The Project Gutenberg eBook, Six Plays, by Florence Henrietta Darwin, Edited by Cecil Sharp This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Six Plays Author: Florence Henrietta Darwin Editor: Cecil Sharp Release Date: December 18, 2014 [eBook #5618] [This file was first posted on July 23, 2002] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIX PLAYS***

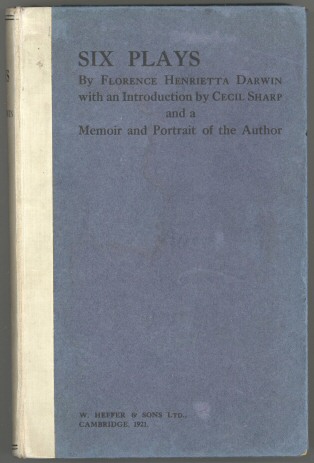

Transcribed from the 1921 W. Heffer & Sons edition by David Price, email [email protected]

Memoir and Portrait of the Author

W. HEFFER & SONS LTD.,

CAMBRIDGE, 1921.

SIX PLAYS BY |

The Plays may be had in paper

covers at 1. LOVERS’ TASKS 2. BUSHES & BRIARS 3. MY MAN JOHN 4. PRINCESS ROYAL } 5. THE SEEDS OF LOVE } In one volume 6. THE NEW YEAR |

W. HEFFER & SONS LTD. |

I have been asked to write a few lines of introduction to these volumes of Country Plays, and I do so, not because I can claim any right to speak with authority on the subject of drama, but in order that I may associate myself and express my sympathy with the endeavour which the author has made to restore to his rightful estate the English peasant with whom my work for twenty years or more has brought me into close relations.

There have been few serious attempts to depict English country life on the stage. Nor, for that matter, can it be said that the English peasant has fared over well in our literature. Nevertheless, the English countryman has qualities all his own, no less distinctive nor less engaging than those of his Irish, Scottish, Russian, or Continental neighbours, even though his especial characteristics have hitherto been for the most part either ignored or grossly travestied by the playwright. Now in these plays, as it seems to me, he has at last come into his own kingdom and is painted, perhaps for the first time on the stage, in his true colours, neither caricatured on the one hand, nor, on the other, sentimentalised, but faithfully portrayed by a peculiarly sympathetic and skilful hand.

It is well, too, that an authentic record should be preserved of the life that has been lived in our country villages year in year out for centuries before its last vestiges—and they are all that now remain—have been completely submerged in the oncoming tide of modern civilisation and progress. Moreover, the songs and dances of the English peasantry that have become widely known in the last few years have awakened a p. vigeneral interest and curiosity in all that concerns the lives and habits of country people and there are many who will be glad to know what manner of men and women were they who created things of so rare and delicate a beauty.

These plays are very simple plays. With one exception, “The New Year,” they rest for their effects upon dialogue rather than upon dramatic action or plot. There is nothing harrowing, problematical, or pathological about any of them. The stories are as simple, obvious and naïve, and have the same happy endings as those which the folk delight to sing about in their own songs, and from which, indeed, judging by the titles she has given to her plays, the author drew her inspiration.

It will be noticed that Lady Darwin has eliminated dialect from the speech which she has put into the mouths of her characters. This is not because the English villager has no vernacular of his own—there are as many dialects in England as there are counties—but because dialect, as no doubt Lady Darwin knew full well, is not of the essence of speech. It is the way in which language is used for the purpose of expression, the order in which words are strung together, the subtle, elusive turns of speech, the character of its figures and metaphors, rather than local peculiarities of intonation and pronunciation, which betray and illumine character. And it is upon these, the essential characteristics of speech, that the author of these plays has wisely and, for the most part, wholly, relied to give life and character to the actors of her dramas. The results she has achieved by these means is nothing less than amazing. So accurately has she caught the peculiar inflections, the inversions, the curious meanderings and involutions of peasant speech, so penetrating—uncanny at times—is her insight into the structure and working of the peasant mind, that, did one not know that this was scarcely the fact, one would have been tempted to suspect that the author had herself been born and bred p. viiin a country village and lived all her days amongst those whose characters and habits of mind she has described with such fidelity.

Take, for instance, the lesson on courtship which My Man John gives to his master—is not the actual phrasing almost photographic in its accuracy? Note, too, the frequent use of homely metaphor:—

’Tis with the maids as ’tis with the fowls when they be come out from moult. They be bound to pick about this way and that in their new feathers.

I warrant she be gone shy as a May bettel when ’tis daylight.

Ah, you take and let her go quiet, same as I lets th’ old mare when her first comes up from grass.

I likes doing things my own way, mother. Womenfolk, they be so buzzing. ’Tis like a lot of insects around of any one on a summer’s day. A-saying this way and that—whilst a man do go at everything quiet and calm-like.

and the following typical sentences:—

Well, mother, I count I’m back a smartish bit sooner nor what you did expect.

There was a cow—well, ’tis a smartish lot of cows as I’ve seen in my time, but this one, why, the king haven’t got the match to she in all his great palace, and that’s the truth, so ’tis.

I bain’t one as can judge of that, my lord, seeing that I be got a poor old badger of a man, and the days when I was young and did carry a heart what could beat with love, be ahind of I, and the feel of them clean forgot.

The task of selection has not been an easy one. “The New Year” is the only Country play on large and ambitious lines which Lady Darwin left behind her, and it is on this account, as well as for its own merits, which I venture to think are very considerable, that it has been included. “Princess Royal” was p. viiiwritten for a special occasion, and is frankly more conventional and artificial than the others, but it will nevertheless appeal to folk-dancers, and for that reason, rather than perhaps for its intrinsic value, room has been found for it. The remaining four are, in their several ways, typical of the author’s work, and I for one have little doubt but that they will make a wide appeal, more especially perhaps to those simple-minded people (of whom I am persuaded there are many, even in these latter-days) who are able to appreciate the unpretentious beauty of an art that is well-nigh artless in its simplicity. Some of them may be too slight in design, too delicate in texture, their beauty too elusive, to succeed on the professional stage; I do not know. But there is a large demand for plays of a non-professional character; and that Lady Darwin’s will be acted with pleasure and listened to with delight in hut or hall or country-house of a winter’s evening, I cannot doubt.

CECIL SHARP.

Florence Henrietta Fisher was born at 3, Onslow Square, London, in the year 1864; but to those of a younger generation it seemed that nearly the whole of her youth had been spent in the New Forest, so largely did it figure in her stories of the past. It was at Whitley Ridge, Brockenhurst, that her earliest plays were written, and many marvellous characters created; their names still live. It was there that she became a very good violin player, as well as a musician in a wider sense. It was in Brockenhurst Church that, in 1886, she married Frederic William Maitland, later Downing professor of the laws of England.

Mr. and Mrs. Maitland lived in Cambridge; for the first two years at Brookside, and afterwards in the West Lodge of Downing College.

Along with her love of music there had begun, and there continued a love of animals, and, from Moses, a dog of Brockenhurst days, there stretched down a long procession of dogs, cats, monkeys, foxes, moles, merecats, mongeese, bush cats and marmosets, accompanied by a variety of birds. If such a thing as a dumb animal has ever existed it certainly was not one of hers, for, besides what they were able to say for themselves, they spoke much through her. Not only were they able to recount all that had happened to them in past home or jungle, they were perfectly able to give advice in every situation and to join in every discussion. Neither were their pens less ready than their tongues, and many were the letters of flamboyant script and misspelt word that came forth from cage or basket.

Frederic William Maitland possessed a small property at Brookthorpe, Gloucestershire; and near this property, in a house in the village of Edge and at the top of the Horsepools hill, he and his wife and their two children p. xspent most of their holidays. They were happy days. Animals increased in number and rejoiced in freedom, fairs were attended, dancing bears and bird carts came at intervals to the door, gipsies were delighted in and protected, and it was there that many friendships with country people were made. Several days a week would find Mrs. Maitland driving down to Brookthorpe in donkey or pony cart to see tenants, to enquire for or feed the sick, to visit the school, to advise and be advised in the many difficulties of human life. With a wonderful memory and power of reproducing that which she had heard, she brought back rare harvest from these expeditions. All through her days she was told more in a week than many people hear in a life-time.

After much illness, Professor Maitland was told that he must leave England, and in 1898 the Maitlands set sail to the island of Grand Canary; and it was there that they spent each winter, with the exception of one in Madeira, until Professor Maitland’s death in 1906. The beauty and warmth of the island were a joy to Mrs. Maitland, washing out all the difficulties of housekeeping and the labour of cooking. The day of hardest work still left her time to set forth, accompanied by a faithful one-legged hen, to seek the shade of chestnut or loquat tree, and there to write. The song of frogs rising from watery palm grove, the hot dusty scent of pepper tree, the cool scent of orange, the mountains sharp and black against the evening sky, the brightly coloured houses crowded to the brink of still brighter sea, were all things she loved, and their images remained with her always. She became an expert talker of what she called kitchen Spanish, and her store of country history increased greatly, for, from Candelaria, the washer-woman to Don Luis the grocer, she met no one who was not ready to tell her all the marvels that ever they knew.

