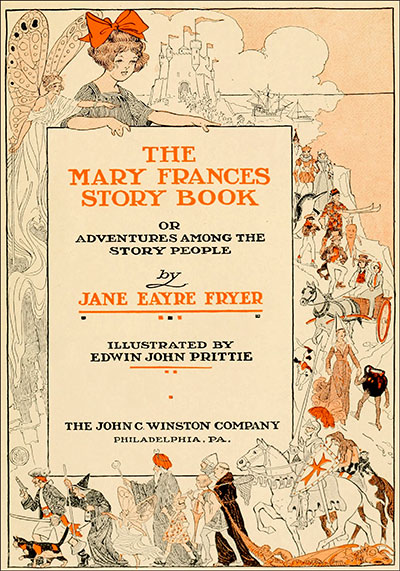

Project Gutenberg's The Mary Frances Story Book, by Jane Eayre Fryer

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

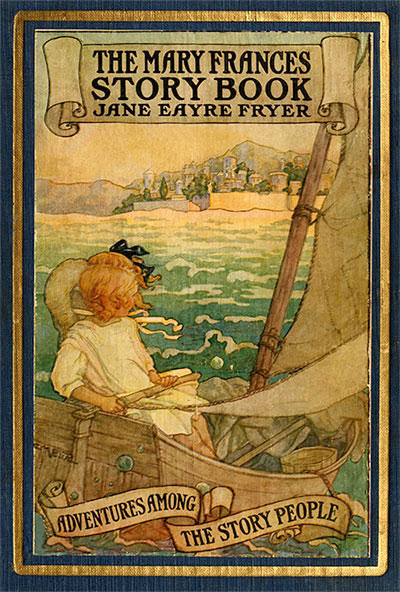

Title: The Mary Frances Story Book

or Adventures Among the Story People

Author: Jane Eayre Fryer

Illustrator: Edwin John Prittie

Release Date: January 6, 2018 [EBook #56322]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MARY FRANCES STORY BOOK ***

Produced by Emmy, MWS and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

This ebook is dedicated to

Emmy

friend, colleague, mentor, role model,

who fell off the planet far too soon.

Books by Jane Eayre Fryer

THE MARY FRANCES COOK BOOK

Or, Adventures Among the Kitchen People

Price $2.00 Net

THE MARY FRANCES SEWING BOOK

Or, Adventures Among the Thimble People

Price $2.00 Net

THE MARY FRANCES HOUSEKEEPER

Or, Adventures Among the Doll People

Price $2.00 Net

THE MARY FRANCES GARDEN BOOK

Or, Adventures Among the Garden People

Price $2.00 Net

THE MARY FRANCES KNITTING AND

CROCHETING BOOK

Or, Adventures Among the Knitting People

Price $2.00 Net

THE MARY FRANCES FIRST AID BOOK

Price $1.25 Net

THE MARY FRANCES STORY BOOK

Or, Adventures Among the Story People

Price $2.00 Net

THE MARY FRANCES BIBLE STORY BOOK

Or, Adventures Among the Bible People

Price $2.00 Net

THE JOHN C. WINSTON COMPANY

Publishers 1006–1016 Arch Street, Philadelphia

Copyright, 1921, by

THE JOHN C. WINSTON COMPANY

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London

All Rights Reserved

Made in the

U.S.A.

The Mary Frances Story Book is different from the other Mary Frances Books. They are part lessons and part story; they teach something about cooking and sewing, knitting and crocheting, housekeeping and gardening, and first-aid—and tell a story, too; but The Mary Frances Story Book is all story.

On a summer afternoon Mary Frances took a holiday and sailed away across the blue water to an island—an island formed by the top of a coral mountain resting in a sea of blue; oh, so blue—a brighter blue than the water in your mother’s bluing tub—not the blue that makes you feel sad and blue, but the blue that makes you laugh with happiness. The island itself and the roofs of the houses were coral white, and the green was the green of the palm and banana and mahogany tree. The breezes that blew over them were the warm, soft breezes of the southern sun. This island was the “enchanted island” of the good story-tellers which Mary Frances was allowed to visit. The story people who lived there believed in truth and beauty, and courage and kindness, and these were the theme of their stories. Like all good islands, this island had enemies, but they came to a bad end, as, in the long run, all evil persons will; and truth and beauty, and courage and kindness won the day, as they always must in every land where the searchlight of the sun flashes its beams.

As may be imagined, when Mary Frances came home she had not only one, but many stories to tell; and they are written in this book.

J. E. F.

Merchantville, N. J.

For kind permission to use copyrighted and other material, the author is indebted to the following: Milton Bradley Company, for “The Closing Door”, from Mother Stories, by Maud Lindsay; Little, Brown & Company, for “Tom Goes Down the Well”, from Mice at Play, by Neil Forest; Presbyterian Board of Publication, for “Gloomy Gus and the Christmas Cat”, by Alfred Westfall, and “Ann Catches a Thief”, by Daisy Gilbert; McLoughlin Brothers, for “Patty and Her Pitcher”; The Beacon Press, for “The Brahmin, the Tiger, and the Jackal”, from First Book of Religion; Cassel & Company, for “Music Bewitched”, by Hartley Richards; American Baptist Publication Society, for “John and Margaret Paton Among Savages”, by Grace E. Craig; Bobbs-Merrill Company, for “Your Flag and My Flag”, from The Trail to Boyland, by Wilbur D. Nesbit, copyright 1904. Acknowledgment is also due to Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Company, for “The Bubble Story”, “Mischievous Anna and Peter”, and “The Cat and the Carrots”.

| THE TRIP TO STORY ISLAND | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| I. | On the Shore | 15 | |

| II. | The Good Ferry Puts Out to Sea | 18 | |

| III. | The Pirate’s Cat | 23 | |

| IV. | The Story of the Lost Story | 26 | |

| V. | Land Ahoy | 29 | |

| VI. | The Old Witch and the Iron-Chain Curtain | 35 | |

| VII. | Finding the Lost Story | 37 | |

| VIII. | The Pirate Chases The Good Ferry | 42 | |

| IX. | The Terrible Punishment of the Pirate and the Old Witch | 44 | |

| X. | The Bubble Story | Anon. | 47 |

| STORIES TOLD THE FIRST DAY | |||

| XI. | Mischievous Anna and Peter | Anon. | 55 |

| XII. | Diamonds and Toads | Macé’s Fairy Tales | 61 |

| XIII. | The Magic Necklace | Macé’s Fairy Tales | 67 |

| XIV. | The Cat and the Carrots | Anon. | 73 |

| XV. | The Brahmin, the Tiger, and the Jackal | Hindu Folk Tale | 79 |

| XVI. | The Red Dragon | Anon. | 82 |

| XVII. | Two Poems | 84 | |

| If I Could Crow | 84 | ||

| The Twins | 85 | ||

| XVIII. | Tiny’s Adventures in Tinytown | 87 | |

| Tiny Gets Lost | 88 | ||

| Tiny Is Put in the Lock-up | 91 | ||

| Tiny Is Adopted | 94 | ||

| Tiny Discovers a Fire | 100 | ||

| 8 XIX. | Tiny Has More Adventures | 102 | |

| Tiny Saves a Baby’s Life | 104 | ||

| Tiny Goes Shopping | 107 | ||

| Tiny’s Mother Finds Her | 111 | ||

| STORIES TOLD THE SECOND DAY | |||

| XX. | The Magic Mask | Old Tale—Retold | 119 |

| XXI. | The Closing Door | Maud Lindsay | 126 |

| XXII. | Tom Goes Down the Well | Neil Forest | 130 |

| XXIII. | Gloomy Gus and the Christmas Cat | Alfred Westfall | 139 |

| XXIV. | Patty and Her Pitcher | Crowquill’s Fairy Tales | 146 |

| In the Magic Circle | 146 | ||

| The Wonderful Pitcher | 147 | ||

| The Well-dressed Stranger | 154 | ||

| Patty in Trouble | 156 | ||

| The Pitcher to the Rescue | 158 | ||

| THE STORIES OF THE THIRD DAY | |||

| XXV. | Sir Galahad | Sir Thomas Malory—Adapted | 165 |

| King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table | 165 | ||

| Galahad Receives the Order of Knighthood | 167 | ||

| The Adventure of the Sword in the Stone | 168 | ||

| Sir Galahad Sits in the Perilous Seat | 170 | ||

| Sir Galahad Wins the Sword of Balin le Savage | 173 | ||

| The Knights of the Round Table Set Out in Quest of the Holy Grail | 176 | ||

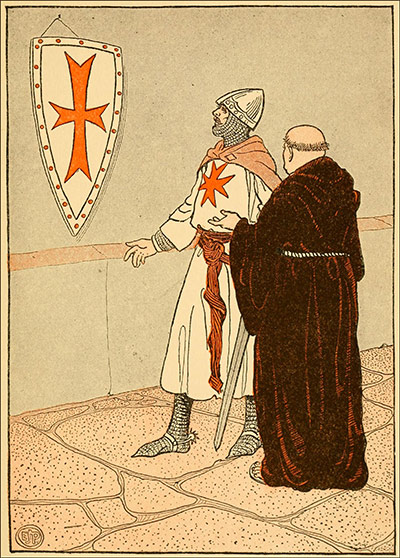

| Sir Galahad Finds a White Shield with a Red Cross | 178 | ||

| Sir Launcelot and Sir Percival Attack Sir Galahad | 182 | ||

| 9 | The Adventure of the Gentlewoman, the Mysterious Ship, and the Sword of the Strange Belt | 185 | |

