Project Gutenberg's Famous Composers and their Works, Vol. 1, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Famous Composers and their Works, Vol. 1

Author: Various

Editor: John Knowles Paine

Theodore Thomas

Karl Klauser

Release Date: June 23, 2017 [EBook #54968]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FAMOUS COMPOSERS, WORKS, VOL 1 ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Jane Robins, with special

credit to Linda Cantoni for the music files, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Edited by

John Knowles Paine

Theodore Thomas and Karl Klauser

Illustrated

Boston

J. B. Millet Company

1906

Copyright, 1891, by

J. B. Millet Company.

This book is dedicated by the Publishers to

Henry L. Higginson

who has advanced the culture of music in America.

| America | ||

|---|---|---|

| Clarence J. Blake | Arthur Foote | John K. Paine |

| Mrs. Ole Bull | Philip Hale | Martin Roeder |

| Charles L. Capen | William J. Henderson | Howard M. Ticknor |

| John S. Dwight | Louis Kelterborn | John Towers |

| Louis C. Elson | Henry E. Krehbiel | George P. Upton |

| Henry T. Finck | Leo R. Lewis | Benj. E. Woolf |

| John Fiske | W. S. B. Mathews | |

| England | France | Germany |

| Edward Dannreuther | Oscar Comettant | Wilhelm Langhans |

| Mrs. Julian Marshall | Adolphe Jullien | Philipp Spitta |

| W. S. Rockstro | Arthur Pougin | |

The originals of the illustrations reproduced for this work were collected from museums, conservatories, antiquaries, public and private libraries, and other authentic sources in England and on the Continent, by Mr. Arthur J. Mundy, who spent several months in making a special search.

The authorities in London, Paris, Rome, Florence, Venice, Vienna, Leipsic, Dresden, Berlin, and other places visited, gladly assisted in making the collection as complete as possible.

This material was placed in the hands of Mr. Karl Klauser, who made valuable additions to it from his private collection of authentic portraits. A lifelong study of this subject enabled him to contribute valuable notes and comments on the illustrations.

The ornamental half-titles, headpieces, and initials were designed by Mr. E. B. Bird, of Boston.

| Page | ||

| Dedication | III | |

| List of Contributors | V | |

| List of Full-page Plates | VIII | |

| Index of Illustrations | IX-XII | |

| General Index | 961 | |

| Orlando di Lasso | W. J. Henderson | 3 |

| The Netherland Masters | W. J. Henderson | 11 |

| Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina | Louis C. Elson | 25 |

| Claudio Monteverde | W. S. B. Mathews | 33 |

| Alessandro Scarlatti | W. S. B. Mathews | 37 |

| Giovanni Battista Pergolese | H. M. Ticknor | 43 |

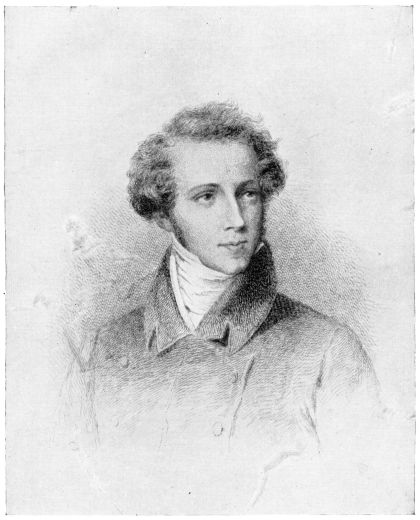

| Gioacchino Rossini | Arthur Pougin | 51 |

| Vincenzo Bellini | H. M. Ticknor | 67 |

| Gaetano Donizetti | H. M. Ticknor | 75 |

| Gasparo Luigi Pacifico Spontini | Adolphe Jullien | 83 |

| Luigi Cherubini | Philipp Spitta | 93 |

| Arrigo Boito | Arthur Pougin | 107 |

| Giovanni Sgambati | Arthur Foote | 111 |

| Guiseppi Verdi | Benj. E. Woolf | 117 |

| Music in Italy | Martin Roeder | 135 |

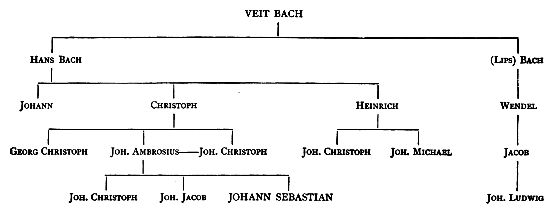

| Johann Sebastian Bach | Philipp Spitta | 163 |

| George Frederick Handel | Philipp Spitta | 195 |

| Christoph Wilibald Gluck | W. Langhans | 219 |

| Franz Joseph Haydn | Benj. E. Woolf | 245 |

| Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | Philip Hale | 269 |

| Ludwig van Beethoven (Biography) | Philip Hale | 309 |

| The Deafness of Beethoven | Clarence J. Blake | 333 |

| Beethoven as Composer | John K. Paine | 337 |

| Franz Peter Schubert | John Fiske | 351 |

| Ludwig Spohr | W. J. Henderson | 375 |

| Carl Maria von Weber | H. E. Krehbiel | 389 |

| Heinrich Marschner | H. E. Krehbiel | 409 |

| Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy | John S. Dwight | 417 |

| Robert Schumann | Louis Kelterborn | 439 |

| Robert Franz | Louis Kelterborn | 463 |

| Giacomo Meyerbeer | Arthur Pougin | 473[vii] |

| Strauss | Henry T. Finck | 487 |

| Joseph Joachim Raff | W. J. Henderson | 497 |

| Johannes Brahms | Louis Kelterborn | 503 |

| Carl Goldmark | W. J. Henderson | 515 |

| Max Bruch | Louis C. Elson | 519 |

| Joseph Gabriel Rheinberger | Louis Kelterborn | 525 |

| Richard Wagner | W. J. Henderson | 533 |

| Music in Germany | John K. Paine and Leo R. Lewis | 569 |

| Jean Baptiste Lully | Oscar Comettant | 609 |

| Jean Philippe Rameau | Oscar Comettant | 615 |

| André Ernest Modeste Grétry | Oscar Comettant | 623 |

| François Adrien Boieldieu | Louis C. Elson | 633 |

| Etienne Nicolas Méhul | Geo. P. Upton | 639 |

| Louis Joseph Ferdinand Hérold | Geo. P. Upton | 645 |

| Daniel François Esprit Auber | Oscar Comettant | 653 |

| Jacques François Fromental Elias Halévy | Benj. E. Woolf | 665 |

| Hector Berlioz | Adolphe Jullien | 675 |

| Ambroise Thomas | Benj. E. Woolf | 691 |

| Alexander César Léopold Bizet | Philip Hale | 697 |

| Camille Saint-Saëns | Oscar Comettant | 703 |

| Jules Emile Frédéric Massenet | Oscar Comettant | 711 |

| Charles Gounod | Arthur Pougin | 719 |

| Music in France | Arthur Pougin | 735 |

| Frederick Chopin | Edward Dannreuther | 759 |

| Anton Dvořák | Henry T. Finck | 779 |

| Michael Ivanovitch Glinka | Philip Hale | 785 |

| Anton Rubinstein | Henry T. Finck | 791 |

| Peter Ilitsch Tschaïkowsky | W. J. Henderson | 803 |

| Franz Liszt | W. Langhans | 813 |

| Eduard Hagerup Grieg | Sara C. Bull and Philip Hale | 831 |

| Niels William Gade | Louis C. Elson | 837 |

| Music in Russia, Poland, Norway, etc. | Henry T. Finck | 845 |

| William Byrd | W. S. Rockstro | 867 |

| Henry Purcell | John Towers | 871 |

| John Field | Chas. L. Capen | 877 |

| William Sterndale Bennett | W. S. Rockstro | 881 |

| Michael William Balfe | Benj. E. Woolf | 885 |

| Arthur Seymour Sullivan | Florence A. Marshall | 891 |

| Charles Hubert Hastings Parry | W. S. Rockstro | 899 |

| Alexander Campbell Mackenzie | Florence A. Marshall | 903 |

| Charles Villiers Stanford | W. S. Rockstro | 907 |

| Music in England | W. S. Rockstro | 913 |

| Music in America | Henry E. Krehbiel | 933 |

| PLATE | PAGE |

| 41 Auber | facing 653 |

| 12 Bach, portrait | 161 |

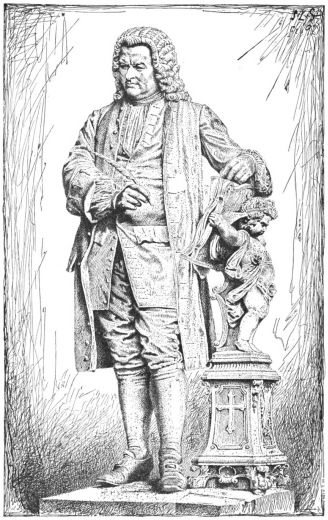

| 13 Bach, statue | 169 |

| 60 Balfe | 885 |

| 18 Beethoven | 307 |

| 5 Bellini | 67 |

| 59 Bennett | 881 |

| 43 Berlioz | 673 |

| 45 Bizet | 697 |

| 38 Boieldieu | 633 |

| 9 Boito | 107 |

| 29 Brahms | 503 |

| 31 Bruch | 519 |

| 8 Cherubini | 91 |

| 49 Chopin | 757 |

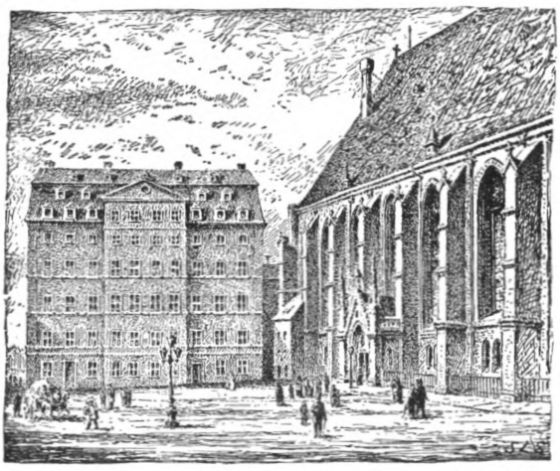

| 72 Conservatory of Music in Leipsic | 593 |

| 6 Donizetti | 75 |

| 50 Dvořák | 779 |

| 58 Field | 877 |

| 25 Franz | 463 |

| 56 Gade | 837 |

| 70 Garden of Harmony | 737 |

| 51 Glinka | 785 |

| 15 Gluck | 217 |

| 30 Goldmark | 515 |

| 48 Gounod | 717 |

| 37 Grétry | 623 |

| 55 Grieg | 831 |

| 42 Halévy | 665 |

| 14 Handel | 193 |

| 16 Haydn | 243 |

| 40 Hérold | 645 |

| 1 Lasso | 1 |

| 54 Liszt | 811 |

| 35 Lully | 609 |

| 63 Mackenzie | 903 |

| 22 Marschner | 409 |

| 47 Massenet | 711 |

| 39 Méhul | 639 |

| 23 Mendelssohn | 415 |

| 26 Meyerbeer | 471 |

| 17 Mozart | 267 |

| 65 Paine | 931 |

| 2 Palestrina | 25 |

| 71 Pantheon of German Musicians | 567 |

| 62 Parry | 899 |

| 57 Purcell | 871 |

| 28 Raff | 497 |

| 36 Rameau | 615 |

| 32 Rheinberger | 525 |

| 4 Rossini | 49 |

| 52 Rubinstein | 791 |

| 46 Saint-Saëns | 703 |

| 3 Scarlatti | 37 |

| 19 Schubert | 349 |

| 24 Schumann | 437 |

| 10 Sgambati | 111 |

| 20 Spohr | 375 |

| 7 Spontini | 83 |

| 64 Stanford | 907 |

| 27 Strauss | 487 |

| 61 Sullivan | 891 |

| 44 Thomas | 691 |

| 53 Tschaïkowsky | 803 |

| 11 Verdi | 115 |

| 33 Wagner | 531 |

| 34 Wagner | 545 |

| 21 Weber | 387 |

(Titles set in small capital letters indicate full-page illustrations.)

