| Number 36. | SATURDAY, MARCH 6, 1841. | Volume I. |

We have already taken occasion more than once to express our admiration of the beautiful and varied scenery which surrounds our city on all sides, and which presents such an endless variety in its general character and individual features as no other city that we are acquainted with in the empire possesses in any thing like an equal degree. Other cities may have scenery in their immediate vicinity of some one or two classes of higher beauty or grandeur than we can boast of; but it is the proud distinction of our metropolis that there is no class of scenery whatsoever of which its citizens have not the most characteristic examples within their reach of enjoyment by a walk or drive of an hour or two; and yet, strange to say, they are not enjoyed or even appreciated. Some suburb of fashionable resort is indeed visited by them, but not on account of any picturesque beauty it may possess, but simply because it is fashionable, and allows us to get into a crowd—as our delightful Musard concerts are attended by the multitude less for the music than to see and be seen, and where we too often show our want of good taste by being listless or silent when we ought to applaud, and express loudly our approbation at some capricious extravagance of the performer that we ought to condemn. The truth is, that in every thing appertaining to taste we are as yet like children, and have very much to learn before we can emancipate ourselves from the trammels of vulgar fashion, and become qualified to enjoy those pure and refined pleasures consequent upon a just perception of the beautiful in art and nature. Till this power is acquired, our green pastoral vallies, our rocky cliffs, mountain glens, and shining rivers, as well as our exhibitions of the Fine Arts, and that pure portion of our literature which disdains to pander to the prejudices of sect or party, must remain less appreciated at home than abroad, and be less known to ourselves than to strangers who visit us, and who in this respect are often infinitely our superiors. It is no fault of ours, however, that we are thus defective in the cultivation of those higher qualities of mind which would so much conduce to our happiness; the causes which have produced such a result are sufficiently obvious to every reflecting mind, and do not require that we should name or more distinctly allude to them. But we have reason to be inspired with cheerful hope that they will not very long continue in operation. Temperance and education are making giant strides amongst us; and when we look at our various institutions for the promotion of science, art, and mechanics, all in active operation, and aided by the growth of a national literature, we can scarcely hesitate to feel assured that the arts of civilized life are taking a firm root in our country, and will be followed by their attendant blessings.

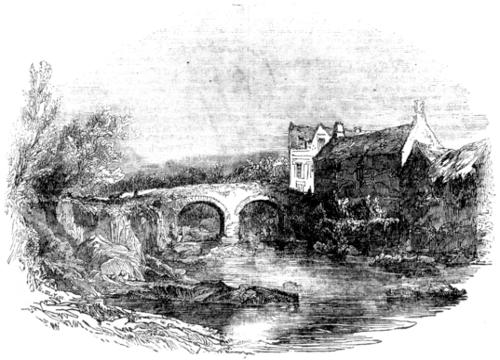

But it may be asked, What have these remarks to do with Miltown Bridge, the subject of our prefixed woodcut? Our answer is, that in presenting our readers with one of the[Pg 282] innumerable picturesque scenes which are found along the courses of our three rivers, the Liffey, the Dodder, and the Tolka, all of which abound in features of the most beautiful pastoral landscapes, we have naturally been led into such a train of thought by the fact that we hold their charms in little esteem, and that few amongst us have the taste to appreciate their beauties, and the consequent desire to enjoy them. The Liffey may perhaps be known to a certain extent to many of our Dublin readers, but we greatly doubt that the Tolka or the Dodder are equally familiar to them; and yet the great poet of nature, Mr Wordsworth, on his visit to our city, made himself most intimately acquainted with the scenery of the former, and thought it not inferior to that of his own Duddon, which his genius has immortalized.

In like manner, the scenery of the Dodder, though so little known to the mass of our fellow citizens, has been often explored by many British as well as native artists, who have filled their portfolios with its picturesque treasures, and have spoken of them with rapturous enthusiasm. Thus, for example, it was, as we well know, from this fount that much of the inspiration of our great self-taught imaginative painter Danby was drawn; and though we could not point to a higher name, we could, if it were necessary, give many other little less illustrious examples of talent cultivated in the same school of nature.

Amongst the many picturesque objects which this little mountain river presents, the Old Bridge of Miltown has always been with those children of genius an especial favourite, and many an elaborate study has been made of its stained and timeworn walls. It is indeed just such a scene as the lover of the picturesque would delight in;—quiet and sombre in its colour, harmonious in its accompanying features of old buildings, rocks, water, and mountain background; and, as a whole, impressed with a poetical sentiment approaching to melancholy, derived from its pervading expression of neglect and ruin. It is for these reasons that we have given old Miltown bridge a place in our topographical collections; and though many of our Dublin readers, for whom, on this occasion, we write especially, may not fully understand our language, or participate in our feelings, the fault is not ours: our object in writing is a kind one. We would desire that they should all acquire the power of enjoying the beautiful in nature, and, as a consequence, in art; knowing as we do that such power is productive of the sweetest as well as the purest of intellectual pleasures of which we are susceptible, and makes us not only happier, but better men.

We are aware also that some of our Dublin readers, whose tastes are not uncultivated, but who have taken less trouble than ourselves to make themselves familiar with our suburban localities, may think that we speak too enthusiastically of the scenery of the Dodder river and its accompanying features. But if such readers would meet us at Miltown some sunny morning in May or June next, and accompany us along the Dodder till we reach its source among the mountains—a moderate walk—we are satisfied that we should be able to remove their scepticism, and give them an enjoyment more delightful than they could anticipate, and for which they would thank us warmly. We could show them not only a varied succession of scenes of picturesque or romantic beauty on the way, but also many contiguous objects of historic interest, on which we would discourse them much legendary lore, and which we should lead them to examine, offering as an excuse for our temporary divergence the beautiful sound of Wordsworth to his favourite Duddon:—

