The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mail Carrier, by Harry Castlemon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Mail Carrier Author: Harry Castlemon Release Date: January 21, 2018 [EBook #56408] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAIL CARRIER *** Produced by David Edwards, Barry Abrahamsen and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Dave, the Mail Carrier.

GUNBOAT SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 6 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

Frank the Young Naturalist. Frank on a Gunboat. Frank in the Woods. Frank before Vicksburg. Frank on the Lower Mississippi. Frank on the Prairie.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

SPORTSMAN’S CLUB SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

GO-AHEAD SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

Tom Newcombe. Go-Ahead. No Moss.

FRANK NELSON SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

Snowed Up. Frank in the Forecastle. Boy Traders.

BOY TRAPPER SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

ROUGHING IT SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

George in Camp.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | “Hark Back!” | 5 |

| II. | A Mighty Hunter | 24 |

| III. | Lester shows his courage | 42 |

| IV. | Don shows his | 55 |

| V. | Godfrey visits the Cabin | 73 |

| VI. | Bob is astonished | 94 |

| VII. | Bob’s Plans | 114 |

| VIII. | Bob in a quandary | 131 |

| IX. | The Runaway | 147 |

| X. | Bob’s first Adventure | 165 |

| XI. | The Cub Pilot | 185 |

| XII. | George at the Wheel | 207 |

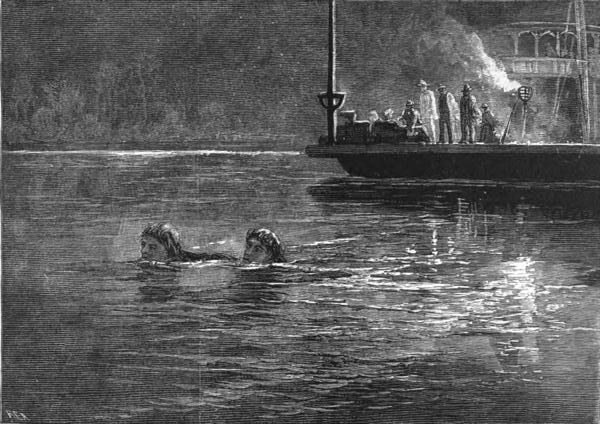

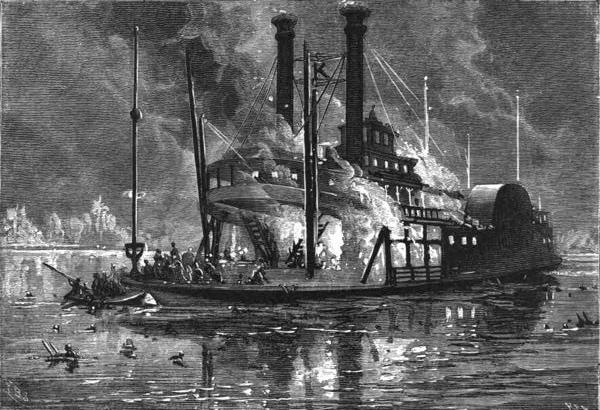

| XIII. | The burning of the Sam Kendall | 227 |

| XIV. | A Specimen Trapper | 246 |

| XV. | The lost Pocket-book | 265 |

| XVI. | Dan makes a discovery | 286 |

| XVII. | Conclusion | 303 |

“LOOK out thar, Dannie! Don’t run over a feller!”

Dan Evans, who was trudging along the dusty road, with his eyes fastened thoughtfully on the ground, and his mind so wholly given up to meditation that he did not know what was going on around him, stopped suddenly when these words fell upon his ear, and looked up to find himself confronted by a horseman, who had checked his nag just in time to prevent the animal from stepping on the boy. He was a small planter in the neighborhood, and Dan was well acquainted with him.

“You’re gettin’ to be sich rich folks up to your house that you look fur everybody to get outen your way, I reckon, don’t you?” continued the planter, with a good-natured smile.

“Rich!” repeated Dan, flushing angrily, as he drew his tattered coat about him. He did not know what the planter meant, and thought he was making sport of his poverty. “I can’t help it kase I don’t wear good clothes like Don and Bert, kin I? I work monstrous hard——”

“And get well paid fur it, too, I tell you,” interrupted the horseman. “I’d be glad of a chance to ’arn that much money myself. You needn’t wear sich clothes as them no longer, kase Dave an’ you is pardners, most likely, an’ he’ll do what’s right by you.”

“Dave!” echoed Dan, who now began to listen more eagerly.

“Yes. He’s a powerful smart boy, Dave is, an’ I’m glad to see him so lucky. He took home a wad of greenbacks this arternoon as big as that,” said the planter, pushing back his sleeve and showing his brawny wrist.

Dan fairly gasped for breath. He backed toward a log by the roadside and seated himself upon it, letting his rifle fall out of his hands in his excitement.

“Yes,” continued the planter, who seemed to be a little surprised at Dan’s behavior; “them quails reached that man up North all right, an’ to-day the money come—a hundred an’ ninety-two dollars an’ a half.”

Dan gasped again, and, taking off his hat, drew his coat-sleeve across his forehead.

“Yes. Silas Jones, he done took twenty-eight dollars outen it fur freight an’ give Dave the balance—a trifle over a hundred an’ sixty-four dollars. I was in the store at the time, an’ it done me good to see Dave take them thar greenbacks an’ walk out.”

“Whar—whar’s the money now?” Dan managed to ask at last.

“Why, he took it home with him, I reckon. What else should he do with it? Now, Dannie, don’t you get on a high hoss an’ say that you won’t look at us common folks any more.”

With this parting advice the planter rode off, leaving Dan sitting on his log, lost in wonder. It was a long time before he recovered himself, and when he did, he jumped to his feet as if he had just thought of something that ought to have been attended to long ago, caught up his rifle and disappeared in the woods.

This incident happened on the same day on which Silas Jones paid David for the quails he had shipped by the steamer Emma Deane. At the close of the second volume of this series, we saw that as soon as David had received the reward of his labors he made all haste to reach home. He found his mother there, but before he said a word to her about his good fortune he walked around the cabin two or three times and looked sharply in every direction, to make sure that his brother Dan was nowhere in the vicinity; and having satisfied himself on this point, he went in and laid the roll of greenbacks in his mother’s lap.

David had reason to feel proud, for he had earned the money in spite of many obstacles. In the first place, there was Dan, who, when he learned that his brother was in a fair way to earn a handsome sum of money by trapping quails and shipping them to a man in the North, who had advertised for them, determined to share in the proceeds of his work, and offered to go into partnership with him; but David would not consent, and this made Dan his enemy. Dan declared that not a quail should be caught in those fields. He would make it his business to hunt up his brother’s traps, and if there were any birds in them he would either liberate them or wring their necks, and then he would smash the traps. But, as it happened, Dan did not carry this threat into execution. An older and wiser person than himself, with whom he held frequent consultations, had another plan to propose, and Dan readily fell in with it.

Godfrey Evans, Dan’s father and David’s, was in deep disgrace. He had robbed Clarence Gordon of twenty dollars on the highway, and for fear that he would be arrested and punished for it, he took to the woods and stayed there. He lived on a little island in the bayou, about two miles from the settlement, which had been his hiding-place during the war, when the Union forces were raiding that part of Mississippi. Here he lived in a miserable brush lean-to, with no companion but his rifle, until his hiding-place was accidentally discovered by Dan, during one of his rambles in the woods.

Of course Godfrey was anxious to know what had been going on in the settlement since he left, and among other things Dan told him that David was going to make himself rich by catching quails, but that he (Dan) had resolved to put a stop to it by breaking his traps. After hearing a statement of the case, Godfrey told his hopeful son that if he wished to be revenged upon David for his refusal to go into partnership with him, there was a better way than that. It was not to their interest to interfere with the Boy Trapper in any manner. Let him go on and catch the birds, and when his work was done and he had received the money for it, then it would be time for them to act. They would take the money themselves and divide it equally between them. Godfrey did not say what he intended to do with his share when he got it, but he drew the most glowing pictures of the comforts and luxuries with which Dan could provide himself when he received the money that would fall to his lot. Dan wanted to live just as Don and Bert Gordon lived. He wanted a spotted pony, a breech-loading shot-gun, a jointed fish-pole and a sail-boat; and in order to insure his earnest assistance in the scheme he proposed, Godfrey held out the idea that for seventy-five dollars (they expected that David would receive one hundred and fifty dollars for his birds, and that would give them just seventy-five dollars apiece, if the money were equally divided) all these nice things could be purchased, and besides something would be left to be invested in good clothes.

