The Project Gutenberg EBook of Captain Salt in Oz, by

Ruth Plumly Thompson and L. Frank Baum

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Captain Salt in Oz

Author: Ruth Plumly Thompson

L. Frank Baum

Illustrator: John R. Neil

Dick Martin

Release Date: November 28, 2017 [EBook #56073]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CAPTAIN SALT IN OZ ***

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By

RUTH PLUMLY THOMPSON

Founded on and continuing the Famous Oz Stories

By

L. FRANK BAUM

"Royal Historian of Oz"

Illustrated by

JOHN R. NEILL

The Reilly & Lee Co.

CHICAGO

Copyright, 1936

by

THE REILLY & LEE CO.

All rights reserved

Printed in the U.S.A.

Dear Boys and Girls:

So keep writing to me about Oz and everything, will you? And remember to put your full name and complete address on the letter. Righto!

And Best till I hear from you!

RUTH PLUMLY THOMPSON.

This book is dedicated

With my best bow and TOP wishes

to my Publisher.

—Ruth Plumly Thompson

| CHAPTER 1 | Sail Ho! |

| CHAPTER 2 | Anchors Aweigh |

| CHAPTER 3 | The Fire Baby |

| CHAPTER 4 | Samuel's First Specimen |

| CHAPTER 5 | Patrippany Island |

| CHAPTER 6 | A Little Wild Man |

| CHAPTER 7 | Strange Specimens for Samuel Salt |

| CHAPTER 8 | Maxims for Monarchs |

| CHAPTER 9 | Sea Legs for Tandy |

| CHAPTER 10 | The City of Bridges |

| CHAPTER 11 | The Prince of the Peaks |

| CHAPTER 12 | Fog |

| CHAPTER 13 | The Sea Forest |

| CHAPTER 14 | The Sea Unicorn! |

| CHAPTER 15 | The Collector Is Collected |

| CHAPTER 16 | The Storm! |

| CHAPTER 17 | The Old Man of the Jungle! |

| CHAPTER 18 | A New Country |

| CHAPTER 19 | Boglodore's Revenge |

| CHAPTER 20 | King Tandy |

| CHAPTER 21 | A Voyage Resumed |

Eight miles east of Pingaree lies the eight-sided island of King Ato the Eighth. While not so large as Pingaree, the Octagon Isle is nevertheless one of the tidiest and most pleasing of the sea realms that dot the great green rolling expanses of the Nonestic Ocean. And Ato himself is as pleasing as his island, enormously fat and jolly with a kind word for everyone.

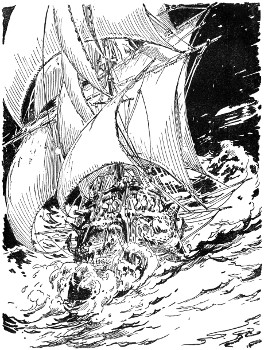

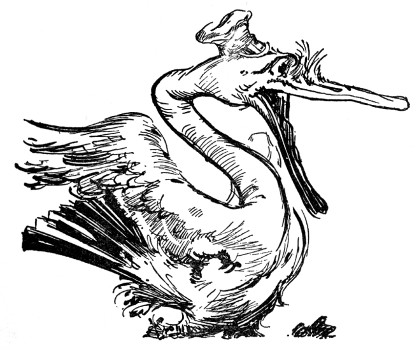

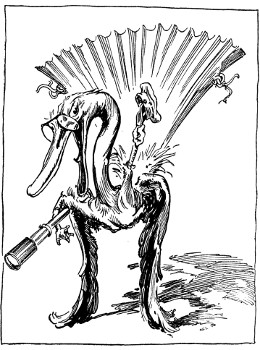

In his eight-sided castle, he has every modern convenience and comfort and some of which even an up-to-date country like our own cannot boast. For instance, take Roger, his Royal Read Bird. Roger, besides knowing eight languages, can read aloud for hours at a time without growing hoarse or weary. So Ato never has to strain his eyes poring over his eight hundred huge volumes of adventure and history, nor his arms holding a newspaper or court document, nor his jaw pronouncing the names of kings and countries in Ev and Oz and other curious places on the mainland west of his own island. And Roger is as handsome as he is handy, his head and bill rather like a duck's, his body shaped and colored like a parrot, but much larger, while his tail opens out into an enormous fan. This is extremely fortunate, for the Octagon Isle is semi-tropical in climate, and on warm sultry days, Roger not only reads to his Majesty, but fans him as well. All in all, Ato's life is decidedly luxurious and lazy.

Sixentwo, Chief Chancellor of the realm, and Four'nfour, its treasurer, attend to all the business of governing, so that Ato and Roger have little to do but enjoy themselves. The Octagon Islanders, one hundred and eighty in number, are a sober and industrious lot, rarely giving any trouble.

Once, it is true, they sailed off and deserted the King entirely, but Ato, with Peter, a Philadelphia boy, and Samuel Salt, a pirate, who landed on the Island at just the right moment, immediately set out after them, using the pirate's stout ship the Crescent Moon, for the purpose.

By a strange coincidence, Samuel Salt's men had also mutinied and sailed away, so that there were two sets of deserters to seek out and discover. After a dangerous and lively voyage, the Crescent Moon reached the rocky shores of Menankypoo on the Mainland. Here they learned that the Octagon Islanders and Samuel Salt's men had been enslaved by Ruggedo, the former Gnome King, and marched off to conquer the Emerald City of Oz. How Peter and the Pirate, Ato and a poetical Pig outwitted the Gnome King is a long and other story. You have probably read it yourself. But ever since their hair-raising experiences with Ruggedo, and their rescue by Ato, the Octagon Islanders have been perfectly satisfied with their own ruler and country. In fact, they were so docile and devoted, so fearfully anxious to please, Ato often wished they would revolt or sass him a little just to relieve the monotony and make life more interesting.

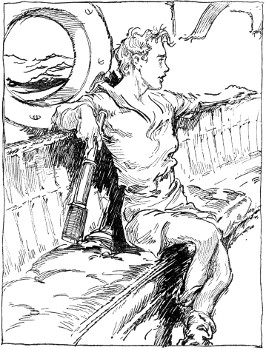

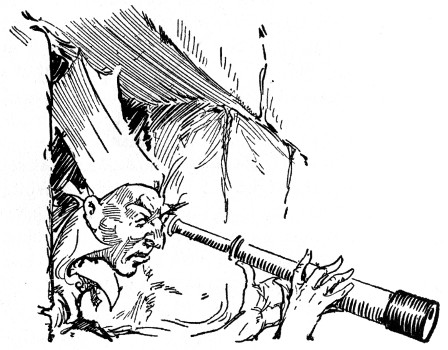

To tell the truth, after serving as cook, mate and able-bodied seaman on the Crescent Moon, Ato found it quite boring to settle down to a humdrum life of a monarch ashore. Roger, too, missed the gay and carefree life he had led as a pirate and could not even pretend an interest in the books of adventure he still dutifully read to his Master. He and Ato now spent most of their time on the edge of the Island—the King in a comfortable hammock swung between two palm trees, Roger on a tall golden perch set close beside him. Whenever the Read Bird paused to yawn or turn a page, Ato would pull himself up to a sitting position, raise the telescope he always had with him and gaze long and wistfully out to sea. Many ships passed Ato's Island, but never a one in the least resembling the splendid three-masted fast sailing ship belonging to the Pirate.

"You'll give yourself a fine squint there," warned Roger one morning, as Ato for about the hundredth time raised his spy glass. "And what is the use of it, pray?" inquired Roger grumpily, ruffling the pages of the Book of Barons. "Samuel Salt has probably forgotten all about us and gone off by himself on a voyage of discovery."

"No! No! Sammy wouldn't do that," said the King, shaking his head positively. "He promised to stop by for us on the very first voyage he made as Royal Discoverer of Oz."

"Ho, one of those seafaring promises!" muttered Roger. "A pirate's promise. Humph! His new honors have gone to his head. Quite a jump from pirating to exploring. I'll wager a wing he's gone back to buccaneering and forgotten us altogether!"

"Now, Roger, how can you say that?" Heaving up his huge bulk with great difficulty, Ato looked reproachfully at his Royal Read Bird. "Sammy never cared for pirating in the first place," wheezed the King earnestly, "and he was so soft-hearted about planking the captives and burning the ships, his band sailed off and left him. They only made him Captain because he was clever at navigating, and you know perfectly well he spent more time looking for flora and fauna than for ships and treasure."

"Ah, then I suppose some wild Flora or Fauna has him in its clutches," observed Roger sarcastically, "and a likely thing that is, seeing the poor Captain weighs but two hundred and twenty pounds and stands six feet in his socks."

"What a tremendous fellow he was," sighed Ato, sinking dreamily back in his hammock and half closing his eyes. "I'll never forget how high and handsome he looked when Queen Ozma asked him to give up buccaneering, and serve her instead as Royal Discoverer and Explorer for Oz! And a fitting reward it was, too, for capturing Ruggedo and saving the Kingdom. Aha, my lad, THAT was a day! And we had our share of glory, too! Remember how they cheered us in the Emerald City of Oz?"

"Aye, I remember THAT day and a good many other days since," sniffed the Read Bird disagreeably. "Six months from that day Samuel Salt was to sail into our Harbor. Well, King—it's been six times six months, and nary a sail nor a sign of him have we seen."

"That long?" said Ato, blinking unhappily.

"That long and longer. Three years, eleven months, twenty-six days and twelve hours, to be exact!"

"Dear, dear and dear! Then something's happened to him," murmured Ato. "He's either been shipwrecked, captured or enchanted! I'll never believe Sammy would forget us or break his promise. Never!"

"Well, whatever you believe, the results are the same." Flapping open his book, Roger prepared to go on with his reading. "And depend upon it," he insisted stubbornly, "we'll never see Samuel Salt again, so you may as well put up your telescope and put your mind on something else for a change. Maybe it's your cooking that's keeping him away," finished the Read Bird, who felt cross and fractious and contrary as a goat.

