The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Class-Book of Biblical History and

Geography, by Henry S. Osborn

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: A Class-Book of Biblical History and Geography

with numerous maps

Author: Henry S. Osborn

Release Date: November 21, 2017 [EBook #56019]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CLASS-BOOK OF BIBLICAL HISTORY ***

Produced by Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

The cover image was provided by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Punctuation has been standardized.

Most abbreviations have been expanded in tool-tips for screen-readers and may be seen by hovering the mouse over the abbreviation.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

Footnotes are identified in the text with a superscript number and have been accumulated in a table at the end of the text.

Transcriber’s Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes have been accumulated in a table at the end of the book and are identified in the text by a dotted underline and may be seen in a tool-tip by hovering the mouse over the underline.

Several maps at the end of this book were displayed over two pages. In reproducing these as illustrations, a small strip was lost due to the binding.

This work is a Class-Book of the Old and the New Testaments treated as consecutive history. It includes the Jewish history of the centuries between the close of the Old Testament and the beginning of the New.

It presents those important elements of Biblical history which distinguish it from all other histories and which illustrate the plan and the purpose of the Bible as one Book. Whatever modern scholarship has accomplished to aid in the understanding of the original languages of Scripture in important points has been made use of, and whatever monumental or topographic discoveries would contribute to a better understanding of the geography or archæology of the text-statements have been introduced where the history required it.

The history of the centuries between the close of the Old Testament canon and the beginning of the Christian era includes that of its Jewish literature. This history greatly helps us to appreciate that singular tenacity with which the earliest Christian church held to the Mosaic ritual.

In the treatment of this history we have allowed no space for mere opinions or speculations. The work is purely historical, and its text is illustrated only by that which is pertinent and well authenticated, in either geographic or archæological discovery.

The entire subject matter is divided into Periods and chapters and subdivided into sections and paragraphs, the latter presented in such a form as generally to suggest to the teacher the question and to the reader the topic of the paragraph.

THE ANTE-DILUVIAN ERA.

Creation, Eden: Chronology and its Sources.

The Significance of Names.

The Descendants of Adam.

The Lineage of the Patriarchs.

The Flood.

THE PATRIARCHAL ERA AFTER THE FLOOD TO THE DEATH OF JACOB.

The Two Ararats. The Sons of Japheth.

The Sons of Ham. Their More Recent Names.

The Descendants of Shem. Job.

The Confusion of Tongues.

The History of Abram and his Times.

The Patriarchs Isaac and Jacob.

Egyptian Testimonies.

THE THEOCRACY TO THE JUDGES.

The Israelites in Egypt.

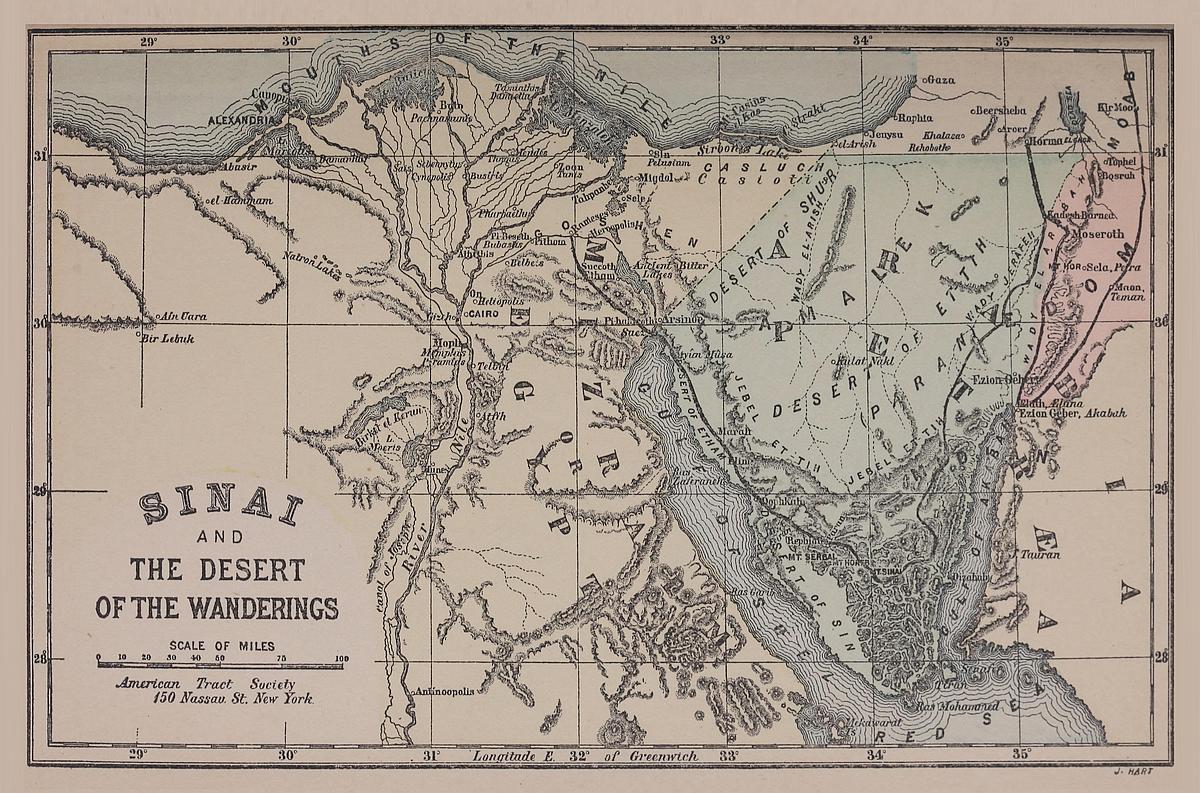

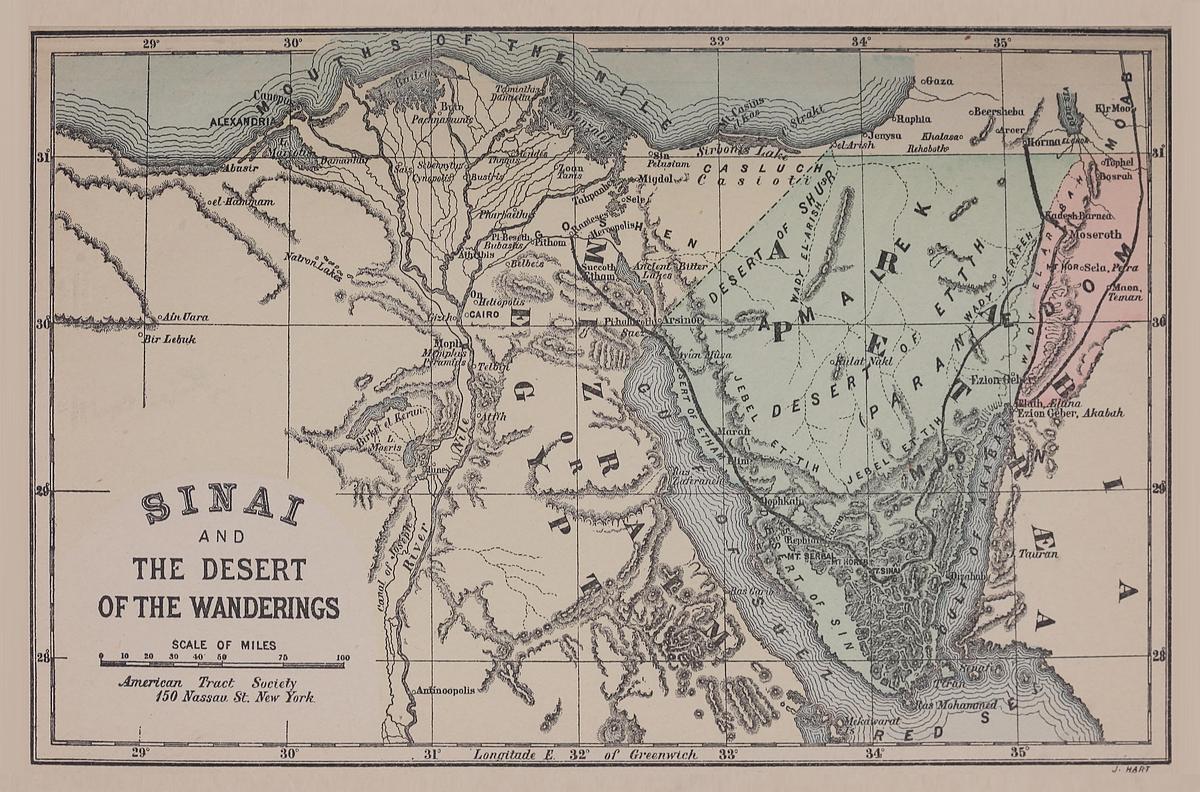

The Physical Geography of Sinai and the Desert.

The Entrance into Canaan.

The Battles of the Conquest.

The Introduction of Idolatry.

THE PERIOD OF THE JUDGES.

The Nature of the Office. The Chronology.

The Scribes of the Age.

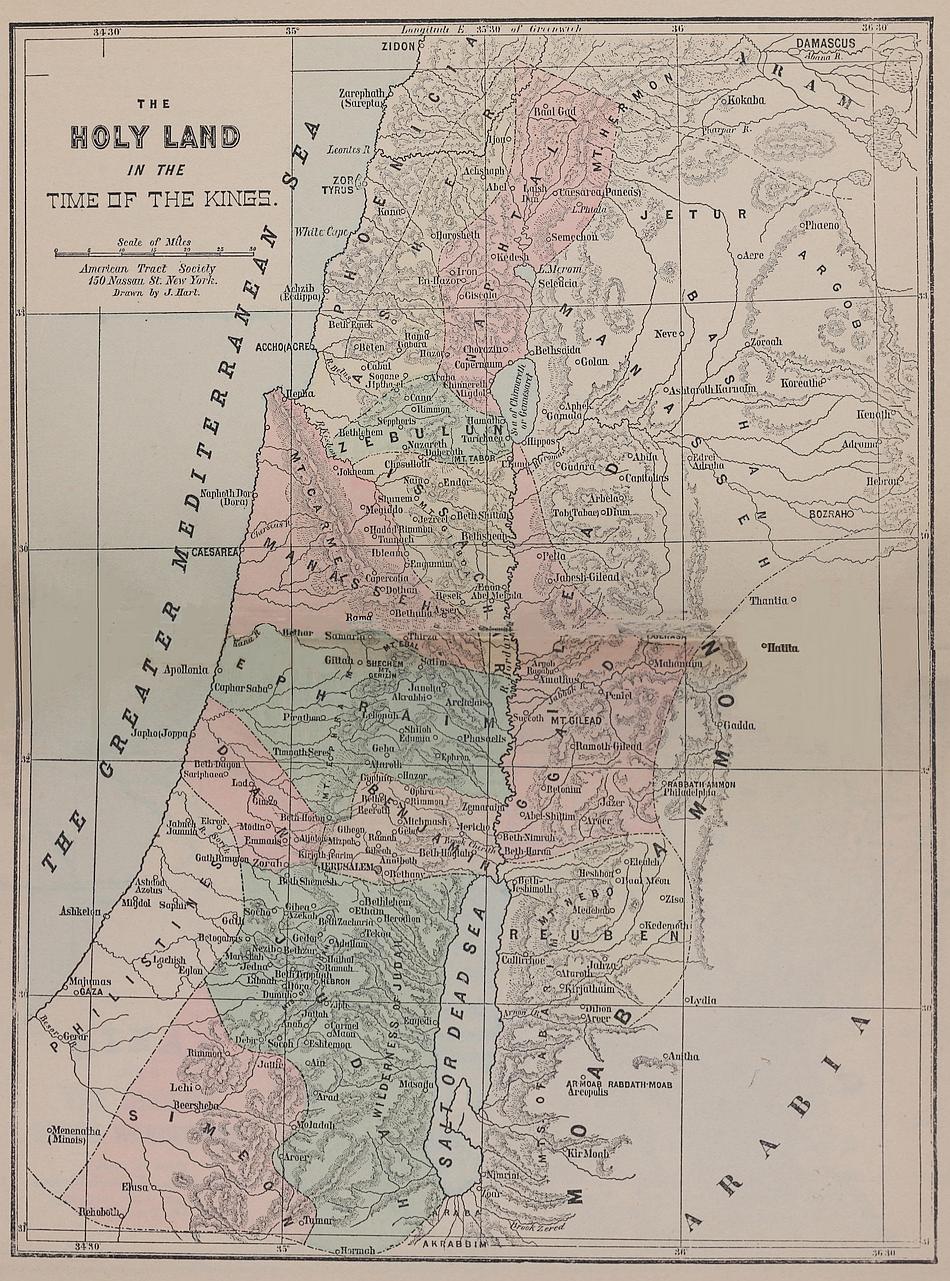

THE PERIOD OF THE KINGS TO THE CAPTIVITY.

