The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Lincoln Country in Pictures, by

Carl Frazier and Rosalie Frazier

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

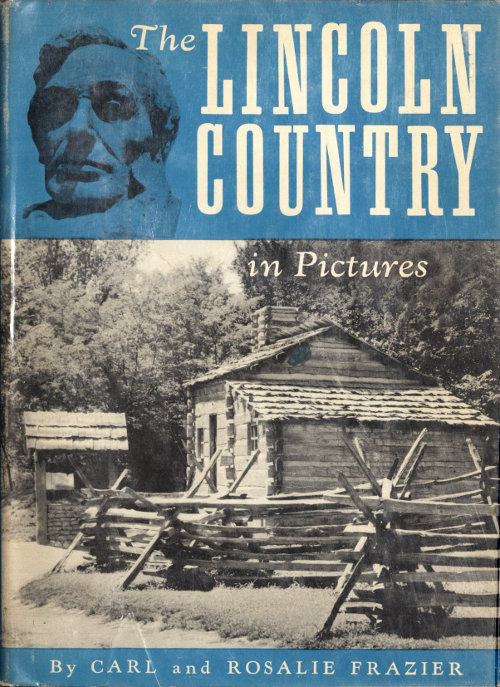

Title: The Lincoln Country in Pictures

Author: Carl Frazier

Rosalie Frazier

Release Date: December 20, 2017 [EBook #56210]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LINCOLN COUNTRY IN PICTURES ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

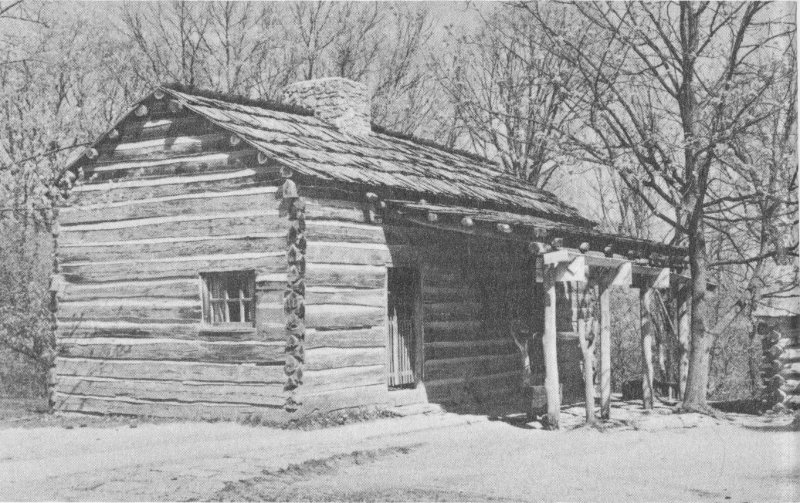

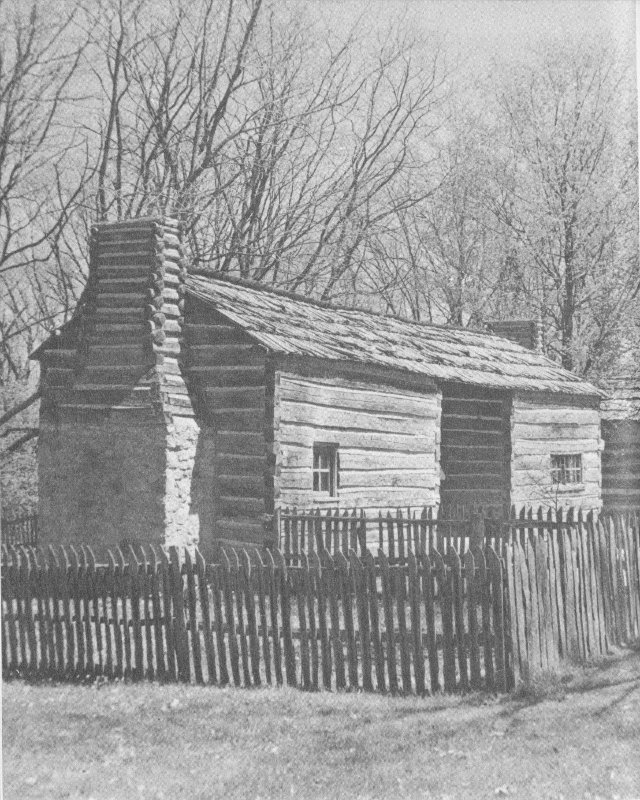

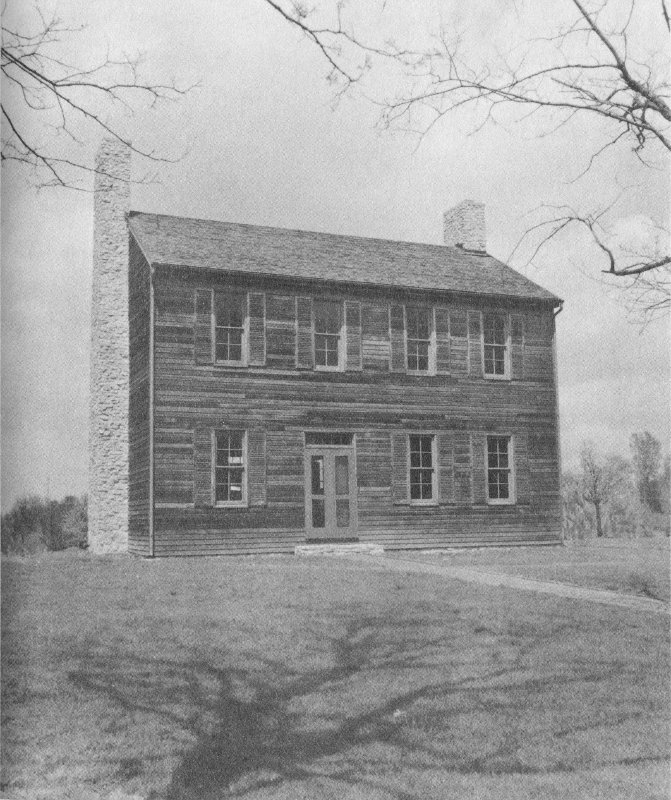

The Isaac Golliher house.

By CARL and ROSALIE FRAZIER

HASTINGS HOUSE Publishers New York 22

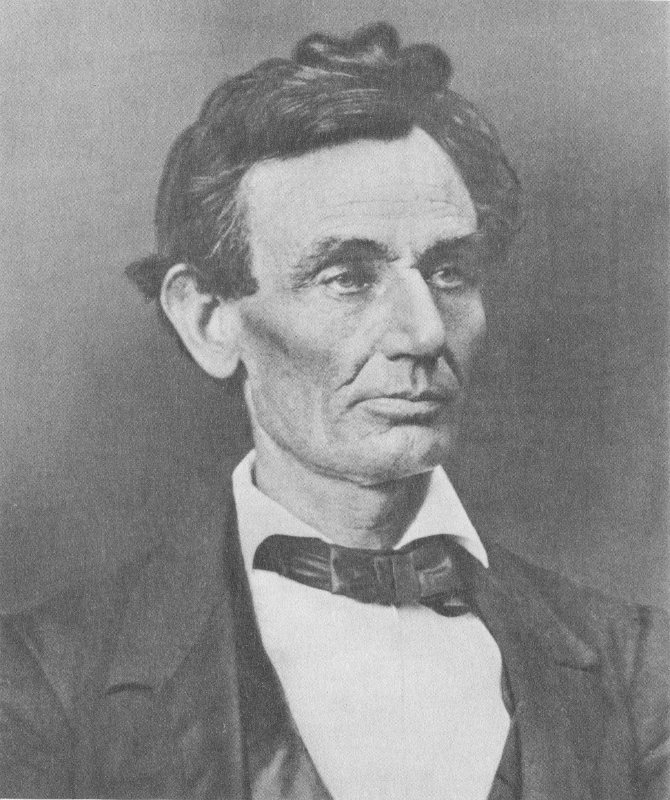

The story of Abraham Lincoln is ever fresh. It appeals to the imagination and grips the vision of many people in various ways. Perhaps that is why millions of visitors make pilgrimages to the humble abodes in which he lived and the places he frequented. Photograph Courtesy Chicago Historical Society.

“Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed by my fellow men, rendering myself worthy of their esteem. How far I shall succeed in gratifying this ambition, is yet to be developed.” —Address to Sangamon County, March 9, 1832.

Copyright © 1963, by Carl and Rosalie Frazier

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

without written permission of the publisher.

Published simultaneously in Canada

by S. J. Reginald Saunders, Publishers, Toronto 2B

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63-19173

Printed in the United States of America

We know it is no longer possible to add anything new to the written word about Lincoln. The hundreds of historians who have attempted to write the life of the Great Emancipator have covered every facet of it. Therefore, we have chosen to present our story of a by-gone day in a series of camera impressions, hoping to arouse in our readers an emotional sense of “present being.”

We have done this for two reasons: first, because Lincoln’s early frontier has achieved a factual and imaginative rebirth through loving care and painstaking efforts after having fallen into ruin for many years. Secondly, we believe as many historians do, that America owes much of the credit for its national character and institutions to the atmosphere of the early frontier. It was the appreciation of the role it played on the character of Lincoln that brought about the restoration of New Salem, Illinois, and those objects which were so closely associated with him. These objects are of special interest because it was among them that he moved slowly forward through a cycle of failures and successes before reaching the high place which destiny had reserved for him. No man in American history has started with so little and achieved so much.

With a certain temerity then, we present our pictorial history of the environment in which Lincoln spent the most formative years of his life. It was from this frontier atmosphere and these frontier people that Lincoln acquired his uncanny understanding of how common folk think and the wisdom that enabled him to hold in his hands the ties that bound a people and made a nation.

| Feb. 12, 1809 | Born on Sinking Spring Farm near Hodgenville, Kentucky. |

| 1811 to 1816 | The family, which included Abe’s sister, Sarah, lived on Knob Creek near Hodgenville, Kentucky. |

| Nov. 1816 | The family moved to Pigeon Creek in Indiana. |

| Oct. 5, 1818 | Abe’s mother died of “milk sickness.” |

| Dec. 2, 1819 | Thomas Lincoln married Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three children, from Elizabethtown, Kentucky. |

| Jan. 20, 1828 | Sister Sarah died. |

| Mar. 1830 | The Lincoln family moved from Indiana to Illinois. |

| Apr. 19, 1831 | Offut’s flatboat piloted by Lincoln got stuck on the dam at New Salem, Illinois. |

| Mar. 9, 1832 | Announced candidacy for the Illinois Legislature. |

| May 8, 1832 | Mustered into U.S. Army for service in Black Hawk War. |

| July 16, 1832 | Mustered out of military service. |

| Aug. 6, 1832 | Defeated for the Legislature. |

| May 7, 1833 | Appointed postmaster at New Salem, Illinois. |

| Aug. 4, 1834 | Elected to the Legislature. |

| Mar. 24, 1836 | Sworn in as a lawyer of the Circuit Court of Sangamon County. |

| Aug. 1, 1836 | Reelected to the Legislature for a second term. |

| Sept. 9, 1836 | Licensed to practice law. |

| Mar. 1, 1837 | Admitted to the bar in Illinois. |

| Mar. 15, 1837 | Moved from New Salem to Springfield, Illinois. |

| Aug. 1, 1838 | Reelected to the Legislature for a third term. |

| Dec. 3, 1839 | Admitted to practice law in the Circuit Court of the United States. |

| Aug. 1, 1840 | Reelected to the Legislature for a fourth term. |

| Nov. 4, 1842 | Married Mary Todd of Lexington, Kentucky. |

| Aug. 1, 1843 | First child, Robert Todd Lincoln, was born. |

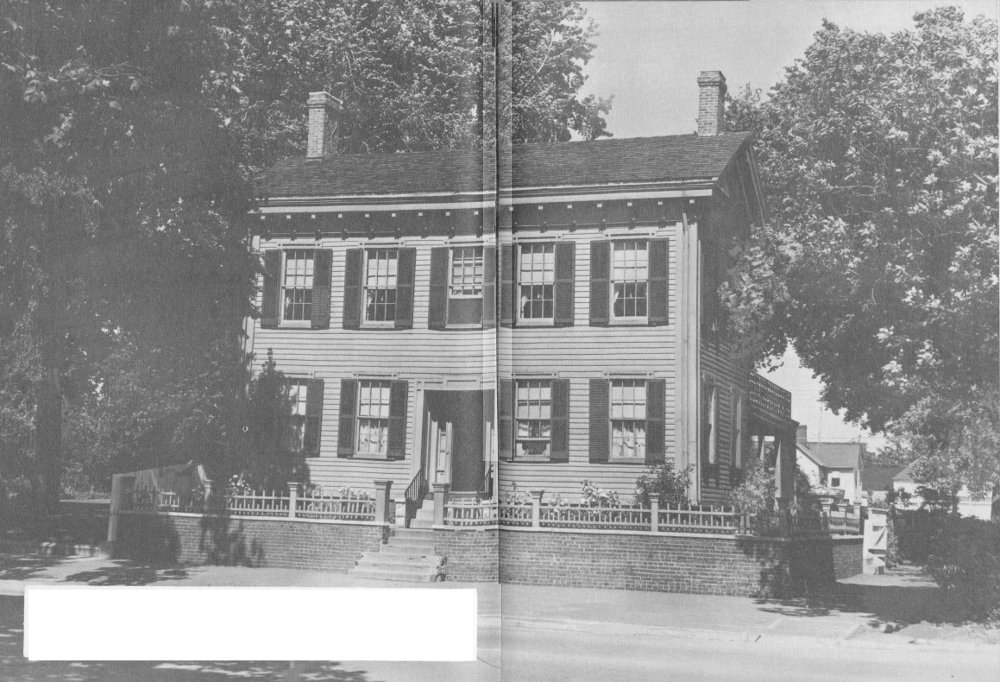

| Jan. 7, 1844 | Bought home in Springfield. |

| Mar. 10, 1846 | Second child, Edward Baker Lincoln, was born. |

| Aug. 3, 1846 | Elected to Congress. |

| Dec. 6, 1847 | Took seat in Congress. |

| Mar. 7, 1849 | Admitted to practice law before United States Supreme Court. |

| Feb. 1, 1850 | Second child, Edward Baker Lincoln, died. |

| Dec. 21, 1850 | Third child, William Wallace Lincoln, was born. |

| Jan. 17, 1851 | Lincoln’s father, Thomas, died. |

| Apr. 4, 1853 | Fourth child, Thomas “Tad” Lincoln, was born. |

| June 16, 1858 | Delivered “house divided” speech at Springfield. |

| Aug. 21, 1858 | First debate, with Stephen A. Douglas at Ottawa, Illinois. |

| Aug. 27, 1858 | Second debate, at Freeport, Illinois. |

| Sept. 15, 1858 | Third debate, at Jonesboro, Illinois. |

| Sept. 18, 1858 | Fourth debate, at Charleston, Illinois. |

| Oct. 7, 1858 | Fifth debate, at Galesburg, Illinois. |

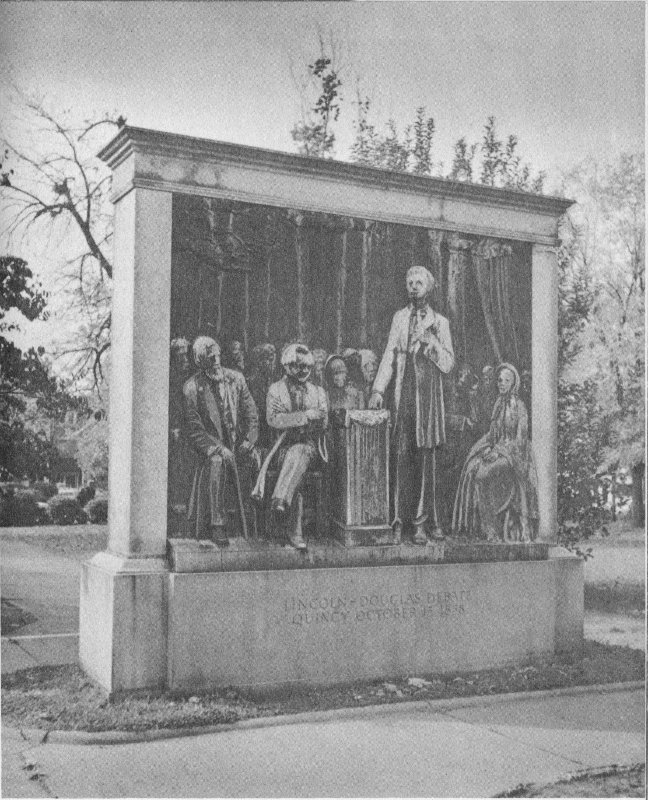

| Oct. 13, 1858 | Sixth debate, at Quincy, Illinois. |

| Oct. 15, 1858 | Seventh and last debate, at Alton, Illinois. |

| Nov. 2, 1858 | Defeated by Douglas for the United States Senate. |

| Nov. 5, 1858 | First mentioned in press for President. |

| May 18, 1860 | Nominated for the Presidency. |

| Nov. 6, 1860 | Elected President. |

| Jan. 31, 1861 | Visited for the last time with his stepmother. |

| Mar. 4, 1861 | Inaugurated as President. |

| Nov. 8, 1864 | Reelected as President. |

| Mar. 4, 1865 | Reinaugurated as President. |

| Apr. 14, 1865 | Shot by Booth. |

| Apr. 15, 1865 | Died in Washington. |

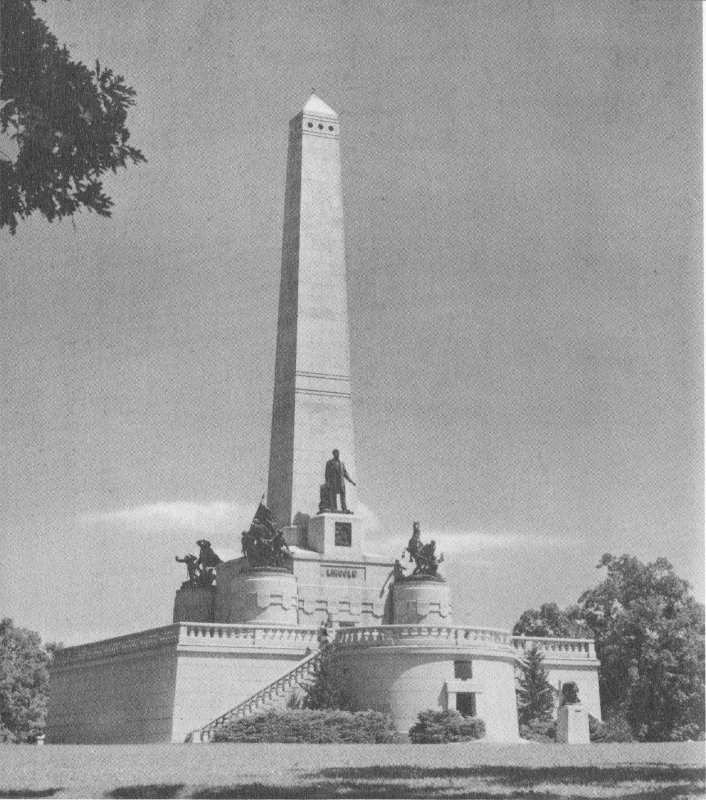

| May 4, 1865 | Buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois. |

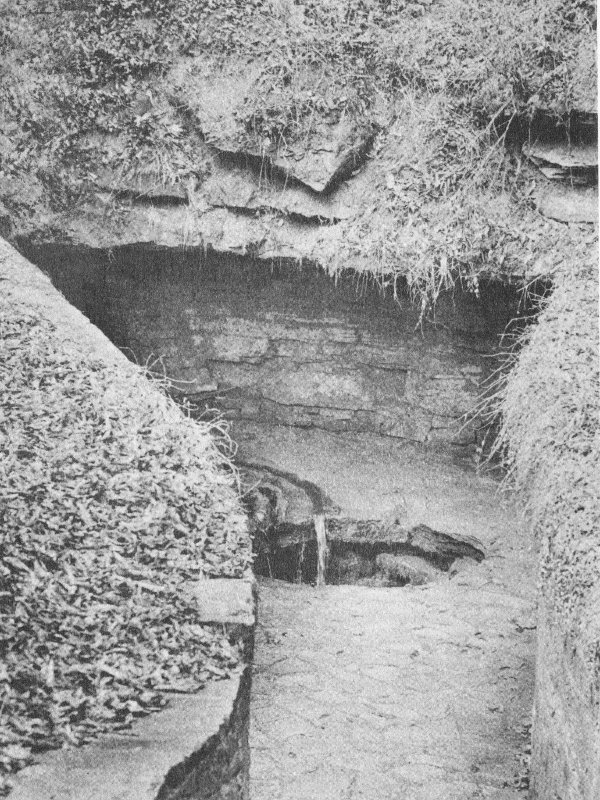

It was from the faithful Sinking Spring, near Hodgenville, Kentucky, that the farm of Lincoln’s nativity got its name.