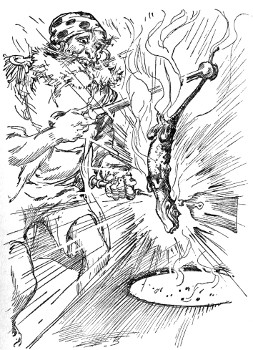

"My cooking?" roared Ato, roused to honest anger at last. "I've a notion to have you plucked and roasted for that. My cooking, indeed! Show me the fellow who can beat up an omelette, a cake, a batch of biscuits, faster than I; who can brown a fowl, broil a steak or toss out a pan of fried potatoes to compare with mine. I—I, why, I'm surprised at you, Roger!"

Roger, ruffling his feathers uncomfortably, was rather surprised at himself, for the King was speaking the exact truth; a more skillful man with a skillet it would be impossible to find in any kingdom. Ever since his voyage on the Crescent Moon, cooking had been Ato's chief pleasure and pastime. The castle chef, though he heartily disapproved of a King in the kitchen, could do nothing to discourage him, so finally stood by in grudging envy and admiration as Ato turned out his delectable puddings, pies, roasts and sauces.

Muttering with hurt pride and indignation, his Majesty continued to frown at the Read Bird, and realizing he had gone too far, Roger started to read as fast as he could from the Book of Barons. As he read on, he could see the King growing calmer and finally, pausing to turn a page, he let his gaze rove idly over the harbor.

"Anchors and animal crackers! What was that?" Stretching up his neck, Roger took another look, then, flinging the Book of Barons high into the air, he spread his wings and started out to sea.

Soothed by the droning voice of the Read Bird, Ato had closed his eyes and the first warning he had of Roger's departure was a terrific thump as the Book of Barons landed on his stomach. Leaping out of the hammock as if he had been shot, the outraged Monarch looked furiously around for his Read Bird. This really was too much. Not satisfied with insulting him, Roger must now be bombarding him with books, cocoanuts and what not.

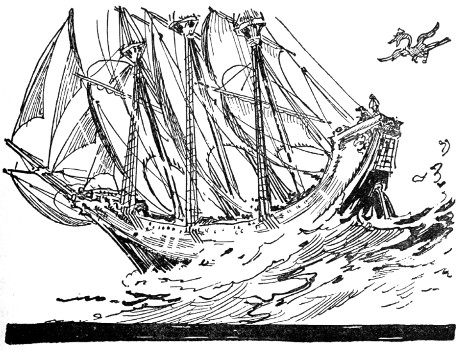

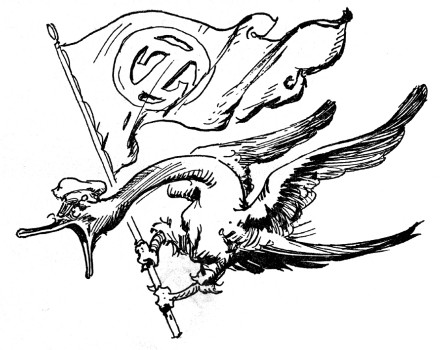

Shading his eyes with his hand, Ato glared up and down the beach and finally out over the rippling blue ocean. At what he saw there, the King forgot his anger as completely as Roger had forgotten his manners. For, swinging jauntily into the Octagon Harbor was the Crescent Moon herself! No mistaking the high-prowed, deep-waisted, powerful craft of the Pirate. But a new and gayer pennant fluttered from the mizzenmast today. Instead of the skull and bones, Samuel was flying the green and white banner of Oz, as befitted the Royal Discoverer and Explorer of the most famous Fairyland in History.

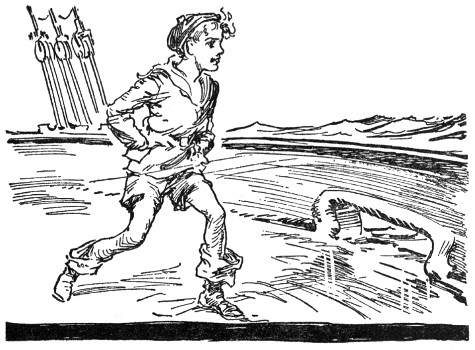

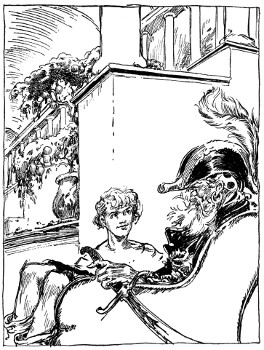

"He's here! He's come!" shouted Ato, running wildly up and down. "Samuel! SAM-U-EL!" In his delight and excitement the King forgot the Royal dock and began wading out into the bay. Peering around his wheel, Sammy saw him coming and broke into a loud cheerful greeting.

"Hi, King! Ho, King! How are you, you son of a Lubber! Wait till I ease her in and I'll be ashore quicker than quick." Roger had already reached the Crescent Moon and, perched on the Captain's shoulder, was chattering away at such a rate Samuel could hardly keep his mind on his steering. But he was an old hand at such matters, and before Ato had half recovered from the shock of seeing him, the shining three-masted vessel was made fast, and its Master striding exuberantly up the wet planks of the royal dock.

"Ahoy! Ahoy!" he boomed boisterously. "What a day for a voyage! Is it really my old cook and shipmate?"

"None other!" puffed Ato, seizing both of the former pirate's hands. "But what have you done to yourself, Sam-u-el? Where's your sash and scimiter? And what's that on your head, may I ask? You don't look natural or seaman-like at all."

"Oh, don't mind these," grinned the Pirate, touching his three-cornered hat and satin coat apologetically. "These are my shore togs for impressing the natives. Can't look like pirates when we go ashore this voyage, Mates. We're explorers and fine gentlemen now, and when we set the flag of Oz on lofty mountains and rocky isles, when we bring savage tribes and strange races under the beneficent rule of Ozma of Oz, we must look like Conquerors. Eh, my lads?"

"Yes—I sup-pose—so!" puffed the King, skipping clumsily to keep up with the long strides of Captain Salt. "But I'm sorry this is going to be a dressy affair, Sammy. How'm I to cook in a cocked hat and lace collar and swab down the deck in velvet pants?"

"Ho, ho! You'll not have to," exploded the Pirate, giving the tail feathers of the Read Bird a sly tweak. "On shipboard we'll dress as we please, for the sea is MY country and free as the wind and sun."

"Well, well, I'm glad to hear you say that. Have you still got my old pirate suit and blunderbuss aboard?" inquired the King anxiously.

"Certain for sure, and a couple of new ones, and WAIT till you see your galley all fitted out with copper pots, and provisions enough below to carry us anywhere and back. Wait till you cast your eyes on 'em, Lubber!"

"Don't you call ME a Lubber!" chuckled Ato, giving Samuel a hearty poke in the ribs. "I'm as able-bodied a seaman as you, Sammy, and you know it."

"SIR Samuel, if you please!" roared the former Pirate, striking himself a great blow on the chest with his clenched fist. "Sir Samuel Salt, Explorer and Discoverer Extraordinary to the Crown of Oz."

"So—oooh! You've been knighted?" breathed Roger, peering round into the Captain's face,

"Sir Samuel Salt! Well, I'll be peppered!" gasped Ato, sinking down on the lower step of the palace which they had reached by this time. "Sir Samuel!"

"Yes, SIR!" boasted the Pirate, rubbing his hands together, "but come on, step lively, boys; how long'll it take you to pack up and heave your dunnage aboard? Mustn't keep a Knight of Oz waiting, you know!"

"Keep you waiting?" Suddenly and determinedly, Ato rose to his feet and shook his finger under Sammy's nose. "Keep YOU waiting? Why, we've been ready and waiting for this voyage three years, eleven months, twenty-six days and twelve hours. Where've you been, you great lazy son of a sea-robber?"

"Four years?" choked the Pirate, falling back in real consternation and dismay. "Never! It's never been four years, Mates. Why, I've scarcely had time to sort out the shells and specimens we picked up on the last voyage, and to fit out the Crescent Moon for the next."

"Where have you been?" repeated Ato, wagging his finger sternly.

"Why, home on Elbow Island, of course. Where else should I have been?" muttered Samuel, looking distinctly worried and crestfallen.

"Then have you no clocks or calendars in your cave?" demanded the King accusingly. "And what would the Crescent Moon be needing? I thought she was about perfect as she was."

"Ah, but wait till you see her now!" exclaimed Samuel, cheering up immediately at mention of his ship. "The Crescent Moon, besides a new coat of paint, has self-hoisting sails and a mechanical steering control in case we wish to take it easy occasionally. The Red Jinn paid me a visit and presented us with these and several other magical contrivances and improvements. I'm minded to make this voyage with no crew but ourselves. It's cozier so, don't you think?"

"Yes, but am I still on bird watch and lookout duty?" demanded Roger jealously.

"Aye, aye!" Samuel Salt assured him heartily.

"I suppose the Red Jinn has supplied you with a mechanical cook in my place as well as a mechanical steering wheel," murmured Ato, tugging uneasily at the cord round his waist.

"In your place!" thundered the Pirate. "Why, shiver my timbers, Mate! Only over my prone and prostrate body shall another man enter my galley to shuffle my rations, sugar my duff or salt my prog!"

"Hooray, then let's get going!" squealed Roger, bouncing up and down on Sammy's shoulder. "I was only saying this very morning that you'd never forget your old friends and shipmates or go on a voyage without us!"

"Huh! So THAT'S what you were saying!" grunted Ato, looking fixedly at the Read Bird. "Well, well, let it go. Come along then!"

"Yes, yes, and hurry," screamed Roger, spreading his wings to fly on ahead.

"Sixentwo! Sevenanone! Where are you?" panted the King, plunging up the steps after Roger two at a time. "Where is everybody? Pack a bag, a chest, a couple of trunks. I'm going on a voyage of discovery!"

"And don't forget the cook book!" bawled Samuel Salt, bounding exuberantly after the King.

With the help of eighteen serving men, eight courtiers, Sixentwo, Sevenanone, and Samuel Salt, who was not above carrying a sea chest or hamper, Ato began stowing his belongings on the Crescent Moon. There was little court apparel or finery in the King's boxes. Most of it consisted of bottles of flavoring extract, spiced sauces, cook books, minced meats, fruits in jars for pies, numerous frying pans, egg beaters, and rolling pins.