| The Gentlewoman Risks Her Life for Another | 191 | ||

| Sir Galahad Meets a Knight in White Armor | 193 | ||

| Sir Galahad Achieves His Quest, and Bears the Holy Grail Across the Sea | 195 | ||

| The Passing of Sir Galahad, the End of Sir Percival, and the Return of Sir Bors to Camelot | 200 | ||

| XXVI. | How Sir Launfal Achieved the Holy Grail | James Russell Lowell—Retold | 203 |

| THE STORIES OF THE FOURTH DAY | |||

| XXVII. | Music Bewitched | Hartley Richards | 211 |

| Bob’s Three Foes | 211 | ||

| Father Pan’s Revenge | 215 | ||

| XXVIII. | Ann Catches a Thief | Daisy Gilbert | 219 |

| XXIX. | John and Margaret Paton Among Savages | Grace E. Craig | 226 |

| XXX. | The Strange Guest | Washington Irving—Retold from The Spectre Bridegroom | 233 |

| The Wedding Feast | 240 | ||

| The Midnight Music | 244 | ||

| XXXI. | Robert of Sicily | Henry W. Longfellow—Retold | 248 |

| XXXII. | The Man Without a Country | Edward Everett Hale—Retold | 254 |

| XXXIII. | Your Flag and My Flag | Wilbur D. Nesbit | 264 |

| THE LAST DAY ON STORY ISLAND | |||

| The Cricket on the Hearth, A Fairy Tale of Home | Charles Dickens—Adapted | 271 | |

| XXXIV. | Chirp the First | 271 | |

| The Peerybingles | 271 | ||

| 10 | The Strange Old Gentleman | 274 | |

| Caleb Plummer | 277 | ||

| Tackleton | 279 | ||

| Dot is Upset | 281 | ||

| XXXV. | Chirp the Second | 285 | |

| Bertha, the Blind Girl, and Her Father | 285 | ||

| Tackleton Comes In | 288 | ||

| Bertha’s Eyes | 291 | ||

| The Carrier’s Cart | 293 | ||

| The Party at Caleb’s | 298 | ||

| The Shadow on the Hearth | 302 | ||

| XXXVI. | Chirp the Third | 306 | |

| John Listens to the Cricket | 306 | ||

| John Blames Himself | 308 | ||

| Caleb Confesses His Deceit | 312 | ||

| The Dead Returns to Life | 316 | ||

| Tackleton Does the Unexpected | 321 | ||

| THE RETURN HOME | |||

| XXXVII. | Good-by, Mary Frances. Come Again! | 325 | |

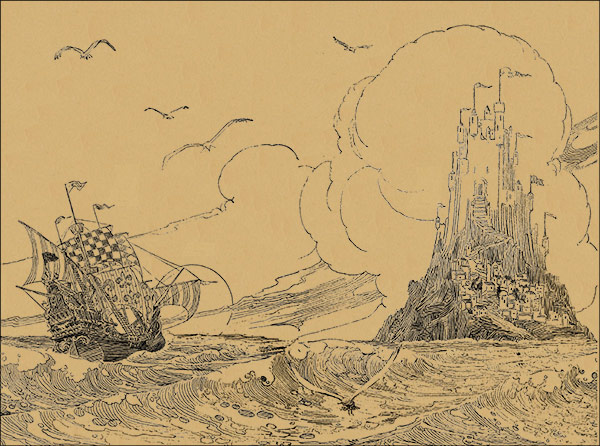

| They Could See that the Pirate’s Ship was Keeping the Distance the Same as at First Between Them | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| Mary Frances Leaned Down and Caught Hold of His Fins | 21 |

| “Just Some Flying Fish,” Answered the Cat | 31 |

| She Fed Him a Little at a Time with a Medicine Dropper | 39 |

| On One of the Flowers was Perched a Tiny Fairy | 49 |

| They were as High Up in the Air as the Top of a Mountain | 57 |

| She Drank Long and Eagerly | 63 |

| He Threw the Necklace Around Coralie’s Neck | 69 |

| “Have You no Feelings?” said the Carrot | 75 |

| “Wow!” shrieked the Dragon | 82 |

| Just at Her Feet Lay the Tiniest Little Bit of a Town | 89 |

| The Pony Cantered All the Way Down the Street | 99 |

| She Ran as Fast as She Could and was Just in Time to Drag the Baby Out of the Way of the Wagon | 105 |

| “Mother!” she Cried. “Oh, Mother!” | 113 |

| The Magic Mask was Ready, and Herlo Tried It on the King’s Face | 123 |

| But All the United Efforts of Bess and Bob and Archie’s Left Arm could not Raise Tom | 135 |

| 12 He Swung Down the Trail with a Speed that Mocked the Wind at His Back | 143 |

| She then Touched the Pitcher with Her Wand | 150 |

| “Be not Alarmed, Dear Mistress,” said the Pitcher | 157 |

| Immediately He Grasped the Sword by the Handle, But could not Stir It | 171 |

| Then Sir Galahad Took His Place in the Field | 175 |

| A Monk Led Him Behind the Altar where the Shield Hung as White as Snow, but in the Center was a Red Cross | 181 |

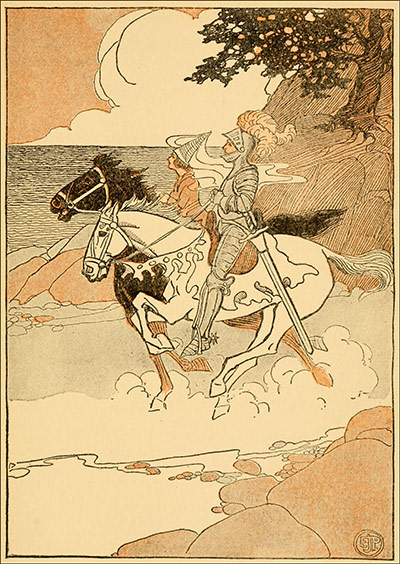

| The Damsel Rode as Fast as Her Horse would Gallop that Night and All The Next Day till They Came in Sight of the Sea | 187 |

| Slowly Sleep Came Upon Him and He Dreamed | 205 |

| Away Went the Schoolmaster’s Legs, Cutting such Capers as the World Never Looked Upon Before | 217 |

| Before the Door of a Low, Thatched Hut Stood a Fair-haired Young Woman | 227 |

| Once He Thought He Saw Them | 237 |

| A Tall Figure Stood Among the Shadows of the Trees | 243 |

| Toward the Very Last, Robert the Jester Rode on a Piebald Pony | 251 |

| He Flung the Book into the Sea | 257 |

| Your Flag and My Flag | 265 |

| “If You Please, I was to be Left till Called For” | 275 |

| There were Houses in It, Furnished and Unfurnished, for Dolls of All Stations in Life | 286 |

| They Jogged on for Some Time in Silence | 297 |

ON THE SHORE.—THE GOOD FERRY PUTS OUT TO SEA.—THE PIRATE’S CAT.—THE LOST STORY.—LAND AHOY.—THE OLD WITCH AND THE IRON-CHAIN CURTAIN.—FINDING THE LOST STORY.—THE PIRATE CHASES THE GOOD FERRY.—THE TERRIBLE PUNISHMENT OF THE PIRATE AND THE OLD WITCH.—THE BUBBLE STORY.

15 THE TRIP TO STORY ISLAND

“IF only—” whispered Mary Frances to herself, as she closed the book she had been reading, “if only one could find the ‘enchanted island,’ and the ‘hidden treasure of stories’—I wish—I wish the story told how to get there!”

She was sitting on the branches of a tree, which were so bent that they formed a sort of hammocky rocking chair. The tree was close to the bank of the river, and away in the distance the whitecaps of the ocean rolled up and broke upon the beach.

“It’s quite a journey,” said a small voice, “quite a long journey.”

Mary Frances looked all around, but could not find where the voice came from.

“You see, it’s out at sea,” continued the voice; “and only one boat and one passenger a year. What’s more——”

This last was uttered with a deep sigh.

“Why, where are you? Who are you?” asked Mary Frances, springing up.

“Here I am, but I won’t be long,” continued the voice. “You’d better look lively, for I can’t cling to this fence much longer. Besides, I am almost out of element!”

Then the little girl saw a dolphin sitting on the top rail of the fence, holding on with one fin.

“Oh!” she cried, “do you really know where the ‘enchanted island’ is? Will you tell me how to get there?”

16 “That I will!” said the dolphin. “That I will, if you’ll get me a little of my element first.”

“What is that?” asked Mary Frances.

“Why, you couldn’t live without yours for one minute! I’ll die if I don’t get some soon!”

“Oh, dear, what can it be? Whatever in the world is your element? I don’t want you to die!”

“Be quick!” cried the dolphin, fanning himself with the other fin. “I feel very faint!”

“I’ll get some water!” Stooping quickly, Mary Frances filled her hat. Before she could dash it over him, the dolphin ducked his head into the hatful of water.

“Thank you,” he said, raising his head. “You’re not so dull after all. Water is my element; air is yours.”

“Of course,” said Mary Frances; but she wondered why the dolphin didn’t jump back into the water.

“The reason is that it takes me so long to climb a fence!”