| PAGE | |

| Abt, Franz | 602 |

| Adam, Adolphe | 751 |

| Albrecht, V. | 4 |

| Allegri, Gregorio | 141 |

| Auber | 653 |

| Auber, medallion | 664 |

| Bach, J. S. | 161 |

| Bach, J. S. | 175 |

| Bach, Emanuel | 583 |

| Balakireff | 852 |

| Balfe | 885 |

| Beethoven | 307 |

| Beethoven, silhouette | 311 |

| Beethoven, miniature | 312 |

| Beethoven, by Gatteux | 317 |

| Beethoven, pencil portrait | 318 |

| Beethoven, by Schimon | 319 |

| Beethoven, by Stieler | 321 |

| Bellini | 67 |

| Bennett | 881 |

| Berlioz | 673 |

| Berlioz, by Signol | 681 |

| Berlioz in his later years | 683 |

| Berlioz, by Hüssener | 685 |

| Berton | 745 |

| Bizet | 697 |

| Boieldieu | 633 |

| Boito | 107 |

| Borodin | 853 |

| Brahms, by Brasch | 503 |

| Brahms in early youth | 505 |

| Brahms, by Weger | 509 |

| Brahms, by Luckhardt | 511 |

| Bruch | 519 |

| Bruch from wood-engraving | 520 |

| Bülow, Hans von | 605 |

| Cherubini | 91 |

| Cherubini, by Quenedey | 95 |

| Cherubini, by Ingres | 105 |

| Chopin | 757 |

| Chopin, by Duval | 761 |

| Chopin, by Winterhalter | 765 |

| Chopin, bas-relief | 769 |

| Cimarosa, Domenico | 148 |

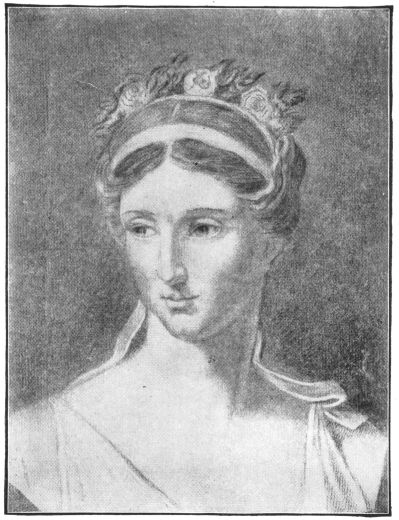

| Colbran, Isabella Angela | 55 |

| Corelli, Arcangelo | 152 |

| Cornelius, Peter | 603 |

| Cramer, Johann Baptist | 590 |

| Cui, César | 847 |

| D'Alayrac | 741 |

| David, Félicien | 753 |

| Donizetti | 75 |

| Donizetti | 77 |

| Dussek, Johann Ludwig | 588 |

| Dvořák | 779 |

| Field | 877 |

| Flotow, Friedrich von | 600 |

| Franz | 463 |

| Franz, by Weger | 465 |

| Franz | 469 |

| Frescobaldi, Girolamo | 151 |

| Gade | 837 |

| Gade | 839 |

| Geyer, Ludwig | 535 |

| Glinka | 785 |

| Glinka in his 39th year | 787 |

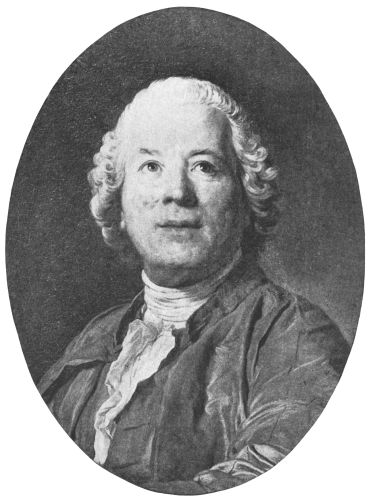

| Gluck, by Duplessis | 217 |

| Gluck, by Duplessis | 223 |

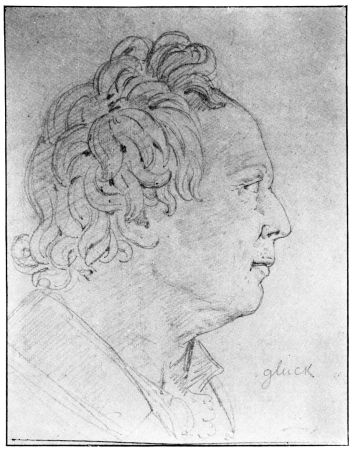

| Gluck, pencil portrait | 227 |

| Gluck, by Aug. de St. Aubin | 241 |

| Goldmark | 515 |

| Gounod, by Nadar | 717 |

| Gounod in his 41st year | 723 |

| Gounod in his Study | 729 |

| Graun, Karl Heinrich | 579 |

| Grétry | 623 |

| Grétry, by Vigée Lebrun | 630 |

| Grieg | 831 |

| Halévy | 665 |

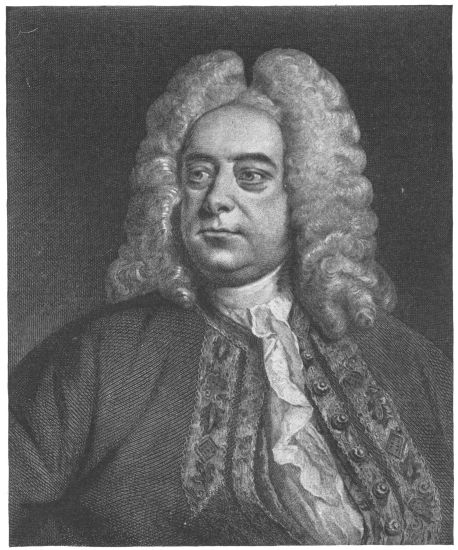

| Handel | 193 |

| Handel's Father | 199 |

| Handel, by Houbraken | 203 |

| Handel, by Mad. Clement | 207 |

| Hassler, Hans Leo | 571 |

| Hauptmann, Moritz | 598 |

| Haydn | 243 |

| Haydn, by Anton Graff | 249 |

| Haydn, silhouette | 255 |

| Haydn, miniature | 257 |

| Haydn in his 49th year | 263 |

| Hensel, William | 423 |

| Hérold | 645 |

| Hérold, medallion | 652 |

| Hiller, Ferdinand | 593 |

| Hummel, Johann N. | 589 |

| Jadassohn, Salomon | 597 |

| Joachim | 863 |

| Lachner, Franz | 596 |

| Lasso | 1 |

| Lasso, in "Penitential Psalms" | 6 |

| Lasso | 7 |

| Lesueur | 743 |

| Liszt | 811 |

| Liszt in his 13th year | 815 |

| Liszt in his 30th year | 821 |

| Liszt in his 75th year | 821 |

| Lortzing, Albert | 599 |

| Lully | 609 |

| Lully, by Bonnart | 611 |

| Lully | 613 |

| Mackenzie | 903 |

| Marcello, Benedetto | 145 |

| Marschner | 409 |

| Martini, Padre | 146 |

| Mascagni, Pietro | 159 |

| Massenet | 711 |

| Massenet in his Study | 713 |

| Méhul | 639 |

| Méhul | 640 |

| Méhul | 641 |

| Mendelssohn | 415 |

| Mendelssohn's father | 419[x] |

| Mendelssohn's mother | 420 |

| Mendelssohn, Fanny | 421 |

| Mendelssohn's wife | 422 |

| Mendelssohn on his death-bed | 424 |

| Mendelssohn in his 12th year | 428 |

| Mendelssohn in his 26th year | 431 |

| Meyerbeer | 471 |

| Meyerbeer in his eighth year | 475 |

| Meyerbeer, from wood-cut | 479 |

| Monte, Philip de | 23 |

| Moszkowski | 858 |

| Mozart | 267 |

| Mozart in his sixth year | 272 |

| Mozart in his ninth year | 272 |

| Mozart in his tenth year | 273 |

| Mozart in his 14th year | 273 |

| Mozart, Maria Anna | 277 |

| Mozart's wife | 280 |

| Mozart Family, by Carmontelle | 281 |

| Mozart family, by de la Croce | 283 |

| Mozart, last portrait of | 293 |

| Mozart, profile portrait | 297 |

| Offenbach | 754 |

| Paderewski | 859 |

| Paganini | 679 |

| Paine, John Knowles | 931 |

| Paisiello, Giovanni | 147 |

| Palestrina, by Böttcher | 25 |

| Palestrina | 27 |

| Palestrina, by Schnorr | 29 |

| Parry | 899 |

| Pergolese | 44 |

| Philidor | 739 |

| Piccini, Nicola | 229 |

| Prés, Josquin des | 17 |

| Purcell | 871 |

| Raff | 497 |

| Rameau | 615 |

| Rameau, by Nesle | 617 |

| Rameau, by Bellinger | 618 |

| Reber | 752 |

| Reichardt, Johann F | 581 |

| Reinecke, Carl | 594 |

| Rheinberger | 525 |

| Rheinberger, by Lützel | 527 |

| Rimsky-Korsakoff | 854 |

| Rore, Cyprian de | 20 |

| Rossini | 49 |

| Rossini in Middle Life | 53 |

| Rossini in his 36th year | 54 |

| Rossini, by Dupré | 57 |

| Rossini on his Death-Bed | 59 |

| Rossini, medallion | 65 |

| Rubinstein | 791 |

| Rubinstein, by Downey | 793 |

| Rubinstein, silhouette | 795 |

| Saint-Saëns | 703 |

| Saint-Saëns, by Raschkow | 705 |

| Scarlatti, A. | 37 |

| Scarlatti, A., by Solimène | 38 |

| Scarlatti, Domenico | 150 |

| Schubert | 349 |

| Schütz, Heinrich | 575 |

| Schulz, Johann Peter | 591 |

| Schumann | 437 |

| Schumann in his 21st year | 442 |

| Schumann, Clara, by Weger | 443 |

| Schumann, Robert and Clara | 445 |

| Schumann, Robert and Clara, by Kaiser | 453 |

| Schumann, Clara, by Hanfstängl | 457 |

| Schumann, Robert and Clara, relief medallion | 461 |

| Senfl, Ludwig | 570 |

| Seroff | 851 |

| Sgambati | 111 |

| Smithson, Miss | 677 |

| Spohr, by Schlick | 375 |

| Spohr, by W. Pfaff | 379 |

| Spontini | 83 |

| Spontini, by Vincent | 84 |

| Spontini, by Jean Guérin | 85 |

| Stanford | 907 |

| Strauss, Johann (senior) | 489 |

| Strauss, Johann (junior) | 487 |

| Strauss, Joseph | 491 |

| Strauss, Richard | 604 |

| Sullivan | 891 |

| Sullivan | 893 |

| Suppé, Franz von | 601 |

| Svendsen | 862 |

| Swelinck | 22 |

| Tartini, Guiseppe | 153 |

| Tausig, Carl | 857 |

| Thomas, Ambroise | 691 |

| Thomas, Ambroise | 695 |

| Tschaïkowsky, by Sarony | 803 |

| Tschaïkowsky, by Shapiro | 805 |

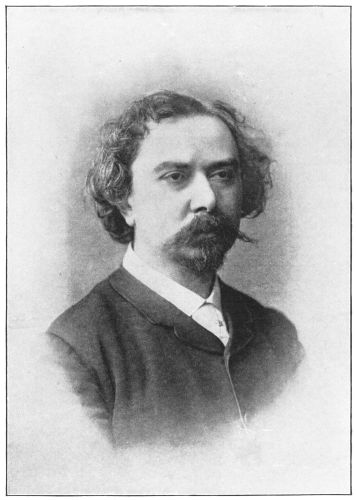

| Verdi | 115 |

| Verdi, by Deblois | 121 |

| Volkmann, Friedrich Robert | 595 |

| Wagner's gondolier, Trevisan | 544 |

| Wagner, by Krauss | 531 |

| Wagner's mother | 536 |

| Wagner, by Herkomer | 559 |

| Wagner | 545 |

| Wagner | 551 |