"Are we gypsies, pan handlers, peddlers or what?" panted Samuel Salt as he dumped the last load breathlessly on the main deck. "Goosewing my topsails, Mate, many's the fish we cleaned with a jackknife, and potato we pared with a dagger on the last voyage. Mean to say an explorer needs to use all these weapons on his pork and beans?"

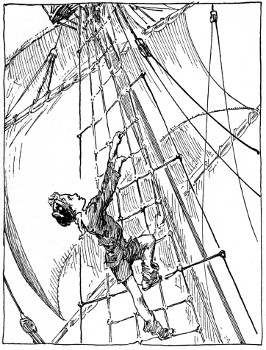

Checking off a list as his stuff was placed in the galley, Ato nodded determinedly, then winking good-humoredly at the perspiring Captain, ducked into the cabin to don his old sea clothes. Samuel was not long following suit and soon, in short red pants, open shirts and carelessly tied head kerchiefs, the two went below to inspect the stores Samuel had laid in for the voyage. Roger, having nothing to bring aboard but a few books and a bottle of feather oil, was already perched in the crosstrees of the fore topgallant mast looking longingly toward the east and waiting impatiently for the ship to get under way. But the booming voice of the Pirate soon drew him to the lower deck and from there he swooped down an open hatchway to the hold.

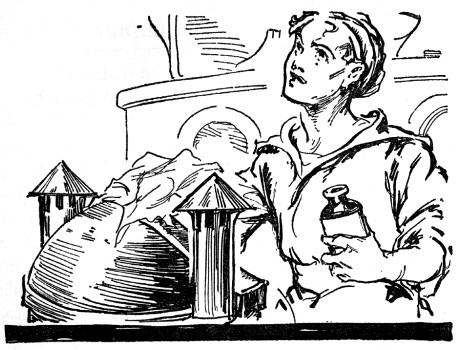

This huge space, usually reserved by the pirates for captives and treasure, had been neatly divided into two sections. In one were the tinned, dried and salted meats, the groceries, vegetables and extra supplies of rope, tar and sail. In the other section there were numerous shelves, many iron cages, aquariums and sea chests.

"For any strange animals or wild natives we may encounter and wish to bring home with us," explained Samuel Salt as Roger looked curiously at the cages. "In those chests are the flags of Oz we shall plant here, there and everywhere as we sail onward!"

"And to think a new and mighty Empire may grow from this flag planting," mused Ato, opening one of the sea chests and thoughtfully fingering one of Ozma's green and white silken banners. "But surely you don't expect to plant all these, Samuel?"

"Why not?" demanded the Royal Discoverer of Oz with a wave of the scimiter he had resumed with his old pirate pants. "The sea is broad and wide and no one's to tell us when we may start or sail home again. But look, Ato, my lad—these will interest you." Turning from the chests, Samuel pointed to a stack of long poles lashed to the side of the ship with leather thongs. "Stilts!" grinned the Pirate as Roger and Ato stared at them in complete mystification. "Fine for keeping the shins dry when we wade ashore and don't feel like lowering the jolly boat. All my own idea." Samuel cleared his throat with pardonable pride. "Of course, it takes a bit of practice, but we'll try 'em on the first island we come to. Eh, boys?"

"Well, thank my lucky stars for wings!" breathed Roger after a long disapproving look at Samuel's stilts. "Two steps and you'll smash yourself to a jellyfish, Ato. Stick to the boats, men. That's MY advice!"

"Too bad he has no confidence in us!" roared Samuel, giving Ato a resounding slap on the back. "Just wait, my saucy bird, and we'll show you how stilting is done. And now, gaze upon this corner I've set aside for my specimens; for rare marine growths, for seaweed, for curious mollusks and other crustacean denizens of the darkest deep."

Samuel coughed apologetically as he always did when he mentioned his collecting mania, and Roger and Ato, exchanging an amused grin, swung about to examine the long shelves with iron boxes clamped down to prevent them from shifting with the motion of the vessel, huge aquariums fitted into brass holders, and large trays bedded with dried moss and sand for Samuel's collection of shells.

"You might even bring home a mermaid in this," murmured Ato, touching the side of an enormous aquarium.

"No women!" snapped Samuel Salt, growing red in the face, for he did not like to be teased about his specimen collecting. "I'll—I'll have no women or mermaids switching their tails around my ship and turning things topsy turvy."

"Right," agreed Ato, giving his belt a vigorous tug. "Then how about shoving off, Sammy? Everything's shipshape, there's a good wind and the best way to begin a voyage is to start."

"I'm for it!" roared the Captain, swinging hand over hand up the wooden ladder. "All hands on deck! Up with your Master's flag, Roger. Cast off the mooring lines, Ato, while I make sail and we'll be out of here in a pig's jiffy."

"Aye! Aye!" croaked Roger, seizing the cord that would send Ato's octagon banner flying to the masthead, directly under the flag of Oz. "Goodbye, all you lubbers ashore! Goodbye Sevenanone. Mind you keep the King's Crown polished and don't forget to feed the silver fish."

"GOODBYE!" called the one hundred and eighty Octagon Islanders drawn up on the beach and dock to see his Majesty sail away. "A fine voyage to your Highness!"

"And neglect not to return!" shouted Sixentwo, using his hands as a megaphone. "You know there is a Crown Council eight days and eight months from yesterday."

"Crown Council be jigged!" sniffed Ato, leaning far over the rail to wave to his cheering subjects. "I'm a cook, an explorer—and a bold bad seafaring man out to collect islands and jungles and jillycome-wiggles for Samuel's shell box. Crown Council, indeed! Don't care if I never see a castle again."

"Me neither!" squalled Roger, flying up to his post in the foremast. "Seven bells and all's well! Buoy off the beam and no land in sight."

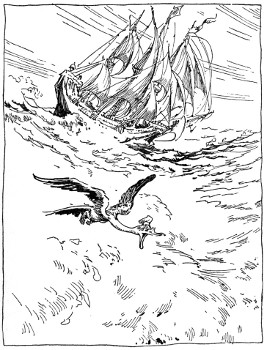

"Unless you look behind you," laughed Samuel, grabbing the wheel with a practiced hand and squinting cheerfully up at the sun. "East by southeast it'll be this voyage, Mates. There's ice in the North Nonestic and I've a craving for tropical isles and the hidden rivers of some deep and mysterious jungle!"

"Remember Snow Island?" smiled Ato, coming over to stand beside the wheel.

"Shiver my shins! DO I? No more of that, me lads! But Ho! Isn't this like old times?" Stretching up his arms exultingly, Samuel Salt let his hands fall heavily on the wheel, and the great ship lifting with the wind plunged her nose eagerly into the southeast swell.

"M—mmm! Like old times, except for the boy," agreed Ato slowly.

"Aye, and we'll surely miss Peter on this trip," sighed the Captain, shaking his head regretfully. "Wonder where the little lubber is now? That's the trouble with these real countries and peoples, there's no getting at them when you need them most. Well, maybe we'll pick up another hand somewhere to serve as cabin boy and keep us lively on the voyage. But take a look at my sail controls, Ato. We can hoist, trim and furl by just touching different buttons, nowadays; set this wheel for any course and just let her ride."

"Splendid!" grunted Ato, rising reluctantly from a coil of rope. "But since there are no buttons on my stove, I'd best be thinking about dinner."

"Tar and tarpaulin, why didn't I have the Red Jinn fix you some?" exclaimed the Pirate regretfully. "I'm sorry as a goat, Mate."

"Ho—I'm not," laughed Ato, waddling happily off toward his galley. "That would have spoiled everything. What'll it be, Captain—a fried sole, a broiled steak, or a roaring huge hot peppery meat pasty?"

"All of 'em!" yelled the Royal Explorer of Oz, exhaling his breath in a mighty blast of anticipation. It seemed to Roger, high in the foremast, that the ship gave an extra little skip at its Captain's mighty roar, then settling easily into her usual graceful pace she ran smoothly before the wind.

Morning found the Crescent Moon forging ahead with a stiff breeze, a choppy sea and the last known island far behind her.

"Ahoy, and this is the life, Mates!" bellowed Samuel Salt, bracing his legs against the pitch and roll of the vessel, and waving largely to the ship's cook who sat on an overturned bucket mending his second best sea shirt. "Anything can happen now!" Lovingly Samuel let his gaze rove over the sparkling Nonestic, and Ato, squinting painfully as he pushed his long needle in and out, nodded portentously.

"By the way, Sammy, what are your plans for this flag planting and discovery business?" inquired the portly cook somewhat later. Having finished his mending, he had dragged a canvas chair and a pot of potatoes aft by the wheel. "Do you look for resistance and rebellion when we start taking possession of this land and that land for the crown of Oz?"

"No, no, nothing like that," mused Samuel, removing his pipe and blowing a cloud of smoke into the rigging. "Everything's to be polite and peaceable this voyage. No guns, knives or scimiters. Queen Ozma particularly does not want any country taken by force or against its will."

"And suppose they object to being taken at all?" said Ato, beginning to pare a fat potato. "What then?"

"Well, then—er then—" Samuel rubbed his chin reflectively, "we'll try persuasion, my lad. We'll explain all the advantages of coming under the flag and protection of a powerful country like Oz. That ought to get them, don't you think?"

"Yes, if they don't get us first," observed Ato, popping a potato dubiously into the pot. "Suppose while we stand there waving flags and persuading, some of these wild fellows have at us with spears, clubs and poison arrows?"

"Well, that would be extremely unfortunate," admitted Samuel, glancing soberly at the compass, "and in that case——"

"I hope you will remember you were once a pirate and act accordingly," Ato blew out his cheeks sternly as he spoke. "The one trouble with you, Sammy, is that you take too long to get mad. So I shall go ashore armed as usual with my kitchen knife and blunderbuss. I don't intend to be sliced into sandwiches while you're talking through your three-cornered hat, and waving flags at a lot of ignorant savages. And I'll have Roger carry the books ashore too."

"Ho, ho!" roared the Captain of the Crescent Moon, giving his knee a great slap. "Just like old times, Ato. Rough, bluff and relentless, Mates, remember?"

