| VOLUME I. |

| VOLUME II. |

| VOLUME III. |

| VOLUME IV. |

| VOLUME V. |

| VOLUME VI. |

CONTENTS

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF MACAULAY.

ON THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LITERATURE.

SCENES FROM “ATHENIAN REVELS.”

CRITICISMS ON THE PRINCIPAL ITALIAN WRITERS.

ON MITFORD’S HISTORY OF GREECE

This edition of Lord Macaulay’s Critical, Historical, and Miscellaneous Essays, contains all the articles published with the author’s correction and revision (3 vols., London: Longman, Green, & Co.) during his lifetime, and all the articles published by his friends (2 vols., London: Longman, Green & Co.) since his death. An Appendix contains several essays attributed to Lord Macaulay, and unquestionably his, not found in any other edition of his miscellaneous writings.

In this edition the Essays have been arranged in chronological order, so that their perusal affords, so to speak, a complete biographical portraiture of the brilliant author’s mind. No other edition possesses the same advantage.

A very full Index has been especially prepared for this edition,—without which the vast stores of historical learning and pertinent anecdote contained in the Essays can be referred to only by the fortunate man who possesses a memory as great as that of Macaulay himself. In this respect it is superior to the English editions, and wholly unlike any other American edition.

This edition also contains the pure text of Macaulay’s Essays. The exact punctuation, orthography, etc. of the English editions have been followed.

The portrait is from a photograph by Claudet, and represents the great historian as he appeared in the latter years of his life.

The biographical and critical Introduction is from the well-known pen of Mr. E. P. Whipple, who is fully entitled to speak with authority in regard to the most brilliant essayist of the age.

The typographical excellence of the publication places it among the best that have issued from the “Riverside” Press. We trust the public will appreciate what has long been needed,—a complete and correct edition, in handsome library style, of Lord Macaulay’s Essays.

Sheldon And Company.

New York, Oct 1860.

The materials for the biography of Lord Macaulay are scanty, and the writer of the present sketch has been able to glean few facts regarding his career which are not generally known. His life was comparatively barren in events, and though he rose to conspicuous social, literary, and political station, he had neither to struggle nor scramble for advancement. Almost as soon as his talents were displayed they were recognized and rewarded, and he attained fortune and power without using any means which required the least sacrifice, either of the integrity or the pride of his character.

Thomas Babington Macaulay was born at Rothley Temple, Leicestershire, on the twenty-fifth of October, 1800. His father, Zachary Macaulay, the son of a Scotch Presbyterian clergyman, was one of the worthiest and ablest antislavery philanthropists and politicians of his time, distinguished, even among such men as Wilberforce, Clarkson, and Stephen, for courage, sagacity, integrity, and religious principle. His mother was the daughter of Thomas Mills, a bookseller in Bristol, and belonged to the Society of Friends. Under her loving care he received his early education, and was not sent from home until his thirteenth year, when he was placed in a private academy. As a boy, he astonished all who knew him, by the brightness and eagerness of his mind, and the extent and variety of his acquisitions. Two lately published letters, written by Hannah More to his father, afford a pleasing glimpse of him, as he appeared to a shrewd and affectionate observer of his early years. She speaks of his “great superiority of intellect and quickness of passion,” at the age of eleven. He ought, she thinks, to have competitors, for “he is like the prince who refused to play with anything but kings.”

“I never,” she says, “saw any one bad propensity in him; nothing except natural frailty and ambition, inseparable perhaps from such talents and so lively an imagination; he appears sincere, veracious, tender-hearted, and affectionate.” He was a fertile versifier, even at that tender age, but she “observed with pleasure that though he was quite wild till the ebullitions of his muse were discharged, he thought no more of them afterwards than the ostrich is said to do of her eggs after she has laid them.” In another letter, written about two years afterwards, when the bright lad was nearly fourteen, she says, “the quantity of reading Tom has poured in, and the quantity of writing he has poured out, is astonishing.” Poetry continued to be his passion, but his venerable friend still testifies to his promising habit of throwing his verses away as soon as he had read them to her. “We have poetry,” she writes, “for breakfast, dinner, and supper. He recited all Palestine, while we breakfasted, to our pious friend, Mr. Whalley, at my desire, and did it incomparably.” She refers to his loquacity, but that quality seems not, in her presence, to have been connected with dogmatism, for she calls him very docile. At that early age he appears to have been sufficiently master of his stores of information to play with them, and his wit kept pace with his understanding. “Several men of sense and learning,” she says, “have been struck with the union of gayety and rationality in his conversation.” Accuracy of expression seems also to have been as striking a trait of the boy’s mind as volubility of utterance. One fault is mentioned, which was probably the result of his absorption in study and composition. Incessantly occupied, mentally, he paid but little attention to his personal appearance, and in dress was something of a sloven. Neither his father nor Hannah More could cure him of this fault, and, up to the time he became a peer, this neglect of externals seems to have been a characteristic trait. A fellow-pupil at the academy to which he was sent, describes him as “rather largely-built than otherwise, but not fond of any of the ordinary physical sports of boys; with a disproportionately large head, slouching or stooping shoulders, and a whitish or pallid complexion; incessantly reading or writing, and often reading or repeating poetry in his walks with his companions.” In October, 1818, the precocious youth entered Trinity College, Cambridge, and during the whole period of his residence at the University his special studies did not divert him from gratifying his thirst for general knowledge, and taste for general literature. In 1819 he gained the chancellor’s medal for a poem on the subject of Pompeii, and in 1821 the same prize for one on Evening. For these, and for all compositions of the kind, he afterwards professed to feel the utmost scorn. Two years after his second success as a prize poet, we find him comparing prize poems to prize sheep. “The object,” he says, “of the competitor for the agricultural premium is to produce an animal fit, not to be eaten, but to be weighed. The object of the poetical candidate is to produce, not a good poem, but a poem of the exact degree of frigidity and bombast which may appear to his censors to be correct or sublime. In general prize sheep are good for nothing but to make tallow candles, and prize poems are good for nothing but to light them.”

In 1821 he was elected Craven University Scholar; and in 1822 he graduated, and received his degree of B. A.; though he did not compete for honors, owing, it is said, to his dislike for mathematics. Between this period and 1824, when he was elected Fellow of his College, he contributed to Knight’s Quarterly Magazine the poems and essays, in which, for the first time, we detect the leading traits of his intellectual character. He possessed the feeling and the faculty of the poet only so far as they are necessary for the interpretative and representative requirements of the historian. He possessed the understanding of the philosopher only so far as it is necessary to throw into relations the vividly conceived facts derived from the records of the annalist. He could not create, but he could reproduce; he could not vitally combine, but he could logically dispose. The fair operation of these mental qualities was disturbed by the peculiarities of his disposition. He had boundless self-confidence, which had been consciously or unconsciously pampered by friends who admired the remarkable brilliancy of his powers. Independence of thought was thus early connected with imperiousness of will and petulant disrespect for other minds. Having no self-distrust, there was nothing to check the positiveness of his judgments. Where more cautious thinkers doubted he dogmatized; their probabilities were his certainties; and generally the tone of his judgments seemed to imply his inward belief in the maxim of the egotist—“difference from me is the measure of absurdity.” Lord Melbourne afterwards acutely touched upon this foible, when he lazily expressed his wish that he “was as sure of anything as Tom Macaulay was of everything.”

A portion of this positiveness is perhaps to be referred as much to the vividness of his perceptions as to the autocracy of his disposition. All that he read he remembered; and his memory, being indissolubly connected with his feelings and his imagination, vitalized all that it retained. Facts and persons of a past age were not to him hidden in the words which pretended to convey them to the mind, but were perceived as actual events and living beings. He could recollect because he could realize and reproduce. To his mental eye the past was present, and he had the delight of the poet in viewing as things what the historian had recorded in words. All men are more positive in regard to what they have seen than in regard to what they have heard. If what they have seen awakens in them joy and enthusiasm, their expression is instinctively dogmatic, especially if they come into collision with persons of fainter and colder perceptions, whose understandings are sceptical because their sensibilities are dull. Such, to some degree, at least, was the dogmatism of Macaulay in his statements of facts. In respect to his positiveness in opinion, it may be said that his leading opinions were blended with his moral passions, and an unmistakable love of truth animates even his fiercest, haughtiest and most disdainful treatment of the opinions of opponents. These qualities do not of course wholly explain or extenuate the leading defect of his character; for behind them, it must be admitted, were the triumphant consciousness of personal vigor, the insolent sense of personal superiority, and the relentlessness of temper which so often accompanies strength of intellectual conviction.