Thus, as we approached towards Rathfarnham, we should ask them to admire that noble classic gateway on the river’s side, which leads into the deserted park of the Loftus family, and which in its present state, clothed with ivy and hastening to decay, cheats the imagination with its appearance of age, and looks an arch of triumph of old Rome. We would then lead them into this noble abandoned park, still in its desolation rich in the magnificence of art and nature; then we would take a meditative look at its general features and at those of the grim yet grand and characteristic castellated mansion which with so much cost it was formed to adorn; and we should ask our companions, why has so much beauty and magnificence been thus abandoned? Here in its silent hall we could still show them original marble busts of Pope and Newton by Roubilliac; and, in the drawing-room, pictures painted expressly for it on the spot by the fair and accomplished hand of Angelica Kaufmann. But the interest of those objects would after all be somewhat a saddening one, and we should return to our cheerful river with renewed pleasure, to relieve our spirits with a view of objects more enlivening. Such an object would be that old mill near Rathfarnham, where paper was first manufactured in Ireland about two centuries since. It was on the paper so made that Usher’s Primordia was printed, and the Annals of the Four Masters were written. The manufacturer was a Dutchman—but what matter? At the Bridge of Templeoge we should probably make another short divergence, to take a look at the old park and mansion of the Talbots and Domvilles; and here, beneath a majestic grove of ancient forest trees, we should show our companions the largest bank of violets that ever came under our observation. But the limits allotted to this article will not permit us to describe or even name a twentieth part of the objects or scenes of interest and beauty that would present themselves in quick succession; and we shall only say a few words on one more—the glorious Glanasmole, or the Valley of the Thrush, in which the Dodder has its source. Reader, have you ever seen this noble valley? Most probably you have not, for we know but few that ever even heard of it; and yet this glen, situated within some six or seven miles of Dublin, presents mountain scenery as romantic, wild, and almost as magnificent, as any to be found in Ireland. In this majestic solitude, with the lovely Dodder sparkling at our feet, and the gloomy Kippure mountain with his head shrouded in the clouds two thousand four hundred feet above us, we have a realization of the scenery of the Ossianic poetry. It is indeed the very locality in which the scenes of some of these legends are laid, as in the well-known Ossianic romance called the Hunt of Glanasmole; and monuments commemorative of the celebrated Fin and his heroes, “tall grey stones,” are still to be seen in the glen and on its surrounding mountains. We could conduct our readers to the well of Ossian, and the tomb of Fin’s celebrated dog Bran, in which, perhaps, the naturalist might find and determine his species by his remains. The monument of Fin himself is on a mountain in the neighbourhood, and that of his wife Finane, according to the legends of the place, gives name to a mountain over the glen, called See-Finane. But there are objects of even greater interest to the antiquary and naturalist than those to be seen in Glanasmole, namely, the three things for which, according to some of these old bardic poems, the glen was anciently remarkable, and which were peculiar to it: these were the large breed of thrushes from which the valley derived its name, the great size of the ivy leaves found on its rocks, and the large berries of the rowan or mountain ash, which formerly adorned its sides. The ash woods indeed no longer exist, having been destroyed to make charcoal above eighty years since, but shoots bearing the large berries are still to be seen, while the thrush continues in his original haunt in the little dell at the source of the river on the side of Kippure, undisturbed and undiminished in size, and the giant ivy clings to the rocks as large as ever; we have seen leaves of it from seven to ten inches diameter. We should also state, that to the geologist Glanasmole is as interesting as to the painter, antiquary, or naturalist, as our friend Dr Schouler will show our readers in some future number of our Journal.

But we must bring our walk and our gossip to a conclusion, or our friends will tire of both, if they are not so already. Let us, then, rest at the little primitive Irish Christian church of Killmosantan, now ignorantly called St Anne’s, seated on the bank of the river amongst the mountains; and having refreshed ourselves with a drink from the pure fountain of the saint, we shall return in silence to the place from which we started, and bid our kind companions a warm farewell.

P.

Most of our readers must have heard of the wonderful discoveries of Cuvier respecting the extinct animals of a former world, and of the sagacity with which that profound anatomist disclosed the history of races, of whose existence the only evidence we possess depends upon the preservation of a few bones or fragments of skeletons. The same subject, which in the hands of genius has afforded such brilliant discoveries, has also afforded wide scope for credulity, and even imposture. The bones of the larger races of extinct animals were formerly believed alike by the learned and the vulgar to be those of giants. Even as late as the seventeenth century, learned anatomists believed that the bones of the extinct elephant belonged to a gigantic race of men. In the year 1577, some bones of the elephant were disinterred near the town of Lucerne, in Switzerland; the magistrates sent them to a professor of anatomy, who decided that they belonged to the skeleton of a giant, and the citizens were so delighted with the discovery that they adopted a giant as the supporter of the arms of their town, an honour which he still retains. In the same century, some bones of the elephant found in Dauphiny were exhibited in different parts of Europe as the remains of the general of the Cimbri who invaded Rome, and who was defeated by the consul Marius some time before the commencement of the Christian era. In this case, however, the mistake was not allowed to pass unnoticed, and the surgeons and physicians of Paris entered into a lengthened discussion respecting the nature of the bones; and the works written on this subject, if collected, would form a small library.

The most extraordinary instance of mystification and credulity upon record is to be found in the history of a book on Petrifactions, published by a German professor at the commencement of the last century. We quote the following notice of this very rare book from a French publication:—

It is related in the life of Father Kircher, one of the most eccentric of men, that some youths, desirous of amusing themselves at his expense, practised the following mystification upon him. They engraved a number of fantastic figures upon a stone, which they afterwards buried in a place where a house was about to be built. The stone was found by the workmen while digging the foundation, and of course found its way to the learned Father, who was quite delighted with the treasure; and after much labour and research, he gave such a translation of the inscription as might have been expected from the whimsical disposition of the man. Kircher had been a professor at Wurzburg where this anecdote became well known, and led to another mystification of a much more serious nature, as it was pushed so far as to occasion the publication of a folio volume.

M. Berenger, physician to the Prince-Bishop of Wurzburg, and a professor in the University, was an enthusiastic collector of natural curiosities. He collected without discrimination, and above all things valued those objects which by their strange forms seemed to contradict the laws of nature. This pursuit drew much ridicule upon M. Berenger, and induced a young man of the name of Rodrich to amuse himself at his expense. Rodrich cut upon stones the figures of different kinds of animals, and caused them to be brought to Berenger, who purchased them and encouraged the search for more. The success of the trick encouraged its author; he prepared new petrifactions, of the most absurd nature imaginable. They consisted of bats with the heads and wings of butterflies, winged crabs, frogs, Hebrew and other characters, snails, spiders with their webs, &c. When a sufficient number of them was prepared, boys who had been taught their lesson brought them to the professor, informing him that they had found them near the village of Eibelstadt, and caused him to pay dearly for the time they had employed in collecting them. Delighted with the ease with which he obtained so many wonders, he expressed a desire to visit the place where they had been found, and the boys conducted him to a locality where they had previously buried a number of specimens. At last, when he had formed an ample collection, he could no longer resist the inclination of making them known to the learned world. He thought he would be guilty of selfishness if he withheld from the public that knowledge which had afforded him so much delight. He exhibited his treasures to the admiration of the learned, in a work containing twenty-one plates, with a Latin text explanatory of the figures.