"Aye, and I should say I do. And I remember Roger had to drop a good many books on your head before you got mad enough to fight. What makes you so calm and peaceable, Sammy? A big born fighting man like yourself."

"Sea life, I reckon," answered the former Pirate, extending his brawny arms in a huge yawn. "The sea's so much bigger than a man, Mate—it rather makes him realize how small and unimportant he really is. But don't fret, Cook dear, no one shall tread on your toes, this voyage. But avast there—it grows warmer and the air smells a bit thunderish. Had you noticed?"

"'Hoy, 'hoy! Deck ahoy!" bawled a shrill voice from above. "Island astern." Both Samuel and Ato stared up in amazement, for Roger was supposed to be resting in the cabin. But the Read Bird, after snatching an hour's nap, had slipped out an open port and, unnoticed, taken his position in the foremast. The Read Bird did not trust Ato, who was supposed to be on watch. Besides, he wanted to be the first to report a new island to the Captain.

"Looks like a mountain," mumbled Ato, setting down his potatoes and waddling over to the rail. "Heave to, Skipper, here's our first discovery."

"Now how in sixes did that get by me?" muttered Samuel Salt, hurrying to shorten sail for the zigzag course, back and in, he would have to take to reach the island at all.

It showed plainly enough now, a rugged gray and purple mass of rock, with apparently no vegetation or dwellings of any kind. As the Crescent Moon drew nearer, the sea became smooth and oily, and the air sulphurous and hot.

"Think likely this is an island we might well pass by," murmured Ato, peering critically through his telescope. "Positively deserted so far as I can see—but there might be valuable minerals in those rocks."

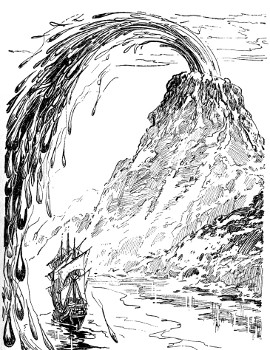

"Don't doubt it!" Samuel Salt curved himself all the way round the wheel in his interest. Mechanical devices were well enough for the open sea, but Samuel preferred to handle his own ship on occasions like this. As there was no harbor or safe place to put in, he decided to anchor off shore and land in the jolly boat. The anchor had just gone clanking and rattling over the side when a horrid hiss and boom from the center of the island made all hands look up in alarm.

"K-kkk cannons!" quavered Ato, dropping his bread knife with a clatter. "Stand by to man the guns!"

But Samuel Salt, instead of heeding the cook's warning, began to sniff the air. "Volcano, Mates," announced the Captain calmly. "And in that case we may be a bit close for comfort. Still, I've always wanted to observe a volcano in action. I've a theory there may be living creatures in the center."

"Living creatures in the center!" raged Ato, tearing off his white apron and dashing it on the deck. "How long will we be living if that fire pot starts boiling? We mayn't be killed, being of magic birth, but we can be jolly well singed, fried, boiled and melted. And after that who'd care to be alive? Quick, Roger, heave in on that chain! Anchors aweigh!"

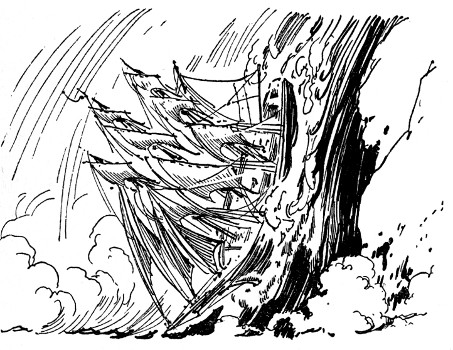

While Samuel stood in rapt contemplation of the volcano, and Ato began frantically winding up the anchor, a long tongue of flame leaped out of the crater and a great jet of bubbling lava shot clear over the Crescent Moon. This occurrence soon brought Samuel out of his revery, and snapping into action and forgetting all about his mechanical devices, he began working like a mad man to get the ship in motion, tugging at the sheets, throwing his whole weight against the halyards, till the ship with quivering sail sped away like a frightened bird, the hot winds from the volcano whistling and rattling through her rigging.

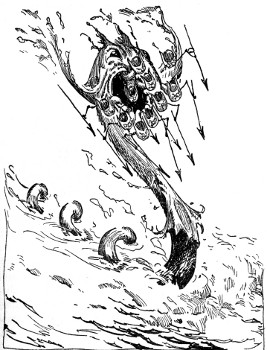

"Where's Roger?" yelled Ato, staggering across the deck with two buckets of water. "Oh, woe! Is he a Read Bird or a just plain Goose? Look yonder, Sammy, he's flown ashore." Outlined against the sky in a sudden flare from the volcano they could see Roger poised over the center of the smoking island. In his claw was a large rippling banner of Oz and as they looked he lifted the banner high above his head and flung it straight into the center of the boiling crater.

"We hereby take complete and absolute possession of this island and declare all its inhabitants lawful subjects of her Majesty, Queen Ozma of Oz!" screamed Roger hysterically.

"Well, hurray, and three cheers for a real Explorer!" shouted Samuel Salt. "He's done it all by himself, the only man among us who remembered his duty under fire. There's a bird for you, Mates. Not even a volcano can turn him from his duty. All we thought of was safety. Poh!" Rubbing the back of his hand across his eyes, which were full of smoke, Samuel looked glumly across at his cook.

"Now, now, don't be too hard on yourself," puffed the King, setting down the fire buckets. "A Captain must think of his ship, even if he is an Explorer. Besides, having wings gives Roger an advantage of us. Still and all, it was a brave and timely act." Ato's further remarks were drowned out in a second tremendous explosion. Sky and sea turned red, whole flaming boulders shot above the ship's spars, while great sullen waves of lava boiled over the crater's edge and rolled smoking and hissing into the sea.

"Missed us again," panted Samuel Salt, hanging desperately to his wheel as the Crescent Moon plunged and pitched in the angry seas. "Wonder what started that?"

"The Oz flag, probably," gasped Ato, feeling around in the dense smoke for his fire buckets. "Hope Roger got off safely. Where is that fool bird? Ho, Sammy! Hi, Sammy! Quick, they've hit us amidships."

Hastily setting his mechanical steering gear, the former Pirate rushed forward to where a glowing lump of lava was burning its way slowly but surely through the deck.

"Fire! Fire!" shrilled Roger, who had dropped down on the rail unnoticed in the smoke and confusion. "Water, Ato! Water, you old Slow Poke!"

"Avast!" puffed Samuel Salt, staring down in astonishment at the glowing lump at his feet. "It's alive, Mates, and lively as a grig. It's a FIRE baby, that's what! HAH! Didn't I just say there was life on a volcano? Well, this proves it and I'm taking this young one along for proof."

"Now stop talking like a book and act like a seaman," choked Ato, in his agitation tripping over a rope but still managing to keep his hold on the water buckets. "Fire baby or not, can't you see it's burning a hole in the deck, you seventh son of a sea-going Jackass? Here, put it out! Dash this water over it before it burns up the whole ship!"

"Avast! Avast and belay!" roared Samuel Salt in a terrible voice as Ato raised his bucket. "I'm still Captain here. Do you wish to destroy a rare specimen of volcanic life? Fetch a shovel from the hold, Roger. A shovel, I said, and don't stand there dithering."

"Aye aye, sir!" sputtered the Read Bird, half falling and half flying down the companionway. Now a bird is a quick and handy fellow about a ship and in half the time it would have taken a seaman, Roger was back with a long handled shovel. Snatching the shovel, which he had often used on former treasure hunts, Samuel scooped up the bawling fire baby and started on a run for the galley.

"It's turning black, it's turning black," wailed the disconsolate collector, crooning to the ugly infant as he ran along as if he were its own mother. "Aye, aye—it's going out!"

"And a good thing, too," panted Ato, who was close behind him. "What in tarry barrels are you fixing to do with it, Sammy?"

Roger, sensible bird that he was, stayed long enough to douse the two buckets of water on the smoking deck, then he, too, made a bee line for the galley. He was just in time to see Samuel lift the lid of the range and slide the baby down on top of the hot coals. No sooner had the squat infant touched the glowing fire than it stopped yelling at once and began to purr and sing like a teakettle set on to boil.

"Well, I'll be swizzled!" gulped Ato, and snatching a wet dish towel from the rack, he wound it round and round his aching head. "Whatever made you think of that?"

"It's my scientific mind," the Pirate told them blandly. "The proper place for any infant that size is bed and I naturally figured that a fire baby belonged in a fire bed, and a bed of hot coals was the nearest to it, so here it is!" Winking solemnly at Roger, who was regarding the little Lavaland Islander with fear and loathing, Samuel picked up the poker and gave the baby an affectionate poke. "It'll do fine here," he predicted happily, "and prove beyond a quibble that volcanos are inhabited."

"It'll do nothing of the sort!" exploded Ato, bringing his fat fist down with a resounding thump on the drain board. "You may be the Captain of the ship, Sammy, but I'm the boss of this galley, and that fire baby will have to go. GO! Do you understand? How'm I to cook with the ugly little monster lolling all over the fire bed and like as not falling into the soup when my back is turned?"

"Hark!" interrupted Roger. "More trouble! Something's up, Master Salt, and it's not an eruption either." And Samuel had to agree with him as groans, moans, shrieks and hisses came whistling after the flying ship.

"Ah, that'll be the rest of them!" exulted the Royal Discoverer, pounding out on deck. "Hah! It's the Lavaland Islanders themselves. Ho—this WILL be interesting!"

"Well, just invite them over and we'll all burn up happily together," suggested Ato bitterly.

Hanging over the taffrail, Samuel paid no attention to the King's sarcastic suggestion. Indeed, he was much too interested, for just showing above the flaming circle of the volcano's crater was a row of immense and thunderous looking natives. They were of transparent rock-like structure and burned and glowed from the molten lava that coursed through their veins. With upraised arms and furious faces they were yelling over and over some strange and indistinguishable threats and phrases. One, shaking the blackened stick of the Oz flag, danced and screamed louder than all the rest put together.

"They do not wish to become subjects of Oz, I take it," sighed Samuel, undecided whether to sail back and argue the matter, or sail away and save his ship from possible destruction.