Origin of the Monarchy. Reign of Saul.

The Reigns of David and of Solomon.

The Division of the Kingdom.

Analysis of the Reigns of Judah and Israel.

The Institution of the Prophetical Office.

THE CAPTIVITY OF JUDAH TO THE CLOSE OF THE CANONICAL PERIOD.

The Various Captivities.

The Comparative Religious Spirit.

The Captivity Ended.

The Canonical Books. Samaritan Pentateuch.

What Was Scripture? The Septuagint.

The Origin of the Talmud.

Concluding Remarks.

THE NEW TESTAMENT ERA.

From the Birth of Christ to his Public Ministry.

The Public Ministry of our Saviour.

From the First Passover to the Second.

From the Second Passover to the Third.

The Third Passover.

The Beginning of the Christian Church.

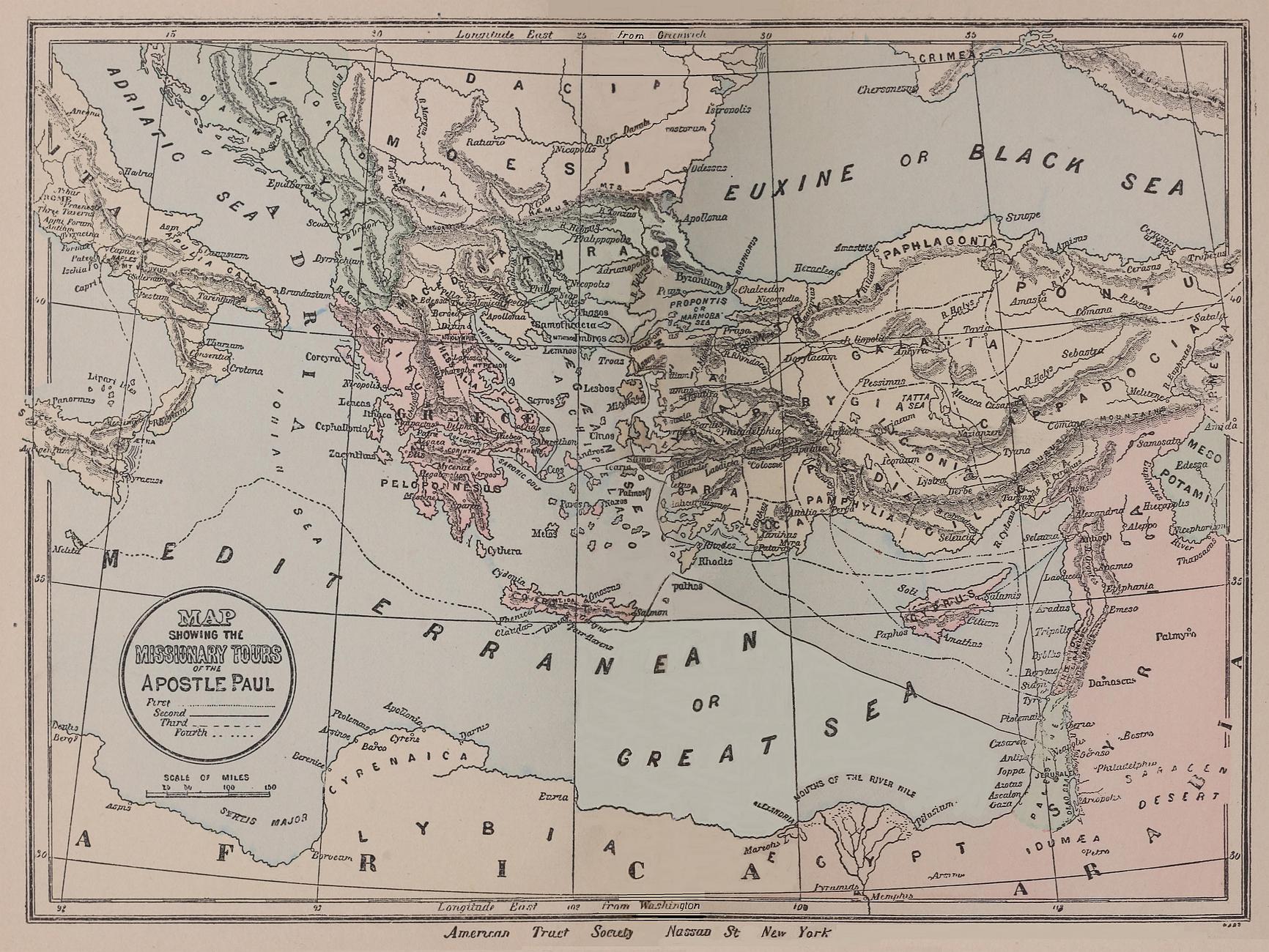

The Gospel for Gentiles as well as Jews. Paul’s First Mission.

The Second and Third Missionary Tours of Paul.

Paul at Rome. The Seven Churches. Colosse and Hierapolis.

1. The first book of the Bible, which is Genesis, begins with a history of the Creation. The words “In the beginning,” with which it opens, give us no chronological data by which we are able to form any estimate of the time. Seven divisions, called “days,” have special appointments assigned to each in that which is usually called “the work of creation,” including the appointment of a day of rest.

Before the beginning of the days there existed a state of chaos, the earth being “without form and void” and darkness being upon the face of the waters.

The first act was the calling into being Light The appointment of Day and Night closed the work of the first day.

The separation of the waters beneath “the firmament,” or expanse, from those above “the firmament” constituted the work of the second day.

The formation of dry land, called earth, and the appearance of vegetable growth, called grass, herbs, and trees, occurred on the third day.

On the fourth day lights appeared in “the firmament,” or expanse, and on the fifth day the first animal life moved in the waters and birds in the air, the latter called “winged fowl.” On the sixth day the earth brought forth living creatures, “cattle, creeping things, and beasts;” and finally man was created, made after God’s image, with dominion over all that had been here created.

The seventh day was set apart as a day of rest, a day of which it is said, “God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it.” Gen. 2:3.

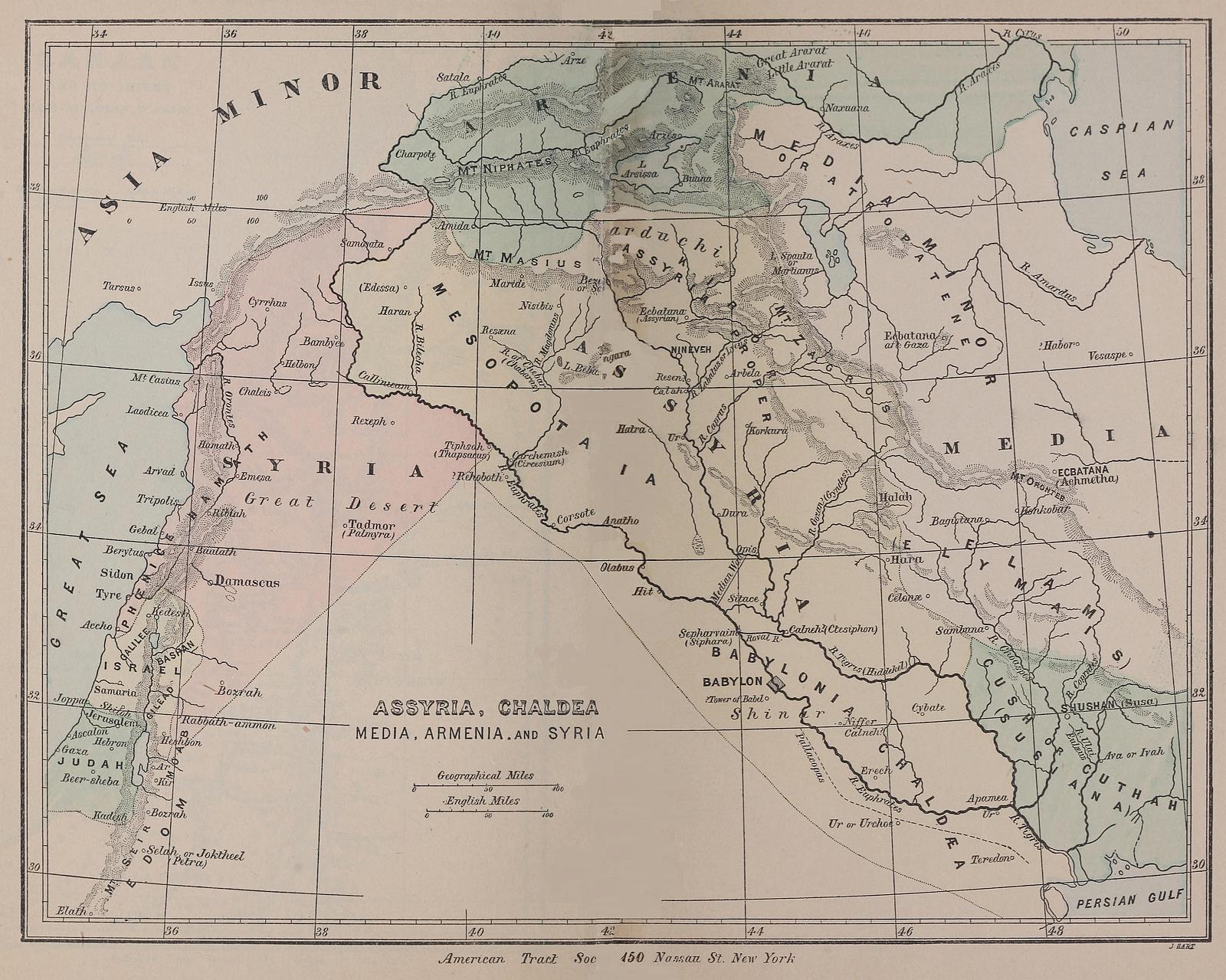

2. After the creation of man he was placed in a garden which the Lord God planted “eastward in Eden.” The locality of Eden is unsettled, but the opinion of many scholars is that it is not far off from the head of the Persian Gulf. The garden is described as “eastward in Eden,” and it is supposed to have been in the eastern part of a district called Eden. Prof. Sayce derives Eden from an ancient word meaning “the desert.” If this be correct, the garden of Eden was more remarkable for its contrast with the great Syrian desert in its immediate vicinity. The rivers mentioned by name are Pison, Gihon, Hiddekel, and Euphrates. The Euphrates at the present day joins the ancient Hiddekel, which is now called the Tigris, at a point one hundred miles northwest from the Persian Gulf, and the stream formed by the union of the two rivers is called the Shat el-Arab. The Pison and Gihon have not been satisfactorily identified.

It should be remembered that the geographical condition of this region is very unlike that which existed at the time we are considering. Dr. Delitzsch calculates that a delta of between forty and fifty miles in length has been formed since the sixth century B. C. Prof. Sayce says that in the time of Alexander, B. C. 323, the Tigris and Euphrates flowed, by different mouths, into the sea (gulf), as did also the Eulæus, or modern Karun, in the Assyrian epoch.1

The increment of land about the delta has been found to be a mile in thirty years, which is about double the increase of any other delta, owing to the nature of the soil over which the rivers pass.2 Under these changes it is probable that any but very large streams might disappear.