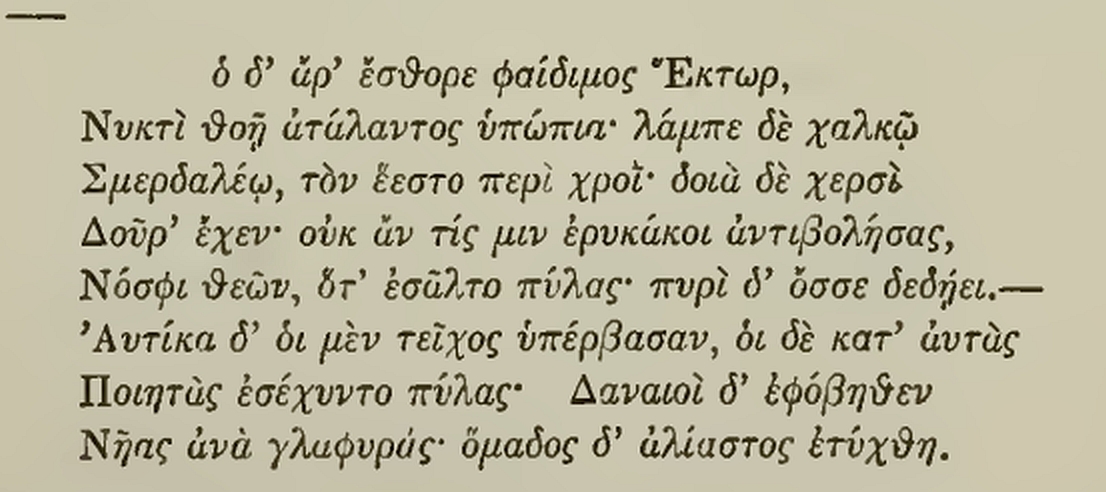

Among his contributions to Knight’s Quarterly Magazine, the Fragment of a Roman Tale and The Athenian Revels, indicate that at college he had studied the ancient classics so thoroughly as to gain no little insight into Greek and Roman life. Alcibiades, Cæsar, and Catiline, seem as real to him as Canning and Wellington. In the papers on Mitford’s History of Greece and The Athenian Orators, the same tendency of mind is displayed in a critical direction. His intellect penetrates to the realities of the society and the individuals he assumes to judge, and the independence, originality, and decision of his thinking, correspond to the clearness of his perceptions. The Conversation between Cowley and Milton is an example of the same sympathetic historic imagination exercised in the discussion of great historical questions, yet angrily debated; and in the poem of The Battle of Naseby, which purports to be written by Obadiah Bind-their-Kings-in-Chains-and-their-Nobles-with- links-of-Iron, Serjeant in Ireton’s Regiment, an attempt is made to reproduce the fiercest and gloomiest religious passions which raged in the breasts of the military fanatics among the Puritans. The critical papers on Dante and Petrarch exhibit the general characteristic of the writer’s later literary criticism—intellectual sympathy superior to rules, but submissive to laws; praising warmly, but at the same time, judging keenly; and as intolerant of faults as sensitive to merits. The style, both of the historical and critical articles, is substantially the style of Macaulay’s more celebrated essays. There is less energy and freedom of movement, a larger use of ornament for the sake of ornament, and a more obvious rhetorical artifice in the declamatory passages, but in essential elements it is the same.

In the choice of a profession, Macaulay fixed upon the law. He was called to the bar in February, 1826, but we hear of no clients; and it is doubtful if he ever mastered the details of his profession. Sydney Smith, who knew him at this time, said afterwards—“I always prophesied his greatness from the first moment I saw him, then a very young and unknown man, on the Northern Circuit. There are no limits to his knowledge, on small subjects as well as great: he is like a book in breeches.” Indeed, politics and literature had, from the first, attractions too strong for him to resist; and before he entered on the practice of his profession, he had, by one article in a review, passed at a bound to a conspicuous place among the writers of the time.

It might have been expected, from his family connections, that he would be a zealous whig and abolitionist, and his first contribution to the Edinburgh Review was on the subject of West India Slavery. It was published in the number for January, 1825, and in extent of information, force and acuteness of argument, severity of denunciation and sarcasm, and fervor and brilliancy of style, it ranks high among the many vigorous productions in which Macaulay has recorded his love of freedom and hatred of oppression, and exhibited his power of making tyranny ridiculous as well as odious. It is curious that this paper, so full of the peculiar traits of his character and style, should not have been generally recognized as his, after his subsequent articles had familiarized the public with his manner of expression. But the date of his first contribution to the Review is still commonly considered to be the month of August, 1825, when his article on Milton appeared, and at once attained a wide popularity. Though when, in 1848, the author collected his Essays, he declared that this article “hardly contained a paragraph that his matured judgment approved,” and regretted that he had to leave it unpruned of the “gaudy and ungraceful ornament” with which it was overloaded, its popularity has survived its author’s harsh judgment.

Whatever were its youthful faults of taste, impertinences of statement, and errors of theory, few articles which had ever before appeared in a British journal contained so much solid matter in so compact and readable a form. If it did not touch the depths of the various topics it so confidently discussed, it certainly contained a sufficient number of strong and striking thoughts to rescue its brilliancy from the charge of superficiality. If the splendor of its rhetoric seemed consciously designed for display, this defect applies in great measure to Macaulay’s rhetoric in general. He popularizes everything. He converts his acquirements into accomplishments, and contrives that their show shall always equal their substance; but in this essay, as in the dazzling-series of essays which succeeded it, a discerning eye can hardly fail to perceive beneath the external glitter of the periods, the presence of two qualities which are sound and wholesome, namely, broad common sense, and earnest enthusiasm.

Following the article on Milton, came, in the Edin burgh Review for February, 1826, the month in which he was called to the bar, a paper on the London University. This was succeeded in March, 1827, by a powerful and well-reasoned, but exceedingly bitter and sarcastic antislavery article on the Social and Industrial Capacities of Negroes. In June of the same year, appeared a paper, evidently written by him, entitled “The Present Administration,” one of the most acrimonious and audacious political articles ever published in the Edinburgh Review. Its tone was so violent and virulent, and excited so much opposition, that, in the next number of the Review, a kind of apology was offered for it under the form of explaining its real meaning. Macaulay’s real meaning is evident; he “meant mischief;” but in the confused sentences of his apologist hardly any meaning is perceptible; and there is something ludicrous in the very supposition that the meaning of the clearest and most decisive of writers could be mistaken by the public he addressed, and especially by the Tories he assailed.

In all editions of his Essays, the admirable article on Machiavelli, one of the ablest, most elaborate, and most thoughtful productions of his mind, succeeds the article on Milton. It was published in the number of the Review for March, 1827. Between 1827 and 1830 appeared the articles on Dryden, History, Hallam’s Constitutional History, Southey’s Colloquies on Society, and the three articles on the Utilitarian Theory of Government. These proved the capacity of the author to discuss both political and literary questions with a boldness, brilliancy, and effectiveness, hardly known before in periodical literature. Each essay included an amount of digested and generalized knowledge which might easily have been expanded into a volume, but which, in its condensed form and sparkling positiveness of expression, was all the more efficient. To the Whig party as well as to the Whig Review, such an ally had claims which could not be disregarded; and in 1830, through the interest of Lord Lansdowne, he was elected a member of Parliament for the borough of Caine. His reputation was so well established that no idea of patronage entered into this arrangement; and he could afterwards boast, with honest pride, that he was as independent when he sat in Parliament as the nominee of Lord Lansdowne as when he represented the popular constituencies of Leeds and Edinburgh.