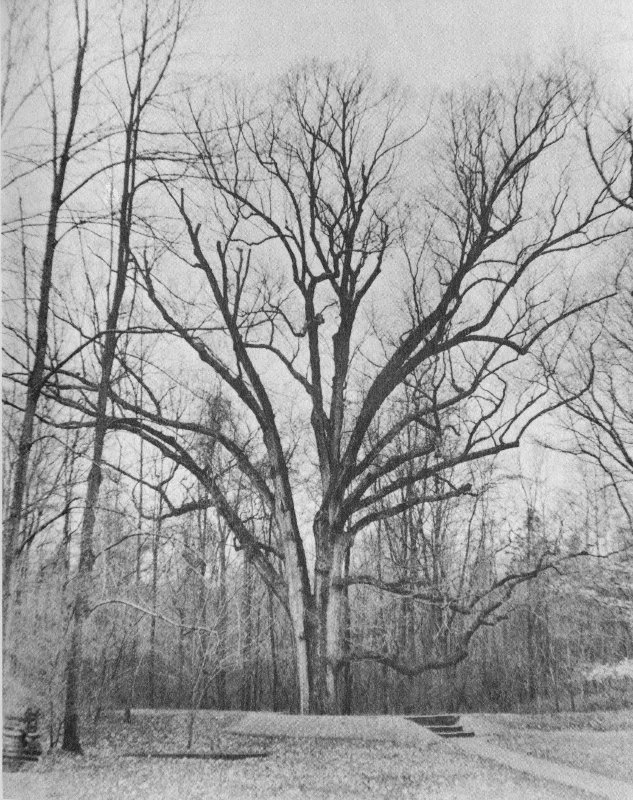

The branches of the Boundary Oak, a landmark for early frontiersmen, still shelter the hallowed birthplace of the man who went to school for perhaps a year, split rails in frontier clearings, traveled the Eighth Circuit as a lawyer, became President of the United States, freed the slaves, spoke the First and Second Inaugurals and the Gettysburg Address.

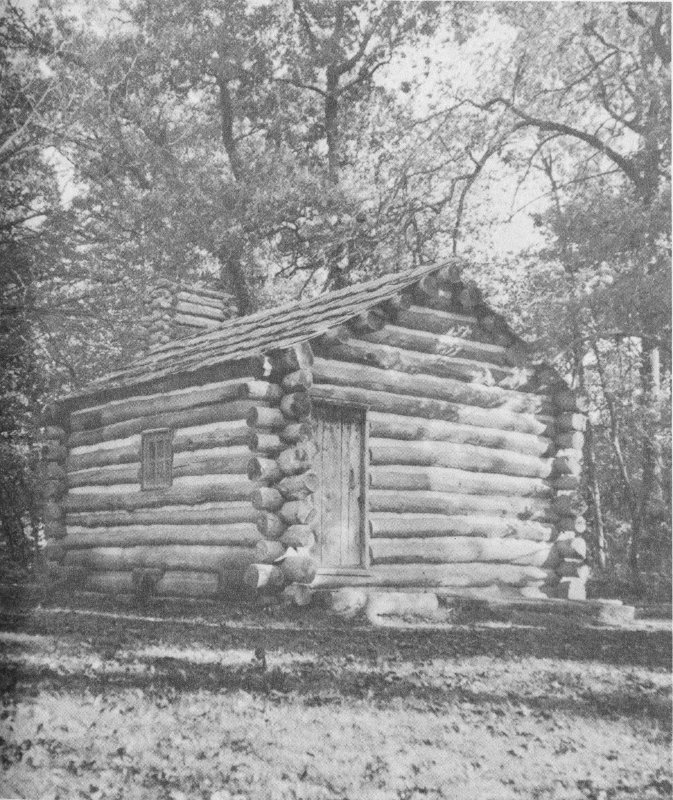

On February 12, 1809, a blizzard raged at Sinking Spring Farm, near Hodgenville, Kentucky. The wind howled down the chimney and through the cracks of the humble log cabin in which Abraham Lincoln was born to Thomas and Nancy Lincoln. The proud parents named the boy Abraham after his grandfather.

When Abe was two years old, his father moved the family to Knob Creek Farm where they lived until Abe was seven. The cabin lay nestled in a valley surrounded by rolling hills and deep gorges. Here Abe played with his friend, Austin Gollaher, gathered firewood from the forest, wild berries from the vales, and for a short time attended Mrs. Hodgen’s “blab” school. Thomas Lincoln decided to move his family across the Ohio River to live on Pigeon Creek in Indiana where the soil was richer and there were no slaves.

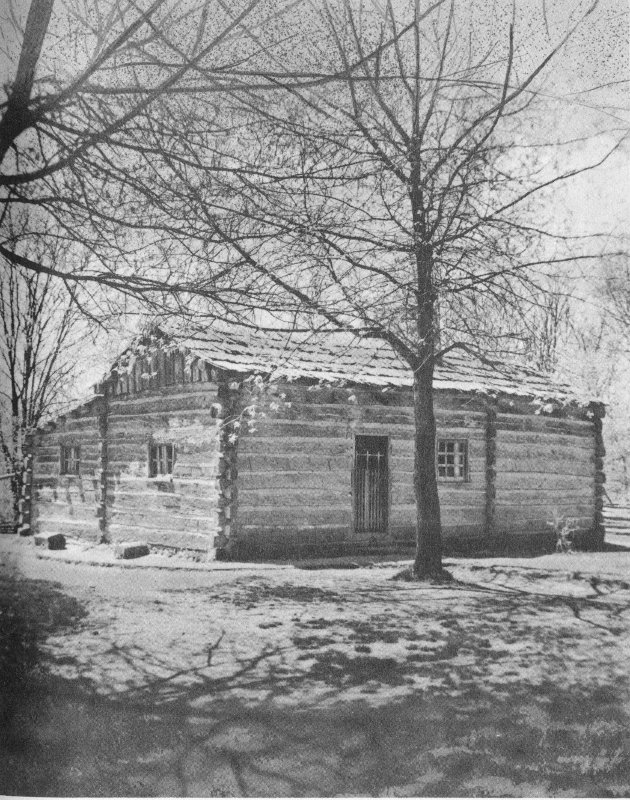

The Lincoln’s erected a new log cabin on Pigeon Creek in Indiana. For the next fourteen years they struggled with the almost impossible odds of a bitter and treacherous wilderness. It was here that Abe’s mother died, and he helped his father lay her to rest in the forest.

In the little Log Schoolhouse near Pigeon Creek, in Indiana, Abe managed to get a few scattered weeks of sporadic schooling in readin’ writin’ and cipherin’ to the rule of three.

Abe did his homework by the light of the smouldering fireplace. He would scrape his charcoal cipherin’ from wooden boards so as to use them over and over again.

The Lincoln family often attended services in the little Baptist Church that Abe helped his father to build, near Pigeon Creek, in Indiana.

This was the home of Josiah Crawford, a neighboring farmer, where Abe alternated working and learning. Mr. Crawford had several books which he lent Abe. When plowing, Abe read at the end of each furrow while he stopped to allow his horse to “breathe.”

In Gentryville, not far from Pigeon Creek, Mr. Gentry, a farmer and storekeeper lived in this two-story log mansion. At times, when his father didn’t need his help, Abe worked in Mr. Gentry’s store and on the farm. He helped Allen, Mr. Gentry’s son, build a flatboat, load it with store produce and float it down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to New Orleans.

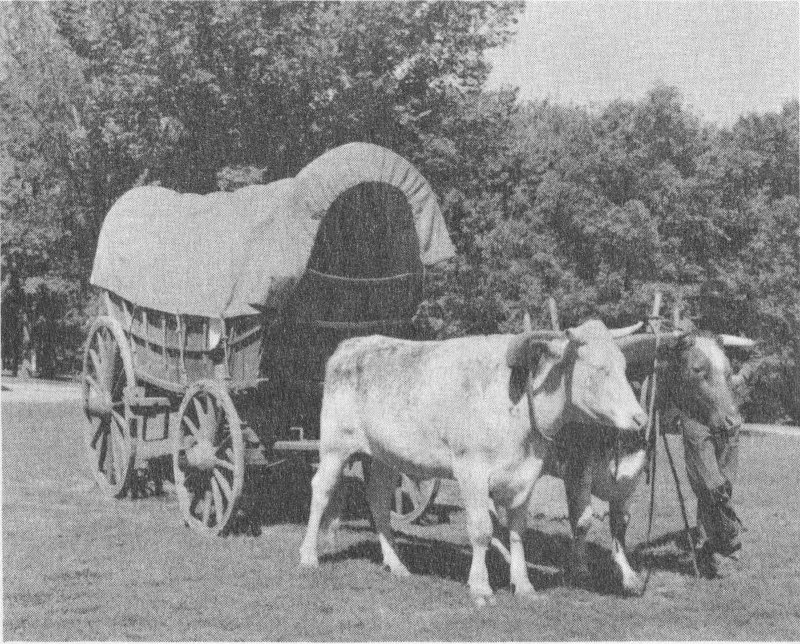

It was early spring of 1830 when the Lincoln’s made the long dismal journey from Indiana to the promising prairies of Illinois. Their stout wagons were piled high with rough-hewn furniture, feather beds, personal belongings, iron pots and pans. There were plows for breaking the “prairie’s sleeping sod” and tools for building a new log cabin.

This rustic abode was the last home of Thomas and Sarah Lincoln. Abe, who was now past twenty-one, had left his parents to seek his fortune on the bustling Illinois frontier.

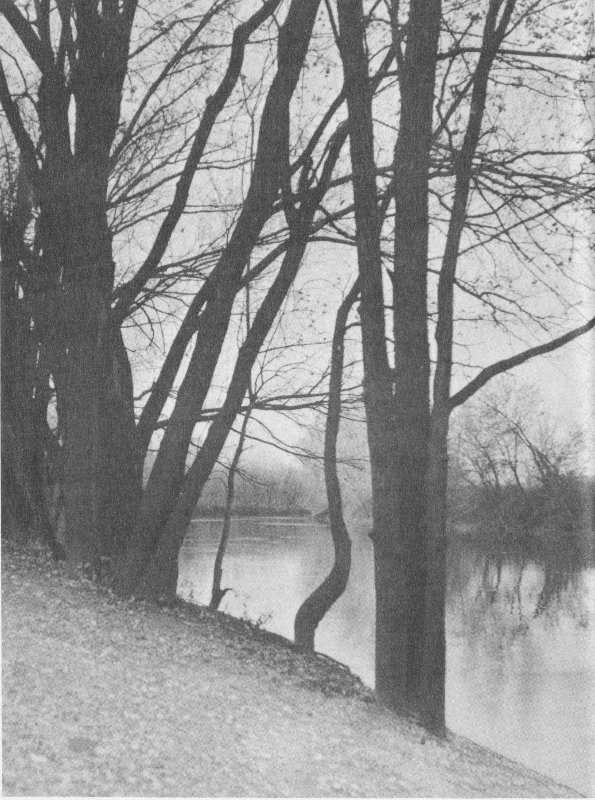

Timber lined the river’s banks and crowned the rolling hills.

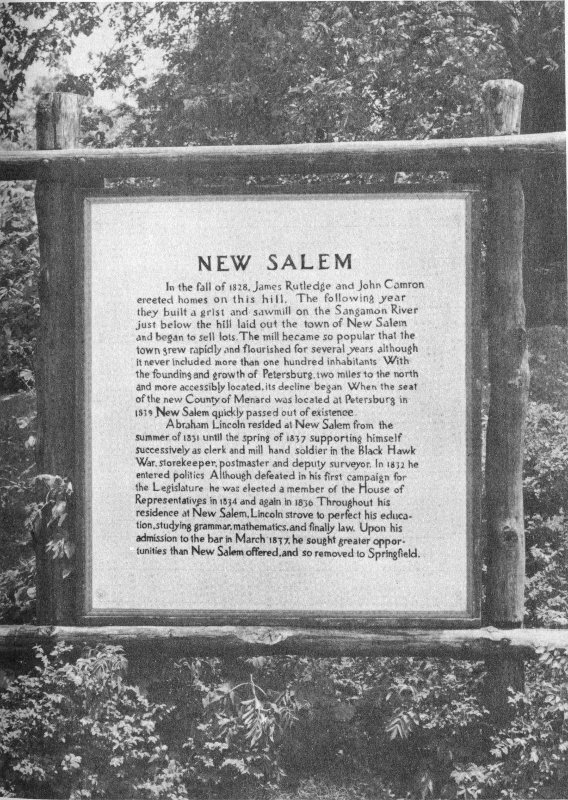

In the fall of 1828, James Rutledge and John Camron erected homes on this hill. The following year they built a grist and sawmill on the Sangamon River just below the hill, laid out the town of New Salem and began to sell lots. The mill became so popular that the town grew rapidly and flourished for several years although it never included more than one hundred inhabitants. With the founding and growth of Petersburg, two miles to the north and more accessibly located, its decline began. When the seat of the new County of Menard was located at Petersburg in 1839, New Salem quickly passed out of existence.

Abraham Lincoln resided at New Salem from the summer of 1831 until the spring of 1837, supporting himself successively as clerk and mill hand, soldier in the Black Hawk War, storekeeper, postmaster and deputy surveyor. In 1832 he entered politics. Although defeated in his first campaign for the Legislature, he was elected a member of the House of Representatives in 1834 and again in 1836. Throughout his residence at New Salem, Lincoln strove to perfect his education, studying grammar, mathematics, and finally law. Upon his admission to the bar in March 1837, he sought greater opportunities than New Salem offered, and so removed to Springfield.

It was on a pleasant April day that the flat-bottomed boat, loaded with barrel pork, corn and live pigs, and piloted by young Abe Lincoln, rounded a bend in the Sangamon River and came to rest on top of the miller’s dam that stretched out across the river. The bow of the boat was raised high into the air. The squeals of the frightened pigs brought the citizens of New Salem hurrying down the bluff to the river bank.

This was Lincoln’s introduction to the people of New Salem. Denton Offut, a swaggering, boastful, hard-drinking frontiersman, was owner of the boat. He became so impressed with the thriving little village that he decided to return after the voyage to New Orleans, and open a store with Lincoln as his clerk. The new store was opened the following September.

Lincoln helped fell the trees from which Offut’s one-room log store was erected. It stands on the bluff that leads down to the grist mill and the river bank. It was the usual type of frontier store, stocked with produce from the prairie farms or objects made at home.

It was while working for Offut that Lincoln decided to improve his education. In fair weather, when there were no customers about, Lincoln could be seen lounging on the porch studying or talking with friends about slavery, crops, politics, cockfighting, horse racing or just telling stories to listening loafers.

At the top of the bluff, among the tall oak trees, stood the cabin of Rowen Herndon. Lincoln boarded here because it was near the store.

Bill Cleary’s saloon stood a short distance down the bluff from Offut’s store. It was the hangout for Jack Armstrong, who challenged Lincoln to a wrestling match. Even though the match ended in a draw, it gave Lincoln the reputation for courage and strength that convinced his associates that he “belonged.”

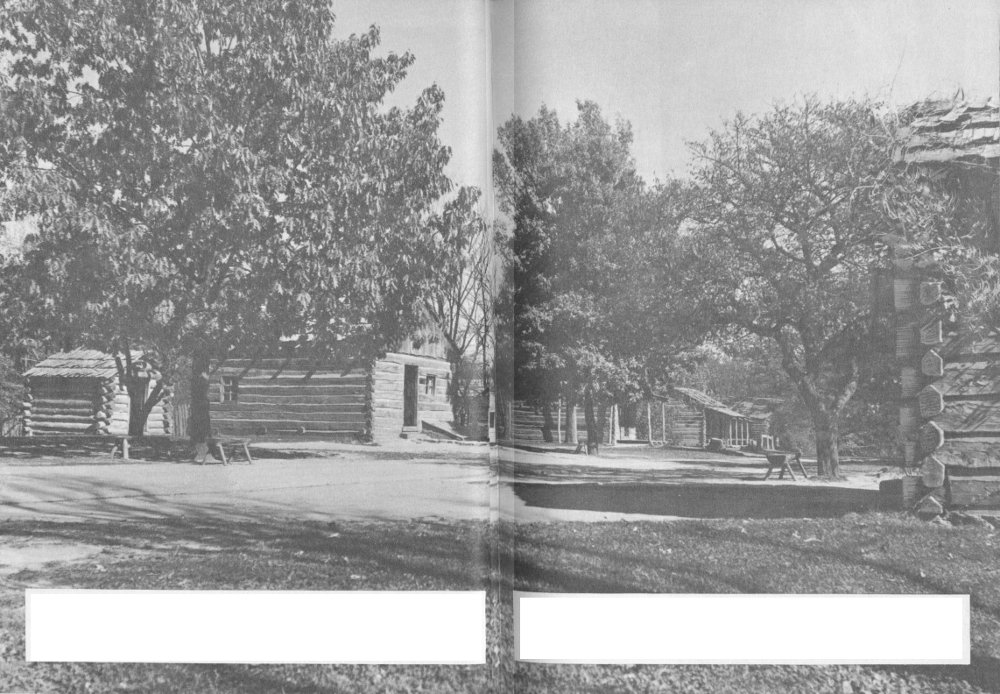

New Salem was a trading post for the farmers who cultivated farms on the surrounding prairies. On Main Street there was a cobbler, a hatter, a cooper, a blacksmith and wagon builder, a wheelwright and several merchants.

These tradesmen had come to New Salem to help fill the needs felt by everyone. At the height of its prosperity, New Salem had a population of a hundred citizens and some twenty-five or thirty buildings.