| Wagner from family group | 555 |

| Weber, Aloysia, and Jos. Lange | 279 |

| Weber, Constanze | 280 |

| Weber | 387 |

| Weber in his 24th year | 393 |

| Weber, by T. Minasi | 395 |

| Willaert, Adrian | 19 |

| Zelter, Carl Friedrich | 591 |

| Auber | 655 |

| Beethoven | 329 |

| Berlioz, by Benjamin | 687 |

| Berlioz, by Carjat | 688 |

| Donizetti | 76 |

| Halévy, by Dantan | 667 |

| Halévy, by Carjat | 671 |

| Handel | 210 |

| Kreisler, Kapellmeister | 455 |

| Liszt | 827 |

| Liszt, by Dantan | 829 |

| Meyerbeer, bust | 476 |

| Meyerbeer | 478 |

| Rossini, by Carjat | 56 |

| Rossini, bust | 63 |

| Rossini from "Panthéon Charivarique" | 64 |

| Strauss, Johann (senior) | 492 |

| Verdi | 129 |

| Auber, music | 661 |

| Auber, letter | 662 |

| Bach, music | 182 |

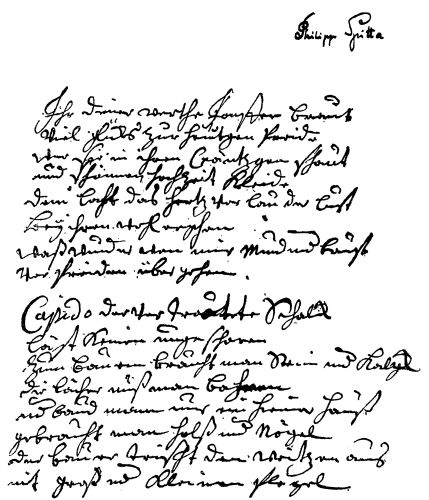

| Bach, poem | 192 |

| Balfe, letter | 889 |

| Balfe, music | 890 |

| Beethoven's creed | 329 |

| Beethoven, music | 336 |

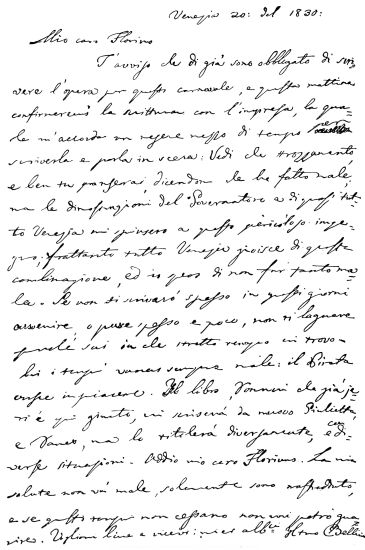

| Bellini, letter | 73 |

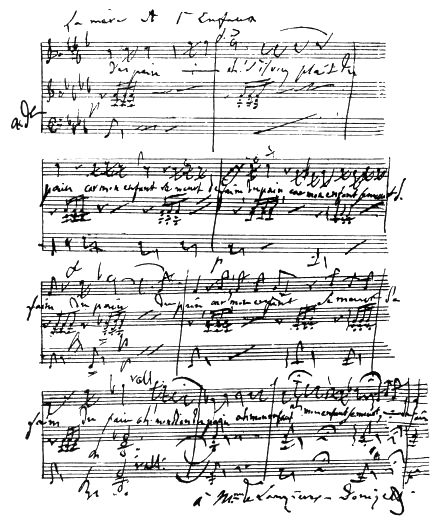

| Bellini, music | 74 |

| Bizet, music | 702 |

| Boieldieu, music | 637 |

| Brahms, music and letter | 506 |

| Bruch, music | 521 |

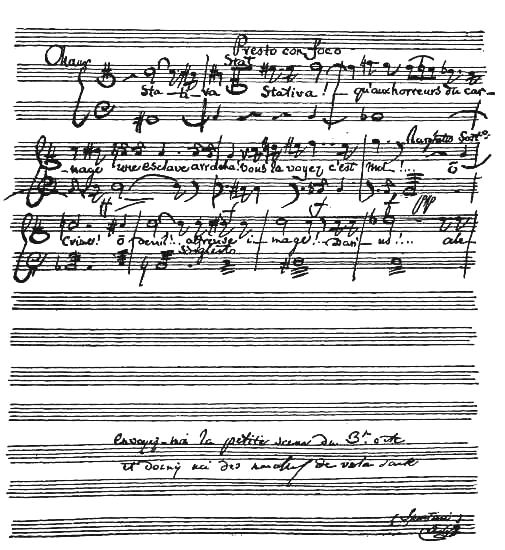

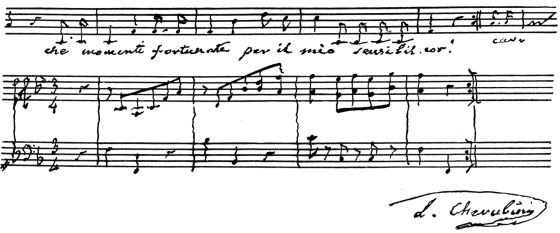

| Cherubini, music | 106 |

| Chopin, music | 775 |

| Donizetti, music | 774 |

| Dvořák, music | 81 |

| Franz, music and letter | 467 |

| Gade, music and letter | 841 |

| Gade, musical autograph | 842 |

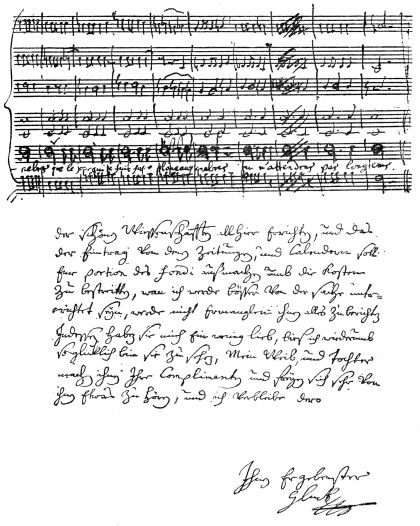

| Gluck, music and letter | 233 |

| Gounod, music | 727 |

| Grétry, music | 629 |

| Grieg, music | 836 |

| Halévy, music | 669 |

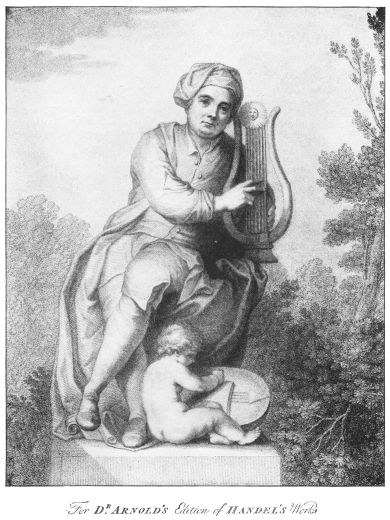

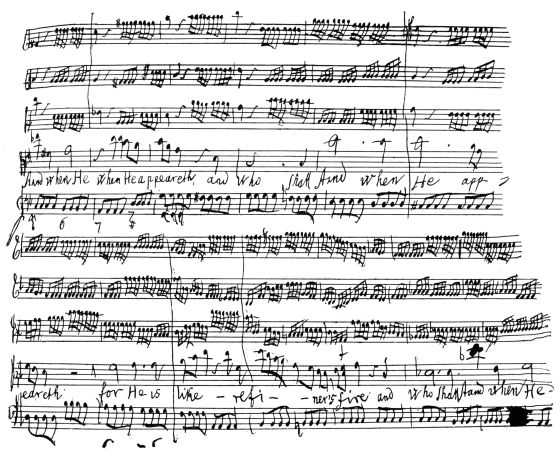

| Handel, music | 211 |

| Haydn, music | 261 |

| Hérold, music and letter | 651 |

| Liszt, music and letter | 825 |

| Marschner, letter | 411 |

| Marschner, music | 413 |

| Massenet, music | 716 |

| Méhul, music | 643 |

| Mendelssohn, letter | 425 |

| Mendelssohn, music | 426 |

| Meyerbeer, music and letter | 483 |

| Mozart, letter | 290 |

| Mozart, music | 292 |

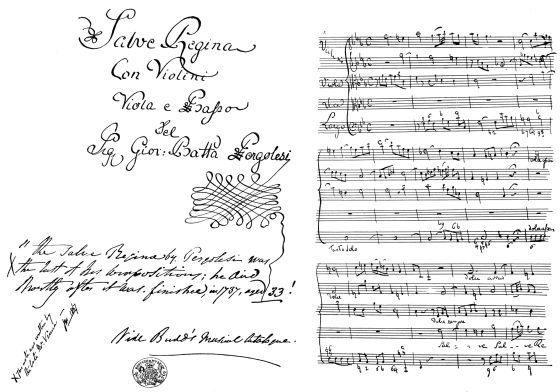

| Pergolese, music | 47 |

| Purcell, music | 873 |

| Raff, letter | 499 |

| Raff, music | 501 |

| Rameau, music | 621 |

| Rheinberger, music | 529 |

| Rossini, music | 61 |

| Rubinstein, letter | 797 |

| Rubinstein, music | 800 |

| Saint-Saëns, music | 707 |

| Scarlatti, music | 40 |

| Schubert, music | 361 |

| Schubert, letter | 371 |

| Schumann, Clara, letter | 449 |

| Schumann, letter | 449 |

| Schumann, music | 450 |

| Schumann, music | 462 |

| Sgambati, music and letter | 113 |

| Spohr, letter | 377 |

| Spohr, music | 383 |

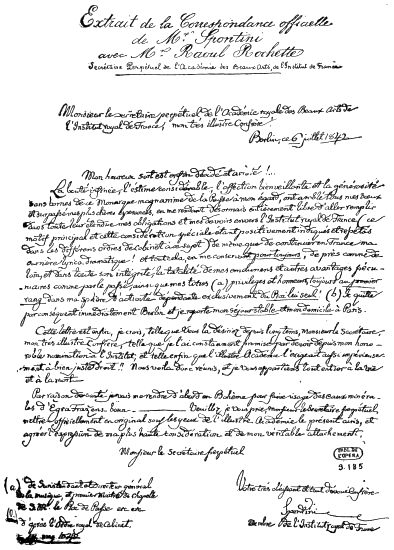

| Spontini, music and letter | 87 |

| Strauss (junior), music | 493 |

| Strauss (senior), music | 493 |

| Sullivan, music | 895 |

| Thomas, Ambroise, music | 693 |

| Tschaïkowsky, music | 807 |

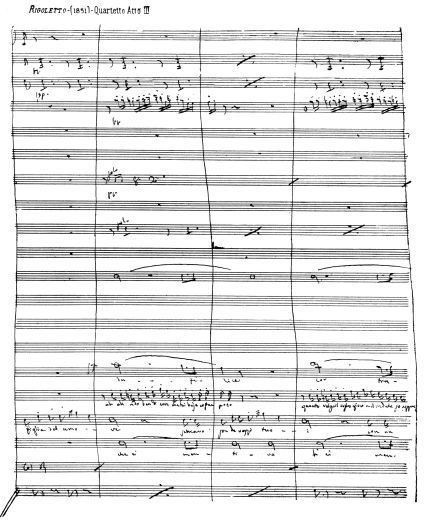

| Verdi, music | 125 |

| Verdi, letter | 132 |

| Wagner, letter | 547 |

| Wagner, music | 548 |

| Wagner, humorous composition | 561 |

| Weber, letter | 401 |

| Weber, music | 407 |

| Auber's residence | 658 |

| Bach's birthplace | 167 |

| Beethoven's birthplace | 310 |

| Beethoven, house where he died | 323 |

| Gluck's birthplace | 221 |

| Gounod's residence | 725 |

| Grétry's Hermitage | 627 |

| Grieg's country house | 833 |

| Handel's house | 201 |

| Haydn's birthplace | 247 |

| Mendelssohn's birthplace | 418 |

| Mendelssohn's residence | 435 |

| Mozart's birthplace | 274 |

| Mozart's residence in Vienna | 287 |

| Mozart, house where he died | 289 |

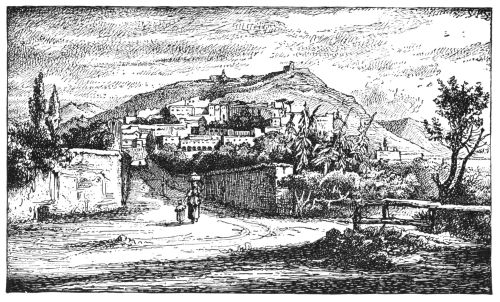

| Palestrina's birthplace | 32 |

| Schubert's birthplace | 353 |

| Schumann's birthplace | 441 |

| Verdi's birthplace | 119 |

| Verdi's residence | 123 |

| Wagner's birthplace | 534 |

| Wagner's residence, Villa Triebschen | 537 |

| Wagner's residence at Bayreuth | 538 |

| Wagner's residence at Venice | 541 |

| Weber's birthplace | 391 |

| Auber, bust | 656 |

| Auber's tomb | 659 |

| Bach, statue | 169 |

| Bach, monument | 185 |

| Balfe, tablet | 887 |

| Beethoven's tomb | 325 |

| Beethoven, Monument in Vienna | 332 |

| Beethoven, Monument in Vienna | 339 |

| Beethoven, bust | 341 |

| Beethoven, monument in Bonn | 345 |

| Beethoven, Mozart, and Schubert, Tombs of | 365 |

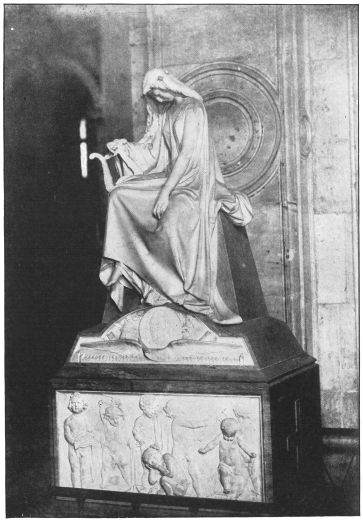

| Bellini, monument | 69 |

| Bellini, bust | 70 |

| Bellini's tomb | 71 |

| Bizet's tomb | 699 |

| Boieldieu, bust | 634 |

| Boieldieu's tomb | 635 |

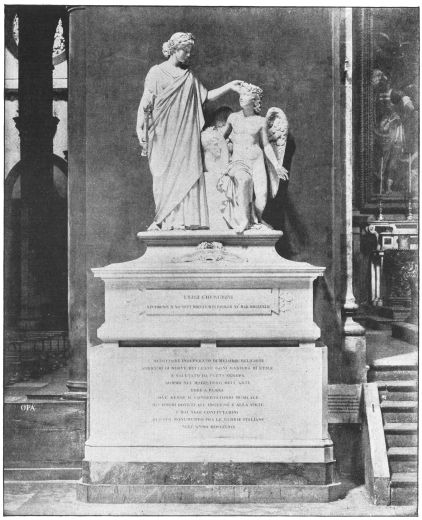

| Cherubini, monument | 99 |

| Cherubini's tomb | 101 |

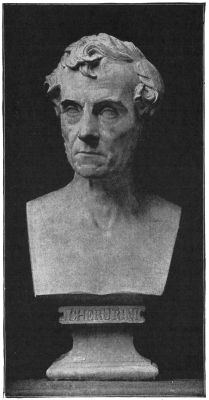

| Cherubini, bust | 103 |

| Chopin's tomb | 773 |

| Donizetti, monument | 79 |

| Donizetti, bust | 80 |

| Glinka, bust | 789 |

| Gluck's grave | 231 |

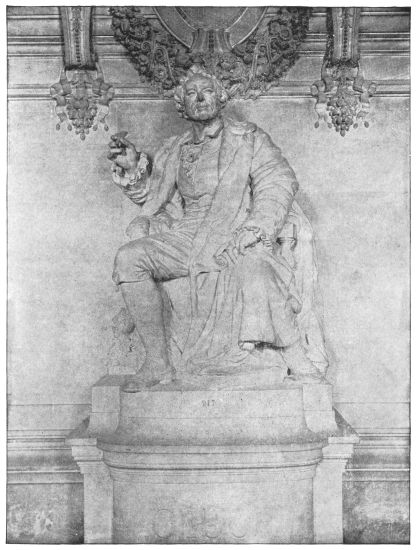

| Gluck, statue | 237 |

| Gluck, Monument | 239 |

| Grétry's tomb | 626 |

| Grétry's Memorial Chapel | 627[xii] |

| Halévy's Tomb | 668 |

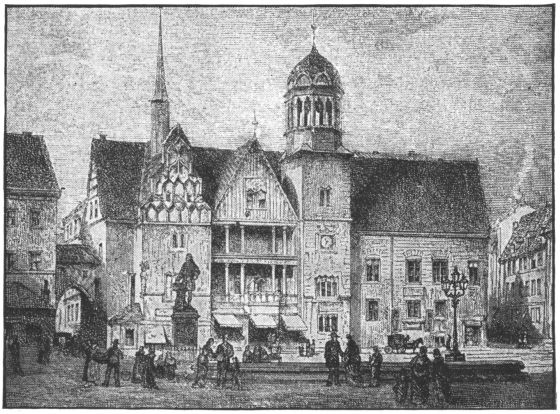

| Handel, monument in Halle | 197 |

| Handel, statue in Vauxhall Gardens | 205 |

| Handel, bust | 209 |

| Handel, statue, Paris Opera House | 213 |

| Haydn, bust | 251 |

| Haydn, monument | 253 |

| Haydn's grave | 259 |

| Hérold, bust | 647 |

| Hérold's Tomb | 649 |

| Lasso, statue in Munich | 5 |

| Mendelssohn, bust | 433 |

| Meyerbeer, bust | 477 |

| Meyerbeer, family tomb | 481 |

| Mozart, statue | 285 |

| Mozart, Monument in Vienna | 291 |

| Mozart, Monument in Salzburg | 299 |

| Mozart, Monument in Vienna | 301 |

| Purcell, memorial tablet | 875 |

| Rameau, statue | 619 |

| Schubert, Monument | 363 |

| Schubert's Tomb | 367 |

| Schumann, monument | 447 |

| Spontini, bust | 88 |

| Verdi, bust | 127 |

| Wagner, bust | 563 |

| Weber, monument | 399 |

| Animated Forge movement | 566 |

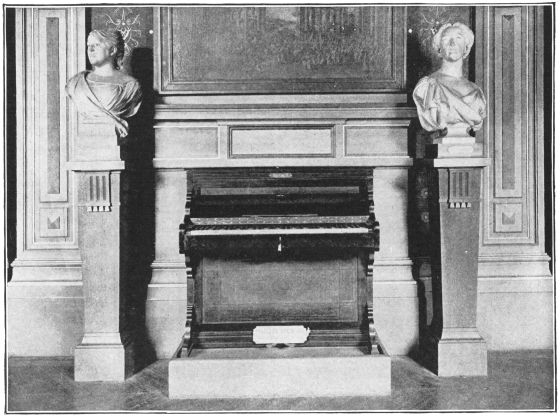

| Auber's Piano | 657 |

| Bach and Family | 171 |

| Bach before Frederick | 181 |

| Bayreuth Hill and Theatre | 540 |

| Beethoven and Mozart | 313 |

| Beethoven's Death Mask | 327 |

| Beethoven's Life Mask | 327 |

| Beethoven leading quartet | 315 |

| Beethoven's Studio | 322 |

| Berlin Opera House | 585 |

| Conservatory of Music at Leipsic | 593 |

| Frescos in Vienna Opera House. | |