Dan was delighted with his father’s plans, and from that hour was as much interested in David’s success as David was himself. It chanced, too, that he was able to defeat a plot which, if carried into execution, would have worked much injury to the boy trapper. It turned out that there were two other persons in the settlement whom David had reason to fear. They were Lester Brigham and Bob Owens; and as they did not expect to share in the money after David earned it, they were determined that he should not earn any at all. They were disappointed applicants for the very contract that had been given to David. When they read the advertisement in the Rod and Gun, calling for fifty dozen live quails, they lost no time in replying to it; but they were just three days too late, the wide-awake Don Gordon having already secured the order for David Evans.

When Bob and Lester found this out they were very angry. Bob wanted a breech-loader as much as Dan did. Almost every boy in the settlement with whom he associated owned one, and seventy-five dollars would put him in possession of one, too. He had long been on the lookout for a chance to earn that amount of money, and when it was almost within his grasp it was snatched from him by that meddlesome Don Gordon and handed over to that ragamuffin Dave Evans. This was the way Bob and his friend looked at the matter, and after they had talked it over they came to the conclusion that David had no business with so much money, and that he should not have it. They wrote to the man who had advertised for the quails, telling him that the person to whom he had given the order was not reliable and could not furnish him with the required number of birds; and then they set to work to make their words good.

The first thing they did was to try to frighten David by threatening him with the terrors of a law which did not exist. Lester told him that if he trapped quails and sent them out of the state he would render himself liable to fine and imprisonment; but David knew better, and positively refused to give up his chances of earning an honest dollar, although Lester threatened to beat him with his riding-whip if he did not. Being defeated at this point, the conspirators tried another plan. They drew up a constitution and by-laws for the government of a Sportsman’s Club, and Lester started out to obtain signers to it. He first called upon Don and Bert Gordon, for he knew that if he could secure their names, he could secure Fred and Joe Packard’s, too, and, through the influence of these four, every young sportsman in the settlement could be brought into the club. But Don and Bert did not like Lester, and neither did they like the object for which the club was to be organized. They saw plainly that Bob and Lester were trying to form a combination against David Evans, and as they could not assist in any such business as that, they declined to put down their names.

Highly enraged over their second failure, Bob and Lester prepared to take vengeance on the brothers, which they did that very night by setting fire to their shooting-box, which was located on the shore of the lake. Then, being determined that they would not give up until David had been driven from the field, they decided upon another plan, which was to set their own traps, which they had made in expectation of receiving the order, capture as many birds as they could, and at the same time watch David’s traps and steal every quail they found in them. But this plan failed also. The quails would not get into their traps and they could not find any of David’s. The reason was because they looked on Godfrey’s plantation for them, and David’s traps were all set in General Gordon’s fields.

The conspirators did not know that Don and Bert were assisting David in his work, but they found it out one morning by accident. They saw the three boys in the act of transferring their captured quails from a trap to a large coop they had placed in a wagon, and following the wagon as it left the field, they saw that when the captives were removed from the coop they were put into one of the general’s unoccupied negro cabins. After comparing notes they made up their minds that the cabin was almost full of birds, and that if they could only force an entrance into it, they would be well repaid for their trouble. They could steal some of them, and those they could not carry away they could liberate. They made the attempt that same night, and were sorry enough for it afterward. Dan Evans was on the watch, and he defeated their designs very neatly by directing the attention of Don’s hounds to them. The fierce animals forced the young robbers to take refuge on the top of the cabin, and there they remained until the general came down and released them in the morning.

While these incidents, which we have so hurriedly described, were taking place in the settlement, some others that have a connection with our story were transpiring a little way out of it. The most important of these was the discovery of Godfrey’s hiding-place by Don and his brother, who went up the bayou duck-hunting. It happened on the same day that Dan discovered it, and led to a good many incidents, some of which we have yet to describe. The most amusing, perhaps, was the stratagem to which Godfrey resorted to drive Don and Bert away from the island.

The brothers landed to take a few minutes’ rest after their long pull, and the first thing Don discovered was his canoe, which he valued highly, and which had been stolen from him a few days before. The thief was Godfrey Evans, who made use of the canoe in passing from the main land to his hiding-place on the island. The fresh footprints which were plainly visible in the soft mud showed that there was somebody besides themselves on the island, and they resolved to find out who he was. While they were advancing along a narrow path leading toward the interior, Godfrey, who with Dan was concealed in the cane at the other end of the path, imitated the growl of some wild animal so perfectly that Don and Bert, who were armed only with their light breech-loaders, made all haste to reach their boat and push off into the stream. Perhaps the remembrance of the scenes that had once been enacted in that same cane brake added to their terror. The place was known as Bruin’s Island, from the fact that a savage old bear had once made his den there, and had been killed only after a severe fight, during which he had wounded two men and destroyed a number of dogs.

Don and Bert really believed that another bear had taken possession of the island, and they resolved to dislodge him; so they secured the services of David Evans and his rusty single-barrel shot-gun, and the next morning returned to the island, accompanied by two good dogs and armed with weapons better adapted to hunting such large game than their little fowling-pieces were, Don being armed with his trusty rifle and Bert with his father’s heavy duck gun. They wanted to shoot the bear if they could, and if they failed in that, they came provided with tools and bait with which to set a trap that would catch him alive.

It is proper to state that there was a bear, which divided his time about equally between the island and the main shore, and the boys thought they would certainly have an opportunity to try their skill upon him on this particular morning, for the hounds scented something that drove them almost wild with excitement. But it was not a bear they scented; it was Godfrey Evans, who waited until both dogs and hunters were hidden from view by the cane, and then stepped into the bayou and struck out for the main land. The boys, however, firmly believed that the dogs had routed a bear, and they spent the day in building a trap for him, hoping that the next time they visited the island they would find the animal in it.

Now Godfrey had found it necessary to spend some of the money of which he had robbed Clarence Gordon, but he still had fourteen dollars of it left. As his pockets could not be depended upon to hold it, being full of holes, he hid the money in a hollow log, where he thought it would be safe. The sudden appearance of the young hunters and their dogs so greatly excited and alarmed him that he never thought of his treasure when he left the island, nor did he ever think of it again until Dan happened to mention it to him a day or two afterward. Then Godfrey swam back to his old hiding-place, but the money could not be found. Don and his companions had changed the appearance of things considerably while they were building the trap. Thickets had been cut down, logs rolled out of the way, and Godfrey could not find the place where he had hidden his ill-gotten gains. Of course he was almost beside himself with fury, and for want of a better way of being revenged on the young hunters, he sprung their trap and carried off the lever, rope and bait. He would have been glad to tear the trap in pieces, but it had been built to resist the strength of a full-grown bear, and Godfrey could not move any of the logs. When Don and Bert came up in their boat, to see if the bear had been caught, they found their trap in the condition we have described. They set it again, and how their efforts were rewarded this time we have yet to tell.

Meanwhile the work of trapping the quails went bravely on. Assisted by Don and Bert, who devoted as many hours to the business as David did himself, the boy trapper saw money coming in every day in the shape of scores of little brown birds, and he would have been as happy as any fellow could well be, had it not been for two unpleasant incidents that happened a short time before the attempt was made to rob the cabin, and which we neglected to notice in their proper place. One of these incidents was brought to his notice by his wide-awake enemies, Bob and Lester.