"That's not it! That's not it!" cried Roger, flapping his wings triumphantly. "I know what's the matter. They want that baby back. You're probably making off with the Crown Prince of the Volcano. See that woman yelling louder than the others and holding out both arms? Well, look—she has a crown on her head and is likely the Queen. She wants her baby back."

"And she should have it, too," stated Ato, blinking his eyes at the frightful racket the Lavaland Islanders were making. "You can't steal people's children like this, Sammy, unless you're going back to buccaneering. It's just plain piracy."

"She threw it at us, didn't she?" muttered the Captain, who was unwilling to part with so valuable a specimen.

"It probably blew out of its cradle when the volcano erupted. Give it back to her, Sammy," begged Ato, who was determined to get rid of the terrible infant at any cost. "After all, she's its mother."

"But do you expect me to sail back there and endanger all of our lives?" Samuel jerked his head angrily. "And how else can it be done?"

"Er—er—let Roger carry it back in that old wire basket we use for clams," proposed the cook eagerly.

"Not on your life," protested Roger in a sulky voice. "The basket would grow red hot and burn my bill. Besides, I'm no stork. Tell you what we could do, though, and we'd better be quick before they start throwing things."

"What?" inquired the Captain, gazing uneasily at the infuriated Islanders.

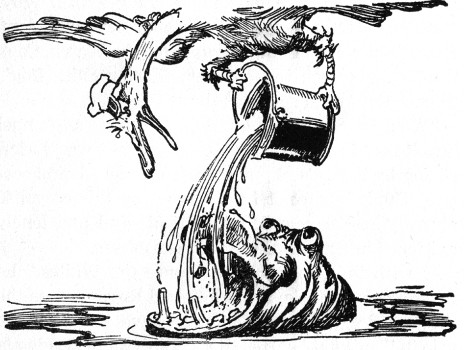

"Why, simply shoot it back," Roger said calmly. "Stuff it in the port cannon and blaze away. You never miss your mark, Master Salt, and if you can't shoot that baby back into its mother's arms, I'll walk on my wings and be done with it."

"Why, Roger, how clever! The very thing!" rejoiced Ato. "I'll go fetch it with the fire tongs and you'll have to hurry, Sammy, or we'll be out of range."

"But it might injure the young one," objected the Captain of the Crescent Moon, shifting his feet uncomfortably.

"Nonsense, it'll be just like a ride in a baby carriage for that little rascal. Prime your gun, Sammy, while I get the child."

By this time the clamor from the Island had become so alarming that even Samuel realized something would have to be decided. So, somewhat mollified by Roger's compliment on his aim, he made ready to fire the port cannon. The baby, hissing lustily, was brought without accident from the galley. Ato held it gingerly before him, using the fire tongs, Roger following along to hold a lighted candle under the little fellow to keep him from going out before he was shot.

The baby fitted nicely into the cannon's mouth and stopped crying instantly. At the last moment Samuel almost lost his courage, but urged on to action by both Ato and Roger, he carefully made his calculations and then shutting both eyes pulled the cord that set off the gun. The terrible explosion shocked the Lavalanders into silence, and almost afraid to look, Samuel opened his eyes.

"Yo, ho, ho! Three cheers for the Skipper!" squealed Ato, snatching the towel from his head and waving it like a banner. "The neatest shot you ever made, Mate, and a lucky shot, too." The baby and the cannon ball which would have shattered a less durable lady had struck the Lava Queen amidships. Dropping the cannon ball carelessly into the crater, the giantess clasped her child in her arms, smiling and screaming her thanks across the tumbling waters.

"Well, was I right, or was I right?" chuckled Roger, teetering backward and forward on the rail and preening his feathers self-consciously. "And I've another idea just as good in case you should be interested."

"Oh, keep it till tomorrow," grumbled Samuel Salt, who felt terribly depressed at the loss of his rare specimen.

"But tomorrow will be too late," persisted Roger, settling on the Captain's shoulder. "Now, while these savages are in a good humor, let me fly over and drop another Oz flag on the Island. Maybe this time they'll let it stand and once it flies over the crater the Island is Ozma's."

"By the tooth of a harpooned whale, you're right! I'm forgetting my duty to Oz," breathed Samuel, straightening up purposefully. "But our kind of flag won't stand the climate yonder."

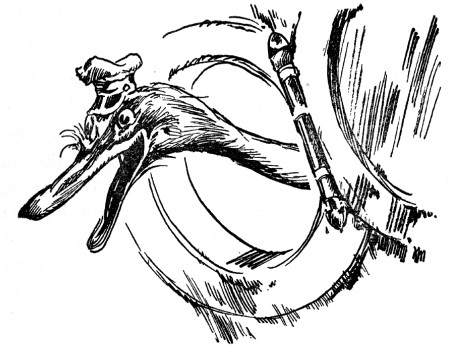

The Read Bird, however, had thought even of that. Taking a sheet of iron from the hold, the resourceful fellow stopped in the galley long enough to burn in the word OZ with the red hot poker. Then, thrusting the poker itself through two slits in his iron banner, he flew jauntily back to the Island.

"Ahoy, and there's a standard bearer for you!" Rubbing his hands together, Samuel strode to the rail. "Bless my buttons, the boy deserves a medal for this, and shall have one, too."

This time the Lavaland Islanders watched Roger's approach with quiet interest and as he hovered uncertainly over their heads held up their hands for the iron flag. But Roger, made daring by their friendliness, swooped down suddenly to the crater's edge, and jamming his banner between two smoking boulders soared aloft.

"Lavaland Islanders!" screamed the Read Bird hoarsely. "You are now under the protection and rule of Queen Ozma of Oz. Lavaland Islanders, you are hereby adjured to keep the peace and the law and LAV one another!"

His voice cracked from fright and excitement, but finishing triumphantly, he spread his wings and skimmed back to the Crescent Moon.

"Hung wung wah HEEE!" yelled the Islanders all together, nodding their heads and waving their arms cheerfully. "Hung wung wah HEEE!"

"What do you make of that?" puffed Samuel Salt as Roger dropped breathlessly down on his shoulder. "Well, 'Hung wung wah HEEE!' it is. Let's give them a cheer for luck." Lifting his great voice, the Royal Discoverer for Oz, helped out by his two shipmates, sent the weird call booming back across the water.

An answering call came from the Island, and then, with a hiss and thud, a small glowing object fell on the deck. Fortunately the fire tongs were still handy and picking up the offending object before it could do any damage, Ato marched sternly off to the galley. Stopping long enough for another wave to the Island, which was growing smaller and smaller as the Crescent Moon sped away, Samuel hastened after his cook, jotting down hurried notes in his journal as to latitude and longitude as he ran along.

"There's something written on this piece of lava," announced Ato, who had dropped the smoking souvenir from Lavaland on the stove. Peering over his shoulder, Samuel could see queer raised symbols and signs on the sulphurous surface of the rock.

"There's something crawling on it, too," volunteered Roger, who was perched on the towel rack above the stove, and had a better view, "a golden frog or a lizard."

"Merciful mustard! What next?" groaned Ato.

"Why, this—this—" Samuel's voice quivered with excitement and disbelief, "this, Mates, is as fine a specimen of a Preoztoric Monster as a scientist could hope for; a real live salamander, a fire lizard, straight from the burning depths of yonder crater. Stars! Tar and Tarrybarrels! This is even better than the baby and will prove my point just as well."

"Does it have to live on my stove?" asked Ato ominously, as the Salamander slid merrily backward and forward over the red hot plates of the range. "Home on the range!" snickered Roger, winking at the Pirate.

"Just till I can fix up a hot box for it," apologized Samuel, "but don't fret, old Toff, it doesn't bite and if it falls on the floor, all you have to do is scoop it up and put it back before it goes out."

"Not only cook, mate and swab, but now I'm nursemaid to a fire lizard." Ato shuddered, and reaching for his tall cook's cap, jammed it down hard on his shiny bald head.

"You can keep it in an iron pot while you cook," suggested Roger practically, "and after all, King dear, it's the only Salamander in captivity. Here, Sally, here Sal—this way, my little crater critter." Tilting the pot on the back of the stove, Roger was delighted to find the Salamander quite willing to answer to her new name. As she slid adventurously into the small cooking vessel, the Read Bird quickly righted the pot and clapped on the cover. "There," he exclaimed with a satisfied nod at his Master, "how's that?"

"Well, I suppose I'll have to put up with it," sighed Ato resignedly. "But in some ways pirating was easier than discovering, Sammy. At least, we never kept the captives on the stove. And NOW—" Ato waved his arms determinedly. "Clear out, both of you. It's three bells and time to stir up the food. And just take that pesky rock along with you. I've meat to broil!"

"When this cools, maybe I'll be able to figure out the language," exulted Samuel, removing the offending piece of lava with a cake turner. "All in all, a most interesting and profitable day, eh, Roger? An island, a visit from a fire baby, and a real live Preoztoric monster."

"Not bad," agreed the Read Bird, transferring himself to the Captain's shoulder. Depositing the piece of lava on an iron hatchway to cool, Samuel strode happily along the deck, stopping to light the red lamps on the port and the green lights on the starboard. Roger himself had just hung a white light in the rigging when a lusty call from the galley sent him flying off to help Ato serve the dinner.

"What could be cozier than a life at sea?" he reflected, winging jauntily into the main cabin with a dish of roast potatoes. Ato puffed cheerfully behind, bearing a huge tray. On the tray a steaming tureen of soup, a pot of coffee, seven dishes of vegetables and two of smoking meats sent up tantalizing whiffs and fragrances. Later when the Read Bird brought in the pudding, he and Sammy soberly agreed it was the tastiest feast Ato had served on the voyage.

The main cabin of the Crescent Moon, with its red leather couches under the ports, its easy chairs and tables clamped to the floor to keep them from shifting, with its ship's clock and ship's lanterns, was a cheery place to be when the day's work was ended. There was a huge fireplace for foggy evenings and every visible space on the wall was covered with pictures of pirate ships, ancient sailing vessels and rough maps and charts of strange and curious islands. While Samuel and Ato sat at their ease to finish off the pudding, Roger took his upon the wing, darting in and out between bites to assure himself that all was well on deck. There was a tiny crescent moon sliding down the sky, and the slap of waves against the side of the ship and the wind creaking in the cordage made as pleasant a tune as the heart of a seaman could wish for.

