the day before, and was soon recognized on the box of the Lord Mayor’s carriage. The crowd shouted, “Vive Monsieur Wright,” and “Vive le cocher du lor Maire” with vehemence, evidently delighted with his jolly appearance. I had corresponded with Sir Joseph Savory with reference to a service in the Embassy Church on the Sunday, and it was decided that a gallery (holding about 100) should be placed at their disposal, although this caused the other parts of the building to be very crowded. In front of the Embassy, which faces the[23] Rue d’Aguesseau, and down the street, police were stationed in force. Had the King himself been coming there would hardly have been a stronger detachment. The whole of the gallery in the Church was filled. The Lord Mayor was invited to a seat in the Embassy gallery. I preached a special sermon to a very attentive congregation upon the labour question. After Divine Service the Lord Mayor and members of the party lunched at the Embassy with Sir Francis and Lady Feodorowna Bertie. In the afternoon the Lord Mayor, accompanied by Sir George Faudel Phillips, Sherriffs Dunn and Crosby, Sir Joseph Savory, and Sir Vesey Strong, paid a visit to the Girls’ Friendly Society. There is usually a large attendance of girls on Sunday afternoon, but on this occasion the hall was crowded in every part. In introducing the Lord Mayor, I explained the objects of the Society, and told something of its good work in Paris. In reply Sir W. Vaughan-Morgan said “He had not expected to find the members of the Society so numerous in Paris. He did not know if he were breaking the rules in paying them a visit, but as Dr. Noyes had brought him in, he also hoped he would find some way of getting him out.” Sir George Faudel Phillips also said some kind words to the ladies and members present. The drives of the civic party in the City in the days that followed were a great delight to the people crowding the streets. I was on the Boulevards on one occasion when the carriages passed, and the remarks of the people at the unusual dresses, and especially the head gear of some of the party, were most amusing. I understand the principal carriage was not brought as it was too large for the railway vans! The Lord[24] Mayor and Corporation very kindly gave me 100 guineas as a memento of their visit, towards the proposed Church House in connection with the Embassy Church—a much-needed institution—part of which will form a club for young British men, and the whole be a centre for church work.

ENTRANCE TO BRITISH EMBASSY.

I lived and worked in Paris during the “reign” of five Presidents of the Republic and four British Ambassadors. When I went abroad M. Sadi Carnot was President. He was assassinated at Lyons in June, 1894, by the Italian Anarchist Caserio Santo. When I left Paris President Fallières had lately come to the Elysée. The interest of the British Colony largely centres in the British Embassy, and the residence of the Ambassador in the Faubourg St. Honoré has been the scene of many notable gatherings. The house itself is a very attractive one, with beautiful gardens extending at the back to the Champs Elysées. It is said to have been built after the design of Mazin, in the eighteenth century, and was originally inhabited by the Princess Pauline Borghése. It may be interesting to some to know that pieces of the Borghése furniture still remain in the Embassy, notably the handsome bedstead. His Majesty the King occupied this when staying at the Embassy. Some beautiful Empire clocks are to be seen in the reception rooms, and are, I understand, unique and very valuable.

It was in the time of the Duke of Wellington that the property was purchased for the English Government. The price said to have been paid was 625,000 frs., a comparatively small sum. It has proved a profitable investment, as property in this part of[26] Paris has greatly increased in value. It is estimated that the property is now worth six millions of francs (£240,000). The following is, I believe, a complete list of the Ambassadors who have resided there:—1816, Sir Charles Stuart; 1825, Viscount Granville; 1829, Lord Stuart de Rothesay. During the reign of Louis Phillipe, Henry, Lord Cowley, and then the Marquis of Normanby, were at the Embassy. 1852, Lord Cowley (son of the former Ambassador); 1868, Lord Lyons; 1887, The Earl of Lytton. Lord Lytton died in June, 1891, and was succeeded by the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava, who retired upon the age limit of seventy in 1896. He was succeeded by Sir Edmund Monson, who also retired from age, and the present occupant is the Right Hon. Sir Francis Bertie, whose wife is a daughter of Lord Cowley, the former Ambassador. I had intended, with the permission of the Ambassador, to put a board in the Embassy Gallery in the Church, recording the above facts and dates, which would be of great interest to many, but I put it off until too late. Perhaps my successor may wish to carry out this idea.