In 1906 Frederic William Maitland landed on the island too ill to reach the house that Mrs. Maitland had gone out earlier to prepare for him. He was taken to an p. xihotel in the city of Las Palmas, and there, on December the 19th, he died.

In the spring of 1907 Mrs. Maitland returned to England.

In 1909 she added on to a small farm house at Brookthorpe, and there she went to live. She was thus able to renew many friendships, and in some slight degree take up the life that had been so dear to her. It was during these last eleven years at Brookthorpe that she wrote all her plays dealing with country people; the first for a class of village children to whom she taught singing, the later ones in response to a growing demand not only from other Gloucestershire villages, but from village clubs and institutes scattered over a large part of England. She saw several of her plays acted by the Oakridge and the Sapperton players, and these performances and letters from other performers gave her great pleasure.

In 1913 she married Sir Francis Darwin. Their life at Brookthorpe was varied by months spent at his house in Cambridge. It was there that she died on March 5th, 1920.

During her last years she had much illness to contend with. Unable to play her violin, she turned to the spinet. She practised for hours, wrote plays, and attended to her house when many would have lain in their beds.

Her religion became of increasingly great comfort and interest to her, and it was in that light that she came, more and more, to look at all things.

In the minds of many who knew her in those years rose up the words: I have fought a good fight.

E. M.

Farmer Daniel,

Elizabeth, his wife.

Millie, her daughter.

Annet, his niece.

May, Annet’s sister, aged ten.

Giles, their brother.

Andrew, a rich young farmer.

George and John, servants to Giles.

An Old Man.

The parlour at Camel Farm.

Time: An afternoon in May.

Elizabeth is sewing by the table with Annet. At the open doorway May is polishing a bright mug.

Elizabeth. [Looking up.] There’s Uncle, back from the Fair.

May. [Looking out of the door.] O Uncle’s got some rare big packets in his arms, he has.

Elizabeth. Put down that mug afore you damage it, May; and, Annet, do you go and help your uncle in.

May. [Setting down the mug.] O let me go along of her too—[Annet rises and goes to the door followed by May, who has dropped her polishing leather upon the ground.

Elizabeth. [Picking it up and speaking to herself in exasperation.] If ever there was a careless little wench, ’tis she. I never did hold with the bringing up of other folks children and if I’d had my way, ’tis to the poor-house they’d have went, instead of coming here where I’ve enough to do with my own.

[The Farmer comes in followed by Annet and May carrying large parcels.

Daniel. Well Mother, I count I’m back a smartish bit sooner nor what you did expect.

Elizabeth. I’m not one that can be taken by surprise, Dan. May, lay that parcel on the table at once, and put away your uncle’s hat and overcoat.

Dan. Nay, the overcoat’s too heavy for the little maid—I’ll hang it up myself.

[He takes off his coat and goes out into the passage to hang it up. May runs after him with his hat.

Annet. I do want to know what’s in all those great packets, Aunt.

Elizabeth. I daresay you’ll be told all in good season. Here, take up and get on with that sewing, I dislike to see young people idling away their time.

[The Farmer and May come back.

May. And now, untie the packets quickly, uncle.

Daniel. [Sinking into a big chair.] Not so fast, my little maid, not so fast—’tis a powerful long distance as I have journeyed this day, and ’tis wonderful warm for the time of year.

Elizabeth. I don’t hold with drinking nor with taking bites atween meals, but as your uncle has come a good distance, and the day is warm, you make take the key of the pantry, Annet, and draw a glass of cider for him.

[She takes the key from her pocket and hands it to Annet, who goes out.

Daniel. That’s it, Mother—that’s it. And when I’ve wetted my mouth a bit I’ll be able the better to tell you all about how ’twas over there.

May. O I’d dearly like to go to a Fair, I would. You always said that you’d take me the next time you went, Uncle.

Daniel. Ah and so I did, but when I comed to think it over, Fairs baint the place for little maids, I says to mother here—and no, that they baint, she answers back. But we’ll see how ’tis when you be growed a bit older, like. Us’ll see how ’twill be then, won’t us Mother?

Elizabeth. I wouldn’t encourage the child in her nonsense, if I was you, Dan. She’s old enough to know better than to ask to be taken to such places. Why in all my days I never set my foot within a fair, pleasure or business, nor wanted to, either.

May. And never rode on the pretty wood horses, Aunt, all spotted and with scarlet bridles to them?

Elizabeth. Certainly not. I wonder at your asking such a question, May. But you do say some very unsuitable things for a little child of your age.

May. And did you get astride of the pretty horses at the Fair, Uncle?

Daniel. Nay, nay,—they horses be set in the pleasure part of the Fair, and where I goes ’tis all for doing business like.

[Annet comes back with the glass of cider. Daniel takes it from her.

Daniel. [Drinking.] You might as well have brought the jug, my girl.

Elizabeth. No, Father, ’twill spoil your next meal as it is.

[The girls sit down at the table, taking up their work.

Daniel. [Putting down his glass.] But, bless my soul, yon was a Fair in a hundred. That her was.

Both Girls. O do tell us of all that you did see there, Uncle.

Daniel. There was a cow—well, ’tis a smartish lot of cows as I’ve seen in my time, but this one, why, the King haven’t got the match to she in all his great palace, and that’s the truth, so ’tis.

Annet. O don ’t tell us about the cows, Uncle, we want to know about all the other things.

May. The shows of acting folk, and the wild animals, and the nice sweets.

Elizabeth. They don’t want to hear about anything sensible, Dan. They’re like all the maids now, with their thoughts set on pleasuring and foolishness.

Daniel. Ah, the maids was different in our day, wasn’t they Mother?

Elizabeth. And that they were. Why, when I was your age, Annet, I should have been ashamed if I couldn’t have held my own in any proper or suitable conversation.

Daniel. Ah, you was a rare sensible maid in your day, Mother. Do you mind when you comed along of me to Kingham sale? “You’re never going to buy an animal with all that white to it,” Dan, you says to me.

Elizabeth. Ah—I recollect.

Daniel. “’Tis true her has a whitish leg,” I says, “but so have I, and so have you, Mother—and who’s to think the worse on we for that?” Ah, I could always bring you round to look at things quiet and reasonable in those days—that I could.

Elizabeth. And a good thing if there were others of the same pattern now, I’m thinking.

Daniel. So ’twould be—so ’twould be. But times do bring changes in the forms of the cattle and I count ’tis the same with the womenfolk. ’Tis one thing this year and ’tis t’other in the next.

May. Do tell us more of what you did see at the Fair, Uncle.

Daniel. There was a ram. My word! but the four feet of he did cover a good two yards of ground; just as it might be, standing.

Elizabeth. Come, Father.

Daniel. And the horns upon the head of he did reach out very nigh as far as might do the sails of one of they old wind-mills.

May. O Uncle, and how was it with the wool of him?

Daniel. The wool, my wench, did stand a good three foot from all around of the animal. You might have set a hen with her eggs on top of it—and that you might. And now I comes to recollect how ’twas, you could have set a hen one side of the wool and a turkey t’other.

May. O Uncle, that must have been a beautiful animal! And what was the tail of it?

Daniel. The tail, my little maid? Why ’twas longer nor my arm and as thick again—’twould have served as a bell rope to the great bell yonder in Gloucester church—and so ’twould. Ah, ’twas sommat like a tail, I reckon, yon.

Elizabeth. Come, Father, such talk is hardly suited to little girls, who should know better than to ask so many teasing questions.

Annet. ’Tisn’t only May, Aunt, I do love to hear what uncle tells, when he has been out for a day or two.

Elizabeth. And did you have company on the way home, Father?

Daniel. That I did. ’Twas along of young Andrew as I did come back.

Elizabeth. Along of Andrew? Girls, you may now go outside into the garden for a while. Yes, put aside your work.

May. Can’t we stop till the packets are opened?

Elizabeth. You heard what I said? Go off into the garden, and stop there till I send for you. And take uncle’s glass and wash it at the spout as you go.

Annet. [Taking the glass.] I’ll wash it, Aunt. Come May, you see aunt doesn’t want us any longer.

May. Now they’re going to talk secrets together. O I should dearly love to hear the secrets of grown-up people. [Annet and May go out together.

Daniel. Annet be got a fine big wench, upon my word. Now haven’t her, Mother?

Elizabeth. She’s got old enough to be put to service, and if I’d have had my way, ’tis to service she’d have gone this long time since, and that it is.