As soon as M. Deckard, a brother professor, who was probably in the plot, was aware of this ridiculous publication, he expressed great regret that the mystification had been pushed so far, and informed M. Berenger of the hoax that had been played upon him. The unfortunate author was now as anxious to recall his work as he had formerly been to give it to the public. Some copies, however, found their way into the libraries of the curious.

Nothing can be imagined more strange than this book, whether we consider the opinions contained in it, or the manner in which they are stated. It deserves to be better known as a monument of the most extravagant credulity, and as an evidence of the follies at which the mind may arrive when it attempts to bend the laws of nature to its chimeras. Nothing can be more absurd than the allegoric engraving placed on the title-page. On the summit of a Parnassus, composed of an enormous accumulation of petrifactions, we observe an obelisk supporting the arms of the Prince-Bishop, and surrounded by Cupids and garlands of flowers. Above the pyramid there is a sun surmounted by the name of the Deity, in Hebrew characters. Different emblematic persons holding petrifactions in their hands are placed on the sides of the mountain. At its base we observe on the right a tonsured Apollo, who doubtless represents the Prince-Bishop, and on the left we see the professor himself demonstrating all these wonders; and also a genius, seated near the centre of the mountain, is writing down his words in Hebrew characters. In the dedication M. Berenger gives an explanation of these allegories. But what is still more remarkable, it appears that even the engraver has amused himself at the expense of the professor. What renders this probable is, that at the base of the engraving are figured pick-axes and spades necessary for extracting petrifactions, and along with them chisels, compass, and mallet, the emblems of sculpture; and what is still more wicked, a bell, the emblem of noise.

The work is dedicated to the Prince-Bishop of Wurzburg, on whom were bestowed the epithets of the New Apollo, Sacred Amulet of the country, the New Sun of Franconia, and others selected with equal taste. The most absurd flattery abounds in this dedication, of which the following may be taken as a sample. “The opinions of philosophers are still unsettled. They hesitate whether to ascribe the wonderful productions of this mountain to the admirable operations of nature, or to the art of the ancients; but, interpreted by the public gratitude, all unite with me in proclaiming that this useless and uncultivated hill has rendered illustrious by its wonders the beginning of your reign, and has honoured a learned Prince, the protector and support of learning, by a hecatomb of petrified plants, flowers, and animals. If it be permitted to attribute these marvels to the industry of antiquity, I can say that Franconia was once the rival of Egypt. By a usage unknown in Europe, Memphis covered her gigantic monuments with hieroglyphics, and I do not hazard an idle conjecture. I state without fear of contradiction, that the obelisk which crowns this mountain exhibits in its petrifactions the emblems of your virtues.” According to the author, the name of the Deity in Hebrew characters indicates the zeal of the Prince for religion. The sun, the moon, and the stars, his beneficence, justice, prudence, and indefatigable vigilance; the comets, contrary to the vulgar idea, which considers them signs of evil, foretell the happy events of his reign; and the fossil shells represent the hearts of his subjects.

It appears from the preface that M. Berenger had solicited and obtained permission from the Prince-Bishop to publish his work. He confesses that the greater number of philosophers and intelligent people he had consulted were of opinion that these petrifactions were the products of art; in opposition to this erroneous opinion, he asserts that he has convinced the sceptics by taking them to the spot where he found his curiosities. Their astonishment, he adds, and their unanimous and perfect conviction, had given him the utmost joy, and amply recompensed him for all his labour and expense.

This work was to have been followed by others. It is divided into fourteen chapters, each chapter being devoted to a single question. Most of these questions are so extraordinary and so singularly treated of, that one can scarcely believe that the author was in earnest. Thus, Chap. 4, The petrifactions of Wurzburg are not relics of Paganism, nor can they be attributed to the art and superstition of the Germans during heathen times.

Chap. 5. The ingenious conjecture which attributes their formation to the plastic power of light.

Chap. 6. The germs of shell-fish and marine animals, mixed with the vapours of the ocean, and scattered over the earth by the showers, are not the source of the fossils of Wurzburg.

Chap. 12. Our petrifactions are not the products of modern art, as some persons have ventured to assert, throwing a cloud of doubts and fables over this subject.

Chap. 13. Grave reasons for considering our petrifactions as the work of nature, and not of art.

The absurdity of the arguments employed in the discussion of these different propositions, exceeds all belief. For example, the author, to refute the opinion of those who attribute these petrifactions to the superstition of the Pagans, demonstrates that none of these specimens in his possession are described in the decrees of the German synods, which proscribed images and sorcery. Neither can they be considered as victims offered to idols, for who ever sacrificed figured stones instead of living animals? They are not amulets which Pagan parents hung around the necks of their children, to preserve them from the charms of witchcraft, for some of them are so heavy that they would strangle the poor infant, and there is no aperture in any of them through which a chain could be passed. Finally, what renders it impossible that these stones are the remains of Paganism, is, that many of them are inscribed with Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, and German characters, expressing the name of the Deity.

This work, as we have stated, was suppressed when he discovered the cruel hoax that had been played upon him. The work, in its original state, is very rare, and is only known to the curious; but after the death of M. Berenger, the copies which he had retained were given to the public by a bookseller, but with a new title-page.

S.

How many a time do we take up the page of news, or the sheet of literary novelty, without reflecting upon the nameless sources whence their contents have been derived; and yet what a fruitful field do they afford for our deepest contemplation, and our holiest and purest sympathies! There may be there brought together, and to the general eye displayed in undistinguished union, contributions over which the jewelled brow of nobility hath been knitted into the frown of thoughtfulness, and side by side with these, chapters wearily traced out by the tremulous hand of unbefriended genius. Upon the former we do not mean to dwell, but we would wish for a few moments to contemplate the heart-trying condition of the latter.

It is hard to conceive a situation more replete with wretchedness than that of the struggling man of letters—of him who has offered his all before the shrine of long-looked-for fame; who has staked health, and peace, and happiness, that he may win her favour, and who nevertheless holds an uncertain tenure even of his “daily bread.” He is poor and in misery, yet he lives in a world of boundless wealth; but in this very thing is to be found the exquisite agony of his condition. What though haggard want wave around him her lean and famished hands, what avails that? Write he must, if it be but to satisfy the cravings of a stinted nature; write he must, though his only reward be the scanty pittance that was greedily covenanted for, and when his due, but grudgingly presented him. And then he must delineate plenty and happiness; he must describe “the short holiday of childhood,” the guileless period of maiden’s modesty, the sunshine of the moment when we first hear that we are loved, the placid calm of peaceful resignation; or it may be, the charms that nature wears in England’s happy vales, the beauty of her scenery, the splendour and wealth of her institutions, the protecting law for the poor man, her admirable code of jurisprudence. All, all these may be the theme of his song, or the subject of his appointed task; but the hours will pass away, and the spirits he has called up will disappear, and his visions of happiness will leave him only, if it be possible, more fearfully alive to his own helplessness—they cannot wake their echo in his soul, and instead of their worthier office of healing and blessedness, they render his wound deeper, deadlier, and more rankling.