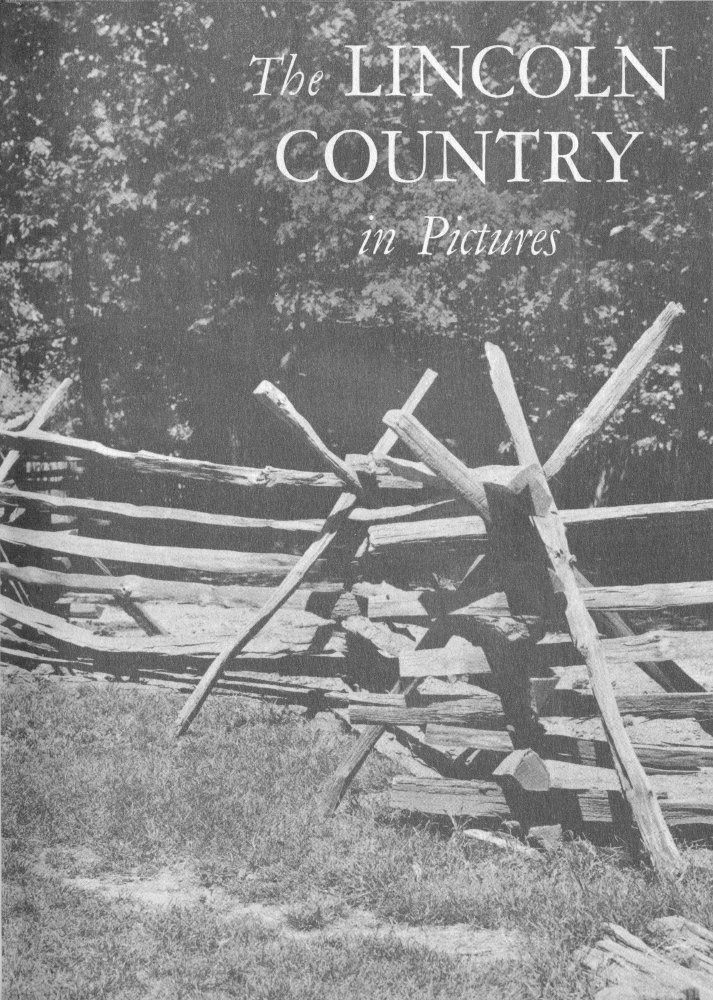

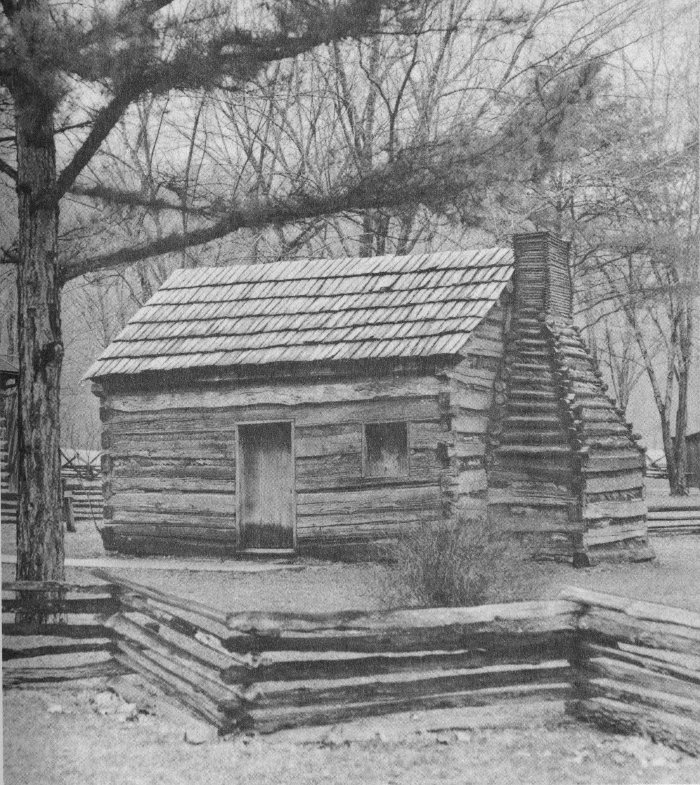

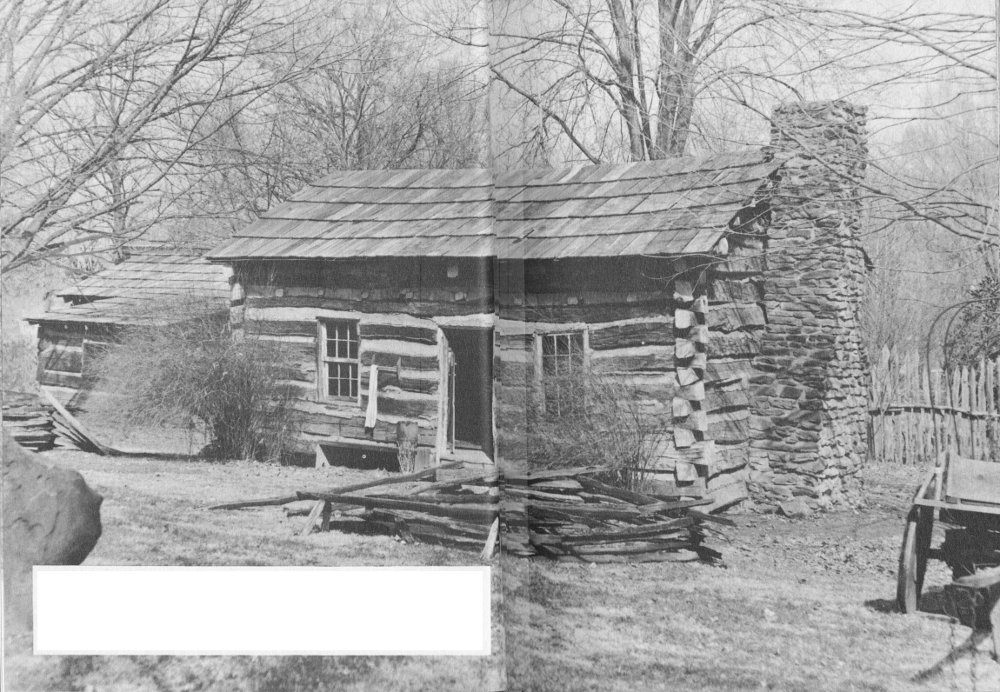

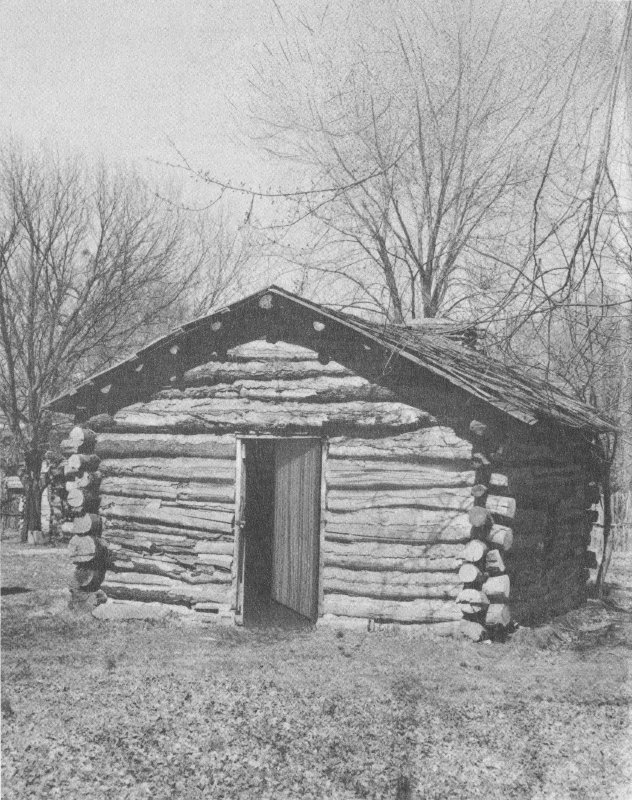

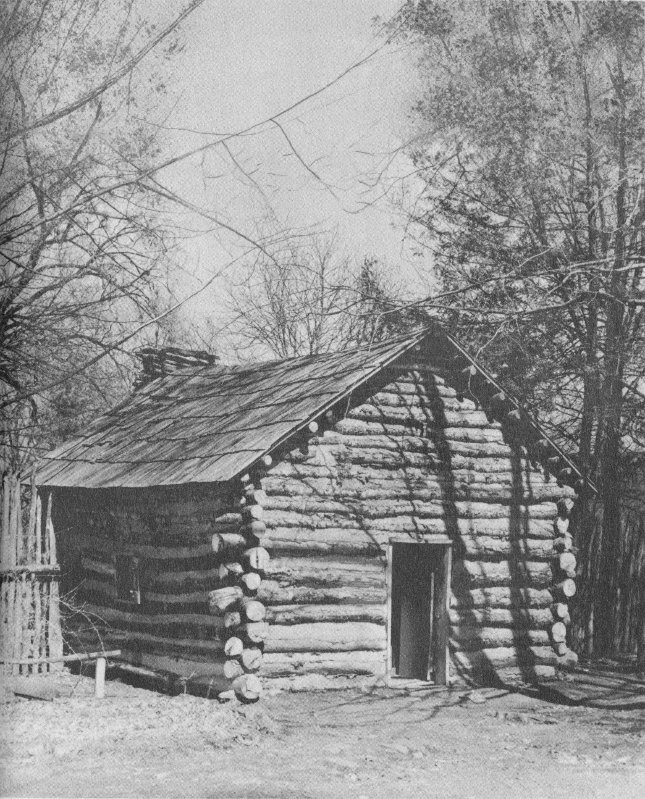

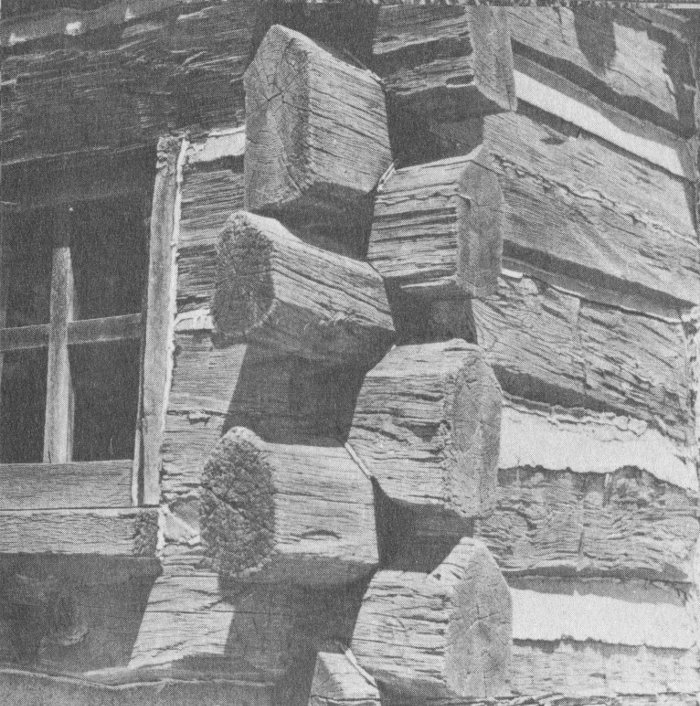

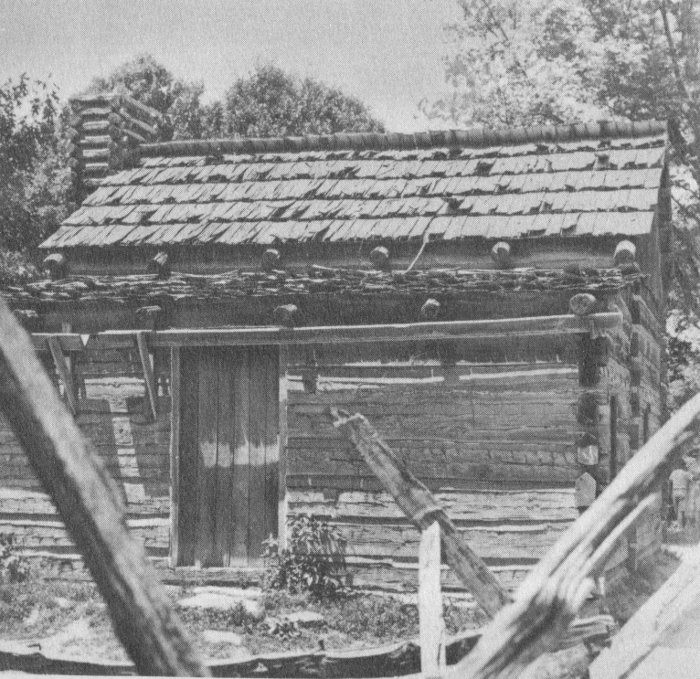

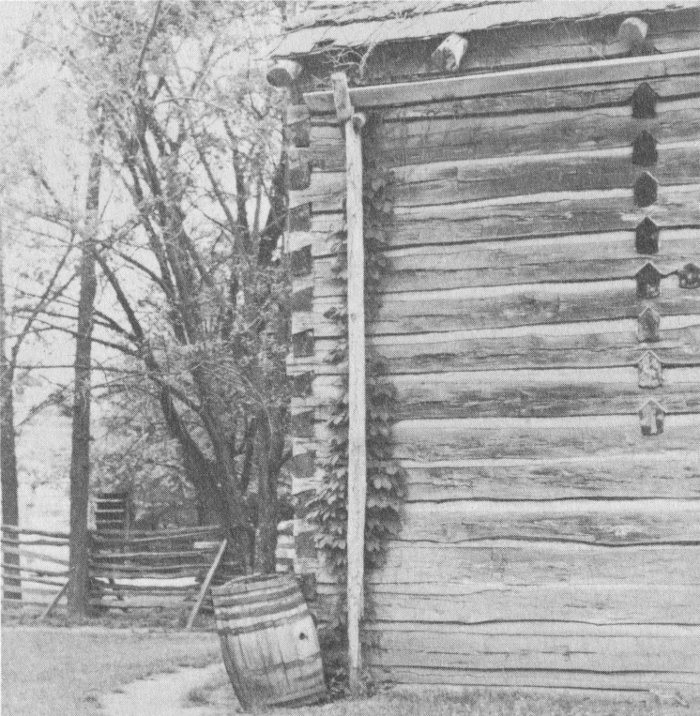

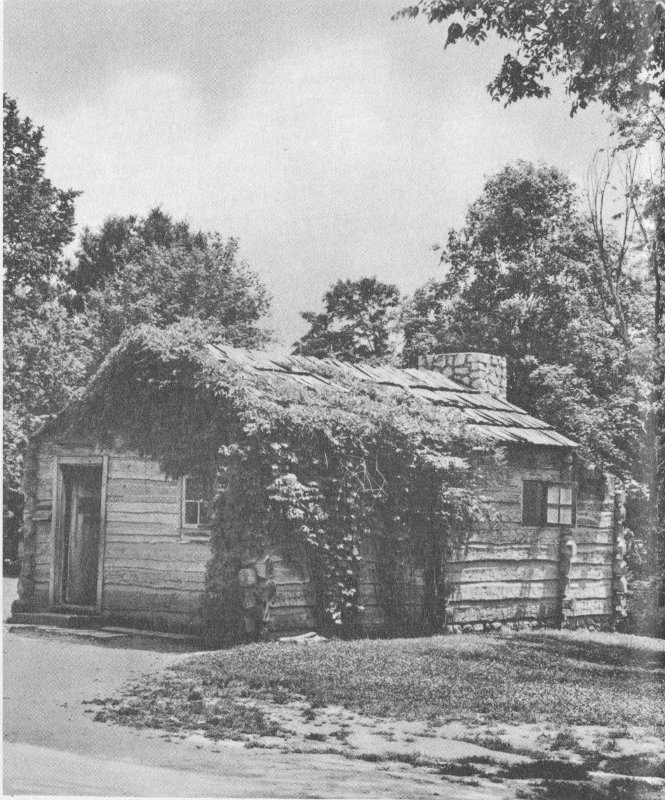

The buildings were made of logs, notched together at the corners and chinked with native clay.

Roofs were pitched and covered with clapboard shingles called “shakes.”

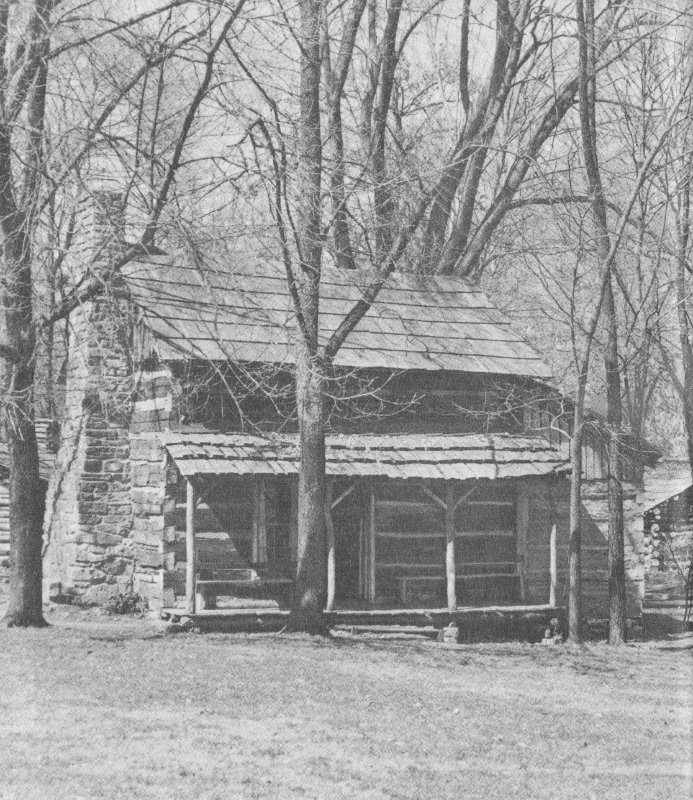

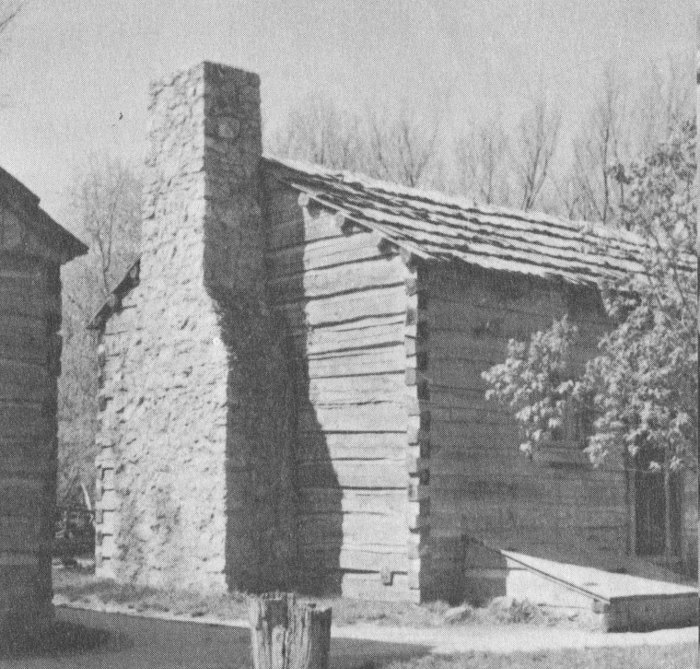

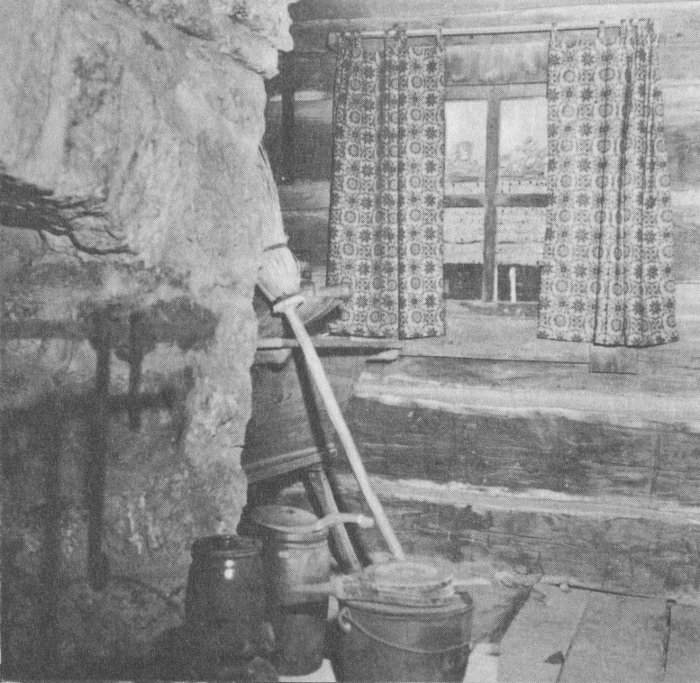

Better homes in New Salem had chimneys made of stone.

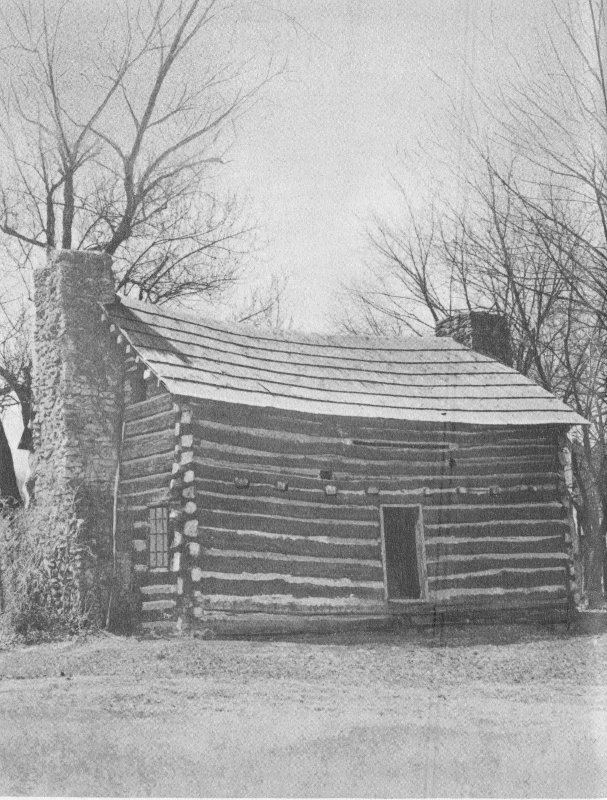

Most homes had “cat and clay” chimneys, made of logs and chinked with native clay. On cold windy days members of the household were kept busy running outside to see whether or not the chimney had caught fire.