“Oh!” said Mary Frances, although she didn’t see why the dolphin had to sit on a fence to talk.

“So that there’ll be no offense!” said the dolphin, after staring at her for a while; “but to refer to the trip—have you a ticket?”

“Why, no, I don’t think I have.” Mary Frances searched in her pockets, and pulled out some ribbon, a doll’s wig, a thimble, and a piece of paper.

“That’s the ticket!” exclaimed the dolphin, pointing with his fin. “All you need to do is to sign it. Have you a pencil?”

Mary Frances searched again in her pockets, while the dolphin looked on anxiously, but couldn’t find one.

“Well, never mind; just pull out one of my whiskers,” he said. “It will write right well.”

“But I might hurt you!” cried Mary Frances.

“Not if you take that loose one,” he said, pointing with his fin.

17 Very gently Mary Frances pulled it, and out it came.

“Sign your name!” cried the dolphin excitedly. “Right at the end of the paper!”

“Excuse me,” said Mary Frances; “my father says that no one should ever sign a paper without reading it.”

“That’s good reading!” said the dolphin. “Read it!”

And Mary Frances read:

Good for

One First Class Passage

to

Story Island

I Believe in All Good Fairies.

Signed ———

No. 1,234,567.

“Of course, I’ll sign that!” said Mary Frances, gravely using the dolphin’s whisker.

At that, the dolphin fell over with a great splash into the water.

“Oh!” screamed Mary Frances, “you’ll be drowned!” But, just at that moment, up came the dolphin’s head out of the water.

“My element!” he said. Then Mary Frances laughed to think how soon she had forgotten.

“Hold your ticket and wait right where you are!” the dolphin called out, swimming away.

Mary Frances watched the splashing tail and shining back flashing in the sun. Two or three times he leaped playfully in the air, turned somersaults in the water, and then disappeared from sight in the little cove near the mouth of the river.

“OH, my,” thought Mary Frances; “oh, my, I hope he won’t forget!”

After a little while, she caught sight of the dolphin swimming around the little high peninsula on one side of the cove. He seemed to be piloting something, for every few seconds he would leap up and look around as if to make sure that everything was as it should be.

Soon Mary Frances saw a beautiful little sailboat rounding the point. Surely it was following the dolphin. As it drew nearer she could read the name in gold letters on the prow, The Good Ferry.

A brisk wind filled the white sails and brought the boat so swiftly up the river that the dolphin had to swim with all his might to keep ahead. As she came to anchor in the shallow water near the bank, the dolphin called out, “Have you your ticket?”

“Yes,” answered Mary Frances, holding it up to view.

“Then step on my back and jump aboard!” said the dolphin.

As Mary Frances placed her foot on the dolphin as on a bridge, he suddenly arched his back and tossed her aboard.

“Take plenty of time to look the ship over,” he called out; “and don’t lose your ticket!”

Then the dolphin, with The Good Ferry following in his wake, swam down the river and put out to sea.

The Good Ferry was a charming little boat, graceful in every line. It wasn’t any longer than a large rowboat, but it seemed to have every comfort provided. There was on deck a comfortable deck chair; upon it was spread a beautiful steamer rug.

19 “I’ll take a nice nap, after I look the boat over,” thought Mary Frances.

As she made her way into the cabin, she uttered a cry of delight—and no wonder. Any girl would have loved it. The walls and woodwork were ivory white. Soft pink and light blue hangings fluttered at the windows. A large bowl, filled with pink roses and turquoise blue larkspurs, stood on the little golden dressing table with its folding mirrors.

A little ivory-white princess dresser, with its full-length mirror, stood across one corner, and an ivory-white bed across the other corner. On the rocking-chair, and bed, and dresser were painted pink and blue flowers, and the covers of the table, bed and dresser were embroidered with the same designs.

There was a wardrobe in a corner, and in it Mary Frances found the loveliest dressing gown of pink crêpe de chine, embroidered with sprays of light blue forget-me-nots, and white daisies with yellow centers, and pink roses; and a pair of light blue bedroom slippers and silk stockings, and a boudoir cap and nightgown, and a big steamer coat and cap—all just the right size.

“Just like a grown-up young lady,” she thought.

There were two more doors; one led to a pretty white bathroom, and the other to a little dining-room, lined with mirrors.

“I can’t get lonesome,” thought Mary Frances, “with so many ‘me’s’ about me;” and she laughed, and, just as she laughed, food appeared on the table. There were chicken soup, and celery, and olives, and crackers.

“Oh, dear! How hungry I am!” she exclaimed. “I guess this is meant for me;” and she sat down on the one chair at the table and began to eat the soup.

“I feel lots better!” said she, finishing the last drop. “It’s not good table manners to tip this plate,” she thought; “but I guess my reflections will excuse me,” and she bowed to the pictures of herself in the mirrors, and laughed.

Then suddenly the soup course disappeared from the table,20 and in its place there were roast turkey and cranberry sauce, and roasted sweet potatoes and apple sauce, and the many other things which go to make an all-around feast.

“How wonderful!” exclaimed Mary Frances, helping herself to turkey. “But how stupid to eat by myself, with only myself for company.” Just then she looked out of the porthole window and saw the dolphin, swimming ahead of the little ship.

“I’ll go invite the dolphin to dinner,” she thought; and went on deck.

Imagine her surprise to find that there was no land in sight. Neither was there any ship. The only other thing than the dolphin was the sea-gulls flying overhead.

“Hallo! Hallo!” shouted Mary Frances, making a trumpet of her hands. “Mr. Dolphin, Mr. Dolphin, one moment, please!”

The dolphin turned and looked at her. “Yes?” he asked, raising one eyebrow.

“Please, Mr. Dolphin, do you ever eat? I am lonesome, eating all alone.”

“I eat only fish,” said the dolphin. “They are in my element, you see. I do not find my food out of my element.”

“Oh, as to that,” replied Mary Frances, “I will fill a bowl with your element, if you will only accept the invitation.”

“Agreed!” said the dolphin, swimming to the rope ladder hanging over the side of the ship. Mary Frances leaned down and caught hold of his fins, when within reach, and helped him up.

When the dolphin reached the deck, she picked up a fire-pail with a rope attached, threw it overside, and brought up a pail of water. Then she hastened to the dining-room and brought a bowl.

After that she helped the dolphin to the dining table. The only chair was clamped in place to the floor, just as on any steamer, and she could not move it. So she changed her place to the side of the table. As the chair was a revolving one, like a desk chair, she turned and turned it until it reached the right height for the dolphin. She placed the bowl of water, “element” she called it, at the dolphin’s place.

22 “Is there anything on the table, Mr. Dolphin,” she asked, “which you would like?”

“Yes,” sighed the dolphin, “I would like some more salt in my element soup.”

Mary Frances gravely shook the salt-shaker over the bowl for a full minute. The dolphin tasted the water. “A little more, please,” he said.

So Mary Frances emptied almost all the rest of the salt out of the shaker into the bowl. The dolphin dipped in his head. “That’s excellent,” he said, smacking his lips.

“Mercy,” thought Mary Frances, “I do hope he won’t turn into a salt mackerel.”

“Salt Smackerel is my pet name,” said the dolphin, smacking his lips again, and wiping them with his fin.

“I hardly dare think,” thought Mary Frances, “yet I can’t help thinking, can I? What queer table manners he has! I suppose his mother never taught him not to smack his lips when he eats—just to chew with the lips closed.”

“I chew all I choose!” exclaimed the dolphin. “My mother never sat at a table, you see.”

“Oh!” said Mary Frances, “did she stand?”

“Three feet high in her stocking feet,” solemnly declared the dolphin, which Mary Frances didn’t consider an answer at all; but was too polite to say anything that might be annoying to a guest.

“I wonder what I can give him for dessert?” she thought.

“If you please,” said the dolphin, and Mary Frances noticed that he was very pale, “if you please, I do not care for any. You see, I have deserted my post—that is enough dessert for me, and I shouldn’t wonder if I’d be punished enough for it in a minute—Oh! Oh! what is that! It’s the pirate’s cat!” and with a scream, he leaped out of the window into the water.

“ME-OW! me-ow!” came the cat’s voice from the door.

“Oh, Kitty! Kitty!” cried Mary Frances, running toward it. “Why, wherever did you come from? I thought I had looked all over the ship.”

“Indeed,” replied the cat, “even if you had, and you have not, you wouldn’t have found me. The pirate’s been watching a year to throw me on board The Good Ferry.”

“Oh,” exclaimed Mary Frances, “the pirate—why, I haven’t seen any pirate!”

“Of course you haven’t,” said the cat; “he’s too smart for that. He’s been watching for a time when the dolphin had deserted his post.”

“Oh, dear,” thought Mary Frances, “it was all my fault;” but out loud she said, “Well, no great harm can come of it, anyway. Won’t you have some dinner?”

“Yes, thank you,” said the cat, looking longingly at the table.

“Take this chair,” invited Mary Frances, pointing to the dolphin’s place.

The cat leaped up on the chair, and carefully tucked a napkin into the collar on its neck. Mary Frances filled a plate with turkey and potatoes and gravy, and set it before the cat, who politely waited for her to take her place and begin to eat.

“Do not wait for me, Kitty,” said his hostess; “I’ve finished this course, thank you.”

Soon nothing was left on the plate.