While these two worthies were discussing their prospects one night, shortly after dark, they detected somebody in the act of robbing Mr. Owens’s smoke-house. They succeeded in getting near enough to the thief to see that it was Godfrey Evans, and this suggested to them another plan for compelling David to leave off trapping the quails. Instead of reporting the matter to Mr. Owens, as they ought to have done, they sought an interview with David, and threatened that in case he did not leave them a clear field, they would have his father arrested for burglary. Of course David had no peace of mind after that; and, as if to add to his troubles, his brother Dan, who had already been the means of swindling Don Gordon out of ten dollars, made an effort to extort ten dollars more from him by stealing his fine young pointer, Dandy. But David was able to defeat this scheme, though at serious loss to himself. He visited his father’s new hiding-place in the woods, and, finding the pointer there, he succeeded in liberating him and starting him toward home; but in his desperate efforts to escape the punishment with which his angry parent threatened him he was obliged to swim the bayou, and in so doing lost his gun. He brought the pointer home, however, and saved Don’s ten dollars.

But if David had more than his share of trouble, he also had about as much good luck as generally falls to the lot of mortals. The quails got into his traps almost as fast as he wanted to take them out; and furthermore, General Gordon, who had long had his eye on the boy, was using his influence to secure for him the responsible position of Mail Carrier; but in so doing the general excited the jealousy of one of his neighbors, who envied him his popularity in the settlement, and would have been glad to injure him by any means in his power. This jealous neighbor was Mr. Owens, Bob’s father.

At first Mr. Owens did not care who took the old mail carrier’s place, so long as it was not some one who was recommended by General Gordon; but after he had talked with Bob about it, it occurred to him that it would be a fine thing if his own son could have the position instead of that low fellow, Dave Evans. Bob thought so, too, and suddenly made up his mind that nothing could suit him better. More than that, he looked upon the matter as settled already. His father promised that he would do the best he could for him; Lester said that his father would furnish the required bonds, if he (Lester) asked him to do so, and Bob thought he needed nothing more. In his estimation, three hundred and sixty dollars a year (that was what the old carrier received) was a sum of money that he would find it hard work to spend, and the belief that he would soon be in a fair way to earn it was all he had to comfort him when he saw David Evans walking up and down the river bank, with his hands in his pockets, surveying with great satisfaction the long line of coops which contained the captured quails, and which were piled there awaiting the arrival of the Emma Deane.

“Just look at him,” said Bob, in great disgust. “One would think, by the airs he puts on, that he was worth a million dollars.”

“Let’s come down here after dark and pitch every coop into the river,” said Lester.

“Why, he will stay here to watch them, won’t he?”

“What of that? If he says a word, we’ll tumble him into the river, too!”

Bob said nothing would please him more. He and his crony rode down to the landing that night, about nine o’clock, fully determined to carry out Lester’s suggestion; but, to their great surprise and disappointment, they found David and his property well guarded. A fire was burning brightly on the bank, and just in front of it was pitched a little lawn tent, which sheltered a merry party, consisting of Don and Bert Gordon and Fred and Joe Packard, who were singing songs and telling stories, while waiting for the lunch and pot of coffee which David was preparing for them. David looked up when he heard the sound of their horses’ feet, and a large, tawny animal arose from his bed on the other side of the fire and growled savagely. Bob and his companion waited to see and hear no more. They had no desire to trouble such fellows as Don Gordon and Fred Packard, either of whom could have whipped them both, and they stood in wholesome fear of that tawny animal behind the fire. It was the hound that had so nearly captured one of them on the night they attempted to break into the cabin in which the quails were confined. Without a word they turned their horses and rode homeward, and David and his property were allowed to rest in peace.

THE shame and mortification which Bob and Lester experienced after being detected in their attempt to break into the negro cabin, were of short duration. They gradually recovered their courage and began to mingle again with their associates; and although they saw one or two sly winks exchanged the first time they went to the post-office, no one said anything to them about being treed on the top of the cabin, and they hoped the circumstance was not known. But still they felt guilty, and were much more at their ease when they were alone.

They had much to talk about. Lester could never cease grumbling because David had succeeded in his enterprise, in spite of all their efforts to defeat him, and Bob, who was full of dreams and glorious ideas, was continually talking about the fine things he would purchase when he became mail carrier and was earning three hundred and sixty dollars a year. Then he and his friend Lester would see no end of fun. They would have a canoe in the lake and a shooting-box on the shore. They would camp out twice a year, as Don and Bert did, and they would have a crowd of fellows with them of their own choosing. As soon as Bob had earned money enough to purchase his breech-loader, he would invest in a dozen or two of decoys, and they would show that conceited Don Gordon that some boys were just as fine marksmen as he was, and could bag just as many birds in the course of a week’s shooting.

Lester readily fell in with these ideas, and suggested that, as they had no better way of passing the time just then, it might be well to make the canoe at once. Then they could explore the lake from one end to the other, and select a good shooting point whereon to build their house. Bob thought so, too, and with the help of one of his father’s negroes, who was handy with the axe and had shaped more than one dugout, they succeeded, after two days’ work, in producing a very nice little canoe, just about large enough to carry two persons and their camp equipage. Having no iron rowlocks, they made two paddles for it; and when they had given it a coat or two of lead-colored paint, they told each other that it was a much better and handsomer craft than Don Gordon’s. On the same day on which David received his money for the quails, they put the canoe into a wagon, hauled it down to the lake and made it fast to a tree in front of Godfrey Evans’s cabin, promising Dan, who happened to be at home, that they would give him a dime or two occasionally, if he would keep an eye on it and see that no one ran off with it.

When they reached home they found Mr. Owens, who had just returned from the landing. They knew by the expression on his face that he had some news for them. Bob thought it must be something that related to his own prospects, and eagerly inquired:

“Have I got the appointment, father? Am I mail carrier now?”

“O, it isn’t time for that,” was the reply. “I have not even made my bid yet. I don’t know that you ought to have it, Bob. A boy who will let a fellow like Dave Evans carry off a pocketful of money from under his very nose, I don’t think much of.”

“Has he received it?” asked Lester.

“I should say so. I saw Silas Jones pay him over a hundred and sixty dollars.”

Lester pulled off his hat and threw himself on the porch beside Mr. Owens’s chair, while Bob, who was so amazed and angry that he could not speak, stood still and looked at his father.

“See what you boys have lost by not having a little more ‘get up’ about you—eighty dollars apiece,” continued Mr. Owens. “Where’s your breech-loader now, Bob?”

“I could have bought one for that amount of money and a nice jointed fish-pole besides,” said the boy, regretfully. “I hope Dave will lose every cent of it.”

“He’ll look out for that,” answered Mr. Owens, with a laugh. “He has worked so hard for it that he’ll not let it slip through his fingers very easily.”

“He never would have got it if it hadn’t been for Don and Bert,” said Bob, spitefully. “But I don’t care—I’ll beat them all yet. Just wait till I get to be mail carrier, and I’ll show them a thing or two. Don’t you think I am sure to get it, father?”

“I think your chances are as good as anybody’s. I haven’t had an opportunity to speak to any one about it yet, but I must be up and doing to-morrow, for the general is busy all the time. He intends to get the contract himself and hire Dave to do the work, and that is the way I shall have to do with you, if I get it. The general was talking about it to-day in the store. He didn’t say a word to me—I suppose he thought I could neither help nor hinder him—but I walked up in front of him and told him very plainly that David was the son of a thief, and not fit to be trusted with such a valuable thing as the mail. You ought to have seen the general open his eyes. When I told him that Godfrey had robbed my smoke-house, he said David wasn’t to blame for that. He couldn’t help what his father did. I made no reply, for I didn’t want to let him know that I am working against him. If I can get the bonds, I think the rest will be easy enough.”

“I’ll speak to my father about it to-morrow night,” said Lester. “Bob and I are going up the lake in the morning, and as soon as we get back I’ll go home and fix the bond business.”

Bob passed a sleepless night. He grew angry every time he thought of David’s success, and jubilant and cheerful when he recalled his father’s encouraging words. The air-castles he built were as numerous and gorgeous as those Godfrey Evans erected when he told his family about the treasure that was buried in the general’s potato-field.

The two boys arose the next morning at an early hour, and as soon as they had eaten breakfast and Mrs. Owens had put up a substantial lunch for them, they shouldered their guns and set out for the lake. Bob carried his father’s muzzle-loading rifle, while Lester was armed with the heavy deer-gun with which he had bowled over so many bears and panthers in the wilds of northern Michigan. Lester delighted to talk of the wonderful exploits he had performed with that same rifle, and as he had a good memory and generally managed to tell the same story twice alike, Bob finally came to believe that he told nothing but the truth; but at the same time he thought it very strange that his friend could never be prevailed upon to give an exhibition of his skill.