"Now what could be better than this?" said Samuel Salt exhaling a cloud of smoke from his pipe and stretching his legs luxuriously under the long table. "A tidy ship, a good wind and the whole wide sea to sail on."

"Suits me!" grinned Ato scraping up the last of the hard sauce and settling back with a grunt of sheer content. "Did you mark up our volcano on the chart Sammy, and what are we calling it Mates? An island must have a name you know."

"I know." Samuel blew another cloud of smoke upward and cleared his throat. "If it's agreeable to all hands and Roger, I'd like to call it Salamander Island after Sally."

"Why not? There's a Sally in our galley and a real nice gal is Sally," warbled Roger, settling on the back of Samuel's chair and wagging his head in time to the music.

"Sing like a bird, don't ye?" muttered Samuel striding over to the map of Oz and surrounding countries and oceans that covered the west wall.

"I AM a bird," screamed Roger fluttering up to his shoulder. "'Bout here she would lie, Master Salt, sixty leagues from Octagon Island."

As Roger talked on, making numerous suggestions, the Captain of the Crescent Moon drew with red chalk a small but effective picture of Salamander Island showing the volcano in action and the Lavaland Islanders grouped around the crater's top.

"Taken this day without a shot or the loss of a single man," printed Samuel in neat letters under his sketch.

"Don't forget, you shot the baby," twittered Roger raising a claw argumentatively.

"Oh, we can't put in small details like that," sniffed the Captain stepping back to admire his drawing.

"Seems odd for us to be discovering and taking possession of islands for a country we know so little about," mused Ato, looking thoughtfully at the map on the west wall. "Why, we've only been to Oz once ourselves."

"Yes, but everybody knows about Oz," Samuel said putting the red chalk back in the table drawer. "Our business is with wild new countries that have never been seen or heard of. Besides, anyone can see that Oz is overpopulated and needs new territories and sea ports. And since Ozma is so clever at governing, and her subjects all so happy and prosperous, the more people who come under her rule the better!"

"Aye! Aye!" agreed Roger, peering with deep interest at the map. Small wonder the Read Bird was interested, for Oz is one of the most exciting and enchanting countries ever discovered. There are four large Kingdoms in Ozma's realm, the Northern Land of the Gillikens, the Eastern Empire of the Winkies, the Southern Country of the Quadlings and the Western domain of the Munchkins. Each forms a triangle in the oblong of Oz. The Emerald City which is the capital, is in the exact center where all these triangles meet. Each of these Kingdoms has its own ruler, but all four are under the sovereign rule and control of Ozma, the small but powerful fairy who lives in the Emerald City. On all sides, Oz is surrounded by a deadly desert and beyond the desert lie the independent Kingdoms of No-Land, Low Land, Ix, Play, Ev, the Dominions of the Gnome King, and many other strange and important Principalities. These countries form a narrow rim around the desert, and beyond this rim lies the Nonestic Ocean itself, stretching in all directions and to no one knows what far and undiscovered shores. Each of the four Kingdoms in Oz shown on Samuel's map was so dotted with smaller Kingdoms, cities, towns, villages and the holdings of ancient Knights and Barons, there was scarcely room for another castle. With young Princes growing up on every hand, Roger could well sympathize with the need of Ozma for more territory.

"Won't the Ozians have too long a way to come before they reach these new islands and countries we discover?" inquired the Read Bird, after staring at the map for some moments in silence.

"Not a bit of it!" Samuel dismissed Roger's objection with a snap of his fingers. "I hear the Wizard of Oz is working on a new fleet of airships, that will make crossing the desert and Nonestic a real lark and enable new settlers to reach these outlying islands in a day or less. So all we have to do is to proceed with our discovering. Ozma will attend to the rest. This volcanic island may not be as useful as some of the others, but one can never tell. How about picking up a few islands for you, Ato, as we ride along?" The former pirate dropped his arm affectionately round the shoulders of his Royal Cook.

"No, thanks," grunted Ato, rolling cheerfully to his feet. "One's enough. What would I want with any more islands? Why I'd never get off on a voyage. But pick yourself a couple, Sammy, why don't you?"

"Who, ME?" Samuel Salt shook his head emphatically. "A ship's all I can handle and I wouldn't trade you two buckets of sea water for all the islands in the Nonestic. One ship and one crew's enough for me, and since you're my crew, you'd better turn in—we've had a hard day and another one coming. I'll take first watch, Cooky, here, shall have middle, and you Roger can be the early bird on morning watch."

"Ho hum! I'm right sleepy at that," admitted Ato, starting to heap up plates. "Give me a lift with the dishes, Roger, will you?"

"Oh, throw 'em overboard," directed Samuel Salt recklessly. "There's plenty more in the hold and I'm agin all extry labor."

"Hurray!" screamed Roger seizing the coffee pot and winging merrily through an open port.

"Avast! Avast there! Not my coffee pot!" pleaded Ato, making after the Read Bird with surprising speed considering his tonnage. "Stop you great Gossoon! How many times must I tell you I'm boss of the galley?" Catching Roger by the leg just as he reached the rail, Ato snatched back his precious coffee pot and hugged it protectively to his bosom. "Why I've just got this contraption broken in proper," he panted indignantly. "A coffee pot's like a pipe, it's got to be sweetened and seasoned. Heave over the plates and cups if you like," he went on, relenting a bit as he noted the keen disappointment on Roger's face, "but save the soup tureen. I'll wager there's not another that size on the ship and the Captain must have his soup. What a splendid pot of soup THIS would make," murmured Ato looking dreamily down at the sea, "a bit salty, perhaps, but full of snapper and porgy and tender young sea shoots. Why that foam's as near to whipping cream as anything I've ever gazed on."

Tearing himself reluctantly from the appetizing sight, the Royal Cook padded off to put the galley in order for the night, while Roger with loud squalls of glee dropped the plates and saucers one by one over the side. In this way the dishes were soon done, the cabin tidy and shipshape, and by eight bells the King and the Read Bird were sleeping soundly and Samuel Salt had the ship to himself.

First, he made a complete round of all decks, glanced at the barometer and compass, and furled the fore and mizzen topsails. Then he took the cooled piece of lava down to the hold. The strange signs and symbols had hardened, and labeling it carefully with the date and name of Salamander Island, Samuel placed it on his shelves for further study. Then returning to the main deck he set a portable ship's lantern on a coil of rope and settled down to fix a hot box for the Salamander. Selecting from the material he had brought from the hold an iron box with a glass lid, he covered the bottom with sand and pebbles. Knowing salamanders require hot water as well as hot air, he placed a tiny flat pan of water in the corner of the box to serve as a swimming pool. A burning glass in the day time and an alcohol lamp under the box at night would supply the necessary heat, and setting the whole contrivance on an iron tray in the cabin, Samuel went joyfully off to fetch the fire lizard.

The Salamander was still in the pot on the back of the stove, and giving her an experimental poke with his finger, Samuel was astonished to find her quite cool to the touch. This was surprising considering she could only live in the most intense heat. But without stopping to figure it out, the Captain picked her up between thumb and forefinger, carried her to the cabin and popped her into the iron box. He had already lighted the lamp under the box so that everything was red hot and cozy for her. The small captive seemed to appreciate her new quarters, wriggling over the hot pebbles and sand, then splashing gaily in her swimming pool.

"Quite a girl!" sighed the pirate, resting his elbows on the table and gazing happily down at the first prize of the voyage. "You're going to be great company for me, Sally." As if she really understood, the lizard gave a squeak and tapped loudly on the glass lid with her tail. The pipe almost dropped from Samuel's mouth at Sally's strange behavior, and lifting the lid he peered inquisitively down at her. Before he had a chance to clap it shut, the Salamander hurled herself upward, landing smartly on the bridge of the Pirate's nose, from where she slid cleverly into the pipe itself.

"Well I'll be scuppered!" gasped the Royal Explorer looking slightly cross-eyed down the bridge of his nose as Sally coiled up comfortably in the bowl of the pipe. "The little rascal wants to keep me company, and so she shall, bless my boots, so she shall! Why this is plumb cute and cozy and something to write in my journal." Puffing away delightedly Samuel stepped out of the cabin and all during his watch, the little Salamander rested contentedly in his pipe. Sometimes she peered up inquisitively over the edge, but mostly she lay quietly on the smoking tobacco, looking with calm interest at the sky and the rippling sails over her head. Not only did she keep his pipe from going out, but never had it drawn so well. So, filled with a vast wonder and content, Samuel strode up and down the deck. Not till midnight when he roused Ato could he bear to put Sally back in her box and only then, after he had promised her another ride in the morning. But when morning came, Samuel had no time to keep his promise, for while Ato was cooking breakfast and the Captain himself catching forty winks in the cabin, the raucous voice of the Read Bird came whistling down from the foremast.

"Land Ho! Land! More Land. Island tuluward, Captain!"

"All hands on deck! Come on! Come on!" yelled Samuel Salt running past Ato's galley dragging on his clothes as he ran. "There's an island tuluward, you lubber."

"Well, 'tain't a flying island is it?" Ato stuck a very red face out the door. "I guess it'll stay there till I turn the bacon, won't it? No cause to burn the biscuits just 'cause an island's sighted is there?" But in spite of his pretended indifference, the ship's cook shoved all his pans on the back of the stove and hurried out on deck. "Rich and jungly, this one," he observed, resting his arms comfortably on the rail, "and from what I can see a good place to grow bananas and whiskers. Look, Sammy, even the trees have beards."

"Moss," muttered Samuel Salt striding over to the wheel. "Fly ashore Roger and see whether there's a good place to put in."

Twittering with importance and curiosity, the Read Bird flung himself into the air. In ten minutes he was back to report a wide river cutting through the center of the island from end to end. The foliage was so dense, Roger had not been able to discover any signs of habitation, but after viewing the mouth of the river through his glasses, the Captain decided to take a chance, and sail through.