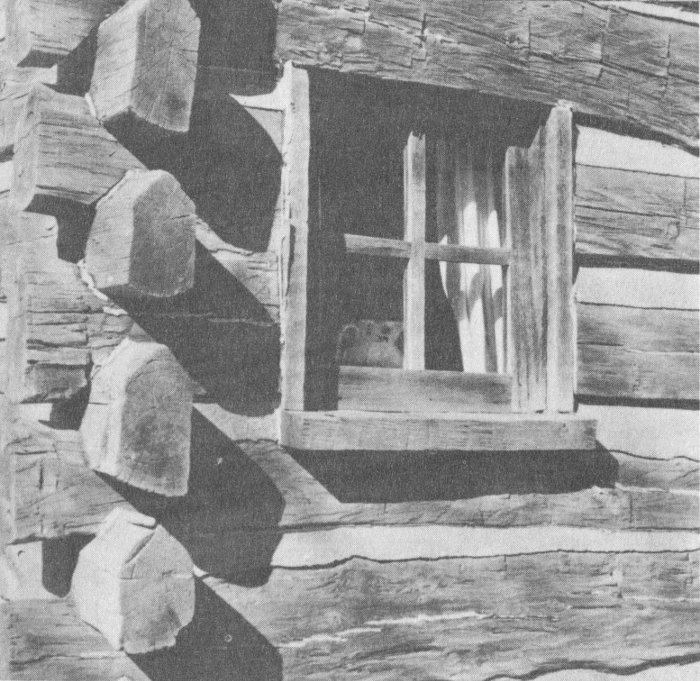

New Salem homes had window panes made of glass.

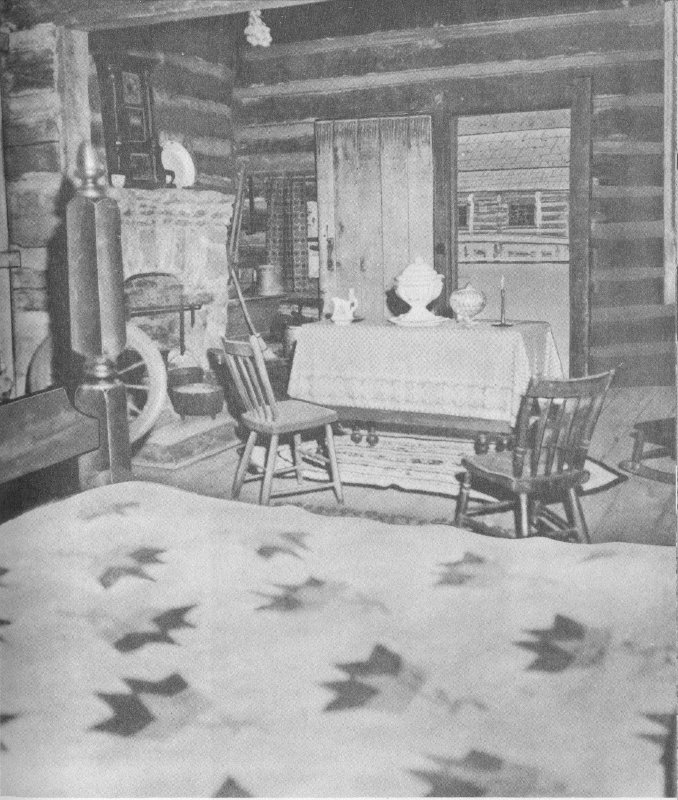

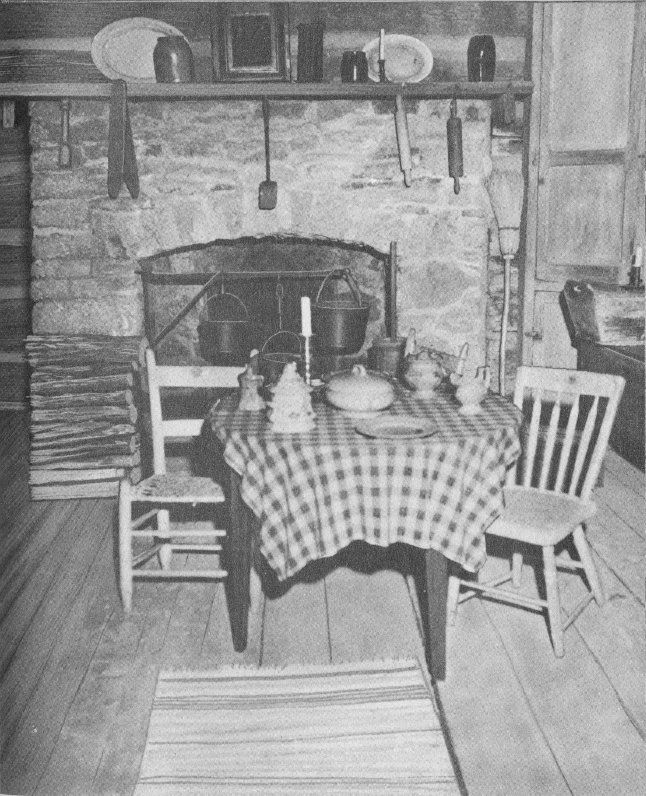

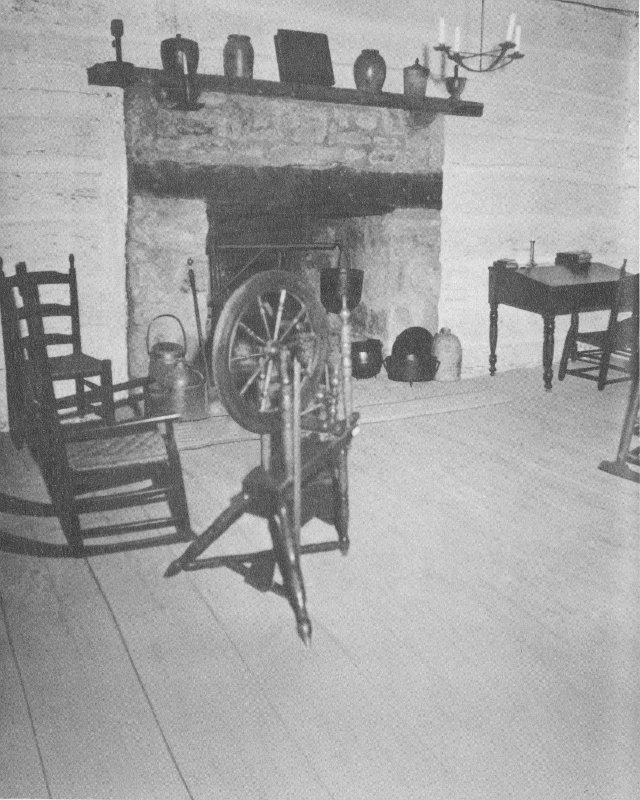

Windows were usually near the fireplace where family activity was carried on.

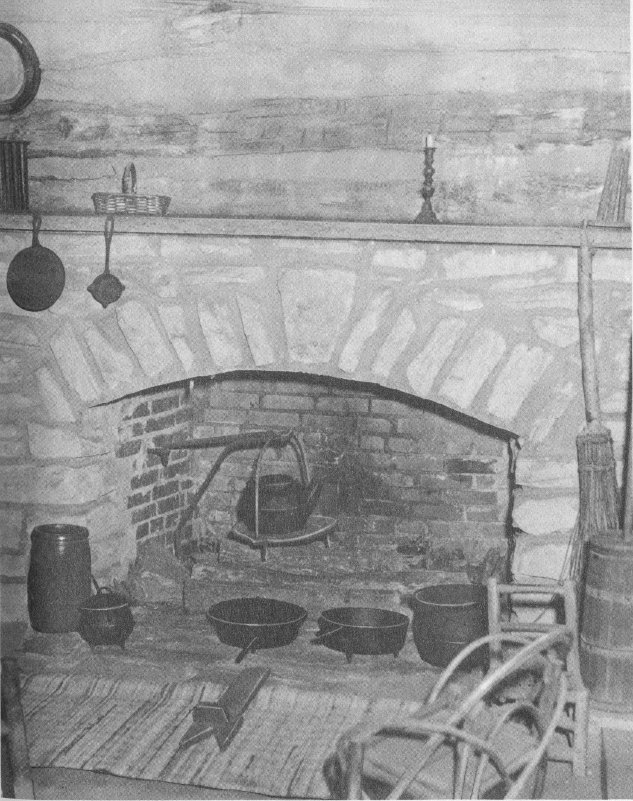

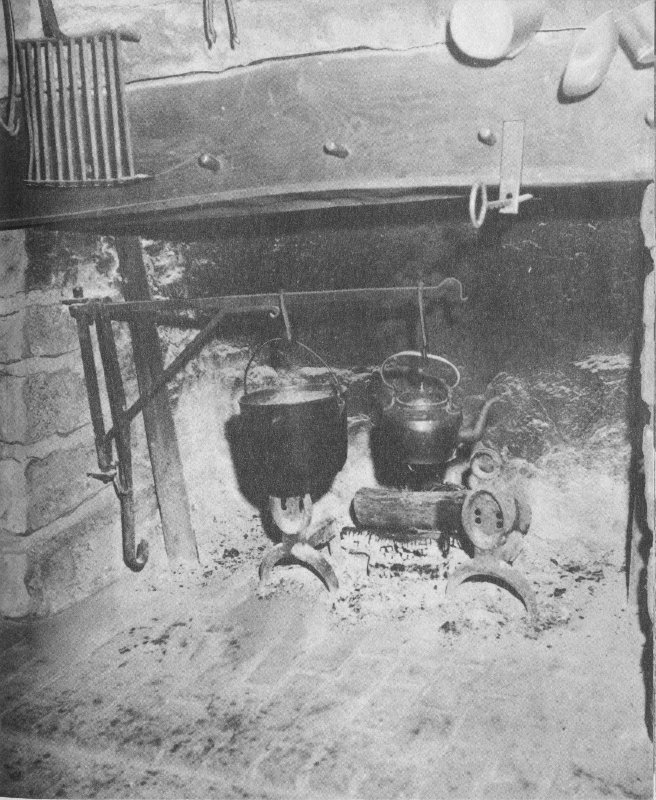

Over an open fire, in iron pots, frying pans and skillets, housewives cooked venison stew, roasted pork and wild game, fried mush, baked corn bread and corn dodgers to a golden brown and often hard enough “to split a board or fell a deer at forty feet.”

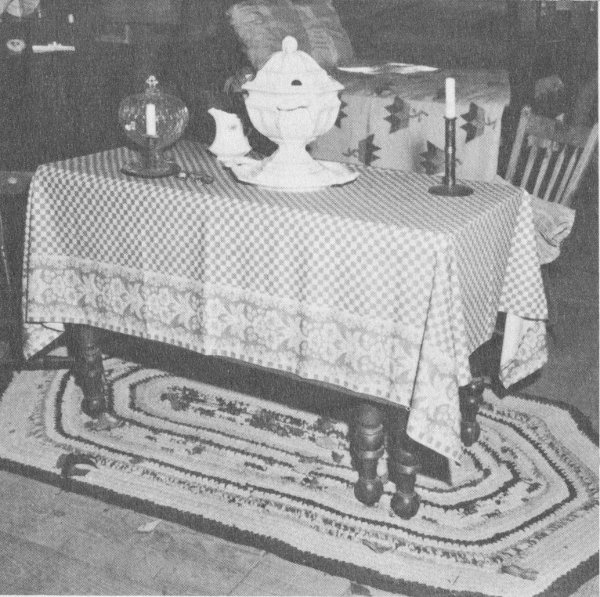

Sturdy trestle tables served the pioneer family well.

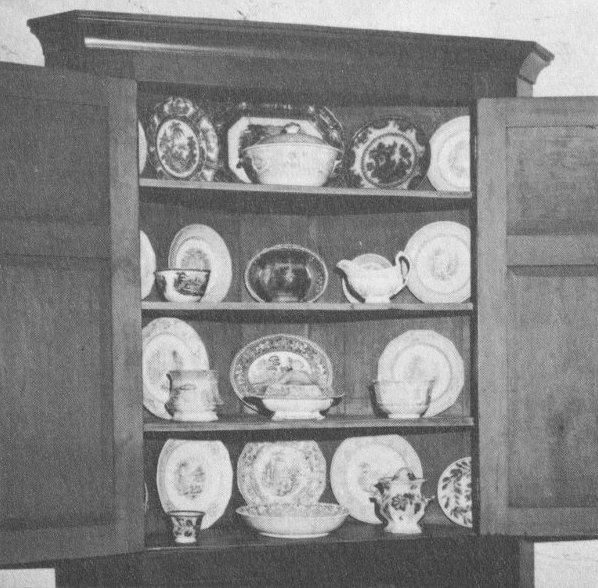

Pioneer women were especially proud of their chinaware.

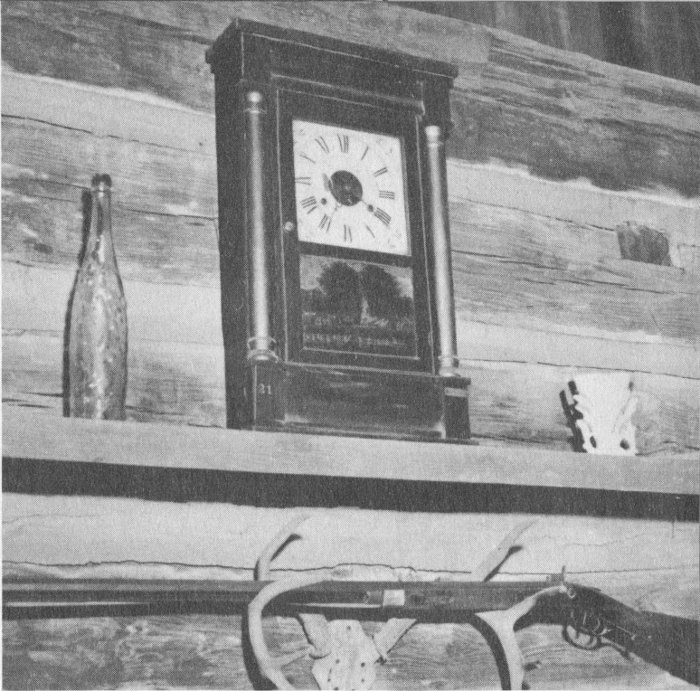

A Seth Thomas clock adorned the mantles of those who were able to afford a touch of elegance.

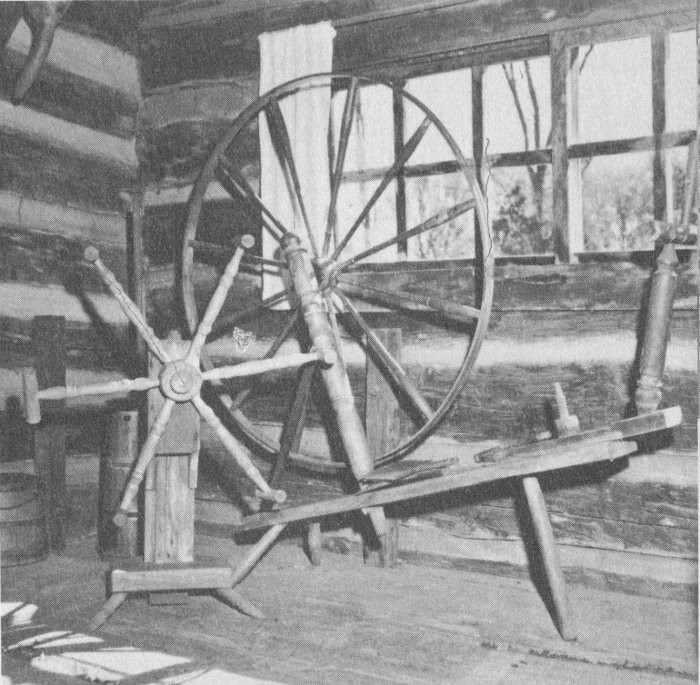

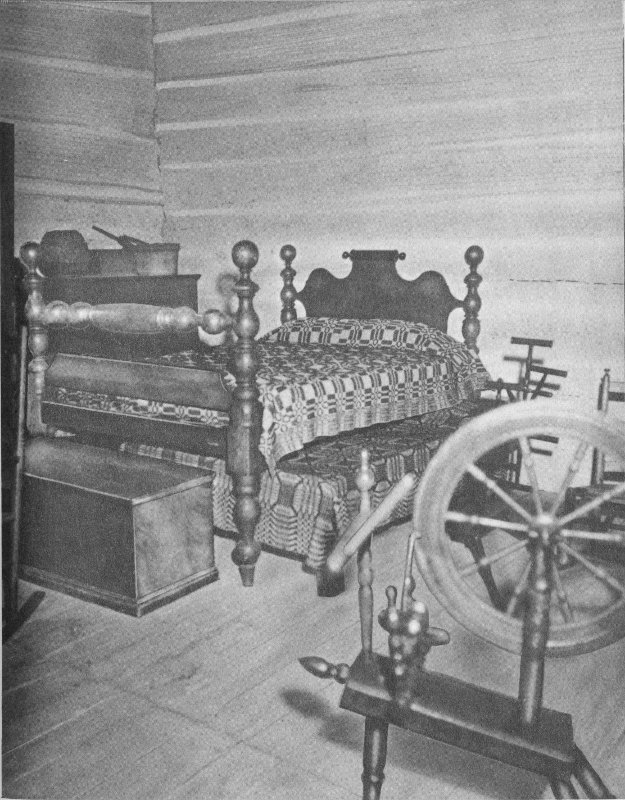

Housewives spun the wool from which they made garments often stiff and too large, but suitable as garments to protect the family from the elements.

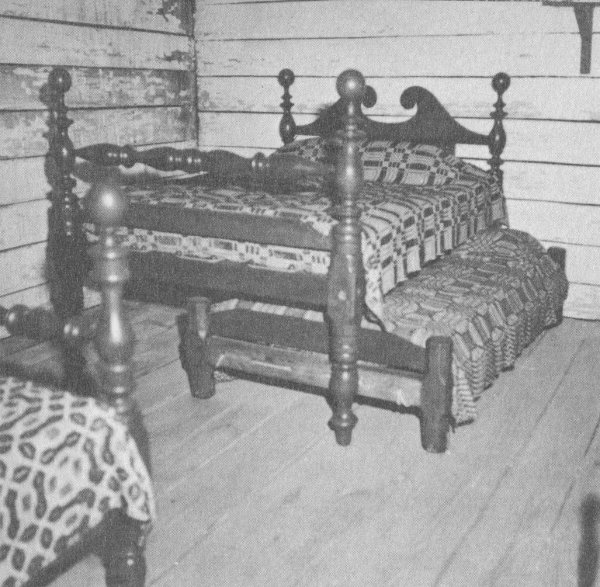

Beds were dressed with home-woven coverlets.

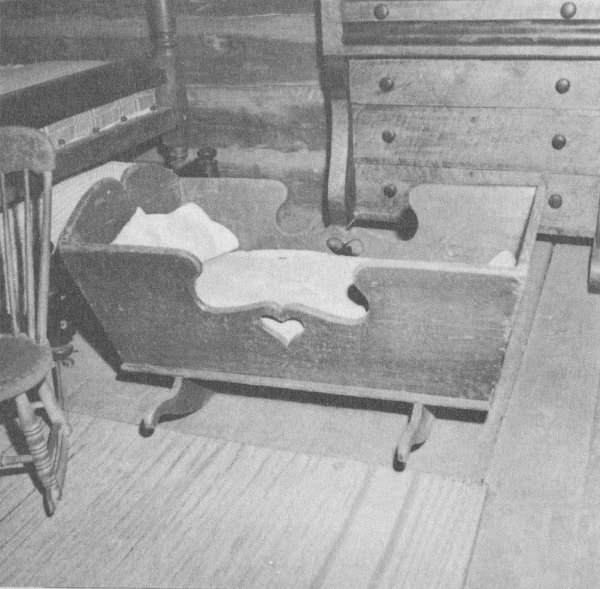

Babies came in annual crops.

Of the humble one-room log house the cooper’s son wrote: “At meal time it was all kitchen. On rainy days, when neighbors came to relate their exploits, how many deer and wild turkey they had killed, it was all sitting room. On Sunday, when the young men all dressed up in their jeans, and the young ladies, in their best bow dresses, it was all parlor. At night it was all bedroom.”