They found Godfrey’s cabin deserted by the family (if they had known what had happened there the night before, their delight would have been unbounded), but the canoe was where they left it, and they knew where to look to find the paddles. While Bob went in search of them, Lester unlocked the chain with which the canoe was secured, put in the lunch basket and weapons, and, when all was ready, they pushed out into the lake.

“Yes, sir, this rifle holds a high place in my estimation,” said Lester, continuing the conversation in which he and Bob had been engaged, as they came along the road. “It has saved my life more than once, as you know. The last bear I shot charged within five feet of me before I dropped him. I put four bullets into him in as many seconds. Where would your muzzle-loader be in such close quarters?”

“Nowhere,” replied Bob. “That’s what makes me so mad every time I think of Dave Evans. I might have ordered a nice gun and had it in my hands in a few days more, if it had not been for him. But I’ll make it up when I get to be mail carrier.”

“I’ll tell you what else I’ve done with this rifle,” continued Lester, who found as much pleasure in dwelling upon his imaginary exploits as Bob did in talking about his future prospects. “Once when I was walking through the woods I shot a gray squirrel out of the very top of the tallest shell-bark hickory I ever saw. It fell about four feet and lodged on a little branch, which, from the ground, looked no larger than a knitting-needle. I wanted that squirrel, as it was the only one I had seen that day, but I didn’t want to climb the tree to get it; so I hauled up off-hand and at the first shot I cut off that limb and brought down the squirrel. What do you think of that?”

“I think you are a splendid marksman,” replied Bob. “Why don’t you go to some of the shooting-matches about here? You would be certain to carry off some of the prizes. Let’s see you take the head off that fellow,” he added, pointing toward the shore.

Lester looked in the direction indicated by his friend’s finger, and saw a quail sitting on a fallen log, close by the water’s edge, evidently keeping watch over the rest of the flock, which were disporting themselves in the dusty road. As Bob spoke, the bird uttered a note of warning, and the flock hurried away into the bushes, but the sentinel kept his place on the log.

“Knock him over,” said Bob. “He’ll make a capital good dinner for us, if we don’t find any ducks.”

“I—I am all out of practice,” replied Lester. “I’ve seen the day that I could do it with my eyes shut.”

“I can do it with my eyes open,” said Bob.

He drew in his paddle as he spoke, picked up his father’s rifle, and, resting his elbow on his knee, drew a bead on the bird’s head and pulled the trigger. Bob was really a fine marksman, and the effect of his shot made Lester open his eyes in astonishment. The bird looked so small that it seemed useless to shoot at its head, but Bob made a centre shot. Lester had never seen anything like it. Bob had never before fired a rifle in his presence (he always used a shot-gun), and the reason was because Lester boasted so loudly of his own skill that Bob was afraid of being beaten.

They paddled ashore after the bird, and when they pushed out into the lake again, Lester had nothing more to say about hunting and shooting. He even showed a desire to abandon the trip up the lake and go home.

“I don’t feel very well this morning,” said he, “and I think we had better go back.”

“O, no,” replied Bob. “You can lie down in the bow of the canoe and I’ll do the paddling. Does your head ache?”

“Dreadfully, and I thought perhaps it would be well to speak to father about those bonds of yours. We don’t want to be beaten again, you know.”

“Of course not, but if you speak to him to-night it will answer every purpose. If my father had been in any hurry he would have told you so. I have a plan to propose that will wake you up and put life into you. You remember that when you went over to get Don to join our Sportsman’s Club, he told you that he and Bert had been frightened off Bruin’s Island by a bear, don’t you? And you told him that perhaps you would go up there some day and shoot him?”

“Ah! yes, I think I remember some such conversation. But I don’t feel like it to-day. Some other time I’ll go up there with you, and if we find any bears there, I’ll show you how to hunt them.”

It was not at all probable that Lester or any other boy in the settlement could have taught Bob anything about bear-hunting. He had ridden to the hounds almost ever since he was large enough to sit on horseback. Nearly every planter in the neighborhood owned a pack of dogs, Mr. Owens among the number, and hunting with them was as much of a pastime as base ball is in the North, and during the proper season was as regularly practised. Many an old bear had Bob seen “stretched” by the dogs, and the rifle he then carried had been the death of more of them than Lester could have counted on the fingers of both hands.

“It is strange that you never come out to any of our hunts,” said Bob. “You have often been invited.”

“I know it, but I can’t see any fun in it,” answered Lester, who knew that if he ever appeared among the hunters they would soon find out that he was a very poor horseman. “It is easy enough to kill a bear when you have a score or two of dogs to hold him for you; but I’d like to see one of you fellows walk into the woods and meet one alone, as I have. There’s where the fun comes in.”

“I should think so,” answered Bob, as, with one sweep of his paddle, he brought the canoe to a stand-still in the mouth of the bayou that led to Bruin’s Island. “What do you say? Shall we go up?”

“Not to-day; my head aches too badly.”

“I was all over that island this last summer,” continued Bob; “you know one can wade out to it when the bayou is low; and I didn’t see any bear sign. More than that, I know there hasn’t been a bear near the island for years; but if we should go up there and find one, and you should shoot him, I don’t know of anything that would make Don Gordon feel more ashamed of himself.”

Lester was quick to catch at the idea thus thrown out. If there was no prospect of finding a bear on the island he had no objections to going there, or, rather, he wanted to go there. He could fearlessly explore the island and rely upon Bob to sound his praises in the settlement, and tell what a brave fellow he was and what a coward Don was.

“I don’t think Don showed much pluck in running away before he saw the bear,” said Lester.

“Of course he didn’t,” replied Bob.

“Are you sure there was no bear there?”

“I know it. Bears don’t use on that island any more.”

“Well, let’s go up and see. If there is one there, I’ll make you a present of his skin.”

This was enough for Bob, who, with one sweep of his paddle, turned the canoe’s head up the bayou. Somewhat to his surprise, his companion, who had been lying in the bow, holding both hands to his head, and acting altogether as if he felt very badly, straightened up and assisted him in propelling their little craft. He recovered from his illness immediately, when he found that he could win a reputation, and at the same time run no risk of being called upon to exhibit the skill and courage of which he had so often boasted.

As they moved up the bayou, the ducks, which now began to arrive in great numbers, being driven from their far Northern homes by the approach of winter, arose from the water in numerous flocks; and after Bob had made two “pot shots” at them, aiming at the birds as they sat on the water, and missing both times, Lester mustered up courage enough to try his deer gun on a flock which swam out from a point a short distance in advance of them. Taking a quick aim at the birds, he managed, by the merest accident, to bag three of them—the ball passing through the head of one of the ducks, through the neck of another and through the body of a third. But the fact was they sat so closely together on the water that he could scarcely have missed them if he had tried.

“Well, I declare!” exclaimed Bob. “Did you shoot at their heads?”

Lester was so greatly astonished at the result of his shot that he could not reply at once. With mouth and eyes wide open, he gazed at the three ducks lying dead upon the water, then at the remainder of the flock, which were flying up the bayou, and then he blew the smoke out of the breech of his rifle and put in a fresh cartridge.

“O, you needn’t try to look so surprised,” exclaimed Bob. “I have always been afraid of you, and now I am satisfied that you can beat me. You are the best shot among the boys in this settlement.”

“Well, you needn’t say so before folks,” replied Lester, as soon as he had somewhat recovered himself.

“Yes, I will,” returned Bob. “I have heard some of the fellows say that they didn’t believe you ever killed any game in your life, and now I can tell them differently. Can you do it again?”

“I am afraid not,” answered Lester, with an air which said he could if he felt like it.

“I believe you can. The fellows around here have no business with you.”

Lester was entirely satisfied with this. He had won a reputation as a marksman, and he had won it very easily. Many a reputation has been made in the same way—by accident. With an assumption of indifference which he was very far from feeling he picked up the ducks as Bob paddled up to them, and fearing that his friend might ask him to try another shot, expressed a desire to be put on the island as soon as possible.