As an orator, he won a reputation second only to his reputation as a man of letters. From all accounts he owed little to his manner of speaking. “His head,” we are told, “was set stiff on his shoulders, and his feet were planted immovable on the floor. One hand was fixed behind him across his back, and in this rigid attitude, with only a slight movement of his right hand, he poured forth, with inconceivable velocity, his sentences.” His first speech was on the Jews’ Disabilities Bill, on the fifth of April, 1830, followed in December by one on Slavery in the West Indies. Both evinced the broad views of the statesman as well as the generous warmth of the reformer. He threw himself with characteristic ardor into the great struggle for Parliamentary Reform, and his speeches on that measure, not only drew forth unbounded applause from his party and unwilling admiration from his opponents, but, as read now, after the excitement of the occasion has subsided, justify in a great degree the enthusiastic praise of those who heard them delivered. Clear and logical in arrangement, abundant in precedents and arguments, fearless in tone, and animated in movement, they are particularly marked by that fusion of intelligence and sensibility which makes passion intelligent and reason impassioned. The rush of the declamation is kept carefully within the channels of the argument; they convince through the very process by which they kindle. Their style is that of splendid and animated conversation; though carefully premeditated they have the appearance of being spontaneous; and indeed were not, as is commonly supposed, originally written out and committed to memory, but thought out and committed to memory. Without writing a word, he could prepare an hour’s speech, in his mind, carefully attending even to the most minute felicities of expression, and then deliver it with a rapidity so great that no reporter could follow him. The effect on the House of these declaimed disquisitions can perhaps be best estimated by quoting a passage from one of his political opponents, whose pen, in the heat of faction, was unrestrained by any of the proprieties of controversy. In the number of the Noctes Ambrosiano, for August, 1831, Macaulay is sneered at as a person whom it is the fashion among a small coterie to call “the Burke of the age.” After admitting him to be “the cleverest declaimer on the Whig side of the House,” the account thus proceeds: “He is an ugly, cross-made, splay-footed, shapeless little dumpling of a fellow, with a featureless face, too—except indeed a good expansive forehead—sleek, puritanical, sandy hair, large glimmering eyes—and a mouth from ear to ear. He has a lisp and burr, moreover, and speaks thickly and huskily for several minutes before he gets into the swing of his discourse; but after that nothing can be more dazzling than his whole execution. What he says is substantially, of course, stuff and nonsense; but it is so well-worded, and so volubly and forcibly delivered—there is such an endless string of epigram and antithesis—such a flashing of epithets—such an accumulation of images—and the voice is so trumpetlike, and the action so grotesquely emphatic, that you might hear a pin drop in the House. Even Manners Sutton himself listens.”

In the Reformed Parliament, which met in January, 1833, Macaulay took his seat as member for Leeds. He was soon after made Secretary of the Board of Control. An economist of his reputation, he did not speak often, but reserved himself for those occasions when he could speak with effect. Throughout his parliamentary career he showed no inclination to mingle in strictly extemporaneous debate, though it seems difficult to conceive that a man of such intellectual hardihood as well as intellectual capacity, and who in conversation was one of the most fluent and well-informed of human beings, lacked the power of thinking on his legs. It is probable that he disliked the drudgery of practical political life, and was incapable of the continuous party passion which sustains the professional politician. An ardent Whig partisan, his partisanship was still roused by the principles of his party rather than by its expedients. Literature and the philosophy of politics had more fascination for him than the contentions of the House of Commons; and he has repeatedly expressed contempt for the sophisms and misstatements which, though they will not bear the test of careful perusal, pass in the House for facts and arguments when volubly delivered in excited debate. Indeed, from 1830 to 1834, the period when he was most ambitious for political distinction and preferment, his contributions to the Edinburgh Review indicate that while in Parliament he gave as much time and thought to literature as he did before he became a member. To this period belong his articles on Saddler’s Law of Population, Bunyan, Byron, Hampden, Lord Burleigh, Mirabeau, Horace Walpole, the elder Pitt, Croker’s Edition of Boswell’s Life of Johnson, the Civil Disabilities of the Jews, and the War of the Succession in Spain. Only one of his speeches can perhaps compare with the best of these articles In range of thought and knowledge, and richness of diction. This was the speech which he delivered as Secretary of the Board of Control, in July 1833, on the new India Bill of the Whig government. Few persons were in the house; but Jeffrey, who was in London, wrote to one of his correspondents in regard to it:—“Mac is a marvellous person. He made the very best speech that has been made this session on India. The Speaker, who is a severe judge, says he rather thinks it the best speech he ever heard.”

Since the time of Burke, no speech in Parliament on the subject of India had equalled this in comprehensiveness of thought and knowledge. It justified his appointment, made a few months after, of member and legal adviser of the Supreme Council of India. Shiel, in a mocking defence of Macaulay from the sneers of some person who questioned his abilities, thus alluded to this appointment:—“Nonsense, sir! Don’t attempt to run down Macaulay. He’s the cleverest man in Christendom. Didn’t he make four speeches on the Reform Bill, and get £10,000 a year? Think of that, and be dumb!” The largeness of the salary, nearly twice that of the President of the United States, was probably Macaulay’s principal inducement to accept the office. His means were small; the gains of the office would in a few years make him independent of the world; and though he seemed, in accepting it, to abandon the objects of his political ambition, he really chose the right course to advance them. Pecuniary independence would relieve him from all imputations of being a political adventurer; and he had every reason to suppose that he might reach, in England, high political office all the more surely if it were understood that the emoluments of high political office were not the primary objects of his ambition. Apart from such considerations as these, there was something in the terms of his appointment eminently calculated to induce him to accept it. The special object of his mission was to prepare a new code of Indian law; and it is impossible to read his articles on the Utilitarian Theory of Government, and Dumont’s Recollections of Mirabeau, without perceiving that he had studied jurisprudence as a science, and that he considered the province of the jurist as even superior to that of the statesman. He went to India in 1834, with the feeling that he could prepare a code at once practical and just. For four years he labored to solve this problem, and the decision of his countrymen appeared to be that, though his solution might be just, it was not practical. In the opinion, especially of those East Indians whose interests were affected by its justice, it was a “Black Code.” When it was published, on his return from India in 1838, it was mercilessly denounced and ridiculed. Alarmists prophesied that, if adopted, it would lead to the downfall of the British power in India. Wits calculated, with malicious accuracy, the number of guineas which each word cost the British people. Between alarmists and wits the whole project fell through. There was a general impression that the code would not work, and, while its ability was admitted, its practicability was denied.

During his absence in India only two of his articles, the review of Mackintosh’s History of the Revolution in England in 1688, and the paper on Bacon, were published in the Edinburgh Review. The sketch of Bacon’s life and philosophy is one of the most elaborate, ingenious and brilliant products of his mind, but it is full of extravagant overstatements. It is biography and criticism in a series of dazzling epigrams; the exaggeration of epigram taints both the account of Bacon’s life and the estimate of Bacon’s philosophy; but the charm of the style is so great that, for a long time yet to come, it will probably influence the opinion which even educated men form of Bacon, though to thoughtful students of the age of Elizabeth and James, and to thoughtful students of the history of scientific and metaphysical speculation, it may seem as inaccurate in its disposition of facts as it is superficial in philosophy.

Soon after his return from India, in June, 1838, Macaulay was offered the office of Judge Advocate, which he declined. In 1839 the whigs of Edinburgh invited him to offer himself as a candidate for the representation of that city in Parliament. In a private letter to Adam Black, he gave the reasons why, if elected, the position would be agreeable to him. “I should,” he wrote, “be able to take part in politics, as an independent Member of Parliament, with the weight and authority which belongs to a man who speaks in the name of a great and intelligent body of constituents. I should, during half the year, be at leisure for other pursuits to which I am more inclined, and for which I am perhaps better fitted; and I should be able to complete an extensive literary work which I have long meditated.” He expressed an unwillingness to accept office under the government he intended to support, on the ground that he disliked the restraints of official life. “I love,” he says, “freedom, leisure, and letters. Salary is no object to me, for my income, though small, is sufficient for a man who has no ostentatious tastes.” In regard to the expenses of the election, he makes one condition which may surprise those American readers, who suppose that none but English politicians who are corrupt, pay money to get into Parliament. “I cannot,” he says, “spend more than £500 on the election. If, therefore, there be any probability that the candidate will be required to pay more than this, I hope you will look round for another person.” On the 29th of May, 1839, he made a speech to the electors, which for clearness and pungency of statement and argument is a model for all orators who are called upon to address a popular audience. It was probably this speech which drew forth the unintentional compliment from the Edinburgh artisan, that he thought he could have made it himself. “Ou! it was a wise-like speech, an’ no that defecshunt in airgument; but, eh! man”—with a pause of intense disappointment—“I’m thinkin’ I could ha’ said the haill o’ it mysel’!”