The success and comfort of the Chaplain in his varied work connected with the Embassy Church, naturally depends largely upon the support and sympathy of the Ambassador and his family. I desire to place it on record that during my sixteen years’ work in Paris, nothing could exceed the kindness and consideration which I received.

EARL OF LYTTON.

My first introduction to the Embassy was when the offer of the chaplaincy came to me. There was then a considerable debt upon the Church, which I was required to undertake, and which caused me to[27] hesitate. I was uncertain how far the Colony would support me. I was advised to go over to Paris and consult with Lady Lytton before I finally decided. I did so, and was most kindly received. We talked the matter over, and I related my difficulties, when Lady Lytton said: “Come, and we will help you to pay off this debt” (£600). Her Excellency promised that she would organise a bazaar, which would no doubt be sufficient. Soon after my arrival a meeting was called and the matter put in hand, but alas! before the sale could be held, the Earl of Lytton died.

It fell to Lady Dufferin—who kindly took the matter up—to make her first public appearance as Ambassadress, at the opening ceremony. The effort proved most successful, the debt was paid, and a balance remained which enabled me to put double doors to the Church, which in the winter time were most necessary. The Earl of Lytton was not a regular Church goer. He used jokingly to say to me: “You are so crowded I can’t get in”; but Lady Lytton and her daughters were most regular, and generally at both morning and afternoon services on Sundays. Her Excellency took a great interest in the British poor and in the various charities, especially in the Victoria Home—paying frequent visits to the old ladies—much to their delight.

It was a sad time in the English Colony when the family left. Personally, we missed them greatly, for we were frequently at the Embassy, our children often played there, and in every way the relationship had been most happy. It was a real pleasure to us to receive several visits from Lady Lytton subsequently in Paris, and to answer her kind enquiries about friends in the Colony.

A change at the Embassy is always, for many reasons, an anxious moment for the English colony. It was with real pleasure that we heard the news that the Earl of Lytton was to be succeeded by the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava, who had been as part of his memorable career both Governor of India and Canada, and whose name was well known to all English people. Lord and Lady Dufferin arrived in Paris in March, 1892.

A hearty welcome was accorded to the Marquis and his family, and it was soon felt that we had in him, not only an Ambassador accredited to the French Republic, but also one who realized his responsibilities to the large Colony of British people always to be found in Paris; and that in this attitude he would be in every way supported by his noble wife. As chaplain to the Embassy Church I was most grateful for the kind reception and encouragement I received from the day of their arrival until their much regretted departure. It was delightful to see the Embassy gallery in church crowded the Sunday after their arrival, and to find they took a lively interest in all religious and philanthropic questions. I was at times during my chaplaincy saddened by the too frequent neglect of the ordinary Church services by the Churchmen on the staff of the Embassy. Why is it that the Diplomatic seems the exception, with respect to a general rule in the public service of at least one attendance at their own Church on Sundays? I had, however, no reason to complain of the attendance during Lord and Lady Dufferin’s time in Paris—the gallery was invariably well filled. I suppose that after all it is in this service, as in others, a matter of example. As[29] is known, the Marquis of Dufferin suffered from deafness in his later years. He used sometimes to bring a book of sermons, which he read while I preached.

COUNTESS OF LYTTON.