And who is there, think you, kind reader, that can feel more acutely the sting of neglect and poverty than the lonely man of genius? Of him how truly may it be said, “he cannot dig, to beg he is ashamed!” His intellect is his world; it is the glorious city in which he abides, the treasure-house wherein his very being is garnered; it is to cultivate it that he has lived; and when it fails him in his wintry hour, is not he indeed “of all men most miserable?”

But let us suppose that his prescribed duty is done, that the required article is written, and that this child of his sick and aching brain is at last dismissed; and can his thoughts follow it? Can his heart bear the reflection that it shall find admission where he durst not make his appearance? He knows that it will be laid on the gorgeous table of the rich and honourable. He knows, too, that it will find its way to the happy fireside, the home where sorrow hath not yet entered—such as once was his own in the days of his childhood. He knows that the unnatural relation who spurned him from his door when he asked the bread of charity, may see it, and without at all knowing the writer, that even his scornful sneer may be thereby relaxed. He knows——but why more? Of himself he knows that want and woe have been his companions, that they are yet encamped around him, and that they will only end their ministry “where the wicked cease from troubling, and the weary are at rest!”

This is by no means—oh, would that it were so!—an ideal picture. In London, amid her “wilderness of building,” there are at this hour hundreds whose sufferings could corroborate it, and whose necessities could give the stamping conviction to its truth. We were ourselves cognizant of the history of one young man’s life, his early and buoyant hopes, his subsequent misfortunes and miseries, and his early and unripe death, to all of which, anything that is painted above bears but a faint and indistinct resemblance. He was an[Pg 285] Irishman, and gifted with the characteristics of his country—a romantic genius, united with feelings the most tremulous, and tender, and impassioned. Many years have since passed away, and over and over again have the wild flowers sprung up, and bloomed, and withered over his narrow resting place, no unmeet emblem of

but never has the memory of his sad story faded from us—never may it fade! His lot was unhappy, and he “perished in his pride.” His reason eventually bowed before his intense sufferings; and excepting the few minutes just before his spirit passed away, his last hours were uncheered by the glimpse of that glorious intellect which had promised to crown him with a chaplet of undying fame. Even as it was, he had attracted notice; his writings were beginning to make for him a name; and the Prime Minister of England did not think it beneath him to visit his lonely lodging, and to endeavour to raise his sinking soul with the promise of almost unlimited patronage. But the restorative came too late: the poison had worked its portion, and in the guise of Fame, Death approached;

We have nothing to add to this. Had we not hoped to strike a chord of sympathy in our reader’s heart, we should never have even advanced so far, or have uplifted the veil so as to exhibit the “latter end” of such. Reader, in conclusion, you know not the toil, and trouble, and bodily labour, and mental inquietude, that furnish you each week with the price of YOUR PENNY!

S. H.

[1] The writer, as will be seen, has had in view solely the literature of London.

No order of men has experienced severer treatment from the various classes into which society is divided, than that of excisemen, or, as they are vulgarly denominated, guagers. If, unlike the son of the Hebrew patriarch, their hand is not raised against every man, yet they may be truly said to inherit a portion of Ishmael’s destiny, for every man’s hand is against them. The cordial and unmitigated hostility of the lower classes follows the guager at every point of his dangerous career, whether his pursuit be smuggled goods, potteen, or unpermitted parliament. Literary men have catered to the gratification of the public at his expense, by exhibiting him in their stories of Irish life under such circumstances that the good-natured reader scarcely knows whether to laugh or weep most at his ludicrous distress. The varied powers of rhyme have been pressed into the service by the man of genius and the lover of fun. The “Diel’s awa’ wi’ the Exciseman” of Burns, and the Irishman’s “Paddy was up to the Guager,” will ever remain to prove the truth of the foregoing assertion.

But the humble historian of this unpretending narrative is happy to record one instance of retributory justice on the part of an individual of this devoted class, which would have procured him a statue in the temple of Nemesis, had his lot been cast among the ancients. Many instances of the generosity, justice, and self-abandonment of the guager, have come to the writer’s knowledge, and these acts of virtue shall not be utterly forgotten. The readers of the Irish Penny Journal shall blush to find men, whose qualities might reconcile the estranged misanthrope to the human family, rendered the butt of ridicule, and their many virtues lost and unknown.

On a foggy evening in the November of a year of which Irish tradition, not being critically learned in chronology, has not furnished the date, two men pursued their way along a bridle road that led through a wild mountain tract in a remote and far westward district of Kerry. The scene was savage and lonely. Far before them extended the broad Atlantic, upon whose wild and heaving bosom the lowering clouds seemed to settle in fitful repose. Round and beyond, on the dark and barren heath, rose picturesque masses of rock—the finger-stones which nature, it would seem, in some wayward frolic, had tossed into pinnacled heaps of strange and multiform construction. About their base, and in the deep interstices of their sides, grew the holly and the hardy mountain ash, and on their topmost peaks frisked the agile goat in all the pride of unfettered liberty.

These men, each of whom led a Kerry pony that bore an empty sack along the difficult pathway, were as dissimilar in form and appearance as any two of Adam’s descendants possibly could be. One was a low-sized, thickset man; his broad shoulders and muscular limbs gave indication of considerable strength; but the mild expression of his large blue eyes and broad, good-humoured countenance, told, as plain as the human face divine could, that the fierce and stormy passions of our kind never exerted the strength of that muscular arm in deeds of violence. A jacket and trousers of brown frieze, and a broad-brimmed hat made of that particular grass named thraneen, completed his dress. It would be difficult to conceive a more strange or unseemly figure than the other: he exceeded in height the usual size of men; but his limbs, which hung loosely together, and seemed to accompany his emaciated body with evident reluctance, were literally nothing but skin and bone; his long conical head was thinly strewed with rusty-coloured hair that waved in the evening breeze about a haggard face of greasy, sallow hue, where the rheumy sunken eye, the highly prominent nose, the thin and livid lip, half disclosing a few rotten straggling teeth, significantly seemed to tell how disease and misery can attenuate the human frame. He moved, a living skeleton: yet, strange to say, the smart nag which he led was hardly able to keep pace with the swinging unequal stride of the gaunt pedestrian, though his limbs were so fleshless that his clothes flapped and fluttered around him as he stalked along the chilly moor.