"Now, Sammy, let's not do anything hasty," begged the ship's cook lifting his floury hands in warning, "nor try to conquer a country on an empty stomach. This may be an important island, so after we eat, let us put on our proper clothes and plant the Oz flags with dignity and decorum."

"Spoken like a King and a seaman," approved Samuel Salt, "and if my eye does not deceive me, I'll have the ship in the river as soon as you have the coffee in the pot. Then we'll ride in with the tide, put on our discovering togs and proceed with the business of the day."

So while Ato returned to his galley and the Read Bird to his post in the foremast, Samuel swung the Crescent Moon in toward the island. Each felt a slight twinge of uneasiness as the ship left the open sea and began to slip rapidly up the broad new and unnavigated jungle stream. Vine covered trees pressed close to the banks, and birds and monkeys in the branches kept up an incessant screech and chattering. A flock of greedy pelicans flopped comically after the ship and as they penetrated deeper and deeper into the jungle it almost seemed as if they were entering some dim green land of goblins.

"A fine target we make for anyone who cares to shoot at us," moaned Ato, as he waddled backward and forward between the cabin and galley with cups and covered dishes. "Ugh!"

"Yes, I wouldn't be surprised to feel an arrow in my back any minute now," assented Samuel Salt brightly, "though I must say I'd much prefer a fried mackerel in my stomach."

"Come on then," shuddered Ato, in no wise cheered by Samuel's remarks, "breakfast's ready and we may as well eat before we die."

"Now never say die!" roared the Royal Explorer of Oz, touching the buttons to furl sail and yelling to Roger to let go the anchor. "Never say die—say dee—dee-scovery is our aim and purpose, Mates. Dee-scovery with a hi de di dide di dough!" sang Samuel vociferously to keep up his own spirits. Finally with the ship motionless amidstream the three shipmates sat down to breakfast. Their nerves were tense and their ears cocked for signs of approaching natives, but except for the noise of the birds and monkeys and the occasional splash of some river creature, there was no sound to indicate the ship had been sighted by the islanders.

"Nobody's home," concluded Samuel, finishing off his third cup of coffee at one toss and hurrying off to his cabin. Roger, having only Oz flags and no shore togs to bother him, generously offered to clear away the dishes and amused himself by throwing scraps and the rest of the biscuits to the pelicans. He had just tossed over the last biscuit when Ato appeared in a grand satin coat and breeches, long cape and three-cornered hat. The elegance of his apparel was somewhat marred by the bread board he had belted round his middle and the bread knife and blunderbuss he had stuck through his sash.

"Ha, hah!" roared Samuel Salt, giving the bread board a resounding whack. "Something to stay your stomach, EH?" Samuel himself was as stylishly attired as the King, his three-cornered hat at a dashing angle. Under his arm he had two pairs of tremendously long stilts. "No need for us to get all grubby lowering the boat. We'll wade ashore this time," explained Samuel as Ato's eyes grew round and questioning. "Easy as walking on crutches; just watch me, Mate."

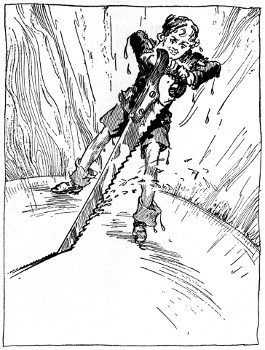

Now Samuel, it must be confessed, had been practicing stilting on Elbow Island, so naturally it came easy to him. First he put his stilts over the side, then vaulting the rail, he seized the tops and settled his feet in the cross pieces at one jump and started walking calmly up and down gleefully calling for Ato to follow. It all looked so simple, Ato handed the basket of lunch he had packed to Roger, and seizing his stilts began anxiously feeling around for the river bottom. Satisfied that it was solid, he climbed boldly up on the rail.

"That's it! That's it!" applauded Samuel. "Now grab the tops, Mate, and start coming."

"Chee tree—tee—hee—!" screeched the monkeys derisively as Ato clung precariously to the rail with one hand and maneuvered his stilts with the other. By some miracle of balance the fat King actually managed to mount and hold on to his perilous walking sticks. Then with a long quivering breath he heaved one forward. He was about to take another step when a desperate scream from Roger almost caused him to topple over backwards.

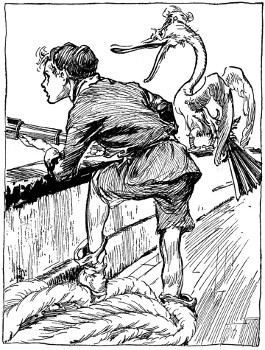

"'Gators!" croaked the Read Bird, beating his wings together violently. "Watch out for those 'gators."

"Why bother him with gaiters at a time like this? They look perfectly all right to me." Samuel Salt frowned up at Roger.

"Not his gaiters, river 'gators, alligators, CROCODILES!" wailed Roger, beginning to fly in agonized circles. "Crocodiles and WORSE."

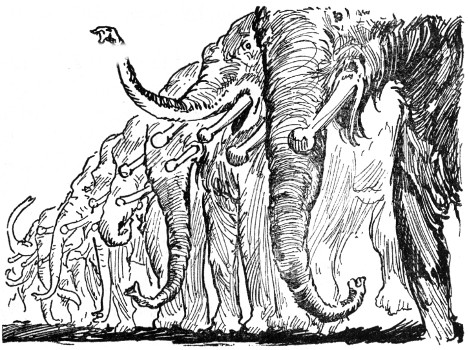

Samuel, eyeing what he had supposed to be a pile of rotten logs on the river bank, saw dozens of the slimy saurians slide into the water and come savagely toward them.

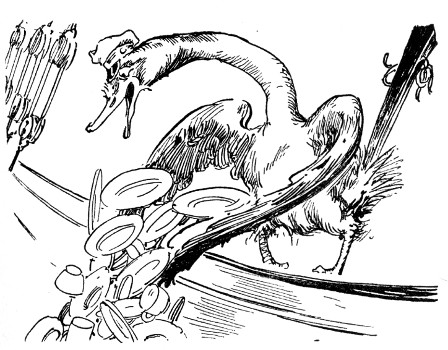

"Back to the ship! Back to the ship!" babbled the Read Bird, clutching Ato's collar with a frantic claw. But the King was too frightened to move. The sight of the bleary-eyed river monsters made him tremble so violently his stilts twittered and swayed like trees in a hurricane. He could not for the life of him take a step in either direction. With a loud cry Samuel started to help him, but a crocodile reached Ato first. Its jaws closed with a vicious snap on the King's left stilt and with a heart-rending shriek Ato plunged into the slimy river.

"There, there! Now you've done it!" sobbed Roger. "Fed the kindest soul who ever served a ship's company to a parcel of crocodiles!" Dropping the Oz flags and lunch basket, he made an unsuccessful grab for his Master's arm. But even if he had caught it, Ato's great weight would have pulled them both under, and now only a circle of bubbles showed where the luckless explorer had disappeared. Firing his blunderbuss to frighten off the rest of the crocodiles, Samuel, striking left and right with his stilts, propelled himself forward, while Roger pecked futilely at the monster that had felled his Master. But just as Samuel, after boldly driving off the dragon-like creature, prepared to dive in and save Ato or perish with him, a dripping head appeared above the water.

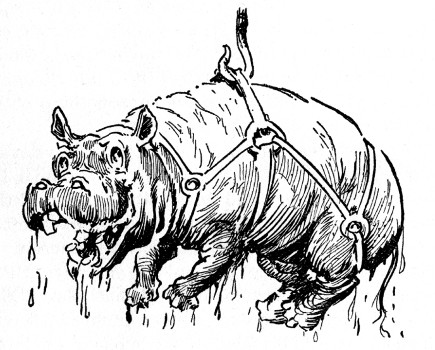

"Thank you. Thank you very much!" murmured a mild voice. "I haven't had as nice a present as this since I was an itty bitty baby. Now what can I do for YOU?" Neither Samuel nor Roger could speak a word, for where the King had gone down, a tremendous hippopotamus was coming up, the lunch basket hanging carelessly out of a corner of its mouth. For a wild moment Samuel thought his enormous friend and shipmate had been transformed by some witchcraft into this ponderous beast. He even imagined he caught an expression of Ato's in the monster's moist eye. But this gloomy idea was soon dispelled, for, as the creature rose higher out of the water, they could see a desperate and bedraggled figure sprawled across its slippery back.

"Ahoy, Mate!" choked Samuel, his heart thumping like a trip hammer. "Is it really you? Are you safe, then?"

"Safe!" quavered the half-drowned and mud-covered King of the Octagon Isle. "SAFE?" He peered dizzily at the churning crocodiles just a boat's length away, and his voice cracked and broke. "I never felt safer in my life. What am I riding, a whale or an elephant?"

"A river horse," explained the hippopotamus, looking kindly over her shoulder. Then, as the crocodiles began to hiss and roar and come rolling toward them, she gave a ferocious bellow and snort. "Away with you! Be off, you river scum!" she squealed viciously. "These travelers are MINE. Shoot your fire stick, Master Long Legs. That will fix them." For a moment the crocodiles held their post, then, as Samuel fired his gun repeatedly, they began to slide sullenly across the river to the opposite bank. "Hold fast, Master Short Legs, and I'll soon have you ashore," wheezed the hippopotamus, speaking out of the corner of her mouth so as not to drop the picnic basket.

"Yes, yes, but what then?" shuddered Ato, trying to get a finger hold on the monster's slippery neck.

"Why, then, we'll both tell our stories, and after that I'll eat," snorted the river horse, paddling joyously toward the bank.

"You'll EAT!" groaned Ato, ready to roll back into the river. "Oh, my father and mother and maiden aunts!"

"Did you hear that?" Dropping to Samuel's shoulder, Roger whispered fiercely. "Quick now, a shot behind the ear, before it gets any further. Are you going to do nothing while this ravenous monster carries off my poor Master?"

"Sh-hh!" warned Samuel, holding up his finger. "These creatures do not eat meat or men. They're herbivorous, my lad, and this one seems uncommonly kind and friendly. But what puzzles me—" the Royal Explorer looked intently into the face of the Read Bird. "What puzzles me is to find this one talking our language. To my knowledge, only animals in Oz, a few in Ev and you on the Octagon Isle have the gift of speech. And I tell you, Mate, this is a valuable discovery, and a simply splendid specimen of a pachydermatous talking aquatic." Whether the last few words in this sentence or a stone in the river bottom tripped up the Captain, Roger never knew, but without any warning Samuel turned a sudden back somersault into the river, going under as completely as Ato had done.