After some inefficient radical opposition, Macaulay, on the fourth of June, was declared duly elected. In September of the same year he was induced to accept the office of Secretary at War, in Lord Melbourne’s administration. In 1841, when Sir Robert Peel came into power, he went into opposition, and some of his ablest speeches were made during the five years the tories were in office. In 1842, his “Lays of Ancient Rome,” were published, and attained a wide popularity. In 1843 he published a collection of his Essays, contributed to the Edinburgh Review, including the masterly biographies of Temple, Clive, Hastings, Frederic the Great, and Addison, and the papers on Church and State, Ranke’s History of the Popes, and the Comic Dramatists of the Restoration, written since his return from India. In July, 1846, on the return of the Whigs to power, he was made Paymaster-General of the Forces. Though his speech and vote on the Maynooth College Bill, in 1845, had roused a serious opposition to him among the dissenters of Edinburgh, he was still reelected to Parliament, though not without a severe struggle, on his acceptance of office. In 1847 Parliament was dissolved. By this time his offences against the theological opinions of his constituents had been increased by his support of what they called the system of “godless education,” which the government to which he belonged had patronized. The publicans and spirit dealers of the city were also in ill-humor with the Whig government, on account of the continuance of “undue restrictions in regard to their licenses.” From the state of the mob that yelled and hissed round the hustings, there would have seemed to be no “undue restriction” on the disposal of spirituous liquors to carry the election. Adam Black sums up the opposition to Macaulay as consisting of “the no-popery men, the godless-education men, the crotchety coteries, and the dealers in spirits.” To all these Macaulay was blunt and unconciliating, strong in the feeling that he had excited their hatred by acts which his conscience prompted and his reason approved. He would not recant a single expression, much less a single opinion.

“The bray of Exeter Hall,” a phrase in his Maynooth speech particularly obnoxious to the dissenters, he would not take back, and it was used against him with great effect. A Mr. Cowan, a man of no note, was selected as the opposing candidate, as if his enemies had determined to mortify his pride as well as deprive him of his seat. His speeches from the hustings were continually interrupted by a mob who, infuriated by fanaticism or whiskey, received his statements with insults, and answered his arguments by jeers. “If,” exclaimed Macaulay in one of his speeches, “your representative be an honest man”—“Ay! but he’s no that!” was a cry that came back from the crowd. To interruptions and to insults, however, he presented a bold front, and met outrage with defiance. He would not condescend to humor at the hustings the prejudices he had offended in Parliament, but reaffirmed his opinions in the most pointed and explicit language. One of his arguments was that, in regal’d to the Maynooth grant, no principle was involved. A sum had always been yearly voted to support that Roman Catholic College; the only cause of complaint against him was that he had spoken and voted for an additional sum. He was therefore opposed, not on a principle, but on a quibble. “And,” he exclaimed, “if you want a representative who will peril the peace of the empire for a mere quibble, that representative I will not be.”

He was defeated, and after it was known that he was defeated, he was hissed. In his speech to the crowd, announcing that his political connection with Edinburgh was dissolved forever, he alluded to this last circumstance as unprecedented in political warfare. To hiss a defeated candidate, he reminded them, was below the ordinary magnanimity of the most factious mob. In his farewell address to the electors, written after he had returned to London, he indicated that, to an honest, honorable, and patriotic statesman, there might be solid consolations, even to personal pride, in the circumstances of his defeat. “I shall always be proud,” he writes, “to think that I once enjoyed your favor, but permit me to say I shall remember, not less proudly, how I risked and how I lost it.” The following noble poem, published since his death, contains, perhaps, the most authentic record of his feelings on the occasion:—

Lines Written In August, 1847.

The day of tumult, strife, defeat, was o’er;

Worn out with toil and noise and scorn

and spleen,

I slumbered, and in

slumber saw once more

A room in an old

mansion, long unseen.

That room, methought, was curtained from the

light;

Yet through the curtains shone

the moon’s cold ray

Full on a cradle,

where, in linen white,

Sleeping life’s

first soft sleep, an infant lay.

Pale flickered on the hearth the dying flame,

And all was silent in that ancient

hall,

Save when by fits on the low

night-wind came

The murmur of the

distant water-fall.

And lo! the fairy queens who rule our birth

Drew nigh to speak the new-born baby’s

doom:

With noiseless step, which left

no trace on earth,

From gloom they

came, and vanished into gloom.

Not deigning on the boy a glance to cast,

Swept careless by the gorgeous Queen

of Gain;

More scornful still, the

Queen of Fashion passed,

With mincing

gait and sneer of cold disdain.

The Queen of Power tossed high her jewelled

head,

And o’er her shoulder threw a

wrathful frown:

The Queen of Pleasure

on the pillow shed

Scarce one stray

rose-leaf from her fragrant crown.

Still Fay in long procession followed Fay;

And still the little couch remained

unblest;

But, when those wayward

sprites had passed away,

Came One, the

last, the mightiest, and the best.

Oh, glorious lady, with the eyes of light

And laurels clustering round thy lofty

brow,

Who by the cradle’s side didst

watch that night,

Warbling a sweet

strange music, who wast thou?

“Yes, darling; let them go;” so ran the

strain:

“Yes; let them go, gain,

fashion, pleasure, power,

And all the

busy elves to whose domain

Belongs the

nether sphere, the fleeting hour.

“Without one envious sigh, one anxious

scheme,

The nether sphere, the

fleeting hour resign.

Mine is the

world of thought, the world of dream,

Mine

all the past, and all the future mine.

“Fortune, that lays in sport the mighty low,

Age, that to penance turns the joys of

youth,

Shall leave untouched the gifts

which I bestow,

The sense of beauty

and the thirst of truth.

“Of the fair brotherhood who share my grace,

I, from thy natal day, pronounce thee

free;

And, if for some I keep a nobler

place,

I keep for none a happier than

for thee.

“There are who, while to vulgar eyes they

seem

Of all my bounties largely to

partake,

Of me as of some rival’s

handmaid deem,

And court me but for

gain’s, power’s, fashion’s sake.

“To such, though deep their lore, though wide

their fame,

Shall my great mysteries

be all unknown:

But thou, through good

and evil, praise and blame,

Wilt not

thou love me for myself alone?

“Yes; thou wilt love me with exceeding love;

And I will tenfold all that love

repay,

Still smiling, though the

tender may reprove,

Still faithful,

though the trusted may betray.

“For aye mine emblem was, and aye shall be,

The ever-during plant whose bough I

wear,

Brightest and greenest then,

when every tree

That blossoms in the

light of Time is bare.

“In the dark hour of shame, I deigned to

stand

Before the frowning peers at

Bacon’s side:

On a far shore I

smoothed with tender hand,

Through

months of pain, the sleepless bed of Hyde:

“I brought the wise and brave of ancient days

To cheer the cell where Raleigh pined

alone:

I lighted Milton’s darkness

with the blaze

Of the bright ranks

that guard the eternal throne.

“And even so, my child, it is my pleasure

That thou not then alone shouldst feel

me nigh,

When, in domestic bliss and

studious leisure,

Thy weeks uncounted

come, uncounted fly;

“Not then alone, when myriads, closely

pressed

Around thy car, the shout of

triumph raise;

Nor when, in gilded

drawing-rooms, thy breast

Swells at

the sweeter sound of woman’s praise.