As the travellers proceeded, the road, which had lately been pent within the huge masses of granite, now expanded sufficiently to allow them a little side-by-side discourse; and the first-mentioned person pushed forward to renew a conversation which seemed to have been interrupted by the inequalities of the narrow pathway.

“An’ so ye war saying, Shane Glas,” he said, advancing in a straight line with his spectre-looking companion, “ye war saying that face of yours would be the means of keeping the guager from our taste of tibaccy.”

“The devil resave the guager will ever squint at a lafe of it,” says Shane Glas, “if I’m in yer road. There was never a cloud over Tim Casey for the twelve months I thravelled with him; and if the foolish man had had me the day his taste o’ brandy was taken, he’d have the fat boiling over his pot to-day, ’tisn’t that I say it myself.”

“The sorrow from me, Shane Glas,” returned his friend with a hearty laugh, and a roguish glance of his funny eye at the angular and sallow countenance of the other, “the sorrow be from me if it’s much of Tim’s fat came in your way, at any rate, though I don’t say as much for the graise.”

“It’s laughing at the crucked side o’ yer mouth ye’d be. I’m thinking, Paddy Corbett,” said Shane Glas, “if the thief of a guager smelt your taste o’ tibaccy—Crush Chriest duin! and I not there to fricken him off, as I often done afore.”

“But couldn’t we take our lafe o’ tibaccy on our ponies’ backs in panniers, and throw a few hake or some oysters over ’em, and let on that we’re fish-joulting?”

“Now, mark my words, Paddy Corbett: there’s a chap in Killarney as knowledgeable as a jailor; Ould Nick wouldn’t bate him in roguery. So put your goods in the thruckle, shake a wisp over ’em, lay me down over that in the fould o’ the quilt, and say that I kem from Decie’s counthry to pay a round at Tubber-na-Treenoda, and that I caught a faver, and that ye’re taking me home to die, for the love o’ God and yer mother’s sowl. Say, that Father Darby, who prepared me, said I had the worst spotted faver that kem to the counthry these seven years. If that doesn’t fricken him off, ye’re sowld” (betrayed.)

By this time they had reached a deep ravine, through which a narrow stream pursued its murmuring course. Here they left the horses, and, furnished with the empty sacks, pursued their onward route till they reached a steep cliff. Far below in the dark and undefined space sounded the hollow roar of the heaving ocean, as its billowy volume broke upon its granite barrier, and formed along the dark outline a zone of foam, beneath whose snowy crest the ever-impelled and angry wave yielded its last strength in myriad flashes of phosphoric light, that sparkled and danced in arrowy splendour to the wild and sullen music of the dashing sea.

“Paddy Corbett, avick,” said Shane Glas, “pull yer legs fair an’ aisy afther ye; one inch iv a mistake, achorra, might[Pg 286] sind ye a long step of two hundred feet to furnish a could supper for the sharks. The sorrow a many would vinture down here, avourneen, barring the red fox of the hill and the honest smuggler; they are both poor persecuted crathurs, but God has given them gumpshun to find a place of shelter for the fruits of their honest industhry, glory be to his holy name!”

Shane Glas was quite correct in his estimate of the height of this fearful cliff. It overhung the deep Atlantic, and the narrow pathway wound its sinuous way round and beneath so many frightful precipices, that had the unpractised feet of Paddy Corbett threaded the mazy declivity in the clear light of day, he would in all probability have performed the saltation, and furnished the banquet of which Shane Glas gave him a passing hint. But ignorance of his fearful situation saved his life. His companion, in addition to his knowledge of this secret route, had a limberness of muscle, and a pliancy of uncouth motion, that enabled him to pursue every winding of the awful slope with all the activity of a weasel. In their descent, the wild sea-fowl, roused by the unusual approach of living things from their couch of repose, swept past on sounding wing into the void and dreary space abroad, uttering discordant cries, which roused the more distant slumberers of the rocks. As they farther descended round the foot of the cliff, where the projecting crags formed the sides of a little cove, a voice, harsh and threatening, demanded “who goes there?” The echo of the questioner’s interrogation, reverberating along the receding wall of rocks, would seem to a fanciful ear the challenge of the guardian spirit of the coast pursuing his nightly round. The wild words blended in horrid unison through the mid air with the sigh of waving wings and discordant screams, which the echoes of the cliffs multiplied a thousand fold, as though all the demons of the viewless world had chosen that hour and place of loneliness to give their baneful pinions and shrieks of terror to the wind.

“Who goes there?” again demanded this strange warder of the savage scene; and again the scream of the sea bird and the echo of human tones sounded wildly along the sea.

“A friend, avick machree,” replied Shane Glas. “Paudh, achorra, what beautiful lungs you have! But keep yer voice a thrifle lower, ma bouchal, or the wather-guards might be after staling a march on ye, sharp as ye are.”

“Shane Glas, ye slinging thief,” rejoined the other, “is that yerself? Honest man,” addressing the new comer, “take care of that talla-faced schamer. My hand for ye, Shane will see his own funeral yet, for the devil another crathur, barring a fox, could creep down the cliff till the moon rises, any how. But I know what saved yer bacon; he that’s born to be hanged—you can repate the rest o’ the thrue ould saying yerself, ye poor atomy!”

“Chorpan Doul,” said Shane Glas, rather chafed by the severe raillery of the other, “is it because to shoulder an ould gun that an honest man can’t tell you what a Judy ye make o’ yerself, swaggering like a raw Peeler, and frightening every shag on the cliff with yer foolish bull-scuttering! Make way there, or I’ll stick that ould barrel in yez—make way there, ye spalpeen!”

“Away to yer masther with ye, ye miserable disciple,” returned the unsparing jiber. “Arrah, by the hole o’ my coat, afther you have danced yer last jig upon nothing, with yer purty himp cravat on, I’ll coax yer miserable carcass from the hangman to frighten the crows with.”

When the emaciated man and his companion had proceeded a few paces along the narrow ledge that lay between the steep cliff and the sea, they entered a huge excavation in the rock, which seemed to have been formed by volcanic agency, when the infant world heaved in some dire convulsion of its distempered bowels. The footway of the subterranean vault was strewn with the finest sand, which, hardened by frequent pressure, sent the tramp of the intruder’s feet reverberating along the gloomy vacancy. On before gleamed a strong light, which, piercing the surrounding darkness, partially revealed the sides of the cavern, while the far space beneath the lofty roof, impervious to the powerful ray, extended dark and undefined. Then came the sound of human voices mixed in uproarious confusion; and anon, within a receding angle, a strange scene burst upon their view.