Daniel. ’Twould be poor work putting one of dead sister’s wenches out to service, so long as us have a roof over the heads of we and plenty to eat on the table.

Elizabeth. Well, you must please yourself about it Father, as you do most times. But ’tis uncertain work taking up with other folks children as I told you from the first. See what a lot of trouble you and me have had along of Giles.

Daniel. Giles be safe enough in them foreign parts where I did send him. You’ve no need to trouble your head about he, Mother—unless ’tis a letter as he may have got sending to Mill.

Elizabeth. No, Father, Giles has never sent a letter since the day he left home. But very often there is no need for letters to keep remembrance green. ’Tis a plant what thrives best on a soil that is bare.

Daniel. Well, Mother, and what be you a-driving at? I warrant as Mill have got over them notions as she did have once. And, look you here, ’twas with young Andrew as I did journey back from the Fair. And he be a-coming up presently for to get his answer.

Elizabeth. All I say is that I hope he may get it then.

Daniel. Ah, I reckon as ’tis rare put about as he have been all this long while, and never a downright “yes” to what he do ask.

[May comes softly in and hides behind the door.

Elizabeth. Well, that’s not my fault, Father.

Daniel. But her’ll have to change her note this day, that her’ll have. For I’ve spoke for she, and ’tis for next month as I’ve pitched the wedding day.

Elizabeth. And you may pitch, Father. You may lead the mare down to the pond, but she’ll not drink if she hasn’t the mind to. You know what Millie is. ’Tisn’t from my side that she gets it either.

Daniel. And ’tain’t from me. I be all for easy going and each one to his self like.

Elizabeth. Yes, there you are, Father.

Daniel. But I reckon as the little maid will hearken to what I says. Her was always a wonderful good little maid to her dad. And her did always know, that when her dad did set his foot down, well, there ’twas. ’Twas down.

Elizabeth. Well, if you think you can shew her that, Father, ’tis a fortunate job on all sides.

[They suddenly see May who has been quiet behind the door.

Elizabeth. May, what are you a-doing here I should like to know? Didn’t I send you out into the garden along of your sister?

May. Yes, Auntie, but I’ve comed back.

Elizabeth. Then you can be off again, and shut the door this time, do your hear?

Daniel. That’s it, my little maid. Run along—and look you, May, just you tell Cousin Millie as we wants her in here straight away. And who knows bye and bye whether there won’t be sommat in yon great parcel for a good little wench.

May. O Uncle—I’d like to see it now.

Daniel. Nay, nay—this is not a suitable time—Aunt and me has business what’s got to be settled like. Nay—’tis later on as the packets is to be opened.

Elizabeth. Get along off, you tiresome child.—One word might do for some, but it takes twenty to get you to move.—Run along now, do you hear me?

[May goes.

Well, Father, I’ve done my share with Millie and she don’t take a bit of notice of what I say. So now it’s your turn.

Daniel. Ah, I count ’tis more man’s work, this here, so ’tis. There be things which belongs to females and there be others which do not. You get and leave it all to me. I’ll bring it off.

Elizabeth. All right, Father, just you try your way—I’ll have nothing more to do with it. [Millie comes in.]

Millie. Why, Father, you’re back early from the Fair.

Daniel. That’s so, my wench. See that package over yonder?

Millie. O, that I do, Father.

Daniel. Yon great one’s for you, Mill.

Millie. O Father, what’s inside it?

Daniel. ’Tis a new, smart bonnet, my wench.

Millie. For me, Father?

Daniel. Ah—who else should it be for, Mill?

Millie. O Father, you are good to me.

Daniel. And a silk cloak as well.

Millie. A silken cloak, and a bonnet—O Father, ’tis too much for you to give me all at once, like.

Daniel. Young Andrew did help me with the choice, and ’tis all to be worn on this day month, my girl.

Millie. Why, Father, what’s to happen then?

Daniel. ’Tis for you to go along to church in, Mill.

Millie. To church, Father?

Daniel. Ah, that ’tis—you in the cloak and bonnet, and upon the arm of young Andrew, my wench.

Millie. O no, Father.

Daniel. But ’tis “yes” as you have got to learn, my wench. And quickly too. For ’tis this very evening as Andrew be coming for his answer. And ’tis to be “yes” this time.

Millie. O no, Father.

Daniel. You’ve an hour before you, my wench, in which to get another word to your tongue.

Millie. I can’t learn any word that isn’t “no,” Father.

Daniel. Look at me, my wench. My foot be down. I means what I says—

Millie. And I mean what I say, too, Father. And I say, No!

Daniel. Millie, I’ve set down my foot.

Millie. And so have I, Father.

Daniel. And ’tis “yes” as you must say to young Andrew when he do come a-courting of you this night.

Millie. That I’ll never say, Father. I don’t want cloaks nor bonnets, nor my heart moved by gifts, or tears brought to my eyes by fair words. I’ll not wed unless I can give my love along with my hand. And ’tis not to Andrew I can give that, as you know.

Daniel. And to whom should a maid give her heart if ’twasn’t to Andrew? A finer lad never trod in a pair of shoes. I’ll be blest if I do know what the wenches be a-coming to.

Elizabeth. There, Father, I told you what to expect.

Daniel. But ’tis master as I’ll be, hark you, Mother, hark you, Mill. And ’tis “Yes” as you have got to fit your tongue out with my girl, afore ’tis dark. [Rising.] I be a’going off to the yard, but, Mother, her’ll know what to say to you, her will.

Millie. Dad, do you stop and shew me the inside of my packet. Let us put Andrew aside and be happy—do!

Daniel. Ah, I’ve got other things as is waiting to be done nor breaking in a tricksome filly to run atween the shafts. ’Tis fitter work for females, and so ’tis.

Elizabeth. And so I told you, Father, from the start.

Millie. And ’tis “No” that I shall say.

[Curtain.]

It is dusk on the same evening.

Millie is standing by the table folding up the silken cloak. Annet sits watching her, on her knees lies a open parcel disclosing a woollen shawl. In a far corner of the room May is seated on a stool making a daisy chain.

Annet. ’Twas very good of Uncle to bring me this nice shawl, Millie.

Millie. You should have had a cloak like mine, Annet, by rights.

Annet. I’m not going to get married, Millie.

Millie. [Sitting down with a sudden movement of despondence and stretching her arms across the table.] O don’t you speak to me of that, Annet. ’Tis more than I can bear to-night.

Annet. But, Millie, he’s coming for your answer now. You musn’t let him find you looking so.

Millie. My face shall look as my heart feels. And that is all sorrow, Annet.

Annet. Can’t you bring yourself round to fancy Andrew, Millie?

Millie. No, that I cannot, Annet, I’ve tried a score of times, I have—but there it is—I cannot.

Annet. Is it that you’ve not forgotten Giles, then?

Millie. I never shall forget him, Annet. Why, ’tis a five year this day since father sent him off to foreign parts, and never a moment of all that time has my heart not remembered him.

Annet. I feared ’twas so with you, Millie.

Millie. O I’ve laid awake of nights and my tears have wetted the pillow all over so that I’ve had to turn it t’other side up.

Annet. And Giles has never written to you, nor sent a sign nor nothing?

Millie. Your brother Giles was never very grand with the pen, Annet. But, O, he’s none the worse for that.

Annet. Millie, I never cared for to question you, but how was it when you and he did part, one with t’other?

Millie. I did give him my ring, Annet—secret like—when we were walking in the wood.

Annet. What, the one with the white stones to it?

Millie. Yes, grandmother’s ring, that she left me. And I did say to him—if ever I do turn false to you and am like to wed another, Giles—look you at these white stones.

Annet. Seven of them, there were, Millie.

Millie. And the day that I am like to wed another, Giles, I said to him, the stones shall darken. But you’ll never see that day. [She begins to cry.

Annet. Don’t you give way, Millie, for, look you, ’tis very likely that Giles has forgotten you for all his fine words, and Andrew,—well, Andrew he’s as grand a suitor as ever maid had. And ’tis Andrew you have got to wed, you know.

Millie. Andrew, Andrew—I’m sick at the very name of him.

Annet. See the fine house you’ll live in. Think on the grand parlour that you’ll sit in all the day with a servant to wait on you and naught but Sunday clothes on your back.

Millie. I’d sooner go in rags with Giles at the side of me.

Annet. Come, you must hearten up. Andrew will soon be here. And Uncle says that you have got to give him his answer to-night for good and all.

Millie. O I cannot see him—I’m wearied to death of Andrew, and that’s the very truth it is.

Annet. O Millie—I wonder how ’twould feel to be you for half-an-hour and to have such a fine suitor coming to me and asking for me to say Yes.

Millie. O I wish ’twas you and not me that he was after, Annet.