The Embassy was practically an open house during this time, and the enthusiasm and devotion of the British Colony remarkable. In May this year a banquet was given in honour of the Queen’s birthday, and was most brilliant. The leading members of the Colony were invited. The banqueting hall was decorated with trophies gathered from many lands, and the table (as always) beautifully arranged with flowers, and some of the many curios the Marquis possessed from Canada, Burmah, India, etc. It was part of my duty to say the Grace on these occasions.

In November of the same year I received a visit from my lamented friend, Lord Plunket, late Archbishop of Dublin, and their Excellencies the Marquis and Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava honoured us by coming to meet him at dinner. The late Canon Meyrick, the Bishop of Clogher, and Père Hyacinthe Loyson were also with us. It was a gathering preliminary to a visit to Spain by Lord Plunket for the consecration of a Reformed Church in Madrid. I have said that the first public act of Lady Dufferin was to open the Bazaar on behalf of the debt on the Church, which she did in a telling little speech, which made a most favourable impression upon all present. But Her Excellency may be said to have been always before the public in Paris. She found time amid the onerous duties of the Embassy to visit the various charitable institutions, and to organize[30] help and give advice wherever needed. I remember on one occasion she came to the meeting of the British Charitable Fund, and sat for a considerable time listening to the various tales of woe that came before us. The applications to Her Excellency from professional beggars were very numerous, but she never gave help without careful enquiry, and I was glad to be of frequent assistance to her in this matter. The Victoria Home for Aged British Women was regularly visited by Lady Dufferin and her daughters, indeed, almost every week, and Her Excellency knew all the inmates and the story of their long life in France. She had no more devoted admirers in the Colony. The Ladies Hermione and Victoria Blackwood were ever welcome, and spared neither time nor trouble to brighten and cheer their lives. Photographs of the Dufferin family hang in many of the rooms, and long after they left the old ladies would make anxious and loving enquiries about them. The Girls’ Friendly Society, as I have stated elsewhere, owes its present prosperous condition to the efforts of Lady Dufferin.

THE MARQUIS OF DUFFERIN AND AVA.

My predecessor, Rev. Howard Gill, realizing the necessity of a central building where the various Church works could be concentrated, and where also much-needed rest and recreation rooms for young men might be established, had ventilated the idea of a Church House. There is no house or room of any kind connected with the Embassy Church. An influential meeting was held in the Mansion House in London in furtherance of the project, but owing to the debt on the church nothing had been done. As this debt had been paid I felt we might move forward, and consulted Lord and Lady Dufferin on[31] the subject. The difficulty was to commence a fund when so large a sum (about £12,000) would be required. Their Excellencies, however, advised me to go forward, and promised me all the assistance they could. Lord Dufferin kindly wrote me a letter which I published with an appeal. A short time after I was told by Lady Dufferin that they had decided to allow a public sale in the Embassy on behalf of the scheme. This proved to be a great success. Lady Dufferin presided over a stall assisted by the ladies of the Embassy, and the Ladies Blackwood conducted a fish pond which was largely patronized. The “clew” of the sale was an exhibition in a private room of all the “curios” belonging to Lord Dufferin, including a gilt filagree stand and drinking cup, which had belonged originally to the King of Burma. His Excellency took the most lively interest in his own “show,” and never tired going round to explain the various objects to the visitors. The nett result of the sale was over 27,000 francs, and the fund was now fairly started; it amounted to between seven and eight thousand pounds when I left Paris. The house can now be purchased, as the balance required can easily be borrowed.

The thoughtful personal kindness I and my wife received from Lord and Lady Dufferin is beyond words to express. I may only give one or two examples. There is no residence attached to the Church, and as I was living some distance away it was very difficult to get back after the eight o’clock Communion Service on Sunday mornings for breakfast, and be down again for Sunday School (held in the Church) at 9.30. Lady Dufferin at once recognized[32] this, and kindly offered me breakfast on Sunday mornings at the Embassy. The rest was most helpful, and I used to look forward to my meal in the pleasant gallery looking out upon the garden—and an occasional chat with Nowell, who waited upon me—as a most pleasant break in the constant work of Sunday. Nowell was the confidential servant of Lord Dufferin for many years, who went with him to Canada in 1872, and had been with him in all his different posts.