“I have got my hand in now,” said he, “and I wouldn’t turn my back on a grizzly.”

“There’s no bear on the island,” replied Bob, “but I wish there was, for I would like to see you shoot him.”

Although Lester was very proud of, and greatly encouraged by the chance shot he had just made, he could not echo his friend’s wish; and if he had had the faintest suspicion that there was a bear within half a mile of him, he could not have been hired to remain in the bayou. He knew nothing whatever of the habits of the animal, but Bob did, and his positive assurance that bears never “used” on the island now was the only thing that induced Lester to consent to visit it. Still his heart beat much faster than usual when they rounded the bend and came within sight of the leaning sycamore behind which Godfrey Evans had been partially concealed when Dan first discovered him. In a few minutes more Bob drove the bow of the canoe so deeply into the mud that the current could not carry it away, and the two boys jumped out on the bank.

“Don Gordon went over to Coldwater a year ago and brought back a bearskin which he showed to every body, with the story that he killed the bear who wore it,” said Bob, who never grew tired of saying hard things about the boy he hated. “I don’t believe it and never did. He has told all around the settlement that he was driven off this island by a bear a few days ago, and that he set a trap for him. I don’t believe that either; but we’ll just take a look around to satisfy ourselves, and then we’ll go back to the settlement and tell the truth about the matter. It is my opinion that Don is trying to make himself famous by telling big yarns; and if we can prove it, it will make him take a back seat, and it will put a feather in our caps besides. Now there used to be a path somewhere about here that led to the camp Godfrey Evans used to occupy while the Yanks were in this country, and I think I can find it.”

Having examined the cap on his rifle, Bob led the way along the beach and Lester fell back, quite willing that his friend should go on in advance; for when he came to look into the dense, dark thicket which covered the interior of the island, his courage began to fail him.

Bob discovered the path in a very few minutes, and, greatly to his surprise, saw that it was not overgrown with reeds and briers, as he had expected to find it, and as it was the last time he saw it. On the contrary it was broad and well-beaten, for Godfrey, while he was hiding there, had often passed over it, and in order to facilitate his progress had broken down the briers and cane on each side. Bob’s face grew pale and his hands began to tremble. He looked closely at the bushes and told himself that they had been borne down by some heavy animal; but he said nothing, for he was afraid that if he opened his mouth his courage would all leave him, and he did not want to show himself a coward in the presence of so mighty a hunter as his friend Lester. Believing that he had one at his back who would stand by him, no matter how much trouble he might get into, he grasped his rifle with a firmer hold, drew back the hammer and advanced slowly along the path.

“What made you cock your gun?” asked Lester, in a startled whisper. “And why do you move so slowly and cautiously?”

The answer almost froze the blood in Lester’s veins.

“Do you see that?” replied Bob, in the same startled whisper, pointing to a footprint in the mud which looked as though it might have been made by a bare-footed man. “Do you see these broken bushes? Do you see that smaller track there?” he added, a moment later, in accents of great alarm. “We are in a dangerous neighborhood, the first thing you know. There have been two bears along here—an old one and a cub; and I shouldn’t wonder if they were on the island at this very minute. Yes, sir, they are, and there’s one of ’em now!”

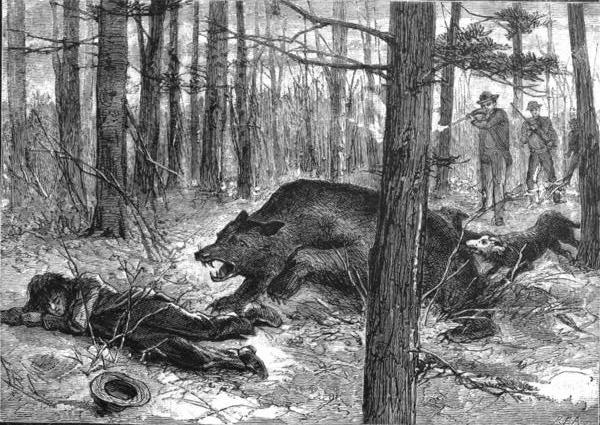

As Bob said this, there was a sudden commotion in the cane in front of them, accompanied by a hoarse growl. Bob beat a hasty retreat on the instant, jumping behind his companion before the latter could prevent it, and Lester found himself standing face to face with the first bear he had ever seen outside of a menagerie.

THE young hunters had advanced nearly to the end of the path and were now standing within a few feet of the clearing in which Godfrey had built his lean-to, and which had been torn down in order to make room for Don Gordon’s bear trap. There were several large trees growing beside the path, and Bob quickly sprang behind one of them, leaving Lester standing alone within twenty yards of one of the largest bears that had ever been seen in that part of the country. Without an instant’s hesitation Bob raised his rifle and pointed it at the breast of the animal, which had reared itself upon its hind legs, but the muzzle of the weapon waved about in the most alarming manner, and he could not hold it still to save his life. He found that there was a vast difference between facing a bear when he had twenty fierce dogs and as many armed horsemen to back him, and confronting the same animal on foot with but a single companion to depend on. After a moment’s reflection he lowered his rifle, for he knew that it would be folly to fire and wound the bear. He thought the safest plan would be to rely upon the superior skill and courage of his companion.

“Go for her!” said Bob, in a scarcely audible whisper. “Shoot her in the eye if you can; if not, take her under the fore leg.”

Bob kept his eyes fastened upon the bear, expecting every instant to see her fall stone dead beneath Lester’s deadly aim; but the animal stood erect, closely regarding the intruders, and finally opening her mouth and showing a frightful array of teeth; she uttered another angry growl and moved slowly along the path. Then Bob looked toward his companion, wondering why he did not shoot. One glance showed him the reason. The hunter who had shot bears and panthers in Michigan, as ordinary hunters shoot squirrels, was overcome with terror. He stood in the middle of the path, holding fast to the stock of his rifle, the muzzle of which he had allowed to fall until it was buried in the mud. His face was as pale as death, and his eyes, which were fastened upon the savage beast before him, seemed to have grown to twice their usual size.

“Shoot! shoot!” cried Bob, in great dismay. “She’ll be right on top of us in a minute more.”

But Lester was past shooting or doing any thing else. His fear had taken away all his strength, and even the knowledge that his life was in danger could not arouse him. Bob saw that something must be done at once. With trembling hands he raised his rifle to his shoulder, and drawing a hasty bead on the bear’s breast, pulled the trigger. Without waiting to see the effect of his shot he threw down his gun, made one or two quick jumps backward and placing his hands upon a small sapling ascended it with the greatest agility.

A very few seconds sufficed to place him in the topmost branches, and when he found that he could go no higher he stopped and looked down to see what was going on below. The bear was just scrambling to her feet and the sight made Bob’s heart bound with excitement and triumph, for then he knew that his bullet had not been thrown away. It had knocked the animal over; but the celerity of her movements and the hoarse growls she uttered proved that it had not reached a vital part, but had only made a wound severe enough to drive her almost frantic with rage. She dropped on all-fours and came down the path at the top of her speed, and there was Lester standing as motionless as ever. Bob might have thought he was waiting for the animal to approach within five feet of him so that he could make that famous shot he had so often talked about, had he not seen his friend’s pale face and noted the position in which he held his rifle.

“Run! run!” gasped Bob, who fully expected to see his companion pulled down and torn in pieces before his eyes. “Take to a tree—a sapling, and then you will be safe, for it is too small for the bear to climb!”

These words, and the sight of the fearful peril to which he was exposed, had the effect of arousing Lester from his lethargy. He let his rifle fall, and with even more agility than Bob had exhibited but a few seconds before, laid hold of a sapling and climbed it like a squirrel. He was none too quick in his movements, for the bear, clumsy as she looked, ran with surprising swiftness, and was at the foot of the sapling before Lester was fairly out of reach. Rising quickly on her hind feet she thrust one of her paws up into the branches, and the loud scream of terror Lester uttered frightened Bob so badly that he came near tumbling out of his perch. As soon as he had taken a firmer hold of the branches he turned to look at his friend, and was greatly relieved to see that he had nothing to fear.