3. The Euphrates passes along a course of more than 1,780 miles from the head-waters of the Mourad Chai3 and for about 700 miles it passes through a nearly level country on the east of the great Syrian desert. It varies in depth from eight to twenty feet to its junction with the Tigris; after its union with the Tigris its depth increases. It is navigable for about 700 miles or more from the Persian Gulf.

The Tigris is shorter, being about 1,150 miles in length, and navigable for rafts for 300 miles. Some of the extreme head-sources of this river approach those of the Euphrates within the distance of two or three miles. The name Hiddekel is the same word as Hidiglat, which is its name in the Assyrian inscriptions, as Purat is the ancient Assyrian for Perath in Hebrew.4

The land of Havilah, which was encompassed entirely by the river Pison, is unknown, but the “Ethiopia” encompassed by the river Gihon is in the Hebrew called Cush, and recent discoveries have proved that in very early times Cushite people inhabited a part of the region near the head of the Persian Gulf.

There is little doubt that the land so called was a part of the plain of Babylonia where the cities of Nimrod were planted, Gen. 10:10, Nimrod being a son of Cush.

These discoveries show that, in after ages, the Cushites left Babylonia and emigrated southward along the Persian Gulf into Arabia, of which they occupied a very large part, and from its southern part crossed over to Africa to the country which in after times was called by the Greek geographers Ethiopia.

Dr. F. Delitzsch supposes that Havilah was the district lying west of the Euphrates and reaching to the Persian Gulf, and that the Cush of the text was the land adjoining on the east, having the present Shat el-Nil for its border line. The long stream west of the Euphrates, which was known to the Greeks as Pallacopas, Dr. Delitzsch considers as the Pison, and the Shat el-Nil as the Gihon (see the map). The Garden of Eden he places at that part where the Euphrates and Tigris approach each other very nearly, being at that place only twenty-five miles apart.5

4. In the Garden of Eden the Lord God put the first pair. Of the man it is said that he was placed in the garden “to dress it and to keep it;” and of the woman, that she should be “a help meet for him.” How long this state of things continued is not related, but, through the serpent, temptation entered into the mind of Eve, and she gave of the forbidden fruit unto her husband and they did eat, “and their eyes were opened,” apparently to the sense of guilt in violating the command which forbade them to “eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.” The curse then followed, and they were driven out from the garden, to which they were never to return.

5. After the expulsion Cain and Abel were born, and the first murder took place in the killing of Abel by Cain, the latter being punished by being driven out “from the presence of the Lord.” Cain went eastward and dwelt in the land of Nod, and his first-born son, Enoch, built the first city, which was named after him, Enoch. Neither the land of Nod nor the city Enoch has been certainly located.

6. We now have an account of the descendants of Adam, with the statement of their several ages. Upon this statement of ages a chronology has been based, usually called the Biblical Chronology. It is derived from that account which is recorded in the Hebrew, the language in which the history was originally written. But there is another account which was given in the earliest extant translation of the Hebrew history, and this is called the Septuagint Greek, made about 286 B. C.; and the chronology of this old translation differs materially from the Hebrew original. There is yet another authority, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the manuscript of which is kept at Shechem, in Palestine, and is the oldest known manuscript of the Bible in the world, having been written before the Captivity and in the old Hebrew letters.6

These are the only three records of any importance, and the variations in these records are seen in the following table:7

|

Lived before birth of sons. |

After birth of sons. |

Total. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEB. | SAM. | SEP. | HEB. | SAM. | SEP. | HEB. | SAM. | SEP. | |

| Adam | 130 | 230 | 800 | 700 | 930 | ||||

| Seth | 105 | 205 | 807 | 707 | 912 | ||||

| Enos | 90 | 190 | 815 | 715 | 905 | ||||

| Cainan | 70 | 170 | 840 | 740 | 910 | ||||

| Mahalaleel | 65 | 165 | 830 | 730 | 895 | ||||

| Jared | 162 | 62 | 162 | 800 | 785 | 800 | 962 | 847 | 962 |

| Enoch | 65 | 65 | 165 | 300 | 300 | 200 | 365 | ||

| Methuselah | 187 | 67 | 187 | 782 | 653 | 782 | 969 | 720 | 969 |

|

Another translation of Septuagint |

167 | 802 | |||||||

| 165 | |||||||||

| Lamech | 182 | 53 | 188 | 595 | 600 | 565 | 777 | 653 | 753 |

| Noah | 500 | ||||||||

It will be seen by the above table that the Hebrew text affords data which give us 1,656 years from the creation of Adam to the Flood, for we must add 100 to Noah’s age of 500, since the Flood began when Noah was 600 years old (Gen. 7:6). The Samaritan text takes away 100 years from the life of Jared, 120 from that of Methuselah, and 129 from that of Lamech, as compared with the Hebrew text, making the Flood occur 1,307 after Adam’s creation, while the Septuagint adds 100 to the lives of each of the first five and to that of Enoch, and six to that of Lamech, making the Flood begin 2,262 years after the creation of Adam, according to one reading of the Septuagint, or 2,242 according to another.

So that the aggregates of time from the Creation to the Flood, as deduced from the Hebrew, the Samaritan, and the Septuagint, severally are 1,656, 1,307, and 2,262. The Samaritan is the oldest manuscript, but it cannot be made certain that the dates as given in that manuscript have suffered no alteration; and hence the Hebrew account has been followed in our entire English version, the chronology of which was arranged by Archbishop Ussher (usually written Usher), A. D. 1580,8 but it “is of no inspired authority and of great uncertainty.”

7. The subject of Biblical Chronology, as derived from data recorded in the Scripture, is necessarily unsettled; and this is so partly because9 the sacred writers speak of descendants of a given progenitor as his sons, in accordance with Eastern custom, and partly perhaps from the use of letters, for figures, in the early manuscripts,10 which have suffered changes in subsequent transcriptions. But although these variations occur, discoveries connected with the remains of other nations than the Jewish, and connected with other histories than the Jewish, are beginning to throw light upon the Scripture history and chronology.

These collateral histories allude to persons and events of Jewish history and afford such data that in many instances we can determine from them the actual year of Scripture events. This aid is particularly important as derived from both Assyrian and Egyptian discoveries, and this we shall have reason hereafter to show.

1. In the earliest periods of human history names, either for persons, places, or things, had meanings which were in some sense applicable to the person, place, or thing named. This was specially true in Hebrew history, and of this we have already had illustrations; for when Eve was brought to Adam “he called her name woman, because she was taken out of man,” but afterwards, because Eve in the Hebrew meant life, he “called his wife’s name Eve, because she was the mother of all living.”

Adam’s name denoted his relation to the ground (Hebrew, Adamah), from the dust of which he was taken; and as Eve’s body was derived from that of Adam, the name of the two was Adam (Gen. 5:2), which was the name given by God “in the day when they were created,” and this name was exclusively the description of the first man and the first woman.

In Gen. 2:23 we have the generic name given to the race in the Hebrew terms “Ish” and “Ishah” for “man” and “woman,” given by Adam to himself and to the woman: “This is now bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh: she shall be called woman (Ishah), because she was taken out of man (Ish).”

2. The root, or primitive meaning, of Ish is uncertain, but from its subsequent use we may infer that it denoted a characteristic of humanity higher than that expressed by the word Adam, and may have occurred to the father of men while naming the animals as an appellative distinguishing his own from the inferior order of the animate creation.11

It is remarkable that the ancient Assyrian name for the first man is Admu or Adamu, the Assyrian form of the Hebrew Adam.12

3. In the Hebrew history, therefore, names are not to be regarded as mere sounds or combinations of sounds, attached at random to certain objects or persons, so as to become the audible signs by which we distinguish them from each other, but very frequently proper names had a deeper meaning and were more closely connected in men’s thoughts with character and condition than among any other ancient nation with the history and literature of which we are acquainted.13 Thus it is that, as Archbishop Trench says, words are often the repositories of historical information.14

1. As the history proceeds it becomes very plain that the descendants of Adam are selected with a purpose, which a general acquaintance with Scripture reveals. That purpose was to record the ancestry of Abraham and so of the children of Israel. Other descendants are occasionally mentioned when any interesting or important event suggests itself to the historian, but the main purpose is never lost sight of.

Thus the descendants of Cain are briefly enumerated through his first-born, Enoch, “the teacher,” as his name signifies. He was the first builder of a city, and may, as Geikie suggests, have been the first to teach men “the culture of city life,” or “the elements of physical life.”

2. His descendants were Irad, “the swift one,” perhaps because of his hunter’s life; Mehujael, “the stricken of God,” for some unrecorded transgression; Methusael, probably bearing the name God in the syllable “el,” and meaning “champion of God,” suggesting some religious act; as if, even among the race of Cain, God “had not left himself without a witness.”15

3. But we find Lamech, “a wild man,” who first introduces polygamy, for ever hereafter to be associated in origin with the race of Cain. One of his two wives was named Adah, a Hebrew term for “ornament,” and is found in the compounds Adaiah, “whom Jehovah adorns,” and Maadiah, “ornament from Jehovah.” There must have been a personal attraction which made the name appropriate.

4. In the other wife’s name, Zillah, it has been supposed that the termination “ah” has reference to the name of Jehovah; it is more probable, however, that the meaning is confined to the root of this word, which signifies “a shade.” To her son, Tubal-Cain, we are indebted for the first work in copper and iron, as the sentence “instructor of every artificer in brass and iron” means. Perhaps we may say “bronze” for “brass,” since brass is a compound of zinc and copper, and bronze is a compound of tin and copper, and the latter has been discovered in the most ancient ruins, which has not been true as to brass. Brass, however, is used in Scripture in some instances as the name for copper.16 Chisels have been taken from ruins in Egypt containing copper 94 per cent., tin 5.9, and iron 0.1; and a bowl from Nimrud, about twenty miles south of Nineveh, was composed of copper 89.57 per cent., and of tin 10.43. In the sepulchral furniture with which the oldest of the Chaldæan tombs were filled we already find more bronze than copper.17 The excavations at Warka, the ancient Erech of Gen. 10:10, ninety-five miles southeast of Babylon, seem to prove that the ancient Chaldæans made use of iron before the Egyptians.18

5. The name given to Jabal, the son of Adah, suggests that he led a pastoral life with his cattle. His name means “wanderer,” and hence he was very appropriately “the father of such as dwell in tents.” “His brother’s name was Jubal; he was the father of all such as handle the harp and organ;” the latter name suggesting some wind instrument or pipe. His name significantly means “the player.”

6. To this list of “first things” may be added the first instance of poetical utterance, for the address of Lamech to his wives is in the form of the earliest Hebrew poetry. Gen. 4:23.

Adah and Zillah, hear my voice,

Wives of Lamech, hear my speech.

I have slain a man for wounding me,

A young man for hurting me.

If Cain shall be avenged seven-fold,

Surely Lamech seventy-and-seven.

With this ends the history of the descendants of Cain. The history of those descendants of Adam through whom the children of Israel traced their lineage is begun in the fifth chapter of Genesis.

1. Ten generations are given, from Adam to the Flood, and the remarkably long lives of the Patriarchs have suggested to many the probability of error or misunderstanding. Some have supposed that each name represents a tribe, the lives of whose leading members have been added together. Others have understood the years to mean only months, and others that numbers and dates are liable in the course of years to become obscured and exaggerated.19

2. But as to all these opinions it must be remembered, First, that the era from the creation of Adam to the Flood, 1,656 years, is to be divided by the number ten, the number of the Patriarchs, which would require an individual length of life much longer than that enjoyed at the present day; and, Secondly, no scientific reasons can be offered why human life should be limited in duration to its present length. It varies now according to the contingencies of accident and disease, and old age itself may be only a modified form of disease and not essential to a human organism. A clock made to run twenty-four hours is expected to run down in about that time, but the clock-maker may, by adding one wheel, or to the length of the weight-cord, or by some other very simple rearrangement, make the very same clock run a week or a month. It is only a question of life, about which, as to its nature, we know little or nothing. Thirdly, as to the historic probability, it is a fact that traditions other than those of the Hebrew nation represent that in the earliest ages there was an enjoyment of exceedingly long lives. The chronology of Berosus, a Chaldæan priest and historian, B. C. 279 to 255, gives to the ten Babylonian kings who in the earliest traditions of that people reigned before the Babylonian deluge 2,221 years, or only 21 years less than the period given in the Septuagint as having elapsed between the Creation and the Deluge.20 The earliest Aryan tradition states that the first man lived 1,000 years in Paradise.