A rather amusing incident once happened. The late Archbishop of York was staying at the Embassy, and we were invited to meet him at dinner on the Saturday evening. While I was at breakfast on Sunday morning he sent his servant down to ask me the way to the other English church!

In 1893-4 my wife had a most serious illness, and was confined to the house for some months. I can truly say that scarcely a day passed without Lady Dufferin coming in to see her, and often to sit with her for a considerable time. Even when His Majesty the King (then Prince of Wales) was in Paris, and lunching at the Embassy, she did not omit this kind office, but apologized for being late. Such kindness can never be rewarded or forgotten.

Our relations with the French were not at this time of the most cordial character, and I often feared that His Excellency had a good deal of anxiety that we knew nothing of—as, of course, we never spoke of “politics” at the Embassy. I once, however, ventured to say that I feared he had been passing through a troublous time, and he took and held my hand in his kind way and said: “My dear Noyes, when one has been through the anxieties of Canada[33] and India, it is not so difficult to support the trouble here.”

THE MARCHIONESS OF DUFFERIN AND AVA.

But if the Embassy had its grave moments it had its gay ones too. One morning, quite early, I received a visit from apparently an old lady (really a very young one), who told me she was in great trouble. She seemed, however, very reluctant to explain, and said she would like to see my wife. As she was not down I proposed she could come later, or, if she preferred, see me in the Vestry, where I usually received such visits. After some demur she promised she would. I learned later in the day that it was one of the ladies from the Embassy—disguised.

She went from me to the Chancery, and equally deceived one of the Attachés. The “make up” was very clever, and I was quite deceived. We were dining at the Embassy the same evening, and His Excellency said, “I wish she had got a franc from you, I should have put it on my watch-chain.”

We had a very enjoyable Christmas party at the Embassy in (I think) 1894. Lady Dufferin had arranged for a sort of magnified charade, in which the family and most of the Attachés took part, and in which they “took off” one another. The scene representing the writing of a dispatch in the Chancery was most amusing, the peculiarities of the different secretaries were cleverly caricatured. I was brought into the play, with some other members of the Colony.

It was a happy coincidence that there were two weddings in the Dufferin family during their stay in Paris. These occasions were peculiarly interesting to me, as I had been in the habit of giving[34] religious instruction to the younger members of the family every week at the Embassy; and also that I had known the Hon. W. Lee Plunket, who married Lady Victoria Blackwood, for some years. His father, the late Archbishop, was an intimate friend, with whom I had travelled much in England, Scotland, Ireland, Spain, and Portugal. The first marriage, that of Lord Terence Blackwood and Miss Flora Davis, took place on Oct. 16th, 1893. Miss Davis being an American, the wedding took place in the Church of the Holy Trinity, Avenue de l’Alma, Dr. Morgan and myself being the officiating clergy. The church was beautifully decorated, and well filled with guests, both the English and American Colonies being largely represented. In the seats reserved for distinguished guests were Lord and Lady Dufferin, the United States Ambassador (Mr. and Mrs. Eustis), the Baron and Baroness de Morenheim from the Russian Embassy, Mrs. J. H. Davis (stepmother of the bride), with some other relations. After the ceremony a reception was held at the British Embassy, very numerously attended by both French and English. The large number of handsome presents—under the charge of Nowell—had many admiring visitors. It was altogether a most interesting and brilliant gathering, and the first marriage from the Embassy for several years.

TRAINBEARERS AT THE LADY PLUNKET’S WEDDING.