| from "Armide" | 242 |

| " "Barber of Seville" | 66 |

| " "Creation" | 266 |

| " "Fidelio" | 348 |

| " the "Huguenots" | 486 |

| " "Jessonda" | 386 |

| " Mozart's operas | 306 |

| " Schubert's "Domestic War" | 374 |

| " the "Water Carrier" | 91 |

| Garden of Harmony | 737 |

| Gewandhaus Concert Hall in Leipsic | 607 |

| Gounod directing | 732 |

| Grétry's Clavichord | 625 |

| Grétry crossing the Styx | 632 |

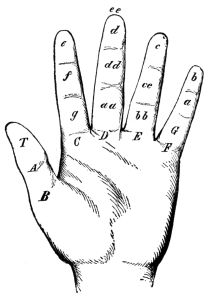

| Guidonian hand | 137 |

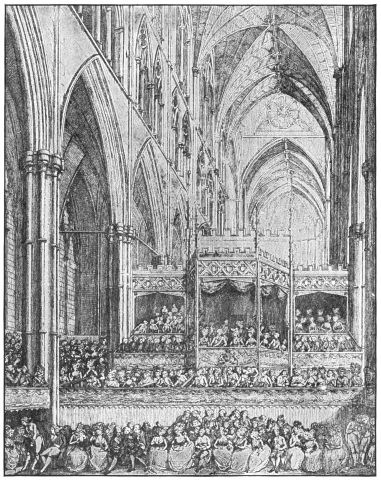

| Handel Commemoration | 215 |

| Handel's harpsichord | 216 |

| Hannibal, Scene from | 576 |

| Huguenots, billboard | 484 |

| Liszt's library and music room | 818 |

| Liszt's organ room | 819 |

| Liszt Playing to His Friends | 817 |

| Memorial Chapel, Grétry | 627 |

| Mendelssohn's hand | 436 |

| Mozart's ear | 295 |

| Mozart's first composition | 270 |

| Mozart's piano and spinet | 276 |

| Mozart, room where he was born | 275 |

| Old Market Square, Dresden | 397 |

| Opera House, Paris | 749 |

| Palazzo Vendramin | 543 |

| Panthéon Musical | 755 |

| Panthéon of German Musicians | 567 |

| Pergolese medal by Mercandetti | 45 |

| Pergolese commemorative medal | 48 |

| Rossini's clay pipe | 60 |

| Salzburg | 271 |

| Schubert and His Friends | 357 |

| Spontini's Piano | 90 |

| Strauss (junior) leading orchestra | 496 |

| St. Thomas's School | 177 |

| Syntagma Musicum, Title-page of | 572 |

| Triumph of Rameau | 622 |

| Vienna Opera House | 606 |

| Wagner and Friends at Bayreuth | 557 |

| Wagner's studio | 539 |

| Weber Leading Opera | 405 |

| Weber's coat-of-arms | 408 |

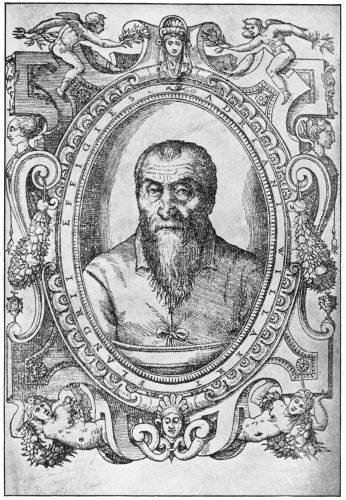

ORLANDO LASSO

Reproduction of an engraving by C. Debluis, after an old German print in the "Cabinet des estampes" in Paris. It bears the inscription, "Orlandus Lassus, musicus excellens."

OLAND DELATTRE is generally

known by the Italian form of his name, Orlando di Lasso. He was the last

great light of the famous school of Netherlands masters who were the

real founders of modern musical art. The history of Lasso's career is

tolerably well known to us, owing to the existence of Vinchant's "Annals

of Hainault" and a sketch by Van Quickelberg published in 1565 in a

biographical dictionary called "Heroum Prosopographia." Although the

former author was born in 1580, and Lasso died in 1594 or 1595, he places

the date of the composer's birth ten years earlier than Van Quickelberg.

Fétis gives plausible reasons for accepting Vinchant's date, yet it is

probable that Van Quickelberg got his data directly from the composer, of

whom he was an intimate friend.

OLAND DELATTRE is generally

known by the Italian form of his name, Orlando di Lasso. He was the last

great light of the famous school of Netherlands masters who were the

real founders of modern musical art. The history of Lasso's career is

tolerably well known to us, owing to the existence of Vinchant's "Annals

of Hainault" and a sketch by Van Quickelberg published in 1565 in a

biographical dictionary called "Heroum Prosopographia." Although the

former author was born in 1580, and Lasso died in 1594 or 1595, he places

the date of the composer's birth ten years earlier than Van Quickelberg.

Fétis gives plausible reasons for accepting Vinchant's date, yet it is

probable that Van Quickelberg got his data directly from the composer, of

whom he was an intimate friend.

At any rate, he was born in Mons in 1520 or 1530 and at the age of seven began his education. Like all musically gifted persons, he displayed his inclination toward the tone art at an early age, and in his ninth year he began the study of music. At that period music meant counterpoint and church singing. Hence Lasso, being endowed with a fine voice, began his career as a boy chorister in the church of St. Nicolas in his native town. There he became celebrated for the beauty of his voice and was twice stolen but recovered by his parents. The third time the little song-bird was carried off, he consented to remain with Ferdinand Gonzague, viceroy of Sicily and at that time commander of the army of Charles V. When the war was over the lad went with Ferdinand to Sicily and afterward to Milan. Van Quickelberg says that after six years his voice broke and at the age of eighteen he was sent by his patron under charge of Constantin Castriotto to Naples with letters of recommendation to the Marquis of Terza. He became a member of that nobleman's household and remained with him three years. At the end of that time he went to Rome, where he stayed six months as the guest of the archbishop of Florence. He was then appointed chapel-master of the famous church of St. John Lateran. While serving there he was informed of the sickness of his parents, and, probably being somewhat conscience stricken, set out for Mons, where he arrived after his father and mother were dead.

He returned to Rome and soon afterward paid a visit to France and England in company with a noble amateur of music called Julius Caeser Brancaccio. From France he went to Antwerp, where he stayed until he went to Munich in 1557 to enter the service of Albert of Bavaria. The doubt as to the date of his birth makes the length of his residence in Rome uncertain. He was there either two years or twelve, according as he was born in 1520 or 1530. The invitation to Munich seems to show that Lasso had acquired a European reputation as a composer. Such a reputation would naturally have been acquired during a long period of service in the Lateran church. If, however, Lasso did remain in Rome twelve years and produce works which gave him European celebrity, they are lost. Nevertheless even Van Quickelberg's testimony goes to show that Lasso's fame as a composer and as a man had preceded him to Munich. The Duke Albert directed him to engage a number of singers for the ducal choir and take them with him to Munich. Albert V. was a lover of art, and he is credited with being highly pleased at the engagement of Lasso. Quickelberg says that report in the Bavarian capital "was busy as to the character and disposition of the man. He was credited with being a great artist and a high-minded gentleman, and the Munich folk were not to be disappointed. The brilliant wit of the master, his amiability of temper, the cheerfulness of his disposition, and the universality of his knowledge, combined to make him a favorite with all. With[4] the duke and the duchess he was especially intimate, and owing to their favor was admitted to the highest social gatherings. His introduction to the court nobility resulted in his marriage in 1558 with Regina Welkinger, a maid of honor attendant on the duchess." [Naumann, History of Music, p. 376.]