No: when on restless night dawns cheerless

morrow,

When weary soul and wasting

body pine,

Thine am I still, in

danger, sickness, sorrow’,

In

conflict, obloquy, want, exile, thine;

“Thine, where on mountain waves the

snow-birds scream.

Where more than

Thule’s winter barbs the breeze,

Where

scarce, through lowering clouds, one sickly gleam

Lights the drear May-day of Antarctic seas;

“Thine, when around thy litter’s track all

day

White sand-hills shall reflect the

blinding glare;

Thine, when, through

forests breathing death, thy way

All

night shall wind by many a tiger’s lair;

“Thine most, when friends turn pale, when

traitors fly,

When, hard beset, thy

spirit, justly proud,

For truth,

peace, freedom, mercy, dares defy

A

sullen priesthood and a raving crowd.

“Amidst the din of all things fell and vile,

Hate’s yell and envy’s hiss and

folly’s bray,

Remember me; and with an

unforced smile

See riches, baubles,

flatterers, pass away.

“Yes: they will pass away; nor deem it

strange:

They come and go, as comes

and goes the sea:

And let them come

and go: thou, through all change,

Fix

thy firm gaze on virtue and on me.”

He now devoted his time to a work he had long meditated, and for which he had not only collected a considerable portion of the materials, but had probably written some portion of the text,—the History of England, from the Accession of James II. The first two volumes of this were published in the autumn of 1848, and gave him a literary reputation far beyond what he had acquired by his historical essays. The book was as popular as any of Scott’s or Dickens’s novels, while its solid merits of research and generalization placed it among the great historical works of the century. Its circulation, large in England, was immense in the United States; and in every portion of the world where English literature is esteemed, it was widely read, either in the original text or in carefully prepared translations.

In 1852, the city of Edinburgh, desirous of repairing the injustice it had done to Macaulay in 1847, elected him its representative without his appearing as a candidate. He accepted the trust, though his health had begun to fail, and he was already visited with the symptoms of the disease which eventually caused his death. He wrote to Adam Black, in August, 1852, that “any excitement, or any violent exertion, instantly brings on a derangement of the circulation, and an uneasy feeling of the heart.” He was unable to perform his parliamentary duties to his own satisfaction from the first, and repeatedly expressed his desire to resign. He was withheld from so doing by the assurances he received from Edinburgh that his constituents were satisfied with his partial attendance on the duties of his post. At length, in January, 1856, he became aware of his incapacity to serve any longer without serious prejudice to his health, and resigned his seat. Meanwhile, two more volumes of his History had been completed and published, evincing that the energy of his mind was not affected by the ills of his body. He also had devoted some time to preparing a volume of his speeches for the press, and published them in 1854. In 1857, without any solicitation on his part, and entirely to his own surprise, he was elevated to the peerage. Though it was known that his health was infirm, there was no apprehension on the part of the public that he would not live to complete a large portion of the immense work he had contemplated. His delightful biographies of Atterbury, Bunyan, Goldsmith, Johnson, and Pitt, contributed to the new edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, proved that his faculties were in their full vigor and splendor. It was therefore with a shock of painful surprise that all readers of the English race heard of his sudden death, by disease of the heart, on the 28th of December, 1859. It was felt, even by those who most vehemently disagreed with him in opinion, that in losing him England lost the man who, beyond all other men, carried in his brain the facts of her history. He was buried, with great pomp, in the Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey, “at the foot of Addison’s monument and beside the remains of Sheridan.”

The first and strongest impression we derive from a consideration of Macaulay’s life and writings is that of the robust and masculine qualities of his intellect and character. Since his death it has become generally known that he was by no means deficient in those tender and benevolent feelings which found little expression in his works. Among his intimate friends and relations he passed as one of the most affectionate of men, and his benevolence to unsuccessful artists and men of letters, absorbed no inconsiderable portion of his income. But in his speeches in parliament, in his essays, and in his history, he makes the impression of a stout, strong, and tough polemic, who is thoroughly well furnished for combat, and who neither gives nor expects quarter. No tenderness to frailty interferes with the merciless severity of his judgments. His own political and personal integrity was without a stain. “You might,” said Sydney Smith, in testifying to his incorruptibility and his patriotism, “lay ribbons, stars, garters, wealth, titles, before him in vain. He has an honest, genuine love of his country, and the world could not bribe him to neglect her interests.” This integrity of character gave a certain puritan relentlessness of tone to his intellectual and moral judgments. He had a warm love for what was beautiful and true, but, in his writings, it generally took the negative form of hatred for what was deformed and false. He abhorred meanness, baseness, fraud, falsehood, conniption, and oppression, with his whole heart and soul, and found a grim delight in holding them up to public execration. His talent for this work, and his enjoyment of it, were so great, that he was tempted at times to hunt after criminality for the pleasure of punishing it. He acquired a diseased taste for character that was morally tainted, in order that he might exercise on its condemnation the rich resources of his scorn and invective. His progress through a tract of history was marked by the erection of the gallows, the gibbet, and the stake, and he was almost as insensible to mitigating circumstances as Judge Jeffreys himself. He seemed to consider that the glory of the judge rested on the number of the executions; and he has hanged, drawn, and quartered many individuals, whose cases are now at the bar of public opinion, in the course of being reheard.

The last and finest result of personal integrity is intellectual conscientiousness, and this Macaulay cannot be said to have attained. His intellect, bright and broad as it was, was the instrument of his individuality. His sympathies and antipathies colored his statements, and he rarely exhibited anything in “dry light.” In this respect, he is inferior to Hallam and Mackintosh, who are inferior to him in extent of information, and genius for narrative. The vividness of his perceptions confirmed the autocracy of his disposition, and his convictions had to him the certainty of facts. It must be admitted that he had some reason for his dogmatism. He excelled all Englishmen of his time in his knowledge of English history. There was no drudgery he would not endure in order to obtain the most trivial fact which illustrated the opinions or the manners of any particular age. Indeed, the minuteness of his information astonished even antiquaries, and in society was sometimes thought “to be erected into a colossal engine of colloquial oppression.” And this information was not a mere assemblage of dead facts. It was vitalized by his passions and imagination; it was all alive in the many-peopled domain of his “vast and joyous memory;” and it was so completely possessed as to be always in readiness to sustain an argument or illustrate a principle. The songs, ballads, satires, lampoons, plays, private correspondence of a period, were as familiar to him as the graver records of its annalists. But in disposing his immense materials he followed the law of his own mind rather than the law inherent in the facts. Instead of viewing things in their relations to each other, he viewed things in their relation to himself. His representation of them, therefore, partook of the limitations of his character. That character was broad, but it would be absurd to say that it was as broad as the English race. He Macaulayized English history as a distinguished poet of the century was said to have Byronized human life. Even in some of his most seemingly triumphant statements it will be found that a different disposition of the facts will result in establishing an opposite opinion. Take the article on Bacon, the most glaring of all the instances in which he has refused to assume the point of view of the person he has resolved to condemn; and any intellect, resolute enough to resist the marvellous fascination of the narrative, can easily redispose the facts so as to arrive at an opposite conclusion.

A prominent cause of Macaulay’s popularity is to be found in the definiteness of his mind. He always aspired to present his matter in such a form as to exclude the possibility of doubt, either in his statement or argument. Of all great English writers he is therefore the least suggestive. All that he demands of a reader is simple receptiveness. Selection, arrangement, reasoning, pictorial representation, are all done by himself. This explicitness, too, is purchased at some sacrifice of truth. His comprehensiveness is apt to be of that kind which arrives at broad generalizations by excluding a number of the facts and principles it ought to include. Real comprehensiveness of mind is impossible unless the interior life of the separate facts included in the sweeping generalization is adequately comprehended. Shakspeare, of all English minds, is the most comprehensive; and Shakspeare, in virtue of his comprehensiveness, would doubt in many instances where Macaulay is most certain. The most perfect exhibition of Macaulay’s talent is his analysis and representation of the character of James II., from a hostile point of view. He catches his victim in a series of cunningly contrived traps, and the poor creature, in Macaulay’s narrative, cannot move a step without falling into the trap marked folly or the trap marked wickedness. Shakspeare’s method of dealing with character was entirely different.