The wedding bells were, however, heard again when the Hon. W. Lee Plunket (now Lord Plunket, Governor of New Zealand) was married in the Embassy Church to Lady Victoria Blackwood, daughter of their Excellencies Lord and Lady Dufferin. The wedding took place on June 4th, 1894, and was a most interesting event. It had been[35] given out that the marriage would be of a semi-private character. Notwithstanding, the church was full to the doors. It was an interesting gathering from both the family and public point of view. Mrs. Rowan Hamilton, Lady Helen Ferguson, Lady Terence Blackwood, Lady Hermione Blackwood, and the Hon. Elizabeth and Olive Plunket (sisters of the bridegroom), were present, and Miss Muriel Stephenson and the Hon. Cynthia Lyttelton were among the bridesmaids. In describing the bridal procession, the “New York Herald” said: “The noble Marquis, who wore the conventional frock coat, appeared deeply moved as he led his beloved daughter to the altar. In close order behind came the eight bridesmaids in their light dresses and broad hats, forming a very gay cortège, the rear of which was brought up by a weeny mite of six years or so in an ample Greenaway white skirt and mob cap, and her brother equally diminutive, a jolly little ‘shaver,’ alert as he could be, his big blue eyes taking in everything, dressed in white knickerbockers and three-cornered white cavalier hat. How sweet they were. Let me introduce them to you—Miss Dora Geraldine Noyes and Master Claude Noyes.” The latter, who had imbibed the idea that this ceremony involved the departure of Lady Victoria from the Embassy, for whom he had a great admiration, was very indignant with Mr. Plunket, and “went for him” later on in the Embassy garden. It was a great pleasure to me to stand on this occasion side by side with Lord Plunket (then Archbishop of Dublin) and to assist in the marriage of his son. The signatories of the marriage contract were the Earl of Dufferin and Ava, Lord[36] Plunket (Archbishop of Dublin), Mr. F. Rowan Hamilton, the Hon. David Plunket, and myself. The reception after the ceremony in the Embassy gardens was a brilliant gathering of “Tout Paris.” M. Hanotaux (the newly appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs) was among those present, and the Diplomatic Corps were “au grand complet.” Many American friends of the family came to wish Godspeed and happiness to the young couple. It was a happy gathering, and the fine old garden—the scene of so many memorable gatherings—looked its best.

In the Diplomatic service Ambassadors retire at the age of seventy; there was real sorrow in the English Colony in Paris when it was known that the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava was nearing this period. It being, however, inevitable, it was decided to render their departure as little sorrowful as possible, so far as the British Colony was concerned. A Committee was formed to consider a presentation to Lord Dufferin, and also a Committee of ladies, who were anxious to mark their appreciation of Her Excellency’s kindness and untiring work in connection with the various charities. It was agreed to present to the Ambassador a portrait of his son, Lord Ava, who was also very popular, and M. Benjamin Constant was commissioned to paint it.

It was unfortunately not ready for the day when the presentation was made, but the subscribers were invited to view it later. It is now, of course, of very special value, owing to the unfortunate death of Lord Ava in South Africa. At the banquet, when the presentation was made, the Earl made a most interesting speech, part of which is well worth recording.[37] He said: “That he felt he was not addressing an audience, but was speaking to a few dear and intimate friends, and therefore would not make a set speech. When one had something to say from one’s heart words came easily. Considering the almost minatory words in Scripture, addressed to those who, like himself, had reached their seventieth year, he hardly knew whether he might consider himself as possessed of a future, or whether he ought not to regard his life as over, and himself as an uninvited guest at a crowded banquet. He consoled himself, however, with the reflection that the words of Holy Scripture were addressed to a people whose life began rather earlier—who married, for instance, sometimes at the age of ten, and whose girls were occasionally mothers at that age. As he had not married till he was thirty-six, he concluded that he was only now beginning his life. Speaking as he did in the British Embassy, he remembered what he felt at his first appearance there. It was in that room that he had ventured upon his first waltz, having been ordered to dance. The lady was, he feared, thoroughly disgusted with her partner. In this room, too, he remembered a performance of the ‘School for Scandal,’ in which three of the characters had been taken by three descendants of Sheridan—the Duchess of Somerset, his mother, and Mr. R. Sheridan. Finally, the room would be after this associated with one of the most gratifying incidents of his life, the presentation of this gift by his friends in Paris. He would like to say a few words on his choice of the present. He had desired something which might descend to his heirs, and remain long afterwards as a memorial of[38] the kind feelings with which he had been regarded in Paris. He had not chosen, therefore, a valuable picture or other object which squandering descendants—such persons were occasionally found in families—would at once sell, but he had asked for a portrait of his son which would grow more valuable with time, and be a long-lasting memorial of his Paris career. It would be among the most treasured of the objects which he had collected at Clandeboy from all parts of the world.”