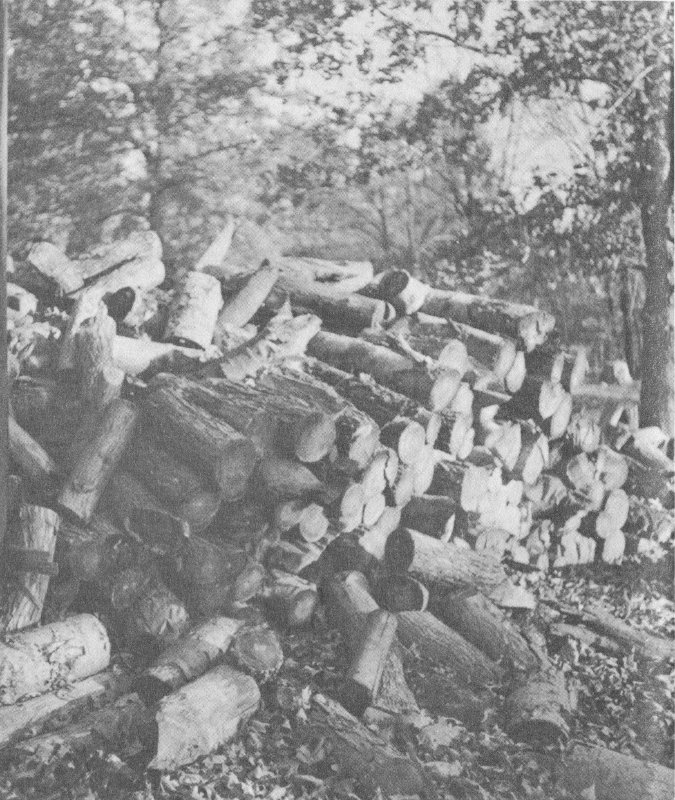

Outside, wood stacked high during the summer, dwindled rapidly as the winter passed.

From the ash hoppers, found in every backyard, lye was leeched for use in making soap.

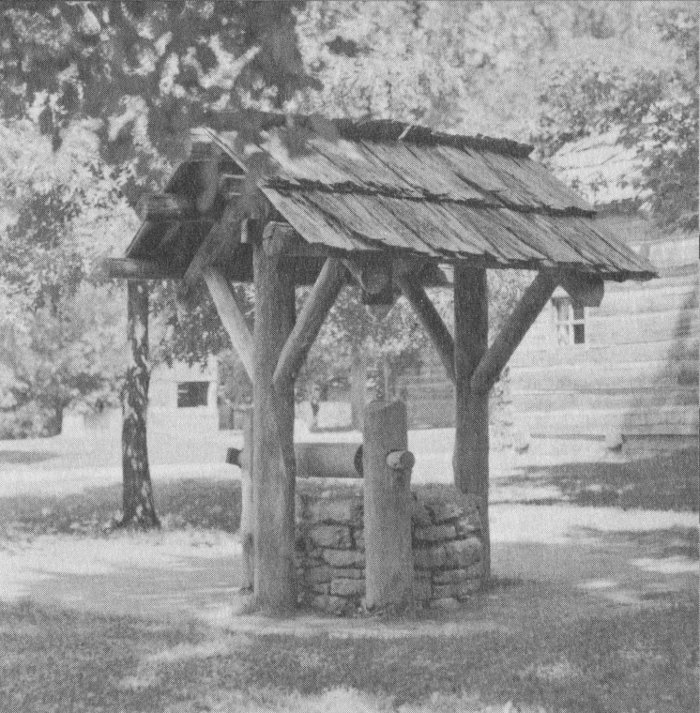

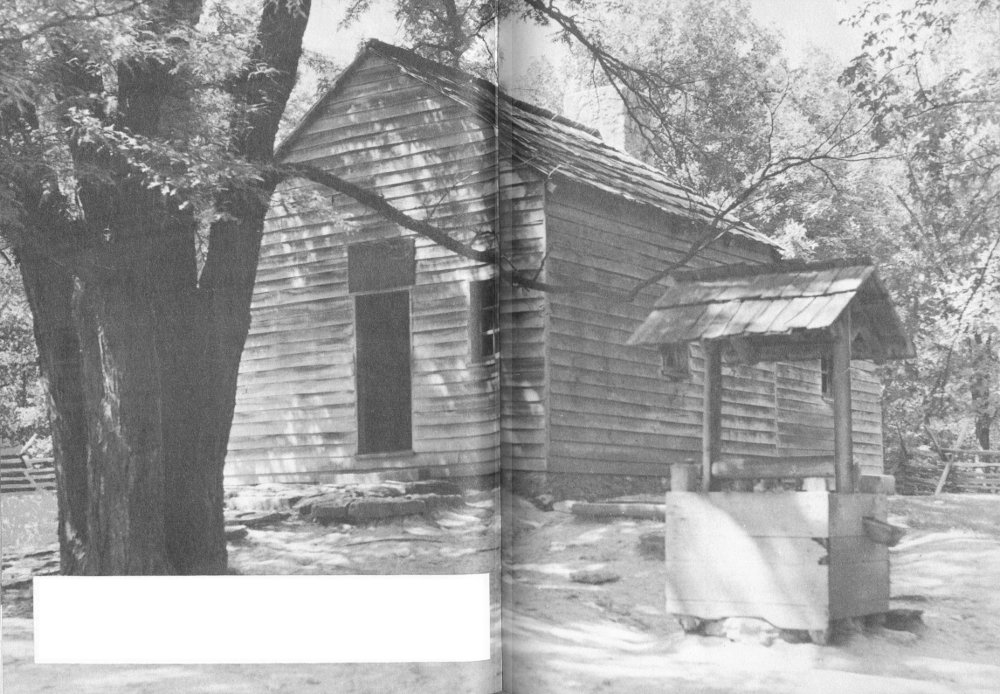

Wells with windlass ropes and wooden buckets supplied the household with needed water.

Rain barrels caught the “soft” water that dripped from the eaves. This water was used for the family washing.

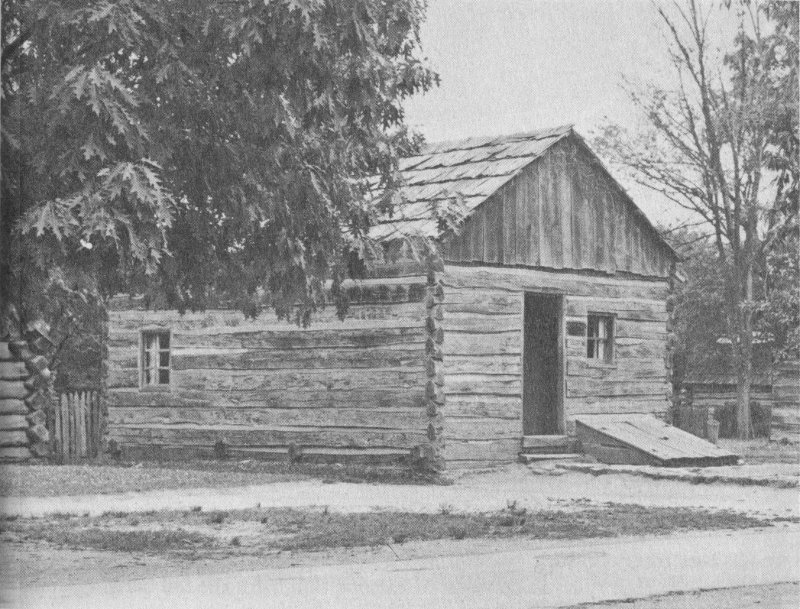

Samuel Hill, New Salem’s most prosperous businessman, owned the only four-room, two-story house in the village.

The opulence reflected in the Hill residence was not common to the homes of New Salem.

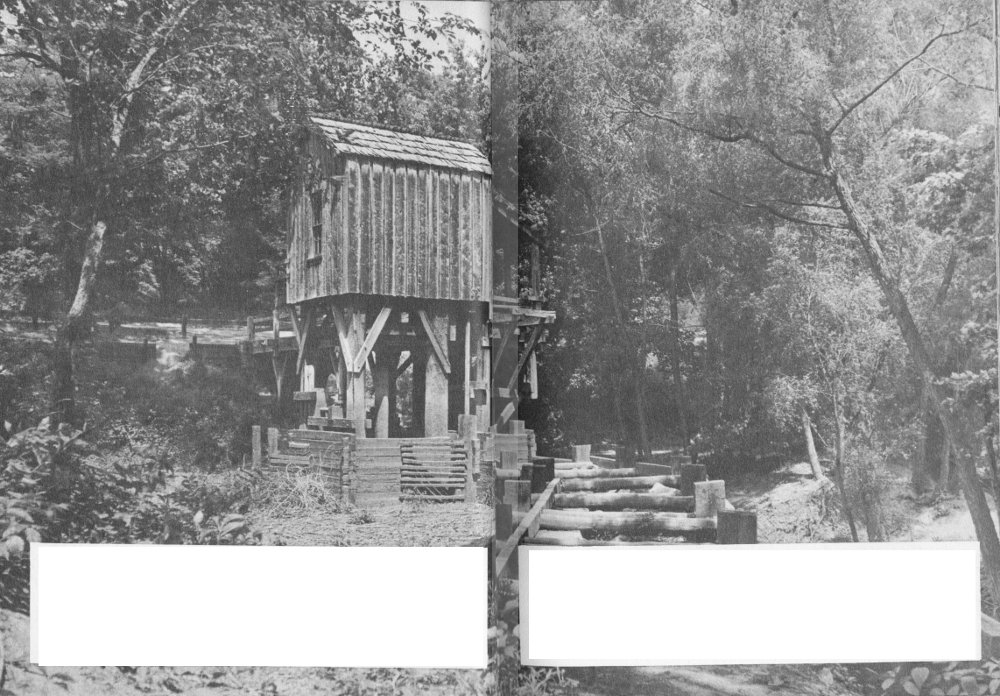

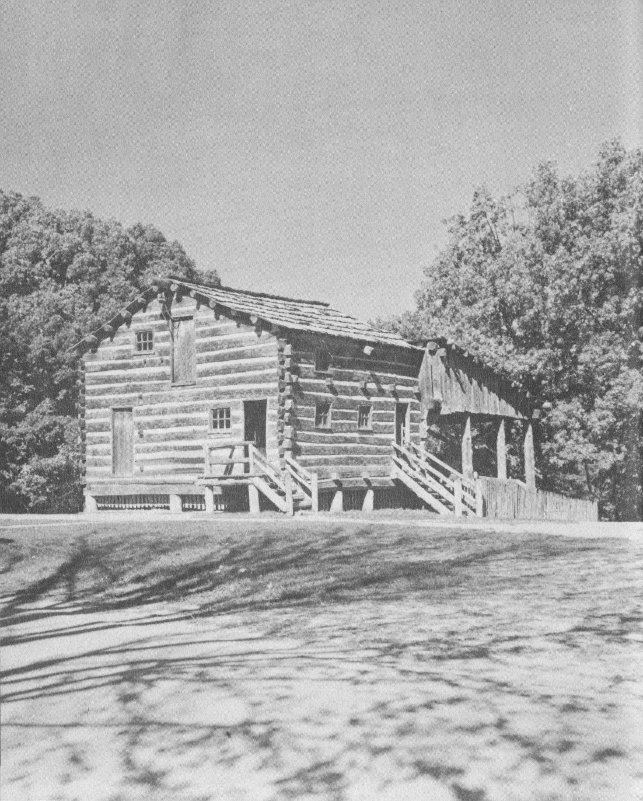

Samuel Hill was also owner of the woolhouse and carding machine. In spring, during wool shearing time, farmers brought their wool to the warehouse in sacks, old bed quilts and petticoats, pinned with thorns from the honey locust.

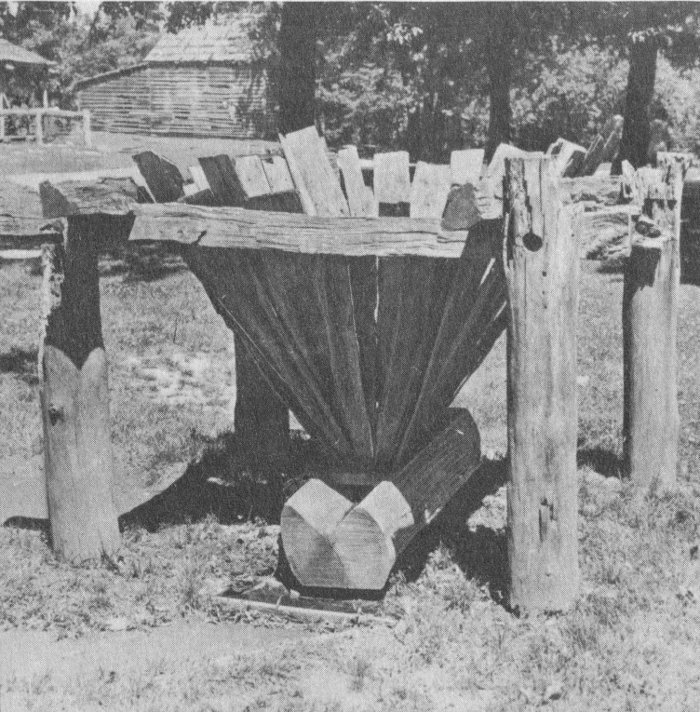

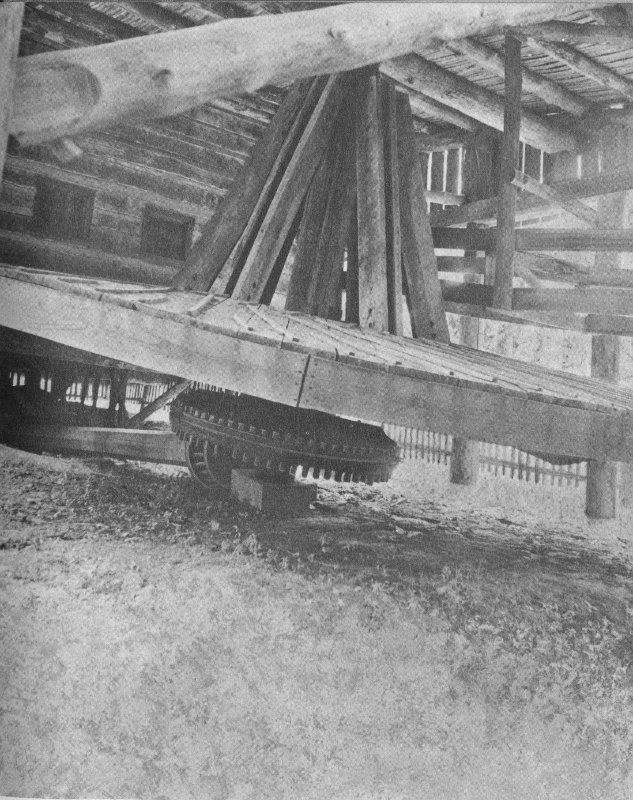

The carding machine in action was New Salem’s most dramatic attraction. From dawn until darkness the weary treading of oxen hoofs on the cleated treadmill powered the squeaking, moaning, wooden gears of the carding machine.

Samuel Hill and John McNeal owned the most successful store in New Salem. It was the center of village life. Under its protective porch people gathered to argue the questions of temperance, travel and human slavery.

Doctor John Allen lived across the road from the Hill-McNeal store. Unconvinced of the virtue of quinine for treating malaria fever, the doctor kept to such old remedies as Peruvian bark, jalop, calomel and boneset tea.

Peter Lukin, the cobbler, lived next door to Doctor Allen. The cobbler shop was in the small lean-to. As winter approached the cobbler converted piles of animal hides into shoes for the community.

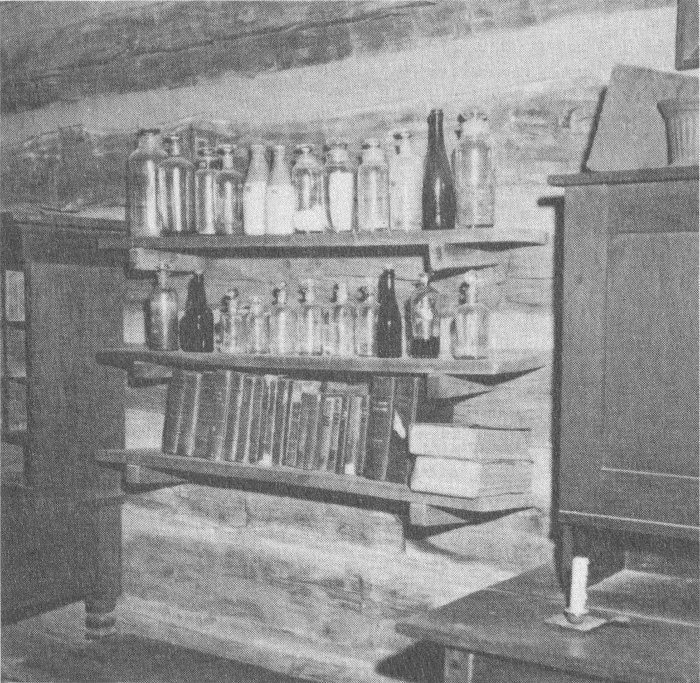

Residence and office of Doctor Francis Regnier, Allen’s capable colleague, who purged, bled, blistered, puked, and salivated his patients.

The Doctor’s medical laboratory and reference library.

This was the home and workshop of Martin Waddell, the village hatter. He made hats from opossum, raccoon and rabbit skins. A rabbitskin hat cost fifty cents. A hat made from an opossum or raccoon skin, with the tail hanging down in the back, cost two dollars.

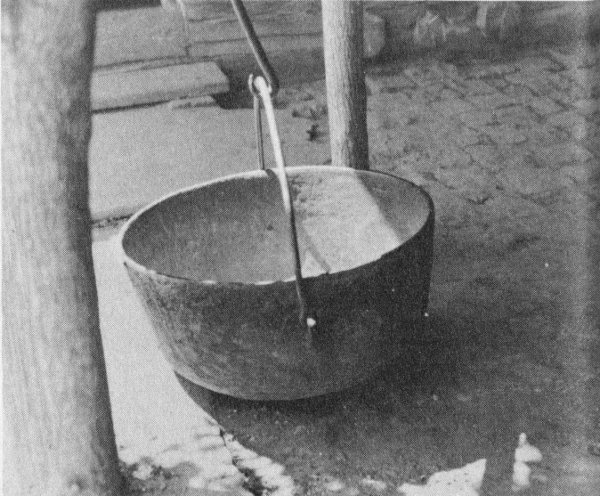

In this kettle Waddell prepared the skins from which he made the hats.

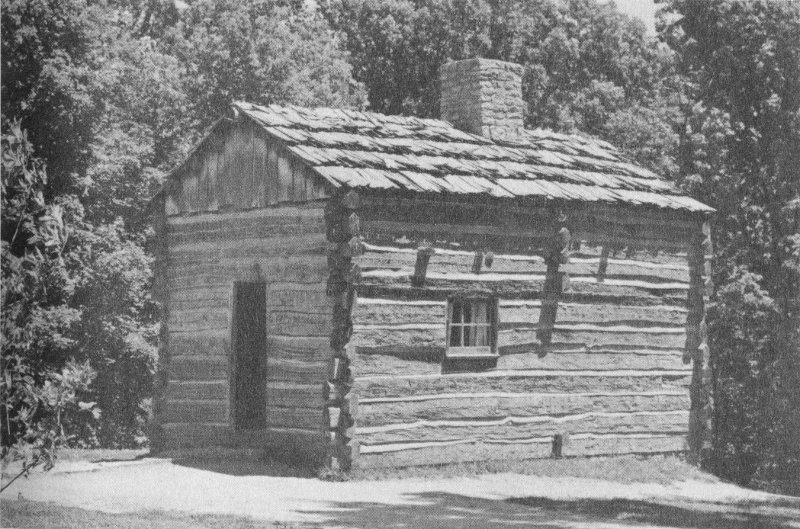

Residence of Isaac Burner. Very little is known about the Burner family.

A familiar sight on Main Street, New Salem.

In the small lean-to in the rear of his cabin, Robert Johnson, the wheelwright and cabinetmaker, painstakingly made spinning wheels, wagon wheels, looms, and sturdy furniture for the community.