Annet. ’Tisn’t likely that anyone such as Master Andrew will ever come courting a poor girl like me, Millie. But I’d dearly love to know how ’twould feel.

[Millie raises her head and looks at her cousin for a few minutes in silence, then her face brightens.

Millie. Then you shall, Annet.

Annet. Shall what, Mill?

Millie. Know how it feels. Look here—’Tis sick to death I am with courting, when ’tis from the wrong quarter, and if I’m to wed Andrew come next month, I’ll not be tormented with him before that time,—so ’tis you that shall stop and talk with him this evening, Annet, and I’ll slip out to the woods and gather flowers.

Annet. How wild and unlikely you do talk, Mill.

Millie. In the dusk he’ll never know that ’tisn’t me. Being cousins, we speak after the same fashion, and in the shape of us there’s not much that’s amiss.

Annet. But in the clothing of us, Mill—why, ’tis a grand young lady that you look—whilst I—

Millie. [Taking up the silken cloak.] Here—put this over your gown, Annet.

Annet. [Standing up.] I don’t mind just trying it on, like.

Millie. [Fastening it.] There—and now the bonnet, with the veil pulled over the face.

[She ties the bonnet and arranges the veil on Annet.

Millie. [Standing back and surveying her cousin.] There, Annet, there May, who is to tell which of us ’tis?

May. [Coming forward.] O I should never know that ’twasn’t you, Cousin Mill.

Millie. And I could well mistake her for myself too, so listen, Annet. ’Tis you that shall talk with Master Andrew when he comes to-night. And ’tis you that shall give him my answer. I’ll not burn my lips by speaking the word he asks of me.

Annet. O Mill—I cannot—no I cannot.

Millie. Don’t let him have it very easily, Annet. Set him a ditch or two to jump before he gets there. And let the thorns prick him a bit before he gathers the flower. You know my way with him.

May. And I know it too, Millie—Why, your tongue, ’tis very near as sharp as when Aunt do speak.

Annet. O Millie, take off these things—I cannot do it, that’s the truth.

May. [Looking out through the door.] There’s Andrew a-coming over the mill yard.

Millie. Here, sit down, Annet, with the back of you to the light.

[She pushes Annet into a chair beneath the window.

May. Can I get into the cupboard and listen to it, Cousin Mill?

Millie. If you promise to bide quiet and to say naught of it afterwards.

May. O I promise, I promise—I’ll just leave a crack of the door open for to hear well.

[May gets into the cupboard. Millie takes up Annet’s new shawl and puts it all over her.

Millie. No one will think that ’tisn’t you, in the dusk.

Annet. O Millie, what is it that you’ve got me to do?

Millie. Never you mind, Annet—you shall see what ’tis to have a grand suitor and I shall get a little while of quiet out yonder, where I can think on Giles.

[She runs out of the door just as Andrew comes up. Andrew knocks and then enters the open door.

Andrew. Where’s Annet off to in such a hurry?

Annet. [Very faintly.] I’m sure I don’t know. [Andrew lays aside his hat and comes up to the window. He stands before Annet looking down on her. She becomes restless under his gaze, and at last signs to him to sit down.

Andrew. [Sitting down on a chair a little way from her.] The Master said that I might come along to-night, Millie—Otherwise—[Annet is still silent.

Otherwise I shouldn’t have dared do so.

[Annet sits nervously twisting the ribbons of her cloak.

The Master said, as how may be, your feeling for me, Millie, might be changed like. [Annet is still silent.

And that if I was to ask you once more, very likely ’twould be something different as you might say.

[A long silence.

Was I wrong in coming, Millie?

Annet. [Faintly.] ’Twould have been better had you stayed away like.

Andrew. Then there isn’t any change in your feelings towards me, Millie?

Annet. O, there’s a sort of a change, Andrew.

Andrew. [Slowly.] O Mill, that’s good hearing. What sort of a change is it then?

Annet. ’Tis very hard to say, Andrew.

Andrew. Look you, Mill, ’tis more than a five year that I’ve been a-courting of you faithful.

Annet. [Sighing.] Indeed it is, Andrew.

Andrew. And I’ve never got naught but blows for my pains.

Annet. [Beginning to speak in a gentle voice and ending sharply.] O I’m so sorry—No—I mean—’Tis your own fault, Andrew.

Andrew. But I would sooner take blows from you than sweet words from another, Millie.

Annet. I could never find it in my heart to—I mean, ’tis as well that you should get used to blows, seeing we’re to be wed, Andrew.

Andrew. Then ’tis to be! O Millie, this is brave news—Why, I do scarcely know whether I be awake or dreaming.

Annet. [Very sadly.] Very likely you’ll be glad enough to be dreaming a month from now, poor Andrew.

Andrew. [Drawing nearer.] I am brave, Millie, now that you speak to me so kind and gentle, and I’ll ask you to name the day.

Annet. [Shrinking back.] O ’twill be a very long distance from now, Andrew.

Andrew. Millie, it seems to be your pleasure to take up my heart and play with it same as a cat does with the mouse.

Annet. [Becoming gay and hard in her manner.] Your heart, Andrew? ’Twill go all the better afterwards if ’tis tossed about a bit first.

Andrew. Put an end to this foolishness, Mill, and say when you’ll wed me.

Annet. [Warding him off with her hand.] You shall have my answer in a new song Andrew, which I have been learning.

[Andrew sits down despondently and prepares to listen.

Annet. Now hark you to this, Andrew, and turn it well over in your mind. [She begins to sing:

Say can you plough me an acre of land

Sing Ivy leaf, Sweet William and Thyme.

Between the sea and the salt sea strand

And you shall be a true lover of mine?

[A slight pause. Annet looks questioningly at Andrew, who turns away with a heavy sigh.

Annet. [Singing.]

Yes, if you plough it with one ram’s

horn

Sing Ivy Leaf, Sweet William and Thyme

And sow it all over with one peppercorn

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

Andrew. ’Tis all foolishness.

Annet. [Singing.]

Say can you reap with a sickle of leather

Sing Ivy Leaf, Sweet William and Thyme

And tie it all up with a Tom-tit’s feather

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

Andrew. [Rises up impatiently.] I can stand no more. You’ve danced upon my heart till ’tis fairly brittle, and ready to be broke by a feather.

Annet. [Very gently.] O Andrew, I’ll mend your heart one day.

Andrew. Millie, the sound of those words has mended it already.

Annet. [In a harder voice.] But very likely there’ll be a crack left to it always.

[Farmer Daniel and Elizabeth come into the room.

Daniel. Well my boy, well Millie?

Andrew. [Boldly.] ’Tis for a month from now.

Daniel. Bless my soul. Hear that, Mother? Hear that?

Elizabeth. I’m not deaf, Father.

Daniel. [Shaking Andrew’s hand.] Ah my boy, I knowed as you’d bring the little maid to the senses of she.

Elizabeth. Millie has not shown any backwardness in clothing herself as though for church.

Daniel. ’Tis with the maids as ’tis with the fowls when they be come out from moult. They be bound to pick about this way and that in their new feathers.

Elizabeth. Well, ’tis to be hoped the young people have fixed it up for good and all this time.

Daniel. Come Mill, my wench, you be wonderful quiet. Where’s your tongue?

Elizabeth. I think we’ve all had quite enough of Millie’s tongue, Father. Let her give it a rest if she’ve a mind.

Daniel. I warrant she be gone as shy as a May bettel when ’tis daylight. But us’ll take it as she have fixed it up in her own mind like. Come, Mother, such a time as this, you won’t take no objection to the drawing of a jug of cider.

Elizabeth. And supper just about to be served? I’m surprised at you, Father. No, I can’t hear of cider being drawn so needless like.

Daniel. Well, well,—have it your own way—but I always says, and my father used to say it afore I, a fine deed do call for a fine drink, and that’s how ’twas in my time.

Elizabeth. Millie, do you call your cousins in to supper.

Daniel. Ah, and where be the maids gone off to this time of night, Mother?

Andrew. Annet did pass me as I came through the yard, Master

[May, quietly opens the cupboard door and comes out.

Elizabeth. So that’s where you’ve been, you deceitful little wench.

Andrew. Well, to think of that, Millie.

Elizabeth. And how long may you have bid there, I should like to know?

Daniel. Come, come, my little maid, ’tis early days for you to be getting a lesson in courtship.

May. O there wasn’t any courtship, Uncle, and I didn’t hear nothing at all to speak of.

Elizabeth. There, run along quick and find your sister. Supper’s late already, and that it is.

Annet. I’ll go with her.

[She starts forward and hurriedly moves towards the door.

Elizabeth. Stop a moment, Millie. What are you thinking of to go trailing out in the dew with that beautiful cloak and bonnet. Take and lay them in the box at once, do you hear?