The speech was delivered in the Earl’s happiest vein, and was listened to with rapt attention, though not without emotion, it being his last public address to the British Colony in Paris.

The Colony, however, were not satisfied with shewing their warm appreciation of the kindness of their Ambassador. Lady Dufferin had won all hearts during her stay by her consideration and goodness to rich and poor. Almost every charity in Paris had benefited from the indefatigable work of Her Excellency, who had gone thoroughly into the affairs of the various agencies and then set herself to strengthen any that were weak. Never did she fail to respond to any appeal, taking a personal interest in every case, often at a sacrifice to the demands upon her diplomatic duties. It was both a glad and a sad gathering in the “Galerie des Champs Elysées” in June, 1896, when the presentation committee and a large gathering of friends met to say farewell to their Ambassadress. The gift was a lovely Louis XVI. clock and candelabras, and was presented on behalf of the donors by the Hon. Mrs. Gye.

In reply Lady Dufferin said: “It is really impossible for me to say what I feel on this occasion,[39] for I am quite overwhelmed by your kindness and by your expressions of friendship and goodwill. However undeserving of such kindness I may feel, it is a very great pleasure to me to receive this assurance of your sympathy. I thank you with all my heart for your generous words, your good wishes, and for this most lovely gift. I thank you also for the many occasions upon which during the last three years you have shewn your sympathy with other members of my family, and for the loyal support you have ever given me in all matters relating to British charities in Paris. It is the duty, and I am sure it is the pleasure, of every English Ambassadress here to interest herself in these institutions, but without the hearty co-operation of the British residents, her fellow subjects, her interest in them could have no practical result. If, therefore, I have been able to promote in the slightest degree the welfare of any British charity here, it is because of the unfailing help and support I have received from you.”

Shortly after, the departure of Lord and Lady Dufferin took place. It was a time and scene not easily forgotten. The whole Embassy staff were gathered in the hall, my wife and myself among them. The Ambassador and Lady Dufferin came down and went round to everyone, shaking hands and saying goodbye. There were few dry eyes. No ceremony marked their departure beyond this, and they drove away in an ordinary “growler”—it was just like them. Lord and Lady Dufferin returned to Paris subsequently—for the Emperor and Empress of Russia’s visit—but stayed at an hotel. I rarely met Lord Dufferin afterwards. The last time was at the cemetery at Mount Jerome, Dublin, when we stood[40] beside the grave of the late Lord Plunket. He then laid his hand on my shoulder, saying: “Noyes, this is a great deal out of your life;” and so it was, for I had been intimate for many years with the Archbishop. It has been our delight to welcome Lady Dufferin on several occasions since.

The death of Lord Ava in South Africa, so deservedly loved, was a great blow to Lord Dufferin, and one of the sorrows which no doubt brought him to the grave.

On that occasion he wrote me the following letter:—

“My dear Noyes,—

“I knew you would feel for us, and my wife and I are deeply grateful to you and Mrs. Noyes for the sympathy you have shewn us. We know no details except that the telegram told us that our poor boy died without having ever recovered consciousness from the time he was struck. It is God’s will, and we must try to submit in patience.

“Yours very sincerely,

“DUFFERIN AND AVA.”