Other nations have kept the same tradition of long lives in the earliest times, which nations could not have received the tradition from the Scriptures.

3. But there is a probability arising from the fitness of long lives, and that is seen in the necessity of a history which could thus be obtained by tradition when no written language existed. It will be seen that from Adam to the Flood tradition was delivered through only one person, so that Lamech could repeat to Noah what Adam had narrated to him of all the dealings of God in Eden and after the expulsion. Although Lamech lived during the lifetimes of all the Patriarchs down to the Flood, which took place 1,656 years after the creation of Adam, he himself was only 777 years old at death. Thus we see that tradition was more trustworthy then than at any time since.

4. Moreover, Shem lived nearly a century before the death of Lamech, who could have narrated the story of Eden and the trials and experiences of his after-life, as well as the history of the Patriarchal times, to Shem, who was alive in the times of Abraham and his son Isaac. By that time writing was invented, and doubtless much of the history of the times before and after the Flood had been committed to writing, which was invented several centuries before the death of Shem, as we learn from the ancient Chaldæan records.

5. After the Flood long lives continued, but in much shorter terms, Arphaxad, Salah, and Eber each lived about four centuries, and each of the next three patriarchs lived over 200 years, and it was not till after the time of Judah, seven centuries after the Flood, that the length of a human life was reduced to about a century.

1. The Scripture statement of the occasion of the Flood is very brief. It is made plain, however, that the wickedness of men was so great that “the earth was filled with violence and corrupt before God.”

2. Noah was commanded to prepare an ark for his own safety and that of his family; and he was also directed to provide for the preservation of a large number of “fowls, cattle, and creeping things.”

3. Between the time of the announcement of the divine intention to destroy “man whom he had created” and the occurrence of the Flood God gave a warning era of 120 years, at the close of which the Flood began. “The waters prevailed upon the earth 150 days.” After this time they were abated, and gradually retired till the earth was dry, and Noah and his family left the ark in which he had remained twelve months and ten days, or from the six hundred and first year, second month, and seventeenth day to the six hundred and second year, second month, and twenty-seventh day of Noah’s life.

4. An interesting fact may here be stated. A few years ago there were discovered by excavations at the ancient site of Nineveh, on the Tigris, the palace of Assur-bani-pal, in which had been stored some 10,000 tablets of a library gathered by this king B. C. 968. These tablets were shipped to the British Museum, of which George Smith, the Assyriologist, was librarian, and a large number of them translated. Among these tablets was found a record of the Deluge, which was read by Mr. Smith in December, 1872, before the Society of Biblical Archæology in London.

5. The record states that the tradition recorded is copied from a more ancient account which was in existence in the times of a king of the city of Accad (Gen. 10) many years after the time of Nimrod, who founded it. The remains of this city have been recently discovered forty-three miles north-northwest from Babylon.

The name of the king of Accad was Sargon I., whose date appears from the monuments to have been about 3800 B. C. This Chaldæan history of the Deluge is so similar to that of the Scriptures as to leave no doubt that both record the same fact.

6. The simple narration as it occurs in Genesis is so free from the irrelevant and unnecessary additions of the Chaldæan account as to show that the Biblical account is a record of true history. As the Chaldæan account is dated long before Abram left Chaldæa, and hence long before the birth of Moses, it could never have been derived from Scripture, and proves that a tradition of such an event as that of the Flood must have existed very early in the history of the race.

1. Although the tradition of the Flood seems to have reached to almost every nation, it has been referred locally to some part of Western Asia, and particularly to that part known as Armenia. The Scriptures tell us that the ark rested upon “the mountains of Ararat,” Gen. 8:4, not upon any particular mountain called Ararat, as it has been assumed.

2. The word Ararat is found in the Assyrian inscriptions for Armenia.21 A mountain 500 miles north of Babylon is called Mt. Ararat by travellers, and seems first to have been announced as the “Mt. Ararat” in A. D. 1250, as Bochart says.

The other claimant is 50 miles north of Nineveh and is called Mt. Kudur, the meaning being “the great ship.”22 This view is supported by older historians, such as Berosus and others. The Mt. Ararat of present travellers is a solitary double peak, called Mt. Massis by the Armenians, which rises 17,500 feet above the sea.

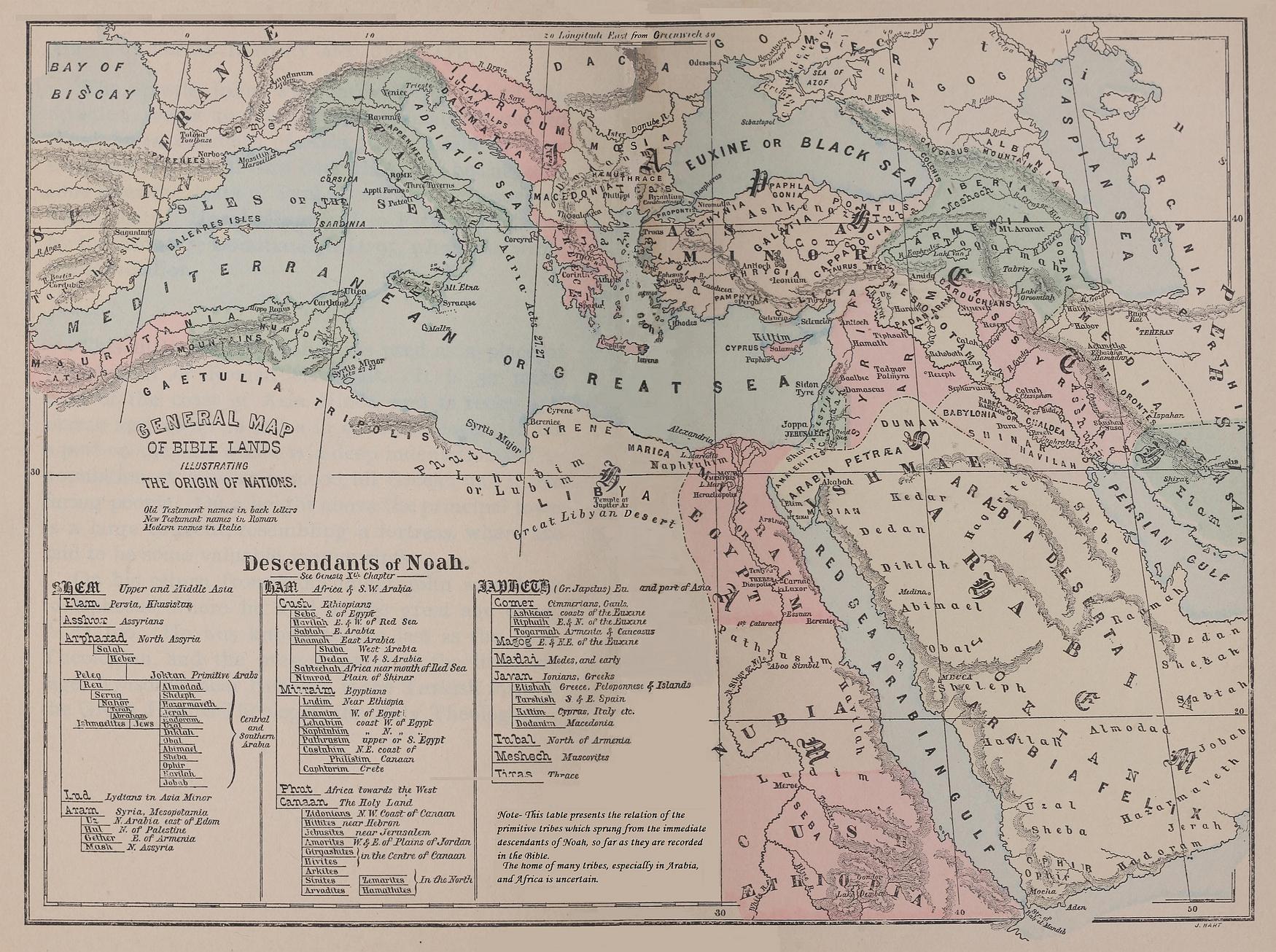

3. The tenth chapter of Genesis is considered one of the most remarkable chapters because of the aid it affords in tracing the early emigrations and distributions of the race. In this chapter the descendants of the three sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth, are given. The descendants of Shem are known among scholars as Shemites or Semites, as those of Ham are known as Hamites. Although Shem is named first in order, Japheth is called the elder (ver. 21), and the genealogy begins with him.

4. (a) Gomer. These were the Cimmerians of antiquity, the Cimbri of Roman times, and the Cymry or Celts still existing. Their ancient country was north of the Black Sea, including the Crimea and the shores of the Sea of Azov.

The name Crimea is a corruption of the ancient name. It is to this north land Ezekiel refers in chap. 38:2, 6. A part of them went southward to Asia Minor when driven out by the Scythians, and some emigrated to the west of Europe and to Britain. The Welsh call themselves Cymry. “The sons of Gomer” were “Ashkenaz, Riphath, and Togarmah.”

5. Ashkenaz. The name means “THE HORSE MILKERS,” and suggests some race of a wandering tribe of the same general country of the Cimmerians or of that land northeast of them. The names Ascanius, a river and lake in Asia Minor, and Scandia and Scandinavia, suggest that they may have entered Phrygia, as Bochart supposes, but the associations are uncertain. They seem in later times to have in some degree returned to a region near Armenia, since Jeremiah associates them with Ararat, Jer. 51:27.

6. Riphath seems to be suggested by the name of the Rhiphæan Mountains in the distant regions of the north of Scythia. More probably we may find some intimation of their presence near Armenia in the name Riphates, which is that of a mountain range in that vicinity.

7. Togarmah is supposed to be represented by the tribes of the Caucasus, Georgians and Armenians, who call themselves “the House of Torgona,” the latter word being the same as Togarmah.

8. (b) Magog, the name of the second son of Japheth, was also the name of a country. Slavonic tribes in the north and northeast of Europe are supposed to be comprehended under this term as descendants from the grandson of Japheth, and the original country of Magog was the Caucasian Mountains and the country around the northern part of the Caspian Sea.

9. In the time of the prophet Ezekiel they had become a powerful people and had overrun the north of Europe. The Russians are, and the Scythians were, the descendants of Magog, and Gog is the “prince of Rosh,” of Meshech, and of Tubal. They are described by Ezekiel, chaps. 38:15 and 39:3, as a wild race of mounted men armed with the bow. This seems also to describe the Scythians who invaded Palestine B. C. 625, and left the evidence of their presence in the city called Scythopolis, formerly Beth-shean, now Beisan, on the Jordan.23

10. (c) Madai is the name by which the Medes are known on the Assyrian monuments. Their country was south of the Caspian Sea.

11. (d) Javan was the progenitor of the Greeks, and the name occurs on the Assyrian monuments as Javanu; a term also used by Darius, the Mede.24

12. The sons of Javan were: (1.) Elishah, who settled in the northwest of Asia Minor from the Propontis eastward throughout Mysia and Lydia and the adjacent islands. (2.) Tarshish, supposed to be the ancestor of the Etruscans who inhabited the northern part of Italy; but the name as it occurs in Isa. 23:6‒10; Ezek. 27:12 and 38:13, seems to refer to a city on the southern coast of Spain whither Jonah attempted to escape. Jonah 1:3. (3.) Kittim. This name is afterwards spelled Chittim, but it is the same word in the Hebrew text. It has the plural ending (im), and therefore refers to a people of that name. In Isa. 23:1, 12, Chittim refers to the island of Cyprus; but when “the isles of Chittim” are mentioned, as in Jer. 2:10 and in Ezek. 27:6, the phrase includes the island of Crete and the islands along the coast of Asia Minor and the Ægean Sea, thus embracing a great sea district, with probably all Greece. In Dan. 11:30 Chittim includes Macedonia, because of its supposed settlement from the former, as Bochart shows.25

(4.) Dodanim is the same as Rodanim, which is also in plural form, and refers to the Greeks of the island of Rhodes, which is particularly one of the islands of Kittim or Chittim.