Before a huge fire which lighted all the deep recess of the high over-arching rock that rose sublime as the lofty roof of a Gothic cathedral, sat five wild-looking men of strange semi-nautical raiment. Between them extended a large sea-chest, on which stood an earthen flaggon, from which one, who seemed the president of the revel, poured sparkling brandy into a single glass that circled in quick succession, while the jest and laugh and song swelled in mingled confusion, till the dinsome cavern rang again to the roar of the subterranean bacchanals.

“God save all here!” said Shane Glas, approaching the festive group. “O, wisha! Misther Cronin, but you and the boys is up to fun. The devil a naither glass o’ brandy: no wonder ye should laugh and sing over it. How goes the Colleen Ayrigh, and her Bochal Fadda, that knows how to bark so purty at thim plundering thieves, the wather-guards?”

“Ah! welcome, Shane,” replied the person addressed; “the customer you’ve brought may be depinded on, I hope. Sit down, boys.”

“’Tis ourselves that will, and welkim,” rejoined Shane. “Depinded on! why, ’scure to the dacenther father’s son from this to himself than Paddy Corbett, ’tisn’t that he’s to the fore.”

“Come, taste our brandy, lads, while I help you to some ham,” said the smuggler. “Shane, you have the stomach of a shark, the digestion of an ostrich, and the gout of an epicure.”

“By gar ye may say that wid yer own purty mouth, Misther Cronin,” responded the garrulous Shane. “Here, gintlemin, here is free thrade to honest min, an’ high hangin’ to all informers! O! murdher maura (smacking his lips), how it tastes! O, avirra yealish (laying his bony hand across his shrunken paunch), how it hates the stummuck!”

“You are welcome to our mansion, Paddy Corbett,” interrupted the hospitable master of the cavern; “the house is covered in, the rent paid, and the cruiskeen of brandy unadulterated; so eat, drink, and be merry. When the moon rises, we can proceed to business.”

Paddy Corbett was about to return thanks when the interminable Shane Glas again broke in.

“I never saw a man, beggin’ yer pardon, Misther Cronin, lade a finer or rolickinger life than your own four bones—drinking an’ coorting on land, and spreading the canvass of the Colleen Ayrigh over the salt say, for the good o’ thrade. Manim syr Shyre, if I had Trig Dowl the piper forninst me there, near the cruiskeen, but I’d drink an’ dance till morning. But here’s God bless us, an’ success to our thrip, Paddy, avrahir;” and he drained his glass. Then when many a successive round went past, and the famished-looking wretch grew intoxicated, he called out at the top of his voice, “Silence for a song,” and in a tone somewhat between the squeak of a pig and the drone of a bagpipe, poured forth a lyric, of which we shall present one or two stanzas to the reader.

Early on a clear sunny morning after this, a man with a horse and truckle car was observed to enter the town of Killarney from the west. He trolled forth before the animal, which, checked by some instinctive dread, with much reluctance allowed himself to be dragged along at the full length of his hair halter. On the rude vehicle was laid what seemed a quantity of straw, upon which was extended a human being, whose greatly attenuated frame appeared fully developed beneath an old flannel quilt. His face, that appeared above its tattered hem, looked the embodiment of disease and famine, which seemed to have gnawed, in horrid union, into his inmost vitals. His distorted features pourtrayed rending agony; and as the rude vehicle jolted along the rugged pavement, he groaned hideously. This miserable man was our acquaintance Shane Glas, and he that led the strange procession no other than Paddy Corbett, who thus experimented to smuggle his “taste o’ tibaccy,” which lay concealed in well-packed bales beneath the sick couch of the wretched simulator.

As they proceeded along, Shane Glas uttered a groan, conveying such a feeling of real agony that his startled companion, supposing that he had in verity received the sudden[Pg 287] judgment of his deception, rushed back to ascertain whether he had not been suddenly stricken to death.

“Paddy, a chorra-na-nea,” he muttered in an undergrowl, “here’s the vagabone thief of a guager down sthreet! Exert yerself, a-lea, to baffle the schamer, an’ don’t forget ’tis the spotted faver I have.”

Sure enough, the guager did come; and noticing, as he passed along, the confusion and averted features of Paddy Corbett, he immediately drew up.

“Where do you live, honest man, an’ how far might you be goin’?” said the keen exciseman.

“O, wisha! may the heavens be yer honour’s bed!—ye must be one o’ the good ould stock, to ax afther the consarns of a poor angishore like me: but, a yinusal-a-chree, ’tisn’t where I lives is worse to me, but where that donan in the thruckle will die with me.”

“But how far are you taking him?”

“O, ’tis myself would offer a pather an’ ave on my two binded knees for yer honour’s soul, if yer honour would tell me that. I forgot to ax the crathur where he should be berrid when we kim away, an’ now he’s speechless out an’ out.”

“Come, say where is your residence,” said the other, whose suspicion was increased by the countryman’s prevarication.

“By jamine, yer honour’s larnin’ bothers me intirely; but if yer honour manes where the woman that owns me and the childre is, ’tis that way, west at Tubber-na-Treenoda; yer honour has heard tell o’ Tubber-na-Treenoda, by coorse?”

“Never, indeed.”

“O, wisha! don’t let yer honour be a day longer that way. If the sickness, God betune us an’ harum, kim an ye, ’twould be betther for yer honour give a testher to the durhogh there, to offer up a rosary for ye, than to shell out three pounds to Doctor Crump.”

“Perhaps you have some soft goods concealed under the sick man,” said the guager, approaching the car. “I frequently catch smuggled wares in such situations.”

“The devil a taste good or saft under him, sir dear, but the could sop from the top o’ the stack. Ketch! why, the devil a haporth ye’ll ketch here but the spotted faver.”

“Fever!” repeated the startled exciseman, retiring a step or two.

“Yes, faver, yer honour; what else? Didn’t Father Darby that prepared him say that he had spotted faver enough for a thousand min! Do, yer honour, come look in his face, an’ thin throw the poor dying crathur, that kem all the way from Decie’s counthry, by raisin of a dhream, to pay a round for his wife’s sowl at Tubber-na-Treenoda: yes, throw him out an the belly o’ the road, an’ let his blood, the blood o’ the stranger, be on yer soul an’ his faver in yer body.”

Paddy Corbett’s eloquence operating on the exciseman’s dread of contagion, saved the tobacco.