As an artist Macaulay is greater in his Essays than in his History of England. Each of his essays is a unit. The results of analysis are diffused through the veins of narration, and details are strictly subordinated to leading conceptions. In his History details are so numerous as to confuse the mind. Events succeed each other in their chronological rather than their intellectual order; and his readers gain an intense perception of particular facts without any general view of the whole field. The power of the author to interest us is as evident in his account of the Bank of England as in his account of the Massacre of Glencoe. We pass from one topic to another without any sense of the connection of topics. Picture succeeds picture as in the anarchy of a panorama. It seems as if we were reading the work of a poet who had turned annalist. By emphasizing everything, interest in particulars is obtained at the expense of general effect. It is only by turning to the table of contents that we are able to generalize the events of a reign. There are scores of pages in the third and fourth volumes which we read as we read a newspaper, where an account of a murder may be succeeded immediately by an account of a masquerade. Prescott, who cannot be named with Macaulay in respect to fulness of matter, fertility of thought, originality of style, and unwearied energy of mind, is still superior to him in the artistic disposition of his materials. In reading Prescott, we have but a faint impression of the author and no feeling at all of the felicity of the style, but the real business of the historian is none the less performed, for we get a large view of facts in their true relations, and are enabled to take in the subject he treats of as a whole. In Macaulay the narrative of particular facts and incidents is incomparably bright and stimulating, but the facts and incidents are not seen from a commanding point.

In his essays, especially his biographical and historical essays, this defect is not observable. They rank among the finest artistic products of the century. They partake of the imperfections of his thinking and the limitations of his character, but they are still perfect of their kind. The articles on Machiavelli, Banyan, Clive, Hastings, Frederic the Great, Barere, Chatham, not to mention others, are eminent specimens of that critical and interpretative biography, in which the character of the biographer appears chiefly to give unity to the representation of facts and the application of principles. The amount of knowledge each of them includes can only be estimated by those who have patiently read the many volumes they so brilliantly condense. In style they show a mastery of English which has been attained by no other English author who did not possess a creative imagination. The art of the writer is shown as much in his deliberate choice of common and colloquial phrases as in those splendid passages in which he almost seems to exhaust the resources of the English tongue. As a narrator, in his own province, it would be difficult to name his equal among English writers; to his narrative, all his talents and accomplishments combined to lend fascination; and in it he exhibited the understanding of Hallam, and the knowledge of Mackintosh, joined to the picturesqueness of Southey, and the wit of Pope.

1(Knight’s

Quarterly Magazine, June 1823.)

I

t was an hour after

noon. Ligarius was returning from the Campus Martins. He strolled through

one of the streets which led to the forum, settling his gown, and

calculating the odds on the gladiators who were to fence at the

approaching Saturnalia. While thus occupied, he overtook Flaminius, who,

with a heavy-step and a melancholy face, was sauntering in the same

direction. The light-hearted young man plucked him by the sleeve.

“Good day, Flaminius. Are you to be of Catiline’s party this evening?”

“Not I.”

“Why so? Your little Tarentine girl will break her heart.”

“No matter. Catiline has the best cooks and the finest wine in Rome. There are charming women at his parties. But the twelve-line board and the dice-box pay for all. The Gods confound me if I did not lose two millions of sesterces last night. My villa at Tibur, and all the statues that my father the prætor 2brought from Ephesus, must go to the auctioneer. That is a high price, you will acknowledge, even for Phonicopters, Chian, and Callinice.”

“High indeed, by Pollux.”

“And that is not the worst. I saw several of the leading senators this morning. Strange things are whispered in the higher political circles.”

“The Gods confound the political circles. I have hated the name of politician ever since Sylla’s proscription, when I was within a moment of having my throat cut by a politician, who took me for another politician. While there is a cask of Falernian in Campania, or a girl in the Suburra, I shall be too well employed to think on the subject.”

“You will do well,” said Flaminius gravely, “to bestow some little consideration upon it at present. Otherwise, I fear, you will soon renew your acquaintance with politicians, in a manner quite as unpleasant as that to which you allude.”

“Averting Gods! what do you mean?”

“I will tell you. There are rumors of conspiracy. The order of things established by Lucius Sylla has excited the disgust of the people, and of a large party of the nobles. Some violent convulsion is expected.”

“What is that to me? I suppose that they will hardly proscribe the vintners and gladiators, or pass a law compelling every citizen to take a wife.”

“You do not understand. Catiline is supposed to be the author of the revolutionary schemes. You must have heard bold opinions at his table repeatedly.”

“I never listen to any opinions upon such subjects, bold or timid.”

“Look to it. Your name has been mentioned.” 3“Mine! good Gods! I call heaven to witness that I never so much as mentioned Senate, Consul, or Comitia, in Catiline’s house.”

“Nobody suspects you of any participation in the inmost counsels of the party. But our great men surmise that you are among those whom he has bribed so high with beauty, or entangled so deeply in distress, that they are no longer their own masters. I shall never set foot within his threshold again. I have been solemnly warned by men who understand public affairs; and I advise you to be cautious.”

The friends had now turned into the forum, which was thronged with the gay and elegant youth of Rome. “I can tell you more,” continued Flaminius; “somebody was remarking to the Consul yesterday how loosely a certain acquaintance of ours tied his girdle. ‘Let him look to himself,’ said Cicero, ‘or the state may find a tighter girdle for his neck.’”

“Good Gods! who is it? You cannot surely mean—”

“There he is.”

Flaminius pointed to a man who was pacing up and down the forum at a little distance from them. He was in the prime of manhood. His personal advantages were extremely striking, and were displayed with an extravagant but not ungraceful foppery. His gown waved in loose folds; his long dark curls were dressed with exquisite art, and shone and steamed with odours; his step and gesture exhibited an elegant and commanding figure in every posture of polite languor. But his countenance formed a singular contrast to the general appearance of his person. The high and imperial brow, the keen aquiline features, 4the compressed mouth, the penetrating eye, indicated the highest degree of ability and decision. He seemed absorbed in intense meditation. With eyes fixed on the ground, and lips working in thought, he sauntered round the area, apparently unconscious how many of the young gallants of Rome were envying the taste of his dress, and the ease of his fashionable stagger.

“Good Heaven!” said Ligarius, “Caius Caesar is as unlikely to be in a plot as I am.”

“Not at all.”

“He does nothing but game, feast, intrigue, read Greek, and write verses.”

“You know nothing of Caesar. Though he rarely addresses the Senate, he is considered as the finest speaker there, after the Consul. His influence with the multitude is immense. He will serve his rivals in public life as he served me last night at Catiline’s. We were playing at the twelve lines.(1)—Immense stakes. He laughed all the time, chatted with Valeria over his shoulder, kissed her hand between every two moves, and scarcely looked at the board. I thought that I had him. All at once I found my counters driven into the corner. Not a piece to move, by Hercules. It cost me two millions of Sesterces. All the Gods and Goddesses confound him for it!”

“As to Valeria,” said Ligarius, “I forgot to ask whether you have heard the news.”

“Not a word. What?”

(1) Duodecim scripta, a game of mixed chance and skill,

which seems to have been very fashionable in the higher

circles of Rome. The famous lawyer Mucius was renowned for

his skill in it.—( Cic. Oral. i. 50.)

“I was told at the baths to-day that Cæsar escorted 5the lady home. Unfortunately old Quintus Lutatius had come hack from his villa in Campania, in a whim of jealousy. He was not expected for three days. There was a fine tumidt. The old fool called for his sword and his slaves, cursed his wife, and swore that he would cut Cæsar’s throat.”

“And Cæsar?”

“He laughed, quoted Anacreon, trussed his gown round his left arm, closed with Quintus, flung him down, twisted his sword out of his hand, burst through the attendants, ran a freed-man through the shoulder, and was in the street in an instant.”

“Well done! Here he comes. Good day, Caius.” Cæsar lifted his head at the salutation. His air of deep abstraction vanished; and he extended a hand to each of the friends.

“How are you after your last night’s exploit?”