Daniel. That’s it, Mill. ’Twouldn’t do for to mess them up afore the day. ’Twas a fair price as I gived for they, and that I can tell you, my girl.

[Annet stops irresolutely. May seizes her hand.

May. Come off, come off, “Cousin Millie”; ’tis not damp outside, and O I’m afeared to cross the rickyard by myself.

[She pulls Annet violently by the hand and draws her out of the door.

Elizabeth. Off with the cloak this minute, Millie.

May. [Calling back.] She’s a-taking of it off, Aunt, she is.

Elizabeth. I don’t know what’s come to the maid. She don’t act like herself to-day.

Daniel. Ah, that be asking too much of a maid, to act like herself, and the wedding day close ahead of she.

Elizabeth. I’d be content with a suitable behaviour, Father. I’m not hard to please.

Daniel. Ah, you take and let her go quiet, same as I lets th’ old mare when her first comes up from grass.

Elizabeth. ’Tis all very well for you to talk, Father but ’tis I who have got to do.

Daniel. Come Mother, come Andrew, I be sharp set. And ’tis the feel of victuals and no words as I wants in my mouth.

Elizabeth. Well, Father, I’m not detaining you. There’s the door, and the food has been cooling on the table this great while.

Daniel. Come you, Andrew, come you, Mother. Us’ll make a bit of a marriage feast this night.

[He leads the way and the others follow him out.

[Curtain.]

A woodland path. Giles comes forward with his two servants, George and John, who are carrying heavy packets.

Giles. ’Tis powerful warm to-day. We will take a bit of rest before we go further.

George. [Setting down his packet.] That’s it, master. ’Tis a rare weight as I’ve been carrying across my back since dawn.

John. [Also setting down his burden.] Ah, I be pleased for to lay aside yon. ’Tis wonderful heavy work, this journeying to and fro with gold and silver.

Giles. Our travelling is very nigh finished. There lies the road which goes to Camel Farm.

George. Oh, I count as that must be a rare sort of a place, master.

John. Seeing as us haven’t stopped scarce an hour since us landed off the sea.

George. But have come running all the while same as the fox may run in th’ early morning towards the poultry yard.

John. Nor broke bread, nor scarce got a drop of drink to wet th’ insides of we.

Giles. ’Tis very little further that you have got to journey, my good lads. We are nigh to the end of our wayfaring.

George. And what sort of a place be we a-coming to, master?

Giles. ’Tis the place out of all the world to me.

John. I count ’tis sommat rare and fine in that case, seeing as we be come from brave foreign parts, master.

Giles. ’Tis rarer, and finer than all the foreign lands that lie beneath the sun, my lads.

George. That’s good hearing, master. And is the victuals like to be as fine as the place?

Giles. O, you’ll fare well enough yonder.

John. I was never one for foreign victuals, nor for the drink that was over there neither.

Giles. Well, the both of you shall rest this night beneath the grandest roof that ever sheltered a man’s head. And you shall sit at a table spread as you’ve not seen this many a year.

George. That’ll be sommat to think on, master, when us gets upon our legs again.

John. I be thinking of it ahead as I lies here, and that’s the truth.

[The two servants stretch themselves comfortably beneath the trees. Giles walks restlessly backwards and forwards as though impatient at any delay. From time to time he glances at a ring which he wears, sighing heavily as he does so.

[An old man comes up, leaning on his staff.

Old Man. Good-morning to you, my fine gentlemen.

Giles. Good-morning, master.

Old Man. ’Tis a wonderful warm sun to-day.

Giles. You’re right there, master.

Old Man. I warrant as you be journeying towards the same place where I be going, my lord.

Giles. And where is that, old master?

Old Man. Towards Camel Farm.

Giles. You’re right. ’Tis there and nowhere else that we are going.

Old Man. Ah, us’ll have to go smartish if us is to be there in time.

Giles. In time for what, my good man?

Old Man. In time for to see the marrying, my lord.

Giles. The marrying? What’s that you’re telling me?

Old Man. ’Tis at noon this day that she’s to be wed.

Giles. Who are you speaking of, old man?

Old Man. And where is your lordship journeying this day if ’tis not to the marrying?

Giles. Who’s getting wed up yonder, tell me quickly?

Old Man. ’Tis th’ old farmer’s daughter what’s to wed come noon-tide.

Giles. [Starting.] Millie! O that is heavy news. [Looking at his hand.] Then ’tis as I feared, for since daybreak yesterday the brightness has all gone from out of the seven stones. That’s how ’twould be, she told me once.

[He turns away from the others in deep distress of mind.

George. Us’ll see no Camel Farm this day.

John. And th’ inside of I be crying out for victuals.

Old Man. Then you be not of these parts, masters?

George. No, us be comed from right over the seas, along of master.

John. Ah, ’tis a fine gentleman, master. But powerful misfortunate in things of the heart.

George. Ah, he’d best have stopped where he was. Camel Farm baint no place for the like of he to go courting at.

John. Ah, master be used to them great palaces, all over gold and marble with windows as you might drive a waggon through, and that you might.

George. All painted glass. And each chair with golden legs to him, and a sight of silver vessels on the table as never you did dream of after a night’s drinking, old man. [Giles comes slowly towards them.

Giles. And who is she to wed, old man?

Old Man. Be you a-speaking of the young mistress up at Camel Farm, my lord?

Giles. Yes. With whom does she go to church to-day?

Old Man. ’Tis along of Master Andrew that her do go. What lives up Cranham way.

Giles. Ah, th’ old farmer was always wonderful set on him. [A pause.

Old Man. I be a poor old wretch what journeys upon the roads, master, and maybe I picks a crust here and gets a drink of water there, and the shelter of the pig-stye wall to rest the bones of me at night time.

Giles. What matters it if you be old and poor, master, so that the heart of you be whole and unbroken?

Old Man. Us poor old wretches don’t carry no hearts to th’ insides of we. The pains of us do come from the having of no victuals and from the winter’s cold when snow do lie on the ground and the wind do moan over the fields, and when the fox do bark.

Giles. What is the pang of hunger and the cold bite of winter set against the cruel torment of a disappointed love?

Old Man. I baint one as can judge of that, my lord, seeing that I be got a poor old badger of a man, and the days when I was young and did carry a heart what could beat with love, be ahind of I, and the feel of them clean forgot.

Giles. Then what do you up yonder at the marrying this morning?

Old Man. Oh, I do take me to those places where there be burying or marriage, for the hearts of folk at these seasons be warmed and kinder, like. And ’tis bread and meat as I gets then. Food be thrown out to the poor old dog what waits patient at the door.

Giles. [Looks intently at him for a moment.] See here, old master. I would fain strike a bargain with you. And ’tis with a handful of golden pieces that I will pay your service.

Old Man. Anything to oblige you, my young lord.

Giles. [To George.] Take out a handful from the bag of gold. And you, John, give him some of the silver.

[George and John untie their bags and take out gold and silver. They twist it up in a handkerchief which they give to the old man.]

Old Man. May all the blessings of heaven rest on you, my lord, for ’tis plain to see that you be one of the greatest and finest gentlemen ever born to the land.

Giles. My good friend, you’re wrong there, I was a poor country lad, but I had the greatest treasure that a man could hold on this earth. ’Twas the love of my cousin Millie. And being poor, I was put from out the home, and sent to seek my fortune in parts beyond the sea.

Old Man. Now, who’d have thought ’twas so, for the looks of you be gentle born all over.

Giles. “Come back with a bushel of gold in one hand and one of silver in t’other” the old farmer said to me, “and then maybe I’ll let you wed my daughter.”

Old Man. And here you be comed back, and there lie the gold and the silver bags.

Giles. And yonder is Millie given in marriage to another.

George. ’Taint done yet, master.

John. ’Tisn’t too late, by a long way, master.

Giles. [To Old Man.] And so I would crave something of you, old friend. Lend me your smock, and your big hat and your staff. In that disguise I will go to the farm and look upon my poor false love once more. If I find that her heart is already given to another, I shall not make myself known to her. But if she still holds to her love for me, then—

George. Go in the fine clothes what you have upon you, master. And even should the maid’s heart, be given to another, the sight of so grand a cloth and such laces will soon turn it the right way again.

John. Ah, that’s so, it is. You go as you be clothed now, master. I know what maids be, and ’tis finery and good coats which do work more on the hearts of they nor anything else in the wide world.

Giles. No, no, my lads. I will return as I did go from yonder. Poor, and in mean clothing. Nor shall a glint of all my wealth speak one word for me. But if so be as her heart is true in spite of everything, my sorrowful garments will not hide my love away from her.

Old Man. [Taking off his hat.] Here you are master.

[Giles hands his own hat to George. He then takes off his coat and gives it to John. The Old Man takes off his smock, Giles puts it on.

Old Man. Pull the hat well down about the face of you, master, so as the smooth skin of you be hid.