Just as Mary Frances was going to suggest that ice cream might make a nice dessert, the cat began to tremble. It trembled so that the ship shook all over.

“Why, what is the matter?” asked Mary Frances. “Are you chilly?”

“Oh, dear, no,” replied the cat, its teeth chattering. “Oh, dear, no; but I forgot! The pirate will hang me! He will! He will!”

“Why will he hang you?” asked Mary Frances, quite bewildered, and a little frightened.

“Speak softly,” said the cat. “Come here, and I’ll whisper.” And behind his upraised paw, he told, “The pirate ordered me to eat the dolphin; and to bring his right fin to prove that I’d done it. And now I’m too full of dinner to do it.”

“Eat him, indeed!” said Mary Frances, angrily. “I’d like to see you!”

“Oh, would you?” cried the cat. “If you only hadn’t given me so much dinner, you might have had the pleasure—that is, if the dolphin had come aboard again. You see, I can’t do it now; I can’t catch him in the water. And the pirate said he’d come for me in an hour and nine minutes. It’s close to that now,” glancing at the clock. “Oh, what shall I do?”

“Why does the pirate want the dolphin killed?”

“Hush!” exclaimed the cat. “Speak softly! Come here! I’ll whisper the reason to you. It’s on account of the lost story. He thinks you might find it, and if the dolphin is destroyed, he can run down The Good Ferry. He can’t do the work himself, for he is bound in chains on his own ship, but he has prisoners on board whom he orders about, just as he did me. He can’t get within miles of The Good Ferry if the dolphin is guiding her. He was so mad that he didn’t notice when the dolphin first came aboard that the foam from his mouth was strong soapsuds, and washed the black decks of the pirate ship snow white.”

25 “But,” said Mary Frances, “you forget—if the dolphin guides the ship, the pirate can’t get you!”

At that the cat began to laugh joyously, and it laughed so hard that Mary Frances laughed too; and suddenly the meat course disappeared off the table and a huge block of ice cream appeared in its place, and Mary Frances and the cat—you know what they did.

“LET’S go on deck,” said Mary Frances, when they had finished, “and perhaps you can tell me more about the lost story. But first you must solemnly promise that you will not eat the dolphin.”

“I solemnly promise,” said the cat, with upraised paw.

“Very well,” said Mary Frances, leading the way to the deck chair, on which she lay down, while the cat curled himself up on a coil of rope near her head.

“It happened in this way,” began the cat, in a low tone of voice, as he nervously looked around. “You know the ‘enchanted island’ is Storyland, and the home of the Story People. The Story King and Queen have ruled there forever. Well, one day a wicked fellow, who had always said there were no such things as fairies, somehow got into the ‘enchanted island’—it has always been a mystery to me how he did it—and stole a story, and carried it away and hid it. The trouble is that no fairy is allowed to find it. The boy or girl who takes it back will be the first person allowed to enter the ‘enchanted island’ since it was lost.”

“Do you know where it is hidden?” asked Mary Frances.

“I have a slight idea,” whispered the cat.

“Is it on board the pirate ship?” she asked.

“It cannot be. I have searched everywhere—everywhere—everywhere-everywhere—” drowsily replied the cat. Mary Frances noticed that his eyes were closing.

“Just one thing more before you go to sleep, Puss; just one27 thing more,” she said. “Do you know how long it will take to reach the ‘enchanted island’?”

murmured the cat; and, shake him as she might, that was the only answer Mary Frances could get, until, at length, she could get no answer at all.

After she was certain he was asleep, she went to the bow of the boat and called softly to the dolphin.

He swam up close alongside. “Are you all right?” he asked.

“I am, indeed,” replied Mary Frances; “but I want to tell you what the cat told me. First, I want to say that he will not hurt you because he is horribly afraid of the pirate, and he knows that he is safe on The Good Ferry as long as you protect it.”

“That’s right!” said the dolphin. “And now, how about the cat’s tale?”

Then Mary Frances told the dolphin the story the cat had told her.

“Why can’t we search for it now?” she asked.

“Well,” replied the dolphin, “I am not exactly sure about the cat’s tale myself, and every year I take one person direct to the island—that’s my orders—that’s my orders. None of them have ever found the lost story—so I’ve taken them direct home. That’s been my orders; that’s been my orders. Better go on, I say; better not take anybody else’s word, I say, I say.”

“All right,” said Mary Frances, “just as you say; but a year’s a pretty long time.”

“That depends,” replied the dolphin.

And away it swam.

And then Mary Frances noticed that the sky was getting dark, and she realized that she was very sleepy. She made her way to the white cabin and undressed and went to bed, wearing the pretty clothing which she found in the wardrobe.

“If I waken suddenly, and want to go on deck, I’ll have on my negligee,” she thought, as she tied the dressing gown in place and slipped on the boudoir cap.

MARY FRANCES awoke with a start, and rubbed her eyes.

“Surely I heard somebody call,” she said.

Again came the call, “Land ahoy! Land ahoy!”

“Why, that is what they called out on Columbus’ ship when they discovered America!” thought Mary Frances, hurriedly dressing. “I wonder if we are discovering anything.”

It was just getting light as she ran out on deck. At first she did not see any living thing except the dolphin, which was swimming ahead of the boat. She gazed around on the water. It was a deep blue color.

“It looks like the tub of bluing water when Nora rinses the clothes,” she thought. “I wonder if it will color anything?” She ran to the railing, dipped up a pailful and dropped in her handkerchief. “Just clear water,” she said; and hung it up to dry.

“Land ahoy!” came the call once more. Mary Frances looked up at the sails. There was the cat. He was sitting on the rope ladder, and holding his forepaws like a telescope. As soon as he saw Mary Frances, he pointed ahead and shouted, “Land ahoy!” Then she saw a dim outline of coast.

The cat scrambled down the rigging, and ran up to her. “Story Island! See!” he said.

“Why,” exclaimed Mary Frances, “why, how long have I been asleep? I thought you said something about a year!”

“Ha, ha!” laughed the cat. “A year and a day, I said, and30 that it nearly is. You have been asleep just three hundred and sixty-five days and some hours.”

“Have I really?” exclaimed Mary Frances; then hearing a sudden splash in the water, “Oh, what was that? Was it the pirate?”

“That? That wasn’t anything to be afraid of—just some flying fish,” answered the cat.

“Do they really have wings?” asked Mary Frances.

“They certainly do. Come, let us look into the water and see if there are any near the boat,” said the cat.

“Oh, oh, oh,” exclaimed Mary Frances, “what a beautiful fish I see! It has a tail of gold and a head of blue—turquoise blue. Isn’t it beautiful! See it, there!”

“Yes, I do,” said the cat; “it is an angel fish.”

“An angel fish! That’s just the right name for it,” said Mary Frances.

“Yes, I believe somebody who tasted one named it that,” said the cat.

“Surely nobody would eat such a beautiful creature,” Mary Frances said.

The cat smiled. “Its beauty is more than skin deep,” he said.

“Well, I wouldn’t eat anything so lovely,” said Mary Frances.

“That reminds me of a rhyme a fish taught me,” said the cat.

“That sounds mighty fishy,” thought Mary Frances, but she did not say anything.

“Shall I say it for you?” and without waiting to hear, he went on:

32 “That is a pretty angelic wish, I’ll say,” added the cat. “Oh, there are some of the flying fish,” pointing to a distance from the boat.

“They are not anything like as pretty as the angel fish,” said Mary Frances.

“Oh, see the whale spouting!” exclaimed the cat, running to the other side of the boat.

And Mary Frances saw the long fountain of water shooting up in the air.

“My,” said the cat, “if I could just catch that whale, I could feed every hungry cat I ever heard of.”

“Why, how big is it?” asked Mary Frances.

“It’s twenty times as long as half again, and double the quarter wide,” said the cat.

“How large is that, if you please?” asked Mary Frances.

“If the length is multiplied by the thickness and then by breadth, it will give the correct volume,” said the cat; “at least, that’s according to tickle.”

“Tickle?” asked Mary Frances. “What is tickle?”

“Tickle is short for arithmetickle,” replied the cat.

“Oh?” said Mary Frances, “we don’t call it arithmetickle; we called it arithmetic.”

“That is nothing like so pretty a name,” said the cat, “and you get the same result.”

“But the size of the whale—” said Mary Frances, “what is it?”

“Can’t you do a simple little problem like that—when I’ve given you the rule?” asked the cat.

Mary Frances did not like to say that she had to give it up.

“Let bygones be bygones,” said the cat, “and look up ‘whales’ in the dictionary when you reach the island.”

“Oh, yes,” exclaimed Mary Frances. “Oh, I can see—I think I can see some houses! Oh, look, Cat, look! They are pure white!”

“Don’t you know why?” asked the cat.

“I suppose they are painted,” said Mary Frances.

“Painted, me whiskers!” exclaimed the cat. “They are not painted. They are made of coral.”

“What is coral?” asked Mary Frances.

“Come, I will show you,” said the cat, leading the way to the middle of the deck.

He lifted a wooden cover. Underneath was a deep box. The bottom of the box was made of glass.

“Now, you can see the bottom of the sea,” said the cat. “See? See? See the bottom of the sea?”

“Oh, look at those white trees!” cried Mary Frances, gazing down into the clear water through the glass.

The cat laughed. “They are not trees,” he said; “they are coral formations;” and he told her about the tiny coral insects which build coral growth by fastening their tiny shell bodies to each other.