ALBRECHT V.

Reproduced from an ancient prayer book.

It may be as well to add here that Lasso and his wife had six children, four sons and two daughters. Ferdinand and Rudolph, the eldest sons, became composers of some note. It was in 1562 that Lasso was made chapel-master to the Duke of Bavaria, thus attaining what was then esteemed as the highest prize in the musical world. He now had under his direction a fine body of singers and instrumentalists, for which a modern composer would have written not only masses, but cantatas and oratorios. We must bear in mind, however, that in Lasso's day church composers preferred the a capella style, and the art of orchestral accompaniment, as we understand it now, was unknown. When instruments were used in conjunction with voices they simply doubled the voice parts. Hence Lasso's great compositions are all written for an unaccompanied choir. It appears that Lasso served for five years as chamber musician before being made chapel-master, because Ludwig Daser was not quite old enough to be retired from the higher post and because the Duke wished Lasso to learn the language before assuming the responsibility of the mastership. In 1562, as stated, Daser was retired, and, as Van Quickelberg tells us, "the Duke, seeing that Master Orlando had by this time learnt the language and gained the good will of all by the propriety and gentleness of his behavior, and that his compositions (in number infinite) were universally liked, without loss of time elected him master of the chapel, to the evident pleasure of all."

From this time forward for several years Lasso was engaged in composing his most noted church works, among them being the famous "Penitential Psalms," which are still held in the highest esteem among lovers of pure old church music. He wrote also some of his finest Magnificats, as well as many pieces of secular music. His fame spread through Europe, and though Palestrina was his contemporary, it was Lasso who was spoken of as the "Prince of Musicians." He was also much praised as a conductor, and contemporary writers bear testimony to the fine precision and spirit with which the ducal choir sang under his direction. In 1570 the Emperor Maximilian honored the composer by making him a knight. The following year Pope Gregory XIII. conferred upon him the order of the Golden Spurs. The ceremony was performed with much pomp in the papal chapel at Munich by the chevaliers Cajetan and Mezzacosta. In the same year the composer made a visit to Paris, where he was received with every mark of distinction by Charles IX. This visit and the favor of the monarch have given rise to one of those pretty stories with which the history of music is dotted, but which unfortunately will not bear scrutiny. The story is that Charles IX., tormented by remorse for the massacre of St. Bartholomew, asked Lasso to write his Penitential Psalms as an expression of the kingly repentance. But dates, which are stubborn things, refuse to be reconciled with this story. These psalms were undoubtedly written at the request of Duke Albert. The first volume of them in manuscript is preserved in the Royal State Library at Munich, and it bears the date 1565. The massacre of St. Bartholomew took place in 1572. The value which[5] Duke Albert set upon these compositions is shown by the manner in which he treated them. They were bound in the most costly manner, in morocco, with silver ornaments which alone cost seven hundred and sixty-four florins. The court painter, Hans Mielich, painted for them portraits of the Duke, Orlando, and of the persons who made the books. J. Sterndale Bennett, in his excellent article on Lasso in Grove's "Dictionary of Music," makes the suggestion that the production of these noble psalms so early in the composer's life at Munich points to the probability that his Roman sojourn was twelve years instead of two, and that he was, therefore, born in 1520 instead of 1530. The inference is hardly avoidable.

To return to the Paris visit, it may be deemed probable that one result of it was the erection of a new Academy of Music, authorized by the king in 1570. The only composition known to have been produced by Lasso in Paris was sent to Duke Albert as "some proof of my gratitude." In 1574 Lasso set out for Paris once more, but when he had gone as far as Frankfort he learned that King Charles IX. was dead; so he returned to Munich, where he resumed the work of composition with undiminished activity. Lasso never left Munich again and a detailed record of his life subsequent to 1575 would consist chiefly of a chronological catalogue of the works which he published. It may be said that he did not produce any large compositions in the years 1578-80. The Duke, who had confirmed him for life in his appointment on his return from Munich, had become ill, and in October, 1579, this generous and high-minded patron of the arts breathed his last.

This was a sad blow to Lasso, whose affection for his princely friend was surely sincere. It was fortunate for the composer's material welfare that Duke Albert's successor was a hearty admirer of his works. The substantial nature of his regard was shown in 1587, when, Lasso having begun to show signs of failing health, the new potentate gave him a country house at Geising on the Ammer. There the composer sought seclusion for a time from the bustle of court life. On April 15, he dedicated twenty-three new madrigals to Dr. Mermann, the court physician, and J. Sterndale Bennett sees in this an evidence of restored health and renewed activity. Near the end of the year, however, he asked to be relieved of some of his numerous duties. The Duke gave him permission to retire from his post and pass a part of each year at Geising with his family, but his salary was to be reduced to two hundred florins per annum. His son Ferdinand, however, was to be appointed a member of the choir at two hundred florins, and Rudolph was to be made organist at the same salary. For some reason Lasso was not satisfied with this arrangement, and so he resumed his labors.