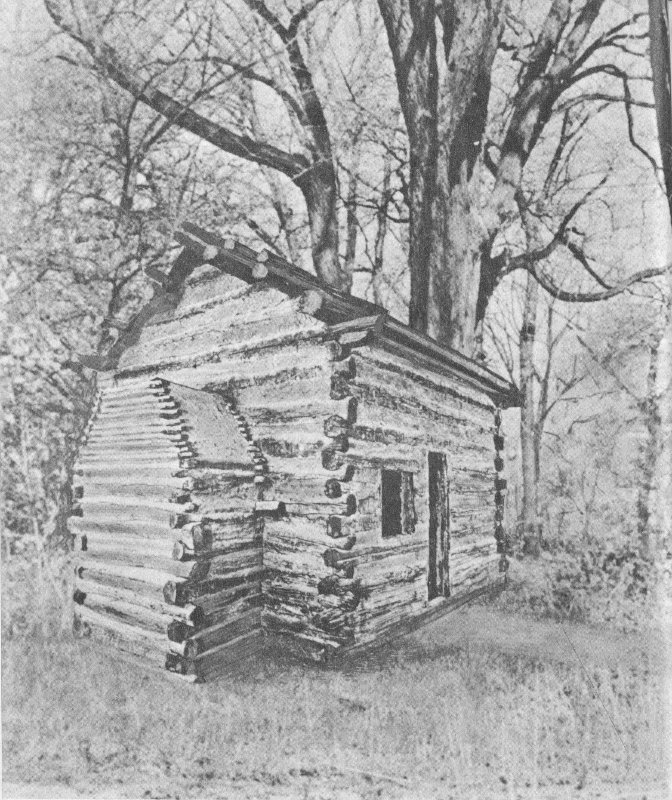

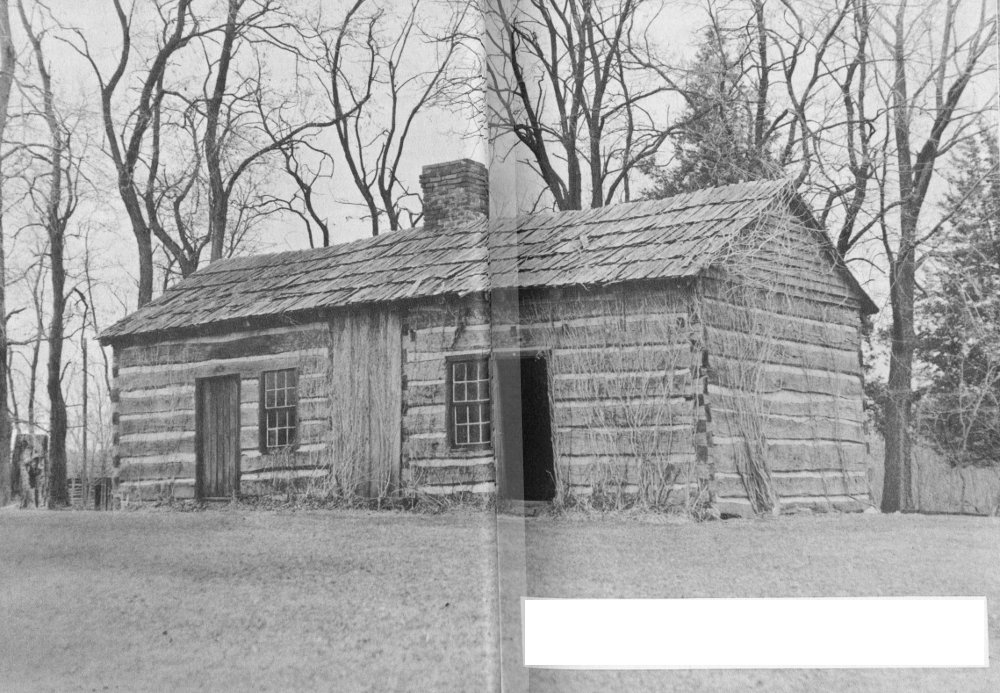

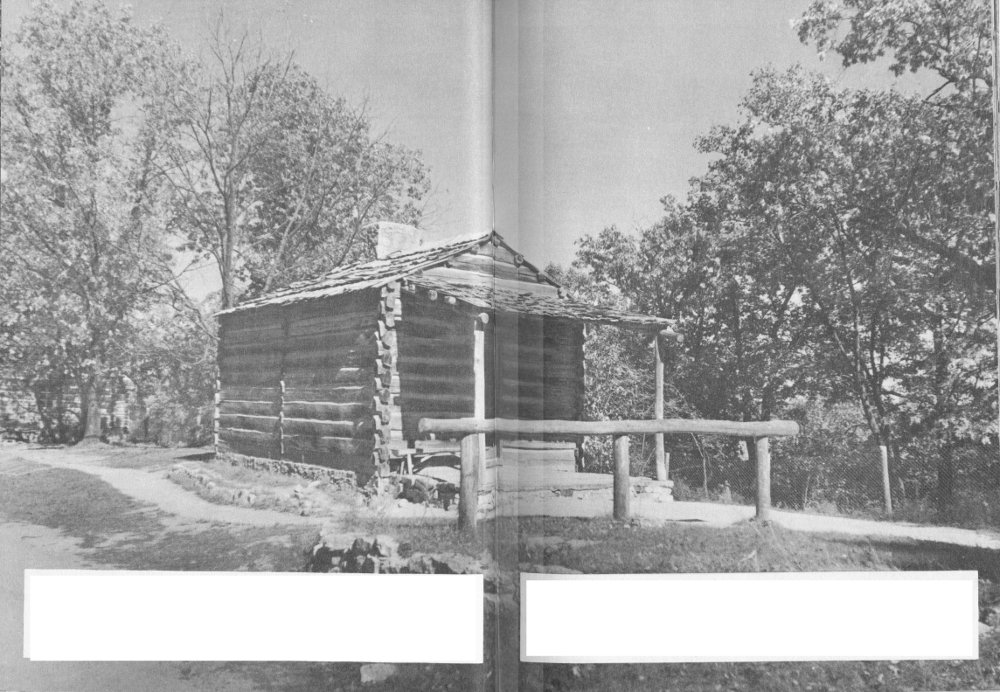

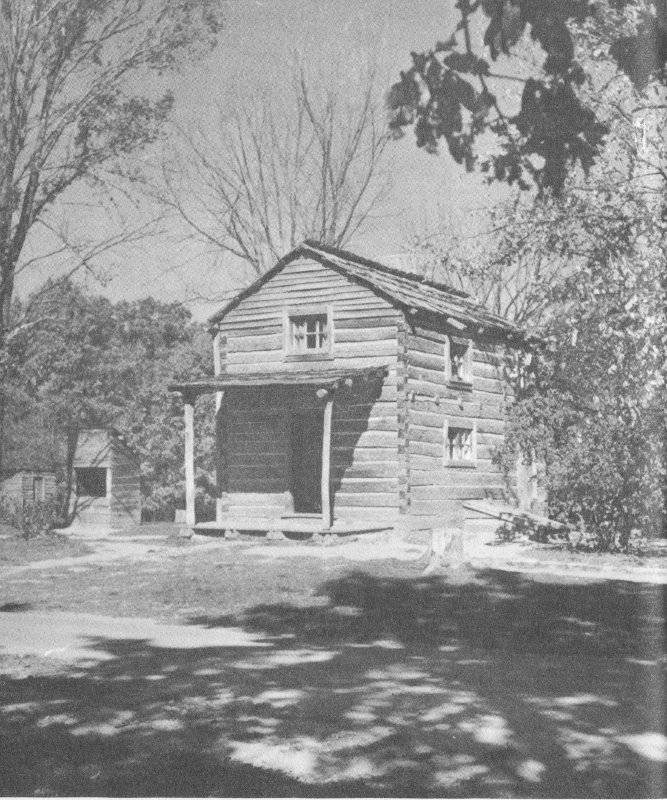

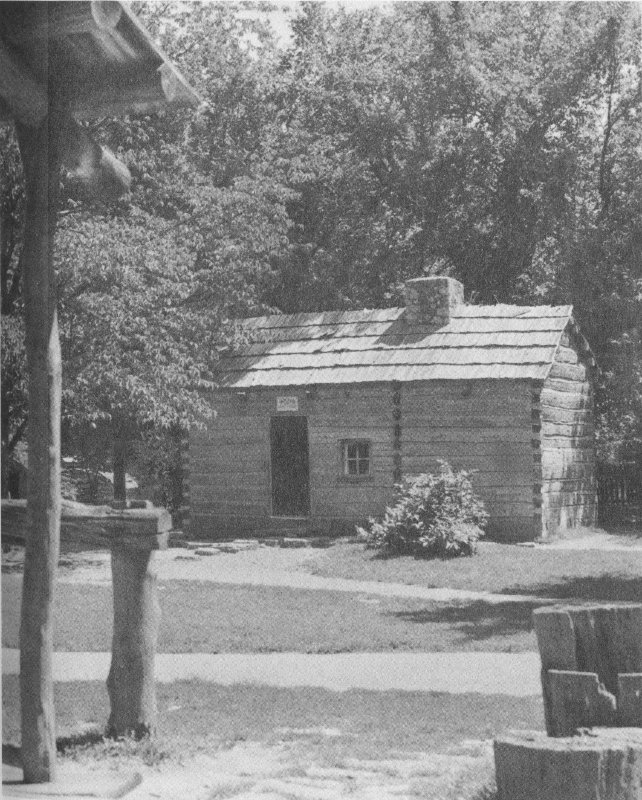

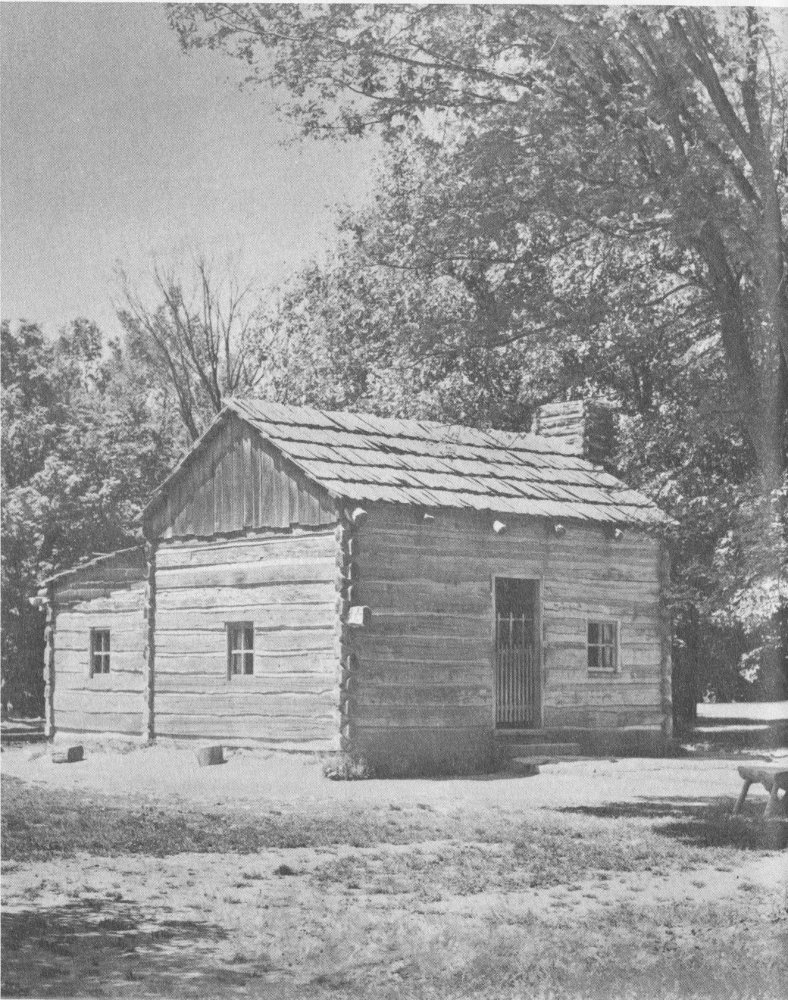

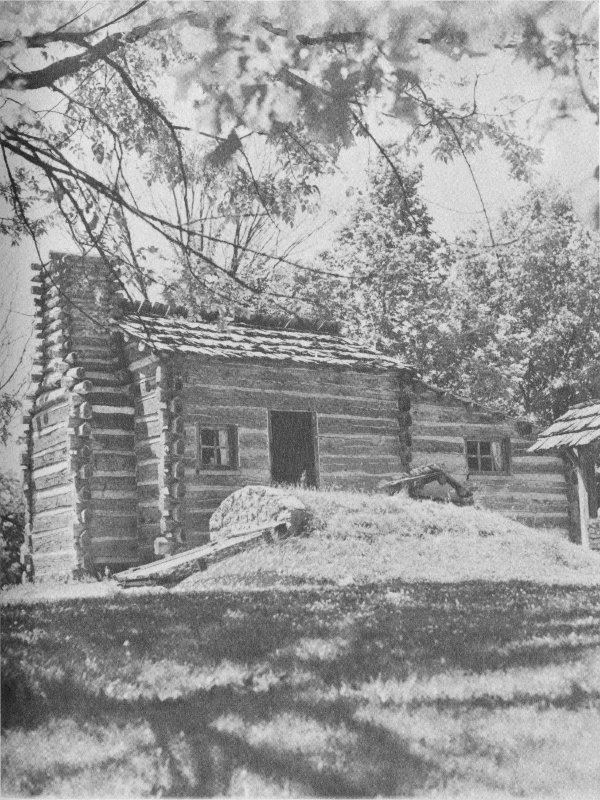

Residence of Isaac Golliher, who had the only root cellar in the village.

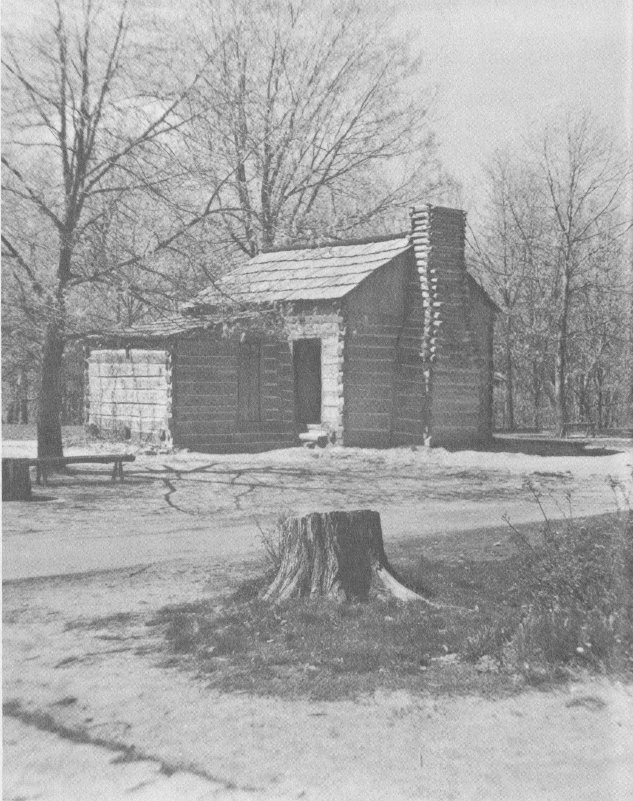

For three years Lincoln was postmaster at New Salem. In this position he became well-acquainted with people for miles around. It was here he began his lifelong habit of reading newspapers, through which, in part, he learned to interpret public opinion. To supplement his earnings as postmaster he did odd jobs, such as clerking in Hill’s store, helping out at the mill or splitting rails.

This was the home of Alexander Trent. When Lincoln became postmaster he was required to furnish bond of five hundred dollars. Alexander Trent was one of his bondsmen.

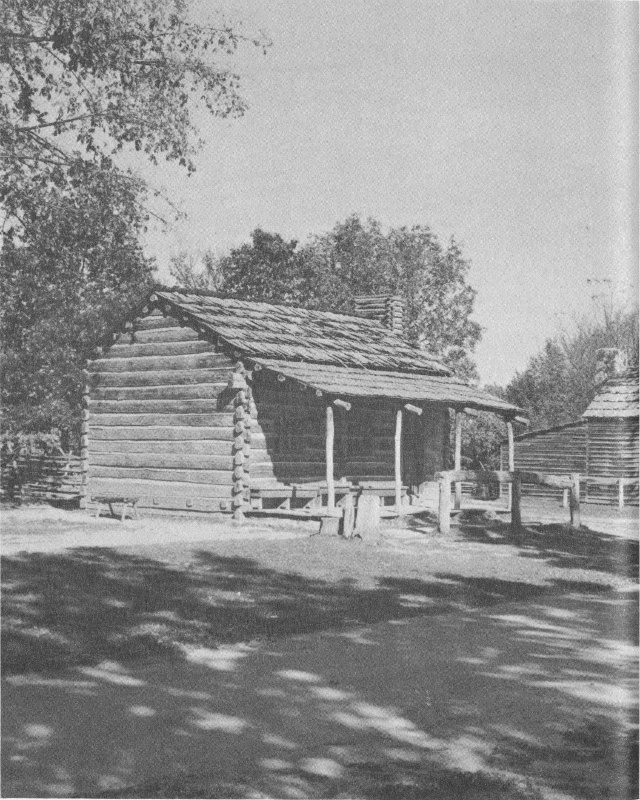

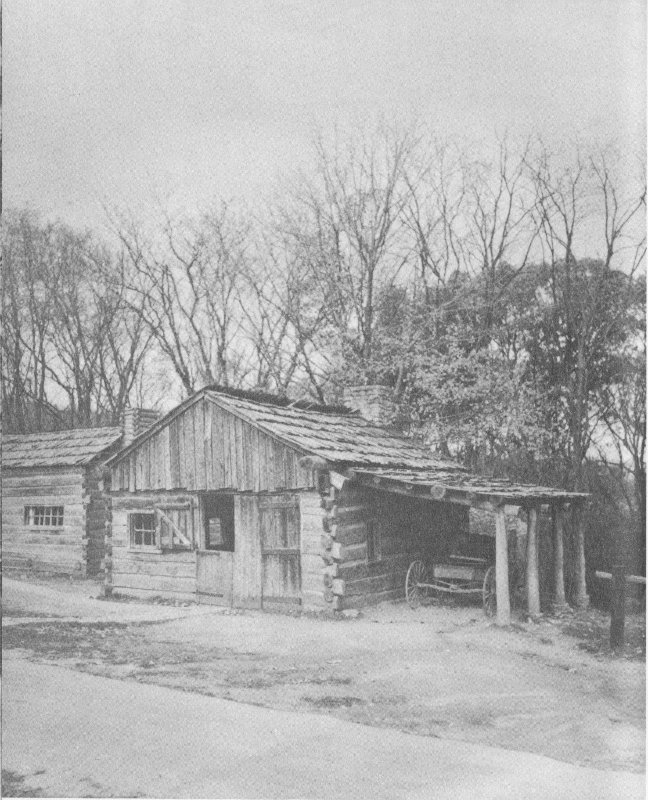

Henry Onstat’s cabin and the cooperage where he made barrels so much in demand by the community of New Salem.

The cooperage was a busy place. There was always a great pile of shavings in the fireplace. Lincoln often came to the cooperage at night and by the glow of the burning shavings he studied mathematics, literature and law.

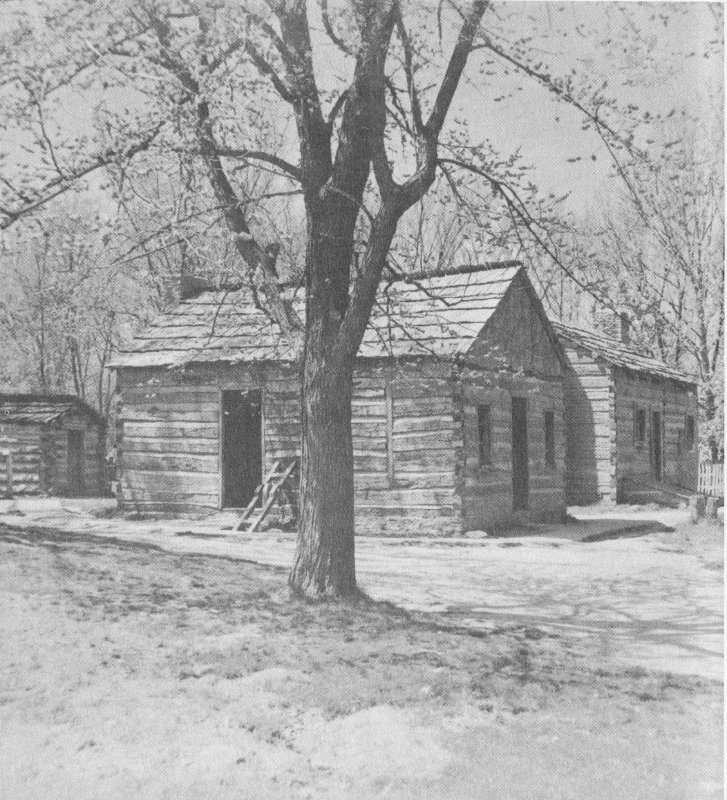

Across the road from the cooperage stood the double cabin of Jack Kelso, philosopher and fisherman, and his brother-in-law, Joshua Miller, the powerful village blacksmith.