“Do they know they are making trees?” asked Mary Frances.

“Oh, my, no,” said the cat. “They just grow naturally, like any other babies. Sometimes they make fan-like forms, or sponge-shaped ones.”

“Did they build the white houses over on the island?” asked Mary Frances.

“Of course not,” said the cat; “what a curious question. They live only in the sea. The houses are up in the air—but they built the island.”

“Not that big island!” exclaimed Mary Frances.

“You have not contradicted me before,” said the cat. “If you know all about it——”

“I beg your pardon,” said Mary Frances, very humbly. “Will you please tell me the rest?”

34 “They rest on the bottom of the ocean,” said the cat. “The houses are made of the coral which is dug out of the cellars,” he went on. “But, come, let us get ready; we are getting near port,” and he began to wash his face and smooth back his whiskers.

Mary Frances took the hint, and went into the cabin.

She tidied her hair, and put on a fresh ribbon, and when she went on deck, she took her pocket mirror with her.

“ARE my whiskers straight? Is my fur smooth? Is my face clean, please?” asked the cat without stopping, as soon as he saw her.

“You may see for yourself,” said Mary Frances, holding the pocket mirror before him.

“Ah,” he said, giving a sigh of relief. “I look absolutely scrubbed; I guess I’ll do!”

“Dear me!” said Mary Frances. “I do wonder how it will seem. Isn’t this a beautiful place? But I wonder why it looks so misty around the island. Can’t we ask the dolphin?”

“I guess we’d better not,” said the cat. “You see, a pilot doesn’t like to be questioned.”

“There is a boat coming this way!” exclaimed Mary Frances.

The cat began to shiver. His fur stood up on end. His tail lashed to and fro.

“It’s the old witch’s boat!” he cried. “She’s the pirate’s wife. I’m not afraid! I’m not afraid! I’m not afraid, though!” And he kept on saying, “I’m not afraid!” so often that Mary Frances began to laugh.

“St-stop that laughing!” came the voice of the old witch. “St-stop that laughing this instant, unless you have the lost st-story!”

“And if we have it, Madam Witch,” called out the cat, “what then?”

By this time the boat was quite near. They could see the old witch tremble. She turned almost as white as snow. Her two front teeth chattered.

“If you had it, the curtain would part!” she suddenly exclaimed, laughing. “I forgot for a moment! Don’t try to fool me, Cat! Away with you! Away with you! Find it, if you can! Find it, if you can! Ha, ha! Ha, ha! Haw, haw, haw!” and she waved an oar at the boat.

Then Mary Frances saw that all around the island was stretched an iron-chain curtain.

“Don’t look at it, S-Sissy,” said the old witch. “It’s so s-strong that s-steel will not s-saw it. It will remain about St-Story Island, and will not open until the lost st-story is found; and until it is found not a boy or girl in the world will hear a new st-story!”

“We will find it!” shouted Mary Frances. “We will find it and bring it back and open the curtain!”

“Ha, ha!” laughed the old witch, holding her sides. “Ha, ha! it’s well hid. It’s well hid. You’ll be old and gray before you find it, I’ll warrant—and as for the cat, he’ll be so old he will sh-shake around in his s-skin, I’ll warrant. Ha, ha! Be off! Be off!” and, quickly turning her boat, she rowed away.

THE cat looked at Mary Frances.

Mary Frances looked at the cat.

“Ha, ha, and ha, ha!” said the cat. “We’ll laugh at her some day!”

“We will!” said Mary Frances, “we will, Puss! Let us call the dolphin.”

The dolphin swam up at that moment.

“Whither now?” it asked. “Where shall we go, Cat?”

“64° 40´ W., 32° 40´ N.,” said the cat; and the dolphin swam ahead, turned the boat, and soon the island was out of sight.

“Come, I am hungry!” said Mary Frances. “Let us go into the dining-room.”

“The dolphin has plenty of element soup,” she thought.

There was the table spread with a fine feast, and both she and the cat enjoyed it.

Just as they were finishing dessert, they heard a pounding noise. They rushed out on deck. The noise was made by the dolphin hitting the side of the boat with its tail.

It whispered two words, “Pirate Ship,” and swam ahead again.

The cat made a telescope with his paws, and looked out over the water. “Sure enough!” he cried, in fear. “Oh, my! Oh, my! and I haven’t eaten the dolphin!”

“For shame!” exclaimed Mary Frances. “For shame! You have forgotten that he can’t come very near while the dolphin is at his post!”

38 “Oh, yes; that is so. Excuse me, please. But what does the pirate mean by coming, I wonder?”

“Do you suppose he thinks we may be near finding the story?” asked Mary Frances.

“That’s it!” exclaimed the cat. “I’ll wager my whiskers that’s his idea. So that if we espy it he’ll get it first.”

“Do you think we’ll find it?” asked Mary Frances.

“My fur feels as though we would,” said the cat. “Please tell me, is it sending out sparks?”

It was growing quite late in the afternoon, and quite dusky. Mary Frances, to her astonishment, saw great showers of electric sparks coming from the cat’s body.

“You look like a sparkler on the Fourth of July, Cat,” she said.

“Oh, isn’t that fine!” said the cat. “You see, it’s this way—the nearer we get to the story, the more sparklier my fur gets.”

“So we must be quite near,” said Mary Frances; “for I don’t see how you could get much more sparklier.”

“I forgot to tell you,” said the cat, “that after we find the story, the dolphin’s power to keep the pirate away is gone. We’ll have to race like a rocket to beat his boat.”

“Oh, my, what is the matter!” exclaimed Mary Frances, as the cat suddenly jumped high in the air, sending out a shower of sparks that fell at her feet on the deck. Over the side of the boat he fell, and all was dark as a pocket.

“Oh, Kitty, Kitty,” cried the frightened girl, running to look into the water, but she saw nothing of the cat. Neither could she see the dolphin. She could see the dim light of the pirate’s ship, and it seemed quite near.

“Whatever shall I do?” thought Mary Frances. “I really believe I am going to cry.”

Just at that minute she heard a scratching on the side of The Good Ferry.

“Who’s there?” she whispered.

40 No answer came. Just another scratching.

“Who’s there?” she asked again.

“Me-ow!” came a faint voice.

Mary Frances could see better now, for her eyes were getting accustomed to the darkness.

“Is it you, Puss?” she asked, peering down into the water.

When she saw it was the cat, she quickly let down the rope ladder, and the cat climbed aboard, and fell in a wet heap at her feet.

She lifted him carefully and carried him to the steamer chair. She did not notice that something dropped from his mouth as she lifted him.

She dried his wet fur, and went to the dining-room to get him a drink of water. There she saw a bowl of beef tea, which she took to him. She fed him a little at a time with a medicine dropper which she had found in the bathroom.

At length he opened his eyes.

“Where is it?” he asked.

“Where is what?” asked Mary Frances.

“The lost story,” whispered the cat. “I carried it in my mouth. That is why I couldn’t answer you when you asked who was there.”

“I didn’t see it,” said Mary Frances.

“Oh, dear, oh dear!” exclaimed the cat. “It must be on deck! Let us look for it!”

“You are not able yet,” said Mary Frances. “Lie still! I will look! Was it a roll or a book?”

“It was a glass bottle,” said the cat, “and it may have rolled back into the sea—if that is what you mean by ‘was it a roll?’”

Mary Frances went down on her hands and knees.

She crept all over the deck, feeling for it in the darkness. After a while the cat helped.

They worked all night, but could find nothing. In the morning, as it grew light, they both saw a dark green bottle caught in41 the top of the rope ladder which was fastened to the side of the boat. So lightly was the bottle held that it might easily have fallen back into the water and been lost again.

Mary Frances lifted it carefully. It was labeled—The Lost Story.

The bottle was sealed with a cork, and inside was a roll of paper.

“Oh, isn’t it too good to be true!” exclaimed Mary Frances. “Where shall we hide it?”

“Let’s label it Catsup and put it on the side table in the dining-room,” said the cat. “Put the new label right over the old one,” he added.

“That’s a splendid idea!” cried Mary Frances. “I’ll do it right away!”

WHEN Mary Frances came on deck again, The Good Ferry was plowing the water so fast that a deep furrow of foam followed her. The dolphin was swimming so fast that it made deep waves with the motion of its tail.

Although going so rapidly, they could see that the pirate’s black ship was keeping the distance the same as at first between them.

“I believe he is gaining,” at length said the cat, who was using his paws for a telescope.

Mary Frances looked a little pale, but smiled. “I think we will make more time in a minute,” she said. “Let’s drop something overboard, and he may stop to pick it up.”

So they filled a suitcase with paper, and dropped it over the side.

They were delighted when they saw the pirate’s ship stop to pick it up. They could hear the loud ravings of the pirate when he found nothing inside.

The rest of the trip was very exciting, for the pirate’s ship at one time was so close that they heard the pirate say to the cook, “Blast ye! Blast ye! Why don’t ye jump aboard? Ye can make it in two jumps!”

“Jump yourself!” replied the cook.

Faster and faster swam the dolphin; faster and faster sailed The Good Ferry. Try as he would, the pirate could not overtake them. They saw him plainly, half a knot behind, jumping up and down on his deck, shaking his angry fists. As they reached the island he turned and gave up the chase in defeat.