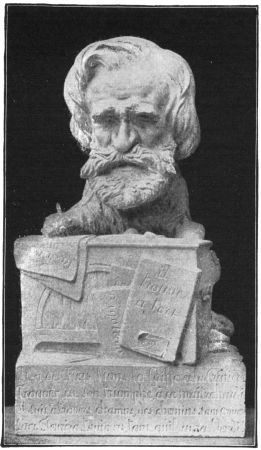

STATUE OF LASSO IN MUNICH

Erected by Ludwig II.

It would be gratifying to be able to picture this great master approaching his end along the green pathway of a serene old age. Unfortunately this cannot be done. His declining years were marked by gloom and morbidity. He talked constantly of death, and became so peevish as to write to Duke William complaining that he had not done all for the composer that Duke Albert had promised. The devoted wife, Regina, united her efforts with those of Princess Maximiliana to remove the evil effects of this letter. The composer sank gradually and died at Munich on June 14, 1594. He was buried in the cemetery of the Franciscans, and his[6] widow erected a fine monument to his memory in their church. According to Fétis this stone was two feet four inches high and four feet eight inches long. It had ornamental bas-reliefs representing the holy sepulchre, Lassus and his family at prayer, and the coat-of-arms conferred upon them by the Emperor Maximilian. The inscription on the base was as follows:

The reader will note the play on the word lassus, weary. The monument was removed when the Franciscan churchyard was dismantled in 1800, and in 1830 the stone disappeared from view. The world of art has to thank the "mad king" Ludwig, of Bavaria (to whom it owes debts of gratitude in connection with Wagner's career), for the erection of a life-size statue in bronze of Orlando Lasso. It stood originally next to the statue of Gluck near the Theatiner Church, but was afterward removed to the public promenade. There is another statue of Lasso at Mons, where he was born.

From portrait in the "Penitential Psalms," set by Lasso, in the Royal State Library at Munich.

Lasso was one of the most prolific composers that ever lived. He is said to have written no less than two thousand five hundred original works. A great number of these have been preserved, but the reader who is not able to decipher antique scores will undoubtedly be most interested in those which have been republished in modern form. These are as follows: his famous seven Penitential Psalms, edited by S. W. Dehn and published in Berlin in 1835; a "Regina coeli," "Salve Regina," "Angelus ad pastores," and "Miserere," Rochlitz's "Sammlung vorzüglicher Gesangstücke," Vol. I., published by Schott in 1838; a setting of the twenty-third Psalm as a motet for five voices, a "Quo properas" for ten voices, and a Magnificat for five, published at Berlin by Schlesinger; "Confirma hoc deus" for six voices, Berlin, Guttentag; six German chansons (four voices) and one dialogue (eight voices) in Dehn's "Sammlung alter Musik," Berlin, Crantz; twelve motets (four to eight voices) in Commer's collection published by Schott of Mainz; twenty motets in Proske's "Musica Divina"; the mass "Qual donna attende" (five voices) in Proske's selection of masses published at Ratisbon, 1856; the mass "Or sus à coup" (four voices), edited by Ferrenberg and published by Heberle at Cologne in 1847. Many more of his works have been edited and are ready for publication, but remain in MS. The above list is taken from Scribner's "Cyclopedia of Music and Musicians," and appears to be correct, as far as it goes. Naumann's "History of Music" contains a very beautiful "Adoramus te Christe," a chorale for four male voices. Lest the reader should fall into the error of supposing that the great bulk of Lasso's works were ecclesiastical, it should be mentioned that he wrote many German songs, fifty-nine canzonets, three hundred and seventy-one French songs, thirty-four Latin songs, and two hundred and thirty-three madrigals. Of these last, at least one—"Matrona, mia cara"—holds its own among the glees of to-day; and its quaint refrain of "Dong, dong, dong, derry, derry, dong, dong," haunts every ear that once has heard it.

To rightly appreciate the value of Lasso's music one must bear in mind the history of the great Netherlands school as a whole. Lasso was the perfect blossom of a plant of long growth. His earliest predecessors had been occupied in manufacturing musical materials, systematizing the old chaotic practice of the mere improvisers and establishing[7] fundamental forms on which the superstructure of modern music was to be reared. In their efforts at perfecting these forms they had fallen into extravagances, often losing sight of the nature and purpose of music, of which at the best they had a very imperfect comprehension. Occasionally, at least once in each period of the existence of the school, a composer arose who urged forward the march of development. A host of imitators would follow, and in imitating the new forms and touches of a creative mind these men could fall back into mere formal ingenuity again, and stay there till another original thinker arose. The progress of musical art, therefore, might be likened to the rising of the ocean tide on the beach, moving forward in a series of waves, each followed by receding water.

ORLANDO DI LASSO.

From a very early period in the rise of the Netherlands school a movement toward beauty and simplicity of form and expression can be traced. This movement came to its destination in Lasso. He did not, it is true, abandon the contrapuntal forms of his predecessors; but he wholly subordinated them to his purpose, and his purpose was plainly the expression of those feelings which belong to man's religious nature. He succeeded in keeping this purpose uppermost, no matter in what style he chose to write. Sometimes he composed simple chorales in which the voices moved simultaneously, and again he wrote hymns in four parts, adding a popular melody as a discant. He moved from either of these styles to the most complicated polyphonic manner of the Des Prés period without sacrifice of dignity, musical beauty or religious fervor. He wrote works for two and three choirs, and he wrote others for only two voices. In the Penitential Psalms he clearly demonstrated that a[8] mass of voices and parts was not necessary to an attainment of impressive effect, for he showed that he could be most powerfully expressive and influential while employing the simplest of means. Some of his writing is extremely old-fashioned even for his time. It might have been handed down from the days of Ockeghem. Again he plunges boldly into the labyrinth of chromatics and makes one think he hears the voice of Cyprian de Rore. In short, we must concede that Lasso displayed in his constructive skill the versatility of a complete master, while through all his work there runs the never-failing current of personal influence that flows only from the masterful individuality of a real genius.

Interesting comparisons have been drawn between the style of Lasso and that of Palestrina. The fact is that in formal arrangement Palestrina's masses bear a close assemblance to the most modern of Lasso's works. It is only when the Flemish master is writing in the style of his predecessors that his construction ceases to bear resemblance to that of the Italian. Both excelled in one style—that in which the profundity of contrapuntal skill results in an appearance of simplicity and in a real conveyance of emotion. The difference between the men lies in the character of their musical thought, and that difference has been most excellently expressed by Ambros, who says: "The one (Palestrina) brings the angelic host to earth; the other raises man to eternal regions, both meeting in the realm of the ideal." Fétis, in his prize essay of 1828, says: "Too many writers in their eulogies of Lasso have called him the Prince of musicians of his age. Whatever be the respect which I have for that great man, I declare that I am not able to acquiesce in this exaggerated admiration. It is sufficient for the glory of Lasso that he equalled the reputation of a musician like Palestrina; it would be unjust to accord him the superiority. In examining the works of these two celebrated artists, one remarks the different qualities which they possess and which gives to them an individual physiognomy. The music of the former is graceful and elegant (for the time in which it was composed); but that of Palestrina has more force and seriousness. That of Lasso is more singable and shows greater imagination, but that of his rival is much more learned. In the motets and madrigals of Palestrina are effects of mass which are admirable; but the French songs of Lasso are full of most interesting details. In fine they deserve to be compared with one another; that is a eulogy of both."

Fétis's assertion that the music of Palestrina is the more learned is a trifle vague. The fact is that the learning of Palestrina's music is greater than that of Lasso's only because the former more successfully conceals itself. Nothing could be more lovely in its simplicity than Lasso's "Adoramus te" given by Naumann, but its simplicity is that of the chorale style. The "Regina Coeli" given by Rochlitz is a fine specimen of double counterpoint. The "Salve Regina," given by the same author, is in free chorale style and is written for solo quartet and chorus. The "Angelus ad pastores," while not strict in its counterpoint, is full of learned work, yet withal is not involved in style. The "Principal Parts of the 51st Psalm," also printed in Rochlitz's work, looks very much like a modern anthem, especially the "Gloria patri." The madrigals of Lasso are charming in their native humor and in the piquancy of their part writing.

The influence of Lasso upon later composers cannot well be separated from the general influence of his time, for the contrapuntal church style was the prevailing manner of composition throughout Europe. The Belgian, Italian, and German music of the time is all built on the model established by the Netherlands masters. But Lasso must be credited with having done almost as much as Palestrina toward showing how ecclesiastical music could be written in an artistic but wholly intelligible manner. The German writers who imitated him (Ludwig Senfl, Paul Gerhardt and others) in their Protestant chorals and motets led the way directly to the motets, cantatas and passion music of the Bach period, and Lasso through his influence on them contributed toward the development of the genius of the immortal Sebastian.

HE improvisatore nursed the infancy

of both poetry and music.

The latter did not grow to the

stature of an art until the rude improvisations

of its early guardians

gave way to the systematic compositions of the

Netherland masters. Systematic composition, however,

presupposes the existence of three fundamental

elements, none of which had assumed tangible

form in the earliest days recorded in musical history.

These elements are harmony, notation and measure.

Huckbald, a Benedictine Monk of St. Armand in

Flanders, is credited with being the first to formulate

rules for harmony about 895 A. D. His ideas

were crude and their results disagreeable to the

modern ear. He used chiefly parallel fourths and

fifths, but he employed another freer style in which

a melody moved flexibly above a fixed bass—the

earliest form of pedal point. Harmony was not

invented by Huckbald, but he must be honored as

the writer of the first treatise on the subject. The

field once opened up was industriously cultivated,

and by the time the era of the Netherland school

began, had been productive of a rich harvest.

Notation was also a plant of slow growth, but the

employment of four lines in a staff, together with

the spaces, was introduced by Guido of Arezzo, who

died in 1050. The formulation of rules for measure

was the work of Franco of Cologne, who flourished

1200 A. D. He adopted four characters to represent

sounds of different lengths. These notes

were the longa,

HE improvisatore nursed the infancy

of both poetry and music.

The latter did not grow to the

stature of an art until the rude improvisations

of its early guardians

gave way to the systematic compositions of the

Netherland masters. Systematic composition, however,

presupposes the existence of three fundamental

elements, none of which had assumed tangible

form in the earliest days recorded in musical history.

These elements are harmony, notation and measure.

Huckbald, a Benedictine Monk of St. Armand in

Flanders, is credited with being the first to formulate

rules for harmony about 895 A. D. His ideas

were crude and their results disagreeable to the

modern ear. He used chiefly parallel fourths and

fifths, but he employed another freer style in which

a melody moved flexibly above a fixed bass—the

earliest form of pedal point. Harmony was not

invented by Huckbald, but he must be honored as

the writer of the first treatise on the subject. The

field once opened up was industriously cultivated,

and by the time the era of the Netherland school

began, had been productive of a rich harvest.