Lincoln was a frequent visitor to the Kelso cabin; he and Jack often sat around the table and by the cheerful glow of the fireplace, read and discussed Shakespeare, Blackstone and Burns. It was Jack Kelso who introduced Lincoln to the classics of literature.

Joshua Miller’s blacksmith shop was the busiest place in town. The ring of his anvil was heard from morning until night throughout the village as he shaped metal into oxen shoes, horseshoes and farm implements.

Lincoln, seeking an occupation that would afford him a better living than odd jobs, considered becoming a blacksmith. For a time his strong arms grappled with the chore, but he preferred lighter work which allowed him more time for studying. He also had thoughts of becoming a merchant.

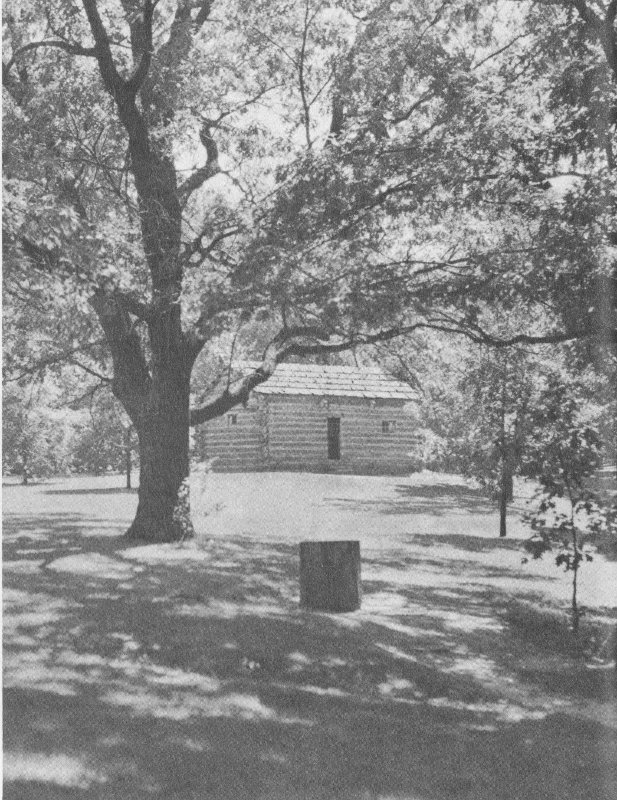

The limbs of the great oak tree still cast their shadows across the Lincoln-Berry store. In fair weather, when housewives were busy and sales were restricted to an occasional pound of sugar or a piece of beeswax, Lincoln, barefoot, lay stretched out under the oak tree, lost in a book.

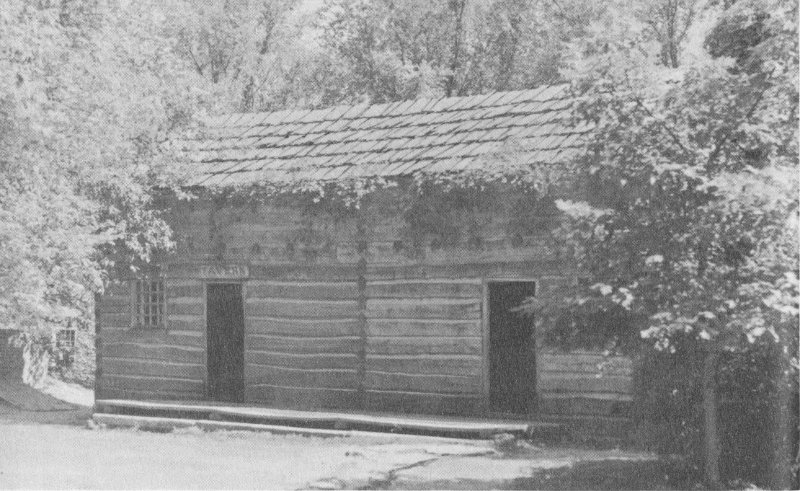

The Rutledge Tavern, where Lincoln courted Ann Rutledge, stood across the road from the Lincoln-Berry store. While waiting on a customer, or studying under the oak tree, he often paused to watch her as she moved about the yard of the tavern.

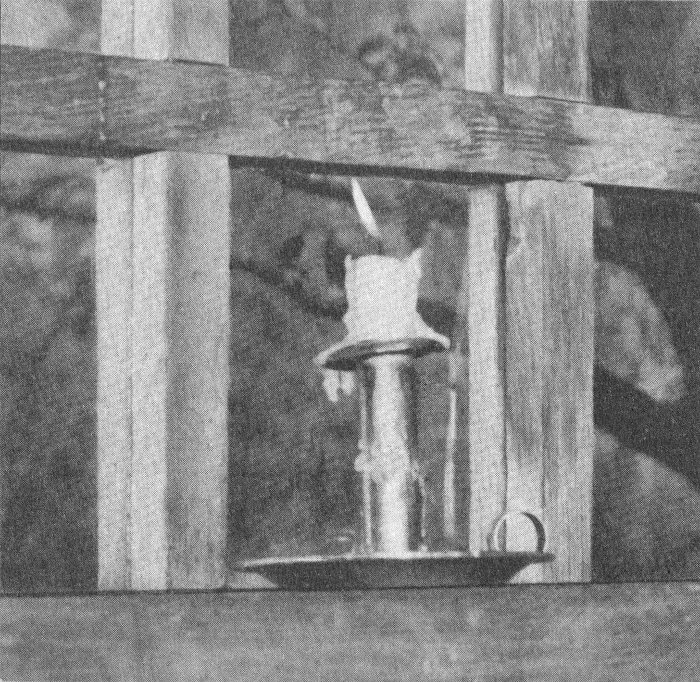

A burning candle in the tavern window welcomed whatever wayfarer might be seeking food and lodging.

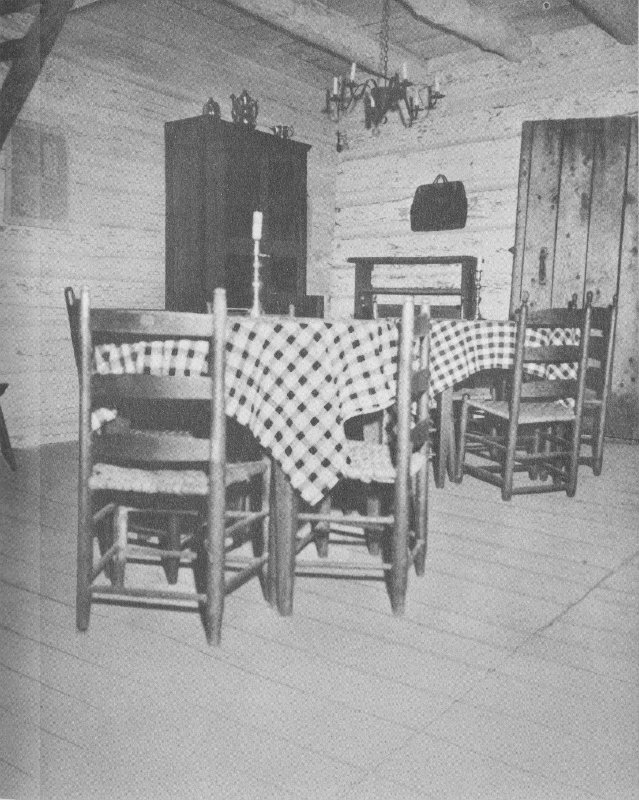

The tavern was a pleasant and comfortable place. Every day brought new guests to the dining room. For a time Lincoln lived at the tavern; his wit and tall tales often made him the center of interest.

While residing at the tavern, Lincoln climbed the rungs of a well-worn ladder to the loft, where he shared a bed with E. Y. Ellis, who says that Lincoln’s wit and stories often kept the other male guests in an uproar until late at night.

The west room of the tavern accommodated the Rutledge family and now and then an overnight lady guest.

On Sunday evenings the Rutledge family and friends gathered before the fireplace to listen to a sermon and to sing hymns. Lincoln stood near Ann and turned the pages of her Missouri Harmony Song Book.

The betrothal of Ann Rutledge and Lincoln ended with her untimely death. Ann’s brother said: “The effect upon Mr. Lincoln’s mind was terrible. He became plunged in despair, and many of his friends feared reason would desert her throne. His extraordinary emotions were regarded as strong evidence of the existence of the tenderest relations between himself and the deceased.”

Lincoln, the ardent student, could be found pursuing his studies in the most unusual places. Squire Godbey, seeing him stretched out on a pile of wood, inquired: “What are you reading Abe?” Lincoln replied: “I am not reading. I am studying Law.” “Law? Good God A’mighty!” exclaimed the surprised squire as he walked away.

The little subscription schoolhouse stands a half mile south of the village near Purkapile “crick.” Schoolmaster Mentor Graham was a constant stimulus to Lincoln and always ready to help and encourage him. After the day’s routine had ended Lincoln often came to the school so that the master might evaluate his progress.

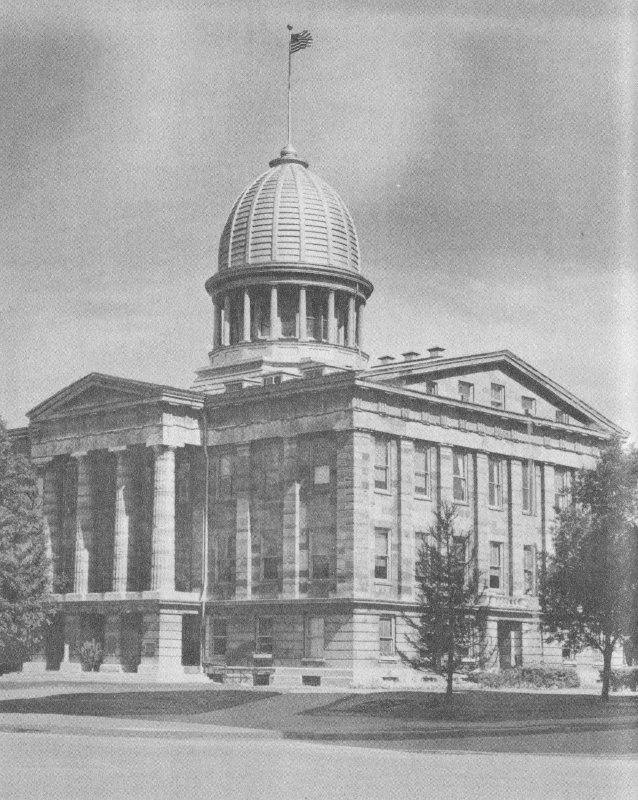

In 1834, Lincoln’s quest for knowledge and esteem was rewarded. The citizens of Sangamon County sent the novice lawmaker to the State Capitol at Vandalia, to take his seat in the Ninth General Assembly of the Legislature of Illinois.

In the Assembly, Lincoln said little, but observed closely and learned much. He was among men of affairs, education and political experience. He became floor leader of the Whigs and an esteemed member of a political group known as the “Long Nine” who were successful in having the State Capitol moved from Vandalia to Springfield.

In March of 1837, after having been admitted to the bar in Illinois, Lincoln moved from New Salem to Springfield. For the next twenty-five years the first State Capitol Building in Springfield became the center of his many activities.

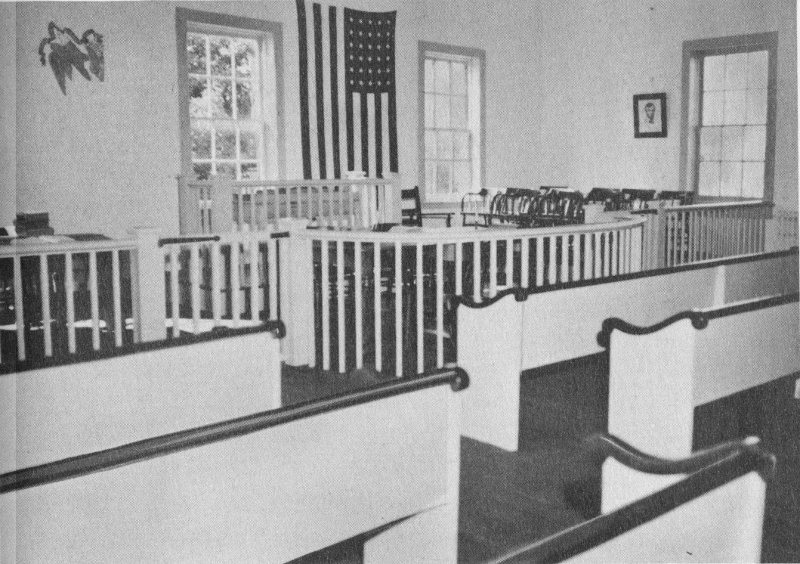

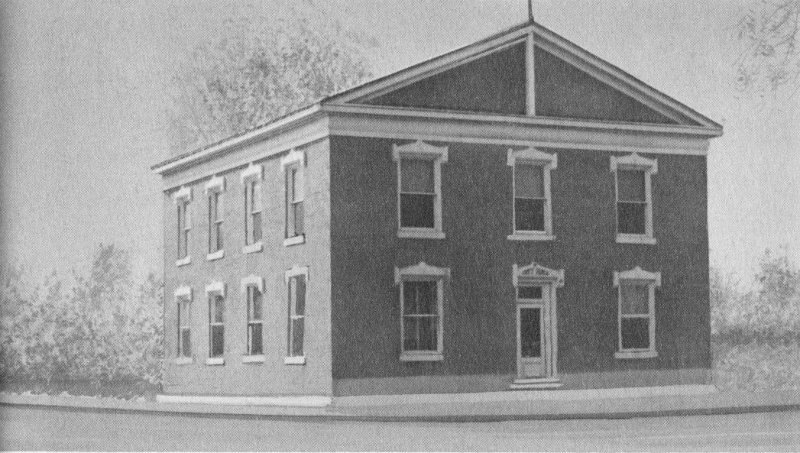

The Postville Courthouse was on the “Old Eighth Circuit.” In Lincoln’s day judges and lawyers rode horseback from one county courthouse to another, so as to make a living by representing the litigants in the suits to be heard. This was known as “riding the circuit.”

The Mount Pulaski Courthouse hasn’t changed much since Lincoln practiced law here more than a hundred years ago.

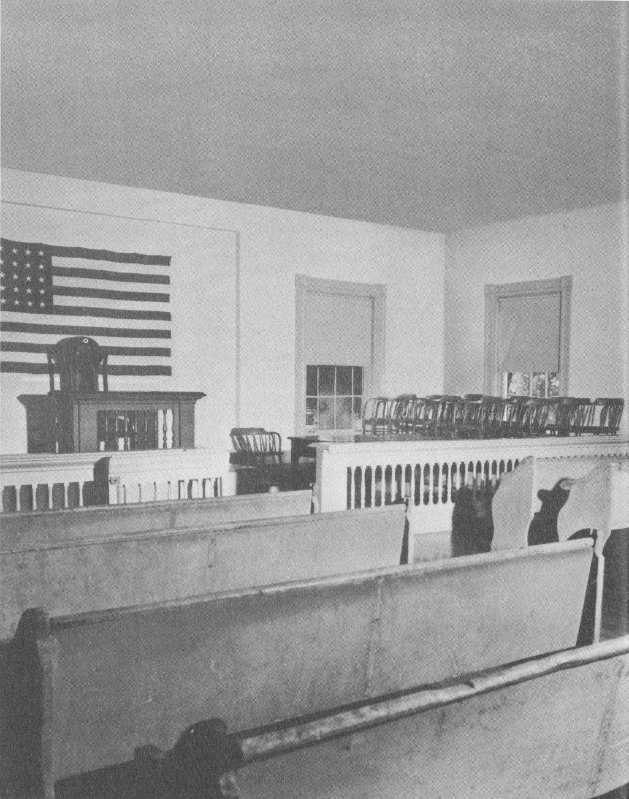

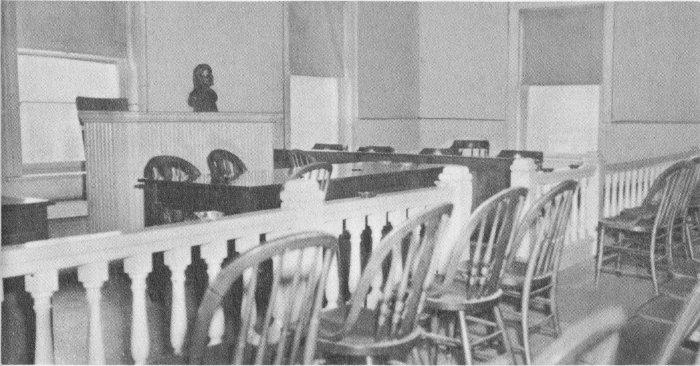

In the court and jury room Lincoln argued cases before such distinguished judges as David Davis, who became a Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

During those inevitable moments of disturbance when the courtroom became unruly, Judge Davis would sound this gavel calling for order in the court.

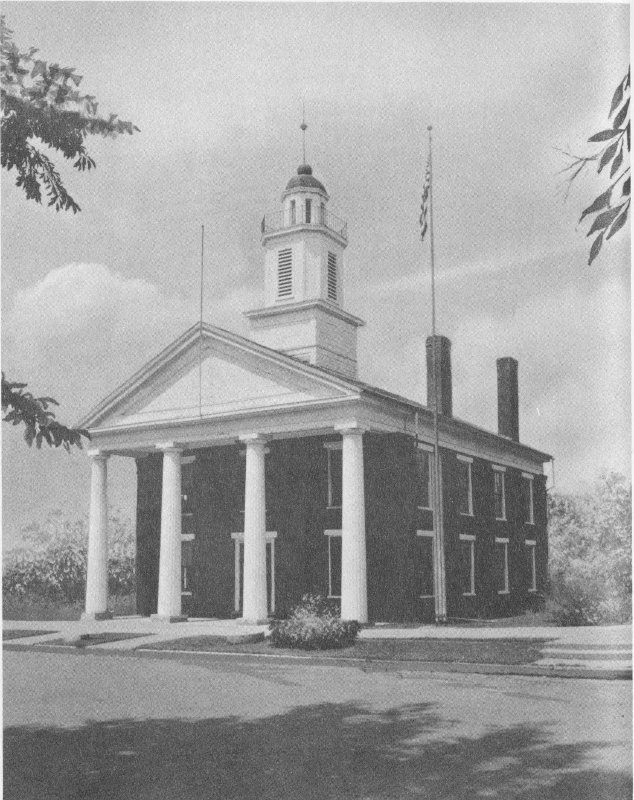

The Metamora Courthouse, dating from 1845, retains the atmosphere of those rugged days when Lincoln and his colleagues came here to plead for justice before the bar.

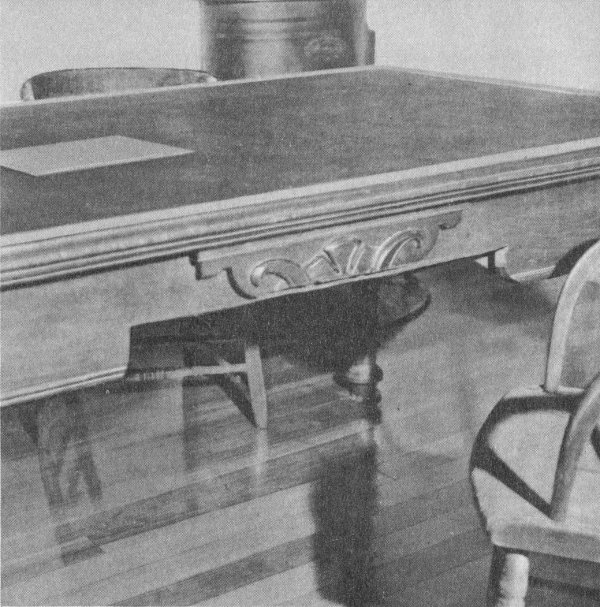

At Metamora, Lincoln sat at this table. The “skirt” was cut away to accommodate his long legs.