13. The other sons of Japheth were: (e) Tubal and (f) Meshech and (g) Tiras. Of these Tubal and Meshech appear as tribes neighboring with the Scythians and other northern tribes, and perhaps remained about the southeastern parts of the Black Sea. The Tubal of Isa. 66:19 was, as supposed, in Spain; but a tribe called Tyrrhenians in later times settled the islands of Lemnos and Imbros.26 The name is supposed to be derived from the turreted walls by which the early Tyrrhenians surrounded their fortifications, and not from Tyre, as some have said; this Bochart shows. Tiras is supposed by some to represent ancient Thrace, but this is doubtful, as the people seem to have been associated with the Achæans, Lydians, Sicilians, and Sardinians fourteen centuries B. C., in an invasion of Egypt, as Chabas shows.27 They seem in remote antiquity to have been seafarers and pirates upon the Italian seas and Greek Archipelago.28

1. (a) Cush was the first mentioned son. Dr. Franz Delitzsch has shown that the Assyrian monuments now prove that Cushites settled in the early ages of the world near the northwest of the Persian Gulf. They afterwards migrated southward along the western shore of the Persian Gulf and onward to the south and southwest of Arabia. Some of these crossed the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb to Africa, and there established themselves in that part now known as Abyssinia, and called first by the Greek geographers Ethiopia.

2. The Hebrew name Cush is translated Ethiopia twenty of the twenty-one times it occurs in the Scripture. There can be no reasonable doubt that in the first mention of the word Ethiopia in Gen. 2:13 the region northwest of the Persian Gulf is meant. In after ages the Cushites had established themselves in Arabia, and the inhabitants in that region were called Cushites, or as it is in our English translation, “Ethiopians,” as in the case of Moses’ wife, who is called an “Ethiopian woman,” Num. 12:1, but it is “Cushite” in the Hebrew.

The varying meanings of the name Cushite afford an indication that all these passages of Scripture could not have been written in the same period of time.

3. The earliest monuments in Egypt make a strong distinction between the Ethiopians south of Egypt and the negro races, for although the Ethiopians were of a dark or dusky skin, they had straight hair, thin noses, and the form of the head of different shape. It is not apparent that any reference in Scripture is made to the negro race as such; the passage in Jer. 13:23, “Can the Ethiopian change his skin?” may apply to the dark Ethiopian and not to the negro, whose native land was west of Ethiopia.29

4. Five races spring from Cush: Seba, Havilah, Sabtah, Raamah, and Sabtecha. These have generally been referred to large tribes settling in Arabia. From Raamah we have the nations Sheba and Dedan. These have been located in Arabia, and it was the queen of the former who visited Solomon, 1 Kin. 10:1 and 2 Chron. 9:1. Dedan was a district north of Sheba, and its inhabitants seem by caravans to have traded and settled northward until the time of Abraham, Gen. 25:3, when their descendants were numerous enough to be known by the old name of their ancestors.

5. Cush begat Nimrod, whose exceptional prowess and enterprise gave him precedence over all his brethren. He was a mighty hunter upon the plains of Babylon, and from the monuments of Assyria it seems that the lion was the chief object of his hunting expeditions. He was the founder of some of the earliest cities. The first mentioned is Babel, afterwards called Babylon by the Greeks, which was built upon the Euphrates.

6. At that early time this city was about one hundred and seventy-five miles northwest from the head of the Persian Gulf, but it is now three hundred miles, the land having been extended southeastward by the annual deposits brought down by the rivers Euphrates and Tigris. Erech, the second city of Nimrod, was seventy-five miles northwest (now 200) of the same gulf; Accad, recently discovered by Rassam, was forty-five miles almost due north from Babylon; and Calneh about fifty miles southeast of Babylon; it is now called Niffer.

7. The land of Shinar was the district corresponding with that now known as the land of Chaldæa. “Out of that land went forth Asshur and builded Nineveh” is the statement made, and the monuments recently discovered have remarkably corroborated this text, for the history shows the importance of Asshur, and that Nineveh, which was the capital of the Assyrian kingdom, was a more recent city than Babylon.30 Its ruins are two hundred and seventy-five miles north by west from Babylon and upon the Tigris River.

8. But it will be seen that Asshur was a son of Shem, while Nimrod was a son of Ham, and recent discovery has sustained the distinction, showing that another people preceded the Assyrians and Babylonians which were not descendants of Shem. In connection with Nineveh are mentioned “the city Rehoboth”31 and Calah: the former is not known, and the latter is supposed to be at the ruins nearly twenty miles south of Nineveh, now called Nimrud, and a few miles north of the latter is supposed to be the site of Resen.

Further excavations are needed to attest the accuracy of these identifications.

9. (b) Mizraim is mentioned as the second son of Cush, and is supposed to have colonized Egypt. The word is in the dual form and indicates the double land of Egypt, which from the earliest times was divided into Upper and Lower Egypt.

(1.) Mizraim’s descendants are Ludim, probably simply a name for the Egyptians themselves; they held themselves “the best of all men,”32 and they were the same as Libyans or Lubim, 2 Chron. 12:3; 16:8; Nah. 3:9. The Libyans of the most ancient era inhabited the west of the Nile and parts near the Mediterranean Sea. They appear of bright complexions as represented upon the Egyptian monuments.

(2.) “Anamim and Lehabim and Naphtuhim and Pathrusim” appear to be only names of the people of the different settlements along the Nile and not distinct races. (3.) The Casluhim have been identified with a people settling east of the Delta near the Mediterranean coast towards Palestine, and seemed to have been of Phœnician origin (Ebers). (4.) Caphtorim were the earliest settlers on the coast of the Delta or on its Mediterranean shore, even before the Egyptians occupied that part of Egypt (Ebers). The Philistines of Palestine (southwest coast) were descendants of both Casluhim and Caphtorim. “Kaft” was the Egyptian name of the latter people, who early settled in the island of Crete, but also, as we have stated, on the seacoast of the Nile, and gradually moved through the lands of the Casluhim to their final resting-place in Palestine.33

10. Thus the passage in Amos 9:7 is explained by the discovery that the Philistines came from Caphtor (Crete), but they passed through the land of the Casluhim. This explains Deut. 2:23, wherein the inhabitants of Azzah (or Gaza) are called Caphtorim, but more distinctly in Jer. 47:4, “the Philistines, the remnant of the country of Caphtor.” So that the Philistines, who came originally from Crete (Caphtor), settled on the Delta coast, and thence passing through the land of Casluhim, settled in Philistia, as Ebers has shown.34

11. A migration of the earliest Phœnicians to the coasts of the Delta is generally accepted as leading to the invention of the alphabet, for these settlers soon learned the new form of hieroglyphics (called the hieratic or priestly form), and afterwards improved these signs, as in the Phœnician alphabet. The most ancient manuscript in hieratic is referred to an age in the third millennium B. C., or perhaps about 2500 B. C. In the trading intercourse between Egypt and Phœnicia this new form was introduced into Phœnicia, where the full alphabetic forms were originated. Wise men of that day must have very generally adopted the improved letters, and in the course of the centuries, but certainly before the time of the Exodus, the alphabet on the Phœnician model was well formed. De Rougé has shown that the Phœnicians adopted these hieratic forms long before the Exodus.35

12. This alphabet must have been known to Moses, and perhaps to all the elders of Israel, and became that Hebrew alphabet which furnished the source of the lettering of the law and its accessories.

The similarity between the old Hebrew and the Phœnician letters has been fully shown in the discoveries of tablets near Tyre and in the Moabite stone, so called, which was discovered at some ruins east of the Dead Sea, upon the site of the ancient Dibon. It is probable therefore that the first elements of the alphabetic form of letters were invented about this era of the world’s history, when the Phœnicians began their trading with the races upon the shores of Egypt, which we have last mentioned.

13. The next son of Ham is (c) Phut. The hieroglyphics of Egypt represent the nation east of the Red Sea and along the northern half of the coast as the people of Punt, and this people is supposed to be meant by Phut or Put. They traded in incense and turquoise (a blue mineral not so hard as quartz but as heavy). They were a wandering tribe of a dusky hue, but entirely distinct from the Cushites on whose confines they dwelt.