When they came to the wharf, there stood the old witch, drinking ink out of a bottle.

“Ha, ha!” she honked. “S-so ye think ye’ve got the lost st-story, do ye? Well, ye haven’t; s-so there!”

Then she began to wave her arms about her head, laughing wildly. As Mary Frances stepped off the boat the old witch tried to snatch the story bottle out of her hand.

“Oh, you can’t scare me,” said Mary Frances. “Step aside, please,” and as she pushed past the wild old witch, the great iron-chain curtain fell with a crash, and before her was Fairyland, or Storyland, which, as you know, are one and the same.

MARY FRANCES heard music and singing. She heard the words:

Then Mary Frances remembered, and stepped forward with the story.

She was met by a beautiful young lady, who introduced herself as the Story Lady, and a small company of story people, who led her to the castle of the King and Queen of Story Island. They took her into the court, where the rulers sat in state.

“Welcome!” said the Story King, rising.

“Welcome!” said the Story Queen, rising.

Then the King made a speech.

“You have done us a great service, young friend,” he said; “and we hope to do something for you to show how much we appreciate it.”

“Sir,” said Mary Frances, handing him the bottle, “if it had not been for the dolphin and the cat, I never could have found the story.”

“The dolphin has been rewarded,” said the Story King; “he has had his head cut off——”

“Oh,” cried Mary Frances, “the poor, dear dolphin!”

“And has been turned again into a prince!” added the Story Queen. “He was the prince who kissed the Sleeping Beauty, and was under the spell of the old witch outside the chain curtain.”

45 “And the cat has been rewarded,” said the King. “He has charge of all the cats and kittens in all the stories ever told, or ever-to-be-told.”

This made Mary Frances happy, for she knew the cat would love that charge.

“Now,” said the Story King, “if you are not too tired, we will get over the business of trying the pirate and the witch!”

“I am not tired, thank you,” said Mary Frances, “for I slept three hundred and sixty-five days and nights on my way here.”

“Good!” said the King. “Please have this seat,” and he led her to a deep blue velvet chair.

The King then touched a button under the table, and a door opened.

In came a large man with a large beard. Mary Frances knew him at once. He was Blue Beard. He was trembling terribly.

“Fetch in the pirate, Blue Beard,” ordered the King.

Blue Beard bowed and left the room. Soon there came the clanging of chains, and Blue Beard led the pirate into the room, all wound up in a great section of the iron-chain curtain. He was dreadfully pale and very angry. His mouth was frothing and his breath was coming out of his nostrils like smoke.

He glowered at Mary Frances as though he would like to bite her, but she was not afraid.

“Behave!” said the King. “You cannot frighten a person who has been so brave as to part the iron-chain curtain. If she had been afraid of the old witch, the curtain would not have parted, and all the children in the world would have been still waiting for new stories.”

He turned to the Queen. “Have you a fitting punishment, my dear?” he asked.

“I have,” said the Queen, very solemnly. “It is this: the pirate shall never again hear a story or read a story!”

On hearing his fate the pirate screamed, “Anything rather than that! Please have mercy!” And he fell down in a dead faint.

46 Blue Beard dragged him out. Immediately after, the King ordered the old witch in.

“Tell the story of the lost story,” ordered the King.

“Oh, S-Sir,” stammered the old witch, “Oh, S-Sir, the pirate st-stole it, and took it on his sh-ship, and I st-stole it from him and put it in a bottle, and was going to bring it back, but I lost it overboard in a st-storm. I didn’t want the pirate to know I took it, for he would have beaten me to death.”

“Why did you try to take it from this young lady?” asked the Queen.

The old witch hung her head. “Because I wanted to keep it for my-s-self,” she said.

“Well, what shall her punishment be, my dear?” asked the King.

“She shall be punished by never hearing the end of a story,” declared the Queen. “Only to the middle of a story shall she hear—never to the end.”

Then the old witch gave a loud shriek, and ran out of the room as fast as she could. The King sent a giant after her, and had him lock both the pirate and the old witch up in big iron baskets, and carry them off to the end of Snowwhere.

“And now, my dear,” said the King, “what is to be our dear little friend’s reward?”

“Two rewards shall be hers,” replied the Queen. “One is that she shall know that all the children of the world can have new stories every day; and the other is that she can stay with us for a visit and hear all the stories she wishes to hear.”

“Very good,” said the King. “Let us now hear the lost story.” And all the Story People sat down to form a double circle.

With that the Story Lady, dressed like a butterfly, came dancing in. The King opened the green bottle, took out the roll of paper and handed it to her. She took her place at the end just where the circle closed, and began to read aloud the lost story, which is entitled “The Bubble Story.”

LILLA walked through the garden, saying—

“I should like to be a princess,” for she had been reading a story about a princess who had only to say “Come,” and anything she wished for came at once.

It was a hot summer day, and she sat down on a mossy bank under an elm tree thinking what she should wish for if she had the power of the princess. All at once the garden seemed strange to her, and she heard a voice saying:

She looked up and saw an aster growing in a green flower-pot which she had never seen before; and on one of the flowers was perched a tiny fairy.

“And you can have everything you can wish for except one thing. If you wish for that you will lose the rose.”

“And what is that?” asked Lilla, taking the rose which the fairy offered her.

“You must never ask for soap bubbles.”

“Oh, soap bubbles? Of course, I shall not wish for them!” said Lilla.

“Whenever you want anything,” said the fairy, “just say:

“You will be a princess as long as you keep the rose. But48 you must never ask for soap bubbles. Good-by; now I must go back to my home.”

So the fairy went to Fairyland, and Lilla went home; but no one knew her, because she was now a princess with long hair and a golden crown.

“I will go up to the castle on the hill,” thought Lilla; “princesses go there to stay.”

At the castle they were expecting a princess, so they thought Lilla must be the one who was coming, and they gave her a grand room, all hung with velvet curtains, to sleep in. On the table was a silver box which Lilla thought just right to keep her rose in.

“Now, I shall try what I can do with my rose,” thought Lilla. So she thought of a box of toys, and said:

Scarcely had she spoken when a maid came to say that a box had come for her.

When the box was opened, Lilla saw so many pretty things that she thought she would like a Christmas tree to hang them on, and again she said:

And in a few minutes a Christmas tree arrived hung all over with gold and silver drops, and colored lights, and bonbons, and still more bonbons, and gifts of all kinds.

The people at the castle had never seen such a beautiful Christmas tree, and they were delighted with the gifts which Lilla divided among them.

Day after day Lilla asked her rose for something new, and every day more and more beautiful things came, till not only her own room, but the whole castle was full of them.

She gave them away to every one, for she soon grew tired of them.

50 Every day she was trying to think of something she did not have, but at last there seemed nothing left to wish for.

That was when she began to long for—soap bubbles, which were the only things she must not have.

“But how beautiful thousands of soap bubbles would look, floating about in the sunshine with rainbow colors upon them,” she thought.

She could think of nothing else, and grew quite sad because she could not ask for soap bubbles.

So one day, she went into the garden, taking her rose with her. “Shall I ask? or shall I not?” she kept thinking, but she could not make up her mind.

So she counted on the buttons of her dress.

“Oh, dear,” sighed Lilla, “I wanted it to come, ‘yes’—I am going to ask for them!”

So she said the magic rhyme:

But no soap bubbles came. She looked all around the garden, even up in the branches of the trees, but no bubbles were to be seen.

Then she grew impatient; she took the rose, and said:

Then suddenly the air was filled with soap bubbles; little ones, big ones, floated all over the garden.

“Oh, aren’t they lovely!” cried Lilla, holding out her arms to catch some; and then a bubble larger than the others opened, and closed around the golden rose, and lifted it out of her hand,51 floated quickly away with it, higher, higher, higher, until Lilla could no longer see it.

She watched and watched until only two soap bubbles were to be seen; then she sank on her knees, and stretched out her hands after them.

But it was too late; her rose was gone, the bubbles were gone, and she was no longer a princess. Her hair was as short as it ever had been, and her crown had disappeared.

It was of no use to return to the castle now, as the people would not know her. Where should she go? What could she do? She was so worried that she cried aloud, and you can imagine how glad she was to hear her own mother’s voice saying:

“Lilla, dear, you must have fallen asleep. Come, wake up! Tell mother about your dream.”

“Why, mother, it was just like a story,” said Lilla, sitting up and rubbing her eyes.

Then she told her mother all about it.

“A very pretty story,” said her mother, “and one that shows you that people who can have almost everything they wish for, are not really happier than others. There is always something just out of their reach, and that makes them discontented with what they have.”

“Yes, even soap bubbles,” said Lilla, laughing.

“That’s a good story—too good to be lost,” said the Story King, when the Story Lady finished.

“Yes, but we have better, and you shall hear some of them to-morrow,” said the Story Queen to Mary Frances, smiling graciously.

Then to the people she announced:

“There will be a reception in the court of honor this evening to our visitor, Mary Frances, the finder of the lost story. As it is now dark, let every one retire and prepare.”

52 Then all the people applauded, formed in line and marched out, each bowing to the King, Queen and Mary Frances, who stood rather timidly in her place with the Story Lady beside her.

After the others were gone, the Story Lady turned to her and said:

“The Queen has planned for you to be in my charge during your visit, and all you wish to see or hear is at your command.”

“How kind, and how perfectly lovely!” exclaimed Mary Frances, clapping her hands. “I couldn’t possibly wish for anything I would rather have than to be with you!”