Giles. [Turning round in his disguise.] How’s that, my friends?

George. You be a sight too straight in the back, master.

Giles. [Stooping.] I’ll soon better that.

John. Be you a-going in them fine buckled shoes, master?

Giles. I had forgot the shoes. When I get near to the house ’tis barefoot that I will go.

George. Then let us be off, master, for the’ time be running short.

John. Ah, that ’tis. I count it be close on noon-day now by the look of the sun.

Old Man. And heaven be with you, my young gentleman.

Giles. My good friends, you shall go with me a little further. And when we have come close upon the farm, you shall stop in the shelter of a wood that I know of and await the signal I shall give you.

George. And what’ll that be, master?

Giles. I shall blow three times, and loudly from my whistle, here.

John. And be we to come up to the farm when we hears you?

Giles. As quickly as you can run. ’Twill be the sign that I need all of you with me.

George and John. That’s it, master. Us do understand what ’tis as we have got to do.

Old Mar. Ah, ’tis best to be finished with hearts that beat to the tune of a maid’s tongue, and to creep quiet along the roads with naught but them pains as hunger and thirst do bring to th’ inside. So ’tis.

[Curtain.]

The parlour at Camel Farm. Elizabeth, in her best dress, is moving about the room putting chairs in their places and arranging ornaments on the dresser, etc. May stands at the door with a large bunch of flowers in her hands.

Elizabeth. And what do you want to run about in the garden for when I’ve just smoothed your hair and got you all ready to go to church?

May. I’ve only been helping Annet gather some flowers to put upon the table.

Elizabeth. You should know better then. Didn’t I tell you to sit still in that chair with your hands folded nicely till we were ready to start.

May. Why, I couldn’t be sitting there all the while, now could I, Aunt?

Elizabeth. This’ll be the last time as I tie your ribbon, mind.

[She smoothes May’s hair and ties it up for her. Annet comes into the room with more flowers.

Elizabeth. What’s your cousin doing now, Annet?

Annet. The door of her room is still locked, Aunt. And what she says is that she do want to bide alone there.

Elizabeth. In all my days I never did hear tell of such a thing, I don’t know what’s coming to the world, I don’t.

May. I count that Millie do like to be all to herself whilst she is a-dressing up grand in her white gown, and the silken cloak and bonnet.

Annet. Millie’s not a-dressing of herself up. I heard her crying pitiful as I was gathering flowers in the garden.

Elizabeth. Crying? She’ll have something to cry about if she doesn’t look out, when her father comes in, and hears how she’s a-going on.

May. I wonder why Cousin Millie’s taking on like this. I shouldn’t, if ’twas me getting married.

Elizabeth. Look you, May, you get and run up, and knock at the door and tell her that ’twill soon be time for us to set off to church and that she have got to make haste in her dressing.

May. I’ll run, Aunt, only ’tis very likely as she’ll not listen to anything that I say. [May goes out.

Elizabeth. Now Annet, no idling here, if you please. Set the nosegay in water, and when you’ve given a look round to see that everything is in its place, upstairs with you, and on with your bonnet, do you hear? Uncle won’t wish to be kept waiting for you, remember.

Annet. I’m all ready dressed, except for my bonnet, Aunt. ’Tis Millie that’s like to keep Uncle waiting this morning. [She goes out.

[Daniel comes in.

Daniel. Well, Mother—well, girls—but, bless my soul, where’s Millie got to?

Elizabeth. Millie has not seen fit to shew herself this morning, Father. She’s biding up in her room with the door locked, and nothing that I’ve been able to say has been attended to, so perhaps you’ll kindly have your try.

Daniel. Bless my soul—where’s May? Where’s Annet? Send one of the little maids up to her, and tell her ’tis very nigh time for us to be off.

Elizabeth. I’m fairly tired of sending up to her, Father. You’d best go yourself.

[May comes into the room.

May. Please Aunt, the door, ’tis still locked, and Millie is crying ever so sadly within, and she won’t open to me, nor speak, nor nothing.

Elizabeth. There, Father,—perhaps you’ll believe what I tell you another time. Millie has got that hardened and wayward, there’s no managing of her, there’s not.

Daniel. Ah, ’twon’t be very long as us’ll have the managing of she. ’Twill be young Andrew as’ll take she in hand after this day.

Elizabeth. ’Tis all very well to talk of young Andrew, but who’s a-going to get her to church with him I’d like to know.

Daniel. Why, ’tis me as’ll do it, to be sure.

Elizabeth. Very well, Father, and we shall all be much obliged to you.

[Daniel goes to the door and shouts up the stairs.

Daniel. Well, Millie, my wench. Come you down here. ’Tis time we did set out. Do you hear me, Mill. ’Tis time we was off.

[Elizabeth waits listening. No answer comes.

Daniel. Don’t you hear what I be saying, Mill? Come you down at once. [There is no answer.

Daniel. Millie, there be Andrew a-waiting for to take you to church. Come you down this minute.

Elizabeth. You’d best take sommat and go and break open the door, Father. ’Tis the sensiblest thing as you can do, only you’d never think of anything like that by yourself.

Daniel. I likes doing things my own way, Mother. Women-folk, they be so buzzing. ’Tis like a lot of insects around of anyone on a summer’s day. A-saying this way and that—whilst a man do go at anything quiet and calm-like. [Annet comes in.

Annet. Please, Uncle, Millie says that she isn’t coming down for no one.

Daniel. [Roaring in fury.] What! What’s that, my wench—isn’t a-coming down for no one? Hear that, Mother, hear that? I’ll have sommat to say to that, I will. [Going to the door.

Daniel. [Roaring up the stairs.] Hark you, Mill, down you comes this moment else I’ll smash the door right in, and that I will.

[Daniel comes back into the room, storming violently.

Daniel. Ah, ’tis a badly bred up wench is Millie, and her’d have growed up very different if I’d a-had the bringing up of she. But spoiled she is and spoiled her’ve always been, and what could anyone look for from a filly what’s been broke in by women folk!

Elizabeth. There, there, Father—there’s no need to bluster in this fashion. Take up the poker and go and break into the door quiet and decent, like anyone else would do. And girls—off for your bonnets this moment I tell you.

[She takes up a poker and hands it to Daniel, who mops his face and goes slowly out and upstairs. Annet and May leave the room. The farmer is heard banging at the door of Millie’s bedroom.

[Elizabeth moves about the room setting it in order. Andrew comes in at the door. He carries a bunch of flowers, which he lays on the table.

Andrew. Good-morning to you, mistress.

Elizabeth. Good-morning, Andrew.

Andrew. What’s going on upstairs?

Elizabeth. ’Tis Father at a little bit of carpentering.

Andrew. I’m come too soon, I reckon.

Elizabeth. We know what young men be upon their wedding morn! I warrant as the clock can’t run too fast for them at such a time.

Andrew. You’re right there, mistress. But the clock have moved powerful slow all these last few weeks—for look you here, ’tis a month this day since I last set eyes on Mill or had a word from her lips—so ’tis.

Elizabeth. You’ll have enough words presently. Hark, she’s coming down with Father now.

[Andrew turns eagerly towards the door. The farmer enters with Millie clinging to his arm, she wears her ordinary dress. Her hair is ruffled and in disorder, and she has been crying.

Daniel. Andrew, my lad, good morning to you.

Andrew. Good morning, master.

Daniel. You mustn’t mind a bit of an April shower, my boy. ’Tis the way with all maids on their wedding morn. Isn’t that so, Mother?

Elizabeth. I wouldn’t make such a show of myself if I was you, Mill. Go upstairs this minute and wash your face and smooth your hair and put yourself ready for church.

Daniel. Nay, she be but just come from upstairs, Mother. Let her bide quiet a while with young Andrew here; whilst do you come along with me and get me out my Sunday coat. ’Tis time I was dressed for church too, I’m thinking.

Elizabeth. I don’t know what’s come to the house this morning, and that’s the truth. Andrew, I’ll not have you keep Millie beyond a five minutes. ’Tis enough of one another as you’ll get later on, like. Father, go you off upstairs for your coat. ’Tis hard work for me, getting you all to act respectable, that ’tis.

[Daniel and Elizabeth leave the room. Andrew moves near Millie and holds out both his hands. She draws herself haughtily away.

Andrew. Millie—’tis our wedding day.

Millie. And what if it is, Andrew.

Andrew. Millie, it cuts me to the heart to see your face all wet with tears.

Millie. Did you think to see it otherwise, Andrew?

Andrew. No smile upon your lips, Millie.

Millie. Have I anything to smile about, Andrew?

Andrew. No love coming from your eyes, Mill.

Millie. That you have never seen, Andrew.

Andrew. And all changed in the voice of you too.

Millie. What do you mean by that, Andrew?