Lester realized his peril now, and was full of life and action. Seizing a branch above his head he drew up his feet and so escaped the savage clutch which the bear made at him. It was a narrow escape, and Lester’s terror was so great that it was all he could do to climb still higher among the branches, and put himself in a place of safety. The slender sapling swayed and rocked as he worked his way upward, and Lester could not yet believe that the danger was over.

“O, Bob! Bob! what shall I do?” he managed to ask, as he clung to his frail support and looked down at the bear’s ugly paw, which was now and then thrust up among the branches, altogether too close to his feet for comfort.

“Crawl up as high as you can and hold fast,” was the reply. “The bear can’t hurt you now.”

“But how am I ever going to get home?” whined Lester.

“I don’t know. We’ll talk about that by and by. All we have to do now is to keep out of her reach. Why didn’t you shoot her as you used to shoot those bears up in Michigan?”

Before Lester had time to reply the attention of himself and companion was called to two new actors which suddenly appeared on the scene. One of them they would have recognised, if they had not been too badly frightened to recognise any thing. It was one of Don Gordon’s hounds. He and his mate rushed straight at the bear, and in a second more a most terrific battle was in progress. The snarls and growls of the combatants made Lester’s blood run cold. A moment later Don’s voice was heard encouraging the dogs.

“Hi! hi! there,” he shouted. “Take him, you rascals. Pull him down!”

The sharp report of a rifle followed his words, and the next thing Lester knew he was plunging headlong through the branches. The sapling in which he had taken refuge received a sudden and violent shock, as if some mighty body had been thrown against it, and Lester, whose extreme terror had rendered him almost helpless, lost his hold and fell to the ground. He caught frantically at the frail twigs as he passed through them, but they did not check his rapid descent, and he landed with a concussion that at almost any other time would have rendered him senseless. But he did not mind his injuries now in the least. He jumped up the instant he touched the ground, and looked about him with the utmost consternation. There were three enraged brutes near him which were making the leaves fly in every direction as they rushed fiercely at one another, but his frightened eyes cheated him into believing that there were four times as many. Just as he gained his feet he saw twelve bears knock twelve dogs down with one stroke of their paws, and then these twelve bears turned and made at him with open mouths. He gave himself up for lost; but at that instant a roar like that of a cannon sounded close to his ear, and the twelve bears sank to the ground all in a heap. So did Lester who could endure the strain no longer. As he fell he saw twelve Don Gordons rush up with heavy double-barrel shot-guns in their hands, and each selecting his bear poured another charge of buckshot into the animal’s head. But there was only one bear there—at least there was only one engaged in the fight—and only one Don Gordon.

The last time we saw Don was on the day David shipped his captured quails up the river on the Emma Deane. He and his brother had labored faithfully to help their humble friend fill his contract, and when this work was done they were ready to accompany their father on a trip to Coldwater, which had long been talked of, and which the general had good-naturedly postponed in order that Don and Bert might assist David in making his enterprise successful. They intended to be absent a week or more. The general went on business, and Don and Bert to visit a young friend whom they had often entertained at their own house, and whose horses and hounds were the envy of all the boys in the country for miles around. They made the journey on horseback and were accompanied by their hounds. Don was armed with his trusty rifle, with which he hoped to make great havoc among the deer and bears that were so abundant in the county in which their friend Bob Harrington lived, while Bert carried his light fowling piece.

How Lester went Bear-Hunting.

Bob Harrington, with whom Bert intended that he and Don should take up their abode in case they had gone on that hunting expedition which the reader will remember was broken up by the arrival of their cousins Clarence and Marshal Gordon, was a young Nimrod—not such a one as Lester Brigham, but one whose exploits had been witnessed by all the men and boys in the settlement in which he lived. His rifle was the truest, his hounds were the stanchest, and his horse was the fleetest, and could take his fences the easiest of any in the county, not even excepting those of Mr. Harrington, Bob’s father, who had been a hunter all his life. Bob never boasted that he would stand still and allow a bear to approach within five feet of him before he would shoot him, for he knew that that would be a harder test than his courage could endure; but he was not afraid to walk up and finish any bear his dogs had hold of, and nearly every hunter in the neighborhood had seen him do it. The magnificent pair of antlers on which Don and Bert were accustomed to hang their gloves and riding-whips, and which were fastened to the wall of their room over their writing table, as well as the soft bearskin that served as a rug by the side of their bed, were presents from their friend Bob, and were only two out of a score or more of such articles which he had sent to his acquaintances all over the state. The animals that once wore these antlers and skins had all been brought low by Bob’s own unerring rifle.

With such a hunter for a companion during a week’s shooting, the boys expected to learn something, especially Don, who told himself that before the visit was ended Master Bob would find that there was at least one boy in Mississippi who was not afraid to follow where he dared lead. And he made his resolution good. While Bert, with Bob’s setter for a companion, was roaming about over Mr. Harrington’s extensive plantation, making double shots on quail, woodcock and snipe, and Mrs. Harrington and the general were seated in their easy-chairs by the huge old-fashioned fire-place, talking over their business matters, Don and Bob were riding to the hounds, braving all sorts of weather, and bringing in so many trophies of their skill that the general and his host were astonished. No dinner in that house was considered complete without its wild turkey or saddle of venison; and as for such game as quails and woodcock, the family feasted on them until they were actually tired of them.

Don was given ample opportunity to test his skill with the rifle and exhibit his nerve in trying situations, and he finally became so accustomed to walking up and shooting a bear when the dogs had him “stretched” that he thought no more of it than he did of bringing a squirrel out of the top of a hickory or stopping a woodcock on the wing. When the visit was ended and he returned to his home, he had more than one bearskin strapped behind his saddle, and, better than that, he carried with him a confidence in his own powers which ultimately proved to be the salvation of one who, had their situations been reversed, would have deserted him in the most cowardly manner.

The boys reached home one night after dark (it was the night of the same day on which David Evans received the money for his quails), and after relating to their mother and sisters as much of the week’s history as they could crowd into two hours’ conversation, they went up stairs and tumbled into bed. They were tired, of course, but still they had energy enough left to plan a campaign for the next day.

“We mustn’t forget our bear trap on the island,” said Bert, as he settled himself snugly between the sheets.

“That’s so,” answered Don. “We’ll go up there the first thing in the morning. If a bear is going to get into that trap at all, he has had plenty of time to do it. Whoever awakes first after daylight must arouse the other. I say, Bert! if I had had as much experience a few weeks ago as I have now, we couldn’t have been driven off the island until we had found out what it was that uttered those horrid growls. I feel ashamed of myself when I think it was nobody but Godfrey Evans.”

“But we didn’t know it at the time,” said Bert.

“Of course not. If we had we should have made him show himself. Just let him try that trick again if he dares.”

As it happened neither one of the boys awoke at daylight. They were locked in a dreamless slumber until they were aroused by the ringing of the breakfast-bell. They dressed themselves with all haste, and with many exclamations of regret, hurried down stairs. They were not so impatient but that they could take time to eat a hearty meal; but still they finished their breakfast before the rest of the family did, and asking to be excused ran off to get ready for their trip to the island. Don went up stairs after the guns and ammunition (he brought down his father’s heavy double-barrel for Bert’s use), and his brother went to the shop after the oars belonging to the canoe, and to call the two hounds which had accompanied them on their former expedition up the bayou. As they did not intend to be absent more than three or four hours no lunch was provided for them.

The brothers met again at the jetty below the summer-house, where they found the canoe riding safely at its moorings. She was quickly loaded and pushed from the shore, and after an hour’s easy rowing the young hunters found themselves within sight of Bruin’s Island. As they approached it, Bert, who was steering, began to believe that if Godfrey Evans had not returned and taken up his abode in his old quarters, they would certainly find somebody or something else there, for the hounds, which up to this moment had been curled up in the bow, now arose to their feet, and after looking all about as if taking their bearings, turned their noses toward the island and eagerly snuffed the air. Did they remember their former experience there, or did the breeze, which was blowing straight down the bayou, bring some taint to their sensitive nostrils? Bert, who closely watched their movements, could not tell until he saw the long hair on the back of Carlo’s neck begin to stand erect. Then the question was answered.

“DON the hounds say there’s something on the island,” said Bert.