This pleased the Story Lady greatly, and she led the way to their apartments.

I wish I had the time and space to tell you more about the wonderful and delightful reception—how Mary Frances stood in line with the King and Queen, and was introduced to all the people of the island as a distinguished visitor whose deed would never be forgotten as long as stories were told.

But if I were to relate all they said and did this book would not hold one-quarter of the stories which the Story Lady had planned for Mary Frances to hear.

The revels continued far into the night; and when at last they ended, Mary Frances retired to her apartment, excited and happy. As the Story Lady kissed her good-night, she said:

“To-morrow will be the first day.”

MISCHIEVOUS ANNA AND PETER.—DIAMONDS AND TOADS.—THE MAGIC NECKLACE.—THE CAT AND THE CARROTS.—THE BRAHMIN, THE TIGER, AND THE JACKAL.—THE RED DRAGON.—TWO POEMS.—TINY’S ADVENTURES IN TINYTOWN.—MORE ADVENTURES.

55 STORIES TOLD THE FIRST DAY

NOW, you must know that the Story People met at a certain hour every day to hear and to tell stories, new and old; for, as you may well believe, it is no small task to provide stories enough to feed the story-hungry children of the world.

Accordingly, when all were assembled, the Story King in his place, and Mary Frances in the seat of honor beside the Story Queen, the Story Lady began to tell the story of Mischievous Anna and Peter.

Anna and Peter were always in mischief. One day they climbed to the top of a high wall. It was a fairy wall, and it grew higher and higher, until at last it went so high that they got frightened, for they did not know how they should get down again. So they held tight by each other and the wall, and began to cry.

But no one heard them. For they were far away from home; besides, they were as high up in the air as the top of a mountain.

“Oh! oh! oh!” sobbed Anna.

“Oh! oh! oh!” sobbed Peter.

And their eyes were red and their faces quite wet and dirty.

“I shall fall,” said Peter.

“I can’t hold on much longer,” said Anna. And then they both sobbed “Oh! oh! oh!” again.

Then they heard a voice saying, “Oh! oh! oh!” after them.56 Only it was not any one crying, for the “oh! oh! oh!” had a very sweet sound.

They could not look round, for they dared not move their heads, and they dared not look down for fear of getting dizzy. But the voice seemed to be coming nearer. And so it was, for a fairy gate, with a tree beside it, and a little bit of ground to stand upon, was shooting up into the air just as the wall had done. And when it was as high as the wall it stopped, and Peter and Anna saw that a boy was leaning against the gate. He was playing on a whistle-pipe, and that made the sound they had heard.

“I will play you a tune,” said the boy. And he played so softly and sweetly that Peter and Anna left off crying.

“How did you come up?” asked Anna.

“On the gate,” said the boy.

“How are you going down?” asked Peter.

“On the gate, to be sure,” said the boy; “I have only to say—

And as he said the words, down he went.

“Let us also try,” said Anna.

Then down went the wall to the ground, and Peter and Anna slid off, and stood staring at the boy, who was still playing on his pipe.

“What do you want most?” asked the boy. “My pipe will bring anything I ask for.”

“A silk frock with a flounce and a sash, and a bonnet with blue ribbons,” said Anna, who was fond of fine clothes.

“A new suit and pair of leather reins to play at horses with,” said Peter.

The boy played a lively tune, and before Anna could say “ready,” she found herself dressed in a fine new frock; while Peter had the reins in his hands, and a new suit of clothes with a great frill and a round hat.

58 Then the boy said “Good-by,” and Peter and Anna went towards home.

“I will go this way,” said Peter.

“I will go that,” said Anna.

So they parted.

Anna, as she walked along, heard little feet behind her; and when she reached the steps leading to her home she looked round, and what was her surprise when she saw a large mouse dressed like a lady, with a parasol in its hand.

said the mouse.

Now Anna was afraid of mice, and she said, “But I do not want you; besides, we have a large cat that will eat you up.”

“No, it will not; I am a fairy mouse, and can eat up the cat if I please.”

Anna was much frightened; this was truly a dreadful mouse.

“Go away! Oh, go away!” she said.

“No,” answered the mouse; “as long as you wear my clothes I shall stay with you and take care of them.”

“They are not yours,” said Anna; “a boy with a whistle-pipe gave them to me.”

“But he piped to me for them,” said the mouse; “I have wardrobes full in my castle. You are quite welcome to them; but I must see that you do not spoil them. I shall sit by you at dinner, and play with you, and walk out with you, and sleep on your pillow at night.”

“Oh dear! oh dear!” said Anna; “I wish I had never asked for a silk frock and bonnet.”

“Shall I take them back?”

“Well, as you have made a rhyme, I will do so,” said the mouse, and she slapped Anna’s arm sharply with her parasol. Then Anna’s new clothes fell off, and she found herself in her old cotton dress again. And the mouse grew larger and larger, and ran away to her castle with the silk frock and the grand bonnet.

Now while this was happening to Anna a queer-looking man in a peaked hat and long overcoat said to Peter, “Shall I be your horse?”

“Yes,” said Peter. And the man took the reins, and they went along merrily enough.

When they were close by his home, Peter said, “I am going in here.”

But the man said—

“They cannot be yours,” said Peter; “a boy with a whistle-pipe gave them to me.”

“Ah, but he got them from me! I am a saddler, and have hundreds of them. And I want some little boys to help me to make more.”

“I don’t want to go,” said Peter.

But he could not loose the reins, and the man pulled him along faster and faster.

said Peter.

“As you have made a rhyme,” said the man, “I’ll take them back, and you may go home.”

Then the man hit Peter sharply with one end of the reins, and his new suit fell off, and he found himself in his old pinafore.

Then Peter went home and told Anna what had happened to him; and Anna told Peter all about the mouse, and they both thought that they had had a lucky escape.

Just then the boy with the pipe came down the street. And the pipe played these words—

Then the boy turned round the corner of the street, and Anna and Peter never saw him again.

“My, but the mouse must have looked cunning!” Mary Frances said. “Thank you for telling me that story. I—I wish——”

“Would you like to hear another—about Isabella and her cruel stepsisters?” asked the Story Lady.

“I should love to hear it!” replied Mary Frances.

The story people smiled and nodded, and the Story Lady proceeded.

ONCE upon a time there was a dear little girl named Isabella. She lived with her father, and her stepmother, and her two stepsisters.

Isabella was a pretty child and had sweet manners. Her stepsisters were not pretty, and they and their mother were jealous of Isabella.

They seldom spoke kindly to her; they made her do the hard work of the home, and treated her in a harsh manner, very much as Cinderella’s stepmother and stepsisters treated Cinderella.

One of her hard duties was to fetch the water for the household from the well just outside the village.

It was quite a long walk to the well, and after Isabella had worked all the morning, cooking, and washing the dishes, and washing and ironing, or sweeping, she felt sometimes that she was too tired to go so far and carry home such a heavy load.

One day after washing and ironing, she said, “I wish one of you girls would go with me to the well to-day, and help me bring back the water. I am so tired.”

“Indeed, they shall not!” exclaimed her stepmother angrily. “What do you think—that my daughters shall wait on you?”

“I do not care to get tanned in the sun,” yawned one.

“I do not wish my hands to look as though I work,” said the other haughtily.

So Isabella set out alone. She sat down to rest several times on her way, but after a while she reached the well. It was an old-fashioned affair, and had a moss-covered bucket on a long chain which wound on a roller. It was not hard work to drop the62 bucket down the well, but it was hard work to turn the handle of the roller until the dripping bucket reached the top. It was still harder work to empty the bucket into the pail she carried.

This day, when Isabella came to the well there was an old woman sitting on the well-curb. She was a wretched-looking old woman. She wore an old shawl about her head and shoulders.

When she saw Isabella she said, “Good-morrow, little maid.”

“Good morning,” said the little girl. “How do you do?”

“I should do very well, thank you,” said the old woman, “if I had a drink of water.”

“That you shall soon have,” said Isabella, forgetting her own tiredness because she felt sorry for her.

Isabella soon had the well bucket up, filled her pail, and then held it so that the thirsty woman could drink out of the side. She drank long and eagerly.

“Thank you,” she said at length. “Dear child, you will never be sorry for your kindness;” and she rose and walked away.

Isabella threw away the rest of the water, and after refilling her pail, set out for home.

When she reached the house, her stepmother said, “You are late! Where have you been?”

Isabella opened her mouth to answer—and what do you think happened? Out fell diamonds and roses.

Quickly the stepmother called her daughters and they began to sweep them up.

“Where have you been?” cried the stepsisters. “What has happened to you?”

Isabella tried to think what could have brought such a thing about, for she was as much surprised as any of them, but she could not think of anything unusual except the meeting with the old woman.

“Speak!” demanded her stepmother. “Are you trying to hide something from us?”

64 Isabella said that she had met a strange old lady at the well, but that she could not remember anything else that had not happened every time she had gone for water.

Every once in a while as she was speaking diamonds and roses fell from her mouth.

“You need not go for the water the next time,” said her stepmother. “I shall send my own girls.”

The next day the two stepsisters went to fetch the water.

When they came to the well, there sat the old ragged woman on the curb.

“Good-morrow, young maidens,” said the old woman.

The stepsisters just stared at her.