Notation was also a plant of slow growth, but the

employment of four lines in a staff, together with

the spaces, was introduced by Guido of Arezzo, who

died in 1050. The formulation of rules for measure

was the work of Franco of Cologne, who flourished

1200 A. D. He adopted four characters to represent

sounds of different lengths. These notes

were the longa, ![]() ; the brevis,

; the brevis, ![]() ;

the duplex longa,

;

the duplex longa,

![]() and the semi brevis,

and the semi brevis, ![]() . He also distinguished

common from triple time, calling the

latter "perfect." Fétis quotes from the introduction

to Franco's "Ars Cantus Mensurabilis" the

following words: "We propose, therefore, to set

forth in this volume this same measured music. We

shall not refuse to make known the good ideas of

others, nor to expose their mistakes; and if we have[11]

invented anything good, we shall support it with

good arguments." Fétis, however, makes this significant

remark: "Néanmoins le profond savoir

qu'on remarque dans l'ouvrage de Francon, et l'obscurité

dans laquelle sont ensevelis et les noms et

les œuvres de ceux, auxquels il attribue la première

invention de la musique mesurée, le feront à jamais

regarder comme le premier auteure de cette importante

découverte." [Fétis, Mémoire sur cette Question:

"Quels out été les mérites des Neerlandais

dans la musique," etc.—Question mise au concours

pour l'année 1828 par la quatrieme classe de l'Institut

des Sciences, de Litterature et des Beaux Arts

du Royaume des Pays-Bas.]

. He also distinguished

common from triple time, calling the

latter "perfect." Fétis quotes from the introduction

to Franco's "Ars Cantus Mensurabilis" the

following words: "We propose, therefore, to set

forth in this volume this same measured music. We

shall not refuse to make known the good ideas of

others, nor to expose their mistakes; and if we have[11]

invented anything good, we shall support it with

good arguments." Fétis, however, makes this significant

remark: "Néanmoins le profond savoir

qu'on remarque dans l'ouvrage de Francon, et l'obscurité

dans laquelle sont ensevelis et les noms et

les œuvres de ceux, auxquels il attribue la première

invention de la musique mesurée, le feront à jamais

regarder comme le premier auteure de cette importante

découverte." [Fétis, Mémoire sur cette Question:

"Quels out été les mérites des Neerlandais

dans la musique," etc.—Question mise au concours

pour l'année 1828 par la quatrieme classe de l'Institut

des Sciences, de Litterature et des Beaux Arts

du Royaume des Pays-Bas.]

With harmony and measure governed by rules and the written page at hand as a conserving power, systematic composition became a possibility. The study of this art was the work of monks, who were the repositories of polite learning in the middle ages, and they naturally sought for their thematic material in the plain chant of the church. Their treatment of this chant was a natural outgrowth of the impromptu production of music which had preceded systematic composition and which clung to existence with great pertinacity. Guido of Arezzo had taught choristers the art of singing with such success that they began the long-honored custom of adding ornaments to their melodies. They carried this practice to such an extent that it became necessary for one singer to intone the melody while another sang the ornamental part. This adding of ornamental parts was called the art of discant; and when the monks took up scientific composition they simply added discants to the liturgical chants of the church. This was the beginning of counterpoint, the art of writing two or more melodies which shall proceed simultaneously without breaking the rules of harmony. The name "counterpoint" was early applied to it by Johannes de Muris, doctor of theology at the University of Paris[12] in the beginning of the fourteenth century. This indicates that by his time the scientific setting of note against note had fully superseded discant, the fanciful elaboration of the singers.

It was in the hands of the great masters of the Netherland school that this counterpoint, the first species of scientific composition, was developed to its highest perfection. In the main the differences between their counterpoint and ours are due to the cramped harmony of their time, which was fettered by the employment of the Gregorian scales. The superiority of Bach's counterpoint over theirs from a technical point of view is the result of his mastery of chromatics and his perfection of the system of equal temperament. With the aesthetic superiority of his work we need not concern ourselves, for we must bear in mind the fact that most of the Netherland masters were absorbed in developing the technical construction of music, and had little to do with the exploration of its emotional possibility.

Systems are not completed in a day. Those writers on musical history who pass immediately from the labors of Franco to the Netherland masters ignore the long series of tentative works of the French composers who flourished between 1100 and 1370 A. D., and of the English composers who flourished between the same years. It is a well established fact that in England there were many writers who showed skill in the early contrapuntal forms. Johannes Tinctoris, a Netherlander, writing in 1460 A. D., went so far as to say that the source of counterpoint was among the English, of whom Dunstable was in his opinion the greatest light. Walter Odington, an Englishman, wrote a learned treatise on counterpoint in 1217, and some authorities accept him as the composer of the notable canonic composition, "Sumer is icumen in." It is pretty clearly established, however, that Odington was a disciple of the French school, while Dunstable, being a contemporary of Binchois, was of later birth than the early French composers. The writer of this paper is of the opinion that the line of contrapuntal development appears to join Flanders with France rather than with England, and he, therefore, prefers to consider chiefly the French school.

The Frenchman, Jean Perotin, then, about 1130 A. D., employed imitation, and one of his immediate successors, Jean de Garlande, says in his treatise on music that double counterpoint was known before his time. He says it is the repetition of the same phrase by different voices at different times. It is impracticable in this article to review in detail the achievements of the French school, but a summary of its work is necessary to a comprehension of the Netherland school. The Frenchmen possessed three kinds of harmonic combinations: the Déchant (discant) or double, the triple and the quadruple, or in other words, contrapuntal compositions in two, three and four parts. Discants were of two kinds. In the first the cantus firmus, or fixed chant of the liturgy, was sung by one voice (called tenor—Latin, teneo, I hold—because it held the tune) while the other added a discant above it. In the second the discant was freely composed, and a lower part, or bass added.

Three-part compositions were of four kinds: fauxbourdon, motet, rondeau and conduit, the last three being written also in four parts. Fauxbourdon was simply a three-voiced chant, the parts having similar motion, the upper and lower being parallel sixths and the middle in fourths with the discant. In the motet each voice had a text of its own. The rondo was secular and was developed from the folk-music of the day. The conduit was uncertain in form, secular in character, and, like the rondo, was written for either voices or instruments. The early French masters made extensive use of the parallel movement of voices, yet had plainly no conception of harmony founded on chords. They show a much clearer purpose in their contrapuntal writings wherein the imitations are plainly devised according to rules. But the entire musical product of France between 1100 and 1250 was the cold, mathematical work of academicians, who nevertheless served the cause of the tone art by laying down indispensable laws. The last great master of this school, William of Machaut, who wrote the celebrated Coronation Mass for the crowning of Charles V., flourished between 1284 and 1369. Naturally enough the teachings of the French spread into the provinces of Belgium, and there grew up a school from which the Netherland masters rose. The most prominent early Belgian composer was Dufay (1350-1432). This writer introduced secular melodies into his masses, forbade the use of consecutive fifths, and freely used interrupted canonic part writing, in which the imitation appears only at occasional effective places. His works show evidences of a vague groping after euphonic beauty. Antoine de Busnois, who died in 1482, was the last of these[13] early masters. His works abound in clever use of the devices of imitation and inversion. His canonic writing is more finished and his harmony bolder than Dufay's. The character of the music produced at this time has been well described by Mr. Rockstro. He says: "At this period, representing the infancy of art, the subject, or canto fermo, was almost invariably placed in the tenor and sung in long sustained notes, while two or more supplementary voices accompanied it with an elaborate counterpoint, written like the canto fermo itself in one or other of the ancient ecclesiastical modes, and consisting of fugal passages, points of imitation, or even canons, all suggested by the primary idea, and all working together for a common end."

Dufay was the connecting link between the French School and the great Netherland masters. At this time the Dutch led the world in painting, in the liberal arts and in commercial enterprise. Their skill in mechanics was unequalled, and we naturally expect to see their musicians further the development of musical technique. We must bear in mind facts to which the writer has had to refer elsewhere ("Story of Music," p. 21). "The general tendency of European thought at this time also had its bearing on the tone art. Scholasticism was in full sway, and such philosophers as Albertus Magnus, John Duns Scotus and William of Ockham were engaged in wondrous metaphysical hair-splitting, endeavoring to reduce Aristotelianism to a Christian basis by the application of the most vigorous logic. This spirit of scholasticism entered music, and contrapuntal science by too much learning was made mad." Yet the essential nature of music could not be wholly suppressed, and as the writers of the time acquired that marvellous mastery of musical material which came from their practice of counterpoint, they began to use their science as a means and not an end; and finally the masters of the Netherland school attained the loftiest heights of church composition. Various divisions of the periods of development of this school have been made. That adopted by the writer is Emil Naumann's with some alterations. It does not appear to be necessary to set the Dutch members of the school apart from the Belgians; and the writer, in his estimate of the comparative importance of the masters, agrees with Kiesewetter and Fétis rather than with Naumann. The division of the school into four periods, as follows, seems to be a fair one:

Netherlands School (1425-1625 A. D.).

First Period, 1425-1512.

Chief masters: Ockeghem, Hobrecht, Brumel.

Second Period, 1455-1526.

Chief masters: Josquin des Près, Jean Mouton.

Third Period, 1495-1572.

Chief masters: Gombert, Willaert, Goudimel, De Rore, Jannequin, Arkadelt.

Fourth Period, 1520-1625.

Chief masters: Orlando Lasso, Swelinck, De Monte.

Johannes Ockeghem, the most accomplished writer of the first period, was born between 1415 and 1430, probably at Termonde in East Flanders. It is likely that he studied music under Binchois, a contemporary of Dufay. At any rate an Ockeghem was one of the college of singers at the Antwerp cathedral in 1443, when Binchois was choir master. About 1444 the youth entered the service of Charles VII. of France, as a singer. He stood high in the favor of Louis XI., who made him treasurer of the church of St. Martin's at Tours. There Ockeghem passed the remainder of his life, retiring from active service about 1490. He died about 1513.

Octavio dei Petrucci, of Fossombrone, invented movable types for printing music in 1502, and obtained a patent for the exclusive use of the process for fifteen years in 1513. By that time the advance in the mastery of counterpoint had left Ockeghem somewhat out of fashion; and it is, therefore, not remarkable that Petrucci's earliest collections contain nothing by this master. Not till years after his death was any mass or motet of his given to the world. Then only one was printed entire. This was his "Missa cujusvis toni," which was plainly selected because of its science. Extracts from his "Missa Prolationum" were used in theoretical treatises; and, indeed, Ockeghem's music seems generally to have been cherished wholly on account of the technical instruction which might be derived from it. The list of his extant compositions, as given in Scribner's "Cyclopedia of Music," is as follows:

"Missa cujusvis toni," in Liber XV., missarum (Petreius, Louvain, 1538); six motets and a sequence (Petrucci, Venice, 1503); an enigmatic canon in S. Heyden's "Ars Canendi" and in Glarean's "Dodekachordon"; fragments of "Missa prolationum" in Heyden's book and in Bellermann's "Kontrapunkt"; mass "De plus en plus," MS. in Pontifical Chapel, Rome; two masses,[14] "Pour quelque peine" and "Ecce ancilla Domini," in the Brussels Library; motets in MS. in Rome, Florence and Dijon; six masses, an Ave and some motets in Van der Straeten; Kyrie and Christe, from "Missa cujusvis toni" in Rochlitz.