Don ceased rowing, faced about and looked at his favorites, whose actions he had learned to read like a book. They were beginning to be very uneasy.

“Yes, sir,” said Don, his countenance brightening, and his eye lighting up with excitement, “there’s something there. I hope it is a bear, for if it should turn out to be nobody but Godfrey Evans I should be provoked. You needn’t be afraid,” he added, with a hasty glance at his brother’s sober face. “If it is a bear he can’t take us unawares while the dogs are with us. They’ll find him and show us where he is.”

“I couldn’t shoot him if I should see him,” said Bert, drawing a long breath. “You know that while we were over on Coldwater all my shooting was done on small game. I never saw a wild bear in my life.”

“You needn’t shoot him. In fact, I’d rather you wouldn’t try; for if you were in the least excited you might shoot the dogs, and I wouldn’t have them hurt for all the bears in Mississippi. You know that all those hunters in Africa have after-riders—men who keep close behind them, and hand them a second gun if they need it. You can do the same by me. If I fail to make a dead shot with my rifle, be ready to give me your double barrel. There are buckshot enough in it to kill any bear I ever saw. Keep close at my heels, and the bear shan’t hurt you, unless he kills or disables me first,” added Don, who took pride in the fact that he was able to act as protector to his weak and timid brother.

“But I don’t want him to hurt you, either,” said Bert.

“I don’t intend that he shall. I am not as much afraid of those fellows as I was a few weeks ago, for I have learned that a quick eye and steady hand are all that are needed to bring one safely through.”

Don laid out all his strength on the oars again, and the canoe rapidly approached the island; but before it had gone many yards the report of a rifle rang out on the air, being followed a moment later by a rustling in the cane which the boys knew was not made by the breeze, and then by loud and rapidly-spoken words which the young hunters could not understand. The words were uttered by Bob Owens, who was calling upon his companion to save himself by flight. Then there was a loud shout of terror, followed by more rustling in the cane, and by repeated cries from some one who was evidently in great distress or threatened by some terrible danger. The hounds bayed loudly in response, Bert’s cheek blanched, and Don rested on his oars and looked first at the island and then at his brother in great astonishment. His inactivity, however, lasted but for a moment. The voices and cries of distress continued to come from the island, and Don, with the remark that there was some one there who was in need of assistance, bent to his oars with redoubled energy.

The canoe moved swiftly along the shore of the island until it reached a point opposite the path leading to the little clearing in which the bear trap was located, and then Bert turned it toward the shore, and Don with a few strong pulls drove the bow deep into the mud. The hounds, hardly waiting for the boat to become stationary, sprang ashore and were out of sight in an instant. Don, shouting directions to his favorites, followed as fast as he was able, and Bert, with his double barrel on his shoulder, kept close to his brother’s side, wondering all the while at the courage he exhibited in doing so. But one never knows how much nerve he has until he is put to the test. Perhaps that pale, quiet friend of yours, who looks as though he had scarcely strength enough to lift his heavy satchel full of books, and who always turns and walks meekly away whenever the great, hulking bully of the school says a harsh word to him, would, if placed in a situation of extreme danger, stand his ground and show the greatest coolness and courage, while that same bully would run for his life.

The young hunters ran swiftly along the path, but before they had made many steps they heard a great crashing in the cane, accompanied by a chorus of snarls and growls that were enough to frighten almost any one. But they did not frighten Don now. He had heard such sounds so often of late that they did not affect his nerves any more than the baying of his own hounds would have done. He ran on faster than ever, and a few more steps brought him around an abrupt bend in the path. There he stopped, greatly astonished at what he saw—a battle between his hounds and a bear. It was not the battle that astonished him, but the size of the animal with which his favorites were contending. It was the largest he had ever seen in all his hunting. It was almost as large as the one which had slaughtered so many dogs in that same canebrake a few years before. She was standing on her hind feet, striking viciously at the dogs, which, altogether too wise to close with so huge an antagonist, were bounding about her, biting her first in one place and then in another, and keeping her spinning around like a top.

Don took in the situation at a glance, and then his rifle slowly and steadily arose to his shoulder, the sight covering the bear’s neck. He fired at the proper moment and the animal fell to the ground, being assisted in her fall by the hounds, which, encouraged by the presence of their master, seized her at the same instant and pulled her with great violence against the nearest sapling. The result was not a little bewildering to Don and his brother. A loud cry of alarm sounded among the branches over their heads, and they looked up just in time to see some heavy body descending through the air. It struck the ground, from which it seemed to bound like a ball, and when it came to an upright position, as it did a moment later, Don saw that it was Lester Brigham, and not a bear, as he had at first supposed. His astonishment was so great that for a moment he could neither move nor speak; but Bert could and did, for he saw that the boy was in danger.

“Look out, Lester! Run for your life!” he cried.

Aroused by the exclamation, Don turned his eyes from Lester to the bear, and saw that the animal had regained her feet, and having knocked down one of the hounds was rushing upon Lester with open mouth. Don was frightened now, for he believed that something dreadful was about to happen; but his nerve did not fail him nor did he hesitate an instant. Dropping his empty rifle, and seizing the double barrel which Bert promptly handed him, already cocked, he drew the weapon to his shoulder, and by a hasty snap-shot saved Lester’s life. The bear and her intended victim both dropped at the report, the one mortally wounded and the other in a dead faint. So closely together did they fall that the bear, in her death struggle, tore Lester’s clothing with her claws. Bert at once dashed forward to drag him out of danger, while Don ended the battle by firing another charge of buckshot into the animal’s head. Lester could now say that he had been within five feet of a bear, and tell nothing but the truth.

“Well, this beats anything I ever heard of,” said Don, as soon as he had made sure that the bear was dead. “How do you suppose Lester got here? I didn’t see any boat on the beach, did you?”

“No,” answered Bert; “I was too badly frightened to see anything.”

“But there’s a boat there all the same,” said a voice.

Don and Bert looked wonderingly at each other. “Who’s that?” demanded the latter, after a moment’s hesitation.

“Bob Owens!”

The rustling among the branches which accompanied these words told the brothers where to look to find the speaker. They walked toward the foot of a neighboring sapling, and, looking upward, saw Bob Owens coming down. His pale face and trembling hands showed that he, as well as Lester, had sustained something of a fright.

“Why, Bob, what in the world brought you here?” exclaimed Bert.

“I came up to find the bear that drove you and Don off the island a few days ago,” replied Bob. “I found her, too,” he added, suddenly pausing in his descent as an angry growl fell upon his ear. It was uttered by one of the hounds, which recognised in Bob the robber who had been compelled to take refuge on the roof of the negro cabin. He looked up at the boy and showed him the teeth he had come so near using on him that night.

“Bose, behave yourself!” exclaimed Don, sharply. “Come down, Bob, and tell us all about it.”

Before Bob could comply, a wild, shrill cry, which, during her life, would have excited the old bear almost to frenzy, sounded from the direction of the clearing, which was a few rods deeper in the cane. The boys all knew what it was. Bob uttered an exclamation of astonishment, and began to mount among the branches of the sapling again, while Bert put fresh cartridges into his old double-barrel, and Don ran back after his rifle, which he began to reload with all haste. While he was thus engaged his eye fell upon Lester’s prostrate form.

“I say, Bob!” he exclaimed, “you had better come down and see to your friend here.”

“What’s the matter with him?” asked Bob, from his perch.

“He has fainted. He was frightened by the bear, and perhaps injured by his fall from the tree. I don’t blame him for being frightened. I don’t suppose he ever saw a bear before in his life.”

“Ha!” exclaimed Bob, “he says he has shot more of them than you ever saw.”

Don did not believe that Lester told the truth when he said this; but he could not stop to argue the point just then, for his mind was too fully occupied with thoughts of what was yet to come. He patched the ball very carefully, and, as he drew the ramrod to drive it home, he said:

“Come down here, and take care of him, Bob. Throw some water in his face, and I think he will come out all right. You will find a cup in our boat.”

“I guess not,” replied Bob. “I’ve no business down there. Don’t you know that that was the cry of a cub we heard just now?”

“Of course I do. But what of it?”

“Don’t you know that if the old one is anywhere around you are in danger down there?”

“I don’t think the old one will trouble us. She’s dead.”