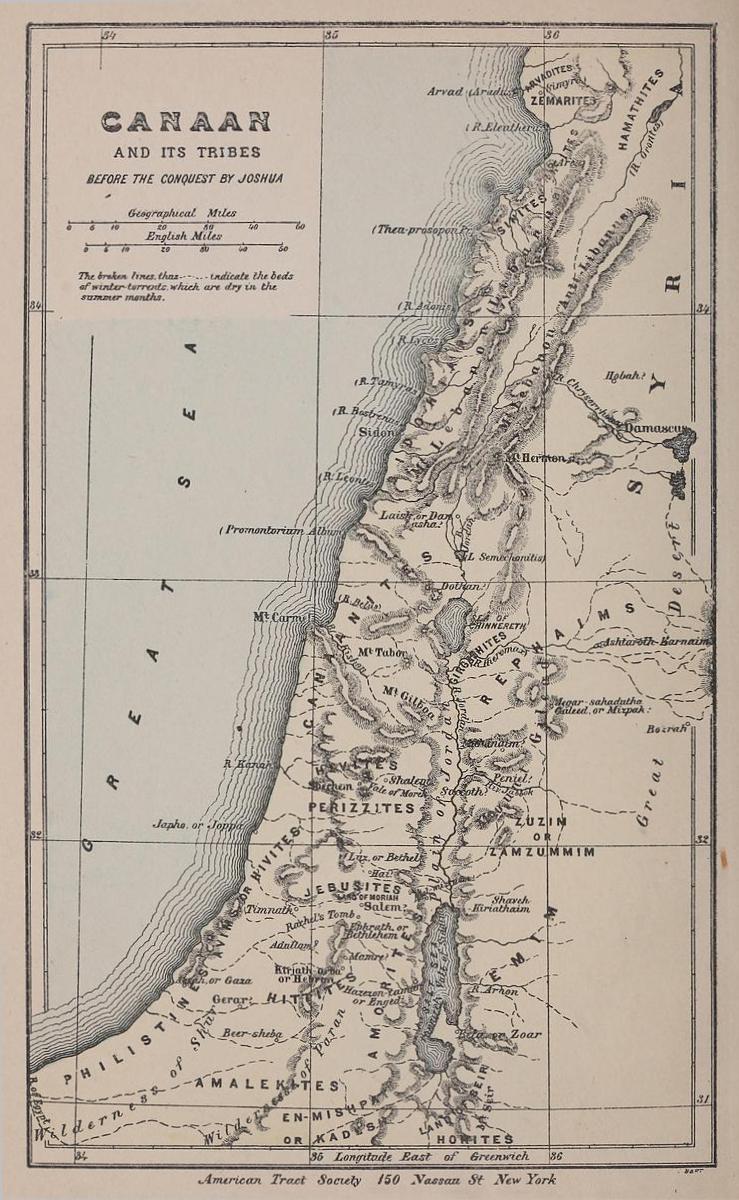

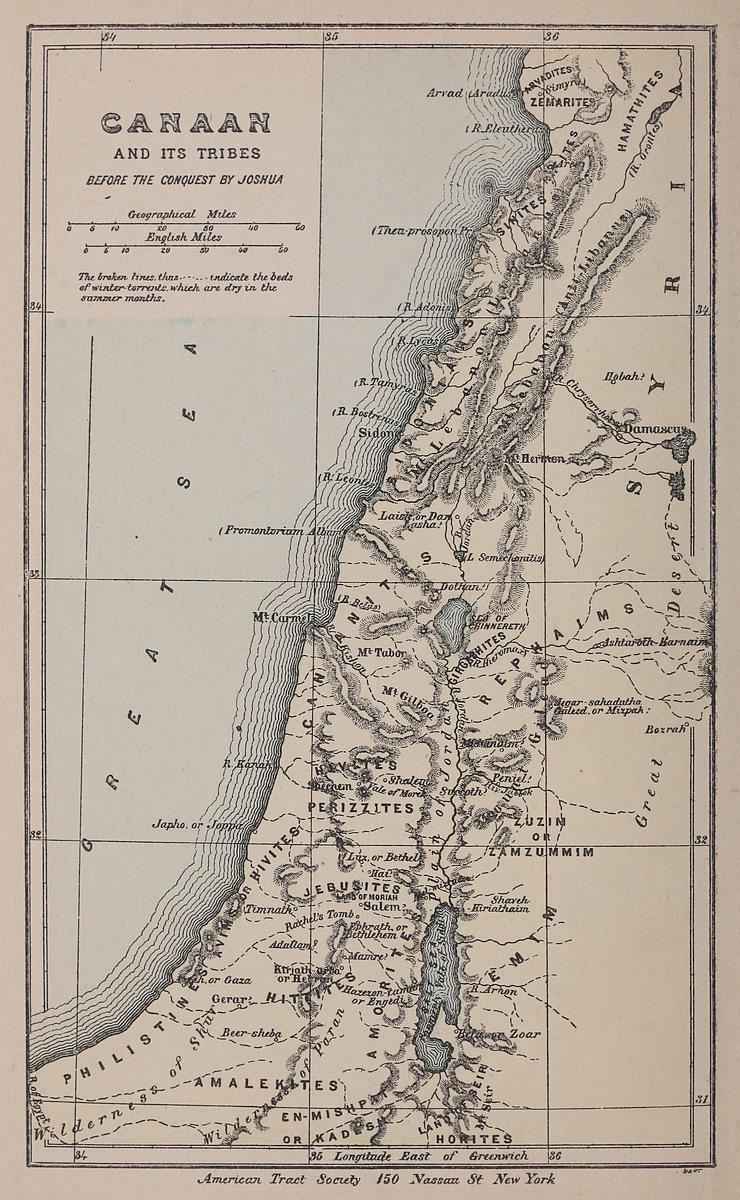

14. The last mentioned descendant of Ham was (d) Canaan. He begat Sidon, the firstborn of eleven heads of tribes or nations. Sidon became in after centuries the name of the chief city of Phœnicia. The rest of the descendants of Canaan formed the Canaanites.

15. A very important fact should be noticed here. These Canaanites spoke a Shemitic language, but they were, as here seen, descendants of Ham through Canaan. Recent discoveries show that long before their settlement in the land of Canaan they are met with first in Southern Arabia, from whence they made their way northward to certain islands in the Persian Gulf, their next resting-place being on the flat shores of the Persian Gulf at the mouth of the Euphrates. They then emigrated to the shores of Phœnicia, carrying the name Canaan, or, as they pronounced it, Chna, “the low-lying,” to their new inheritance on the shores of Phœnicia. Their associations were Shemitic and their language also, although they were by descent Hamitic.

The temples still standing in the times of the Romans upon the islands in the Persian Gulf were Phœnician, and the inhabitants claimed to be the original stock of the famous race of Palestine.36 “Canaanite” in after times became the term used to signify a merchant or trader, from the habits of the people.37

16. The people of Heth, another son of Canaan, became in later times a very powerful nation, whose history has only recently been brought to light. Their name as Hittites has been found in the Egyptian records, from which it is shown that at one time, so early as that of Moses, they were sufficiently powerful to resist the forces of the king, Rameses II., of Egypt. On one of the Egyptian monuments they are represented as making a treaty with the Egyptian monarch which was as favorable to them as to him, B. C. 1333 (Brugsch).

17. Sidon, the city of that name, was early a fishing station of the Phœnicians on the coast of the Mediterranean west of the Lebanon Mountains, twenty-two miles north of Tyre. This place, now in existence, yet bears the name of the ancient son of Canaan.

18. The Canaanites were “spread abroad” over what is now known as Palestine, from Sidon to Gaza and Gerar, “as thou goest to Sodom and Gomorrah and Admah and Zeboim, even unto Lasha,” Gen. 10:19. Gaza is well known, being 150 miles southwest of Sidon and about two miles from the shore of the Mediterranean, and is now a town of 15,000 inhabitants. Sodom and Gomorrah are not certainly located, being by some supposed to have been at the south end of the Dead Sea, but by others at the north end. Neither of the remaining names can be identified with any known sites. But it is plain that the Canaanites occupied the whole of Palestine west of the Jordan and as far north as the Lebanon Mountains, the Arvadites and Hamathites extending beyond them more than 130 miles north of Sidon. See the map.

1. The descendants of Shem are next given: (a) Elam was north of the Persian Gulf and east of the Tigris; Shushan was its capital in later times. (b) Asshur was the origin of the name Assyria. The Assyrian monuments show that Nineveh was built after Babylon, and that the Assyrians were a later people than the Babylonians and derived their literature from them, and also that they were a Shemitic nation. (c) Arphaxad was settled north of Assyria on the table-land between Oroomiah and Van. (d) Lud appears to be represented by Lydia in western Asia Minor, though at first it was a wider district. (e) Aram settled in Syria near the Upper Euphrates, and as far west as the Upper Lebanon Mountains north of Palestine, which we learn from the Assyrian inscriptions. The four children of Aram are Uz, Hul, Gether, and Mash. Uz is thought to be the district east of the Jordan known as the Hauran, parts of which are very fertile. This was the land of Job, and is reckoned in Arabia by Josephus.38 The remaining three names are associated with the following lands: first, Hul, with el-Huleh, a region in Northern Palestine, at the head-waters of the Jordan; second, Gether, with the district of Ituræa between the waters of the lake el-Huleh and Uz; third Mash, with a site known as Maisel Jebel. But these identifications are only probable.

2. Arphaxad had a son Salah who begat Eber, whose descendants were the ancestors of Abraham through Peleg, in whose days “was the earth divided.” Peleg appears to have settled near the Euphrates, since a city named Phaliga once existed at the place where the river Chaboras falls into the Euphrates from the east.

3. The descendants of Peleg’s brother, Joktan, thirteen in number, seem to have found their early settlements in Southern Arabia and as far south as Isfor on the southeast coast, which is supposed to represent the Sephar of the text, Gen. 10:30.

This closes a table which is generally considered to be the most important as well as the most ancient list of nations in existence.

4. This history is contained in the book of the same name. The author of this book is not known. It may have been written by Job himself. The history is that apparently of a chief who lived in the land of Uz, which was probably in the region we have already described. Many think that the land of Uz was in Northern Arabia or in Idumæa.

5. Job, according to one writer (Wamys) was an Arabian prince, who is represented as living in his family and enjoying a life of unalloyed prosperity, the consequence of his exemplary piety and rectitude. Suddenly the scene changes, and this excellent man is visited by a series of overwhelming calamities, which are the result of a transaction which passed in the council of the Most High, into the secret of which the reader is for the moment admitted, as stated in Job 1:8‒13. During his affliction Job is visited by his friends. Instead of comforting him, these friends ascribe his calamities to some great sin, for which he is now punished. Job’s friends affirm that great suffering is a proof of great guilt, and exhort him to repent and confess.39 Job denies this, Job 4:5‒31:40. At the close of their dialogue another and younger friend of the patriarch intervenes to modify the view taken by the others.

6. At length the Lord condescends to interpose in the controversy. From the midst of a whirlwind, in words of incomparable grandeur and sublimity he silences the murmurings of his servant, bidding him reflect on the glory of creation and learn the stupendous power and wisdom of Him whose purposes are good, though unexplained, and with whom it is useless for a created being to contend. Thereupon Job acknowledges his error, and the whole party are convinced of forming false estimates of the Lord’s administration. Job is restored to prosperity and prays for his friends, who are accepted in their offering and received back into favor.

7. The book of Job, from internal evidence, is probably one of the earliest productions of Biblical literature. The names of his friends, the Temanite and the Shuhite, and the mention of the Sabæans, indicate the Idumæan parts of Northern Arabia as the scene of the history. The long life of Job, which appears to have been about 200 years, indicates a period in the second or third century following the Flood, or before the time of Abraham. But neither the date of the composition nor the location of Uz can be settled any further than we have already stated.

One of the proofs of the very early origin of this composition is found in its reference to the ancient seal, Job 38:14, which was rolled over the clay, covering it with figures; hence the illustration used in the above passage. The cylindrical seals were used in the early Babylonian era.

1. The next subject which is presented in the sacred text is the confusion of tongues at the building of the tower of Babel, Gen. 11:1‒10. In this passage of the Scripture history we have an extremely condensed view of an event which must have been one of greater importance than would appear from the very concise manner in which it is described. All that we know from Scripture is that a certain part of the human race coming from the East settled upon the plains of Shinar, and there began the erection of the highest known tower, with the purpose of making themselves a name before they were “scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.” They began the tower, using brick from the clay which abounds upon the plain of Babylon and bitumen, called “slime” in the text, for mortar. During the building of this city and tower their language, which up to this period was the same, became confused, so that, being unable to understand each other, they were forced to desist, “and they left off to build the city.” This is the brief history.

2. From the recently discovered Assyrian history, recorded upon the tablets now in the British Museum, it appears that the Babylonians of the earliest ages had a tradition of this tower and of the sudden confusion of tongues. The event seems to indicate that the determination of the early descendants of Noah, probably under Nimrod or his immediate successors, was to settle on the plains and build a vast metropolis and a tower, whose height should serve the double purpose of a means of direction or as a guide to the city, and also of an advertisement of their immense wealth and enterprise amid the surrounding tribes.

3. The divine intention was, however, that the command given to Noah and his descendants, that they should replenish the earth, should be literally executed, and it was the divine intervention which prevented all the people from remaining in that land.

As we have said, the word Babel in the Greek form is Babylon; but the word which originally meant “confusion” in the Hebrew seems to have been changed from that form originally given it into Bab, or “gate,” el, of “God,” for the actual original Hebrew word for “confusion,” as Buxtorf shows from the Rabbinical word for “confusion,” is Bilbal, or Bilbul. Oppert40 has shown that the word is distinctly of Assyrian derivation, from Balal, to “confound.” Similar changes from original forms have frequently occurred. Thus Beth-lehem is now Beit-lahm the former meaning “house of bread,” and the latter “house of meat.” Borsippa, the name of the ruined tower near Babylon, supposed to be the Tower of Babel, is now called Bar-Sab, the former (Borsippa) meaning the “tower of languages,” the latter (Bar Sab) meaning the “shattered altar,” as Geikie has mentioned.

4. In studying the early parts of Biblical history the student should be mindful that history and traditions as recorded by the Assyrians were borrowed, or, more truly speaking, derived, from the early records of the Babylonian and Chaldæan nations, as in some cases is stated upon Assyrian tablets. This fact we have illustrated, page 26. The original records were kept at the old Chaldæan city of Erech, 90 miles southeast of Babylon, at the present ruins of Warka. Assur-bani-pal, the Assyrian king, beside being a great warrior, was also one who encouraged literature and had an immense library, for those days, 10,000 tablets from which were removed to the British Museum. In his time, 668‒647 B. C., the ancient Chaldæan tongue was translated into Assyrian, and in this library at Nineveh was a lexicon of the Chaldæo-Turanian language with the meaning of the words put in Assyrian cuneiform.41 This showed that so many years had passed that the ancient Chaldæan language was, at that time, nearly lost.

5. Those records, both of the Chaldæan and of the later Assyrian ages, have not only been of great service to the student of ancient history, but they have added much to the explanation and corroboration of Biblical history, as we shall hereafter have occasion to show.