Our adventurers considering it rather dangerous to seek a buyer in Killarney, directed their course eastward to Kanturk. The hour of evening was rather advanced as they entered the town; and Shane, who could spell his way without much difficulty through the letters of a sign-board, seeing “entertainment for man and horse” over the door, said they would put up there for the night, and then directed Paddy to the shop of the only tobacconist in town, whither for some private motive he declined to attend him. Mr Pigtail was after dispatching a batch of customers when Paddy entered, who, seeing the coast clear, gave him the “God save all here,” which is the usual phrase of greeting in the kingdom of Kerry. Mr Pigtail was startled at the rude salutation, which, though a beautiful benediction, and characteristic of a highly religious people, is yet too uncouth for modern “ears polite,” and has, excepting among the lowest class of peasants, entirely given way to that very sincere and expressive phrase of address, “your servant.”

Now, Mr Pigtail, who meted out the length of his replies in exact proportion to the several ranks and degrees of his querists, upon hearing the vulgar voice that uttered the more vulgar salute, hesitated to deign the slightest notice, but, measuring with a glance the outward man of the saluter, he gave a slight nod of acknowledgement, and the dissyllabic response “servant;” but seeing Paddy Corbett with gaping mouth about to open his embassy, and that, like Burns’s Death,

he immediately added, “Honest man, you came from the west, I believe?”

“Thrue enough for yer honour,” said Pat; “my next door neighbours at that side are the wild Ingins of Immeriky. A wet and could foot an’ a dhry heart I had coming to ye; but welkim be the grace o’ God, sure poor people should make out an honest bit an’ sup for the weeny crathurs at home; an’ I have thirteen o’ thim, all thackeens, praise be to the Maker.”

“And I dare say you have brought a trifle in my line of business in your road?”

“Faith, ’tis yerself may book it: I have the natest lafe o’ tibaccy that ever left Connor Cro-ab-a-bo. I was going to skin an the honest man—Lord betune us an’harum, I’d be the first informer of my name, any how. But, talking o’ the tibaccy, the man that giv it said a sweether taste never left the hould of his ship, an’ that’s a great word. I’ll give it dog chape, by raison o’ the long road it thravelled to yer honour.”

“You don’t seem to be long in this business,” said Mr Pigtail.

“Thrue for ye there agin, a-yinusal; ’tis yourself may say so. Since the priest christened Paddy an me, an’ that’s longer than I can remimber, I never wint an the sachrawn afore. God comfort poor Jillian Dawly, the crathur, an’ the grawls I left her. Amin, a-hierna!”

Now, Mr Pigtail supposed from the man’s seeming simplicity, and his inexperience in running smuggled goods, that he should drive a very profitable adventure with him. He ordered him to bring the goods privately to the back way that led to his premises; and Paddy, who had the fear of the guager vividly before him, lost no time in obeying the mandate. But when Mr Pigtail examined the several packages, he turns round upon poor Paddy with a look of disapprobation, and exclaims, “This article will not suit, good man—entirely damaged by sea water—never do.”

“See wather, anagh!” returns Paddy Corbett; “bad luck to the dhrop o’ wather, salt or fresh, did my taste o’ tibaccy ever see. The Colleen Ayrigh that brought it could dip an’ skim along the waves like a sea-gull. There are two things she never yet let in, Mr Pigtail, avourneen—wather nor wather-guards: the one ships off her, all as one as a duck; and the Boochal Fadda on her deck keeps t’other a good mile off, more spunk to him.” This piece of nautical information Paddy had ventured from gleanings collected from the rich stores which the conversation of Shane Glas presented along the road, and in the smugglers’ cave.

“But, my good man, you cannot instruct me in the way of my business. Take it away—no man in the trade would venture an article like it. But I shall make a sacrifice, rather than let a poor ignorant man fall into the hands of the guager. I shall give you five pounds for the lot.”

Paddy Corbett, who had been buoyed up by the hope of making two hundred per cent. of his lading, now seeing all his gainful views vanish into thin air, was loud and impassioned in the expression of his disappointment. “O, Jillian Dawly!” he cried, swinging his body to and fro, “Jillian, a roon manima, what’ll ye say to yer man, afther throwing out of his hand the half year’s rint that he had to give the agint? O! what’ll ye say, aveen, but that I med a purty padder-napeka of myself, listening to Shane Glas, the yellow schamer; or what’ll Sheelabeg, the crathur, say, whin Tim Murphy won’t take her without the cows that I won’t have to give her? O, Misther Pigtail, avourneen, be marciful to an honest father’s son; don’t take me short, avourneen, an’ that God might take you short. Give me the tin pounds it cost me, an’ I’ll pray for yer sowl, both now an’ in the world to come. O! Jillian, Jillian, I’ll never face ye, nor Sheelabeg, nor any o’ the crathurs agin, without the tin pound, any how. I’ll take the vestmint, an’ all the books in Father Darby’s house of it.”

“Well, if you don’t give the tobacco to me for less than that, you can call on one Mr Prywell, at the other side of the bridge; he deals in such articles too. You see I cannot do more for you, but you may go farther and fare worse,” said the perfidious tobacconist, as he directed the unfortunate man to the residence of Mr Paul Prywell, the officer of excise.

With heavy heart, and anxious eye peering in every direction beneath his broad-leafed hat, Paddy Corbett proceeded till he reached a private residence having a green door and a brass knocker. He hesitated, seeing no shop nor appearance of business there; but on being assured that this was indeed the house of Mr Prywell, he approached, and gave the door three thundering knocks with the butt end of his holly-handled whip. The owner of the domicile, roused by this very unceremonious mode of announcement, came forth to demand the[Pg 288] intruder’s business, and to wonder that he would not prefer giving a single rap with the brass knocker, as was the wont of persons in his grade of society, instead of sledging away at the door like a “peep-o’-day boy.”

“Yer honour will excuse my bouldness,” said Paddy, taking off his hat, and scraping the mud before and behind him a full yard; “excuse my bouldness, for I never seed such curifixes on a dure afore, an’ I wouldn’t throuble yer honour’s house at all at all, only in regard of a taste of goods that I was tould would shoot yer honour. Ye can have it, a yinusal, for less than nothing, case I don’t find myself in heart to push on farther; for the baste is slow, the crathur, an’ myself that’s saying it, making buttons for fear o’ the guager.”

“Who, might I ask,” said the astonished officer of excise, “directed you here to sell smuggled tobacco?”

“A very honest gintleman, but a bad buyer, over the bridge, sir. He’d give but five pound for what cost myself tin—foreer dhota, that I had ever had a hand in it! I put the half year’s rint in it, yer honour; and my thirteen femul grawls an’ their mother, God help ’em, will be soon on the sachrawn. I’ll never go home without the tin pound, any how. High hanging to ye, Shane Glas, ye tallow-faced thief, that sint me smuggling. O! Jillian, ’tis sogering I’ll soon be, with a gun an my shoulder.”