"Ugh—gr—ugh!" he gurgled, coming up full of mud and disgust. "How did that happen?"

"Stilts!" sniffed Roger, whose wings had saved him from going down with Samuel. "A splendid way to get ashore, Master Salt, so neat and tidy. And a fine Discoverer you look now."

Sighing deeply, Samuel watched his stilts floating out of reach, then shaking his head violently to get the water out of his eyes, he swam thoughtfully after the hippopotamus. As he dragged himself up on the bank, a monkey swinging by its tail from the lower branches of a tree snatched his three-cornered hat and scittered all the way to the tree top, at which all the other monkeys let out shrill hoots of mocking merriment.

"Ah! The welcome committee!" sniffled Ato, rolling off the hippopotamus. "Well, Sammy, wherever it is, here we are and a nice mess you've made of the landing. Clothes ruined, weapons gone," (Ato felt his middle dejectedly for his bread knife and blunderbuss), then hitching up the bread board at his waist looked long and accusingly at the Leader of the Expedition.

"Now you mustn't mind a little mud," said the hippopotamus, setting down the picnic basket and gazing from one to the other with frank interest and curiosity. "Mud is beautiful and SO healthy."

"Not for me," frowned Samuel Salt, endeavoring to remove the thick green slime from his hair and ears with his damp silk handkerchief. "But I suppose we'll dry off in time and—"

"Proceed with the business of the day," finished Ato sarcastically, as he squeezed the water out of his silk pantaloons and coat tails. "But I hope you don't mind my saying that a seaman should stick to his boats, Samuel. If I had not fallen in with this kind and obliging hippopotamus, I'd have been a crocodile's lunch by this time."

"Oh, I'd have got you out somehow," muttered Samuel, smoothing back his hair sulkily. "And those stilts really saved your life. Suppose that animal had bitten your leg instead of your stilt? By the way, what's the name of this island, Mate?" Anxious to change the subject, Samuel turned to Ato's tremendous rescueress.

"Mate?" repeated the hippopotamus, wiggling her ears inquiringly, "What may that mean?"

"It is what a seaman calls his crew and his friends," explained Samuel, grinning in spite of himself.

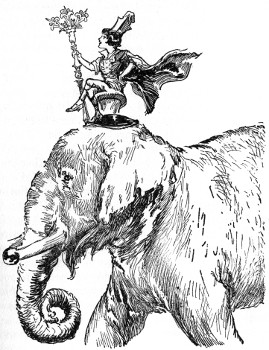

"Seaman? Mate?" mused the hippopotamus in a rapt voice. "How cozy, how beautiful!" Overcome with emotion, the mighty monster leaned forward and lapped up the picnic basket, Oz flags, lunch and everything. "I shall remember this as long as I live," she assured them with a gulp as one of the flags went sideways down her throat. "Nikobo, Little Daughter of the Biggenlittle River People, bids you welcome to Patrippany Island."

"Little daughter!" exclaimed Ato in a smothered voice. "Ha, ha! Patrippany Island. Ho, ho! This is interesting. I knew there was a trip in it somewhere, a wet trip for us, eh, Samuel?"

"But what I don't understand," said the Royal Explorer of Oz, briskly massaging his beard with his handkerchief, "is how you happen to speak our language. Do all the creatures on this Island talk? I don't mean that monkey chatter above."

"No, none of the other creatures here speak the language of man," answered Nikobo solemnly. "I never knew I could speak it myself till five moons ago last Herb Day."

"Herb Day? Dear, dear and dear! How confusing it all grows," sighed Ato, emptying the water out of his hat which had somehow survived his river ducking. "Do you suppose she means Thursday? Roger! ROGER! Keep away from those monkeys. Do you wish to lose all your tail feathers?"

"Oh, it's all very simple," Nikobo rolled her eyes from side to side. "One day I eat herbs and that is Herb Day. One day I eat twigs and that is Twig Day, and one day I eat grass and that is Grass Day, and—"

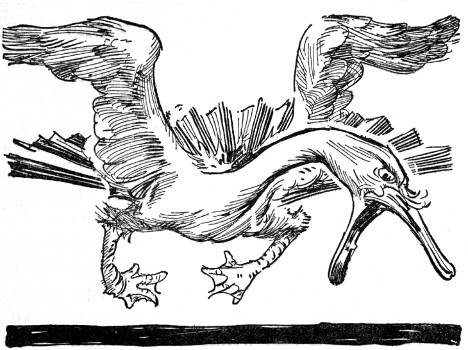

"And one day you eat lunch baskets and Oz flags, and I suppose that makes it Flag Day," chuckled Roger, coming down from a little excursion in the tree tops. "She's swallowed the Oz flags, Skipper, and if that doesn't make her a citizen of Oz, I'll eat my feathers."

"Go ahead, if it will keep you any quieter," said Samuel Salt, who did not want this interesting conversation interrupted by Roger's nonsense. "So you only began to speak our language five moons ago last Herb Day? What made you do that?"

"A boy," confided Nikobo with a ponderous wag of her head.

"Ah, now we're getting somewhere." Feeling in his pocket, Samuel pulled out a small note book and pencil, still damp but usable. "Was it a native boy?" he asked eagerly.

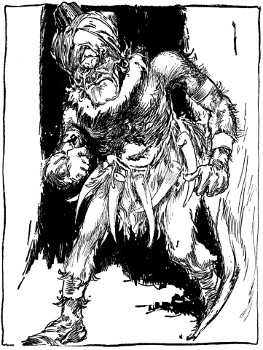

"No, no, certainly NOT." The hippopotamus panted a little at the very idea of such a thing. "The Leopard Men speak a strange roaring language I have never been able to make head or tail of. Besides, to speak to them would not be safe nor desirable. The Leopard Men have long tusks and spears and—"

"Leopard Men!" yelled Ato, flinging both arms round the trunk of a tree. "Oh! Oh! and OH! I wish we were safely back at pirating, Sammy. Here we are marooned on this miserable monkey island, inhabited by Leopard Men, surrounded by crocodiles and no way of getting back to the ship."

"You forget me," murmured the hippopotamus. Lumbering over to Ato, she gave him a gentle nudge with her moist pink snout. "Nikobo, Little Daughter of the Biggenlittle River People, will carry you anywhere you wish to go."

"Not yet, not yet," protested Samuel Salt as Ato made a clumsy attempt to mount the hippopotamus. "Why, we've only just come, Mate. We can't go without seeing these Leopard Men and this strange boy who speaks our language."

"Oh, CAN'T we?" Drawing in his breath, Ato made a flying leap at Nikobo, and this time managing an ear hold, pulled himself determinedly up on her moist, slippery back. "Goodbye, Samuel," said the King with a firm wave of his hand. "If you bring any Leopard Men back to the Crescent Moon, you can discover yourself another cook. No Leopard Men. Mind, now!"

"Oh, you needn't worry about that." The hippopotamus closed one eye and smiled knowingly to herself. Thoroughly annoyed by the desertion of Ato and the superior grin of the river horse, Samuel snatched a long rapier from his belt and glowered belligerently around him.

"Shiver my timbers! You think I'm not strong enough nor smart enough to fight these savages? HUWHERE are these Leopard Men?" roared the former Pirate in such a reverberating voice the monkeys fled silently to the tree tops, and even Roger put his head under his wing.

"Gone, all gone!" explained Nikobo as she started calmly down toward the river bank.

"You mean there are no Leopard Men on this Island now?" Looking with horror and aversion at the crocodile-infested river, Ato began tugging at Nikobo's ear. "Not so fast, my good creature! Wait a moment, my buxom lass! Perhaps I'll stay with Sammy after all."

"Well, just as you say." With scarcely a pause in her stride, the hippopotamus turned round and waddled amiably back to the strip of sand where Samuel Salt stood staring sternly into the jungle beyond.

"This is a great disappointment to me, Mates," sighed the Captain of the Crescent Moon mournfully wringing out the lace ruffles of his cuffs. "To have taken a Leopard Man back to the Court of Oz would have been an achievement worth the whole voyage."

"Now there's where we're different," murmured Ato, settling into a more comfortable position on the back of the river horse. "I myself would rather be disappointed than speared by a savage, and I don't care how many Leopard Men I miss seeing. Rather be spared than speared, ha, ha! Tee, HEE, HEE!" Ato chuckled from sheer relief.

"Shall I fly back to the ship for some more Oz flags?" Roger flapped his wings inquiringly. "If the Leopard Men are really gone, then Patrippany Island is ours without a spear thrown."

"That's so," mused Samuel Salt, thrusting his rapier back into its sheath and beginning to show a little interest in the island itself. "Fly ahead, my Hearty."

"And bring back some ship's biscuit," called Ato. "All this diving and mud turtling has left me weak as a fish. And while we're waiting for Roger, perhaps Nikobo will tell us a little about these Islanders. Were they little or big, black or brown?"

"Yellow," answered the hippopotamus gravely. "Big and yellow with brown spots all over their hides. They had brown hair, mane and eyes, and rough snarling voices. They used neither huts nor shelter, but roamed like the animals through the jungle, hunting, fishing and fighting. They had hollowed out logs for use in the water and last Twig Day every Leopard man, woman and child climbed into the long boats and paddled out to sea. Shortly afterward—" Nikobo's eyes grew round and shiny at the mere memory, "shortly afterward a great hurricane arose and my family and I, watching from the mouth of the Biggenlittle River, saw the boats and men swept under the waves. Some of the logs floated back to the islands, but the Leopard Men and women we never saw again."

"Not even ONE?" exclaimed Samuel peevishly.

"Not even one," Nikobo assured him solemnly. "And to tell the truth," the hippopotamus flashed a sudden and expansive sigh, "it is much better and safer without them. The one problem is the boy, and I've been feeding him myself."

"Oh, yes, the boy who speaks our language," mused Samuel, still lost in bitter reflections of the Leopard Men he should never see face to face.