“But suppose the father of the family should be in the neighborhood? Take to a tree, quick!” exclaimed Bob, as the cub once more set up his shrill cry. “Bring your rifle up with you, and if the other old one comes around you can shoot him easy enough.”

“That’s not my way of doing business,” replied Don, somewhat surprised at the proposition. “Why, Bob, I thought you had hunted bears all your life.”

“So I have; but I always had a good horse under me, and plenty of dogs to back me up. You’ll never again catch me on foot around where one of these animals is. I’ve had enough of it to-day.”

The loud baying of the hounds, which had dashed down the path as soon as the cry of the cub fell upon their ears, now echoed through the woods, and Don having by this time loaded his rifle, ran toward the clearing, leaving Bob to help his friend Lester, or not, just as he pleased. Bert, in his capacity of gun-bearer, kept close behind his brother as he ran.

A few rapid steps brought the hunters to the edge of the clearing, and there they stopped to reconnoitre the ground before going farther. They did not want to run into the clutches of another old bear if they could help it. The hounds were standing on their hind legs with their fore feet resting against the body of a small tree, looking up into the branches and baying loudly. Don looked, too, and saw a young bear about the size of a Newfoundland dog perched in the fork.

“O, Bert,” exclaimed Don, “why didn’t we think to bring an axe with us? It wouldn’t be any trouble at all to cut the tree down and take that fellow alive.”

Before Bert could say anything in reply, the hounds suddenly left the tree, and dashing across the clearing, threw themselves against the trap, toward which Don had not before thought to look, and thrusting their noses between the logs, made desperate efforts to reach something on the inside; while whatever it was on the inside ran about and squalled as if greatly alarmed. Then Don saw that the top of the trap was down. He ran quickly to it and looking between the logs saw crouching in the furthermost corner the mate to the young bear in the tree. The huge animal he had shot in the path was the mother of the two cubs.

“We’ve got two of them,” he exclaimed in great glee. “Are we not in luck? Don’t you remember father told us that if we could trap a cub Silas Jones would give us twenty dollars for him? We’ll have forty dollars to give David. We don’t need the money and he does.”

“Of course he does,” replied Bert. “We’ll leave the dogs here and go home and get help.”

“That’s the idea. We shall need plenty of it, too, for that bear is pretty heavy, and it will take a strong force to drag her to the bayou and put her into the boat. Here, boys,” he added, calling to his dogs and placing his hand on the tree in which the young bear had taken refuge, “keep your eyes on him and don’t let him come down.”

The hounds understood him and seemed quite willing to remain and watch the game. They had passed many a night in the woods guarding a coon tree, and we know how faithfully they and the rest of Don’s pack watched Lester and Bob while they were on the top of the negro cabin. All they had to do was to “keep their eyes” on the bear in the tree; the one in the trap could not possibly escape.

Don now shouldered his rifle and retraced his steps along the path, followed by his faithful gun-bearer. When they reached the scene of the fight they found Lester Brigham sitting up with his back supported against a tree and Bob Owens kneeling beside him in the act of handing him a cup of water.

After the brothers ran toward the clearing Bob waited and listened, expecting every instant to hear the sounds of another desperate struggle; but as nothing but the baying of the hounds came to his ears, he made up his mind that there were no more old bears about, and finally mustered up courage enough to go to the assistance of his companion as Don had suggested. He made his way to the ground and stopping long enough to take a good look at the huge animal which had been the cause of so much alarm to him, he ran up the path to see how Lester was getting on. The latter was beginning to show some signs of returning animation, and the cup of water that Bob dashed into his face brought all his faculties back to him. He opened his eyes and seemed instantly to recall all the exciting incidents that had so recently occurred. He jumped to his feet with a cry of alarm, but was so weak that if Bob had not caught him in his arms he would have fallen to the ground. Bob propped him up against a tree and after assuring him that the bear was dead, hurried off to the bayou after another cup of water.

“How do you feel, Lester?” asked Don, with some anxiety.

“All done up,” was the scarcely audible reply. “I feel as if every bone in my body was broken. I’ll tell you what it is: if I had been in practice, as I was when I took my last hunt in Michigan, you wouldn’t have had a chance to shoot that bear. I’ve killed dozens of them; but this one came upon me so suddenly that I couldn’t do anything.”

“I guess you are all right,” thought Don, with a sly glance at his brother. “As long as a boy can tell falsehoods there’s not much the matter with him.” Then aloud he asked: “Can we be of any assistance to you?”

“O, no,” replied Lester, who wanted nothing to do with the boys he had wronged. “I shall be able to walk in a few minutes and Bob will take care of me.”

“Very well; then we will go home. We must have help to get this old bear into a boat, and besides there are two cubs back there in the clearing that we want to capture alive. They are worth twenty dollars apiece, and the money belongs to Dave Evans.”

“Dave Evans!” sneered Lester, as soon as the brothers were out of sight in the cane. “There’s nobody in this settlement but Dave Evans.”

“Twenty dollars apiece,” said Bob, pulling off his hat and dashing it spitefully upon the ground. “That makes forty dollars, which added to a hundred and sixty makes two hundred dollars. Wouldn’t I have a breech-loader if I had that amount of money in my pocket? But I haven’t got a cent, and here’s this miserable fellow rich already. I wish I dared go back there and shoot those cubs. I would if the hounds were not there. I’d shoot the dogs, too, if I thought Don wouldn’t suspect me.”

Meanwhile Don was laying out all his strength on the oars, and the canoe was moving rapidly down the bayou. When it reached the lake, and was passing Godfrey’s cabin, Don and his brother, who had not seen the boy trapper since their return, and consequently knew nothing of his good fortune, looked all around for him, intending, if they saw him, to tell him that he had some valuable property up in the woods which was waiting to be secured. “I don’t see any thing of him,” said Bert, “and we are in too great a hurry to stop and hunt him up.”

“Never mind,” said Don. “He’ll be around as soon as he finds out that we are at home. Now, Bert, if you will make the canoe fast and put our guns in the sail-boat, and get her all ready for the start, I’ll run up to the house and ask father if he will let a couple of the darkies go with us after those bears. We don’t want any lunch, do we?”

No, Bert didn’t want any. There was too much sport in prospect, and he couldn’t eat a mouthful until it was all over.

When the canoe reached the wharf Don sprang out, and Bert was preparing to make her fast at her usual moorings, when they heard a loud shout, and looking toward the road saw David Evans running along the beach. “I’ll wait until I hear how he succeeded with his quails,” said Don.

“And won’t he be surprised when he learns that he will have forty dollars more in his pocket to-night,” said Bert. “David ought to be very happy and contented now, for he is getting on nicely.”

“Well, he doesn’t act to me like a very happy boy this morning,” said Don, in a low tone, as David came nearer. “There’s something the matter with him. He doesn’t usually hang his head that way.”

Bert, having made the canoe fast to the tree, straightened up, and when he had taken a good look at David, told himself that his brother was right. There was something the matter with him. While he was wondering what new misfortune had fallen to the lot of the boy trapper, Don called out:

“We’ve just been talking about you, Dave. How goes the battle?”

David tried to answer, but could not utter a word. Don, believing that it was because he was out of breath after his rapid run, continued:

“You’ve had plenty of time to hear from those quails, and I suppose you’ve got a pocketful of money now, haven’t you?”

David had by this time approached so close to the brothers that they could see that his face was very pale, and that his eyes were red and swollen with weeping. He stepped upon the shore end of the jetty, and throwing himself down upon it, covered his face with his hands and rocked back and forth, sobbing violently. Don and his brother looked at each other in great surprise, and at length the former managed to ask: “What’s the matter?”

“O, Don!” cried David.

“Well, I can’t make any thing of that reply,” exclaimed the boy. “Tell me what’s the matter with you. Hasn’t your money come?”

“O, yes, it came,” sobbed David.

These words, and the tone in which they were spoken, let Don into the secret of his friend’s trouble. Impatient to know the worst at once, he walked up and caught David by the arm. “Out with it,” said he. “Where’s your money now?”

“I worked so hard for it,” cried David, “and mother needed it so much; but now it’s gone—all gone. I’ve lost every red cent of it!”