“My, it is a warm day,” said the old woman, “and I am very thirsty. Will you give me a drink of water?”

“Indeed, we will not!” said the older one haughtily.

“The very idea!” exclaimed the younger one, looking at the old woman’s ragged clothes. “I should think not!”

Then they drew the water, all the time complaining and groaning about the hard work.

When they started to go home, the old woman spoke.

“You are not kind,” she said, “you will be sorry.” But they only laughed and hurried away.

Their mother met them at the door.

“Well, my dears,” she said, “how fared you? Did you meet any good fortune?”

“All we saw was an old woman at the well—such a ragged, wretched old thing she was, too!” answered one girl.

“And she wanted us to give her a drink of water. The idea!” the other girl said at the same time.

With the last words, out of their mouths fell several snakes and toads, which went scudding across the floor.

Their mother screamed and, gathering her skirts about her, jumped on a chair.

“Oh, where have you been?” she cried. “What has happened to you?”

65 And when the girls told her that they did not know, more snakes and toads fell from their mouths.

“This is an outrage!” exclaimed their mother. “Isabella has formed some terrible plot against you. She is to blame! Go bring her here, and I shall punish her. I shall whip her until she tells us the charm she has found.”

The girls ran out, and soon came back dragging Isabella between them.

Just as they reached their mother a bright light appeared in the room, and suddenly a beautiful fairy stood before them.

“Do not touch Isabella!” she said to the stepmother. “She is not in the least to blame for your children’s misfortune. Their cruel fate is their own fault. When I met Isabella at the well and asked her for a drink of water, she gave it to me gladly and willingly, but when I met your daughters and asked them for a drink they treated me proudly and unkindly.”

“You!” exclaimed the stepmother, looking upon the radiant creature with her shining fairy robes about her. “Met you, and would not give you a drink of water!”

The fairy smiled. “Ah, yes; it was I, but I did not look then as I now do. I was the ragged old woman at the well.”

“If they had known it was you—” said the stepmother.

“If they had known it was I,” the fairy said, “how could I have judged whether they were kind of heart, and polite to old people, and helpful to people in need?”

“When I met Isabella,” the fairy went on, “I looked just as when I met your daughters, and she was very polite and kind to me, and gave me a drink, holding the pail while I drank, even though she was very tired. Because only polite and kind words came from her mouth, I gave her a good fairy gift, and because only impolite and unkind words came from the mouths of your daughters, I gave them another kind of gift.”

“Oh, please take back the one you gave them,” pleaded the mother.

66 “Do you mean Isabella’s gift, too?” asked the fairy.

“Oh, no,” the mother said. “Let her have her gift—but please, please take away the awful gift of my daughters!”

“Let me see,” said the fairy, “what Isabella says about that. Shall I take back the gift of your stepsisters, my dear?”

“Oh, please, please do!” cried Isabella. “I am so sorry that they are unhappy.”

“Very well, then,” said the fairy. “For Isabella’s sake, I shall take their gifts back, but only on one condition—that they promise to be kind and polite from now on.”

“Oh, we promise! We promise!” cried both stepsisters at once.

“Unless you keep your promise,” said the fairy, “the snakes and toads will come from your mouths again.” And the fairy disappeared as suddenly as she had come.

But the snakes and toads did not come again, for the stepsisters and their mother were very kind to every one ever after, and Isabella lived a happy life from that day.

“They just had to keep their promise, didn’t they?” commented Mary Frances. “I am glad they did, for I do not like people to break promises.”

“Neither do I,” agreed the Story Lady; “and that reminds me of one of our favorite stories—Coralie and the Magic Necklace.”

“Oh,” said Mary Frances, “but I like a story with magic in it.”

“Very well,” said the Story Lady, “I will tell you the story.”

ONCE there was a girl whose name was Coralie. She was a very pretty girl, and very clever. She was so bright in her lessons at school that all she needed to do was to read them over once, and she knew them.

She lived in a pretty home, and was a great pet. Her parents loved her dearly, and although they were not well off, they gave Coralie everything she wished for that they could afford. So, you see, she had all the comforts of life, if not the luxuries.

You would think she would have been a very happy child, wouldn’t you? Well, she would have been if she had not had one very dreadful fault. Sometimes she told only half the truth; sometimes she told only quarter the truth; sometimes she stretched the truth so far that she broke it.

Her parents did everything they could to cure her of her dreadful fault, but everything failed. Even being in her room for a whole day with only bread and butter and milk did not help her. At last they became almost desperate.

One evening, after Coralie had gone to bed, her father said, “There is only one thing left, I suppose. We must take Coralie to the magician, Merlin.”

“Yes,” replied her mother with a sigh, “it is the only thing I can think of. You need not go, dear husband, for it will mean the loss of several days’ work. I will take her myself. We can start to-morrow morning.”

So in the morning, her mother and Coralie set out on their journey.

Now, the enchanter, Merlin, knew untruthful people even a long way off. He could tell them by their odor. So as Coralie and her mother drew near his palace, which was built of frosted glass, he threw some incense on the fire to keep himself from becoming ill.

At length, Coralie’s mother rang the door bell, and Merlin himself came to the door. “Good afternoon,” he said.

“Good afternoon,” replied Coralie’s mother; “we have come a long distance to see you, sir, because——”

Merlin raised his hand. “I know all about the reason,” he said. “You have come to see me because you cannot make your daughter tell the truth. She is one of the most untruthful children that ever lived. I know, because her lies often make me ill. When I smelled her coming, I had to burn incense;” and he frowned terribly.

You can imagine how this frightened Coralie. She hid behind her mother. Her mother seemed frightened, too.

“Oh, sir,” she begged, “please deal as gently with her as you can. We love her so dearly. We are so grieved that we cannot cure her our own selves.”

“Do not fear,” answered the magician. “I am not going to hurt her. All that I wish to do is to make her a present.”

So he invited them into the palace, and led the way to his workroom. All the woodwork in the room was light green. The windows were studded with red and blue and green jewels, and they threw rainbow colors on the floor.

Merlin went to a golden table, and, opening a drawer, took out a beautiful amethyst necklace, with a diamond clasp. He threw the necklace around Coralie’s neck.

“That is all,” he said to her mother. “You may go. I am going to lend my magic necklace of truth to Coralie. I shall come for it in one year.” Then he turned to Coralie, and said, “Do not take it off. If you do, great harm may come to you. Good-by,” and he clapped his hands twice.

70 Two slaves appeared, and after bowing before Merlin, showed Coralie and her mother to the door.

Coralie, of course, was delighted with the necklace. All her life long she had wished for jewelry, but her parents could not afford to get her anything but the pretty seal ring which she wore. As to getting such a necklace as Merlin had given her, it would have taken everything they owned in the world to so much as buy the diamond clasp.

When she went back to school, the girls all gathered about her and began to admire the necklace.

“Isn’t it beautiful!” they exclaimed. “What a lucky girl! Your people must have fallen heirs to a fortune!”

“Isn’t it pretty!” said Coralie, lifting the sparkling string for them to see better. “Yes, my father and mother gave it to me. You see, I have been ill, and they were so glad when I got well that they gave me this for a present.”

“Oh! Oh! Oh!” cried the girls.

And no wonder they did, for all the sparkle left the necklace, and it looked dull and old and scratched.

“What is the matter?” asked Coralie. “Don’t you think my parents could give it to me? They bought it, and paid an immense sum for it.”

At that falsehood, the necklace turned from the light purple amethyst color to a dull gray agate, and the diamond clasp to a mud-color shade. Then Coralie saw what had happened, and she was frightened.

“No,” she said, “they did not give it to me. We went to the magician, Merlin, and he lent it to me.”

At these truthful words, the necklace became as beautiful as ever. But the children began to laugh.

“What are you laughing at?” asked Coralie. “You needn’t make fun. Merlin was very glad to see us. When he saw us in the distance he sent his carriage to meet us. It was drawn by two fawn-colored horses, and the coachman wore livery. There was a71 great feast spread for us, and each of us had a servant in back of our chairs. We had golden plates to eat from, and——”

Suddenly Coralie stopped speaking, for the children were laughing at her harder than ever. She looked down at her necklace. No wonder they laughed. It was dull again in color, and had grown so long it rested upon the ground.

“Ho, ho, Coralie!” cried one. “Come, now! You are stretching the truth! Set us right!”

“Well,” confessed Coralie, “Merlin didn’t send any one to meet us. We walked, and we were in his palace only a little while.”

At these words, the necklace shrank to its right size, and resumed its own beautiful color.

“But now, Coralie,” cried the children, “but now tell us truly where you got the necklace. Did the magician give it to you?”

“Yes,” said Coralie, “he just handed it to me without saying a word. I think he——”

She did not finish the sentence, for the necklace had suddenly grown so tight that it was choking her, and she was gasping for breath.

“Come, come, Coralie!” cried one of the girls. “You are keeping back part of the truth! Tell the truth! What happened?”

“He said I was one of the most untruthful persons in the world,” admitted Coralie; and the necklace became itself again.

And so things kept on. Every time Coralie tried to say one untruthful thing, the necklace behaved in some queer, frightful way. Even the children became sorry for her, for she began to look worried all the time.

“If I were you, I’d take the necklace back,” one of the girls told her. “It gives you no happiness at all.”

“Indeed it doesn’t,” said Coralie, “I wish I——”

“Why don’t you take it back?” the girl asked.