This list is probably correct except the six motets and a sequence set down as published by Petrucci in 1503. Ambros, who is always trustworthy and who mentions all these works and also three songs ("D'ung aultre mer," "Aultre Venus" and "Rondo Royal") and a motet ("Alma redemptoris") in MS. at Florence, did not discover any publications by Petrucci. The enigmatical canon was solved by Kiesewetter, Burney, Hawkins and other historians; but the solution believed to be most nearly correct is that of the profound contrapuntist and excellent historian, Fétis. Glareanus (Dodekachordon, p. 454) speaks also of a motet for thirty-six voices. This was, no doubt, originally written for six or nine voices, the other parts being derived from them by canons. It is not certain, however, that Ockeghem ever wrote such a work. The "Missa cujusvis toni" ("A mass in any tone," or scale, as we should say now) may have been written as an exercise for the master's pupils, as some historians conjecture, but it seems more probable that it was a natural outgrowth of the puzzle-building spirit of the time and of Ockeghem's especial fondness for displays of musical ingenuity. The peculiarity of the mass is that it employs in a remarkable manner all the church modes or scales. It was sung in Munich many years after Ockeghem's death and a corrected copy of it is still preserved in the chapel.

Fétis says: "As a professor, Ockeghem was also very remarkable, for all the most celebrated musicians at the close of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth century were his pupils." In the "Complaint" written after his death by William Grespel, appear the following lines:

Antoine Brumel achieved the greatest distinction among these pupils. He was born about 1460 and died about 1520. His personal history is lost. The present age possesses, however, a fuller record of his work than it has of his master's. In one volume printed by Petrucci in 1503 and to be found in the Royal Library at Berlin, there are five of his masses. Another mass by this composer is in a volume of works by various writers, printed also by Petrucci. A copy of this composition is in the British Museum. A number of masses and motets of his are scattered through other collections of Petrucci's. Others exist in MS. in Munich. Brumel's motet, "O Domine Jesu Christe, pastor bone," quoted by Naumann, is written in a clear and dignified style, abounds in full chords, and contains only such passages of imitation as would readily suggest themselves. A better example of the style of the period is his canonic, "Laudate Dominum," given by Foskel and Kiesewetter.

Jacob Hobrecht, the principal Dutch master of the first Netherland period, was born about 1430, at Utrecht, where he subsequently became chapel-master. It does not appear on record anywhere that he was a pupil of Ockeghem, but he was unquestionably a disciple of that composer. He achieved celebrity in his life time and was honored with many distinctions. He wrote a mass for the choir of the Bruges Cathedral, and the whole body journeyed to Antwerp to pay him homage. It is stated that he also received a visit from Bishop Borbone of Cortona, leader of the papal choir. Hobrecht became chapel-master at Utrecht, about 1465, and had there a choir of seventy voices. A part of his life was spent in Florence at the court of Lorenzo the Magnificent, where he met Josquin des Près.

The indefatigable Ambros goes into a careful discussion of eight masses of Hobrecht's, published in the Petrucci collections. Of these the best, known as the "Fortuna desperata," was published in modern notation at Amsterdam in 1870. Examples of Hobrecht's writing are also to be found in the works of Burney, Forkel, Kiesewetter, and Naumann. One of Hobrecht's musical feats was the composition of a mass in a single night. His works contain all the canonic inventions employed by Ockeghem, and are a mine of contrapuntal learning. Doubtless when sung by the trained cathedral choirs of their period, they were impressive to ears not attuned to modern tonality.

So much for the personal history of the most brilliant lights of the time. More instructive will be a review of the musical character of their work.

It is the prevailing influence of one or two masters in each period that marks its extent. Its char[15]acter was formed by that influence, and salient features of the style of each period may be fairly distinguished. The first period was marked by the extreme development of the canon. Perhaps for the benefit of the reader who may not have studied counterpoint it would be well to give here one or two elementary definitions. Imitation, in the words of Sir Frederick A. Gore-Ouseley, is "a repetition, more or less exact, by one voice of a phrase or passage previously enunciated by another. If the imitation is absolutely exact as to intervals it becomes a canon." Canon is the most rigorous species of imitation. Naturally then, as imitation is the foundation of fugal writing, the first occupation of musicians was its perfection. Thus we see that the composers of the first period of the Netherland school were almost wholly engaged in exploring the resources of canonic composition, and the most celebrated of their number, Ockeghem, was he who displayed the greatest ingenuity in this style. To describe the various forms of canonic jugglery invented by Ockeghem and his contemporaries would weary the reader; but a few may be mentioned as examples of the craft exercised at that time.

First, there was the "cancriza," or backward movement of the cantus firmus, in which the melody was repeated interval by interval, beginning at the last note and moving toward the first. Second, there was the inverted canon, in which the inversion consisted of beginning at the original first note and proceeding with each interval reversed, so that a melody which had ascended would, in the inversion, descend. In the canon by augmentation the subject reappears in one of the subsidiary parts in notes twice as long as those in which it was originally announced. Conversely in the canon by diminution the subject is repeated in notes of smaller duration than those first used. These four forms are still extant and have been employed by most great composers of modern music from Bach to the present time. The canon by augmentation is often used in choral music, especially in the bass, with superb effect. Indeed all the varieties described are to be found in the music of Handel and Bach, the latter being a complete master of their use in instrumental as well as choral composition.

But the composers of the first Netherland period employed kinds of canonic writing which are now looked upon as mere curiosities. Among these were the repetition of the cantus firmus beginning with the second note and ending with the first; the repetition with the omission of all the rests; the perfect repetition of the whole melody; a repetition half forward and half backward; and another with the omission of all the shortest notes. Naumann is of the opinion that these forms "arose from an earnest desire to consolidate a system of part-writing which could only exist after a complete mastery had been obtained over all kinds of musical contrivances." Kiesewetter, also generous in his views, says that these writers excel their predecessors in possessing "a greater facility in counterpoint and fertility in invention; their compositions, moreover, being no longer mere premeditated submissions to the contrapuntal operation, but for the most part being indicative of thought and sketched out with manifest design, being also full of ingenious contrivances of an obligato counterpoint, at that time just discovered, such as augmentation, diminution, inversion, imitation; together with canons and fugues of the most manifold description."

Of Ockeghem in particular, Rochlitz ("Sammlung vorzüglicher Gesangstücke," Vol. I., p. 22) says: "His style was distinguished from that of his predecessors, especially Dufay, principally in two ways: it was more artistic and was not founded on well-known melodies, but in part on freely made melodic movements contrapuntally developed, which rendered the style richer and more varied."

This statement is undoubtedly true, and may be taken for all it is worth. But the prima facie evidence of the works of these masters is that the writers were bent on exhausting the resources of canonic ingenuity, that their private study was all devoted to the exploration of academic counterpoint, that they worked in slavish obedience to the contrapuntal formulas which they themselves had contrived, and that their most ambitious compositions were nothing more or less than brilliant specimens of technical skill. To this estimate of their work excellent support is given by the significant criticism of Martin Luther on the writing of Josquin des Près, chief master of the second period. The great reformer said: "Josquin is a master of the notes; they have to do as he wills, other composers must do as the notes will." Furthermore the Latin formulas used in noting canons in Ockeghem's day go far toward proving that it was the mechanical ingenuity of the form which appealed to the masters of that time. They were in the habit of putting[16] forth a canonic subject with the general indication "Ex una plures," signifying that several parts were to be evolved from one, and a special direction, such as "Ad medium referas, pausas relinque priores," darkly hinting at the manner of the working out. These riddle canons date back to Dufay's time, but they were the special delight of Ockeghem and his contemporaries. The results of such practice could only be musical mathematics, yet the masters of this period performed a lasting service to art; for they laid down rules for this kind of composition and in their own works indicated the path by which artistic results might be reached by their successors. The highest praise that can be awarded to their works is that they are profound in their scholarship, not without evidences of taste in the selection of the formulas to be employed, and certainly imbued with a good deal of the dignity which would inevitably result from a skilful contrapuntal treatment of the church chant. Ambros finds evidences of design in one of Ockeghem's motets, from which he quotes, but the design is certainly not of the kind which would call for praise if discovered in contemporaneous music. Naumann, who is quite carried away by the improvement of the first Netherlands compositions over those of the French contrapuntists, is warm in his praise of these early canonists. He says:

"Almost at the beginning of the Netherland school, mechanical invention was made subservient to idea. It was no longer contrapuntal writing for counterpoint's sake. Excesses were toned down, and the desire unquestionable was that the contrapuntist's art should occupy its proper position as a means to an end. Euphony and beauty of expression were the objects of the composer. In part writing each voice was made to relate to the other in a manner totally unknown to the Paris masters. Such were the first beginnings of the 'canonic' form, and fugato system of writing, the herald of that scholarly class of compositions known as fugues, the end and aim of which it is to connect in the closest possible manner the various component parts. It was this complete mastery over counterpoint in all its varying details that gave to the tone-masters such unbounded artistic liberty. No longer was it necessary that they should, like the organists, cantors, and magisters of Paris and Tournay, exhibit their power over newly-acquired contrivances, but, as inheritors of a system of inventive skill, the devices and contrivances fell into their proper and natural channel, and were regarded as merely subordinate to a purer tonal expression of feelings than had hitherto been attempted. Henceforth counterpoint was but a means to an end, and art-music began to assume for the first time the characteristics of folk-music, i. e., the free, pure and natural outflow of heart and mind, with the invaluable addition, however, of intellectual manipulation."

Naumann's comments are the result of his overvaluation of the purely tentative labors of the early French school and his manifest eagerness to find grounds for laudation of the writers of the first Netherland period. It is a plain fact, to which all evidence points, that the man looked up to as the chief master of the period was a profound academician and that he was greater as a teacher than as a composer. That his successors did achieve something in the way of euphonic beauty and freedom of style is certainly true, as can be demonstrated by an examination of the works of Josquin des Près. Even the Dutchmen Hobrecht and Brumel sometimes struggled toward a simpler and purer musical expression than was to be attained through Ockeghem's canonic labyrinths, but the famous teacher's influence prevailed over the spirit of his time, and the musicians were, for the most part, like the Mastersingers, slaves of the contemporaneous leges tabulaturae. The unbounded delight which they took in the solution of riddle canons is a proof of the view they took of their art. Dr. Langhans, who is too calm a critic to be led into special pleading, says:

"The origin of the methods of notation which were in favor with the Netherlandic composers is to be sought in the fact that the newly acquired art of counterpoint was regarded preëminently as a means of exercising the sagacity of the composer as well as of the performer." The author continues pointing out that "at last there existed so many signs, not strictly belonging to notation, that a composition for many voices, even when these entered together, could be written down with but one series of notes, it being left to the sagacity of the performers to divine the composer's intention by means of the annexed signs."

Thus we see that the first period of the Netherland school was characterized by a search after ingenious forms, and this search was carried to such an extent that the composer, having found a new[17] form, gave a hint at it and then invited the executant to do a little searching on his own account. The writer believes that his assertion that this was an era of pure mechanics in music is sound and is supported by sufficient evidence.

JOSQUIN DES PRÈS.

From Van der Straeten's "Musique aux pay bas," loaned by the Newberry Library, Chicago.

But it was an era of short duration. Although Ockeghem and his closest imitators carried the mechanical period up to 1512, it overlapped the beginning of the second period, in which euphony sought and found recognition in music. The chief master of the period, Josquin des Près (his name appears in different places as Jodocus a Prato and a Pratis), was the first real genius in the history of modern music.