“As well as possible,” said Cæsar laughing.

“In truth we should rather ask how Quintus Lutatius is.”

“He, I understand, is as well as can be expected of a man with a faithless spouse and a broken head. His freed-man is most seriously hurt. Poor fellow! he shall have half of whatever I win to-night. Flaminius, you shall have your revenge at Catiline’s.”

“You are very kind. I do not intend to be at Catiline’s till I wish to part with my town-house. My villa is gone already.”

“Not at Catiline’s, base spirit! You are not of his mind, my gallant Ligarius. Dice, Chian, and the loveliest Greek singing-girl that was ever seen. Think of that, Ligarius. By Venus, she almost made me adore her, by telling me that I talked Greek with the most Attic accent that she had heard in Italy.” 6“I doubt she will not say the same of me,” replied Ligarius. “I am just as able to decipher an obelisk as to read a line of Homer.”

“You barbarous Scythian, who had the care of your education?”

“An old fool,—a Greek pedant,—a Stoic. He told me that pain was no evil, and flogged me as if he thought so. At last one day, in the middle of a lecture, I set fire to his enormous filthy beard, singed his face, and sent him roaring out of the house. There ended my studies. From that time to this I have had as little to do with Greece as the wine that your poor old friend Lutatius calls his delicious Samian.”

“Well done, Ligarius. I hate a Stoic. I wish Marcus Cato had a beard that you might singe it for him. The fool talked his two hours in the Senate, yesterday, without changing a muscle of his face. He looked as savage and as motionless as the mask in which Roscius acted Alecto. I detest everything connected with him.”

“Except his sister, Servilia.”

“True. She is a lovely woman.”

“They say that you have told her so, Caius.”

“So I have.”

“And that she was not angry.”

“What woman is?”

“Aye,—but they say—”

“No matter what they say. Common fame lies like a Greek rhetorician. You might know so much, Ligarius, without reading the philosophers. But come, I will introduce you to little dark-eyed Zoe.”

“I tell you I can speak no Greek.”

“More shame for you. It is high time that you should begin. You will never have such a charming* 7instructress. Of what was your father thinking when he sent for an old Stoic with a long beard to teach you? There is no language-mistress like a handsome woman. When I was at Athens, I learnt more Greek from a pretty flower-girl in the Peiræus than from all the Portico and the Academy. She was no Stoic, Heaven knows. But come along to Zoe. I will be your interpreter. Woo her in honest Latin, and I will turn it into elegant Greek between the throws of dice. I can make love and mind my game at once, as Flaminius can tell you.”

“Well, then, to be plain, Cæsar, Flaminius has been talking to me about plots, and suspicions, and politicians. I never plagued myself with such things since Sylla’s and Marius’s days; and then I never could see much difference between the parties. All that I am sure of is, that those who meddle with such affairs are generally stabbed or strangled. And, though I like Greek wine and handsome women, I do not wish to risk my neck for them. Now, tell me as a friend, Caius;—is there no danger?”

“Danger!” repeated Cæsar, with a short, fierce, disdainful laugh: “what danger do you apprehend?”

“That you should best know,” said Flaminius; “you are far more intimate with Catiline than I. But I advise you to be cautious. The leading men entertain strong suspicions.”

Cæsar drew up his figure from its ordinary state of graceful relaxation into an attitude of commanding dignity, and replied in a voice of which the deep and impassioned melody formed a strange contrast to the humorous and affected tone of his ordinary conversation. “Let them suspect. They suspect because they know what they have deserved. What have they done 8for Rome?—What for mankind?—Ask the citizens. Ask the provinces. Have they had any other object than to perpetuate their own exclusive power, and to keep us under the yoke of an oligarchical tyranny, which unites in itself the worst evils of every other system, and combines more than Athenian turbulence with more than Persian despotism?”

“Good Gods! Cæsar. It is not safe for you to speak, or for us to listen to, such things, at such a crisis.”

“Judge for yourselves what you will hear. I will judge for myself what I will speak. I was not twenty years old, when I defied Lucius Sylla, surrounded by the spears of legionaries and the daggers of assassins. Do you suppose that I stand in awe of his paltry successors, who have inherited a power which they never could have acquired; who would imitate his proscriptions, though they have never equalled his conquests?”

“Pompey is almost as little to be trifled with as Sylla. I heard a consular senator say that, in consequence of the present alarming state of affairs, he would probably be recalled from the command assigned to him by the Manilian law.”

“Let him come,—the pupil of Sylla’s butcheries,—the gleaner of Lucullus’s trophies,—the thief-taker of the Senate.”

“For heaven’s sake, Caius!—if you knew what the Consul said—”

“Something about himself, no doubt. Pity that such talents should be coupled with such cowardice and coxcombry. He is the finest speaker living,—infinitely superior to what Horten sins was, in his best days;—a charming companion, except when he tells over for the twentieth time all the jokes that he made at 9Verres’s trial. But he is the despicable tool of a despicable party.”

“Your language, Caius, convinces me that the reports which have been circulated are not without foundation. I will venture to prophecy that within a few months the republic will pass through a whole Odyssey of strange adventures.”

“I believe so; an Odyssey of which Pompey will be the Polyphemus, and Cicero the Siren. I would have the state imitate Ulysses: show no mercy to the former; but contrive, if it can be done, to listen to the enchanting voice of the other, without being seduced by it to destruction.”

“But whom can your party produce as rivals to these two famous leaders?”

“Time will show. I would hope that there may arise a man, whose genius to conquer, to conciliate, and to govern, may unite in one cause an oppressed and divided people;—may do all that Sylla should have done, and exhibit the magnificent spectacle of a great nation directed by a great mind.”

“And where is such a man to be found?”

“Perhaps where you would least expect to find him. Perhaps he may be one whose powers have hitherto been concealed in domestic or literary retirement. Perhaps he may be one, who, while waiting for some adequate excitement, for some worthy opportunity, squanders on trifles a genius before which may yet be humbled the sword of Pompey and the gown of Cicero. Perhaps he may now be disputing with a sophist; perhaps prattling with a mistress; perhaps——-” and, as he spoke, he turned away, and resumed his lounge, “strolling in the Forum.” 10It was almost midnight. The party had separated. Catiline and Cethegus were still conferring in the supper-room, which was, as usual, the highest apartment of the house. It formed a cupola, from which windows opened on the flat roof that surrounded it. To this terrace Zoe had retired. With eyes dimmed with fond and melancholy tears, she leaned over the balustrade, to catch the last glimpse of the departing form of Cæsar, as it grew more and more indistinct in the moonlight. Had he any thought of her? Any love for her? He, the favourite of the high-born beauties of Rome, the most splendid, the most graceful, the most eloquent of its nobles? It could not be. His voice had, indeed, been touchingly soft whenever he addressed her. There had been a fascinating tenderness even in the vivacity of his look and conversation. But such were always the manners of Cæsar towards women. He had wreathed a sprig of myrtle in her hair as she was singing. She took it from her dark ringlets, and kissed it, and wept over it, and thought of the sweet legends of her own dear Greece,—of youths and girls, who, pining away in hopeless love, had been transformed into flowers by the compassion of the Gods; and she wished to become a flower, which Cæsar might sometimes touch, though he should touch it only to weave a crown for some prouder and happier mistress.

She was roused from her musings by the loud step and voice of Cethegus, who was pacing furiously up and down the supper-room.

“May all the gods confound me, if Cæsar be not the deepest traitor, or the most miserable idiot, that ever intermeddled with a plot!”

Zoe shuddered. She drew nearer to the window. She stood concealed from observation by the curtain 11of fine network which hung over the aperture, to exclude the annoying insects of the climate.

“And you, too!” continued Cethegus, turning fiercely on his accomplice; “you to take his part against me!—you, who proposed the scheme yourself!”

“My dear Caius Cethegus, you will not understand me. I proposed the scheme; and I will join in executing it. But policy is as necessary to our plans as boldness. I did not wish to startle Cæsar—to lose his co-operation—perhaps to send him off with an information against us to Cicero and Catulus. He was so indignant at your suggestion, that all my dissimulation was scarcely sufficient to prevent a total rupture.”