The successor to the Marquis of Dufferin in Paris was Sir Edmund Monson, Bart., who had held many and important posts in the public service. He came to the Faubourg St. Honoré in October, 1896, having been Ambassador Extraordinary, and Plenipotentiary to the Emperor of Austria since 1893. He was appointed a Royal Commissioner for the Paris Exhibition of 1900, and was made an honorary D.C.L. of Oxford in 1898. He also received the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour from the French Government.

Sir Edmund and Lady Monson received a hearty welcome from Parisians generally, and the Ambassador soon won his way with us all by his kindly manner and warm interest in whatever concerned the British Colony. There were many important events during the time Sir E. Monson was with us, among which was the celebration of the Jubilee of Queen Victoria, which took place in June, 1897. A garden party was given at the Embassy, which was very largely attended. The “Figaro” said there were about four thousand present. The entire Diplomatic Corps, artistic, political, and literary celebrities, distinguished visitors to Paris, and the leading members of the British Colony were included. Madame Felix Fauré and Mlle. Lucie Fauré, wife and daughter of the President, M. Hanotaux, and many others well known in French politics and society, were amongst the guests. General Horace Porter, the American Ambassador, was supported by a large number of the American Colony. The following day a Children’s Fête was held at St. Cloud. Special boats conveyed the young Britishers to the rendezvous, and a most enjoyable day was spent. Between eight and nine hundred sat down to tea, when patriotic speeches were made amid hearty demonstrations of loyalty to the Throne. It is not an unimportant part of the chaplain’s work to keep “green” in the hearts of the young living in Paris the home feeling, and to prevent their slipping away from attachment to their Sovereign.

The following year was marked by the “Fashoda” incident, which, it will be remembered, caused much excitement in both countries. Relations were somewhat strained, and all sorts of[42] exaggerated rumours got abroad. I remember it being reported that Sir E. Monson had gone to the Elysée with an “Ultimatum” in his pocket; and again, that the Embassy had commenced to pack up with a view to removal! In December, 1898, the British Chamber of Commerce gave a banquet, at which Sir Edmund Monson made a speech which caused considerable excitement. On arrival, I found the journalists, who had seen a copy of the speech before it was delivered, in a considerable flutter, M. Blowitz of the “Times” being especially active. There was marked silence during the delivery of the speech by the Ambassador. The following is the most striking passage: “I would entreat the French Nation to resist the temptation to try to thwart British enterprise by petty manœuvres; such as I grieve to see suggested by the proposal to set up educational establishments as rivals to our own in the newly acquired provinces of the Soudan. Such ill-considered provocation, to which I confidently trust no official countenance will be given, might well have the effect of converting that policy of forbearance from taking the full advantage of our recent victories, and our present position, which has been enunciated by our highest authority into the adoption of measures, which, though they evidently find favour with no inconsiderable party in England, are not, I presume, the object at which French sentiment is aiming.”

COURT YARD, BRITISH EMBASSY.

In February of the next year, President Felix Fauré died quite unexpectedly. There was a certain mystery about his death which has never been quite cleared up to the public satisfaction. The wildest rumours were spread in Paris. I visited the Elysée, and the salon where the dead President lay. He[43] looked much as I had often seen him in life. He was dressed in evening clothes, the prevailing custom in France. The funeral was most imposing. But “Le Roi est mort, vive le Roi.” Very soon the question of a successor came on, and the grand Salon at Versailles (where the German Emperor was crowned in 1870) was filled with the deputies to elect their President. The choice fell upon M. Loubet—contrary to the expectation of many—and the event showed that he was the right man, for during his Presidency France had a comparatively quiet period.

Next year (1900) came the great Exhibition, when we were flooded with visitors from all parts of the world. Sir Edmund Monson kindly placed the ballroom at the Embassy at my disposal for an overflow service on the Sunday mornings, as the church proved too small.