“Shane Glas!” said the exciseman; “do you know Shane Glas; I’d give ten pounds to see the villain.”

“’Tis myself does, yer honour, an’ could put yer finger an him, if I had ye at Tubber-na-Treenoda, saving yer presence; but as I was setting away, he was lying undher an ould quilt, an’ I heard him telling that the priest said he had spotted faver enough for a thousand min.”

“That villain will never die of spotted fever, in my humble opinion,” said the exciseman.

“A good judgment in yer mouth, sir, achree. I heard the rogue himself say, ‘Bad cess to the thief! that a cup-tosser tould him he’d die of stoppage of breath.’ But won’t yer honour allow me to turn in the lafe o’ tibaccy?”

The officer of excise was struck with deep indignation at the villany of him who would ruin a comparatively innocent man when he failed in circumventing him, and was resolved to punish his treachery. “My good fellow,” said he, “you are now before the guager you dread so much, and I must do my duty, and seize upon the tobacco. However, it is but common justice to punish the false-hearted traitor that sent you hither. Go back quickly, and say that he can have the lot at his own terms; I shall follow close, and yield him the reward of his treachery. Act discreetly in this good work of biting the biter, and on the word of a gentleman I shall give you ten pounds more.”

Paddy was on his knees in a twinkling, his hands uplifted in the attitude of prayer, and his mouth opened, but totally unable between terror and delight to utter a syllable of thanks.

“Up, I say,” exclaimed the exciseman, “up and be doing; go earn your ten pounds, and have your sweet revenge on the thief that betrayed you.”

Paddy rapidly retraced his steps, ejaculating as he went along, “O, the noble gintleman, may the Lord make a bed in Heaven for his sowl in glory! O, that chating imposthor, ’twas sinding the fox to mind the hins sure enough. O, high hanging to him of a windy day!—the informer o’ the world, I’ll make him sup sorrow.”

“Have you seen the gentleman I directed you to?” said Mr Pigtail.

“Arrah, sir dear, whin I came to the bridge an looked about me, I thought that every roguish-looking fellow I met was the thief of a guager, an’ thin afther standing a while, quite amplushed, with the botheration and the dread upon me, I forgot yer friend’s name, an’ so kim back agin to ax it, if ye plase.”

“You had better take the five pounds than venture again; there’s a guager in town, and your situation is somewhat dangerous.”

“A guager in town!” cried Paddy Corbett, with well-affected surprise, “Isas Mauri! what’ll I do at all at all? now I’m a gone man all out. Take it for any thing ye like, sir dear, an’ if any throuble like this should ever come down an ye, it will be a comfort an’ a raycreation to yer heart to know that ye had a poor man’s blessing, avick deelish machree, an’ I give it to ye on the knees of my heart, as ye desarved it, an’ that it may go in yer road, an’ yer childre’s road, late an’ early, eating an’ dhrinking, lying an’ rising, buying an’ selling.”

Our story has approached its close: the tobacco was safely stowed inside, in order to be consigned to Mr Pigtail’s private receptacle for such contraband articles. Paddy had just pocketed his five pounds, and at that moment in burst Mr Prywell. The execration which ever after pursued the tobacconist for his treacherous conduct, and the heavy fine in which he was amerced, so wrought upon his health and circumstances, that in a short time he died in extreme poverty. His descendants became homeless wanderers, and it is upon record, among the brave and high-minded men of Duhallow, that Jeffrey Pigtail of Kanturk was the only betrayer that ever disgraced the barony.

E. W.

Speed on Railways.—In the first of a course of lectures on railways, delivered in the early part of last year at Manchester by Dr Lardner, he gave the following account of the speed attained by locomotive engines at different periods: “Since the great questions which had been agitated respecting the effect which an increased width of rails would have on railway transit, and the effect which very large drawing wheels, of great diameter, would have on certain railways, the question of very vastly increased speed had acquired considerable interest. Very recently two experiments had been made, attended with most surprising results. One was the case of the Monmouth express. A dispatch was carried from Twyford to London on the Great Western Railway, a distance of thirty miles, in thirty-five minutes. This distance was traversed very favourably, and being subject to less of those casual interruptions to which a longer trip would be liable, it was performed at the rate of six miles in seven minutes, or six-sevenths of a mile in one minute (very nearly fifty-one and a half miles an hour). He had experimented on speed very largely on most of the railways of the country, and he had never personally witnessed that speed. The evaporating power of those engines was enormous. Another performance, which he had ascertained since he arrived in this neighbourhood, showed that great as was the one just mentioned, they must not ascribe it to any peculiar circumstance attending the large engines and wide gauge of the Great Western Railway. An express was dispatched a short time since from Liverpool to Birmingham, and its speed was stated in the papers. One engine, with its tender, went from Liverpool, or rather from the top of the tunnel at Edge Hill, to Birmingham, in two hours and thirty-five minutes. But he had inquired into the circumstances of that trip, and it appeared that the time the engine was actually in motion, after deducting a variety of stoppages, was only one hour and fifty minutes in traversing ninety-seven miles. The feat on the Great Western was performed on a dead level, while on the Grand Junction the engine first encountered the Whiston incline, where the line rises 1 in 96 for a mile and a half; and after passing Crewe, it encountered a plane of three miles to the Madeley summit, rising 20 feet a mile, succeeded by another plane, for three miles more, rising 30 feet a mile; yet with all these impediments it performed the ninety-seven miles in one hour and fifty minutes, or 110 minutes; consequently the distance traversed in each minute was 97 divided by 110, or 52 ¹⁰⁄₁₁ths, nearly 53 miles an hour—a speed which, he confessed, if he had not evidence of it, he could scarcely have believed to be within the bounds of mechanical possibility. The engine which performed this feat had driving wheels of 5½ feet diameter; their circumference would be 17¼ feet. Taking the speed at 53 miles an hour, it was within a very minute fraction of 80 feet in a second of time. This was not the greatest speed of the engine, but the average speed spread over 97 miles and there could be little doubt that it must have exceeded sixty miles an hour during a considerable portion of the distance.”

That man should be happy, is so evidently the intention of the Creator, the contrivances to that end are so multitudinous and so striking, that the perception of the aim may be called universal. Whatever tends to make men happy, becomes a fulfilment of the will of God. Whatever tends to make them miserable, becomes opposition to his will.—Harriet Martineau.

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; Slocombe and Simms, Leeds; Fraser and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.