“Indignant! The gods confound him!—He prated about humanity, and generosity, and moderation. By Hercules, I have not heard such a lecture since I was with Xenochares at Rhodes.”

“Cæsar is made up of inconsistencies. He has boundless ambition, unquestioned courage, admirable sagacity. Yet I have frequently observed in him a womanish weakness at the sight of pain. I remember that once one of his slaves was taken ill while carrying his litter. He alighted, put the fellow in his place, and walked home in a fall of snow. I wonder that you could be so ill-advised as to talk to him of massacre, and pillage, and conflagration. You might have foreseen that such propositions would disgust a man of his temper.”

“I do not know. I have not your self-command, Lucius. I hate such conspirators. What is the use of them? We must have blood—blood,—hacking and tearing work—bloody work!”

“Do not grind your teeth, my dear Caius; and lay 12down the carving-knife. By Hercules, you have cut up all the stuffing of the couch.”

“No matter; we shall have couches enough soon,—and down to stuff them with,—and purple to cover them,—and pretty women to loll on them,—unless this fool, and such as he, spoil our plans. I had something else to say. The essenced fop wishes to seduce Zoe from me.”

“Impossible! you misconstrue the ordinary gallantries which he is in the habit of paying to every handsome face.”

“Curse on his ordinary gallantries, and his Akerses, and his compliments, and his sprigs of myrtle! If Cæsar should dare—by Hercules, I will tear him to pieces in the middle of the Forum.”

“Trust his destruction to me. We must use his talents and influence—thrust him upon every danger—make him our instrument while we are contending—our peace-offering to the Senate if we fail—our first victim if we succeed.”

“Hark! what noise was that?”

“Somebody in the terrace!—lend me your dagger.” Catiline rushed to the window. Zoe was standing in the shade. He stepped out. She darted into the room—passed like a flash of lightning by the startled Cethegus—flew down the stairs—through the court—through the vestibule—through the street. Steps, voices, lights, came fast and confusedly behind her;—but with the speed of love and terror she gained upon her pursuers. She fled through the wilderness of unknown and dusky streets, till she found herself, breathless and exhausted, in the midst of a crowd of gallants, who, with chaplets on their heads, and torches in their hands, were reeling from the portico of a stately mansion. 13The foremost of the throng was a youth whose slender figure and beautiful countenance seemed hardly consistent with his sex. But the feminine delicacy of his features rendered more frightful the mingled sensuality and ferocity of their expression. The libertine audacity of his stare, and the grotesque foppery of his apparel, seemed to indicate at least a partial insanity. Flinging one arm round Zoe, and tearing away her veil with the other, he disclosed to the gaze of his thronging companions the regular features and large dark eyes which characterise Athenian beauty.

“Clodius has all the luck to-night,” cried Ligarius. “Not so, by Hercules,” said Marcus Colius; “the girl is fairly our common prize: we will fling dice for her. The Venus (1) throw, as it ought to do, shall decide.”

“Let me go—let me go, for Heaven’s sake,” cried Zoe, struggling with Clodius.

“What a charming Greek accent she has. Come into the house, my little Athenian nightingale.”

“Oh! what will become of me? If you have mothers—if you have sisters——”

“Clodius has a sister,” muttered Ligarius, “or he is much belied.”

“By Heaven, she is weeping,” said Clodius.

“If she were not evidently a Greek,” said Colius, “I should take her for a vestal virgin.”

“And if she were a vestal virgin,” cried Clodius fiercely, “it should not deter me. This way;—no struggling—no screaming.”

“Struggling! screaming!” exclaimed a gay and commanding voice; “You are making very ungentle love, Clodius.”

(1) Venus was the Roman term for the highest throw on the

dice. 14The whole party started. Cæsar had mingled with

them unperceived.

The sound of his voice thrilled through the very heart of Zoe. With a convulsive effort she burst from the grasp of her insolent admirer, flung herself at the feet of Cæsar, and clasped his knees. The moon shone full on her agitated and imploring face: her lips moved; but she uttered no sound. He gazed at her for an instant—raised her—clasped her to his bosom. “Fear nothing, my sweet Zoe.” Then, with folded arms, and a smile of placid defiance, he placed himself between her and Clodius.

Clodius staggered forward, flushed with wine and rage, and uttering alternately a curse and a hiccup.

“By Pollux, this passes a jest. Cæsar, how dare you insult me thus?”

“A jest! I am as serious as a Jew on the Sabbath. Insult you; For such a pair of eyes I would insult the whole consular bench, or I should be as insensible as King Psammis’s mummy.”

“Good Gods, Cæsar!” said Marcus Colius, interposing; “you cannot think it worth while to get into a brawl for a little Greek girl!”

“Why not? The Greek girls have used me as well as those of Rome. Besides, the whole reputation of my gallantry is at stake. Give up such a lovely woman to that drunken boy! My character would be gone for ever. No more perfumed tablets, full of vows and raptures? No more toying with fingers at the Circus. No more evening walks along the Tiber. No more hiding in chests, or jumping from windows. I, the favoured suitor of half the white stoles in Rome, could never again aspire above a freed-woman. You a man of gallantry, and think of such 14a thin, lovely woman to that drunken boy! My character would be gone for ever. No more perfumed tablets, full of vows and raptures? No more toying with fingers at the Circus. No more evening walks along the Tiber. No more hiding in chests, or jumping from windows. I, the favoured suitor of half the white stoles in Rome, could never again aspire above a freed-woman. You a man of gallantry, and think of such 15a thing! For shame, my dear Colius! Do not let Clodia hear of it.”

While Cæsar spoke he had been engaged in keeping Clodius at arm’s length. The rage of the frantic libertine increased as the struggle continued. “Stand back, as you value your life,” he cried; “I will pass.”

“Not this way, sweet Clodius. I have too much regard for you to suffer you to make love at such disadvantage. You smell too much of Falernian at present. Would you stifle your mistress? By Hercules, you are fit to kiss nobody now, except old Piso, when he is tumbling home in the morning from the vintners.” (1)

Clodius plunged his hand into his bosom, and drew a little dagger, the faithful companion of many desperate adventures.

“Oh, Gods! he will be murdered!” cried Zoe.

The whole throng of revellers was in agitation. The street fluctuated with torches and lifted hands. It was but for a moment. Cæsar watched with a steady eye the descending hand of Clodius, arrested the blow, seized his antagonist by the throat, and flung him against one of the pillars of the portico with such violence that he rolled, stunned and senseless, on the ground.

“He is killed,” cried several voices.

“Fair self-defence, by Hercules!” said Marcus Colius. “Bear witness, you all saw him draw his dagger.”

“He is not dead—he breathes,” said Ligarius. “Carry him into the house; he is dreadfully bruised.”

The rest of the party retired with Clodius. Colius turned to Cæsar.

“By all the Gods, Caius! you have won your (1) Cic. in Pis. 16lady fairly. A splendid victory! You deserve a triumph.”

“What a madman Clodius has become!”

“Intolerable. But come and sup with me on the Nones. You have no objection to meet the Consul?”

“Cicero? None at all. We need not talk politics. Our old dispute about Plato and Epicurus will furnish us with plenty of conversation. So reckon upon me, my dear Marcus, and farewell.”

Caesar and Zoe turned away. As soon as they were beyond hearing, she began in great agitation:—

“Cæsar, you are in danger. I know all. I overheard Catiline and Cethegus. You are engaged in a project which must lead to certain destruction.”

“My beautiful Zoe, I live only for glory and pleasure. For these I have never hesitated to hazard an existence which they alone render valuable to me. In the present case, I can assure you that our scheme presents the fairest hopes of success.”

“So much the worse. You do not know—you do not understand me. I speak not of open peril, but of secret treachery. Catiline hates you;—Cethegus hates you;—your destruction is resolved. If you survive the contest, you perish in the first hour of victory. They detest you for your moderation;—they are eager for blood and plunder. I have risked my life to bring you this warning; but that is of little moment. Farewell!—Be happy——”

Cæsar stopped her. “Do you fly from my thanks, dear Zoe?”