6. The ruins of both Nineveh and Babylon bear some names which are reminiscences of Nimrod, but these seem to have been applied at some comparatively recent date. The chief structure bearing the name of Nimrod is the Birs Nimrud, or Tower of Nimrod, ten miles southwest of the modern town of Hillah, which is near the ruins of Babylon. The large mass of burned brick at this place seems to have been originally erected in the form of a steep pyramid some six hundred feet in height and of the same length at its base. It is extremely ancient, as its Assyrian name proves, which name, Saggatu, “the high temple,” is an old Accadian word.

7. Nebuchadnezzar, B. C. 604‒562, one of the greatest builders among the Babylonian kings, says of himself that he builded additions to it, although Tiglath-pileser repaired it one hundred years before. It is now a bare hill of yellow sand and bricks a few miles west of the banks of the Euphrates, reaching a height of about 200 feet, a vast mass of brick-work jutting from the mound to a further height of 37 feet. It is very probable that these are the most ancient remains to be found in Babylonia, and in its form seems to have furnished a universal model for all succeeding temples and towers in that region.42

1. The promise that in his seed should all the nations of the earth be blessed renders the history of Abram one of great interest, especially as recent discoveries of the monuments and literature of ancient Chaldæa have given us more correct knowledge of those early ages than had been acquired for more than 3,000 years. In the eleventh chapter of Genesis, beginning at the tenth verse, is given the ancestry of Abraham, the father of the Hebrews. Abram, afterward called Abraham, for reasons stated in chapter 17:5, was the ninth from Shem. Until the birth of Abram his ancestors appear to have lived in the region known as Chaldæa. Abram’s birthplace was Ur, 150 miles southeast of Babylon and a few miles west of the Euphrates. The ruins of Ur include, at the present day, a part of an ancient temple dedicated to the moon. This temple seems to have been erected many years before the days of Abram. A vast number of tombs surround it and the city, in the times of Abram, must have been a place for burial and considered sacred. Eupolemus, a Greek writer who is quoted by Eusebius, speaks of it in his time, about 446 B. C., as “the place of the Chaldees.”43 Its ruins on a vast mound are so largely cemented with bitumen that this fact has given rise to its present name, Mugheir, which means “bitumen.” The tablets and bricks bear the ancient name of Ur as well as the names of its earliest kings and the builder of its temples.

2. Although at the present day the Persian Gulf is about 140 miles distant from Ur, only the deposits from the rivers Euphrates and Tigris have removed the waters of the gulf to this distance. Certain coast marks show that the sea must have sent its waters up the river to a distance of nearly, if not quite, 124 miles, and in the time of Abram Ur must have been a maritime city.

3. From this city Terah, Abram’s father, removed with his family to Haran. This city was 580 miles northwest of Ur on the banks of a small tributary stream which runs seventy miles southward before it joins the Euphrates. Both Ur and Haran were the seats of the Moon-god, called “Sin” in the Chaldee language. This deity was masculine in the same language and the Sun-god was feminine, as is apparent from the omens of that day as seen in the following translations of certain priestly utterances and directions by Prof. Sayce.44

Of the month Elul it is said: He shall make his free-will offering to the Sun, the mistress of the world, and to the Moon, the supreme god.... The fifteenth day is sacred to the Sun, the Lady of the House of Heaven.... The Moon the Lord of the month.

4. In this age we read that the seventh day was “a day of rest,” and the very ancient name for “rest” was very similar to the word Sabbath used in the Hebrew, and special observance of the day was ordered by the priests; thus “the shepherd of mighty nations (king) must not eat flesh cooked on the fire or in the smoke. He must not drive a chariot. He must not issue royal decrees; the lifting up of his hands finds favor with the god,” etc.45

5. It is plain therefore that the seventh day was a day of rest, a sacred day, in the time of ancient Babylonish kings. It was so in the era of earliest Chaldæan records, and it was not an institution derived only from the Jewish nation, but the day was regarded as a Sabbath among the Chaldæans in the time and long before the days of Abram, for the records above translated and preserved in the library of Assur-bani-pal, King of Assyria, as we have said, page 26, were derived from far more ancient records, existing even before the Deluge, of which latter event they give a history. So that the Chaldæan records of the Creation, the Deluge, and the Sabbath may very reasonably have been derived from one and the same source.

6. The name Abram is of Babylonish-Assyrian derivation, but was changed by the Lord into Abraham, which was a purely Hebrew name, as is recorded in Gen. 17:5.46

7. It is not stated how long Terah remained in Ur after the birth of Abram, Nahor, and Haran, but the removal was not made until Lot was born to Haran and until the death of the latter. Then Terah left Ur for Haran, six hundred miles northwest, where they remained probably many years (see Gen. 12:5).

8. The fact that Abram’s name occurs first in the mention of the three is no proof, judging from the Scripture method of naming sons, that Abram was the oldest, but only that he was the most important character, for Shem is mentioned first in the three Shem, Ham, and Japheth, although Japheth is called the elder, Gen. 10:21, Shem being the most important as the head of the Hebrew race.

Abram was probably born when Terah was 130 years old, for it must be remembered that there is no good reason for supposing that the three sons of Terah were born in the same year, but only that one of the three mentioned (Gen. 11:26) was born when Terah was 70 years of age and the two others at some time after. If Abram was born when Terah was 130 and lived to be 75 years old at the death of his father, his father’s age would have been 205 as given in the text. It seems that Haran was the elder of the three, though mentioned last as in the case of Noah’s three sons.

9. Abram, at the call of the Lord, left with a large retinue of servants and crossed the Euphrates and came into Canaan, probably by the way of Damascus. He immediately entered into the land known then as Canaan, and the first place named on his way is “Sichem, unto the plain of Moreh.” Sichem is the place also called Shechem, and the word Sichem is in the Hebrew precisely the same as Shechem, the variation being one due only to the translator of the Hebrew name into English.

10. Shechem is almost exactly half way between Dan on the north and Beersheba on the south. It was therefore not till Abram arrived in the midst of the land that he erected an altar to Jehovah after the Lord had promised that to his seed He would give this land, Gen. 12:7. Various tribes of Canaanites occupied the whole future land of Israel, Gen. 10:19.

11. The plain of Moreh was a mile east of the city, or town, of Shechem. It is evident that both Moreh and Shechem were names of Canaanites, as Shechem is seen in Gen. 33; 34; Num. 26:31; Josh. 17:2, and other places, as a personal name.

12. The word translated “plain” is equally applicable to a grove of trees, and it may be that Abram chose this grove as a shelter from the heat. Twenty-seven miles north of Shechem is probably the hill called in Judg. 7:1, after the same person, the hill of Moreh. The city of Shochen, which exists at the present time, is between the high hills of Gerizim on the south and Ebal on the north.

For the reasons why the word “plain” should be rendered “oak” see Josh. 24:26 and Judg. 9:6, wherein it is evident that a pillar by the oak is meant. Also see that the word “oak” is in the Hebrew exactly the same as that translated “plain” in the text referred to above, Gen. 12:6, and this identical oak seems to have been used for an important purpose many years after. In Deut. 11:30 the name is in the plural, leading us to suppose that it was a grove continuing through many centuries. Groves always were important and sometimes sacred, as it appears from the action of Abraham, for in Gen. 21:33 it is stated that “Abraham planted a grove in Beersheba and called there on the name of the Lord, the everlasting God.”

13. The next place visited by Abram was an unknown place between Bethel and Hai.47 Bethel was not so named until 160 years afterwards, by Jacob, Gen. 28:19. Hai and Ai48 are the same, and this place was probably a Canaanitish town at this time. The distance south of Shechem was 20 miles to the place occupied by the patriarch, where he seems to have remained only to build an altar and then moved on, evidently seeking pasture for his flocks and herds.

14. The name of Egypt occurs now for the first time in Scripture, and we may judge of its importance from the fact that the name occurs six hundred and thirteen times, twenty-four of which number are to be found in the New Testament. In this instance the mention is made about 1920 B. C.,49 and the kingdom is referred to as fully established and well known.

The occasion of Abram’s visit was the famine existing in the land of Canaan. Abram journeys southward with the intention of entering Egypt to provide sustenance for himself and his retinue against this famine.

15. The condition of Egypt at or just before the time of Abram’s first visit was one of great prosperity. The reigning Pharaohs, generally called those of the twelfth dynasty, were most probably the Usertesens and the Amen-emhats. Under this dynasty the sceptres of Upper and Lower Egypt were united. All the kings were powerful and prosperous and art flourished, the Sun temple at Heliopolis (six miles northeast of the present Cairo) was magnificently restored, and in the Fayum on the west of the Nile (about 50 miles southwest of Cairo) the practice of building pyramids was revived. Here was the vast lake or inland sea made by Amen-emhat III., to receive the overplus waters of the annual overflow of the Nile and to distribute them in case of need. This king also built the great labyrinth in the Fayum, the latter name being an alteration of the Egyptian word for “sea,” namely “Piom.”

16. During this period fortifications were erected on the northeastern frontier of Egypt, which appear to have extended across the whole of the present isthmus of Suez (Socin). The term Shur used six times in Scripture is now supposed to refer to this “wall.”50

17. As the pyramids of Gizeh were built in the fourth dynasty (the most recent date of which is given by Wilkinson as 2450 B. C.), they had been in existence more than 400 years before Abram’s visit. The Sphinx was then existing also, as seems probable from an inscription found by M. Mariette, which indicates that there was a “temple of the Sphinx” in the time of Cheops,51 the builder of the great pyramid. It seems also probable that the rule of the foreigners, called the Shepherd Kings, had begun before Abram’s visit.

18. These foreigners took possession of Lower Egypt and drove the original rulers up the Nile to Thebes and other parts of Upper Egypt. Long before this period emigrants from the East had been admitted to Egypt and had settled in various places upon the rich lands of the Delta, until, finding themselves sufficiently powerful, they usurped all authority without a battle. They were called the Shepherd kings, or Hyksos, from what was supposed to be their employment. They governed Lower Egypt for about five hundred years, until they were finally driven out by the Egyptian royal family.

19. Abram’s first visit seems to have been made at or near the beginning of the Hyksos era. The most recent date of the beginning of the rule of the Shepherd Kings is that of Wilkinson, 2091 B. C., and if the date usually given for the visit of Abram was 1920 B. C., then these invaders had already had possession of the land for over 170 years. Egypt was therefore renowned and its rulers were of a race acquainted with the employments to which Abram was not a stranger. They spoke the dialect of Canaan, as it is very evident that many came from the region of Canaan.

20. In this age the horse is not mentioned as in Egypt. Oxen and asses and sheep are found depicted upon the walls and tablets, but the horse does not appear in Egypt till the reign of Thothmes I., who met with them in his wars in Assyria. This king was the third Pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty.52 This dynasty began immediately after the expulsion of the Hyksos. So that while it is probable that the horse might have been known only as a foreign animal, it was introduced into Lower Egypt by Thothmes I., and Egypt became known after this for its fine breed of horses, which took the place of the asses previously used throughout the land. It is for this reason that Abram’s list of animals excludes the horse, Gen. 12:16.

21. The next important occurrence in the history of Abram is that of the first battle mentioned in Scripture. Abram had returned to Canaan with large additions to his herds. This increase brought about a necessary separation between Abram and Lot. Abram settled in Hebron, while Lot chose his residence in the region of Sodom and Gomorrah, the cities of the plain. Soon after four kings from Chaldæa approached Canaan on a tour of conquest, and passing to the south and east of the Dead Sea went down to Mt. Seir and thence to Kadesh, then called En-mishpat, and thence north to Hazezon-tamar. They then met the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah in battle, defeated them, and carried off Lot and others captives. Upon knowledge of this captivity Abram set out to overtake the invaders. He was joined by the forces of the three Amorites confederate with him, and found the kings at Dan, about 140 miles from Hebron northward, as they were leaving the country on their way home to Chaldæa. A battle now took place at night, and the four kings were defeated, and Lot and other captives, together with the stolen goods, were all retaken and brought back in safety.