Andrew. Listen, Millie—’tis a month since I last spoke with you. Do you recollect? ’Twas the evening of the great Fair.

Millie And what if it was?

Andrew. Millie, you were kinder to me that night than ever you had been before. I seemed to see such a gentle look in your eyes then. And when you spoke, ’twas as though—as though—well—’twas one of they quists a-cooing up in the trees as I was put in mind of.

Millie. Well, there’s nothing more to be said about that now, Andrew. That night’s over and done with.

Andrew. I’ve carried the thought of it in my heart all this time, Millie.

Millie. I never asked you to, Andrew.

Andrew. I’ve brought you a nosegay of flowers, Mill. They be rare blossoms with grand names what I can’t recollect to all of them.

[Millie takes the nosegay, looks at it for an instant, and then lets it fall.

Millie. I have no liking for flowers this day, Andrew.

Andrew. O Millie, and is it so as you and me are going to our marriage?

Millie. Yes, Andrew. ’Tis so. I never said it could be different. I have no heart to give you. My love was given long ago to another. And that other has forgotten me by now.

Andrew. O Millie, you shall forget him too when once you are wed to me, I promise you.

Millie. ’Tis beyond the power of you or any man to make me do that, Andrew.

Andrew. Millie, what’s the good of we two going on to church one with t’other?

Millie. There’s no good at all, Andrew.

Andrew. Millie, I could have sworn that you had begun to care sommat more than ordinary for me that last time we were together.

Millie. Then you could have sworn wrong. I care nothing for you, Andrew, no, nothing. But I gave my word I’d go to church with you and be wed. And—I’ll not break my word, I’ll not.

Andrew. And is this all that you can say to me to-day, Mill?

Millie. Yes, Andrew, ’tis all. And now, ’tis very late, and I have got to dress myself.

Elizabeth. [Calling loudly from above.] Millie, what are you stopping for? Come you up here and get your gown on, do.

[Millie looks haughtily at Andrew as she passes him. She goes slowly out of the room.

[Andrew picks up the flowers and stands holding them, looking disconsolately down upon them. May comes in, furtively.

May. All alone, Andrew? Has Millie gone to put her fine gown on?

Andrew. Yes, Millie’s gone to dress herself.

May. O that’s a beautiful nosegay, Andrew. Was it brought for Mill?

Andrew. Yes, May, but she won’t have it.

May. Millie don’t like you very much, Andrew, do she?

Andrew. Millie’s got quite changed towards me since last time.

May. And when was that, Andrew?

Andrew. Why, last time was the evening of the Fair, May.

May. When I was hid in the cupboard yonder, Andrew?

Andrew. So you were, May. Well, can’t you recollect how ’twas that she spoke to me then?

May. O yes, Andrew, and that I can. ’Twas a quist a-cooing in the tree one time—and then—she did recollect herself and did sharpen up her tongue and ’twas another sort of bird what could drive its beak into the flesh of anyone—so ’twas.

Andrew. O May—you say she did recollect herself—what do you mean by those words?

May. You see, she did give her word that she would speak sharp and rough to you.

Andrew. What are you talking about, May? Do you mean that the tongue of her was not speaking as the heart of her did feel?

May. I guess ’twas sommat like that, Andrew.

Andrew. O May, you have gladdened me powerful by these words.

May. But, O you must not tell of me, Andrew.

Andrew. I will never do so, May—only I shall know better how to be patient, and to keep the spirit of me up next time that she do strike out against me.

May. I’m not a-talking of Mill, Andrew.

Andrew. Who are you talking of then, I’d like to know?

May. ’Twas Annet.

Andrew. What was?

May. Annet who was dressed up in the cloak and bonnet of Millie that night and who did speak with you so gentle and nice.

Andrew. Annet!

Elizabeth. [Is heard calling.] There, father, come along down and give your face a wash at the pump.

May. Let’s go quick together into the garden, Andrew, and I’ll tell you all about it and how ’twas that Annet acted so.

[She seizes Andrew’s hand and pulls him out of the room with her.

[Curtain.]

A few minutes later.

Elizabeth stands tying her bonnet strings before a small mirror on the wall. Daniel is mopping his face with a big, bright handkerchief. Annet, dressed for church, is by the table. She sadly takes up the nosegay of flowers which Andrew brought for Millie, and moves her hand caressingly over it.

Elizabeth. If you think that your neckerchief is put on right ’tis time you should know different, Father.

Daniel. What’s wrong with it then, I’d like to know?

Elizabeth. ’Tis altogether wrong. ’Tis like the two ears of a heifer sticking out more than anything else that I can think on.

Daniel. Have it your own way, Mother—and fix it as you like.

[He stands before her and she rearranges it.

Annet. These flowers were lying on the ground.

Elizabeth. Thrown there in a fine fit of temper, I warrant.

Daniel. Her was as quiet as a new born lamb once the door was broke open and she did see as my word, well, ’twas my word.

Elizabeth. We all hear a great deal about your word, Father, but ’twould be better for there to be more do and less say about you.

Daniel. [Going over to Annet and looking at her intently.] Why, my wench—what be you a-dropping tears for this day?

Annet. [Drying her eyes.] ’Twas—’twas the scent out of one of the flowers as got to my eyes, Uncle.

Daniel. Well, that’s a likely tale it is. Hear that, Mother? ’Tis with her eyes that this little wench do snuff at a flower. That’s good, bain’t it?

Elizabeth. I haven’t patience with the wenches now-a-days. Lay down that nosegay at once, Annet, and call your cousin from her room. I warrant she has finished tricking of herself up by now.

Daniel. Ah, I warrant as her’ll need a smartish bit of time for to take the creases out of the face of she.

[Andrew and May come in.]

Daniel. Well, Andrew, my lad, ’tis about time as we was on the way to church I reckon.

Andrew. I count as ’tis full early yet, master.

[He takes up the nosegay from the table and crosses the room to the window where Annet is standing, and trying to control her tears.

Andrew. Annet, Millie will have none of my blossoms. I should like it well if you would carry them in your hand to church this day.

Annet. [Looking wonderingly at him.] Me, Andrew?

Andrew. Yes, you, Annet. For, look you, they become you well. They have sommat of the sweetness of you in them. And the touch of them is soft and gentle. And—I would like you to keep them in your hands this day, Annet.

Annet. O Andrew, I never was given anything like this before.

Andrew. [Slowly.] I should like to give you a great deal more, Annet—only I cannot. And ’tis got too late.

Elizabeth. Too late—I should think it was. What’s come to the maid! In my time girls didn’t use to spend a quarter of the while afore the glass as they do now. Suppose you was to holler for her again, Father.

Daniel. Anything to please you, Mother—

May. I hear her coming, Uncle. I hear the noise of the silk.

[Millie comes slowly into the room in her wedding clothes. She holds herself very upright and looks from one to another quietly and coldly.

May. Andrew’s gived your nosegay to Annet, Millie.

Millie. ’Twould have been a pity to have wasted the fresh blossoms.

May. But they were gathered for you, Mill.

Millie. Annet seems to like them better than I did.

Daniel. Well, my wench—you be tricked out as though you was off to the horse show. Mother, there bain’t no one as can beat our wench in looks anywhere this side of the country.

Elizabeth. She’s right enough in the clothing of her, but ’twould be better if her looks did match the garments more. Come, Millie, can’t you appear pleasanter like on your wedding day?

Millie. I’m very thirsty, Mother. Could I have a drink of water before we set out?

Elizabeth. And what next, I should like to know?

Millie. ’Tis only a drink of water that I’m asking for.

Daniel. Well, that’s reasonable, Mother, bain’t it?

Elizabeth. Run along and get some for your cousin, May. [May runs out of the room.

Daniel. Come you here, Andrew, did you ever see a wench to beat ourn in looks, I say?

Andrew. [Who has remained near Annet without moving.] ’Tis very fine that Millie’s looking.

Daniel. Fine, I should think ’twas. You was a fine looking wench, Mother, the day I took you to church, but ’tis my belief that Millie have beat you in the appearance of her same as the roan heifer did beat th’ old cow when the both was took along to market. Ah, and did fetch very near the double of what I gived for the dam.

[May returns carrying a glass bowl full of water.

May. Here’s a drink of cold water, Millie. I took it from the spring.

[Millie takes the bowl. At the same moment a loud knocking is heard at the outside door.

Elizabeth. Who’s that, I should like to know?

[Millie sets down the bowl on the table. She listens with a sudden intent, anxiety on her face as the knock is repeated.

Daniel. I’ll learn anyone to come meddling with me on a day when ’tis marrying going on.

[The knocking is again heard.

Millie. [To May, who would have opened the door.] No, no. ’Tis I who will open the door.

[She raises the latch and flings the door wide open. Giles disguised as a poor and bent old man, comes painfully into the room.