Indeed, nothing could exceed the interest and kindness of the Ambassador in all Church matters. During this year the Annual Conference of Continental Chaplains was held in Paris, as it gave them the opportunity to visit the Exhibition. Halls suitable for such a gathering were very expensive, but again the Ambassador came to our aid, and we held the Conference in the ballroom at the Embassy. He also gave a banquet to the chaplains, which was much appreciated. I unfortunately caught typhoid fever at the end of the year, and so was debarred from many of the closing functions which were crowded into that time.

In 1901 came our great National loss in the death of England’s greatest Queen. I have described elsewhere the deep feeling manifested in the British[44] Colony in Paris, and the services held in connection with that sad event.

I have spoken above of the kindness of Sir E. Monson in all Church matters. When the time of his departure drew near, I wrote to tell him how much the British Colony, and especially the congregation of the Embassy Church, appreciated what he had done. He wrote me the following letter:—

“My dear Dr. Noyes,—

“I am deeply touched by your kind letter of yesterday; and it is a real gratification to me to think that our association during the last eight years has been productive of such relations of friendship as have constantly existed between us, and that our steady co-operation in the interests of the English community here has never failed to be advantageous.

“In the many posts which I have occupied in Her Majesty’s service, it has always been one of my chief pleasures to come into contact with the English chaplains, and it has so happened that wherever I have been I have had opportunities of making a general acquaintance with all the accessible clergy. I have had special experience of their devotion to their work, and though differences of opinion are inevitable, I have never found that such differences have seriously interfered with social liking and harmony. It has consequently been always a real pleasure to my wife and myself to welcome the chaplains whenever a general meeting calls them together at the post we may be occupying. It is not so easy at Paris as it is elsewhere to be in touch with a large British community, but everyone with whom we have made acquaintance has given us evidence of interest for which we cannot but be very grateful.[45] We hope to be from time to time in Paris, and whether we have a sort of home here or not, we shall at any rate look upon the Rue d’Aguesseau Church as a spot in which we have a vested interest, and where we shall never be regarded as strangers. With my wife’s very kind regards to yourself and Mrs. Noyes, I remain, dear Dr. Noyes,

“Most sincerely yours,

“EDMUND MONSON.”

Sir Edmund Monson left us at the close of 1904, to the sincere regret of all his friends. He was succeeded by the present Ambassador, the Right Hon. Sir Francis Bertie, K.C.M.G., etc., who came into residence in January, 1905.

The staff at the Embassy is continually changing, so that during my long chaplaincy in Paris I made the acquaintance of many, and the friendship of some now serving King and country in different parts of the world. It would, I think, be difficult to find in the public service a finer body of men than those in Diplomacy.

The journalist has no doubt minimised to some extent the work formerly done by the Diplomatist—as Sir Edmund Monson pointed out in one of his speeches. But the adjustment of international difficulties, and the solving of delicate questions continually arising—the “keeping of the buttons tight”—leaves a vast amount of work with which Diplomacy only can deal, and for which the careful technical training for that service alone supplies the knowledge.

One of the best-known figures at the Embassy is Sir Henry Austin Lee, C.B., etc., who has been[46] many years attached to the Embassy, and is universally loved and respected. He has had, as is well known, a very distinguished career.

Among the many important appointments he has held, it will be remembered that he was attached to the late Marquis of Salisbury’s special Embassy to Constantinople in 1876, and the special Embassy during the Congress in Berlin in 1878, being assistant private secretary to the late Earl of Beaconsfield. He is now Commercial Attaché in Paris, and Councillor of the Embassy, and also Director and member of the Managing Committee of the Suez Canal Company. Sir Henry Lee takes the warmest interest in the British charities in Paris, and is Chairman of the Schools and member of the Committee of the British Charitable Fund. His marriage was the last held in the Embassy. I officiated with his brother at the ceremony. Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales (then Princess May) was present on the occasion, and H.R.H. the Duke of Teck one of the witnesses.