22. The exact location of these cities has not yet been discovered. They were, with the other cities of the plain, situated very near the Dead Sea, and the traditions place them at the western part of the southern end, where there is a salt hill five miles long, called the hill of Sodom, Jebel Usdum. There are good reasons for supposing that when Abram and Lot stood overlooking the land from the heights near Bethel, Lot chose the region north of the Dead Sea, which was visible, in preference to the southern part, which was more than forty miles distant. But from the Scripture account, considered in view of the evident volcanic nature of this part of Palestine and the fearful earthquakes which have happened in the vicinity in recent times, there is reason to believe that some terrible convulsion not only buried the cities, but submerged the plain at the south end of the sea, and no other interpretation seems to suit the history, which definitely states that the plain and all that grew upon it were destroyed, the water system of the plain being all entirely changed. The submerged plain at the south, therefore, which is covered for the area of about fifty square miles with water only a few feet deep, has given occasion for the theory that the cities of the plain are to be sought beneath these waters, which are by some supposed to cover the vale of Siddim.

23. Hazezon-tamar is the same as En-gedi, 2 Chron. 20:2. It is upon the west shore of the Dead Sea, twenty-three miles south of the mouth of the Jordan. Hobah, whither Abram pursued the kings, is two miles north of Damascus.

24. Abram was near Hebron, twenty miles west of the Dead Sea, when the news reached him of the defeat of the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah and the capture of Lot. Hebron is almost equidistant from the north and south ends of the Dead Sea, at an elevation of nearly 3,000 feet above the Mediterranean, while the waters of the Dead Sea are 1,293 feet below those of the Mediterranean.

25. The recent discoveries in Chaldæa and the surrounding countries show that the names of these four kings—Amraphel king of Shinar, Arioch king of Ellasar, Chedorlaomer king of Elam, and Tidal king of nations, are names which have in large part been found on the tablets and in the history of the countries mentioned. Amraphel is the same in the Hebrew as Amarphal, and it was so translated in the Septuagint made more than 250 B. C. This name was that of a viceroy of Sumir, the district around and south of Babylon, called Shinar in Genesis, and the name Amar-pal has been found “borne by private persons on two cylinders of ancient workmanship” (Lenormant). The Septuagint has for Tidal, Thargal, which seems to be the proper spelling; the difference between the two spellings in the original Hebrew is only that between an r and a d, which in that language is exceedingly small. In the Akkadian (same as Accadian), which was the language used in the ancient Chaldæan times, Turgal meant “great chief.”53 This king was chief of a people called the Gutium in the monumental inscriptions, and this tribe or small nation has been identified with the Goim of the Hebrew text, which in our English version is translated “nations.” So that the “Tidal king of nations,” of the text in Genesis, is shown to be the “great chief” of a tribe living in Northern Babylonia, of which one part became afterwards the nation of the Assyrians.54

Chedorlaomer, the monuments show us, was truly an Elamite name, Chedor, or Kudur, forming part of several names of the early kings of that district, and Laomer, or Lagamar, being the name of a most important Elamite god. The name Arioch is very similar to that of the son of an Elamite king who was king of Larsa, which itself is similar to the Hebrew name Ellasar, and the circumstances have led the best Assyriologists to believe that they are the very same.

26. The monumental records show that this king of Elam, on a previous occasion, when Abram was still at Haran, had passed over the Euphrates and conquered Phœnicia and a country to the south. He is called both king of Elam and king of Phœnicia, as the land of Canaan was called by name “Martu,” “the land of the setting sun,” or Phœnicia. So that 14 years before, at the time when Chedorlaomer crossed the Euphrates on his first expedition, Abram may have beheld the troops of that king whom he afterward conquered, with his viceroys, when they came on their second invasion of Canaan. At that time Abram was with his father Terah at Haran, as we may see from the dates in the context, Gen. 16:3; 14:5.

27. Some years after this battle we have the account of the birth of Ishmael, the son of Abram by Hagar. As the descendants of Ishmael exerted great influence in years afterward, it is well at this point to study the early history of this son of Abram. When Isaac was born Ishmael was about 16 years of age, Gen. 17:21, 25; 21:1, 8, and until the day of the divine promise to Abram, at which time his name was changed to Abraham, he was evidently, from the context, greatly attached to Ishmael. Moreover, Abram was considered by his neighbors as “a mighty prince among them,” Gen. 23:6. Under these circumstances this only son must have been allowed privileges and attentions at the hands of the hundreds of Abram’s servants such as an heir apparent to all the wealth of Abram would be certain to receive. When, however, Sarah became the mother of Isaac a change necessarily transpired. Ishmael was no longer the expected heir. Hagar’s spirit of self-importance, which showed itself before so positively that she was forced to leave the family, was now repeated in some disagreeable actions of her son Ishmael, and, despite the persistent love of Abraham, Ishmael and his mother were summarily dismissed from the family.

28. There can be no reasonable doubt that the action of Abraham in sending Hagar and her son out upon the desert with only sufficient food to support them for a time was greatly or almost entirely influenced by the direct revelation to Abraham that the divine interference would be exerted on behalf of the exiles. That had been assured, as we see in verses 12 and 13 of chapter 21. At the same time both the mother and son, after all the preceding years of privilege, would naturally imagine that a great wrong had been done them, and Ishmael readily became a wild wanderer upon the vast deserts east of Egypt.

He was the progenitor of twelve great tribes whose names in part are recognized among some of the tribes existing at the present day and whose characters are accurately represented in the description of what they were to be, as it occurs in Gen. 16:12, and the expression “he shall dwell in the presence of his brethren” simply alludes to the fact that his race should be wanderers upon the desert without any fixed habitation, this being the life of all the most pleasurable to the desert Arabs.

29. As Abraham was 99 years of age when Ishmael was 13, Gen. 17:24, 25, and died at 175, it is plain that Ishmael must have been about 90 years of age at Abraham’s death. The love and reverence which Ishmael had for the patriarch were apparent after this long time in the fact that at the death of the latter, Isaac and Ishmael united to perform the burial at the cave of Machpelah at Hebron, Gen. 25:9.

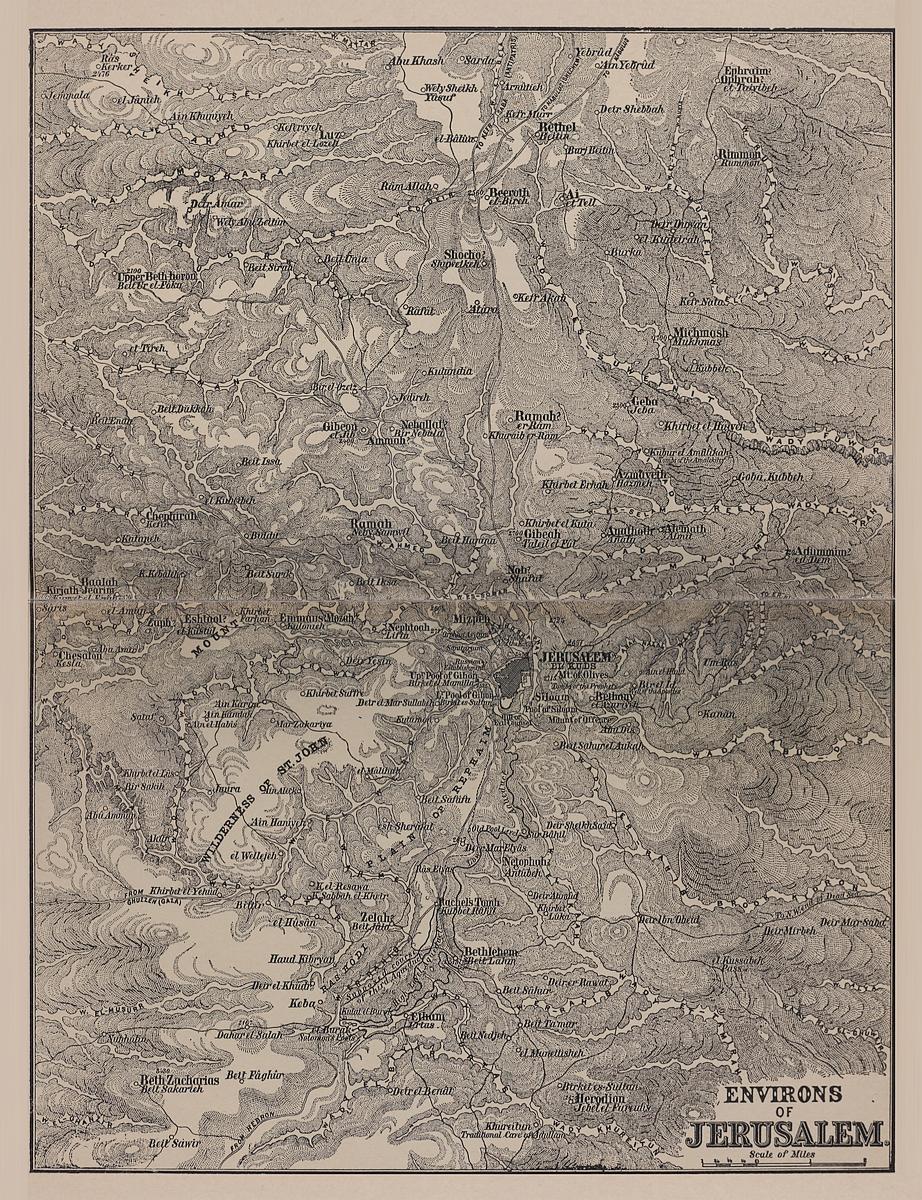

30. Hebron is a very old city, having been founded long before Abram’s time, and it is in existence at present. It is south of Jerusalem eighteen miles, and is unlike nearly all the cities in Palestine in that it is situated in a valley. The cave of Machpelah is on the east side of the valley, which runs nearly north and south.

This city becomes important in Biblical history at the time when Sarah, the wife of Abraham, died, and then this cave was purchased by Abraham as a family burying-place. It was the first spot possessed by any of the ancestors of the Hebrew race in Palestine. Here Sarah and Abraham were buried and in after times Leah and Isaac, and Jacob’s remains were, by his desire, removed from Egypt and placed by the side of his wife Leah.

Although Hebron has suffered several attacks and partial destruction, it is probable that the sacredness of the place may have protected it so that the actual remains of some of the bodies deposited there may yet be there, under Moslem guardianship.

After the birth of Isaac, Abraham remained in the region of Gerar, whose precise location is not known, although it must have been in the southwest of Canaan and in the land of the Philistines. From thence he removed to Beersheba.55

31. Beersheba bears, at the present day, the same name and contains two wells, one about 12 feet in diameter, the other about 5 feet. The larger appears to be very old and may well have existed since the days of the patriarch. It is about 40 feet deep to the water and is still used daily by the Arabs. The exact distance from Hebron to Beersheba is twenty-six and a half miles southwest. There are some ruins 24 miles southwest by south from Beersheba, called Umel Jerar, which possibly may indicate where the ancient Gerar was.

32. From Beersheba Abraham travelled with Isaac to Mt. Moriah, which was at the present site of Jerusalem and distant in an air line 45 miles northeast. Here his obedience and faith were severely tried in the command to offer up, as a burnt-offering, his only son Isaac. This act might have been more trying to the faith of Abraham because it was the practice of the Canaanites at that time. That the immolation of children was practised by the Phœnicians at that age and in the land of Chaldæa is proved by an Accadian text which expressly states that sin may be expiated by the vicarious sacrifice of the eldest son.56 In after times it was practised by the Moabites, 2 Kings 3:27. But Abraham’s faith never failed him, and the offering was accepted, though the act was arrested.

33. Abraham after this purchased the cave of Machpelah, of which we have spoken, where Sarah was buried, and he himself was laid away in the same place at his death, having given all his possessions to his son Isaac, except some smaller gifts to his other children by his second wife Keturah, when he sent them away from Isaac his son “unto the east country.”