Elizabeth. We don’t want no beggars nor roadsters here to-day, if you please.

Daniel. Ah, and that us don’t. Us be a wedding party here, and ’tis for you to get moving on, old man.

Millie. He is poor and old. And he has wandered far, in the heat of the morning. Look at his sad clothing.

Andrew. [To Annet.] I never heard her put so much gentleness to her words afore.

Millie. And ’tis my wedding day. He shall not go uncomforted from here.

Elizabeth. I never knowed you so careful of a poor wretch afore, Millie. ’Tis quite a new set out, this.

Millie. I am in mind of another, who may be wandering, and hungered, and in poor clothing this day.

May. Give him something quick, Aunt, and let him get off so that we can start for the wedding.

Millie. [Coming close to Giles.] What is it I can do for you, master?

Giles. ’Tis only a drink of water that I ask, mistress.

Millie. [Taking up the glass bowl.] Only a drink of water, master? Then take, and be comforted.

[She holds the bowl before him for him to drink. As he takes it, he drops a ring into the water. He then drinks and hands the bowl back to Millie. For a moment she gazes speechless at the bottom of the bowl. Then she lifts the ring from it and would drop the bowl but for May, who takes it from her.

Millie. Master, from whom did you get this?

Giles. Look well at the stones of it, mistress, for they are clouded and dim.

Millie. And not more clouded than the heart which is in me, master. O do you bring me news?

Giles. Is it not all too late for news, mistress?

Millie. Not if it be the news for which my heart craves, master.

Giles. And what would that be, mistress?

[Millie goes to Giles, and with both hands slowly pushes back his big hat and gazes at him.

Millie. O Giles, my true love. You are come just in time. Another hour and I should have been wed.

Giles. And so you knew me, Mill?

Millie. O Giles, no change of any sort could hide you from the eyes of my love.

Giles. Your love, Millie. And is that still mine?

Millie. It always has been yours, Giles. O I will go with you so gladly in poor clothing and in hunger all over the face of the earth.

[She goes to him and clasps his arm; and, standing by his side, faces all those in the room.

Elizabeth. [Angrily.] Please to come to your right senses, Millie.

Daniel. Come, Andrew, set your foot down as I’ve set mine.

Andrew. Nay, master. There’s naught left for me to say. The heart does shew us better nor all words which way we have to travel.

May. And are you going to marry a beggar man instead of Andrew, who looks so brave and fine in his wedding clothes, Millie?

Millie. I am going to marry him I have always loved, May—and—O Andrew, I never bore you malice, though I did say cruel and hard words to you sometimes.—But you’ll not remember me always—you will find gladness too, some day.

Andrew. I count as I shall, Millie.

Daniel. Come, come, I’ll have none of this—my daughter wed to a beggar off the highway! Mother, ’tis time you had a word here.

Elizabeth. No, Father, I’ll leave you to manage this affair. ’Tis you who have spoiled Mill and brought her up so wayward and unruly, and ’tis to you I look for to get us out of this unpleasant position.

May. Dear Millie—don’t wed my brother Giles. Why, look at his ragged smock and his bare feet.

Millie. I shall be proud to go bare too, so long as I am by his side, May.

[Giles goes to the door and blows his whistle three times and loudly.

May. What’s that for, Giles?

Giles. You shall soon see, little May.

Daniel. I’ll be hanged if I’ll stand any more of this caddling nonsense. Here, Mill—the trap’s come to the door. Into it with you, I say.

Giles. I beg you to wait a moment, master.

Daniel. Wait!—’Tis a sight too long as we have waited this day. If all had been as I’d planned, we should have been to church by now. But womenfolk, there be no depending on they. No, and that there bain’t.

[George, John and the Old Man come up. George and John carry their packets and the Old Man has Giles’ coat and hat over his arm.

Elizabeth. And who are these persons, Giles?

[George and John set down their burdens on the floor and begin to mop their faces. The Old Man stretches out his fine coat and hat and buckled shoes to Giles.

Old Man. Here they be, my lord, and I warrant as you’ll feel more homely like in they, nor what you’ve got upon you now. [Giles takes the things from him.

Giles. Thank you, old master. [He turns to Millie.] Let me go into the other room, Millie. I will not keep you waiting longer than a few moments.

[He goes out.

Elizabeth. [To George.] And who may you be, I should like to know? You appear to be making very free with my parlour.

George. We be the servants what wait upon Master Giles, old Missis.

Elizabeth. Old Missis, indeed. Father, you shall speak to these persons.

Daniel. Well, my men. I scarce do know whether I be a-standing on my head or upon my heels, and that’s the truth ’tis.

George. Ah, and that I can well understand, master, for I’m a married man myself, and my woman has a tongue to her head very similar to that of th’ old missis yonder—so I know what ’tis.

Elizabeth. Put them both out of the door, Father, do you hear me? ’Tis to the cider as they’ve been getting. That’s clear.

Millie. My good friends, what is it that you carry in those bundles there?

George. ’Tis gold in mine.

John. And silver here.

Elizabeth. Depend upon it ’tis two wicked thieves we have got among us, flying from justice.

Millie. No, no—did not you hear them say, their master is Giles.

George. And a better master never trod the earth.

John. And a finer or a richer gentleman I never want to see.

Elizabeth. Do you hear that, Father? O you shocking liars—’tis stolen goods that you’ve been and brought to our innocent house this day. But, Father, do you up and fetch in the constable, do you hear?

May. O I’ll run. I shall love to see them going off to gaol.

Millie. Be quiet, May. Can’t you all see how ’tis. Giles has done the cruel hard task set him by Father—and is back again with the bushel of silver and that of gold to claim my hand. [Giles enters.] But Giles—I’d have given it to you had you come to me poor and forlorn and ragged, for my love has never wandered from you in all this long time.

Andrew. No, Giles—and that it has not. Millie has never given me one kind word nor one gentle look all the years that I’ve been courting of her, and that’s the truth. And you can call witness to it if you care.

Giles. Uncle, Aunt, I’ve done the task you set me years ago—and now I claim my reward. I went from this house a poor wretch, with nothing but the hopeless love in my heart to feed and sustain me. I have returned with all that the world can give me of riches and prosperity. Will you now let me be the husband of your daughter?

Millie. O say ye, Uncle, for look how fine and grand he is in his coat—and the bags are stuffed full to the brim and ’tis with gold and silver.

Elizabeth. Well—’tis a respectabler end than I thought as you’d come to, Giles. And different nor what you deserved.

Daniel. Come, come, Mother.—The fewer words to this, the better. Giles, my boy—get you into the trap and take her along to the church and drive smart.

Andrew. Annet—will you come there with me too?

Annet. O Andrew—what are you saying?

Daniel. Come, come. Where’s the wind blowing from now? Here, Mother, do you listen to this.

Elizabeth. I shall be deaf before I’ve done, but it appears to me that Annet’s not lost any time in making the most of her chances.

Daniel. Ah, and she be none the worse for that. ’Tis what we all likes to do. Where’d I be in the market if I did let my chances blow by me? Hear that, Andrew?

Andrew. I’m a rare lucky man this day, farmer.

Daniel. Ah, and ’tis a rare good little wench, Annet—though she bain’t so showy as our’n. A rare good little maid. And now ’tis time we was all off to church, seeing as this is to be a case of double harness like.

May. O Annet, you can’t be wed in that plain gown.

Annet. May, I’m so happy that I feel as though I were clothed all over with jewels.

Andrew. Give me your hand, Annet.

May. [Mockingly.] Millie—don’t you want to give a drink of water to yon poor old man?

Millie. That I will, May? Here—fetch me something that’s better than water for him.

Elizabeth. I’ll have no cider drinking out of meal times here.

Millie. Then ’twill I have to be when we come back from church.

Old Man. Bless you, my pretty lady, but I be used to waiting. I’ll just sit me down outside in the sun till you be man and wife.

Elizabeth. And that’ll not be till this day next year if this sort of thing goes on any longer.

Daniel. That’s right, Mother. You take and lead the way. ’Tis the womenfolk as do keep we back from everything. But I knows how to settle with they—[roaring]—come Mill, come Giles, Andrew, Annet, May. Come Mother, out of th’ house with all of you and to church, I say.

[He gets behind them all and drives them before him and out of the room. When they have gone, the Old Man sinks on a bench in the door-way.

Old Man. I’m done with all the foolishness of life and I can sit me down and sleep till it be time to eat.

[Curtain.]

Thomas Spring, a farmer, aged 35.

Emily, his wife, the same age.

Clara, his sister, aged 21.

Jessie and Robin, the children of Thomas and Emily, aged 10 and 8.

Joan, maid to Clara.

Miles Hooper, a rich draper.

Luke Jenner, a farmer.

Lord Lovel.

George, aged 28.

A wood. It is a morning in June.