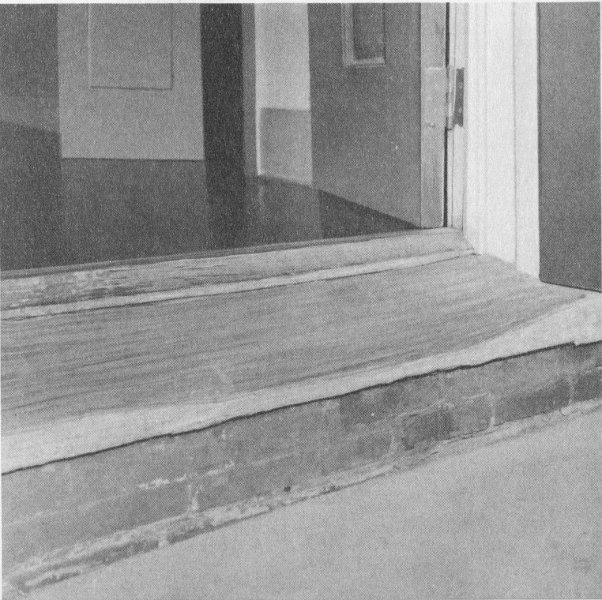

The well-worn courthouse doorstep is evidence of one court room visitor’s observations: “Court week is a general holiday. Not only suitors, jurors and witnesses, but all who can spare the time brush up their coats and brush down their horses to go to court.”

An atmosphere of exultation pervaded the Metamora courtroom when Lincoln was present. He was the most popular of all the barristers who traveled the Eighth Circuit.

The Old Cass County Courthouse in Beadstown, Illinois, was the scene of the “Duff” Armstrong murder trial in which Lincoln defended the son of “Aunt Hanna” Armstrong, who had befriended him when he lived in New Salem. During the trial Lincoln proved, by referring to an almanac, that the moon was not shining brightly at the time of the murder. It is said that tears stood in Lincoln’s eyes as he pleaded for the boy’s life and that the hardened pioneer jurymen wept with him. Young Armstrong was acquitted.

On the evening of July 29, 1858, Lincoln, Republican Candidate for the United States Senate and the incumbent Democratic Senator, Stephen A. Douglas, were guests at the Bryant Home. It was here that the two politicians agreed to their seven debates.

Lincoln occupied the chair below during the evening’s discussion.

On this table Douglas wrote a letter to Lincoln confirming the schedule for seven debates.

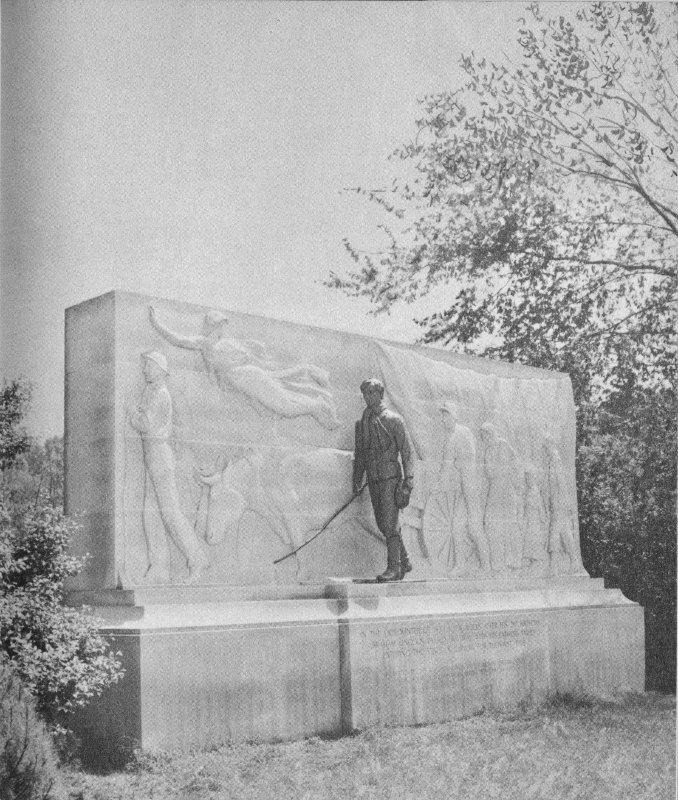

This memorial to the Lincoln-Douglas debates, at Quincy, Illinois, stands as a symbol of Lincoln’s moral and spiritual convictions. They enabled him to match wits with Stephen A. Douglas, who was blind to the evils of slavery and deaf and dumb to those who expressed a desire to abolish it.

Lincoln had crossed the threshold of his greatest ambition when he and his family became frequent visitors to the Governor’s Mansion, where they mingled with the elite both politically and socially. Lincoln’s name had been mentioned in the press as a possible candidate for the Presidency.

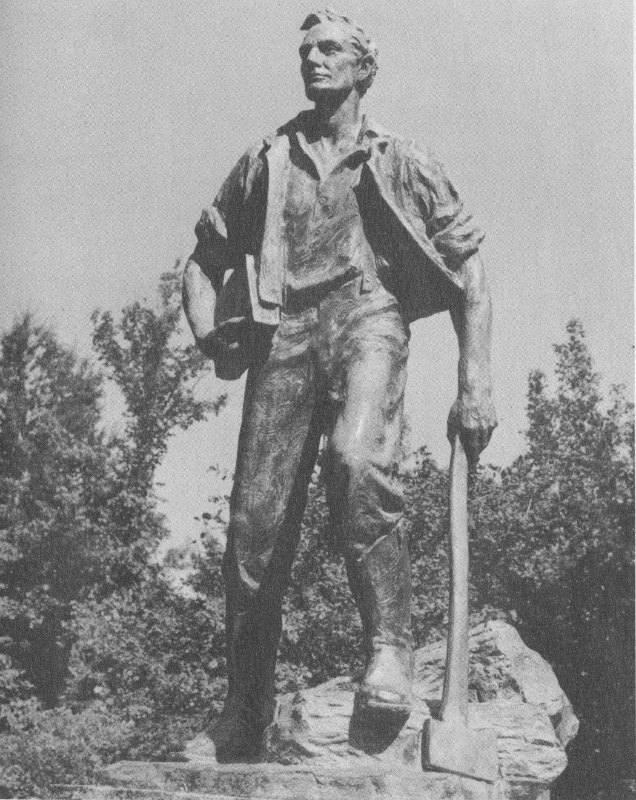

“The Rail Splitter.” Lincoln acquired this nickname during the 1860 convention in Chicago, where he became known as “The Rail Splitter” candidate for President of the United States.

It was to this house, Lincoln’s Springfield residence, that the appointed committee came on May 19, 1860 to notify “The Rail Splitter” candidate of his nomination for the Presidency.

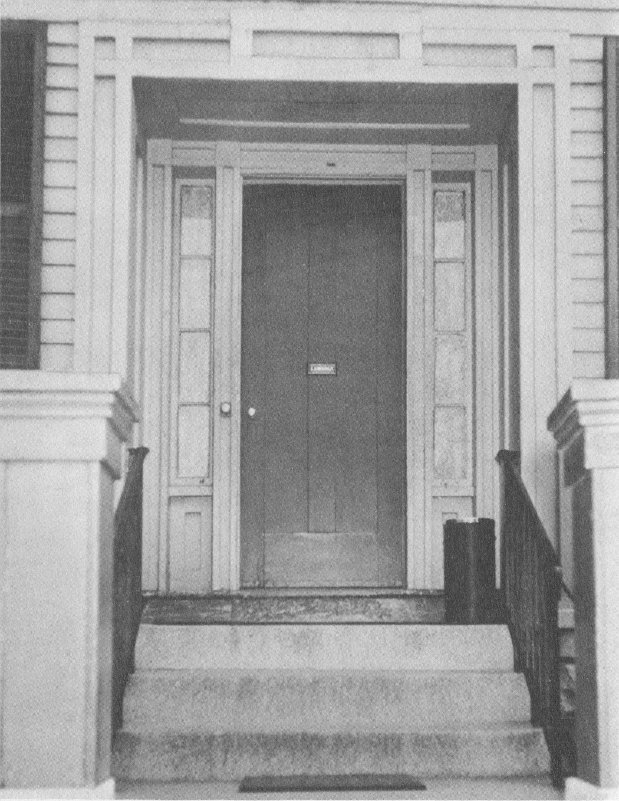

One of the committeemen rang the front doorbell, which has announced visitors to the Lincoln house for more than a hundred years.

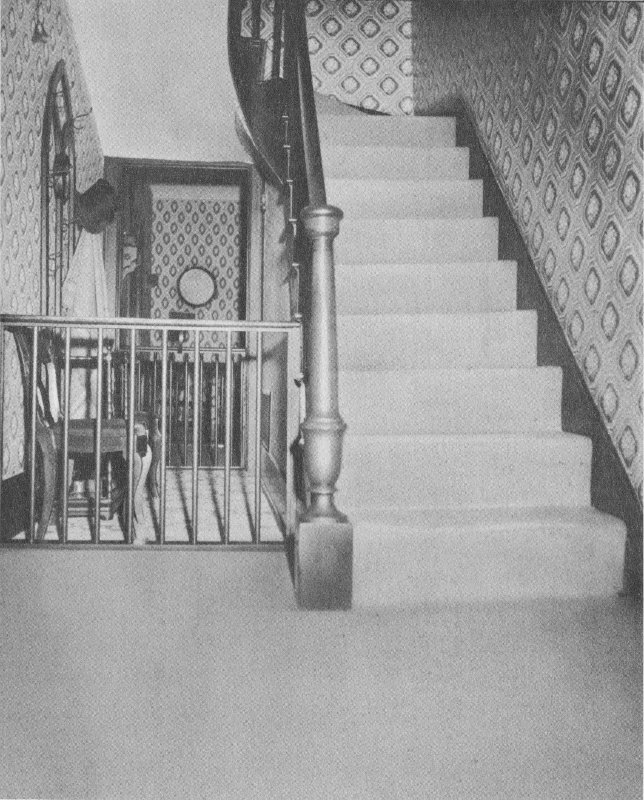

“The Rail Splitter” himself opened the front door and welcomed the committee into the entrance hall, where both the humble and the great had always been welcome visitors.

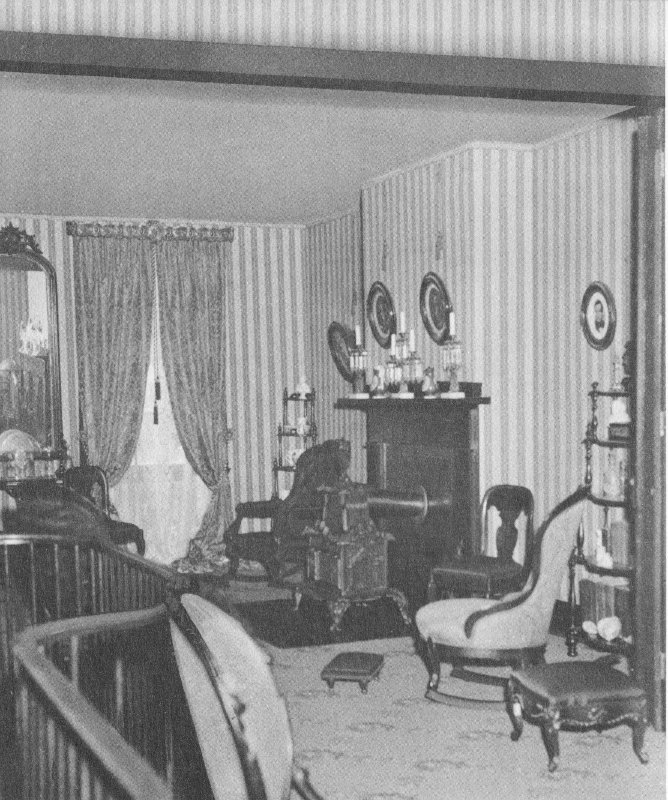

It was in the north parlor that the committee spokesman, George Ashmun, delivered to Lincoln the letter which confirmed his nomination, a copy of the Republican platform and a short congratulatory speech. “The Rail Splitter” candidate stood tall and dignified, a grave expression on his rugged countenance.

The committee was introduced to Mrs. Lincoln in the south parlor, where she served refreshments and water. Later “The Rail Splitter” opined that the water seemed a sufficient stimulant.

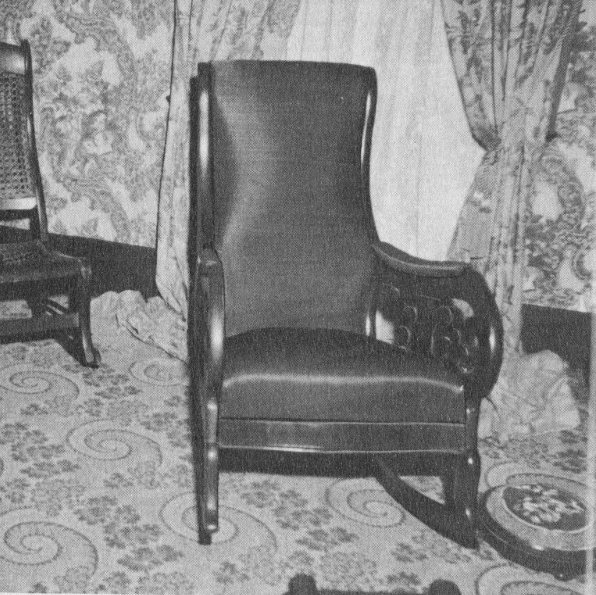

Mr. Lincoln’s favorite rocker.

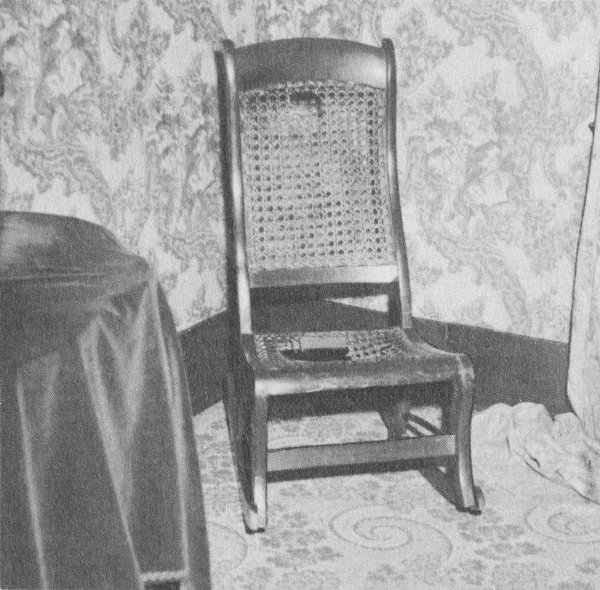

Mrs. Lincoln’s sewing rocker.

When Mrs. Lincoln was entertaining friends, “Honest Abe” often retired to the kitchen where he stretched out on the floor to read a book or newspaper.

It was a cold January day when Lincoln journeyed from Springfield to this quaint little house near Charleston, Illinois, to visit for the last time with his beloved stepmother, before leaving for Washington and his inauguration.

While sitting before the glowing fireplace, Lincoln and his stepmother must have reminisced about those formidable days in the forests of Indiana and the first few years on the prairies of Illinois.

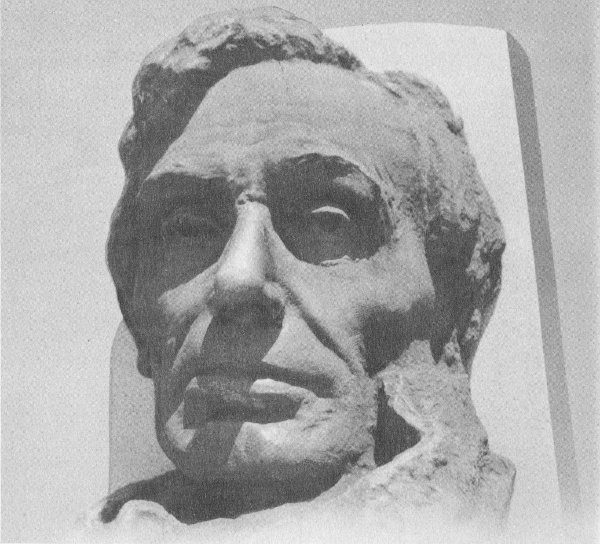

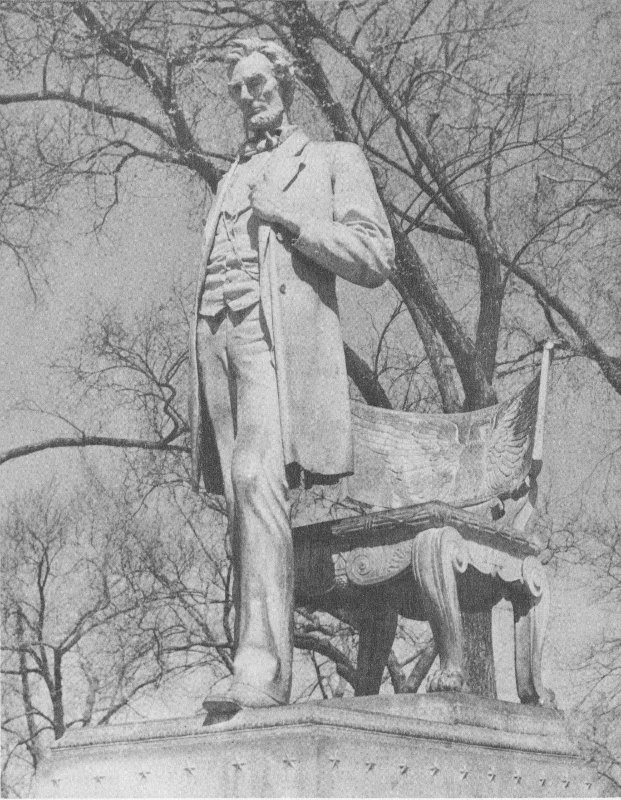

“How slowly, and yet by happily prepared steps, he came to his place,” said Emerson. This statue is in Chicago’s Lincoln Park.

At the dedication of the memorial and tomb to the Great Emancipator in Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois, Governor Richard Oglesby spoke these words: “And now under the gracious favor of Almighty God, I dedicate this monument to the memory of the obscure boy, the honest man, the illustrious statesman, the great liberator, and the martyr President Abraham Lincoln, and to the keeping of Time.”

Perhaps no man in American history has been viewed with such respect and reverence by the American people as has Abraham Lincoln. School children and scholars alike have been moved by the humanity of his deeply lined face, have marveled at his rise from poverty to the Presidency, have sorrowed anew at the tragedy of his death, have read his words and been unable to erase them from their memory. If there is one historic person most of us would like to know, it is Abraham Lincoln.

Here—in these pages which recreate the world Lincoln knew as a child and a young man—the reader can come close to Lincoln. In these fine photographs, which carefully depict the familiar, everyday scenes of young Abe’s manhood, he can see Lincoln’s world as Lincoln saw it. As the authors say: “It was from this frontier atmosphere and these frontier people that Lincoln acquired his uncanny understanding of how common folk think and the wisdom that enabled him to hold in his hands the ties that bound a people and made a nation.”

It is this atmosphere that the authors have captured in over 100 photographs, and it is the rhythm of frontier life that they have caught in the factual simplicity of the text. 98 Here is the farm in Kentucky where Lincoln was born; here are reconstructed the smithy, the tavern, the houses of New Salem, Illinois where Lincoln was a clerk, where he studied law, where he was elected to the state legislature. Here is the Springfield that Lincoln knew when he was first elected to Congress, the town where his sons were born, where in 1860 he learned that he was a candidate for the Presidency. This is Lincoln’s country. As the reader follows Lincoln through the pages of this book, he will feel suddenly close to the man who left such an indelible imprint on the history of this nation—and upon its people.

CARL and ROSALIE FRAZIER live in Chicago, Illinois where they pursue their professions as artists and photographers. Their knowledge of Abraham Lincoln comes from their considerable and extensive research into Lincoln’s life and their many pilgrimages to those places where he lived in Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois.

The Fraziers became interested in trying to capture through the lenses of their cameras that certain something which attracts visitors by the thousands to the Lincoln shrines every year. They hope this picture book will preserve, or at least refresh the memories of these observant visitors, and bring to those who may never have this opportunity a better mental picture of this benevolent man’s environment.

HASTINGS HOUSE • PUBLISHERS

New York 22

The Rutledge Tavern where Abraham Lincoln often stayed. The well-worn ladder leads to his bed in the loft.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Lincoln Country in Pictures, by

Carl Frazier and Rosalie Frazier

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LINCOLN COUNTRY IN PICTURES ***

***** This file should be named 56210-h.htm or 56210-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/6/2/1/56210/

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.